Verlet Integration in Molecular Dynamics: A Guide to Accurate Atomic Position Updates for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Verlet integration method for updating atomic positions in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, a cornerstone technique in computational drug discovery.

Verlet Integration in Molecular Dynamics: A Guide to Accurate Atomic Position Updates for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Verlet integration method for updating atomic positions in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, a cornerstone technique in computational drug discovery. Tailored for researchers and pharmaceutical development professionals, it covers the foundational mathematics of the algorithm, its key variants like Velocity Verlet and Leap-Frog, and their implementation in major MD software. The scope extends to practical troubleshooting of common artifacts, guidelines for parameter selection to ensure stability, and a critical validation against other integrators. Finally, the article highlights the method's crucial role in achieving reliable, atomic-scale insights for target validation, ligand binding, and formulation development.

The Core Physics and Mathematics of Verlet Integration

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the ability to accurately and efficiently compute the evolution of a system's atomic positions and velocities over time is foundational. This process, known as numerical integration, is performed by the simulation's integrator. The choice of integrator is critical, as it directly impacts the simulation's accuracy, stability, and ability to conserve energy—properties essential for producing physically meaningful results that can guide scientific discovery and drug development [1] [2]. Among the various algorithms available, the family of Verlet integrators has become the cornerstone of modern MD due to its favorable numerical properties [3].

The Mathematical Foundation of Verlet Integration

The core problem in MD is solving Newton's equations of motion for a system of N particles. For a particle i with mass m~i~, the equation is m~i~a~i~(t) = F~i~(r(t)), where the force F~i~ is derived from the potential energy function V of the entire system configuration r [3]. The Verlet algorithm integrates this second-order differential equation without explicitly requiring velocity for the core position update.

The most fundamental form, the Position Verlet or Størmer-Verlet algorithm, is derived by combining Taylor expansions for the positions at times t + Δt and t - Δt [3] [4] [5]. Adding these expansions cancels out the velocity terms, yielding the update formula: r(t + Δt) = 2r(t) - r(t - Δt) + a(t)Δt² + O(Δt⁴) where r is position and a is acceleration [3]. This formulation provides excellent numerical stability and time-reversibility, and because it is a symplectic integrator, it preserves the phase-space volume of Hamiltonian systems, leading to superior long-term energy conservation [3] [1].

A Comparative Analysis of Verlet Integration Variants

The basic Verlet algorithm has been adapted into several variants, each designed to address specific computational needs or limitations. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of the most widely used variants.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Verlet Integration Variants

| Variant | Core Integration Formulas | Key Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Position Verlet [6] | r(t + Δt) = 2r(t) - r(t - Δt) + a(t)Δt² | High stability; Time-reversible; Compact and efficient [6] | Spring, rope, and cloth simulations [6] |

| Velocity Verlet [5] | 1. v(t + Δt/2) = v(t) + (1/2)a(t)Δt 2. r(t + Δt) = r(t) + v(t + Δt/2)Δt 3. v(t + Δt) = v(t + Δt/2) + (1/2)a(t + Δt)Δt | Synchronous positions and velocities; Self-starting; Highly stable and energy-conserving [6] [5] [2] | Molecular dynamics; Systems with velocity-dependent forces (damping/friction) [6] |

| Leapfrog Verlet [5] | 1. v(t + Δt/2) = v(t - Δt/2) + a(t)Δt 2. r(t + Δt) = r(t) + v(t + Δt/2)Δ*t | High stability; Time-reversibility; Slightly simpler than Velocity Verlet [6] | Game physics; Particle systems [6] |

A critical difference between these algorithms lies in their handling of velocity. The basic Position Verlet does not store velocity, which must be inferred from positions if needed (e.g., for kinetic energy calculation) [7]. In contrast, the Velocity and Leapfrog variants explicitly calculate velocity, but are structured differently. The Velocity Verlet algorithm maintains synchrony between positions and velocities at the same time point, which is often more convenient for analysis [2]. The Leapfrog method is computationally efficient, but its velocities are staggered at half-step intervals relative to positions [5].

Implementation and Workflow in MD Simulations

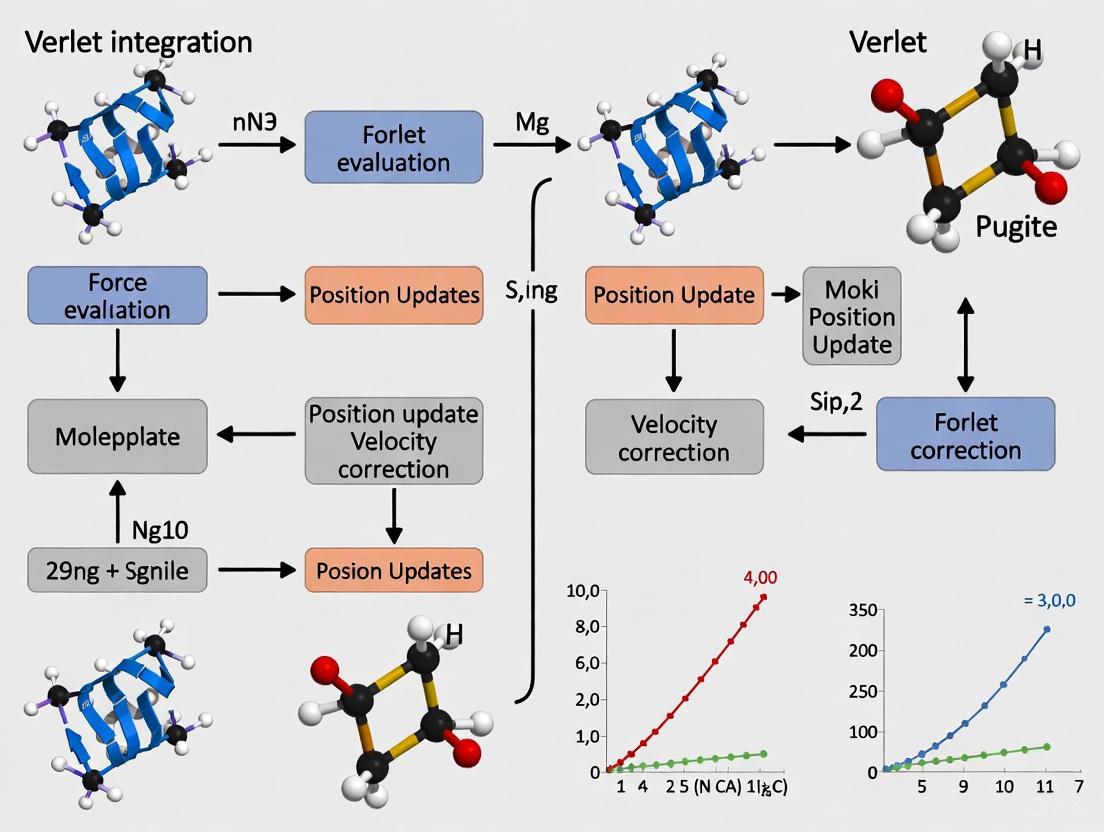

The integration algorithm is the core of a larger MD simulation workflow. The following diagram illustrates the standard procedure, with the Velocity Verlet integrator as a specific, widely-adopted example.

Diagram 1: MD Simulation Workflow with Velocity Verlet Integration

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Velocity Verlet Integration

The following protocol, corresponding to the workflow above, details the steps for implementing the Velocity Verlet algorithm in an MD simulation cycle [5] [2].

Initialization:

- Input Initial Conditions: Provide the initial positions r(t) and velocities v(t) for all atoms. Velocities are often drawn from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution corresponding to the desired simulation temperature [8].

- Compute Initial Forces: Calculate the initial forces F(t) acting on each atom from the negative gradient of the potential energy function: F(t) = -∇V(r(t)) [8]. The initial acceleration is a(t) = F(t)/m.

Integration Cycle (for each time step Δt):

- Half-Step Velocity Update: Update the velocities of all atoms for the first half of the time step using the current acceleration [5] [2]: v(t + Δt/2) = v(t) + 0.5 × a(t) × Δt

- Full-Step Position Update: Update the positions of all atoms to the next time step using the newly computed half-step velocities [5] [2]: r(t + Δt) = r(t) + v(t + Δt/2) × Δt

- Force Calculation at New Positions: Using the new positions r(t + Δt), compute the new potential energy and forces F(t + Δt). From these, calculate the new acceleration a(t + Δt) [8] [2].

- Final Half-Step Velocity Update: Complete the velocity update for the full time step using the new acceleration [5] [2]: v(t + Δt) = v(t + Δt/2) + 0.5 × a(t + Δt) × Δt

Analysis and Output: After the integration step, calculate and record observables such as total energy, temperature, and pressure [8].

Loop: Repeat the integration cycle for the required number of time steps.

Practical Considerations and Optimization in Research

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for an MD Simulation

Table 2: Key Components of a Molecular Dynamics Simulation

| Component | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Initial Coordinates | The starting atomic positions (e.g., from protein data bank files) for the system [8]. |

| Force Field | A set of empirical functions and parameters defining bonded and non-bonded interactions (potential V) [8]. |

| Integration Algorithm | The numerical solver (e.g., a Verlet variant) that propagates the system in time [2]. |

| Neighbor List | A list of atom pairs within a specified cut-off distance, used to compute non-bonded forces efficiently. This list is updated periodically [8]. |

| Thermodynamic Ensembles | Algorithms (e.g., thermostats, barostats) to maintain simulation conditions like constant temperature (NVT) or pressure (NPT). |

| Analysis Tools | Software for processing simulation trajectories to compute properties such as radial distribution functions, diffusion coefficients, and free energies. |

Critical Implementation Parameters

Successful simulation requires careful parameter selection. The time step (Δt) is particularly crucial; it must be small enough to capture the highest frequency motion in the system (e.g., bond vibrations involving hydrogen atoms), typically around 1-2 femtoseconds (fs) [6]. Using a time step that is too large leads to instability and energy drift [6]. For better performance, the neighbor list used for force calculations is constructed with a slightly larger cut-off (e.g., using a "Verlet buffer") than the interaction cut-off and is updated at a fixed frequency, a technique that avoids the computational cost of rebuilding the list every step while maintaining accuracy [8].

Verlet integration provides a class of robust, efficient, and symplectic algorithms that form the computational backbone of molecular dynamics. Its variants, particularly the Velocity Verlet and Leapfrog methods, offer a powerful and versatile approach for reliably updating atomic positions and velocities, enabling researchers to probe the structural and dynamical properties of biomolecular systems with high fidelity. This capability is indispensable for advancing research in areas such as drug discovery, where understanding atomic-level interactions over time is key to rational design.

Newton's Equations of Motion as the Foundation for MD

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a powerful computational technique for analyzing the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. This whitepaper examines the foundational role of Newton's equations of motion in MD, with specific emphasis on the Verlet family of integration algorithms. We explore how these numerical methods solve Newtonian mechanics to predict atomic trajectories, thereby enabling the study of complex biological and material systems. The technical discussion encompasses the mathematical foundations of integration algorithms, their implementation protocols, and quantitative performance comparisons, providing drug development researchers with essential insights for selecting appropriate computational methodologies for their simulation workflows.

Molecular dynamics is a computer simulation method for analyzing the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time [9]. In MD simulations, the trajectories of atoms and molecules are determined by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for a system of interacting particles, where forces between particles and their potential energies are calculated using interatomic potentials or molecular mechanical force fields [9]. The method finds extensive applications in chemical physics, materials science, and biophysics, particularly in drug development where it aids in understanding protein-ligand interactions, protein folding, and structure-based drug design [9].

At the heart of MD lies Newton's second law of motion, which for a system of N particles states that the force on each atom i is equal to its mass multiplied by its acceleration: Fᵢ = mᵢaᵢ [10]. The force Fᵢ can also be expressed as the negative gradient of the potential energy function V with respect to the atom's position: Fᵢ = -∂V/∂rᵢ [10]. This differential equation forms the mathematical foundation that MD simulations solve numerically to predict how atomic positions and velocities evolve over time.

The challenge in MD arises from the fact that molecular systems typically consist of a vast number of particles, making it impossible to determine properties analytically [9]. MD simulation circumvents this problem by using numerical integration methods, but these long simulations are mathematically ill-conditioned, generating cumulative errors in numerical integration that can be minimized with proper algorithm selection but not entirely eliminated [9]. This whitepaper explores how Verlet integration algorithms address these challenges while conserving essential physical properties of the system.

Numerical Integration in Molecular Dynamics

The Time Step Discretization Challenge

Molecular dynamics simulations solve Newton's equations of motion by taking a small step in time and using approximate numerical methods to predict new atom positions and velocities [2]. At these new positions, atomic forces are recalculated, and another time step is taken. This procedure repeats many thousands of times in a typical simulation [2]. The core challenge lies in selecting an appropriate time step (Δt) – the finite time interval between successive calculations. Since molecular motions occur on the scale of approximately 10⁻¹⁴ seconds, a typical MD time step is on the order of femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ s) [10]. This small value is necessary to accurately capture the fastest vibrations in the system, particularly bond stretching involving hydrogen atoms.

The numerical method used to advance the system by one time step is known as an integration algorithm. An ideal integration algorithm in MD must satisfy multiple criteria [2]:

- Accuracy: The algorithm should faithfully reproduce atomic motion

- Stability: It should conserve system energy and temperature

- Simplicity: Program implementation should be straightforward

- Speed: Calculations should execute efficiently

- Economy: Minimum computing resources, particularly memory, should be used

Most integration algorithms approximate the time evolution of atomic positions and velocities using Taylor series expansions, expressing future positions in terms of current and past values along with their derivatives [10].

The Verlet Integration Family

The most popular group of integration algorithms among MD programmers are the Verlet algorithms, which provide an optimal balance of the desirable properties [2]. The original Verlet algorithm, devised by L. Verlet in the early days of molecular simulation, uses a simple but robust approach that has since been superseded by its derivatives [2]. There are three primary forms of Verlet integration in common use today, all of equivalent accuracy and stability but differing in implementation details and utility.

Table 1: Comparison of Verlet Integration Algorithms

| Algorithm | Stored Variables | Velocity Calculation | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Verlet | rₙ, rₙ₋₁ | vₙ = (rₙ₊₁ - rₙ₋₁)/(2Δt) | Simple, economical | Velocities behind positions |

| Leapfrog | rₙ, vₙ₋₁/₂ | vₙ₊₁/₂ = vₙ₋₁/₂ + aₙΔt | Numerically stable | Positions and velocities out of sync |

| Velocity Verlet | rₙ, vₙ, aₙ | vₙ₊₁ = vₙ + ½(aₙ + aₙ₊₁)Δt | Synchronous position and velocity updates | Requires multiple force calculations per step |

The Verlet Integration Methodology

Mathematical Foundation

The Verlet algorithm and its variants derive from Taylor expansions of the position function. The position of an atom at time t+Δt can be expressed as:

r(t+Δt) = r(t) + v(t)Δt + ½a(t)Δt² + ⅙b(t)Δt³ + O(Δt⁴)

where v is velocity, a is acceleration, and b is the third derivative of position with respect to time [3]. Similarly, the position at time t-Δt is:

r(t-Δt) = r(t) - v(t)Δt + ½a(t)Δt² - ⅙b(t)Δt³ + O(Δt⁴)

Adding these two equations eliminates the odd-order terms, including the velocity term, yielding the fundamental Verlet algorithm:

r(t+Δt) = 2r(t) - r(t-Δt) + a(t)Δt² + O(Δt⁴)

This formulation provides excellent numerical stability with an error term of order Δt⁴ [3]. The acceleration a(t) is computed from the force acting on the atom at time t using Newton's second law: a(t) = F(t)/m, where F(t) is the force obtained from the potential energy function.

Velocity Verlet Integration Protocol

The velocity Verlet algorithm is currently the most widely used integration method in MD simulations due to its numerical stability and synchronous output of positions and velocities [10]. The algorithm proceeds in three distinct phases per time step:

Half-step velocity update: v(t+Δt/2) = v(t) + ½a(t)Δt

Full-step position update: r(t+Δt) = r(t) + v(t+Δt/2)Δt

Force calculation and completion of velocity update: a(t+Δt) = F(t+Δt)/m v(t+Δt) = v(t+Δt/2) + ½a(t+Δt)Δt

This formulation requires only one set of positions, velocities, and accelerations to be stored at any time, making it memory-efficient [2]. The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow of a molecular dynamics simulation using the velocity Verlet algorithm:

Figure 1: Molecular Dynamics Simulation Workflow Using Velocity Verlet Integration

Advanced Integration Considerations

Discretization Error and Time Reversibility

The local error in the Verlet algorithm is proportional to Δt⁴, making it more accurate than simpler integration methods like Euler integration [3]. This high accuracy stems from the time symmetry inherent in the method, which eliminates odd-degree terms in the Taylor expansion. A crucial property of the Verlet algorithm is its time reversibility – running the simulation backward in time should ideally retrace the forward trajectory. This mirrors the time-reversible nature of Newton's fundamental equations of motion.

The velocity Verlet algorithm preserves the symplectic form on phase space, meaning it conserves the geometric properties of Hamiltonian flow [3]. This symplectic property ensures that the numerically propagated system closely follows a Hamiltonian trajectory, leading to excellent long-term energy conservation without systematic drift. The algorithm achieves this at no significant additional computational cost over simpler methods like Euler integration [3].

Recent Algorithmic Improvements

Recent research has addressed specialized challenges in Verlet integration. In discrete element method (DEM) simulations of granular flows, the standard velocity-Verlet algorithm can produce unphysical results for large particle size ratios (R > 3) due to a Δt/2 phase difference between position and velocity calculations [11]. An improved velocity-Verlet implementation synchronizes these calculations, eliminating spurious pendular motion of fine particles between larger particles [11].

Machine learning approaches are now being explored to extend integration time steps while preserving geometric structure. These methods learn structure-preserving maps equivalent to learning the mechanical action of the system, maintaining symplectic and time-reversible properties even with larger time steps [12]. This addresses the fundamental challenge in MD where the time scale gap between fast atomic vibrations and slow collective motions limits computational efficiency.

Table 2: Integration Algorithm Performance Characteristics

| Algorithm Property | Basic Verlet | Leapfrog | Velocity Verlet | Improved Velocity Verlet |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memory Requirements | Medium | Low | Medium | Medium |

| Time Reversibility | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Symplectic Property | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Velocity Accuracy | O(Δt²) | O(Δt²) | O(Δt²) | O(Δt²) |

| Position Accuracy | O(Δt⁴) | O(Δt⁴) | O(Δt⁴) | O(Δt⁴) |

| Error Accumulation | Low | Low | Low | Very Low |

| Implementation Complexity | Low | Medium | Medium | High |

Practical Implementation Protocols

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Protocol

Implementing a complete MD simulation requires careful execution of the following steps, which form the core methodology cited in research literature:

System Initialization

- Define the molecular system with initial atomic coordinates

- Assign initial velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution corresponding to the desired temperature

- Remove center-of-mass motion to prevent overall drift [8]

Force Field Selection

- Choose appropriate potential functions (e.g., EAM for metals, Tersoff for covalent materials) [13]

- Set parameters for bonded (bond stretching, angle bending) and non-bonded (van der Waals, electrostatic) interactions

Neighbor List Construction

- Implement the Verlet cut-off scheme with buffer regions for efficient non-bonded force calculations [8]

- Update neighbor lists periodically to track interacting atom pairs

Time Step Iteration Loop

- Compute forces based on current positions

- Integrate equations of motion using the velocity Verlet algorithm

- Apply temperature and pressure coupling if simulating NVT or NPT ensembles

- Enforce periodic boundary conditions

Data Collection and Analysis

- Record trajectories, energies, and other properties at specified intervals

- Analyze structural and dynamical properties from the simulation data

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential MD Components

Table 3: Essential Components for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Component | Function | Examples/Values |

|---|---|---|

| Integration Algorithm | Numerically solves equations of motion | Velocity Verlet, Leapfrog |

| Potential Functions | Describes interatomic interactions | EAM, Tersoff, Lennard-Jones |

| Simulation Software | Implements MD algorithms | LAMMPS, GROMACS |

| Periodic Boundary Conditions | Mimics bulk systems | Cubic, Triclinic boxes |

| Thermostats | Regulates temperature | Nose-Hoover, Langevin |

| Barostats | Regulates pressure | Parrinello-Rahman |

| Neighbor Lists | Efficient non-bonded force calculations | Verlet list with buffer |

| Time Step | Integration interval | 0.5-2 femtoseconds |

The relationship between different Verlet algorithm variants and their evolution can be visualized as follows:

Figure 2: Evolution of Verlet Integration Algorithms

Applications in Drug Development and Beyond

Molecular dynamics simulations employing Verlet integration have become indispensable tools in pharmaceutical research. In structure-based drug design, MD simulations help identify conserved binding regions and critical intermolecular contacts between drug candidates and their target proteins [9]. Researchers like Pinto et al. have implemented MD simulations of Bcl-xL complexes to calculate average positions of critical amino acids involved in ligand binding [9]. Similarly, Carlson et al. used MD simulations to identify compounds that complement a receptor while causing minimal disruption to the conformation and flexibility of the active site [9].

Beyond pharmaceutical applications, MD simulations with Verlet integration are crucial in materials science, including the study of ultrasonic welding processes. MD enables detailed visualization of material interactions and structural changes at atomic/molecular levels during ultrasonic welding, helping researchers predict how different process parameters affect weld quality and rapidly identify viable solutions [13]. This reduces experimental iterations and lowers R&D costs across multiple industries.

The Verlet integration method remains the foundation for these diverse applications due to its robust numerical properties and conservation of key physical invariants. As MD simulations continue to evolve, with recent advances incorporating machine learning to enable longer time steps while preserving geometric structure [12], the Verlet algorithm continues to adapt to new computational challenges while maintaining its fundamental connection to Newton's equations of motion.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the fundamental task is to solve Newton's equations of motion for a system of atoms to predict their trajectories over time. The core challenge lies in finding numerical methods that are both computationally efficient and physically accurate for integrating these equations. The Basic Verlet Algorithm stands as one of the most historically significant and fundamentally important integration schemes in the field, providing a position-based approach that uses current and past atomic positions to predict future configurations. [2] [3]

This algorithm solves Newton's second law, ( \mathbf{F}i = mi \mathbf{a}i ), where the force ( \mathbf{F}i ) on an atom ( i ) is determined from the negative gradient of the potential energy function ( V ), according to ( \mathbf{F}i = -\frac{\partial V}{\partial \mathbf{r}i} ). [8] By discretizing time into small steps ( \Delta t ), the Verlet algorithm advances the system state without requiring explicit velocity calculations in its primary integration step. [2] Its simplicity, numerical stability, and time-reversibility have made it and its derivatives the foundation for countless MD simulations, enabling the study of complex systems from proteins to materials. [3] [14]

Mathematical Derivation

The derivation of the Basic Verlet Algorithm begins with the Taylor series expansions for the position of a particle at times ( t + \Delta t ) and ( t - \Delta t ):

[ \begin{aligned} \mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) &= \mathbf{r}(t) + \mathbf{v}(t)\Delta t + \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2 + \frac{1}{6}\mathbf{b}(t)\Delta t^3 + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) \ \mathbf{r}(t - \Delta t) &= \mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{v}(t)\Delta t + \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2 - \frac{1}{6}\mathbf{b}(t)\Delta t^3 + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) \end{aligned} ]

Here, ( \mathbf{r} ) represents position, ( \mathbf{v} ) velocity, ( \mathbf{a} ) acceleration, and ( \mathbf{b} ) the third derivative of position with respect to time (jerk). [3]

Adding these two expansions causes the odd-order terms to cancel:

[ \mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) + \mathbf{r}(t - \Delta t) = 2\mathbf{r}(t) + \mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2 + \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) ]

Rearranging this equation yields the core position update formula of the Basic Verlet Algorithm:

[ \mathbf{r}{n+1} = 2\mathbf{r}n - \mathbf{r}{n-1} + \mathbf{a}n \Delta t^2 ]

where ( \mathbf{r}{n+1} \approx \mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) ), ( \mathbf{r}n \approx \mathbf{r}(t) ), ( \mathbf{r}{n-1} \approx \mathbf{r}(t - \Delta t) ), and ( \mathbf{a}n = \mathbf{F}_n / m ) is the acceleration at time step ( n ). [2] [3] The cancellation of the third-order error term makes the algorithm locally accurate to order ( \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^4) ), while globally it has an error of order ( \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2) ). [3] [15]

Although velocities do not explicitly appear in the position update, they can be computed retrospectively for analysis or for initializing simulations requiring initial velocities:

[ \mathbf{v}n = \frac{\mathbf{r}{n+1} - \mathbf{r}_{n-1}}{2\Delta t} ]

This velocity calculation is accurate to order ( \mathcal{O}(\Delta t^2) ). [2]

The Algorithm in Molecular Dynamics Workflow

The Basic Verlet Algorithm functions as the core integrator within a broader MD simulation workflow. The following diagram illustrates its role in this process.

Figure 1: Workflow of a Molecular Dynamics Simulation Using the Basic Verlet Algorithm. The core integration step is highlighted in blue, showing how positions are updated using current and previous positions along with current acceleration. [2] [8]

The algorithm requires storing positions from two previous time steps (( \mathbf{r}n ) and ( \mathbf{r}{n-1} )) and calculates velocities as a secondary quantity, which can lead to velocities being "one time step behind" the corresponding positions. [2] This workflow repeats for thousands to millions of time steps, with typical time steps (( \Delta t )) on the order of femtoseconds (1-2 fs for all-atom models, potentially 4 fs with hydrogen mass repartitioning). [14]

Key Properties and Comparison with Other Integrators

The Basic Verlet Algorithm possesses several mathematical and numerical properties that make it particularly suitable for MD simulations.

Fundamental Properties

- Time-Reversibility: The algorithm is symmetric in time. If the sign of ( \Delta t ) is reversed, the algorithm will trace back the trajectory, a property shared with the exact solution to Hamilton's equations. [14] [15]

- Symplectic Nature: As a symplectic integrator, it preserves a geometric structure in phase space (( d\mathbf{q} \wedge d\mathbf{p} )), which leads to excellent long-term energy conservation rather than systematic energy drift. [3] [15]

- Numerical Stability: The algorithm provides good numerical stability, though the maximum stable time step is limited by the highest frequency vibration in the system (e.g., bonds with hydrogen atoms, which have ~10 fs periods, limiting ( \Delta t ) to ~1-2 fs). [3] [14]

- Memory Efficiency: The core algorithm requires storing only atomic positions, not velocities, though in practice most implementations store velocities as well for analysis and thermostatting. [2]

Comparison with Verlet Variants and Other Integrators

The Basic Verlet Algorithm has several derivative algorithms that address its minor inconveniences while maintaining its core advantages. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these related integrators.

Table 1: Comparison of the Basic Verlet Algorithm with Common Numerical Integrators

| Algorithm | Position Update | Velocity Update | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Verlet [2] | ( \mathbf{r}{n+1} = 2\mathbf{r}n - \mathbf{r}{n-1} + \mathbf{a}n \Delta t^2 ) | ( \mathbf{v}n = \frac{\mathbf{r}{n+1} - \mathbf{r}_{n-1}}{2\Delta t} ) | Simple, memory efficient, time-reversible, symplectic | Velocities lag positions, requires position history |

| Leap-Frog Verlet [2] [14] | ( \mathbf{r}{n+1} = \mathbf{r}n + \mathbf{v}_{n+1/2} \Delta t ) | ( \mathbf{v}{n+1/2} = \mathbf{v}{n-1/2} + \mathbf{a}_n \Delta t ) | Explicit velocities, better energy conservation | Velocities and positions at different time points |

| Velocity Verlet [2] [14] | ( \mathbf{r}{n+1} = \mathbf{r}n + \mathbf{v}n \Delta t + \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{a}n \Delta t^2 ) | ( \mathbf{v}{n+1} = \mathbf{v}n + \frac{1}{2}(\mathbf{a}n + \mathbf{a}{n+1}) \Delta t ) | Positions and velocities synchronized at same time | Slightly more complex implementation |

| Euler Method [14] | ( \mathbf{r}{n+1} = \mathbf{r}n + \mathbf{v}_n \Delta t ) | ( \mathbf{v}{n+1} = \mathbf{v}n + \mathbf{a}_n \Delta t ) | Simplest to implement | Not energy conserving, not time-reversible |

While the Euler method is the simplest approach, it lacks the energy conservation and time-reversibility essential for accurate MD simulations. [14] The Velocity Verlet algorithm, which provides positions and velocities at the same instant and is considered "the most complete form of Verlet algorithm," has largely superseded the Basic Verlet algorithm in modern MD packages like LAMMPS and GROMACS. [2] [14]

Practical Implementation in Molecular Dynamics Research

Integration with Force Calculations and Neighbor Lists

In practical MD simulations, the Verlet algorithm is coupled with efficient methods for force computation. The most computationally intensive part of an MD simulation is typically the calculation of non-bonded forces, which scale as ( O(N^2) ) for a naive implementation. [16] This is optimized using Verlet neighbor lists, which track particles within a cutoff radius and are updated periodically rather than at every step. [8] Modern MD packages like GROMACS use a Verlet cut-off scheme with a buffered pair list, where the list cutoff is slightly larger than the interaction cutoff, ensuring that as particles move between list updates, forces between nearly all particles within the cutoff are calculated. [8]

Research Applications and Protocols

The Verlet algorithm and its derivatives serve as the fundamental engine for MD simulations across diverse scientific domains:

- Materials Science: Nano-indentation studies of chromium films using Embedded Atom Method (EAM) potentials for Cr-Cr interactions and Morse potentials for Cr-C interactions. [16]

- Drug Discovery: Simulation of biomolecular systems like proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids to understand binding events and conformational changes. [13]

- Complex Fluid Research: Investigation of self-diverting acidizing technology for coal seam seepage mechanics, studying viscoelastic surfactant aggregation under different acid concentrations. [17]

A typical MD protocol utilizing the Verlet integrator involves:

- System Preparation: Building the initial atomic coordinates, defining the simulation box, and assigning force field parameters.

- Energy Minimization: Relaxing the structure to remove bad contacts.

- Equilibration: Running MD in the NVT (constant Number, Volume, Temperature) and NPT (constant Number, Pressure, Temperature) ensembles to stabilize temperature and density.

- Production Run: Performing extended simulation with Verlet integration to collect trajectory data for analysis.

Table 2: Essential Components for MD Simulations Using Verlet Integration

| Component | Function | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | Describe potential energy as a function of nuclear coordinates | EAM for metals [13] [16], Tersoff for covalent materials [13], AMBER/CHARMM for biomolecules |

| Software Packages | Implement integration algorithms and force calculations | LAMMPS (versatile, large-scale systems) [13] [16], GROMACS (optimized for biomolecules) [13] [14] |

| Potential Functions | Mathematical forms for different interaction types | Bond stretching, angle bending, Lennard-Jones, Coulomb [13] [18] |

| Ensemble Thermostats | Maintain constant temperature | Berendsen, Nosé-Hoover, Langevin dynamics [14] |

| Constraint Algorithms | Freeze fastest vibrations to enable larger time steps | SHAKE, LINCS, SETTLE [14] |

Advanced Computational Techniques

For high-performance computing, modern MD implementations combine the Verlet algorithm with sophisticated parallelization strategies:

- Hybrid MPI-OpenMP: Uses Message Passing Interface (MPI) for communication between cluster nodes and OpenMP threads for parallelization within each node. [16]

- Multiple Time-Stepping (MTS): The r-RESPA algorithm computes different force components at different frequencies, with fast-varying bonded interactions evaluated every time step and slow-varying non-bonded interactions evaluated less frequently. [18]

- GPU Acceleration: Offloads force calculations to graphics processing units for significant speedup. [16]

The Basic Verlet Algorithm represents a cornerstone in the numerical foundation of molecular dynamics simulations. Its position-based approach, deriving from Taylor series expansions and leveraging cancellation of error terms, provides a robust method for integrating Newton's equations of motion. The algorithm's key properties—time-reversibility, symplectic nature, and numerical stability—make it particularly suitable for simulating conservative physical systems over long time scales.

While modern MD packages often implement more advanced variants like the Velocity Verlet or Leap-Frog algorithms that address the minor inconveniences of the original formulation, the fundamental position-update approach introduced by Verlet remains at the core of these methods. The continued evolution of this algorithm, including combinations with neighbor lists, multiple time-stepping, and machine-learning approaches for longer time steps [12], ensures that Verlet integration will remain essential for MD simulations as computational power increases and scientific questions grow more complex. For researchers in drug development and materials science, understanding this fundamental algorithm provides crucial insight into the capabilities and limitations of the simulation methods that drive modern molecular-level investigation.

Understanding the Velocity-Verlet Variant for Explicit Velocity Tracking

The Velocity Verlet algorithm stands as a cornerstone of modern molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, providing the numerical foundation for predicting atomic trajectories by solving Newton's equations of motion. This integration scheme is renowned for its superior numerical stability and excellent energy conservation properties compared to simpler methods like Euler integration. Its explicit tracking of atomic velocities makes it particularly valuable for researchers and drug development professionals who require accurate thermodynamic sampling and dynamic analysis of biomolecular systems, such as protein-ligand complexes. This technical guide details the algorithm's formulation, implementation, and practical application within the broader context of Verlet integration methods used in MD research.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulates the physical motions of atoms and molecules over time. The core computational challenge involves solving Newton's second law, ( \mathbf{F}i = mi \mathbf{a}_i ), for a system of N particles, where forces are derived from the potential energy function ( V ). As an exact analytical solution is infeasible for complex systems, numerical integration algorithms are employed to approximate the atomic positions and velocities at discrete time steps. The successive application of this procedure, sometimes for millions of steps, generates a trajectory that reveals the system's dynamic behavior.

The choice of integrator is critical, as it must balance several competing demands: accuracy, stability, computational efficiency, and the preservation of physical properties like energy conservation and time-reversibility. The family of Verlet integrators, including the Velocity Verlet algorithm, has become the de facto standard in the field because they successfully meet these requirements. These algorithms are symplectic, meaning they preserve the geometric structure of Hamiltonian flow, which is key to their long-term stability and near-conservation of energy.

The Mathematical Foundation of the Velocity Verlet Algorithm

The Velocity Verlet algorithm is designed to provide the positions and velocities of all particles at the same instant in time, a feature not inherent in the original Verlet formulation. It is mathematically equivalent to the original Verlet algorithm but offers greater convenience, particularly when initializing a simulation or when velocities are required for analysis.

The core mathematical equations that define the Velocity Verlet algorithm are as follows:

- Position Update: ( \mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t) + \mathbf{v}(t)\Delta t + \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2 )

- Velocity Half-Step Update: ( \mathbf{v}\left(t + \frac{\Delta t}{2}\right) = \mathbf{v}(t) + \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t )

- Force/Acceleration Update at New Position: ( \mathbf{a}(t + \Delta t) = \frac{\mathbf{F}(\mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t))}{m} )

- Velocity Full-Step Update: ( \mathbf{v}(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{v}\left(t + \frac{\Delta t}{2}\right) + \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{a}(t + \Delta t)\Delta t )

In practice, the half-step velocity is often handled implicitly, leading to a more compact three-step computation sequence. This formulation offers second-order accuracy in the time step ( \Delta t ) and is both time-reversible and symplectic.

Comparative Analysis of Integration Algorithms

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of the Velocity Verlet algorithm against other common numerical integrators.

Table 1: Comparison of Numerical Integration Algorithms in Molecular Dynamics

| Algorithm | Formulation | Accuracy Order | Stability & Conservation | Primary Advantages | Common Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euler Method | ( \mathbf{r}{n+1} = \mathbf{r}n + \mathbf{v}n \Delta t ) ( \mathbf{v}{n+1} = \mathbf{v}n + \mathbf{a}n \Delta t ) | First-Order | Low stability; not energy-conserving; not time-reversible [19] | Simplicity | Not recommended for production MD; used for Brownian dynamics [14] |

| Original Verlet | ( \mathbf{r}{n+1} = 2\mathbf{r}n - \mathbf{r}{n-1} + \mathbf{a}n \Delta t^2 ) | Second-Order [3] | High stability; energy-conserving; time-reversible [14] | Simplicity and robustness [2] | Historical and educational use |

| Leap-Frog Verlet | ( \mathbf{v}{n+1/2} = \mathbf{v}{n-1/2} + \mathbf{a}n \Delta t ) ( \mathbf{r}{n+1} = \mathbf{r}n + \mathbf{v}{n+1/2} \Delta t ) | Second-Order | High stability; energy-conserving; time-reversible [2] [14] | Computational economy [2] | Default in many MD packages (e.g., GROMACS md integrator) [14] [8] |

| Velocity Verlet | ( \mathbf{r}{n+1} = \mathbf{r}n + \mathbf{v}n \Delta t + \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{a}n \Delta t^2 ) ( \mathbf{v}{n+1} = \mathbf{v}n + \frac{1}{2}(\mathbf{a}n + \mathbf{a}{n+1}) \Delta t ) | Second-Order [2] | High stability; energy-conserving; time-reversible [14] [6] | Explicit velocities at integer time steps; simplicity and stability [2] [6] | Standard for most modern MD simulations; required for accurate velocity-dependent properties |

Practical Implementation and Workflow

The Velocity Verlet algorithm is typically implemented as a sequence of three distinct operations per time step, seamlessly integrating into the broader MD simulation cycle.

Figure 1: The three-step computational workflow of the Velocity Verlet algorithm within a single molecular dynamics time step.

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol

Initialization: The simulation begins with a set of initial atomic positions ( \mathbf{r}(t0) ) and velocities ( \mathbf{v}(t0) ). Velocities are often drawn from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution corresponding to the desired simulation temperature [8]. The initial forces ( \mathbf{F}(t0) ) and accelerations ( \mathbf{a}(t0) ) are computed from the potential energy function ( V ).

Position Update (Equation A): The atomic positions are advanced to ( t + \Delta t ) using the current positions, velocities, and accelerations. This step is computationally straightforward, involving only vector multiplications and additions.

Force/Acceleration Recalculation: This is the most computationally intensive step. After updating the positions, the forces ( \mathbf{F}(t + \Delta t) ) acting on each atom are recalculated based on the new configuration. This involves evaluating all bonded and non-bonded interactions (e.g., bonds, angles, dihedrals, van der Waals, and electrostatic forces). The new accelerations ( \mathbf{a}(t + \Delta t) ) are then derived from the new forces.

Velocity Update (Equation C): The velocities are updated using the average of the accelerations at the beginning and end of the time step. This symmetric treatment is key to the algorithm's time-reversibility and stability. After this step, the system is fully described at time ( t + \Delta t ), and the process repeats for the next step.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for MD with Velocity Verlet

Table 2: Key "Research Reagent Solutions" for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Item / Component | Function / Role in Simulation | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Integration Algorithm | Advances the system in time by updating atomic coordinates and velocities. | Velocity Verlet is the recommended choice for its stability and explicit velocity handling [14] [19]. |

| Force Field | A mathematical model describing the potential energy ( V ) of the system as a function of nuclear coordinates. | Defines bonded and non-bonded interactions; critical for accuracy (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS). |

| Simulation Software | The computational engine that implements the integration algorithm and force field. | Examples: GROMACS (md-vv), NAMD, AMBER. The choice affects setup and performance [14]. |

| Initial Coordinates | The starting 3D atomic structure of the system (e.g., protein, DNA, ligand). | Often obtained from experimental structures (Protein Data Bank) or modeled. |

| Constraint Algorithms (e.g., LINCS, SHAKE) | Used to freeze the fastest vibrational degrees of freedom (e.g., bonds with hydrogen). | Allows for a larger integration time step ( \Delta t ), improving computational efficiency [14]. |

| Thermostat / Barostat | Regulates temperature and pressure to mimic experimental conditions (NVT, NPT ensembles). | Couples the system to an external bath; essential for simulating realistic conditions. |

Advanced Considerations and Protocol for Time Step Selection

A critical parameter in any MD simulation is the integration time step ( \Delta t ). Its maximum stable value is fundamentally limited by the highest frequency vibration in the system, which is typically the stretching of bonds to hydrogen atoms (period ~10 fs). The Verlet family of algorithms is stable for ( \Delta t \leq \frac{1}{\pi f} ), where ( f ) is this highest frequency [14]. In practice, a time step of 1 femtosecond (fs) is often used as a safe starting point.

To enhance computational efficiency, the fastest vibrations can be constrained using algorithms like LINCS (in GROMACS) or SHAKE, which effectively remove them from the dynamics, allowing for a time step of 2 fs. Further increases to 4 fs are possible with techniques like hydrogen mass repartitioning, which artificially increases the mass of hydrogen atoms, thereby lowering the associated vibration frequency [14].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Basic Velocity Verlet Simulation in GROMACS

The following protocol outlines the key steps to set up and run a simulation using the Velocity Verlet integrator in the GROMACS software, a common tool in drug discovery research.

System Preparation: Obtain the initial structure (e.g., a protein-ligand complex). Use the

pdb2gmxtool to generate the topology, assigning parameters from a chosen force field. Solvate the system in a water box usinggmx solvateand add ions to neutralize the charge withgmx genion.Energy Minimization: Create a parameter file (

em.mdp) withintegrator = steepto perform energy minimization. This relieves any steric clashes and prepares the system for equilibration. Run usinggmx gromppandgmx mdrun.Equilibration (NVT and NPT Ensembles):

- NVT Equilibration: Create a parameter file (

nvt.mdp) specifyingintegrator = md-vvanddt = 0.001(for a 1 fs time step). Couple the system to a thermostat (e.g.,tcoupl = V-rescale) and run for a short duration (e.g., 100 ps) to stabilize the temperature. - NPT Equilibration: Create another parameter file (

npt.mdp), again withintegrator = md-vv. In addition to the thermostat, add a barostat (e.g.,pcoupl = Berendsen) to stabilize the pressure. Run for another 100-200 ps.

- NVT Equilibration: Create a parameter file (

Production Simulation: Finally, create the production run parameter file (

md.mdp). Setintegrator = md-vv,dt = 0.002(if using constraints), andnsteps = 500000for a 1 ns simulation. This step generates the trajectory used for analysis.Trajectory Analysis: Analyze the resulting trajectory using GROMACS tools to calculate properties such as Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF), and solvent accessible surface area (SASA) to understand system stability and dynamics [20].

The Velocity Verlet algorithm represents a mature, robust, and highly efficient solution for the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion in molecular dynamics. Its explicit velocity tracking, second-order accuracy, and excellent conservation properties make it the integrator of choice for a wide range of applications, from fundamental studies of protein folding to industrial drug design. By providing a stable and physically sound framework for propagating atomic trajectories, it enables researchers to extract meaningful dynamic and thermodynamic information from simulations, thereby bridging the gap between static structural data and biological function. As MD continues to evolve, with emerging trends including machine-learned integrators for longer time steps [12] and increasingly complex multi-scale simulations [21], the Velocity Verlet algorithm remains a foundational pillar of the field.

Time-Reversibility, Symplecticity, and Energy Conservation

Within the broader thesis on how Verlet integration updates atomic positions in Molecular Dynamics (MD) research, understanding its foundational numerical properties is paramount. The Verlet family of algorithms, which forms the computational backbone of MD simulations, predicts new atomic positions and velocities by taking small, discrete steps in time to numerically solve Newton's equations of motion [2]. The efficacy of this procedure, repeated many thousands of times in a typical simulation, hinges on the algorithm's ability to faithfully conserve the system's fundamental physical properties over long simulation periods [2]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the three core properties—time-reversibility, symplecticity, and energy conservation—that make Verlet integration the preferred choice for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. These properties ensure numerical stability and physical fidelity, enabling reliable simulation of biomolecular processes, which is critical for applications such as drug design.

Core Principles of Verlet Integration

The Verlet algorithm and its variants, including the leapfrog and velocity Verlet methods, are explicit numerical integration schemes used to update the system's configuration [2] [8]. The molecular dynamics method solves Newton's equations of motion for atoms by taking a small step in time and using approximate numerical methods to predict the new atom positions and velocities at the end of the step [2]. At the new positions, the atomic forces are re-calculated, and another step is made, a procedure repeated many thousands of times [2].

The velocity Verlet algorithm, widely used in modern software like GROMACS and ASE, is often regarded as the most complete form as it provides atomic positions and velocities at the same instant [2] [22]. It splits the update into three distinct steps. First, it calculates a half-step velocity using the force and velocity from time step n. Then, it updates the positions to time step n+1. Finally, using forces from the new positions, it updates the half-step velocity to the full-step velocity [2]. This formulation is convenient as it requires less computer memory because only one set of positions, forces, and velocities need to be carried at any one time [2].

Diagram 1: The workflow of the Velocity Verlet integration algorithm, demonstrating the sequential steps involved in updating the system state from time step n to n+1.

Key Mathematical Properties

Time-Reversibility

Time-reversibility is a fundamental property of Verlet integration algorithms where the numerical equations can be run forward in time and then backward to return to the initial state. This characteristic mirrors the time-reversible nature of Newton's fundamental equations of motion [23]. In practical terms, if one reverses the sign of the time step (Δt → -Δt) and the velocities, the system should theoretically retrace its trajectory back to its initial conditions.

This property emerges from the symmetric formulation of the Verlet algorithm. Research has shown that time-reversible integrators, particularly when combined with symplecticity, enable significantly more stable simulations with larger time steps compared to non-reversible alternatives [23]. The importance of time-reversibility is particularly evident in rigid molecule simulations, where specialized time-reversible integrators have been developed for microcanonical, canonical, and isothermal-isobaric ensembles, allowing for enhanced numerical stability [23].

Symplecticity

Symplecticity refers to the preservation of the geometric structure of Hamiltonian systems in phase space throughout the numerical integration process. Verlet algorithms belong to a class of geometric integrators that are symplectic, meaning they conserve the area in phase space [23]. This property is crucial for the long-term stability of molecular dynamics simulations as it ensures that the numerical solution respects the underlying Hamiltonian mechanics.

The significance of symplectic integrators lies in their excellent long-term behavior in terms of momenta and energy preservation [24]. This structure-preserving nature is a hallmark of symplectic and time-reversible integrators, providing numerical benefits including exact momenta preservation [24]. In the context of various statistical ensembles, integrators can be designed to be both time-reversible and symplectic for microcanonical ensembles, while for canonical and isothermal-isobaric ensembles, they are developed using approaches like the chain thermostat according to generalized Nosé-Hoover and Andersen methods [23].

Energy Conservation

Energy conservation in Verlet integration manifests as the bounded fluctuation of the total system energy around a stable mean value over long simulation timeframes. Unlike some higher-order integration methods that may show excellent short-term energy preservation but suffer from slow energy drift over longer timescales, symplectic algorithms like velocity Verlet provide very good long-term stability of the total energy even with quite large time steps [22].

In practice, the quality of energy conservation serves as a key diagnostic for verifying the appropriate choice of time step. A well-tuned simulation using a Verlet integrator should exhibit minimal drift in the conserved quantity, whether in NVE, NVT, or other ensembles [25]. For accurate results, the long-term drift in the conserved quantity should be less than 1 meV/atom/ps for publishable results, though drifts of up to 10 meV/atom/ps may be acceptable for qualitative simulations [25].

Interrelationship of Key Properties

The three properties of time-reversibility, symplecticity, and energy conservation are profoundly interconnected in Verlet integration schemes. The symplectic nature of the algorithm ensures the phase space volume is conserved, which directly contributes to long-term stability and prevents the systematic energy drift that can plague non-symplectic integrators [22] [24]. This symplectic property, when combined with time-reversibility, creates a robust numerical framework that mirrors the fundamental physics of conservative systems.

This relationship can be mathematically represented as follows. Time-reversibility ensures that the mapping from state (rn, vn) to (r{n+1}, v{n+1}) is invertible, while symplecticity guarantees the preservation of the differential form drn ∧ dvn = dr{n+1} ∧ dv{n+1} in phase space. Together, these properties enforce bounded energy oscillations rather than monotonic energy drift, creating a computational structure that reliably mimics the behavior of physical systems.

Diagram 2: The interrelationship between the three key properties of Verlet integration, demonstrating how symplecticity and time-reversibility collectively enable energy conservation and long-term stability.

Quantitative Comparison of Verlet Algorithm Variants

Table 1: Comparison of different Verlet integration algorithm variants and their numerical properties

| Algorithm Variant | Time-Reversible | Symplectic | Energy Conservation | Key Advantages | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Verlet | Yes | Yes | Excellent long-term | Simplicity and robustness | Stores three position sets; velocities lag positions [2] |

| Velocity Verlet | Yes | Yes | Excellent long-term | Positions and velocities synchronized; minimal memory usage [2] | Requires multiple force evaluations per step [26] |

| Leapfrog Verlet | Yes | Yes | Excellent long-term | Economical memory usage; simpler programming [2] | Velocities half-step out of phase with positions [2] |

| Langevin BAOAB | Yes | Yes (modified) | Good (with thermostat) | Efficient for NVT ensemble; allows larger timesteps [22] | Stochastic elements; not pure NVE [22] |

Experimental Protocols for Verification

Protocol for Testing Energy Conservation

The following methodology provides a systematic approach for verifying the energy conservation properties of a Verlet integration implementation:

System Setup: Initialize a system in the NVE (microcanonical) ensemble with known initial conditions, including positions, velocities, and forces [22]. For validation purposes, it can be beneficial to start with a simple harmonic oscillator system where analytical solutions are known [26].

Simulation Execution: Run the molecular dynamics simulation for a substantial number of time steps (typically thousands to millions depending on system size and required precision) while periodically recording the total energy, potential energy, and kinetic energy of the system [25].

Energy Drift Measurement: Calculate the drift in the total energy by monitoring the change in the conserved quantity over time. For publishable results, the long-term drift should be less than 1 meV/atom/ps, though drifts up to 10 meV/atom/ps may be acceptable for qualitative simulations [25].

Time-Reversibility Test: To verify time-reversibility, run the simulation forward for a set number of steps, record the final state, then reverse the direction of time (negating the time step and velocities) and run for the same number of steps. A time-reversible integrator should return the system to its initial state within numerical precision [23].

Protocol for Timestep Selection and Stability Analysis

Selecting an appropriate timestep is critical for balancing computational efficiency with numerical accuracy:

Nyquist Criterion Application: Determine the period of the fastest vibration in the system (e.g., ~11 fs for a C-H bond stretching at 3000 cm⁻¹). The timestep should be less than half this period, typically 5 fs or smaller for systems with light atoms [25].

Stability Threshold Testing: Sequentially increase the timestep while monitoring energy conservation. The maximum stable timestep is identified when energy fluctuations exceed acceptable thresholds (e.g., 1 part in 5000 of the total system energy per twenty timesteps) [25].

Advanced Techniques: For systems with high frequency vibrations, consider constraint algorithms like SHAKE or RATTLE to effectively remove the fastest vibrational modes, or mass repartitioning to allow larger timesteps while maintaining stability [24].

Table 2: Recommended timestep selection guidelines for different molecular systems

| System Type | Recommended Timestep (fs) | Stability Considerations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metallic Systems | 5 | Generally stable with 5 fs timestep [22] | Metal alloys, nanoparticles |

| Biomolecular (with constraints) | 2 | SHAKE constraints allow 2 fs timestep despite C-H bonds [25] | Protein folding, drug binding |

| Light Atom Systems (H, C) | 0.25-2 | Strong bonds and light masses require smaller steps [25] [22] | Hydrogen dynamics, organic molecules |

| Coarse-Grained | 10+ | Reduced stiffness enables larger timesteps | Large-scale biomolecular complexes |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential computational tools and their functions in Verlet-based molecular dynamics research

| Tool/Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Velocity Verlet Integrator | Core algorithm for numerical integration of equations of motion | ase.md.verlet.VelocityVerlet(atoms, timestep) [22] |

| NVE Ensemble | Microcanonical ensemble for testing energy conservation | Newton's second law with no thermostating [22] |

| Langevin Thermostat | Stochastic temperature control for NVT ensemble | ase.md.langevin.Langevin(atoms, timestep, temperature_K, friction) [22] |

| Neighbor Lists | Efficient force calculation using Verlet cut-off scheme | GROMACS Verlet scheme with buffered pair lists [8] |

| Energy Drift Monitor | Quantitative assessment of conservation quality | Track total energy fluctuation < 1 meV/atom/ps for publication [25] |

| Structure Preserving Maps | Machine-learning enhanced integration for larger timesteps | Action-derived ML integrator preserving symplecticity [27] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The unique properties of Verlet integration have enabled its application across diverse domains of molecular simulation. In drug development, these algorithms facilitate the study of protein-ligand interactions, folding dynamics, and binding kinetics with the necessary numerical stability to capture rare events. The structure-preserving nature of Verlet algorithms makes them particularly suitable for long-timescale simulations where energy drift would otherwise corrupt results.

Recent research has focused on overcoming the timestep limitations imposed by the fastest vibrations in the system. Semi-analytical approaches leveraging exponential integrators have demonstrated the ability to increase timesteps by three orders of magnitude while maintaining the explicit, symplectic, and time-reversible nature of the integration scheme [24]. These methods efficiently approximate the exact integration of strong harmonic forces through matrix functions, offering significant speedups while preserving the essential numerical properties [24].

Machine learning approaches are also emerging that learn structure-preserving (symplectic and time-reversible) maps to generate long-time-step classical dynamics [27]. These action-derived ML integrators eliminate pathological behavior while serving as corrections to computationally cheaper direct predictors, potentially offering the best of both worlds: the physical fidelity of structure-preserving integration with significantly enhanced computational efficiency [27].

Diagram 3: Current research directions addressing the fundamental challenge of timestep limitations in molecular dynamics while preserving crucial numerical properties.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, accurately integrating Newton's equations of motion is essential for predicting how systems evolve at the atomic level. The core challenge involves numerically solving the equation ( mi \frac{d^2\mathbf{r}i}{dt^2} = \mathbf{F}i(\mathbf{r}) ) for each atom ( i ) in the system, where ( \mathbf{F}i = -\nabla V(\mathbf{r}) ) is the force derived from the potential energy function ( V ) [28] [3]. The Leap-Frog method has emerged as a mathematically equivalent yet computationally distinctive alternative to the foundational Verlet integration algorithm. Its design is particularly suited to the demands of modern MD research, including drug development, where long-term stability and energy conservation are critical for obtaining physically meaningful trajectories [29] [30]. By providing a stable and efficient mechanism for updating atomic positions and velocities, the Leap-Frog method enables researchers to simulate the dynamic behavior of biomolecules, such as protein-ligand interactions, with high fidelity.

The Mathematical Foundation of Verlet Integration

The family of Verlet integrators solves the equations of motion using a finite difference method, where time is discretized into small steps ( \Delta t ), typically on the order of femtoseconds ((10^{-15}) s) to accurately capture atomic vibrations [10]. The classic Störmer-Verlet algorithm calculates a new position using the current and previous positions, along with the current acceleration [3]:

[ \mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) = 2\mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(t - \Delta t) + \mathbf{a}(t) \Delta t^2 ]

This formulation is derived by adding the Taylor expansions for ( \mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) ) and ( \mathbf{r}(t - \Delta t) ), which causes the first-order velocity terms to cancel out, resulting in a third-order local truncation error for the position [3] [31]. A key property of this algorithm is its time-reversibility; integrating forward ( n ) steps and then backward ( n ) steps returns the system to its initial state [32]. Furthermore, it is a symplectic integrator, meaning it conserves a Hamiltonian that is slightly perturbed from the original, leading to excellent long-term energy conservation—a critical property for MD simulations [32].

However, a significant limitation is that velocities are not explicitly computed, which are required for calculating kinetic energy and temperature. They must be approximated as ( \mathbf{v}(t) \approx \frac{\mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) - \mathbf{r}(t - \Delta t)}{2\Delta t} ), an operation prone to precision loss because it subtracts two similar numbers [3] [31] [10]. The algorithm is also not self-starting, as it requires knowledge of ( \mathbf{r}(t - \Delta t) ) at the initial step [10].

The Leap-Frog Integrator: A Mathematically Equivalent Formulation

The Leap-Frog algorithm addresses the velocity limitation of the basic Verlet method by staggering the updates of positions and velocities in time [5] [32]. It is mathematically equivalent to the original Verlet algorithm but offers improved numerical properties [33].

Core Algorithm and Workflow

In the Leap-Frog scheme, velocities are stored at half-integer time steps (e.g., ( t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t )) while positions remain at integer time steps (e.g., ( t )) [5] [32]. The algorithm proceeds with the following steps at each iteration:

- Compute forces and acceleration: Calculate the force ( \mathbf{F}i(t) ) on each atom from the potential ( V ), and thus the acceleration ( \mathbf{a}i(t) = \mathbf{F}i(t)/mi ) [28] [5].

- Update velocities: Advance the velocities by a full time step using the current acceleration: [ \mathbf{v}i\left(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t\right) = \mathbf{v}i\left(t - \frac{1}{2}\Delta t\right) + \mathbf{a}_i(t) \Delta t ]

- Update positions: Advance the positions to the next integer time step using the newly updated half-step velocities: [ \mathbf{r}i(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{r}i(t) + \mathbf{v}_i\left(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t\right) \Delta t ]

This sequence creates the characteristic "leapfrogging" pattern where velocities jump over positions, and then positions jump over velocities [32] [10]. The following diagram illustrates this staggered update cycle and its key outputs.

Equivalence to the Verlet Algorithm

The mathematical equivalence between the Leap-Frog and Verlet methods can be shown by derivation. Writing the Leap-Frog position update for the next step: [ \mathbf{r}(t + 2\Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) + \mathbf{v}(t + \frac{3}{2}\Delta t) \Delta t ] and substituting the Leap-Frog velocity update ( \mathbf{v}(t + \frac{3}{2}\Delta t) = \mathbf{v}(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) + \mathbf{a}(t + \Delta t) \Delta t ) yields: [ \mathbf{r}(t + 2\Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) + [\mathbf{v}(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) + \mathbf{a}(t + \Delta t) \Delta t] \Delta t ] From the previous position update, ( \mathbf{v}(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) = [\mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) - \mathbf{r}(t)] / \Delta t ). Substituting this in: [ \mathbf{r}(t + 2\Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) + \frac{\mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) - \mathbf{r}(t)}{\Delta t} \Delta t + \mathbf{a}(t + \Delta t) \Delta t^2 ] which simplifies to the Verlet formula: [ \mathbf{r}(t + 2\Delta t) = 2\mathbf{r}(t + \Delta t) - \mathbf{r}(t) + \mathbf{a}(t + \Delta t) \Delta t^2 ] This confirms their mathematical equivalence [32].

Comparative Analysis of MD Integration Algorithms

The Velocity Verlet Algorithm

A widely used alternative is the Velocity Verlet algorithm, which synchronously updates both positions and velocities at the same time points [5]. Its steps are:

- ( \mathbf{v}i(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) = \mathbf{v}i(t) + \frac{1}{2} \mathbf{a}_i(t) \Delta t )

- ( \mathbf{r}i(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{r}i(t) + \mathbf{v}_i(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) \Delta t )

- Compute forces ( \mathbf{F}i(t+\Delta t) ) and acceleration ( \mathbf{a}i(t+\Delta t) )

- ( \mathbf{v}i(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{v}i(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) + \frac{1}{2} \mathbf{a}_i(t+\Delta t) \Delta t )

This formulation is algebraically equivalent to both the standard Verlet and Leap-Frog methods but provides direct access to synchronized velocities [33] [5].

Quantitative Comparison of Integrator Properties

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of the main MD integration algorithms, highlighting the distinctive trade-offs.

Table 1: Comparison of Molecular Dynamics Integration Algorithms

| Property | Verlet (Original) | Leap-Frog | Velocity Verlet |

|---|---|---|---|

| Position Update | ( \mathbf{r}(t+\Delta t) = 2\mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(t-\Delta t) + \mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2 ) | ( \mathbf{r}(t+\Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t) + \mathbf{v}(t+\frac{1}{2}\Delta t)\Delta t ) | ( \mathbf{r}(t+\Delta t) = \mathbf{r}(t) + \mathbf{v}(t)\Delta t + \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t^2 ) |

| Velocity Update | Not explicit; approximated: ( \mathbf{v}(t) \approx \frac{\mathbf{r}(t+\Delta t) - \mathbf{r}(t-\Delta t)}{2\Delta t} ) | ( \mathbf{v}(t+\frac{1}{2}\Delta t) = \mathbf{v}(t-\frac{1}{2}\Delta t) + \mathbf{a}(t)\Delta t ) | ( \mathbf{v}(t+\Delta t) = \mathbf{v}(t) + \frac{1}{2}[\mathbf{a}(t) + \mathbf{a}(t+\Delta t)]\Delta t ) |

| Velocity Synchronization | Not synchronized (requires approximation) | Half-step offset (asynchronous) | Synchronized (available at same time as positions) |

| Self-Starting | No (requires ( \mathbf{r}(t-\Delta t) )) | No (requires ( \mathbf{v}(t-\frac{1}{2}\Delta t) )) | Yes |

| Numerical Stability | High (symplectic, time-reversible) | Very High (symplectic, time-reversible) | High (symplectic, time-reversible) |

| Computational Cost | Low | Low | Low (similar to Leap-Frog) |

| Primary Advantage | Conceptual simplicity, low memory | Excellent energy conservation, stability | Synchronous velocities, self-starting |

Practical Implications for MD Simulations

The Leap-Frog method's stability and efficiency make it the default integrator in major MD software packages like GROMACS [28] [30]. Its requirement for initial half-step velocities ( \mathbf{v}(t_0 - \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) ) is handled in practice by generating initial atomic velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at the desired temperature and then applying a backward step [28] [30]. A critical operational consideration is that one cannot switch between the Velocity Verlet and Leap-Frog integrators mid-simulation because they store velocities at different time points (integer vs. half-integer steps), which would create inconsistencies in the trajectory [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for Leap-Frog MD

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Component | Function in MD Simulation | Implementation Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Potential Energy Function (Force Field) | Defines the potential ( V ) from which forces ( \mathbf{F}_i = -\nabla V ) are derived; governs all interatomic interactions. | Examples include AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS; choice determines accuracy and applicability to specific molecular systems. |

| Initial Atomic Coordinates | Provides the starting configuration ( \mathbf{r}(t_0) ) for the simulation. | Often obtained from experimental structures (e.g., Protein Data Bank) or through molecular modeling. |

| Initial Velocities | Provides the initial atomic velocities ( \mathbf{v}(t0) ); for Leap-Frog, the half-step initial velocity ( \mathbf{v}(t0 - \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) ) is needed. | Typically generated from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at the simulation temperature [28] [30]. |

| Neighbor List | A critical performance optimization that tracks which atom pairs are within interaction range, avoiding costly ( O(N^2) ) force calculations. | Updated periodically using a Verlet buffer scheme to maintain accuracy as atoms move [28] [30]. |

| Thermostat (Temperature Coupling) | Regulates the system temperature by scaling velocities or adding stochastic terms, mimicking a thermal bath. | Essential for NVT ensemble simulations; methods like Berendsen or Nosé-Hoover can be applied. |

| Periodic Boundary Conditions | Simulates a bulk environment by embedding the system in a repeating box; avoids surface artifacts. | Requires careful handling of long-range interactions, typically via Ewald summation or PME. |

Advanced Considerations and Protocol for the Leap-Frog Method

Energy Conservation and Time Step Selection

While the Leap-Frog algorithm is symplectic and thus exhibits excellent long-term energy conservation, the measured total energy may appear to fluctuate when kinetic energy is calculated using the half-step velocities ( \mathbf{v}(t+\frac{1}{2}\Delta t) ) and positions ( \mathbf{r}(t) ) [29]. These fluctuations primarily represent interpolation errors rather than true energy drift, and a more accurate assessment of energy conservation can be obtained through specialized procedures [29]. The choice of time step ( \Delta t ) is critical; it must be small enough to resolve the fastest molecular vibrations (e.g., bond stretching involving hydrogen atoms) while being large enough to make the simulation computationally feasible. Research suggests that standard step sizes used in practice may be more conservative than necessary for accurate sampling, potentially allowing for modest increases to improve efficiency [29].

Detailed Protocol for Implementing the Leap-Frog Integrator

The following workflow outlines the key steps for initializing and running an MD simulation using the Leap-Frog method, incorporating essential MD components.

Procedure Steps:

System Initialization:

- Load the molecular topology and force field parameters defining the potential energy function ( V ) [28].

- Provide initial atomic coordinates ( \mathbf{r}(t_0) ) [28] [30].

- Generate initial atomic velocities ( \mathbf{v}(t0) ) from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at the desired temperature ( T ) [28] [30]. For the Leap-Frog algorithm, calculate the required half-step initial velocity ( \mathbf{v}(t0 - \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) = \mathbf{v}(t0) - \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{a}(t0)\Delta t ), where ( \mathbf{a}(t_0) ) is derived from the initial forces.

Simulation Execution:

- Construct the initial neighbor list for non-bonded force calculations [28] [30].

- For each time step ( \Delta t ) (commonly 1-2 fs for atomistic models):

- Compute forces ( \mathbf{F}i(t) ) on all atoms from the potential ( V ) [28].

- Update all velocities: ( \mathbf{v}i(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) = \mathbf{v}i(t - \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) + \frac{\mathbf{F}i(t)}{mi} \Delta t ) [5] [32].

- Update all positions: ( \mathbf{r}i(t + \Delta t) = \mathbf{r}i(t) + \mathbf{v}i(t + \frac{1}{2}\Delta t) \Delta t ) [5] [32].

- If simulating in the NVT (canonical) ensemble, apply a thermostat algorithm to regulate the temperature [28].

- Apply periodic boundary conditions to particles that have moved outside the simulation box [28] [30].

- Periodically (e.g., every 10-20 steps), update the neighbor list to account for atomic motion [28] [30].

- Output positions, velocities, energies, and other observables at the desired frequency.

Post-processing and Analysis:

- Analyze the resulting trajectory to compute properties of interest, such as root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), radial distribution functions, or diffusion coefficients.

- Monitor the total energy and temperature for stability to ensure the simulation has produced physically valid results.

The Leap-Frog method stands as a pillar of modern molecular dynamics, providing a robust, efficient, and mathematically sound framework for integrating the equations of motion. Its equivalence to the Verlet algorithm, combined with its superior handling of velocities and exceptional stability, underpins its widespread adoption in production-level MD software. For researchers in drug development and computational biophysics, understanding the operational details of this integrator—from its initial half-step velocity requirement to its synchronous force calculation—is crucial for designing and executing reliable simulations. As MD continues to evolve, the Leap-Frog method remains a testament to the enduring value of symplectic, time-reversible integration schemes in advancing our understanding of atomic-scale dynamics.

Implementing Verlet Integration in Practice: From Code to Pharmaceutical Research

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a foundational tool in computational physics, chemistry, and materials science, enabling researchers to study the temporal evolution of molecular systems at atomic resolution. The core of any MD simulation lies in its integration algorithm, which numerically solves Newton's equations of motion to propagate the system through time. Among available algorithms, the Velocity-Verlet integrator has emerged as a predominant choice due to its favorable numerical stability, symplectic properties, and computational efficiency. This technical guide provides a comprehensive breakdown of the Velocity-Verlet algorithm, detailing its mathematical foundation, practical implementation through pseudocode, and essential considerations for its effective application within molecular dynamics research, particularly in pharmaceutical and materials science contexts.

Core Principles of the Velocity-Verlet Algorithm

The Velocity-Verlet algorithm belongs to a family of symplectic integrators that preserve the phase-space volume of Hamiltonian systems, leading to superior long-term energy conservation compared to non-symplectic methods. The algorithm derives from Taylor expansions of atomic position and velocity terms, offering second-order accuracy in time step while maintaining time-reversibility. In molecular dynamics simulations, the algorithm updates atomic positions and velocities through a carefully sequenced series of steps that interleave position updates, force evaluations, and velocity corrections.

The mathematical foundation begins with the standard formulation of Newton's equations of motion. For any atom i with mass mᵢ, the equation of motion is expressed as:

Fᵢ = mᵢaᵢ = -∇V(rᵢ) [34]

where Fᵢ represents the force vector acting on atom i, aᵢ its acceleration, rᵢ its position vector, and V the potential energy function describing interatomic interactions. The Velocity-Verlet algorithm discretizes this continuous differential equation into manageable time steps (Δt), enabling iterative numerical solution.

Algorithm Pseudocode and Step-by-Step Breakdown

The Velocity-Verlet algorithm can be decomposed into distinct computational phases that ensure numerical stability while minimizing rounding errors. The following pseudocode delineates the complete implementation workflow:

Table 1: Velocity-Verlet Algorithm Breakdown

| Step | Mathematical Operation | Physical Quantity Updated | Dependencies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initialization | Fᵢ = -∂V/∂rᵢ |

Initial forces | Positions, potential function |

| Step 1 | rᵢ(t+Δt) = rᵢ(t) + vᵢ(t)Δt + 0.5(Fᵢ(t)/mᵢ)Δt² |