Validating Molecular Dynamics Simulations with Experimental NMR Data: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations using experimental Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) data, a critical synergy for advancing structural biology and rational drug design.

Validating Molecular Dynamics Simulations with Experimental NMR Data: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations using experimental Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) data, a critical synergy for advancing structural biology and rational drug design. It covers the foundational principles linking NMR observables to structural dynamics, practical methodologies for calculating NMR parameters from MD trajectories, strategies for troubleshooting common force field and sampling limitations, and robust validation protocols comparing simulations with experimental results. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, the content highlights how integrating computational and experimental approaches yields atomically detailed, dynamically aware models of protein behavior, from structured proteins to challenging intrinsically disordered systems, ultimately enhancing the reliability of MD for understanding biological function and guiding therapeutic development.

The Dynamic Duo: Understanding the Synergy Between MD Simulations and NMR Spectroscopy

The Limitation of Static Snapshots in Understanding Function

Proteins and nucleic acids are inherently dynamic molecules whose functions—such as catalysis, ligand binding, and allosteric regulation—are intimately connected to their motions across multiple timescales. Traditional static structures, while foundational, obscure these conformational dynamics that are essential for biological activity. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful computational microscope, revealing the atomistic details of biomolecular motions that underlie function. However, the accuracy of these simulations must be rigorously validated against experimental data. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy provides a unique set of tools for quantifying biomolecular dynamics in solution, making it an indispensable benchmark for validating MD simulations. This synergy creates a powerful framework for moving beyond static structures to truly understand the dynamic nature of biological macromolecules.

Complementary Techniques: MD Simulations and NMR Spectroscopy

Molecular Dynamics Simulations as a "Virtual Molecular Microscope"

MD simulations employ computational methods to probe the dynamical properties of atomistic systems, providing insights into molecular behavior that complement traditional biophysical techniques. Beginning with early simulations in the 1970s, MD has evolved into a sophisticated tool that visualizes proteins in action, investigating the relationship between form and function. These simulations can reveal the "hidden" atomistic details of protein dynamics, including conformational changes that occur across temporal and spatial scales spanning several orders of magnitude. However, two fundamental factors limit MD's predictive capabilities: the sampling problem (lengthy simulations required to describe dynamical properties) and the accuracy problem (insufficient mathematical descriptions of physical and chemical forces governing dynamics).

NMR Spectroscopy as an Experimental Benchmark

NMR spectroscopy provides atomic-resolution information on biomolecular dynamics with sensitivity across picosecond to millisecond timescales for molecules in solution. Unlike crystallographic approaches, NMR captures proteins in their native-like solution environments and can probe various aspects of dynamics through different experimental measurements:

- Relaxation parameters (T₁, T₂, NOE) report on overall and internal motions

- Chemical shifts provide information on local electronic environments

- Residual dipolar couplings offer insights into bond vector orientations

- Hydrogen exchange rates reveal dynamics at longer timescales

This rich experimental data makes NMR uniquely suited for validating the conformational ensembles produced by MD simulations.

Methodologies for Validating MD Simulations with NMR Data

Direct Comparison of Relaxation Parameters

A robust approach for MD validation involves computing NMR relaxation parameters directly from simulation trajectories and comparing them with experimental measurements. The spectral density function J(ω), which describes how energy is distributed over different frequencies in the molecular motions, can be derived from both MD simulations and NMR experiments, enabling direct comparison.

Table 1: Key NMR Relaxation Parameters for MD Validation

| Parameter | Physical Significance | Timescale Sensitivity | MD Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal Relaxation (R₁) | Energy transfer between spin system and lattice | Ps-ns | Calculated from spectral density functions derived from MD trajectories |

| Transverse Relaxation (R₂) | Loss of coherence in xy-plane | Ps-ms | Derived from correlation functions of bond vectors in simulation |

| Nuclear Overhauser Effect (NOE) | Cross-relaxation between spins | Ps-ns | Computed from dipolar interactions along MD trajectory |

| Order Parameters (S²) | Amplitude of bond vector motion | Ps-ns | Plateau value of internal correlation function or equilibrium expression |

The computational workflow involves:

- Running MD simulations with appropriate force fields and water models

- Calculating bond vector correlation functions from the trajectory

- Deriving spectral density functions from these correlations

- Computing relaxation parameters using standard NMR equations

- Comparing calculated values with experimental NMR measurements

Model-Free Analysis

The Lipari-Szabo model-free approach parameterizes the correlation function of bond vectors in terms of amplitudes (order parameters, S²) and corresponding correlation times (τ). This analysis provides a simplified yet powerful description of dynamics that can be compared between simulation and experiment. For bond vectors undergoing complex motions, an extended two-exponential form is used: Ci(t) = S² + (1 - Sf²)e^(-t/τf) + (Sf² - S²)e^(-t/τs), where S² represents the tail value of the time correlation function and the f and s subscripts denote "fast" and "slow" motions respectively.

Domain-Elongation Strategy for Complex Biomolecules

For flexible multi-domain molecules where internal motions couple with overall tumbling, a domain-elongation NMR strategy combined with MD analysis provides a sophisticated validation approach. This method involves:

- Experimentally elongating one helical domain to dominate overall tumbling

- Using this elongated domain as a fixed reference frame in MD analysis

- Computing relaxation parameters relative to this reference frame

- Directly comparing MD-derived and experimental relaxation data

This approach has been successfully applied to RNA systems like HIV-1 TAR RNA, where internal and overall motions are naturally coupled.

Quantitative Validation: Benchmarking MD Force Fields and Packages

Rigorous validation studies have compared the performance of different MD simulation packages and force fields against NMR benchmarks. These studies reveal that while modern force fields have improved significantly, important differences remain in their ability to reproduce experimental dynamics.

Table 2: MD Force Field and Package Performance Against NMR Benchmarks

| Simulation Package | Force Field | Water Model | Agreement with NMR S² Parameters | Limitations and Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | AMBER ff99SB-ILDN | TIP4P-EW | Significantly improved agreement over earlier force fields | Better performance for native state dynamics than larger conformational changes |

| GROMACS | AMBER ff99SB-ILDN | Varies by study | Good overall agreement at room temperature | Subtle differences in conformational distributions compared to other packages |

| NAMD | CHARMM36 | Varies by study | Generally good agreement | Performance may vary more for larger amplitude motions |

| ilmm | Levitt et al. | Varies by study | Competitive agreement for well-folded domains | Less extensively validated across diverse protein systems |

A comprehensive study comparing four MD packages (AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD, and ilmm) with three different force fields found that while overall agreement with NMR data was good at room temperature, subtle differences emerged in underlying conformational distributions. The divergence between packages became more pronounced when simulating larger amplitude motions, such as thermal unfolding, with some packages failing to allow proper unfolding at high temperatures or providing results inconsistent with experimental observations.

Experimental Protocols for MD-NMR Integration

Protocol 1: Validating Force Fields with Backbone Dynamics

- Sample Preparation: Prepare uniformly ¹⁵N-labeled protein sample in appropriate buffer conditions

- NMR Data Collection: Acquire ¹⁵N relaxation data (T₁, T₂, NOE) at multiple field strengths

- MD Simulations: Perform triplicate simulations of 200+ nanoseconds each using best practices for the chosen package

- Order Parameter Calculation: Compute S² values from both NMR data (using model-free analysis) and MD trajectories (using correlation function analysis)

- Statistical Comparison: Quantitatively compare MD-derived and experimental order parameters using correlation analysis and root-mean-square deviations

Protocol 2: Chemical Shift Validation of Amorphous Forms

- MD Simulation: Run extended MD simulations of the target biomolecule or compound

- Conformational Sampling: Extract multiple snapshots from the trajectory representing conformational diversity

- Chemical Shift Prediction: Calculate chemical shifts using machine learning approaches or quantum mechanical calculations on sampled conformations

- Averaging: Compute ensemble-averaged chemical shifts that account for dynamic processes

- Experimental Comparison: Compare predicted chemical shifts with experimental NMR measurements, analyzing both shifts and line widths

Table 3: Key Research Resources for MD-NMR Integration Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Services | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD, ilmm | Perform molecular dynamics simulations using empirical force fields |

| Force Fields | AMBER ff99SB-ILDN, CHARMM36, Levitt et al. | Provide parameter sets describing atomic interactions and potentials |

| NMR Data Analysis | NMRPipe, UCSF Sparky, XEASY, CCPN | Process, analyze, and visualize multidimensional NMR spectra |

| Chemical Shift Prediction | ML-based approaches, DFT calculations | Predict NMR chemical shifts from molecular structures |

| Reference Datasets | 100-protein NMR spectra dataset, BMRB | Provide standardized benchmark data for method validation |

| Specialized NMR Experiments | CEST, CPMG relaxation dispersion | Characterize conformational exchange processes and "invisible" excited states |

Visualization of Methodologies

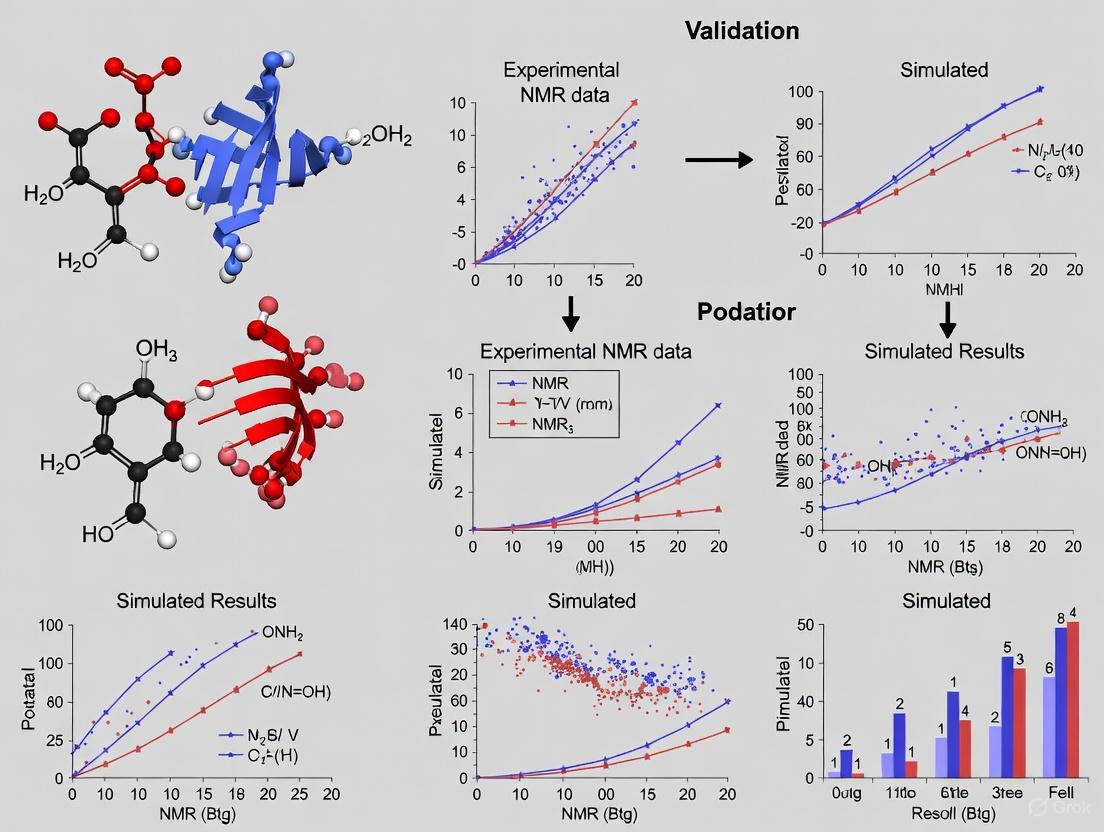

Diagram 1: MD-NMR Validation Workflow. This diagram illustrates the synergistic relationship between MD simulations and NMR experiments in validating biomolecular dynamics, leading to scientifically robust insights.

Diagram 2: Force Field Validation Protocol. This workflow outlines the key steps in validating molecular dynamics force fields against experimental NMR data, ensuring accurate representation of biomolecular dynamics.

Emerging Frontiers and Future Directions

The integration of artificial intelligence with both MD and NMR is revolutionizing biomolecular dynamics research. Deep learning approaches are dramatically improving the acquisition and analysis of NMR spectra, enhancing the accuracy and reliability of measurements, while also enabling the development of novel NMR experiments previously unattainable. Additionally, large-scale standardized datasets are emerging as critical resources for method development and validation. The 100-protein NMR spectra dataset, comprising 1329 2D-4D NMR spectra with associated reference data, provides an invaluable benchmark for developing and testing computational approaches. Similarly, multimodal datasets combining IR and NMR spectra for organic molecules are enabling new machine learning applications for spectral prediction and interpretation.

The essential synergy between MD simulations and NMR spectroscopy continues to advance our understanding of biomolecular dynamics, moving beyond static structures to reveal the dynamic nature of biological function. As both computational and experimental methodologies evolve, this integrated approach promises to further revolutionize structural biology, enhance our understanding of complex biomolecular systems, and accelerate drug discovery efforts.

NMR Spectroscopy as a Unique Probe of Protein Dynamics Across Multiple Timescales

Proteins are not static entities; their biological function is intimately linked to their ability to move and change conformation across a broad spectrum of timescales. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for elucidating mechanisms in catalysis, allosteric regulation, and molecular recognition—processes fundamental to drug design. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy stands as a unique experimental technique capable of probing these functionally relevant biomolecular dynamics at atomic resolution under near-physiological conditions [1]. Unlike methods that provide static structural snapshots, NMR characterizes the energy landscape by quantifying the kinetics, thermodynamics, and structural features of conformational substates [2]. This capability makes NMR data an indispensable benchmark for validating computational models, particularly Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. The synergy between NMR and MD is powerful: MD provides atomically detailed trajectories of motion, while NMR offers experimental data to test the accuracy of these simulations [3] [4] [5]. This guide objectively compares the performance of various NMR techniques and their role in validating computational models for studying protein dynamics.

NMR Techniques for Probing Dynamics Across Timescales

NMR relaxation experiments are designed to characterize different types of motion based on their characteristic timescales. The following table summarizes the primary NMR methods used to investigate protein dynamics across a range of time windows.

Table 1: NMR Methods for Probing Protein Dynamics Across Timescales

| Timescale | Dynamic Process | Primary NMR Methods | Measurable Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Picoseconds to Nanoseconds (ps-ns) | Bond vector fluctuations, local loop dynamics [4] | R₁, R₂ Relaxation, NOE [4] [5] |

Generalized Order Parameter (S²), correlation times [6] |

| Microseconds to Milliseconds (µs-ms) | Conformational exchange, folding/unfolding, ligand binding [2] [7] | Relaxation Dispersion (CPMG, R₁ρ) [2] [7] | Exchange rates (kₑₓ), populations, chemical shift differences [2] |

| Seconds (s) | Large-scale conformational changes | ZZ-exchange, Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (CEST) [1] | Exchange rates (kₑₓ), population distributions [1] |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting the appropriate NMR experiment based on the dynamic process and timescale of interest.

Fast Dynamics (ps-ns) and theS²Order Parameter

Motions on the picosecond to nanosecond timescale involve local fluctuations, such as bond vector librations and loop motions. NMR characterizes these via longitudinal (R₁), transverse (R₂), and heteronuclear Nuclear Overhauser Effect (NOE) relaxation measurements [4] [5]. The key parameter derived from these experiments is the generalized order parameter, S², which quantifies the spatial restriction of the motion, with 1 representing complete rigidity and 0 indicating isotropic disorder [6]. This S² parameter is a critical benchmark for validating MD simulations. Early work by Lipari, Szabo, and Levy demonstrated that while 96-ps MD simulations of basic pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (PTI) could capture the relative flexibility of different residues, the simulations systematically indicated less motion (higher S²) than was observed experimentally [6]. Modern studies continue to use these metrics to benchmark force fields, showing that IDP-tested force fields like Amber14SB/TIP4P-D can successfully reproduce experimental S² values for diverse intrinsically disordered proteins [4].

Conformational Exchange (µs-ms) via Relaxation Dispersion

Processes like enzyme catalysis and ligand binding often occur on the microsecond to millisecond timescale, involving the exchange between a dominant ground state and one or more "invisible" excited states. Relaxation dispersion (RD) experiments are uniquely powerful for characterizing these processes [2]. The two primary RD techniques are the Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) experiment, which uses a train of 180° pulses to refocus magnetization, and the R₁ρ experiment, which uses a continuous spin-lock field [7]. Analysis of the dispersion profile (the change in the effective transverse relaxation rate, R₂,eff, as a function of pulse repetition or spin-lock strength) allows researchers to extract the kinetic rate of exchange (k_ex), the population of the minor state, and the chemical shift difference (Δω) between states, which contains structural information about the excited state [2]. Recent methodological advances, such as ¹HN extreme CPMG (E-CPMG), have extended the detectable window of fast dynamics down to ~2.5-5.5 µs, revealing previously undetectable motions in proteins like ubiquitin [7]. However, it is important to note that while kinetics can be reliably measured, the structural features of the minor states fitted from RD data can have significant uncertainties and are highly sensitive to experimental noise [2].

Validating Molecular Dynamics Simulations with NMR Data

A Framework for MD Validation

Molecular Dynamics simulations provide atomically detailed models of protein motion, but these models require rigorous experimental validation to ensure their accuracy. NMR data serves as a gold standard for this purpose. The validation process involves running all-atom MD simulations using a specific force field and water model, calculating NMR parameters from the simulation trajectories, and then quantitatively comparing these computed parameters with experimental NMR data [3] [4]. This cycle can be repeated with different force fields to identify which combination most faithfully reproduus the experimental reality.

Comparative Performance of Force Fields and Water Models

The choice of force field and water model is critical for the accuracy of an MD simulation. Legacy force fields parameterized for folded proteins often cause intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) to adopt overly compact conformations or overly stable secondary structures [4]. The development of IDP-tested force fields has markedly improved the agreement with NMR data.

Table 2: Validation of MD Force Fields and Water Models with NMR Data

| Computational Model | Performance Against NMR Data | Key Experimental Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Legacy Force Fields (e.g., Amber99SB-ILDN/TIP3P) | Poor agreement for IDPs; induces collapse of disordered regions [4]. | S², R₂, Chemical Shifts, D_tr |

| IDP-Tested Force Fields (e.g., Amber14SB/TIP4P-D, Amberff03ws/TIP4P/2005) | Good agreement for both conformational and dynamic properties of IDPs and folded domains [4]. | S², R₂, Chemical Shifts, D_tr |

| Water Model: TIP4P-Ew | Produces overly compact conformational ensemble for H4 peptide [3]. | Translational Diffusion Coefficient (D_tr) |

| Water Models: TIP4P-D & OPC | Produces conformational ensembles consistent with experimental D_tr and ¹⁵N relaxation [3]. |

Translational Diffusion Coefficient (D_tr), ¹⁵N Relaxation |

A key study highlighting this validation process used the translational diffusion coefficient (D_tr), measurable by pulsed field gradient NMR, to test MD models of a disordered histone H4 fragment. The study found that simulations using the TIP4P-Ew water model produced an overly compact peptide ensemble, whereas TIP4P-D and OPC water models yielded D_tr values consistent with experiment [3]. Furthermore, the study cautioned against using empirical programs like HYDROPRO to predict D_tr for highly flexible IDPs, recommending first-principle calculations from MD trajectories as a more reliable benchmark [3].

Experimental Protocols for Key NMR Dynamics Experiments

Protocol:¹HNE-CPMG Relaxation Dispersion

The ¹HN E-CPMG experiment is a state-of-the-art method for characterizing fast µs-ms dynamics in the protein backbone [7].

- Sample Preparation: A 1 mM sample of perdeuterated, uniformly

¹⁵N-labeled human ubiquitin in 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.5), containing 5% D₂O, 0.05% NaN₃, and 50 µM DSS, transferred to a 3 mm NMR tube [7]. - Instrumentation: Experiments are performed on high-field spectrometers (e.g., 600-800 MHz) equipped with a cryogenically cooled probe and an Avance Neo console. The probe must be capable of delivering high-power

¹Hpulses (~30-40 kHz) [7]. - Data Collection: The constant-time

¹HNE-CPMG pulse sequence is used. A series of 2D spectra are acquired with a constant total relaxation period but varying the repetition rate (ν_CPMG) of the¹H180° pulse train. Theν_CPMGis typically varied from ~100 Hz to the hardware limit of ~30-40 kHz to build the dispersion profile [7]. - Data Analysis: The peak intensity in each 2D spectrum is extracted and fitted to an exponential decay to obtain the effective transverse relaxation rate,

R₂,eff, for eachν_CPMG. TheR₂,effvalues are then fitted for each residue to the Bloch-McConnell equations to extract the exchange parameters:k_ex, the population of the minor state (p_B), and the chemical shift difference (Δω) [2] [7].

Protocol: Measuring Translational Diffusion to Validate MD

Pulsed field gradient NMR can measure the translational diffusion coefficient (D_tr), which reports on the global hydrodynamic radius of a protein and is useful for validating the compactness of conformational ensembles from MD simulations [3].

- Sample Preparation: The protein or peptide of interest is prepared at a known concentration in the desired buffer.

- Data Collection: A pulsed field gradient spin-echo (PGSE) experiment is performed. The intensity of the NMR signal is measured as a function of systematically varied gradient strength. The signal decay is directly related to the diffusion coefficient [3].

- Data Analysis & MD Validation: The experimental

D_tris determined by fitting the signal decay. For MD validation, the simulation trajectory is used. The translational diffusion is calculated from the mean-square displacement of the peptide's center of mass over time using the Einstein relation. The simulated and experimentalD_trvalues are directly compared [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Protein Dynamics NMR

| Reagent / Material | Function and Importance in NMR Dynamics Studies |

|---|---|

Isotopically Labeled Proteins (¹⁵N, ¹³C, ²H) |

Enables detection of protein signals; deuteration improves resolution and allows study of larger proteins. Essential for all biomolecular NMR. |

| NMR Buffer Components (e.g., Phosphate, NaCl) | Maintains protein stability and physiological pH. Ionic strength can affect dynamics. |

| Internal Chemical Shift Reference (e.g., DSS) | Critical for accurate and reproducible chemical shift referencing, which is vital for dynamics analysis [8]. |

| Deuterated Solvent (e.g., D₂O) | Provides the lock signal for spectrometer field stability. |

| IDP-Tested Force Fields (e.g., Amber14SB/TIP4P-D) | Essential for running accurate MD simulations of disordered proteins that can be validated against NMR data [4]. |

Limitations and Complementary Approaches

While powerful, NMR has limitations. The structural information about "invisible" minor states from relaxation dispersion can be imprecise and sensitive to noise [2]. Other experimental techniques provide complementary data. Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) informs on the overall size and shape of proteins in solution [4], while Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) can measure distances between specific sites [4]. Computational metrics like the predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT) from AlphaFold2 are excellent for identifying ordered and disordered regions but fail to capture the gradations in dynamics observed by NMR in flexible regions [5]. Similarly, Normal Mode Analysis (NMA) provides low-cost flexibility estimates from a single structure but does not fully represent the nuanced dynamics seen in solution [5]. Therefore, a multi-technique approach that integrates NMR with other biophysical and computational methods yields the most comprehensive understanding of protein dynamics.

Mapping NMR Observables to Structural and Dynamic Properties

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy has emerged as a cornerstone technique in structural biology and drug discovery, providing unparalleled atomic-level insight into molecular structure, dynamics, and interactions. Unlike static techniques such as X-ray crystallography, NMR uniquely captures the dynamic behavior of biomolecules under near-native solution conditions, revealing conformational flexibility critical for understanding biological function [9] [10]. The intrinsic quantitative nature of NMR parameters—chemical shifts, J-coupling constants, and relaxation rates—makes them ideally suited for validating and refining computational models, particularly molecular dynamics (MD) simulations [11]. This synergy between experimental NMR observables and computational methods has created a powerful framework for mapping dynamic structural properties essential for modern drug development pipelines.

The integration of NMR with computational approaches addresses significant limitations in standalone methods. While X-ray crystallography provides high-resolution structural snapshots, it cannot capture the dynamic behavior of protein-ligand complexes or resolve hydrogen atom positions critical for understanding molecular interactions [12]. Similarly, MD simulations alone may produce models that drift from experimentally observable reality without validation constraints. This guide objectively compares the current methodologies for mapping NMR observables to structural and dynamic properties, providing researchers with a clear framework for selecting appropriate techniques based on their specific research requirements.

Fundamental NMR Parameters and Their Structural Significance

NMR spectroscopy measures several key parameters that serve as experimental proxies for structural and dynamic properties. The chemical shift (δ), expressed in parts per million (ppm), represents the resonant frequency of a nucleus relative to a standard reference compound. This parameter is exquisitely sensitive to the local electronic environment, influenced by factors including bond hybridization, electronegativity of neighboring atoms, and magnetic anisotropy effects [13]. For example, protons in alkyl groups typically resonate between 1-2 ppm, while aromatic protons appear further downfield (7-8 ppm) due to ring current effects [13].

Scalar coupling constants (J) provide direct information about molecular geometry through their dependence on dihedral angles. These through-bond interactions, typically measured in Hertz (Hz), connect nuclei separated by defined bond pathways and follow well-established mathematical relationships such as the Karplus equation [14]. Additional NMR parameters including nuclear Overhauser effects (NOEs), relaxation rates, and chemical exchange measurements provide distance constraints and information about molecular motions across various timescales [9]. Together, these observables form a comprehensive set of experimental constraints for structural modeling and dynamics validation.

Computational Methods for Interpreting NMR Data

Quantum Chemical Calculations

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has established itself as a pivotal tool in computational NMR, offering an optimal balance between computational cost and predictive accuracy for NMR parameters [9] [14]. DFT methods excel at predicting chemical shifts and coupling constants by accurately modeling electronic structures, enabling direct comparison between computational results and experimental spectra for structure verification [9]. These quantum chemical approaches provide first-principles interpretations of NMR observables, making them particularly valuable for characterizing novel compounds, elucidating reaction mechanisms, and studying diverse chemical systems from small organic molecules to complex biomolecular structures [9].

The theoretical completeness of NMR spectroscopy makes it uniquely suited for computational prediction compared to other analytical techniques. As noted in recent reviews, "The chemical shifts and J-couplings observed in NMR are directly linked to a molecule's electronic structure, making them highly amenable to accurate predictions using quantum chemical methods" [9]. This first-principles computability enables researchers to construct complete NMR spectra from computed parameters using density matrix formalism, capturing spin dynamics for various one-dimensional or multidimensional NMR experiments [9].

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Methods for NMR Parameter Prediction

| Method | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFT | Chemical shift prediction, J-coupling calculations, structural validation [9] [14] | Strong theoretical foundation, broadly applicable [9] | High computational cost for large systems [9] | Chemical shifts: ~0.1-0.3 ppm; J-couplings: ~1-2 Hz [14] |

| Machine Learning | Chemical shift prediction from structure, spectral analysis [9] [11] | Rapid prediction, handles large systems [9] [11] | Requires extensive training data [9] | Varies by model; comparable to DFT when well-trained [11] |

| Hybrid QM/MM | Protein-ligand interactions, large biomolecular systems [9] | Balances accuracy and computational efficiency [9] | Implementation complexity [9] | Dependent on QM method and MM boundary treatment [9] |

Machine Learning Approaches

Machine learning (ML) techniques represent a transformative advancement in computational NMR, leveraging extensive datasets and advanced algorithms to identify complex patterns in spectral data [9]. ML models efficiently automate spectral assignments, predict chemical shifts, and analyze complex NMR data with significantly reduced computational effort compared to quantum mechanical methods [9]. Deep learning approaches further enhance the nonlinear modeling between molecular structures and spectra, improving both speed and accuracy for various NMR prediction tasks [9].

Recent implementations such as ShiftML2 demonstrate the powerful synergy between ML and molecular dynamics simulations. This expanded model, trained on over 14,000 structures from the Cambridge Structural Database, predicts magnetic shieldings for multiple nuclei (H, C, N, O, S, F, P, Cl, Na, Ca, Mg, and K) with improved precision [11]. As demonstrated in studies of amorphous drug forms, "ML-based predictors of magnetic shieldings can handle arbitrarily large systems with very modest computational resources" [11], enabling researchers to connect features observed in NMR spectra to molecular behavior through dynamic structural ensembles.

Molecular Dynamics Integration

Molecular dynamics simulations provide the essential bridge between static structural models and experimentally observed NMR parameters by sampling molecular conformations over time. The integration of MD with NMR data addresses a fundamental challenge in structural biology: the inherent dynamic nature of biomolecules that cannot be captured by single-conformation models [11]. By averaging NMR parameters across MD trajectories, researchers can account for the dynamic behavior that influences experimental observables, particularly in flexible systems such as amorphous materials or intrinsically disordered proteins [11].

The critical importance of dynamics in interpreting NMR data was highlighted in recent work on amorphous irbesartan, where researchers observed that "the local environments are highly dynamic well below the glass transition, and averaging over the dynamics is essential to understanding the observed NMR shifts" [11]. This approach enables the rational interpretation of spectral features that cannot be understood through static models alone, such as the differing 13C shifts associated with tetrazole tautomers in irbesartan, which can be explained by "differing conformational dynamics associated with the presence of an intramolecular interaction in one tautomer" [11].

Diagram 1: Workflow for Validating MD Simulations with Experimental NMR Data. This framework integrates computational and experimental approaches to generate dynamic structural ensembles.

Experimental Benchmarking Data and Protocols

Standardized Datasets for Method Validation

The development of rigorously validated experimental NMR datasets has been crucial for benchmarking computational methods. A significant recent contribution includes over 1,000 accurately defined experimental long-range proton-carbon (nJCH) and proton-proton (nJHH) scalar coupling constants, accompanied by assigned 1H/13C chemical shifts and corresponding 3D structures for fourteen complex organic molecules [14]. This comprehensive dataset comprises 775 nJCH, 300 nJHH, 332 1H chemical shifts, and 336 13C chemical shifts, all validated against DFT-calculated values to identify potential misassignments [14]. For benchmarking purposes, researchers have identified a subset of 565 nJCH, 205 nJHH, 172 1H chemical shifts, and 202 13C chemical shifts from rigid molecular portions that are particularly valuable for evaluating computational prediction methods [14].

The value of such curated datasets extends throughout the analytical community, serving as essential resources for developing and testing empirical methods, machine learning approaches, and quantum mechanical calculations of NMR parameters [14]. These standardized collections enable objective comparison between different computational methodologies and provide reference points for assessing prediction accuracy across diverse chemical environments. As noted by the creators of one such dataset, "The value of experimental datasets to the analytical community is widespread: acting as sources of data for developing and testing empirical methods, such as variations of the well-known Karplus equation, and more recently machine-learning approaches for predicting these NMR parameters" [14].

Table 2: Experimental NMR Dataset for Benchmarking Computational Methods [14]

| Parameter Type | Complete Set | Breakdown | Benchmarking Subset | Breakdown |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1H Chemical Shifts | 332 | 280 sp3, 52 sp2 | 172 | 146 sp3, 46 sp2 |

| 13C Chemical Shifts | 336 | 218 sp3, 118 sp2 | 237 | 163 sp3, 74 sp2 |

| nJHH Coupling Constants | 300 | 63 2JHH, 200 3JHH, 28 4JHH, 9 5+JHH | 205 | 49 2JHH, 134 3JHH, 16 4JHH, 6 5+JHH |

| nJCH Coupling Constants | 775 | 241 2JCH, 481 3JCH, 79 4JCH, 4 5+JCH, 30 MCP | 570 | 187 2JCH, 337 3JCH, 70 4JCH, 3 5+JCH, 27 MCP |

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Measurement

Robust experimental protocols are essential for obtaining high-quality NMR parameters suitable for validating computational models. For scalar coupling constants, researchers have evaluated various pulse sequences and found that EXSIDE and IPAP-HSQMBC techniques can extract nJCH values with relatively high accuracy (<0.4 Hz average deviations), with IPAP-HSQMBC offering substantially better time-efficiency when measuring values for multiple protons in the same study [14]. These methods enable the comprehensive measurement of coupling constants that are critical for 3D structure determination but have traditionally been underrepresented in the literature due to measurement challenges [14].

For chemical shift assignment, researchers typically employ a combination of one-dimensional and multidimensional NMR experiments, including HSQC, HMBC, and TOCSY, to achieve complete signal assignment [15]. Multiplet simulation of 1H spectra and direct measurement from 13C{1H} spectra provide the foundation for chemical shift determination, with careful attention to experimental conditions including solvent, temperature, and referencing to ensure data consistency [14]. The integration of these experimental measurements with computational validation creates a robust framework for ensuring data quality, as "the assignments (including to diastereotopic nuclei) of these NMR parameters were verified by comparison with DFT-calculated values" [14].

NMR-Driven Structure-Based Drug Design

Advantages Over Traditional Methods

NMR spectroscopy provides unique capabilities for structure-based drug design that address significant limitations of alternative structural methods. While X-ray crystallography remains widely used, it faces challenges including low success rates for crystallization, difficulty establishing high-throughput soaking systems, inability to directly observe molecular interactions, and lack of dynamic information about protein-ligand complexes [12]. Furthermore, X-ray crystallography is "blind" to hydrogen information, cannot observe approximately 20% of protein-bound waters, and cannot elucidate the enthalpy-entropy compensation that fundamentally influences binding interactions [12].

In contrast, NMR captures dynamic protein-ligand interactions in solution under physiological conditions, providing direct observation of hydrogen bonding through 1H chemical shifts and enabling detection of transient states and conformational exchange processes [10] [12]. These capabilities make NMR particularly valuable for studying complex biological systems, including proteins with flexible regions, multi-domain proteins with flexible linkers, and intrinsically disordered proteins that resist crystallization [12]. The non-destructive nature of NMR further allows researchers to conduct repeated measurements under varying conditions and monitor binding events in real time [10].

Diagram 2: Structural Techniques Comparison for Drug Design. NMR provides unique capabilities for studying dynamic interactions in solution that complement other structural methods.

Practical Applications in Drug Discovery

The integration of NMR observables with computational methods has demonstrated significant practical impact across multiple stages of drug discovery. In fragment-based drug design, NMR provides direct access to atomistic information that helps identify non-covalent interactions in protein-ligand systems, favorably contributing to the enthalpic component of binding free energy [12]. The information encoded in the 1H chemical shift is especially valuable as it directly reports on hydrogen-bonding interactions, with downfield chemical shifts indicating classical hydrogen bond donors and upfield shifts corresponding to CH-π and Methyl-π interactions [12].

The combination of NMR with MD simulations has proven particularly powerful for characterizing challenging systems such as amorphous drug forms. In studies of amorphous irbesartan, researchers used MD simulations with ML-predicted chemical shifts to understand local environments, observing that "averaging over the dynamics is essential to understanding the observed NMR shifts" [11]. This approach enabled the rational interpretation of 1H shifts associated with hydrogen bonding in terms of "differing average frequencies of transient hydrogen bonding interactions" [11], demonstrating how integrating computational and experimental methods provides insights inaccessible to either approach alone.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NMR Studies of Molecular Structure and Dynamics

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-labeled Amino Acid Precursors | Selective isotopic labeling of proteins for NMR studies | NMR-driven structure-based drug design; signal assignment in large proteins [12] |

| Deuterated Solvents | Field-frequency lock for NMR spectrometers; reduction of strong solvent proton signals | Standard NMR sample preparation; exchangeable proton studies [13] |

| Reference Compounds | Chemical shift calibration | Tetramethylsilane (0 ppm) for 1H/13C NMR [13] |

| Internal Calibrants | Quantitative NMR concentration determination | Purity assessment of pharmaceuticals [15] |

| Shift Reagents | Induced chemical shift changes for chiral analysis | Stereochemistry determination of chiral compounds [10] |

| Cryogenically Cooled Probes | Enhanced NMR sensitivity | Detection of low-concentration samples; reduced experiment time [9] |

The integration of NMR observables with computational methods has created a powerful paradigm for mapping structural and dynamic properties of biomolecules essential for modern drug discovery. Quantum chemical calculations, particularly DFT, provide first-principles interpretations of NMR parameters, while machine learning approaches enable rapid prediction for large systems. Molecular dynamics simulations serve as the critical bridge between static models and experimental observables by sampling conformational ensembles over time. The continued development of standardized benchmarking datasets and robust experimental protocols ensures the objective evaluation of computational methods, driving advancements in prediction accuracy. As structural biology increasingly focuses on dynamic processes and complex systems, the synergy between NMR spectroscopy and computational modeling will remain indispensable for elucidating the relationship between molecular structure, dynamics, and function in drug design and development.

The Critical Need for Validation in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has established itself as an indispensable "virtual molecular microscope," providing atomistic insights into the dynamic behavior of proteins, nucleic acids, and other biological macromolecules that often remain hidden to traditional biophysical techniques [16]. The sophistication of force fields, algorithms, and computational hardware has continuously advanced, enabling simulations of increasingly complex systems at biologically relevant timescales [17]. However, this very power introduces a critical challenge: the inherent limitations in the degree to which molecular simulations accurately and quantitatively describe molecular motions. Without rigorous validation against experimental data, there remains considerable ambiguity about which simulation results are correct, as computational models may produce structurally plausible yet physically inaccurate trajectories [16].

This challenge is particularly acute in the context of force field selection and parameterization. While differences between simulation outcomes are often attributed to force fields themselves, multiple other factors significantly influence results, including the water model, algorithms that constrain motion, treatment of atomic interactions, and the simulation ensemble employed [16]. Even when different MD packages reproduce experimental observables equally well overall, subtle but functionally important differences in underlying conformational distributions and sampling extent can persist [16]. This review examines the critical synergy between MD simulations and experimental validation, with particular emphasis on nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy as a powerful validation tool that provides both structural and dynamic information across multiple temporal and spatial scales.

Comparative Performance of MD Simulation Packages

Quantitative Assessment of Sampling and Accuracy

Evaluations of different MD simulation packages reveal significant variations in their ability to reproduce experimental observables and sample conformational space. A systematic study comparing four popular MD packages (AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD, and ilmm) with three different protein force fields (AMBER ff99SB-ILDN, Levitt et al., and CHARMM36) demonstrated that while overall agreement with experimental data was similar at room temperature, substantial divergence occurred for larger amplitude motions and thermal unfolding processes [16].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of MD Simulation Packages

| MD Package | Force Field | Water Model | Room Temp Performance | High Temp Unfolding | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | ff99SB-ILDN | TIP4P-EW | Reproduces experimental observables | Allows unfolding at 498K | Sampling dependent on starting structure |

| GROMACS | ff99SB-ILDN | SPC/E | Good overall agreement | Some packages fail unfolding | Underlying conformational distributions vary |

| NAMD | CHARMM36 | TIP3P | Matches experimental data | Results at odds with experiment | Force field and parameter sensitivity |

| ilmm | Levitt et al. | TIP4P | Comparable to others | Variable success | Implementation-specific artifacts |

The differences between packages become particularly pronounced when simulating large-scale conformational changes such as thermal unfolding. Some packages fail to allow proteins to unfold at high temperature or produce results inconsistent with experimental observations [16]. This divergence underscores that force fields alone are not solely responsible for simulation accuracy—implementation details, integration algorithms, and treatment of non-bonded interactions significantly impact outcomes.

Water Model Effects on Simulation Accuracy

The choice of water model introduces another critical variable in MD validation. Studies on intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) reveal how different water models directly influence conformational sampling accuracy. For a 25-residue N-terminal fragment of histone H4, predictions of translational diffusion coefficients varied significantly across water models [3].

Table 2: Water Model Effects on IDP Simulations

| Water Model | Predicted Dₜᵣ | Conformational Ensemble | Consistency with NMR |

|---|---|---|---|

| TIP4P-Ew | Underestimated | Overly compact | Poor agreement |

| TIP4P-D | Accurate | Properly expanded | Good agreement |

| OPC | Accurate | Properly expanded | Good agreement |

| TIP3P | Variable | Depends on force field | Inconsistent |

These findings demonstrate that validation against diffusion measurements from pulsed field gradient NMR can identify systematic biases in MD models, particularly for flexible systems like IDPs where traditional structural validation may prove insufficient [3]. The viscosity of MD water models largely determines predicted diffusion coefficients, highlighting the importance of validating both structural and dynamic properties.

NMR Spectroscopy as a Validation Tool for MD Simulations

The Unique Advantages of NMR for MD Validation

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy provides a powerful suite of validation tools for MD simulations due to its ability to probe both structural features and dynamic processes across multiple timescales [17]. Unlike techniques that provide static structural snapshots, NMR observables are inherently ensemble-averaged and time-averaged, making them ideally suited for comparing with the conformational ensembles generated by MD simulations [17]. This averaging has profound implications for structural interpretation, particularly for mobile or disordered states where single-structure representations are inadequate.

The key advantage of NMR lies in the diversity of experimental observables it provides, each reporting on different aspects of molecular structure and dynamics:

- Distance information from nuclear Overhauser effects (NOEs) and paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) experiments

- Angular constraints from through-bond J-couplings related to dihedral angles via Karplus relationships

- Chemical shifts that are sensitive to local electronic environment and secondary structure

- Relaxation parameters that probe dynamics on picosecond-to-nanosecond timescales

- Translational diffusion coefficients from pulsed field gradient experiments that report on global molecular dimensions [17] [3]

This multifaceted nature of NMR data enables cross-validation of MD simulations against multiple independent experimental measures, providing a more comprehensive assessment of simulation accuracy than any single parameter could offer.

The ANSURR Method for Systematic Validation

The ANSURR (Accuracy of NMR Structures using Random Coil Index and Rigidity) method represents a significant advance in systematic validation of MD simulations against NMR data [18]. This approach compares local rigidity derived from backbone chemical shifts (using the Random Coil Index method) with rigidity predicted from atomic structures using mathematical rigidity theory (implemented in the FIRST software) [18].

Diagram 1: ANSURR Validation Workflow (65 characters)

The ANSURR method produces two complementary validation scores [18]:

- Correlation Score: Assesses whether rigid and flexible regions align between simulation and experiment, primarily validating secondary structure placement

- RMSD Score: Measures overall agreement in rigidity patterns, sensitive to hydrogen bonding networks and sidechain packing

This approach demonstrates that crystal structures tend to be too rigid in loop regions while NMR structures are typically too floppy overall, highlighting systematic biases in different structure determination methods that can be identified and corrected through MD validation [18].

Experimental Protocols for MD Validation

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Standards

Robust validation of MD simulations requires standardized protocols for system preparation, simulation parameters, and production runs. For protein simulations, best practices include [16]:

- System Setup: Begin with high-resolution crystal structures from the Protein Data Bank, remove crystallographic waters, and add explicit solvent molecules in a periodic box extending at least 10Å beyond protein atoms

- Force Field Selection: Choose modern, well-validated force fields (AMBER ff99SB-ILDN, CHARMM36, etc.) with compatible water models (TIP3P, TIP4P-EW, SPC/E)

- Equilibration Protocol: Implement multi-stage minimization with positional restraints on protein atoms, followed by gradual heating and equilibration in NVT and NPT ensembles

- Production Simulations: Run triplicate or multiple independent simulations (≥200 ns each) to improve conformational sampling, using periodic boundary conditions and appropriate temperature/pressure coupling

- Enhanced Sampling: For slow processes, employ replica-exchange or other advanced sampling techniques to overcome energy barriers

These standardized approaches facilitate meaningful comparisons between simulation results and experimental data, while also enabling reproducibility across research groups.

NMR Data Acquisition for Validation

For effective validation of MD simulations, NMR data should encompass multiple experimental observables to provide comprehensive structural and dynamic constraints [17] [19]:

- Chemical Shift Assignment: Obtain backbone (HN, N, Cα, Cβ, Hα, C') and sidechain chemical shifts through triple resonance experiments on isotopically labeled proteins

- NOE Distance Restraints: Collect NOESY spectra with appropriate mixing times to identify short-range (≤5Å) and medium-range (≤6Å) distance restraints, accounting for spin diffusion effects

- J-Coupling Constants: Measure three-bond J-couplings (³JHN-HA, ³JHN-CB, etc.) to derive dihedral angle constraints via Karplus relationships

- Relaxation Parameters: Determine T₁, T₂, and heteronuclear NOE values to characterize picosecond-to-nanosecond dynamics

- Diffusion Coefficients: Use pulsed field gradient experiments to measure translational diffusion coefficients reporting on global molecular dimensions [3]

The forward calculation of NMR observables from MD trajectories requires careful consideration of averaging effects and appropriate theoretical models to connect atomic coordinates with experimental measurements [17].

Integrative Approaches: Combining MD and NMR

Strategies for Integrating Simulations and Experiments

The integration of MD simulations with experimental data has evolved beyond simple validation to include sophisticated approaches that leverage the complementary strengths of both techniques [20]. These integration strategies exist along a spectrum of methodological complexity:

Table 3: Integrative Approaches for MD and Experimental Data

| Integration Strategy | Methodology | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Validation | Compare simulation results with independent experimental data | Assess force field accuracy; Transferable insights | Does not improve sampling of flawed simulations |

| Qualitative Restraints | Use experimental data to guide sampling without quantitative fitting | Simple implementation; Good for initial model building | Subjective; May bias results |

| Maximum Parsimony | Select subset of structures from ensemble that match experiments (sample-and-select) | Simple conceptually; Reduces ensemble complexity | May oversimplify; Depends on initial sampling |

| Maximum Entropy | Reweight ensemble to match experiments while minimizing bias | Maximizes agreement while preserving dynamics | Requires sufficient initial sampling; Convergence issues |

| Force Field Refinement | Optimize force field parameters to match experimental data | Transferable to new systems; Long-term benefit | Computationally intensive; Risk of overfitting |

These integrative methods are particularly valuable for studying RNA structural dynamics, where force fields are less mature and conformational heterogeneity is often functionally important [20]. Similar approaches have proven successful for membrane systems, where combining MD with NMR and X-ray scattering provides insights into bilayer structure and dynamics that neither approach could deliver alone [21].

Machine Learning-Enhanced Validation

Recent advances in machine learning have created new opportunities for enhancing MD validation against experimental data. For amorphous drug forms, ML-based predictors of magnetic shieldings (ShiftML2) enable efficient calculation of chemical shifts from MD snapshots, facilitating direct comparison with experimental NMR spectra [11]. This approach captures the dynamic nature of local environments, where averaging over molecular motions is essential for interpreting observed NMR shifts [11].

Large-scale datasets combining MD simulations with computed spectroscopic properties now provide benchmarks for validating computational methodologies. The IR-NMR multimodal computational spectra dataset offers anharmonic IR spectra derived from MD simulations with ML-accelerated dipole moment predictions alongside DFT-calculated NMR chemical shifts for over 177,000 molecules [22]. Such resources enable more rigorous validation of MD force fields and simulation protocols against experimental spectroscopic data.

Software and Computational Tools

Successful validation of MD simulations requires specialized software tools for simulation execution, analysis, and comparison with experimental data:

Table 4: Essential Software Tools for MD Validation

| Tool Name | Function | Application in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD simulation package | High-performance production simulations [16] |

| AMBER | MD simulation package | Specialized biomolecular simulations [16] |

| NAMD | MD simulation package | Scalable parallel simulations [16] |

| MDBenchmark | Performance benchmarking | Optimizing simulation parameters and resource allocation [23] |

| ANSURR | Structure validation | Comparing NMR-derived and predicted rigidity [18] |

| FIRST | Rigidity analysis | Predicting flexible and rigid regions from structures [18] |

| ShiftML2 | Chemical shift prediction | ML-based calculation of NMR chemical shifts [11] |

| HYDROPRO | Hydrodynamic properties | Calculating diffusion coefficients (limited for IDPs) [3] |

Force Fields and Water Models

The selection of appropriate force fields and water models represents a critical decision point in MD studies, with different combinations exhibiting distinct strengths and limitations:

- AMBER ff99SB-ILDN: Well-validated for proteins, particularly in combination with TIP4P-EW water model [16]

- CHARMM36: Provides accurate lipid membrane simulations and good protein performance [16]

- GAFF/GAFF2: General purpose force field for small molecules and drug-like compounds [11] [22]

- OPC and TIP4P-D: Advanced water models showing improved performance for IDPs and diffusion properties [3]

- TIP3P: Historically popular water model, but may produce overly compact conformations for flexible systems [3]

Validation of molecular dynamics simulations against experimental NMR data remains a critical endeavor for ensuring the reliability and predictive power of computational models. The synergistic combination of these techniques leverages the atomic-resolution detail of MD with the experimental constraints of NMR, leading to more accurate structural ensembles and deeper mechanistic insights. As force fields continue to improve and computational resources expand, rigorous validation will become even more essential—not less—as simulations tackle increasingly complex biological questions.

The development of systematic validation methods like ANSURR, standardized benchmarking tools like MDBenchmark, and large-scale multimodal datasets represents significant progress toward more objective and reproducible validation practices. For researchers in drug development and structural biology, embracing these validation approaches will enhance confidence in simulation results and enable more reliable predictions of molecular behavior under physiologically and therapeutically relevant conditions.

Diagram 2: MD Validation Cycle (52 characters)

The ongoing refinement of this validation cycle—where discrepancies between simulation and experiment drive improvements in force fields and methods—ensures that molecular dynamics will continue to grow as a robust tool for exploring biological phenomena at atomic resolution. For the scientific community, commitment to rigorous validation represents the foundation upon which trustworthy computational discoveries are built.

The integration of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy has transformed structural biology and drug discovery. This synergy provides a powerful framework for probing biomolecular structure, dynamics, and function. MD simulations model atomic movements over time, offering insights into conformational flexibility, while NMR spectroscopy experimentally measures atomic-level parameters sensitive to local environment and dynamics. This review traces the historical evolution of MD-NMR comparisons, detailing key methodological advancements, validation benchmarks, and emerging applications in pharmaceutical research. We objectively compare the performance of integrated MD-NMR approaches against alternative structural methods and provide supporting experimental data, emphasizing their critical role in validating molecular simulations.

Molecular dynamics (MD) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy have evolved from independent techniques to deeply integrated methodologies. MD simulations computationally model the time-dependent behavior of molecular systems, providing atomic-resolution insights into conformational changes, binding events, and thermodynamic properties. NMR spectroscopy experimentally measures parameters such as chemical shifts, relaxation rates, and scalar couplings that are exquisitely sensitive to local electronic environment, molecular conformation, and dynamics across multiple timescales [9] [1].

The inherent complementarity between these techniques lies in their shared capacity to probe biomolecular dynamics. While X-ray crystallography typically provides static structural snapshots, both MD and NMR capture the inherent flexibility of biological macromolecules. This convergence has made their integration particularly valuable for studying complex molecular processes, including protein folding, ligand binding, and allosteric regulation [12]. The evolution of this synergy represents a paradigm shift in computational biophysics, enabling researchers to move beyond static structures toward dynamic ensembles that more accurately represent molecular behavior in solution.

Historical Evolution of Methodological Approaches

Early Foundations: Basic Parameter Comparisons

The initial phase of MD-NMR integration focused on straightforward comparisons of simple parameters. Early studies typically involved:

- Direct chemical shift comparisons: Calculating isotropic shieldings from MD snapshots using quantum mechanical (QM) methods and comparing to experimental NMR chemical shifts [9]

- Relaxation parameter analysis: Using MD trajectories to predict NMR relaxation rates and comparing them to experimental values [24]

- Scalar coupling constants: Calculating J-couplings from MD structures and validating against experimental NMR measurements [14]

These early approaches established the fundamental validation paradigm but faced significant limitations in accuracy and applicability due to computational constraints and simplified physical models.

The Force Field Revolution: Improving Physical Realism

As MD force fields became more sophisticated, the accuracy of dynamics predictions improved substantially. Key advancements included:

- Specialized biomolecular force fields: Development of AMBER, CHARMM, and GROMOS parameter sets optimized for proteins and nucleic acids

- Explicit solvation models: Transition from implicit to explicit solvent representations for more realistic hydration dynamics

- Polarizable force fields: Incorporation of electronic polarization effects for improved treatment of electrostatic interactions

- Long-range electrostatics: Implementation of particle-mesh Ewald methods for accurate electrostatic calculations

These improvements enabled more meaningful comparisons with NMR data, particularly for dynamic processes and subtle conformational transitions.

The QM/MM Integration: Bridging Accuracy and Efficiency

The integration of quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) approaches represented a significant advancement by combining the accuracy of QM methods with the efficiency of classical force fields:

MD-NMR Integration Workflow

This hybrid approach allows accurate prediction of NMR parameters while maintaining computational feasibility for biological systems [9]. QM/MM methods enable precise calculation of chemical shifts and coupling constants for regions of interest while treating the remainder of the system with classical mechanics.

The Machine Learning Revolution: Accelerating Predictions

Recent advances incorporate machine learning (ML) to dramatically accelerate NMR parameter predictions from MD trajectories:

- ShiftML and ShiftML2: Neural network models trained on DFT-calculated shieldings predict chemical shifts for arbitrary molecular structures with minimal computational cost [11] [22]

- Deep Potential (DP) frameworks: ML potentials trained on QM data enable accurate MD simulations with QM-level accuracy [22]

- Ensemble learning approaches: ML models that capture the relationship between conformational ensembles and NMR observables

These approaches have reduced the computational cost of NMR parameter predictions by several orders of magnitude, making ensemble-based comparisons routine [11].

Quantitative Comparison of MD-NMR Integration Methods

Table 1: Evolution of Computational Methods for NMR Parameter Prediction

| Method | Computational Cost | Accuracy | System Size Limit | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemical (DFT) | Very High | High (Chemical shifts: ~0.1-0.3 ppm error) | Small molecules (<100 atoms) | Chemical shift benchmarking, conformational analysis [9] [14] |

| Classical MD + QM/MM | High | Medium-High (Chemical shifts: ~0.3-0.8 ppm error) | Medium systems (<1000 atoms) | Protein-ligand complexes, dynamic processes [9] |

| Classical MD + ML | Low | Medium (Chemical shifts: ~0.5-1.0 ppm error) | Large systems (>10,000 atoms) | Amorphous materials, biomolecular condensates [11] [22] |

| Ab Initio MD | Very High | Very High | Small systems (<100 atoms) | Solvent effects, chemical reactions [22] |

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Different NMR Parameters

| NMR Parameter | Most Accurate Method | Typical Agreement with Experiment | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13C Chemical Shifts | DFT (mPW1PW91/6-311g(dp)) | ~1-2 ppm for rigid molecules [14] | Sensitive to dynamics, solvation effects |

| 1H Chemical Shifts | DFT/ML hybrid approaches | ~0.1-0.3 ppm [11] | Highly sensitive to local environment |

| J-Coupling Constants | DFT (optimized functionals) | ~0.5-1 Hz for ³JHH [14] | Conformational dependence |

| 15N CSA | MD with site-specific values | ~5-10% error [24] | Requires high magnetic fields |

| Relaxation Rates (R₁, R₂) | MD with accurate CSA | ~5-10% for ps-ns dynamics [24] | Complex dynamics challenging |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Protocol for Amorphous Material Characterization

Recent research on amorphous pharmaceuticals demonstrates a sophisticated MD-NMR integration protocol:

Sample Preparation:

- Generate amorphous materials through quench cooling or milling

- Ensure sample homogeneity and stability during data acquisition

- Control humidity and temperature to maintain amorphous state [11]

MD Simulation Workflow:

- System setup: Build initial coordinates with random molecular orientations

- Energy minimization: Remove high-energy contacts using steepest descent algorithms

- Equilibration:

- NVT ensemble (constant particle count, volume, temperature): 500 ps at 300 K

- NPT ensemble (constant particle count, pressure, temperature): 10 ns at 300 K and 1 bar

- Production run: 200 ns in NPT ensemble with snapshots every 400 ps [11]

NMR Data Acquisition:

- Acquire ¹³C, ¹⁵N, and ¹H spectra under standard conditions

- Implement temperature control to match simulation conditions

- Use appropriate referencing standards (TMS for ¹H/¹³C, nitromethane for ¹⁵N)

Data Integration:

- Pass MD snapshots to ShiftML2 for chemical shift prediction

- Convert shieldings to chemical shifts using reference compounds

- Generate synthetic spectra by convolution with appropriate lineshape functions

- Compare predicted and experimental spectra iteratively [11]

Protocol for Protein Dynamics Studies

For studying protein dynamics, a specialized approach is required:

NMR Relaxation Measurements:

- Measure ¹⁵N R₁, R₂, and ¹H-¹⁵N NOE at multiple magnetic fields

- Implement CPMG relaxation dispersion for μs-ms dynamics

- Utilize CEST experiments for characterizing excited states [1]

MD Simulation Parameters:

- Implement explicit solvation with appropriate water models

- Use physiological ionic strength (150 mM NaCl)

- Run multi-copy simulations (3-5 replicas) of 1-2 μs each

- Employ enhanced sampling techniques for rare events [24]

Model-Free Analysis Integration:

- Calculate site-specific CSA values from MD trajectories

- Extract order parameters (S²) and correlation times

- Compare with model-free analysis of experimental relaxation data [24]

Table 3: Key Computational and Experimental Resources for MD-NMR Studies

| Resource | Type | Function | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| ShiftML2 | Software | ML-based chemical shift prediction from structures | Academic use [11] |

| GROMACS | Software | High-performance MD simulation package | Open source [11] |

| GAFF/GAFF2 | Force Field | General Amber Force Field for small molecules | Academic license [22] |

| CPMD | Software | DFT code for QM/MM calculations | Commercial/academic [22] |

| DeePMD-kit | Software | Deep learning MD potential framework | Open source [22] |

| PANACEA | NMR Method | Simultaneous acquisition of multiple NMR experiments | Specialist implementation [9] |

| IPAP-HSQMBC | NMR Method | Accurate measurement of heteronuclear couplings | Standard NMR suites [14] |

| USPTO-Spectra Dataset | Data Resource | Multimodal IR-NMR spectra for 177K molecules | Public (Zenodo) [22] |

| Validated NMR Dataset | Data Resource | Experimental J-couplings and chemical shifts | Public [14] |

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Structural Methods

Structural Biology Method Relationships

Table 4: Comparison of Integrated MD-NMR with Alternative Structural Methods

| Method | Strengths | Limitations | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD-NMR Integration | Captures dynamics at atomic resolution; Validates simulations experimentally; Solves solution-state structures | Limited to small-medium proteins; Computationally intensive; Requires specialist expertise | Dynamic processes; Amorphous materials; Protein-ligand interactions [11] [12] |

| X-ray Crystallography | High resolution; Large systems; Well-established workflows | Static picture; Crystallization required; May capture non-physiological states | Rigid structures; High-throughput screening [12] |

| Cryo-EM | Large complexes; No crystallization needed; Increasing resolution | Limited resolution for small proteins; Sample preparation challenges; Minimal dynamics information | Membrane proteins; Large macromolecular assemblies [12] |

| SAXS | Solution state; No size limit; Minimal sample requirements | Low resolution; Ensemble averaging; Limited structural details | Shape analysis; Large-scale conformational changes |

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

Pharmaceutical Applications

The MD-NMR synergy has enabled critical advances in drug discovery:

Amorphous Drug Development:

- Characterize local environments in amorphous pharmaceuticals

- Rationalize spectral differences between tautomers through differential dynamics

- Understand hydrogen bonding patterns and their dynamics [11]

Membrane Protein Drug Targeting:

- Study ligand binding to membrane-embedded targets

- Characterize allosteric mechanisms in GPCRs and ion channels

- Optimize drug candidates using dynamic structural information

Protein-Protein Interaction Inhibition:

- Identify cryptic binding pockets revealed by dynamics

- Design inhibitors that exploit dynamic allosteric networks

- Optimize binding kinetics through dynamic characterization

Technological Frontiers

Emerging methodologies are expanding the MD-NMR frontier:

Ultra-High Field NMR:

- Magnetic fields above 1 GHz enable study of larger systems

- Enhanced resolution and sensitivity for complex biomolecules

- Site-specific CSA measurements for improved dynamics analysis [24]

AI-Enhanced Structure Prediction:

- Integration of AlphaFold2 with MD-NMR validation

- ML-accelerated parameter prediction for high-throughput applications

- Generative models for designing molecules with specific dynamic properties

Multi-Modal Data Integration:

- Joint refinement against NMR, cryo-EM, and X-ray data

- Dynamic structural ensembles consistent with multiple experimental constraints

- Bayesian inference frameworks for uncertainty quantification

The evolution of MD-NMR comparisons represents a remarkable journey from simple validation exercises to deeply integrated methodological frameworks. This synergy has transformed our understanding of biomolecular dynamics, enabling researchers to move beyond static structural snapshots to dynamic ensembles that capture the intrinsic flexibility of biological macromolecules. The continued development of computational methods, experimental techniques, and integrative frameworks promises to further expand the applications of this powerful combination across structural biology, materials science, and drug discovery.

As the field advances, key challenges remain in improving force field accuracy, enhancing conformational sampling, and developing more sophisticated models for relating MD trajectories to NMR observables. However, the relentless pace of methodological innovation, particularly in machine learning and multi-modal integration, ensures that MD-NMR comparisons will continue to provide unique insights into molecular structure and dynamics across increasingly complex biological systems.

A Practical Guide: Calculating NMR Observables from MD Simulation Trajectories

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy provides unique, atomic-level insights into biomolecular structure, dynamics, and interactions under near-native conditions, making it an indispensable tool for validating Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations [9]. Unlike static structural techniques, NMR captures the conformational flexibility and dynamic behavior essential for biological function [9]. The integration of computational methods, particularly MD, with experimental NMR data has created a powerful synergistic framework for exploring biomolecular dynamics and assessing force-field quality [9] [25]. This guide compares the key experimental NMR parameters—spin relaxation, J-couplings, and Nuclear Overhauser Effects (NOEs)—used to validate and refine MD simulations, providing researchers with protocols, quantitative benchmarks, and practical tools to enhance the reliability of their computational models.

Core NMR Parameters for MD Validation

Spin Relaxation and Order Parameters (S²)

Experimental Principle: Spin relaxation measurements probe the reorientational motions of nuclear spin vectors, typically N-H bonds in proteins, on picosecond-to-nanosecond timescales. The generalized order parameter, S², quantifies the spatial restriction of these motions, with values ranging from 1 (completely restricted) to 0 (completely isotropic) [1] [25].

Connection to MD Validation: S² parameters calculated from MD trajectories are directly comparable to experimental values derived from NMR relaxation data (e.g., T₁, T₂, and heteronuclear NOEs). This comparison judges how well the force field reproduces the amplitude of fast, internal backbone dynamics [25].

Table 1: Key Considerations for Validating MD with S² Parameters

| Aspect | Experimental NMR Measurement | MD-Derived Calculation | Validation Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Timescale | Ps-ns motions | Ps-ns trajectories | Quality of fast dynamics reproduction |

| Key Parameter | Generalized order parameter S² | S² from bond vector autocorrelation function | Amplitude of internal motion |

| Sensitivity | High in flexible loops/regions | Highly dependent on starting structure and sampling [25] | Force-field accuracy in flexible areas |

| Critical Factor | Experimental accuracy | Adequate sampling (~100 ns) and short time-window analysis (~1 ns) [25] | Prevents fortuitous agreement |

Critical Protocol Note: A seminal study on hen egg white lysozyme demonstrated that MD-derived S² parameters can exhibit significant dependence on the starting structure, especially in flexible loop regions. Differences due to starting conformation can be larger than those attributed to different force fields. To obtain consistent and accurate results:

- Adequate sampling of at least 100 ns for flexible regions is necessary.

- S² parameters should be averaged over short time windows (e.g., 1-5 ns) rather than calculated over the entire trajectory [25].

Scalar J-Couplings

Experimental Principle: Scalar J-couplings (spin-spin couplings) are transmitted through chemical bonds and are exquisitely sensitive to dihedral angles, particularly the protein backbone phi angle and side-chain chi angles [9] [8].

Connection to MD Validation: J-couplings provide precise geometric restraints. Comparing experimental J-values to those back-calculated from an MD ensemble assesses the simulation's accuracy in reproducing local conformational preferences and torsional angles over time.

Table 2: J-Couplings as Validation Tools

| Aspect | Experimental NMR Measurement | MD-Derived Calculation | Validation Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Dihedral angles (e.g., φ, χ) | Dihedral angle distribution from trajectory | Local conformational accuracy |

| Key Parameter | Measured coupling constant (Hz) | J-value predicted from Karplus relationship using MD dihedrals | Fidelity of local bonding geometry |

| Common Types | 3J(HN-HA), 3J(Hα-C') | Same, calculated for simulation frames | Backbone φ angle fidelity |

| Strength | Direct structural restraint, angle-specific | Provides time-averaged view of geometry | Quantifies conformational equilibrium |

Nuclear Overhauser Effects (NOEs)

Experimental Principle: The NOE arises from dipole-dipole cross-relaxation between nuclear spins, and its intensity is proportional to the inverse sixth power of the distance between atoms (<1/r⁶). This makes it a powerful tool for measuring interatomic distances, typically up to ~5-6 Å [8] [1].