Validating Machine Learning Potentials Against Quantum Calculations: A Guide for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to validate Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) against high-fidelity quantum mechanics calculations.

Validating Machine Learning Potentials Against Quantum Calculations: A Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to validate Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) against high-fidelity quantum mechanics calculations. It explores the foundational synergy between machine learning and quantum chemistry, details cutting-edge methodological approaches for creating robust MLPs like graph neural networks, and addresses key challenges such as noise and scalability. A central focus is placed on rigorous validation and benchmarking protocols to ensure predictive accuracy for molecular properties, binding affinities, and reaction pathways, ultimately outlining a path toward accelerated and reliable drug discovery.

The Confluence of Machine Learning and Quantum Chemistry

Quantum chemistry aims to solve the Schrödinger equation to understand and predict the properties of molecules and materials from first principles. However, the computational resources required for accurate solutions scale exponentially with the number of interacting quantum particles (electrons) in the system [1]. This exponential scaling represents the core "quantum chemistry bottleneck," making precise calculations for anything beyond the smallest molecules prohibitively expensive, and in many cases, practically impossible with current computational technology. For decades, this bottleneck has constrained progress in fields ranging from drug discovery to materials science, where accurate molecular-level understanding is crucial.

The fundamental object of a many-body quantum system—the wave function—typically requires storage capacities exceeding all hard-disk space on Earth for systems of meaningful size [1]. This staggering requirement stems from the quantum nature of electrons, which exist in complex, entangled states that cannot be described by considering particles in isolation. As system size increases, the number of possible configurations grows exponentially, creating an insurmountable computational barrier for conventional simulation methods. This article explores the origins of this bottleneck, compares computational approaches, and examines how machine learning (ML) and quantum computing offer pathways to overcome these fundamental limitations.

The Roots of the Bottleneck: Mathematical and Computational Complexity

The Quantum Many-Body Problem

At the heart of quantum chemistry lies the quantum many-body problem—predicting the behavior of systems comprising many interacting quantum particles, such as electrons in molecules and materials [1]. The mathematical complexity arises because these systems are governed by the principles of quantum mechanics, where particles do not have definite positions but rather exist in probability distributions described by wave functions. When particles interact, their wave functions become entangled, meaning the state of one particle cannot be described independently of the others. This entanglement creates a computational challenge where the required resources grow exponentially with system size, as the number of possible configurations that must be considered becomes astronomically large.

The core mathematical challenge can be understood through the structure of the wave function. For a system with N quantum particles, the wave function typically requires storage capacity that scales as M^N, where M represents the number of possible states per particle [1]. For electrons in a molecule, this translates to an exponential scaling with the number of electrons, making exact solutions computationally intractable for all but the smallest systems. This "curse of dimensionality" means that doubling the system size increases the computational requirements by orders of magnitude, creating the fundamental bottleneck in quantum chemistry.

Approximation Methods and Their Limitations

Table: Computational Scaling of Quantum Chemistry Methods

| Method | Computational Scaling | Accuracy | Typical Application Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Force Fields | O(N) to O(N²) | Low | Millions of atoms (materials, proteins) |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | O(N³) to O(N⁴) | Medium | Hundreds to thousands of atoms |

| Hartree-Fock | O(N⁴) | Medium-low | Tens to hundreds of atoms |

| MP2 (Møller-Plesset) | O(N⁵) | Medium-high | Tens of atoms |

| Coupled Cluster (CCSD(T)) | O(N⁷) | High | Small molecules (≤10 heavy atoms) |

| Full Configuration Interaction | Exponential | Exact (in principle) | Very small molecules (≤5 heavy atoms) |

To manage this complexity, quantum chemists have developed a hierarchy of approximation methods, each with different trade-offs between computational cost and accuracy. Density Functional Theory (DFT) has emerged as the most widely used compromise, offering reasonable accuracy for many chemical systems with polynomial (typically O(N³) to O(N⁴)) scaling [2]. However, DFT has well-known limitations, particularly for systems with strong electron correlation, such as transition metal complexes and frustrated quantum magnets [1].

More accurate methods like Coupled Cluster with single, double, and perturbative triple excitations (CCSD(T)) provide higher accuracy but scale as O(N⁷), restricting their application to small molecules [3]. This severe scaling limitation means that even with modern supercomputers, high-accuracy calculations are restricted to systems with relatively few atoms, creating the central bottleneck that impedes progress in computational chemistry and materials discovery.

Benchmark Datasets for Machine Learning Potentials

Established Quantum Chemistry Datasets

The development of machine learning potentials requires large, high-quality datasets of quantum chemical calculations for training and validation. Several benchmark datasets have become standards in the field, each with specific characteristics and limitations.

Table: Prominent Quantum Chemistry Benchmark Datasets

| Dataset | Molecules | Heavy Atoms | Properties Calculated | Level of Theory | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QM7/QM7b | 7,165 | Up to 7 (C, N, O, S) | Atomization energies, electronic properties, excitation energies | PBE0, ZINDO, SCS, GW | Molecular energy prediction, multitask learning |

| QM9 | ~134,000 | Up to 9 (C, N, O, F) | Geometries, energies, harmonic frequencies, dipole moments, polarizabilities | B3LYP/6-31G(2df,p) | Property prediction, generative modeling, methodological development |

| QCML (2025) | Systematic coverage | Up to 8 | Energies, forces, multipole moments, Kohn-Sham matrices | DFT (33.5M) and semi-empirical (14.7B) | Foundation models, force field training, molecular dynamics |

The QM9 dataset has served as a foundational resource, featuring approximately 134,000 small organic molecules with up to nine heavy atoms (CONF) from the GDB-17 chemical universe [3]. For each molecule, QM9 provides optimized 3D geometries and 13 quantum-chemical properties—including atomization energies, electronic properties (HOMO, LUMO, energy gap), vibrational properties, dipole moments, and polarizabilities—calculated at the B3LYP/6-31G(2df,p) level of density functional theory [3]. This dataset has enabled the systematic evaluation of machine learning methods, particularly graph neural networks (GNNs) and message-passing neural networks (MPNNs), for property prediction.

The more recent QCML dataset (2025) represents a significant expansion in scope and scale, containing reference data from 33.5 million DFT and 14.7 billion semi-empirical calculations [2]. This dataset systematically covers chemical space with small molecules consisting of up to 8 heavy atoms and includes elements from a large fraction of the periodic table. Unlike earlier datasets that primarily focused on equilibrium structures, QCML includes both equilibrium and off-equilibrium 3D structures, enabling the training of machine-learned force fields for molecular dynamics simulations [2]. The hierarchical organization of QCML—with chemical graphs at the top, conformations in the middle, and calculation results at the bottom—provides a comprehensive foundation for training broadly applicable models across chemical space and different downstream tasks.

Experimental Protocols for ML Potential Validation

The validation of machine learning potentials against quantum mechanical calculations follows rigorous experimental protocols to ensure predictive accuracy and generalization. A standard workflow begins with data acquisition and preprocessing, where molecular structures are collected from diverse sources including PubChem, GDB databases, and systematically generated chemical graphs [2]. For each chemical graph, multiple 3D conformations are generated through conformer search and normal mode sampling at temperatures between 0 and 1000 K, ensuring coverage of both equilibrium and off-equilibrium structures.

The core of the protocol involves high-fidelity quantum chemical calculations using established methods. For the QM9 dataset, this involves geometry optimization followed by property calculation at the B3LYP/6-31G(2df,p) level of DFT [3]. More comprehensive datasets like QCML employ multi-level calculations, starting with semi-empirical methods for initial screening followed by DFT calculations for selected structures [2]. The calculated properties typically include energies, forces, multipole moments, and electronic properties such as Kohn-Sham matrices.

For model training and validation, the dataset is split into training, validation, and test sets using standardized splits (such as the five predefined splits in QM7) to enable fair comparison across different ML approaches [4]. Models are then evaluated based on their ability to reproduce quantum chemical properties, with key metrics including mean absolute error (MAE) relative to chemical accuracy (1 kcal/mol for energies), geometric and energetic similarity, and for generative tasks, metrics such as validity, uniqueness, and Fréchet distances [3]. The ultimate validation involves using ML potentials in molecular dynamics simulations and comparing the results against reference ab initio MD simulations or experimental data.

Machine Learning Solutions to the Quantum Bottleneck

Neural Network Potentials and Kernel Methods

Machine learning offers a promising path to bypass the quantum chemistry bottleneck by learning the relationship between molecular structure and chemical properties from reference data, enabling predictions with quantum-level accuracy at dramatically reduced computational cost. The key insight is that while the full quantum mechanical description of molecules is exponentially complex, the mapping from chemical structure to most chemically relevant properties appears to be efficiently learnable by modern machine learning models.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs) have demonstrated remarkable success in predicting molecular properties from structural information [3]. These architectures operate directly on molecular graphs, where atoms represent nodes and bonds represent edges, naturally encoding chemical structure. On the QM9 benchmark, GNNs and MPNNs have achieved accuracy surpassing older hand-crafted descriptors like Coulomb matrices or bag-of-bonds representations [3]. Advanced techniques such as weighted skip-connections have improved interpretability by allowing models to learn the importance of different representation layers, with atom-type embeddings dominating due to chemical composition's fundamental role in energy variation [3].

Kernel methods using compact many-body distribution functionals (MBDFs) and local descriptors (FCHL, SOAP) have shown exceptional performance in kernel ridge regression and Gaussian process frameworks for rapid property prediction [3]. These approaches benefit from their strong theoretical foundations and ability to provide uncertainty estimates, which are crucial for reliable deployment in chemical discovery pipelines. Recent work has also demonstrated that mutual information maximization, which incorporates variational information constraints on edge features, leads to significant improvements in regression accuracy and generalization by preserving relational chemical information [3].

Performance Comparison: ML Methods vs Traditional Quantum Chemistry

Table: Performance Comparison on QM9 Property Prediction (Mean Absolute Error)

| Method | Atomization Energy [meV] | HOMO Energy [meV] | Dipole Moment [Debye] | Computational Cost (Relative to DFT) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (B3LYP) | Reference | Reference | Reference | 1× |

| GNN (MPNN) | ~12 | ~38 | ~0.03 | ~0.0001× |

| Kernel Ridge | ~15 | ~45 | ~0.05 | ~0.001× |

| Classical Force Field | ~500 | N/A | ~0.3 | ~0.000001× |

Machine learning potentials can achieve accuracy comparable to medium-level quantum chemistry methods (such as DFT) while reducing computational costs by several orders of magnitude. On the QM9 benchmark, state-of-the-art GNNs achieve mean absolute errors of approximately 12 meV for atomization energies, approaching chemical accuracy (1 kcal/mol ≈ 43 meV) without explicit solution of the Schrödinger equation [3]. This performance is particularly impressive considering the massive speedup: where a DFT calculation for a medium-sized molecule might take hours on a computer cluster, the ML inference requires milliseconds on a GPU.

The minimum-step stochastic reconfiguration (minSR) technique, developed in the mlQuDyn project, represents a groundbreaking advancement in machine learning for quantum systems [1]. This approach compresses the information of the wave function into an artificial neural network, overcoming traditional limitations to offer more accurate and efficient simulations. The method has successfully tackled some of the most challenging quantum physics problems, including frustrated quantum magnets and the Kibble-Zurek mechanism, which were previously difficult to simulate due to their underlying complexity [1]. By enabling 2D representations of complex quantum many-body systems for the first time, this approach significantly advances the predictive power of quantum theory.

The Quantum Computing Pathway

Quantum Algorithms for Chemistry

Quantum computing offers a fundamentally different approach to overcoming the quantum chemistry bottleneck by using controlled quantum systems to simulate other quantum systems—an insight first articulated by Richard Feynman. For quantum chemistry, the most promising near-term application is the calculation of molecular energies and properties through algorithms such as Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) and Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE).

QPE is particularly powerful for simulating quantum materials but faces significant practical challenges on current hardware. It is computationally expensive due to high gate overhead, highly sensitive to noise, and difficult to scale within the constraints of Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices [5]. Recent work with Mitsubishi Chemical Group demonstrated a novel Quantum Phase Difference Estimation (QPDE) algorithm that reduced the number of CZ gates—a primary measure of circuit complexity—from 7,242 to just 794, representing a remarkable 90% reduction in gate overhead [5]. This improved efficiency led directly to a 5x increase in computational capacity over previous QPE methods, enabling wider and more complex quantum circuits and setting a new world record for the largest QPE demonstration [5].

Current Limitations and Hybrid Approaches

Despite promising advances, current quantum hardware faces significant limitations including gate errors, decoherence, and imprecise readouts that restrict circuit depth and qubit count [6]. The barren plateau phenomenon, where gradients vanish exponentially with system size, presents another major challenge for training quantum models [6]. These limitations have made hybrid quantum-classical workflows the most prevalent design in current quantum machine learning applications [6].

In these hybrid approaches, classical computers handle data preprocessing, parameter optimization, and post-processing, while quantum processors execute specific subroutines that theoretically offer quantum advantage. For instance, quantum-enhanced kernel methods embed classical data into high-dimensional quantum states, enabling linear classifiers to separate complex classes [6]. These methods have been tested on real quantum hardware and have achieved competitive classification accuracy despite noise, though challenges such as kernel concentration must be addressed to scale these methods to larger systems [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Quantum Chemistry and ML

| Resource | Type | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| QM9 Dataset | Benchmark Data | Training and evaluation of ML models for property prediction | Molecular property prediction, generative modeling, method benchmarking |

| QCML Dataset | Comprehensive Database | Training foundation models for quantum chemistry | Force field development, molecular dynamics, chemical space exploration |

| Fire Opal | Quantum Performance Software | Optimization and error suppression for quantum algorithms | Quantum phase estimation, quantum chemistry simulations on NISQ hardware |

| Variational Quantum Circuits | Quantum Algorithm | Parameterized quantum circuits for hybrid quantum-classical ML | Molecular energy calculation, quantum feature mapping |

| Graph Neural Networks | ML Architecture | Learning directly from molecular graph representations | Property prediction, molecular dynamics with ML potentials |

| Quantum Kernels | Quantum ML Method | Enhanced feature mapping for classification and regression | Quantum-enhanced support vector machines, data separation in Hilbert space |

Visualization of Methodologies and Workflows

Computational Pathways in Quantum Chemistry

The quantum chemistry bottleneck presents a fundamental challenge rooted in the exponential complexity of many-body quantum systems. Traditional computational approaches face severe scaling limitations that restrict high-accuracy calculations to small molecules. However, the convergence of machine learning and quantum computing offers promising pathways to overcome these limitations.

Machine learning potentials trained on comprehensive datasets like QM9 and QCML can already achieve near-quantum accuracy at dramatically reduced computational cost, enabling high-throughput screening and molecular dynamics simulations previously considered impossible [3] [2]. Meanwhile, advances in quantum algorithms and error mitigation techniques are gradually making quantum hardware a viable platform for specific quantum chemistry problems [5].

The most productive near-term approach appears to be hybrid quantum-classical workflows that leverage the strengths of both paradigms [6]. As machine learning foundation models for quantum chemistry continue to improve and quantum hardware matures, we can anticipate increasingly accurate and scalable solutions to quantum chemical problems, ultimately transforming drug discovery, materials design, and our fundamental understanding of molecular systems.

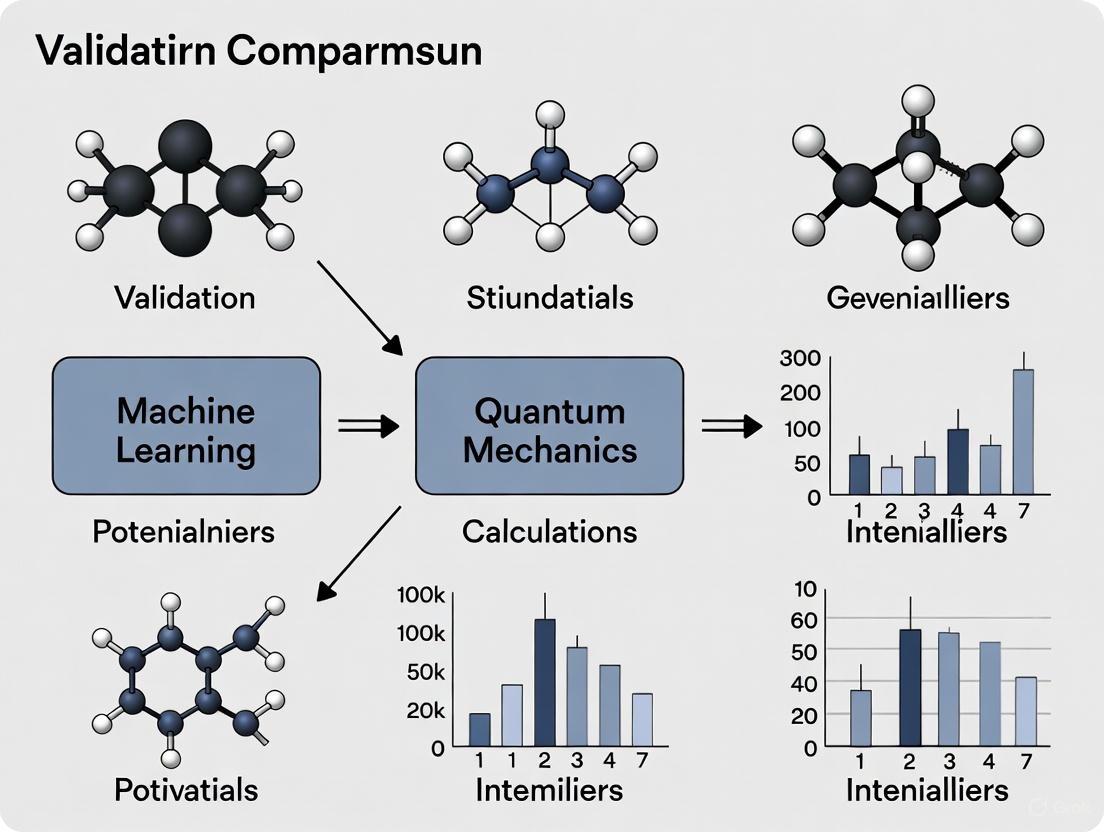

The validation of machine learning (ML) potentials against quantum mechanics (QM) calculations represents a cornerstone of modern computational science, particularly in drug development and materials discovery. This process ensures that the accelerated predictions made by ML models remain physically meaningful and quantitatively accurate. The advent of quantum computing introduces a transformative paradigm: using quantum computers to generate quantum-mechanical data or to enhance ML models directly, creating a powerful, closed-loop validation system. This guide objectively compares the emerging performance of Quantum Machine Learning (QML) against established classical ML approaches within this validation context. As we move through 2025, the field is witnessing a pivotal shift. Experts note that quantum computing is evolving beyond traditional metrics, with a growing focus on Quantum Error Correction (QEC) to achieve the stability required for useful applications, a necessary precursor to reliable QML [7]. Furthermore, the industry is seeing quantum computers begin to leave research labs for deployment in real-world environments, marking a critical step towards their practical application in research pipelines [7].

This comparison focuses on the core thesis: that machine learning acts as a catalyst, leveraging data from quantum systems (whether from classical simulations or quantum computers) to dramatically accelerate the prediction of molecular properties, chemical reactions, and material behaviors, all while being validated against the gold standard of quantum mechanics.

Performance Comparison: Quantum-Enhanced vs. Classical Machine Learning

To objectively assess the current state of QML, we compare its performance against highly optimized classical ML models on tasks relevant to drug discovery, such as molecular property prediction and molecular optimization. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from experimental studies and benchmarks.

Table 1: Comparative Performance on Molecular Property Prediction Tasks

| Model / Algorithm | Dataset / Task | Key Metric | Classical ML Performance | Quantum ML Performance | Notes / Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Neural Network (QNN) [8] | Synthetic Quantum Data | Prediction Error | Classical NN: High Error [8] | Quantum Model: Lower Error [8] | Advantage demonstrated on an engineered, quantum-native dataset. |

| Quantum Kernel Method [8] | Text Classification (NLP) | Classification Accuracy | N/A | ~62% (5-way classification) [8] | Implemented on trapped-ion quantum computer; 10,000+ data points. |

| Classical Graph Neural Network [9] | MAGL Inhibitor Potency | Potency Improvement | 4,500-fold improvement to sub-nanomolar [9] | N/A | Represents state-of-the-art classical AI in hit-to-lead optimization. |

Table 2: Performance in Integrated Sensing & Communication (Simulated Results)

| System Configuration | Task | Communication Rate | Sensing Accuracy (Precision) | Trade-off Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Superdense Coding [10] | Pure Communication | High | Low | Traditional either-or choice. |

| Variational QISAC (8-level Qudit) [10] | Joint Sensing & Communication | Medium | Medium | Tunable, simultaneous operation. |

| Variational QISAC (10-level Qudit) [10] | Pure Sensing | Zero | High (Near Heisenberg Limit) | System can be tuned for sensing-only. |

Analysis of Comparative Data

The experimental data reveals a nuanced landscape. While classical ML, particularly deep graph networks, demonstrates formidable performance in real-world drug discovery tasks—such as achieving a 4,500-fold potency improvement in optimizing MAGL inhibitors [9]—QML's advantages are currently more specialized.

Demonstrations of quantum advantage have been most successful in learning tasks involving inherently quantum-mechanical data. For instance, a study showed that a quantum computer could learn properties of physical systems using exponentially fewer experiments than a classical approach [8]. This is a significant proof-of-concept for the validation thesis, as it suggests QML could more efficiently learn and predict quantum properties directly. However, for classical data types (e.g., molecular structures represented as graphs), classical models currently hold a strong advantage in terms of maturity, scalability, and performance on complex, real-world benchmarks [9] [8].

A critical development is the demonstration of Quantum Integrated Sensing and Communication (QISAC). This approach, while still simulated, shows that a single quantum system can be tuned to balance data transmission with high-precision environmental sensing [10]. This capability could eventually underpin distributed quantum sensing networks that generate and process quantum data in real-time.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The evaluation of ML and QML models for quantum chemistry applications relies on rigorous, reproducible protocols. Below are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in this guide.

Protocol: Variational Quantum Algorithm for Quantum Data Learning

This protocol is adapted from experiments that demonstrated a quantum advantage in learning from quantum data [8] [10].

- Problem Setup: Define a task of learning an unknown property of a quantum system, such as the expectation value of a specific observable.

- Data Preparation: Instead of classical data, the training set consists of quantum states. These are prepared on the quantum processor or are outputs from a quantum simulation.

- Ansatz Design: Construct a parameterized quantum circuit (PQC), or ansatz. The architecture (e.g., number of layers, type of gates) is chosen based on the problem's anticipated complexity.

- Hybrid Quantum-Classical Loop:

- The PQC is executed on the quantum hardware (or simulator) with current parameters.

- The output is measured, and a cost function (e.g., difference between predicted and target observable) is calculated on a classical computer.

- A classical optimizer (e.g., gradient descent, parameter-shift rule) computes new parameters for the PQC.

- The loop repeats until the cost function converges.

- Validation: The trained quantum model is evaluated on a test set of held-out quantum states to assess its generalization error.

Protocol: Classical AI for Hit-to-Lead Acceleration

This protocol summarizes the industry-standard approach for AI-driven molecular optimization, as demonstrated in recent high-impact studies [9].

- Virtual Library Generation: Using a deep graph network or similar model, generate a vast virtual library of molecular analogs (e.g., 26,000+ compounds) based on an initial hit compound.

- In-Silico Screening: Employ molecular docking simulations (e.g., with AutoDock) and QSAR/ADMET prediction platforms (e.g., SwissADME) to triage the virtual library. This prioritizes candidates based on predicted binding affinity, drug-likeness, and safety.

- Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) Cycle:

- Design: Select the most promising candidates from the in-silico screen.

- Make: Synthesize the selected compounds using high-throughput, miniaturized chemistry techniques.

- Test: Experimentally validate the compounds in vitro for potency and selectivity (e.g., IC50 determination).

- Analyze: Feed the experimental results back into the AI model to refine the next round of virtual library generation.

- Target Engagement Validation: Crucially, confirm the mechanistic hypothesis using functional assays in intact cells. The Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) is used to quantitatively confirm direct drug-target engagement and stabilization in a physiologically relevant environment [9].

Protocol: Quantum Kernel Method for Classification

This protocol is based on the large-scale NLP classification task performed on IonQ hardware [8].

- Classical Pre-processing: Convert classical data (e.g., text) into a numerical representation using classical word embeddings or feature extraction.

- Quantum Feature Mapping: Encode the classical feature vectors into a quantum state using a feature map circuit. This projects the data into a high-dimensional quantum Hilbert space.

- Kernel Estimation: For each pair of data points in the dataset, compute the quantum kernel. This is the inner product between their corresponding quantum states, estimated by repeatedly preparing the states and measuring on the quantum computer.

- Classical Training: Use the computed quantum kernel matrix to train a classical support vector machine (SVM) classifier.

- Prediction: To classify a new data point, its kernel is estimated with the support vectors from the training set, and the classical SVM makes the final prediction.

Visualization of Workflows and Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the core logical relationships and experimental workflows described in this guide.

Quantum-Enhanced Validation Loop for Drug Discovery

Integrated Quantum Sensing & Communication (QISAC)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Platforms

This section details key hardware, software, and experimental platforms essential for research at the intersection of machine learning and quantum mechanics.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for QML and Validation

| Tool / Platform | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| IBM Qiskit [11] | Software Framework | Open-source SDK for quantum circuit design, simulation, and execution. | Prototyping and running QML algorithms (e.g., VQCs, QKMs) on simulators or real hardware. |

| Amazon Braket [11] | Cloud Service | Provides access to multiple quantum computing backends (superconducting, ion-trap, etc.). | Comparing QML model performance across different quantum hardware architectures. |

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) [9] | Wet-Lab Assay | Measures drug-target engagement directly in intact cells and tissues. | Provides critical, functionally relevant validation of predictions from both classical and quantum ML models. |

| AutoDock / SwissADME [9] | Software Tool | Performs molecular docking and predicts pharmacokinetic properties in silico. | Rapid virtual screening and triaging of compounds generated by AI/ML models before synthesis. |

| Trapped-Ion Quantum Computer (e.g., IonQ) [8] | Quantum Hardware | Offers high-fidelity qubit operations and all-to-all connectivity. | Executing larger-scale QML experiments (e.g., >10,000 data points) with lower error rates. |

| Variational Quantum Circuits (VQCs) [8] [10] | Algorithm | A hybrid quantum-classical algorithm for optimization and learning. | The leading paradigm for implementing QML models on current noisy quantum devices. |

Atomistic simulations are indispensable tools in industrial research and development, aiding in tasks from drug discovery to the design of new materials for energy applications [12]. The core of these simulations is the accurate description of the Potential Energy Surface (PES), which determines the energy and forces for a given atomic configuration [12]. Traditionally, two main approaches have been used:

- Quantum Mechanical (QM) Methods: These are considered the most accurate, as they describe the electronic structure of a system. However, they are computationally prohibitive, typically limiting simulations to small systems (a few hundred atoms) and short timescales (picoseconds) [12].

- Molecular Mechanics (MM) / Classical Force Fields: These employ analytical functions with parameters often derived from experiments. They are computationally efficient but suffer from limited transferability and cannot describe the breaking and forming of chemical bonds [12].

Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) have emerged as a powerful alternative, promising to bridge this gap by offering near-QM accuracy at a computational cost comparable to classical force fields [12] [13]. MLPs are trained on data from QM calculations and can learn the complex relationship between atomic structures and their energies and forces. Recently, Universal MLPs (uMLIPs) have been developed that can model diverse chemical systems without requiring system-specific retraining [13]. This guide provides a comparative benchmark of these uMLIPs against QM calculations, detailing their performance, validation methodologies, and the essential tools for researchers.

Performance Benchmark: Accuracy Across System Dimensionalities

A critical test for any MLP is its performance across systems of different dimensionalities—from zero-dimensional (0D) molecules to three-dimensional (3D) bulk materials. A 2025 benchmark study evaluated 11 universal MLPs on exactly this, revealing a general trend of decreasing accuracy as system dimensionality reduces [13]. The table below summarizes the performance of leading uMLIPs.

Table 1: Benchmark Performance of Universal MLPs Against QM Reference Data [13]

| Model Name | Key Performance Summary | Typical Position Error (Å) | Typical Energy Error (meV/atom) |

|---|---|---|---|

| eSEN (equivariant Smooth Energy Network) | Best overall for energy accuracy; excellent for geometry optimization. | 0.01–0.02 | < 10 |

| ORB-v2 | Top performer for geometry optimization (atomic positions). | 0.01–0.02 | < 10 |

| EquiformerV2 (eqV2) | Excellent performance for geometry optimization. | 0.01–0.02 | < 10 |

| MACE-mpa-0 | Strong general performance. | Not specified | Not specified |

| DPA3-v1-openlam | Strong general performance. | Not specified | Not specified |

| M3GNet | An early uMLIP model; included as a baseline, with lower performance compared to newer models. | Not specified | Not specified |

The benchmark concluded that the best-performing uMLIPs, including eSEN, ORB-v2, and EquiformerV2, have reached a level of accuracy where they can serve as direct replacements for Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations for a wide range of systems at a fraction of the computational cost [13]. This opens new possibilities for modeling complex, multi-dimensional systems like catalytic surfaces and interfaces.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Validating an MLP against QM benchmarks requires a rigorous and consistent methodology. The following workflow, based on contemporary benchmark studies, outlines the standard protocol for training and evaluating uMLIPs.

Diagram 1: MLP Validation Workflow

Key Methodological Details

Dataset Curation and Splitting: The benchmark uses datasets encompassing various dimensionalities: 0D (molecules, clusters), 1D (nanowires, nanotubes), 2D (atomic layers), and 3D (bulk crystals) [13]. A crucial step is ensuring the training and test sets are split to evaluate both interpolation (within the distribution of training data) and extrapolation (outside the training distribution). Common splitting strategies include:

- Property-based split: Testing on data points with property values outside the training range.

- Structure-cluster-based split: Using clustering algorithms to separate structurally distinct molecules into training and test sets [14].

QM Reference Calculations: Consistency in the QM methodology is paramount. Using different exchange-correlation functionals (e.g., PBE vs. B3LYP) across datasets can introduce systematic errors that mislead the evaluation of an MLP's transferability [13]. The benchmark should use a consistent level of theory for all reference calculations.

Error Metrics: The primary metrics for evaluating MLP performance are:

- Forces (F): Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of the predicted atomic forces, critical for molecular dynamics simulations.

- Energies (E): MAE of the total energy per atom (meV/atom).

- Atomic Positions: Error in the predicted positions of atoms after geometry optimization (e.g., in Ångströms) [13].

To conduct research in this field, scientists rely on a suite of standardized datasets, software, and descriptors. The following table details these essential "research reagents."

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for MLP and QM Benchmarking

| Category | Item / Resource | Function and Description |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Benchmark Datasets | QM7, QM7b, QM8, QM9 [4] | Curated datasets of small organic molecules with associated QM properties (e.g., atomization energies, excitation energies, electronic spectra). Used for training and benchmarking ML models for quantum chemistry. |

| Universal MLP Software/Packages | eSEN, ORB, EquiformerV2, MACE, DPA3 [13] | Software implementations of state-of-the-art universal machine learning interatomic potentials. They are trained on massive datasets and can be applied out-of-the-box to diverse systems. |

| Quantum Mechanics Descriptors | QMex Dataset [14] | A comprehensive set of quantum mechanical descriptors designed to improve the extrapolative performance of ML models on small experimental datasets, enhancing prediction for novel molecules. |

| Analytical Models | Interactive Linear Regression (ILR) [14] | An interpretable linear regression model that incorporates interaction terms between QM descriptors and molecular structure categories. It combats overfitting and maintains strong extrapolative performance on small data. |

The relationship between the computational methods, their cost, and their domain of applicability is summarized in the following diagram.

Diagram 2: Method Comparison Landscape

The comprehensive benchmarking of universal MLPs demonstrates that they have matured into powerful and reliable tools for atomistic simulation. Models like eSEN, ORB-v2, and EquiformerV2 now provide accuracy sufficient to replace direct QM calculations for many applications, from geometry optimization to energy prediction, across a wide spectrum of material dimensionalities [13]. While challenges remain—particularly in ensuring robust extrapolation and managing dataset biases—the experimental protocols and research reagents outlined in this guide provide a solid foundation for their validation and application. For researchers in drug development and materials science, these potentials offer a viable path to access the large system sizes and long timescales required for industrially relevant discoveries, all while maintaining the accuracy of quantum mechanics.

Accurately calculating molecular properties and binding free energies is a fundamental challenge in computational chemistry and drug discovery. While quantum mechanical (QM) methods provide high accuracy by explicitly treating electrons, they are computationally prohibitive for sampling the vast conformational space of biomolecules. Conversely, faster classical molecular mechanics (MM) methods lack quantum accuracy. This guide examines a transformative solution: the integration of machine learning (ML) to enhance quantum calculations.

This review objectively compares traditional quantum methods against new hybrid ML-enhanced workflows. We focus on two case studies that provide experimental data demonstrating how ML integration mitigates the limitations of standalone quantum computations, enabling more accurate and efficient simulations for pharmaceutical research.

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. ML-Enhanced Quantum Methods

The table below summarizes the core performance metrics of traditional methods versus the ML-enhanced approaches featured in our case studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Quantum Calculation Methods

| Method | Key Application | Reported Performance Metric | Result | Reference / Case Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional QM/MM | Molecular Energy Calculation | Mean Absolute Error | Baseline (Two orders of magnitude higher than pUCCD-DNN) | [15] |

| pUCCD-DNN (ML-Enhanced) | Molecular Energy Calculation | Mean Absolute Error | Reduced by two orders of magnitude vs. non-ML pUCCD | [15] |

| Classical MM Force Fields | Protein-Ligand Binding Free Energy | Systematic Error | Limited for molecules with transition metals | [16] |

| Hybrid ML/MM Potential | Protein-Ligand Binding Free Energy | Accuracy vs. QM/MM | Retains QM-level accuracy while enabling large-scale sampling | [16] |

| Classical DeepLOB | Financial Mid-Price Prediction (FI-2010, 40 features) | Weighted F1 Score | 40.05% | [17] |

| Quantum-Enhanced Signature Kernel (QSK) | Financial Mid-Price Prediction (FI-2010, 24 features) | Weighted F1 Score | 68.71% | [17] |

Case Study 1: ML-Optimized Wavefunction for Molecular Energy Calculations

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

A 2025 study demonstrated a hybrid quantum-classical method, pUCCD-DNN, which integrates a deep neural network (DNN) with a quantum computational ansatz to calculate molecular energies with superior accuracy and efficiency [15].

The methodology proceeded as follows:

- Ansatz Selection: The paired Unitary Coupled-Cluster with Double Excitations (pUCCD) ansatz was selected to prepare the trial wavefunction on a quantum computer. This ansatz effectively captures electron correlations while respecting conservation symmetries.

- Quantum Computation: The quantum processor computes the energy expectation value for the prepared pUCCD trial wavefunction.

- Classical Optimization via DNN: Instead of traditional "memoryless" optimizers, a Deep Neural Network (DNN) was trained on system data from the current wavefunction and global parameters. Crucially, the DNN learns from past optimizations of other molecules, using this knowledge to inform and dramatically improve the efficiency of new optimizations.

- Iterative Refinement: The parameters optimized by the DNN are fed back to the quantum computer to prepare a new, refined trial wavefunction. This hybrid loop continues until the energy converges to a minimum.

This workflow is depicted in the following diagram:

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for the pUCCD-DNN Workflow

| Research Reagent | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| pUCCD Ansatz | A parameterized quantum circuit that prepares the trial wavefunction, capturing crucial electron correlation effects while maintaining computational feasibility. |

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | The overarching hybrid algorithm that variationally minimizes the molecular energy by iterating between the quantum and classical processors. |

| Deep Neural Network (DNN) Optimizer | Replaces traditional classical optimizers; learns from previous optimization trajectories to efficiently find optimal wavefunction parameters, reducing calls to quantum hardware. |

| Classical Computational Resources | Handles the execution of the DNN, data storage from quantum calculations, and the overall coordination of the hybrid workflow. |

Case Study 2: ML Potentials for Protein-Ligand Binding Free Energies

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

Researchers have developed a general and automated workflow that uses Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) to perform accurate and efficient binding free energy simulations for protein-drug complexes, including those with transition metals that challenge classical force fields [16].

The detailed, end-to-end protocol is as follows:

- System Preparation: The protein-ligand complex is partitioned into a QM region (e.g., the drug molecule and key binding site residues) and an MM region (the rest of the protein and solvent).

- Active Learning and Data Generation: An automated, active learning loop is initiated:

- The SCINE framework coordinates distributed computing resources to run QM/MM calculations on diverse molecular configurations [16].

- A Query-by-Committee strategy identifies new configurations where the ML potential's predictions are uncertain, ensuring comprehensive sampling of the relevant chemical space [16].

- ML Potential Training: The energies and forces from the QM/MM calculations are used to train an ML potential. This study proposed an extension of element-embracing atom-centered symmetry functions (eeACSFs) as a descriptor to efficiently handle the many different chemical elements in protein-drug complexes and the QM/MM partitioning [16].

- Free Energy Simulation: The trained ML potential, which retains near-QM accuracy but runs at MM speed, is then used to drive extensive alchemical free energy (AFE) simulations or nonequilibrium (NEQ) switching simulations. This allows for the efficient calculation of the binding free energy.

The complete workflow is visualized below:

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for the ML Potential Workflow

| Research Reagent | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Hybrid QM/MM Calculations | Provides the high-accuracy reference data (energies and forces) used to train the ML potential. The QM region is typically treated with density functional theory (DFT). |

| ML Potential (e.g., HDNNP) | A machine learning model, such as a high-dimensional neural network potential, trained to reproduce the QM/MM potential energy surface with high fidelity but at a fraction of the computational cost. |

| Element-Embracing ACSFs (eeACSFs) | A structural descriptor that translates atomic coordinates into a format the ML potential can use. It is engineered to efficiently handle systems with many different chemical elements. |

| SCINE Framework | An automated computational framework that manages the workflow, including the distribution of QM/MM calculations and the active learning process. |

| Alchemical Free Energy (AFE) | A simulation method that calculates binding free energies by simulating non-physical (alchemical) pathways between the bound and unbound states, enabled by the fast ML potential. |

The experimental data and protocols presented confirm a powerful trend: machine learning is no longer just an application of quantum computing but a critical enhancer of it. As shown in the case studies, ML integration directly addresses the core bottlenecks of quantum calculations—prohibitive computational cost and noise susceptibility—by creating efficient, accurate surrogates and intelligent optimizers. This synergy validates the use of hybrid ML-quantum methods as a superior pathway for tackling complex problems in quantum chemistry and drug discovery, offering researchers a practical tool that delivers quantum-grade insights with drastically improved efficiency.

Building and Applying Robust Machine Learning Potentials

The accurate prediction of molecular properties stands as a critical challenge in computational chemistry and drug discovery. The validation of machine learning potentials against high-fidelity quantum mechanics (QM) calculations represents a fundamental research axis, aiming to bridge the gap between computational efficiency and physical accuracy. Within this paradigm, Graph Neural Networks have emerged as a powerful architectural framework for modeling molecular systems, naturally representing atoms as nodes and bonds as edges in a graph structure [18]. The strategic integration of domain-specific features, particularly quantum mechanical descriptors, is a pivotal development enhancing the scientific rigor of these models. This guide provides a comparative analysis of architectural paradigms for GNNs employing domain-specific feature mapping, focusing on their validation against quantum mechanical calculations to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Architectural Paradigms in Molecular Representation

Molecular representation forms the foundational step in any computational drug discovery pipeline. The evolution from traditional, rule-based descriptors to modern, data-driven learned embeddings represents a significant paradigm shift, with GNNs positioned at its forefront [19].

Traditional vs. Modern AI-Driven Approaches

- Traditional Representations: These methods rely on explicit, pre-defined feature engineering.

- Molecular Descriptors: Quantifiable properties like molecular weight, hydrophobicity, or topological indices [19].

- Molecular Fingerprints: Binary or numerical strings encoding substructural information, such as the widely used Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP) [19].

- String-Based Representations: Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) provides a compact string encoding of chemical structures but struggles to capture complex molecular interactions [19].

- Modern AI-Driven Representations: These approaches leverage deep learning to learn continuous, high-dimensional feature embeddings directly from data.

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Model molecules as graphs, using message-passing mechanisms to learn from atomic neighborhoods and bond connectivity [18]. Popular architectures include Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs), Graph Attention Networks (GATs), and Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs) [18].

- Language Model-Based: Treat molecular sequences like SMILES as a chemical language, using transformer-based models to learn representations [19].

- Multimodal and Contrastive Learning: Combine multiple representation types or use self-supervision to learn robust embeddings without extensive labeled data [19].

The Role of Domain-Specific Feature Mapping

A key architectural decision is the type of input features mapped onto the molecular graph. While basic atomic properties (symbol, degree) are common, integrating domain-specific features is a paradigm aimed at improving model generalizability and physical plausibility.

- Basic Feature Mapping: Initial node embeddings are typically constructed from atomic properties such as Atomic Symbol, Formal Charge, Degree, IsAromatic, and IsInRing [20]. This provides a foundational representation of the graph's topology and composition.

- Quantum Mechanical (QM) Descriptor Mapping: This paradigm involves augmenting the basic graph structure with computationally derived QM descriptors. These descriptors—calculated at the atom, bond, or molecular level—encode electronic and quantum properties that are expensive to compute but offer a more direct link to the underlying physics governing molecular behavior [21]. The core hypothesis is that this integration creates a more physics-informed model.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the comparative pipeline between a standard GNN and one enhanced with QM descriptors.

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

Validating machine learning potentials against QM calculations requires rigorous experimental protocols. A systematic investigation by Li et al. provides a foundational framework for evaluating the impact of QM descriptors on GNN performance [21].

Key Methodologies for QM-Augmented GNNs

- Model Architecture: The core model used in such studies is often a Directed Message Passing Neural Network (D-MPNN), a state-of-the-art architecture for molecular property prediction. The QM descriptors are typically integrated as additional node, edge, or global molecular features input to the network [21].

- Dataset Selection: To ensure comprehensive evaluation, experiments should span diverse datasets:

- Validation Protocol: Standard practices include:

- Train/Test Splits: Strict separation of training and hold-out test sets to evaluate generalization [22].

- Cross-Validation: k-fold cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold) on the training data for robust hyperparameter optimization and model selection [22].

- Performance Benchmarking: Comparative analysis of models with and without QM descriptors using standardized metrics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key computational "reagents" and resources essential for conducting research in this field.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for GNN & QM Validation

| Item Name | Type | Function & Application | Example Sources / Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Datasets | Data | Provides standardized benchmarks for training and evaluating models on specific molecular properties. | ESOL, FreeSolv, Lipophilicity, Tox21 [18] |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Software | Performs ab initio calculations to generate high-fidelity QM descriptors for molecules. | Gaussian, GAMESS, ORCA, PSI4 |

| QM Descriptor Toolkit | Software/Tool | A high-throughput workflow to compute QM descriptors for integration into machine learning pipelines [21]. | Enhanced Chemprop implementation [21] |

| GNN Framework | Software | Provides implementations of core GNN architectures (GCN, GAT, MPNN) tailored for molecular graphs. | DeepGraph, Chemprop, DGL-LifeSci, TorchDrug |

| Directed-MPNN (D-MPNN) | Model Architecture | A specific GNN variant known for state-of-the-art performance on molecular property prediction tasks [21]. | Chemprop |

| Evaluation Metrics | Metric Suite | Quantifies model performance for regression (MAE, RMSE, R²) and classification (AUC-ROC, AUPR) tasks [18]. | Scikit-learn, native framework metrics |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Empirical data is crucial for understanding the practical value of integrating QM descriptors. The following table synthesizes quantitative findings from key studies, focusing on the performance of GNNs with and without QM feature mapping.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of GNN Architectures with and without QM Descriptors

| Model Paradigm | Target Property / Task | Dataset Size | Key Performance Metric | Reported Result | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-MPNN (Baseline) | Various Chemical Properties | Small (~hundreds) | Predictive Accuracy (e.g., MAE, R²) | Lower performance | Struggles with extrapolation, higher error [21] |

| D-MPNN + QM Descriptors | Various Chemical Properties | Small (~hundreds) | Predictive Accuracy (e.g., MAE, R²) | Improved performance | Beneficial for data-efficient modeling [21] |

| D-MPNN (Baseline) | Various Chemical Properties | Large (~100k-1M) | Predictive Accuracy (e.g., MAE, R²) | High performance | Sufficient data to learn complex patterns [21] |

| D-MPNN + QM Descriptors | Various Chemical Properties | Large (~100k-1M) | Predictive Accuracy (e.g., MAE, R²) | Negligible gain or potential degradation | QM descriptors can add noise without benefit [21] |

| GNN-Hybrid (e.g., GNN + Causal ML) | Aggregate Prediction (Vehicle KM) | 288 observations | Cross-Validation R² | ≈ 0.87 [22] | Optimized for high predictive accuracy on observed data [22] |

| Causal ML + Conformal Prediction | Causal Effect Estimation | 288 observations | Cross-Validation MAE | 124,758.04 [22] | Designed for high-fidelity causal inference, not raw prediction [22] |

Critical Interpretation of Performance Data

The data in Table 2 reveals a nuanced picture, leading to several key conclusions:

- Data Efficiency is Key: The primary benefit of QM descriptors is observed in small-data regimes. When labeled experimental or QM data is scarce (e.g., a few hundred molecules), GNNs augmented with QM descriptors show marked improvement in predictive accuracy. The descriptors provide a strong physical inductive bias, helping the model generalize beyond the limited training examples [21].

- Diminishing Returns with Big Data: For very large datasets (e.g., hundreds of thousands of molecules), the value of explicitly adding QM descriptors diminishes. In these cases, the GNN has sufficient data to learn complex patterns directly from the basic graph structure. Introducing QM descriptors can then become computationally expensive without yielding significant benefits and may even introduce unwanted noise that degrades performance [21].

- Paradigm Dictates Purpose: A direct comparison of predictive R² scores can be misleading, as different architectures are optimized for different goals. A GNN hybrid might achieve a high R² for aggregate prediction, while a Causal ML framework—though potentially having a lower R²—is superior for estimating the unbiased causal impact of interventions, as indicated by a lower causal effect estimation error [22]. This underscores the importance of selecting an architecture aligned with the research question.

Advanced Architectural Implementations

Beyond simple feature augmentation, more complex architectural paradigms have been developed to refine how domain-specific knowledge is integrated and processed.

Substructure-Aware GNNs

Models like GNNBlockDTI address the challenge of balancing local substructural features with global molecular properties. This architecture uses a GNNBlock—a unit comprising multiple GNN layers—to capture hidden structural patterns within local ranges (substructures) of the drug molecular graph. This is followed by feature enhancement strategies and gating units to filter redundant information, leading to more expressive molecular representations that are highly competitive in tasks like Drug-Target Interaction (DTI) prediction [20]. The following diagram illustrates this sophisticated substructure encoding process.

Emerging Frontiers: Quantum Graph Neural Networks

An emerging paradigm is the exploration of Quantum Graph Neural Networks (QGNNs). These models aim to harness the principles of quantum computing, such as superposition and entanglement, to process graph-structured data. The theoretical potential lies in handling the combinatorial complexity of graph problems more efficiently than classical computers. Proposed architectures include:

- Hybrid Quantum-Classical Models: Integrating variational quantum circuits (VQCs) as layers within a classical GNN framework [23].

- Quantum-Enhanced Feature Encoding: Using quantum circuits to map node/edge features into higher-dimensional quantum states [23].

- Quantum Walk-Based Message Passing: Replacing classical message aggregation with quantum walk dynamics for more efficient graph exploration [23].

While currently constrained by Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) hardware, QGNNs represent a frontier for potentially revolutionary advancements in modeling molecular systems [23].

The architectural landscape of Graph Neural Networks is richly varied, with domain-specific feature mapping serving as a critical lever for enhancing model performance and physical grounding. The experimental evidence indicates that the paradigm of augmenting GNNs with quantum mechanical descriptors is most impactful in data-scarce scenarios, providing a crucial inductive bias for generalizability. As the field progresses, the choice of architecture must be guided by the specific research objective—be it high aggregate prediction, unbiased causal inference, or exploration of entirely new chemical spaces. Advanced implementations focusing on substructure encoding and the nascent field of quantum-enhanced GNNs promise to further refine our ability to validate machine learning potentials against the gold standard of quantum mechanics, ultimately accelerating robust and reliable drug discovery.

The emerging field of quantum machine learning (QML) promises to leverage the principles of quantum mechanics to tackle computational problems beyond the reach of classical algorithms. As theoretical frameworks mature into practical applications, the critical bottleneck has shifted from model design to data generation and curation—the process of sourcing accurate quantum mechanical training data. This challenge is particularly acute in mission-critical domains like drug discovery and materials science, where the predictive accuracy of QML models hinges directly on the quality and veracity of their underlying quantum data [6] [24].

The quantum technology landscape is experiencing rapid growth, with the total market projected to reach up to $97 billion by 2035 [25]. Within this expansion, quantum computing is emerging as a cornerstone for generating and processing complex chemical and molecular data. However, current QML approaches face a fundamental tension: while they operate in exponentially large Hilbert spaces that offer vast representational capacity, they are constrained by the limited availability of reliable quantum data and the difficulty of validating model outputs against ground-truth quantum calculations [6]. This comparison guide examines the current methodologies for sourcing and curating quantum mechanical training data, objectively evaluating their performance characteristics and practical implementation requirements.

Comparative Analysis of Quantum Data Sourcing Methodologies

Quantum versus Classical Data Generation Approaches

The selection of an appropriate data generation methodology represents a fundamental trade-off between computational fidelity and practical feasibility. The table below compares the primary approaches for generating quantum mechanical training data.

Table 1: Comparison of Quantum Mechanical Data Generation Approaches

| Methodology | Theoretical Basis | Accuracy Profile | Computational Cost | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-Principles Quantum Calculations | Ab initio quantum chemistry methods (e.g., coupled cluster, configuration interaction) | High-fidelity ground truth | Extremely high; scales exponentially with system size | Validation datasets, small molecule systems |

| Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) | Parameterized quantum circuits optimized via classical methods | Variable; depends on ansatz selection and error mitigation | Moderate to high; suitable for NISQ devices | Quantum chemistry, molecular property prediction |

| Classical Quantum Circuit Simulators | State vector simulation or tensor network methods | Noiseless, ideal quantum operations | High for perfect fidelity; memory-bound | Algorithm development, training data synthesis |

| GPU-Accelerated Quantum Emulation | Quantum circuit execution on classical hardware (e.g., NVIDIA CUDA-Q) | Near-perfect emulation of quantum states | High but scalable across GPU resources | Large-scale training data generation, hybrid validation |

Performance Benchmarking of Quantum Data Generation Platforms

Recent empirical studies have quantified the performance characteristics of different quantum data generation and processing platforms. The following table synthesizes key performance metrics from published implementations.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Quantum Data Processing Platforms

| Platform/Approach | Qubit Capacity | Speed-up vs. CPU | Algorithm Validation | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA CUDA-Q (H200) | 18+ qubit emulation | 60-73x (forward propagation) 34-42x (backward propagation) | Drug candidate discovery using QLSTM, QGAN, QCBM | Seamless integration with classical HPC workflows [24] |

| NVIDIA GH200 | 18+ qubit emulation | 22-24% faster than H200 | Same as above | Superior performance for hybrid quantum-classical algorithms [24] |

| Amazon Braket Hybrid Jobs | Variable across quantum hardware providers | Dependent on selected QPU | Variational Quantum Linear Solver, optimization problems | Managed service with multiple quantum backends [26] |

| PennyLane (Classical Simulation) | Limited by classical hardware | Baseline (CPU reference) | Comprehensive benchmark of VQAs for time series prediction | Noiseless environment for algorithm validation [27] |

Experimental Protocols for Quantum Data Validation

Workflow for Cross-Platform Quantum Data Generation

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive experimental workflow for generating and validating quantum mechanical training data across multiple computational platforms:

Benchmarking Protocol for Quantum Machine Learning Models

Rigorous benchmarking against classical counterparts is essential for validating the performance of QML models trained on quantum mechanical data. The following diagram outlines a standardized benchmarking protocol:

Detailed Experimental Methodology

The experimental protocols referenced in the performance tables follow these rigorous methodologies:

Quantum AI Algorithm Validation for Drug Discovery

Norma's validation protocol for quantum AI algorithms in drug development exemplifies a comprehensive benchmarking approach [24]:

Algorithm Selection: Implementation of quantum-enhanced algorithms including Quantum Long Short-Term Memory (QLSTM), Quantum Generative Adversarial Networks (QGAN), and Quantum Circuit Born Machines (QCBM) for chemical space exploration.

Platform Configuration: Algorithms were executed on NVIDIA CUDA-Q platform with two hardware configurations: H200 GPUs and GH200 Grace Hopper Superchips.

Performance Metrics: Precisely measured execution times for both forward propagation (quantum circuit execution and measurement) and backward propagation (loss function-based correction process).

Comparative Baseline: Performance was compared against traditional CPU-based methods to calculate exact speed-up factors.

Application Validation: Algorithms were applied to real drug candidate discovery problems in collaboration with Kyung Hee University Hospital to assess practical utility beyond synthetic benchmarks.

Large-Scale Benchmarking of Quantum Time Series Prediction

A comprehensive 2025 benchmark study established rigorous protocols for evaluating quantum versus classical models for time series prediction [27]:

Model Selection: Five quantum models (dressed variational quantum circuits, re-uploading VQCs, quantum RNNs, QLSTMs, and linear-layer enhanced QLSTMs) and three classical baseline models.

Task Diversity: Evaluation across 27 time series prediction tasks of varying complexity derived from three chaotic systems.

Optimization Protocol: Extensive hyperparameter optimization for all models to ensure fair comparison.

Performance Metrics: Assessment of predictive accuracy, convergence speed, and robustness to noise and distribution shifts.

Simulation Environment: Quantum models were classically simulated under ideal, noiseless conditions using PennyLane to establish an upper bound on quantum performance.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Solutions for Quantum Data Generation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Quantum Data Generation

| Tool/Category | Representative Examples | Primary Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Simulation Platforms | PennyLane, NVIDIA CUDA-Q | Noiseless validation of quantum algorithms and data generation | CPU/GPU memory constraints; optimal for algorithm development before hardware deployment |

| Quantum Hardware Access | Amazon Braket, IBM Quantum | Execution on real quantum processing units (QPUs) | Limited qubit counts, gate fidelity issues, and queue times necessitate error mitigation |

| Hybrid Workflow Orchestration | AWS Batch, AWS ParallelCluster | Management of hybrid quantum-classical algorithms | Critical for coordinating classical pre/post-processing with quantum circuit execution |

| Error Mitigation Solutions | Q-CTRL Fire Opal | Improvement of algorithm performance on noisy hardware | Essential for extracting meaningful signals from current NISQ-era devices |

| Optimized Quantum Algorithms | Quantum Deep Q-Networks, Variational Quantum Linear Solver | Specialized applications in optimization and simulation | RealAmplitudes ansatz shows superior convergence in some applications [28] |

| Performance Enhancement Tools | NVIDIA H200/GH200 GPUs | Acceleration of quantum circuit simulation | 60-73x speedup reported for 18-qubit circuits in drug discovery applications [24] |

The generation and curation of accurate quantum mechanical training data remains a multifaceted challenge requiring careful methodological selection. Current evidence suggests that hybrid quantum-classical approaches leveraging GPU-accelerated simulation platforms like NVIDIA CUDA-Q offer the most practical pathway for generating high-quality training data at scale, with demonstrated speed-ups of 60-73× over conventional CPU-based methods in drug discovery applications [24].

While quantum models theoretically operate in exponentially large Hilbert spaces that could potentially capture complex quantum correlations, recent comprehensive benchmarking indicates that they often struggle to outperform simple classical counterparts of comparable complexity when evaluated on equal footing [27]. This performance gap highlights the critical importance of rigorous cross-platform validation and suggests that claims of quantum advantage must be tempered by empirical evidence from standardized benchmarks.

For researchers in drug development and related fields, the optimal strategy involves a tiered approach: utilizing classical simulations for initial data generation and model prototyping, while strategically employing quantum hardware for specific subroutines where quantum processing may offer measurable benefits. As the quantum hardware ecosystem matures—with projected market growth to $97 billion by 2035 [25]—the tools and methodologies for quantum data generation will continue to evolve, potentially unlocking new opportunities for scientific discovery through quantum machine learning.

Training Strategies for High-Dimensional Chemical Space

The exploration of high-dimensional chemical space represents a fundamental challenge in modern drug discovery and materials science. With estimates suggesting the existence of up to 10^60 drug-like compounds, the systematic evaluation of this vast landscape through traditional experimental approaches is practically impossible [29]. Computational methods have dramatically increased the reach of chemical space exploration, but even these techniques become unaffordable when evaluating massive numbers of molecules [29]. This limitation has catalyzed the development of sophisticated machine learning strategies that can navigate these expansive chemical territories efficiently.

Within the context of validating machine learning potentials against quantum mechanics calculations, the selection of appropriate training strategies becomes paramount. The "needle in a haystack" problem of drug discovery—searching for highly active compounds within an immense possibility space—requires intelligent sampling and prioritization methods [29]. This guide objectively compares the primary computational frameworks and experimental protocols designed to address this challenge, with particular emphasis on their applicability for machine learning potential validation against quantum mechanical reference data.

Comparative Analysis of Key Training Strategies

The following table summarizes the core training strategies employed for navigating high-dimensional chemical spaces, along with their key characteristics and experimental considerations.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Training Strategies for Chemical Space Exploration

| Strategy | Core Principle | Experimental Implementation | Data Efficiency | Scalability | Validation Against QM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Learning with Oracle | Iterative selection of informative candidates for expensive calculation [29] | Cycles of ML prediction → Oracle evaluation → Model retraining [29] | High (Explicitly minimizes expensive evaluations) | Moderate (Oracle cost remains bottleneck) | Direct (Oracle can be QM calculation) |

| Feature Tree Similarity Search | Reduced pharmacophoric representation enabling scaffold hopping [30] | Mapping node-based molecular representations preserving topology [30] | Moderate (Requires careful query selection) | High (Efficient for vast spaces without full enumeration) | Indirect (Requires correlation between similarity and property) |

| Chemical Space Visualization & Navigation | Dimensionality reduction for human-in-the-loop exploration [31] | Projection of chemical structures to 2D/3D maps using t-SNE, PCA, or deep learning [31] | Variable (Depends on human intuition) | High for visualization, lower for decision-making | Complementary (Visual validation of QSAR models) |

| Deep Generative Modeling | Learning underlying data distribution to generate novel structures [31] | Training neural networks on existing chemical data to produce new candidates [31] | High after initial training | High (Rapid generation once trained) | Requires careful validation against QM |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Active Learning Strategies for PDE2 Inhibitors

| Selection Strategy | Compounds Evaluated by Oracle | High-Affinity Binders Identified | Computational Cost | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Selection | 100% of library | Baseline | Prohibitive for large libraries | Simple implementation |

| Greedy Selection | ~1-5% of library | Moderate | Low | Focuses on promising regions |

| Uncertainty Sampling | ~1-5% of library | Variable | Low | Improves model robustness |

| Mixed Strategy | ~1-5% of library | High | Moderate | Balances exploration & exploitation |

| Narrowing Strategy | ~1-5% of library | Highest | Moderate | Combines breadth with focused search |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Active Learning with Free Energy Calculation Oracle

Active learning represents one of the most effective frameworks for navigating chemical spaces with minimal computational expense. The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for an active learning protocol implementing a free energy calculation oracle:

Active Learning Workflow for Chemical Exploration

Protocol Details

The optimized active learning protocol consists of the following methodological components, as demonstrated in the prospective search for PDE2 inhibitors [29]:

Step 1: Library Generation and Preparation

- Construct an in silico compound library sharing a common core with a known crystal structure reference (e.g., PDE2 inhibitor from 4D09 crystal structure) [29]

- Generate binding poses for each ligand through constrained embedding using the ETKDG algorithm as implemented in RDKit, selecting the structure with smallest RMSD to the reference [29]

- Refine ligand binding poses using molecular dynamics simulations in vacuum with hybrid topology morphing from reference inhibitor to target ligand [29]

Step 2: Ligand Representation and Feature Engineering

- Implement multiple consistent, fixed-size vector representations for machine learning:

- 2D_3D representation: Constitutional, electrotopological, and molecular surface area descriptors combined with molecular fingerprints [29]

- Atom-hot representation: Grid-based encoding of 3D ligand shape in binding site (2Å voxels counting atoms by element) [29]

- PLEC fingerprints: Protein-ligand interaction contacts between ligand and each protein residue [29]

- Interaction energy representations: Electrostatic and van der Waals interaction energies between ligand and protein residues [29]

Step 3: Selection Strategy Implementation

- Employ the "mixed strategy" which identifies 300 ligands with strongest predicted binding affinity, then selects 100 ligands with most uncertain predictions [29]

- Initialize models using weighted random selection (probability inversely proportional to similar ligand count in t-SNE embedded space) [29]

- For the first three iterations, use R-group-only versions of representations in addition to complete ligand representations [29]

Step 4: Oracle Implementation and Model Training

- Utilize alchemical free energy calculations as the oracle for training ML models [29]

- Train machine learning models using the obtained affinity data with multiple representation schemes

- Identify the 5 models with lowest cross-validation RMSE for candidate selection in narrowing strategy [29]

Feature Tree Similarity Search Protocol

For extremely large chemical spaces where complete enumeration is impossible, Feature Tree similarity searching provides an efficient alternative:

Step 1: Query Compound Selection

- Select 100 query compounds as reference points in chemical universe [30]

- Apply drug-like filters: Lipinski's rule violations < 2, molecular weight < 600 Da, clogP < 6, polar surface area < 150 Ų, rotatable bonds < 12 [30]

- Use random selection from marketed drugs or target-specific compound sets [30]

Step 2: Feature Tree Representation and Comparison

- Reduce molecular structures to Feature Tree representations with nodes representing pharmacophoric units (rings, functional groups) and connections representing molecular topology [30]

- Implement node mapping algorithm that preserves topology with connected nodes mapping to connected nodes [30]

- Calculate overall similarity as average of local Tanimoto similarities of mapped node pairs, reduced by penalty for non-matching nodes [30]

Step 3: Space Navigation and Hit Retrieval

- Retrieve 10,000 most similar molecules from each chemical space for each query using FTrees-FS extension for fragment spaces [30]

- Analyze overlap of hit sets across different spaces using traditional fingerprint similarity (e.g., MDL public keys) [30]

- Assess chemical feasibility of hits using Ertl and Schuffenhauer's SAscore and rsynth retrosynthetic analysis [30]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chemical Space Exploration

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cheminformatics Toolkits | RDKit [29], Open Drug Discovery Toolkit [29] | Molecular fingerprint generation, descriptor calculation, structural manipulation | Open-source; provides comprehensive descriptor sets and molecular operations |

| Free Energy Calculation Suites | pmx [29], Gromacs [29] | Alchemical free energy calculations for binding affinity prediction | Computationally demanding but high accuracy; suitable as oracle in active learning |

| Molecular Representations | 2D_3D descriptors [29], PLEC fingerprints [29], Atom-hot encoding [29] | Convert molecular structures to machine-readable features | Choice significantly impacts model performance; multiple representations recommended |

| Chemical Spaces | BICLAIM [30], REAL Space [30], KnowledgeSpace [30] | Large libraries of synthesizable compounds for virtual screening | Vary in size (10^9 to 10^20 compounds) and synthetic feasibility |

| Similarity Search Tools | FTrees-FS [30] | Efficient similarity searching in non-enumerated fragment spaces | Enables scaffold hopping through pharmacophoric representation |