Using Radial Distribution Function to Analyze Atomic Structure from MD: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on utilizing the Radial Distribution Function (RDF) to extract critical structural insights from Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations.

Using Radial Distribution Function to Analyze Atomic Structure from MD: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on utilizing the Radial Distribution Function (RDF) to extract critical structural insights from Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. It covers the fundamental theory of RDF, practical implementation methods using popular software tools, optimization techniques for enhanced performance, and validation approaches against experimental data. The content explores applications in characterizing biomolecular interactions, solvation shells, and drug-binding sites, with specific examples from cancer research involving EGFR and H-Ras proteins. This resource bridges computational analysis with experimental validation, offering practical strategies for advancing drug discovery and materials design.

Understanding Radial Distribution Functions: From Basic Theory to Molecular Insights

What is the RDF? Defining the Fundamental Concept and Mathematical Formulation

The Radial Distribution Function (RDF), denoted as ( g(r) ), is a fundamental concept in statistical mechanics that describes the probability of finding a particle at a distance ( r ) from a reference particle in a homogeneous and isotropic system [1]. It serves as a powerful tool for characterizing the atomic and molecular structure of materials, providing a quantitative measure of how particle density varies with distance from a reference point [2] [3]. By revealing the spatial arrangement of particles, the RDF provides crucial insights into the structure of various condensed matter systems, including ordered crystals, disordered materials, and liquids, making it one of the most effective tools for characterizing the nature and structure of substances, particularly fluids and fluid mixtures [1].

The significance of the RDF extends beyond structural description, as it forms a critical bridge between microscopic interactions and macroscopic thermodynamic properties [1]. This function enables researchers to connect the arrangements and interactions of individual atoms or molecules with bulk material properties that can be measured experimentally. Knowledge of the RDF is crucial for multiple reasons: it bridges macroscopic thermodynamic properties with interparticle interactions; it plays a crucial role in fluctuation theory; and it provides a clear view of particle correlations and how these interactions decay with distance [1]. In the context of molecular dynamics (MD) research, the RDF serves as an essential analytical tool for validating simulations against experimental data and for understanding the structural features of complex molecular systems at the atomic level [4].

Mathematical Formulation

Fundamental Definition

The radial distribution function is mathematically defined for a system of ( N ) particles in volume ( V ) at temperature ( T ) as follows. For particles of types ( a ) and ( b ), the RDF ( g_{ab}(r) ) is given by:

[ g{ab}(r) = \frac{1}{N{a}} \frac{1}{N{b}/V} \sum{i=1}^{Na} \sum{j=1}^{Nb} \langle \delta(|\mathbf{r}i - \mathbf{r}_j| - r) \rangle ]

which is normalized so that the RDF becomes 1 for large separations in a homogeneous system [5]. The RDF effectively counts the average number of ( b ) neighbours in a shell at distance ( r ) around an ( a ) particle and represents it as a density [5].

In the canonical ensemble (( N,V,T )), the RDF can be expressed through the generalized expression:

[ g^{(n)}(\mathbf{r}1, \ldots, \mathbf{r}n) = \frac{V^{N}}{N!} \left( \prod{i=n+1}^{N} \frac{1}{V} \int \mathrm{d}^3 \mathbf{r}i \right) \frac{1}{ZN} \sum{\pi \in SN} e^{-\beta U(\mathbf{r}{\pi(1)}, \ldots, \mathbf{r}_{\pi(N)})} ]

where ( Z_N ) is the configurational integral, ( \beta = 1/kT ), and ( U ) is the potential energy function [2].

Key Mathematical Relationships

From the radial distribution function, several important related functions can be derived. The radial cumulative distribution function is defined as:

[ G{ab}(r) = \int0^r !!dr' 4\pi r'^2 g_{ab}(r') ]

and the average number of ( b ) particles within radius ( r ) is:

[ N{ab}(r) = \rho G{ab}(r) ]

where ( \rho ) is the appropriate number density [5]. The latter function is particularly useful for computing coordination numbers, such as the number of neighbors in the first solvation shell, where the upper limit ( r_1 ) is typically taken as the position of the first minimum in ( g(r) ) [5].

In practice, for molecular dynamics simulations, the continuous function ( p(r) ) is replaced with a histogram on a grid:

[ p(r) = \frac{1}{N{\text{frame}}} \sumi^{N{\text{frame}}} \sum{j \in \text{sel1}} \sum{k \in \text{sel2}; k \neq j} \sum{\text{all } \kappa} d{\kappa}(r; r{ijk}) ]

where ( N{\text{frame}} ) is the number of frames, ( r{ijk} ) is the distance between atom ( j ) and atom ( k ) for frame ( i ), and ( d{\kappa} ) is a function that is ( 1/\Delta r ) if ( r{\kappa} \leq r \leq r{\kappa} + \Delta r ) and ( r{\kappa} \leq r{ijk} \leq r{\kappa} + \Delta r ), and 0 otherwise [4].

Table 1: Key Mathematical Functions in RDF Analysis

| Function | Mathematical Expression | Physical Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radial Distribution Function ( g(r) ) | ( g{ab}(r) = \frac{1}{Na} \frac{1}{Nb/V} \sum{i=1}^{Na} \sum{j=1}^{N_b} \langle \delta( | \mathbf{r}i - \mathbf{r}j | - r) \rangle ) | Probability density of finding particle b at distance r from particle a |

| Cumulative Distribution ( G(r) ) | ( G{ab}(r) = \int0^r dr' 4\pi r'^2 g_{ab}(r') ) | Integrated probability within radius r | ||

| Coordination Number ( N(r) ) | ( N{ab}(r) = \rho G{ab}(r) ) | Average number of b particles within radius r of a |

Computation from Molecular Dynamics Trajectories

Core Algorithm and Workflow

The calculation of radial distribution functions from molecular dynamics trajectory data involves a computationally expensive analysis task where the rate-limiting step is building a histogram of the distances between atom pairs in each trajectory frame [4]. The general algorithm involves:

- Selection of atom pairs from the groups of interest

- Distance calculation between all relevant atom pairs, accounting for periodic boundary conditions via the minimum image convention

- Histogram accumulation of these distances across multiple simulation frames

- Normalization of the histogram by the expected density of an ideal gas

The probability distribution ( p(r) ) is calculated as an average over a thermodynamic ensemble. In MD simulations, frames are chosen from trajectories sampling the thermodynamic ensemble of interest:

[ p(r) = \frac{1}{N{\text{frame}}} \sumi^{N{\text{frame}}} \sum{j \in \text{sel1}} \sum{k \in \text{sel2}; k \neq j} \delta(r - r{ijk}) ]

where ( \delta ) is the Dirac delta function, replaced in practice by a histogram binning function [4].

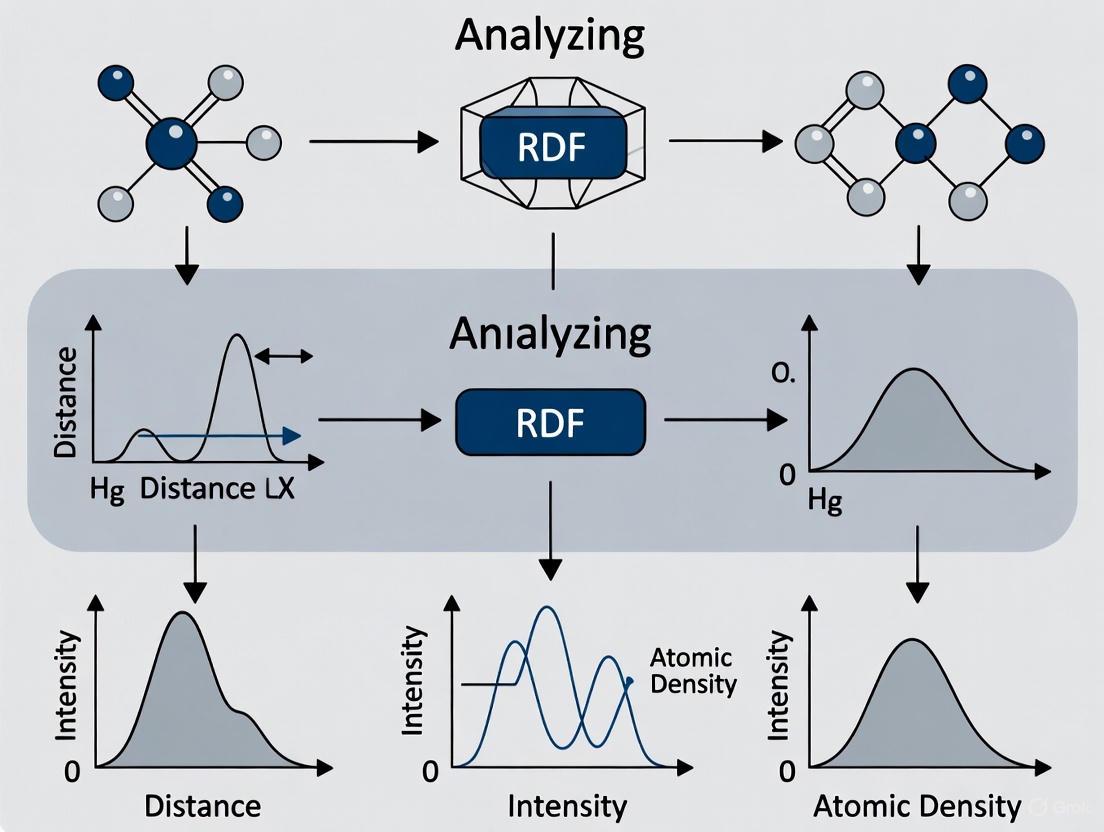

RDF Computation Workflow: Diagram illustrating the key steps in calculating radial distribution functions from molecular dynamics trajectories.

Accounting for Periodic Boundary Conditions

A critical aspect of RDF calculation in MD simulations is proper handling of periodic boundary conditions (PBC). Assuming the upper bound of the histogram is less than or equal to half the width of the periodic box, the distance ( r_{ijk} ) is calculated as the distance between atom ( j ) and the closest periodic image of atom ( k ) [4]. For example, the magnitude of the x-component of the shortest vector connecting atom ( j ) to a periodic image of atom ( k ) is given by:

[ |x{ijk}| = \begin{cases} |xk - xj| & \text{if } |xk - xj| \leq a/2 \ a - |xk - x_j| & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} ]

where ( xj ) and ( xk ) are the x-coordinates of atoms ( j ) and ( k ), and ( a ) is the length of the periodic box in the x-direction [4]. Similar calculations are performed for the y and z components, with the minimum distance then computed using the standard Euclidean formula.

Advanced Computational Implementations

Due to the computational expense of RDF calculations for large systems (O(N²) complexity), significant effort has been dedicated to optimizing these algorithms. State-of-the-art implementations leverage:

Graphics Processing Units (GPUs): Modern implementations utilize massive parallelism on GPUs, with specialized tiling schemes to maximize data reuse at the fastest levels of the GPU memory hierarchy [4]. The use of atomic memory operations allows the fast, limited-capacity on-chip memory to be used more efficiently, resulting in significant performance increases compared to versions without atomic operations [4].

Parallelization Strategies: Multi-GPU implementations with dynamic load balancing allow high performance on heterogeneous GPU configurations. One implementation running on four NVIDIA GeForce GTX 480 GPUs achieved a 92x speedup compared to a multithreaded CPU implementation [4].

Specialized Software Tools: Packages like MDAnalysis, VMD, LAMMPS, and OVITO provide optimized RDF analysis capabilities. For example, MDAnalysis offers both averaged and site-specific RDF implementations with various normalization options and exclusion capabilities to avoid counting correlated atoms within the same molecule [5] [6] [7].

RDF Analysis in Materials and Drug Development

Interpretation of RDF Features

The radial distribution function provides distinct signatures that characterize different states of matter and specific atomic-level interactions:

Liquids: Show decaying oscillatory behavior, with the first peak representing the first solvation shell, and subsequent peaks indicating higher-order coordination shells. The oscillations eventually dampen to a value of 1 at large distances, indicating no long-range order [3] [1].

Crystalline Solids: Exhibit sharp, well-defined peaks that extend to large distances, reflecting the long-range periodic order of the crystal lattice [1].

Gases: Display a single peak at small interatomic distances, with the RDF quickly approaching 1, reflecting the lack of structure in gaseous systems [3].

Glasses and Disordered Materials: Show broad peaks that typically decay within a few atomic diameters, indicating short-range order but no long-range periodicity [8].

Table 2: Characteristic RDF Features for Different Material Phases

| Material Phase | First Peak Characteristics | Long-Range Behavior | Coordination Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gas | Single broad peak at small r | Rapidly approaches g(r)=1 | Low and poorly defined |

| Liquid | Sharp first peak, broader subsequent peaks | Oscillations decay to g(r)=1 | Well-defined first shell |

| Amorphous Solid | Broadened peaks | Short-range order only (2-3 peaks) | Reasonably well-defined |

| Crystalline Solid | Sharp, narrow peaks | Long-range order (many peaks) | Precisely defined |

Applications in Drug Development and Biomolecular Systems

RDF analysis plays a crucial role in understanding molecular interactions relevant to drug development, particularly in studying solvation effects, binding processes, and specific molecular recognition events:

Solvation Studies: The RDF helps understand binding processes aided by solvent, providing insights into hydration shells around drug molecules and biomolecular targets [8]. Changes in RDF can indicate alterations in water-protein interactions, which are crucial for understanding ligand binding and biomolecular stability [8].

Hydrogen Bonding Analysis: In biological systems, RDF offers quantitative insight into hydrogen-bonded systems such as proteins and DNA [1]. The first peak between hydrogen (donor) and acceptor atoms (O-H or N-H groups) typically appears at 1.5-2.5 Å, with the intensity of this peak providing information about hydrogen bond strength and stability [1].

Protein-Ligand Interactions: Site-specific RDF analysis enables researchers to study solvation shells of ligands in binding sites or the solvation of specific residues in proteins [5] [6]. This provides atomic-level insights into interaction mechanisms and binding affinity.

Coordination Analysis: RDF between specific atom types (e.g., Si and O in MCM-41 wall structure) clarifies coordination states and structural uniformity, with implications for drug delivery systems and catalytic applications [8].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Computational Protocol Using MDAnalysis

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for calculating radial distribution functions using the MDAnalysis library in Python:

For site-specific RDF analysis, where individual atomic contributions are of interest:

Advanced Protocol with Exclusion Rules

For complex molecular systems, proper exclusion of directly bonded atoms and atoms within the same molecule is crucial for meaningful RDF interpretation:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for RDF Analysis

| Tool/Software | Application Context | Key Functionality |

|---|---|---|

| MDAnalysis | Python library for MD analysis | Provides InterRDF and InterRDF_s classes for RDF calculations with various normalization options and exclusion rules [5] [6] |

| VMD with GPU acceleration | Visualization and analysis of MD trajectories | Implements highly optimized multi-GPU RDF algorithms for large systems (up to 1,000,000 atoms) [4] |

| LAMMPS | MD simulation package | Built-in RDF computation during simulation runs for various particle types [3] |

| OVITO | Visualization and analysis | User-friendly RDF calculation with graphical interface [3] |

| GROMACS | MD simulation package | g_rdf program for RDF analysis from trajectories, integrated with Xmgrace for plotting [8] |

Relationship to Thermodynamic Properties and Advanced Applications

Connecting RDF to Macroscopic Properties

The radial distribution function serves as the fundamental link between microscopic structure and macroscopic thermodynamic properties. For a pure fluid, the RDF enables calculation of several key thermodynamic quantities:

Internal Energy: The energy can be obtained from the integral of the pair potential weighted by the RDF: [ E = \frac{3}{2}NkT + 2\pi\rho \int_0^{\infty} u(r) g(r) r^2 dr ] where ( u(r) ) is the pair potential [1].

Pressure: The equation of state follows from the virial theorem: [ P = \rho kT - \frac{2\pi\rho^2}{3} \int_0^{\infty} \frac{du(r)}{dr} g(r) r^3 dr ]

Compressibility: The isothermal compressibility relates to long-wavelength density fluctuations: [ \rho kT \kappaT = 1 + 4\pi\rho \int0^{\infty} [g(r) - 1] r^2 dr ]

These relationships demonstrate how the RDF bridges atomic-level interactions with measurable bulk properties, making it invaluable for predicting material behavior from molecular simulations [1].

Specialized Applications in Drug Development

RDF analysis provides critical insights for rational drug design through several specialized applications:

Hydration Shell Analysis: By calculating RDFs between drug molecules and water, researchers can characterize hydration patterns that influence solubility, permeability, and binding affinity. Changes in RDF peaks indicate alterations in water-drug interactions, which can be crucial for understanding formulation effects [8].

Binding Site Solvation: Site-specific RDF analysis around binding pockets reveals water structure and displacement energetics, informing the design of ligands with optimal binding characteristics. The RDF between protein atoms and water molecules identifies tightly bound water molecules that may mediate protein-ligand interactions [5].

Ion Coordination Studies: For ionizable drugs or metal-containing therapeutics, RDF analysis characterizes ion coordination environments and binding geometries, supporting the design of more effective metallodrugs and understanding their mechanism of action [8].

Polymer-Based Drug Delivery: RDF analysis of polymer-drug systems reveals molecular-level interactions that control drug loading and release kinetics, guiding the design of improved delivery systems [1].

The radial distribution function thus represents a fundamental analytical tool that connects molecular-level structural details with macroscopic material properties and biological functions, making it an indispensable component of modern molecular dynamics research in materials science and drug development.

The Radial Distribution Function (RDF), denoted as (g_{AB}(r)), is a fundamental structural descriptor in molecular simulation that quantifies how the density of particle type (B) varies as a function of distance from particle type (A) [9]. In molecular dynamics (MD) research, the RDF provides crucial insights into the spatial arrangement of atoms, molecules, and ions within a system, serving as a bridge between microscopic configurations and macroscopic thermodynamic properties [10]. This application note details the interpretation of RDF features—specifically peaks, valleys, and their structural significance—within the context of analyzing atomic structures from MD simulations, with particular relevance for researchers in structural biology and drug development.

The RDF is formally defined in GROMACS through the equation: [ g{AB}(r) = \frac{\langle \rhoB(r) \rangle}{\langle\rhoB\rangle{local}} = \frac{1}{\langle\rhoB\rangle{local}}\frac{1}{NA} \sum{i \in A}^{NA} \sum{j \in B}^{NB} \frac{\delta( r{ij} - r )}{4 \pi r^2} ] where (\langle\rhoB(r)\rangle) represents the particle density of type (B) at distance (r) from particles (A), and (\langle\rhoB\rangle{local}) is the average particle density of type (B) over all spheres around particles (A) with radius (r{max}) [9]. In MDAnalysis, this is implemented with equivalent physical meaning, calculating the probability of finding particle (B) at distance (r) from particle (A) compared to an ideal gas [5] [11].

Quantitative Interpretation of RDF Features

Characteristic Features and Their Structural Significance

The RDF profile contains specific features—peaks, valleys, and their properties—that directly correlate with the system's structural properties. Table 1 summarizes the quantitative relationships between RDF features and their structural interpretations, particularly for Lennard-Jones fluids, which serve as important reference systems [10].

Table 1: Structural Interpretation of RDF Features in Lennard-Jones Fluids

| RDF Feature | Structural Meaning | Quantitative Relationship | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Peak Position ((r_{peak})) | Most probable distance to nearest neighbors | Shorter (r) with increasing temperature [10] | Indicates strong repulsive/attractive force balance |

| First Peak Height ((g_{peak})) | Probability of finding neighbors at (r_{peak}) | (g{peak} = g{peak}(\rho^, \beta^)) [10] | Measures structural order/thermal motion |

| First Valley Position ((r_{valley})) | Boundary of first coordination shell | Integration limit for coordination number [10] | Defines nearest neighbor sphere |

| Coordination Number ((CN)) | Number of nearest neighbors | (CN = \int0^{r{valley}} 4\pi\rho r^2 g(r) dr) [10] | Quantifies local packing density |

For LJ fluids, empirical correlations connect RDF features to thermodynamic state variables. The height of the first peak follows: [ g{peak} = g{peak}(\rho^, \beta^) ] where (\rho^* = \rho\sigma^3) is the reduced density and (\beta^* = \epsilon/kBT) is the reduced inverse temperature [10]. Similarly, the position of the first peak (r{peak}^*) shows a deterministic relationship with the system's state point, enabling researchers to infer thermodynamic conditions from structural data alone [10].

Advanced Structural Descriptors Derived from RDF

Beyond the basic RDF, several derived quantities provide additional structural insights:

- Cumulative Distribution Function: (G{ab}(r) = \int0^r dr' 4\pi r'^2 g_{ab}(r')) provides the integral of the RDF up to distance (r) [5]

- Cumulative Coordination Number: (N{ab}(r) = \rho G{ab}(r)) gives the average number of (b) particles within radius (r) of an (a) particle [5]

- Angle-Dependent RDF: (g_{AB}(r,\theta)) extends structural analysis to anisotropic systems by incorporating orientation dependence [9]

The first minimum in the RDF ((r_1)) is particularly important as it defines the boundary of the first coordination shell, enabling calculation of coordination numbers for direct solvation analysis [5].

Experimental Protocols for RDF Analysis

Computational Methodology for RDF Calculation

The following protocol outlines the standard methodology for calculating and analyzing RDFs from molecular dynamics trajectories using modern analysis tools.

Figure 1: RDF Analysis Workflow from MD Trajectories

Protocol 1: RDF Calculation Using MDAnalysis

System Preparation: Define atom groups for analysis

- Select reference group (A) and target group (B)

- Consider chemical specificity (e.g., oxygen-oxygen, protein-ligand atoms)

Parameter Selection:

- Set histogram bins (

nbins=75typically sufficient) - Define distance range (

range=(0.0, 15.0)Å appropriate for most solvation shells) - Apply exclusion rules for bonded atoms (

exclude_same="residue")

- Set histogram bins (

Calculation Execution:

Normalization Method Selection:

- Use

norm='rdf'for standard (g_{ab}(r)) - Use

norm='density'for single particle density (n_{ab}(r)) - Use

norm='none'for raw particle counts [5]

- Use

Protocol 2: Site-Specific RDF Analysis

For detailed binding site analysis, particularly in drug discovery contexts:

Identify Specific Interaction Sites:

- Select ligand atoms and protein binding site residues

- Define multiple pairs for site-specific analysis:

ags = [[A1, B1], [A2, B2], ...]

Execute Site-Specific Calculation:

Access Individual Site Results:

- Results stored in

rdf_s.results.rdf[i]for i-th atom pair - Access specific interactions:

rdf_s.results.rdf[0][0, 0]for first atom in A1 with first atom in B1 [5]

- Results stored in

RDF Analysis in Force Field Validation

RDF analysis plays a critical role in force field validation and development. Table 2 showcases the application of RDF analysis in validating the GROMOS 54A8 force field, demonstrating how structural comparisons inform parameter refinement [12].

Table 2: RDF Analysis in GROMOS 54A8 Force Field Validation

| System Analyzed | RDF Application | Key Finding | Significance for Drug Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Electrolytes | Ion-ion vs ion-water RDFs | Good agreement for oligoatomic ions (acetate, methylammonium) | Improves accuracy of protein-ligand binding simulations |

| Protein Surface Residues | Solvation shell analysis | Charged residues more hydrated in 54A8 vs 54A7 | Enh prediction of solvent-exposed binding sites |

| Salt Bridge Formation | Interionic distance distributions | Equivalent in 54A7 and 54A8 parameter sets | Maintains stability of protein-protein interactions |

As demonstrated in GROMOS 54A8 validation, RDF analysis confirmed that "the side chains of arginine, lysine, aspartate, and glutamate residues appear slightly more hydrated and present a slight excess of oppositely-charged solution components in their vicinity" compared to its predecessor [12]. This precise structural insight is crucial for accurate prediction of binding affinities in drug design.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for RDF Analysis

| Tool/Solution | Function in RDF Analysis | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

GROMACS gmx rdf |

Calculates standard and angle-dependent RDFs | General biomolecular simulation analysis [9] |

| MDAnalysis InterRDF | Average RDF between two atom groups | Python-based analysis workflow [5] |

| MDAnalysis InterRDF_s | Site-specific RDF for detailed interactions | Ligand-binding site analysis [5] [11] |

| GROMOS 54A8 Force Field | Provides nonbonded parameters for charged groups | Accurate simulation of protein-ligand systems [12] |

| Lennard-Jones Reference Data | Empirical RDF-state point correlations [10] | Force field validation and calibration |

The precise interpretation of peaks, valleys, and structural features in radial distribution functions provides indispensable insights for molecular dynamics research in drug development. Through the protocols and quantitative relationships presented herein, researchers can extract meaningful structural information about solvation shells, binding sites, and molecular packing that directly informs therapeutic design. The integration of RDF analysis with modern force fields such as GROMOS 54A8 and computational tools like MDAnalysis creates a robust framework for advancing structural biology and rational drug design.

Connecting RDF to Thermodynamic Properties and System Energy

The radial distribution function (RDF), denoted as (g(r)), is a fundamental structural metric in statistical mechanics that describes how the density of particles varies as a function of distance from a reference particle [13] [2]. In the context of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which predict the trajectory of atoms over time based on a molecular mechanics force field [14] [15] [16], the RDF provides a bridge between the microscopic atomic structure of a system and its macroscopic thermodynamic properties [13] [2]. By statistically averaging the local particle density, the RDF reveals the short-range order and solvation shell structure in dense, disordered systems like liquids and solutions [13]. This structural information is critical because the thermodynamic state of a system is a direct consequence of the interactions and spatial arrangement of its constituent atoms [17] [16]. This article details the protocols and application notes for extracting thermodynamic properties and system energy from RDF analysis within MD research, with a particular focus on applications relevant to drug development, such as studying solvation and binding.

Theoretical Foundation: From Structure to Thermodynamics

Defining the Radial Distribution Function

The RDF, (g(r)), is defined as the ratio of the average local number density of particles at a distance (r), (\langle \rho (r) \rangle), to the bulk density of particles, (\rho) [13] [2]: [g(r) =\dfrac{\langle \rho (r) \rangle }{\rho}] In a typical dense fluid, (g(r)) is zero at the core (excluding the reference particle), rises to a peak at the distance of the first solvation shell, exhibits dampening oscillations at further distances, and finally approaches a value of 1, indicating a loss of correlation and a homogeneous fluid [13]. The probability of finding a particle in a spherical shell of thickness (dr) at distance (r) is given by (P(r) = 4 \pi r^{2} g(r) dr) [13].

Linking RDF to Energy and Thermodynamic Properties

The RDF provides a complete statistical description of the pair interactions in a system. This information can be used to compute several key thermodynamic properties, as the potential energy of the system is directly related to the interactions between particle pairs [2] [16]. The tables below summarize the core quantitative relationships.

Table 1: Fundamental RDF Definitions and Probability Measures

| Concept | Mathematical Formula | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Radial Distribution Function | (g(r) = \dfrac{\langle \rho (r) \rangle }{\rho}) [13] | Measures the influence of a central particle on the local density of its neighbors. |

| Pair Correlation Function | (g{ab}(r)= \left \langle \rho{ab}(r)\right \rangle /\rho) [13] | The RDF between different types of particles 'a' and 'b'. |

| Probability Density | (P(r)=4 \pi r^{2} g(r)\ \mathrm{d} r) [13] | The probability of finding a particle at a distance (r) in a shell of thickness (dr). |

Table 2: Key Thermodynamic Properties Derived from the RDF

| Property | Mathematical Relation | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Average Number of Particles | (N{ab}(r) = \rho \int0^r !!dr' 4\pi r'^2 g_{ab}(r')) [7] | Calculates coordination numbers, e.g., the number of water molecules in the first solvation shell of an ion. |

| Internal Energy (Dense Fluid) | ( U \approx \frac{N}{2} \rho \int_{0}^{\infty} 4\pi r^2 g(r) u(r) \, dr ) [2] (where (u(r)) is the pair potential) | The potential energy contribution from non-bonded interactions (Lennard-Jones and electrostatic) can be computed from (g(r)) and the force field's potential functions [16]. |

| Pressure (Virial Equation) | ( P = \rho kB T - \frac{\rho^2}{6} \int{0}^{\infty} 4\pi r^2 g(r) \, r \frac{du(r)}{dr} \, dr ) [2] | Relates system pressure to the derivative of the pair potential and the RDF. This is particularly sensitive to the repulsive part of the potential. |

| Structure Factor | ( S(k) = 1 + \rho \int d\vec{r} \, e^{-i\vec{k}\cdot\vec{r}} [g(r)-1] ) [2] | Connects the RDF to scattering experiments (X-ray, neutron), allowing for direct validation of simulation results. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Calculating RDFs from a Molecular Dynamics Trajectory

This protocol outlines the steps for calculating a site-specific radial distribution function using MDAnalysis, a common tool for analyzing MD simulation trajectories [7].

Objective: To determine the radial distribution function (g_{ab}(r)) between two groups of atoms (or molecules) from an MD simulation trajectory.

Software and Prerequisites:

- Software: MDAnalysis library (Python) installed [7].

- Inputs:

- A molecular dynamics trajectory file (e.g., in XTC, TRR, DCD format).

- A topology file (e.g., in GRO, PDB format) describing the system.

- An atom selection query for groups

AandB.

Procedure:

- Load the Trajectory and Topology:

- Select Atom Groups: Define the groups of atoms between which the RDF will be calculated. For example, to study solvation of a protein backbone, Group A could be protein backbone atoms, and Group B could be water oxygen atoms.

- Initialize the RDF Analysis Module:

Set up the

InterRDFanalyzer, specifying the two groups, the number of bins for the histogram (nbins), and the distance range (range) to analyze. - Run the Analysis:

Execute the analysis over the desired frames of the trajectory. Use the

start,stop, andstepparameters to control the analysis range for better statistical sampling or to manage computational cost. - Access and Plot Results:

The results are stored in

rdf_analyzer.bins(the bin centers) andrdf_analyzer.rdf(the (g(r)) values).

Interpretation of RDF Output:

- Peak Position: The location of the first major peak indicates the most probable distance to the first solvation shell.

- Peak Area/Height: The magnitude of the peak relates to the probability of finding a particle at that distance. The area under the first peak, when used in the cumulative distribution function (N_{ab}(r)), gives the coordination number [7].

- Number of Peaks: The presence of secondary peaks indicates longer-range order, typically observable in more structured liquids or near solid surfaces.

Workflow: From MD Simulation to Thermodynamic Properties

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for connecting an MD simulation to thermodynamic insights via RDF analysis, a process foundational to the protocols described.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Software and Analysis Tools for RDF-Based Research

| Item Name | Function / Application Note |

|---|---|

| GROMACS | A robust and widely used MD simulation suite that supports most major force fields. It is used for running the production MD simulations that generate the trajectories for RDF analysis [18]. |

| MDAnalysis | A Python library specifically designed for the analysis of MD trajectories. It contains built-in modules (MDAnalysis.analysis.rdf) for efficient calculation of both average and site-specific RDFs [7]. |

| CHARMM/AMBER Force Fields | Classical molecular mechanics force fields that provide the empirical parameters (bonded and non-bonded interactions) for the potential energy function ((U_N)) used in the MD simulation [15] [16]. |

| COMPASS Force Field | A force field used in MD simulations that enables accurate prediction of thermophysical properties, as demonstrated in studies of refrigerants like R-454B [17]. |

| VMD / PyMOL | Molecular visualization software used for visual inspection of the initial protein structure, rendered trajectories, and validation of atom selections used in RDF analysis [18] [15]. |

| PC-SAFT Equation of State | An advanced equation of state that can be parameterized using data from MD simulations (e.g., saturated density) to predict derivative thermodynamic properties like speed of sound and Joule-Thomson coefficients [17]. |

The Radial Distribution Function (RDF), typically denoted as g(r), is a fundamental statistical measure in molecular dynamics (MD) research that quantifies how particle density varies as a function of distance from a reference particle [19]. This function provides critical insights into the spatial arrangement and internal structure of materials, serving as a bridge between microscopic particle interactions and macroscopic thermodynamic properties. In molecular simulations, the RDF reveals the probability of finding a particle at a specific distance relative to the probability expected for a completely random distribution, such as in an ideal gas [19]. This makes it an indispensable tool for researchers and drug development professionals who need to characterize atomic-scale structural features that influence material behavior and binding interactions.

The power of RDF analysis lies in its ability to distinguish different states of matter through their characteristic signatures. By analyzing these signatures, scientists can infer important structural information such as coordination numbers, bonding distances, and degree of disorder within a system. Furthermore, the RDF serves as a crucial link to thermodynamic properties, enabling the calculation of system energy, pressure, and other parameters essential for understanding material behavior under different conditions [20]. For drug development applications, this structural understanding can inform decisions about molecular interactions, solvation effects, and binding affinities that are critical to pharmaceutical efficacy.

Theoretical Background: RDF Signatures Across Phases

Characteristic RDF Profiles

Each primary phase of matter exhibits a distinctive RDF signature that reflects its underlying structural organization, providing researchers with a diagnostic tool for material characterization:

Solid Phase: The RDF of crystalline solids displays sharp, well-defined peaks at specific distances that correspond to distinct coordination shells [19]. These peaks persist to large radial distances, indicating long-range order where the positions of atoms remain correlated over considerable distances. The number, position, and relative heights of these peaks reveal information about the crystal lattice type, coordination numbers, and bond lengths characteristic of the material's ordered structure.

Liquid Phase: Liquids exhibit a more complex RDF characterized by short-range order with diminishing correlations at larger distances [21]. The function typically shows several oscillating peaks that gradually decay to a constant value of 1, reflecting the transient local ordering of particles. The liquid state has been recently reinterpreted as a dynamic mixture of gas-like and solid-like states with alternating domination between these mechanisms [21]. This dual nature manifests in the RDF through features that suggest some residual local structure (solid-like) while lacking long-range periodicity (gas-like).

Gas Phase: In ideal or dilute gases, the RDF is essentially flat at a value of 1 for all distances beyond the immediate exclusion zone, indicating no structural correlation between particles [19]. For real gases at higher densities, a small peak may appear at the collision diameter due to intermolecular interactions, but the rapid decay to unity confirms the absence of sustained structural organization.

Table 1: Characteristic RDF Features Across Different Phases of Matter

| Phase | Short-Range Order | Long-Range Order | Peak Characteristics | Structural Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid | Yes | Yes | Sharp, well-defined peaks that persist | Regular, repeating lattice structure |

| Liquid | Yes | No | Damped oscillations that decay to unity | Local clustering without long-range correlation [21] |

| Gas | No | No | Flat at g(r)=1 (or minimal initial peak) | No structural correlation between particles |

Theoretical Interpretation of RDF Profiles

The theoretical foundation for understanding RDF profiles stems from statistical mechanics, where g(r) connects microscopic particle interactions to macroscopic observables. In solids, the persistent oscillatory behavior in g(r) reflects the mathematical periodicity of the lattice structure, with peak positions corresponding to rational interatomic distances dictated by the crystal symmetry. The progressive damping of peak intensities with increasing distance arises from thermal vibrations and defects that slightly disrupt perfect periodicity.

In liquids, the theoretical interpretation is more complex due to the dynamic nature of the phase. The prominent first peak in the RDF corresponds to the first solvation shell, representing the most probable distance between neighboring particles. Subsequent peaks indicate second and third coordination shells, with the rapid decay of these peaks demonstrating how particle correlations diminish over distance. Recent research suggests this behavior reflects the compromise in competition between potential energy and kinetic energy in the system, where molecules transiently occupy both localized (solid-like) and delocalized (gas-like) states [21].

For gases, the theoretical expectation of a flat RDF profile derives from the assumption of minimal intermolecular interactions except during brief collision events. The theoretical connection between the RDF and thermodynamic properties enables researchers to extract quantitative information about system energy, pressure, and equation of state parameters through integral equations that relate pair distribution functions to intermolecular potentials.

Computational Protocols for RDF Analysis

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Setup

The accurate calculation of radial distribution functions requires careful implementation of molecular dynamics simulations with appropriate parameters and conditions:

System Preparation: Begin with an initial configuration of particles in a simulation box with periodic boundary conditions applied in all three dimensions to minimize surface effects. For solids, this may be a perfect crystal lattice; for liquids, a randomized configuration; and for gases, a sparse random distribution.

Force Field Selection: Choose appropriate interatomic potentials based on the system under investigation. For argon or other simple fluids, the Lennard-Jones potential is commonly employed with parameters (σ = 3.405 Å, ε = 119.8 K) that accurately reproduce physical behavior [21]. For molecular systems, more complex force fields incorporating bond stretching, angle bending, and torsion terms may be necessary.

Equilibration Protocol: Conduct an extensive equilibration procedure to ensure the system reaches thermodynamic equilibrium before data collection. This typically involves:

- Energy minimization to remove bad contacts

- Gradual heating to the target temperature over 50-100 ps

- Extended equilibration (100-500 ps) in the NVT ensemble using a Nosé-Hoover thermostat

- Further equilibration (100-500 ps) in the NPT ensemble using a Parrinello-Rahman barostat to achieve correct density

Production Run: Perform extended sampling in the NVE or NVT ensemble for 1-10 ns with a time step of 1-2 fs, saving trajectory frames every 1-10 ps for subsequent analysis. Longer simulations may be required for systems with slow dynamics or rare events.

RDF Calculation Methodology

The radial distribution function is calculated from MD trajectories using a histogram-based approach that accumulates pair distances over multiple simulation frames:

Distance Binning: Define a histogram with bins of width Δr (typically 0.01-0.05 Å) covering the range from 0 to Rmax (usually half the box length to obey the minimum image convention).

Pair Distance Sampling: For each reference particle i, compute distances rij to all other particles j ≠ i within the cutoff radius, excluding pairs where j is a periodic image of i.

Histogram Accumulation: For each configuration analyzed, accumulate the count of particle pairs found within each spherical shell between r and r+Δr:

Table 2: RDF Calculation Parameters for Different Phases

Parameter Solid Phase Liquid Phase Gas Phase Bin Width (Δr) 0.01-0.02 Å 0.02-0.05 Å 0.05-0.1 Å Maximum Radius (Rmax) L/2 L/2 L/2 Number of Configurations 100-1000 500-5000 1000-10000 Sampling Frequency Every 10-100 fs Every 50-500 fs Every 100-1000 fs Normalization: Normalize the accumulated histogram by the expected count for an ideal gas with the same density:

g(r) = [n(r) / V(r)] / ρ

where n(r) is the histogram count between r and r+Δr, V(r) = 4πr²Δr is the volume of the spherical shell, and ρ = N/V is the number density of the system.

Averaging: Average the g(r) over multiple time frames and over all particles in the system to improve statistics, particularly important for disordered systems like liquids and gases where thermal fluctuations significantly impact local structure.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete RDF analysis protocol from simulation setup to final interpretation:

Application Notes: Structural Analysis Through RDF

Quantitative Structural Metrics from RDF

The radial distribution function provides several quantitative metrics that enable detailed structural analysis of different phases:

Coordination Numbers: The area under the first peak of g(r) yields the average number of nearest neighbors:

CN = 4πρ ∫₀^(r_min) r²g(r)dr

where r_min is the position of the first minimum after the initial peak. This coordination number distinguishes local packing efficiency across phases, with solids typically showing higher, integer values (e.g., 12 for FCC), liquids having intermediate values (e.g., 10-11 for simple liquids), and gases showing minimal coordination.

Peak Positions and Intensities: The location of the first peak (r_max) indicates the most probable interparticle distance, reflecting the balance between attractive and repulsive intermolecular forces. Peak height correlates with structural stability, with sharper, more intense peaks indicating more well-defined coordination shells.

Structural Parameters for Different Phases of Argon:

Table 3: Structural Parameters for Argon at 85 K (Solid), 110 K (Liquid), and 150 K (Gas) at 1 bar

Parameter Solid (FCC) Liquid Gas First Peak Position (Å) 3.76 3.72 ~5.2 (weak) First Peak Height 3.8-4.5 2.5-3.2 ~1.1 Coordination Number 12 10.5-11.2 <1 Long-Range Order Yes No No

Advanced RDF Applications in Material Characterization

Beyond basic structural assessment, RDF analysis supports several advanced material characterization applications:

Phase Transitions: Monitoring changes in g(r) during temperature or pressure variations provides direct evidence of phase transitions [19]. The melting of a solid manifests as a disappearance of long-range peaks in g(r), while vaporization leads to complete loss of oscillatory structure. Recent research has utilized the temperature dependence of RDF profiles to quantify the gas-like fraction in liquids, revealing the dynamic equilibrium between different molecular states [21].

Liquid State Analysis: The complex nature of liquids makes RDF analysis particularly valuable for this phase. By applying the two-phase model (2PT) that divides liquid into solid-like and gas-like components, researchers can calculate thermodynamic properties including entropy and free energy [21]. The gas-like fraction can be determined through careful analysis of the RDF profile and its evolution with temperature.

Material Properties Prediction: The RDF serves as input for calculating various thermodynamic properties through statistical mechanical relationships. The system energy can be obtained through:

U = (3/2)NkT + 2πNρ ∫₀^∞ g(r)u(r)r²dr

where u(r) is the pair potential. Similarly, pressure can be calculated using the virial equation incorporating g(r). These relationships enable researchers to connect structural information to macroscopic material behavior.

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of RDF analysis requires appropriate computational tools and theoretical frameworks:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for RDF Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | MD Software | High-performance molecular dynamics simulator | Primary simulation engine for trajectory generation |

| GROMACS | MD Software | Molecular dynamics package with optimized algorithms | Alternative simulation platform, especially for biomolecules |

| VMD | Analysis Tool | Visualization and analysis of molecular trajectories | RDF calculation, structure visualization, and trajectory analysis |

| MDAnalysis | Python Library | Toolkit for trajectory analysis and data processing | Custom RDF analysis workflows and batch processing |

| Lennard-Jones Potential | Force Field | Simple pair potential for spherical particles | Modeling noble gases (e.g., argon) and simple fluids [21] |

| Two-Phase Model (2PT) | Theoretical Framework | Separates liquid into solid-like and gas-like components | Calculating entropy and free energy of liquids [21] |

| Hypernetted Chain Closure | Integral Equation Theory | Approximate closure relation for Ornstein-Zernike equation | Calculating RDF from pair potentials without simulation |

Radial distribution function analysis represents a powerful methodology for characterizing atomic-scale structure across different phases of matter within molecular dynamics research. The distinctive RDF signatures of solids, liquids, and gases provide fundamental insights into their structural organization, from the long-range order in crystals to the dynamic mixture of states in liquids [21]. The protocols outlined in this application note provide researchers with a comprehensive framework for implementing RDF analysis, from careful simulation setup through to advanced structural interpretation.

For drug development professionals, these techniques offer valuable approaches for understanding molecular interactions, solvation environments, and binding phenomena at atomic resolution. The continuing development of more sophisticated analysis methods, including improved definitions of gas-like fractions in liquids and more accurate integral equation theories, promises to further enhance the utility of RDF analysis in materials science and pharmaceutical research.

The Crucial Role of RDF in Characterizing Molecular Interactions and Hydrogen Bonding

The Radial Distribution Function (RDF), often denoted as g(r), serves as a fundamental statistical measure in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for quantifying the probability of finding particle pairs separated by a distance r. This function provides a powerful bridge between microscopic atomic arrangements and macroscopic observable properties, offering unique insights into the structure of liquids, amorphous materials, and biological systems. For researchers investigating molecular interactions, the RDF is particularly indispensable for identifying and characterizing hydrogen bonding networks that govern the stability, dynamics, and function of biomolecular systems and complex liquid mixtures [22] [23].

In the broader context of analyzing atomic structure from MD research, RDF analysis transforms complex, time-evolving atomic coordinates into statistically robust, quantitative structural descriptors. This enables direct comparison with experimental techniques like X-ray and neutron diffraction, making MD simulations a validated "computational microscope" with exceptional resolution for observing atomic-scale phenomena that are often difficult or impossible to access experimentally [23].

Theoretical Foundation of RDF

Mathematical Formalism and Physical Interpretation

The RDF is formally defined through the relationship between the local number density of particles at a distance r from a reference particle and the global average number density of the system. For a three-dimensional system, the RDF, g(r), is calculated as:

g(r) = (1/(4πr²ρN)) · Σ Σ δ(r - rᵢⱼ)

where ρ represents the global particle number density, N is the total number of particles, and rᵢⱼ is the distance between particles i and j. The double summation is performed over all particle pairs and multiple time frames from the MD trajectory to ensure statistical significance.

The characteristic profile of an RDF plot provides immediate insights into the physical state and structural order of the system. Crystalline solids exhibit sharp, periodic peaks extending to large distances, reflecting their long-range ordered lattice arrangements. Liquids and amorphous materials display broadened peaks that decay to unity within a few molecular diameters, indicating only short-range order. In the gas phase, where atomic interactions are minimal, the RDF remains close to 1 across all distances, confirming the absence of significant structural correlation [23].

Quantitative Structural Parameters from RDF

The RDF enables extraction of precise quantitative parameters that characterize atomic-scale environments. The following table summarizes key structural information obtainable from RDF analysis:

Table 1: Quantitative Structural Parameters Derived from RDF Analysis

| Parameter | Description | Extraction Method | Structural Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Positions | Distances corresponding to high coordination probability | Local maxima in g(r) plot | Characteristic interatomic distances (e.g., first coordination shell) |

| Coordination Number | Average number of particles within a specific distance | Integral of 4πr²ρg(r) between limits r₁ and r₂ | Quantifies local packing density and solvation |

| Peak Intensity | Relative probability at specific distances | Height of g(r) peaks | Strength and specificity of interactions at distance r |

| Peak Width | Distribution of interatomic distances | Full width at half maximum (FWHM) of peaks | Structural flexibility and thermal disorder |

Integration of the RDF up to the first minimum provides the coordination number, representing the average number of neighboring particles within the first coordination shell. This parameter is particularly valuable for quantifying solvation environments and local packing densities in disordered systems [23].

RDF in Hydrogen Bonding Analysis

Characterizing Hydrogen Bond Networks

Hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) play a vital role in the stability and functioning of biomolecules, influencing protein folding, molecular recognition, and material properties. RDF analysis provides a powerful methodology for investigating the structure and dynamics of these intricate hydrogen-bonded networks. By calculating site-specific RDFs between donor (D) and acceptor (A) atoms—such as O-H∙∙∙O, N-H∙∙∙O, or O-H∙∙∙N pairs—researchers can identify characteristic H-bonding distances and quantify their relative prevalence under different conditions [22].

In complex multi-component systems, RDFs enable comparative analysis of competing molecular interactions. A study on alcohol-aniline mixtures demonstrated this capability effectively, where RDF analysis revealed the predominance of OH∙∙∙O interactions over other possible hydrogen bonds. The research further showed a "bunching of alcohol-alcohol hydrogen bonds for lower aniline concentrations, while the aniline-aniline interactions are not affected by changes in the concentration," highlighting how RDF can decipher subtle reorganization within hydrogen-bonded networks in response to changing composition [22].

Integrating RDF with Complementary Analysis Techniques

For comprehensive characterization of hydrogen bonding, RDF is typically integrated with other analytical methods:

- Hydrogen Bond Statistics: Counting specific donor-acceptor pairs within geometrically defined criteria (typically distance and angle cutoffs) to determine H-bond populations and lifetimes [22].

- Graph Theoretical Analysis (GTA): Representing hydrogen-bonded systems as mathematical graphs where atoms are nodes and H-bonds are edges, enabling analysis of network connectivity, cyclic structures, and stability using tools like the Python package NetworkX [22].

This multi-technique approach, centered around RDF analysis, provides both quantitative and topological insights into hydrogen-bonded assemblies, linking molecular-level interactions to macroscopic system properties.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Setup

The following workflow outlines the key steps for performing MD simulations to generate trajectories for RDF analysis, with specific protocols for system preparation:

Figure 1: Comprehensive workflow for MD simulations from initial structure preparation to trajectory analysis for RDF calculation.

A. Initial System Preparation

- Obtain Protein Coordinates: Download the initial structure from the Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/). Visually inspect the structure using molecular visualization tools like RasMol [18].

- Structure Preprocessing: Use a text editor to remove external water molecules and non-standard ligands. For missing atoms or residues, employ modeling tools such as Modeller or PepBuild [18].

- Force Field Selection and Topology Generation: Convert the PDB file to a GROMACS format (.gro) and generate a topology file (.top) using the

pdb2gmxcommand: During this step, select an appropriate force field (e.g.,ffG53A7in GROMACS 5.1 for proteins with explicit solvent) [18].

B. Simulation System Setup

- Define Simulation Box: Create a periodic boundary condition box around the protein using the

editconfcommand. A cubic box with a minimum 1.4 nm distance from the protein periphery is commonly used: The-cflag centers the protein in the box [18]. - Solvation: Add water molecules to solvate the simulation box using the

solvatecommand: This updates the topology file to include water molecules [18]. - System Neutralization: Add counter ions to neutralize the system charge using the

genioncommand. First, generate a pre-processed input file withgrompp, then rungenion: This adds sodium (NA) and chloride (CL) ions as needed to achieve overall charge neutrality [18].

C. Energy Minimization and Equilibration

- Energy Minimization: Perform energy minimization to remove steric clashes and unfavorable contacts using the

mdruncommand: - System Equilibration: Equilibrate the system in two phases—first with position restraints on heavy atoms under NVT conditions (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature), followed by NPT equilibration (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) to achieve proper density.

D. Production Simulation and Analysis

- Production MD Run: Execute a production simulation without restraints to generate the trajectory for analysis. The simulation should be sufficiently long to ensure proper sampling of the phenomena of interest.

- Trajectory Analysis: Extract structural and dynamic properties, including RDF calculations, from the saved trajectory frames [18].

RDF Calculation Protocol

The specific protocol for calculating RDF from MD trajectories using GROMACS involves:

- Trajectory Preparation: Ensure the trajectory file is properly formatted and, if necessary, corrected for periodic boundary conditions using the

trjconvcommand. - RDF Calculation: Use the

rdfanalysis module in GROMACS to compute the radial distribution function between selected atom groups: This example calculates the RDF of water oxygen atoms around protein atoms. - Site-Specific RDF for H-Bonds: To analyze hydrogen bonding, calculate site-specific RDFs between donor and acceptor atoms. For example, to study hydrogen bonding between alcohol and aniline molecules, compute RDFs between hydroxyl hydrogen (H) of alcohol and nitrogen (N) of aniline, and between hydroxyl oxygen (O) of alcohol and amine hydrogen (H) of aniline [22].

Essential Software and Analysis Packages

Successful implementation of MD simulations and RDF analysis requires a suite of specialized software tools. The following table details key research reagent solutions in the computational domain:

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for MD Simulations and RDF Analysis

| Tool Name | Type/Category | Primary Function | Application in RDF Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [18] | MD Simulation Suite | High-performance MD simulation engine | Generates atomic trajectories for RDF calculation; contains built-in rdf analysis tool |

| VMD [22] | Molecular Visualization | Trajectory visualization and analysis | Visualizing hydrogen bond networks; preliminary analysis |

| Python | Programming Language | Custom analysis scripting | Implementing specialized RDF calculations; data processing |

| NetworkX [22] | Python Library | Graph theory analysis | Analyzing topology of hydrogen-bonded networks |

| MDAnalysis [24] | Python Library | Trajectory analysis | Flexible RDF calculations and integration with other analyses |

| MDTraj [24] | Python Library | Trajectory analysis | Fast RDF calculations supporting multiple MD formats |

Hardware Considerations

The computational demands of MD simulations vary significantly based on system size and simulation duration:

- Initial Setup and Preprocessing: A desktop workstation with multicore processors (e.g., Intel Core i5/i7), 16+ GB RAM, and standard graphics cards is sufficient for system setup, minimization, and equilibration [18].

- Production MD and Analysis: For production runs of biologically relevant systems, high-performance computing (HPC) resources with many cores (100+), large memory (128+ GB), and fast interconnects are typically required to achieve microsecond timescales in reasonable wall-clock time [18].

Advanced Applications and Integration

The application of RDF extends beyond simple structural characterization to advanced analysis of dynamic processes and material properties. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) can be applied to MD trajectories to extract essential collective motions from the high-dimensional coordinate data. When combined with RDF analysis, this approach helps link large-scale conformational changes to specific alterations in local atomic environments and hydrogen-bonding patterns [23].

Furthermore, RDF serves as a critical validation metric for comparing simulation results with experimental data. The direct relationship between RDF and experimentally accessible structure factors from X-ray or neutron diffraction makes it an essential tool for assessing force field accuracy and simulation reliability [23]. This validation is particularly crucial when studying hydrogen-bonded networks in binary mixtures or biomolecular systems, where accurate representation of interaction energies is essential for predictive simulations [22].

The integration of graph theoretical analysis with RDF represents a particularly powerful approach for characterizing hydrogen-bonded networks. By representing atoms as nodes and hydrogen bonds as edges, researchers can apply mathematical graph theory to quantify network connectivity, identify cyclic structures, and calculate stability metrics, providing a comprehensive topological perspective that complements the spatial statistics derived from RDF analysis [22].

Practical Implementation: Calculating RDF from MD Simulations and Biomedical Applications

Step-by-Step RDF Calculation Using MDAnalysis and LAMMPS

The Radial Distribution Function (RDF), denoted as (g(r)), is a fundamental statistical mechanics concept that characterizes the spatial arrangement of particles in a system. It describes the probability of finding a particle at a specific distance from a reference particle, providing crucial insights into the structure of liquids, ordered crystals, and disordered materials [1]. In molecular dynamics (MD) research, particularly in drug development, RDF analysis serves as an essential bridge between microscopic molecular interactions and macroscopic thermodynamic properties, enabling researchers to understand solvation shells, hydrogen bonding patterns, and ligand-protein interactions at atomic resolution [1].

The RDF effectively counts the average number of b neighbours in a shell at distance r around an a particle and represents it as a density [5]. Mathematically, for particles of type a and b, the RDF (g_{ab}(r)) is defined as:

[ g{ab}(r) = \frac{1}{N{a}} \frac{1}{N{b}/V} \sum{i=1}^{Na} \sum{j=1}^{Nb} \langle \delta(|\mathbf{r}i - \mathbf{r}_j| - r) \rangle ]

which normalizes to 1 for large separations in a homogeneous system [5] [9]. The RDF's value lies in its ability to quantify structural features that directly influence thermodynamic properties including internal energy, pressure, chemical potential, and entropy [1].

Theoretical Foundation of RDF Analysis

Key Mathematical Formulations and Structural Interpretations

The radial distribution function provides a quantitative measure of local structure against the background of a global average. When (g(r) = 1), the local density at distance (r) equals the bulk density, indicating no special structural organization. Peaks in the RDF indicate distances where neighboring atoms are more likely to be found (coordinated shells), while troughs indicate excluded dis[tances [1].

The coordination number, representing the average number of particles within a specific radius, can be derived from the RDF through the radial cumulative distribution function and the relation (N{ab}(r) = \rho G{ab}(r)), where (\rho) is the appropriate density and (G{ab}(r)) is the cumulative integral of (g{ab}(r)) [5]. This is particularly valuable for identifying solvation shell occupancies in drug-binding studies.

Table 1: Characteristic RDF Features Across Material Phases

| Phase | RDF Profile Characteristics | Structural Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Crystalline Solids | Sharp, distinct peaks extending to large distances | Long-range ordered atomic arrangement |

| Liquids | Damped oscillatory profile with 2-3 visible peaks | Short-range order with no long-range correlation |

| Gases | Single peak at short distance, quickly approaching 1 | Minimal structural correlation beyond direct collisions |

RDF Connections to Thermodynamic Properties and Drug Development

For pharmaceutical researchers, the RDF provides critical insights into intermolecular interactions that govern drug efficacy and binding affinity. The hydrogen bond interactions essential for protein folding and protein-ligand recognition manifest as distinct peaks in the 1.5–2.5 Å range in RDF plots between donor and acceptor atoms [1]. Analysis of these specific RDF signatures enables quantitative characterization of binding site interactions and solvation effects, directly informing rational drug design approaches.

Computational Approaches for RDF Calculation

Multiple computational packages can calculate RDFs from molecular dynamics trajectories, each with distinct strengths and applications. The choice of software often depends on the simulation engine used, system size, and specific analysis requirements.

Table 2: Computational Tools for RDF Analysis from MD Simulations

| Software Tool | Primary Use Case | Key Features | Trajectory Format Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDAnalysis | Analysis of massive trajectories [25] | Rich analysis tools, Python API, periodic boundary condition handling | LAMMPS dump, AMS, GROMACS, CHARMM, AMBER |

| LAMMPS compute rdf | On-the-fly analysis during simulation [26] | Built-in computation, minimal storage requirements, coordination number output | Native LAMMPS trajectories |

| AMS Trajectory Analysis | AMS or GCMC simulation analysis [27] | Integration with AMS package, convergence checking | AMS .rkf format |

| MDTraj | Small trajectories, quick analyses [25] | NumPy integration, straightforward API | Multiple formats including LAMMPS |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for RDF Calculations

| Reagent Solution | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Distance Calculation Engine | Computes pairwise distances between atoms with PBC consideration | MDAnalysis distances module, LAMMPS neighbor lists |

| Histogramming Algorithm | Bins distances into radial shells for probability distribution | NumPy histogram, LAMMPS binning with Nbin parameter |

| Normalization Routine | Converts raw counts to probability density relative to bulk | Volume normalization by spherical shell volume |

| Exclusion Handling | Prevents counting of correlated atoms (bonded pairs) | exclusion_block in MDAnalysis, special_bonds in LAMMPS |

| Trajectory Reader | Parses MD trajectory frames for sequential analysis | MDAnalysis Universe, LAMMPS dump commands |

Protocol 1: RDF Calculation with MDAnalysis

Experimental Setup and Workflow

Diagram Title: MDAnalysis RDF Calculation Workflow

Step-by-Step Implementation

Load Trajectory and Structure Files

Select AtomGroups for Analysis

Configure and Run InterRDF Analysis

Access and Visualize Results

Advanced Configuration Parameters

Table 4: MDAnalysis InterRDF Configuration Parameters

| Parameter | Type | Default | Description | Recommended Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

nbins |

Integer | 75 | Number of histogram bins | 100-200 for high resolution |

range |

Tuple | (0.0, 15.0) | Distance range in Ångströms | System size-dependent |

norm |

String | 'rdf' | Normalization mode: 'rdf', 'density', or 'none' | 'rdf' for standard analysis |

exclusion_block |

Tuple | None | Prevents counting atoms from same residue/molecule | (1,1) for molecular exclusion |

exclude_same |

String | None | Excludes same residue/segment/chain | 'residue' for intramolecular exclusion |

Protocol 2: RDF Calculation with LAMMPS

Experimental Setup and Workflow

Diagram Title: LAMMPS RDF Calculation Workflow

Step-by-Step Implementation

Basic RDF Calculation for All Atom Types

This computes the RDF with 100 bins and outputs every 10 steps averaging over 1000 steps.

Specific Atom Type Pair RDF Analysis

Advanced Configuration with Cutoff Control

Output Interpretation and Key Considerations

LAMMPS compute rdf generates a global array with the bin coordinates followed by RDF and coordination number values for each specified atom type pair [26]. The output columns follow this structure:

Table 5: LAMMPS RDF Output Format Description

| Column Index | Content | Units | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bin center | Distance units | Center of radial bin |

| 2 | g(r) for pair 1 | Unitless | RDF for first atom type pair |

| 3 | coord(r) for pair 1 | Number | Coordination number for first pair |

| 4 | g(r) for pair 2 | Unitless | RDF for second atom type pair |

| 5 | coord(r) for pair 2 | Number | Coordination number for second pair |

Critical Implementation Notes:

- For bonded systems, adjust

special_bondssettings or usereruncommand to include excluded pairs [26] - When using

cutoffkeyword > force cutoff, ensure proper ghost atom communication withcomm_modify cutoff[26] - Use wildcard asterisks for type ranges (e.g.,

1*3for types 1-3) for efficient analysis of multiple type pairs

Data Analysis and Interpretation Protocol

Quantitative Analysis of RDF Features

Identifying Solvation Shells

- Locate the first maximum in g(r) → position of first solvation shell

- Locate the first minimum after the peak → boundary of first solvation shell

- Calculate coordination number at first minimum → occupancy of solvation shell

Coordination Number Calculation

Validation and Error Analysis

- Convergence Testing

Table 6: Troubleshooting Common RDF Calculation Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Unphysical spikes in g(r) | Counting bonded atoms | Implement exclusion_block or adjust special_bonds |

| g(r) not reaching 1 at large r | Insufficient sampling | Increase trajectory frames or simulation time |

| Inconsistent coordination numbers | Incorrect density normalization | Verify system volume and particle counts |

| High noise in RDF profile | Inadequate ensemble averaging | Increase sample frames or use longer simulation |

Application in Drug Development Research

Case Study: Protein-Ligand Binding Analysis

RDF analysis provides critical insights into drug binding mechanisms through:

Hydration Shell Analysis: Calculate RDF between ligand atoms and water oxygen to identify tightly bound water molecules that mediate protein-ligand interactions.

Direct Interaction Quantification: Compute RDF between ligand functional groups and protein binding site residues to identify and quantify specific interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts).

Solvent Accessibility: Use RDF to characterize changes in solvent structure upon ligand binding, informing entropy contributions to binding free energy.

Protocol for Binding Site Water Analysis

This protocol has detailed comprehensive methodologies for calculating and analyzing radial distribution functions using both MDAnalysis and LAMMPS. Key recommendations for robust RDF analysis in pharmaceutical research include:

Convergence Validation: Always perform block averaging to ensure sufficient sampling, particularly for structured systems like protein-ligand complexes.

Appropriate Exclusion Settings: Carefully exclude bonded atom pairs to avoid unphysical correlations while maintaining relevant intermolecular interactions.

Coordination Number Integration: Use the cumulative distribution function to translate RDF profiles into quantitative coordination numbers for direct comparison with experimental data.

Multi-Software Validation: For critical results, consider implementing parallel analysis with both MDAnalysis and LAMMPS to verify methodological consistency.

The RDF remains an indispensable tool in molecular dynamics research, providing fundamental insights into atomic-scale structure that directly connects to macroscopic properties and biological function in drug development applications.

Selection Strategies for Reference and Target Atom Groups

In molecular dynamics (MD) research, the radial distribution function (RDF) is a fundamental tool for quantifying the structure of materials and biomolecular systems. It describes how atoms are spatially distributed around a reference atom as a function of radial distance r, providing insights into local ordering, solvation shells, and material phase states [23] [3]. The validity of RDF analysis depends critically on the appropriate selection of reference and target atom groups, as improper selection can lead to physically meaningless results or the obscuring of relevant structural features. This protocol provides comprehensive guidance for defining these atom groups across diverse research scenarios, enabling researchers to extract maximum insight from their MD simulations.

Table 1: Core Definitions for RDF-Based Analysis

| Term | Definition | Role in RDF Calculation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Atom Group | The initial set of atoms from whose perspective the local structure is probed. | Defines the center points around which spherical shells are constructed for counting neighboring atoms. | ||

| Target Atom Group | The set of atoms whose density distribution around the reference atoms is being measured. | Provides the "neighbor" atoms counted within the spherical shells centered on each reference atom. | ||

| RDF (gₐb(r)) | The probability of finding a target atom at distance r from a reference atom, normalized by the bulk density [5]. |

`gₐb(r) = (1/Nₐ) × (1/(Nբ/V)) × ΣΣ⟨δ( | rᵢ - rⱼ | - r)⟩` where Nₐ and Nբ are the numbers of reference and target atoms, respectively [5]. |

Atom Selection Syntax Across Common MD Packages

Different MD analysis packages implement similar but syntactically distinct atom selection languages. Understanding these differences is crucial for implementing portable and reproducible analysis protocols.

Table 2: Atom Selection Syntax Comparison Across MD Analysis Packages

| Selection Type | CHARMM | MDAnalysis | MDTraj |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Atoms | SELE PROT END |

"protein" |

"protein" |

| Backbone Atoms | SELE BACKBONE END |

"backbone" |

"backbone" |

| Residue Name | SELE RESNAME LYS END |

"resname LYS" |

"resname LYS" |

| Atom Name | SELE NAME CA END |

"name CA" |

"name CA" |

| Range Query | SELE RESID 10 20 END |

"resid 10:20" or "resid 10-20" |

"resid 10 to 20" |

| Boolean Logic | SELE PROT .AND. ( .NOT. RESNAME ALA ) END |

"protein and not resname ALA" |

"protein and not resname ALA" |

| Geometric | Not standard | "around 3.5 protein" |

"water and within 0.5 of resname LYS" (different implementation) |

Strategic Selection for Common Research Scenarios

The appropriate strategy for selecting reference and target groups depends fundamentally on the research question. The following scenarios illustrate proven approaches for different scientific contexts.

Table 3: Selection Strategies for Common Research Scenarios

| Research Scenario | Reference Group | Target Group | Key Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ion Solvation Shell | Specific ion type (e.g., "resname NA" or "type NA") |

Solvent atoms (e.g., "water" or "name OW" for water oxygen) |

Hydration number, ion-oxygen distance, shell stability [23] |

| Protein Hydration | Protein surface atoms (e.g., "protein and not name H*") |

Water oxygen atoms (e.g., "water and name O") |

Solvent-accessible surface area, binding site water occupancy |

| Membrane-Protein Interface | Protein transmembrane residues (requires specific resid selection) | Lipid headgroup atoms (e.g., "resname POPC and name P" for phosphate) |

Lipid binding sites, annular vs. non-annular lipid interactions |

| Alloy Local Ordering | One metal element (e.g., "type Al") |

Another metal element (e.g., "type Ni") |

Short-range ordering, compound formation tendencies, clustering |

| Polymer Sidechain Interactions | Specific sidechain atoms (e.g., "resname PHE and name CZ") |

Another polymer segment (e.g., "backbone and name O") |

Intra- vs. inter-molecular contacts, driving forces for folding |

Atom Selection Workflow for RDF Analysis

Detailed Experimental Protocol for RDF Analysis

System Preparation and Preprocessing

Before calculating RDFs, proper trajectory preprocessing is essential to remove global motions that would otherwise obscure the local structure information contained in RDFs.

- Trajectory Alignment: Fit each frame of the trajectory to a reference structure to remove rotational and translational degrees of freedom. This is particularly critical for biomolecular systems where global tumbling would otherwise dominate the apparent atomic displacements [28].

- Periodic Boundary Condition Handling: Ensure continuous coordinates across periodic images. Most modern RDF implementations automatically account for periodic boundaries, but verification is recommended [28].

- Trajectory Formatting for Analysis: Reshape coordinate data as needed for analysis packages. For example, scikit-learn's PCA expects 2D input while MD trajectories typically store 3D coordinates [28]:

RDF Calculation with Exclusion Settings

Implementation specifics vary by software package, but the core algorithm remains consistent: counting target atoms in spherical shells around reference atoms.

MDAnalysis Implementation:

The

exclusion_blockparameter can exclude specific pairs from the analysis, which is particularly important for excluding bonded neighbors or atoms within the same residue [5].Interpreting RDF Output:

- Peak Positions: Correspond to preferred interatomic distances (e.g., first solvation shell).

- Peak Areas: Proportional to coordination numbers (number of neighbors in each shell).

- Long-Range Behavior: Convergence to 1.0 indicates bulk-like behavior at large distances [23].

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for RDF Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Selection Syntax Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Engines | CHARMM [29], AMBER [30], GROMACS [30], NAMD [30] | Generate MD trajectories | Engine-specific (often similar to CHARMM) |