Troubleshooting Energy Minimization in MD Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for understanding and resolving common energy minimization failures in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, a critical step in computational drug discovery and biomolecular modeling.

Troubleshooting Energy Minimization in MD Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for understanding and resolving common energy minimization failures in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, a critical step in computational drug discovery and biomolecular modeling. We first establish the foundational principles of energy minimization and its role in achieving a stable system configuration. The guide then details practical methodologies, including the selection and application of minimization algorithms like Steepest Descent and Conjugate Gradient. A core focus is a systematic troubleshooting protocol for diagnosing and fixing convergence errors, high forces, and instability, supported by real-world case studies. Finally, we cover validation techniques to confirm minimization success and ensure the reliability of simulation results for downstream biomedical applications.

Understanding Energy Minimization: The Bedrock of Stable MD Simulations

Defining Energy Minimization and Its Critical Role in the MD Pipeline

Energy minimization is a foundational step in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. Its primary role is to reduce the potential energy of a molecular system to a local minimum, resolving any unrealistic atomic clashes, strained bond angles, or torsions that may be present in the initial configuration, such as one derived from experimental coordinates [1]. This process is critical because initiating a dynamics simulation from a high-energy state can lead to numerical instabilities, simulation crashes, or the propagation of unrealistic structural artifacts. A properly minimized structure provides a stable and physically meaningful starting point for subsequent MD simulation steps.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why did my energy minimization fail to converge? Failure to converge often occurs when the initial structure is highly distorted, leading to extremely high initial forces. This can be addressed by starting with the steepest descent algorithm for the first 10-100 steps before switching to a more efficient method like conjugate gradients [1]. Additionally, check for atomistic clashes in your initial model and ensure your convergence criteria (e.g., maximum force) are not set too stringently for the system's initial state.

2. How do I choose the right minimization algorithm? The choice depends on your system's size and its current state of optimization [2] [3] [1].

- Steepest Descent: Robust and best for the initial stages of minimization when the structure is far from a minimum and forces are high. It is less efficient closer to the minimum.

- Conjugate Gradients: More efficient than steepest descent as the system approaches a minimum. It is the method of choice for systems too large for Newton-style minimizers. Note that it cannot be used with constraints in some software [3].

- L-BFGS: A quasi-Newtonian method that often converges faster than conjugate gradients. However, it may not yet be parallelized in some MD software [3].

3. What is a reasonable convergence criterion for my simulation? The required convergence threshold depends on the objective of your minimization [1].

- Pre-dynamics relaxation: A maximum force of

1.0 kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻¹is often sufficient. - Normal mode analysis: Requires a very high degree of convergence, with a maximum force below

10⁻⁵ kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻¹.

4. When should I use constraints or restraints during minimization? Constraints and restraints are useful for controlling the minimization process [1].

- Docking studies: To pull specific atoms (e.g., a donor and acceptor) together to form a hydrogen bond.

- Incomplete systems: To tether atoms in regions where parts of the model are missing (e.g., unresolved loops in a protein crystal structure) to prevent artifactual movement.

- Relaxing crystal structures: A multi-stage approach where heavy atoms are fixed to relax hydrogens first, followed by side chains, and finally the entire backbone, to gently relax the system without moving away from the experimental structure.

Troubleshooting Guide

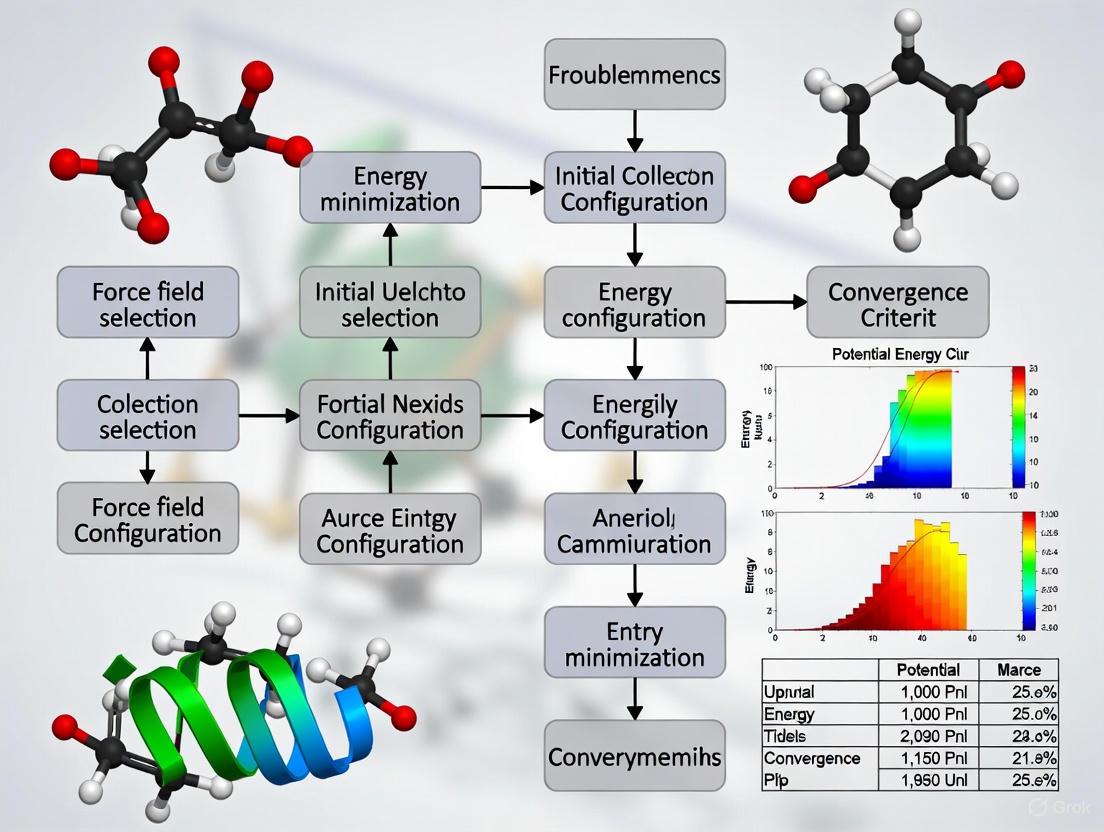

The following flowchart outlines a logical procedure for diagnosing and resolving common energy minimization failures.

★ Key Algorithm Comparison

Table: Comparison of Common Energy Minimization Algorithms in MD

| Algorithm | Typical Use Case | Advantages | Limitations | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steepest Descent [3] [1] | Initial minimization; highly distorted structures | Robust, stable when far from minimum | Slow convergence near minimum; inefficient | emstep (max displacement), nsteps |

| Conjugate Gradient [2] [3] | Intermediate to final minimization stages | More efficient than steepest descent near minimum | May not be compatible with all constraints [3] | emtol (force tolerance), nsteps |

| L-BFGS [2] [3] | Final minimization stages | Fast convergence; low memory requirements | Not fully parallelized in some software [3] | emtol (force tolerance), nsteps |

Experimental Protocols

Standard Protocol for Relaxing a Crystal Structure

This protocol is essential for preparing experimentally derived structures for MD simulation, as it gently relieves steric clashes without causing large, artifactual movements away from the native state [1].

Minimize added atoms with fixed heavy atoms

- Objective: Allow added hydrogens and solvent molecules to adjust to the static protein environment.

- Method: Fix the coordinates of all non-hydrogen atoms. Use the steepest descent algorithm.

- Convergence: Stop when the energy derivatives are on the order of ~10 kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻¹ [1].

Minimize side chains with restrained backbone

- Objective: Relax the side chains, particularly those on the surface.

- Method: Apply positional restraints to the main chain (backbone) atoms while allowing side chains to move freely. Steepest descent is recommended initially.

- Convergence: Continue until derivatives are less than ~10 kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻¹.

Gradually relax the entire system

- Objective: Achieve a fully relaxed, unperturbed conformation.

- Method: Progressively reduce the force constant of the positional restraints on the backbone atoms until they can be completely removed. Switch from steepest descent to conjugate gradients or L-BFGS for final convergence [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential "Research Reagent Solutions"

Table: Key Software Parameters and Components for Energy Minimization

| Item / Reagent | Function / Description | Typical Settings / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Integrator (mdp option) [2] | Specifies the minimization algorithm. | steep (steepest descent), cg (conjugate gradient), l-bfgs |

Force Tolerance (emtol) [3] |

Defines the convergence criterion based on the maximum force. | 1.0-1000 kJ mol⁻¹ nm⁻¹ for pre-dynamics; much lower for normal modes. |

Maximum Steps (nsteps) [2] |

Sets the maximum number of minimization steps allowed. | -1 (no limit) or a fixed number (e.g., 1000). |

| Constraints [1] | Used to freeze or tether specific atoms during minimization to guide the process. | Positional restraints on protein backbone during initial stages. |

| Simple Forcefield [1] | A forcefield without cross terms or complex potentials; improves stability for highly distorted structures. | Using a forcefield with simple quadratic functional forms. |

FAQ: What are the fundamental components of a potential energy function in molecular dynamics?

The total potential energy (V) of a molecular system in a molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is typically calculated as the sum of bonded and non-bonded interaction energies [4] [5]. This is formally expressed with the equation:

V = Vbonded + Vnon-bonded

The bonded interactions describe the energy associated with the covalent chemical structure, while the non-bonded interactions describe the energy from forces between atoms that are not directly bonded [4]. This separation allows force fields to efficiently model the complex energetics of biological macromolecules.

FAQ: What specific terms constitute the bonded interactions?

The bonded energy term is itself a sum of several components, each governing a specific aspect of the molecular geometry [4] [5]. The table below summarizes these core bonded interactions.

Table 1: Core Bonded Interaction Energy Terms

| Term | Mathematical Form | Description | Governs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretch | ( \sum{bonds} Kb(b - b_0)^2 ) | Energy required to stretch or compress a covalent bond from its ideal length, ( b_0 ). | Bond lengths |

| Angle Bend | ( \sum{angles} K{\theta}(\theta - \theta_0)^2 ) | Energy required to bend the angle between two adjacent bonds from its ideal value, ( \theta_0 ). | Bond angles |

| Torsional Dihedral | ( \sum{dihedrals} [K{\phi}(1 + cos(n\phi - \delta))] ) | Energy associated with rotation around a central bond, defined by periodicity (n), phase (δ), and force constant (Kφ). | Dihedral angles |

| Improper Dihedral | ( \sum{impropers} K{\omega}(\omega - \omega_0)^2 ) | Energy used to maintain chirality at a central atom or to enforce planarity in groups like aromatic rings. | Out-of-plane bending |

FAQ: What are the non-bonded interactions and why are they critical?

The non-bonded interactions act between atoms that are not connected by covalent bonds, and they are crucial for determining the tertiary structure of proteins, binding affinity of ligands, and solvent-solute interactions [4] [6] [5]. They are primarily composed of two terms:

Table 2: Core Non-Bonded Interaction Energy Terms

| Term | Mathematical Form | Physical Origin |

|---|---|---|

| van der Waals | ( \sum{VDW} \left[ \left( \frac{A{ij}}{R{ij}^{12}} \right) - \left( \frac{B{ij}}{R_{ij}^{6}} \right) \right] ) | Models short-range repulsive and attractive (dispersion) forces due to fluctuating electron clouds. Often represented with a Lennard-Jones potential. |

| Electrostatic | ( \sum{Electrostatic} \frac{qi qj}{\epsilon R{ij}} ) | Models the long-range Coulombic interaction between partial or full atomic charges (qi, qj). |

A common combination rule for the van der Waals parameters between two different atoms i and j is: ( A{ij} = \sqrt{Ai Aj} ) and ( B{ij} = \sqrt{Bi Bj} ) [4]. A weighting function is typically applied to exclude non-bonded interactions for atoms directly connected by a bond or angle, and to scale them for atoms connected through three bonds (1-4 interactions) [4].

Troubleshooting Guide: My energy minimization fails with high forces and non-convergence. What should I do?

Energy minimization failure is a common issue where the algorithm cannot reduce the maximum force (Fmax) below a requested threshold. This often manifests with error messages about high forces on specific atoms [7] [8]. The following workflow provides a systematic diagnostic approach.

Diagnosis and Solutions

Symptom: Minimization stops with a very high Fmax (e.g., > 10,000 kJ/mol/nm) on a specific atom, often reported in the .log file [7] [9] [8].

Symptom: Bad contacts or atomic clashes are found upon visualization [9].

- Action: The initial molecular geometry may be physically unrealistic, often resulting from automated structure preparation or docking. Manually edit the initial coordinate file to resolve severe clashes before re-running minimization.

Symptom: The high-force atoms are located at the edge of the simulation box, potentially in a periodic system like a zeolite or a crystal [9].

- Action: This suggests missing covalent bonds across the periodic boundary. The topology file must explicitly list all bonds, including those that connect a unit cell to its periodic image. Check the

[ bonds ]section of your topology. For some systems, settingperiodic-molecules = yesin your .mdp file may be necessary, though this does not automatically create the bonds [9].

- Action: This suggests missing covalent bonds across the periodic boundary. The topology file must explicitly list all bonds, including those that connect a unit cell to its periodic image. Check the

Symptom: The problem occurs with a non-standard molecule like a drug ligand.

- Action: Incorrect parametrization of the ligand is a likely cause. Re-check the process used to generate the ligand's topology and parameters, paying close attention to partial atomic charges, bond types, and the assignment of atom types.

Troubleshooting Guide: Are there limitations to what energy minimization can achieve?

Yes, energy minimization has fundamental limitations that every researcher must understand. Minimization finds a local minimum on the potential energy surface, which is highly dependent on the starting configuration [10]. It does not account for thermal fluctuations or entropic effects, which are critical for understanding biological function and selectivity at physiological temperatures [10].

- Pitfall: Relying on a single minimized structure to calculate properties like ion selectivity can lead to erroneous and misleading conclusions, as the energy difference between different local minima can be large and unpredictable [10].

- Best Practice: For properties related to binding, stability, or selectivity, always follow minimization with molecular dynamics simulations to perform proper thermodynamic averaging over an ensemble of configurations [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Energy Minimization

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Software | Function in Energy Minimization |

|---|---|

| MD Engine (e.g., GROMACS, CHARMM, AMBER) | Executes the minimization algorithm, calculates energy/forces, and integrates the equations of motion. |

| Molecular Visualization Tool (e.g., VMD, PyMOL) | Critical for diagnosing errors by visually inspecting atomic clashes and the environment around high-force atoms. |

| Force Field (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS) | Provides the parameters (Kb, b0, q, Aij, Bij) for the potential energy function. |

| Steepest Descents Algorithm | A robust minimization algorithm often used for the initial steps to relieve severe clashes from poor starting structures. |

| Conjugate Gradient Algorithm | A more efficient minimization algorithm typically used after steepest descents for finer convergence. |

| Position Restraints | A computational tool (harmonic potential) applied to atom positions to allow solvent/lipids to relax around a fixed protein scaffold. |

Fundamental Concepts: The Potential Energy Surface

What is a Potential Energy Surface (PES)?

A Potential Energy Surface (PES) describes the energy of a collection of atoms as a function of their nuclear positions [11]. Conceptually, it represents an "energy landscape" where the height corresponds to energy and the geographical coordinates correspond to geometrical parameters of the molecular system [11]. The PES is obtained by solving the time-independent Schrödinger equation under the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which separates nuclear and electronic motion because electrons move much faster than nuclei [12].

What are stationary points and why are they important?

Stationary points are specific geometries on the PES where the energy gradient (first derivative) with respect to all nuclear coordinates is zero [12] [11]. They have profound physical significance:

- Energy Minima: Correspond to physically stable chemical species [11]. These can be:

- Saddle Points: Transition states that represent the highest energy point on the lowest energy pathway connecting two minima [11].

Key Challenges in Energy Minimization

Why is finding the global minimum so difficult?

Finding the global minimum on a PES is classified as an NP-hard problem, meaning its complexity grows exponentially with system size [13]. Key challenges include:

- Rugged Landscapes: PES for molecular systems typically contain enormous numbers of local minima. For example, a 13-atom cluster system can have over 12,000 minima and 54,000 transition states [13].

- Short-Ranged Potentials: Potentials with shorter interaction ranges create more rugged landscapes with higher barriers and more localized rearrangements, making escape from local minima more difficult [13].

- Structural Similarity: Pathways to certain minima (e.g., decahedral structures) may be fewer and longer than to others (e.g., icosahedral structures), creating "hard-to-reach" regions on the PES [13].

What common computational errors occur during geometry optimization?

Table 1: Common Geometry Optimization Errors and Solutions

| Error Message | Possible Causes | Troubleshooting Steps |

|---|---|---|

| "Stepsize too small, or no change in energy. Converged to machine precision, but not to the requested Fmax" [14] | Energy minimization limit reached; High water content systems | Interpret Fmax value; Consider double precision; Different minimization methods [14] |

| "Energy minimization has stopped because the force on at least one atom is not finite" [14] | Atoms too close in input coordinates | Check initial coordinates; Use soft-core potentials [14] |

| "Cannot do Conjugate Gradients with constraints" [14] | Algorithm incompatibility with constraints | Use alternative algorithms that support constraints [14] |

| Discontinuities in force evaluation [15] | Bond order cutoff issues in ReaxFF | Decrease BondOrderCutoff; Use 2013 torsion angles; Enable TaperBO [15] |

Methodologies and Algorithms

What algorithms are used for geometry optimization?

Table 2: Energy Minimization Algorithms Comparison

| Algorithm | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steepest Descent [3] | Moves atoms opposite to energy gradient direction | Robust, easy to implement; Good for initial optimization steps | Slow convergence near minimum; Inefficient for complex landscapes |

| Conjugate Gradient [3] | Uses conjugate direction vectors for search | More efficient closer to energy minimum; Faster convergence than steepest descent | Cannot be used with constraints in some implementations [14] |

| L-BFGS [3] | Quasi-Newton method approximating inverse Hessian | Fast convergence; Lower memory requirements than full BFGS | Not yet parallelized in some implementations; Sensitive to interaction cutoffs |

What global optimization strategies effectively explore the PES?

- Physical Insight Construction: Building structures that maximize favorable interactions (e.g., maximizing nearest-neighbor contacts for clusters) followed by local minimization [13].

- Molecular Dynamics Sampling: Using high-energy runs to sample large PES regions and low-energy runs for detailed local searching [13].

- Basin Hopping Techniques: Using eigenvector-following to step directly between minima combined with Monte Carlo sampling to walk down basins containing multiple minima [13].

Experimental Protocols

Standard Geometry Optimization Protocol

- Initial Structure Preparation: Create or obtain starting structure from databases or publications [12].

- Coordinate System Selection: Convert Cartesian coordinates to internal coordinates to eliminate translational and rotational degrees of freedom ($3N-6$ internal coordinates for $N$ atoms) [12].

- Algorithm Selection:

- Convergence Monitoring: Iteratively calculate energy gradients and displace atoms until maximum force components fall below threshold (typically 1-10 kJ mol$^{-1}$ nm$^{-1}$) [3].

- Result Validation: Confirm optimized geometry corresponds to a minimum (not a saddle point) through frequency analysis.

Troubleshooting Failed Optimizations

- For discontinuous forces: In ReaxFF, decrease

BondOrderCutoffor enableTaperBOto smooth energy derivatives [15]. - For constrained systems: Avoid conjugate gradients; use steepest descent or specialized constraint algorithms [14].

- For system instability: Ensure thorough energy minimization and equilibration before dynamics runs; validate topology parameters [14].

Essential Research Tools

Visualization of PES Navigation Strategies

Frequently Asked Questions

How can I distinguish between a local minimum and the global minimum?

There is no guaranteed method to prove a structure is the global minimum for complex systems [13]. Effective approaches include:

- Using multiple diverse starting structures for optimization

- Applying different global optimization algorithms

- Comparing energies of all found minima

- For clusters, known structural motifs (icosahedral, decahedral, fcc) provide candidate templates [13]

Why do my optimizations converge slowly or oscillate?

Slow convergence may result from:

- Inappropriate step sizes: The algorithm takes steps that are too large (causing oscillation) or too small (slow progress) [3]

- Rugged PES topography: The energy landscape has many closely spaced minima [13]

- Discontinuous forces: Sudden changes in force evaluation, common with bond order cutoffs in reactive force fields [15]

What is the relationship between PES features and chemical reactivity?

- Attractive (early-downhill) PES: Transition state resembles reactants; product energy released primarily as vibrational energy [11]

- Repulsive (late-downhill) PES: Transition state resembles products; energy released primarily as translational energy [11]

- For endothermic reactions, translational energy is most effective for attractive surfaces while vibrational excitation works better for repulsive surfaces [11]

When is a structure "sufficiently optimized" for further calculations?

A structure is sufficiently optimized when:

- Maximum force components are below a reasonable threshold (1-10 kJ mol$^{-1}$ nm$^{-1}$ depending on system and purpose) [3]

- Further optimization does not significantly change the energy or structure

- The resulting geometry has physically reasonable bond lengths and angles

- For subsequent property calculations, ensure the geometry represents a minimum, not a transition state [12]

FAQs: Troubleshooting Energy Minimization

My energy minimization fails with "the forces have not converged" or "Fmax is too high". What does this mean?

This common error indicates that the energy minimization algorithm stopped before the forces in your system were reduced to an acceptable level. The following table summarizes the core aspects of this problem and its solutions.

Table: Troubleshooting "Forces Not Converged" Errors

| Error Symptom | Likely Cause | Immediate Action | Long-term Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

High Fmax and Epot after max steps [7] |

Atom overlaps: Atoms are too close, creating infinite repulsive forces [16]. | Check atom 2089 (or the reported atom) for clashes, especially in ligands [7] [16]. | Visually inspect structure; use -ignore flag in pdb2gmx sparingly; ensure correct protonation states [17]. |

Fmax = inf (infinite force) [16] |

Severe atomic clashes: Critical overlaps in the initial structure [16]. | Inspect and correct the coordinates of the offending atom (e.g., atom 1251) [16]. | Verify ligand topology matches coordinate file; correct any atom name mismatches [16]. |

Convergence to machine precision, but Fmax still high [7] |

Local energy minimum: Minimizer is "stuck" and cannot find a lower energy path [7]. | Switch from steepest descent to conjugate gradient minimizer. | Increase the maximum number of steps (nsteps) or try a two-step minimization protocol. |

Detailed Methodology for Resolution:

- Identify the Problem Atom: The log file specifies the atom with the maximum force (e.g.,

atom= 2089). Note this number [7]. - Visual Inspection: Use a molecular visualization tool (e.g., PyMOL, VMD) to center your view on this specific atom. Look for unrealistic bond lengths or atoms occupying the same space, particularly in newly added ligands or solvent molecules [16].

- Correct the Topology: A frequent cause for ligands is a mismatch between the atom names or coordinates in the structure file (

.gro/.pdb) and the topology file (.top). Ensure they are consistent [16]. - Adjust Minimization Parameters: If no severe clashes are found, the system may be trapped. Modify your

em.mdpfile:- Increase

nsteps = 100000to allow more minimization steps. - Change the integrator to

integrator = cg(conjugate gradients), which can be more effective for certain systems. - As a last resort for severe clashes, consider using soft-core potentials as suggested in the error message [16].

- Increase

I get an "Atom index in position_restraints out of bounds" error. How do I fix it?

This error occurs when the atom indices in your position restraint file (posre.itp) do not match the actual atom order in your system. This is almost always caused by an incorrect ordering of #include statements in your master topology file (topol.top).

Detailed Methodology for Correction:

The solution is to ensure that the position restraints for a molecule are included immediately after the topology for that same molecule. The correct structure for your topol.top file is [17]:

The following workflow illustrates the correct and incorrect ways to include position restraints when building your system.

Correct vs. Incorrect Position Restraint Inclusion

What should I do if pdb2gmx fails with "Residue not found in topology database"?

This error means the force field you selected does not have a definition for a specific residue or molecule in your input structure file [17].

Detailed Methodology for Handling Unparameterized Residues:

- Check Residue Name: Verify the residue name in your

.pdbfile matches the expected name in the force field. For example, an N-terminal alanine in the AMBER force field should be namedNALA, notALA[17]. - Find an Existing Topology: Search online repositories for a pre-made topology file (

.itp) for your molecule that is compatible with your chosen force field. - Parameterize the Residue Yourself: If no topology exists, you must create one. This involves:

- Creating an RTP Entry: Define the residue's atoms, bonds, and angles in a Residue Topology Parameter (RTP) file for your force field [17].

- Deriving Parameters: Assign non-bonded parameters (atom types) and bonded parameters (bond, angle, dihedral force constants). This often requires ab initio quantum mechanics calculations and is a non-trivial task [17].

- Use a Different Tool: For non-standard molecules like drugs, consider using specialized tools like

x2topor web-based servers (e.g., CGenFF, ATB, PRODRG) to generate the initial topology, which you can then include in your system [17].

My minimization stops with "atoms are overlapping". How can I resolve this?

This is a specific and severe instance of a convergence failure, where the force on an atom becomes infinite due to a physical impossibility in the structure [16].

Detailed Methodology for Resolving Atomic Overlaps:

- Locate the Overlap: The error log will specify the atom number with infinite force (e.g.,

atom= 1251). Use visualization software to find this atom [16]. - Inspect the Local Environment: Check if this atom is unnaturally close to or inside another atom. This is common in manually built or modified structures, and particularly for ligands that were not properly energy-minimized before insertion [16].

- Correct the Structure:

- Manual Adjustment: In your visualization program, manually move the offending atom or its neighbor to a chemically reasonable position.

- External Minimization: Perform a preliminary energy minimization on the problematic molecule (e.g., your ligand) in a vacuum using a molecular modeling suite like MOE or Avogadro before inserting it into the larger system [16].

- Check Topology-Structure Consistency: Ensure the ligand's topology and coordinate file are consistent. Mismatches here can create perceived "overlaps" where the topology expects different atom names or connectivities [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table: Key Tools for MD System Setup and Minimization

| Tool Name | Function | Key Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|

pdb2gmx |

Generates topology and position restraints for proteins/nucleic acids from a PDB file [17]. | Selects the force field; cannot handle arbitrary organic molecules without a defined residue template [17]. |

grompp |

Assembles the molecular dynamics parameter (.mdp) file, topology, and coordinates into a portable binary (.tpr) for simulation [17]. |

Checks for parameter consistency; warnings should be reviewed carefully [17]. |

mdrun |

The main simulation engine that executes energy minimization and production MD [7] [16]. | Use the -v (verbose) and -deffnm (default filename) flags for clearer logging [7]. |

solvate |

Adds explicit solvent molecules (e.g., water) to the simulation box around the solute [17] [18]. | Ensure the box size provides sufficient padding (>1.0 nm) from the solute to prevent artifacts [18]. |

genion |

Replaces solvent molecules with ions to neutralize the system's charge or achieve a physiological concentration [18]. | Ions are placed based on the electrostatic potential; check the final ion distribution for realism [18]. |

| Molecular Viewer (VMD/PyMOL) | Visualizes structures, checks for errors, and analyzes trajectories post-simulation [18]. | Critical for inspecting atoms flagged in error messages and verifying system integrity [16]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Energy Minimization Workflow

The following diagram outlines a robust workflow for system setup and energy minimization, incorporating checks to prevent common errors.

Energy Minimization and Error Checking Workflow

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Diagnosing and Resolving High-Energy Issues

1. How can I identify a steric clash in my structure, and what is the best way to resolve it?

Steric clashes occur when atoms are positioned unrealistically close together, resulting in a sharp, localized spike in potential energy due to strong van der Waals repulsion.

- Diagnosis: Visualize your structure using molecular visualization software (e.g., PyMOL, VMD) and enable the display of van der Waals radii. Look for atoms whose radii significantly overlap. Energetically, this will manifest as a very high contribution from the Lennard-Jones term in your energy output.

- Resolution: The most direct method is to perform energy minimization before beginning your production simulation. This allows the atoms to "relax" into a geometry that relieves the clash. For severe clashes, consider rebuilding the problematic region or checking the initial model construction.

2. My simulation has unrealistic bond lengths or angles. What causes "bad dihedrals" and how do I fix them?

In molecular mechanics, "bad dihedrals" typically refer to incorrect torsional angles that place the molecule in a high-energy conformation not supported by quantum mechanical data [19]. This can lead to inaccurate conformational distributions.

- Diagnosis: Analyze the torsional energy profiles of your molecule. Compare the energy barriers and stable states predicted by your force field against higher-level quantum mechanical (QM) calculations. Large discrepancies indicate problematic dihedral parameters [19].

- Resolution:

- Refit Parameters: For a custom molecule, the best practice is to refit the dihedral parameters to QM torsion scans [19] [20]. This involves running QM calculations to map the energy as a function of the dihedral angle and then optimizing the force field parameters to reproduce this profile.

- Use a Modern Force Field: Consider using a machine-learned force field like Grappa or ByteFF, which use neural networks to predict more accurate parameters directly from the molecular graph, often leading to better dihedral profiles [19] [21].

3. Why does my molecule have high energy in solvent, and how can I address solvent conflicts?

Solvent conflicts, or poor solvation, arise when a molecule's polarity and surface characteristics are mismatched with its solvent environment. This is a major driver of errors in free energy calculations [22] [23].

- Diagnosis: High non-bonded energy (electrostatic and van der Waals) between the solute and solvent is a key indicator. Experimentally, this might be reflected in large errors when calculating solvation free energies [22].

- Resolution:

- Check Partial Charges: Ensure the partial charges on your small molecule are accurately derived, for example, from a QM-calculated electrostatic potential (ESP). Using fixed charges that don't account for polarization in the binding site can significantly impact accuracy [23].

- Validate with Solvation Free Energy: Use alchemical free energy calculations to compute the solvation free energy of your molecule and compare it to experimental values. A large error suggests issues with the non-bonded parameters [22].

- Advanced Methods: For the highest accuracy, protocols that combine QM/MM calculations to derive context-dependent charges for the ligand have been shown to significantly improve binding free energy estimates [23].

4. What are the best practices for setting up a system to avoid common energy issues?

A proper system setup is the first line of defense against high-energy states.

- Use a Validated Force Field: Select a force field appropriate for your system (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS). For drug-like molecules, modern, data-driven force fields like ByteFF offer broad chemical space coverage [19].

- Solvate Correctly: Place your molecule in a sufficiently large box of explicit solvent molecules (e.g., TIP3P water) and add ions to neutralize the system's total charge [24].

- Apply Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC): Use PBC to simulate a bulk solution environment and avoid edge effects. Be aware that molecules will freely diffuse across the box boundaries, which is normal but must be handled correctly for analysis [25].

- Always Perform Minimization: Before heating and equilibration, always run an energy minimization step to relieve any steric clashes introduced during system building.

Quantitative Data and Protocols

Table 1: Characteristic Signs of Common High-Energy Problems

| Issue | Primary Energy Component Affected | Structural Signature | Computational Diagnostic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steric Clashes | Lennard-Jones (van der Waals repulsion) | Overlapping van der Waals radii [24] | High individual interatomic forces; failed energy minimization |

| Bad Dihedrals | Torsional Energy | Incorrect rotational state around bonds [19] | Large deviation from QM torsion energy profiles [19] |

| Solvent Conflicts | Non-bonded (Electrostatics & Lennard-Jones) | Poor interaction with solvent shell; incorrect binding pose | Large errors in solvation or binding free energy calculations [22] [23] |

| Issue | Standard Resolution | Advanced/Data-Driven Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Steric Clashes | Energy Minimization | - |

| Bad Dihedrals | Manual refitting to QM torsion scans [19] [20] | Machine-learned force fields (e.g., Grappa, ByteFF) [19] [21] |

| Solvent Conflicts | Reparametrization of partial charges | QM/MM-derived charges; ML-potentials in alchemical protocols [22] [23] |

Experimental Protocol: QM/MM Charge Derivation for Improved Solvation

This protocol outlines the method for deriving improved partial charges for a ligand in a protein binding pocket to address solvent/solvation conflicts, as used in high-accuracy binding free energy estimation [23].

- Generate Initial Pose: Use a classical method (e.g., docking, MM minimization) to generate a likely binding pose for the ligand-protein complex.

- Define QM and MM Regions: Set up a QM/MM calculation where the ligand is the QM region (treated with quantum mechanics) and the protein and solvent are the MM region (treated with the molecular mechanics force field).

- Calculate Electrostatic Potential (ESP): Perform a QM calculation on the QM region in the presence of the MM environment to compute the electrostatic potential around the ligand.

- Fit Partial Charges: Fit the partial charges of the ligand's atoms so that they reproduce the QM-derived ESP. This results in charges that are polarized by the protein environment.

- Run Free Energy Calculations: Use these new QM/MM-derived charges in subsequent free energy calculations (e.g., using the Mining Minima method or alchemical perturbation) [23].

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram: Troubleshooting High Energy in MD Simulations

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Used in modern force fields like Grappa and ByteFF to predict more accurate molecular mechanics parameters (bonds, angles, dihedrals) directly from a molecule's structure, mitigating bad dihedrals [19] [21]. |

| Alchemical Free Energy Calculations | A rigorous thermodynamic method used to compute free energy differences (e.g., solvation free energy, binding free energy). It is a key diagnostic for validating non-bonded parameters and identifying solvent conflicts [22]. |

| QM/MM (Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics) | A hybrid method where a small, critical region (e.g., a ligand) is treated with accurate QM, and the surroundings are treated with MM. Used to generate polarized partial charges for ligands, improving the treatment of electrostatics and solvation [23]. |

| Beutler-type Soft Core Potentials | A modified potential energy function used in alchemical calculations to prevent numerical singularities when atoms are "created" or "annihilated," ensuring smooth and convergent free energy estimates [22]. |

A Practical Guide to Minimization Algorithms and Their Implementation

Energy minimization is a critical first step in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, aimed at reaching the nearest local minimum of the potential energy surface by reducing excessive forces and relieving steric clashes in the initial molecular configuration [26]. The choice of minimization algorithm directly impacts the stability of your simulation, the time to solution, and the quality of your final results. Within the context of a broader thesis on troubleshooting MD research, this guide provides a technical comparison and practical troubleshooting for three core algorithms: the robust Steepest Descent, the more efficient Conjugate Gradient, and the advanced L-BFGS.

This technical support center is designed to help you diagnose common issues, understand the trade-offs between different methods, and implement effective solutions to ensure your energy minimization converges to a stable configuration.

Algorithm Comparison Table

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three main energy minimization algorithms to help you make an informed choice.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Energy Minimization Algorithms

| Feature | Steepest Descent | Conjugate Gradient | L-BFGS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Moves in the direction of the negative gradient (steepest force) [27]. | Uses conjugate directions to avoid re-visiting previous minimization paths [28]. | Approximates the inverse Hessian matrix using a history of updates [3]. |

| Convergence Speed | Linear convergence rate; can be slow [27]. | Faster than Steepest Descent near the minimum [3]. | Faster than Conjugate Gradients [3]. |

| Memory Requirements | Low | Low | Moderate (proportional to system size and correction steps) [3]. |

| Robustness | High; excellent for initial steps and poorly-structured systems [3]. | High, but cannot be used with all constraints (e.g., SETTLE for water) [3]. | High, but performance can be affected by switched/shifted interactions [3]. |

| Best Use Case | Initial minimization of structures with high energy and clashes [3]. | Minimization prior to normal-mode analysis or when higher accuracy is needed [3]. | Efficient minimization for large systems like biomolecules [3]. |

| Key Limitation | "Zigzag" phenomenon slows convergence in ill-conditioned problems [27]. | Not compatible with constraints like SETTLE water [3]. | Not yet fully parallelized in some implementations (e.g., GROMACS) [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: My energy minimization stops abruptly, reporting that "forces have not converged." What should I do?

This is a common issue where the algorithm halts because it can no longer make progress, even though the target force tolerance (Fmax) has not been met. The system is deemed converged to the best of its ability given the starting configuration and parameters [29] [30].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Check for Steric Clashes: A very high potential energy or maximum force often indicates severe atomic clashes in your initial structure [30]. Visualize the system, paying close attention to the atoms listed in the error output (e.g.,

Maximum force = 7.0742570e+04 on atom 1447) [29]. - Verify Position Restraints: Ensure you are not accidentally using position restraints (e.g.,

define = -DPOSRESin your MDP file) that might be preventing the system from relaxing [30]. - Adjust Minimization Parameters:

- Switch Algorithms: If Steepest Descent gets stuck, it is often recommended to use its output as the starting point for a more efficient algorithm like Conjugate Gradient or L-BFGS [29] [3].

FAQ 2: How do I choose between Steepest Descent and Conjugate Gradient for my protein-in-water system?

The choice involves a trade-off between robustness and final accuracy.

- Use Steepest Descent when you need a robust method to quickly relieve severe clashes and bring a poorly-structured system to a lower energy state. Its simplicity makes it reliable for the initial, rough minimization [3].

- Use Conjugate Gradient when your system is already reasonably well-structured and you require a more accurate minimization for subsequent analysis. It is more efficient than Steepest Descent closer to the energy minimum [3].

Critical Constraint Note: If your system uses the SETTLE algorithm for water (which is standard for rigid water models like SPC, TIP3P, etc.), you cannot use Conjugate Gradient. In this case, you must either use Steepest Descent or switch to a flexible water model [3].

FAQ 3: What does a "Segmentation fault" during minimization indicate, and how can I resolve it?

A segmentation fault is a serious error indicating the program tried to access memory it was not permitted to, leading to a crash [29]. This is often unrelated to the choice of algorithm itself and points to a deeper problem.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Software or Hardware Issue: A faulty installation of GROMACS, incompatible libraries, or hardware problems can cause this.

- System Corruption: The structure of your system may be corrupted or contain invalid parameters that trigger an error during force calculation.

- GPU Acceleration Issues: If running on a GPU, try running on CPU only (

-nb cpu -pme cpu) to rule out GPU-related issues. - Check Your Topology: Carefully inspect your topology file (

.top) for errors, especially if you have modified it or added non-standard residues [29].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol 1: Implementing Steepest Descent in GROMACS

The Steepest Descent algorithm is implemented in GROMACS with an adaptive step size. The force is used to calculate the new positions, and the step size is adjusted based on whether the step leads to a lower energy [3].

MDP File Parameters:

Core Algorithm Workflow:

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of the Steepest Descent algorithm as implemented in GROMACS, showing its adaptive step-size mechanism.

Protocol 2: Implementing Conjugate Gradient and L-BFGS

For scenarios requiring higher efficiency after an initial rough minimization, Conjugate Gradient or L-BFGS are recommended.

MDP File Parameters (Conjugate Gradient):

Key Implementation Insight for L-BFGS: Unlike full BFGS, which builds a full inverse Hessian matrix, L-BFGS (Limited-memory BFGS) uses a sliding window of previous steps to approximate it. This makes it suitable for large biomolecular systems where storing the full matrix would be prohibitive [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key files and parameters you will need to configure and run a successful energy minimization.

Table 2: Essential "Research Reagents" for Energy Minimization

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Molecular Structure File (.gro, .pdb) | Contains the initial atomic coordinates of the system to be minimized. |

| Topology File (.top) | Defines the molecules in the system, their connectivity, and all force field parameters. |

| Molecular Dynamics Parameters (.mdp) | The input file specifying the minimization algorithm, step size, convergence tolerance, and other run parameters. |

| Run Input File (.tpr) | The portable binary file produced by grompp, containing all information to run the simulation. |

| Position Restraint File (.itp) | Used to apply restraints to specific atoms (e.g., protein backbone) during minimization. |

| Force Field (e.g., ff19SB, OPLS) | A set of mathematical functions and parameters defining the potential energy of the system. |

| Water Model (e.g., SPC, TIP4P) | Defines the water molecules' geometry and interaction parameters. Choice may constrain algorithm selection (e.g., SETTLE with Conjugate Gradient) [3]. |

| emtol | The force tolerance (Fmax) in kJ mol⁻¹ nm⁻¹. Minimization stops when the maximum force drops below this value [26]. |

| emstep | The initial step size (nm) for Steepest Descent, or a related parameter for other algorithms [3]. |

Troubleshooting Workflow Diagram

When faced with a failed minimization, follow this logical troubleshooting pathway to diagnose and resolve the issue.

A technical guide for molecular dynamics practitioners

FAQs: Core Concepts of Steepest Descent Minimization

Q1: What is the primary advantage of the steepest descent algorithm in energy minimization?

The steepest descent algorithm is prized for its robustness and simplicity of implementation. While it is not the most efficient algorithm for the final stages of minimization, its stability makes it particularly well-suited for the initial stages of energy minimization, where it can effectively handle rough energy landscapes and remove large forces, such as those from atomic clashes, in a system [3].

Q2: When should I consider using steepest descent over other algorithms like conjugate gradient or L-BFGS?

You should prioritize steepest descent in the following scenarios [3]:

- For initial minimization steps, especially when starting from a structure that may have severe atomic overlaps (e.g., after manual model building or docking).

- When your system requires constraints (e.g., on bonds involving hydrogen). Note that the conjugate gradient algorithm in GROMACS cannot be used with constraints [3].

- When you need a reliable and predictable minimization process, even if it is slower in the final convergence stages.

Conversely, conjugate gradient or L-BFGS are more efficient for achieving final convergence but are best applied after the largest forces have been eliminated by steepest descent [3].

Q3: How does the steepest descent algorithm work in practice?

The algorithm iteratively moves atoms in the direction of the force (the negative energy gradient) to find a local energy minimum. Here is a simplified workflow [3]:

Q4: What does convergence mean in the context of energy minimization?

An energy minimization is considered converged when the maximum force (Fmax) in the system falls below a user-defined tolerance threshold (emtol). This signifies that the structure has reached a local minimum on the potential energy surface, where the net force on every atom is negligible [3] [7] [29].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem 1: Forces Fail to Converge (Fmaxremains high)

Error Message:

Solutions:

Verify System Topology: Incorrect topology is a leading cause of high, non-converging forces.

- Check for Missing Atoms: The initial structure may have missing atoms that cause long bonds and high forces. Check the

pdb2gmxoutput for warnings like "atom X is missing in residue Y" [31]. - Validate Residue and Atom Names: Ensure all residue and atom names in your coordinate file match the entries in the force field's residue topology database (rtp file). Mismatches will cause

pdb2gmxto fail in assigning correct parameters [31]. - Review Ligand Parameters: If your system includes a non-standard ligand, confirm that its topology and parameters (generated separately) are correct and properly included in the system's top file.

- Check for Missing Atoms: The initial structure may have missing atoms that cause long bonds and high forces. Check the

Adjust Minimization Parameters: Loosen the parameters to allow the minimizer to take larger, more effective steps.

- Increase the maximum displacement: The initial maximum step size (

emstep) might be too small. Start with a value of 0.01 nm [3]. - Reduce the force tolerance: For the initial, rough minimization, a loose tolerance (e.g.,

emtol = 1000.0) is sufficient and can be tightened in a subsequent step with a different algorithm [29].

- Increase the maximum displacement: The initial maximum step size (

Relax Constraints: Overly restrictive constraints can prevent the system from relaxing.

Problem 2: Minimization Stops Abruptly with Segmentation Fault

Error Message:

Solutions:

Check for Topology and Parameter Errors: A segmentation fault during or immediately after minimization often points to a fundamental problem in the system definition.

- Incorrect Position Restraints Order: In your top file, ensure that position restraint files (

posre.itp) are included immediately after their corresponding molecule definition. Placing all restraints at the end of the top file can cause atom index errors [31]. - Force Field Incompatibility: When simulating complexes (e.g., protein-DNA), ensure all force field parameters (protein, nucleic acid, ions, cofactors) are compatible. Using mismatched or poorly parameterized force fields can lead to instabilities and crashes [29] [32].

- Incorrect Position Restraints Order: In your top file, ensure that position restraint files (

System Preparation Issues:

- Solvation and Periodic Boundaries: Ensure your system is properly solvated and that periodic boundary conditions are correctly defined. An error here can cause atoms to be too close to their own periodic images, creating infinite forces [33].

- Start with a Simple Test: Begin with a small, simplified version of your system (e.g., just the protein in water) to isolate the problematic component [33].

Algorithm Comparison & Parameters

The table below summarizes key energy minimization algorithms available in GROMACS.

Table 1: Characteristics of Energy Minimization Algorithms

| Algorithm | Key Features | Best Use Cases | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steepest Descent | Robust, easy to implement, works with constraints [3]. | Initial clash removal on rough energy landscapes [3]. | Slower convergence near the minimum [3]. |

| Conjugate Gradient | More efficient than steepest descent close to the minimum [3]. | Final convergence before MD; minimization for normal-mode analysis [3]. | Cannot be used with constraints (e.g., SETTLE water) [3]. |

| L-BFGS | Quasi-Newton method; often faster convergence than conjugate gradients [3]. | Efficient minimization for large systems when constraints are not required [3]. | Not yet parallelized; requires more memory than conjugate gradients [3]. |

Table 2: Key Parameters for Steepest Descent Minimization

| Parameter (mdp option) | Description | Recommended Value for Initial Minimization |

|---|---|---|

integrator |

Specifies the minimization algorithm. | = steep |

emtol |

Force tolerance for convergence (kJ mol⁻¹ nm⁻¹). Stop when Fmax < emtol. | = 1000.0 (Can be tightened to 10.0 for production) |

emstep |

Initial maximum displacement step size (nm). | = 0.01 |

nsteps |

Maximum number of minimization steps. | = 50000 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for a Minimization Experiment

| Item | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field | Defines the potential energy function and parameters for all interactions in the system. | Choose one appropriate for your molecules (e.g., DES-Amber for protein-nucleic acid complexes [32]). |

| Residue Topology File (.rtp) | A database of "building blocks" (residues) within a force field, defining their atoms, bonds, and charges. | pdb2gmx uses this to assign topologies; residue names in your PDB must match entries here [31]. |

| Position Restraints File (.itp) | Applies harmonic restraints to heavy atoms of specific molecules, allowing the solvent to relax around them. | Generated by genre; crucial for equilibration phases after initial minimization [29] [31]. |

| Water Model | Solvent model (e.g., TIP3P, SPC). | Must be a flexible model if using conjugate gradient minimization [3]. |

| Ion Parameters | Parameters for ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻, Mg²⁺) to neutralize the system. | Must be compatible with the chosen force field and water model [32]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Minimization Workflow

The following diagram outlines a robust, multi-stage protocol for energy minimization and equilibration, which efficiently handles even challenging systems.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Conjugate Gradient Solver Did Not Converge

Problem: Your simulation halts with a "conjugate gradient solver did not converge" error, often accompanied by warnings about reversed flow in initial iterations.

Solutions:

- Reduce relaxation factors to improve stability during early iterations [34]

- Enable cell quality remediation and remove invalid cells by right-clicking regions [34]

- Check constraint compatibility: When using water models, ensure compatibility with flexible water specifications if constraints are disabled [35]

- Monitor initial reversed flow: This often clears up after several iterations and may not indicate a fatal error [34]

Application Context: This commonly occurs in molecular dynamics packages like GROMACS and STAR-CCM+ when system preparation introduces instability or when constraint settings conflict with conjugate gradient requirements [34] [35].

Guide 2: Handling Constraint Incompatibility in GROMACS

Problem: Warnings about unused macros (e.g., FLEXIBLE) when generating input files for conjugate gradient minimization.

Root Cause: CHARMM-GUI typically generates topologies for rigid water models, while conjugate gradient in GROMACS requires flexible water models without constraints [35].

Solutions:

- Modify topology files: Ensure water topologies contain

#ifdef FLEXIBLEstatements to allow constraint switching [35] - Consider algorithm alternatives: If convergence issues persist, L-BFGS or steepest descent may provide more reliable minimization [35]

- Adjust restraint expectations: Position restraints may interfere with achieving very low force thresholds in conjugate gradient [35]

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: When should I choose conjugate gradient over other minimization methods?

A: Conjugate gradient is particularly effective for large-scale systems where storing the Hessian matrix is computationally prohibitive [36]. It typically converges faster than steepest descent while avoiding the computational expense of Newton's method [37]. Use it when you need efficient convergence for systems with thousands of variables.

Q: Why does my conjugate gradient minimization oscillate or stagnate?

A: This often indicates numerical precision issues or ill-conditioned systems [36] [38]. Implement preconditioning strategies such as Jacobi preconditioning or incomplete Cholesky factorization to improve condition number [38]. For non-quadratic problems, use restarting strategies (e.g., every n iterations) to maintain conjugacy [36].

Q: Is conjugate gradient suitable for normal mode analysis?

A: While strict convergence is theoretically required for normal mode analysis, in practice, conjugate gradient may not always achieve the necessary precision. Some researchers report better success with L-BFGS for this specific application [35].

Q: How do I know if my conjugate gradient implementation is working correctly?

A: Monitor the residual norm reduction across iterations. For well-conditioned systems, you should observe steady reduction in residuals [38]. Implement convergence criteria based on gradient norms or relative function value changes, typically requiring at least 2-3 orders of magnitude reduction [36].

Method Comparison Table

Table 1: Comparison of Energy Minimization Methods

| Method | Convergence Rate | Memory Requirements | Computational Cost per Step | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conjugate Gradient | Linear/Superlinear [36] | Low (stores only vectors) [36] | Moderate (matrix-vector products) [38] | Large sparse systems [28] [36] |

| Steepest Descent | Linear [37] | Very Low (stores only gradient) | Low (gradient calculation only) | Initial minimization, very rough landscapes |

| Newton-Raphson | Quadratic [39] | High (stores full Hessian) | High (Hessian computation and inversion) | Small systems, final refinement |

| L-BFGS | Superlinear [35] | Moderate (stores limited history) | Moderate to High | Medium-sized systems, non-quadratic functions |

Table 2: Convergence Performance in Real Applications

| Application Context | Method | Iterations to Convergence | Final Energy Tolerance | Computation Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cobalt-Copper Nanostructure Energy Minimization [40] | Steepest Descent | >100 (did not converge fully) | 0.001 | >600 seconds |

| Cobalt-Copper Nanostructure Energy Minimization [40] | Conjugate Gradient | 27 | 0.001 | 363.03 seconds |

| Diabetes Drug Molecule Optimization [40] | Conjugate Gradient | Significantly fewer than Steepest Descent | Lower final energy | Reduced computation time |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Conjugate Gradient Implementation

Purpose: Solve linear systems Ax = b where A is symmetric positive definite [38]

Algorithm:

- Initialize:

Iterate until convergence (for k = 0, 1, 2, ...):

Termination criteria:

Protocol 2: Energy Minimization for Molecular Systems

Purpose: Find molecular configuration with minimum potential energy [40] [39]

Procedure:

- Represent molecular coordinates as vector x = (r₁ₓ, r₁y, r₁z, r₂ₓ, r₂y, r₂z, ...) [40]

- Define potential energy function V(x) incorporating bonded and non-bonded terms [39]

- Compute interatomic forces as negative gradient -∇V(x) [40]

- Apply conjugate gradient minimization:

- Convergence testing:

Workflow Visualization

Title: Conjugate Gradient Energy Minimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Preconditioners (Jacobi, Incomplete Cholesky) [38] | Improves condition number of linear systems | Accelerates convergence for ill-conditioned problems |

| Flexible Water Models [35] | Enables conjugate gradient with water molecules | Molecular dynamics with explicit solvent |

| Polya-Gamma Auxiliary Variables [41] | Enables Gibbs sampling for logistic regression | Bayesian sparse regression in large datasets |

| Line Search Algorithms (Wolfe conditions) [36] | Determines optimal step size | General non-linear conjugate gradient implementation |

| Sparse Matrix Storage Formats | Enables efficient matrix-vector multiplication | Large-scale systems with sparse matrices |

▎Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My energy minimization stops with a warning that "the forces have not converged to the requested precision." What does this mean and how can I fix it?

This is a common issue indicating that the minimization process ended before the maximum force in the system was reduced below your target force tolerance (emtol). This can occur for two main reasons: the algorithm can no longer find a lower energy path (step size becomes too small), or the energy has stopped changing [42] [43]. To address this:

- Check Your Starting Structure: Highly strained systems with bad steric clashes, overlapping atoms, or unusual torsions are a common root cause [44]. Visually inspect your initial structure for such issues.

- Adjust Parameters: You can increase the maximum number of steps (

nsteps) or slightly reduce the minimization step size (emstep) to allow for more gentle relaxation [44]. - Relax Constraints: As suggested in the GROMACS output, you might need to increase your constraint accuracy or turn off constraints altogether by setting

constraints = nonein your mdp file [42] [43]. - Re-evaluate

emtol: Ensure your requested force tolerance is achievable. For very strained initial systems, you may need to use a looser tolerance (higheremtolvalue) for an initial minimization, followed by a second minimization with a tighter tolerance [44].

Q2: How do I choose between the 'steep' and 'cg' integrators for energy minimization?

The choice depends on the state of your system and the desired balance between robustness and efficiency.

- steep (Steepest Descent): This algorithm is more robust and is recommended for the initial minimization of very distorted structures, as it is better at escaping from high-energy clashes. It is less efficient than conjugate gradient for later stages of minimization [45].

- cg (Conjugate Gradient): This algorithm is more efficient than steepest descent once the initial bad contacts have been resolved and is well-suited for achieving tighter convergence. The GROMACS manual notes that for a minimization prior to normal mode analysis, which requires very high accuracy, double precision compilation is recommended when using CG [45].

A common strategy is to use the steep algorithm first to quickly remove the largest forces, followed by the cg algorithm to refine the structure to a lower energy state.

Q3: Is it safe to proceed with my simulation if energy minimization did not fully converge to the desired Fmax?

This depends on the severity of the non-convergence. You should check two key metrics [44]:

- Potential Energy (

Epot): This should be negative and of a reasonable magnitude for your system size (e.g., on the order of 10^5 to 10^6 for a protein in water). - Maximum Force (

Fmax): Note how far the finalFmaxis from your targetemtol.

If the potential energy is reasonable and the Fmax is only slightly above the threshold, it may be safe to proceed, especially if you are only using minimization to prepare for a subsequent equilibration phase. However, if the discrepancy is large or the potential energy is positive or unusually high, further troubleshooting is strongly recommended [44].

▎Troubleshooting Guide: Parameter Configuration Scenarios

The following table outlines common problems, their symptoms, and recommended parameter adjustments to resolve energy minimization issues.

| Problem Scenario | Symptom / Error Message | Recommended Action / Parameter Adjustment |

|---|---|---|

| Highly Strained System(e.g., from manual model building) | - Fmax is extremely high or 'inf' at the start [43].- Minimization stops with "step size too small" [42]. | - Use integrator = steep [45].- Set a loose emtol (e.g., 1000-5000) [43].- Use a small emstep (e.g., 0.001-0.01) [43].- Consider constraints = none for the first round [42]. |

| Failure to Converge to Tight Tolerance | - Fmax plateaus just above a strict emtol target.- Reaches nsteps limit before convergence. |

- Increase nsteps (e.g., from 5000 to 50000) [42] [43].- Use integrator = cg for more efficient convergence [45].- Verify that the stricter tolerance is necessary for your goal. |

| LINCS Warnings | - "Relative constraint deviation after LINCS" [43].- "Bonds that rotated more than 30 degrees" [43]. | - Ensure your emstep is not too large. A smaller step (e.g., 0.01) is often needed with constraints [43].- Check for potential issues in your topology. |

▎Experimental Protocol: Diagnosing Energy Minimization Failures

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology to systematically diagnose and resolve energy minimization failures.

▸Objective

To identify the root cause of a failed energy minimization run and implement a corrective parameter strategy to achieve a stable, low-energy starting configuration for molecular dynamics simulations.

▸Materials and Reagents (Computational)

- Software: GROMACS simulation package.

- Input Files:

- Initial molecular structure file (e.g.,

.gro,.pdb) - Molecular topology file (

.top) - Parameter file (

.mdp)

- Initial molecular structure file (e.g.,

- Computing Resources: High-performance computing (HPC) cluster or workstation.

▸Workflow Diagram

The following diagram outlines the logical decision process for troubleshooting energy minimization failures.

▸Step-by-Step Procedure

Initial Run and Symptom Identification: Execute the energy minimization using

gmx mdrun. When the job finishes, note the final values for the Potential Energy (Epot) and the Maximum force (Fmax) from the log output [44]. Check for any warnings, such as LINCS errors or notes about the step size being too small [42] [43].Structural Diagnosis:

- If

Fmaxstarted asinfor is extremely high, the initial structure likely has severe steric clashes [43]. - Use a molecular visualization tool (e.g., VMD, PyMOL) to visually inspect the atomic coordinates. Pay close attention to regions with high forces reported by GROMACS.

- Corrective Action: For severe clashes, the primary strategy is to use the robust

steepintegrator with a looseemtoland a smallemstepto gently relax the system without causing further instability.

- If

Parameter Tuning and Iteration:

- Based on the diagnosis, modify your

.mdpparameter file. Refer to the "Troubleshooting Guide" table above for specific parameter adjustments. - For tight tolerance failures: The core strategy is to allow the algorithm more iterations (

nsteps) and/or use a more efficient minimizer (cg) for the final convergence [45]. - Rerun the minimization with the new parameters and repeat the assessment. This may be an iterative process.

- Based on the diagnosis, modify your

Final Assessment and Decision:

- A successful minimization is characterized by a significant drop in

Epotto a negative value and anFmaxat or below the specifiedemtol. - If

Fmaxis only slightly aboveemtoland the energy is reasonable, you may decide to proceed to the next stage of simulation, but you should monitor the equilibration phase closely for any instability [44].

- A successful minimization is characterized by a significant drop in

▎Research Reagent Solutions: Key mdp Parameters

The table below details the essential "research reagents" – the critical parameters in your GROMACS .mdp file – for configuring a successful energy minimization.

| Parameter (mdp option) | Function & Purpose | Recommended Values & Notes |

|---|---|---|

integrator |

Selects the minimization algorithm. | steep (robust for initial straining), cg (efficient for final convergence) [45]. |

emtol |

Force tolerance (kJ mol⁻¹ nm⁻¹). Defines the target maximum force for convergence. | 10-1000 [42] [43]. Start with a higher value for very strained systems. |

nsteps |

Maximum number of minimization steps allowed. | 5000 - 50000+ [42] [43]. Increase if minimization hits the step limit. |

emstep |

Initial step size (nm) for minimization. | 0.001 - 0.01 [43]. A smaller step is more stable for strained systems or when constraints are active. |

constraints |

Specifies which bonds are constrained during minimization. | h-bonds (typical), none (can help resolve severe clashes) [42] [43]. |

nstlist |

Frequency of neighbor list update. | 10-40. Can impact performance; GROMACS may suggest increasing it [43]. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between a constraint and a restraint?

Answer: In molecular dynamics and computational refinement, the terms "constraint" and "restraint" refer to distinct concepts, though they are sometimes used interchangeably in error.

- Constraint: A constraint removes degrees of freedom from the system by imposing a strict, mathematical condition that must be satisfied at all times during the simulation or refinement. It is a hard condition. Common examples include freezing atom positions entirely (setting their force to zero) or using algorithms like SHAKE and LINCS to fix bond lengths involving hydrogen atoms, thereby allowing for a longer time step [46] [47].

- Restraint: A restraint adds a biasing potential to the energy function to encourage the system to adopt a particular geometry or value, but does not completely forbid deviation. It is a soft condition. A harmonic positional restraint, for instance, applies an energy penalty proportional to the square of the displacement from a reference position, allowing atoms to "jiggle" but preventing large movements [47] [48].

The table below summarizes the key differences:

Table 1: Constraints vs. Restraints

| Feature | Constraint | Restraint |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Form | Equation (e.g., fixed distance) | Added energy term (e.g., harmonic potential) |

| Freedom of Atoms | Degrees of freedom are eliminated | Degrees of freedom are retained but biased |

| Numerical Handling | Requires special algorithms (e.g., SHAKE, LINCS) | Added to the total potential energy of the system |

| Common Examples | Frozen atoms, rigid bonds, rigid water models (SETTLE) | Position restraints, dihedral restraints, distance restraints |

FAQ 2: During energy minimization, my system has extremely high potential energy and won't converge. The highest forces are on frozen atoms. What went wrong?

Answer: This is a common issue, often stemming from a misunderstanding of how frozen atoms are handled.

- Root Cause: When you freeze atoms using a method like

freezegrpsin GROMACS, you are not eliminating the calculation of forces on those atoms. You are only preventing their positions from being updated. If the initial structure has severe steric clashes (e.g., atoms too close together) involving frozen atoms, the potential energy will be very high, and the minimization algorithm cannot resolve these clashes because the offending atoms are frozen in place [9]. - Solution: Do not freeze atoms that are in conflict with the rest of the system. Instead, use strong positional restraints. Positional restraints apply a harmonic potential that holds atoms near their starting positions but allows them enough freedom to relax and resolve bad contacts [9]. As an expert in a forum discussion advises, "Restraints and constraints work very differently on the theoretical level. The former, as you say, just allow for some wiggle a tiny bit around the reference position... The latter require special treatment in the algorithms" [9].

Table 2: Troubleshooting High Energy in Minimization

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Very high potential energy, non-convergence, high forces on frozen atoms | Steric clashes involving frozen atoms | Replace atom freezing with strong positional restraints |

| High energy and forces localized at the periodic boundary | Missing bonds across the periodic boundary or an incorrectly sized box | Check topology for bonds across PBC and ensure the box size fits the system correctly [9] |

| General high energy after building the system | Inherent steric clashes from the initial model | Perform initial minimization with strong positional restraints on the protein/ solute, then gradually release them |

FAQ 3: I applied position restraints, but the atoms still moved from their original positions during minimization. Is this expected?

Answer: Yes, this is the intended and correct behavior.

- Position restraints do not fully fix atoms. They apply a restoring force that is proportional to the displacement from a reference position. The formula for this harmonic potential is typically ( E = \frac{1}{2} k (r - r0)^2 ), where ( k ) is the force constant and ( (r - r0) ) is the displacement [48].

- If the forces from steric clashes or other interactions are stronger than the restraint force, a small displacement will occur to lower the overall potential energy. A sufficiently high force constant will keep the movement very small. If the observed displacement is larger than desired, you should increase the force constant of the restraints [9].

FAQ 4: When should I use rigid bodies versus positional restraints?

Answer: The choice depends on the goal of the simulation and the system's characteristics.

- Rigid Bodies: Use this approach to maintain the exact internal geometry of a molecule or fragment. This is computationally efficient and useful for:

- Solvent: Holding water molecules rigid using algorithms like SETTLE [46].

- Drug Docking: Keeping a ligand rigid during initial docking screens.

- System Preparation: Restraining a large part of the system (e.g., a protein backbone) while allowing side chains to relax.

- Positional Restraints: Use this approach when you need to maintain the overall position and orientation of a group of atoms while allowing for small internal relaxations. This is ideal for:

- Equilibration: Restraining protein heavy atoms during initial solvent equilibration to prevent unfolding.

- Preventing Drift: Holding a specific part of the system in place while studying a process in another region.

- Resolving Clashes: As a safer alternative to fully frozen atoms during energy minimization [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Constraint and Restraint Implementation

| Tool / Software | Primary Function | Key Features for Constraints/Restraints |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Molecular Dynamics Simulation | freezegrps (atom freezing), define = -DPOSRES (position restraints), constraints keyword (for bonds), LINCS/SETTLE algorithms [45] [9] |

| NAMD | Molecular Dynamics Simulation | rigidBonds (bond constraints), fixedAtoms (position fixing), extraBonds (for additional restraints) [46] |

| CHARMM | Molecular Dynamics & Analysis | CONS HARM (harmonic positional restraints), CONS DIHE (dihedral restraints), CONS IC (internal coordinate restraints) [48] |

| SHELXL/RESTRAIN | Crystallographic Refinement | Restraint-based least-squares refinement using geometric targets (bond lengths, angles, etc.) [47] [49] |

| Plumed | Enhanced Sampling & Analysis | A versatile plugin for defining complex collective variables and applying advanced restraints and biases in MD simulations [50] |

Experimental Protocol: A Workflow for Stable Energy Minimization

The following diagram outlines a robust protocol for energy minimization, integrating constraints and restraints to avoid common pitfalls.

Diagram Title: Energy Minimization with Restraints Workflow

Detailed Steps:

- Analyze the Initial Structure: Visually inspect your initial model (e.g., in VMD or PyMol) to identify obvious steric clashes, especially in the region you intend to immobilize. Pay close attention to the periodic boundaries [9].

- Define the Region to Restrain: Clearly identify the atoms (e.g., a protein backbone, a large receptor, or a specific chain) that need to be held in place. Avoid restraining atoms that are in severe conflict with their environment.

- Apply Position Restraints: In your MD engine's parameter file (e.g.,

.mdpin GROMACS), use positional restraints instead of atom freezing. For example, in GROMACS, this is often done by using the-DPOSRESdefine flag which includes a topology file with pre-defined harmonic restraints [45] [9]. Start with a strong force constant (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm²). - Perform Energy Minimization: Run the initial minimization with these strong restraints. The goal is to allow the unrestrained parts (e.g., solvent, side chains) to relax and resolve clashes without the restrained core moving significantly.

- Check for Convergence: Verify that the minimization has converged by checking that the maximum force (