Thermostat and Barostat Algorithms for MD Ensembles: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of thermostat and barostat algorithms used in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, crucial for researchers in drug development and computational biology.

Thermostat and Barostat Algorithms for MD Ensembles: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of thermostat and barostat algorithms used in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, crucial for researchers in drug development and computational biology. We explore the foundational principles of ensemble sampling, detail the mechanisms and implementations of major algorithms including Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen, Langevin, and Parrinello-Rahman, and provide practical guidance for parameter selection and troubleshooting common issues. Through systematic validation and benchmarking studies, we compare algorithmic performance on physical properties, sampling accuracy, and computational efficiency. This guide bridges theoretical knowledge with practical application, enabling researchers to optimize their MD workflows for more reliable predictions of drug solubility, protein dynamics, and molecular interactions.

Understanding Ensemble Fundamentals: From Newtonian Dynamics to Statistical Mechanics

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations serve as a computational microscope, revealing the atomistic details of biomolecular mechanisms critical to drug discovery and development. The foundation of any MD simulation lies in the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion, which describe the trajectory of a system of particles over time. The microcanonical, or NVE ensemble, in which the Number of particles, Volume, and total Energy of the system are conserved, represents the most fundamental approach, deriving directly from these equations without external perturbation. This guide examines the basis of NVE simulations, objectively compares its performance and characteristics against other common ensembles, and situates it within a broader research context focused on evaluating thermostat and barostat algorithms.

Theoretical Foundation: Newtonian Mechanics and the NVE Ensemble

The core algorithm of an MD simulation is a iterative numerical process that computes forces and updates particle positions and velocities [1].

- Compute Forces: The force, (\mathbf{F}i), on each atom (i) is calculated as the negative gradient of the potential energy function (V) with respect to the atom's position, (\mathbf{r}i): (\mathbf{F}i = - \frac{\partial V}{\partial \mathbf{r}i}). This potential energy encompasses both non-bonded interactions (e.g., Lennard-Jones and Coulombic potentials) and bonded interactions [1].

- Update Configuration: The forces are used to numerically integrate Newton's equations of motion to update atomic velocities and positions. The leap-frog algorithm is a common method for this integration, solving (\frac{{\mbox{d}}^2\mathbf{r}i}{{\mbox{d}}t^2} = \frac{\mathbf{F}i}{mi}) where (mi) is the mass of the atom [1].

The NVE ensemble is the direct outcome of this process. In statistical mechanics, it is defined as the set of all possible states of an isolated system with constant energy (E), volume (V), and number of particles (N) [2]. It is considered the most fundamental ensemble as it follows naturally from the conservation of energy in an isolated system [3] [2]. However, a pure NVE simulation can be challenging to achieve in practice. Slight drifts in total energy can occur due to numerical errors in the integration process [3]. Furthermore, as the system's sole thermodynamic driver is the conservation of energy, the temperature (T) and pressure (P) are derived quantities that fluctuate around average values [2].

The following diagram illustrates the core MD algorithm within the NVE ensemble, highlighting the cyclical process of force calculation and configuration updates.

Performance and Characteristics of the NVE Ensemble

While the NVE ensemble is conceptually pure, its practical application has specific performance implications when compared to ensembles that use thermostats and barostats to control temperature and pressure.

Comparison of MD Ensembles

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, performance considerations, and typical use cases for the NVE ensemble and other common ensembles.

| Ensemble | Fixed Variables | Controlled via | Key Performance & Characteristics | Primary Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVE (Microcanonical) | Number (N), Volume (V), Energy (E) | N/A (Isolated system) | - Energy conserved (minor numerical drift) [3].- Temperature/pressure fluctuate freely.- Minimal perturbation of trajectory [3]. | - Studying inherent system dynamics [3].- Data collection after equilibration in other ensembles [3]. |

| NVT (Canonical) | Number (N), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Thermostat (e.g., Nosé–Hoover, Bussi, Langevin) | - Represents a system in a heat bath.- Thermostat choice impacts sampling & efficiency [4].- Less trajectory perturbation vs. NPT [3]. | - Standard for most solution-state biomolecular simulations.- Conformational sampling at constant T. |

| NPT (Isothermal-Isobaric) | Number (N), Pressure (P), Temperature (T) | Thermostat + Barostat | - Maintains correct density & pressure [3].- Mimics common experimental conditions.- Introduces coupling to both T and P baths. | - Equilibration to target density [3].- Simulating lab conditions (e.g., 1 atm, 310 K). |

| NPT (Constant-Enthalpy) | Number (N), Pressure (P), Enthalpy (H) | Barostat | - Enthalpy H = E + PV is conserved.- Temperature is a derived, fluctuating quantity. | - Less common; specific studies where enthalpy is key. |

Performance Implications of Thermostat Choice

The choice of algorithm for temperature control is a critical factor in MD performance. While the NVE ensemble does not use a thermostat, its behavior is a key benchmark against which thermostated simulations are compared. Recent benchmarking studies highlight the trade-offs involved:

- Sampling and Time-Step Dependence: A 2025 study benchmarking thermostat algorithms found that while the Nosé–Hoover chain and Bussi velocity rescaling methods provide reliable temperature control, the resulting potential energy can show a pronounced dependence on the integration time step [4].

- Computational Cost and Diffusion: The same study reported that Langevin dynamics, another thermostat method, typically incurs approximately twice the computational cost of other methods due to the overhead of random number generation. It can also systematically decrease molecular diffusion coefficients with increasing friction, potentially affecting the accuracy of simulated dynamics [4].

- Energy Drift in NVE: In contrast, a primary concern in NVE simulations is energy drift. The Verlet-type integration algorithms used in packages like GROMACS can introduce a very slow change in the center-of-mass velocity and total kinetic energy over long simulations if not properly managed [1].

Experimental Validation of MD Simulations

Validating the physical accuracy of any MD simulation, regardless of ensemble, is paramount. This is typically done by comparing simulation-derived observables against experimental data.

Key Experimental Observables for Validation

The table below lists common experimental measurements used to validate MD simulations and the corresponding properties calculated from the simulation trajectory.

| Experimental Observable | Corresponding Simulation Measurement | Validation Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Density vs. Pressure [5] | Average box size and density (from NPT ensemble). | Validates force field parameters and pressure control [5]. |

| Chemical Shifts (NMR) | Chemical shifts predicted from simulated structures. | Assesses accuracy of conformational sampling [6]. |

| Radius of Gyration | Radius of gyration calculated from atom positions. | Probes global compactness and folding state. |

| Self-Diffusion Coefficient [5] | Mean-squared displacement of molecules over time. | Validates dynamical properties and solvation [5]. |

| Enthalpy of Vaporization [5] | Energy difference between liquid and gas phases. | Tests the balance of intermolecular interactions [5]. |

Validation Protocols and Findings

A critical study compared four major MD packages (AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD, and ilmm) using different force fields. It found that while overall performance in reproducing experimental observables at room temperature was similar across packages, there were subtle differences in conformational distributions and sampling extent [6]. This underscores that simulation outcomes are influenced not just by the force field, but also by the software's specific implementation, including its integration algorithms and treatment of non-bonded interactions [6].

Furthermore, the study revealed that differences between packages became more pronounced under conditions of large-amplitude motion, such as thermal unfolding. Some packages failed to allow the protein to unfold at high temperature or produced results inconsistent with experiment, highlighting how algorithmic differences can significantly impact outcomes in demanding simulations [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This table details key computational tools and their functions in setting up and running MD simulations, particularly for studies comparing ensembles and thermostat algorithms.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in MD Simulation | Example Application in Ensemble Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field | Empirical mathematical functions defining potential energy. | Comparing protein dynamics across force fields reveals their influence on results [6]. |

| Water Model | A parameterized set of molecules representing solvent. | Different models (TIP4P-EW, SPC/E) used with different packages to solvate proteins [6]. |

| Thermostat Algorithm | Regulates system temperature by modifying velocities. | Benchmarking Nosé–Hoover, Bussi, and Langevin methods for temperature control and sampling [4]. |

| Barostat Algorithm | Regulates system pressure by adjusting simulation box volume. | Used in NPT and NPH ensembles to maintain constant pressure [3]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Software package implementing MD algorithms. | Comparing GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD reveals impact of codebase on results [6]. |

| Trajectory Analysis Tools | Programs/scripts to calculate properties from simulation output. | Used to compute RMSD, SASA, and other properties from saved trajectories [7]. |

The NVE ensemble, grounded directly in Newton's equations of motion, remains a cornerstone of molecular dynamics. Its value lies in its minimal algorithmic perturbation, making it ideal for studying a system's intrinsic behavior and for production simulations after equilibration. However, for most applications mimicking experimental conditions, the NVT and NPT ensembles are more appropriate. The choice between ensembles, and the subsequent selection of thermostat and barostat algorithms within them, involves tangible trade-offs in sampling efficiency, computational cost, and physical accuracy. A robust research workflow therefore necessitates careful ensemble selection, informed by benchmark studies, and rigorous validation against experimental data to ensure the reliability of the insights gained.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations have become a cornerstone of modern scientific research, providing atomistic insights into the behavior of materials and biomolecules. The reliability of these simulations, however, hinges on the choice of statistical ensemble and the algorithms used to maintain constant temperature and pressure. This guide provides an objective comparison of thermostat and barostat algorithms, connecting simulation conditions to the physical properties they aim to reproduce.

In MD simulations, a statistical ensemble defines the collection of microscopic states the system can adopt under specific macroscopic constraints. While the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble, which conserves energy, is the default in MD, most experimental conditions correspond to the canonical (NVT) or isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensembles. Thermostats and barostats are algorithms designed to maintain constant temperature and pressure, respectively, steering the system to sample the desired ensemble [8]. The choice of algorithm is not merely a technical detail; it fundamentally influences both the static and dynamic properties of the simulated system. An inappropriate choice can suppress natural fluctuations, distort dynamics, or fail to sample a correct thermodynamic ensemble, leading to unsound comparisons with experimental data [9] [8].

Comparative Analysis of Thermostat Algorithms

Thermostat algorithms can be broadly categorized into deterministic (extended system) and stochastic (collisional) types. The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of several commonly used thermostats.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Thermostat Algorithms in MD Simulations

| Thermostat Algorithm | Type | Key Mechanism | Sampling | Impact on Dynamics | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosé-Hoover (Chain) [9] [8] | Deterministic | Extended system with a friction variable | Correct NVT | Minimal disturbance (no random forces) | General NVT production for stable systems |

| Bussi (V-rescale) [9] [8] | Stochastic | Stochastic velocity rescaling | Correct NVT | Minimal disturbance; stronger coupling | Efficient equilibration & NVT production |

| Langevin [9] [8] | Stochastic | Friction + random noise force | Correct NVT | Dampens diffusion; depends on friction | Systems requiring strong temperature control |

| Andersen [8] | Stochastic | Random velocity reassignment | Correct NVT | Violently damps dynamics; unphysical | Not recommended for dynamics properties |

| Berendsen [8] | Deterministic | First-order velocity scaling | Incorrect NVT (suppresses fluctuations) | Weak perturbation of dynamics | Rapid equilibration only |

Performance and Property Dependence

The choice of thermostat has a measurable impact on simulated physical properties:

- Time-step dependence: A systematic study on a binary Lennard-Jones glass-former found that while thermostats like Nosé-Hoover chains and Bussi provide reliable temperature control, the potential energy can show a pronounced dependence on the integration time step [9].

- Configurational vs. kinetic sampling: Among Langevin thermostats, the Grønbech-Jensen–Farago (GJF) scheme provided the most consistent sampling of both temperature and potential energy across time steps [9].

- Computational cost: Stochastic methods, particularly Langevin dynamics, can incur approximately twice the computational cost due to the overhead of random number generation [9].

- Diffusion coefficients: Langevin dynamics exhibits a systematic decrease in diffusion coefficients with increasing friction coefficient, a critical consideration for simulating transport properties [9].

Comparative Analysis of Barostat Algorithms

For simulations under constant pressure, the barostat controls the system's volume or box dimensions. The two most common algorithms are compared below.

Table 2: Comparison of Common Barostat Algorithms in MD Simulations

| Barostat Algorithm | Type | Key Mechanism | Sampling | Impact on System | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parrinello-Rahman [8] | Deterministic | Extended Lagrangian for box vectors | Correct NPT | Allows box shape/size change; can oscillate | General NPT production |

| Berendsen [8] | Deterministic | First-order scaling of coordinates/box | Incorrect NPT (suppresses fluctuations) | Rapid relaxation | Rapid equilibration only |

Connecting Algorithm Choice to Experimental Reality

The ultimate goal of an MD simulation is often to compute properties that can be validated against, or used to interpret, experimental data. The thermostat and barostat must be chosen to match the experimental conditions without unduly influencing the results.

Matching the Physical Ensemble

The first step is to select the ensemble that corresponds to the experimental reality [10]:

- NVE: Use for isolated systems or when calculating IR spectra from velocity correlation functions [10].

- NVT: Appropriate for comparing to experiments in a fixed volume, though this is rare in condensed matter [10].

- NPT: The most common choice for simulating condensed phases (liquids, solids) as most bench experiments are conducted at constant pressure and temperature [8] [10].

Preserving Physical Properties

Different scientific questions require the preservation of different physical properties:

- For structural and thermodynamic properties: Algorithms that correctly sample the ensemble (e.g., Nosé-Hoover, Bussi, Parrinello-Rahman) are essential. Berendsen methods should be avoided for production runs as they suppress energy and volume fluctuations [8].

- For dynamical properties: Stochastic thermostats like Andersen and Langevin can artificially dampen particle dynamics. The Nosé-Hoover chain and Bussi thermostats are generally preferred as they "minimally disturb the particles' (Newtonian) dynamics" [8].

- In non-equilibrium MD (NEMD): Simulations like those of viscous flow require more efficient (stronger) coupling to evacuate heat, for which the Bussi thermostat is often suitable [8].

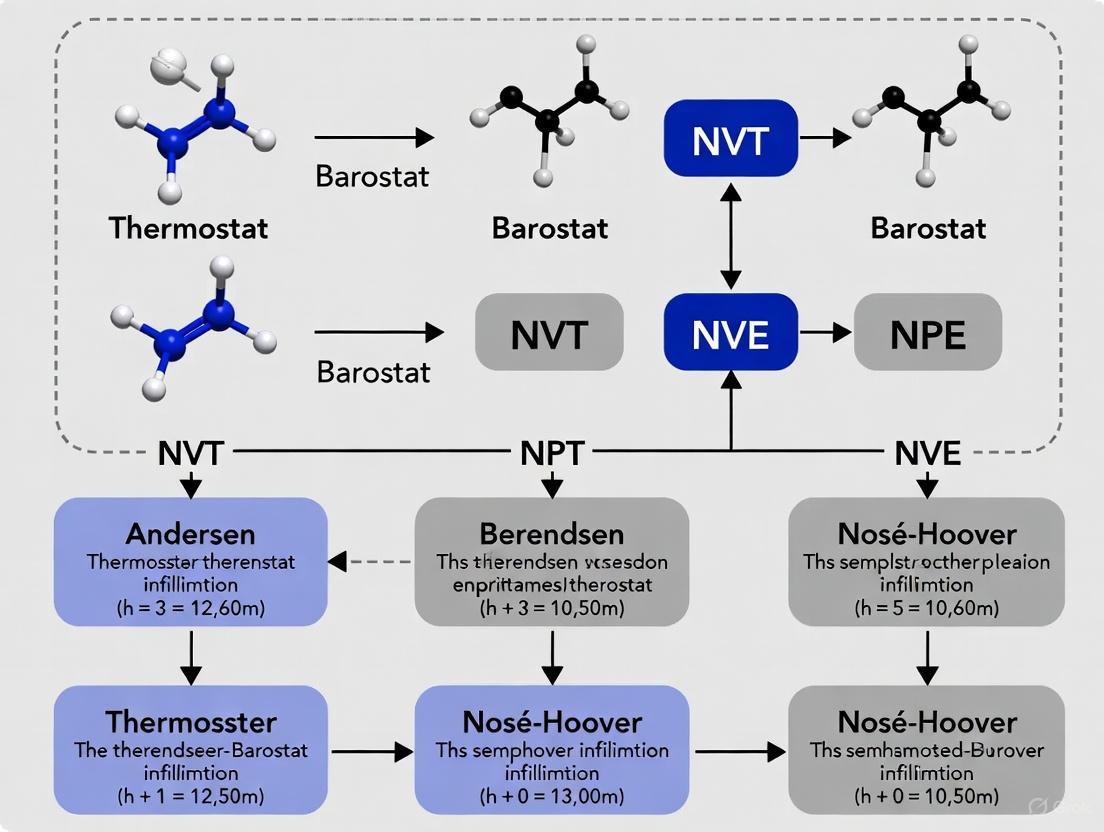

The following workflow diagram outlines a decision-making process for selecting an appropriate thermostat and barostat based on your simulation goals.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and accurate comparison, the methodology for benchmarking these algorithms must be clearly defined. The following protocol is adapted from recent systematic studies [9].

Protocol: Benchmarking Thermostats on a Binary Lennard-Jones Glass-Former

1. System Preparation

- Model: Use the Kob-Andersen binary Lennard-Jones mixture (80% A, 20% B particles) [9].

- Parameters: Follow the original model for interaction energies (ε) and diameters (σ): εAB/εAA = 1.5, εBB/εAA = 0.5, σAB/σAA = 0.8, σBB/σAA = 0.88 [9].

- System Size: Simulate N=1000 particles in a cubic box with periodic boundary conditions at a number density of ρ = 1.2 [9].

- Potential: Apply a smoothed cutoff at rc,AA = 1.5 σAA and rc,AB = 2.5 σAB [9].

2. Simulation Execution

- Thermostats for Comparison: Include NHC1, NHC2, Bussi, and multiple Langevin schemes (BAOAB, ABOBA, GJF) [9].

- Control Parameters: Run simulations at a target temperature of T=0.5 (in reduced units). Use identical initial conditions for all thermostats [9].

- Time Step Analysis: Investigate the influence of the integration time step (e.g., Δt = 0.001-0.01 in reduced units) on measured observables [9].

3. Data Collection and Analysis

- Kinetic Properties: Collect the instantaneous temperature and particle velocities. Analyze the distribution to verify it follows the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution [9].

- Configurational Properties: Calculate the potential energy and its distribution. Monitor for time-step dependence [9].

- Structural Properties: Compute the radial distribution function (RDF) to assess errors induced by the integration time step [9].

- Dynamical Properties: Calculate the mean-squared displacement (MSD) to extract diffusion coefficients and observe the impact of friction (for Langevin thermostats) [9].

- Computational Cost: Measure the computational time per simulation step for each thermostat, noting the overhead of random number generation in stochastic methods [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key components and their functions for setting up and running reliable MD simulations of condensed matter systems.

Table 3: Essential Toolkit for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Item / Component | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field | Defines potential energy function; describes particle interactions. | Lennard-Jones parameters [9], CHARMM36m [11], a99SB-disp [11] |

| Solvent Model | Represents the solvent environment explicitly or implicitly. | TIP3P water model [11], a99SB-disp water [11] |

| Simulation Software | Software package to perform energy calculations and integrate equations of motion. | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, LAMMPS |

| Thermostat Algorithm | Maintains constant temperature, sampling the NVT ensemble. | Nosé-Hoover Chain, Bussi (V-rescale) [9] [8] |

| Barostat Algorithm | Maintains constant pressure, sampling the NPT ensemble. | Parrinello-Rahman barostat [8] |

| Analysis Tools | Programs and scripts to calculate properties from simulation trajectories. | MDAnalysis, VMD, GROMACS analysis tools |

Key Recommendations for Practitioners

Based on the comparative data and experimental findings, the following recommendations are provided:

- For common NVT/NPT production simulations, the Nosé-Hoover chain or Bussi (V-rescale) thermostat coupled with the Parrinello-Rahman barostat is generally recommended for their accurate sampling and minimal disturbance of dynamics [8].

- For systems requiring strong temperature control or in NEMD, stochastic thermostats like Langevin or Bussi with stronger coupling may be necessary [8].

- Always avoid the Berendsen thermostat and barostat for production runs where correct fluctuation sampling is required, as they suppress kinetic energy and volume fluctuations [8].

- Be cautious with Andersen and Langevin thermostats when studying dynamic properties like diffusion or viscosity, as the stochastic collisions can artificially dampen the natural dynamics [8].

- Validate your choice by checking that key properties, such as potential energy and diffusion coefficients, are stable with respect to changes in algorithm parameters like time step and friction coefficient [9].

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the system naturally evolves while conserving total energy, sampling the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble. However, to match common experimental conditions, simulations often need to be run at a constant temperature, sampling the canonical (NVT) ensemble. Thermostats are algorithms designed for this purpose, and they primarily fall into two fundamental categories: velocity randomizing and velocity scaling methods [8] [12]. The choice of thermostat is not merely a technical detail; it profoundly influences both the thermodynamic accuracy and the dynamic properties of the simulated system. Velocity randomizing algorithms, such as Andersen and Stochastic Dynamics, control temperature by introducing random collisions. In contrast, velocity scaling algorithms, including Berendsen, V-rescale, and Nosé-Hoover, achieve this through deterministic or stochastic scaling of particle velocities [8]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these approaches, supported by experimental data, to inform researchers and scientists in selecting the appropriate algorithm for their MD ensembles research.

Algorithmic Fundamentals and Classification

The core function of a thermostat is to maintain the average temperature of a system by ensuring that the average kinetic energy agrees with the equipartition theorem, (\langle K \rangle = \frac{3}{2}Nk_BT), while allowing instantaneous fluctuations [12]. The two algorithmic classes achieve this through fundamentally different mechanisms.

Velocity Scaling Algorithms

These algorithms operate by uniformly scaling the velocities of all particles in the system by a factor (\lambda), so that (vi^{new} = vi^{old} \cdot \lambda) [12].

- Berendsen Thermostat: This algorithm mimics a system weakly coupled to an external heat bath. It scales velocities with a factor (\lambda = \sqrt{1+\frac{\delta t}{\tau} \left( \frac{T{bath}}{T(t)}-1\right)}), leading to an exponential decay of temperature deviations: (dT/dt = (T0 - T)/\tau) [8] [12]. The parameter (\tau) represents the coupling strength, with smaller values leading to stronger coupling and faster equilibration but suppressed energy fluctuations.

- V-rescale Thermostat: An extension of the Berendsen thermostat, this stochastic algorithm enforces the correct kinetic energy distribution by adding a random force. Its kinetic energy evolves as (dK = (K0 - K)\frac{dt}{\tauT} + 2\sqrt{\frac{KK0}{Nf}}\frac{dW}{\sqrt{\tau_T}}), where (dW) is a Wiener process [8]. This allows it to correctly sample the canonical ensemble.

- Nosé-Hoover Thermostat: This extended Lagrangian method introduces an additional degree of freedom (a "thermal reservoir") into the system Hamiltonian. It adds a friction term to the equations of motion: (d^2\mathbf{r}i/dt^2 = \mathbf{F}i/mi - p{\xi} d\mathbf{r}i/dt), where the momentum of the reservoir (p{\xi}) evolves via (dp{\xi}/dt = (T - T0)) [8]. The mass parameter (Q) of the reservoir controls the coupling strength.

Velocity Randomizing Algorithms

These algorithms incorporate stochastic collisions that periodically reassign particle velocities.

- Andersen Thermostat: This method randomly selects particles at each time step with a probability (\nu \Delta t) and reassigns their velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at the target temperature [8]. The time between collisions for a given atom follows a Poisson distribution. A variant, "Andersen-Massive," reassigns velocities for all particles at every (\tau_T/\Delta t) step.

- Stochastic Dynamics (Langevin Thermostat): This algorithm integrates the Langevin equation of motion: (mi d^2\mathbf{r}i/dt^2 = -\nabla V - mi \gammai d\mathbf{r}i/dt + \mathbf{R}i(t)) [8] [13]. Here, a deterministic friction force ((-mi \gammai \mathbf{v}i)) damps the velocity, while a stochastic force ((\mathbf{R}i(t))) provides random kicks, collectively thermalizing the system. The damping constant (\gamma) determines the coupling strength.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Thermostat Algorithms

| Algorithm | Classification | Core Mechanism | Key Controlling Parameter | Ensemble Sampled |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berendsen | Velocity Scaling | First-order kinetic relaxation | Coupling time constant τ |

Incorrect (suppresses fluctuations) |

| V-rescale | Velocity Scaling | Stochastic rescaling of kinetic energy | Coupling time constant τ |

Canonical (NVT) |

| Nosé-Hoover | Velocity Scaling | Extended Lagrangian with friction | Reservoir mass Q |

Canonical (NVT) |

| Andersen | Velocity Randomizing | Stochastic velocity reassignment | Collision frequency ν |

Canonical (NVT) |

| Stochastic Dynamics | Velocity Randomizing | Langevin equation (friction + noise) | Damping constant γ |

Canonical (NVT) |

Comparative Analysis of Key Properties

The fundamental differences in mechanism lead to significant practical consequences for simulation accuracy and efficiency. A critical distinction lies in how these thermostats affect the dynamics of the simulated system. While all can correctly sample configurational properties (i.e., equilibrium distributions), they perturb the natural Newtonian dynamics to different degrees [8] [13].

Impact on Dynamics and Fluctuations

Velocity randomizing thermostats directly interfere with particle trajectories through random kicks. Studies show that Andersen and Stochastic Dynamics thermostats can violently perturb particle dynamics, leading to inaccurate transport properties like diffusivity and viscosity [8]. For example, in water simulations, the diffusion constant decreases with increasing coupling strength (γ or ν). Similarly, conformational dynamics of polymers and proteins can be artificially slowed down [13]. The Berendsen thermostat, while efficient for equilibration, is known to suppress fluctuations of kinetic energy and thus fails to generate a correct canonical ensemble [8] [12]. In contrast, the V-rescale and Nosé-Hoover thermostats are designed to produce correct fluctuations and are generally recommended for production simulations [8].

Performance in Different Simulation Scenarios

The optimal choice of thermostat can depend on the type of simulation being performed.

- Equilibration vs. Production: The Berendsen thermostat is highly effective for the initial equilibration phase due to its robust and fast relaxation to the target temperature. However, for production runs, V-rescale or Nosé-Hoover are superior choices as they ensure proper sampling [8] [12].

- Non-Equilibrium MD (NEMD) and NPT Simulations: These simulations often place a greater demand on the thermostat. Research indicates that NPT or NEMD simulations may require stronger coupling (e.g., a smaller

τor largerγ) than NVT equilibrium simulations to maintain the temperature close to the target, especially when viscous heating or rapid volume changes occur [8].

Experimental Data and Performance Benchmarks

Empirical studies provide critical insights into the practical performance of different thermostats across a range of physical properties.

Protocol for Benchmarking Thermostats

A typical benchmarking study involves simulating a standard system, such as a liquid (e.g., water or an ionic liquid) or a small protein, and comparing the results against theoretical values from statistical mechanics or experimental data [8]. The key steps are:

- System Preparation: A box of the liquid or a solvated protein is energy-minimized and equilibrated.

- Simulation Setup: Multiple independent NVT simulations are run using different thermostat algorithms and coupling parameters. For barostatted runs, a barostat like Parrinello-Rahman is often used [8].

- Data Collection: Properties are calculated from the production trajectories, including:

- Validation: The simulated fluctuations are compared against theoretical values for the canonical ensemble, while dynamic properties are compared against NVE simulation results or experimental data [8] [13].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of Common Thermostats

| Algorithm | Static/Structural Properties | Energy/Volume Fluctuations | Dynamic/Transport Properties | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berendsen | Accurate on average | Inaccurate (Suppressed) [8] | Moderately perturbed | System equilibration [12] |

| V-rescale | Accurate | Accurate [8] | Minimally perturbed | Production NVT/NPT [8] |

| Nosé-Hoover | Accurate | Accurate [8] | Minimally perturbed (may oscillate far from equilibrium) [8] | Production NVT/NPT [8] |

| Andersen | Accurate | Accurate | Inaccurate (Over-damped) [8] | Specialized studies |

| Stochastic Dynamics | Accurate | Accurate | Inaccurate (Dependent on γ) [8] [13] | Solvent dynamics, coarse-grained MD |

Key Findings on Thermostat-Induced Distortions

Research highlights that complex and dynamical properties are more sensitive to thermostat choice than simple structural properties [8]. A 2021 study specifically investigated the distortion of protein dynamics by the Langevin thermostat, finding that it systematically dilates time constants for molecular motions [13]. Overall rotational correlation times of proteins were significantly increased, while sub-nanosecond internal motions were more modestly affected. The study also presented a correction scheme to contract these time constants and recover dynamics that agree well with NMR relaxation data [13].

Decision Workflow and Research Toolkit

Thermostat Selection Workflow

The following diagram outlines a decision process for selecting and applying a thermostat algorithm in molecular dynamics research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software and Parameters for Thermostat Implementation

| Item | Function / Description | Example in GROMACS |

|---|---|---|

| Velocity Verlet Integrator | Core algorithm for numerically solving Newton's equations of motion; required for all thermostated MD [14]. | integrator = md |

| Leap-Frog Integrator | An alternative, often default, algorithm for updating atomic coordinates and velocities [15]. | integrator = md (legacy) |

| Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution | The probability distribution from which initial velocities and stochastic thermostat kicks are drawn [15] [14]. | gen_vel = yes |

| Coupling Strength / Time Constant (τ) | For scaling thermostats (Berendsen, V-rescale): time constant for temperature relaxation. Larger τ means weaker coupling [8] [12]. | tau_t = 0.1 (in ps) |

| Damping Constant (γ) | For Langevin thermostat: friction coefficient (ps⁻¹) determining strength of coupling to bath [8] [13]. | bd-fric = 1.0 (in ps⁻¹) |

| Collision Frequency (ν) | For Andersen thermostat: frequency of stochastic collisions (ps⁻¹) [8]. | N/A (implementation specific) |

| Mass Parameter (Q) | For Nosé-Hoover thermostat: effective mass of the thermal reservoir, controlling oscillation period [8] [12]. | N/A (often determined automatically) |

The fundamental dichotomy between velocity randomizing and velocity scaling thermostats presents a clear trade-off: stochastic algorithms can guarantee correct ensemble sampling but at the cost of perturbing dynamical properties, while deterministic scaling algorithms can preserve dynamics but risk incorrect fluctuations if not carefully chosen. Current evidence, synthesizing findings on liquids and proteins, recommends Nosé-Hoover or V-rescale thermostats with moderate coupling strength for common NVT/NPT production simulations, as they provide a robust balance of accurate ensemble sampling and minimal dynamic distortion [8]. The Berendsen thermostat remains a valuable tool for equilibration, while stochastic thermostats should be used with caution when accurate dynamics are required. Future research will continue to refine these algorithms and develop correction schemes, like the one proposed for Langevin dynamics in proteins [13], further bridging the gap between simulated and experimental observables. This progression will enhance the role of MD as a predictive tool in drug development and materials science.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, barostats are essential algorithms that maintain constant pressure, enabling the simulation of isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensembles that mirror common laboratory conditions. These algorithms control pressure by adjusting the system volume, typically through coordinate scaling techniques, allowing the instantaneous pressure to fluctuate while maintaining a target average pressure over time [16]. The fundamental equation governing pressure in MD simulations is the virial equation, P = (NKBT)/V + (1/3V)⟨ΣrijFij⟩, where the first term represents the ideal gas contribution and the second accounts for internal forces between atoms [17]. By implementing barostats, researchers can investigate pressure-dependent phenomena such as phase transitions, thermal expansion, and material properties under various pressure conditions, making these algorithms indispensable for simulating realistic physical systems in computational chemistry, materials science, and drug development [18].

Theoretical Foundation of Pressure Control

Fundamental Relationship Between Volume and Pressure

The core principle underlying all barostat algorithms is the inverse relationship between system volume and internal pressure. When atoms are compressed within a smaller volume, they experience more frequent collisions and greater repulsive forces, resulting in increased pressure [16]. Conversely, expanding the volume reduces atomic crowding and decreases pressure. Barostats exploit this relationship by systematically adjusting the simulation box dimensions and atom positions to maintain a target pressure. In practice, this is achieved by scaling atomic coordinates by a factor λ¹′³, which corresponds to changing the system volume by a factor of λ [16]. This coordinate scaling approach forms the mathematical foundation for pressure regulation across different barostat algorithms.

Statistical Mechanical Ensembles

Barostats enable sampling of the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble, where particle number (N), pressure (P), and temperature (T) remain constant. This differs from the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble where energy is conserved, and the canonical (NVT) ensemble where temperature is controlled [17] [19]. Proper ensemble sampling requires that barostats not only maintain the correct average pressure but also produce appropriate volume fluctuations that match theoretical predictions for the NPT ensemble [8]. Different barostat algorithms vary in their ability to correctly sample these fluctuations, with some methods suppressing natural volume variations or introducing artificial oscillations.

Classification of Barostat Algorithms

Barostat algorithms can be categorized into four primary classes based on their underlying methodology and approach to pressure control [17]:

Table 1: Fundamental Classes of Barostat Algorithms

| Algorithm Class | Mechanism | Key Features | Ensemble Sampling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weak Coupling Methods | Scales coordinates proportional to pressure difference | Fast equilibration; suppresses fluctuations | Incorrect for production |

| Extended System Methods | Introduces additional degree of freedom (volume) | Time-reversible; allows anisotropic changes | Correct with proper implementation |

| Stochastic Methods | Adds damping and random forces | Fast convergence; reduced oscillation | Correct |

| Monte Carlo Methods | Random volume changes with MC acceptance | Does not require virial computation | Correct |

Weak Coupling Methods

The Berendsen barostat represents the most common weak coupling approach, designed for efficient equilibration rather than production simulations. This algorithm scales the volume by an increment proportional to the difference between the internal and external pressure, following the equation: dP/dt = (P₀ - P)/τ, where τ is the coupling time constant [17] [8]. The coordinates are scaled by a factor λ¹′³, where λ = [1 - (kΔt/τ)(P(t) - Pbath)], with k representing the isothermal compressibility [16]. While highly efficient for reaching target pressure conditions, the Berendsen barostat suppresses volume fluctuations and does not generate a correct NPT ensemble, making it unsuitable for production simulations where accurate fluctuation properties are required [17] [8].

Extended System Methods

Extended system methods incorporate the volume as a dynamic variable with its own equation of motion. The Andersen barostat introduces a piston mass (Q) that controls the volume fluctuations, scaling coordinates as rinew = riold · V¹′³ [16]. The Parrinello-Rahman method extends this approach by allowing changes in both box size and shape, making it particularly valuable for studying structural transformations in solids under external stress [17]. The equations of motion for the Parrinello-Rahman method include additional terms for the cell vectors and a pressure control variable η: ḣ = ηh, where h represents the simulation cell vectors [18]. The Nosé-Hoover barostat and its extension, the MTTK (Martyna-Tuckerman-Tobias-Klein) barostat, further refine this approach with improved performance for small systems [17].

Stochastic and Monte Carlo Methods

Stochastic barostats incorporate random forces to improve sampling efficiency. The Langevin piston method adds damping and stochastic forces to the equations of motion, similar to the MTTK approach but with better convergence properties due to reduced oscillations [17]. Stochastic Cell Rescaling represents an improved version of the Berendsen barostat that adds a stochastic term to the rescaling matrix, producing correct fluctuations for the NPT ensemble [17]. Monte Carlo barostats generate random volume changes that are accepted or rejected based on standard Monte Carlo probabilities, avoiding the need for virial pressure calculations during runtime [17]. These methods can be highly efficient but may not provide pressure information at simulation time.

Comparative Analysis of Barostat Performance

Algorithmic Properties and Implementation

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Barostat Algorithms

| Barostat Type | Ensemble Accuracy | Volume Fluctuations | Equilibration Speed | Recommended Use | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berendsen | Does not sample correct NPT | Suppressed | Very fast | Initial equilibration only | τP (coupling constant) |

| Andersen | Correct NPT | Natural but may oscillate | Moderate | Isotropic NPT production | Piston mass (Q) |

| Parrinello-Rahman | Correct NPT | Natural, may oscillate with wrong mass | Moderate | Production, anisotropic systems | pfactor (τP²B), W mass matrix |

| Nosé-Hoover/MTTK | Correct for large systems | Natural | Moderate | Production NPT | Piston mass |

| Langevin Piston | Correct NPT | Natural with reduced oscillation | Fast | Production NPT | Friction coefficient |

| Stochastic Cell Rescaling | Correct NPT | Natural | Fast | All simulation stages | τP, compressibility |

Effects on Physical Properties

Research demonstrates that different barostats significantly impact calculated physical properties, particularly for complex and dynamic characteristics. Studies comparing Berendsen and Parrinello-Rahman barostats reveal that while simple properties like density may show minimal differences between algorithms, more complex properties such as diffusion constants and viscosity are strongly affected by the choice of barostat [8]. The Berendsen barostat's suppression of volume fluctuations leads to inaccurate estimation of fluctuation-derived properties and can produce artifacts in inhomogeneous systems such as aqueous biopolymers or liquid-liquid interfaces [17] [8]. The Parrinello-Rahman barostat, when coupled with appropriate thermostats, generally produces more accurate physical properties across a broader range of system types [8].

Experimental Protocols and Parameterization

Implementation in Molecular Dynamics Packages

Barostat algorithms are implemented differently across popular MD software packages:

Table 3: Barostat Implementation in Major MD Packages

| MD Package | Berendsen | Parrinello-Rahman | MTTK | Stochastic Cell Rescaling | Monte Carlo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | pcoupl = Berendsen | pcoupl = Parrinello-Rahman | pcoupl = MTTK | pcoupl = C-rescale | barostat = 2 |

| NAMD | Berendsen | Langevin | |||

| AMBER | barostat = 1 | LangevinPiston on |

Parameter Selection Guidelines

Proper parameter selection is crucial for barostat performance. For the Berendsen barostat, the coupling constant τP determines how quickly the system responds to pressure deviations. Small values (0.1-1 ps) enable rapid equilibration but may cause instability, while larger values (2-5 ps) provide gentler adjustment [17]. For the Parrinello-Rahman barostat, the key parameter is the pfactor (τP²B), where B is the bulk modulus. For crystalline metal systems, values of 10⁶-10⁷ GPa·fs² typically provide good convergence and stability [18]. For the Andersen barostat, the piston mass Q controls oscillation frequency, with larger masses resulting in slower volume fluctuations [16].

Experimental protocols for NPT simulations typically recommend using Berendsen or weak coupling methods during initial equilibration phases, then switching to extended system or stochastic methods for production simulations [17] [8]. For example, a typical protocol for simulating biomolecular systems might employ Berendsen pressure coupling for 100-500 ps during equilibration, followed by Parrinello-Rahman or Langevin piston methods for production trajectories [8].

Workflow and Application

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Barostat Applications

| Reagent/Parameter | Function | Typical Values | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coupling Constant (τP) | Controls response speed to pressure deviations | 1-5 ps | Smaller values for faster equilibration, larger for stability |

| Piston Mass (Q) | Determines oscillation frequency in extended systems | System-dependent | Larger mass for slower fluctuations, smaller for faster response |

| Isothermal Compressibility (β) | Defines material response to pressure changes | 4.5×10⁻⁵ bar⁻¹ (water) | System-specific; critical for Berendsen barostat |

| pfactor | Combined parameter for Parrinello-Rahman barostat | 10⁶-10⁷ GPa·fs² | Must be estimated from bulk modulus |

| Target Pressure (P₀) | Reference pressure for simulation | 1 bar (atmospheric) | Match experimental conditions |

| Annealing Protocol | Temperature and pressure control during equilibration | Multiple step process | Critical for preventing simulation instability |

Barostat algorithms represent a critical component in molecular dynamics simulations, enabling researchers to model realistic experimental conditions at constant pressure. The fundamental principle of controlling pressure through volume and coordinate scaling unifies diverse algorithmic approaches, from simple weak-coupling methods to sophisticated extended system techniques. Current research indicates that while the Berendsen barostat remains valuable for rapid equilibration, production simulations requiring accurate fluctuation properties benefit from extended system methods like Parrinello-Rahman or stochastic approaches like the Langevin piston [17] [8]. Proper parameter selection remains essential for achieving physically meaningful results, with coupling strengths and piston masses requiring system-specific optimization. As molecular dynamics continues to advance in drug development and materials science, understanding these fundamental barostat principles becomes increasingly important for generating reliable, reproducible computational results.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the choice of statistical ensemble is fundamental, directly determining which thermodynamic variables are controlled and thereby influencing the physical relevance of the simulated system. The microcanonical (NVE), canonical (NVT), and isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensembles each serve distinct purposes in mimicking experimental conditions. This guide objectively compares these ensemble types within the critical context of thermostat and barostat algorithm selection, providing researchers with practical insights backed by recent experimental and simulation data. Proper algorithm implementation is not merely a technical detail but a significant factor in ensuring that simulated properties—from simple energies to complex dynamical behaviors—accurately reflect realistic physical systems [8].

Understanding the Core Ensemble Types

The foundation of MD simulation accuracy lies in selecting the appropriate ensemble, which defines the thermodynamic state of the system and determines which properties are controlled during the simulation.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Molecular Dynamics Ensembles

| Ensemble | Controlled Variables | Physical Correspondence | Primary Applications | Key Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVE | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Energy (E) | Isolated system | Study of energy conservation; fundamental Newtonian dynamics | Velocity Verlet |

| NVT | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | System in contact with a heat bath | Simulating systems at specific temperatures | Nosé-Hoover, Bussi, Langevin |

| NPT | Number of particles (N), Pressure (P), Temperature (T) | System in contact with heat and pressure baths | Matching experimental lab conditions (most common) | Nosé-Hoover + Parrinello-Rahman |

NVE Ensemble

The NVE, or microcanonical, ensemble is the most fundamental MD approach, integrating Newton's equations of motion without temperature or pressure control. It naturally conserves the total energy of the system and serves as the default for simulations where energy conservation is paramount. However, its limitation lies in its poor correspondence to most experimental conditions, where temperature and pressure are typically controlled variables [8].

NVT Ensemble

The NVT, or canonical, ensemble maintains a constant number of particles, volume, and temperature, corresponding to a system in contact with a thermal reservoir. This ensemble is essential for investigating temperature-dependent processes and properties at constant volume. Accurate temperature control requires sophisticated thermostat algorithms that minimally perturb the system's natural dynamics while correctly sampling the canonical distribution [9] [8].

NPT Ensemble

The NPT, or isothermal-isobaric, ensemble maintains constant temperature and pressure, directly corresponding to the conditions of most laboratory experiments. This makes it the most widely used ensemble for simulating biomolecular systems, materials, and liquids under realistic conditions. Reproducing accurate NPT ensembles requires the combined use of a thermostat and a barostat, introducing additional complexity in algorithm selection and parameterization [8].

Thermostat and Barostat Algorithms: A Performance Comparison

Thermostat and barostat algorithms can be broadly categorized into deterministic and stochastic methods, each with distinct strengths and weaknesses in sampling accuracy and dynamic properties.

Table 2: Algorithm Performance in NVT and NPT Ensembles

| Algorithm | Type | Ensemble Sampled | Strengths | Weaknesses | Impact on Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosé-Hoover Chain (NHC) | Deterministic | Correct NVT/NPT | Reliable temp control; well-established | Pronounced time-step dependence in potential energy [9] | Minimal disturbance when well-tuned |

| Bussi (v-rescale) | Stochastic | Correct NVT | Fast equilibration; correct kinetics | Global control can mask local effects | Minimal disturbance on Hamiltonian dynamics [9] |

| Langevin (GJF/BAOAB) | Stochastic | Correct NVT | Excellent configurational sampling [9] | High computational cost (2x); reduces diffusion at high friction [9] | Can dampen natural dynamics |

| Berendsen | Deterministic | Incorrect NVT/NPT | Very fast equilibration | Suppresses energy/volume fluctuations [8] | Generally preserves dynamics |

| Andersen | Stochastic | Correct NVT | Simple implementation | Violently perturbs particle dynamics [8] | Artificially randomizes velocities |

Deterministic Approaches

Deterministic thermostats extend the Hamiltonian to include additional variables that mediate thermal exchange. The Nosé-Hoover thermostat and its chain generalization (NHC) provide rigorous canonical sampling through an extended Hamiltonian formalism [9]. While generally providing reliable temperature control with minimal disturbance to dynamics, these methods can exhibit pronounced time-step dependence in configurational properties like potential energy [9]. The Berendsen thermostat, though popular for rapid equilibration due to its exponential decay of temperature deviations, fails to produce correct ensemble averages and suppresses energy fluctuations, making it unsuitable for production simulations [8].

Stochastic Approaches

Stochastic methods incorporate random forces and friction to maintain temperature. The Bussi thermostat (also known as v-rescale) extends the Berendsen approach by incorporating a stochastic term that ensures correct kinetic energy distribution while minimizing disturbance to Hamiltonian dynamics [9]. Langevin dynamics implementations, particularly the Grønbech-Jensen-Farago (GJF) and BAOAB schemes, provide excellent configurational sampling but typically incur approximately twice the computational cost due to random number generation overhead [9]. A significant drawback of Langevin methods is their systematic reduction of diffusion coefficients with increasing friction parameters, which can alter dynamical properties [9].

Barostat Considerations

For NPT simulations, barostat selection is equally critical. The Berendsen barostat provides rapid pressure equilibration but suppresses volume fluctuations analogous to its thermostat counterpart. The Parrinello-Rahman barostat, which allows independent variation of unit cell vectors, correctly samples the NPT ensemble but may produce unphysical oscillations when systems deviate far from equilibrium [8]. For production NPT simulations, the Parrinello-Rahman barostat with moderate coupling strength is generally recommended [8].

Experimental Correlation and Validation Protocols

Validating ensemble generation against experimental data is essential for establishing simulation reliability. Different experimental techniques provide benchmarks for various aspects of simulated ensembles.

Diagram 1: Experimental Validation Workflow for MD Ensembles (Short title: MD Validation Workflow)

Validation with Experimental Observables

Multiple research studies have demonstrated systematic approaches for correlating simulation ensembles with experimental data:

- Structural Properties: For binary Lennard-Jones glass-formers, structural properties showed relatively minor sensitivity to thermostat choice compared to dynamic properties, though errors induced by integration time step varied across algorithms [9].

- Dynamical Properties: Diffusion coefficients and relaxation dynamics show significant sensitivity to thermostat choice. Stochastic methods like Langevin dynamics particularly affect diffusion coefficients, which decrease systematically with increasing friction parameters [9].

- Complex Biomolecular Systems: For intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), maximum entropy reweighting approaches can integrate MD simulations with NMR and SAXS data to determine accurate conformational ensembles. When different force fields initially produce similar agreement with experimental data, reweighted ensembles often converge to highly similar conformational distributions, suggesting force-field-independent solutions [11].

- RNA Dynamics: Integration of MD with NMR, cryo-EM, SAXS, and chemical probing data enables quantitative validation of RNA structural ensembles. Different force fields can be assessed by their ability to reproduce ensemble-averaged experimental observables [20].

Case Study: Binary Lennard-Jones Glass Former

A recent systematic benchmarking study [9] provides a robust protocol for evaluating thermostat performance:

- System Preparation: A Kob-Andersen binary Lennard-Jones mixture (80:20 ratio) with N=1000 particles at density ρ=1.2 was used as a standard glass-former model.

- Simulation Protocol: Seven thermostat schemes were compared under identical initial conditions, including Nosé-Hoover chains (1 and 2 degrees of freedom), Bussi thermostat, and four Langevin variants (BAOAB, ABOBA, GJF, GJF-2GJ).

- Observables Measured: Temperature distributions, potential energies, structural properties, and dynamical relaxations were quantified across different time steps.

- Key Findings: While Nosé-Hoover chain and Bussi thermostats provided reliable temperature control, potential energy showed pronounced time-step dependence. The GJF Langevin scheme provided the most consistent sampling of both temperature and potential energy but at approximately twice the computational cost.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Ensemble Simulations

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Example Applications | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | Biomolecular simulation with extensive thermostat/barostat options | Protein, nucleic acid simulations; constant pH MD | [21] |

| GROMACS | High-performance MD with multiple ensemble support | Membrane proteins; IDP ensemble validation | [6] |

| NAMD | Scalable parallel MD simulations | Large complexes; multiscale modeling | [6] |

| LAMMPS | Materials-focused MD simulator | Solid-state physics; polymer composites | - |

| ATAT/PhaseForge | Phase diagram calculation from MLIPs | Alloy phase stability; high-entropy alloys | [22] |

| MaxEnt Reweighting | Integrate experimental data with MD ensembles | IDP conformational ensembles; RNA dynamics | [11] [20] |

Practical Recommendations for Ensemble Selection

Based on current benchmarking studies, the following recommendations emerge for selecting and applying ensembles in molecular dynamics simulations:

For Production NVT Simulations: The Nosé-Hoover chain thermostat or Bussi thermostat are generally recommended, providing reliable temperature control with minimal disturbance to dynamics. The Bussi method may be preferable for faster equilibration while maintaining correct ensemble sampling [9] [8].

For Production NPT Simulations: Combine Nosé-Hoover or Bussi thermostats with the Parrinello-Rahman barostat for accurate ensemble sampling. NPT simulations typically require stronger thermostat coupling than NVT simulations to maintain temperature effectively [8].

For Accurate Configurational Sampling: The GJF Langevin thermostat provides excellent configurational sampling, though at higher computational cost and with potential alteration of dynamical properties at high friction levels [9].

For Efficient Equilibration: The Berendsen thermostat and barostat offer rapid equilibration but should be avoided for production runs due to suppressed fluctuations and incorrect ensemble sampling [8].

For Validation Against Experiment: Always compare multiple thermostats/barostats when correlating with experimental data, as dynamical properties are particularly sensitive to these choices. Implement maximum entropy reweighting approaches when integrating diverse experimental datasets [11] [20].

The selection of appropriate ensemble types and control algorithms represents a critical decision point in molecular dynamics simulations that significantly impacts the physical validity of results. While the NPT ensemble most directly corresponds to experimental conditions, its accurate implementation requires careful selection of both thermostat and barostat algorithms. Recent benchmarking studies demonstrate that deterministic methods like Nosé-Hoover chains and stochastic approaches like the Bussi thermostat generally provide the most reliable performance for production simulations. The emerging paradigm of integrating multiple experimental datasets with simulation ensembles through maximum entropy reweighting offers a promising path toward force-field-independent structural models, particularly for challenging systems like intrinsically disordered proteins and nucleic acids. As MD simulations continue to complement experimental techniques across materials science, biochemistry, and drug development, understanding these fundamental relationships between ensemble choice, algorithm implementation, and experimental correlation remains essential for producing meaningful computational results.

Algorithm Deep Dive: Mechanisms, Implementation, and Biomedical Applications

In Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, thermostat algorithms are essential for maintaining a constant temperature, enabling the study of systems under realistic experimental conditions that correspond to the canonical (NVT) ensemble. These algorithms control the simulated system's temperature by modifying particle velocities, but their approaches—ranging from deterministic extended Lagrangians to stochastic collisions and velocity rescaling—differ significantly in their theoretical foundations and practical effects on simulation outcomes [23]. The choice of a thermostat can profoundly influence both the thermodynamic and dynamic properties of the system, making an informed selection critical for the reliability of results in fields like drug development and materials science [13]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of four prevalent thermostat algorithms: Nosé–Hoover, Berendsen, Langevin, and Bussi velocity rescaling, drawing on current research to outline their strengths, limitations, and ideal application scenarios.

Algorithmic Foundations and Theoretical Underpinnings

Nosé–Hoover Thermostat

The Nosé–Hoover thermostat introduces an additional degree of freedom, 's', representing the heat bath, into the system's Hamiltonian [23]. This approach generates a continuous, deterministic dynamics that, in its ideal implementation, produces trajectories consistent with the canonical ensemble [9]. The method is derived from an extended Lagrangian formalism, with a parameter Q representing the "mass" of the heat bath, which determines the coupling strength and the rate of temperature fluctuations [23]. While the Nosé–Hoover thermostat properly conserves phase space volume, it can suffer from ergodicity issues in certain systems, where it fails to sample all available microstates sufficiently. To address this limitation, the Nosé–Hoover chain variant introduces multiple additional variables connected in a chain, improving ergodicity and making it one of the most reliable deterministic methods for canonical sampling [9].

Berendsen Thermostat

The Berendsen thermostat employs a weak-coupling approach that scales particle velocities at each time step to steer the system temperature toward the desired value [24]. The rate of temperature correction is governed by the parameter τ_T (the relaxation time constant), with smaller values resulting in tighter temperature control [25] [24]. Although computationally efficient and effective for rapid thermalization, this method does not produce a correct canonical ensemble because it suppresses legitimate temperature fluctuations [25] [24]. This fundamental limitation, along with its tendency to cause the "flying ice cube" artifact (where kinetic energy is artificially redistributed, potentially freezing internal motions), has led to recommendations that it should be primarily used for initial equilibration rather than production simulations [25].

Langevin Thermostat

Langevin dynamics incorporates stochastic and frictional forces to emulate a system's interaction with a implicit heat bath [13]. The equation of motion for each particle includes a friction term (-ζmẋ) and a random force (R(t)), with the friction coefficient ζ determining the coupling strength [13]. This thermostat rigorously generates the canonical ensemble [9]. Modern implementations use sophisticated discretization schemes like BAOAB and GJF (Grønbech-Jensen–Farago) to enhance sampling accuracy [9]. A significant consideration is that Langevin dynamics distorts protein dynamics by dilating time constants, particularly for slow, collective motions like overall rotational diffusion, though faster internal motions remain less affected [13].

Bussi Velocity Rescaling

Bussi and colleagues developed the stochastic velocity rescaling method as an extension of the Berendsen thermostat [26]. While Berendsen scales all velocities by a uniform factor, Bussi's approach incorporates a stochastic term that ensures the correct fluctuations in kinetic energy characteristic of the canonical ensemble [9] [26]. This method corresponds to the global thermostat form of Langevin dynamics and is designed to minimize disturbance to the system's natural Hamiltonian dynamics [9]. It has demonstrated excellent performance in producing proper canonical distributions for diverse systems including liquid water and Lennard-Jones fluids [9].

Table 1: Theoretical Foundations and Ensemble Behavior of Thermostat Algorithms

| Algorithm | Type | Theoretical Basis | Ensemble Produced | Key Control Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosé–Hoover | Deterministic | Extended Lagrangian with heat bath variable | Canonical (when ergodic) | Heat bath mass (Q) |

| Berendsen | Deterministic | Weak coupling to external bath | Does not produce correct ensemble | Relaxation time (τ_T) |

| Langevin | Stochastic | Friction + random noise | Canonical | Friction coefficient (ζ) |

| Bussi | Stochastic | Stochastic velocity rescaling | Canonical | Relaxation time (τ_T) |

Performance Comparison and Practical Considerations

Temperature Control and Sampling Accuracy

The effectiveness of thermostat algorithms varies significantly across different simulation scenarios. In stringent tests modeling energetic cluster deposition on diamond surfaces, the Berendsen method and Nosé–Hoover thermostat effectively removed excess energy during early deposition stages, but resulted in higher final equilibrium temperatures compared to other methods [23]. The study found that for large enough substrates at moderate incident energies, the Generalized Langevin Equation (GLEQ) approach provided sufficient energy removal, while modified GLEQ approaches performed better at high incident energies [23].

For biomolecular simulations, Langevin thermostats with moderate friction coefficients (e.g., 1-2 ps⁻¹) are widely used, but they systematically dilate time constants for protein dynamics, particularly affecting slow motions like overall rotational diffusion [13]. This distortion can be corrected by applying a contraction factor to the computed time constants [13]. In contrast, the Nosé–Hoover chain thermostat generally provides reliable temperature control with minimal dynamic distortion when properly tuned [9].

Recent benchmarking studies on binary Lennard-Jones glass-formers reveal that while Nosé–Hoover chain and Bussi thermostats provide reliable temperature control, they exhibit pronounced time-step dependence in potential energy measurements [9]. Among Langevin methods, the GJF scheme delivered the most consistent sampling of both temperature and potential energy across different time steps [9].

Computational Efficiency and Dynamic Properties

Computational cost varies considerably among thermostat algorithms. Langevin dynamics typically incurs approximately twice the computational overhead of deterministic methods due to the extensive random number generation required [9]. This performance impact should be considered when planning large-scale simulations. The Bussi thermostat strikes a favorable balance between computational efficiency and sampling accuracy, making it popular for production simulations of biomolecular systems [9] [26].

The choice of thermostat significantly influences dynamic properties. Langevin dynamics causes a systematic decrease in diffusion coefficients with increasing friction, directly affecting transport properties [9]. This friction dependence follows Kramers' theory, where isomerization rates of molecules reach a maximum at intermediate friction values [13]. The Berendsen thermostat is known to artificially preserve hydrodynamic flow patterns, which can be desirable for certain applications but generally unphysical [25].

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Practical Applications

| Algorithm | Computational Cost | Effect on Dynamics | Recommended Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosé–Hoover | Moderate | Minimal distortion when properly tuned | General purpose MD; production simulations | Ergodicity issues in small systems |

| Berendsen | Low | Preserves hydrodynamics; "flying ice cube" artifact | Initial equilibration only | Incorrect ensemble; not for production |

| Langevin | High (2x deterministic) | Dilation of slow motions; reduced diffusion | Systems requiring stochastic solvent implicitation | Distorts dynamics; friction-dependent |

| Bussi | Moderate | Minimal disturbance to Hamiltonian dynamics | Production runs; biomolecular systems | Limited documentation in legacy codes |

Thermostat Selection Guidelines for Specific Research Applications

Biomolecular Simulations and Drug Development

For biomolecular simulations targeting drug development, accurate representation of both structural and dynamic properties is crucial. When comparing simulation results with NMR relaxation data, corrections for Langevin thermostat-induced dilation of time constants are essential [13]. The correction factor takes the form of a linear function (a + bτi), where τi is the time constant to be corrected [13]. For studies focusing on conformational dynamics or ligand binding, the Nosé–Hoover chain or Bussi thermostats are generally preferable as they cause minimal distortion to the system's natural dynamics [9] [13].

The Bussi thermostat has been successfully employed in force field parameterization studies, including the validation of AMBER ff99SB*-ILDN parameters against NMR relaxation data for ubiquitin [13]. Its stochastic velocity rescaling approach provides correct sampling without significantly altering the dynamic properties of proteins, making it particularly valuable for drug development applications where accurate representation of molecular flexibility is critical.

Energetic Processes and Material Science

Simulations of non-equilibrium processes like cluster deposition on surfaces present distinct challenges for temperature control. In these scenarios, the thermostat must effectively absorb excess energy waves generated by collisions to prevent nonphysical reflections from system boundaries [23]. Research shows that the optimal thermostat choice depends on both the incident energy and substrate size [23]. For high-energy impacts, modified Langevin approaches or combined thermostats outperform standard methods [23].

For simulating glass-forming systems like the Kob–Andersen binary Lennard-Jones mixture, the GJF Langevin thermostat provides the most consistent sampling across different time steps, making it ideal for studying phase transitions and nucleation phenomena [9]. Its ability to maintain accurate configurational sampling even with larger time steps offers significant computational advantages for these computationally intensive studies.

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Standardized Benchmarking Approaches

Systematic evaluation of thermostat performance requires standardized benchmarking protocols. A recommended approach involves simulating a binary Lennard-Jones glass-former (Kob–Andersen mixture) with 1000 particles (800 type A, 200 type B) at density ρ = 1.2, using identical initial conditions across all thermostat methods [9]. Key observables to monitor include:

- Temperature distributions: Should follow Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics

- Potential energy: Particularly sensitive to time-step variations

- Radial distribution functions: Assess structural preservation

- Diffusion coefficients: Evaluate dynamic property preservation

Simulations should be performed across a range of time steps (from 0.002 to 0.01 in reduced units) to assess stability and discretization errors [9] [27]. For biomolecular validation, comparison of overall rotational correlation times and internal motion time constants against NVE simulations provides quantitative measures of dynamic distortion [13].

Specialized Validation for Biomolecular Systems

For protein simulations, a comprehensive validation protocol involves:

- Running replicate simulations (≥4) of globular proteins of varying sizes (e.g., 18-129 amino acids) for 500-1000 ns [13]

- Calculating time correlation functions for backbone NH bond vectors and side-chain methyl groups

- Fitting correlation functions to exponential decays to determine time constants (τ_i)

- Comparing results against NVE simulations and experimental NMR relaxation data

- Applying correction factors when using Langevin thermostats based on the relationship τcorrected = τobserved/(1 + bτ_observed) [13]

This approach reliably identifies thermostat-induced distortions and enables quantitative corrections to restore accurate dynamic properties.

Essential Research Tools and Implementation

Table 3: Essential Resources for Thermostat Method Development and Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Systems | Binary Lennard-Jones glass-former [9], TIP4P water [27], Globular proteins (GB3, Ubiquitin) [13] | Standardized systems for method validation and comparison |

| Analysis Metrics | Temperature distributions, Potential energy trends, Radial distribution functions, Diffusion coefficients [9] [27] | Quantifying sampling accuracy and dynamic properties |

| Validation Data | NMR relaxation parameters (R₁, R₂) [13], Rotational correlation times [13], Experimental diffusion constants | Experimental benchmarks for validating dynamic properties |

| MD Packages | AMBER [13], LAMMPS, GROMACS | Production MD implementations with multiple thermostat options |

Workflow Diagram: Thermostat Selection Strategy

The following diagram illustrates a systematic approach for selecting appropriate thermostat algorithms based on research objectives and system characteristics:

Diagram Title: Thermostat Selection Workflow for MD Simulations

The selection of an appropriate thermostat algorithm for molecular dynamics simulations requires careful consideration of research objectives, system characteristics, and the trade-offs between sampling accuracy and dynamic preservation. The Nosé–Hoover chain thermostat provides reliable canonical sampling for general-purpose simulations, while the Bussi velocity rescaling method offers an excellent balance of accuracy and computational efficiency for biomolecular studies. The Berendsen thermostat remains useful solely for initial equilibration due to its ensemble violations, and Langevin approaches, while rigorous, require corrections for dynamic distortions in biomolecular applications. As MD simulations continue to advance in temporal and spatial scales, with increasing integration into drug development pipelines, informed thermostat selection and appropriate validation against experimental data become ever more critical for generating physically meaningful, reproducible results.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, barostats are essential algorithms for controlling system pressure, mirroring the role of thermostats in temperature control. Proper pressure control is critical for simulating realistic conditions, especially when studying pressure effects on biological systems and materials [28]. Simulations of proteins from piezophiles that live under extreme pressures as high as 1100 atmospheres, for instance, have revealed that pressure-tolerant enzymes exhibit altered dynamics with increased flexibility at high pressures [28]. Similarly, studies of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) under various external pressures require accurate pressure control to understand transition mechanisms [29]. Most barostat implementations require calculating a system property known as the virial, defined as the change in energy with respect to volume (dU/dV), which consists of both internal (potential-derived) and kinetic components [28]. The instantaneous pressure is calculated as Pinst = (2 × KE - W)/(3 × V), where KE is kinetic energy, W is the internal virial, and V is volume [28]. This foundational understanding enables us to explore and compare three specific barostat implementations: Berendsen, Parrinello-Rahman, and Martyna-Tobias-Klein (MTK).

Theoretical Foundations of Barostat Algorithms

The Virial Equation and Pressure Calculation

Accurate pressure calculation forms the basis of all barostat algorithms. In periodic systems with pairwise interactions, the pressure is computed using the virial equation:

[P = \frac{NkbT}{V} + \frac{1}{6V}\sum{ij,i

where (kb) is Boltzmann's constant, (ri) is the position of the ith atom, and (f_i) is the force on atom i due to all other atoms in the system [30]. For accurate pressure assessment, the full atomic virial must be calculated during each force calculation rather than after forces on atoms have been computed [30]. The thermodynamic pressure of the system is then defined as the time average of this instantaneous pressure P(t). This calculation is particularly crucial for complex force fields like AMOEBA, where implementing the internal virial enables pressure control methodologies beyond basic Monte Carlo approaches [28].

Equations of Motion for Constant Pressure Ensembles

Different barostats extend the Hamiltonian equations of motion to include volume or box vectors as dynamic variables. For the NPT (isobaric-isothermal) ensemble, the MTK barostat equations of motion are expressed as:

[\dot{r}i = \frac{pi}{mi} + \frac{1}{3}\frac{\dot{V}}{V}ri]

[\dot{p}i = fi - \frac{1}{3}\frac{\dot{V}}{V}p_i]

[\ddot{V} = \frac{1}{W}[P(t) - P_{ext}] - \gamma\dot{V} + R(t)]

Here, (ri) and (pi) are atom i's position and momentum, respectively, γ is the collision frequency, W is the piston mass, and R(t) is a random force drawn from a Gaussian distribution [30]. The Langevin piston method, which implements a second-order dampening motion, effectively removes the "ringing" artifact associated with piston degrees of freedom in the MTK algorithm [30].

Comparative Analysis of Barostat Algorithms

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Barostat Algorithms

| Feature | Berendsen Barostat | Parrinello-Rahman Barostat | MTK Barostat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ensemble | Does not produce correct ensembles | NPT (correct) | NPT (correct) |

| Relaxation Method | Exponential relaxation toward target pressure | Uses extended Hamiltonian with box vectors as dynamic variables | Uses extended Hamiltonian with volume as dynamic variable |

| Computational Cost | Lower | Higher | Higher |

| Rigidity of Control | Strong coupling to pressure bath | More flexible response | More flexible response |

| Recommended Use | Initial equilibration only | Production simulations | Production simulations |

| Implementation in MD Packages | Tinker-OpenMM, GROMACS | apoCHARMM, GROMACS | apoCHARMM |

Table 2: Performance Characteristics in Practical Applications

| Characteristic | Berendsen Barostat | Parrinello-Rahman Barostat | MTK Barostat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equilibration Speed | Fast | Moderate | Moderate |

| Energy Conservation | Poor (does not conserve energy) | Good | Good |

| Volume Distribution | Incorrect | Correct | Correct |