The NVT Ensemble in Molecular Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide from Theory to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the canonical (NVT) ensemble, a cornerstone of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations.

The NVT Ensemble in Molecular Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide from Theory to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the canonical (NVT) ensemble, a cornerstone of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we cover the foundational statistical mechanics of the NVT ensemble, detail practical implementation methods including various thermostats, and address common troubleshooting and optimization scenarios. Furthermore, the guide delves into critical validation protocols and comparative analyses against other ensembles and experimental data, offering a complete resource for leveraging NVT simulations to study biomolecular stability, ligand-receptor interactions, and other clinically relevant phenomena under constant temperature and volume conditions.

What is the NVT Ensemble? Understanding the Foundation of Constant-Temperature MD

The canonical ensemble, universally designated as the NVT ensemble, constitutes a foundational concept in statistical mechanics and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. It describes a system characterized by a constant number of particles (N), a fixed volume (V), and a constant temperature (T) [1]. This ensemble is paramount for studying the thermodynamic properties of systems at a fixed temperature, thereby providing a critical bridge between microscopic particle interactions and macroscopic observable phenomena [1]. In the context of MD, the NVT ensemble is employed to simulate conditions where volume changes are negligible, making it ideal for investigating processes such as ion diffusion in solids, adsorption, and reactions on slab-structured surfaces or clusters, where the system's volume is not expected to fluctuate significantly [2].

The core principle of the NVT ensemble involves the system being in thermal contact with a much larger heat bath, which allows for the exchange of energy to maintain a constant average temperature [1]. The probability of the system occupying a particular microstate with energy Eᵢ is governed by the Boltzmann distribution, which is central to the canonical partition function [1]. This relationship enables the calculation of key thermodynamic properties, including the Helmholtz free energy, entropy, and specific heat capacity, from the microscopic behavior of the system.

Thermostat Methods for Temperature Control

In molecular dynamics simulations, maintaining a constant temperature is achieved algorithmically through the use of thermostats. These methods effectively mimic the energy exchange with a heat bath. The choice of thermostat impacts the quality of the sampling, the naturalness of the dynamics, and the suitability of the simulation for specific types of analysis. The table below summarizes the primary thermostat algorithms used to sample the NVT ensemble.

Table 1: Comparison of Thermostat Methods for NVT Ensemble Molecular Dynamics

| Thermostat Method | Type | Key Mechanism | Strengths | Weaknesses | Common MD Codes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosé-Hoover [3] [2] | Deterministic | Introduces an additional degree of freedom (friction) that evolves to maintain target T. | Reproduces correct canonical ensemble; widely used and universal. | Can exhibit non-ergodic behavior for small or special systems. | VASP (MDALGO=2), GPUMD (nvt_nhc) |

| Andersen [3] | Stochastic | Randomly selects atoms and assigns new velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. | Simple to implement; guarantees correct sampling. | Dynamics are artificial due to stochastic collisions; not good for transport properties. | VASP (MDALGO=1) |

| Langevin [3] [2] | Stochastic | Applies a random force and a friction force to all atoms. | Good for systems in mixed phases; robust sampling. | Trajectories are not deterministic; not suitable for precise trajectory analysis. | VASP (MDALGO=3), GPUMD (nvt_lan, nvt_bao) |

| Berendsen [2] [4] | Deterministic | Scales velocities to relax the system temperature to the desired value. | Fast and robust convergence to target temperature. | Does not produce a correct canonical ensemble; can cause "flying ice cube" effect. | GPUMD (nvt_ber) |

| CSVR [3] | Stochastic | Uses a canonical sampling through velocity rescaling with a stochastic term. | Correctly samples the canonical distribution. | Similar to other stochastic methods, it perturbs natural dynamics. | VASP (MDALGO=5) |

Implementation in MD Packages: VASP and GPUMD

Different molecular dynamics packages implement these thermostats with specific keywords and parameters. For instance, in VASP, the MDALGO tag selects the thermostat algorithm, and additional tags are required for its configuration [3]. An example INCAR file for a Nosé-Hoover thermostat is provided below:

In GPUMD, the ensemble command is used with parameters for the thermostat, such as initial and final target temperatures and a coupling constant [4]. For example, the command for a Berendsen thermostat would be ensemble nvt_ber <T_1> <T_2> <T_coup>.

Experimental Protocol: NVT-MD Simulation of Melting in FCC-Aluminum

To illustrate a practical application, the following is a detailed methodology for an NVT molecular dynamics simulation to study the melting of face-centered cubic (fcc) Aluminum, as adapted from an ASE tutorial [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Software

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Solutions for the Featured NVT Experiment

| Item Name / Software | Function / Description | Key Parameters / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ASE (Atomistic Simulation Environment) | A Python library for setting up, managing, visualizing, and analyzing atomistic simulations. | Provides the framework for the simulation, including thermostats and loggers. |

| ASAP3/EMT Calculator | An efficient classical potential (Effective Medium Theory) to compute interatomic forces and energies. | Faster than ab initio methods, suitable for large systems and long time scales. |

| fcc-Al Crystal Structure | The initial atomic configuration for the simulation, built as a bulk crystal. | Lattice parameter ~4.3 Å; supercell (e.g., 3x3x3) to create a sufficient number of atoms. |

| Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution | Algorithm to initialize atomic velocities corresponding to the desired initial temperature. | MaxwellBoltzmannDistribution(atoms, temperature_K=1000, force_temp=True) |

| Berendsen Thermostat (NVT) | The temperature control algorithm used in this specific protocol. | Coupling time taut is a critical parameter affecting the rate of temperature adjustment. |

| MDLogger | A utility for recording the simulation data at regular intervals. | Logs energy, temperature, stress, etc., to an output file for post-processing. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

System Initialization: Construct the initial atomic system. This involves creating a bulk fcc-Al crystal with a specified lattice constant (e.g., 4.3 Å) and then replicating it to form a 3x3x3 supercell, resulting in a system of 108 atoms [2].

Calculator Assignment: Attach an interatomic potential to the atoms to calculate energies and forces. The Effective Medium Theory (EMT) potential is used here for its computational efficiency [2].

Velocity Initialization: Set the initial atomic velocities to match the desired starting temperature (e.g., 1000 K) using a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. To prevent the entire system from drifting, the total momentum is set to zero [2].

Integrator and Thermostat Setup: Initialize the molecular dynamics integrator with the chosen NVT thermostat. In this example, the Berendsen thermostat is used with a coupling time

tautthat determines the strength of the temperature control [2].Logging and Trajectory Output: Attach a logger and a trajectory writer to monitor the simulation and save the atomic positions at regular intervals for subsequent analysis [2].

Run the Simulation: Execute the dynamics for a predetermined number of steps (e.g., 1,000,000 steps) [2].

The thermodynamic evolution of the system, including total energy, instantaneous temperature, and stresses, is monitored throughout the simulation to observe the melting transition and ensure the stability of the NVT ensemble.

Thermodynamic and Statistical Foundations

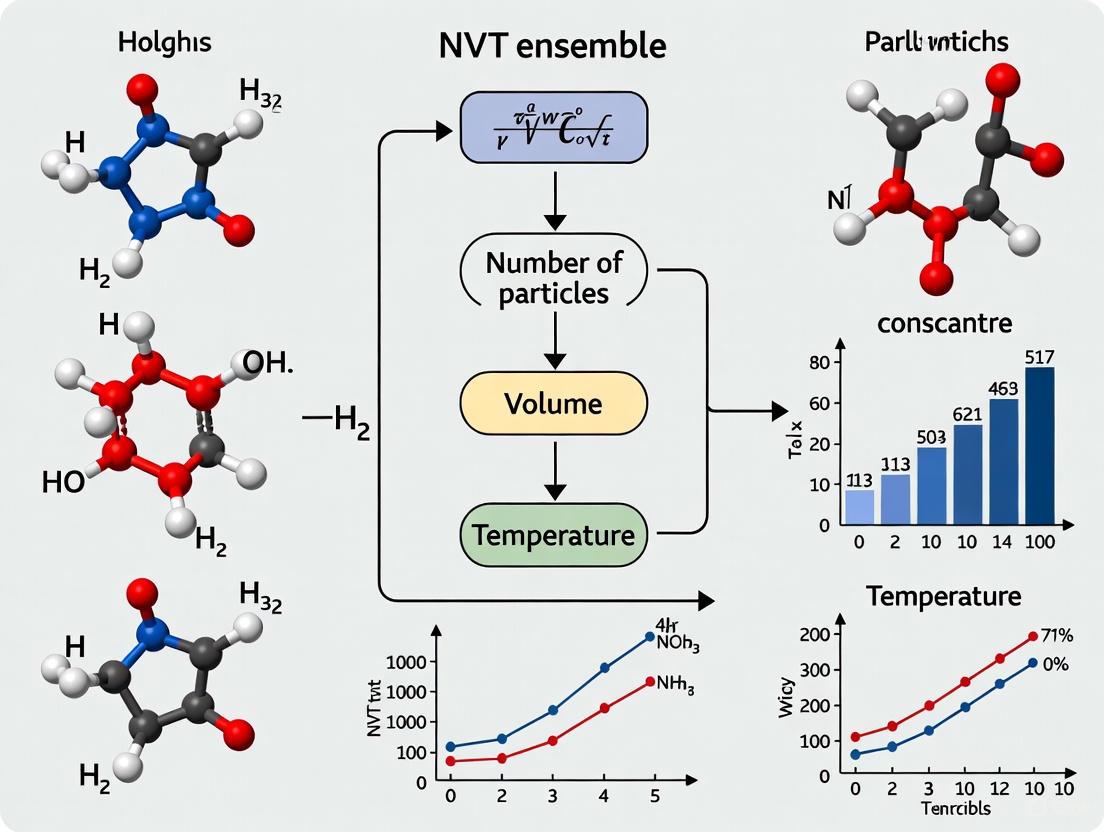

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the NVT ensemble's fixed parameters, the role of the thermostat, and the resulting thermodynamic outputs and distributions.

Diagram 1: NVT core principles.

NVT-MD Simulation Workflow

The complete workflow for setting up and running an NVT molecular dynamics simulation, from system preparation to analysis, is summarized in the diagram below.

Diagram 2: NVT simulation workflow.

The canonical ensemble, also known as the NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, constant Volume, and constant Temperature), represents a cornerstone concept in statistical mechanics for describing systems in thermal equilibrium with a heat bath at a fixed temperature [5]. This ensemble provides the fundamental theoretical framework for understanding how microscopic interactions give rise to macroscopic thermodynamic behavior in systems ranging from simple gases to complex biomolecules. Unlike the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble which describes completely isolated systems, the canonical ensemble accounts for the reality that most physical systems can exchange energy with their surroundings while maintaining a constant temperature [5] [6]. The principal thermodynamic variable governing the probability distribution of states in this ensemble is the absolute temperature (T), which determines the likelihood of the system occupying any particular microstate with energy Eᵢ [5].

The canonical ensemble assigns a probability P to each distinct microstate according to the Boltzmann distribution, which can be expressed in two mathematically equivalent formulations [5]:

- Probability in terms of free energy: (P = e^{(F-E)/(kT)})

- Probability in terms of partition function: (P = \frac{1}{Z}e^{-E/(kT)})

In these expressions, E represents the total energy of the microstate, k is Boltzmann's constant, T is the absolute temperature, F denotes the Helmholtz free energy, and Z is the canonical partition function, where (Z = e^{-F/(kT)}) [5]. The Helmholtz free energy F serves dual roles: it provides a normalization factor ensuring probabilities sum to unity, and it enables direct calculation of important ensemble averages through its partial derivatives [5]. The canonical ensemble was first described by Boltzmann in 1884 and was later reformulated and extensively investigated by Gibbs in 1902, establishing it as a fundamental pillar of statistical mechanics [5].

The Canonical Ensemble in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the canonical ensemble provides the theoretical foundation for simulating systems under constant temperature conditions, mirroring typical laboratory environments where temperature remains fixed while energy fluctuates [7]. MD simulations numerically solve Newton's equations of motion for a set of atoms from a given initial configuration, discretizing time into small intervals called time steps using integrators such as the velocity Verlet algorithm [8]. The basic MD workflow involves computing forces acting on atoms, updating atomic positions and velocities, and repeating this process for thousands to millions of steps to generate trajectories in phase space [9].

The NVT ensemble is particularly valuable in MD simulations for several compelling reasons. From a practical implementation perspective, maintaining constant volume is computationally simpler than allowing volume fluctuations, as implementing moving periodic boundaries or simulating walls requires additional equations of motion and force calculations [7]. For many applications, especially those involving condensed phases with relatively incompressible materials, constant volume simulations provide excellent approximations to constant pressure conditions, with the equivalence becoming exact in the thermodynamic limit of large particle numbers [7]. Additionally, thermostating methods that maintain constant temperature help mitigate numerical error accumulation that would otherwise cause energy drift in microcanonical simulations [7].

A common practice in MD simulations involves using the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble during initial equilibration to determine the appropriate simulation box size that yields the desired average pressure (e.g., 1 atm), followed by production runs in the NVT ensemble where the simulation box dimensions remain fixed [7]. This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of both ensembles: NPT for establishing realistic density conditions and NVT for efficient production sampling with fixed geometry. The NVT ensemble finds particular application in studying ion diffusion in solids, adsorption and reaction on slab-structured surfaces, and processes involving clusters where volume changes are negligible [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Thermodynamic Ensembles in Molecular Dynamics

| Ensemble | Constants | Fluctuating Quantities | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVE (Microcanonical) | N, V, E | Temperature, Pressure | Isolated systems, fundamental dynamics |

| NVT (Canonical) | N, V, T | Energy, Pressure | Most production MD, condensed phases |

| NPT (Isothermal-Isobaric) | N, P, T | Energy, Volume | Equilibration, atmospheric conditions |

| μVT (Grand Canonical) | μ, V, T | Energy, Particle Number | Open systems, adsorption studies |

Thermostats: Implementing Temperature Control

Implementing the canonical ensemble in molecular dynamics requires mechanisms to maintain constant temperature despite energy fluctuations. These mechanisms, known as thermostats, modify the equations of motion to ensure the system samples the Boltzmann distribution [3]. Different thermostats employ distinct mathematical approaches to achieve temperature control, each with specific advantages and limitations.

The Nosé-Hoover thermostat extends the physical system by introducing a fictitious variable that represents the heat bath, creating a coupled system that generates the canonical distribution [3] [8]. This deterministic approach generally provides excellent sampling quality and is considered one of the most reliable methods for NVT simulations [8]. A potential limitation emerges in systems with slow energy exchange, where the basic Nosé-Hoover method may not ergodically sample phase space, leading to the development of Nosé-Hoover chains that employ multiple thermostats in series to improve sampling [8].

The Langevin thermostat implements stochastic dynamics by adding friction and random force terms to the equations of motion, mimicking collisions with particles from a virtual heat bath [3] [8]. This method provides strong coupling to the heat bath and is particularly effective for systems with multiple phases or components [8] [2]. However, the random forces alter particle trajectories, making the Langevin thermostat unsuitable for studying dynamical properties that require realistic temporal evolution [8].

The Berendsen thermostat employs a simple proportional scaling algorithm that adjusts particle velocities toward the desired temperature with an exponential relaxation [8]. While this method offers numerical stability and rapid convergence, it does not generate exactly correct canonical distributions, making it primarily suitable for equilibration rather than production simulations [8]. The CSVR thermostat (Canonical Sampling through Velocity Rescaling) and Andersen thermostat provide additional approaches, with the latter implementing stochastic collisions that randomly reassign particle velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution [3].

Table 2: Comparison of Thermostat Methods for NVT Molecular Dynamics

| Thermostat | Type | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosé-Hoover | Deterministic | Extended Lagrangian with heat bath variable | Correct canonical sampling, generally reliable | May require chains for some systems |

| Langevin | Stochastic | Friction + random forces | Strong coupling, good for mixed phases | Alters dynamics, not for trajectory analysis |

| Berendsen | Deterministic | Velocity scaling toward target T | Rapid equilibration, stable | Incorrect ensemble sampling |

| Andersen | Stochastic | Random velocity reassignments | Simple implementation | Disrupts dynamics |

| CSVR | Stochastic | Canonical velocity rescaling | Correct sampling | Similar to Langevin |

Practical Implementation and Protocols

Initialization and Equilibration

Successful NVT-MD simulations require careful initialization to ensure proper sampling of the canonical ensemble. The process begins with defining the system topology, including atomic positions and force field parameters, which remain static throughout the simulation [9]. For the simulation box, it is often convenient to use orthogonal cells, particularly when the system size may change during equilibration stages [8]. Initial velocities are typically assigned from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution corresponding to the target temperature T [9] [8]:

(p(vi) = \sqrt{\frac{mi}{2 \pi kT}}\exp\left(-\frac{mi vi^2}{2kT}\right))

where mᵢ is the mass of atom i, k is Boltzmann's constant, T is the temperature, and vᵢ is the velocity component [9]. To prevent artificial drifting of the entire system, the center-of-mass motion is usually removed after velocity initialization and monitored throughout the simulation [9].

The time step (Δt) represents a critical parameter that balances computational efficiency and numerical accuracy. The chosen time step should be small enough to resolve the highest frequency vibrations in the system, typically requiring smaller values for systems containing light atoms such as hydrogen [8]. For most systems, a time step of 1 femtosecond provides a safe starting point, which can be potentially increased if constraints are applied to fast degrees of freedom [8]. During equilibration, key observables such as temperature, pressure, and energy should be monitored until they stabilize around stationary values, indicating that the system has reached thermal equilibrium [8].

Example Protocol: NVT-MD of Aluminum Crystal

The following protocol illustrates a typical NVT-MD simulation using the Berendsen thermostat to study the thermal behavior of an aluminum crystal, adapted from a documented example [2]:

System Setup: Create an FCC aluminum crystal with lattice parameter 4.3 Å and replicate to create a 3×3×3 supercell containing 108 atoms.

Calculator Configuration: Select an appropriate potential energy function (e.g., EMT calculator for aluminum).

Initialization:

- Set initial velocities using Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at 1000 K

- Remove center-of-mass motion

- Apply periodic boundary conditions

Simulation Parameters:

- Time step: 1.0 fs

- Temperature: 1000 K

- Thermostat coupling constant (taut): 1.0 fs

- Total simulation steps: 1,000,000

- Trajectory output interval: 10,000 steps

Production Run: Execute dynamics using the NVTBerendsen integrator.

Analysis: Monitor total energy, instantaneous temperature, and stress tensor components throughout the simulation.

This protocol demonstrates how the NVT ensemble can reveal temperature-dependent material behavior, such as lattice stability near the melting point [2].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Components for NVT-MD

Table 3: Essential Computational Components for NVT Molecular Dynamics

| Component | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Thermostat Algorithms | Maintain constant temperature | Nosé-Hoover, Langevin, Berendsen, CSVR, Andersen [3] |

| Time Integrators | Numerically solve equations of motion | Velocity Verlet, Leap-Frog [9] [8] |

| Force Fields | Calculate potential energy and forces | Classical MM potentials, EMT for metals [10] [2] |

| Periodic Boundary Conditions | Mimic bulk environment | Triclinic, Orthorhombic, Cubic boxes [9] |

| Neighbor Lists | Efficient non-bonded force calculation | Verlet lists with buffering [9] |

| Initial Velocity Generators | Initialize kinetic energy | Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution [9] [8] |

Applications and Special Considerations

The canonical ensemble finds diverse applications across computational chemistry and materials science. In drug development, NVT simulations model protein-ligand interactions under physiological temperature conditions, providing insights into binding affinities and conformational dynamics [10]. For materials science, NVT-MD reveals atomic-scale mechanisms of diffusion, phase transitions, and thermal transport properties [2]. The fixed volume constraint makes NVT particularly suitable for studying surface adsorption processes, cluster dynamics, and confined systems where volume changes are negligible [2].

When implementing NVT simulations, several special considerations ensure physical meaningfulness. The thermostat timescale parameter controls how aggressively the system couples to the heat bath, with smaller values providing tighter temperature control but potentially interfering more significantly with natural dynamics [8]. For accurate measurement of dynamical properties such as diffusion coefficients or vibrational spectra, weaker thermostat coupling or NVE simulations following equilibration may be preferable [8] [7]. Additionally, the ergodicity of the sampling should be verified, particularly for systems with slow conformational changes or metastable states where inadequate sampling may yield unreliable ensemble averages.

The theoretical foundation of the canonical ensemble ensures its broad applicability across system sizes, from small clusters to macroscopic materials [5]. However, practical implementation requires attention to finite-size effects, particularly for small systems where fluctuations may differ significantly from thermodynamic limit behavior. When properly implemented with appropriate thermostat selection and simulation parameters, the NVT ensemble provides a powerful framework for connecting microscopic molecular behavior to macroscopic thermodynamic properties through the rigorous foundation of statistical mechanics.

Why NVT? Practical Advantages over NVE and NPT for Production Runs

Within the broader context of canonical ensemble research in molecular dynamics (MD), the NVT (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) ensemble remains a cornerstone for production simulations across diverse scientific domains. While the microcanonical (NVE) and isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensembles serve specific purposes in MD workflows, NVT offers unique practical advantages for production runs aimed at quantifying structural properties, transport phenomena, and equilibrium behavior. This technical guide examines the theoretical foundations, implementation methodologies, and practical benefits of NVT simulations, supported by quantitative comparisons and contemporary case studies. We demonstrate that NVT provides an optimal balance between experimental relevance, computational stability, and physical accuracy for numerous applications, from materials science to drug development.

Molecular dynamics simulations enable the investigation of thermodynamic and kinetic properties at atomic resolution, with the choice of statistical ensemble fundamentally influencing the results and their interpretation. The NVT, or canonical, ensemble models a system that exchanges energy with a surrounding virtual heat bath while maintaining constant volume and particle number [11]. This contrasts with the NVE ensemble (isolated system, constant energy) and NPT ensemble (constant pressure, allowing volume fluctuations).

In practical MD workflows, NVT often serves as a critical equilibration step preceding production runs [12]. However, its utility extends far beyond initial stabilization. For many scientific inquiries, particularly those investigating structural ensembles, transport properties under confinement, and temperature-dependent phenomena, NVT emerges as the ensemble of choice for production simulations due to its unique combination of experimental relevance, computational efficiency, and minimal perturbation of natural dynamics.

Theoretical Foundations of MD Ensembles

Ensemble Equivalence and Differences

In the thermodynamic limit (infinite system size), ensembles are theoretically equivalent away from phase transitions [13]. However, practical MD simulations involve finite systems, making ensemble choice non-trivial with measurable impacts on simulated properties.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Primary MD Ensembles

| Ensemble | Conserved Quantities | System Type | Primary Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVE | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Energy (E) | Isolated system | Gas-phase reactions, conserving natural dynamics, spectroscopic calculations [13] [11] |

| NVT | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Closed system with heat exchange | Structural properties, confined systems, temperature-dependent studies [11] [14] |

| NPT | Number of particles (N), Pressure (P), Temperature (T) | Closed system with heat and volume exchange | Laboratory condition mimicry, density calculations, atmospheric processes [13] [11] |

The mathematical foundation of NVT sampling derives from the canonical partition function, which connects microscopic simulations to macroscopic observables. While NVE simulations directly solve Newton's equations without external controls, NVT implementations employ thermostats to maintain constant temperature by scaling velocities or modifying equations of motion [11] [12].

Thermostat Implementation in NVT

NVT ensemble fidelity depends critically on thermostat selection, each with distinct advantages:

- Nosé-Hoover Thermostat: Extends the Hamiltonian to include a thermal reservoir, producing correct canonical ensemble distributions. Recommended for production simulations requiring accurate sampling [8].

- Berendsen Thermostat: Provides strong temperature coupling and rapid stabilization but does not exactly reproduce canonical distributions. Optimal for equilibration phases [8].

- Langevin Thermostat: Implements stochastic collisions and friction, ideal for sampling but significantly perturbs natural dynamics [8].

- Bussi-Donadio-Parrinello Thermostat: Stochastic variant of Berendsen that correctly samples the canonical ensemble [8].

Thermostat choice involves tradeoffs between sampling accuracy and dynamic preservation. For example, Nosé-Hoover's "thermostat timescale" parameter controls how quickly the system approaches the target temperature - smaller values tighten coupling but increase interference with natural particle dynamics [8].

Comparative Analysis: NVT vs. NVE and NPT

Advantages of NVT over NVE

While NVE preserves true Hamiltonian dynamics, it presents significant practical limitations for production simulations:

- Temperature Control: NVE maintains constant total energy, but temperature fluctuates substantially in finite systems. NVT provides stable, experimentally relevant temperature conditions [11].

- Energy Drift: Numerical integration errors cause energy drift in NVE simulations, whereas NVT thermostats compensate for these artifacts [11].

- Barrier Crossing: In NVE with energy just below a reaction barrier, the rate is zero. NVT allows thermal energy fluctuations that enable barrier crossing, providing more realistic kinetics [13].

- Experimental Correspondence: Most experiments occur at constant temperature, not constant energy, making NVT more directly comparable [13].

Advantages of NVT over NPT

NPT mimics common laboratory conditions, but NVT offers distinct advantages in specific scenarios:

- Reduced Perturbation: NPT requires barostat coupling that perturbs trajectories more than NVT thermostats alone. NVT preserves natural dynamics better when volume fluctuations are unimportant [11].

- Structural Studies: For investigating structural properties of confined systems or solids where volume is inherently fixed, NVT provides more appropriate constraints [11] [15].

- Computational Stability: Barostat coupling in NPT introduces additional numerical complexity and potential instability, especially for anisotropic systems [8].

- Transport Properties: For diffusion calculations in confined environments or materials with fixed volumes, NVT provides more physically relevant conditions [15].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Ensemble Performance in Specific Applications

| Application | Optimal Ensemble | Key Metric | Performance Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Membrane Transport [15] | NVT | Diffusion Coefficient | Maintains fixed volume relevant to confined membrane environments |

| Protein Structural Ensembles [14] | NVT | RMSD/Fluctuations | Stable temperature enables accurate fluctuation measurements |

| Liquid Phase Dynamics [13] | NPT | Density | Naturally accommodates density fluctuations |

| Spectroscopic Validation [13] | NVE | Energy Conservation | Preserves true dynamics for correlation functions |

Practical Implementation Guidelines

NVT Workflow Integration

A standardized MD protocol typically employs multiple ensembles sequentially:

- Energy Minimization: Removes steric clashes and high-energy contacts

- NVT Equilibration: Brings the system to target temperature [12]

- NPT Equilibration (optional): Adjusts density to target pressure

- Production Run: NVT or NPT depending on research objectives

For production phases, the selection between NVT and NPT depends on which thermodynamic variables naturally fluctuate in the experimental system being modeled. The following decision workflow illustrates appropriate ensemble selection:

Thermostat Selection Criteria

For production NVT simulations, thermostat selection should align with research goals:

- Nosé-Hoover Chains: Default choice for most production runs, providing correct canonical sampling with minimal dynamic distortion when using appropriate coupling constants [8].

- Langevin Thermostat: Preferred for systems with slow relaxation or when enhanced sampling is required, despite greater dynamic perturbation [8].

- Bussi-Donadio-Parrinello: Optimal alternative when Berendsen's stability is needed with proper ensemble sampling [8].

The thermostat coupling strength should be tuned to balance temperature control with dynamic preservation. Weaker coupling (larger time constants) better preserves natural dynamics but may allow larger temperature fluctuations.

Case Studies: NVT in Contemporary Research

Ion Exchange Polymer Characterization

In studying perfluorinated sulfonic acid (PFSA) polymers for fuel cell applications, Varshney and Koorata (2025) employed NVT production runs to quantify structural and transport properties [15]. Their methodology involved:

- System: PFSA polymer with hydronium ions and water molecules

- Equilibration: Combined NVT/NPT protocol to achieve target density

- Production: NVT ensemble for diffusion coefficient calculations

- Rationale: Membrane confinement creates effectively fixed volume conditions

The researchers found that NVT production runs provided accurate diffusion coefficients for water and hydronium ions that matched experimental neutron scattering data, demonstrating NVT's suitability for confined transport phenomena [15].

Temperature-Dependent Protein Ensembles

Recent advances in machine learning for structural biology leverage NVT simulations for training data generation. Stiller et al. (2025) developed a deep generative model (aSAMt) trained exclusively on NVT MD simulations to predict temperature-dependent protein structural ensembles [14]. Their approach:

- Training Data: NVT simulations at multiple temperatures (320-450K)

- Validation: Comparison against long NVT reference simulations

- Result: Accurate prediction of temperature-dependent ensemble properties

This work demonstrates how NVT production runs provide the foundational data for developing predictive models that capture thermal behavior in biomolecules [14].

Methodological Protocols

Standard NVT Production Protocol

For typical NVT production runs, we recommend the following protocol based on current best practices:

System Preparation

- Obtain equilibrated structure from prior NPT/NVT equilibration

- Verify system density matches experimental or target values

- Ensure sufficient solvent padding for isolated systems

Parameter Configuration

- Integration time step: 1-2 fs for atomistic systems with hydrogen

- Thermostat: Nosé-Hoover chains (chain length = 3-5)

- Thermostat coupling constant: 0.1-1.0 ps for most applications

- Neighbor list update frequency: Every 10-20 steps

- Bond constraints: LINCS for all bonds involving hydrogen

Simulation Execution

- Duration: Sufficient to observe convergence of target properties

- Trajectory saving frequency: Balanced between storage and resolution

- Logging interval: Monitor temperature, energy, and pressure stability

Validation Checks

- Temperature stability around target value

- Energy fluctuation patterns consistent with canonical ensemble

- Structural stability of ordered elements

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for NVT Simulations

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in NVT Simulations |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | GROMACS [9], QuantumATK [8] | Implements integration algorithms and thermostat methods |

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS | Provides potential energy functions for different material classes |

| Thermostat Algorithms | Nosé-Hoover, Langevin, Berendsen [8] | Maintains constant temperature with different sampling characteristics |

| Analysis Tools | MDTraj, VMD, GROMACS utilities | Quantifies structural and dynamic properties from trajectories |

| Validation Suites | MolProbity [14], WASCO [14] | Assesses physical plausibility of generated structures |

The NVT ensemble remains indispensable for production-phase molecular dynamics simulations where constant temperature and fixed volume conditions align with experimental systems or natural environments. Its practical advantages over NVE include superior temperature control and compensation for numerical artifacts, while its benefits over NPT include reduced trajectory perturbation and more appropriate constraints for confined systems. Contemporary research continues to validate NVT's effectiveness for quantifying transport properties in polymers, characterizing temperature-dependent biomolecular ensembles, and generating training data for machine learning approaches.

As MD simulations expand to larger systems and longer timescales, the fundamental tradeoffs between ensemble choices persist. NVT occupies a crucial middle ground—preserving more natural dynamics than NPT while providing better experimental correspondence than NVE. For researchers investigating structural properties, confined environment phenomena, and temperature-dependent processes, NVT offers an optimal balance of physical accuracy and practical implementability for production simulations.

Key Physical Quantities and Fluctuations Accessible in the NVT Ensemble

The canonical (NVT) ensemble is a cornerstone of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, describing systems that exchange energy with a surrounding heat bath, maintaining a constant number of particles (N), constant volume (V), and constant temperature (T). This ensemble is particularly valuable for studying material properties under controlled temperature conditions where volume changes are negligible, such as in solids, surface-adsorbed systems, or pre-equilibrated liquids [3] [2] [12]. Within the broader context of molecular dynamics research, the NVT ensemble provides a fundamental framework for understanding thermodynamic behavior at the atomic scale, enabling researchers to probe equilibrium properties and fluctuations that would be challenging to access experimentally.

This technical guide examines the key physical quantities, fluctuation properties, and methodological implementations of the NVT ensemble, with specific attention to applications in pharmaceutical development and materials science. We present comprehensive data on measurable observables, detailed protocols for reliable sampling, and current research insights regarding thermostat selection and parameterization.

Theoretical Foundation of the NVT Ensemble

In statistical mechanics, the NVT ensemble represents systems in thermal equilibrium with a heat bath at temperature T. The probability of finding the system in a microstate (i) with energy (E_i) is given by the Boltzmann distribution:

[pi = \frac{e^{-\frac{Ei}{kB T}}}{\sumi e^{-\frac{Ei}{kB T}}}]

where (kB) is Boltzmann's constant [7]. The denominator in this expression is the canonical partition function (Z{NVT}), which connects microscopic states to macroscopic thermodynamics through the Helmholtz free energy, (A = -kB T \ln Z{NVT}) [13].

Unlike the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble where total energy is conserved, the NVT ensemble allows energy fluctuations that enable sampling of relevant thermodynamic states at experimental conditions. For large systems, ensembles become equivalent in the thermodynamic limit, but for practical MD simulations with finite particle numbers, the choice of ensemble significantly impacts sampling efficiency and physical interpretation [13].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key components of an NVT-MD simulation:

NVT-MD Simulation Workflow. This diagram outlines the logical flow in a typical NVT molecular dynamics simulation, from system initialization through the application of a thermostat, integration of equations of motion, calculation of physical quantities, and final fluctuation analysis.

Key Physical Quantities and Their Fluctuations

In NVT ensemble simulations, researchers can access both thermodynamic averages and fluctuation properties that provide deep insight into system behavior. The fixed volume condition makes NVT particularly suitable for systems where volume is naturally constrained or has been previously equilibrated.

Primary Thermodynamic Observables

Table 1: Primary Physical Quantities Accessible in NVT Ensemble Simulations

| Quantity | Mathematical Expression | Physical Significance | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Energy | (E_{total} = K + U) | Sum of kinetic (K) and potential (U) energy; fluctuates around mean value | Monitoring system stability and equilibration |

| Kinetic Energy | (K = \sum{i=1}^N \frac{1}{2} mi v_i^2) | Directly related to instantaneous temperature via (T = \frac{2K}{3Nk_B}) | Verification of proper thermostat function |

| Potential Energy | (U = U(\mathbf{r}^N)) | Configuration-dependent interaction energy | Studying structural stability and phase transitions |

| System Temperature | (\langle T \rangle = \frac{2\langle K \rangle}{3Nk_B}) | Controlled ensemble parameter averaged over simulation | Ensuring correct thermodynamic state sampling |

| Pressure | (P = \frac{NkBT}{V} + \frac{1}{3V}\langle \sum{i |

Instantaneous pressure fluctuates significantly; only meaningful as average | Assessing suitability of fixed volume approximation |

| Chemical Potential | (\mu = -T\left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial N}\right)_{V,T}) | Free energy cost to add/remove particles | Solvation thermodynamics, binding affinity |

The potential energy (U) encompasses all interatomic interactions, including bonded terms (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and non-bonded terms (van der Waals, electrostatic) [2]. In NVT simulations, the pressure is not controlled but can be calculated from the virial theorem, exhibiting substantial fluctuations that require extensive sampling for reliable averaging [16].

Fluctuation-Derived Properties

Table 2: Properties Derived from Fluctuations in the NVT Ensemble

| Property | Fluctuation Formula | Physical Interpretation | Experimental Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat Capacity | (CV = \frac{\langle E^2 \rangle - \langle E \rangle^2}{kB T^2}) | Energy response to temperature changes | Calorimetric measurements |

| Isothermal Compressibility | (\kappaT = \frac{\langle V^2 \rangle - \langle V \rangle^2}{V kB T}) | Not directly accessible (V fixed) | - |

| Thermal Pressure Coefficient | (\gammaV = \frac{\langle E P \rangle - \langle E \rangle \langle P \rangle}{kB T^2}) | Pressure change with temperature at constant volume | Equation of state parameters |

| Dielectric Constant | (\varepsilon = 1 + \frac{4\pi}{3Vk_BT} \left( \langle \mathbf{M}^2 \rangle - \langle \mathbf{M} \rangle^2 \right)) | Response to electric fields from total dipole moment (\mathbf{M}) fluctuations | Spectroscopy measurements |

The heat capacity at constant volume, (C_V), is a particularly important fluctuation property that can reveal information about phase transitions and conformational changes in biomolecular systems [17]. Recent research has highlighted that accurate calculation of these fluctuation properties requires careful attention to integration time-step selection, as excessively large steps can break equipartition between translational and rotational degrees of freedom, leading to systematic errors in computed observables [17].

Methodological Implementation

Thermostat Selection and Configuration

Temperature control in NVT simulations is implemented through thermostats, algorithms that modulate atomic velocities to maintain the desired temperature. The choice of thermostat impacts both sampling accuracy and dynamical properties.

Table 3: Thermostat Methods for NVT Ensemble Sampling

| Thermostat | Algorithm Type | Key Parameters | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosé-Hoover | Deterministic | SMASS (virtual mass) | Reproduces correct NVT ensemble; deterministic trajectories | Can be non-ergodic for small systems or harmonic oscillators |

| Langevin | Stochastic | LANGEVIN_GAMMA (friction coefficient) | Good for mixed phases; efficient sampling | Alters dynamics; stochastic nature affects trajectory reproducibility |

| Berendsen | Deterministic | tau_t (coupling time) | Fast temperature convergence; simple implementation | Does not produce correct kinetic energy fluctuations |

| CSVR | Stochastic | CSVR_PERIOD (resampling interval) | Correct fluctuation distribution; robust performance | Similar to Langevin, modifies natural dynamics |

The Nosé-Hoover thermostat extends the dynamical system with additional degrees of freedom that represent the heat bath, while stochastic thermostats like Langevin and CSVR apply random forces and friction to maintain temperature [3] [2]. For biomolecular systems, the Langevin thermostat is often preferred when accurate dynamics are not critical, as it handles energy dissipation effectively and can improve sampling of conformational states [2].

Integration and Time-Step Considerations

Recent research emphasizes the critical importance of integration time-step selection in NVT simulations. For systems containing rigid water molecules, time-steps as small as 0.5 fs may be necessary to maintain equipartition between translational and rotational degrees of freedom [17]. Violations of equipartition can significantly affect computed properties; for example, simulations of liquid water with the SPC/E model showed that larger time-steps (2.0 fs) produced systematically different volumes and hydration free energies compared to smaller time-steps (0.5 fs) [17].

Hydrogen mass repartitioning (HMR), which increases the mass of hydrogen atoms while decreasing the mass of heavy atoms to allow larger time-steps, provides some improvement but may not fully resolve equipartition failures at commonly used time-steps [17]. These findings have profound implications for drug development applications where hydration free energies and binding affinities are critical parameters.

Research Applications and Protocols

Pharmaceutical and Biomolecular Applications

The NVT ensemble finds extensive application in drug development research, particularly through the following use cases:

- Ion diffusion in solids: Studying ionic conductivity in solid electrolytes for battery applications [2]

- Adsorption and reaction on surfaces: Investigating catalyst behavior and reaction mechanisms on well-defined surfaces [2]

- Ligand binding studies: Calculating interaction energies and conformational changes in protein-ligand complexes [18]

- Hydration free energy components: Decomposing electrostatic and van der Waals contributions to solvation, crucial for pharmacokinetic profiling [17]

- RNA dynamics with small molecules: Modeling cooperative binding of chemical reagents to RNA structures at controlled concentrations [18]

Recent investigations of the hydration free energy of the BBA protein demonstrated that the electrostatic and van der Waals components are sensitive to integration time-step, with differences between δt = 2.0 fs and δt = 0.5 fs exceeding the folding free energy reported for this protein [17]. This highlights the critical importance of technical parameters in obtaining quantitatively accurate results for drug development applications.

Experimental Protocol: NVT Simulation of a Protein Hydration System

The following protocol outlines a typical NVT simulation procedure for studying hydration effects on a protein system, based on current best practices:

System Preparation:

- Obtain protein coordinates from experimental structure (e.g., PDB ID 1FME)

- Solvate the protein in a pre-equilibrated water box (TIP3P or SPC/E models)

- Add ions to neutralize system charge and achieve physiological concentration (0.15 M NaCl)

- Energy minimization using steepest descent algorithm until convergence (<1000 kJ/mol/nm)

Equilibration Phase:

- Initial NVT equilibration for 100-500 ps with position restraints on protein heavy atoms

- Use stochastic thermostat (CSVR or Langevin) with coupling constant of 1-2 ps

- Employ integration time-step of 1-2 fs (or 0.5 fs for highest accuracy)

- Monitor temperature and energy stability to ensure proper equilibration

Production Simulation:

- Remove position restraints and continue NVT simulation for 100 ns - 1 μs

- Maintain temperature using Nosé-Hoover chains or CSVR thermostat

- Use multiple independent replicates (3-5) to improve statistical sampling

- Save trajectory data at 10-100 ps intervals for analysis

Analysis Methods:

- Calculate potential energy components (electrostatic, van der Waals) and their fluctuations

- Compute radial distribution functions between protein atoms and water

- Analyze hydrogen bonding patterns and residence times

- Determine root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSF) of protein atoms

- Extract dipole moment fluctuations for dielectric constant calculation

This protocol emphasizes the importance of sufficient equilibration and multiple replicates to obtain reliable fluctuation properties, which typically require longer simulation times and better statistics than average values [17] [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

Table 4: Essential Software and Force Field Components for NVT Simulations

| Tool/Component | Category | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermostat Algorithms | Sampling Method | Maintain constant temperature with proper fluctuations | Nosé-Hoover, Langevin, CSVR, Berendsen |

| Force Fields | Interaction Potential | Define bonded and non-bonded interatomic interactions | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS, Martini |

| Water Models | Solvent Representation | Describe water-water and water-solute interactions | SPC/E, TIP3P, TIP4P, TIP5P |

| Long-Range Electrostatics | Algorithm | Handle electrostatic interactions beyond cutoff distance | Particle Mesh Ewald (PME), PPPM |

| Constraint Algorithms | Numerical Method | Maintain rigid bonds to allow longer time-steps | SHAKE, RATTLE, SETTLE, P-LINCS |

| Analysis Packages | Software Tool | Compute physical quantities and fluctuations from trajectories | GROMACS, VASP, PLUMED, MDAnalysis |

The PLUMED library is particularly valuable for enhanced sampling and free energy calculations within NVT simulations, providing a wide array of collective variables and analysis methods [19]. For pharmaceutical applications, the choice of water model and force field parameters significantly impacts the accuracy of hydration free energy predictions, with recent research indicating that specific parameter combinations may require smaller integration time-steps than commonly used [17].

The NVT ensemble provides a powerful framework for investigating thermodynamic properties and fluctuations in molecular systems, with particular relevance to drug development and materials research. Key physical quantities accessible in NVT simulations include total energy, pressure, heat capacity, and dielectric constant, all of which can be derived from appropriate averages and fluctuations of simulation trajectories. Current research highlights the critical importance of technical implementation details, particularly integration time-step selection and thermostat choice, in obtaining quantitatively accurate results. For pharmaceutical applications, proper implementation of NVT protocols enables precise calculation of hydration free energies, binding affinities, and conformational fluctuations that directly impact drug design decisions. As simulation methodologies continue to advance, the NVT ensemble remains an essential tool for connecting atomic-scale interactions to macroscopic observables in molecular systems.

Implementing NVT in MD Simulations: Thermostats, Protocols, and Real-World Applications

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the canonical, or NVT, ensemble is a fundamental statistical mechanical distribution where the number of particles (N), the volume (V), and the temperature (T) are held constant. This ensemble is crucial for simulating experimental conditions where temperature, rather than total energy, is controlled. The primary goal of thermostats in MD is to maintain the average temperature of the system by ensuring that the average kinetic energy conforms to the relation ⟨E˅kin⟩ = (3/2)Nk˅BT, while allowing instantaneous kinetic energy and particle velocities to fluctuate naturally as they would in a canonical ensemble [20] [2].

The necessity for thermostat algorithms arises because standard MD simulations are performed in the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble, which conserves energy and does not represent typical laboratory conditions. Several thermostatting methods have been developed to control temperature, each with distinct theoretical foundations, advantages, and limitations. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of four prevalent thermostats: the deterministic Nosé-Hoover, the stochastic Langevin thermostat, the weak-coupling Berendsen thermostat, and the canonical sampling through velocity rescaling (CSVR) method, framing them within the context of canonical ensemble MD research for scientists and drug development professionals [20] [21] [3].

Theoretical Foundations of Thermostat Algorithms

The Statistical Mechanical Basis of the NVT Ensemble

The canonical ensemble describes a system in thermal equilibrium with a much larger heat bath at a constant temperature T. In MD, thermostats are algorithms designed to mimic this heat bath, allowing energy to flow in and out of the simulated system to maintain the target temperature. A key challenge is that different thermostats do not necessarily generate trajectories that are consistent with the canonical ensemble; some may produce artifacts or incorrect distributions, especially in small systems or systems with constrained degrees of freedom [20] [22].

Classification of Thermostat Methods

Thermostat algorithms can be broadly classified into two categories based on their operational mechanism: deterministic and stochastic. Deterministic thermostats, such as Nosé-Hoover, extend the classical Hamiltonian by introducing additional dynamical variables that represent the heat bath. The time evolution of the system is then described by a set of coupled differential equations, and the dynamics remain reversible. In contrast, stochastic thermostats, like the Langevin thermostat, incorporate random forces and friction to emulate collisions with particles from an implicit heat bath. This introduces randomness into the dynamics, which can aid in sampling but alters the natural Newtonian trajectory of the system [20] [21] [2]. A third category, velocity-rescaling methods, includes the Berendsen and CSVR thermostats, which operate by scaling particle velocities at each time step. However, as will be discussed, naive rescaling can lead to significant artifacts, prompting the development of more sophisticated approaches like CSVR that incorporate stochastic elements to ensure correct sampling [23].

In-Depth Analysis of Key Thermostats

Nosé–Hoover Thermostat

The Nosé-Hoover thermostat is a deterministic algorithm that introduces an additional degree of freedom, 's', representing the heat bath. The original formulation by Shuichi Nosé proposed an extended Hamiltonian [20]:

H(P,R,p˅s,s) = ∑ᵢ [ pᵢ² / (2m s²) ] + (1/2) ∑ᵢⱼ,ᵢ≠ⱼ U(rᵢ - rⱼ) + (p˅s² / 2Q) + gk˅B T ln(s)

Here, the first term is the kinetic energy of the particles with scaled momenta (pᵢ/s), the second is the potential energy, the third is the kinetic energy of the heat bath variable with momentum p˅s and mass Q, and the fourth is a potential energy term for the heat bath, where g is the number of independent momentum degrees of freedom [20].

William Hoover later reformulated this approach using the phase-space continuity equation (a generalized Liouville equation), eliminating the need for explicit time scaling and leading to the more commonly used Nosé-Hoover equations of motion. Despite its elegance and widespread use for generating a canonical ensemble, the Nosé-Hoover thermostat is known to be non-ergodic for small systems like a single harmonic oscillator, failing to generate a correct canonical distribution. This limitation has spurred the development of extensions such as Nosé-Hoover chains, where multiple thermostats are coupled to the system to improve ergodicity [20].

Table 1: Key Parameters and Properties of the Nosé-Hoover Thermostat

| Feature | Description | Practical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Type | Deterministic | Dynamics are time-reversible. |

| Ensemble | Canonical (NVT) | Correctly samples the canonical ensemble for ergodic systems. |

| Key Parameter | Thermostat mass (Q or SMASS) | Determines the coupling strength and response time of the thermostat. |

| Ergodicity | Non-ergodic for small systems | Fails for a single harmonic oscillator; use chains for small systems. |

| Computational Cost | Low | Adds only one additional degree of freedom. |

Langevin Thermostat

The Langevin thermostat employs a stochastic approach, controlling temperature by subjecting particles to a friction force and a random force. The equation of motion for each particle is modified as follows [24] [21]:

mᵢ aᵢ = -∇ᵢ U(rᵢ) - γ mᵢ vᵢ + Fᵢᵣᵣ

Here, γ is the friction coefficient, and Fᵢᵣᵣ is a random force obtained from a Gaussian distribution with a mean of zero and a variance related to the temperature and the friction coefficient, as dictated by the fluctuation-dissipation theorem. This method mimics the random collisions of particles in a solvent, making it particularly suitable for simulating solvated systems in drug development [24] [21].

A key characteristic of the Langevin thermostat is that it is a "massive" thermostat, meaning it acts locally on individual particles. This ensures proper thermalization even for heterogeneous systems, such as mixed phases. However, because of the random forces, the trajectories are not deterministic; repeating a simulation with different random seeds will produce different trajectories. This makes the Langevin thermostat unsuitable for calculating precise dynamical properties that depend on deterministic trajectories, such as time correlation functions, unless the thermostat's influence is carefully considered. Furthermore, the random number generation introduces computational overhead, with some studies reporting approximately twice the computational cost compared to deterministic methods [24] [25] [2].

Berendsen Thermostat

The Berendsen thermostat is a weak-coupling method that scales the velocities of all particles at each time step to steer the system temperature toward a desired target. The algorithm is designed to cause the system temperature to relax exponentially toward the target temperature T₀ [21] [22]:

dT(t)/dt = (T₀ - T(t)) / τ

Here, τ is a coupling parameter, or temperature relaxation time. The scaling factor ζ for the velocities is derived from the finite-difference form of this equation [21]:

ζ² = 1 + (Δt / τ) ( T₀ / T(t) - 1 )

While the Berendsen thermostat is highly efficient at rapidly driving a system to a target temperature and is therefore often used for initial equilibration, it does not generate a correct canonical ensemble. The main issue is that it suppresses the natural fluctuations of kinetic energy present in the canonical ensemble. More critically, it can lead to a violation of the equipartition theorem, known as the "flying ice cube" effect. In this artifact, kinetic energy is artificially transferred from high-frequency vibrational modes to translational and rotational modes, leading to unphysical dynamics. For this reason, its use in production simulations is generally discouraged, and it has been largely superseded by more rigorous thermostats like CSVR [21] [22] [26].

CSVR Thermostat (Canonical Sampling Through Velocity Rescaling)

The CSVR thermostat, developed by Bussi et al., is a stochastic velocity-rescaling method designed to correct the flaws of naive rescaling algorithms like Berendsen. Instead of rescaling velocities to a fixed target kinetic energy, CSVR rescales them to a stochastic target kinetic energy Kₜ that evolves according to an auxiliary stochastic differential equation [23]:

dK = (𝐾̄ - K) (dt / τ) + 2 √( (K 𝐾̄) / N˅f ) (dW / √τ)

Here, 𝐾̄ is the desired average kinetic energy, N˅f is the number of degrees of freedom, and dW is a Wiener noise (random increment). This formulation ensures that the kinetic energy is sampled from the correct canonical distribution [23]:

P(Kₜ) dKₜ ∝ Kₜ^(N˅f/2 - 1) e^( -Kₜ / k˅B T ) dKₜ

The CSVR thermostat provides correct canonical sampling, avoids the "flying ice cube" effect, and has a well-defined conserved quantity (effective energy). Importantly, studies have shown that it does not significantly affect the evaluation of dynamical properties, such as velocity autocorrelation functions or diffusion coefficients, making it a robust and reliable choice for both equilibrium and dynamical studies [23].

Table 2: Comparative Summary of Thermostat Algorithms

| Thermostat | Algorithm Type | Generates Canonical Ensemble? | Key Strength | Key Weakness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosé-Hoover | Deterministic | Yes (for large, ergodic systems) | Well-defined extended Lagrangian; time-reversible. | Non-ergodic for small systems (e.g., harmonic oscillator). |

| Langevin | Stochastic | Yes | Excellent for solvated systems; good ergodicity. | Alters dynamics; trajectories are not reproducible; higher computational cost. |

| Berendsen | Velocity Rescaling | No | Fast temperature relaxation and stabilization. | Suppresses kinetic energy fluctuations; causes "flying ice cube" artifact. |

| CSVR | Stochastic Velocity Rescaling | Yes | Corrects Berendsen's flaws; good for dynamics. | Slightly more complex than simple rescaling. |

Practical Implementation and Protocol Guidance

Decision Workflow for Thermostat Selection

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for selecting an appropriate thermostat based on the research goals and system characteristics, synthesized from the comparative analysis of the search results.

Example Implementation Protocols

Protocol for NVT Equilibration Using the Nosé-Hoover Thermostat in VASP

For first-principles MD using software like VASP, the Nosé-Hoover thermostat can be implemented with the following INCAR parameters [3]:

The SMASS parameter controls the effective mass of the thermostat, influencing the frequency of temperature oscillations. A value of 1.0 is often a reasonable starting point, but optimization may be required for specific systems [3].

Protocol for Langevin Dynamics in GROMACS

In the GROMACS package, the Langevin thermostat is activated by setting the integrator to sd (stochastic dynamics) in the molecular dynamics parameter (.mdp) file. When this integrator is used, the tcoupl setting for temperature coupling is ignored, and the inverse friction coefficient tau-t is interpreted per degree of freedom [24].

It is important to note that the Langevin thermostat functions independently of the chosen pressure-coupling algorithm [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Parameters

Table 3: Key Parameters and "Reagents" for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Item / Parameter | Function / Role | Typical Value / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Coupling Constant (τ) | Determines relaxation time of the thermostat. | 0.1 - 1.0 ps [21] |

| Friction Coefficient (γ) | In Langevin dynamics, controls the strength of the damping and random forces. | 1.0 ps⁻¹ [24] |

| Thermostat Mass (Q/SMASS) | In Nosé-Hoover, the mass of the fictitious thermostat particle. | 1.0 (dimensionless) [3] |

| CSVR_PERIOD | In CSVR, the characteristic timescale (τ) of the thermostat. | Must be set by user [23] |

| Time Step (Δt) | The integration step for the equations of motion. Critical for stability. | 1-2 fs for atomistic systems [3] [2] |

| Random Seed | For stochastic thermostats (Langevin, CSVR), initializes the random number generator. | System time or fixed value for reproducibility. |

Performance Benchmarking and Artifact Analysis

Recent systematic benchmarks provide critical insights into thermostat performance. A 2025 study comparing thermostats on a binary Lennard-Jones glass-former model found that while the Nosé-Hoover chain and Bussi (CSVR) thermostats provided reliable temperature control, the potential energy showed a pronounced time-step dependence across all methods. Among Langevin methods, the Grønbech-Jensen–Farago scheme offered the most consistent sampling of both temperature and potential energy. However, Langevin dynamics generally incurred approximately twice the computational cost due to random number generation overhead and systematically reduced diffusion coefficients with increasing friction [25].

The most significant artifact associated with improper velocity rescaling is the "flying ice cube" effect, which is prominent in the Berendsen thermostat. This effect is a violation of the equipartition theorem where kinetic energy is systematically drained from vibrational modes and transferred into translational and rotational degrees of freedom. Research has demonstrated that this is due to a violation of detailed balance in the algorithm. In contrast, the CSVR thermostat, which rescales velocities to the canonical ensemble's kinetic energy distribution, satisfies detailed balance and does not exhibit this artifact [26]. This underscores the recommendation to discontinue the use of the Berendsen thermostat for production runs, reserving it only for initial equilibration if at all [22] [26].

The choice of a thermostat in molecular dynamics simulations is not merely a technical detail but a critical decision that influences the quality, reliability, and physical meaning of the simulation results. For researchers in fields like drug development, where accurate sampling of configurational spaces is paramount, selecting a thermostat that correctly generates a canonical ensemble is essential.

- For production runs requiring exact canonical sampling, the CSVR thermostat is highly recommended due to its robust sampling, avoidance of common artifacts, and minimal impact on dynamical properties.

- For deterministic dynamics and well-behaved, larger systems, the Nosé-Hoover chain thermostat is an excellent choice, as it corrects the ergodicity issues of the basic Nosé-Hoover algorithm.

- For simulating solvated biomolecules or where stochasticity is acceptable, the Langevin thermostat provides good control and thermalization, though at a higher computational cost and with altered dynamics.

- For initial equilibration and rapid stabilization, the Berendsen thermostat can still be used with caution, but it should never be used for sampling production data due to its known artifacts and incorrect ensemble distribution.

As MD simulations continue to play a pivotal role in scientific discovery and industrial application, a thorough understanding of these fundamental algorithms remains a cornerstone of reliable computational research.

The canonical (NVT) ensemble is a cornerstone of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, enabling the study of biomolecular systems under constant particle number, volume, and temperature conditions. This technical guide provides a comprehensive protocol for NVT equilibration, a critical step in preparing biomolecular systems for production MD runs. Within the broader context of canonical ensemble research, we detail the theoretical underpinnings, practical implementation steps, and validation methodologies essential for obtaining reliable thermodynamic and dynamic properties. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this whitepaper integrates current best practices from leading MD software packages, addresses common pitfalls, and provides standardized procedures for achieving stable temperature equilibration across diverse biomolecular systems.

The NVT, or canonical, ensemble is a statistical mechanical ensemble characterized by a constant Number of particles (N), constant Volume (V), and constant Temperature (T). In molecular dynamics simulations, this ensemble is used to study material properties under conditions where temperature fluctuates around an equilibrium value [3]. For biomolecular systems, NVT equilibration represents a crucial preparatory phase after energy minimization, serving to bring the system to the desired simulation temperature and stabilize it before proceeding to constant-pressure (NPT) equilibration for density adjustment [27] [2].

The theoretical foundation of NVT MD relies on coupling the system to a thermal bath that mimics the exchange of energy with an infinite reservoir at temperature T. Unlike microcanonical (NVE) ensemble simulations that conserve energy, NVT simulations require algorithmic modifications to maintain constant temperature, inevitably influencing system dynamics [28]. While all thermostats are designed to produce correct equilibrium thermodynamic properties at a given temperature, they invariably perturb the dynamic (time-dependent) properties of biomolecular systems [28]. Understanding these fundamental principles is essential for proper implementation and interpretation of NVT equilibration results.

Theoretical Framework and Thermostat Selection

Principles of Temperature Control

In molecular dynamics, temperature is proportional to the average kinetic energy of the system through the relation: [ \langle Ek \rangle = \frac{3}{2}NkBT ] where (\langle Ek \rangle) is the average kinetic energy, (N) is the number of atoms, (kB) is Boltzmann's constant, and (T) is the absolute temperature. During NVT equilibration, thermostats work by adjusting atomic velocities to maintain this relationship, either by scaling velocities directly or through the application of stochastic and frictional forces [28].

The choice of thermostat involves important trade-offs between sampling efficiency, dynamic fidelity, and numerical stability. While all thermostats should generate the correct equilibrium distribution, their different mathematical formulations can significantly impact both the rate and quality of conformational sampling [28] [29].

Comparative Analysis of Thermostat Algorithms

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Thermostat Algorithms for NVT Equilibration

| Thermostat Type | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations | Recommended Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosé-Hoover [3] [2] | Extended Lagrangian with virtual mass | Reproduces correct NVT ensemble; Deterministic trajectories | May show non-ergodicity in small systems; Requires mass parameter (SMASS) | General biomolecular systems; Extended production runs |

| Langevin [28] [2] | Stochastic collisions + friction | Good thermalization; Handles mixed phases well | Distorts protein dynamics; Non-reproducible trajectories | Systems with large solvation effects; Enhanced sampling |

| Berendsen [27] [2] | Velocity scaling proportional to T difference | Rapid convergence; Numerical stability | Does not produce correct canonical ensemble; "Flying ice cube" problem | Initial equilibration stages only |

| CSVR (Stochastic Velocity Rescaling) [3] | Stochastic velocity rescaling | Correct sampling; Minimal dynamic distortion | Limited implementation in MD packages | Sensitive dynamics where accurate timescales are needed |

Each thermostat algorithm employs distinct mathematical approaches to maintain constant temperature. The Nosé-Hoover method introduces an additional degree of freedom representing the heat bath, with the SMASS parameter controlling the inertia of the thermal reservoir [3] [2]. In contrast, the Langevin thermostat applies two additional terms to Newton's equation of motion for each degree of freedom: [ m\ddot{x} = F - \zeta m\dot{x} + R(t) ] where (F) is the systematic force, (\zeta) is the damping constant, and (R(t)) is a Gaussian random force [28]. The Berendsen thermostat scales velocities by a factor proportional to the difference between the desired and current temperatures, providing strong coupling to the heat bath but generating incorrect fluctuations [2].

Recent research has highlighted that the Langevin thermostat, particularly at common damping constants (ζ = 1 ps⁻¹), can significantly dilate protein dynamics, with ns-scale time constants for overall rotation dilated more substantially than sub-ns time constants for internal motions [28]. This has important implications for drug discovery professionals comparing simulation results with experimental NMR data.

Standard NVT Equilibration Protocol

System Preparation and Initialization

Prior to NVT equilibration, the system must be properly prepared through energy minimization and initial configuration:

Input Structure Preparation: Begin with a successfully energy-minimized structure, typically in GRO file format for GROMACS users [27]. This structure should have reasonable stereochemistry and solvent orientation.

Initial Velocity Assignment: If initial velocities are not available from a previous simulation, generate them according to a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at the target temperature: [ p(vi) = \sqrt{\frac{mi}{2 \pi kT}}\exp\left(-\frac{mi vi^2}{2kT}\right) ] where (m_i) is the mass of atom (i), (k) is Boltzmann's constant, and (T) is the target temperature [9]. Modern MD packages can implement this automatically.

Center-of-Motion Removal: Set the center-of-mass velocity to zero initially and at every subsequent step to prevent spurious translation of the entire system, which can artificially inflate the kinetic energy [9].

Parameter Configuration

Table 2: Essential Parameters for NVT Equilibration

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameters | Recommended Settings | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integration Parameters | Time step (Δt) | 1-2 fs | Constrain bonds involving hydrogens with SHAKE/LINCS |

| Number of steps | 25,000-50,000 | Corresponding to 50-100 ps simulation time | |

| Temperature Coupling | Reference temperature | Target simulation temp (e.g., 300 K) | Consistent with velocity generation temperature |

| Thermostat type | V-rescale, Nosé-Hoover, or Langevin | See Table 1 for selection guidance | |

| Time constant (τ) | 0.5-1.0 ps | Weaker coupling for more natural dynamics | |

| Coupling groups | Protein, Non-Protein | Multiple groups for heterogeneous systems | |

| Force Calculation | Non-bonded cut-off | 0.8-1.2 nm | Balance between accuracy and speed |

| Neighbor list update frequency | Every 10-20 steps | With Verlet buffer of 0.1-0.2 nm | |

| Constraints | Bond constraints | All bonds to H | Enables longer time steps |

| Position restraints | Backbone heavy atoms | Optional for stable protein core during initial equilibration |

The integration time step must be chosen considering the highest frequency vibrations in the system. For all-atom simulations of biomolecules, 2 fs is typically the maximum stable time step, requiring constraints on bonds involving hydrogen atoms [28] [27]. The neighbor searching algorithm employs a buffered Verlet cut-off scheme, where the pair list includes particles within a distance slightly larger than the interaction cut-off, updated periodically (e.g., every 10-20 steps) to maintain accuracy while optimizing computational efficiency [9].

Temperature coupling can be applied to different groups within the system (e.g., protein and solvent separately) to account for different thermal relaxation timescales. The coupling strength, determined by the time constant parameter, should be strong enough to maintain the target temperature but weak enough to avoid artificial damping of natural temperature fluctuations [27].

Figure 1: NVT Equilibration Workflow Decision Tree

Execution and Monitoring

During NVT equilibration, several key properties must be monitored to assess progress:

Temperature Stability: The instantaneous temperature will fluctuate around the target value, but the running average should converge and stabilize. Typically, 50-100 ps is sufficient for most biomolecular systems, though larger systems or those with significant initial strain may require longer equilibration [27].

Potential and Kinetic Energies: Both should stabilize, with the total energy exhibiting small fluctuations around a stable mean. Significant energy drift indicates improper equilibration.

System Stability: Monitor root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of protein backbone atoms. While some conformational adjustment is expected, dramatic changes may indicate improper initial structure preparation.

The NVT equilibration is complete when the running average of the temperature has reached a plateau at the desired value with fluctuations consistent with the statistical mechanics of the canonical ensemble. If the temperature has not stabilized after the initial equilibration period, additional NVT simulation can be performed using the final coordinates and velocities from the previous run as starting points [27].

Validation and Troubleshooting

Assessment of Equilibration Quality

Validating successful NVT equilibration requires both qualitative and quantitative assessments:

Temperature Convergence: Plot the instantaneous temperature and its running average versus time. The running average should approach the target temperature asymptotically, with fluctuations consistent with the expected statistical variance for the canonical ensemble [27].

Energy Stabilization: Both potential and kinetic energy components should reach stable averages with characteristic fluctuations. The total energy should not show a systematic drift.

Structural Integrity: While some structural adjustment is expected, the protein core should maintain proper folding. Calculate backbone RMSD to the starting structure; it should plateau rather than increase continuously.

Research indicates that thermostat choice significantly impacts dynamic properties. For instance, Langevin thermostats with damping constants of 1 ps⁻¹ have been shown to increase protein rotational correlation times by approximately 50% compared to NVE simulations [28]. Users comparing simulation dynamics with experimental measurements should account for these effects.

Common Issues and Solutions

Failure to Reach Target Temperature: If the system temperature remains consistently below or above the target value, ensure proper velocity initialization and check for excessive position restraints that may be inhibiting energy exchange.

Temperature Oscillations: Large, periodic temperature swings may indicate an inappropriate thermostat time constant or issues with the numerical integration. Adjust the coupling constant or reduce the time step.

Energy Drift: Significant energy drift may result from inaccurate force calculations, particularly related to cut-off artifacts or improper treatment of long-range interactions. Verify non-bonded interaction parameters and ensure sufficient neighbor list buffering [9].

Recent studies have demonstrated that thermostat-induced dynamic distortions can be corrected post-simulation by applying a contraction factor to time constants, with the correction factor being a linear function of the time constant itself [28]. This approach has shown success in reconciling simulated dynamics with NMR relaxation data.

Performance Considerations and Benchmarking