The NPH Ensemble: A Practical Guide to Constant-Enthalpy and Constant-Pressure Simulations for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the isoenthalpic-isobaric (NPH) ensemble, a fundamental tool in molecular dynamics (MD) for researchers and scientists.

The NPH Ensemble: A Practical Guide to Constant-Enthalpy and Constant-Pressure Simulations for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the isoenthalpic-isobaric (NPH) ensemble, a fundamental tool in molecular dynamics (MD) for researchers and scientists. It covers the foundational thermodynamics of the NPH ensemble, where the number of particles (N), pressure (P), and enthalpy (H) are conserved, explaining its distinction from more common ensembles like NPT. The guide details practical implementation methodologies in popular MD software like VASP and GROMACS, including critical parameter settings. It further addresses common troubleshooting and optimization strategies, validates the ensemble's performance through application case studies like phase diagram determination for water/ice systems, and offers a comparative analysis with other ensembles to guide appropriate usage in biomedical and materials research.

Understanding the NPH Ensemble: Core Concepts and Thermodynamic Principles

Definition and Key Characteristics of the Isoenthalpic-Isobaric Ensemble

The isoenthalpic-isobaric ensemble, commonly designated the NPH ensemble, represents a foundational pillar in statistical mechanics and molecular simulation for studying systems under constant enthalpy (H), pressure (P), and particle number (N). Developed by H. C. Andersen in 1980, this ensemble provides the theoretical framework for simulating adiabatic, isobaric processes, enabling the investigation of material properties without the energy exchange characteristic of temperature-controlled ensembles [1] [2]. This technical guide delineates the ensemble's core thermodynamics, outlines detailed protocols for its implementation in molecular dynamics, and presents its critical applications in modern computational research, including the calculation of melting temperatures and the study of stress anisotropy in solid-liquid systems [3].

In statistical mechanics, an ensemble describes a collection of all possible microstates of a system that conform to a set of macroscopic constraints, such as constant energy or constant temperature. The choice of ensemble dictates which thermodynamic properties are controlled during a simulation and which are allowed to fluctuate, thereby influencing the calculation of observables and system properties [4]. The isoenthalpic-isobaric ensemble occupies a unique position within this framework as the constant-pressure analogue to the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble. Unlike the more common isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble, which maintains constant temperature through heat exchange with a thermostat, the NPH ensemble conserves enthalpy, allowing temperature to fluctuate naturally in response to energy changes from pressure-volume work [5] [4]. This characteristic makes it particularly valuable for modeling physically isolated systems under constant external pressure, where the total heat content remains unchanged.

Theoretical Foundations of the NPH Ensemble

Thermodynamic Definition and Relationship to Enthalpy

The isoenthalpic-isobaric ensemble is defined by its conserved quantities: the number of particles (N), system pressure (P), and enthalpy (H). Enthalpy, a thermodynamic potential, is defined as H = E + PV, where E is the internal energy, P is the pressure, and V is the volume [1] [2]. In this ensemble, the system can exchange pressure-volume work with its surroundings but does not exchange heat or particles, creating what can be conceptually described as an "adiabatic, impermeable 'balloon' of variable volume in a constant-pressure environment" [5].

The fundamental thermodynamic connection for this ensemble arises from the first law of thermodynamics. For a system where N, P, and H are constant (dN = 0, dP = 0, dH = 0), the relationship simplifies to:

dH = δQ - VdP + μdN = δQ = 0 [5]

This mathematical formulation confirms that the system undergoes adiabatic processes (no heat transfer), with changes in internal energy arising solely from pressure-volume work: dU = -PdV [5].

Statistical Mechanical Formulation

In statistical mechanical terms, the NPH ensemble assigns equal probability to all microstates that satisfy the condition of constant enthalpy at fixed pressure and particle number. The development of this ensemble required treating system volume as a dynamical variable with associated potential and kinetic energy terms [2]. This innovative approach allowed volume to fluctuate during simulations while maintaining constant pressure, extending molecular dynamics capabilities beyond fixed-volume ensembles.

The connection between statistical mechanics and thermodynamics in the NPH ensemble is established through fluctuation relations. Ray, Graben, and Haile (1981) demonstrated that mean square volume fluctuations in this ensemble relate directly to the isobaric heat capacity [6] [7]. Furthermore, their work established new relations connecting cross-fluctuations to the volume expansivity, providing a statistical foundation for deriving thermodynamic properties from simulation data [6].

Table 1: Key Thermodynamic and Statistical Relations in the NPH Ensemble

| Property | Mathematical Relation | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Conserved Quantity | H = E + PV | Total enthalpy remains constant |

| Heat Transfer | δQ = 0 | Adiabatic process (no heat exchange) |

| Work Exchange | dU = -PdV | Internal energy changes only through P-V work |

| Volume Fluctuations | ⟨(ΔV)²⟩ ∝ C_P | Related to isobaric heat capacity [6] |

| Cross-Fluctuations | ⟨ΔVΔE⟩ ∝ α_P | Related to volume expansivity [6] |

Practical Implementation in Molecular Dynamics

Core Algorithm and Equations of Motion

Implementing the NPH ensemble in molecular dynamics requires modified equations of motion that incorporate volume as a dynamic variable. Andersen's original method introduced a Lagrangian that allows the simulation box size and shape to vary in response to pressure differences [1] [7]. The equations of motion include additional terms that account for the coupling between particle coordinates and the fluctuating volume, effectively creating a barostat mechanism that maintains constant pressure without introducing artificial dissipation when properly configured [8].

The inertial response of the simulation box to pressure differentials is controlled by a parameter often referred to as the "barostat mass" (PMASS in VASP), which determines the timescale of volume fluctuations [8]. Proper selection of this parameter is crucial for achieving accurate sampling of the ensemble while maintaining numerical stability during integration of the equations of motion.

Step-by-Step Simulation Protocol

Implementing a functional NPH ensemble simulation requires careful parameter selection and initialization. The following protocol outlines the essential steps for configuring an NPH molecular dynamics simulation, particularly within the VASP framework:

Initial System Equilibration: Prior to NPH production runs, equilibrate the system using an NPT (isothermal-isobaric) ensemble to achieve the desired temperature and pressure. This preliminary step ensures the system begins in an appropriate thermodynamic state before transitioning to constant-enthalpy conditions [8].

Ensemble Selection and Parameter Configuration:

- Set

MDALGO = 3to select the Langevin dynamics algorithm [8]. - Set

ISIF = 3to enable computation of the stress tensor and allow changes to both box volume and shape [8]. - Configure the barostat by setting

LANGEVIN_GAMMA_L = 0to remove the stochastic and friction terms, ensuring the box updates depend solely on the kinetic stress tensor [8]. - Disable the thermostat by setting

LANGEVIN_GAMMA = 0for all species, effectively removing temperature control and allowing the system to evolve adiabatically [8]. - Specify the barostat inertia through the

PMASStag, which controls the timescale of volume fluctuations [8].

- Set

Production Simulation and Trajectory Analysis: Execute the molecular dynamics simulation for a sufficient number of timesteps to ensure proper sampling of the phase space. Analyze trajectory data with emphasis on conserved quantities (enthalpy), fluctuating properties (temperature, volume), and the physical properties of interest.

Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Simulation Parameters

Table 2: Key Parameters for NPH Ensemble Simulations in VASP

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Function |

|---|---|---|

| MDALGO | 3 | Selects Langevin dynamics algorithm for barostat implementation [8] |

| ISIF | 3 | Enables stress tensor calculation and allows volume/shape changes [8] |

| LANGEVINGAMMAL | 0.0 | Disables stochastic and friction terms for the barostat [8] |

| LANGEVIN_GAMMA | 0.0 (for all species) | Disables thermostat, enabling adiabatic evolution [8] |

| PMASS | System-dependent | Controls inertia of lattice degrees of freedom; impacts volume fluctuation timescale [8] |

| NSW | 10,000+ | Number of MD steps for sufficient phase space sampling [8] |

Applications in Materials Science and Chemistry

Melting Temperature Calculations

The NPH ensemble provides significant advantages for calculating melting temperatures using the solid-liquid coexistence method [3]. In this application, a system containing both solid and liquid phases is simulated under constant pressure and enthalpy conditions. The NPH ensemble naturally resolves the stress anisotropy problem (where P~xx~ ≠ P~yy~ ≠ P~zz~) that commonly occurs at solid-liquid interfaces in constant-volume simulations, as it allows all components of the stress tensor to adjust to match the target pressure [3]. Zou et al. (2019) systematically compared melting temperature calculation methods and found that the two-phase method implemented in the NPH ensemble produces reliable results by enabling natural regulation of the stress tensor components [3].

Study of Adiabatic Processes and Energy Conservation

For simulating physically isolated systems under constant external pressure, the NPH ensemble provides the most natural representation. Unlike NPT simulations, where temperature control introduces artificial heat exchange, the NPH ensemble preserves the adiabatic nature of such processes, making it invaluable for studying:

- High-pressure material behavior in shock physics

- Rapid compression/expansion processes where insufficient time exists for heat exchange

- Natural temperature evolution in mechanically stressed systems without external thermal intervention

Comparative Analysis with Other Ensembles

The distinguishing feature of the NPH ensemble is its treatment of energy exchange. While the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble permits both heat and work exchange with its environment, the NPH ensemble allows only pressure-volume work, making it the constant-pressure equivalent of the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble [4]. This fundamental difference in constraint implementation leads to distinct fluctuation properties and applications.

Table 3: Comparison of Common Molecular Dynamics Ensembles

| Ensemble | Conserved Quantities | Exchange Mechanisms | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVE (Microcanonical) | N, V, E | None | Isolated system dynamics; fundamental mechanics studies [4] |

| NVT (Canonical) | N, V, T | Heat exchange | Constant-temperature studies; conformational sampling [4] |

| NPT (Isothermal-Isobaric) | N, P, T | Heat and work exchange | Standard conditions for material properties; equilibration [4] |

| NPH (Isoenthalpic-Isobaric) | N, P, H | Work exchange only | Adiabatic processes; melting temperature calculations; stress anisotropy resolution [4] [3] |

The isoenthalpic-isobaric ensemble represents more than a specialized statistical mechanical construct; it provides an essential framework for simulating adiabatic processes under constant pressure conditions. Its capacity to conserve enthalpy while allowing volume fluctuations makes it uniquely suited for investigating phenomena ranging from melting behavior to high-pressure material response. The rigorous statistical mechanical foundation established by Andersen and further developed by Ray, Graben, and Haile enables direct connection of fluctuation properties to thermodynamic derivatives, creating a powerful bridge between microscopic simulation and macroscopic observables [1] [6]. As molecular dynamics continues to expand its reach in materials science, chemistry, and drug development, the NPH ensemble remains an indispensable tool in the computational researcher's arsenal, particularly for systems where natural temperature response to mechanical perturbation must be preserved without artificial thermal regulation.

The thermodynamic identity for enthalpy, H = E + PV, defines a state function that is conserved in the isoenthalpic-isobaric (NPH) ensemble, a cornerstone for molecular simulations conducted at constant pressure and enthalpy [1]. This ensemble provides a critical framework for investigating material properties and biological processes under realistic experimental conditions. Within pharmaceutical sciences, the binding enthalpy (ΔH), a direct experimental observable, serves as a key indicator of drug-target interaction quality, with enthalpically optimized compounds demonstrating superior affinity and selectivity profiles [9] [10]. This technical guide explores the fundamental principles of enthalpy conservation, details its implementation in molecular dynamics simulations, and highlights its profound implications for computational material science and rational drug design, with a specific focus on the NPH ensemble.

The enthalpy (H) of a thermodynamic system is defined as the sum of its internal energy (E) and the product of its pressure (P) and volume (V): H = E + PV [11] [1]. This identity is a Legendre transform of the internal energy that shifts the analysis from a constant-volume to a constant-pressure framework, which is more relevant for most experimental and natural processes. As a state function, the change in enthalpy (ΔH) conveniently expresses the heat exchanged during a process at constant pressure, making it indispensable in chemical and biological thermodynamics.

In statistical mechanics, the set of all possible system states under specific constraints is called a statistical ensemble. The NPH ensemble, also known as the isoenthalpic-isobaric ensemble, is defined by a constant number of particles (N), constant pressure (P), and constant enthalpy (H) [8] [1]. It is the constant-pressure analogue of the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble, where instead of energy E, its enthalpy H is conserved [4]. The conservation of enthalpy, however, is not absolute but holds "up to numerical inaccuracies" during molecular dynamics simulations, much like energy conservation in the NVE ensemble [8]. This ensemble is particularly useful for studying the mechanical behavior of materials and biomolecules under experimentally relevant conditions where pressure, rather than volume, is controlled [1].

Fundamental Principles and Theoretical Framework

Derivation and Meaning of the Enthalpy Identity

The first law of thermodynamics states that the change in a system's internal energy is equal to the heat added to the system (Q) minus the work done by the system (W): ΔE = Q - W [11]. For a gas expanding against a constant external pressure, the work is primarily pressure-volume work, given by W = PΔV. Substituting this into the first law gives ΔE = Q - PΔV. Rearranging this expression yields Q = ΔE + PΔV. At constant pressure, the right-hand side of this equation is equal to the change in a new state function, which is defined as enthalpy: ΔH = ΔE + PΔV [11].

The total specific enthalpy, which is crucial for analyzing flowing systems, incorporates kinetic energy and is expressed as ht = h + u²/2, where h is the specific static enthalpy (h = e + Pv, with e as specific internal energy and v as specific volume) and u is velocity [11]. This form demonstrates that enthalpy encompasses both the thermal and mechanical energy content of a system, facilitating the analysis of energy conservation in open and flowing systems.

The Isoenthalpic-Isobaric (NPH) Ensemble in Statistical Mechanics

The NPH ensemble is a statistical mechanical construct used to study material properties under conditions of constant particle number (N), constant pressure (p), and constant enthalpy (H) [8]. In this ensemble, the system's volume fluctuates to maintain constant pressure, while the total enthalpy is conserved. This makes the NPH ensemble ideal for simulating processes where the system is thermally isolated but mechanically coupled to a pressure bath, a common scenario in material deformation and Earth sciences.

The relationship between different statistical ensembles and their corresponding thermodynamic potentials is summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Summary of Common Statistical Ensembles and Their Characteristics

| Ensemble Name | Acronym | Constant Parameters | Associated Free Energy | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microcanonical | NVE | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Energy (E) | - | Isolated systems, energy conservation studies |

| Canonical | NVT | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Helmholtz Free Energy (A) | Systems in contact with a thermal bath |

| Isobaric-Isothermal | NPT | Number of particles (N), Pressure (P), Temperature (T) | Gibbs Free Energy (G) | Most common experimental conditions |

| Isoenthalpic-Isobaric | NPH | Number of particles (N), Pressure (P), Enthalpy (H) | - | Adiabatic processes at constant pressure |

Computational Implementation and Protocols

Molecular Dynamics in the NPH Ensemble

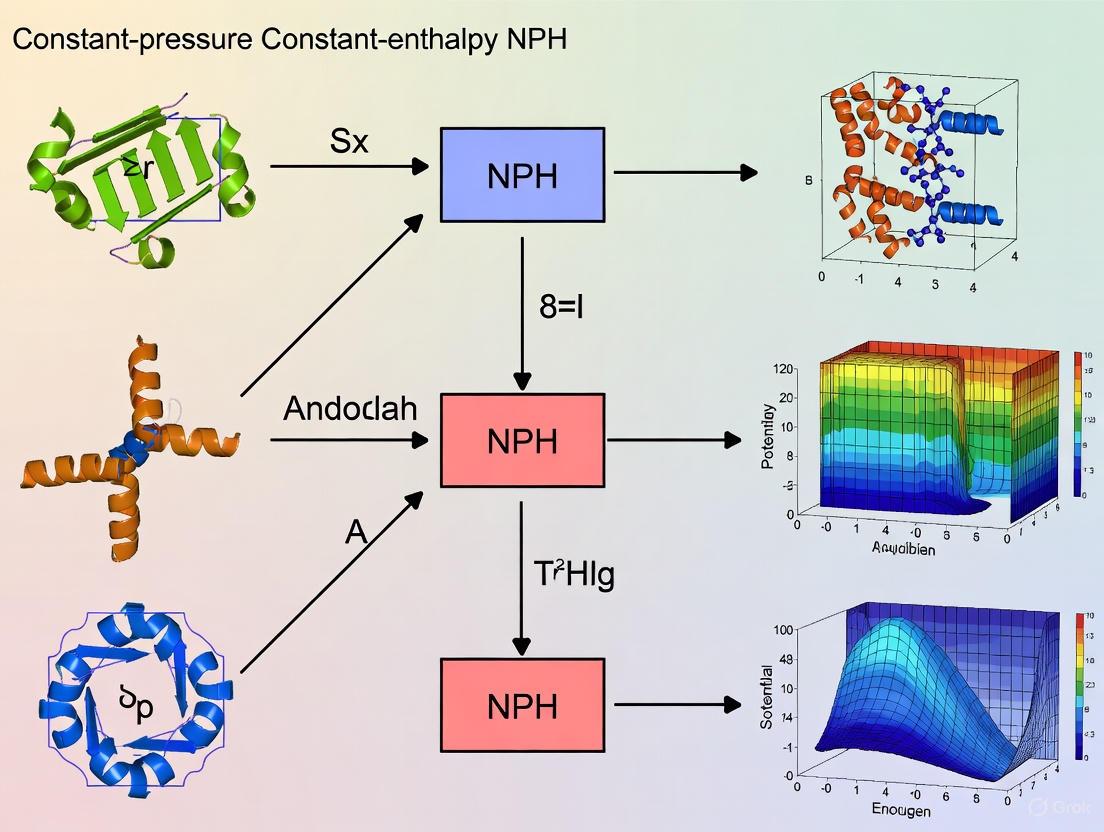

Performing a molecular dynamics (MD) simulation in the NPH ensemble requires specific algorithms to maintain constant pressure and conserve enthalpy. The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key parameter choices for configuring an NPH simulation.

Diagram 1: NPH Ensemble Simulation Workflow

A typical INCAR file configuration for an NPH run using the VASP software package, for instance, includes the key parameters shown in the workflow [8]:

MDALGO = 3to select the Langevin thermostat algorithm.ISIF = 3to ensure the stress tensor is computed and the box volume and shape are allowed to change.LANGEVIN_GAMMA = 0.0andLANGEVIN_GAMMA_L = 0.0to disable the stochastic and friction terms of the Langevin thermostat and barostat, respectively. This leaves the box dynamics to be governed solely by the kinetic stress tensor, creating the conditions for an isoenthalpic ensemble.PMASSdefines the mass of the barostat, controlling the inertia of the lattice degrees of freedom.

It is highly recommended to first equilibrate the system with an NPT molecular dynamics run to achieve the desired temperature and pressure before switching to the NPH ensemble for production data collection [8].

Application in Melting Point Calculations

The NPH ensemble has proven particularly valuable in methods for calculating melting temperatures (TM) via molecular dynamics simulation. In the two-phase coexistence method, a system containing both solid and liquid phases is simulated. While this can be done in the NPT ensemble, it can lead to stress anisotropy (Pxx ≠ Pyy ≠ Pzz) due to interfacial stress. Performing the simulation in the NPH ensemble solves this problem because the three principal components of the stress tensor can be regulated to match the given pressure, leading to more accurate results [3].

Table 2: Comparison of Methods for Calculating Melting Temperature (TM)

| Method | Ensemble(s) Used | Key Principle | Reported Accuracy/Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two-Phase Coexistence | NPT, NVT, NPH | Direct simulation of solid-liquid equilibrium; TM is where both phases coexist. | High accuracy when stress anisotropy is handled (e.g., with NPH). |

| Hysteresis | NPT | Heating solid and cooling liquid; TM estimated empirically from hysteresis loop. | Low accuracy; strongly dependent on heating/cooling rate. |

| Interface Pinning | NPT | Uses an order parameter to pin the interface and measure chemical potential difference. | High accuracy, but ignores interface disorder. |

| Frenkel-Ladd (Thermodynamic Integration) | NVT | Calculates absolute Gibbs free energy for solid and liquid phases. | Very high accuracy, but computationally expensive and complex. |

| Void Method | NPT | Introduces a void to catalyze melting; TM is observed from property discontinuity. | Moderate accuracy; observational without firm thermodynamic principle. |

Experimental Measurement of Binding Enthalpy

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

In pharmaceutical research, the binding enthalpy (ΔH) is not merely a theoretical concept but a measurable parameter with profound implications for drug candidate quality. The primary experimental technique for directly measuring the binding enthalpy is Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) [9]. ITC works by titrating a ligand solution into a protein solution and precisely measuring the heat released or absorbed upon binding. A single ITC experiment provides the binding constant (Ka), the stoichiometry (n), and the binding enthalpy (ΔH). The entropy change (ΔS) is then calculated using the relationship ΔG = ΔH - TΔS = -RT ln Ka [12] [13].

The Enthalpy Screen Protocol

To overcome the traditional low-throughput limitation of ITC, an "Enthalpy Screen" protocol has been developed. This method allows for the rapid determination of binding enthalpy for hundreds of ligands, making it suitable for the early stages of drug discovery following high-throughput screening [12].

The core principle involves injecting a small volume of a concentrated protein solution into a calorimetric cell containing the ligand at a concentration significantly exceeding its dissociation constant ([Ligand] >> Kd). This ensures that >99% of the injected protein binds to the ligand, and the measured heat effect is directly proportional to the binding enthalpy, requiring no complex fitting to a binding model [12]. The binding enthalpy is calculated using the equation:

ΔH = (QInh - QBuf) / (VInj × [P])

where QInh is the heat from injecting protease into the inhibitor solution, QBuf is the heat of dilution from injecting into buffer alone, VInj is the injection volume, and [P] is the concentration of active protein [12].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for ITC and Enthalpy Screening

| Reagent / Material | Specification / Function | Example from HIV-1 Protease Study [12] |

|---|---|---|

| Target Protein | Purified, active protein; concentration must be accurately determined. | HIV-1 protease (88% active concentration). |

| Ligands / Inhibitors | Compounds of interest dissolved in a compatible solvent. | KNI-series inhibitors (e.g., KNI-10769, KNI-577). Clinical inhibitors (e.g., amprenavir, indinavir). |

| Buffer System | Provides stable pH and ionic strength; must be free of contaminating reactants. | 10 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.0. |

| Solvent | Dissolves ligands; must be accounted for in control experiments. | DMSO (2% final concentration in experiments). |

| Calorimeter | Instrument for precise measurement of heat changes. | Affinity ITC (TA Instruments) with autosampler. |

| 96-Well Plates | For high-throughput automated screening of multiple compounds. | Used by the autosampler for storing protein and ligand solutions. |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Development

The thermodynamic signature of a drug candidate—the balance of enthalpic (ΔH) and entropic (-TΔS) contributions to binding—has emerged as a critical metric for assessing compound quality. Favorable binding enthalpy is associated with strong, specific interactions such as hydrogen bonds and van der Waals contacts that are geometrically optimal [12] [10]. Conversely, an unfavorable binding enthalpy often indicates that polar groups in the drug have been desolvated without forming productive new bonds with the target, a energetically costly process [12].

The evolution of two major drug classes, HIV-1 protease inhibitors and statins (cholesterol-lowering drugs), reveals a clear trend: later-generation "best in class" drugs consistently show more favorable binding enthalpies compared to the "first in class" pioneers [9] [10]. For example, the potent HIV-1 protease inhibitor darunavir has a markedly favorable binding enthalpy of -12.7 kcal/mol [10]. This improvement is not typically the primary goal of optimization efforts, which focus on potency, selectivity, and pharmacokinetics. However, it appears that achieving these goals often results in a molecule with a superior enthalpic profile, underscoring its importance as an indicator of overall compound quality.

A significant challenge in enthalpic optimization is the phenomenon of enthalpy-entropy compensation, where a gain in binding enthalpy is offset by a loss of binding entropy, resulting in little net improvement in affinity [9]. Overcoming this compensation is a primary objective in modern drug design. Strategies include ensuring that newly formed hydrogen bonds are geometrically optimal and that conformational flexibility is minimized before binding, reducing the entropic penalty upon complex formation [9] [10].

The thermodynamic identity H = E + PV and the principle of enthalpy conservation in the NPH ensemble provide a powerful framework for understanding and manipulating the behavior of systems at constant pressure. From computational material science, where the NPH ensemble enables accurate determination of properties like melting points, to experimental drug discovery, where the direct measurement of binding enthalpy guides the optimization of therapeutic compounds, the implications are vast and profound. The integration of thermodynamic principles, particularly through the use of enthalpy screens and structure-thermodynamic relationships, is paving the way for a new generation of highly optimized, "best in class" drugs. As molecular simulation tools and calorimetric techniques continue to advance, the explicit consideration of enthalpy and its interplay with entropy will undoubtedly become even more deeply embedded in the rational design of novel materials and pharmaceuticals.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the choice of statistical ensemble is foundational, determining the thermodynamic conditions and the fundamental properties of the system under study. An ensemble is a collection of system microstates that represent possible scenarios under a set of controlled macroscopic parameters [14]. Within a broader research context on the constant-pressure constant-enthalpy (NPH) ensemble, understanding its unique role and how it contrasts with the more common microcanonical (NVE), canonical (NVT), and isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensembles is critical for advanced applications in materials science and drug development. These ensembles are artificial constructs that facilitate the calculation of macroscopic properties by holding different variables constant, thereby mimicking various experimental conditions [4] [14]. This guide provides a technical comparison of these ensembles, with a specific focus on elucidating the NPH ensemble's principles, implementation, and application.

Theoretical Foundations of Statistical Ensembles

Definition of Ensembles and Partition Functions

The mathematical description of an ensemble is encapsulated by its partition function, which contains all the thermodynamic information about the system [15]. The following table summarizes the core characteristics of the four ensembles examined in this overview.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Molecular Dynamics Ensembles

| Ensemble | Name | Constant Parameters | Partition Function Relation | Conserved Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVE | Microcanonical | Number (N), Volume (V), Energy (E) | [15] | Total Energy (E) |

| NVT | Canonical | Number (N), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | [15] | Helmholtz Free Energy (F) |

| NPT | Isothermal-Isobaric | Number (N), Pressure (P), Temperature (T) | [15] | Gibbs Free Energy (G) |

| NPH | Isoenthalpic-Isobaric | Number (N), Pressure (P), Enthalpy (H) | [15] | Enthalpy (H = E + PV) |

The NPH Ensemble: A Detailed Examination

The NPH ensemble is the analogue of the constant-volume, constant-energy (NVE) ensemble but under constant pressure conditions [4]. In this ensemble, the enthalpy (H), which is the sum of the internal energy (E) and the product of pressure and volume (PV), is conserved, barring numerical inaccuracies [8]. The partition function for the NpH ensemble is derived from the number of microstates consistent with a given enthalpy, H [15]. This ensemble visualizes a system of N particles in a box without rigid boundaries that is thermally isolated from its surroundings. The absence of rigid sides allows the volume and shape to change in response to pressure differences, causing the instantaneous pressure to fluctuate around the desired value [15].

Comparative Analysis of Ensemble Properties and Equations of Motion

Thermodynamic and Dynamic Control

The core difference between ensembles lies in which thermodynamic variables are controlled and which are allowed to fluctuate. These differences necessitate different algorithms and "extended system" methods to integrate the equations of motion while respecting the ensemble's constraints [16] [17].

Table 2: Operational Comparison of MD Ensembles

| Ensemble | Fluctuating Quantities | Common Algorithms & Control Methods | Energy Conservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVE | Temperature, Pressure | Newton's Equations; Verlet/Velocity Verlet integrator [4] [18] | Yes (in theory) [14] |

| NVT | Energy, Pressure | Thermostats (e.g., Nosé-Hoover, Andersen, Berendsen) [14] [19] | No (dH/dt ≠ 0) [14] |

| NPT | Energy, Volume | Thermostat + Barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) [14] [16] | No |

| NPH | Temperature, Volume | Barostat only (e.g., in VASP: MDALGO=3 with zero Langevin constants) [8] | Yes (Enthalpy, H) [4] |

Practical Implications of Fluctuations

The choice of ensemble directly impacts the physical significance of fluctuations in the simulation. For instance, in the NVE ensemble, the total energy is a constant of motion, but temperature fluctuates as the system explores regions of high and low potential energy on a fixed Potential Energy Surface (PES) [14]. In contrast, the NVT ensemble uses a thermostat to maintain a constant temperature, allowing the total energy to fluctuate. This means the system can effectively move from one PES to another, which is particularly useful for overcoming energy barriers [14]. The NPT ensemble introduces volume fluctuations on top of energy fluctuations, allowing the system's density to equilibrate at a given temperature and pressure. The NPH ensemble, conserving enthalpy, is characterized by fluctuations in temperature and volume, making it suitable for simulating adiabatic processes.

A Workflow for Ensemble Selection in Molecular Dynamics

The following diagram illustrates a logical decision-making process for selecting an appropriate ensemble based on the goals of a molecular dynamics simulation, positioning the NPH ensemble within the broader context of MD research.

Figure 1: MD Ensemble Selection Workflow. This diagram outlines the decision pathway for choosing the most appropriate statistical ensemble for a molecular dynamics simulation, based on the thermodynamic constraints of the system and the research objectives.

Detailed Experimental Protocol for NPH Ensemble Simulation

Prerequisites and Equilibration

Before initiating a production run in the NPH ensemble, it is strongly recommended to first equilibrate the system using an NPT molecular dynamics simulation. This ensures the system reaches the desired temperature and pressure, establishing a stable starting point for the subsequent NPH run [8].

Step-by-Step NPH Setup in VASP

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for configuring an NPH ensemble simulation within the VASP software environment, a common tool in computational materials science [8].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for NPH Ensemble Simulation in VASP

| Item (INCAR Tag) | Function / Setting | Technical Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Algorithm (MDALGO) | Selects the MD algorithm and thermostat. | Must be set to 3 to use the Langevin framework [8]. |

| Langevin Barostat Friction (LANGEVINGAMMAL) | Controls the friction and stochastic term for the barostat. | Must be set to 0.0 to remove stochastic/friction terms, leaving box updates dependent on the kinetic stress tensor [8]. |

| Langevin Thermostat Friction (LANGEVIN_GAMMA) | Controls the friction and stochastic term for the atomic thermostat. | Must be set to 0.0 for all atomic degrees of freedom to disable thermostatting, allowing velocities to be determined solely by interatomic forces [8]. |

| Lattice Mass Parameter (PMASS) | Controls the inertia of the lattice degrees of freedom. | Must be set to a value > 0.0; specific value depends on the system and desired dynamics [8]. |

| Integration Time Step (POTIM) | Defines the time step for numerical integration. | Typically 1.0 fs for systems with atoms, but can be system-dependent [19]. |

| Stress Tensor Control (ISIF) | Determines whether volume/shape is fixed or allowed to change. | Set to 3 to compute the stress tensor and allow changes in box volume and shape [8] [19]. |

Procedure:

- Initial Configuration: Prepare a

POSCARfile containing the atomic positions of a sufficiently large supercell [19]. - INCAR Parameterization: In the main input file (

INCAR), set the following critical tags as specified in Table 3 [8]:IBRION = 0(to enable MD)MDALGO = 3ISIF = 3LANGEVIN_GAMMA_L = 0.0LANGEVIN_GAMMA = 0.0PMASS = [value](user-defined)POTIM = [value](e.g., 1.0)NSW = [number_of_steps]

- Execution: Compile VASP with the

-Dtbdynpreprocessor flag and execute the program [19]. - Validation: Monitor the output (e.g., in

OUTCARorOSZICAR) to confirm that the enthalpy (H) is conserved throughout the simulation and that the pressure fluctuates around the target equilibrium value.

Applications and Best Practices

Recommended Use Cases for Each Ensemble

- NVE Ensemble: Primarily used for studying fundamental dynamic properties and energy conservation, or for exploring a system's Potential Energy Surface (PES) [4] [14]. It is not recommended for equilibration as it cannot drive the system to a desired temperature [4].

- NVT Ensemble: The default choice for many simulations, especially when conformational searches are performed in vacuum or without periodic boundary conditions [4]. It is ideal when the system volume and lattice vectors must be held constant, such as in simulations of solids or when measuring pressure at system boundaries is a concern [14].

- NPT Ensemble: The ensemble of choice when correct pressure, volume, and density are critical, as it best mimics standard experimental conditions [4]. It is essential for studying phase transitions, self-assembly processes (e.g., bilayer formation), and for achieving equilibrium density [14] [20].

- NPH Ensemble: As an analogue to NVE under constant pressure, it is useful for simulating adiabatic processes where no heat exchange occurs. It is also employed as a test for numerical stability and to check if a system is sufficiently equilibrated before starting production runs [20].

Critical Considerations for Practitioners

- Ergodicity and Sampling: All ensembles should, in principle, produce consistent averages for the same state point, but their fluctuations differ [4]. Inadequate sampling can violate ergodicity, leading to incorrect time-averaged properties [14].

- Physical Meaning without PBCs: Without Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBCs), volume, pressure, and density are not well-defined. Therefore, constant-pressure dynamics (NPT, NPH) cannot be performed, and NVT is the appropriate choice [4] [20].

- Numerical Stability: Energy drift in NVE due to integration errors is common [4]. Running a system in NVE after equilibration is often used as a stability test for the simulation parameters and potentials [20].

The study of thermodynamic ensembles provides the foundation for understanding and predicting the behavior of molecular systems. The isoenthalpic–isobaric (NPH) ensemble, where particle number (N), pressure (P), and enthalpy (H) remain constant, represents a specific set of natural conditions crucial for simulating various physical processes. Enthalpy (H) is defined as the sum of a thermodynamic system's internal energy (U) and the product of its pressure and volume (pV), expressed as H = U + pV [21]. This state function becomes particularly valuable when examining systems at constant external pressure, a condition conveniently provided by Earth's ambient atmosphere in experimental settings [21].

Understanding when a system naturally maintains constant enthalpy is fundamental to multiple scientific domains, including drug development, where accurate simulation of biomolecular interactions under specific thermodynamic conditions can predict binding affinities and stability. The NPH ensemble serves as the constant-pressure analogue to the constant-volume, constant-energy (NVE) ensemble, making it indispensable for studying processes where energy exchange occurs through work rather than heat transfer [4]. This technical guide explores the theoretical foundations, practical implementations, and research applications of isoenthalpic systems within the broader context of constant-pressure, constant-enthalpy ensemble research.

Theoretical Foundations of Constant Enthalpy

The Isoenthalpic–Isobaric (NPH) Ensemble

The isoenthalpic–isobaric ensemble maintains constant enthalpy (H) and constant pressure (P) while allowing volume (V) to fluctuate [1]. In this ensemble, the system can exchange energy with its environment through work (pV work) but not through heat transfer, creating an adiabatic system at constant pressure. The conservation of enthalpy in this ensemble arises directly from its definition: H = E + PV, where E represents the internal energy [1].

In statistical mechanics, the NPH ensemble provides a framework for calculating thermodynamic averages when pressure rather than volume is the controlled variable. This proves particularly useful for comparing simulation results with experimental measurements, which are often conducted under constant pressure conditions [4]. The connection between molecular dynamics and the NPH ensemble emerges from the equations of motion, which can be formulated to conserve enthalpy while allowing the simulation box volume to adjust in response to pressure differences.

Natural Conditions for Constant Enthalpy

A system naturally maintains constant enthalpy under specific physical conditions, primarily characterized by the absence of heat exchange with the environment while pressure remains constant. These adiabatic, isobaric processes occur when:

- Perfect Thermal Insulation: The system is completely isolated from heat transfer with its surroundings (adiabatic condition) [22].

- Constant External Pressure: The system experiences a fixed external pressure, typically from the environment [21].

- No Non-pV Work: The system does not perform or receive work other than pressure-volume work [22].

Under these conditions, any change in the system's internal energy (ΔU) must equal the negative of the pV work done (-PΔV), leading to zero change in enthalpy (ΔH = ΔU + PΔV = 0) [21]. In molecular dynamics simulations, these conditions are engineered through specific algorithms that control pressure without implementing a thermostat, allowing the temperature to fluctuate freely while conserving enthalpy [8].

Table 1: Characteristic Conditions for Constant Enthalpy in Different System Types

| System Type | Adiabatic Condition | Pressure Condition | Resulting Enthalpy Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated Physical System | Perfect thermal insulation | Constant external pressure | Naturally constant enthalpy |

| NPH Molecular Dynamics | No thermostat applied | Barostat maintains constant pressure | Enthalpy conserved (within numerical precision) |

| Chemical Reaction | No heat exchange with surroundings | Open to atmosphere | Enthalpy change approximately zero |

NPH Ensemble in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Implementation and Equations of Motion

In molecular dynamics simulations, the NPH ensemble is implemented through specialized integrators that modify the equations of motion to maintain constant pressure while conserving enthalpy. The equations of motion for NPH dynamics are given by [23]:

Where:

- ri and pi are atom i's position and momentum, respectively

- mi is the mass of atom i

- fi is the force on atom i

- V is the system volume

- W is the piston mass parameter

- P(t) is the instantaneous pressure

- Pext is the external pressure

- γ is the collision frequency

- R(t) is a random force (zero when implementing pure NPH)

These equations describe a system where the volume adjusts dynamically in response to pressure differences through a "piston" with mass W, while no thermal coupling exists to maintain constant temperature [23]. The absence of a thermostat results in temperature fluctuations that maintain constant enthalpy as the volume changes.

Table 2: Key Parameters in NPH Molecular Dynamics Implementation

| Parameter | Symbol | Role in NPH Dynamics | Typical Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Piston Mass | W | Controls inertia of volume fluctuations; affects stability and oscillation frequency | amu (atomic mass units) |

| External Pressure | Pext | Target pressure value maintained by barostat | bar, atm, MPa |

| Instantaneous Pressure | P(t) | Current internal pressure of system, calculated from virial | bar, atm, MPa |

| Collision Frequency | γ | Damping coefficient for piston motion (zero in pure NPH) | ps-1 |

| Time Step | Δt | Integration interval for equations of motion | fs (femtoseconds) |

Practical Simulation Protocols

Implementing NPH ensemble simulations requires specific configuration of molecular dynamics packages. For example, in VASP, an NPH simulation is configured as follows [8]:

- Ensemble Selection: Set

MDALGO = 3to use the Langevin thermostat algorithm - Thermostat Disabling: Set

LANGEVIN_GAMMA = 0.0andLANGEVIN_GAMMA_L = 0.0to remove stochastic and friction terms - Barostat Configuration: Set

ISIF = 3to compute stress tensor and allow volume changes - Piston Mass: Adjust

PMASSto control the inertia of lattice degrees of freedom

Similar implementations exist in other molecular dynamics engines. For instance, apoCHARMM supports NPH dynamics using a Langevin piston barostat with the random force term disabled [23]. CASTEP includes NPH as one of its core thermodynamic ensembles, particularly useful for studying materials under pressure [24].

A critical prerequisite for successful NPH simulations is proper system equilibration. It is recommended to first equilibrate the system using an NPT (constant temperature and pressure) ensemble to achieve the desired temperature and pressure before switching to NPH production runs [8]. This ensures the system starts from appropriate initial conditions while maintaining constant enthalpy throughout the data collection phase.

Research Applications and Experimental Considerations

Phase Transition Studies

The NPH ensemble proves particularly valuable for studying phase transitions in materials, as it naturally captures the enthalpy changes associated with these transformations. In one documented approach, researchers simulate supercooled liquids and detect phase transitions by slowly reducing enthalpy in a series of NPH runs, artificially extracting kinetic energy through velocity rescaling between simulations [25]. This method enables direct observation of latent heat release during phase transitions, as at constant pressure, changes in enthalpy equal the heat that enters or leaves the system [25].

This application highlights a key advantage of the NPH ensemble: the direct correspondence between enthalpy changes and heat transfer at constant pressure makes it ideal for quantifying thermodynamic properties associated with phase transformations. The ability to control enthalpy rather than temperature provides a more natural framework for studying these processes, particularly when comparing simulation results with experimental calorimetry data.

Comparison with Other Thermodynamic Ensembles

The NPH ensemble occupies a specific niche within the spectrum of thermodynamic ensembles used in molecular simulations. Understanding its relationship to other ensembles helps researchers select the appropriate method for their specific research questions.

Table 3: Comparison of Major Molecular Dynamics Ensembles

| Ensemble | Fixed Quantities | Fluctuating Quantities | Primary Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVE | Number of particles, Volume, Energy | Temperature, Pressure | Energy-conserving dynamics; fundamental studies [4] |

| NVT | Number of particles, Volume, Temperature | Energy, Pressure | Conformational sampling; biomolecular folding [4] |

| NPT | Number of particles, Pressure, Temperature | Energy, Volume | Standard conditions matching experiments; equilibration [4] |

| NPH | Number of particles, Pressure, Enthalpy | Energy, Temperature, Volume | Phase transitions; adiabatic processes [4] [24] |

The following diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting an appropriate ensemble based on the natural conditions of the system being studied:

Systematic selection of thermodynamic ensembles for molecular simulations

Implementing NPH ensemble research requires both specific computational tools and theoretical frameworks. The following table details key resources essential for conducting isoenthalpic-isobaric simulations.

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for NPH Ensemble Simulations

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Method | Function in NPH Research |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Software | VASP [8], apoCHARMM [23], CASTEP [24] | Implements NPH equations of motion; provides barostat algorithms |

| Barostat Algorithms | Langevin Piston [23], Parrinello-Rahman [24] | Maintains constant pressure by adjusting simulation box volume |

| Analysis Methods | Enthalpy Calculation [21], Virial Computation [23] | Monitors enthalpy conservation; calculates pressure from atomic forces |

| Theoretical Frameworks | Isoenthalpic–isobaric Ensemble Theory [1] | Provides statistical mechanical basis for interpreting results |

| System Preparation | NPT Equilibration Protocol [8] | Achieves target temperature/pressure before NPH production runs |

The theoretical basis for when a system naturally maintains constant enthalpy is firmly rooted in the conditions of the isoenthalpic–isobaric ensemble: adiabatic boundaries that prevent heat transfer, constant external pressure, and the absence of non-pV work. These conditions create an environment where enthalpy remains constant despite internal energy and volume fluctuations. The NPH ensemble provides both a theoretical framework and practical methodology for studying such systems through molecular dynamics simulations.

For researchers in drug development and materials science, understanding and utilizing the NPH ensemble offers unique insights into processes where enthalpy, rather than temperature, serves as the controlling thermodynamic variable. Phase transition studies, materials under pressure, and processes mimicking adiabatic conditions in real-world applications all benefit from the isoenthalpic perspective. As molecular dynamics software continues to advance, with packages like apoCHARMM providing enhanced virial calculations and more efficient NPH implementations [23], the research applications of constant-enthalpy simulations will continue to expand, offering new opportunities for connecting simulation data with experimental observations under naturally occurring isoenthalpic conditions.

Fundamental Properties and Fluctuations Accessible in the NPH Ensemble

The isoenthalpic-isobaric (NPH) ensemble represents a fundamental statistical mechanical framework for studying materials under constant particle number (N), pressure (P), and enthalpy (H). Unlike the more commonly employed NPT ensemble that maintains constant temperature, the NPH ensemble provides direct access to adiabatic processes and thermodynamic properties derivable from enthalpy conservation. This technical guide explores the core theoretical foundations, practical implementation methodologies, and key applications of NPH ensemble simulations, with particular emphasis on the analysis of fluctuations and their relationship to material properties. Designed for computational researchers and drug development professionals, this work establishes the NPH ensemble's unique capabilities for investigating pressure-induced phase transitions, nanomaterial behavior, and biological systems under physiologically relevant conditions.

Theoretical Foundations of the NPH Ensemble

The NPH ensemble is characterized by fixed particle number (N), pressure (P), and enthalpy (H), making it the constant-pressure analogue to the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble [4]. The fundamental thermodynamic potential conserved in this ensemble is enthalpy, defined as H = E + PV, where E represents the internal energy and PV denotes the pressure-volume work term [1]. This conservation relationship dictates that fluctuations in internal energy are directly coupled to fluctuations in the system volume through the constant pressure constraint.

In molecular dynamics simulations, the NPH ensemble enables the study of systems where energy exchange occurs through mechanical work rather than heat transfer with a thermal reservoir. The statistical sampling in the NPH ensemble provides direct access to the isothermal compressibility (κₜ) through volume fluctuations according to the relation [4]:

[ \langle (\Delta V)^2 \rangle = kB T V \kappaT ]

where ⟨(ΔV)²⟩ represents the mean-squared volume fluctuations, k_B is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, V is volume, and κₜ is the isothermal compressibility. This relationship demonstrates how measurable fluctuations in simulation observables connect to fundamental thermodynamic response functions.

The NPH ensemble is particularly valuable for investigating adiabatic processes where no heat exchange occurs, making it ideally suited for modeling rapid compression/expansion phenomena, shock waves, and other processes where thermal equilibration with the environment is significantly slower than the timescale of mechanical work transfer. For drug development applications, this corresponds to physiological processes involving rapid pressure changes or mechanical stress on biological macromolecules.

Practical Implementation in Molecular Dynamics

Simulation Methodology

Implementing the NPH ensemble in molecular dynamics requires specific algorithmic approaches and parameter configurations. In the VASP software package, the NPH ensemble is activated by setting MDALGO = 3 while disabling thermostatting through appropriate parameter selection [8]. The key implementation steps include:

Equation of Motion Integration: The NPH ensemble utilizes extended Lagrangian formulations that incorporate barostat degrees of freedom to maintain constant pressure. The lattice vectors fluctuate in response to the difference between the internal and external pressure, with the inertia of these fluctuations controlled by the PMASS parameter [8].

Barostat Configuration: Proper selection of the barostat mass parameter (PMASS) is critical for achieving efficient sampling without introducing artificial oscillatory behavior in volume fluctuations. The recommended practice involves system equilibration using the NPT ensemble before transitioning to NPH production runs [8].

Numerical Stability Considerations: The absence of thermostating in NPH simulations necessitates careful monitoring of numerical drift. Using time-reversible integrators and sufficiently small timesteps (typically 1-2 femtoseconds for atomistic systems) ensures acceptable energy conservation within the discrete integration scheme [8].

Table 1: Key Parameters for NPH Ensemble Implementation in VASP

| Parameter | Required Value | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDALGO | 3 | Selects Langevin dynamics algorithm | Must be combined with appropriate ISIF setting |

| ISIF | 3 | Enables stress tensor calculation and volume/shape changes | Essential for pressure control |

| LANGEVIN_GAMMA | 0.0 | Disables thermostat friction term | Creates isoenthalpic conditions |

| LANGEVINGAMMAL | 0.0 | Disables barostat stochastic term | Maintains constant enthalpy |

| PMASS | Variable | Sets inertia of lattice degrees of freedom | System-dependent optimization required |

Simulation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for setting up and running an NPH ensemble simulation, from system preparation through to data analysis:

Sample Input Configuration

A representative INCAR file for NPH ensemble simulations in VASP demonstrates the critical parameter combinations [8]:

This configuration maintains constant enthalpy by eliminating stochastic and frictional terms from both thermostats and barostats, allowing the system to evolve according to the deterministic equations of motion under constant pressure conditions.

Key Properties and Fluctuation Analysis

Accessible Thermodynamic Properties

The NPH ensemble provides direct measurement capabilities for several important thermodynamic response functions through the analysis of trajectory fluctuations. The conserved enthalpy constraint creates specific relationships between energy and volume fluctuations that can be exploited to extract material properties.

Table 2: Thermodynamic Properties Accessible from NPH Ensemble Fluctuations

| Property | Fluctuation Relation | Physical Significance | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isothermal Compressibility (κₜ) | ⟨(ΔV)²⟩ = kBT V κₜ | Resistance to uniform compression | Hydration behavior in drug binding |

| Thermal Expansion Coefficient (α) | ⟨ΔV ΔH⟩ = kBT² V α / κₜ | Volume change with temperature at constant pressure | Polymer swelling in physiological conditions |

| Constant-Pressure Heat Capacity (Cₚ) | ⟨(ΔH)²⟩ = kBT² Cₚ | Energy required to raise temperature at constant pressure | Protein stability under pressure stress |

| Adiabatic Compressibility (κₛ) | κₛ = κₜ - TVα²/Cₚ | Compression at constant entropy | Sound propagation in biomaterials |

Successful implementation of NPH ensemble simulations requires both specialized software tools and carefully parameterized force fields. The following table details essential components of the computational researcher's toolkit for NPH investigations:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for NPH Ensemble Simulations

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| VASP | First-principles molecular dynamics with NPH capability | Implements NPH via MDALGO=3; suitable for periodic systems [8] |

| LAMMPS | Classical molecular dynamics with extended Lagrangian methods | Supports NPH using fix nph command; extensive force field compatibility |

| AMBER | Biomolecular simulation package | Specialized for pharmaceutical applications; constant-pressure methods |

| CHARMM | All-atom empirical force field | Optimized for proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids in NPH contexts |

| GAUSSIAN | Electronic structure calculations | Provides quantum mechanical reference data for force field parameterization |

| PLUMED | Enhanced sampling and analysis | Facilitates calculation of fluctuation-based thermodynamic properties |

Applications in Drug Development and Materials Research

The NPH ensemble offers unique advantages for pharmaceutical applications where pressure fluctuations occur naturally or represent an important experimental variable. In drug delivery systems, the behavior of lipid bilayers, polymeric nanoparticles, and protein therapeutics under pressure stress can be directly simulated using NPH methodologies.

For encapsulated drug formulations, the NPH ensemble enables prediction of stability under various pressure conditions encountered during manufacturing, storage, and administration. The volume fluctuations accessible through NPH simulations correlate directly with packing efficiency and void distribution in amorphous solid dispersions—critical factors influencing drug recrystallization and release kinetics.

Additionally, pressure-induced denaturation of biopharmaceuticals represents an important degradation pathway that can be systematically investigated using NPH approaches. The ensemble's ability to model adiabatic compression events provides molecular-level insights into protein unfolding transitions under high-pressure processing conditions used for sterilization of therapeutic proteins.

The fluctuation properties derived from NPH simulations further enable prediction of thermodynamic stability boundaries for polymorphic drug crystals, supporting the design of robust crystalline forms with optimal bioavailability and processing characteristics.

The NPH ensemble constitutes a powerful framework for investigating thermodynamic properties and material behavior under constant-pressure, constant-enthalpy conditions. Through careful implementation and fluctuation analysis, researchers can access fundamental response functions including compressibility, thermal expansion, and heat capacity—properties essential for rational design in pharmaceutical development and advanced materials engineering. The continued refinement of NPH simulation methodologies promises enhanced predictive capabilities for systems subject to mechanical stress and pressure perturbations, bridging molecular-scale interactions with macroscopic material performance.

Implementing NPH Simulations: Setup, Workflow, and Real-World Applications

Step-by-Step Guide to Configuring an NPH Simulation in VASP (MDALGO=3)

The isoenthalpic-isobaric (NpH) ensemble is a fundamental tool in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for studying materials under constant pressure and enthalpy conditions. This ensemble is particularly valuable for investigating systems where energy exchange is restricted, mimicking adiabatic processes common in high-pressure physics, materials science, and drug development research. Within the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP), the NpH ensemble is implemented through specific MD algorithms and parameter configurations. This technical guide provides researchers with a comprehensive framework for configuring, executing, and validating NpH simulations in VASP using the MDALGO = 3 parameter, enabling accurate modeling of materials behavior under controlled thermodynamic conditions.

Theoretical Foundations of the NpH Ensemble

Ensemble Theory and Thermodynamic Relationships

In statistical mechanics, the NpH ensemble represents a collection of systems with constant particle number (N), constant pressure (p), and constant enthalpy (H). The isoenthalpic-isobaric partition function is mathematically defined as:

[

X(N,p,H) = \sum{H-\delta H

The NpH ensemble can be visualized as an N-particle system in a box without rigid boundaries that is thermally isolated from its surroundings. Since the box has no fixed sides, the volume and shape fluctuate according to the pressure difference between the interior and exterior of the simulation cell. In practical simulations, the instantaneous pressure fluctuates around the target value, while the enthalpy remains conserved within numerical precision [15]. This makes the NpH ensemble particularly suitable for modeling processes in materials science and pharmaceutical development where systems experience pressure changes without heat exchange with the environment.

Comparison with Other Ensembles

The NpH ensemble occupies a distinct position in the landscape of statistical ensembles commonly used in molecular dynamics simulations:

Microcanonical (NVE) ensemble: Characterized by constant particle number (N), volume (V), and energy (E), this ensemble completely isolates the system from its environment. Unlike NpH, it maintains fixed volume rather than fixed pressure.

Canonical (NVT) ensemble: Maintains constant particle number (N), volume (V), and temperature (T) through thermal contact with a heat bath. While NVT allows energy exchange, NpH allows volume changes while conserving enthalpy.

Isothermal-isobaric (NpT) ensemble: Keeps constant particle number (N), pressure (p), and temperature (T) through contact with both a heat bath and volume reservoir. The key distinction from NpH is that NpT allows energy exchange to maintain temperature, while NpH conserves enthalpy through thermal isolation [15].

The relationship between these ensembles becomes particularly important when designing multi-stage simulation protocols, where equilibration in one ensemble precedes production sampling in another.

Configuration Methodology for NpH Simulations

Core Parameter Specification

Implementing an NpH ensemble simulation in VASP requires precise configuration of key parameters in the INCAR file. These parameters control the molecular dynamics algorithm, thermostat behavior, and barostat settings to achieve the correct thermodynamic conditions.

Table 1: Essential INCAR Parameters for NpH Ensemble Simulations

| Parameter | Required Value | Physical Significance | Technical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

MDALGO |

3 | Selects Langevin dynamics | Enables the appropriate equations of motion for sampling the NpH ensemble |

ISIF |

3 | Controls stress tensor handling | Computes stress tensor and allows changes to box volume and shape |

LANGEVIN_GAMMA |

0.0 for all species | Friction coefficient for atomic degrees of freedom | Disables thermostatting by removing friction and stochastic forces |

LANGEVIN_GAMMA_L |

0.0 | Friction coefficient for lattice degrees of freedom | Disables barostat damping, leaving box evolution determined by kinetic stress |

PMASS |

User-defined (e.g., 10) | Fictitious mass for lattice degrees of freedom | Controls the inertia and dynamics of cell shape/volume fluctuations |

PSTRESS |

Optional | External pressure target | Sets the desired external pressure in kB |

The MDALGO = 3 parameter activates the Langevin thermostat framework, which can sample various ensembles depending on additional parameter settings [26]. For NpH simulations, the critical distinction lies in completely disabling the stochastic and friction terms through zero values for both LANGEVIN_GAMMA and LANGEVIN_GAMMA_L. This ensures that the system evolves according to Newton's equations modified only by the barostat for pressure control, without thermal coupling that would alter the enthalpy [27].

The PMASS parameter deserves special attention as it controls the timescale of cell fluctuations. Heavier masses result in slower cell oscillations, while lighter masses may introduce artificial dynamics. Empirical testing is recommended to determine optimal values for specific systems, with typical values ranging from 5-20 atomic mass units for most materials.

Complete INCAR Template for NpH Simulations

Below is a comprehensive INCAR template configured for NpH ensemble simulations, incorporating both the essential dynamics parameters and recommended electronic structure settings:

This template represents a minimal configuration for NpH simulations. The electronic structure parameters (PREC, ENCUT, etc.) should be optimized for the specific system under investigation, while the core MD parameters remain consistent for NpH sampling [27].

Workflow Implementation and Experimental Protocol

Pre-equilibration Procedures

Proper equilibration is critical for obtaining physically meaningful results from NpH simulations. We recommend a multi-stage equilibration protocol:

Initial Geometry Optimization: Begin with a conjugate gradient relaxation (

IBRION = 2) of the initial structure to eliminate high-energy configurations and ensure a reasonable starting geometry.NVT Equilibration: Perform canonical ensemble equilibration using either Nosé-Hoover (

MDALGO = 2) or Langevin dynamics (MDALGO = 3withLANGEVIN_GAMMA > 0) to thermalize the system at the target temperature. Typical simulation lengths should encompass at least 5-10 ps for most systems.NpT Equilibration: Transition to isothermal-isobaric ensemble simulations (

MDALGO = 3with appropriateLANGEVIN_GAMMAandLANGEVIN_GAMMA_Lvalues) to equilibrate the density at the target pressure and temperature. This stage allows the system to reach the appropriate volume for the specified thermodynamic conditions.NpH Production: Finally, initiate the NpH production simulation using the parameter specifications outlined in Section 2.1, using the final configuration from the NpT equilibration as the starting point [27].

This sequential equilibration approach ensures that the system reaches proper thermodynamic equilibrium before beginning production sampling in the NpH ensemble, minimizing transient effects and improving the statistical quality of the results.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for NpH simulations, from initial setup to production and analysis:

NpH Simulation Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Materials

Essential Software Components

Successful NpH simulations require careful preparation of computational "reagents" - the input files and parameters that define the simulation. These components function analogously to laboratory reagents in experimental research:

Table 2: Essential Computational Materials for NpH Simulations

| Component | Format | Function | Preparation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| INCAR | Text file | Controls simulation parameters | Must contain specific NpH tags: MDALGO=3, ISIF=3, LANGEVIN_GAMMA=0, LANGEVIN_GAMMA_L=0 |

| POSCAR | Crystallographic | Defines initial atomic positions | Should originate from equilibrated NpT simulation; supercell size must accommodate long-wavelength vibrations |

| POTCAR | Pseudopotential | Describes electron-ion interactions | Must match atomic species in POSCAR; consistent functional (PAW-PBE recommended) |

| KPOINTS | Reciprocal space | Specifies k-point sampling | Should provide sufficient Brillouin zone sampling; Gamma-point may suffice for large supercells |

The POSCAR file deserves particular attention in NpH simulations. Since the ensemble allows volume fluctuations, the initial structure should represent a reasonable starting density for the target pressure. Using a structure from a pre-equilibrated NpT simulation at the same pressure is strongly recommended. For complex molecular systems, such as those relevant to drug development, special care must be taken to ensure the simulation cell is large enough to minimize periodic image interactions [28].

Advanced Configuration: Machine Learning Force Fields

For systems requiring extended sampling beyond the capabilities of direct ab initio MD, machine learning force fields (MLFF) can be integrated with NpH simulations to dramatically enhance computational efficiency. The MLFF implementation in VASP enables on-the-fly learning of interatomic potentials during an initial ab initio MD simulation, which can then be deployed for extended sampling [29].

Key MLFF parameters for NpH simulations include:

ML_LMLFF = .TRUE.activates the machine learning force field capabilityML_ISTART = 0initiates training of a new force fieldML_CTIFORsets the threshold for adding new configurations to the training set based on Bayesian error estimates

When combining MLFF with NpH simulations, the force field training occurs during the initial equilibration stages, with the production NpH simulation potentially using the trained force field for enhanced sampling. This approach can extend accessible timescales by 2-3 orders of magnitude while maintaining ab initio accuracy [29] [30].

Validation and Analysis Protocols

Ensemble Validation Metrics

Verifying proper sampling of the NpH ensemble requires monitoring specific thermodynamic quantities throughout the simulation:

Enthalpy Conservation: The total enthalpy ( H = U + pV ) should remain constant throughout the simulation, with fluctuations attributable only to numerical integration error. Significant drift indicates improper isolation or parameter issues.

Pressure Fluctuations: The instantaneous pressure should fluctuate around the target value (

PSTRESS), with the average matching the external pressure setting.Drift Monitoring: The cumulative energy drift should be monitored to detect numerical instabilities or inadequate integration parameters.

The following diagram illustrates the key validation relationships and monitoring targets:

NpH Validation Metrics

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Even with proper configuration, NpH simulations may encounter numerical issues that require intervention:

Energy Drift: Significant enthalpy drift may indicate that

POTIMis too large. Reduce the timestep by 25-50% and test for improved conservation.Cell Oscillations: Excessive oscillation of cell parameters suggests that

PMASSis too small. Increasing this parameter by a factor of 2-5 typically dampens artificial dynamics.Pressure Deviation: Consistent deviation from the target pressure may require adjustment of the

PSTRESSvalue or verification of the stress tensor calculation through convergence testing ofENCUTand k-point sampling.

For systems with significant atomic mass disparities, the LANGEVIN_GAMMA parameters may need species-specific tuning, though they remain zero for strict NpH sampling. In such cases, minimal values that stabilize the dynamics without significant thermal coupling may be employed.

Applications in Research and Development

The NpH ensemble enables investigation of diverse phenomena across multiple disciplines. In pharmaceutical research, it facilitates study of drug molecule behavior under pressure conditions mimicking various administration routes or manufacturing processes. For materials science, NpH simulations provide insights into phase transitions, mechanical properties, and material responses to extreme pressure conditions.

Recent advances in specialized hardware, such as Molecular Dynamics Processing Units (MDPUs), promise to accelerate NpH simulations by up to 10³ times compared to conventional CPU/GPU implementations while maintaining ab initio accuracy [30]. These developments will make previously intractable problems accessible to molecular simulation, particularly in drug development where complex molecular systems require extensive sampling.

When properly configured and validated, NpH simulations in VASP provide a powerful tool for investigating pressure-induced phenomena across scientific disciplines, from fundamental materials physics to applied pharmaceutical research. The rigorous approach outlined in this guide ensures researchers can implement this technique with confidence in its thermodynamic foundation and numerical stability.

The NpH ensemble, or constant-pressure constant-enthalpy ensemble, provides a critical framework for studying materials and molecular systems under experimentally relevant conditions where pressure fluctuates around an equilibrium value while enthalpy is conserved. This technical guide details the strategic selection of three core parameters—PMASS, LANGEVIN_GAMMA, and ISIF—within the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) to correctly configure and execute reliable NpH simulations. Aimed at researchers and scientists in computational drug development and materials science, this whitepaper synthesizes current best practices, quantitative parameter recommendations, and experimental protocols to ensure accurate sampling of the isoenthalpic-isobaric ensemble for predictive molecular design.

In molecular dynamics (MD), the statistical ensemble defines the thermodynamic conditions under which a simulation proceeds. The NpH ensemble is characterized by a constant number of particles (N), a pressure that fluctuates around a fixed equilibrium value (p), and a conserved enthalpy (H) [8]. This makes it exceptionally valuable for simulating processes where the system exchanges energy with its environment as work, rather than heat, such as in the study of structural phase transitions, material response to mechanical stress, or biomolecular conformations in different pressure environments.

Within VASP, the NpH ensemble is activated by setting MDALGO = 3 (Langevin dynamics) and disabling thermostatting by setting both LANGEVIN_GAMMA = 0 and LANGEVIN_GAMMA_L = 0 [8]. This configuration ensures that the velocity of atoms is governed solely by the Hellmann-Feynman forces, and the box dynamics (barostatting) is driven exclusively by the kinetic stress tensor, without stochastic or frictional interference. The successful sampling of this ensemble hinges on the precise configuration of three interdependent parameters: PMASS (barostat mass), LANGEVIN_GAMMA (atomic friction), and ISIF (degree of cell freedom). Their careful selection is not merely a technical detail but a fundamental prerequisite for generating physically meaningful results that can underpin a broader thesis on constant-enthalpy research.

Theoretical Foundation and Parameter Definitions

The Langevin Equation in Extended System Dynamics

The implementation of the barostat in VASP's NpH ensemble is based on the Parrinello-Rahman method, extended for stochastic dynamics [8] [26]. The core equation of motion for the atoms incorporates the barostat coupling and, in its general form for the NpT ensemble, includes a Langevin thermostat. For the NpH ensemble, however, the thermostat terms are disabled. The simplified equation governing the lattice vectors can be conceptualized as:

ML * Ä = (Pinternal - Pexternal) * V - γL * M_L * Ȧ

Here, M_L is the inertia of the lattice degrees of freedom, controlled by PMASS, Ä and Ȧ are the second and first derivatives of the lattice vectors, P_internal and P_external are the internal and external pressures, V is the cell volume, and γ_L is the friction coefficient for the lattice, set to zero via LANGEVIN_GAMMA_L = 0 in NpH [8]. This equation describes a driven, damped oscillation of the cell shape and size around the equilibrium defined by the external pressure.

Core Parameter Definitions

- PMASS: Also known as the "fictitious mass" of the barostat, PMASS (in amu) determines the inertia of the lattice degrees of freedom. A higher PMASS leads to slower, more sluggish cell oscillations, while a lower value makes the cell respond more quickly to pressure differences.

- LANGEVIN_GAMMA: This parameter (in ps⁻¹) specifies the friction coefficient for the atomic degrees of freedom when using a Langevin thermostat [26] [31]. In the NpH ensemble, this is set to zero for all species, effectively turning off temperature control and allowing the system to evolve under adiabatic conditions [8].

- ISIF: This tag controls which degrees of freedom of the simulation cell are allowed to change and whether the stress tensor is calculated [8] [26]. For a fully flexible cell in the NpH ensemble,

ISIF=3must be used, which computes the stress tensor and allows changes to the cell's volume, shape, and ions' positions [8].

Quantitative Parameter Tables and Selection Guidelines

The selection of parameters is a balance between numerical stability, sampling efficiency, and physical accuracy. The following tables consolidate recommended values and their implications.

Table 1: Core INCAR Tags and Values for NpH Ensemble Simulations in VASP

| INCAR Tag | Required Value for NpH | Function | Critical Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

MDALGO |

3 | Selects Langevin dynamics algorithm [8]. | Must be combined with ISIF=3. |

ISIF |

3 | Calculates stress tensor and allows changes to cell volume and shape [8]. | Enables barostat action. |

LANGEVIN_GAMMA |

0.0 (for all species) | Disables atomic thermostatting [8]. | Essential for isoenthalpic conditions. |

LANGEVIN_GAMMA_L |

0.0 | Disables lattice thermostatting [8]. | Critical for NpH ensemble fidelity. |

PMASS |

System-dependent (e.g., 100-1000 amu) | Sets the fictitious mass of the barostat [8]. | Key determinant of pressure oscillation frequency. |

Table 2: Guidelines for Selecting PMASS Based on System Properties

| System Type | Recommended PMASS (amu) | Rationale | Expected Pressure Relaxation Time (fs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light, Stiff Materials (e.g., Carbides, Li-ion battery materials) | 100 - 500 | Faster intrinsic cell vibrations require a lower barostat mass for adequate coupling [32]. | ~500 - 1500 |

| Heavy, Soft Materials (e.g., Lead, Gold) | 500 - 1000 | Slower cell dynamics permit a higher mass for smoother, more controlled oscillations [32]. | ~1500 - 3000 |

| Molecular Crystals & Biomolecules (e.g., Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients) | 200 - 600 | Balance needed to capture flexible molecular motions and cell deformation [17]. | ~800 - 2000 |