The Computational Microscope: How Molecular Dynamics Simulations Reveal Hidden Biological Processes

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations function as a powerful computational microscope, providing atomistic resolution into the dynamic behavior of proteins and other biomolecules that is often inaccessible to experimental techniques.

The Computational Microscope: How Molecular Dynamics Simulations Reveal Hidden Biological Processes

Abstract

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations function as a powerful computational microscope, providing atomistic resolution into the dynamic behavior of proteins and other biomolecules that is often inaccessible to experimental techniques. This article explores the foundational principles of MD, its diverse methodological applications in areas like drug discovery and protein folding, the critical limitations and troubleshooting strategies for reliable simulations, and the essential process of validating computational results against experimental data. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes how MD serves as an indispensable tool for guiding experimental efforts, rational drug design, and making genuine discoveries in modern biomedical research.

What is a Computational Microscope? The Core Principles of Molecular Dynamics

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful "computational microscope," allowing researchers to visualize the dynamic motion of atoms and molecules with unprecedented detail [1]. At the heart of this methodology lies the molecular dynamics trajectory—a time-ordered sequence of snapshots representing the atomic coordinates of a simulated system [2]. These trajectories transform static structural data into dynamic movies, revealing the physical mechanisms that govern biological function and facilitating rational drug design [3] [1].

The Molecular Dynamics Trajectory: A Core Concept

A molecular dynamics trajectory is the principal output of an MD simulation, capturing the evolution of a molecular system over time. In essence, trajectories are sequential snapshots of the simulated molecular system, representing atomic coordinates at specific time intervals [2].

Technical Composition and Significance

From a technical perspective, trajectory files contain the three-dimensional positional data for all atoms in a simulation system across numerous time steps. The information content of these trajectories is vast, encoding:

- Structural Evolution: The trajectory records the pathway of conformational changes, from subtle side-chain rotations to large-scale domain movements [2] [4].

- Energetic Landscape: When combined with force field parameters, trajectories enable the calculation of potential and kinetic energy fluctuations throughout the simulation [2].

- Temporal Dynamics: The sequential nature of frames allows researchers to analyze the kinetics and rates of molecular processes [3].

The profound value of MD trajectories lies in their ability to extend static structural biology into the dynamic realm. While experimental methods like X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM provide crucial structural snapshots, MD trajectories animate these structures, revealing how they move, flex, and interact over time [3]. This dynamic information is essential for understanding the fundamental mechanisms of biological processes such as protein folding, ligand binding, and allosteric regulation [1].

MD as a Computational Microscope

The metaphor of MD simulations as a "computational microscope" powerfully captures their ability to reveal biological processes inaccessible to direct experimental observation [3] [1]. This virtual instrument provides unprecedented spatial and temporal resolution into molecular phenomena.

Bridging Spatial and Temporal Scales

The computational microscope achieves its power by bridging critical gaps in our observational capabilities:

| Scale Type | Experimental Challenge | MD Capability | Biological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial | Membrane proteins difficult to crystallize [2]; Limited by wavelength of light | Atomic-level resolution of large complexes (>100 million atoms) [5] | Visualization of viral capsids, ribosomes, and entire organelles [5] |

| Temporal | Fast processes beyond experimental time resolution; Slow processes impractical to observe | Femtosecond resolution; Microsecond to millisecond reach with advanced methods [1] | Observation of protein folding, ligand binding, and conformational changes [3] |

Validation Through Experimental Correlation

The predictive power of the computational microscope has been validated through several landmark studies:

- Titin Mechanics: SMD simulations of the muscle protein titin revealed forced unfolding pathways that complemented atomic force microscopy (AFM) experiments, establishing the molecular basis of muscle elasticity [3].

- CRISPR-Cas9 Dynamics: Gaussian accelerated MD (GaMD) simulations predicted the structure of the active CRISPR-Cas9 complex before experimental characterization, with remarkable correspondence between simulation and subsequent experimental results [1].

- Viral Protein Modeling: MD simulations have successfully refined predicted structures of viral proteins like HCV core protein, improving model quality to near-experimental accuracy [6].

These examples demonstrate how the computational microscope can not only interpret but also predict molecular behavior, establishing MD as a genuine discovery tool in structural biology [3].

Generation and Analysis of MD Trajectories

The process of generating and analyzing MD trajectories follows a structured workflow that transforms initial molecular coordinates into scientifically meaningful dynamic information.

Trajectory Generation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for generating MD trajectories:

This workflow consists of several critical phases:

- System Preparation: Initial 3D structures, typically from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), are prepared by adding solvent molecules, ions, and other components to create a biologically relevant environment [2].

- Minimization: The system's energy is minimized to remove steric clashes and unfavorable contacts [7].

- Heating: The temperature is gradually increased from near absolute zero to the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) while allowing the system to adjust [7].

- Equilibration: The system is allowed to stabilize at the target temperature and pressure until properties like energy and density reach steady states [7].

- Production Simulation: The actual data-collection phase where trajectories are saved at regular intervals (typically 1-100 ps) for subsequent analysis [7].

Trajectory Analysis Techniques

Once trajectories are generated, various analytical methods extract meaningful biological insights:

| Analysis Type | Key Metrics | Biological Information | Example Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometric Analysis | Root mean square deviation (RMSD), radius of gyration (Rg), dihedral angles [6] | Structural stability, compactness, conformational changes [6] | GROMACS, MDAnalysis |

| Dynamic Analysis | Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), B-factors [6] | Regional flexibility, residue mobility | VMD, CHARMM |

| Energetic Analysis | Potential energy, hydrogen bonding, interaction energies | Stability, key interactions, binding affinities | NAMD, AMBER |

| Pathway Analysis | Principal component analysis (PCA), free energy landscapes | Conformational pathways, metastable states | PyEMMA, MDAnalysis |

Quantitative analysis of trajectories enables researchers to move beyond qualitative observation to statistically rigorous characterization of molecular behavior. For example, calculating the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of backbone atoms provides a measure of structural stability, while root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) of Cα atoms reveals regions of flexibility and mobility within the protein structure [6].

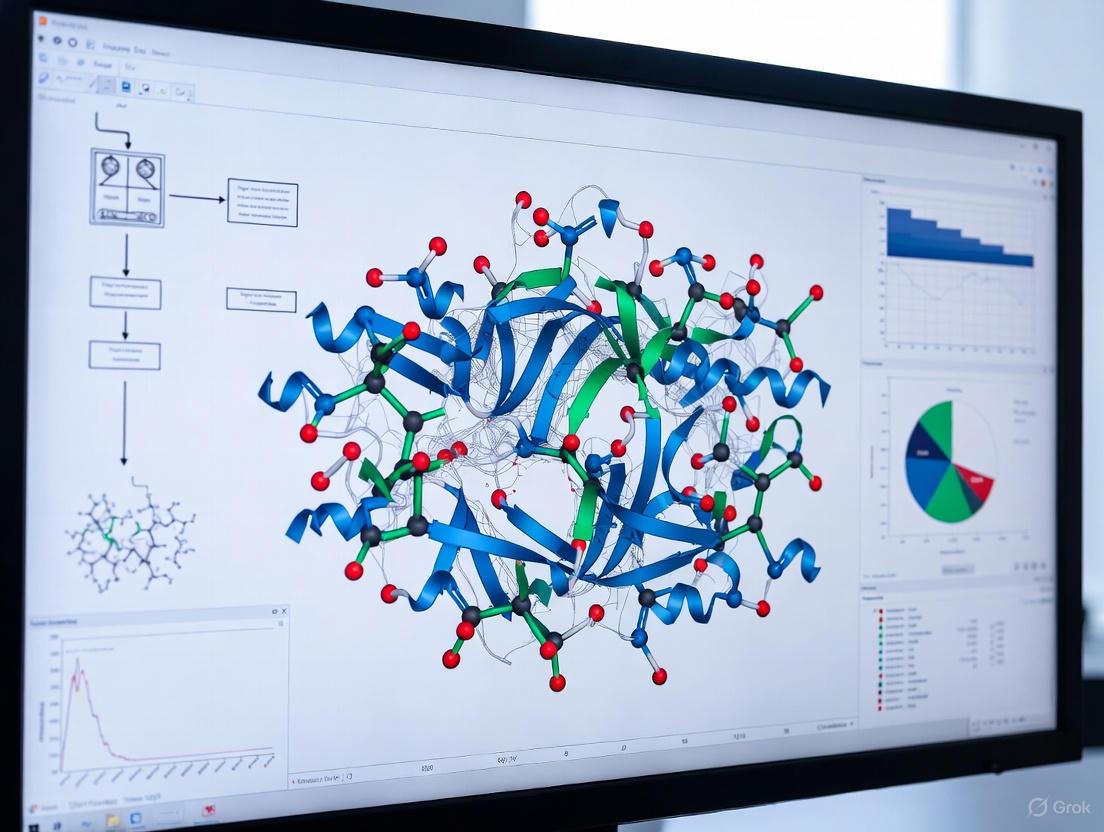

Visualization Methodologies

Effective visualization is crucial for interpreting the complex spatial and temporal data contained in MD trajectories [5]. The field has evolved from simple frame-by-frame animation to sophisticated multi-scale representations.

Visualization Techniques and Tools

The computational microscopy paradigm relies heavily on visualization to communicate dynamic molecular processes:

Advanced visualization tools have been developed specifically for MD trajectory analysis:

- VMD (Visual Molecular Dynamics): A specialized tool for visualization and analysis of biological systems like proteins, nucleic acids, and lipid membranes [2]. It supports numerous file formats, handles large datasets, and offers extensive visualization and rendering capabilities [2].

- Web-Based Tools: Increasingly popular platforms like Mol* offer accessible trajectory visualization directly in web browsers, facilitating collaboration and data sharing [5].

- Virtual Reality Environments: Immersive VR systems allow researchers to "step inside" molecular simulations, providing intuitive understanding of complex 3D dynamics [5].

Design Principles for Effective Communication

When creating visualizations of MD trajectories for educational or communicative purposes, several design principles help avoid common misconceptions [8]:

- Avoid Molecular Agency: Representations should not depict molecules as having purpose or intention; instead, they should illustrate stochastic motion driven by physical forces [8].

- Balance Abstraction and Realism: The appropriate level of detail depends on the audience—experts can interpret higher abstraction, while novices may require more contextual cues [8].

- Represent Accurate Temporal Scales: Animations should respect the actual relative timescales of molecular processes, from rapid bond vibrations (femtoseconds) to slow conformational changes (microseconds to milliseconds) [8].

Advanced Applications and Current Frontiers

MD trajectory analysis continues to evolve, pushing the boundaries of what can be studied with the computational microscope.

Accelerated Dynamics Methods

A significant challenge in conventional MD is the timescale gap between simulation and biologically relevant processes. Advanced sampling methods address this limitation:

- Gaussian Accelerated MD (GaMD): This technique smooths the potential energy surface, reducing energy barriers and accelerating simulations by thousands to millions of times [1]. GaMD has enabled studies of previously inaccessible processes like CRISPR-Cas9 complex formation and drug dissociation from protein targets [1].

- Steered MD (SMD): Applying external forces to simulate mechanical manipulation of molecules, SMD has been particularly valuable for studying protein folding and mechanical strength in proteins like titin and fibrinogen [3].

Emerging Frontiers

Current research is expanding the capabilities of the computational microscope in several directions:

- Extreme Scale Simulations: Recent achievements include simulations of complete viral envelopes (305 million atoms) and entire minimal cells, providing system-level understanding of biological processes [5].

- Machine Learning Integration: Deep learning approaches are being used to embed high-dimensional trajectory data into lower-dimensional latent spaces, revealing essential features and patterns that might be missed by conventional analysis [5].

- Interactive Visualization: Web-based platforms and virtual reality environments are making trajectory data more accessible and interpretable, allowing researchers to explore complex dynamics intuitively [5].

Researchers working with MD trajectories utilize a comprehensive suite of software tools and resources:

| Tool Category | Key Resources | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Engines | GROMACS [2], NAMD [2] [3], AMBER, CHARMM [2] | Performing MD simulations and generating trajectories |

| Analysis Packages | VMD [2], MDAnalysis, pDynamo [7] | Trajectory visualization, measurement, and analysis |

| Specialized Methods | GaMD [1], SMD [3] | Enhanced sampling for accelerated dynamics |

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS | Mathematical descriptions of interatomic interactions |

This toolkit enables the full trajectory lifecycle—from system setup through simulation, analysis, and visualization—providing researchers with a complete workflow for computational microscopy.

Molecular dynamics trajectories transform atomic coordinates into dynamic movies of biological processes, providing the core data that powers the computational microscope. As MD methodologies continue to advance—through improved force fields, enhanced sampling algorithms, and more sophisticated visualization techniques—the resolution and scope of this virtual microscope will continue to expand. These advances promise deeper insights into the molecular mechanisms of health and disease, accelerating drug discovery and expanding our fundamental understanding of life at the atomic scale. The trajectory concept remains central to this endeavor, serving as both the computational record of molecular motion and the bridge between static structures and biological function.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a powerful computational microscope, allowing researchers to observe the motion of atoms and molecules over time. The core engine that drives this microscope is the force field, a computational model that describes the forces between atoms within molecules or between molecules [9]. Within the framework of Newtonian physics, these forces determine the acceleration of every particle in the system, enabling the prediction of their future positions and velocities. This combination provides an atomistic view of processes that are often impossible to see in a wet lab, from protein folding to drug binding, making it an indispensable tool in modern computational chemistry, biology, and materials science [10].

The Mathematical Foundation of Force Fields

The Basic Functional Form

In the context of chemistry and molecular modeling, a force field refers to the functional form and parameter sets used to calculate the potential energy of a system of atoms [9]. The total potential energy ((E_{total})) in a typical additive force field for molecular systems is a sum of bonded and non-bonded interactions, and can be expressed as:

[E{\text{total}} = E{\text{bonded}} + E_{\text{nonbonded}}]

Where the bonded interactions themselves are a sum of several components:

[E{\text{bonded}} = E{\text{bond}} + E{\text{angle}} + E{\text{dihedral}}]

And the non-bonded interactions comprise:

[E{\text{nonbonded}} = E{\text{electrostatic}} + E_{\text{van der Waals}}]

This decomposition provides a physically motivated model for the various interactions that govern molecular structure and dynamics [9].

Connecting Force to Motion: Newton's Second Law

The connection between the force field and molecular motion is established through Newton's second law of motion. The force field is used to calculate the potential energy, and the force ((\vec{F}_i)) acting on each particle (i) is derived as the negative gradient of this potential energy with respect to the particle's coordinates [9]:

[\vec{F}i = -\nablai E_{\text{total}}]

This force is then related to the particle's acceleration ((\vec{a}_i)) through Newton's famous equation:

[\vec{F}i = mi \vec{a}_i]

Where (m_i) is the mass of the particle. By numerically integrating these equations of motion, MD simulations predict the trajectory of the system through time [11].

Components of a Classical Force Field

Bonded Interactions

Bonded interactions describe the energy associated with the covalent bond structure of molecules.

Bond Stretching: The energy required to stretch or compress a bond between two atoms from its equilibrium length. This is most often modeled using a harmonic potential [9]: [E{\text{bond}} = \frac{k{ij}}{2}(l{ij} - l{0,ij})^2] where (k{ij}) is the force constant, (l{ij}) is the current bond length, and (l_{0,ij}) is the equilibrium bond length.

Angle Bending: The energy associated with the deviation of the angle between three bonded atoms from its equilibrium value. This is also typically modeled with a harmonic potential.

Dihedral/Torsional Interactions: The energy related to the rotation around a central bond connecting four atoms. The functional form for dihedral energy is more variable between different force fields [9].

Table 1: Bonded Interactions in a Typical Force Field

| Interaction Type | Mathematical Form | Description | Atoms Involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | (E = \frac{k}{2}(l - l_0)^2) | Harmonic potential for bond length variation | 2 |

| Angle Bending | (E = \frac{k{\theta}}{2}(\theta - \theta0)^2) | Harmonic potential for bond angle variation | 3 |

| Dihedral/Torsion | (E = k_{\phi}(1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta))) | Periodic potential for bond rotation | 4 |

Non-Bonded Interactions

Non-bonded interactions describe the forces between atoms that are not directly connected by covalent bonds, and are computationally the most intensive part of force field calculations.

Van der Waals Interactions: These short-range forces account for dispersion and repulsion. They are often modeled using the Lennard-Jones potential [9]: [E_{\text{van der Waals}} = 4\epsilon \left[ \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{6} \right]] where (\epsilon) is the depth of the potential well, (\sigma) is the distance at which the potential is zero, and (r) is the distance between atoms.

Electrostatic Interactions: These long-range forces between charged particles are described by Coulomb's law [9]: [E{\text{Coulomb}} = \frac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon0} \frac{qi qj}{r{ij}}] where (qi) and (qj) are the partial atomic charges, (r{ij}) is the distance between them, and (\frac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon_0}) is the Coulomb constant.

Table 2: Non-Bonded Interactions in a Typical Force Field

| Interaction Type | Mathematical Form | Description | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Van der Waals | (E = 4\epsilon \left[ \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{6} \right]) | Lennard-Jones potential for dispersion/repulsion | Short |

| Electrostatic | (E = \frac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon0} \frac{qi qj}{r{ij}}) | Coulomb's law for charge-charge interactions | Long |

Workflow of a Molecular Dynamics Simulation

The following diagram illustrates the core cycle of a Molecular Dynamics simulation, showing how the force field and Newton's laws are applied iteratively to generate a trajectory.

Parameterization and the Scientist's Toolkit

Force Field Parameterization

The parameters for a chosen energy function are derived from classical laboratory experiment data, calculations in quantum mechanics, or a combination of both [9]. The assignment of atomic charges often follows quantum mechanical protocols with some heuristics, which can lead to significant deviation in representing specific properties. Heuristic force field parametrization procedures have been very successful for many years, but recently criticized since they are usually not fully automated and therefore subject to some subjectivity of the developers [9].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Components

Table 3: Essential Force Field Components and Research Reagents

| Component/Reagent | Function in Simulation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field Software | Implements the mathematical models to calculate forces and energies. | Examples: GROMACS, AMBER, CHARMM, OpenMM [11]. |

| Parameter Sets | Provide specific numerical values for bond lengths, angles, charges, etc. | Transferability vs. specificity; AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS are common [9]. |

| Atom Typing Rules | Define atom categories based on element and chemical environment. | Determines parameter assignment; crucial for accuracy [9]. |

| Water Models | Simulate solvent effects (e.g., TIP3P, SPC, TIP4P). | Choice significantly affects biomolecular simulation results. |

| Quantum Chemistry Codes | Generate reference data for force field parameterization (e.g., Gaussian). | Provide target energies and forces for fitting [9]. |

Advanced Force Field Types and Future Directions

Beyond Classical Force Fields

While the functional forms described above are common in biomolecular simulation, different modeling challenges require specialized force fields:

- Reactive Force Fields: Methods like ReaxFF are designed to simulate bond breaking and formation, which is not possible with standard harmonic bond potentials [11].

- Polarizable Force Fields: These go beyond fixed atomic charges to account for the fact that the electronic distribution of an atom can be distorted by its environment, offering improved accuracy at increased computational cost [9].

- Machine-Learned Force Fields (ML-FFs): A cutting-edge approach that uses machine learning to construct force fields with the accuracy of high-level ab initio quantum mechanical calculations, but at a fraction of the computational cost. These models can learn complex potential energy surfaces directly from reference quantum data, potentially enabling "spectroscopic accuracy" in molecular simulations [10].

The Future: Machine-Learned Force Fields

A 2018 study in Nature Communications demonstrated a symmetrized gradient-domain machine learning (sGDML) approach that faithfully reproduces global force fields at a quantum-chemical CCSD(T) level of accuracy [10]. This approach incorporates spatial and temporal physical symmetries into the model in a data-driven way, allowing for converged molecular dynamics simulations with fully quantized electrons and nuclei. Such ML-FFs provide the key missing ingredient for achieving spectroscopic accuracy in molecular simulations, pushing the resolution of the "computational microscope" to new limits [10].

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have undergone a revolutionary transformation, evolving from limited picosecond-scale observations to comprehensive millisecond-scale studies, effectively serving as a computational microscope for researchers. This evolution, largely driven by breakthroughs in advanced computing hardware and algorithms, has enabled the detailed study of complex biomolecular processes that are central to drug discovery and development. By applying Newton's laws of motion to atomic-level systems, MD simulations provide an unparalleled view into the dynamic behavior of proteins and other biomolecules, capturing everything from conformational changes and ligand binding to protein folding and functional mechanisms. The integration of specialized hardware, sophisticated software suites, and enhanced sampling techniques has narrowed the gap between computational models and actual cellular conditions, making MD an indispensable tool in modern medicinal chemistry and biomedical research.

The concept of a "computational microscope" perfectly encapsulates the transformative power of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in biomedical research. Just as a microscope reveals a world invisible to the naked eye, MD simulations provide a window into the intricate, dynamic world of biomolecular processes, predicting how every atom in a protein or other molecular system will move over time based on the physics governing interatomic interactions [12]. These simulations capture structural flexibility and molecular interactions with exceptional detail, offering insights that are often difficult or impossible to obtain through experimental means alone [13] [12].

The foundational principle of MD is straightforward: given the positions of all atoms in a biomolecular system, one can calculate the force exerted on each atom by all other atoms and use Newton's laws of motion to predict atomic spatial positions over time [12]. The resulting trajectory is essentially a three-dimensional movie describing the atomic-level configuration of the system throughout the simulated period, typically at femtosecond (10^-15 seconds) temporal resolution [12]. This fine resolution allows researchers to observe molecular events with precision that complements various experimental structural biology techniques, including X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) [12].

Historical Trajectory: Expanding Timescales in MD Simulations

The evolution of MD simulation capabilities represents one of the most significant advancements in computational biochemistry, with simulation timescales expanding by approximately six orders of magnitude over several decades.

Table: Historical Progression of MD Simulation Timescales

| Time Period | Typical Maximum Timescale | Key Technological Enablers | Representative Simulable Processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970s-1980s | Picoseconds (10^-12 s) to Nanoseconds (10^-9 s) | Early supercomputers, Basic force fields | Local side-chain motions, Bond vibrations |

| 1990s-2000s | Nanoseconds (10^-9 s) to Microseconds (10^-6 s) | Improved algorithms, Distributed computing | Small protein folding, Loop motions |

| 2010s-Present | Microseconds (10^-6 s) to Milliseconds (10^-3 s) | GPU computing, Specialized hardware (Anton) | Large protein folding, Ligand binding, Conformational changes in membrane proteins |

The first MD simulations of simple gasses were performed in the late 1950s, with the first protein MD simulation following in the late 1970s [12]. The groundwork enabling these early simulations was among the achievements recognized by the 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry [12]. For years, most high-impact MD work required supercomputer access, but recent introductions of computer hardware, particularly graphics processing units (GPUs), have made powerful simulations accessible at modest cost [12]. This hardware revolution, combined with substantial improvements in the physical models underlying MD simulations, has enabled the field to progress from picosecond-scale observations to millisecond-scale studies, capturing biologically relevant timescales for numerous critical processes [12].

Successful MD simulations require careful selection of software, hardware, and theoretical frameworks. The table below summarizes key "research reagent solutions" essential for modern MD investigations.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Software Packages | GROMACS, AMBER, DESMOND, NAMD, DL_POLY | Provides simulation engines with implemented algorithms and force fields | Biomolecular simulation, Drug binding studies, Material science [13] [14] [15] |

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER | Mathematical functions describing potential energy and interatomic forces | Determining interaction parameters for proteins, nucleic acids, lipids [13] [16] |

| Specialized Hardware | NVIDIA GPUs (RTX 4090, RTX 6000 Ada), AMD Threadripper PRO CPUs | Accelerates computational intensive calculations through parallel processing | Speeding up simulations of large systems (>100,000 atoms), Multiple parallel runs [15] |

| Sampling Methods | Replica Exchange, Metadynamics | Enhances sampling of conformational space and rare events | Protein folding, Drug binding/unbinding studies [16] |

| Analysis Tools | Built-in package utilities, VMD, MDAnalysis | Processes trajectory data to extract structural and dynamic properties | Calculating binding free energies, RMSD, Principal components [17] |

Force Fields: The Physical Heart of MD

Force fields represent the mathematical foundation of MD simulations, providing the potential energy functions that describe how atoms interact with each other [16]. These approximations of quantum mechanical interactions include terms for electrostatic (Coulombic) interactions, spring-like terms for covalent bond lengths, and other interatomic interactions [12]. The selection of an appropriate force field is essential, as it significantly influences simulation reliability [13]. Widely adopted force fields like CHARMM and AMBER have been rigorously tested and show consistent performance across diverse biological applications [13] [16].

Computational Hardware: From CPUs to GPUs

The computational demands of MD simulations require specialized hardware configurations. While traditional central processing units (CPUs) remain important, graphics processing units (GPUs) have revolutionized the field by dramatically accelerating simulation speeds [12] [15]. For molecular dynamics workloads, the key factor when selecting a CPU is to prioritize processor clock speeds over core count, with well-suited choices including mid-tier workstation CPUs with a balance of higher base and boost clock speeds, like the AMD Threadripper PRO 5995WX [15].

For GPUs, NVIDIA's offerings—particularly the RTX 4090, RTX 6000 Ada, and RTX 5000 Ada—have proven exceptional for MD simulations [15]. The RTX 6000 Ada, with 48 GB of GDDR6 VRAM and 18,176 CUDA cores, is ideal for memory-intensive simulations, while the RTX 4090 provides an excellent balance of price and performance for smaller simulations [15]. Multi-GPU setups can further dramatically enhance computational efficiency and decrease simulation times for software packages like AMBER, GROMACS, and NAMD [15].

Key Methodologies: Experimental Protocols in MD

Ensemble Selection: NVE, NVT, and NPT

The choice of thermodynamic ensemble is fundamental to MD simulation design, defining which thermodynamic quantities are held constant during the simulation [16]. The three primary ensembles include:

- NVE Ensemble (Microcanonical Ensemble): Maintains constant Number of particles, Volume, and Energy. This ensemble is typically used for isolated systems where energy conservation is crucial, such as in gas-phase simulations or molecular reactions [16].

- NVT Ensemble (Canonical Ensemble): Maintains constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature. This ensemble is appropriate for simulating systems at fixed temperature, such as biological systems at physiological conditions. Temperature is typically regulated using methods like the Nose-Hoover thermostat [16].

- NPT Ensemble (Isothermal-Isobaric Ensemble): Maintains constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature. This is ideal for studying systems under constant pressure and temperature, such as liquid simulations or large biomolecular systems, with pressure control often managed by the Berendsen barostat [16].

Simulation Workflow: From System Setup to Analysis

A complete MD simulation follows a structured workflow that can be conceptually divided into three main phases, as illustrated in the following diagram:

MD Simulation Workflow

The workflow begins with system setup, which involves obtaining initial coordinates from experimental structure determination methods or homology modeling, placing the molecular system in a simulation box with appropriate dimensions, adding solvent molecules (typically water), and introducing ions to neutralize the system's charge [17]. This is followed by energy minimization, which removes steric clashes and unfavorable contacts by finding the nearest local energy minimum through methods like steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithms [16].

The equilibration phase brings the system to the desired temperature and pressure through simulated annealing and pressure coupling algorithms [16]. During the crucial production run, the actual data collection occurs as the system evolves according to Newton's laws of motion, typically using integration algorithms like Verlet with time steps of 1-2 femtoseconds [16]. Finally, trajectory analysis extracts biologically relevant information from the raw coordinate data, calculating properties such as root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), radius of gyration, hydrogen bonding patterns, and principal components of motion [17].

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

To address the challenge of simulating rare events that occur beyond typical MD timescales, researchers employ enhanced sampling methods:

- Metadynamics: This technique accelerates the exploration of free energy surfaces by adding history-dependent bias potentials along selected collective variables, effectively filling energy wells and pushing the system to explore new configurations [16].

- Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD): Also known as parallel tempering, this method runs multiple simulations of the same system at different temperatures simultaneously, periodically attempting exchanges between replicas according to a Metropolis criterion, thus enhancing conformational sampling [16].

MD as a Computational Microscope: Applications in Drug Development

Molecular dynamics simulations serve as a powerful computational microscope across multiple stages of drug discovery and development, particularly for neurological and neurodegenerative disorders.

Studying Protein-Ligand Interactions

MD simulations provide critical insights into drug binding mechanisms, capturing the dynamic process of ligand recognition and binding to therapeutic targets [13] [12]. This is particularly valuable for studying proteins critical to neuronal signaling and those representing targets of most neuroscience medications, including ion channels, neurotransmitter transporters, and G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) [12]. Simulations reveal binding pathways, residence times, and conformational changes induced by ligand binding—information crucial for rational drug design [13].

Investigating Protein Misfolding and Aggregation

MD simulations have proven invaluable for studying pathological protein aggregation associated with neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases [12] [18]. Researchers use MD to reveal mechanisms of protein misfolding and oligomer formation, providing molecular-level insights into disease progression and identifying potential therapeutic intervention points [12] [18]. In Alzheimer's disease research specifically, computational methods including MD have contributed to understanding pathological mechanisms at the molecular level, target identification, and lead compound discovery [18].

Enhancing Structure-Based Drug Design

The atomic-level detail provided by MD simulations complements experimental structural biology by modeling the structural flexibility and dynamics of drug targets [13] [12]. This is particularly important for membrane proteins, which have historically been difficult to study experimentally but represent prominent drug targets [12]. Recent breakthroughs in crystallographic structure determination and cryo-EM have delivered numerous such structures, providing starting points for MD simulations that investigate functional mechanisms and assist in structure-based drug design [12].

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite remarkable progress, MD simulations face several significant challenges that guide future development directions. The table below summarizes these challenges and corresponding emerging solutions.

Table: Challenges and Future Directions in MD Simulations

| Current Challenge | Impact on Research | Emerging Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High Computational Cost | Limits system size and simulation timescale; restricts sampling | GPU acceleration, Machine learning potentials, Cloud computing [15] [16] |

| Force Field Accuracy | Affects reliability of simulation results, especially for novel molecules | Integration of quantum mechanics (QM/MM), Machine learning-derived force fields [13] [16] |

| Limited Sampling of Rare Events | Incomplete understanding of slow biological processes (e.g., protein folding) | Enhanced sampling methods, Markov state models [12] [16] |

| Bridging Scales | Difficulty connecting atomic-level events to cellular phenomena | Multiscale modeling, Coarse-graining methods [13] |

Machine Learning Integration

The integration of machine learning and artificial intelligence with MD simulations represents one of the most promising future directions [13] [16]. Machine learning algorithms can speed up MD simulations by providing more accurate predictions of molecular interactions without relying solely on traditional force fields [16]. AI-driven approaches can also discover new force fields or optimize simulation parameters, significantly improving both speed and accuracy [16]. This integration is expected to dramatically accelerate progress in this evolving field [13].

Quantum Mechanics and Multi-Scale Modeling

Recent advancements in hybrid methods that combine quantum mechanics with classical MD (QM/MM methods) have shown promise in studying complex systems such as enzyme catalysis, where electronic structure effects play a critical role [16]. Additionally, researchers are increasingly using MD to study complex materials, including nanomaterials and soft matter systems, with applications expanding to biomaterials design for medical devices or drug delivery systems [16].

Molecular dynamics simulations have truly evolved from picosecond curiosities to millisecond-scale biological observatories, faithfully serving as computational microscopes that reveal the intricate dynamics of molecular life. This journey has been propelled by remarkable advances in computing hardware, particularly GPU technology, sophisticated software packages, and increasingly accurate physical models. As MD simulations continue to bridge the gap between computational models and actual cellular conditions, their role in drug discovery and development becomes increasingly indispensable. With the ongoing integration of machine learning, quantum mechanics, and enhanced sampling techniques, MD simulations are poised to remain at the forefront of computational biochemistry, providing unprecedented insights into molecular mechanisms and driving therapeutic innovation for years to come.

Molecular dynamics (MD) serves as a computational microscope, allowing researchers to observe the detailed motion and interactions of biological molecules at an atomic level. This guide details the core workflow, from an initial protein structure to a production MD simulation, providing the framework for understanding dynamic processes that are often inaccessible through experimental methods alone [19] [20].

The journey of an MD simulation involves three critical, sequential stages, each with distinct objectives and outputs that feed into the next. The entire process transforms a static protein structure into a dynamic trajectory that captures its motion over time.

Stage A: System Setup

The setup phase prepares the protein for simulation by embedding it in a realistic molecular environment and ensuring the system is physically stable.

Structure Preparation and Force Field Selection

The basic ingredient for MD is a protein structure file, typically in PDB format [19]. The initial structure requires preprocessing, which includes adding missing hydrogen atoms and may involve removing crystallographic water molecules or separately defining ligands not recognized by the MD software [19]. A critical early choice is the force field, which describes the physical system as collections of atoms held together by interatomic forces [19]. Using the Gromacs pdb2gmx command is a common approach:

This command generates the molecular topology (.top) and a software-specific coordinate file (.gro) [19].

Solvation and Neutralization

To mimic a physiological environment, the protein is placed in a box of explicit solvent molecules [19]. Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC) are applied to the simulation box to minimize edge effects on surface atoms [19]. The system is then solvated, and counterions are added to neutralize its overall net charge, which is essential for simulation stability [19]. The topology file is automatically updated to include the added solvent and ions [19].

Energy Minimization and Equilibration

Before data collection, the system must be relaxed. Energy minimization removes any steric clashes or unrealistic geometry introduced during setup. This is followed by equilibration, a short simulation where the system is stabilized at the desired temperature and pressure. This step ensures the system has reached a realistic, stable state before commencing the production run [19].

Stage B: Production Simulation

The production run is the core data-generation step. Here, the equations of motion are solved iteratively to simulate the actual dynamics of the system. The system's coordinates and velocities are saved at regular intervals to form a trajectory, which is the primary output for all subsequent analysis [19] [20]. Recent advancements leverage high-throughput simulations to generate thousands of trajectories for machine learning analysis, creating comprehensive datasets for properties like packing density and enthalpy of mixing [21].

Stage C: Trajectory Analysis

The simulated trajectory is analyzed to compute properties and extract biological insights. Key analyses include:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures structural stability by quantifying the deviation from a reference structure over time [22] [20].

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Identifies flexible regions within the protein structure [22].

- Radius of Gyration: Assesses the overall compactness of the protein [22].

- Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA): Measures the surface area of the protein accessible to a solvent molecule, important for understanding solvation and interactions [20].

These MD-derived properties are highly effective in predicting critical experimental parameters such as aqueous drug solubility when used as features in machine learning models [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit

The following table details the essential components required to perform an MD simulation.

| Component | Description | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure (PDB) [19] | 3D atomic coordinates from databases like RCSB PDB. | The initial input structure for the simulation. |

| Force Field [19] | A set of mathematical functions and parameters (e.g., GROMOS, CHARMM, AMBER). | Defines the potential energy and interatomic forces in the system. |

| MD Simulation Suite [19] [22] | Software like GROMACS or OpenMM for running simulations. | The core engine that performs the calculations and integrates the equations of motion. |

| Molecular Topology File [19] | A file (e.g., .top) describing the molecule(s), including bonds, angles, and force field parameters. |

Provides the structural and interaction rules for the system. |

| Simulation Box [19] | A defined boundary (e.g., cubic, dodecahedron) around the molecule. | Applies Periodic Boundary Conditions to avoid edge effects. |

| Explicit Solvent Model [19] | Water molecules (e.g., SPC, TIP3P) added to the box. | Mimics a physiological or specific solvent environment for the solute. |

| Counter Ions [19] | Ions (e.g., Na+, Cl-) added to the solvated system. | Neutralizes the net charge of the system for simulation stability. |

| Parameter File (.mdp) [19] | A file specifying simulation control parameters (temperature, pressure, timestep, etc.). | Defines the specific conditions and algorithms for the simulation run. |

Quantitative Simulation Parameters

The table below summarizes key quantitative parameters from MD studies, illustrating how simulation-derived data connects to experimental properties.

Table 1: Experimentally Validated MD Simulation Parameters

| Property Simulated | MD Software & Force Field | Simulation Time | Correlation with Experiment (R²) | Key Application / Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density of Pure Solvents [21] | OPLS4 Force Field | NPT Ensemble | 0.98 | Validates simulation protocol against experimental density measurements. |

| Heat of Vaporization (ΔHvap) [21] | OPLS4 Force Field | NPT Ensemble | 0.97 | Used to predict cohesion energy and its correlation with viscosity. |

| Enthalpy of Mixing (ΔHm) [21] | OPLS4 Force Field | NPT Ensemble | 0.84 | Provides insight into solubility and phase stability of mixtures. |

| Aqueous Solubility (logS) [20] | GROMACS 5.1.1 / GROMOS 54a7 | NPT Ensemble | 0.87 (ML Model R²) | MD properties (SASA, LJ, etc.) used by ML to predict drug solubility. |

MD as a Computational Microscope

The standard MD workflow empowers researchers to use the technique as a computational microscope. By providing atomic-level spatial resolution and femtosecond temporal resolution, MD simulations reveal the dynamic processes that underlie biological function and molecular interactions [20] [21]. The workflow's power is amplified when integrated with modern data science approaches. For instance, machine learning analysis of properties derived from MD trajectories (like SASA and Coulombic interactions) can predict critical experimental outcomes such as drug solubility with high accuracy, demonstrating how MD serves as a foundational tool for in-silico discovery and design [20]. Furthermore, agentic AI systems like MDCrow are now emerging, capable of autonomously executing complex MD workflows by leveraging large language models to reason and operate specialized tools, thereby making this "computational microscope" more accessible and efficient [22].

MD in Action: Key Applications in Drug Discovery and Protein Science

The study of protein dynamics is fundamental to understanding biological function, yet observing these nanoscale, millisecond processes experimentally remains a profound challenge. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful "computational microscope," allowing researchers to visualize biomolecular processes at atomic resolution and with femtosecond temporal precision. This whitepaper explores how MD simulations illuminate the functional dynamics of two biologically crucial but structurally distinct systems: the giant muscle protein titin and the genome-editing complex CRISPR-Cas9. Through these case studies, we demonstrate how computational approaches reveal mechanistic insights inaccessible to experimental methods alone, providing researchers and drug development professionals with powerful tools for interrogating molecular function.

The Computational Microscope: Methodological Foundations

Molecular dynamics simulations numerically solve Newton's equations of motion for all atoms in a molecular system, generating a trajectory that depicts the system's structural evolution over time. Modern implementations harness exascale computing architectures and advanced GPU acceleration to achieve microsecond-to-millisecond timescales for systems comprising hundreds of thousands of atoms [23]. Several specialized methodologies have been developed to overcome the inherent timescale limitations of conventional MD:

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

Gaussian accelerated MD (GaMD) applies a harmonic boost potential to reduce energy barriers, enabling comprehensive sampling of conformational states without predefined reaction coordinates [23]. This method has proven particularly valuable for capturing large-scale conformational transitions in CRISPR-Cas9.

Advanced Analysis and Visualization

Trajectory maps represent a novel visualization method that transforms multidimensional simulation data into intuitive two-dimensional heatmaps. These maps display protein backbone movements during simulations, with the x-axis representing simulation time, the y-axis showing residue numbers, and color intensity indicating the magnitude of movement from starting positions [24]. This approach enables direct comparison of multiple simulations and pinpoints the timing and location of conformational events.

Multiscale and Hybrid Approaches

Quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) partitions the system, treating the reactive center with quantum mechanical methods while handling the surrounding environment with classical MD. This approach is essential for studying bond formation and cleavage events, such as the DNA cleavage mechanism catalyzed by CRISPR-Cas9 [23] [25].

Table 1: Key Computational Methods for Protein Dynamics Visualization

| Method | Timescale | Spatial Resolution | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| All-Atom MD | ns-μs | Atomic | Local flexibility, conformational dynamics |

| GaMD | μs-ms | Atomic | Large conformational transitions, rare events |

| Trajectory Maps | ns-ms | Residue-level | Visualizing backbone movements, comparing simulations |

| QM/MM | fs-ps | Electronic structure | Chemical reactions, enzymatic mechanisms |

| Graph Theory | N/A | Residue-level | Allosteric networks, signal transduction |

Case Study I: Titin - Molecular Spring of Muscle

Structural Organization and Mechanical Function

Titin, the largest known human protein (3.0-3.7 MDa), spans half the sarcomere in striated muscle, with its N-terminus anchored in the Z-disk and C-terminus in the M-line [26]. This giant molecular chain acts as a complex molecular spring that determines passive muscle elasticity and maintains sarcomeric structural integrity. Titin's chain folds into a series of approximately 300 immunoglobulin-like (Ig) and fibronectin-type (Fn3) domains, connected by flexible linkers that create a "beads-on-a-string" architecture [27].

Multiphase Elasticity Mechanism Revealed by Simulation

MD simulations have elucidated the hierarchical mechanism of titin's elasticity, which proceeds through distinct phases under increasing tension:

Phase 1: Domain straightening - At low forces, the flexible linkers between Ig/Fn3 domains straighten, allowing reversible extension without domain unfolding [26]. The persistence length (Lp) of monomeric titin is estimated at 9-19 nm, reflecting significant bending flexibility at physiological forces [26].

Phase 2: PEVK extension - The proline-glutamate-valine-lysine (PEVK) rich region, a largely disordered segment, unfolds under moderate tension, providing substantial contour length increase [27].

Phase 3: Domain unfolding - At high forces, individual Ig domains unravel, a process thought to occur primarily under pathological conditions [26].

Table 2: Titin Elastic Elements and Their Properties

| Elastic Element | Structural Characteristics | Mechanical Response | Contribution to Elasticity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunoglobulin Domains | β-sandwich folds, ~4 nm length | Hinge bending, domain unfolding | Short-range elasticity, overextension protection |

| Fibronectin Domains | β-sandwich folds, found in A-band | Bending, interaction with thick filament | Structural stability |

| PEVK Region | Disordered, proline-rich | Unfolding and extension | Intermediate elasticity |

| N2-B Unique Sequence | Differentially expressed in cardiac titin | Unknown | Tissue-specific elasticity |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Sample Preparation: Purified titin molecules can be visualized via electron microscopy with metal shadowing or negative staining, revealing strings ~1 μm long and 4 nm in diameter [26].

Simulation Setup: All-atom MD simulations of titin fragments require:

- System Construction: Building multidomain constructs (e.g., 6 Ig domains from PDB 3b43) in explicit solvent [27]

- Force Field Selection: Specialized force fields (CHARMM36, AMBER) parameterizing Ig domain interactions

- Equilibration Protocol: Gradual relaxation of positional restraints on protein atoms

- Production Simulation: Multi-nanosecond to microsecond trajectories using GPU-accelerated codes

Analysis Methods: Persistence length calculations from end-to-end distance fluctuations; contact map analysis for interdomain interactions; force-probe simulations for mechanical unfolding.

Case Study II: CRISPR-Cas9 - Genome Editing Dynamics

Conformational Activation Pathway

CRISPR-Cas9, the revolutionary genome-editing tool, undergoes extensive conformational changes during its functional cycle. MD simulations have been instrumental in mapping these dynamics, particularly the transition from DNA recognition to catalytic activation [23].

RNA Recruitment: GaMD simulations revealed that Cas9's recognition lobe (Rec) undergoes large-scale conformational changes upon RNA binding, with Rec1-3 domains moving in opposed directions to create a positively charged RNA-binding cavity [23]. A critical intermediate state features an arginine-rich helix that facilitates guide RNA recruitment.

DNA Recognition and Activation: Upon PAM (protospacer adjacent motif) recognition, Cas9 matches the guide RNA with the target DNA strand, displacing the non-target strand (NTS). MD simulations demonstrated that NTS binding within the RuvC groove facilitates HNH domain docking at the cleavage site [23].

Catalytic Complex Formation: The highly flexible HNH domain samples multiple conformational states before adopting the active configuration. Enhanced simulations identified a thermodynamically stable active conformation later confirmed by cryo-EM structures (RMSD 2.47±0.14 Å) [23].

Allosteric Regulation and Off-Target Mechanisms

MD simulations have provided crucial insights into two critical aspects of CRISPR-Cas9 function:

Allosteric Network: Graph theory analysis of MD trajectories revealed that PAM binding induces population shifts and highly coupled motions between spatially distant HNH and RuvC catalytic domains [23] [25]. The L1/L2 loops act as "signal transducers" in this allosteric network, with mutations in these regions (e.g., eCas9, HypaCas9) improving specificity.

Off-Target Effects: Simulations introducing base pair mismatches in the RNA:DNA hybrid revealed that DNA unwinding is the primary determinant of Cas9 activity [23]. Off-target binding occurs through a kinetic competition between R-loop formation and collapse, with mismatches creating energy barriers to R-loop expansion [28].

Table 3: Key CRISPR-Cas9 Dynamics Revealed by Computational Methods

| Process | Computational Method | Key Findings | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Binding | GaMD, Essential Dynamics | Rec lobe opening; arginine-rich helix recruitment | Mutational studies confirming role of bridging helix [23] |

| HNH Activation | GaMD, Long-timescale MD | Rec2-3 domain opening enables HNH docking | Cryo-EM structure of active state [23] |

| Allosteric Regulation | Graph Theory, Correlation Analysis | PAM as allosteric effector; L1/L2 as signal transducers | Specificity-enhanced variants (eCas9, HypaCas9) [23] |

| Off-target Effects | Mismatch Simulations, Random Walk Modeling | DNA unwinding as key determinant; kinetic competition mechanism | Single-molecule FRET experiments [28] |

| Catalytic Mechanism | QM/MM | Two-metal mechanism for RuvC; single-metal for HNH | Biochemical studies of metal dependence [25] |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Single-Molecule DNA Twist Experiments:

- Sample Preparation: DNA molecules surface-grafted and tethered to magnetic beads

- Data Acquisition: Magnetic tweezers apply negative supercoiling while monitoring DNA length changes proportional to R-loop formation [28]

- Analysis: Dwell times of intermediate R-loops quantified to determine kinetics

Random Walk Modeling of R-loop Dynamics:

- Landscape Construction: One-dimensional free energy landscape with R-loop length as reaction coordinate

- Parameterization: Free energy penalties for initiation (ΔGini), locking (ΔGlock), supercoiling bias (ΔGbias), and mismatches (ΔGMM)

- Kinetic Modeling: Single base-pair stepping rates (kstep) with Arrhenius treatment of biased transitions [28]

Enhanced Sampling Simulations:

- System Setup: All-atom models of Cas9 with guide RNA and target DNA in explicit solvent

- GaMD Protocol: Application of harmonic boost potential to system potential energy

- Trajectory Analysis: Free energy landscape reconstruction using simulated trajectories

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource | Type | Function/Application | Access/Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Software | Molecular dynamics simulation package | Open source (www.gromacs.org) |

| AMBER | Software | Molecular dynamics simulation & analysis | Commercial & academic licensing |

| Mol* | Visualization Tool | Web-based 3D visualization of large biomolecular structures | Open source (molstar.org) |

| TrajMap.py | Analysis Tool | Python script for generating trajectory maps from MD simulations | Open source Python script [24] |

| CHARMM36 | Force Field | Parameters for biomolecular simulations | Bundled with simulation packages |

| Cascade Complex | Protein Reagent | CRISPR surveillance complex for single-molecule studies | Recombinant expression [28] |

| Magnetic Tweezers | Instrument | Single-molecule manipulation and supercoiling measurements | Custom-built or commercial systems |

Molecular dynamics simulations have fundamentally transformed our ability to visualize and understand protein function, serving as a powerful computational microscope that reveals biological mechanisms at unprecedented spatial and temporal resolution. Through the case studies of titin and CRISPR-Cas9, we have demonstrated how MD simulations provide unique insights into conformational dynamics, allosteric regulation, and functional mechanisms. For titin, simulations have elucidated the hierarchical multi-phase elasticity that enables its function as a molecular spring in muscle. For CRISPR-Cas9, computational methods have mapped the complete activation pathway, revealed the allosteric networks governing specificity, and provided mechanistic understanding of off-target effects. As MD methodologies continue to advance, integrating with machine learning approaches and exploiting exascale computing resources, the resolving power of this computational microscope will only increase, offering drug development professionals and researchers ever more detailed views of the molecular machinery underlying health and disease.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful "computational microscope," enabling researchers to probe the atomic-level dynamics of biomolecular systems critical to drug discovery [3] [29]. By simulating the jiggling and wigglings of atoms over time, MD provides insights into protein flexibility, binding site identification, and ligand energetics that are often inaccessible through experimental methods alone [29]. This technical guide explores how MD serves as this computational microscope, bridging the gap between static structural data and the dynamic reality of molecular interactions.

The Computational Microscope: Visualizing Molecular Motion

The fundamental power of MD simulations lies in their ability to extend static structural data into the dynamic domain, creating detailed "movies" of biomolecular behavior [3]. Unlike traditional molecular docking, which typically treats proteins as rigid entities, MD accounts for full flexibility, sampling conformational states and revealing transient binding pockets crucial for drug design [30] [29].

- From Static Structures to Dynamic Ensembles: MD simulations transform single, static protein structures into ensembles of conformations, capturing the intrinsic flexibility that characterizes functional biomolecules. This is particularly valuable for identifying cryptic pockets—transient binding sites not visible in crystallographic structures that emerge during protein dynamics [30].

- Physical Basis: MD simulations employ Newtonian physics to simulate atomic motions, using force fields (AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS) to calculate forces between atoms [29]. These calculations advance the system in femtosecond to picosecond timesteps, ultimately generating trajectories that capture complex biomolecular processes.

- Validation: The accuracy of the computational microscope is supported by strong agreement with experimental data, particularly NMR measurements of molecular dynamics [29].

Enhanced Sampling Methods for Identifying Binding Sites

Conventional MD simulations face limitations in crossing substantial energy barriers within practical simulation timescales. Enhanced sampling methods address this challenge by smoothing the potential energy landscape, enabling more thorough exploration of conformational space [30].

Accelerated Molecular Dynamics (aMD) and Gaussian Accelerated MD (GaMD)

These methods apply a boost potential to the system's energy surface, reducing energy barriers and accelerating transitions between low-energy states [30].

- Implementation: A positive boost potential is added to the system when the potential energy falls below a reference energy, decreasing the effective height of energy barriers [31].

- Ligand GaMD (LiGaMD): This extension applies a selective boost to ligand nonbonded potential energy, particularly enhancing sampling of ligand binding and dissociation events [31]. LiGaMD2 further refines this approach by applying boost potential to both the ligand and protein residues around the binding pocket [31].

- Performance: GaMD simulations can capture repetitive ligand binding and unbinding events within microsecond timescales, allowing simultaneous characterization of binding thermodynamics and kinetics [31].

The Relaxed Complex Scheme

This systematic approach leverages MD-generated conformational ensembles for docking studies, addressing the critical limitation of protein flexibility in traditional structure-based drug design [30].

Workflow of the Relaxed Complex Scheme

This method successfully contributed to the development of the first FDA-approved inhibitor of HIV integrase, where MD simulations revealed significant flexibility in the active site region that informed drug design [30].

Predicting Ligand Binding Energetics

Accurate prediction of binding free energies remains a central challenge in structure-based drug design. MD-based approaches span a spectrum of rigor and computational cost, from end-state methods to alchemical techniques [32].

Alchemical Free Energy Calculations

These theoretically rigorous methods compute absolute binding free energies by coupling/decoupling the ligand from its environment in the bound and unbound states [32] [33].

- Mathematical Foundation: Alchemical methods evaluate ratios of partition functions to estimate binding free energies, including entropic contributions and full molecular flexibility [32].

- Absolute vs Relative: Absolute binding free energy (ABFE) calculations decouple the entire ligand from both protein and solvent environments, while relative binding free energy (RBFE) calculations transform one ligand to another, requiring less sampling but needing reference compounds [33].

Performance of Free Energy Methods on Model Systems

| Methodology | System Tested | RMS Error (kcal/mol) | Key Advancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Docking | T4 Lysozyme L99A | Not quantified (poor correlation R=0.51) | Ligand flexibility only [32] |

| Alchemical Free Energy (Single Pose) | T4 Lysozyme L99A | 3.51 ± 0.04 | Includes entropic effects but limited pose sampling [32] |

| Alchemical Free Energy (Multiple Poses) | T4 Lysozyme L99A | 1.9 | Accounts for symmetry-equivalent orientations [32] |

| Prospective Alchemical Prediction | T4 Lysozyme L99A | 0.6 (blind test) | Correct discrimination of true ligands vs decoys [32] |

| Equilibrium FEP with HREX | BRD4(1) inhibitors | 0.8 | Enhanced sampling protocol [33] |

| Non-equilibrium FEP | BRD4(1) inhibitors | Comparable to equilibrium | Bi-directional transitions [33] |

Equilibrium vs. Non-Equilibrium Approaches

Recent advances have demonstrated that both equilibrium and non-equilibrium approaches can achieve comparable accuracy when properly implemented [33].

- Equilibrium FEP: Simulations are run at discrete λ values connecting bound and unbound states, with free energy differences computed using Bennett's Acceptance Ratio or Multistate BAR [33].

- Non-Equilibrium FEP: Rapid transitions drive the system between states, with work values collected and free energies recovered using Jarzynski's equality (uni-directional) or the Crooks Fluctuation Theorem (bi-directional) [33].

- Optimal Parameters: For absolute binding free energies, transition times of 500 ps provide sufficient work distribution overlap for reliable estimates [33].

Free Energy Calculation Workflow Comparison

Integrated Workflows and Protocols

Combining enhanced sampling with free energy calculations creates powerful protocols for drug discovery applications.

Exemplary Protocol: Binding Site Identification and Energetics

System Preparation

- Obtain protein structure from PDB or AlphaFold prediction [30]

- Parameterize ligands using appropriate force fields

- Solvate system in explicit water molecules and add ions for physiological concentration

Enhanced Sampling Simulation

- Run GaMD or LiGaMD simulation for 100-500 ns to explore conformational space [31]

- Identify cryptic pockets through volume analysis of trajectory

- Cluster structures to identify representative conformations

Binding Pose Characterization

- Use the Relaxed Complex Scheme to dock ligands against MD-derived conformations [30]

- Run short MD simulations (10-20 ns) to refine poses

- Identify stable binding modes for free energy calculations

Free Energy Calculation

- Set up alchemical transformation for absolute binding free energy

- Use 20-30 λ windows for equilibrium FEP or 500+ non-equilibrium transitions [33]

- Employ Hamiltonian replica exchange to enhance sampling between windows

- Compute binding free energy using BAR or Crooks Fluctuation Theorem

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

Table: Key Methodologies and Their Applications in MD-Driven Drug Discovery

| Methodology | Primary Function | Key Advantages | Representative Software |

|---|---|---|---|

| GaMD/LiGaMD | Enhanced sampling of binding events | Captures full binding/dissociation events; Improves kinetics estimation | AMBER, NAMD [31] |

| Alchemical FEP | Binding free energy prediction | Rigorous statistical mechanics foundation; High accuracy when converged | CHARMM, GROMACS, SOMD [32] [33] |

| Relaxed Complex Scheme | Binding site identification | Accounts for protein flexibility; Identifies cryptic pockets | AutoDock, Vina with MD trajectories [30] |

| Coarse-Grained MD | Extended timescale sampling | Reduces computational cost; Enables millisecond sampling | Martini [34] |

| Non-equilibrium FEP | Binding free energy prediction | Computational efficiency; Bi-directional validation | Custom implementations [33] |

Future Perspectives

The field of MD-driven drug discovery continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends promising to enhance both the accuracy and scope of the computational microscope.

- Integration with Machine Learning: Combining MD with AI approaches is expected to improve force fields, sampling efficiency, and binding affinity predictions [35] [30].

- Coarse-Grained Methods: Approaches like coarse-grained funnel metadynamics bridge the gap between all-atom accuracy and computational efficiency, showing comparable results to all-atom methods at reduced cost [34].

- Specialized Hardware: Dedicated processors like Anton and GPU acceleration are extending accessible timescales, with millisecond simulations now possible for some systems [29].

- Force Field Refinement: Development of polarizable force fields that account for electronic polarization will improve accuracy, particularly for charged systems and metal ions [29].

As these methodologies mature, molecular dynamics as a computational microscope will play an increasingly central role in accelerating drug discovery, from initial target identification to lead optimization, ultimately reducing the time and cost associated with bringing new therapeutics to market.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as a powerful computational microscope, enabling researchers to observe and manipulate molecular systems at spatial and temporal scales often inaccessible to conventional experimental techniques. By providing atomic-level resolution of drug-carrier interactions, stability, and release mechanisms, MD serves as a vital bridge between theoretical design and experimental implementation in drug delivery optimization. This computational approach offers unprecedented insights into the dynamic behavior of nanocarriers and their payloads under biologically relevant conditions, allowing researchers to overcome the limitations of traditional resource-intensive experimental methods [36]. The framework of MD simulations facilitates the detailed examination of molecular mechanisms influencing drug behavior, effectively serving as a virtual laboratory for testing and optimizing next-generation drug delivery systems for cancer therapy and other applications [36].

Fundamental Principles of MD in Drug Delivery

Theoretical Foundations

Molecular dynamics simulations operate on principles of statistical mechanics, numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for all atoms within a molecular system. This approach generates trajectories that reveal time-dependent evolution of molecular configurations, providing insights into structural stability, binding affinities, and dynamic interactions critical for drug delivery optimization. The atomic-level resolution offered by MD enables researchers to predict how nanocarriers encapsulate therapeutic agents, how these complexes maintain stability in biological environments, and how controlled release occurs at target sites [36].

The power of MD as a computational microscope lies in its ability to capture transient molecular states and interaction mechanisms that often elude experimental detection. By applying empirical force fields that describe potential energy surfaces based on nuclear positions, MD simulations can model systems ranging from simple drug molecules in solution to complex heterogeneous environments involving nanocarriers, membranes, and biological fluids [5]. Recent advances in high-performance computing have extended these simulations to biologically relevant timescales and system sizes, enabling the study of increasingly complex delivery systems with millions to billions of atoms [5].

Simulation Workflows for Drug Delivery Systems

The typical workflow for MD simulations in drug delivery applications follows a structured approach from system construction to analysis. Figure 1 illustrates this generalized workflow, highlighting the key stages researchers employ to optimize nanocarrier formulations.

Figure 1: Generalized workflow for MD simulations of drug delivery systems, illustrating the sequential steps from initial system setup to final analysis and validation.

This workflow begins with system setup, where researchers construct atomic models of nanocarriers and drug molecules based on experimental data or computational predictions. For cancer therapeutics specifically, common simulated drugs include Doxorubicin (DOX), Gemcitabine (GEM), and Paclitaxel (PTX), which are studied in conjunction with various nanocarriers [36]. The subsequent solvation and neutralization stage places the drug-carrier system in a biologically relevant environment, typically employing water models such as TIP3P or SPC/E and adding ions to achieve physiological concentration and neutrality.

Energy minimization follows, removing steric clashes and unfavorable interactions through algorithms like steepest descent or conjugate gradient methods. Equilibration then brings the system to target temperature and pressure using thermostats (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) and barostats (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman). Production simulation, the core of the MD process, collects trajectory data for analysis over timescales ranging from nanoseconds to microseconds, depending on system size and computational resources. Finally, trajectory analysis extracts meaningful physicochemical properties and validation compares computational predictions with experimental observations [36] [5].

Key Nanocarrier Systems Simulated via MD

Carbon-Based Nanocarriers

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), particularly functionalized carbon nanotubes (FCNTs) and double-walled carbon nanotubes (DWCNTs), have demonstrated exceptional potential as drug delivery vehicles in MD simulations. These systems exhibit high drug-loading capacity and structural stability, making them particularly suitable for protecting therapeutic compounds from degradation and facilitating targeted delivery [36].

A recent study investigating the anticancer drug ZD1694 (Tomudex) encapsulated within seven layers of DWCNTs revealed remarkable protective capabilities. The research demonstrated that DWCNT shielding significantly reduced molecular deformation under mechanical pressure from a gold tip, with a substantial decrease in mean squared displacement (0.872 Ų) compared to unshielded configurations (2.39 Ų) [37]. This enhanced stability directly translates to improved drug integrity during delivery. Furthermore, the DWCNT-shielded system exhibited dramatically improved mechanical properties, with a 10.85-fold increase in elastic modulus (3.17 × 10⁻² GPa) and a 10.83-fold increase in shear modulus (4.76 × 10⁻² GPa) compared to the non-shielded system [37].

Lipid and Polymer-Based Systems

Lipid-based nanocarriers represent another major category extensively studied through MD simulations. Liquid crystalline nanoparticles (LCNPs), including hexosomes, have shown particular promise for enhancing drug absorption, solubility, and chemical stability [38]. All-atom MD simulations of hexagonal liquid crystalline phases composed of phytantriol and farnesol (90:10 ratio) have provided molecular-level insights into drug partitioning and release mechanisms [38].

These simulations demonstrated that highly lipophilic drugs like clarithromycin predominantly associate with the lipid phase, while drugs with both hydrophobic and hydrophilic residues, such as vancomycin, tend to localize at the water-lipid interface, interacting with both phases [38]. The incorporation of Pluronic F127 polymers at the hexosomal interface further modified release kinetics by facilitating water permeation and reducing energy barriers for drug release, as confirmed by umbrella sampling simulations and in vitro release studies [38].

Additional nanocarrier systems successfully characterized through MD simulations include chitosan-based nanoparticles, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and human serum albumin (HSA) carriers, each offering distinct advantages in biodegradability, reduced toxicity, and controlled release profiles [36].

Table 1: Key Nanocarrier Systems Studied via MD Simulations

| Nanocarrier Type | Key Advantages | Representative Drugs | Simulation Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes (FCNTs) | High drug-loading capacity, stability | Doxorubicin, Gemcitabine | Enhanced encapsulation efficiency, controlled release mechanisms [36] |

| Double-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (DWCNTs) | Superior shielding, mechanical strength | ZD1694 (Tomudex) | Reduced molecular deformation (MSD: 0.872 Ų), improved elastic modulus (3.17×10⁻² GPa) [37] |

| Liquid Crystalline Nanoparticles | Enhanced absorption, tunable solubility | Vancomycin, Clarithromycin | Drug partitioning based on lipophilicity, polymer-facilitated release [38] |

| Chitosan-Based Nanoparticles | Biodegradability, reduced toxicity | Paclitaxel, Doxorubicin | Molecular-level understanding of mucoadhesion, controlled release [36] |

| Human Serum Albumin (HSA) | Biocompatibility, natural targeting | Various anticancer agents | Drug-binding mechanisms, stability in physiological conditions [36] |

Critical Characterization Parameters and Methods

Structural and Dynamic Properties

MD simulations enable the calculation of essential structural and dynamic properties that predict nanocarrier performance in biological systems. These parameters include radial distribution functions (RDF) that reveal spatial atomic organization and interaction sites, mean squared displacement (MSD) that quantifies particle mobility and diffusion coefficients, and various energy profiles that determine system stability and interaction strengths [37].

Umbrella sampling simulations, a specialized MD technique, provide particularly valuable insights into drug release mechanisms by calculating potential of mean force (PMF) along specified reaction coordinates. This approach was effectively employed in studying drug release from hexagonal liquid crystalline phases, where energy profiles revealed that polymer-lipid-water interactions at the interface reduce energy barriers for drug release [38]. The simulations demonstrated that vancomycin, with its lower energy barrier, exhibited higher release compared to clarithromycin, findings subsequently confirmed through in vitro release studies [38].

Physicochemical Characterization

The physicochemical properties of nanocarriers significantly influence their bioavailability, stability, cellular uptake, and biodistribution [39]. MD simulations provide atomic-level data on these critical parameters, complementing experimental characterization techniques. Key properties include particle size and size distribution, surface charge (zeta potential), hydrophobicity, and morphological characteristics [39].

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between key characterization parameters and their impact on nanocarrier performance, highlighting how MD simulations connect molecular-level properties to macroscopic behavior.

Figure 2: Relationship between molecular properties derived from MD simulations and key performance metrics for nanocarrier drug delivery systems.