The Complete Guide to Molecular Dynamics Workflows: From Fundamentals to AI-Driven Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to molecular dynamics (MD) workflows, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Complete Guide to Molecular Dynamics Workflows: From Fundamentals to AI-Driven Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to molecular dynamics (MD) workflows, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of MD, explores traditional and emerging AI-driven methodological approaches, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and discusses validation techniques. By integrating insights from recent advancements, including automated AI agents and machine learning analysis, this guide serves as a practical resource for implementing robust MD simulations to study biomolecular interactions, protein folding, and drug solubility, ultimately accelerating biomedical research.

Understanding Molecular Dynamics: Core Principles and Scientific Value

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful computational technique that analyzes the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time [1]. By numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for a system of interacting particles, MD provides a dynamic view of molecular evolution, allowing researchers to observe processes that are often impossible to probe experimentally [2]. This method has become an indispensable tool across chemical physics, materials science, and biophysics, earning the description as a "computational microscope" with exceptional resolution for visualizing atomic-scale dynamics [2] [3].

The core value of MD lies in its ability to bridge static structural information with dynamic functional insights. While experimental techniques like X-ray crystallography provide exquisite pictures of average molecular structures, MD simulations reveal how these structures move, fluctuate, and interact—transforming static snapshots into dynamic movies that offer profound insights into biological function and malfunction [2] [4].

Fundamental Principles and Methodological Framework

Core Theoretical Foundation

At its essence, MD simulation tracks the time evolution of a molecular system by calculating the forces acting on each atom and updating their positions accordingly [1] [5]. The process begins with defining a force field—a mathematical model describing the potential energy surfaces of molecules based on their composition and structure [5]. These force fields include parameters for bond lengths, angles, dihedral angles, and non-bonded interactions such as van der Waals forces and electrostatic interactions [1] [5].

The simulation proceeds through numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion using small time steps, typically around 1 femtosecond (10⁻¹⁵ seconds), to accurately capture the fastest atomic motions [2] [3]. Common integration algorithms include the Verlet and leap-frog methods, which provide better energy conservation and stability over long simulations [3]. At each step, forces on each atom are computed as the negative gradient of the potential energy, and positions and velocities are updated accordingly [5].

The Time-Scale Challenge and Enhanced Sampling

A significant challenge in conventional MD is the vast discrepancy between the femtosecond time steps required for numerical stability and the millisecond-to-second timescales of important biological processes [2]. Simulating these slower processes using conventional methods could take decades of computational time [2].

To bridge this gap, advanced enhanced sampling methods have been developed. Gaussian accelerated Molecular Dynamics (GaMD) represents a particularly innovative approach that smoothes the potential energy surface, reducing energy barriers and accelerating simulations by thousands to millions of times [2]. This enables the study of complex biochemical processes—such as conformational changes in CRISPR-Cas9 during genome editing or drug binding to viral proteins—that were previously beyond reach [2].

Table 1: Key MD Simulation Algorithms and Their Applications

| Method | Fundamental Principle | Time Scale | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional MD | Numerical integration of Newton's equations | Nanoseconds to microseconds | Local flexibility, small-scale conformational changes |

| GaMD | Smoothes potential energy surface | Microseconds to milliseconds | Protein folding, large conformational changes, ligand binding |

| Replica Exchange MD | Parallel simulations at different temperatures | Enhanced sampling across energy barriers | Complex energy landscapes, protein folding |

| Metadynamics | Adds history-dependent bias potential | Accelerated transition sampling | Rare events, reaction pathways |

Molecular Dynamics Workflow: A Step-by-Step Framework

The process of conducting an MD simulation follows a systematic workflow that transforms initial structural data into dynamic behavioral insights.

Initial Structure Preparation

Every MD simulation begins with preparing the initial atomic coordinates of the target system [3]. Structures are often obtained from experimental databases such as the Protein Data Bank (PDB) for biomolecules or the Materials Project for crystalline materials [3]. However, database structures frequently require correction of missing atoms or incomplete regions through structural modeling tools [3]. For novel systems without experimental templates, initial structures may be built from scratch using predictive approaches, including AI-based tools like AlphaFold2 which received the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry [3].

System Initialization

Once the initial structure is prepared, the simulation system must be initialized [3]. This involves solvation (placing the molecule in explicit solvent water models like TIP3P or implicit solvent environments), adding counterions to neutralize charge, and assigning initial atomic velocities sampled from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution corresponding to the desired simulation temperature [3] [1]. The choice between explicit and implicit solvent represents a critical trade-off between computational expense and physical accuracy [1].

Force Calculation and Time Integration

The computational core of MD involves calculating forces between atoms using the selected force field [3]. This represents the most computationally intensive step, often employing cutoff methods to ignore interactions beyond certain distances and spatial decomposition algorithms to distribute workload across multiple processors [3] [1]. Recent advances include Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) trained on quantum chemistry data, which offer remarkable precision and efficiency for complex material systems [3].

Forces are then used to solve Newton's equations of motion through time integration algorithms [3]. The Verlet algorithm is particularly valued for its numerical stability and energy conservation properties [3] [1]. The integration time step must balance accuracy and efficiency—typically 0.5-2.0 femtoseconds—and can be extended using constraint algorithms that fix the fastest vibrations (e.g., hydrogen atoms) in place [3] [1].

Trajectory Analysis

The final and most critical phase involves analyzing the simulation trajectory—the time-series data of atomic positions and velocities [3]. Raw coordinate data must be transformed into chemically and biologically meaningful insights through various analytical approaches:

- Radial Distribution Function (RDF): Quantifies how atoms are spatially arranged around each other, particularly useful for analyzing liquid and amorphous structures [3]

- Mean Square Displacement (MSD): Measures atomic mobility and enables calculation of diffusion coefficients [3]

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Identifies dominant modes of collective motion from high-dimensional trajectory data [3]

- Clustering Algorithms: Group similar conformations to identify significant structural states [5]

Table 2: Essential Analysis Techniques for MD Trajectories

| Analysis Method | Physical Property Measured | Key Applications | Example Software Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radial Distribution Function | Spatial atom distribution | Liquid structure, solvation shells | GROMACS, MOE |

| Mean Square Displacement | Particle mobility | Diffusion coefficients, ion conductivity | GROMACS, CHARMM |

| Principal Component Analysis | Collective motions | Domain movements, allosteric changes | CPPTRAJ, MDTraj |

| Clustering Algorithms | Representative conformations | State identification, ensemble reduction | PyMOL, VMD |

Integrating MD with Experimental Data

MD simulations rarely exist in isolation; their true power emerges when integrated with experimental data. Several strategic frameworks have been developed for this integration [6] [4] [7]:

Independent Approach

Experimental and computational protocols are performed separately, with results compared afterward [6] [7]. This approach can reveal unexpected conformations but may struggle with rare events that require extensive sampling [7].

Guided Simulation (Restrained) Approach

Experimental data are incorporated as external energy terms that guide the conformational sampling during simulation [6] [7]. This efficiently limits the conformational space but requires implementation directly in the simulation software [7].

Search and Select (Reweighting) Approach

A large ensemble of conformations is generated first, then experimental data is used to filter and select compatible structures [6] [7]. This allows simpler integration of multiple data types but requires the initial pool to contain the correct conformations [7].

Guided Docking

Experimental information defines binding sites to assist in predicting complex formation between molecules [6] [7]. Programs like HADDOCK and pyDockSAXS incorporate such experimental restraints [6].

A compelling example of integration appears in studies combining MD with single-molecule FRET (smFRET). Researchers achieved quantitative comparison between sub-millisecond time-resolution smFRET measurements and 10-second MD simulations of the LIV-BPSS biosensor protein, providing atomistic interpretations of conformational changes observed experimentally [8].

Practical Implementation: The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful implementation of MD requires familiarity with key software tools and computational resources.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for MD Simulations

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | GROMACS, CHARMM, OpenMM, AMBER | Software packages that perform the numerical integration and force calculations |

| Visualization Tools | PyMOL, VMD, UCSF Chimera | Render molecular structures and trajectories for analysis and presentation |

| Force Fields | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS | Mathematical models defining potential energy surfaces and atomic interactions |

| No-Code Platforms | Prithvi | Web-based interfaces that simplify MD setup and analysis for non-specialists |

| Specialized Hardware | GPUs, Anton Supercomputer | Accelerate computationally intensive force calculations |

Visualization Advances

As simulations grow in scale and complexity, visualization challenges intensify [9]. Modern approaches include virtual reality environments for immersive trajectory exploration, web-based tools for collaborative analysis, and deep learning techniques to emulate photorealistic visualization styles from simpler representations [9]. These advances help researchers comprehend the enormous data output from modern simulations, which can encompass billions of atoms representing entire cellular organelles [9].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Materials Science

MD simulations have become invaluable in pharmaceutical research, particularly in structure-based drug design [2] [1]. They help identify drug binding modes, predict binding affinities, and understand how proteins change shape upon ligand interaction [5]. In the fight against COVID-19, GaMD simulations helped design drug candidates targeting the SARS-CoV-2 main protease and captured inhibitor binding to the ACE2 receptor [2].

In materials science, MD enables the computation of stress-strain curves at the atomic scale, providing insights into mechanical properties including Young's modulus, yield stress, and tensile strength [3]. The direct observation of microscopic events like plastic deformation nucleation makes MD indispensable for predicting mechanical behavior across diverse materials [3].

Molecular Dynamics truly represents a "computational microscope" that has revolutionized our ability to observe and understand molecular processes at atomic resolution. As methods like GaMD overcome traditional time-scale limitations, and integration with experimental data becomes more sophisticated, MD continues to expand its transformative impact across biochemistry, pharmacology, and materials science. The ongoing development of more accurate force fields, enhanced sampling algorithms, machine learning potentials, and accessible platforms ensures that this computational microscope will continue to provide increasingly powerful insights into the molecular mechanisms that govern biological function and material behavior.

Molecular dynamics (MD) is a computational method that simulates the natural motions of atoms and molecules over time. At its heart, MD relies on Newton's equations of motion to calculate how a system of interacting particles evolves from a given starting configuration. This powerful approach provides atomic-level insights into dynamic processes in chemistry, biology, and materials science, making it indispensable for understanding biomolecular interactions, material properties, and facilitating modern drug development [10].

The fundamental principle of MD is straightforward: given initial positions and velocities of all atoms, along with a description of the forces acting upon them, one can numerically solve Newton's equations to predict the system's trajectory. This capability to simulate complex molecular behavior has made MD an essential tool in the researcher's toolkit, bridging the gap between static structural data and dynamic functional understanding [11].

The Mathematical Foundation: Newton's Equations of Motion

The Fundamental Equations

MD simulations are built upon Newton's second law of motion, which states that force equals mass times acceleration: F = ma [11]. In molecular dynamics, this foundational principle translates into a set of equations that govern atomic motion:

- Forces derive from the potential energy of the system: F = -∇U, where U represents the potential energy function that models all interactions between particles [11]

- Acceleration is calculated from these forces and determines how particle velocities and positions evolve over time

These equations form a deterministic system: given initial atomic positions and velocities, along with a force field describing molecular interactions, the subsequent trajectory is uniquely determined.

Numerical Integration Algorithms

Since analytical solutions to Newton's equations are impossible for complex molecular systems, MD employs numerical integration algorithms to approximate particle trajectories. These algorithms discretize time into small steps (typically 0.5-2 femtoseconds) and update positions and velocities iteratively [11].

Table 1: Core Integration Algorithms in Molecular Dynamics

| Algorithm | Key Features | Advantages | Common Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Verlet | Uses positions and accelerations to update positions without explicit velocity storage [11] | Computationally efficient; good energy conservation | General purpose simulations; systems with memory constraints |

| Leap-frog | Updates positions and velocities at interleaved half-time steps [11] | Improved numerical stability; direct velocity calculation | Simulations requiring kinetic energy monitoring |

| Velocity Verlet | Simultaneously updates positions, velocities, and accelerations [11] | Better energy conservation; positions and velocities at same time points | Modern MD software packages (GROMACS, NAMD); most current applications |

The Velocity Verlet algorithm has emerged as a preferred method in many modern MD implementations. It combines the advantages of both Verlet and leap-frog methods while providing improved accuracy for longer time steps [11]. The algorithm implements a two-step process:

- Position and velocity updates based on current forces

- Force recalculation and velocity correction based on new positions

Practical Implementation: From Theory to Simulation

Time Step Selection and Numerical Stability

Appropriate time step selection is crucial for accurate MD simulations. The time step determines the temporal resolution of the simulation and represents a balance between computational efficiency and numerical stability [11]:

- Smaller time steps (0.5-1 fs) increase accuracy but require more computational resources

- Larger time steps (2 fs or more) improve efficiency but may lead to numerical instabilities

- The Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem guides time step selection: it should be at least an order of magnitude smaller than the fastest motion in the system [11]

For atomistic simulations of biomolecules, typical time steps range from 0.5 to 2 femtoseconds, constrained by the period of the fastest vibrations (C-H bonds) [11].

Energy Conservation and Symplectic Integrators

Energy conservation serves as a key indicator of simulation accuracy. In isolated systems (microcanonical ensemble), the total energy should remain constant [11]. Symplectic integrators are particularly valuable for MD because they preserve the geometric structure of Hamiltonian systems, maintaining long-term stability and energy conservation [11]. Both Velocity Verlet and leap-frog algorithms classify as symplectic integrators, making them suitable for extended simulations where non-symplectic methods might exhibit energy drift [11].

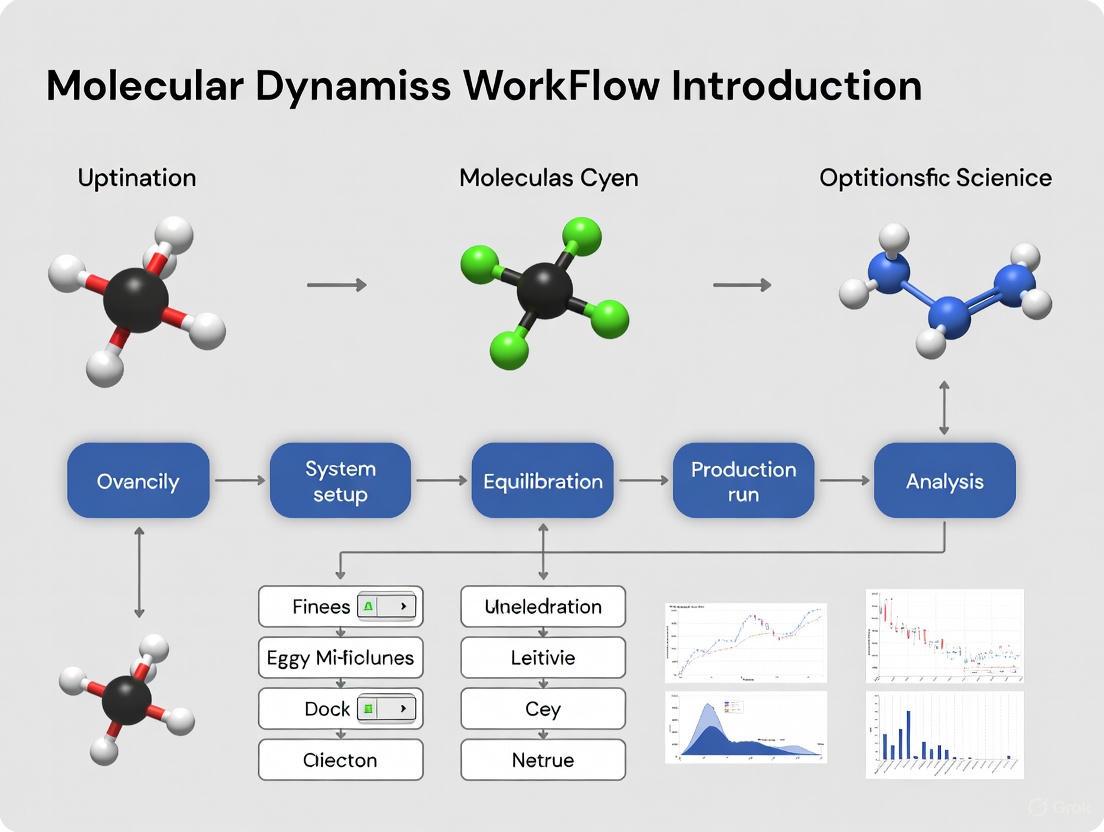

Figure 1: Core Molecular Dynamics Simulation Workflow

MD in Action: Experimental Validation and Applications

Quantitative Comparison with Experimental Data

MD simulations gain credibility when validated against experimental data. Recent research has demonstrated quantitative comparisons between sub-millisecond time resolution single-molecule FRET measurements and long-timescale MD simulations [8]. In one study of the LIV-BPSS biosensor protein, researchers performed all-atom structure-based simulations spanning multiple cycles of clamshell-like conformational changes on the scale of seconds, directly correlating these events with experimental smFRET measurements [8].

This approach provided valuable information on:

- Local dynamics of fluorophores at their attachment sites

- Correlations between fluorophore motions and large-scale conformational changes

- Determinations of Förster radius (R₀) and fluorophore orientation factor (κ²)

The congruence between simulation and experiment demonstrates MD's predictive power when simulations achieve temporal regimes overlapping with experimental observables [8].

Protein Structure Prediction and Refinement

MD simulations play a crucial role in refining predicted protein structures. In a study modeling the hepatitis C virus core protein (HCVcp), researchers found that neural network-based prediction tools like AlphaFold2, Robetta, and trRosetta provided good initial models, but subsequent MD simulations were essential for obtaining compactly folded structures of good quality [12]. The root mean square deviation of backbone atoms, root mean square fluctuation of Cα atoms, and radius of gyration were calculated to monitor structural changes and convergence during simulations [12].

Table 2: Time Step Parameters for Different Simulation Types

| Simulation Type | Recommended Time Step | Fastest Motion Constrained | Constraint Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomistic (all-atom) | 1-2 fs | C-H bond vibrations | SHAKE, LINCS |

| Coarse-grained | 10-20 fs | Effective bead vibrations | None typically required |

| Implicit solvent | 2-4 fs | C-H bond vibrations | SHAKE |

| Explicit solvent | 1-2 fs | C-H bond vibrations + water modes | SETTLE for water |

Guiding Protein Engineering

MD simulations can guide rational protein design by predicting how mutations affect structure and function. In developing a brighter variant of superfolder Green Fluorescent Protein, researchers used short time-scale MD modeling to predict changes in local chromophore interaction networks and solvation [13]. Simulations revealed that replacing histidine 148 with serine formed more persistent H-bonds with the chromophore phenolate group and increased the residency time of an important water molecule [13]. This single mutation resulted in a protein 1.5 times brighter than the parent with 3-fold increased resistance to photobleaching [13].

Figure 2: Molecular Force Calculation Process

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Modern MD simulations require both specialized software and careful parameter selection. The following table outlines key components essential for successful MD research in drug development and biochemical applications.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Dynamics

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | OpenMM [14], GROMACS, NAMD [11] | Performs the numerical integration of equations of motion | GPU acceleration; support for multiple force fields |

| Analysis Packages | MDTraj [14] | Analyzes simulation trajectories; calculates properties | RMSD, radius of gyration, secondary structure analysis |

| Force Fields | CHARMM [14], AMBER [14] | Defines potential energy functions and parameters | Protein, nucleic acid, lipid parameters; water models |

| System Preparation | PDBFixer [14], PackMol [14] | Prepares structures for simulation; adds solvent | Structure cleaning; solvation; ion addition |

| Automation Tools | MDCrow [14] | Automates MD workflows using LLM agents | Handles file processing; simulation setup; analysis |

| Visualization | NGLview [14] | Visualizes molecular structures and trajectories | Web-based; interactive trajectory playback |

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

Workflow Automation and Accessibility

Recent advances have focused on making MD more accessible through workflow automation. MDCrow represents one such approach—an LLM-based assistant capable of automating MD workflows using over 40 expert-designed tools for handling files, setting up simulations, analyzing outputs, and retrieving relevant information from literature and databases [14]. This system can perform complex tasks including downloading PDB files, performing multiple simulations, and conducting analyses with minimal user intervention [14].

Integration with Experimental Data

As MD simulations reach longer timescales, they increasingly overlap with experimental observables, enabling direct quantitative comparisons. For example, all-atom structure-based simulations calibrated against explicit solvent simulations can sample multiple cycles of protein conformational changes on the scale of seconds, directly informing the interpretation of smFRET data [8]. This integration provides atomic-level insights into conformational dynamics that complement experimental findings.

Accelerated Sampling and AI Integration

Traditional MD faces limitations in sampling rare events due to computational constraints. Recent research addresses this through accelerated sampling methods and AI integration. Generative artificial intelligence frameworks can now accelerate MD simulations for crystalline materials by reframing the task as conditional generation of atomic displacements [10]. Machine-learned potentials enable full-cycle device-scale simulations of complex materials like phase-change memory devices [10]. These advances continue to expand the boundaries of what MD can simulate within practical computational limits.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a computational method for analyzing the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion [1]. The method is founded on classical mechanics principles, where the force on any particle is calculated as the negative gradient of the potential energy function: ( \vec{F} = -\nabla U(\vec{r}) ) [15]. MD simulations have become indispensable across chemical physics, materials science, and biophysics, enabling researchers to investigate molecular processes at atomic resolution that are often inaccessible to experimental observation [1].

The reliability and physical meaningfulness of any MD simulation depend critically on the proper specification of three foundational components: the initial conditions that define the starting state of the system, the topology that describes the connectivity between particles, and the force field that governs their interactions. These elements collectively determine the system's Hamiltonian and thus its subsequent evolution through phase space. This technical guide examines each component in detail, providing researchers with the fundamental knowledge required to construct accurate and thermodynamically consistent molecular systems for computational investigation.

Initial Conditions

The initial conditions of a molecular dynamics simulation establish the starting point from which the system evolves. Proper initialization is essential for generating physically realistic trajectories and ensuring efficient convergence of thermodynamic properties.

Components of System Initialization

Initial conditions encompass several key elements that must be defined prior to simulation:

Atomic Coordinates: The initial positions ( \mathbf{r} ) of all atoms in the system, typically obtained from experimental structures (e.g., X-ray crystallography or NMR) or through system-building tools [16]. For simulations of proteins and other biomolecules, coordinates are commonly provided in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) format, which specifies atomic positions, residue names, chain identifiers, and other structural metadata [15].

Atomic Velocities: The initial velocities ( \mathbf{v} ) of all particles, which determine the initial kinetic energy and temperature of the system [16]. When velocities are not available from experimental data, they are commonly assigned randomly from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at the target temperature [16] [15]:

[ p(vi) = \sqrt{\frac{mi}{2 \pi kT}}\exp\left(-\frac{mi vi^2}{2kT}\right) ]

where ( k ) is Boltzmann's constant, ( T ) is the temperature, and ( m_i ) is the mass of atom ( i ) [16].

System Boundaries and Periodicity: The simulation box size and shape, defined by three basis vectors ( \mathbf{b}1, \mathbf{b}2, \mathbf{b}_3 ) that determine the unit cell for periodic boundary conditions [16]. System builders like packmol can create initial configurations with specified density and composition [17].

Solvent Environment: The choice between explicit solvent molecules (e.g., TIP3P, SPC/E water models) or implicit solvent representations [1]. Explicit solvents provide more realistic solvation dynamics but increase computational cost substantially.

Practical Implementation

In practice, initial system preparation often involves multiple stages. For biomolecular systems, the process typically begins with a PDB file containing atomic coordinates. Missing hydrogen atoms may be added, and protonation states adjusted according to the physiological pH of interest. The structure is then solvated in a water box, with ions added to neutralize the system and achieve physiological ionic strength [15].

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters for System Initialization

| Parameter | Typical Values | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Initial velocity assignment | Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution | Velocities are often rescaled after assignment to ensure the center-of-mass velocity is zero [16] |

| Solvent density | 1.0 g/cm³ (aqueous systems) [17] | Density affects system size and computational cost |

| Number of atoms | 200 - 1,000,000+ | System size balances computational cost with biological relevance [17] [1] |

| Box dimensions | Varies by system | Must accommodate the solute with sufficient padding for cutoffs |

| Ionic concentration | 0.15 M for physiological conditions | Affects electrostatic interactions and protein stability |

After initial configuration, systems typically undergo energy minimization to remove steric clashes, followed by gradual heating and equilibration to the target temperature and pressure. This stepwise approach ensures stable integration of the equations of motion before production simulation begins.

System Topology

The topology of a molecular system defines the structural relationships between its constituent atoms, including bonding patterns, chemical identity, and molecular connectivity that remain constant throughout a classical MD simulation.

Topology Components and Representation

Molecular topology encompasses several key aspects:

Atomic Identity and Masses: Element type and mass for each particle in the system, which determine its inertial properties and contributions to kinetic energy [15].

Bond Connectivity: Specification of covalent bonds between atoms, which constrains their relative motion and defines the molecular graph [16]. In proteins, this includes the backbone and sidechain bonds that maintain structural integrity.

Residue and Chain Organization: Hierarchical organization of atoms into residues (monomers) and chains (polymers), preserving the chemical identity of molecular components [15].

Exclusion Lists: Specification of atom pairs that are bonded or closely related and should be excluded from non-bonded interactions, or for which non-bonded interactions require special treatment [16].

The topology is typically represented in specialized file formats that encode these relationships. For example, GROMACS uses top files that define molecule types, atom characteristics, and interaction parameters [16].

Topology in Force Field Context

The system topology works in conjunction with the force field to define the complete potential energy function. While the topology specifies which atoms are connected, the force field provides the specific functional forms and parameters for interactions between them. This separation allows the same topology to be used with different force fields, though this requires careful validation [15].

Table 2: Topology Components Across Molecular Systems

| Topology Element | Small Molecule | Protein | Nucleic Acid | Complex System |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond connectivity | Defined by chemical structure | Peptide bonds + sidechains | Sugar-phosphate backbone + bases | Multiple molecular entities |

| Residue organization | Single residue | Amino acid residues | Nucleotide residues | Mixed residue types |

| Special interactions | Torsional parameters | Backbone dihedrals, sidechain rotamers | Base pairing, stacking | Interface contacts |

| Exclusion rules | 1-2, 1-3 neighbors | Intra-residue and inter-residue | Base pairing partners | Inter-molecular exclusions |

Force Fields

Force fields provide the mathematical framework and parameters that describe the potential energy of a system as a function of atomic coordinates. They approximate the complex quantum mechanical interactions between atoms using empirically parameterized functions that are computationally efficient to evaluate.

Force Field Energy Components

The total potential energy in a molecular mechanics force field is typically decomposed into bonded and non-bonded contributions:

[ U(\vec{r}) = U{bonded}(\vec{r}) + U{non-bonded}(\vec{r}) ]

Bonded Interactions

Bonded interactions describe the energy associated with covalent connectivity:

Bond Stretching: The energy required to deviate from equilibrium bond length, typically modeled as a harmonic oscillator:

[ V{Bond} = kb(r{ij} - r0)^2 ]

where ( kb ) is the force constant and ( r0 ) is the equilibrium bond length [18] [15].

Angle Bending: The energy associated with deviation from equilibrium bond angles, also typically harmonic:

[ V{Angle} = k\theta(\theta{ijk} - \theta0)^2 ]

where ( k\theta ) is the angle force constant and ( \theta0 ) is the equilibrium angle [18] [15].

Torsional Potentials: The energy associated with rotation around chemical bonds, typically modeled as a periodic function:

[ V{Dihed} = k\phi[1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta)] ]

where ( k_\phi ) is the dihedral force constant, ( n ) is the periodicity, and ( \delta ) is the phase angle [18] [15].

Improper Dihedrals: Potentials that enforce planarity in chemical groups such as aromatic rings or peptide bonds:

[ V{Improper} = k\phi(\phi - \phi_0)^2 ]

Non-Bonded Interactions

Non-bonded interactions describe forces between atoms that are not directly bonded:

van der Waals Interactions: The attractive and repulsive forces between atomic electron clouds, typically modeled with the Lennard-Jones potential:

[ V_{LJ}(r) = 4\epsilon\left[\left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{6}\right] ]

where ( \epsilon ) is the well depth and ( \sigma ) is the van der Waals radius [18]. Some force fields use the Buckingham potential as an alternative [18].

Electrostatic Interactions: The Coulombic attraction or repulsion between partial atomic charges:

[ V{Elec} = \frac{qi qj}{4\pi\epsilon0 r_{ij}} ]

where ( qi ) and ( qj ) are partial atomic charges and ( \epsilon_0 ) is the dielectric constant [18].

Force Field Classification

Force fields are commonly categorized into classes based on their complexity and treatment of molecular interactions:

Class I Force Fields: Employ simple harmonic potentials for bonds and angles with no cross-terms. Examples include AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS, and OPLS [18].

Class II Force Fields: Include anharmonic terms for bonds and angles, along with cross-terms coupling internal coordinates. Examples include MMFF94 and UFF [18].

Class III Force Fields: Explicitly incorporate polarization effects using methods such as Drude oscillators or inducible dipoles. Examples include AMOEBA, CHARMM-Drude, and OPLS5 [18].

Most biomolecular simulations currently employ Class I force fields, though Class III polarizable force fields are increasingly used for systems where electronic polarization effects are significant.

Combining Rules and Cutoffs

A critical aspect of force field implementation is the treatment of interactions between different atom types. Combining rules determine how Lennard-Jones parameters are calculated for heterogeneous atom pairs [18]. The most common approaches include:

Lorentz-Berthelot Rules: Used in CHARMM and AMBER force fields:

[ \sigma{ij} = \frac{\sigma{ii} + \sigma{jj}}{2}, \quad \epsilon{ij} = \sqrt{\epsilon{ii}\epsilon{jj}} ]

Geometric Mean Rules: Used in GROMOS and OPLS force fields:

[ \sigma{ij} = \sqrt{\sigma{ii}\sigma{jj}}, \quad \epsilon{ij} = \sqrt{\epsilon{ii}\epsilon{jj}} ]

Non-bonded interactions are typically evaluated using a cut-off scheme to maintain computational efficiency, with long-range electrostatic interactions treated using Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) methods [16].

Diagram 1: Hierarchical organization of force field energy components showing bonded and non-bonded interaction categories.

Integration of Components in MD Workflow

The three components—initial conditions, topology, and force field—work together in a coordinated manner throughout the MD simulation workflow. Understanding their integration is essential for proper simulation design and execution.

System Setup Protocol

A typical MD workflow integrates the three key components systematically:

Structure Preparation: Initial atomic coordinates are obtained from experimental data or molecular modeling, establishing the initial conditions.

Topology Generation: The molecular structure is analyzed to define bonding patterns, residue organization, and molecular connectivity.

Force Field Assignment: Appropriate parameters are assigned to all interactions based on atom types and connectivity.

System Assembly: The solute is placed in a simulation box, solvated, and ionized to create the complete simulation environment.

Energy Minimization: The system is relaxed to remove steric clashes and prepare for dynamics.

Equilibration: The system is gradually brought to the target temperature and pressure while maintaining appropriate constraints.

Production Simulation: Unconstrained data collection for analysis of structural and dynamic properties.

Diagram 2: Sequential workflow for molecular dynamics system setup showing how initial conditions, force field, and topology integrate to produce a simulation-ready system.

Practical Considerations for Researchers

When designing MD simulations, researchers should consider several practical aspects:

Consistency Between Components: Ensure that the force field parameters match the atom types and bonding patterns defined in the topology, and that the initial coordinates are chemically plausible for the chosen force field [15].

Temperature and Pressure Control: Implement appropriate thermostats and barostats during equilibration to achieve the desired ensemble conditions while maintaining Hamiltonian consistency.

Constraint Algorithms: For efficiency, consider constraining bonds involving hydrogen atoms using algorithms like SHAKE or LINCS, which allow longer integration time steps [1].

Neighbor Searching: Implement efficient pair list generation with appropriate buffering to maintain energy conservation while minimizing computational overhead [16].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for MD Simulations

| Tool/Component | Function | Examples/Formats |

|---|---|---|

| Structure visualization | Visual inspection of initial coordinates | VMD, PyMol, ChimeraX |

| Force field parameterization | Define interaction potentials | CHARMM, AMBER, GROMOS, OPLS |

| Topology builders | Generate molecular connectivity | pdb2gmx, CHARMM-GUI, tleap |

| System solvation tools | Add solvent and ions | packmol, GROMACS solvation utilities [17] |

| Energy minimization algorithms | Remove steric clashes | Steepest descent, conjugate gradient |

| Dynamics integrators | Solve equations of motion | Velocity Verlet, Leap-frog [16] [15] |

The three foundational components of a molecular dynamics system—initial conditions, topology, and force fields—work in concert to determine the physical validity and numerical stability of simulations. Initial conditions establish the starting point in phase space, topology defines the covalent structure and molecular connectivity, and force fields provide the physical model governing atomic interactions. Mastery of these components enables researchers to design simulations that accurately capture the thermodynamic and dynamic properties of molecular systems, from small drug-like compounds to complex biomolecular assemblies. As MD simulations continue to evolve with advances in polarizable force fields, enhanced sampling methods, and machine learning approaches, the proper implementation of these core elements remains essential for generating scientifically meaningful results across computational chemistry and structural biology.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool in research and development for materials, chemistry, and drug discovery, acting as a "microscope with exceptional resolution" to visualize atomic-scale dynamics [3]. The accuracy of these simulations is fundamentally dependent on the force field—a mathematical model that calculates the potential energy of a system of atoms and molecules based on their positions [3]. The choice of force field introduces a bias that can significantly influence simulation outcomes, making its selection a critical step [19]. This guide explores the core principles of force fields and provides a comparative analysis of three widely used families: AMBER, CHARMM, and GROMOS, within the context of a standard MD workflow.

Force Field Fundamentals

At its core, a force field describes the potential energy of a molecular system as a function of its nuclear coordinates. This energy is typically partitioned into several terms that capture different types of atomic interactions:

- Bonded Interactions: These describe the energy associated with the covalent bond structure of the molecule, including bond stretching, angle bending, and dihedral torsions.

- Non-bonded Interactions: These describe interactions between atoms that are not directly bonded, primarily consisting of van der Waals forces (modeled with a Lennard-Jones potential) and electrostatic interactions (described by Coulomb's law).

The parameters for these equations—such as equilibrium bond lengths, force constants, and partial atomic charges—are derived from a combination of quantum mechanical calculations and experimental data. The fidelity of a force field in representing a real molecular system hinges on the accuracy and breadth of its parameterization.

Comparative Analysis of AMBER, CHARMM, and GROMOS

A comparative study on the Aβ21-30 peptide fragment highlighted the significant bias that different force fields can introduce. While measures like the radius of gyration were similar across force fields, secondary structure content and hydrogen-bonding patterns varied considerably [19].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, performance, and recommended use cases for AMBER, CHARMM, and GROMOS force fields.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of AMBER, CHARMM, and GROMOS Force Fields

| Feature | AMBER | CHARMM | GROMOS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Name | Assisted Model Building with Energy Refinement | Chemistry at HARvard Macromolecular Mechanics | GROningen MOlecular Simulation |

| Common Biomolecular Applications | Proteins, Nucleic Acids [19] | Proteins, Lipids, Carbohydrates [19] | Proteins, Carbohydrates [19] |

| Typical Water Models | TIP3P, TIP4P [19] | TIP3P, TIP4P [19] | SPC [19] |

| Performance on Aβ21-30 (Helical Content) | High helical content and variety of intrapeptide H-bonds [19] | Readily increases helical content (CHARMM27-CMAP) [19] | Suppresses helical structure (GROMOS53A6) [19] |

| Recommended Use Case (Based on Aβ21-30 study) | Systems where helical content is desirable [19] | Systems where helical content is desirable [19] | Better choice for modeling Aβ21-30, as it suppresses unrealistic helix formation [19] |

Integrating Force Fields into the Molecular Dynamics Workflow

The force field is the computational engine at the heart of the MD simulation workflow. Its selection directly impacts the results at every stage, from system preparation to trajectory analysis.

The Molecular Dynamics Workflow

The following diagram outlines the standard MD workflow, highlighting the critical role of the force field.

Detailed Workflow and Protocols

Prepare Initial Structure: The process begins with obtaining or building the initial atomic coordinates of the target system. Sources include the Protein Data Bank for biomolecules, the Materials Project for crystals, or PubChem for small molecules [3]. The structure must be carefully checked and prepared, as its quality directly impacts simulation reliability.

Initialize Simulation System: The initial structure is solvated in a water box, ions are added to neutralize the system's charge or achieve a specific ionic concentration, and the system is energy-minimized to remove bad contacts. Initial atomic velocities are assigned from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution corresponding to the desired simulation temperature [3].

Force Calculation from Interatomic Potential: This is the most computationally intensive step, where the chosen force field calculates the potential energy and forces for the entire system. The selection of AMBER, CHARMM, or GROMOS here is critical, as it determines the physical behavior of the system [19] [3]. Modern simulations often use spatial decomposition and GPU acceleration for efficiency [3].

Time Integration and Trajectory Generation: Forces are used to numerically integrate Newton's equations of motion. Algorithms like Verlet or leap-frog are commonly used for their stability and energy conservation properties [3]. A time step of 0.5–1.0 femtoseconds is typical, and this cycle of force calculation and integration is repeated millions of times to generate a trajectory [3].

Trajectory Analysis: The raw trajectory—a time-series of atomic coordinates and velocities—is analyzed to extract meaningful insights. Key analyses include [3]:

- Radial Distribution Function (RDF): To quantify structural features and coordination shells.

- Mean Square Displacement (MSD): To calculate diffusion coefficients and particle mobility.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): To identify essential collective motions from complex dynamics.

- Stress-Strain Calculations: To evaluate mechanical properties like Young's modulus.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Force Fields (AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS) | Provides the set of parameters and functions to calculate the potential energy and forces in a molecular system. |

| Water Models (TIP3P, TIP4P, SPC/E) | Represents water molecules in the simulation; different models can affect simulation outcome [19]. |

| MD Software (AMS, GROMACS, NAMD, OpenMM) | The simulation engine that performs the numerical integration and manages the simulation process [17] [20]. |

| System Building Tools (packmol) | Used to build the initial simulation system, including solvation and ion placement [17]. |

| Reference Quantum Mechanics Engines (ADF, BAND) | Provides high-accuracy data for parameterizing force fields or training machine-learning potentials in advanced workflows [20]. |

| Trajectory Analysis Tools | Software and scripts (e.g., in Python, VMD, CPPTRAJ) to process MD trajectories and compute physical properties [3]. |

Emerging Trends and Machine Learning Potentials

A significant advancement is the use of Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials. MLIPs are trained on large datasets from quantum chemistry calculations and can predict atomic energies and forces with high accuracy and efficiency, enabling simulations of complex systems that were previously prohibitive [3]. Furthermore, Active Learning workflows are now being implemented. These workflows automatically run MD, pause to launch new reference calculations, retrain the ML potential, and then continue the simulation, ensuring its accuracy on-the-fly [20].

The choice of a force field is a foundational decision that critically influences the results and interpretation of molecular dynamics simulations. As demonstrated, force fields like AMBER, CHARMM, and GROMOS can exhibit distinct biases, for instance, in the secondary structure propensity of peptides. Therefore, researchers must carefully select a force field that is appropriate for their specific system, often guided by previous validation studies. The ongoing integration of machine learning promises to further enhance the accuracy and scope of these simulations, solidifying the critical role of force fields in computational discovery.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a transformative tool in biomedical research, functioning as a "computational microscope" that provides atomic-level resolution into the dynamic processes governing life itself [3]. These simulations enable researchers to track the temporal evolution of biological systems, from the folding of proteins to the precise molecular interactions that occur when a drug binds to its receptor. The integration of MD with experimental methods has created a powerful paradigm for rational drug design, allowing scientists to move beyond static structural snapshots to understand the critical role of dynamics in biological function and therapeutic intervention [21]. This technical guide examines the core principles, methodologies, and applications of MD within biomedical research, with a particular focus on its growing impact on drug discovery and development processes.

Fundamental MD Workflow in Biomedical Research

The execution of a molecular dynamics simulation follows a systematic workflow that transforms a static molecular structure into a dynamic trajectory rich with thermodynamic and kinetic information [3].

The standard MD protocol comprises several sequential stages, each with specific objectives and technical requirements. Figure 1 illustrates this generalized workflow for a typical biomedical simulation.

Figure 1. Generalized MD Workflow for Biomedical Research. This diagram outlines the sequential stages of a molecular dynamics simulation, from initial structure preparation to final biological interpretation.

Initial Structure Preparation and System Building

The foundation of any reliable MD simulation is an accurate initial atomic structure. For biomedical applications, these structures are typically sourced from:

- Protein Data Bank (PDB): The primary repository for experimentally determined protein structures via X-ray crystallography, NMR, or cryo-EM [3].

- AlphaFold2 Predictions: AI-predicted protein structures with remarkable accuracy, particularly valuable for targets without experimental structures [22].

- PubChem/ChEMBL: Databases containing small molecule structures for drug-like compounds [3].

Structure preparation involves adding missing atoms (particularly hydrogens), assigning protonation states, and ensuring proper assignment of histidine tautomers. For protein-ligand systems, careful parameterization of the small molecule is essential, using tools such as CGenFF for CHARMM force fields or GAAMP for AMBER force fields [3].

System Setup and Equilibration Protocols

Once the molecular structure is prepared, it must be embedded in a biologically relevant environment:

- Solvation: Placement in a water box (e.g., TIP3P, TIP4P water models) with a minimum 10-12 Å buffer between the solute and box edge.

- Neutralization: Addition of counterions (e.g., Na+, Cl-) to achieve system electroneutrality.

- Physiological Conditions: Further addition of ions to approximate physiological concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).

The system then undergoes energy minimization (typically 5,000-10,000 steps) using steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithms to remove steric clashes, followed by a two-stage equilibration [3]:

- NVT Ensemble: Constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature for 100-500 ps to stabilize temperature.

- NPT Ensemble: Constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature for 1-5 ns to stabilize density.

Production Simulation and Trajectory Analysis

Production simulations employ an integration time step of 0.5-2.0 femtoseconds, with trajectory frames typically saved every 10-100 ps for analysis [17] [3]. Long-range electrostatics are handled using Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) methods, and temperature/pressure are maintained using thermostats (e.g., Berendsen, Nosé-Hoover) and barostats (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman). The resulting trajectory data is analyzed using both built-in and external analysis tools to extract biologically relevant information, as detailed in Section 4.

Key Biomedical Applications

Advanced Drug Delivery System Optimization

MD simulations provide critical insights into the molecular-level interactions between drug compounds and their carrier systems, enabling rational design of delivery platforms with optimized properties [21]. Table 1 summarizes key nanocarrier systems studied using MD simulations.

Table 1: MD Applications in Drug Delivery System Design

| Delivery System | Key Advantages | MD Simulation Insights | Representative Drugs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes (FCNTs) | High drug-loading capacity, stability, cellular uptake efficiency [21] | Drug-nanotube interaction energy, encapsulation stability, release kinetics | Doxorubicin, Gemcitabine [21] |

| Chitosan-based Nanoparticles | Biodegradability, reduced toxicity, mucoadhesive properties [21] | Polymer-drug binding affinity, degradation behavior, controlled release mechanisms | Paclitaxel, protein therapeutics [21] |

| Human Serum Albumin (HSA) Carriers | Natural biocompatibility, long circulation half-life, tumor targeting [21] | Drug-binding site interactions, allosteric effects on carrier structure | Anticancer agents, antiviral drugs [21] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Tunable porosity, high surface area, surface functionalization [21] | Host-guest chemistry, diffusion pathways through porous structures | Chemotherapeutic agents [21] |

Protein-Ligand Binding and Interaction Analysis

Understanding the structural basis and energetics of drug-receptor interactions represents one of the most significant applications of MD in drug discovery. The DeepICL framework exemplifies how MD can be leveraged for interaction-guided drug design by incorporating universal patterns of protein-ligand interactions—hydrogen bonds, salt bridges, hydrophobic interactions, and π-π stackings—as prior knowledge to enhance generalizability, even with limited experimental data [23]. This approach enables researchers to:

- Identify Interaction Hot Spots: Map key interaction sites within binding pockets that contribute significantly to binding affinity [23].

- Assess Binding Pose Stability: Monitor the stability of docked poses over simulation time to discriminate between correct and incorrect binding modes.

- Calculate Binding Free Energies: Employ advanced sampling methods (e.g., Free Energy Perturbation, Thermodynamic Integration) to quantitatively predict binding affinities [22].

- Guide Molecular Optimization: Use interaction fingerprints to inform structural modifications that enhance potency and selectivity [23].

Enhanced Sampling for Rare Events

Conventional MD simulations may be insufficient to observe biologically relevant rare events (e.g., ligand unbinding, large conformational changes) within practical computational timescales. Enhanced sampling methods address this limitation:

- Metadynamics: Uses a history-dependent bias potential to discourage revisiting of previously sampled configurations, effectively accelerating escape from local minima.

- Umbrella Sampling: Applies harmonic restraints along a predetermined reaction coordinate to efficiently sample high-energy regions and reconstruct free energy profiles.

- Replica Exchange MD: Simultaneously runs multiple simulations at different temperatures or Hamiltonian parameters, allowing exchanges between replicas to overcome energy barriers.

Analysis Methods for Biomedical Insights

The raw trajectory data generated by MD simulations must be processed through appropriate analytical methods to extract biologically meaningful information.

Structural and Energetic Analysis

Radial Distribution Function (RDF) The RDF, denoted as g(r), quantifies how particle density varies as a function of distance from a reference particle [3]. For biomedical applications, RDF analysis can reveal:

- Solvation shells around drug molecules or protein surfaces

- Ion distribution around DNA, RNA, or membrane surfaces

- Local ordering in amorphous drug formulations The coordination number, obtained by integrating the RDF, provides quantitative information about binding stoichiometry and solvation [3].

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) PCA identifies collective motions in biomolecules by diagonalizing the covariance matrix of atomic positional fluctuations [3]. This method:

- Reduces high-dimensional trajectory data to a few essential dynamics modes

- Identifies functionally relevant domain motions in proteins

- Distinguishes between different conformational states

- Can be combined with clustering to identify metastable states and construct free energy landscapes [3]

Kinetic and Thermodynamic Properties

Mean Square Displacement (MSD) and Diffusion The MSD measures the average squared displacement of particles over time and is used to calculate diffusion coefficients through the Einstein relation: D = lim(t→∞) ⟨MSD(t)⟩/6t for 3D diffusion [3]. This analysis provides insights into:

- Drug mobility in delivery matrices and through biological barriers

- Water and ion diffusion in protein channels and pores

- Molecular mobility in amorphous solid dispersions

Free Energy Calculations Free energy landscapes provide comprehensive descriptions of biomolecular stability and transitions. These landscapes are constructed using:

- Umbrella Sampling along carefully chosen reaction coordinates

- Metadynamics for exploring multidimensional free energy surfaces

- Markov State Models (MSMs) to infer kinetics and thermodynamics from many short simulations

Interaction Analysis

Protein-Ligand Interaction Fingerprints Interaction fingerprints provide a concise representation of specific contacts between a drug and its target over the simulation trajectory. These include:

- Hydrogen bonds (distance and angle criteria)

- Hydrophobic contacts

- π-π stacking and cation-π interactions

- Ionic interactions/salt bridges Monitoring the persistence and dynamics of these interactions helps explain structure-activity relationships and guide molecular optimization [23].

Reactive MD for Reaction Discovery

Specialized non-equilibrium MD methods have been developed to promote chemical reactions and explore reaction networks, with significant implications for drug metabolism studies and prodrug design.

Nanoreactor and Lattice Deformation Methods

The Reactions Discovery tool implements two primary approaches for accelerating chemical reactivity [17]:

Nanoreactor MD This method employs cyclic compression and diffusion phases to drive reactive events [17]:

- Compression Phases: Apply inward acceleration with high force constants (0.01 Ha/bohr²) to promote molecular encounters

- Diffusion Phases: Allow system evolution at controlled temperature (default 500 K) with lower constraints

- Cyclic Protocol: Typically runs 10+ cycles to sample diverse reaction pathways [17]

Lattice Deformation MD Applicable to periodic systems, this method oscillates the simulation cell volume between initial and compressed states (MinVolumeFraction typically 0.3-0.6) with defined periodicity (default 100 fs) [17]. The resulting pressure and density fluctuations create conditions conducive to chemical reactions.

Table 2 compares the key parameters for these reactive MD methods.

Table 2: Reactive MD Method Parameters for Reaction Discovery

| Parameter | Nanoreactor MD | Lattice Deformation MD |

|---|---|---|

| System Requirements | No periodic boundary conditions [17] | Requires 3D-periodic system [17] |

| Compression | Spherical boundary with increasing force constant [17] | Volume oscillation between V₀ and V₀×MinVolumeFraction [17] |

| Key Parameters | DiffusionTime (default 250 fs), MinVolumeFraction (default 0.6), Temperature (default 500 K) [17] | MinVolumeFraction (default 0.3), Period (default 100 fs), Temperature (default 500 K) [17] |

| Typical Applications | Reaction discovery in molecular clusters, solution chemistry [17] | Solid-state reactions, materials under mechanical stress [17] |

| Number of Cycles | NumCycles (default 10) [17] | NumCycles (default 10) [17] |

Workflow for Reactive MD

The implementation of reactive MD follows a specialized workflow, particularly for the Nanoreactor approach, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Reactive MD Workflow for Chemical Reaction Discovery. This diagram illustrates the cyclic process of compression and diffusion phases used in Nanoreactor MD simulations to promote and identify chemical reactions.

Table 3 provides a comprehensive overview of essential tools, databases, and platforms for conducting MD simulations in biomedical research.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Biomedical MD Simulations

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | AMS (SCM), GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER, OpenMM, CHARMM | MD simulation engines with varying force fields and accelerated sampling methods | General biomolecular simulation, enhanced sampling, free energy calculations [17] [24] |

| Force Fields | CHARMM36, AMBER (ff14SB, GAFF), OPLS-AA, CGenFF | Mathematical representation of interatomic potentials and interactions | Protein, nucleic acid, lipid, and small molecule parameterization [3] |

| Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB), AlphaFold Database, PubChem, ChEMBL | Sources of initial atomic coordinates for proteins and small molecules | Structure acquisition, model building, system setup [22] [3] |

| Analysis Tools | MDTraj, MDAnalysis, VMD, PyMOL, PLIP (Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler) [23] | Trajectory analysis, visualization, and interaction mapping | Structural analysis, dynamics quantification, interaction fingerprinting [23] [3] |

| Specialized Platforms | DeepICL (Interaction-aware generative model) [23] | 3D molecular generation conditioned on protein-ligand interactions | De novo ligand design, interaction-guided molecular optimization [23] |

| Machine Learning Potentials | MLIPs (Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials) | High-accuracy force prediction using ML models trained on quantum chemistry data | Accurate simulation of reactive processes and complex materials [3] |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of molecular dynamics continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends poised to expand its impact on biomedical research:

Integration with Artificial Intelligence Machine learning approaches are transforming multiple aspects of MD simulations. MLIPs enable quantum-mechanical accuracy at classical MD costs, while generative models like DeepICL create novel molecular structures optimized for specific interaction patterns [23] [3]. AlphaFold2 has revolutionized initial structure prediction, making high-quality protein models accessible for virtually any target of biomedical interest [22].

Enhanced Sampling and High-Performance Computing Advances in both algorithms and hardware continue to push the boundaries of accessible timescales and system sizes. Specialized processors (e.g., GPUs, TPUs) combined with increasingly sophisticated enhanced sampling methods enable the simulation of biologically relevant timescales (microseconds to milliseconds) for complex systems, including full viral capsids and molecular crowded cellular environments [21].

Multi-scale Modeling Frameworks Future developments will focus on integrating MD with coarse-grained models and systems biology approaches to connect molecular-level events with cellular phenotypes. This hierarchical modeling paradigm will provide a more comprehensive understanding of how drug interactions at atomic scale translate to physiological effects.

As these technical capabilities mature, MD simulations will become increasingly central to drug discovery pipelines, providing unprecedented insights into the dynamic interplay between therapeutic compounds and their biological targets. The continued integration of MD with experimental validation creates a powerful feedback loop that accelerates the development of more effective and targeted therapies for human disease.

Executing MD Simulations: Traditional and AI-Enhanced Workflows in Practice

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide a powerful computational microscope for investigating atomic-scale processes in materials science, drug discovery, and biosciences [3]. The reliability of any MD simulation hinges on the careful construction of the molecular system and the precise configuration of simulation parameters. This technical guide details the critical stages of initial system setup, equilibration protocols, and parameter tuning, framed within the broader context of molecular dynamics workflow research for scientific and pharmaceutical applications.

Initial System Setup

Structure Preparation and Modeling

The foundation of a successful MD simulation is a high-quality initial atomic structure. Researchers typically source initial configurations from experimental databases or de novo modeling.

- Database Sourcing: Experimentally resolved structures are available from repositories like the Protein Data Bank for biomolecules, the Materials Project for crystalline materials, and PubChem or ChEMBL for small organic molecules [3].

- Structure Completion and Validation: Database structures often require completion of missing atoms or regions using molecular modeling tools. Emerging generative AI technologies, such as AlphaFold2, can predict molecular and material structures, though expert assessment remains crucial to verify physical and chemical plausibility [3].

- System Assembly: For complex systems such as protein-ligand complexes, structures must be assembled and oriented correctly within the simulation box. For the simulation of viral helicases, such as SARS-CoV-2 NSP13, this entails preparing the protein structure in its apo form or complexed with inhibitors like CID4 [25].

Simulation Box and Solvation

After preparing the molecular structure, the subsequent steps involve placing it in a realistic environment, which is essential for modeling physiological or specific experimental conditions.

- Box Type Selection: The choice of simulation box (e.g., cubic, rhombic dodecahedron) affects computational efficiency and the accuracy of simulating isotropic conditions.

- Solvent Addition: Explicit solvent molecules, typically water models like SPC/E or TIP3P, are added to fill the box. The minimum distance between the solute and the box edge should exceed the non-bonded interaction cutoff.

- Ion Addition: Ions are added to neutralize the system's net charge and to achieve a physiologically relevant ionic concentration, such as 150 mM NaCl.

Energy Minimization

Energy minimization relieves steric clashes and unfavorable geometric strain introduced during the system preparation stage.

- Objective: The primary goal is to find the nearest local energy minimum by adjusting atomic coordinates, which prevents system instability when dynamics commence.

- Algorithm Selection: The GROMACS

mdpoptions include several algorithms [26]:- Steepest descent (

integrator=steep): Robust for initially highly distorted structures. - Conjugate gradient (

integrator=cg): More efficient for later minimization stages. - L-BFGS (

integrator=l-bfgs): A quasi-Newtonian method that often converges faster than conjugate gradients.

- Steepest descent (

Table 1: Key Parameters for Energy Minimization

| Parameter | mdp Option |

Typical Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrator | integrator |

steep or cg |

Minimization algorithm |

| Force Tolerance | emtol |

100-1000 kJ/mol/nm | Convergence criterion |

| Maximum Step Size | emstep |

0.01 nm | Initial step size (steepest descents) |

| Number of Steps | nsteps |

-1 (no max) or a high number | Maximum minimization steps |

System Equilibration

Equilibration brings the system to the desired thermodynamic state (temperature and pressure) through a series of carefully controlled simulation phases.

Equilibration Workflow

A typical equilibration protocol consists of sequential steps to gradually relax the system.

Diagram 1: System Equilibration Workflow

NVT Equilibration (Constant Number, Volume, and Temperature)

The NVT ensemble, also termed the isothermal-isochoric ensemble, stabilizes system temperature.

- Goal: To allow atomic velocities to equilibrate to a Boltzmann distribution at the target temperature (e.g., 300 K).

- Thermostat Choices: Common thermostats include:

- Berendsen: Provides weak coupling for initial heating but does not produce a correct ensemble.

- Nosé-Hoover: Generates a canonical ensemble, suitable for production equilibration.

- Velocity Rescale: An improved thermostat that yields the correct kinetic energy distribution [26].

- Duration: Typically 50-100 ps. Monitor temperature stability and potential energy drift.

NPT Equilibration (Constant Number, Pressure, and Temperature)

The NPT ensemble, also termed the isothermal-isobaric ensemble, allows the simulation box size to adjust to reach the correct density.

- Goal: To achieve the experimental density for the simulated conditions.

- Barostat Choices:

- Berendsen: Efficiently scales the box to reach target pressure but may cause "dead leaves" effect.

- Parrinello-Rahman: A more responsive barostat that generates a correct isobaric ensemble, recommended for production simulation.

- Duration: Typically 100-200 ps, or until density plateaus. For the SAMSON GROMACS Wizard, ensuring temperature and pressure coupling values remain consistent with the NVT and NPT equilibration steps is crucial [27].

Table 2: Equilibration Parameters in GROMACS

| Parameter | mdp Option |

NVT Value | NPT Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrator | integrator |

md |

md |

Leap-frog integrator |

| Temperature | ref-t |

Target (e.g., 300 K) | Target (e.g., 300 K) | Reference temperature |

| Thermostat | tcoupl |

v-rescale |

v-rescale |

Temperature coupling |

| Tau-T | tau-t |

0.1-1.0 ps | 0.1-1.0 ps | Thermostat time constant |

| Pressure | pcoupl |

no |

Parrinello-Rahman |

Pressure coupling |

| Ref Pressure | ref-p |

- | 1.0 bar | Reference pressure |

| Tau-P | tau-p |

- | 1.0-5.0 ps | Barostat time constant |

| Duration | nsteps |

25,000-50,000 | 50,000-100,000 | For dt=2 fs |

Production Parameter Tuning

Following equilibration, production simulation parameters are configured to balance computational efficiency with physical accuracy.

Integrator and Time Step

The numerical integrator and time step are pivotal for simulation stability and accuracy.

- Integration Algorithms [26]:

- Leap-frog (

integrator=md): The default and most widely used algorithm in packages like GROMACS, offering a good balance of efficiency and stability. - Velocity Verlet (

integrator=md-vv): A more accurate, symmetric integrator, beneficial for advanced thermodynamic coupling schemes.

- Leap-frog (

- Time Step (

dt): Governs the interval between force evaluations.

Non-Bonded Interactions

The treatment of non-bonded interactions constitutes the major computational cost in MD simulations.

- Short-Range Cutoffs: A cutoff of 1.0-1.2 nm is typical for Van der Waals interactions. Electrostatic short-range interactions use the same cutoff within particle mesh Ewald.

- Long-Range Electrostatics: The Particle Mesh Ewald method is the standard for accurate calculation of long-range electrostatic interactions in periodic systems.

- Neighbor Searching: The Verlet list method is efficient, with updates (

nstlist) typically every 20 steps.

Constraint Algorithms

Constraint algorithms permit a larger integration time step by freezing the fastest bond vibrations.

- SHAKE and LINCS: These algorithms constrain bond lengths involving hydrogen atoms.

- SHAKE: The standard method, with

shake=1in xTB for constraining X-H bonds only [28]. - LINCS: Generally more accurate and efficient, particularly for constraining all bonds.

- SHAKE: The standard method, with

Table 3: Key Production MD Parameters and Typical Values

| Parameter Category | mdp Option |

Typical Value | Impact on Simulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrator | integrator |

md (leap-frog) |

Balance of stability/speed |

| Time Step | dt |

0.002 ps (2 fs) | Limits maximum frequency |

| Temperature Coupling | tcoupl |

v-rescale |

Correct canonical ensemble |

| Pressure Coupling | pcoupl |

Parrinello-Rahman |

Correct isobaric ensemble |

| vdW Cutoff | rvdw |

1.0-1.2 nm | Short-range interaction range |

| Electrostatics | coulombtype |

PME |

Accurate long-range forces |

| Constraints | constraints |

h-bonds |

Enables 2 fs time step |

| Neighbor List | nstlist |

20-40 steps | Frequency of list updates |

Simulation Control and Workflow Automation

Automated workflow platforms streamline the process of running and analyzing MD simulations, enhancing reproducibility.

- Galaxy Workflows: Automated Galaxy workflows exist for performing and analyzing atomistic MD simulations of viral helicases, enabling researchers to reproduce previous findings and apply them to new systems [25].

- SAMSON GROMACS Wizard: Simplifies parameter configuration with pre-set parameters optimized for typical runs and advanced options for finer control, reducing the risk of configuration errors [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MD Simulations

| Tool/Category | Example Software | Primary Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Engines | GROMACS [26], AMBER [25], LAMMPS [29], NAMD [30] | Core MD simulation execution | High-performance, parallel computing, various force fields |

| Force Fields | CHARMM [30], AMBER [30], GROMOS [30], OPLS-AA [30] | Define interatomic potentials | Parameter sets for different molecule types |

| Quantum Mechanics | CP2K [30], Quantum ESPRESSO [30] | Ab initio MD and force field parametrization | Electron structure calculation for accurate bonding |

| System Building | Avogadro [30], PDB Database [3], PubChem [3] | Molecular structure creation and sourcing | 3D model building, database access |

| Visualization & Analysis | VMD [30], SAMSON [27] | Trajectory visualization and analysis | Plotting, measurement, structure rendering |

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is a computational technique that predicts the time-dependent behavior of every atom in a molecular system. Often described as a "computational microscope," it provides atomic-resolution insights into dynamic processes that are frequently impossible to observe experimentally [31] [3]. The fundamental principle governing all MD methods is Newton's second law of motion, F = ma. By calculating the force (F) on each atom, the acceleration is determined, and the atomic positions and velocities are updated over a series of very short time steps, typically 0.5 to 1.0 femtoseconds [3]. This process generates a trajectory—essentially a three-dimensional movie—depicting the system's evolution over time [31]. The core differentiator between MD approaches lies in how these interatomic forces are calculated, balancing computational cost against physical accuracy. This guide provides an in-depth comparison of Classical and Ab Initio MD methods, enabling researchers to select the optimal approach for their specific investigations in materials science and drug development.

Classical Molecular Dynamics: Speed and Empiricism

Force Fields and Mathematical Foundations

Classical Molecular Dynamics (CMD), also referred to as Molecular Mechanics, utilizes empirically parameterized force fields to describe interatomic interactions [32]. These force fields decompose the total potential energy of a system (E) into a sum of bonded and non-bonded terms, each governed by simple potential functions [32].

The total energy is typically expressed as: [ E = \sum{bonds} kb(r - r0)^2 + \sum{angles} ka(a - a0)^2 + \sum{dihedrals} \frac{Vn}{2} [1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta)] + \sum{non-bonded} 4\epsilon{ij} \left[ \left(\frac{\sigma{ij}}{r{ij}}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma{ij}}{r{ij}}\right)^6 \right] + \sum{non-bonded} \frac{qi qj}{4\pi\epsilon0 r_{ij}} ]

Key energy components include [32]:

- Bonded Terms: Harmonic potentials for bond stretching (kb, r0) and angle bending (ka, a0), and a periodic cosine series for torsional dihedral angles (Vn, δ, φ).

- Non-Bonded Terms: Lennard-Jones potential for van der Waals interactions (εij, σij) and Coulomb's law for electrostatic interactions (qi, qj).

The parameters for these terms (e.g., kb, r0, ε, σ) are derived from a combination of experimental data, quantum mechanical calculations, and Monte Carlo simulations, as seen in the parameterization of the AMBER force field [32].

Methodological Workflow and Best Practices

A robust CMD simulation follows a structured workflow to ensure reliable and reproducible results [3].

Critical steps in the CMD workflow include:

- Initial Structure Preparation: Atomic coordinates are sourced from experimental databases like the Protein Data Bank or the Materials Project [3]. Missing atoms or regions must be modeled and completed.

- Force Field Selection: Choosing an appropriate force field is paramount. Parameters may require system-specific optimization [33].

- System Initialization: The simulation box is constructed with solvation, ions for neutrality, and periodic boundary conditions. Atoms are assigned initial velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution corresponding to the target temperature [3].