Strategies for Reducing Computational Cost of Long MD Simulations: Machine Learning and Hardware Advances

Long-timescale molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are crucial for studying biomolecular processes and materials science but are often limited by prohibitive computational costs.

Strategies for Reducing Computational Cost of Long MD Simulations: Machine Learning and Hardware Advances

Abstract

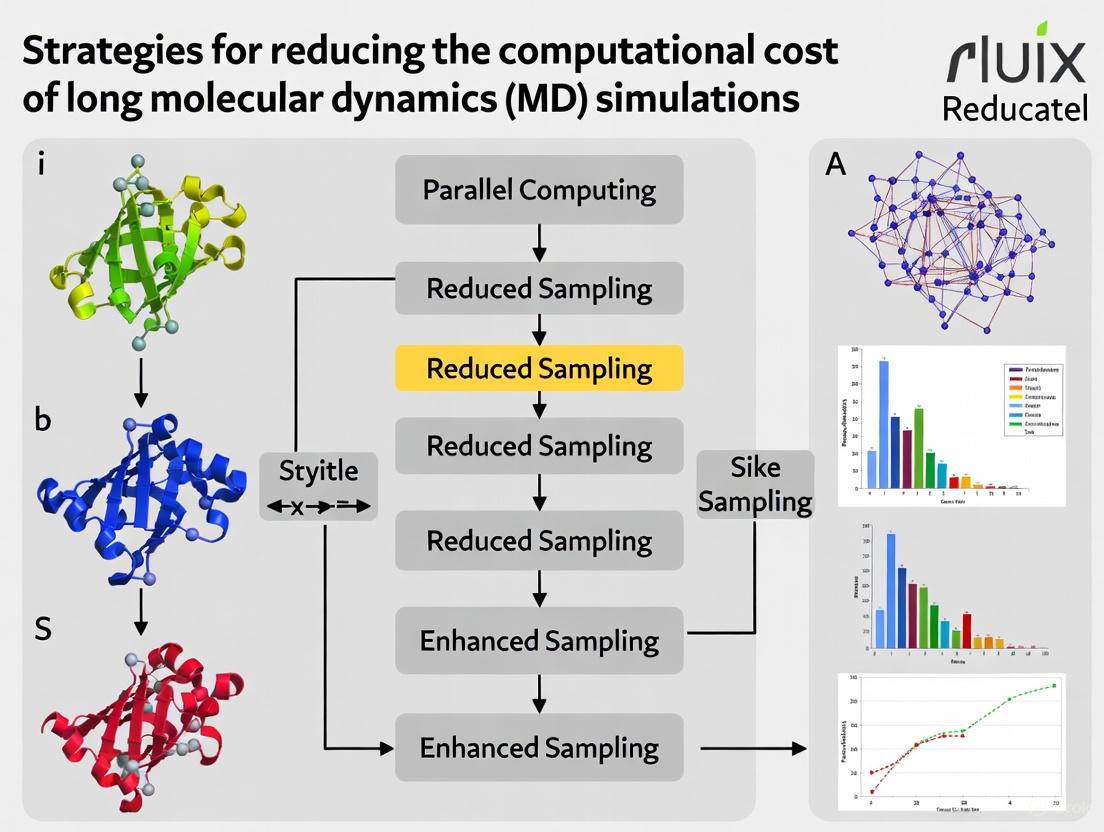

Long-timescale molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are crucial for studying biomolecular processes and materials science but are often limited by prohibitive computational costs. This article provides a comprehensive overview of strategies to overcome this barrier, covering foundational concepts, cutting-edge machine learning methods like neural network potentials and long-stride prediction, practical hardware optimization for CPUs and GPUs, and essential validation techniques. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes recent advances to enable more efficient and accessible long-scale MD simulations for biomedical discovery.

Understanding the Computational Bottleneck in Molecular Dynamics

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, researchers perpetually navigate a fundamental trade-off: the pursuit of high accuracy in results versus the need for reasonable simulation speed. This balance is crucial, as MD simulations predict how every atom in a molecular system will move over time based on physics governing interatomic interactions [1]. The computational cost arises from the very nature of the method: simulations must evaluate millions of interatomic interactions over billions of time steps, each typically just a few femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ seconds), to capture biologically relevant processes that occur on microsecond or millisecond timescales [1]. This article explores practical strategies for managing this trade-off, providing a technical support framework to help researchers optimize their MD workflows within the broader context of reducing computational costs for long-timescale simulations.

Understanding the Trade-Off: Key Concepts and Terminology

What Governs Accuracy and Speed?

The accuracy and speed of an MD simulation are influenced by several interconnected factors:

- Force Field Accuracy: The molecular mechanics force field calculates forces between atoms. While inherently approximate, these force fields have improved substantially but remain a primary source of uncertainty [1].

- Spatial Discretization: The system size and boundary conditions must be carefully chosen to balance representativeness with computational load.

- Temporal Resolution: The simulation time step must be short enough (typically 0.5-2.0 femtoseconds) to accurately capture the fastest atomic motions, particularly bond vibrations involving hydrogen atoms [2].

- Sampling Adequacy: Sufficient conformational sampling is needed to obtain statistically meaningful results, which can require prohibitively long simulation times for complex biomolecular processes.

Understanding potential error sources helps prioritize accuracy considerations:

- Modeling Error: Arises from incomplete description of underlying physics [3]

- Discretization Error: Stems from the finite representation of continuous equations [3]

- Truncation Error: Results from neglected higher-order terms during discretization [3]

- Iterative Error: Emerges from incomplete convergence of iterative procedures [3]

- Round-off Error: Accumulates from finite-precision arithmetic in computations [3]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How can I estimate how long my MD simulation will take?

Answer: The most reliable approach is to perform a short benchmarking run. As one expert advises: "Reduce the amount of dynamics that you simulate from 10ns to say a several hundred picoseconds thereby reducing the computational time required. This way, you can achieve a very small calculation, at the end of which, you would see the computational speed prediction from the MD software (usually in the form of hours/ns or ns/day)" [4].

GROMACS-Specific Protocol:

- Use the

-maxhoption withgmx mdrunto run for a fixed wall time (e.g., 1 hour) - Multiply the resulting simulation length by 24 to estimate ns/day performance

- Use this metric to project total simulation time for your production run

- Note that performance can vary between runs, so include a safety margin [4]

FAQ 2: What are the most effective strategies to reduce computational cost without sacrificing essential accuracy?

Answer: Consider these tiered approaches:

Table: Computational Cost-Reduction Strategies

| Strategy | Implementation | Computational Saving | Accuracy Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning Potentials | Multi-fidelity Physics-Informed Neural Networks (MPINN) | 50-90% reduction [5] | Errors <3% compared to full MD [5] |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | Bias potentials, replica exchange, metadynamics | Dramatically improves sampling efficiency [6] | Preserves physical accuracy when properly implemented |

| Hardware Optimization | GPU acceleration vs. CPU implementation | ~30x speedup for equivariant MPNNs [7] | No inherent accuracy loss |

| System Size Minimization | Implicit solvent, strategic truncation | Scaling with atom count reduction | Requires validation for specific application |

FAQ 3: How does the choice between invariant and equivariant models affect the speed-accuracy trade-off?

Answer: Equivariant models incorporate directional information (beyond just pairwise distances) to capture interactions depending on the relative orientation of neighboring atoms. This allows them to "discriminate interactions that can appear inseparable to simpler models" and learn more transferable interaction patterns [7]. However, this comes at a computational cost: "SO(3) convolutions scale as l_max⁶, which can increase the prediction time per conformation by up to two orders of magnitude compared to an invariant model" [7]. Emerging architectures like SO3krates aim to overcome this limitation by "combining sparse equivariant representations with a self-attention mechanism that separates invariant and equivariant information, eliminating the need for expensive tensor products" [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Multi-Fidelity Physics-Informed Neural Network (MPINN) Workflow

This approach combines limited high-fidelity MD simulations with more numerous low-fidelity simulations to reduce computational costs by 50-90% while maintaining errors below 3% [5].

Detailed Protocol:

High-Fidelity Data Generation:

- Perform conventional MD simulations with full relaxation to equilibrium

- Use appropriate ensembles (NVT or NPT) with complete relaxation procedures

- Ensure system energy stabilization before production runs

- Export system energy, radial distribution functions, and ion density distributions

Low-Fidelity Data Generation:

- Run MD simulations without relaxation procedures

- Use identical temperature and concentration conditions as high-fidelity runs

- Note: Relaxation can consume "up to half of the total simulation time in a molecular dynamics simulation" [5]

Neural Network Training:

- Input variables: ambient temperature and NaCl concentration

- Output variables: system energy, Na-O radial distribution function, Na⁺ and Cl⁻ ion density distributions

- Train MPINN using both low-fidelity (without relaxation) and high-fidelity (with relaxation) datasets

- Validate prediction accuracy against held-out high-fidelity data

Production Prediction:

- Use trained MPINN to predict system behavior for new conditions

- Eliminates need for additional expensive relaxation procedures

Multi-Fidelity Neural Network Training Workflow

Benchmarking and Performance Optimization Protocol

System Configuration Analysis:

Hardware Selection Testing:

- Compare GPU vs. CPU performance for your specific system size

- Test different core counts to identify optimal parallelization (more cores isn't always faster due to communication overhead) [4]

- Consider specialized hardware (e.g., Google TPUs) for ML-enhanced approaches

Software-Specific Optimization:

- For GROMACS: Use built-in performance optimization tools

- Adjust neighbor searching frequency and cutoff parameters

- Optimize file I/O frequency to reduce writing overhead

- Test different ensemble implementations (NVE often faster than NPT) [4]

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

Table: Essential Computational Tools for MD Simulations

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER, OpenMM | Core MD simulation engines with varying optimization characteristics |

| Machine Learning Potentials | SO3krates, MPINN, NequIP | Accelerate force calculations while maintaining accuracy [5] [7] |

| Enhanced Sampling | Plumed, MetaDynamics | Improve conformational sampling efficiency [6] |

| Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB), Materials Project, PubChem | Source initial structures for simulations [2] |

| Analysis Tools | MDTraj, MDAnalysis, VMD | Process trajectory data and calculate observables |

Advanced Strategies: Machine Learning Approaches

Machine-Learned Force Fields (MLFFs)

Traditional MLFF development has focused on achieving low test errors, but "recent research indicates that there is only a weak correlation between MLFF test errors and their performance in long-timescale MD simulations, which is considered the true measure of predictive usefulness" [7]. Key considerations include:

- Equivariant Representations: Provide "better data efficiencies than invariant models" and enable "discrimination of interactions that can appear inseparable to simpler models" [7]

- Architecture Efficiency: New architectures like SO3krates demonstrate "stable MD simulations with a speedup of up to a factor of ~30 over equivariant MPNNs with comparable stability and accuracy" [7]

- Transferability: The ability to "detect physically-valid minima conformations which have not been part of the training data" is essential for practical applications [7]

Workflow Integration

Machine Learning Force Field Development Workflow

The fundamental trade-off between accuracy and simulation speed in MD remains a central challenge in computational chemistry and drug discovery. However, emerging approaches—particularly machine learning potentials and enhanced sampling methods—are progressively relaxing this trade-off. The key insight for researchers is to adopt a purpose-driven approach: "Researchers often strive for maximum precision in parameter settings to minimize errors, though this approach extends the computation and execution time" unnecessarily for many applications [3]. By carefully matching method selection to research questions and employing the troubleshooting strategies outlined in this guide, scientists can significantly reduce computational costs while maintaining the accuracy necessary for insightful biomolecular simulation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary computational advantage of using a Machine Learning Potential instead of running direct quantum mechanics calculations?

MLPs are fitted to reference data from accurate but computationally expensive electronic-structure methods. Their advantage does not primarily come from simplified physical models but from avoiding redundant calculations through interpolation. This allows them to stay close to the accuracy of the reference method while being orders of magnitude faster, facilitating the simulation of large systems and long time scales that are prohibitive for direct quantum methods [8] [9].

FAQ 2: My MLP is not generalizing well to new, unseen configurations in my molecular dynamics simulation. What strategies can improve its transferability?

Poor transferability often stems from a training set that does not adequately cover the chemical and structural space of your simulation. To address this:

- Implement Active Learning: Use a preliminary MLP to perform molecular dynamics. When the simulation encounters a configuration that is too different from the training set (detected by high model uncertainty), this configuration is sent for recalculation with the reference first-principles method and is used to update the MLP, making it more robust [9].

- Refine Training Data: Reduce redundancy in large initial data sets by using structural similarity analysis combined with farthest point sampling. This can create a concise, representative training set. Research has shown that potentials trained on a refined subset of 400 configurations can achieve accuracy comparable to those trained on an initial set of over 6000 configurations [10].

- Leverage Universal Models: Consider using pre-trained universal MLIPs (uMLIPs) like M3GNet, MACE, or ORB, which are trained on massive, diverse datasets encompassing the entire periodic table and multiple structural motifs, giving them a strong foundational knowledge of chemical space [11].

FAQ 3: How can I ensure the functional properties (e.g., spectral predictions) from my MLP simulations are accurate, not just the energies and forces?

Predicting functional properties accurately is an advanced challenge. The key is to use integrated ML models that are specifically designed to predict these properties beyond just the potential energy surface. While the algebraic structure of properties like NMR shieldings or electron density is different from a global energy, many modern MLPs construct the total potential as a sum of atom-centered terms, which can be adapted. Ensure that the MLP framework you choose has demonstrated capability and has been trained on data for the specific functional property you wish to calculate [9].

FAQ 4: For a project with a tight computational budget, what type of MLP offers the best balance of speed and accuracy?

Ultra-fast linear MLPs, which use effective two- and three-body potentials in a cubic B-spline basis, are an excellent choice. They are designed to be physically interpretable, sufficiently accurate for applications, as fast as the fastest traditional empirical potentials (like Morse or Lennard-Jones), and two to four orders of magnitude faster than many state-of-the-art non-linear MLPs [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Computational Cost during MLP Evaluation

Problem: The evaluation of the MLP is too slow, limiting the desired system size or simulation time. Solution: Select or develop a model with a more efficient architecture.

| Solution Strategy | Underlying Principle | Key Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Use linear models over non-linear ones. | Linear regression with spline basis is faster to train and evaluate than deep neural networks [8]. | Employ the Ultra-Fast (UF) potential using regularized linear regression with cubic B-spline basis functions for two- and three-body interactions [8]. |

| Use basis functions with compact support. | Functions that are non-zero only within a defined cutoff radius minimize unnecessary computations [8]. | Represent N-body terms using a cubic B-spline basis with compact support [8]. |

| Leverage traditional potentials as a baseline. | Use a fast semi-empirical method and a MLP only to correct the difference to a higher level of theory [9]. | Combine Density Functional Tight Binding (DFTB) with a MLP correction term [9]. |

Issue 2: Inaccurate Energy and Force Predictions

Problem: The MLP's predictions for energies and forces deviate significantly from reference quantum mechanics calculations during validation or application. Solution: Systematically verify and improve the training data and model.

| Step | Action | Details/Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Diagnose Data Coverage | Use an ensemble of models to predict on your target system. A large standard deviation in the ensemble's predictions indicates the system is outside the training data distribution [9]. |

| 2 | Refine the Training Set | Apply structural similarity analysis (e.g., using a algorithm like CUR) followed by the farthest point sampling (FPS) method to select a diverse, non-redundant subset of configurations from a larger pool of data [10]. |

| 3 | Apply Free-Energy Perturbation | For accurate thermodynamics, select uncorrelated configurations from your MLP simulation and compute the free-energy correction using the formula: Δ_ML→REF = k_B T ln M⁻¹ Σ_A^M e^(-(V_REF(A) - V_ML(A)) / k_B T) This corrects the MLP's free energies to the reference level of theory [9]. |

Issue 3: Poor Performance on Low-Dimensional Systems

Problem: A universal MLP performs well on bulk 3D materials but shows degraded accuracy for molecules (0D), nanowires (1D), or surfaces/slabs (2D). Solution: Understand model biases and select a specialist or high-performing universal model.

Background: Universal MLPs are often trained on datasets biased toward 3D crystalline structures (e.g., Materials Project). Their accuracy can systematically reduce as dimensionality decreases [11]. Recommended Action:

- Benchmark your system: Test the uMLIP on your specific low-dimensional structure. The best-performing models for geometry optimization across all dimensionalities, as of recent benchmarks, include ORB-v2, Equivariant Transformer V2 (eqV2), and the equivariant Smooth Energy Network (eSEN) [11].

- Expected Performance: State-of-the-art uMLIPs can achieve errors in atomic positions of 0.01–0.02 Å and energy errors below 10 meV/atom across all dimensionalities when using the best models [11].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Active Learning for Robust Potential Generation

This protocol ensures your MLP encounters and learns from a diverse set of atomic configurations during its development.

Diagram Title: Active Learning Cycle for MLP Training

Protocol 2: Training Data Set Refinement via Structural Similarity

This methodology reduces redundancy in large datasets, lowering computational costs without sacrificing accuracy [10].

Detailed Steps:

- Initial Data Collection: Generate a large initial set of configurations (e.g., via ab initio molecular dynamics, random structure search, or perturbation of known structures).

- Structural Featurization: Represent each atomic configuration in the set using a descriptor vector (e.g., a smooth overlap of atomic positions (SOAP) descriptor or another material structure descriptor).

- Similarity Matrix Construction: Compute the similarity (or distance) between every pair of configurations based on their feature vectors.

- Subset Selection:

- Use a structural similarity analysis algorithm (e.g., the CUR matrix decomposition) to identify and remove highly redundant configurations.

- Apply the Farthest Point Sampling (FPS) method on the remaining structures. FPS iteratively selects the configuration that is the farthest away (least similar) from all previously selected configurations, ensuring maximum diversity.

- Model Training & Validation: Train your MLP on the refined subset and validate its performance on a separate test set, comparing its accuracy to a model trained on the full dataset.

Quantitative Performance of MLP Architectures

Table 1: Comparison of Machine Learning Potential Architectures and Performance

| Model Type | Key Feature | Computational Speed | Reported Accuracy (Mean Absolute Error) | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Fast (UF) Linear MLP [8] | Cubic B-spline basis; linear regression. | As fast as classical potentials (LJ, Morse); 2-4 orders of magnitude faster than other MLPs. | Close to state-of-the-art MLPs for energies, forces, phonons, elastic constants. | Large systems & long time-scale MD. |

| High-Dimensional Neural Network Potential (HDNNP) [12] | Atom-centered symmetry functions; feed-forward neural networks. | Slower than UF potentials; faster than DFT. | High, comparable to reference DFT data. | General purpose; systems where precise nonlinear fitting is needed. |

| Universal MLPs (uMLIPs) [11] | Pre-trained on massive datasets (millions of structures). | Fast evaluation after training; training is very expensive. | Varies by model & dimensionality. Best models: <10 meV/atom energy error; 0.01-0.02 Å force/position error. | Rapid deployment across diverse chemical systems without specific training. |

Performance Across Dimensionalities

Table 2: Benchmarking Universal MLPs Across Different System Dimensionalities [11]

| Model Name (Tag) | Zero-D (0D) Molecules/Clusters | One-D (1D) Nanowires | Two-D (2D) Layers/Slabs | Three-D (3D) Bulk Materials | Overall Top Performer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORB-v2 (ORB-2) | Good | Good | Good | Excellent | (Geometry) |

| Equivariant Transformer V2 (eqV2) | Good | Good | Good | Excellent | (Geometry) |

| eSEN (eSEN) | Good | Good | Good | Excellent | (Energy & Geometry) |

| M3GNet (M3GNet) | Lower Accuracy | Lower Accuracy | Lower Accuracy | Good |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software and Model Solutions for MLP Research

| Item / Software | Function / Purpose | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| UF3 (Ultra-Fast Force Fields) [8] | Open-source Python code for generating ultra-fast linear MLPs. | Interface with VASP and LAMMPS. Focus on interpretability and speed. |

| AML (Amsterdam Modeling Suite) [12] | Commercial software suite with a dedicated MLPotential engine. | Supports various backends (AIMNet2, M3GNet); active learning with ParAMS. |

| LAMMPS [8] | Widely-used open-source molecular dynamics simulator. | Supports many MLP formats, including spline-based potentials for high efficiency. |

| Universal MLP Models (MACE, ORB, eSEN) [11] | Pre-trained, ready-to-use potentials for a wide range of elements and systems. | Saves time and resources; performance varies by dimensionality. Check benchmarks before use. |

| Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) [12] | Python library for atomistic simulations. | Serves as a calculator interface, enabling interoperability between different MLP codes and MD engines. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ: What are the primary factors that determine the computational cost of an MD simulation? The computational cost is primarily driven by three factors: the number of atoms in your system (system size), the number of time steps you need to simulate (which is determined by the physical timescale of the event you're studying and the size of each step), and the computational effort required to calculate the forces between all atoms at every step. [1] [13]

FAQ: How can I estimate how long my simulation will take to run?

The most reliable method is to perform a short benchmark run. Run your simulation for a short physical time (e.g., 100 picoseconds) and use the performance output (often reported as ns/day) to extrapolate the total time required for your full production run. [4] Most MD software, like GROMACS, provides this performance metric.

FAQ: My simulation is running slower than expected. What should I check? First, verify that you are using an appropriate number of CPU cores; adding more cores does not always speed up the simulation and can sometimes reduce performance by increasing communication overhead. [4] Second, for multi-node simulations, ensure that a high-performance interconnect like Elastic Fabric Adapter (EFA) is enabled, as its absence can cause performance to plateau with just a few nodes. [14]

FAQ: Is a larger simulation box always better for accuracy? No. While a box that is too small can introduce size effects and inaccurate results, an excessively large box needlessly increases computational cost. Research suggests that for some amorphous systems like epoxy resin, a system size of around 15,000 to 40,000 atoms can provide a good balance between statistical precision and computational efficiency. [15] The optimal size depends on your specific material and the property you are investigating.

FAQ: Why are the time steps in MD simulations so small? Time steps are typically on the order of 1-2 femtoseconds (fs) to ensure numerical stability. [1] [13] This is necessary to accurately capture the fastest vibrations in the system, which are often the bonds involving hydrogen atoms. Using a larger time step without adjustments can lead to discretization errors and simulation failure.

Performance Data and Guidelines

The tables below summarize key quantitative findings from research to help you make informed decisions about your computational setup.

Table 1: Single-Node GROMACS Performance on AWS EC2 Instances (benchPEP: 12M atoms) [14]

| Instance Type | vCPUs | Performance (ns/day) | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| c5.24xlarge | 48 | ~0.93 | Highest core count and memory channels for fastest single-node performance. |

| c5n.18xlarge | 36 | ~0.72 | Balanced option with high-frequency cores and EFA support. |

| c6gn.16xlarge | 32 | ~0.47 (ARM-based Graviton2) | Cost-effective option with good price-performance. |

Table 2: Effect of System Size on Precision and Cost for an Epoxy Resin [15]

| Number of Atoms | Simulation Cost (Relative Time) | Precision of Predicted Thermo-Mechanical Properties |

|---|---|---|

| 5,265 | Lowest | Low precision, high statistical uncertainty |

| 14,625 | Medium | Converging precision |

| 31,590 | High | Good precision |

| 36,855 | Highest | High precision, but with diminishing returns |

Table 3: Multi-Node Scaling with High-Performance Interconnects [14]

| Number of Nodes | Performance with EFA (ns/day) | Performance without EFA (ns/day) |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | ~1.8 | ~1.5 (plateau) |

| 64 | ~9.5 | ~2.0 (severe plateau) |

| 128 | ~16.0 | Not Recommended |

Experimental Protocols for Cost Optimization

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Simulation Performance and Cost

This protocol allows you to empirically determine the runtime and cost for your specific system and hardware. [4]

- Prepare Input: Set up your simulation input files for the full system and desired timescale.

- Run Short Test: Execute a short simulation (e.g., 1-10 ps of physical time). In GROMACS, you can use the

-maxhflag to limit the run to a specific wall time (e.g., 1 hour). - Extract Performance: After the run, check the output log for the performance, which is typically reported as nanoseconds per day (ns/day) or day per nanosecond (day/ns).

- Calculate Total Time: Use the performance metric to estimate the total runtime for your production simulation.

- Total Runtime (hours) = [Production Time (ns)] / [Performance (ns/day)] * 24

Protocol 2: Determining the Optimal System Size

This methodology, based on published research, outlines a systematic approach to find a system size that balances cost and precision. [15]

- Build Replicates: Construct multiple independent molecular models (replicates) for a range of system sizes (e.g., from 5,000 to 40,000 atoms).

- Cross-Linking & Equilibration: For polymeric systems, perform cross-linking and thorough equilibration using the NPT ensemble at the target temperature and pressure. The "REACTER" protocol in LAMMPS is an example for simulating cross-linking reactions. [15]

- Property Prediction: Simulate the thermal and mechanical properties of interest (e.g., density, elastic modulus, glass transition temperature) for each replicate.

- Analyze Convergence: Calculate the average and standard deviation for each property across the replicates for each system size. The optimal size is the smallest system where the standard deviation of key properties has converged to an acceptable level, indicating sufficient statistical sampling.

Protocol 3: Accelerating Simulations through Parallelization

This protocol guides the setup for running large, computationally intensive simulations across multiple compute nodes. [14]

- Cluster Setup: Use an HPC cluster management tool like AWS ParallelCluster with a scheduler (e.g., SLURM) to configure a cluster with queues of the desired instance types. [14]

- Enable EFA: Ensure that the Elastic Fabric Adapter (EFA) is enabled on all compute instances. This is critical for reducing communication overhead and achieving linear scaling across multiple nodes. [14]

- Optimize Core Configuration: Experiment with the ratio of MPI processes to OpenMP threads per node. The optimal configuration is hardware and system-size dependent and is key to maximizing performance.

- Submit Scaled Job: Submit your job to run across multiple nodes. The benchmarking data in Table 3 can serve as a reference for expected scaling behavior.

Computational Workflow and Bottlenecks

The following diagram illustrates the core MD simulation cycle and identifies where the major computational expenses originate.

Diagram: The MD Simulation Cycle and Bottlenecks

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Software and Hardware for MD Simulations

| Item | Function | Reference / Example |

|---|---|---|

| MD Software Packages | Provides the engine to perform the simulation, including force calculations, integration, and analysis. | GROMACS, [14] LAMMPS, [15] NAMD |

| Force Fields | Mathematical models that describe the potential energy of the system as a function of atomic coordinates; determines the accuracy of interatomic interactions. | CHARMM, [4] AMBER, INTERFACE Force Field (IFF) [15] |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | A collection of computers linked by a high-speed network to distribute the massive computational load of MD simulations. | AWS ParallelCluster, [14] on-premise clusters |

| Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) | Specialized hardware that dramatically accelerates the force calculations at the heart of MD, making longer and larger simulations feasible. [1] | NVIDIA GPUs, AMD GPUs |

| Elastic Fabric Adapter (EFA) | A high-performance network interface for Amazon EC2 instances that significantly reduces communication overhead in multi-node simulations, enabling better scaling. [14] | AWS EC2 (c5n, m5n, etc.) [14] |

Machine Learning and Advanced Algorithms for Efficient MD

Leveraging Neural Network Potentials for DFT-Level Accuracy at Lower Cost

FAQ: Fundamental Concepts

What are Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) and how do they reduce computational cost? Neural Network Potentials are machine learning models trained on data from quantum mechanical calculations like Density Functional Theory (DFT). They learn the relationship between a material's atomic structure and its potential energy, enabling the prediction of energies and forces for new configurations without performing explicit DFT calculations. This bypasses the need to solve the computationally expensive Kohn-Sham equations, reducing the cost from approximately O(N³) to O(N), where N is the number of atoms, enabling simulations of thousands of atoms with quantum accuracy [16] [17].

What is the difference between a purely machine-learned force field and the Δ-DFT approach? A standard machine-learned force field is trained to predict total energies and forces directly from atomic structures. In contrast, the Δ-DFT (Delta-DFT) approach trains a model to predict only the correction between a low-cost, approximate DFT calculation and a high-accuracy one, such as the coupled-cluster (CCSD(T)) method. This "Δ-learning" significantly reduces the amount of expensive training data required and focuses the model on learning the complex error of the cheaper method, often leading to faster convergence and higher data efficiency [18].

Why is rotational equivariance a critical property for NNPs in electronic structure prediction? In quantum mechanics, the Hamiltonian—which describes the system's energy—must transform correctly (i.e., be equivariant) when the atomic structure is rotated. Equivariant Graph Neural Networks (eGNNs) are designed to inherently respect this physical symmetry. This ensures that a global rotation of the input molecular structure results in a correctly rotated output Hamiltonian matrix. Architecturally enforcing this property leads to more physically meaningful models that learn effectively with less data compared to models that are not equivariant [16] [19].

Troubleshooting Guide

Model Training and Performance Issues

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Model Generalization to New Structures | Insufficient diversity in training data; training set does not represent target conformational space. | Sample training geometries from finite-temperature DFT-based MD simulations to cover a wide range of likely atomic environments, including bond stretching and compression [18]. |

| High Training Error | Inaccurate descriptors or input densities. | For Δ-DFT, ensure the input electron densities (e.g., from a standard PBE functional) are well-converged. The accuracy of the correction depends on the quality of the base calculation [18]. |

| Long-Range Interactions Not Captured | Graph cutoff radius (rcut) is too small. |

Increase the graph cutoff radius beyond 10 Å to encompass a sufficient fraction of non-zero orbital interactions, as required by the electronic structure of many materials [16]. |

| Memory Limits Exceeded During Training | Large, densely connected graphs from large rcut and high-dimensional features. |

Use distributed eGNN implementations that leverage multi-GPU training and optimized graph partitioning to distribute memory load [16]. |

Technical Implementation and Workflow Issues

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Forces and Stresses are Inaccurate | Model is trained only on energies, lacking force labels. | Include atomic forces and stress tensors as explicit training targets in the loss function. The use of the electron density as an intermediate step has been shown to improve the accuracy of these derived properties [17]. |

| Integration with MD Codes Fails | Incompatible data formats or interfaces between the NNP and MD engine. | Use MD codes like LAMMPS that support plug-in ML potentials. Ensure the NNP inference code complies with the i-PI socket protocol or other supported interfaces for client-server communication [20]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing Δ-DFT for Quantum Chemical Accuracy

This protocol outlines the steps to correct a standard DFT calculation to a higher level of theory, such as CCSD(T), using a machine-learned Δ-correction [18].

Objective: Achieve coupled-cluster (CCSD(T)) accuracy for molecular dynamics simulations at the cost of a standard DFT calculation.

Workflow:

Generate Training Data:

- Run molecular dynamics simulations using a low-cost DFT functional (e.g., PBE) on your target system to sample a diverse set of molecular geometries.

- For a subset of these geometries, compute both the low-cost DFT energy and the high-accuracy target energy (e.g., CCSD(T)).

- Calculate the difference (ΔE) for each data point:

ΔE = E_CCSD(T) - E_DFT.

Train the Δ-Model:

- Use the electron density from the low-cost DFT calculation (

n_DFT) as the primary input descriptor for the machine learning model. - Train a model (e.g., using Kernel Ridge Regression) to learn the mapping:

n_DFT → ΔE. - Pro Tip: Incorporating molecular point group symmetries into the training data can drastically reduce the amount of required high-accuracy training data.

- Use the electron density from the low-cost DFT calculation (

Production MD Simulation:

- For a new geometry, perform a standard DFT calculation to obtain

E_DFTandn_DFT. - Pass

n_DFTto the trained Δ-model to predict the energy correctionΔE_predicted. - The final, corrected energy is:

E_corrected = E_DFT + ΔE_predicted. - This allows "on-the-fly" correction of DFT-based MD trajectories to CCSD(T) quality.

- For a new geometry, perform a standard DFT calculation to obtain

Protocol 2: Emulating DFT with an End-to-End Deep Learning Framework

This protocol describes a framework that uses a neural network to predict the electron density, which is then used to compute other properties, fully emulating the DFT workflow [17].

Objective: Bypass the explicit, iterative solution of the Kohn-Sham equations to achieve orders-of-magnitude speedup while maintaining chemical accuracy.

Workflow:

Fingerprinting the Atomic Structure:

- Convert the atomic configuration into a machine-readable descriptor. The AGNI fingerprint is a suitable choice, as it is translation, permutation, and rotation invariant and describes the structural and chemical environment of each atom.

Predict the Electron Density:

- Use a deep neural network to map the atomic fingerprints to a representation of the electron density.

- The model can learn to decompose the density into atom-centered Gaussian-type orbitals (GTOs), learning the optimal exponents and constants from the data.

Predict Electronic and Atomic Properties:

- Use the predicted electron density, combined with the atomic fingerprints, as a joint input to subsequent neural networks.

- These networks then predict a host of other properties, including:

- Electronic Properties: Density of States (DOS), band gap.

- Atomic Properties: Total potential energy, atomic forces, stress tensor.

Model Training and Validation:

- Train the model on a large database of structures and their corresponding DFT-computed properties.

- Validate the model on an independent test set, ensuring accuracy for energy (e.g., errors below 1 kcal/mol), forces, and electronic properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

| Item | Function / Relevance |

|---|---|

| LAMMPS | A highly flexible, open-source classical MD simulator that can be integrated with ML potentials, allowing for large-scale simulations with DFT-level accuracy [20]. |

| HamGNN | An E(3)-equivariant Graph Neural Network framework designed to predict ab initio tight-binding Hamiltonians from atomic structures, compatible with DFT codes like OpenMX and SIESTA [19]. |

| Equivariant Graph Neural Networks (eGNNs) | The underlying architecture for many modern NNPs. They respect physical symmetries (rotation/translation), leading to data-efficient and physically correct learning of Hamiltonian matrices [16]. |

| AGNI Fingerprints | Atomic descriptors that represent the structural and chemical environment of each atom in a way that is invariant to translation, permutation, and rotation. They serve as input for many ML-DFT models [17]. |

| Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR) | A machine learning algorithm frequently used in the development of early NNPs and Δ-learning schemes for its effectiveness in learning the mapping from electron density to energy corrections [18]. |

| Distributed GPU Training | A computational approach essential for handling the large memory requirements of eGNNs when dealing with massive, densely connected graphs representing systems with thousands of atoms [16]. |

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a cornerstone of computational physics, chemistry, and materials science, providing critical insights into atomic-scale processes. However, its widespread application has been persistently hindered by a significant trade-off between computational expense and the achievable timescales. Traditional MD must integrate the equations of atomic motion using extremely small time steps (on the order of 1 femtosecond) to accurately capture the fastest atomic vibrations, making the simulation of experimentally relevant timescales computationally prohibitive [21] [22].

Machine learning interatomic potentials have partially addressed the cost of force evaluation but remain bound to the same minuscule integration steps [22]. FlashMD represents a paradigm shift. It is a machine learning-based method designed to directly predict the evolution of atomic positions and momenta over much longer time intervals, or "strides." By skipping the intermediate steps required by traditional numerical integrators like velocity Verlet, FlashMD achieves strides that are one to two orders of magnitude longer than typical MD time steps. This direct prediction bypasses both explicit force calculations and numerical integration, leading to a dramatic reduction in computational cost and enabling access to previously inaccessible long-time-scale phenomena [21] [22] [23].

FlashMD Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core innovation of FlashMD compared to traditional MD or ML potentials? A1: Traditional MD and standard Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials rely on iterative force calculations and numerical integration with small time steps. FlashMD's core innovation is its ability to directly map a molecular state at time t to its state at time t + Δτ, where Δτ is a large time stride. This eliminates the need for intermediate force evaluations and integration steps, which is the primary source of computational savings [22].

Q2: Over what stride lengths has FlashMD been validated? A2: FlashMD is designed to predict evolution over strides that are between 10x and 100x longer than the femtosecond-scale steps used in conventional MD. The exact achievable stride depends on the system and the specific model, but the method is fundamentally built to skip these intermediate steps [21] [23].

Q3: Can FlashMD be used to simulate different thermodynamic ensembles (e.g., NVT, NpT)? A3: Yes, a key contribution of FlashMD is its generalization beyond the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble. The architecture incorporates techniques that allow for the simulation of various experimentally relevant thermodynamic ensembles, such as constant-temperature (NVT) and constant-pressure (NpT) ensembles [22].

Q4: How does FlashMD ensure physical correctness and long-term stability? A4: The architecture incorporates physical and mathematical considerations of Hamiltonian dynamics. Crucially, it includes techniques for higher accuracy, such as enforcing exact conservation of energy at inference time. This has been proven to be essential for stabilizing trajectories and reproducing physically correct behavior over long simulations [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Unphysical Energy Drift in Long Simulations

- Problem: The total energy of the system exhibits a significant drift over time, rather than being conserved.

- Diagnosis: This is a common failure mode for long-stride predictors and indicates a violation of the symplectic structure of Hamiltonian dynamics.

- Solution:

- Verify Energy Conservation Enforcement: Ensure that the inference-time procedure for exact energy conservation is enabled and correctly implemented [22].

- Reduce Stride Length: The chosen stride length might be too long for the model's current accuracy. Try reducing the stride and benchmarking stability [21].

- Check Training Data: Ensure the model was trained on a diverse and representative set of trajectories that cover the relevant phase space.

Issue 2: Poor Prediction of Kinetic Properties

- Problem: While equilibrium properties may seem correct, time-dependent transport properties (e.g., diffusion coefficients) are inaccurate.

- Diagnosis: The model may be failing to correctly capture the dynamics of momentum.

- Solution:

- Architecture Inspection: Confirm that the model architecture jointly and equivariantly predicts both positions and momenta, as their coupling is fundamental to dynamics [22].

- Validation Protocol: Use a validation metric specifically designed for dynamic properties, not just static configurations.

Issue 3: Model Fails to Generalize to New System

- Problem: A model trained on one system performs poorly when applied to a different molecular system.

- Diagnosis: The model lacks universality and has overfitted to the training data.

- Solution:

- Use a Universal Model: Employ or train a "universal" FlashMD model designed for a wide range of chemical systems, as mentioned in the research [22].

- Transfer Learning: Fine-tune a pre-trained universal model on a small amount of data from the new system. This strategy, effective for other ML potentials, is likely applicable to FlashMD [24].

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes key quantitative data related to the performance and validation of the FlashMD approach.

Table 1: Summary of FlashMD Performance and Validation Data

| Metric | Reported Value / Finding | Context / Validation Method |

|---|---|---|

| Stride Length | 1 to 2 orders of magnitude larger than traditional MD step [21] [22] | Core methodological innovation. |

| Traditional MD Time Step | ~1 femtosecond (fs) [22] | Baseline for comparison. |

| Accuracy Validation | Accurately reproduces equilibrium and time-dependent properties [22] | Compared against standard MD simulations. |

| Energy Conservation | Exact conservation enforced at inference; critical for stability [22] | Technique to mitigate a key failure mode of long-stride predictors. |

| Model Generality | Capable of using both system-specific and general-purpose models [22] | Increases broad applicability. |

Table 2: Common Error Patterns and Resolutions

| Error Pattern | Likely Cause | Recommended Resolution Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous energy increase/decrease | Non-symplectic predictions, stride too long | Enable energy conservation; reduce stride length [22]. |

| Structural collapse or explosion | Severe force/prediction error | Check model on short, known trajectories; verify training data quality. |

| Correct thermodynamics, wrong kinetics | Poor momentum dynamics capture | Validate model architecture for coupled position/momentum prediction [22]. |

| Good on trained system, poor on new one | Lack of transferability | Utilize a universal model or apply transfer learning [22] [24]. |

Experimental Protocol for Validating FlashMD

This protocol outlines the key steps for benchmarking a FlashMD model against a reference conventional MD simulation, a critical process for any thesis work in this domain.

Objective: To validate that a FlashMD model accurately reproduces both equilibrium structural properties and dynamic transport properties from a reference trajectory.

Materials:

- Reference Dataset: A long, conventional MD trajectory (computed with a well-validated MLIP or force field) with atomic positions and momenta saved at high frequency.

- Computing Resources: GPU-accelerated computing environment suitable for running the FlashMD model.

- Software: FlashMD model implementation and analysis tools (e.g., for calculating RDFs, MSDs).

Methodology:

- Data Preparation:

- Generate a reference MD trajectory using a standard integrator (e.g., velocity Verlet) with a small time step (e.g., 1 fs).

- From this trajectory, create training data by sampling state pairs

(S(t), S(t + Δτ)), whereΔτis the desired long stride (e.g., 50 fs, 100 fs). - Split the data into training and validation sets, ensuring the validation set contains trajectories not seen during training.

Model Training & Inference:

- Train the FlashMD model on the training pairs. The model learns the function that maps

S(t)directly toS(t + Δτ). - Use the trained model for iterative inference: starting from an initial state

S(t0), generate a new trajectory by repeatedly applying the model:S(t0 + Δτ) = Model(S(t0)),S(t0 + 2Δτ) = Model(S(t0 + Δτ)), and so on [22].

- Train the FlashMD model on the training pairs. The model learns the function that maps

Validation and Benchmarking:

- Equilibrium Properties: Calculate the Radial Distribution Function (RDF) from the FlashMD-generated trajectory and compare it to the RDF from the reference MD trajectory. A close match indicates accurate structural sampling.

- Dynamic Properties: Calculate the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) of atoms or molecules from both trajectories. The diffusion coefficient, derived from the slope of the MSD, should be statistically consistent between the two methods.

- Energy Conservation: Monitor the total energy of the system throughout the FlashMD trajectory. While small fluctuations are normal, a significant drift indicates instability that must be addressed using the methods in the troubleshooting guide [22].

Workflow Diagram: Traditional MD vs. FlashMD

The following diagram illustrates the core computational difference between traditional Molecular Dynamics and the FlashMD approach, highlighting the source of computational savings.

Diagram 1: Computational Workflow Comparison. FlashMD bypasses iterative force calculations and integration, directly predicting the state after a long stride.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational "reagents" and their functions in developing and applying FlashMD.

Table 3: Essential Components for FlashMD Research

| Item / Component | Function / Role in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| Reference MD Trajectories | Serves as the ground-truth dataset for training and validating the FlashMD model. Requires high-quality forces from DFT or MLIPs [22]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | The core architecture for the FlashMD model. Processes the atomic system as a graph, naturally preserving permutation and translation invariance [22]. |

| Hamiltonian Dynamics Constraints | Physical prior built into the model to respect the structure of classical mechanics, improving stability and correctness [22]. |

| Thermodynamic Ensemble Controller | Algorithmic component (e.g., stochastic thermostat) integrated with the predictor to enable simulations in NVT, NpT, etc., ensembles [22]. |

| Universal Pre-trained Model | A FlashMD model pre-trained on diverse chemical systems, providing a strong foundation for transfer learning to new, specific systems [22] [24]. |

| Transfer Learning Framework | A protocol to fine-tune a universal FlashMD model on a small, system-specific dataset, maximizing performance with minimal data [24]. |

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations are vital tools in computational physics, chemistry, and drug development for exploring complex systems. However, a significant challenge persists: while machine learning potentials (MLPs) dramatically reduce computational costs compared to ab initio methods, their predictive accuracy often degrades over the long timescales required for meaningful scientific insight. Dynamic Training (DT) has emerged as a methodological solution designed to enhance the sustained accuracy of models throughout extended MD simulations. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers successfully implement DT, directly supporting the broader thesis of developing strategies to reduce the computational cost of long MD simulations.

Understanding Dynamic Training: Core Concepts

What is Dynamic Training (DT) in the context of Machine Learning Potentials?

Dynamic Training is a method designed to improve the accuracy of a machine learning model over the course of an extended Molecular Dynamics simulation. Unlike conventional training which uses a static dataset, DT involves continuously or periodically updating the model with new data generated on-the-fly during the simulation. This allows the model to adapt to new configurations and physical states it encounters, preventing the accumulation of errors and maintaining high fidelity over long simulation times [25].

How does DT directly support the goal of reducing computational costs for long MD simulations?

DT contributes to computational cost reduction through improved efficiency and accuracy:

- Preventing Costly Failures: By maintaining model accuracy, DT reduces the likelihood of simulation crashes or unphysical results that would require simulations to be restarted from the beginning, thus wasting computational resources.

- Enabling Longer Simulations with MLPs: It makes long-lasting simulations with MLPs more reliable, reducing the need to fall back to more computationally intensive ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) for accurate results [25] [26].

- Efficient Data Generation: The simulation itself generates targeted training data, optimizing the data generation process for the specific thermodynamic region being explored.

Technical Specifications and Methodology

The following table summarizes the key components of a typical DT framework as applied to an Equivariant Graph Neural Network (EGNN) for a system involving a hydrogen molecule and a palladium cluster [25].

Table 1: Key Components of a Dynamic Training Framework

| Component | Description | Function in the DT Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Base Model (e.g., EGNN) | An equivariant graph neural network that serves as the Machine Learning Potential. | Provides the core energy and force predictions for the MD simulation. |

| Simulation Engine | Software that performs the MD simulation (e.g., GROMACS, LAMMPS). | Propagates the system through time using forces from the MLP. |

| Data Selector | Algorithm that decides which new configurations to add to the training set. | Identifies novel or uncertain configurations encountered during the simulation to expand the training data. |

| Training Loop | Process that updates the model parameters. | Periodically retrains the MLP on the augmented dataset (initial + new data). |

| Validation Check | Routine that assesses model performance on a hold-out set or checks for energy drift. | Ensures that retraining improves the model without overfitting, maintaining generalizability. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Dynamic Training

The workflow for implementing Dynamic Training in a long MD simulation project involves several key stages, from initial setup to continuous operation. The following diagram visualizes this cyclical process:

Diagram 1: Dynamic Training Workflow for MD Simulations

Detailed Methodology:

Initial Model Pre-Training: Begin with a machine learning potential (e.g., an Equivariant Graph Neural Network) that has been trained on a diverse, static dataset generated from short ab initio calculations. This model should provide a reasonable starting point for the system's potential energy surface [25] [26].

Launch Initial MD Simulation: Start the production MD simulation using the pre-trained MLP to compute atomic forces.

Configuration Selection and Query: During the simulation, employ a query strategy to identify configurations that should be added to the training set. Common strategies include:

- Uncertainty Estimation: Selecting frames where the model's prediction uncertainty is high.

- Novelty Detection: Identifying geometries that are far from the existing training data distribution.

- Energy/Force Deviation: Flagging steps where energies or forces deviate significantly from expected physical behavior [25].

Dataset Augmentation: Extract the selected configurations and compute their accurate energies and forces using the reference ab initio method (e.g., DFT). Add these new {structure, energy, force} pairs to the growing training dataset.

Model Retraining: Periodically pause the simulation and retrain the MLP on the augmented dataset. This step updates the model's parameters, incorporating knowledge of the newly sampled configurations.

Simulation Continuation: Restart the MD simulation from a recent checkpoint using the updated, more accurate model. This cycle of simulation, selection, and retraining continues throughout the project's duration [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software and Tools for DT-MD Research

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function | Relevance to DT |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [27] | MD Engine | High-performance MD simulation package. | Executes the dynamics using forces from the MLP. |

| TensorFlow/PyTorch [26] | Deep Learning Framework | Libraries for building and training neural networks. | Used to develop, train, and update the MLP (e.g., EGNN). |

| ACPyPE [27] | Topology Generator | Tool to generate topologies for small molecules for MD. | Prepares ligand parameters for initial simulations. |

| Open Babel [27] | Chemical Toolbox | Program for converting chemical file formats and adding hydrogens. | Preprocessing of molecular structures before topology generation. |

| Galaxy [27] | Computational Platform | Web-based platform for accessible, reproducible computational analysis. | Can host and manage HTMD and analysis workflows. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: My dynamically trained model is becoming computationally expensive to retrain. How can I manage this cost?

- Problem: The growing dataset from long simulations makes each retraining cycle slower and more resource-intensive.

- Solution:

- Implement Active Learning: Instead of saving every new configuration, use a robust query strategy (see Diagram 1) to only select the most informative samples for training. This keeps the dataset lean and relevant.

- Dataset Pruning: Periodically remove redundant or less important samples from the training set to control its size.

- Transfer Learning: Consider using the final model from one simulation as a pre-trained model for a new, related system to reduce total training time.

FAQ 2: How do I prevent my model from overfitting to the newly sampled data during retraining?

- Problem: The model performs well on recent configurations but loses generalizability, degrading performance on previously learned regions of the potential energy surface.

- Solution:

- Retain Initial Data: Always include a representative subset of the original, static training dataset in every retraining cycle. This anchors the model to its foundational knowledge.

- Use a Hold-Out Validation Set: Maintain a separate, static validation set that is not used for training. Monitor performance on this set during retraining to detect overfitting.

- Regularization: Apply standard deep learning regularization techniques (e.g., L2 regularization, dropout) during the retraining process.

FAQ 3: My simulation is unstable shortly after switching to the MLP, even before DT can start. What is wrong?

- Problem: The initial pre-trained model is not accurate enough for the starting configuration, leading to immediate failure.

- Solution:

- Improve Pre-Training: Ensure your initial model is trained on a diverse and representative dataset that covers the expected initial geometries and energies of your system.

- Check System Preparation: Verify that the system has been properly minimized and equilibrated. Errors in topology generation, such as incorrect protonation states or missing parameters for ligands, are a common source of early crashes. Use tools like ACPyPE and Open Babel to carefully prepare your initial structure [27].

- Run Shorter Test Simulations: Begin with short, stable simulations to validate the MLP before committing to long, production-level runs.

FAQ 4: How often should I perform the retraining step in a DT workflow?

- Problem: There is a trade-off between frequent retraining (high accuracy, high cost) and infrequent retraining (lower cost, risk of error accumulation).

- Solution: The optimal frequency is system-dependent. A common strategy is to:

- Use a Metric-Based Trigger: Instead of a fixed time interval, trigger retraining based on a performance metric, such as when the model's uncertainty exceeds a threshold or when the potential energy shows an unphysical drift.

- Start Conservatively: For initial experiments, retrain more frequently to understand the system's dynamics, and then adjust the frequency based on observed stability.

Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: My transferred model is performing poorly on the new system. Is this "negative transfer" and how can I fix it?

A: Poor performance after transfer learning is a common issue known as negative transfer. It occurs when the knowledge from the source domain is not sufficiently relevant to the target task, thereby reducing model performance instead of improving it [28].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Diagnose the Problem: Quantify the similarity between your source and target domains. For drug discovery tasks, you can assess latent data representations learned by graph neural networks pre-trained on each task [28].

- Meta-Learning Solution: Implement a meta-learning framework to algorithmically balance the transfer. This method identifies an optimal subset of source data samples for pre-training, effectively filtering out irrelevant information that causes negative transfer [28].

- Refine Your Source Data: If meta-learning is not feasible, manually curate your source dataset to ensure it is more closely aligned with the physics or chemistry of your target system.

Q2: I only have a few quantum calculations for my target molecule. How can I build a reliable potential?

A: This is a classic small-data challenge. The solution is to use a two-step transfer learning approach that leverages a large dataset of inexpensive calculations and a small, high-accuracy dataset [29] [30].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Initial Training (Low-Cost): Train a Machine Learning Interatomic Potential (MLIP), such as a Behler-Parrinello Neural Network, on a large dataset generated with a low-cost method like Density Functional Theory (DFT). This teaches the model the general chemistry of the system [29].

- Fine-Tuning (High-Accuracy): Refine the pre-trained model using your small dataset of high-accuracy calculations (e.g., from Unitary Coupled Cluster methods or more accurate DFT functionals). This step corrects the model to the higher level of theory [29] [30].

- Active Learning: Use an active learning query-by-committee approach to intelligently select the most informative molecular geometries for your costly quantum calculations, maximizing the value of each data point [29].

Q3: My molecular dynamics simulations are unstable when using the MLIP. What is wrong?

A: Instability in simulations often arises because the model has not been trained on enough diverse configurations to cover the relevant phase space, or the underlying representation lacks generalizability.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Improve the Training Data: Ensure your training dataset includes a diverse set of atomic configurations, including those far from equilibrium. Use active learning to iteratively find and add these missing configurations to your training set [31].

- Use a Universal Potential: Start from a general-purpose, pre-trained potential (like MACE-MP-0) that has been trained on millions of diverse configurations. These models are more likely to be stable out-of-the-box [31].

- Employ a Robust Framework: Use a transfer learning framework like

franken, which is specifically designed to create stable and data-efficient potentials. It can build a potential capable of stable MD simulations with as few as tens of training structures by leveraging representations from pre-trained graph neural networks [31].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: How does transfer learning actually reduce computational costs in MD simulations?

A: Transfer learning reduces costs by minimizing the number of expensive, high-fidelity quantum mechanical calculations needed. Instead of running thousands of costly target calculations, you generate a large dataset with a cheap method (like a lower-level DFT functional) and then correct the model with a much smaller set of high-fidelity data. This can reduce the required quantum computations by orders of magnitude [29] [30].

Q: What is the difference between "Sim2Real" transfer learning and other types?

A: "Sim2Real" specifically refers to transferring knowledge from a simulation or computational domain to a real-world or experimental domain. For example, a model pre-trained on massive molecular dynamics simulation data is fine-tuned to predict real, experimentally measured polymer properties. Other types of transfer learning might involve transferring between two different simulation methods or two different molecular systems [32].

Q: Are there scaling laws for transfer learning that can help me plan my project?

A: Yes, recent research has identified power-law scaling relationships in simulation-to-real (Sim2Real) transfer learning. The prediction error on real systems decreases as a power-law function of the size of the computational data used for pre-training. Observing this scaling behavior can help you estimate the computational dataset size required to achieve your desired performance target on experimental data [32].

Quantitative Data on Transfer Learning Performance

The following tables summarize key quantitative results from recent studies, demonstrating the effectiveness of transfer learning in reducing computational cost and improving data efficiency.

Table 1: Data Efficiency of Transfer Learning for Molecular Potentials

| System | Method | Training Set Size | Key Result | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Monomer/Dimer | DFT → VQE Transfer Learning | Tens of quantum data points | Captured high-accuracy energy surface needed for dynamics | [29] |

| Bulk Water & Pt(111)/Water | franken Framework (with Random Features) |

~10s of structures | Enabled stable and accurate Molecular Dynamics simulations | [31] |

| 27 Transition Metals | franken Framework |

N/A | Reduced model training time from tens of hours to minutes on a single GPU | [31] |

Table 2: Sim2Real Transfer Learning Scaling for Polymer Properties

| Property | Size of Experimental Data (m) | Scaling Factor (α) | Observation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Conductivity | 39 | Power-law | Prediction error decreases as computational data increases | [32] |

| Refractive Index | 234 | Power-law | Scaling law helps estimate required computational data size | [32] |

| Specific Heat Capacity | 104 | Power-law | Generalization error converges to a transfer gap C |

[32] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Two-Step Training for Quantum-Accurate Molecular Dynamics

This protocol outlines the method for training a machine-learned potential energy surface (PES) using transfer learning between classical and quantum computational data [29].

Workflow Diagram: Two-Step Training for Quantum-Accurate Potentials

Detailed Methodology:

Phase 1: Learn General Chemistry (Low-Cost)

- Generate Low-Cost Dataset: Use Density Functional Theory (DFT) with a standard functional (e.g., PBE0) and a small basis set (e.g., STO-6G) to compute energies for thousands of molecular geometries. Geometries should be systematically sampled along internal coordinates (e.g., bond lengths, angles) [29].

- Train Initial ML Model: Train a machine learning model (e.g., a Behler-Parrinello Neural Network) to map atomic geometries to the DFT-computed energies. This model now represents a low-cost PES.

Phase 2: Refine for High Accuracy (High-Cost)

- Generate High-Accuracy Dataset: Use a high-accuracy method (e.g., Unitary Coupled Cluster) to compute energies for a small set (tens to hundreds) of critically important molecular geometries. These points should be selected via active learning to ensure they provide the most new information to the model [29].

- Fine-Tune the Model: Take the pre-trained model from Phase 1 and continue its training (fine-tune its parameters) on the small, high-accuracy dataset. This critically adjusts the PES to quantum mechanical accuracy.

Protocol 2: Fine-Tuning a Universal Potential withfranken

This protocol describes using the franken framework for fast and data-efficient adaptation of a general-purpose MLIP [31].

Workflow Diagram: Fine-Tuning a Universal Potential with franken

Detailed Methodology:

- Obtain a Pre-Trained Model: Start with a general-purpose MLIP that has been trained on a large, diverse dataset (e.g., MACE-MP-0 trained on the Materials Project) [31].

- Generate Target System Data: Perform a limited number of DFT calculations on your specific system of interest. Dozens of structures may be sufficient [31].

- Model Surgery with

franken:- Extract the atomic environment descriptors from the pre-trained graph neural network. These descriptors encapsulate chemical knowledge.

- Use random Fourier features—a scalable approximation of kernel methods—to efficiently learn the mapping from these pre-trained descriptors to the energies and forces of your target system.

- Fast Fine-Tuning: The framework allows for a closed-form fine-tuning solution or rapid retraining, minimizing hyperparameter tuning and reducing training time from hours to minutes [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Transfer Learning in Molecular Simulation

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Transfer Learning | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

franken |

Software Framework | Lightweight transfer learning for MLIPs; enables fast fine-tuning of universal potentials. | [31] |

| MACE-MP-0 | Pre-trained Model | A "universal" MLIP providing a strong foundational model for transfer to new systems or theory levels. | [31] |

| UMA (Universal Model of Atoms) | Pre-trained Model | An equivariant GNN trained across diverse systems (inorganic, organic) demonstrating positive transfer learning. | [33] |

| RadonPy | Database & Library | Provides a large source dataset of polymer properties from MD simulations for Sim2Real pre-training. | [32] |

| OpenCatalyst, Materials Project | Databases | Large-scale DFT datasets used for pre-training general-purpose potentials. | [31] |

| Behler-Parrinello Neural Networks (BPNN) | Algorithm | A classic MLIP architecture used in transfer learning between levels of theory. | [29] |

| Random Fourier Features | Algorithm | A scalable mathematical technique to approximate kernel methods, drastically speeding up training. | [31] |

| Active Learning (Query-by-Committee) | Strategy / Protocol | Intelligently selects the most valuable data points for costly quantum calculations, maximizing data efficiency. | [29] |

Practical Hardware and Workflow Optimization for MD

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the fundamental difference between core count and clock speed? Core count determines how many tasks a CPU can handle simultaneously, while clock speed (measured in GHz) affects how fast each individual task is executed. [34]

For Molecular Dynamics, should I prioritize more cores or higher clock speed? For most Molecular Dynamics workloads, you should prioritize higher clock speeds over a very high core count. This is because the performance of many MD algorithms is often limited by the speed of a few critical threads rather than pure parallelization across many cores. [35]

Why isn't a CPU with the highest possible core count always the best choice? CPUs with extremely high core counts often have lower base clock speeds to manage heat and power. This can result in slower performance for the parts of your simulation that cannot be perfectly parallelized. Furthermore, memory bandwidth can become a bottleneck as more cores compete for access to the same memory channels. [34] [36]

Do all MD applications scale efficiently with hundreds of cores? No. Performance gains diminish beyond a certain point due to communication overhead between cores and the inherent serial portions of the code. The optimal core count is application-specific and depends on system size and simulation parameters. [34] [37]

Besides the CPU, what other hardware is critical for MD performance? GPUs are paramount. Modern MD software heavily offloads computation to GPUs, which can accelerate simulations by orders of magnitude. Sufficient system memory (RAM) and fast storage for reading/writing trajectory files are also essential. [35] [1] [38]

How does CPU choice affect software licensing costs? Some commercial simulation software is licensed on a per-core basis. Using a CPU with fewer, faster cores can significantly reduce licensing costs while maintaining strong performance for MD workloads. [34]

Troubleshooting Guide: CPU-Related Performance Issues

Problem: Simulation runtime is much longer than expected.

- Check CPU utilization. Use system monitoring tools (e.g.,

htop,top). If only a few cores are at 100% while others are idle, your simulation is likely limited by single-threaded performance.- Solution: Consider a CPU with a higher base and boost clock speed. [35]

- Check for memory bandwidth saturation. If all cores are active but performance is poor, the CPU may be waiting for data from memory.

- Solution: Ensure your CPU is paired with high-speed RAM (e.g., DDR5). Using a CPU with a more moderate core count can also increase the available memory bandwidth per core. [34]

Problem: Performance does not improve when using more CPU cores.

- Identify the scaling bottleneck. Run strong scaling tests (same problem size, increasing core count) and plot the speedup.

- Solution: The simulation may have reached its parallel efficiency limit. Beyond this point, adding more cores is ineffective. Consult application-specific benchmarks to find the sweet spot for your typical system size. [37]

- Verify MPI and thread configuration. Incorrect settings for the number of MPI processes and OpenMP threads can lead to poor performance.

- Solution: Refer to your MD software's documentation for optimal parallel configuration guidelines. This often involves binding processes to specific CPU cores to minimize communication overhead.

Problem: Simulation runs but fails or freezes with large atom counts.

- Check system memory (RAM) capacity. The simulation may be exhausting available physical memory, leading to swapping onto slow disk storage.

Hardware Selection Data

This table summarizes the key considerations for choosing a CPU for MD simulations, helping to balance computational performance with project budgets and goals.

| CPU Characteristic | High Core Count Focus | High Clock Speed Focus | Balanced Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Use Case | Highly parallelizable workloads (e.g., virtual screening, multi-template analysis). Running multiple simultaneous simulations. [34] [39] | Classical MD simulations where performance is bound by single-thread or lightly-threaded performance (common in NAMD, GROMACS). [34] [35] | Mixed workload environments; MD simulations that show good but not perfect parallel scaling. [34] |

| Performance Goal | Maximize overall throughput for many independent jobs. | Minimize time-to-solution for a single, critical simulation. | A blend of good single-thread performance and parallel efficiency. |

| Pros(Advantages) | - Higher throughput for perfectly parallel tasks.- Better for running multiple VMs or jobs. [36] | - Faster execution for serial code sections.- Often lower cost for the CPU itself.- Can reduce per-core software licensing costs. [34] | - Versatile for different types of computational tasks.- Provides a good balance for most real-world MD scenarios. |

| Cons(Disadvantages) | - Diminishing returns on performance scaling.- Lower single-threaded performance.- Potential memory bandwidth constraints. [34] | - Lower overall throughput when many jobs are run in parallel.- Not ideal for workloads that are "embarrassingly parallel." [36] | - May not be the absolute best at either throughput or single-job speed. |

| Suggested CPU Families | AMD EPYC, Intel Xeon Scalable (for dual-socket systems). [34] [35] | AMD Ryzen Threadripper PRO (last-gen, high clock), high-frequency Intel Xeon W series. [34] [35] | AMD Threadripper PRO (balanced models), Intel Xeon W-3400 series. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

This table details key hardware and software "reagents" required for conducting MD simulations.

| Item | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER, LAMMPS) [38] | The primary application used to set up, run, and analyze molecular dynamics simulations. Different packages have varying optimizations for CPU core count and GPU offloading. |

| Molecular Mechanics Force Field [1] | A set of mathematical functions and parameters that model the interatomic interactions (bonds, angles, electrostatics) within the simulation, defining the physics of the system. |

| System Topology & Coordinate Files | The input files that describe the specific molecules in the simulation: the topology defines the chemical structure and force field parameters, while the coordinates provide the starting atomic positions. |

| High-Performance GPU (e.g., NVIDIA RTX 4090, Ada Lovelace series) [35] [1] | A graphics processing unit that massively accelerates the calculation of non-bonded interactions and other parallelizable tasks in MD, often providing the largest performance gain. |

| High-Speed System Memory (RAM) | Provides working memory for the operating system and MD application. Large and complex biological systems require substantial RAM to hold all atom data during calculation. [35] |

| Fast Local Scratch Storage (NVMe SSD) | High-speed storage is critical for quickly reading input files and writing trajectory data, which can easily reach terabytes in size for long simulations. [40] |

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking CPU Performance for MD

Objective: To empirically determine the optimal CPU configuration (core count vs. clock speed) for a specific MD software and a representative molecular system.

Methodology: