Steered Molecular Dynamics Protocols: A Practical Guide for Studying Atomic Motions in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD) protocols for researchers and drug development professionals.

Steered Molecular Dynamics Protocols: A Practical Guide for Studying Atomic Motions in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD) protocols for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of applying external forces to probe molecular mechanisms, details practical methodologies for studying protein-ligand interactions and rare events, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and outlines validation techniques against experimental data. By integrating recent case studies from FABP4 and EED inhibitor research, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to implement SMD effectively for accelerating structure-based drug design.

Understanding SMD Fundamentals: Principles and Scope for Probing Biomolecular Motions

Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD) is a computational technique that applies external forces to molecules to simulate physical processes like mechanical unfolding or ligand unbinding. By applying these forces, researchers can steer a system along a desired coordinate, such as pulling apart a protein to study its unfolding pathway. This method directly mimics experimental techniques like Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), allowing for the quantification of forces and energies involved in biomolecular interactions that are difficult to capture through physical experimentation alone [1] [2]. The core hypothesis underpinning many SMD applications is that a protein's resistance to unfolding under simulated stress is indicative of its structural stability and, by extension, its accuracy relative to the native fold [2].

Key Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

General SMD Simulation Setup

A typical SMD protocol involves several key stages, from system preparation to trajectory analysis [3].

- System Preparation: Begin with an initial atomic structure, typically obtained from the Protein Data Bank. The protein must be solvated in an explicit or implicit solvent model. For transmembrane proteins, this involves insertion into a pre-equilibrated lipid bilayer. Counter-ions may be added to neutralize the system's charge [1].

- Force Field Selection: Employ a suitable force field such as YAMBER3, CHARMm, charmm36, or CGenFF [3] [1]. The MATCH method can be used for typing ligands with the charmm36 force field [1].

- Simulation Parameters:

- Temperature and Pressure: Hold constant at 300 K and 1 atm, respectively (NPT ensemble) [3].

- Periodic Boundary Conditions: Used to simulate a continuous system.

- Electrostatic Interactions: Calculated using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method [3].

- Long-Range Interactions: A force cutoff of approximately 7.86 Å is recommended [3].

- Pulling Simulation: A constant velocity or constant force is applied to a specific atom or group of atoms (e.g., the C-terminus of a protein), while another atom or group (e.g., the N-terminus) is held fixed. This induces structural rearrangement and unfolding.

- Analysis: The resulting force-extension profile is analyzed to identify "break forces," which are the peak forces required for major structural rearrangements [2]. The free energy landscape can be estimated from a set of MD trajectories [1].

Specific Protocol: SMD with YASARA

The following detailed protocol is adapted from a resource dedicated to improving research reproducibility [3].

- Obtain Starting Coordinates: Acquire the bent and extended crystal structures of your protein of interest from the Protein Data Bank (e.g., PDB IDs 1G1T, 4CSY).

- Software and Force Field: Perform simulations using the YASARA package with the YAMBER3 self-parameterizing force field.

- Run Simulations: Execute free-dynamics and SMD simulations. All simulations should be run at least four times with different starting velocities to ensure statistical significance.

- Trajectory Analysis: Perform Principle Component Analysis (PCA) of the MD trajectories using software such as Bio3D and R software packaged developed by the Grant lab.

- Visualization: Create cartoon renditions of the resulting structures with UCSF Chimera, an extensible molecular modeling system.

Enhanced Sampling: Gaussian accelerated Molecular Dynamics (GaMD)

Gaussian accelerated Molecular Dynamics (GaMD) is an advanced method implemented in BIOVIA Discovery Studio for simultaneous unconstrained enhanced sampling and free energy calculations [1]. The protocol involves:

- Configuring and running a GaMD equilibration to automatically parameterize the necessary boost potentials.

- Running and restarting GaMD simulations.

- Estimating a free energy landscape from a set of MD trajectories, allowing for statistical reweighting of GaMD simulations [1].

Quantitative Data and Analysis

SMD simulations generate quantitative data that can be used to assess model quality and stability.

Table 1: Example SMD Results for Protein Model Assessment

| Target Protein | Model GDT-TS Score | Break Force (pN) | Structural Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| T0700 | 18.1 | Low | Rapid unfolding |

| T0700 | 49.2 | Medium | Partial stability |

| T0650 | 42.7 | High | High resistance to unfolding |

| T0659 | 76.3 | Very High | Near-native stability |

Table 2: Standard SMD Simulation Parameters

| Parameter | Setting | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 300 K | Simulates physiological conditions [3] |

| Pressure | 1 atm | Simulates physiological conditions [3] |

| Force Cutoff | 7.86 Å | Recommended value for long-range interactions [3] |

| Electrostatics | Particle Mesh Ewald | Accurate handling of long-range electrostatic forces [3] |

| Boundary Conditions | Periodic | Prevents edge effects in the simulation box [3] |

| Solvent | Explicit/Implicit | Depending on system and software (NAMD/CHARMM) [1] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Tools for SMD

| Research Reagent | Function in SMD |

|---|---|

| YASARA | A package of MD programs used for running free-dynamics and SMD simulations with the YAMBER3 force field [3]. |

| NAMD & CHARMm | Best-in-class molecular simulation programs within BIOVIA Discovery Studio for explicit solvent MD and minimizations [1]. |

| BIOVIA Discovery Studio | A comprehensive modeling and simulation environment that implements CHARMm, NAMD, and GaMD for SMD and free energy calculations [1]. |

| UCSF Chimera | An extensible molecular modeling system used for the visualization and creation of cartoon renditions of simulation results [3]. |

| Bio3D / R Software | Packages used for performing Principle Component Analysis (PCA) on MD trajectories to analyze conformational changes [3]. |

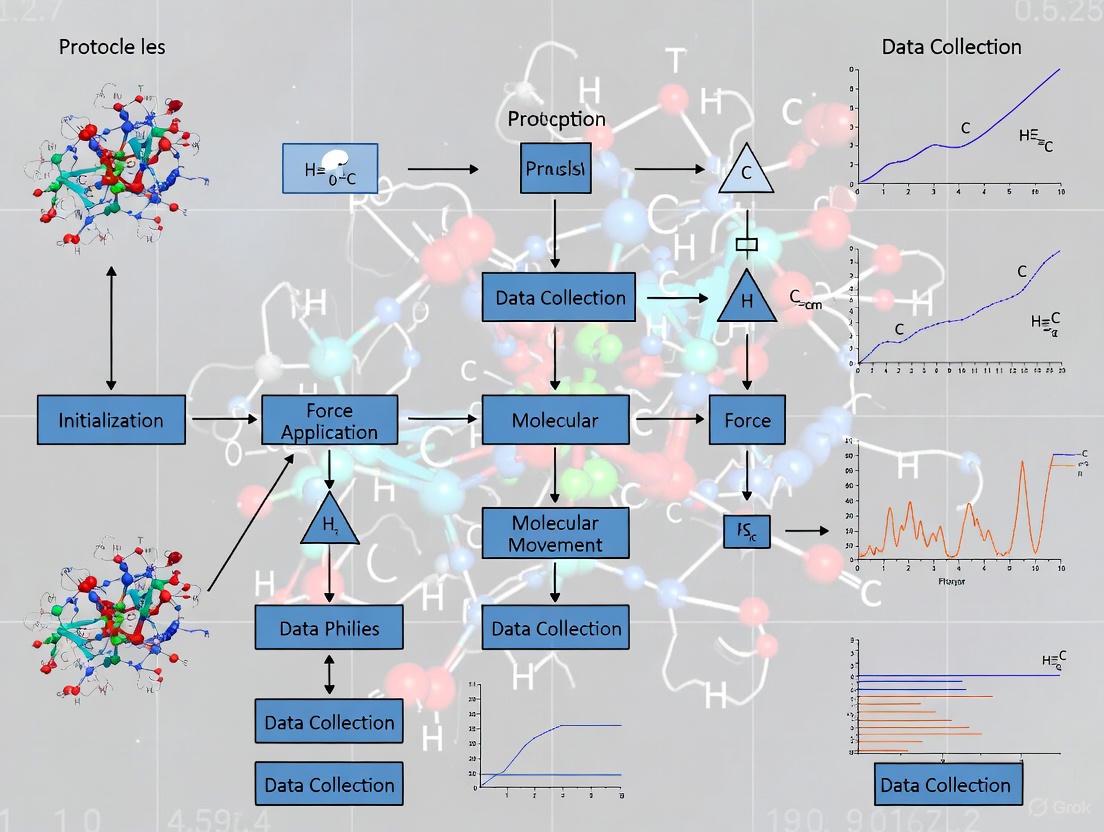

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a typical SMD study, from initial model preparation to final analysis.

Application in Protein Structure Assessment

SMD is a powerful tool for protein quality assessment (QA). A study involving 4,929 computational models from CASP (Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction) demonstrated that near-native models (those with high GDT-TS scores) often exhibit higher break forces under SMD-induced stress, indicating greater stability [2]. This allows researchers to select the most accurate structural models by examining their mechanical resistance. The study found that the stability measured by break forces is influenced by bonded interactions, electrostatic interactions, and solvent interactions [2]. However, it is important to note that some near-native models may exhibit lower break forces, suggesting that while high break force is a strong indicator of a correct model, low break force does not automatically rule out model accuracy [2].

Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD) and rare event sampling algorithms represent powerful computational frameworks for investigating molecular processes that occur on timescales inaccessible to conventional molecular dynamics (MD). These methods provide critical insights into fundamental biological events, such as protein-ligand unbinding, and facilitate the study of rare but physiologically significant conformational transitions. By applying external biases or implementing sophisticated path-sampling techniques, researchers can accelerate these slow processes, enabling the extraction of kinetic parameters, the identification of unbinding pathways, and the exploration of free energy landscapes. This application note details standardized protocols and benchmarking frameworks essential for obtaining rigorous, reproducible results in these advanced simulation domains, with particular emphasis on applications in drug discovery and protein engineering.

Steered Molecular Dynamics for Protein-Ligand Unbinding

Core Principles and Rationale

Protein-ligand unbinding is a critical process in drug discovery, governing residence time and therapeutic efficacy. However, this process occurs over timescales ranging from microseconds to seconds, making it challenging to study with conventional MD [4]. SMD overcomes this limitation by applying an external force to the ligand, systematically pulling it away from the binding pocket to simulate unbinding. This approach generates force-displacement profiles that reveal key interaction barriers and pathways [4]. A critical aspect of SMD setup involves properly restraining protein backbone flexibility to prevent unrealistic system drift while preserving relevant conformational motions during ligand dissociation.

Optimized Restraint Protocol for Protein Flexibility

The choice of restraint strategy significantly influences SMD results. Based on systematic comparisons, restraining all heavy atoms or all Cα atoms overly constrains the system, while restraining too few atoms allows unrealistic protein rotation [4]. An optimized protocol recommends:

- Selection Criteria: Restrain Cα atoms located more than 1.2 nm from the ligand in the initial bound structure [4].

- Force Constant: Apply a harmonic potential with a force constant of 1000 kJ/(mol·nm²) for optimal restraint [4].

- Implementation: This targeted restraint strategy prevents overall protein drift while allowing natural flexibility in the binding site region, leading to more physiologically relevant unbinding pathways.

Table 1: Comparison of Protein Restraint Methods in SMD Simulations

| Restraint Method | Description | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Heavy Atoms | Restrains all non-hydrogen protein atoms | Prevents overall drift effectively | Overly rigid, may neglect protein motion contributions to unbinding |

| All Cα Atoms | Restrains only alpha-carbon atoms | Reduces excessive rigidity | May still restrict relevant backbone movements |

| Distance-Based Cα Selection | Restrains Cα atoms >1.2 nm from ligand | Balanced approach; prevents drift while maintaining binding site flexibility | Requires careful distance measurement in initial structure |

System Preparation and Simulation Parameters

- Force Fields: Utilize the AMBER ff99SB-ILDN force field for proteins [4].

- Ligand Parameterization: Optimize ligand geometries at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level and derive atomic charges using the RESP method with the General Amber Force Field (GAFF) [4].

- Solvation: Solvate systems in explicit water with a minimum 0.6 nm distance between the protein surface and box boundaries [4].

- Electrostatics: Apply the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method for long-range electrostatic interactions [4].

- Simulation Conditions: Maintain temperature at 300 K using a Langevin thermostat and pressure at 1 atm using a Monte Carlo barostat [4].

Advanced Rare Event Sampling Frameworks

Weighted Ensemble Sampling for Protein Dynamics

For simulating rare events without external steering forces, weighted ensemble (WE) methods provide enhanced conformational sampling. The WESTPA (Weighted Ensemble Simulation Toolkit with Parallelization and Analysis) implementation enables efficient exploration of protein conformational space by running multiple parallel trajectories and periodically resampling them based on progress coordinates [5].

- Progress Coordinates: Utilize Time-lagged Independent Component Analysis (TICA) to define progress coordinates that capture slow conformational modes [5].

- Resampling Strategy: WE simulations run multiple replica trajectories and periodically resample them based on user-defined progress coordinates, enabling better exploration of rare conformational states [5].

- Benchmarking: This approach has been validated across nine diverse proteins ranging from 10-224 residues, spanning various folding complexities and topologies [5].

Enhanced Sampling for Transient Events

Rare, transient events like extreme weather patterns pose particular challenges for sampling algorithms due to their short duration relative to ensemble dispersion times [6]. The TEAMS (Trying-Early Adaptive Multilevel Splitting) algorithm addresses this by:

- Advance Splitting: Perturbing simulations in advance of the target event to allow sufficient ensemble diversification [6].

- Adaptive Multilevel Splitting: Using a progress coordinate to identify promising trajectories for cloning and less promising ones for pruning [6].

- Statistical Reweighting: Applying proper statistical accounting to maintain unbiased probability estimates despite the biased sampling [6].

This approach achieves 5-10 times acceleration in estimating long return periods for extreme events compared to conventional simulation [6].

Standardized Benchmarking and Evaluation

Comprehensive Metrics for Method Validation

Robust benchmarking requires standardized evaluation metrics. A proposed framework includes over 19 different metrics and visualizations across multiple domains [5]:

- Structural Fidelity: Analysis of radius of gyration distributions, contact map differences, and local structural features.

- Slow-Mode Accuracy: Comparison of TICA energy landscapes and identification of slow conformational transitions.

- Statistical Consistency: Calculation of Wasserstein-1 and Kullback-Leibler divergences between simulated and reference distributions.

- Local Geometry: Distributions of bond lengths, angles, and dihedrals compared to reference data.

Benchmark Protein Dataset

A standardized dataset of nine diverse proteins enables consistent method evaluation [5]:

Table 2: Standardized Protein Benchmark Set for Molecular Dynamics Validation

| Protein | Residues | Fold Type | Description | PDB ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chignolin | 10 | β-hairpin | Tests basic secondary structure formation | 1UAO |

| Trp-cage | 20 | α-helix | Fast-folding with hydrophobic collapse | 1L2Y |

| BBA | 28 | ββα | Mixed secondary structure competition | 1FME |

| Protein B | 53 | 3-helix | Helix packing dynamics | 1PRB |

| Homeodomain | 54 | 3-helix bundle | DNA-binding domain with stable fold | 1ENH |

| Protein G | 56 | α/β | Complex topology formation | 1PGA |

| WW Domain | 37 | β-sheet | Challenging β-sheet topology | 1E0L |

| a3D | 73 | 3-helix | Synthetic helical bundle, tests designability | 2A3D |

| λ-repressor | 224 | 5-helix | Tests scalability for large proteins | 1LMB |

Visualization and Workflow Diagrams

SMD Unbinding Protocol Workflow

Weighted Ensemble Sampling Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| WESTPA 2.0 | Software | Weighted ensemble sampling implementation | Open-source; enables efficient rare event sampling [5] |

| OpenMM | Software | High-performance MD simulation | Supports both CPU and GPU acceleration [5] |

| AMBER ff99SB-ILDN | Force Field | Protein force field parameters | Provides accurate protein dynamics [4] |

| GAFF | Force Field | General Amber Force Field for small molecules | Used for ligand parameterization [4] |

| GROMACS | Software | Molecular dynamics package | Version 2020+; used for system preparation [4] |

| PyMOL | Software | Molecular visualization | Repairs missing residues in PDB structures [4] |

| Gaussian 16 | Software | Quantum chemistry package | Optimizes ligand geometry and calculates electrostatic potentials [4] |

The integration of Steered Molecular Dynamics and rare event sampling algorithms provides a powerful framework for investigating molecular processes critical to drug discovery and protein engineering. The protocols detailed herein—particularly the optimized restraint strategies for SMD and standardized benchmarking approaches for enhanced sampling—enable rigorous investigation of protein-ligand unbinding and conformational transitions. By adopting these standardized methods and utilizing the comprehensive benchmarking tools, researchers can achieve more reproducible and biologically relevant insights into molecular mechanisms, ultimately accelerating therapeutic development and our understanding of biomolecular function.

Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD) is a powerful computational technique that applies external forces to biomolecular systems to simulate processes like ligand unbinding and protein unfolding. The reliability and quantitative accuracy of SMD simulations are critically dependent on the careful selection of three fundamental parameters: pulling force, pulling velocity, and the reaction coordinate. These parameters govern the non-equilibrium work applied to the system and determine how closely the simulation mimics real-world biological processes. Proper configuration of these elements is essential for obtaining meaningful kinetic and thermodynamic data, which is increasingly valuable in drug discovery for predicting properties such as ligand residence times and binding affinities [7] [8] [9].

Within drug development, SMD has emerged as a crucial tool for evaluating ligand-receptor interactions, providing atomic-level insights that complement experimental data. The temporal stability of ligand-receptor complexes, characterized by the residence time (RT), is now recognized as a critical factor influencing drug efficacy and pharmacodynamics. As conventional affinity-based parameters often fall short in predicting in vivo effectiveness, SMD offers a pathway to estimate the dissociation rate constant (k~off~), the inverse of which defines the RT [9]. This application underscores the importance of precise parameter selection in SMD simulations to generate biologically relevant data for kinetic-based drug development.

Theoretical Foundation of SMD

The Jarzynski Equality and Non-Equilibrium Dynamics

SMD operates under non-equilibrium conditions, where continuously changing the distance between molecular groups applies work to the system. The Jarzynski equality provides the theoretical foundation for extracting equilibrium free-energy differences from these non-equilibrium simulations. It states that the equilibrium free-energy difference, ΔG~AB~, between two states A and B can be obtained from an exponential average of the work, W~AB~, performed over many non-equilibrium paths:

ΔG~AB~ = -k~B~T log⟨e^(-βW~AB~)⟩~A~

where k~B~ is Boltzmann's constant, T is the absolute temperature, β = 1/k~B~T, and the angular brackets denote averaging over a canonical ensemble of the initial state A [10]. This relationship enables researchers to derive meaningful thermodynamic information from the forced processes simulated in SMD, bridging the gap between non-equilibrium manipulations and equilibrium properties.

The Bell-Evans Model for Kinetic Insights

For investigating dissociation kinetics, the Bell-Evans model offers a framework to connect SMD results with experimental observables. This model relates the unbinding force (F~R~) measured in simulations to the dissociation rate constant (k~off~) at equilibrium:

F~R~ = (k~B~T / x~b~) ln[(F'x~b~) / (k~B~T k~off~)]

In this equation, x~b~ represents the reaction coordinate projection between the bound and transition state, and F' is the loading rate (the product of the force constant and pulling velocity) [8]. This theoretical foundation allows researchers to predict absolute residence times of drug candidates, such as ligands targeting G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), by analyzing forced unbinding events [8].

Critical SMD Parameters and Their Optimization

Pulling Velocity

Pulling velocity is perhaps the most critical parameter in SMD simulations, as it directly influences the magnitude of force required for dissociation and the biological relevance of the results. While faster pulling speeds enable computationally efficient sampling, they introduce non-equilibrium effects that can distort the energy landscape and mechanism. The selection of appropriate pulling velocities depends on the specific system and research question, with slower velocities generally providing more physiologically relevant data.

Table 1: Typical Pulling Velocity Ranges in SMD Studies

| System Type | Pulling Velocity Range | Application Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand-Protein Unbinding [8] | 0.0001 - 0.0010 nm/ps | GPCR-ligand dissociation | Slower velocities (e.g., 0.0001 nm/ps) approximate closer to equilibrium conditions |

| Membrane Extraction [11] | 0.5 nm/ns (5 Å/ns) | Small molecule and peptide affinity | Constant velocity pulling with sufficiently large force constant |

| Protein Unfolding [12] | Varies by method | Talin rod subdomain unfolding | High speeds generate artificial structural states; balance with computational cost |

Pulling Force and Spring Constant

The pulling force in SMD simulations is typically applied through a harmonic potential, with the spring constant (elastic constant) determining the stiffness of this connection. This parameter controls the sensitivity of the method and influences the pathway of the forced reaction. A balance must be struck—too soft a spring may not adequately transfer the pulling force, while too stiff a spring may suppress thermal fluctuations essential for exploring natural pathways.

Table 2: Spring Constants and Force Application Methods

| Parameter | Typical Values | Impact on Simulation | Representative Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spring Constant [8] [11] | 600 kJ/mol/nm² / 2.4 kcal/mol/Ų | Softer springs allow more system flexibility; stiffer springs provide tighter control | GPCR-ligand unbinding; small molecule membrane extraction |

| Constant Force Pulling [10] | Applied directly | Linear potential, no reference distance | Less common for free energy calculations |

| Umbrella Pulling [10] | Harmonic potential | Force proportional to displacement | Common in SMD for its numerical stability |

The selection of spring constant significantly affects the simulation outcome. Studies on membrane-interacting molecules revealed that spring stiffness is "crucially important to reveal specific events that occur during the molecule behavior," directly influencing methodological sensitivity [11]. Similarly, the choice of pulling group "highly influenced the reaction pathway," making force profiles unique "fingerprints" of these induced pathways [11].

Reaction Coordinates and Pulling Geometries

Reaction coordinates define the collective variables along which the system is steered, serving as computational observables that map the progression of the molecular process. GROMACS refers to this as the "pull code," which applies forces or constraints on these collective variables [10]. The appropriate selection of reaction coordinates is essential for efficiently sampling the relevant conformational changes and obtaining meaningful results.

Table 3: Common Reaction Coordinate Geometries in SMD

| Geometry Type | Definition | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distance [10] | Distance between two groups' centers of mass | Ligand unbinding, molecular dissociation | Most common; follows natural separation vector |

| Direction [10] | Pulling along a defined vector | Membrane protein pulling against fixed orientation | Avoid with freely oriented reference groups |

| Direction-relative [10] | Pulling along a vector defined by two additional groups | Systems without fixed orientation | Prevents unwanted torque forces |

| Cylinder [10] | 1D distance with cylindrical reference | Layered systems (e.g., lipid bilayers) | Dynamically uses reference atoms within cylinder radius |

| Angle/Dihedral [10] | Angle between vectors defined by multiple groups | Conformational changes, rotational motions | Requires 4 groups for angle, 6 for dihedral |

For complex systems like lipid bilayers, specialized geometries such as the cylinder geometry can provide more locally relevant reaction coordinates. This approach dynamically selects only those reference atoms within a defined cylinder around the pull vector, with distance-based weighting to minimize radial force effects [10]. For periodic systems where plain center-of-mass definitions become problematic, such as water slabs connected through periodic boundaries, cosine-shaped weighting profiles can provide unique and continuous reference positions [10].

Experimental Protocols for SMD Simulations

Protocol 1: Ligand-Protein Unbinding Kinetics

This protocol outlines the procedure for estimating ligand residence times through forced unbinding simulations, adapted from studies on GPCR-ligand systems [8].

Step 1: System Preparation and Equilibration

- Obtain the initial ligand-protein complex structure from experimental data or molecular docking.

- Solvate the system in an appropriate water model (e.g., TIP3P) and add ions to physiological concentration (e.g., 0.15 M KCl).

- Energy minimization using steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm until convergence.

- Equilibration with position restraints on protein heavy atoms (typically 100-1000 kJ/mol/nm²):

- NVT ensemble equilibration for 100-500 ps

- NPT ensemble equilibration for 1-5 ns

- Unrestrained production MD simulation for 50-100 ns to ensure system stability.

Step 2: SMD Simulation Setup

- Select starting structure from the equilibrated trajectory based on root mean-square deviation (RMSD) stability.

- Define the reaction coordinate as the distance between the ligand's center of mass and the binding pocket center.

- Configure pulling parameters:

- Pulling velocity: 0.0001-0.0010 nm/ps

- Spring constant: 600 kJ/mol/nm²

- Pulling geometry: distance (along the vector between groups)

Step 3: Running SMD Simulations

- Perform multiple SMD runs (minimum 3-5 replicates) with different initial velocities.

- For each simulation, record:

- Time-dependent pulling force

- Reaction coordinate value (separation distance)

- Work performed on the system

- Key interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts)

Step 4: Data Analysis and Residence Time Calculation

- Extract maximum unbinding force (F~max~) and total work from each trajectory.

- Apply the Bell-Evans model to estimate k~off~ values.

- Calculate residence time as RT = 1/k~off~.

- Compare with experimental data if available for validation.

Protocol 2: Small Molecule Membrane Permeability Assessment

This protocol describes the use of SMD for studying the membrane affinity and permeation of small molecules, based on methodologies for analyzing membrane-interacting molecules [13] [11].

Step 1: Membrane System Preparation

- Construct a lipid bilayer representative of the biological membrane of interest (e.g., POPC for mammalian cells).

- Hydrate the bilayer with appropriate water model.

- Insert the small molecule of interest at the membrane-water interface.

- Minimize and equilibrate the full system:

- Energy minimization with restraints on lipid and solute atoms.

- Gradual relaxation of restraints over multiple equilibration steps.

- Unrestrained equilibration for 20-100 ns until membrane properties stabilize.

Step 2: SMD Parameter Optimization

- Test different spring constants (e.g., 2.4-10 kcal/mol/Ų) to balance sensitivity and pathway exploration.

- Select pulling velocity based on system size and computational resources (e.g., 0.5-5 Å/ns).

- Choose appropriate pulling groups that represent the molecular orientation during permeation.

- Define reaction coordinate as the distance between molecule center of mass and membrane center along the bilayer normal.

Step 3: Extraction Simulations

- Perform multiple SMD runs pulling the molecule from the membrane interior to the water phase.

- Vary the initial position and orientation within the membrane.

- Record force profiles, work values, and molecular orientation during extraction.

- Identify key interactions with lipid headgroups and hydrocarbon chains.

Step 4: Potential of Mean Force (PMF) Calculation

- Use the Jarzynski equality to estimate PMF from multiple nonequilibrium work values.

- Alternatively, combine with umbrella sampling for more accurate free energy profiles.

- Analyze the energy barriers associated with membrane crossing.

- Correlate with experimental permeability data when available.

Visualization and Workflow Diagrams

SMD Simulation Workflow: This diagram outlines the comprehensive workflow for conducting steered molecular dynamics simulations, from initial system preparation to final results interpretation.

SMD Parameter Optimization Logic: This diagram illustrates the decision process and evaluation criteria for optimizing critical SMD parameters to ensure reliable and biologically relevant results.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for SMD

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role in SMD |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software [10] [12] | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER, CHARMM | Primary engines for running SMD simulations with implemented pulling algorithms |

| Force Fields [14] | CHARMM27, CHARMM36, AMBER, GROMOS | Provide empirical potential energy functions for different molecular types |

| Analysis Tools | GROMACS analysis suite, VMD, MDAnalysis | Process trajectories, calculate forces, work, and monitor interactions |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods [12] | Umbrella Sampling, Boxed MD (BXD) | Complement SMD for free energy calculations and improved sampling |

| Visualization Software | VMD, PyMOL, Chimera | System setup, trajectory analysis, and result presentation |

| Specialized Pulling Geometries [10] | Distance, direction, cylinder, angle/dihedral | Define reaction coordinates matched to specific biological questions |

The rigorous application of SMD in studying specific atomic motions demands careful attention to three essential parameters: pulling velocity, which must balance computational efficiency with biological realism; pulling force and spring constant, which control the sensitivity and pathway of the forced process; and reaction coordinates, which must accurately capture the relevant molecular motions. The protocols and guidelines presented here provide a framework for researchers to implement SMD techniques effectively across various applications, from drug discovery to membrane permeability studies. As MD methodologies continue to advance, the precision in parameter selection will further enhance the value of SMD in bridging molecular simulations with experimental observables, particularly in the critical assessment of binding kinetics and drug-target interactions.

Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD) is a powerful computational technique that applies external forces to a molecular system to induce specific motions or processes, such as ligand unbinding or conformational changes, on computationally accessible timescales [15]. This method is particularly valuable for studying biological events that occur too slowly for standard MD simulations to capture efficiently. Within the broader thesis on SMD protocols for studying specific atomic motions, this document provides detailed application notes and protocols for configuring and executing SMD simulations within realistic membrane and solvent environments, which are critical for studying biologically relevant systems like membrane-embedded receptors.

Key Concepts and Energetics

Understanding the forces and energies governing molecular systems is fundamental to designing effective SMD simulations. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent multiscale simulation studies.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Data from Multiscale Simulation Studies

| System / Parameter Studied | Computational Method | Key Quantitative Finding | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO₂ Capture in Aqueous MEA [16] | Steered Rare-Event (COLVARS) | Effective 1D diffusivity: 8.46 × 10⁻¹¹ m²/s | Two orders lower than bulk diffusivity, reveals kinetic bottleneck before chemical binding. |

| CO₂ Binding to MEA Amine Group [16] | DFT-D3 | Binding Energy: -0.37 eV | Confirms stronger binding to amine vs. hydroxyl group (-0.25 eV), guiding solvent design. |

| CO₂-MEA Reaction Barrier [16] | CI-NEB | Forward Barrier: 0.11 eV; Reverse Barrier: 0.39 eV | Supports kinetic feasibility of the CO₂ capture reaction. |

| GPCR Intracellular Opening [17] | Classical MD (556.5 µs dataset) | Transition time (apo): Closed→Intermediate ~0.5 µs; Closed→Open ~7.8 µs | Reveals spontaneous "breathing" motions and the impact of ligand binding on receptor dynamics. |

| SPEEK Membrane Proton Conductivity [18] | Classical MD (Parameter Analysis) | DREIDING FF Tg: 461 K; COMPASS III conductivity: 16.6 mS/cm | Highlights critical impact of force field selection on matching different experimental properties. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key components required to set up and run SMD simulations of biological systems in realistic environments.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Realistic Membrane and Solvent Simulations

| Item Name | Function / Description | Example / Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular System Builder | Software to assemble the initial atomic coordinates of the protein, membrane, and solvent. | CHARMM-GUI, PACKMOL-Memgen, VMD's Membrane Plugin. |

| Force Field | A set of empirical parameters defining potential energy functions for the interactions between atoms. | CHARMM36, AMBER, OPLS-AA; Selection is critical for accuracy [18]. |

| Membrane Lipid Types | Pre-equilibrated lipid bilayers of defined composition to create a realistic membrane environment. | POPC, POPE, or complex mixtures mimicking native membranes (e.g., for GPCR studies [17]). |

| Explicit Solvent Model | Water molecules and ions placed around the solute to mimic a physiological aqueous environment. | TIP3P, SPC/E water models; ion concentration (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl) to neutralize charge. |

| Steering & Analysis Tool | Software package that implements SMD algorithms and tools for analyzing the resulting trajectories. | NAMD (with Tcl scripting), GROMACS (with pull code), COLVARS module [16]. |

| Enhanced Sampling Module | Advanced sampling modules for rare-event sampling alongside or in place of direct steering. | PLUMED, COLVARS (for metadynamics, umbrella sampling) [16]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: SMD Simulation of a Ligand Exiting a GPCR via a Lateral Membrane Pathway

This protocol outlines the steps to investigate ligand egress pathways from a membrane-embedded GPCR using SMD, based on insights from large-scale MD datasets [17].

I. System Preparation

- Initial Structure: Obtain a high-resolution structure of the GPCR-ligand complex from the PDB or GPCRmd [17]. For apo systems, remove the ligand.

- Membrane and Solvent Embedding: a. Use a system builder (e.g., CHARMM-GUI) to embed the receptor in an asymmetric lipid bilayer representative of native membranes. b. Solvate the entire system in a rectangular water box using a model like TIP3P. c. Add ions to neutralize the system's net charge and then add more salt to achieve a physiological concentration (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl).

- Energy Minimization and Equilibration: a. Perform steepest descent energy minimization to remove bad atomic contacts. b. Equilibrate the system in stages, first restraining the protein and ligand heavy atoms, then gradually releasing the restraints over several hundred nanoseconds under NPT ensemble conditions. Use the Berendsen barostat for pressure coupling, which has been shown to provide stable control [18].

II. Steered Molecular Dynamics Setup

- Collective Variable (CV) Definition: Define a CV that describes the ligand's dissociation path. For lateral egress, this could be the distance between the ligand's center of mass and the center of the membrane bilayer, combined with its radial coordinate within the membrane plane.

- SMD Parameters: a. Steering Method: Use constant velocity pulling. b. Selection of Atoms: Attach the virtual spring to the heavy atoms of the ligand. Restrain the Cα atoms of the transmembrane helices of the GPCR to prevent unrealistic rigid-body motion of the protein. c. Pulling Speed: Apply a slow, constant velocity (e.g., 0.5-1.0 Å/ns) to the CV to approximate quasi-adiabatic pulling. Multiple trials with different speeds can be used to check for speed-dependence. d. Force Constant: Use a sufficiently high spring constant (e.g., 100-500 kcal/mol/Ų) to keep the ligand close to the intended path.

III. Production Run and Analysis

- Execute SMD: Run multiple, independent SMD simulations (≥10) to account for stochasticity and identify consistent pathways.

- Monitor Key Metrics: Record the time series of the applied force, the CV, and the work performed on the system.

- Pathway Analysis: Cluster the successful egress trajectories to identify common pathways and intermediates. Analyze the protein-lipid interactions around the egress site, as lipid insertions can mark allosteric sites and lateral gateways [17].

- Potential of Mean Force (PMF): Use the Jarzynski equality [15] or umbrella sampling on the identified pathway to calculate the free energy profile (PMF) associated with ligand egress.

Protocol: Multiscale Modeling of Solvent-Solute Interactions

This protocol describes a three-tier approach, combining DFT, classical MD, and steered rare-event sampling to study specific interactions, such as CO₂ capture by amine-based solvents [16].

I. Electronic Structure Calculations (DFT)

- Objective: Characterize the strength and mechanism of the core chemical interaction.

- Procedure: a. Model the solute (e.g., CO₂) and the binding site (e.g., MEA molecule) in a gas-phase or implicit solvent QM calculation. b. Perform geometry optimization to find the stable bound state and the transition state for the reaction using methods like CI-NEB [16]. c. Calculate the binding energy and electronic properties like charge transfer. Apply external fields if relevant to study their effect on the interaction [16].

II. Classical Molecular Dynamics (MD)

- Objective: Understand the structure, dynamics, and transport at the gas-liquid or solution interface.

- Procedure: a. Build a system with explicit solvent molecules (e.g., 26 wt% MEA in water [16]). b. Run classical MD simulations in the NPT ensemble to equilibrate density and study bulk properties. c. Analyze radial distribution functions (RDFs) to determine preferential association (e.g., CO₂ with amine groups). Calculate bulk diffusion coefficients from mean squared displacement (MSD).

III. Steered Rare-Event Sampling (COLVARS)

- Objective: Resolve the kinetically hindered association step at the interface.

- Procedure: a. Define a collective variable that captures the approach of the solute to the binding site. b. Use the COLVARS module to perform biased sampling along this CV, such as umbrella sampling or metadynamics. c. Extract the effective diffusivity along the reaction coordinate and reconstruct the free energy profile [16].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for integrating multiscale modeling and SMD protocols.

Implementing SMD Protocols: Setup, Execution, and Analysis for Drug Discovery

The accuracy of steered molecular dynamics (sMD) simulations is fundamentally dependent on the initial construction and solvation of the protein-ligand system. Proper system preparation ensures that the simulated atomic motions and forces reflect near-physiological conditions, providing reliable insights into molecular mechanisms. This protocol details the comprehensive process of building biologically relevant protein-ligand complexes and applying appropriate solvation models, specifically tailored for sMD studies of specific atomic motions. We provide quantitative comparisons of solvation methods and step-by-step methodologies to ensure reproducibility in computational drug discovery research.

Solvation Models: A Quantitative Comparison

Solvation models approximate the effect of solvent on biomolecular structure and dynamics, with significant implications for simulation accuracy and computational cost. The choice between implicit and explicit solvation involves balancing physical realism with computational efficiency.

Table 1: Comparison of Implicit Solvation Models for MD Simulations

| Model Type | Theoretical Basis | Computational Speed | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SASA [19] [20] | Solvation free energy proportional to solvent-accessible surface area | Very Fast | Simple calculation; direct free energy estimation; suitable for quick screening | Neglects specific electrostatic effects and hydrogen bonding |

| Generalized Born (GB) [19] [20] | Approximates Poisson-Boltzmann electrostatics using pairwise interactions | Fast | Good balance of speed and accuracy for electrostatic interactions; widely used | Accuracy can vary for non-standard molecular shapes; parameter-dependent |

| Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) [19] [20] | Numerical solution of the continuum electrostatics equation | Slow | High accuracy for electrostatic interactions; considered a gold standard for implicit electrostatics | Computationally expensive; requires numerical grid calculation |

| EEF1 [19] | Gaussian exclusion model with volume integration | Fast | 50% faster than vacuum simulations; used in CHARMM19 force field | Simplifies electrostatics; ionic side chains are neutralized |

Implicit solvation represents the solvent as a continuous medium rather than individual molecules, significantly accelerating simulations by reducing the number of particles and smoothing the energy landscape [19] [20]. The Generalized Born (GB) model augmented with a hydrophobic solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) term, often termed GBSA, is among the most commonly used implicit solvent combinations in molecular mechanics (MM/GBSA) [20]. While valuable for conformational sampling, implicit models have limitations: they lack explicit hydrogen bonding with solvent molecules, neglect viscosity that affects solute motion, and require additional terms to account for the hydrophobic effect [20].

Explicit solvation, in contrast, places individual water molecules around the solute, providing a more physically realistic representation of specific solute-solvent interactions, such as hydrogen bond fluctuations and water bridging effects [19]. However, this comes at a high computational cost, requiring significant resources for simulating the large number of water molecules and achieving proper equilibrium [19] [21]. For sMD simulations, where enhanced sampling of specific pathways is often the goal, a trade-off between realism and efficiency must be carefully considered.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Protein-Ligand Complex Construction via Molecular Docking

Objective: To generate a structurally accurate and physically plausible protein-ligand complex for subsequent solvation and sMD simulation.

Materials and Software:

- Protein Data Bank (PDB) file of the target protein.

- 2D or 3D chemical structure file of the ligand (e.g., MOL2, SDF).

- Molecular docking software (e.g., AutoDock Vina, Glide, SurfDock).

- Visualization software (e.g., PyMOL).

Methodology:

- Protein Preparation:

- Obtain the protein structure from the PDB. Remove crystallographic water molecules and heteroatoms unless they are known to be functionally critical.

- Add missing hydrogen atoms appropriate for the physiological pH (e.g., 7.4).

- Assign partial atomic charges using force field parameters (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM). Ensure histidine protonation states are correct.

Ligand Preparation:

- Generate a 3D conformation of the ligand from its 2D structure.

- Minimize the ligand geometry using molecular mechanics to relieve steric clashes.

- Assign accurate partial charges and determine rotatable bonds. Gasteiger charges are commonly used for docking.

Binding Site Definition:

- If the binding site is known from experimental data, define the search space using a grid box centered on the site. A typical box size is 20-25 Å per side.

- For blind docking, encompass the entire protein surface within the grid.

Molecular Docking:

- Run the docking simulation to generate multiple ligand poses (e.g., 10-20).

- Select the top-ranked pose based on the docking scoring function. However, be cautious, as a favorable score does not guarantee biological relevance [22].

Pose Validation and Selection:

- Critically assess the physical plausibility of the selected pose. Use tools like PoseBusters to check for geometric distortions, steric clashes, and correct stereochemistry [22].

- Prioritize poses that recapitulate known key interactions from crystallographic data, such as hydrogen bonds with charged residues (aspartate, arginine, histidine) which are highly frequent in binding pockets [23].

- Visually inspect the pose in PyMOL to ensure the ligand orientation is reasonable.

Visualization Workflow for Complex Analysis:

Protocol 2: Solvation of the Protein-Ligand Complex

Objective: To embed the docked protein-ligand complex in a solvated environment, preparing it for stable MD and sMD simulations.

Materials and Software:

- Prepared protein-ligand complex from Protocol 1.

- Solvation software (e.g.,

gmx solvatefrom GROMACS,LEaPfrom AMBER,tleap). - Force field parameter files for water (e.g., TIP3P, SPC).

Methodology: A. Explicit Solvation Setup:

- Place Complex in a Simulation Box:

- Center the protein-ligand complex in a predefined box (e.g., cubic, dodecahedral). The box should extend at least 10 Å from the solute surface to avoid periodic image artifacts.

- Add Solvent Molecules:

- Fill the box with explicit water molecules. The TIP3P model is a common choice for simulating biomolecules.

- For physiological conditions, replace random water molecules with ions (e.g., Na+, Cl-) to neutralize the system's net charge and achieve a desired salt concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).

B. Implicit Solvation Setup (for specific applications):

- Model Selection:

- Choose an appropriate implicit solvent model based on the research question (see Table 1). For a balance of speed and accuracy, GBSA is often recommended.

- Parameterization:

- In the MD simulation input parameters, specify the implicit solvent model (e.g.,

GBSAin AMBER) instead of defining an explicit water box. No further system building is required, as the solvent is modeled mathematically.

- In the MD simulation input parameters, specify the implicit solvent model (e.g.,

Diagram: Solvation Model Selection Logic:

Protocol 3: System Validation via Energy Minimization and Equilibration

Objective: To ensure the solvated system is stable and has no steric conflicts before initiating production sMD runs.

Methodology:

- Energy Minimization:

- Perform steepest descent or conjugate gradient minimization to remove any bad van der Waals contacts introduced during solvation.

- Run until the maximum force falls below a specified tolerance (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm).

- Equilibration:

- Conduct a short (100-200 ps) MD simulation in the NVT (constant Number, Volume, Temperature) ensemble to stabilize the system temperature (e.g., 310 K).

- Follow with a short (100-200 ps) NPT (constant Number, Pressure, Temperature) ensemble simulation to stabilize the system density and pressure (e.g., 1 bar).

- Monitor the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the protein backbone and ligand. A stable RMSD (typically 1-2 Å) indicates the system has equilibrated [23].

Results and Data Presentation

Proper system preparation leads to stable simulations that can provide meaningful data for sMD studies. Key metrics to monitor during and after preparation include structural stability and interaction consistency.

Table 2: Expected Ranges for Key Validation Metrics Post-Equilibration [24] [23]

| Metric | Description | Stable Range | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Backbone RMSD | Measures overall protein stability relative to the starting structure. | 1.5 - 2.5 Å | Values ≤ 2-3 Å indicate a stable protein fold. |

| Ligand RMSD | Measures ligand stability within the binding pocket. | 1.0 - 2.0 Å | Values ≤ 2 Å suggest the ligand is stably bound. |

| Binding Residue RMSD | Measures stability of residues directly interacting with the ligand. | 0.7 - 1.5 Å (IQR*) | Low fluctuation is crucial for reliable sMD starting points. |

| SASA (Min/Max) | Toggles the solvent exposure of binding residues. | ~2.7 / ~3.2 Ų (median) | Indicates a consistent binding interface with limited solvent penetration. |

| H-bond Occupancy | Percentage of simulation time a specific H-bond is maintained. | >70% (High Occupancy) | Sustained H-bonds are critical for stable binding and realistic sMD steering. |

IQR: Interquartile Range [23].

Analysis of 100 target-ligand complexes revealed that 86.5% of key binding residues form hydrogen bonds with high occupancy (maintained for 71-100% of the simulation time) [23]. This underscores the importance of validating that prepared systems can replicate such persistent, biologically relevant interactions. Furthermore, binding pockets are frequently enriched with charged residues (56%), particularly aspartate, histidine, and arginine, which should be correctly modeled and protonated during protein preparation [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Force Fields for System Preparation

| Item Name | Function / Application | Reference / Source |

|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Molecular docking software for predicting protein-ligand binding poses and affinity. | [22] |

| Glide (Schrödinger) | High-performance molecular docking tool with rigorous scoring functions for pose prediction. | [22] |

| GROMACS | Versatile MD simulation package used for system solvation, energy minimization, equilibration, and production runs. | [24] [21] |

| AMBER Tools | Suite of programs for MD simulations, including the tleap module for system building and solvation. |

[19] |

| PyMOL | Molecular visualization system for analyzing protein-ligand complexes, checking poses, and creating publication-quality images. | [25] [26] |

| CHARMM Force Field | A set of parameters for molecular mechanics, dynamics, and solvation energy calculations of biomolecules. | [19] [20] |

| AMBER Force Field | Another widely used set of parameters for simulating biomolecules, often used with the Generalized Born solvation model. | [19] [20] |

| PoseBusters | A validation toolkit to check the physical plausibility and chemical correctness of AI-generated molecular docking poses. | [22] |

Defining Pulling Groups and Reaction Coordinates for Specific Atomic Motions

Steered molecular dynamics (SMD) simulations enable researchers to investigate specific atomic motions by applying external forces to biomolecular systems. This application note details established protocols for defining pulling groups and reaction coordinates, which are critical for studying processes like ligand unbinding and protein domain rearrangement. We summarize quantitative parameters from foundational studies and provide a detailed methodology for implementing SMD in GROMACS, facilitating its application in drug development research.

In Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD), a reaction coordinate is an abstract one-dimensional coordinate that represents the progress of a molecular process along a chosen pathway [27]. It parameterizes the reaction at the level of the molecular entities involved, often corresponding to a geometric parameter like a distance or angle that changes during the conversion [27]. The careful definition of this coordinate and the groups to which force is applied is paramount for obtaining meaningful thermodynamic and kinetic information.

The core hypothesis underpinning SMD applications is that a biomolecular structure's resistance to an externally applied force correlates with its stability and structural accuracy [2]. This principle allows SMD to be used for assessing protein model quality, exploring unfolding pathways, and studying mechanical resistance in molecular interactions.

Theoretical Framework

The Reaction Coordinate in Chemical Physics

A reaction coordinate is formally a function that maps any point in the system's high-dimensional phase space to a single real number [28]. For complex processes in condensed phase and biomolecular systems, the natural reaction coordinate can be defined as a maximally predictive one-dimensional projection of the system's dynamics [28]. This means that, of all possible one-dimensional measurements, the natural reaction coordinate is the most informative about the system's future evolution, effectively capturing the dynamics of the rate-limiting bottlenecks.

For SMD and other enhanced sampling methods, collective variables (CVs) are employed. A collective variable is a function of a set of atomic coordinates, ( CV = A\{x_i\} ), which reduces the many atomic degrees of freedom to a lower-dimensional set that still describes the crucial characteristics of the system [27]. The reaction coordinate itself is then a continuous function of these collective variables [27].

Common Reaction Coordinate Geometries

The choice of geometry for the reaction coordinate depends on the biological process being simulated. The table below summarizes the most common types.

Table 1: Common Reaction Coordinate Geometries in SMD

| Geometry Type | Mathematical Description | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Distance | Pulling along the vector connecting two groups [29]. | Ligand unbinding from a protein active site [29]. |

| Directional Distance | Distance projection along a specific vector (e.g., pull_coord1_dim = N N Y for Z-axis only) [29]. |

Guiding a molecule through a protein channel or pore. |

| Bond Rotation | Dihedral angle between groups on two atoms [30]. | Conformational analysis of side chains or linkers. |

| Radius of Gyration | Overall compactness of a molecule [31]. | Protein folding/unfolding studies. |

| Center of Mass Distance | Distance between the centers of mass of two groups [31]. | Domain separation in multi-domain proteins. |

Experimental Protocols

Defining Pulling Groups and Parameters in GROMACS

The following protocol details the setup for a ligand unbinding simulation using GROMACS, a widely used MD software package.

1. System Preparation:

- Prepare your protein-ligand complex structure file (e.g.,

.pdbor.gro). - Generate a topology for the entire system, ensuring the ligand parameters are correctly defined.

- Solvate the system in a suitable water model (e.g., TIP3P) and add ions to neutralize the charge.

2. Define Pulling Groups:

In your .mdp (molecular dynamics parameters) file, specify the groups to be pulled. It is generally recommended to use a large, stationary group (like the protein) as the reference and pull the smaller group (like the ligand) relative to it [29].

3. Configure the Reaction Coordinate: This example uses a directional distance geometry to pull the ligand away from the protein along the Z-axis.

4. Execution and Output:

- Run the SMD simulation using

gmx mdrun. - Key output files include

pullf.xvg(containing the applied force over time) andpullx.xvg(containing the position of the pulled group over time).

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for setting up and running an SMD simulation.

SMD Setup and Execution Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section lists key reagents and computational tools essential for conducting SMD simulations.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for SMD

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Engine | Software to perform the numerical integration of the equations of motion. | GROMACS [29], AMBER [32], NAMD. |

| Biomolecular Force Field | A set of empirical potentials that describe the interatomic interactions. | CHARMM, AMBER ff99SB/parmbsc0 [32], Martini (coarse-grained) [31]. |

| Visualization Software | For visualizing the trajectory, monitoring the pull, and debugging. | VMD, PyMol, ChimeraX. |

| Analysis Tools | Built-in or community scripts for processing SMD output. | GROMACS gmx analyze, gmx wham for Umbrella Sampling. |

| Elastic Network Model | Applied to folded domains to maintain their rigidity while allowing flexible linkers to move freely [31]. | Harmonic potential on backbone beads (force constant ~500 kJ mol⁻¹ nm⁻²) [31]. |

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

Successful application of SMD requires careful parameter selection and systematic troubleshooting.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common SMD Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Ligand does not move | Force constant too low; steric clashes; incorrect group definition. | Increase pull_coord1_k (e.g., to 1500); check group indices in .mdp [29]. |

| Simulation crashes with "Pull reference distance... needs to be non-negative" | The reference distance for the pulling coordinate has become negative [29]. | Ensure the larger group is set as the reference; check pulling direction; increase force constant [29]. |

| Ligand moves but not along desired path | Incorrect geometry or pulling dimension. | Use pull_coord1_dim to restrict pulling to a specific axis (e.g., N N Y for Z-axis) [29]. |

| Pulling induces unrealistic distortion | Pulling speed is too high. | Reduce pull_coord1_rate (e.g., to 0.001 nm/ps) to approach quasi-equilibrium pulling. |

| Ligand cannot pass through a channel | The protein structure might be in a closed state [29]. | Consider using an experimentally determined open-state structure if available [29]. |

A critical best practice is to invert the pulling direction by changing the sign of the pull_coord1_rate parameter [29]. For instance, if a positive rate pulls a ligand "down," a negative rate will pull it "up," though the success of this depends on the steric accessibility of the new path [29].

Practical Workflow in GROMACS and Other MD Software Packages

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a cornerstone of computational chemistry and structural biology, enabling researchers to investigate the dynamic motions and energetics of biomolecular systems at atomic resolution. Several software packages have been developed to perform these simulations, each with unique strengths, force field implementations, and hardware optimization strategies. The selection of an appropriate MD engine depends on multiple factors, including the biological question, system size, available computational resources, and required sampling techniques. For studies focusing on specific atomic motions, particularly through steered molecular dynamics (SMD) protocols, the choice of software and workflow implementation critically determines the validity and interpretability of the results.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Molecular Dynamics Software Packages

| Software | License | GPU Acceleration | Key Strengths | Primary Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Free, open-source (GPL/LGPL) | Yes (Extensive) | High performance, excellent parallel scaling, extensive analysis tools | Biomolecular simulations, high-throughput MD, large systems [33] [34] |

| AMBER | Proprietary (free for academics) | Yes (Early & optimized) | Well-validated force fields, rigorous free-energy workflows | Binding affinity prediction, nucleic acids simulations [34] |

| CHARMM | Proprietary (academic license) | Limited | Scriptable control language, method development platform | Novel methodology development, complex simulation protocols [34] |

| NAMD | Free for academic use | Yes (CUDA) | Fast parallel MD, excellent scalability on large clusters | Very large complexes (e.g., viral capsids), interactive visualization [33] [34] |

| OpenMM | Free, open-source (MIT) | Yes (Highly flexible) | Extreme GPU optimization, Python scriptability | Custom force fields, advanced sampling method development [33] [34] |

For researchers investigating specific atomic motions, GROMACS often emerges as the preferred tool due to its exceptional simulation throughput, robust implementation of enhanced sampling methods like SMD, and no financial barrier to access. Its combination of performance, continuous algorithm development, and strong community support makes it particularly suitable for complex protocols requiring extensive sampling or multiple replicas.

A Standard GROMACS Workflow for System Preparation

A typical MD simulation in GROMACS follows a structured pipeline to ensure physical reliability and numerical stability. This process systematically prepares the molecular system, removes unfavorable atomic clashes, and gradually introduces realistic thermodynamic conditions before production simulation can begin. The following workflow describes the setup for a solvated protein, which serves as the foundation for more advanced techniques like SMD.

Initial System Setup

The process begins with a cleaned Protein Data Bank (PDB) file, where all non-protein atoms (water, ions, ligands) have been removed. The gmx pdb2gmx tool converts this structure file into three essential components [35]:

- Topology File (.top): Defines the molecular structure for simulation, including atom masses, bond lengths and angles, and partial charges, based on a selected force field.

- GRO File: The GROMACS structure file containing centered atomic coordinates.

- Position Restraint File: Used during equilibration to hold the protein in place while allowing solvent to relax.

Critical choices at this stage include the force field (e.g., OPLS/AA, CHARMM, AMBER) and water model (e.g., SPC/E), which determine the physical representation of molecular interactions [35]. The simulation box is then defined around the protein using gmx editconf, with a rhombic dodecahedron being the most computationally efficient shape due to its minimal solvent volume requirement [35].

Solvation and Energy Minimization

The protein is solvated using gmx solvate, which fills the simulation box with water molecules. The system's net charge is then neutralized by adding ions (e.g., Na⁺ or Cl⁻) using gmx genion [35]. This solvated system invariably contains steric clashes and unusual geometries that create artificially high potential energy. Energy minimization is performed using the steepest descent algorithm to relieve these strains by iteratively adjusting atom positions to find the nearest local energy minimum [35]. Typical parameters include a Coulomb cut-off of 1.0 nm and 50,000 steps or until the maximum force falls below a specified tolerance (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm) [35].

System Equilibration

Before production simulation, the system must be equilibrated under realistic physiological conditions in two sequential phases:

- NVT Equilibration: This phase, also known as the isothermal-isochoric ensemble, holds the Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature constant. The protein backbone is typically restrained using the previously generated position restraint file, allowing solvent water to organize around the protein while maintaining the experimental structure. Temperature is usually coupled to 300 K using algorithms like Berendsen or velocity rescaling.

- NPT Equilibration: This subsequent phase, the isothermal-isobaric ensemble, holds the Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature constant. It allows the density of the system to adjust to 1 bar pressure, ensuring proper system density. This two-stage equilibration typically requires 100-200 ps total simulation time and produces a stable, well-equilibrated system ready for production MD or advanced sampling [35].

Implementing Steered Molecular Dynamics in GROMACS

Steered molecular dynamics applies external forces to a molecular system to accelerate rare events and study force-induced transitions, such as ligand unbinding, protein unfolding, or ion channel permeation. This technique is particularly valuable for mapping energy barriers and understanding direction-dependent mechanical responses.

Configuring the Pull Code

SMD in GROMACS is implemented through the "pull code" in the molecular dynamics parameters (MDP) file. A typical configuration for pulling a ligand away from a protein binding site includes [29]:

Table 2: Key SMD Parameters and Their Functions

| Parameter | Example Value | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| pullcoord1geometry | distance |

Defines the reaction coordinate type | Alternatives: direction, direction-periodic |

| pullcoord1dim | N N Y |

Enables pulling along X, Y, and/or Z axes | Y Y Y for 3D; N N Y for Z-axis only |

| pullcoord1rate | 0.01 (nm/ps) |

Speed of pulling (10 nm/ns) | Negative value reverses direction [29] |

| pullcoord1k | 1000 (kJ/mol/nm²) |

Force constant of pulling spring | Higher values (>1500) may be needed to overcome barriers [29] |

| pullcoord1groups | 1 2 |

Defines reference (1) and pulled (2) groups | Large group should typically be reference [29] |

Multidirectional SMD and Vector Sampling

Conventional SMD explores a single pulling direction, but many biological processes exhibit significant mechanical anisotropy. The multiSMD Python tool automates the setup and analysis of multidirectional SMD simulations in GROMACS and NAMD [36]. It systematically probes forces along multiple spatial vectors to capture direction-dependent phenomena that remain hidden in single-axis approaches.

The multiSMD tool generates a comprehensive set of pulling vectors by varying theta and phi angles in spherical coordinates, with default settings sampling three theta angles (0°, 45°, 90°) and four phi angles (0°, 90°, 180°, 270°) for a total of nine distinct pulling directions covering a hemisphere [36]. This approach is particularly valuable for applications such as:

- Anisotropic unbinding in protein-protein complexes

- Ligand dissociation pathway discovery

- Force-induced remodeling of intrinsically disordered protein regions [36]

Troubleshooting Common SMD Issues

Successful implementation of SMD requires careful attention to potential pitfalls:

- Ligand Not Moving: If the ligand fails to move in the desired direction despite applying force, increase the force constant (e.g., from 1000 to 1500 kJ/mol/nm² or higher) and ensure no steric barriers or closed conformational states block the pathway [29].

- Simulation Crashes with Negative Reference Distance: This fatal error occurs when the reference distance becomes negative, often when the pulled group cannot move toward the reference group due to atomic obstructions. Solution: Verify the protein channel is in an open state if applicable, and consider using a larger group as the reference [29].

- Direction Control: To reverse pulling direction, change the sign of

pull_coord1_rate(e.g., from 0.01 to -0.01) and ensurepull_coord1_groupsis set with the larger protein as group 1 and ligand as group 2 [29].

Post-Simulation Analysis and Visualization

Trajectory Analysis

GROMACS includes extensive built-in analysis tools, and the CHAPERONg package further automates up to 20 different post-simulation analyses [37]. Key analyses for SMD trajectories include:

- Force Analysis: Extract maximum rupture forces and work values from pullf.xvg and pullx.xvg files using

gmx analyze. - Hydrogen Bond Evolution: Track formation and breakage of specific interactions during pulling using

gmx hbond. - Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Monitor structural changes in the protein during forced unfolding or unbinding.

- Free Energy Landscapes: Construct using the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) or other techniques from umbrella sampling simulations.

Visualization Tools

Advanced visualization enhances interpretation and communication of SMD results:

- VMD and PyMOL: Standard tools for initial trajectory inspection and figure generation [38].

- BlendMol: A Blender plugin that imports VMD or PyMOL scenes into Blender for industry-standard rendering techniques, producing publication-quality images and animations with photorealistic lighting and shadows [38].

- multiSMD Visualization: The package includes a Tcl script for VMD that renders all specified pulling directions as vectors originating from the center of mass, providing direct visual representation of the sampling strategy [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Tools for GROMACS-based Steered Molecular Dynamics

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in SMD Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Engines | GROMACS, NAMD | Core simulation execution, SMD implementation [36] |

| Automation Tools | CHAPERONg, multiSMD | Automated simulation setup, trajectory analysis, multidirectional SMD [36] [37] |

| System Preparation | pdb2gmx, solvate, genion | Structure conversion, solvation, ionization [35] |

| Visualization Software | VMD, PyMOL, BlendMol | Trajectory inspection, figure generation, advanced rendering [38] |

| Analysis Tools | GROMACS built-in, MDAnalysis | Hydrogen bonding, RMSD, force analysis [36] [35] |

| Enhanced Sampling | Umbrella Sampling, PLUMED | Free energy calculations, reaction coordinate analysis [37] |

The practical workflow for GROMACS-based steered molecular dynamics represents a powerful methodology for investigating specific atomic motions in biomolecular systems. By following the structured pipeline of system preparation, equilibration, and carefully configured SMD simulations, researchers can obtain mechanistically insightful data on processes ranging from ligand unbinding to force-induced conformational changes. The integration of multidirectional approaches through tools like multiSMD and workflow automation via CHAPERONg significantly enhances the efficiency and scope of these investigations. When combined with advanced visualization and robust analysis protocols, these techniques provide a comprehensive framework for understanding the directional dependence of molecular forces, ultimately bridging computational predictions with experimental observables from techniques like atomic force microscopy and optical tweezers.

Fatty Acid Binding Protein 4 (FABP4) has emerged as a promising therapeutic target for multiple pathological conditions, including metabolic syndrome, diabetes, atherosclerosis, and various cancers [7] [39]. Understanding the molecular mechanisms governing inhibitor binding and dissociation is crucial for rational drug design. This case study details the application of steered molecular dynamics (SMD) simulations to elucidate FABP4-inhibitor dissociation pathways and quantify the associated energetics, providing researchers with a comprehensive protocol for studying these critical processes at atomic resolution.

FABP4 functions as an intracellular lipid chaperone, facilitating the uptake and intracellular trafficking of fatty acids [40]. The protein features a ten-stranded β-barrel structure that encloses a substantial interior cavity housing the ligand binding site [40] [41]. The portal region, composed of helix αII and loops between βC-βD and βE-βF, serves as the primary entry and exit point for ligands, with Phe57 (also referred to as Phe58 in some studies) acting as a critical gatekeeper residue [40] [41]. Research has demonstrated that FABP4 inhibition presents therapeutic potential, with studies showing suppressed tumor growth and metastasis in pancreatic cancer models and disrupted lipid metabolism in osteosarcoma through FABP4 targeting [39] [42].

Theoretical Background

FABP4 Structure and Ligand Access Mechanisms

The crystal structure of FABP4 reveals a conserved β-barrel architecture with a small α-helical domain that functions as a lid over the binding cavity [40]. Structural studies have identified that ligands access the binding site through a portal region where the latch residue Phe58 undergoes conformational changes during ligand entry and exit [40]. This portal region exhibits conformational flexibility that is strongly influenced by ligand properties, with different ligands inducing distinct biological outcomes through modulation of FABP4's membrane association and nuclear import capabilities [40].

Molecular dynamics simulations have revealed that FABP4 interconverts between open and closed states, with ligand-free FABP4 preferring the closed state, while ligand binding induces a conformational transition to the open state [41]. This dynamic behavior is coupled with distinct ligand binding modes, suggesting the existence of multiple FABP4-ligand binding conformations that can be exploited for drug design [41].

Steered Molecular Dynamics Fundamentals

SMD applies external forces to simulate the mechanical manipulation of biomolecules, enabling the investigation of processes that occur on timescales inaccessible to conventional MD simulations [7]. In a typical SMD simulation of protein-ligand complexes, one terminus of the ligand receives an external pulling vector while the protein remains constrained, allowing researchers to observe the forced dissociation process and quantify the stabilizing interactions [7]. The Jarzynski equality provides the theoretical foundation for extracting equilibrium information from these non-equilibrium simulations, relating the work done during the steering process to the free energy difference between states [7].

Experimental Design and Computational Methods

System Preparation

Initial Structure Selection and Preparation:

- Source the crystal structure of FABP4 (e.g., PDB entries: 1ALB for apo-FABP4, 1ADL for FABP4-arachidonic acid complex, 2ANS for FABP4-ANS complex) [41]

- Employ protein preparation workflows to add missing hydrogen atoms, assign protonation states, and optimize hydrogen bonding networks

- For the ligand, extract coordinates from the complex and perform geometry optimization using quantum chemical methods (e.g., B3LYP functional with 6-31G* basis set) [41]

- Generate electrostatic potential (ESP) charges and determine atomic RESP charges through fitting procedures [41]

Force Field Parameters:

- Apply Amber ff03 force field for the protein parameters [41]

- Utilize the General Amber Force Field (GAFF) for ligand parameters [41]

- Employ TIP3P water model for explicit solvation [41]

System Solvation and Equilibration:

- Solvate the protein-ligand complex in a rectangular water box with a minimum distance of 10 Å between the complex and box edges [41]

- Add chloride ions to neutralize system charges, with additional NaCl to achieve 0.15 M ionic concentration mimicking physiological conditions [41]

- Perform multi-step energy minimization: initially constrain heavy atoms while minimizing waters, hydrogen atoms, and ions; subsequently conduct full-system minimization without restraints [41]

- Gradually heat the system from 10 K to 300 K over 20 ps using a Langevin thermostat, followed by 40 ps at constant volume (NVT) [41]

- Equilibrate for 200 ps in the NPT ensemble (300 K, 1 bar) using a Langevin thermostat and isotropic position scaling [41]

SMD Simulation Protocol

Reaction Coordinate Definition:

- Define the pulling direction along the vector connecting the center of mass (COM) of the ligand to the COM of the protein's portal region [7]

- Select a pulling velocity of 0.01 Å/ps to approximate quasi-adiabatic conditions [7]

- Apply a harmonic restraint with spring constant of 50 kcal/mol/Ų to the SMD atom [7]

Simulation Parameters:

- Conduct production simulations in the NVT ensemble at 300 K using a Langevin thermostat [41]

- Utilize a time step of 2 fs with constraints on all bonds involving hydrogen atoms (SHAKE algorithm) [41]

- Treat long-range electrostatic interactions with the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method [41]

- Implement periodic boundary conditions throughout the simulation [41]

- Perform triplicate simulations with different initial velocity distributions to ensure statistical robustness [7]

Workflow Implementation:

Data Analysis Methods

Unbinding Force and Work Calculations: