Statistical Mechanics and Molecular Dynamics: The Computational Engine Driving Modern Drug Discovery

This article elucidates the fundamental statistical mechanics principles that underpin Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, a cornerstone computational method in structural biology and drug development.

Statistical Mechanics and Molecular Dynamics: The Computational Engine Driving Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article elucidates the fundamental statistical mechanics principles that underpin Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, a cornerstone computational method in structural biology and drug development. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the theoretical foundation of statistical ensembles that connect atomic-level simulations to macroscopic thermodynamic properties. The content details core methodological approaches, including free energy calculations and potential of mean force, for evaluating biomolecular recognition and ligand binding. We further address practical challenges, optimization strategies for managing computational cost, and the critical validation of MD predictions against experimental data. By synthesizing theory, application, and verification, this guide provides a comprehensive resource for leveraging MD simulations to accelerate and refine the therapeutic discovery pipeline.

From Atoms to Averages: The Statistical Mechanics Engine of MD

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide atomic-resolution models of biomolecules by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for each atom in a system [1]. However, connecting these microscopic trajectories—which depict the precise positions and momenta of all particles over time—to macroscopic thermodynamic properties observable in experiments requires a fundamental bridge. This bridge is provided by statistical mechanics, which uses probability theory to connect the deterministic motions of individual particles at the microscopic scale to the probabilistic thermodynamic behavior observed at the macroscopic scale [1] [2]. For molecular dynamics research, particularly in pharmaceutical applications like drug development, statistical ensembles form the theoretical foundation that enables researchers to calculate essential properties such as binding free energies, entropy contributions, and solvation effects from MD simulation data [1].

Theoretical Foundations: From Microstates to Macrostates

The Microstate-Macrostate Connection

Statistical mechanics links the microscopic description of a system to its macroscopic observable properties through several key concepts [2]:

- Microstates: These represent specific, detailed configurations of all particles in a system, including their precise positions and momenta. For a system of N particles in 3D space, this corresponds to a point in a 6N-dimensional phase space [2].

- Macrostates: These describe the observable, bulk properties of a system, such as temperature, pressure, and volume. A single macrostate typically corresponds to an enormous number of microstates [2].

- Statistical Weight: The number of microstates (Ω) that correspond to a particular macrostate determines its probability. Systems evolve toward macrostates with higher statistical weight [2].

The Ergodic Hypothesis

A fundamental principle connecting MD simulations to statistical mechanics is the ergodic hypothesis, which posits that the time average of a property in a single system (as computed through MD) equals the ensemble average of that property across many copies of the system at one instant [2]. This equivalence justifies using MD trajectories to compute thermodynamic averages.

Fundamental Ensembles in Statistical Mechanics

Statistical ensembles are idealizations consisting of a large number of virtual copies of a system, considered simultaneously, each representing a possible state that the real system might be in [3]. The three primary ensembles defined by Gibbs provide the foundation for molecular dynamics simulations [3].

The Microcanonical Ensemble (NVE)

The microcanonical ensemble describes isolated systems with fixed particle number (N), fixed volume (V), and fixed energy (E) [1] [3].

- Physical Situation: A system completely isolated from its environment, unable to exchange energy or particles [3].

- Fundamental Relation: The entropy (S) is directly related to the number of accessible microstates through Boltzmann's famous equation: [ S = k \log \Omega ] where k is Boltzmann's constant and Ω is the number of microstates [1].

- Molecular Dynamics Connection: NVE simulations directly correspond to this ensemble, conserving total energy throughout the simulation [1].

The Canonical Ensemble (NVT)

The canonical ensemble describes closed systems that can exchange energy with a heat bath at fixed temperature [1] [3].

- Physical Situation: A system in thermal equilibrium with its environment at constant temperature (T), with fixed particle number (N) and volume (V) [1] [3].

- Mathematical Description: The system's energy fluctuates around an equilibrium value, while the temperature remains constant [1].

- Partition Function: The canonical partition function ( Z = \sumi e^{-\beta Ei} ), where ( \beta = 1/kT ), connects microscopic states to thermodynamic properties [2].

- MD Implementation: Achieved through thermostating algorithms that maintain constant temperature while allowing energy fluctuations.

The Grand Canonical Ensemble (μVT)

The grand canonical ensemble describes open systems that can exchange both energy and particles with a reservoir [2] [3].

- Physical Situation: A system in contact with a reservoir with fixed chemical potential (μ), volume (V), and temperature (T) [3].

- Fluctuations: Both energy and particle number can fluctuate in this ensemble [2].

- Applications: Particularly useful for studying adsorption, phase transitions, and systems where particle exchange is important.

Table 1: Characteristics of Fundamental Thermodynamic Ensembles

| Ensemble Type | Fixed Parameters | Fluctuating Quantities | Partition Function | Typical MD Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microcanonical (NVE) | N, V, E | Temperature, Pressure | ( \Omega(E,V,N) ) | Isolated biomolecule in vacuum |

| Canonical (NVT) | N, V, T | Energy, Pressure | ( Z(T,V,N) ) | Solvated protein in a thermostat |

| Grand Canonical (μVT) | μ, V, T | Energy, Particle Number | ( \Xi(\mu,V,T) ) | Ion channel permeation studies |

Connecting Ensembles to Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Statistical Mechanics of Biomolecular Recognition

Molecular recognition processes central to drug action—such as protein-ligand binding—can be understood through statistical ensembles [1]. The non-covalent interactions driving these processes involve complex networks between atoms in both the biomolecules and their surrounding solvent, occurring across multiple timescales [1]. Statistical ensembles allow computation of the thermodynamic properties essential for understanding these interactions.

Free Energy Calculations from MD Simulations

Several computational methods leverage statistical ensembles within MD frameworks to calculate free energy differences [1]:

- Alchemical Transformations: Use non-physical pathways to compute free energy differences between related systems.

- Potential of Mean Force (PMF) Calculations: Determine free energy profiles along reaction coordinates.

- End-Point Calculations: Estimate free energy differences from initial and final states only.

- Harmonic and Quasi-Harmonic Analysis: Calculate entropic contributions from vibrational modes.

Table 2: Quantitative Data from Experimental Studies of T4 Lysozyme (Model System)

| Mutation Site | Experimental ΔG (kcal/mol) | Calculated ΔG (kcal/mol) | Enthalpic Contribution | Entropic Contribution | Method Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Type | Reference | Reference | -12.5 ± 0.8 | -TΔS = +3.2 ± 0.9 | ITC/Thermodynamic Integration |

| L99A | -3.2 ± 0.4 | -3.5 ± 0.5 | -8.9 ± 0.6 | -TΔS = +5.7 ± 0.7 | Alchemical Transformation |

| F153A | +1.8 ± 0.3 | +1.6 ± 0.4 | -5.2 ± 0.4 | -TΔS = +7.0 ± 0.5 | Potential of Mean Force |

Computational Methodologies and Protocols

Free Energy Calculation Protocols

Protocol 1: Thermodynamic Integration (TI)

Purpose: Calculate free energy differences between two states using alchemical transformations [1].

- Define End States: State A (initial) and State B (final) with Hamiltonians HA and HB.

- Parameterize Coupling Parameter: Define H(λ) = (1-λ)HA + λHB, where λ varies from 0 to 1.

- Run MD Simulations: Perform independent simulations at discrete λ values (typically 10-20 points).

- Compute Derivatives: Calculate ⟨∂H/∂λ⟩ at each λ value during simulations.

- Numerical Integration: Compute ΔG = ∫₀¹ ⟨∂H/∂λ⟩_λ dλ.

Key Considerations:

- Ensure sufficient sampling at each λ window.

- Use overlapping sampling to minimize errors.

- Typical simulation length: 1-10 ns per window.

Protocol 2: Potential of Mean Force (PMF) Calculation

Purpose: Determine free energy profile along a reaction coordinate [1].

- Define Reaction Coordinate: Select a physically meaningful coordinate (e.g., distance, angle, torsion).

- Apply Restraints: Use harmonic restraints or umbrella sampling at various points along the coordinate.

- Run Constrained MD: Perform simulations at each restraint position.

- Unbiased Analysis: Use WHAM or MBAR to reconstruct the unbiased free energy profile.

Applications: Ligand binding/unbinding, conformational changes, ion permeation.

Entropy Calculations from MD Trajectories

Quasi-Harmonic Analysis Protocol

Purpose: Estimate conformational entropy from MD simulations [1].

- Trajectory Collection: Run production MD simulation and save coordinates at regular intervals.

- Covariance Matrix Calculation: Compute the mass-weighted covariance matrix of atomic fluctuations.

- Diagonalization: Perform principal component analysis to obtain eigenvalues.

- Entropy Calculation: [ S = k \sum{i=1}^{3N} \left[ \frac{\hbar\omegai/kT}{e^{\hbar\omegai/kT}-1} - \ln(1-e^{-\hbar\omegai/kT}) \right] ] where ω_i are frequencies derived from eigenvalues.

Limitations: Assumes harmonic approximation, which may break down for large-amplitude motions.

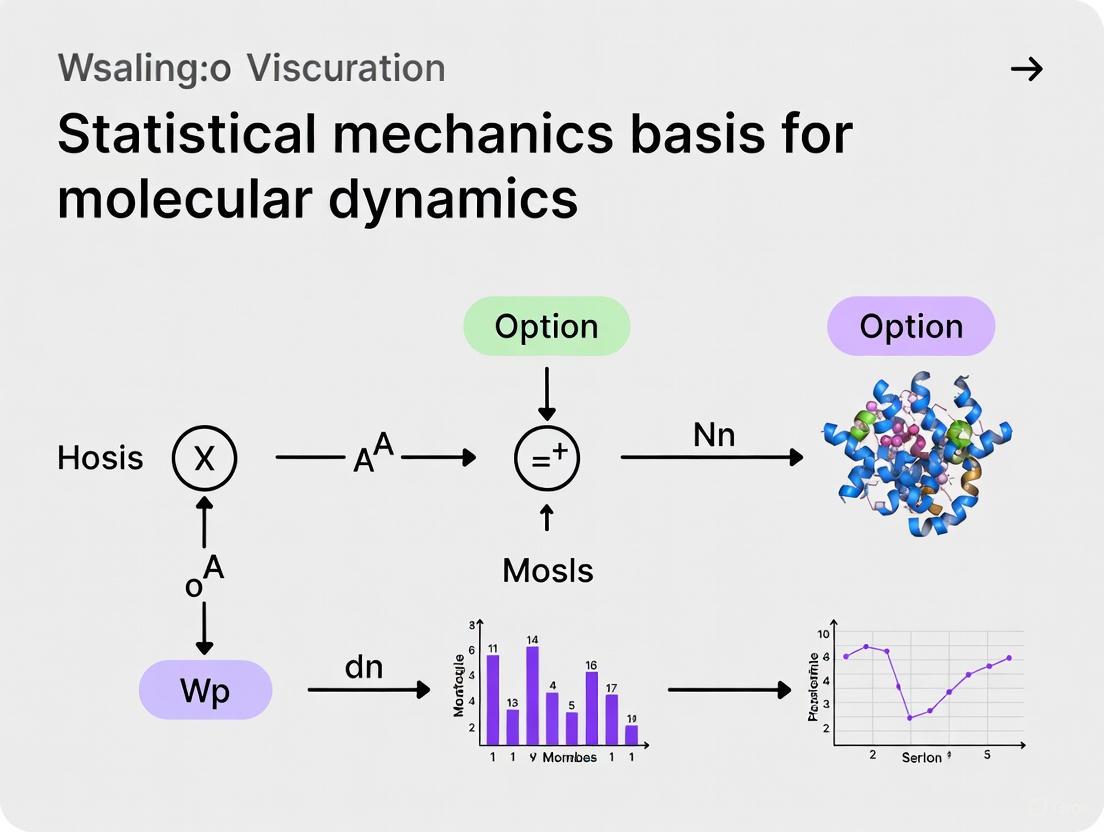

Visualization of Statistical Ensemble Relationships

Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Dynamics Studies

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Ensemble-Based Molecular Dynamics

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Force Field | Function in Ensemble Studies | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomolecular Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS-AA | Parameterize potential energy functions for different molecular systems | Protein-ligand binding studies, membrane simulations |

| MD Engines | NAMD, GROMACS, OpenMM, AMBER | Perform numerical integration of equations of motion with ensemble control | High-performance production simulations on GPUs/CPUs |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | PLUMED, COLVARS | Implement advanced sampling techniques for rare events | Free energy calculations, conformational transitions |

| Free Energy Analysis | WHAM, MBAR, TI, FEP | Analyze simulation data to extract thermodynamic properties | Binding affinity prediction, solvation free energies |

| Visualization & Analysis | VMD, PyMOL, MDAnalysis | Visualize trajectories and compute structural properties | Result interpretation, publication-quality figures |

| Thermostat/Thermostat Algorithms | Nosé-Hoover, Langevin, Berendsen | Maintain correct ensemble temperature/pressure | NVT and NPT simulations with temperature control |

Applications in Drug Development

Statistical ensembles and molecular dynamics provide powerful tools for rational drug design by enabling researchers to predict and optimize key properties [1]:

Protein-Ligand Binding Affinity Prediction

Using canonical ensemble approaches, researchers can compute binding free energies for drug candidates [1]. The statistical mechanics framework allows decomposition of binding energies into enthalpic and entropic contributions, providing insights for optimizing drug specificity and potency [1].

Role of Conformational Entropy and Solvent Effects

Studies using ensemble approaches have revealed that conformational entropy changes and solvent reorganization play critical roles in molecular recognition [1]. For example, analysis of T4 lysozyme mutations shows how entropy-enthalpy compensation can significantly impact binding affinities [1].

Limitations and Future Directions

While statistical ensembles provide the theoretical foundation for molecular dynamics in drug development, current methods face limitations in accurately capturing all relevant physical effects, particularly for large conformational changes and systems with slow dynamics [1]. Ongoing research focuses on developing more efficient sampling algorithms and improved force fields to increase predictive accuracy.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful computational technique that analyzes the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. The trajectories of these particles are determined by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for a system of interacting particles, where forces are calculated using interatomic potentials or molecular mechanics force fields. Within this framework, thermodynamic ensembles provide the critical statistical mechanical foundation that connects the deterministic time evolution of a finite simulation to the macroscopic thermodynamic properties of experimental interest. A statistical ensemble provides a way to derive thermodynamic properties of a system through the laws of mechanics by defining a collection of systems representing all possible states under specified macroscopic constraints.

The choice of ensemble determines which state variables remain constant during a simulation, effectively defining the thermodynamic boundary conditions between the system and its environment. This selection is not merely academic; it directly controls the sampling of phase space and determines which thermodynamic free energy is naturally accessed. The NVE and NVT ensembles represent two fundamental approaches with distinct physical interpretations and applications. The NVE ensemble models isolated systems with fixed energy, while the NVT ensemble models systems in thermal equilibrium with a heat bath at constant temperature. Understanding their theoretical basis, practical implementation, and appropriate domains of application is essential for meaningful molecular dynamics research, particularly in fields like drug development where accurate thermodynamic profiling is crucial.

Theoretical Foundations: From Mechanics to Statistical Ensembles

The Statistical Mechanics Basis of Molecular Dynamics

The theoretical framework of statistical mechanics, largely developed by Boltzmann and Gibbs in the 19th century, connects the microscopic motion of particles to macroscopic observables. The fundamental premise is that macroscopic phenomena result from the average of microscopic events along particle trajectories. In equilibrium, Boltzmann postulated that microscopic states distribute according to a suitable probability density, or ensemble. This framework enables the calculation of thermodynamic properties through ensemble averages, where properties are averaged over all accessible microstates rather than along a single trajectory.

Molecular Dynamics implements this statistical mechanical framework by evolving a system of particles according to specified dynamical rules. For a system described by classical mechanics, the state is defined by the positions and momenta of all N particles. In the Hamiltonian formulation, the equations of motion conserve the total energy of a mechanically isolated system, naturally leading to sampling of the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble. However, most experimental conditions correspond to different thermodynamic environments, necessitating modified dynamics that sample other ensembles like NVT.

The Equivalence and Distinctness of Ensembles

In the thermodynamic limit of infinite system size, different ensembles yield equivalent results for macroscopic properties, a principle known as ensemble equivalence. However, for finite systems simulated in MD, the choice of ensemble matters significantly. As noted in foundational texts, "ensembles are essentially artificial constructs" that "produce averages that are consistent with one another when they represent the same state of the system" only in the thermodynamic limit or away from phase transitions [4] [5]. The fluctuations of thermodynamic variables, however, differ between ensembles and are related to thermodynamic derivatives like specific heat or isothermal compressibility.

Table 1: Fundamental Thermodynamic Ensembles in Molecular Dynamics

| Ensemble | Constant Parameters | Thermodynamic Potential | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microcanonical (NVE) | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Energy (E) | Entropy | Isolated system, no energy or particle exchange |

| Canonical (NVT) | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Helmholtz Free Energy | System in thermal contact with heat bath |

| Isothermal-Isobaric (NPT) | Number of particles (N), Pressure (P), Temperature (T) | Gibbs Free Energy | System in thermal and mechanical contact with reservoir |

| Grand Canonical (μVT) | Chemical potential (μ), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Grand Potential | Open system exchanging particles and energy |

The Microcanonical Ensemble (NVE): Natural Dynamics of Isolated Systems

Theoretical Definition and Dynamics

The NVE ensemble, also known as the microcanonical ensemble, represents a completely isolated system with constant number of particles (N), constant volume (V), and constant energy (E). This ensemble corresponds to the natural outcome of integrating Newton's equations of motion without external interference, where the system cannot exchange energy or matter with its environment. In the NVE ensemble, the total energy is conserved, with continuous exchange between potential and kinetic energy while their sum remains constant [6].

Mathematically, for a system with coordinates q and momenta p, the NVE ensemble samples states according to the probability distribution proportional to δ(E - H(q,p)), where H is the Hamiltonian and E the fixed total energy. The primary macroscopic variables are the total number of particles (N), the system's volume (V), and the total energy (E), all assumed constant throughout the simulation [7].

Practical Implementation and Considerations

In practice, true energy conservation is compromised by numerical rounding and integration errors, though quality implementations minimize this drift. The Verlet leapfrog algorithm, commonly used in NVE simulations, introduces minor fluctuations because potential and kinetic energies are calculated half a step out of synchrony [5].

A significant challenge with NVE simulations arises during equilibration. Since the system cannot exchange energy with a heat bath, achieving a desired temperature requires careful initialization. As a result, "constant-energy simulations are not recommended for equilibration because, without the energy flow facilitated by temperature control methods, the desired temperature cannot be achieved" [5]. However, once equilibrated, NVE dynamics are valuable for probing the natural constant-energy surface of conformational space without perturbations from thermal coupling.

Table 2: NVE Ensemble Characteristics and Applications

| Characteristic | Description | Implications for Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Conservation | Total energy E = K + V remains constant (within numerical error) | Natural dynamics without external perturbation |

| Temperature Behavior | Fluctuates as kinetic and potential energy exchange | Initial conditions determine average temperature |

| Equilibration Limitations | Difficult to achieve target temperature | Best used after equilibration in other ensembles |

| Physical Analog | Isolated system in vacuum | Appropriate for gas-phase reactions without buffer gas [4] |

| Common Applications | Spectroscopy calculations [4], studying intrinsic dynamics | After equilibration for data collection [5] |

The Canonical Ensemble (NVT): Connecting to Constant Temperature Experiments

Theoretical Basis and Physical Interpretation

The NVT ensemble, or canonical ensemble, maintains constant number of particles (N), constant volume (V), and constant temperature (T). This represents a system in thermal equilibrium with a much larger heat bath at temperature T, allowing energy exchange to maintain constant temperature while the total energy of the system fluctuates. The canonical ensemble corresponds to the Helmholtz free energy (A = E - TS), which is the appropriate thermodynamic potential for systems at constant volume and temperature [6] [4].

In statistical mechanical terms, the NVT ensemble samples states with probability proportional to exp(-H(q,p)/kBT), where kB is Boltzmann's constant and T the absolute temperature. This exponential weighting (Boltzmann factor) accounts for the fact that, while energy can fluctuate, states with lower energy are preferentially sampled according to the prescribed temperature.

Temperature Control Methods (Thermostats)

Maintaining constant temperature in MD simulations requires algorithms that mimic the energy exchange with a heat bath. These thermostats employ different physical and mathematical approaches to control temperature, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Berendsen Thermostat: Rapidly converges to target temperature by weakly coupling the system to a heat bath through velocity rescaling. However, it does not generate a correct canonical ensemble, especially for small systems, though it yields roughly correct results for large systems [8] [7].

Nosé-Hoover Thermostat: Extends the physical system with additional dynamical variables representing the heat bath. In principle, it reproduces the correct NVT ensemble and is widely used, though it can exhibit non-ergodic behavior for simple systems like harmonic oscillators [8] [7].

Langevin Thermostat: Models implicit solvent effects through random forces and frictional damping terms. It controls temperature by applying random forces to individual atoms, providing good sampling even for mixed phases. However, the stochastic nature disrupts true dynamical trajectories, making it unsuitable for precise kinetic studies [8] [9] [7].

Anderson Thermostat: Couples the system to a heat bath through stochastic collisions that act occasionally on randomly selected particles, assigning new velocities from the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution [7].

Practical Implementation: Simulation Methodologies and Protocols

Ensemble Selection in Research Practice

The choice between NVE and NVT ensembles depends on the specific research goals, property calculations, and experimental conditions being modeled. As noted by experts, "If you are modelling a gas-phase reaction, you probably want the NVE ensemble. Unless there is a buffer gas, then you probably want the NVT. If the process takes place in the liquid phase, you probably want NPT" [4]. For comparing with most laboratory experiments, constant temperature ensembles (NVT or NPT) are more appropriate as they directly correspond to experimental conditions.

A critical consideration is that different ensembles provide access to different thermodynamic free energies. "NVE gives you back the internal energy. NVT gives you back the Helmholtz free energy. NPT gives you back the Gibbs free energy" [4]. This distinction is particularly important in drug development where binding free energies determine potency and specificity.

Standard Simulation Protocols

A typical MD workflow employs multiple ensembles sequentially to properly equilibrate the system before production simulation. The standard procedure involves:

Energy Minimization: Initial unstable structures with high potential energy are minimized to remove steric clashes and unrealistic geometries.

NVT Equilibration: The system is brought to the desired temperature using a thermostat, allowing thermal equilibration while maintaining fixed volume [6].

NPT Equilibration (if needed): For condensed phase systems, pressure is equilibrated using a barostat to achieve proper density [6].

Production Simulation: The final trajectory for analysis is run in the appropriate ensemble for the properties of interest - often NVT or NPT for comparison with experiment, or NVE for certain spectroscopic calculations [6] [4].

The following diagram illustrates this standard workflow and the role of different ensembles:

Example Protocol: Magnesium Ion Hydration Study

A comprehensive study comparing Mg²⁺ ion models demonstrates proper ensemble usage in practice [10]. The protocol for calculating structural and thermodynamic properties included:

System Preparation:

- Build cubic simulation boxes with ~1000 water molecules and one Mg²⁺ ion

- Employ three-site water models (SPC/E, TIP3P) or four-site models (TIP4PEw)

- Set initial ion-water distance based on expected coordination

Equilibration Phase:

- Perform energy minimization using steepest descent until convergence (<1000 kJ/mol/nm)

- Execute NVT equilibration for 100 ps using Nosé-Hoover thermostat at 298.15 K

- Conduct NPT equilibration for 200 ps using Parrinello-Rahman barostat at 1 bar

Production Simulation:

- Run NVT production for 20-50 ns using Langevin thermostat or Nosé-Hoover chain

- Employ 2 fs time step with constraints on bonds involving hydrogen

- Use particle mesh Ewald for long-range electrostatics with 1.0 nm real-space cutoff

Analysis Methods:

- Radial distribution functions from coordinate saving every 1 ps

- Solvation free energies via free energy perturbation

- Diffusion coefficients from mean squared displacement calculations

- Residence times from continuous trajectory analysis

Comparative Analysis: NVE vs. NVT Ensemble Properties

Thermodynamic and Dynamic Properties

The choice between NVE and NVT ensembles significantly impacts both thermodynamic and dynamic properties accessible from simulations. The following table summarizes key differences:

Table 3: Comparison of NVE and NVT Ensemble Properties and Applications

| Property | NVE Ensemble | NVT Ensemble |

|---|---|---|

| Conserved Quantity | Total Energy | Temperature |

| Fluctuating Quantity | Temperature | Total Energy |

| Thermodynamic Potential | Entropy (S) | Helmholtz Free Energy (A) |

| Physical System | Isolated system | System in heat bath |

| Temperature Control | None (natural fluctuations) | Thermostat maintains constant T |

| Equilibration Efficiency | Poor for reaching target T | Excellent for thermalization |

| Dynamical Properties | True Hamiltonian dynamics | Modified dynamics (thermostat-dependent) |

| Appropriate Applications | Gas-phase reactions [4], spectroscopic calculations [4] | Condensed phase systems, comparison to most experiments |

| Barrier Crossing | Rate zero if barrier height > total energy [4] | Finite rate due to thermal fluctuations [4] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 4: Essential Tools for Ensemble Simulations in Molecular Dynamics

| Tool Category | Specific Methods/Implementations | Function and Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Thermostats | Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen, Langevin, Andersen | Maintain constant temperature in NVT simulations |

| Integrators | Velocity Verlet, Leap-Frog, LINCS, SHAKE | Numerically integrate equations of motion |

| Force Fields | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS, GROMOS | Calculate potential energies and forces |

| Water Models | SPC/E, TIP3P, TIP4P, TIP4PEw | Represent solvent water structure and properties |

| Software Packages | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, LAMMPS, VASP | Implement MD algorithms and analysis tools |

| Analysis Methods | RMSD, RDF, MSD, PCA, Free Energy Calculations | Extract physical properties from trajectories |

Advanced Topics and Current Research Directions

Ensemble-Dependent Phenomena and Limitations

The formal equivalence of ensembles in the thermodynamic limit does not hold for many practical simulations with finite system sizes. A telling example is barrier crossing: "Consider the calculation of the rate, but assume that the barrier height is just below the total energy for the NVE ensemble. The rate is 0: it can never cross the barrier. However, in NVT with an average energy equal to the energy of your NVE ensemble, the rate will not be zero! Sometimes the thermal energy is enough to push you over the barrier" [4].

Additionally, different thermostats within the NVT ensemble can produce varying results for dynamic properties. As noted in discussions of thermostats, "With fix nvt you can sample at true NVT statistical mechanical ensemble... with fix langevin you have a different mechanism" [9]. The Langevin thermostat, while excellent for sampling structural properties, modifies dynamics through random forces, making it unsuitable for calculating transport properties or precise dynamical correlation functions.

Relationship to Other Ensembles

While this review focuses on NVE and NVT ensembles, the complete picture requires understanding their relationship to other important ensembles. The isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble maintains constant temperature and pressure, making it ideal for simulating laboratory conditions where reactions occur at constant pressure. The grand canonical (μVT) ensemble allows particle exchange, useful for studying adsorption and open systems. As noted in foundational texts, "the vast majority of experimental observations are performed within an NPT, μVT, and NVT ensemble" while "microcanonical ensembles are rarely used in real experiments" [6].

The following diagram illustrates the relationships between major ensembles and their corresponding thermodynamic potentials:

The NVE and NVT ensembles provide fundamental frameworks for connecting molecular dynamics to thermodynamics. The NVE ensemble represents the natural consequence of Newtonian mechanics for isolated systems, conserving total energy and providing the most direct implementation of Hamiltonian dynamics. The NVT ensemble, by maintaining constant temperature through thermostat algorithms, connects simulations to experimental conditions where temperature is controlled and enables calculation of Helmholtz free energies.

Understanding the statistical mechanical basis of these ensembles is essential for designing appropriate simulation protocols and interpreting results correctly. While formal equivalence exists in the thermodynamic limit, practical simulations with finite systems require careful ensemble selection based on the target properties and experimental conditions being modeled. For drug development professionals, this understanding is particularly crucial when calculating binding affinities, solvation free energies, and other thermodynamic properties that directly impact compound optimization. The continued development of advanced thermostat methods and multi-ensemble approaches promises enhanced accuracy in connecting molecular dynamics simulations to experimental observables across chemical and biological domains.

The ergodic hypothesis serves as a foundational pillar in statistical mechanics, providing the crucial theoretical justification for equating time-averaged properties from molecular dynamics simulations with ensemble averages from statistical thermodynamics. This principle asserts that over sufficiently long periods, a system's trajectory will uniformly explore all accessible regions of its phase space, thereby making the time average of any observable property equal to its average over an ensemble of systems. Within computational drug discovery, this hypothesis enables researchers to extract meaningful thermodynamic and kinetic information from molecular dynamics trajectories, bridging microscopic atomic movements with macroscopic experimental observables. This whitepaper examines the mathematical foundations of ergodicity, its practical implications for molecular simulation methodologies, and its critical role in advancing structure-based drug design, while also addressing important limitations and cases of ergodicity breaking in pharmaceutical research contexts.

The ergodic hypothesis, initially formulated by Ludwig Boltzmann in the late 19th century, represents a cornerstone concept in statistical mechanics that enables the connection between microscopic dynamics and macroscopic observables [11] [12] [13]. This principle posits that over sufficiently long time periods, a system's trajectory will visit all accessible microstates consistent with its energy, with the time spent in any region of phase space being proportional to that region's volume [11]. The profound implication of this hypothesis is that the time average of a system property—obtained by following the system's evolution—equals the ensemble average—calculated across a large collection of identical systems at a single instant [12] [13].

In the context of molecular dynamics research for drug discovery, this hypothesis provides the essential theoretical justification for using simulation trajectories to compute thermodynamic properties that would otherwise require impractical or impossible experimental measurements. The ergodic assumption allows computational scientists to extract meaningful thermodynamic and kinetic information from the temporal evolution of simulated molecular systems, effectively bridging the gap between Newtonian dynamics and statistical thermodynamics [14] [15]. When a simulated system exhibits ergodic behavior, researchers can confidently relate properties calculated from a single, long trajectory—such as binding free energies, conformational equilibria, or fluctuation patterns—to the ensemble properties that define the system's thermodynamic state [16] [12].

Table 1: Fundamental Concepts in Ergodic Theory

| Concept | Mathematical Definition | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Time Average | $\langle A \ranglet = \lim{T \to \infty} \frac{1}{T} \int_0^T A(t) dt$ | Value obtained by measuring property A over an extended duration for a single system |

| Ensemble Average | $\langle A \rangle_e = \frac{1}{\Omega} \int A(\Gamma) \rho(\Gamma) d\Gamma$ | Value obtained by averaging property A across many identical systems at one time |

| Ergodic Hypothesis | $\langle A \ranglet = \langle A \ranglee$ | The equivalence between temporal and statistical averaging |

| Phase Space | $\Gamma = (\vec{q}1, \vec{q}2, ..., \vec{q}N; \vec{p}1, \vec{p}2, ..., \vec{p}N)$ | Multidimensional space encoding all possible positions and momenta of the system |

The significance of ergodicity extends throughout modern computational drug discovery, where molecular dynamics simulations have become indispensable tools for understanding drug-receptor interactions, predicting binding affinities, and characterizing protein flexibility [14] [17] [15]. By relying on the ergodic principle, researchers can justify the use of simulation data to approximate experimentally relevant quantities, enabling insights into molecular processes that occur on timescales or under conditions difficult to access through laboratory experiments alone.

Mathematical Foundations of Ergodicity

Theoretical Framework

The mathematical formulation of ergodicity rests on a rigorous framework from dynamical systems theory and statistical mechanics. The ergodic theorem, formally proved by George Birkhoff in 1931, establishes that for measure-preserving dynamical systems, the time average of an integrable function along trajectories exists almost everywhere and equals the space average [13]. Mathematically, this is expressed as:

$$\lim{T \to \infty} \frac{1}{T} \int0^T f(T^t x) dt = \int f(x) d\mu(x)$$

where $T^t$ represents the time evolution operator, $x$ denotes a point in phase space, and $\mu$ is an invariant measure [13]. For isolated Hamiltonian systems with constant energy, the relevant measure is the microcanonical ensemble, which assigns equal probability to all accessible microstates [11] [13].

A critical connection between dynamics and statistics emerges through Liouville's theorem, which states that for a Hamiltonian system, the local density of microstates following a particle path through phase space remains constant as viewed by an observer moving with the ensemble [11]. This conservation principle implies that if microstates are uniformly distributed in phase space initially, they remain so at all times, though it's important to note that Liouville's theorem alone does not guarantee ergodicity for all Hamiltonian systems [11]. The combination of Liouville's theorem with the ergodic hypothesis provides the mathematical foundation for statistical mechanics, justifying the use of ensemble averages to compute thermodynamic properties.

The Ergodic Hierarchy and Mixing Properties

Ergodic systems exist within a broader classification scheme known as the ergodic hierarchy, which categorizes dynamical systems based on their statistical properties and degree of randomness [13]. This hierarchy includes:

- Ergodic systems: Where time averages equal ensemble averages for almost all initial conditions

- Mixing systems: Where correlations between states decay to zero over time

- K-systems: Exhibiting positive Kolmogorov-Sinai entropy and sensitive dependence on initial conditions

- Bernoulli systems: With the strongest statistical properties, equivalent to completely random processes

Most molecular systems relevant to drug discovery exhibit some form of weak ergodicity, where sufficient sampling of relevant configurations occurs within computationally accessible simulation timescales, though they may not satisfy the strictest definitions of ergodicity [16] [13]. The concept of mixing is particularly important for establishing the convergence of time averages in practical simulations, as it ensures that the system gradually "forgets" its initial conditions and explores phase space more uniformly.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Technical Framework

Fundamentals of MD Methodology

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide the computational methodology for applying ergodic principles to molecular systems in drug discovery. MD simulations numerically solve Newton's equations of motion for all atoms in a molecular system, generating a trajectory that describes how atomic positions and velocities evolve over time [14] [18]. The core algorithm involves iterating through force calculations and position updates using integration methods like velocity-Verlet or leap-frog, typically with time steps of 1-2 femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ seconds) to maintain stability [14].

The forces governing atomic motions derive from empirical potential energy functions known as force fields, which include terms for bonded interactions (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and non-bonded interactions (electrostatics, van der Waals) [14] [18]. Commonly used force fields in drug discovery include AMBER, CHARMM, and GROMOS, each parameterized to reproduce quantum-mechanical calculations and experimental data for specific classes of biomolecules [18]. Simulations are typically performed under periodic boundary conditions to minimize edge effects, with special techniques like Ewald summation handling long-range electrostatic interactions [14].

Table 2: Key Components of Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Component | Function | Examples/Values |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field | Defines potential energy surface | AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS [18] |

| Integration Algorithm | Advances system in time | Velocity-Verlet, Leap-frog (1-2 fs timestep) [14] |

| Ensemble | Defines thermodynamic conditions | NVE (microcanonical), NPT (isothermal-isobaric) |

| Boundary Conditions | Handles system boundaries | Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC) [14] |

| Long-Range Electrostatics | Manages non-bonded interactions | Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) [14] |

| Thermostat/Barostat | Regulates temperature/pressure | Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen, Parrinello-Rahman |

Ergodicity in MD Sampling

The connection between MD simulations and the ergodic hypothesis emerges through configuration space sampling. In principle, a sufficiently long MD trajectory should explore all thermally accessible configurations of the molecular system, with the relative time spent in each region proportional to its Boltzmann weight [12] [13]. This ergodic sampling enables the calculation of thermodynamic averages from MD trajectories using the formula:

$$\langle A \rangle = \lim{T \to \infty} \frac{1}{T} \int0^T A(t) dt \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^N A(ti)$$

where $A(t)$ is the instantaneous value of an observable, and the approximation becomes exact as the simulation time $T$ approaches infinity [12]. In practice, finite simulation times and energy barriers introduce limitations on ergodic sampling that must be addressed through specialized techniques.

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the ergodic hypothesis and its application in molecular dynamics for drug discovery:

Diagram 1: Logical workflow connecting the ergodic hypothesis to molecular dynamics applications in drug discovery.

Practical Applications in Drug Discovery

Structure-Based Drug Design

Molecular dynamics simulations leveraging the ergodic hypothesis have revolutionized structure-based drug design (SBDD) by addressing one of its most significant challenges: target flexibility [15]. Traditional molecular docking methods often treat proteins as rigid structures, but MD simulations capture their dynamic nature, revealing cryptic pockets and alternative conformations that emerge over time [15] [18]. The Relaxed Complex Method (RCM) represents a powerful application of ergodic sampling, where multiple receptor conformations extracted from MD trajectories are used for docking studies, significantly improving virtual screening outcomes [15].

For example, MD simulations played a crucial role in developing the first FDA-approved inhibitor of HIV integrase by revealing flexibility in the active site region that was not apparent in static crystal structures [15]. Similarly, studies of the acetylcholine binding protein demonstrated how loop motions create distinct binding pocket conformations selectively stabilized by different classes of ligands [18]. These applications depend fundamentally on the ergodic principle that simulations adequately sample the relevant conformational space accessible to the drug target.

Binding Energetics and Kinetics

The ergodic hypothesis enables the calculation of binding free energies from MD simulations through various advanced sampling techniques:

- Free Energy Perturbation (FEP): Computes free energy differences by gradually transforming one state to another

- Thermodynamic Integration (TI): Similar to FEP but using numerical integration over coupling parameters

- Umbrella Sampling: Enhances sampling along predefined reaction coordinates using bias potentials

- Metadynamics: Fills energy basins with repulsive potentials to encourage exploration

These methods rely on the ergodic assumption that simulations sufficiently sample the important configurations contributing to binding thermodynamics [14] [18]. When ergodicity holds, researchers can obtain accurate estimates of binding affinities (ΔG) that correlate well with experimental measurements, providing crucial insights for lead optimization in drug discovery campaigns [14] [17].

Beyond equilibrium properties, ergodic sampling also enables the study of binding kinetics from MD trajectories. By observing multiple binding and unbinding events—either directly in very long simulations or through enhanced sampling techniques—researchers can estimate association and dissociation rates, which provide important insights into drug residence times and efficacy [15] [18].

Advanced Sampling Methodologies

While conventional MD simulations face limitations in crossing high energy barriers within practical timeframes, several enhanced sampling techniques have been developed to improve ergodic sampling:

- Accelerated MD (aMD): Applies a boost potential to smooth the energy landscape, lowering barriers and accelerating transitions between states [15]

- Replica Exchange MD (REMD): Runs multiple simulations at different temperatures, allowing exchanges that prevent trapping in local minima

- Gaussian Accelerated MD (GaMD): An improved version of aMD that applies a harmonic boost potential with more uniform acceleration

These methods effectively enhance ergodic sampling while maintaining correct thermodynamics, making them particularly valuable for studying complex biomolecular processes like protein folding, conformational changes, and ligand binding [15]. The development of these techniques represents an acknowledgment of the practical challenges to ergodicity while still operating within its theoretical framework.

Limitations and Ergodicity Breaking

Theoretical and Practical Challenges

Despite its foundational role, the ergodic hypothesis faces significant limitations in both theory and practice. The original formulation by Boltzmann—that a system's trajectory would pass through every point on the energy surface—has been shown to be mathematically problematic [16] [13]. The Fermi-Pasta-Ulam-Tsingou experiment of 1953 provided an early counterexample, demonstrating that certain nonlinear systems do not equilibrate as expected but instead exhibit recurrent behavior [11] [16].

Further complications arise from Kolmogorov-Arnold-Moser (KAM) theory, which reveals that many Hamiltonian systems contain stable regions (KAM tori) that trajectories cannot leave, preventing exploration of the entire energy surface [16]. In molecular systems, this manifests as non-ergodic behavior when:

- Energy barriers between states are too high to cross on simulation timescales

- The system becomes trapped in metastable states or local minima

- Hidden symmetries or conservation laws restrict phase space exploration

From a practical perspective, the Poincaré recurrence theorem presents another challenge, stating that systems will eventually return arbitrarily close to their initial state, though the recurrence times for molecular systems are typically astronomically large [13].

Ergodicity Breaking in Pharmaceutical Systems

Several biologically relevant systems exhibit broken ergodicity, where the fundamental assumption of uniform phase space exploration fails:

- Glassy systems: Including structural glasses, spin glasses, and some polymers characterized by extremely slow relaxation and complex energy landscapes with many local minima [11] [13]

- Membrane proteins: GPCRs and ion channels may sample distinct conformational substates on timescales inaccessible to conventional MD

- Intrinsically disordered proteins: Which explore heterogeneous conformational ensembles without settling into stable structures

- Molecular aggregates: Such as amyloid fibrils or protein complexes with very slow exchange kinetics

In these cases, standard MD simulations may provide inadequate sampling, leading to inaccurate thermodynamic predictions. For drug discovery applications, this ergodicity breaking is particularly relevant when studying allosteric mechanisms, slow conformational transitions, or systems with multiple metastable states [11] [13].

Table 3: Manifestations and Consequences of Ergodicity Breaking

| System Type | Characteristic Behavior | Impact on Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Glassy Systems | Extremely slow relaxation, aging phenomena | Poor prediction of binding kinetics and residence times |

| Proteins with High Energy Barriers | Trapping in metastable states | Incomplete mapping of conformational landscape |

| Systems with Cryptic Pockets | Rare transitions between open and closed states | Failure to identify potential binding sites |

| Membrane Proteins | Slow lipid rearrangement and protein relaxation | Limited sampling of relevant physiological states |

Experimental Protocols and Research Tools

Methodologies for Testing Ergodicity

Validating ergodic behavior in molecular systems requires specialized computational approaches:

Protocol 1: Ergodic Hypothesis Testing via Coordinate Deviation

- Perform multiple independent MD simulations from different initial conditions

- Track the evolution of key observables (RMSD, radius of gyration, dihedral angles)

- Calculate running time averages for each observable across all trajectories

- Compare the convergence of time averages from different starting points

- Apply statistical tests (such as Kolmogorov-Smirnov) to determine if distributions become indistinguishable

Protocol 2: Phase Space Coverage Assessment

- Define relevant collective variables (CVs) that capture essential dynamics

- Project simulation trajectories into the CV space to create probability distributions

- Compare distributions from different simulation segments using similarity metrics

- Calculate the effective sample size to quantify exploration efficiency

- Monitor the growth of visited phase space volume over simulation time

These protocols help researchers determine whether their simulations achieve sufficient sampling for the ergodic hypothesis to provide meaningful results, or whether enhanced sampling methods are necessary to overcome ergodicity breaking.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Ergodicity-Informed MD

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Ergodicity Research |

|---|---|---|

| MD Software | GROMACS [14], AMBER [14] [18], NAMD [14], CHARMM [14] [18] | Core simulation engines for generating trajectories |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | aMD [15], GaMD, Replica Exchange, Metadynamics | Overcome energy barriers to improve ergodic sampling |

| Force Fields | AMBER [18], CHARMM [18], GROMOS [18], OPLS | Define potential energy surfaces and atomic interactions |

| Analysis Tools | MDTraj, MDAnalysis, VMD, PyEMMA | Quantify phase space exploration and convergence |

| Specialized Hardware | GPU Clusters [18], Anton Supercomputer [18] | Enable longer simulations for better ergodic sampling |

The ergodic hypothesis remains an essential conceptual foundation for molecular dynamics simulations in drug discovery, providing the theoretical justification for extracting thermodynamic information from time-averaged trajectory data. While mathematical purity is often unattainable in practical applications, the concept of effective ergodicity—where systems sufficiently sample functionally relevant configurations within accessible timescales—continues to enable significant advances in structure-based drug design [15] [18].

Future developments in this field will likely focus on addressing the challenges of ergodicity breaking through improved sampling algorithms, more accurate force fields, and specialized computing hardware [14] [18]. The integration of machine learning approaches with molecular dynamics shows particular promise for identifying collective variables that capture essential dynamics and developing more efficient enhanced sampling methods [15]. As these methodologies mature, researchers will increasingly overcome current limitations in conformational sampling, enabling more reliable predictions of drug binding affinities, kinetics, and specificity.

For drug discovery professionals, understanding the principles and limitations of ergodicity is crucial for designing appropriate simulation protocols and interpreting computational results. By recognizing situations where ergodic assumptions may break down—and employing suitable enhanced sampling techniques to address these challenges—researchers can maximize the predictive power of molecular simulations throughout the drug development pipeline. The continued dialogue between theoretical advances in statistical mechanics and practical applications in pharmaceutical research ensures that ergodic principles will remain central to computational drug discovery for the foreseeable future.

Biomolecular stability governs fundamental biological processes, including protein folding, molecular recognition, and drug-target binding. Understanding the physical basis of these processes requires a deep knowledge of the thermodynamic forces that drive them, namely entropy and free energy [1]. While experimental techniques provide invaluable data, a complete picture of intermolecular interactions is often difficult to obtain from experiments alone [1]. Computational methods, particularly molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, have therefore become indispensable tools, offering atomic-resolution insights into the thermodynamics of biomolecular systems [1] [19]. This guide details the statistical mechanical foundations that connect microscopic simulations to macroscopic thermodynamic properties, the computational methodologies for quantifying entropy and free energy, and the application of these principles in modern biomolecular research.

Theoretical Foundations: From Statistical Mechanics to Thermodynamics

Statistical mechanics bridges the microscopic world of atoms and molecules with the macroscopic thermodynamic observables that dictate biomolecular stability. This connection is established through the concept of statistical ensembles.

The Microcanonical Ensemble (NVE)

The microcanonical ensemble describes a system completely isolated from its environment, with a constant number of particles (N), constant volume (V), and constant energy (E). A fundamental postulate is that all accessible microstates are equally probable. The entropy (S) of such a system is given by the famous Boltzmann relation: [ S = k \log \Omega ] where (k) is the Boltzmann constant and (\Omega) is the number of accessible microstates [1]. This equation provides a direct link between the microscopic configuration space and the macroscopic property of entropy.

The Canonical Ensemble (NVT)

Biomolecular processes typically occur in thermal equilibrium with their environment, making the canonical ensemble more relevant. This ensemble represents a system with constant N, V, and temperature (T). Here, the system can exchange energy with a thermal reservoir, and its energy is not constant but fluctuates around an average value [1]. The connection to thermodynamics is made through the Helmholtz free energy, (F = E - TS), which serves as the criterion for stability and determines the population of different states sampled by a biomolecule [20].

Computational Methodologies for Free Energy and Entropy

Calculating the absolute entropy (S) and free energy (F or G) from MD simulations is challenging because these quantities depend on the total probability distribution and partition function, which are not directly provided by standard simulations [20]. A variety of sophisticated methods have been developed to address this problem.

Free Energy Calculation Methods

These methods can be broadly categorized into those that calculate free energy differences and those that aim for absolute values.

Table 1: Key Methods for Free Energy Calculation

| Method | Fundamental Approach | Primary Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Integration (TI) / Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) | Alchemically transforms one molecule into another via a non-physical pathway [1] [20]. | Calculating relative binding free energies of ligands; solvation free energies [21] [20]. | Robust and versatile; requires careful setup of intermediate states to ensure overlap [20]. |

| Potential of Mean Force (PMF) | Computes free energy as a function of a reaction coordinate (e.g., a distance or angle) [1]. | Studying dissociation processes, conformational changes, and barrier crossings [1]. | Provides a detailed view of the energy landscape along a specific coordinate. |

| End-Point Free Energy Methods | Estimates free energy using only snapshots from the bound and unbound (or initial and final) states [1]. | Rapid screening of binding affinities in drug design [1]. | Less computationally intensive than TI/FEP but can be less accurate. |

| Absolute Free Energy Calculations | Transforms a quantitative model into an analytically tractable reference system to compute absolute free energy [22]. | Determining the absolute stability of a molecule or the equilibrium between its different free energy basins [22] [20]. | Avoids the need for a physical transformation path between two states [20]. |

Entropy Calculation Methods

Entropy can be calculated directly or as part of an energy-entropy (EE) scheme where the free energy is ( G = H - TS ) [19].

- Quasiharmonic (QH) Analysis & Normal Mode Analysis (NMA): These methods approximate the potential energy surface as harmonic. NMA uses the curvature at an energy minimum, while QHA uses coordinate covariance matrices from an MD simulation to estimate vibrational entropy [1] [19]. They should be used with caution for highly anharmonic systems [20].

- Inhomogeneous Solvation Theory (IST): This method is applicable to solvent entropy calculations and uses solute-solvent density distributions to compute the water entropy around a biomolecule [19].

- Multiscale Cell Correlation (MCC): A general EE method that calculates the total free energy of a hydrated biomolecule. It decomposes entropy into contributions from correlated units of atoms at multiple length scales (polymer, monomer, united-atom) and includes both vibrational entropy within energy wells and topographical entropy across different wells [19]. The formula for protein entropy is: [ S{\text{prot}}^{\text{total}} = S{P{\text{trans}}}^{\text{vib}} + S{P{\text{ro}}}^{\text{vib}} + S{M{\text{trans}}}^{\text{vib}} + S{M{\text{ro}}}^{\text{vib}} + S{UA{\text{trans}}}^{\text{vib}} + S{UA{\text{ro}}}^{\text{vib}} + S{UA}^{\text{topo}} ]

The following workflow diagram illustrates how these methods are integrated within a molecular dynamics simulation framework to compute thermodynamic properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

The accuracy of MD simulations is critically dependent on the underlying force fields and solvation models, which act as the "research reagents" of computational science.

Table 2: Key Force Field Families and Their Performance

| Force Field Family | Representative Versions | Description / Approach | Reported RMSE for Solvation Free Energy (kJ mol⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMOS | 2016H66, 54A7 | United-atom representation; parametrized for condensed-phase simulations [23]. | 2.9 (2016H66) to 4.8 (ATB) [21] [23] |

| OPLS | OPLS-AA, OPLS-LBCC | All-atom force field; widely used for organic liquids and biomolecules [23]. | 2.9 (AA) to 3.3 (LBCC) [23] |

| AMBER | GAFF, GAFF2 | All-atom force fields originally developed for proteins and nucleic acids; Generalized Amber Force Field (GAFF) for small organic molecules [23]. | 3.4 (GAFF) to 3.6 (GAFF2) [23] |

| CHARMM | CGenFF | All-atom force field with a focus on consistent parameter derivation across diverse molecules [23]. | ~4.0 [23] |

| OpenFF | OpenFF | Part of the Open Force Field Initiative, emphasizing open science, automation, and reproducibility [23]. | ~3.6 [23] |

Solvation Models:

- Explicit Solvent: Uses individual water molecules (e.g., SPC, TIP3P models [23]). Most accurate but computationally demanding.

- Implicit Solvent: Models solvent as a continuous dielectric medium (e.g., Generalized-Born, Poisson-Boltzmann) [19] [22]. Faster but approximates solvent effects.

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies in Practice

Protocol: Free Energy Calculation via Alchemical Transformation

This protocol is used for calculating relative binding free energies or solvation free energies [1] [20].

- System Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the protein and ligand. Parameterize the ligand using the chosen force field (e.g., GAFF2). Solvate the complex in an explicit water box and add ions to neutralize the system.

- Equilibration: Run a series of MD simulations to relax the system, first by minimizing energy, then by gradually heating to the target temperature (e.g., 298.15 K) and applying constant pressure (1 bar).

- Alchemical Transformation Setup: Define the initial state (A) and the final state (B). For a relative binding calculation, this involves mutating one ligand into another. A coupling parameter, (\lambda), is introduced, which scales the Hamiltonian of the system from (\lambda=0) (state A) to (\lambda=1) (state B).

- Sampling at Intermediate States: Perform multiple independent MD simulations at intermediate (\lambda) values (e.g., (\lambda = 0.0, 0.1, 0.2, ... 1.0)). This ensures a gradual transformation and adequate overlap between successive states.

- Free Energy Analysis: Use the Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) or Thermodynamic Integration (TI) formula to compute the free energy difference, (\Delta G). For TI, (\Delta G = \int{0}^{1} \left\langle \frac{\partial H(\lambda)}{\partial \lambda} \right\rangle\lambda d\lambda), where the ensemble average of the derivative of the Hamiltonian with respect to (\lambda) is computed at each window [1] [20].

Protocol: Total Free Energy Analysis of a Hydrated Protein using EE-MCC

This protocol calculates the absolute stability of a protein and its hydration shell [19].

- MD Simulation: Run a long, equilibrium MD simulation of the fully hydrated protein under conditions of constant temperature and pressure (NPT ensemble) to ensure proper sampling.

- Energy Calculation: Calculate the enthalpy (H) of the system as the average of the system Hamiltonian from the MD simulation.

- Entropy Calculation via MCC:

- Unit Definition: Decompose the system into units at multiple scales: the entire protein (polymer), individual residues (monomer), and heavy atoms with their hydrogens (united-atom).

- Vibrational Entropy Calculation: For each unit, compute the translational and rotational vibrational entropy from the covariance matrices of forces, accounting for correlations between units.

- Topographical Entropy Calculation: At the united-atom level, calculate the entropy associated with the distribution of different conformational states and energy wells, defined based on unit contacts.

- Total Entropy: Sum the vibrational and topographical entropy contributions from all scales to obtain the total entropy (S) for the protein and hydration water [19].

- Free Energy Calculation: Compute the total Gibbs free energy as ( G = H - TS ).

Applications and Fundamental Insights

Applying these methodologies has yielded profound insights into the physical basis of biomolecular stability and recognition.

- The Role of Conformational Entropy: Entropy is not just a background factor but a key driver. Upon binding, a ligand and protein often lose conformational entropy, which can be partially compensated by a gain in solvent entropy (the hydrophobic effect) [1]. Understanding this balance is crucial for rational drug design.

- The Central Role of Water: The solvent is not a passive spectator. Water molecules form structured networks around biomolecules, and their stability (or destabilization) significantly influences binding affinity and specificity. Studies show water is most stable around anionic residues and least stable around hydrophobic residues [19].

- Force Field Validation: The performance of different force fields can be systematically evaluated against experimental matrices of cross-solvation free energies. Such studies show that while modern force fields perform similarly, differences in root-mean-square errors (e.g., from 2.9 to 4.8 kJ mol⁻¹) are statistically significant and distributed heterogeneously across different types of compounds [21] [23]. This guides the selection of the most appropriate force field for a specific system.

Computational Tools for Real-World Problems: MD Methods in Drug Discovery

Alchemical Transformations and Potential of Mean Force for Free Energy Calculations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool for probing biochemical processes at an atomic level, providing insights that are often inaccessible through experimental methods alone [1]. A central challenge in computational biology and drug discovery is the accurate calculation of free energy differences, which ultimately govern molecular recognition, binding affinity, and reaction rates [14]. Two powerful computational approaches have emerged to address this challenge: alchemical transformation methods and potential of mean force (PMF) calculations. These techniques are firmly rooted in statistical mechanics, allowing researchers to bridge the gap between microscopic simulations and macroscopic thermodynamic observables [1]. The statistical mechanics basis for these methods originates from the fundamental connection between a system's microscopic states and its macroscopic thermodynamic properties, as formalized through the concepts of the microcanonical (NVE) and canonical (NVT) ensembles [1].

This technical guide explores the theoretical foundations, methodological frameworks, and practical applications of these complementary approaches, with particular emphasis on their implementation within modern drug discovery pipelines. By leveraging the rigorous connection between statistical mechanics and thermodynamics, these methods enable the quantitative prediction of binding affinities, solvation energies, and enzymatic mechanisms, thereby accelerating pharmaceutical development and expanding our understanding of biomolecular function [24] [14].

Theoretical Foundations in Statistical Mechanics

Ensemble Theory and Free Energy

The calculation of free energies in molecular systems derives from the fundamental principles of statistical mechanics, which connect the microscopic states of a system to its macroscopic thermodynamic properties [1]. For the microcanonical ensemble (NVE), where particle number (N), volume (V), and energy (E) remain constant, the entropy is given by Boltzmann's fundamental equation:

$$S = k \log \Omega$$

where $\Omega$ represents the number of accessible microstates equally probable under the ergodic hypothesis, and $k$ is Boltzmann's constant [1].

In practice, most biomolecular simulations employ the canonical ensemble (NVT), which maintains constant temperature (T) through thermal equilibrium with a much larger surrounding system (heat bath) [1]. The Helmholtz free energy (A) in the NVT ensemble connects the microscopic system details with thermodynamic observables through the relationship:

$$A = -kT \ln Q$$

where $Q$ represents the canonical partition function, which sums over all possible microstates of the system [1]. This fundamental relationship enables the calculation of free energy differences from molecular dynamics simulations, forming the theoretical basis for both alchemical and PMF approaches.

Free Energy Perturbation and Thermodynamic Integration

Two foundational approaches for computing free energy differences from simulations are free energy perturbation (FEP) and thermodynamic integration (TI), both of which can be employed in alchemical transformation methods [25]. The FEP method, derived from Zwanzig's formulation, calculates the free energy difference between two states (0 and 1) using the ensemble average:

$$\Delta A = -kBT \cdot \ln \langle \exp[-(U1 - U0)/kB T] \rangle_0$$

where $U0$ and $U1$ represent the potential energies of the initial and final states, respectively, and the angle brackets denote an average over configurations sampled from state 0 [25].

Alternatively, thermodynamic integration employs a continuous coupling parameter $\lambda$ to interpolate between the initial and final states, with the free energy difference given by:

$$\Delta A = \int0^1 \langle \partial U(\lambda)/\partial \lambda \rangle\lambda d\lambda$$

where $\langle \partial U(\lambda)/\partial \lambda \rangle_\lambda$ represents the ensemble average of the derivative of the potential energy with respect to $\lambda$ at a fixed value of $\lambda$ [25]. This approach requires simulations at multiple intermediate $\lambda$ values to numerically evaluate the integral, but typically demonstrates better convergence properties than FEP for large system transformations.

Potential of Mean Force (PMF) Methodology

Theoretical Framework

The potential of mean force (PMF) represents the free energy profile along a specific inter- or intramolecular coordinate, incorporating the effects of all other degrees of freedom, including solvent effects [26]. Mathematically, for a system with N particles, the PMF $w^{(n)}$ for a subset of n particles is defined such that the average force on particle j equals the negative gradient of the PMF:

$$-\nablaj w^{(n)} = \frac{\int e^{-\beta V}(-\nablaj V)dq{n+1}\dots dq{N}}{\int e^{-\beta V}dq{n+1}\dots dq{N}},~j=1,2,\dots,n$$

where $\beta = 1/k_BT$, $V$ represents the full potential energy of the system, and the integration is performed over all coordinates except those defining the reaction pathway [26].

For the specific case of a pair interaction ($n=2$), the PMF $w^{(2)}(r)$ is directly related to the radial distribution function $g(r)$ through:

$$g(r) = e^{-\beta w^{(2)}(r)}$$

This relationship provides a direct connection between structural information obtained from simulations (or experiments) and the free energy profile [26].

Umbrella Sampling and Enhanced Sampling Techniques

Standard MD simulations often fail to adequately sample regions of high free energy along a reaction coordinate due to energetic barriers [26]. Umbrella sampling addresses this limitation by applying biasing potentials to ensure sufficient sampling throughout the reaction pathway [24]. The typical workflow involves:

- Reaction Coordinate Selection: Choosing a physically meaningful coordinate that describes the process of interest (e.g., distance between atoms, torsional angle, or solvent coordinate)

- Window Definition: Dividing the reaction coordinate into multiple overlapping windows

- Biased Simulations: Running independent simulations in each window with harmonic restraints centered at different points along the coordinate

- WHAM Analysis: Using the weighted histogram analysis method to combine data from all windows and reconstruct the unbiased PMF

Table 1: Key Parameters for Umbrella Sampling PMF Calculations

| Parameter | Description | Typical Values |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Windows | Parallel simulations along reaction coordinate | 20-50 depending on system size |

| Force Constant | Strength of harmonic biasing potential | 100-1000 kJ/mol/nm² |

| Simulation Length | Sampling time per window | 10-100 ns |

| Window Overlap | Recommended histogram overlap between adjacent windows | 20-40% |

Alchemical Transformation Methods

Fundamental Principles

Alchemical free energy methods employ a nonphysical pathway, parameterized by a coupling parameter $\lambda$, to interpolate between reference (state A) and target (state B) states [25]. This approach allows the calculation of free energy differences between chemically distinct states without requiring a physically realizable pathway. The $\lambda$-dependent hybrid Hamiltonian $U(\vec{q}; \lambda)$ smoothly connects the two end states, with $\lambda = 0$ corresponding to state A and $\lambda = 1$ corresponding to state B [25].

A critical consideration in alchemical transformations is the avoidance of endpoint singularities, particularly when particles are created or annihilated. This is addressed through the implementation of soft-core potentials, which modify the van der Waals and Coulombic interactions to prevent numerical instabilities [25]. For Lennard-Jones interactions, a standard soft-core potential takes the form:

$$U{LJ}(r{ij};\lambda) = 4\epsilon{ij}\lambda\left( \frac{1}{[\alpha(1-\lambda) + (r{ij}/\sigma{ij})^6]^2} - \frac{1}{\alpha(1-\lambda) + (r{ij}/\sigma_{ij})^6} \right)$$

where $\alpha$ is a predefined soft-core parameter that controls the smoothness of the transformation [25].

Thermodynamic Cycles and Binding Free Energy Calculations

In drug discovery applications, alchemical methods are frequently employed to compute relative binding free energies through the use of thermodynamic cycles [14]. This approach avoids the challenging direct calculation of absolute binding free energies by instead focusing on the difference in binding affinity between similar compounds:

Thermodynamic Cycle for Relative Binding

The relative binding free energy is then calculated as:

$$\Delta \Delta G{bind} = \Delta G{bound}(A \rightarrow B) - \Delta G_{solv}(A \rightarrow B)$$

where $\Delta G{bound}(A \rightarrow B)$ represents the alchemical transformation in the protein-bound state, and $\Delta G{solv}(A \rightarrow B)$ represents the same transformation in solution [14] [25].

Computational Protocols and Implementation

Workflow for PMF Calculations

PMF Calculation Workflow

The PMF calculation workflow begins with the critical step of selecting an appropriate reaction coordinate that captures the essential physics of the process under investigation [26] [24]. Following system preparation and equilibration, the reaction coordinate is divided into multiple windows, with harmonic restraints applied to ensure adequate sampling of all regions, including high-energy transition states [24]. The simulations are typically run in parallel across multiple computing nodes, with production times varying from nanoseconds to microseconds per window depending on system size and complexity [24].

Workflow for Alchemical Free Energy Calculations

Alchemical Calculation Workflow

Alchemical calculations require careful preparation of a hybrid topology that encompasses both the initial and final states [25]. The $\lambda$ schedule must be designed to provide sufficient overlap between adjacent states, typically employing 12-24 intermediate values with closer spacing in regions where the free energy changes rapidly [25]. Modern implementations often incorporate Hamiltonian replica exchange (HREX) between $\lambda$ values to enhance sampling and improve convergence [25].

Table 2: Comparison of Free Energy Calculation Methods

| Feature | Potential of Mean Force | Alchemical Transformation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Reaction pathways, binding/unbinding events, conformational changes | Relative binding affinities, solvation free energies, mutation studies |

| Reaction Coordinate | Physical coordinate (distance, angle, etc.) | Non-physical alchemical parameter (λ) |

| Sampling Enhancement | Umbrella sampling, metadynamics | Hamiltonian replica exchange, λ-dynamics |

| Computational Cost | Moderate to high (multiple windows) | Moderate (multiple λ states) |

| Key Output | Free energy profile along coordinate | Free energy difference between states |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Free Energy Calculations

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function |

|---|---|---|

| MD Software | GROMACS [14], AMBER [14], NAMD [14], CHARMM [14] | Core simulation engines for trajectory generation |

| Force Fields | CHARMM36 [14], AMBERff [14], OPLS-AA [14] | Empirical potential functions for energy calculation |

| Analysis Tools | WHAM [24], MBAR [25], alchemical analysis tools [25] | Free energy estimation from simulation data |

| Enhanced Sampling | Plumed, COLVARS | Implementation of advanced sampling algorithms |

| Visualization | VMD, PyMOL, Chimera | Trajectory analysis and figure generation |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Enzymology

Pharmaceutical Development

Molecular dynamics free energy calculations have become increasingly valuable in the modern drug development process [14]. In the target validation phase, MD studies provide critical insights into the dynamics and function of potential drug targets such as sirtuins, RAS proteins, and intrinsically disordered proteins [14]. During lead discovery and optimization, alchemical free energy calculations facilitate the evaluation of binding energetics and kinetics of ligand-receptor interactions, guiding the selection of candidate molecules for further development [14]. The inclusion of explicit biological membrane environments in simulations of membrane proteins, particularly G-protein coupled receptors and ion channels, has significantly improved the accuracy of binding affinity predictions for these important drug targets [14].

Enzyme Catalysis

PMF simulations have proven particularly valuable in elucidating enzymatic mechanisms, where they help overcome sampling challenges in specific regions of the energy landscape [24]. By computing the free energy profile along the reaction coordinate, researchers can quantify activation barriers and identify transition states and intermediates that are difficult to characterize experimentally [24]. The combination of PMF approaches with hybrid quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) methods has enabled the detailed investigation of bond-breaking and formation processes in enzymatic active sites, providing atomic-level insights into catalytic mechanisms [24].