Self-Diffusion vs. Mutual Diffusion: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical and Materials Research

This article provides a detailed exploration of self-diffusion and mutual diffusion coefficients, two fundamental parameters governing molecular transport.

Self-Diffusion vs. Mutual Diffusion: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical and Materials Research

Abstract

This article provides a detailed exploration of self-diffusion and mutual diffusion coefficients, two fundamental parameters governing molecular transport. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it clarifies the conceptual distinctions, measurement methodologies, and practical applications of these coefficients. The scope ranges from foundational theory and experimental techniques to troubleshooting common challenges, validating data, and leveraging computational predictions. Special emphasis is placed on implications for pharmaceutical development, including drug diffusion through biological barriers and the optimization of analytical chromatography.

Core Concepts: Demystifying Self-Diffusion and Mutual Diffusion

Diffusion, the process of mass transport driven by the random thermal motion of molecules, is a fundamental phenomenon with profound implications across scientific and industrial domains. In chemical engineering, it dictates the efficiency of reactors and separation processes [1]; in pharmacology, it determines the rate at which a drug penetrates biological barriers to reach its target [2]; and in materials science, it controls processes like alloy hardening and phase transformations [3]. The quantitative analysis of diffusion is universally described by Fick's laws, which relate the diffusive flux to the concentration gradient via the diffusion coefficient (D), a parameter that is highly sensitive to the specific physical context. Within the broader thesis of self-diffusion coefficient versus mutual diffusion coefficient research, it is crucial to delineate these core concepts clearly. This guide provides an in-depth examination of three principal diffusion types—self-diffusion, mutual diffusion, and tracer diffusion—framed for researchers and drug development professionals. It will detail their conceptual foundations, present modern experimental methodologies for their measurement, and summarize quantitative data in an accessible format, thereby establishing a rigorous technical reference for the field.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Self-Diffusion

Self-diffusion refers to the translational motion of atoms or molecules of a single species in the absence of any net chemical potential gradient. It is the spontaneous, random motion of particles in a pure substance or a component in a uniform mixture. Since there is no macroscopic concentration gradient, self-diffusion does not result in net mass transport. The coefficient quantifying this motion is the self-diffusion coefficient (D*). It is a measure of the intrinsic mobility of particles due to their thermal energy and is often probed by techniques that can track the motion of labeled but otherwise identical particles, such as Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) [4]. For example, the self-diffusion of water molecules in pure water is a key parameter in understanding fluid dynamics at the molecular level.

Mutual Diffusion

Mutual diffusion (also known as chemical or inter-diffusion) describes the mass transfer process that occurs in a mixture driven by a macroscopic concentration gradient of one or more components. The coefficient quantifying this process is the mutual diffusion coefficient (D₁₂). It is this coefficient that appears in Fick's first law for a binary system: J₁ = -D₁₂ * (∂C₁/∂x) where J₁ is the flux of component 1, and ∂C₁/∂x is its concentration gradient [4]. This is the most commonly referenced diffusion coefficient in engineering applications, such as modeling the diffusion of a drug molecule through a static fluid or the interdiffusion of two gases or liquids [1] [2]. In a binary solution, the mutual diffusion coefficient D₁₂ is equal to D₂₁.

Tracer Diffusion

Tracer diffusion involves monitoring the diffusion of a tiny amount of a labeled component (the "tracer") within a chemically identical or different host medium under conditions of no net concentration gradient. The coefficient measured is the tracer diffusion coefficient (Dₜ). A classic example is the diffusion of a radioactive isotope of zirconium within a matrix of natural zirconium [3]. When the tracer and host are chemically identical, the tracer diffusion coefficient is, in principle, equal to the self-diffusion coefficient. However, if there is a slight mass difference between the tracer and host atoms, a kinetic isotope effect may cause a minor discrepancy. Tracer diffusion is a powerful tool for studying diffusion mechanisms in solids and complex fluids [5].

Conceptual Relationships

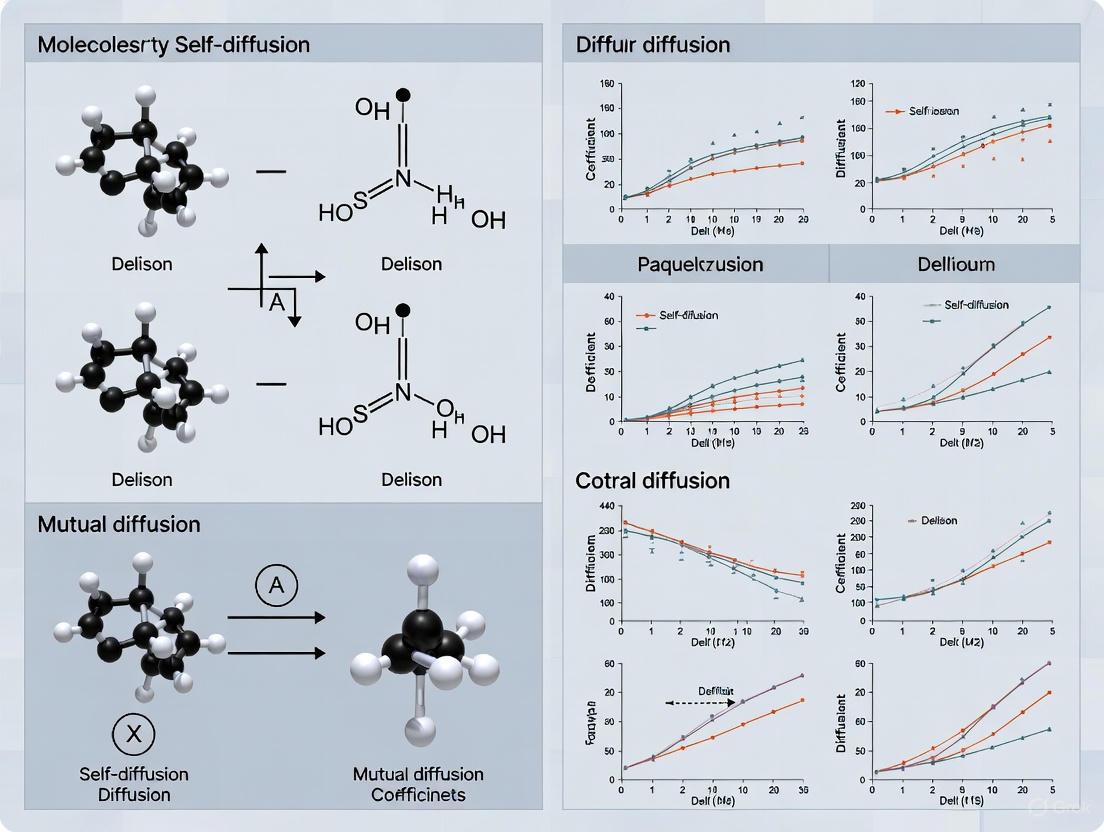

The relationships between these diffusion coefficients are foundational. In a thermodynamically ideal binary mixture, the mutual diffusion coefficient D₁₂ is equal to the tracer diffusion coefficients of the individual components at infinite dilution. In non-ideal systems, thermodynamic factors must be considered. For a single component, the self-diffusion coefficient and the tracer diffusion coefficient are equivalent. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and primary measurement contexts for these three diffusion types.

Quantitative Data and Trends

Diffusion coefficients vary over orders of magnitude depending on the state of matter, temperature, and the specific system. The following tables consolidate representative data and key relationships.

Table 1: Representative Diffusion Coefficients in Various Systems

| System | State | Temp. (°C) | Diffusion Coefficient (m²/s) | Type | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | Liquid | 25 | ~2.30 × 10⁻⁹ | Self-Diffusion | [3] |

| Glucose in Water | Liquid | 25 | ~6.70 × 10⁻¹⁰ | Mutual (Infinite Dilution) | [1] |

| Sorbitol in Water | Liquid | 25 | ~5.80 × 10⁻¹⁰ | Mutual (Infinite Dilution) | [1] |

| Theophylline in Mucus | Gel-like | 37 | 6.56 × 10⁻¹⁰ | Tracer/Mutual | [2] |

| Albuterol in Mucus | Gel-like | 37 | 4.66 × 10⁻¹⁰ | Tracer/Mutual | [2] |

| Ethylene Glycol in Water | Liquid | 25 | ~1.11 × 10⁻⁹ | Mutual (Infinite Dilution) | [6] |

| α-Zr (self-diffusion) | Solid | ~856 | 1.00 × 10⁻¹⁷ | Self-Diffusion | [3] |

Table 2: Factors Influencing Diffusion Coefficients and Common Correlations

| Factor | Effect on D | Correlation / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Increases D | Arrhenius Law: D = D₀ exp(-ED / RT), where ED is diffusion activation energy [6]. |

| Viscosity (η) | Decreases D | Stokes-Einstein (Spherical particles): D = kT / (6πηr) [1] [7]. |

| Molecular Size/Weight | Decreases D | Inverse relationship; for non-spherical molecules, the hydrodynamic radius is used. |

| Surfactants | Can increase D | Reduces effective activation energy E_D in liquid systems, enhancing rate at constant T [6]. |

| Concentration | Variable | Mutual diffusion coefficient D can be a strong function of concentration C, requiring D(C) measurement [4]. |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

A diverse array of experimental techniques exists to measure the different types of diffusion coefficients. The choice of method depends on the system's state (liquid, solid, gas), the available equipment, and the required accuracy.

Taylor Dispersion Method

This method is widely used for measuring mutual diffusion coefficients in liquid solutions due to its experimental simplicity and reliability [1] [8].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Apparatus Setup: A long (e.g., 20 m), narrow-bore (e.g., 0.4 mm internal diameter) capillary tube, typically made of Teflon, is coiled and immersed in a thermostated bath for temperature stability. The system includes a precision pump, an injection valve, and a differential refractive index detector at the outlet.

- Procedure: A solvent stream is pumped at a precise, low flow rate to ensure laminar (parabolic) flow. A small, sharp pulse (e.g., 0.5 mL) of solution with a slightly different concentration is injected into this stream.

- Data Collection: As the pulse flows through the capillary, it disperses axially due to the velocity profile and radially due to diffusion. The detector records the concentration profile (a Gaussian-shaped peak) at the outlet over time.

- Data Analysis: The mutual diffusion coefficient D is determined by fitting the temporal concentration profile to the solution of the dispersion equation. The variance of the peak is inversely proportional to D [1] [8]. The workflow is as follows:

Optical Interferometry (Digital Holographic Interferometry)

This non-contact, high-precision method directly measures the concentration distribution in a diffusion cell to determine mutual diffusion coefficients [4].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Apparatus Setup: A diffusion cell is placed in the path of a coherent laser beam. The system is based on an interferometer (e.g., Mach-Zehnder).

- Procedure: The cell is carefully filled, typically with a denser solution below a lighter solvent to initiate a one-dimensional diffusion process while minimizing convection.

- Data Collection: As diffusion proceeds, the changing concentration profile alters the refractive index, which shifts the interference fringes. A camera records these interferograms over time.

- Data Analysis: The fringe patterns are processed to reconstruct the time-dependent concentration field, C(x, t). Advanced data processing methods, such as those based on the Finite Volume Method (FVM), fit this data to Fick's second law to extract the mutual diffusion coefficient, D, even when it is concentration-dependent, D(C) [4].

Tracer Diffusion Techniques

Tracer methods are indispensable for measuring self-diffusion and tracer diffusion coefficients, especially in solids and complex media.

Detailed Experimental Protocol (Using Radioactive Tracers):

- Tracer Deposition: A thin layer of a radioactive isotope of the material under study (e.g., ⁶⁵Zn for zinc) is deposited on a carefully prepared surface of the sample.

- Annealing Diffusion: The sample is sealed in an ampoule and annealed at a specific temperature for a known time, allowing the tracer atoms to diffuse into the bulk.

- Sectioning and Counting: After annealing, thin layers of the material are sequentially removed (e.g., by precision grinding or ion-beam sputtering). The radioactivity of each removed section is measured.

- Data Analysis: The tracer penetration profile is constructed from the activity vs. depth data. This profile is fitted to the solution of Fick's second law for thin-film geometry, yielding the tracer diffusion coefficient Dₜ [5].

Detailed Experimental Protocol (Using ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy): This method is powerful for studying drug diffusion through biological barriers like artificial mucus [2].

- Apparatus Setup: An artificial mucus layer is placed on an Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) crystal in an FTIR spectrometer.

- Procedure: A drug solution is placed in contact with the upper surface of the mucus layer. The lower surface is in contact with the ATR crystal.

- Data Collection: Time-resolved FTIR spectra are collected. The intensity of absorption peaks unique to the drug molecule is monitored, which correlates with its concentration at the crystal interface via Beer-Lambert law.

- Data Analysis: The concentration-time data at the interface is analyzed using a model based on Fick's second law (e.g., Crank's solution for a semi-infinite medium) to determine the effective diffusion coefficient of the drug through the mucus [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Diffusion Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in Diffusion Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| D(+)-Glucose | Model solute for studying diffusion in aqueous biological and chemical systems. | Measuring mutual diffusion coefficients in water for reactor design [1]. |

| D-Sorbitol | Model solute and product in hydrogenation reactions. | Studying diffusion in ternary systems (glucose-sorbitol-water) [1]. |

| Artificial Mucus | Synthetic simulant of the pulmonary mucus barrier. | Measuring tracer diffusion coefficients of asthma drugs (e.g., Theophylline, Albuterol) [2]. |

| Radioactive Tracers (e.g., ⁶⁵Zn, ⁶³Ni) | Isotopically labeled atoms to track self-diffusion and tracer diffusion. | Measuring tracer diffusion coefficients in metallic alloys [3] [5]. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Benzene Sulfonate (Surfactant) | Modifies interfacial properties and liquid structure. | Studying the effect of reduced activation energy on enhancing mutual diffusion rates in alcohol-water systems [6]. |

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) | Standard reference solute with well-documented diffusion data. | Validation and calibration of new experimental setups for measuring mutual diffusion coefficients [6] [4]. |

| Fluorescent Microspheres | Monodisperse colloidal tracers for optical methods. | Validating novel diffusion measurement setups via comparison with Stokes-Einstein predictions [7]. |

| LiTFSI (Lithium Bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide) | Salt solute for non-aqueous and advanced electrolyte systems. | Measuring concentration-dependent mutual diffusion coefficients in aqueous solutions [4]. |

Within the broader research context comparing self-diffusion and mutual diffusion coefficients, this guide has delineated their fundamental definitions, relationships, and measurement paradigms. Self-diffusion coefficients probe intrinsic mobility, while mutual diffusion coefficients describe macroscopic mass transfer, with tracer diffusion serving as a vital experimental bridge. The quantitative data and detailed protocols underscore that the accurate determination of these parameters is not a one-size-fits-all endeavor but requires careful selection of a methodology—be it Taylor dispersion, interferometry, or tracer techniques—tailored to the system's physical state and the research question at hand. For drug development professionals, this is particularly critical, as the efficacy of inhalation therapeutics hinges on their tracer diffusion coefficient through mucus [2]. Likewise, materials scientists rely on precise tracer data to model microstructural evolution [3] [5]. As research advances, the development of novel methods, such as non-equilibrium molecular dynamics simulations [9] and advanced finite volume analysis of interferometry data [4], promises to further refine our understanding and control of these foundational transport phenomena.

In both biological and industrial contexts, the transport of molecules through various media is a process governed by fundamental physical driving forces. For researchers and drug development professionals, a precise understanding of diffusion—the migration process caused by particle movement that results in directional mass transfer—is critical for optimizing processes ranging from drug release kinetics to membrane-based separations [6]. The diffusion coefficient (D) serves as the key quantitative descriptor of this speed, yet its accurate determination and prediction remain challenging in complex systems [10].

This whitepaper examines diffusion through the dual lenses of entropy and thermodynamics, focusing specifically on the distinction between self-diffusion and mutual diffusion coefficients. Self-diffusion characterizes the movement of a particle due solely to thermal motion, while mutual diffusion describes the net transport resulting from a chemical potential gradient [6]. Within the framework of a broader thesis on diffusion coefficient research, we explore how entropy, as a statistical driver toward disorder, and thermodynamic forces, as responses to energy gradients, collectively govern molecular transport phenomena. The interplay between these forces becomes particularly critical in pharmaceutical applications where controlling diffusion rates directly impacts drug efficacy, release profiles, and delivery system design.

Theoretical Foundations: Entropy and Diffusion

The Role of Entropy as a Driving Force

Entropy, a scientific concept most commonly associated with states of disorder, randomness, or uncertainty, serves as a fundamental driver in diffusion processes [11]. In statistical mechanics, entropy is interpreted as a measure of the number of possible microscopic arrangements (microstates) available to a system. The second law of thermodynamics dictates that isolated systems evolve spontaneously toward states of higher entropy, representing increased molecular disorder [11].

This progression toward disorder manifests physically as the diffusive spreading of molecules. When concentration gradients exist, the number of microstates (and thus entropy) increases as molecules redistribute from ordered, concentrated states to disordered, evenly distributed states. As one physicist explains, "Entropy transfer is associated with non-work energy transfer (aka heat transfer). The driving force for heat transfer is a temperature difference. On a more fundamental level, entropy generation within a system is associated with dissipation of useable energy as a result of finite driving forces for heat transfer (temperature gradients), momentum transfer (velocity gradients), mass transfer (concentration gradients), and chemical reactions (chemical potential differences)" [12].

Thermodynamic Formalism of Diffusion

The thermodynamic treatment of diffusion formalizes this relationship through the definition of chemical potential. The mutual diffusion coefficient, which characterizes net transport due to chemical potential gradients, can be expressed as the product of a mobility coefficient and a thermodynamic factor that accounts for non-ideal interactions [10]:

D = D₁ · Θ

Where:

- D represents the mutual diffusion coefficient

- D₁ is the self-diffusion coefficient (mobility term)

- Θ is the thermodynamic factor accounting for deviations from ideal behavior

For binary polymer-solvent systems, the thermodynamic factor can be expressed as: Θ = (1 - Φ₁) · (1 - 2χ₁ₚΦ₁) where Φ₁ is the solvent volume fraction and χ₁ₚ is the Flory-Huggins interaction parameter [10].

This framework distinguishes between two key diffusion coefficients central to current research:

- Self-diffusion coefficient: Describes molecular motion due to thermal energy alone, measured in the absence of chemical potential gradients.

- Mutual diffusion coefficient: Characterizes the collective diffusion process driven by chemical potential gradients, relevant to mass transfer applications.

Table 1: Key Diffusion Coefficients in Research

| Diffusion Type | Driving Force | Research Significance | Typical Measurement Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-diffusion | Thermal motion (entropy) | Molecular mobility in homogeneous systems | Pulsed-field gradient NMR, Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) |

| Mutual diffusion | Chemical potential gradient | Mass transfer in concentration gradients | Optical interferometry, Taylor dispersion, Membrane cell methods |

Experimental Determination of Diffusion Coefficients

Gravitational Technique for Polymer Systems

For polymer-solvent systems, determining diffusion coefficients often involves bringing the polymer into contact with specific solvents and monitoring mass changes over time. The gravitational technique, which tracks mass variation as solvent penetrates the polymer matrix, allows researchers to identify diffusion mechanisms and select appropriate mathematical models [10]. Structural changes in the polymer during experimentation can lead to diffusion anomalies, requiring careful data interpretation.

Experimental data processed through this technique has revealed how diffusion mechanisms are influenced by structural variations caused by concentration and temperature changes. For instance, in the cellulose triacetate (CTA)-dichloromethane (DCM) system, the diffusion coefficient at 303 K ranges between 4.5 and 8·10⁻¹¹ m²/s across various concentrations, while for the polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)-water system, D = 4.1·10⁻¹² m²/s at 303 K, increasing to D = 6.5·10⁻¹² m²/s at 333 K [10].

Equal-Refractive-Index Thin-Layer Method

Recent advances in diffusion measurement employ the equal-refractive-index thin-layer method based on liquid-core cylindrical lenses (SLCL-Doublet). This approach visualizes the diffusion process with a simple experimental setup, short measurement time, and high accuracy [6]. The methodology involves:

Experimental Setup: An attenuated laser beam passes through a collimation and expansion system, then perpendicularly irradiates an SLCL-Doublet filled with diffusion liquids. The intensity distribution of the laser beam exiting the liquid-core cylindrical lens is captured by a CCD camera, recording the dynamic change of the diffusion zone [6].

Data Processing: The diffusion coefficient is determined from the relationship between the diffusion zone width and time using the equation: D = k²/4a², where k is the slope of the line fitted to the experimental data of the diffusion zone width versus the square root of time [6].

Uncertainty Analysis: The standard deviation of the thin-layer position used for fitting is calculated according to the uncertainty formula of the least-squares method, accounting for both fitting uncertainties and systematic errors from environmental vibrations and temperature fluctuations [6].

Surfactant-Enhanced Diffusion

Recent investigations have explored methods to enhance diffusion rates without temperature increases, particularly valuable for diffusion-sensitive molecules in pharmaceutical applications. The addition of trace amounts of surfactant (e.g., sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate) to alcohol-water diffusion systems has been shown to effectively reduce diffusion activation energy (E_D) and increase liquid diffusion coefficients at room temperature [6].

This approach measures infinite dilution diffusion values of alcohols (ethylene glycol, glycerol, triethylene glycol) diffusing in water with and without surfactant across multiple temperatures. Results demonstrate that appropriate surfactants reduce diffusion activation energy E_D, thereby accelerating the diffusion process—a finding with significant implications for drug delivery systems where temperature sensitivity is a concern [6].

Table 2: Surfactant Impact on Diffusion Parameters

| System | Temperature (K) | Diffusion Coefficient without Surfactant (m²/s) | Diffusion Coefficient with Surfactant (m²/s) | Activation Energy Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethylene Glycol-Water | 298 | 1.15 × 10⁻⁹ | 1.38 × 10⁻⁹ | Reduction observed |

| Glycerol-Water | 298 | 0.87 × 10⁻⁹ | 1.12 × 10⁻⁹ | Reduction observed |

| Triethylene Glycol-Water | 298 | 0.52 × 10⁻⁹ | 0.71 × 10⁻⁹ | Reduction observed |

Mathematical Modeling Approaches

Free Volume Theory

The free volume concept, introduced by Cohen and Turnbull in 1959, forms the theoretical basis for many diffusion models in polymer systems [10]. This approach posits that diffusive displacement occurs due to voids generated by the redistribution of free volume, with the diffusion constant expressed as:

D = A · exp[-γv*/v_f]

where v* represents the critical hole free volume required for a molecular jump, and v_f is the average free volume per molecule [10].

The Fujita model, derived from this concept, describes the relationship between diffusion coefficient and free volume as:

D = A · R · T · exp(-B/f_v)

where f_v represents the fractional free volume [10]. While effective for polymer-organic solvent systems, this model provides less reliable results for polymer-water systems due to significant molecular interactions.

Advanced Predictive Frameworks

Vrentas-Duda Model

For concentrated polymer solutions, Vrentas and Duda developed a more comprehensive free volume theory that divides polymer volume into three elements: occupied volume (van der Waals volume), interstitial free volume (from vibrational energy), and hole free volume (from volume relaxation and plasticization) [10]. The self-diffusion coefficient in this model is expressed as:

D₁ = D₀ · exp(-(ω₁V̂₁* + ξ₁ₚωₚV̂ₚ*) / (V̂_FH/γ))

where:

- D₀ is a pre-exponential factor

- ωᵢ is the mass fraction of component i

- V̂ᵢ* is the specific critical hole free volume of component i

- ξ₁ₚ is the ratio of critical molar volumes of solvent and polymer

- V̂_FH is the average hole free volume per gram of mixture [10]

Entropy Scaling Framework

Recent advances in predictive modeling include entropy scaling for diffusion coefficients in fluid mixtures. This framework enables predictions of both self-diffusion and mutual diffusion coefficients across wide temperature and pressure ranges, including gaseous, liquid, supercritical, and metastable states—even for strongly non-ideal mixtures [13].

The entropy scaling approach leverages information from the self-diffusion coefficients of pure components and infinite-dilution diffusion coefficients, utilizing the mixture entropy derived from molecular-based equations of state. This thermodynamically consistent method represents a significant advancement for predicting diffusion behavior in complex pharmaceutical systems where experimental data is limited [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Diffusion Studies

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Example Systems | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | Polymer matrix for studying water diffusion | PVA-Water systems for hydrogel drug delivery research | Diffusion coefficient: 4.1·10⁻¹² m²/s at 303 K [10] |

| Cellulose Acetate (CA) | Membrane material for organic solvent diffusion studies | CA-Tetrahydrofuran (THF) systems | D = 2.5∙10⁻¹² m²/s at 303 K [10] |

| Sodium Dodecyl Benzene Sulfonate | Anionic surfactant for enhancing diffusion rates | Alcohol-water systems at room temperature | Reduces diffusion activation energy [6] |

| Ethylene Glycol | Model compound for diffusion studies | EG-water systems with/without surfactants | Baseline D: 1.15 × 10⁻⁹ m²/s at 298 K [6] |

| Liquid-Core Cylindrical Lenses (SLCL-Doublet) | Optical component for equal-refractive-index method | Visualization of diffusion zone dynamics | Corrects aberration for accurate measurement [6] |

| KCl Solutions | Density modifier for experimental configuration | Aqueous diffusion systems | Creates stable stratification in diffusion cells [6] |

The investigation of physical driving forces behind diffusion reveals entropy and thermodynamics as complementary rather than competing explanations. Entropy provides the statistical impetus toward disorder that underlies all diffusion phenomena, while thermodynamic formalism quantifies how chemical potential gradients direct this disordered motion into net transport. The distinction between self-diffusion coefficients (governed primarily by entropic driving forces) and mutual diffusion coefficients (driven by combined entropic and energetic factors) represents a fundamental consideration for research in drug development where both molecular mobility and net mass transfer are critical.

Emerging techniques, including surfactant-enhanced diffusion at constant temperature and advanced predictive frameworks like entropy scaling, offer powerful new approaches for controlling and modeling diffusion processes. These advancements hold particular promise for pharmaceutical applications where precise manipulation of diffusion rates can optimize drug release profiles, enhance delivery efficiency, and improve therapeutic outcomes. As research continues to bridge theoretical understanding with practical application, the interplay between entropy and thermodynamics will remain central to advancing diffusion science in biological and synthetic systems.

In the study of diffusion within binary mixtures, a fundamental distinction exists between self-diffusion and mutual diffusion. Self-diffusion coefficient ((D_{self})) describes the random Brownian motion of a single tagged particle in a homogeneous medium, while mutual diffusion coefficient ((\tilde{D})), also called chemical or interdiffusion coefficient, describes the macroscopic flux of components driven by a concentration gradient in a mixture [14]. Understanding the relationship between these two distinct phenomena is critical for predicting mass transport in materials design, chemical processes, and pharmaceutical development.

The Darken Equation, introduced by Lawrence Stamper Darken in 1948, provides a foundational theoretical framework that bridges these concepts [15]. This equation successfully relates the easily measurable mutual diffusion coefficient to the intrinsic self-diffusion coefficients of the individual components, while accounting for the non-ideality of the mixture through a thermodynamic factor. For decades, Darken's model has remained indispensable in metallurgy, materials science, and increasingly in chemical engineering and pharmaceutical research for predicting diffusion behavior in binary systems.

This technical guide examines the Darken Equation's theoretical derivation, experimental validation, practical application methodologies, and its modern extensions in contemporary research settings, particularly highlighting its relevance for researchers and drug development professionals working with complex multicomponent systems.

Theoretical Foundation

The Two Darken Equations

Darken's analysis produced two seminal equations that together describe diffusion in binary systems where components have different diffusion coefficients.

Darken's First Equation describes the velocity of the lattice frame ((\nu)) in a diffusion couple relative to a fixed laboratory frame, often visualized through the motion of inert markers in the famous Kirkendall experiment [15]:

[ \nu = (D1 - D2)\frac{\partial N1}{\partial x} = (D2 - D1)\frac{\partial N2}{\partial x} ]

Where:

- (\nu) = marker velocity (m/s)

- (D1, D2) = intrinsic diffusion coefficients of components 1 and 2 (m²/s)

- (N1, N2) = mole fractions of components 1 and 2

- (x) = spatial coordinate (m)

Darken's Second Equation provides the relationship between the mutual diffusion coefficient and the self-diffusion coefficients [15]:

[ \tilde{D} = (N1D2 + N2D1)\left(1 + N1\frac{\partial \ln a1}{\partial \ln N_1}\right) ]

Where:

- (\tilde{D}) = mutual diffusion coefficient (m²/s)

- (D1, D2) = self-diffusion coefficients of components 1 and 2 (m²/s)

- (a_1) = activity of component 1

- The term (\left(1 + N1\frac{\partial \ln a1}{\partial \ln N_1}\right)) is known as the thermodynamic factor ((\Gamma))

Table 1: Key Variables in Darken's Equations

| Symbol | Term | Definition | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| (\tilde{D}) | Mutual diffusion coefficient | Measures collective mixing driven by concentration gradients | m²/s |

| (D_i) | Self-diffusion coefficient | Measures mobility of individual species i in the mixture | m²/s |

| (N_i) | Mole fraction | Concentration of species i in the mixture | Dimensionless |

| (\nu) | Marker velocity | Velocity of lattice frame in diffusion couple | m/s |

| (\Gamma) | Thermodynamic factor | (\left(1 + N1\frac{\partial \ln a1}{\partial \ln N_1}\right)), accounts for non-ideality | Dimensionless |

Derivation Framework

The derivation of Darken's equations begins with Fick's first law applied to a binary system, considering fluxes in both laboratory-fixed and marker-fixed reference frames [15] [16]. For a binary system with components A and B, the fluxes in the lattice-fixed frame are given by:

[ JA = -DA\frac{\partial CA}{\partial x}, \quad JB = -DB\frac{\partial CB}{\partial x} ]

Assuming constant total concentration (C = CA + CB), the concentration gradients are equal and opposite: (\frac{\partial CA}{\partial x} = -\frac{\partial CB}{\partial x}). The net flux of atoms relative to the lattice frame creates a net vacancy flux that must be compensated by lattice motion, yielding the marker velocity (\nu) [16]:

[ \nu = \frac{1}{C0}(DA - DB)\frac{\partial CA}{\partial x} ]

where (C_0) is the total number of atoms per unit volume. When this lattice drift is accounted for in the laboratory-fixed frame, the net flux for component A becomes:

[ JA' = -DA\frac{\partial CA}{\partial x} + \nu CA ]

Substituting the expression for (\nu) and converting to mole fractions yields:

[ JA' = -(NA DB + NB DA)\frac{\partial CA}{\partial x} ]

Thus, the mutual diffusion coefficient is identified as:

[ \tilde{D} = NA DB + NB DA ]

For non-ideal systems, this relationship is modified by the thermodynamic factor to account for the deviation from ideal mixing behavior, giving the complete Darken's second equation [15].

Diagram 1: Logical relationship between diffusion phenomena and the Darken Equation framework, showing how self-diffusion, mixture composition, and non-ideal thermodynamics combine to predict mutual diffusion.

Experimental Validation & Historical Context

The Kirkendall Experiment

Darken's first equation was directly validated by the seminal Kirkendall experiment, which demonstrated that different components in a binary system can diffuse at different rates [15]. In this experiment, inert molybdenum wires were placed at the interface between copper and brass components, and their motion was monitored during annealing. The observation that these markers moved toward the brass region provided definitive evidence that zinc diffuses out of brass faster than copper diffuses in, creating a net vacancy flux that drives lattice motion [15].

Experimental Protocol:

- Diffusion Couple Preparation: A copper/brass interface is established with inert molybdenum wire markers positioned at the planar interface

- Annealing Process: The couple is heated to appropriate temperature (typically 700-1000°C) for controlled time duration to allow substantial interdiffusion

- Marker Tracking: The displacement of markers from the original interface is measured post-annealing

- Concentration Profiling: Composition across the diffusion zone is determined via techniques such as electron microprobe analysis

- Velocity Calculation: Marker velocity ((\nu)) is calculated from displacement and annealing time

- Diffusivity Determination: Intrinsic diffusion coefficients are extracted using Darken's first equation

This experiment confirmed that the diffusion mechanism in metallic systems occurs primarily through vacancy exchange rather than direct atom interchange, fundamentally changing the understanding of solid-state diffusion.

Johnson's Experiment and Thermodynamic Factors

Darken's second equation was validated through W. A. Johnson's experiments on gold-silver systems using radioactive tracers [15]. These experiments measured self-diffusion coefficients of gold and silver in their binary alloys, revealing that the mutual diffusion coefficient could not be explained by simple averaging of the component self-diffusivities.

Key Findings:

- The mutual diffusion coefficient showed significant deviation from ideal mixing behavior

- The thermodynamic factor played a crucial role in explaining these deviations

- Radioactive isotopes demonstrated similar mobility to non-radioactive elements, validating the tracer methodology

Practical Implementation & Methodologies

Applying Darken's Equation: A Step-by-Step Protocol

For researchers applying Darken's equation to determine mutual diffusion coefficients, the following methodology provides a reliable approach:

Determine Self-Diffusion Coefficients:

- Obtain (D1) and (D2) for the mixture components at the relevant composition and temperature

- Use techniques: Pulsed-field gradient NMR, radioactive tracer methods, or quasi-elastic neutron scattering [17] [14]

- For predictive work, molecular dynamics simulations with appropriate finite-size corrections can be employed [14]

Characterize Thermodynamic Behavior:

- Determine activity coefficients ((γ_i)) as a function of composition

- Use techniques: Vapor-liquid equilibrium measurements, Gibbs-Duhem integration, or molecular simulations

- Calculate the thermodynamic factor: (\Gamma = 1 + N1\frac{\partial \ln γ1}{\partial \ln N_1})

Compute Mutual Diffusion Coefficient:

- Apply Darken's equation: (\tilde{D} = (N1D2 + N2D1) \cdot \Gamma)

- Validate against experimental mutual diffusion data when available (e.g., Taylor dispersion, optical interferometry)

Account for System Non-Ideality:

- For highly non-ideal systems near phase boundaries, apply additional corrections for thermodynamic factor accuracy

- Consider finite-size effects in simulation-derived data [14]

Table 2: Comparison of Diffusion Coefficient Types and Measurement Techniques

| Diffusion Type | Definition | Measurement Techniques | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Diffusion | Motion of tagged particle in homogeneous medium | NMR, radioactive tracers, quasi-elastic neutron scattering, MD simulations | Understanding molecular mobility, segmental dynamics in polymers |

| Mutual Diffusion | Macroscopic mixing driven by concentration gradient | Taylor dispersion, optical interferometry, Boltzmann-Matano analysis | Process design, membrane transport, drug release kinetics |

| Intrinsic Diffusion | Diffusion of component in a lattice-fixed frame | Kirkendall marker experiments, diffusion couple analysis | Metallurgical applications, alloy design |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Materials for Diffusion Studies Using Darken's Equation

| Material/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Inert Markers (Mo, W, ThO₂ particles) | Reference points for lattice frame motion | Kirkendall experiments to measure intrinsic diffusivities and marker velocity |

| Radioactive Tracers (³H, ¹⁴C, ²²Na, ⁶⁵Zn isotopes) | Label molecules to track self-diffusion without chemical potential gradients | Measuring self-diffusion coefficients in binary mixtures |

| Binary Diffusion Couples (Cu/Zn, Au/Ag, Fe/Ni) | Model systems for interdiffusion studies | Experimental validation of Darken equations in metallic alloys |

| Lennard-Jones Potential Models | Simplified interaction potential for molecular simulation | Fundamental studies of diffusion in model fluids, validation of predictive models [18] [14] |

| Thermodynamic Database (Activity coefficients, phase diagrams) | Source of thermodynamic factors for non-ideal systems | Calculating Γ for Darken equation application to real systems |

Modern Research & Extensions

Addressing the Self-Diffusion Prediction Challenge

A significant limitation in applying Darken's equation has been the scarcity of composition-dependent self-diffusion coefficient data. Recent work by Wolff et al. (2018) has addressed this through a predictive model for composition-dependent self-diffusion coefficients in nonideal binary liquid mixtures [17]. Their model correlates nonideal diffusion effects with the thermodynamic factor and extends the McCarty and Mason correlation for ideal binary gas mixtures to liquid systems.

The model requires only:

- Self-diffusion coefficients at infinite dilution

- Self-diffusion coefficients of the pure substances

- The thermodynamic factor

Validation across 9 systems showed a 2× improvement in accuracy compared to previous correlations, significantly expanding the practical applicability of Darken-based models [17].

Finite-Size Effects in Molecular Simulations

Molecular dynamics simulations have become powerful tools for computing diffusion coefficients, but they suffer from finite-size effects where computed diffusivities increase with system size. Moultos et al. (2018) proposed a correction for Maxwell-Stefan diffusion coefficients based on the thermodynamic factor [14]:

[ Đ{MS}^∞ = Đ{MS} + \frac{k_B T Γ}{6 π η L} ]

Where:

- (Đ_{MS}^∞) = Maxwell-Stefan diffusivity at thermodynamic limit

- (Đ_{MS}) = finite-size Maxwell-Stefan diffusivity from simulation

- (η) = shear viscosity of the system

- (L) = simulation box length

- (Γ) = thermodynamic factor

This correction is particularly important for mixtures near demixing, where finite-size effects can be substantial [14].

Critical Perspectives and Mathematical Scrutiny

While widely applied, Darken's equation has faced mathematical scrutiny. Okino (2013) argued that the derivation contains mathematical inconsistencies, particularly in treating partial differential equations as ordinary differential equations [19]. This critique highlights that the intrinsic diffusion concept might be mathematically problematic, though the practical utility of Darken's equation for predicting concentration profiles remains acknowledged in the field.

Applications in Pharmaceutical & Materials Development

The Darken equation framework finds important applications in pharmaceutical and advanced materials development:

Polymer-Solvent Systems

In pharmaceutical formulation, understanding drug release from polymer matrices requires knowledge of mutual diffusion coefficients. The Hartley-Crank extension of Darken's equation applies to polymer solutions:

[ \tilde{D} = (N1D2 + N2D1) \cdot \left(1 + N1\frac{\partial \ln a1}{\partial \ln N_1}\right) ]

Where component 1 is typically the solvent and component 2 the polymer. For concentrated solutions, the polymer self-diffusion coefficient becomes negligible, simplifying the expression [20].

Microemulsion Systems

In drug delivery systems based on microemulsions, mutual diffusion coefficients provide critical information about droplet interactions and stability. The pseudo-binary approximation with constant water-to-surfactant ratios allows application of Darken-based models to these complex systems [20].

The Darken Equation remains a cornerstone of diffusion theory, providing an essential bridge between self-diffusion and mutual diffusion in binary systems. Its strength lies in physically connecting microscopic molecular mobility with macroscopic mixing phenomena while accounting for thermodynamic non-ideality through the thermodynamic factor. While mathematical scrutiny continues to refine fundamental understanding, the practical utility of Darken's framework is undeniable across metallurgy, chemical engineering, and pharmaceutical development.

Modern extensions addressing composition-dependent self-diffusion prediction and finite-size effects in molecular simulations continue to enhance the applicability of Darken-based models. For drug development professionals and researchers working with complex multicomponent systems, the Darken Equation provides a foundational approach for predicting diffusion behavior essential to process optimization, formulation design, and material performance assessment.

Within the fields of chemical engineering, materials science, and pharmaceutical development, the accurate prediction of molecular transport is critical for designing processes ranging from catalytic reactors to drug delivery systems. This transport is fundamentally governed by diffusion, the process by which molecules move from regions of high concentration to low concentration. Two principal coefficients are used to quantify this phenomenon: the self-diffusion coefficient and the mutual diffusion coefficient [21]. Despite being interrelated, they describe distinct physical scenarios. The self-diffusion coefficient (e.g., ( D{i,self} )) characterizes the intrinsic mobility of a single molecule within a uniform chemical environment, tracing its random Brownian motion at thermodynamic equilibrium. In contrast, the mutual diffusion coefficient (e.g., ( D{ij} ) or ( \mathcal{D}_{AB} )) describes the macroscopic, net mass transfer that occurs down a concentration gradient in a mixture, driving the system toward composition homogeneity [21] [22].

Understanding the nuanced differences in how these coefficients depend on concentration and system composition is not merely an academic exercise; it is a practical necessity. For instance, in drug development, the self-diffusion coefficient of an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) can predict its mobility within a homogeneous carrier medium, while the mutual diffusion coefficient governs its release rate from a concentrated formulation into the body [23] [24]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide, framed within ongoing research, to elucidate the key differences between these two coefficients, with a specific focus on their concentration dependence and behavior in different system compositions.

Fundamental Definitions and Theoretical Frameworks

Self-Diffusion Coefficient

The self-diffusion coefficient (( D{self} )) quantifies the mean-square displacement of a particle (atom or molecule) due solely to thermal motion in a system with no net concentration gradient [21]. It is an equilibrium property. In a pure substance, it is the mobility of molecules in their own substance. In a mixture, the self-diffusion coefficient of component ( i ) (( D{i,self} )) measures its mobility within the mixture environment.

This coefficient is fundamentally rooted in statistical mechanics. It can be calculated using the Einstein relation, which connects it to the mean-square displacement (MSD) of a molecule over time [23] [24]: [ D{i,self} = \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{1}{6t} \langle | \mathbf{r}i(t) - \mathbf{r}i(0) |^2 \rangle ] where ( \mathbf{r}i(t) ) is the position of molecule ( i ) at time ( t ), and the angle brackets denote an ensemble average. Alternatively, the Green-Kubo formula relates ( D{self} ) to the integral of the velocity autocorrelation function [24]: [ D{i,self} = \frac{1}{3} \int0^\infty \langle \mathbf{v}i(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}i(t) \rangle dt ] where ( \mathbf{v}_i(t) ) is the velocity of molecule ( i ) at time ( t ).

Mutual Diffusion Coefficient

The mutual diffusion coefficient (( D{ij} ) or ( \mathcal{D}{AB} )), also known as the interdiffusion or chemical diffusion coefficient, is a non-equilibrium property defined by Fick's first law [25]. For a binary mixture A-B, it relates the diffusive flux ( JA ) of component A to its concentration gradient: [ JA = - \mathcal{D}{AB} \nabla cA ] Here, ( \mathcal{D}{AB} ) is the mutual diffusion coefficient, and ( cA ) is the molar concentration of A. This coefficient quantifies the collective, cooperative motion of components as they interdiffuse to eliminate a concentration gradient.

A critical advancement in understanding mutual diffusion is its relationship with thermodynamics. For a binary system, the mutual diffusion coefficient is related to the self-diffusion coefficients and the thermodynamic factor (( \Gamma )) [22]: [ \mathcal{D}{AB} = (xA D{B,self} + xB D{A,self}) \, \Gamma ] where ( xA ) and ( xB ) are mole fractions, and ( D{A,self} ), ( D{B,self} ) are the self-diffusion coefficients. The thermodynamic factor ( \Gamma ) is defined as: [ \Gamma = 1 + \frac{\partial \ln \gammaA}{\partial \ln xA} ] where ( \gammaA ) is the activity coefficient of component A. This factor accounts for non-ideal mixing effects. In an ideal mixture, ( \Gamma = 1 ), and the relationship simplifies. This framework illustrates that mutual diffusion is influenced by both the intrinsic mobilities of the individual components (via the self-diffusion coefficients) and the thermodynamic driving force stemming from chemical potential gradients (via ( \Gamma )) [21] [22].

The relationship between self-diffusion and mutual diffusion in a binary system can be visualized as follows, incorporating the key influences of mobility and thermodynamics:

Concentration Dependence

The response of diffusion coefficients to changes in concentration is a key differentiator and is critical for modeling real-world systems.

Concentration Dependence of Self-Diffusion Coefficients

In general, the self-diffusion coefficient of a component in a mixture decreases as its own concentration decreases. This is because a molecule in a dilute solution encounters a different microenvironment—dominated by solvent molecules—which can offer different frictional resistance compared to its native environment. The concentration dependence can be complex and is often system-specific. A recent thermodynamic method proposes a relationship for binary mixtures, introducing the concept of a "system self-diffusion coefficient" (( D{sys} )), which is a mole-fraction-weighted average of the component self-diffusion coefficients [23]: [ D{sys} = \frac{xA D{A,self} + xB D{B,self}}{xA + xB} = xA D{A,self} + xB D{B,self} ] This framework allows for analyzing the deviation of ( D{sys} ) from a simple linear combination (additivity) and can be used to relate the concentration dependences of ( D{A,self} ) and ( D_{B,self} ) [23]. In associated liquids (e.g., those with hydrogen bonding like methanol-water mixtures), the concentration dependence can be highly non-linear due to changes in molecular association, which affect the effective hydrodynamic radius and thus the mobility [23].

Concentration Dependence of Mutual Diffusion Coefficients

The mutual diffusion coefficient's dependence on concentration is more complex because it incorporates both kinetic (mobility) and thermodynamic factors [21]. Its behavior varies significantly with the nature of the mixture:

- Ideal or Regular Solutions: The concentration dependence is often modest. The Darken equation, ( \mathcal{D}{AB} = (xB D{A,self} + xA D{B,self}) \Gamma ), is commonly applied. Here, the weighted average of the self-diffusion coefficients and the thermodynamic factor ( \Gamma ) determine the value of ( \mathcal{D}{AB} ) [22].

- Non-Ideal and Associated Systems: The mutual diffusion coefficient can exhibit strong, non-monotonic concentration dependence. The thermodynamic factor ( \Gamma ) can deviate significantly from unity. For example, in systems exhibiting phase separation, ( \Gamma ) can approach zero, leading to a dramatic decrease in ( \mathcal{D}_{AB} ), a phenomenon known as critical slowing down [22].

- Polymer Solutions: A classic example of opposing trends. The self-diffusion coefficient of polymer chains (( Ds )) decreases with increasing concentration (( c )) due to entanglement. In contrast, the mutual diffusion coefficient (( Dm )) often increases with ( c ) in the semi-dilute regime because it is driven by the osmotic pressure gradient, which becomes steeper with concentration [21].

Table 1: Summary of Concentration Dependence in Different System Types

| System Type | Self-Diffusion Coefficient (( D_{self} )) | Mutual Diffusion Coefficient (( \mathcal{D}_{AB} )) | Primary Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal Mixture | Generally decreases for a component as its concentration decreases. | Moderate concentration dependence. | Molecular size, shape, and solvent viscosity. |

| Non-Ideal Mixture | Non-linear dependence due to specific intermolecular interactions. | Can be strongly concentration-dependent. | Thermodynamic factor (Γ), activity coefficients. |

| Associated Liquids | Can show minima/maxima due to changing molecular aggregates. | Often complex, non-monotonic behavior. | Degree of molecular self- and hetero-association. |

| Polymer Solutions | Decreases sharply with increasing concentration. | Increases with concentration in the semi-dilute regime. | Entanglements (for Ds), osmotic compressibility (for Dm). |

Dependence on System Composition

The composition of a system, particularly in multicomponent mixtures, adds another layer of complexity.

Binary vs. Multicomponent Systems

In binary systems, the relationship between self- and mutual diffusion, while not simple, is more direct, as captured by frameworks like the Darken equation [22].

In multicomponent systems (three or more components), the diffusion process becomes significantly more complex. The flux of one component can depend on the concentration gradients of all other components. The diffusion coefficient is no longer a scalar but a matrix of coefficients (( \mathcal{D}{ij} )) [26]. The interdiffusion coefficient in a multicomponent system can be estimated using an expression derived from the Maxwell-Stefan equations [25]: [ \mathcal{D}'A = \frac{1 - yA}{\frac{yB}{\mathcal{D}{AB}} + \frac{yC}{\mathcal{D}{AC}} + \cdots} ] where ( \mathcal{D}'A ) is the diffusion coefficient of component A in the mixture, ( yi ) are the mole fractions, and ( \mathcal{D}{AB}, \mathcal{D}_{AC} ) are the binary diffusion coefficients. This highlights that the diffusivity of a component is influenced by its interactions with every other component in the mixture.

The Role of Entropy Scaling

A recent and powerful approach for predicting transport properties across wide ranges of state conditions is entropy scaling. This method posits that suitably scaled transport properties, including self-diffusion coefficients, are a monovariate function of the residual entropy [22]. This framework has been successfully extended to mixtures.

For mixture self-diffusion coefficients, entropy scaling treats the infinite-dilution diffusion coefficient ( Di^\infty ) (a pseudo-pure property) as a basis. The concentration dependence of the self-diffusion coefficient ( Di ) of a component in a mixture can then be predicted using combination rules that are functions of the pure component and infinite-dilution values, all within an entropy-scaling framework [22]. This allows for thermodynamically consistent predictions of both self- and mutual diffusion coefficients from gaseous to liquid states, including for strongly non-ideal mixtures, based on limited initial data.

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Accurate determination of both types of diffusion coefficients relies on specialized techniques.

Measuring Self-Diffusion Coefficients

The primary experimental method for measuring self-diffusion coefficients is Pulsed Field Gradient Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (PFG-NMR), also known as Pulsed Gradient Spin-Echo (PGSE) NMR [23] [24].

- Principle: The method uses magnetic field gradients to label the spatial position of nuclear spins. After a known time interval, the signal is decoded. The attenuation of the NMR signal due to diffusion is measured.

- Protocol (PGSE-NMR): The self-diffusion coefficient ( D ) is obtained using the Stejskal-Tanner equation [24]:

[

\frac{S}{S0} = \exp\left( -\gamma^2 g^2 \delta^2 D \left( \Delta - \frac{\delta}{3} \right) \right)

]

where:

- ( S ) and ( S0 ) are the signal intensities with and without the gradient pulse, respectively.

- ( \gamma ) is the gyromagnetic ratio of the nucleus being observed.

- ( g ) is the strength of the pulsed gradient.

- ( \delta ) is the duration of the gradient pulse.

- ( \Delta ) is the time interval between the two gradient pulses.

- Applications: This method is versatile and can be applied to a wide range of liquids, including pure components and complex mixtures, as demonstrated in studies of benzene-methanol-ethanol systems [23].

Measuring Mutual Diffusion Coefficients

Several techniques exist, with a novel optical method being the Shift of Equivalent Refractive Index Slice (SERIS) [27].

- Principle: This method uses a Double Liquid-Core Cylindrical Lens (DLCL). One core acts as a diffusion cell and an imaging lens. The dynamic diffusion process creates a refractive index (RI) gradient, which causes a shift in the image of a specific "slice" of liquid on a CMOS sensor.

- Protocol (SERIS):

- The DLCL's front liquid core is filled with two contacting liquids of different concentrations (e.g., heavy water and normal water).

- Monochromatic collimated light passes through the DLCL. The RI gradient formed during diffusion projects a dynamic image onto a CMOS chip.

- The position ( Zi ) of a sharp image point (corresponding to a specific RI, ( nc )) is tracked over time.

- The mutual diffusion coefficient ( D ) is calculated from the slope ( k1 ) of a linear fit of ( Zi ) versus ( \sqrt{t} ), using the equation derived from Fick's second law [27]: [ D = \frac{k1^2}{4 \cdot [\text{erfinv}(\Omega)]^2} ] where ( \Omega ) is a constant determined by the initial concentrations and the selected ( nc ).

Computational Determination

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation is a powerful computational tool for calculating both self- and mutual diffusion coefficients from first principles.

- For Self-Diffusion: The Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) method is most common. After running an MD simulation to generate particle trajectories, ( D{self} ) is calculated from the slope of the MSD versus time plot [24] [28]: [ D{self} = \frac{1}{6N} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \sum{i=1}^N \langle | \mathbf{r}i(t) - \mathbf{r}i(0) |^2 \rangle ] where ( N ) is the number of molecules. Modern force fields like OPLS4 have demonstrated excellent agreement with experimental self-diffusion data for diverse liquids [24].

- For Mutual Diffusion: Calculation is more complex and often involves non-equilibrium MD (NEMD) or equilibrium methods that relate concentration fluctuations to the mutual diffusion coefficient. Recent advances involve Machine Learning (ML) and Symbolic Regression (SR). SR can derive simple, physically consistent analytical expressions for the self-diffusion coefficient based on macroscopic variables like density (( \rho )), temperature (( T )), and confinement width (( H )) [28]. For example, a derived symbolic expression for a reduced self-diffusion coefficient ( D^* ) in bulk fluids takes the form: [ D^_{SR} = \alpha_1 T^{\alpha2} \rho^{*\alpha3} - \alpha4 ] where ( \alphai ) are fluid-specific parameters. This bypasses the need for computationally expensive trajectory analysis [28].

The following workflow summarizes the decision process for selecting the appropriate measurement or simulation technique based on research goals:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for Diffusion Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., D₂O) | Used in PFG-NMR to provide a lock signal; also as a tracer for mutual diffusion studies due to distinct RI and NMR properties. | Measuring mutual diffusion of heavy water in normal water via SERIS [27]. |

| Associated Liquids (Methanol, Ethanol) | Model systems for studying the effect of hydrogen bonding (self- and hetero-association) on concentration dependence. | Studying self-diffusion in benzene-methanol and ethanol-methanol systems [23]. |

| PGSE-NMR Spectrometer | The primary instrument for measuring self-diffusion coefficients in liquid phases. | Determining 547 self-diffusion coefficients for diverse pure liquids [24]. |

| Double Liquid-Core Cylindrical Lens (DLCL) | Key component in the SERIS method, acting as both diffusion cell and imaging element for visualizing mutual diffusion. | Visualizing and measuring mutual diffusion coefficient of D₂O in H₂O [27]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., Desmond) | Performs all-atom MD simulations to calculate diffusion coefficients from generated particle trajectories. | Calculating self-diffusion coefficients using OPLS4 force field [24]. |

| OPLS4 Force Field | A potential function for MD simulations providing parameters for interatomic interactions; critical for accurate prediction of dynamic properties. | Achieving high accuracy in predicting self-diffusion coefficients for chemically diverse liquids [24]. |

The distinction between the self-diffusion coefficient and the mutual diffusion coefficient is fundamental. The self-diffusion coefficient is a measure of intrinsic molecular mobility at equilibrium, while the mutual diffusion coefficient is a measure of collective, net mass transport driven by a chemical potential gradient. Their dependence on concentration and system composition diverges significantly. The self-diffusion coefficient is primarily governed by the local frictional environment and specific molecular interactions. In contrast, the mutual diffusion coefficient is a product of both mobility (often related to weighted averages of self-diffusion coefficients) and thermodynamics (the thermodynamic factor Γ), making its behavior in non-ideal and multicomponent systems particularly complex.

Cut-edge research is providing powerful new frameworks to unify the understanding of these properties. Entropy scaling offers a path to predict both coefficients over wide state ranges based on fundamental thermodynamic properties. Simultaneously, advances in experimental techniques like SERIS and computational methods like machine learning-enhanced MD are enabling more accurate and high-throughput determination of these critical parameters. For researchers in drug development and materials science, a deep understanding of these differences is no longer just theoretical—it is an essential tool for rationally designing and optimizing formulations and processes where precise control over molecular transport is paramount.

The Role of Thermodynamic Factors and Activity Coefficients in Mutual Diffusion

In the broader context of diffusion research, a fundamental distinction exists between the self-diffusion coefficient, which quantifies the intrinsic mobility of a molecule in a uniform environment, and the mutual diffusion coefficient, which describes the macroscopic flux of a species down a concentration gradient in a mixture. While self-diffusion is primarily a measure of mobility, mutual diffusion is governed by both the kinetic mobility of the molecules and the thermodynamic forces driving the system toward equilibrium. This in-depth guide explores the critical role of thermodynamic factors and activity coefficients in determining mutual diffusion, a relationship that is paramount for accurately predicting mass transfer in non-ideal systems encountered in fields from chemical engineering to pharmaceutical sciences. The central challenge lies in the fact that the mutual diffusion coefficient is not only a function of molecular friction but is also modulated by the thermodynamics of the mixture, which can either accelerate or retard the diffusion process relative to the self-diffusion of its components.

Theoretical Foundation: From Fick's Law to the Thermodynamic Factor

The Fundamental Relationship

The canonical description of diffusion is provided by Fick's first law, which states that the flux of a species is proportional to its concentration gradient. However, for non-ideal mixtures, the true driving force for diffusion is the chemical potential gradient. This leads to a more fundamental expression for the flux, which, when reconciled with Fick's law, reveals that the Fickian or mutual diffusion coefficient comprises two distinct parts [21] [29]:

D~Fick~ = D~MS~ × Γ

Here, D~MS~ is the Maxwell-Stefan (MS) diffusion coefficient, which represents an inverse friction coefficient characterizing the molecular mobility. The factor Γ is the thermodynamic factor, which corrects for the non-ideality of the mixture. For a binary system, the thermodynamic factor is defined as [29]:

Γ = 1 + (∂ ln γ / ∂ ln x)

where γ is the activity coefficient of the diffusing species and x is its mole fraction. In an ideal mixture, Γ = 1, and the mutual diffusion is governed solely by mobility. In non-ideal systems, Γ can be greater or less than 1, significantly altering the mutual diffusion coefficient. For strongly non-ideal systems, such as those exhibiting phase separation, Γ can even become negative, leading to the seemingly paradoxical phenomenon of "uphill diffusion" where a species diffuses against its concentration gradient (though still down its chemical potential gradient).

Relating Mutual and Self-Diffusion Coefficients

The connection between mutual diffusion and the self-diffusion coefficients of the individual components is often described by models such as the Darken equation. In its simplest form, the Darken equation relates the mutual diffusion coefficient to the self-diffusion coefficients and the thermodynamic factor [30]:

D~m~ = (x₂D~s1~ + x₁D~s2~) Γ

Here, D~m~ is the mutual diffusion coefficient, D~s1~ and D~s2~ are the self-diffusion coefficients of components 1 and 2, respectively, and x₁ and x₂ are their mole fractions. This equation highlights that mutual diffusion is an average of the component mobilities, scaled by the thermodynamic factor. Recent research has shown that the accuracy of this family of models can be improved by introducing a scaling power on the thermodynamic factor, i.e., Γ^α^, where α is an optimized parameter [30].

Table 1: Key Diffusion Coefficients and Their Characteristics

| Diffusion Coefficient Type | Symbol | Driving Force | Represents | Measurement Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutual (Fickian) | D~m~, D~Fick~ | Concentration Gradient | Macroscopic interdiffusion of components | Non-equilibrium (concentration gradient) |

| Self-Diffusion | D~s~ | Thermal Energy (Brownian motion) | Mobility of a single species in a uniform environment | Equilibrium (no chemical potential gradient) |

| Tracer | D~*~ | Thermal Energy | Mobility of a labeled tracer in a chemically identical environment | Equilibrium |

| Maxwell-Stefan | D~MS~ | Chemical Potential Gradient | Inverse friction coefficient between species | Relates to molecular mobility |

Experimental Methodologies for Measurement and Analysis

The Shift of Equivalent Refractive Index Slice (SERIS) Method

The SERIS method is a modern optical technique for visualizing and quantifying mutual diffusion in liquid systems. The core of the setup is a Double Liquid-Core Cylindrical Lens (DLCL), where the front liquid core acts as both the diffusion cell and an imaging lens [27].

Experimental Protocol:

- Apparatus Setup: A DLCL is aligned in a path of monochromatic collimated light (e.g., λ = 589.0 nm). A high-resolution CMOS camera is positioned at the focal plane of the DLCL.

- Calibration: The relationship between the concentration (C) and refractive index (n) for the binary system (e.g., heavy water and normal water) is established at the experimental temperature using an Abbe refractometer. A linear relationship, C = a·n + b, is typically found [27].

- Loading Solutions: The front liquid core of the DLCL is carefully filled with the two solutions of interest (e.g., normal water and heavy water), creating a sharp initial interface at Z=0.

- Data Acquisition: Diffusion commences upon contact. The CMOS camera captures dynamic images of the "beam waist" formed due to the refractive index gradient. The position Z~c~ of a specific, sharply imaged liquid slice (with a constant refractive index n~c~) is tracked over time.

- Data Analysis: The position Z~c~ is plotted against the square root of time (t^1/2^). According to Fick's second law, this relationship is linear. The mutual diffusion coefficient D is calculated from the slope k~1~ of this line using the formula D = k₁² / (4 [erfinv(Ω)]²), where erfinv is the inverse error function and Ω is a constant derived from the initial concentrations and the selected n~c~ [27].

This method allows for direct visualization of the diffusion process and can achieve high resolution, with a minimum resolvable refractive index change (δn) as small as 6.15 × 10⁻⁵ [27].

Diaphragm Cell and Interferometry

Traditional methods for measuring mutual diffusion coefficients include the diaphragm cell and interferometry.

- Diaphragm Cell: This method involves two chambers separated by a porous diaphragm. The change in concentration in each chamber over time is monitored, and the diffusion coefficient is calculated from the rate of equilibration. A significant disadvantage is that the cell constant requires calibration [27].

- Interferometry: This optical method leverages the fact that concentration changes alter the refractive index, which causes a shift in the interference fringes. While highly accurate, it requires an extremely stable experimental environment to prevent vibrational noise [27].

Computational and Predictive Modeling Approaches

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

MD simulations provide a powerful bottom-up approach for calculating diffusion coefficients by tracking the motion of individual atoms over time. Two primary methods are used within MD [31] [32]:

1. Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) Method (Einstein Relation): This is the most straightforward and recommended method. The self-diffusion coefficient is calculated from the slope of the MSD versus time plot: MSD(t) = ⟨[r(0) - r(t)]²⟩ = 2nD~s~t where n is the dimensionality (typically 3 for 3D diffusion). The diffusion coefficient is extracted as D~s~ = slope(MSD) / 2n [31] [32].

2. Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) Method (Green-Kubo Relation): This method calculates the self-diffusion coefficient by integrating the VACF: D~s~ = (1/3) ∫₀^∞^ ⟨v(0) · v(t)⟩ dt While theoretically equivalent to the MSD method, it can be more sensitive to statistical noise and requires a high sampling frequency of velocities [31].

To compute the mutual diffusion coefficient, the self-diffusion coefficients obtained from MD must be combined with the thermodynamic factor, which can be calculated separately using methods like the Permuted Widom Test Particle Insertion (PWTPI) or its more advanced variant, the Continuous Fractional Component Monte Carlo (CFCMC) method, which is efficient even for dense liquids [29].

Experimental Protocol for MD Simulation of Diffusion [31]:

- System Preparation: Obtain or build the initial molecular structure (e.g., from a CIF file for crystals). Equilibrate the system using energy minimization and a preliminary MD run in the NPT ensemble to relax the density.

- Production MD Run: Perform a longer MD simulation in the NVT ensemble at the desired temperature. Use a thermostat (e.g., Berendsen) to maintain temperature. The simulation must be long enough for the MSD to enter a linear regime (typically nanoseconds).

- Trajectory Analysis: Save atomic coordinates and velocities at regular intervals. Use these trajectories to calculate the MSD or VACF for the atoms of interest.

- Calculation of D: For MSD analysis, perform a linear fit to the MSD vs. time curve after the initial ballistic regime. The diffusion coefficient is one-sixth of the slope in 3D.

Predictive Free Volume Theory and QSPR Models

For engineering applications, predictive models are essential. The Vrentas-Duda free volume theory is a widely used framework for predicting diffusion coefficients in polymer-solvent and polymer-drug systems [33]. This model describes the dependence of diffusion on temperature, concentration, and the free volume available in the mixture.

Furthermore, Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) models can be developed using multiple linear regression or artificial neural networks. These models relate molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, van der Waals volume, topological indices) to the parameters of the free volume theory, enabling the prediction of diffusion coefficients based solely on molecular structure [33]. This is particularly valuable in drug delivery for in-silico screening of polymer carriers for controlled release devices.

Table 2: Comparison of Mutual Diffusion Coefficient Prediction Models for Non-Ideal Mixtures [30]

| Model Type | Key Principle | Typical Inputs Required | Reported Accuracy (AARD*) | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Darken-based (with scaling) | Averages self-diffusion coefficients, scaled by (Γ)^α^ | D~s1~, D~s2~, Γ, α | 1 - 20% | General non-ideal mixtures |

| Viscosity-based (Vis-SF) | Relates diffusivity to mixture viscosity and Γ | η~mixture~, Γ | ~14% | Systems with known viscosity |

| Vignes-based (V-Gex) | Uses excess Gibbs free energy | G^ex^ data | ~25% | Less reliable than Darken |

| Dimerization Model | Accounts for molecular association | Association constants | Inaccurate (except aqueous) | Mixtures containing water |

*Absolute Average Relative Deviation

Applications in Controlled Drug Delivery

The principles of mutual diffusion are critically applied in the design of controlled-release drug delivery devices. In these systems, a drug is encapsulated within a polymer matrix, and its release rate is often controlled by diffusion through the polymer. The key property governing this release is the mutual diffusion coefficient of the drug in the polymer [33].

The drug release profile from a monolithic device can be modeled by solving Fick's second law of diffusion. The mutual diffusion coefficient used in this equation is a strong function of the drug-polymer interactions, which are captured by the activity coefficient and the thermodynamic factor. A predictive model for the diffusion coefficient allows for reverse engineering: selecting or designing a polymer that will provide a desired drug release profile, thereby significantly reducing the time and cost of development [33]. For example, such models have been applied to systems like paclitaxel in polycaprolactone and hydrocortisone in polyvinylacetate.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function in Diffusion Research |

|---|---|

| Double Liquid-Core Cylindrical Lens (DLCL) | Serves as both a diffusion cell and an imaging element in the SERIS method, enabling visualization and measurement of refractive index gradients [27]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., AMS, GROMACS) | Simulates the motion of atoms and molecules over time, used to calculate self-diffusion coefficients from MSD or VACF [31] [32]. |

| Force Fields (e.g., GAFF, ReaxFF) | Define the potential energy functions and parameters for atoms in MD simulations, determining the accuracy of predicted mobilities and thermodynamic properties [31] [32]. |

| Activity Coefficient Model (e.g., NRTL) | Used to model vapour-liquid equilibrium data and calculate the crucial thermodynamic factor (Γ) for predicting mutual diffusion in non-ideal mixtures [30]. |

| Abbe Refractometer | Measures the refractive index of liquids with high precision, essential for calibrating concentration-refractive index relationships in optical methods like SERIS [27]. |

Visualizing Relationships and Workflows

Conceptual Relationship Between Diffusion Coefficients

The following diagram illustrates the core conceptual relationship between self-diffusion and mutual diffusion, mediated by thermodynamics.

Workflow for Predicting Mutual Diffusion

This workflow charts the integrated path for predicting the mutual diffusion coefficient, combining computational simulations and thermodynamic modeling.

Measurement and Impact: Techniques and Real-World Applications

The measurement of self-diffusion coefficients is crucial for understanding molecular transport in diverse systems, from biological tissues to porous materials and industrial solvents. Within the broader context of diffusion coefficient research, a critical distinction exists between the self-diffusion coefficient, which describes the random, thermally-driven motion of a single particle in a uniform environment, and the mutual diffusion coefficient, which characterizes the collective flow of particles down a concentration gradient. This technical guide focuses on two powerful techniques for investigating self-diffusion: Pulsed Field Gradient Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (PFG-NMR) and Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation. PFG-NMR provides an experimental window into molecular displacement, while MD simulation offers a computational approach based on first principles, enabling atomic-level insight into diffusion processes. The complementary nature of these methods is increasingly leveraged in modern research, as highlighted by combined PFG-NMR and MD studies on complex systems like covalent organic frameworks [34].

Pulsed Field Gradient Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (PFG-NMR)

Theoretical Foundation and Basic Principles

PFG-NMR measures self-diffusion by using magnetic field gradients to label the spatial positions of nuclear spins and detecting the attenuation of the NMR signal due to their translational displacement over a known time interval. The technique is rooted in the dependence of the Larmor frequency (ωL) on the amplitude of the applied magnetic field [35]. When a magnetic field gradient is applied, the precessional frequency of nuclear spins becomes spatially encoded, allowing their positions to be tracked over time.

The fundamental pulse sequences used are the spin echo (SE) and the stimulated echo (STE) sequences, each incorporating at least a pair of identical gradient pulses (see Section 2.3 for workflows) [35]. The first gradient pulse (duration δ, amplitude g) encodes spin positions by imparting a position-dependent phase. After a diffusion time (Δ), the second gradient pulse decodes the phase. Molecules that have moved during Δ do not experience perfect phase refocusing, leading to signal attenuation. For a population of molecules undergoing normal (Fickian) diffusion, the signal attenuation ψ is described by the Stejskal-Tanner equation [35]:

where S and S0 are the signal intensities with and without the gradient pulses, γ is the gyromagnetic ratio of the nucleus, and D is the self-diffusion coefficient. By measuring the signal attenuation as a function of gradient strength (g) or duration (δ), the diffusion coefficient D can be extracted.

Critical Experimental Parameters and Protocol