Sampling Conformational Space of Disordered Proteins: From Dynamic Ensembles to Druggable Targets

Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), constituting 30-40% of the human proteome, lack stable tertiary structures and exist as dynamic conformational ensembles, presenting unique challenges and opportunities for structural biology and drug...

Sampling Conformational Space of Disordered Proteins: From Dynamic Ensembles to Druggable Targets

Abstract

Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), constituting 30-40% of the human proteome, lack stable tertiary structures and exist as dynamic conformational ensembles, presenting unique challenges and opportunities for structural biology and drug discovery. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on sampling the conformational landscape of IDPs. We explore the fundamental principles of IDP dynamics, critically evaluate traditional and emerging computational methods—from molecular dynamics and enhanced sampling to generative deep learning and hybrid AI approaches—and outline rigorous validation protocols that integrate experimental data. Furthermore, we address common troubleshooting scenarios and demonstrate how accurate ensemble modeling is revolutionizing therapeutic development for previously 'undruggable' targets, offering a roadmap for leveraging conformational diversity in biomedical research.

Understanding Intrinsically Disordered Proteins: Why Conformational Ensembles Matter

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide: IDP Conformational Sampling

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when studying the conformational ensembles of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs).

Troubleshooting Scenarios and Solutions

| Problem Scenario | Symptoms & Root Cause | Resolution Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Conformational Sampling [1] | • Limited diversity in generated ensembles• Failure to capture transient states• Poor agreement with experimental data (e.g., NMR, SAXS) | 1. Increase Training Data Diversity: Incorporate long-timescale MD simulations or data from multiple techniques [1].2. Utilize Generative Models: Implement deep learning (e.g., ICoN) to learn physical principles and sample novel conformations beyond training data [1].3. Latent Space Interpolation: Use the model's latent space to systematically explore intermediate states [1]. |

| Handling Highly Dynamic IDPs (e.g., Aβ42) [1] [2] | • Inability to resolve distinct conformational clusters• Difficulty rationalizing aggregation-prone states or disease-related findings | 1. Cluster Analysis: Perform structural clustering on synthetic conformations to identify stable sub-populations [1].2. Validate with Experiments: Correlate computational clusters with EPR data or amino acid substitution studies [1].3. Analyze Interactions: Examine atomistic details of side-chain rearrangements in synthetic conformations [1]. |

| IDP Aggregation in Experimental Assays [2] | • Formation of toxic inclusions in cellular models• Disruption of normal cellular function• Aberrant liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) | 1. Modify Buffer Conditions: Optimize salt concentration and pH to modulate electrostatic interactions.2. Utilize Chaperones: Add molecular chaperones (e.g., Hsps) to assist folding and prevent abnormal phase transitions [2].3. Monitor LLPS: Use microscopy to observe stress granule dynamics and identify conditions promoting pathological solidification [2]. |

| Weak or Transient Binding Signals [3] | • Poor signal-to-noise in binding assays (e.g., SPR, ITC)• Inconsistent results between techniques• Difficulty quantifying affinity for "fuzzy" complexes | 1. Optimize Kinetic Measurements: Use techniques with high temporal resolution (e.g., stopped-flow) to capture fast association rates [3].2. Probe Folding-Upon-Binding: Employ NMR or smFRET to monitor coupled folding and binding events [3].3. Check Modification Status: Ensure post-translational modifications (e.g., phosphorylation) are present/absent as needed for binding [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of using generative deep learning over traditional molecular dynamics (MD) for sampling IDP conformations? [1] A1: Generative deep learning models, like ICoN, can rapidly identify novel synthetic conformations with sophisticated large-scale side chain and backbone arrangements by learning the underlying physical principles from MD data. This approach can provide a more comprehensive sampling of the conformational landscape and identify states not included in the original training data, often at a lower computational cost than running extremely long MD simulations.

Q2: How can I determine if a pre-formed secondary structure in my IDP is functionally important for partner binding? [3] A2: The functional role of pre-formed structure is sequence- and context-dependent. You can investigate this by creating variants that stabilize (e.g., through helix-favoring amino acid substitutions or stapling) or destabilize the proposed secondary structure and then measuring the binding kinetics and affinity for the target. Be cautious, as stabilizing helix formation can sometimes destabilize the complex or upset delicate functional balances in signaling pathways [3].

Q3: Our team has identified a novel nonnatural enzymatic reaction. What computational strategies can we use to design a biosynthetic pathway incorporating it? [4] A3: Computational tools for nonnatural pathway design fall into two major categories. Template-based methods rely on known biochemical reaction rules and enzyme templates, while template-free methods (e.g., using bioretrosynthesis) can propose novel biochemical transformations. The best approach often involves using these tools to generate candidate pathways and then evaluating them for potential challenges like metabolic burden or toxic intermediate accumulation before experimental construction [4].

Q4: Why is the misfolding and aggregation of specific IDPs like TDP-43 and α-synuclein so strongly linked to neurodegenerative diseases? [2] A4: The pathological aggregation of IDPs such as TDP-43, FUS, Tau, α-synuclein, and Huntingtin is a hallmark of diseases like ALS, Alzheimer's, and Parkinson's. These aggregates form toxic inclusions that disrupt cellular function. Furthermore, the dysregulation of cellular proteostasis mechanisms—including the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy—fails to clear these misfolded proteins effectively. An emerging key player is aberrant liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), where these IDPs undergo a pathogenic transition from liquid-like condensates into solid aggregates, a process that may be a key driver of neurodegeneration [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Key Resources for IDP Conformational Analysis

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Generative Deep Learning Models (e.g., ICoN) [1] | Learns from simulation data to rapidly sample novel, physically plausible conformations of highly dynamic proteins like Aβ42. |

| ENSEMBLE / pE-DB [3] | Software and a public database for depositing and accessing conformational ensembles of IDPs, primarily based on NMR and SAXS data. |

| Molecular Chaperones (e.g., Hsps) [2] | Used in experiments to assist protein folding, prevent abnormal phase transitions, and mitigate toxic aggregation of IDPs. |

| Disorder Prediction Servers (e.g., IUPRED, PONDR) [3] | Bioinformatics tools to identify intrinsically disordered regions from amino acid sequence based on composition and complexity. |

| D2P2 Database [3] | An interactive resource providing a compilation of disorder predictions for entire proteomes, using multiple algorithms and a consensus. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Protocol 1: Utilizing Generative Deep Learning for Conformational Sampling [1]

- Data Preparation: Collect a diverse set of conformational data for the target IDP. This can be derived from long-timescale molecular dynamics (MD) simulations or experimental structural data.

- Model Training: Train a generative deep learning model, such as the Internal Coordinate Net (ICoN), on the prepared dataset. The model learns the physical principles governing conformational changes.

- Conformation Generation: Use the trained model to sample new conformations. This can be done via random sampling or, more effectively, through strategic interpolation within the model's learned latent space to explore specific conformational transitions.

- Ensemble Analysis and Validation:

- Perform cluster analysis on the generated synthetic conformations to identify distinct conformational states.

- Validate the results by comparing the computational ensembles against experimental data from techniques like electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) or amino acid substitution studies.

- Analyze the atomistic details of the conformations, focusing on side-chain rearrangements and backbone dynamics to rationalize biological function or aggregation propensity.

Detailed Protocol 2: Characterizing Coupled Folding and Binding Kinetics [3]

- Sample Preparation: Purify the intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) and its structured binding partner. Ensure the IDP is in a monomeric, non-aggregated state, confirmed by techniques like size-exclusion chromatography or analytical ultracentrifugation.

- Equilibrium Binding Measurements: Use a method like Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) to determine the binding affinity (KD) and stoichiometry of the interaction.

- Stopped-Flow Kinetics:

- Rapidly mix the IDP and its partner in a stopped-flow instrument.

- Monitor a signal that changes upon binding and folding (e.g., fluorescence, circular dichroism).

- Fit the resulting kinetic traces to determine the association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants.

- Mutational Analysis: Create variants of the IDP to test the role of specific residues or putative pre-formed structural elements. Measure the kinetics of these variants to dissect the molecular mechanism of the binding-induced folding.

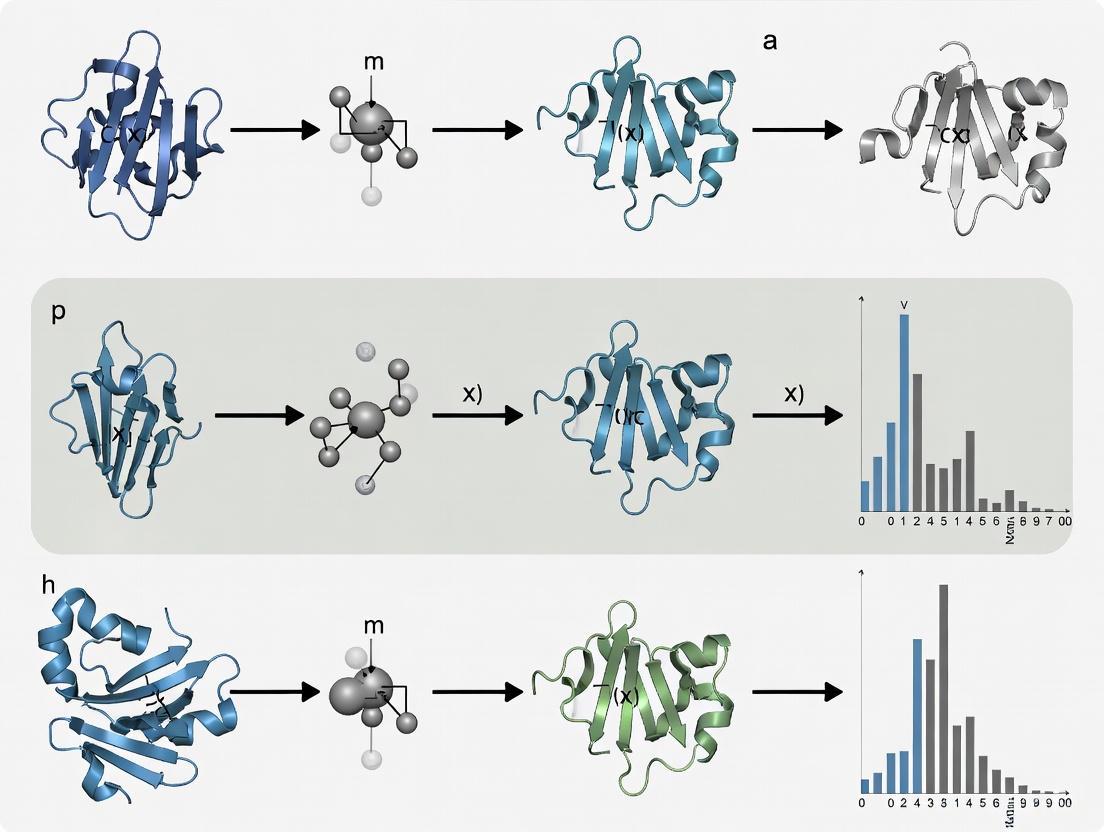

Methodology Visualization

Conformational Sampling & Validation

In protein chemistry, conformational ensembles, also known as structural ensembles, are models describing the structure of intrinsically unstructured proteins. Such proteins are flexible in nature and cannot be accurately described by a single structural representation [5]. The conformational ensemble concept recognizes that many proteins, especially intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), exist as a dynamic collection of interconverting structures rather than a single, static conformation [5] [6].

This paradigm represents a fundamental shift from traditional structural biology, extending the structure-function relationship from folded proteins to IDPs. These ensembles provide crucial insights into biological functions, molecular recognition mechanisms, and disease-related processes such as protein aggregation [7] [1]. For researchers studying dynamic proteins, thinking in terms of ensembles is essential because most experimental measurements report on ensemble-averaged properties rather than individual conformations [6].

Key Methodologies for Ensemble Determination

Experimental Approaches for Ensemble Generation

Several experimental techniques provide data for constructing and validating conformational ensembles:

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy: Provides atomic-level information on chemical shifts, paramagnetic relaxation enhancements (PREs), and nuclear Overhauser effects (NOEs) that report on structural dynamics and distances [5] [8].

- Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS): Yields low-resolution information about the global dimensions and shape of proteins in solution [5] [8].

- Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR): Probes sidechain rearrangements and local structural environments [7] [1].

- Covalent Protein Painting (CPP): A structural proteomics method that maps solvent accessibility of lysine residues in vivo to identify conformational changes and protein misfolding events [9].

Computational Sampling Methods

Computational approaches generate atomic-resolution conformational ensembles:

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: All-atom MD simulations provide atomically detailed structural descriptions but face challenges with sampling timescales and force field accuracy [8] [6]. Enhanced sampling methods like replica exchange solute tempering (REST) can improve efficiency [10].

- Generative Deep Learning: Models like Internal Coordinate Net (ICoN) learn physical principles of conformational changes from MD simulation data and rapidly generate novel synthetic conformations through interpolation in latent space [7] [1].

- RFdiffusion: Generates binders to IDPs/IDRs by sampling both target and binding protein conformations starting only from the target sequence [11].

- Coarse-Grained Models: Ultra-coarse-grained (UCG) models simplify molecular representations to study larger systems and longer timescales, then can be backmapped to higher resolution [12].

- Maximum Entropy Reweighting: Integrates MD simulations with experimental data (NMR, SAXS) to determine accurate atomic-resolution ensembles through a robust, automated reweighting procedure [8].

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Sampling Methods

| Method | Key Features | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| All-Atom MD | Atomistic detail, physical force fields | Studying local dynamics, solvent effects | Computationally expensive, limited timescales |

| Generative Deep Learning (ICoN) | Rapid sampling, learns from MD data | Exploring conformational landscapes of IDPs like Aβ42 | Dependent on quality of training data |

| RFdiffusion | Sequence-only input, samples target and binder conformations | Designing binders to IDPs/IDRs | Requires substantial computational resources |

| Coarse-Grained Models | Extended timescales, larger systems | Long-range conformational changes, protein complexes | Loss of atomic detail |

| Maximum Entropy Reweighting | Integrates computation and experiment, force-field independent | Determining accurate atomic-resolution ensembles | Requires extensive experimental data |

Experimental Protocols

Maximum Entropy Reweighting Protocol for Atomic-Resolution Ensembles

This protocol integrates MD simulations with experimental data to determine accurate conformational ensembles [8]:

Perform unbiased MD simulations: Generate initial conformational ensemble using state-of-the-art force fields (e.g., a99SB-disp, Charmm22*, Charmm36m). Recommended simulation length: ≥30μs for sufficient sampling.

Collect experimental data: Acquire extensive NMR and SAXS data. Key NMR parameters include chemical shifts, J-couplings, PREs, and NOEs. SAXS provides data on global dimensions.

Calculate experimental observables: Use forward models to predict experimental measurements from each frame of the MD ensemble.

Apply maximum entropy reweighting:

- Define the desired effective ensemble size using the Kish ratio (typically K=0.10, retaining ~3000 structures).

- Automatically balance restraint strengths from different experimental datasets.

- Minimally perturb the computational model to match experimental data.

Validate the ensemble: Assess agreement with experimental data not used in reweighting. Compare ensembles derived from different force fields to identify force-field independent features.

Deposit in database: Submit final ensemble to the Protein Ensemble Database (pE-DB) for community access.

RFdiffusion Protocol for Designing Binders to IDPs

This protocol designs high-affinity binders to intrinsically disordered proteins starting from sequence alone [11]:

Input target sequence: Provide the amino acid sequence of the IDP or IDR of interest.

Run RFdiffusion: Use the flexible target fine-tuned version of RFdiffusion to generate complexes. The algorithm:

- Simultaneously samples conformations of both the target and potential binder

- Does not require pre-specification of target geometry

- Generates shape-complementary interfaces through induced fit

Design sequences: Use ProteinMPNN to design sequences for generated backbones.

Filter designs: Apply AlphaFold2 to assess monomer conformation and complex formation.

Optimize with partial diffusion: Implement two-sided partial diffusion to sample varied target and binder conformations for improved shape complementarity.

Experimental validation: Express and purify designs, then test binding affinity using biolayer interferometry (BLI) or similar techniques.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why can't I use a single structure to represent my dynamic protein? A: Single structures cannot capture the conformational heterogeneity of IDPs and highly dynamic proteins. As one study illustrated, three different systems can have the same average for an observable but dramatically different underlying distributions—tightly clustered, broadly distributed, or multimodal [6]. The average conformation may be improbable and not representative of the underlying ensemble at all.

Q: My MD simulations of an IDP don't match my experimental data. What should I do? A: This common challenge can be addressed through maximum entropy reweighting [8]. This approach integrates your MD simulations with experimental data without requiring additional sampling. The automated reweighting procedure introduces minimal perturbation to your simulation ensemble to achieve agreement with experiments, effectively identifying the most accurate aspects of your force field.

Q: How can I target IDPs with designed binders when they lack stable structures? A: Use RFdiffusion with sequence-only input [11]. This method samples both target and binder conformations simultaneously, allowing the algorithm to identify specific conformations from the broad ensemble that can form high-affinity interactions. The resulting binders typically interact with a specific subregion of the target in a specific conformation via an induced fit mechanism.

Q: What's the advantage of generative deep learning over traditional MD for sampling conformational space? A: Models like ICoN can rapidly explore conformational landscapes by learning physical principles from MD data and generating novel synthetic conformations through interpolation in latent space [7] [1]. This approach can identify conformations with important interactions not sufficiently sampled in the original MD training data, providing more comprehensive coverage of the conformational landscape.

Q: How do I handle the underdetermination problem in ensemble modeling? A: The underdetermination problem (where many different ensembles can explain limited experimental data) can be addressed by: 1) Increasing the variety and amount of experimental data, 2) Using integrative methods that combine computation and experiment [8], and 3) Applying robust validation with data not used in ensemble generation. Maximum entropy reweighting with extensive datasets has shown that in favorable cases, ensembles converge to highly similar distributions regardless of the initial force field [8].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent ensemble models from different experimental datasets. Solution: Use an automated maximum entropy framework that objectively balances restraints from different data sources based on the desired ensemble size rather than subjective weight adjustments [8].

Problem: Inability to sample rare but functionally important conformations. Solution: Combine enhanced sampling MD (such as REST) with generative deep learning. The deep learning model can extrapolate from existing data to identify novel conformations not adequately sampled in simulations [7] [10].

Problem: Difficulty in studying conformational changes of membrane proteins like CFTR in vivo. Solution: Implement Covalent Protein Painting (CPP), which maps solvent accessibility of lysine residues in native cellular environments to detect conformational changes and misfolding events [9].

Problem: Low affinity of designed binders to disordered protein targets. Solution: Utilize two-sided partial diffusion in RFdiffusion, which allows both target and binder conformations to adapt during the design process, resulting in improved shape complementarity and more extensive interactions [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Purpose | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| RFdiffusion | Generative AI for protein design | Creating binders to IDPs/IDRs starting from sequence alone [11] |

| Internal Coordinate Net (ICoN) | Deep learning for conformational sampling | Exploring conformational landscapes of dynamic proteins like Aβ42 [7] [1] |

| Charmm36m, a99SB-disp | Protein force fields for MD simulations | Accurate simulation of IDPs and flexible proteins [8] |

| ProteinMPNN | Protein sequence design | Designing sequences for backbone structures generated by RFdiffusion [11] |

| AlphaFold2 | Structure prediction | Filtering and validating designed protein structures [11] |

| ENSEMBLE, ASTEROIDS | Selection algorithms for ensemble calculation | Fitting conformational ensembles to experimental data [5] |

| Covalent Protein Painting (CPP) reagents | Amine-reactive labeling compounds | Mapping solvent accessibility and conformational changes in vivo [9] |

Workflow Visualization

Conformational Ensemble Determination Workflow

Binder Design for Disordered Proteins

FAQs on Core Conceptual Challenges

FAQ 1: What makes the energy landscape of IDPs different from that of folded proteins, and why is this a challenge for sampling?

The energy landscape of folded proteins is often described as "funneled," guiding the protein toward a single, unique global energy minimum (the native state). In contrast, IDPs exist on a structural and dynamic continuum, characterized by a rugged landscape with many local energy minima separated by low energy barriers [13]. Instead of one stable structure, an IDP samples a quasi-continuum of rapidly interconverting conformations [13]. This fundamental difference presents two primary challenges for sampling:

- Lack of a Reference Structure: The absence of a single native state makes it difficult to define reaction coordinates (e.g., RMSD) that can effectively map the landscape [13].

- Weakly Funneled Landscape: The energy surface is "weakly funneled," meaning there is no strong thermodynamic drive toward a single state, resulting in a highly heterogeneous ensemble that is difficult to characterize [13].

FAQ 2: Why is capturing rare, transient states so difficult, and why does it matter?

Rare, transient states are low-population conformations that a protein adopts only fleetingly. They are challenging to capture for two main reasons:

- Computational Cost: Using molecular dynamics (MD), sampling these rare events requires simulations that span very long timescales (microseconds to milliseconds), which are computationally prohibitive for most systems [14].

- Experimental Limitations: Techniques like NMR spectroscopy and Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering provide ensemble-averaged data. The signal from transient states is often obscured by the dominant, more populous conformations, making them difficult to detect [8] [14]. These states are critically important because they can be biologically relevant conformations for functions like binding or aggregation. For example, a transient helical structure in an IDP might be the conformation recognized by a binding partner [15].

FAQ 3: What are the major limitations of Molecular Dynamics force fields when simulating IDPs?

While MD is a powerful tool, its accuracy for IDPs is highly dependent on the physical model, or force field, used. Key limitations include:

- Balance of Interactions: Many traditional force fields were parameterized using data from folded proteins and can struggle to correctly balance the protein-solvent and protein-protein interactions that govern IDP behavior. This can lead to ensembles that are either too compact or too extended compared to experimental data [16] [8].

- Energy-Entropy Balance: accurately capturing the delicate trade-off between energetic favorability and conformational entropy is a significant challenge. Recent work suggests that advanced polarizable (many-body) force fields may better capture this balance [16].

Troubleshooting Guides for Technical Challenges

Challenge 1: My MD-generated ensemble does not match experimental data.

Problem: When you calculate experimental observables (e.g., NMR chemical shifts, SAXS profiles) from your simulation ensemble, they do not agree with the actual lab data.

Solution: Employ integrative modeling by reweighting your MD ensemble using the maximum entropy principle.

- 1. Run Unbiased MD Simulation: Perform a long-timescale, all-atom MD simulation of your IDP using a modern force field [8].

- 2. Calculate Theoretical Observables: Use forward models (software that predicts experimental data from atomic coordinates) to compute the expected experimental values for every frame in your simulation trajectory [8].

- 3. Apply Maximum Entropy Reweighting: Use an automated procedure to assign new statistical weights to each simulation frame. The goal is to find the set of weights that provides the best fit to the experimental data while introducing the minimal possible perturbation to the original simulation ensemble [8].

- 4. Validate the Ensemble: Check that the reweighted ensemble not only fits the data used for reweighting but also agrees with other experimental data not used in the process.

Challenge 2: My simulations fail to sample functionally important rare states.

Problem: Functionally crucial conformations, such as partially ordered states primed for binding, are not observed in your simulation trajectory.

Solution 1: Utilize Enhanced Sampling MD.

- Method: Gaussian accelerated MD (GaMD). This method adds a harmonic boost potential to the system's energy landscape, which smooths the energy barriers and accelerates the transition between states without biasing the final ensemble properties [14].

- Protocol: Implement GaMD in a MD engine like AMBER or NAMD. Carefully select the boost potential parameters to ensure accurate reconstruction of the original free energies. This method has been successfully used to capture rare events like proline isomerization in IDPs [14].

Solution 2: Leverage Generative Deep Learning.

- Method: Train a deep learning model on existing MD data to learn the physical principles of conformational changes and generate novel, plausible conformations.

- Protocol: A model like the Internal Coordinate Net can be trained on a long MD simulation. Once trained, the model can interpolate in its learned latent space to rapidly generate a comprehensive set of conformations, including rare states with distinct side-chain arrangements that may have been missed in the original MD data [1].

Challenge 3: I need to characterize the kinetic pathways between states in my ensemble.

Problem: You have a collection of conformations but lack understanding of the transitions and time scales connecting them.

Solution: Build a Markov State Model from multiple, shorter MD simulations.

- 1. Generate High-Throughput Simulation Data: Run many parallel, unbiased MD simulations starting from different initial conditions to broadly sample the conformational landscape [15].

- 2. Cluster and Discretize: Cluster the aggregated simulation data into a set of microstates based on structural similarity (e.g., using backbone dihedrals or contact maps).

- 3. Build and Validate the MSM: Count the transitions between these microstates to construct a transition probability matrix. Validate the model's robustness by checking its self-consistency.

- 4. Analyze Kinetics and Pathways: The MSM allows you to compute key kinetic properties, such as the mean first-passage time between states, and to use Transition Path Theory to identify the most probable pathways connecting different conformational states [15].

Method Selection and Data Table

Table 1: Key Metrics from a Recent Study on Determining Accurate IDP Ensembles [8]

| IDP Name | Length (residues) | Key Feature | Agreement after Reweighting (across force fields) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aβ40 | 40 | Little-to-no residual secondary structure | High similarity |

| α-synuclein | 140 | Little-to-no residual secondary structure | High similarity |

| ACTR | 69 | Regions of residual helical structure | High similarity |

| drkN SH3 | 59 | Regions of residual helical structure | Converged to the most accurate ensemble |

| PaaA2 | 70 | Two stable helices with a flexible linker | Converged to the most accurate ensemble |

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Resources

| Research Reagent Solution | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| All-Atom Force Fields (a99SB-disp, CHARMM36m) | Physics-based models defining atomic interactions for MD simulations. | Simulating IDP conformational dynamics in explicit solvent [8]. |

| Generative Deep Learning Model (ICoN) | AI model that learns from simulation data to generate novel conformations. | Efficiently sampling the conformational landscape of amyloid-β [1]. |

| Maximum Entropy Reweighting Software | Integrates MD ensembles with experimental data via automated reweighting. | Determining a force-field independent, accurate ensemble of an IDP [8]. |

| Markov State Model (MSM) Builders | Software to construct kinetic models from many short MD simulations. | Identifying and characterizing transient, partially ordered states in p53 [15]. |

| Knowledge-Based Samplers (IDPConformerGenerator) | Rapidly generates statistical ensembles from protein structure databases. | Initial conformer generation for IDPs/IDRs and their complexes [16]. |

Experimental Protocol Workflows

Diagram 1: Workflow for determining an accurate IDP ensemble by integrating MD simulations with experimental data [8].

Diagram 2: Workflow for constructing a Markov State Model to study kinetics and pathways [15].

Relationship Between Conformational Dynamics and Biological Function

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support center addresses common challenges researchers face when studying the conformational dynamics of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and their role in biological function.

FAQ Category: Sampling and Ensemble Determination

Q: My molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of an IDP are not agreeing with my experimental NMR data. What is the most robust method to reconcile them?

A: A highly effective method is the maximum entropy reweighting procedure. This approach integrates all-atom MD simulations with experimental data (e.g., NMR chemical shifts, SAXS) to refine the conformational ensemble. It works by applying minimal perturbation to your initial simulation to match the experimental restraints, thus preserving physically realistic dynamics while achieving agreement with data [8].

- Troubleshooting Tip: The success of this method depends on a reasonable initial agreement between your simulation and data. If the initial MD ensemble is too biased, the reweighting may fail. Ensure you are using a modern force field like CHARMM36m or a99SB-disp, which are better balanced for IDPs [8] [17].

Q: Enhanced sampling is too slow for my protein of interest. How can I identify the best collective variables (CVs) to accelerate conformational changes?

A: The optimal CVs are the true reaction coordinates (tRCs), which are the essential coordinates that determine the progression of a conformational change. New methods now allow for the computation of tRCs from energy relaxation simulations, starting from a single protein structure. Biasing these tRCs can accelerate conformational changes by many orders of magnitude (e.g., 10⁵ to 10¹⁵-fold) and ensure the simulated pathways are physically realistic [18].

- Troubleshooting Tip: If using empirical CVs (e.g., radius of gyration, RMSD) leads to non-physical transition pathways, it indicates a "hidden barrier" problem. Switching to a tRC-based method should provide more efficient and accurate sampling [18].

Q: What are some efficient hybrid methods to sample large-scale conformational changes at atomic resolution?

A: Several hybrid methods combine the efficiency of coarse-grained models with the detail of all-atom MD. The table below compares four recent methods [19]:

| Method Name | Core Approach | Key Utility |

|---|---|---|

| MDeNM | MD excited along Normal Modes from an Elastic Network Model. | Efficiently explores large-scale, cooperative motions around a starting structure. |

| CoMD | Collective Modes-driven MD combining ENM and targeted MD. | Adaptively generates conformers between known functional states. |

| ClustENM | Generates, clusters, and energy-minimizes conformers from ENM deformations. | Rapidly produces a diverse set of full-atom conformers for docking studies. |

| ClustENMD | Extension of ClustENM that refines generated conformers with short MD simulations. | Improves structural realism and accounts for local atomic details. |

FAQ Category: Function and Dysfunction

Q: How can a protein have a function if it doesn't have a single stable structure?

A: For many proteins, function emerges from the dynamic equilibrium between multiple conformational states, not from a single static structure. The population of these states determines activity. For example, wild-type kinases predominantly populate inactive states, but even a minor population of active states can be selected and stabilized by binding partners or oncogenic mutations, shifting the ensemble and activating signaling [20].

Q: We have a static structure from AlphaFold2. How do we move beyond it to understand function?

A: AlphaFold2 solves the structure prediction problem, but the next challenge is to identify alternative conformations and the transitions between them [18]. To do this, you can:

- Use the static structure as a starting point for MD simulations or hybrid sampling methods [19].

- Employ new AI-powered tools like BioEmu, which uses diffusion models to generate equilibrium conformational ensembles from a single sequence, achieving high thermodynamic accuracy [21].

- Integrate experimental data from NMR or SAXS to refine computational ensembles, moving from a single structure to a probabilistic description of conformational states [17].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Atomic-Resolution Conformational Ensembles for IDPs

This protocol describes how to integrate MD simulations with experimental data to determine an accurate conformational ensemble for an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) [8].

1. Principle Generate an atomic-resolution ensemble that agrees with ensemble-averaged experimental measurements by reweighting an initial MD simulation using the maximum entropy principle.

2. Key Research Reagents & Solutions

| Reagent/Solution | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD) to generate the initial atomic-resolution conformational ensemble. |

| State-of-the-Art Force Fields | CHARMM36m, a99SB-disp. Provide a physically accurate starting model for IDP simulations [8] [17]. |

| Experimental Data (NMR, SAXS) | NMR chemical shifts, J-couplings, PREs; SAXS curves. Provide ensemble-averaged restraints for reweighting. |

| Forward Calculation Software | Programs to predict experimental observables (NMR chemical shifts, SAXS profiles) from each MD snapshot. |

| Reweighting Algorithm | A maximum entropy reweighting procedure to compute new statistical weights for each snapshot to match experiments. |

3. Step-by-Step Workflow

4. Critical Parameters

- Force Field Selection: Use a force field validated for IDPs, such as CHARMM36m or a99SB-disp, to ensure a reasonable starting ensemble [8].

- Kish Ratio (K): This parameter controls the effective ensemble size. A typical threshold of K=0.10 ensures the final ensemble contains a robust number of conformations (~3000 from 30,000 snapshots) without overfitting [8].

- Experimental Data Quality: The method requires extensive and accurate experimental data (NMR and SAXS) to reliably constrain the ensemble.

Protocol 2: Accelerated Sampling of Functional Conformational Changes

This protocol uses true reaction coordinates (tRCs) to overcome the time-scale limitation of simulating rare conformational transitions [18].

1. Principle Identify the few essential protein coordinates (tRCs) that control a conformational change and apply a bias potential to them to achieve highly accelerated, yet physically realistic, sampling.

2. Key Research Reagents & Solutions

| Reagent/Solution | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Single Protein Structure | The input, typically a ground-state structure from PDB or AlphaFold2. |

| Energy Relaxation Simulation | A short MD simulation used to compute potential energy flows and identify tRCs. |

| Generalized Work Functional (GWF) Method | The computational method that analyzes energy flow to disentangle tRCs from other coordinates. |

| Enhanced Sampling Software | (e.g., Plumed) to apply a bias potential (e.g., in metadynamics) to the identified tRCs. |

3. Step-by-Step Workflow

4. Critical Parameters

- Identification of tRCs: The success of the entire protocol hinges on the correct identification of tRCs using the GWF method from energy relaxation data [18].

- Bias Potential: Carefully choose the parameters for the bias potential (e.g., deposition rate, hill height in metadynamics) to ensure efficient sampling without distorting the underlying energy landscape.

- Validation: The resulting trajectories should pass through conformations with a range of committor probabilities (pB) to confirm they follow a natural transition pathway [18].

Computational Methods for Sampling IDP Conformational Space: From MD to AI

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the most critical factor in choosing a force field for simulating disordered proteins?

For simulating intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) or proteins with disordered regions, the force field must be specifically validated for such systems. The CHARMM36m force field is a reliable choice as it has been parameterized and tested to accurately capture the properties of both structured and intrinsically disordered regions. Using a force field not validated for IDPs can lead to inaccurate conformational ensembles and unreliable results [22].

FAQ 2: Why am I getting LINCS warnings in my GROMACS simulation, and how can I fix them?

LINCS warnings indicate that the linear constraint solver is struggling to maintain correct bond lengths. Common causes and solutions include [23]:

- Cause: Incorrect initial geometry or steric clashes.

- Solution: Always perform thorough energy minimization and gradual equilibration (NVT and NPT) before the production run.

- Cause: A timestep that is too large.

- Solution: Reduce the integration timestep, typically to 2 fs when using bond constraints.

- Cause: Inaccurate force field parameters for your specific molecules.

- Solution: Validate that the force field you are using is appropriate for all components of your system (e.g., proteins, lipids, ligands).

FAQ 3: What does the "Residue not found in residue topology database" error mean in GROMACS?

This error occurs when pdb2gmx cannot find the parameters for a residue in your input structure within the selected force field's database. To resolve this [24]:

- Check residue name: Ensure the residue name in your PDB file matches the name defined in the force field's residue topology database.

- Parameterize the residue: If the residue is missing (e.g., a non-standard ligand), you will need to obtain or create a topology for it manually. You cannot use

pdb2gmxfor arbitrary molecules. - Use a different force field: Check if another supported force field contains parameters for the residue.

FAQ 4: What is the key difference between enhanced sampling methods that focus on conformations versus transition pathways?

Enhanced sampling techniques can be broadly divided into two branches [18]:

- Sampling Metastable Conformations: Methods like umbrella sampling [25] and metadynamics aim to efficiently explore and identify stable low-energy states (valleys on the energy landscape) and calculate free energies.

- Sampling Transition Dynamics: Methods like Transition Path Sampling (TPS) focus on the rare pathways between stable states, generating unbiased reactive trajectories to understand the mechanism of transition.

FAQ 5: How can I accelerate the sampling of slow protein conformational changes?

The most effective strategy is to bias the simulation along the True Reaction Coordinates (tRCs), which are the essential coordinates that control the conformational change. Biasing these coordinates can lead to accelerations of 10⁵ to 10¹⁵-fold for processes like ligand dissociation. Since tRCs are often unknown, advanced methods like the Generalized Work Functional (GWF) method can be used to identify them from energy relaxation simulations, even starting from a single protein structure [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Force Field Selection and Parameterization

Problem: Inaccurate simulation results due to an inappropriate or poorly parameterized force field.

Solution Guide:

- Identify Your System's Nature: Match the force field to your molecular components [22].

- Proteins/Nucleic Acids: Use AMBER, CHARMM, or OPLS-AA.

- Intrinsically Disordered Proteins: Use CHARMM36m.

- Membranes: Use specialized force fields like CHARMM36 or LIPID21.

- Unique Bacterial Lipids: Consider newly developed force fields like BLipidFF [26].

- Choose the Resolution: Balance accuracy and computational cost [22].

- All-Atom (AA): Highest detail, includes all hydrogens (e.g., AMBERff14SB).

- United-Atom (UA): Groups aliphatic carbons and hydrogens, faster than AA.

- Coarse-Grained (CG): Groups several atoms into one "bead" (e.g., MARTINI), allowing for much larger and longer simulations.

- Validate and Test: Before running production simulations [22]:

- Review the literature for studies on similar systems.

- Perform preliminary tests (energy minimization, short MD) to check for stability.

- Compare results with available experimental data.

Issue 2: Inefficient Conformational Sampling

Problem: The simulation is trapped in a local energy minimum and fails to explore the biologically relevant conformational space.

Solution Guide:

- Employ Enhanced Sampling Methods: Utilize techniques that apply a bias to encourage exploration.

- Umbrella Sampling (US): Restrains the simulation at different points along a pre-defined reaction coordinate (e.g., a distance or angle) via harmonic potentials. The windows are then combined using the Weighted Histogram Analysis Method (WHAM) to compute the free energy profile [25].

- True Reaction Coordinate (tRC) Sampling: For maximum efficiency, identify and bias the true reaction coordinates using methods like GWF, which can be derived from energy relaxation simulations [18].

- Hamiltonian Replica Exchange (H-REX): Runs multiple replicas of the system with differently scaled biasing potentials. Periodic attempts to swap configurations between replicas enhance sampling across energy barriers [27].

- Use Advanced Protocols: Simple MD can be made more efficient with smart protocols. For example, PaCS-MD involves running multiple short simulations from carefully selected initial structures ("seeds") that have high potential to transition, effectively promoting conformational changes [28].

Issue 3: Simulation Instability and Crash (GROMACS)

Problem: Simulation crashes with errors like "LINCS warnings" or "Atom index out of bounds."

Solution Guide:

- Check System Preparation:

- Ensure proper solvation and ion concentration.

- Perform complete energy minimization to remove steric clashes.

- Conduct gradual system equilibration in two stages: first at constant volume (NVT), then at constant pressure (NPT) [23].

- Verify Simulation Parameters:

- Timestep: Use 2 fs as a starting point. Reduce to 1 fs if warnings persist [23].

- Constraints: Apply constraints to bonds involving hydrogen atoms [23].

- Topology Order: Ensure directives in your topology (

.top) file are in the correct order (e.g.,[defaults]must be first). An invalid order will causegromppto fail [24].

- Review Topology and Position Restraints:

- The error "Atom index in position_restraints out of bounds" often means your position restraint files are included in the wrong order. Each position restraint file must immediately follow the

[moleculetype]it belongs to [24].

- The error "Atom index in position_restraints out of bounds" often means your position restraint files are included in the wrong order. Each position restraint file must immediately follow the

Table 1: Key Enhanced Sampling Methods for Conformational Sampling

| Method | Key Principle | Best For | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Umbrella Sampling (US) [25] | Uses harmonic biases along a pre-defined Reaction Coordinate (RC) to sample specific regions. | Calculating free energy profiles along a known, low-dimensional RC. | Requires a priori knowledge of a good RC; can suffer from hidden barriers if RC is poor. |

| True Reaction Coordinate (tRC) Sampling [18] | Applies bias to the true, physically optimal coordinates controlling the transition. | Maximally accelerating conformational changes (e.g., ligand unbinding, flap opening in proteins). | tRCs must be identified first, e.g., via the Generalized Work Functional (GWF) method. |

| Hamiltonian Replica Exchange (H-REX) with bpCMAP [27] | Multiple replicas run with scaled biasing potentials (based on CMAP); exchanges are attempted to enhance sampling. | Sampling complex molecules with multiple torsional degrees of freedom (e.g., oligosaccharides). | More efficient than temperature replica exchange for large systems in explicit solvent. |

| PaCS-MD / FFM / OFLOOD [28] | Cycles of multiple short MD simulations restarted from "outlier" structures selected for their transition potential. | Promoting large-scale conformational transitions without requiring a pre-defined RC. | A post-processing step (e.g., US+WHAM) is often needed to compute free energies. |

Table 2: Force Field Selection Guide for Biomolecular Simulations

| Force Field | Class | Recommended For | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM36m [22] | All-Atom | Proteins (especially IDPs), Nucleic Acids, Lipids | Optimized for intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs). |

| AMBER (e.g., ff14SB) [22] | All-Atom | Proteins, Nucleic Acids | Widely used and validated for biological simulations. |

| BLipidFF [26] | All-Atom | Mycobacterial/Bacterial Membrane Lipids | Specialized for complex bacterial lipids like mycolic acids. |

| MARTINI [22] | Coarse-Grained | Large systems (e.g., membranes, protein complexes), Long timescales | Speed and efficiency; lower atomic resolution. |

| AutoDock4 [22] | All-Atom | Molecular Docking, Virtual Screening | Grid-based approach for fast docking calculations. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Tools for MD Simulations

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | Engine for running MD simulations. | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER, CHARMM. |

| Force Field Database | Provides parameters for molecular interactions. | CHARMM36, AMBER, BLipidFF (for bacterial lipids) [26]. |

| Analysis Tools | For processing trajectory data and calculating properties. | Built-in GROMACS tools, VMD, MDAnalysis, WHAM (for Umbrella Sampling) [25]. |

| Enhanced Sampling Plugins/Code | Implements advanced sampling algorithms. | PLUMED (integrates with many MD codes), custom methods for tRC sampling [18]. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Parameterizing new molecules for a force field. | Gaussian09, Multiwfn (for RESP charge fitting) [26]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary challenges when using generative deep learning models for sampling the conformational space of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs)?

Generative models face several key challenges when applied to IDP conformational sampling:

- Force Field Dependence: The accuracy of atomic-resolution conformational ensembles generated from Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations is highly dependent on the physical models, or force fields, used. Discrepancies between simulations and experiments remain even among the best-performing force fields [8].

- Data Sparsity and Interpretation: Experimental datasets for IDPs are often sparse and report on ensemble-averaged properties. Techniques like NMR and SAXS are consistent with many possible conformational distributions, and the data can be challenging to interpret and predict [8].

- Designability Bias: Generative models optimized for designability can impose a bias toward idealized, rigid structures (enriched in alpha helices and beta sheets) at the expense of loops and other complex, flexible motifs that are critical for IDP function. This leads to an undersampling of the full observed protein structure space [29].

- Physical Correctness: In broader physics simulation tasks, generative models can achieve high speedups but often show strong limitations in physical correctness, underlining the need for new methods to enforce physical laws [30].

FAQ 2: How can experimental data be integrated with simulations to create more accurate generative models for IDPs?

Integrative approaches, where experimental data is used to refine computational models, are essential. One robust method is maximum entropy reweighting [8].

- Principle: This approach seeks to introduce the minimal perturbation to a computational model (e.g., an ensemble from an MD simulation) required to match a set of experimental data.

- Procedure: A fully automated maximum entropy reweighting procedure can integrate all-atom MD simulations with extensive experimental datasets from NMR and SAXS. The strengths of restraints from different experimental datasets are automatically balanced based on the desired effective ensemble size of the final calculated ensemble [8].

- Outcome: This method can produce force-field independent conformational ensembles of IDPs at atomic resolution that show exceptional agreement with experimental data and minimal overfitting [8].

FAQ 3: What metrics are used to evaluate the coverage and quality of generated conformational ensembles?

Evaluating generative model coverage requires metrics beyond simple designability (the ability to find a sequence that folds into the backbone).

- Fréchet Protein Distance (FPD): This metric quantifies the distributional similarity between a set of generated structures and a reference dataset (e.g., native structures from CATH). A lower FPD indicates greater distributional coverage of the native protein structure space [29].

- Structural Embeddings (SHAPES Framework): This involves computing learned representations of protein structures across multiple structural hierarchies, from local geometries to global architectures. By visualizing these embeddings (e.g., using principal components), one can identify regions of protein structure space that are over-sampled or undersampled by a generative model [29].

- TERtiary Motifs (TERMs) Frequency: Analyzing the frequency of complex functional motifs in generated samples helps validate coverage trends, as these motifs are often found in models with greater coverage of the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [29].

FAQ 4: What are the advantages of physics-informed generative models for general physical simulation?

Physics-informed generative models integrate real physical laws directly into the AI architecture.

- Enhanced Realism: For tasks like fluid simulation, incorporating equations like Navier-Stokes enables the generation of dynamic, physically plausible animations from a single still image [31].

- Data Efficiency: By embedding physical priors, these models can learn complex physical relations from data more efficiently and are less likely to produce physically impossible outcomes [30] [31].

- Simulation Speedup: Generative models have the potential to achieve significant speedups compared to traditional differential equation-based simulations, though this must be balanced against physical correctness [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Generated IDP Conformational Ensembles Are Overly Idealized and Lack Structural Diversity

- Issue: The model's outputs are biased toward rigid secondary structures and fail to capture the flexible, heterogeneous nature of IDPs.

- Solution:

- Adjust Sampling Parameters: Increase the sampling temperature or noise scale in the generative model. This broadens the exploration of conformational space, though it may require subsequent filtering for designability [29].

- Incorporate Experimental Restraints: Use a maximum entropy reweighting protocol to bias the ensemble toward experimental observations. This pulls the simulation-derived ensemble toward a more physically realistic distribution [8].

- Evaluate with Comprehensive Metrics: Move beyond designability and RMSD. Use the SHAPES framework and FPD to quantitatively assess whether your generated ensembles cover the diversity of undesignable but native-like regions of structure space [29].

Problem: Discrepancies Between Conformational Ensembles Generated from Different Force Fields

- Issue: MD simulations started from the same initial state but using different force fields (e.g., a99SB-disp, Charmm22*, Charmm36m) produce divergent conformational distributions [8].

- Solution:

- Generate Long-Timescale Simulations: Ensure the unbiased MD simulations are sufficiently long to achieve convergence for the IDP of interest.

- Apply Integrative Reweighting: Use an automated maximum entropy procedure to reweight each force field's ensemble against the same set of extensive experimental data (NMR, SAXS).

- Assess Convergence: Compare the reweighted ensembles. In favorable cases, ensembles from different force fields will converge to highly similar conformational distributions after reweighting, providing a force-field independent approximation of the solution ensemble [8]. If they do not converge, the experimental data can help identify the most accurate force field.

Problem: Generative Model Fails to Learn Higher-Order Physical Relations from Image Pairs

- Issue: When trained on image-pairs representing physical simulations, the model achieves high speed but fails to capture complex, higher-order physical relations, leading to physically incorrect predictions [30].

- Solution:

- Physics-Informed Loss Functions: Incorporate physical laws directly into the model's loss function during training to penalize physically implausible outputs [30].

- Hybrid Architecture: Consider grey-box models that embed known physical constraints or differential equations within the generative AI architecture [30].

- Benchmarking: Systematically evaluate the model on a benchmark like PhysicsGen, which provides diverse tasks (wave propagation, lens distortion, motion dynamics) to test the model's ability to learn different types of physical relations [30].

Table 1: Benchmark Performance of Generative Models on Physical Simulation Tasks (PhysicsGen)

| Simulation Task | Generative Model | Speedup vs. Simulation | Physical Accuracy (Perc.) | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban Sound Propagation | Pix2Pix (GAN) | High | Good for 1st order | Fails on higher-order relations [30] |

| Lens Distortion | U-Net | High | Good | Struggles with complex geometries [30] |

| Motion Dynamics | Diffusion Models | High | Low | Fundamental problems with higher-order physics [30] |

Table 2: Evaluation of Generative Protein Structure Models via SHAPES Framework

| Generative Model | FPD (ESM3 Embeddings) | Loop Content | Designability Rate | Coverage Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFdiffusion | Medium | Low | High | Undersamples immunoglobulin folds [29] |

| Protpardelle | Higher | Medium | Medium | Covers more undesignable space [29] |

| Chroma | Medium | Low | High | Samples novel idealized helices [29] |

| Native CATH (Reference) | 0 | High | 56.3% | Contains full diversity of structural motifs [29] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Maximum Entropy Reweighting for Atomic-Resolution IDP Ensembles [8]

Objective: To determine an accurate conformational ensemble of an IDP by integrating all-atom MD simulations with experimental data from NMR and SAXS.

Materials:

- Computational Model: A long-timescale, unbiased all-atom MD simulation trajectory of the IDP (e.g., 30μs).

- Experimental Data: Extensive datasets from NMR (e.g., chemical shifts, J-couplings, residual dipolar couplings) and SAXS.

- Software: Forward model calculators to predict experimental observables from each MD simulation frame.

Workflow:

- Generate Unbiased Ensemble: Run MD simulations of the IDP using one or more state-of-the-art force fields (e.g., a99SB-disp, Charmm36m).

- Calculate Theoretical Observables: For every frame in the MD ensemble, use forward models to predict the values of all experimental measurements used as restraints.

- Determine Initial Weights: Assign a preliminary statistical weight to each conformation in the unbiased ensemble.

- Apply Maximum Entropy Principle: Iteratively adjust the weights of each conformation to achieve the best agreement with the experimental data, while minimizing the divergence from the original unbiased distribution (maximizing entropy).

- Control Ensemble Size: Use the Kish ratio to define the effective number of conformations in the final ensemble. A typical threshold is K=0.10, meaning the final reweighted ensemble contains about 10% of the original structures with significant weight.

- Validation: The reweighted ensemble should show excellent agreement with the input experimental data and provide a robust, force-field independent model of the IDP's conformational landscape.

Protocol 2: Assessing Generative Model Coverage with the SHAPES Framework [29]

Objective: To evaluate the distributional coverage of a generative protein structure model and identify undersampled regions of protein structure space.

Materials:

- Generative Model: A trained model for protein structure generation (e.g., Chroma, RFdiffusion, Protpardelle).

- Reference Dataset: A curated set of native protein domains (e.g., from CATH), filtered by resolution and quality.

- Embedding Models: Pre-trained models to generate structural embeddings (e.g., Foldseek, ESM3, ProtDomainSegmentor).

Workflow:

- Sample Structures: Generate a large set of protein structures from the generative model, matching the length distribution of the reference CATH dataset.

- Compute Embeddings: For both the generated and native (CATH) structures, compute multiple structural embeddings that capture features from local geometries to global architecture.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the embeddings to visualize the data in two dimensions.

- Visual Inspection: Create rasterized plots of the generated and native structures in the PCA space. Look for "streaks" (novel, non-native structures) and "gaps" (undersampled native regions).

- Quantitative Analysis: Calculate the Fréchet Protein Distance (FPD) between the distributions of generated and native embeddings. A lower FPD indicates better coverage.

- Interpret Findings: Identify the specific structural elements (e.g., loops, TERMs) that are missing from the generated samples by examining structures from the undersampled regions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Generative Modeling of IDP Conformational Space

| Item Name | Function / Application | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NoiseModelling Framework [30] | Simulates sound propagation for physical benchmark data. | Used in PhysicsGen to create image-pairs for urban sound propagation tasks [30]. |

| Maximum Entropy Reweighting Protocol [8] | Integrates MD simulations with experimental data. | Fully automated; uses Kish ratio to control ensemble size; produces force-field independent ensembles [8]. |

| SHAPES Framework [29] | Evaluates generative model coverage of protein structure space. | Uses multi-level structural embeddings and FPD; identifies undersampled functional motifs [29]. |

| Chroma [29] | Generative model for protein structures. | Introduces correlated noise for polymer chain structure; can be assessed for coverage with SHAPES [29]. |

| a99SB-disp Force Field [8] | All-atom MD simulation of proteins and IDPs. | Often shows reasonable initial agreement with IDP experimental data, suitable for subsequent reweighting [8]. |

In the study of protein conformational landscapes, particularly for challenging targets like intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), a fundamental challenge is bridging the gap between computational efficiency and atomic-level accuracy. Hybrid methods, which strategically combine fast coarse-grained (CG) simulations with detailed all-atom refinement, directly address this challenge. These approaches leverage the strength of CG models to rapidly explore vast regions of conformational space, while subsequent all-atom refinement recovers critical atomic details and corrects for the simplifications inherent in coarse-graining [32] [33]. This methodology is exceptionally powerful for mapping the free energy surface of proteins, revealing metastable states, cryptic pockets, and allosteric pathways that are difficult to capture with either approach alone [33]. Within the context of disordered proteins research, these techniques are invaluable for generating structural ensembles that reflect the dynamic and heterogeneous nature of IDPs and their molecular recognition features (MoRFs) [34].

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

How do I determine if my conformational sampling is sufficient?

Problem: Your hybrid simulation converges on a limited set of structures, and you suspect incomplete sampling of the conformational landscape, especially for a dynamic IDP.

Solution:

- Quantitative Metrics: Monitor the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) and radius of gyration (Rg) over the course of your CG simulation. A well-sampled system will show fluctuations back to previously visited states, not just a monotonic drift [32] [35].

- Cluster Analysis: Perform clustering (e.g., using RMSD) on the generated conformers. If a single cluster dominates your ensemble, or if new clusters continue to appear even in late stages of a long simulation, your sampling is likely insufficient [32].

- Compare to Experiment: Validate your final ensemble against any available experimental data. A significant discrepancy with Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) profiles or NMR chemical shifts is a strong indicator that your sampled landscape is not representative [33].

Preventative Measures:

- Enhanced Sampling: In the CG phase, employ techniques like parallel tempering (replica-exchange) to overcome energy barriers [35].

- Multi-Modal Excitation: For methods like MD with excited normal modes (MDeNM), exciting multiple linear combinations of low-frequency modes can help explore different conformational directions [32].

My refined all-atom models have high energy or steric clashes. What went wrong?

Problem: After refining CG-derived structures in an all-atom force field, the resulting models exhibit poor geometry, high energy terms, or atomic clashes.

Solution:

- Check the CG Output: The initial CG structure might already be in a high-energy conformation. Ensure your CG model produces physically plausible structures before refinement. A malformed CG input will be difficult for the all-atom refiner to correct [35].

- Refinement Protocol: Use a staged refinement protocol. Start with strong positional restraints on the backbone and gradually release them, allowing the side chains and local geometry to relax first. The Rosetta Relax protocol is specifically designed for this kind of gradual optimization [36].

- Inspect the Transition: The jump in resolution from CG to all-atom can be drastic. Consider using a multi-scale approach that employs a hybrid all-atom/CG force field as an intermediate step to gently guide the system into an atomistically realistic conformation [33].

Preventative Measures:

- Energy Minimization: Always perform a careful energy minimization of the CG-to-all-atom converted structure before beginning any dynamics-based refinement.

- Protocol Choice: For particularly challenging cases, consider a memetic algorithm that combines a global optimization algorithm (like Differential Evolution) with a local refiner (like Rosetta Relax). This can more effectively escape local energy minima than refinement alone [36].

How do I validate a conformational ensemble generated by a hybrid method?

Problem: You have generated a set of conformations but are unsure how to rigorously assess its quality and accuracy, a critical step for any meaningful scientific conclusion.

Solution:

- Internal Consistency: The ensemble should be structurally diverse yet thermodynamically reasonable. Calculate the free energy landscape using collective variables like RMSD and fraction of native contacts. You should observe distinct, metastable basins rather than a single, narrow minimum [35].

- Comparison to Experimental Structures: If multiple experimental structures are available (e.g., from the PDB), use them as a benchmark. Compute the principal components (PCs) of both the experimental and computational ensembles. A successful method will sample a conformational space that overlaps significantly with the experimental space [32].

- Recapitulate Experimental Observables:

- Crystallographic B-factors: Compare the root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSF) from your ensemble to experimental B-factors [32].

- NMR Data: For IDPs, back-calculate NMR chemical shifts or residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) from your ensemble and compare directly to experimental data [34].

- SAXS: Compute the theoretical SAXS profile from your ensemble and check the fit against the experimental scattering curve [33].

Table: Key Validation Metrics for Conformational Ensembles

| Metric | Description | What a Good Result Indicates |

|---|---|---|

| Principal Component Overlap [32] | Measures the similarity between the principal components of motion in predicted vs. experimental ensembles. | The computational method captures the essential, collective motions of the protein. |

| Free Energy Landscape [35] | A plot of free energy as a function of collective variables (e.g., RMSD, Rg). | The simulation has identified metastable states and the barriers between them. |

| RMSF vs. B-factors [32] | Correlation between calculated residue fluctuations and experimental crystallographic B-factors. | The model's dynamic behavior is consistent with crystal lattice observations. |

| Ensemble Fit to SAXS [33] | The chi-squared (χ²) fit between a computed SAXS profile and the experimental data. | The ensemble's average shape and size distribution match solution-based data. |

Can I use hybrid methods for drug design and cryptic pocket discovery?

Problem: You are studying a protein target with a seemingly rigid binding site and want to use hybrid methods to discover transient, "cryptic" pockets for drug targeting.

Solution:

- Yes, this is a primary application. Cryptic pockets are often revealed by large-scale conformational changes that are efficiently sampled by CG models [33].

- Workflow:

- Use long-timescale CG simulations or normal-mode-based sampling (e.g., ClustENM, MDeNM) to generate a diverse set of global conformations [32].

- Cluster the trajectories and select representative structures that show novel surface cavities or altered surface topology.

- Refine these candidate structures with and without the putative pocket in an open state using all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) to assess the pocket's stability.

- Perform ensemble docking against the entire refined set of structures, not just a single static crystal structure. This dramatically increases the chances of identifying compounds that bind to cryptic sites [32] [33].

Troubleshooting:

- If no new pockets are found, you may need to run longer CG simulations or use enhanced sampling techniques to push the protein further from its starting conformation.

- If the pocket collapses during all-atom refinement, consider using harmonic restraints during the initial refinement stages to gently maintain the pocket's openness.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Standard ClustENM/ClustENMD Workflow

This protocol uses an elastic network model to generate conformations, which are then refined with short MD simulations [32].

- System Preparation: Obtain a starting protein structure, preferably from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Remove ligands and crystallographic waters unless they are critical for stability.

- Coarse-Grained Sampling (ClustENM):

- Construct an Elastic Network Model (ENM) of the protein.

- Compute the low-frequency normal modes of the ENM.

- Generate a large pool of conformers (e.g., 10,000) by displacing the structure along linear combinations of the most collective modes.

- Cluster the generated conformers using an RMSD-based algorithm to identify distinct conformational states.

- All-Atom Refinement (ClustENMD):

- Select representative structures from the top clusters.

- Solvate each representative structure in an explicit solvent box and add ions to neutralize the system.

- Run a short MD simulation (e.g., nanoseconds) for each representative using a molecular dynamics package (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD). This step relaxes the structures, removes steric clashes introduced by the CG deformation, and incorporates atomic detail.

- Analysis: The final output is a multi-structure PDB file representing the refined conformational ensemble, ready for validation and analysis.

Protocol 2: Workflow for Disordered Protein Ensembles

This protocol is adapted for generating structural ensembles of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) or Regions (IDRs), integrating predictions from deep learning tools [34].

- Initial Structure Generation:

- Use AlphaFold2 or similar tools to generate a starting model. Note that for IDPs, the per-residue confidence (pLDDT) scores will be low in disordered regions.

- Alternatively, generate extended or random coil structures for the disordered segments.

- Coarse-Grained Sampling:

- Employ a machine-learned, transferable CG model (e.g., as described in [35]) that has been trained on diverse protein sequences and can simulate disordered states.

- Run extensive PT (Parallel Tempering) MD simulations to achieve a converged equilibrium distribution of conformations.

- All-Atom Refinement:

- Select a diverse subset of CG snapshots from the simulation.

- Convert these snapshots to all-atom resolution.

- Perform explicit-solvent MD refinement with a force field known to perform well for disordered proteins (e.g., a99SB-disp, CHARMM36m).

- Validation:

- Crucially, validate the final ensemble by comparing computed NMR chemical shifts or SAXS profiles with experimental data [34]. Iterate on the sampling or refinement steps if the agreement is poor.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Software | Function in Hybrid Methods |

|---|---|

| GROMACS/NAMD/OpenMM | Molecular dynamics engines for running all-atom refinement simulations in explicit solvent. |

| Rosetta Relax Protocol [36] | A widely used software and protocol for refining protein structures by optimizing side-chain rotamers and backbone angles. |

| Martini Coarse-Grained Force Field [33] [35] | A popular CG force field for simulating biomolecules; often used in hybrid all-atom/CG methodologies. |

| ClustENM & ClustENMD [32] | Specific software tools for generating conformers via ENM normal modes and refining them with short MD. |

| AlphaFold2 Predicted Structures [34] [37] | Provides high-accuracy starting models for the structured regions of a protein, which can be combined with CG sampling for flexible loops and linkers. |

| Machine-Learned Coarse-Grained Model [35] | A next-generation, transferable CG model trained on all-atom data, enabling extrapolative MD on new sequences. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of a generic hybrid method, integrating elements from the protocols above.

In the field of structural biology, accurately predicting the conformational landscape of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) remains a significant challenge. Unlike their structured counterparts, IDPs do not adopt a single, stable conformation but exist as dynamic ensembles of interconverting states. This flexibility is crucial to their biological function but makes them notoriously difficult to study. Traditional single-structure prediction methods, while revolutionary for structured proteins, fall short in capturing this inherent disorder. This technical support center article explores the FiveFold methodology and similar ensemble approaches, providing researchers with practical guidance for implementing these advanced techniques to sample the conformational space of disordered proteins effectively.

Understanding the FiveFold Ensemble Methodology

What is the FiveFold methodology and how does it address IDP conformational sampling?

The FiveFold methodology is an ensemble-based protein structure prediction framework specifically designed to model conformational diversity, particularly for intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs). It addresses the critical limitation of single-structure prediction methods by integrating predictions from five complementary algorithms: AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, OmegaFold, ESMFold, and EMBER3D [38].

This approach operates on the principle that combining multiple computational strategies creates a more comprehensive predictive framework than any single algorithm can provide. The system strategically pairs multiple sequence alignment (MSA)-dependent methods (AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold) with MSA-independent methods (OmegaFold, ESMFold, and EMBER3D) to mitigate individual algorithmic weaknesses while amplifying collective strengths [38]. For IDPs, which comprise approximately 30-40% of the human proteome and often lack sufficient evolutionary information for MSA-based methods, this combination is particularly valuable.

The framework employs two innovative technical components:

- Protein Folding Shape Code (PFSC): A standardized representation system that assigns specific characters to different folding elements (e.g., 'H' for alpha helices, 'E' for extended beta strands), enabling quantitative comparison of conformational differences [38].

- Protein Folding Variation Matrix (PFVM): A systematic framework for capturing and visualizing conformational diversity across the five algorithmic predictions, preserving information about alternative conformational states [38].

Through these components, FiveFold generates multiple plausible conformations rather than attempting to identify a single "correct" structure, making it particularly valuable for drug discovery targeting previously "undruggable" proteins that require strategies accounting for conformational flexibility [38].

How do the component algorithms in FiveFold differ in their approach?

The five algorithms integrated within FiveFold represent complementary methodological approaches to protein structure prediction, each with distinct strengths and limitations for conformational sampling.

Table: Comparison of FiveFold Component Algorithms

| Algorithm | Input Requirements | Key Strengths | IDP Handling Capability |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | MSA-dependent | Exceptional accuracy for well-folded proteins; captures long-range contacts and complex fold topologies | Limited for highly flexible regions; tends to predict static conformations [38] |

| RoseTTAFold | MSA-dependent | Three-track network analyzing sequence, distance, and 3D structure collectively; good for complex topologies | Similar limitations as AlphaFold2 for disordered regions [38] [39] |

| OmegaFold | MSA-independent | Handles orphan sequences with limited homology; computationally efficient | Improved for proteins lacking evolutionary information [38] |

| ESMFold | MSA-independent | Uses protein language models; fast predictions suitable for high-throughput applications | Effective for sequences with limited homologous information [38] |

| EMBER3D | MSA-independent | Computationally efficient approach; complements other methods | Addresses gaps in conformational sampling [38] |