Reducing the Computational Cost of MLIP Training: Practical Strategies for Drug Discovery Researchers

Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) are revolutionizing molecular dynamics simulations in drug discovery, but their high computational cost remains a significant barrier.

Reducing the Computational Cost of MLIP Training: Practical Strategies for Drug Discovery Researchers

Abstract

Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) are revolutionizing molecular dynamics simulations in drug discovery, but their high computational cost remains a significant barrier. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers seeking to optimize MLIP training efficiency. We begin by exploring the fundamental cost drivers in MLIP architectures like NequIP, MACE, and Allegro. We then detail actionable methodological approaches, including active learning, dataset distillation, and transfer learning. A dedicated troubleshooting section addresses common bottlenecks and performance issues, followed by a validation framework to assess the cost-accuracy trade-off. The conclusion synthesizes best practices for accelerating MLIP deployment in biomedical research, from early-stage ligand screening to protein dynamics studies.

Understanding the High Cost of MLIPs: Why Training Machine Learning Potentials is So Computationally Expensive

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Data Generation & Curation

Q1: My DFT data generation for the initial training set is taking weeks, exceeding my project timeline. What are my options?

A: You are likely generating an unnecessarily large or complex dataset. Optimize using an active learning or uncertainty sampling loop from the start.

- Protocol: Implement the "Committee Model" approach.

- Train 3-5 model instances with different initial weights on a small seed dataset (e.g., 100 configurations).

- Use these models to predict energies/forces for a large, unlabeled pool of candidate structures (e.g., from MD snapshots).

- Select configurations where the model predictions have the highest disagreement (variance). These are where the model is most uncertain.

- Run DFT calculations only on this high-disagreement subset.

- Add the new data to the training set and retrain. This reduces DFT calls by ~70-80% in early stages.

Q2: I'm getting "NaN" losses when training on my mixed dataset (clusters, surfaces, bulk). How do I debug this?

A: This is often due to extreme value mismatches or corrupted data in different subsets. Follow this validation protocol:

- Scale Check: Plot distributions (histograms) of energies, forces, and stresses per data subset. Look for outliers or incompatible units (e.g., eV vs. meV).

- Filtering: Use interquartile range (IQR) filtering per subset. Remove configurations where any component exceeds

Q3 + 1.5*IQRor is belowQ1 - 1.5*IQR. - Normalization: Apply per-property, per-subset standardization for initial training, then gradually move to a unified scalar.

Table 1: Example Data Statistics Pre- and Post-Cleaning

| Data Subset | Configurations | Energy Range (eV) Raw | Force Max (eV/Ã…) Raw | Energy Range Cleaned | Force Max Cleaned |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk Crystal | 10,000 | -15892.1 to -15845.3 | 0.021 | -15875.2 to -15850.1 | 0.018 |

| Nanoparticle | 5,000 | -224.5 to 101.8 | 15.4 | -210.2 to 45.3 | 8.7 |

| Surface Slab | 8,000 | -4033.7 to -4010.2 | 2.5 | -4030.1 to -4012.5 | 1.9 |

Model Training & Convergence

Q3: My validation loss plateaus early, but training loss continues to decrease. Is this overfitting, and how can I fix it without more data?

A: Yes, this indicates overfitting to the training set. Employ regularization techniques and a structured learning rate schedule.

- Protocol: Combined Regularization Strategy.

- Add Noise: Inject Gaussian noise (σ=0.01-0.1) to atomic positions during training (augmentation).

- Weight Decay: Use AdamW optimizer with weight decay parameter between

1e-4and1e-6. - Learning Rate Schedule: Use a warm-up followed by a cosine annealing or reduce-on-plateau scheduler.

- Early Stopping: Monitor validation loss and stop when it fails to improve for 20-50 epochs.

Q4: Training my large-scale GNN-MLP is memory-intensive and slow. What are the key hyperparameters to adjust for computational cost optimization?

A: Focus on model architecture and batch composition. The following table summarizes the primary cost levers.

Table 2: Hyperparameters for Computational Cost Optimization

| Hyperparameter | Typical Default | Optimization Target for Cost Reduction | Expected Impact on Cost/Speed | Potential Accuracy Trade-off |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radial Cutoff | 6.0 Ã… | Reduce to 4.5-5.0 Ã… | High (Less neighbor data) | Moderate (Loss of long-range info) |

| Batch Size | 8-32 configs | Maximize within GPU memory | High (Better GPU utilization) | Low |

| Hidden Features | 128-256 | Reduce to 64-128 | High (Smaller matrices) | Moderate-High |

| Number of Layers | 3-6 | Reduce to 2-4 | Moderate | Moderate |

| Precision | Float32 | Use Mixed (Float16/32) Precision | High (Faster ops, less memory) | Low (if implemented well) |

Model Evaluation & Deployment

Q5: My model converges with low loss but performs poorly in MD simulation, causing unrealistic bond stretching or atom clustering. Why?

A: This is a failure in force/curvature prediction, often due to insufficient diverse force samples in training data.

- Protocol: Enhanced Force Sampling for MD Stability.

- Analyze Failure Modes: Run a short, high-temperature MD, identify the step where energy/forces diverge.

- Extract Configurations: Save the trajectory from just before the failure.

- Active Learning on Forces: Compute the mean absolute error (MAE) of forces on these configurations. Explicitly add configurations with high force MAE to your next DFT batch for labeling.

- Stress Weight: Increase the loss weight for stress components during retraining to improve stability under deformation.

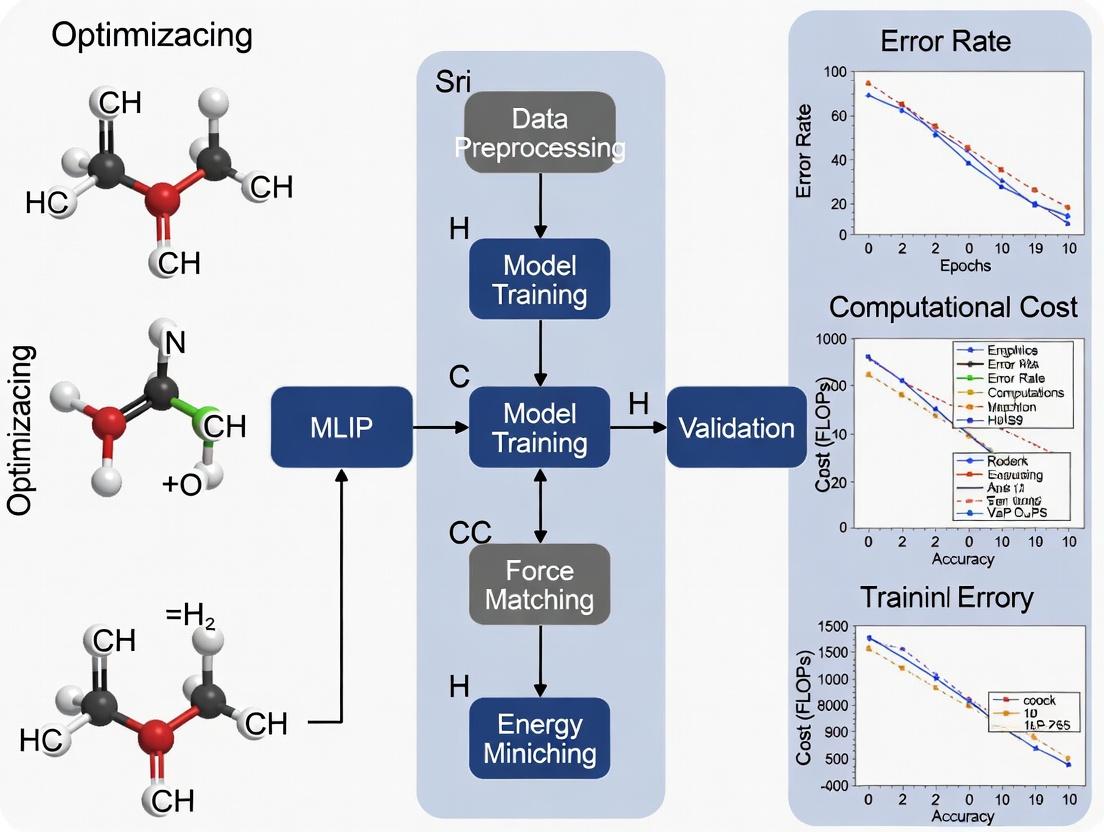

Workflow & System Diagrams

Diagram 1: MLIP Training & Active Learning Pipeline

Diagram 2: Computational Cost Distribution in MLIP Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software & Tools for MLIP Development

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function in Pipeline | Key Consideration for Cost Opt. |

|---|---|---|---|

| VASP / Quantum ESPRESSO | DFT Calculator | Generates the ground-truth training data (E, F, S). | Largest cost center. Use hybrid functionals sparingly; optimize k-points & convergence criteria. |

| LAMMPS / ASE | Atomic Simulation Environment | Performs MD, generates candidate structures, and serves as inference engine for MLIPs. | ASE is lighter for prototyping; LAMMPS is optimized for large-scale production MD. |

| PyTorch Geometric / DeepMD-kit | ML Framework | Provides neural network architectures (GNNs) and training utilities specifically for atomic systems. | DeepMD-kit is highly optimized for MD force fields. PyTorch offers more flexibility for research. |

| FLARE / MACE | MLIP Codebase | End-to-end pipelines for uncertainty-aware training and active learning. | FLARE's Bayesian approach is compute-heavy per iteration but reduces total DFT calls. |

| WandB / MLflow | Experiment Tracking | Logs hyperparameters, losses, and validation metrics across multiple runs. | Critical for identifying optimal, cost-effective hyperparameter sets without redundant trials. |

| DASK / SLURM | HPC Workload Manager | Parallelizes DFT calculations and hyperparameter search across clusters. | Efficient job scheduling is paramount to reduce queueing overhead for massive datasets. |

| magnesium;2-ethylhexanoate | magnesium;2-ethylhexanoate, MF:C16H30MgO4, MW:310.71 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Biliverdin dihydrochloride | Biliverdin dihydrochloride, MF:C33H36Cl2N4O6, MW:655.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

This support center addresses common issues encountered when implementing and optimizing Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Attention Mechanisms, and Symmetry-Adapted Networks in the context of Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIP) training. The guidance is framed within computational cost optimization research for large-scale molecular and materials simulations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My Symmetry-Adapted Network (SA-Net) fails to converge or shows high energy errors during MLIP training. What are the primary culprits? A: This is often related to symmetry enforcement and feature representation. First, verify that the irreducible representation (irrep) features are being correctly projected and that the Clebsch-Gordan coefficients for your chosen maximum angular momentum (l_max) are accurate. A mismatch here breaks physical constraints. Second, check the radial basis function (RBF) parameters; an insufficient number of basis functions or incorrect cutoff can lose critical atomic interaction information. Ensure the Bessel functions or polynomial basis is well-conditioned.

Q2: The memory usage of my Attention-based GNN scales quadratically with system size, making large-scale simulations impossible. How can I mitigate this? A: The O(N²) memory complexity of standard self-attention is a known cost driver. Implement one or more of the following optimizations: 1) Neighbor-List Attention: Restrict attention to atoms within a local cutoff radius, similar to classical message-passing. 2) Linear Attention Approximations: Use kernel-based (e.g., FAVOR+) or low-rank approximations to decompose the attention matrix. 3) Hierarchical Attention: Use a two-stage process where atoms are first clustered (coarse-grained), attention is applied at the cluster level, and then messages are distributed back to atoms.

Q3: During distributed training of a large GNN-MLIP, I experience severe communication bottlenecks. What are the best partitioning strategies? A: For molecular systems, spatial decomposition (geometric partitioning) is typically most efficient. Use a library like METIS to partition the molecular graph or atomic coordinate space into balanced subdomains, minimizing the edge-cut (inter-partition communication edges). For periodic systems, ensure your strategy accounts for ghost/halo atoms across periodic boundaries. The key metric to monitor is the ratio of halo atoms to core atoms within each partition; a high ratio indicates poor partitioning and excessive communication.

Q4: The training loss for my equivariant network plateaus, and forces are not predicted accurately. How should I debug this? A: Follow this structured debugging protocol:

- Sanity Check: Run a forward pass on a single, small configuration (e.g., a diatomic molecule). Manually verify that the output energies are invariant to random rotations and translations of the input structure, and that the forces (negative energy gradients) transform correctly as vectors.

- Feature Inspection: Visualize the learned equivariant features (e.g., spherical harmonics coefficients) for intermediate layers. Are they non-zero and changing across layers? If features vanish, check for normalization issues.

- Loss Component Weights: The total loss is L = λ_E * L_Energy + λ_F * L_Forces. If forces are poor, gradually increase

λ_Frelative toλ_E. A typical starting ratio (Energy:Forces) is 1:1000.

Q5: How do I choose between a simple invariant GNN, an attention-based model, and a full equivariant SA-Net for my specific application? A: The choice is a direct trade-off between representational capacity, computational cost, and data efficiency. Refer to the decision table below.

Quantitative Cost Driver Analysis

Table 1: Architectural Cost & Performance Trade-offs

| Architecture Type | Computational Complexity (Per Atom) | Memory Scaling | Typical RMSE (Energy) [meV/atom] | Data Efficiency | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invariant GNN (e.g., SchNet) | O(N) | O(N) | 8-15 | Low | High-throughput screening of similar chemistries |

| Attention GNN (e.g., Transformer-MLP) | O(N²) (Global) / O(N) (Local) | O(N²) / O(N) | 5-10 | Medium | Medium-sized systems with long-range interactions |

| Equivariant SA-Net (e.g., NequIP, Allegro) | O(N * l_max³) | O(N) | 1-5 | High | High-accuracy MD, complex alloys, reactive systems |

Table 2: Optimized Hyperparameter Benchmarks (for a 50-atom system)

| Parameter | Typical Value Range | Impact on Cost | Impact on Accuracy | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radial Cutoff | 4.0 - 6.0 Ã… | Linear increase | Critical: Too low loses info, too high increases noise. | Start at 5.0 Ã…. |

| Max Angular Momentum (l_max) | 1-3 | Cubed (l_max³) increase in tensor operations | Major: Higher l_max captures more complex torsion. | Start with l_max=1, increase to 2 if accuracy plateaus. |

| Neighbor List Update Frequency | 1-100 MD steps | High: Frequent rebuilds are costly. | Low if system diffuse, high if dense/rapid. | Use dynamic strategy based on max atomic displacement. |

| Attention Heads | 4-8 | Linear increase | Marginal beyond a point; risk of overfitting. | Use 4 heads for local attention. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ablation Study for Cost Driver Identification Objective: Isolate the computational cost contribution of each network component. Methodology:

- Baseline Model: Train a simple 3-layer invariant GNN with a fixed hidden dimension and radial cutoff.

- Incremental Modifications: Sequentially add/modify one component:

- Step A: Add a full self-attention layer between message-passing steps.

- Step B: Replace invariant features with equivariant features (lmax=1).

- Step C: Increase the equivariant feature order (lmax=2).

- Metrics: For each model variant, log: (a) Average training time per epoch, (b) Peak GPU memory usage, (c) Test set energy/force RMSE.

- Analysis: Plot cost vs. accuracy. The steepest cost increase pinpoints the primary architectural cost driver.

Protocol 2: Symmetry-Adapted Network Convergence Test Objective: Validate the correct physical implementation of an equivariant network. Methodology:

- Dataset: Create a small test set (10 configurations) of a water molecule with randomized rotations.

- Forward Pass: Run the trained model on each rotated configuration without gradient computation.

- Validation Metrics: Calculate the standard deviation of the predicted total energy across all rotations. The correct result should be zero (within machine precision). For forces, compute the Frobenius norm of the difference between predicted forces and the correctly rotated reference force vector.

- Tolerance: Energy variance < 1e-6 meV; force norm error < 1e-3 meV/Ã….

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Primary MLIP Architectural Cost Drivers & Impacts

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting Workflow for Cost & Accuracy Issues

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software & Libraries for MLIP Development

| Tool / Library | Primary Function | Key Benefit for Cost Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| e3nn / e3nn-jax | Building blocks for E(3)-equivariant neural networks. | Provides optimized, validated operations (spherical harmonics, tensor products), preventing costly implementation errors. |

| JAX / PyTorch Geometric | Differentiable programming & GNN framework. | JAX enables seamless GPU/TPU acceleration and automatic differentiation; PyG offers efficient sparse neighbor operations. |

| DeePMD-kit | High-performance MLIP training & inference suite. | Integrated support for distributed training and model compression, directly addressing production cost drivers. |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | Atomistic simulations and dataset manipulation. | Standardized interface for building datasets, running symmetry tests, and validating model outputs. |

| LIBXSMM | Library for small matrix multiplications. | Can dramatically accelerate the dense, small tensor operations prevalent in equivariant network kernels. |

| Bursin | Bursin, MF:C14H25N7O3, MW:339.39 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1-Methoxy-4-methylpentane | 1-Methoxy-4-methylpentane, CAS:3590-70-3, MF:C7H16O, MW:116.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My model’s training time has increased dramatically after doubling my dataset. Is this linear scaling expected?

A: No, it is often exponential, not linear. The relationship is governed by scaling laws. Increased data volume demands more epochs, larger models to prevent underfitting, and significantly more optimizer steps. Check your effective compute budget, defined as C ≈ N * D, where N is model parameters and D is training tokens/data points. Doubling D with a fixed N often requires more than double the steps for convergence.

Q2: How can I quantify if low-quality, noisy data is the cause of extended training times? A: Implement a data quality ablation protocol. Train three models:

- Baseline: Full dataset.

- High-Quality Subset: A rigorously curated, smaller subset.

- Noise-Augmented: Artificially noised high-quality data. Track time-to-target-validation-loss. If the high-quality subset converges fastest despite smaller size, data quality is your bottleneck.

Q3: What are the first diagnostic steps when compute time exceeds projections? A: Follow this protocol:

- Profile Compute: Use tools (e.g., PyTorch Profiler, TensorBoard) to identify bottlenecks (data loading vs. GPU compute).

- Analyze Learning Curves: Plot training & validation loss vs. steps and wall-clock time. A flat curve in loss vs. time indicates a system bottleneck; a steep curve in loss vs. steps suggests a data/model complexity issue.

- Validate Data Pipeline: Ensure data preprocessing and loading are not blocking the GPU. Use asynchronous data loading and prefetching.

Q4: Are there optimal stopping criteria to save compute when data is suboptimal? A: Yes. Implement early stopping based on a moving average of validation loss. More advanced criteria include:

- Generalization Gap Threshold: Stop if

(Train_Loss - Val_Loss) > Threshold, indicating overfitting to noisy patterns. - Plateau Detection: Stop after

Nepochs with no improvement in a smoothed validation metric.

Table 1: Estimated Compute Multipliers for Data Changes (Theoretical)

| Change Factor | Data Size Multiplier | Assumed Model Size Adjustment | Estimated Compute Time Multiplier | Primary Driver |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2x More, Same Quality | 2.0x | None (Fixed Model) | 2.1x - 2.5x | More optimizer steps |

| 2x More, Same Quality | 2.0x | Scale ~1.2x (Chinchilla-Optimal) | 3.0x - 4.0x | Larger model + more steps |

| Same Size, 2x Noise/Error Rate | 1.0x | None | 1.5x - 3.0x | Slower convergence, more epochs |

| 2x More, 2x Noisier | 2.0x | May require scaling | 4.0x - 8.0x+ | Combined negative effects |

Table 2: Experimental Results from Data Quality Curation Study

| Experiment Condition | Dataset Size (Samples) | Avg. Sample Quality Score | Time to Target Loss (Hours) | Relative Compute Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw, Uncurated Data | 1,000,000 | 65 | 120.0 | 1.00x (Baseline) |

| Curation (Filter + Correct) | 700,000 | 92 | 63.5 | 0.53x |

| Curation + Active Learning Augmentation | 850,000 | 90 | 78.2 | 0.65x |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring the Data Quality Impact on Convergence Objective: Isolate the effect of label noise on training compute time. Method:

- Start with a high-quality, trusted dataset

D_clean. - Create degraded versions by randomly corrupting labels for

X%of samples (e.g., 10%, 25%, 40%). - Train identical model architectures on

D_clean,D_noisy10,D_noisy25,D_noisy40. - Use identical hyperparameters, hardware, and a fixed target validation loss

L_target. - Record the wall-clock time and number of training steps until each run reaches

L_target. - Plot

Time_to_L_targetvs.Noise_Level.

Protocol 2: Determining Data-Quality-Aware Early Stopping Threshold Objective: Dynamically stop training to conserve compute when data noise limits gains. Method:

- During training, maintain an exponential moving average (EMA) of the validation loss.

- Define a patience window

P(e.g., 20,000 steps). - Calculate the improvement rate:

(EMA_loss[beginning of window] - EMA_loss[current]) / P. - If the improvement rate falls below a threshold

Ï„(e.g., 1e-7 per step), trigger stopping. - Calibration: Set

τbased on initial clean validation cycles—the point where improvement on clean holdout data plateaus.

Visualizations

Diagram Title: Root Causes of Exponential Compute Growth

Diagram Title: Data Quality Ablation Experiment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Compute & Data Efficiency Research

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose | Relevance to Compute Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Data Curation Suite (e.g., CleanLab, Snorkel) | Identifies label errors, estimates noise, and programs training data. | Reduces dataset noise, improving convergence rate and reducing required training steps. |

| Active Learning Framework (e.g., MODAL, ALiPy) | Selects the most informative data points for labeling/model training. | Maximizes learning per sample, allowing smaller, higher-quality datasets that lower compute needs. |

| Compute Profiler (e.g., PyTorch Profiler, NVIDIA Nsight) | Identifies bottlenecks in training pipeline (CPU/GPU/IO). | Distinguishes between data/system bottlenecks and inherent algorithmic compute requirements. |

| Hyperparameter Optimization (e.g., Ray Tune, Optuna) | Automates search for optimal model & training parameters. | Finds configurations that converge faster, directly saving compute time per experiment. |

| Scaled Loss Monitoring (e.g., Weights & Biases, TensorBoard) | Tracks loss vs. wall-clock time (not just steps). | Provides the true metric for compute cost and identifies inefficiencies early. |

| Dataset Distillation Tools (Emerging Research) | Creates synthetic, highly informative training subsets. | Aims to learn from small synthetic sets, dramatically cutting data size and associated compute. |

| beta-Fenchyl alcohol | beta-Fenchyl alcohol, CAS:64439-31-2, MF:C10H18O, MW:154.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Aluminum;chloride;hydroxide | Aluminum;chloride;hydroxide, MF:AlClHO+, MW:79.44 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technical Support Center

FAQ & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: My distributed training job crashes with "CUDA out of memory" errors, but a single GPU runs the same model. What are the primary causes and solutions?

A: This is often due to the memory overhead introduced by distributed training paradigms.

- Cause: Data Parallelism replicates the model on each GPU, and the all-reduce operation for gradient synchronization requires additional buffer memory. The default

torch.nn.DataParallelor evenDistributedDataParallel(DDP) can have significant overhead. - Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Profile Memory: Use

torch.cuda.memory_allocated()andtorch.cuda.max_memory_allocated()before and after the forward/backward pass to establish a baseline. - Enable Gradient Checkpointing: Recompute activations during backward pass instead of storing them. Use

torch.utils.checkpoint. - Use FP16/BF16 Mixed Precision: Halves the memory footprint of model parameters and activations. Use

torch.cuda.amp. - Consider Model Parallelism: For extremely large models, split layers across GPUs (e.g.,

tensor_parallelorpipeline_parallel).

- Profile Memory: Use

Q2: During multi-node training, I observe low GPU utilization (<50%) and long iteration times. Network communication seems to be the bottleneck. How can I diagnose and mitigate this?

A: This indicates a severe node-to-node communication bottleneck, often in the all-reduce step.

- Diagnosis Protocol:

- Measure Communication Time: Use the profiler in your framework (e.g., PyTorch's

torch.profiler). Focus onncclAllReduceoperations. - Check Network Topology: Ensure nodes are connected via a high-bandwidth link (e.g., InfiniBand or high-speed Ethernet). Use

ibstatorethtoolto verify. - Benchmark: Run a pure NCCL test:

nccl-tests/build/all_reduce_perf -b 8G -e 8G -f 2 -g <num_gpus>.

- Measure Communication Time: Use the profiler in your framework (e.g., PyTorch's

- Mitigation Strategies:

- Use Gradient Bucketing (DDP): DDP buckets multiple gradients into one all-reduce operation to improve efficiency.

- Increase Batch Size: Reduces the frequency of communication relative to computation.

- Implement Overlap: Ensure computation (backward pass) and communication (gradient sync) overlap. DDP does this by default.

- Topology-Aware Communication: Ensure processes on the same physical node communicate via NVLink/PCIe before going to the network.

Q3: My data preprocessing pipeline is slow, causing GPUs to stall frequently. The data is stored on a parallel file system (e.g., Lustre, GPFS). How can I optimize storage I/O?

A: This is a classic storage I/O bottleneck where data loading cannot keep up with GPU consumption.

- Optimization Protocol:

- Profile the DataLoader: Use PyTorch's

torch.utils.bottleneckor a simple timestamp log to measure data loading time per batch. - Implement Caching: For small, frequently accessed datasets, cache the entire dataset in node-local NVMe storage or CPU memory.

- Optimize File Access:

- Use Fewer, Larger Files: Concatenate millions of small files into larger archives (e.g., TFRecord, HDF5) to reduce metadata overhead.

- Stripe Files Correctly: Align Lustre stripe count and size with your read patterns. For large sequential reads, use a stripe count matching the number of data-serving OSTs.

- Use FUSE-based Solutions: Implement a FUSE filesystem like

gtarfsto read tar archives directly, avoiding extraction overhead.

- Profile the DataLoader: Use PyTorch's

Quantitative Data Summary

Table 1: Impact of Mixed Precision on GPU Memory and Throughput

| Precision | Model Memory (10B params) | Activation Memory (Batch 1024) | Relative Training Speed |

|---|---|---|---|

| FP32 | ~40 GB | ~8 GB | 1.0x (Baseline) |

| FP16/BF16 | ~20 GB | ~4 GB | 1.5x - 2.5x |

Table 2: Effective Bandwidth for Different Interconnects

| Interconnect Type | Theoretical Bandwidth | Effective All-Reduce BW (per GPU)* | Typical Latency |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCIe 4.0 (x16) | 32 GB/s | ~25 GB/s | 1-3 µs |

| NVLink 3.0 | 600 GB/s | ~450 GB/s | <1 µs |

| InfiniBand HDR | 200 Gb/s | ~23 GB/s | 0.7 µs |

| 100Gb Ethernet | 100 Gb/s | ~11 GB/s | 2-5 µs |

*Measured with 8 MB message size using NCCL tests.

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Node-to-Node Communication

Objective: Quantify the communication bottleneck in a multi-node setup. Methodology:

- Setup: Provision two identical nodes, each with 8 GPUs interconnected via NVLink. Connect nodes with InfiniBand.

- Tool: Use the NCCL test suite (

nccl-tests). - Procedure:

- Compile

nccl-testswith CUDA and NCCL support. - Run intra-node benchmark:

mpirun -np 8 -H localhost ./all_reduce_perf -b 8M -e 128M -f 2. - Run inter-node benchmark:

mpirun -np 16 -H node1:8,node2:8 ./all_reduce_perf -b 8M -e 128M -f 2.

- Compile

- Metrics: Record bus bandwidth (GB/s) for varying message sizes. Plot bandwidth vs. message size for intra-node and inter-node scenarios to identify the crossover point where network becomes the limiting factor.

Visualization: Distributed Training Dataflow with Potential Bottlenecks

Title: ML Training Hardware Bottlenecks Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software & Hardware Tools for MLIP Training Optimization

| Tool / Reagent | Function & Purpose | Key Consideration for MLIP |

|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA NCCL | Optimized collective communication library for multi-GPU/multi-node. | Essential for scaling to hundreds of GPUs across nodes for large MD simulations. |

| PyTorch DDP | Distributed Data Parallel wrapper for model replication and gradient synchronization. | The primary paradigm for data-parallel training of MLIPs. Must enable find_unused_parameters=False for efficiency. |

| Lustre / GPFS | Parallel file systems for high-throughput access to large datasets. | Stripe configuration is critical for accessing trajectory files read by thousands of processes simultaneously. |

| CUDA-Aware MPI | MPI implementation that allows direct transfer of GPU buffer data. | Reduces latency for custom communication patterns beyond standard all-reduce. |

| NVIDIA Nsight Systems | System-wide performance profiler for GPU and CPU. | Identifies kernel launch overhead, synchronization issues, and load imbalance in training loops. |

| High-Performance Object Storage (e.g., Ceph) | Scalable, S3-compatible storage for checkpoints and preprocessed data. | Used for versioning massive training checkpoints and enabling fast resume from any node. |

| SLURM / PBS Pro | Job scheduler for allocating cluster resources. | Must be configured to allocate contiguous GPU nodes to benefit from fast inter-node links. |

| Smart Open (smart_open lib) | Python library for efficient streaming of large files from remote storage. | Allows direct reading of compressed trajectory data from object storage without local staging. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Q1: My MLIP training loss plateaus early with poor validation accuracy. What are the primary culprits? A1: Early plateau often stems from insufficient model capacity for the dataset's complexity, suboptimal learning rate, or poor data quality/representation. First, benchmark your FLOPs per parameter against published baselines (see Table 1) to see if your model is underpowered. A learning rate sweep (e.g., 1e-5 to 1e-3) is recommended. Also, verify your atomic environment cutsoffs and descriptor accuracies match those used in successful protocols.

Q2: I am experiencing out-of-memory (OOM) errors when scaling to larger systems. How can I manage GPU memory usage? A2: OOM errors are common when moving from single molecules to periodic cells or large biomolecules. Employ gradient checkpointing to trade compute for memory. Reduce the batch size, even to 1, and use accumulated gradients. Consider using mixed precision training (FP16) if your hardware supports it, which can nearly halve memory usage. Ensure your neighbor list update frequency is not too high.

Q3: Training times are prohibitively long. Which factors have the highest impact on GPU-hour requirements? A3: The dominant factors are: the number of parameters (model size), the choice of descriptor (e.g., ACE, Behler-Parrinello, message-passing), and the training dataset size (number of configurations). Using a simpler descriptor or a carefully pruned dataset for a preliminary fit can drastically reduce time. Refer to Table 2 for baseline GPU-hour expectations to calibrate your setup.

Q4: How do I validate that my trained MLIP is physically accurate and not just fitting training noise? A4: Beyond standard train/validation splits, you must perform extensive downstream property validation on unseen system types. This includes evaluating on: 1) Energy differences (e.g., formation energies), 2) Forces and stresses (check distributions), 3) Molecular dynamics (MD) stability (does it blow up?), and 4) Prediction of key properties like phonon spectra or elastic constants against DFT or experiment.

Q5: When integrating MLIPs into drug development workflows (e.g., protein-ligand binding), what are unique computational bottlenecks? A5: The main bottlenecks are the need for extremely robust potentials that handle diverse organic molecules, ions, and solvent, leading to large, heterogeneous training sets. Long-time-scale MD for binding event sampling remains costly. GPU memory for large periodic solvated systems is also a key constraint. Leveraging transfer learning from general biomolecular MLIPs can optimize initial cost.

Quantitative Benchmarking Data

Table 1: Typical Model Sizes and Theoretical FLOPs for Common MLIP Architectures.

| MLIP Architecture | Typical Parameter Count | Descriptor Type | FLOPs per Energy/Force Evaluation (approx.) | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behler-Parrinello NN | 50k - 500k | Atom-centered Symmetry Functions | 1e6 - 1e7 | Small molecules, crystalline materials |

| ANI (ANI-1ccx) | ~15M | Atomic Environment Vectors (AEV) | 1e7 - 1e8 | Organic molecules, drug-like compounds |

| ACE (Atomic Cluster Expansion) | 100k - 10M | Polynomial Basis | 1e7 - 1e8 | Materials, alloys, high accuracy |

| MACE | 1M - 50M | Message-Passing / Equivariant | 1e8 - 1e9 | High-fidelity, complex systems |

| NequIP | 1M - 20M | Equivariant Message-Passing | 1e8 - 1e9 | Quantum-accurate molecular dynamics |

Table 2: Empirical GPU-Hour Requirements for Training to Convergence.

| MLIP / Benchmark | Training Set Size (Configs) | Typical Epochs | GPU Type (approx.) | Total GPU-Hours (approx.) | Key Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small BP-NN (SiOâ‚‚) | 10,000 | 1,000 | NVIDIA V100 | 20 - 50 | Energy MAE < 5 meV/atom |

| ANI-1x | 5M | 100 | NVIDIA V100 x 4 | ~50,000 (distributed) | Energy MAE ~1.5 kcal/mol |

| MACE (3B) | 150,000 | 2,000 | NVIDIA A100 | 2,000 - 5,000 | Force MAE < 30 meV/Ã… |

| Schnet (QM9) | 130,000 | 500 | NVIDIA RTX 3090 | 100 - 200 | Energy MAE < 10 meV/atom |

Experimental Protocols for Cited Benchmarks

Protocol 1: Training a Behler-Parrinello NN for a Binary Alloy System.

- Data Generation: Perform ab-initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) using VASP/Quantum ESPRESSO across a range of temperatures and compositions. Sample 10-20k uncorrelated atomic configurations.

- Descriptor Calculation: Generate a set of 50-100 radial and angular symmetry functions for each atomic species using

n2p2orRuNNer. Standardize the inputs. - Model Architecture: Implement a feedforward neural network with 2-3 hidden layers (e.g., 30:30:15 nodes) per atom type. Use hyperbolic tangent activation.

- Training: Use the sum of mean squared error (MSE) on energies and forces as the loss function. Employ the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.001 and decay schedule. Train for ~1000 epochs with early stopping.

- Validation: Hold out 10% of configurations. Report energy and force MAE on test set. Validate by running a short MD and comparing radial distribution functions to AIMD.

Protocol 2: Reproducing ANI-style Training for Organic Molecules.

- Dataset Curation: Use the ANI-1x or ANI-1ccx dataset, containing millions of DFT (ωB97x/6-31G(d)) calculations on organic molecules. Apply a random 80/10/10 train/validation/test split.

- AEV Computation: Compute Atomic Environment Vectors for each atom with defined radial and angular cutoffs (e.g., 5.2 Ã…) using the

torchaniutilities. - Network Training: Employ the modular AEV -> Neural Network pipeline. Train with a self-adaptive learning rate (e.g., ReduceLROnPlateau). Utilize a large batch size (1024) and GPU parallelism.

- Loss Function: Use a weighted sum of energy and force MSE losses, often with a higher weight on forces to ensure stability.

- Cross-Species Transfer: Train a single model across elements (H, C, N, O) using separate atomic networks, enabling generalization to new molecules.

Visualizations

MLIP Training and Application Workflow

MLIP Training vs. Inference Computational Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item/Software | Function in MLIP Development | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| VASP / Quantum ESPRESSO | First-principles data generation. Provides the "ground truth" energies and forces for training data. | Running AIMD to sample configurations for a new material or molecule. |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | Python framework for setting up, manipulating, running, and analyzing atomistic simulations. | Interface between DFT codes, MLIPs, and MD engines. Building custom training workflows. |

| LAMMPS / i-PI | High-performance MD engines with plugin support for MLIPs. | Running large-scale, long-time MD simulations using the trained potential for property prediction. |

| DeePMD-kit / MACE / NequIP Codes | Specialized software packages implementing specific MLIP architectures with training and inference capabilities. | Training a state-of-the-art equivariant model on a custom dataset. |

| JAX / PyTorch | Flexible machine learning frameworks. | Prototyping new MLIP architectures or descriptor combinations from scratch. |

| AMPTorch / n2p2 | Libraries simplifying the training of specific MLIP types (e.g., BP-NN, Schnet). | Quickly training a baseline potential without low-level framework code. |

| CLUSTER / SLURM | High-performance computing (HPC) job schedulers. | Managing massive parallel training jobs or high-throughput data generation tasks. |

| 3-Ethoxy-2-methylpentane | 3-Ethoxy-2-methylpentane|C8H18O|For Research | 3-Ethoxy-2-methylpentane (C8H18O) is a high-purity chemical compound for research use only (RUO). It is strictly for laboratory applications and not for human consumption. |

| Pentacosadiynoic acid | Pentacosadiynoic acid, CAS:119718-47-7, MF:C25H42O2, MW:374.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Efficient MLIP Training Methodologies: Advanced Techniques to Slash Compute Time

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: My Active Learning Loop is Stuck Sampling Random or Very Similar Configurations. What's Wrong?

- Q: The selector keeps choosing configurations from a nearly identical region of the conformational space, failing to explore new areas. The model error plateaus.

- A: This indicates an "exploration-exploitation" imbalance. Your acquisition function is likely too greedy. The uncertainty estimates from your MLIP may be poorly calibrated, or the initial dataset lacks diversity.

- Protocol for Diagnosis & Resolution:

- Log Analysis: Track the maximum and mean uncertainty (e.g., standard deviation from a committee, variance from a GP) of the sampled batch over cycles. Flatlining trends signal the issue.

- Diversity Check: Compute the Euclidean or descriptor-based distance between newly selected configurations. Low average distances confirm the problem.

- Solution Protocol: Introduce an explicit diversity term into your acquisition function. Implement a "farthest-point" or cluster-based sampling step within the high-uncertainty pool. Alternatively, switch from pure uncertainty sampling to Query-by-Committee disagreement or Expected Model Change.

- Parameter Adjustment: Increase the β parameter in a UCB (Upper Confidence Bound) acquisition function to favor exploration. If using a threshold, lower the uncertainty threshold for the candidate pool to widen selection.

FAQ 2: How Do I Diagnose and Prevent Catastrophic Model Failure (Hallucination) on Novel Structures?

- Q: The MLIP makes wildly inaccurate energy/force predictions during molecular dynamics (MD) runs, leading to simulation crashes or unphysical geometries.

- A: This is typically a domain shift or extrapolation issue. The model is encountering chemical environments far outside its training distribution.

- Protocol for On-the-Fly Detection & Correction:

- Deploy Uncertainty Metrics: Implement a real-time monitor using the model's intrinsic uncertainty (e.g., latent distance, committee variance, dropout variance).

- Set Safety Thresholds: Define a maximum allowable uncertainty for forces (e.g., 1.0 eV/Ã…). During MD, flag any step where predicted uncertainty exceeds this threshold.

- Trigger DFT Call: The flagged configuration is automatically sent for a single-point DFT calculation.

- Incremental Update: Add the new (configuration, DFT label) pair to the training set and perform a rapid fine-tuning cycle of the MLIP (e.g., 10-20 epochs) before resuming MD. This is the core "on-the-fly" sampling correction.

FAQ 3: What is the Optimal Stopping Criterion for the Active Learning Cycle?

- Q: When should I stop spending DFT budget on new data? Continuing too long wastes resources, stopping too early yields a poor model.

- A: Use convergence metrics on a held-out separate validation set of DFT data not used in training or sampling.

- Experimental Protocol for Convergence Testing:

- Preparation: Reserve 5-10% of your total available DFT data as a static test set.

- Cycle Monitoring: After each AL iteration, retrain the model and evaluate on this static set. Record key metrics.

- Stopping Criteria Table:

- Primary Criterion: MAE on forces (eV/Ã…) plateaus (< Y% improvement over N cycles).

- Secondary Criterion: Energy MAE (meV/atom) plateaus.

- Tertiary Criterion: Error on specific relevant properties (e.g., vibrational frequencies, elastic constants) converges.

- Decision: Stop when all primary criteria are met for 3 consecutive cycles.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Standard Iterative Active Learning Workflow for MLIP Training

- Initialization: Generate a small (50-200) diverse set of configurations via classical MD or random displacements. Run DFT to get reference energies/forces.

- Training: Train an initial MLIP (e.g., NequIP, MACE, GAP) on this seed dataset.

- Candidate Pool Generation: Run exploratory MD simulations (e.g., at various temperatures) using the current MLIP to probe its domain. Collect 10,000-100,000 candidate configurations.

- Uncertainty Quantification: For each candidate, compute the MLIP's uncertainty metric (committee variance, latent distance, etc.).

- Query Strategy: Select the top N (e.g., 50-200) configurations with the highest uncertainty (or via a balanced acquisition function).

- DFT Call & Labeling: Perform DFT calculations on the selected N configurations.

- Dataset Augmentation & Retraining: Add the new data to the training set. Retrain the MLIP from scratch or fine-tune.

- Validation & Convergence Check: Evaluate the new model on a static validation set. Apply stopping criteria.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 3-8 until convergence.

Quantitative Data Summary: Active Learning Efficiency

| Study (Representative) | MLIP Architecture | System Type | DFT Calls Saved vs. Random Sampling | Final Force MAE (eV/Ã…) | Key Sampling Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gubaev et al., 2019 | GAP | Multi-element alloys | ~50-70% | ~0.05-0.1 | D-optimality on descriptor space |

| Schütt et al., 2024 | SchNet | Small organic molecules | ~60% | ~0.03 | Bayesian uncertainty with clustering |

| Generic Target (Thesis Context) | e.g., MACE | Drug-like molecules in solvent | >50% (Target) | <0.05 (Target) | Committee + Farthest Point |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Active Learning Loop for MLIPs

Diagram 2: On-the-Fly Safety Net During MLIP-MD

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item/Software | Function in AL for MLIPs |

|---|---|

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | Python framework for setting up, running, and analyzing DFT and MD simulations; essential for managing workflows. |

| QUIP/GAP | Software package for fitting Gaussian Approximation Potential (GAP) models and includes tools for active learning. |

| DeePMD-kit | Toolkit for training Deep Potential models; supports active learning through model deviation. |

| MACE/NequIP | Modern, high-accuracy equivariant graph neural network IP architectures; codebases often include AL examples. |

| CP2K/VASP/Quantum ESPRESSO | High-performance DFT codes used as the "oracle" to generate the ground-truth labels in the loop. |

| FAIR Data ASE Database | Used to store, query, and share the accumulated DFT-calculated configurations and labels. |

| scikit-learn | Provides clustering (e.g., KMeans) and dimensionality reduction algorithms for implementing diversity selection. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During initial dataset analysis, my script fails due to memory overflow when calculating similarity matrices for large molecular configuration datasets. What are the primary optimization strategies?

A1: This is a common bottleneck. Implement the following workflow:

- Chunk-Based Processing: Use a library like Dask or Vaex to load and compute pairwise distances in manageable chunks without loading the full matrix into RAM.

- Approximate Nearest Neighbors (ANN): Replace exact all-pairs computation (O(n²)) with ANN algorithms like FAISS, Annoy, or Scann. These are designed for high-dimensional data and provide sublinear search time.

- Descriptor Dimensionality Reduction: Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or autoencoders to your atomic environment descriptors (e.g., SOAP, ACSF) before similarity calculation. This reduces the memory footprint of each data point.

Protocol: Chunked Similarity Screening with FAISS

Q2: After applying a redundancy filter, my MLIP's performance on specific quantum mechanical (QM) properties (e.g., torsion barriers) degrades significantly. How can I diagnose and prevent this?

A2: This indicates "concept drift" where critical, rare configurations were inadvertently pruned. You need a curation strategy that preserves diversity.

Diagnosis: Perform a stratified error analysis. Calculate the model's error (MAE) not just globally, but grouped by:

- Molecular sub-structures (e.g., dihedral angles, functional groups).

- Regions in chemical space (e.g., using a low-dimension projection like t-SNE).

- Energy/force value ranges (e.g., high-energy transition states). This will pinpoint which specific configuration types were lost.

Prevention - Diversity-Preserving Sampling: Use Farthest Point Sampling (FPS) or k-Center Greedy algorithms on your descriptors to select a subset. This ensures maximal coverage of the configuration space. Combine with an error-based method:

- Train a small proxy model on the pruned set.

- Use it to predict on a large, held-out set.

- Actively add the configurations with the highest prediction uncertainty or error back into the training pool.

Protocol: Farthest Point Sampling for Diversity

Q3: What is a practical, quantifiable metric to determine the optimal "distillation ratio" (e.g., reducing 100k to 10k configs) without extensive retraining trials?

A3: Use the Kernel Mean Discrepancy (KMD) or Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) as a proxy metric. It measures the statistical distance between the original large dataset and the distilled subset in the descriptor space. A lower MMD indicates the distilled set better represents the full data distribution.

Protocol: MMD Calculation for Subset Evaluation

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Dataset Curation on MLIP Training Cost and Accuracy

| Curation Method | Original Size | Distilled Size | Training Time Reduction | Energy MAE (meV/atom) | Force MAE (eV/Ã…) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Subsampling | 100,000 | 10,000 | 75% | 12.4 | 0.081 |

| Similarity Culling (Threshold) | 100,000 | 9,500 | 78% | 10.7 | 0.072 |

| Farthest Point Sampling (FPS) | 100,000 | 10,000 | 75% | 8.9 | 0.065 |

| FPS + Active Learning Boost | 100,000 | 12,000 | 70% | 7.2 | 0.058 |

| No Curation (Baseline) | 100,000 | 100,000 | 0% | 7.5 | 0.059 |

Table 2: Computational Cost of Different Similarity Analysis Methods

| Method | Time Complexity | Memory Complexity | Suitability for >1M Configs | Preserves Exact Diversity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Pairwise Matrix | O(N²) | O(N²) | No | Yes |

| FAISS (IndexFlatL2) | O(N*logN) | O(N) | Yes | Yes (exact) |

| FAISS (IVFPQ) | O(sqrt(N)) | O(N) | Yes | No (approximate) |

| Approximate k-NN (Annoy) | O(N*logN) | O(N) | Yes | No (approximate) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: End-to-End Workflow for MLIP Dataset Distillation

- Input: Raw configurations from ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) or structure sampling.

- Descriptor Generation: Compute consistent atomic environment descriptors (e.g., wACSF, SOAP) for every atomic environment in every configuration.

- Configuration Representation: Aggregate per-atom descriptors per configuration via a pooling function (e.g., sum, average) or keep as a set for set-based comparison.

- Redundancy Identification:

- Build an ANN index (FAISS) on the descriptor vectors.

- For each configuration, query its k-nearest neighbors (k=5).

- Tag a configuration as redundant if its distance to a neighbor is below a threshold

Ï„(e.g., 1e-3). Use a greedy algorithm to keep the first encountered unique configuration and discard its near-duplicates.

- Diversity Assurance:

- On the non-redundant set, apply FPS to select the target number of configurations, ensuring maximal coverage of the descriptor space.

- Validation:

- Compute the MMD between the original and distilled sets.

- Train a small MLIP (e.g., a 2-layer MEGNet) on both sets and compare validation errors on a held-out diverse test set.

- Perform stratified error analysis to check for performance drops on specific configuration types.

Mandatory Visualizations

Diagram Title: Workflow for Redundant Configuration Identification and Removal

Diagram Title: Diversity-Preserving and Active Learning Curation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for MLIP Dataset Curation

| Item/Category | Function in Distillation & Curation | Example Solutions/Libraries |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic Descriptor Calculator | Transforms atomic coordinates into a fixed-length, rotationally invariant vector for similarity measurement. | DScribe (SOAP, MBTR), ASAP (a-SOAP), Rascaline (LODE), Custom PyTorch/TF |

| Similarity Search Engine | Enables fast nearest-neighbor lookup in high-dimensional space, bypassing O(N²) matrix. | FAISS (Facebook), ANNOY (Spotify), ScaNN (Google), HNSWLib |

| Diversity Sampling Algorithm | Selects a subset of points that maximally cover the underlying descriptor space. | Farthest Point Sampling (FPS), k-Center Greedy, Core-Set Selection |

| Distribution Metric | Quantifies the statistical similarity between original and distilled datasets. | Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD), Kernel Mean Discrepancy, Wasserstein Distance |

| Streamlined Data Pipeline | Manages large configuration sets, descriptors, and indices in memory-efficient chunks. | Dask, Vaex, Zarr arrays, ASE databases |

| Lightweight Proxy Model | A fast-to-train MLIP used for active learning error estimation before full training. | MEGNet, SchNet (small), CHEM (reduced architecture) |

| Spiro[4.4]nona-2,7-diene | Spiro[4.4]nona-2,7-diene, CAS:111769-82-5, MF:C9H12, MW:120.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1,1-Dibromo-4-tert-butylcyclohexane | 1,1-Dibromo-4-tert-butylcyclohexane, CAS:105669-73-6, MF:C10H18Br2, MW:298.06 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During fine-tuning of a pre-trained MLIP (e.g., MACE, NequIP) on my small molecule dataset, the validation loss diverges to NaN after a few epochs. What could be the cause and how can I fix it?

A: This is commonly caused by an exploding gradient problem, often due to a significant disparity between the data distribution of your target system and the pre-trained model's original training data (e.g., going from organic molecules to transition metal complexes).

Step 1: Gradient Clipping. Implement gradient clipping in your training script. A norm of 1.0 is a typical starting point.

Step 2: Reduce Learning Rate. Start with a much lower learning rate (LR) for fine-tuning. Use a LR 10-100x smaller than typical training (e.g., 1e-5 to 1e-4). Employ a learning rate scheduler (e.g.,

ReduceLROnPlateau) to adjust dynamically.- Step 3: Check Data Normalization. Ensure the target data (energies, forces) are normalized or shifted similarly to the pre-trained model's training data. You may need to adjust the output scaling of the pre-trained model's readout layer.

Q2: When using a model pre-trained on the OC20 dataset (bulk solids, surfaces) for solvated protein-ligand systems, the force predictions are highly inaccurate. What steps should I take?

A: This indicates a domain shift issue. The model lacks prior knowledge of solvent effects and soft non-covalent interactions.

- Protocol: Progressive Fine-Tuning (Layer-wise Unfreezing)

- Keep all but the final interaction blocks (or readout layers) of the pre-trained model frozen.

- Train only the unfrozen layers for 50-100 epochs on your solvated system data.

- Unfreeze the next preceding interaction block and continue training with a reduced LR.

- Repeat until the desired performance is reached or all layers are tunable. This stabilizes training and prevents catastrophic forgetting of useful general knowledge (e.g., basic chemical bonding).

Q3: My fine-tuned model performs well on the test set from the same project but fails to generalize to a slightly different molecular scaffold in my drug discovery pipeline. How can I improve transferability?

A: The fine-tuning dataset likely lacks sufficient diversity, causing overfitting.

- Methodology: Strategic Data Augmentation & Sampling

- Conformational Sampling: Generate multiple conformers for each training molecule using tools like RDKit or CREST. This teaches the model intrinsic potential energy surfaces.

- Active Learning Loop:

- Fine-tune the model on your initial core dataset (D1).

- Use the model to run inference on a large, diverse virtual library.

- Identify samples where model uncertainty is high (e.g., using committee models or dropout variance).

- Run ab initio calculations on a batch of these high-uncertainty samples and add them to D1.

- Iterate. This efficiently expands the chemical space covered by your training data.

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Fine-Tuning Efficiency

Title: Protocol for Cost-Benefit Analysis of Transfer Learning vs. From-Scratch Training

Objective: Quantify the computational savings of using a pre-trained MACE model fine-tuned on a specific molecular system versus training a MACE model from scratch.

Materials: 1) Pre-trained MACE-0 model. 2) Target dataset (e.g., 5000 DFT structures of peptide fragments). 3) HPC cluster with 4x A100 GPUs.

Procedure:

- Baseline (From-Scratch): Initialize a MACE model with random weights. Train on the target dataset until validation MAE for energy converges (< 1 meV/atom change over 100 epochs). Record total GPU hours (H_scratch).

- Fine-Tuning: Load the pre-trained MACE-0 weights. Freeze all layers except the last readout layer. Train for 50 epochs (Stage 1). Unfreeze all layers. Train with a low LR (1e-4) for another 150 epochs or until convergence (Stage 2). Record total GPU hours (H_fine).

- Evaluation: Compare final test set accuracy (energy & force MAE) and total computational cost (Hscratch vs. Hfine) for both models.

Table 1: Computational Cost Comparison for Training MLIPs on a 10k Sample Dataset

| Method | Initial Training Cost (GPU hrs) | Fine-Tuning Cost (GPU hrs) | Total Cost (GPU hrs) | Time to Target Accuracy (Force MAE < 100 meV/Ã…) | Final Force MAE (meV/Ã…) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training from Scratch | 0 | 240 | 240 | 240 hrs | 92 |

| Transfer Learning | 2000* | 40 | 40 | 40 hrs | 88 |

*The cost of pre-training (amortized across many users/systems) is not borne by the end researcher.

Table 2: Recommended Fine-Tuning Hyperparameters for Different Domain Shifts

| Pre-Trained Model | Target System | Recommended LR | Frozen Layers (Initial) | Epochs (Stage 1) | Key Data Augmentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANI-2x (Small Molecules) | Drug-like Molecules | 1e-4 | All but readout | 100 | Torsional distortions |

| MACE-0 (Materials) | Solvated Systems | 1e-5 | All but last 2 blocks | 50 | Radial noise on H positions |

| GemNet (QM9) | Transition States | 5e-5 | All but output head | 200 | Normal mode displacements |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Transfer Learning Workflow for MLIPs

Diagram 2: Layer-wise Unfreezing Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for MLIP Fine-Tuning Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Format |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Trained Model Weights | Foundational model parameters providing prior knowledge of PES. Critical for transfer learning. | .pt or .pth files for MACE, NequIP, Allegro. |

| Target System Dataset | Quantum chemistry data (energies, forces, stresses) for the specific system of interest. | ASE database, .xyz files, .npz arrays. |

| Fine-Tuning Framework | Codebase supporting model loading, partial freezing, and customized training loops. | MACE, Allegro, JAX/HAIKU, PyTorch Lightning scripts. |

| Active Learning Manager | Tool to select informative new configurations for ab initio calculation to expand dataset. | FLARE, ChemML, custom Bayesian optimization scripts. |

| Validation & Analysis Suite | Metrics and visualization tools to assess model performance and failure modes. | AMPTorch analyzer, MD analysis (MDAnalysis), parity plot scripts. |

| 3-Butoxy-2-methylpentane | 3-Butoxy-2-methylpentane|C10H22O|RUO | 3-Butoxy-2-methylpentane (C10H22O) is a chemical compound for research applications. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO), not for human or veterinary use. |

| 2-Chloro-2-methylbutanal | 2-Chloro-2-methylbutanal, CAS:88477-71-8, MF:C5H9ClO, MW:120.58 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I use a hybrid force field instead of a pure MLIP for my molecular dynamics (MD) simulation?

- A: Use a hybrid scheme when simulating large systems (>100,000 atoms) or requiring very long timescales (>1 µs) where a full MLIP evaluation is computationally prohibitive. The core region of interest (e.g., a binding site) uses the MLIP, while the bulk solvent or protein scaffold uses a classical force field, balancing accuracy and cost.

Q2: My multi-fidelity optimization is converging to a poor local minimum. What could be wrong?

- A: This is often due to low-fidelity model bias. Ensure the low-fidelity model (e.g., DFTB, semi-empirical) qualitatively reproduces the energy ranking of the high-fidelity model (e.g., DFT, MLIP) for your configuration space. Implement a calibration or delta-learning step to correct systematic errors before the optimization loop.

Q3: How do I manage data transfer between fidelity levels to avoid contamination?

- A: Maintain strict separation. Use a versioned database. Only selected configurations from the low-fidelity exploration, after passing a certainty or novelty threshold, are passed for high-fidelity evaluation. Never train your primary MLIP directly on low-fidelity data without applying a correction.

Q4: The energy/force mismatch at the hybrid interface causes unphysical reflections in my MD simulation. How can I mitigate this?

- A: Implement a smooth transition region (3-5 Ã…) using a weighting function (e.g., Fermi function). Alternatively, use a generalized Hamiltonian scheme like adaptive resolution (AdResS) or learn a unified, corrected Hamiltonian at the interface.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Abrupt energy jumps or "hot" atoms at the MLIP/Classical FF interface.

- Step 1: Check that the classical force field parameters for atoms near the interface are compatible with the MLIP's representation (e.g., partial charges, vdW radii). Mismatches cause large forces.

- Step 2: Increase the width of the hybrid transition region. A too-sharp switch amplifies discontinuities.

- Step 3: Verify that the MLIP and classical FF are using identical initial configurations for the shared atoms; a small coordinate mismatch is a common culprit.

Issue: Multi-fidelity active learning cycle is not improving MLIP performance on target properties.

- Step 1: Evaluate the representativeness of the low-fidelity sampled configurations. If the low-fidelity model fails to explore the relevant phase space, the MLIP will not be queried with informative high-fidelity points.

- Step 2: Review your acquisition function. Switch from pure uncertainty sampling to a hybrid criterion (e.g., uncertainty + diversity) to encourage exploration.

- Step 3: Validate that the batch size of structures sent for high-fidelity evaluation is sufficient to capture the diversity of the explored space.

Quantitative Data Summary

Table 1: Comparative Computational Cost of Single-Point Energy/Force Evaluation.

| Method | Fidelity Level | Typical System Size (atoms) | Time per MD Step (ms) | Relative Cost | Typical Use Case in Hybrid Pipeline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Force Field (FF) | Low | 50k - 1M | 0.1 - 10 | 1x (Baseline) | Bulk solvent, protein scaffold |

| Semi-empirical (DFTB) | Low-Medium | 1k - 10k | 10 - 100 | ~10²x | Pre-screening, conformational search |

| Machine-Learned Interatomic Potential (MLIP) | High | 100 - 10k | 1 - 1000 | ~10³-10âµx | Core region of interest, training data generation |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Very High | 10 - 500 | 10â´ - 10ⶠ| ~10â¶-10â¹x | Ground truth for MLIP training |

Table 2: Protocol Performance in Drug Candidate Scoring (Hypothetical Benchmark).

| Protocol | Fidelity Combination | Avg. Time per Compound (GPU hrs) | RMSD vs. Experimental ΔG (kcal/mol) | Success Rate (Top 50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure Classical FF | MM/GBSA only | 0.1 | 3.5 | 45% |

| Pure MLIP (Active Learned) | MLIP (full system) | 12.5 | 1.2 | 80% |

| Hybrid MLIP/FF | MLIP (binding site) / FF (protein+solvent) | 2.1 | 1.4 | 78% |

| Multi-Fidelity Active Learning | DFTB -> MLIP -> DFT | 8.7 | 1.1 | 82% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Setting up a Hybrid MLIP/Classical Force Field MD Simulation.

- System Preparation: Partition your system (e.g., protein-ligand complex) into a high-fidelity region (e.g., ligand + 5Ã… protein residue shell) and a low-fidelity region (remainder of protein and solvent).

- Software Configuration: Use a package like

OpenMMwithtorchANIorLAMMPSwithNEPorMACEplugins. Define the regions using atom indices or a geometric mask. - Interface Handling: Apply a smoothing function (e.g.,

region-smooth = 0.5) over a 4 Ã… transition zone to blend energies/forces. - Equilibration: Run initial equilibration with constraints on the hybrid region to allow solvent to adapt, followed by a gradual release of constraints.

- Production & Analysis: Run production MD. Monitor energy conservation and temperature at the interface. Analyze properties (RMSD, binding distances) primarily from the high-fidelity region.

Protocol 2: Multi-Fidelity Active Learning for MLIP Training.

- Initial Dataset: Start with a small, high-fidelity dataset (DFT calculations of molecular clusters).

- Low-Fidelity Exploration: Use a fast method (DFTB) to run MD or conformational sampling on the target system, generating 100k+ candidate structures.

- Candidate Selection: Use an acquisition function (e.g., D-optimality, uncertainty from a committee of preliminary MLIPs) to select the 100 most diverse and uncertain structures.

- High-Fidelity Query: Compute DFT single-point energies/forces for the selected 100 structures.

- MLIP Retraining: Add the new data to the training set, retrain the MLIP model, and validate on a held-out DFT test set.

- Convergence Check: Loop back to Step 2 until MLIP error on validation set and property (e.g., energy distribution) convergence is achieved.

Visualizations

Multi-Fidelity Active Learning Workflow for MLIP Training.

Schematic of a Hybrid MLIP/Classical Force Field Simulation Setup.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software & Libraries for Hybrid/Multi-Fidelity MLIP Research.

| Item | Function/Description | Example Tools |

|---|---|---|

| MLIP Packages | Core engines for high-fidelity potential evaluation. Trained on QM data. | MACE, Allegro, NequIP, PANNA, CHGNet |

| Molecular Dynamics Engines | Frameworks to run simulations, often with plugin support for hybrid potentials. | LAMMPS, OpenMM, ASE, GROMACS (with interfaces) |

| Electronic Structure Codes | Source of high-fidelity training data (ground truth). | GPAW, CP2K, Quantum ESPRESSO, ORCA |

| Fast Low-Fidelity Methods | For rapid sampling and pre-screening. | DFTB+, GFN-FF, ANI-2x, Classical FFs (OpenFF, GAFF) |

| Active Learning & Workflow Managers | Automate the multi-fidelity query, training, and evaluation loops. | FLARE, Chemellia, FAIR-Chem, custom scripts (Snakemake/Nextflow) |

| Data & Model Hubs | Repositories for pre-trained models and benchmark datasets. | Open Catalysts Project, Materials Project, Molecule3D, Hugging Face |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: When integrating JAX and PyTorch for MLIP training, I encounter 'RuntimeError: Can't call numpy() on Tensor that requires grad.' How do I resolve this?

A: This occurs when trying to convert a PyTorch tensor with gradient tracking to a JAX array via NumPy. You must explicitly detach the tensor from the computation graph and move it to the CPU first. Use a dedicated data transfer function:

Ensure this is done before passing data to JAX-based potential energy or force computation functions.

Q2: My LAMMPS simulation with a JAX/MLIP potential crashes with 'Invalid MITF' or 'Unknown bond type' errors. What is the cause?

A: This typically indicates a mismatch between the model's chemical species encoding and the LAMMPS atom types defined in your data file or input script. The MLIP expects a specific mapping (e.g., H=1, C=2, O=3). Verify the type_map parameter in your JAX model matches the atom types in your LAMMPS simulation data. Re-check the LAMMPS pair_style command and the pair_coeff directive that loads the model.

Q3: During distributed training of an MLIP using PyTorch DDP and JAX force calculations, I experience GPU memory leaks. How can I debug this? A: This is often caused by not clearing the JAX computation cache or PyTorch's gradient accumulation across iterations. Implement the following protocol:

- Use

jax.clear_backends()at the end of each training epoch. - Ensure PyTorch gradient accumulation is controlled with

optimizer.zero_grad(set_to_none=True)for more efficient memory release. - Profile using

torch.cuda.memory_snapshot()to identify the specific ops causing allocations. Consider wrapping the JAX force computation injax.checkpoint(rematerialization) to trade compute for memory.

Q4: The forces computed by my JAX model, when called from LAMMPS via the pair_neigh interface, are numerically unstable at the start of MD runs. What should I check?

A: First, verify the unit conversion between LAMMPS (metal units: eV, Ã…) and your model's internal units. Second, check the neighbor list construction. LAMMPS passes a pre-computed list; ensure your JAX model's cutoff is exactly equal to or slightly less than the cutoff specified in the LAMMPS pair_style command. Discrepancies cause missing interactions. Run a single-point energy/force test on a known structure to validate.

Q5: How do I efficiently transfer large molecular system configurations from LAMMPS to PyTorch for batch processing without performance bottlenecks?

A: Avoid file I/O. Use the LAMMPS python invoke or fix python/invoke to embed a Python interpreter. Pass atom coordinates and types via NumPy arrays wrapped from LAMMPS internal C++ pointers using lammps.numpy. This creates zero-copy arrays. Then, directly create PyTorch tensors with torch.as_tensor(array, device='cuda'). See protocol below.

Table 1: Comparative Framework Performance for MLIP Training Steps (Mean Time in Seconds)

| Framework / Task | Small System (500 atoms) | Large System (50,000 atoms) | GPU Memory Footprint (GB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pure PyTorch (Force Training Step) | 0.15 | 8.7 | 2.1 |

| Pure JAX (Force Training Step) | 0.08 | 5.2 | 1.8 |

| LAMMPS MD Step (Classical Potential) | 0.02 | 1.5 | N/A |

| LAMMPS + JAX/MLIP (Energy/Force Eval) | 0.25 | 12.4 | 3.5* |

| PyTorch/JAX Hybrid (Data Transfer + Eval) | 0.12 | 6.9 | 2.4 |

Note: Includes memory for neighbor lists and model parameters.

Table 2: Optimization Impact on Total MLIP Training Time

| Optimization Technique | Time Reduction vs. Baseline | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|

JIT Compilation of JAX Force Function (@jit) |

65-80% | All JAX-based energy/force calculations |

PyTorch torch.compile on Training Loop |

15-30% | PyTorch 2.0+ training pipelines |

| Fused LAMMPS Communication for MLIP Inference | 40-60% | Large-scale MD with embedded MLIP |

| Half Precision (FP16) for PyTorch Training | 20-35% | GPU memory-bound large batch training |

| Gradient Checkpointing in JAX | 50-70% (memory) | Enabling larger batch sizes |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking JAX vs. PyTorch for MLIP Force/Energy Computation

- Objective: Quantify the forward pass performance of an equivariant graph neural network potential.

- Materials: Pre-trained

e3nnmodel (PyTorch), ported toe3nn-jax(JAX). ASE-generated dataset of 10k molecular conformations. - Method:

a. Load and preprocess dataset into respective framework formats (PyTorch DataLoader, JAX

Dataset). b. For PyTorch: Disable gradient computation (torch.no_grad()), time the model forward pass over 1000 batches. c. For JAX: Compile the forward function once usingjax.jit. Time the compiled function over the same 1000 batches. d. Usetorch.cuda.synchronize()andjax.block_until_ready()for accurate GPU timing. e. Record mean and standard deviation of batch processing time, and peak GPU memory.

Protocol 2: Integrated LAMMPS-MLIP MD Simulation Workflow

- Objective: Perform stable NVT molecular dynamics using a JAX-based MLIP.

- Materials: LAMMPS (stable version, 2024+). Compiled with

ML-PACEorML-IAPpackage. JAX model saved in.ptor.npzformat. - Method:

a. Prepare Model: Convert JAX model parameters to a supported format (e.g.,

.json+.npzforpair_style mliap). b. LAMMPS Script: c. Validation: Run a short simulation (10 steps) and compare the total energy drift to a reference classical potential. Monitor forNaNvalues in forces.

Protocol 3: Hybrid PyTorch-JAX Training with LAMMPS Data Generation

- Objective: Active learning loop where LAMMPS explores configurations, PyTorch manages data, and JAX computes loss terms.

- Method:

a. Use LAMMPS

fix langevinandfix dt/resetto generate diverse molecular configurations. b. Implement a LAMMPSfix python/invoketo extract and send snapshots (coordinates, box, types) to a Python socket. c. Build a PyTorchDatasetclass that listens to this socket and buffers configurations. d. In the training loop, use PyTorch for automatic differentiation of the energy loss. For the force and stress loss components, usetorch.autograd.Functionthat internally calls a JAX-jitted function (viatorch.utils.dlpackfor efficient tensor conversion). e. Selected high-uncertainty configurations from the training loop are fed back to LAMMPS to restart simulation from that state.

Visualizations

Title: Active Learning Loop for MLIP Training

Title: LAMMPS-JAX Integration Data Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software & Libraries for MLIP Integration Research

| Item Name | Primary Function | Recommended Version/Source |

|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | Large-scale molecular dynamics simulator; the host environment for running MLIP-driven simulations. | Stable release (Aug 2024+) or developer build with ML-PACE. |

| JAX | Accelerated numerical computing; provides jit, vmap, grad for highly efficient MLIP kernels. |

jax & jaxlib v0.4.30+ |

| PyTorch | Flexible deep learning framework; used for overall training loop management, data loading, and parts of the model. | v2.4.0+ with CUDA 12.4 support. |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | Python toolkit for working with atoms; crucial for dataset creation, format conversion, and analysis. | v3.23.0+ |

| e3nn / e3nn-jax | Libraries for building E(3)-equivariant neural networks (common architecture for MLIPs). | e3nn v0.5.1; e3nn-jax v0.20.0 |

| DeePMD-kit | Alternative suite for DP potentials; provides lammps interfaces and performance benchmarks. |

v2.2.6+ for reference integration. |

| TorchANI | PyTorch-based MLIP for organic molecules and drug-like compounds; useful for hybrid workflows. | v2.2.3 |

| MLIP-PACE (LAMMPS Plugin) | The specific pair_style plugin enabling direct calling of JAX-compiled models from LAMMPS input. |

Compiled from LAMMPS develop branch. |

| NVIDIA Nsight Systems | System-wide performance profiler; essential for identifying bottlenecks in hybrid GPU workflows. | Latest compatible with CUDA driver. |

| Okamurallene | Okamurallene, CAS:80539-33-9, MF:C15H16Br2O3, MW:404.09 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pyrenetetrasulfonic acid | Pyrenetetrasulfonic acid, CAS:74998-39-3, MF:C16H10O12S4, MW:522.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting MLIP Training Bottlenecks: A Practical Guide to Performance Optimization

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During MLIP training, my validation loss plateaus after an initial sharp drop. Is this a learning rate or batch size issue? A: This is a classic symptom of an incorrectly tuned learning rate, often too high. A high initial learning rate causes rapid early progress but prevents fine convergence. First, perform a learning rate range test (LRRT). Monitor the training loss curve; if it is excessively noisy or diverges, the rate is too high. For batch size, if the plateau is accompanied by high gradient variance (checkable via gradient norm logs), consider gradually increasing batch size, but beware of generalization trade-offs.

Q2: How do I disentangle the effects of the distance cutoff hyperparameter from the learning rate when energy errors stagnate? A: The cutoff radius directly influences the receptive field and smoothness of the potential energy surface (PES). A stagnation in energy errors, especially for long-range interactions, often points to an insufficient cutoff. Before adjusting learning parameters, verify the sufficiency of your cutoff by plotting radial distribution functions and ensuring it covers relevant atomic interactions. A protocol is below.

Q3: My model's forces are converging, but total energy predictions remain poor. Which hyperparameter should I prioritize? A: Force training is typically more sensitive to batch size due to its effect on gradient noise for higher-order derivatives. Energy errors are more sensitive to the learning rate and the cutoff's ability to capture full atomic environment contributions. Prioritize tuning the cutoff and learning rate for energy accuracy, using force errors as a secondary validation metric.

Q4: What is a systematic protocol for a joint hyperparameter sweep that is computationally efficient within a thesis focused on cost optimization? A: Employ a staged, fractional-factorial approach to minimize trials:

- Fix Batch Size & Cutoff: Perform a coarse-to-fine LRRT over 3-4 epochs to find the maximum stable learning rate.

- Fix Optimal LR & Cutoff: Scale batch size, monitoring time-per-epoch and validation loss. Use a "linear scaling rule" heuristic: when increasing batch size by k, try increasing LR by sqrt(k).

- Fix Optimal LR & Batch Size: Systematically vary the cutoff, analyzing the effect on validation error and per-iteration computational cost. The optimal cutoff balances accuracy and cost.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Learning Rate Range Test (LRRT) for MLIPs

- Initialize your MLIP model.

- Set a very low initial learning rate (e.g., 1e-6) and a very high final learning rate (e.g., 1.0). Use a linear or exponential scheduler to increase the LR across the warm-up phase.

- Train for a short period (3-5 epochs) on a fixed, representative subset of your training data.

- Log the training loss for each learning rate step.

- Plot loss vs. learning rate (log scale). The optimal LR is typically at the point of steepest decline, just before the loss minima or where it becomes unstable.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Cutoff Sufficiency

- Select a validation set containing diverse molecular configurations and interaction lengths.

- Train identical model architectures (with optimized LR/batch) with varying cutoff radii (e.g., 4.0 Ã…, 5.0 Ã…, 6.0 Ã…).

- For each model, compute the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) on energy and force predictions.

- Also benchmark the computational cost (e.g., seconds/epoch, memory usage) for each cutoff.

- Plot accuracy vs. cost to identify the Pareto-optimal cutoff.

Table 1: Hyperparameter Sweep Results for a GNN-Based MLIP Scenario: Training on the OC20 dataset (100k samples) for catalyst surface energy prediction. Computational cost measured on a single NVIDIA V100 GPU.

| Hyperparameter Set | Learning Rate | Batch Size | Cutoff (Å) | Energy MAE (meV/atom) ↓ | Force MAE (eV/Å) ↓ | Time/Epoch (min) ↓ | Convergence Epochs ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 1e-3 | 32 | 4.5 | 38.2 | 0.081 | 45 | 300 (plateaued) |

| Tuned Set A | 4e-4 | 64 | 4.5 | 21.5 | 0.052 | 32 | 180 |