Optimizing Large-Scale Molecular Dynamics Performance: A 2025 Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This guide provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to optimize molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for large-scale biomedical systems.

Optimizing Large-Scale Molecular Dynamics Performance: A 2025 Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to optimize molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for large-scale biomedical systems. It covers foundational hardware selection, advanced methodological strategies for modern HPC and AI, practical troubleshooting for common performance bottlenecks, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing the latest benchmarks and performance-portable coding practices, this article enables scientists to dramatically accelerate simulation throughput, efficiently scale to million-atom systems, and enhance the reliability of computational drug discovery.

Building Your MD Foundation: Hardware, Algorithms, and System Setup

Molecular Dynamics (MD) is a cornerstone of modern computational chemistry, biophysics, and drug discovery, enabling researchers to simulate the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. The computational cost of these simulations is immense, making hardware selection a critical factor for research efficiency. The Central Processing Unit (CPU) acts as the orchestral conductor of the entire simulation. This guide provides a detailed framework for selecting the optimal CPU by balancing core count and clock speed, ensuring your computational resources are perfectly aligned with your specific MD research objectives.

Core Technical Principles: CPU Clock Speed vs. Core Count

The Fundamental Trade-off

The performance of a CPU in any task, including MD, is governed by two primary characteristics: core count and clock speed. Understanding their distinct roles is the first step in making an informed decision.

- Clock Speed: Measured in gigahertz (GHz), clock speed indicates how many computational cycles a single CPU core can execute per second. A higher clock speed means each individual task is completed faster. This is crucial for serial or single-threaded portions of a workload, which cannot be easily broken down into parallel tasks.

- Core Count: This refers to the number of independent processing units within a single CPU chip. A higher core count allows a computer to execute many tasks simultaneously, a capability known as parallel processing.

In an ideal world, a CPU would have both high core counts and high clock speeds. However, due to power and thermal constraints (among others), there is a fundamental engineering trade-off. Processors with very high core counts typically operate at lower base clock speeds.

The MD Workload Dichotomy

The choice between clock speed and core count is not arbitrary; it is dictated by how the MD software you use distributes its computational load.

- GPU-Native Workloads: Software like AMBER and GROMACS are heavily optimized to offload the most computationally intensive tasks—primarily the calculation of forces between atoms—to the Graphics Processing Unit (GPU). GPUs possess thousands of cores ideal for this type of mass parallelization. In this scenario, the CPU's role shifts. It is primarily responsible for managing the simulation, handling I/O operations (reading/writing data), and feeding the GPU. These tasks are often more sequential. Therefore, a CPU with higher per-core clock speeds will provide better performance than one with more cores [1] [2].

- GPU-Accelerated and CPU-Centric Workloads: Some applications, or specific stages within them, still rely significantly on the CPU for complex computations. If your workflow involves such software or includes extensive pre- and post-processing (e.g., trajectory analysis, system setup), a CPU with a more balanced profile of both high clock speed and a sufficient number of cores becomes advantageous [2].

Decision Framework and Hardware Selection

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: For a system with multiple GPUs, should I prioritize CPU core count to "match" the GPUs? No. The relationship is not one-to-one. Even in multi-GPU setups, the CPU's role in MD simulation management does not require a core for each GPU. The general recommendation is that 2 to 4 CPU cores per GPU are more than sufficient for GPU-native MD codes like AMBER and GROMACS. Excess cores beyond this will likely remain idle. The financial investment is better spent on CPUs with higher clock speeds or on additional GPU power [2].

Q2: My simulation software can use both the CPU and GPU. How do I choose? Your software documentation is the best resource. Check for keywords like "GPU-offload," "GPU-accelerated," or "CUDA/OpenCL support." For software that is explicitly "GPU-native," the performance gain from using a GPU is so dramatic that prioritizing a high-clock-speed CPU to support the GPU is the optimal strategy [2].

Q3: Are there situations where a high core count CPU is beneficial for MD research? Yes. While the simulation itself may be GPU-native, the broader research workflow often isn't. A higher core count CPU is valuable for:

- Running multiple, independent simulations concurrently (e.g., for parameter screening or ensemble modeling).

- Performing computationally intensive trajectory analysis and data post-processing on the same workstation.

- Handling other tasks like virtual screening or machine learning model training alongside simulations [3].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Low GPU Utilization During Simulation

- Symptoms: GPU usage consistently below 90% in monitoring tools (e.g.,

nvidia-smi), while simulation is slow. - Potential Cause 1: The CPU is a bottleneck. A CPU with insufficient single-threaded performance (low clock speed) cannot prepare and send data to the GPU fast enough, leaving the GPU underutilized.

- Solution: Verify your CPU's single-core performance using benchmarks. For your next upgrade, prioritize a CPU with higher boost clock speeds.

- Potential Cause 2: Incorrect software configuration or command-line flags, leading to part of the computation being forced onto the CPU.

- Solution: Consult the software manual to ensure all possible computations are being offloaded to the GPU. Verify your run command includes the appropriate flags for GPU execution.

Problem: Inability to Run Multiple Simulations Efficiently

- Symptoms: System becomes unresponsive when launching a second simulation, or simulations run much slower than when executed alone.

- Potential Cause: The CPU has an insufficient number of cores and/or RAM to handle the parallel workload, leading to resource contention.

- Solution: Consider a CPU with a higher core count (e.g., AMD Threadripper or Intel Xeon W-series) and ensure sufficient RAM is allocated. This allows the operating system to efficiently schedule multiple simulation processes without them competing for the same resources.

CPU Recommendation Tables

The following tables summarize recommended CPU models based on different optimization strategies and workload scales.

Table 1: Recommended CPUs for MD Workstations (Single Socket)

| CPU Model | Core Count | Base/Boost Clock (Approx.) | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMD Threadripper 7965WX [2] | 24 | 4.2 GHz / Higher | High Clock Speed: Ideal for 1-2 GPU setups running GPU-native codes like AMBER, GROMACS. |

| AMD Threadripper 7985WX [2] | 64 | 3.2 GHz / Higher | Balanced: Excellent for mixed workloads: single large GPU-native simulations + concurrent analysis or smaller simulations. |

| AMD Threadripper 7995WX [2] | 96 | 2.5 GHz / Higher | High Core Count: For running many concurrent simulations; not optimal for a single GPU-native simulation. |

| Intel Xeon W5-3425 [2] | 12 | 3.2 GHz / Higher | High Clock Speed: A strong option for a dedicated, single-GPU simulation node. |

Table 2: Recommended CPUs for MD Servers (Dual Socket Capable)

| CPU Model | Core Count | Base/Boost Clock (Approx.) | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMD EPYC 9274F [2] | 24 | 4.1 GHz / Higher | High Clock Speed: Optimal for dense, multi-GPU server nodes where each GPU needs fast CPU support. |

| AMD EPYC 9474F [2] | 48 | 3.6 GHz / Higher | Balanced: For servers aimed at a mix of large-scale GPU-accelerated simulations and CPU-heavy preprocessing. |

| Intel Xeon Gold 6444Y [2] | 16 | 3.6 GHz / Higher | High Clock Speed: Intel's alternative for high-frequency performance in a server platform. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software and Hardware "Reagents" for Computational Research

| Item | Function / Relevance |

|---|---|

| MD Software (AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD) [1] | The primary application for running simulations; each has specific optimizations for CPU and GPU. |

| NVIDIA GPU (RTX 4090, RTX 6000 Ada) [1] | The primary computational accelerator for GPU-native MD codes, responsible for >90% of the calculation workload. |

| High-Speed RAM (64GB+ DDR5/4) [1] | Stores the atomic coordinates, velocities, and force fields of the simulated system for rapid access by the CPU and GPU. |

| High-Performance Storage (NVMe SSD) | Critical for quickly reading initial system files and writing massive trajectory data files generated during the simulation. |

| Machine Learning Potentials (e.g., Meta's UMA) [4] | Next-generation force fields powered by AI that dramatically increase simulation speed and accuracy, relying heavily on both CPU and GPU. |

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Your CPU Configuration

To empirically determine the optimal CPU configuration for your specific workflow, follow this benchmarking methodology.

Objective: To measure the performance impact of CPU clock speed versus core count on the time-to-solution for a standard MD simulation.

Materials and Software:

- A workstation with a CPU that supports adjustable clock speeds and core activation (common in modern BIOS/UEFI settings).

- A standard GPU (e.g., NVIDIA RTX 4090 or similar) for acceleration.

- Your chosen MD software (e.g., GROMACS 2023 or AMBER 22).

- A benchmark system (e.g., a soluted protein like DHFR in water, which is a standard benchmark case for MD software).

Procedure:

- Baseline Configuration: In the BIOS/UEFI, set the CPU to its default settings. Boot into the OS and note the all-core sustained clock speed under load using a monitoring tool.

- High Clock Speed Test:

- Disable half of the CPU cores (e.g., if you have 16 cores, disable 8).

- Enable any BIOS settings that permit sustained higher turbo frequencies (e.g., "Multi-Core Enhancement").

- Run the MD benchmark simulation and record the completion time.

- High Core Count Test:

- Re-enable all CPU cores.

- In the BIOS, set the CPU to a lower, fixed frequency that is close to its base clock speed.

- Run the exact same MD benchmark simulation and record the completion time.

- Analysis: Compare the completion times. In nearly all cases for GPU-native software, the High Clock Speed Test configuration will result in a faster time-to-solution, demonstrating the higher value of per-core performance.

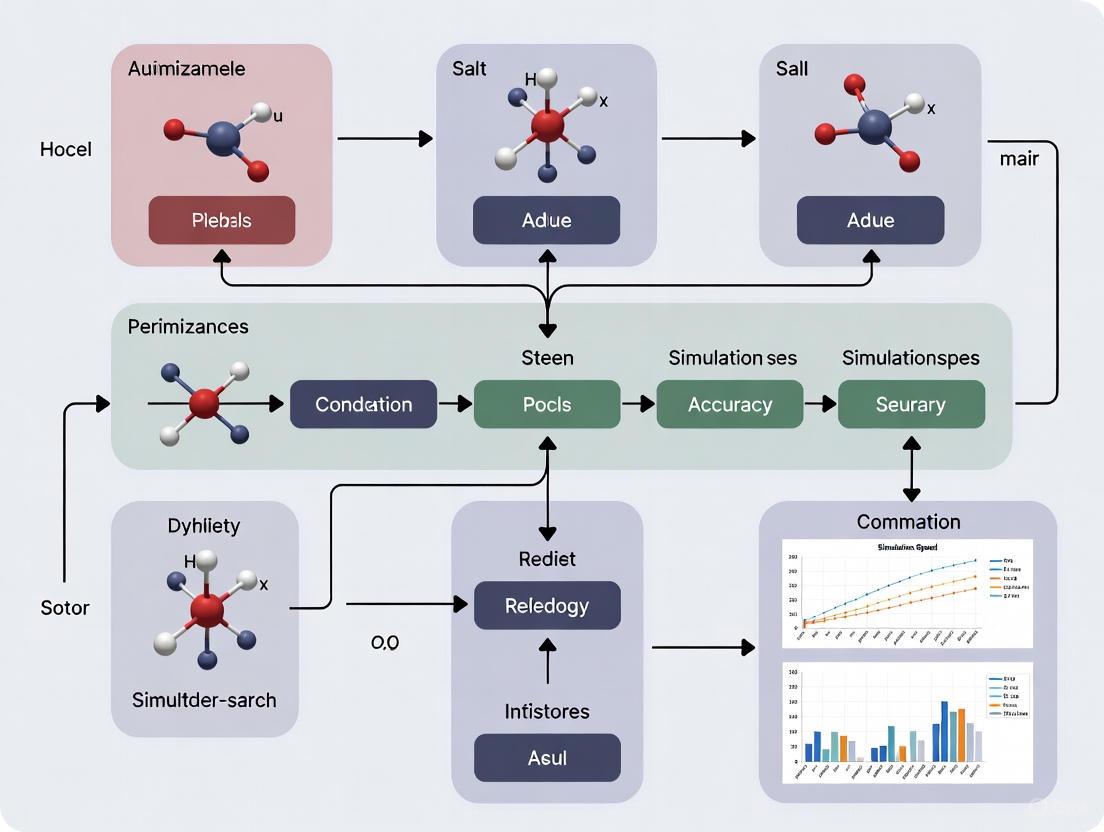

Visual Guide: CPU Selection Logic for MD Workloads

The following diagram summarizes the logical decision process for selecting a CPU based on your primary MD workload.

Diagram 1: CPU Selection Logic for Molecular Dynamics Workloads. This flowchart guides researchers through key questions to determine the optimal CPU configuration, leading to one of three primary recommendations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key architectural improvements in the Ada Lovelace architecture that benefit molecular dynamics simulations?

The Ada Lovelace architecture introduces several key improvements that significantly accelerate computational workloads like molecular dynamics (MD) [5] [6]:

- Third-Generation RT Cores: Deliver up to 2x the ray-tracing performance of the previous generation. While often associated with graphics, these cores can accelerate certain types of complex spatial calculations [5].

- Fourth-Generation Tensor Cores: Designed to accelerate AI and transformative AI technologies. These cores unleash structured sparsity and FP8 precision for up to 4x higher inference performance over the previous generation, which can be leveraged in machine-learning potentials for MD [5].

- Enhanced CUDA Cores: Bring double-speed processing for single-precision floating-point (FP32) operations, providing significant performance gains for simulation and compute workflows [5].

- Massive L2 Cache: Features a substantial increase in L2 cache (up to 96 MB on the AD102 die). This allows the GPU to keep more frequently accessed data on-die, reducing the need to fetch from slower GDDR memory, which is highly beneficial for the repetitive, data-intensive calculations in MD [6].

Q2: For a research lab focused on large-scale MD, which is more suitable: the GeForce RTX 4090 or the RTX 6000 Ada?

The choice depends on the priorities of your research lab, balancing raw speed against stability, memory, and support. The table below summarizes the key differences:

Table: GPU Comparison for Large-Scale MD Research

| Feature | GeForce RTX 4090 | RTX 6000 Ada |

|---|---|---|

| GPU Memory | 24 GB GDDR6X [7] | 48 GB GDDR6 with ECC [8] |

| Memory Error Protection | No | Yes (ECC) [8] |

| Form Factor & Power | Consumer, typically 3-4 slots [6] | Workstation, dual-slot (300W) [8] |

| Software Support & Certification | GeForce Driver | NVIDIA RTX Enterprise Driver & AI Enterprise [8] |

| Virtualization (vGPU) Support | No | Yes (NVIDIA vWS) [8] |

| Primary Use Case | High-performance desktop computing | Enterprise-grade visualization, AI, and compute [5] [8] |

Recommendation: The RTX 6000 Ada is the superior choice for production environments and large-scale systems where data integrity (ECC), larger memory capacity for big datasets, virtualization, and certified drivers are critical. The RTX 4090 offers exceptional raw performance for the cost and may be suitable for individual researcher workstations where its hardware and power constraints can be managed.

Q3: Which software packages for molecular dynamics are optimized for Ada Lovelace GPUs?

Most mainstream MD packages that support GPU acceleration will benefit from the Ada Lovelace architecture's general performance improvements. Key optimized packages include [9]:

- OpenMM: A high-performance MD library designed specifically for GPU acceleration. It employs a GPU-oriented approach, running nearly the entire calculation on the GPU for maximum throughput [9].

- LAMMPS: A classical MD code with a modular design. It uses a hybrid approach where the GPU calculates non-bonded interactions while the CPU handles bonded forces and other tasks [9].

- GROMACS: A versatile package for biomolecular systems. It features heterogeneous parallelization, efficiently splitting workloads between CPU and GPU [9].

Table: MD Software Implementation Comparison

| Feature | LAMMPS | OpenMM |

|---|---|---|

| GPU Computation Focus | Non-bonded interactions | Non-bonded and bonded interactions |

| CPU-GPU Communication | Frequent and moderate | Infrequent and minimal |

| GPU Memory Usage | Lower | Higher |

| Best For | Diverse, complex systems with custom features | Biomolecular systems with standard force fields |

Q4: What are the specific performance benchmarks for these GPUs in common MD and AI tasks?

Independent benchmarks provide a clear comparison of raw throughput. The following table shows performance in various deep learning models, which often correlate with performance in AI-driven MD analysis and machine learning potentials.

Table: Deep Learning AI Performance Benchmarks (Throughput - Images/Sec) [7]

| Benchmark Test | RTX 4090 (1 GPU) | RTX 6000 Ada (1 GPU) | RTX 6000 Ada (8 GPUs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet-50 (FP16) | 1,720 | 1,800 | 16,968 |

| ResNet-50 (FP32) | 927 | 709 | 7,607 |

| ResNet-152 (FP16) | N/A | 729 | 7,004 |

| Inception V3 (FP16) | N/A | 1,086 | 8,931 |

| VGG16 (FP16) | N/A | 642 | 8,977 |

Key Insight: The RTX 6000 Ada shows a significant performance scaling advantage in multi-GPU configurations, which is crucial for scaling MD research across large server nodes [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: GPU Operator Pods Stuck in "Init" State in Kubernetes Clusters

Observation: When deploying the NVIDIA GPU Operator in a Kubernetes environment for containerized MD workloads, pods like nvidia-device-plugin-daemonset and nvidia-container-toolkit-daemonset remain in the Init:0/1 state [10].

Diagnosis and Resolution:

Detailed Steps:

Check Driver Daemonset Logs:

Look for errors related to downloading driver packages or loading kernel modules [10].

Investigate

nouveauDriver Conflict: The open-sourcenouveaudriver can conflict with the NVIDIA driver. Check if it's loaded and disable it [10]:If it is loaded, follow your OS distribution's instructions to denylist the

nouveaudriver.Check Kernel Logs for GPU Errors: Use

dmesgto look for deeper hardware/driver issues from the Linux kernel [10]:

Issue 2: "No runtime for 'nvidia' is configured" Error

Observation: When attempting to run a GPU-accelerated MD simulation pod, it fails to start with the error: Failed to create pod sandbox: rpc error: code = Unknown desc = failed to get sandbox runtime: no runtime for "nvidia" is configured [10].

Diagnosis and Resolution:

Detailed Steps:

Check Container Toolkit Logs: This service is responsible for configuring the container runtime.

Errors here often point to a prerequisite failure, typically an issue with the GPU driver itself [10].

Verify Container Runtime Configuration: Ensure the

nvidiacontainer runtime handler is correctly defined.- For Containerd:

- For CRI-O:

The output should show a runtime with

name = "nvidia"pointing to thenvidia-container-runtimebinary [10].

Issue 3: Performance Scaling Inconsistencies in Multi-GPU MD Simulations

Observation: When running MD simulations (e.g., with GROMACS or LAMMPS) across multiple Ada Lovelace GPUs, performance does not scale linearly, or one GPU shows significantly lower utilization.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

Profile PCIe Bus Utilization: Lower-than-expected scaling can be caused by bottlenecks in CPU-GPU and GPU-GPU communication. Ada Lovelace GPUs support PCIe 4.0. Ensure your motherboard and CPUs support PCIe 4.0 and that GPUs are installed in the correct slots to maximize PCIe lane allocation [6].

Check for Process Affinity and Memory Locality: In multi-socket server systems, improper NUMA (Non-Uniform Memory Access) configuration can cripple performance.

- Use

numactlto bind the MD process to the specific CPU NUMA node closest to the GPU(s) it is using. - Tools like

nvidia-smi topo -mcan show the topological relationship between GPUs and CPUs, helping to optimize placement.

- Use

Inspect GPU Utilization and Power: Use

nvidia-smito monitor power draw and GPU utilization in real-time.If a GPU is not reaching its expected power limit or clock speed, it may be thermally throttled or encountering another bottleneck.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table: Key Hardware and Software for GPU-Accelerated MD Research

| Item / Solution | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada GPU | Primary compute engine. Offers 48GB ECC memory for large systems, high FP32 throughput, and certified drivers for stable production research [8]. |

| NVIDIA AI Enterprise Software | Provides a supported, cloud-native platform for AI and data science workflows, including optimized containers and frameworks for running MD software [8]. |

| OpenMM MD Suite | A high-performance, GPU-optimized library for molecular simulation. Its design minimizes CPU-GPU communication overhead, making excellent use of Ada's architecture [9]. |

| LAMMPS MD Package | A flexible, scriptable classical MD code. Its hybrid CPU-GPU approach allows it to handle a wide variety of complex systems and custom interactions [9]. |

| NVIDIA NVENC AV1 Encoder | The 8th-gen hardware encoder supports AV1 format. Useful for efficiently creating high-resolution, high-fidelity visualizations of simulation trajectories for analysis and presentation [5] [6]. |

| NVIDIA vGPU Software (vWS) | Allows a single RTX 6000 Ada GPU to be partitioned into multiple virtual GPUs. This enables multiple researchers to securely share the resources of a powerful workstation node [5] [8]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How much VRAM is needed for a billion-particle molecular dynamics simulation? For billion-particle systems, VRAM requirements can easily reach dozens of gigabytes. The exact need depends on the simulation's complexity, including the force field, number of integrator steps, and whether machine learning potentials are used.

- Recommended Configuration: For such large-scale systems, professional or data center GPUs with 48 GB of VRAM or more are recommended. The NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada (48 GB GDDR6) is explicitly highlighted as ideal for the most memory-intensive simulations [11]. For context, a recent study simulating a 532,980-atom model required substantial computational resources; scaling this to a billion particles necessitates significantly larger VRAM [12].

- Multi-GPU Setups: If a single GPU's VRAM is insufficient, multi-GPU configurations can be used. The total VRAM of all GPUs in the system must be able to hold the model and the computation overhead [11] [13].

Q2: What is the optimal amount of system RAM for large-scale MD simulations? System RAM (memory) is critical for holding the initial simulation data and handling input/output operations during the simulation run.

- General Rule: A good rule of thumb is that the system should have at least the same amount of system memory as the sum of the GPU memory in that system [13]. For a server with two 48 GB GPUs, this means a minimum of 96 GB of system RAM.

- Specific Recommendations:

- Workstation/Server Deployments: For flagship workstations or 2U servers with 8 DIMM slots, populating them with 32GB DIMMs is optimal, equating to 256 GB of RAM to handle larger workloads [14].

- Larger Systems: For billion-particle systems, even more RAM may be necessary, especially when using polyhedral meshes or complex physics [13].

Q3: Should I prioritize GPU VRAM or system RAM for MD performance? For MD software like AMBER, GROMACS, and NAMD, the GPU is the primary workhorse for performing the complex mathematical calculations [14]. Therefore, you should first ensure your GPU(s) have sufficient VRAM to fit your billion-particle system. Once the VRAM requirement is met, provision system RAM according to the guidelines above.

Q4: What storage solution is best for handling the large data outputs from long MD trajectories? While the search results do not specify exact storage capacities, they emphasize the need for fast and ample storage.

- Recommendation: High-speed NVMe storage is recommended due to its fast read/write speeds, which are crucial for saving trajectory files and checkpoints without creating a bottleneck [14]. Configurations of 2TB to 4TB are suggested for workstations to accommodate the large datasets generated [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Simulation fails with a "out of GPU memory" error.

- Solution 1: Reduce Problem Size. If possible, start with a smaller system or a shorter trajectory to estimate memory usage before scaling up.

- Solution 2: Use a Multi-GPU Setup. Distribute the computational load across multiple GPUs. Ensure your MD software supports multi-GPU execution for your specific workflow [11] [15].

- Solution 3: Optimize Simulation Parameters. Review parameters that increase memory footprint, such as neighbor list frequency, and adjust them if possible.

- Solution 4: Upgrade Hardware. Consider upgrading to GPUs with higher VRAM capacity, such as the NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada (48 GB) or similar data center GPUs [11].

Problem: Simulation runs but performance is slower than expected.

- Solution 1: Check CPU-GPU Balance. Ensure your CPU is not a bottleneck. For software like GROMACS and NAMD, which also utilize the CPU, a balanced system with a CPU featuring high clock speeds and a sufficient number of cores (e.g., 32-64 cores) is important [11] [14].

- Solution 2: Verify Hardware Compatibility. Ensure that your GPU drivers and CUDA/ROCm libraries are correctly installed and compatible with your MD software version [13].

- Solution 3: Profile Memory Bandwidth. Use profiling tools to check if the application is limited by memory bandwidth. GPUs with higher memory bandwidth (e.g., NVIDIA H100) can significantly improve performance for memory-bound applications [15] [13].

Hardware Specification Tables

Table 1: Recommended GPUs for Billion-Particle MD Simulations

| GPU Model | Architecture | VRAM | Memory Type | Key Feature for MD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada | Ada Lovelace | 48 GB | GDDR6 | Top contender for speed & memory capacity [11] |

| NVIDIA H100 | Hopper | 80 GB | HBM2e | Ideal for large-scale, multi-GPU simulations [15] |

| NVIDIA A100 | Ampere | 40/80 GB | HBM2e | High performance for large datasets [15] |

| NVIDIA RTX 4090 | Ada Lovelace | 24 GB | GDDR6X | Cost-effective for raw processing; may require multi-GPU for largest systems [11] |

Table 2: Recommended System RAM Configurations

| System Type | DIMM Slots | Recommended DIMM Size | Total RAM | Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer Desktop | 4 | 32 GB | 128 GB | Smaller systems or pre-screening [14] |

| Workstation/Server | 8 | 32 GB | 256 GB | Recommended starting point for billion-particle systems [14] |

| High-Performance Server | 16+ | 64 GB or larger | 512 GB+ | For the most complex and lengthy simulations |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Hardware for MD Simulations This protocol helps researchers determine the optimal hardware configuration for their specific MD workload.

- Define Baseline System: Start with a representative molecular system of a known size.

- Run Scaling Tests: Execute the simulation on a single GPU to establish a baseline performance metric (e.g., ns/day).

- Test Multi-GPU Scaling: Run the same simulation using multiple GPUs to measure parallel scaling efficiency [12].

- Profile Memory Usage: Use system monitoring tools (e.g.,

nvidia-smi) to track peak VRAM and system RAM usage during the simulation. - Analyze and Scale Up: Use the profiling data to extrapolate hardware requirements (VRAM, RAM) for the target billion-particle system.

Protocol 2: Workflow for a Full-Cycle Device-Scale Simulation This protocol is based on methodologies used in recent, large-scale MD research [12].

- Potential Development: Develop and train a machine-learned interatomic potential (e.g., using the Atomic Cluster Expansion framework) on a comprehensive DFT dataset [12].

- Model Construction: Build the initial atomic model representing the device geometry, which can contain millions of atoms [12].

- Performance Scaling Tests: Conduct strong and weak scaling tests on an HPC system (e.g., ARCHER2) to determine the optimal number of CPU cores for efficient simulation [12].

- Simulation Execution: Apply non-isothermal heating and cooling protocols to simulate the full SET (crystallization) and RESET (amorphization) cycle of the device [12].

- Data Analysis: Analyze the resulting trajectories to observe structural evolution and property changes at the device scale [12].

Diagram 1: MD Hardware Provisioning Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Materials for Large-Scale MD

| Item | Function in MD Research | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Machine-Learned Potentials | Accelerates force calculations by orders of magnitude compared to ab initio MD, enabling billion-particle simulations [12]. | Atomic Cluster Expansion (ACE) [12] |

| MD Software Suites | Specialized software packages optimized for GPU acceleration to perform the numerical integration of equations of motion. | AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD [11] [14] |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Systems | Provides the necessary parallel computing resources, either on-premise or via cloud, to run simulations in a feasible timeframe. | ARCHER2 (CPU-based), E2E Cloud (GPU cloud services) [15] [12] |

| Visualization & Analysis Tools | Software used to post-process trajectory files, analyze results, and visualize atomic structures and dynamic processes. | Not specified in results, but VMD, OVITO are common in the field. |

Frequently Asked Questions: Core Algorithms

Q1: What is the difference between the 'md' and 'md-vv' integrators, and when should I choose one over the other?

The md and md-vv integrators are both for deterministic dynamics but use different numerical methods.

mdis a leap-frog algorithm and is the default in packages like GROMACS. It is highly efficient and accurate enough for most production simulations [16].md-vvis a velocity Verlet algorithm. It provides more accurate integration for advanced coupling schemes like Nose-Hoover and Parrinello-Rahman, and outputs (slightly too small) full-step velocities. This comes at a higher computational cost, especially in parallel simulations [16].

Use md for most standard production runs. Use md-vv if you require higher accuracy for specific thermodynamic ensembles or need full-step velocities [16].

Q2: My large membrane simulation is buckling unrealistically. What could be causing this?

This is a documented artifact often traced to missed non-bonded interactions due to suboptimal neighbor-searching parameters [17]. When the neighbor list is updated too infrequently (nstlist is too high) or the outer buffer (rlist) is too short, particles can move from outside the interaction cutoff to inside it between list updates. This causes small, systematic errors in the pressure tensor, which a semi-isotropic barostat amplifies into major box deformations [17].

Q3: How can I enable a larger time step without losing simulation stability?

You can use the mass repartitioning technique. This involves scaling up the masses of the lightest atoms (typically hydrogens) and subtracting the added mass from the atoms they are bound to. With constraints = h-bonds, a mass-repartition-factor of 3 often enables a 4 fs time step [16].

Q4: What does the "Verlet-buffer-tolerance" parameter actually do?

The verlet-buffer-tolerance (VBT) is a target for the maximally allowed energy drift per particle due to missed interactions. GROMACS uses this value to automatically determine a suitable combination of the neighbor list update frequency (nstlist) and the buffer size (rlist). A default VBT of 0.005 kJ·mol⁻¹·ps⁻¹ is typically conservative, and the actual drift is often lower [17] [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Unphysical System Deformations in Large-Scale Simulations

- Symptoms: Asymmetric box deformation, membrane buckling, or crumpling when using a barostat [17].

- Cause: The primary cause is missed non-bonded interactions from an overly short neighbor list buffer (

rlist) and/or an infrequent neighbor list update (nstlist). This leads to an imbalanced pressure tensor [17]. - Solution:

- Diagnose: Monitor the components of the instantaneous pressure tensor in your output. Look for systematic oscillations or imbalances [17].

- Adjust Parameters: Manually increase the

rlistparameter or reduce thenstlistinterval. Disabling the automatic VBT buffer (by settingverlet-buffer-tolerance = -1) is necessary for full manual control [17]. - General Guideline: Ensure the buffer

rlist - rcis sufficiently large to account for particle diffusion overnstliststeps. The required buffer size depends on temperature, particle mass, and the update interval [18].

Issue 2: Energy Drift in NVT Simulations

- Symptoms: The total energy of a system in the NVT ensemble slowly increases or decreases over time, indicating a violation of energy conservation.

- Cause: This drift can be caused by several factors, but one common algorithmic reason is the same as above: particles diffusing into the interaction cut-off sphere between neighbor list updates, causing their interactions to be missed [18].

- Solution:

- The automatic VBT algorithm is designed to minimize this drift. First, try using the default VBT setting [18].

- If the drift persists, you can manually tighten the VBT (e.g., to 0.001 kJ·mol⁻¹·ps⁻¹) to force a larger buffer and more frequent updates [17] [18].

- For ultimate control, manually set a larger

rlistand a smallernstlist.

Integrator Comparison Table

The choice of integrator is crucial for the physical accuracy and computational efficiency of your simulation. Below is a summary of common algorithms [16].

| Integrator | Algorithm Type | Key Characteristics | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| md | Leap-frog | Default, efficient, analytically identical to velocity Verlet from same point [16]. | Standard production MD simulations [16]. |

| md-vv | Velocity Verlet | More accurate for advanced coupling; outputs full-step velocities; higher cost [16]. | Simulations requiring precise integration of Nose-Hoover or Parrinello-Rahman coupling [16]. |

| sd | Stochastic Dynamics (Leap-frog) | Accurate and efficient Langevin dynamics; temperature controlled by friction coefficient [16]. | Simulating stochastic processes or as a thermostat [16]. |

| steep | Steepest Descent | Simple, moves downhill in energy landscape; requires step size (emstep) [16]. |

Energy minimization [16]. |

| cg | Conjugate Gradient | More efficient minimization than steepest descent; uses tolerance (emtol) [16]. |

Efficient energy minimization, especially when combined with occasional steepest descent steps [16]. |

Neighbor-Searching Parameters and Artifacts

Optimizing neighbor-searching is key to performance and accuracy. The following table outlines critical parameters and the consequences of their misconfiguration.

| Parameter | Function | Default (GROMACS) | Impact of Improper Use & Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

nstlist |

Steps between neighbor list updates [17] [18] | 10 [17] | Too high: Causes missed interactions, pressure artifacts, energy drift [17]. Solution: Decrease value. |

rlist |

Outer cutoff for neighbor list (rl) [17] [18] | Set by VBT [17] | Too short: Same as high nstlist [17]. Solution: Increase buffer size (rlist - rc). |

verlet-buffer-tolerance |

Target for max. allowed energy drift per particle [17] [18] | 0.005 kJ·mol⁻¹·ps⁻¹ [17] | Too loose: Can allow noticeable drift. Too tight: Unnecessary performance cost. Solution: Adjust based on observed drift. |

rc |

Interaction cut-off radius | (Force-field dependent) | Too short: Physical inaccuracy. Too long: High computational cost. Solution: Use recommended force-field value. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for MD Simulations

| Item | Function in the "Experiment" |

|---|---|

| Force Field | An empirical energy function that defines the potential energy of the system as a sum of bonded and non-bonded terms; the physical "law" of the simulation [19]. |

| Integrator | The core algorithm that numerically solves Newton's equations of motion to update particle positions and velocities over time [16] [18]. |

| Neighbor List | A list of particle pairs within a cutoff (plus buffer) that is updated periodically to efficiently compute non-bonded forces without checking all pairs every step [18]. |

| Thermostat | An algorithm (e.g., stochastic dynamics sd) that regulates the temperature of the system by modifying particle velocities [16]. |

| Barostat | An algorithm (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) that regulates the pressure of the system by adjusting the simulation box dimensions [17]. |

| Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) | A method for handling long-range electrostatic interactions by splitting them into short-range (real-space) and long-range (reciprocal-space) calculations [19]. |

Experimental Protocol: Diagnosing Neighbor List Artifacts

This protocol is based on the methodology used to identify and resolve unphysical membrane deformations [17].

System Preparation:

- Set up a large simulation system, such as a lipid bilayer comprising at least 1024 lipids [17].

- Use standard force field parameters and a semi-isotropic pressure coupling scheme.

Simulation with Default Parameters:

- Run an initial simulation using the default neighbor-searching parameters (e.g., in GROMACS:

nstlist = 10,verlet-buffer-tolerance = 0.005). - Use the Parrinello-Rahman barostat [17].

- Run an initial simulation using the default neighbor-searching parameters (e.g., in GROMACS:

Data Collection and Analysis:

- Primary Observation: Visually inspect the trajectory for membrane buckling or asymmetric box deformation [17].

- Pressure Tensor Analysis: Plot the instantaneous components of the pressure tensor (e.g.,

Pxx,Pyy,Pzz) over time. Look for systematic oscillations and sustained imbalances between the lateral and normal directions [17]. - Energy Drift Calculation: Monitor the total energy in an NVT simulation of a simpler system (like neat water) to check for a steady drift, which indicates missed interactions [18].

Intervention and Validation:

- Parameter Adjustment: Manually increase the

rlistbuffer (e.g., by 0.1 to 0.2 nm) and/or reducenstlist. This requires settingverlet-buffer-tolerance = -1[17]. - Re-run and Compare: Repeat the simulation with the adjusted parameters. The artifacts (buckling, pressure oscillations) should be significantly reduced or eliminated [17].

- Parameter Adjustment: Manually increase the

Workflow Diagram: Core MD Algorithm Logic

Neighbor-Searching with a Verlet Buffer

FAQs: Node Interconnects and Cluster Topologies

Q1: My HPC job is pending for a long time. What interconnect-related resources might it be waiting for?

While a common reason for job pending states is insufficient memory [20], it can also be due to the unavailability of specific interconnect hardware. Use commands like bhosts and lshosts to check the status of nodes equipped with the required high-speed network adapters (e.g., InfiniBand) [20].

Q2: After a system update, my application fails to communicate over InfiniBand. What could be wrong? A known issue exists where older versions of Mellanox OFED (OpenFabrics Enterprise Distribution) drivers can become incompatible with newer Linux kernels, potentially causing boot failures or communication problems [21]. The solution is to upgrade to a compatible driver version, such as Mellanox OFED 5.3-1.0.0.1 or later [21].

Q3: I am using non-SR-IOV virtual machines (e.g., H16r). How do I configure InfiniBand? Non-SR-IOV and SR-IOV-enabled VMs require different driver stacks. For non-SR-IOV VMs, you must use the Network Direct (ND) drivers instead of the OFED drivers typically used for SR-IOV-enabled systems [21].

Q4: My InfiniBand job fails to start, and I see errors referencing a device named mlx5_1 instead of mlx5_0. How can I fix this?

The introduction of Accelerated Networking on certain Azure HPC VMs can cause the InfiniBand interface to be named mlx5_1 instead of the expected mlx5_0 [21]. This requires tweaking your MPI command lines. When using UCX (common with OpenMPI and HPC-X), you may need to explicitly specify the device. For example: --mca btl_openib_if_include mlx5_1 [21].

Q5: What are the key differences between traditional pluggable optics and co-packaged optics (CPO) for interconnects? Pluggable optical transceivers connect to switches externally and are suited for rack-to-rack scale-out networks, but the path involves multiple electrical-optical conversions, leading to higher latency and power use [22]. Co-packaged optics (CPO) integrate the optical engine (OE) much closer to the switch ASIC (Application-Specific Integrated Circuit) within the same package. This drastically reduces power consumption and latency while enabling a massive increase in bandwidth, making it ideal for scale-up domains within a rack [23] [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Diagnosing and Resolving InfiniBand Interface Naming Issues

Problem: After enabling Accelerated Networking on your HB-series or similar VM, MPI jobs fail because they cannot find the expected InfiniBand interface (mlx5_0).

Diagnosis:

- Check the available InfiniBand devices using the

ibstatcommand. - You will likely see that the active port is on a device named

mlx5_1.

Solution: Modify your MPI job submission script to explicitly bind to the correct device. The exact command depends on your MPI implementation.

- For OpenMPI/HPC-X with UCX: Add the following parameter to your

mpiruncommand: - For OpenMPI with the

openibBTL: Use:

Verification: Resubmit your job. Monitor the standard output and error logs to confirm the job starts and utilizes the InfiniBand network.

Guide: Addressing "Duplicate MAC" Error on Ubuntu HPC VMs

Problem: An Ubuntu-based HPC VM fails to boot properly or encounters network errors, with logs showing: "duplicate mac found! both 'eth1' and 'ib0' have mac" [21].

Cause: A known issue with cloud-init on Ubuntu VM images when trying to bring up the InfiniBand (IB) interface [21].

Resolution: Apply the following workaround on your VM image:

- Deploy a standard Ubuntu 18.04 marketplace VM image.

- Install the necessary packages to enable InfiniBand.

- Edit the

waagent.conffile and setEnableRDMA=y. - Disable network configuration in

cloud-init: - Remove the cloud-init-generated MAC configuration and create a new Netplan configuration:

Comparison of Photonic Interconnect Technologies

Table 1: Key attributes of current and emerging photonic interconnect technologies for HPC [22].

| Attribute | 2D Co-Packaged Optics (CPO) | 2D Optical Chiplets | 3D CPO | Active 3D Photonic Interposer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integration Approach | Pre-packaged OE module on substrate | PIC with integrated UCIe/SerDes on substrate | EIC 3D-stacked on PIC | All electronic dies 3D-stacked on a reticle-sized PIC |

| Proximity to ASIC | Fanned out on substrate (10s of mm) | Mounted closer on organic substrate | 3D-stacked or on interposer | Directly 3D-stacked |

| Max Bi-di Bandwidth | ~6 Tbps | Similar to 2D CPO | 10s of Tbps | 100+ Tbps |

| I/O Placement | Shoreline-bound | Shoreline-bound | Edgeless I/O | Edgeless I/O |

| Key Limitation | High package area use; thermal challenges | Suboptimal area/power efficiency; limited scalability | Complexity of 3D integration | Highest complexity in design and manufacturing |

HPC Hardware Market Forecast (2025-2035)

Table 2: Forecasted growth of the overall HPC hardware market and key segments from 2025 to 2035 [23].

| Hardware Segment | Forecast Details | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Overall HPC Hardware | Reaches US$581 billion by 2035 with a CAGR of 13.6% [23]. | Driven by exascale computing and AI workloads. |

| High Bandwidth Memory (HBM) | ~95% of accelerators in HPC now employ HBM [23]. | Crucial for meeting the bandwidth demands of AI accelerators and GPUs. |

| Thermal Management | Cold plate cooling is expected to remain the dominant technology [23]. | Preferred to reduce the massive capital expenses of building large HPC systems. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Benchmarking Molecular Dynamics Performance on AWS Graviton3E

This protocol outlines the steps to build and benchmark popular MD software like GROMACS and LAMMPS on AWS Hpc7g instances, which are powered by Graviton3E processors [24].

1. HPC Environment Setup:

- Tool: Use AWS ParallelCluster to deploy a scalable HPC environment with Slurm as the job scheduler [24].

- Compute Instances: Use

Hpc7g.16xlargeinstances, which feature Graviton3E processors, DDR5 memory, and a 200 Gbps Elastic Fabric Adapter (EFA) network interface [24]. - Storage: Deploy a high-performance parallel file system, specifically Amazon FSx for Lustre (e.g., 4.8 TB,

PERSISTENT_2type), to ensure sufficient I/O performance for MD workloads [24].

2. Development Tooling Configuration:

- Compiler: Use the Arm Compiler for Linux (ACfL) version 23.04 or later. This compiler is now available at no cost [24].

- Math Library: Use the Arm Performance Library (ArmPL) version 23.04 or later, which is included with ACfL [24].

- MPI: Use Open MPI version 4.1.5 or later, linked with Libfabric to enable EFA [24].

3. Application Build Instructions:

- For GROMACS:

- Use CMake for configuration.

- The critical configuration parameter is

-DGMX_SIMD=ARM_SVEto enable Scalable Vector Extension support for Graviton3E. - Building with ACfL and SVE has been shown to outperform GNU compilers and NEON/ASIMD instructions by 6-28%, depending on the test case [24].

- For LAMMPS:

- Use the provided Makefiles optimized for Arm architecture (

Makefile.aarch64_arm_openmpi_armplfor ACfL). - Add the

-march=armv8-a+sveflag to enable SVE instructions and-fopenmpto enable OpenMP support [24].

- Use the provided Makefiles optimized for Arm architecture (

4. Execution and Benchmarking:

- Test Cases: Use standardized benchmarks like the Unified European Application Benchmark Suite (UEABS) for GROMACS, which includes systems ranging from ~142,000 atoms to ~28 million atoms [24].

- Performance Measurement: Run simulations across a single node and multiple nodes to measure both single-node performance and multi-node scalability. Performance for GROMACS on Hpc7g has demonstrated near-linear scalability when using EFA [24].

Logical Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential software and hardware "reagents" for HPC-based molecular dynamics research.

| Tool / Component | Function / Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| AWS ParallelCluster | An open-source cluster management tool to deploy and manage a scalable HPC environment on AWS in minutes [24]. |

| Slurm Workload Manager | A job scheduler that manages and allocates resources (compute nodes, memory) in an HPC cluster [24]. |

| Arm Compiler for Linux (ACfL) | A compiler suite optimized for Arm architecture, crucial for achieving peak performance on Graviton processors for MD applications [24]. |

| Open MPI | A high-performance Message Passing Interface (MPI) implementation for enabling parallel execution of MD codes across multiple nodes [24]. |

| Elastic Fabric Adapter (EFA) | A network interface for AWS HPC instances that enables low-latency, high-bandwidth inter-node communication, essential for MPI applications [24]. |

| FSx for Lustre | A fully-managed, high-performance parallel file system that provides the fast I/O necessary for handling large MD simulation data sets [24]. |

| GROMACS | A widely-used open-source molecular dynamics software package for simulating the physical movements of atoms and molecules [24]. |

| LAMMPS | A classical molecular dynamics code for particle-based modeling of materials, distributed by Sandia National Laboratories [24]. |

Advanced Implementation: Performance-Portable Code and AI-Driven Simulations

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is GPU-resident computing, and how does it differ from traditional GPU acceleration? Traditional GPU acceleration offloads specific computational tasks from the CPU to the GPU, requiring data to be copied back and forth between CPU and GPU memory for each step. This creates a significant "data copy tax" and PCIe bus bottleneck [25]. GPU-resident computing inverts this model: the GPU becomes the primary computational engine, with data persisting in GPU memory (VRAM) and the CPU acting mainly as an orchestrator and I/O controller. This eliminates per-step data transfers, which can lead to performance gains greater than 2x in applications like molecular dynamics [25].

FAQ 2: My molecular dynamics simulation is slower than expected after enabling GPU support. What is the most likely cause?

The most common cause is that your simulation is not fully GPU-resident. Many codes only offload the force calculation to the GPU, requiring full atom data to be transferred between CPU and GPU memory at every timestep [26]. Check your software documentation for a "GPU-resident" or "GPU-only" mode (e.g., the -nb gpu -pme gpu -update gpu flags in GROMACS) [27]. If such a mode exists and is not enabled, your simulation is likely suffering from PCIe transfer latency.

FAQ 3: How can I check if my application is bottlenecked by CPU-GPU data transfers? Use profiling tools like NVIDIA Nsight Systems or the PyTorch Profiler [28]. Look for the following in the profiling timeline:

- High occupancy of operations labeled

cudaMemcpy(or similar), indicating significant time spent on data transfer. - Large gaps in GPU compute activity (kernel execution), where the GPU is idle waiting for data from the CPU. If data transfer time is a substantial fraction of the total step time, you have a communication bottleneck [25] [28].

FAQ 4: I am getting "out-of-memory" (OOM) errors on the GPU when running large systems. What strategies can I use? OOM errors occur when your model, atom data, and intermediate calculations exceed the GPU's VRAM capacity [27]. Consider these strategies:

- Reduce Precision: Use mixed-precision training (e.g., FP16 or BF16) with frameworks like PyTorch AMP, which can halve memory usage [28].

- Optimize Model: For machine learning potentials, apply techniques like pruning or quantization to reduce the model's memory footprint [28].

- Domain Decomposition: Use multi-GPU setups with efficient domain decomposition, as implemented in LAMMPS-KOKKOS, to distribute the system across multiple GPU memories [26] [29].

- Memory Management: Explicitly free unused tensors (e.g.,

torch.cuda.empty_cache()) to combat memory fragmentation [28].

FAQ 5: What hardware factors are most critical for maximizing GPU-resident performance in scientific simulations? The key hardware factors are:

- GPU Memory (VRAM) Bandwidth: Higher bandwidth allows the GPU cores to be fed with data faster. Newer architectures like NVIDIA H100 (3.3 TB/s) and AMD MI300A (5.3 TB/s) offer massive bandwidth [26].

- VRAM Capacity: Determines the maximum problem size you can fit on a single GPU. GPUs like the RTX 6000 Ada (48 GB) are suited for large models [29].

- Interconnect Technology: For multi-GPU/node workflows, high-speed interconnects like NVLink are essential to minimize communication latency between GPUs [25]. For CPU-GPU communication, PCIe 4.0/5.0 is critical.

FAQ 6: Are consumer-grade GPUs like the NVIDIA RTX 4090 suitable for GPU-resident molecular dynamics? For many MD codes like GROMACS, AMBER, and LAMMPS, yes. These applications often use mixed precision, where the high FP32 (single-precision) performance of consumer GPUs excels [27] [29]. However, if your specific code or solver requires true double precision (FP64) throughout, the intentionally limited FP64 performance of consumer GPUs will be a severe bottleneck. In such cases, data-center GPUs (e.g., NVIDIA A100/H100, AMD MI250X) with strong FP64 performance are necessary [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low GPU Utilization During Simulation

Symptoms:

- GPU usage, as reported by tools like

nvidia-smi, fluctuates dramatically or remains consistently low (e.g., below 50%). - Simulation performance (e.g., ns/day) is far below published benchmarks for your hardware.

Diagnosis and Solutions: This typically indicates that the GPU is waiting for data or instructions, often due to a CPU-bound bottleneck or inefficient data pipeline.

- Profile the Application: Run a profiler like NVIDIA Nsight Systems to identify where time is being spent. Look for long CPU-bound sections between GPU kernels [28].

- Optimize the Data Loader: If your workflow involves loading data (e.g., for machine learning potentials), ensure your data pipeline is not the bottleneck.

- Use the

DataLoaderclass in PyTorch with multiple worker processes (num_workers> 0). - Prefetch data to the GPU asynchronously using

torch.cuda.Streamto overlap data loading with computation [28].

- Use the

- Verify GPU-Resident Mode: Confirm that all major computational kernels (non-bonded forces, PME, position update) are running on the GPU. Consult your software manual to enable full GPU offloading [27].

Issue 2: Performance Inconsistency Across Different GPU Generations or Vendors

Symptoms: A simulation runs well on one GPU (e.g., an NVIDIA V100) but shows poor performance on another (e.g., an AMD MI250X), even when using performance-portable code.

Diagnosis and Solutions: Different GPU architectures have varying strengths in compute throughput, memory bandwidth, and cache hierarchies.

- Analyze the Kernel's Bottleneck: Determine if your simulation is compute-bound or memory-bound. Tools like Nsight Compute can help.

- Consult Performance Tables: Understand the hardware capabilities. A kernel limited by memory bandwidth will perform better on an H100 (3.3 TB/s) than on a V100 (0.9 TB/s) [26].

Table: Key Specifications for HPC/AI GPUs [26]

| GPU Model | Memory Bandwidth | VRAM Capacity | FP64 Performance (peak) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA V100 | 0.9 TB/s | 16 GB | 7.8 TFLOPS |

| NVIDIA A100 | 1.5 TB/s | 40 GB | 9.7 TFLOPS |

| NVIDIA H100 | 3.3 TB/s | 80 GB | 34 TFLOPS |

| AMD MI250X | 1.6 TB/s | 64 GB | 24 TFLOPS |

| AMD MI300A | 5.3 TB/s | 128 GB | 61 TFLOPS |

| Intel PVC (Stack) | 1.6 TB/s | 64 GB | 26 TFLOPS |

- Use Performance-Portable Programming Models: Frameworks like Kokkos (as used in LAMMPS-KOKKOS) and OpenMP allow a single codebase to run efficiently on GPUs from NVIDIA, AMD, and Intel by abstracting the underlying hardware [26]. Ensure you are using a build of your software that supports these portability layers for your specific hardware.

Issue 3: Implementing a Custom Machine Learning Potential with LAMMPS

Symptoms: You have a custom PyTorch-based machine learning interatomic potential (MLIP) and want to integrate it with LAMMPS for scalable, GPU-accelerated MD simulations without introducing CPU-GPU transfer bottlenecks.

Solution: Use the ML-IAP-Kokkos Unified Interface [30] This interface allows seamless connection of PyTorch models to LAMMPS, ensuring end-to-end GPU acceleration.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Environment Setup:

- Install LAMMPS (September 2025 release or later) compiled with Kokkos, MPI, ML-IAP, and Python support [30].

- Ensure you have a working Python environment with PyTorch and your model's dependencies.

Implement the

MLIAPUnifiedAbstract Class:- Create a Python class that inherits from

MLIAPUnified. - The

__init__function must defineelement_types,ndescriptors=1,rcutfac, andnparams=1. - The core is the

compute_forces(data)function. LAMMPS passes a data object containing atomic positions, types, and neighbor lists. You must use this data to compute forces and energies using your PyTorch model. - Serialize and save your model object:

torch.save(MyMLModel(["H", "C", "O"]), "my_model.pt")[30].

- Create a Python class that inherits from

Run LAMMPS with the Unified Interface:

- In your LAMMPS input script, use the

pair_style mliap unifiedcommand to load your serialized model. - Launch LAMMPS with Kokkos GPU support:

lmp -k on g 1 -sf kk -pk kokkos newton on neigh half -in sample.in[30].

- In your LAMMPS input script, use the

This workflow keeps the entire force calculation on the GPU, as the PyTorch model operates directly on GPU tensors, avoiding the "data copy tax."

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Enabling GPU-Resident Mode in LAMMPS via Kokkos

Objective: Configure LAMMPS to run molecular dynamics simulations in a fully GPU-resident manner, minimizing data transfers over the PCIe bus.

Methodology:

- Build LAMMPS with KOKKOS Package:

- Obtain the LAMMPS source code.

- Configure the build with CMake, enabling the

KOKKOSpackage and the desired backend for your GPU (e.g.,Kokkos_ENABLE_CUDA=ONfor NVIDIA GPUs). - Compile LAMMPS. This creates an executable that can execute code on GPUs using the Kokkos performance portability layer [26].

Prepare the Input Script:

- Use the

-k on,-sf kk, and-pk kokkoscommand-line flags to enable Kokkos at runtime. - Specify the number of GPUs per node (e.g.,

g 1). - Critical: Use pair, fix, and compute styles that have been ported to Kokkos (they typically have a

/kksuffix). Using non-Kokkos styles will force data back to the CPU, breaking residency.

- Use the

Verification:

- Monitor the log file for messages confirming Kokkos and GPU usage.

- Use profiling tools to confirm that no major data transfers occur during the simulation timesteps.

The diagram below illustrates the architectural difference between traditional offloading and the GPU-resident model implemented in LAMMPS-KOKKOS.

Diagram: CPU-GPU Data Flow in Different Computing Models.

Protocol: Benchmarking GPU-Resident Performance

Objective: Quantify the performance benefit of a GPU-resident setup and identify the optimal configuration for your specific simulation.

Methodology:

- Select a Benchmark System: Choose a representative molecular system (e.g., a protein in water) that is large enough to fully utilize the GPU but small enough to run quickly.

- Define a Metric: Common metrics are simulation throughput (nanoseconds per day) or iterations per second.

- Establish a Baseline: Run the benchmark using a traditional CPU-only or basic GPU-offload mode.

- Test GPU-Resident Mode: Run the same benchmark in the GPU-resident configuration (e.g., LAMMPS-KOKKOS).

- Systematic Variation: Test different parameters to find the optimal setup:

- Precision: Compare double (FP64), single (FP32), and mixed precision.

- GPU Count: Perform strong scaling tests (same problem size, increasing GPUs) to find the point where communication overhead outweighs compute gains.

- Batch Size (for ML): For training ML potentials, find the largest batch size that fits in GPU memory [28].

Table: Example Benchmark Results for a Lennard-Jones System on Different GPUs (Simulation Throughput in ns/day) [26]

| Hardware | LAMMPS (CPU-only) | LAMMPS (Basic GPU) | LAMMPS-KOKKOS (GPU-Resident) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA A100 | 1.0 (Baseline) | 4.5 | 9.8 |

| AMD MI250X | 0.9 | 4.1 | 10.5 |

| Intel PVC | 0.8 | 3.8 | 8.7 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table: Key Software and Hardware for GPU-Resident Molecular Dynamics

| Item | Function / Relevance | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | A highly flexible, open-source MD code that supports GPU-resident computing via its KOKKOS and GPU packages [26]. | Use the -k on and -sf kk flags to enable the Kokkos backend. |

| ML-IAP-Kokkos | A unified interface for LAMMPS that allows PyTorch-based machine learning potentials to run with end-to-end GPU acceleration [30]. | Enables seamless integration of custom AI models without data transfer bottlenecks. |

| GROMACS | A high-performance MD package optimized for biomolecular systems. It supports extensive GPU offloading [27]. | Use flags like -nb gpu -pme gpu -update gpu to maximize GPU residency. |

| Kokkos / OpenMP | Performance portability libraries that allow a single C++ codebase to run efficiently on multi-core CPUs and GPUs from NVIDIA, AMD, and Intel [26]. | Essential for writing future-proof, vendor-agnostic HPC code. |

| NVIDIA Nsight Systems | A system-wide performance profiler that provides a timeline of CPU and GPU activity, ideal for pinpointing data transfer bottlenecks [28]. | The first tool to use when performance is below expectations. |

| NVIDIA H100/A100 GPU | Data-center GPUs with high memory bandwidth (H100: 3.3 TB/s) and, for A100, strong double-precision (FP64) performance, suited for large, precision-sensitive simulations [25] [26]. | |

| NVIDIA RTX 4090/6000 Ada | Consumer and workstation GPUs with high single-precision (FP32) performance and large VRAM, offering excellent cost-effectiveness for mixed-precision MD workloads [27] [29]. | RTX 6000 Ada's 48 GB VRAM is ideal for very large systems. |

| PyTorch with AMP | A deep learning framework with Automatic Mixed Precision (AMP) support, crucial for training and inferring ML potentials with reduced memory usage and increased speed [30] [28]. | Use torch.cuda.amp.autocast() for mixed precision. |

FAQs: Kokkos for Performance Portability in Molecular Dynamics

What is Kokkos and what problem does it solve in molecular dynamics?

Kokkos is a C++ performance portability programming model designed for writing applications that run efficiently on all major High-Performance Computing (HPC) platforms. Its core purpose is to abstract parallel execution and data management, enabling a single codebase to target complex node architectures with N-level memory hierarchies and multiple types of execution resources (e.g., CPUs, GPUs from NVIDIA, AMD, and Intel). The Kokkos ecosystem includes several components, with kokkos providing the fundamental parallel execution and memory abstraction [31]. For molecular dynamics codes like LAMMPS, which must operate on diverse exascale computing architectures, Kokkos allows developers to avoid writing and maintaining multiple, vendor-specific versions of their code (e.g., one for CUDA, one for HIP, one for SYCL), thus ensuring performance portability [32] [26] [33].

Which molecular dynamics codes actively use Kokkos?

Among the major molecular dynamics software, LAMMPS has a deeply integrated KOKKOS package. This package was one of the first serious applications of Kokkos, with some of Kokkos's design features even being inspired by use-cases from LAMMPS [26]. The integration allows large parts of the LAMMPS code, including force calculations for various potentials, to run seamlessly on different GPU accelerators [32] [34]. The available information does not indicate that GROMACS uses the Kokkos library for performance portability. GROMACS employs its own internal methods for acceleration on GPUs and other architectures [35] [36].

I am getting poor performance with LAMMPS compared to GROMACS. What should I check?

It is a recognized phenomenon that standard compute kernels in GROMACS can be much faster than those in the standard LAMMPS distribution, as GROMACS often makes more aggressive default optimization choices that may sacrifice some flexibility [37]. If you are using LAMMPS and encountering slower-than-expected performance, consider these steps:

- Verify Your Compilation: Ensure LAMMPS is compiled with the KOKKOS package (or other accelerator packages like GPU or INTEL) and that the appropriate backend for your hardware (e.g., CUDA, HIP, OpenMP) is correctly specified [26].

- Use Optimized Packages: Within your LAMMPS input script, use pair styles and other styles that are part of the KOKKOS, GPU, or OPT packages, as these contain the optimized kernels. The standard C++ styles are not accelerated [37].

- System Decomposition: Performance can be severely impacted if the simulation domain is decomposed into subdomains that are too small. Check the LAMMPS log file for warnings about "subdomains are too small" [37].

- Benchmark with Simple Potentials: When setting up a new system, benchmark performance with a simple potential (like Lennard-Jones) first to establish a performance baseline before moving to more complex, computationally expensive potentials [34].

- Utilize Tuning Tools: LAMMPS provides tools like

fix tune/kspaceto automatically adjust parameters for the long-range electrostatic solver (PPPM) to increase speed, mimicking one of GROMACS's aggressive optimizations [37].

When should I choose LAMMPS over GROMACS, and vice versa?

The choice depends heavily on your research domain and specific simulation needs.

LAMMPS is typically the better choice for:

- Materials Science and Solid-State Physics: Its flexibility makes it ideal for simulating polymers, metals, semiconductors, and granular materials [35].

- Multi-Scale and Complex Systems: It supports an exceptionally wide range of atomistic, mesoscopic, and coarse-grained models [35].

- Customization and Extensibility: Its highly modular design allows users to develop their own features or plugins for specific interactions or simulation protocols [37] [35].

- Extreme-Scale Parallelism: It is designed to scale efficiently across thousands of processors for very large-scale simulations [35].

GROMACS is typically the better choice for:

- Biomolecular Simulations: It is highly optimized for proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, and other biochemical molecules, often delivering superior performance out-of-the-box for these systems [35].

- High-Throughput Biomolecular Screening: Its speed and efficiency make it suitable for projects requiring a large number of simulations [35].

- Standardized Workflows: It offers a more streamlined and user-friendly interface for common biomolecular simulation tasks [35].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Low Performance in LAMMPS-KOKKOS

This guide helps you systematically identify the cause of performance issues when running LAMMPS with the KOKKOS package.

Step 1: Verify Kokkos Configuration and Hardware Backend First, confirm that LAMMPS was compiled with the KOKKOS package and is using the correct backend for your hardware. An incorrect backend (e.g., using the CUDA backend on an AMD GPU) will lead to poor performance or failure to run.

- Action: Check your compilation log and the first few lines of the LAMMPS output log. It should explicitly state the Kokkos backend that was enabled (Cuda, Hip, OpenMP, etc.).

- Solution: Recompile LAMMPS with the correct

-DKokkos_ARCH_...setting for your specific GPU or CPU architecture.

Step 2: Check Input Script for Kokkos-Accelerated Styles

Using standard, non-Kokkos styles in your input script will not leverage GPU acceleration. The pair, fix, and compute styles must have the /kk suffix or be from the KOKKOS package.

- Action: Review your input script. For a Lennard-Jones system, use

pair_style lj/cut/kkinstead ofpair_style lj/cut. Similarly, usefix nve/kk. - Solution: Consult the LAMMPS documentation for your chosen potentials to find the corresponding Kokkos-accelerated style names.

Step 3: Analyze the LAMMPS Log File The LAMMPS log file provides a detailed breakdown of where time is spent during the simulation.

- Action: Look at the "MPI task timing breakdown" section in your log file.

- Diagnosis:

- High

Pairtime: Expected for complex potentials; consider if a simpler model is adequate. - High

PPPM(Kspace) time: This long-range electrostatic solver can be a bottleneck. Consider usingfix tune/kspaceto optimize parameters or switching to a different method if appropriate [37]. - High

Neightime: The neighbor list build is expensive. Adjust theneigh_modifycommand to build lists less frequently. - High

Commtime: This indicates inter-processor communication overhead. The problem decomposition may be suboptimal.

- High

Step 4: Check Domain Decomposition Inefficient domain decomposition can cripple performance by creating load imbalance and excessive communication.

- Action: Run LAMMPS with the

-sf kkand-pk kokkos ...commands to let it automatically choose good Kokkos settings. Also, check the log file for warnings about "subdomains are too small". - Solution: Adjust the number of MPI tasks and/or the

processorsgrid layout to create more balanced subdomains.

Guide 2: Selecting the Right Performance Portability Strategy

This guide helps researchers decide on the best approach for their computational project.

Table 1: Strategy Selection Guide

| Your Research Context | Recommended Strategy | Key Actions & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Biomolecular Systems (Proteins, Lipids) | Start with GROMACS | Leverage its highly optimized, domain-specific kernels for superior out-of-the-box performance on biomolecules [35]. |

| Non-Biological Materials (Polymers, Metals) | Choose LAMMPS | Utilize its extensive, flexible library of potentials and models tailored for materials science [35]. |

| Requiring Custom Forces or Novel Algorithms | Use LAMMPS with Kokkos | Extend LAMMPS with your own code using Kokkos abstractions, ensuring your customizations are also performance-portable [26]. |

| Running on Multi-Vendor HPC Hardware (e.g., Frontier, Aurora) | Use LAMMPS with Kokkos | Compile LAMMPS-Kokkos with the appropriate backend (HIP for AMD, SYCL for Intel) to run a single codebase across different architectures [32] [34] [33]. |

Experimental Protocols & Benchmarking

Protocol 1: Benchmarking LAMMPS-KOKKOS on a New Platform

This protocol outlines the steps to evaluate the performance of LAMMPS-KOKKOS on a new computing system, such as a cluster with GPUs.

1. System Compilation and Configuration:

- Compile LAMMPS with the KOKKOS package, ensuring the

-DKokkos_ARCH_...flag matches the node architecture (e.g.,-DKokkos_ARCH_AMPERE80for NVIDIA A100). - Choose the appropriate backend using the

-DKokkos_ENABLE_...=ONflag (e.g.,-DKokkos_ENABLE_CUDA=ONfor NVIDIA GPUs).

2. Selection of Benchmark Potentials:

- To ensure a comprehensive performance assessment, select a suite of interatomic potentials that represent different computational profiles [32] [34]:

- Lennard-Jones (LJ): A simple, short-range pairwise potential. Useful for testing basic memory bandwidth and peak FLOP rates.

- Tersoff/EAM: Many-body potentials that are more computationally intensive and test different memory access patterns.

- SNAP (Spectral Neighbor Analysis Potential): A machine-learning-based quantum-accurate potential that is computationally demanding and memory-intensive [33].

- ReaxFF: A complex reactive force field that requires frequent neighbor list rebuilds and exhibits high computational load [34].

3. Execution and Data Collection:

- Run strong scaling tests (where the total problem size is fixed, but the number of processors/GPUs is increased) for each potential.

- Collect key performance metrics from the LAMMPS log file:

- Wall time per timestep (or total simulation time).

- Performance in timesteps per second (a common metric in MD).

- The MPI task timing breakdown for

Pair,Neigh,Kspace, andComm.

4. Analysis:

- Plot performance (timesteps/sec) versus the number of nodes/GPUs.

- Identify scaling efficiency and performance bottlenecks (e.g., communication overhead at high node counts).

- Compare achieved performance against the hardware's theoretical peak (roofline) model, as done in studies on systems like Crusher (AMD MI250X) and Summit (NVIDIA V100) [34].

Protocol 2: Comparing LAMMPS and GROMACS Performance Fairly

To conduct a fair and meaningful performance comparison between LAMMPS and GROMACS, follow this methodology.

1. Standardize the System and Compiler:

- Use the exact same CPU and GPU hardware for both codes.

- Use the same compiler family and version (e.g., GCC 11.2.0) where possible, with comparable optimization flags (

-O3).

2. Prepare Equivalent Inputs:

- Model the same physical system (number of atoms, density, composition) in both codes.

- Use functionally identical force fields and parameters. For example, if using a Lennard-Jones fluid in LAMMPS, use the same cutoffs and parameters in GROMACS.

3. Match Simulation Parameters:

- Ensure parameters like timestep, neighbor list cutoffs and update frequency, and treatment of long-range electrostatics (e.g., PPPM vs. PME) are as consistent as possible between the two packages.

4. Run Scaling Tests:

- Perform both strong scaling (fixed system size, increasing cores/GPUs) and weak scaling (fixed system size per core/GPU, increasing total system size and resources) tests.

- Use a system size relevant to production runs (e.g., >30,000 atoms). Performance on very small systems (e.g., ~1,000 atoms) can be misleading due to overhead [37].

5. Measure and Compare:

- The key metric is wall-clock time to solution for a fixed amount of simulated time (e.g., nanoseconds per day).

- Analyze where each code spends its time (e.g., LAMMPS's log file vs. GROMACS's log file) to understand the source of any performance differences.

Table 2: Essential Software and Hardware Components

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Performance-Portable MD |

|---|---|---|

| Kokkos Core Library | Software Library | Provides the fundamental C++ abstractions for parallel execution and data management, enabling a single codebase to target multiple hardware platforms (CPUs, NVIDIA/AMD/Intel GPUs) [31]. |

| LAMMPS KOKKOS Package | Software Package / Module | An optional package within LAMMPS that uses the Kokkos library to make a large portion of LAMMPS's functionality performance-portable across diverse architectures [26]. |

| AMD MI250X (e.g., Frontier) | Hardware | An AMD GPU accelerator. LAMMPS-Kokkos uses the HIP backend to run on this architecture, which is the core of the Frontier exascale supercomputer [32] [34]. |

| NVIDIA H100 (e.g., Eos) | Hardware | An NVIDIA GPU accelerator. LAMMPS-Kokkos uses the CUDA backend to run on this architecture [32]. |

| Intel GPU Max (e.g., Aurora) | Hardware | An Intel GPU accelerator. LAMMPS-Kokkos uses the SYCL backend to run on this architecture [32]. |

| HIP FFT / cuFFT | Software Library | Vendor-specific Fast-Fourier Transform libraries. The LAMMPS PPPM long-range solver was ported to use hipFFT for AMD GPUs, mirroring its use of cuFFT on NVIDIA GPUs, to improve performance [34]. |

Multi-GPU and Multi-Node Parallelization Strategies for AMBER, NAMD, and GROMACS

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My multi-GPU NAMD run fails with "CUDA error...out of memory." What should I check?

This error indicates that the GPU's memory is insufficient for the assigned task [38]. First, verify that your system size is appropriate for the GPU's memory capacity. For a multi-GPU run, ensure the number of MPI processes per GPU is correctly configured. Using the +ignoresharing flag can help if not all devices are visible to each process, but the optimal solution is to adjust the number of processes to evenly divide the number of GPUs or specify a subset of devices with the +devices argument [38].

Q2: I am not getting good performance scaling when using 4 GPUs with AMBER. Is this normal? Scaling efficiency depends heavily on the system size. For large systems, scaling to 4 GPUs can be effective [39]. However, for many typical simulations, the scaling from 2 to 4 GPUs may not be linear and can sometimes be inefficient on modern hardware [39]. For the best overall throughput on a multi-GPU node, consider running multiple independent simulations concurrently, as the AMBER GPU code places minimal load on the CPU [39].

Q3: What is the most efficient way to use a node with 4 GPUs for a GROMACS simulation?

The most efficient strategy often involves running an ensemble of simulations (using the multi-dir approach) rather than using all 4 GPUs for a single simulation [40]. This better overlaps communication with computation. For a single simulation, you can assign multiple MPI ranks to a single GPU to overlap communications, CPU, and GPU execution more efficiently. Also, consider leaving bonded computation and/or update constraints to the CPU to utilize all available CPU cores [40].

Q4: What are the key hardware considerations for a multi-GPU molecular dynamics workstation? The key is a balanced design to avoid bottlenecks. This includes:

- Power Supply and Cooling: The system must be specced to handle the thermal and power load of multiple GPUs running flat out; unexpected shutdowns are a sign of a badly designed system [39].

- CPU: Prioritize processors with higher clock speeds over extreme core counts for optimal MD performance [41].

- GPUs: Modern NVIDIA GPUs like the RTX 4090, RTX 6000 Ada, and RTX 5000 Ada offer a good balance of CUDA cores and VRAM for different budget and performance tiers [41].

Q5: How do I enable direct communication between GPUs in GROMACS to reduce latency?

On systems with high-speed interconnects like NVLink, you can enable direct GPU communication by setting two environment variables before running mdrun [40]:

export GMX_GPU_DD_COMMS=1: Enables direct halo exchange between domains.export GMX_GPU_PME_PP_COMMS=1: Allows Particle-Particle (PP) and Particle-Mesh Ewald (PME) ranks to communicate directly. Use this feature cautiously and report your experiences to the GROMACS developers, as it is not as thoroughly tested as other features [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Resolving "Out of Memory" Errors in NAMD

Symptoms:

- Simulation fails with fatal errors like

CUDA error cudaMallocHost... out of memory[38]. - Error message indicates that the number of devices is not a multiple of the number of processes [38].

Diagnosis and Solutions: