NVT Ensemble in Vacuum Simulations: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the application of the NVT (Canonical) ensemble in vacuum simulations for biomedical and drug discovery research.

NVT Ensemble in Vacuum Simulations: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the application of the NVT (Canonical) ensemble in vacuum simulations for biomedical and drug discovery research. It covers the foundational principles of the NVT ensemble, where the number of particles, volume, and temperature are held constant, explaining its critical role in stabilizing systems after energy minimization and before production runs. The article details methodological protocols for setting up NVT simulations in vacuum environments, highlighting applications in studying drug-membrane interactions, protein-ligand complexes, and material properties. A significant focus is placed on troubleshooting common pitfalls, such as negative pressure and thermalization failures, offering practical optimization strategies. Finally, the article outlines rigorous validation techniques and comparative analyses with other ensembles, establishing a framework for ensuring the reliability and physical accuracy of simulation results to advance rational drug design.

Understanding the NVT Ensemble: Why Constant Volume and Temperature Matter in Vacuum Simulations

The NVT ensemble, also known as the canonical ensemble, is a fundamental concept in statistical mechanics and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. It describes a system characterized by a constant number of particles (N), a constant volume (V), and a constant temperature (T). This ensemble is particularly valuable for studying material properties under conditions where volume changes are negligible, making it ideal for investigating processes like ion diffusion in solids, adsorption phenomena, and reactions on surfaces or clusters where the simulation box dimensions remain fixed [1].

In the NVT ensemble, the system is not isolated but can exchange energy with a surrounding virtual heat bath, which maintains the temperature around an equilibrium value. Unlike the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble where total energy is conserved, the temperature in an NVT simulation will naturally fluctuate around a set point, and the role of the thermostat is to ensure these fluctuations are of the correct size and that the average temperature is accurate [2] [3]. This setup mimics realistic experimental conditions for many material science and biological applications where temperature is controlled, but volume is fixed.

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundation

The NVT ensemble is defined by its three conserved quantities: the number of particles (N), the volume of the system (V), and the temperature (T). The fixed volume means that the simulation cell's size and shape do not change during the simulation. Consequently, there is no control over pressure, and its average value will depend on the initial configuration provided for the system, such as the lattice parameters in the POSCAR file for VASP simulations [2].

The temperature, unlike volume, is not a static property at the atomic scale. In MD simulations, the "instantaneous temperature" is computed from the total kinetic energy of the system via the equipartition theorem. The primary goal of a thermostat in an NVT simulation is not to keep the temperature perfectly constant, but to ensure that the average temperature over time is correct and that the fluctuations in temperature are of the correct magnitude for the simulated system [3]. For small systems, these fluctuations can be significant, and it is only by averaging over a sufficiently long time that a stable temperature emerges.

Thermostats: Methods for Temperature Control

A thermostat is the algorithmic component that couples the system to a virtual heat bath. Several thermostat algorithms are available, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The choice of thermostat depends on the desired balance between accurate ensemble sampling and minimal interference with the system's natural dynamics.

Table 1: Common Thermostats in NVT Ensemble Simulations

| Thermostat | MDALGO (VASP) | Key Principle | Strengths | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosé-Hoover [2] [4] | 2 | Extends the system with a fictitious thermal reservoir. | Generally reliable; reproduces correct canonical ensemble. | Can exhibit persistent temperature oscillations in some cases. |

| Nosé-Hoover Chain [2] | 4 | Uses a chain of thermostats for improved control. | Mitigates oscillations from standard Nosé-Hoover. | Requires setting chain length (e.g., default of 3 is often sufficient). |

| Andersen [2] | 1 | Stochastic collisions reassign particle velocities. | Good for sampling conformational space. | Can disrupt the natural dynamics of the system. |

| Langevin [2] [4] | 3 | Applies friction and stochastic forces to each particle. | Tight temperature control; good for equilibration. | Suppresses natural dynamics; not ideal for measuring diffusion. |

| CSVR [2] | 5 | Stochastic velocity rescaling (Canonical Sampling Through Velocity Rescaling). | Good sampling properties. | Period parameter (e.g., CSVR_PERIOD) needs to be set. |

| Berendsen [4] [1] | N/A | Scales velocities to rapidly approach target temperature. | Fast and stable convergence. | Does not produce a correct canonical ensemble; best for equilibration. |

| Bussi-Donadio-Parrinello [4] | N/A | Stochastic variant of Berendsen thermostat. | Correctly samples the canonical ensemble. | A recommended upgrade over the standard Berendsen method. |

Practical Thermostat Selection and Configuration

The choice of thermostat and its parameters can significantly impact the results of a simulation. For production runs where accurate sampling of the canonical ensemble is required, the Nosé-Hoover thermostat is often the recommended choice [4]. Its key parameter, SMASS in VASP, determines the virtual mass of the thermal reservoir and affects the oscillation frequency of the temperature [2].

The strength of the coupling to the heat bath is controlled by parameters like the thermostat timescale (or its inverse, the coupling constant). A tight coupling (short timescale) forces the system temperature to closely follow the target but can interfere with the system's natural dynamics. A weak coupling (long timescale) minimizes this interference but may take longer to equilibrate. For precise measurement of dynamical properties, a weak coupling or even a switch to the NVE ensemble after equilibration is advisable [4].

Application Notes for Vacuum and Surface Simulations

The NVT ensemble is particularly well-suited for simulations where the volume is naturally fixed. A prime example is the study of processes in a vacuum environment or on solid surfaces, often modeled using a slab geometry with a large vacuum layer to separate periodic images. In such setups, the volume of the simulation box must remain constant.

- Adsorption and Reactions on Surfaces: When modeling the adsorption of molecules or catalytic reactions on a solid surface (e.g., a metal or oxide slab), the underlying lattice of the slab is typically held rigid or has fixed lattice parameters. Using the NVT ensemble ensures that the surface area and the height of the vacuum layer remain constant throughout the simulation, allowing researchers to study the dynamics of the adsorbates without the influence of a fluctuating cell [1].

- Cluster Simulations: Studying isolated molecules or nanoclusters in vacuum is another key application. The simulation box must be large enough to prevent interactions between the cluster and its periodic images. The NVT ensemble fixes this box size, while the thermostat controls the temperature of the cluster, which is essential for simulating phenomena like thermal unfolding or studying finite-temperature properties [1].

A critical prerequisite for NVT simulations is ensuring the system is well-equilibrated at the desired volume. It is "often desirable to equilibrate the lattice degrees of freedom, for example, by running an NpT simulation or by performing a structure and volume optimization" prior to the NVT production run [2]. This ensures that the fixed volume in the NVT simulation is representative of the thermodynamic state point of interest.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Below is a detailed protocol for setting up and running an NVT molecular dynamics simulation for a system such as a molecule adsorbed on a surface in a vacuum.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for an NVT MD Simulation

| Component | Description | Function in the Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Atomic Structure | A file containing the initial coordinates of all atoms (e.g., POSCAR, .xyz). | Defines the starting configuration of the system (adsorbate, surface slab, etc.). |

| Interatomic Potential | A force field, neural network potential (e.g., EMFF-2025 [5]), or DFT calculator. | Describes the energetic interactions between atoms, determining the forces. |

| Simulation Software | MD package such as VASP [2], QuantumATK [4], ASE [1], or GROMACS [3]. | Provides the engine to integrate equations of motion and apply ensemble constraints. |

| Thermostat Algorithm | e.g., Nosé-Hoover, Langevin, or CSVR. | Maintains the system temperature at the desired setpoint. |

| Periodic Boundary Conditions | Defined by the simulation cell vectors. | Mimics an infinite system and avoids surface effects; crucial for slab-vacuum models. |

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: System Preparation and Geometry Optimization

- Construct the initial atomic configuration, for example, a slab structure with a vacuum layer for surface studies.

- Perform a volume optimization (e.g., using

IBRION = 1 or 2andISIF > 2in VASP) or a short NpT simulation to find the equilibrium volume at the target temperature [2]. This is a critical step to ensure the fixed volume in the subsequent NVT run is physically meaningful.

Step 2: Equilibration in the NVT Ensemble

- Start the MD simulation using the optimized volume. In the input file (e.g., INCAR for VASP), set the parameters for an NVT run:

IBRION = 0(to choose molecular dynamics)MDALGO = 2(to select the Nosé-Hoover thermostat, for example)ISIF = 2(to ensure the stress tensor is computed but the volume/shape is not changed)TEBEG = 300(set the target temperature in Kelvin)SMASS = 1.0(set the virtual mass for the Nosé-Hoover thermostat) [2]

- Use a reasonable time step (e.g., 0.5 to 2.0 femtoseconds), ensuring it is small enough to capture the fastest atomic vibrations [4].

- Assign initial velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution corresponding to the target temperature.

- Run the simulation until key observables (e.g., potential energy, temperature) plateau, indicating equilibration.

Step 3: Production Simulation and Trajectory Analysis

- Continue the simulation with the same NVT parameters to collect trajectory data for analysis.

- Ensure that the

Log Intervalor equivalent setting is appropriate to write snapshots to disk without generating excessively large files [4]. - Analyze the trajectory to compute properties of interest, such as:

- Radial distribution functions

- Mean-squared displacement for diffusion coefficients

- Structural order parameters

- Adsorbate binding configurations

Critical Considerations and Best Practices

- Temperature Fluctuations are Normal: The instantaneous temperature in an MD simulation will fluctuate. The role of the thermostat is to ensure these fluctuations are correct for the ensemble, not to eliminate them. Pressure can fluctuate even more dramatically, with variations of hundreds of bar being typical, especially in small systems [3].

- Avoid Over-Coupling the Thermostat: Using a thermostat that is too "strong" (i.e., a very short coupling constant) can artificially suppress the natural dynamics of the system. This is particularly important if the goal is to compute time-dependent properties like diffusion constants [4].

- Do Not Over-Split Thermostat Groups: It is generally not a good practice to use separate thermostats for every component of your system (e.g., one for a small molecule, another for protein, and another for water). A group must be of sufficient size to justify its own thermostat. For a typical simulation, using

tc-grps = Protein Non-Proteinis usually best [3]. - Interpreting Average Structures: Be cautious when calculating an "average structure" from an NVT trajectory. If the system samples multiple distinct metastable states, the average position may be a physically meaningless point halfway between these states, potentially showing unphysical bond lengths or geometries [3].

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the canonical (NVT) ensemble is crucial for studying material properties under conditions of constant particle number (N), constant volume (V), and constant temperature (T). This ensemble is particularly valuable for investigating systems where volume changes are negligible, such as ion diffusion in solids, adsorption and reaction processes on surfaces and clusters, and simulations in vacuum environments [1] [2]. Maintaining a constant temperature in these systems requires sophisticated algorithms known as thermostats, which mimic the energy exchange between the simulated system and a hypothetical heat bath.

Within the context of vacuum simulations research—where systems lack implicit solvent effects and often involve smaller, more constrained environments—the selection of an appropriate thermostat becomes critically important. Different thermostats vary in their theoretical foundations, numerical stability, and ability to reproduce correct statistical mechanical ensembles. This application note provides a detailed comparison of three predominant thermostats—Berendsen, Nosé-Hoover, and Langevin—with specific emphasis on their implementation, performance characteristics, and suitability for vacuum simulation scenarios commonly encountered in materials science and drug development research.

Thermostat Comparison Tables

Key Characteristics and Applications

Table 1: Comparative overview of thermostat properties and typical use cases.

| Thermostat | Algorithm Type | Ensemble Correctness | Primary Advantages | Recommended Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berendsen | Deterministic, velocity rescaling | Does not guarantee correct NVT ensemble [6] | Simple implementation, fast convergence, good numerical stability [1] | System equilibration, preliminary heating stages [7] |

| Nosé-Hoover | Deterministic, extended Lagrangian | Reproduces correct NVT ensemble in most cases [1] | Universally applicable, time-reversible, suitable for production simulations [7] | Production runs for larger systems, trajectory analysis [1] [7] |

| Langevin | Stochastic, random forces | Guarantees Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution [6] [8] | Effective for small systems, enhances sampling, good for mixed phases [1] [7] | Free energy calculations, small systems, vacuum simulations [8] [7] |

Mathematical Foundations and Parameters

Table 2: Mathematical formulation and key implementation parameters for each thermostat.

| Thermostat | Fundamental Equation | Key Control Parameters | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Berendsen | Scales velocities by factor λ = [1 + (Δt/τ)(T₀/T - 1)]¹/² | τ (coupling constant) - determines strength of temperature coupling [1] | Can cause "flying ice-cube" effect (unphysical energy transfer) [6] |

| Nosé-Hoover | Extended system with virtual mass: d²η/dt² = (T/T₀ - 1) | SMASS (virtual mass parameter) or time constant [2] [7] | Requires initialization; may not thermalize small systems with harmonic modes [7] [9] |

| Langevin | MẌ = -∇U(X) - γẊ + √(2γkBT)R(t) [8] | γ (damping coefficient/friction) [8] | Stochastic nature prevents reproducible trajectories; mimics viscous damping [1] [8] |

Detailed Thermostat Protocols

Berendsen Thermostat Protocol

The Berendsen thermostat employs a weak-coupling algorithm that scales velocities to maintain temperature, making it particularly useful for rapid equilibration phases of simulation.

Detailed Methodology:

- Initialization: Prepare the system configuration. For vacuum simulations, ensure appropriate periodicity and sufficient vacuum padding to prevent spurious interactions between periodic images [9] [10].

- Parameter Setting: Set the target temperature (T₀) and the coupling constant (τ). The parameter τ represents the time constant of the thermostat, with smaller values resulting in stronger coupling. A typical value is 0.1-1.0 ps [1].

- Integration: At each MD time step (Δt):

- Calculate the current instantaneous temperature (T) from the kinetic energy.

- Compute the scaling factor λ = [1 + (Δt/τ)(T₀/T - 1)]¹/².

- Scale all velocities by λ: vᵢ → λvᵢ.

- Duration: For equilibration protocols, apply the Berendsen thermostat for 50-100 ps to smoothly bring the system to the target temperature before switching to a production thermostat like Nosé-Hoover [7].

Nosé-Hoover Thermostat Protocol

The Nosé-Hoover thermostat introduces an extended Lagrangian formulation with a dynamic variable representing the heat bath, providing a deterministic approach that generates a correct canonical ensemble.

Detailed Methodology:

- System Setup: Begin with an equilibrated system, preferably pre-heated using a method like Berendsen or velocity rescaling.

- Parameter Selection:

- Integration: Utilize a time-reversible integrator such as velocity Verlet. The equations of motion couple the particle velocities to the thermostat variable, allowing dynamic energy exchange between the system and the thermal reservoir [7].

- Equilibration Verification: Monitor the potential energy and temperature until they stabilize around the set point with small fluctuations. For a 200-atom system in vacuum, this typically requires 50,000-150,000 iterations [6] [9].

- Production Run: Continue the simulation in the NVT ensemble for the desired production length, ensuring the Nosé-Hoover chain variable moves chaotically, indicating proper equilibration.

Langevin Thermostat Protocol

The Langevin thermostat applies a stochastic damping force combined with random impulses, making it particularly effective for small systems and vacuum environments where other thermostats may struggle.

Detailed Methodology:

- Initial Configuration: Prepare the system, noting that Langevin is especially suitable for vacuum simulations as it doesn't rely on continuous coupling to a large bath [7] [11].

- Parameterization:

- Set the target temperature (T).

- Choose a damping coefficient (γ). For vacuum simulations, a relatively low γ (e.g., 1-10 ps⁻¹) is often appropriate to minimize unphysical damping while maintaining temperature control [8] [7].

- In LAMMPS: Use the

fix langevincommand [6]. - In ASE: Implement using the

Langevinclass fromase.mdmodule [1].

- Dynamics Propagation: At each time step:

- Apply the deterministic forces: -∇U(X).

- Apply the frictional damping force: -γv.

- Add the random force: √(2γkₚT/Δt)ξ, where ξ is Gaussian white noise [8].

- Trajectory Analysis: Note that the stochastic nature prevents exact trajectory reproducibility. Focus on ensemble-averaged properties rather than individual particle paths [1].

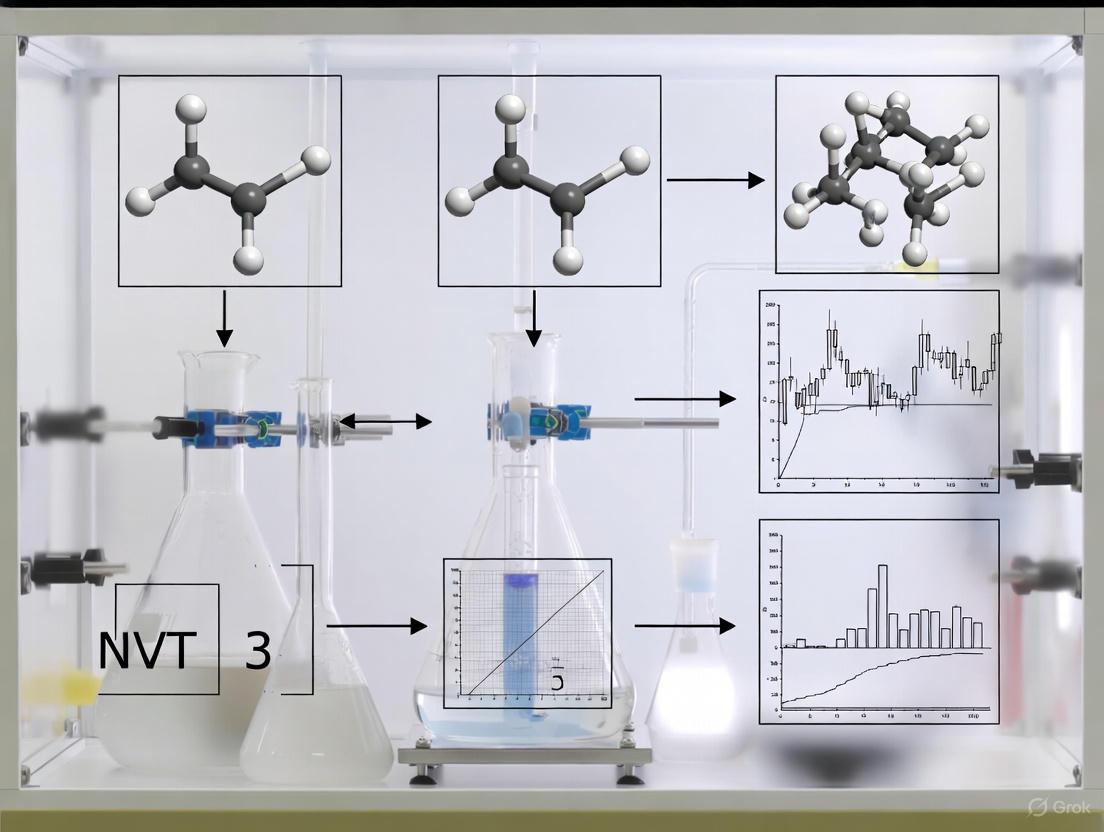

Workflow Visualization

Thermostat Selection Logic

General NVT-MD Simulation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools for molecular dynamics simulations in vacuum environments.

| Tool/Solution | Function/Purpose | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| ASE (Atomistic Simulation Environment) | Python framework for setting up, running, and analyzing simulations [1] | NVTBerendsen, NVTNoseHoover classes for thermostat implementation [1] |

| LAMMPS | MD simulator with extensive thermostat options [6] | fix nvt, fix langevin commands for temperature control [6] |

| VASP | Ab initio MD package for electronic structure calculations [2] | MDALGO=2 for Nosé-Hoover, MDALGO=3 for Langevin dynamics [2] |

| GROMACS | MD package with comprehensive thermostat implementations [12] | integrator=sd for stochastic dynamics, integrator=md-vv with Nose-Hoover coupling [12] |

| OpenMM | Toolkit for MD simulations with GPU acceleration [11] | LangevinMiddleIntegrator for vacuum and solution simulations [11] |

| Velocity Verlet Integrator | Time-reversible algorithm for integrating equations of motion [12] | Used with Nosé-Hoover thermostat for accurate dynamics propagation [12] |

The selection of an appropriate thermostat for NVT ensemble simulations, particularly in vacuum environments, requires careful consideration of system size, desired properties, and methodological constraints. The Berendsen thermostat serves as an effective tool for rapid equilibration but should be avoided in production phases due to its failure to generate a correct canonical ensemble. The Nosé-Hoover thermostat provides a robust, deterministic approach suitable for most production simulations, especially for larger systems with sufficient degrees of freedom. For vacuum simulations involving small systems or cases where enhanced sampling is required, the Langevin thermostat offers distinct advantages despite its stochastic nature. By matching thermostat capabilities to specific research requirements—particularly in pharmaceutical and materials science applications—researchers can ensure both the efficiency and statistical validity of their molecular simulations.

The canonical (NVT) ensemble is a cornerstone of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, maintaining a constant Number of atoms (N), constant Volume (V), and a Temperature (T) fluctuating around an equilibrium value. This ensemble is particularly indispensable for studies conducted in vacuum conditions, where it facilitates proper system equilibration and enables the investigation of intrinsic material properties without the complicating effects of a solvent or pressure variables. Within the context of vacuum simulations, the NVT ensemble ensures that the energy distribution among the system's degrees of freedom corresponds to a desired temperature, which is critical for achieving physically meaningful results before proceeding to production runs or for studying processes where volume is a controlled parameter. Its application ranges from preparing a system for subsequent analysis in other ensembles to directly probing surface phenomena and nanoscale interactions where the system size inherently limits the validity of a barostat.

Theoretical Foundation and Practical Implementation

Thermostat Selection for NVT Simulations

In NVT simulations, the temperature is controlled by a thermostat, which acts as a heat bath. The choice of thermostat can influence the quality of the dynamics and the reliability of the sampled ensemble. Several thermostats are available in modern MD software packages, each with distinct characteristics and suitable application domains, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Common Thermostats for NVT Ensemble Simulations

| Thermostat | MDALGO (VASP) | Key Characteristics | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nosé-Hoover | 2 | Deterministic; extended Lagrangian. | General purpose; larger systems. |

| Andersen | 1 | Stochastic; random velocity rescaling. | Rigid systems; rapid equilibration. |

| Langevin | 3 | Stochastic; includes friction term. | Biomolecules; systems with friction. |

| CSVR | 5 | Stochastic; canonical sampling. | Accurate canonical distribution. |

For instance, in VASP, an NVT simulation using the Nosé-Hoover thermostat is set up with MDALGO = 2 and requires the SMASS tag to define the virtual mass for the thermostat [2]. It is crucial to set ISIF < 3 to ensure the volume remains fixed throughout the simulation [2].

Workflow for a Typical NVT Simulation in Vacuum

The following diagram illustrates the standard protocol for setting up and running an NVT simulation in a vacuum environment, from initial structure preparation to final analysis.

Diagram 1: Workflow for an NVT simulation in vacuum. The standard path involves energy minimization followed directly by NVT equilibration. An optional NPT pre-equilibration can be used to first obtain a specific box volume.

Key Application Notes and Protocols

Application Note 1: System Equilibration Preceding Production Runs

- Protocol Objective: To achieve a thermally equilibrated system with stable energy distributions for subsequent production simulations in the NVE ensemble or other studies.

- Rationale: Before any production MD run, a system must be equilibrated to ensure that the temperature and energy distributions have stabilized. In vacuum, where there is no solvent to provide a natural heat bath, the NVT ensemble is the primary method for this thermalization. This step is crucial after processes like energy minimization, which removes steric clashes but results in a configuration with zero kinetic energy.

- Detailed Protocol:

- Initial Structure: Use an energy-minimized structure as the starting point.

- Simulation Box: Define a vacuum box with sufficient padding to avoid periodic image interactions. For surface slabs, a vacuum gap of >10 Å is often used, but ~18 Å may be necessary to minimize spurious self-interactions across the periodic boundary [9].

- Thermostat Selection: Choose an appropriate thermostat. The Nosé-Hoover thermostat (

MDALGO=2in VASP) is a robust deterministic choice for many systems [2]. For small systems with discrete phonon spectra, stochastic thermostats like CSVR may thermalize more effectively [9]. - Parameter Setup: Set the target temperature (

TEBEG), the number of steps (NSW), and the time step (POTIM). A common initial equilibration runs for 100-500 ps. - Equilibration Criteria: Monitor the potential energy and temperature of the system. The simulation is considered equilibrated when these properties fluctuate around a stable average value.

Application Note 2: Surface and Interface Studies

- Protocol Objective: To investigate the structure, dynamics, and reactivity of surfaces and thin films in isolation or under controlled deposition.

- Rationale: The NVT ensemble is ideal for surface science studies because the volume (and thus the surface area) is fixed. This allows for the direct investigation of phenomena like molecular orientation on substrates, which is a critical factor in organic semiconductor performance [13], or the erosion of materials by plasma [14] [15].

- Detailed Protocol:

- Surface Model Construction: Create a slab model of the surface with a thickness of several atomic layers. The bottom layer(s) may be constrained to their bulk positions to mimic a semi-infinite solid.

- Vacuum Layer Introduction: Add a vacuum layer along the z-axis (non-periodic direction) that is thick enough to prevent interactions between periodic images of the slab. As noted in [9], a larger vacuum gap (~18 Å) can help avoid unphysical, resonant vibrational modes that hinder proper thermalization.

- Deposition or Interaction Simulation: For deposition studies, molecules can be randomly oriented and introduced into the vacuum above the surface [13]. For erosion studies, reactive species like atomic oxygen can be directed at the surface with specific kinetic energies [14].

- NVT Simulation Run: Perform the MD simulation in the NVT ensemble to model the adsorption, orientation, or reaction of molecules/atoms with the surface at a specific temperature. The fixed volume is essential for calculating accurate surface densities and adsorption geometries.

- Analysis: Key analyzable properties include:

- Molecular Orientation: Calculate the angle (θ) of molecular transition dipole moments relative to the substrate normal and the orientation order parameter, ( S = \frac{1}{2}(3\langle \cos^2 \theta \rangle - 1) ) [13].

- Damage Depth/Erosion Yield: Track the number of sputtered substrate atoms over time [14] [15].

Application Note 3: Tensile Deformation and Mechanical Failure

- Protocol Objective: To compute the mechanical response and tensile strength of materials or hybrid interfaces under uniaxial strain.

- Rationale: Tensile tests using MD are naturally performed in the NVT ensemble. The simulation box is deformed at a constant strain rate along one axis while the transverse dimensions are allowed to relax, effectively simulating a Poisson contraction. This protocol is used for systems ranging from bulk polymers to polymer-calcite interfaces [16].

- Detailed Protocol:

- System Equilibration: First, equilibrate the entire system (e.g., a polymer-calcite composite) in the NVT ensemble at the target temperature and zero pressure until energy stabilization is achieved [16].

- Deformation Setup: Apply a uniaxial strain by progressively elongating the simulation box along the tensile direction at a constant strain rate (e.g., 0.001 ps⁻¹). The transverse dimensions of the box are typically kept constant or controlled to maintain zero lateral pressure.

- Stress Calculation: At each deformation step, allow the system to relax briefly while calculating the stress tensor. The component of the stress tensor along the strain direction is the key metric.

- Failure Analysis: Continue the deformation until material failure (a sharp drop in stress) is observed. Analyze the stress-strain curve to extract properties like Young's modulus, yield strength, and ultimate tensile strength. The failure mechanism (e.g., chain slippage vs. bond breaking) can be visualized.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key "Research Reagent Solutions" for NVT Vacuum Simulations

| Item / Software | Function / Description | Example in Application |

|---|---|---|

| VASP | A package for atomic-scale materials modeling, e.g., from first principles. | Used for NVT MD of surfaces with MDALGO=2 and ISIF=2 [2]. |

| GROMACS | A versatile MD simulation package for biomolecular and materials systems. | Forum users discuss NVT equilibration protocols to fix negative pressure [17]. |

| ReaxFF | A reactive force field for MD simulations of chemical reactions. | Models bond breaking in fused silica under oxygen plasma bombardment [14]. |

| IFF-R | A reactive force field using Morse potentials for bond breaking. | Enables simulation of material failure while being ~30x faster than ReaxFF [18]. |

| CHARMM/AMBER | Biomolecular force fields for proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids. | Compatible with IFF-R for simulating reactive processes in biomolecules [18]. |

Critical Considerations and Troubleshooting

A common challenge in NVT simulations within a vacuum is achieving proper thermalization, especially for small systems. When a system is too small or has a large vacuum gap, its phonon spectrum can be too discrete, causing thermostats like Nosé-Hoover to fail in redistributing energy effectively between the system's harmonic vibrational modes [9]. In such cases, switching to a stochastic thermostat (e.g., CSVR or Andersen) can improve thermalization.

Another frequent issue, particularly in explicit-solvent MD, is encountering large negative pressures after NVT equilibration, which often indicates an simulation box that is too large for the number of particles [17]. The recommended solution is not to adjust the box size manually within an NVT framework, but to first run an NPT equilibration at the target pressure. This allows the barostat to find the correct density, after which one can switch back to NVT for production using the equilibrated box dimensions [17].

The canonical (NVT) ensemble, which maintains a constant Number of atoms (N), constant Volume (V), and constant Temperature (T), serves as a critical bridge between energy minimization and production simulations in molecular dynamics. This equilibration phase allows a system to achieve a thermally stable state consistent with a target temperature while preserving the system volume. Within vacuum simulation research, particularly for systems with explicit vacuum interfaces (e.g., vacuum/surfactant/water systems), NVT equilibration plays a specialized role by permitting energy redistribution and thermal stabilization without altering the simulation box dimensions [19] [1]. This is especially vital for studies of surface phenomena, adsorption, and biomolecular conformations in diluted or interfacial environments where maintaining a specific geometry and volume is paramount. The process effectively prepares the system for subsequent isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble simulations or for production runs where volume control remains essential, such as in simulating ion diffusion in solids or reactions on slab-structured surfaces and clusters [1].

Theoretical Foundations of NVT Equilibration

Following energy minimization, which relieves steepest gradients and steric clashes, a system possesses minimal potential energy but lacks appropriate kinetic energy and a physically realistic distribution of velocities. The NVT equilibration phase addresses this by coupling the system to a thermostat, a computational algorithm designed to maintain the target temperature. Several thermostat methods are commonly implemented, each with distinct advantages and limitations for vacuum simulation research [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Thermostat Methods in NVT Simulations

| Thermostat Method | Theoretical Basis | Advantages | Limitations | Suitability for Vacuum Simulations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berendsen [1] | Scales velocities uniformly towards a target temperature with an exponential decay. | Simple, fast convergence. | Produces unphysical velocity distributions; does not generate a correct canonical ensemble. | Good for initial, rapid equilibration but not for production. |

| Nosé-Hoover [1] | Introduces an extended Lagrangian with a fictitious variable representing a heat bath. | Reproduces the correct canonical ensemble; widely applicable. | Can exhibit non-ergodic behavior for small or stiff systems. | Excellent for most systems, including vacuum interfaces. |

| Langevin [1] | Applies random and frictional forces to individual atoms. | Good for mixed phases and dissipative systems; controls temperature locally. | Trajectories are not deterministic (not reproducible). | Ideal for solvated systems and preventing "flying ice cube" effect. |

The core challenge during NVT equilibration, especially in systems with vacuum interfaces or large density variations, is achieving thermal stability without inducing artificial density artifacts. The fixed volume constraint means that if the initial solvation density is incorrect, the system cannot adjust to reach the proper equilibrium density for the given temperature, potentially leading to the formation of vacuum bubbles or empty regions as water molecules coalesce [19] [20]. This phenomenon is a classic manifestation of surface tension at work in a fixed volume [20].

Detailed Experimental Protocol for NVT Equilibration

This protocol is designed for a complex interface system, such as vacuum/surfactant/water/surfactant/vacuum, using the GROMACS simulation package, a standard in biomolecular simulations [19] [21].

System Setup Preceding NVT

- Construct the Molecular Assembly: Build the initial configuration, placing surfactants at the desired interface with vacuum layers.

- Energy Minimization: Run a steepest descent or conjugate gradient minimization to remove any steric clashes and achieve a minimum energy configuration. A sample GROMACS MDP file configuration is provided below.

- Initial Velocity Generation: Assign initial velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at the target temperature (e.g., 294.15 K) at the beginning of the NVT equilibration [19].

NVT Equilibration Parameters

The following configuration outlines key parameters for a successful NVT equilibration run in GROMACS, incorporating lessons from common pitfalls [19].

Workflow and Decision Logic

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for NVT equilibration and the subsequent steps based on the outcome, which is critical for avoiding instability.

Troubleshooting Common NVT Equilibration Artifacts

A frequently encountered issue in interface and vacuum simulations is the formation of holes or bubbles within the solvent region during NVT equilibration [19] [20]. These are not errors but a physical consequence of the fixed volume constraint and an initially suboptimal solvent density.

- Symptom: Empty regions or voids appear in the solvent (e.g., water) region in the output trajectory, while the overall box size remains unchanged.

- Root Cause: The NVT ensemble fixes the volume. If the initial solvation step placed too few solvent molecules in the box to achieve the correct density for the target temperature, or if strong positional restraints prevent the system from relaxing, the solvent will naturally coalesce due to cohesive forces, leaving behind vacuum bubbles [19] [20]. As one expert notes, "It’s NVT, so the box is not changing, and once you turn on the dynamics... the water molecules are going to 'stick' to each other" [19].

- Solutions:

- Proceed to NPT: The most straightforward solution is to continue with NPT equilibration, which allows the box size to adjust and the density to relax to its correct equilibrium value, thereby collapsing the bubbles [19] [20].

- Modify Restraints: Overly strong or extensive positional restraints can frustrate the system. Running a short NPT equilibration without position restraints on key molecules (e.g., surfactants) can allow the system to find a natural density before applying restraints for subsequent steps [19].

- Improved System Preparation: Equilibrate a pure solvent box first to its correct density in NPT. Then, use this pre-equilibrated solvent when solvating the solute (e.g., surfactant/protein) system. This ensures a much better starting density [19].

- Alternative Solvation: Manually add more solvent molecules to the dry system to compensate for the underestimated density, taking care not to insert them too close to the solutes of interest [20].

Another common warning encountered after NVT, when proceeding to NPT, is "Pressure scaling more than 1%". This strongly indicates that the system density from the NVT phase is far from equilibrium, and the pressure coupling must work aggressively to correct it. Using a robust barostat like C-rescale is recommended in such cases [19].

Research Applications and Case Studies

NVT equilibration is a foundational step across numerous research domains. The following table summarizes key applications and the specific role of NVT in each context.

Table 2: Research Applications of NVT Equilibration in Vacuum and Interface Studies

| Field of Study | System Description | Role & Importance of NVT Equilibration | Key Findings Enabled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Thermal Stability [21] | Wild-type vs. mutant BrCas12b protein (apo form). | To equilibrate the system at ambient and elevated temperatures (e.g., 300K, 400K) before analyzing unfolding. | Revealed increased flexibility in the PAM-interacting domain of the mutant at high temperatures, providing insights for CRISPR-based diagnostic design. |

| Peptide Mutational Analysis [22] | Neuropeptide Y (NPY) and its tyrosine-to-phenylalanine mutants. | To thermally stabilize the system post-minimization for subsequent production runs analyzing hairpin stability. | Uncovered unusually large increases in melting temperatures (ΔTm ~20-30°C) in mutants, linked to enhanced self-association into hexamers. |

| Surface Science & Catalysis [1] | Adsorption and reactions on slab-structured surfaces or clusters. | To maintain a constant surface area and volume while bringing the system to the reaction temperature. | Enables the study of reaction mechanisms and binding energies on well-defined surfaces without volume fluctuations. |

| Interface Systems [19] | Vacuum/Surfactant/Water/Surfactant/Vacuum. | To achieve thermal stability for the entire system while keeping the interface geometry and vacuum layer sizes fixed. | Allows the study of surfactant behavior at interfaces before allowing the box volume to relax in a subsequent NPT step. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Tools for NVT Simulations in Biomolecular Research

| Tool Name | Category | Function in NVT Equilibration |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [19] [21] | MD Software Suite | A high-performance molecular dynamics package used to perform energy minimization, NVT/NPT equilibration, and production simulations. |

| CHARMM36m [21] | Force Field | Provides parameters for the potential energy function, defining bonded and non-bonded interactions for proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. |

| TIP3P [21] | Water Model | A rigid, three-site model for water molecules that is commonly used with the CHARMM force field for solvating systems. |

| V-Rescale Thermostat [19] [21] | Algorithm | A modified Berendsen thermostat that provides a correct canonical ensemble by stochastic rescaling of kinetic energy. |

| LINCS [21] | Algorithm | Constrains bond lengths to hydrogen atoms, allowing for a longer time step (e.g., 2 fs) during the simulation. |

| Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) [21] | Algorithm | Handles long-range electrostatic interactions accurately in systems with periodic boundary conditions. |

| Position Restraints [19] | Simulation Technique | Used to restrain heavy atoms of solutes (e.g., proteins, surfactants) to their initial positions, allowing the solvent to relax around them. |

Implementing NVT Vacuum Simulations: Protocols for Drug Discovery and Biomolecular Research

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the canonical (NVT) ensemble, which maintains a constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature, serves as a critical bridge between energy-minimized structures and production simulations. This ensemble is particularly crucial in vacuum simulations research, where it allows the system to reach the desired temperature and stabilize its kinetic energy distribution without the complicating factors of pressure coupling. For drug development professionals, proper NVT equilibration ensures that simulated protein-ligand complexes or small molecules in solvent-free environments have achieved thermal stability before proceeding to advanced sampling or production runs, thereby providing more reliable data for binding affinity predictions or conformational analysis.

Theoretical foundations of NVT MD involve integrating Newton's equations of motion while controlling temperature using specialized algorithms. As described in MD theory, the simulation "generates successive configurations of a given molecular system, by integrating the classical laws of motion as described by Newton" [23]. The temperature is maintained through thermostats that scale velocities or couple the system to an external heat bath, with the NVT ensemble being "applied when the volume change is negligible for the target system" [1]. In the context of vacuum simulations, this is particularly relevant as the absence of solvent reduces system complexity while maintaining control over thermal fluctuations.

Theoretical Framework: NVT Ensemble and Thermostat Selection

The NVT ensemble, also known as the canonical ensemble, represents a fundamental statistical mechanical distribution where the number of particles, system volume, and temperature remain constant. This ensemble is ideally suited for systems where volume changes are negligible, such as solid-state materials, confined systems, or vacuum simulations where periodic boundary conditions may not be applied [1]. In drug discovery applications, NVT equilibration is frequently employed for systems where maintaining a specific density is not the primary concern, but controlling temperature is essential for replicating experimental conditions or preparing the system for subsequent simulation stages.

Several thermostat algorithms are available for maintaining constant temperature in MD simulations, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

- Berendsen Thermostat: Provides exponential relaxation of the system temperature toward the desired value with good numerical stability. It uniformly scales atomic velocities, which can sometimes suppress natural temperature fluctuations [24] [1].

- Nosé-Hoover Chains (NHC): Extends the Nosé-Hoover thermostat with multiple thermostats coupled in series, typically producing more correct canonical sampling compared to Berendsen. The

tdampparameter (τₜ) determines the first thermostat mass as Q = NₑᵣₑₑkBTₛₑₜτₜ², where τₜ corresponds to the period of characteristic oscillations [24]. - Langevin Dynamics: Applies random forces and friction to individual atoms, providing good temperature control even for heterogeneous systems. However, its stochastic nature makes trajectories non-reproducible, limiting its use for precise pathway analysis [1].

For vacuum simulations of biomolecular systems, the Nosé-Hoover Chains thermostat often provides the best balance between accurate sampling and numerical stability, particularly for well-equilibrated systems where natural temperature fluctuations are important.

Experimental Protocol: Step-by-Step Workflow

System Preparation and Energy Minimization

Before initiating NVT equilibration, proper system preparation and energy minimization are essential to remove steric clashes and unrealistic geometries that could destabilize the dynamics.

Initial Structure Preparation: Obtain or generate the initial molecular structure. For proteins, this may involve downloading from the RCSB PDB, ensuring proper protonation states, and removing crystallographic waters and heteroatoms unless specifically relevant to the study [23]. For small molecules or drug-like compounds, ensure proper geometry optimization and assignment of partial charges compatible with your chosen force field.

Force Field Selection: Choose an appropriate force field for your system. For biomolecular simulations, widely used options include AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS, and OPLS. The AMBER99SB-ILDN force field is frequently recommended for proteins as it "reproduces fairly well experimental data" [23]. For drug-like molecules containing elements H, C, N, O, F, S, Cl, and P, recent neural network potentials such as DPA-2-Drug can provide "chemical accuracy compared to our reference DFT calculations" while being computationally efficient [25].

Vacuum Environment Setup: For vacuum simulations, simply place your molecule in a sufficiently large box to prevent periodic images from interacting. Alternatively, disable periodic boundary conditions entirely if your MD engine supports non-periodic simulations.

Energy Minimization: Perform steepest descent or conjugate gradient minimization to relax the structure:

- Step 1: Apply position restraints on heavy atoms and minimize for 500-1000 steps to relax hydrogen atoms and resolve minor clashes.

- Step 2: Perform full-system minimization without restraints for 1000-5000 steps or until the maximum force falls below a reasonable threshold (typically 100-1000 kJ/mol/nm depending on system size and required precision).

NVT Equilibration Parameters and Procedure

Once the system is properly minimized, proceed with NVT equilibration to bring the system to the desired temperature.

Temperature Coupling:

- Set the reference temperature appropriate for your study (typically 300-310 K for biological systems).

- For the Berendsen thermostat, set

tau_t(temperature damping constant) to 0.1-1.0 ps. This parameter "determines the relaxation time" for temperature coupling [24]. - For Nosé-Hoover Chains, the characteristic oscillation period is typically set to a similar range (0.1-1.0 ps).

Integration Parameters:

- Set the integration time step to 1-2 femtoseconds, which is "large enough to sample significant dynamics but not as large as to cause problems during the calculations" [23].

- For hydrogen-heavy systems, consider using constrained algorithms such as LINCS or SHAKE to allow for a 2-fs time step.

Initial Velocity Generation:

- Assign random velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution corresponding to the target temperature.

- Use different random seeds for replicate simulations to ensure sampling of different initial conditions.

Simulation Duration:

- Run the NVT equilibration for a sufficient duration to achieve temperature stabilization. "Typically, 50-100 ps should be sufficient. If the desired temperature has not been achieved or has not yet stabilized, additional time will be required" [26].

- For larger systems or more complex biomolecules, longer equilibration times may be necessary.

Monitoring and Validation:

- Monitor the temperature, potential energy, and root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) throughout the equilibration.

- The "running average of the temperature of the system should reach a plateau at the desired value" [26] before considering the equilibration complete.

- Check that the potential energy has stabilized and that structural RMSD has reached a plateau, indicating the system has adapted to the simulation temperature.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete process from system preparation through NVT equilibration:

Key Parameters and Research Reagent Solutions

Critical NVT Equilibration Parameters

Table 1: Essential Parameters for NVT Equilibration in Vacuum Simulations

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Technical Description | Impact on Simulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ensemble | NVT (Canonical) | Constant Number of particles, Volume, Temperature | Allows system to reach target temperature while maintaining fixed density |

| Thermostat | Nosé-Hoover Chains (NHC) or Berendsen | Algorithm for temperature control | NHC provides better canonical sampling; Berendsen has faster stabilization |

| Target Temperature | 300-310 K (biological) | Reference temperature for coupling | Should match experimental conditions or desired simulation state |

| Temperature Coupling Constant (τₜ) | 0.1-1.0 ps | Relaxation time for temperature coupling | Shorter values provide tighter control but may affect dynamics |

| Integration Time Step | 1-2 fs | Interval for solving equations of motion | 2 fs possible with hydrogen constraints; affects simulation stability |

| Simulation Duration | 50-100 ps (minimum) | Time for temperature stabilization | "Typically, 50-100 ps should be sufficient" [26] |

| Velocity Generation | Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution | Initial atomic velocities | "Set the momenta corresponding to the given temperature" [1] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for NVT Equilibration

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in NVT Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, LAMMPS | Performs the actual dynamics calculations and integration of equations of motion |

| Thermostat Algorithms | Berendsen, Nosé-Hoover Chains, Langevin | Maintains constant temperature during simulation |

| Force Fields | AMBER99SB-ILDN, CHARMM36, DPA-2-Drug (NN potential) | Defines potential energy function and parameters for molecular interactions |

| Analysis Tools | GROMACS analysis suite, VMD, MDAnalysis | Processes trajectories to assess equilibration progress and system properties |

| Visualization Software | PyMOL, VMD, Chimera | Provides structural insight and validation of simulation behavior |

| Neural Network Potentials | ANI-2x, DPA-2-Drug | Offers "QM accuracy at a limited computational cost" for drug-like molecules [25] |

Troubleshooting and Quality Control

Common Issues and Solutions

Even with careful preparation, NVT equilibration may encounter issues that require intervention:

Temperature Instability: If the system temperature fails to stabilize or exhibits large oscillations, check for incomplete energy minimization, increase the temperature coupling constant (τₜ), or extend the equilibration duration. For systems with disparate time scales, consider using the "separate damping for translational, rotational, and vibrational degrees of freedom" by setting

imdmet=1anditdmet=7in ReaxFF implementations [24].System Drift: In vacuum simulations, the entire molecule may drift due to non-zero total momentum. Apply center-of-mass motion removal every step to prevent this artifact.

Insufficient Equilibration: If the system has not reached the target temperature or stabilized after the planned duration, simply "run the NVT equilibration step again by providing the input data from the previous NVT equilibration step" [26].

Validation Metrics

Before proceeding from NVT equilibration to production simulations, verify the following quality control metrics:

Temperature Stability: The instantaneous temperature should fluctuate around the target value with a running average that has reached a stable plateau. "The plots are automatically generated and saved when the job is finished" showing "the evolution of the system's temperature over simulation time" [26].

Energy Equilibration: Both potential and total energy should reach stable values with fluctuations consistent with the canonical ensemble.

Structural Stability: The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of atomic positions relative to the minimized structure should plateau, indicating the system has adapted to the simulation temperature without undergoing large conformational changes.

The following decision diagram guides the selection of appropriate thermostat algorithms based on system characteristics:

Applications in Drug Discovery and Vacuum Simulations

The NVT equilibration protocol finds particular utility in structure-based drug design, where it helps prepare systems for subsequent molecular dynamics analyses. Recent studies have demonstrated that "molecular dynamics simulations evaluated using RMSD, RMSF, Rg, and SASA analysis, revealed that compounds significantly influenced the structural stability of the αβIII-tubulin heterodimer compared to the apo form" [27]. Similarly, in antibiotic resistance research, "MD simulations, trajectory analyses, including root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF), and hydrogen bond monitoring, confirmed the structural stability" of drug-protein complexes [28].

For vacuum simulations specifically, NVT equilibration provides a controlled environment to study intrinsic molecular properties without solvent effects. This is particularly valuable for:

- Gas-Phase Molecular Properties: Studying conformational preferences and energy landscapes of drug-like molecules without solvent interference.

- Protein-Ligand Complex Pre-screening: Rapid assessment of binding stability before committing to more expensive solvated simulations.

- Nanomaterial Characterization: Investigating the thermal stability of drug delivery nanoparticles or nanostructures.

When performing multiple simulations for statistical analysis, "you'd probably be much better off doing 9 separate NVT runs (with different seeds of course) and using the last conformation of each one" rather than sampling multiple frames from a single trajectory [29]. This approach ensures proper equilibration for each replicate and provides better sampling of initial conditions.

By following this comprehensive protocol, researchers can ensure proper thermal equilibration of their systems, providing a solid foundation for subsequent production simulations and reliable scientific conclusions in drug discovery applications.

The development of therapeutics against the Ebola virus (EBOV) represents a critical frontier in infectious disease research. EBOV causes severe hemorrhagic fever with high mortality rates, and the development of effective antiviral drugs remains a pressing global health challenge [30]. A key stage in the virus's life cycle is its entry into the host cell, a process mediated by the viral glycoprotein (GP) that culminates in the fusion of the viral envelope with the endosomal membrane [31] [32]. Disrupting this entry mechanism offers a promising strategy for antiviral intervention.

The process of membrane permeation and fusion is highly dynamic and occurs within the specific chemical environment of the late endosome, characterized by acidic pH, the presence of calcium ions (Ca²⁺), and unique anionic phospholipids [32]. Experimental observation of these molecular-scale events is exceptionally difficult. Consequently, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as an indispensable tool for probing the biophysical details of drug-target interactions and the fusion process, providing insights that are often inaccessible to laboratory experiments alone. This application note details the integration of MD simulation methodologies, particularly within the NVT (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) ensemble, to study the permeation of promising anti-EBOV therapeutic candidates and their mechanism of action.

Scientific Background

Ebola Virus Entry and the Glycoprotein as a Drug Target

The Ebola virus glycoprotein (GP) is the sole viral protein responsible for mediating host cell attachment and entry. GP is a trimer composed of GP1 and GP2 subunits; GP1 facilitates receptor binding, while GP2 drives the membrane fusion process [31] [32]. Viral entry occurs via macropinocytosis, after which the virus is trafficked to the late endosome. Here, the chemical environment—acidic pH and elevated Ca²⁺ levels—triggers essential conformational changes in GP, leading to the insertion of its fusion loop into the endosomal membrane and subsequent fusion [32]. Key mutations in GP, such as the epidemic variant A82V, have been shown to increase fusion loop dynamics and enhance viral infectivity [31]. This makes the GP-membrane interaction a prime target for small-molecule inhibitors.

The Role of the Endosomal Environment

The late endosome provides a specific chemical milieu that regulates GP conformation and membrane binding. Critical factors include:

- Acidic pH: Promotes global conformational changes in GP, repositioning the fusion loop and making it available for membrane insertion [32].

- Calcium Ions (Ca²⁺): Interact with anionic residues in the fusion loop, promoting local conformational changes and electrostatic interactions with anionic phospholipids in the target membrane [32].

- Anionic Lipids: The late endosomal membrane is rich in phosphatidylserine (PS) and bis(monoacylglycero)phosphate (BMP). BMP, in particular, is critical for determining the Ca²⁺-dependence of the GP-membrane interaction [32].

Table 1: Key Environmental Factors in the Late Endosome Affecting EBOV GP

| Factor | Role in Viral Entry | Experimental/Simulation Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Acidic pH | Triggers conformational changes in GP | smFRET imaging shows low pH repositions the fusion loop [32] |

| Ca²⁺ Ions | Mediates GP-membrane electrostatic interaction | Mutagenesis of residues D522/E540 disrupts Ca²⁺ binding and membrane interaction [32] |

| BMP Lipid | Enhances Ca²⁺-dependent membrane binding | Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy (FCS) shows BMP is critical for efficient GP-membrane interaction [32] |

Computational Methodologies

MD simulations model the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. The NVT ensemble, also known as the canonical ensemble, is a fundamental computational condition wherein the number of atoms (N), the volume of the simulation box (V), and the temperature (T) are kept constant. This is particularly useful for studying system behavior at a stabilized temperature, such as biomolecular conformational changes or ligand-protein interactions under controlled conditions.

Key Simulation Approaches

Several advanced MD techniques are employed to study membrane permeation and drug binding:

- Equilibrium MD (EMD): Used to study system behavior at equilibrium, such as the stability of a drug-protein complex. Simulations are often run for hundreds of nanoseconds to ensure robustness [30].

- Non-Equilibrium MD (NEMD): Applied to study transport phenomena, such as the permeation of solvents or ions through membranes. Boundary-driven (BD-NEMD) and moving wall (MW-NEMD) are common approaches for simulating pressure-driven flow [33].

- Enhanced Sampling Methods: Techniques such as calculating the Potential of Mean Force (PMF) are used to determine the free energy landscape and identify energy barriers for processes like membrane translocation [33].

Case Study: Simulating Anti-EBOV Inhibitors

Promising Therapeutic Candidates

Recent computational studies have identified several small molecules as promising EBOV inhibitors. A comprehensive in silico evaluation of six compounds—Latrunculin A, LJ001, CA-074, CA-074Me, U18666A, and Apilimod—identified CA-074 as a leading candidate [30]. CA-074 exhibits a strong binding affinity to Cathepsin B (-40.87 kcal/mol), a host cysteine protease crucial for Ebola virus entry.

Table 2: In Silico Profiles of Selected Anti-EBOV Inhibitors [30]

| Compound | Primary Target | Docking Score (kcal/mol) | Key ADMET Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| CA-074 | Cathepsin B | -40.87 | Fulfills Lipinski/Veber rules; no hERG inhibition/mutagenicity |

| Apilimod | Not Specified | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided |

| LJ001 | Viral Entry | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided |

| U18666A | Not Specified | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided |

Other research has focused on designing novel entry inhibitors. Optimization of diarylsulfide hits led to diarylamine derivatives with confirmed antiviral activity against replicative EBOV and significantly improved metabolic stability. These compounds target the EBOV glycoprotein (GP), with residue Y517 in GP2 being critical for their biological activity [34].

Simulation Workflow for Drug-Membrane Permeation

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational workflow for evaluating anti-EBOV therapeutics, from candidate identification to assessing membrane interaction and binding.

Diagram Title: Workflow for Simulating Anti-EBOV Therapeutics

Protocol: Simulating Inhibitor Binding to Ebola GP

This protocol outlines the key steps for simulating the interaction between a small-molecule inhibitor and the Ebola virus glycoprotein, a target for entry inhibitors [34] [32].

1. System Setup and Preparation

- Protein Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the EBOV GP trimer from a database like the Protein Data Bank (e.g., PDB ID 4M0Q for VP24 protein [35]). Remove crystallographic water molecules and heteroatoms. Add missing hydrogen atoms and assign protonation states to residues appropriate for the late endosomal pH using a tool like the H++ server [35].

- Ligand Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the small-molecule inhibitor (e.g., a diarylamine derivative [34] or CA-074 [30]). Perform geometry optimization and assign partial atomic charges using quantum chemical methods or force field tools.

- Membrane Modeling: Construct a model late endosomal membrane containing anionic lipids such as Phosphatidylserine (PS) and Bis(monoacylglycero)phosphate (BMP) using membrane builder tools (e.g., in CHARMM-GUI) [32].

- Solvation and Ionization: Place the protein-ligand complex or the membrane system in a simulation box filled with explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P model). Add ions (Na⁺, Cl⁻) to neutralize the system's charge and to achieve a physiologically relevant salt concentration (e.g., 0.15 M). Include Ca²⁺ ions to model the endosomal environment [32].

2. Molecular Dynamics Simulation (NVT Ensemble)

- Energy Minimization: Run a steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm to remove any steric clashes and bad contacts in the initial system, typically for 5,000-50,000 steps.

- System Equilibration: Gradually heat the system to the target temperature (e.g., 310 K) over 100-500 ps while applying positional restraints to the protein and ligand heavy atoms. Use a thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen) to maintain temperature. This step allows the solvent and ions to relax around the solute.

- Production Run: Run an NVT simulation for a duration sufficient to observe the phenomenon of interest (e.g., 100-300 ns [30] [35]). Use a time step of 2 fs. Constrain bonds involving hydrogen atoms using algorithms like LINCS or SHAKE. Calculate long-range electrostatic interactions using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method.

3. Analysis of Trajectory and Binding

- Binding Affinity: Calculate the binding free energy using methods such as Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) or Linear Interaction Energy (LIE).

- Intermolecular Interactions: Analyze hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and salt bridges formed between the inhibitor and key GP residues (e.g., Y517, T519, E100, D522 [34]).

- Structural Stability: Monitor the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) of the protein backbone and the ligand to assess the stability of the complex throughout the simulation.

- Fusion Loop Dynamics: Calculate the Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) of the GP fusion loop residues to understand the effect of the inhibitor on the mobility of this critical functional region [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item/Solution | Function/Description | Application in EBOV Research |

|---|---|---|

| CHARMM36 Force Field | A set of parameters for simulating biomolecules (proteins, lipids, nucleic acids). | Provides accurate energy calculations for EBOV GP and membrane interactions [36] [32]. |

| GROMACS | A software package for performing MD simulations. | Used for high-throughput simulation of drug-protein binding and membrane permeation [30]. |

| AutoDock Vina | A program for molecular docking and virtual screening. | Predicts binding poses and affinity of small molecules to EBOV targets like GP or VP24 [35]. |

| BMP Lipid | Bis(monoacylglycero)phosphate, a late endosome-specific anionic lipid. | Critical component in model membranes for studying Ca²⁺-dependent GP-membrane binding [32]. |

| LigDream | A deep learning-based tool for de novo molecular design. | Generates novel molecular scaffolds based on a parent compound (e.g., BCX4430) for anti-EBOV drug discovery [35]. |

Molecular dynamics simulations provide a powerful framework for investigating the permeation and mechanism of anti-Ebola therapeutics. By employing NVT ensembles and other advanced computational methods, researchers can unravel the complex interactions between drug candidates, the viral glycoprotein, and the endosomal membrane at an atomic level. The insights gained from these simulations, such as the critical role of the endosomal environment and the identification of key residues like Y517 in GP [34] and the pH-sensing mechanisms [32], are invaluable for rational drug design. This integrated computational approach accelerates the identification and optimization of potent EBOV entry inhibitors, paving the way for more effective treatments against Ebola virus disease.

Analyzing Protein-Ligand Complex Stability in Vacuum-like Environments

The analysis of protein-ligand complex stability in vacuum-like environments represents a specialized niche in computational biophysics, providing critical insights into the intrinsic thermodynamic and kinetic properties of molecular interactions absent solvent effects. Such environments, typically created through implicit solvent models or gas-phase simulations, are methodologically framed within the NVT (canonical) ensemble, which maintains a constant number of particles (N), volume (V), and temperature (T). This approach is particularly valuable for isolating the fundamental interaction energetics between proteins and ligands without the complicating effects of explicit water molecules [37]. The controlled conditions enable researchers to probe the essential physics of binding, including conformational stability, interaction fingerprints, and the free energy landscape, which might otherwise be obscured by bulk solvent fluctuations [38] [39].

While full physiological relevance requires eventual transition to explicit solvent models, vacuum-like analyses serve as an important methodological foundation for understanding binding mechanisms, facilitating rapid screening in drug design, and providing benchmark data for force field validation. This application note details the experimental protocols, computational methodologies, and analytical frameworks required to conduct such investigations effectively.

Theoretical Background

NVT Ensemble in Vacuum-like Simulations

The NVT ensemble is characterized by a constant number of atoms (N), a fixed simulation volume (V), and a regulated temperature (T). In the context of vacuum-like protein-ligand simulations, this ensemble enables the study of the system's intrinsic behavior by effectively removing the extensive thermodynamic bath of explicit water molecules. Temperature control is typically maintained using algorithms such as the Langevin thermostat, which adds friction and random forces to mimic collisions with a heat bath [37]. This is particularly crucial in vacuum simulations where the absence of solvent can lead to inadequate energy redistribution.

The theoretical foundation rests on statistical mechanics, where the NVT ensemble samples configurations according to the Boltzmann distribution. This allows for the calculation of equilibrium properties relevant to protein-ligand stability, such as binding free energies and conformational entropies, albeit in a simplified environment that highlights the direct molecular interactions.

Key Stability Metrics in Vacuum-like Conditions

In the absence of solvent, the assessment of protein-ligand complex stability relies on a different set of metrics than those used in explicit solvent simulations:

- Interaction Fingerprints: A qualitative scoring function based on the conservation of non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, ionic interactions) between the protein and ligand throughout the simulation trajectory. The loss of these interactions indicates decreasing stability [37].

- Free Energy Landscape (FEL): Constructed from simulation data to visualize the relationship between system conformation and free energy. FEL analysis reveals low-energy basins corresponding to stable states and the energy barriers between them, providing insight into conformational stability and transitions [40].

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the average atomic displacement of the protein or ligand relative to a reference structure. Lower RMSD values suggest greater structural integrity and complex stability under vacuum-like conditions [40].

- Constraint Forces: In constrained molecular dynamics, the mean constraint force required to maintain a specific protein-ligand distance is integrated to obtain the potential of mean force (PMF), which is a direct measure of the free energy profile along the chosen reaction coordinate [38].

Table 1: Key Stability Metrics and Their Significance in Vacuum-like Analyses

| Metric | Description | Information Provided |

|---|---|---|

| Interaction Fingerprints | Conservation of native non-covalent contacts | Qualitative binding mode stability [37] |

| Free Energy Landscape (FEL) | Conformational distribution mapped to free energy | Identifies stable states and transition pathways [40] |

| RMSD | Atomic displacement from reference structure | Overall structural integrity of the complex [40] |

| Constraint Forces | Mean force along a reaction coordinate | Free energy profile for binding/unbinding [38] |

Computational Protocols

System Preparation and Minimization

The initial setup of the protein-ligand system is a critical step that determines the reliability of subsequent simulations.

- Structure Retrieval and Preparation: Obtain three-dimensional coordinates of the protein-ligand complex from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Using a molecular modeling suite like Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), process the structure by assigning the highest occupancy conformations to alternates, rebuilding missing loops via homology modeling, and correcting any discrepancies between the primary sequence and tertiary structure. Remove all non-protein and non-ligand atoms, except for crystallographic water molecules within 4.5 Å of the ligand, which may be crucial for specific interactions [37].

- Protonation State Assignment: Employ a tool like "Protonate3D" in MOE to add missing hydrogen atoms and determine the most probable protonation states of titratable residues at the desired pH (typically 7.4). The ligand's protonation state should also be assigned, considering the most abundant protomer at the simulation pH and any specific interaction networks within the binding pocket that might favor an alternative state [37].

- Parameter and Topology Generation: Parameterize protein atoms using a force field such as ff14SB. For the ligand, use the General Amber Force Field (GAFF). Partial atomic charges for the ligand should be assigned using the AM1-BCC method [37].

- Energy Minimization: Subject the prepared system to energy minimization using a conjugate-gradient algorithm (e.g., for 500 steps) to remove atomic clashes, bad contacts, and unrealistically high potential energy, resulting in a stable starting structure for dynamics [37].

Thermal Titration Molecular Dynamics (TTMD)

The TTMD protocol provides a qualitative yet robust method for assessing the relative stability of protein-ligand complexes by challenging them with increasing thermal stress.

- Equilibration: Before production runs, equilibrate the minimized system in two stages. First, perform a short simulation (e.g., 0.1 ns) in the NVT ensemble with harmonic positional restraints (5 kcal mol⁻¹ Å⁻²) on both protein and ligand atoms. Second, conduct a longer simulation (e.g., 0.5 ns) in the NPT ensemble, applying restraints only to the ligand and protein backbone to allow side-chain relaxation [37].

- Production Simulations: Launch a series of independent MD simulations in the NVT ensemble using the equilibrated structure as the starting point. Each simulation in the series should be performed at a progressively increasing temperature (e.g., 310 K, 350 K, 400 K, 450 K, 500 K). Maintain a constant temperature for each run using a Langevin thermostat. Use an integration timestep of 2 fs and constrain bonds involving hydrogen atoms with an algorithm like M-SHAKE [37].

- Trajectory Analysis: For each temperature trajectory, calculate the interaction fingerprints between the protein and ligand at regular intervals. The stability of the complex is qualitatively estimated by the temperature at which the native binding mode (i.e., the pattern of specific non-covalent interactions) is lost. Complexes that retain their native interaction fingerprints at higher temperatures are deemed more stable [37].

Constrained MD for Unbinding Pathways

This protocol uses a geometric constraint to force the dissociation of the ligand and compute the associated free energy profile.

- Reaction Coordinate (RC) Selection: Choose a suitable RC that describes the unbinding pathway. A common and often effective choice is the distance between the centers of mass (COM) of the ligand and the protein binding pocket [38].

- Constrained Simulation: Apply a holonomic constraint to the chosen RC during an MD simulation. To map the unbinding process, perform either a "slow-growth" simulation where the constraint value is gradually changed, or a series of simulations at fixed values of the RC spanning from the bound state to the fully dissociated state [38].

- Mean Force and PMF Calculation: In the fixed-distance approach, the mean constraint force is recorded at each RC value. The Potential of Mean Force (PMF), which is equivalent to the free energy profile along the RC, is obtained by integrating the mean force over the distance: ΔG(R) = -∫

dR. This profile reveals energy barriers and stable intermediate states along the dissociation path [38]. - Kinetic Parameter Estimation: The free energy barrier extracted from the PMF (ΔG‡) can be used within the framework of transition state theory to estimate the dissociation rate constant: koff = (kB T / h) exp(-ΔG‡ / k_B T). A higher barrier corresponds to a slower dissociation rate and a longer complex residence time [38].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for setting up and running these vacuum-like stability simulations.

Free Energy Landscape (FEL) Analysis

This protocol analyzes simulation trajectories to construct a Free Energy Landscape, revealing the conformational stability of the complex.

- Collective Variable (CV) Selection: Choose one or two Collective Variables that capture the essential motions related to stability or binding. Common choices include the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) of the protein-ligand interface, radius of gyration (Rg), or number of native contacts [40].

- Trajectory Projection: Project the entire MD trajectory onto the chosen CVs. For each frame of the simulation, calculate the values of the CVs.

- Landscape Construction: Create a 2D histogram of the CVs from the trajectory data. Convert this population histogram into a free energy landscape using the relation: ΔG(X) = -k_B T ln P(X), where P(X) is the probability distribution along the CVs. The resulting landscape will show basins (low free energy, stable states) and barriers (high free energy, unstable transitions) [40].