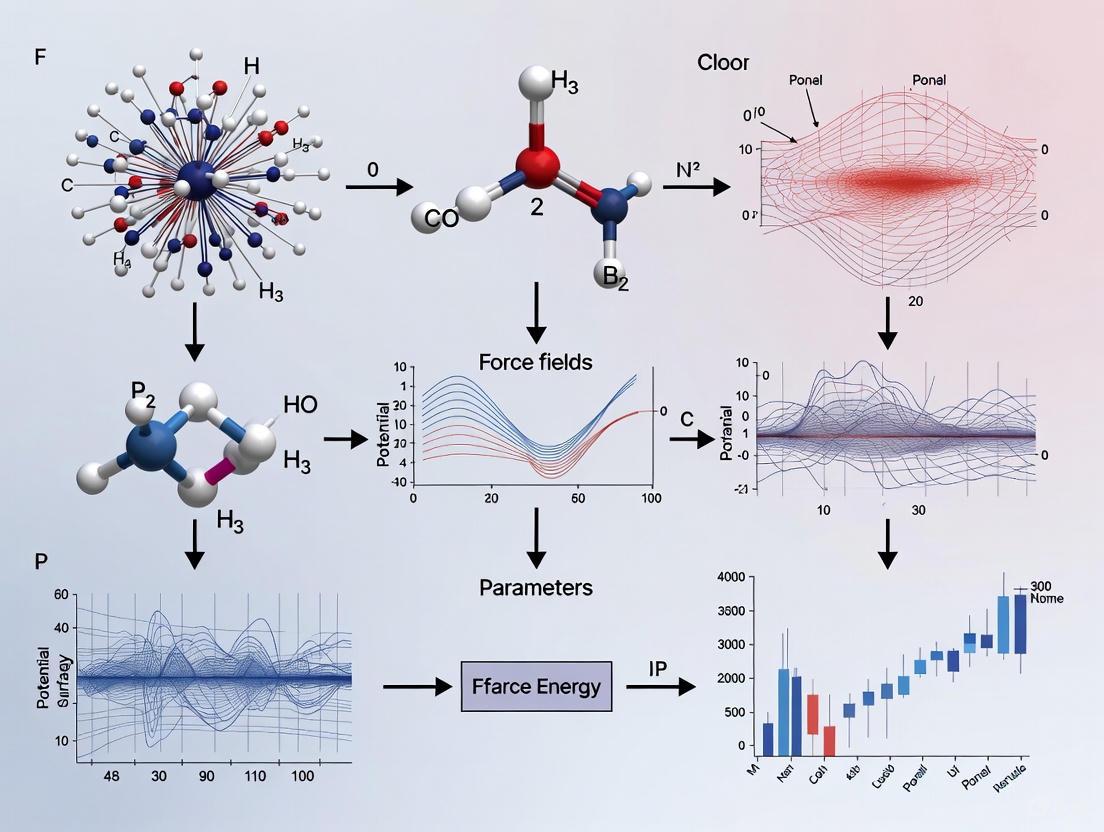

Navigating Force Field Inaccuracies: From Foundational Challenges to Advanced Solutions in Biomolecular Simulation

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on understanding, identifying, and overcoming inaccuracies in molecular force field parameters.

Navigating Force Field Inaccuracies: From Foundational Challenges to Advanced Solutions in Biomolecular Simulation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on understanding, identifying, and overcoming inaccuracies in molecular force field parameters. It covers the foundational limitations of traditional force fields, explores advanced methodological approaches including polarizable models and machine learning, offers practical troubleshooting strategies, and establishes robust validation protocols. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging technologies, this resource aims to enhance the reliability of molecular dynamics simulations in biomedical research, ultimately supporting more accurate drug design and development outcomes.

Understanding the Roots: Why Force Field Inaccuracies Occur and Their Impact on Simulation Outcomes

The Fundamental Limitations of Additive Force Fields and the Missing Polarization

FAQs: Understanding Force Field Limitations

What is the fundamental limitation of "additive" force fields? The primary limitation is their treatment of electrostatic interactions as purely pairwise-additive. These force fields assign fixed partial charges to each atom, meaning the electron distribution cannot respond to changes in its molecular environment, such as a protein moving from vacuum into an aqueous solution or a binding pocket interacting with different ligands [1] [2]. This ignores the physical phenomenon of electronic polarization, where an atom's electron cloud is redistributed by the electric field from surrounding atoms and molecules.

Why is the missing polarization a problem for my simulations? The lack of explicit polarization leads to several specific inaccuracies:

- Inaccurate Dielectric Response: The models cannot correctly replicate how a molecule's electronic structure adapts to different environments (e.g., water versus a lipid membrane) [2].

- Poor Treatment of Many-Body Effects: The interaction between two molecules is always the same, regardless of whether a third, polarizing molecule is present. This neglects non-additive interactions, which are crucial for an accurate physical model [3].

- Compromised Transferability: Because the fixed charges are often parameterized for a specific condition (like aqueous solvation), the force field may perform poorly when applied to different states or systems, such as predicting properties for both the liquid and solid phases of the same molecule [3].

In which research scenarios are these limitations most critical? Polarization effects are particularly important in:

- Simulating Membrane Proteins: The protein experiences a steep dielectric gradient between the aqueous pore, the protein itself, and the lipid membrane [4].

- Studying Enzyme Catalysis: The electronic rearrangements are critical for describing chemical reactions and ligand binding accurately [4].

- Investigating Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs): Their dynamic nature and interaction with various partners are highly sensitive to the environment [1].

- Performing Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) Calculations: The accuracy of absolute or relative binding affinity predictions is inherently limited by the force field's ability to describe the electrostatics of the bound and unbound states [1].

- Designing Molecular Glues and PROTACs: These complex, three-body systems require a highly accurate and transferable description of interactions [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: My simulation shows unrealistic hydrogen bonding or misrepresented protein-water interactions.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate description of water dispersion and polarization. [3] | Compare the average dipole moment of water in your simulation against the known value for your water model (e.g., ~2.3 D for TIP3P). A significant deviation may indicate issues. | Switch to a polarizable water model (e.g., SWM4-NDP, TIP4P-FQ) or a force field that uses an optimized water model designed to better mimic polarization effects. |

| Fixed-charge force field failing in a heterogeneous environment. | Check if the issue is more pronounced at interfaces (e.g., protein-water, membrane-water). | Consider using a polarizable force field (e.g., CHARMM-Drude, AMBERff19POL) for systems with strong dielectric heterogeneity. |

Issue: My calculated binding free energies are consistently inaccurate compared to experimental data.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed partial charges on the ligand do not adapt to the protein binding pocket. [4] | Perform a QM calculation on the ligand in different dielectric environments (e.g., ε=4 for protein, ε=80 for water) and compare the charge distributions. Large differences suggest polarization is important. | For a quick fix, re-parameterize ligand charges in a context resembling the binding site using QM. For a robust solution, adopt a polarizable force field for the entire system. |

| Implicit many-body effects in the binding site are not captured. [3] | Use a QM method to calculate the interaction energy of a protein-ligand fragment in the presence and absence of key surrounding residues. A large energy difference indicates significant many-body effects. | A polarizable force field is required to correctly capture these cooperative interactions. |

Issue: Simulation of a protein with post-translational modifications (PTMs) or non-standard residues yields unstable structures.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of reliable parameters for the modified residue in the additive force field. [1] | Use tools like antechamber (AMBER) or CGenFF (CHARMM) to generate parameters, but verify their quality by comparing QM and MM geometries and conformational energies of a small model compound. |

Develop system-specific parameters using high-level QM calculations as a target, ensuring compatibility with the chosen additive force field. For complex modifications, a polarizable framework may provide more transferable parameters. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Diagnosing Missing Polarization with Quantum Mechanics (QM)

Purpose: To determine if electronic polarization is a significant factor in your system by comparing interactions from molecular mechanics (MM) and QM.

- System Preparation: Isolate a critical fragment from your simulation, such as a ligand interacting with key amino acids from the binding pocket.

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the geometry of the fragment using the MM force field you are troubleshooting.

- Single-Point QM Calculation: Using the MM-optimized geometry, perform a single-point energy calculation with a QM method (e.g., DFT with a dispersion correction, such as ωB97X-D/6-31G*).

- Energy Decomposition Analysis: Use a method like Symmetry-Adapted Perturbation Theory (SAPT) to decompose the QM interaction energy into components: electrostatics, exchange-repulsion, induction (polarization), and dispersion.

- Comparison: Compare the relative contribution of the induction (polarization) energy from the QM analysis to the electrostatic energy from the MM force field. If the induction energy is a substantial fraction (e.g., >15-20%) of the total interaction energy, polarization effects are likely critical and missing from your additive force field model [2].

Protocol 2: Parameterization for a Non-Standard Residue

Purpose: To develop missing parameters for a post-translationally modified amino acid or a novel cofactor for use with an additive force field.

- Model Compound Selection: Choose a small molecule that accurately represents the chemical moiety of the non-standard residue.

- Target Data Generation:

- Geometry: Perform a QM geometry optimization of the model compound.

- Electrostatics: Calculate the electrostatic potential (ESP) around the optimized structure using a high-level QM method. Fit the partial atomic charges (e.g., using the RESP method) to reproduce this ESP.

- Conformational Energies: Perform a relaxed scan of key dihedral angles in the molecule to generate a target potential energy surface.

- Parameter Optimization: Derive bond and angle parameters from the QM-optimized geometry's Hessian (second derivative matrix). Iteratively optimize torsion parameters to reproduce the QM conformational energy profile.

- Validation: Validate the final parameters by ensuring they can reproduce liquid-state properties (density, enthalpy of vaporization) of a simple liquid analogous to the model compound, if available.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Additive Force Fields (AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS-AA) | Provide a fast, computationally efficient model for routine simulation of proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids in their native, aqueous environment. The foundation of most current biomolecular simulation. [5] [4] |

| Polarizable Force Fields (AMBERff19POL, CHARMM-Drude, OPLS-PFF) | Introduce explicit electronic degrees of freedom via methods like Drude oscillators or fluctuating charges, allowing electron clouds to respond to the local electric field. Used for systems where polarization is critical. [1] [4] |

| Coarse-Grained Force Fields (MARTINI) | Simplify the system by representing groups of atoms as single "beads," enabling the simulation of larger systems and longer timescales. Essential for studying large assemblies like membrane remodeling or protein aggregation. [1] [5] |

| Quantum Mechanics (QM) Software (Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem) | Used as a source of "ground truth" data for parameterizing new molecules, diagnosing force field errors, and studying systems where chemical bonds are formed or broken. [2] |

| Automated Parameterization Tools (antechamber, CGenFF) | Assist researchers in generating initial force field parameters for small molecule ligands, streamlining the setup process for simulation. Generated parameters should always be checked for quality. [1] |

Logical Workflow for Force Field Selection and Diagnosis

The following diagram outlines a logical decision process for selecting a force field and diagnosing potential related issues within a research project.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common sources of error in force field parameters? The most common sources of error stem from limitations in chemical transferability and electrostatic approximations. Force fields are often parameterized using limited data sets, such as neat liquids or small molecule hydration free energies, which may not adequately represent the diverse interactions in complex systems like protein-ligand interfaces. This can introduce chemical biases that hamper transferability [6] [7]. Additionally, the use of fixed point-charge electrostatic models, which do not account for electronic polarization, is a known source of error, particularly for ionic groups or in heterogeneous environments [8].

FAQ 2: My binding free energy calculations are inaccurate. Could my water model or partial charge assignment be the cause? Yes, the choice of water model and charge assignment method significantly impacts accuracy. Studies validating free energy perturbation (FEP) calculations have shown that combinations like AMBER ff14SB/TIP3P/AM1-BCC can yield a mean unsigned error (MUE) of 0.82 kcal/mol, while switching to a RESP charge model with the same protein force field and water model can increase the MUE to 1.03 kcal/mol [9]. It is crucial to use a consistent and well-validated set of parameters.

FAQ 3: When is it necessary to develop new Lennard-Jones (LJ) parameters instead of using existing ones? New LJ parameters should be developed when existing parameters fail to reproduce key experimental or quantum mechanical (QM) target data. This is often the case for molecules with novel atom types not covered by existing force fields. Optimization is recommended when you cannot satisfactorily reproduce interaction energies with noble gases, pure solvent properties (e.g., density, heat of vaporization), or free energies of solvation [10].

FAQ 4: What are the pitfalls of using approximate electrostatic force formulas? Using simplified formulas outside their intended scope can introduce significant errors. For example, applying the Linear Superposition Approximation (LSA), derived for low surface potentials (<25 mV), to systems with high surface potentials can lead to large inaccuracies in calculated forces and subsequent errors in fitted properties like surface potential or charge density [11]. Always ensure the approximation's underlying assumptions match your system's conditions.

FAQ 5: How can I assess and improve the transferability of a training set for a data-driven model? Use a Transferability Assessment Tool (TAT) which involves training a model on set A and testing it on set B. The transferability can be quantified with a matrix ( T_{B@A} ) [6]. To improve transferability, curate your training set based on three principles: 1) Reaction Diversity (cover a broad range of chemical processes), 2) Elemental Diversity (include various atom types), and 3) Transferable Diversity (ensure the set yields good performance across diverse chemical behaviors) [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Systematic Errors in Binding Enthalpy Calculations

Symptoms: Computed binding enthalpies for host-guest systems show large, systematic deviations from experimental measurements.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Inadequate Lennard-Jones (LJ) Parameters. The LJ component often makes a dominant, favorable contribution to binding enthalpy. Systematic errors can indicate non-optimal LJ parameters for key atoms involved in the binding interaction [7].

- Solution: Perform sensitivity analysis to calculate the derivative of the binding enthalpy with respect to the LJ parameters. This gradient can guide parameter adjustments to improve agreement with experiment [7].

- Protocol:

- Compute the binding enthalpy (( \Delta H )) for your training set of complexes.

- Calculate the partial derivative ( \frac{\partial \Delta H}{\partial \lambda} ) for the LJ parameter (( \lambda )) of the atom in question. This measures how sensitive the enthalpy is to changes in that parameter.

- Adjust the parameter in the direction that reduces the error between calculation and experiment.

- Iterate until agreement is satisfactory, then validate the new parameters on a separate test set.

Cause 2: Use of an Inappropriate Water Model. Different water models perform differently in the context of binding calculations, even if they yield similar results for hydration free energies [7].

- Solution: Benchmark different water models (e.g., TIP3P, SPC/E, TIP4P-EW) for your specific system [9].

- Protocol:

- Select a set of water models available in your MD software (e.g., TIP3P, SPC/E, TIP4P-EW).

- Run identical binding affinity calculations for a well-characterized benchmark system.

- Compare the Mean Unsigned Error (MUE) and root-mean-square error (RMSE) against experimental data to identify the best-performing model for your application [9].

Troubleshooting Poor Transferability in Machine-Learned Force Fields

Symptoms: A machine-learned force field or density functional approximation (DFA) performs excellently on its training data but fails to generalize to new, unseen chemical systems.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Chemically Biased Training Data. The training set may over-represent certain types of chemistry (e.g., typical organic bonds) and under-represent others (e.g., transition metal chemistry), limiting the model's applicability [6].

- Solution: Curate training sets with transferable diversity. Simply adding more data of the same type is insufficient; the data must encompass a wide range of chemical behaviors [6].

- Protocol:

- Use a Transferability Assessment Tool (TAT) to compute the transferability matrix ( T_{B@A} ) for various benchmark sets.

- Analyze the matrix to identify which chemical domains transfer well and which do not.

- Design a compact but diverse training set (e.g., T100) that includes reaction, elemental, and transferable diversity, ensuring it covers a broad range of the periodic table and chemical processes [6].

Cause 2: Over-reliance on Human Intuition in Data Curation. Human-curated training sets often contain unconscious biases that can hamper the model's ability to extrapolate to truly novel chemistry [6].

- Solution: Use data-driven, principled strategies for benchset curation that explicitly maximize diversity and transferability metrics rather than relying solely on chemical intuition [6].

Table 1: Performance of Different Parameter Sets in Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) Calculations. The table below summarizes the accuracy of various force field, water model, and charge model combinations on a benchmark of 199 compounds, as measured by Mean Unsigned Error (MUE), Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE), and correlation coefficients. Data from [9].

| Parameter Set | Protein Forcefield | Water Model | Charge Model | MUE (kcal/mol) | RMSE (kcal/mol) | R² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEP+ (Reference) | OPLS2.1 | SPC/E | CM1A-BCC | 0.77 | 0.93 | 0.66 |

| AMBER TI (Reference) | AMBER ff14SB | SPC/E | RESP | 1.01 | 1.30 | 0.44 |

| 1 | AMBER ff14SB | SPC/E | AM1-BCC | 0.89 | 1.15 | 0.53 |

| 2 | AMBER ff14SB | TIP3P | AM1-BCC | 0.82 | 1.06 | 0.57 |

| 3 | AMBER ff14SB | TIP4P-EW | AM1-BCC | 0.85 | 1.11 | 0.56 |

| 4 | AMBER ff15ipq | SPC/E | AM1-BCC | 0.85 | 1.07 | 0.58 |

| 5 | AMBER ff14SB | TIP3P | RESP | 1.03 | 1.32 | 0.45 |

| 6 | AMBER ff15ipq | TIP4P-EW | AM1-BCC | 0.95 | 1.23 | 0.49 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Sensitivity Analysis for Lennard-Jones Parameter Optimization

This protocol uses sensitivity analysis to refine LJ parameters based on host-guest binding enthalpy data [7].

- System Preparation: Select a training set of host-guest complexes (e.g., 4 aliphatic guests for cucurbit[7]uril). Build the systems in solution using your MD software.

- Baseline Calculation: Compute the absolute binding free energies and enthalpies for all complexes using the unmodified force field (e.g., GAFF). Compare the calculated binding enthalpies (( \Delta H{calc} )) to experimental values (( \Delta H{exp} )) to establish the baseline error.

- Sensitivity Analysis: For a selected atom's LJ parameter (( \lambda )), compute the partial derivative of the binding enthalpy with respect to that parameter, ( \frac{\partial \Delta H}{\partial \lambda} ). This measures how a small change in the parameter will affect the computed enthalpy.

- Parameter Adjustment: Use the sensitivity information to predict a new parameter value that will minimize the error ( \Delta H{calc} - \Delta H{exp} ).

- Validation: Recompute the binding enthalpies and free energies for the training set with the new parameter. Assess improvement. Finally, validate the transferability of the optimized parameter on a test set of different, unseen guests.

Protocol: Validating Electrostatic Parameters with Noble Gas PES

This protocol, implemented in tools like FFParam-v2.0, uses Potential Energy Scans (PES) to optimize and validate LJ parameters [10].

- Target Selection: Identify the specific atom in your model compound for which you need to optimize or validate LJ parameters.

- QM Calculation Setup: Generate input files for a QM program (e.g., Gaussian, Psi4) to calculate the interaction energy between the model compound and a noble gas atom (He or Ne). The scan should vary the distance between the target atom and the noble gas.

- MM Calculation Setup: Perform the same potential energy scan using your molecular mechanics (MM) engine (e.g., OpenMM, CHARMM) with the current force field parameters.

- Comparison and Fitting: Plot the QM and MM interaction energies against the scan distance. Use a Monte Carlo Simulated Annealing (MCSA) algorithm to adjust the LJ parameters of the target atom to minimize the difference between the QM and MM PES curves.

- Condensed Phase Validation: As a final check, run MD simulations of the pure liquid (if applicable) and calculate bulk properties like density and heat of vaporization to ensure the new parameters reproduce experimental condensed-phase data [10].

Workflow and Process Diagrams

Diagram Title: Force Field Parameter Error Diagnosis and Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Force Field Parameterization and Validation.

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features / Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| FFParam-v2.0 | Comprehensive parameter optimization for CHARMM/Drude FFs | Optimizes electrostatic, bonded, and LJ parameters; uses QM target data and condensed phase validation. | [10] |

| Alchaware (OpenMM) | Automated Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) workflow | Validates force field performance by predicting relative binding affinities. | [9] |

| Transferability Assessment Tool (TAT) | Measures model generalization | Quantifies how well a model trained on set A performs on set B via matrix ( T_{B@A} ). | [6] |

| ffTK | Force field parameter optimization | Aids in optimizing additive FF parameters for CHARMM and AMBER within VMD. | [10] |

| CGenFF Program | Initial parameter assignment | Provides initial atom types and parameters for CHARMM force fields. | [10] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the typical accuracy I can expect from rigorous free energy calculations like FEP? The accuracy of Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) is now often comparable to the reproducibility of experimental measurements. On large, diverse datasets, FEP can achieve a mean unsigned error (MUE) of approximately 0.8-1.0 kcal/mol for relative binding free energies [9] [12]. This aligns with the reported reproducibility of relative binding affinity measurements from different experimental assays, which can show root-mean-square differences of 0.77-0.95 kcal/mol [12]. This means that in many cases, the methodological inaccuracies of FEP are on par with the inherent noise in the experimental data used for validation.

FAQ 2: My FEP calculations are inaccurate. Could the force field's partial charge assignment be the cause? Yes, the method for assigning partial atomic charges to ligands is a critical potential source of inaccuracy. Different charge models can yield similar performance in protein-ligand binding free energy calculations, even if they perform very differently for other properties like hydration free energy (HFE). For instance, the GAFF2/AM1-BCC and GAFF2/ABCG2 force field parametrizations demonstrate comparable accuracy in relative binding free-energy (RBFE) predictions, despite GAFF2/ABCG2 being specifically optimized for and significantly improving HFE accuracy [13]. This indicates that force field optimization for one property (like HFE) does not guarantee improvement for the more complex environment of a protein binding pocket [13].

FAQ 3: What are the most common sources of error in binding free energy calculations? Common error sources form a hierarchy that researchers must address:

- Force Field Inaccuracies: Inadequate torsion parameters, non-polarizable electrostatics, and inaccurate partial charges can introduce systematic errors [9] [13].

- Inadequate Conformational Sampling: If the simulation fails to capture key protein or ligand motions, relevant low-energy states may be missed, biasing the result. Enhanced sampling techniques like replica exchange are often needed to overcome energy barriers [9] [14].

- Structural and Chemical Preparation Errors: Incorrect protonation states of protein residues or ligands, improper tautomer selection, and flawed binding pose modeling can lead to catastrophic errors [12].

FAQ 4: How do inaccuracies in force field parameters impact real-world drug discovery projects? Inaccurate parameters can mislead a drug discovery campaign by providing false positives (predicting a weak binder as strong) or false negatives (dismissing a potent compound). This can waste significant resources on synthesizing and testing poor compounds or, worse, lead to promising candidates being overlooked. Accurate force fields are essential for correctly ranking a series of compounds by their predicted binding affinity, which is a primary goal of FEP in lead optimization [13] [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Remedying Sampling and Convergence Issues

Problem: Calculations fail to converge, or results are unstable and highly variable between simulation repeats. This often manifests as poor agreement with experimental data for transformations that involve significant structural rearrangement.

Symptoms:

- Large statistical errors in the calculated free energy difference.

- High sensitivity to the initial structure or simulation parameters.

- Poor cycle closure in perturbation networks.

Solutions:

- Implement Enhanced Sampling: Use Hamiltonian Replica Exchange (HRE) or Replica Exchange with Solute Tempering (REST2) to improve sampling efficiency. These methods help the simulation escape local energy minima and sample the relevant conformational space more effectively [9] [14].

- Extend Simulation Time: Increase the simulation length for each lambda window. This is a straightforward but computationally expensive way to improve sampling.

- Verify Lambda Scheduling: Ensure a sufficient number of lambda (λ) states are used, especially in regions where the system's energy changes rapidly. A

λ-dependent softcore potential can prevent numerical instabilities at endpoints where atoms might disappear or appear [14].

The following workflow outlines a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving these issues:

Guide 2: Addressing Force Field Parameter Inaccuracies

Problem: Systematic errors are observed across multiple calculations, often linked to specific functional group transformations.

Symptoms:

- Consistent under- or over-prediction of binding affinity for ligands containing specific chemical moieties (e.g., sulfonamides, halogen atoms).

- Poor accuracy for certain types of transformations, such as charge-changing perturbations.

Solutions:

- Benchmark Force Field Combinations: Test different protein force field and water model combinations on a known benchmark set for your target. As shown in the table below, the choice of parameters can significantly impact accuracy [9].

- Validate Charge Models: If you are generating charges for novel ligands, compare different methods (e.g., AM1-BCC vs. RESP). Be aware that a model optimized for one property may not transfer to others [13].

- Consider Advanced Protocols: For critical projects, consider more advanced protocols that incorporate quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) to derive ligand charges in the context of the protein binding pocket, which can improve electrostatic description [15].

Table 1: Performance of Different Parameter Sets in FEP Calculations (MUE in kcal/mol) [9]

| Parameter Set | Protein Forcefield | Water Model | Charge Model | MUE (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEP+ [9] | OPLS2.1 | SPC/E | CM1A-BCC | 0.77 |

| AMBER TI [9] | AMBER ff14SB | SPC/E | RESP | 1.01 |

| Alchaware 2 [9] | AMBER ff14SB | TIP3P | AM1-BCC | 0.82 |

| Alchaware 5 [9] | AMBER ff14SB | TIP3P | RESP | 1.03 |

| Alchaware 6 [9] | AMBER ff15ipq | TIP4P-EW | AM1-BCC | 0.95 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software and Force Field Components for Free Energy Calculations

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|

| OpenMM [9] | An open-source, high-performance toolkit for molecular simulation. It is used as the engine for running FEP calculations in various automated workflows. | Provides the core molecular dynamics engine. |

| AMBER Force Fields (e.g., ff14SB, ff15ipq) [9] | A family of widely used molecular mechanical force fields for simulating proteins and nucleic acids. The choice (e.g., ff14SB vs ff15ipq) can impact prediction accuracy. | Defines energy terms for the protein. |

| Ligand Force Fields (e.g., GAFF/GAFF2) [9] [13] | The "General AMBER Force Field" provides parameters for small organic molecules, making it compatible with AMBER protein force fields. | Defines energy terms for the small molecule ligand. |

| Charge Models (AM1-BCC, RESP) [9] [13] | Methods for assigning partial atomic charges to ligands. AM1-BCC is fast and reasonably accurate, while RESP charges are derived from QM electrostatic potentials. | Critical for modeling electrostatic interactions. |

| Water Models (TIP3P, SPC/E, TIP4P-EW) [9] | Explicit water models that differ in their geometry and parametrization. The choice (e.g., TIP3P vs TIP4P-EW) can affect the solvation properties and overall simulation outcome. | Solvent environment for simulations. |

| Alchaware [9] | An automated tool for setting up and running FEP calculations using the open-source OpenMM package. | An example of an automated FEP workflow. |

| QM/MM Packages [15] | Software that allows combined quantum mechanics and molecular mechanics calculations. Used in advanced protocols to generate polarized charges for ligands inside protein binding sites. | For improving electrostatic description beyond standard force fields. |

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Force Field Parameters

This protocol provides a methodology for systematically evaluating the performance of different force field parameter sets, a critical step in ensuring accurate free energy calculations [9] [12].

Objective: To quantitatively assess the accuracy of a given force field combination (protein force field, ligand force field, water model, charge model) for predicting protein-ligand binding affinities.

Required Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" in Section 3.

Procedure:

- Test Set Selection: Curate a benchmark set of protein-ligand systems. The set should include high-quality experimental binding affinity data (K~d~, K~i~, IC~50~) and, ideally, crystal structures. Publicly available sets like the "JACS set" are commonly used [9] [12].

- System Preparation:

- Protein Preparation: Obtain protein structures from the PDB. Add missing hydrogen atoms, assign protonation states to key residues (e.g., His, Asp, Glu) using tools like H++ or PROPKA, and ensure the binding site is properly modeled [9].

- Ligand Preparation: Generate 3D structures for all ligands. Determine the most likely protonation states and tautomers at physiological pH. For each force field combination being tested, generate the necessary parameter and topology files for the ligands (e.g., using

antechamberfor GAFF/AM1-BCC) [9] [13].

- Simulation Setup:

- Solvate the protein-ligand complex in a pre-equilibrated water box (e.g., using TIP3P, SPC/E, or TIP4P-EW water models) with appropriate counterions to neutralize the system [9].

- Set up the FEP simulation workflow. This includes defining the λ schedule for the alchemical transformation and configuring enhanced sampling parameters, such as Hamiltonian Replica Exchange [9] [14].

- Production Runs & Analysis:

- Run multiple independent FEP simulations for each transformation to ensure reproducibility.

- Use analysis tools (e.g.,

alchemical-analysis) to compute the relative binding free energy (ΔΔG) for each ligand pair. - Compare the predicted ΔΔG values to the experimental data. Calculate statistical metrics including Mean Unsigned Error (MUE), Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE), and Pearson's correlation coefficient (R) to quantify accuracy [9].

The logical flow of this benchmarking protocol is visualized below:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between traditional additive force fields and modern polarizable force fields?

Traditional additive force fields, such as AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS, use a fixed set of point charges assigned to each atom to model electrostatic interactions. These charges do not change in response to their molecular environment [16] [17]. While computationally efficient, this approach fails to capture the critical many-body effect of electronic polarization—the redistribution of electron density when a molecule moves from one environment to another (e.g., from a protein's hydrophobic core to an aqueous solution) [16] [17].

Polarizable force fields explicitly model this response by allowing the electrostatic properties of atoms to change dynamically. The three primary models for achieving this are:

- Induced Dipole Model: Each atom is assigned a polarizability, allowing it to develop an induced dipole in response to the local electric field [16].

- Drude Oscillator Model: Also known as the "charge-on-spring" model, this attaches a mobile charged particle (a Drude particle) to an atom via a harmonic spring, creating an inducible dipole [16] [17].

- Fluctuating Charge (FQ) Model: Atomic charges are allowed to "flow" between atoms to equalize electronegativity (chemical potential) across the molecule [16].

This fundamental shift enables a more physical representation of interactions in heterogeneous environments like binding pockets and membrane interfaces.

Q2: In which specific research applications have polarizable force fields demonstrated a clear advantage?

Research has shown that the explicit inclusion of polarization can significantly improve accuracy in several key areas, though challenges remain in others. The table below summarizes some key findings:

Table 1: Performance Advantages of Polarizable Force Fields in Specific Applications

| Application Area | Demonstrated Advantage | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Refinement | Improved Accuracy | Polarizable force fields generate refined structures closer to experimental targets. | [18] |

| Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) | More Accurate Conformational Ensembles | They produce conformational ensembles for IDPs that better approximate experimental data. | [18] |

| Binding Affinity Calculation | Improved Treatment of Electrostatics | A more physical representation of electrostatic interactions in complex environments like binding sites can improve free energy perturbation (FEP) predictions. | [9] [16] |

| Protein Folding | Limited Advantage (Challenge) | One study found it difficult for polarizable force fields to approach the native structure in de novo folding simulations, potentially due to imbalances in protein-water interactions. | [18] |

Q3: My binding free energy calculations using traditional force fields show systematic errors. Could polarization be the cause?

Yes, this is a recognized source of error. Fixed-charge force fields lack the ability to adjust to the different electrostatic environments a ligand experiences when moving from solution to a protein binding pocket [16] [19]. This can lead to inaccurate estimates of solvation free energies and, consequently, binding affinities. Polarizable force fields directly address this limitation by allowing the charge distribution of the ligand and the protein to adapt to their surroundings, providing a more accurate description of the underlying physics [9] [16]. For critical lead optimization in drug discovery, this can lead to more reliable predictions and better compound prioritization [9].

Q4: What are the practical trade-offs when considering a switch to polarizable force fields?

The primary trade-off is computational cost. Calculating induced dipoles or optimizing the positions of Drude particles requires iterative self-consistent field (SCF) calculations or the use of an extended Lagrangian, which increases simulation time significantly compared to additive force fields [16] [20]. Additionally, polarizable force fields are less mature and have less extensive parameter coverage for exotic molecules than well-established additive force fields like AMBER or CHARMM [17]. Researchers must weigh the need for higher accuracy in specific properties against these increased computational and practical demands.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inaccurate Conformational Sampling in Drug-Like Molecules

Background: Inadequate torsion parameters in a force field can lead to incorrect predictions of a molecule's low-energy conformations, severely impacting the calculation of conformational energies and protein-ligand binding affinities [21].

Solution: Employ a Data-Driven Parameterization Workflow Modern approaches move beyond traditional look-up tables to data-driven methods that ensure broad chemical space coverage. The following diagram illustrates a state-of-the-art workflow for generating accurate, molecule-specific parameters:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Accurate Parameterization

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Predicts bonded and non-bonded force field parameters directly from molecular structure, preserving chemical symmetry. | Models like Espaloma and ByteFF use GNNs to achieve chemical space coverage far beyond traditional methods [21]. |

| ByteFF / OpenFF Dataset | A large-scale, highly diverse quantum mechanics (QM) dataset used to train machine-learned force fields. | Includes millions of optimized molecular fragment geometries and torsion profiles at the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP level of theory [21]. |

| AMBER ff15ipq | A second-generation protein force field using implicitly polarized charges (IPolQ). | Derived to include implicit polarization effects in an additive framework; can be tested in FEP workflows for improved accuracy [9]. |

| Alchaware & OpenMM | An automated tool for running Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) calculations using open-source force fields. | Allows for systematic benchmarking of different protein force fields and water models on your specific system [9]. |

Problem: Systematic Errors in Solvation Free Energies and Mixture Properties

Background: Traditional force fields often parameterize van der Waals (Lennard-Jones) terms using only data from pure substances (e.g., liquid density and enthalpy of vaporization). This can fail to accurately capture the interactions between different molecule types (A-B interactions) in mixtures, leading to errors in solvation free energies [19].

Solution: Retrain Force Field Parameters Using Condensed-Phase Mixture Data A modern strategy to combat this is to include experimental data from binary mixtures in the parameter training set.

Experimental Protocol:

- Training Set Curation: Assemble a dataset containing experimental measurements for:

- Liquid densities (ρl) of pure components.

- Enthalpies of vaporization (ΔHvap) of pure components.

- Densities (ρl(x)) of binary liquid mixtures across various concentrations.

- Enthalpies of mixing (ΔHmix(x)) for binary mixtures [19].

- Simulation and Optimization: Select a target force field (e.g., OpenFF). Run molecular dynamics simulations to calculate the properties above for molecules in the training set.

- Parameter Refinement: Systematically adjust the Lennard-Jones (vdW) parameters of the force field to minimize the error between the simulated properties and the experimental data. This can be done using optimization algorithms like Bayesian optimization [19].

- Validation: The refined force field must be validated against a separate set of experimental data, particularly solvation free energies in various solvents, to ensure its transferability and improved performance [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Resources for Force Field Selection and Validation

| Category | Item | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Software & Tools | Alchaware (OpenMM) | Automated FEP setup and calculation for binding affinity benchmarking [9]. |

| AMBER, CHARMM, NAMD | Major MD simulation packages supporting both additive and polarizable (e.g., Drude) force fields [17]. | |

| Force Fields | OPLS4, CHARMM36, AMBER ff19 | State-of-the-art additive force fields with extensive biomolecular parameter sets. |

| CHARMM Drude, AMOEBA+ | Leading polarizable force fields for applications requiring high electrostatic fidelity [16] [17]. | |

| ByteFF, OpenFF | Modern, machine-learned force fields for small molecules with expansive chemical space coverage [21]. | |

| Validation Data | JACS Benchmark Set | A standard set of 8 protein-ligand systems (BACE, CDK2, etc.) for validating FEP predictions [9]. |

| ThermoML Archive | A public database of experimental thermodynamic properties, essential for training and validating force fields [19]. |

Advanced Approaches: Implementing Accurate and Polarizable Force Fields in Your Research

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the choice of force field is a foundational decision that directly determines the accuracy and reliability of your research outcomes. A force field, comprising mathematical functions and a set of parameters, calculates the potential energy of a system of atoms. Its ability to faithfully represent atomic interactions governs how well your simulation can predict real-world molecular behavior. Within the context of academic and industrial drug discovery, where computational predictions are increasingly used to prioritize compounds for synthesis, the limitations of force fields—such as their functional group inaccuracies and fixed-charge approximations—become critical research variables that must be actively managed [22] [9].

This guide provides a structured framework for selecting and troubleshooting the most common all-atom force fields—AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS, and GAFF—with a specific focus on diagnosing and combating parameter inaccuracies. The subsequent sections offer comparative data, experimental protocols, and practical solutions designed to empower researchers in making informed decisions and implementing corrective strategies when force field limitations threaten to compromise simulation integrity.

Force Field Comparison and Performance Data

Understanding the philosophical underpinnings and performance characteristics of each force field is the first step in making an appropriate selection. The table below summarizes the core attributes and documented performance issues of the major force fields.

Table 1: Core Characteristics and Performance of Common Force Fields

| Force Field | Primary Domain | Charge Model | Key Strengths | Known Limitations & Inaccuracies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER/GAFF | Proteins, Nucleic Acids, Drug-like Molecules [20] | RESP (fit to electrostatic potential) [22] | Accurate molecular structures & non-bonded energies [20]; Good for protein-ligand binding affinity [9] | Over-solubilization of carboxyl groups; Under-solubilization of nitro-groups [22] |

| CHARMM/CGenFF | Biomolecules, Drug-like Molecules [20] | Charge interaction with TIP3P water [22] | Consistent biomolecular modeling; Condensed phase polarization capture [22] | Under-solubilization of amines and nitro-groups [22] |

| OPLS-AA | Liquid & Condensed Phase Properties [20] | Not Specified | Excellent thermodynamic & solvation properties [20] [23] | Performance can be system-dependent; Requires validation [23] |

Quantitative benchmarking is essential for contextualizing these limitations. A study assessing the accuracy of relative binding free energy (RBFE) predictions, critical for lead optimization in drug discovery, provides the following performance data for AMBER force fields when combined with different water and charge models.

Table 2: AMBER Force Field Performance in Binding Affinity Prediction (MUE in kcal/mol) [9]

| Protein Force Field | Water Model | Charge Model | Mean Unsigned Error (MUE) | Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER ff14SB | SPC/E | AM1-BCC | 0.89 | 1.15 |

| AMBER ff14SB | TIP3P | AM1-BCC | 0.82 | 1.06 |

| AMBER ff14SB | TIP4P-EW | AM1-BCC | 0.85 | 1.11 |

| AMBER ff15ipq | SPC/E | AM1-BCC | 0.85 | 1.07 |

| AMBER ff14SB | TIP3P | RESP | 1.03 | 1.32 |

Troubleshooting Common Force Field Issues

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My simulation results show large deviations from experimental data for solvation or binding properties. Which specific functional groups are most likely to be the cause?

A1: Evidence consistently points to certain functional groups as common sources of error. Studies on hydration free energy (HFE) have shown that nitro-groups are problematic, often being under-solubilized in aqueous medium. Similarly, amine-groups are frequently under-solubilized, an issue more pronounced in CHARMM/CGenFF than in GAFF. Conversely, carboxyl groups tend to be over-solubilized, particularly in GAFF [22]. If your ligand contains these groups, they should be the first target for scrutiny and validation.

Q2: What are the practical strategies to improve accuracy when my chosen force field has known inaccuracies for my system of interest?

A2: Several strategies can mitigate these inaccuracies:

- Use of Restraints: In structural refinement simulations, applying geometric restraints to target specific regions can help steer the model toward a more accurate state, compensating for force field deficiencies [24].

- Explore Charge Models: As shown in Table 2, the choice of charge assignment (e.g., AM1-BCC vs. RESP) can significantly impact prediction error. Testing different charge models for your specific molecule is a recommended practice [9].

- Leverage Machine Learning: Emerging data-driven approaches can predict force field parameters across a broad chemical space. Tools like ByteFF, an Amber-compatible force field, demonstrate state-of-the-art accuracy by training on expansive quantum chemical datasets, offering an alternative to traditional parameterization [25].

Q3: How do I handle missing parameters for a novel residue or ligand in my simulation?

A3: This is a common hurdle, especially in drug discovery. The recommended steps are:

- Check Alternative Names: Ensure the residue name in your structure file exactly matches the entry in the force field's residue topology database [26].

- Search the Literature: Investigate if parameters for your molecule, consistent with your force field, have been published.

- Parameterize the Molecule: If no parameters exist, you must derive them yourself. This involves substantial work, often using quantum mechanical (QM) calculations to fit the necessary bonded and non-bonded parameters [26]. Utilizing a machine-learning-based approach can also be a powerful method for parameterizing new chemical space [22].

Troubleshooting Guide: Parameter Implementation

Even with a correct theoretical choice, practical implementation can fail. The following workflow helps diagnose and resolve common parameterization and simulation errors.

Experimental Protocols for Force Field Validation

When applying a force field to a new system, or to diagnose suspected inaccuracies, it is critical to follow rigorous validation protocols. The workflow below outlines a general process for validating a force field against key experimental observables.

Protocol 1: Calculating Absolute Hydration Free Energy (HFE) [22]

Objective: To compute the HFE (ΔGhydr), a critical property for solvation and binding affinity, and validate the force field's performance.

Methodology:

- System Setup: Place the solute molecule in a cubic box of explicit water (e.g., TIP3P model), ensuring a minimum distance (e.g., 14 Å) between the solute and box edges. Apply periodic boundary conditions.

- Alchemical Transformation: Use a thermodynamic cycle to annihilate the solute's non-bonded interactions (electrostatics and Lennard-Jones) in both the aqueous phase and in vacuo. This is implemented using a hybrid Hamiltonian

H(λ) = λH₀ + (1-λ)H₁, where λ is the coupling parameter that progresses from 0 to 1. - Simulation & Analysis: Run molecular dynamics simulations at multiple λ windows. The free energy difference for each leg (ΔGvac and ΔGsolvent) is calculated using methods like MBAR or BAR. The HFE is then obtained from: ΔGhydr = ΔGvac - ΔGsolvent.

Protocol 2: Assessing Force Fields for Liquid Membrane Systems [23]

Objective: To evaluate the suitability of a force field for simulating complex, multi-component systems like liquid membranes.

Methodology:

- Property Calculation: Using a model substance like Diisopropyl Ether (DIPE), simulate a range of properties:

- pvT Properties: Calculate density over a temperature range (e.g., 243-333 K) and compare with experimental data.

- Transport Properties: Compute shear viscosity, a key property for permeability.

- Thermodynamic Properties: Estimate mutual solubility with water, interfacial tension, and partition coefficients for solutes like ethanol.

- Benchmarking: Systematically compare the results from multiple force fields (e.g., GAFF, OPLS-AA/CM1A, CHARMM36, COMPASS) against experimental data to identify the most accurate model for the system of interest.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 3: Key Software and Resources for Force Field Applications

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Force Field Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM/pyCHARMM [22] | MD Software | Simulation suite with Python framework. | Built-in workflows for alchemical free energy calculations (HFE). |

| OpenMM [9] | MD Engine | High-performance, open-source simulation toolkit. | Enables benchmarking of force fields and free energy protocols. |

| Alchaware [9] | Automated Tool | Wrapper for OpenMM. | Facilitates high-throughput FEP calculations to assess force field performance. |

| GROMACS [26] | MD Software | Extremely fast and popular MD package. | Includes pdb2gmx for topology generation; extensive force field support. |

| SHAP Framework [22] | Analysis Method | Explains machine learning output. | Attributes HFE prediction errors to specific functional groups. |

| ByteFF [25] | Data-Driven Force Field | Amber-compatible parameter prediction. | Covers expansive drug-like chemical space using a graph neural network. |

Harnessing Machine Learning and AI for Rapid and Accurate Parameter Generation

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Common Issues in AI-Driven Force Field Generation

This guide addresses specific, high-priority problems researchers encounter when implementing machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) workflows for force field parameter generation. The following sections provide targeted questions, diagnostics, and solutions to ensure the accuracy and reliability of your simulations.

FAQ 1: My simulations using a machine-learned force field show poor agreement with quantum mechanical (QM) reference data and experimental observables. What is the source of this inaccuracy?

Diagnosis: Inaccuracies typically stem from three areas: insufficient training data, poor model generalization, or an inadequate loss function during the ML model training phase.

Solution:

- Action 1: Augment and Curate Training Data

- Ensure your training set comprehensively covers the chemical space of interest. For drug-like molecules, this includes diverse functional groups and conformers [27].

- Use high-quality QM calculations (e.g., DFT with a validated functional and basis set) to generate reference data for energies, forces, and charges [27].

- The PFD workflow suggests that fine-tuning a universal pre-trained model can achieve first-principles accuracy with one to two orders of magnitude less training data than training from scratch [28].

- Action 2: Implement Robust Uncertainty Quantification and Validation

- Employ Bayesian inference methods, like the Bayesian Inference of Conformational Populations (BICePs) algorithm, to account for random and systematic errors in both QM calculations and experimental training data [29].

- Beyond QM validation, always validate your final force field against ensemble-averaged experimental measurements (e.g., NMR observables, solvation free energies) to ensure it reproduces macroscopic properties [29] [27].

- Action 3: Refine the Optimization Algorithm

- For complex parameter spaces, consider advanced optimization algorithms. A hybrid Simulated Annealing and Particle Swarm Optimization (SA+PSO) framework has been shown to efficiently find global minima and avoid local traps for reactive force fields (ReaxFF) [30].

FAQ 2: The inference speed of my AI-generated force field is too slow for large-scale molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. How can I improve performance?

Diagnosis: Large, complex models like universal force fields or detailed neural network potentials can have high computational overhead.

Solution:

- Action: Apply Knowledge Distillation

- Use a distillation process to transfer knowledge from a large, accurate, but slow "teacher" model (e.g., a fine-tuned universal model) to a smaller, faster "student" model.

- The PFD workflow explicitly uses distillation after fine-tuning to boost inference speed, making the final force field suitable for large-scale molecular simulations [28].

- Action: Optimize Model Architecture and Implementation

- Explore simpler, more efficient neural network architectures for the potential energy function.

- Ensure the force field code is optimized for your hardware (e.g., using GPU acceleration).

FAQ 3: My force field parameter optimization fails to converge or converges to a physically unrealistic parameter set.

Diagnosis: This is often a sign of the optimization process being trapped in a local minimum or the objective function being poorly defined.

Solution:

- Action 1: Utilize Global Optimization Algorithms

- Replace local optimization methods with global optimizers. Genetic Algorithms (GA), Simulated Annealing (SA), and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) are well-established for this purpose [30].

- The hybrid SA+PSO algorithm demonstrates higher efficiency and avoids premature convergence compared to using either method alone [30].

- Action 2: Enhance the Objective Function

- Design a multi-objective function that balances the reproduction of various QM properties (energy, forces, charges) and experimental data.

- Incorporate the BICePs score as a robust objective function that automatically handles uncertainty and can be used for variational optimization of parameters [29].

- Action 3: Apply Collective Atomic Motion (CAM)

- A recent ReaxFF study showed that introducing a trick that pays more attention to representative key data, such as optimal structures, during optimization (a CAM-like approach) can significantly improve the physical accuracy of the final parameters [30].

Experimental Protocol: The PFD (Fine-Tuning and Distillation) Workflow

This protocol details the methodology for generating a material-specific, high-speed force field from a universal pre-trained model, as outlined in recent literature [28].

1. Objective: To create a machine-learning force field for a specific material system that achieves high accuracy (comparable to first-principles methods) and fast inference speed for large-scale MD simulations.

2. Materials and Software:

- Pre-trained Universal Model: A foundational force field model generalizable across the periodic table.

- Target-Specific QM Data: A dataset of DFT-calculated energies, forces, and stresses for configurations of your target material.

- Computing Resources: GPU-accelerated computing clusters.

- Software: ML force field training code (e.g., based on PyTorch or TensorFlow) with support for fine-tuning and distillation. MD software (e.g., LAMMPS, GROMACS) for validation.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Data Preparation for Fine-Tuning

- Generate a dataset of material configurations (e.g., via active learning or classical MD sampling).

- Perform DFT calculations to obtain the target energy, forces, and stress tensors for each configuration.

- This dataset can be relatively small, as the fine-tuning process is data-efficient [28].

Step 2: Fine-Tuning the Pre-trained Model

- Initialize the model weights with the universal pre-trained model.

- Continue training the model on your target-specific QM dataset. This adapts the general model to your specific system of interest.

- The loss function is typically a weighted sum of errors in energy and forces.

Step 3: Knowledge Distillation for Speed-Up

- Use the fine-tuned model from Step 2 as the "teacher."

- Train a smaller, more efficient "student" model architecture to mimic the teacher's predictions on a large set of configurations.

- The student model learns to reproduce the teacher's accuracy but with a faster inference time.

Step 4: Validation

- Validate the final student model on a held-out test set of QM data to ensure accuracy.

- Run MD simulations and compare properties (e.g., radial distribution functions, diffusion coefficients) against experimental data or benchmark AIMD simulations.

Table 1: Comparison of Force Field Parameter Optimization Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations / Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFD (Fine-Tuning & Distillation) [28] | Leverages a universal pre-trained model; uses fine-tuning for accuracy and distillation for speed. | High data efficiency (1-2 orders of magnitude less data required); achieves first-principles accuracy; fast inference speed. | Dependent on the quality and breadth of the pre-trained universal model. |

| Bayesian Inference (BICePs) [29] | Uses Bayesian statistics to sample posterior distribution of parameters and conformational populations, handling uncertainty. | Robust to sparse/noisy data; accounts for systematic/random errors; provides uncertainty estimates; useful for model selection. | Computationally intensive due to MCMC sampling; requires careful setup of likelihoods and priors. |

| Hybrid SA + PSO [30] | Combines Simulated Annealing's global search with Particle Swarm Optimization's efficiency. | Avoids local minima; higher optimization efficiency and accuracy than SA or PSO alone. | Can still be computationally demanding for very large parameter sets. |

| AI-Generated Partial Charges [27] | ML model trained on DFT-calculated atomic charges to predict charges for new molecules. | Rapid prediction (<1 minute); high accuracy comparable to DFT; good for high-throughput screening. | Accuracy is limited by the quality and chemical space coverage of the training data. |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AI Force Field Development

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained Universal Force Field | A foundational ML model trained on diverse materials across the periodic table. | Serves as the starting point for the PFD workflow, providing a robust initial set of weights for fine-tuning [28]. |

| Quantum Mechanical (QM) Reference Data | High-fidelity data (energies, forces, atomic charges) from DFT or ab initio calculations. | Serves as the "ground truth" for training and validating ML force fields [28] [27]. |

| Bayesian Inference of Conformational Populations (BICePs) | A software algorithm for reweighting structural ensembles against sparse/noisy experimental data. | Used for force field validation and refinement against experimental observables [29]. |

| Reaction Force Field (ReaxFF) | A bond-order based force field capable of simulating chemical reactions. | A common target for parameter optimization using global search algorithms like SA and PSO [30]. |

Workflow Visualization

Fundamental Concepts: Force Fields in Drug Discovery

What is force field parameterization and why is it critical for drug discovery?

Force field parameterization is the process of determining the mathematical parameters that define the potential energy of a molecular system in molecular mechanics simulations. These parameters describe the energy costs of bond stretching, angle bending, torsion rotations, and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals and electrostatic forces). Accurate parameterization is foundational for Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD), as it enables reliable prediction of small molecule behavior, binding affinities, and conformational dynamics, which are essential for successful drug development [31] [32].

Despite improvements, modern force fields still face several challenges:

- Discontinuous energy functions: The derivative of the ReaxFF energy function can have discontinuities, often related to the bond order cutoff. When a bond order crosses this cutoff value between optimization steps, the force experiences a sudden change that can break optimization convergence [33].

- Inconsistent parameters: Warnings about inconsistent van der Waals parameters between different atom types in a force field can indicate potential accuracy issues [33].

- Polarization catastrophes: In the electronegativity equalization method (EEM), poor parameterization can lead to unrealistic charge transfer between atoms at short interatomic distances if the relationship between eta and gamma parameters doesn't satisfy η > 7.2γ [33].

- Protonation state limitations: Traditional force fields may not adequately account for changing protonation states of residues during simulations, affecting protein stability and accuracy [24].

Step-by-Step Parameterization Protocol

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive parameterization workflow for novel drug-like molecules:

Detailed Methodology

Step 1: Initial Structure Preparation and Quantum Chemical Calculations

Begin with high-quality quantum chemical calculations to establish reference data:

- Perform geometry optimization at an appropriate DFT level (e.g., B3LYP/6-31G*) to obtain the minimum energy conformation

- Calculate electrostatic potentials using methods such as RESP (Restrained Electrostatic Potential) for partial charge assignment

- Compute vibrational frequencies to derive force constants for bond and angle parameters

- Perform torsional scans to parameterize dihedral terms by rotating around flexible bonds

Step 2: Initial Parameter Assignment

Assign preliminary parameters through analogy and database mining:

- Identify similar chemical fragments in existing parameter databases (e.g., CGenFF for CHARMM, GAFF for AMBER)

- Use automated parameter assignment tools when available (e.g., CHARMM GUI for small molecules)

- Document all analogies and assumptions for future refinement

Step 3: Target Data Generation

Generate high-quality training data for parameter optimization:

- Calculate interaction energies with water molecules to refine solvation parameters

- Compute lattice energies and cell parameters for crystalline forms if available

- Calculate vibrational spectra for comparison with experimental IR/Raman data

- Determine conformational energies for different rotameric states

Step 4: Parameter Optimization Using Advanced Algorithms

Systematically refine parameters against target data using optimization algorithms:

Table 1: Comparison of Force Field Parameter Optimization Methods

| Method | Best For | Advantages | Limitations | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-start Local Optimization (Simplex, Levenberg-Marquardt, POUNDERS) | Systems with good initial parameters | Fast convergence, computationally efficient | May get trapped in local minima | Reaches low error quickly with good starting point [34] |

| Single-Objective Genetic Algorithm | Complex parameter spaces with multiple minima | Global optimization, less dependent on initial guess | Computationally intensive, many function evaluations | Effective for finding global minimum in complex spaces [34] |

| Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm | Balancing multiple conflicting target properties | Finds Pareto-optimal solutions, preserves trade-offs | Increased complexity in implementation and analysis | Ideal when conflicting objectives exist [34] |

Step 5: Validation Against Experimental Data

Validate optimized parameters against experimental observables not used in training:

- Compare calculated density and enthalpy of vaporization with experimental values for liquids

- Validate aqueous solvation free energies against experimental measurements

- Check diffusion coefficients and viscosity for liquids against experimental data

- Compare conformational preferences with NMR NOE data if available

Step 6: Production Simulation and Analysis

Execute final molecular dynamics simulations with validated parameters:

- Run extended MD simulations (≥100 ns) to assess stability

- Calculate binding free energies for protein-ligand complexes using methods like MM/PBSA or FEP

- Analyze conformational dynamics and ligand properties relevant to drug discovery

Troubleshooting Common Parameterization Issues

FAQ: Addressing Frequent Challenges

Q: My geometry optimization fails to converge. What should I check?

A: Geometry optimization issues in ReaxFF are often caused by discontinuities in the energy derivative. Implement these solutions:

- Switch to 2013 torsion angles: Set

Engine ReaxFF%Torsionsto 2013 for smoother torsion potential at lower bond orders [33] - Decrease bond order cutoff: Reduce

Engine ReaxFF%BondOrderCutoffto include more angles in computation, reducing discontinuity [33] - Enable bond order tapering: Use

Engine ReaxFF%TaperBOto implement tapered bond orders by Furman and Wales for smoother transitions [33]

Q: How do I handle protonation states of residues during simulation?

A: Protonation state issues require specialized approaches:

- Use constant pH simulation methods where available

- Implement the newly developed solution for GROMACS (not yet in main code base) that properly handles protonation states [24]

- For specific residues, manually set protonation states based on pKa predictions and environmental context

Q: I'm getting "inconsistent vdWaals-parameters" warnings. Should I be concerned?

A: These warnings indicate that not all atom types in your force field have consistent van der Waals screening and short-range repulsion parameters. This should be addressed by:

- Checking parameter derivation methods for consistency

- Ensuring all atom types follow the same parameterization philosophy

- Verifying mixing rules for cross-term parameters [33]

Q: What's the most efficient optimization strategy for my system?

A: The optimal strategy depends on your system complexity and starting point:

- For systems with reasonable initial parameters, multi-start local optimization (POUNDERS) provides the best efficiency [34]

- For completely novel chemistries with poor initial parameters, genetic algorithms offer better chances of finding global minima despite higher computational cost [34]

- For balancing multiple objectives (e.g., accuracy for different property types), multi-objective GA identifies optimal trade-offs [34]

Advanced Optimization Strategies

Multi-Parameter Optimization Approaches

Modern drug discovery requires simultaneous optimization of multiple parameters, comparable to solving a Rubik's cube where adjusting one face affects others [35]. Effective strategies include:

- Weighted scoring functions: Assign weights to different properties based on their importance

- Pareto-based methods: Identify non-dominated solutions where no single objective can be improved without worsening another [35]

- Machine learning-guided optimization: Use predictive models to prioritize parameter space regions most likely to yield good results

Algorithm Performance Comparison

The effectiveness of optimization approaches differs when using test data with known ground truth versus real DFT data [34]. Always validate with both known benchmarks and real quantum chemical data.

Table 2: Optimization Algorithm Performance Guide

| Scenario | Recommended Approach | Expected Outcome | Validation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Refining existing parameters | Multi-start local optimization (POUNDERS) | Fast convergence to low error | Compare with high-level quantum calculations |

| Novel molecular motifs | Single-objective Genetic Algorithm | Better chance of global minimum | Multiple property validation |

| Balancing conflicting properties | Multi-objective Genetic Algorithm | Pareto-optimal solutions | Trade-off analysis between properties |

| Limited computational resources | Simplex or Levenberg-Marquardt | Reasonable results with fewer evaluations | Focus on critical properties only |

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Force Field Parameterization

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER/GAFF, ReaxFF | Provides functional forms and base parameters | CHARMM for biomolecules; GAFF for small molecules; ReaxFF for reactive systems [36] |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Gaussian, ORCA, GAMESS | Generate target data for parameterization | Geometry optimization, frequency calculations, energy computations |

| Optimization Algorithms | POUNDERS, Genetic Algorithms, Simplex | Refine parameters against target data | Global vs. local optimization depending on system [34] |

| Validation Tools | MD simulation packages (GROMACS, NAMD, LAMMPS) | Validate parameters in production simulations | Assessment of stability, properties, and behavior [24] |

| Specialized Solutions | Tapered bond orders, 2013 torsion formulae | Address specific force field limitations | Improving convergence and stability [33] |

Integration with Modern Drug Discovery Workflows

Connecting to AI-Driven Drug Discovery

Force field parameterization plays a crucial role in modern AI-driven drug discovery platforms:

- Physics-based simulations complement AI: Companies like Schrödinger combine physics-based simulations with machine learning for more reliable predictions [37]

- AI-accelerated parameterization: Machine learning can predict initial parameters for novel molecules, reducing quantum chemical computation requirements

- High-throughput validation: Automated workflows enable rapid parameter validation across multiple drug candidates [38]

Best Practices for Different Molecular Classes

Small molecule drugs: Focus on accurate solvation free energies and membrane permeability predictions Protein degraders (PROTACs): Prioritize accurate linker flexibility and protein-protein interaction parameters [31] Covalent inhibitors: Require special attention to reaction parameters and transition state modeling Ionizable compounds: Need careful parameterization of protonation states and pH-dependent behavior [24]

By following these structured guidelines and troubleshooting approaches, researchers can develop accurate force field parameters for novel drug-like molecules, enhancing the reliability of molecular simulations in drug discovery campaigns.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My MD simulations of bacterial membranes show unrealistic fluidity. Could general force fields be the issue? A: Yes, this is a common problem. General force fields like GAFF or CHARMM36 are not parameterized for the unique, complex lipids found in bacterial membranes, such as the exceptionally long-chain mycolic acids (C60-C90) in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Using a specialized force field like BLipidFF (Bacteria Lipid Force Fields), which derives its parameters from quantum mechanical calculations specific to these lipids, can accurately capture membrane properties like rigidity and diffusion rates, bringing simulations in line with biophysical experiments [39] [40].

Q2: For protein complex prediction, how can I improve AlphaFold-Multimer's accuracy, especially when paired MSAs are weak? A: When sequence-based co-evolutionary signals are weak (e.g., in antibody-antigen complexes), you can use pipelines like DeepSCFold. It leverages deep learning to predict protein-protein structural similarity and interaction probability directly from sequence, providing a structure-aware foundation for building paired MSAs. This approach has been shown to improve interface prediction success rates by over 24% compared to standard AlphaFold-Multimer in such challenging cases [41].

Q3: What is a robust method for optimizing coarse-grained force fields for nucleic acids? A: A powerful strategy is based on the maximum-likelihood principle. This method involves fitting the simulated conformational ensembles to experimental data and can be combined with a least-squares fit of heat-capacity curves. This approach has successfully optimized the NARES-2P force field, significantly improving its reproduction of both structural and thermodynamic data for DNA molecules compared to its original parameterization [42].

Q4: Which nucleic acid quantification method is most reliable for low-concentration samples like NGS libraries? A: For low-concentration samples, fluorometry and qPCR are the most reliable. Fluorometry offers high sensitivity and specificity, while qPCR provides extremely high sensitivity and can specifically detect molecules with adapters, which is crucial for accurate NGS library quantification. In contrast, UV-Vis spectrophotometry is not sensitive enough and can overestimate concentrations due to contaminants [43].

Troubleshooting Common Scenarios

| Scenario | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unrealistically high lateral diffusion in a mycobacterial lipid membrane simulation [39]. | Use of a general force field lacking parameters for long, rigid lipid tails. | Switch to a specialized force field (e.g., BLipidFF) with quantum mechanics-derived parameters for lipids like α-mycolic acid. |

| AlphaFold3 predicts a protein-protein complex with high overall TM-score but poor interfacial polar interactions [44]. | Inaccurate prediction of hydrogen bonding and apolar-apolar packing at the interface. | Use the predicted structure as a starting point for physics-based refinement with molecular dynamics simulations, but be aware that quality may deteriorate. |

| A coarse-grained simulation of DNA fails to reproduce experimental melting behavior [42]. | The force field weights are not optimized for thermodynamic properties. | Apply a maximum-likelihood force field optimization strategy that explicitly fits to experimental heat-capacity data. |

| Inconsistent nucleic acid concentration readings from a UV-Vis spectrophotometer [43]. | Contamination from proteins, solvents, or salts, which absorb at or near 260 nm. | Use a purification step and/or switch to a more specific method like fluorometry, which uses dyes that bind specifically to nucleic acids. |

Key Experimental Protocols and Data

Protocol 1: Development of a Specialized Lipid Force Field (BLipidFF)

This protocol outlines the creation of accurate force field parameters for unique bacterial membrane lipids, as demonstrated for Mycobacterium tuberculosis outer membrane components [39].

1. Atom Type Definition:

- Define new, specialized atom types based on the atom's location and chemical environment.

- Example: sp³ carbons are subdivided into

cA(headgroup) andcT(lipid tail). Special types likecXare defined for unique motifs like cyclopropane rings [39].

2. Partial Charge Calculation via Quantum Mechanics:

- Divide-and-Conquer: Segment the large lipid molecule into manageable modules.

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize each segment's structure at the B3LYP/def2SVP level in vacuum.

- Charge Derivation: Calculate electrostatic potential and derive partial charges using the RESP fitting method at the B3LYP/def2TZVP level.

- Conformational Averaging: Repeat steps ii-iii for multiple (e.g., 25) conformations and use the average charge to reduce error.

- Software: Gaussian09 for QM calculations; Multiwfn for RESP fitting [39].

3. Torsion Parameter Optimization:

- Further subdivide the molecule into smaller elements for tractable QM calculations.

- Optimize torsion parameters (Vn, n, γ) to minimize the difference between quantum mechanical and classical potential energy surfaces [39].

4. Validation:

- Validate the final force field by running MD simulations of lipid bilayers and comparing properties like rigidity and lateral diffusion coefficients to biophysical experimental data (e.g., Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching) [39] [40].

Diagram 1: Force field parameterization workflow.

Protocol 2: Constructing Structure-Aware Paired MSAs for Complex Prediction

This protocol details the DeepSCFold method for building paired multiple sequence alignments (pMSAs) that enhance protein complex structure prediction, especially when sequence co-evolution is weak [41].

1. Generate Monomeric MSAs:

- Individually search for homologs of each protein chain in large sequence databases (UniRef30, UniRef90, BFD, etc.) using tools like Jackhammer or MMseqs2 [41].

2. Rank and Filter Monomeric MSAs:

- Use a deep learning model to predict a pSS-score (protein-protein structural similarity) between the query sequence and its homologs.