MSD vs VACF: A Comprehensive Guide to Accuracy in Biomolecular Diffusion Analysis

This article provides a critical comparison of the Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) electrochemiluminescence platform and the Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) method for researchers and professionals in drug development.

MSD vs VACF: A Comprehensive Guide to Accuracy in Biomolecular Diffusion Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a critical comparison of the Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) electrochemiluminescence platform and the Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) method for researchers and professionals in drug development. It covers the foundational principles of both techniques, their practical application in quantifying biomolecular interactions and transport properties, strategies for troubleshooting and optimization, and a rigorous validation framework. By synthesizing current research and methodological insights, this guide aims to empower scientists in selecting the most accurate and efficient method for their specific research and development goals, from early discovery to clinical validation.

Understanding MSD and VACF: Core Principles and Theoretical Foundations

Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) technology is a proprietary platform for the quantitative measurement of molecules in biological samples, designed to profile biomarkers with a direct impact on drug discovery and human health. The system's exceptional performance stems from the combination of electrochemiluminescence (ECL) detection and MULTI-ARRAY technology, providing researchers with a powerful tool for sensitive, multiplexed biological assays [1].

Electrochemiluminescence Detection

Electrochemiluminescence represents the fundamental detection mechanism that differentiates MSD from other platforms. This technology offers a unique combination of sensitivity, dynamic range, and convenience unmatched by other detection methodologies. The ECL process involves a electrochemical reaction that generates light without the background interference common in fluorescent or colorimetric systems. This results in reliable, high-quality data across a wide variety of sample types, making it ideal for diverse biological assay requirements. The platform achieves femtogram-level sensitivity and a broad dynamic range spanning 4-5 logs, significantly reducing the need for sample dilutions that complicate traditional workflows [1] [2] [3].

MULTI-ARRAY and Multiplexing Capabilities

The MULTI-ARRAY technology integrates electrochemiluminescence with array-based spatial addressing to deliver speed and high information density in biological assays. This technology is implemented through MULTI-SPOT plates, which enable precise quantitation of multiple analytes from a single sample simultaneously. The multiplexing capability means researchers can obtain more comprehensive biological information from limited sample volumes while reducing hands-on time and effort compared to single-plex platforms. MSD's U-PLEX platform further enhances this flexibility by allowing researchers to configure custom multiplex panels according to their specific research needs [1] [3].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The advantages of MSD technology become evident when comparing its performance metrics directly against traditional methods such as ELISA and other multiplexing platforms. The following tables summarize key performance characteristics based on manufacturer specifications and independent validation studies.

Table 1: MSD Platform vs. Traditional ELISA Performance Characteristics

| Parameter | Traditional ELISA | MSD Technology |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Volume Requirement | 50-100 μL (per analyte) | 10-25 μL (for up to 10 analytes) |

| Multiplexing Capability | No | Yes (up to 10 analytes simultaneously) |

| Dynamic Range | 1-2 logs | 3-4+ logs |

| Sensitivity | Limited | Femtogram level (ultra-sensitive) |

| Assay Protocol | Multiple wash steps | Minimal washes (typically 1-3) |

| Plate Read Time | Slow | 1-3 minutes per plate |

| Instrument Maintenance | Daily cleaning and calibration | No user maintenance required |

| Matrix Effects | Significant | Greatly reduced |

Data source: [3]

Table 2: Concordance Rates Between MSD and Bio-Plex Pro SARS-CoV-2 Serology Assays

| Assay Target | Concordance Rate | Spearman Correlation (r) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-RBD IgG | 90.5% (412/455 tests) | 0.65 to 0.92 | P < 0.0001 |

| Anti-N IgG | 87.0% (396/455 tests) | 0.65 to 0.92 | P < 0.0001 |

Data source: [4]

Experimental Protocol: SARS-CoV-2 Serology Assay

The following detailed protocol is adapted from the methods used in the comparative study between MSD and Bio-Plex Pro assays for detecting SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, as published in PMC [4]. This protocol exemplifies the standard workflow for MSD multiplex serological analysis.

Materials and Reagents

- MSD V-PLEX COVID-19 Panel 1 Kit (contains spotted plates, detection antibodies, calibrators, and controls)

- Patient serum or plasma samples

- MSD Blocker A solution

- MSD Read Buffer T (or other appropriate read buffer)

- Wash buffer (compatible Tris-based wash buffer)

Equipment

- MESO QuickPlex SQ 120MM Reader (or compatible MSD instrument)

- Plate shaker capable of ~750 rpm

- Multi-channel pipettes and reagent reservoirs

- Plate washer (optional, manual washing possible)

Step-by-Step Procedure

Plate Blocking:

- Add 150 μL of Blocker A solution to each well of the MSD MULTI-ARRAY plate.

- Incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature with shaking at approximately 750 rpm.

- Wash the plate 3 times with 150 μL wash buffer per well using an automated plate washer or manual process.

Sample and Control Addition:

- Prepare serum samples at manufacturer-recommended dilutions in provided diluent (typically 1:100 to 1:50,000 depending on target analytes).

- Add 25 μL of diluted samples, calibrators, and controls to appropriate wells.

- Incubate plate for 2 hours at room temperature with shaking at ~750 rpm.

- Wash plate 3 times with wash buffer as described in step 1.

Detection Antibody Incubation:

- Add 25 μL of SULFO-TAG conjugated detection antibody solution to each well.

- Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature with shaking at ~750 rpm.

- Wash plate 3 times with wash buffer as previously described.

Signal Detection:

- Add 150 μL of MSD Read Buffer to each well.

- Immediately read plate on MESO QuickPlex SQ 120MM instrument using DISCOVERY WORKBENCH software.

- The instrument applies an electrical potential to the plate electrodes, inducing electrochemiluminescence from SULFO-TAG labels in proximity to the electrode surface.

Data Analysis:

- Use DISCOVERY WORKBENCH software to convert electrochemiluminescence signals to quantitative values based on calibration curves.

- Report antibody levels in appropriate units (e.g., BAU/mL after conversion using WHO standard).

Technology Comparison in Research Context

The performance of MSD technology must be evaluated within the broader context of method comparison studies, particularly when assessing accuracy against other established platforms. The comparative study between MSD and Bio-Plex Pro highlighted in the search results provides valuable insights into real-world performance characteristics [4].

Concordance Analysis

In the comparative assessment of SARS-CoV-2 serological assays, researchers observed 90.5% concordance for anti-RBD IgG classification and 87% concordance for anti-N IgG when using assay-defined cutoffs to classify samples as positive or negative. The quantitative antibody levels converted to the WHO standard BAU/mL demonstrated statistically significant correlations for all isotypes (IgG, IgM, and IgA) and SARS-CoV-2 antigen targets common to both assays, with Spearman correlation coefficients ranging from 0.65 to 0.92 (P < 0.0001) [4].

Application in Therapeutic Monitoring

Both MSD and Bio-Plex platforms successfully identified diminished host-derived IgG immune responses in participants treated with bamlanivimab (a monoclonal antibody therapeutic) compared to placebo recipients in the ACTIV-2/A5401 clinical trial. This demonstrates the utility of multiplex immunoassays for characterizing immune responses in therapeutic contexts. Notably, MSD assays detected stronger anti-N IgG responses at day 28 in individuals who developed monoclonal antibody resistance (median 2.18 log BAU/mL) compared to those who did not develop resistance (median 1.55 log BAU/mL) [4].

Instrumentation Portfolio

MSD provides a range of instruments designed to accommodate varying laboratory needs, from basic research to high-throughput screening environments. The instrumentation portfolio includes:

Table 3: MSD Instrument Comparison for Different Laboratory Needs

| Parameter | MESO QuickPlex Q 60MM | MESO QuickPlex SQ 120MM | MESO SECTOR S 600MM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Cost-effective research | Versatile applications | High-throughput screening |

| Multiplex Capability | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 96-Well Plate Support | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 384-Well Plate Support | No | No | Yes |

| Plate Read Time | 1 min 23 sec - 2 min 45 sec | 1 min 30 sec - 2 min 45 sec | 1 min 10 sec |

| Plate Stack Capacity | 5 plates | 5 plates | 50 (96-well) or 75 (384-well) plates |

| Computer Included | Laptop | Laptop | Desktop |

| Software Compatibility | Methodical Mind Required | Methodical Mind Enabled | Methodical Mind Enabled |

Data source: [2]

All MSD instruments share common advantages, including minimal maintenance requirements due to the absence of fluidics, broad dynamic range that reduces sample dilution needs, multiplexing capability for efficient experimental design, and ultra-sensitive detection superior to traditional ELISAs. The platforms are driven by the Methodical Mind software suite, which supports experimental design, data capture, and analysis while streamlining team collaboration [2].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of MSD technology requires specific reagents and materials optimized for the platform. The following table outlines essential components for establishing robust MSD assays.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for MSD Assays

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SULFO-TAG Conjugates | Electrochemiluminescent labels that emit light upon electrical stimulation | Detection antibodies, streptavidin, or other binding proteins conjugated to ruthenium-based tags |

| MULTI-SPOT Microplates | Array plates with predefined capture molecule spots | Available in 96-well and 384-well formats with custom or predefined analyte panels |

| Blocker A Solution | Blocking agent to minimize non-specific binding | Applied before sample addition to reduce background signal |

| MSD Read Buffers | Specialized buffers containing tripropylamine coreactant | Initiates electrochemiluminescence reaction when electrical current is applied |

| Calibrators and Controls | Quantitative standards for curve generation and quality control | Often traceable to international standards (e.g., WHO standards for infectious disease) |

| Diluent Solutions | Matrix-appropriate sample diluents | Reduces matrix effects in complex biological samples |

| Wash Buffers | Tris-based buffers for plate washing | Compatible with both manual and automated washing systems |

Meso Scale Discovery's technology platform represents a significant advancement in immunoassay capabilities, combining the sensitivity of electrochemiluminescence with the efficiency of multiplex array technology. The platform's broad dynamic range, minimal sample requirements, and robust performance in complex matrices make it particularly valuable for modern biomedical research and drug development applications. When evaluated against other methodologies in rigorous comparison studies, MSD demonstrates strong concordance and correlation with established platforms while providing additional advantages in throughput and multiplexing capability. For researchers considering platform selection, MSD offers a compelling combination of technical performance and practical workflow benefits that can accelerate biomarker discovery and validation efforts.

The Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) is a fundamental quantity in statistical mechanics and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations that provides deep insight into the dynamical behavior of particles in a system. It plays an important role for dynamical quantities and serves as a cornerstone for understanding transport phenomena and diffusion processes in condensed matter systems [5]. Within the framework of linear response theory, transport coefficients for dynamical processes can be obtained from autocorrelation functions of dynamical quantities calculated at equilibrium [5]. This makes the VACF particularly valuable for researchers investigating molecular motion in complex systems, including those relevant to drug development where understanding molecular diffusion and interaction dynamics is critical.

The VACF's relationship to the self-diffusion coefficient, DS, establishes its practical significance in quantifying particle mobility [5]. In molecular dynamics simulations, the VACF is evaluated by tracking and correlating particle velocities over time, providing a temporal map of how a particle's motion becomes decorrelated from its initial state due to interactions with its environment. This function effectively captures the memory effects in particle motion, revealing how long a particle "remembers" its initial velocity direction and magnitude before collisions and interactions randomize its trajectory.

Mathematical Definition and Formulation

Fundamental Equation

The Velocity Autocorrelation Function is mathematically defined as the time-correlation function of a particle's velocity vector with itself at different time instances. For a system of N particles, the VACF is given by:

[ \langle \vec{v}(t) \cdot \vec{v}(t - \Delta t) \rangle = \frac{1}{M} \sum{v=1}^{M} \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} \vec{vi}(tv) \cdot \vec{vi}(tv - \Delta t) ]

where (\vec{v}(t)) represents the velocity vector at time (t), (\Delta t) is the time difference, (N) is the number of particles, and (M) represents the number of time steps over which the averaging is performed [5]. The angle brackets (\langle \cdots \rangle) denote the ensemble average, which in practice is computed as an average over all particles and multiple time origins in the simulation trajectory.

Connection to Diffusion Coefficient

The VACF provides a fundamental route to calculating the self-diffusion coefficient through the Green-Kubo relation:

[ DS = \frac{1}{3} \int0^{\infty} \langle \vec{v}(t) \cdot \vec{v}(0) \rangle dt ]

This integral relationship demonstrates that the diffusion coefficient is directly proportional to the area under the VACF curve [5]. Alternatively, diffusion coefficients can be determined through the Einstein relation, which links them to the long-time slope of the mean-squared displacement (MSD) [5]:

[ Di = \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{1}{6t} \langle |\delta r_i(t)|^2 \rangle ]

where (\delta r_i(t)) is the displacement of individual ion (i) in time (t). Both approaches provide consistent measures of diffusion, with the VACF-based method offering additional insights into the short-time dynamics of the system.

Computational Protocol for VACF Calculation

Molecular Dynamics Implementation

The practical computation of the VACF within molecular dynamics simulations follows a systematic protocol:

Step 1: Trajectory Generation - Conduct an MD simulation while recording atomic velocities at regular intervals throughout the production phase. The sampling frequency should be sufficient to capture the relevant dynamics, typically on the order of femtoseconds to picoseconds for atomic systems.

Step 2: Data Collection - Store velocities for all particles not only for the present time step but also for earlier ones. In practice, most implementations maintain a history of velocities for the last several hundred time steps to enable the correlation computation [5].

Step 3: Correlation Calculation - For a given time difference (\Delta t), evaluate the VACF by multiplying the velocity of each particle at time (t) with the velocity of the same particle at time (t - \Delta t), then average these products over all particles and multiple time origins in the trajectory [5].

Step 4: Ensemble Averaging - Perform additional averaging over multiple independent simulation runs or over different time origins within a single long trajectory to improve statistical accuracy.

Technical Considerations

Table 1: Critical Parameters for VACF Calculation in MD Simulations

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Time Step | 0.5-2.0 fs | Ensures numerical stability and proper sampling of atomic vibrations |

| Sampling Frequency | Every 1-10 steps | Balances temporal resolution with storage requirements |

| Correlation Length | 100-1000 steps | Determines the maximum time lag for correlation analysis |

| System Size | ≥256 molecules | Minimizes finite-size effects; 512+ recommended [5] |

| Simulation Temperature | System-dependent | Maintains appropriate thermodynamic ensemble |

| Total Simulation Time | Sufficient for decay to zero | Ensures proper sampling of long-time dynamics |

The calculated VACF primarily gives information about vibrational modes at (q = 0) due to restrictions on periodic boundary conditions [5]. To access other modes in the first Brillouin Zone, a "zone-folding" process of super-cells is required. The super-cell size significantly affects the quality of the density of states (DOS) obtained from any integration across the Brillouin Zone [5]. For accurate DOS calculations, a super-lattice cell of at least 5×5×5 unit cells (512 water molecules for ice Ih) is recommended, with 8×8×8 super-lattice cells (over 2000 water molecules) being more appropriate if computational resources allow [5].

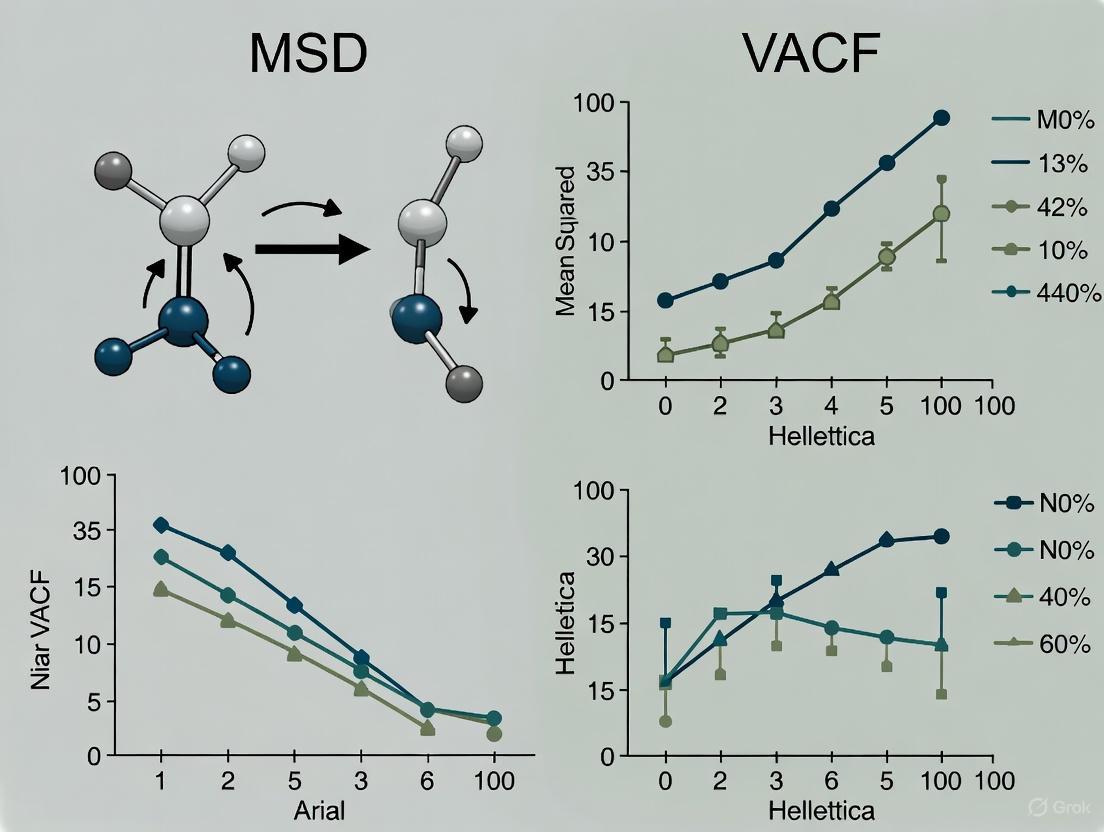

Comparative Analysis: VACF vs. Mean-Squared Displacement

Fundamental Differences in Approach

The VACF and MSD provide complementary perspectives on particle dynamics, with each method offering distinct advantages and limitations:

Temporal Scope: The VACF emphasizes short-time dynamics, capturing the initial decay of velocity correlations, while the MSD primarily reflects long-time diffusive behavior.

Information Content: VACF contains more detailed information about the microscopic collision processes and memory effects, whereas MSD provides a more direct measure of spatial exploration.

Computational Considerations: MSD calculations are generally more straightforward to implement and converge more rapidly for the diffusion coefficient, while VACF calculations can be noisier, particularly at long times.

Quantitative Comparison

Table 2: Comparison of VACF and MSD Methods for Diffusion Analysis

| Characteristic | Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) | Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Definition | (\langle \vec{v}(t) \cdot \vec{v}(0) \rangle) | (\langle | \vec{r}(t) - \vec{r}(0) | ^2 \rangle) |

| Diffusion Coefficient | (D = \frac{1}{3} \int_0^{\infty} \langle \vec{v}(t) \cdot \vec{v}(0) \rangle dt) | (D = \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{1}{6t} \langle | \delta r_i(t) | ^2 \rangle) |

| Time Regime | Short-time dynamics | Long-time behavior | ||

| Information Captured | Memory effects, collision processes, vibrational modes | Spatial exploration, anomalous diffusion, confinement effects | ||

| Statistical Noise | Higher at long times due to integration of noise | Generally lower, especially for long trajectories | ||

| Computational Cost | Moderate (requires velocity storage and correlation) | Lower (straightforward displacement calculation) | ||

| Sensitivity to Anomalous Diffusion | Reveals underlying mechanisms through functional form | Directly identifies through power-law exponent |

Method Accuracy Considerations

Within the context of method accuracy comparison research, several critical factors emerge:

System Size Dependence: The VACF shows significant size effects in calculated density of states, with small systems (64-128 molecules) producing structured noise that could be mistaken for real peaks in complex systems [5]. The MSD approach is generally less sensitive to system size for diffusion coefficient calculation.

Time Resolution: The VACF requires higher temporal resolution to accurately capture the initial decay, which contains important information about collision processes and memory effects. MSD calculations can often use coarser time resolution, particularly when only the long-time diffusive behavior is of interest.

Statistical Precision: The MSD typically converges more rapidly for diffusion coefficient estimation, as the VACF integral can be sensitive to noise in the long-time tail where the function approaches zero.

Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Dynamics

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for VACF and Dynamics Research

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in VACF Research |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Packages | GROMACS, LAMMPS, NAMD, AMBER | Generate particle trajectories with velocity information |

| Analysis Tools | MDTraj, MDAnalysis, VMD plugins | Calculate VACF, MSD, and other correlation functions |

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS, TIP4P (for water) | Define interatomic potentials governing particle dynamics |

| Visualization Software | VMD, PyMol, Ovito | Visualize particle trajectories and dynamic behavior |

| Programming Environments | Python (NumPy, SciPy), MATLAB, Julia | Implement custom analysis scripts and data processing |

Visualizing VACF Relationships and Workflows

VACF Calculation and Application Pathway

VACF vs MSD Method Comparison

Advanced Applications in Drug Development Research

The VACF finds important applications in pharmaceutical research, particularly in understanding molecular mobility and interaction dynamics in complex biological systems:

Protein Dynamics: Analysis of VACF in protein simulations reveals residue-specific mobility and internal friction, which can influence drug binding kinetics and molecular recognition processes.

Membrane Permeation: VACF analysis of drug molecules in lipid bilayers provides insights into local friction coefficients and barrier crossing events, relevant for predicting bioavailability and membrane transport properties.

Solvation Dynamics: The VACF of solvent molecules around pharmaceutical compounds characterizes hydration shell stability and solvent reorganization timescales that can impact binding affinities and solubility.

For researchers in drug development, the VACF offers a microscopic view of molecular mobility that complements experimental techniques and provides mechanistic insights into molecular-level processes governing drug behavior in biological systems. When combined with MSD analysis, it provides a comprehensive picture of molecular dynamics across multiple timescales, from initial ballistic motion to long-range diffusive behavior.

The Green-Kubo relations provide an exact mathematical framework for calculating transport coefficients from the microscopic fluctuations that occur in a system at equilibrium [6]. These relations form a cornerstone of linear response theory, connecting equilibrium fluctuations to non-equilibrium transport properties. For scientists investigating diffusion phenomena, the Green-Kubo relation for the self-diffusion coefficient is of particular importance, as it establishes a fundamental connection between the diffusion coefficient and the velocity autocorrelation function (VACF) of the particles within the system.

In the context of comparing methodological accuracy between mean-squared displacement (MSD) and VACF approaches, the Green-Kubo formalism offers a theoretically rigorous pathway for computing diffusion coefficients that complements the more direct MSD method. Whereas the MSD approach calculates the diffusion coefficient from the long-time slope of the mean-squared displacement, the Green-Kubo method extracts the same information from the time integral of the VACF [6]. This dual approach provides researchers with a valuable cross-verification mechanism for validating computational results, which is especially crucial in complex systems like ionic liquids or biomolecular environments where sampling challenges and statistical noise can affect accuracy.

The fundamental Green-Kubo relation for the self-diffusion coefficient ( D ) states that:

[ D = \frac{1}{3}\int_{0}^{\infty} \langle \vec{v}(t) \cdot \vec{v}(0) \rangle dt ]

where ( \langle \vec{v}(t) \cdot \vec{v}(0) \rangle ) represents the velocity autocorrelation function, which measures how a particle's velocity correlates with itself over time [6]. In practice, this integration is performed numerically over a finite time range, introducing specific methodological considerations for achieving accurate results.

Theoretical Foundation

Mathematical Formulation

The Green-Kubo relation for diffusion coefficients emerges from the broader framework of linear response theory, which systematically connects equilibrium fluctuations to non-equilibrium transport coefficients. The general Green-Kubo expression for a transport coefficient ( \gamma ) is given by:

[ \gamma = \int_{0}^{\infty} \langle \dot{A}(t) \dot{A}(0) \rangle dt ]

where ( \dot{A}(t) ) represents the time derivative of a dynamical variable ( A(t) ) [6]. For the specific case of self-diffusion, the relevant dynamical variable is the particle velocity, leading to the VACF-based expression shown previously.

This relationship can be intuitively understood by recognizing that relaxations resulting from random fluctuations in equilibrium are physically indistinguishable from those arising from weak external perturbations in the linear response regime [6]. The Green-Kubo formula thus captures how microscopic velocity fluctuations decay over time and quantitatively links this decay to macroscopic mass transport.

Extension to Anomalous Diffusion

Traditional Green-Kubo relations assume normal diffusive behavior where mean-squared displacement grows linearly with time. However, many complex systems exhibit anomalous diffusion characterized by non-linear growth of mean-squared displacement [7]. For such systems, a scaling Green-Kubo relation has been developed that extends the traditional formalism to systems with long-range correlations or non-stationary dynamics [7].

This generalized approach becomes necessary when the velocity autocorrelation function exhibits specific scaling behavior rather than exponential decay. The scaling form can handle both stationary systems with power-law correlations and aging systems whose properties depend on the system's age [7]. In these cases, the anomalous diffusion coefficient ( D\nu ) and exponent ( \nu ) (where ( \langle x^2(t) \rangle \simeq 2D\nu t^\nu )) can be extracted from the scaling form of the VACF, significantly expanding the applicability of the Green-Kubo approach to diverse physical systems including those described by fractional Langevin equations or Lévy walk processes [7].

Computational Implementation

Current Autocorrelation Function Calculation

In practical molecular dynamics simulations, the discrete nature of trajectory data requires specific computational treatments of the correlation functions. For a molecular dynamics trajectory with ( N ) steps and time step ( \Delta t ), the current autocorrelation function (CAF) at lag time ( k\Delta t ) is computed as:

[ Ck = \frac{1}{N-k} \sum{i=0}^{N-k-1} \vec{J}{i+k} \cdot \vec{J}i ]

where ( \vec{J}_k ) represents the microscopic current at step ( k ) [8]. To improve statistical accuracy, the trajectory is often divided into ( M ) independent intervals, with the final CAF obtained by averaging the correlation functions from each interval:

[ Ck = \frac{1}{M} \sum{A=1}^M \langle \vec{J} \cdot \vec{J} \rangle_k^{(A)} ]

The statistical uncertainty of the CAF at each time point is quantified by:

[ u(Ck) = \frac{\sigmak}{\sqrt{M(N-k)}} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{M(N-k)-1}} \left[ \frac{1}{M} \sum{A=1}^M \langle (\vec{J})^2 \cdot (\vec{J})^2 \ranglek^{(A)} - (C_k)^2 \right]^{1/2} ]

where ( \sigma_k ) is the standard deviation of the ( k )-th CAF value across intervals [8]. This uncertainty quantification is crucial for determining optimal integration limits and assessing result reliability.

Numerical Integration with Uncertainty Propagation

The transport coefficient is obtained through numerical integration of the current autocorrelation function using a trapezoidal scheme:

[ Ik = \frac{\Delta t}{2} \sum{i=0}^k (Ci + C{i+1}) ]

with the uncertainty propagating according to:

[ u(Ik) = \frac{\Delta t}{2} \sqrt{ \sum{i=0}^k \left[ u^2(Ci) + u^2(C{i+1}) \right] } ]

This uncertainty grows approximately as ( \sqrt{k} ) with increasing time, meaning that points in the integration plateau have varying statistical significance [8]. The kute algorithm addresses this challenge by implementing a weighted averaging scheme that accounts for the increasing uncertainty at longer times, eliminating the need for arbitrary integration cutoffs that could potentially bias results [8].

The running transport coefficient is defined as the weighted average:

[ \gammai = \frac{ \sum{k=i}^N Ik / u^2(Ik) }{ \sum{k=i}^N u^{-2}(Ik) } ]

with corresponding uncertainty:

[ u(\gammai) = \frac{ 1 }{ N-i } \sqrt{ \frac{ \sum{k=i}^N (\gammai - Ik)^2 / u^2(Ik) }{ \sum{k=i}^N u^{-2}(I_k) } } ]

The plateau in the ( \gamma_i ) sequence identifies the transport coefficient value, with the statistical uncertainty determining the precision of this estimate [8].

Isotropic Averaging for Bulk Systems

For isotropic systems, the individual components of the transport coefficient tensor are averaged to obtain the scalar transport coefficient:

[ \gammai = \frac{ \sum\alpha \gammai^{\alpha\alpha} / u^2(\gammai^{\alpha\alpha}) }{ \sum\alpha u^{-2}(\gammai^{\alpha\alpha}) } ]

with uncertainty:

[ u(\gammai) = \frac{1}{2} \sqrt{ \frac{ \sum\alpha (\gammai^{\alpha\alpha} - \gammai)^2 / u^2(\gammai^{\alpha\alpha}) }{ \sum\alpha u^{-2}(\gamma_i^{\alpha\alpha}) } } ]

This isotropic averaging improves statistical precision while providing a single diffusion coefficient value for comparison with experimental measurements [8].

Experimental Protocol: Application to Ionic Liquids

System Preparation and Simulation Details

The following protocol outlines the application of the Green-Kubo method for calculating diffusion coefficients in a protic ionic liquid, specifically ethylammonium nitrate (EAN), which serves as an excellent test system due to its complex hydrogen-bonding network and relevance in electrochemical applications.

- Force Field Selection: Employ the polarizable CL&Pol force field developed by Goloviznina et al. to properly capture polarization effects and hydrogen-bonding interactions [8].

- System Construction: Create 10 independent simulation boxes containing 500 ion pairs each using PACKMOL to ensure adequate sampling of configurational space [8].

- Energy Minimization: Perform energy minimization with a tolerance of 10 kJ/mol to remove steric clashes and high-energy configurations [8].

- Equilibration Protocol:

- NpT ensemble stabilization for 10 ns to achieve proper density at the target temperature and pressure.

- NVT ensemble equilibration for 5 ns using the final density from the NpT simulation.

- Production Simulation: Conduct a 50 ns NVT production simulation with a 1 fs time step, saving trajectories at intervals appropriate for correlation function calculation (typically 10-50 fs) [8].

- Constraint Handling: Keep bonds involving hydrogen atoms constrained using appropriate algorithms such as LINCS or SHAKE to permit longer time steps.

Current Calculation and Correlation Analysis

- Velocity Extraction: From the production trajectory, extract atomic velocities at each saved time step, ensuring consistent units (typically Å/ps).

Current Definition: For ionic conductivity calculations, compute the charge current as:

[ \vec{J}c(t) = \sumi qi \vec{v}i(t) ]

where ( qi ) and ( \vec{v}i ) are the charge and velocity of ion ( i ), respectively. For diffusion coefficients, use the mass current or simply the velocity VACF.

- Correlation Function Computation:

- Divide the trajectory into ( M ) statistically independent blocks (typically 10-20 blocks).

- For each block, compute the current autocorrelation function using Fast Fourier Transform methods for computational efficiency.

- Average the correlation functions across all blocks and compute the standard error for each time point.

- Numerical Integration:

- Perform numerical integration of the averaged correlation function using the trapezoidal rule.

- Compute the uncertainty of the running integral at each time point through error propagation.

Transport Coefficient Extraction

- Plateau Identification: Apply the kute algorithm to identify the plateau region in the running transport coefficient, using the weighted averaging scheme that accounts for increasing uncertainty at longer times [8].

- Result Reporting: Report the plateau value as the transport coefficient with its uncertainty, ensuring that the reported value represents a consistent plateau over a reasonable time range rather than a single point estimate.

Comparative Methodologies

Green-Kubo vs. Mean-Squared Displacement Approaches

The diffusion coefficient can be calculated through either the Green-Kubo (VACF) method or the Einstein relation (MSD) approach, providing complementary methodologies for validation.

Table 1: Comparison of VACF and MSD Approaches for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

| Feature | Green-Kubo (VACF) Approach | Einstein (MSD) Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical basis | Fluctuation-dissipation theorem | Random walk theory |

| Fundamental relation | ( D = \frac{1}{3}\int_0^\infty \langle \vec{v}(t)\cdot\vec{v}(0) \rangle dt ) | ( D = \lim_{t\to\infty} \frac{1}{6t} \langle |\vec{r}(t)-\vec{r}(0)|^2 \rangle ) |

| Required computation | Integration of correlation function | Slope of MSD vs. time |

| Statistical noise | Higher at long times due to cumulative integration | Lower at long times for well-converged MSD |

| Sensitivity to initial conditions | More sensitive to velocity correlations | Less sensitive, depends on positional displacements |

| Convergence behavior | Typically requires longer sampling for smooth decay | Can appear converged even with limited sampling |

| Anomalous diffusion detection | Through scaling of VACF [7] | Through non-linear MSD growth |

Alternative Machine Learning Approaches

Recent advances have introduced symbolic regression as an alternative method for estimating diffusion coefficients, potentially bypassing traditional numerical methods based on VACF or MSD calculations. This machine learning approach correlates diffusion coefficients with macroscopic variables such as density, temperature, and confinement width through equations derived from genetic programming [9].

For bulk fluids, the symbolic regression approach typically yields expressions of the form:

[ D{SR} = \alpha1 T^{\alpha2} \rho^{\alpha3 - \alpha_4} ]

where ( \alpha_i ) are fluid-specific parameters, ( T ) is temperature, and ( \rho ) is density [9]. This methodology offers computational efficiency once parameterized but requires extensive MD simulation data for training and may lack the fundamental physical insight provided by the Green-Kubo approach.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function/Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| kute Python package | Implements uncertainty-aware Green-Kubo transport property calculation | Provides robust estimation of transport coefficients without arbitrary cutoffs [8] |

| OpenMM MD engine | High-performance molecular dynamics simulator with GPU acceleration | Enables long-time scale polarizable simulations of ionic systems [8] |

| CL&Pol force field | Polarizable force field for ionic liquids | Accurately captures charge screening and hydrogen bonding in protic ILs [8] |

| PACKMOL | Solvation and packing tool for initial system configuration | Creates realistic initial configurations for complex ionic systems [8] |

| Symbolic regression framework | Genetic programming-derived equations connecting macro/micro properties | Bypasses traditional VACF/MSD calculations for rapid estimation [9] |

Visualizing the Green-Kubo Workflow

Conceptual Framework Diagram

Graph 1: Green-Kubo Workflow for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation. This diagram illustrates the sequential process from MD simulations to the final diffusion coefficient, highlighting the central role of uncertainty quantification at each stage.

Method Comparison Diagram

Graph 2: Comparative Methodologies for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation. This diagram illustrates three distinct pathways for obtaining diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics data, highlighting the Green-Kubo approach alongside MSD and emerging machine learning methods.

The Green-Kubo relation provides a powerful and theoretically rigorous framework for connecting microscopic velocity fluctuations to macroscopic diffusion coefficients. For researchers comparing methodological accuracy between VACF and MSD approaches, the Green-Kubo method offers valuable complementary information that can validate results obtained through Einstein relations. The development of uncertainty-aware algorithms like kute represents a significant advancement in Green-Kubo analysis, eliminating subjective integration cutoffs and providing robust error estimates [8].

When applying the Green-Kubo method to complex systems such as ionic liquids, particular attention must be paid to force field selection, simulation length, and statistical uncertainty quantification. The protocol outlined here for ethylammonium nitrate provides a template that can be adapted to other systems of interest. For applications requiring rapid estimation of diffusion coefficients across multiple conditions, emerging machine learning approaches based on symbolic regression offer promising alternatives, though they lack the fundamental physical insight of the Green-Kubo formalism [9].

The continued development of scaling relations for anomalous diffusion systems [7] further extends the utility of the Green-Kubo approach to non-traditional diffusion processes, ensuring its relevance for future research in complex soft matter and biological systems.

Application Notes

Immunogenicity testing is a critical component in the development of biopharmaceuticals, as the ability of a therapeutic protein or antibody to provoke an immune response can significantly impact both its efficacy and patient safety [10]. Regulators require a multi-tiered testing approach, typically beginning with highly sensitive screening assays, followed by confirmatory assays to eliminate false positives, and culminating in further characterization, such as cell-based neutralizing antibody (NAb) assays [11].

The Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) platform, which utilizes MULTI-ARRAY technology, has become a prominent method for Anti-Drug Antibody (ADA) testing. Its key advantages include [11]:

- Superior sensitivity for detecting both low- and high-affinity ADAs.

- High drug tolerance, which minimizes interference from ADA-drug complexes.

- A wide dynamic range, reducing the need for repeated sample dilutions.

- Support for a variety of protocols, including cell-based NAb assays.

In contrast, while not explicitly detailed in the search results, other methods may not offer the same level of sensitivity or drug tolerance, potentially affecting the accuracy of immunogenicity risk assessment.

A robust immunogenicity assessment facilitates lead candidate selection and helps de-risk molecules by identifying areas within the protein sequence that can be engineered to reduce immunogenicity potential [10]. This is crucial for supporting a strong Investigational New Drug (IND) submission.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Immunogenicity Assays

| Characteristic | MSD Platform | Traditional ELISA |

|---|---|---|

| Assay Sensitivity | Superior sensitivity for low/high-affinity ADAs [11] | Information not available in search results |

| Drug Tolerance | High [11] | Information not available in search results |

| Dynamic Range | Wide [11] | Information not available in search results |

| Support for Cell-Based NAb Assays | Yes [11] | Information not available in search results |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Immunogenicity Assay for Anti-Drug Antibody (ADA) Detection using MSD

Principle: This protocol uses an MSD electrochemiluminescence-based bridging assay to detect and confirm the presence of ADAs in biological samples. The drug is labeled with biotin and SULFO-TAG. ADAs in the sample form a bridge, creating a complex that is captured on a streptavidin-coated MSD plate and detected by electrochemiluminescence [11].

Materials:

- MSD Streptavidin Gold Microplates: Solid substrate for immobilizing the assay complex.

- Biotinylated Drug: Serves as the capture reagent.

- SULFO-TAG Labeled Drug: Serves as the detection reagent.

- MSD Read Buffer T: Contains the tripropylamine (TPA) necessary for the electrochemical reaction.

- ADA Positive Control: A known positive control antibody for assay qualification.

- ADA Negative Control: A pool of naive matrix (e.g., serum or plasma) for establishing baseline signal.

- Blocking Buffer: (e.g., 1-3% BSA in PBS) to minimize non-specific binding.

Procedure:

- Plate Coating: Coat an MSD Streptavidin plate with the biotinylated drug according to optimized concentrations and incubate.

- Blocking: Block the plate with an appropriate blocking buffer to prevent non-specific binding.

- Sample Incubation: Add test samples, controls, and a cocktail of the biotinylated and SULFO-TAG-labeled drug to the plate. Incubate to allow for complex formation.

- Washing: Wash the plate thoroughly to remove unbound materials.

- Signal Detection: Add MSD Read Buffer T and read the plate on an MSD instrument to measure the electrochemiluminescence signal.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the assay cut-point using statistical analysis of negative control samples to distinguish positive from negative samples.

Protocol 2: T-cell Immunogenicity Assay (EpiScreen Platform)

Principle: This ex vivo assay measures CD4+ T-cell responses, the primary drivers of memory-based immunogenicity, to evaluate the potential of a drug candidate to elicit a cellular immune response [10].

Materials:

- Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) from multiple healthy donors.

- Test Article: The therapeutic protein or antibody candidate.

- Positive Control: e.g., an antigen known to stimulate T-cells, such as keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH).

- Negative Control: e.g., vehicle or buffer control.

- Cell Culture Medium: Appropriate medium (e.g., RPMI-1640) supplemented with serum and cytokines.

- Flow Cytometry Reagents: Antibodies for detecting T-cell activation markers (e.g., CD25, CD134, CD69) and intracellular cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ, IL-2).

Procedure:

- PBMC Isolation: Isolate PBMCs from donor blood samples using density gradient centrifugation.

- Cell Culture: Seed PBMCs into culture plates and stimulate with the test article, positive control, or negative control.

- Incubation: Incubate the cells for several days to allow for T-cell activation and proliferation.

- Analysis: Harvest cells and analyze T-cell responses using flow cytometry to measure proliferation and the expression of activation markers.

- Data Interpretation: Compare the response to the test article against the negative control to determine the relative immunogenicity risk.

Visualization

ADA Detection Workflow

Immunogenicity Testing Strategy

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Immunogenicity Testing

| Reagent / Material | Function in Assay |

|---|---|

| MSD Multi-Array Microplates | The solid-phase platform with integrated electrodes that enables multiplexed electrochemiluminescence detection [11]. |

| SULFO-TAG Label | An electrochemiluminescent label that emits light upon electrochemical stimulation, enabling highly sensitive detection of analytes [11]. |

| Biotinylated Reagents | Used in conjunction with streptavidin-coated plates to efficiently capture assay components, a common format for ADA bridging assays [11]. |

| Anti-Drug Antibody (ADA) Controls | Qualified positive and negative controls essential for validating assay performance and establishing the screening cut-point [11]. |

| Human PBMCs | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells used in ex vivo T-cell immunogenicity assays (like EpiScreen) to predict potential cellular immune responses to a biologic [10]. |

Comparative Strengths: High-Throughput Screening (MSD) vs. Fundamental Transport Property Analysis (VACF)

In the landscape of modern drug discovery, the selection of an appropriate analytical methodology is pivotal for generating reliable and physiologically relevant data. This application note provides a detailed comparative analysis of two distinct approaches: High-Throughput Screening (HTS) employing Multivariate Statistical Distance (MSD) tests, and Fundamental Transport Property Analysis utilizing Velocity Auto-Correlation Function (VACF). Framed within a broader thesis on method accuracy comparison, this document delineates the operational protocols, quantitative performance, and specific application domains for each method. It is designed to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the practical knowledge to select the optimal technique based on their project requirements, whether for rapid compound prioritization or for deep mechanistic understanding of molecular dynamics.

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) and the Multivariate Statistical Distance (MSD) Test

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) is an automated, robotics-driven method for rapidly conducting millions of chemical, genetic, or pharmacological tests to identify active compounds (hits) that modulate a specific biomolecular pathway [12]. Its core principle is the miniaturization and parallelization of assays in microtiter plates (with 96 to 6144 wells) to enable the rapid interrogation of vast compound libraries [12] [13]. A critical aspect of analyzing HTS output, especially in applications like dissolution profiling, is the comparison of multivariate data profiles. The f₂ test has been a standard tool for this purpose, but it fails under conditions of high variability [14]. In such cases, regulatory bodies like the FDA and EMA frequently propose the Multivariate Statistical Distance (MSD) test as a robust alternative [14]. The MSD test overcomes several drawbacks of other methods by operating on all raw dissolution data points up to the first point greater than 85% dissolution, effectively capturing the complete profile shape without relying on model-dependent parameters [14].

Detailed Experimental Protocol for HTS with MSD Analysis

Protocol Title: Primary HTS Campaign with Post-Hoc MSD Analysis for Dissolution Profile Comparison

Objective: To identify novel bioactive compounds ("hits") against a specific protein target and to compare compound-induced phenotypic dissolution profiles using the MSD test.

Materials and Reagents:

- Assay Plates: 384-well or 1536-well microtiter plates [12].

- Compound Library: Typically 100,000 to over 1 million compounds from carefully catalogued stock plates [12] [15].

- Biological Target: Purified enzyme, cell line, or animal embryos relevant to the disease pathway [12].

- Liquid Handling Systems: Automated pipettors and dispensers for nanoliter-volume transfers [12].

- Detection Instrumentation: Plate readers capable of fluorescence, luminescence, absorbance, or specialized polarized light reflectivity measurements [12]. High-throughput Mass Spectrometry (HT-MS) systems like RapidFire-MS or MALDI-TOF are increasingly used for label-free detection [16].

- Integrated Robotic System: Central robot with a gripper for transporting microplates between stations for sample addition, mixing, incubation, and final readout [12] [13].

- Data Processing/Control Software: For scheduling robotic operations, controlling instruments, and data acquisition [12].

Procedure:

- Assay Plate Preparation: Using liquid handling devices, transfer a small volume (nanoliters) of compounds from stock plates to the corresponding wells of empty assay plates [12].

- Biological Reaction Setup: Dispense the biological entity (e.g., protein or cells) into all wells of the assay plate. Incubate for a predetermined time to allow for reaction [12].

- Primary Screening and Data Collection: Run the assay plate through the detection instrument. A high-capacity analysis machine can measure dozens of plates in minutes, generating a grid of numeric values (e.g., dissolution percentages over time) for each well [12] [14].

- Hit Selection (Primary): Apply robust statistical methods (e.g., z-score, SSMD) to the primary screen data to identify initial "hits" – compounds with a desired size of effects [12].

- MSD Test for Profile Comparison (Secondary Analysis): a. For studies requiring dissolution profile comparison (e.g., following up on hits that alter cellular transport), compile the data series for each test and reference formulation. b. MSD Calculation: Perform the MSD test on all raw dissolution data points from the start of the experiment up to the first time point where dissolution exceeds 85%. The test incorporates the entire data vector without using time as an explicit parameter, effectively measuring the statistical distance between multivariate profiles [14]. c. Decision Making: A smaller MSD value indicates greater similarity between the two dissolution profiles. Establish a predefined MSD threshold to determine if profiles are equivalent.

- Confirmatory Screening: For hits identified in the primary screen, perform dose-response (DR) experiments to calculate potency (e.g., IC₅₀ values) and confirm activity [12] [15].

- Analog Expansion: Synthesize and test structurally related analogs of confirmed hits to establish initial Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR) and improve compound properties [15].

Research Reagent Solutions for HTS

Table 1: Essential materials and reagents for an HTS campaign.

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates (384-/1536-well) | The key labware for miniaturization; enables testing of thousands of compounds in parallel with minimal reagent use [12] [13]. |

| Positive/Negative Controls | Critical for quality control; allows for calculation of Z-factor and SSMD to assess assay robustness and signal window [12]. |

| Label-Free MS Reagents | HT-MS assays (e.g., using RapidFire systems) avoid fluorescent labels, reducing false positives from compound interference and enabling direct measurement of native substrates/products [16]. |

| Cryopreserved Cell Lines | Provide a consistent, ready-to-use source of cellular models for phenotypic screening, ensuring assay reproducibility [13]. |

| Aptamers | Nucleic acid-based reagents used for high-affinity binding to protein targets; optimized for speed and compatibility with various detection strategies in HTS assays [13]. |

HTS Workflow Visualization

Diagram Title: HTS-MS-D Analysis Workflow

Fundamental Transport Property Analysis (VACF)

Fundamental Transport Property Analysis, often leveraging molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, probes the physical basis of molecular motion and interactions at an atomic scale. A key quantity in this analysis is the Velocity Auto-Correlation Function (VACF), which provides insights into the diffusive behavior and transport properties of molecules. The VACF measures how a particle's velocity correlates with itself over time. Its time integral is directly related to the diffusion coefficient, a fundamental transport property. This "computational microscope" allows researchers to study phenomena that are difficult or impossible to observe experimentally, such as how molecular interactions influence drug release rates from a delivery device or the permeation of a compound through a cell membrane [17]. While specific VACF protocols were not detailed in the search results, its power lies in revealing the mechanistic underpinnings of cellular transport processes that HTS measures in a more aggregate, phenotypic manner.

Detailed Experimental Protocol for VACF Analysis

Protocol Title: Molecular Dynamics Simulation for Transport Property Analysis via VACF

Objective: To compute the diffusion coefficient of a small molecule (e.g., a drug candidate) within a specific biological environment (e.g., lipid bilayer, cytosol mimic) through MD simulation and VACF analysis.

Materials and Software:

- High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster: Essential for running nanoseconds to microseconds of simulation time.

- Molecular Dynamics Software: Packages such as GROMACS, NAMD, or AMBER.

- Molecular Viewer Software: VMD or PyMOL for system setup and trajectory analysis.

- Force Field Parameters: For the drug molecule, solvent (e.g., water), and biological components (e.g., lipids, proteins).

- Initial Coordinate Files: PDB file for the protein (if applicable); structure data file for the small molecule.

Procedure:

- System Setup: a. Solvation: Place the molecule of interest (the "ligand") in a simulation box filled with solvent molecules (e.g., SPC water). b. Neutralization: Add ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to neutralize the system's total charge. c. Energy Minimization: Run a steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm to remove steric clashes and bad contacts, relaxing the system to a local energy minimum.

- Equilibration: a. NVT Ensemble: Run a short simulation (50-100 ps) with constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature (NVT) to stabilize the system temperature. b. NPT Ensemble: Follow with a longer simulation (100-200 ps) with constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature (NPT) to stabilize the system density.

- Production Run: Execute a long, unbiased MD simulation (tens to hundreds of nanoseconds). The trajectory from this phase is used for all subsequent analysis. Save the atomic coordinates and velocities at regular intervals (e.g., every 1-10 ps).

- Trajectory Analysis - VACF Calculation: a. Extract the velocity components (vₓ, vᵧ, v_z) for the center of mass of the ligand for every saved time step from the production trajectory. b. Compute the VACF: For a given time origin t₀, the VACF is defined as ‹v(t₀)·v(t₀+t)›, where the angle brackets denote an average over all time origins and all molecules of the same type. In practice, this is calculated for a range of time delays t. c. Calculate the Diffusion Coefficient (D): The diffusion coefficient is obtained from the Green-Kubo relation, which integrates the VACF over time: D = (1/3) ∫₀∞ ‹v(t₀)·v(t₀+t)› dt.

- Validation and Interpretation: a. Ensure the simulation has converged by checking if the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) is linear in time and the VACF has decayed to zero. b. Compare the computed diffusion coefficient with experimental values, if available, to validate the force field and simulation protocol.

Research Reagent Solutions for VACF Analysis

Table 2: Essential components for MD simulations and VACF analysis.

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Software (GROMACS/NAMD) | The core computational engine that performs the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion for all atoms in the system. |

| Biomolecular Force Fields (CHARMM/AMBER) | Provide the set of parameters (bond lengths, angles, dihedrals, non-bonded interactions) that define the potential energy of the system, determining the accuracy of the simulation. |

| HPC Cluster with GPUs | Provides the necessary computational power; GPUs dramatically accelerate the calculation of non-bonded interactions, which is the bottleneck in MD simulations. |

| Solvation Model (TIP3P/SPC water) | An accurate water model is critical for simulating biological systems and correctly capturing solvation dynamics and diffusion. |

| Trajectory Analysis Tools | Custom scripts (Python, C++) or built-in software utilities are required to process the massive trajectory files and compute the VACF and related properties. |

VACF Workflow Visualization

Diagram Title: VACF Analysis Workflow

Quantitative Data Comparison

Method Capabilities and Outputs

Table 3: Comparative analysis of HTS/MSD and VACF methodologies.

| Parameter | High-Throughput Screening (HTS) with MSD | Fundamental Transport Analysis (VACF) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Rapid identification of bioactive "hit" compounds from large libraries; comparison of complex phenotypic profiles [12] [14]. | Understanding fundamental mechanisms of molecular motion, diffusion, and transport at the atomic level [17]. |

| Theoretical Basis | Empirical measurement of biochemical or cellular activity; statistical comparison of multivariate data vectors (MSD) [12] [14]. | Statistical mechanics; Newton's laws of motion integrated over time to generate ensemble-averaged transport properties. |

| Typical Outputs | Hit rates, IC₅₀/EC₅₀ values, dissolution profiles, SSMD/Z-scores, MSD p-values [12] [14] [15]. | Diffusion coefficients (D), velocity autocorrelation functions, mean-squared displacement (MSD), free energy profiles. |

| Throughput | Very High (up to 100,000+ compounds per day) [12] [15]. | Very Low (one system simulated over days/weeks). |

| Data Variability Handling | Uses robust statistical tests like MSD and SSMD specifically designed for high-variability HTS data [12] [14]. | Inherently accounts for stochastic dynamics; uncertainty is estimated through block averaging or repeated simulations. |

| Key Strength | Unmatched speed for screening vast chemical space; directly experimentally verifiable; applicable to complex cellular phenotypes [12] [16]. | Provides atomic-level resolution and mechanistic insight into why a molecule behaves in a certain way; not limited by assay design [17]. |

| Key Limitation | Prone to false positives/negatives from assay artifacts; provides little mechanistic insight on its own [16] [15]. | Extremely computationally expensive; limited timescales; accuracy dependent on force field quality [17]. |

Integrated Application in Drug Discovery

The true power of these methods is realized when they are used complementarily. A typical integrated workflow could involve:

- Primary Screening: Using HTS to rapidly sift through a million-compound library to identify 500 preliminary hits that inhibit a specific enzyme target [15].

- Hit Confirmation and Profiling: Applying an MSD test to compare the dissolution or phenotypic profiles of these hits against a reference compound, ensuring they act via the desired mechanism and not through non-specific effects [14].

- Lead Optimization: For the top 10 confirmed hits, employ VACF analysis via MD simulations to understand how each lead compound diffuses through and interacts with a model cell membrane. This provides a mechanistic rationale for differences in cellular permeability observed in follow-up assays [17].

- Informed Decision-Making: The HTS data provides the activity and selectivity, while the VACF analysis offers a physical explanation for permeability, guiding medicinal chemists to optimize the molecular scaffold intelligently for improved pharmacokinetics.

This synergistic approach combines the breadth of HTS with the depth of fundamental transport analysis, leading to a more efficient and insightful drug discovery process.

Practical Implementation: Protocols for MSD Assays and VACF Calculations

The Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) platform represents a significant advancement in immunoassay technology, leveraging electrochemiluminescence detection to achieve superior sensitivity and a broad dynamic range compared to traditional methods like standard ELISA [1]. This protocol details the application of an MSD immunoassay for quantifying full-length TDP-43 protein in human biofluids, a crucial biomarker for neurodegenerative disorders such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal lobar degeneration [18]. The exceptional performance of MSD assays—with a documented limit of detection for TDP-43 at 4 pg/mL and a wide working range of 4–20,000 pg/mL [18]—makes them particularly valuable for comparative methodological research, including investigations into the relative accuracy of the MSD immunoassay versus the Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) method used in molecular dynamics simulations [19]. This detailed guide provides researchers with a reliable framework for generating robust, high-quality data suitable for such analytical comparisons.

Principles of MSD Electrochemiluminescence

The MSD platform's performance is rooted in its use of electrochemiluminescence (ECL). The core of the technology involves a SULFO-TAG label, which is a ruthenium-based compound that emits light upon electrochemical stimulation [18]. The key differentiator from colorimetric or chemiluminescent methods is the direct application of an electric current to the assay plate's integrated electrodes.

The detection process involves the following principles [1] [18]:

- Electrochemiluminescence Triggering: When an appropriate electrical voltage is applied to the assay plate in the presence of a co-reactant containing tripropylamine (TPrA), the SULFO-TAG labels undergo an oxidation-reduction cycle.

- Signal Generation: This cycle produces an excited state of the ruthenium complex, which then relaxes to its ground state, emitting a photon of light at a specific wavelength.

- Signal Measurement: The emitted light is detected by a dedicated MSD instrument. The key advantage is that the signal is generated precisely at the electrode surface, which minimizes background noise from unbound reagents in the solution, thereby conferring the platform's unsurpassed sensitivity and wide dynamic range [1].

- MULTI-ARRAY Technology: This refers to the carbon electrode spots at the bottom of the assay plates, which are configured to allow simultaneous, high-density measurement of multiple analytes from a single, small-volume sample [1].

The following diagram illustrates the signaling pathway and workflow of the MSD immunoassay:

Diagram 1: MSD Assay Workflow and Signaling Pathway. This illustrates the sequential binding and detection process.

Materials and Reagent Preparation

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues the essential materials and reagents required for establishing the MSD immunoassay.

Table 1: Essential Reagents and Materials for MSD Immunoassay

| Item | Function / Description | Source / Catalog Number Example |

|---|---|---|

| MSD GOLD 96-Well Plate | Solid-phase plate with embedded electrodes for ECL signal generation. | Meso Scale Discovery (e.g., Catalog #L15XA) [18] |

| Capture Antibody | Binds target analyte (TDP-43) and immobilizes it on the plate. | TDP-43 Rabbit Polyclonal Antibody (Proteintech #10782-2-AP) [18] |

| Detection Antibody | Binds the captured analyte; is conjugated for detection. | Human TDP-43/TARDBP Mouse mAb (R&D Systems #MAB77782) [18] |

| SULFO-TAG Anti-Species Ab | Ruthenium-labeled secondary antibody for ECL detection. | SULFO-TAG Anti-Mouse Antibody (MSD #R32AC-1) [18] |

| Assay Diluent | Matrix for reconstituting calibrants and diluting samples. | Iron Horse Assay Diluent (IHAD) [18] |

| Read Buffer A | Co-reactant solution containing TPrA to enable ECL. | Meso Scale Discovery (e.g., Catalog #R92TC) [18] |

| Recombinant TDP-43 | Calibrant for generating standard curve. | OriGene (Catalog #TP710010) [18] |

Reagent Preparation Guidelines

- Coating Buffer: Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) is typically used as a coating buffer. Prepare a 1X solution from a 10X concentrate, ensuring a pH of 7.4.

- Wash Buffer: A solution of PBS with 0.05% to 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST) is recommended for washing steps to minimize non-specific binding.

- Antibody Stock Solutions: Reconstitute lyophilized antibodies according to the manufacturer's instructions. Prepare working aliquots of the capture and detection antibodies in a suitable buffer (e.g., PBS with 1-5% BSA) to maintain stability and prevent repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

- Blocking Buffer: A 3-5% solution of Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or the proprietary Iron Horse Assay Diluent (IHAD) in PBS can be used effectively [18].

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Plate Coating and Blocking

Plate Coating:

- Dilute the capture antibody to a recommended concentration (typically 1-10 µg/mL) in PBS.

- Dispense a suitable volume (e.g., 30 µL/well) into each well of an MSD GOLD 96-well plate.

- Seal the plate and incubate overnight (approximately 16 hours) at 2-8°C on an orbital shaker.

- Following incubation, decant the coating solution from the plate.

Blocking:

- Add 150 µL/well of blocking buffer (e.g., 3% BSA/PBS or IHAD) to each well.

- Seal the plate and incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature on an orbital shaker.

- After blocking, wash the plate three times with wash buffer (e.g., PBST). A squirt bottle or automated plate washer can be used, ensuring 150-300 µL per well per wash. After the final wash, invert the plate and tap it firmly on absorbent paper to remove residual liquid.

Sample and Calibrant Incubation

Calibrant Curve Preparation:

- Prepare a dilution series of the recombinant TDP-43 calibrant in the same matrix as the samples (e.g., IHAD). A range from 4 pg/mL to 20,000 pg/mL is recommended to cover the assay's dynamic range [18]. Include a blank (zero calibrant).

Sample Preparation:

- Thaw biofluid samples (e.g., plasma, serum) on ice and centrifuge briefly to pellet any precipitates.

- Dilute samples as necessary in the chosen assay diluent. Optimal dilution factors should be determined empirically.

Assay Run:

- Add prepared calibrants, controls, and samples to the designated wells of the blocked and washed plate. A volume of 25-50 µL per well is standard.

- Seal the plate and incubate for 2 hours at room temperature on an orbital shaker.

- After incubation, wash the plate as described in the blocking step (3x with wash buffer).

Signal Detection and Development

Detection Antibody Incubation:

- Dilute the detection antibody to its optimal working concentration in assay diluent.

- Add the diluted detection antibody to all wells (e.g., 25-50 µL/well).

- Seal the plate and incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature with shaking.

- Wash the plate 3x with wash buffer.

SULFO-TAG Label Incubation:

- Dilute the SULFO-TAG conjugated anti-species antibody (e.g., SULFO-TAG Anti-Mouse Ab) in assay diluent according to the manufacturer's recommendation.

- Add the solution to all wells (e.g., 25-50 µL/well).

- Seal the plate and incubate for 1 hour at room temperature, protected from light.

- Perform a final wash cycle (3x with wash buffer), ensuring all unbound label is removed.

Electrochemiluminescence Readout:

- Add 150 µL/well of Read Buffer A (containing TPrA) to the plate.

- Immediately measure the ECL signal using an MSD plate reader (e.g., SECTOR series). The instrument applies a voltage to the plate electrodes, triggering the light emission from the SULFO-TAG labels, which is quantified as relative light units (RLUs).

The overall experimental workflow is summarized below:

Diagram 2: MSD Experimental Protocol Flow. A sequential guide from plate preparation to signal detection.

Data Analysis and Performance Metrics

Quantitative Assay Performance

The developed MSD immunoassay for TDP-43 demonstrates exceptional performance characteristics, as quantified in the following table. These metrics are critical for evaluating the assay's utility in biomarker research and for any comparative analysis with other quantification platforms.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of the TDP-43 MSD Assay

| Performance Parameter | Result | Experimental Context / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | 4 pg/mL | Defined as the concentration 2.5 standard deviations above the mean zero calibrant signal [18]. |

| Working Range | 4 - 20,000 pg/mL | The range of concentrations that can be reliably quantified [18]. |

| Total Assay Time | ~16 hours | Includes overnight coating and incubation steps [18]. |

| Dynamic Range | >3.5 logs | The linear range of the standard curve, demonstrating wide dynamic range [18]. |

| Analytical Sensitivity | Very High | Enables detection of TDP-43 in biofluids like plasma and serum [18]. |

Data Interpretation and Normalization

- Standard Curve Fitting: The RLU data from the calibrants should be plotted against their known concentrations. A four-parameter logistic (4-PL) or five-parameter logistic (5-PL) nonlinear regression model is typically the most appropriate fit for the sigmoidal standard curve generated by MSD assays.

- Sample Concentration Calculation: The fitted model is used to interpolate the unknown concentrations of samples and quality controls from their measured RLU values.

- Data Normalization: In the context of comparing MSD to other methods like VACF, which computes diffusion coefficients from particle trajectories [19], it is crucial to report MSD-derived concentrations in standardized units (e.g., pg/mL or mol/L) and to account for sample-specific dilution factors and matrix effects.

Troubleshooting and Technical Notes

- High Background Signal: This can result from insufficient washing, non-optimal blocking, or antibody concentrations that are too high. Re-optimize blocking conditions and antibody titrations, and ensure thorough washing between steps.

- Low Signal Intensity: Potential causes include low antigen concentration, loss of antibody activity, improper preparation of the Read Buffer, or expired SULFO-TAG conjugate. Check reagent integrity and prepare fresh dilutions. Ensure the assay is within its dynamic range; samples may require less dilution.

- Poor Replicate Precision (High CV%): Inconsistent liquid handling during pipetting steps is a common cause. Ensure proper pipetting technique and that all wells are washed uniformly and thoroughly.

- Non-Specific Signal: Use a species-specific and target-specific antibody pair to minimize cross-reactivity. The inclusion of a control well with no capture antibody can help identify non-specific binding of the detection antibody or SULFO-TAG conjugate.

Calculating Diffusion from Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD) using the Einstein Relation

Theoretical Foundation

The Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD) is a fundamental measure in quantifying the spatial extent of random particle motion and serves as a primary method for calculating diffusion coefficients through the Einstein relation. This approach is widely employed in diverse fields including biophysics, materials science, and drug development for characterizing molecular mobility [20].

The Einstein relation states that for a pure Brownian (random) diffusion process, the MSD increases linearly with time. The proportionality constant depends on the dimensionality of the system and the diffusion coefficient D [21] [20].

For n-dimensional Euclidean space, the relation is expressed as: ( MSD = 2nDt ) [20]

Where:

- MSD = Mean Squared Displacement

- n = dimensionality of the diffusion (1, 2, or 3)

- D = self-diffusion coefficient

- t = time lag

The general MSD calculation for an ensemble of N particles is defined as [20]: [ MSD \equiv \left\langle \left| \mathbf{x}(t) - \mathbf{x0} \right|^2 \right\rangle = \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} \left| \mathbf{x^{(i)}}(t) - \mathbf{x^{(i)}}(0) \right|^2 ]

For single-particle tracking (SPT) experiments with discrete time points, the time-averaged MSD is commonly calculated as [21] [20]: [ MSD(n\Delta t) \equiv \frac{1}{N-n} \sum{i=1}^{N-n} \left| \mathbf{r}{i+n} - \mathbf{r}i \right|^2 ] where ( n = 1, \ldots, N-1 ) represents the lag number, and ( \mathbf{r}i ) is the particle position at time point i.

MSD Analysis and Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

MSD Curves and Diffusion Regimes

The temporal evolution of MSD provides critical information about the nature of particle motion:

- Pure Brownian motion: MSD increases linearly with time lag (slope = 1 on log-log plot) [21]

- Subdiffusion: MSD increases more slowly than linear time (slope < 1 on log-log plot), often observed in crowded environments like cells [21]

- Superdiffusion: MSD increases faster than linear time (slope > 1 on log-log plot), indicating active transport processes [21]

- Confined diffusion: MSD plateaus at longer time lags [21]

For anomalous diffusion, the MSD can be fitted to a general law [21]: [ MSD(\tau) = 2\nu D\alpha \tau^\alpha ] where ( D\alpha ) is the generalized diffusion coefficient, ( \alpha ) is the anomalous exponent, and ( \nu ) is the dimensionality.

Practical Calculation of Diffusion Coefficients

To accurately determine the self-diffusivity D from MSD data:

- Identify the linear regime: Plot MSD versus time lag and identify the region where MSD increases linearly [22]

- Exclude non-linear regions: Short-time ballistic trajectories and long-time poorly averaged data should be excluded from the fit [22]

- Perform linear regression: Fit the linear portion of the MSD curve to extract the slope [22]

The diffusion coefficient is then calculated as [22]: [ D = \frac{\text{slope}}{2d} ] where d is the dimensionality of the MSD analysis.

Table 1: MSD Characteristics for Different Diffusion Types

| Motion Type | MSD Form | Anomalous Exponent (α) | Typical Environments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pure Brownian | MSD ~ τ | α ≈ 1 | Dilute solutions |

| Subdiffusive | MSD ~ τ^α | α < 1 | Crowded intracellular environments |

| Superdiffusive | MSD ~ τ^α | α > 1 | Active transport, directed motion |

| Confined | MSD ~ constant | - | Trapped particles, microdomains |

Computational Protocols

Implementation Algorithms

Windowed Algorithm (Direct Method)

- Computes MSD by averaging over all possible time lags for each trajectory

- Computational complexity scales as O(N²) with respect to trajectory length [22]

- More intuitive but computationally intensive for long trajectories

FFT-Based Algorithm

- Utilizes Fast Fourier Transform for efficient computation

- Computational complexity scales as O(N log N) [22]

- Requires the tidynamics package in MDAnalysis implementation [22]

- Recommended for long trajectories due to superior computational efficiency

Critical Implementation Considerations

Trajectory Requirements:

Data Quality Assessment:

Error Sources:

Table 2: Computational Methods for MSD Analysis

| Method | Computational Complexity | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Windowed (Direct) | O(N²) | Simple implementation, intuitive | Computationally expensive for long trajectories |

| FFT-Based | O(N log N) | Computationally efficient | Requires specialized packages, more complex implementation |

| Single-Particle Tracking | Depends on tracking algorithm | High spatial resolution | Statistical limitations from short trajectories |

Experimental Protocol for MD Analysis

Sample Protocol Using MDAnalysis

This protocol provides detailed steps for calculating diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics trajectories using the EinsteinMSD class in MDAnalysis.

Protocol for Single-Particle Tracking Data

For experimental SPT data, the protocol differs in data preprocessing:

Trajectory Reconstruction:

- Extract particle positions from microscopy images

- Link positions into trajectories using tracking algorithms

- Filter trajectories by length and quality

MSD Calculation:

- Compute time-averaged MSD for each trajectory

- Ensemble-average MSDs from multiple particles

- Account for localization uncertainty in fitting [21]

Diffusion Analysis:

- Classify trajectories by motion type using MSD shape

- Calculate diffusion coefficients for Brownian subsets

- Report population averages and distributions

Visualization of MSD Workflow

MSD Analysis Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for MSD-Based Diffusion Analysis

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| MD Software | GROMACS [23], NAMD [24] | Molecular dynamics simulation generating trajectories |

| Analysis Packages | MDAnalysis [22], tidynamics [22] | MSD calculation and diffusion analysis |

| Tracking Software | TrackMate, u-track | Single-particle trajectory reconstruction from microscopy |

| Visualization | Matplotlib [22], VMD [24] | Data plotting and trajectory visualization |

| Programming | Python, R | Custom analysis scripts and statistical evaluation |