Molecular Dynamics vs. Monte Carlo Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide for Computational Drug Discovery

This article provides a comparative analysis of Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC) simulation methods, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Molecular Dynamics vs. Monte Carlo Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide for Computational Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comparative analysis of Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC) simulation methods, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It covers the foundational principles of both deterministic MD and probabilistic MC approaches, explores their methodological workflows and specific applications in biomolecular modeling and drug optimization, addresses common challenges and advanced sampling techniques, and offers a direct comparison to guide method selection. The review synthesizes key takeaways and discusses the future trajectory of these integrated computational tools in accelerating biomedical research.

First Principles: Unpacking the Core Mechanics of MD and MC

In the realm of computational science, particularly in molecular simulation, two dominant paradigms have emerged: deterministic Molecular Dynamics (MD) and probabilistic Monte Carlo (MC). These methodologies serve as foundational pillars for investigating the structural, thermodynamic, and dynamic properties of biomolecular systems, materials, and other complex phenomena. Their philosophical and operational differences dictate their applicability, strengths, and limitations within scientific research and drug development. Molecular Dynamics operates on deterministic principles, following fixed physical laws to simulate the time evolution of a system. In contrast, Monte Carlo methods rely on probabilistic sampling to generate representative configurations of a system at equilibrium [1] [2]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these approaches, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform researchers in selecting the appropriate tool for their specific investigations.

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundations

Molecular Dynamics: The Deterministic Trajectory

Molecular Dynamics is a deterministic simulation method because it relies on numerical integration of classical equations of motion. Given the same initial conditions, an MD simulation will produce an identical trajectory [3]. The foundation of MD is Newton's second law: F = ma. The force F on each atom is derived as the negative gradient of the potential energy function U(r^N), which depends on the positions (r^N) of all N atoms in the system [2]. This results in a system of coupled differential equations that are solved iteratively to generate a trajectory of atomic positions and velocities over time.

[ mi \frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}i}{dt^2} = -\nabla_i U(\mathbf{r}^N) ]

This deterministic nature makes MD particularly valuable for studying kinetic processes, transport properties, and time-dependent phenomena [2]. The method provides a direct link to dynamical properties, allowing researchers to observe how molecular systems evolve at an atomic level, making it indispensable for studying protein folding pathways, ligand binding kinetics, and diffusion processes.

Monte Carlo: The Probabilistic Framework

Monte Carlo methods are fundamentally probabilistic, employing random sampling to explore the configuration space of a system [4]. Unlike MD, MC does not simulate physical dynamics; instead, it generates a sequence of states (configurations) according to a Markov chain designed to sample from a desired probability distribution, typically the Boltzmann distribution for systems at thermal equilibrium [2].

The probability of a state with energy E_i is given by the Boltzmann factor:

[ Pi = \frac{e^{-Ei/k_BT}}{Z} ]

where Z is the canonical partition function, k_B is Boltzmann's constant, and T is the temperature [2]. MC algorithms, particularly the Metropolis-Hastings method, generate these sequences by randomly perturbing the system and accepting or rejecting new configurations based on their relative probabilities. This approach makes MC particularly powerful for calculating equilibrium thermodynamic properties, free energies, and efficiently sampling complex energy landscapes where deterministic dynamics might become trapped in local minima [4] [2].

Comparative Analysis: Key Differentiating Factors

The table below summarizes the fundamental differences between Molecular Dynamics and Monte Carlo approaches based on their core methodologies, outputs, and applications.

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between MD and MC Methods

| Factor | Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Monte Carlo (MC) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Deterministic; follows Newton's equations of motion [3] | Probabilistic; uses random sampling based on statistical weights [4] |

| Output | Time-evolving trajectory; dynamical properties [2] | Ensemble of configurations; equilibrium properties [2] |

| Temporal Information | Provides direct time evolution and kinetics [2] | No real-time dynamics; generates equilibrium distributions [2] |

| Handling of Uncertainty | Requires precise initial conditions and force fields [1] | Designed to handle uncertainty through statistical inference [1] |

| Typical Applications | Protein folding pathways, transport phenomena, rheology [2] | Free energy calculations, phase transitions, equilibrium averages [4] [2] |

| Adaptability | Manual updates required for force fields or protocols [1] | Can automatically adapt sampling based on probability landscapes [1] |

| On-lattice Models | Not suitable for fixed lattice systems [3] | Well-suited for lattice models and discrete systems [3] |

Workflow and Algorithmic Comparison

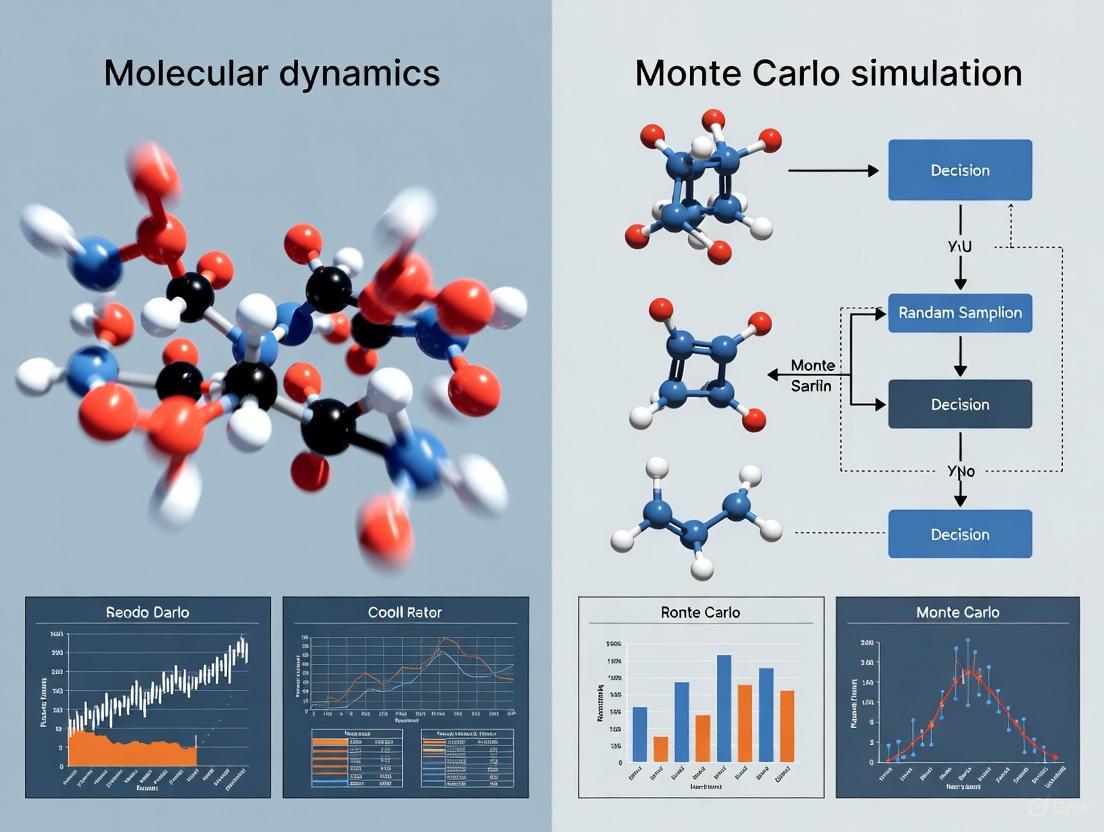

The following diagrams illustrate the fundamental workflows for Molecular Dynamics and Monte Carlo simulations, highlighting their deterministic versus probabilistic decision pathways.

Diagram 1: Molecular Dynamics Workflow

Diagram 2: Monte Carlo Workflow

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Case Study: Peptide Folding Simulations

A rigorous study applied both MD and MC principles to simulate eight helical peptides and validate against experimental circular dichroism measurements [5]. The protocol employed Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD), which combines MD with a probabilistic temperature swapping approach.

Detailed REMD Protocol:

- Force Field: AMBER94 with generalized Born implicit solvent model [5]

- Temperature Ladder: 30 exponentially spaced temperatures from target (273-298K) to 624K [5]

- Simulation Time: Each replica ran for cycles of 1000 MD steps (2 ps) between swap attempts [5]

- Swap Criteria: Probabilistic exchange between adjacent temperatures based on Metropolis criterion [5]

- Convergence Monitoring: Statistical analysis of trajectory blocks to ensure adequate sampling [5]

This hybrid approach demonstrates how deterministic and probabilistic elements can be combined to enhance configurational sampling while maintaining physical dynamics in specific regions.

Case Study: High-Entropy Alloy Formation

A recent comparative study of a Cu-Fe-Ni-Mo-W multicomponent alloy directly contrasted pure MD and MC simulations with experimental results [6]. The research revealed significant differences in predictive accuracy:

Table 2: Comparison of MD and MC Predictions for Alloy Formation

| Method | Initial Structure | Predicted Phase Outcome | Agreement with Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics | bcc | Single-phase bcc solid solution [6] | Poor |

| Molecular Dynamics | fcc | Single-phase fcc structure [6] | Poor |

| Monte Carlo | bcc | Two-phase mixture [6] | Moderate |

| Monte Carlo | fcc | bcc Fe-Mo-W phase + fcc Cu-Ni structure [6] | Strong |

Experimental validation through arc furnace production and powder milling confirmed a two-phase mixture of bcc and fcc structures, demonstrating MC's superior predictive power for this materials system [6]. The MC approach achieved lower potential energy states that more closely matched experimental observations.

Performance and Accuracy Comparison

Quantitative Assessment of Convergence and Sampling

The statistical nature of MC provides inherent advantages for certain types of equilibrium calculations, while MD excels at capturing dynamical behavior. The table below summarizes performance characteristics based on comparative studies:

Table 3: Performance Metrics for MD and MC Methods

| Metric | Molecular Dynamics | Monte Carlo |

|---|---|---|

| Equilibrium Sampling | Requires long simulations for ergodicity [5] | Efficient for Boltzmann sampling [2] |

| Parallelizability | Highly parallelizable (spatial decomposition) | Difficult to parallelize (sequential chain) [3] |

| Free Energy Calculation | Requires enhanced sampling techniques | Directly suited through ensemble generation [2] |

| Handling of Rare Events | May require specialized methods (metadynamics) | Natural handling through probabilistic jumps |

| Computational Cost | Costly for small timesteps (fs scale) [2] | Independent of timescales; configuration-based [2] |

| Accuracy for Dynamics | Provides realistic kinetics with proper force fields [5] | No natural time scale [2] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of either MD or MC simulations requires specialized computational tools and force fields. The following table outlines essential "research reagents" for molecular simulations.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Molecular Simulations

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS, OPLS [5] | Define potential energy functions and parameters for molecular interactions |

| Solvation Models | Generalized Born, PME, Explicit Water Models [5] | Represent solvent effects and electrostatic interactions |

| Software Platforms | AMBER, GROMACS, LAMMPS, NAMD [5] | Provide simulation engines, integration algorithms, and analysis tools |

| Monte Carlo Engines | Cassandra, towhee, custom codes [2] | Specialized software for MC simulations with various ensemble capabilities |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | Replica Exchange, Metadynamics, Umbrella Sampling [5] | Accelerate configuration space exploration and rare event sampling |

| Analysis Tools | MDAnalysis, VMD, PyMOL, custom scripts [5] | Process trajectories, calculate properties, and visualize results |

The choice between deterministic Molecular Dynamics and probabilistic Monte Carlo simulations must be guided by specific research questions and the nature of the properties under investigation. Molecular Dynamics is indispensable for studying time-dependent processes, transport phenomena, and dynamic behavior where temporal evolution is critical [2]. Conversely, Monte Carlo methods excel at calculating equilibrium properties, free energies, and sampling complex energy landscapes where physical dynamics would be prohibitively slow [4] [2].

Emerging hybrid approaches, such as Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics [5] and specialized Monte Carlo techniques [6], demonstrate the power of combining deterministic and probabilistic elements to overcome the limitations of either method alone. As computational resources grow and algorithms advance, the integration of these complementary paradigms will continue to push the boundaries of predictive simulation in molecular science and drug development.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC) are two foundational methods in computational physics and chemistry. While both are used to study molecular systems, their underlying principles and applications differ significantly. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these methods, focusing on the performance of specialized MD hardware and software against alternative simulation approaches.

Core Principles: Molecular Dynamics vs. Monte Carlo

The following table outlines the fundamental differences between Molecular Dynamics and Monte Carlo simulation methods.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Molecular Dynamics and Monte Carlo Methods

| Feature | Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Monte Carlo (MC) |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Solves Newton's equations of motion to generate deterministic, time-evolving trajectories [7] [8]. | Uses random sampling based on the Metropolis criterion to generate probabilistic, energy-weighted configurations [9] [10]. |

| Primary Output | Time-series of atomic coordinates and velocities; reveals dynamical properties [8]. | Sequence of system states; provides structural and thermodynamic averages [6]. |

| Key Strengths | Calculates time-dependent properties (e.g., diffusion coefficients, mechanical properties) [8]. Efficiently explores complex free energy landscapes and is less constrained by system size [9] [6]. | |

| Inherent Limitations | Computationally expensive; limited by the femtosecond time-step, restricting access to long timescales [7] [9]. | Does not provide genuine dynamical information or kinetics [9]. |

| Typical Applications | Protein folding, drug binding kinetics, material deformation [7] [8]. | Protein folding thermodynamics, phase separation, multi-component alloy structure prediction [9] [6]. |

The core workflow of a Molecular Dynamics simulation involves iteratively calculating forces and integrating motion, as shown in the diagram below.

MD Simulation Cycle

Performance Comparison of Simulation Software

Specialized hardware like the MD-Engine was an early solution designed to accelerate the most computationally intensive part of MD: calculating non-bonding interactions, achieving good linear scaling with system size [11]. Today, this performance is largely delivered through GPU acceleration in software packages. The table below compares leading MD software tools.

Table 2: Performance and Features of Major Molecular Dynamics Software

| Software | Key Performance Features | Specialized Hardware/Acceleration | License |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD-Engine | Custom hardware accelerator; calculates pairwise potentials/forces in parallel; good linear scaling with system size [11]. | Dedicated, special-purpose MD processor [11]. | Proprietary Hardware |

| GROMACS | Extremely high throughput; multi-level parallelism; full GPU-resident workflows; among the highest single-GPU performance [12]. | GPU acceleration (CUDA/OpenCL); multi-node HPC scaling [12]. | Open Source (GPL/LGPL) |

| AMBER | Early and aggressive GPU optimization (PMEMD.CUDA); high throughput for single simulations on a single GPU [12]. | GPU acceleration; optimized for single-node, multi-GPU setups [12]. | AmberTools (Open Source), Full PMEMD (Paid) |

| NAMD | Fast, parallel MD; designed for parallel scalability across large CPU clusters; CUDA support [13]. | GPU acceleration; optimized for large-scale parallel CPU clusters [13]. | Free for Academic Use |

| CHARMM | Versatile MD engine with a rich set of features; effective parallel scaling on CPU clusters for moderate numbers of processors [12]. | Historically CPU-focused; less GPU-optimized than GROMACS/AMBER [12]. | Proprietary (Academic) |

| OpenMM | Highly flexible, scriptable via Python; high performance MD on GPUs [13]. | GPU acceleration; highly optimized for a wide range of GPUs [13]. | Open Source (MIT) |

| LAMMPS | Highly versatile for soft materials, solids, and coarse-grained systems; supports GPU acceleration [13]. | GPU acceleration; supports a wide range of interatomic potentials [13]. | Open Source (GPL) |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

Protocol for MD/MC Alloy Formation Study

A 2023 study directly compared MD and hybrid MD/MC for simulating a multi-component Cu-Fe-Ni-Mo-W high-entropy alloy [6].

- System Preparation: Initial structures were created as both Body-Centered Cubic (BCC) and Face-Centered Cubic (FCC) crystals.

- Simulation Parameters: Simulations were run from 10K up to the melting point of the alloy. The hybrid method combined MD's dynamical moves with MC's configurational sampling.

- Outcome Analysis: The resulting phases (BCC solid solution, FCC solid solution, or two-phase mixture) were analyzed and compared against experimentally produced samples using X-ray diffraction [6].

Performance Data: The study found that MD simulations starting from a BCC structure produced a single-phase BCC solid solution. In contrast, MC simulations produced a two-phase mixture, a result that was closer to the experimental findings, confirming MC's strength in predicting thermodynamic equilibrium structures [6].

Protocol for Enhanced Sampling MD with Machine Learning

To overcome the timescale limitation, MD is often combined with enhanced sampling and Machine Learning (ML) [7].

- Explorative MD: Run a preliminary, unbiased MD simulation to collect data on the system's fluctuations.

- ML Analysis: Apply ML algorithms (e.g., Dimensionality Reduction, Markov State Models) to the trajectory data to identify key collective variables (CVs) that describe the slowest, most important motions in the system [7].

- Informed Resampling: Use the identified CVs to perform biased sampling simulations (e.g., metadynamics), which selectively accelerate the exploration of these relevant pathways [7].

Performance Data: This MD/ML approach enhances sampling efficiency by focusing computational resources on the most relevant degrees of freedom, allowing for the calculation of free energy landscapes and the observation of rare events that would be inaccessible to standard MD [7].

Protocol for Large-Scale Cellular Monte Carlo

A 2025 study extended the MCell4 platform to simulate large-scale cellular dynamics, such as T cell immune synapse formation [10].

- Model Building: Create 3D meshes of cells (e.g., from microscopy or AI-generated models) and populate membranes with diffusing receptors and ligands.

- Force Integration: Introduce physical forces (kinetic, elastic, pressure) into the Monte Carlo framework, allowing molecular interactions to drive morphological changes.

- Simulation Execution: Run the Monte Carlo simulation, where steps are accepted or rejected based on a Metropolis criterion that considers the energy changes from both molecular interactions and membrane deformations [10].

Performance Data: This coupled MC approach successfully simulated the correlation between molecular interactions and the spreading dynamics of a T cell on an activating surface, demonstrating the ability of modern MC to handle complex, multi-scale biological feedback loops [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Software and Force Fields for Molecular Simulation

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| PLUMED [7] | Software Library | Enhances MD codes (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER) for enhanced sampling and free-energy calculations by biasing collective variables. |

| CHARMM-GUI [12] | Web Server | Simplifies the setup of complex simulation systems, such as membranes and protein-ligand complexes, for various MD engines. |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIP) [8] | Force Field | Uses ML models trained on quantum chemistry data to perform highly accurate MD simulations at near-quantum accuracy and reduced cost. |

| Reactive Force Field (ReaxFF) [14] | Force Field | Enables MD simulations of chemical reactions by describing bond formation and breaking, bridging classical and quantum MD. |

| AlphaFold2 [8] | AI Model | Predicts 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences, providing reliable initial configurations for MD simulations. |

| VMD / PyMOL [13] [12] | Visualization Software | Used for visualizing simulation trajectories, analyzing molecular structures, and preparing figures for publication. |

The logical relationship between these tools in a modern simulation workflow is summarized below.

Modern Simulation Workflow

In computational science, particularly in fields like drug development, molecular dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC) simulations serve as indispensable tools for investigating molecular systems beyond the reach of experimental measurement [15]. While both methods aim to extract meaningful thermodynamic and structural properties from model systems, their fundamental sampling approaches differ significantly. At the core of many MC methods lies the Metropolis criterion, a decisive algorithm that enables efficient exploration of complex probability landscapes by strategically accepting or rejecting proposed moves [16]. This guiding principle allows MC methods to generate representative ensembles of molecular configurations without tracking system dynamics. In contrast, MD simulations numerically solve Newton's equations of motion to produce deterministic trajectories through phase space, capturing time-dependent phenomena but potentially facing challenges in crossing energy barriers. Understanding the performance characteristics, limitations, and complementary strengths of these approaches is crucial for researchers selecting appropriate methodologies for specific scientific challenges, from protein-ligand binding to materials design. This guide provides an objective comparison of these sampling engines, with particular emphasis on the role of the Metropolis criterion in MC methods and its impact on sampling efficiency in molecular simulation.

Core Algorithmic Foundations

The Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm

The Metropolis-Hastings algorithm is a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method for obtaining a sequence of random samples from a probability distribution when direct sampling is difficult [16]. This algorithm operates through an iterative propose-and-decide process:

- Proposal Mechanism: From the current state ( xt ), a candidate state ( x' ) is generated from a proposal distribution ( g(x' \mid xt) ).

- Acceptance Probability: The candidate is accepted with probability ( \min(1, \alpha) ), where ( \alpha = \frac{P(x')}{P(x_t)} ) for symmetric proposal distributions [16].

- Markov Chain Construction: If accepted, ( x{t+1} = x' ); otherwise, ( x{t+1} = x_t ).

For Bayesian inference, where ( P(\theta \mid y) ) is the posterior distribution, the acceptance ratio simplifies to ( \frac{P(y \mid \theta2) P(\theta2)}{P(y \mid \theta1) P(\theta1)} ), eliminating the need to compute the typically intractable marginal likelihood [17]. This property makes the algorithm particularly valuable for practical Bayesian computation.

Molecular Dynamics Sampling

In contrast to MC's probabilistic state transitions, Molecular Dynamics employs numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion to simulate system evolution. The continuous equations ( F = ma ) are discretized using finite difference methods (e.g., Verlet algorithm), producing deterministic trajectories constrained to constant energy surfaces. To sample canonical ensembles, MD incorporates thermostats (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) that modify the equations of motion to maintain temperature, fundamentally altering the system dynamics [18]. This approach naturally captures time-dependent phenomena and transport properties but may suffer from slow convergence when energy landscapes contain high barriers that are rarely crossed during practical simulation timescales.

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Benchmarks

Sampling Efficiency in Coarse-Grained Polymer Systems

A comparative study of coarse-grained heteropolymers revealed significant methodological differences in sampling performance [18]. The researchers analyzed thermodynamic quantities and autocorrelation times using Andersen MD, Nosé-Hoover MD, and replica-exchange Monte Carlo methods, with the following key observations:

Table 1: Sampling Performance for Coarse-Grained Heteropolymers

| Method | Accuracy | Convergence Rate | Autocorrelation | Computational Cost per Step |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metropolis MC | High for equilibrium properties | Slow for rugged landscapes | High | Low |

| Replica-Exchange MC | Highest for multi-modal distributions | Fast due to barrier crossing | Reduced through exchange | High (multiple replicas) |

| Andersen MD | Moderate | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Nosé-Hoover MD | Variable (serious quantitative differences found) | System-dependent | System-dependent | Medium |

The study found "serious quantitative differences" when using the Nosé-Hoover chain thermostat, highlighting how implementation details can significantly impact results [18]. MC methods demonstrated particular advantages for calculating equilibrium statistical properties where dynamical fidelity was unnecessary.

Reproducibility in Molecular Simulation

A comprehensive 2025 benchmarking study evaluated the replicability of MD and MC simulations for predicting alkane densities using the Molecular Simulation Design Framework (MoSDeF) [15]. The research involved multiple simulation engines performing identical simulation tasks:

Table 2: Density Prediction Performance Across Methods

| Method Type | Average Deviation from Experimental Density | Inter-method Variability | Statistical Uncertainty | Required Sampling Iterations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monte Carlo (NpT) | Within 1% for most alkanes | Lower with standardized workflows | Small but consistently outside combined uncertainties | Varies by system; ~10^5-10^6 steps typically sufficient |

| Molecular Dynamics (NpT) | Within 1% for most alkanes | Higher due to implementation differences | Similar to MC | Dependent on integration time step; ~10^6-10^9 steps |

Notably, while most predicted densities were "reasonably close (mostly within 1%), the data often fell outside of the combined statistical uncertainties of the different simulations," indicating inherent methodological variations beyond random error [15]. The study concluded that "unavoidable errors inherent to molecular simulations" persist despite careful methodology, affecting both MD and MC approaches.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standardized Benchmarking Methodology

To ensure fair comparison between MC and MD methods, the 2025 reproducibility study implemented rigorous standardized protocols [15]:

System Initialization: The MoSDeF toolkit initialized all system topologies, applied force fields consistently, and defined thermodynamic constraints uniformly across engines.

Ensemble Specification: Simulations were performed in the isothermal-isobaric (NpT) ensemble at identical state points for direct comparability.

Equilibration Criteria: Systems were equilibrated until properties (density, energy) stabilized with monitoring of running averages.

Production Sampling: Following equilibration, extended production runs generated statistical samples for analysis:

- MC: Minimum of 10^5 Monte Carlo steps after equilibration

- MD: Minimum of 10^6 integration steps with timesteps appropriate to the method (1-2 fs for atomistic)

Convergence Assessment: Block averaging techniques evaluated statistical uncertainties, with simulations extended until uncertainties fell below threshold values.

This workflow ensured that differences originated from methodological rather than implementation variability, providing a rigorous foundation for comparison.

Metropolis-Hastings Implementation Protocol

For the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm specifically, a standard implementation follows these steps [16] [17]:

Initialization: Start from an arbitrary point ( x_t ) in the parameter space.

Iteration Loop: For each iteration t:

- Proposal: Generate a candidate ( x' ) from the proposal distribution ( g(x' \mid x_t) ).

- Acceptance Ratio: Compute ( \alpha = f(x')/f(x_t) ) (ratio of target densities).

- Decision: Generate a uniform random number ( u \in [0,1] ):

- If ( u \leq \alpha ), accept candidate: ( x_{t+1} = x' )

- If ( u > \alpha ), reject candidate: ( x{t+1} = xt )

Termination: After a sufficient number of iterations (typically 10^3-10^6 depending on system complexity), the Markov chain's samples approximate the target distribution.

Hamiltonian Monte Carlo Protocol

As an advanced MC variant, Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) employs a physical approach to proposal generation [19]:

Momentum Sampling: Draw an initial momentum vector from a Gaussian distribution.

Hamiltonian Dynamics: Simulate trajectory evolution using discretized Hamiltonian equations:

- Number of steps (10-100) and step size adapted during warmup

- Uses gradient information for efficient high-dimensional sampling

Metropolis Acceptance: Apply standard Metropolis criterion to the proposed state at trajectory end.

No-U-Turn Extension: The No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS) automatically determines optimal path lengths [19].

Key Software Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Simulation

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Method Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stan | Probabilistic Programming | Bayesian inference using HMC and NUTS samplers | MC (HMC/NUTS) |

| MoSDeF | Workflow Framework | Standardized initialization of molecular simulations | Both MD and MC |

| signac | Workflow Management | Data management and workflow organization for simulation projects | Both MD and MC |

| REMC | Algorithm | Replica-exchange for enhanced sampling in multi-modal distributions | MC |

| Nosé-Hoover | Thermostat | Temperature control for constant-temperature MD simulations | MD |

Critical Algorithmic Components

Metropolis Criterion: The decision rule that accepts or rejects proposed state transitions with probability ( \min(1, \alpha) ), ensuring detailed balance and correct sampling of the target distribution [16].

Proposal Distribution: The function ( g(x' \mid x) ) that suggests new candidate states, significantly impacting sampling efficiency through optimal step size selection [16].

Force Field: The mathematical model describing interatomic interactions (e.g., Lennard-Jones potentials, bonded terms), common to both MD and MC simulations [15].

Thermodynamic Ensemble: The statistical mechanical constraints (NpT, NVT, etc.) applied to the system, with MC naturally accommodating various ensembles through modified acceptance criteria [15].

Comparative Analysis: Strategic Selection Guidelines

Method Selection Criteria

Choosing between MC and MD approaches requires careful consideration of research objectives:

Prefer MC Methods When:

- Sampling equilibrium distributions without dynamical information

- Working with complex boundary conditions or variable particle numbers

- System has high energy barriers that benefit from specialized moves

- Implementing enhanced sampling techniques like replica-exchange

Prefer MD Methods When:

- Studying time-dependent phenomena and transport properties

- Investigating kinetics and pathway mechanisms

- System requires natural dynamics without artificial moves

- Analyzing correlation functions and spectral properties

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The convergence of MD and MC methodologies represents a significant trend in molecular simulation. Modern implementations increasingly incorporate strengths from both approaches:

- Hybrid Methods: Combining MD's local exploration with MC's barrier-crossing capabilities

- Enhanced Sampling: Techniques like metadynamics and parallel tempering borrowing concepts from both traditions

- Machine Learning Integration: Neural networks guiding proposal generation in MC and force evaluation in MD

- Workflow Standardization: Frameworks like MoSDeF enabling direct comparison and method validation [15]

The 2025 MCM conference will highlight cutting-edge developments in these areas, particularly advancements in Hamiltonian Monte Carlo and non-equilibrium candidate Monte Carlo methods [20].

The Metropolis criterion continues to serve as the fundamental engine driving Monte Carlo sampling methods, providing a mathematically rigorous foundation for exploring complex molecular systems. While Molecular Dynamics offers unique capabilities for investigating temporal evolution and dynamic processes, MC methods maintain distinct advantages for equilibrium sampling, particularly when enhanced with modern algorithms like Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. The demonstrated 1% accuracy in density prediction for both approaches [15] confirms their reliability for many drug discovery applications, from hERG channel liability assessment [21] to protein classification. As the field progresses toward standardized workflows and TRUE (Transparent, Reproducible, Usable-by-others, Extensible) principles [15], researchers can select between these complementary approaches with greater confidence, leveraging their respective strengths to address the complex challenges of modern molecular design and drug development.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC) simulations are foundational techniques in computational physics and chemistry. While they share the goal of sampling molecular configurations, their core principles and primary outputs differ significantly. MD simulations generate realistic temporal dynamics by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion, providing insights into time-dependent processes. In contrast, MC simulations utilize random sampling to generate thermodynamic ensembles, excelling at calculating equilibrium properties and free energies. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methods, supported by current research and experimental data, to help researchers select the appropriate tool for their scientific objectives.

Methodological Comparison: Core Principles and Outputs

The fundamental difference between MD and MC lies in their sampling approach and the type of information they yield. The table below summarizes their key characteristics.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of MD and MC Simulation Methods

| Feature | Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Monte Carlo (MC) |

|---|---|---|

| Sampling Basis | Numerical integration of equations of motion; deterministic time evolution [22]. | Stochastic random moves based on acceptance criteria; sequence of states without time correlation [9]. |

| Primary Output | Trajectories in phase space; temporal evolution and dynamic properties [22]. | Thermodynamic ensembles (e.g., NVT, NPT); equilibrium averages and free energies [9]. |

| Key Strength | Calculation of time-dependent properties (e.g., diffusion coefficients, viscosity) [23]. | Efficient sampling of complex energy landscapes and calculation of equilibrium properties [9]. |

| Inherent Limitation | Computationally expensive; can struggle to sample rare events or complex landscapes [22]. | Does not provide genuine kinetic information or time scales [9]. |

| Typical Application | Studying transport properties, protein folding pathways, and finite-temperature dynamics [24] [23]. | Determining stable molecular crystal forms, protein folding equilibria, and phase transitions [25] [9]. |

Quantitative Performance Data from Recent Studies

Recent applications highlight the complementary strengths of MD and MC in predicting different classes of properties. Performance is highly dependent on the specific scientific question and the quality of the underlying force field or potential.

Table 2: Comparison of Key Outputs from Recent MD and MC Studies

| System Studied | Methodology | Key Predicted Outputs | Agreement with Experiment | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water (across a broad temperature range) | MD with a machine-learned potential (NEP-MB-pol) | Dynamic Properties: Self-diffusion coefficient, viscosity, thermal conductivity.Thermodynamic Properties: Density, heat capacity.Structural Properties: Radial distribution function. | Quantitative agreement for all three transport coefficients and structural properties [23]. | [23] |

| Molecular Crystals (X23 dataset) | MC and MD simulations with Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) | Thermodynamic Properties: Sublimation enthalpies, lattice energies, finite-temperature stability [25]. | Sub-chemical accuracy (< 4 kJ mol⁻¹) for sublimation enthalpies [25]. | [25] |

| Bounded One-Component Plasma (BOCP) | MD with explicit boundary conditions | Thermodynamic Properties: Total electrostatic energy, ionic compressibility factor, ionic equation of state [26]. | Estimated relative error ~0.1% for electrostatic energy; provides reference data for other methods [26]. | [26] |

| Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) | MD (GaMD) for conformational sampling | Dynamic/Temporal Output: Conformational ensembles, proline isomerization events, identification of transient states [22]. | Generated ensembles aligned with experimental circular dichroism data [22]. | [22] |

| Protein-Ligand Binding | MD simulations in explicit solvent | Thermodynamic Output: Change in heat capacity (ΔCp) upon ligand binding [27]. | Predictions were similar to experimental values and could discriminate effective inhibitors [27]. | [27] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for MD Simulation of Ion Transport in Solids

A compact guide for performing reliable MD simulations of ion transport in solids outlines a critical workflow [28]:

- System Preparation: Carefully construct the simulation cell, avoiding common pitfalls that lead to incorrect results.

- Equilibration: Systematically examine and determine the optimal equilibration time for the system.

- Production Simulation: Execute the MD run, confirming the transition from subdiffusive to diffusive behavior of ions.

- Data Analysis: Evaluate diffusion data as a function of temperature. Extrapolate data and interpret results in the context of experimental findings [28].

Protocol for Monte Carlo in Biomolecular Systems

A workshop on atomistic MC simulations for biomolecular systems details its application [9]:

- System Setup: Parametrize the model, often using a physics-based force field for full transferability.

- Sampling: Perform Markov-chain Monte Carlo sampling to generate states. This often involves:

- Unbiased Folding Simulations: To explore the free energy landscape of processes like protein folding.

- Combination with MD: Using MC to circumvent time-scale barriers typical for MD alone.

- Analysis: Generate and analyze free energy landscapes. The primary outputs are equilibrium ensembles and thermodynamic properties, not time-series data [9].

Workflow for Predicting Protein-Ligand Binding Thermodynamics via MD

A study on predicting heat capacity changes (ΔCp) upon ligand binding uses the following MD protocol [27]:

- System Preparation: Create four systems in a water sphere: the protein, the free ligand, the protein-ligand complex, and pure water. The number of water molecules must be identical in all spheres.

- Calibration: Perform separate MD simulations of pure water under identical conditions to calibrate the solvent's contribution to the heat capacity.

- Simulation Series: Run MD simulations for the protein, ligand, and complex across a range of temperatures (e.g., 280 K to 320 K).

- Energy Calculation: For each temperature, calculate the average total energy

<U>for each system. - Heat Capacity Calculation: Subtract the calibrated water contribution from the total heat capacity of each system. The change in heat capacity upon binding,

ΔCp, is then calculated using the formula:ΔCp = [∂<U>/∂<T>]_complex - [∂<U>/∂<T>]_protein - [∂<U>/∂<T>]_ligand[27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Modern simulations, both MD and MC, rely on a suite of software and models to achieve accuracy and efficiency.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool / Solution | Type | Primary Function | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) | Model / Potential | Bridges the accuracy of quantum mechanics and the speed of classical force fields for MD and MC energy calculations [25] [23]. | [25] [23] |

| MACE-MP-0 | Foundation ML Model | A pre-trained MLIP that can be fine-tuned with minimal data (~200 structures) for accurate simulations of molecular crystals [25]. | [25] |

| Neuroevolution Potential (NEP) | Machine-Learned Potential | A framework for generating highly efficient MLPs; used for accurate modeling of water's thermodynamic and transport properties via MD [23]. | [23] |

| OMol25 Dataset | Training Data | A massive dataset of high-accuracy quantum chemical calculations used to train neural network potentials for improved molecular modeling [29]. | [29] |

| Path-Integral Molecular Dynamics (PIMD) | Simulation Method | An MD technique that accounts for nuclear quantum effects, crucial for accurately predicting properties like heat capacity and diffusion [23]. | [23] |

| ProFASi Software | Simulation Software | A software package for performing Monte Carlo simulations of proteins, enabling tasks like unbiased protein folding [9]. | [9] |

| LAMMPS | Simulation Engine | A widely used molecular dynamics simulator that can be adapted for specialized simulations like one-component plasma [26]. | [26] |

MD and MC are not competing methods but rather complementary tools in the computational scientist's arsenal. The choice between them is dictated by the research question. MD is indispensable for investigating kinetics, transport coefficients, and any process where the time-evolution and dynamical nature of the system are paramount. MC is superior for efficiently sampling complex equilibrium ensembles, calculating absolute free energies, and determining the relative stability of states, particularly when realistic dynamics are not required. The integration of machine-learning potentials is enhancing the accuracy and scope of both techniques, pushing the boundaries of what is possible in computational molecular science.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC) simulations are foundational techniques in computational materials science and drug development. Despite their methodological differences, both approaches rely on the accurate description of interatomic interactions through force fields and the calculation of system energies to predict material behavior and molecular properties. This guide provides a detailed comparison of their performance, supported by experimental data and protocols.

Force Fields: The Common Computational Backbone

Force fields are mathematical expressions that describe the potential energy of a system as a function of the nuclear coordinates. Both MD and MC simulations utilize these force fields to model interactions, making their accuracy paramount. A typical force field includes terms for bonded interactions (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals, electrostatic).

Table 1: Common Force Field Terms and Their Mathematical Expressions

| Energy Component | Mathematical Expression | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | $E{bond} = \sum{bonds} kb(r - r0)^2$ | Harmonic potential for covalent bond vibration. |

| Angle Bending | $E{angle} = \sum{angles} k{\theta}(\theta - \theta0)^2$ | Harmonic potential for angle vibration. |

| Torsional Dihedral | $E{dihedral} = \sum{dihedrals} \frac{V_n}{2}[1 + \cos(n\phi - \gamma)]$ | Periodic potential for bond rotation. |

| van der Waals | $E{vdW} = \sum{i |

Lennard-Jones potential for dispersion/repulsion. |

| Electrostatic | $E{elec} = \sum{i |

Coulomb's law for interactions between partial charges. |

The parameterization of these force fields is critical. For example, in hydration free energy (HFE) calculations, the OPLS-AA force field combined with the TIP4P water model has been a standard, though it systematically overestimates the hydrophobicity of hydrocarbons. Recent work shows that scaling the Lennard-Jones interactions between water oxygen and carbon atoms by a factor of 1.25 can reduce the mean unsigned error in HFE predictions from 1.0-1.2 kcal/mol to 0.4 kcal/mol [30]. Furthermore, Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) are emerging as a promising avenue to retain quantum mechanical accuracy at a reduced computational cost, as demonstrated by the Organic_MPNICE model achieving sub-kcal/mol errors on a diverse set of organic molecules [31].

Methodological Comparison: Divergence in Application

While MD and MC share a foundation in force fields, their core algorithms and the properties they can efficiently probe differ significantly. The choice between them depends on the specific scientific question.

Core Algorithmic Principles

Molecular Dynamics (MD) is a deterministic method that numerically integrates Newton's equations of motion. It generates a time-evolving trajectory of the system, providing direct insight into dynamical properties such as diffusion coefficients, viscosity, and time-dependent responses [3]. Its strength lies in capturing realistic system dynamics but is limited to relatively short timescales (typically nanoseconds to microseconds).

Monte Carlo (MC) is a probabilistic method that generates a series of random states, accepting or rejecting them based on a probabilistic criterion (e.g., the Metropolis criterion). It excels at sampling configuration space to efficiently compute equilibrium properties and free energies but contains no inherent concept of time [30] [3]. This makes it unsuitable for studying kinetic or transport properties directly.

Performance in Free Energy Calculations

Free energy is a key thermodynamic property critical for predicting binding affinities in drug discovery and solubility in materials science. MC simulations, particularly with Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) theory, have a long history of providing highly accurate results for these properties [30].

Table 2: Comparison of HFE Calculation Performance (OPLS-AA Force Field)

| Method / Model | System / Test Case | Mean Unsigned Error (kcal/mol) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| MC/FEP (Standard) | 50 organic molecules | 1.0 - 1.2 | Systematic overestimation of hydrophobicity. |

| MC/FEP (Scaled LJ) | 50 organic molecules | 0.4 | Scaling LJ interactions improves accuracy [30]. |

| MLFF (Organic_MPNICE) | 59 organic molecules | < 1.0 | Achieves ab initio quality without parameter tuning [31]. |

| Classical MD/FEP | Varies | Typically > 1.0 | Accuracy limited by force field, not MD methodology. |

Experimental Protocol for MC/FEP HFE Calculation:

- System Setup: A single solute molecule is placed in a periodic cubic box containing 500 TIP4P water molecules for the solution phase, and in vacuum for the gas phase [30].

- Sampling: MC simulations are performed in the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble at 25°C and 1 atm. The solute's internal degrees of freedom are sampled using a Z-matrix.

- Annihilation: The solute is "annihilated" (its interactions are turned off) in both the gas and solution phases using FEP. This involves running a series of 20+ "windows" where a coupling parameter (λ) gradually scales the solute's Coulomb and Lennard-Jones interactions to zero.

- Free Energy Calculation: The free energy change for annihilation in both phases is computed from the simulations. The difference between these values yields the absolute hydration free energy: ΔGhyd = ΔGsolv - ΔGgas [30].

Simulating Complex Materials: High-Entropy Alloys

The performance of MD and MC can diverge significantly when modeling complex, multi-component systems. A study on a Cu-Fe-Ni-Mo-W high-entropy alloy highlights this difference.

Experimental Protocol for Alloy Phase Formation [6]:

- Model Construction: Initial structures were created as either body-centered cubic (bcc) or face-centered cubic (fcc) lattices.

- Simulation Execution: Hybrid MD/MC simulations were performed, heating the models from 10K up to their melting points.

- Analysis: The final phase composition and potential energy of the systems were analyzed and compared to experimentally produced alloys (via arc melting and powder milling).

Results: MD simulations starting from a bcc structure predicted a single-phase bcc solid solution. In contrast, MC simulations produced a two-phase mixture of a bcc Fe-Mo-W phase and a fcc Cu-Ni phase. This MC result aligned closely with the experimental data, which also showed a two-phase mixture, demonstrating MC's superior capability in predicting equilibrium phase separation in this complex system [6].

Hybrid Methods: Bridging the Timescale Gap

A major limitation of standard MD is its inability to access the long timescales required for slow processes like solid-state diffusion. Kinetic Monte Carlo (kMC) can address this but often relies on simplified, rigid-lattice models. A powerful solution is to combine the strengths of both methods in a hybrid approach.

Workflow of a Hybrid MD/kMC Algorithm for Accelerated Diffusion [32]:

- KMC Step Initiation: A random atom is selected within an MD simulation.

- Neighbor Identification: All first-nearest-neighbor atoms of the selected atom are identified.

- Swap Attempt and Acceptance: A swap between the selected atom and one of its neighbors is attempted. The move is accepted or rejected based on the energy change and the kMC acceptance probability.

- MD Simulation Continuation: The standard MD simulation continues from the new atomic configuration. This process artificially accelerates diffusion to a rate observable on MD timescales [32].

This MD/kMC hybrid, implemented in LAMMPS, allows researchers to study diffusion-dependent phenomena like precipitate growth and solute drag effects without needing a priori knowledge of all possible atomic transition states, a requirement for traditional kMC [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software and Force Fields for Molecular Simulation

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | Software | A highly versatile and widely-used MD simulator. | Large-scale atomic/molecular modeling; supports hybrid MD/kMC [32]. |

| BOSS | Software | A general modeling program for MC simulations. | Specialized for free energy calculations (FEP) in organic and biochemical systems [30]. |

| OPLS-AA | Force Field | An all-atom force field for organic molecules. | Predicting properties of liquids and free energies of hydration [30]. |

| TIP4P | Water Model | A 4-site rigid water model. | The solvent model of choice for many accurate MC/FEP hydration studies [30]. |

| Organic_MPNICE | Machine Learning FF | A broadly trained ML force field. | Achieving quantum-mechanical accuracy in HFE predictions for diverse molecules [31]. |

In Practice: Methodological Workflows and Drug Discovery Applications

Molecular Dynamics (MD) represents a cornerstone technique in computational molecular sciences for studying system evolution over time. Unlike its probabilistic counterpart, Monte Carlo (MC), which excels at sampling equilibrium configurations but cannot model time-dependent processes, MD is a deterministic method that solves equations of motion to simulate dynamical trajectories [3]. This fundamental difference dictates their respective applications: MD is indispensable for investigating kinetic properties, transport phenomena, and non-equilibrium processes, while MC often proves more efficient for determining equilibrium states and thermodynamic properties in systems where dynamics are not the primary concern [3]. The choice between them hinges on whether the scientific question requires temporal resolution or focuses solely on equilibrium sampling. Within this broader context of computational sampling methodologies, this guide details the established workflow for MD simulations, from initial system preparation through to trajectory analysis, highlighting how this approach complements MC techniques in the researcher's toolkit.

The Core Molecular Dynamics Workflow

A robust MD workflow consists of several interconnected stages, each critical for ensuring the physical relevance and statistical reliability of the simulation results. The entire process is iterative, with analysis often informing refinements to the system setup or simulation parameters.

Figure 1: The core, iterative stages of a Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation workflow.

System Setup

The initial phase involves constructing the molecular system and defining the computational environment. For a protein-ligand complex in drug discovery, this entails obtaining the 3D structure from a database like the Protein Data Bank (PDB), parameterizing the ligand using tools like antechamber (if using AMBER) or CGenFF (if using CHARMM), and embedding the system in a solvent box (e.g., TIP3P water model) with added ions to neutralize the system's charge and achieve physiological ionic strength [33]. The choice of force field (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER, GROMOS) is critical, as it defines the potential energy function and associated parameters governing atomic interactions [33] [34]. For materials science applications, such as simulating Calcium Aluminosilicate Hydrate (CASH), the initial configuration might be built from a crystalline template like tobermorite, followed by atomic substitutions and hydration to model the amorphous gel structure [34].

Energy Minimization and Equilibration

Before dynamics can begin, the system must be relaxed to remove unfavorable atomic clashes and high-energy strains introduced during setup. Energy minimization employs algorithms like steepest descent or conjugate gradient to find the nearest local energy minimum. Subsequently, equilibration is performed to bring the system to the desired thermodynamic state (e.g., NVT and NPT ensembles). During NVT equilibration, the system's temperature is gradually increased and stabilized using thermostats (e.g., Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen), while NPT equilibration adjusts the system's density using barostats (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) to reach the target pressure [34]. This phase ensures the system is stable and representative of the experimental conditions before data collection begins.

Production Run and Trajectory Analysis

The production phase involves integrating Newton's equations of motion over a defined period (nanoseconds to microseconds) to generate the trajectory—a file containing the atomic coordinates and velocities over time. The length of this simulation is determined by the biological or physical process of interest. Analysis of this trajectory extracts scientifically meaningful information. Key properties include the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), which measures structural stability; the Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF), which identifies flexible regions; the Radius of Gyration, which assesses compactness; and the Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA), which quantifies surface exposure [35] [33]. For solvation studies, properties like the Average number of solvents in the Solvation Shell (AvgShell) and Estimated Solvation Free Energies (DGSolv) are critical [35].

Comparative Analysis: MD vs. Monte Carlo Performance

The choice between MD and MC is not merely philosophical but has practical implications for computational cost, accuracy, and the type of information that can be obtained. The table below summarizes key differentiators based on recent research.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of Molecular Dynamics and Monte Carlo simulation methods.

| Feature | Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Monte Carlo (MC) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Deterministic; integrates Newton's equations of motion [3] | Probabilistic; accepts/rejects configurations based on Boltzmann probability [3] |

| Native Simulation Ensemble | Microcanonical (NVE), but others can be simulated [3] | Canonical (NVT), Isothermal-isobaric (NPT) [3] |

| Temporal Resolution | Provides realistic time evolution and dynamics [3] | No real-time dynamics; only samples equilibrium states [3] |

| Handling of Complex Potentials | Formally more exact but can suffer from slow convergence [36] | Efficient for on-lattice models; challenging for fully flexible molecules [3] |

| Parallelization | Highly parallelizable (e.g., in GPUs) [3] | Difficult to parallelize due to sequential acceptance/rejection steps [3] |

| Applicability to Non-Equilibrium | Suitable for both equilibrium and non-equilibrium systems [3] | Primarily suited for equilibrium sampling [3] |

| Performance in Alloy Formation | Predicted incorrect single-phase BCC solid solution [6] | Correctly predicted two-phase mixture, matching experiments [6] |

| Computational Demand for Folding | Very expensive for all-atom protein folding simulations [3] | Can be more efficient for conformational sampling at equilibrium [3] |

Experimental data from a 2023 study on a Cu–Fe–Ni–Mo–W high-entropy alloy provides a concrete performance comparison. The MD simulation, starting from a body-centered cubic (BCC) structure, incorrectly predicted the formation of a single-phase BCC solid solution. In contrast, the MC simulation accurately produced a two-phase mixture, a result later confirmed by experimental production using arc furnace and powder milling [6]. This demonstrates MC's potential superiority in predicting certain equilibrium phase distributions.

In polymer science, a 2021 study compared MD, Self-Consistent Field (SCF) theory, and a hybrid Monte Carlo SCF (MC-SCF) method for modeling polymer stars. The MD approach was noted as "formally the most exact" but was hampered by "reasonable convergence" issues. The hybrid MC-SCF method successfully combined the benefits of accurate sampling with computational efficiency, performing well across a range of solvent conditions [36].

Experimental Protocols and Data Analysis

Detailed Protocol: Drug Solubility Prediction via MD

A 2025 study on predicting drug aqueous solubility (logS) offers a detailed MD protocol suitable for biomolecular applications [35].

Methodology:

- System Preparation: A dataset of 211 drugs was compiled. Each drug molecule was placed in a cubic simulation box (e.g., 4 nm side length) solvated with water molecules.

- Force Field and Software: Simulations were conducted using GROMACS 5.1.1 with the GROMOS 54a7 force field [35].

- Simulation Parameters: Simulations were run in the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) to mimic experimental conditions.

- Production Run: A production MD run was performed to generate a stable trajectory for analysis.

- Property Extraction: Ten MD-derived properties were extracted from the trajectory for each drug, including SASA, Coulombic and Lennard-Jones (LJ) interaction energies, DGSolv, RMSD, and AvgShell. The octanol-water partition coefficient (logP) was also included from experimental literature.

- Machine Learning Modeling: These properties were used as features to train ensemble machine learning models (e.g., Gradient Boosting) to predict experimental logS.

Results and Analysis: The study found that a subset of seven properties—logP, SASA, Coulombic_t, LJ, DGSolv, RMSD, and AvgShell—were highly effective predictors of solubility. The Gradient Boosting model achieved a predictive R² of 0.87 and an RMSE of 0.537 on the test set, demonstrating that MD-derived properties have predictive power comparable to models based solely on structural fingerprints [35].

Table 2: Key MD-derived properties used for predicting drug aqueous solubility with machine learning [35].

| Property | Description | Role in Solubility |

|---|---|---|

| logP | Octanol-water partition coefficient (experimental) | Measures hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity |

| SASA | Solvent Accessible Surface Area | Quantifies surface exposed to solvent |

| Coulombic_t | Coulombic interaction energy with solvent | Measures polar interactions with water |

| LJ | Lennard-Jones interaction energy with solvent | Measures van der Waals interactions |

| DGSolv | Estimated Solvation Free Energy | Overall energy change upon solvation |

| RMSD | Root Mean Square Deviation | Indicates conformational stability |

| AvgShell | Avg. number of solvents in Solvation Shell | Describes the local solvation environment |

Workflow Automation with AI Agents

Recent advances have introduced automation to the complex MD workflow. The MDCrow framework, an LLM (Large Language Model) agent, exemplifies this trend. It uses over 40 expert-designed tools for tasks like retrieving PDB files, cleaning structures with PDBFixer, setting up simulations in OpenMM, adding solvent with PackMol, and performing analysis with MDTraj for properties like RMSD and radius of gyration [33]. This automation reduces the expert intuition traditionally required for parameter selection and multi-step preprocessing and analysis, making MD more accessible and reproducible.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential software and tools for a modern Molecular Dynamics workflow.

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Simulation Software | High-performance MD package for simulating Newtonian dynamics [35] |

| AMBER | Simulation Software | Suite of programs for simulating biomolecules [33] |

| CHARMM | Simulation Software | Versatile MD simulation program with extensive force fields [33] |

| OpenMM | Simulation Software | Toolkit for MD simulation with high GPU performance [33] |

| MDTraj | Analysis Library | Software library for analyzing MD simulations [33] |

| PDBFixer | Utility Tool | Corrects common problems in PDB files (e.g., missing residues) [33] |

| PackMol | Utility Tool | Prepulates initial configurations by packing molecules in a simulation box [33] |

| MDCrow | Workflow Automation | LLM agent for automating setup, simulation, and analysis tasks [33] |

| Simple Active Learning | Advanced Workflow | Workflow for on-the-fly training of machine learning potentials during MD [37] |

A typical MD workflow is a structured process encompassing system setup, energy minimization, equilibration, production simulation, and trajectory analysis. While MD is a powerful and deterministic tool for studying time-dependent phenomena, its position in research is defined in contrast to the Monte Carlo method. MC, as a probabilistic sampler, often proves more efficient and sometimes more accurate for predicting equilibrium properties, as evidenced by its success in modeling alloy phase behavior [6]. The choice between them should be guided by the research question: MD for dynamics and kinetics, MC for equilibrium thermodynamics. Future directions point toward greater automation through AI agents [33] and the integration of machine learning potentials to enhance accuracy and speed [37], further solidifying the role of MD as an indispensable tool in computational science.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC) simulations represent two foundational pillars in computational molecular science. While both aim to sample molecular configurations to compute thermodynamic properties, their fundamental approaches differ significantly. MD simulations generate ensembles by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion, providing a time-evolving trajectory of the system. In contrast, MC methods utilize random sampling to generate configurations according to appropriate statistical mechanical distributions, typically calculating thermodynamic properties via an ensemble average rather than a time average.

For ergodic systems, these approaches converge to identical results, yet each offers distinct advantages and limitations that make them suitable for different research scenarios. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these methodologies, focusing specifically on elucidating the typical MC workflow for configuration generation and observables calculation, while contextualizing its performance relative to MD approaches.

The Core MC Workflow: From Configurations to Observables

A typical Monte Carlo simulation follows a structured workflow to generate statistically independent molecular configurations and compute observable properties from them. The process involves careful preparation, iterative configuration generation, and rigorous statistical analysis, with particular attention to quantifying uncertainty.

The following diagram illustrates the standard MC workflow, highlighting the cyclical nature of configuration generation and the critical steps for calculating observables with proper uncertainty quantification:

Configuration Generation Methodology

Configuration generation in MC relies on Markov chain Monte Carlo methods, where new configurations are generated through random perturbations of the current state. The core algorithm follows these steps:

Initialization: The simulation begins with an initial configuration, which could be a crystal lattice, random arrangement, or pre-equilibrated structure. The choice of statistical ensemble (NVT, NPT, etc.) determines which thermodynamic variables remain fixed.

Random Move Proposal: The algorithm proposes a random modification to the current configuration. Common moves include:

- Translating a randomly selected particle

- Rotating a molecule or molecular fragment

- Changing molecular conformation (e.g., dihedral angle rotation)

- Modifying simulation box dimensions (in NPT ensemble)

- Cluster moves or swap moves for complex systems

Energy Evaluation: After each move, the potential energy change (ΔE) between the new and old configurations is computed using the chosen force field or potential energy function.

Metropolis Criterion: The move is accepted or rejected based on the Metropolis acceptance criterion, which depends on the Boltzmann factor of the energy change:

- If ΔE ≤ 0, the move is always accepted

- If ΔE > 0, the move is accepted with probability exp(-ΔE/kBT) This ensures detailed balance and generates configurations according to the Boltzmann distribution.

Observables Calculation and Uncertainty Quantification

Once configurations are generated, observables are calculated as ensemble averages over the sampled states. For a general observable O, the ensemble average is computed as:

⟨O⟩ = (1/N) Σ O(config_i)

where the sum runs over N statistically independent configurations.

A critical aspect often overlooked in MC simulations is proper uncertainty quantification (UQ). Statistical uncertainties must be reported alongside any simulated observable to communicate the significance and limitations of the results [38]. Key statistical concepts include:

- Arithmetic mean: The estimate of the true expectation value of a random quantity

- Experimental standard deviation: An estimate of the true standard deviation of a random variable

- Standard uncertainty: Uncertainty in a result expressed in terms of a standard deviation

- Experimental standard deviation of the mean: An estimate of the standard deviation of the distribution of the arithmetic mean (often called "standard error") [38]

For correlated data, special care must be taken. The correlation time (τ) is the longest separation in "time" (simulation steps) for which configurations remain correlated. For observables computed from correlated data, the effective sample size is reduced to N/τ, which increases the statistical uncertainty [38].

In specialized MC variants like Diagrammatic Quantum Monte Carlo, where configurations can have complex weights w(c) = φ_c|w(c)|, observables are calculated using a modified approach:

⟨O⟩ = ⟨Oφc⟩{|w(c)|} / ⟨φc⟩{|w(c)|}

where the averages on the right-hand side are taken with respect to the absolute value of the weights. In such cases, the average complex sign ⟨φ_c⟩ must be real, and the real parts of both numerator and denominator are typically used to obtain real-valued observables [39].

Comparative Analysis: MC vs. MD Performance

Methodological Comparison

Table 1: Fundamental methodological differences between MC and MD approaches

| Aspect | Monte Carlo (MC) | Molecular Dynamics (MD) |

|---|---|---|

| Sampling Basis | Random walks in configuration space | Time evolution via Newton's equations |

| Ensemble Generation | Direct sampling of desired ensemble (NVT, NPT, μVT, etc.) | Typically starts with microcanonical (NVE), requires thermostats/barostats for other ensembles |

| Physical Dynamics | No physical pathway information | Preserves physical dynamical trajectories |

| Configuration Acceptance | Metropolis criterion based on energy change | All configurations accepted (deterministic dynamics) |

| Conserved Quantities | No inherent conservation laws | Conserves energy and momentum (in NVE) |

| Temperature Control | Naturally incorporated through Boltzmann factors | Requires specialized thermostating algorithms |

Performance and Sampling Characteristics

Table 2: Performance comparison and sampling characteristics

| Characteristic | Monte Carlo (MC) | Molecular Dynamics (MD) |

|---|---|---|

| Sampling Efficiency | Can use non-physical moves to escape barriers | Limited by physical dynamics and energy barriers |

| Parallelization | Trivially parallelizable but sequential moves | Highly parallelizable (force calculations distributed) |

| Complex Molecules | Challenging due to low acceptance of large moves | Naturally handles complex conformational changes |

| Code Availability | Fewer optimized packages, often custom implementations | Mature, highly optimized codes (GROMACS, LAMMPS, etc.) |

| Statistical Mechanics Foundation | Naturally provides ensemble averages | Provides time averages (equivalent for ergodic systems) |

| Barostat/Thermostat Implementation | Simple and theoretically rigorous | Complex, multiple algorithms with varying rigor |

The fundamental difference lies in their approach to configuration generation: MC samples configuration space directly through random moves, while MD follows physical trajectories through phase space. For ergodic systems, both provide equivalent thermodynamic properties, but MC typically achieves better sampling efficiency for systems with high energy barriers, as it can employ non-physical moves that bypass actual transition states [40].

MD's primary advantage emerges when studying dynamical processes or when using highly optimized simulation packages that leverage extensive algorithmic development and parallel computing architectures [40].

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

MC for Complex Systems: Advanced Sampling Protocols

Advanced MC techniques extend beyond simple single-particle moves to address challenging sampling problems:

Cluster Moves: For spin systems or associating molecules, flipping clusters of spins or molecules simultaneously dramatically accelerates equilibration near critical points or in strongly interacting systems [40].

Configurational Bias MC: For complex molecules with dense packing, standard moves exhibit low acceptance rates. Configurational bias MC grows molecules segment by segment, biasing the growth toward favorable configurations while correcting for the bias in the acceptance probability.

Parallel Tempering: Multiple replicas at different temperatures simulate concurrently, with periodic configuration swaps according to a Metropolis-like criterion. This enables configurations to escape deep energy minima by visiting higher temperatures.

Recent advances in neural network potentials (NNPs) trained on massive quantum chemical datasets like Meta's Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) are revolutionizing both MC and MD approaches. These universal models for atoms (UMA) provide quantum-mechanical accuracy at dramatically reduced computational cost, enabling more accurate potential energy evaluations in MC sampling [29].

MD Validation and Quantitative Prediction Protocols

MD simulations have demonstrated remarkable success in quantitative materials prediction. Recent case studies illustrate rigorous protocols for connecting simulation with experiment:

Polymer Tensile Strength Prediction: MD simulations systematically study the dependence of tensile strength on simulation volume and strain rate. Strength decreases with increasing simulation volume (following Weibull statistics) and decreasing strain rate. Through dual extrapolation to experimental volumes and strain rates, MD achieves quantitative agreement with experimental tensile strength measurements [41].

Crystal Structure Prediction: MD simulations predict assembly structures of bowl-shaped π-conjugated molecules by analyzing energy landscapes, thermal factors, and potential of mean force (PMF). Comparing herringbone versus columnar arrangements, MD correctly identifies stable structures matching experimental crystals and provides insight into molecular-level stabilization mechanisms [42].

These protocols demonstrate how careful finite-size scaling, rate adjustments, and free energy calculations enable quantitatively predictive simulation using both MD and MC approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential computational tools and resources for molecular simulation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| OMol25 Dataset | Dataset | Massive quantum chemistry dataset (100M+ calculations) for training neural network potentials [29] |

| Universal Models for Atoms (UMA) | Neural Network Potential | Unified architecture providing quantum accuracy for diverse molecular systems [29] |

| eSEN Models | Neural Network Potential | Equivariant transformer-style potentials with conservative force training [29] |

| GROMACS | MD Software | Highly optimized, parallel MD package with extensive force fields and algorithms [42] |

| Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) Framework | Analytical Method | Statistical tools for estimating uncertainties and assessing sampling quality [38] |

| Metropolis Criterion | Algorithm | Core MC acceptance rule ensuring correct Boltzmann sampling |

| Potential of Mean Force (PMF) | Analytical Method | Free energy profile along reaction coordinates from umbrella sampling [42] |

Both Monte Carlo and Molecular Dynamics offer powerful, complementary approaches for molecular simulation and property prediction. The choice between them depends critically on the specific research question, system characteristics, and available computational resources.

MC excels in efficient equilibrium sampling, particularly for systems where non-physical moves can accelerate barrier crossing or where specific ensembles are required. Its theoretically rigorous ensemble averaging and simple implementation of thermodynamic conditions make it ideal for computing thermodynamic properties. However, it sacrifices dynamical information and benefits less from decades of algorithmic optimization invested in MD codes.

MD provides natural physical dynamics and access to time-dependent phenomena, with the advantage of highly optimized, parallelized software packages. Its primary sampling limitations arise from being constrained by physical motion pathways, though enhanced sampling methods partially address this.

The emerging integration of both approaches with machine-learned quantum potentials like those trained on the OMol25 dataset represents the future of computational molecular science, promising unprecedented accuracy and efficiency in molecular modeling and design [29].

Understanding protein-ligand interactions stands as a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, requiring atomic-level insights into binding mechanisms and associated protein motions. Within this domain, Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC) simulations have emerged as powerful computational techniques, each with distinct philosophical and methodological approaches to sampling molecular configurations. While MC simulations efficiently generate thermodynamic ensembles through random perturbations that do not follow physical pathways, MD simulations solve Newton's equations of motion to model the physical trajectory of a system over time, providing direct insight into dynamic processes [40]. This capability makes MD particularly valuable for studying the mechanistic events of protein-ligand association and dissociation, as it captures the temporal sequence of structural changes that occur during binding [43]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methods, focusing on their application in modeling protein-ligand binding modes and conformational changes, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols.

Methodological Comparison: MD vs. MC in Molecular Simulations

The fundamental difference between MD and MC lies in their sampling approach. MD simulations model the system's evolution over time by numerically integrating equations of motion, providing information about dynamics and kinetics [40]. In contrast, MC methods generate an ensemble of representative configurations through random perturbations, focusing solely on thermodynamic properties without providing time-evolution information [2]. This distinction becomes particularly important when studying processes like ligand binding, where the pathway and kinetics can be as important as the final bound state.

Advantages and Limitations: MD's primary advantage is its ability to follow physical pathways, making it suitable for studying processes like conformational changes and binding events [40]. However, MD can be computationally demanding and may struggle to escape local energy minima. MC, while not providing dynamical information, can often sample configuration space more efficiently, especially with advanced techniques like cluster moves or multiple-minimum sampling [40] [44]. MC also more easily handles constant temperature and pressure conditions, while MD requires more complicated thermostats and barostats [40].