Molecular Dynamics vs Monte Carlo: A Comprehensive Guide for Computational Drug Discovery

This article provides a detailed comparison of Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC) simulation methods for researchers and professionals in computational biology and drug development.

Molecular Dynamics vs Monte Carlo: A Comprehensive Guide for Computational Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparison of Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC) simulation methods for researchers and professionals in computational biology and drug development. It explores the foundational principles of both stochastic (MC) and deterministic (MD) approaches, highlighting their unique strengths in sampling conformational space and simulating time evolution. The scope covers core methodologies, diverse applications in biomolecular simulation and drug design, strategies for troubleshooting sampling efficiency and system setup, and quantitative comparisons of performance and reliability. The review synthesizes these insights to offer practical guidance on method selection and discusses future directions for integrating these techniques in biomedical research.

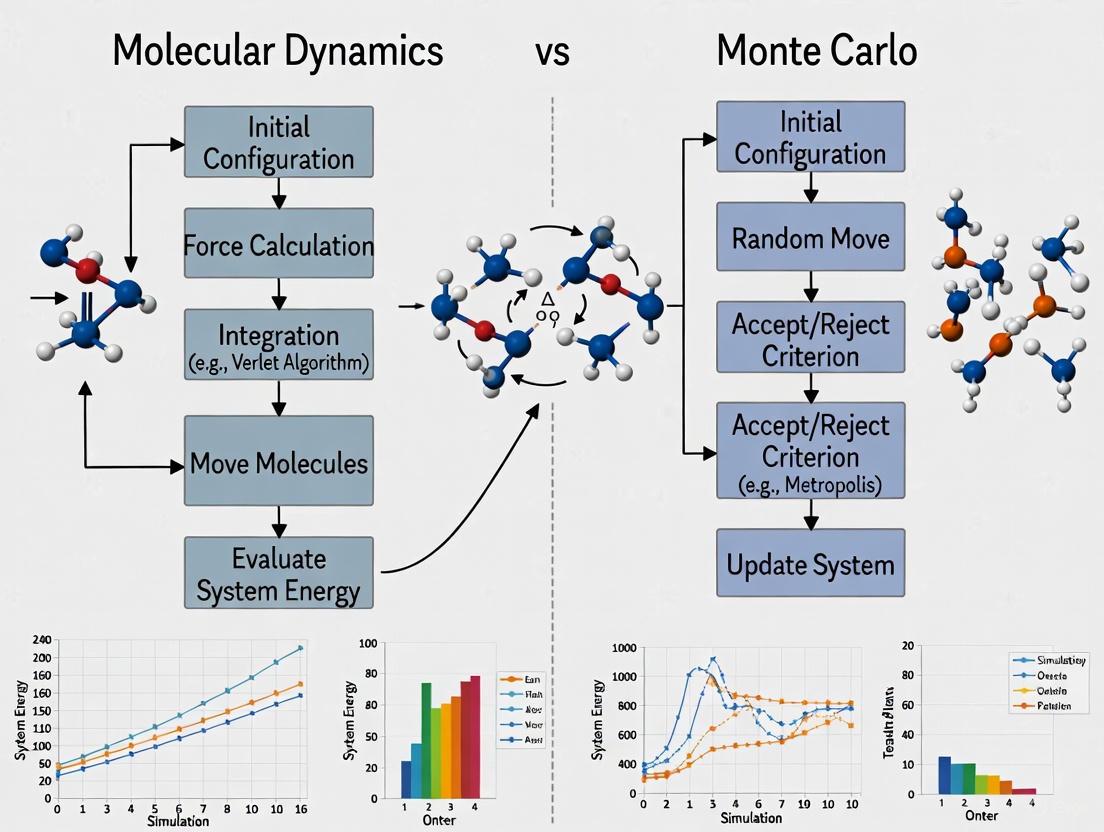

Core Principles: Understanding the Stochastic and Deterministic Foundations of MD and MC

In computational chemistry and materials science, Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC) simulations represent two foundational paradigms for investigating molecular systems. Their core distinction lies in their fundamental approach: MD is deterministic, based on numerical integration of classical equations of motion, while MC is stochastic, relying on random sampling to explore configuration space [1] [2]. This deterministic-stochastic dichotomy dictates their respective applications, strengths, and limitations. MD simulations are unparalleled for studying time-dependent phenomena and dynamic processes, providing actual trajectories of molecular motion over time [2]. In contrast, MC simulations excel at calculating equilibrium thermodynamic properties and sampling complex energy landscapes, though they do not provide real-time dynamical information [3] [2]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methods, focusing on their performance in research applications, particularly in drug discovery and materials science, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies.

Core Methodological Differences and Theoretical Foundations

The following table summarizes the fundamental differences between Molecular Dynamics and Monte Carlo methods.

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Molecular Dynamics and Monte Carlo Methods

| Feature | Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Monte Carlo (MC) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Deterministic; solves Newton's equations of motion [2] | Stochastic; based on random sampling and probability distributions [2] |

| Time Evolution | Explicitly simulates time evolution, providing dynamic trajectories [2] | Does not involve real time; focuses on state space sampling [2] |

| Primary Output | Time series of coordinates and velocities; dynamic properties [2] | Set of sampled configurations; thermodynamic averages [2] |

| Key Applications | Protein folding, chemical reaction pathways, molecular docking [2] | Calculation of free energy, phase transitions, equilibrium constants [2] |

| Handling of Temperature | Controlled via thermostats (e.g., Berendsen, Nose-Hoover) [4] | Incorporated via acceptance criteria (e.g., Metropolis criterion) [2] |

| Algorithm Basis | Numerical integration (e.g., Velocity Verlet) with a time step [4] | Generation of random moves accepted/rejected based on energy change [2] |

The deterministic nature of MD means that, given an identical starting configuration and the same force field, an MD simulation will produce the same trajectory every time. It achieves this by calculating forces from a potential energy function and numerically integrating Newton's equations of motion to update atomic positions and velocities over a series of small time steps [2]. This process provides a direct link to dynamical properties.

Conversely, MC methods are inherently probabilistic. They explore the configuration space of a system by generating random changes (moves) to the current configuration. The core of many MC algorithms is the Metropolis criterion, where a newly generated configuration is accepted if it lowers the system's energy, or accepted with a probability proportional to the Boltzmann factor if it raises the energy [2]. This procedure ensures the system is sampled according to the desired thermodynamic ensemble (e.g., NVT or NPT), but it contains no information about the kinetics of the process.

Table 2: Comparative Advantages and Limitations in Research

| Aspect | Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Monte Carlo (MC) |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | Provides detailed dynamic behavior and time evolution [2]; Reveals binding mechanisms and reaction pathways [2]; High precision in simulating real molecular motions [2] | High computational efficiency for large systems [2]; No time step limitation, can overcome energy barriers efficiently [2]; Lower dependence on initial structure [2] |

| Limitations | Extremely high computational cost for large systems/long timescales [2]; Results can be sensitive to initial structure and force field choice [2] | Cannot provide time-dependent or kinetic information [2]; May suffer from insufficient sampling if simulations are too short [2]; Relies on assumptions about system state [2] |

Experimental Protocols and Simulation Workflows

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for researchers, this section outlines standard protocols for implementing MD and MC simulations. Adherence to these methodologies is critical for generating reliable and comparable scientific data.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Protocol

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for a typical Molecular Dynamics simulation.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Workflow

Step 1: System Preparation. The initial 3D structure of the target molecule or complex is obtained from experimental sources (e.g., Protein Data Bank) or predicted structures (e.g., AlphaFold models) [5]. The system's protonation states and disulfide bonds are assigned correctly.

Step 2: Force Field Selection. An appropriate molecular mechanics force field (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS) is selected to define the potential energy function, which includes bonded terms (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and non-bonded terms (van der Waals, electrostatic interactions) [6].

Step 3: Solvation and Neutralization. The system is placed in a simulation box (e.g., cubic, rhombic dodecahedron) and solvated with explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P, SPC/E models). Ions are added to neutralize the system and achieve a physiologically relevant ionic concentration [4].

Step 4: Energy Minimization. The system's energy is minimized using algorithms like steepest descent or conjugate gradient to remove bad contacts and steric clashes, resulting in a stable starting configuration for dynamics [4].

Step 5: System Equilibration. The system is gradually heated to the target temperature (e.g., 310 K for physiological conditions) using a thermostat (e.g., Berendsen, Nose-Hoover) in the NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature). This is followed by equilibration in the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) using a barostat (e.g., Berendsen, Parrinello-Rahman) to achieve the correct density [4].

Step 6: Production Simulation. The equilibrated system is simulated for an extended period (nanoseconds to microseconds, depending on the system and scientific question) with a time step of typically 1-2 femtoseconds. Coordinates and velocities are saved at regular intervals for subsequent analysis [4] [2].

Step 7: Trajectory Analysis. The saved trajectory is analyzed to compute properties of interest, which may include root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) for structural stability, radius of gyration, hydrogen bonding patterns, distance measurements between residues, or free energy calculations using methods like MM/PBSA [2].

Monte Carlo Simulation Protocol

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for a typical Monte Carlo simulation.

Monte Carlo Simulation Workflow

Step 1: System and Ensemble Definition. The molecular system is defined, and the appropriate statistical mechanical ensemble is selected (e.g., canonical/NVT, isothermal-isobaric/NPT, or grand canonical/μVT ensemble) based on the properties of interest [2].

Step 2: Initial Configuration. An initial configuration of the system is generated, which could be a crystal structure, a random arrangement of molecules, or a structure taken from another simulation.

Step 3: Move Proposal. A random trial move is proposed to perturb the current configuration. Common moves include:

- Displacement: Translating a randomly selected molecule or atom by a small random vector.

- Rotation: Rotating a molecule around a randomly chosen axis by a random angle.

- Volume Change: For NPT ensemble simulations, randomly changing the simulation box volume.

- Particle Insertion/Deletion: For grand canonical (μVT) ensemble simulations, randomly inserting or deleting a molecule [2].

Step 4: Energy Calculation. The potential energy of the new trial configuration (Enew) is calculated and compared to that of the old configuration (Eold). The energy difference, ΔE = Enew - Eold, is computed.

Step 5: Acceptance Criterion. The Metropolis criterion is applied: if ΔE ≤ 0, the move is automatically accepted. If ΔE > 0, the move is accepted with probability Paccept = exp(-ΔE/kB T), where kB is Boltzmann's constant and T is the temperature. This is implemented by comparing Paccept to a random number uniformly distributed between 0 and 1 [2].

Step 6: Configuration Update. If the trial move is accepted, the new configuration becomes the current state. If rejected, the old configuration is retained and counted again in the averaging process.

Step 7: Sampling and Repetition. After the acceptance decision, the current configuration (whether new or old) is used to sample the properties of interest (e.g., energy, density, order parameters). Steps 3-6 are repeated for millions of iterations to ensure adequate sampling of the relevant regions of configuration space.

Step 8: Averaging and Analysis. Once the simulation is deemed to have converged and sufficient sampling has been achieved, thermodynamic properties are computed as averages over the sampled configurations. For example, the average energy ⟨U⟩ is a simple arithmetic mean of the energies of all sampled states [2].

Performance Comparison in Drug Discovery Applications

The distinct capabilities of MD and MC make them suitable for different stages of the drug discovery pipeline. The following table compares their performance across key application areas.

Table 3: Application-Based Performance Comparison in Drug Discovery

| Application | Molecular Dynamics (MD) Performance | Monte Carlo (MC) Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Virtual Screening | Computationally expensive for ultra-large libraries; used for refining top hits from docking [5] | Efficient for sampling binding poses and estimating binding affinities for a smaller set of candidates [6] |

| Binding Affinity Prediction | Good for relative binding free energies via alchemical methods (e.g., FEP); provides structural insights [6] | Excellent for absolute binding free energy calculations using methods like Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) with Monte Carlo sampling [6] |

| Target Flexibility & Conformational Sampling | Excellent for capturing full atomistic flexibility and dynamics; can reveal cryptic pockets via enhanced sampling [5] | Limited in sampling large-scale protein backbone motions; efficient for side-chain and ligand conformational sampling [2] |

| Solubility & Partition Coefficients | Less efficient due to slow diffusion in explicit solvent; requires long simulation times | Highly efficient for calculating thermodynamic properties like logP and solubility via statistical sampling [2] |

| ADMET Prediction | Can provide insights into specific metabolic reaction pathways via QM/MM-MD [6] | Effective for predicting bulk properties related to absorption and distribution [6] |

In structure-based drug design (SBDD), MD simulations have become crucial for addressing the challenge of target flexibility. Most molecular docking tools treat the protein as largely rigid, but proteins and ligands are highly flexible in solution [5]. Advanced MD techniques, such as accelerated MD (aMD), smooth the system's potential energy surface, decreasing energy barriers and accelerating transitions between different low-energy states. This allows for more efficient sampling of distinct biomolecular conformations and helps identify cryptic pockets not visible in the original crystal structure [5]. The Relaxed Complex Method (RCM) is a notable approach that uses representative target conformations from MD simulations, including those with novel cryptic binding sites, for subsequent docking studies [5].

MC methods, particularly those employing Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) with Monte Carlo sampling, offer a rigorous theoretical framework for calculating binding free energy changes [6]. This is crucial for lead optimization, where small chemical modifications are made to improve a compound's affinity and specificity. FEP/MC calculations can predict the relative binding free energies between related compounds with high accuracy, guiding medicinal chemists toward more potent analogs.

Hybrid Methods and Advanced Integration

Recognizing that neither MD nor MC is universally superior, researchers often combine them to leverage their respective strengths. These hybrid approaches are particularly powerful for simulating complex biomolecular processes.

Table 4: Overview of Hybrid MD-MC Methods

| Hybrid Method | Description | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Replica Exchange MD (REMD) | Multiple MD simulations run in parallel at different temperatures, with periodic exchange of configurations based on a Metropolis-like criterion [2] | Protein folding, studying thermodynamic behavior of large molecular systems, enhanced sampling [2] |

| Meta-Dynamics | An external history-dependent bias potential is added to the Hamiltonian to discourage the system from revisiting already sampled states, effectively accelerating the escape from local energy minima [2] | Free energy calculations, exploring chemical reaction paths, and studying complex conformational changes [2] |

| MC-Assisted Free Energy Calculations | MD simulations provide dynamic trajectories, while MC sampling is used to calculate free energy differences and binding affinities with high efficiency [6] | Drug design optimization, calculating binding affinities in complex systems [6] |

The following diagram illustrates how MD and MC are integrated in a hybrid approach for advanced sampling.

Hybrid MD-MC Sampling Strategy

These hybrid methods are widely applied in drug design, materials science, and protein folding research. In drug design, MD simulations reveal dynamic interactions between drug candidates and their target proteins, while MC simulations help calculate binding free energies and optimize candidate structures [2]. In materials science, MD simulations study mechanical properties and time-dependent behavior, while MC simulations calculate thermodynamic properties like phase transitions [2].

Successful implementation of MD and MC simulations requires both specialized software and access to computational resources. The following table details key solutions used in the field.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Type | Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | AMS [4], GROMACS, NAMD, LAMMPS, AMBER, CHARMM | Software packages that perform molecular dynamics simulations using various force fields and integration algorithms [4]. |

| MC Simulation Software | Various specialized MC packages, ProtoMS, MCCCS Towhee | Software designed for Monte Carlo sampling, often with specific capabilities for free energy calculations [2]. |

| Force Fields | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS-AA, GAFF | Parameter sets defining potential energy functions, including bonded and non-bonded interactions, for different classes of molecules [6]. |

| Enhanced Sampling Tools | PLUMED [4], Meta-Dynamics [2] | Plugins and algorithms that enhance the sampling of rare events and calculate free energies. |

| Quantum Chemistry Data | Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) dataset [7] | Large-scale DFT datasets used to train Machine Learned Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) for more accurate force fields [7]. |

| High-Performance Computing | Cloud computing (e.g., AWS, Google Cloud), GPU clusters [5] | Essential computational resources for handling ultra-large virtual screenings and long timescale simulations [5]. |

The recent release of massive computational datasets like Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25), which contains over 100 million 3D molecular snapshots with properties calculated using Density Functional Theory (DFT), is revolutionizing the field [7]. Such datasets are used to train Machine Learned Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs), which can provide DFT-level accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost, thereby enhancing both MD and MC simulations [7].

Molecular Dynamics and Monte Carlo simulations represent two powerful but philosophically distinct paradigms for computational research. MD's deterministic nature provides unparalleled insights into time-dependent processes and molecular mechanisms, making it indispensable for studying dynamics, folding, and binding pathways. MC's stochastic approach offers superior efficiency for calculating thermodynamic equilibrium properties and free energies. The choice between them is not a matter of which is better, but which is more appropriate for the specific scientific question at hand. Furthermore, the growing trend of hybrid methods, which leverage the strengths of both approaches, alongside the integration of machine-learning potentials trained on massive quantum chemical datasets, points toward a future where the boundaries between these paradigms become increasingly blurred, leading to more comprehensive and predictive computational models in drug discovery and materials science.

In the quest to understand and predict the behavior of molecular systems, from drug molecules interacting with their protein targets to the self-assembly of complex materials, researchers rely on computational methods to navigate the intricate energy landscapes that govern molecular stability and function. An energy landscape is a conceptual mapping of all possible configurations of a molecular system against their corresponding energy levels. Within this landscape, low-energy valleys represent stable states, while high-energy peaks represent barriers to change. Two powerful computational techniques dominate this exploration: Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC). Though sometimes used to address similar problems, their fundamental approaches are philosophically and technically distinct. MD simulation is a deterministic method that produces a time-evolving narrative of atomic motion, effectively creating a movie of molecular life [1] [8]. In contrast, MC simulation is a probabilistic method that generates a statistical collection of snapshots, focusing on the system's equilibrium properties without reference to a temporal dimension [1] [2]. This guide provides an objective comparison of how these two methods are used to explore energy landscapes, detailing their performance, supported by experimental data and protocols.

Core Principles: Dynamics vs. Sampling

The Molecular Dynamics (MD) Approach

MD simulation predicts the trajectory of a molecular system by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for every atom in the system [8] [2]. The core principle is that by knowing the forces acting on each atom (calculated from a molecular mechanics force field) and the initial atomic positions and velocities, one can determine the acceleration, and subsequently update the positions and velocities over a series of very short time steps (femtoseconds, 10⁻¹⁵ s) [8] [9]. This results in a time-series of atomic coordinates—a trajectory—that captures the dynamic evolution of the system, including its fluctuations and rare events, as it navigates its energy landscape [9].

The Monte Carlo (MC) Approach

MC simulation, in its most common form for molecular systems, explores the energy landscape through random sampling of configurations [10] [2]. Unlike MD, it is not based on classical mechanics and does not model the physical pathway between states. Instead, it generates new random configurations that are then accepted or rejected based on a probabilistic criterion (e.g., the Metropolis criterion) designed to ensure that the ensemble of sampled configurations conforms to the desired statistical distribution, such as the Boltzmann distribution for a canonical ensemble [11]. The primary output is therefore not a trajectory, but a set of statistically independent configurations used to compute equilibrium thermodynamic averages [2].

Table 1: Foundational Differences Between MD and MC

| Feature | Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Monte Carlo (MC) |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Classical (Newtonian) mechanics [8] | Statistics and probability theory [10] |

| Time Evolution | Explicitly simulated [2] | Not simulated [2] |

| Primary Output | Trajectory (time-series of coordinates) [9] | Set of uncorrelated configurations [2] |

| Key Controlled Variables | Energy, Volume, Number of atoms (NVE) or Temperature (NVT) or Pressure (NPT) [12] | Temperature, Chemical Potential, Volume (μVT) or others, depending on ensemble [11] |

| Nature of Method | Deterministic [1] | Stochastic (Probabilistic) [1] |

Comparative Performance: Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis

The choice between MD and MC has profound implications for the type of information a researcher can extract. Their performance differs significantly across various types of analysis.

Observable Properties and Performance

MD is unparalleled for calculating properties that are inherently time-dependent. The analysis of the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) of atoms or molecules over time allows for the direct calculation of transport properties like the diffusion coefficient [9]. Similarly, time correlation functions from MD trajectories can be used to determine rates and spectroscopic properties. In material science, MD can simulate the direct application of strain to a system and calculate the resulting stress, enabling the computation of mechanical properties like Young's modulus from a stress-strain curve [9].

MC, by contrast, excels at calculating thermodynamic equilibrium properties and free energies [2]. Because it can efficiently sample phase space without being trapped by energy barriers in the same way as MD (through the use of specialized moves), it is often the method of choice for studying phase transitions, determining solubility parameters, and calculating binding affinities in drug design by estimating the free energy of binding [2].

Table 2: Comparison of Observable Properties and Computational Performance

| Analysis Type | Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Monte Carlo (MC) |

|---|---|---|

| Time-dependent Phenomena | Excellent (e.g., protein folding, diffusion, kinetics) [8] [9] | Not Applicable [2] |

| Thermodynamic Properties | Possible, but may be inefficient for large barriers | Excellent (e.g., free energy, phase equilibrium) [2] |

| Mechanical Properties | Directly calculable (e.g., via stress-strain curves) [9] | Not directly accessible |

| Handling Energy Barriers | Can be inefficient (requires waiting for rare events) | More efficient with specialized moves (e.g., configurational bias) |

| Inherent Parallelizability | Highly parallelizable (e.g., across atoms, spatial domains) [9] | Difficult to parallelize [1] |

| Typical System Constraints | Atoms must be freely movable (off-lattice) [1] | Can simulate both on-lattice and off-lattice models |

Experimental Data and Validation

The validation of both methods often comes from comparing their results with experimental data. For instance, MD simulations have been extensively used to study asphalt materials. In one such study, MD was used to calculate the cohesive energy density of an asphalt model, which was then used to derive the solubility parameter, a key thermodynamic property used to predict compatibility between materials. The simulation result was found to be in close agreement with experimental values, validating the model and the method [12].

In the field of pharmacometrics, a study evaluated the performance of a Monte Carlo Parametric Expectation Maximization (MC-PEM) algorithm, a specific MC-type method used for complex mechanistic models in drug development. The study involved a model with 45 estimated parameters and 14 differential equations. The results demonstrated that the MC-PEM algorithm provided unbiased and precise parameter estimates, with the median estimated-to-true value ratio for model parameters being 1.01 for rich data sampling, demonstrating high accuracy and robustness even with poor initial estimates [13].

Methodological Deep Dive: Protocols and Workflows

A Standard MD Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the typical, iterative workflow of an MD simulation, from initial setup to final analysis.

Detailed MD Protocol:

- Prepare Initial Structure: The simulation begins with a starting atomic configuration, often obtained from experimental sources like the Protein Data Bank (PDB) for biomolecules or crystal structure databases for materials [9]. Missing atoms or regions may need to be modeled.

- System Initialization: Initial velocities are assigned to every atom, typically sampled from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution corresponding to the desired simulation temperature [9].

- Force Calculation: This is the most computationally intensive step. The forces acting on each atom are calculated based on a molecular mechanics force field, which is a mathematical model describing the potential energy of the system as a sum of terms for bonds, angles, dihedrals, and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals and electrostatics) [8] [9].

- Time Integration: The forces are used to numerically integrate Newton's equations of motion. Algorithms like the Verlet or leap-frog algorithm are commonly used due to their stability and good energy conservation properties over long simulations. This step updates the atomic positions and velocities for the next time step (e.g., 1-2 femtoseconds) [9].

- Trajectory Analysis: The raw output of atomic coordinates over time (the trajectory) is analyzed to compute properties of interest, such as radial distribution functions, diffusion coefficients, or root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of a protein structure [9].

A Standard MC Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the workflow of a typical Metropolis-based Monte Carlo simulation, highlighting its stochastic, cycle-based nature.

Detailed MC Protocol:

- Generate Initial Configuration: The simulation starts with an initial molecular configuration.

- Perturb Configuration: A random change is made to the system. This could be the displacement of a randomly chosen atom, a rotation around a chemical bond, or even a more complex move like swapping particles [11].

- Calculate Energy Change: The energy of the new, perturbed configuration (Enew) is calculated and compared to the energy of the previous configuration (Eold). The energy difference, ΔE = Enew - Eold, is computed.

- Metropolis Criterion: This stochastic step determines whether the new configuration is accepted and becomes the current state, or is rejected, in which case the old configuration is recounted.

- If ΔE ≤ 0, the new, lower-energy configuration is always accepted.

- If ΔE > 0, the new, higher-energy configuration is accepted with a probability of exp(-ΔE/kBT), where kB is the Boltzmann constant and T is the temperature [11]. This criterion ensures that the sampling converges to the Boltzmann distribution.

- Sample Configuration: If the move is accepted, the new configuration becomes the current state. Regardless of acceptance or rejection, the current configuration (or its properties) is added to the running averages being computed.

- Iterate: Steps 2-5 are repeated for millions of cycles until the thermodynamic averages of interest (e.g., average energy, pressure) have converged.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of MD and MC simulations requires a suite of software and computational "reagents." The table below details key resources for different stages of the workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Relevance to MD/MC |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS) | Mathematical models that define the potential energy surface and interatomic forces. They include parameters for bonds, angles, and non-bonded interactions. | Critical for both [12] [8] |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD, LAMMPS, AMBER, Desmond) | Specialized software packages that implement the algorithms for MD simulation, including force calculation, integration, and parallelization. | Primarily MD [8] |

| Monte Carlo Software (e.g., Cassandra, Towhee, MC Packages in LAMMPS) | Software designed to perform MC simulations, often with a library of available "moves" for different types of molecules and ensembles. | Primarily MC |

| Structure Visualization (e.g., VMD, PyMol) | Tools to visualize initial structures, analyze simulation trajectories, and render molecular graphics for publication. | Critical for both |

| Trajectory Analysis Tools (e.g., MDTraj, GROMACS tools) | Scripts and software modules for analyzing simulation outputs to compute properties like RMSD, RDF, MSD, and more. | Primarily MD |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) / GPUs | Central Processing Units (CPUs), and especially Graphics Processing Units (GPUs), provide the massive computational power required for simulations of biologically relevant timescales and system sizes. | Critical for both [8] [9] |

Molecular Dynamics and Monte Carlo are complementary, not competing, tools in the computational scientist's arsenal. The decision to use one over the other is not a matter of which is "better," but which is more appropriate for the specific research question.

- Choose Molecular Dynamics when the research goal requires understanding time-dependent behavior, kinetic pathways, or transport properties. MD is the definitive choice for simulating processes like protein folding, ligand binding kinetics, ion diffusion through a channel, or the mechanical response of a material to deformation [9] [2].

- Choose Monte Carlo when the primary interest is in equilibrium thermodynamic properties, such as free energy, phase equilibria, or binding affinity. MC is often more efficient for sampling complex energy landscapes with high barriers and is inherently suited for studying systems at a defined chemical potential [2].

Furthermore, the lines between these methods are increasingly blurred by the development of hybrid techniques. Methods like Replica Exchange MD (REMD) incorporate MC-like temperature swaps between parallel MD simulations to enhance sampling [2]. Similarly, Meta-Dynamics adds a history-dependent bias to MD to push the system away from already-visited states, achieving more efficient exploration akin to MC [2]. The astute researcher will select the core methodology based on their primary objective while leveraging these advanced hybrids to overcome the inherent limitations of any single technique.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC) simulations are foundational techniques in computational chemistry and materials science. While both methods aim to sample the configurations of a system, their underlying principles dictate the specific observables they can efficiently and naturally compute. MD simulations generate a time-evolving trajectory by numerically integrating Newton's equations of motion, making them uniquely suited for calculating time-dependent properties. In contrast, MC simulations generate a sequence of states through stochastic moves designed to sample from a specific statistical ensemble (e.g., NVT, NPT), making them highly efficient for determining equilibrium thermodynamic properties. This guide provides a structured comparison of the performance and applications of these two methods, focusing on the distinct types of observables they are best equipped to handle.

Comparative Analysis of Key Observables

The table below summarizes the core observables accessible through MD and MC simulations, highlighting the inherent strengths of each method.

Table 1: Key Observables Accessible via Molecular Dynamics and Monte Carlo Simulations

| Observable Category | Specific Observable | Primary Method | Performance & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-Dependent/Dynamic Properties | Diffusion Coefficient | MD | Directly calculated from Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) over time [14]. |

| Viscosity | MD | Computed from stress-tensor autocorrelation functions [14]. | |

| Reaction Rates | MD | Derived from time-correlation functions or by measuring transition times between states [14]. | |

| Relaxation Rates (NMR) | MD | Obtained from autocorrelation functions of spin vectors or dipolar interactions [14]. | |

| Thermal Conductivity | MD | Calculated from heat current autocorrelation functions (Green-Kubo relation) [14]. | |

| Equilibrium Thermodynamic Properties | Enthalpy of Vaporization | MC / MD | Both can calculate, but MC often reaches equilibrium faster; can be used for force field training [14]. |

| Radial Distribution Function | MC / MD | Both can compute this structural property; MC can be more efficient for dense systems [14]. | |

| Phase Diagrams | MC | Highly efficient for determining phase coexistence conditions (e.g., via Gibbs Ensemble MC) [15]. | |

| Free Energy Differences | MC | Specialized methods (e.g., Free Energy Perturbation, Umbrella Sampling) are often implemented in MC. | |

| Potential Energy | MC / MD | A fundamental output of both simulations; MC excels at sampling the configurational energy. |

Methodological Protocols and Workflows

The computational workflow for extracting these observables differs significantly between MD and MC, as illustrated in the following diagram.

Protocol for Calculating Time-Dependent Properties with MD

The power of MD for dynamic properties is exemplified by calculating a self-diffusion coefficient, a key observable inaccessible to standard MC.

- System Setup: Construct the atomic system (e.g., 895 water molecules in a periodic box [14]) and assign initial velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution.

- Equilibration: Run an initial MD simulation in the NVT (canonical) or NPT (isothermal-isobaric) ensemble to stabilize temperature and density. Thermostats (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) and barostats are applied here.

- Production Run: Perform a long MD simulation in the NVE (microcanonical) or NVT ensemble, saving atomic coordinates at regular intervals (e.g., every 1-10 fs for water).

- Trajectory Analysis:

- For each atom i, calculate the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) as a function of time: ( \text{MSD}(t) = \langle | \vec{r}i(t) - \vec{r}i(0) |^2 \rangle ), where the angle brackets denote an average over all atoms and time origins.

- The self-diffusion coefficient D is obtained from the Einstein relation: ( D = \frac{1}{6} \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(t) ).

- Validation: The calculated D can be compared directly to experimental measurements, such as pulsed-field gradient NMR data, and used to top-down train force fields via methods like reversible simulation [14].

Protocol for Calculating Thermodynamic Properties with MC

The efficiency of MC for thermodynamics is demonstrated by calculating an enthalpy of vaporization ((\Delta H_{vap})), a critical equilibrium property.

- System Definition: Define the system in a specific ensemble (e.g., NVT for a liquid). No initial velocities are needed.

- Sampling: Use the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm to generate new configurations. A typical move is randomly displacing a single atom. The move is accepted with probability ( P{accept} = \min(1, e^{-\beta \Delta U}) ), where ( \Delta U ) is the change in potential energy and ( \beta = 1/kB T ). This ensures sampling from the Boltzmann distribution.

- Equilibration: Discard an initial number of steps until the potential energy fluctuates around a stable average, indicating equilibrium has been reached.

- Ensemble Averaging:

- The enthalpy of vaporization is calculated using the thermodynamic definition: ( \Delta H{vap} = \langle E{gas} \rangle - \langle E_{liquid} \rangle + RT ), where ( \langle E \rangle ) is the average potential energy per molecule from separate simulations of the gas and liquid phases.

- The Radial Distribution Function (RDF), ( g(r) ), is calculated by averaging the histogram of interatomic distances over the entire MC ensemble [14].

- Application: These averaged properties are central to the parameterization and validation of force fields, as done in tools like ForceBalance [14] and for studying phase equilibria in complex alloys [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key computational "reagents" and software essential for conducting research in this field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Tool Name | Type/Function | Key Application in MD/MC Research |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [16] | MD Simulation Software | High-performance MD package used for simulating biomolecular systems and calculating dynamic trajectories. |

| Rosetta Backrub [16] | Monte Carlo Algorithm | Models backbone flexibility in proteins based on high-resolution crystal structures; used for conformational sampling. |

| ForceBalance [14] | Force Field Optimization Tool | An ensemble reweighting method used to automatically parameterize force fields against experimental data. |

| DeePMD-kit [17] | Machine Learning Interatomic Potential | Framework for building and running ML-based potentials, enabling accurate and large-scale MD simulations. |

| Reversible Simulation [14] | Differentiable Simulation Method | A memory-efficient approach to train force fields (both classical and ML-based) to match experimental data, including dynamic observables. |

| Maximum Entropy Reweighting [18] | Integrative Analysis Protocol | A robust procedure to combine MD simulations with experimental data (e.g., NMR, SAXS) to determine accurate conformational ensembles of biomolecules like IDPs. |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (ML-IAPs) [17] [19] | Advanced Force Fields | Data-driven potentials (e.g., MACE, NequIP) that offer near-ab initio accuracy with the computational efficiency of classical MD, expanding the scope of both MD and MC studies. |

MD and MC are complementary, not competing, techniques. The choice between them is dictated by the scientific question. MD is indispensable for investigating kinetics, transport, and any time-dependent phenomenon, providing a direct window into dynamical processes. MC is the tool of choice for high-efficiency sampling of equilibrium thermodynamics, including free energies and phase behavior. Modern research increasingly leverages their synergies, using MC-generated ensembles as initial states for MD or using ML-potentials trained on ab initio data to enhance the accuracy of both methods. Understanding their distinct strengths, as outlined in this guide, is fundamental for designing robust computational studies in chemistry, materials science, and drug development.

In computational science, Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC) simulations represent two foundational pillars for studying complex molecular systems. While they can sometimes be used to answer similar scientific questions, their underlying mathematical frameworks and operational principles are fundamentally different. MD is fundamentally rooted in the deterministic principles of Hamiltonian and Lagrangian mechanics, tracing physical trajectories through time by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion. In contrast, MC methods, with the Metropolis algorithm at their core, rely on stochastic sampling to generate configurations according to a desired probability distribution, making no attempt to model physical dynamics [20].

This guide provides a comprehensive, objective comparison of these methodologies. It examines their theoretical foundations, computational performance, hardware requirements, and practical implementation to assist researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting the most appropriate technique for their specific research challenges.

The mathematical engines driving MD and MC are distinct, leading to different strengths and application domains.

Molecular Dynamics: Deterministic Dynamics

Molecular Dynamics simulations are governed by classical mechanics:

- Lagrangian Mechanics: The Lagrangian framework, defined as ( L = T - V ) (where ( T ) is kinetic energy and ( V ) is potential energy), is used to derive the equations of motion via the Euler-Lagrange equation. This approach is particularly powerful in handling constraints.

- Hamiltonian Mechanics: The Hamiltonian, ( H = T + V ), represents the total energy of the system. Hamilton's equations describe the evolution of the system's coordinates and momenta in phase space, forming the basis for many integration algorithms, including those that conserve energy.

These frameworks ensure that MD simulations follow a physically-realistic path, providing access to dynamic properties and non-equilibrium processes [20].

Monte Carlo: Stochastic Sampling

The Metropolis-Hastings algorithm, a workhorse of MC simulations, enables sampling from complex probability distributions (like the Boltzmann distribution) without requiring physical dynamics:

- A random move is proposed from the current state to a new state.

- The energy change (( \Delta E )) between the states is computed.

- The move is accepted with a probability ( \min(1, e^{-\Delta E / k_B T}) ).

This stochastic process ensures detailed balance and, for ergodic systems, generates a sequence of states that correctly samples the equilibrium distribution. A key advantage is that the proposed moves need not follow a physically allowed process, which can be exploited to accelerate sampling through techniques like cluster moves or configuration bias [20].

Conceptual Workflows

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental operational difference between the MD and MC workflows.

Performance and Hardware Benchmarking

The computational characteristics of MD and MC differ significantly, influencing hardware choices and cost-effectiveness.

Molecular Dynamics Performance

MD simulations are highly computationally intensive and have been extensively optimized for modern hardware, particularly GPUs. The table below summarizes benchmark data for popular MD software running on different hardware configurations.

Table 1: Benchmark performance of MD software on various hardware (system: T4 Lysozyme, ~44,000 atoms) [21] [22].

| MD Software | Hardware Configuration | Performance (ns/day) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| OpenMM | NVIDIA H200 (GPU) | 555 ns/day | Peak performance, ideal for time-critical projects [22]. |

| OpenMM | NVIDIA L40S (GPU) | 536 ns/day | Best value, excellent cost-efficiency [22]. |

| OpenMM | NVIDIA T4 (GPU) | 103 ns/day | Budget option, slower but low hourly cost [22]. |

| GROMACS | Multi-GPU (e.g., 2x A100) | Varies by system | Good strong scaling for large systems; requires -nb gpu -pme gpu -update gpu flags [21]. |

| AMBER (PMEMD) | Single GPU (e.g., V100) | Varies by system | A single simulation typically does not scale beyond 1 GPU [21]. |

| NAMD 3 | Multi-GPU (e.g., 2x A100) | Varies by system | Good scaling; uses namd3 +p<CPUs> +idlepoll for execution [21]. |

Monte Carlo Performance and Efficiency

MC performance is less about raw speed and more about sampling efficiency, measured by how effectively a Markov chain explores the configuration space and converges to the equilibrium distribution. Advanced algorithms are crucial for tackling complex, high-dimensional problems.

Table 2: Advanced MCMC algorithms for improving sampling efficiency [23] [24].

| Algorithm | Key Mechanism | Advantages | Typical Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive Metropolis (AM) | Recursively updates proposal covariance using the entire sampling history [23]. | Improves global exploration; asymptotic convergence guarantees [23]. | General-purpose Bayesian inverse problems. |

| DREAM (Differential Evolution Adaptive Metropolis) | Uses genetic algorithm-inspired mechanisms and multiple parallel chains [23]. | Efficiently traverses high-dimensional and multimodal posteriors [23]. | Complex hydrogeological inversions, tall panel datasets. |

| CMAM (Covariance Matrix Adaptation Metropolis) | Integrates population-based CMA-ES optimization with Metropolis sampling [23]. | Dynamically adjusts proposal orientation and scale; robust convergence [23]. | High-dimensional, multimodal Bayesian inverse problems. |

| ASIS (Ancillarity-Sufficiency Interweaving Strategy) | Alternates between sufficient (centered) and ancillary (non-centered) parameterizations [24]. | Alleviates correlation between parameters (e.g., random & fixed effects); optimal convergence rate [24]. | Bayesian hierarchical panel data models. |

Hardware and Cost Analysis

Choosing the right hardware is critical for computational efficiency. The following diagram and table outline key considerations and recommendations.

Table 3: Hardware selection guide for MD and large-scale MC simulations [25] [26] [22].

| Component | Recommendation | Rationale & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GPU for MD | NVIDIA RTX 4090 / 5090 or L40S (cost-effective); H200 (peak performance) [25] [22]. | MD codes (GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD) use mixed precision, where consumer GPUs excel. L40S offers the best cost-efficiency, while H200 is fastest [26] [22]. |

| GPU for FP64 Workloads | NVIDIA A100/H100 (Data Center GPUs) [26]. | Some quantum chemistry/MC codes require strong double-precision (FP64) throughput, which is limited on consumer GPUs [26]. |

| CPU | AMD Threadripper PRO or Intel Xeon Scalable Processors [25]. | Prioritize clock speeds over core count for many MD workloads. Dual CPU setups are viable for workloads requiring very high core counts or RAM [25]. |

| RAM | Minimum 4GB per CPU core; scale with system size [21]. | Essential for handling large molecular systems and trajectory data. |

| Cost Metric | €/ns/day for MD; Cost per result for other simulations [26]. | Enables objective comparison between cloud and on-premise hardware. Benchmark a small case first [26] [22]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Reproducibility is paramount. Below are detailed protocols for running benchmarks and ensuring sampling efficiency.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Protocol

A standard MD benchmark protocol for a protein-ligand system in explicit solvent involves the following stages. The specific commands are for GROMACS but are analogous in other packages like AMBER and NAMD [21].

- System Preparation: Obtain a protein structure from the PDB (e.g., 4W52). Use a tool like

pdb2gmxto generate topology and assign a force field. Solvate the protein in a water box (e.g., TIP3P) and add ions to neutralize the system's charge. Energy Minimization: Run a steepest descent algorithm to remove steric clashes.

Equilibration:

- NVT Ensemble: Equilibrate the system at a constant temperature (e.g., 300 K) for 100 ps, restraining heavy atom positions.

- NPT Ensemble: Equilibrate at constant pressure (1 bar) for 100 ps, with restraints on heavy atoms.

Production Run: Run an unrestrained simulation. The following example shows a GPU-accelerated GROMACS run. The number of steps (e.g.,

-nsteps 50000) defines the simulation length.Performance Analysis: The key output is the simulation throughput in nanoseconds per day (ns/day). This is calculated by the software and reported in the log file.

Monte Carlo Sampling Efficiency Protocol

Assessing the quality of an MCMC simulation is different from MD. The focus is on convergence and sampling quality.

- Algorithm Selection: Choose a sampler appropriate for the problem (e.g., Adaptive Metropolis for simple problems; DREAM or CMAM for high-dimensional/multimodal posteriors) [23].

- Chain Initialization: Run multiple (e.g., 4-8) chains from dispersed starting points to diagnose convergence.

- Convergence Diagnostics: Monitor the Gelman-Rubin statistic ((\hat{R})), which compares within-chain and between-chain variance. (\hat{R} \leq 1.05) for all parameters indicates convergence.

- Efficiency Metrics:

- Effective Sample Size (ESS): Calculate the ESS for each parameter, which estimates the number of independent samples. Higher is better.

- Integrated Autocorrelation Time: Measures the number of steps needed to get an independent sample. Lower is better.

- Reproducibility: For both MD and MC, always record a "run card": a text file with the exact input parameters, software versions, CPU/GPU models, and seed values for stochastic elements [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section details essential software and hardware resources for conducting MD and MC research.

Table 4: Key research tools and resources for MD and MC simulations.

| Tool / Resource | Function / Purpose | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Engines | Software to perform the numerical integration of equations of motion. | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, LAMMPS, OpenMM [21] [22]. |

| MC Simulation Software | Software for stochastic sampling and risk analysis. | Stand-alone: Analytica, GoldSim. Excel add-ins: @RISK, Analytic Solver, ModelRisk [27]. |

| Force Fields | Mathematical models describing interatomic potentials. | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS. Define the "rules" of interaction for MD. |

| System Preparation Tools | Prepare molecular structures for simulation. | PDB2GMX (GROMACS), tleap (AMBER), CHARMM-GUI. |

| Visualization & Analysis | Analyze trajectories and simulation outputs. | VMD, Chimera, MDAnalysis, GROMACS analysis tools. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Hardware for running simulations in a reasonable time. | GPUs: NVIDIA A100, H100, RTX 4090, L40S. CPUs: AMD Threadripper, Intel Xeon [25] [22]. |

| Optimization & Sampling Enhancers | Advanced algorithms to improve convergence and efficiency. | For MC: Adaptive MCMC, DREAM, CMAM, ASIS [23] [24]. For MD: Hydrogen mass repartitioning (enables 4 fs timesteps) [21]. |

Molecular Dynamics and Monte Carlo methods are powerful yet distinct computational frameworks. The choice between them should be guided by the specific scientific question.

- Choose Molecular Dynamics when investigating time-dependent phenomena, dynamic processes, transport properties, or non-equilibrium systems. Its foundation in Hamiltonian/Lagrangian mechanics provides a physically intuitive path for studying how systems evolve.

- Choose Monte Carlo methods when the primary goal is efficient equilibrium sampling, computing thermodynamic averages, or navigating complex, high-dimensional landscapes. The Metropolis algorithm and its modern adaptive extensions excel at generating statistically rigorous ensembles without the overhead of simulating dynamics.

Modern research often leverages the strengths of both methods, and the ongoing development of more efficient algorithms and powerful, cost-effective hardware like the NVIDIA L40S GPU continues to push the boundaries of what is possible in computational molecular science.

Practical Implementation and Key Applications in Biomolecular Simulation and Drug Design

Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC) simulations are foundational techniques for studying molecular behavior and interactions. The core distinction lies in their fundamental approach: MD is a deterministic method that tracks the time evolution of a system by solving equations of motion, providing detailed insights into dynamic processes like protein folding or chemical reactions. In contrast, MC is a probabilistic method that explores the state space of a system through random sampling, making it ideal for calculating thermodynamic equilibrium properties such as free energy and phase transitions [1] [2]. This guide provides a detailed, step-by-step comparison of their operational procedures, supported by experimental data and protocols.

Core Algorithmic Walkthroughs

A Typical Molecular Dynamics Time-Step

Molecular Dynamics simulations numerically simulate the motion of atoms and molecules over time. The following workflow outlines the sequential steps executed for every time-step in an MD simulation, typically on the order of femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ seconds).

Step 1: Force Calculation The simulation calculates the net force Fᵢ acting on each atom i in the system. This is typically derived from a force field, which is a mathematical model of the interatomic potential energy U(rᴺ). The force is the negative gradient of this potential: Fᵢ = -∇ᵢU. This calculation is often the most computationally intensive part of the time-step, as it involves evaluating all non-bonded interactions (e.g., Lennard-Jones and Coulombic potentials) [21]. For large systems, techniques like Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) are used to handle long-range electrostatic interactions efficiently [22].

Step 2: Integration of Equations of Motion Using the calculated forces, the simulation integrates Newton's equations of motion, Fᵢ = mᵢaᵢ, to update the atomic velocities and positions. Common integration algorithms include the Verlet and Leap-frog methods. This step determines the new state of the system a short time (the time-step, Δt) later. The choice of Δt is critical for stability and is often limited to 1-2 femtoseconds, though can be extended to 4 fs with techniques like hydrogen mass repartitioning [21].

Step 3: Update Positions and Velocities The integrator yields new atomic positions and velocities. In modern MD software, this "update and constraints" step can be offloaded to a GPU for better performance, especially when the GPU is fast relative to the CPU [28]. Constraints, often applied to bonds involving hydrogen atoms, are enforced using algorithms like LINCS or SHAKE to allow for a larger time-step.

Step 4: Data Output Finally, relevant data for the current time-step—such as atomic coordinates (trajectory), energies, and temperatures—are written to output files. To avoid I/O becoming a significant bottleneck, trajectory frames are saved at intervals (e.g., every 1,000-10,000 steps) rather than at every step [22].

A Typical Monte Carlo Move

Monte Carlo simulations generate a sequence of system configurations (or "microstates") through random moves, with the goal of sampling from a desired statistical ensemble, such as the canonical (NVT) ensemble. The following workflow outlines the procedure for a single Monte Carlo "move."

Step 1: System Perturbation A trial move is generated by randomly perturbing the current configuration of the system. In a simulation of molecules in a box, a common move is to randomly select a single particle and displace it by a small, random vector. The size of this displacement is a tunable parameter that can affect the simulation's efficiency [2].

Step 2: Energy Change Calculation The energy of the new, trial configuration, E{new}, is calculated and compared to the energy of the previous configuration, *E*{old}. The core output of this step is the energy difference, ΔE = E{new} - *E*{old}. Unlike in MD, there is no calculation of forces.

Step 3: Acceptance Decision The trial move is not automatically accepted. The decision is made based on the Metropolis criterion:

- If ΔE ≤ 0, the move is always accepted because it lowers the system's energy.

- If ΔE > 0, the move is accepted with a probability P{accept} = exp(-Δ*E* / kB T), where k_B is Boltzmann's constant and T is the temperature [1] [2]. This probabilistic acceptance is the hallmark of the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm.

Step 4: Update or Revert If the move is accepted, the new configuration becomes the current state of the system. If the move is rejected, the system reverts to its previous configuration. In either case, the configuration (even if it's a repeat of the old one) is added to the sampling chain used for calculating thermodynamic averages.

Key Differences at a Glance

Table 1: Fundamental differences between Molecular Dynamics and Monte Carlo simulation methods.

| Feature | Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Monte Carlo (MC) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Deterministic; follows classical mechanics [1] | Probabilistic; based on random sampling and statistics [1] [2] |

| Time Evolution | Explicitly simulates real-time dynamics [2] | Does not simulate physical time; focuses on equilibrium states [2] |

| Core Calculation | Force calculation and integration of Newton's laws [2] | Energy difference calculation and Metropolis acceptance rule [2] |

| Primary Output | Trajectories (time-series data) [2] | Sequence of uncorrelated configurations for statistical averages [2] |

| Handling of Kinetics | Suitable for studying rates and dynamic pathways [2] | Generally not suitable for kinetic studies [2] |

| Conserved Properties | Conserves total energy (in NVE ensemble); temperature is controlled via thermostats | Natural sampling at constant temperature (NVT ensemble) |

| Parallelization | Easier to parallelize, especially with GPUs [1] [22] | Challenging to parallelize due to sequential acceptance/rejection [1] [29] |

Experimental Protocols & Performance Benchmarks

Example MD Protocol: T4 Lysozyme in Explicit Solvent

To illustrate a real-world MD setup, we summarize a benchmark protocol used for GPU performance testing [22].

- System: T4 Lysozyme (PDB: 4W52) solvated in explicit water.

- Total Atoms: ~43,861 atoms.

- Software: OpenMM via the UnoMD Python package [22].

- Parameters:

- Integration Time-step: 2 fs.

- Electrostatics: Particle Mesh Ewald (PME).

- Simulation Length: 100 ps for benchmark purposes.

- Precision: Mixed precision on GPU.

- Trajectory Saving: Every 1,000-10,000 steps to optimize I/O performance [22].

Performance and Cost-Efficiency Data

The following table compiles performance metrics from a cloud-based GPU benchmarking study for the MD protocol described above [22]. The data highlights that raw speed does not always equate to cost-effectiveness.

Table 2: GPU performance and cost-efficiency benchmarks for MD simulations (adapted from [22]). Performance is for a ~44,000 atom system simulated using OpenMM. Costs are normalized to the AWS T4 baseline.

| GPU Provider | GPU Model | Speed (ns/day) | Normalized Cost per 100 ns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nebius | H200 | 555 | 0.87 (13% reduction) |

| Nebius | L40S | 536 | 0.40 (60% reduction) |

| AWS | T4 | 103 | 1.00 (baseline) |

| AWS | V100 | 237 | 1.33 (33% increase) |

| Hyperstack | A100 | 250 | 0.90 (10% reduction) |

| Scaleway | H100 | 450 | 0.85 (15% reduction) |

The data shows that the L40S GPU offers the best value, providing near-top speed at the lowest cost, while high-end GPUs like the H200 are optimal for time-critical or AI-hybrid workflows [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 3: Key software and computational resources for molecular simulation.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [21] | MD Software | A high-performance MD package optimized for both CPUs and GPUs, widely used for biomolecular systems. |

| OpenMM [22] | MD Software & Library | An open-source library for MD simulation with a focus on GPU acceleration and flexibility. |

| AMBER [21] | MD Software | A suite of programs for MD simulations of biomolecules, particularly proteins and nucleic acids. |

| LAMMPS | MD Software | A versatile MD simulator popular in materials science. |

| Meta's eSEN/UMA [30] | Neural Network Potential (NNP) | Pre-trained models that provide quantum-mechanical accuracy at a fraction of the cost, usable in MD. |

| CUDA Platform | Computing Platform | API for NVIDIA GPUs, essential for running accelerated MD and MC simulations. |

| NeBius / Scaleway L40S [22] | Cloud GPU | A cost-effective cloud GPU instance identified as highly efficient for traditional MD workloads. |

Molecular Dynamics and Monte Carlo are complementary tools in computational science. The choice between them should be dictated by the scientific question at hand.

Use Molecular Dynamics when your research requires an understanding of time-dependent phenomena, such as protein folding pathways, drug binding kinetics, transport properties, or any process where the dynamic trajectory of the system is of intrinsic interest [2]. Its deterministic nature provides a direct link to real-time dynamics.

Use Monte Carlo when the goal is to efficiently compute thermodynamic equilibrium properties, such as free energies, phase diagrams, binding constants, or average structural properties [2]. Its ability to perform large, random jumps in configuration space makes it exceptionally efficient for sampling equilibrium states, unconstrained by the time-step limitations of MD.

For complex problems, hybrid approaches like Replica Exchange MD (REMD) combine the strengths of both methods, using MD for time evolution and MC-based exchange between replicas to enhance sampling and more accurately determine thermodynamic properties [2].

Molecular simulations are a cornerstone of modern computational chemistry and materials science, enabling researchers to study the properties, structure, and function of molecular systems. The two primary particle-based simulation techniques are Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC). A fundamental aspect of setting up these simulations is the choice of the statistical mechanical ensemble, which defines the macroscopic conditions under which the system is studied. The most common ensembles are the microcanonical (NVE), canonical (NVT), and isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensembles. This guide provides a detailed comparison of sampling in these ensembles using both MD and MC methods, framing the discussion within the context of a broader thesis comparing these two foundational simulation approaches. It is designed to help researchers, particularly those in drug development, make informed choices based on their specific scientific questions.

Theoretical Foundations of Sampling Ensembles

Molecular Dynamics and Monte Carlo are the principal workhorses of atomistic simulation, but they operate on fundamentally different principles for generating system configurations.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD): MD relies on numerically integrating Newton's equations of motion to generate a time-evolving trajectory of the system [31]. The forces on each particle are calculated from the potential energy function, and integration algorithms propagate the positions and velocities forward in time. This approach naturally allows MD to simulate real dynamical processes and calculate both thermodynamic and transport properties [31].

- Monte Carlo (MC): In contrast, MC methods use probabilistic rules to generate new system configurations from the current state [31]. A key feature is that MC simulations lack any concept of time [31]. Instead, they construct a random walk through configuration space that, when done correctly (e.g., using the Metropolis algorithm), samples from a desired statistical ensemble. Consequently, MC can calculate structural and thermodynamic properties but not time-dependent dynamic properties.

The core difference lies in their sampling philosophy: MD provides a deterministic dynamical trajectory, while MC generates a stochastic sequence of states representative of the ensemble.

Definition and Purpose of Statistical Ensembles

An ensemble is a collection of all possible system microstates under specific macroscopic constraints. The choice of ensemble is critical because it determines which thermodynamic free energy is naturally sampled.

- Microcanonical (NVE) Ensemble: This ensemble describes an isolated system where the Number of particles (N), the Volume (V), and the total Energy (E) are conserved [32] [33]. It is the most natural ensemble for basic MD, as it directly results from integrating Newton's laws without modification. In the thermodynamic limit, it yields the entropy, S(E,V,N).

- Canonical (NVT) Ensemble: This ensemble describes a system in contact with a heat bath at a fixed Temperature (T) [33]. The system can exchange energy with the bath, so its total energy fluctuates while the average temperature remains constant. The probability of a microstate follows the Boltzmann distribution [33]. This ensemble is used to sample the Helmholtz free energy, A(N,V,T).

- Isothermal-Isobaric (NPT) Ensemble: This ensemble describes a system in contact with both a heat bath and a pressure bath, maintaining constant Temperature (T) and Pressure (P) [33]. This allows both energy and volume to fluctuate and is often considered the most realistic for comparing with laboratory experiments conducted at constant temperature and atmospheric pressure [32] [33]. It naturally samples the Gibbs free energy, G(N,P,T).

Comparative Analysis of Ensembles and Methods

The following table provides a direct comparison of the three primary ensembles, highlighting their implementation in MD versus MC.

Table 1: Comparison of NVE, NVT, and NPT Ensembles in MD and MC Simulations

| Ensemble (Constant) | Molecular Dynamics (MD) Approach | Monte Carlo (MC) Approach | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVE (Microcanonical) | Native; direct integration of Newton's equations [34]. Energy conservation is a key metric [34]. | Not commonly used as a primary ensemble in standard MC. | Studying isolated systems; fundamental equation testing; production runs after equilibration for accurate dynamics [33]. |

| NVT (Canonical) | Requires a thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) to couple the system to a heat bath [34]. | Native; the Metropolis acceptance criterion naturally samples the Boltzmann distribution [35]. | Simulating systems at constant volume and temperature; studying properties where volume is fixed by the environment [32] [33]. |

| NPT (Isothermal-Isobaric) | Requires both a thermostat and a barostat to control pressure, allowing cell volume to fluctuate [34]. | Requires a barostat; involves volume move attempts in addition to particle moves. | Simulating realistic laboratory conditions (constant T, P) [32] [33]; material properties under pressure; binding free energies in solution. |

Key Differences and Practical Considerations

- Equivalence and Choice: In the thermodynamic limit (infinite particles), ensembles are equivalent and should yield the same equilibrium properties [32]. However, for finite systems typical in simulations, the choice matters. The best practice is to choose the ensemble that matches the experimental conditions or the thermodynamic potential you wish to calculate [32]. For example, liquid-phase reactions are often best modeled in the NPT ensemble [32].

- Ease of Implementation:

- For MD, the historical and computational complexity increases from NVE (simplest) to NVT to NPT (most complex) [33]. Implementing a barostat for NPT is "numerically annoying" as it requires equations of motion for the simulation box boundaries [33].

- For MC, NVT is the most straightforward ensemble to implement. The NPT ensemble is also readily accessible but requires an additional type of Monte Carlo move to change the volume [35].

- A Common Workflow: A frequent practice in MD simulations is to use the NPT ensemble for equilibration to find the correct density of a system at a target temperature and pressure (e.g., 1 atm). This is followed by a production run in the NVT ensemble with the fixed, equilibrated box size for analysis [33]. This avoids dealing with fluctuating box sizes during production, which can complicate the analysis of certain properties.

Table 2: Suitability of Ensembles for Different Research Goals

| Research Goal | Recommended Ensemble(s) | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Calculate Dynamic Properties | NVE (with MD) | NVE-MD provides the most realistic dynamics, as thermostats/barostats can introduce artificial perturbation to trajectories [33]. |

| Compare with Lab Experiments at Fixed P | NPT | Most bench experiments are at constant pressure and temperature, making NPT the most direct comparison [32]. |

| Calculate Thermodynamic Properties | NVT or NPT | NVT gives the Helmholtz free energy; NPT gives the Gibbs free energy. Choose based on the process being modeled [32]. |

| Simulate a Gas-Phase Reaction | NVE | In the absence of a solvent or buffer gas, the system is effectively isolated [32]. |

| Study Adsorption/Deformation | Hybrid MC/MD or NPT-MD | Coupling adsorption (MC) with structural relaxation (MD) or using NPT allows observation of pressure-induced deformation [36]. |

Essential Research Toolkit

This table outlines the key "reagent solutions" or components required to set up and run simulations in the different ensembles.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Ensemble Simulations

| Item | Function | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field | Defines the potential energy function, including bonded and non-bonded interactions [31]. | AMBER, CHARMM, GAFF, Tersoff (for solids). Parameters (masses, charges, LJ ε/σ) are specified in the FIELD file [35]. |

| Initial Configuration | The starting 3D atomic coordinates and simulation box definition [31]. | Specified in the CONFIG file, including cell vectors and particle positions in fractional or Cartesian coordinates [35]. |

| Simulation Control Engine | The software that performs the numerical integration (MD) or stochastic sampling (MC). | GROMACS, AMBER, LAMMPS, DESMOND, CHARMM, DL_MONTE, QuantumATK [37] [34]. |

| Thermostat | Algorithm to maintain constant temperature in NVT/NPT MD. | Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen, Langevin. Not needed for MC-NVT, which uses the Metropolis criterion [34]. |

| Barostat | Algorithm to maintain constant pressure in NPT MD or MC. | Berendser, Parrinello-Rahman, Martyna-Tobias-Klein (for MD) [34]. Volume moves (for MC) [35]. |

| Neighbor List | Optimizes non-bonded force calculations by tracking nearby particles. | Critical for performance in both MD and MC; can be set to "auto" update [35]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

General Workflow for Molecular Simulations

The diagram below illustrates a generalized protocol for setting up and running molecular simulations, applicable to both MD and MC in various ensembles.

Diagram 1: Generalized simulation workflow

Protocol for NVT Ensemble Simulation with MC

The following is a detailed methodology for running an NVT simulation of a Lennard-Jones fluid using the DL_MONTE software, as derived from a tutorial example [35].

Input File Preparation:

- FIELD File: This file defines the molecular system.

- Specify the number of atom types (e.g.,

ATOM TYPES 1). - Define atom properties (e.g.,

LJ core 1.0 0.0for mass=1.0, charge=0.0). - Define molecular types and the maximum number of atoms per molecule type.

- Specify interatomic potentials (e.g.,

VDW 1for one van der Waals potential, with parametersLJ core LJ core lj 1.0 1.0for ε=1.0, σ=1.0). - Set the interaction cutoff (e.g.,

CUTOFF 2.5).

- Specify the number of atom types (e.g.,

- CONFIG File: This file provides the initial atomic configuration.

- Define the simulation cell type and vectors (e.g., a cubic cell with side 11.7452 Å).

- Provide the number of molecules and the initial fractional or Cartesian coordinates for all atoms.

- CONTROL File: This file directs the simulation execution.

- Set the ensemble conditions (e.g.,

temperature 1.428). - Define the simulation length (e.g.,

steps 10000). - Specify the move type (e.g.,

move atom 1 100for particle displacement moves). - Set sampling and output frequencies (e.g.,

print 1000).

- Set the ensemble conditions (e.g.,

- FIELD File: This file defines the molecular system.

Simulation Execution:

- The MC engine (e.g., DLMONTE) performs the Metropolis algorithm:

- Step 1: A particle is selected at random, and its current energy (U(\mathbf{r}1)) is calculated.

- Step 2: The particle is given a random displacement within a cube of side length (\Delta{max}), and its new energy (U(\mathbf{r}2)) is calculated.

- Step 3: The move is accepted with probability (P{\mathrm{acc}} = \min(1, \exp {-\beta [U(\mathbf{r}2) - U(\mathbf{r}1)] } )), where (\beta = 1/kB T) [35].

- The MC engine (e.g., DLMONTE) performs the Metropolis algorithm:

Data Analysis:

- Properties like potential energy, pressure, and radial distribution functions are averaged over the accepted configurations generated after the equilibration period.

Protocol for Multi-Ensemble Workflow with MD

A robust MD protocol often involves sequentially using different ensembles for equilibration and production, as demonstrated in QuantumATK tutorials [34].

System Preparation:

- Build or import the initial atomic structure (e.g., a bulk crystal or a solvated protein).

- Assign a force field calculator (e.g., Tersoff for solids, AMBER for biomolecules).

NPT Equilibration:

- Goal: Relax the system density to the target temperature and pressure.

- Method: Use an NPT integrator like "NPT Martyna Tobias Klein."

- Parameters: Set reservoir temperature (e.g., 300 K) and pressure (e.g., 1 bar). Use an isotropic barostat to allow the cell to change shape uniformly [34].

- Analysis: Monitor the volume fluctuation until it oscillates around a stable average. The final volume from this run provides the correct box size for the experimental conditions.

NVT Production Run:

- Goal: Perform the main simulation with fixed, equilibrated volume for analysis.

- Method: Use an NVT integrator like "Nose-Hoover" with the temperature set to 300 K.

- Parameters: Use the final configuration and box size from the NPT run.

- Analysis: The trajectory from this run is used to compute ensemble averages for structural and thermodynamic properties. The temperature should fluctuate around the set value.

Diagram 2: Comparison of MD and MC simulation pathways

The choice between NVE, NVT, and NPT ensembles, and between MD and MC methods, is not a matter of one being universally superior. Instead, it is a strategic decision based on the research objective. MD is indispensable for studying kinetics and dynamical processes, while MC offers a highly efficient and native path for sampling thermodynamic equilibrium states, particularly in the NVT ensemble. The NPT ensemble is often the most experimentally relevant for condensed matter and biological systems. A deep understanding of the principles outlined in this guide—supported by robust experimental protocols and a well-stocked computational toolkit—enables researchers to design simulations that yield reliable, reproducible, and meaningful data, thereby accelerating scientific discovery and molecular design.

Computational methods for predicting the binding affinity of small molecules to biological targets have become indispensable tools in modern drug discovery. Among the most rigorous approaches are alchemical free energy calculations, which provide a physics-based route to estimating binding free energies through statistical mechanics. These methods are primarily implemented using Molecular Dynamics (MD) or, to a lesser extent, Monte Carlo (MC) simulations, and they can be broadly categorized into calculations for Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) and Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE). This guide provides an objective comparison of these methods, their performance, and their implementation, contextualized within the broader thesis of comparing MD and MC simulation approaches.

Theoretical Foundations: Alchemical Free Energy Methods

Alchemical free energy calculations compute free energy differences by simulating non-physical (alchemical) pathways that connect physical states of interest. Because free energy is a state function, the result is independent of the path taken [38].

Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE): ABFE calculations predict the binding affinity of a single ligand for its target. This is typically achieved using the double decoupling method, where the ligand is alchemically annihilated in the binding site and then in solution [38]. The absolute binding free energy (ΔGb) is related to the experimental binding affinity (Ka) by the equation: ΔGb° = -RT ln(KaC°) where R is the gas constant, T is the temperature, and C° is the standard-state concentration (1 mol/L) [38].