Molecular Dynamics Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide to Best Practices from Setup to AI Integration

This article provides a comprehensive guide to best practices in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide to Best Practices from Setup to AI Integration

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to best practices in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of MD, including force field selection and simulation setup. The guide then delves into advanced methodological approaches, troubleshooting common challenges like insufficient sampling, and techniques for validating and optimizing simulations for high-performance computing environments. Special emphasis is placed on the transformative role of machine learning and artificial intelligence in enhancing the accuracy, efficiency, and scalability of modern MD workflows, offering a complete roadmap for conducting robust and reliable simulations.

Understanding Molecular Dynamics: Core Principles and Pre-Simulation Planning

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are a cornerstone of computational research in chemistry, biology, and materials science. The choice between quantum mechanical and classical force field methods is fundamental, as it directly determines the accuracy, computational cost, and scope of your scientific inquiries. This guide provides a structured comparison, practical protocols, and troubleshooting advice to help researchers select and implement the most appropriate simulation methodology for their specific projects.

Method Comparison: Key Characteristics

The table below summarizes the core attributes of major simulation approaches to help you make an informed initial selection.

| Method | Accuracy | Computational Cost | System Size | Time Scale | Key Capabilities | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Force Fields | Low to Moderate [1] [2] | Low [3] | ~1,000,000 atoms [2] | Nanoseconds to Microseconds [3] | Simulating large biomolecules (proteins, DNA); efficient dynamics [4] [5] | Cannot simulate bond breaking/forming; accuracy limited by empirical parameters [1] [2] |

| Ab Initio MD (AIMD) | High (DFT level) [1] [3] | Very High [1] [3] | Hundreds of atoms [3] | Picoseconds [3] | Modeling chemical reactions; electronic property analysis [3] [4] | System size and time scale restrictions due to high computational expense [1] [3] |

| Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFF) | High (near-DFT or CCSD(T)) [1] [2] | Moderate (10-100x slower than classical) [3] | ~1,000,000 atoms [2] | Nanoseconds [2] | "Reactive MD"; bond formation/breaking; high accuracy for large systems [3] [2] | Training data quality dependency; initial dataset generation can be costly [1] [3] |

| Hybrid Quantum/Classical | Varies with method and fragment size [6] | High (leverages quantum hardware) [6] | Molecular fragments (27-32 qubits demonstrated) [6] | N/A (energy calculations) | Exploring quantum algorithms; simulating strongly correlated electrons [6] | Extreme hardware requirements; noise and error mitigation challenges; currently limited to small fragments [6] |

Method Selection Guide

The following decision flowchart provides a visual guide for selecting the most suitable simulation method based on your research goals and constraints.

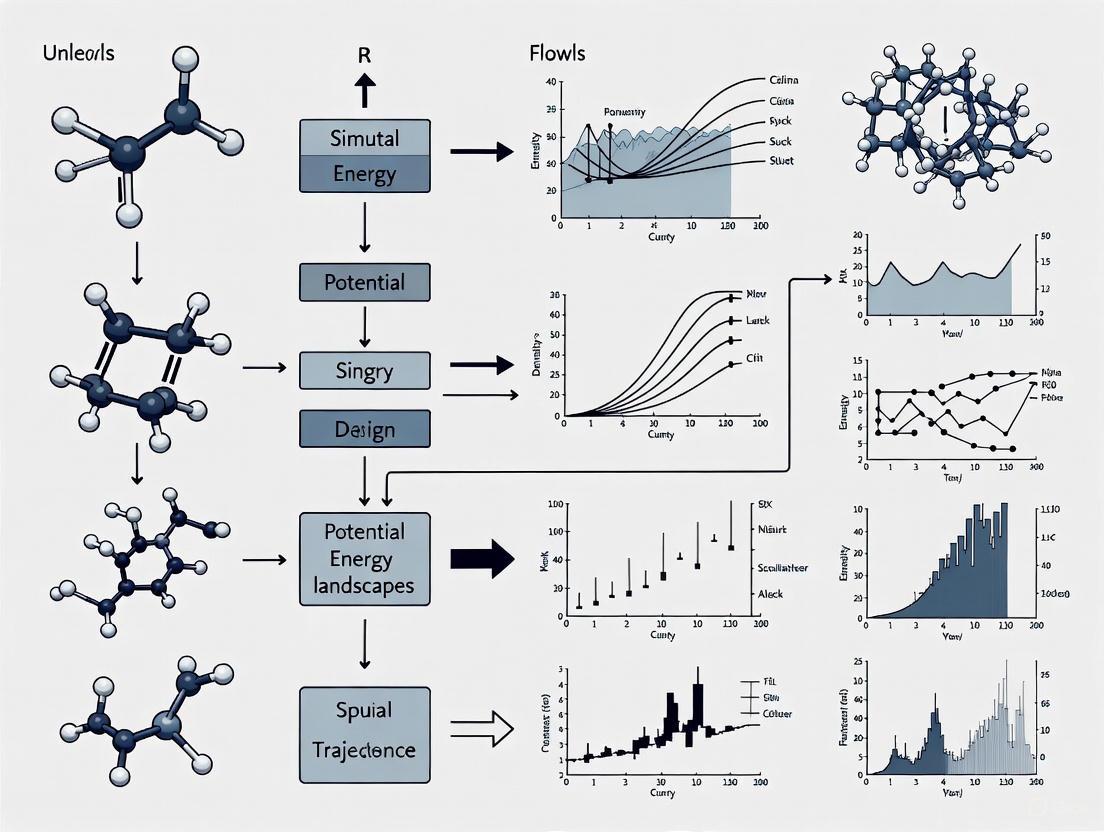

Machine Learning Force Field Development

For researchers developing their own MLFFs, the workflow involves several key stages from data generation to model deployment, as illustrated below.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Foundation ML Force Field

This protocol outlines the steps for creating a general-purpose, quantum-accurate machine learning force field for biomolecular systems, based on the FeNNix-Bio1 model [2].

Dataset Generation (Jacob's Ladder Strategy)

- Perform Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations on a diverse set of molecular structures (water, ions, amino acids, small peptides) to generate a broad baseline dataset.

- Select a subset of configurations for higher-accuracy calculations using Quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) and multi-determinant Configuration Interaction (CI) methods. This provides near-exact reference data.

- Use exascale high-performance computing (HPC) resources to manage the computational load, particularly for the demanding QMC force calculations.

Model Training with Transfer Learning

- Train a neural network (e.g., symmetrized Gradient-Domain Machine Learning, sGDML) initially on the large DFT dataset to learn the general landscape of molecular interactions [1] [2].

- Refine the model using transfer learning on the smaller, high-accuracy QMC/CI dataset. The model learns the "delta" or correction between DFT and the higher-level theory, effectively propagating quantum accuracy throughout its predictions [2].

Validation and Deployment

- Validate the final model on unseen molecular systems and benchmark against experimental data (e.g., hydration free energies, protein-ligand binding affinities).

- Integrate the validated force field into an MD engine to run stable, nanosecond-scale simulations of large biomolecular systems (up to ~1 million atoms).

Protocol 2: Running a Hybrid Quantum-Classical Simulation

This protocol describes how to set up a DMET-SQD (Density Matrix Embedding Theory with Sample-Based Quantum Diagonalization) simulation for a molecular fragment on current quantum hardware [6].

System Fragmentation

- Using a classical computer, define the target molecule and partition it into a smaller, chemically relevant fragment and an external environment.

- Perform a mean-field calculation (e.g., Hartree-Fock) for the entire molecule to define the embedding potential for the fragment.

Quantum Subsystem Simulation

- Map the electronic structure problem of the fragment onto a quantum circuit compatible with the available qubits (e.g., 27-32 qubits).

- Execute the SQD algorithm on the quantum processor. This involves sampling quantum circuits and projecting results into a subspace to solve the Schrödinger equation for the fragment.

- Apply error mitigation techniques (e.g., gate twirling, dynamical decoupling) to counteract noise in the quantum device.

Classical Post-Processing and Iteration

- The quantum processor returns the fragment's reduced density matrix to the classical computer.

- The classical algorithm updates the embedding potential and checks for self-consistency between the fragment and the environment.

- Iterate until convergence is reached, yielding the total energy and electronic properties of the full molecule.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I consider using a machine learning force field over a traditional classical force field? Consider an MLFF when you need near-quantum accuracy for systems or processes that are too large for direct AIMD, such as simulating chemical reactions in enzymes, modeling complex solvation environments with high fidelity, or calculating precise thermodynamic properties without the parametric errors of classical force fields [3] [2]. MLFFs are particularly valuable when you have resources to generate a robust training dataset for your system of interest.

Q2: My classical MD simulation of an ionic liquid shows inaccurate transport properties. What are my options? This is a known limitation of fixed-charge classical force fields, which often fail to fully capture polarization effects [3]. Your options are:

- Switch to a polarizable force field, though this increases computational cost [3].

- Use a neural network force field like NeuralIL, which is trained on DFT data and can accurately capture the structure and dynamics of ionic liquids without explicitly parameterizing polarization [3].

- Employ AIMD for validation and generating short reference trajectories, though this is not feasible for calculating properties requiring long timescales [3].

Q3: Can I use MD to refine a predicted RNA structure, and what are the pitfalls? Yes, short MD simulations (10-50 ns) can modestly improve high-quality starting RNA models by stabilizing stacking and non-canonical base pairs [5]. However, a key pitfall is that poorly predicted initial models rarely benefit and often deteriorate further during simulation. Longer simulations (>50 ns) frequently induce structural drift and reduce model quality. Use MD for fine-tuning reliable models, not as a universal corrective tool [5].

Q4: What is the practical value of hybrid quantum-classical simulations today? Current hybrid methods, like DMET-SQD, demonstrate that even noisy quantum processors can achieve chemical accuracy (within 1 kcal/mol) for specific molecular fragments and conformer problems [6]. Their primary practical value is for algorithm development and for validating the potential of quantum computing in chemistry. They are not yet a replacement for classical simulations for most practical drug discovery applications, but they represent a critical step toward that future [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Application/Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| sGDML | Software / ML Model | Constructs accurate force fields from high-level ab initio calculations [1]. | Reproduces global force fields at CCSD(T) level accuracy; incorporates physical symmetries [1]. |

| NeuralIL | Software / ML Force Field | Neural network potential for simulating complex charged fluids like ionic liquids [3]. | Corrects pathological deficiencies of classical FFs for ILs; handles weak hydrogen bonds and proton transfer [3]. |

| ReaxFF | Reactive Force Field | Simulates bond breaking and formation during chemical processes [4]. | Models chemical reactions in materials science applications (e.g., CMP) [4]. |

| AMBER (with χOL3) | Classical Force Field / MD Suite | Simulation and refinement of biomolecules, particularly nucleic acids and proteins [5]. | RNA-specific parameterization for structure refinement and stability testing [5]. |

| FeNNix-Bio1 | Foundation ML Model | A general-purpose, quantum-accurate force field for biomolecular systems [2]. | Unified framework for reactive MD, proton transfer, and large-scale (million-atom) simulations [2]. |

| DMET-SQD | Hybrid Quantum-Classical Algorithm | Fragments molecules to solve the electronic structure on a quantum processor [6]. | Enables simulation of molecular fragments on current quantum hardware (27-32 qubits) [6]. |

What is a force field and what is its role in molecular dynamics simulations?

A force field is a computational model consisting of mathematical functions and parameters that describe the potential energy of a system of atoms based on their relative positions [7] [8]. It defines the interaction potentials between atoms within molecules or between different molecules, serving as the physical foundation for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations [9] [8]. The force field's primary role is to calculate the forces acting on every particle, derived as the gradient of the potential energy with respect to particle coordinates [8]. This enables the simulation of atomic motion over time, providing insights into molecular structure, dynamics, and function [7].

What are the core components of a standard force field?

The total potential energy in a typical additive force field is composed of bonded and non-bonded interaction terms [7] [8] [10]. The general form can be summarized as: E~total~ = E~bonded~ + E~non-bonded~ [8]

Where the bonded term includes:

- Bond stretching: Energy from covalent bond extension/contraction, typically modeled with a harmonic potential: E~bond~ = k~ij~/2(l~ij~ - l~0,ij~)^2^ [7] [8]

- Angle bending: Energy when bond angles deviate from equilibrium, also using a harmonic potential [7]

- Torsional potential: Energy changes from rotation around chemical bonds, affecting molecular conformation [7]

The non-bonded term includes:

- Van der Waals interactions: Modeled with a Lennard-Jones potential: E~vdW~ = ε~ij~[(R~min,ij~/r~ij~)^12^ - 2(R~min,ij~/r~~ij~)^6^] [7] [10]

- Electrostatic interactions: Calculated using Coulomb's law: E~electrostatic~ = (1/4πε~0~)(q~i~q~j~/r~ij~) [7] [8] [10]

Force Field Comparison and Selection

What are the main types of force fields and their key characteristics?

Force fields can be categorized by their representation of atoms and treatment of electronic polarizability [11] [8] [10]. The table below summarizes the main types:

Table 1: Main Types of Force Fields and Their Characteristics

| Force Field Type | Atomistic Detail | Computational Efficiency | Key Features | Example Force Fields |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-Atom (AA) | Explicitly models every atom, including hydrogen [11] [8] | Lower | More realistic representation of hydrogen bonding and solvation effects [11] | CHARMM36 [12], AMBER ff14SB [11], OPLS-AA [9] [11] |

| United-Atom (UA) | Treats nonpolar carbons and bonded hydrogens as a single particle [11] [13] | Medium | Reduces system size and computational cost while maintaining reasonable accuracy [11] | CHARMM19 [11], GROMOS 54a7 [13] |

| Coarse-Grained | Groups several atoms into one interaction site [11] [8] | Higher | Sacrifices atomic detail for longer timescales and larger systems [11] | MARTINI [11] |

| Additive (Non-polarizable) | Uses fixed atomic charges [12] [10] | Higher | Treats polarization implicitly; widely used and validated [10] [14] | AMBER [7], CHARMM36 [12], OPLS-AA [10] |

| Polarizable | Explicitly models electronic polarization response [12] [10] | Lower | More accurate electrostatic properties across different environments [10] | Drude [12] [10], AMOEBA [11] [12] |

How do major biomolecular force fields compare for different applications?

The table below provides a comparative overview of commonly used force fields for biomolecular simulations:

Table 2: Comparison of Major Force Fields for Biomolecular Simulations

| Force Field | Strengths and Best Applications | Compatible Water Models | System Types | Software Availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM | Excellent for proteins, lipids, membrane systems; good for protein-ligand interactions [7] [9] | TIP3P, modified TIP3P [13] | Proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, carbohydrates [7] [12] | CHARMM, GROMACS [13], NAMD [12] |

| AMBER | Highly effective for proteins, nucleic acids, protein-ligand interactions, and folding studies [7] [12] | TIP3P, SPC, TIP4P [12] | Proteins, DNA, RNA, small molecules (via GAFF) [7] [12] | AMBER, GROMACS [13] |

| OPLS | Originally for liquids; good for organic molecules and protein-ligand binding [7] [11] | TIP4P [9] | Small molecules, proteins, liquids [7] [10] | BOSS, MCPRO, GROMACS [13] |

| GROMOS | United-atom; efficient for large-scale systems and longer timescales [7] [13] | SPC [13] | Proteins, nucleic acids, lipids [7] | GROMOS, GROMACS [13] |

System-Specific Selection Guidelines

Which force field should I choose for my specific biomolecular system?

Selection depends heavily on your specific system and research goals. The following table summarizes recommendations based on biomolecular type:

Table 3: System-Specific Force Field Recommendations

| System Type | Recommended Force Fields | Key Considerations | Validation Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins & Peptides | AMBER (ff19SB, ff14SB) [7] [12], CHARMM36 [7] [12] | Accuracy in backbone dihedral angles and secondary structure stability [7] [12] | Check stability of native fold, compare secondary structure to experimental data [12] |

| Nucleic Acids (DNA/RNA) | AMBER (BSC1, OL3) [7] [12], CHARMM36 [7] | Proper base pairing, helical parameters, and sugar pucker conformations [7] | Verify helical parameters, base pair distances, and groove dimensions [7] |

| Lipids & Membranes | CHARMM36 [7] [9], GROMOS [7] | Accurate lipid bilayer properties, area per lipid, and membrane thickness [7] [9] | Check area per lipid, bilayer thickness, and order parameters against experiments [9] |

| Small Molecules/Drug-like Compounds | GAFF [10], CGenFF [10], OPLS-AA [7] [10] | Broad chemical space coverage and compatibility with biomolecular force fields [10] | Validate density, enthalpy of vaporization, and solvation free energy [10] |

| Intrinsically Disordered Proteins | CHARMM36m [11] | Balanced secondary structure propensities and chain compaction [11] | Compare radius of gyration and secondary structure populations to experimental data [11] |

How do I handle force field selection for complex multi-component systems?

For systems containing multiple components (e.g., protein-ligand in membrane environment):

- Prioritize compatibility: Ensure all components use the same force field family or compatible parameter sets [7] [10]

- Use hybrid approaches: For systems requiring different levels of theory, consider QM/MM methods where a small region (e.g., active site) uses quantum mechanics while the remainder uses molecular mechanics [7]

- Leverage transferable force fields: For drug-like molecules, use GAFF (with AMBER) or CGenFF (with CHARMM) to ensure compatibility [10]

- Validate interfaces: Pay special attention to interaction energies and geometries at component interfaces [7]

Diagram 1: Force field selection workflow for molecular dynamics simulations. This decision process incorporates system composition, accuracy requirements, and validation steps to guide researchers toward appropriate force field choices.

Troubleshooting Common Force Field Issues

What are common problems caused by force field incompatibility and how can I resolve them?

Force field incompatibility can manifest in various ways. The table below outlines common issues and solutions:

Table 4: Troubleshooting Force Field Compatibility Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| System instability(unphysical bond stretching, atom flying away) | Incompatible van der Waals parameters between different molecule types [7] | Check energy components during minimization and early MD | Use consistent force field family for all components; adjust LJ parameters if needed [7] |

| Incorrect density | Poorly optimized parameters for specific compounds [9] | Calculate density from NPT simulation and compare to experimental data [9] | Switch to better-validated force field (e.g., CHARMM36 over GAFF for ethers) [9] |

| Poor structural agreement | Incorrect torsion potentials or improper dihedral terms [12] | Compare simulated structures to experimental crystallographic data | Use updated force field versions with improved backbone (e.g., CHARMM36 over older versions) [12] |

| Inaccurate viscosity/ diffusion | Inadequate parameterization of transport properties [9] | Calculate viscosity from simulation and compare to experiments | Select force fields parameterized for transport properties (e.g., CHARMM36 for liquids) [9] |

How do I validate my chosen force field for a new system?

Follow this systematic validation protocol:

Equilibrium properties validation:

Structural validation:

Dynamic properties validation:

Interaction validation:

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

What is a standard protocol for setting up simulations with a chosen force field?

The workflow below describes a general methodology for setting up and validating MD simulations:

Step 1: System Preparation

- Obtain or generate initial coordinates for all components

- For small molecules: Use automated parameter generation tools (AnteChamber for GAFF, CGenFF program for CHARMM) [10]

- Ensure all components use compatible force field parameters [7]

Step 2: Solvation and Ion Addition

- Select water model compatible with your force field (TIP3P for CHARMM/AMBER, SPC for GROMOS) [13] [14]

- Add ions using parameters consistent with the force field [12]

Step 3: Energy Minimization

- Use steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm

- Check for reasonable final energies and no large forces

Step 4: Equilibration

- Gradually heat system from low temperature (e.g., 0K to target temperature) [15]

- Use position restraints on solute heavy atoms during initial equilibration

- Perform equilibration in NVT then NPT ensembles

Step 5: Production Simulation

- Use appropriate integration time step (typically 1-2 fs for all-atom, 2-4 fs for united-atom) [15]

- Employ temperature and pressure coupling algorithms consistent with force field parameterization

- Run simulation for sufficient duration to observe phenomena of interest

Step 6: Validation and Analysis

- Compare simulation properties to available experimental data

- Verify stability of key structural features

- Calculate experimental observables for direct comparison

The table below lists essential "research reagent solutions" for force field-based simulations:

Table 5: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MD Simulations

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Examples/Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Biomolecular Force Fields | Provide parameters for proteins, nucleic acids, lipids | CHARMM36 [12] [13], AMBER ff19SB [12], GROMOS 54a7 [13] |

| Small Molecule Force Fields | Parameters for drug-like molecules, ligands | CGenFF [10], GAFF [9] [10], OPLS-AA [10] |

| Water Models | Solvation environment | TIP3P [13] [14], SPC [14], TIP4P [9] |

| Parameter Generation Tools | Automated parameter assignment for novel molecules | AnteChamber (GAFF) [10], CGenFF program [10], SwissParam [10] |

| MD Software Packages | Simulation execution and analysis | GROMACS [13], AMBER [13], CHARMM [13], NAMD [12] |

| Polarizable Force Fields | Explicit electronic polarization for accurate electrostatics | Drude oscillator [12] [10], AMOEBA [11] [12] |

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

When should I consider using polarizable force fields?

Consider polarizable force fields in these scenarios:

- Heterogeneous environments: When molecules move between environments with different polarities (e.g., membrane permeation, protein binding) [10]

- Ionic systems: For accurate treatment of ion solvation and distribution at interfaces [10]

- Spectroscopic properties: When calculating properties sensitive to electronic distribution [12]

- Binding free energies: For improved accuracy in protein-ligand binding studies [10]

What are the current limitations and future directions in force field development?

Current limitations:

- Additive force fields lack explicit polarization, limiting transferability between environments [10] [14]

- Parameterization often relies on heuristics and may contain subjective elements [8]

- Balancing computational efficiency with physical accuracy remains challenging [11]

Emerging approaches:

- Polarizable force fields: Wider adoption as computational resources increase [12] [10]

- Machine-learned force fields: Using ab-initio data to create more accurate potentials [15]

- System-specific parametrization: Automated parametrization workflows for novel molecules [8]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key factors when selecting software for biomolecular simulations? Choosing the right software depends on your system and research goals. For high-speed biomolecular simulations, GROMACS is optimized for performance on CPUs and GPUs and is widely used for proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [16] [17]. For simulating material properties or coarse-grained systems, LAMMPS offers a versatile set of potentials [17] [18]. For detailed biomolecular modeling, packages like AMBER and CHARMM provide comprehensive, specialized force fields and analysis tools [17] [19].

FAQ 2: How do I choose between a CPU and a GPU for my molecular dynamics project? The choice hinges on the scale of your system and the software's optimization. GPUs are pivotal for accelerating computationally intensive tasks. For general molecular dynamics with software like GROMACS, the NVIDIA RTX 4090 offers a strong balance of price and performance with 16,384 CUDA cores and 24 GB of memory [20]. For the largest and most complex simulations that require extensive memory, the NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada with 48 GB of VRAM is the superior choice [20]. CPUs should prioritize clock speeds; a mid-tier workstation CPU with a balance of higher base and boost clock speeds is often well-suited [20].

FAQ 3: What level of theory is sufficient for drug discovery applications, such as solubility prediction? Molecular dynamics simulations can effectively predict key drug properties like aqueous solubility using classical mechanics force fields. Research has shown that MD-derived properties such as Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA), Coulombic and Lennard-Jones interaction energies, and Estimated Solvation Free Energy (DGSolv) are highly effective descriptors when used with machine learning models [21]. This approach can achieve performance comparable to models based solely on structural fingerprints [21].

FAQ 4: How can I design an MD experiment to study a property like membrane permeability? Studying passive membrane permeability requires careful setup to capture the atomistic detail of the process. Key steps include:

- System Preparation: Construct a realistic lipid bilayer and embed the drug molecule in the desired location.

- Simulation Setup: Apply enhanced sampling techniques to overcome the timescale limitations of passive diffusion.

- Trajectory Analysis: Extract properties related to the free energy of translocation and the kinetics of crossing the lipid bilayer [22].

FAQ 5: What is the role of artificial intelligence in modern molecular dynamics research? AI is transforming MD research by creating powerful feedback loops. AI models can generate thousands of promising molecular candidates optimized for specific properties. MD simulations can then validate these candidates in silico, and the results—including data on failed candidates—are fed back into the AI model to improve its predictive power and guide more targeted experimentation [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Simulation performance is slower than expected.

- Possible Cause 1: Suboptimal hardware for your specific software.

- Solution: Consult Table 2 to match your primary MD software with the recommended GPU. For GROMACS, prioritize GPUs with high CUDA core counts like the RTX 4090. For large systems in AMBER, consider the RTX 6000 Ada for its extensive VRAM [20].

- Possible Cause 2: Improper CPU selection.

- Solution: Avoid CPUs with excessively high core counts if your software and system size cannot utilize them. Prioritize processors with higher single-core clock speeds for many MD workloads [20].

- Possible Cause 3: Inefficient use of available resources.

- Solution: For very large systems, investigate multi-GPU setups, which can dramatically enhance computational efficiency and decrease simulation times in supported software like AMBER, GROMACS, and NAMD [20].

Issue: My simulation results do not agree with experimental data.

- Possible Cause 1: Inadequate sampling.

- Possible Cause 2: Incorrect force field or system parameters.

- Solution: Validate your force field choice for your specific molecule type (e.g., biomolecule, polymer, metal). Carefully check protonation states, ion concentrations, and hydration levels in your system setup [24].

Issue: The simulation crashes due to memory limitations.

- Possible Cause: The GPU's video memory (VRAM) is insufficient for the system size.

- Solution: Reduce the system size, use a more memory-efficient simulation setup (e.g., smaller water box), or upgrade to a GPU with higher VRAM capacity, such as the NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada (48 GB) [20].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Table 1: Key Software for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

This table summarizes critical software tools, their primary applications, and key features to guide selection.

| Software | Primary Application | Key Features | License |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [16] [19] | High-speed biomolecular simulations | Exceptional performance on CPUs/GPUs; Free open source (GPL) | Free, Open Source |

| NAMD [17] [19] | Scalable biomolecular simulations | Excellent parallel scalability for massive systems; CUDA acceleration | Free for academic use |

| LAMMPS [17] [18] | Simulating material properties & soft matter | Potentials for solids and coarse-grained systems; Highly flexible | Free, Open Source (GPL) |

| AMBER [17] [19] | Modeling biomolecular systems | Comprehensive force fields & analysis tools | Proprietary, Commercial / Free open source |

| CHARMM [17] [19] | Detailed biomolecular modeling | Detail-driven approach; Extensive force fields | Proprietary, Commercial / Free |

Table 2: Recommended GPU Hardware for MD Software (2024)

This table provides a summary of recommended GPUs for popular MD software, based on performance benchmarks. [20]

| MD Software | Recommended GPU | Key Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 | High CUDA core count (16,384) offers excellent performance for computationally intensive simulations. |

| AMBER | NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada | 48 GB of VRAM is ideal for large-scale, complex simulations with extensive particle counts. |

| NAMD | NVIDIA RTX 4090 / RTX 6000 Ada | High parallel processing capabilities (16,384+ CUDA cores) significantly enhance simulation times. |

Detailed Methodology: Predicting Drug Solubility with MD and Machine Learning

The following workflow is adapted from a published study that used MD properties to predict aqueous solubility with high accuracy [21].

1. Data Curation

- Compile a dataset of compounds with experimentally measured logarithmic solubility (logS). The referenced study used 211 drugs from diverse classes [21].

- Incorporate additional experimental descriptors known to influence solubility, such as the octanol-water partition coefficient (logP) [21].

2. MD Simulation Setup

- Software: Use an MD package like GROMACS [21].

- Force Field: Select an appropriate force field (e.g., GROMOS 54a7) [21].

- System Setup:

- Place the molecule in a cubic simulation box with a simple point-charge water model.

- Example box size:

4 nm x 4 nm x 4 nm[21].

- Simulation Parameters:

- Ensemble: NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature).

- Run a simulation long enough to achieve equilibrium and collect sufficient data for analysis.

3. Property Extraction After simulation, extract time-dependent and average properties from the trajectory. The study found the following seven properties to be highly effective for solubility prediction [21]:

- logP: Octanol-water partition coefficient (experimental).

- SASA: Solvent Accessible Surface Area.

- Coulombic_t: Coulombic interaction energy.

- LJ: Lennard-Jones interaction energy.

- DGSolv: Estimated Solvation Free Energy.

- RMSD: Root Mean Square Deviation.

- AvgShell: Average number of solvents in the solvation shell.

4. Machine Learning Modeling

- Use the extracted MD properties as input features for machine learning algorithms.

- The referenced study achieved best performance with the Gradient Boosting algorithm (test set R² = 0.87, RMSE = 0.537) [21].

- Other suitable ensemble algorithms include Random Forest, Extra Trees, and XGBoost [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential computational "reagents" and their functions in a typical MD-driven drug discovery project.

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| GROMACS Software [16] | A free, open-source MD software suite used to perform high-performance molecular dynamics simulations and analysis. |

| GROMOS 54a7 Force Field [21] | A set of mathematical parameters that defines the potential energy of a molecular system, governing atomic interactions during the simulation. |

| Machine Learning Models (e.g., Gradient Boosting) [21] | Algorithms used to identify complex, non-linear relationships between MD-derived molecular properties and experimental outcomes like solubility. |

| NVIDIA RTX GPU [20] | Hardware that provides massive parallel processing power, drastically accelerating the computation of forces and integration of equations of motion in MD. |

Workflow Visualization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common sources of error in Molecular Dynamics force fields? Classical force fields often fail to capture key quantum effects, which limits their predictive power. Common issues include the inability to accurately describe anisotropic charge distributions (like σ-holes and lone pairs), the neglect of polarization effects (where the electrostatic environment affects atomic charges), and the omission of geometry-dependent charge fluxes (where local geometry changes alter charge distribution) [25]. These deficiencies can lead to inaccuracies in simulating molecular conformations, interaction energies, and thermodynamic properties.

FAQ 2: My simulations get trapped in specific conformations. How can I improve sampling? Inadequate sampling occurs because canonical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations can become trapped at local energy minima, especially at low temperatures. To overcome energy barriers and enhance sampling, you should employ advanced techniques such as the Replica-Exchange Method (REM), which simulates multiple copies of the system at different temperatures and swaps configurations between them. Umbrella Sampling is another effective method that uses biasing potentials along a reaction coordinate, with the resulting data analyzed using the Weighted Histogram Analysis Method (WHAM) to reconstruct unbiased properties [26].

FAQ 3: How do I choose a trajectory analysis method for my process?

The choice of trajectory analysis method depends on whether your biological process is best represented as a simple linear progression or a complex branched pathway. For instance, the TSCAN algorithm is highly effective for identifying branched trajectories. It works by clustering cells, constructing a minimum spanning tree (MST) on cluster centroids, and then mapping cells onto this tree to compute pseudotime values along each branch [27]. In contrast, principal curves analysis (e.g., with the slingshot package) is ideal for identifying a single, continuous path through the data [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Force Field Inaccuracies

Problem: Simulation results show large deviations from experimental data on protein conformations or interaction energies.

Diagnosis: This is a frequent problem arising from the functional form and parameterization of classical force fields. The fixed-charge model used in many force fields does not account for polarization or the anisotropic nature of electron clouds [25].

Solutions:

- Consider a Polarizable Force Field: For systems where electronic polarization is critical, use a polarizable force field like AMOEBA+, which explicitly models how the charge distribution of a molecule responds to its environment [25].

- Apply Empirical Corrections: For specific known deficiencies, such as the inaccurate representation of halogen atoms (σ-holes), some force fields offer solutions like attaching off-centered positive charges to atoms to better model their electrostatic potential [25].

- Explore Machine-Learned Force Fields: For small molecules, consider using a machine-learned force field like the symmetrized gradient-domain machine learning (sGDML) model. This approach can construct force fields from high-level ab initio calculations (like CCSD(T)), offering spectroscopic accuracy for molecules with up to a few dozen atoms [1].

Recommended Experimental Protocol: Force Field Validation

- Select a Validation Dataset: Choose a set of molecules with high-quality experimental data for properties relevant to your study (e.g., conformational energies, liquid densities, solvation free energies, or crystal lattice parameters).

- Run Benchmark Simulations: Perform MD simulations using the candidate force field(s) to compute the same properties.

- Quantitative Comparison: Calculate the error between your simulation results and the experimental data. Use statistical measures like root-mean-square error (RMSE) to quantify the force field's performance.

- Iterate: If the agreement is poor, consider re-parameterizing specific terms or switching to a more advanced force field.

Issue 2: Inefficient Conformational Sampling

Problem: The simulation fails to explore the full conformational landscape within a feasible simulation time, leading to poor statistical averages.

Diagnosis: The system has high energy barriers that are insurmountable on typical MD timescales. This is particularly common in protein folding simulations and simulations of glassy or semi-rigid systems [28] [26].

Solutions:

- Implement Enhanced Sampling: Utilize generalized-ensemble methods to facilitate barrier crossing.

- Replica-Exchange MD (REMD): Simulate multiple replicas at different temperatures. Exchanges between replicas are attempted periodically and accepted based on a Metropolis criterion, allowing conformations to escape deep energy wells [26].

- Metadynamics: Apply a history-dependent biasing potential to collective variables (CVs) to discourage the system from revisiting already sampled states, thus filling energy wells and pushing the system to explore new areas [26].

- Use Coarse-Grained Models: For an initial exploration of the conformational landscape, use a coarse-grained model that reduces the number of degrees of freedom. This can provide a ~4000-fold increase in efficiency, allowing you to identify key low-energy regions before refining with all-atom simulations [26].

Recommended Experimental Protocol: Replica-Exchange MD (REMD)

- System Setup: Prepare the system (e.g., a solvated protein) as you would for a standard MD simulation.

- Choose Temperature Distribution: Select a set of temperatures (typically 16-64) for the replicas. The highest temperature should be high enough to cause rapid conformational changes. Use an adaptive feedback-optimized algorithm to ensure good exchange rates between neighboring replicas [26].

- Run Equilibration: Equilibrate each replica independently at its assigned temperature.

- Production Run: Run the REMD simulation, attempting exchanges between neighboring replicas at regular intervals (e.g., every 1-2 ps).

- Analysis: Use the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) to combine data from all replicas and compute thermodynamic properties at the temperature of interest.

Issue 3: Interpreting Complex Trajectories

Problem: You have a trajectory from a process like cell differentiation or protein folding, but you struggle to characterize the progression and identify key pathways.

Diagnosis: High-dimensional trajectory data is complex and cannot be intuitively understood by looking at raw coordinates. A dedicated trajectory analysis is required to reduce dimensionality and define a measure of progression [27].

Solutions:

- Define a Pseudotime Ordering: Use algorithms like TSCAN or Slingshot to project high-dimensional data onto a trajectory and assign a "pseudotime" value to each cell or frame. This value quantifies the relative progression of each data point along the inferred path [27].

- Handle Branched Trajectories: For processes with multiple outcomes (e.g., a bifurcation during differentiation), use a method like TSCAN that can construct a minimum spanning tree (MST). This will identify branch points and assign separate pseudotime values for each path [27].

- Fit a Principal Curve: For a single, continuous process, fit a principal curve (a non-linear generalization of PCA) to the data. The projection of data points onto this curve defines the pseudotime ordering [27].

Recommended Experimental Protocol: Trajectory Analysis with TSCAN

- Dimensionality Reduction: Perform PCA on your high-dimensional data (e.g., single-cell RNA-seq counts or protein conformational snapshots) to denoise and compact the data [27].

- Clustering: Cluster the data in the low-dimensional PC space.

- Build Minimum Spanning Tree (MST): Calculate the centroid of each cluster and construct an MST on these centroids. Consider using an "outgroup" to avoid connecting unrelated populations or using mutual nearest neighbor (MNN) distances to improve connectivity [27].

- Map Cells and Calculate Pseudotime: Project each cell onto the closest edge of the MST. Calculate the pseudotime as the distance along the MST from a defined root node (e.g., an undifferentiated cell or unfolded protein state) using the

orderCells()function [27]. - Visualize and Interpret: Plot the MST and pseudotime values onto a low-dimensional embedding (e.g., t-SNE). Model gene expression or other variables against pseudotime to identify features that change along the trajectory.

| Method | Principle | Best For | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canonical MD [26] | Numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion. | General equilibrium properties, straightforward simulations. | Can get trapped in local minima; time step limited to ~1-2 fs. |

| Replica-Exchange MD (REMD) [26] | Parallel simulations at different temperatures with configuration swaps. | Overcoming high energy barriers, efficient exploration of rugged landscapes. | Computational cost scales with number of replicas; requires careful temperature distribution. |

| Metadynamics [26] | History-dependent bias potential added to collective variables. | Calculating free energy surfaces, sampling specific transitions. | Choice of collective variables is critical; bias deposition rate must be tuned. |

| Monte Carlo (MC) [26] [29] | Random conformational perturbations accepted/rejected by Metropolis criterion. | Exploring conformational space, systems with complex move sets (e.g., chain growth). | Efficiency depends on move set design; does not provide dynamical information. |

Table 2: Comparison of Trajectory Inference Methods

| Method | Trajectory Type | Key Strength | Key Weakness |

|---|---|---|---|

| TSCAN [27] | Branched | Fast, intuitive, uses existing cluster annotations. | Sensitive to over/under-clustering; cannot handle cycles or "bubbles". |

| Slingshot (Principal Curves) [27] | Linear or Curved | Flexible, makes no assumptions about cluster structure. | Single path; less suited for complex branching processes. |

Workflow Visualization

Trajectory Analysis with TSCAN

Enhanced Sampling Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Force Fields for MD Simulations

| Item | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| AMBER [25] | A family of all-atom force fields and simulation software. | Focused on accurate structures and non-bonded energies for proteins and nucleic acids. Uses RESP charges fitted to QM electrostatic potential. |

| CHARMM [25] | A family of all-atom force fields and simulation software. | Developed for proteins and nucleic acids, with a focus on structures and interaction energies. |

| GROMOS [25] | A united-atom force field and software package. | Geared toward accurate description of thermodynamic properties like solvation free energies and liquid densities. |

| OPLS-AA [25] | An all-atom force field for organic molecules and proteins. | Optimized for liquid-phase properties and conformational energies. |

| AMOEBA+ [25] | A polarizable force field. | Includes advanced electrostatics with charge penetration and intermolecular charge transfer for higher accuracy. |

| sGDML [1] | A machine-learning framework for constructing force fields. | Creates force fields from high-level ab initio data (e.g., CCSD(T)) for spectroscopic accuracy in small molecules. |

| Slingshot [27] | R package for trajectory inference using principal curves. | Infers smooth, continuous trajectories and pseudotime for linear processes. |

| TSCAN [27] | R package for trajectory inference using minimum spanning trees. | Infers branched trajectories by ordering clusters. |

Executing Robust MD Simulations: A Step-by-Step Workflow from Setup to Production

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Solvation and Neutralization

FAQ 1: My simulation crashes during energy minimization. What is the most likely cause? A common cause is poor preparation of the starting structure. If your initial molecular model contains steric clashes, missing atoms, or incorrect protonation states, the energy minimization process may fail to converge or cause a catastrophic crash. Before running a simulation, always check for and correct these issues using structure preparation tools [30].

FAQ 2: After solvation, my system is not electrically neutral. How can I fix this?

A non-neutral system can lead to unrealistic electrostatic interactions. To neutralize the system, you can add ions. In OpenMM, this is typically handled automatically when creating the system. When using AMBER parameter files, you can ensure the createSystem method includes arguments for adding ions to neutralize the system's net charge [31].

FAQ 3: Are the implicit solvent parameters in my AMBER parameter files (prmtop) compatible with OpenMM's GBSA models?

There can be differences. OpenMM's documentation notes that the GBSA-OBC parameters in its XML files are "designed for use with Amber force fields, but they are different from the parameters found in the AMBER application" [32]. For consistency and best practices, especially when using implicit solvent models like GBSA-OBC (IGB2/5), it is recommended to use the force field XML files provided with OpenMM rather than relying solely on parameters from AMBER-generated prmtop files [32].

FAQ 4: My simulation is unstable after adding explicit water. What should I check? First, verify that you have performed adequate energy minimization and equilibration. Rushing these steps is a common mistake. Minimization removes bad contacts and high-energy strains, while equilibration allows temperature and pressure to stabilize in the desired ensemble (NPT, NVT). Always confirm that key thermodynamic properties (potential energy, temperature, density) have reached a stable plateau before starting your production run [30].

FAQ 5: How do I choose between an implicit and explicit solvent model? The choice depends on your research question and computational resources. Explicit solvent models (like TIP3P) are more physically realistic for studying specific solvent-solute interactions but are computationally expensive. Implicit solvent models (like GBSA) are faster and suitable for studying conformational changes or folding where the averaging effect of solvent is acceptable. For stability and accurate dynamics in detailed studies, explicit solvent is often preferred [31] [32].

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Workflow for System Preparation

The following workflow outlines a robust methodology for preparing a solvated and neutralized molecular system for Molecular Dynamics simulation, using tools like OpenMM [31].

Detailed Methodology

Initial Structure Preparation

- Source Your PDB: Obtain your initial structure from a protein data bank or model it.

- Fix Common Issues: Use a tool like

PDBFixerto add missing atoms, residues, and hydrogen atoms. - Assign Protonation States: Determine the correct protonation states of residues (e.g., for Histidine) at your desired pH using a tool like

H++[30]. An incorrect protonation state will affect electrostatics and solubility.

Parameterization using OpenMM XML Files

- Select a Force Field: Choose an appropriate force field (e.g.,

amber19-all.xmlfor proteins). - Select a Water Model: Choose an explicit (e.g.,

amber19/tip3pfb.xml) or implicit solvent model. - Create the System: In your script, use the

ForceFieldobject to create the system. Specify options like a 1 nm non-bonded cutoff, Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) for long-range electrostatics, and constraints for bonds involving hydrogen [31].

pdb = PDBFile('prepared_structure.pdb') forcefield = ForceField('amber19-all.xml', 'amber19/tip3pfb.xml') system = forcefield.createSystem(pdb.topology, nonbondedMethod=PME, nonbondedCutoff=1*nanometer, constraints=HBonds)- Select a Force Field: Choose an appropriate force field (e.g.,

Solvation

- Explicit Solvation: The chosen water model is automatically added to the simulation box during system creation, surrounding the solute.

- Implicit Solvation: If an implicit solvent model is specified in the

ForceFieldline, the system is treated as being in a continuum solvent, and no explicit water molecules are added [31].

Neutralization

- Add Ions: The system's net charge is neutralized by adding a corresponding number of counterions (e.g., Na⁺ or Cl⁻). In OpenMM, this can be done during system creation by specifying the

ionicStrengthargument or by using theModellerclass to add specific ions [31].

- Add Ions: The system's net charge is neutralized by adding a corresponding number of counterions (e.g., Na⁺ or Cl⁻). In OpenMM, this can be done during system creation by specifying the

Energy Minimization

- Minimize the Structure: Perform local energy minimization to relieve any residual steric clashes or geometric strains introduced during the solvation and neutralization steps.

- Minimize the Structure: Perform local energy minimization to relieve any residual steric clashes or geometric strains introduced during the solvation and neutralization steps.

System Equilibration

- Thermalize and Pressurize: Gradually heat the system to the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) and equilibrate the density at the target pressure (e.g., 1 bar) in a step-wise fashion. This is typically done using a Langevin integrator for temperature control and a Monte Carlo barostat for pressure control over hundreds of picoseconds to nanoseconds.

- Verify Stability: Monitor the potential energy, temperature, and density to ensure they have reached a stable plateau before proceeding to production MD [30].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of the system preparation protocol:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key materials and software used in the system preparation workflow.

| Item Name | Function / Purpose in System Preparation |

|---|---|

AMBER Force Fields (amber19-all.xml) |

Provides mathematical parameters for bonded and non-bonded interactions for proteins, DNA, and other molecules [31]. |

| TIP3P-FB Water Model | A specific, widely-used explicit water model that defines the geometry and interactions of water molecules in the simulation [31]. |

| GBSA-OBC Implicit Solvent | An implicit solvation model that approximates water as a continuous medium, computationally faster than explicit water for some studies [32]. |

| Langevin Middle Integrator | An algorithm used to integrate the equations of motion during simulation, which also controls temperature via a stochastic term [31]. |

| Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) | A standard method for accurately calculating long-range electrostatic interactions in a system with periodic boundary conditions [31]. |

| Ions (Na⁺/Cl⁻) | Counterions added to the system to neutralize the net charge of the solute, preventing unrealistic electrostatic behavior [31]. |

Energy minimization is a foundational step in computational molecular dynamics (MD), aimed at transforming a molecular structure into a low-energy state by relieving structural stresses like atomic clashes. This process produces a statistically favored configuration that is more likely to represent the natural state of the system, providing a stable and physically realistic starting point for subsequent MD simulations [33]. A properly minimized structure is crucial for the stability and accuracy of production MD runs, as high potential energy or unresolved clashes can lead to simulation failure or non-physical results [34]. This guide integrates troubleshooting and best practices for energy minimization within the broader context of preparing reliable MD simulations [35] [36].

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving High Potential Energy

A frequent challenge during energy minimization is the occurrence of excessively high potential energy, which prevents the convergence of forces (Fmax) to an acceptable threshold. The table below summarizes common causes and solutions.

| Observed Issue | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Very high potential energy (e.g., > 1e+07) and Fmax not converging [34]. | Atomic clashes in the initial structure, often due to faulty model building or preprocessing. | Visually inspect the structure around atoms with the highest forces; manually correct unreasonable clashes [34]. | GROMACS Forum [34] |

High energy persists when using freezegrps to immobilize parts of the system (e.g., a ribosome) [34]. |

Freezing atoms prevents their movement but does not eliminate force calculations. Clashes involving frozen atoms cannot be resolved. | Replace atom freezing with strong position restraints. This allows minor vibrations while largely maintaining the initial structure without introducing unresolvable clashes [34]. | GROMACS Forum [34] |

| High forces and instability are localized at the periodic boundary [34]. | Incomplete bonding across periodic boundaries in materials like zeolites or polymers, leading to unrealistic interactions. | Ensure the topology includes all necessary bonds across periodic boundaries. For complex solids, use specialized tools to generate a correct topology and set periodic-molecules = yes in the .mdp file [34]. |

GROMACS Forum [34] |

| Position-restrained atoms still exhibit noticeable displacement [34]. | Position restraints are harmonic and do not fully fix atoms; they allow small movements. Incorrect .mdp settings may also fail to activate restraints. |

Verify that position restraints are correctly enabled in the .mdp file and check the simulation log for the associated energy term. Increase the force constant of the restraints if necessary [34]. |

GROMACS Forum [34] |

| System drift or segmentation faults during equilibration (NVT/NPT) after minimization [34]. | Underlying instability from poorly minimized structure, or an incorrectly sized simulation box that creates strain at the boundaries. | Re-check the minimization procedure and ensure the box size is appropriate for the system to avoid artificial boundary pressures [34]. | GROMACS Forum [34] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between freezing atoms and applying position restraints?

Freezing atoms (freezegrps) completely excludes them from the integration of motion—their positions are not updated during simulation steps. However, forces are still calculated for these atoms, meaning clashes involving them will contribute to high potential energy and cannot be relieved [34]. Position restraints, in contrast, apply a harmonic potential that tethers atoms to their reference positions. This calculates a restraining force that penalizes movement but still allows small vibrations and, crucially, enables the algorithm to resolve clashes by adjusting the positions of all atoms [34].

2. My energy minimization fails with extremely high potential energy. What is the first thing I should check?

The first and most critical step is to visually inspect the structure at the location of the atoms reported to have the highest forces by mdrun [34]. Automated processing or modeling tools can sometimes generate physically impossible geometries, such as side chains passing through aromatic rings. Identifying and manually correcting these major steric clashes is often necessary for successful minimization [34].

3. Can I skip force calculations for certain atoms to save computational time?

While modifying the source code to skip force calculations is theoretically possible, it is not recommended. In most molecular systems, the majority of computational time is spent calculating solvent interactions, not the forces for a fixed subset of atoms [34]. A more legitimate and effective strategy to save time is to extract a smaller, functionally relevant subsystem of your large complex for simulation, applying appropriate restraints at the newly created interfaces if necessary [34].

4. How does energy minimization fit into a broader molecular dynamics workflow?

Energy minimization is a prerequisite for MD simulation, which involves simulating the coupled electron-nuclear dynamics of molecules, often in excited states [35]. A stable, minimized structure is essential for subsequent steps like equilibration in the desired thermodynamic ensemble (NVT, NPT) and production MD runs used for analysis and comparison with experiment [35] [36]. It is one of the key initial steps in a comprehensive MD protocol [35].

5. What are the best practices for running MD simulations on modern HPC architectures like AWS Graviton3E?

For optimal performance on AWS Graviton3E (Hpc7g instances), use the Arm Compiler for Linux (ACfL) with the Scalable Vector Extension (SVE) enabled [37]. This combination, paired with the Arm Performance Library (ArmPL) and Open MPI with Elastic Fabric Adapter (EFA) support, has been shown to significantly outperform binaries built with GNU compilers or those using NEON/ASIMD instructions, especially for popular MD packages like GROMACS and LAMMPS [37].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Workflow Diagram: Energy Minimization for MD Prep

The diagram below outlines the logical workflow for preparing a system, from initial structure handling to a minimized system ready for MD.

Protocol 1: Standard Energy Minimization with Position Restraints

This protocol is suitable for preparing a protein-ligand complex for simulation.

- System Setup: Begin with a preprocessed structure file (e.g., from a PDB). Add missing hydrogen atoms using a tool like

pdb2gmx(GROMACS) or the integrated functions in SeeSAR's Protein Editor Mode [33]. - Solvation: Place the molecular system in a solvent box (e.g., TIP3P water) and add ions to neutralize the system's net charge.

- Restraint Definition: Generate a strong position restraint file for the atoms you wish to remain relatively fixed (e.g., the protein backbone or a large receptor). In GROMACS, this is typically done using the

genrestrcommand. In tools like YASARA integrated with SeeSAR, you can choose between a rigid backbone (stronger restraints) or a flexible backbone (weaker restraints) to simulate an induced fit [33]. - Parameter Configuration: In your minimization parameter file (e.g.,

.mdpfor GROMACS), ensure the following key parameters are set:define = -DPOSRES(to activate the position restraints included in your topology)integrator = steep(orcgfor conjugate gradients)nsteps = 5000(or until convergence)emtol = 1000.0(Force max threshold, kJ/mol/nm)

- Execution and Validation: Run the minimization. Validate the output by confirming that the maximum force (Fmax) is below the specified threshold and that the potential energy is a large, negative value, indicating a stable state.

Protocol 2: Induced Fit for Expanding a Binding Site

Energy minimization can be used to simulate an induced fit, where both the ligand and the target adapt to create more space [33].

- Initial Placement: Manually dock a ligand into a binding site that is too narrow, temporarily tolerating steric clashes.

- Flexible Minimization: Apply energy minimization with a flexible protein backbone option. This allows both the ligand and the protein residues to adjust their conformations to relieve clashes [33].

- Analysis: Examine the optimized structure for newly formed interactions with side chains, the backbone, or water molecules, which can provide deeper insights into the binding mode and improve scoring predictions [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The table below details key computational tools and parameters used in energy minimization and MD setup.

| Item Name | Type/Format | Primary Function | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields (AMBER, CHARMM, YASARA2) [33] | Parameter Set | Provides the collection of formulas and parameters (bond lengths, angles, dihedrals, non-bonded interactions) to calculate the potential energy of the atomic system. | YAMBER3 and YASARA2 are force fields available within YASARA that have performed well in community benchmarks [33]. |

| AutoSMILES (YASARA) [33] | Automated Algorithm | Automatically assigns force field parameters to a given structure, including pH-dependent bond order assignment and semi-empirical charge calculations, covering ~98% of PDB entries without manual intervention [33]. | Preparing a ligand from a PDB entry for simulation by automatically generating its topology. |

| Position Restraints | Topology Include File | Applies a harmonic potential to restrain specified atoms around their initial coordinates, preventing large-scale drift while allowing relaxation of clashes. | #include "posre_Protein_chain_A.itp" in a GROMACS topology file, activated via define = -DPOSRES in the .mdp file [34]. |

| Steepest Descent Integrator | Algorithm | An energy minimization algorithm that moves atoms in the direction of the negative energy gradient. Robust for initially highly strained systems. | Setting integrator = steep in a GROMACS .mdp file for the initial minimization steps. |

| Arm Compiler for Linux (ACfL) [37] | Compiler Suite | A compiler optimized for Arm architectures, which, when used with SVE enabled, produces the fastest GROMACS and LAMMPS binaries on AWS Graviton3E processors [37]. | Compiling GROMACS with -DGMX_SIMD=ARM_SVE for optimal performance on Hpc7g instances [37]. |

Performance Data and Optimization

The choice of compiler and simulation parameters can significantly impact performance. The following table summarizes performance gains observed for GROMACS on AWS Graviton3E (Hpc7g) instances [37].

| Test Case | System Size (Atoms) | Compiler & SIMD | Relative Performance | Key Takeaway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ion Channel (A) | 142,000 | ACfL with SVE | 100 (Baseline) | For small systems, SVE provides a moderate (~9-10%) performance gain over NEON/ASIMD [37]. |

| ACfL with NEON/ASIMD | ~90-91 | |||

| Cellulose (B) | 3.3 Million | ACfL with SVE | 100 (Baseline) | For medium systems, the performance gain from SVE is more substantial (~28%) [37]. |

| ACfL with NEON/ASIMD | ~72 | |||

| STMV Virus (C) | 28 Million | ACfL with SVE | 100 (Baseline) | For large systems, SVE maintains a significant performance advantage (~19%) and scales near-linearly with EFA [37]. |

| ACfL with NEON/ASIMD | ~81 |

Force Field Selection Diagram

This diagram provides a decision tree for selecting an appropriate force field for energy minimization.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful computational technique that models the time evolution of a molecular system by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion. A critical step in any MD workflow is equilibration, the process of bringing a system to a stable thermodynamic state at the desired temperature and density before production simulations can begin. Without proper equilibration, simulation results may reflect artifacts of the initial configuration rather than true physical properties, potentially invalidating scientific conclusions.

This guide addresses the crucial role of equilibration protocols in achieving stable NVT (canonical ensemble, constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) and NPT (isothermal-isobaric ensemble, constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) ensembles. We focus specifically on methodologies for obtaining correct system density, a fundamental property that influences virtually all other computed physical characteristics in condensed phase simulations. The protocols discussed here are framed within the broader context of best practices for molecular dynamics research, with particular attention to applications in pharmaceutical development and materials science.

Fundamental Concepts: NVT and NPT Ensembles

Theoretical Background

In statistical mechanics, an ensemble refers to a collection of all possible systems which have different microscopic states but have the same macroscopic or thermodynamic state. MD simulations commonly utilize two primary ensembles during the equilibration process:

NVT Ensemble (Canonical Ensemble): This ensemble maintains a constant number of particles (N), constant volume (V), and constant temperature (T). It is typically used for the initial stage of equilibration to stabilize the system temperature after energy minimization. The NVT ensemble allows the system to reach the target temperature while keeping the volume fixed.

NPT Ensemble (Isothermal-Isobaric Ensemble): This ensemble maintains a constant number of particles (N), constant pressure (P), and constant temperature (T). Following NVT equilibration, the NPT ensemble allows the system volume to adjust to achieve the correct density at the target temperature and pressure, mimicking common laboratory conditions.

The proper application of these ensembles during equilibration is essential for obtaining physically meaningful results. As noted in best practices documentation, simulations are "usually conducted under conditions of constant temperature and pressure to mimic laboratory conditions for which special algorithms are available" [38].

The Critical Role of System Density

Achieving the correct system density is a key indicator of successful equilibration. Density serves as a fundamental validation metric because:

- It is easily comparable to experimental values

- It influences diffusion rates, structural properties, and thermodynamic behavior

- An unstable density indicates the system has not reached equilibrium

A recent study emphasizes that "achieving equilibration to get target density is a computationally intensive step" that requires careful protocol design [39]. Without proper density equilibration, properties like radial distribution functions, diffusion coefficients, and energy distributions will not reflect the true physical system.

Established Equilibration Protocols

Conventional Approaches

Traditional equilibration methods often employ iterative annealing cycles or extended simulation times to achieve target density:

Table 1: Comparison of Conventional Equilibration Methods

| Method | Typical Protocol | Computational Efficiency | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annealing Method | Sequential NVT and NPT ensembles across temperature ranges (300K-1000K) with multiple cycles [39] | Low (~1x baseline) | Complex polymer systems, glassy states |

| Lean Method | Extended NPT simulation at target temperature followed by NVT ensemble [39] | Moderate (~6x more efficient than annealing) | Simple liquid systems, pre-equilibrated structures |

| Proposed Ultrafast Approach | Optimized multi-step protocol with specific parameter controls [39] | High (~200% more efficient than annealing, ~600% more efficient than lean method) | Large systems, high-throughput screening |

The annealing method, while robust, involves "sequential implementation of processes corresponding to the NVT and NPT ensembles within a temperature range of 300 K to 1000 K" with iterative cycles until desired density is achieved [39]. For example, one study employed "twenty annealing cycles conducted within a temperature range of 300 K to 1000 K" specifically to obtain the desired density [39].

An Ultrafast Molecular Dynamics Approach

Recent research has introduced a more efficient equilibration protocol that significantly reduces computational requirements while maintaining accuracy. This approach demonstrates particular effectiveness for complex systems like ion exchange polymers, with reported efficiency improvements of "~200% more efficient than conventional annealing and ~600% more efficient than the lean method" [39].

The key advantages of this optimized approach include:

- Reduced variation in diffusion coefficients (water and hydronium ions) as the number of polymer chains increases

- Significantly reduced errors observed in 14 and 16 chain models, even at elevated hydration levels

- More rapid convergence to target density values

This method addresses the critical need for "computational robustness" especially in large simulation cells, avoiding "iterative and often time-consuming process to arrive at definitive solutions in terms of physical properties" [39].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Equilibration Issues

Density Convergence Problems

Table 2: Troubleshooting Density Equilibration Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Density fails to stabilize | Insufficient equilibration time, incorrect pressure coupling, improper initial configuration | Extend NPT simulation time, verify pressure coupling parameters (time constant, compressibility), check initial volume |

| System density significantly deviates from experimental values | Force field inaccuracies, insufficient system size, missing interaction parameters | Validate force field for your specific system, increase system size if finite-size effects are suspected, verify all interaction parameters |

| Oscillating density values | Too strong pressure coupling, incorrect compressibility settings, unstable integration algorithm | Adjust pressure coupling time constant, verify system compressibility, reduce integration time step |

| Different density values with various simulation software | Algorithmic differences, varying implementation of pressure coupling, different cut-off treatments | Consistent protocol use across software, verify parameter equivalence, check long-range interaction treatment |

A critical consideration in equilibration is verifying that "the system reached true equilibrium" [40]. This can be particularly challenging with complex biomolecules where convergence checks must be rigorously applied.

Temperature and Pressure Control Challenges

Issue: Temperature Instability During NVT Equilibration

- Symptoms: Large temperature fluctuations, failure to reach target temperature

- Solutions: Adjust temperature coupling time constant, verify initial velocity distribution, check for high-energy contacts in initial structure

- Underlying principle: The system "must be first heated and pressurized to the target values" before true equilibration can occur [40]

Issue: Pressure Oscillations in NPT Ensemble

- Symptoms: Large pressure fluctuations, unstable density values, simulation crashes

- Solutions: Verify compressibility settings appropriate for your system, adjust pressure coupling time constant, check for system instabilities

- Advanced troubleshooting: For complex systems, consider using semi-isotropic or anisotropic pressure coupling for non-cubic systems

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How long should equilibration typically run before proceeding to production simulation?

A: There is no universal duration for equilibration, as it depends on system size, complexity, and the properties of interest. Rather than using a fixed time, monitor convergence through observables like potential energy, temperature, pressure, and particularly density. The system can be considered equilibrated when these properties fluctuate around stable average values. For complex systems like polymers, "multi-microsecond trajectories" may be needed for full convergence of some properties [40].

Q2: What are the key indicators that my system has reached equilibrium?

A: The primary indicators include:

- Stable fluctuations of potential energy around a constant average value

- System density maintaining the target experimental value with small fluctuations

- Temperature and pressure maintaining their set values with appropriate fluctuations

- Root mean square deviation (RMSD) of atomic positions reaching a plateau

As noted in recent studies, "a standard way to check for equilibration is to plot several magnitudes calculated from the simulation, as a function of time, and see if they have reached a relatively constant value (a plateau in the graph)" [40].

Q3: Why is the NVT ensemble typically used before NPT during equilibration?

A: The NVT ensemble allows the system to stabilize at the target temperature before introducing pressure control. This stepwise approach prevents simultaneous adjustment to multiple thermodynamic variables, which can improve stability and convergence. The system is "first heated and pressurized to the target values" in a controlled sequence [40].

Q4: What are the consequences of insufficient equilibration on simulation results?

A: Inadequate equilibration can lead to:

- Incorrect density values that propagate errors to all computed properties

- Artificial structural artifacts from the initial configuration

- Unrealistic dynamics and diffusion behavior

- Invalid thermodynamic averages and free energy calculations

As emphasized in recent literature, "the essential and often overlooked assumption that, left unchecked, could invalidate any results from it: is the simulated trajectory long enough, so that the system has reached thermodynamic equilibrium, and the measured properties are converged?" [40].

Q5: How does system size affect equilibration time and protocol selection?

A: Larger systems generally require longer equilibration times due to more complex energy landscapes and slower relaxation of collective motions. Research on ion exchange polymers has shown that "the variation in diffusion coefficients (water and hydronium ions) reduces as the number of chains increases, with significantly reduced errors observed in 14 and 16 chains models" [39]. This suggests that smaller systems may show greater property variation, requiring careful protocol selection.

Experimental Protocols: Best Practices

Standard Equilibration Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a robust equilibration workflow that integrates both NVT and NPT phases with appropriate convergence checks:

Step-by-Step Protocol for Density Equilibration

Initial System Preparation

- Construct system with appropriate dimensions and composition

- Solvate using suitable water model (SPC, TIP3P, TIP4P)

- Add ions to neutralize system charge and achieve physiological concentration

Energy Minimization

- Use steepest descent algorithm until maximum force < 1000 kJ/mol/nm

- Eliminate bad contacts and high-energy configurations

- Protocol: "The steepest descent method was initially used until the maximum interatomic force was below 100 kJ/mol nm in steps of 0.01 nm" [41]

NVT Equilibration

- Duration: Typically 50-500 ps depending on system size

- Temperature coupling: Use Berendsen or velocity rescale for initial equilibration

- Parameters: "Position-constrained MD simulation" for initial stability [41]

- Monitoring: Check temperature stability and kinetic energy distribution

NPT Equilibration

- Duration: Typically 1-10 ns for dense systems

- Pressure coupling: Use Parrinello-Rahman or Berendsen barostat

- Monitoring: Track density convergence to experimental values

- Verification: Ensure potential energy fluctuates around stable average

Convergence Validation

- Verify multiple properties have reached stable fluctuations

- Compare density to known experimental values

- Check for drift in potential energy and other observables

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Molecular Dynamics Equilibration

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Equilibration |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | GROMACS [41], AMBER [38], NAMD [38], CHARMM [38] | Provides algorithms for integration, temperature/pressure coupling, and force calculations |

| Force Fields | GROMOS [41], AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS | Defines potential energy function and empirical parameters for different molecule types |

| Water Models | SPC [41], TIP3P [41], TIP4P | Solvation environment with appropriate dielectric properties and density |

| Temperature Coupling Algorithms | Berendsen thermostat, Velocity rescale, Nose-Hoover | Maintains system temperature at target value during NVT and NPT ensembles |

| Pressure Coupling Algorithms | Berendsen barostat, Parrinello-Rahman barostat | Maintains system pressure at target value during NPT ensemble |

| Analysis Tools | GROMACS analysis suite, VMD [41], Python/MATLAB scripts | Monitor convergence through properties like density, energy, RMSD |

Proper equilibration is a fundamental requirement for generating physically meaningful molecular dynamics simulations. The protocols outlined in this guide provide researchers with robust methodologies for achieving stable NVT and NPT ensembles with correct system density. By implementing these best practices—selecting appropriate protocols based on system characteristics, carefully monitoring convergence metrics, and addressing common equilibration issues—scientists can ensure the reliability of their simulation results.