Molecular Dynamics Simulation: A Comprehensive Guide to Applications in Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has become an indispensable computational microscope, providing atomic-level insights into biomolecular processes that are often impossible to observe experimentally.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation: A Comprehensive Guide to Applications in Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

Abstract

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has become an indispensable computational microscope, providing atomic-level insights into biomolecular processes that are often impossible to observe experimentally. This article explores the foundational principles, diverse methodological applications, and current challenges of MD simulations, with particular emphasis on their transformative role in drug discovery, including protein-ligand binding, membrane permeability, and allosteric modulation. We examine how machine learning and advanced sampling techniques are addressing longstanding limitations in force field accuracy and conformational sampling, while also discussing validation frameworks that ensure computational findings translate to real-world biomedical breakthroughs. For researchers and drug development professionals, this review offers a comprehensive understanding of how MD simulations accelerate therapeutic design and fundamental biological discovery.

The Atomic-Level Microscope: Understanding the Core Principles of Molecular Dynamics

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation represents a cornerstone computational technique in modern scientific research, enabling the investigation of biological and chemical systems at an atomic level of detail. Fundamentally, MD solves Newton's equations of motion for a system of interacting atoms, tracing their trajectories over time to reveal dynamic processes that are often inaccessible to experimental observation. This "computational microscope" has become indispensable across numerous fields, particularly in drug discovery and materials science, where it provides insights into molecular mechanisms, binding interactions, and thermodynamic properties. The power of MD lies in its foundation in statistical mechanics, which bridges the gap between atomic-level simulations and macroscopic observables, allowing researchers to predict system behavior and properties from first principles. As computational resources have expanded and algorithms have matured, MD has evolved from studying small proteins in vacuum to simulating complex biological machines in physiologically realistic environments, making it an essential tool for researchers seeking to understand and design molecular systems.

Theoretical Foundations: From Newton to Statistical Mechanics

The theoretical framework of molecular dynamics rests upon established physical principles that connect microscopic behavior to macroscopic observables. At its core, MD utilizes classical mechanics to describe atomic motion, though modern implementations often incorporate elements from quantum mechanics and statistical physics to enhance accuracy and interpretation.

Fundamental Equations of Motion

The molecular dynamics approach is fundamentally built upon Newton's second law of motion, expressed as Fᵢ = mᵢaᵢ, where Fᵢ is the force acting on atom i, mᵢ is its mass, and aᵢ is its acceleration. This differential equation is solved numerically for all atoms in the system through finite difference methods, with the force calculated as the negative gradient of the potential energy function: Fᵢ = -∇ᵢU. The potential energy function U, known as the force field, mathematically describes the dependence of energy on nuclear positions and comprises both bonded and non-bonded interaction terms [1] [2].

The integration of Newton's equations proceeds through small, discrete time steps (typically 1-2 femtoseconds), with each step calculating new positions and velocities for all atoms. This iterative process generates a trajectory - a chronological series of atomic positions that documents the system's evolution through phase space. From these trajectories, macroscopic properties are calculated using the principles of statistical mechanics, which establish that the time average of a molecular property equals its ensemble average (the ergodic hypothesis) [2].

Force Field Components

The mathematical representation of interatomic interactions is encapsulated in the force field, which typically includes these components:

- Bonded interactions: Chemical bonds are treated as harmonic springs (Ebond = kb(r - r₀)²), with similar harmonic terms for bond angles (Eangle = kθ(θ - θ₀)²) and dihedral angles (Edihedral = kφ(1 + cos(nφ - δ)) that describe torsional rotations around bonds.

- Non-bonded interactions: These include van der Waals forces, typically modeled with a Lennard-Jones potential (ELJ = 4ε[(σ/r)¹² - (σ/r)⁶]), and electrostatic interactions described by Coulomb's law (Eelec = (qᵢqⱼ)/(4πε₀r)).

The parameters for these functions (force constants, equilibrium values, partial charges, etc.) are derived from both experimental data and high-level quantum mechanical calculations, with different force fields (CHARMM, AMBER, GROMOS) optimized for specific classes of biomolecules [3] [2].

Table 1: Core Components of a Molecular Mechanics Force Field

| Interaction Type | Mathematical Form | Physical Description | Parameters Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | Ebond = kb(r - r₀)² | Energy required to stretch/bond from equilibrium length | k_b (force constant), r₀ (equilibrium bond length) |

| Angle Bending | Eangle = kθ(θ - θ₀)² | Energy required to bend bond angle from equilibrium | k_θ (force constant), θ₀ (equilibrium angle) |

| Torsional Rotation | Edihedral = kφ(1 + cos(nφ - δ)) | Energy barrier for rotation around a bond | k_φ (barrier height), n (periodicity), δ (phase angle) |

| van der Waals | E_LJ = 4ε[(σ/r)¹² - (σ/r)⁶] | Short-range repulsion and London dispersion attraction | ε (well depth), σ (collision diameter) |

| Electrostatics | E_elec = (qᵢqⱼ)/(4πε₀r) | Coulombic interaction between charged atoms | qᵢ, qⱼ (partial atomic charges) |

Statistical Mechanics Foundation

The connection between MD trajectories and thermodynamic observables is established through statistical mechanics. The microscopic states sampled during a simulation are used to calculate macroscopic properties through ensemble averages. For instance, the temperature of the system is calculated from the average kinetic energy (⟨∑(1/2)mᵢvᵢ²⟩ = (3/2)Nk_BT), while free energy differences - crucial for understanding binding affinities and conformational changes - can be determined through specialized methods such as free energy perturbation or umbrella sampling [3].

This theoretical foundation enables MD to serve as a computational bridge between the atomic world and experimentally measurable quantities, providing a powerful framework for predicting system behavior and interpreting experimental results.

Methodological Framework: A Practical Implementation Guide

The successful execution of a molecular dynamics simulation requires careful attention to multiple preparatory and analytical steps. The general workflow proceeds through system setup, energy minimization, equilibration, production dynamics, and trajectory analysis, with each stage serving a distinct purpose in ensuring physical relevance and numerical stability.

System Setup and Preparation

The initial stage involves constructing a biologically relevant simulation environment starting from an atomic structure:

- Structure Preparation: Molecular dynamics simulations begin with obtaining atomic coordinates, typically from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The structure must be processed to add missing hydrogen atoms, assign protonation states to ionizable residues, and handle any missing loops or residues. Tools like

pdb2gmxin GROMACS convert PDB files to MD-ready formats while assigning force field parameters [2]. - Solvation and Ionization: The protein is placed in a simulation box surrounded by explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P, SPC models) using commands like

solvate. The system is then neutralized by adding counterions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) viagenionto mimic physiological ionic strength, replacing solvent molecules at optimal positions [2]. - Periodic Boundary Conditions: To eliminate edge effects and simulate a continuous environment, periodic boundary conditions (PBC) are applied. The simulation box (typically cubic, dodecahedral, or octahedral) is replicated infinitely in all directions, with particles exiting one side re-entering the opposite side [2].

Energy Minimization and Equilibration

Before production dynamics, the system must be relaxed to remove steric clashes and unfavorable interactions:

- Energy Minimization: Using algorithms like steepest descent or conjugate gradient, the system's potential energy is minimized to achieve a stable starting configuration. This step resolves atomic overlaps that would cause numerically unstable forces during dynamics [2].

- System Equilibration: The minimized system is gradually brought to the target temperature and pressure through a series of controlled simulations. Typically, the system is first equilibrated with position restraints on heavy atoms (NVT ensemble) to allow solvent relaxation, followed by unrestrained equilibration (NPT ensemble) to achieve correct density [2].

Production Dynamics and Analysis

The equilibrated system then proceeds to production simulation, where trajectory data is collected for analysis:

- Integration Algorithms: Equations of motion are solved using numerical integrators such as the leap-frog algorithm or Velocity Verlet, which update positions and velocities at discrete time steps while conserving energy [2].

- Temperature and Pressure Control: Thermostats (e.g., Nosé-Hoover, velocity rescaling) and barostats (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) maintain constant temperature and pressure by adjusting velocities and box dimensions [2].

- Trajectory Analysis: The saved trajectory is analyzed to extract biologically relevant information, including root mean square deviation (RMSD) for structural stability, root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) for residue flexibility, radius of gyration for compactness, and hydrogen bonding patterns for interaction networks [2].

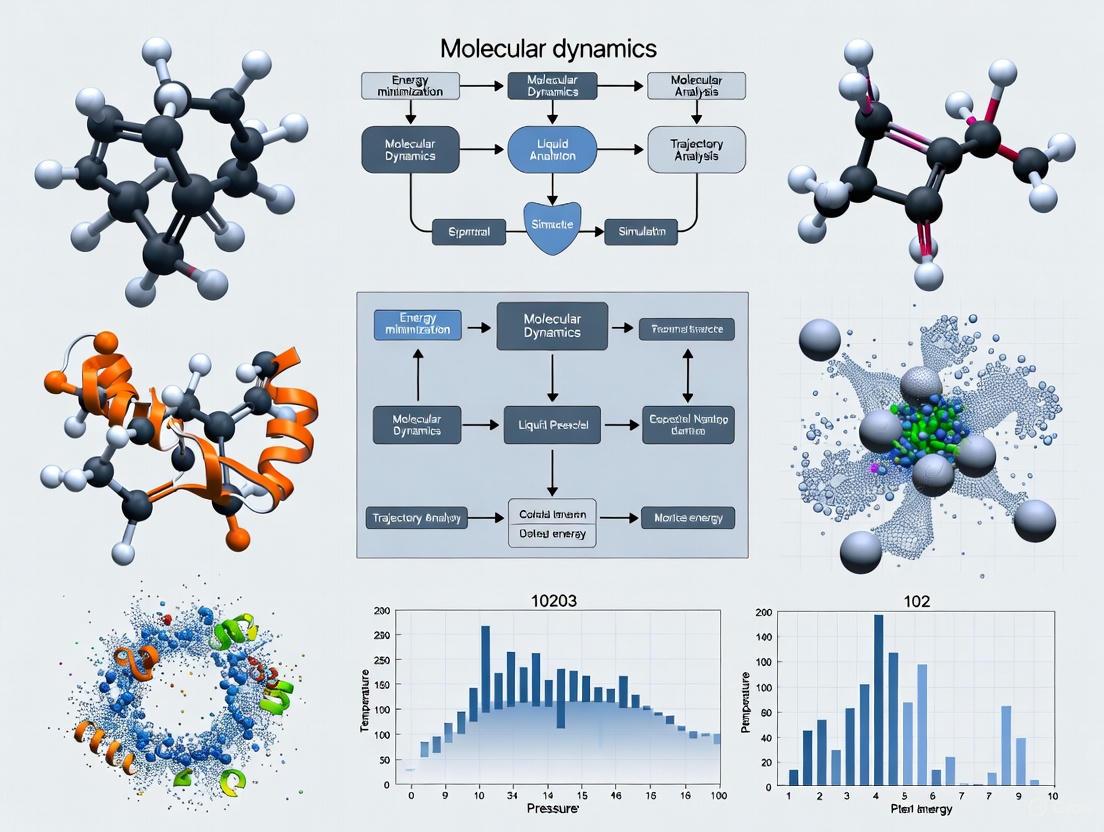

Diagram 1: MD simulation workflow

Research Applications: From Molecular Design to Chemical Kinetics

Molecular dynamics simulations have become indispensable across numerous scientific domains, providing atomic-level insights that complement experimental approaches. The applications span drug discovery, materials science, and chemical kinetics, with each field leveraging MD's unique capability to resolve temporal processes and molecular interactions.

Biomolecular Simulations and Drug Discovery

In pharmaceutical research, MD simulations provide critical insights for structure-based drug design:

- Protein-Ligand Binding: MD reveals the dynamic process of ligand binding to biological targets, capturing induced fit conformational changes and calculating binding free energies through methods like free energy perturbation (FEP) and thermodynamic integration (TI). BIOVIA Discovery Studio implements these approaches for lead optimization in drug discovery programs [3].

- Allosteric Mechanism Elucidation: Long-timescale simulations can identify allosteric networks and cryptic binding pockets that are not evident in static crystal structures, providing opportunities for novel therapeutic intervention strategies [3].

- Antibody Design: MD facilitates the design and screening of antibody libraries by predicting stability and binding characteristics, accelerating the development of biologic therapeutics [4].

The OpenEye software platform demonstrates the industrial application of these methods, using physics-based design for hit identification, hit-to-lead optimization, and affinity predictions through advanced MD simulations [4].

Enhanced Sampling and Free Energy Calculations

Conventional MD faces limitations in sampling rare events due to the short timescales accessible to simulation. Enhanced sampling methods address this challenge:

- Gaussian Accelerated MD (GaMD): This method adds a harmonic boost potential to smooth the energy landscape, enabling simultaneous unconstrained enhanced sampling and free energy calculations without predefined reaction coordinates. BIOVIA Discovery Studio has implemented GaMD for studying complex biomolecular processes [3].

- Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD): By applying external forces, SMD accelerates processes like ligand unbinding, allowing estimation of binding free energies and identification of dissociation pathways [3].

- Multi-Site Lambda Dynamics (MSLD): This approach efficiently calculates relative binding free energies for combinatorial libraries of ligands, significantly accelerating lead optimization in drug discovery [3].

Reactive MD and Chemical Kinetics

Beyond biomolecular applications, MD provides insights into chemical reactivity and reaction networks:

- Combustion Chemistry: The recently developed ChemXDyn framework represents a significant advancement for analyzing reactive MD simulations in combustion systems. This dynamics-aware methodology integrates temporal interatomic distance analysis with valence and coordination consistency to reliably detect bond formation, dissociation, and molecular connectivity [5].

- Kinetic Parameter Extraction: ChemXDyn overcomes limitations of traditional frame-by-frame analysis methods (e.g., ChemTraYzer, ReacNetGenerator) that often misinterpret vibrational fluctuations as chemical events. It enables reliable extraction of rate constants from MD trajectories, as demonstrated in hydrogen oxidation systems where it corrected key reactions in established combustion mechanisms [5].

- Nonequilibrium Chemistry: MD simulations can probe systems under vibrational nonequilibrium conditions, revealing how mode-specific excitation reshapes radical chemistry and accelerates processes like ignition [5].

Table 2: Key Software Platforms for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Software Platform | Specialized Capabilities | Noteworthy Features | Application Domains |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | High-performance MD, Free energy calculations | Open-source, Extensive analysis tools, GPU acceleration | Academic research, Biomolecular simulations [2] |

| BIOVIA Discovery Studio | CHARMm, NAMD, GaMD | GUI-driven workflow, Comprehensive molecular design | Pharmaceutical drug discovery [3] |

| OpenEye Applications | Virtual screening, Free energy predictions | High-throughput molecular docking, Cloud-native | Drug discovery, Formulations [4] |

| Schrödinger Platform | Desmond MD, FEP, QM/MM | Integrated drug discovery platform, Machine learning | Therapeutics development, Materials science [6] |

| ChemXDyn | Reactive MD analysis, Kinetic parameter extraction | Dynamics-aware species identification, Combustion chemistry | Chemical kinetics, Combustion research [5] |

Advanced Techniques and Future Directions

As molecular dynamics continues to evolve, several cutting-edge methodologies and emerging trends are expanding its capabilities and applications. These advancements address fundamental challenges in sampling, accuracy, and scalability while opening new frontiers in molecular design and prediction.

Multiscale and Hybrid Approaches

No single computational method can efficiently address all aspects of complex molecular systems, leading to the development of multiscale strategies:

- QM/MM Methods: Quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics approaches combine the accuracy of quantum chemical calculations for the reactive region with the efficiency of molecular mechanics for the environment. DMol3/CHARMm implementations in Discovery Studio enable these hybrid simulations for studying chemical reactions in biological systems [3].

- Machine Learning Potentials: Neural network potentials trained on quantum mechanical data are revolutionizing MD by enabling ab initio level accuracy at classical MD costs. ChemXDyn has demonstrated applications to methane oxidation using machine-learned potentials, successfully reconstructing the complete CH₄ → CO₂ oxidation sequence [5].

- Markov State Models: These approaches combine many short MD simulations to construct kinetic networks that describe slow conformational processes, effectively extending the accessible timescales for studying biomolecular dynamics [7].

Machine Learning Integration

The integration of machine learning with molecular dynamics represents one of the most promising frontiers in computational molecular design:

- Enhanced Sampling: ML approaches can identify collective variables and develop biasing potentials to accelerate sampling of rare events, addressing timescale limitations in conventional MD [1].

- Analysis Automation: Unsupervised learning methods can automatically identify metastable states and conformational clusters from high-dimensional trajectory data, replacing laborious manual analysis [1] [7].

- Property Prediction: Neural networks can learn structure-property relationships from MD data, enabling rapid prediction of molecular characteristics without explicit simulation [1].

Future Research Directions

The field of molecular dynamics is rapidly advancing toward several key objectives that will expand its capabilities and applications:

- Multiscale Simulation Methodologies: Future research will focus on developing robust frameworks that seamlessly connect electronic, atomic, mesoscopic, and continuum scales for comprehensive system modeling [1].

- High-Performance Computing: Exploiting emerging computing architectures, including exascale systems and specialized hardware, will enable longer timescales and larger systems [1] [4].

- Experimental-Simulation Integration: Developing systematic approaches for combining experimental data (e.g., from smFRET, cryo-EM) with simulation results will enhance validation and provide a more complete understanding of molecular systems [7].

- Environmental Impact Assessment: MD will increasingly be applied to assess the environmental impact of chemicals and polymers, fostering the development of sustainable technologies [1].

Diagram 2: MD conceptual framework

Successful molecular dynamics simulations require both specialized software tools and carefully parameterized molecular components. This toolkit encompasses the essential resources researchers employ to set up, execute, and analyze MD simulations across various application domains.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | CHARMM36, AMBER, GROMOS, CGenFF | Define potential energy functions and parameters for different molecule types | Selection depends on system composition; CGenFF specialized for drug-like molecules [3] [2] |

| Solvation Models | TIP3P, SPC, implicit solvent | Represent aqueous environment around solutes; balance accuracy vs. computational cost | Explicit water more accurate but computationally demanding; implicit solvent faster for screening [2] |

| Ion Parameters | Sodium, chloride, potassium, calcium | Neutralize system charge; mimic physiological ion concentrations | Parameters must match chosen force field for consistency [2] |

| Lipid Membranes | POPC, DPPC, membrane builder tools | Model membrane environments for transmembrane proteins | Specialized setup required for membrane-protein systems [3] |

| Software Suites | GROMACS, NAMD, CHARMm, Desmond | MD simulation engines with varying algorithms and capabilities | GROMACS popular in academia; commercial suites offer GUI workflows [3] [2] |

| Analysis Tools | MDTraj, VMD, ChemXDyn, custom scripts | Extract biologically relevant information from trajectory data | ChemXDyn specialized for reactive MD in combustion chemistry [5] |

| Enhanced Sampling | GaMD, FEP, MSLD, metadynamics | Accelerate rare events; improve conformational sampling | GaMD implemented in Discovery Studio for unconstrained enhanced sampling [3] |

Molecular dynamics simulation has matured into an indispensable methodology that bridges theoretical physics with practical applications in drug discovery, materials science, and chemical engineering. From its foundation in Newton's equations of motion, MD has evolved to incorporate statistical mechanics, quantum chemistry, and increasingly, machine learning approaches. The technique continues to advance through developments in multiscale modeling, enhanced sampling algorithms, and high-performance computing, progressively expanding the temporal and spatial scales accessible to simulation. As MD frameworks like ChemXDyn demonstrate the extraction of chemically accurate kinetics from atomistic simulations [5], and platforms from OpenEye and Schrödinger enable the screening of billions of molecules [4] [6], the impact on molecular design continues to grow. By providing atomic-level insights into dynamic processes that remain challenging for experimental observation, molecular dynamics serves as a computational microscope that will undoubtedly continue to drive innovation across scientific disciplines, from developing sustainable energy solutions to designing novel therapeutics.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has undergone a profound evolution, transforming from a theoretical tool for studying simple gases into an indispensable method for modeling the complex molecular machinery of life. This article traces the technical journey of MD, detailing its foundational principles, key methodological advancements, and its critical role in modern research, particularly in drug development and structural biology.

The Foundational Journey: From Atoms to Cells

The genesis of molecular dynamics simulation dates back to the late 1950s, with the first simulations focused on the behavior of simple gases [8]. These early studies provided proof-of-concept that the physical movements of atoms and molecules could be predicted using computational algorithms based on Newtonian mechanics [9]. A significant milestone was reached in the late 1970s with the first MD simulation of a protein, marking the technique's entry into the biological sciences [8]. The foundational work enabling these simulations was later recognized by the 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry [8].

For decades, performing biologically meaningful simulations required supercomputing resources, limiting their accessibility. A major shift occurred with the adoption of Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) for molecular computing, which allowed powerful simulations to be run locally at a modest cost, dramatically broadening the tool's user base [8]. This increased accessibility coincided with an explosion in experimental structural data for complex biological targets, such as membrane proteins, providing high-quality starting points for simulations and solidifying MD's role as a bridge between static structural snapshots and dynamic biological mechanism [10] [8].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Molecular Dynamics

| Time Period | Simulation Focus | Typical System Size & Timescale | Key Hardware & Software Advancements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Late 1950s [8] | Simple Gases [8] | Dozens of atoms; Nanoseconds | Basic computational algorithms |

| Late 1970s [8] | First Protein [8] | Thousands of atoms; Picoseconds to Nanoseconds | Supercomputing resources |

| Early 2000s | Biomolecules in Solvent | Hundreds of thousands of atoms; Nanoseconds | Improved force fields; Particle Mesh Ewald method [10] |

| ~2010s Onward [8] | Complex Cellular Environments (e.g., proteins in membranes) [8] | Millions of atoms; Microseconds to Milliseconds | GPU computing [8]; Specialized hardware (e.g., Anton) [8] |

Methodological Foundations and Protocols

At its core, an MD simulation predicts the trajectory of every atom in a system over time. The process begins with an initial atomic-level structure, often derived from X-ray crystallography, NMR, or cryo-EM [8]. The fundamental procedure involves calculating the force on each atom based on a molecular mechanics force field and then using Newton's laws of motion to update the atom's position and velocity. This process is repeated for millions or billions of time steps, each typically a few femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ seconds), to capture biochemical events [8].

Explicit Solvent MD Protocol using AMBER

A common protocol for simulating RNA nanostructures or other biomolecules using the AMBER MD package involves several key stages [10]:

- System Preparation: The target structure (e.g., an RNA duplex) is placed in a box of explicit water molecules, with ions added to neutralize the system's charge and mimic physiological ionic strength.

- Energy Minimization: The system undergoes energy minimization to remove any steric clashes introduced during the solvation process, resulting in a stable starting configuration.

- System Equilibration: A two-phase equilibration is performed:

- The system is heated to the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) while applying positional restraints on the solute atoms, allowing the solvent to relax around the structure.

- Restraints are gradually released, and the system density is adjusted under constant pressure (NPT ensemble) conditions to achieve a stable, equilibrated system [10].

- Production Simulation: Unrestrained MD is run for the desired timescale, generating the trajectory data used for subsequent analysis. Long-range electrostatic interactions are typically handled using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method [10].

- Post-Simulation Analysis: The trajectory is analyzed to characterize dynamics, using methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify major motions, or MM-PB(GB)SA to estimate binding free energies [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful MD simulations rely on a suite of software, hardware, and analytical tools.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Molecular Dynamics

| Item/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | Provides the mathematical model for interatomic forces, governing simulation accuracy. | AMBER force fields for nucleic acids [10]; Continuous refinement based on quantum chemical calculations [10]. |

| MD Software Packages | The core engine that performs the simulation calculations. | AMBER [10], NAMD [10], GROMACS [10], CHARMM [10]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Provides the computational power required for simulating large systems over long timescales. | GPU clusters [8]; Specialized hardware (e.g., Anton) [8]. |

| Visualization & Analysis Tools | Enables researchers to view trajectories, measure distances, angles, and perform quantitative analysis. | VMD, PyMOL; Integrated with packages like AMBER for analysis [10]. |

| Solvation Models | Mimics the aqueous or membrane environment of a biomolecule. | TIP3P water model (explicit solvent); Generalized Born (implicit solvent) [10]. |

Diagram 1: MD Simulation Workflow

Research Applications: From Drug Design to Cellular Mechanics

MD simulations provide a detailed, time-resolved perspective that is often difficult or impossible to obtain through experiments alone [8]. Their applications span a wide range of biomedical research.

Drug Discovery and Design

In pharmaceutical research, MD simulations are used to identify how potential drug molecules interact with their target proteins, such as G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and ion channels [8]. Simulations reveal critical details about binding affinities, conformational changes induced upon ligand binding, and the stability of the complex over time [9]. This allows for the refinement of drug compounds before costly laboratory testing, increasing virtual screening hit rates and reducing failure rates in clinical trials [9].

Protein Folding and Misfolding

Understanding how proteins fold into their functional three-dimensional structures is a central problem in biology. MD simulations can reveal folding pathways, stability, and interactions with other molecules [8]. This knowledge is crucial for identifying disease mechanisms, such as those involving misfolded proteins linked to neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer's disease [8].

RNA Nanostructure and Nanotechnology

In the field of nanotechnology, MD simulations are used to fix steric clashes in computationally designed RNA nanostructures, characterize their dynamics, and investigate interactions with delivery agents and membranes [10]. Simulations have been instrumental in studying the self-stabilization phenomena of RNA rings and in coarse-graining approaches to model larger nanostructures [10].

Chemical Reaction and Enzyme Catalysis Modeling

For processes involving changes to covalent bonds, more advanced simulation techniques are employed. Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) simulations model a small, reactive part of the system with quantum mechanics while treating the surroundings with molecular mechanics [8]. This allows researchers to study chemical reaction mechanisms, optimize catalysts, and elucidate the dynamics of enzyme-substrate interactions, informing the design of more efficient biocatalysts [11].

Diagram 2: Key Research Applications

The trajectory of MD simulation points toward a future of increased power and accessibility. By 2025, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning is expected to enhance predictive accuracy and speed, potentially enabling real-time simulations [9]. Cloud computing will further reduce hardware barriers, allowing more research groups to leverage this technology [9]. Emerging trends also point toward increased integration with experimental data, more user-friendly interfaces, and broader adoption in personalized medicine and sustainable technology development [9]. As MD simulations continue to evolve from modeling simple gases to capturing the complexity of entire cellular environments, they will remain a cornerstone tool for unraveling the mysteries of biological function and driving innovation in drug development.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has become an indispensable tool in computational chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery, providing atomic-level insights into the dynamic behavior of biological and chemical systems over time. By numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for all atoms in a system, MD simulations reveal structural changes, binding processes, and functional mechanisms that are difficult or impossible to observe experimentally [12] [13]. The integration of MD with machine learning approaches and advanced hardware acceleration has recently expanded its applications, enabling researchers to study increasingly complex systems with greater accuracy and efficiency [14] [12]. In pharmaceutical research specifically, MD simulations help overcome the limitations of static structure-based drug design by accounting for full protein flexibility and capturing pharmacologically relevant conformational changes that impact drug binding [15] [12].

Fundamental Principles of Molecular Dynamics

At its core, molecular dynamics simulation computes the temporal evolution of a molecular system by calculating the forces acting on each atom and updating their positions accordingly. The global MD algorithm implemented in packages like GROMACS follows a consistent workflow [13]:

- Input initial conditions including potential interactions, atomic positions, and velocities

- Compute forces on atoms based on the potential energy function

- Update configuration by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion

- Output step writing positions, velocities, energies, and other properties at specified intervals

The force calculation represents the most computationally intensive step, requiring evaluation of both bonded interactions (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals, electrostatic) between atoms [13]. Modern MD implementations employ sophisticated neighbor-searching algorithms with buffered pair lists that are updated periodically to efficiently handle these calculations, particularly for large systems [13].

Step-by-Step Molecular Dynamics Workflow

System Preparation and Building

The initial step in any MD simulation involves constructing the atomic system that will be simulated. For drug discovery applications, this typically begins with obtaining a protein structure from experimental sources like the Protein Data Bank or predicted models from AlphaFold, which has provided over 214 million unique protein structures [15]. The BuildSystem functionality in MD packages enables automated construction of simulation systems either as a sphere (for nanoreactor simulations) or a cubic box (for periodic boundary conditions) [16]. Key parameters include:

- System Composition: Defined through molecule blocks containing SMILES strings or system references with respective mole fractions

- Density: Typically ~1.0 g/cm³ for aqueous biological systems

- Number of Atoms: Often set to ~200 atoms for efficient sampling, adjustable based on system complexity and computational resources [16]

This stage may include adding solvent molecules, ions, and other cofactors to create a biologically relevant environment, potentially using tools like PackMol [16] [17].

Force Field Selection and Parameterization

The choice of force field fundamentally influences simulation accuracy, as it determines how potential energies and atomic forces are calculated. Force fields approximate atomic interactions using mathematical functions with empirically derived parameters [12]. Popular force fields include CHARMM, AMBER, and GROMOS, each with specific strengths for different biomolecular systems [18] [17]. The GROMOS 54a7 force field, for instance, was used in a recent drug solubility study to model neutral conformations of drug molecules [18]. Emerging approaches integrate machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) trained on quantum mechanical calculations to enhance accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency [14] [12].

Energy Minimization and Equilibration

Before production MD, systems must undergo energy minimization to remove steric clashes and bad contacts, followed by equilibration to stabilize temperature and pressure. A short 250 fs equilibration simulation is often sufficient for packmol-generated structures [16]. Equilibration typically employs:

- Thermostats: Berendsen or Nosé-Hoover algorithms to maintain target temperature

- Barostats: Parrinello-Rahman method for pressure control

- Ensembles: NVT (constant Number, Volume, Temperature) followed by NPT (constant Number, Pressure, Temperature) to achieve experimental conditions [19]

This step ensures the system has reached appropriate thermodynamic conditions before data collection begins.

Production Simulation

Production MD involves running the fully parameterized and equilibrated system for extended timescales to collect statistical data on structural and dynamic properties. Integration algorithms like Verlet (particularly the leap-frog variant) numerically solve equations of motion with typical timesteps of 0.5-2.0 fs, constrained by the fastest vibrational frequencies (typically C-H bonds) [16] [19]. Critical considerations include:

- Simulation Length: Determined by the biological processes of interest

- Frame Saving Frequency: Often 10-100 fs intervals, balancing resolution and storage requirements

- Number of Replicas: Multiple simulations (recommended: 4+) improve statistical significance [16]

Advanced methods like accelerated MD apply boost potentials to smooth energy landscapes, enhancing conformational sampling [15]. Specialized non-equilibrium methods like the Nanoreactor and Lattice Deformation actively promote chemical reactions through compression-expansion cycles, useful for reaction discovery [16].

Analysis and Trajectory Processing

The final workflow stage involves extracting biologically or chemically relevant information from simulation trajectories. Modern analysis encompasses both traditional and machine-learning enhanced approaches:

- Structural Metrics: Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Radius of Gyration, Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA)

- Dynamic Properties: Hydrogen bonding, coordination numbers, distance fluctuations

- Energetics: Binding free energies via MM/GB(PB)SA or alchemical methods

- Machine Learning: Automated detection of states and transitions [18] [12] [17]

For drug solubility studies, key analyes include Coulombic and Lennard-Jones interaction energies between solutes and water, SASA, and solvation shell properties, which can be used as features in machine learning models [18].

Advanced MD Applications in Drug Discovery

Ensemble Docking and the Relaxed Complex Method

The Relaxed Complex Method addresses a fundamental limitation of traditional docking by incorporating protein flexibility through MD-generated conformational ensembles [15]. This approach involves:

- Running MD simulations of the target protein

- Clustering trajectories to identify representative conformations

- Docking compound libraries against multiple structural snapshots

- Ranking compounds using ensemble-average or ensemble-best scores

This method effectively captures cryptic pockets that appear during dynamics but are absent in crystal structures, significantly expanding druggable target space [15]. An early application successfully identified the first FDA-approved inhibitor of HIV integrase by revealing flexibility in the active site region that informed drug design [15].

Binding Free Energy Calculations

MD simulations provide the foundation for rigorous binding free energy calculations through either MM/GB(PB)SA methods or more computationally intensive alchemical approaches like free energy perturbation (FEP) [12]. These methods:

- Estimate binding affinities by calculating energy differences between bound and unbound states

- Account for solvation effects and entropy contributions

- Can prioritize compounds for synthesis and testing

Machine learning enhances these approaches by guiding simulation-frame selection, refining energy term calculations, and reducing required sampling [12]. AlphaFold-predicted models now provide sufficiently accurate structures for FEP calculations, expanding applications to targets without experimental structures [12].

Machine Learning-Enhanced Workflows

Integration of machine learning with MD simulations has created powerful synergies for drug discovery. A recent TGR5 agonist study demonstrated a comprehensive workflow combining Random Forest classification with MD simulations to identify potential type 2 diabetes treatments [20]. Similarly, ML analysis of MD-derived properties (SASA, Coulombic interactions, LJ energies, DGSolv, RMSD) achieved accurate prediction of drug solubility (R²=0.87) using Gradient Boosting algorithms [18]. These integrations allow researchers to:

- Screen ultra-large chemical libraries (billions of compounds) efficiently

- Extract meaningful patterns from high-dimensional MD data

- Predict complex physicochemical properties from simulation trajectories

- Focus experimental resources on most promising candidates [18] [20]

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Nanoreactor Simulations for Reaction Discovery

The Nanoreactor method implements special non-equilibrium MD to promote chemical reactions through compression-expansion cycles [16]:

Protocol Setup:

- Set

MolecularDynamics%Type = NanoReactor - Define cycle parameters:

NumCycles(default: 10),DiffusionTime(default: 250 fs),Temperature(default: 500 K) - Specify compression intensity:

MinVolumeFraction(default: 0.6)

Execution Phases:

- Pre-compression: 25 fs, volume fraction 1.05, thermostat 250 K

- Compression: 25 fs, minimum volume fraction, thermostat 250 K

- Post-compression: 100 fs, volume fraction 1.05, thermostat 250 K

- Diffusion: DiffusionTime, Temperature setting

The radius during each phase is calculated as: r_nanoreactor = (volume fraction)^1/3 × InitialRadius [16]

Solubility Prediction Workflow

The ML-driven solubility analysis protocol demonstrates how MD properties can predict pharmaceutical relevant properties [18]:

System Preparation:

- Conduct MD simulations in NPT ensemble using GROMACS

- Employ GROMOS 54a7 force field

- Use cubic simulation box with appropriate dimensions

- Neutralize system with counterions if needed

Property Extraction:

- Calculate SASA (Solvent Accessible Surface Area)

- Compute Coulombic and Lennard-Jones interaction energies (Coulombic_t, LJ)

- Determine Estimated Solvation Free Energies (DGSolv)

- Extract RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation)

- Calculate Average number of solvents in Solvation Shell (AvgShell)

- Incorporate experimental logP values

Machine Learning Implementation:

- Split dataset: 80% training, 20% validation

- Test multiple algorithms: Random Forest, Extra Trees, XGBoost, Gradient Boosting

- Evaluate using R² and RMSE metrics

- Identify most predictive features through feature importance analysis [18]

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) Protocol

Alchemical methods like FEP provide rigorous binding free energy estimates [12]:

System Setup:

- Prepare protein-ligand complex structure

- Solvate with explicit water molecules

- Add ions to physiological concentration

Simulation Parameters:

- Run equilibration with position restraints on heavy atoms

- Use 2 fs timestep with bonds to hydrogen constrained

- Maintain temperature with Nosé-Hoover thermostat (298 K)

- Control pressure with Parrinello-Rahman barostat (1 atm)

FEP Specifics:

- Define λ values for alchemical transformation (typically 12-16 windows)

- Run each window for sufficient equilibration and production

- Use overlap sampling methods to ensure proper phase space coverage

- Analyze using MBAR or TI methods for free energy estimation [12]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 1: Essential Software Tools for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Engine | High-performance MD simulations | Production simulations with excellent performance [18] [13] |

| AMBER | MD Engine | Biomolecular simulations | Force field development and drug binding studies [17] |

| OpenMM | MD Engine | GPU-accelerated MD | Rapid sampling and algorithm development [17] |

| LAMMPS | MD Engine | Materials simulation | Nanoreactor and materials properties [21] [14] |

| CHARMM | Force Field | Biomolecular force field | Protein-ligand interaction studies [17] |

| GROMOS | Force Field | Biomolecular force field | Drug solubility and solvation studies [18] |

| PackMol | System Building | Initial system construction | Solvation and mixture preparation [16] [17] |

| MDTraj | Analysis | Trajectory analysis | RMSD, SASA, and geometric calculations [17] |

| DeePMD | ML Potential | Machine learning force fields | Accurate quantum-mechanical properties [21] [14] |

| ML-IAP-Kokkos | Interface | ML potential integration | Connecting PyTorch models with LAMMPS [14] |

Table 2: Key MD-Derived Properties for Drug Solubility Prediction

| Property | Description | Computational Method | Predictive Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| SASA | Solvent Accessible Surface Area | Geometric calculation from trajectory | High - measures solvent exposure [18] |

| Coulombic_t | Coulombic interaction energy | Non-bonded energy calculation | High - electrostatic interactions with solvent [18] |

| LJ | Lennard-Jones interaction energy | Non-bonded energy calculation | High - van der Waals interactions [18] |

| DGSolv | Estimated Solvation Free Energy | Free energy calculations | Medium - thermodynamic driving force [18] |

| RMSD | Root Mean Square Deviation | Structural alignment and comparison | Medium - conformational stability [18] |

| AvgShell | Average solvents in Solvation Shell | Radial distribution analysis | Medium - local solvation environment [18] |

| logP | Octanol-water partition coefficient | Experimental or predicted | Very High - established solubility correlate [18] |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of molecular dynamics continues to evolve rapidly, with several trends shaping its future research applications. Automated workflow systems like MDCrow leverage large language models to streamline simulation setup, execution, and analysis, making MD more accessible to non-specialists [17]. Specialized hardware including GPUs, ASICs, and FPGAs dramatically accelerate calculations, enabling millisecond-scale simulations of complex biological processes [12]. The integration of AlphaFold-predicted structures with MD simulations addresses initial model limitations by correcting side chain placements and generating conformational ensembles [15] [12]. Multi-scale simulations now routinely handle systems with 100+ million atoms, providing realistic subcellular environments that capture macromolecular crowding effects [12]. Finally, AI-driven approaches like DeePMD and ML-IAP-Kokkos combine the accuracy of quantum mechanics with the speed of classical simulations, particularly for modeling chemical reactions and complex materials [21] [14].

These advancements collectively enhance the role of MD simulations as a bridge between static structural information and dynamic biological function, solidifying their position as essential tools in modern drug discovery and materials research. As simulations continue to increase in temporal and spatial scale while improving in accuracy, they will provide increasingly insightful predictions to guide experimental research across the chemical and biological sciences.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a computational method that analyzes the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time [22]. By predicting the trajectory of every atom in a system, MD simulations provide atomic-level insight into biomolecular processes—such as conformational change, ligand binding, and protein folding—that are critical for research in drug discovery, neuroscience, and structural biology [8]. This technical guide details the core components that enable these simulations: the force fields that define potential energy, and the integration algorithms that solve the equations of motion.

Force Fields: The Mathematical Heart of Molecular Dynamics

In MD, a force field refers to the combination of a mathematical formula and associated parameters that describe the potential energy of a molecular system as a function of its atomic coordinates [23]. Force fields are built on the molecular mechanics approach, which uses classical physics to approximate the energy landscape, thereby making simulations of large biomolecules computationally feasible.

The total potential energy of a system is typically calculated as the sum of several bonded and non-bonded interaction terms [8] [24]:

[ E{\text{total}} = E{\text{bond}} + E{\text{angle}} + E{\text{torsion}} + E{\text{electrostatic}} + E{\text{van der Waals}} ]

The following table summarizes these key components of a standard molecular mechanics force field.

Table 1: Core Components of a Molecular Mechanics Force Field

| Energy Term | Mathematical Form (Representative) | Description | Physical Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | $E{\text{bond}} = \sum{\text{bonds}} kb (r - r0)^2$ | Energy required to stretch or compress a covalent bond from its equilibrium length. | Treats bonds as harmonic springs. |

| Angle Bending | $E{\text{angle}} = \sum{\text{angles}} k{\theta} (\theta - \theta0)^2$ | Energy required to bend the angle between three bonded atoms from its equilibrium value. | Treats bond angles as harmonic springs. |

| Torsional Dihedral | $E{\text{torsion}} = \sum{\text{dihedrals}} \frac{V_n}{2} [1 + \cos(n\phi - \gamma)]$ | Energy associated with rotation around a central bond, defining the conformational preferences of the molecule. | Models the periodicity of rotational barriers. |

| Van der Waals | $E{\text{vdW}} = \sum{i |

Models short-range repulsion and long-range dispersion (London) forces between non-bonded atoms. | Typically uses the Lennard-Jones potential [22]. |

| Electrostatic | $E{\text{elec}} = \sum{i |

Models the Coulombic attraction or repulsion between partial atomic charges. | Critical for simulating hydrogen bonding, salt bridges, and solvation effects [22]. |

Several widely used biomolecular force fields have been developed, each with specific parameterization protocols and target applications. The choice of force field is a critical decision in simulation design.

Table 2: Comparison of Widely Used Protein Force Fields

| Force Field | Functional Form & Coverage | Parameterization Philosophy | Common Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | Includes bond, angle, torsion, electrostatic (partial charges fitted to HF/6-31G* ESP), and van der Waals terms. Covers proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, carbohydrates [23]. | Parameters derived to reproduce experimental data and quantum mechanical calculations for small molecule analogs [23]. | Simulation of proteins, DNA, RNA; often used in drug discovery. |

| CHARMM | Comprehensive energy terms similar to AMBER. Includes specific parameters for lipids and carbohydrates [23]. | Empirical fitting to experimental data for crystal structures, vibrational frequencies, and liquid-state properties [23]. | Studies of membrane proteins, lipid bilayers, and biomolecular complexes. |

| GROMOS | Uses a united-atom approach (hydrogens on carbon atoms are implicit). Parameterized for consistency with thermodynamic properties [23]. | Parameterized for consistency with free enthalpies of hydration and apolar solvation, and thermodynamic properties [23]. | Efficient simulation of proteins in aqueous or non-polar solutions. |

| OPLS-AA | All-atom force field. Functional form similar to AMBER and CHARMM [23]. | Parameters optimized to reproduce experimental densities and enthalpies of vaporization for organic liquids [23]. | Protein-ligand binding, condensed-phase simulations. |

Integration Algorithms: Propagating the System Through Time

The core of an MD simulation is the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion for every atom in the system [8] [22]. The fundamental equation is F = ma, where the force F is the negative gradient of the potential energy defined by the force field (F = -∇E). Given the force on an atom, its acceleration is calculated, and its position and velocity are updated forward in time by a small timestep, typically on the order of 1-2 femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ s) [22]. The most common integration algorithm is the Verlet algorithm and its variants, such as the Leap-frog and Velocity Verlet methods [22].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of a molecular dynamics simulation, from initialization to production trajectory.

Advanced Methodologies: Implicit Solvent and Free Energy Calculations

For many research applications, such as rapid sampling or calculating binding affinities, explicit solvent models can be prohibitively expensive. Implicit solvent models, like the Poisson-Boltzmann/Surface Area (PBSA) model, offer an alternative by representing the solvent as a continuous medium rather than explicit water molecules [24].

In the MM/PBSA approach, the free energy of a solvated system is given by: [ G{\text{total}} = E{\text{MM}} + G{\text{polar}} + G{\text{non-polar}} - TS ] where ( E{\text{MM}} ) is the molecular mechanics gas-phase energy, ( G{\text{polar}} ) is the polar solvation free energy computed by solving the Poisson-Boltzmann equation, ( G_{\text{non-polar}} ) is the non-polar solvation contribution (proportional to the solvent-accessible surface area), and ( -TS ) is the entropic term [24].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Role | Example Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Biomolecular Force Fields (AMBER, CHARMM) | Provides the physics-based potential energy functions and parameters for atoms in the system [23]. | Essential for all-atom simulations of protein folding, ligand binding, and conformational changes. |

| Explicit Solvent Models (TIP3P, SPC/E) | Represents water molecules individually, capturing specific solute-solvent interactions and hydrodynamics [22]. | Studying processes where water structure is critical, such as ion permeation through channels or protein-ligand recognition. |

| Implicit Solvent Models (MM/PBSA, GB/SA) | Approximates solvent as a dielectric continuum, drastically reducing the number of particles and computation time [24]. | Rapid binding affinity calculations, protein folding studies, and long-timescale conformational sampling. |

| Specialized Hardware (GPUs, Anton) | Provides the massive computational power required to integrate millions of equations of motion for millions of time steps [8]. | Enables simulations on biologically relevant timescales (microseconds to milliseconds) for complex biomolecular processes. |

The workflow for an MM/PBSA calculation to estimate protein-ligand binding free energy, for instance, often involves running an explicit solvent MD simulation to generate conformational snapshots, which are then post-processed using the implicit solvent model.

Force fields and integration algorithms form the essential foundation of molecular dynamics simulations. The continued improvement in the accuracy of force fields and the efficiency of integration methods, coupled with advances in computational hardware, has dramatically expanded the impact of MD in molecular biology and drug discovery [8]. By providing atomic-level insight into dynamic processes that are often difficult to observe experimentally, MD serves as a powerful tool for deciphering functional mechanisms of proteins, uncovering the structural basis of disease, and aiding in the design of small molecules and therapeutics [8] [22].

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation has become an indispensable computational tool for investigating material and biological phenomena at the atomic scale. By numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for a system of atoms over time, MD allows researchers to study dynamical processes, calculate a broad range of properties, and gain insights that are often difficult or impossible to obtain experimentally [25]. This technical guide focuses on three fundamental analysis techniques in MD simulations: radial distribution functions for structural characterization, diffusion coefficients for transport properties, and stress-strain analysis for mechanical behavior.

The power of MD lies in its ability to provide atomic-level visualization and quantification of system evolution under predefined conditions such as temperature, pressure, and external forces [25]. The interactions between atoms can be calculated using various methods, from classical force fields to more sophisticated quantum mechanical approaches, depending on the system size and properties of interest [26] [25]. The resulting trajectories—series of snapshots describing system evolution in phase space—serve as the foundation for extracting meaningful physical properties through various analytical methods.

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical reference for implementing these essential analysis methods, complete with quantitative benchmarks, experimental protocols, and practical implementation tools.

Radial Distribution Functions: Analyzing Atomic-Scale Structure

The Radial Distribution Function (RDF), denoted as g(r), is a fundamental measure in statistical mechanics that describes how the density of particles varies as a function of distance from a reference particle [26]. It provides crucial insights into the structure and organization of materials at the atomic scale, revealing characteristic distances between atom types, coordination numbers, and phase identification.

Theoretical Foundation and Calculation

Mathematically, the RDF is calculated as:

[ g(r) = \frac{\langle \rho(r) \rangle}{\rho} ]

where (\rho(r)) is the local density at a distance (r) from the reference particle, and (\rho) is the average density of the system [26]. In practice, RDFs are computed from MD trajectories by counting atomic pairs within specific distance bins and normalizing by the expected number for a uniform distribution.

The RDF has profound significance in structural analysis. For crystalline materials, it exhibits sharp peaks at well-defined distances corresponding to lattice coordination shells. In liquids and amorphous systems, it typically shows a characteristic splitting of the second peak, indicating short-range order but long-range disorder. The coordination number—the number of particles within a specific cutoff distance—can be obtained by integrating the RDF up to the first minimum.

Practical Applications and Research Insights

In applied research, RDFs have proven invaluable for understanding material behavior. A study on radiation-grafted fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) membranes as proton exchange membranes utilized RDFs to investigate the microstructure and transport behavior of water molecules and hydronium ions [27]. The research revealed that with increasing side chain length in sulfonated styrene grafted FEP membranes, the average sulfur-hydronium ion separation slightly increased, while the coordination number of H3O+ around sulfonic acid groups decreased, indicating changes in the local environment that affect proton conductivity [27].

Another study demonstrated the use of RDFs in analyzing hydrogen-induced healing of cluster-damaged silicon surfaces [25]. By comparing the RDF of a damaged silicon surface after hydrogen exposure with the RDF of bulk crystalline silicon, researchers confirmed that the surface had regained its crystalline structure, with silicon atoms from deposited clusters becoming incorporated into the repaired substrate lattice [25].

Table 1: Key RDF Features and Their Structural Significance

| RDF Feature | Structural Significance | Example System |

|---|---|---|

| First Peak Position | Most probable interatomic distance | Si-Si in silicon (≈2.35Å) |

| First Peak Height | Strength of local ordering | Higher in crystals than liquids |

| First Minimum Position | First coordination sphere cutoff | Used for coordination number |

| Second Peak Splitting | Evidence of amorphous structure | Observed in glasses and liquids |

Diffusion Coefficients: Quantifying Atomic Transport

Diffusion coefficients are crucial transport properties that quantify the rate at which particles (atoms, molecules, ions) spread through a material due to random thermal motion. In MD simulations, diffusion coefficients are primarily calculated from mean squared displacement or velocity autocorrelation function analysis.

Calculation Methods and Theoretical Background

The most common approach for calculating diffusion coefficients in MD simulations is through the Mean Squared Displacement, defined as:

[ MSD(t) = \langle [\textbf{r}(0) - \textbf{r}(t)]^2 \rangle ]

where (\textbf{r}(t)) is the position of a particle at time (t), and the angle brackets denote an average over all particles and time origins [28]. For normal diffusion, the MSD increases linearly with time, and the diffusion coefficient (D) is obtained from the Einstein relation:

[ D = \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{\langle \Delta r^2(t) \rangle}{6t} ]

in three dimensions [26] [28]. The factor 6 becomes 4 in two-dimensional systems.

An alternative method uses the Velocity Autocorrelation Function, where the diffusion coefficient is calculated as:

[ D = \frac{1}{3} \int{t=0}^{t=t{max}} \langle \textbf{v}(0) \cdot \textbf{v}(t) \rangle \rm{d}t ]

with (\textbf{v}(t)) being the velocity of a particle at time (t) [28]. The VACF approach sometimes offers better convergence for certain systems but requires storing velocity data at high frequency.

Practical Implementation and Considerations

A tutorial on calculating diffusion coefficients of lithium ions in a Li(_{0.4})S cathode highlights several practical considerations [28]. The MSD should be calculated only from the production phase of the simulation after the system reaches equilibrium. The diffusion coefficient is determined from the slope of the MSD versus time plot in the linear regime, avoiding short-time ballistic and long-time saturation regions.

Recent research emphasizes that uncertainty in MD-derived diffusion coefficients depends not only on simulation data but also on the analysis protocol, including statistical estimators and data processing decisions [29]. Different regression methods (ordinary least squares, weighted least squares) applied to the same MSD data can yield different diffusion coefficients with varying uncertainties.

For systems with limited diffusion on practical simulation timescales, researchers often calculate diffusion coefficients at elevated temperatures and extrapolate to lower temperatures using the Arrhenius equation:

[ D(T) = D0 \exp{(-Ea / k_{B}T)} ]

where (Ea) is the activation energy, (kB) is Boltzmann's constant, and (T) is temperature [28]. This approach requires simulations at multiple temperatures to determine (Ea) and (D0).

Table 2: Experimentally Derived Diffusion Coefficients from MD Studies

| System | Temperature (K) | Diffusion Coefficient (m²/s) | Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li(_{0.4})S | 1600 | 3.09 × 10⁻⁸ | MSD | [28] |

| Li(_{0.4})S | 1600 | 3.02 × 10⁻⁸ | VACF | [28] |

| Binary Lennard-Jones mixtures | Various | Within 10-20% of experimental | Penetration lengths | [30] |

Stress-Strain Analysis: Probing Mechanical Properties

Stress-strain analysis in MD simulations provides insights into the mechanical behavior and deformation mechanisms of materials at the atomic scale. While direct simulation of stress-strain curves is computationally demanding, MD offers unique advantages for studying fundamental deformation mechanisms and extracting elastic constants.

Fundamentals of Mechanical Properties from MD

In continuum mechanics, the fundamental equations governing stress-strain relationships begin with the equilibrium equation:

[ \nabla\cdot\sigma + f = 0 ]

where (\sigma) is the Cauchy stress tensor, and (f) is the body force per unit volume [31]. The strain tensor (\varepsilon) is derived from the displacement field (u):

[ \varepsilon = \frac{1}{2}[\nabla u + (\nabla u)^\top] ]

In MD simulations, the atomic-level stress tensor for a group of atoms is calculated using the virial formula, which includes both kinetic energy contributions from atomic velocities and potential energy contributions from interatomic forces. Strain is typically applied by deforming the simulation cell, and the resulting stress is measured to construct stress-strain curves.

For linear elastic materials, Hooke's law governs the stress-strain relationship:

[ \sigma = C : \varepsilon ]

where (C) is the fourth-order elasticity tensor [31]. For nonlinear materials, more complex constitutive models are required:

[ \sigma = F(\varepsilon, \dot{\varepsilon}, p) ]

where (\dot{\varepsilon}) is the strain rate and (p) represents internal state variables [31].

Integration with Data-Driven Approaches

Recent advances combine MD with data-driven methods for enhanced mechanical property prediction. The Stress-Strain Adaptive Predictive Model integrates multi-sensor image fusion with domain-aware deep learning, bridging physics-based modeling and machine learning for more robust stress-strain prediction [31]. This hybrid approach embeds physics-informed constraints and uses reduced-order modeling for computational scalability.

Another innovative methodology called 'Brilearn' leverages machine learning and finite element analysis to predict stress-plastic strain curves of metallic materials from Brinell hardness tests [32]. This data-driven approach uses a novel model for predicting hardening curves, the classical Tabor model for yield stress prediction for materials with yield stress lower than 100 MPa, and an XGBoost model for metals with higher yield stress [32]. Validated against experimental data, this model achieves error predictions of 8.4 ± 8.5% for yield stress and 3.2 ± 4% for complete curves, demonstrating the powerful synergy between simulation and machine learning.

Integrated Workflow and Experimental Protocols

Successfully implementing MD simulations with RDF, diffusion coefficient, and stress-strain analysis requires careful attention to workflow and protocols. This section outlines standardized methodologies for these computational experiments.

General MD Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for MD simulations incorporating the three analysis methods discussed in this guide:

Diagram 1: Comprehensive MD Analysis Workflow

Protocol: Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

This protocol details the steps for calculating diffusion coefficients of lithium ions in a Li(_{0.4})S cathode material, as presented in an MD tutorial [28]:

System Preparation: Import the crystal structure from a CIF file. Insert 51 Li atoms into the sulfur system using builder functionality or Grand Canonical Monte Carlo for more accurate placement.

Geometry Optimization: Perform geometry optimization including lattice relaxation using the ReaxFF force field with the LiS.ff parameter set. Verify the unit cell volume has increased significantly (e.g., from 3300 ų to 4400 ų).

Simulated Annealing for Amorphous Structure:

- Set up MD simulation with 30,000 steps.

- Configure temperature profile: 300 K for first 5,000 steps, heat from 300 K to 1600 K over next 20,000 steps, cool to 300 K over final 5,000 steps.

- Use Berendsen thermostat with damping constant of 100 fs.

- Relax the resulting amorphous structure with geometry optimization including lattice relaxation.

Production Simulation for Diffusion Analysis:

- Run MD at target temperature (e.g., 1600 K) with 100,000 production steps after 10,000 equilibration steps.

- Set sampling frequency to 5 steps (writing positions and velocities every 5 steps).

- Use Berendsen thermostat with appropriate damping constant (100 fs).

Diffusion Coefficient Calculation:

- For MSD method: Calculate MSD for Li atoms, set appropriate time range (e.g., 2000-22001 steps), use maximum MSD frame of 5000. Determine D from slope of MSD versus time: ( D = \text{slope(MSD)}/6 ).

- For VACF method: Compute velocity autocorrelation function for Li atoms with same parameters, integrate to obtain D.

Multi-Temperature Extrapolation:

- Repeat simulations at multiple temperatures (e.g., 600 K, 800 K, 1200 K, 1600 K).

- Create Arrhenius plot of (\ln(D(T))) against (1/T).

- Extract activation energy (Ea) and pre-exponential factor (D0).

- Extrapolate to lower temperatures using Arrhenius equation.

Protocol: RDF Analysis for Membrane Structure

This protocol outlines RDF analysis for studying hydrated sulfonated styrene grafted fluorinated ethylene propylene membranes based on published research [27]:

Membrane Model Construction:

- Build atomistic models of radiation-grafted FEP membranes with different sulfonic styrene side chain lengths.

- Hydrate the membrane models with water molecules and hydronium ions at appropriate concentrations.

Equilibration Procedure:

- Perform energy minimization using steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm.

- Equilibrate system in NVT ensemble for 100-500 ps at target temperature.

- Further equilibrate in NPT ensemble for 100-500 ps to achieve correct density.

Production Simulation:

- Run production MD simulation for sufficient duration to capture structural properties (typically 1-10 ns).

- Save trajectory frames frequently enough to capture structural fluctuations (every 1-10 ps).

RDF Calculation:

- Calculate sulfur-sulfur RDFs to understand membrane backbone structure.

- Compute sulfur-hydronium ion RDFs to characterize ionic coordination.

- Determine sulfur-water oxygen RDFs to analyze hydration structure.

- Integrate RDF peaks to obtain coordination numbers.

Cluster Analysis:

- Identify water clusters using clustering algorithms based on oxygen-oxygen distances.

- Analyze cluster size distribution and percolation pathways.

Validation:

- Compare simulated RDFs with experimental data where available.

- Relate structural features to experimental proton conductivity measurements.

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

The following table details essential software tools and computational resources that form the modern "reagent solutions" for MD simulations and analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MD Simulations

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| ReaxFF | Force Field | Reactive force field for chemical reactions | Lithiated sulfur cathode materials [28] |

| UFF | Force Field | Universal force field for various elements | Methane system simulations [33] |

| VMD | Visualization | Molecular visualization and trajectory analysis | Studying motion of atoms over time [26] |

| PyMOL | Visualization | Molecular visualization and rendering | Gaining insights into reaction mechanisms [26] |

| AMS | MD Engine | Advanced molecular simulation platform | Li-ion diffusion calculations [28] [33] |

| PLAMS | Scripting | Python library for automated simulations | Running complex simulation workflows [33] |

| Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models | AI Method | Generative AI for enhanced sampling | Predicting membrane partitioning of drugs [34] |

Radial distribution functions, diffusion coefficients, and stress-strain analysis represent three cornerstone analysis methods in molecular dynamics simulations, each providing unique insights into material behavior at the atomic scale. When implemented with careful attention to the protocols and considerations outlined in this guide, these methods enable researchers to establish robust structure-property relationships that bridge computational predictions and experimental observations.

The continuing evolution of MD methodology, particularly through integration with machine learning and enhanced sampling approaches, promises to further expand the capabilities of these computational techniques. For researchers in drug development, materials science, and chemical engineering, mastery of these fundamental analysis methods provides a powerful toolkit for investigating and designing novel materials with tailored properties.

From Theory to Therapy: Key Applications Driving Drug Discovery and Materials Science

Protein-ligand interactions represent a fundamental cornerstone in biochemical processes and pharmaceutical development, governing cellular signaling, metabolic pathways, and therapeutic interventions. These interactions occur when a small molecule (ligand) binds to a specific site on a protein, modulating its activity, stability, or localization [35]. Understanding the precise mechanisms and binding affinity—the strength of interaction between protein and ligand—is crucial in drug discovery, as it directly correlates with drug efficacy and specificity [36]. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a transformative computational methodology that provides atomistic insights into these interactions, overcoming limitations of experimental approaches by capturing the dynamic nature of biomolecular systems and accurately predicting binding affinities [37] [38]. This technical guide explores how MD simulations, particularly when integrated with machine learning and quantum computing, are revolutionizing the study of protein-ligand interactions and accelerating rational drug design.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations: From Static Structures to Dynamic Processes

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies

Molecular dynamics simulations computational technique that applies Newton's laws of motion to simulate atomic-level movements in biomolecular systems over time [39]. Unlike static experimental structures from crystallography, MD simulations capture the dynamic behaviors of proteins and their interactions with ligands, providing in-depth insights into conformational changes, binding pathways, and mechanisms underlying protein-ligand interactions [36]. The simulations employ mathematical force fields—empirical functions describing potential energy based on atomic parameters—to model interactions between atoms, with popular families including CHARMM, AMBER, GROMOS, and OpenFF [39]. Through numerical integration of equations of motion, MD generates trajectories that reveal how proteins and ligands structurally evolve over time, offering critical information about binding kinetics and thermodynamics that static structures cannot provide [35].

Technical Advancements Enabling Drug Discovery Applications

Recent technological advancements have significantly expanded MD capabilities in drug discovery. High-throughput MD (HTMD) approaches now enable screening multiple small molecules in parallel, dramatically increasing efficiency in assessing potential drug candidates [39]. Enhanced sampling techniques, increasingly refined by artificial intelligence and machine learning, allow researchers to explore vast conformational spaces of biological molecules and capture dynamic behaviors over biologically relevant timescales [40]. The integration of machine learning algorithms with MD simulations has revolutionized the field by rapidly processing complex simulation data, identifying patterns, and predicting binding affinities with remarkable accuracy [40]. Furthermore, emerging quantum computing applications promise to overcome classical computing limitations, particularly for simulating quantum mechanical phenomena and enabling more accurate simulations of larger systems over extended timescales [40].

Quantitative Binding Affinity Prediction: MM/PBSA and Large-Scale Datasets

Molecular Mechanics with Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA)

The Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) method has become a widely adopted approach for calculating binding free energies from MD trajectories [37] [38]. This method estimates binding affinity by combining molecular mechanics energy calculations with implicit solvation models:

where:

- ΔEMM represents the gas-phase molecular mechanics energy (sum of electrostatic ΔEele and van der Waals ΔE_vdw interactions)

- ΔGsolv constitutes the solvation free energy (sum of polar ΔGpol and non-polar ΔG_np contributions)

- TΔS accounts for the entropy change upon binding [37]

MM/PBSA provides not only overall binding affinities but also individual energy components, offering valuable insights for lead optimization and target-specific drug design [38]. The method has demonstrated superior correlation with experimental binding affinities compared to traditional docking scores, making it particularly valuable in virtual screening for identifying potential lead compounds [37] [38].

Large-Scale MD Datasets for Machine Learning Applications

The development of large-scale MD datasets has catalyzed advances in binding affinity prediction through machine learning. The following table summarizes key datasets enabling ML applications in drug discovery:

Table 1: Large-Scale MD Datasets for Protein-Ligand Binding Affinity Prediction

| Dataset | Size | Simulation Details | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLAS-5k [38] | 5,000 PL complexes | 5 independent simulations per complex | Binding affinities + energy components (electrostatic, vdW, polar/non-polar solvation) | Baseline ML models (OnionNet retraining) |

| PLAS-20k [37] | 19,500 PL complexes | 97,500 independent simulations | Extended heterogeneity of proteins/ligands, classification of strong/weak binders | Enhanced ML accuracy, drug-likeness assessment (Lipinski's Rule) |

| Protocol [37] [38] | AMBER ff14SB/GAFF2 fields | OpenMM 7.2.0, MMPBSA | TIP3P water model, 300K, 1 atm pressure | High-throughput screening, lead optimization |

These datasets address a critical gap in traditional machine learning models that relied predominantly on static crystal structures, enabling the incorporation of dynamic features essential for understanding biomolecular processes like protein folding, conformational changes, and ligand binding [37]. The PLAS-20k dataset has demonstrated particular utility in classifying strong and weak binders and assessing drug-likeness according to Lipinski's Rule of Five [37].

Experimental Protocols: Comprehensive Workflow for Binding Affinity Studies

System Preparation and Parameterization

The preparation of protein-ligand systems for MD simulations follows a rigorous protocol to ensure accurate and reliable results:

Structure Retrieval and Preparation: Experimental protein-ligand complex structures are obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Proteins with missing residues are completed using modeling tools like MODELLER or UCSF Chimera, followed by protonation at physiological pH (7.4) using servers such as H++ [37] [38].