Molecular Dynamics for Homology Model Refinement: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

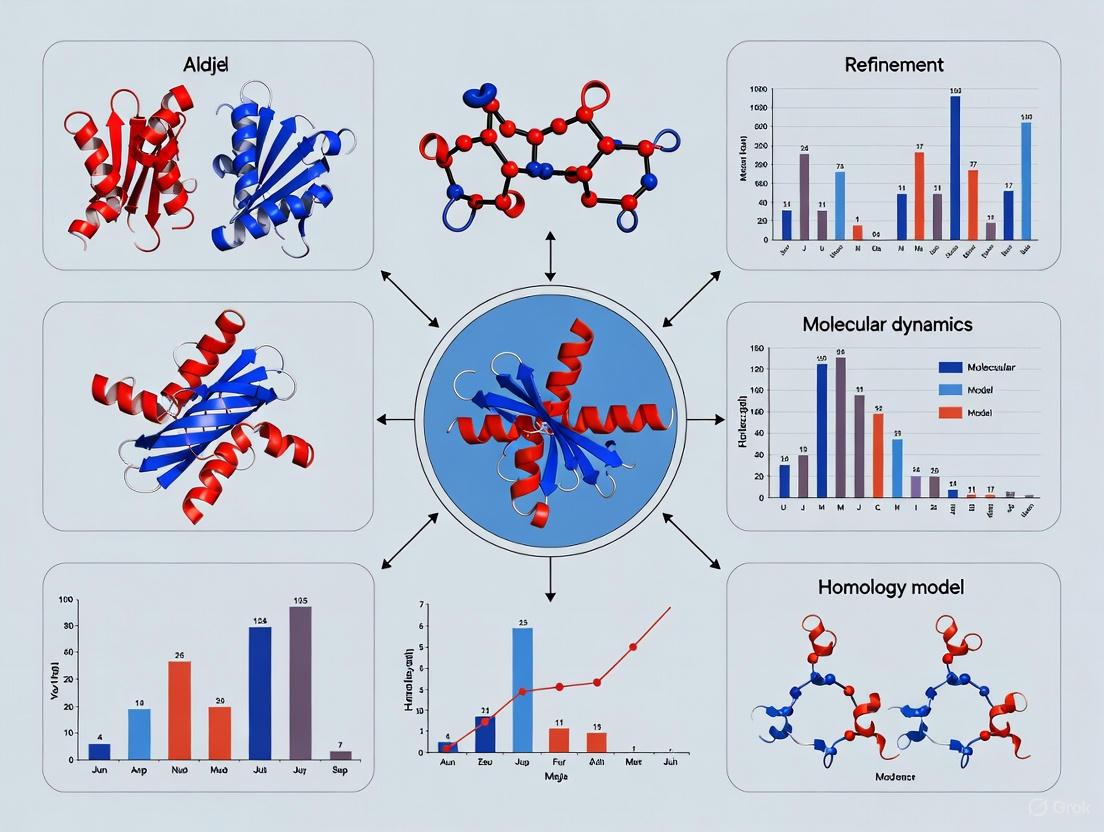

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to refine protein homology models.

Molecular Dynamics for Homology Model Refinement: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to refine protein homology models. It covers the fundamental principles of how MD can improve model quality, details step-by-step methodological protocols for setup and execution, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, and presents rigorous validation techniques and comparative analyses of alternative refinement methods. By synthesizing findings from CASP competitions and recent literature, this resource offers practical insights for achieving higher-resolution structural models critical for applications in rational drug design and functional characterization.

The Foundation: Understanding MD's Role in Homology Model Refinement

The explosion of protein sequence data from advanced sequencing techniques has dramatically outpaced the experimental determination of protein structures, creating a significant sequence-structure gap. While homology modeling and emerging deep learning methods like AlphaFold2 can generate initial structural models, these predictions often require refinement to achieve near-native accuracy suitable for detailed mechanistic studies or drug design. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful physics-based method for refining protein structures by sampling conformations under the guidance of empirical force fields, effectively bridging this critical gap.

The fundamental premise of MD-based refinement lies in allowing an initially incorrect model to evolve toward a physically more reasonable, lower free energy structure. As simulations explore the conformational landscape, they can correct residue packing errors, adjust secondary structure elements, and improve local geometry. However, significant challenges remain, including the presence of kinetic barriers on a relatively flat energy landscape and the risk of unfolding initially misfolded structures rather than reaching the native state. Carefully designed refinement protocols that incorporate restrained sampling and enhanced sampling techniques have demonstrated consistent improvements in both global and local model quality, making MD an indispensable tool in the structural biologist's toolkit.

Molecular Dynamics Fundamentals for Refinement

Molecular dynamics simulations solve Newton's equations of motion for all atoms in a molecular system, generating a trajectory that reveals how positions and velocities change over time. For protein structure refinement, MD provides several key advantages: it employs physics-based force fields that describe atomic interactions, explicitly models solvent effects through water molecules and ions, and naturally captures protein flexibility and dynamics that static models cannot represent.

The theoretical foundation of MD-based refinement posits that simulations started from an incorrect model will fold toward a physically more reasonable, lower free energy structure under force field guidance. The CHARMM 36m force field and modified versions of AMBER have proven particularly effective for refinement applications, balancing accuracy with computational efficiency. These force fields combined with explicit solvent models such as TIP3P water can correct structural inaccuracies by allowing the protein to sample more thermodynamically favorable conformations while maintaining physically realistic bonding geometries and non-bonded interactions.

Table 1: Key Force Fields and Solvent Models for MD-Based Refinement

| Force Field/Solvent | Application in Refinement | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| CHARMM 36m | Protein structure refinement | Optimized for folded proteins and membrane systems |

| AMBER (ffG53A7) | Homology model refinement | Recommended for proteins with explicit solvent |

| TIP3P water model | Solvation in refinement | Three-site water model compatible with major force fields |

| CGenFF | Ligand parameterization | Provides parameters for small molecules during refinement |

Current MD Refinement Protocols and Applications

Standard MD Refinement Protocol

A typical MD-based refinement protocol consists of three major stages: system setup, equilibration, and production sampling. The system setup begins with obtaining initial protein coordinates, adding missing hydrogen atoms, placing the protein in an appropriately sized simulation box, solvating with water molecules, and adding ions to neutralize the system. For membrane proteins, this stage includes embedding the protein in a lipid bilayer such as POPC (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine).

The equilibration phase involves gradually relaxing the system through energy minimization, heating to the target temperature (often 360 K for enhanced sampling), and brief preliminary simulations with position restraints on protein atoms to allow solvent molecules to adjust. The production sampling stage then performs extended simulations, often with multiple replicas, to extensively sample the conformational landscape. Modern protocols may incorporate hydrogen mass repartitioning to allow longer integration time steps (4 fs) and apply carefully designed restraints to prevent unfolding while permitting sufficient flexibility for refinement.

Advanced Sampling Strategies

To address the challenge of limited conformational sampling in conventional MD, advanced protocols incorporate enhanced sampling techniques. The Feig group's CASP14 protocol implemented sampling at elevated temperature (360 K) with an optimized use of biasing restraints and multiple starting models. This approach generally improved model quality, particularly for regions with greater structural variation within protein families such as loops. Other advanced methods include:

- Replica Exchange MD (ReMDFF): Utilizes multiple simulations running at different temperatures or with different Hamiltonians, with periodic exchange between replicas to enhance conformational sampling.

- Cascade MDFF (cMDFF): Sequentially refines a search model against a series of maps of progressively higher resolutions, enabling a larger radius of convergence.

- Markov State Models: Provide a framework for analyzing extensive MD sampling data to map energy landscapes and identify kinetic barriers between states.

These advanced methods have demonstrated particular success in refining protein models derived from cryo-electron microscopy, as evidenced by applications to β-galactosidase and TRPV1 ion channel structures.

Practical Implementation: A Step-by-Step Refinement Protocol

System Preparation

The refinement process begins with careful system preparation. For a typical protein refinement using GROMACS, the first step converts Protein Data Bank (PDB) format coordinates into GROMACS-specific format (.GRO) while generating topology information:

This command prompts selection of an appropriate force field (e.g., ffG53A7 for proteins with explicit solvent) and adds missing hydrogen atoms. The resulting topology file contains complete molecular descriptions including parameters, bonding information, and charges. The system is then placed in a simulation box with Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC) to minimize edge effects:

This creates a cubic box with approximately 1.4 nm distance between the protein and box edges, keeping the protein centered. The box is solvated with water molecules using the solvate command, and ions are added to neutralize the system charge using genion.

Table 2: Essential Software Tools for MD-Based Refinement

| Software Tool | Application Role | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD simulation engine | High performance, versatile analysis tools |

| AMBER | MD simulation suite | Specialized force fields, extensive validation |

| NAMD | Scalable MD simulations | Efficient parallelization for large systems |

| CHARMM-GUI | System building | Web-based interface for membrane proteins |

| Rosetta | Hybrid refinement | Combines physics and knowledge-based potentials |

Equilibration and Production

The solvated and neutralized system undergoes energy minimization (typically 500-5000 steps) using algorithms like l-BFGS-b to remove steric clashes. The minimized system is then gradually heated to the target temperature (often 360 K for refinement) and equilibrated with position restraints on protein heavy atoms to allow solvent relaxation. For refinement applications, production simulations often employ elevated temperatures (360 K) to enhance conformational sampling while applying restraints to prevent unfolding:

Multiple independent replicas (typically 3-5) of 100-500 ns each provide more robust sampling. The restraint strategy evolves during simulation, gradually switching from Cartesian restraints to distance-based restraints to balance confinement near the initial model with flexibility for refinement.

Assessment of Refinement Quality

Evaluating refinement success requires multiple complementary metrics. Global quality measures include:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures overall structural change from initial model

- Global Distance Test (GDT): Assesss similarity to reference structure

- Template Modeling Score (TM-score): Evaluates global fold preservation

Local quality indicators include:

- MolProbity scores: Evaluate stereochemical quality and clash scores

- EMRinger scores: Assess sidechain placement in cryo-EM maps

- Local cross-correlation: Measures fit to experimental density

Recent studies demonstrate that MD-based refinement typically improves model quality by several units in both global and local metrics, though substantial improvements are more likely with moderate-quality starting models than with either very poor or exceptionally high-quality initial structures.

Research Reagent Solutions for MD Refinement

Successful implementation of MD-based refinement requires specific computational "reagents" and tools. The table below details essential components for establishing an effective refinement pipeline:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MD-Based Refinement

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | Describes interatomic forces | CHARMM 36m, AMBER ffG53A7 |

| Solvent Models | Represents aqueous environment | TIP3P, SPC/E water models |

| Ion Parameters | Models physiological ionic strength | CHARMM monovalent ion parameters |

| Lipid Force Fields | Membrane simulations | CHARMM 36 lipid force field |

| Ligand Parameterization | Small molecule handling | CGenFF for drug-like molecules |

| Enhanced Sampling Algorithms | Accelerates conformational search | Replica Exchange, Metadynamics |

| Analysis Tools | Trajectory processing and metrics | GROMACS analysis suite, VMD |

| Validation Servers | Independent quality assessment | MolProbity, PDB Validation |

Future Directions and Challenges

The emergence of highly accurate deep learning-based structure predictions like AlphaFold2 presents both opportunities and challenges for MD-based refinement. While initial tests suggested MD could improve earlier machine learning models, recent results indicate that refining already high-quality AF2 models often decreases their quality. This suggests a shifting role for MD refinement toward addressing specific limitations of AI predictions, including:

- Sampling conformational ensembles beyond single static structures

- Refining binding sites for drug design applications

- Incorporating physiological conditions including membranes, ligands, and macromolecular crowding

- Modeling transient states and allosteric mechanisms

Significant challenges remain, particularly the presence of large kinetic barriers in refinement pathways and the need to account for inter-domain and oligomeric contacts in simulations. Future advances will likely integrate physics-based and knowledge-based approaches, leveraging the complementary strengths of MD simulations and deep learning to achieve unprecedented accuracy in protein structure modeling.

Molecular dynamics simulations provide a powerful physics-based approach for refining protein homology models and addressing the persistent sequence-structure gap. Through carefully designed protocols that incorporate enhanced sampling, appropriate restraints, and thorough validation, MD-based refinement can significantly improve model quality by correcting structural inaccuracies and optimizing physical chemistry. As structure prediction methods continue to evolve, MD refinement will likely adapt to serve more specialized roles in modeling conformational dynamics, complex formation, and physiological environments—ensuring its continued relevance in the structural biology toolkit.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful computational technique for refining protein structures, particularly those generated through homology modeling. MD refinement aims to enhance the accuracy of initial protein models by using physics-based force fields to sample conformational space and relax structural models into more native-like states. The core principle involves simulating the physical movements of atoms over time, allowing the protein to explore low-energy conformations that may be closer to the native structure than the initial model. This approach is especially valuable in structural biology and drug discovery, where accurate protein models are essential for understanding function and facilitating structure-based drug design [1] [2].

The refinement process addresses a fundamental challenge in protein structure prediction: while homology modeling can often produce correct overall folds, these models frequently contain local inaccuracies that limit their practical utility. MD simulations help mitigate these issues by allowing atomic adjustments guided by empirical force fields that account for bonded interactions, van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions, and solvation effects. When applied to homology models, MD can optimize side-chain packing, correct backbone deviations, and relieve steric clashes, ultimately improving the model's quality and biological relevance [3].

Key Challenges and Limitations in MD Refinement

Despite its theoretical promise, MD-based refinement faces several significant challenges that have limited its widespread success. A primary limitation identified in long-timescale MD studies is force field accuracy. Research has shown that in many cases, simulations initiated from homology models drift away from rather than toward the native structure, suggesting that inaccuracies in current force fields may be a fundamental constraint [4]. This problem appears particularly pronounced when simulations are allowed to run unrestricted for extended periods (e.g., >100 μs).

The sampling problem represents another major challenge. The conformational space available to even a small protein is astronomically large, and achieving adequate sampling of near-native states within practical computational timeframes remains difficult. This challenge is compounded by the rough energy landscapes typical of protein systems, where local minima can trap conformations far from the global minimum corresponding to the native state [5].

For intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), additional complications arise. Standard force fields and water models may produce overly compact conformational ensembles, as evidenced by discrepancies between computed and experimentally measured translational diffusion coefficients [6]. This highlights the need for specialized force fields and validation approaches for disordered protein regions.

Recent approaches have attempted to mitigate these limitations by restricting sampling to the neighborhood of initial models or incorporating experimental restraints to guide the refinement process. These strategies have shown promising results, achieving improvements comparable to other leading refinement methods [4].

Methodological Approaches for MD Refinement

Conventional All-Atom Molecular Dynamics

Conventional all-atom MD simulations in explicit solvent represent the foundational approach for protein structure refinement. This methodology involves simulating every atom in the system, including solvent water molecules and ions, using classical force fields. The standard protocol includes several key steps: system setup (placing the protein in a water box with appropriate ions), energy minimization, equilibration (often with positional restraints on the protein backbone), and finally production simulation where all restraints are typically removed [1].

Studies have demonstrated that simulations on the tens to hundreds of nanoseconds timescale can provide useful refinement for small to medium-size proteins, with significant improvements observed in the deviation from experimental structures in several test cases [3]. The effectiveness of this approach depends critically on factors including the accuracy of the initial model, the simulation length, and the specific force field employed.

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

To address the sampling limitations of conventional MD, various enhanced sampling methods have been developed. Replica-exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) has shown particular promise for refinement applications. In REMD, multiple simulations (replicas) are run in parallel at different temperatures, with periodic exchanges between replicas according to a Metropolis criterion. This approach facilitates escape from local energy minima and more thorough exploration of conformational space [7].

Research combining REMD with statistical potentials for model selection demonstrated sampling of near-native conformational states starting from high-quality homology models, with improvements in backbone RMSD of secondary structure elements by 0.5-1.0 Å in most test cases [7]. The protocol proved particularly effective for the refinement of high-quality models of small proteins, though limitations in scoring functions remained a challenge for consistently identifying the most accurate structures.

Integration with Experimental Data

A powerful refinement strategy incorporates experimental data as restraints during MD simulations. The TrioSA protocol exemplifies this approach, combining NOE-derived distance restraints, torsion angle potentials, implicit solvation models, and simulated annealing to refine protein structures against NMR data [8]. This method demonstrated significant improvements in structural quality, including reduced NOE violations and better geometric validation metrics compared to initial NMR structures.

Similarly, MD simulations can be validated against NMR diffusion data for intrinsically disordered proteins, providing a rigorous assessment of whether the simulation produces a physically realistic conformational ensemble [6]. This approach has revealed important distinctions between different water models, with some producing overly compact IDP ensembles while others better match experimental observations.

Deep Learning-Guided Refinement

Recent advances have integrated deep learning with MD simulations to create more effective refinement protocols. The DeepAccNet framework uses 3D convolutional neural networks to predict per-residue accuracy and residue-residue distance errors, then uses these predictions to guide Rosetta-based refinement [5]. This approach provides specific information on what parts of the structure need improvement and how they should move, addressing a key limitation of earlier refinement methods.

The network incorporates multiple features including local atomic environments, backbone torsion angles, Rosetta energy terms, and coevolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments. When used to guide refinement, this deep learning-informed approach significantly increased the accuracy of resulting protein structure models compared to conventional methods [5].

Quantitative Assessment of Refinement Performance

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Different MD Refinement Methods

| Method | Simulation Length | RMSD Improvement | Key Limitations | Applicable Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional all-atom MD [4] [3] | 5-400 ns | Variable; significant in some cases, drift in others | Force field inaccuracies, limited sampling | Small to medium-sized proteins |

| Replica-exchange MD [7] | Varies by replica count | 0.5-1.0 Å SSE-RMSD improvement for 15/21 cases | Scoring function selection | High-quality homology models |

| TrioSA with NMR restraints [8] | Simulated annealing cycles | Reduced NOE violations, improved geometric validation | Requires experimental NMR data | NMR structure determination |

| DeepAccNet-guided [5] | Not specified | Considerably increased accuracy vs conventional | Performance declines with protein size | Diverse protein types |

Table 2: Key Software Tools for MD-Based Refinement

| Software Package | Key Features | Applicability to Refinement | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [1] | High performance, free license | Excellent for conventional all-atom MD | Steep learning curve |

| AMBER [1] | Comprehensive force fields, tools | Suitable for conventional and enhanced MD | Well-established for biomolecules |

| CHARMM [8] [1] | Extensive energy functions, NMR support | TrioSA protocol implementation | Compatible with various force fields |

| Rosetta [5] | Knowledge-based potentials, deep learning integration | DeepAccNet-guided refinement | Combines physics and statistics |

| HOMA [9] | Homology modeling with validation | Model assessment pre/post refinement | Useful for quality evaluation |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standard All-Atom MD Refinement Protocol

The following protocol outlines a typical workflow for refining homology models using conventional all-atom molecular dynamics simulations:

System Setup

- Obtain initial homology model from preferred modeling software

- Place the protein in a simulation box with appropriate dimensions (e.g., 1.0-1.5 nm minimum distance between protein and box edge)

- Solvate the system using a water model (e.g., TIP3P, TIP4P, SPC)

- Add ions to neutralize the system and achieve physiological salt concentration (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl)

Energy Minimization

- Perform steepest descent or conjugate gradient minimization to remove steric clashes

- Apply positional restraints on protein heavy atoms during initial minimization

- Continue until maximum force falls below a specified threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm)

Equilibration

- Run simulation with positional restraints on protein heavy atoms (NVT ensemble, 100-500 ps)

- Continue equilibration with restraints only on protein backbone (NPT ensemble, 100-500 ps)

- Ensure system density and temperature stabilize at target values

Production Simulation

- Run unrestrained simulation for the desired length (typically tens to hundreds of nanoseconds)

- Maintain constant temperature and pressure using appropriate thermostats and barostats

- Save trajectory frames at regular intervals (e.g., every 100 ps) for analysis

Analysis and Model Selection

- Cluster trajectories to identify representative conformations

- Calculate RMSD, RMSF, and other quality metrics

- Select lowest-energy structures or average coordinates for final refined model [3]

TrioSA NMR Refinement Protocol

The TrioSA protocol provides a specialized approach for refining protein structures against NMR data:

Experimental Data Preparation

- Obtain experimental NMR restraints from Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank (BMRB) or similar sources

- Convert NOE-derived distance restraints and dihedral angle restraints to CHARMM format

- Preprocess protein structures (consider disulfide bonds, remove non-standard atoms)

Energy Term Preparation

- Apply statistical torsion angle potentials (STAP) for φ-ψ, φ-χ1, ψ-χ1, and χ1-χ2 angles

- Incorporate implicit solvation model (e.g., GBSW) to account for solvent effects

- Set up flat-bottom harmonic potentials for dihedral angle constraints

Simulated Annealing Refinement

- Implement torsion angle dynamics for efficient sampling

- Apply temperature cycles from 100 K to 1000 K, then cool to 25 K

- Use CHARMM36 all-atom force field for energy calculations

- Ensure convergence through multiple annealing cycles

Validation

- Assess reduction in NOE violations and dihedral angle restraint violations

- Evaluate improvement in geometric validation scores (MolProbity, PROCHECK)

- Verify enhanced accuracy in biological applications (e.g., protein-ligand docking) [8]

Visualization of MD Refinement Workflows

Diagram 1: Workflow for conventional all-atom MD refinement of protein structures, showing the sequential steps from initial model preparation to final validated structure.

Diagram 2: Integrated refinement workflow combining deep learning guidance with enhanced sampling methods and experimental validation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for MD Refinement

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in Refinement | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [1] | MD Software | High-performance MD engine | Optimal for conventional all-atom MD on CPUs/GPUs |

| CHARMM [8] | MD Software | TrioSA protocol implementation | Specialized for NMR structure refinement |

| AMBER Force Fields [1] | Force Field | Physics-based energy functions | Well-validated for protein simulations |

| CHARMM36 Force Field [8] | Force Field | All-atom empirical force field | Compatible with CHARMM software suite |

| TIP3P/TIP4P Water [6] [1] | Solvent Model | Explicit solvent representation | Critical for realistic solvation effects |

| OPC Water Model [6] | Solvent Model | Advanced 4-point water model | Better for IDP conformational ensembles |

| DeepAccNet [5] | Deep Learning Tool | Accuracy estimation and guidance | Identifies regions needing refinement |

| HYDROPRO [6] | Analysis Tool | Diffusion coefficient prediction | Limited utility for disordered proteins |

| Verify3D/ProsaII [9] | Validation Tool | Model quality assessment | Distinguishes correct from incorrect folds |

| BMRB Database [8] | Data Resource | Experimental NMR restraints | Essential for NMR-guided refinement |

Molecular dynamics simulations provide a powerful framework for protein structure refinement, with multiple methodological approaches offering distinct advantages for different scenarios. While conventional all-atom MD remains valuable for straightforward refinement tasks, more sophisticated methods incorporating enhanced sampling, experimental restraints, and deep learning guidance show promise for addressing the fundamental challenges of force field accuracy and conformational sampling.

The future of MD-based refinement likely lies in hybrid approaches that combine physical principles with data-driven methods. As force fields continue to improve and computational resources expand, MD simulations are poised to play an increasingly important role in protein structure prediction and validation, with significant implications for structural biology and drug discovery applications. Continued development and integration of validation metrics, particularly against experimental data such as NMR diffusion measurements, will be essential for advancing the field and ensuring the biological relevance of refined protein models.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as a powerful computational technique for refining protein structures, particularly homology models that approximate but do not achieve experimental accuracy. MD refinement aims to bridge the gap between computationally predicted models and native structures by sampling conformational space using physics-based force fields. The core challenge lies in the fact that initial homology models, while often capturing correct topology, typically deviate from experimental structures by 2-5 Å Cα root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) [10]. Successful refinement requires a sophisticated interplay of restraint strategies to guide the simulation, accurate force fields to properly represent atomic interactions, and enhanced sampling methods to overcome the high energy barriers that separate homology models from native states. This protocol examines these key conceptual areas, providing researchers with a framework for implementing MD refinement protocols that can achieve experimental accuracy, with studies demonstrating refinement to within 0.8-1.0 Å RMSD of native structures for specific protein systems [10] [7].

Theoretical Framework: Essential Concepts and Metrics

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) in Structural Validation

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) serves as the principal quantitative metric for assessing structural similarity in refinement protocols. It measures the average distance between atoms—typically backbone Cα atoms—of two superimposed protein structures [11]. The mathematical formulation for calculating RMSD between two sets of atomic coordinates v and w is:

[RMSD(v,w) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^{n}\|vi - wi\|^2} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^{n}((v{ix}-w{ix})^2 + (v{iy}-w{iy})^2 + (v{iz}-w{iz})^2)}]

where n represents the number of atoms being compared [11]. In X-ray crystallography, RMSD values below 0.5 Å generally indicate high model accuracy, while values exceeding 2 Å suggest significant structural discrepancies [12]. For MD refinement, the goal is to progressively minimize the RMSD between the starting homology model and the experimentally determined native structure throughout the simulation.

Relationship Between RMSD and Experimental B-Factors

Experimental B-factors from X-ray crystallography provide crucial information about atomic positional variance that relates directly to RMSD measurements. Under a set of conservative assumptions, the ensemble-average pairwise RMSD is mathematically related to average B-factors through the root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) [13]:

[RMSFi^2 = \frac{3Bi}{8\pi^2}]

This relationship enables researchers to quantify global structural diversity directly from experimental data, with typical ensemble-average pairwise backbone RMSD values for protein X-ray structures measuring approximately 1.1 Å [13]. This theoretical connection provides a critical bridge between simulation metrics and experimental observables in refinement protocols.

Restraint Strategies in MD Refinement

The Role of Restraints

Restraints in MD simulations serve to bias conformational sampling toward regions of configuration space consistent with experimental data or structural knowledge. They are particularly crucial in refinement applications where imperfect force fields might otherwise lead simulations away from native states rather than toward them [10]. By incorporating external information, restraints effectively reduce the conformational space that must be sampled, accelerating the refinement process and increasing its reliability. Studies have demonstrated that without appropriate restraints, initial models often drift away from native states even during simulations exceeding 100 microseconds [10].

Types of Restraints and Implementation

Table 1: Categories of Restraints Used in MD Refinement

| Restraint Type | Basis | Application Context | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positional Restraints | Reference atomic coordinates | Equilibration; maintaining known structural elements | Force constant (K); reference positions |

| Diffraction-Based Density Restraints | Experimental electron density | Membrane systems; structures with diffraction data | Force constants (KZ, Kσ); target values (Z, σ) |

| Statistical Potentials | Knowledge-based potentials from known structures | Model selection; scoring refined ensembles | Potential functions derived from structural databases |

Positional Restraints

Positional restraints maintain atoms near specified reference positions, particularly useful during initial equilibration phases or for preserving known structural elements while allowing uncertain regions to relax. In GROMACS implementations, these are defined in the molecular topology file using [ position_restraints ] directives and activated via preprocessor definitions such as -DPOSRES [14]. The harmonic potential takes the form:

[V{\text{posres}} = \frac{1}{2}K|\vec{r}i - \vec{r}_{i,0}|^2]

where K represents the force constant, rᵢ the atomic position, and rᵢ,₀ the reference position [14].

Experimental Density Restraints

For systems with experimental structural data, diffraction-based restraints can directly incorporate experimental measurements. As implemented for membrane systems, these restraints use a two-term harmonic potential acting on group distributions [15]:

[V = Vz + V\sigma = \frac{1}{2}Kz(Z - Z^*)^2 + \frac{1}{2}K\sigma(\sigma - \sigma^*)^2]

where Z and σ represent the instantaneous mean position and standard deviation of specified atom groups, while Z* and σ* are target values from experimental data [15]. This approach has successfully produced lipid bilayer structures consistent with experimental diffraction data and enabled the determination of membrane-bound peptide conformations at atomic resolution.

Protocol: Implementing Diffraction-Based Restraints

- Define restraint groups: Identify atoms corresponding to experimentally probed components (e.g., double-bonds, water, peptide groups)

- Set restraint parameters: Determine target values (*Z, *σ) from experimental Gaussian distributions

- Apply force constants: Typically use K_z = 100 kcal/mol/Ų and K_σ = 200 kcal/mol/Ų as starting values [15]

- Configure simulation: Implement the restraint potential at each MD step, calculating instantaneous group means and widths using: [Z = \frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^{n} zi] [\sigma = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^{n} (zi - Z)^2}]

- Apply forces: Compute and apply restraint forces to each atom according to: [Fi = -\frac{\partial V}{\partial zi} = -\left[(Z - Z^)K_z\frac{\partial Z}{\partial z_i} + (\sigma - \sigma^)K\sigma\frac{\partial \sigma}{\partial zi}\right]]

Force Fields for MD Refinement

Force Field Selection

The choice of force field fundamentally determines the physical accuracy of MD refinement simulations. Modern force fields such as CHARMM27, AMBER, and OPLS provide parameter sets that have been optimized for biomolecular simulations [15] [16]. Selection criteria should consider the specific system characteristics—membrane proteins may benefit from CHARMM lipid parameters, while AMBER's GAFF works well for small molecules [14].

Force Field Implementation Workflow

Parameterization of Novel Molecules

For small molecules or non-standard residues not included in standard force fields, several tools enable parameter generation:

- CHARMM: Use the SWISSPARAM server for automated parameter generation compatible with CHARMM force fields [14]

- AMBER/GAFF: Employ the antechamber package to generate General Amber Force Field parameters, followed by conversion to GROMACS format [14]

- OPLS: Utilize the LigParGen server for OPLS-based parameterization [14]

- GROMOS: Access the Automated Topology Builder (ATB) for GROMOS-compatible parameters [14]

Conversion between force field formats requires careful attention to units and functional forms. For example, when converting GAFF to GROMACS format, non-bonded parameters transform as εgro = εGAFF · 4.184 and σgro = 0.17818 · RGAFF [14].

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

Overcoming Sampling Limitations

The timescales of conformational transitions relevant to refinement (microseconds to milliseconds) far exceed the practical limits of conventional MD simulations (nanoseconds to microseconds). Enhanced sampling methods address this timescale problem by modifying the simulation algorithm to accelerate barrier crossing and improve configuration space exploration [17]. These methods are particularly crucial for refinement, where the energy landscape between homology models and native structures often features significant kinetic barriers requiring microsecond timescales to cross [10].

Classification of Enhanced Sampling Methods

Table 2: Enhanced Sampling Methods for MD Refinement

| Method Category | Key Principle | Representative Techniques | Best Applications in Refinement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biasing Methods | Modify potential with bias potential along collective variables | Metadynamics, Umbrella Sampling | Targeted refinement of specific structural features |

| Adaptive Sampling Methods | Strategically initialize simulation batches based on prior sampling | Markov State Models, Weighted Ensemble | Exploring alternative conformations from homology models |

| Generalized Ensemble Methods | Simulate in modified ensembles with different temperatures/Hamiltonians | Replica Exchange MD (REMD) | Overcoming kinetic traps in refinement landscape |

Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD)

REMD operates multiple simulation replicas at different temperatures, periodically attempting exchanges between replicas based on Metropolis criteria. This approach allows conformations to overcome energy barriers at high temperatures and sample low-energy states at low temperatures. REMD has demonstrated particular success in refinement applications, sampling near-native conformational states starting from high-quality homology models with backbone RMSD improvements of 0.5-1.0 Å [7]. The combination of REMD with statistical potentials for model selection has proven effective for global refinement of small protein models [7].

Machine Learning-Enhanced Sampling

Recent advances integrate machine learning (ML) with enhanced sampling to automatically identify relevant collective variables and optimize bias potentials [17]. ML approaches address the critical challenge of selecting appropriate collective variables—low-dimensional representations that capture the essential dynamics of the system. Techniques such as variationally enhanced sampling (VES) and reinforcement learning have shown promise in accelerating the sampling of rare events relevant to refinement [17].

Integrated Refinement Protocol

Complete Workflow for MD Refinement

Step-by-Step Implementation Guide

Initial System Setup

- Obtain homology model in PDB format

- Solvate the system in appropriate water model (TIP3P, SPC)

- Add ions to neutralize system charge and achieve physiological concentration

- Generate topology using selected force field

Energy Minimization

- Use steepest descent algorithm for initial minimization (emax=1000 kJ/mol/nm)

- Switch to conjugate gradient for finer convergence (emtol=10 kJ/mol/nm)

- Ensure all stereochemical irregularities are resolved

Equilibration Phase

- Run NVT equilibration (100 ps) with position restraints on protein heavy atoms (force constant: 1000 kJ/mol/nm²)

- Follow with NPT equilibration (100-200 ps) with reduced restraints on protein backbone (force constant: 400 kJ/mol/nm²)

- Monitor temperature, pressure, and density stabilization

Production Simulation with Enhanced Sampling

- Configure enhanced sampling method based on system size and computational resources

- For REMD: Use 24-48 replicas with exponential temperature distribution (300-500K)

- For Metadynamics: Define collective variables based on suspected refinement coordinates

- For large systems, employ multiple time-stepping (MTS) with mts-level2-forces = longrange-nonbonded and mts-level2-factor = 2-4 [18]

- Consider mass repartitioning (mass-repartition-factor = 3) to enable 4-fs timestep when using constraints = h-bonds [18]

- Configure enhanced sampling method based on system size and computational resources

Trajectory Analysis and Model Selection

- Calculate RMSD time series relative to both initial model and native structure (if known)

- Perform clustering (e.g., using GROMOS method) to identify dominant conformations

- Use statistical potentials or other scoring functions to rank structures [7]

- Select ensemble of low-energy structures for final refined model

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for MD Refinement

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application in Refinement Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics simulation engine | Production MD simulations with support for enhanced sampling methods and restraints [18] |

| AMBER | MD software with specialized force fields | Alternative simulation engine with sophisticated weighting algorithms [16] |

| NAMD | Scalable MD for large systems | Membrane-protein systems and very large complexes [15] |

| VMD | Trajectory visualization and analysis | RMSD calculations, structure visualization, and trajectory analysis [15] |

| SWISSPARAM | CHARMM parameter generation | Small molecule parameterization for novel ligands [14] |

| LigParGen | OPLS parameter generation | Web-based force field generation for small molecules [14] |

| Markov Modeling | MSM construction and analysis | Identifying kinetic pathways and states from ensemble simulations [10] |

Successful MD refinement of homology models requires careful integration of restraints to incorporate experimental information, accurate force fields to properly represent physical interactions, and enhanced sampling methods to overcome the formidable kinetic barriers on the energy landscape. The protocols outlined provide a framework for researchers to implement these key concepts in practical refinement applications. While significant challenges remain—particularly in force field accuracy and scoring function development—current methods can consistently produce structures with improved experimental accuracy when appropriately applied. Future advances in machine learning-enhanced sampling and more accurate force fields promise to further enhance the capability of MD simulations to bridge the gap between homology models and experimentally determined structures.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have revolutionized structural biology by providing dynamic insights into biomolecular systems, playing a critical role in the refinement of homology models. MD refinement leverages physics-based force fields and statistical mechanics to correct structural errors in computationally predicted models, bridging the gap between static homology models and biologically functional conformations. The evolution of MD refinement from its early applications to current sophisticated protocols represents a significant advancement in computational structural biology. This progression has transformed MD from a specialized theoretical tool into an indispensable method for improving model accuracy in homology modeling, cryo-electron microscopy, and drug discovery. This article traces the historical development of MD refinement methodologies, details current protocols and applications, and provides practical resources for researchers seeking to implement these techniques in their structural biology and drug discovery workflows.

Historical Progression of MD Refinement

The application of molecular dynamics in structural refinement has evolved through distinct phases, driven by advancements in computational power, force field development, and methodological innovations. The journey began with foundational studies in the 1970s and 1980s that established the basic principles of MD simulations for biological macromolecules. The first MD simulation of a biomolecule was achieved by McCammon et al. in 1977, simulating bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (58 residues) for just 9.2 ps [1]. These early simulations demonstrated the potential of MD to capture biomolecular dynamics but were severely limited by computational resources and simplified force fields.

During the 1990s and early 2000s, MD refinement emerged as a specialized application for improving template-based models. A practical introduction to MD for homology model refinement was formalized in 2012, providing stepwise guidance for using packages like AMBER to refine cytochrome P450 structures [19]. This period saw MD transition from analyzing known structures to actively correcting and refining predicted models. The introduction of explicit solvent models, improved force fields, and longer simulation timescales significantly enhanced the biological relevance of refinement protocols.

The 2010s marked a critical turning point with the development of structured refinement protocols specifically designed for CASP targets. Researchers began implementing systematic approaches involving restraints, ensemble averaging, and advanced sampling techniques [20]. A seminal 2012 study established a protocol combining MD sampling in explicit solvent using CHARMM force fields with sophisticated scoring and ensemble selection methods [20]. This protocol demonstrated consistent refinement across multiple CASP targets, addressing fundamental challenges in sampling and model identification. The integration of physical force fields with statistical potentials represented a hybrid approach that significantly improved refinement outcomes.

Recent advances have focused on automating refinement processes and adapting them for emerging structural biology techniques. The development of correlation-driven MD for cryo-EM refinement exemplifies this trend, utilizing gradual resolution increase and simulated annealing to achieve automated, accurate fitting of atomic models into experimental densities [21]. Concurrently, specialized protocols have emerged for challenging systems like flexible histone peptides, with systematic exploration of MD parameters significantly improving docked geometries [22]. The integration of artificial intelligence with MD refinement represents the current frontier, with methods being developed to address limitations in deep learning-based structural predictions [22].

Table 1: Key Milestones in MD Refinement Evolution

| Time Period | Key Advancement | Representative Example | Impact on Refinement Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1977 | First biomolecular MD simulation | Bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (9.2 ps simulation) [1] | Established feasibility of MD for proteins |

| 2000s | Formalized refinement protocols | AMBER-based homology model refinement [19] | Provided standardized approaches for model improvement |

| 2012 | Structured refinement for CASP targets | CHARMM protocol with ensemble averaging [20] | Achieved consistent refinement across multiple targets |

| 2019+ | Automated refinement for cryo-EM | Correlation-driven MD (CDMD) [21] | Enabled automated fitting into experimental densities |

| 2024+ | Specialized protocols for flexible systems | Histone peptide refinement with explicit hydration [22] | Addressed challenging flexible peptide systems |

Current Applications and Performance

Contemporary MD refinement protocols have demonstrated significant utility across diverse applications in structural biology and drug discovery. The quantitative performance of these methods varies based on system characteristics, refinement protocols, and initial model quality, but consistent improvements have been documented across multiple studies and target types.

In protein structure prediction, MD refinement has proven particularly valuable for improving template-based models. The 2012 CASP assessment demonstrated that sub-microsecond MD sampling combined with ensemble averaging produced moderate but consistent refinement for most systems [20]. This protocol achieved successful refinement across 26 CASP targets, with improvements measured in both RMSD and GDT-HA scores. The study highlighted that restrained MD simulations outperformed unrestrained approaches, as unrestrained simulations tended to drift away from native structures [20]. For successful refinement, proper restraint selection was crucial, typically focusing on core secondary structure elements presumed to be more accurate in initial models.

Cryo-EM structure refinement has emerged as a major application area for advanced MD techniques. Correlation-driven molecular dynamics has demonstrated particular effectiveness for maps at resolutions ranging from near-atomic to subnanometer [21]. CDMD utilizes a gradual increase in resolution and map-model agreement combined with simulated annealing, allowing fully automated refinement without manual intervention or additional rotamer-specific restraints. In comparative assessments, CDMD performed better than established methods like Phenix real space refinement, Rosetta, and Refmac across multiple challenging systems [21]. This approach successfully overcomes sampling issues in rugged density regions that commonly challenge MD-based refinement in high-resolution maps.

In drug discovery, MD refinement has become invaluable for improving docked poses of challenging ligand classes, particularly flexible peptides. Recent work on histone peptide complexes demonstrated that post-docking MD refinement could achieve a median of 32% improvement over initial docked structures in terms of RMSD from experimental references [22]. These complexes are especially challenging due to large conformational flexibility, extensive hydration, and weak interactions with shallow binding pockets. The success of MD refinement in these systems depended critically on explicit hydration of interface regions to avoid empty cavities and accurate modeling of water-mediated hydrogen bond networks.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of MD Refinement Across Applications

| Application Domain | Typical Initial RMSD Range (Å) | Refinement Improvement | Key Success Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homology Model Refinement [20] | 1.5-6.5 Å | 0.25-1.0 Å RMSD improvement; 1% GDT-TS improvement | Proper restraint selection; ensemble averaging; explicit solvent |

| Cryo-EM Model Refinement [21] | 2-8 Å | Significant improvement in map-model correlation | Adaptive resolution; simulated annealing; correlation-driven biasing |

| Flexible Peptide Docking Refinement [22] | ~9.0 Å average | 32% median RMSD improvement | Explicit hydration; interface water networks; appropriate sampling time |

| General Protein Refinement [20] | 1.3-6.9 Å | Consistent but system-dependent improvement | Force field accuracy; sufficient sampling; reliable model selection |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standard MD Refinement Protocol for Homology Models

The following protocol adapts established methodologies for MD-based refinement of homology models using the GROMACS simulation package [23], incorporating best practices from recent literature.

System Setup:

- Initial Structure Preparation: Obtain homology model structure in PDB format. Add missing hydrogen atoms using the

pdb2gmxtool, selecting an appropriate force field (e.g.,ffG53A7for explicit solvent simulations) [23]. - Solvation: Solvate the protein in a cubic box of water (e.g., SPC, TIP3P, or TIP4P models) with a minimum distance of 10-14 Å between any protein atom and the box edge [23].

- Neutralization: Add ions (Na+/Cl-) to neutralize system charge and achieve physiological concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).

- Energy Minimization: Perform steepest descent energy minimization until the maximum force is below 1000 kJ/mol/nm to remove steric clashes and bad contacts.

Equilibration:

- Position-Restrained MD: Conduct equilibration with position restraints on protein heavy atoms (force constant of 1000 kJ/mol/nm²) to allow solvent relaxation around the protein.

- Thermalization: Gradually heat the system from 0 K to target temperature (typically 300 K) over 100-200 ps using a modified Berendsen thermostat.

- Pressure Equilibration: Apply isotropic pressure coupling (Parrinello-Rahman barostat) to achieve target pressure (1 bar) with continued position restraints.

Production MD:

- Unrestrained MD: Perform production simulation without restraints using a 2-fs time step. For refinement applications, simulation lengths of 50-100 ns are typically sufficient, though longer times may be needed for larger systems.

- Restraint Application: For regions of the model with high confidence, apply gentle backbone restraints (force constant 10-100 kJ/mol/nm²) to prevent overfitting and structural drift [20].

- Trajectory Output: Save coordinates every 10-100 ps for subsequent analysis.

Analysis and Model Selection:

- Stability Assessment: Calculate RMSD of protein backbone to ensure simulation stability and convergence.

- Ensemble Generation: Extract snapshots from the stabilized trajectory region (typically after RMSD plateau).

- Clustering: Perform clustering (e.g., using GROMACS

clustertool with linkage algorithm) to identify representative conformations. - Model Selection: Select final refined model based on lowest average energy, cluster population, or agreement with additional validation metrics.

Standard MD Refinement Workflow

Correlation-Driven MD for Cryo-EM Refinement

The CDMD protocol represents an advanced approach specifically designed for cryo-EM map refinement, automating the process while maintaining stereochemical quality [21].

Initial Setup:

- Map and Model Preparation: Obtain experimental cryo-EM map and initial atomic model. Align model to map density.

- System Building: Solvate the system in a simulation box with 10-Å padding from the protein. Add ions for neutralization.

CDMD Simulation:

- Low-Resolution Phase: Start with the simulated map blurred to very low resolution (e.g., 10-15 Å). Use moderate biasing force constant.

- Progressive Resolution Increase: Gradually increase the resolution of the simulated map over 1-2 ns until reaching the experimental map resolution.

- Force Constant Adjustment: Simultaneously increase the biasing force constant to enhance map-model agreement at higher resolutions.

- Simulated Annealing: Apply high-temperature phases (e.g., 500 K) for enhanced sampling, particularly for side-chain rotamer fitting.

- Final Refinement: Conduct extended simulation at target resolution with optimal biasing strength.

Validation:

- Cross-Validation: Refine against a working map subset and validate against withheld map portion to prevent overfitting.

- Geometry Assessment: Validate stereochemical quality using MolProbity or similar tools.

- Map Correlation: Calculate final correlation coefficient between model and experimental map.

CDMD Cryo-EM Refinement Protocol

Post-Docking Refinement for Flexible Peptides

This specialized protocol addresses the challenges of refining docked poses of flexible histone peptides, incorporating explicit hydration of binding interfaces [22].

Interface Hydration:

- Cavity Identification: Identify empty cavities at the protein-peptide interface using cavity detection algorithms.

- Targeted Hydration: Solvate interface regions with explicit water molecules, ensuring complete hydration of binding pockets.

- Water Equilibration: Perform restrained equilibration of water molecules alone, followed by equilibration of entire system.

MD Refinement:

- Restrained Dynamics: Apply gentle positional restraints to protein backbone atoms distant from binding site (force constant 100-500 kJ/mol/nm²).

- Enhanced Sampling: Utilize temperature-based (simulated annealing) or Hamiltonian-based enhanced sampling for peptide conformational exploration.

- Extended Sampling: Conduct relatively long simulations (50-200 ns) to adequately sample peptide flexibility and water rearrangements.

- Multiple Replicas: Perform 3-5 independent simulations from the same starting structure to improve sampling.

Analysis and Selection:

- Interface Stability: Monitor hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and water-bridged interactions throughout trajectories.

- Cluster Analysis: Perform clustering on peptide conformations and interface water positions.

- Scoring and Selection: Rank structures using combination of energy criteria and structural metrics (e.g., interface surface complementarity).

- Hydration Analysis: Identify conserved water molecules mediating protein-peptide interactions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for MD Refinement

| Category | Item | Specification/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Packages | GROMACS [23] | High-performance MD suite with multi-level parallelism | Homology model refinement; Standard MD protocols |

| AMBER [19] | Suite of biomolecular simulation programs | Homology model refinement; Force field development | |

| CHARMM [20] | Molecular mechanics and dynamics program | CASP target refinement; Membrane protein simulations | |

| NAMD [1] | Parallel molecular dynamics code | Large system simulations; Quantum-classical hybrids | |

| Force Fields | ffG53A7 [23] | GROMOS force field for explicit solvent protein simulations | Standard protein refinement in aqueous solution |

| CHARMM36 [20] | All-atom force field for proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids | Refinement with membrane environments; CASP targets | |

| AMBER force fields [19] | Family of force fields including ff14SB, ff19SB | Protein refinement; Drug discovery applications | |

| Martini [1] | Coarse-grained force field for biological membranes | Large system refinement; Membrane protein dynamics | |

| Solvent Models | TIP3P [23] | Transferable Intermolecular Potential 3P water model | Standard explicit solvent simulations |

| TIP4P [23] | Four-site water model with improved properties | Enhanced accuracy in electrostatic interactions | |

| SPC [23] | Simple Point Charge water model | Computational efficiency in large systems | |

| Analysis Tools | GROMACS analysis tools [23] | Built-in trajectory analysis utilities | RMSD, RMSF, energy, and cluster analysis |

| VMD [1] | Visual molecular dynamics program | Visualization; Trajectory analysis; Structure rendering | |

| PyMOL | Molecular visualization system | Publication-quality images; Structural comparisons | |

| Validation Resources | MolProbity | All-atom structure validation tool | Stereochemical quality assessment |

| PDB Validation Server | Worldwide PDB validation service | Standardized structure validation |

The evolution of MD refinement from early methodological developments to current sophisticated applications represents a remarkable advancement in computational structural biology. The historical progression has transformed MD from a limited tool for small-scale simulations to an essential method for improving structural models across diverse applications. Current protocols demonstrate consistent success in refining homology models, cryo-EM structures, and challenging flexible peptide complexes through innovative approaches like correlation-driven MD and explicit hydration of binding interfaces. The continued development of automated protocols, integration with experimental data, and adaptation to emerging challenges like AI-predicted structure refinement ensures MD will remain indispensable for structural biology and drug discovery. As force fields, sampling algorithms, and computational resources continue to advance, MD refinement methodologies will further bridge the gap between computational predictions and experimentally accurate structural models.

When Does MD Refinement Succeed? Analyzing Success Stories from CASP Competitions

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as a powerful technique for refining protein structure predictions, particularly within the rigorous blind testing environment of the Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP). This application note analyzes successful MD refinement strategies deployed in CASP competitions, identifying that success hinges on the intelligent application of restrained MD simulations, effective ensemble averaging, and template-dependent refinement protocols. We present quantitative evidence of refinement success from multiple CASP rounds, detailed experimental methodologies employed by top-performing groups, and practical protocols for implementing these approaches in research and drug development contexts. The analysis reveals that while MD refinement consistently improves model geometry, successful coordinate refinement requires carefully balanced strategies to navigate local energy minima and avoid model degradation.

The CASP refinement category, introduced at CASP8 in 2008, systematically tests methods for improving initial protein structure predictions towards experimental accuracy [24] [25]. While Molecular Dynamics (MD) was initially envisioned as a primary refinement tool, early experiments revealed significant challenges: unrestrained MD simulations of template-based models typically drift away from native structures, and refined models often cannot be reliably identified from simulation trajectories [20] [25]. Successful refinement requires navigating a narrow convergence radius around the true structure while avoiding the many local minima that can degrade model quality [25].

Analysis of CASP results from rounds 8 through 14 demonstrates that successful MD refinement protocols share common features: dependence on physics-based force fields to judge alternative conformations, use of MD to relax models to local minima with restraints to prevent excessive movements, and sophisticated model selection techniques [25]. The following sections analyze quantitative success metrics, detail effective protocols, and provide practical implementation guidance.

Quantitative Analysis of MD Refinement Success in CASP

CASP8-9: Establishing MD Refinement Benchmarks

Analysis of CASP8 and CASP9 targets demonstrated that MD-based sampling combined with ensemble averaging could produce moderate but consistent refinement for most systems. A study involving 26 refinement targets achieved consistent improvement using explicit solvent MD with the CHARMM force field, positional restraints, and ensemble averaging [20]. The table below summarizes representative results:

Table 1: MD Refinement Performance on Selected CASP8 and CASP9 Targets [20]

| Target | Residues | Initial RMSD (Å) | Initial GDT-HA | Refinement Strategy | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TR592 | 105 | 1.26 | 72.9 | Restraints on 17-29;36-46;58-67;76-121 | Consistent refinement achieved |

| TR453 | 87 | 1.47 | 71.3 | Restraints on 5-34;45-91 | Moderate improvement |

| TR462a | 75 | 1.76 | 57.7 | Multiple restraint regions (1-5;10-16; etc.) | Successful refinement |

| TR469 | 63 | 2.18 | 63.5 | Restraints on core secondary elements | Structural improvement |

| TR454 | 192 | 3.24 | 42.3 | Extensive restraint regions (5-24;29-34; etc.) | Challenging but refinable |

The protocol involved restraining presumably accurate regions (based on CASP suggestions or core secondary structure elements), explicit solvent MD, and ensemble averaging to identify improved structures [20]. This approach proved particularly effective for targets where initial models already had relatively high accuracy (GDT-HA > 50).

CASP13-14: Evolution of Refinement Approaches

By CASP13, only 7 of 32 groups performed better than a "naïve predictor" who simply resubmitted the starting model, highlighting the continued difficulty of reliable refinement [25]. Successful groups employed restrained MD approaches that prevented large structural deviations while allowing local optimization.

In CASP14, the introduction of "double-barrelled" targets presented both high-quality AlphaFold2-derived predictions and lower-quality models for refinement. The AF2-derived models proved largely unimprovable as their deviations often resided at domain and crystal lattice contacts rather than reflecting true errors [24]. This underscores the importance of assessing whether model inaccuracies represent true errors or context-dependent structural variations.

Table 2: MD Refinement Success Metrics Across CASP Rounds

| CASP Round | Targets Refined | Successful Groups | Key Advancement | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASP8 | 12 | 1 group improved average GDT_TS | Established refinement category | Most methods degraded models |

| CASP9 | 14 | Multiple groups | Geometry improvement demonstrated | Coordinate refinement remained difficult |

| CASP13 | 29 | 7 of 32 groups beat naïve predictor | Conservative, restrained approaches succeeded | Large targets (>200 residues) problematic |

| CASP14 | ~25 | 4 groups outperformed naïve predictor | AF2 models identified as unimprovable | Lattice contact deviations misleading |

YASARA's Success in CASP8: A Case Study

In CASP8, YASARA's molecular dynamics simulations won 3 of 12 refinement targets using fully automated predictions without human intervention [26]. Their success was attributed to eight years of research on increasing force field accuracy, making MD competitive with Monte-Carlo based approaches like Rosetta [26]. Key features included:

- Knowledge-based dihedral potentials optimized to yield stable energy minima close to native X-ray structures

- Integration of WHAT IF for model quality assessment

- CONCOORD to speed up sampling under certain conditions

This success demonstrated that with sufficiently accurate force fields, MD could achieve competitive refinement performance, though consistent improvement across all targets remained elusive.

Experimental Protocols for Successful MD Refinement

Restrained MD Simulation Protocol

The most consistently successful MD refinement approach involves molecular dynamics simulations with strategically applied positional restraints [20] [25]. The following protocol has demonstrated effectiveness across multiple CASP targets:

Step 1: Restraint Selection and Definition

- For CASP targets, use organizer-provided refinement regions when available [20]

- When specific refinement regions are not provided, restrain core secondary structure elements presumed to be more accurate [20]

- Define restraint regions using residue ranges (e.g., "17-29;36-46;58-67" for TR592) [20]

- Apply harmonic restraints with force constants typically between 1-10 kcal/mol/Ų

Step 2: System Preparation

- Build missing hydrogens using standard tools (e.g., HBUILD in CHARMM) [20]

- Solvate the protein in a cubic water box with minimum 10 Å distance between protein atoms and box edge [20]

- Neutralize system by adding Na+/Cl- counterions to balance overall charge [20]

Step 3: Equilibration Protocol

- Minimize the system to remove steric clashes

- Gradually heat from 50K to 298K through short simulations (1 ps each at 50K, 100K, 150K, 200K, 250K, 298K) [20]

- Use weak position restraints on protein heavy atoms during equilibration

Step 4: Production Simulation

- Run production simulations at 298K and 1 bar pressure [20]

- Use explicit solvent models (TIP3P, TIP4P) for accurate solvation effects

- Employ periodic boundary conditions

- Utilize integration time steps of 2 fs with constraints on bonds involving hydrogen atoms

- Simulation length: sub-microsecond timescales have proven effective for most systems [20]

Step 5: Trajectory Analysis and Ensemble Selection

- Extract snapshots at regular intervals (e.g., every 100-500 ps)

- Calculate quality metrics for each snapshot (RMSD, GDT-HA, MolProbity scores)

- Select subsets of structures for ensemble averaging based on native-likeness [20]

Figure 1: Workflow for Restrained MD Refinement Protocol

Ensemble Averaging and Model Selection Protocol

A critical challenge in MD refinement is identifying the most native-like structures from simulation trajectories. Ensemble averaging has proven effective for this purpose:

Step 1: Trajectory Clustering

- Cluster MD snapshots using RMSD-based clustering algorithms

- Identify major conformational families

- Select representative structures from dominant clusters

Step 2: Quality Assessment

- Score structures using statistical potentials (e.g., DFIRE) [20]

- Calculate geometry quality metrics (MolProbity scores, Ramachandran outliers)

- Evaluate physical plausibility through energy calculations

Step 3: Ensemble Generation

- Select top-performing structures based on quality metrics

- Generate ensemble averages through structural alignment

- Optionally, create hybrid models combining best regions from different snapshots

Step 4: Validation

- Compare refined models to starting structures using GDT-HA, RMSD, and lDDT

- Assess improvement in steric clashes and torsion angles

- Validate against experimental data when available

Template-Dependent Refinement Strategy

The refinability of a structure depends significantly on its initial quality and template characteristics:

For High-Quality Initial Models (GDT-HA > 65):

- Employ minimal restraints focused only on preserved core regions

- Use shorter simulation times (10-100 ns) to avoid drift

- Focus on side-chain optimization and loop refinement

For Medium-Quality Models (GDT-HA 40-65):

- Apply moderate restraints on secondary structure elements

- Use extended sampling (100-500 ns) for local backbone adjustments

- Consider multi-copy simulations to enhance sampling

For Low-Quality Models (GDT-HA < 40):

- Implement extensive restraints on all presumably correct regions

- Employ enhanced sampling techniques (REMD, metadynamics)

- Focus on identifying and correcting major topological errors

Successful implementation of MD refinement requires both computational tools and methodological components. The following table details essential "research reagents" for protein structure refinement projects:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MD Refinement Projects

| Reagent Category | Specific Tools/Components | Function in Refinement Protocol | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, YASARA Force Field | Provide physical energy functions for MD simulations | YASARA's force field optimized for refinement accuracy [26] |

| Solvation Models | TIP3P, TIP4P water models | Mimic aqueous environment and solvation effects | Explicit solvent crucial for accuracy [20] |

| Restraint Methods | Harmonic position restraints, Dihedral restraints | Preserve accurate regions while allowing refinement | Region selection critical for success [20] [25] |

| Sampling Enhancers | Replica-exchange MD, Langevin dynamics | Accelerate conformational sampling | Particularly valuable for difficult refinement targets |

| Quality Metrics | GDT-HA, RMSD, MolProbity, DFIRE | Assess refinement success and select best models | DFIRE effective for model selection [20] |

| Analysis Tools | MDAnalysis, VMD, PyMOL | Trajectory analysis and visualization | MDAnalysis enables efficient analysis of simulation data [27] |

Discussion: Key Success Factors and Practical Recommendations

Critical Success Factors for MD Refinement

Analysis of successful CASP refinement approaches reveals several critical factors:

Judicious Restraint Application: Successful methods avoid unrestrained simulations that drift away from native structures, instead using restraints to preserve correct regions while allowing refinement in uncertain areas [20] [25].

Balanced Sampling: Overly aggressive sampling typically degrades models, while conservative approaches with local relaxation yield gradual improvements [25].

Effective Model Selection: The ability to identify the most native-like structures from MD trajectories is as important as generating them [20].

Template Quality Awareness: Recognition that high-quality models (particularly AF2-derived) may be essentially unimprovable, especially when deviations represent crystal contacts rather than true errors [24].

Implementation Recommendations for Research Applications

For researchers applying MD refinement to homology models in drug development and basic research:

Prioritize Conservative Refinement: Small, consistent improvements are more valuable than aggressive approaches that sometimes succeed but often fail

Validate Against Experimental Data: When available, use experimental constraints (NMR, HDX-MS, mutagenesis) to guide and validate refinement

Invest in Model Selection: Develop robust model selection pipelines using multiple quality metrics

Consider End Use: Tailor refinement strategy to the model's application - small improvements may suffice for drug docking, while structural biology applications may require more extensive refinement

The continued evolution of MD refinement methodologies in CASP demonstrates that while challenges remain, physics-based simulation approaches can consistently improve protein structure models when applied with careful restraint strategies and sophisticated model selection techniques.

Methodology in Action: Practical Protocols for MD-Based Refinement

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as a powerful technique for refining homology models, bridging the gap between initial template-based structures and experimentally accurate models. While homology modeling often produces topologically correct structures, achieving experimental accuracy throughout the model remains challenging. MD-based refinement protocols can consistently improve model quality by sampling near-native conformations and selecting optimal structures using advanced scoring functions. This protocol details the complete workflow for refining homology models of both soluble and membrane proteins using physics-based MD simulations, incorporating recent advances in sampling methodologies and scoring function selection.

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive MD refinement workflow for homology models, from initial preparation through final model selection.

Experimental Protocols

Initial Model Preparation and Quality Assessment

Begin with homology models generated using standard tools such as MODELLER based on alignments from PSI-BLAST [28]. The initial refinement of local stereochemistry is critical before MD simulation.

Protocol:

- Generate initial homology models using template structures with known experimental structures

- Refine local stereochemistry using locPREFMD or similar tools [28]

- Validate initial model quality using MolProbity or similar validation servers

- For membrane proteins, calculate hydrophobic length using tools like MEMH to ensure proper membrane positioning [28]

System Setup and Solvation

Proper system setup is essential for physiologically relevant simulations. The choice between aqueous solvent and explicit lipid bilayers depends on protein type.

Protocol: For soluble proteins:

- Solvate in explicit water using TIP3P or similar water models

- Add ions to neutralize system charge and achieve physiological concentration (0.15M NaCl)

For membrane proteins:

- Embed in explicit lipid bilayers matching biological context (DMPC, DPPC, or DLPC) [28]

- Solvate with water on both sides of the membrane

- Use calculated hydrophobic lengths to ensure proper membrane positioning

- Apply periodic boundary conditions to emulate natural environment [29]

Energy Minimization and Equilibration

Stable simulation systems require careful preparation before production MD.

Protocol:

- Perform energy minimization using steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithms (5,000-10,000 steps)

- Apply positional restraints on protein heavy atoms (force constant: 1000 kJ/mol/nm²)

- Gradually heat system from 0K to target temperature (300-310K) over 100-500ps

- Equilibrate in NPT ensemble (1 atm pressure) until density stabilizes (typically 1-5ns)

- Remove positional restraints gradually during equilibration phase

Production MD Sampling

Extended sampling is crucial for adequate conformational exploration.

Protocol:

- Run production MD simulations for timescales sufficient for protein relaxation (50ns-1μs) [28]

- Maintain constant temperature (300-310K) using Nosé-Hoover or Berendsen thermostats

- Maintain constant pressure (1 atm) using Parrinello-Rahman or Berendsen barostats

- Use 2-fs time step with constraints on hydrogen-heavy atom bonds (LINCS or SHAKE)

- Save trajectory frames at appropriate intervals (10-100ps) for analysis

Trajectory Analysis and Snapshot Selection

Select representative structures using multiple scoring approaches.

Protocol:

- Calculate RMSD, RMSF, and radius of gyration throughout trajectory

- Cluster structures based on backbone conformations

- Score snapshots using knowledge-based (DFIRE, RWplus) or physics-based scoring functions [28]

- For membrane proteins, consider implicit membrane models (HDGBv3, HDGBvdW) for scoring [28]

- Select top-ranked snapshots based on scoring function evaluation

Structure Averaging and Final Refinement

Generate final models through averaging and local refinement.

Protocol:

- Average coordinates of selected snapshots to create composite structure

- Perform final energy minimization to relieve local strains

- Use local refinement tools (locPREFMD) for stereochemical optimization [28]

- Validate final models using multiple quality metrics (MolProbity scores, Ramachandran plots)

The Scientist's Toolkit