Molecular Dynamics Demystified: Simulating Newton's Equations from Theory to Biomedical Application

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the principles and practices of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, a computational technique that solves Newton's equations of motion to model atomic-scale systems.

Molecular Dynamics Demystified: Simulating Newton's Equations from Theory to Biomedical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the principles and practices of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, a computational technique that solves Newton's equations of motion to model atomic-scale systems. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational physics behind MD, details the complete simulation workflow from initial structure preparation to trajectory analysis, and addresses common challenges and optimization strategies. Furthermore, it covers advanced topics including the integration of machine learning interatomic potentials and methods for validating simulation results against experimental data, offering a crucial resource for leveraging MD in biomedical research and therapeutic design.

The Physics Engine of Atoms: Newton's Laws as the Foundation of Molecular Dynamics

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is an indispensable computational method that predicts the time evolution of molecular systems. The technique provides a dynamic, atomic-resolution view of processes critical to biochemistry, structural biology, and drug discovery, including protein folding, ligand binding, and conformational changes [1]. Despite the complexity of biological systems and the sophisticated software used to simulate them, the core of MD rests upon a fundamental Newtonian framework. At its essence, an MD simulation answers a straightforward question: given the positions of all atoms in a system and a description of the forces acting upon them, how will the system change over time? The solution is obtained by repeatedly applying Newton's second law of motion, F=ma, to every atom in the system [1]. This article delineates the core Newtonian framework of MD, tracing the direct path from the classical equations of motion to the computed atomic trajectories that provide profound insights into molecular behavior.

The Theoretical Foundation: Newton's Laws and the Force Field

Newton's Second Law as the Governing Equation

The motion of every atom in an MD simulation is governed by Newton's second law, expressed as the gradient of potential energy [2]: [ \vec{F}i = - \nablai V\left( { \vec{r}j } \right) ] where ( \vec{F}i ) is the force acting on atom (i), ( \nablai ) is the gradient with respect to the position of atom (i), ( V ) is the potential energy function of the system, and ( { \vec{r}j } ) represents the positions of all atoms [2]. Using the identity F=ma, this translates into an equation of motion for each atom: [ mi \frac{d^2 \vec{r}i}{dt^2} = - \nablai V\left( { \vec{r}j } \right) ] Here, ( mi ) is the mass of atom (i), and ( \frac{d^2 \vec{r}i}{dt^2} ) is its acceleration [2]. The potential energy function ( V ) encapsulates the complete physical model for all interatomic interactions, and its gradient determines the force on each atom.

The Molecular Mechanics Force Field

The potential energy function ( V ) is described by a molecular mechanics force field, an empirical model that approximates the true electronic potential energy surface. Force fields are constructed from relatively simple analytical functions whose parameters are fit to quantum mechanical calculations and experimental data [1]. A typical force field decomposes the total potential energy into contributions from bonded and non-bonded interactions:

[ V({\vec{r}j}) = V{\text{bonds}} + V{\text{angles}} + V{\text{torsions}} + V{\text{electrostatic}} + V{\text{van der Waals}} ]

Table 1: Components of a Classical Molecular Mechanics Force Field

| Interaction Type | Mathematical Form | Physical Description |

|---|---|---|

| Bonds | ( V{\text{bonds}} = \sum{\text{bonds}} \frac{1}{2} kb (r - r0)^2 ) | Energetic cost of stretching/compressing covalent bonds from equilibrium length (r_0). |

| Angles | ( V{\text{angles}} = \sum{\text{angles}} \frac{1}{2} k\theta (\theta - \theta0)^2 ) | Energetic cost of bending bond angles from equilibrium angle (\theta_0). |

| Torsions | ( V{\text{torsions}} = \sum{\text{torsions}} k_\phi [1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta)] ) | Energy associated with rotation around a bond, defined by dihedral angle (\phi). |

| van der Waals | ( V{\text{vdW}} = \sum{i |

Short-range interaction accounting for Pauli repulsion ((r^{-12})) and London dispersion attraction ((r^{-6})). |

| Electrostatic | ( V{\text{elec}} = \sum{i |

Long-range Coulomb interaction between partial atomic charges (qi) and (qj). |

The force field is a critical approximation. It replaces the need to solve the computationally intractable quantum mechanical Schrödinger equation for the entire system with a classical model, thereby making the simulation of large biomolecules feasible [3]. The accuracy of any MD simulation is inherently tied to the quality of its underlying force field.

Numerical Integration: From Forces to Trajectories

The Time-Stepping Algorithm

Given the initial atomic positions and the force field ( V ), the task is to solve Newton's equations of motion for all atoms. This is accomplished using a numerical integration algorithm. The simulation is divided into small, discrete time steps, ( \Delta t ), typically 1-2 femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ s) [4]. This short step is necessary to accurately capture the fastest motions in the system (e.g., bond vibrations) and maintain numerical stability.

The Verlet integrator is a widely used algorithm for this purpose. It is derived from the Taylor expansion of the atomic position ( \vec{r}(t) ) forward and backward in time [2]. The most common form, the Velocity Verlet algorithm, updates positions and velocities as follows:

- Calculate the force ( \vec{F}(t) ) on each atom from the potential ( V ) at position ( \vec{r}(t) ).

- Update the velocity for half a time step: ( \vec{v}(t + \frac{1}{2} \Delta t) = \vec{v}(t) + \frac{\vec{F}(t)}{m} \frac{\Delta t}{2} ).

- Update the position: ( \vec{r}(t + \Delta t) = \vec{r}(t) + \vec{v}(t + \frac{1}{2} \Delta t) \Delta t ).

- Calculate the new force ( \vec{F}(t + \Delta t) ) at the new position ( \vec{r}(t + \Delta t) ).

- Update the velocity for the second half of the time step: ( \vec{v}(t + \Delta t) = \vec{v}(t + \frac{1}{2} \Delta t) + \frac{\vec{F}(t + \Delta t)}{m} \frac{\Delta t}{2} ).

This cycle is repeated millions or billions of times to generate a continuous trajectory of the system [1].

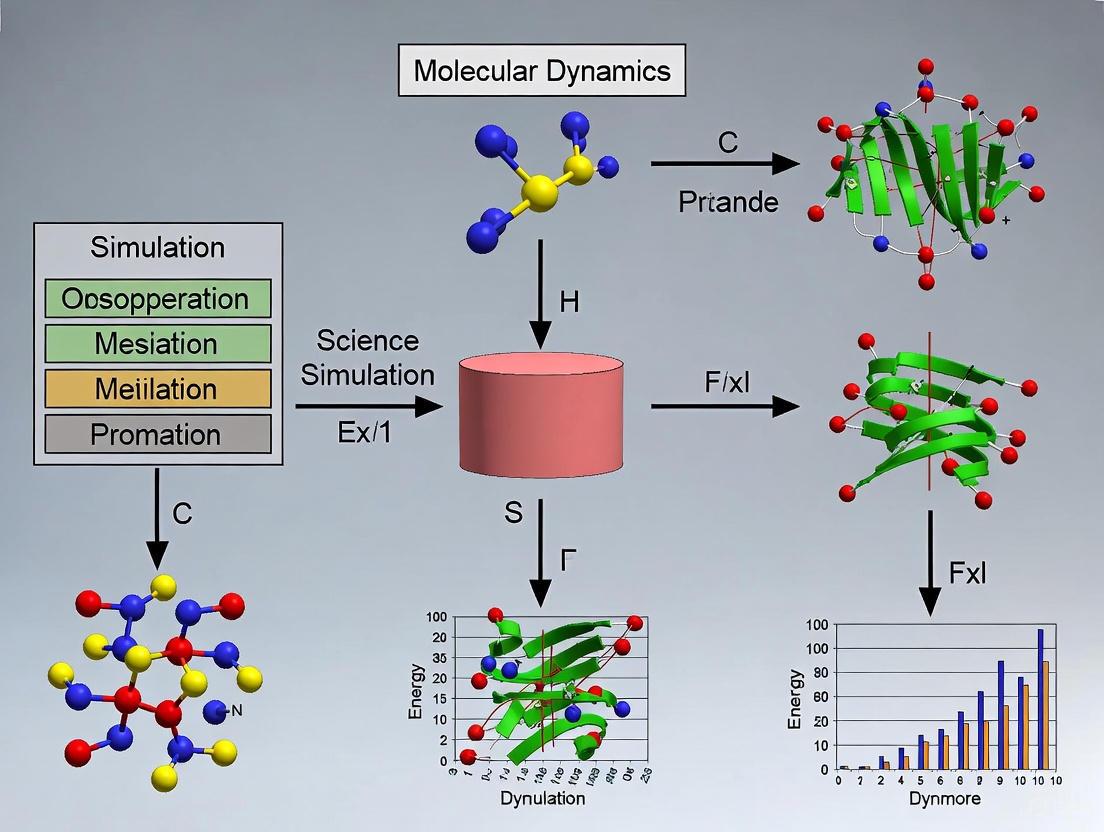

Figure 1: The core MD integration loop, illustrating the cyclic process of force calculation and coordinate updates based on the Velocity Verlet algorithm.

A Simple Example: A Diatomic Molecule

Consider a hydrogen molecule (H₂) in vacuum, modeled as two atoms connected by a spring with force constant ( k ) and equilibrium bond length ( r0 ) [3]. The potential energy is ( V(r) = \frac{1}{2}k(r - r0)^2 ). The force on atom 1 due to the bond is ( \vec{F}1 = -k(|\vec{r}1 - \vec{r}2| - r0) \cdot \hat{r}{12} ), where ( \hat{r}{12} ) is the unit vector pointing from atom 1 to atom 2.

Table 2: Simulation Parameters for a Hydrogen Molecule (Sample Values)

| Parameter | Symbol | Example Value |

|---|---|---|

| Force Constant | ( k ) | 0.1 kJ·mol⁻¹·Å⁻² |

| Equilibrium Bond Length | ( r_0 ) | 0.5 Å |

| Atomic Mass | ( m_H ) | 1.0 g/mol |

| Initial Position (Atom 1) | ( \vec{r}_1 ) | [0.7, 0.0, 0.0] Å |

| Initial Position (Atom 2) | ( \vec{r}_2 ) | [0.0, 0.0, 0.0] Å |

| Initial Velocity (Atom 1) | ( \vec{v}_1 ) | [-0.1, 0.0, 0.0] Å/fs |

| Initial Velocity (Atom 2) | ( \vec{v}_2 ) | [0.1, 0.0, 0.0] Å/fs |

| Time Step | ( \Delta t ) | 2 fs |

| Number of Steps | ( N ) | 5 |

Following the Velocity Verlet algorithm, the simulation would proceed step-by-step, calculating the force, updating the velocity and position for each atom at each step, ultimately producing a trajectory of the oscillating H₂ molecule.

Practical Implementation in Biomolecular Simulation

Preparing a Biological System

Simulating a protein or other biomolecule requires careful preparation. The initial atomic coordinates often come from experimental structures determined by X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM [1]. The system must be prepared with the following components:

- Solvation: Biomolecules exist in an aqueous environment. An explicit solvent model (e.g., TIP3P water) places thousands of water molecules around the solute, making simulations more physically realistic but computationally expensive [3].

- Ions: To neutralize the system's charge and mimic physiological ionic strength, ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) are added.

- Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC): To simulate a bulk environment and avoid artificial surface effects, the system is placed in a box (e.g., a cube), and PBC are applied. As a molecule exits one side of the box, it re-enters from the opposite side [3]. This creates a pseudo-infinite system while simulating only the particles in the primary box.

Figure 2: The relationship between system inputs, the force field, and the final output trajectory in a biomolecular MD simulation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for an MD Simulation

Table 3: Essential Materials and Software for Running an MD Simulation

| Item | Function | Example Tools/Formats |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Structure | Provides the starting 3D atomic coordinates for the simulation. | PDB file format [1] |

| Topology File | Defines the molecular system: atom types, bonds, angles, dihedrals, and force field parameters. | .top (GROMACS), .prmtop (AMBER) [3] |

| Force Field | The set of mathematical functions and parameters defining the potential energy ( V ). | AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS, OPLS [3] |

| MD Engine | The software that performs the numerical integration of Newton's equations. | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, OpenMM [1] |

| Solvent Model | Represents the aqueous environment surrounding the biomolecule. | Explicit: TIP3P, SPC; Implicit: Generalized Born [3] |

Analysis and Validation of the Generated Trajectory

The primary output of an MD simulation is a trajectory—a file containing the positions (and sometimes velocities) of all atoms at many time points [3]. Analyzing this trajectory is key to extracting biological meaning. Common analyses include:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the conformational stability of a protein by calculating the average distance of atoms from a reference structure (often the starting configuration) after optimal alignment [5].

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Quantifies the flexibility of individual residues over the course of the simulation, often highlighting mobile loops or hinge regions [5] [6].

- Radius of Gyration (Rgyr): Assesses the global compactness of a protein structure, which can indicate folding or unfolding events [5] [6].

- Trajectory Maps: A novel visualization method that plots protein backbone movements as a heatmap, with time on the x-axis, residue number on the y-axis, and the magnitude of movement (shift) represented by color. This provides an intuitive overview of the location, timing, and magnitude of conformational events [5].

Validation is crucial. The reproducibility and statistical significance of results from MD must be assessed, often by running multiple independent simulations and applying statistical tests to ensure observed effects are not due to random sampling variations [6]. Furthermore, results should be compared with experimental data where available, such as from SAXS or NMR, to validate the computational model [6].

Molecular Dynamics simulation is a powerful technique that bridges the gap between static structural snapshots and the dynamic reality of biomolecular function. While the computational machinery is complex, its core principle remains elegantly simple: the application of Newton's second law of motion to a system of interacting atoms. By defining interactions through a molecular mechanics force field and numerically integrating the equations of motion over femtosecond time steps, MD simulations generate atomic-level trajectories that provide unparalleled insight into biological processes. This robust Newtonian framework continues to be the foundation upon which advances in simulation accuracy, scale, and application are built, making MD an indispensable tool in modern scientific research and drug development.

In the realm of computational chemistry and materials science, the Potential Energy Surface (PES) serves as the fundamental map that dictates the dynamic evolution of atomic systems. As a multidimensional landscape defining the potential energy of a molecular system as a function of its nuclear coordinates, the PES provides the critical connection between microscopic interactions and macroscopic observables [7]. Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation leverages this relationship by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for systems of interacting particles, where forces between particles and their potential energies are calculated using interatomic potentials or molecular mechanical force fields [8]. The PES thus becomes the indispensable guide that determines how atoms and molecules move and interact over time, enabling researchers to simulate and analyze physical movements that are impossible to observe directly through experimental means alone.

The accuracy of any MD simulation is intrinsically tied to the quality of the underlying PES. For decades, classical potentials relied on physically motivated functional forms whose accuracy was limited by their predetermined mathematical structure [9]. However, recent advances in machine learning (ML) methods have revolutionized this field through models such as BPNN, DeepPMD, EANN, and NequIP, which offer extraordinary flexibility and fitting capability in high-dimensional spaces [9]. Despite these advances, most ML potentials are still fitted to density functional theory (DFT) calculations, whose accuracy limitations inevitably constrain the reliability of the resulting PES [9]. This fundamental challenge has driven the development of novel approaches that refine the PES by learning directly from experimental data, bridging the gap between theoretical simulation and experimental observation.

Theoretical Foundation: PES and Newton's Equations of Motion

Mathematical Definition of the PES

The Potential Energy Surface represents the energy of a molecular system as a function of the nuclear coordinates. For a system comprising N atoms, the molecular geometry (R) can be expressed as a set of atomic positions: R = (r₁, r₂, ..., r_N) [10]. The PES, denoted as V(R), describes how the potential energy changes as these atomic positions vary. The specific mathematical form of V(R) depends on the chosen interatomic potential, with the Lennard-Jones potential serving as one of the most frequently used models for neutral atoms and molecules [8] [7].

The Lennard-Jones Potential (V) is given by:

$$V(r) = 4\epsilon \left[ \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{6} \right]$$

where ε is the well depth representing the strength of particle attraction, σ is the distance where the intermolecular potential is zero, and r is the separation distance between particles [7]. This mathematically simple model captures both attractive (the (σ/r)⁶ term) and repulsive (the (σ/r)¹² term) interactions between non-ionic particles [7]. The PES encompasses all such interactions within a complex, multidimensional energy landscape where minima correspond to stable molecular configurations and saddle points represent transition states between them.

Connecting PES to Newtonian Mechanics

Molecular Dynamics simulations transform the static PES into dynamic atomic trajectories by applying Newton's second law of motion. For each atom i in the system, the force F_i is determined as the negative gradient of the potential energy with respect to its position:

$$Fi = -\frac{\partial V}{\partial ri}$$

This fundamental relationship means the PES directly determines the forces acting on each atom [10]. Using Newton's second law (F = ma), the acceleration a_i of each atom can be calculated as:

$$ai = \frac{Fi}{mi} = -\frac{1}{mi} \frac{\partial V}{\partial r_i}$$

where m_i is the mass of atom i [10]. This acceleration, derived from the slope of the PES at each point in the configuration space, ultimately governs how atomic positions evolve over time. The numerical integration of these equations of motion generates the trajectories that form the basis for analyzing structural, dynamic, and thermodynamic properties of the molecular system.

Computational Framework: From PES to Atomic Trajectories

Molecular Dynamics Integration Algorithms

The translation from PES to atomic motion requires numerical integration algorithms that solve Newton's equations of motion in discrete time steps. Since analytical solutions are impossible for systems with more than two atoms, MD relies on finite difference methods that divide the integration into small time steps (δt), typically on the order of femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ s) to accurately capture molecular vibrations [10].

Table 1: Comparison of MD Integration Algorithms

| Algorithm | Key Features | Equations | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verlet | Uses current and previous positions | (r(t + \delta t) = 2r(t) - r(t- \delta t) + \delta t^2 a(t)) | Time-reversible, good energy conservation | No explicit velocity term, not self-starting |

| Velocity Verlet | Explicit position and velocity update | (r(t + \delta t) = r(t) + \delta t v(t) + \frac{1}{2} \delta t^2 a(t)) (v(t+ \delta t) = v(t) + \frac{1}{2}\delta t[a(t) + a(t + \delta t)]) | Positions, velocities, and accelerations synchronized | Requires multiple force evaluations per step |

| Leapfrog | Staggered position and velocity update | (v\left(t+ \frac{1}{2}\delta t\right) = v\left(t- \frac{1}{2}\delta t\right) +\delta ta(t)) (r(t + \delta t) = r(t) + \delta t v \left(t + \frac{1}{2}\delta t \right)) | Computationally efficient | Velocities and positions not synchronized in time |

The Velocity Verlet algorithm has emerged as one of the most widely used integration methods in MD simulation due to its numerical stability and synchronous calculation of positions, velocities, and accelerations at each time step [10]. This algorithm first updates atomic positions using current velocities and accelerations, computes new accelerations from the force field at these new positions, and finally updates velocities using the average of current and new accelerations.

Workflow of Molecular Dynamics Simulation

The process of converting the PES into atomic trajectories follows a systematic workflow with five key components: boundary conditions, initial conditions, force calculation, integration/ensemble, and property calculation [7]. The following diagram illustrates the core computational cycle in MD simulations:

Figure 1: The MD Simulation Cycle. This workflow shows the iterative process of computing forces from the PES and integrating Newton's equations of motion to generate atomic trajectories.

The force calculation step represents the most computationally intensive component of MD simulations, as it requires evaluating the potential energy and its derivatives for all interacting particles in the system [10] [8]. In traditional approaches, non-bonded interactions scale as O(N²) with system size, though advanced algorithms like particle-mesh Ewald and neighbor lists can reduce this to O(N log N) or O(N) [8]. The integration of Newton's equations uses the algorithms described in Table 1 to propagate the system through time, while the choice of ensemble (NVE, NVT, NPT) ensures appropriate thermodynamic conditions are maintained throughout the simulation.

Advanced Methods: Refining and Enhancing the PES

Energy Minimization and PES Exploration

Locating minima on the PES is essential for identifying stable molecular configurations. Energy minimization (or geometry optimization) algorithms navigate the complex multidimensional PES to find equilibrium structures corresponding to local or global energy minima [7]. These procedures are mathematically formulated as iterative processes where new geometries (xnew) are updated from current geometries (xold) according to: xnew = xold + correction [7].

Table 2: Energy Minimization Methods for PES Exploration

| Method | Mathematical Foundation | Computational Cost | Convergence Behavior | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steepest Descent | (x{new} = x{old} - \gamma E'(x_{old})) | Low per step, many steps required | Stable but slow convergence; oscillates near minima | Initial stages of minimization from poor starting structures |

| Conjugate Gradient | Incorporates previous search direction | Moderate per step | Faster convergence than steepest descent | Intermediate minimization stages |

| Newton-Raphson | Uses full second derivative matrix | High per step (requires Hessian) | Quadratic convergence near minima | Final stages of minimization with good starting structures |

The Steepest Descent method provides robust convergence from poor initial structures by always moving opposite to the direction of the largest gradient, while the Newton-Raphson method offers superior convergence efficiency near minima through the use of second derivative information [7]. In practical applications, researchers often employ a hybrid approach, beginning with Steepest Descent to rapidly reduce high-energy clashes before switching to more refined methods for final optimization.

Machine Learning Approaches to PES Development

Recent advances in machine learning have dramatically transformed PES construction through Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs). These models learn the relationship between atomic configurations and potential energies from quantum mechanical calculations, typically using Density Functional Theory (DFT) as reference data [9] [11]. The Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) dataset represents a landmark achievement in this area, containing over 100 million 3D molecular snapshots with DFT-calculated properties [11]. With an unprecedented computational cost of six billion CPU hours, this dataset enables the training of MLIPs that can deliver DFT-level accuracy at speeds approximately 10,000 times faster than direct DFT calculations [11].

A particularly innovative approach addresses the inverse problem of spectroscopy: refining the PES directly from experimental dynamical data rather than solely from quantum mechanical calculations [9]. This method uses automatic differentiation (AD) techniques to efficiently optimize potential parameters by comparing simulated properties with experimental observables. Through a combination of adjoint methods and gradient truncation, researchers can circumvent previous limitations associated with memory overflow and gradient explosion in trajectory differentiation [9]. The differentiable MD framework enables both transport coefficients and spectroscopic data to improve DFT-based ML potentials toward higher accuracy, effectively extracting microscopic interactions from vibrational spectroscopic data [9].

Practical Applications and Research Implementations

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for PES Exploration and MD Simulation

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function/Purpose | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | Lennard-Jones Potential, AMBER, CHARMM | Describes interatomic interactions as a function of nuclear coordinates | Mathematical models capturing bonded and non-bonded interactions; parameters optimized for specific chemical systems |

| Integration Algorithms | Velocity Verlet, Leapfrog | Numerically solves Newton's equations of motion | Time-reversible, energy-conserving properties; appropriate for different simulation ensembles |

| Differentiable MD Infrastructures | JAX-MD, TorchMD, SPONGE, DMFF | Enables gradient-based optimization of potential parameters | Automatic differentiation through MD trajectories; potential refinement from experimental data |

| Training Datasets | Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) | Provides reference data for ML potential development | 100M+ molecular configurations with DFT properties; includes biomolecules, electrolytes, metal complexes |

| Energy Minimization Tools | Steepest Descent, Conjugate Gradient, Newton-Raphson | Locates minima on the PES corresponding to stable structures | Various convergence properties and computational requirements; used sequentially for optimal performance |

Case Study: Differentiable MD for PES Refinement

A cutting-edge application of PES refinement through differentiable molecular simulation demonstrates how both thermodynamic and spectroscopic data can boost the accuracy of DFT-based ML potentials [9]. The following diagram illustrates this innovative workflow:

Figure 2: PES Refinement via Differentiable MD. This workflow uses automatic differentiation to refine potential parameters by comparing simulated dynamical properties with experimental data.

In this approach, the loss function L is defined as the squared deviation between simulated and experimental observables: L = (〈O〉 - O)², where 〈O〉 represents simulated properties (such as diffusion coefficients or spectroscopic signals) and O represents experimental references [9]. The gradient of this loss function with respect to potential parameters θ (∂L/∂θ) is computed efficiently using adjoint methods, enabling targeted improvements to the PES [9]. This methodology has shown particular promise for water models, where combining thermodynamic and spectroscopic data leads to more robust predictions for properties such as radial distribution functions, diffusion coefficients, and dielectric constants [9].

Applications in Drug Development and Materials Science

The accurate description of PES has profound implications for drug development, particularly in optimizing drug delivery systems for cancer therapy. MD simulations provide atomic-level insights into interactions between drugs and their carriers, enabling more efficient study of drug encapsulation, stability, and release processes compared to traditional experimental methods [12]. Recent research has demonstrated the value of MD simulations for assessing diverse drug delivery systems, including functionalized carbon nanotubes (FCNTs), chitosan-based nanoparticles, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and human serum albumin (HSA) [12]. Case studies involving anticancer drugs like Doxorubicin (DOX), Gemcitabine (GEM), and Paclitaxel (PTX) showcase how MD simulations can improve drug solubility and optimize controlled release mechanisms [12].

In materials science, MD simulations with accurate PES descriptions facilitate the examination of atomic-level phenomena such as thin film growth and ion subplantation, while also enabling the prediction of physical properties of nanotechnological devices before their physical creation [8]. The development of machine learning potentials with polarizable long-range interactions further extends these capabilities by more accurately capturing electrostatic interactions and atomic charges, which are critical for modeling complex materials behavior [13].

The Potential Energy Surface serves as the fundamental map guiding atomic motion in molecular dynamics simulations, providing the critical link between Newton's equations of motion and the dynamic evolution of molecular systems. Through continued advances in machine learning potentials, differentiable simulation frameworks, and computational infrastructure, researchers are overcoming traditional limitations in PES accuracy and transferability. The emerging paradigm of refining PES through comparison with experimental data represents a particularly promising direction, effectively closing the loop between simulation and observation. As these methodologies continue to mature, they will undoubtedly accelerate progress across diverse fields including drug development, materials design, and fundamental molecular science, enabling increasingly accurate predictions of molecular behavior across extended spatial and temporal scales.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, force fields are the fundamental mathematical models that translate the complex quantum mechanical interactions between atoms into calculable forces, enabling the application of Newton's equations of motion to molecular systems. MD is a computer simulation method for analyzing the physical movements of atoms and molecules by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for a system of interacting particles [8]. The forces between particles and their potential energies are calculated using interatomic potentials or molecular mechanical force fields [8]. This translation is crucial because molecular systems typically consist of a vast number of particles, making it impossible to determine their properties analytically; MD simulation circumvents this problem through numerical methods [8]. The accuracy of these simulations in predicting molecular behavior, from simple liquids to complex biological systems, hinges entirely on the fidelity of the force field employed.

The development of force fields represents an ongoing effort to balance computational efficiency with physical accuracy. These empirical mathematical expressions provide simplified but effective methods for calculating the interactions between atoms in a molecular system [14]. Traditional additive force fields describe the potential energy of a system by considering both bonded interactions (bond stretching, angle bending, and torsional rotation) and nonbonded interactions (van der Waals forces and electrostatic interactions) [14]. As computational power has increased and scientific applications have expanded, force fields have evolved from simple classical representations to increasingly sophisticated models that incorporate electronic polarization, reactive chemistry, and most recently, machine learning approaches to achieve quantum-level accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost.

Mathematical Foundations of Force Fields

Fundamental Components and Functional Forms

Force fields express the total potential energy of a molecular system as a sum of individual energy contributions, typically divided into bonded and non-bonded interactions. The general form can be represented as:

[ U{\text{total}} = U{\text{bonded}} + U_{\text{non-bonded}} ]

Where the bonded terms include: [ U{\text{bonded}} = U{\text{bond}} + U{\text{angle}} + U{\text{torsion}} ] And non-bonded terms include: [ U{\text{non-bonded}} = U{\text{van der Waals}} + U_{\text{electrostatic}} ]

The specific mathematical representation of each term varies across force field classifications. In Class I force fields—the most commonly used type for organic molecules—these terms take relatively simple forms [15]. Bond stretching is typically modeled as a harmonic oscillator: ( U{\text{bond}} = \sum{\text{bonds}} kr(r - r0)^2 ), where ( kr ) is the force constant, ( r ) is the actual bond length, and ( r0 ) is the equilibrium bond length. Similarly, angle bending is represented as: ( U{\text{angle}} = \sum{\text{angles}} k\theta(\theta - \theta0)^2 ), where ( k\theta ) is the angle force constant, ( \theta ) is the actual bond angle, and ( \theta0 ) is the equilibrium bond angle.

Torsional potentials, which describe the energy barrier for rotation around bonds, are typically modeled with a cosine series: ( U{\text{torsion}} = \sum{\text{torsions}} \frac{Vn}{2} [1 + \cos(n\phi - \gamma)] ), where ( Vn ) is the rotational barrier, ( n ) is the periodicity, ( \phi ) is the torsional angle, and ( \gamma ) is the phase angle. Non-bonded interactions include van der Waals forces, commonly represented by the Lennard-Jones potential: ( U{\text{vdW}} = \sum{i

From Potential Energy to Atomic Forces

Once the total potential energy of the system is calculated using the force field, the force on each atom is derived as the negative gradient of the potential energy with respect to the atom's position: [ \vec{F}i = -\nablai U{\text{total}} ] where ( \vec{F}i ) is the force vector on atom i, and ( \nabla_i ) represents the gradient with respect to the coordinates of atom i.

These forces are then used to numerically integrate Newton's equations of motion (( F = ma )) to obtain new atomic positions and velocities at each timestep. The most common integration algorithms in MD, such as the Verlet method [8], calculate the time evolution of the system using the Taylor expansion of particle positions: [ x(t + \Delta t) = 2x(t) - x(t - \Delta t) + \frac{F(t)}{m}\Delta t^2 + O(\Delta t^4) ] where ( x ) is position, ( t ) is time, ( \Delta t ) is the timestep (typically 1-2 femtoseconds), ( F ) is force, and ( m ) is mass [15].

Table 1: Key Mathematical Components of Classical Force Fields

| Energy Component | Mathematical Form | Parameters Required | Physical Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | ( kr(r - r0)^2 ) | ( kr ), ( r0 ) | Covalent bonds |

| Angle Bending | ( k\theta(\theta - \theta0)^2 ) | ( k\theta ), ( \theta0 ) | Bond angles |

| Torsional Rotation | ( \frac{V_n}{2} [1 + \cos(n\phi - \gamma)] ) | ( V_n ), ( n ), ( \gamma ) | Dihedral angles |

| van der Waals | ( 4\epsilon{ij} \left[ \left(\frac{\sigma{ij}}{r{ij}}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma{ij}}{r_{ij}}\right)^6 \right] ) | ( \epsilon{ij} ), ( \sigma{ij} ) | Dispersion/repulsion |

| Electrostatics | ( \frac{qi qj}{4\pi\epsilon0 r{ij}} ) | ( qi ), ( qj ) | Partial charges |

Classification and Evolution of Force Fields

Classical Force Field Hierarchies

Force fields are systematically classified into categories based on their complexity and the physical effects they incorporate. Class I force fields, which include widely used frameworks such as AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS, and GAFF (Generalized Amber Force Field), represent the most fundamental level, containing only the basic bonded and non-bonded terms described in Section 2.1 [15]. These force fields use fixed point charges and relatively simple functional forms, making them computationally efficient and suitable for simulating large biomolecular systems over extended timescales.

Class II force fields, such as PCFF (Polymer Consistent Force Field), introduce additional complexity through cross-coupling terms that account for interactions between different internal coordinates [15]. For example, they may include bond-bond terms where the equilibrium length of one bond depends on the length of an adjacent bond, or bond-angle terms where the stiffness of a bond angle depends on the lengths of the constituent bonds. These couplings provide a more accurate description of molecular vibrations and deformations, particularly for systems under mechanical stress or in condensed phases.

Class III force fields incorporate even more sophisticated physical effects, most notably electronic polarization [15]. Unlike Class I and II force fields that use fixed atomic charges, polarizable force fields such as AMOEBA allow the charge distribution to respond to changes in the local electrostatic environment. This is achieved through various methods, including fluctuating charges, induced atomic dipoles, or Drude oscillators. While significantly more computationally expensive, these models provide more accurate descriptions of heterogeneous environments, such as interfaces between materials with different dielectric properties or binding events where charge transfer occurs.

Table 2: Comparison of Force Field Types and Characteristics

| Force Field Type | Key Features | Representative Examples | Relative Speed | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | Basic bonded + non-bonded terms; fixed charges | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS, GAFF | 1 (reference) | Proteins, nucleic acids, drug-like molecules |

| Class II | Cross-coupling terms between internal coordinates | PCFF, CFF | ~0.5x | Polymers, materials under mechanical stress |

| Class III | Polarizable electrons; environment-responsive charges | AMOEBA, CLaP | ~0.1x | Heterogeneous systems, interfaces, ion channels |

| Reactive FFs | Bond formation/breaking; variable connectivity | ReaxFF | ~0.01x | Chemical reactions, combustion, catalysis |

| Machine Learning FFs | Quantum accuracy via neural networks; no fixed functional form | DeepMD, ANI | ~0.01x | Quantum-accurate MD; training from DFT or experimental data |

| Ab Initio | Direct electronic structure calculation | DFT, CCSD(T) | <0.0001x | Benchmarking; electronic properties |

Specialized and Advanced Force Fields

Beyond the classical hierarchy, specialized force fields have been developed for particular applications. Reactive force fields, most notably ReaxFF, enable the simulation of bond formation and breaking by using a bond-order formalism that dynamically describes chemical bonding based on interatomic distances [15]. This approach allows ReaxFF to model complex chemical reactions in large systems where quantum mechanical methods would be computationally prohibitive.

Machine learning force fields (MLFFs) represent a paradigm shift in molecular simulations. Rather than relying on predetermined functional forms with fitted parameters, MLFFs use neural networks to learn the relationship between atomic configurations and potential energies directly from quantum mechanical calculations [16] [15]. For instance, recent approaches leverage both Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations and experimentally measured mechanical properties and lattice parameters to train ML potentials that concurrently satisfy all target objectives [16]. These methods can achieve accuracy接近 quantum methods while being several orders of magnitude faster than ab initio MD [17]. The foundation model paradigm is now transforming MLFFs, with recent research focusing on distilling large foundation models into smaller, specialized "simulation engines" that can be up to 20 times faster while maintaining accuracy [18].

Methodologies for Force Field Development and Validation

Parameterization Approaches and Data Fusion

The development of accurate force fields requires careful parameterization against experimental and quantum mechanical data. Traditional parameterization involves iterative adjustment of force field parameters to reproduce target data, which may include experimental measurements (such as crystal structures, vibrational spectra, and thermodynamic properties) and quantum mechanical calculations (such as conformational energies and interaction energies) [14].

A cutting-edge approach demonstrated for titanium involves fusing both DFT calculations and experimental data in training machine learning potentials [16]. This methodology employs alternating optimization between a DFT trainer and an experimental (EXP) trainer. The DFT trainer performs standard regression to match energies, forces, and virial stresses from DFT calculations, while the EXP trainer optimizes parameters such that properties computed from ML-driven simulations match experimental values using the Differentiable Trajectory Reweighting (DiffTRe) method [16]. This fused approach successfully corrects inaccuracies of DFT functionals at target experimental properties while maintaining accuracy for off-target properties.

The following diagram illustrates this integrated training methodology:

Diagram 1: Force field training methodology with fused data

Validation Protocols and Assessment Metrics

Comprehensive validation is essential to ensure force field reliability. For biomolecular force fields, this typically involves extended MD simulations of proteins and nucleic acids followed by comparison of structural, dynamic, and thermodynamic properties with experimental data. A recent systematic assessment of RNA force fields exemplifies this approach, where multiple 1 microsecond MD simulations were conducted for various RNA-ligand complexes and analyzed using multiple metrics [19].

Key validation metrics include:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures structural conservation during simulation compared to experimental starting structures [19].

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Quantifies per-residue flexibility and compares to experimental B-factors or NMR data [19].

- Contact Map Analysis: Evaluates the preservation of native contacts and identification of non-native interactions by calculating residue-residue contact frequencies throughout trajectories [19].

- Helical Parameters: For nucleic acids, parameters like major groove width, twist, and sugar puckering are computed and compared to experimental norms [19].

- Ligand Stability: For drug-target systems, ligand-only RMSD (LoRMSD) measures ligand mobility relative to the biomolecule after aligning the simulation frames to the receptor backbone [19].

In the RNA force field assessment, researchers defined a contact as occurring when the minimum distance between any pair of heavy atoms from two non-contiguous residues was less than 4.5 Å [19]. They computed contact occupancy (fraction of frames where a contact was present) and contact-occupancy variation (standard deviation of occupancy), which provides a measure of contact stability without arbitrary thresholds [19].

Applications and Research Reagent Solutions

Key Research Applications

Force fields enable diverse applications across scientific disciplines. In structural biology, they facilitate the refinement of 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids based on experimental constraints from X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy [8]. In drug discovery, MD simulations inform pharmacophore development and structure-based drug design by identifying critical intermolecular contacts in ligand-protein complexes [8]. Recent work has demonstrated the capability of force field-based simulations to accurately predict adsorption energies and assembly of organic molecules on metal surfaces with up to 8 times higher accuracy than density functional calculations at a million-fold faster speed [17].

In materials science, force fields allow the design of functional metal-organic frameworks by predicting physical properties and guiding data-driven parameterization approaches [14]. Specialized force fields have been developed for simulating interfacial systems, such as the INTERFACE force field (IFF), which accurately predicts binding and assembly of organic molecules, ligands, and biological molecules on metal surfaces without additional fit parameters [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Force Field Development and Application

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Field Software | MD Engines | Perform molecular dynamics simulations | AMBER, GROMACS, GENESIS, J-OCTA |

| Parameterization Tools | Parameter Generation | Generate force field parameters for novel molecules | ACpype, GAUSSIAN, ANTECHAMBER |

| Quantum Chemistry Codes | Ab Initio Software | Generate reference data for force field development | SIESTA, Gaussian, DFTB+ |

| Specialized Force Fields | Pre-parameterized Models | Specific applications with validated parameters | INTERFACE FF (metal surfaces), TIP4P (water models), OL3 (RNA) |

| Validation Databases | Curated Datasets | Benchmark force field performance | HARIBOSS (RNA complexes), Gen2-Opt, DES370K |

| Analysis Packages | Trajectory Analysis | Extract properties from simulation data | VMD, MDAnalysis, Contact Map Explorer |

Force fields serve as the essential bridge that translates fundamental atomic interactions into calculable forces for molecular dynamics simulations, enabling researchers to solve Newton's equations of motion for systems ranging from simple liquids to complex biomolecular machinery. The continued evolution of force fields—from simple classical potentials to machine learning models trained on fused experimental and quantum mechanical data—represents a relentless pursuit of both accuracy and efficiency in molecular simulation. As these tools become increasingly sophisticated through the incorporation of polarization effects, reactive chemistry, and adaptive learning, they expand the frontiers of computational molecular science. For researchers in drug development and materials design, understanding the capabilities, limitations, and appropriate application of these computational reagents is paramount for leveraging their full potential in scientific discovery and innovation.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful computational technique that describes how a molecular system evolves, providing critical insights into structural flexibility and molecular interactions that are invaluable for fields like drug discovery [20] [21]. At its core, MD solves Newton's equations of motion for a system of atoms by taking small, sequential steps in time to predict new atomic positions and velocities [22]. For a system containing N atoms, the molecular geometry at time t is described by R = (r₁, r₂, ..., rₙ), where rᵢ represents the position of the i-th atom [10].

The fundamental challenge arises from applying Newton's second law (F=ma) to each atom i in the system: Fᵢ = mᵢaᵢ, where the force Fᵢ is derived from the potential energy V of the system as Fᵢ = -∂V/∂rᵢ [10]. This leads to the critical realization that for systems with more than two atoms, no analytical solution exists for these equations of motion [10]. Consequently, researchers must resort to numerical integration algorithms—the focus of this technical guide—to approximate the system's trajectory over time. These algorithms discretize the integration into many small finite time steps (δt), typically on the order of femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ s), to accurately capture molecular vibrations and other rapid motions [10].

The Necessity of Numerical Integration Algorithms

Fundamental Requirements for Integration Schemes

The selection of an appropriate numerical integration algorithm is paramount to achieving reliable MD simulations. These algorithms must satisfy multiple competing requirements [22]:

- Accuracy: The algorithm must faithfully reproduce the true atomic motion given the potential energy surface.

- Stability: The algorithm should conserve the system's total energy and temperature, preventing unphysical drift.

- Simplicity: Implementation should be straightforward enough to facilitate programming and debugging.

- Speed: Calculations must proceed efficiently to simulate biologically relevant timescales.

- Economy: The algorithm should minimize computational resources, particularly memory usage.

Without specialized numerical techniques, direct solution of Newton's equations remains intractable for many-body systems. The finite difference method underpins most approaches, where the integration is divided into small time steps, and the molecular position, velocity, and acceleration at time t are used to predict these values at time t+δt [10]. This procedure generates a trajectory comprising a series of discrete configurations at different time steps rather than a continuous path [10].

Mathematical Foundation: Taylor Expansion Approximations

Most integration algorithms for molecular dynamics derive from a common mathematical foundation—the Taylor series expansion. The position r(t+δt) and velocity v(t+δt) at a future time can be approximated from their current values as [10]:

$$ r(t+\delta t) = r(t) + \delta t v(t) + \frac{1}{2} \delta t^2 a(t) + \frac{1}{6} \delta t^3 b(t) + \dots $$

$$ v(t+\delta t) = v(t) + \delta t a(t) + \frac{1}{2} \delta t^2 b(t) + \dots $$

where a(t) represents acceleration and b(t) represents the third derivative of position with respect to time. The accuracy of this approximation improves with smaller δt [10]. Different algorithms emerge from how these expansions are manipulated and which terms are retained or eliminated.

Comparative Analysis of Common Integration Algorithms

The Verlet Family of Algorithms

The Verlet algorithm and its variants represent the most widely used integration schemes in molecular dynamics due to their optimal balance of accuracy, stability, and computational efficiency [22].

Basic Verlet Algorithm

The basic Verlet algorithm uses current positions r(t), accelerations a(t), and positions from the previous time step r(t-δt) to compute new positions r(t+δt) [10]. The algorithm derives from summing the forward and reverse Taylor expansions:

$$ r(t + \delta t) = 2r(t) - r(t- \delta t) + \delta t^2 a(t) $$

Although simple and robust, this approach has significant limitations: velocities do not appear explicitly and must be calculated indirectly as v(t) = [r(t+δt) - r(t-δt)]/(2δt), and the algorithm is not self-starting as it requires positions from a previous time step [10].

Velocity Verlet Algorithm

The velocity Verlet algorithm addresses these limitations by providing both positions and velocities simultaneously at the same instant in time [22]. This algorithm is implemented in three distinct steps within each time cycle:

- Calculate half-step velocity: v(t + ½δt) = v(t) + ½δt a(t)

- Update position: r(t + δt) = r(t) + δt v(t + ½δt)

- Update velocity: v(t + δt) = v(t + ½δt) + ½δt a(t + δt)

This approach requires only one set of positions, velocities, and forces to be stored at any time, making it memory-efficient [22]. The Democritus molecular dynamics program is based on this algorithm [22].

Leapfrog Algorithm

The leapfrog algorithm employs a different strategy, where velocities are calculated at half-time steps while positions are calculated at full-time steps [22] [10]:

$$ v(t+ \frac{1}{2}\delta t) = v(t- \frac{1}{2}\delta t) +\delta t a(t) $$

$$ r(t + \delta t) = r(t) + \delta t v(t + \frac{1}{2}\delta t) $$

In this scheme, velocities "leapfrog" over positions, hence the algorithm's name [10]. If full-step velocities are needed, they can be approximated as v(t) = ½[v(t-½δt) + v(t+½δt)] [22].

Additional Integration Schemes

While Verlet algorithms dominate molecular dynamics simulations, several other approaches warrant discussion for historical context and specialized applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Molecular Dynamics Integration Algorithms

| Algorithm | Global Error | Stability | Memory Requirements | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euler | O(δt) | Poor | Low | Simple implementation | Energy drift, unstable for oscillatory systems |

| Euler-Cromer | O(δt) | Moderate | Low | Better stability than Euler | First-order accuracy |

| Midpoint | O(δt²) for position, O(δt) for velocity | Moderate | Low | Second-order accuracy for position | Errors may accumulate |

| Half-step | O(δt²) | Good | Moderate | Stable, common in textbooks | Not self-starting |

| Velocity Verlet | O(δt²) | Excellent | Moderate | Simultaneous position and velocity, energy conservation | Requires multiple force calculations per step |

| Leapfrog | O(δt²) | Excellent | Low | Efficient, good energy conservation | Velocities and positions out of sync |

The Euler algorithm, the simplest approach, advances the solution using only derivative information at the beginning of the interval [23]:

$$ v{n+1} = vn + an dt $$ $$ x{n+1} = xn + vn dt $$

However, this method suffers from limited accuracy and frequently generates unstable solutions [23]. The Euler-Cromer modification improves stability by using the updated velocity for position integration [23]:

$$ v{n+1} = vn + an dt $$ $$ x{n+1} = xn + v{n+1} dt $$

The half-step (or Verlet leapfrog) algorithm offers superior stability [23]:

$$ v{n + \frac{1}{2}} = v{n-\frac{1}{2}} + an dt $$ $$ x{n+1} = xn + v{n+\frac{1}{2}} dt $$

Note that this approach requires a special starting procedure, such as using the Euler algorithm for the first half-step: v½ = v₀ + ½a₀dt [23].

Practical Implementation and Protocol Design

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for a molecular dynamics simulation, highlighting the role of numerical integration at its core:

Diagram 1: Molecular Dynamics Simulation Workflow

Detailed Implementation of the Velocity Verlet Algorithm

For researchers implementing integration algorithms, the velocity Verlet method offers an excellent balance of accuracy and stability. The following protocol details its implementation:

Initialization Phase:

- System Setup: Define initial atomic positions r(0) and velocities v(0)

- Parameter Selection: Choose an appropriate time step (typically 0.5-2.0 fs for biomolecular systems)

- Force Calculation: Compute initial forces F(0) from the potential energy function V

- Acceleration Calculation: Derive initial accelerations a(0) = F(0)/m

Time Step Cycle:

- Velocity Half-Step Update:

- Calculate v(t + ½δt) = v(t) + ½δt a(t)

- This represents velocity at the mid-point of the time step

Position Update:

- Compute new positions r(t + δt) = r(t) + δt v(t + ½δt)

- Apply boundary conditions if necessary (periodic, etc.)

Force Recalculation:

- Calculate new forces F(t + δt) from the potential energy at the new positions

- This is typically the most computationally intensive step

Acceleration Update:

- Compute new accelerations a(t + δt) = F(t + δt)/m

Velocity Finalization:

- Complete velocity update: v(t + δt) = v(t + ½δt) + ½δt a(t + δt)

Property Calculation:

- Compute system properties (energy, temperature, pressure) as needed

This cycle repeats for the duration of the simulation, which may encompass thousands to millions of time steps depending on the biological process being studied [22].

Table 2: Essential Resources for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| MD Software Packages | GROMACS, AMBER, DESMOND, NAMD [20] [24] [25] | Provide implemented integration algorithms, force fields, and analysis tools |

| Force Fields | GROMOS 54a7 [24], CHARMM [25], AMBER | Mathematical description of atomic interactions and potential energy |

| Analysis Tools | Built-in trajectory analysis, VMD, MDAnalysis | Process simulation trajectories to extract biologically relevant information |

| Specialized Hardware | GPUs, High-performance computing clusters [25] | Accelerate computationally intensive force calculations |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | Drude oscillator model [25] | Incorporate induced polarization effects for increased accuracy |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Medicinal Chemistry

Molecular dynamics simulations employing these integration algorithms have become indispensable in modern drug discovery, providing insights that bridge the gap between structural biology and therapeutic development [20]. MD simulations help elucidate protein behavior and interactions with inhibitors across various disease contexts [20]. The selection of appropriate force fields and integration algorithms significantly influences the reliability of these simulation outcomes [20].

Recent advances combine MD with machine learning to predict critical drug properties. For instance, one study used MD-derived properties including Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA), Coulombic and Lennard-Jones interaction energies (Coulombic_t, LJ), Estimated Solvation Free Energies (DGSolv), and Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) to predict aqueous solubility—a crucial factor in drug bioavailability [24]. Gradient Boosting algorithms applied to these MD-derived properties achieved a predictive R² of 0.87 with an RMSE of 0.537, demonstrating the power of integrating physical simulations with data-driven approaches [24].

The following diagram illustrates how numerical integration enables drug discovery applications through molecular dynamics:

Diagram 2: From Numerical Integration to Drug Discovery

Numerical integration algorithms serve as the fundamental engine that enables molecular dynamics simulations by providing practical methods to solve Newton's equations of motion for many-body systems. The Verlet family of algorithms, particularly the velocity Verlet and leapfrog variants, have emerged as the dominant choices due to their favorable balance of accuracy, stability, and computational efficiency [22] [10]. These algorithms transform the intractable analytical problem of solving coupled differential equations for thousands of atoms into a manageable iterative procedure that progresses through discrete time steps.

Despite current successes, challenges remain in enhancing the accuracy and expanding the scope of molecular dynamics simulations. Future developments will likely focus on increasing time step sizes through techniques like hydrogen mass repartitioning, incorporating more sophisticated physical models such as polarizable force fields [25], and tighter integration with artificial intelligence methods to accelerate both simulation and analysis [20] [24]. As these computational strategies evolve, numerical integration algorithms will continue to play a central role in enabling molecular dynamics to address increasingly complex biological questions and accelerate therapeutic development.

The MD Simulation Workflow: A Step-by-Step Guide from Structure to Analysis

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a computational method that uses Newton's equations of motion to simulate the time evolution of a set of interacting atoms, serving as a "computational microscope" with exceptional resolution for investigating atomic-scale processes [13] [26]. The accuracy and reliability of any MD simulation are fundamentally constrained by the quality of the initial atomic structure, making system preparation the critical first step in the research workflow. This initial phase transforms abstract scientific questions into computationally tractable models, creating the foundational architecture upon which all subsequent simulations are built. For researchers investigating complex biological systems, materials properties, or drug interactions, rigorous system preparation establishes the necessary conditions for simulating Newtonian physics at the atomic scale, where forces calculated from interatomic potentials determine particle acceleration according to Newton's second law of motion [26].

The process of system preparation requires meticulous attention to structural accuracy and physical realism, as errors introduced at this stage propagate through the entire simulation, potentially compromising the validity of scientific conclusions. This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for sourcing, constructing, and validating initial atomic structures for MD simulations, with specific consideration for the diverse requirements of materials science and biomolecular research. We present standardized protocols, quantitative data on available resources, and visual workflows to equip researchers with methodologies that ensure both efficiency and reproducibility in computational studies across various domains of molecular science.

Sourcing Initial Structures from Scientific Databases

The most reliable approach for obtaining initial structures begins with retrieving experimentally determined configurations from established scientific databases. These repositories provide empirically validated starting points that reduce initial guesswork and accelerate model development.

Table 1: Major Databases for Sourcing Initial Atomic Structures

| Database Name | Primary Application Domain | Content Type | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project | Materials Science | Crystalline structures, inorganic compounds | Web API, GUI |

| AFLOW | Materials Science | Crystalline materials, alloys | Online database |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Biochemistry, Drug Discovery | Experimental 3D structures of proteins, nucleic acids, complexes | Web portal, API |

| PubChem | Drug Discovery, Biochemistry | Small organic molecules, bioactive compounds | Web interface, FTP |

| ChEMBL | Drug Discovery | Bioactive drug-like molecules, assay data | Web services, downloads |

These databases provide experimentally validated structural information obtained through techniques such as X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy [26]. For materials scientists, platforms like the Materials Project and AFLOW offer comprehensive crystallographic information files (CIF) containing lattice parameters, atomic coordinates, and space group symmetry. For biomedical researchers, the Protein Data Bank serves as the authoritative resource for macromolecular structures, while PubChem and ChEMBL provide extensive libraries of small molecules relevant to drug development [26].

Practical Considerations for Database Retrieval

When sourcing structures from these databases, researchers should implement several validation checks. First, assess the experimental resolution of structures—for proteins, resolutions better than 2.5Å generally provide more reliable atomic coordinates. Second, identify and address any missing residues or atoms in the structure, which is particularly common in protein loops and flexible regions. Third, verify chemical consistency, ensuring that ligands, cofactors, and modified residues are properly annotated and structurally complete. These quality control measures prevent the propagation of structural errors into the simulation phase, where they can cause artifactual behavior or system instability.

Building and Modifying Atomic Structures

When suitable experimental structures are unavailable, researchers must construct atomic models through computational methods. This approach is essential for studying novel materials, engineered proteins, or molecular systems without experimental precedents.

Table 2: Methods for Building and Modifying Atomic Structures

| Method | Application Context | Key Tools/Approaches | Complexity Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homology Modeling | Protein structures with known homologs | Sequence alignment, template selection, loop modeling, side-chain placement | Moderate to High |

| Ab Initio Structure Prediction | Novel proteins without homologs | Deep learning (AlphaFold2), fragment assembly, conformational sampling | High |

| De Novo Materials Design | Novel crystalline materials, nanoparticles | Crystal structure prediction, lattice generation, defect engineering | Moderate to High |

| Small Molecule Construction | Drug-like compounds, ligands | Chemical sketching tools, conformational search, geometry optimization | Low to Moderate |

The emergence of generative artificial intelligence for structures, most notably AlphaFold2 which was awarded the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, has dramatically transformed structure prediction capabilities, enabling researchers to predict molecular and material structures with increasing accuracy [26]. However, expert assessment remains crucial to ensure predicted structures are physically and chemically plausible and align with known structural motifs [26].

Structure Completion and Refinement Protocols

Database-derived structures often require completion and refinement before simulation. The following protocol outlines a systematic approach for structure preparation:

- Missing Atom/Residue Identification: Use computational tools to scan structures for gaps in atomic connectivity or sequence alignment.

- Loop Modeling: For protein structures with missing loops, employ knowledge-based or ab initio methods to generate structurally plausible conformations.

- Protonation State Assignment: Determine appropriate protonation states for ionizable residues based on physiological pH and local environment.

- Structural Optimization: Perform limited energy minimization to relieve steric clashes while preserving overall structural integrity.

- Validation Metrics Assessment: Calculate quantitative quality scores (e.g., Ramachandran plot favorability for proteins, bond length/angle distributions for materials) to verify structural integrity.

This refinement process ensures the initial structure represents a physically realistic starting configuration before proceeding to simulation setup and parameterization.

Workflow Visualization: From Structure Sourcing to Simulation Readiness

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for preparing initial atomic structures, integrating both sourcing and building approaches into a unified protocol for achieving simulation-ready systems.

Structure Preparation Workflow depicts the decision process for transforming research objectives into simulation-ready atomic models. The pathway begins with research objective definition and proceeds through database queries, structure assessment, and appropriate routing based on data availability. The critical validation checkpoint ensures structural integrity before the model advances to simulation, with feedback mechanisms for addressing identified issues.

Successful structure preparation requires specialized computational tools and resources. The following table catalogs essential solutions for sourcing, constructing, and validating atomic models.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Structure Preparation

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | Classical MD simulation with focus on materials modeling | Solid-state materials, soft matter, coarse-grained systems | Open source, GPLv2 [27] |

| AlphaFold2 | Protein structure prediction from amino acid sequence | Protein modeling, homology detection, confidence estimation | Web server, local installation |

| PyMOL | Molecular visualization and analysis | Structure assessment, quality control, figure generation | Commercial, educational license |

| Avogadro | Molecular editing and optimization | Small molecule construction, geometry optimization | Open source |

| MD Simulation Suites | Integrated simulation environments | Biomolecular simulation setup, parameterization | Various licensing models |

| Force Fields | Interatomic potential parameter sets | Physics-based energy calculation | Publicly available |

These tools represent essential infrastructure for modern computational research, enabling the transformation of abstract chemical concepts into atomically detailed models suitable for MD simulation. LAMMPS exemplifies this category, functioning as a classical molecular dynamics code with capabilities for modeling diverse material classes and serving as a flexible platform for implementing custom interaction potentials [27].

Integration with Molecular Dynamics Workflow

System preparation represents the initial phase in a comprehensive MD workflow that progresses through several interconnected stages. Following structure preparation, researchers must initialize the simulation system by assigning velocities sampled from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution corresponding to the target temperature [26]. The simulation then advances through force calculation based on interatomic potentials, with recent advancements including machine learning interatomic potentials trained on quantum chemistry datasets for improved accuracy and efficiency [26]. Time integration algorithms such as Verlet or leap-frog methods numerically solve Newton's equations of motion to update atomic positions and velocities, typically using time steps of 0.5-1.0 femtoseconds to accurately capture atomic vibrations while maintaining computational efficiency [26].

Throughout this workflow, the initial atomic structure serves as the foundational template that determines the physical realism and scientific validity of the entire simulation. By investing rigorous effort in the system preparation phase, researchers establish conditions that enable accurate simulation of Newtonian dynamics across diverse molecular systems, from protein folding and drug binding to material deformation and phase transitions. This methodological foundation supports the growing application of MD simulations as indispensable tools in materials design, drug discovery, and fundamental molecular science [26].

Within the broader thesis of how molecular dynamics (MD) simulates Newton's equations of motion, the initialization of the system represents a critical first step. MD simulations explicitly calculate the time evolution of a system by numerically integrating Newton's second law of motion for all atoms, which requires initial positions and initial velocities [28] [29]. The initial assignment of atomic velocities is not arbitrary; it must correspond to a physically meaningful thermodynamic state. Setting temperatures using Maxwell-Boltzmann velocities establishes the initial kinetic energy of the system, directly influencing its subsequent dynamics and ensuring the simulation starts from a correct and reproducible statistical mechanical foundation [30] [31]. This step bridges the macroscopic concept of temperature with the microscopic motions of individual atoms, enabling the simulation of realistic thermodynamic behavior.

Theoretical Foundation: From Macroscopic Temperature to Microscopic Velocities

The Equipartition Theorem and Instantaneous Temperature

The fundamental link between the macroscopic variable of temperature and the microscopic motions of atoms is provided by the equipartition theorem. This principle states that every degree of freedom that appears as a squared term in the Hamiltonian for the system has an average energy of (kB T / 2) associated with it, where (kB) is the Boltzmann constant and (T) is the thermodynamic temperature [30]. For atomic velocities, which contribute to the kinetic energy, this leads to the definition of the instantaneous temperature, (T_{\text{inst}}), in an MD simulation [30]:

[ \langle E{\text{kin}} \rangle = \frac{1}{2} \sum{i=1}^{N} mi vi^2 = \frac{Nf}{2} kB T ]

where (\langle E{\text{kin}} \rangle) is the average kinetic energy, (Nf) is the number of unconstrained degrees of freedom, (mi) and (vi) are the mass and velocity of atom (i), and (N) is the total number of atoms [30]. For a periodic system, the number of degrees of freedom is (N_f = 3N - 3) to account for the conservation of total momentum [30]. The instantaneous temperature is then calculated from the total kinetic energy and the number of degrees of freedom, providing a crucial diagnostic throughout the simulation [30].

The Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution

The Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution describes the probability distribution of particle speeds in an idealized gas at thermodynamic equilibrium [32]. For a three-dimensional system, the probability density function for the atomic speed (v) is given by [32]:

[ f(v) = \left( \frac{m}{2\pi kB T} \right)^{3/2} 4\pi v^2 \exp\left( \frac{-mv^2}{2kB T} \right) ]

This distribution, with a scale parameter of (a = \sqrt{k_B T / m}), dictates the likelihood of an atom having a particular speed at a given temperature (T) [32]. When initializing an MD simulation, velocities are not assigned a single value but are instead randomly drawn from this distribution, ensuring the system's kinetic energy correctly represents the desired temperature from the outset.

Table 1: Key Statistical Measures of the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution for Particle Speed

| Measure | Formula | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Speed | (\langle v \rangle = 2a \sqrt{\frac{2}{\pi}}) | The average speed of all particles. |

| Most Probable Speed | (v_p = \sqrt{2} a) | The speed most likely to be observed in a particle. |

| Root-Mean-Square Speed | (v_{\text{rms}} = \sqrt{\langle v^2 \rangle} = \sqrt{3} a) | Proportional to the square root of the average kinetic energy. |

Note: The scale parameter is (a = \sqrt{k_B T / m}) [32].

Practical Implementation: Methodologies and Protocols

Workflow for Velocity Initialization

The following diagram illustrates the standard protocol for initializing a molecular dynamics simulation, from setting up the atomic structure to achieving a stable, equilibrated system at the desired temperature.

Detailed Protocol and Code Example

The workflow outlined above is implemented in practice using MD software packages. The following Python code snippet, utilizing the Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE), demonstrates a concrete implementation for initializing a system of FCC Aluminum at 1600 K [28].

This code highlights key steps [28]:

- System Creation: A crystal structure is defined and replicated.

- Velocity Assignment: The

MaxwellBoltzmannDistributionfunction directly draws velocity components from the Gaussian distribution corresponding to the specified temperature. - Momentum Correction: The

Stationaryfunction is called to prevent the entire system from drifting in space. - Verification: The instantaneous temperature is calculated from the kinetic energy for logging and validation.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Software Solutions

Table 2: Key Software Solutions for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Software / Tool | Primary Function | Relevance to Initialization & Sampling |

|---|---|---|

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | A Python library for atomistic simulations [28] [31]. | Provides high-level functions (e.g., MaxwellBoltzmannDistribution) for easy and correct system setup [28]. |

| LAMMPS | A widely-used, classical MD simulator with a focus on high performance [33]. | Its velocity command creates velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. Can be integrated with ML potentials [33]. |

| Schrödinger | A comprehensive commercial platform for drug discovery [34]. | Uses physics-based and ML-driven methods for initial system setup within a robust GUI and workflow environment [35] [34]. |

| MOE (Chemical Computing Group) | An all-in-one platform for molecular modeling and drug design [35]. | Offers tools for structure preparation and solvation prior to dynamics simulation. |

| Rowan | A modern platform combining ML and physics-based simulations [36]. | Leverages fast, AI-driven property predictions to inform and accelerate the simulation setup process. |

Advanced Considerations and Temperature Control

Relationship to Thermostats and Ensemble Generation

Initializing with a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution is crucial for both the NVE (microcanonical) and NVT (canonical) ensembles.

- In NVE simulations, the total energy is conserved. The initial velocity assignment determines the starting point on the constant-energy hypersurface, and the temperature will naturally fluctuate around a stable average value if the system is at equilibrium [31].

- In NVT simulations, the initial Maxwell-Boltzmann velocities provide the correct starting state, but a thermostat is required to maintain the temperature by stochastically or deterministically exchanging energy with a heat bath [30] [31]. Modern thermostats like Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen, and Langevin are applied after the initial velocity assignment to maintain the temperature throughout the simulation [30] [31].

Table 3: Comparison of Common Thermostat Methods for NVT Ensembles

| Method | Type | Mechanism | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Berendsen | Deterministic scaling | Exponentially relaxes kinetic energy to target value [30]. | Not recommended for production; it suppresses energy fluctuations [31]. Good for equilibration [30]. |

| Nosé-Hoover | Deterministic extended Lagrangian | Treats the thermostat as a dynamic variable with a fictitious mass [30] [31]. | Recommended (with a chain of thermostats). Correctly samples the canonical ensemble [31]. |

| Langevin | Stochastic | Adds a friction force and a random noise force [31]. | Recommended. Simple and correctly samples the ensemble [31]. |

| Bussi (e.g., V-rescale) | Stochastic velocity rescaling | Rescales velocities stochastically to ensure correct energy fluctuations [31]. | Recommended. Simple and corrects the flaw in Berendsen's method [31]. |

Best Practices and Potential Pitfalls

- Choosing the Right Tool: For rapid equilibration, the Berendsen thermostat or simple velocity scaling can be useful, but for production runs that require correct sampling of thermodynamic properties, the Nosé-Hoover, Langevin, or Bussi thermostats are superior choices [30] [31].

- System Size and Degrees of Freedom: The calculation of the instantaneous temperature, (T{\text{inst}}), depends on the number of unconstrained degrees of freedom, (Nf). For a periodic system, (Nf = 3N - 3), which accounts for the conservation of total linear momentum [30]. Using the incorrect value for (Nf) will result in a systematic error in the reported temperature.

- Convergence and Equilibration: A simulation should be allowed to equilibrate after initialization before properties are measured. Monitoring the stability of the temperature and potential energy is essential to confirm the system has reached equilibrium.

In molecular dynamics (MD), force calculation is the fundamental engine that drives the simulation of a system's time evolution. The technique analyzes the physical movements of atoms and molecules by allowing them to interact for a fixed period, providing a view of the system's dynamic evolution [8]. This process is governed by Newton's second law of motion, where for each atom i, the force F~i~ is equal to its mass m~i~ multiplied by its acceleration a~i~ [10]. Since acceleration is the second derivative of position with respect to time, the force directly determines how atomic positions change throughout the simulation.