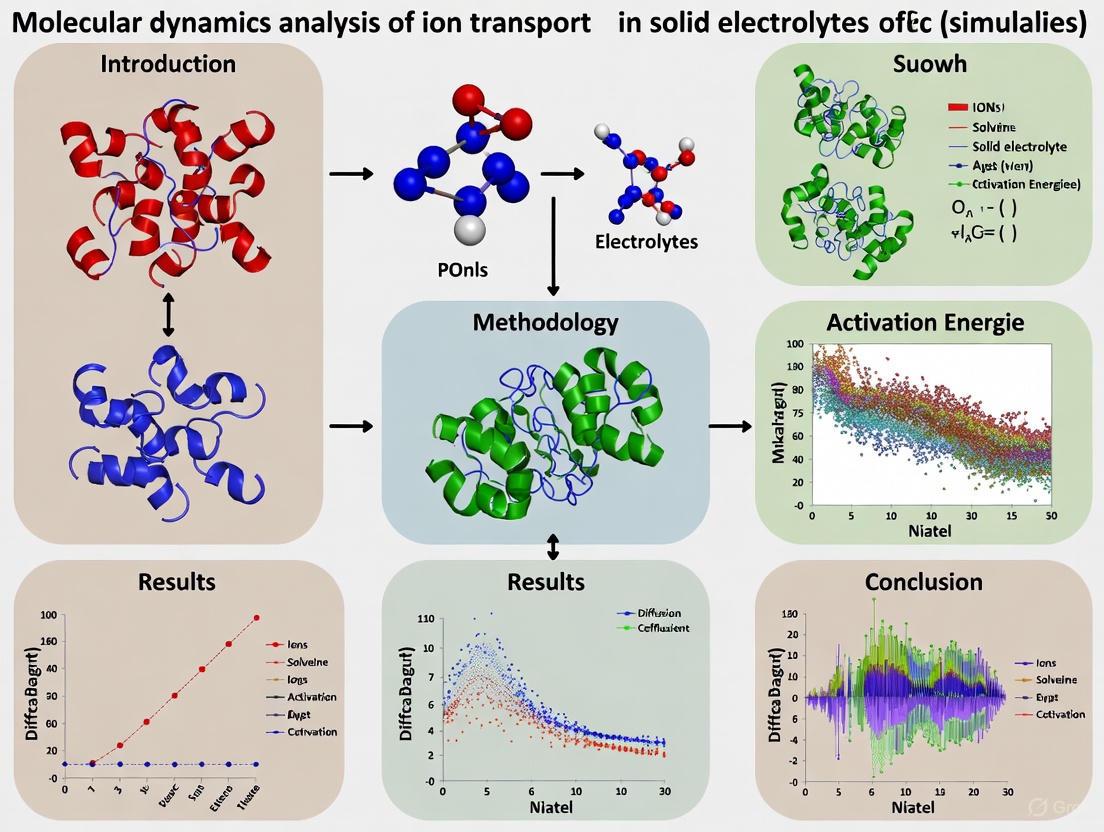

Molecular Dynamics Analysis of Ion Transport in Solid Electrolytes: From Fundamental Mechanisms to Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations are revolutionizing the understanding and development of solid electrolytes for advanced battery technologies.

Molecular Dynamics Analysis of Ion Transport in Solid Electrolytes: From Fundamental Mechanisms to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations are revolutionizing the understanding and development of solid electrolytes for advanced battery technologies. It explores the fundamental atomic-scale mechanisms of lithium-ion transport across diverse material classes, including inorganic solids, polymers, and hybrid systems. The content details critical methodological approaches, from force field selection to the analysis of dynamical properties, and addresses key challenges such as interfacial resistance and transport bottlenecks. By synthesizing findings from recent validation and comparative studies, this resource offers researchers and scientists a unified framework to bridge simulation data with experimental observations, ultimately guiding the design of next-generation energy storage materials with enhanced safety and performance.

Unraveling Atomic-Scale Ion Transport Mechanisms in Solid Electrolytes

Understanding ion transport mechanisms is fundamental to advancing solid-state battery technology. In solid electrolytes, ion movement can be characterized by three distinct regimes: ballistic, diffusive, and trapping. Ballistic transport describes the unimpeded flow of ions over relatively long distances without scattering, occurring when the system size is smaller than the ion's mean free path [1]. In contrast, diffusive transport involves frequent scattering events where ions constantly change direction and energy, leading to a stochastic "random walk" motion described by ⟨x²(t)⟩ = Dt, where D is the diffusion coefficient [2]. Trapping dynamics represents periods where ions become temporarily immobilized in local energy minima before escaping to continue migration.

The transition between these regimes profoundly impacts overall ionic conductivity. A unified theoretical framework has been established through the Boltzmann transport equation, which incorporates generalized boundary conditions to bridge ballistic and diffusive regimes [3]. In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of solid polymer electrolytes, ion transport mechanisms are categorized through tracking cation coordination changes, revealing three primary modes: ion hopping, continuous motion (successive exchange of the coordination sphere), and vehicular transport [4]. Recent research on sulfide-based solid electrolytes further demonstrates that structural disorder can significantly enhance ionic conductivity by creating favorable pathways for ion migration [5].

Theoretical Framework and Quantitative Comparison

Fundamental Transport Equations

The semiclassical Boltzmann transport equation (BTE) provides a unified framework for describing electron and ion transport across different regimes. In the relaxation time approximation, the BTE is expressed as:

∂f/∂t + ṙ⋅∇ᵣf + ḱ⋅∇ₖf = −(f − f̄)/τ₀

where f(k,r) denotes the nonequilibrium distribution function, f̄ represents the local equilibrium Fermi-Dirac distribution, and τ₀ is the relaxation time [3]. The electron dynamics are governed by semiclassical equations of motion:

ṙ = (1/ℏ)∇ₖεₖ − ḱ × Ω ḱ = −(e/ℏ)E

where Ω represents the Berry curvature, and E is the external electric field [3]. In the context of ion transport, these principles translate to understanding how ions navigate through complex energy landscapes in solid electrolytes.

Quantitative Comparison of Transport Regimes

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Fundamental Transport Regimes

| Parameter | Ballistic Transport | Diffusive Transport | Trapping Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Free Path | Longer than device dimensions [1] | Shorter than device dimensions [6] | Localized motion |

| Distance Scaling | ⟨x²(t)⟩ ∝ t² [2] | ⟨x²(t)⟩ = Dt [2] | ⟨x²(t)⟩ approaches constant |

| Scattering Frequency | Negligible [1] | Frequent [6] | Intermittent |

| Energy Dissipation | Minimal in conductor [1] | Significant due to scattering [6] | Energy landscape dependent |

| Primary Transport Mechanism | Coherent wave propagation [1] | Random walk stochastic process [2] | Temporary localization & release |

| Temperature Dependence | Weak (through phonon scattering) [1] | Strong (increases with T) [6] | Arrhenius behavior for escape |

| Dominant in Solid Electrolytes | Short timescales/localized pathways [5] | Bulk material behavior [4] | High-disorder regions [5] |

Table 2: Transport Properties in Different Solid Electrolyte Materials

| Material System | Ionic Conductivity (S/cm) | Activation Energy (eV) | Dominant Transport Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Li₃PS₄ (Crystalline) | ~10⁻⁴ | 0.30-0.50 | Vacancy-assisted diffusion [5] | [5] |

| Glassy Li₃PS₄ | Enhanced over crystalline | Reduced barriers | Disorder-enhanced hopping [5] | [5] |

| PEO:LiTFSI (Polymer) | ~10⁻⁵–10⁻⁴ | ~0.1-0.3 | Continuous motion (polymer-mediated) [4] | [4] |

| PCL:LiTFSI (Polymer) | ~10⁻⁵–10⁻⁴ | ~0.1-0.3 | Continuous motion (high transference) [4] | [4] |

| Li₁₀GeP₂S₁₂ (LGPS) | >10⁻² | ~0.2-0.3 | 1D concerted migration [7] | [7] |

Experimental and Simulation Protocols

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Workflow

Diagram 1: MD Simulation Workflow for Ion Transport Analysis

System Preparation and Equilibration

Protocol Title: All-Atom Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Solid Polymer Electrolytes

Objective: To investigate ion transport mechanisms in solid polymer electrolytes through trajectory analysis of lithium cation coordination environments.

Materials and Methods:

- Simulation Software: GROMACS (version 2021) or equivalent MD package [4]

- Force Field: General AMBER force field (GAFF) parameters with scaled particle charges (0.75 factor for ions) [4]

- System Composition: Polymer (PEO or PCL) with LiTFSI salt at varying concentrations (r = [Li⁺]/[monomer] = 0.08, 0.7, 1.0) [4]

- System Size: Simulation boxes containing 1000 monomer units total [4]

Step-by-Step Procedure:

System Construction

- Generate initial configuration using PACKMOL (version 17.333) or similar packing software [4]

- Ensure appropriate salt concentration and polymer chain arrangement

Energy Minimization

- Employ steepest descent algorithm to minimize total system energy [4]

- Continue until maximum force < 1000 kJ/mol/nm

NVT Ensemble Equilibration

- Perform 5 ns simulation at 400 K using modified Berendsen thermostat [4]

- Maintain constant number of particles, volume, and temperature

NPT Ensemble Equilibration

Final NPT Equilibration

- Execute 10 ns simulation at target temperature (e.g., 440 K) [4]

- Verify stability of thermodynamic parameters

Production Run

Transport Mechanism Categorization

Protocol Title: Coordination-Based Analysis of Ion Transport Mechanisms

Objective: To categorize individual ion transport events into ballistic, diffusive, or trapping mechanisms based on coordination environment changes.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Trajectory Processing

- Extract lithium cation trajectories from production run data

- Calculate mean squared displacement (MSD) for individual ions and ensemble average

Coordination Analysis

- Compute radial distribution functions g(r) between Li⁺ and coordinating atoms (O from polymers, O/T from TFSI⁻) [4]

- Identify coordination numbers and species in Li⁺ solvation shells

- Track evolution of coordination environments over time

Transport Event Categorization

Quantitative Analysis

- Calculate residence times of coordinating species

- Determine correlation times for coordination changes

- Compute fractional contributions of each mechanism to total transport

Machine Learning-Enhanced Simulations

Protocol Title: Deep Learning Potential for Disordered Solid Electrolytes

Objective: To simulate ion transport in complex disordered solid electrolytes with ab initio accuracy using machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIP).

Materials and Methods:

- Software Framework: DeePMD-kit or equivalent MLIP package [5]

- Training Data: Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) trajectories [5]

- System: Li₃PS₄ in crystalline (β-phase), glassy, and glass-ceramic forms [5]

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Training Data Generation

- Perform AIMD simulations of Li₃PS₄ at various temperatures and compositions

- Extract diverse local environments covering possible atomic configurations

Neural Network Potential Training

- Train Deep Potential model on AIMD data

- Validate against DFT calculations for energies, forces, and structural properties

Enhanced Sampling Simulations

- Perform microsecond-scale MLIP-MD simulations

- Analyze lithium ion pathways and hopping statistics

Softness Parameter Analysis

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function/Application | Specifications/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics simulation package [4] | Version 2021+, optimized for polymer electrolytes |

| AMBER Force Field | Describes interatomic interactions [4] | GAFF parameters with charge scaling (0.75×) [4] |

| PACKMOL | Initial system configuration builder [4] | Version 17.333+ for complex polymer-salt systems |

| DeePMD-kit | Machine learning interatomic potential [5] | For accurate simulation of disordered materials |

| LiTFSI Salt | Lithium source for polymer electrolytes [4] | Bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide lithium salt |

| PEO Polymer | Poly(ethylene oxide) host matrix [4] | Various molecular weights (e.g., Mn = 1119.33 g/mol) |

| PCL Polymer | Poly(ε-caprolactone) host matrix [4] | Biodegradable alternative with high transference number |

| VASP/Quantum ESPRESSO | Ab initio calculations for training data [5] | DFT calculations for MLIP training |

Visualization and Analysis Techniques

Data Analysis Workflow

Diagram 2: Transport Data Analysis Workflow

Key Analysis Metrics

Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) Analysis:

- Calculate MSD from trajectory data: ⟨Δr²(t)⟩ = ⟨|r(t+t₀) − r(t₀)|²⟩

- Ballistic regime: ⟨Δr²(t)⟩ ∝ t² (for short timescales)

- Diffusive regime: ⟨Δr²(t)⟩ ∝ t (for long timescales)

- Trapping manifestations: Subdiffusive behavior with ⟨Δr²(t)⟩ ∝ tᵅ (α < 1)

Van Hove Correlation Function:

- Compute self part: Gₛ(r,t) = ⟨δ(r − [r(t+t₀) − r(t₀)])⟩

- Reveals heterogeneous dynamics and hopping events

Non-Gaussian Parameter (NGP):

- Calculate α₂(t) = (3⟨Δr⁴(t)⟩)/(5⟨Δr²(t)⟩²) − 1

- Identifies dynamic heterogeneity and deviation from normal diffusion

- Peaks in NGP indicate timescale of heterogeneous hopping events

The systematic characterization of ballistic, trapping, and diffusive transport regimes provides critical insights for designing next-generation solid electrolytes. The protocols outlined herein enable researchers to quantitatively deconvolute the complex interplay between these mechanisms, with particular relevance for materials exhibiting structural disorder where conventional models fail. The integration of machine learning approaches with molecular dynamics simulations represents a powerful paradigm for accelerating the discovery of materials with enhanced ionic conductivity through controlled manipulation of transport regime dominance.

For researchers implementing these protocols, particular attention should be paid to: (1) sufficient sampling of ion coordination environments through long simulation timescales (≥500 ns), (2) careful validation of force fields or machine learning potentials against experimental structural data, and (3) systematic analysis of dynamic heterogeneity beyond simple mean-squared displacement measurements. The combination of these advanced simulation approaches with experimental techniques such as pulsed-field gradient NMR provides the most comprehensive understanding of ion transport mechanisms in solid electrolytes.

Within the broader scope of MD analysis of ion transport in solid electrolytes, understanding the mechanistic role of structural disorder is paramount for designing superior materials. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for investigating the structural origins of ion hopping, with a focus on the enhanced ionic conductivity observed in disordered and glassy phases. The principles are framed within the context of lithium thiophosphate (LiPS) systems, which serve as exemplary models for studying disorder-induced phenomena [5].

Theoretical Framework and Key Findings

Ion transport in solid electrolytes transitions from well-defined pathways in crystalline materials to a landscape of irregular, dynamic sites in disordered and glassy systems. This disorder creates a distribution of energy barriers, which fundamentally alters ionic diffusion mechanisms [5].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Findings from MD Studies on Disordered LiPS Systems

| System / Parameter | β-Li3PS4 (Crystalline) | Glassy Li3PS4 | Glass-Ceramic Li3PS4 | Notes / Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activation Energy (eV) | 0.30 - 0.50 | Lower than crystalline | Intermediate | Experiment/NMR: ~0.40 eV for β-Li3PS4 [5] |

| Ionic Conduction | Two-dimensional (ac plane) | Isotropic, homogeneous | Enhanced at interfaces | Disorder enables 3D pathways [5] |

| Structural Descriptor | Defined Li sites (Li1, Li2) | No regular sites; irregular energy landscape | "Soft" ions at disordered interfaces | "Softness" identifies fast hoppers [5] |

| Primary MD Technique | Classical MD/AIMD | MLIP-based MD | MLIP-based MD | MLIP enables bond-breaking/formation [5] |

A pivotal concept is the "softness" parameter, a machine learning-based structural fingerprint that classifies lithium ions based on their local atomic environment. Ions residing in "soft" spots, characterized by a more favorable local structure, exhibit higher hopping probabilities and dominate the conduction process. This metric directly links local structural features to dynamic behavior [5].

Detailed Methodological Protocols

This section outlines the core protocols for employing molecular dynamics simulations to probe ion hopping mechanisms.

Protocol 1: Building and Validating a Machine Learning Interatomic Potential (MLIP)

For accurate and efficient simulation of bond-breaking and complex ion dynamics in disordered LiPS systems, an MLIP is recommended.

Workflow:

- Generate Training Data: Perform Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD) simulations on representative configurations of the target system (e.g., crystalline, glassy Li3PS4) at relevant temperatures.

- Extract Data: Collect atomic coordinates, forces, and total energies from the AIMD trajectories.

- Train the Potential: Train a Deep Potential (DeePMD) model or similar MLIP on the AIMD dataset. The potential should be validated by comparing its predictions of:

- Pair distribution functions (PDFs) against AIMD results.

- Lattice parameters and ionic conductivity against known experimental and DFT-calculated values [5].

Protocol 2: Simulating Systems with Engineered Disorder

To isolate the effect of disorder, create and compare three system models.

Procedure:

- Crystalline Model: Construct a simulation cell for the ordered phase (e.g., β-Li3PS4, space group Pnma).

- Glassy Model:

- Heat the crystalline structure well above its melting point.

- Hold at high temperature for equilibration.

- Quench the system rapidly to room temperature (e.g., 300 K) to generate a glassy state.

- Glass-Ceramic Model: Employ a multi-step annealing process on the glassy structure to nucleate and grow crystalline domains within the glassy matrix, creating a partially crystalline system [5].

Protocol 3: Quantifying Dynamics and Identifying "Soft" Hopping Ions

Once the models are prepared and equilibrated, the following analyses should be performed.

Analysis Workflow:

- Run Production MD: Perform extended MD simulations (NVT or NPT ensemble) using the validated MLIP.

- Calculate Dynamical Properties:

- Compute the Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD) of Li ions to derive the diffusion coefficient and ionic conductivity via the Nernst-Einstein relation.

- Calculate the van Hove correlation function and non-Gaussian parameter (α₂) to quantify dynamic heterogeneity [5].

- Compute Structural Fingerprint:

- For each Li ion's local environment in a simulation snapshot, calculate its "softness" using a pre-trained classification model [5].

- Correlate the softness parameter with observed ion displacements to identify which structural motifs promote hopping.

The logical relationship between these protocols and core concepts is visualized below.

Figure 1: A 760px-wide workflow diagram illustrating the sequential research protocol for investigating ion hopping in disordered solid electrolytes, from potential development to final analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Computational and Analytical "Reagents" for Ion Hopping Studies

| Item / Solution | Function / Role in Protocol | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potential (MLIP) | Provides near-ab initio accuracy for simulating bond-breaking and ion dynamics at a fraction of the computational cost of AIMD. Essential for modeling glassy systems [5]. | DeePMD model trained on AIMD data for Li-P-S systems [5]. |

| Ab Initio MD (AIMD) | Generates high-quality training data for MLIP and serves as a benchmark for validating force fields. Based on Density Functional Theory (DFT) [8]. | Software: VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO. |

| "Softness" Fingerprint | A ML-based classifier that analyzes the local atomic environment to identify Li ions with a high propensity to hop ("soft" ions) [5]. | Enables a direct structure-dynamics link [5]. |

| Dynamical Analysis Scripts | Codes for calculating key properties from MD trajectories: Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD), van Hove function, non-Gaussian parameter, and ionic conductivity [5]. | In-house scripts or features in MD analysis suites (e.g., MDANALYSIS, TRAVIS). |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Necessary computational infrastructure to run large-scale MD simulations (10-1000 atoms for nanoseconds) with MLIP or AIMD [8] [5]. | Access to GPU/CPU clusters. |

Free Energy Landscapes and Desolvation Barriers at Critical Interfaces

In the molecular dynamics (MD) analysis of ion transport within solid electrolytes, the interplay between free energy landscapes and desolvation barriers presents a critical determinant of macroscopic conductivity. The free energy landscape governs the thermodynamic and kinetic pathways available to migrating ions, while desolvation barriers represent the energetic penalties ions must overcome when shedding their coordination environments during transit. Free energy landscapes provide a quantitative map of the stable states, intermediates, and transition states that define ion migration pathways, revealing the atomic-scale interactions controlling transport mechanisms [9]. Simultaneously, desolvation barriers emerge from the energy cost associated with displacing solvent molecules or reorganizing coordination shells prior to ion movement, a phenomenon extensively documented in both biological and solid-state systems [10] [11]. Together, these concepts form a foundational framework for understanding and engineering improved solid electrolytes, particularly for energy storage applications where ion mobility directly impacts device performance.

The investigation of these phenomena through MD simulations offers unique insights into the dynamic processes governing ion transport at atomic resolution. By employing advanced sampling techniques and statistical mechanical analyses, researchers can quantify the free energy changes accompanying ion migration and identify the molecular origins of resistive barriers [12] [9]. This approach has proven particularly valuable in solid electrolyte research, where experimental characterization of transient states and elementary migration steps remains challenging. The following sections detail the methodological framework, key findings, and practical protocols for investigating free energy landscapes and desolvation barriers in solid electrolyte systems.

Theoretical Framework and Key Concepts

Free Energy Landscapes in Ion Transport

Free energy landscapes represent the potential of mean force (PMF) acting on ions as they navigate through electrolyte materials. These landscapes delineate the thermodynamic stability of various states along the ion migration pathway and determine the kinetics of transport through the activation barriers between these states. In solid polymer and ceramic electrolytes, the free energy landscape typically features multiple minima corresponding to stable or metastable coordination sites, separated by energy barriers that ions must overcome through thermal activation [11] [12].

The mathematical representation of free energy landscapes derives from statistical mechanics, where the PMF is computed as a function of carefully chosen reaction coordinates that capture the essential physics of the ion migration process. For lithium ions in solid electrolyte interphases, MD simulations have revealed free energy profiles characterized by three distinct dynamical regimes: ballistic motion at short timescales, trapping at intermediate times, and diffusive behavior at long timescales [11]. The trapping regime reflects the temporary confinement of ions in local energy minima, with residence times that directly correlate with the depth of these minima. The transition between trapping and diffusive behavior marks the onset of long-range ion transport and determines the overall ionic conductivity of the material.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Free Energy Regimes in Ion Transport

| Regime | Timescale | MSD Behavior | Atomic-Level Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ballistic | Femtoseconds to picoseconds | ~t² | Ions move freely without significant interactions with their surroundings |

| Trapping | Picoseconds to nanoseconds | Plateau | Ions oscillate within local energy minima, coordinated by surrounding atoms |

| Diffusive | Nanoseconds and longer | ~t | Ions undergo hopping or continuous motion between coordination sites |

Molecular Origins of Desolvation Barriers

Desolvation barriers represent the energy costs associated with the rearrangement of an ion's local coordination environment during migration. In the context of solid electrolytes, "solvation" refers to the coordination of mobile ions by surrounding species, which may include polymer chains, anions, or solvent molecules in hybrid systems. The concept of desolvation barriers originated in biological contexts, where ligand binding to protein active sites requires the displacement of bound water molecules [10]. MD simulations of the anticancer drug Dasatinib binding to src kinase revealed that the ligand must surmount a free energy barrier resulting from "the free energy cost for almost complete desolvation of the binding pocket" [10].

In solid electrolyte systems, analogous processes occur during ion migration. For instance, lithium ions in polymer electrolytes are typically coordinated by ether oxygens in poly(ethylene oxide) or carbonyl groups in other polymer hosts. To migrate between coordination sites, Li+ must partially or completely shed this coordination shell, incurring an energy penalty that manifests as a desolvation barrier [4] [13]. Similarly, in ceramic solid electrolytes, ions must overcome the energy cost of breaking favorable coordination geometries before hopping to adjacent sites [12]. The magnitude of these barriers depends critically on the strength of ion-coordinating group interactions and the flexibility of the host matrix to reorganize and facilitate ion passage.

Computational Methodologies

Free Energy Calculation Techniques

Several advanced sampling methods have been developed to efficiently map free energy landscapes in MD simulations of ion transport:

Umbrella Sampling employs harmonic biasing potentials along a predefined reaction coordinate to enhance sampling of regions that would otherwise be inaccessible in conventional MD due to high energy barriers. The weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) is then used to reconstruct the unbiased free energy profile from multiple biased simulations [9]. For ion transport in solid electrolytes, typical reaction coordinates include the ion position along migration pathways or coordination numbers with surrounding atoms.

Metadynamics enhances sampling by adding history-dependent repulsive potentials that discourage the system from revisiting previously sampled configurations [4]. This approach is particularly valuable for exploring complex free energy surfaces with multiple minima and for discovering unexpected migration pathways without predefined reaction coordinates.

The String Method identifies the minimum free energy path (MFEP) between initial and final states by evolving a discrete representation of the path in collective variable space [9]. This method has proven effective for characterizing coupled ion transport and conformational changes in complex systems, as demonstrated in studies of the melibiose transporter where it revealed "asymmetrical free energy profiles of melibiose translocation, which is tightly coupled to protein conformational changes" [9].

Table 2: Comparison of Free Energy Calculation Methods for Ion Transport Studies

| Method | Key Principles | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Umbrella Sampling | Harmonic biasing along reaction coordinate | Direct free energy calculation; Well-established protocol | Requires prior knowledge of reaction coordinate; Can be inefficient for high-dimensional spaces | Ion migration barriers; Binding affinities |

| Metadynamics | History-dependent bias deposition | Explores unknown pathways; Minimal prior assumptions | Convergence assessment challenging; Choice of collective variables critical | Complex transport mechanisms; Unknown intermediates |

| String Method | Evolution of minimum free energy path | Identifies optimal pathways; Handles coupled motions | Computationally intensive; Requires endpoint definitions | Coupled ion transport and conformational changes |

Analyzing Desolvation Processes

Desolvation processes in solid electrolytes can be quantified through several analytical approaches:

Coordination Number Analysis tracks changes in the number and identity of atoms coordinating the mobile ion during migration events. The radial distribution function g(r) and its integral (running coordination number) provide insights into the stability of coordination environments and the distance at which desolvation occurs [11]. For instance, in Li₂EDC—a model solid electrolyte interphase component—coordination numbers remain relatively constant with temperature, suggesting a rigid, glassy matrix that imposes significant desolvation barriers [11].

Residence Time Correlation Functions measure the persistence of specific ion-coordinating group interactions, with longer residence times indicating stronger interactions that likely contribute to higher desolvation barriers. In polymer electrolytes, the residence time of Li⁺ with ether oxygens in PEO or carbonyl groups in poly(ε-caprolactone) directly influences ionic conductivity [4].

Spatial Decomposition of Free Energy techniques, such as the identification of "drying transitions" or water-occupancy analysis used in biomolecular systems [10], can be adapted to solid electrolytes to pinpoint the precise locations where desolvation barriers emerge along ion migration pathways.

Application Notes: Case Studies in Solid Electrolytes

Lithium Ion Transport in Model SEI Components

The solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) critically influences battery performance by regulating Li⁺ transport between electrodes and electrolytes. MD simulations of dilithium ethylene dicarbonate (Li₂EDC), a primary SEI component, have revealed distinctive free energy landscapes characterized by deep trapping sites and significant desolvation barriers [11]. The mean-squared displacement (MSD) of Li⁺ in Li₂EDC shows three regimes: ballistic motion (<1 ps), trapping (1-1000 ps), and diffusive behavior (>1000 ps). The extended trapping regime reflects the high energy barriers associated with Li⁺ desolvation from its carbonate coordination environment.

Van Hove correlation functions and non-Gaussian parameters further quantify the deviation from normal diffusion in this glassy matrix, with significant non-Gaussian behavior observed at intermediate timescales corresponding to the trapping regime [11]. The vibrational power spectrum of Li⁺ in Li₂EDC reveals a bimodal distribution, with peaks near 400 cm⁻¹ and 700 cm⁻¹ corresponding to cage vibrations and carbonate scissoring motions, respectively. These molecular-scale insights help explain the low conductivity of Li₂EDC (∼4.5 × 10⁻⁹ S/cm) and provide design principles for improved SEI components with reduced desolvation barriers.

Ion Transport Mechanisms in Polymer Electrolytes

The classification of ion transport mechanisms in solid polymer electrolytes reveals how desolvation barriers influence macroscopic conductivity. MD simulations of PEO-LiTFSI and PCL-LiTFSI systems have identified three primary transport mechanisms: vehicular transport (ion moves with its solvation shell), continuous motion (successive exchange of coordinating groups), and ion hopping (complete desolvation between sites) [4]. Contrary to conventional wisdom, the dominant mechanism in these systems is continuous motion rather than hopping, with polymer-mediated transport prevailing at low salt concentrations and anion-mediated transport becoming significant at higher concentrations.

The free energy barriers for Li⁺ migration in polymer electrolytes depend critically on salt concentration. At low concentrations, Li⁺ is primarily coordinated by polymer chains, and the desolvation barrier involves breaking Li⁺-ether oxygen interactions. At high concentrations (>1 M), ion clustering becomes prevalent, and Li⁺ must overcome additional barriers associated with rearranging anion-rich coordination environments [13]. These clusters typically exhibit asymmetric composition, with more anions than cations, creating localized electrostatic environments that further influence Li⁺ desolvation energies.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Calculating Free Energy Landscapes via Umbrella Sampling

Objective: Determine the free energy profile for Li⁺ migration between two coordination sites in a solid electrolyte.

System Preparation:

- Build the atomic model of the electrolyte system using crystallographic data or amorphous structure generation tools.

- Equilibrate the system in the NPT ensemble (298 K, 1 atm) for 5 ns using a Nosé-Hoover thermostat and barostat.

- Switch to the NVT ensemble and equilibrate for an additional 2 ns.

- Identify the reaction coordinate (e.g., distance between Li⁺ and a reference atom, or coordination number).

Umbrella Sampling Execution:

- Define 20-40 windows along the reaction coordinate, spaced 0.1-0.5 Å apart.

- For each window, run steered MD to generate initial configurations.

- Perform production MD simulations (50-200 ps each) with harmonic restraints (force constant 10-50 kcal/mol/Ų) applied to the reaction coordinate.

- Ensure sufficient overlap in sampling between adjacent windows.

Analysis:

- Extract the probability distribution of the reaction coordinate for each window.

- Use the WHAM algorithm to combine distributions and reconstruct the unbiased free energy profile.

- Estimate errors through block averaging or bootstrapping methods.

- Validate convergence by comparing profiles from independent simulations.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Desolvation Barriers Through Coordination Dynamics

Objective: Characterize the desolvation barrier for Li⁺ transitioning between coordination environments in a polymer electrolyte.

Simulation Setup:

- Prepare a system containing polymer chains (e.g., PEO), Li⁺ ions, and counterions (e.g., TFSI) at desired concentration.

- Employ GAFF or similar force field with scaled partial charges (0.75) to improve agreement with experimental transport properties [4].

- Equilibrate using the following sequence: energy minimization, NVT (400 K, 5 ns), NPT (400-1000-400 K thermal cycling, 10 ns), final NPT production (440 K, 500-800 ns).

Coordination Analysis:

- Calculate the radial distribution function g(r) between Li⁺ and coordinating atoms (e.g., ether oxygens, anion atoms).

- Determine the running coordination number to identify preferred coordination environments.

- Track changes in coordination number during Li⁺ migration events.

Free Energy Calculation:

- Define collective variables capturing both ion position and coordination environment.

- Employ metadynamics or umbrella sampling to map the free energy as a function of these variables.

- Identify transition states where coordination numbers decrease significantly, indicating desolvation.

- Correlate the height of desolvation barriers with specific atomic interactions through energy decomposition analysis.

Visualization of Ion Transport Mechanisms

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Free Energy and Desolvation Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application in Ion Transport |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Packages | GROMACS [4], LAMMPS [14], NAMD | Molecular dynamics engine | Sampling atomic trajectories; Calculating transport properties |

| Free Energy Analysis | PLUMED, WHAM, MFTP | Enhanced sampling and analysis | Calculating PMFs; Identifying reaction pathways |

| Force Fields | OPLS-AA [10], GAFF [4], AMBER | Interatomic potential functions | Describing molecular interactions; Ion coordination energetics |

| Trajectory Analysis | MDTraj, VMD, MDAnalysis | Processing simulation trajectories | Calculating MSD; Coordination numbers; RDFs |

| Quantum Chemistry | Gaussian, VASP, CP2K | Electronic structure calculations | Validating force fields; Charge distributions |

Data Presentation and Analysis

Table 4: Characteristic Free Energy Barriers and Transport Properties in Solid Electrolytes

| Material System | Transport Mechanism | Free Energy Barrier (eV) | Desolvation Contribution | Conductivity (S/cm) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Li₃PS₄ | Cooperative hopping | 0.2-0.3 | Moderate | 10⁻³ - 10⁻⁴ | [12] |

| PEO-LiTFSI | Continuous motion | 0.3-0.5 | Significant | 10⁻⁴ - 10⁻⁵ | [4] [15] |

| PCL-LiTFSI | Continuous motion | 0.4-0.6 | Significant | 10⁻⁵ - 10⁻⁶ | [4] |

| Li₂EDC (SEI) | Trapping and hopping | 0.5-0.7 | Dominant | 10⁻⁸ - 10⁻⁹ | [11] |

The data presented in Table 4 illustrates the correlation between free energy barriers, desolvation contributions, and macroscopic ionic conductivity. Systems with lower overall barriers and reduced desolvation penalties generally exhibit higher conductivity, highlighting the importance of managing coordination strength in solid electrolyte design.

The integration of free energy landscape analysis with desolvation barrier characterization provides a powerful framework for understanding and optimizing ion transport in solid electrolytes. MD simulations have revealed that the coordination environment of mobile ions—whether in polymer, ceramic, or hybrid materials—creates distinct energy landscapes that govern transport mechanisms and overall conductivity. The predominance of continuous motion over ion hopping in many polymer electrolyte systems suggests that moderate, easily surmountable barriers promote higher conductivity than mechanisms requiring complete desolvation [4].

Future research directions should focus on extending these analyses to more complex multi-component systems, including interfaces between electrolytes and electrodes where desolvation barriers may be particularly pronounced. The development of accurately polarized force fields will improve the quantification of ion-coordinating group interactions, while advanced machine learning approaches may accelerate free energy calculations and enable high-throughput screening of promising solid electrolyte materials. By systematically correlating atomic-scale free energy landscapes with macroscopic transport properties, researchers can establish definitive design principles for next-generation solid electrolytes with optimized ion transport characteristics.

Comparative Analysis of Transport in Inorganic, Polymer, and Hybrid Solid Electrolytes

Solid-state batteries (SSBs) are poised to revolutionize energy storage by replacing flammable liquid electrolytes with safer, more energy-dense solid alternatives. The key component enabling this transition is the solid-state electrolyte (SSE), which serves as both ion conductor and separator. SSEs are generally categorized into three families: inorganic ceramic electrolytes, solid polymer electrolytes (SPEs), and hybrid/composite solid electrolytes (CSEs) that combine organic and inorganic materials. Each class exhibits distinct ion transport mechanisms, interfacial behaviors, and electrochemical properties that determine their suitability for different applications. Understanding these fundamental differences is crucial for selecting appropriate characterization methodologies and guiding the development of next-generation energy storage systems. This review provides a comparative analysis of transport phenomena across these electrolyte systems, with particular emphasis on insights gained from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and experimental validation techniques.

Fundamental Ion Transport Mechanisms

Polymer Electrolytes

In solid polymer electrolytes, ion transport occurs primarily through segmental motion of polymer chains in amorphous regions above the glass transition temperature (Tg). The widely accepted mechanism involves Li+ coordination with electron-donating groups on polymer chains (e.g., ether oxygens in PEO), with ion movement facilitated by continuous bond formation and dissociation as polymer chains rearrange [16] [17].

Molecular dynamics simulations have revealed three specific transport mechanisms in PEO-based systems:

- Intra-hopping: Li+ ions move along the same polymer chain

- Inter-hopping: Li+ ions jump between different polymer chains or distant sites on the same chain

- Co-diffusion: Li+ ions move while maintaining coordination with polymer sites [18]

The ionic conductivity in SPEs depends strongly on salt concentration. At low concentrations, conductivity increases with salt content due to more charge carriers, but decreases beyond an optimal concentration due to ion pairing and cluster formation [18]. MD simulations show that the size and number of LiTFSI clusters increase with salt concentration, reducing ion diffusivity [18].

Inorganic Solid Electrolytes

Inorganic solid electrolytes employ fundamentally different transport mechanisms dominated by ionic hopping migration through crystal structures. The specific mechanism varies by material class:

- Oxide-based electrolytes (e.g., garnets, NASICON): Transport occurs through vacancy or interstitial mechanisms within rigid crystal lattices [16] [19]

- Sulfide-based electrolytes: Typically exhibit higher ionic conductivity due to more polarizable sulfur atoms and favorable crystal structures for Li+ migration [19]

- Halide-based electrolytes: Emerging materials showing promising conductivity with tunable properties [19]

Unlike polymer electrolytes, ion transport in inorganic systems is not dependent on segmental motion but rather on crystal lattice defects, carrier concentrations, and migration pathways with low activation energies [16]. The ionic conductivity in these systems follows Arrhenius behavior, with temperature dependence governed by hopping activation energies.

Hybrid/Composite Electrolytes

Hybrid or composite solid electrolytes combine organic polymer matrices with inorganic fillers to leverage advantages of both systems. Two primary ion transport mechanisms operate in CSEs:

- Space charge layer effect: Disparities in Na+/Li+ concentration between inorganic fillers and polymer matrices create spontaneous Na+/Li+-rich space charge regions that serve as efficient ion transport channels [16]

- Functional group interaction: Surface functional groups on inorganic fillers interact with polymer matrices and salts, weakening polymer-cation interaction and increasing free cation concentration on filler surfaces [16]

In these systems, fillers are classified as either active (containing mobile ions, e.g., NASICON-type, LLZO) or inert (no mobile ions, e.g., Al2O3, TiO2, SiO2) [16] [17]. The shape and dimensionality of fillers (0D, 1D, 2D, 3D) further influence percolation pathways and interface properties [16].

Quantitative Comparison of Transport Properties

Table 1: Comparative Transport Properties of Major Solid Electrolyte Classes

| Electrolyte Type | Ionic Conductivity (S/cm) | Activation Energy (eV) | Transference Number | Dominant Transport Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer (PEO-based) | 10⁻⁷ - 10⁻⁴ at RT [17] | 0.1 - 0.3 [15] | ~0.2-0.3 [18] [15] | Segmental motion + ion hopping |

| Oxide Ceramics | 10⁻⁶ - 10⁻³ [19] | 0.2 - 0.5 | ~1 (for Li⁺) | Vacancy/interstitial hopping |

| Sulfide Ceramics | 10⁻⁴ - 10⁻² [19] | 0.1 - 0.3 | ~1 (for Li⁺) | Hopping through lattice |

| Hybrid/Composite | 10⁻⁵ - 10⁻³ [16] | 0.1 - 0.4 | 0.3-0.6 [16] | Combined mechanisms |

Table 2: Effect of Filler Characteristics in Composite Electrolytes

| Filler Property | Impact on Ionic Conductivity | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Type | ||

| Active fillers (NASICON, LLZO) | High enhancement | Provide additional ion conduction pathways |

| Inert fillers (Al₂O₃, SiO₂) | Moderate enhancement | Inhibit polymer crystallization, create space charge layers |

| Size/Dimension | ||

| 0D (nanoparticles) | Moderate improvement | Increase amorphous content, Lewis acid-base interactions |

| 1D (nanowires) | Good improvement | Form continuous ion conduction pathways |

| 2D (nanosheets) | High improvement | Create 2D fast ion channels at interfaces |

| Loading Content | Optimal at 5-20 wt% | Excessive filler increases agglomeration and resistance |

Molecular Dynamics Analysis Protocols

MD Simulation Framework for Transport Studies

Objective: To investigate ion transport mechanisms, compute transport coefficients, and correlate molecular structure with macroscopic properties in solid electrolytes.

Computational Methodology:

- System Setup:

- Build polymer-salt systems with specified concentration (r = [Li]/[O])

- Employ united-atom (UA) or all-atom force fields (e.g., TraPPE-UA, CHARMM)

- Use appropriate force fields for ions (e.g., Wu et al. model for LiTFSI [18])

Equilibration Protocol:

- Perform energy minimization using conjugate gradient algorithm

- Conduct annealing procedure to achieve stable equilibrium state

- Run NPT simulations (100 ps) at target temperature and pressure

- Execute production run in NVT ensemble (150 ns) at experimental temperatures [18]

Transport Property Calculation:

- Compute mean-squared displacement (MSD) of ions: ( D\alpha = \frac{1}{6N\alpha t} \left\langle \sum{i=1}^{N\alpha} |ri(t) - ri(0)|^2 \right\rangle )

- Calculate ionic conductivity from Einstein relation: ( \sigma = \frac{F^2}{RT} \sum\alpha z\alpha^2 c\alpha D\alpha )

- Determine Onsager coefficients for transference number computation [15]

Coordination and Hopping Analysis:

- Analyze Li+ coordination number with polymer oxygen atoms and anions

- Calculate residence time autocorrelation functions for solvation motifs

- Quantify inter/intra-hopping rates and distances [18]

Bridging MD Simulations and Experimental Validation

Challenge: Direct comparison between MD simulations and experiments requires careful consideration of reference frames and temperature effects.

Solutions:

- Temperature Referencing:

- Compute glass transition temperature (Tg) of model system

- Use normalized inverse temperature 1000/(T - Tg + 50) for comparing Li+ self-diffusion coefficients between MD and experiments [15]

Reference Frame Reconciliation:

- Account for different reference frames in experimental measurements (lab frame) and MD simulations (mass, mole, or solvent-fixed frames)

- Apply Onsager theory with proper reference frame transformation for transference number comparison [15]

Force Field Validation:

- Validate against experimental diffusion coefficients and ionic conductivity

- Compare coordination structures with spectroscopic data (e.g., NMR) [20]

Experimental Characterization Protocols

Ionic Conductivity Measurement

Objective: Determine total ionic conductivity of solid electrolyte samples.

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare electrolyte as thin film (50-200 μm thickness) between blocking electrodes (stainless steel)

- Ensure good electrode-electrolyte contact with controlled pressure

Impedance Spectroscopy:

- Use frequency range: 1 Hz - 1 MHz with amplitude of 10 mV

- Measure across temperature range (25°C - 80°C) for activation energy determination

- Extract bulk resistance (Rb) from Nyquist plot intercept on real axis

Calculation:

Transference Number Determination

Objective: Measure the fraction of current carried by Li+ ions.

Bruce-Vincent Method Protocol:

- DC Polarization:

- Apply small DC voltage (10-30 mV) across Li|electrolyte|Li symmetric cell

- Monitor current decay over time until steady state is reached

Impedance Measurement:

- Measure initial and final interface resistance using EIS

Calculation:

- Compute transference number: ( t^+{BV} = \frac{I{ss}(\Delta V - I0 R{i,0})}{I0(\Delta V - I{ss} R{i,ss})} ) where I₀ = initial current, Iss = steady-state current, R{i,0} and R{i,ss} = initial and steady-state interface resistances [15]

Solvation Structure Analysis

Objective: Characterize local coordination environment of Li+ ions.

Multimodal Protocol:

- NMR Spectroscopy:

- Acquire ¹H NMR spectra at high field (e.g., 700 MHz)

- Monitor chemical shift changes of solvent protons with salt concentration

- Perform T₁ relaxation measurements to probe dynamics [20]

- Computational Integration:

- Perform DFT calculations (B3LYP/6-31G(d)) for geometry optimization and NMR prediction

- Conduct MD simulations to determine species residence times and coordination numbers

- Correlate experimental chemical shifts with computed solvation structures [20]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Solid Electrolyte Research

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrices | PEO, P(2EO-MO), PVDF-HFP, PMMA | Provide Li+ coordination sites and mechanical stability |

| Lithium Salts | LiTFSI, LiFSI, LiPF₆, LiClO₄ | Source of charge carriers (Li⁺ ions) |

| Active Fillers | LLZO, NASICON-type, LATP, Li₂O | Provide additional Li⁺ conduction pathways |

| Inert Fillers | Al₂O₃, SiO₂, TiO₂, ZrO₂ | Suppress crystallization, create space charge layers |

| Solvents | Acetonitrile, DOL, THF | Processing solvents for membrane casting |

| Characterization | Blocking electrodes (stainless steel), Li metal electrodes | Electrochemical testing and interface studies |

Advanced Hybrid Electrolyte Architectures

Gradient Electrolyte Design

Recent advances in hybrid electrolytes employ gradient architectures that optimize properties at different length scales. One innovative approach utilizes Li₂O microparticles dispersed in polymerizable 1,3-dioxolane (DOL) that undergoes ring-opening polymerization inside battery cells [21]. This creates hybrid electrolytes with gradient properties:

- Particle scale: Li₂O retards polymerization near particle surfaces, creating fluid-like regions for efficient ion transport

- Cell scale: Gravity-assisted settling creates physical and electrochemical gradients

- Functionality: Li₂O particles participate in reversible redox reactions, increasing Coulombic efficiency in anode-free cells to ~100% [21]

Asymmetric Solid-State Electrolytes (ASSEs)

Asymmetric designs address the asynchronous demands of cathodes and anodes through multilayer structures:

- Cathode-facing layer: Optimized for high voltage stability

- Anode-facing layer: Designed for reduction stability and dendrite suppression

- Interlayer functionality: Gradient composition to mitigate interfacial resistance [22]

These ASSEs exhibit Janus-like properties that simultaneously address multiple interface challenges, though interface compatibility between different electrolyte layers remains a significant development hurdle [22].

The comparative analysis of transport mechanisms across inorganic, polymer, and hybrid solid electrolytes reveals distinct advantages and limitations for each system. Inorganic ceramics offer high transference numbers and excellent oxidative stability but suffer from poor processability and interfacial contact. Polymer electrolytes provide superior flexibility and electrode compatibility but exhibit lower ionic conductivity at room temperature. Hybrid/composite electrolytes emerge as the most promising approach, leveraging the benefits of both materials while mitigating their individual limitations.

Future research directions should focus on:

- Multiscale modeling bridging first-principles calculations, MD simulations, and continuum models

- Advanced characterization using in-situ/operando techniques to probe dynamic interface evolution

- Machine learning approaches for accelerated materials discovery and optimization

- Standardized protocols for unambiguous comparison of transport properties across different laboratories

- Scalable manufacturing processes compatible with existing battery production infrastructure

The integration of molecular dynamics simulations with sophisticated experimental validation provides a powerful framework for unraveling complex ion transport phenomena and guiding the rational design of next-generation solid electrolytes for safe, high-energy-density batteries.

MD Simulation Methodologies for Quantifying Ion Transport Properties

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has become an indispensable tool for investigating ion transport mechanisms in solid electrolytes, a critical component for the development of next-generation batteries and fuel cells. [23] [24] The reliability of these simulations is entirely contingent upon the force field (FF)—the parametric model that encodes interatomic interactions. Currently, researchers face a tripartite choice among non-polarizable force fields, polarizable force fields, and the emerging machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs). Each approach presents distinct trade-offs between computational efficiency, physical rigor, and accuracy. This application note provides a structured framework for selecting appropriate force fields for MD analysis of ion transport in solid electrolytes, supported by quantitative comparisons, detailed protocols, and practical implementation guidelines tailored for research scientists.

Force Field Architectures and Theoretical Foundations

Non-Polarizable Force Fields

Non-polarizable force fields, such as OPLS-AA and GAFF, employ fixed point charges and predefined empirical functions to describe intermolecular interactions. [24] Their primary advantage lies in computational efficiency, making them suitable for large-system and long-timescale simulations. However, their rigid architecture cannot capture key physics in electrolyte systems, such as electron polarization and charge penetration effects, which are crucial for accurately modeling ion-solvent interactions and transport dynamics. Their parameters typically require refinement using experimental data, which may be inaccessible for novel materials. [24]

Polarizable Force Fields

Polarizable force fields incorporate electronic response by modeling how the charge distribution of atoms or molecules changes in their local environment. The PhyNEO-Electrolyte framework represents a modern implementation that includes explicit atomic multipoles, induced dipoles, and higher-order dispersion interactions. [24] Its energy expression is given by:

E_PhyNEO = E_{nb}^{lr} + E_{nb}^{sr} + E_{nb}^{NN-corr} + E_{bond}^{sgnn}

where the long-range nonbonding terms (E{nb}^{lr}) describe electrostatic, polarization, and dispersion interactions, the short-range terms (E{nb}^{sr}) capture exchange-repulsion and charge penetration effects, and a neural network correction (E_{nb}^{NN-corr}) addresses residual inaccuracies. [24] This approach rigorously restores long-range asymptotic behavior critical for electrolyte systems but requires more sophisticated parameterization and increased computational resources.

Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials

MLIPs replace predetermined functional forms with trainable neural networks that map atomic configurations to energies and forces. Prominent examples include Moment Tensor Potentials (MTPs), MatterSim, MACE, and CHGNet. [23] [25] These potentials learn from quantum mechanical (e.g., density functional theory) data and can achieve near-DFT accuracy while being several orders of magnitude faster than direct quantum calculations. [25] For instance, MTPs developed for ionic conductors Ba7Nb4MoO20 and Sr3V2O20 accurately reproduced DFT-derived forces with RMSEs of 0.149 eV/Å and 0.114 eV/Å, respectively, while successfully predicting diffusion coefficients and conductivities. [23]

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Force Field Performance for Solid Electrolytes

| Performance Metric | Non-Polarizable FF | Polarizable FF (PhyNEO) | MLIP (MatterSim) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force RMSE vs. DFT (eV/Å) | Not explicitly reported | Not explicitly reported | 0.149 (for MTP on Ba7Nb4MoO20) [23] |

| Energy Error (meV/atom) | Not explicitly reported | Not explicitly reported | <3.0 (for MTP on Sr3V2O8) [23] |

| Lithium-ion Diffusivity | Limited transferability | Quantitative prediction possible | Excellent agreement with reference values [25] |

| Computational Cost | Low | Medium | High training cost, efficient inference [24] [25] |

| Explicit Polarization | No | Yes (Induced dipoles, multipoles) | Implicitly captured via training [24] |

| Long-range Interaction Treatment | Approximate (e.g., cutoff) | Rigorous (Ewald sum with multipoles) | Often limited; requires hybrid approaches [24] |

| Data Efficiency | High (based on physical functions) | Medium (hybrid approach) | Low (requires extensive ab initio data) [24] |

Decision Framework for Force Field Selection

The choice of force field should be guided by research objectives, material complexity, and available computational resources. The following diagram outlines a systematic selection workflow:

Application-Specific Recommendations

Screening Novel Materials and High-Throughput Computation: For initial screening of large chemical spaces, non-polarizable force fields offer the best balance between speed and reasonable accuracy, particularly for homogeneous systems. [24]

Mechanistic Studies of Ion Transport: For investigating detailed ion transport mechanisms (e.g., vacancy, interstitial, or interstitialcy mechanisms) in complex crystalline electrolytes like Ba7Nb4MoO20 or Sr3V2O8, MLIPs are superior. They provide near-DFT accuracy for diffusion coefficients and migration barriers, as demonstrated by MTPs. [23]

Interface and Interphase Phenomena: For studying interfaces such as the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) in lithium-ion batteries, where polarization effects and complex compositional gradients are critical, polarizable force fields like PhyNEO-Electrolyte or hybrid MLIPs are recommended. Their physically rigorous treatment of long-range interactions is essential for modeling these heterogeneous environments. [26] [24]

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Protocol 1: Validation of MLIPs for Oxide-Ion Conductors

This protocol outlines the validation process for Moment Tensor Potentials (MTPs) applied to solid oxide fuel cell electrolytes, as described in recent research. [23]

1. Training Set Construction:

- Generate diverse atomic configurations using ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) at high temperatures (e.g., 1200 K) to ensure sampling of relevant phase space.

- Include configurations with intrinsic defects (vacancies, interstitials) that may occur under operational conditions, as their omission limits predictive power. [27]

- Extract energies, forces, and stresses from density functional theory (DFT) calculations for training.

2. Potential Training and Accuracy Metrics:

- Train the MTP using passive and active learning techniques on the DFT dataset.

- Validate by comparing MTP-predicted forces and energies against DFT values. Target a root mean square error (RMSE) for forces below 0.15 eV/Å and energy errors below 3 meV/atom. [23]

- Calculate correlation plots between MTP and DFT forces; strong diagonal clustering indicates good agreement.

3. Property Prediction and Experimental Comparison:

- Perform molecular dynamics simulations using the validated MTP on larger systems (e.g., >1000 atoms) and extended timescales (e.g., 10 ns).

- Calculate mean squared displacement (MSD) of mobile ions (e.g., oxide ions or protons) and derive diffusion coefficients using the Einstein relation.

- Compute ionic conductivity from the diffusion coefficients using the Nernst-Einstein relation.

- Validate predictions by comparing with experimental conductivity measurements and AIMD results. [23]

Protocol 2: Hybrid Physics-Driven ML Potential for Electrolytes

This protocol details the development of the PhyNEO-Electrolyte force field for liquid and solid electrolytes. [24]

1. Monomer and Dimer Data Generation:

- Compute isolated monomer properties: perform TD-DFT calculations to obtain atomic charges, multipoles (up to quadrupole), polarizabilities, and dispersion coefficients (up to C10) using methods like ISA/ISA-pol.

- Generate dimer interaction data: use symmetry-adapted perturbation theory (SAPT(DFT)) to decompose interaction energies into exchange, electrostatic, polarization, dispersion, and delta Hartree-Fock components.

2. Potential Energy Surface Construction:

- Build long-range interactions (E_{nb}^{lr}) using atomic multipoles and induced dipoles, employing a Thole damping scheme and Ewald summation for accurate computation.

- Fit short-range nonbonding interactions (E_{nb}^{sr}) to the SAPT(DFT) dimer data using Slater-type functions.

- Train a pairwise neural network correction term (E_{nb}^{NN-corr}) on the dimer data to capture residual effects like charge transfer.

- Model bonding interactions (E_{bond}^{sgnn}) using a topology-based sub-graph neural network (sGNN).

3. Bulk Phase Validation:

- Run MD simulations of the bulk electrolyte and compare predicted properties (density, ion diffusivity, viscosity) with experimental data.

- Ensure the model reproduces key structural properties such as radial distribution functions and solvation structures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for Force Field Development and Validation

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moment Tensor Potential (MTP) | Machine Learning Potential | Accurately reproduces AIMD data for forces, energies, and stresses | Predicting oxide-ion and proton transport in complex crystals [23] |

| PhyNEO-Electrolyte | Hybrid Physics-ML Force Field | Provides physically rigorous long-range interactions with ML corrections | Multi-component electrolyte design with high data efficiency [24] |

| MatterSim | Universal MLIP (uMLIP) | High-accuracy force field for complex material systems | Systematic screening of solid-state electrolytes; top performer in benchmarks [25] |

| VASP | Ab Initio Simulation Package | Calculates reference DFT data for training and validation | Energy/force calculations; NEB migration barriers [23] |

| SAPT(DFT) | Quantum Chemical Method | Decomposes dimer interaction energies into physical components | Training data for physics-driven ML force fields [24] |

Implementation Workflow for Machine Learning Potentials

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end process for developing and deploying an MLIP for solid electrolyte research:

The force field landscape for simulating ion transport in solid electrolytes has expanded significantly with the advent of sophisticated polarizable models and machine learning approaches. While non-polarizable force fields remain useful for high-throughput screening, polarizable force fields and MLIPs offer superior accuracy for mechanistic studies and property prediction. The recent development of hybrid frameworks like PhyNEO-Electrolyte, which marry physical rigor with data-driven corrections, represents a promising direction for achieving both high accuracy and data efficiency. As universal MLIPs continue to mature and demonstrate robust performance across diverse material systems, they are poised to become the standard tool for accelerating the discovery and optimization of next-generation solid electrolytes. [24] [25]

Within the broader scope of thesis research on molecular dynamics (MD) analysis of ion transport in solid electrolytes, the precise characterization of dynamical properties is fundamental. Understanding ion diffusion at the atomic level is critical for designing next-generation all-solid-state batteries with enhanced safety and energy density. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for two principal analytical techniques: Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD) and Van Hove Correlation Functions. These methods, when applied to MD simulation trajectories, enable researchers to quantify diffusivity, identify distinct transport regimes, and detect correlated ionic motion, providing unparalleled insight into the mechanisms governing ionic conductivity in solid-state electrolyte materials [12] [28].

Theoretical Foundation of Dynamical Analysis

The dynamical properties of ions within a solid electrolyte matrix are direct indicators of the material's macroscopic ionic conductivity. Molecular dynamics simulations serve as a computational microscope, capturing the trajectories of every atom over time. The primary challenge lies in extracting meaningful, quantitative parameters from this vast positional data. The Mean-Squared Displacement analysis provides a direct link between atomic-scale jumps and the macroscopic diffusion coefficient, while the Van Hove function offers a deeper, more statistically robust view of the dynamics, revealing the extent to which ionic motions are correlated in space and time. The activation energy and attempt frequency, derivable from temperature-dependent MSD analysis, are critical for understanding the temperature dependence of conductivity and the fundamental jump processes [12]. The analysis of these properties moves beyond simply calculating a diffusion coefficient; it provides a thorough understanding of the diffusion pathways, collective motions, and jump mechanisms, which is indispensable for the rational design of improved solid electrolyte materials [12].

Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD) Analysis

Protocol for MSD Calculation

The following protocol details the steps for calculating the Mean-Squared Displacement from a molecular dynamics trajectory.

- Trajectory Preparation: Ensure your MD trajectory file includes the positions of all Li ions (or other diffusing species) for a sufficient number of consecutive time steps. The simulation must be long enough to observe clear diffusive behavior beyond the initial ballistic regime.

- Data Extraction: For every Li ion i in the system, extract its position vector (\mathbf{r}_i(t)) at each time step t.

- Reference Time Setting: Choose a reference time (t_0). The MSD can be calculated for multiple, overlapping time origins to improve statistical averaging.

- Displacement Calculation: For each ion i and for a series of time intervals (\Delta t), compute the squared displacement: ([\mathbf{r}i(t0 + \Delta t) - \mathbf{r}i(t0)]^2).

Ensemble Averaging: Average the squared displacements over all N Li ions and all equivalent time origins (t_0) in the trajectory:

[\text{MSD}(\Delta t) = \frac{1}{N} \left\langle \sum{i=1}^{N} [\mathbf{r}i(t0 + \Delta t) - \mathbf{r}i(t0)]^2 \right\rangle{t_0}]

where d is the dimensionality of the diffusion (e.g., 1, 2, or 3) [12].

- Linear Regression: Plot (\text{MSD}(\Delta t)) versus (\Delta t). In the diffusive regime, the relationship becomes linear. Fit a line to this linear portion.

Data Interpretation and Key Parameters

The slope of the MSD curve in the diffusive regime is directly related to the tracer diffusivity ((D^*)) via the Einstein relation:

[D^* = \frac{1}{2d} \lim_{\Delta t \to \infty} \frac{\text{MSD}(\Delta t)}{\Delta t}]

where d is the dimensionality [12]. This tracer diffusivity can be approximated to the ionic conductivity ((\sigma)) using the Nernst-Einstein relation (assuming a Haven ratio of 1):

[\sigma = \frac{n e^2 z^2 D^*}{k_B T}]

where n is the density of diffusing ions, e is the elementary charge, z is the ionic charge, k_B is Boltzmann's constant, and T is the temperature [12].

Analysis of Li-ion transport in a model Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) has demonstrated that MSD analysis can distinguish three distinct dynamical regimes [28]:

- Ballistic Regime: At very short times, ions vibrate within their cages, and MSD is proportional to ((\Delta t)^2).

- Trapping Regime: Ions remain temporarily localized, characterized by a plateau or sub-diffusive behavior in the MSD.

- Diffusive Regime: Ions undergo successful long-range jumps, and MSD scales linearly with (\Delta t).

Table 1: Key Parameters Obtainable from MSD Analysis

| Parameter | Symbol | Extraction Method from MSD | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tracer Diffusivity | (D^*) | Slope of linear fit to MSD(Δt) in the diffusive regime [12]. | Measures the long-range, macroscopic diffusion capability of ions. |

| Ionic Conductivity | (\sigma) | Calculated from (D^*) via the Nernst-Einstein equation [12]. | Key performance metric for solid electrolyte materials. |

| Activation Energy | (E_a) | Arrhenius fit of (D^*(T)) obtained at multiple temperatures [12]. | Energy barrier for ion migration; lower values indicate faster kinetics. |

| Dynamic Regimes | --- | Identification of ballistic, trapping, and diffusive slopes on a log-log plot [28]. | Reveals local ion dynamics and the timescale for successful jumps. |

Van Hove Correlation Function Analysis

Protocol for Van Hove Calculation

The Van Hove function provides a time-dependent, pair-wise distribution function, offering a more nuanced view of dynamics than MSD. The following protocol outlines the calculation of the self-part of the Van Hove function, (G_s(\mathbf{r}, t)), which measures the probability of finding a particle at a position (\mathbf{r}) at time t given it was at the origin at time zero.

- Trajectory Preparation: Use the same MD trajectory of Li ion positions as for MSD analysis.

- Displacement Vector Calculation: For a specific time interval t, compute the displacement vector for every ion i: (\Delta \mathbf{r}i(t) = \mathbf{r}i(t0 + t) - \mathbf{r}i(t_0)).

- Histogram Construction: Create a 3D histogram (or a radial histogram for the isotropic case) of all displacement vectors (\Delta \mathbf{r}i(t)) for all ions *i* and all time origins (t0).

Probability Normalization: Normalize the histogram such that its integral over all space is unity. This normalized distribution is the self-part of the Van Hove function, (G_s(\mathbf{r}, t)).

[Gs(r, t) = \frac{1}{N} \left\langle \sum{i=1}^{N} \delta[\mathbf{r} + \mathbf{r}i(0) - \mathbf{r}i(t)] \right\rangle]

In practice, for a radial function, it is the probability of observing a displacement of magnitude r in time t [28] [29].

- Analysis for Correlated Motion: To detect correlated jumps between different species (e.g., Li-Li or Li-anion), compute the distinct part of the Van Hove function, which involves the relative displacements between pairs of different particles [29].

Data Interpretation and Key Parameters

The Van Hove function is a powerful tool for identifying deviations from simple, uncorrelated diffusion.

- Gaussian Behavior: In a simple, uncorrelated liquid-like system, (G_s(r, t)) follows a Gaussian distribution. Significant deviations from this Gaussian shape indicate complex dynamics [28].

- Non-Gaussian Parameter: The presence of distinct peaks in (G_s(r, t)) at distances corresponding to interatomic spacings in the crystal lattice is a signature of jump diffusion. This indicates that ions spend most of their time vibrating around stable sites and occasionally make discrete jumps to neighboring sites [28].

- Correlated Motion: The distinct part of the Van Hove function, (G_d(r, t)), can directly reveal the correlated motion of different ionic species. For instance, it can show the preferential movement of water molecules around anions in aqueous solutions, a concept that can be extended to the correlated motion of Li ions with matrix anions or other Li ions in solid electrolytes [29].

Table 2: Key Parameters and Insights from Van Hove Analysis

| Analysis Type | Function | Key Observation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Van Hove | (G_s(r, t)) | Shape of the distribution at a given time t [28]. | Gaussian shape suggests simple liquid-like diffusion; non-Gaussian peaks indicate heterogeneous dynamics or jump diffusion. |

| Self-Van Hove | (G_s(r, t)) | Peak at a distance corresponding to a known Li-Li site distance [28]. | Direct evidence of a dominant jump distance, confirming a specific diffusion mechanism. |

| Distinct Van Hove | (G_d(r, t)) | Time-evolving peaks between different particle types (e.g., Li-Anion) [29]. | Reveals spatially and temporally correlated motion between different species in the material. |

Integrated Workflow for Dynamical Analysis

The analysis of MSD and Van Hove functions is most powerful when these tools are used in concert. The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical sequence for a comprehensive analysis of ion dynamics from an MD trajectory.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

The following table lists essential materials and computational tools frequently employed in MD studies of ion transport in solid electrolytes, as evidenced by the search results.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function / Role in Research | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| β-Li₃PS₄ | A prototypical thiophosphate solid electrolyte material used for benchmarking simulation methodologies and understanding fundamental Li-ion diffusion mechanisms [12]. | Used to demonstrate how jump processes between bc planes limit conductivity, and how doping can enhance 3D diffusion [12]. |

| LiTFSI Salt | Lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide; a common lithium salt used in polymer electrolyte studies due to its high stability and dissociation constant [18]. | Used in MD simulations with PEO and P(2EO-MO) polymers to study the effect of salt concentration on ion clustering and diffusivity [18]. |

| PEO Polymer | Poly(ethylene oxide); the benchmark polymer matrix for solid polymer electrolytes, facilitating ion transport via segmental motion of its chains [18]. | Studied to analyze intra-hopping (along the chain) and inter-hopping (between chains) transport mechanisms [18]. |

| P(2EO-MO) Polymer | Poly(diethylene oxide-alt-oxymethylene); an alternative polymer electrolyte studied for its potentially superior transport number compared to PEO [18]. | Investigated to understand how polymer morphology affects Li-ion solvation and hopping behavior [18]. |

| Li₂EDC | Dilithium ethylene dicarbonate; a major component of the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) formed on anode surfaces [28]. | Used in a model SEI to study Li-ion trapping and transport in a glassy, inorganic-like environment [28]. |

| MD Analysis Code | Custom scripts (e.g., in MATLAB or Python) for automated analysis of trajectories (MSD, Van Hove, jump analysis) [12]. | A freely available MATLAB code was used to extract diffusional properties like jump rates and attempt frequencies from β-Li₃PS₄ simulations [12]. |

The development of high-performance solid-state batteries hinges on the discovery and optimization of solid electrolytes (SEs), which replace flammable liquid electrolytes to improve safety and energy density. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations serve as a powerful tool to study diffusion processes in battery electrolyte and electrode materials, providing atomic-level insights that are often challenging to obtain experimentally [30]. From MD simulations, researchers can extract three fundamental performance metrics that characterize ionic transport: diffusivity, which describes the rate of ionic migration; conductivity, which quantifies a material's ability to conduct ions; and transference numbers, which represent the fraction of current carried by a specific ion type. Accurately computing these metrics is essential for understanding ion conduction mechanisms and directing the design of improved solid electrolyte materials [30] [12]. This protocol details computational methodologies for determining these critical performance parameters within the context of MD analysis of ion transport in solid electrolytes research.

Key Performance Metrics: Definitions and Computational Frameworks

Table 1: Fundamental Performance Metrics for Solid Electrolyte Analysis

| Metric | Symbol | Definition | Key Computational Formula | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tracer Diffusivity | ( D^* ) | Measure of ionic mobility from mean squared displacement. | ( D^* = \frac{1}{2dt} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^N \left\langle \left| \mathbf{r}i(t+t0) - \mathbf{r}i(t0) \right|^2 \right\rangle ) [12] | Foundation for calculating conductivity; provides insight into diffusion mechanisms. |

| Ionic Conductivity | (\sigma) | Measure of a material's ability to conduct ions. | ( \sigma = \frac{ne^2z^2}{k_B T} D^* ) (from Nernst-Einstein, assuming Haven ratio=1) [12] | Primary indicator of solid electrolyte performance; target: >10(^{-3}) S/cm at room temperature [31]. |

| Transference Number | ( t_+ ) | Fraction of total current carried by the cation (e.g., Li(^+)). | ( t+ = \frac{I+}{I} = \frac{\lambda_+}{\Lambda} ) [32] | Critical for battery performance; values close to 1 reduce concentration polarization. |

| Activation Energy | ( E_a ) | Energy barrier for ion migration. | Determined from Arrhenius behavior of ( D^* ) or (\sigma) vs. (1/T) [30] | Key descriptor of temperature dependence and diffusion difficulty. |

| Attempt Frequency | (\nu^*) | Rate at which ions attempt to overcome migration barriers. | Obtained from Fourier transform of atomic displacement derivatives in MD [12] | Fundamental kinetic parameter for jump processes. |

Advanced Properties from MD Analysis

Table 2: Additional Diffusional Properties Obtainable from MD Simulations

| Property | Description | Utility in Material Design |

|---|---|---|

| Diffusion Pathways | Crystallographic routes taken by migrating ions. | Identifies bottlenecks; enables structural engineering for improved pathways. |

| Jump Rates | Frequency of ionic jumps between specific sites. | Pinpoints rate-limiting steps in the diffusion process. |

| Correlation Factor | Measure of cooperative ion motions. | Quantifies deviation from uncorrelated random walk model. |

| Collective Jumps | Simultaneous movement of multiple ions. | Reveals complex diffusion mechanisms not apparent from static calculations. |

| Site Occupancies | Distribution of mobile ions among available crystallographic sites. | Informs how doping or composition changes affect ion distribution and mobility. |

| Radial Distribution Functions | Probability of finding atoms at specific distances. | Reveals local coordination environments and their dynamics. |

Computational Methodologies and Protocols

Equilibrium Molecular Dynamics (EMD) for Diffusivity and Conductivity

Principle: EMD simulations model the system at thermodynamic equilibrium, using the spontaneous fluctuations in particle positions over time to compute diffusion properties.

Protocol 1: Calculating Tracer Diffusivity via Mean Squared Displacement (MSD)

- Simulation Setup: Perform an MD simulation in an appropriate ensemble (NVT or NPT) for a sufficient duration to achieve well-converged diffusion statistics. Ensure the simulation cell is large enough to minimize finite-size effects.