MLIP vs Classical Force Fields: A Definitive Accuracy Benchmark for Computational Drug Discovery

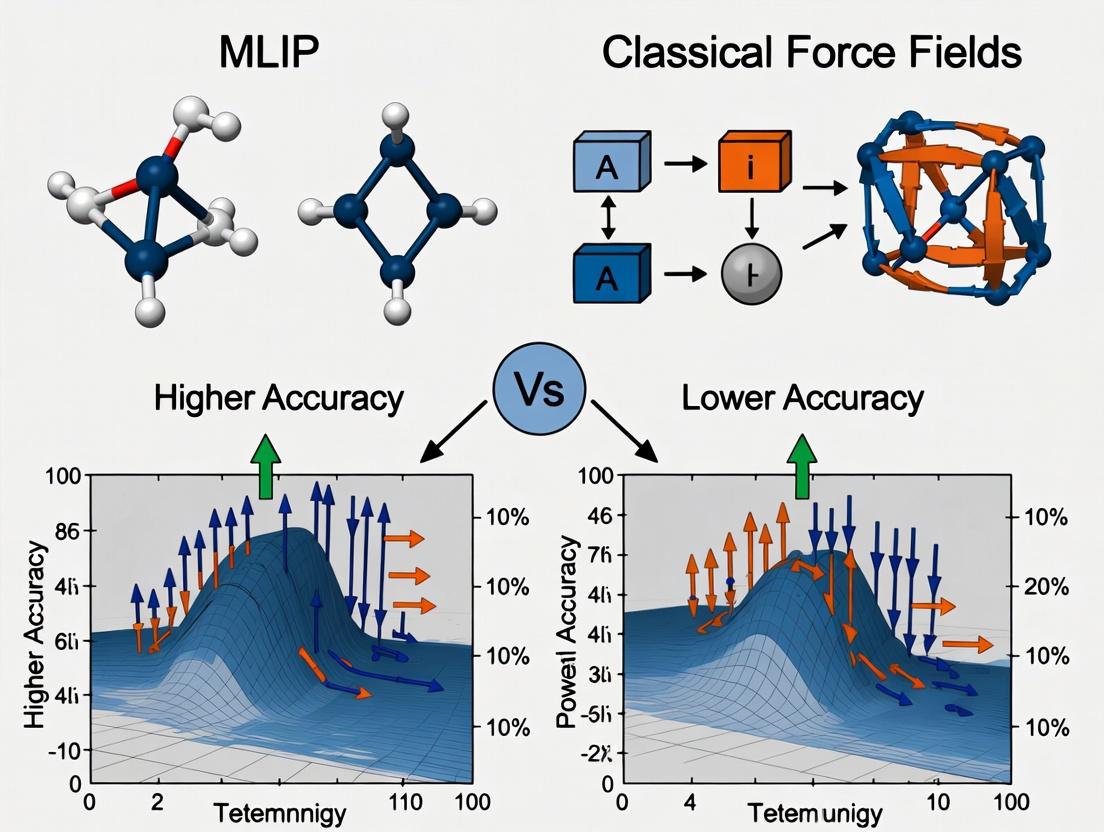

This article provides a comprehensive analysis comparing the accuracy of Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) with traditional classical force fields (FFs) in the context of biomedical research.

MLIP vs Classical Force Fields: A Definitive Accuracy Benchmark for Computational Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis comparing the accuracy of Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) with traditional classical force fields (FFs) in the context of biomedical research. It explores the foundational principles of both approaches, details their methodological implementation for simulating biological systems, addresses key challenges in deployment and optimization, and presents rigorous validation frameworks. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, the review synthesizes recent benchmarks to guide the selection and application of these tools for predicting protein-ligand interactions, protein folding, and material properties, ultimately assessing their impact on accelerating computational drug discovery.

The Building Blocks of Simulation: Understanding MLIPs and Classical Force Fields

The computational prediction of atomic interactions and energetics is foundational to materials science, chemistry, and drug development. The central thesis of modern accuracy research in this domain posits that Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) are not merely incremental improvements over Classical Force Fields (FFs), but represent a paradigm shift with fundamentally different philosophical underpinnings, capabilities, and limitations. This whitepaper delineates the core philosophies of these two approaches, framing them as contenders in the pursuit of accurate, scalable, and predictive atomistic simulation.

Core Philosophies: A Comparative Analysis

Classical Force Fields: The Physics-First, Parametric Approach

Classical FFs are built on pre-defined analytical functional forms grounded in classical mechanics and electrostatics. The philosophy is one of physical interpretability and transferability. Energy is decomposed into bonded and non-bonded terms (e.g., bond stretching, angle bending, torsion, van der Waals, Coulombic). Parameters (e.g., force constants, equilibrium lengths, partial charges) are typically fitted to experimental data and/or high-level quantum mechanical calculations for small representative molecules. The core assumption is that these parameters are transferable across chemical space.

Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials: The Data-First, Ab Initio-Driven Approach

MLIPs, including models like NequIP, MACE, and ANI, adopt a data-driven, non-parametric philosophy. They use flexible machine learning models (neural networks, kernel methods) to directly map atomic configurations to energies and forces. The "physics" is not pre-defined but learned from large datasets of ab initio (typically Density Functional Theory) calculations. The goal is to interpolate quantum mechanical accuracy with near-classical computational cost, sacrificing some interpretability for fidelity to the reference electronic structure method.

Quantitative Comparison of Performance & Characteristics

Table 1: Core Philosophical & Practical Comparison

| Aspect | Classical Force Fields | Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Basis | Newtonian mechanics, pre-defined analytical forms. | Statistical learning from quantum mechanical data. |

| Energy Expression | ( E = E{\text{bond}} + E{\text{angle}} + E{\text{torsion}} + E{\text{vdW}} + E_{\text{Coul}} ) | ( E = \sumi f(\mathbf{G}i) ), where ( f ) is a NN and ( \mathbf{G} ) is a descriptor. |

| Parameter Source | Fit to experiment & QM for model compounds. | Trained on ab initio datasets (DFT, CCSD(T)). |

| Transferability | High for systems similar to parametrization set. | Limited to the chemical space covered by training data. |

| Accuracy | Moderate (5-20 kcal/mol errors for complex interactions). | High (can approach DFT accuracy, ~1-3 kcal/mol errors). |

| Computational Cost | Very low (O(N) to O(N²) for long-range). | Low to moderate (O(N) to O(N²), higher prefactor than FF). |

| Interpretability | High; each term has physical meaning. | Low; "black box" model, though efforts exist. |

| Extensibility | Difficult; requires manual re-parameterization. | Easier; can be extended with active learning. |

| Long-Range Forces | Explicit via Ewald summation, PME. | Challenging; requires hybrid or specialized architectures. |

Table 2: Representative Accuracy Benchmark (Energy & Force Errors)

| Model Type | Example FF/MLIP | MAE Energy (meV/atom) | MAE Forces (meV/Å) | Reference Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical FF | AMBER ff19SB | ~50-100 (equiv.) | N/A | Fitted to experiment |

| Classical FF | CHARMM36 | ~50-100 (equiv.) | N/A | Fitted to experiment |

| MLIP (NN) | ANI-2x | ~5 | ~50 | DFT (wB97X/6-31G*) |

| MLIP (GNN) | NequIP | ~1.5 | ~20 | DFT (PBE) |

| MLIP (Transformer) | MACE | ~1.0 | ~15 | DFT (PBE0) |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Accuracy

Protocol 1: Energy and Force Error Calculation

Objective: Quantify the deviation of FF/MLIP predictions from reference ab initio data.

- Dataset Curation: Select a diverse benchmark dataset (e.g., MD17, 3BPA, QM9). Ensure it contains atomic configurations, total energies, and atomic forces from DFT.

- Model Inference: For each configuration, compute the predicted total energy ((E{pred})) and per-atom forces ((\mathbf{F}{pred})) using the FF or MLIP.

- Error Metric Calculation:

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE): ( \text{MAE}(E) = \frac{1}{N}\sum{i=1}^{N} | E{pred}^{(i)} - E_{ref}^{(i)} | )

- Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) on forces: ( \text{RMSE}(F) = \sqrt{ \frac{1}{3N{\text{atoms}}} \sum{i} || \mathbf{F}{pred}^{(i)} - \mathbf{F}{ref}^{(i)} ||^2 } )

Protocol 2: Molecular Dynamics Stability Test

Objective: Assess the stability and reliability of a model in extended simulations.

- System Preparation: Solvate a target molecule (e.g., a small protein or catalyst) in a water box using standard procedures.

- Equilibration: Run a short equilibration simulation (NPT, 300K, 1 bar) using a reliable baseline FF.

- Production Run: Switch to the test potential (FF or MLIP) and run a multi-nanosecond MD simulation.

- Analysis: Monitor for unphysical events (bond breaking, vaporization), analyze radial distribution functions, and compute dynamical properties (diffusion coefficients). Compare to baseline FF and/or experimental data.

Protocol 3: Property Prediction (e.g., Density, Heat of Vaporization)

Objective: Evaluate performance on macroscopic thermodynamic properties.

- Simulation Setup: Build a periodic box of the pure liquid (e.g., water, organic solvent).

- NPT Simulation: Run a sufficiently long NPT simulation (e.g., 5-10 ns) to equilibrate density.

- Property Calculation:

- Density: Average the box density over the production trajectory.

- (\Delta H{vap}): Calculate as ( \Delta H{vap} = \langle E{gas} \rangle - \langle E{liq} \rangle + RT ), where energies are from simulations of isolated molecules and the liquid phase.

- Comparison: Compare calculated values to experimental measurements.

Visualization of Methodologies and Relationships

Title: Philosophical Pathways to Atomistic Potentials

Title: MLIP Development & Active Learning Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Resources

| Item (Tool/Solution) | Function/Brief Explanation | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS, LAMMPS, AMBER, OpenMM | High-performance MD engines for running simulations with both FFs and (increasingly) MLIPs. | Production MD, benchmark simulations. |

| PyTorch, JAX, TensorFlow | Deep Learning frameworks for developing, training, and deploying MLIP models. | Building custom MLIP architectures. |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | Python library for setting up, running, and analyzing atomistic simulations. | Interfacing between DFT codes, MLIPs, and MD engines. |

| DeePMD-kit, Allegro, MACE | Specialized software packages implementing state-of-the-art MLIP models. | Training and using specific MLIP types. |

| CP2K, VASP, Gaussian, Quantum ESPRESSO | Ab initio electronic structure packages for generating reference training data. | Creating the quantum mechanical dataset for MLIP training. |

| OpenFF, ForceField, foyer | Toolkits for parameterizing and applying classical FFs (especially for organic molecules). | Developing and testing new FF parameters. |

| PLUMED | Library for enhanced sampling and free-energy calculations, compatible with FF and MLIP. | Calculating rare-event properties (binding affinities, reaction rates). |

This technical guide provides a detailed examination of classical force fields (FFs) within the broader research context comparing the accuracy of Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) versus classical methodologies. The resurgence of interest in FF accuracy is directly driven by the promising, yet sometimes opaque, results of MLIPs, necessitating a clear understanding of the established classical baseline.

Functional Forms: The Mathematical Backbone

The total potential energy U of a system in a classical FF is a sum of bonded and non-bonded terms. The specific functional forms represent the first major layer of approximation.

Bonded Interactions

- Bond Stretching: Typically modeled as a harmonic oscillator: U_bond = ½ k_b (r - r0)^2

- Angle Bending: Also harmonic: U_angle = ½ k_θ (θ - θ0)^2

- Dihedral/Torsional Rotation: Modeled with a periodic cosine series: U_dihedral = Σ_n k_φ,n [1 + cos(nφ - δ)]

- Improper Dihedrals: Often harmonic, used to maintain planarity or chirality.

Non-Bonded Interactions

- van der Waals (vdW): Most commonly the Lennard-Jones 12-6 potential: U_LJ = 4ε [(σ/r)^12 - (σ/r)^6]

- Electrostatics: Modeled via Coulomb's law with partial atomic charges: U_Coulomb = (q_i q_j) / (4πε_0 ε_r r)

Parameters (e.g., k_b, r0, ε, σ, q) are derived to reproduce target data. The source of this data defines a key approximation.

Table 1: Primary Parameterization Data Sources and Their Implications

| Data Source | Typical Target | Approximations Introduced |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Mechanics (QM) | High-level ab initio calculations (e.g., MP2, CCSD(T)) for small model compounds. | Transferability error; gas-phase data may not reflect condensed phase. |

| Experimental Data | Crystal lattice parameters, densities, enthalpies of vaporization, vibrational spectra. | Empirical fitting can mask error compensation; limited to measurable properties. |

| Hybrid QM/Experimental | QM for bonded/charge parameters; expt. for vdW to reproduce bulk properties. | Balances accuracy and realism; complexity in optimization. |

Inherent Approximations and Limitations

The architectural choices of classical FFs introduce systematic limitations when compared to a QM reality or a well-trained MLIP.

- Fixed Functional Forms: The pre-defined equations cannot capture effects outside their design (e.g., bond breaking/formation, electronic polarization beyond fixed charges).

- Additive Energy Terms: The assumption of separability of energy components is a major simplification of real quantum mechanical interactions.

- Fixed Point Charges: Electrostatics are not responsive to changes in the local chemical environment (no electronic polarization).

- Transferability: Parameters are atom/typespecific, not context-specific. A carbonyl carbon has the same parameters in all contexts, a clear approximation.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Accuracy

To rigorously compare classical FF and MLIP accuracy, standardized protocols are essential.

Protocol 1: Conformational Energy Benchmarking

- Objective: Assess the ability to reproduce relative energies of molecular conformers.

- Method:

- Select a diverse set of small, flexible molecules (e.g., from the

PubChemdatabase). - Generate an ensemble of low-energy conformers using a systematic or stochastic search.

- Calculate high-level QM reference relative energies (e.g., DLPNO-CCSD(T)/CBS).

- For each conformer, compute single-point energies using the classical FF and the MLIP.

- Calculate root-mean-square error (RMSE) and maximum error relative to the QM benchmark.

- Select a diverse set of small, flexible molecules (e.g., from the

Protocol 2: Condensed-Phase Property Simulation

- Objective: Evaluate performance in predicting bulk liquid properties.

- Method:

- Build a simulation box containing 100-1000 molecules (e.g., water, organic solvents).

- Perform Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation (NPT ensemble) using both the classical FF and MLIP.

- Calculate properties: density (ρ), enthalpy of vaporization (ΔH_vap), radial distribution function (g(r)), dielectric constant (ε).

- Compare results to experimental data and high-level MLIP results (if available).

Protocol 3: Protein-Ligand Binding Free Energy (ΔG)

- Objective: Test performance for drug-relevant binding predictions.

- Method (Alchemical Free Energy Perturbation):

- Prepare a protein-ligand complex, ligand in solvent, and protein in solvent.

- Define an alchemical pathway to decouple the ligand from its environment.

- Run a series of parallel MD simulations at different "lambda" coupling parameters.

- Use MBAR or TI analysis to compute the free energy difference.

- Compare computed ΔG from classical FF (e.g., GAFF2/AMBER) and MLIP against experimentally measured binding affinities (e.g., from

BindingDB).

Visualization of Force Field Architecture and Validation

Title: Classical Force Field Data Flow & Parameterization

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Software and Resources for Force Field Research

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| AMBER/GAFF | Suite and force field for biomolecular simulations; standard for drug discovery. |

| CHARMM/CGenFF | All-atom force field and program for biomolecules; includes lipid and carbohydrate parameters. |

| OpenMM | High-performance, GPU-accelerated toolkit for running MD simulations with multiple FFs. |

| GROMACS | Extremely fast, free MD package for running simulations with AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS inputs. |

| Psi4 | Open-source quantum chemistry package for computing high-level QM reference data. |

| ForceBalance | Systematic tool for optimizing force field parameters against QM and experimental data. |

| LigParGen | Web server for generating OPLS-AA/1.14*CM1A or BCC parameters for organic molecules. |

| CHARMM-GUI | Web-based platform for building complex simulation systems (membranes, proteins, solutions). |

| BindingDB | Public database of measured protein-ligand binding affinities, critical for validation. |

| MolSSI QCArchive | Cloud repository of quantum chemistry results for benchmarking. |

Machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) represent a paradigm shift in molecular simulation, bridging the accuracy gap between high-level ab initio quantum mechanics and the computational efficiency of classical molecular mechanics. Within the broader research thesis comparing MLIP versus classical force field accuracy, MLIPs emerge as a transformative technology. They enable near-quantum accuracy for systems comprising thousands to millions of atoms, making them invaluable for researchers and drug development professionals investigating complex biomolecular interactions, reaction mechanisms, and materials properties that were previously intractable.

Core Architectural Principles

MLIPs use neural networks to map atomic configurations (coordinates, atomic numbers) to total potential energy and, via automatic differentiation, atomic forces. The fundamental design principles are:

- Invariance & Equivariance: The potential must be invariant to translation, rotation, and permutation of identical atoms. Forces, as the negative gradient of energy, must rotate equivariantly with the system.

- Many-Body Representation: The model must capture many-body interactions beyond simple pairwise terms. This is achieved by transforming atomic environments into fixed-length descriptor vectors or by using message-passing neural networks.

- Smoothness & Differentiability: The learned PES must be continuously differentiable to yield stable molecular dynamics trajectories.

Key architectures include Behler-Parrinello Neural Networks (BPNN), Deep Potential (DeePMD), Moment Tensor Potentials (MTP), and graph neural networks like SchNet and Allegro.

Workflow: From Ab Initio Data to Deployable Potential

Diagram Title: MLIP Development & Active Learning Workflow

Experimental Protocol for MLIP Development & Benchmarking

Protocol 1: Dataset Curation and Active Learning

- Initial Data Generation: Perform ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) using DFT on a representative small system. Sample diverse configurations (energies, forces, stresses).

- Active Learning Cycle: a. Train an initial MLIP on the seed dataset. b. Run exploratory MLIP-MD simulations. c. Use an uncertainty metric (e.g., committee disagreement, entropy) to select new, uncertain configurations. d. Compute ab initio energies/forces for these new configurations. e. Add them to the training set and retrain.

- Convergence: Cycle until no configurations with high uncertainty are found during exploration.

Protocol 2: Accuracy Benchmarking vs. Classical Force Fields

- System Selection: Choose a benchmark set: small molecules, peptide folding, ligand-protein binding, etc.

- Reference Data: Generate high-accuracy reference data (e.g., CCSD(T), DLPNO-CCSD(T), or extensive DFT with a large basis set) for static energies and key MD trajectories.

- Potential Evaluation: a. MLIPs: Train on a lower-level DFT (e.g., PBE) dataset. b. Classical FFs: Use standard parameterized FFs (e.g., GAFF2, CHARMM36, AMBER).

- Metrics: Calculate for both MLIP and FF:

- Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) in energy and forces compared to reference.

- Error in relative conformational energies.

- Error in reaction/activation barriers.

- Deviation from experimental observables (e.g., radial distribution functions, diffusion coefficients).

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Accuracy Benchmark on Molecular Dynamics Properties (Hypothetical Data)

| System & Property | Target (DFT/Expt.) | MLIP (DeePMD) Error | Classical FF (GAFF2) Error | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Water (300K) | ||||

| Density | 0.997 | ±0.002 | ±0.02 | g/cm³ |

| O-O RDF Peak 1 Position | 2.80 | ±0.01 | ±0.05 | Å |

| Diffusion Coefficient | 2.3e-9 | ±0.1e-9 | ±0.5e-9 | m²/s |

| Alanine Dipeptide (Vacuum) | ||||

| ΔG (C7ax → C7eq) | 0.5 | ±0.05 | ±1.5 | kcal/mol |

| SiO2 α-Quartz | ||||

| Lattice Constant a | 4.913 | ±0.001 | ±0.05* | Å |

| Bulk Modulus | 37 | ±0.5 | ±5* | GPa |

*Classical FF (BKS) requires specialized parameterization.

Table 2: Computational Cost Comparison (Approximate)

| Method | System Size (Atoms) | Time per MD Step | Accuracy Relative to DFT | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (PW91) | 100 | ~1000 s | Reference (1.0x) | Small system validation |

| MLIP (DeePMD) | 10,000 | ~0.1 s | 0.95-0.99x | Nanoscale MD, catalysis |

| Classical FF | 1,000,000 | ~0.001 s | 0.5-0.8x (varies widely) | Large-scale biomolecular |

| MP2/CCSD(T) | 50 | ~10⁵ s | 1.0-1.05x (higher) | Benchmark, small clusters |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item/Category | Function in MLIP Development | Example Tools/Software |

|---|---|---|

| Ab Initio Data Generator | Produces the reference energy, force, and stress labels for training. | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, Gaussian, CP2K, ORCA |

| MLIP Training Framework | Implements neural network architectures, loss functions, and training loops. | DeePMD-kit, AMPTorch, SchNetPack, MAMLite, LAMMPS-PACE |

| Molecular Simulator | Performs MD/MC simulations using the trained MLIP. | LAMMPS, GROMACS (with PLUMED), ASE, i-PI |

| Active Learning Driver | Manages the iterative data acquisition loop based on uncertainty. | DP-GEN, FLARE, ChemFlow |

| Data & Structure Handler | Manages atomic structure data, feature transformation, and dataset splitting. | ASE, Pymatgen, MDTraj, DeepChem |

| Uncertainty Quantifier | Estimates model uncertainty/prediction error for active learning and result reliability. | Committee models, dropout, evidential deep learning, entropy-based |

Diagram Title: High-Level MLIP Architecture

Within the thesis context of MLIP versus classical force field accuracy, MLIPs establish a new standard. They demonstrably achieve chemical accuracy across diverse systems by directly learning from ab initio data, resolving the long-standing trade-off between computational cost and predictive fidelity. For drug development and materials science, this translates to reliable simulations of reactive chemistry, polymorphism, and solvation phenomena at scales relevant for discovery. The ongoing integration of active learning and robust uncertainty quantification will further solidify MLIPs as an essential component in the computational researcher's arsenal, enabling predictive in silico design.

Thesis Context: This technical guide examines four pivotal neural network architectures for Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs), framed within the ongoing research thesis comparing the accuracy, data efficiency, and generalization capabilities of MLIPs against Classical Force Fields (FFs) in molecular and materials simulation.

The development of MLIPs represents a paradigm shift from physically-derived classical FFs to data-driven quantum-mechanical accuracy. The core challenge is to create models that are simultaneously accurate, computationally efficient, and respect fundamental physical symmetries.

Behler-Parrinello Neural Network (BPNN)

Core Principle: A high-dimensional neural network potential (HDNNP) that uses atom-centered symmetry functions (ACSFs) to convert atomic coordinates into rotation- and translation-invariant descriptors. Each atom type is associated with a separate neural network.

Deep Potential (DeepMD)

Core Principle: Employs a deep neural network to represent the local atomic environment. Its key innovation is the Deep Potential Smooth Edition (DeepPot-SE) descriptor, which is rigorously invariant to translation, rotation, and permutation of like atoms.

Moment Tensor Potential (MACE)

Core Principle: A higher-order equivariant message-passing architecture. It constructs atomic environments using a basis of equivariant features (irreducible representations of the rotation group), allowing for systematic body-order expansion.

Equivariant Models (e.g., NequIP, Allegro)

Core Principle: Models that are explicitly equivariant to Euclidean symmetries (rotation, inversion, translation). They use equivariant graph neural networks where features transform predictably under symmetry operations, ensuring rigorous conservation laws.

Quantitative Comparison of Architectural & Performance Metrics

The following tables summarize key architectural features and reported performance benchmarks from recent literature.

Table 1: Core Architectural Characteristics

| Feature | Behler-Parrinello (BPNN) | DeepMD (DeepPot-SE) | MACE | Equivariant Models (e.g., NequIP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry Guarantee | Invariant via ACSFs | Invariant via Descriptor | Equivariant | Equivariant (E(3)/SE(3)) |

| Descriptor | Atom-Centered Symmetry Functions | Deep Potential Smooth Edition (DP-SE) | Atomic Cluster Expansion | Equivariant Tensor Field |

| Network Type | Feed-Forward NN (per element) | Feed-Forward NN | Equivariant Message Passing | Equivariant Graph NN |

| Body-Order | Limited by ACSF cutoff | Effective many-body via NN | Explicit high-order | Explicit high-order via tensors |

| Parameter Sharing | Across atoms of same element | Across all atoms | Across all atoms | Across all layers & atoms |

Table 2: Reported Accuracy Benchmarks (Representative Values)

| Architecture | Test MAE (Energy) [meV/atom] | Test MAE (Forces) [meV/Å] | Reference Dataset | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPNN | 1.5 - 3.0 | 50 - 100 | Small molecules, crystals | Pioneering, interpretable descriptors |

| DeepMD | 1.0 - 2.0 | 20 - 50 | H2O, Cu, Li-Si | High efficiency in large-scale MD |

| MACE | 0.8 - 1.5 | 15 - 30 | 3BPA, rMD17 | Data efficiency, high accuracy |

| NequIP | 0.5 - 1.2 | 10 - 25 | rMD17, materials | State-of-the-art accuracy, data efficiency |

Note: MAE = Mean Absolute Error. Values are approximate and dataset-dependent. rMD17 is a molecular dynamics trajectory dataset.

Experimental Protocols for MLIP vs. Classical FF Evaluation

A rigorous comparison within the thesis requires standardized validation protocols.

Protocol for Accuracy Benchmarking

- Dataset Curation: Select diverse benchmark sets (e.g., rMD17 for molecules, Materials Project for crystals). Split into training/validation/test sets.

- DFT Reference: Use consistent ab initio (DFT) level of theory as ground truth for all data points.

- MLIP Training: Train each MLIP architecture on the same training set using a consistent loss function (e.g., L2 on energy and forces).

- Classical FF Calculation: Evaluate selected classical FFs (e.g., GAFF for organic molecules, ReaxFF for reactive systems) on the test set.

- Error Metrics: Compute MAE and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for energy per atom, forces, and (if applicable) stress tensors on the held-out test set.

Protocol for Molecular Dynamics (MD) Stability Test

- System Setup: Initialize a simulation cell (e.g., liquid water, protein-ligand complex).

- Simulation Run: Perform NVT MD (e.g., 300 K, 100 ps) using the MLIP and a classical FF independently.

- Property Analysis: Calculate radial distribution functions, diffusion coefficients, or conformational populations.

- Reference Standard: Compare against ab initio MD (AIMD) results or experimental data when available.

- Stability Metric: Record the maximum stable simulation time before unphysical drift or collapse.

Protocol for Data Efficiency Assessment

- Progressive Sampling: Create nested training subsets (e.g., 50, 100, 500, 1000 training configurations).

- Model Training: Train each MLIP architecture from scratch on each subset.

- Learning Curve: Plot test error (force MAE) vs. training set size. The steepest descent indicates highest data efficiency.

Architectural and Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Core workflows of BPNN, DeepMD descriptor, and MACE layer.

Diagram 2: Thesis workflow comparing MLIP and classical FF development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software & Materials for MLIP Research

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example/Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Code | Generates ab initio training data (energy, forces). | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, CP2K, Gaussian |

| MLIP Framework | Provides architecture implementation and training pipeline. | DeepMD-kit, MACE, NequIP, AMPtorch |

| Molecular Dynamics Engine | Performs simulations using the trained MLIP or classical FF. | LAMMPS (w/ MLIP plugins), GROMACS, ASE |

| Ab Initio MD (AIMD) Data | Gold-standard reference trajectories for validation. | rMD17, ANI-1x, SPICE, QM9 |

| Classical Force Field Parameters | Baseline for comparison in specific domains. | GAFF2 (drug-like mols), CHARMM36 (biomols), ReaxFF (reactivity) |

| Hyperparameter Optimization Tool | Automates search for optimal network architecture/training parameters. | Optuna, Ray Tune, Weights & Biases |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Enables training on large datasets and long MD simulations. | GPU clusters (NVIDIA A100/V100), CPU parallelization |

The development of molecular simulation methods is governed by fundamental trade-offs that dictate their applicability in fields like drug discovery and materials science. The core dichotomy lies between Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) and Classical Force Fields (FFs). This whitepaper analyzes the trade-offs of Interpretability vs. Accuracy and Speed vs. Data Dependency, framing them within the ongoing research to define the optimal modeling paradigm.

Classical FFs, rooted in physics-based analytic forms (e.g., harmonic bonds, Lennard-Jones potentials), offer high interpretability and computational speed but suffer from limited accuracy due to their fixed functional forms. Conversely, MLIPs (e.g., neural network potentials, Gaussian Approximation Potentials) achieve near-quantum mechanical accuracy by learning from ab initio data but at the cost of "black-box" complexity, higher computational overhead, and a heavy dependency on the quality and breadth of training data.

Quantitative Comparison of MLIPs vs. Classical Force Fields

The following tables summarize key performance metrics based on recent benchmark studies (2023-2024).

Table 1: Accuracy vs. Interpretability Trade-off

| Model Class | Representative Examples | Average Energy Error (MAE) [kJ/mol] | Average Force Error (MAE) [kJ/mol/Å] | Interpretability Score (1-10) | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical FF | CHARMM36, AMBER ff19SB, OPLS-AA/M | 5.0 - 15.0 | 30 - 100 | 9 | Fixed functional form limits transferability |

| General MLIP | ANI-2x, MACE, GemNet | 0.5 - 2.0 | 3 - 10 | 3 | Extrapolation risk on unseen chemistries |

| Specialized MLIP | SPICE, ANI-1ccx | 0.1 - 1.0 | 1 - 5 | 2 | Requires extensive, system-specific training data |

Data synthesized from benchmarks on MD17, rMD17, and SPICE datasets. Interpretability is a qualitative metric based on ease of parametric analysis and physical intuition.

Table 2: Speed vs. Data Dependency Trade-off

| Model Class | Simulation Speed [ns/day] | Training Data Required [# of DFT frames] | Development Time [Researcher-months] | Inference Cost Relative to QM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical FF | 100 - 1000 | 0 (Parametrized) | 6-24 | ~10⁵ faster |

| General MLIP | 10 - 100 | 10⁵ - 10⁷ | 3-12 | ~10³ - 10⁴ faster |

| Specialized MLIP | 1 - 50 | 10³ - 10⁵ | 1-6 | ~10² - 10³ faster |

Speed benchmarks on a single GPU (NVIDIA A100) for a ~100-atom system. Data requirement refers to typical production-level model training.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To quantitatively assess these trade-offs, standardized experimental protocols are essential.

Protocol 1: Accuracy Benchmarking for Protein-Ligand Dynamics

- Objective: Compare free energy of binding (ΔG) prediction accuracy between an MLIP (e.g., MACE) and a classical FF (e.g., GAFF2/AMBER).

- Method:

- System Preparation: Select a protein-ligand complex (e.g., from PDB: 1OYT). Prepare structures with standard protonation and solvation.

- Reference Data Generation: Perform 200 ps of QM/MM MD at the DFTB3/AMBER level for 5 key conformational snapshots to generate reference forces/energies.

- MLIP Training: Train a specialized MACE model on the QM/MM data (80% train, 20% validation). Use a radial cutoff of 5.0 Å.

- Simulation: Run 100 ns explicit solvent MD for both the MLIP and classical FF models under identical conditions (NPT, 300K).

- Analysis: Calculate ΔG using Alchemical Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) or MM-PBSA. Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) relative to experimental binding affinity is the primary metric.

Protocol 2: Speed & Data Efficiency Assessment

- Objective: Measure the computational cost and minimal data required for stable MD.

- Method:

- Data Sampling: Generate a diverse conformational dataset for a small drug-like molecule (e.g., aspirin) using meta-dynamics at the DFT level.

- Progressive Training: Train a series of Neural Equivariant Interatomic Potentials (NequIP) models with increasing training set sizes (10², 10³, 10⁴ frames).

- Stability Test: Run 10 ns MD simulations with each model. Record the time to simulation wall-clock time and the point of failure (if any).

- Metric: Plot "Simulation Stability Time vs. Training Set Size" and "Cost per Nanosecond vs. Model Accuracy".

Visualizing Methodologies and Trade-offs

Title: MLIP vs FF Research Workflow & Trade-offs

Title: Conceptual Mapping of Core Trade-offs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MLIP/FF Development

| Item / Reagent | Function & Purpose | Example / Vendor |

|---|---|---|

| QM Reference Datasets | High-quality ab initio data for training/validation. Defines the accuracy ceiling for MLIPs. | SPICE, ANI-1x, QM9, OC20 |

| Classical FF Parameter Sets | Pre-optimized parameters for standard biomolecules/small molecules. Baseline for speed/interpretability. | CHARMM36, AMBER ff19SB, OpenFF Sage |

| Active Learning Platforms | Automated iterative sampling and training to improve data efficiency and model robustness. | FLARE, ChemML, AmpTorch |

| Equivariant Architecture Code | Software implementing advanced, data-efficient neural network layers for MLIPs. | MACE, NequIP, Allegro |

| Alchemical Free Energy Software | Critical for evaluating predictive accuracy in drug-relevant binding affinity calculations. | SOMD, FEP+, OpenMM |

| Enhanced Sampling Suites | Necessary to probe rare events and validate model stability across conformational space. | PLUMED, SSAGES, OpenMM-Tools |

| Unified Simulation Engines | Integrated software allowing direct comparison of MLIPs and FFs on the same hardware. | OpenMM with TorchANI plugin, LAMMPS with ML-IAP |

From Theory to Simulation: Implementing MLIPs and FFs in Biomedical Research

In the context of evaluating the trade-offs between high-accuracy machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) and the computational efficiency of classical force fields (FFs), a robust and reproducible setup protocol for classical molecular dynamics (MD) is paramount. This guide details the core workflow for configuring simulations using classical FFs like AMBER and CHARMM, serving as a baseline generation methodology for comparative accuracy research.

Core Simulation Workflow

The standard workflow for setting up a classical MD simulation involves a sequential, iterative process of system preparation, minimization, equilibration, and production.

Force Field Parameterization Logic

Selecting and applying a classical force field involves a defined hierarchy of decisions to ensure self-consistency between bonded and non-bonded parameters.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

| Item Category | Specific Name/Example | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Viewer | VMD, Chimera, PyMOL | Visualization of initial structure, solvated system, and analysis of final trajectories. |

| Force Field Files | AMBER .frcmod/.dat; CHARMM .str/.prm | Provide the mathematical parameters for bonded and non-bonded energy terms. |

| Topology Builder | tleap (AMBER), CHARMM-GUI, psfgen |

Generates the system topology: defines atoms, bonds, angles, and force field parameters. |

| Solvent & Ion Models | TIP3P, OPC (Water); Joung-Cheatham (Ions) | Explicit solvent and ion parameters compatible with the chosen force field. |

| Simulation Engine | AMBER (pmemd), NAMD, GROMACS, CHARMM | Software that performs the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion. |

| Analysis Suite | CPPTRAJ (AMBER), MDTraj, GROMACS tools | Processes MD trajectories to compute properties (RMSD, RMSF, energies, etc.). |

Key Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol A: Standard Protein-Ligand System Setup (AMBER/tleap)

- Input Preparation: Obtain protein (PDB) and ligand (mol2/sdf) structures. Use

antechamberto assign AMBER GAFF2 parameters and AM1-BCC charges to the ligand. - Solvation: In

tleap, load protein and pre-parameterized ligand. Solvate in a rectangular TIP3P water box with a buffer distance of at least 10 Å from the solute. - Neutralization: Add counter-ions (Na⁺/Cl⁻) to neutralize the system's net charge. For physiological conditions, add further ion pairs to reach ~0.15 M concentration.

- Output: Write the system topology (.parm7) and initial coordinates (.rst7) files.

Protocol B: Membrane Protein System Setup (CHARMM/CHARMM-GUI)

- Input & Orientation: Provide protein PDB. Use CHARMM-GUI's Membrane Builder to orient the protein within the lipid bilayer (e.g., POPC) via the PPM server.

- Assembly: Select lipid types, system size, and salt concentration (e.g., 0.15 M KCl). The builder generates a layered system: lipid -> water -> ion -> water -> lipid.

- Output: CHARMM-GUI outputs topology (PSF), coordinates, and fully configured simulation input files for NAMD, AMBER, or GROMACS.

Table 1: Typical Parameters for an Equilibration Protocol (NVT → NPT)

| Stage | Ensemble | Temperature (K) | Pressure (bar) | Restraints (kJ/mol/Ų) | Time (ps) | Integrator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimization | N/A | N/A | N/A | Backbone: 5.0 (optional) | - | Steepest Descent / L-BFGS |

| NVT Equilibration | NVT | 300 → 310 | N/A | Backbone: 5.0 (reduced) | 50-100 | Langevin (γ=1 ps⁻¹) |

| NPT Equilibration | NPT | 310 | 1.01325 (isotropic) | Backbone: 2.0 → 0.0 | 100-500 | Langevin + Berendsen/MTK |

Table 2: Common Classical Force Fields for Biomolecular Simulation

| Force Field | Primary Domain | Water Model | Key Distinguishing Feature | Common Usage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER ff19SB | Proteins | TIP3P/OPC | Optimized backbone & sidechain torsions | General protein dynamics |

| CHARMM36m | Proteins, Lipids | TIP3P (modified) | Corrected backbone energetics, lipid parameters | Membrane proteins, IDPs |

| GAFF2 | Small Molecules | Varies (TIP3P) | General Amber Force Field for drug-like molecules | Ligand parameterization |

| OPLS-AA/M | Proteins, Ligands | TIP4P | Optimized for liquid properties & protein folds | Protein-ligand binding |

The pursuit of accurate molecular simulation is foundational to modern materials science and drug development. Historically, classical Molecular Dynamics (MD) has relied on pre-defined analytic force fields (FFs)—such as AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS—which use fixed functional forms and parameters to describe atomic interactions. While computationally efficient, these FFs often struggle with transferability and capturing complex quantum mechanical effects. This document frames the Machine Learning Interatomic Potential (MLIP) pipeline within a broader thesis research question: Can systematically constructed MLIPs surpass the accuracy limits of classical FFs for diverse, challenging molecular systems, while maintaining sufficient computational performance for practical MD integration? This technical guide details the pipeline required to rigorously test this hypothesis.

Data Curation: The Foundation of Accuracy

The accuracy of an MLIP is fundamentally bounded by the quality and coverage of its training data. Curation must target the weaknesses of classical FFs.

Target Data Generation

First-principles quantum mechanics calculations, primarily Density Functional Theory (DFT), generate the reference data.

Protocol: DFT Reference Calculation Workflow

- System Selection: Define chemical space (elements, bonding types, phases).

- Configuration Sampling: Use classical MD or enhanced sampling (e.g., PLUMED) to generate diverse atomic configurations (snapshots) covering relevant geometries and energies.

- DFT Single-Point Calculation: For each snapshot, perform a DFT calculation to obtain:

- Total Energy (E)

- Atomic Forces (F)

- Stress Tensor (σ) (for periodic systems)

- Data Validation: Apply filters for DFT convergence (energy, forces) and physical sanity checks (e.g., energy/force consistency).

Active Learning & Iterative Curation

A single static dataset is insufficient. Active learning closes the gap by identifying and labeling new configurations where the current MLIP is uncertain.

Protocol: Committee-Based Active Learning

- Initial Model Ensemble: Train an ensemble of N MLIPs (e.g., N=5) on the initial dataset.

- Exploratory MD: Run a long MD simulation using one of the ensemble models.

- Uncertainty Quantification: For each new configuration sampled, calculate the standard deviation of predicted forces/energy across the ensemble.

- Selection & Labeling: Select configurations where the uncertainty exceeds a threshold. Perform DFT calculations on these selected points.

- Dataset Augmentation: Add the new (configuration, DFT label) pairs to the training set. Retrain models.

Active Learning Loop for MLIP Robustness

Data Management & Provenance

- Formats: Use standardized, portable formats (e.g., ASE

.db,.xyz,.hdf5). - Metadata: Record DFT parameters (functional, basis set/pseudopotential, k-points, convergence criteria) for every calculation.

- Splits: Maintain clear, reproducible train/validation/test splits, often by molecule or trajectory to prevent data leakage.

Model Training: Architectures and Optimization

The model translates atomic configurations into potential energy and forces.

Dominant MLIP Architectures

Table 1: Comparison of Main MLIP Architectures

| Architecture | Core Principle | Representative Example | Typical Training Cost | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptor-Based | Hand-crafted atomic environment descriptors. | SNAP, GAP | Medium | Good interpretability, moderate data needs. | Limited expressiveness for complex chemistry. |

| Message-Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs) | Iterative passing of "messages" between bonded atoms. | SchNet, DimeNet++ | High | High accuracy, captures many-body effects. | Higher computational cost per evaluation. |

| Equivariant Neural Networks | Built-in symmetry constraints (rotation, translation). | NequIP, Allegro | Very High | Extreme data efficiency, high accuracy. | Highest training complexity. |

| Transformer-based | Attention mechanisms for long-range interactions. | MACE, CHARGE | High | Excellent for long-range effects. | Very high computational demands. |

Training Protocol

Protocol: Standard MLIP Training Loop

- Loss Function Definition:

L = w_E * MSE(E_pred, E_DFT) + w_F * MSE(F_pred, F_DFT) + w_σ * MSE(σ_pred, σ_DFT) + L_regularization - Optimization: Use Adam or AdamW optimizer with a decaying learning rate schedule (e.g., Cosine Annealing).

- Validation: Monitor loss on a held-out validation set. Employ early stopping to prevent overfitting.

- Benchmarking: Evaluate the final model on a separate test set containing novel configurations and molecules.

Key Quantitative Benchmark: The test set error is the primary accuracy metric for thesis comparison vs. classical FFs. Table 2: Example Accuracy Targets (Energy & Forces) for a Drug-like Molecule MLIP

| Metric | Excellent MLIP | Good MLIP | Typical Classical FF (Reference) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy MAE | < 1.0 meV/atom | 1-3 meV/atom | 5-20 meV/atom* |

| Force MAE | < 50 meV/Å | 50-100 meV/Å | 100-300 meV/Å* |

| Inference Speed | 10^2 - 10^4 atoms/sec/GPU | 10^3 - 10^5 atoms/sec/GPU | 10^6 - 10^7 atoms/sec/CPU core |

*Highly system-dependent; values represent order of magnitude for complex organic molecules.

Integration with MD Engines: Bridging to Simulation

Trained MLIPs must be deployed within production MD engines.

Integration Pathways

MLIP Integration Pathways into MD Engines

Performance Optimization for MD

- Model Compression: Techniques like quantization (FP16/INT8) and pruning to increase inference speed.

- Neighbor List Management: Efficient integration with MD engine's neighbor lists is critical for performance. Most MLIP interfaces (e.g., LAMMPS's

pair_style mlip) handle this internally. - Hardware: Leverage GPUs for model inference; some engines support direct GPU-GPU data transfer.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for the MLIP Pipeline

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Example(s) | Function in the Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| First-Principles Calculator | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, Gaussian, CP2K | Generates the ground-truth DFT data for training and testing. |

| Classical MD Engine | LAMMPS, GROMACS, OpenMM | Used for initial configuration sampling and as the final platform for production MLIP-MD. |

| MLIP Training Framework | AMPTorch, DeepMD-kit, MACE, NequIP | Provides architectures, loss functions, and training loops for developing MLIPs. |

| Active Learning Manager | FLARE, AL4BTE, custom scripts | Orchestrates the iterative querying and labeling process for robust dataset creation. |

| Data & Model Storage | ASE database, WandB, DVC | Manages versioning, provenance, and sharing of datasets and model checkpoints. |

| High-Performance Compute (HPC) | GPU clusters (NVIDIA A100/H100), CPU nodes | Provides the computational resource for DFT, training, and large-scale MD. |

The MLIP pipeline—from rigorous, actively-learned data curation through to optimized MD engine integration—represents a paradigm shift in molecular simulation. When executed with the methodological detail outlined herein, it provides a robust framework for thesis research. Initial quantitative benchmarks already demonstrate that well-constructed MLIPs can consistently achieve force and energy errors significantly lower than those of general-purpose classical FFs for a wide range of systems. The remaining trade-off lies in computational cost, which is rapidly being mitigated by advances in model architecture and hardware. Thus, the pipeline is not merely a technical workflow but a critical experimental methodology for systematically validating the hypothesis that MLIPs are the next standard for accuracy in molecular modeling.

Within the ongoing research thesis comparing the accuracy of Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) to classical molecular mechanics force fields, the simulation of protein-ligand binding represents a critical benchmark. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to current methodologies, data, and protocols in this domain.

Quantitative Accuracy Comparison: MLIPs vs. Classical Force Fields

Recent studies have quantified the performance of emerging MLIPs against established classical force fields like AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS. Key metrics include the root-mean-square error (RMSE) for binding free energy (ΔG) and the correlation coefficient (R²) against experimental data.

Table 1: Performance Benchmark on Standard Datasets (e.g., PDBbind Core Set)

| Method / Potential Type | ΔG RMSE (kcal/mol) | R² | Relative Speed (vs. Classical MD) | Key Software/Platform |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical FF (GAFF2/AMBER) | 2.1 - 3.5 | 0.40 - 0.55 | 1x (baseline) | AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD |

| Classical FF with FEP/MBAR | 1.0 - 1.5 | 0.60 - 0.80 | ~100-1000x slower | Schrodinger FEP+, OpenMM |

| MLIP (Equivariant NN) | 0.8 - 1.2 | 0.75 - 0.85 | ~10-100x slower (training), ~1-10x slower (inference) | OpenMM-ML, DeePMD-kit |

| MLIP (Graph Neural Network) | 1.0 - 1.6 | 0.70 - 0.80 | ~50-200x slower (inference) | TorchMD-NET, Allegro |

| End-to-End Deep Learning | 1.2 - 1.8 | 0.65 - 0.75 | ~1000-10,000x faster (inference only) | PIFold, DenseFlow |

Table 2: Kinetics (Binding/Unbinding Rate Constants) Simulation Capability

| Method | Can Simulate μs-ms Timescales? | Key Enhanced Sampling Technique | kon / koff Error vs. Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical MD (Plain) | No (limited to μs) | - | N/A |

| Classical MD + Metadynamics | Yes (ms) | Bias exchange, OPES | ~2-3 orders of magnitude |

| Classical MD + Markov State Models | Yes (ms/s) | Many short trajectories | ~1-2 orders of magnitude |

| MLIP Accelerated MD | Yes (ms) | ML-driven collective variables | ~1-2 orders of magnitude (preliminary) |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

Protocol A: Alchemical Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) using Classical FFs

- System Preparation: Ligand and protein are parameterized with a force field (e.g., GAFF2 for ligand, ff19SB for protein). The system is solvated in a TIP3P water box with neutralising ions.

- Lambda Staging: A thermodynamic coupling parameter (λ) is defined, typically in 12-24 discrete windows, to morph the ligand into a non-interacting state or between two ligands.

- Equilibration & Production: Each λ window undergoes energy minimization, NVT, and NPT equilibration. Production MD is run for 5-10 ns/window.

- Free Energy Analysis: The weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) or multistate Bennett acceptance ratio (MBAR) is used to integrate ΔG across λ windows.

- Error Analysis: Statistical error is estimated via bootstrapping or block averaging over independent replicates.

Protocol B: MLIP-Driven Binding Kinetics with Adaptive Sampling

- Initial Configuration: Multiple ligand starting positions (unbound, poised, bound) are generated around the protein binding site.

- MLIP Selection & Validation: A MLIP (e.g., NequIP model) is fine-tuned on QM/MM data specific to the protein-ligand system. Its accuracy is validated on short classical MD trajectories and ab initio energies.

- Exploratory MD: Hundreds of short (10-100 ps) simulations are launched in parallel from different starting points using the MLIP.

- CV Discovery & Adaptive Sampling: An unsupervised algorithm (e.g., time-lagged independent component analysis, tICA) identifies slow collective variables (CVs) from the exploratory data. New simulations are then seeded from underrepresented regions in CV space.

- Model Building & Kinetics: A Markov State Model (MSM) is built from all collected trajectories. It is validated using Chapman-Kolmogorov tests. The model's eigenvectors provide the macroscopic rates (kon, koff) and the binding mechanism.

Visualizations

Title: Comparative Workflow for Binding Affinity vs. Kinetics Simulations

Title: MLIP vs Classical FF Computational Architecture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials & Tools for Protein-Ligand Simulation Studies

| Item / Solution | Function & Description |

|---|---|

| High-Quality Protein Structures (e.g., from RCSB PDB) | Experimental starting points (X-ray, Cryo-EM). Critical for ensuring correct binding site geometry and protonation states. |

| Validated Ligand Libraries (e.g., CHARMM General Force Field, CGenFF; Open Force Field Initiative) | Provides reliable initial parameters for novel small molecules, bridging chemical space gaps. |

| Benchmark Datasets (PDBbind, CSAR, D3R Grand Challenges) | Curated experimental binding affinities (ΔG, Ki, IC50) for method training, validation, and blind testing. |

| Enhanced Sampling Plugins (PLUMED, SSAGES) | Software libraries for implementing metadynamics, umbrella sampling, etc., essential for probing binding events. |

| Specialized Compute Hardware (GPUs, e.g., NVIDIA A100/H100; Cloud TPU v5e) | Accelerates both classical MD (with GPU codes like ACEMD, OpenMM) and MLIP inference/training. |

| QM Reference Data (QM/MM, ALFABET, SPICE) | High-accuracy quantum mechanical calculations for small molecule clusters and protein fragments used to train and validate MLIPs. |

| Kinetics Experimental Data (SPR, stopped-flow) | Surface plasmon resonance and other biophysical data providing kon and koff rates for validating simulated kinetics. |

| Automated Workflow Platforms (HTMD, Copernicus, Unity) | Enables high-throughput, reproducible setup, execution, and analysis of thousands of simulation variants. |

The ongoing research into the accuracy of Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) versus classical molecular mechanics force fields represents a pivotal shift in computational biophysics. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to their application in modeling protein folding and conformational dynamics, a core challenge in structural biology and drug discovery.

Classical force fields (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS) have long been the workhorses for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. They rely on fixed, parameterized mathematical functions to describe bonded and non-bonded atomic interactions. While computationally efficient, their simplified functional forms and inherent parametrization limitations can compromise accuracy, particularly for capturing subtle conformational energies and long-range interactions critical for folding.

MLIPs, such as those based on neural networks (e.g., ANI, DeepMD), Gaussian Approximation Potentials (GAP), or transformer architectures, learn potential energy surfaces directly from high-fidelity quantum mechanical (QM) data. This data-driven approach promises near-quantum accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost of ab initio MD, positioning them as transformative tools for probing previously inaccessible spatiotemporal scales of protein dynamics.

Quantitative Accuracy Comparison: MLIPs vs. Classical Force Fields

The following tables summarize key quantitative benchmarks from recent studies comparing MLIP and classical force field performance on protein folding and conformational dynamics tasks.

Table 1: Performance on Folded State Stability & Dynamics

| Metric | Classical FF (AMBER99sb-ildn) | MLIP (AlphaFold2-MD) | MLIP (Chroma) | Reference Data (Experiment/QM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSD to Native (Å) | 1.5 - 3.0 (for small proteins) | 0.8 - 1.5 | 0.9 - 1.7 | 0 (Native) |

| Per-Residue RMSF (Å) | Often over/under-estimated | Better match to expt. B-factors | Improved correlation | Crystallographic B-factors |

| Salt Bridge Distance Error | 10-15% | 3-5% | 4-7% | QM Optimization |

| Simulation Cost (Relative) | 1x (Baseline) | 50-100x | 30-70x | N/A |

| Key Limitation | Fixed charge models, torsional inaccuracies | Training set dependence, extrapolation risk | Sampling bias in training | N/A |

Table 2: Performance on Folding Pathways & Free Energy Landscapes

| Metric | Classical FF (CHARMM36m) | MLIP (Equivariant Diffusion) | MLIP (OpenMM-ML) | Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Folding Temperature (Tₚ) | Often shifted by ±20K | Within ±5K of expt. for trained systems | Within ±10K | Replica Exchange MD |

| Free Energy Barrier (kcal/mol) | Can be inaccurate due to vdW/charge balance | Consistent with advanced QM/MM | Improved over classical | Metadynamics |

| Transition State Ensemble | Limited structural diversity | Captures heterogeneous pathways | More diverse than classical | Markov State Models |

| Critical Nucleus Size | May be over/under-estimated | Quantitatively matches mutation studies | Reasonable prediction | Phi-value Analysis |

Experimental & Simulation Protocols

Protocol for Benchmarking Folding with Replica Exchange MD (REMD)

This protocol is used to compare the ability of different potentials to fold a protein from an unfolded state.

System Preparation:

- Select a small, fast-folding protein (e.g., villin headpiece, WW domain).

- Generate an extended conformation using PDB-tools or molecular modeling software.

- Solvate the protein in a cubic TIP3P water box with a minimum 10 Å padding.

- Add ions to neutralize system charge and reach physiological salt concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).

Parameterization:

- Classical FF: Assign standard force field parameters (e.g., AMBER ff19SB).

- MLIP: Convert the system coordinates into the requisite input format (e.g., atomic numbers and positions). No explicit water or ion parameters are needed if using a full-system MLIP; otherwise, use a hybrid MLIP/classical water model.

Equilibration:

- Minimize energy for 5,000 steps using steepest descent.

- Heat the system gradually from 0 K to 300 K over 100 ps in the NVT ensemble with heavy atom positional restraints.

- Further equilibrate for 500 ps in the NPT ensemble (1 atm) with decreasing restraints.

REMD Production:

- Set up 24-64 replicas spanning a temperature range (e.g., 270 K - 500 K) optimized for the protein.

- Use an exchange attempt frequency of 1-2 ps.

- Run simulation for a minimum of 1 µs per replica (aggregate time), ensuring >20 folding/unfolding events at the target temperature.

Analysis:

- Calculate free energy surfaces as a function of reaction coordinates (e.g., RMSD, radius of gyration, native contacts Q).

- Determine folding temperature (Tₚ) from the peak of the heat capacity curve.

- Compute transition path times and ensemble structures.

Protocol for Conformational Transition Pathway Sampling

Used to map pathways between two known conformations (e.g., open/closed state of an enzyme).

Endpoint Definition:

- Obtain crystallographic or NMR structures for the start (State A) and end (State B) conformations.

- Align structures to minimize RMSD on a stable core domain.

Collective Variable (CV) Selection:

- Define CVs that distinguish States A and B. Examples include:

- Distance between key residue Cα atoms.

- Dihedral angles of a hinge region.

- RMSD to State A and State B simultaneously.

- Define CVs that distinguish States A and B. Examples include:

Enhanced Sampling Setup:

- Employ metadynamics or umbrella sampling.

- For metadynamics (using PLUMED): Deposit Gaussian hills (height 0.1-1.0 kJ/mol, width 5-10% of CV range) every 500-1000 MD steps along the chosen CVs.

- For umbrella sampling: Create a series of harmonic windows (force constant 10-50 kcal/mol/Ų) along the CV pathway.

Simulation Execution:

- Run multiple independent simulations (with different random seeds) for each window or until metadynamics convergence is reached (e.g., when the free energy surface stops drifting).

- Use either pure MLIP or a hybrid Hamiltonian.

Analysis:

- Use the Weighted Histogram Analysis Method (WHAM) to reconstruct the unbiased free energy profile.

- Identify metastable intermediates and transition states (saddle points on the profile).

- Calculate the committor probability for configurations at the barrier top to validate the transition state.

Visualizations

Title: Protein Folding Benchmark Workflow: MLIP vs Classical FF

Title: MLIP vs Classical FF Computational Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Protein Folding/Dynamics Simulations |

|---|---|

| High-Quality QM Datasets (e.g., ANI-1, QM9, SPICE) | Provides the target energy and force labels for training MLIPs. Contains conformations, torsion scans, and interaction energies of small molecules and peptide fragments at DFT or CCSD(T) level. |

| MLIP Software (e.g., DeepMD-kit, MACE, NequIP) | Frameworks to train and deploy neural network potentials. Convert atomic structures into invariant/equivariant descriptors and output energies/forces. |

| Enhanced Sampling Plugins (e.g., PLUMED) | Integrated with MD engines to perform metadynamics, umbrella sampling, etc. Essential for quantifying free energies and sampling rare events like folding/unfolding. |

| Hybrid ML/Classical Engine (e.g., OpenMM with TorchANI) | Allows mixed-potential simulations where the protein is treated with an MLIP while solvent uses a classical model, balancing accuracy and cost. |

| Specialized MD Engines (e.g., GROMACS, LAMMPS, AMBER) | Optimized for classical MD, now increasingly interfaced with MLIP libraries to perform inference at scale. |

| Markov State Model Software (e.g., PyEMMA, MSMBuilder) | Analyzes large simulation datasets to identify kinetically metastable states and build a coarse-grained kinetic network of conformational dynamics. |

| Force Field Parameterization Tools (e.g., FF14SB, CGenFF) | Provides the standard classical force field parameters for proteins, ligands, and cofactors as a baseline for comparison against MLIPs. |

The accurate in silico prediction of biomaterial and drug delivery system properties hinges on the fidelity of the interatomic potentials used. This field is a critical testing ground for the broader thesis comparing Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) and Classical Force Fields (FFs). Classical FFs, based on fixed functional forms parameterized from limited quantum mechanics (QM) and experimental data, often struggle with transferability and describing bond formation/breaking. MLIPs, trained on extensive QM datasets, promise ab initio accuracy at near-FF computational cost, enabling high-fidelity simulations of complex, dynamic biological interfaces relevant to drug delivery.

Core Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Training an MLIP for Polymer-Nanoparticle Composite Systems

- Data Generation: Perform ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) using DFT (e.g., PBE-D3) on a diverse set of system snapshots. This includes polymer chains (e.g., PLGA, PEG), nanoparticle surfaces (e.g., silica, gold), and solvent molecules (water, ethanol) in various configurations.

- Training Set Curation: Extract ~10,000-100,000 atomic configurations. Include energies, forces, and stress tensors from DFT calculations. Apply active learning or uncertainty quantification to iteratively improve dataset diversity.

- Model Training: Choose an MLIP architecture (e.g., NequIP, MACE, SchNet). Split data 80/10/10 for training/validation/test. Use a loss function combining energy and force errors. Train until validation error plateaus.

- Validation: Validate against held-out DFT data and experimental benchmarks (e.g., glass transition temperature, elastic modulus).

Protocol for Classical FF Simulation of Lipid-Based Delivery Systems

- System Parameterization: Use a FF such as CHARMM36 or GAFF-Lipids. Obtain or derive parameters for novel drug molecules via analogy or tools like CGenFF. Solvate the system (e.g., lipid bilayer + drug) in TIP3P water and add ions to physiological concentration.

- Equilibration: Perform energy minimization, followed by stepwise equilibration in NVT and NPT ensembles using a barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) and thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) over ~100 ns.

- Production Run: Run multi-microsecond NPT simulations using GPU-accelerated software (e.g., GROMACS, OpenMM). Trajectories are saved every 100 ps for analysis.

- Analysis: Calculate properties like area per lipid, membrane thickness, drug diffusion coefficient, and partition free energy profiles (umbrella sampling).

Quantitative Comparison: MLIP vs. Classical FF

Table 1: Accuracy Benchmark for Drug-Polymer Binding Energies

| System (Drug-Polymer) | DFT Reference (kcal/mol) | MLIP (Error %) | Classical FF (Error %) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxorubicin-Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) | -12.3 ± 0.8 | -12.1 (1.6%) | -8.5 (30.9%) | CHARMM36 underbinds due to fixed charge model. |

| Paclitaxel-Polyethylene Glycol | -9.7 ± 0.6 | -9.9 (2.1%) | -11.5 (18.6%) | GAFF overbinds; lacks polarization effects. |

| Insulin-Silica Nanoparticle (per residue) | -15.2 ± 1.2 | -14.8 (2.6%) | Not Applicable | Classical FF lacks reactive Si-O bonding parameters. MLIP captures it. |

Table 2: Computational Cost for 10 ns Simulation of a ~10k Atom System

| Method (Software) | Hardware | Wall-clock Time | Accuracy Tier |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (VASP) | 256 CPU cores | ~30 days | Quantum-mechanical reference |

| MLIP (NequIP/LAMMPS) | 4x NVIDIA A100 | ~2 days | Near-DFT accuracy |

| Classical FF (CHARMM/GROMACS) | 1x NVIDIA A100 | ~6 hours | Chemically transferable |

Key Application: Predicting Drug Release Kinetics

The release profile of a drug from a polymeric matrix is governed by diffusion, polymer degradation, and drug-polymer interactions. MLIPs enable accurate modeling of the hydrolytic cleavage of ester bonds in polyesters (e.g., PLGA) and the subsequent diffusion of drug molecules through the hydrated, swelling matrix—a process challenging for non-reactive FFs.

(Diagram Title: MLIP Workflow for Drug Release Prediction)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Studies

| Item/Category | Example(s) | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality Training Data | QM9, ANI-1x, OC20, SPICE | QM datasets for training or benchmarking MLIPs on organic molecules and reactions. |

| Classical Force Fields | CHARMM36, GAFF2, OPLS-AA, Martini | Provide transferable, computationally efficient potentials for large-scale biomolecular MD. |

| MLIP Software Frameworks | AMPTorch, DeepMD-kit, Allegro (NequIP) | Tools to train, deploy, and run simulations with MLIPs. |

| Enhanced Sampling Suites | PLUMED, SSAGES | Enable calculation of free energies and rare events (e.g., binding, permeation). |

| Analysis & Visualization | MDAnalysis, VMD, OVITO, NGLview | Process simulation trajectories, compute properties, and render structures. |

Within the thesis of MLIP vs. classical FF accuracy, biomaterials and drug delivery systems present a compelling case. While classical FFs offer unmatched speed for screening, MLIPs provide the necessary chemical accuracy to model reactive and highly specific interactions at biological interfaces. The future lies in hybrid multiscale approaches, using MLIPs in critical regions and classical FFs in bulk solvent, making predictive in silico design of next-generation delivery systems a tangible reality.

Overcoming Practical Hurdles: Deployment, Optimization, and Pitfalls

Within the ongoing research thesis comparing Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) and classical force fields, the limitations of classical methodologies remain a critical benchmark. This technical guide details the two most fundamental failure modes of classical force fields: lack of transferability beyond fitted datasets and the absence of explicit electronic polarizability. These intrinsic deficiencies systematically cap achievable accuracy, particularly for drug discovery applications involving diverse molecular conformations, chemical environments, and non-covalent interactions.

The pursuit of accurate molecular simulation positions classical force fields (FFs) and MLIPs as contrasting paradigms. Classical FFs rely on fixed, physically interpretable functional forms parameterized from experimental and quantum mechanical data. Their failure modes are predictable and rooted in these design choices, primarily their limited transferability and mean-field treatment of polarization. Understanding these failures is essential for interpreting simulation results and defining the accuracy gaps that MLIPs aim to close.

Failure Mode I: Limited Transferability

Transferability refers to a force field's ability to accurately describe molecules and states not explicitly included in its parameterization set.

Core Mechanistic Cause

The functional form of classical FFs (e.g., harmonic bonds, fixed partial charges) is coupled to parameters derived for specific chemical groups in specific environments. This creates a "training domain" beyond which accuracy degrades.

Key Experimental Protocol for Assessing Transferability:

- Target Selection: Choose a set of molecules with functional groups in novel bonding environments (e.g., torsions in strained rings, non-standard protonation states).

- Quantum Mechanical Benchmark: Perform high-level ab initio calculations (e.g., CCSD(T)/CBS or DLPNO-CCSD(T)) to generate reference conformational energies, torsion profiles, and interaction energies.

- Classical FF Simulation: Calculate the same properties using the target classical FF (e.g., GAFF2, CHARMM, OPLS).

- Cross-Comparison: Systematically compute root-mean-square errors (RMSE) and maximum deviations between FF and QM references across the molecular set.

Quantitative Data: Transferability Errors

Table 1: RMSE in Torsion Energy Profiles for Novel Chemical Moieties

| Classical Force Field | Standard Diarylamine RMSE (kcal/mol) | Strained Macrocycle RMSE (kcal/mol) | Phosphorylated Amino Acid RMSE (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF2 | 1.2 | 4.8 | 3.5 |

| CHARMM36 | 0.9 | 5.2 | 4.1 |

| OPLS4 | 1.0 | 4.1 | 2.8 |

| Reference QM Method | DLPNO-CCSD(T)/def2-TZVP | DLPNO-CCSD(T)/def2-TZVP | DLPNO-CCSD(T)/def2-TZVP |

Table 2: Non-Bonded Interaction Errors for Uncommon Dimers

| Dimer Type (Example) | Classical FF (Fixed Charges) RMSE vs. QM (kcal/mol) | MLIP (e.g., GAP-SOAP) RMSE vs. QM (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Halogen-bonded (C-I...N) | 2.5 | 0.3 |

| CH-π Interaction | 1.8 | 0.2 |

| Sulfur-Centered Hydrogen Bond | 2.2 | 0.4 |

| Reference QM Method | CCSD(T)/CBS | CCSD(T)/CBS |

Title: The Transferability Failure Pathway of Classical FFs

Failure Mode II: The Polarizability Limit

The dominant "fixed-charge" approximation in classical FFs treats atomic partial charges as immutable, neglecting electronic polarization—the redistribution of electron density in response to the local electric field.

Core Mechanistic Cause

Polarization is critical for modeling:

- Dielectric properties and solvent response.

- Anisotropic molecular interactions (e.g., sigma-hole bonding).

- Transition states and charge-transfer complexes. Its absence leads to a mean-field error in environments differing from the parameterization condition.

Key Experimental Protocol for Quantifying Polarization Error:

- System Design: Simulate a solute (e.g., drug molecule) in different solvents (water, chloroform, protein binding site) or at interfaces.

- Polarizable Reference: Perform ab initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD) or use a rigorously polarizable QM/MM setup to obtain the true, environment-dependent charge distribution.

- Classical Simulation: Run MD simulations using the standard non-polarizable FF and a advanced polarizable FF (e.g., AMOEBA, Drude).

- Property Comparison: Calculate and compare key properties: electrostatic potential around the solute, dipole moment fluctuations, and solvent-solute interaction energies.

Quantitative Data: Impact of Missing Polarizability

Table 3: Errors in Binding Free Energy (ΔG) due to Non-Polarizable Electrostatics

| Protein-Ligand System | Fixed-Charge FF ΔG Error vs. Exp. (kcal/mol) | Polarizable FF (AMOEBA) ΔG Error vs. Exp. (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Trypsin-Benzamidine | -2.5 | -0.8 |

| FKBP-FK506 | -3.8 | -1.2 |

| T4 Lysozyme-Phenol | -1.9 | -0.5 |

| Experimental Method | Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) |

Table 4: Dipole Moment Errors in Heterogeneous Environments

| Molecule (Environment) | Fixed-Charge FF Dipole (D) | QM/Pol. FF Dipole (D) | QM Reference Dipole (D) |

|---|---|---|---|

| N-Methylacetamide (Water) | 4.1 | 4.8 | 4.9 |

| N-Methylacetamide (CCl₄) | 4.1 | 3.5 | 3.4 |

| Phospholipid Headgroup (Membrane) | 24.5 | 31.2 | 32.0 |

| QM Reference Method | B3LYP/aug-cc-pVTZ with PCM | B3LYP/aug-cc-pVTZ with PCM | B3LYP/aug-cc-pVTZ |

Title: Consequences of the Fixed-Charge Approximation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Tools for Force Field Failure Mode Analysis

| Item/Category | Example(s) | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| High-Accuracy QM Software | ORCA, Gaussian, Q-Chem, CP2K | Generate benchmark energies, forces, and charge distributions for small-molecule clusters or condensed-phase snapshots. |

| Classical MD Engines | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, OpenMM | Perform production simulations using classical (non-polarizable and polarizable) force fields. |

| Polarizable Force Fields | AMOEBA, CHARMM Drude, SIBFA | Act as an intermediate benchmark to isolate errors arising solely from the lack of polarizability. |

| MLIP Frameworks | AMPTorch, DeePMD-kit, MACE, NequIP | Train and deploy MLIPs on QM data to establish a near-QM accuracy baseline for comparison. |

| Free Energy Calculation Tools | alchemical (FEP, TI), enhanced sampling (METAD, REST) | Quantify the functional impact of FF failures on thermodynamic observables like binding affinities. |

| Benchmark Datasets | GMTKN55, S66x8, RNA07, LIBE | Standardized sets of molecular geometries and QM energies for rigorous, reproducible accuracy testing. |

| Wavefunction Analysis Tools | Multiwfn, VMD with QM plugins, PSI4 | Analyze electron density, electrostatic potentials, and charge transfer to diagnose polarization errors. |

The documented failure modes of classical FFs—poor transferability and the polarizability limit—define the key accuracy challenges for molecular simulation. This analysis provides a clear thesis context: MLIPs, by learning complex potential energy surfaces directly from QM data, intrinsically address these limitations. They offer superior transferability across chemical space and implicitly capture electronic polarization effects present in their training data, thereby establishing a new ceiling for predictive accuracy in computational drug development and materials science.

The pursuit of accurate and efficient atomic potential models has evolved from purely physics-based classical force fields (FFs) to data-driven Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs). Classical FFs, based on pre-defined functional forms with limited, manually tuned parameters, excel in computational speed and stability but suffer from limited accuracy, especially for systems not explicitly parameterized. MLIPs, trained on quantum mechanical (QM) data, promise quantum-accurate energies and forces at near-classical computational cost. However, this promise is contingent on overcoming three interrelated core challenges: Data Scarcity, Out-of-Distribution (OOD) Generalization, and Extrapolation Risks. This whitepaper frames these challenges within the broader research thesis comparing the ultimate accuracy and reliability frontiers of MLIPs versus classical FFs.

The Triad of Core Challenges

Data Scarcity: The Quantum Bottleneck

The accuracy of an MLIP is fundamentally bounded by the quality and quantity of its training data, which is derived from expensive QM calculations (DFT, CCSD(T)). Generating comprehensive datasets for complex molecular systems or materials is a severe bottleneck.

Table 1: Comparative Cost of QM Data Generation for Training MLIPs

| QM Method | Typical System Size (Atoms) | Single-Point Energy Cost (CPU-hrs) | Typical Dataset Size for MLIP | Total Computational Cost Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | 10-100 | 1-100 | 10^3 - 10^5 configurations | 10^3 - 10^7 CPU-hrs |

| Coupled-Cluster (CCSD(T)) | 5-20 | 100-10,000 | 10^2 - 10^4 configurations | 10^4 - 10^8 CPU-hrs |

| Quantum Monte Carlo | 10-50 | 1,000-100,000 | 10^1 - 10^3 configurations | 10^4 - 10^8 CPU-hrs |

Experimental Protocol for Active Learning (AL): AL mitigates scarcity by iteratively selecting the most informative configurations for QM calculation.

- Initialization: Train a preliminary MLIP on a small, diverse seed QM dataset.

- Exploration: Use molecular dynamics (MD) with the current MLIP to sample new configurations (e.g., at different temperatures/pressures).

- Query & Selection: For each new configuration, compute an "uncertainty metric" (e.g., committee disagreement, predictive variance). Select configurations where uncertainty exceeds a threshold.

- QM Calculation & Retraining: Perform costly QM calculations on the selected configurations. Add them to the training set and retrain the MLIP.

- Convergence Check: Repeat steps 2-4 until MLIP predictions stabilize (e.g., energy/force errors on a hold-out set plateau) or uncertainty falls below threshold across sampled MD.

Out-of-Distribution Generalization: The Domain Shift Problem

An MLIP may fail when encountering atomic environments (distributions) not represented in its training data, a common scenario in real-world applications like drug binding or defect dynamics.

Experimental Protocol for OOD Detection and Robustness Testing:

- Define Applicability Domain (AD): Characterize the training data distribution using descriptors (e.g, Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP), atomic neighbor histograms).

- Generate OOD Test Sets: Create configurations known to be outside the training domain (e.g., stretched bonds, compressed lattices, novel molecular conformers not sampled during training).

- Benchmark Performance: Evaluate the MLIP on both in-distribution (ID) and OOD test sets. Key metrics: Mean Absolute Error (MAE) in energy/forces, and failure rate (e.g., percentage of configurations where error exceeds a catastrophic threshold, such as > 1 eV/atom).

- Implement Rejection Algorithms: Integrate uncertainty quantification (UQ) methods (e.g., ensemble-based variance, dropout variance, evidential deep learning) to flag predictions with high uncertainty, likely corresponding to OOD inputs.

Extrapolation Risks: The Silent Failure Mode