Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) in Biomedical Research: From Derivation to Advanced Applications in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the theory, calculation, and application of Mean Squared Displacement (MSD).

Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) in Biomedical Research: From Derivation to Advanced Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the theory, calculation, and application of Mean Squared Displacement (MSD). It covers the foundational derivation of MSD for normal and anomalous diffusion, explores advanced methodological applications in single-particle tracking and materials characterization, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges in experimental data analysis, and discusses validation frameworks and comparative analysis of stochastic processes. By synthesizing classical statistical approaches with modern machine learning techniques, this guide aims to enhance the accuracy and interpretability of diffusion measurements in complex biological environments and pharmaceutical systems.

The Fundamentals of Mean Squared Displacement: Derivation and Theoretical Framework

Mathematical Definition and Statistical Mechanics Foundation of MSD

In the study of dynamic processes within biological and soft matter systems, the mean squared displacement (MSD) serves as a fundamental metric for quantifying particle motion. In statistical mechanics, the MSD, also called mean square displacement, average squared displacement, or mean square fluctuation, is a measure of the deviation of the position of a particle with respect to a reference position over time [1]. It represents the most common measure of the spatial extent of random motion and can be thought of as measuring the portion of the system "explored" by the random walker [1]. This technical guide establishes the mathematical foundation of MSD analysis, derives its theoretical basis from statistical mechanics, and provides practical methodologies for its application in diffusion research, particularly in pharmaceutical and biophysical contexts where understanding molecular mobility is crucial for drug development.

Mathematical Definition and Core Formalism

The MSD provides a quantitative measure of the deviation of a particle's position from a reference position over time, offering crucial insights into the nature of particle motion. The fundamental mathematical definition and its practical computational implementations form the basis for extracting meaningful diffusion parameters from experimental and simulation data.

Fundamental Mathematical Definition

The ensemble-averaged MSD at time ( t ) is universally defined as:

[ \text{MSD} \equiv \left\langle \left| \mathbf{x}(t) - \mathbf{x0} \right|^2 \right\rangle = \frac{1}{N}\sum{i=1}^{N} \left| \mathbf{x}^{(i)}(t) - \mathbf{x}^{(i)}(0) \right|^2 ]

where ( \mathbf{x}^{(i)}(0) = \mathbf{x_0}^{(i)} ) is the reference position of particle ( i ), and ( \mathbf{x}^{(i)}(t) ) is its position at time ( t ) [1]. The angle brackets ( \langle \ldots \rangle ) denote the ensemble average over all ( N ) particles in the system.

For single-particle tracking (SPT) experiments with time lags, the MSD is computed differently. For a trajectory ( \vec{r}(t) = [x(t), y(t)] ) measured at discrete time points ( 1\Delta t, 2\Delta t, \ldots, N\Delta t ), the MSD for a specific lag time ( n\Delta t ) is calculated as [1]:

[ \overline{\delta^2(n)} = \frac{1}{N-n} \sum{i=1}^{N-n} \left( \vec{r}{i+n} - \vec{r}_i \right)^2, \qquad n = 1, \ldots, N-1 ]

Table: MSD Definitions Across Different Contexts

| Context | Mathematical Definition | Averaging Method | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Mechanics | ( \left\langle \left | \mathbf{x}(t) - \mathbf{x_0} \right | ^2 \right\rangle = \frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}^{N} \left | \mathbf{x}^{(i)}(t) - \mathbf{x}^{(i)}(0) \right | ^2 ) | Ensemble average over N particles |

| Single-Particle Tracking | ( \overline{\delta^2(n)} = \frac{1}{N-n} \sum{i=1}^{N-n} \left( \vec{r}{i+n} - \vec{r}_i \right)^2 ) | Time average over trajectory frames | ||||

| Continuous Time Series | ( \overline{\delta^2(\Delta)} = \frac{1}{T-\Delta} \int_0^{T-\Delta} [r(t+\Delta) - r(t)]^2 dt ) | Time average over continuous measurement |

Computational Implementation

The computation of MSD can be implemented through different algorithms with varying computational complexity. The standard "windowed" approach computes the MSD for all possible lag times ( \tau \leq \tau{max} ), where ( \tau{max} ) is the trajectory length, thereby maximizing the number of samples [2]. However, this method scales quadratically ( (N^2) ) with respect to ( \tau_{max} ), making it computationally intensive for long trajectories.

An optimized algorithm based on Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) computes the MSD with ( N \log(N) ) scaling [2]. This FFT-based approach requires significantly less computational resources for long trajectories but depends on the availability of specialized packages like tidynamics. The choice between these algorithms depends on the specific application constraints and trajectory lengths.

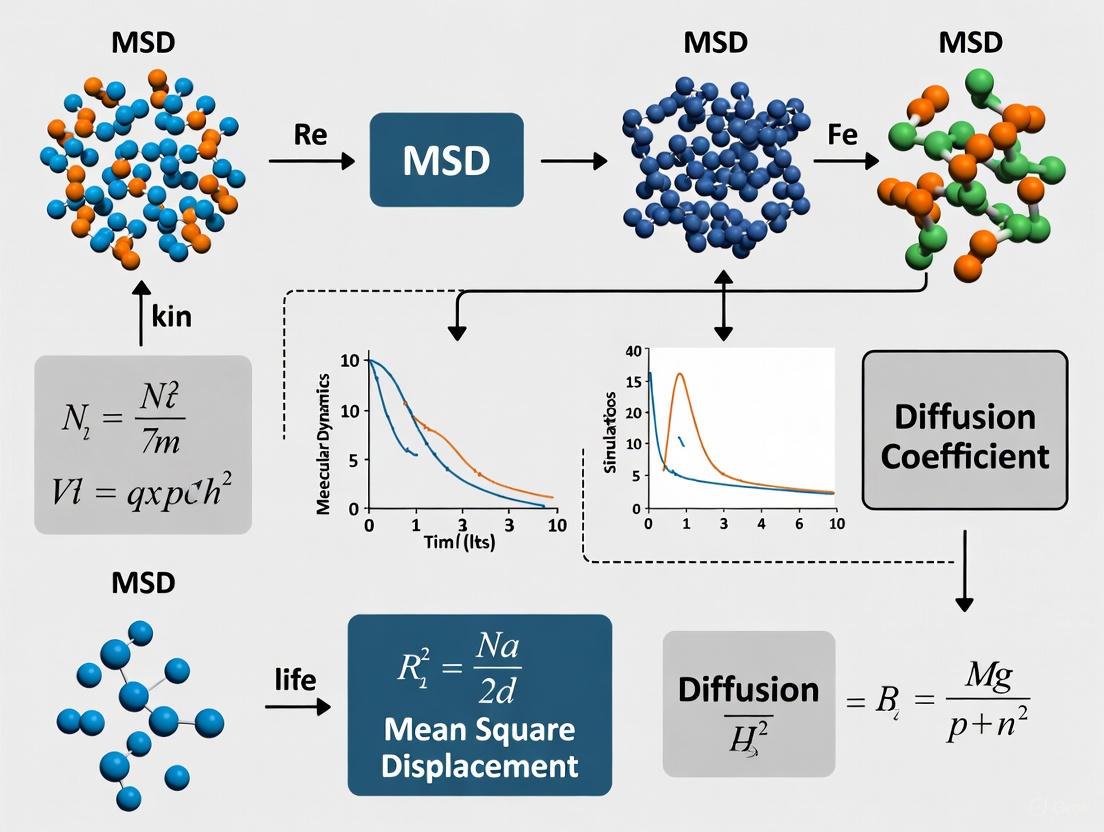

Figure 1. MSD Computation Workflow: This diagram illustrates the procedural pathway for calculating Mean Squared Displacement from particle trajectory data, highlighting critical preprocessing requirements and algorithmic choices that impact computational efficiency and accuracy.

Statistical Mechanics Foundation

The theoretical foundation of MSD is rooted in statistical mechanics, particularly through the diffusion equation and the principles of Brownian motion. This foundation provides the necessary framework for connecting microscopic particle motion to macroscopic diffusion phenomena.

Derivation for a Brownian Particle in 1D

The probability density function (PDF) for a particle in one dimension is found by solving the one-dimensional diffusion equation, which states that the position probability density diffuses out over time [1]. This approach was originally used by Einstein to describe Brownian motion:

[ \frac{\partial p(x,t \mid x0)}{\partial t} = D \frac{\partial^2 p(x,t \mid x0)}{\partial x^2}, ]

with the initial condition ( p(x,t=0 \mid x0) = \delta(x - x0) ), where ( D ) is the diffusion coefficient with units ( m^2s^{-1} ) [1].

The solution to this differential equation takes the form of the 1D heat kernel:

[ P(x,t) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{4\pi Dt}} \exp\left( -\frac{(x - x_0)^2}{4Dt} \right). ]

The MSD is then derived as the second moment of the displacement:

[ \text{MSD} \equiv \left\langle (x(t) - x_0)^2 \right\rangle. ]

Using the moment-generating function approach with the characteristic function ( G(k) = \langle e^{ikx} \rangle ), the cumulants ( \kappa_m ) of the distribution can be obtained. For the Gaussian solution of the diffusion equation, the characteristic function is:

[ G(k) = \exp(ikx_0 - k^2 Dt). ]

The first cumulant is ( \kappa1 = x0 ) (the mean), and the second cumulant is ( \kappa_2 = 2Dt ) (the variance) [1]. Therefore:

[ \left\langle (x(t) - x_0)^2 \right\rangle = 2Dt. ]

This establishes the fundamental relationship that for pure Brownian motion in one dimension, the MSD grows linearly with time, with a slope of ( 2D ).

Extension to Multiple Dimensions

For a Brownian particle in higher-dimension Euclidean space, its position is represented by a vector ( \mathbf{x} = (x1, x2, \ldots, xn) ), where each coordinate ( x1, x2, \ldots, xn ) performs an independent 1D Brownian motion [1].

The n-variable probability distribution function is the product of the fundamental solutions in each variable:

[ P(\mathbf{x},t) = P(x1,t)P(x2,t) \ldots P(x_n,t) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{(4\pi Dt)^n}} \exp\left( -\frac{\mathbf{x} \cdot \mathbf{x}}{4Dt} \right). ]

The MSD in n dimensions is defined as:

[ \text{MSD} \equiv \left\langle |\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x0}|^2 \right\rangle = \left\langle (x1(t) - x1(0))^2 + (x2(t) - x2(0))^2 + \cdots + (xn(t) - x_n(0))^2 \right\rangle. ]

Since all coordinates are independent, their deviation from the reference position is also independent. Therefore:

[ \text{MSD} = \left\langle (x1(t) - x1(0))^2 \right\rangle + \left\langle (x2(t) - x2(0))^2 \right\rangle + \cdots + \left\langle (xn(t) - xn(0))^2 \right\rangle. ]

For each coordinate, following the same derivation as in the 1D scenario, the MSD in that dimension is ( 2Dt ). Thus, for n dimensions:

[ \text{MSD} = 2nDt. ]

Table: MSD Scaling in Different Dimensions

| Dimensionality | MSD Formula | Probability Distribution | Theoretical Slope | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1D | ( \left\langle (x(t) - x_0)^2 \right\rangle = 2Dt ) | ( P(x,t) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{4\pi Dt}} \exp\left( -\frac{(x - x_0)^2}{4Dt} \right) ) | ( 2D ) | ||||

| 2D | ( \left\langle | \mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x_0} | ^2 \right\rangle = 4Dt ) | ( P(\mathbf{x},t) = \frac{1}{4\pi Dt} \exp\left( -\frac{ | \mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x_0} | ^2}{4Dt} \right) ) | ( 4D ) |

| 3D | ( \left\langle | \mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x_0} | ^2 \right\rangle = 6Dt ) | ( P(\mathbf{x},t) = \frac{1}{(4\pi Dt)^{3/2}} \exp\left( -\frac{ | \mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x_0} | ^2}{4Dt} \right) ) | ( 6D ) |

Diffusion Coefficient Estimation from MSD

The primary application of MSD analysis in experimental research is the determination of diffusion coefficients, which serve as crucial parameters for understanding molecular mobility in various environments.

Self-Diffusivity Calculation

Self-diffusivity is closely related to the MSD through the fundamental relationship:

[ Dd = \frac{1}{2d} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(r_d) ]

where ( d ) is the dimensionality of the MSD [2]. From the MSD, self-diffusivities ( D ) with the desired dimensionality ( d ) can be computed by fitting the MSD with respect to the lag-time to a linear model.

The optimal approach involves identifying a linear segment of the MSD plot, which represents the "middle" region where ballistic trajectories at short time-lags are excluded along with poorly averaged data at long time-lags [2]. The diffusion coefficient is then calculated from the slope of this linear segment:

[ D = \frac{\text{slope}}{2d} ]

where ( d ) is the dimensionality factor (3 for 3D MSD, 2 for 2D MSD).

Practical Considerations and Optimal Fitting

The accurate estimation of diffusion coefficients from MSD analysis requires careful consideration of several practical factors. A critical control parameter is the reduced localization error ( x = \sigma^2/D\Delta t ), where ( \sigma ) is the localization uncertainty, ( D ) is the diffusion coefficient, and ( \Delta t ) is the frame duration [3].

When ( x \ll 1 ) (localization uncertainty is small compared to diffusion), the best estimate of the diffusion coefficient is obtained using the first two points of the MSD curve (excluding the (0,0) point). When ( x \gg 1 ) (localization uncertainty dominates), the standard deviation of the first few MSD points is dominated by localization uncertainty, and therefore a larger number of MSD points are needed to obtain a reliable estimate of D [3].

The optimal number of MSD points ( p{min} ) to be used depends on both ( x ) and ( N ) (the number of points in the trajectory). For small ( N ), the optimal number ( p{min} ) of points may sometimes be as large as ( N ), while for large ( N ), ( p_{min} ) may be relatively small [3].

Figure 2. Diffusion Coefficient Extraction: This workflow outlines the systematic procedure for calculating diffusion coefficients from MSD data, emphasizing the critical role of localization uncertainty in determining the optimal fitting strategy.

Advanced Applications and Methodological Considerations

Modern MSD analysis has evolved to address complex diffusion behaviors and experimental challenges, particularly in biological systems where heterogeneity and non-ideal conditions prevail.

Anomalous Diffusion and Heterogeneity Analysis

Beyond normal Brownian diffusion, many biological systems exhibit anomalous diffusion characterized by MSD scaling relationships of the form:

[ \text{MSD} \propto t^\alpha ]

where ( \alpha \neq 1 ) [4]. For subdiffusion, ( 0 < \alpha < 1 ), while for superdiffusion, ( \alpha > 1 ). The accurate determination of the anomalous diffusion exponent ( \alpha ) presents significant challenges when analyzing the short trajectories typical of single-particle tracking experiments [5].

Recent approaches have addressed these challenges through ensemble-based correction methods. For an ensemble of trajectories of fixed length T, the variance of the estimate ( \hat{\alpha} ) obtained by the TA-MSD method follows the relationship:

[ \text{Var}[\hat{\alpha}] \propto 1/T ]

where T is the trajectory length [5]. This relationship highlights the fundamental limitation of analyzing short trajectories, where limited temporal sampling leads to substantial uncertainties in parameter estimation.

Experimental Protocols and Best Practices

The reliable application of MSD analysis in experimental research requires adherence to established protocols and methodological rigor.

Single-Particle Tracking Protocol:

- Data Acquisition: Perform live-cell single-molecule imaging with appropriate temporal and spatial resolution based on the expected diffusion characteristics [4]

- Trajectory Extraction: Apply single-particle tracking algorithms to extract particle trajectories from video data, implementing appropriate localization precision optimization [3]

- Preprocessing: Ensure coordinates are in unwrapped convention (critical for correct MSD computation) and address missing positions through appropriate interpolation or filtering [2]

- MSD Computation: Calculate MSD using either standard windowed or FFT-based algorithms based on trajectory length and computational constraints [2]

- Diffusion Analysis: Fit linear region of MSD curve to extract diffusion parameters, using optimal number of points based on localization uncertainty [3]

Ensemble Analysis Protocol:

- Trajectory Collection: Combine multiple single-particle trajectories with similar characteristics while preserving individual trajectory information [5]

- MSD Calculation: Compute ensemble-averaged MSD and time-averaged MSD for comparison

- Heterogeneity Assessment: Evaluate distribution of diffusion parameters across the ensemble to identify subpopulations and heterogeneity [4]

- Bias Correction: Apply ensemble-based correction to individual trajectory estimates to compensate for noise and bias inherent in single-trajectory analysis [5]

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for MSD Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| MDAnalysis Library [2] | Python package for trajectory analysis and MSD computation | Molecular dynamics simulations analysis |

| and |

Derivation of MSD for Brownian Motion in 1D and n-Dimensions

Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) serves as a fundamental measure in statistical mechanics for quantifying the spatial extent of random motion, providing critical insights into the dynamics of particles undergoing Brownian motion. In the realm of drug development and biomedical research, MSD analysis enables researchers to characterize diffusion behaviors of therapeutic compounds, study cellular trafficking mechanisms, and understand molecular transport within biological systems. The MSD represents the most common measure of random motion spatial extent, conceptually capturing the portion of a system "explored" by a random walker [1]. This technical guide presents a comprehensive derivation of MSD for Brownian motion in one dimension and extends these principles to n-dimensional Euclidean space, providing researchers with the mathematical foundation necessary for applications ranging from molecular dynamics simulations to single-particle tracking in live cells.

The profound significance of MSD analysis stems from its direct relationship to the diffusion coefficient through the Einstein relation, which establishes that for pure Brownian motion in an isotropic medium, the MSD grows linearly with time. The general form of this relationship can be expressed as ⟨x²(t)⟩ = 2nDt, where n represents the dimensionality of the system and D denotes the diffusion coefficient [1]. This fundamental principle enables researchers to extract quantitative information about transport phenomena from observed particle trajectories, making MSD analysis an indispensable tool across scientific disciplines.

Mathematical Derivation of MSD in One Dimension

The Diffusion Equation and Probability Density Function

The derivation of MSD for a Brownian particle in one dimension begins with the one-dimensional diffusion equation, which describes how position probability density evolves over time. This equation, used by Einstein to characterize Brownian motion, states:

∂p(x,t∣x₀)/∂t = D ∂²p(x,t∣x₀)/∂x²

subject to the initial condition p(x,t=0∣x₀) = δ(x-x₀), where x(t) represents the particle's position at time t, x₀ is the reference position, and D is the diffusion coefficient with units m²s⁻¹ [1]. The solution to this differential equation takes the form of the fundamental solution to the 1D heat equation, known mathematically as the Heat kernel:

P(x,t) = 1/√(4πDt) exp(-(x-x₀)²/(4Dt))

This probability density function (PDF) represents a Gaussian distribution that broadens with time, with the Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) scaling as √t [1]. The Gaussian nature of this solution reflects the random nature of Brownian motion, where the most probable position remains the origin, but the uncertainty in position increases with time.

Moment Calculation via Characteristic Function

The MSD is defined as the expectation value MSD ≡ ⟨(x(t)-x₀)²⟩. To compute this quantity, we employ the method of characteristic functions, which provides an efficient approach for calculating moments of probability distributions. The characteristic function G(k) is defined as:

G(k) = ⟨e^(ikx)⟩ ≡ ∫e^(ikx)P(x,t∣x₀)dx

For the Gaussian PDF describing Brownian motion, the characteristic function evaluates to:

G(k) = exp(ikx₀ - k²Dt)

The natural logarithm of the characteristic function generates the cumulants κ_m of the distribution:

ln(G(k)) = Σ(m=1)^∞ (ik)^m/m! κm

For this distribution, the first cumulant is κ₁ = x₀ (the mean position), and the second cumulant is κ₂ = 2Dt (the variance) [1]. The second moment μ₂ = ⟨x²⟩ can be obtained from the cumulants through the relationship μ₂ = κ₂ + κ₁² = 2Dt + x₀².

MSD Calculation in 1D

Using these results, we can now compute the MSD directly:

⟨(x(t)-x₀)²⟩ = ⟨x²⟩ + x₀² - 2x₀⟨x⟩ = (2Dt + x₀²) + x₀² - 2x₀(x₀) = 2Dt

This elegant result demonstrates that for a Brownian particle in one dimension, the mean squared displacement grows linearly with time, with a proportionality constant of 2D [1]. This linear dependence on time is the hallmark of normal diffusion and forms the basis for characterizing more complex transport phenomena through deviations from this relationship.

Table 1: Key Results for 1D Brownian Motion

| Quantity | Symbol | Expression | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probability Density Function | P(x,t) | 1/√(4πDt) exp(-(x-x₀)²/(4Dt)) | Gaussian distribution broadening with time |

| Characteristic Function | G(k) | exp(ikx₀ - k²Dt) | Moment generating function |

| First Cumulant | κ₁ | x₀ | Mean position |

| Second Cumulant | κ₂ | 2Dt | Variance of the distribution |

| Mean Squared Displacement | MSD | 2Dt | Linear growth with time |

Extension to n-Dimensional Brownian Motion

Multidimensional Probability Density Function

For a Brownian particle in higher-dimension Euclidean space, its position is represented by a vector x = (x₁, x₂, ..., xₙ), where each coordinate x₁, x₂, ..., xₙ evolves independently according to one-dimensional Brownian motion. The n-variable probability distribution function factors into the product of the fundamental solutions in each variable:

P(x,t) = P(x₁,t)P(x₂,t)...P(xₙ,t) = 1/√((4πDt)ⁿ) exp(-x·x/(4Dt))

This factorization property significantly simplifies the analysis of multidimensional Brownian motion, reducing complex problems to products of independent one-dimensional processes [1].

MSD Calculation in n Dimensions

The MSD in n dimensions is defined as:

MSD ≡ ⟨|x - x₀|²⟩ = ⟨(x₁(t)-x₁(0))² + (x₂(t)-x₂(0))² + ⋯ + (xₙ(t)-xₙ(0))²⟩

Since all coordinates are independent, their deviations from reference positions are also independent. Therefore, the MSD separates into a sum of contributions from each dimension:

MSD = ⟨(x₁(t)-x₁(0))²⟩ + ⟨(x₂(t)-x₂(0))²⟩ + ⋯ + ⟨(xₙ(t)-xₙ(0))²⟩

From the one-dimensional derivation, we know that each coordinate contributes 2Dt to the MSD. Consequently, for n dimensions:

MSD = 2nDt

This result establishes that the mean squared displacement in n-dimensional Brownian motion maintains its linear time dependence, with a slope proportional to both the dimensionality of the system and the diffusion coefficient [1].

Table 2: MSD Dependence on Dimensionality

| Dimensionality | MSD Expression | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 1D | 2Dt | Diffusion along a line |

| 2D | 4Dt | Diffusion in a plane |

| 3D | 6Dt | Diffusion in three-dimensional space |

| nD | 2nDt | General case for n dimensions |

Practical Implementation and Computational Approaches

MSD Calculation from Trajectory Data

In experimental and computational settings, MSD is calculated from discrete trajectory data obtained through techniques such as single-particle tracking (SPT) or molecular dynamics simulations. For a trajectory r→(t) = [x(t), y(t)] measured at time points 1Δt, 2Δt, ..., NΔt, the MSD for a specific time lag nΔt is computed as:

δ²(n)¯ = 1/(N-n) Σ(i=1)^(N-n) (r→(i+n) - r→_i)² for n = 1, ..., N-1

For continuous time series, the equivalent formulation is:

δ²(Δ)¯ = 1/(T-Δ) ∫₀^(T-Δ) [r(t+Δ) - r(t)]² dt

These formulations employ a "windowed" approach where the MSD is averaged over all possible time lags, thereby maximizing statistical sampling [1] [6].

Diffusion Coefficient Extraction

The diffusion coefficient D is determined from the MSD through the Einstein relation:

Dd = 1/(2d) lim(t→∞) d/dt MSD(r_d)

where d represents the desired dimensionality of the MSD [6]. In practice, this involves fitting a straight line to the MSD curve over an appropriate time interval:

MSD(t) = 2nDt + C

where C accounts for measurement error and localization uncertainty [3]. The linear segment used for fitting should exclude short-time ballistic regimes and long-time poorly averaged regions [6]. Visual inspection of log-log plots can help identify the appropriate fitting region, where the MSD exhibits a slope of 1 [6].

Figure 1: Computational workflow for MSD analysis and diffusion coefficient extraction from particle trajectory data.

Critical Implementation Considerations

Several crucial factors must be considered when implementing MSD analysis:

Unwrapped Coordinates: For simulations with periodic boundary conditions, coordinates must be unwrapped to ensure continuous particle paths [6] [7]. In GROMACS, this can be achieved using

gmx trjconvwith the-pbc nojumpflag [6].Linear Region Selection: The MSD curve typically exhibits three regimes: short-time ballistic motion (MSD ∝ t²), middle-time diffusive behavior (MSD ∝ t), and long-time fluctuations due to poor averaging [6]. Only the linear diffusive regime should be used for D extraction.

Localization Uncertainty: Experimental MSD analysis must account for localization errors, which manifest as a positive y-intercept in the MSD plot [3] [8]. The reduced localization error x = σ²/DΔt determines the optimal number of MSD points to use for reliable diffusion coefficient estimation [3].

Computational Efficiency: Direct MSD calculation scales as O(N²) with trajectory length. For long trajectories, FFT-based algorithms with O(N log N) scaling can significantly improve computational efficiency [6] [7].

Research Applications and Tools

Experimental Protocols for MSD Analysis

For single-particle tracking experiments, the following protocol ensures reliable MSD analysis:

Data Acquisition: Obtain particle trajectories with appropriate temporal resolution (Δt) and sufficient length (N frames) to capture the diffusion process while minimizing localization errors [3].

Trajectory Preprocessing: Apply filtering to remove localization artifacts and correct for drift in the imaging system.

MSD Calculation: Compute the time-averaged MSD for all available time lags, considering the trade-off between statistical accuracy and computational cost [1].

Diffusion Coefficient Extraction: Perform linear regression on the identified linear region of the MSD curve, typically using 10-90% of the total trajectory length unless limited by localization uncertainty [9] [3].

Error Estimation: Calculate confidence intervals through bootstrapping or by dividing the trajectory into segments and analyzing the distribution of obtained diffusion coefficients [9].

Computational Tools for MSD Analysis

Several software packages provide robust implementations of MSD analysis:

GROMACS: The

gmx msdcommand computes MSD from molecular dynamics trajectories and extracts diffusion coefficients through linear fitting, with options for controlling fitting ranges and handling periodic boundary conditions [9].MDAnalysis: The

EinsteinMSDclass in themsdmodule implements both standard and FFT-accelerated MSD calculations, supporting various dimensionalities (1D, 2D, 3D) and selection of atom groups [6] [7].AMBER: The

diffusioncommand calculates MSD plots using distance traveled from initial positions, with automatic imaging of atoms to ensure continuous paths [10].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for MSD Analysis

| Tool/Software | Application Context | Key Functionality |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [9] | Molecular Dynamics Simulations | gmx msd with automated linear fitting and error estimation |

| MDAnalysis [6] [7] | Trajectory Analysis | EinsteinMSD class with FFT acceleration for long trajectories |

| Single-Particle Tracking Algorithms [3] | Experimental Microscopy | Localization with uncertainty estimation and MSD calculation |

| FFT-Based MSD Algorithms [6] | Computational Efficiency | O(N log N) scaling for long trajectories via tidynamics package |

Interpretation of MSD Behavior in Different Motion Regimes

The time dependence of MSD provides crucial insights into the nature of particle motion:

Normal Diffusion: MSD ∝ t (linear relationship) indicates unconstrained Brownian motion in a homogeneous medium [8].

Subdiffusion: MSD ∝ t^α with α < 1 suggests constrained motion, often observed in crowded intracellular environments or viscoelastic materials [11].

Superdiffusion: MSD ∝ t^α with α > 1 signifies active, directed motion typically associated with motor-protein transport or flow effects [8].

Constrained Motion: MSD plateau at long times reveals spatial confinement, with the plateau height corresponding to the square of the confinement size [8].

The intercept of the MSD plot provides information about localization uncertainty, as at zero time lag, the measured displacement reflects measurement error rather than actual particle motion [8].

The derivation of MSD for Brownian motion establishes the fundamental relationship between random particle motion and diffusion coefficients across dimensionalities. From the one-dimensional solution of the diffusion equation to the n-dimensional generalization MSD = 2nDt, this mathematical framework provides researchers with powerful tools for quantifying transport phenomena in diverse systems. For drug development professionals, MSD analysis offers critical insights into drug diffusion through biological barriers, intracellular trafficking of therapeutic agents, and molecular mobility in pharmaceutical formulations. The continued development of computational tools and experimental methodologies ensures that MSD analysis remains an essential technique for characterizing dynamics across scales from single molecules to cellular systems.

Anomalous diffusion describes a class of particle transport processes that deviate from classical Brownian motion, characterized by a non-linear relationship between the mean squared displacement (MSD) and time. In normal diffusion, the MSD grows linearly with time (MSD ∝ t), as described by Einstein's seminal work on Brownian motion. In contrast, anomalous diffusion exhibits a power-law scaling of the form MSD(t) ∼ tα, where the exponent α determines the diffusion class: subdiffusion (α < 1), normal diffusion (α = 1), or superdiffusion (α > 1), which includes ballistic motion (α = 2) [12] [13].

This phenomenon is ubiquitous across scientific disciplines, observed in systems ranging from quantum physics and biological systems to finance and ecology [14] [13]. In cell biology, anomalous diffusion arises from molecular crowding, where the densely packed intracellular environment impedes particle motion, leading to subdiffusion of proteins, lipids, and other biomolecules [15]. Conversely, active transport processes driven by molecular motors can produce superdiffusive motion [12]. Understanding and characterizing anomalous diffusion is therefore crucial for elucidating fundamental mechanisms in fields like drug delivery, intracellular transport, and material science.

Quantitative Framework of MSD Scaling

The mean squared displacement provides the fundamental metric for classifying diffusion types. For a d-dimensional trajectory, the ensemble-averaged MSD is defined as ⟨r2(t)⟩ = ⟨|r(t + τ) - r(τ)|2⟩, where the average is taken over multiple particles and initial time points τ [16].

Table 1: Classes of Anomalous Diffusion Based on MSD Scaling

| Diffusion Type | MSD Exponent (α) | Physical Characteristics | Common Occurrences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subdiffusion | 0 < α < 1 | Slower than normal spreading; constrained motion | Crowded intracellular environments, porous media, polymer networks [12] [15] |

| Normal Diffusion | α = 1 | Linear time dependence; standard Brownian motion | Dilute solutions, ideal gases [13] |

| Superdiffusion | 1 < α < 2 | Faster than normal spreading; persistent motion | Active transport by molecular motors, animal foraging, financial markets [12] [13] |

| Ballistic Motion | α = 2 | Quadratic time dependence; constant velocity motion | Particle in vacuum, idealized mechanical systems [12] |

The anomalous diffusion exponent α is not merely an empirical parameter but reflects the underlying physical mechanism of the transport process. Subdiffusion often arises from crowding, binding events, or trapping in disordered environments, while superdiffusion typically indicates directed motion or long-range correlations in the step directions [15] [13].

Theoretical Models and Experimental Evidence

Prominent Theoretical Models

Several theoretical models have been developed to describe the microscopic mechanisms leading to anomalous diffusion:

- Continuous-Time Random Walk (CTRW): Characterized by random waiting times between jumps, leading to subdiffusion when waiting times have a power-law distribution [14] [13].

- Fractional Brownian Motion (FBM): Incorpor long-range correlations between steps via the Hurst exponent H, where α = 2H [14] [13].

- Lévy Walks: Feature power-law distributed step lengths, enabling long jumps and producing superdiffusion [13].

- Scaled Brownian Motion (SBM): Utilizes a time-dependent diffusion coefficient D(t) ∝ tα-1 [13].

These models generate distinct statistical signatures beyond MSD scaling, including different ergodic properties and displacement distributions [13].

Experimental Observations in Biological Systems

Anomalous diffusion has been extensively documented in cellular environments. Single-particle tracking experiments reveal subdiffusion of cytoplasmic proteins, membrane receptors, and nuclear components [15]. For example, telomeres in mammalian cell nuclei exhibit transient anomalous diffusion with α ≈ 0.7-0.8 [12]. Surprisingly, computational studies suggest that subdiffusion may enhance target-finding probabilities for nearby molecules, potentially benefiting cellular functions like signal propagation and complex formation despite slower spreading [15].

Methodologies for Analysis and Characterization

Traditional Statistical Methods

Traditional approaches for characterizing anomalous diffusion rely on statistical estimators:

- Time-Averaged MSD (TA-MSD): Calculated from a single trajectory as δ2(Δ) = (1/(T-Δ)) ∫0T-Δ [r(t+Δ) - r(t)]2 dt, where T is trajectory length and Δ is timelag [13].

- Ensemble-Averaged MSD (EA-MSD): Computed as the average over multiple particle trajectories at specific timelags [13].

- Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF): Reveals persistence or anti-persistence in particle motion [14].

- Non-Gaussianity Parameter (α₂): Quantifies deviations from Gaussian displacement distributions: α₂(t) = (3⟨r⁴(t)⟩ - 5⟨r²(t)⟩²) / (5⟨r²(t)⟩²) [16].

These methods face limitations with short, noisy trajectories, heterogeneous systems, and non-ergodic processes where time and ensemble averages differ [13].

Machine Learning Approaches

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful tool for analyzing anomalous diffusion, particularly through the Anomalous Diffusion Challenge (AnDi) [14] [13]. ML methods excel at:

- Inference of Diffusion Parameters: Accurately determining α and diffusion coefficients from single trajectories [14].

- Model Classification: Identifying the underlying theoretical model (FBM, CTRW, etc.) [13].

- Trajectory Segmentation: Detecting changes in diffusion properties within heterogeneous trajectories [14] [13].

These approaches typically outperform traditional methods across various tasks, especially for short trajectories and noisy conditions [13].

Table 2: Comparison of Anomalous Diffusion Analysis Methods

| Method Category | Key Techniques | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional MSD Analysis | EA-MSD, TA-MSD, VACF, non-Gaussian parameter | Physically intuitive, strong interpretability | Requires long trajectories, sensitive to noise, struggles with heterogeneity [13] |

| Machine Learning Approaches | Deep neural networks, random forests, feature-based classification | High accuracy for short trajectories, robust to noise, handles heterogeneity | "Black box" interpretation, requires extensive training data [14] [13] |

| Specialized Statistical Tests | Detrended fluctuation analysis, p-variation test, likelihood methods | Model-specific optimal performance | Limited to specific models, may require prior knowledge [14] |

Protocols for Experimental Characterization

A robust protocol for characterizing anomalous diffusion from single-particle tracking data:

- Data Acquisition: Obtain trajectory data with sufficient temporal resolution and localization precision. 3D tracking is preferable for intracellular studies [15].

- MSD Calculation: Compute both ensemble and time-averaged MSD, assessing ergodicity through their comparison [13].

- Power-Law Fitting: Fit MSD to power law over appropriate time ranges, avoiding short-time ballistic regimes and long-time saturation effects [16].

- Model Selection: Apply multiple statistical tests or ML classifiers to identify the appropriate physical model [13].

- Heterogeneity Assessment: Check for multiple diffusion states within trajectories using changepoint detection algorithms [14] [13].

For intracellular studies, account for the transient nature of anomalous diffusion, as crowding-induced subdiffusion often crosses over to normal diffusion at longer timescales [15].

Research Toolkit: Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Anomalous Diffusion Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Tracking Probes | Fluorescent nanoparticles, labeled proteins, quantum dots | Generate trajectories for MSD analysis in biological and materials systems [15] |

| Simulation Frameworks | Langevin dynamics with memory, Weierstrass-Mandelbrot function, CTRW generators | Simulate anomalous diffusion paths for method validation and theoretical studies [15] |

| Analysis Software | AnDi Challenge algorithms, custom MATLAB/Python scripts | Implement ML and statistical methods for parameter inference and model classification [14] [13] |

| Benchmark Platforms | AnDi Challenge datasets | Provide standardized data for method comparison and validation [14] [13] |

Implications for Drug Development and Therapeutics

Understanding anomalous diffusion has profound implications for pharmaceutical research and development. In drug delivery, nanoparticle transport through biological hydrogels and extracellular matrices often exhibits subdiffusive behavior due to structural barriers and binding interactions [15]. Rational design of delivery systems must account for these transport limitations to optimize targeting efficiency.

Intracellular drug transport frequently demonstrates anomalous characteristics, where molecular crowding significantly reduces mobility compared to dilute solutions [15]. This subdiffusion impacts drug bioavailability, target engagement kinetics, and ultimately therapeutic efficacy. Computational models incorporating anomalous diffusion can improve predictions of drug behavior in cellular environments.

Furthermore, pathological conditions that alter cellular architecture (e.g., fibrosis, cancer) may modify anomalous diffusion parameters, offering potential diagnostic indicators based on transport measurements. The enhanced target-finding capability observed in some subdiffusive systems suggests biological optimization principles that could inform therapeutic design strategies [15].

Connecting MSD to Material Properties via the Complex Shear Modulus

This technical guide explores the theoretical and practical framework for connecting Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) measurements to material properties, specifically the complex shear modulus (G*). While MSD analysis of tracer particle diffusion provides a powerful method for characterizing complex materials like colloidal suspensions and intracellular fluids, this guide highlights critical limitations and methodological considerations. Recent research demonstrates that identical MSD scaling can emerge from fundamentally different physical environments, potentially leading to misinterpretation of material properties. This whitepaper provides researchers with advanced protocols for properly discriminating between stochastic processes and accurately deriving viscoelastic properties from particle tracking data, with particular relevance for biomaterials and drug delivery system characterization.

Theoretical Foundations

Mean Squared Displacement Fundamentals

The Mean Squared Displacement is a fundamental measure in statistical mechanics that quantifies the spatial extent of random particle motion over time. For a particle with position vector r at time t, the MSD is defined as:

[MSD(t) = \langle | \mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0) |^2 \rangle]

where the angle brackets denote an ensemble average [1]. In practical applications, this is computed as an average over multiple particles or time origins:

[\delta^2(n) = \frac{1}{N-n}\sum{i=1}^{N-n} \left|\vec{r}{i+n} - \vec{r}_i\right|^2]

where N is the total number of frames in the trajectory, and n is the lag time index [1]. For pure Brownian motion in an isotropic medium, the MSD exhibits a linear relationship with time:

[MSD(t) = 2nDt]

where D is the diffusion coefficient, and n is the dimensionality of the system [1] [6].

Complex Shear Modulus

The complex shear modulus (G*) describes the viscoelastic response of a material to shear stress and is defined through the constitutive relation:

[\tau^* = G^\gamma^]

where (\tau^) is the complex shear stress and (\gamma^) is the complex shear strain [17]. This complex modulus can be decomposed into two components:

[G^* = G' + iG'']

where G' is the storage modulus (elastic component), and G'' is the loss modulus (viscous component) [17]. The loss factor, (\tan\delta = G''/G'), quantifies the ratio of energy dissipated to energy stored during deformation [17].

Table 1: Typical Shear Modulus Values for Various Materials

| Material | Shear Modulus (GPa) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Diamond | 478.0 | [18] |

| Steel | 79.3 | [18] |

| Copper | 44.7 | [18] |

| Glass | 26.2 | [18] |

| Aluminum | 25.5 | [18] |

| Polyethylene | 0.117 | [18] |

| Rubber | 0.0006 | [18] |

| Food Grade Gelatin | ~2.89×10⁻⁶ | Biomaterial substitute [17] |

Connecting MSD to Complex Shear Modulus

Theoretical Framework

The fundamental connection between MSD and complex shear modulus emerges from generalized Stokes-Einstein relationship, which relates the time-dependent mean-squared displacement of embedded tracer particles to the frequency-dependent complex shear modulus G*(ω) of the material. For a particle of radius a in a viscoelastic medium, the complex shear modulus can be obtained through:

[G^*(\omega) = \frac{k_BT}{\pi a i\omega F{MSD(t)}}]

where F{MSD(t)} denotes the Fourier transform of the MSD, k_B is Boltzmann's constant, and T is temperature [19].

Critical Limitations and Discrimination of Stochastic Processes

A crucial limitation in connecting MSD to material properties is that identical MSD scaling can emerge from fundamentally different physical environments [19] [20]. For example:

- Fractional Brownian Motion (FBM): Describes diffusion in viscoelastic fluids where memory effects are present

- Obstructed Diffusion (OD): Occurs in static fractal obstacles without viscoelasticity

Both FBM and OD can exhibit identical sublinear MSD scaling ((\langle r^2(t)\rangle \sim t^\alpha) with α < 1), but deriving a complex shear modulus for OD is meaningless as the system lacks viscoelasticity [19]. Proper discrimination requires analysis beyond MSD, including:

- Gaussianity of increments: FBM typically shows Gaussian increments while OD may not

- Trajectory asphericity: Quantifies the shape of particle trajectories

- Single-particle tracking: Essential for discriminating similar random processes [19]

Figure 1: MSD Interpretation Decision Pathway - Proper discrimination between stochastic processes is essential for meaningful material property assessment

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Single-Particle Tracking for MSD Analysis

Protocol 1: MSD Calculation from Particle Trajectories

- Data Acquisition: Obtain particle trajectories with high temporal and spatial resolution using microscopy techniques

- Trajectory Preprocessing: Ensure coordinates are in unwrapped convention (account for periodic boundary conditions without artificial wrapping) [6]

- MSD Computation: Use the windowed algorithm for optimal statistics: [ \delta^2(n) = \frac{1}{N-n}\sum{i=1}^{N-n} (\vec{r}{i+n} - \vec{r}_i)^2 ] where N is trajectory length, n is time lag [1]

- Efficient Computation: Implement FFT-based algorithms for O(N log N) scaling rather than O(N²) [6] [21]

Critical Consideration: Localization uncertainty significantly impacts MSD analysis, particularly for short trajectories or small displacements. The reduced localization error parameter (x = \sigma^2/D\Delta t) (where σ is localization uncertainty, D is diffusion coefficient, and Δt is frame duration) determines the optimal number of MSD points for reliable diffusion coefficient estimation [3].

Molecular Dynamics Approaches

Protocol 2: Diffusion Coefficient Calculation from MD Simulations [22]

System Preparation:

- Import or generate atomic structure

- Equilibrate system using energy minimization and thermalization

- For amorphous systems, employ simulated annealing (heating followed by rapid cooling)

Production Simulation:

- Run molecular dynamics with appropriate thermostat (e.g., Berendsen)

- Set sample frequency to capture relevant dynamics

- Ensure sufficient simulation length for statistical accuracy

Diffusion Coefficient Calculation:

- MSD Method (Recommended): [ D = \frac{\text{slope}(MSD)}{2d} ] where d is dimensionality [22]

- Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) Method: [ D = \frac{1}{3}\int0^{t{max}} \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle dt ]

Table 2: Comparison of Diffusion Coefficient Calculation Methods

| Method | Advantages | Limitations | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSD Analysis | Direct implementation, intuitive interpretation | Requires linear segment identification, finite-size effects | Slope fitting range, dimensionality |

| VACF Integration | Avoids MSD linear fitting, provides complementary information | Requires high-frequency sampling, sensitive to noise | Integration upper limit, velocity correlation decay |

| Experimental SPT | Applicable to real materials, in situ measurement | Localization uncertainty, limited trajectory length | Reduced localization error (x), optimal MSD points [3] |

Complex Shear Modulus Measurement

Protocol 3: Nanoindentation for Biomaterials [17]

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare biomaterial samples (e.g., food-grade gelatin as tissue substitute)

- Ensure smooth, uniform surface

- Apply thin glass coverslip to provide engagement surface

Instrument Calibration:

- Measure instrument stiffness (Kᵢ) and damping (Dᵢω) without sample contact

- Use flat-ended cylindrical punch tip (e.g., 100-107.7 μm diameter)

Measurement Procedure:

- Engage surface with known pre-test compression (e.g., 10 μm)

- Apply oscillatory stress at target frequency (e.g., 145 Hz)

- Measure composite stiffness (K) and damping (Dω)

Data Analysis:

- Calculate contact stiffness: S = K - Kᵢ

- Calculate contact damping: Dₛω = Dω - Dᵢω

- Compute storage modulus: (G' = S(1-\nu)/(2D))

- Compute loss modulus: (G'' = D_s\omega(1-\nu)/(2D))

- Assume Poisson's ratio ν = 0.5 for incompressible biomaterials [17]

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Material Characterization - Multiple complementary approaches for connecting diffusion measurements to viscoelastic properties

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for MSD and Shear Modulus Studies

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tracer Particles | Probe local mechanical environment | Size, surface chemistry, and concentration must be optimized for specific system |

| Flat-Punch Indenter | Apply controlled shear stress | Critical for direct G* measurement; diameter affects measurement uncertainty [17] |

| Biomaterial Substrates (e.g., gelatin) | Model biological systems | Food-grade gelatin provides consistent, tunable mechanical properties [17] |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., AMS) | Simulate atomic-scale dynamics | ReaxFF force field for complex materials [22] |

| MSD Analysis Packages (e.g., MDAnalysis, freud) | Compute MSD from trajectories | Implement efficient FFT-based algorithms; require unwrapped coordinates [6] [21] |

| Unwrapped Trajectories | Accurate MSD computation | Used with -pbc nojump in GROMACS or similar tools [6] |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Optimal MSD Analysis Parameters

The accuracy of diffusion coefficients derived from MSD analysis depends critically on selecting the appropriate number of MSD points for linear fitting [3]. The optimal number of points (p_min) depends on:

- Trajectory length (N)

- Reduced localization error (x = σ²/DΔt)

- Measurement dimensionality

For large localization errors (x ≫ 1), more MSD points are needed, while for minimal localization error (x ≪ 1), the first two MSD points may suffice [3].

Temperature Dependence and Arrhenius Extrapolation

Diffusion coefficients show strong temperature dependence described by the Arrhenius equation:

[ D(T) = D0 \exp(-Ea/k_BT) ]

[ \ln D(T) = \ln D0 - \frac{Ea}{k_B} \cdot \frac{1}{T} ]

where E_a is the activation energy, and D₀ is the pre-exponential factor [22]. This relationship allows extrapolation of diffusion coefficients to physiologically relevant temperatures when direct measurement is challenging.

Table 4: Key Experimental Factors and Recommendations

| Factor | Impact on Measurement | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Localization Uncertainty | Dominates MSD variance at short times | Characterize σ experimentally; use optimal p_min [3] |

| Finite Trajectory Length | Poor statistics at long lag times | Use windowed averaging; combine multiple trajectories [6] |

| Camera Exposure Time | Increases effective localization uncertainty | Use shortest practical exposure; correct for motion blur [3] |

| Particle Size | Affects Stokes-Einstein relationship | Match particle size to material microstructure |

| Temperature Control | Critical for accurate D measurement | Use precise thermostating; report temperature uncertainties |

Connecting MSD measurements to material properties via the complex shear modulus provides a powerful framework for characterizing soft materials and biomaterials. However, researchers must exercise caution in interpreting MSD data, as identical scaling can arise from fundamentally different physical processes. Proper discrimination between stochastic processes like FBM and OD requires analysis beyond simple MSD scaling, including Gaussianity and trajectory asphericity metrics. Through careful implementation of the protocols and considerations outlined in this guide, researchers can reliably extract meaningful material properties from particle diffusion measurements, advancing applications in drug delivery system characterization, biomaterial development, and complex fluid analysis. Future methodological developments should focus on improving discrimination between similar stochastic processes and standardizing measurement protocols across experimental platforms.

This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of two key stochastic processes essential for understanding complex diffusion phenomena: Fractional Brownian Motion (FBM) and Obstructed Diffusion. Within the broader context of mean squared displacement (MSD) derivation and diffusion research, these models represent crucial frameworks for interpreting anomalous transport behavior in complex environments ranging from biological systems to materials science. The MSD, defined as (\text{MSD} \equiv \langle |\mathbf{x}(t)-\mathbf{x_0}|^{2} \rangle), serves as the fundamental metric for quantifying the spatial extent of random motion, providing critical insights into the underlying physical mechanisms governing particle mobility [1].

Fractional Brownian Motion generalizes classical Brownian motion by incorporating long-range temporal correlations, making it particularly valuable for modeling systems with memory effects. In contrast, Obstructed Diffusion addresses how physical barriers and microstructural obstacles impede molecular transport, leading to modified diffusion coefficients and anomalous behavior. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the distinction between these processes is paramount for accurately interpreting experimental data, particularly in intracellular drug delivery and pharmaceutical targeting where cellular components create complex obstructed environments.

Core Theoretical Principles

Fractional Brownian Motion: A Correlated Process

Fractional Brownian Motion is a continuous-time Gaussian process (BH(t)) defined by its covariance function, which for (s, t \geq 0) is given by [23]: [ E[BH(t)BH(s)] = \frac{1}{2}\left(|t|^{2H} + |s|^{2H} - |t-s|^{2H}\right) ] where (H) is the Hurst index ((0 < H < 1)). This process exhibits self-similarity, meaning (BH(at) \sim |a|^H B_H(t)) in distribution [23]. The Hurst parameter (H) fundamentally determines the nature of the motion:

- (H = 1/2): Independent increments equivalent to standard Brownian motion [23] [24]

- (H > 1/2): Positively correlated increments (persistent motion) leading to superdiffusion [23]

- (H < 1/2): Negatively correlated increments (anti-persistent motion) leading to subdiffusion [23]

The MSD for an n-dimensional FBM follows the power law [1]: [ \text{MSD} = 2nKt^\alpha ] where (K) is the generalized diffusion coefficient and (\alpha) is the anomalous diffusion exponent. For FBM, (\alpha = 2H), directly linking the Hurst parameter to the diffusion classification [25].

FBM displays long-range dependence (LRD) for (H > 1/2), where the autocorrelation function decays slowly as a power law: (\rho(n) \approx n^{-\alpha}) with (0 < \alpha < 1), resulting in non-convergent correlation sums [24]. This mathematical property makes FBM particularly suited for modeling systems with long-term memory effects.

Obstructed Diffusion: A Geometric Restriction Model

Obstructed diffusion describes the hindered motion of particles through environments containing physical barriers or obstacles. Unlike FBM, which modifies the temporal correlation structure, obstructed diffusion primarily arises from spatial constraints that limit available pathways. The fundamental equation governing macroscopic transport in obstructed systems is the homogenized diffusion equation [26]: [ \frac{\partial c}{\partial t} = \tau D \nabla^2 c = D{\text{eff}} \nabla^2 c ] where (D) is the free diffusion coefficient, (c) is concentration, (\tau) is the tortuosity factor, and (D{\text{eff}} = \tau D) is the effective diffusion coefficient [26].

The MSD in obstructed environments relates to the tortuosity factor through [26]: [ \langle r^2(t) \rangle = 2d\tau Dt ] where (d) is the spatial dimensionality. This expression demonstrates how obstacles reduce diffusion efficiency through the tortuosity factor (\tau < 1), which quantifies the additional path length particles must traverse due to obstructive elements.

In complex biological systems like skeletal muscle fibers, obstructed diffusion manifests as anisotropic transport, with different diffusion rates in radial versus longitudinal directions relative to myofilament organization [26]. This direction-dependent behavior emerges from the preferential alignment of obstructive elements within the tissue microstructure.

Comparative Analysis: Key Differences and Characteristics

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of FBM and Obstructed Diffusion

| Characteristic | Fractional Brownian Motion | Obstructed Diffusion |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Mechanism | Long-range temporal correlations | Spatial restrictions/barriers |

| MSD Scaling | (\langle r^2(t) \rangle \sim t^\alpha) with (\alpha \neq 1) | (\langle r^2(t) \rangle \sim t) with reduced (D_{\text{eff}}) |

| Increment Correlation | Correlated increments (dependent on H) | Typically uncorrelated increments |

| Primary Control Parameter | Hurst index H ((0 < H < 1)) | Tortuosity factor τ ((0 < \tau \leq 1)) |

| Anomalous Diffusion Type | Subdiffusion (H<0.5) or superdiffusion (H>0.5) | Typically subdiffusive behavior |

| Mathematical Formulation | Gaussian process with specific covariance | Modified diffusion equation with effective coefficients |

| Spatial Dependence | Typically homogeneous | Strongly dependent on obstacle geometry |

| Experimental Systems | Polymer dynamics, intracellular transport, financial markets | Biological tissues, porous materials, lipid bilayers |

Table 2: Applications in Biological and Materials Systems

| Application Domain | FBM Relevance | Obstructed Diffusion Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Intracellular Transport | Cytosolic macromolecule dynamics | Nuclear pore transit, organelle crowding |

| Drug Delivery | Nanoparticle behavior in complex fluids | Tissue penetration through extracellular matrix |

| Membrane Dynamics | Lipid and protein motion with memory | Protein diffusion in crowded membranes |

| Neurological Research | Serotonergic fiber growth modeling [25] | Diffusion in brain extracellular space |

| Materials Science | Polymer chain dynamics | Transport through porous catalysts |

Experimental Methodologies and Analysis Techniques

Monte Carlo Simulation for Obstructed Diffusion

Monte Carlo methods provide a powerful approach for studying obstructed diffusion in complex geometries. The standard algorithm implements a random walk on a discrete lattice with reflection at obstacle boundaries [26]:

- Obstacle Definition: Define obstacles occupying domain (\hat{\Omega})

- Tracer Movement: Update particle position using: [ \tilde{x}{j+1} = xj + \etaj \sqrt{6D\Delta t} ] where (\etaj) is a random unit vector

- Obstacle Interaction: Apply reflection rule: [ x{j+1} = \begin{cases} \tilde{x}{j+1}, & \text{if } (\tilde{x}{j+1} + \Psi) \cap \hat{\Omega} = \emptyset \ xj, & \text{if } (\tilde{x}_{j+1} + \Psi) \cap \hat{\Omega} \neq \emptyset \end{cases} ] where (\Psi) defines the tracer geometry [26]

This approach has been successfully applied to model diffusion in skeletal muscle fibers, revealing how myofilaments and myosin heads generate diffusion anisotropy consistent with experimental observations [26]. Similar methodologies have elucidated obstruction effects in mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum structures [27] [28].

Mean Squared Displacement Analysis

MSD analysis represents the primary method for characterizing diffusion behavior from single-particle tracking data. For a trajectory with positions (\vec{r}(t) = [x(t), y(t)]) measured at discrete times, the MSD for time lag (n\Delta t) is calculated as [1]: [ \overline{\delta^2(n)} = \frac{1}{N-n}\sum{i=1}^{N-n} \left(\vec{r}{i+n} - \vec{r}_i\right)^2 ]

Critical considerations for accurate MSD analysis include:

- Localization Uncertainty: The reduced localization error (x = \sigma^2/D\Delta t) significantly impacts MSD estimation, particularly for short trajectories [3]

- Optimal Point Selection: The number of MSD points used for diffusion coefficient estimation must be optimized based on trajectory length and localization precision [3]

- Anomaly Detection: MSD curve shape analysis can identify anomalous diffusion, with obstructed systems often showing characteristic "long tails" in recovery curves [27]

For continuous time series, the MSD is defined as [1]: [ \overline{\delta^2(\Delta)} = \frac{1}{T-\Delta}\int_0^{T-\Delta} [r(t+\Delta) - r(t)]^2 dt ]

Research Reagent Solutions for Diffusion Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Supported Lipid Bilayers | Model membrane system for obstruction studies | Phase-separated DLPC/DSPC bilayers with gel-phase domains [29] |

| Fluorescent Tracers | Single-particle tracking probes | Varying sizes to probe obstruction dependence on molecular dimensions [26] |

| Photobleaching Systems | Measuring diffusion coefficients | FRAP analysis in organelle models [27] [28] |

| Monte Carlo Simulation Platforms | Computational modeling of diffusion | Custom algorithms for random walks in obstructed geometries [26] [27] |

| Homogenization Theory Software | Calculating effective diffusion coefficients | Solving partial differential equations for tortuosity factors [26] |

Advanced Concepts and Recent Developments

Interacting Fractional Brownian Motion

Recent research has extended FBM to incorporate particle interactions, creating more biologically realistic models. The mean-density interaction approach couples each particle to the gradient of the time-integrated ensemble density, mimicking repulsive interactions observed in growing serotonergic fibers [25]. This model exhibits a critical threshold at (\alpha = 4/3), where behavior transitions from interaction-dominated motion ((\alpha < 4/3)) to noise-dominated motion ((\alpha > 4/3)) [25].

The equations governing this process incorporate both fractional noise and density-dependent drift: [ x{n+1} = xn + \xin + \kappa \nabla \rho(xn, tn) ] where (\xin) is fractional Gaussian noise with covariance given by equation (4), and (\rho(x,t)) represents the accumulated ensemble density [25].

Anisotropic Diffusion in Biological Tissues

In skeletal muscle fibers, obstructed diffusion manifests as strong anisotropy due to the regular arrangement of myofilaments. The myosin and actin filaments form a hexagonal lattice that creates direction-dependent tortuosity factors [26]. Experimental measurements and Monte Carlo simulations reveal significantly slower diffusion in radial versus longitudinal directions, with tortuosity factors dependent on tracer size due to steric hindrance effects [26].

Fractional Brownian Motion and Obstructed Diffusion represent fundamentally distinct mechanisms for anomalous transport, with FBM arising from temporal correlations and obstructed diffusion stemming from spatial restrictions. While both can produce similar MSD scaling behavior, their underlying physical origins differ significantly, requiring careful experimental discrimination through correlation analysis, size-dependent studies, and direct visualization.

For drug development professionals, this distinction carries practical implications for optimizing delivery strategies. Intracellular targeting must account for both the viscoelastic properties of the cytoplasm (often modeled with FBM) and the physical barriers created by organelles and cytoskeletal elements (requiring obstructed diffusion models). Future research directions include developing unified frameworks that incorporate both temporal memory and spatial heterogeneity, potentially leading to more accurate predictors of therapeutic agent mobility in complex biological environments.

Practical MSD Analysis: From Single-Particle Tracking to Drug Development Applications

Single-Particle Tracking (SPT) and Trajectory Reconstruction for MSD Calculation

Single-Particle Tracking (SPT) is an established technique for observing the behavior of single entities at high spatial and temporal resolution (nanometers and milliseconds) across various scientific fields including biology, chemistry, and physics [30]. In life sciences, SPT has been applied to resolve the working mechanisms of molecules, organelles, and viruses. The technique involves reconstructing trajectories of single particles visualized in real time, with trajectory analysis representing a fundamental step for deciphering the underlying mechanisms driving molecular motion [30] [31].

The mean squared displacement (MSD) analysis serves as the cornerstone of SPT studies, providing a measure of the deviation of a particle's position with respect to a reference position over time [1]. MSD quantifies the average squared distance traveled by a particle in a certain time, making it the most common measure of the spatial extent of random motion. It can be thought of as measuring the portion of the system "explored" by the random walker, playing prominent roles in the Debye-Waller factor and in the Langevin equation describing diffusion of a Brownian particle [1].

This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for SPT and trajectory reconstruction specifically focused on accurate MSD calculation, presenting both foundational principles and advanced methodologies to address current challenges in quantitative diffusion analysis.

Theoretical Foundations of Mean Squared Displacement

Mathematical Definition and Formulations

The MSD measures the average squared displacement of particles over time intervals, providing crucial insights into diffusion characteristics. For a single particle trajectory, the time-averaged MSD (TAMSD) is calculated as:

Where N is the total number of points in the trajectory r(t), sampled at times Δt, 2Δt, ... NΔt, τ is the time lag, and the Euclidean distance is used [30] [31].

For an ensemble of particles, the ensemble-averaged MSD is defined as:

Where x⁽ⁱ⁾(0) = x₀⁽ⁱ⁾ is the reference position of the i-th particle, and x⁽ⁱ⁾(t) is its position at time t [1].

For n-dimensional Brownian motion, the MSD follows the fundamental relationship:

Where D is the diffusion coefficient and τ is the time lag [1]. In two dimensions, this becomes MSD = 4Dτ, which serves as the basis for calculating diffusion coefficients from experimental data.

MSD Profiles for Different Diffusion Regimes

The functional form of the MSD curve reveals fundamental information about the mode of particle motion:

- Brownian diffusion: MSD increases linearly with time lag [30]

- Subdiffusion: MSD follows a power law with exponent

α < 1, characteristic of confined or obstructed motion [30] - Superdiffusion: MSD follows a power law with exponent

α > 1, indicating active transport processes [30] - Confined motion: MSD exhibits asymptotic saturation at longer time scales [30]

For anomalous diffusion, the MSD can be fitted with the general law:

Where Dₐ is the generalized diffusion coefficient (anomalous diffusion constant), α is the anomalous exponent, and ν is the dimensionality [30]. A log-log plot of MSD versus time is commonly used, where α is the slope of the curve [30].

Table 1: MSD Characteristics for Different Motion Types

| Motion Type | MSD Pattern | Anomalous Exponent (α) | Typical System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immobile | Constant ~0 | - | Tethered molecules |

| Brownian | Linear with τ | ~1 | Unobstructed fluids |

| Subdiffusive | Power law with τ | <1 | Crowded environments |

| Superdiffusive | Power law with τ | >1 | Active transport |

| Confined | Saturates at large τ | Variable | Membrane domains |

Trajectory Acquisition and Reconstruction Methods

Traditional SPT Imaging Modalities

Traditional SPT employs wide-field fluorescence microscopy techniques such as TIRF (Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence) to track single particles with high spatial and temporal resolution. These approaches typically involve:

- Particle detection and localization: Achieving sub-pixel resolution through Gaussian fitting of spot intensity profiles, providing typical accuracy of tens of nanometers [32]

- Trajectory linking: Connecting localized positions through time using algorithms such as those implemented in uTrack software [32]

- Overcoming photobleaching: Using organic dyes conjugated to genetically encoded protein tags, though observations are typically limited to a few seconds before photobleaching occurs [33]

The accuracy of these methods depends critically on factors such as signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), particle density, and temporal resolution [32].

Advanced Tracking Methodologies

Recent technological advances have significantly expanded SPT capabilities:

DNA-PAINT-SPT circumvents photobleaching limitations by using short dye-labeled DNA oligonucleotides that transiently bind to target-bound complementary docking strands [33]. This approach enables extended trajectory acquisition with observation times extending to minutes rather than seconds, while allowing dual-color studies of molecular interactions [33].

MINFLUX microscopy provides a recently introduced super-resolution approach that performs SPT at runtime through iterative single particle localization [34]. MINFLUX uses a doughnut-shaped excitation beam displaced in predefined patterns around estimated emitter positions, achieving exceptional spatiotemporal resolution [34]. The method requires careful parameter optimization including TCP (Target Coordinate Pattern) diameter, dwell time, and photon limits to balance tracking fidelity and localization precision [34].

SpeedyTrack leverages the native sub-microsecond vertical shifting capability of EM-CCDs to achieve microsecond wide-field single-molecule tracking [35]. By staggering wide-field single-molecule images along the CCD chip at ~10-row spacings between consecutive timepoints, SpeedyTrack effectively projects the time domain to the spatial domain, enabling tracking of molecules diffusing at up to 1000 μm²/s at 50 μs temporal resolutions [35].

Table 2: Comparison of SPT Methodologies

| Method | Temporal Resolution | Spatial Precision | Key Advantage | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Wide-field | ~10-100 ms | 20-50 nm | Established workflow | Limited by photobleaching |

| DNA-PAINT-SPT | Seconds-minutes | <20 nm | Extended trajectory lengths | Restricted excitation geometry needed |

| MINFLUX | Milliseconds | <5 nm | Highest spatial resolution | Complex parameter optimization |

| SpeedyTrack | ~50 μs | ~20 nm | Microsecond dynamics | Requires specialized analysis |

Trajectory Reconstruction Algorithms

Accurate trajectory reconstruction is essential for meaningful MSD analysis. Traditional approaches include:

- Linear linking: Connecting nearest-neighbor positions between consecutive frames [36]

- kymographs: Graphical representations of spatial motion over time [36]

Both approaches approximate velocity as constant between frames, limiting analysis of complex motions with rapid velocity changes [36]. Advanced space-time trajectory reconstruction techniques now enable higher-order polynomial reconstruction of 4D (3D+time) particle trajectories, allowing assessment of instantaneous velocity and acceleration at any time point along the trajectory [36].

Figure 1: SPT and Trajectory Reconstruction Workflow. Key steps in processing raw image data into quantitative diffusion parameters through trajectory reconstruction and MSD analysis.

Experimental Protocols for SPT-MSD Studies

Dual-Color DNA-PAINT-SPT for Molecular Interaction Studies

Materials and Reagents:

- Orthogonal docking-imager strand pairs (e.g., poly(TC)/GA and poly(AC)/GT)

- His-tagged target proteins

- Nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA-Ni)-containing supported lipid bilayers (SLBs)

- Benzylguanine (BG)-modified DNA docking strands

- Ligand solutions for dimerization studies

Protocol:

- Prepare SLBs containing lipids modified with integrin-recognition peptide (DSPE-PEG2000-RGD) to promote cell attachment while minimizing nonspecific binding [33]

- Anchor His-tagged target proteins to NTA-Ni-containing SLBs

- Label proteins via SNAPtag using orthogonal sets of BG-modified DNA docking strands

- Reconstitute labeled proteins in equimolar amounts

- Add complementary imager strands carrying fluorophores (e.g., Cy3B)

- Image using TIRF microscopy with appropriate excitation/emission settings for each channel

- Record single-molecule trajectories with appropriate temporal resolution (typically 10-100 ms frames)

- Process data to identify co-diffusion events indicating molecular interactions

Validation: Perform control experiments without dimerization agent to confirm DNA-PAINT-SPT label itself does not introduce interactions [33].

MINFLUX Parameter Optimization for SPT

Critical Parameters:

- TCP (Target Coordinate Pattern) diameter

L - Dwell time

t_dwell - Photon Limit (PL)

- Excitation laser power

- Time-to-localization

t_loc = η · t_dwell + t_hw^η[34]

Optimization Strategy:

- Determine maximum trackable diffusion rate for system:

D_max ≈ L²/(8t_loc)[34] - Balance localization precision and tracking fidelity by adjusting

Landt_dwell - Set PL to ensure sufficient photons for localization while minimizing

t_loc - Account for particle movement during localization process:

σ_diffusion = √(2dD·t_loc)[34] - Iteratively refine parameters using control samples with known diffusion characteristics

SpeedyTrack Implementation for Microsecond Tracking

Hardware Requirements:

- EM-CCD with fast vertical shifting capability (0.3-0.5 μs/row)

- Standard TIRF microscopy setup

- High-numerical aperture objective (NA > 1.4)

Acquisition Protocol:

- Set exposure time to 40-300 μs depending on fluorophore brightness

- Configure vertical shift δ = 10-15 rows between exposures

- Repeat exposure-shift scheme 50-100 times to fill CCD chip

- Read out collective signal as one SpeedyTrack frame

- Process streaks to reconstruct spatial trajectories by deducting known vertical shifts [35]

Analysis Considerations:

- Typical trajectory lengths: 4-40 timepoints (exponentially distributed)

- Recommended single-molecule image density: <500 per frame to avoid overlapping trajectories

- MSD calculation from collapsed trajectories using conventional methods [35]

Quantitative MSD Analysis and Interpretation

Accurate MSD Calculation Methods

The correct approach for MSD calculation uses vector displacement between time-lagged positions:

Where the average is taken over all pairs of points separated by time lag τ [37]. This method should be distinguished from incorrect approaches that calculate displacement from a fixed origin, which do not properly capture diffusion characteristics [37].

For experimental trajectories with finite length, the MSD is estimated as:

For n = 1, ..., N-1, where N is the number of points in the trajectory [1].

Addressing Experimental Uncertainties

MSD analysis must account for several sources of error:

- Static error (localization uncertainty): Produces a positive offset in the MSD curve [31]

- Dynamic error (motion blur during integration): Produces a negative offset in the MSD curve [31]

The corrected MSD function accounting for these effects is:

Where σ² is the variance of immobile particle positions, R is the motion blur coefficient, and Δτ is the integration time [31].

Temporal Resolution Considerations

Temporal resolution (Δt) significantly impacts diffusion coefficient estimation:

- Short Δt provides more accurate diffusivity estimates but yields shorter trajectories [32]

- Long Δt causes underestimation of diffusion coefficients, particularly for faster-diffusing particles [32]

- Confinement effects become more pronounced at longer Δt due to boundary interactions [32]

For membrane protein studies (D ≈ 0.5-1 μm²/s), optimal temporal resolution typically falls between 1-50 ms, balancing tracking accuracy and trajectory length [32].

Table 3: Impact of Experimental Parameters on MSD Accuracy

| Parameter | Effect on MSD | Compensation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Localization uncertainty | Positive offset | Measure static error from immobilized particles |

| Motion blur | Negative offset | Incorporate blur coefficient in fitting |

| Short trajectories | Increased variance | Use weighted least squares fitting |

| Heterogeneous populations | Biased averaging | Analyze distributions rather than means |

| Temporal undersampling | Underestimated D | Use appropriate Δt for expected diffusivity |

Advanced Analysis Approaches

Beyond MSD: Complementary Analysis Methods

While MSD remains fundamental, several complementary approaches provide additional insights:

- Angle distribution analysis: More sensitive for quantifying caging and distinguishing rare transport mechanisms [30]

- Hidden Markov Models: Identify different diffusive states, their populations, and switching kinetics [30] [31]

- Moment scaling spectrum: Characterizes heterogeneous diffusion patterns [30]

- Velocity and acceleration analysis: Enabled by high-order trajectory reconstruction techniques [36]

Machine Learning for Trajectory Classification

Machine learning approaches have recently expanded trajectory analysis capabilities:

- Random forest and deep learning classify trajectory motions based on defined features or automatically identified patterns [30]

- Model-free approaches identify distinctive trajectory features without presupposing specific motion models [31]

- Transfer learning enables application to experimental data after training on simulated trajectories [30]

These methods demonstrate particular advantages for detecting hidden phenomena and extracting information from short, noisy trajectories that challenge conventional MSD analysis [30] [31].

Figure 2: Integrated Trajectory Analysis Framework. Combined approaches using MSD analysis with complementary methods provide robust motion classification and characterization.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for SPT Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Organic dyes (Cy3B, Alexa Fluor) | Fluorescent labeling | High brightness and photostability preferred |

| DNA docking strands (e.g., poly(TC), poly(AC)) | Target anchoring for DNA-PAINT | Orthogonal sequences enable multiplexing |

| Imager strands (e.g., GA, GT) | Transient binding for visualization | Concentration optimized for binding kinetics |

| Supported lipid bilayers (SLBs) | Mimic cellular membranes | NTA-Ni containing for His-tagged protein binding |

| PLL-PEG/PLL-PEG-RGD | Surface passivation | Reduces nonspecific binding while promoting cell adhesion |

| BG-modified DNA docking strands | SNAPtag labeling | Enable specific protein conjugation |

| His-tagged target proteins | Model transmembrane proteins | Enable specific anchoring to SLBs |