Mastering the Constant-Stress NST Ensemble in MD Simulation: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the constant-stress (NST) ensemble in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, a crucial tool for accurately modeling material and biomolecular responses to anisotropic mechanical stress.

Mastering the Constant-Stress NST Ensemble in MD Simulation: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the constant-stress (NST) ensemble in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, a crucial tool for accurately modeling material and biomolecular responses to anisotropic mechanical stress. We cover the foundational theory behind the NST ensemble, distinguishing it from common ensembles like NPT. A detailed, practical methodology for implementing NST simulations in popular MD software is outlined, alongside best practices for troubleshooting and optimizing simulation parameters. The guide concludes with strategies for validating simulations and a comparative analysis of when the NST ensemble is superior to other methods, with specific implications for biomedical research, including studying protein mechanics under stress and advanced drug delivery system design.

What is the NST Ensemble? Core Concepts and Thermodynamic Foundations

The constant-stress (NST) ensemble represents a foundational advancement in molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, enabling precise control over the full stress tensor rather than just isotropic hydrostatic pressure. This technical guide examines the theoretical underpinnings, computational methodologies, and practical applications of NST simulations, with particular emphasis on recent algorithmic developments including stochastic cell rescaling and their implications for materials science and drug development. By providing researchers with comprehensive protocols and quantitative frameworks, this work establishes the NST ensemble as an indispensable tool for investigating anisotropic mechanical responses in complex molecular systems.

Molecular dynamics simulations compute the time evolution of a molecular system by integrating Newton's equations of motion for all atoms, typically using femtosecond timesteps to ensure numerical stability [1]. The statistical ensemble defines the macroscopic state of the system by specifying which state variables (energy, temperature, volume, pressure, etc.) remain constant during the simulation [2]. While most biological simulations have historically employed the NVT (canonical) or NPT (isothermal-isobaric) ensembles, these approaches only control scalar thermodynamic variables—temperature and hydrostatic pressure, respectively [2].

The constant-stress (NST) ensemble extends this capability by enabling control over all components of the stress tensor, allowing the simulation box shape and size to fluctuate in response to both normal and shear stresses [2] [3]. This capability is particularly crucial for simulating solids, biomembranes, and other anisotropic materials where mechanical properties directionally. The NST ensemble samples conformations from the probability distribution [3]:

[ P{NST}({qi,pi},h) \propto \det h^{-2} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{kB T}\left[K + U + P0 \det h + U{el}(h)\right]\right) ]

where (h) is the matrix of lattice vectors defining the simulation cell, (K) is kinetic energy, (U) is potential energy, (P0) is external hydrostatic pressure, and (U{el}(h)) is an optional term for applying anisotropic external stress [3].

Theoretical Foundations of the Constant-Stress Ensemble

Stress Tensor Formulation

In the NST ensemble, the internal pressure tensor (P_{\text{int}}) is defined as [3]:

[ P{\text{int},\alpha\beta} = -\frac{kB T}{V} \sumi h{\beta i} \frac{\partial (K + U)}{\partial h_{\alpha i}} ]

where (V = \det h) is the instantaneous volume of the simulation cell, and the indices (\alpha,\beta) represent the Cartesian components x, y, z. The derivatives must account for how both atomic positions and momenta are affected by changes in the lattice vectors [3].

For polarizable force fields, the stress tensor derivation becomes more complex. In polarizable Gaussian Multipole (pGM) electrostatics, the total electrostatic energy includes contributions from permanent and induced dipoles [4]:

[ U{\text{pGM}} = \sumi^N \frac{1}{2} (qi + \vec{\mu}i \cdot \nablai) \phii^0 + \sumi^N \frac{1}{2} (\vec{p}i \cdot \nablai) \phii^0 ]

where (qi), (\vec{\mu}i), and (\vec{p}i) represent charge, permanent dipole, and induced dipole on atom i, respectively, and (\phii^0) is the electrostatic potential [4]. The stress tensor for such systems requires specialized formulation to account for these complex electrostatic interactions under periodic boundary conditions.

Comparison of Molecular Dynamics Ensembles

Table 1: Key Statistical Ensembles in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Ensemble | Constants | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVE (Microcanonical) | Number of particles, Volume, Energy | Fundamental research; testing force fields; studying energy conservation | Does not correspond to typical experimental conditions |

| NVT (Canonical) | Number of particles, Volume, Temperature | Standard for conformational sampling; studying systems with fixed density | Constant volume constraints natural density fluctuations |

| NPT (Isothermal-Isobaric) | Number of particles, Pressure, Temperature | Simulating biomolecules in solution; modeling liquids | Only controls hydrostatic pressure (isotropic cell fluctuations) |

| NST (Constant-Stress) | Number of particles, Stress Tensor, Temperature | Studying solids, phase transitions, mechanical properties; simulating anisotropic materials | Complex implementation; requires careful parameter tuning |

Methodological Implementations

Anisotropic Barostat Algorithms

Parrinello-Rahman Method

The Parrinello-Rahman algorithm represents the pioneering approach for constant-stress simulations, employing an extended Lagrangian formalism where the simulation cell matrix (h) is treated as a dynamic variable with an associated inertia tensor [3]. The algorithm propagates the nine components of the lattice vectors using a second-order differential equation:

[ \frac{d^2 h}{dt^2} = V(P{\text{int}} - P0 I) h^{-T} ]

where (P{\text{int}}) is the internal pressure tensor, (P0) is the external pressure, and (I) is the identity matrix [3]. While powerful, this method can exhibit oscillatory behavior that requires careful damping, particularly during equilibration phases.

Stochastic Cell Rescaling

Stochastic Cell Rescaling (SCR) represents a recent first-order alternative that overcomes limitations of second-order methods [3]. The anisotropic SCR algorithm uses the following equation of motion for the lattice vectors:

[ dh = -\frac{\betaT}{3\taup} \left[ (P0 I - P{\text{int}} - \frac{kB T}{V} I) h \right] dt + \sqrt{\frac{2\betaT kB T}{3V\taup}} dW h ]

where (\betaT) is the isothermal compressibility, (\taup) is the barostat relaxation time, and (dW) is a Wiener noise matrix [3]. This approach provides exponential decay of correlation functions and is suitable for both equilibration and production phases.

Experimental Protocols for NST Simulations

System Setup and Equilibration

For reliable NST simulations, proper system preparation is essential. The following protocol has been validated for polyimide systems [5] and can be adapted for other materials:

- Initial Minimization: Perform energy minimization using steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithms to remove high-energy contacts [6] [5]

- NVT Equilibration: Run 100-500 ps with temperature control to stabilize the system density

- NPT Equilibration: Use isotropic pressure control for initial volume relaxation (100-500 ps)

- NST Production: Switch to constant-stress ensemble with anisotropic pressure coupling for the production trajectory (1-100 ns depending on system)

For polymeric systems, Odegard et al. demonstrated that the OPLS-AA force field provides accurate mechanical properties when used with this protocol [5].

Parameter Selection Guidelines

Table 2: Key Parameters for Anisotropic Stochastic Cell Rescaling

| Parameter | Recommended Value | Physical Significance | System Dependence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barostat Relaxation Time ((\tau_p)) | 1-10 ps | Controls timescale of volume/shape fluctuations | Longer for larger systems; shorter for smaller systems |

| Isothermal Compressibility ((\beta_T)) | 4.5×10⁻⁵ bar⁻¹ (water) | Relates volume changes to pressure variations | Material-specific; crucial for correct volume fluctuations |

| Time Step ((\Delta t)) | 1-2 fs (all-atom), 2-4 fs (coarse-grained) | Integration interval for equations of motion | Smaller for systems with high-frequency vibrations |

| Stress Tensor Coupling | Anisotropic (all components independent) | Allows independent response to normal and shear stresses | Essential for solids; optional for liquids |

Workflow for Constant-Stress Simulations

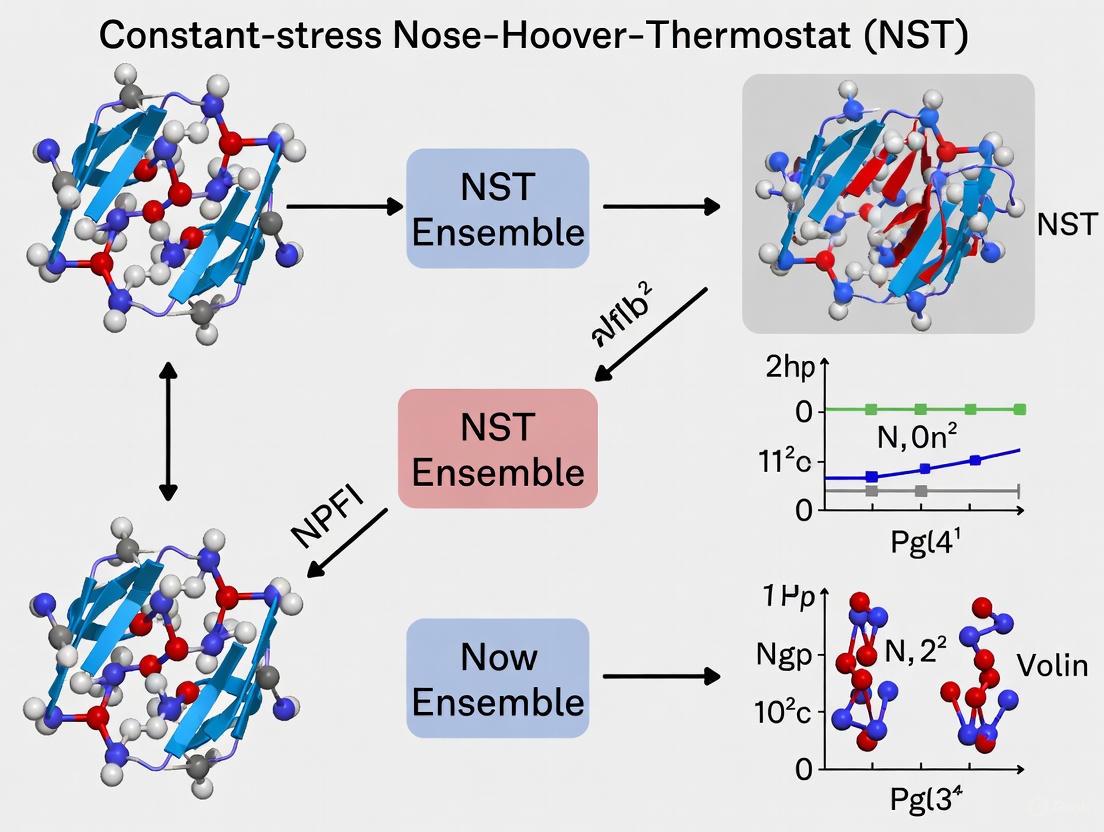

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for setting up and running constant-stress MD simulations:

Diagram Title: NST Simulation Workflow

Applications and Case Studies

Material Science Applications

Polyimide Mechanical Properties

Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of NST simulations for predicting mechanical properties of polyimides. Using the OPLS-AA force field, researchers obtained Young's modulus values for Kapton (PMDA-ODA) of 2.97 GPa in continuous deformation mode simulations, closely matching experimental values of 2.90 GPa [5]. The simulations employed a 21-step equilibration protocol alternating between NVT and NPT ensembles before switching to the NST ensemble for production runs [5].

Phase Transitions in Lennard-Jones Solids

The anisotropic SCR algorithm has been successfully applied to study phase transitions in Lennard-Jones solids, demonstrating superior stability compared to traditional Parrinello-Rahman methods [3]. The first-order stochastic formulation effectively dampens unphysical oscillatory behavior while maintaining correct sampling of the isothermal-stress ensemble.

Pharmaceutical Research Applications

Heat Capacity Calculations for Drug Binding

While not exclusively using NST ensembles, advanced MD simulations have enabled calculation of heat capacity changes ((\Delta Cp)) upon drug binding, a critical parameter in pharmaceutical development [7]. For HIV protease inhibitors, computational estimates of (\Delta Cp) using thermodynamic integration methods successfully discriminated between effective inhibitors and non-inhibitory binders [7]. The methodology involves:

[ \Delta Cp = \left(\frac{\partial \langle U \rangle}{\partial \langle T \rangle}\right){\text{complex}} - \left(\frac{\partial \langle U \rangle}{\partial \langle T \rangle}\right){\text{protein}} - \left(\frac{\partial \langle U \rangle}{\partial \langle T \rangle}\right){\text{ligand}} ]

where (\langle U \rangle) is the average total energy and (\langle T \rangle) is the average temperature [7].

Stress-Strain Relationships in Biomaterials

Constant-stress simulations enable the computational determination of stress-strain curves for biomaterials without imposing artificial deformation protocols [3] [5]. The natural fluctuations of the simulation cell under constant stress provide direct access to elastic constants through fluctuation formulas or by analyzing the strain response to applied stress.

Quantitative Comparison of Mechanical Properties

Table 3: Comparison of Simulated vs. Experimental Mechanical Properties

| Material | Simulation Method | Predicted Young's Modulus | Experimental Value | Force Field |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kapton (PMDA-ODA) | Continuous Deformation (NST) | 2.97 GPa | 2.90 GPa | OPLS-AA [5] |

| Kapton (PMDA-ODA) | Relaxation Mode | 3.40 GPa | 2.90 GPa | OPLS-AA [5] |

| PMDA-BIA | Continuous Deformation (NST) | 4.20 GPa | N/A | OPLS-AA [5] |

| Lennard-Jones Solid | Anisotropic SCR | Consistent with theoretical values | N/A | Lennard-Jones [3] |

Software Implementations

Multiple major MD packages now support constant-stress simulations:

- GROMACS: Implements both Parrinello-Rahman and stochastic cell rescaling barostats [6] [3]

- LAMMPS: Features various constant-stress algorithms including the Anisotropic SCR method [3] [5]

- AMBER: Includes constant-pressure capabilities with ongoing development for full stress tensor control [4]

- SANDER: Specialized implementations for polarizable force fields like pGM [4]

Force Fields and Potential Functions

The choice of force field critically influences the accuracy of NST simulations:

- EAM (Embedded Atom Method): Suitable for metallic systems like the γ-TiAl alloy studied in stress relaxation experiments [8]

- OPLS-AA (All-Atom): Provides accurate mechanical properties for polymeric materials [5]

- pGM (Polarizable Gaussian Multipole): Advanced electrostatic treatment for systems where polarization effects are significant [4]

- Morse Potential: Used for describing interactions between different material types (e.g., indenter-workpiece interactions) [8]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Constant-Stress Simulations

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integration Algorithms | Velocity Verlet, Leapfrog | Numerical integration of equations of motion | Verlet methods preferred for stability with 1-2 fs timesteps [9] |

| Thermostats | Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen, Stochastic | Temperature control | Global thermostats may require center-of-mass corrections [3] |

| Barostats | Parrinello-Rahman, SCR, MTK | Pressure/stress control | SCR provides first-order dynamics suitable for equilibration [3] |

| Electrostatic Methods | PME (Particle Mesh Ewald) | Long-range interaction treatment | Essential for polarizable force fields [4] |

| Potential Functions | EAM, OPLS-AA, pGM | Interatomic force calculation | Selection depends on material type and properties of interest [8] [5] |

The constant-stress ensemble represents a sophisticated extension of molecular dynamics methodology that enables realistic simulation of materials under anisotropic stress conditions. The development of stochastic cell rescaling algorithms addresses key limitations of earlier approaches, providing robust first-order dynamics suitable for both equilibration and production phases. As demonstrated in applications ranging from polyimide mechanics to drug binding thermodynamics, NST simulations provide unique insights into mechanical behavior at the atomic scale.

Future developments will likely focus on improved efficiency for large-scale systems, enhanced coupling between structural transitions and stress response, and more accurate force fields capable of capturing complex mechanical behavior. The integration of machine learning approaches with constant-stress sampling presents a particularly promising direction for high-throughput screening of material mechanical properties in pharmaceutical and materials science applications.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations rely on statistical ensembles to control the state of a system and mimic experimental conditions. An ensemble is an artificial construct representing a collection of all possible system states under specific constraints on thermodynamic variables like energy (E), temperature (T), pressure (P), volume (V), and number of particles (N) [2] [10]. The choice of ensemble determines which quantities remain fixed and which fluctuate, thereby influencing the structural, energetic, and dynamic properties calculated from the simulation [2]. While averages of properties are generally consistent across ensembles representing the same system state, the fluctuations differ and are related to various thermodynamic derivatives [2]. In the thermodynamic limit for infinite systems, ensembles are generally equivalent, but for practical MD simulations with finite particles, the choice of ensemble can significantly impact results [11].

The most common ensembles include NVE (microcanonical), NVT (canonical), and NPT (isothermal-isobaric). This guide focuses on the critical distinctions between the NPT ensemble and the more specialized NST ensemble, providing researchers with the knowledge to select the appropriate ensemble for their specific applications, particularly in materials science and drug development.

Fundamental Ensemble Definitions

The NPT Ensemble

The constant-temperature, constant-pressure ensemble (NPT), also known as the isothermal-isobaric ensemble, maintains a fixed number of atoms (N), pressure (P), and temperature (T) [2] [10]. In this ensemble, the system volume (V) fluctuates to maintain constant pressure, while energy (E) fluctuates to maintain constant temperature [10]. This requires coupling to both a thermostat (to control temperature) and a barostat (to control pressure) [10].

NPT simulations are the ensemble of choice when correct pressure, volume, and density are critical to the simulation [2]. They are particularly valuable for mimicking experimental conditions where temperature and pressure are controlled, for detecting phase transitions, and for computing equilibrium density [10]. Under NPT, the system explores different potential energy surfaces with volume fluctuations, creating a more complex sampling that mimics real material response [10].

The NST Ensemble

The constant-temperature, constant-stress ensemble (NST) extends the concept of the constant-pressure ensemble [2]. While the standard NPT ensemble typically applies hydrostatic pressure isotropically (uniformly in all directions), the NST ensemble provides control over the individual components of the stress tensor [2] [3]. This allows application of anisotropic external stress, where the xx, yy, zz, xy, yz, and zx components can be controlled independently [2].

In mathematical terms, the NST ensemble samples conformations from the probability distribution [3]: [ P{NST}({qi,pi},h) \propto \det(h)^{-2} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{kB T}[K + U + P0 \det(h) + U{el}(h)]\right) ] where (h) is the cell matrix, (K) is kinetic energy, (U) is potential energy, (P0) is external hydrostatic pressure, and (U{el}(h)) is an optional term allowing for anisotropic external stress [3].

Table: Key Characteristics of NPT vs. NST Ensembles

| Feature | NPT Ensemble | NST Ensemble |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled Variables | Number of atoms (N), Pressure (P), Temperature (T) | Number of atoms (N), Stress (S), Temperature (T) |

| Fluctuating Variables | Volume (V), Energy (E) | Cell shape and volume, Energy (E) |

| Pressure Application | Isotropic (hydrostatic) | Anisotropic (full stress tensor control) |

| Cell Flexibility | Volume changes only | Shape and volume changes |

| Primary Applications | Liquids, solvated molecules, biological systems | Solids, polymeric materials, stress-strain studies |

Technical Implementation and Methodologies

Barostat Algorithms and Equations of Motion

Implementing the NPT ensemble typically involves isotropic barostats that adjust system volume uniformly. The Berendsen barostat uses a first-order approach that effectively equilibrates systems but doesn't correctly sample the true isobaric ensemble, while the Parrinello-Rahman and Martyna-Tobias-Klein (MTTK) algorithms use extended Lagrangian formalisms with second-order differential equations for the lattice vectors [3].

For the NST ensemble, fully anisotropic barostats are required. The Parrinello-Rahman method pioneered this approach by introducing an extended Lagrangian formalism that propagates the nine variables associated with the periodic lattice vectors [3]. The cell is provided with inertia, and its acceleration is controlled by the difference between the internal pressure and external stress [3].

Recently, first-order stochastic algorithms like Stochastic Cell Rescaling (SCR) have been developed as alternatives to traditional second-order methods. The SCR barostat resembles the Berendsen barostat but includes a stochastic contribution that results in the correct isobaric distribution [3]. The equations of motion for the anisotropic Stochastic Cell Rescaling can be expressed as [3]: [ dh = -\frac{\betaT}{3\taup}\left[P0 I - P{int} - \frac{kB T}{V}I + \frac{h\Sigma h^T}{V}h\right]dt + \sqrt{\frac{2\betaT kB T}{3V\taup}}dW h ] where (\betaT) is the isothermal compressibility, (\taup) is the relaxation time, (P_{int}) is the internal pressure tensor, (\Sigma) controls the external stress, and (dW) is a noise matrix [3].

Practical Simulation Protocols

NPT Simulation Setup

For NPT simulations using the Parrinello-Rahman algorithm in packages like VASP, key parameters must be properly configured [12]:

- ISIF=3: Enables computation of the stress tensor and allows changes to box volume and shape

- MDALGO=3: Specifies the use of the Langevin thermostat

- LANGEVIN_GAMMA: Sets the friction coefficient for atomic degrees of freedom

- LANGEVINGAMMAL: Defines the friction coefficient for lattice degrees of freedom

- PMASS: Assigns a fictitious mass to the lattice degrees of freedom

An example NPT simulation protocol involves first energy minimization, followed by NVT equilibration to stabilize temperature, and finally production NPT runs to achieve the desired pressure and density [13].

NST Simulation Workflow

NST Simulation Workflow

A typical NST simulation workflow involves:

- System Initialization: Prepare initial coordinates and cell structure

- Energy Minimization: Reduce high-energy contacts and prepare a stable starting configuration

- NVT Equilibration: Equilibrate the system at the target temperature with fixed cell dimensions

- Stress Tensor Definition: Specify the external stress tensor components based on the desired deformation or stress state

- NST Production: Run extended simulations with anisotropic barostat to sample the NST ensemble

- Analysis: Calculate relevant properties including strain tensors, mechanical properties, and structural changes

For accurate NST simulations, the internal stress tensor must be correctly calculated, considering all contributions from bonded and non-bonded interactions, which for complex force fields like polarizable Gaussian Multipole (pGM) models requires specialized formulations [4].

Applications and Research Implications

Materials Science Applications

The NST ensemble is particularly valuable for studying the mechanical behavior of solids, including stress-strain relationships in polymeric and metallic materials [2]. Unlike liquids, solids resist shear deformation, making the ability to control different stress components essential for realistic simulations of mechanical loading [3]. NST simulations enable researchers to:

- Simulate phase transitions under anisotropic stress conditions

- Calculate stress-strain curves for material deformation studies

- Investigate material response to complex loading scenarios

- Determine elastic constants and mechanical properties

- Study phenomena like plasticity, fracture, and creep

For Lennard-Jones solids, ice, gypsum, and gold, anisotropic barostats have been effectively applied to study structural transformations and mechanical behavior [3].

Pharmaceutical and Biophysical Applications

In drug development and biophysical research, the choice of ensemble significantly impacts simulation outcomes. A case study comparing NPT and NVT equilibrated simulations for aluminate oligomerization demonstrated significantly different results, with NVT simulations showing the expected trend toward hexa-coordinated alumina, while NPT results indicated tetra-coordinated structures remained stable [13]. This highlights how ensemble choice can qualitatively alter scientific conclusions.

For complex biomolecular systems like the huntingtin protein exon 1 (Htt-ex1) associated with neurodegenerative diseases, appropriate ensemble selection is crucial for studying aggregation mechanisms [14]. While NPT is often preferred for biomolecular simulations in solution, NST might be relevant for studying mechanical properties of protein fibrils or membrane deformation.

Table: Ensemble Selection Guide for Different System Types

| System Type | Recommended Ensemble | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Gas-phase reactions | NVE | No environmental coupling [11] |

| Solvated biomolecules | NPT | Mimics experimental solution conditions [11] |

| Liquid systems | NPT (isotropic) | Liquids don't resist shear [3] |

| Crystalline solids | NST (anisotropic) | Allows shape relaxation [3] |

| Polymeric materials | NST | Study stress-strain relationships [2] |

| Membranes, interfaces | NST (semi-isotropic) | Constant surface tension [3] |

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Computational Tools and Software

Successful implementation of NST simulations requires specialized software and computational tools:

- GROMACS: Includes implementations of stochastic cell rescaling barostat for NST simulations [3]

- LAMMPS: Supports various anisotropic barostats for materials simulations [3]

- VASP: Implements Parrinello-Rahman algorithm for NpT simulations with ISIF=3 setting [12]

- Amber/SANDER: Contains specialized implementations for constant pressure simulations with polarizable force fields [4]

- SimpleMD: Educational MD software with basic barostat implementations [3]

Key Parameters and Theoretical Reagents

Theoretical Components for NST Simulations

From a theoretical perspective, "research reagents" for NST simulations include:

- Stress Tensor (Σ or S): Defines the external stress state with components for normal and shear stresses [3]

- Relaxation Time (τₚ): Controls the timescale of volume/shape fluctuations, typically set to 1-10 ps [3]

- Isothermal Compressibility (βₜ): System property that determines volume response to pressure changes [3]

- Fictitious Mass (PMASS): In extended Lagrangian methods, determines the inertial response of the cell [12]

- Reference Cell (h₀): Reference cell dimensions for defining strain in variable-cell simulations [3]

- Friction Coefficients (LANGEVINGAMMAL): Control coupling to the pressure bath for stochastic methods [12]

The choice between NPT and NST ensembles represents a critical decision point in molecular dynamics simulation design. While NPT ensembles suffice for isotropic systems like liquids and solvated molecules, NST ensembles provide essential capabilities for studying anisotropic materials under complex stress states. The development of advanced barostat algorithms, particularly first-order stochastic methods, has improved the stability and sampling efficiency of constant-stress simulations.

For researchers in drug development and materials science, understanding these distinctions enables more physiologically and physically realistic simulations. As MD applications expand to increasingly complex systems, appropriate ensemble selection remains fundamental to generating meaningful, predictive computational results.

In the realm of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the stress tensor is a fundamental quantity that provides a complete description of the mechanical state of a system at the atomic scale. Unlike the single scalar value of pressure used for isotropic fluids, the stress tensor is essential for understanding how forces are distributed internally within a material, especially when those forces are direction-dependent or anisotropic [15]. In the context of advanced statistical ensembles, particularly the constant-stress NST ensemble, a precise understanding of the stress tensor components is crucial for simulating realistic conditions that materials experience in experimental settings, from biological systems under mechanical stress to the deformation of crystalline solids [2] [15]. The NST ensemble, which allows for independent control of the temperature and the various components of the stress tensor, is the preferred method for studying phenomena such as phase transitions and stress-strain relationships in complex materials [2].

This technical guide decodes the six independent components of the symmetric stress tensor, explaining their physical significance, their calculation from first principles in MD, and their critical role in governing the dynamics of the NST ensemble. For researchers in drug development, this knowledge is instrumental in simulating the mechanical properties of pharmaceutical crystals, the interaction of drugs with flexible protein targets, or the behavior of biomaterials under non-isotropic stress.

Mathematical Foundations of the Stress Tensor

In continuum mechanics, the Cauchy stress tensor, denoted by σ, is a second-rank tensor that describes the state of stress at a point within a material [16]. The tensor is represented as a 3x3 matrix:

[ \sigma = \begin{pmatrix} \sigma{xx} & \sigma{xy} & \sigma{xz} \ \sigma{yx} & \sigma{yy} & \sigma{yz} \ \sigma{zx} & \sigma{zy} & \sigma_{zz} \end{pmatrix} ]

The fundamental principle states that the stress vector T acting on a surface with a unit normal vector n is given by the linear transformation T = n · σ [16]. For a system in static equilibrium, conservation of angular momentum requires that the stress tensor is symmetric [16]. This symmetry implies that:

(\sigma{xy} = \sigma{yx}, \quad \sigma{xz} = \sigma{zx}, \quad \sigma{yz} = \sigma{zy})

Consequently, only six of the nine components are independent, forming the set {σₓₓ, σᵧᵧ, 𝓏𝓏, σₓᵧ, σₓ𝓏, σᵧ𝓏} that fully defines the stress state [17].

In molecular dynamics, the macroscopic stress tensor is derived from the microscopic states and interactions of the atoms. The total stress tensor in an MD simulation is the sum of two distinct parts: a kinetic energy contribution from atomic motion and a virial (or configurational) contribution from interatomic forces [18]. The general expression for the total stress tensor is:

[ \sigma^{\alpha\beta} = \frac{W^{\alpha\beta} + \sum{i} mi vi^{\alpha} vi^{\�}}{V} ]

Here, (W^{\alpha\beta}) is the virial tensor, (mi) is the mass of atom *i*, (vi^{\alpha}) is the velocity component of atom i in the α-direction, and V is the volume of the system [18]. The virial tensor itself is calculated from the interatomic forces and positions. For a simple pairwise force formulation, the virial can be expressed as ( \mathbf{W} = -\frac{1}{2} \sum{i} \sum{j \neq i} \boldsymbol{r}{ij} \otimes \boldsymbol{F}{ij} ), where (\boldsymbol{r}{ij}) is the position vector between atoms *i* and *j*, and (\boldsymbol{F}{ij}) is the force on atom i due to atom j [18].

Physical Interpretation of the Tensor Components

Diagonal Components (Normal Stresses)

The diagonal components of the stress tensor (σₓₓ, σᵧᵧ, σ𝓏𝓏) are known as the normal stresses. They represent the force per unit area acting perpendicular to the coordinate planes. Physically, σₓₓ is the stress acting normal to the plane perpendicular to the x-axis, and similarly for σᵧᵧ and σ𝓏𝓏 [17] [15].

- Tensile and Compressive Stress: In the sign convention commonly used in materials science and engineering, a positive value for a normal stress indicates tensile stress, which acts to pull the system apart along that axis. A negative value indicates compressive stress, which acts to push the system together [15].

- Pressure Relationship: In an isotropic fluid at equilibrium, the normal stresses are equal in all directions ((\sigma{xx} = \sigma{yy} = \sigma{zz})) and are related to the thermodynamic pressure *P* by (\sigma{xx} = \sigma{yy} = \sigma{zz} = -P), where the negative sign arises from the convention that pressure is positive for compression [15].

Off-Diagonal Components (Shear Stresses)

The off-diagonal components of the stress tensor (σₓᵧ, σₓ𝓏, σᵧ𝓏) are known as the shear stresses. They represent the forces per unit area acting parallel to the coordinate planes. For instance, σₓᵧ represents the stress in the y-direction acting on the plane perpendicular to the x-axis [17] [15].

- Symmetry and Stress Coupling: The symmetry of the stress tensor (σₓᵧ = σᵧₓ) means that the shear stress component that would cause a rotation around the z-axis is balanced, ensuring no unphysical rotation of the material element occurs [17].

- Inducing Shape Change: The presence of non-zero shear stresses indicates that the system is experiencing forces that tend to change its shape without changing its volume, such as during a shearing deformation.

Table 1: Interpretation of the Six Independent Stress Tensor Components

| Component | Name | Physical Interpretation | Sign Convention (Engineering) |

|---|---|---|---|

| σₓₓ | Normal Stress | Force/Area normal to YZ-plane (x-direction) | Positive = Tension; Negative = Compression |

| σᵧᵧ | Normal Stress | Force/Area normal to XZ-plane (y-direction) | Positive = Tension; Negative = Compression |

| σ𝓏𝓏 | Normal Stress | Force/Area normal to XY-plane (z-direction) | Positive = Tension; Negative = Compression |

| σₓᵧ | Shear Stress | Force in y-dir. on plane normal to x-dir. | Positive in direction of increasing axis |

| σₓ𝓏 | Shear Stress | Force in z-dir. on plane normal to x-dir. | Positive in direction of increasing axis |

| σᵧ𝓏 | Shear Stress | Force in z-dir. on plane normal to y-dir. | Positive in direction of increasing axis |

The following diagram illustrates the physical meaning of these components on a unit cube of material:

Calculation in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

The accurate calculation of the stress tensor is paramount for faithful MD simulations, especially in the NST ensemble. The methodology hinges on the virial theorem, which connects the macroscopic stress to the microscopic atomic motions and interactions [15].

The Virial Theorem and Stress Formulation

The instantaneous pressure function P in an MD simulation is defined from the virial, given by:

[ P = \frac{2}{3V} \left[ \sumi \frac{1}{2} mi vi^2 + \frac{1}{2} \sumi \sum{j \neq i} \boldsymbol{r}{ij} \cdot \boldsymbol{f}_{ij} \right] ]

Here, the first term is the kinetic energy contribution, and the second term is the virial contribution from interatomic forces [15]. This scalar pressure is extended to the tensor form by considering the contributions along specific directions. The general expression for the total stress tensor component σᵅᵝ is [18]:

[ \sigma^{\alpha\beta} = \frac{1}{V} \left[ \sum{i} mi vi^{\alpha} vi^{\beta} + W^{\alpha\beta} \right] ]

Where (W^{\alpha\beta}) is the αβ-component of the virial tensor. For a system with periodic boundary conditions—essential for simulating bulk materials—the calculation must account for interactions between atoms in the primary unit cell and their periodic images. When using pairwise interactions, the virial contribution can be efficiently computed as [15]:

[ W = \frac{1}{2} \sum{i} \sum{j \neq i} \boldsymbol{r}{ij} \otimes \boldsymbol{f}{ij} ]

Advanced Electrostatics and Polarizability

For force fields that include polarizability, such as the polarizable Gaussian Multipole (pGM) model, the derivation of the internal stress tensor becomes more complex [4]. The total electrostatic energy includes contributions from permanent charges, permanent (covalent) dipoles, and induced dipoles. The stress tensor (virial) must be derived by differentiating the system's Lagrangian with respect to the system shape parameters (the matrix h formed by the unit cell vectors) [4]:

[ \vec{V}{pGM} = -\frac{\partial U{pGM}}{\partial h} \cdot h^T ]

This requires identifying all quantities that depend on the simulation box size and shape, including atomic coordinates, covalent dipoles defined relative to molecular geometry, the system volume, and the reciprocal lattice vectors used in Ewald summation for long-range electrostatics [4]. Formulations have been derived for flexible, rigid, and short-range screened systems to enable constant-pressure MD simulations with advanced polarizable force fields [4].

The Stress Tensor in the NST Ensemble

The Constant-Stress Ensemble

The NST ensemble is a cornerstone for simulating materials under specific mechanical boundary conditions. It is an extension of the constant-pressure ensemble (NPT) that allows for independent control of the six components of the stress tensor, in addition to the temperature and the number of particles [2]. This ensemble is "constant-stress" because the externally applied stress tensor is a controlled parameter, and the system's cell vectors are allowed to fluctuate in response to maintain equilibrium with this applied stress [15]. This is particularly useful for studying the stress-strain relationship in polymeric or metallic materials, where the response to non-isotropic (directional) stress is of primary interest [2].

The Parrinello-Rahman Method

The most common method for implementing the NST ensemble in MD simulations is the Parrinello-Rahman method [15]. This technique allows both the size and the shape of the simulation cell to change dynamically in response to the imbalance between the internal stress of the system and an externally applied target stress.

- Lagrangian Formulation: The core of the method is a modification of the system's Lagrangian to include terms representing the kinetic energy of the cell itself (governed by a user-defined fictitious mass W) and an elastic energy potential related to the applied stress [15].

- Equations of Motion: New equations of motion are derived for both the atomic coordinates and the cell vectors. The motion of the cell vectors is driven by the difference between the internal stress tensor, calculated via the virial, and the externally applied target stress tensor [15].

- Elastic Energy Term: For simulations under a full stress tensor, the elastic energy term ( p ) in the Lagrangian is given by [15]: [ p = V \sum{\alpha,\beta} (S{\alpha\beta}^{ext} - P^{ext}\delta{\alpha\beta}) (h^{-1}){\alpha\beta} ] Here, ( S^{ext} ) is the external stress tensor, ( P^{ext} ) is the external pressure, ( V ) is the cell volume, ( h ) is the matrix of cell vectors, and ( \delta_{\alpha\beta} ) is the Kronecker delta.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the feedback loop at the heart of the Parrinello-Rahman method in an NST simulation:

Practical Considerations and Parameters

Successful application of the NST ensemble requires careful parameter selection:

- Fictitious Cell Mass (W): This parameter controls the timescale of the cell fluctuations. A large W results in slow, heavy cell motion, which, in the limit of infinity, reverts to constant-volume dynamics. A small W allows the cell to change rapidly but can induce artificial periodic motions and prevent proper equilibration. A default value of 20 has been found satisfactory for some polymer systems, but testing is required [15].

- Stress Fluctuations and Cutoff: The instantaneous internal stress tensor can exhibit significant fluctuations and may even be negative. The calculated stress is sensitive to the non-bonded interaction cutoff distance; a cutoff that is too short can lead to inaccurate averages. It is recommended to test the effect of the cutoff distance on the measured stress [15].

Table 2: Key Parameters for an NST Ensemble MD Simulation

| Parameter | Symbol/Name | Description | Considerations for Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Stress Tensor | σ_ext |

The 6 independent components of the externally applied stress. | Set based on experimental conditions or the specific stress state to be studied. |

| Cell Mass | W (Parrinello-Rahman) |

A fictitious mass governing the inertia of the simulation cell. | Too small: artificial cell oscillations. Too large: slow stress equilibration. Requires testing. |

| Pressure Relaxation Time | τ_p (Berendsen) |

The time constant for pressure scaling. | Relevant for isotropic pressure control. Not used in full Parrinello-Rahman. |

| Isotropic Compressibility | β |

The compressibility of the system, used in some methods like Berendsen. | User-defined. An estimate is needed for the pressure bath coupling. |

| Interaction Cutoff | r_c |

The distance cutoff for non-bonded interactions. | A short cutoff can lead to inaccurate stress calculations. Test for convergence. |

Experimental Protocol: Setting Up an NST Simulation

This section provides a detailed methodology for setting up and running a molecular dynamics simulation in the NST ensemble, using the Parrinello-Rahman method as an example.

System Preparation and Minimization

- Initial Coordinates and Box: Obtain the initial atomic coordinates for the system of interest (e.g., a protein, a crystal, or a polymer). Place the system in a simulation box with periodic boundary conditions. The initial box shape should be chosen appropriately; for example, a cubic box for an isotropic system or an orthorhombic box for a system with known anisotropy.

- Energy Minimization: Perform a series of energy minimizations to remove any bad contacts or steric clashes in the initial structure. This is typically done first with positional restraints on the solute to relax solvent/solute interactions, followed by a full minimization without restraints.

- Initial Equilibration: Equilibrate the system in the NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) for a suitable duration (e.g., 100-500 ps). This allows the system to reach the target temperature and stabilizes the velocities before introducing stress control.

NST Production Simulation

- Parameter Specification: In the MD input configuration, specify the ensemble type as

NST(or the equivalent keyword for your software). Set the target temperature and the six components of the target stress tensor (sxx,syy,szz,sxy,sxz,syz). For hydrostatic pressure, setsxx=syy=szz=Pand the shear components to zero. - Setting the Cell Mass: Define the Parrinello-Rahman fictitious mass parameter

W. If no prior knowledge exists, start with the software's default value (e.g., 20 in some packages [15]) and monitor the box fluctuation and stability. Adjust if necessary to avoid large oscillations. - Run Configuration: Execute the production simulation for a duration sufficient to sample the desired properties. For many materials, this may require tens to hundreds of nanoseconds. The timestep should be chosen carefully, typically 1-2 fs for systems with light atoms and fast vibrations, to ensure energy conservation and stability [9].

- Trajectory and Data Output: Configure the output to save the atomic trajectory at regular intervals. Crucially, also output the time evolution of the simulation box vectors (cell lengths and angles), the internal stress tensor components, the density, and the system energy.

Analysis and Validation

- Equilibration Check: Plot the time series of the box vectors, density, and potential energy. Discard the initial part of the trajectory where these quantities show a clear drift, and use only the equilibrated portion for analysis.

- Stress and Pressure: Calculate the average and fluctuations of the internal stress tensor components from the production trajectory. Verify that the average internal stress matches the applied target stress, confirming that the system has reached a state of mechanical equilibrium.

- Property Calculation: From the equilibrated NST trajectory, compute the structural and dynamic properties of interest, such as radial distribution functions, diffusion coefficients, or stress-strain correlations.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Stress Tensor Simulations

| Item / Software | Category | Function in Research | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | MD Software Package | Implements force fields, dynamics integrators, and ensembles like NST for biomolecular simulations. | Used in studies implementing stress tensor for polarizable models like pGM [4]. |

| Discover | MD Software Package | Provides tools for dynamics in various ensembles (NVE, NVT, NPT, NST) and pressure/stress control methods. | Offers Berendsen and Parrinello-Rahman methods for pressure/stress control [15]. |

| Parrinello-Rahman Algorithm | Computational Method | The primary algorithm for performing MD in the NST ensemble, allowing cell shape and size to fluctuate. | Essential for studying phase transitions and material properties under non-isotropic stress [15]. |

| Polarizable Force Field (e.g., pGM) | Force Field | A more advanced physical model that explicitly accounts for electronic polarization, improving the accuracy of stress calculations. | pGM model screens short-range electrostatic interactions to avoid "polarization catastrophe" [4]. |

| Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) | Computational Algorithm | A standard method for accurately and efficiently calculating long-range electrostatic forces and their contribution to the virial in periodic systems. | Critical for a correct evaluation of the electrostatic part of the stress tensor [4]. |

| Berendsen Barostat | Computational Method | A simpler method for pressure control that scales coordinates and box size isotropically. Does not control shear stress. | Suitable for pre-equilibration or for liquid systems where shape change is not required [15]. |

The Role of NST in Studying Stress-Strain Relationships

The constant-temperature, constant-stress ensemble (NST) represents a specialized framework in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, extending capabilities beyond conventional constant-pressure ensembles. While the constant-pressure, constant-temperature (NPT) ensemble applies hydrostatic pressure isotropically, the NST ensemble provides granular control over the individual components of the stress tensor, enabling detailed investigation of anisotropic deformation and material response under mechanical stress [2]. This technical guide examines the foundational principles, implementation methodologies, and practical applications of NST simulations, with emphasis on its critical role in elucidating stress-strain relationships at the molecular level for biomedical and materials research.

Within the hierarchy of statistical ensembles, NST occupies a unique position by allowing researchers to control the xx, yy, zz, xy, yz, and zx components of the stress tensor, sometimes termed the pressure tensor [2]. This capability proves particularly valuable when studying stress-strain relationships in complex molecular systems, including polymeric biomaterials and pharmaceutical compounds, where directional mechanical properties significantly influence functionality and stability. The NST ensemble facilitates direct simulation of experimental conditions such as uniaxial tension, biaxial compression, and pure shear, bridging computational predictions with empirical observations.

Theoretical Foundations of NST Simulations

Statistical Mechanical Basis

The NST ensemble maintains constant particle number (N), constant stress (σ), and constant temperature (T), with the stress tensor serving as the controlled variable rather than a scalar pressure value. The statistical mechanical formulation of this ensemble derives from the isostress-isothermal partition function, which describes system behavior under these constraints. Within this framework, the simulation cell vectors become dynamic variables that fluctuate in response to the applied stress tensor, allowing the system to find its equilibrium shape and volume under the specified external stress conditions.

The equations of motion in NST simulations incorporate additional terms accounting for the coupling between the system and the stress bath, analogous to temperature coupling in canonical ensembles. Proper implementation requires careful specification of the stress tensor components, which may include both diagonal (normal stresses) and off-diagonal (shear stresses) elements. This specification enables researchers to simulate diverse loading scenarios, from hydrostatic compression to complex shear deformation patterns relevant to biological interfaces and drug delivery systems.

Comparison of MD Statistical Ensembles

Table 1: Characteristics of Primary Statistical Ensembles in Molecular Dynamics

| Ensemble | Constant Parameters | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVE | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Energy (E) | Studying energy conservation; exploring constant-energy conformational space | Not suitable for equilibration; temperature drift may occur |

| NVT | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Conformational sampling without pressure effects; standard for vacuum simulations | Constant volume may not reflect experimental conditions |

| NPT | Number of particles (N), Pressure (P), Temperature (T) | Simulating biological conditions; achieving correct density and pressure | Only isotropic pressure control; limited for anisotropic materials |

| NST | Number of particles (N), Stress (σ), Temperature (T) | Studying stress-strain relationships; anisotropic deformation analysis | Complex setup; requires careful stress tensor specification |

Implementation and Protocol Design

Workflow for NST Simulations

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for implementing NST ensemble simulations, from system preparation through analysis:

System Preparation and Force Field Selection

Initial system preparation requires careful attention to atomic-level details that influence mechanical properties. For biomolecular systems, this includes completing missing residues, adding hydrogen atoms, and assigning appropriate protonation states consistent with physiological conditions [19]. Force field selection critically influences simulation outcomes, with popular choices including AMBER99SB-ILDN for proteins [20] [19], CHARMM36 for biomolecules [20], and specialized force fields like TraPPE-UA for organic compounds and materials [21]. The selection should be guided by the specific system under investigation and validated against known experimental data where possible.

For stress-strain investigations, particular attention must be paid to the treatment of nonbonded interactions, which significantly contribute to mechanical response. Long-range electrostatic interactions typically employ particle mesh Ewald (PME) summation, while van der Waals interactions utilize a cutoff scheme with potential shift functions or switching functions to ensure smooth truncation. The water model must be compatible with the chosen force field, with TIP3P [19], TIP4P-EW [20], and SPC/E representing common choices for aqueous biological systems.

Equilibration Protocol

Before initiating production NST simulations, systems must undergo careful equilibration to establish stable baseline conditions. A typical protocol proceeds through multiple stages:

Energy Minimization: Initial steepest descent minimization (500-1000 steps) followed by conjugate gradient minimization (500-1000 steps) relieves steric clashes and incorrect geometries [20]. Positional restraints on protein or polymer heavy atoms (force constant 100-1000 kJ/mol/nm²) may be applied during initial minimization stages.

Solvent Equilibration: Solvent and ions are relaxed while maintaining restraints on solute atoms, typically running for 50-100 ps in the NVT ensemble with temperature coupling using algorithms like Berendsen thermostat or velocity rescale.

Full System Equilibration: All restraints are removed, and the system evolves in the NPT ensemble for 1-5 ns using advanced thermostats (Nosé-Hoover, velocity rescale) and barostats (Parrinello-Rahman) to achieve target temperature and pressure [22].

Only after successful equilibration, confirmed by stable potential energy, temperature, pressure, and density, should production NST simulations commence.

Production Simulation Parameters

Production NST simulations require specific parameterization to maintain constant stress conditions:

Stress Tensor Specification: Define all six independent components of the stress tensor (σxx, σyy, σzz, σxy, σxz, σyz) according to the desired loading conditions. For uniaxial tension, only one diagonal component would be non-zero; for pure shear, specific off-diagonal components would be specified.

Barostat Coupling: Employ extended Lagrangian approaches, such as the Parrinello-Rahman barostat, which treats simulation cell vectors as dynamic variables. The coupling constant typically ranges from 2-10 ps, determining how rapidly the cell responds to stress imbalances.

Integration Parameters: Use timesteps of 1-2 fs for all-atom systems with bonds involving hydrogen atoms constrained using LINCS or SHAKE algorithms [20]. For coarse-grained representations, longer timesteps (10-30 fs) may be possible [22].

Simulation Duration: Conduct simulations for sufficient duration to observe relevant structural responses to applied stress, typically ranging from nanoseconds for small molecules to microseconds for complex biomolecules [20] [22].

Analysis Methods for Stress-Strain Relationships

Mechanical Property Calculation

The NST ensemble enables direct computation of key mechanical properties through monitoring system response to applied stress:

Elastic Constants: The stiffness tensor components Cij can be derived from stress-strain fluctuations or direct deformation simulations.

Young's Modulus: Calculated from uniaxial deformation simulations by applying tensile stress along one axis while allowing lateral contraction.

Shear Modulus: Determined from simulations with applied shear stress components.

Bulk Modulus: Computed from volume fluctuations during isotropic stress application.

These properties emerge from analysis of the simulation trajectory, particularly the relationship between applied stress tensor components and the resulting strain tensor, which is computed from the simulation cell vectors over time.

Structural Analysis Techniques

Complementary analysis methods provide molecular-level insights into structural changes under stress:

Radial Distribution Functions (RDFs): Reveal changes in local packing and intermolecular interactions under deformation [21].

Angular Distribution Functions (ADFs): Quantify changes in molecular orientation and bonding angles under stress [21].

Dihedral Angle Distributions: Monitor conformational changes in polymer backbones or biomolecular structures during deformation.

End-to-End Distance Analysis: Particularly relevant for polymeric systems, tracking chain extension under tensile stress [21].

Table 2: Key Analytical Methods for Stress-Strain Characterization

| Analysis Method | Structural Information | Relevance to Mechanical Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Stress-Strain Correlation | Direct mechanical response | Elastic constants, yield strength, failure points |

| Radial Distribution Functions | Interatomic packing density | Changes in local order under deformation |

| Angular Distribution | Bond angle deformation | Bending rigidity, anisotropic response |

| Dihedral Angle Distribution | Molecular conformation changes | Chain stiffness, torsional resistance |

| Domain Distance Analysis | Global structural changes | Molecular extensibility, unfolding behavior |

Research Toolkit for NST Simulations

Implementation of NST simulations requires specialized software packages, each with distinct capabilities:

LAMMPS (Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator): A highly flexible MD code with comprehensive support for various stress ensembles, including NST simulations with full stress tensor control [21]. Particularly well-suited for complex materials and nanoscale systems.

GROMACS: A high-performance MD package optimized for biomolecular systems, with capabilities for constant-stress simulations using Parrinello-Rahman barostat [23] [19]. Known for exceptional computational efficiency on CPU and GPU architectures.

NAMD: A parallel MD code designed for large biomolecular systems, supporting constant-stress simulations with extensive thermostating and barostating options [20].

AMBER: Specialized for biomolecular simulations, with implementations supporting constant-stress conditions through the Berendsen and Monte Carlo barostats [20].

Automation tools such as StreaMD provide streamlined workflows for MD simulations, handling system preparation, parameterization, and execution across distributed computing environments [19]. These tools reduce the expertise required for proper simulation setup while ensuring consistent implementation of best practices.

Force Fields and Parameterization

Accurate force field selection is paramount for reliable NST simulations:

AMBER99SB-ILDN: A widely used force field for proteins, providing improved side-chain torsion potentials and Lindorff-Larsen et al. corrections for enhanced conformational sampling [20] [19].

CHARMM36: An all-atom force field for proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, with optimized parameters for biomolecular simulations under mechanical stress [20].

Martini: A coarse-grained force field enabling simulation of larger systems and longer timescales, particularly useful for complex biomolecular assemblies and polymers [22]. Recent version 3 improvements better capture protein-solvent interactions.

TraPPE-UA: A united-atom force field optimized for hydrocarbons and organic compounds, validated for thermophysical properties under varying pressure conditions [21].

Applications in Biomedical Research

The NST ensemble provides unique insights into molecular-scale mechanical phenomena relevant to drug development and biomedical engineering. By simulating specific stress conditions, researchers can probe deformation mechanisms in pharmaceutical crystals, protein aggregates, lipid membranes, and polymeric delivery systems. These simulations reveal molecular responses to mechanical stress that complement experimental techniques like atomic force microscopy, nanoindentation, and rheology.

For drug development professionals, NST simulations offer predictive capabilities for formulation stability, tablet compaction behavior, and mechanical properties of biopharmaceuticals. The ability to simulate anisotropic mechanical response at atomic resolution enables rational design of materials with tailored mechanical properties, contributing to improved drug delivery systems and biomedical devices with optimized performance characteristics.

The constant-stress NST ensemble represents a powerful methodology within the molecular dynamics toolkit, enabling detailed investigation of stress-strain relationships at atomic resolution. Through careful implementation of the protocols outlined in this technical guide, researchers can leverage this approach to uncover fundamental mechanisms of mechanical response in diverse molecular systems. As force fields continue to improve and computational resources expand, NST simulations will play an increasingly vital role in bridging molecular structure with macroscopic mechanical properties across biomedical and materials research domains.

The fundamental goal of statistical mechanics is to describe the macroscopic properties of matter by starting from the laws governing its microscopic constituents, namely atoms and electrons. [24] This theoretical framework, laid down in the 19th century by Boltzmann and Gibbs, is built upon the atomistic hypothesis: matter is made of particles obeying Newton's equations. [24] The core challenge is that directly solving the equations of motion for a system of Avogadro's number of particles is impossible. Instead, statistical mechanics provides a bridge between the microscopic and macroscopic worlds through the concept of ensembles. [25]

An ensemble, or statistical ensemble, is an idealization consisting of a large number of copies of a system, considered all at once, each of which represents a possible state that the real system might be in. [25] A thermodynamic ensemble is a statistical ensemble that is in statistical equilibrium. It provides a powerful method to derive the properties of real thermodynamic systems from the laws of classical and quantum mechanics by replacing impractical time averages with ensemble averages. [24] This document details the role of these ensembles as the foundational bedrock for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, with a specific focus on the constant-stress NST ensemble and its applications in modern research, including drug development.

Foundational Theory of Ensembles

The Microcanonical (NVE) Ensemble

The microcanonical ensemble represents a system that is completely isolated from its surroundings. [25] There is no transfer of energy or matter, and the system's volume remains fixed. In other words, this is a physical system where the total number of particles (N), the total volume (V), and the total energy (E) are constant, leading to its abbreviation as the NVE ensemble. [2] [25]

In this ensemble, the total energy is a constant, but temperature is not a defined variable. [25] Temperature can only be meaningfully defined for systems that are in thermal contact with their surroundings. Isolated systems are described solely by their composition, volume, and total energy. In the context of MD, the NVE ensemble is generated by solving Newton's equations of motion without any temperature or pressure control. [2] Although energy conservation is the ideal, slight energy drift can occur due to numerical rounding and truncation errors during the integration process. [2] Constant-energy simulations are less suited for equilibration but are valuable for exploring the constant-energy surface of conformational space during data collection without the perturbations introduced by thermostat or barostat coupling. [2]

The Canonical (NVT) Ensemble

The canonical ensemble describes a system whose volume is fixed and which is immersed in a large heat bath at a constant temperature (T), allowing energy to transfer across the boundary, but not matter. [25] This ensemble is defined by a constant number of particles, constant volume, and constant temperature, hence the abbreviation NVT. [2]

Because the system and surroundings are in thermal contact, heat is exchanged until thermal equilibrium is reached. Unlike the microcanonical ensemble, the temperature (T) in the canonical ensemble is a defined constant. [25] This ensemble is critically important for calculating the Helmholtz free energy (A) of a system, which represents the maximum amount of work a system can perform at constant volume and temperature. [25] In MD simulations, this is the default ensemble for many scenarios, particularly for conformational searches of molecules in vacuum without periodic boundary conditions, where volume, pressure, and density are not defined. [2] It is also appropriate when pressure is not a significant factor, as it introduces less perturbation to the trajectory than constant-pressure methods. [2]

The Isothermal-Isobaric (NPT) Ensemble

The isothermal-isobaric ensemble models a system that can exchange energy with its surroundings and whose volume can change to ensure its internal pressure matches the constant external pressure applied by the surroundings. [25] This ensemble maintains a constant number of particles, constant temperature (T), and constant pressure (p), leading to its abbreviation NpT. [25]

This ensemble is exceptionally important in chemistry and pharmacology since most experimental conditions, including crucial chemical reactions and biological processes, occur under constant pressure. [25] The NPT ensemble plays a vital role in describing the Gibbs free energy (G) of a system, which is the maximum amount of work a system can do at constant pressure and temperature. [25] In MD, this ensemble is the preferred choice when correct pressure, volume, and system density are critical for the simulation. [2] It is also highly effective for equilibration to achieve a desired temperature and pressure before potentially switching to another ensemble for production data collection. [2]

The Constant-Pressure, Constant-Enthalpy (NPH) Ensemble

The constant-pressure, constant-enthalpy ensemble is the analogue of the constant-volume, constant-energy (NVE) ensemble but under constant pressure conditions. [2] In this NPH ensemble, the enthalpy (H), which is the sum of the internal energy (E) and the product of pressure and volume (PV), remains constant while the pressure is kept fixed without any temperature control. [2] This ensemble is less commonly used for routine simulation but serves specific purposes in theoretical studies and advanced sampling.

Table 1: Summary of Key Thermodynamic Ensembles in Molecular Simulation

| Ensemble Name | Abbreviation | Constant Variables | Key Applications and Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microcanonical | NVE | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Energy (E) | Exploring constant-energy surfaces; foundation of basic MD. [2] [25] |

| Canonical | NVT | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Conformational searches at fixed volume; Helmholtz free energy. [2] [25] |

| Isothermal-Isobaric | NPT | Number of particles (N), Pressure (P), Temperature (T) | Mimicking standard lab conditions; Gibbs free energy; system density. [2] [25] |

| Constant-Stress | NST | Number of particles (N), Stress (S), Temperature (T) | Studying stress-strain relationships in complex materials. [2] |

| Constant-Enthalpy | NPH | Number of particles (N), Pressure (P), Enthalpy (H) | Theoretical studies; constant-enthalpy processes. [2] |

The Constant-Stress (NST) Ensemble in Molecular Dynamics

Theoretical Definition and Relation to Other Ensembles

The constant-stress ensemble, abbreviated as the NST ensemble, is a sophisticated and powerful extension of the constant-pressure (NPT) ensemble. [2] While the NPT ensemble typically controls the hydrostatic pressure applied isotropically (the same in all directions), the NST ensemble provides granular control over the individual components of the stress tensor, also known as the pressure tensor. [2] This tensor includes the three normal stress components (xx, yy, zz) and the three shear stress components (xy, yz, zx). [2] By allowing independent control over these six components, the NST ensemble enables researchers to simulate complex mechanical conditions beyond simple isotropic compression or expansion.

Key Applications in Research

The NST ensemble is particularly powerful for investigating the stress-strain relationship in a wide range of materials. [2] This capability is indispensable in fields like polymer science and metallurgy, where understanding how materials deform under complex, anisotropic (direction-dependent) stress is critical for designing new materials with tailored mechanical properties. For instance, simulating the application of shear stress can reveal how a crystalline metal will plastically deform or how a polymer chain will align and stretch. Furthermore, in drug development, the mechanical properties of drug delivery carriers, such as polymeric nanoparticles or lipid bilayers, can be probed using these methods to predict their stability and release kinetics under physiological stress.

Molecular Dynamics Methodology and Ensembles

The Molecular Dynamics Algorithm

Molecular dynamics simulation is a computational technique that generates a trajectory of a system of particles by numerically integrating their equations of motion. [26] [9] The core algorithm can be summarized in a few key steps, as implemented in software packages like GROMACS. [26]

- Input Initial Conditions: The simulation requires an initial set of particle positions (r), potential interaction (V) as a function of these positions, and optionally, initial velocities (v). If velocities are not provided, they are typically generated from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at a given temperature. [26]

- Compute Forces: At each step, the force on each atom (Fi) is computed as the negative gradient of the potential energy with respect to its position (Fi = -∂V/∂ri). This involves summing forces from non-bonded interactions (e.g., van der Waals and electrostatic) and bonded interactions (e.g., bonds, angles, dihedrals). [26] [9]

- Update Configuration: The atoms' positions and velocities are updated by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion: d²ri/dt² = Fi/mi, where mi is the mass of the atom. [26] [9] This is done using integrators like the Verlet leapfrog or Verlet velocity algorithms. [26] [9]

- Output: At specified intervals, properties such as positions, velocities, energies, temperature, and pressure are written to output files for analysis. [26]

This cycle is repeated for the millions of steps required to simulate a meaningful period of time.

Integrating Ensembles into MD: Thermostats and Barostats

The basic MD algorithm naturally conserves energy, simulating the NVE ensemble. To simulate other ensembles like NVT, NPT, or NST, the algorithm must be modified to maintain constant temperature or pressure. This is achieved by coupling the system to an external heat bath (thermostat) and/or pressure bath (barostat). [2]

- Temperature Control (for NVT, NPT, NST): The system is coupled to a heat bath at a defined temperature. This allows energy to flow between the system and the bath, maintaining a constant temperature on average. This is crucial for mimicking experimental conditions where temperature is controlled. [2] [25]

- Pressure/Stress Control (for NPT, NST): For constant-pressure simulations, the volume of the simulation box is allowed to change. In the NPT ensemble, this adjustment is typically isotropic. In the NST ensemble, the box vectors are adjusted more flexibly to maintain the specified values for the individual components of the stress tensor, allowing for anisotropic deformation of the simulation cell. [2]

Table 2: Essential "Research Reagent Solutions" for Ensemble-Based MD Simulations

| Item / Component | Function in the Simulation | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field | Provides the potential energy function (V) to calculate forces between atoms. Defines bonded and non-bonded interactions. [27] [9] | Choice is critical (e.g., EAM for metals [28], Morse for interfaces [28]). Accuracy vs. computational cost trade-off. [27] [29] |

| Integration Algorithm | Numerically solves Newton's equations of motion to update atomic positions and velocities over time. [9] | Verlet variants (leapfrog, velocity) are popular for stability and efficiency. [26] [9] The timestep must be chosen carefully (e.g., 1-2 fs for atomistic) to avoid instability. [9] |

| Thermostat | Acts as a heat bath to maintain the system at a constant temperature (for NVT, NPT, NST). [2] | Prevents energy drift and ensures correct sampling of the canonical ensemble. Different algorithms (e.g., Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen) have different properties. |

| Barostat / Stressostat | Maintains constant pressure or stress by adjusting the simulation box volume and shape. [2] | Essential for NPT and NST ensembles. Allows control of isotropic pressure (NPT) or full stress tensor (NST). |

| Periodic Boundary Conditions | Mimics a macroscopic system by treating the simulation box as a repeating unit cell, minimizing surface effects. [26] | Crucial for simulating liquids and solids. Requires careful handling of long-range interactions. |

| Neighbor Search Algorithm | Efficiently identifies atom pairs within interaction range, a computationally demanding step. [26] | Verlet cut-off scheme with a buffer is standard for efficiency and accuracy, updated periodically. [26] |

Workflow for an NST Ensemble MD Simulation

The following diagram outlines a generalized protocol for setting up and running an MD simulation in the NST ensemble, incorporating the key components listed above.

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- System Preparation: Construct the initial atomic coordinates of the molecule or material system (e.g., a protein, polymer, or metal crystal). Solvate the system in a suitable solvent if required, and add ions to neutralize the system's charge. [26]

- Force Field Selection: Choose and assign an appropriate force field. The force field defines the potential energy function and is paramount for accuracy (e.g., using an EAM potential for a metallic alloy system or a specific bio-oriented force field for a protein). [28]

- Energy Minimization: Perform an energy minimization on the initial structure. This step removes any bad contacts, high strains, or unphysical geometries that could cause the simulation to become unstable, especially in the first steps of dynamics. [9]

- NVT Equilibration: Begin dynamics by equilibrating the system in the NVT ensemble for a suitable duration. This allows the system to reach the target temperature while the volume is held fixed. The temperature is controlled by a thermostat. [2]

- NST Equilibration: Switch to the NST ensemble, applying the desired stress tensor components (e.g., specific shear or normal stresses). The system's box size and shape are now allowed to fluctuate to reach the target stress state while the thermostat maintains temperature. This step ensures the system is at the correct density and internal stress before data collection. [2]

- NST Production Run: Once equilibrated, a long production run is performed in the NST ensemble. This trajectory is used for analysis, as it samples the system's configurations according to the NST statistical distribution.

- Trajectory & Data Analysis: Analyze the production trajectory to compute properties of interest. For the NST ensemble, this could include stress-strain curves, material moduli, analysis of structural changes under stress, or diffusion coefficients under mechanical load.

Thermodynamic ensembles are not merely abstract concepts in statistical mechanics; they are the very foundation that enables molecular dynamics to serve as a powerful, predictive tool across scientific disciplines. From the fundamental NVE ensemble to the experimentally relevant NPT and the mechanically sophisticated NST ensemble, each provides a unique statistical lens through which to view and manipulate molecular systems. The NST ensemble, in particular, extends the reach of MD into the critical area of materials mechanics, allowing researchers to probe deformation and failure mechanisms at the atomic scale. As MD continues to evolve, integrating with machine learning and benefiting from specialized hardware, [29] the rigorous application of ensemble theory will remain paramount for generating reliable, thermodynamically meaningful results in fields ranging from drug development to advanced materials engineering.

Implementing NST Simulations: A Step-by-Step Practical Guide

The constant-stress, or No-shear Stress Tensor (NST), ensemble is a cornerstone of modern molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, enabling researchers to study materials and biomolecules under realistic thermodynamic conditions. This ensemble, often referred to as the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) with full stress tensor control, allows simulation box dimensions and shapes to fluctuate in response to applied external stress. For drug development professionals and research scientists, mastering NST simulations is crucial for investigating pressure-induced structural changes in proteins, nucleic acids, and their complexes, as well as for understanding material properties under mechanical stress.

Theoretical foundations of constant-stress MD trace back to the pioneering work of Parrinello and Rahman, who extended the original constant-pressure method of Andersen to include variable cell shapes. This formalism enables the simulation box to change not only its volume but also its shape in response to the applied stress tensor, making it indispensable for studying anisotropic systems, phase transitions, and mechanical properties. In pharmaceutical research, this capability allows for the investigation of ligand binding under physiological pressure conditions, membrane protein dynamics in lipid bilayers, and the mechanical properties of drug delivery systems.

Comparative Analysis of MD Software for NST Simulations

Software Feature Comparison

MD software packages vary significantly in their implementation of constant-stress algorithms, performance characteristics, and usability features. The table below provides a systematic comparison of major platforms capable of NST ensemble simulations:

Table 1: Comparison of Molecular Dynamics Software Supporting NST Ensembles

| Software | NST Implementation | GPU Acceleration | Key Force Fields | License | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAMMPS | fix npt/nph with full stress tensor control | Yes [30] [31] | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS, ReaxFF, AIREBO [31] | Open Source (GPL) [30] | Highly flexible; extensive documentation; tutorials available [31] |

| AMBER | iwrap=1 with ntpr options | Yes [30] [32] | AMBER (ff94, ff99, ff14SB), OL15, bsc1 [33] [34] | Proprietary (free academic) [30] [32] | Optimized for biomolecules; well-validated DNA force fields [33] |

| GROMACS | mdrun with berendsen/parrinello-rahman barostat | Yes [30] [32] | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS, GROMOS [32] | Open Source (LGPL) [30] [32] | High performance; excellent parallel scaling [32] |

| CHARMM | DYNA CPT with TSTRess | Limited [32] | CHARMM (proteins, lipids, nucleic acids) [33] [32] | Proprietary (academic) [30] [32] | Scriptable control language; CHARMM-GUI for setup [32] |

| NAMD | LangevinPiston with useGroupPressure | Yes [30] | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS [30] | Free (academic) [30] | Excellent scalability; integrated with VMD [30] |

| OpenMM | MonteCarloBarostat | Yes [30] | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS [30] | Open Source (MIT) [30] | Python scriptable; exceptional GPU performance [30] |

Performance and Usability Considerations