Mastering NPT Ensemble for Biomolecular Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide from Theory to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the NPT (isothermal-isobaric) ensemble for biomolecular simulations in solution, a fundamental technique for studying biological systems under experimentally relevant conditions.

Mastering NPT Ensemble for Biomolecular Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide from Theory to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the NPT (isothermal-isobaric) ensemble for biomolecular simulations in solution, a fundamental technique for studying biological systems under experimentally relevant conditions. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational statistical mechanics principles and modern methodological approaches, including machine learning force fields and coarse-grained models. The content delivers practical troubleshooting strategies for common simulation issues and outlines rigorous validation protocols against experimental data such as NMR. By integrating these four core intents, this guide serves as an essential resource for achieving accurate, reliable, and physiologically meaningful simulation results in biomedical research.

The NPT Ensemble Explained: Statistical Mechanics for Biomolecular Stability in Solution

The NPT ensemble, also known as the isothermal-isobaric ensemble, is a cornerstone of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, particularly in biomolecular research. It defines a system under conditions of constant particle Number (N), constant Pressure (P), and constant Temperature (T). These parameters mirror typical laboratory environments where experiments are conducted at ambient pressure and controlled temperature, making NPT the ensemble of choice for simulating biological systems in solution and for calculating properties relevant to experimental observables [1] [2].

For biomolecular simulations, the NPT ensemble is indispensable for achieving realistic system densities and for studying conformational dynamics under physiologically relevant conditions. It allows the simulation box size and shape to fluctuate, enabling the system to stabilize at its equilibrium density [3]. This is critical for investigations into protein folding, ligand-binding events, and the structural characterization of polymers and membranes, where accurate volume and density are paramount for obtaining meaningful, reproducible results that can be validated against experimental data [1] [2].

Theoretical Foundation and Thermodynamic Relations

In statistical mechanics, the NPT ensemble describes the behavior of a system that is in thermal equilibrium with a heat bath at temperature T and mechanical equilibrium with a pressure reservoir at pressure P. The partition function, Δ, for the NPT ensemble provides a connection between microscopic dynamics and macroscopic thermodynamics and is given by:

Δ = ∑∫∫ (1 / (h³ᴺ N!)) * exp(-β(H(r, p) + P V)) dV dr dp

Where h is Planck's constant, N is the number of particles, β = 1/kᴮT, H is the Hamiltonian of the system, P is the pressure, V is the volume, and r and p represent the positions and momenta of the particles, respectively. From this partition function, all thermodynamic properties, such as Gibbs free energy (G = -kᴮT lnΔ), enthalpy, and volume fluctuations, can be derived.

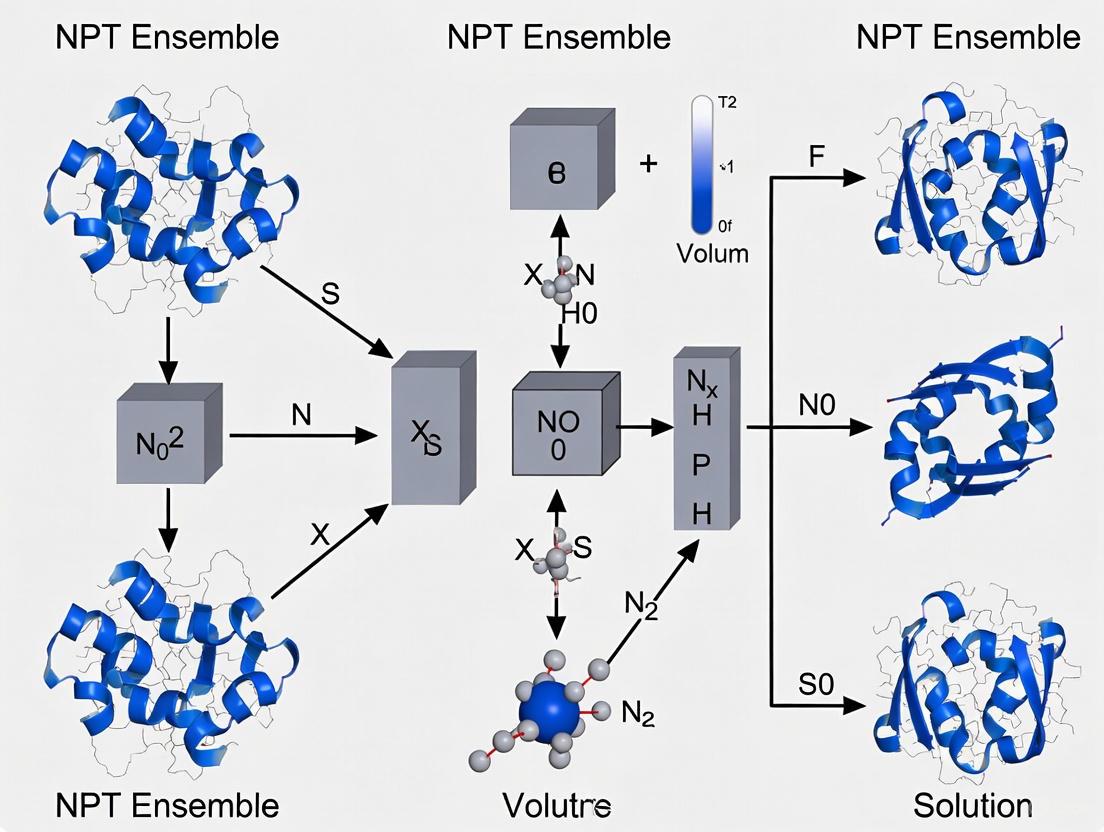

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the defining constants of the NPT ensemble, the algorithms used to maintain them, and the resulting thermodynamic properties and outputs of a simulation.

Coupling Algorithms: Thermostats and Barostats

Maintaining constant temperature and pressure in an MD simulation requires algorithms that couple the system to external thermostats and barostats. The choice of algorithm can significantly influence the quality of the simulation and the physical validity of the generated ensemble [3] [2].

Thermostats control the temperature by scaling particle velocities. Common methods include the Berendsen thermostat, which provides weak coupling to a heat bath, and the Nose-Hoover thermostat, which produces a correct canonical ensemble and is widely used in conjunction with the NPT ensemble for biomolecular simulations [3]. Barostats control the pressure by scaling the simulation box dimensions. The Berendsen barostat offers a simple relaxation scheme, while the Parrinello-Rahman barostat allows for full anisotropic cell fluctuations, which is crucial for simulating crystalline materials or membranes under tension [3]. The Anderson-Hoover NPT ensemble combines a Nose-Hoover thermostat with a barostat for a rigorously correct NPT sampling [3].

Essential Parameters for NPT Simulations in Biomolecular Research

The setup of an NPT simulation requires careful selection of parameters, which are often defined in a molecular dynamics parameter file (e.g., an mdp file in GROMACS) [4]. The tables below summarize the critical parameters and their typical values for biomolecular simulations.

Table 1: Core NPT Control Parameters in MD Software

| Parameter | Description | Common Options & Typical Values |

|---|---|---|

| Integrator | Algorithm for integrating equations of motion. | md (leap-frog), md-vv (velocity Verlet) [4] |

| Ensemble Type | Defines the thermodynamic ensemble. | NPT (selected via imdmet=9,10,11 in ReaxFF; tcoupl and pcoupl in GROMACS) [3] |

| Temperature Coupling | Thermostat algorithm. | Nose-Hoover (NHC), Berendsen [3] |

| Pressure Coupling | Barostat algorithm. | Parrinello-Rahman, Berendsen [3] |

| Compressibility | Isothermal compressibility of the system. | ~4.5e-5 bar⁻¹ for water [4] |

| Coupling Frequency | Interval for applying thermostat/barostat. | Every 1-100 steps (nsttcouple, nstpcouple) [4] |

Table 2: Advanced and System-Specific NPT Parameters

| Parameter | Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| τ_T (tau-t) | Characteristic time constant for temperature coupling. | ~0.5-2.0 ps; slower for production, faster for equilibration [4] |

| τ_P (tau-p) | Characteristic time constant for pressure coupling. | ~1.0-5.0 ps; relates to period of pressure fluctuations [3] |

| Pressure Tensor | Defines which box vectors are allowed to fluctuate. | Isotropic, Semi-isotropic, Anisotropic (e.g., imdmet=10 for fixed-angle cell) [3] |

| Mass Repartitioning | Scales masses of light atoms to enable larger timesteps. | Factor of 3 with constraints=h-bonds for 4 fs timestep [4] |

Experimental Protocol: Equilibration of a Hydrated Protein-Ligand System

This protocol details a robust equilibration procedure for a solvated protein-ligand complex, a common scenario in drug development. The goal is to relax the system from its initial coordinates to a stable state at the target temperature and pressure before beginning production simulation.

The workflow for the NPT equilibration protocol, from system construction to production simulation, is visualized below.

Step-by-Step Methodology

System Preparation

- Obtain the protein structure from a database (e.g., PDB). Prepare the structure using tools like

pdb2gmx(GROMACS) ortleap(AMBER) to assign protonation states, add missing residues, and select an appropriate force field (e.g., AMBER ff99SB-ILDN, CHARMM36) [2]. - Place the ligand in the binding pocket. Generate ligand parameters using tools like

acpypeor the GAFF force field. - Solvate the protein-ligand complex in a periodic box of explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P, TIP4P-EW) with a margin of at least 10 Å from the protein to its nearest box image [2].

- Add ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to neutralize the system's net charge and to achieve a physiologically relevant salt concentration (e.g., 150 mM).

- Obtain the protein structure from a database (e.g., PDB). Prepare the structure using tools like

Energy Minimization

- Objective: Remove any bad van der Waals contacts and steric clashes introduced during system building, relaxing the structure to the nearest local energy minimum.

- Protocol: Use a steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm for 5,000-50,000 steps until the maximum force is below a specified tolerance (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm for initial steepest descent, then 100 kJ/mol/nm for conjugate gradient) [4] [2].

- Parameters:

integrator=steeporcgemtol= 1000.0nsteps= 50000

NVT Equilibration

- Objective: Gently heat the system to the target temperature (e.g., 310 K) while restraining the heavy atoms of the protein and ligand, allowing the solvent and ions to equilibrate around the solute.

- Protocol: Run a short simulation (100-500 ps) in the NVT ensemble.

- Parameters:

integrator=mddt= 0.002 (ps)nsteps= 50000 (for 100 ps)tcoupl=Nose-Hoover(orBerendsenfor initial heating)tau_t= 0.1-1.0 (ps)ref_t= 310 (K)pcoupl=no

NPT Equilibration

- Objective: Allow the system to reach the target density and stable pressure by releasing the positional restraints and allowing the box volume to fluctuate. This is a critical step for achieving a physiologically realistic system [1].

- Protocol: Run a simulation for 1-5 ns in the NPT ensemble. It is often advisable to run this in two phases: first with weak restraints on protein backbone atoms, and then completely unrestrained.

- Parameters:

integrator=mddt= 0.002 (ps)nsteps= 500000 (for 1 ns)tcoupl=Nose-Hoovertau_t= 1.0 (ps)ref_t= 310 (K)pcoupl=Parrinello-Rahman(for production quality) orBerendsen(for faster equilibration)tau_p= 2.0-5.0 (ps)ref_p= 1.0 (bar)compressibility= 4.5e-5 (bar⁻¹)

Production Simulation

- Objective: Collect data for analysis once the system properties (temperature, pressure, density, total energy, protein RMSD) have stabilized.

- Protocol: Continue the NPT simulation for tens to hundreds of nanoseconds, or longer, using the same parameters as the final NPT equilibration stage but without any restraints. The specific duration depends on the biological process being studied.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NPT Biomolecular Simulations

| Item | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Explicit Solvent Models | Environment for solvating biomolecules; parameterized water molecules. | TIP3P, SPC/E, TIP4P-EW for simulating proteins in aqueous solution [2]. |

| Ion Parameters | Cations and anions for neutralizing system charge and modeling salt concentration. | Na⁺, Cl⁻, K⁺, Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺ parameters compatible with the chosen force field. |

| Biomolecular Force Fields | Empirical potential energy functions defining interatomic interactions. | CHARMM36, AMBER ff99SB-ILDN, GROMOS 54a7 for proteins, lipids, nucleic acids [2]. |

| Small Molecule Force Fields | Specialized parameters for drug-like molecules and ligands. | General Amber Force Field (GAFF), CGenFF for generating parameters for novel ligands. |

| MD Simulation Software | Software packages that perform the numerical integration of the equations of motion. | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER, Desmond; implement NPT algorithms [2] [5]. |

| System Preparation Tools | Programs for building, solvating, and parameterizing simulation systems. | pdb2gmx (GROMACS), tleap (AMBER), CHARMM-GUI, PackMol. |

| Analysis Suites | Software for processing simulation trajectories to compute properties. | Built-in GROMACS tools, VMD, MDAnalysis, PyTraj for calculating RMSD, RDF, MSD, etc. |

Validation and Analysis of NPT Simulations

A critical final step is to validate that the simulation has reached a state of equilibrium and that the sampled ensemble is physically meaningful and reproducible [2]. Key metrics for validation include:

- Convergence of System Properties: Monitor the potential energy, temperature, pressure, and density over time. These should fluctuate stably around a constant average value after the equilibration phase. The density of a hydrated protein system, for instance, should converge to a value close to that of pure water (~997 kg/m³ at 300 K, depending on the water model used).

- Structural Stability: Calculate the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the protein backbone and the ligand. A stable or converged RMSD indicates that the protein has not undergone large, unphysical conformational changes and is sampling a stable basin in the energy landscape.

- Comparison with Experimental Observables: Whenever possible, validate the simulation against experimental data. This can include comparing calculated radii of gyration with those from small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), or validating the structure against NMR-derived observables such as spin-spin coupling constants or residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) [2]. As noted in validation studies, while different simulation packages and force fields may reproduce average experimental observables equally well, the underlying conformational distributions can differ, highlighting the need for careful benchmarking [2].

By rigorously following these protocols and validation steps, researchers can ensure that their NPT simulations provide reliable and meaningful insights for drug development and biomolecular research.

Why NPT is the Gold Standard for Simulating Biological Conditions in Solution

The isothermal–isobaric (NPT) ensemble, where the number of particles (N), system pressure (P), and temperature (T) are kept constant, represents the most physiologically relevant environment for simulating biomolecular processes in solution. Unlike simulations conducted at constant volume (NVT), the NPT ensemble allows the simulation box size to fluctuate, enabling the system to maintain a realistic density that matches experimental conditions. For biomedical researchers and drug development professionals, employing the NPT ensemble is crucial for obtaining quantitatively accurate results that can reliably inform experimental design and interpretation. This protocol outlines the theoretical foundations, practical implementation, and key applications of NPT simulations for biomolecular systems, with a particular focus on achieving and validating proper equilibration.

Theoretical Foundation of the NPT Ensemble

In molecular dynamics (MD), the choice of statistical ensemble directly controls the thermodynamic conditions of the simulation. For biological systems in solution, the NPT ensemble mirrors natural environments where biomolecules experience constant temperature (maintained by a thermostat) and constant atmospheric pressure (maintained by a barostat). The barostat continuously adjusts the simulation box dimensions to maintain the target pressure, allowing the system density to stabilize at its experimental value [6].

This contrasts with NVT simulations, where the fixed box volume can generate an internal pressure that deviates significantly from the desired 1 bar, potentially distorting molecular structures and dynamics. The ability of the NPT ensemble to reproduce correct system densities makes it indispensable for calculating thermodynamic properties, studying conformational changes, and preparing systems for production runs that require physiologically relevant conditions.

Practical Implementation: Protocols for Robust NPT Equilibration

Standard NPT Equilibration Protocol

A typical equilibration protocol for a biomolecular system (e.g., a protein in explicit solvent) involves a two-step process to gradually relax the system before production simulation:

- Step 1: NVT Equilibration. The system is first equilibrated with position restraints applied to the heavy atoms of the biomolecule. This allows the solvent and ions to relax around the fixed solute, typically for 50-100 ps. The temperature is maintained at the target value (e.g., 300 K) using a thermostat such as Nose-Hoover or Berendsen.

- Step 2: NPT Equilibration. All position restraints are removed, and the simulation proceeds in the NPT ensemble. The barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman or Berendsen) is activated to maintain constant pressure. This step typically requires 100-500 ps for the system density to stabilize, though larger systems may require longer.

Addressing the "Leaky Membrane" Effect in Charged Systems

Standard equilibration protocols can encounter specific challenges with chemically complex systems. As noted in assessments of glycolipid membrane simulations, a "leaky membrane effect" occasionally occurs where water molecules improperly enter the hydrophobic region during early NPT equilibration [7]. This artifact stems from very high initial pressure during the first steps of equilibration, which can cause a small box expansion that allows water infiltration.

Recommended Modified Protocol for Charged Glycolipids:

- Short NVT Pre-equilibration: Begin with a brief NVT simulation (e.g., 20-50 ps) at the target temperature.

- Stepwise NPT Equilibration: Implement a stepwise thermalization NPT protocol, gradually increasing the temperature (e.g., 100 K → 200 K → 300 K) under NPT conditions.

- Extended NPT at Target Conditions: Conduct extended NPT equilibration at the final temperature and pressure until density and potential energy stabilize.

This modified approach distributes the pressure adjustment more gradually, preventing the rapid box expansion that can compromise membrane integrity during equilibration [7].

Workflow for NPT Simulation Setup and Equilibration

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for establishing a properly equilibrated NPT system, incorporating the specialized protocol for sensitive structures:

Key Applications and Validation

Free Energy Calculations and Protein Folding

The NPT ensemble enables precise free-energy calculations for biomolecular processes. Recent advances in artificial intelligence-based ab initio biomolecular dynamics systems (AI2BMD) demonstrate the power of NPT simulations for studying protein folding and unfolding processes with ab initio accuracy [8]. These simulations can derive accurate 3J couplings that match nuclear magnetic resonance experiments and estimate thermodynamic properties such as melting temperatures of fast-folding proteins that align well with experimental measurements [8].

Calculating Diffusion Coefficients

Accurate calculation of translational diffusion coefficients from MD simulations requires special consideration of trajectory unwrapping in NPT ensembles. Since the barostat constantly rescales particle positions based on box fluctuations, standard unwrapping algorithms can introduce artifacts [6].

Recommended Practice:

- Use the toroidal-view-preserving (TOR) unwrapping scheme rather than heuristic lattice-view approaches

- Apply unwrapping to molecular centers of mass rather than individual atoms

- Ensure molecules are made "whole" before unwrapping to prevent bond stretching artifacts

The TOR scheme preserves the dynamics of the wrapped trajectory by summing minimal displacement vectors within the simulation box, providing more reliable diffusion coefficient estimates from NPT simulations [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Essential computational tools and their functions in NPT biomolecular simulations

| Tool/Reagent | Type/Function | Application in NPT Simulations |

|---|---|---|

| AMOEBA Force Field [8] | Polarizable force field | Models explicit solvent polarization effects for accurate electrostatic interactions |

| Berendsen/Parrinello-Rahman Barostat [7] [6] | Pressure-coupling algorithm | Maintains constant pressure by adjusting box dimensions; Berendsen for equilibration, Parrinello-Rahman for production |

| Nose-Hoover Thermostat [7] | Temperature-coupling algorithm | Maintains constant temperature using extended Lagrangian formalism |

| AI2BMD Potential [8] | Machine learning force field | Provides ab initio accuracy for energy/force calculations with significantly reduced computational cost |

| GROMACS [7] [6] | MD simulation software | Implements various barostats, thermostats, and trajectory analysis tools for NPT ensembles |

| TOR Unwrapping Scheme [6] | Trajectory analysis method | Correctly unwraps molecular trajectories from NPT simulations for accurate diffusion calculations |

Quantitative Comparison of Simulation Ensembles

Table 2: Comparative analysis of NPT versus NVT ensembles for biomolecular simulations

| Parameter | NPT Ensemble | NVT Ensemble |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled Variables | Number of particles, Pressure, Temperature | Number of particles, Volume, Temperature |

| System Density | Fluctuates, converges to experimental value | Fixed, may not match experimental conditions |

| Physiological Relevance | High - mimics lab/physiological conditions | Moderate - constant volume is artificial constraint |

| Pressure Artifacts | Minimal - pressure is controlled | Possible - internal pressure may deviate from target |

| Applications | Protein folding, material properties, solvation studies | Specific studies requiring fixed volume |

| Equilibration Complexity | Higher - requires pressure coupling | Lower - no pressure coupling |

| Diffusion Coefficient Accuracy | High when using proper unwrapping schemes [6] | Generally straightforward but may have density errors |

The NPT ensemble remains the gold standard for biomolecular simulations in solution due to its ability to replicate experimentally relevant thermodynamic conditions. Through careful implementation of equilibration protocols—including specialized approaches for charged systems like glycolipid membranes—and proper trajectory analysis techniques, researchers can obtain quantitatively accurate results that reliably connect simulation data with experimental observables. As force fields and sampling methods continue to advance, particularly with the integration of machine learning approaches like AI2BMD, the NPT ensemble will continue to provide an essential foundation for understanding biological processes at atomic resolution and accelerating drug development efforts.

Statistical Mechanical Theory of the Isothermal-Isobaric Ensemble

The isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble is a cornerstone of molecular simulation, particularly for biomolecular systems in solution. This ensemble maintains a constant number of particles (N), constant pressure (P), and constant temperature (T), thereby closely mimicking the natural experimental conditions under which most biological processes occur. The theoretical foundation of the NPT ensemble derives from statistical mechanics, where the partition function Δ(N,P,T) provides the connection between microscopic molecular behavior and macroscopic thermodynamic observables. For biomolecular simulations, the NPT ensemble is indispensable for reproducing correct densities, solvation environments, and conformational equilibria, as it allows the simulation box size and shape to fluctuate in response to internal and external pressures.

The relevance of NPT simulations in drug development and biomedical research cannot be overstated. Accurate modeling of biomolecules such as proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids in their native aqueous environments enables the study of ligand-binding affinities, conformational dynamics, and solvation effects—all critical factors in rational drug design. The NPT ensemble ensures that the simulated system occupies the appropriate volume and maintains realistic intermolecular distances, providing a reliable platform for predicting properties that can be validated against experimental data [9].

Core Theoretical Framework

Partition Function and Thermodynamics

The isothermal-isobaric ensemble is defined by its partition function, which for a one-component system is given by:

Δ(N, P, T) = C ∫∫ exp[-βH(q, p) - βPV] dq dp dV

where β = 1/kBT, H(q,p) is the system Hamiltonian, V is the volume, and C is a constant that ensures proper normalization. This partition function connects to thermodynamics through the Gibbs free energy:

G(N, P, T) = -kBT ln Δ(N, P, T)

The NPT ensemble thus provides a foundation for calculating equilibrium properties under conditions that mirror most laboratory experiments for systems in solution. The thermodynamic connection enables the extraction of key properties including enthalpy, entropy, and volume fluctuations that provide insights into biomolecular stability and interactions [10].

Equations of Motion and Barostats

In molecular dynamics (MD) implementations of the NPT ensemble, the equations of motion are extended to include volume fluctuations. This is typically achieved through the incorporation of barostats that adjust the simulation cell dimensions to maintain constant pressure. Modern simulation packages employ sophisticated algorithms such as the Parrinello-Rahman barostat, which allows for fully flexible simulation cells, or the Nosé-Hoover Langevin piston for robust control of pressure dynamics.

The resulting volume fluctuations provide direct access to important thermodynamic derivatives, including the isothermal compressibility βT:

βT = -1/V (∂V/∂P)T,N = ⟨(δV)²⟩ / (kBTV)

where ⟨(δV)²⟩ represents the volume fluctuations in the NPT ensemble. This relationship highlights how microscopic fluctuations in the simulation connect to macroscopic material properties [10].

Computational Protocols for NPT Biomolecular Simulations

System Setup and Equilibration

Initial Structure Preparation Begin with a high-quality atomic structure of the biomolecule from experimental sources (e.g., Protein Data Bank) or homology modeling. For the solvated environment, embed the biomolecule in an appropriate water box (typically TIP3P, SPC/E, or TIP4P water models) with a minimum of 10-15 Å padding between the solute and box edges. Add physiological ion concentrations (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl) to mimic biological conditions, ensuring charge neutrality.

Energy Minimization Perform steepest descent or conjugate gradient minimization to remove bad contacts and high-energy configurations. Protocol: 5,000-10,000 steps until the maximum force falls below 100-1000 kJ/mol/nm, preparing the system for stable dynamics.

Stepwise Equilibration

- NVT Equilibration: Run 100-500 ps with position restraints on heavy atoms of the biomolecule (force constant of 1000 kJ/mol/nm²) while allowing solvent and ions to relax. Use a Langevin thermostat or Nosé-Hoover chain to maintain temperature at 300 K.

- NPT Equilibration: Run 1-5 ns with mild position restraints (force constant of 100-500 kJ/mol/nm²) on biomolecule heavy atoms, employing a barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman or Berendsen) to maintain pressure at 1 bar. This allows the solvent density to equilibrate properly.

- Unrestrained NPT Production: Remove all restraints and conduct extended NPT simulation for timescales appropriate to the biological process being studied (typically 50 ns to 1 μs for most biomolecular applications) [11].

Property Calculation and Analysis

Thermodynamic Properties The NPT ensemble enables calculation of various thermodynamic properties through fluctuation formulas and direct averaging:

Table 1: Key Thermodynamic Properties Accessible from NPT Simulations

| Property | Mathematical Expression | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal expansion coefficient | αP = 1/V (∂V/∂T)P,N = ⟨δVδH⟩ / (kBTV) | Volume changes with temperature relevant for thermal stability |

| Isobaric heat capacity | CP = (∂H/∂T)P,N = ⟨(δH)²⟩ / (kBT²) | Energy requirements for conformational changes |

| Isothermal compressibility | βT = -1/V (∂V/∂P)T,N = ⟨(δV)²⟩ / (kBTV) | Membrane mechanical properties and compressibility |

| Thermal pressure coefficient | γV = (∂P/∂T)V,N = αP/βT | Pressure effects on protein denaturation |

Structural Properties Analyze root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) for structural stability, radius of gyration for compactness, and solvent-accessible surface area for hydration effects. For lipid bilayer systems, calculate electron density profiles and order parameters for comparison with experimental data [9] [12].

Application Case Studies in Biomolecular Research

RNA Structure Refinement

In CASP15 community-wide assessment, NPT-MD simulations were systematically benchmarked for RNA structure refinement using Amber with the RNA-specific χOL3 force field. The study revealed that short NPT simulations (10-50 ns) provided modest improvements for high-quality starting models by stabilizing base stacking and non-canonical base pairs. However, poorly predicted models rarely benefited and often deteriorated, highlighting the importance of initial model quality. The optimal protocol employs NPT-MD as a fine-tuning tool rather than a universal corrective method, with early simulation dynamics (5-10 ns) diagnostic of refinement potential [11].

Table 2: NPT-MD Refinement Outcomes for RNA Models in CASP15

| Starting Model Quality | Simulation Length | Typical RMSD Change (Å) | Key Structural Improvements |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-quality | 10-50 ns | -0.1 to -0.3 | Stabilized stacking, optimized non-canonical pairs |

| Medium-quality | 10-50 ns | -0.05 to +0.2 | Variable improvements, occasional deterioration |

| Low-quality | 10-50 ns | +0.3 to +1.5 | Structural drift, loss of native contacts |

| Any quality | >50 ns | Typically positive | Increased drift, reduced fidelity to experimental data |

Biomembrane Dynamics and Validation

A comprehensive dynamic landscape of fully hydrated palmitoyl-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine (POPC) bilayers was constructed by combining 13C NMR relaxation data with 8.4 μs NPT-MD simulations. This integrated approach enabled separation of molecular motions by type and timescale, revealing vast differences in motional amplitudes and correlation times depending on molecular position within the bilayer. The NPT ensemble was critical for maintaining appropriate membrane packing and hydration during these simulations, enabling direct validation of simulation results against experimental NMR data through detector analysis methodology [12].

Reactive Simulations for Bond Breaking

The implementation of reactivity in MD simulations using harmonic force fields (Reactive INTERFACE Force Field, IFF-R) enables simulation of bond dissociation and failure in NPT ensembles. By replacing harmonic bond potentials with reactive, energy-conserving Morse potentials, IFF-R maintains compatibility with standard biomolecular force fields (CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS-AA) while enabling bond breaking at approximately 30 times the computational speed of reactive bond-order potentials. This approach is particularly valuable for studying mechanical failure in polymer-protein composites and chemical reactions in biomolecular systems under constant pressure conditions [13].

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: NPT Simulation Workflow for Biomolecular Systems. This workflow outlines the standard protocol for setting up and running NPT simulations of biomolecules in solution, progressing from initial structure preparation through production simulation to final analysis.

Diagram 2: NPT Simulation Analysis and Validation Pathway. This diagram illustrates the major analysis pathways for NPT simulations and their connection to experimental validation methods, highlighting the importance of experimental corroboration for simulation results.

Table 3: Essential Tools for NPT Biomolecular Simulations

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in NPT Simulations | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Engines | Software | Integrates equations of motion with barostats for NPT ensemble | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER, OpenMM, LAMMPS |

| Force Fields | Parameters | Defines bonded and non-bonded interactions for biomolecules | CHARMM36, AMBER, OPLS-AA, GROMOS |

| Barostat Algorithms | Algorithm | Maintains constant pressure by adjusting simulation cell dimensions | Parrinello-Rahman, Berendsen, Martyna-Tobias-Klein |

| Thermostat Algorithms | Algorithm | Maintains constant temperature by controlling kinetic energy | Nosé-Hoover, Langevin, Velocity Rescaling |

| Solvation Models | Parameters | Represents aqueous environment for biomolecular simulations | TIP3P, SPC/E, TIP4P water models |

| Analysis Tools | Software | Processes trajectory data to extract structural and thermodynamic properties | MDAnalysis, VMD, CPPTRAJ, GROMACS tools |

| Validation Databases | Data Repository | Provides experimental data for validation of simulation results | MolMod Database [10], GPCRmd [14] |

Advanced Methodologies and Emerging Approaches

FAIR-Compliant Data Management

The increasing complexity and volume of NPT simulation data necessitates robust data management strategies aligned with FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) principles. PostgreSQL-based storage solutions coupled with specialized metadata schemas offer a promising approach for maintaining the essential connection between simulation parameters and resulting trajectories. Such systems enable researchers to efficiently track system compositions, force field assignments, boundary conditions, and thermodynamic ensemble settings—critical information for ensuring the reproducibility and reusability of NPT simulation data [14].

Multi-Scale and Multi-Ensemble Integration

Modern molecular simulation tools like ms2 (release 5.0) demonstrate the trend toward integrated simulation environments that provide access to multiple statistical ensembles, including the NPT ensemble. These platforms implement advanced methodologies such as the Lustig formalism for on-the-fly sampling of thermodynamic properties including isobaric heat capacity, thermal expansion coefficient, and isothermal compressibility directly during NPT simulations. Such capabilities facilitate more efficient calculation of thermodynamic derivatives without requiring multiple separate simulations [10].

The isothermal-isobaric ensemble remains an essential tool in the molecular simulation toolkit for biomolecular research, providing the most physiologically relevant conditions for studying biological processes in solution. The theoretical foundation of the NPT ensemble enables direct connection between microscopic simulations and macroscopic experimental observables, while continued methodological advances improve the accuracy, efficiency, and scope of NPT applications. As force fields continue to refine their parameters for biomolecular systems and simulation methodologies expand to include reactive processes and enhanced sampling, the utility of NPT simulations in drug development and basic biomedical research will continue to grow. Proper implementation of NPT protocols, coupled with rigorous validation against experimental data, ensures that molecular simulations provide reliable insights into biomolecular structure, dynamics, and function.

Comparing NPT with NVT, μVT, and Gibbs Ensembles for Biological Systems

The selection of a statistical ensemble is a foundational step in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, directly determining the thermodynamic state of the system and the relevance of the simulation to experimental conditions. For biological simulations in solution, researchers must choose an ensemble that not only ensures computational efficiency but also accurately models the realistic environmental conditions under which biomolecules operate. This application note provides a detailed comparison of the NPT (isothermal-isobaric), NVT (canonical), µVT (grand canonical), and Gibbs ensembles, with a specific focus on their theoretical underpinnings and practical applications in biomolecular simulation. The NPT ensemble, which maintains constant particle number (N), pressure (P), and temperature (T), is particularly crucial for simulating biological systems in solution as it most closely replicates laboratory conditions where experiments are conducted at atmospheric pressure and controlled temperature [15] [16]. Within the broader thesis of this work, we establish that proper use of the NPT ensemble is indispensable for obtaining biologically relevant structural, dynamic, and thermodynamic data from molecular simulations of solvated biomolecules.

Theoretical Foundation of Statistical Ensembles

In statistical mechanics, an ensemble is defined as an idealization consisting of a large number of virtual copies of a system, considered simultaneously, each representing a possible state that the real system might be in [17]. The concept was formally introduced by J. Willard Gibbs in 1902 to connect microscopic molecular behavior to macroscopic thermodynamic observables. Different ensembles correspond to different sets of macroscopic constraints, leading to distinct statistical characteristics and applications [17].

Mathematical Definitions of Key Ensembles

Microcanonical Ensemble (NVE): Describes completely isolated systems with fixed particle number (N), volume (V), and energy (E). It forms the foundation of statistical mechanics but has limited practical application for biological systems which typically exchange energy with their environment [17].

Canonical Ensemble (NVT): Characterizes closed systems that can exchange energy with a thermal reservoir at temperature T, maintaining constant particle number (N) and volume (V). The partition function for the NVT ensemble is defined as ( Q(N,V,T) = \sumi e^{-\beta Ei} ), where ( \beta = 1/k_B T ) [17].

Isobaric-Isothermal Ensemble (NPT): Models closed systems that can exchange both energy and volume with a reservoir at constant pressure P and temperature T, with fixed particle number N. The NPT partition function is given by ( \Delta(N,P,T) = \int dV \sumi e^{-\beta (Ei + PV)} ) [16].

Grand Canonical Ensemble (µVT): Describes open systems that exchange both energy and particles with a reservoir at constant chemical potential (µ), volume (V), and temperature (T). This ensemble is particularly valuable for studying systems with fluctuating particle numbers, such as binding processes or phase interfaces [17].

Gibbs Ensemble: A specialized ensemble that enables direct simulation of phase equilibria by maintaining thermal and mechanical equilibrium between two or more distinct regions or phases, with constant total number of particles, total volume, and temperature (NV₂T) or constant temperature and pressure (NPT) for each phase [18].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Statistical Ensembles

| Ensemble | Fixed Parameters | Fluctuating Quantities | Partition Function | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVE | N, V, E | Temperature, Pressure | ( \Omega(N,V,E) ) | Fundamental studies; isolated systems |

| NVT | N, V, T | Energy, Pressure | ( Q(N,V,T) ) | Structural studies in confined volume |

| NPT | N, P, T | Energy, Volume | ( \Delta(N,P,T) ) | Biomolecules in solution |

| µVT | µ, V, T | Energy, Particle Number | ( \Xi(\mu,V,T) ) | Solvation, adsorption, binding |

| Gibbs | N₁+N₂, V₁+V₂, T (or P) | Energy, Volume distribution, Particle distribution | Specialized forms | Phase equilibria, membrane partitioning |

Comparative Analysis of Ensembles for Biological Applications

NPT Ensemble: The Gold Standard for Biomolecular Simulations

The NPT ensemble is generally considered the most appropriate choice for simulating biomolecular systems in solution, as it accurately replicates standard laboratory conditions where experiments are performed at controlled temperature and atmospheric pressure [15] [16]. In this ensemble, the system can adjust its volume in response to internal forces and external pressure, allowing for natural density fluctuations that are essential for proper biomolecular solvation and hydration. For proteins in aqueous solution, the use of NPT conditions ensures that water molecules maintain appropriate density (approximately 1 g/cm³ for TIP3P and SPC water models at 300 K and 1 bar) and that the simulated system does not develop unrealistic internal pressures that could distort protein structure or dynamics [19].

The theoretical foundation of the NPT ensemble involves an extended Hamiltonian that includes a barostat to regulate pressure and a thermostat to maintain temperature. The definition of instantaneous pressure for microscopic systems can be derived from the minimum energy principle for the Helmholtz free energy [19]. For discrete/continuum approaches like the General Liquid Optimized Boundary (GLOB) model, which is particularly useful for biomolecular simulations, the pressure coupling can be implemented through extended phase-space schemes that account for the boundary between explicit and implicit solvent regions [19].

NVT Ensemble: Applications and Limitations

The NVT ensemble maintains a constant volume, which can be advantageous for specific applications such as comparing directly with experimental data collected under confined conditions or when simulating crystal structures where unit cell dimensions are fixed. However, for biomolecular simulations in solution, the fixed volume constraint presents significant limitations. Without the ability to adjust volume, the system may develop non-physical internal pressures, particularly during equilibration stages or when significant conformational changes occur. This can lead to distorted hydrogen-bonding networks, improper solvation shell structures, and ultimately unrealistic protein dynamics [15].

Despite these limitations, NVT simulations can be useful as part of a multi-stage equilibration protocol, where an initial NVT simulation might precede production NPT simulations to achieve gradual relaxation of the system. Additionally, NVT may be appropriate for short simulations aimed at specific properties that are less sensitive to volume fluctuations.

µVT and Gibbs Ensembles: Specialized Applications

The µVT ensemble is particularly valuable for studying processes involving variable particle numbers, such as ligand binding, ion permeation through channels, or adsorption phenomena. In this ensemble, the chemical potential (µ) of specific components is fixed, allowing particles to enter or leave the simulation volume. This makes µVT ideal for calculating binding affinities, studying competitive solvation, or modeling systems at interfaces [18]. Recent advances in kinetic Monte Carlo (kMC) schemes have improved the accuracy of chemical potential calculations in dense phases where traditional Widom insertion methods fail [18].

The Gibbs ensemble provides a powerful methodology for studying phase equilibria without constructing an explicit interface between phases. By simulating two distinct regions that can exchange particles and volume while maintaining constant total particle number and either total volume (NV₂T) or pressure (NPT), researchers can directly observe phase separation and calculate coexistence properties. This ensemble has been successfully applied to study vapor-liquid equilibria in simple fluids and more complex associating fluids relevant to biological systems [18].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Different Ensembles for Biomolecular Simulations

| Ensemble | Computational Efficiency | Sampling Effectiveness | Accuracy for Aqueous Systems | Ease of Implementation | Recommended Simulation Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPT | High (after equilibration) | Excellent for equilibrium properties | Excellent (density ~1 g/cm³) | Straightforward in most MD packages | ≥100 ns for protein folding |

| NVT | High | Good for structural properties | Good (with careful volume selection) | Very straightforward | 10-100 ns for dynamics |

| µVT | Moderate to Low (depends on insertion success) | Excellent for open systems | Good for solvation thermodynamics | Complex (requires particle exchange moves) | Varies widely with system |

| Gibbs | Moderate | Excellent for phase equilibria | Good for membrane systems | Complex (requires multiple regions) | Varies with phase transition rates |

Practical Protocols for Ensemble Implementation

Standard NPT Simulation Protocol for Proteins in Solution

The following protocol outlines a robust methodology for conducting NPT simulations of biomolecules in explicit solvent, suitable for implementation in common MD packages such as GROMACS, AMBER, or NAMD.

System Preparation

- Initial Structure: Obtain protein coordinates from PDB or predicted structures. Remove crystallographic artifacts and add missing atoms/residues if necessary.

- Solvation: Place the biomolecule in a suitably sized simulation box (typically rectangular or dodecahedral) with a minimum of 1.0-1.5 nm between the protein and box edges. Add explicit water molecules using models such as TIP3P, TIP4P, or SPC, which have been parameterized for use with specific force fields [19] [16].

- Neutralization: Add counterions (typically Na⁺ or Cl⁻) to neutralize the system net charge. Additional ions may be added to achieve specific physiological concentrations (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).

Energy Minimization and Equilibration

- Energy Minimization: Perform steepest descent or conjugate gradient minimization (5,000-10,000 steps) to remove bad contacts and high-energy configurations.

- NVT Equilibration: Equilibrate the system for 100-500 ps in the NVT ensemble to stabilize temperature. Use thermostats such as Berendsen (for initial equilibration) or Nosé-Hoover (for production) with coupling constants of 0.1-1.0 ps.

- NPT Equilibration: Conduct extended equilibration (1-5 ns) in the NPT ensemble to stabilize both temperature and pressure. Use barostats such as Berendsen (equilibration) or Parrinello-Rahman (production) with coupling constants of 1.0-5.0 ps and compressibility set to 4.5×10⁻⁵ bar⁻¹ for water.

Production Simulation

- Parameter Settings: Use a time step of 2 fs with constraints applied to all bonds involving hydrogen atoms (LINCS or SHAKE algorithms). Employ Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) for long-range electrostatics with a real-space cutoff of 1.0-1.2 nm. Apply similar cutoffs for van der Waals interactions.

- Duration: Run production simulations for timescales appropriate to the biological process of interest: typically 100 ns - 1 µs for local conformational changes, and >1 µs for large-scale transitions or folding events [15].

- Data Collection: Save trajectory frames every 10-100 ps for analysis, ensuring a balance between storage requirements and temporal resolution.

Advanced Protocol: µVT Simulations for Ligand Binding Studies

For simulations requiring the µVT ensemble, such as ligand binding or hydration studies, the following specialized protocol is recommended:

System Setup and Preparation

- Simulation Box: Create a solvated system with the protein or binding pocket of interest. Identify the chemical potential reservoir region if using a multi-region approach.

- Parameterization: Define the chemical potential (µ) for the species of interest based on experimental data or preliminary simulations. This may require calibration through iterative simulations.

Monte Carlo/Molecular Dynamics Hybrid Approach

- MD Phase: Perform short molecular dynamics steps (1-100 ps) to sample molecular motions and configurations.

- MC Phase: Implement Monte Carlo moves for particle insertion/deletion and identity changes. The acceptance criteria for identity changes follows: min[1, exp(-βδU + N₂βδμ)] where δU is the energy difference and δμ is the chemical potential difference [18].

- Balancing: Adjust the ratio of MD steps to MC attempts to maintain an acceptance rate of 15-40% for particle exchanges, which typically provides optimal sampling efficiency.

Validation and Analysis Methods

Regardless of the ensemble chosen, rigorous validation against experimental data is essential for establishing simulation reliability:

- Convergence Assessment: Monitor key properties (RMSD, energy, density, radius of gyration) to ensure they have reached stable equilibrium distributions before beginning production analysis.

- Experimental Comparison: Compare simulation results with available experimental data, such as NMR order parameters [20], J-couplings, scattering profiles, or thermodynamic measurements.

- Ensemble Validation: For advanced applications, verify consistency between ensembles by comparing observables that should be ensemble-independent in properly converged simulations [18].

Diagram 1: Standard workflow for biomolecular simulation in the NPT ensemble.

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Ensemble Simulations

| Item | Function/Purpose | Example Implementations | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | Describes interatomic interactions | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS, GROMOS | Select based on target system (proteins, nucleic acids, lipids) |

| Water Models | Solvent representation | TIP3P, TIP4P, SPC, TIP5P | Match to force field parameterization [19] |

| Thermostats | Temperature control | Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen, velocity rescale | Use weak coupling (0.1-1.0 ps) for biomolecular systems |

| Barostats | Pressure control | Parrinello-Rahman, Berendsen, MTK | Compressibility ~4.5×10⁻⁵ bar⁻¹ for aqueous systems [16] |

| MD Software | Simulation engine | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, OpenMM | Choose based on hardware compatibility and efficiency |

| Analysis Tools | Trajectory processing | MDAnalysis, VMD, CPPTRAJ | Implement multiple analysis methods for validation |

The selection of an appropriate statistical ensemble is a critical decision point in biomolecular simulation that directly impacts the physical relevance and interpretability of results. For most simulations of biological systems in solution, the NPT ensemble provides the most realistic representation of experimental conditions, allowing natural volume fluctuations that maintain proper system density and hydration. The NVT ensemble serves important but more specialized roles, particularly in systems with constrained volumes or as part of multi-stage equilibration protocols. The µVT and Gibbs ensembles offer powerful capabilities for studying open systems and phase equilibria, respectively, though with increased computational complexity and specialized implementation requirements.

Emerging methodologies, particularly machine learning force fields and advanced sampling techniques, are expanding the horizons of what is possible with each ensemble. Systems like AI2BMD demonstrate how artificial intelligence can achieve ab initio accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency, potentially enabling more sophisticated applications of these ensembles to challenging biological questions [8]. Furthermore, the integration of advanced Monte Carlo schemes with traditional molecular dynamics continues to improve the sampling of complex thermodynamic ensembles, particularly for dense systems and phase interfaces [18].

As the field progresses toward increasingly complex biological questions and multi-scale simulations, the appropriate selection and implementation of statistical ensembles will remain fundamental to generating reliable, experimentally relevant computational data for drug development and basic biological research.

The Critical Role of Pressure Control in Mimicking Physiological Environments

The accurate simulation of physiological conditions is paramount in computational biochemistry for obtaining biologically relevant results. The NPT (isothermal-isobaric) ensemble, which maintains constant particle number (N), pressure (P), and temperature (T), is the cornerstone of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations aimed at replicating these native environments [21]. Within this framework, pressure control emerges as a critical factor, directly influencing system density, volume, and the fundamental energetics of biomolecular interactions [22]. Proper pressure control is not merely a technicality but a physiological necessity; for instance, the electrostatic environment surrounding membrane proteins, characterized by a low dielectric constant, is essential for processes like GPCR activation and ligand binding, and its accurate representation depends on appropriate environmental parameters [23]. This application note details the protocols and considerations for implementing pressure control in MD simulations to faithfully mimic physiological conditions, thereby enhancing the reliability of research in drug development and structural biology.

Theoretical Foundation of Pressure Control

In MD simulations, pressure (P) is a computed property derived from the virial equation, which accounts for both the kinetic energy of particles and the internal forces acting upon them [24]. The role of a barostat, or pressure control algorithm, is to maintain this pressure at a target value by dynamically adjusting the volume of the simulation cell [24].

The choice of barostat significantly influences the quality of the simulation and the physical accuracy of the generated ensemble. Available methods fall into several categories, each with distinct strengths and weaknesses, making them suitable for different stages of research, from system equilibration to production runs.

- Weak Coupling Methods: The Berendsen barostat is a classic example that scales particle coordinates and cell dimensions by an increment proportional to the difference between the instantaneous and target pressure [25] [24]. While highly efficient for rapidly equilibrating a system and driving it to the target pressure, it does not produce a correct thermodynamic ensemble because it suppresses pressure fluctuations [24]. Its use is therefore generally recommended for equilibration only.

- Extended System Methods: These algorithms introduce additional degrees of freedom to represent the system's volume. The Parrinello-Rahman barostat allows for changes in both the size and shape of the simulation cell, making it particularly useful for studying solids under stress or anisotropic systems [22] [26]. The Nosé-Hoover barostat and its refinement, the Martyna-Tuckerman-Tobias-Klein (MTTK) barostat, are other extended system methods that are time-reversible and generate a correct NPT ensemble [24].

- Stochastic Methods: The Langevin Piston method combines the extended system approach with stochastic dynamics. By applying a damping force and random collisions to the piston controlling the volume, it effectively controls oscillations and often converges faster than purely deterministic methods [25] [24]. Stochastic Cell Rescaling is an improved version of the Berendsen barostat that adds a stochastic term, enabling correct fluctuations and making it suitable for production simulations [24].

- Monte-Carlo Methods: These methods involve periodically attempting random changes to the simulation cell volume, accepting or rejecting these changes based on a Metropolis criterion. They do not require the calculation of the virial and are another valid approach for sampling the NPT ensemble [24].

Barostat Selection Guide

The table below provides a comparative overview of common barostats to guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate method.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Pressure Control Algorithms (Barostats)

| Barostat Method | Type | Key Features | Strengths | Weaknesses | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berendsen [25] [24] | Weak Coupling | Exponential decay of pressure deviation. | Fast equilibration; numerically stable. | Suppresses fluctuations; incorrect ensemble. | System equilibration only. |

| Parrinello-Rahman [22] [24] | Extended System | Allows full cell shape/size fluctuations. | Correct ensemble; good for anisotropic solids. | "Piston mass" parameter (pfactor) is system-dependent. | Production runs (solids, anisotropic systems). |

| Nosé-Hoover / MTTK [24] | Extended System | Constant enthalpy; correct NPT ensemble. | Correct ensemble; time-reversible. | Can be sensitive to piston mass parameter. | Production runs (general use). |

| Langevin Piston [25] [24] | Stochastic | Damping and random forces on the piston. | Fast convergence; damped oscillations. | Requires setting a damping coefficient. | Production runs (general use, liquids). |

| Stochastic Cell Rescaling [24] | Stochastic | Adds noise to Berendsen's scaling matrix. | Fast and correct fluctuations. | Relatively newer method. | All stages, including production. |

Practical Implementation and Protocols

Successfully implementing pressure control requires careful attention to parameter selection and system setup. The following protocols provide a guideline for configuring barostats in biomolecular simulations.

General Configuration Parameters

Regardless of the barostat chosen, several universal parameters must be defined.

Table 2: Universal Barostat Parameters and Typical Values for Biomolecular Simulations

| Parameter | Description | Typical Values / Considerations |

|---|---|---|

Target Pressure (BerendsenPressureTarget, Parrinello-Rahman Target) |

The desired average pressure of the system. | 1.01325 bar (atmospheric pressure) is standard for mimicking physiological conditions [25]. |

| Pressure Coupling Type | Defines which cell dimensions are allowed to fluctuate. | Isotropic: Uniform scaling in all directions (standard for solution simulations). Semi-isotropic: Different scaling in x-y and z (for bilayers). Anisotropic: Fully flexible cell (for solids) [25] [22]. |

Coupling Frequency (BerendsenPressureFreq) |

How often the barostat is applied. | Typically every 1-20 MD steps. Must be a multiple of other algorithmic frequencies [25]. |

Protocol 1: System Equilibration using the Berendsen Barostat

This protocol is designed for the initial rapid equilibration of a solvated biomolecular system to the target pressure and density.

- System Preparation: Begin with a solvated and neutralized biomolecular system, typically pre-minimized to remove steric clashes.

- Thermostat Configuration: Apply a thermostat (e.g., Berendsen or Nosé-Hoover) to control the temperature. A relaxation time constant (

ttime) of 0.1-1.0 ps is often suitable. - Barostat Configuration:

- Set the barostat to Berendsen.

- Set the

Target Pressureto 1.01325 bar. - Set the

Pressure Relaxation Time(BerendsenPressureRelaxationTime) to 100-500 fs. A shorter time provides stronger coupling and faster equilibration. - Set the

Compressibility(BerendsenPressureCompressibility) to 4.57e-5 bar⁻¹, the experimental value for water [25]. - Use isotropic pressure coupling.

- Simulation Run: Run a short simulation (typically 100-500 ps). Monitor the system density and box volume until they stabilize around equilibrium values.

- Switch to Production Barostat: Once equilibrated, switch the barostat to a method suitable for production (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman or Nosé-Hoover) before beginning the production simulation.

Protocol 2: Production Simulation using the Parrinello-Rahman Barostat

This protocol outlines the setup for a production-level simulation that correctly samples the NPT ensemble, using the Parrinello-Rahman method as an example.

- Initial Equilibration: Ensure the system has been pre-equilibrated using a protocol like the one described above.

- Thermostat Configuration: Use a robust thermostat like Nosé-Hoover or Langevin for temperature control.

- Barostat Configuration:

- Set the barostat to Parrinello-Rahman.

- Set the

Target Pressureto 1.01325 bar. - Define the

Piston Massparameter. In software like ASE, this is often set indirectly via thepfactor(τₚ²B). For a system like fcc-Cu, a value on the order of 10⁶ to 10⁷ GPa·fs² is a good starting point. For biomolecular systems in aqueous solution, extensive testing may be required to find an optimal value that allows for natural fluctuations without causing instability [22]. - Use the appropriate pressure coupling type for your system (e.g., isotropic for a protein in solution).

- Simulation Run: Execute the production simulation. Monitor the pressure and volume to confirm they fluctuate stably around the target values.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting and applying barostats in a typical MD study.

Diagram 1: MD Barostat Selection Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Successful NPT simulations rely on a combination of force fields, software tools, and molecular models. The following table lists key resources used in advanced simulation studies.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for NPT Biomolecular Simulations

| Category | Item / Software | Function in Simulation | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | OPLS/AA [23], AMBER, CHARMM | Define potential energy functions governing atomic interactions; foundational for accurate dynamics. | Used to parameterize peptides and membrane proteins in low electrostatic environments [23]. |

| MD Software | NAMD [25], GROMACS [24], LAMMPS [27], AMBER | Software engines that integrate equations of motion and implement algorithms for thermostats and barostats. | NAMD used for its implementation of Langevin Piston and Berendsen barostats [25]. |

| Water Models | TIP4P/ϵflex, FBA/ϵ [23] | Solvent molecules parameterized to reproduce key properties like density and dielectric constant. | Reparameterized to create low electrostatic water (LEw) models (FBAmem, TIP4Pmem) for membrane simulations [23]. |

| Analysis Tools | UCSF Chimera [23], OVITO [27], VMD | Visualization and analysis of trajectories; calculation of properties like RMSD, RMSF, and hydrogen bonding. | UCSF Chimera used to build missing residues in peptide structures [23]. OVITO used to visualize atom trajectories [27]. |

| Specialized Scripts | Inflategro [23], LigParGen [23] | Pre-processing tools for setting up complex systems like membrane-protein complexes or generating ligand parameters. | Inflategro used to embed proteins like GPR40 and Rv2617c into a DPPC lipid bilayer [23]. |

Application in Drug Development: A Case Study

The impact of accurate environmental modeling is clearly illustrated in the design of l-amino acid-based alternatives to Ketorolac (KTR), a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) [28]. A primary goal of this research was to design a compound with comparable efficacy but fewer side effects than KTR.

In this study, researchers employed a comprehensive computational workflow, including molecular docking followed by extensive MD simulations in the NPT ensemble. The stability of the proposed drug candidate (AVH) bound to its protein target was assessed through analyses of root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) and root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF). Crucially, the use of the NPT ensemble ensured that the simulations were conducted under physiologically relevant conditions of constant temperature and pressure. This accurate environmental control was fundamental for reliably evaluating the strength of protein-ligand interactions, which were analyzed through hydrogen bond analysis and calculated binding free energies using the Molecular Mechanics-Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM-PBSA) method [28].

The results demonstrated that the AVH structure exhibited strong interactions with the protein and, in some cases, improved stability compared to KTR. The binding energy for AVH, while slightly higher than for KTR, remained thermodynamically favorable [28]. This case underscores how precise control over simulation parameters like pressure is not an academic exercise but a practical necessity for obtaining trustworthy data in computer-aided drug design, ultimately guiding the selection of the best candidates for synthesis and experimental testing.

The meticulous implementation of pressure control is a foundational aspect of biomolecular simulations that aspire to model physiological environments with high fidelity. Moving beyond simple equilibration tools like the Berendsen barostat to more advanced, fluctuation-preserving algorithms such as Parrinello-Rahman or Langevin Piston is critical for generating statistically correct ensembles in production simulations. As demonstrated in fields ranging from membrane protein biophysics [23] to rational drug design [28], this rigor directly translates to more reliable predictions of molecular behavior, stability, and binding. By adhering to the detailed protocols and guidelines outlined in this application note, researchers can enhance the credibility of their computational findings and strengthen the bridge between in silico modeling and experimental reality.

Implementing NPT Simulations: From System Setup to Advanced AI-Driven Workflows

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a "computational microscope" for life sciences research, enabling the study of dynamic molecular processes that are difficult to observe experimentally [8]. The usefulness of these simulations depends critically on their accuracy and efficiency [8]. For biomolecular simulations in solution, employing the correct thermodynamic ensemble is essential for generating physically meaningful results that can be compared with experimental data.

The NPT ensemble, which maintains constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature, is particularly valuable for modeling biomolecules in their native aqueous environments. This ensemble allows the simulation box size to fluctuate, enabling the system to reach a realistic density before production simulation [29]. Achieving the correct system density is fundamental for meaningful MD results, as skipping proper NPT equilibration or settling for "good enough" density often leads to artifacts in production MD [29]. This protocol outlines a comprehensive workflow from system preparation through production simulation, with particular emphasis on proper NPT equilibration procedures.

Theoretical Framework and Key Concepts

Thermodynamic Ensembles in MD Simulation

MD simulations employ different thermodynamic ensembles to mimic various experimental conditions:

- NVT Ensemble (Constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature): Used for initial thermal equilibration, allowing the system to reach the target temperature while keeping the volume fixed.

- NPT Ensemble (Constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature): Used for density equilibration, allowing the system to reach realistic density under constant pressure conditions.

The Berendsen Barostat for NPT Simulations

The Berendsen barostat provides a robust method for pressure control in NPT simulations [30]. It implements weak coupling to a pressure bath and can be used for both isotropic and anisotropic pressure coupling:

- Isotropic Coupling: All cell vectors are rescaled by the same factor, using the isotropic pressure ( P = \frac{1}{3} (P{xx} + P{yy} + P_{zz} ) [30].

- Anisotropic Coupling: Each degree of freedom of the cell vectors is rescaled independently [30].

The barostat is particularly useful for biomolecular systems where maintaining physiological conditions is essential for obtaining meaningful results.

Computational Protocol: A Step-by-Step Workflow

System Preparation

Table 1: System Preparation Steps

| Step | Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Structure | Obtain protein coordinates from PDB or design models | Resolve missing residues/loops; assess protonation states |

| Solvation | Embed biomolecule in explicit solvent box | Ensure sufficient padding (typically 1.0-1.2 nm) from box edges |

| Ion Addition | Add ions to neutralize system charge and achieve physiological concentration | Counterions for neutrality; additional ions for specific concentration |

Energy Minimization

Energy minimization relieves steric clashes and unfavorable geometry introduced during system preparation:

- Method: Steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithms

- Termination Criteria: Maximum force should typically be below 100-1000 kJ/mol/nm

- Importance: Creates a stable starting configuration for subsequent equilibration phases

NVT Equilibration

The NVT phase stabilizes the system temperature:

- Duration: Typically 50-100 ps, though membrane systems may require longer [31]

- Temperature Coupling: Use algorithms like Berendsen or Nosé-Hoover thermostat

- Monitoring: Confirm temperature stabilization at target value before proceeding

For membrane protein simulations, special considerations apply. The temperature should be above the lipid phase transition temperature (e.g., 323 K for DPPC) [31]. Temperature coupling groups should be defined separately for the protein-lipid complex and aqueous components due to their different diffusion rates [31].

NPT Equilibration

Table 2: NPT Equilibration Parameters for Different System Types

| Parameter | Standard Soluble Protein | Membrane Protein | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration | 100 ps (may need extension) | Several nanoseconds | Extend until density stabilizes [31] |

| Pressure Coupling | Isotropic | Semi-isotropic (after membrane formation) | Isotropic recommended initially for membrane self-assembly [32] |

| Barostat Time Constant | 500-1000 fs [30] | 5.0 ps [32] | |

| Reference Pressure | 1.0 bar [30] | 1.0 bar (semi-isotropic: 1.0 bar in x-y and z) [32] | |

| Compressibility | 4.5×10⁻⁵ bar⁻¹ [32] | 4.5×10⁻⁵ bar⁻¹ [32] | System-dependent |

The NPT equilibration phase is crucial for achieving the correct system density. During this phase, the running average of the system density should reach a plateau at the desired value [33]. Pressure tends to fluctuate widely throughout equilibration, so monitoring density stabilization is more informative than watching instantaneous pressure values [33].

For membrane systems in particular, the orientation of the lipid bilayer relative to the pressure coupling directions is critical. When using semi-isotropic pressure coupling, the membrane normal should be aligned with the z-direction to prevent artifacts [32]. If the membrane orientation is unknown (as in self-assembly simulations), begin with isotropic pressure coupling until the membrane forms, then potentially rotate the system for semi-isotropic production simulations [32].

Production Simulation

Once the system is properly equilibrated (with stabilized temperature and density), proceed to production MD:

- Duration: System-dependent, from nanoseconds to microseconds

- Frame Output Interval: Adjust based on analysis needs and storage constraints

- Ensemble: Typically NPT for biomolecular simulations in solution

- Validation: Continuously monitor key system properties (RMSD, energy, density)

Workflow Visualization

Biomolecular Simulation Workflow - This diagram illustrates the sequential steps for setting up and running molecular dynamics simulations of biomolecules, from initial preparation through production simulation and analysis.

Table 3: Essential Tools for Biomolecular MD Simulations

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| NPT Berendsen Integrator | Algorithm | Pressure and temperature control during simulation | Maintaining constant pressure in biomolecular simulations [30] |

| Polarizable Force Fields | Force Field | More accurate treatment of electronic polarization | Explicit solvent modeling with AMOEBA [8] |

| Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFF) | Force Field | Ab initio accuracy with reduced computational cost | AI2BMD for efficient protein simulations [8] |

| Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) | Method | Calculating relative binding affinities | Drug discovery applications [34] |

| Semi-isotropic Pressure Coupling | Method | Independent pressure control in membrane normal and plane | Membrane protein simulations [32] |

Advanced Applications and Considerations

Special Cases: Membrane Proteins and Self-Assembling Systems

Membrane proteins require special treatment during equilibration. Unlike soluble proteins, these systems contain multiple phases (lipid, aqueous, protein) that equilibrate at different rates [31]. Lipid reorientation around the protein and water reorientation around lipid headgroups can take several nanoseconds [31]. For membrane self-assembly simulations, begin with isotropic pressure coupling until the membrane forms and its orientation is established, then switch to semi-isotropic coupling for production [32].

Advanced Sampling with AI-Driven Approaches

Recent advances in machine learning have enabled new approaches to biomolecular simulation. AI2BMD, for example, uses protein fragmentation and machine learning force fields to achieve ab initio accuracy for proteins comprising more than 10,000 atoms, reducing computational time by several orders of magnitude compared to density functional theory [8]. Such approaches demonstrate potential for efficiently exploring conformational space of peptides and proteins while maintaining high accuracy [8].

Validation and Quality Control

Proper validation is essential for generating reliable simulation results. For NPT equilibration, the simulation should continue until density values stabilize around the expected value [33]. The expected density for water models is approximately 1000 kg/m³ (SPC/E model: ~1008 kg/m³), and deviations from this value after sufficient equilibration may indicate issues with the simulation setup [33].

When applying these methods in drug discovery contexts, Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) calculations can achieve accuracy comparable to experimental reproducibility when careful preparation of protein and ligand structures is undertaken [34]. This makes MD simulations increasingly valuable for prospective drug design applications.

The step-by-step workflow presented here—from energy minimization through NVT and NPT equilibration to production simulation—provides a robust framework for conducting biomolecular simulations in solution. Particular attention to the NPT equilibration phase, with careful monitoring of density stabilization, is crucial for obtaining physically meaningful results. As MD methodologies continue to advance, incorporating machine learning approaches and improved force fields, the accuracy and applicability of these simulations for drug discovery and basic research will further increase.

Practical Guide to NPT Simulation Parameters in Packages like GROMOS and GROMACS

Within the context of biomolecular simulations in solution research, the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble is a fundamental computational framework. It models a system under constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature, thereby closely mimicking standard experimental conditions [33] [35]. After stabilizing a system's temperature through NVT equilibration, the system may still not have reached the appropriate density [36]. NPT equilibration addresses this by applying pressure to the system until it reaches the correct, stable density, ensuring proper system compactness [33] [36]. This step is critical for the quality of subsequent production simulations, as an improperly equilibrated system can lead to unrealistic densities and simulation artifacts. For researchers in drug development, employing the NPT ensemble is indispensable for simulating realistic biological conditions, such as protein-ligand binding in an aqueous environment, thereby ensuring that derived thermodynamic and kinetic properties are meaningful and reliable.

Core NPT Simulation Parameters

The accuracy and efficiency of an NPT simulation are governed by the parameters defined in the molecular dynamics parameter (.mdp) file. These settings control the integrator, the coupling to temperature and pressure baths, and the treatment of non-bonded interactions.

Integration and Pressure Coupling Parameters

The following table summarizes the key parameters for controlling the integration algorithm and pressure coupling in GROMACS.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Integration and Pressure Coupling in NPT Simulations

| Parameter | Common Setting(s) | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

integrator |

md (leap-frog), md-vv (velocity Verlet) |

Algorithm for integrating Newton's equations of motion. | md is typically accurate enough for most production runs [37]. |

dt |

0.001, 0.002 [ps] | Integration time step. | A 2 fs step is common with constraints; 4 fs may be possible with mass repartitioning [37] [38]. |

nsteps |

e.g., 50000 | Number of integration steps to run. | For a 100 ps simulation with dt=0.002, set nsteps=50000 [33]. |

pcoupl |

Berendsen, c-rescale |

Barostat type for pressure coupling. | c-rescale (exponential relaxation) is recommended for equilibration [33] [35]. |

pcoupltype |

isotropic |

Type of pressure coupling for the box shape. | Suitable for standard cubic, octahedral, or dodecahedral boxes. |

tau_p |

5.0 [ps] | Time constant for pressure coupling. | Determines how tightly the system is coupled to the pressure bath [33]. |

ref_p |

1.0 [bar] | Reference pressure for the system. | The target pressure for the simulation [35]. |

compressibility |

4.5e-5 [bar^-1] | Isothermal compressibility of the medium. | For water, this value is typically 4.5e-5 [35]. |

constraints |

h-bonds, all-bonds |

Algorithm for constraining bond lengths. | Allows for a longer dt. h-bonds constrains bonds involving hydrogen only [39]. |

Force Field Specific Parameters: The Case of GROMOS

When using the GROMOS 54A7 force field, particular attention must be paid to non-bonded interaction parameters due to historical differences in parametrization.

Table 2: Recommended Non-Bonded Parameters for GROMOS 54A7 in GROMACS

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

cutoff-scheme |

Verlet |

The old group scheme is deprecated; Verlet is required in recent GROMACS versions [40]. |

coulombtype |

PME |

Particle Mesh Ewald provides accurate handling of long-range electrostatics [39] [38]. |

rcoulomb |