Markov State Models vs. Replica Exchange Sampling: A Comprehensive Guide for Computational Drug Discovery

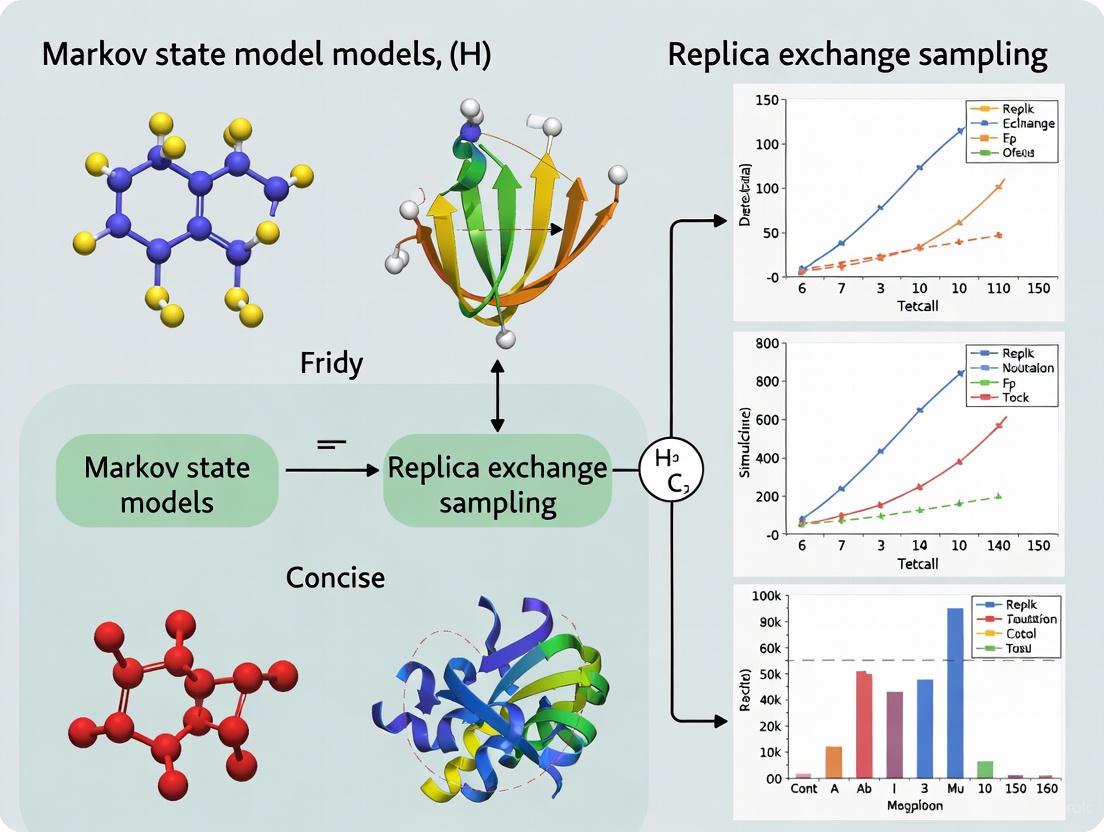

This article provides a comparative analysis of two powerful computational methods for simulating biomolecular dynamics and conformational changes: Markov State Models (MSMs) and Replica Exchange (RE) sampling.

Markov State Models vs. Replica Exchange Sampling: A Comprehensive Guide for Computational Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comparative analysis of two powerful computational methods for simulating biomolecular dynamics and conformational changes: Markov State Models (MSMs) and Replica Exchange (RE) sampling. Aimed at researchers and professionals in computational chemistry and drug development, we explore the foundational principles of both techniques, from the state-to-state kinetics framework of MSMs to the enhanced sampling power of RE. The article details methodological workflows and applications in protein folding, ligand binding, and free energy calculations, including hybrid approaches like Markov State Models of Replica Exchange (MSMRE). We address common challenges, optimization strategies, and systematic validation protocols. Finally, a comparative analysis guides the selection of the appropriate method based on specific research goals, providing a roadmap for leveraging these tools to accelerate biomedical discovery.

Understanding the Core Principles: From State Transitions to Enhanced Sampling

The study of biomolecular processes, such as protein folding and conformational change, presents a significant challenge due to the vast difference between the femtosecond timesteps required for stable molecular dynamics (MD) integration and the microsecond-to-second timescales on which these processes occur [1]. For decades, this timescale problem has limited the utility of MD simulation. Markov State Models (MSMs) have emerged as a powerful computational framework to overcome this barrier, representing a paradigm shift from anecdotal single-trajectory approaches to a comprehensive statistical methodology for analyzing biomolecular dynamics [2]. This approach allows researchers to predict both kinetic and thermodynamic properties on biologically relevant timescales using data from multiple, shorter simulations [1]. As MSMs gain adoption in fields from protein folding to drug discovery, understanding their theoretical foundation, construction methodology, and relationship to alternative sampling approaches like replica exchange is essential for computational researchers and drug development professionals.

Theoretical Foundation of Markov State Models

Core Mathematical Framework

At its core, an MSM is a discrete-state stochastic model of biomolecular dynamics composed of two key elements: (1) a discretization of the high-dimensional molecular state space into disjoint conformational sets (S₁, S₂, ..., Sₙ), and (2) a matrix of conditional transition probabilities between these states estimated from simulation data [1]. The model is characterized by the equation:

Pᵢⱼ(τ) = Prob(xₜ₊τ ∈ Sⱼ | xₜ ∈ Sᵢ)

where Pᵢⱼ(τ) represents the probability of transitioning from state i to state j after a lag time τ [1]. This transition matrix P enables the calculation of both kinetic and thermodynamic properties through the eigenvalue problem:

πᵀP = πᵀ

where π represents the stationary distribution of the system [1]. The eigenvalues λᵢ of the transition matrix relate directly to molecular relaxation timescales through tᵢ = -τ/ln|λᵢ(τ)|, while the corresponding eigenvectors identify the structural changes associated with each timescale [1].

The Variational Principle and Modern Interpretation

Recent theoretical advances have refined the understanding of MSMs through connections to the variational principle of conformation dynamics [1]. This perspective reveals that MSM-derived relaxation timescales are always underestimated except when using the true eigenfunctions of the Markov operator as basis functions [1]. This insight has shifted the discretization strategy from maximizing metastability (state lifetimes) to minimizing the approximation error of the Markov operator's slow eigenspaces [1]. Standard "crisp partitioning" MSMs represent a special case where basis functions are constant on discrete states [1].

Table 1: Key Theoretical Components of Markov State Models

| Component | Mathematical Representation | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| State Space Discretization | S₁, S₂, ..., Sₙ | Conformation sets representing distinct biomolecular structures |

| Transition Matrix | P(τ) = (Pᵢⱼ(τ)) | Conditional probabilities of transitioning between states after time τ |

| Stationary Distribution | π = (π₁, π₂, ..., πₙ) | Equilibrium populations of each state, representing thermodynamic stability |

| Eigenvalues | λᵢ(τ) | Molecular relaxation timescales: tᵢ = -τ/ln|λᵢ(τ)| |

| Eigenvectors | rᵢ | Structural changes occurring at timescale tᵢ |

MSM Construction Methodology

State Discretization and Microstate Clustering

Constructing a kinetically meaningful state discretization presents a fundamental challenge in MSM development. The process typically begins with structural clustering (e.g., k-means or k-centers) using a structural metric like root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) to create thousands of "microstates" [2]. Due to the large number of microstates, conformations within the same microstate typically have RMSDs of no more than 2Å to 3Å, ensuring high structural similarity that implies kinetic similarity [2]. This high-resolution discretization enables parameterization from relatively short MD trajectories because the kinetic distance between adjacent states is small, making transitions observable even in brief simulations [2].

The appropriate number of microstates depends more on the complexity of the state space than protein length alone [2]. For example, beta-sheet proteins like NTL9-39 exhibit more complex state spaces than alpha-helical proteins of similar length due to their non-local contact requirements [2]. After creating microstates, researchers assign each structure in MD trajectories to the closest microstate, translating continuous trajectories into discrete state sequences [2].

Transition Matrix Estimation and Validation

With discrete state sequences, researchers construct a count matrix Cᵢⱼ(τ) that records observed transitions from state i to state j at lag time τ [2]. This count matrix is then converted to a transition probability matrix through maximum likelihood estimation or Bayesian approaches. A critical validation step involves testing the Markov property by examining the implied timescales tᵢ(τ) = -τ/ln|λᵢ(τ)| as a function of lag time [3]. When τ is sufficiently long, these timescales become constant, indicating Markovian behavior [3].

Table 2: MSM Construction Workflow

| Step | Methodology | Purpose | Common Tools/Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | MD simulations (multiple shorter trajectories) | Generate conformational sampling | MD software (GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM) |

| Featurization | Calculate structural features (distances, angles, contacts) | Represent molecular geometry | MDTraj, PyEMMA, MSMBuilder |

| Dimensionality Reduction | tICA, PCA | Identify slow collective variables | PyEMMA, scikit-learn |

| Microstate Clustering | k-means, k-centers | Create fine-grained state discretization | RMSD, torsion angles |

| Macrostate Lumping | PCCA+, spectral clustering | Group microstates into metastable states | Chapman-Kolmogorov test [3] |

| Model Validation | Implied timescales, CK test | Verify Markov property and model quality | Implied timescales plot [3] |

Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics

Fundamental Principles

Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD) represents an alternative enhanced sampling approach that addresses the timescale problem through parallel simulations running at different thermodynamic states (typically different temperatures) [4]. In REMD, a Markov chain alternates between (1) updates of molecular configurations using MD independently for each replica at fixed thermodynamic states (the "move" process), and (2) coordinated attempted swaps of thermodynamic states among replicas (the "exchange" process) [4]. Together, these processes constitute a replica exchange cycle [4].

The exchange process must satisfy detailed balance:

PRE({S};x⃗₁,x⃗₂,...,x⃗M)TSS′ = PRE({S′};x⃗₁,x⃗₂,...,x⃗M)TS′S

where PRE is the joint probability distribution of a RE configuration, {S} represents a specific assignment of replicas to thermodynamic states, and TSS′ is the transition probability between state assignments [4]. The acceptance probability follows the Metropolis criterion:

AccpSS′ = min{1, exp(-Σᵢβs′[ᵢ]Es′ᵢ) / exp(-Σᵢβs[ᵢ]E_sᵢ)}

This formulation enables replicas to diffuse across temperatures, overcoming energy barriers that trap simulations at single temperatures [4].

Efficiency Considerations

REMD efficiency depends critically on cycle construction parameters, including the number of MD steps per cycle and the number of exchange attempts per cycle [4]. Markov State Models of Replica Exchange (MSMRE) have been developed as "simulations of simulations" to systematically optimize these parameters [4]. MSMRE analysis reveals that increasing exchange attempts improves sampling efficiency, approaching the "infinite swapping" limit where replicas instantaneously sample all possible state assignments [4].

Comparative Analysis: MSMs vs. Replica Exchange

Methodological Comparison

While both MSMs and REMD address biomolecular sampling challenges, they employ fundamentally different strategies with complementary strengths and limitations. REMD enhances sampling by facilitating barrier crossing through temperature exchanges, directly modifying the simulation conditions. In contrast, MSMs extract kinetic and thermodynamic information from standard MD data through statistical modeling, without modifying the underlying Hamiltonian [2] [4].

REMD provides enhanced sampling of configuration space but requires careful parameter tuning (temperature distribution, exchange attempts) for optimal efficiency [4]. MSMs can be constructed from various simulation types, including REMD data, through state discretization and transition counting [2]. A significant advantage of MSMs is their ability to predict long-timescale dynamics from short simulations, whereas REMD primarily addresses equilibrium thermodynamic properties despite its kinetic benefits [2] [1].

Table 3: MSMs vs. Replica Exchange: Methodological Comparison

| Feature | Markov State Models | Replica Exchange MD |

|---|---|---|

| Sampling Approach | Statistical analysis of MD data | Enhanced sampling through temperature swaps |

| Timescale Extension | Predicts long-timescale kinetics from short simulations | Accelerates barrier crossing through temperature elevation |

| Data Requirements | Multiple short trajectories (can be non-equilibrium) | Parallel trajectories at different temperatures |

| Key Parameters | Lag time (τ), number of states, clustering method | Temperature distribution, exchange attempts, cycle length |

| Primary Output | Transition probabilities, rates, pathways, committors | Free energy landscapes, thermodynamic averages |

| Kinetic Information | Directly provides kinetic rates and mechanisms | Limited direct kinetic information |

| Implementation Scale | Post-processing of existing simulation data | Requires simultaneous parallel simulations |

Practical Applications and Performance

Recent applications highlight the complementary strengths of both methods. In studying LRRK2 kinase mutations associated with Parkinson's disease, researchers combined extensive MD simulations (6 μs total) with MSMs to elucidate nucleotide-dependent activation mechanisms [3]. The resulting MSM identified four metastable states with distinct dimerization extents, revealing how disease mutations alter conformational equilibrium and allosteric signaling [3].

For ion channel permeation, MSMs constructed from MD trajectories successfully predicted single-channel currents by incorporating a flux matrix that tracks charge movement between states [5]. This approach enabled accurate current prediction from microsecond-scale simulations through state reduction to five key states with significant equilibrium occupancy [5].

REMD excels in binding affinity calculations and free energy estimation, where thorough configuration space sampling is essential [4]. MSMRE analysis has demonstrated that optimal REMD efficiency requires balancing MD steps and exchange attempts, with performance approaching the infinite swapping limit as exchange attempts increase [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Software (GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, NAMD) | Generate atomic-level trajectory data | Both MSM and REMD simulations |

| MSM Construction Packages (PyEMMA, MSMBuilder, Enspara) | State discretization, transition matrix estimation, validation | MSM building and analysis |

| Replica Exchange Implementations | Parallel tempering simulations | REMD sampling |

| Markov State Models of RE (MSMRE) | Analyze and optimize RE parameters | REMD efficiency improvement |

| Dimensionality Reduction (tICA, PCA) | Identify slow collective variables | MSM featurization |

| Clustering Algorithms (k-means, k-centers) | Create microstate discretization | MSM state definitions |

| Validation Methods (Implied timescales, Chapman-Kolmogorov test) | Verify model quality and Markov property | MSM validation |

| Flux Analysis Tools | Calculate currents through states | Ion channel permeation MSMs [5] |

Markov State Models and Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics represent complementary paradigms in computational structural biology. MSMs provide a powerful framework for extracting kinetic and thermodynamic information from molecular dynamics simulations, enabling researchers to predict long-timescale behavior from shorter simulations through statistical modeling. The MSM approach has shifted the simulation paradigm from anecdotal single-trajectory observations to comprehensive statistical analysis, facilitating quantitative comparison with experimental data [2] [1]. Replica Exchange enhances sampling through parallel simulations at different temperatures, particularly valuable for calculating free energies and overcoming kinetic barriers [4]. As both methodologies continue to evolve, their integration offers particular promise—using REMD for efficient configuration space sampling and MSMs for extracting kinetic insights from the resulting data. For drug development professionals and researchers, understanding the strengths, limitations, and appropriate application domains of each approach is essential for designing efficient computational studies of biomolecular systems.

In the fields of computational chemistry and biology, where simulating the complex dynamics of biomolecules is paramount, the Markov property serves as a foundational principle enabling powerful analytical approaches. This property, essential to Markov processes, describes a condition of memorylessness where the future state of a system depends only on its present state, independent of its historical path [6] [7]. Formally, for a discrete-time process, this is expressed as ( P(X{n+1} = x{n+1} | Xn = xn, \dots, X1 = x1) = P(X{n+1} = x{n+1} | Xn = xn) ) for all ( n \in \mathbb{N} ) [7]. In practical terms, this means that predictions about a system's future behavior can be made based solely on its current state, without requiring knowledge of its entire history [6].

This conceptual framework underpins two influential methodologies in computational biophysics: Markov State Models (MSMs) and Replica Exchange (RE) sampling. While both approaches leverage the Markov property, they operationalize it differently to overcome the fundamental challenge of sampling complex molecular configurations. MSMs explicitly construct a network of states with Markovian transitions between them, enabling the modeling of long-timescale processes from numerous short simulations [2]. In contrast, RE employs a parallel sampling strategy where multiple replicas of a system simulate under different conditions, periodically attempting to exchange states according to a Markov chain that alternates between molecular dynamics steps and coordinated swap attempts [4]. Understanding how these methods implement and rely upon the Markov property provides crucial insights for researchers aiming to study molecular folding, binding, and conformational changes underlying drug development processes.

Theoretical Foundation of Markov Processes

Core Principles and Mathematical Definition

A Markov process is a stochastic process that satisfies the Markov property, characterized by its "memoryless" nature [6]. The future evolution of such a process depends exclusively on its current state, making historical states irrelevant for predicting future transitions [7]. When the state space is discrete, these processes are typically called Markov chains [6]. The mathematical description involves a state space ( S ) (the set of all possible states) and transition probabilities ( p{ij} = Pr[X{t+1} = j | X_t = i] ) that define the likelihood of moving from state ( i ) to state ( j ) in one time step [8].

These transition probabilities can be assembled into a transition matrix ( P ), where each entry ( P{ij} ) represents the probability of transitioning from state ( i ) to state ( j ), with rows summing to 1 [8]. For a Markov chain, the n-step transition probabilities are given by ( p^{(n)}{ij} = (P^n)_{ij} ), and the evolution of a probability distribution ( x ) over states follows ( xP ) after one time step, and ( xP^n ) after ( n ) steps [8]. This matrix formulation enables powerful analytical techniques for understanding long-term behavior through spectral analysis of the transition matrix.

Critical Concepts in Markov Chain Theory

Several key concepts are essential for understanding Markov chains and their application to molecular simulations:

Classification of States: States in a Markov chain are classified as either transient (probability of eventual return < 1) or persistent (probability of eventual return = 1) [8]. Persistent states are further categorized as null persistent (infinite mean recurrence time) or non-null persistent (finite mean recurrence time) [8]. For finite Markov chains, all states are either transient or non-null persistent [8].

Irreducibility: A Markov chain is irreducible if every state can be reached from every other state, forming a single strongly connected component [8]. This property ensures the chain cannot become trapped in isolated subsets of the state space.

Stationary Distribution: An irreducible Markov chain has a stationary distribution ( \pi ) (satisfying ( \pi P = \pi )) if and only if all its states are non-null persistent [8]. For finite irreducible chains, a unique stationary distribution always exists, with ( \pii = 1/\mui ), where ( \mu_i ) is the mean recurrence time of state ( i ) [8].

Aperiodicity: The period of a state is the greatest common divisor of the times at which return is possible [8]. An aperiodic chain (all states have period 1) combined with irreducibility guarantees convergence to the stationary distribution regardless of initial conditions [8].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental structure and relationships in a Markov process:

Diagram 1: The Markov property establishes that the future state depends only on the present state, not on the historical path.

Markov State Models (MSMs): Principles and Implementation

Foundation and Construction of MSMs

Markov State Models are kinetic models constructed from molecular dynamics simulations to study complex processes like protein folding [2]. The fundamental goal of MSMs is to create a simplified representation of molecular kinetics that is both quantitatively predictive and humanly understandable [2]. This approach represents a paradigm shift from anecdotal single-trajectory analysis to comprehensive statistical modeling of biomolecular dynamics [2].

The construction of MSMs involves several methodical steps:

Initial Data Collection: MSMs begin with molecular dynamics simulations, which can vary from data-rich regimes (many long trajectories connecting states) to data-poor regimes (fewer, shorter trajectories) [2]. These simulations may come from various sources, including conventional MD, enhanced sampling methods, or simplified force fields [2].

Microstate Definition: Structures from simulations are clustered into many "microstates" (typically 10,000-100,000 for proteins) using structural metrics like RMSD [2]. The high resolution ensures structural and kinetic similarity within each microstate [2].

Transition Matrix Construction: MD trajectories are assigned to microstates, creating a sequence of state visits over time [2]. A count matrix ( C_{ij}(\tau) ) is built by tallying transitions between microstates ( i ) and ( j ) at a specific lag time ( \tau ) [2]. This is converted to a transition probability matrix ( T(\tau) ) by normalizing rows.

Validation: The Markov assumption is tested by verifying that the implied timescales ( ti = -\tau / \ln \lambdai (\tau) ) become constant beyond a certain lag time, where ( \lambda_i ) are the eigenvalues of ( T(\tau) ) [2].

Key Advantages and Applications

MSMs offer several significant benefits for studying molecular systems:

Timescale Extension: MSMs can predict dynamics on timescales much longer than the individual simulations used to construct them [2]. This enables the study of processes like protein folding that occur beyond the reach of direct simulation.

Adaptive Sampling: The initial MSM can guide further simulation by identifying poorly sampled states [2]. This "adaptive sampling" uses computational resources efficiently to refine the model [2].

Quantitative Prediction: Properly constructed MSMs can predict experimental observables such as relaxation timescales and population distributions [2].

Mechanistic Insight: By coarse-graining microstates into macrostates corresponding to functional conformations, MSMs provide human-interpretable models of complex mechanisms [2].

The following workflow illustrates the MSM construction process:

Diagram 2: Markov State Model construction workflow from molecular dynamics data.

Replica Exchange Sampling: Principles and Implementation

Foundation of Replica Exchange Methodology

Replica Exchange (RE) is a generalized ensemble sampling technique designed to enhance conformational exploration on rugged free energy landscapes [4]. Also known as Parallel Tempering, RE addresses the fundamental problem of kinetic trapping in local energy minima by running multiple parallel simulations (replicas) under different conditions, typically at various temperatures or Hamiltonians [4].

The RE method operates through a cyclic process with two essential components:

Move Process: Each replica evolves independently through molecular dynamics or Monte Carlo steps at its assigned thermodynamic state [4]. This allows local exploration of the energy landscape.

Exchange Process: After a fixed number of move steps, the algorithm attempts to swap the state assignments between replicas according to a Metropolis criterion that preserves detailed balance [4]. The acceptance probability for swapping replicas at states ( i ) and ( j ) with configurations ( xi ) and ( xj ) is:

[ \text{Accp} = \min\left{1, \exp\left[-\left(\betai E(xj) + \betaj E(xi) - \betai E(xi) - \betaj E(xj)\right)\right]\right} ]

where ( \betai = 1/(kB T_i) ) is the inverse temperature and ( E(x) ) is the potential energy [4].

Unlike serial generalized ensemble methods that require predetermined weights, RE automatically ensures each replica visits all states with equal probability without prior knowledge of free energies [4]. This makes it particularly valuable for complex biomolecular systems where free energy landscapes are unknown a priori.

Advanced Concepts and Optimization Strategies

The efficiency of RE simulations depends critically on several implementation details:

Exchange Proposals: The scheme for selecting replica pairs for exchange attempts significantly impacts sampling efficiency [4]. Common approaches include adjacent swaps and randomized pairing.

Cycle Construction: The balance between MD steps per cycle and exchange attempts per cycle affects overall performance [4]. Increasing exchange attempts accelerates convergence toward the infinite swapping limit [4].

Infinite Swapping Limit: This theoretical limit represents maximum exchange efficiency, where state assignments are continuously equilibrated relative to conformational sampling [4]. Practical implementations like Suwa and Todo's algorithm approach this limit [4].

Hamiltonian Variants: Beyond temperature RE, methods like Hamiltonian RE modify the potential energy function instead of temperature, often targeting specific degrees of freedom for enhanced sampling [4].

RE has proven successful for diverse applications including protein folding, protein-ligand binding, conformational free energy estimation, and protein structure refinement [4]. Its popularity stems from relative ease of implementation and robustness across various molecular systems.

Direct Comparison: MSMs versus Replica Exchange

Methodological Comparison and Performance Metrics

The following table summarizes the key methodological differences and performance characteristics between Markov State Models and Replica Exchange sampling:

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of Markov State Models and Replica Exchange sampling methodologies

| Aspect | Markov State Models (MSMs) | Replica Exchange (RE) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Approach | Post-processing of multiple short MD trajectories to build kinetic model | Enhanced sampling through parallel simulations with state-swapping |

| State Definitions | Explicit state decomposition (microstates → macrostates) | Implicit through continuous conformational space |

| Markov Property Utilization | Explicitly assumed and validated at chosen lag time | Embedded in exchange process between replicas |

| Sampling Efficiency | Extracts long-timescale kinetics from short simulations; efficient use of data | Prevents kinetic trapping; enhances barrier crossing |

| Computational Scaling | Memory-intensive for large state spaces; computation mainly post-processing | CPU-intensive; scales with number of replicas (typically 8-64) |

| Key Parameters | Lag time (τ), number of microstates, clustering method | Replica spacing, MD steps per cycle, exchange attempt frequency |

| Convergence Diagnostics | Implied timescales, Chapman-Kolmogorov test | Replica mixing, state population equilibration |

| Theoretical Guarantees | Converges to true kinetics when Markov assumption holds | Converges to proper Boltzmann distribution at each state |

| Best-Suited Applications | Modeling folding pathways, metastable state identification | Thermodynamic calculations, rugged energy landscapes |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Recent research has provided quantitative comparisons of sampling efficiency between MSM and RE approaches. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from comparative studies:

Table 2: Quantitative performance metrics for MSM and RE sampling approaches

| Performance Metric | Markov State Models | Replica Exchange |

|---|---|---|

| Time to Convergence | Varies with system complexity; can reach milliseconds from nanoseconds of aggregate data [2] | Typically faster initial convergence for thermodynamics; slower for kinetics |

| State Mixing Rate | Explicitly modeled through transition probabilities | Measured by replica state transition rates |

| Memory Requirements | High for large microstate spaces (thousands to millions of states) [2] | Moderate (linear in number of replicas) |

| Parallelization Efficiency | Embarrassingly parallel during data collection | Naturally parallel during MD phases; requires synchronization for exchanges |

| Infinite Swapping Limit | Not applicable | Approaches maximum theoretical efficiency [4] |

| Adaptive Capability | Strong: can guide further sampling [2] | Limited: parameters typically fixed during simulation |

Integrated Approaches: Markov State Models of Replica Exchange

MSMRE Framework and Implementation

A powerful synthesis of these methodologies has emerged in the form of Markov State Models of Replica Exchange (MSMRE), which uses MSMs to analyze and optimize RE simulations [4]. This approach creates "simulations of simulations" by building Markov models that describe the RE process itself, enabling rapid exploration of parameter space without computationally expensive molecular dynamics [4].

The MSMRE framework implements several key innovations:

Dual Transition Matrices: The model incorporates both conformational transitions (from MSMs) and state permutation transitions (from RE exchange rules) [4].

Efficiency Optimization: MSMRE analyzes how parameters like MD steps per cycle and exchange attempts per cycle affect the largest implied timescale of the RE simulation [4].

Infinite Swapping Estimation: The diagonal elements of the exchange transition matrix help estimate the infinite swapping limit from relatively short RE runs [4].

This integrated approach addresses critical questions about RE efficiency, particularly relevant given that RE simulations are frequently not fully converged in practice [4]. By modeling RE as a Markov process, researchers can systematically optimize cycle construction parameters before committing to production simulations.

Experimental Protocol for MSMRE Analysis

The methodology for constructing and applying MSMRE involves these key steps, derived from published protocols [4]:

Base MSM Construction:

- Perform long MD simulations of the target system at multiple thermodynamic states

- Cluster structures into microstates using kinetic criteria

- Build transition matrices for each state using a chosen lag time

- Validate Markov property through implied timescale analysis

RE Process Modeling:

- Define RE parameters: number of replicas, temperature ladder, exchange scheme

- Implement alternating move and exchange processes in the model

- Run MSMRE simulations mimicking weeks of actual RE within hours on desktop computers

Efficiency Analysis:

- Measure largest implied timescale as function of cycle parameters

- Estimate infinite swapping limit from exchange matrix diagonals

- Optimize balance between MD steps and exchange attempts

The following diagram illustrates the integrated MSMRE framework:

Diagram 3: Integrated MSMRE framework combining Markov State Models with Replica Exchange optimization.

Research Reagent Solutions for Markov-Based Sampling

Successful implementation of MSM and RE methodologies requires specific computational tools and theoretical frameworks. The following table details essential "research reagents" for these approaches:

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools for Markov-based sampling methods

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Concepts | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| MSM Construction Software | MSMBuilder, PyEMMA, Enspara | Automated pipeline for microstate clustering, transition matrix estimation, and validation [2] |

| RE Simulation Packages | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, OpenMM | Molecular dynamics engines with built-in replica exchange capabilities [4] |

| Theoretical Frameworks | Chapman-Kolmogorov equation, Perron-Frobenius theorem, Markov chain theory | Mathematical foundation for validating models and guaranteeing convergence [8] |

| State Decomposition Algorithms | K-means, K-centers, PCA, TICA | Dimensionality reduction and clustering for microstate definition [2] |

| Validation Metrics | Implied timescales, Chapman-Kolmogorov test, eigenvalue spectrum | Quantitative assessment of Markov assumption and model quality [2] |

| Enhanced Sampling Variants | Hamiltonian RE, Temperature RE, Solute Tempering | Specialized RE flavors targeting specific sampling challenges [4] |

| Analysis Libraries | MDAnalysis, MDTraj, NumPy, SciPy | Trajectory analysis and numerical computations for model construction [2] |

The Markov property, with its fundamental assertion that future states depend only on the present, provides the theoretical foundation for two powerful approaches to molecular simulation: Markov State Models and Replica Exchange sampling. While MSMs explicitly construct and validate Markovian state-to-state dynamics, RE implements a Markov process in the exchange of replicas between thermodynamic states. Both methodologies face the challenge of satisfying the Markov assumption at practical observation timescales, with MSMs addressing this through validation at appropriate lag times and RE through careful parameterization of the exchange process.

The emerging integration of these approaches in MSMRE frameworks represents a significant advancement, enabling researchers to optimize enhanced sampling parameters while leveraging the theoretical guarantees of Markov processes [4]. For computational drug development professionals, this synthesis offers promising directions for efficiently navigating complex biomolecular energy landscapes. As these methodologies continue to evolve, their capacity to extract long-timescale kinetics from shorter simulations while maintaining physical fidelity will remain crucial for studying pharmaceuticaly relevant processes like protein folding, ligand binding, and conformational changes underlying biological function.

Replica Exchange (RE), also known as Parallel Tempering, is a powerful enhanced sampling technique designed to overcome the quasi-ergodic problem in molecular simulations. It is particularly valuable for studying complex molecular systems, such as protein folding and biomolecular recognition, which are characterized by rugged free energy landscapes with multiple high barriers that trap conventional simulations in local minima [4] [9]. The method falls under the category of generalized ensemble algorithms and operates by running multiple parallel simulations (replicas) of the same system under different conditions, periodically attempting to swap their states to promote better sampling of the conformational space [4]. This guide objectively compares RE's performance against alternative sampling methods, framed within ongoing research that also encompasses Markov State Models (MSMs), providing experimental data and protocols to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Mechanism of Replica Exchange

The fundamental operation of RE can be decomposed into two alternating processes:

- Move Phase: Each replica undergoes independent conformational sampling via Molecular Dynamics (MD) or Monte Carlo (MC) at its assigned thermodynamic state (e.g., a specific temperature or Hamiltonian) [4].

- Exchange Phase: After a predetermined number of steps, swaps of the thermodynamic state assignments between replicas are attempted. The acceptance of these swaps is governed by a Metropolis criterion that ensures detailed balance is maintained, preserving the correct Boltzmann distribution at each state [4] [10].

For the common case of Temperature Replica Exchange (T-REMD), the acceptance probability for a swap between two replicas at inverse temperatures ( \betai ) and ( \betaj ) (with ( \beta = 1/kB T )) and with potential energies ( Ei ) and ( Ej ) is given by [11] [10]: [ \text{Accp} = \min\left(1, \exp\left[ (\betai - \betaj)(Ei - E_j) \right] \right) ] This criterion allows a configuration trapped in a local energy minimum at a low temperature to be "heated" to a higher temperature, where it can escape the minimum, and later "cooled" back down, thus facilitating a random walk in temperature space and accelerating the exploration of the entire conformational landscape [10].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow and the crucial exchange mechanism:

Replica Exchange Variants and Alternatives

The basic RE framework has been extended into several specialized variants to improve efficiency or target specific problems. The table below compares the most prominent ones.

Table 1: Comparison of Replica Exchange Sampling Methods

| Method | Core Perturbation | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature REMD (T-REMD) [12] | Global Temperature | Simple to implement; no prior system knowledge needed. | Number of replicas scales with system size; inefficient for large solvated systems. | Protein folding; general conformational sampling. |

| Hamiltonian REMD (H-REMD) [12] [9] | Force Field (Hamiltonian) | Fewer replicas needed; targets specific solute degrees of freedom. | Requires careful parameterization of the modified Hamiltonians. | Protein-ligand binding; RNA folding. |

| REST2 (Solute Tempering) [9] | Scaled Solute-Solute & Solute-Solvent Interactions | Highly efficient for explicit solvent simulations; focuses enhancement on the solute. | Does not specifically target high-barrier collective variables. | Sampling of solvated biomolecules (e.g., carbohydrates, drugs). |

| Multidimensional REMD (M-REMD) [12] [9] | Multiple (e.g., Temperature & Hamiltonian) | Superior sampling convergence by combining the strengths of multiple dimensions. | Computational cost scales as the product of replicas in each dimension (N1 × N2). | Complex systems with multiple, distinct sampling barriers. |

| Simulated Tempering (ST) [11] | Temperature (Serial) | Requires only a single simulation thread; can exhibit faster random walk in temperature space. | Requires prior knowledge or iterative estimation of partition functions for weight determination. | Systems where pre-computation of weights is feasible. |

Performance and Efficiency Comparison

Quantitative comparisons reveal critical trade-offs in acceptance probabilities and convergence rates between different methods.

Acceptance Probabilities

A theoretical analysis under the Gaussian approximation for the energy distribution shows a fundamental relationship between the acceptance ratios (AR) of Simulated Tempering (ST) and Replica Exchange (RE) [11]: [ \text{erfc}^{-1}(\text{AR}\text{RE}) = \sqrt{2} \times \text{erfc}^{-1}(\text{AR}\text{ST}) ] This translates to significantly higher acceptance probabilities for ST under the same simulation conditions. For instance, when ST has an acceptance ratio of 15%, RE's acceptance ratio is only about 4% [11]. This higher acceptance probability in ST can lead to a faster rate of traversing the energy space between different temperatures.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Sampling Efficiency

| System | Method | Key Performance Metric | Result | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ising Model & LJ Fluid [11] | Simulated Tempering (ST) vs. Replica Exchange (RE) | Acceptance Ratio | ST consistently showed higher AR than RE for equivalent temperature spacing. | ST provides more efficient state transitions for simple systems. |

| RNA Tetranucleotide r(GACC) [12] | H-REMD (8 replicas) vs. M-REMD (192 replicas) | Convergence of Cluster Populations | M-REMD showed significantly better agreement between independent runs; H-REMD failed to sample some rare conformations. | Multidimensional exchanges are crucial for converging complex biomolecular landscapes. |

| Host-Guest Binding System [4] | MSM of RE (MSMRE) | Implied Time Scale | Efficiency depends on the interaction between MD steps per cycle and exchange attempts per cycle. | Optimal cycling parameters are system-dependent and can be tuned via MSMRE. |

| N-Glycans [9] | HREST-BP (1D combined Hamiltonian) | Sampling of Local vs. Long-range DOFs | Efficiently sampled both localized glycosidic linkages and long-distance inter-monosaccharide motions. | Combined Hamiltonian strategies maximize efficiency while minimizing replica count. |

Case Study: Converging an RNA Tetranucleotide Ensemble

Experimental Protocol: A detailed study on the RNA tetranucleotide r(GACC) provides a clear protocol for comparing H-REMD and M-REMD [12].

- System Preparation: The RNA was solvated in a box of TIP3P water molecules and neutralized with sodium ions using the ff12SB force field.

- Simulation Setup:

- H-REMD: 8 replicas were used, employing the Accelerated MD (aMD) method where a boosting potential was applied specifically to the torsional degrees of freedom. The boost energy was included in the Hamiltonian for exchange probability calculations.

- M-REMD: 192 replicas were used, combining the aMD Hamiltonian dimension with a temperature dimension.

- Analysis: Conformational ensembles were analyzed using cluster analysis. Convergence was assessed by running multiple independent simulations and comparing the populations of the resulting clusters.

Result: The M-REMD simulations achieved dramatically better convergence between independent runs and sampled rare conformations that were missing from the H-REMD ensembles. This demonstrates that for systems with complex, rugged landscapes, the enhanced state-space mixing provided by multidimensional exchanges is worth the increased computational cost [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of RE simulations requires both software and methodological "reagents". The table below details key components.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Replica Exchange Simulations

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example Implementation / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Generalized Ensemble Framework | Provides the theoretical basis for running parallel simulations with different thermodynamic parameters and exchanging states. | Implemented in various MD software packages like AMBER, GROMACS, and NAMD [12]. |

| Metropolis Acceptance Criterion | Ensures detailed balance is maintained during replica exchanges, guaranteeing convergence to the correct Boltzmann distribution. | The core equation for T-REMD is ( \min(1, \exp[ (\betai - \betaj)(Ei - Ej) ] ) ) [4] [10]. |

| Temperature Ladder | The set of temperatures chosen for T-REMD. | Spacing is critical; optimal distributions exist to ensure non-negligible exchange rates between neighbors [12]. |

| Modified Hamiltonians (for H-REMD) | Altered potential energy functions used to enhance sampling in specific dimensions. | Includes methods like solute tempering (REST2) [9], dihedral force constant scaling [12], and accelerated MD[aMD] [12]. |

| Collective Variables (CVs) & Biasing Potentials | Low-dimensional descriptors of a process of interest (e.g., a distance, angle, or dihedral) used to apply targeted biases in H-REMD. | Allows focused enhancement on specific high-barrier transitions, such as glycosidic linkage rotations in carbohydrates [9]. |

| Markov State Model (MSM) Analysis | A framework for building kinetic models from many short simulation trajectories, which can be used to analyze the output of RE simulations. | Can be used to model the RE process itself (MSMRE) to optimize simulation parameters like cycle composition [4]. |

Advanced and Emerging Hybrid Methods

To address the limitations of standard RE, several advanced hybrid methods have been developed, illustrating the ongoing innovation in this field. The diagram below outlines the structure of one such method, HREST-BP, which synergistically combines two Hamiltonian scaling approaches.

HREST-BP: This 1D H-REMD method concurrently combines REST2 solute scaling, which enhances overall conformational transitions of the solute, with biasing potentials applied to predefined collective variables (e.g., glycosidic torsion angles). This balances broad sampling with targeted barrier crossing, efficiently sampling complex systems like N-glycans with a minimal number of replicas [9].

Replica Exchange SGLD (reSGLD): Emerging from machine learning, reSGLD applies the RE framework to Stochastic Gradient Langevin Dynamics. It uses multiple chains at different temperatures to sample complex, multimodal posteriors in Bayesian inference and deep learning, overcoming the trapping problems of single-chain SGLD. Advanced versions incorporate variance reduction and bias correction for the swap moves to account for noisy energy estimates [13].

Replica Exchange remains a cornerstone technique for enhanced sampling, particularly effective for navigating rugged energy landscapes. Its performance relative to alternatives like Simulated Tempering and standard Markov State Models is nuanced: while ST can offer higher acceptance rates, RE is simpler to implement without prior weight estimation. The choice between T-REMD, H-REMD, and more advanced hybrids like HREST-BP depends critically on the system size, the specific sampling problem, and available computational resources. For the most challenging systems, such as flexible biomolecules in drug development, multidimensional and combined Hamiltonian methods, despite their higher computational cost, provide the most robust path to a converged ensemble. Future developments will continue to refine these hybrids and improve their integration with analysis frameworks like MSMs to maximize sampling efficiency.

In computational sciences, particularly in fields like drug development and molecular simulation, efficiently sampling complex systems is a fundamental challenge. The architectural choice between parallel and serial sampling strategies profoundly influences the efficiency, scalability, and application suitability of computational experiments. Parallel sampling involves executing multiple independent sampling processes simultaneously, whereas serial sampling employs a sequential, often iterative, approach where each step builds upon previous results.

This guide objectively compares these core architectures, focusing on their applications in advanced sampling methods like Markov State Models (MSMs) and Replica Exchange Sampling, providing researchers with a structured framework for selecting an optimal strategy.

Core Architectural Principles and Definitions

Parallel Sampling

Parallel sampling operates on the principle of independent diversity. Multiple computational processes (e.g., MCMC chains, replicas, or reasoning paths) are executed concurrently and independently. The final result is achieved by aggregating outputs from all processes, often through a simple majority vote or averaging. This approach assumes that running many independent trials provides robust error filtering and a more comprehensive exploration of the state space [14] [15]. Its inherent independence makes it highly suitable for distributed computing environments.

Serial Sampling

Serial sampling leverages sequential refinement. A single process or a series of processes are executed in sequence, with each subsequent step explicitly referencing, refining, or building upon the outputs of previous steps. This architecture enables unique mechanisms like iterative error correction, progressive context accumulation, and focused resource allocation that are unattainable in parallel methods [14]. It is an inherently temporal process, where information from past computations directly informs future directions.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following tables summarize experimental data comparing the performance of parallel and serial sampling across different domains, including AI reasoning, clinical trials, and medical imaging.

Table 1: Performance Comparison in AI Reasoning and Clinical Trials

| Domain / Metric | Parallel Sampling | Serial Sampling | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI Reasoning Accuracy | Baseline | +46.7% improvement (gains up to)Outperformed in 95.6% of configurations [14] | 5 open-source models, 3 reasoning benchmarks [14] |

| Clinical Trial Power | Baseline (Standard SPCD) | Enhanced via adaptive promising zone design [16] | Sequential Parallel Comparison Design (SPCD) for high placebo-response trials [16] |

| Key Advantage | Independent diversity, simplicity | Error correction, context accumulation, focused computation [14] |

Table 2: Efficiency and Hardware Utilization

| Characteristic | Parallel Sampling | Serial Sampling | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inference Speed | Baseline | Up to 7x faster [17] | Wrist X-ray anomaly detection with hybrid models [17] |

| GPU Memory Usage | Comparable (~3.7 GB) | Comparable (~3.7 GB) [17] | Wrist X-ray anomaly detection [17] |

| Fault Tolerance | Lower (fails if any processor fails) | Higher (runs asynchronously) [18] | Distributed computing environments [18] |

| Sampling Efficiency | High correlation, long burn-in | Reduced correlation, shorter burn-in [15] | MCMC sampling of multimodal densities [15] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Sequential vs. Parallel Reasoning in AI Models

This protocol is based on experiments evaluating test-time scaling for language model reasoning [14].

- Objective: To determine whether multiple independent chains (parallel) or fewer, iteratively refining chains (sequential) are more effective at an equal token budget and compute.

- Models: 5 state-of-the-art open-source models (e.g., GPT-OSS family, Qwen3 family, Kimi-K2) [14].

- Benchmarks: 3 challenging reasoning benchmarks (AIME-2024/2025, GPQA-Diamond) requiring multi-step logical inference [14].

- Parallel Method (Self-Consistency): Multiple independent reasoning paths were sampled. Final answers were aggregated via majority voting [14].

- Sequential Method (Iterative Refinement): Starting with an initial problem, the model generated a preliminary attempt. Each subsequent step used a continuation prompt that supplied the model with its previous reasoning chain to prompt improvements or corrections [14].

- Novel Aggregation (IEW Voting): A novel Inverse-Entropy Weighted voting method assigned weights to sequential chain answers based on the Shannon entropy of their reasoning chains, where lower entropy indicated higher model confidence [14].

Protocol: Serial Replica Exchange Method (SREM)

This protocol outlines the method for sampling conformational states of proteins as an alternative to standard Replica Exchange (REM) [18].

- Objective: To reproduce REM efficiency for sampling rough energy landscapes asynchronously on a distributed network.

- System: A single alanine dipeptide molecule in explicit water [18].

- Standard REM: Requires synchronous runs of N replicas at different temperatures, with periodic configuration exchange attempts between neighbors accepted based on an acceptance probability satisfying detailed balance [18].

- SREM Workflow:

- Potential Energy Distribution (PEDF) Estimation: Approximate energy distributions at each temperature are generated using a short preliminary REM run.

- Serial Walk: A Monte Carlo or MD walk is initiated at a temperature Tn. After a number of steps, the energy E is determined.

- Asynchronous Exchange: From the known PEDF at a neighboring temperature (Pn+1(E; Tn+1)), an energy E' is sampled. A move to Tn+1 is attempted and accepted/rejected using the standard REM acceptance probability.

- Iteration: The walk continues, potentially at the new temperature, and the process repeats. A single walker thus samples all temperatures without synchronous processor communication [18].

Protocol: Markov State Model (MSM) from Ultra-Long Trajectories

This protocol describes using MSMs as an analysis tool for data from ultra-long molecular dynamics trajectories [19].

- Objective: To construct a kinetic model from simulation data to discover folding pathways and predict functional mechanisms.

- System & Data: FiP35 WW domain, using two previously reported 100 μs trajectories from the Anton supercomputer [19].

- State Discretization (Clustering): All saved simulation snapshots were clustered using a k-centers algorithm, generating a 26,104-state microstate model. A 200-state macrostate model was constructed for visualization and qualitative analysis [19].

- Transition Matrix Estimation: A transition matrix was built by counting transitions between the discrete states at a specified Markov lag time (15 ns). The model was validated by checking for implied timescale invariance [19].

- Validation & Analysis:

- Recapitulation: The MSM's ability to reproduce the original trajectory dynamics was tested by comparing autocorrelation functions of observables like RMSD.

- Experiment Mimicry: The model was used to mimic a temperature-jump experiment by stochastically perturbing equilibrium populations and observing the relaxation of an observable (Trp8 SASA) back to equilibrium, yielding folding timescales [19].

- Pathway Analysis: The transition matrix's eigenvectors and eigenvalues were analyzed to identify the slowest dynamical processes and statistically significant folding pathways [19].

Architectural Workflow Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental difference in information flow between parallel and serial sampling architectures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Frameworks

| Tool/Solution | Function | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|

| MSMBuilder2 | Software package for constructing and analyzing Markov State Models from molecular dynamics data [19]. | Protein folding studies, functional dynamics prediction [19]. |

| OpenRouter API | Provides consistent, reproducible API access to a variety of large language models for running reasoning experiments [14]. | Evaluating sequential vs. parallel reasoning chains in AI models [14]. |

| Folding@Home | A worldwide distributed computing environment capable of sub-millisecond protein simulations, ideal for running asynchronous algorithms like SREM [18]. | Sampling conformational states of biological systems without a massive local cluster [18]. |

| Inverse-Entropy Weighted (IEW) Voting | A training-free aggregation method that weights answers based on the inverse entropy (confidence) of their reasoning chains [14]. | Boosting the accuracy of sequential reasoning scaling in AI models [14]. |

| Promising Zone Framework | An adaptive sample size re-estimation method used in clinical trials that increases sample size if conditional power at an interim analysis falls within a "promising" range [16]. | Enhancing the efficiency of Sequential Parallel Comparison Designs (SPCDs) [16]. |

The choice between parallel and serial sampling is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather of strategic alignment with the problem's structure and computational constraints.

- Choose Parallel Sampling when you require broad, independent exploration of a state space, when the problem can be easily decomposed into independent tasks, and when you have access to reliable, synchronous parallel computing resources. It remains a robust, straightforward baseline [14] [15].

- Choose Serial Sampling when the problem benefits from iterative refinement, error correction, and knowledge accumulation. It is particularly advantageous in scenarios with limited or asynchronous computing resources, when tackling complex, multi-step reasoning tasks, and when seeking to reduce sample correlations and burn-in time in MCMC sampling [14] [18] [15].

Emerging hybrid approaches that leverage the initial breadth of parallel exploration followed by the targeted depth of serial refinement are likely to represent the next evolutionary step in sampling architecture, offering a powerful synthesis of both paradigms' strengths.

The evolution of Markov State Models (MSMs) represents a fundamental paradigm shift in computational biology, transitioning from subjective, anecdotal trajectory analysis to a rigorous statistical science. This transformation has positioned MSMs as a powerful alternative to established enhanced sampling techniques like Replica Exchange (RE). Where RE methods, such as Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD), enhance sampling through parallel simulations at different temperatures or Hamiltonians, MSMs achieve a similar goal by constructing a kinetic model from many short, distributed simulations, enabling the study of biomolecular processes on experimentally relevant timescales. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, detailing their theoretical foundations, experimental protocols, and performance in tackling complex biological problems such as protein folding and ligand binding.

The computational study of biomolecular dynamics, including protein folding and conformational changes, has long been constrained by the problem of insufficient sampling. Biomolecules navigate rough energy landscapes with many local minima separated by high-energy barriers, making it difficult for conventional Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to adequately explore conformational space within accessible simulation timescales [20]. For decades, simulation-based research relied on "anecdotal single-trajectory approaches," which provided limited insights and suffered from poor statistical significance [2].

The field witnessed a paradigm shift with the move toward comprehensive statistical approaches, chief among them being Markov State Models (MSMs). MSMs have evolved from a specialized analytical art into a robust science by providing a framework to integrate data from many short simulations into a single quantitative model. Concurrently, Replica Exchange (RE) methods emerged as a powerful parallel sampling technique to accelerate barrier crossing. The historical development of these methods represents two complementary paths toward solving the sampling problem: one (RE) focused on enhancing the sampling process itself, and the other (MSM) focused on extracting maximal insight from existing data through sophisticated modeling.

Theoretical Foundations and Historical Context

Replica Exchange: Enhancing Sampling Through Parallelism

Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD), also known as Parallel Tempering, is a generalized-ensemble algorithm designed to improve the dynamic properties of Monte Carlo and MD simulations. The fundamental concept involves running multiple parallel simulations (replicas) of the same system at different temperatures or Hamiltonians [21] [20].

The strength of REMD lies in its ability to prevent simulations from becoming trapped in local energy minima. High-temperature replicas can cross energy barriers more easily and explore broader regions of conformational space. The periodic exchange of configurations between replicas, governed by a Metropolis criterion based on potential energies and temperatures, allows low-temperature replicas to access these better-sampled configurations [21] [10]. The acceptance probability for a swap between replicas i and j with energies E_i and E_j at inverse temperatures β_i and β_j is given by:

p = min(1, exp((E_i - E_j)(β_i - β_j))) [21]

This approach creates a random walk in temperature space, facilitating better sampling of complex energy landscapes. REMD has since diversified into various specialized forms, including Hamiltonian REMD (H-REMD) for different force field parameters and constant pH REMD for studying protonation states [20].

Markov State Models: A Framework for Data Integration

Markov State Models approach the sampling problem from a different perspective. Rather than modifying the simulation protocol, MSMs provide a mathematical framework for constructing a kinetic model from many short, parallel MD simulations [2]. The core assumption is the Markov property, which posits that future states depend only on the current state, not on the full history of the system [22].

The historical development of MSMs marked a transition toward a more comprehensive statistical approach to simulation analysis. The methodology involves:

- State Discretization: Conformational space is divided into many (thousands) of "microstates" through structural clustering, typically using metrics like root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) [2].

- Transition Matrix Construction: A transition count matrix C_ij(τ) is built by counting transitions between states i and j at a specific lag time τ from MD trajectories [2].

- Kinetic Clustering: Microstates are coarse-grained into larger "macrostates" based on kinetic properties, creating a simplified model that retains the essential dynamics of the system [2].

This approach allows researchers to integrate data from multiple simulations, even those that start from different initial conditions and never observe complete transitions, making it particularly valuable for studying rare events.

The Convergence of Approaches

Historically, RE and MSMs developed along parallel tracks, but recent advancements have seen their convergence. MSM-based analysis has been applied to RE simulations themselves, creating "MSMRE" models that help optimize RE parameters and analyze their efficiency [4]. Furthermore, hybrid methods like Replica Exchange with Collective-Variable Tempering (RECT) combine the strengths of both approaches by integrating metadynamics (an importance sampling method) within a Hamiltonian replica-exchange scheme [23].

Table 1: Key Historical Developments in RE and MSMs

| Year | Development | Method | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1986 | Replica Monte Carlo | RE [21] | First introduction of replica exchange concept |

| 1999 | Replica Exchange MD | REMD [21] [20] | Adapted RE for molecular dynamics simulations |

| ~2000s | Early MSM Concepts | MSM [2] | Initial application of Markov modeling to biomolecular simulations |

| 2010 | MSM Review | MSM [2] | Formalization of MSM methodology for non-experts |

| 2015 | RECT Method | Hybrid [23] | Combined metadynamics with Hamiltonian REMD |

| 2016 | MSMRE Framework | Hybrid [4] | Applied MSMs to analyze and optimize RE simulations |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Replica Exchange Protocol

The implementation of REMD follows a well-established cyclic protocol [4]:

- Replica Initialization: Initialize N replicas of the system, each assigned to a different temperature (T-REMD) or Hamiltonian (H-REMD). Temperature spacing is crucial and must provide sufficient overlap between energy distributions of adjacent replicas [21] [20].

- Move Phase: Each replica evolves independently for a fixed number of MD steps (typically hundreds to thousands) under its assigned thermodynamic conditions.

- Exchange Phase: After the move phase, attempt to swap configurations between adjacent replicas. The swap is accepted with probability: Accp_{SS'} = min(1, exp(-Σ[β{s'[m]}E{s'[m]}(xm) - β{s[m]}E{s[m]}(xm)])) [4]

- Repetition: Repeat steps 2-3 for thousands of cycles to achieve sufficient sampling.

The efficiency of REMD depends critically on parameters such as the number of replicas, temperature range and distribution, MD steps per cycle, and exchange attempt frequency [4].

Markov State Model Construction

Building an MSM involves a systematic workflow that has been standardized over years of development [2]:

- Data Generation: Run an ensemble of MD simulations, which can be initiated from different structural states. These simulations need not be long enough to observe the full process of interest.

- Feature Selection: Identify relevant structural features (e.g., distances, angles, dihedrals) that characterize the system's dynamics.

- Microstate Clustering: Use structural clustering algorithms (e.g., k-means, k-centers) to partition the conformational data into thousands of microstates. The objective is to create states within which structural and kinetic properties are homogeneous [2].

- Transition Matrix Estimation: Assign every MD frame to a microstate and count transitions between pairs of states at a specified lag time τ to build a count matrix C_ij(τ).

- Model Validation: Test the self-consistency of the MSM by verifying that implied timescales are independent of the chosen lag time τ.

- Coarse-Graining: Use algorithms like PCCA+ to group microstates into a smaller number of macrostates that represent functionally distinct conformations.

- Analysis: Extract kinetic and thermodynamic properties from the model, including free energy surfaces, transition pathways, and rates.

Table 2: Core Methodological Components Comparison

| Component | Replica Exchange | Markov State Models |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Strength | Enhanced barrier crossing | Maximizing information from limited data |

| Sampling Approach | Modified simulation conditions | Post-processing of standard MD |

| Key Parameters | Temperature set, exchange frequency | Lag time, state discretization |

| Data Requirements | Long or multiple parallel simulations | Many short simulations |

| Output | Thermodynamic ensemble | Kinetic model and thermodynamics |

| Computational Scaling | High (many simultaneous replicas) | Moderate (many serial simulations) |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Metrics for Sampling Efficiency

When comparing RE and MSM approaches, several quantitative metrics are essential for objective evaluation:

- Convergence Rate: The simulation time required for thermodynamic and kinetic properties to stabilize within statistical error.

- Sampling Comprehensiveness: The ability to visit all relevant conformational states, particularly those separated by high free energy barriers.

- Computational Efficiency: The total computational cost required to achieve a target level of statistical precision.

- Kinetic Accuracy: The precision of transition rates between states compared to experimental or reference values.

For RE simulations, a key metric is the round-trip time for a replica to travel from the lowest to highest temperature and back, which measures the efficiency of the random walk in temperature space [4]. For MSMs, the central validation test is the lag-time independence of implied timescales, which ensures the Markov assumption is satisfied [2].

Application-Based Performance Comparison

Table 3: Performance Comparison on Biomolecular Systems

| System Type | REMD Performance | MSM Performance | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Proteins (e.g., villin, NTL9) | Efficient folding observation; efficiency depends on activation enthalpy [20] | Quantitative prediction of experimental data; millisecond timescales from microsecond simulation data [2] | MSMs enabled simulation on experimentally relevant timescales [2] |

| Host-Guest Binding | Effective for binding affinity estimation [4] | Built from long MD simulations at multiple states; used to create MSMRE [4] | MSMRE model systematically optimized RE parameters [4] |

| RNA Tetranucleotide | Challenging even with specialized REMD variants [23] | RECT (hybrid method) outperformed dihedral-scaling REMD [23] | Hybrid approach addressed limitations of individual methods [23] |

| Protein-Ligand Binding | Successful with constant pH REMD and λ-REMD [20] | Adaptive sampling directs simulations to functionally relevant regions [2] | Both enable study of molecular recognition |

Integrated Workflows: The Best of Both Worlds

Recent developments demonstrate how integrating RE and MSM methodologies creates synergistic benefits:

MSMRE for RE Optimization: Markov State Models of Replica Exchange (MSMRE) use long MD simulations to build MSMs that then simulate RE in silico, enabling rapid testing of RE parameters without the expense of full simulations [4]. This approach has been used to optimize the number of exchange attempts per cycle and MD steps per cycle.

Adaptive Sampling: MSMs can guide where to initiate new simulations, including new RE replicas. This "adaptive sampling" uses the current model to identify under-sampled or high-uncertainty regions, directing computational resources more efficiently [2].

RECT and Related Hybrids: Replica Exchange with Collective-Variable Tempering uses concurrent metadynamics within a Hamiltonian RE scheme to bias multiple collective variables across different replicas [23]. This addresses the limitation of both high-dimensional biasing in metadynamics and the non-targeted nature of standard REMD.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools and Their Functions

| Tool/Resource | Function | Method Application |

|---|---|---|

| MSM Software (e.g., MSMBuilder) | Builds and validates Markov State Models from MD data | MSM Construction [2] |

| REMD Plugins (e.g., for GROMACS, NAMD) | Implements replica exchange molecular dynamics | REMD Simulation [20] |

| Collective Variable Packages | Defines and monitors order parameters for sampling | Metadynamics, RECT [23] |

| Global Configuration Database | Stores and shares configurations across replicas | Advanced RE Schemes [24] |

| Q-RepEx Pipeline | Interfaces with Q package for REMD-EVB simulations | Enhanced Sampling for Chemical Reactivity [25] |

Visualizing Methodologies

Markov State Model Construction Workflow

Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics Cycle

The evolution of Markov State Models from an art to a science represents a fundamental advancement in computational biology, paralleling the development of sophisticated enhanced sampling methods like Replica Exchange. While REMD addresses the sampling problem by modifying the simulation process to enhance barrier crossing, MSMs provide a powerful framework for extracting maximal information from existing simulation data through statistical modeling. The historical trajectory of these methods is now converging toward integrated approaches that leverage the strengths of both paradigms, such as MSMRE for RE optimization and RECT for targeted enhanced sampling. For researchers tackling complex biomolecular systems, understanding the comparative strengths, limitations, and appropriate application domains of these methods is crucial for designing efficient and informative computational studies. As both methodologies continue to mature, their integration promises to further accelerate our ability to simulate and understand biological processes at atomic resolution.

From Theory to Practice: Implementation and Real-World Applications

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation generates vast amounts of high-dimensional data tracking atomic motions over time, creating a critical challenge for researchers: how to extract meaningful mechanistic understanding from these complex trajectories [2]. This challenge has driven the development of sophisticated analysis frameworks, primarily Markov State Models (MSMs) and Replica Exchange (RE) sampling methods [4]. While both approaches aim to overcome the sampling limitations of conventional MD, they represent fundamentally different paradigms. MSMs construct kinetic models from existing MD data by identifying metastable states and transition probabilities [2] [26], whereas RE is an enhanced sampling technique that improves the generation of MD data itself by facilitating barrier crossing through temperature or Hamiltonian exchange [4] [10]. This review systematically compares these methodologies, their performance characteristics, and their appropriate applications in computational biology and drug development.

The Markov State Model Construction Pipeline

Building an MSM involves a multi-stage process that transforms raw MD trajectories into a kinetic model. The quality of the final model depends critically on decisions made at each step [2] [26].

Feature Selection and Dimensionality Reduction

The initial step converts atomic coordinates into features that capture essential conformational changes. While Cartesian coordinates or dihedral angles are common starting points [27], the choice of features significantly impacts model quality. Research demonstrates that further reducing representation dimensionality in a non-parametric, data-driven manner improves MSM quality by providing better state space discretization [28].

Table 1: Feature Selection and Dimensionality Reduction Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Finds linear combinations of input coordinates that maximize variance [26] | Computationally efficient; intuitive interpretation | High-variance directions may not correspond to slow kinetic processes |

| Time-structure Independent Component Analysis (tICA) | Identifies slowest decorrelating degrees of freedom [26] | Kinetically motivated; better state decomposition | Requires lag time parameter selection |

| Ultrafast Shape Recognition (USR) | Describes molecular shape via distance distributions to specific atoms [28] | Alignment-free; low-dimensional; captures essential shape features | May overlook atomic-level details |

State Discretization and Clustering

Conformations are grouped into microstates (typically thousands) based on structural similarity, followed by further aggregation into macrostates (metastable states) based on kinetic properties [2] [29]. The identification of macrostates is a central decision that impacts MSM quality, with theory suggesting that structures capable of rapid interconversion should be aggregated into the same macrostate [28].

Transition Matrix Estimation and Validation

The final step involves counting transitions between states at a specific lag time (τ) to estimate a transition probability matrix [2]. Rigorous validation through various statistical tests is essential, including implied timescale analysis to ensure Markovian behavior and Chapman-Kolmogorov tests to validate model predictions [30] [27].

The following diagram illustrates the complete MSM construction pipeline:

Replica Exchange Sampling Methodology

Replica Exchange (RE), also known as Parallel Tempering, addresses the sampling problem at the data generation stage rather than during analysis [4]. The fundamental principle involves running multiple parallel simulations (replicas) at different temperatures or Hamiltonian states, with periodic attempts to exchange configurations between adjacent replicas according to a Metropolis acceptance criterion [4] [10]. This approach enables more thorough exploration of conformational space by allowing systems to overcome energy barriers in elevated-temperature replicas.

The exchange acceptance probability between replicas i and j follows:

[ p{\text{acc}}^{\text{RE}} = \min\left{1, \frac{p{\betai}(x^jk)}{p{\betai}(x^ik)} \times \frac{p{\betaj}(x^ik)}{p{\betaj}(x^j_k)}\right} ]

where ( p_{\beta}(x) ) represents the probability of configuration x at inverse temperature β [10].

Performance Comparison: MSM vs. Replica Exchange

Quantitative Assessment of Sampling Efficiency

Table 2: Performance Comparison Between MSM and RE Approaches

| Performance Metric | Markov State Models | Replica Exchange |

|---|---|---|

| Timescale Access | Extends to seconds via kinetic modeling [2] | Limited by simulation length (nanoseconds to microseconds) |

| Barrier Crossing | Identifies states and rates but doesn't enhance barrier crossing | Actively enhances barrier crossing through temperature/Hamiltonian switching [4] |

| Data Requirements | Can work with many short simulations; suitable for distributed computing [2] | Requires multiple parallel long simulations; higher immediate resource demand [4] |

| Experimental Validation | Direct comparison with NMR relaxation, single-molecule FRET [31] | Primarily validates through thermodynamics; kinetics less accessible |

| System Size Limitations | Challenged by large systems (e.g., IgG antibodies) [28] | Efficiency decreases with system size due to reduced exchange acceptance |

| Force Field Dependence | Can incorporate experimental data to correct force field errors (AMMs) [31] | Completely dependent on force field accuracy |

Case Study: Antibody Dynamics and Protein Folding

Recent research on Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody dynamics demonstrates MSM's capability with large molecular systems. A 2022 study showed that using fewer dimensions and more structures results in a better MSM, with USR coordinates outperforming conventional representations in statistical tests of model quality [28]. This approach revealed how antigen binding affects antibody dynamics, advancing understanding of antibody-antigen recognition.

For protein folding, MSMs have successfully characterized the folding pathways of proteins like NTL9 and Fs peptide. One study utilizing tICA-based distance metrics demonstrated marked improvement over conventional distance metrics, revealing the role of non-native contacts in creating slow timescales associated with compact states [26].

Advanced Methodologies and Protocols

Experimental Protocols for MSM Construction

Protocol 1: Standard MSM Construction Using PyEMMA/MSMBuilder

Trajectory Preparation: Gather MD trajectories, ensuring adequate sampling of states of interest. For Fs peptide, researchers used 28 XTC trajectories with a PDB topology file [27].

Featurization: Transform raw coordinates into relevant features. Common choices include:

- Dihedral angles (phi/psi/chi)

- Root mean square deviation (RMSD)

- Contacts between key residues

Execute via:

msmb DihedralFeaturizeror equivalent [27].

Dimensionality Reduction: Apply tICA or PCA with appropriate lag time (e.g., 5-20 ns). For Fs peptide, tICA with lag time of 5 ns (100 steps) effectively revealed folding coordinates [27].

Clustering: Use k-means or k-centers to generate 100-10,000 microstates. Cluster in the reduced space: