Mapping Protein-Ligand Binding Pathways: A Comprehensive Guide to Molecular Dynamics Simulations in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on using Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to analyze protein-ligand binding pathways.

Mapping Protein-Ligand Binding Pathways: A Comprehensive Guide to Molecular Dynamics Simulations in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on using Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to analyze protein-ligand binding pathways. It covers foundational principles, from why dynamics matter beyond static docking, to advanced methodological applications including enhanced sampling techniques like accelerated MD (aMD) for capturing rare binding events. The guide details practical troubleshooting for simulation setup and convergence, hardware selection for optimal performance, and rigorous validation protocols using energetic and geometric metrics. By synthesizing insights from foundational concepts to current best practices, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to leverage MD simulations effectively for elucidating binding mechanisms, improving drug candidate selection, and accelerating rational drug design.

Why Dynamics Matter: Moving Beyond Static Snapshots in Protein-Ligand Interaction Analysis

The "lock-and-key" model, which depicts proteins as static structures, provides an incomplete picture of molecular recognition. It is now widely understood that protein flexibility and induced fit—where both the ligand and the binding site adjust conformations upon binding—are fundamental to biological function and drug discovery [1]. Relying solely on static crystal structures risks overlooking critical dynamic aspects of binding, such as alternative pathways, allosteric mechanisms, and the population of transient intermediate states.

This Application Note outlines the limitations of static structural analysis and presents advanced molecular dynamics (MD) protocols to capture the dynamic binding processes essential for modern drug development, framed within a thesis on protein-ligand binding pathway analysis.

The Critical Shortcomings of Static Models

The Theoretical Spectrum of Binding Mechanisms

Static structures are inherently limited in their ability to represent the continuous spectrum of binding mechanisms. The prevailing models have evolved from the initial "lock-and-key" hypothesis to more dynamic concepts [1]:

- Induced Fit: The binding partner induces a conformational change in the protein.

- Conformational Selection: The ligand selects a pre-existing, complementary conformation from an ensemble of protein states, shifting the conformational equilibrium.

- Extended Conformational Selection: This generalized model includes a repertoire of selection and adjustment processes. Induced fit can be viewed as a subset of this model, where the contribution of adjustment is significant [1].

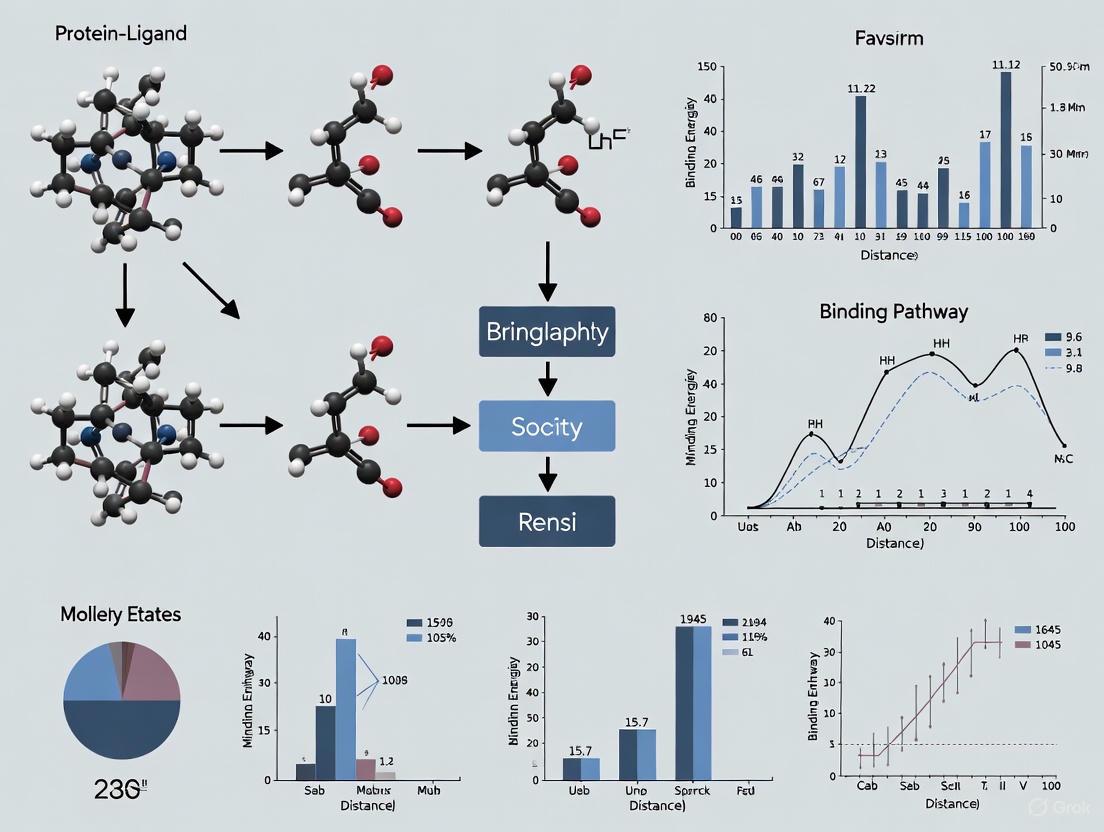

The following diagram illustrates this spectrum of binding mechanisms, from the most rigid to the fully dynamic model.

Quantitative Evidence of Static Model Limitations

The practical implications of these theoretical limitations are significant. In drug development, static models are often used for predicting metabolic drug-drug interactions (DDIs) via cytochrome P450 enzymes. However, a large-scale 2024 simulation study demonstrates that static and dynamic models are not equivalent for this critical task [2].

The study compared static calculations with dynamic simulations (Simcyp V21) across 30,000 hypothetical DDIs. Discrepancy was defined as an inter-model discrepancy ratio (IMDR) outside the interval of 0.8–1.25.

Table 1: Discrepancy Rates Between Static and Dynamic DDI Predictions [2]

| Simulation Representative | Inhibitor Concentration Used | IMDR < 0.8 (Under-prediction) | IMDR > 1.25 (Over-prediction) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Average steady-state (Cavg,ss) | 85.9% | 3.1% |

| Vulnerable Patient | Average steady-state (Cavg,ss) | Not Specified | 37.8% |

This data shows that static models can be misleadingly simplistic, particularly for vulnerable patient populations where DDI risk is most concerning. The authors conclude that "caution is warranted in drug development if static... approaches are used alone to evaluate metabolic DDI risks" [2].

Molecular Dynamics Protocols for Capturing Dynamic Binding

MD simulations provide a powerful suite of methods to overcome the limitations of static structures by sampling the temporal evolution of the protein-ligand system at an atomic level.

Protocol 1: Hypersound-Accelerated MD for Sampling Slow Binding Events

Capturing slow binding events (microseconds to seconds) with conventional MD is computationally prohibitive. This protocol uses high-frequency ultrasound perturbation to accelerate the dynamics, making it feasible to observe binding events on standard high-performance computers [3].

- Application: Ideal for initial exploration of ligand binding pathways and kinetics, especially for slow-binding inhibitors.

- Workflow:

- Key Steps:

- System Setup: Prepare the protein-ligand complex in an explicit solvent box, neutralize with ions, and minimize energy.

- Apply Hypersound Field: Introduce a high-frequency (e.g., 625 GHz) perturbation to generate local high-temperature/pressure regions, increasing the probability of observing binding events by 10-20 times compared to conventional MD [3].

- Run Simulations and Analyze: Perform multiple short (100-200 ns) simulations. Analyze trajectories to identify diverse binding pathways and conformational states.

- Estimate Kinetics: Calculate association rates and energy barriers from the observed binding events.

Protocol 2: Pathway Analysis with Adaptive Biasing (MAZE)

Understanding the multiple pathways a ligand can take to reach its binding site is crucial. The MAZE module in PLUMED is designed to discover ligand binding and unbinding pathways without prior knowledge of the reaction coordinate [4].

- Application: Mapping multiple ligand egress and ingress pathways, identifying metastable states, and determining the preferred binding route.

- Workflow:

- System Preparation: Equilibrate the protein-ligand complex in explicit solvent using a standard MD protocol.

- Define a Contact Function: Use a loss function that describes the contacts between the inhibitor and protein atoms (e.g., ( Q = \sum{kl} \exp(-r{kl})/r{kl} ), where ( r{kl} ) is the distance between protein and ligand atoms) [4].

- Run Adaptive Simulations: Launch multiple MD simulations where the ligand is "pulled" from the protein by minimizing the contact function. The adaptive biasing allows the system to find the path of least resistance.

- Pathway Clustering and Analysis: Cluster the resulting trajectories to identify dominant pathways and compute the free-energy profile along each path using techniques like umbrella sampling.

Protocol 3: Absolute Binding Free Energy Calculation with BFEE2

Quantifying the binding affinity is a primary goal. The Binding Free-Energy Estimator 2 (BFEE2) provides a streamlined protocol for calculating standard binding free energies (( \Delta G^\circ )) with high accuracy [5].

- Application: Predicting binding affinities for lead optimization in drug discovery.

- Key Steps:

- Input Preparation: Starting from a known bound structure (from X-ray or docking), BFEE2 automates the preparation of all necessary simulation inputs.

- Define Collective Variables (CVs): The protocol uses a set of carefully designed CVs that describe the separation, orientation, and conformation of the ligand relative to the protein.

- Run Adaptive Biasing Force (ABF) Simulations: Perform simulations that apply a biasing force along the CVs to efficiently sample the alchemical pathway from bound to unbound states.

- Post-Processing: The software performs automated post-treatment of the simulation data to yield the final estimate of ( \Delta G^\circ ), typically achieving chemical accuracy (within 1 kcal/mol).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Solutions

Table 2: Key Software and Computational Tools for Analyzing Protein Flexibility

| Tool/Solution | Primary Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| SLIDE | Docking tool that models minimal side-chain and ligand flexibility to achieve steric complementarity. | Effectively mimics experimentally observed side-chain motions without requiring large conformational changes, balancing accuracy and computational cost [6]. |

| PLUMED (MAZE) | Plugin for enhanced sampling MD simulations; MAZE module discovers binding pathways. | Identifies multiple ligand unbinding pathways without pre-defined coordinates, revealing how slight structural changes in ligands alter egress routes [4]. |

| GROMACS | High-performance MD simulation package. | The core engine for running MD simulations, often patched with PLUMED for enhanced sampling [4]. |

| BFEE2 | Automated, graphical interface for absolute binding free-energy calculations. | Limits human intervention, streamlines input preparation and post-processing, and delivers reliable ( \Delta G^\circ ) estimates [5]. |

| Simcyp Simulator | PBPK/PD platform for predicting drug disposition and DDIs in populations. | A dynamic model that incorporates time-variable concentrations and inter-individual variability, outperforming static models in DDI risk assessment [2]. |

The limitation of static structures is not merely a theoretical concern but a practical challenge with direct consequences for predicting drug efficacy and safety. As demonstrated, static models can fail to accurately predict critical interactions like DDIs, particularly in vulnerable populations [2]. The protocols and tools outlined herein—including hypersound-accelerated MD, adaptive pathway finding, and free-energy calculations—provide a robust framework for integrating protein flexibility and induced fit into research workflows. For a thesis focused on binding pathway analysis, embracing these dynamic methods is indispensable for moving beyond simplistic snapshots and capturing the rich, complex reality of molecular recognition.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool in computational biophysics and drug discovery, enabling researchers to probe biological processes at an atomic level of detail. This application note focuses on how MD simulations, particularly when enhanced with advanced sampling and machine learning techniques, address three fundamental biological questions: elucidating protein-ligand unbinding pathways, predicting binding and unbinding kinetics, and identifying metastable states that are crucial for understanding protein function and ligand efficacy. These capabilities are transforming structure-based drug design by providing insights that extend far beyond static structural analysis, allowing scientists to understand not just where ligands bind, but how they get there, how long they remain, and what conformational states they stabilize along the way.

Quantitative Insights from MD Simulations

The table below summarizes key quantitative data and biological insights that can be derived from MD simulations for studying protein-ligand interactions.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters from MD Simulations of Protein-Ligand Interactions

| Parameter Category | Specific Measurable | Biological Significance | Typical MD Approach | Representative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unbinding Kinetics | Dissociation rate constant (koff) | Determines drug residence time & efficacy [7] | Metadynamics [7] | koff predictions for trypsin-benzamidine matching experimental values (ms-s timescales) [7] |

| Binding Kinetics | Association rate constant (kon) | Determines binding efficiency | Metadynamics & Markov Models [7] | kon estimation from koff and binding affinity calculations [7] |

| Pathway Analysis | Identified unbinding pathways | Reveals molecular mechanism of dissociation | Multiple biased trajectories [7] | Discovery of solvent-assisted hydrogen bond breaking in trypsin-benzamidine unbinding [7] |

| Metastable States | Intermediate state lifetimes & populations | Identifies transiently stable conformations | Markov State Models (MSMs) [7] | Detection of apo trypsin states with 0.7 ms lifetimes that preclude ligand binding [7] |

| Pathway Energetics | Free energy profiles | Quantifies thermodynamic stability of states | Metadynamics/Umbrella Sampling [7] [8] | Energy barriers and well depths along the reaction coordinate [8] |

Elucidating Unbinding Pathways and Mechanisms

Protocol: Metadynamics for Unbinding Pathway Exploration

Objective: To generate multiple unbinding trajectories and identify the dominant pathways and associated structural bottlenecks for a protein-ligand complex.

System Preparation:

- Initial Structure: Start with the crystallographic binding pose of the protein-ligand complex.

- Solvation: Embed the complex in an explicit solvent box with appropriate counterions to neutralize the system.

- Force Field: Apply an all-atom force field (e.g., OPLS4/OPLS5 [9], AMBER, CHARMM).

- Equilibration: Perform energy minimization and equilibration runs under NPT conditions.

Collective Variables (CVs) Selection:

- Path-Based CVs: Define a set of collective variables that can distinguish between the bound and unbound states. These often include:

- The distance between the protein and ligand centers of mass.

- Specific key atomic distances between protein residues and the ligand.

- Solvation parameters, such as the number of water molecules in the binding pocket [7].

Metadynamics Execution:

- Bias Deposition: Apply a history-dependent bias potential (typically Gaussian functions) along the selected CVs.

- Parameters: Set the Gaussian height and width to balance between exploration efficiency and resolution.

- Multiple Trajectories: Run multiple independent metadynamics simulations (e.g., 21 trajectories as in the trypsin-benzamidine study [7]) to ensure adequate sampling of different pathways.

- Convergence Monitoring: Monitor the exploration of the CV space to ensure the simulation has sufficiently sampled the transition from bound to fully solvated state.

Analysis:

- Trajectory Clustering: Cluster the generated unbinding trajectories based on structural similarity to identify dominant pathways.

- Bottleneck Identification: Analyze the trajectories for common structural intermediates and critical residues that form dynamical bottlenecks.

- Water Analysis: Monitor the entry and positioning of water molecules that may assist in breaking key interactions (e.g., shielded hydrogen bonds) [7].

Key Findings and Biological Insights

Advanced MD simulations have revealed that unbinding is rarely a simple, direct reversal of binding. For the trypsin-benzamidine complex, simulations showed that solvent molecules play an active role in the unbinding process by entering the binding pocket and assisting in the breakage of key, shielded hydrogen bonds through the formation of water bridges [7]. Furthermore, analysis of multiple trajectories uncovered a complex network of pathways with several intermediate states where the ligand resides for times ranging from nanoseconds to milliseconds, providing a rich, dynamic picture of the dissociation process that is inaccessible to experimental observation alone [7].

Predicting Binding and Unbinding Kinetics

Protocol: Calculating koff and kon from Enhanced Sampling

Objective: To compute the dissociation (koff) and association (kon) rate constants from MD simulations.

Prerequisite: Successful application of the "Metadynamics for Unbinding Pathway Exploration" protocol (Section 3.1).

Kinetic Extraction from Metadynamics:

- Residence Time Calculation: For each successful unbinding trajectory i, record the physical simulation time required for the transition, ti.

- Bias Acceleration Factor: Calculate the time acceleration factor, α, provided by the metadynamics bias for each trajectory using the running average: α = ⟨eβV(s,t)⟩, where β is the inverse temperature, and V(s,t) is the bias potential experienced at time t [7].

- Unbiased Unbinding Time: Compute the unbiased unbinding time for each trajectory as τi = α ⋅ ti.

- koff Estimation: The dissociation rate constant is the inverse of the mean unbiased residence time: koff = 1 / ⟨τi⟩, where the average is taken over all independent trajectories.

Markov Model Construction for Comprehensive Kinetics:

- State Discretization: From the unbinding trajectories, identify all major intermediates and stable states.

- Transition Matrix: Calculate the rates for all possible transitions between these defined states.

- Model Validation: Ensure the model's overall escape rate agrees with the direct koff estimation from the mean residence time [7].

- kon Calculation: Use the computed koff and the independently calculated binding affinity (e.g., from free energy calculations) to derive the association rate: kon = KA ⋅ koff, where KA is the association constant.

Statistical Validation:

- Poisson Statistics: Perform a Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test to verify that the escape times from the bound state obey time-homogeneous Poisson statistics, validating the underlying assumptions of the kinetic analysis [7].

Key Findings and Biological Insights

The ability to predict kinetics computationally is a major advance. In the case of trypsin-benzamidine, metadynamics simulations successfully reached timescales of seconds and yielded koff and kon values that were in reasonable agreement with experimental measurements [7]. This demonstrates that MD can now predict not only the strength of a protein-ligand interaction (affinity) but also its duration (residence time), the latter being increasingly recognized as a critical factor for in vivo drug efficacy.

Identifying and Characterizing Metastable States

Protocol: Markov State Modeling (MSM) for Metastable State Analysis

Objective: To identify, characterize, and quantify the lifetimes of metastable intermediate states from a set of MD trajectories.

System Preparation and Trajectory Generation:

- Ensemble of Trajecties: Generate a large ensemble of MD trajectories, which can be derived from enhanced sampling methods (like metadynamics) or from many short, parallel, unbiased simulations.

- Reaction Coordinate: Use a relevant collective variable (e.g., protein-ligand distance) to frame the initial analysis.

State Discretization and Model Building:

- Dimensionality Reduction: Project the high-dimensional trajectory data onto a lower-dimensional space using techniques like time-lagged independent component analysis (tICA) to identify slow collective variables.

- Clustering: Cluster the conformational snapshots from all trajectories into microstates based on structural similarity (e.g., using RMSD or contact maps).

- Transition Count Matrix: Construct a matrix that counts the observed transitions between each pair of microstates within a specific lag time (τ).

- Model Validation: Validate the Markovian assumption by testing the Chapman-Kolmogorov equation and ensuring the implied timescales are constant for a range of lag times.

Metastable State Analysis:

- PCCA+ Analysis: Perform Perron Cluster Cluster Analysis (PCCA+) to lump the many microstates into a few long-lived, metastable macrostates.

- Free Energy Landscape: Calculate the free energy landscape from the MSM to visualize the stable basins (metastable states) and the barriers between them.

- Committor Analysis: For a given state, compute the committor probability—the probability that a trajectory starting from that state reaches the bound state before the unbound state (or vice versa). The Transition State Ensemble (TSE) is defined by states with a committor probability of ~0.5 [7].

- State Lifetimes: Calculate the mean first passage times (MFPTs) to escape each metastable state, which defines its lifetime.

Key Findings and Biological Insights

MSM analysis of unbinding trajectories can reveal functionally critical states that are not visible in crystal structures. For instance, in addition to the expected bound and unbound states, simulations of trypsin identified a distorted apo state of the protein with a remarkably long lifetime of nearly 0.7 ms, during which the ligand cannot bind [7]. The identification of such states is crucial for understanding allosteric regulation and for designing drugs that can either stabilize or avoid these conformations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 2: Key Software and Computational Tools for Protein-Ligand MD Studies

| Tool Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in Research | Key Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Desmond [9] | High-Performance MD Engine | GPU-accelerated molecular dynamics simulations | Performing explicit solvent MD simulations of protein-ligand complexes for trajectory generation. |

| Metadynamics [7] | Enhanced Sampling Algorithm | Accelerates rare events (e.g., unbinding) and calculates free energies | Exploring unbinding pathways and predicting koff for protein-ligand complexes. |

| DynamicBind [10] | Deep Generative Model | Predicts ligand-specific protein conformations and binding poses | "Dynamic docking" that adjusts apo protein structures to holo-like states for targets with large conformational changes. |

| Markov State Models (MSMs) [7] | Kinetic Model | Identifies metastable states and computes transition rates between them | Building a kinetic model of unbinding from an ensemble of MD trajectories. |

| FEP+ [9] | Free Energy Calculator | Computes relative binding affinities | Predicting the effect of ligand modifications on binding strength. |

| OpenMM | MD Simulation Toolkit | Open-source library for running MD simulations | A flexible platform for implementing custom simulation protocols. |

| PLUMED | Plugin | Adds enhanced sampling algorithms to MD codes | Implementing metadynamics and other advanced sampling techniques. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational workflow for addressing key biological questions through MD simulations, from system setup to final analysis.

Integrated MD Workflow for Protein-Ligand Analysis

Molecular Dynamics simulations have evolved into a powerful, predictive platform for addressing fundamental questions in structural biology and drug discovery. By moving beyond static structures, MD allows researchers to visualize the dynamic pathways ligands take when binding and unbinding, to quantitatively predict the kinetic parameters that govern these processes, and to discover hidden metastable states that are critical for protein function. The integration of enhanced sampling methods with machine learning approaches, as exemplified by tools like metadynamics and DynamicBind, is pushing the boundaries of what is computationally feasible, enabling the study of increasingly complex and biologically relevant systems. As force fields become more precise and algorithms more efficient, MD simulations will continue to provide an unparalleled atomic-resolution view of the dynamical ballet that underpins biomolecular function.

In structure-based drug design, understanding the precise energetics of protein-ligand binding is paramount. The binding affinity, quantified as the binding free energy (ΔG), determines the strength of molecular interaction and is a key predictor of drug efficacy [11]. This free energy is not a single static value but the result of a complex interplay of forces explored along a multidimensional energy landscape. This landscape governs the pathway a ligand takes as it binds to or unbinds from its protein target. Navigating this landscape requires a well-defined reaction coordinate, a computational descriptor that maps the progression of the binding event.

Computational methods like Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations have become indispensable for probing these landscapes at atomistic resolution. However, spontaneous binding and unbinding events often occur on timescales that are prohibitively long for conventional MD simulations. This article details advanced protocols, such as dissociation Parallel Cascade Selection MD (dPaCS-MD) and interactive MD in Virtual Reality (iMD-VR), which overcome this barrier. These methods, combined with robust analysis techniques like the Markov State Model (MSM), provide a framework for calculating free energy profiles and obtaining quantitative insights into binding mechanisms, ultimately enabling more rational drug design [12] [13].

Core Concepts and Key Quantitative Data

Foundational Principles

The process of protein-ligand binding can be conceptualized as a journey across a free energy landscape. This landscape features stable energy basins, or metastable states, separated by energy barriers.

- Energy Landscape: A hypersurface that describes the free energy of a system as a function of all its relevant degrees of freedom. A key feature of this landscape is the existence of multiple "binding modes" or subbasins within the primary bound state, each characterized by distinct intermolecular interactions [14].

- Reaction Coordinate (RC): A simplified, low-dimensional representation of the complex molecular process. A good RC distinguishes between the initial (bound), final (unbound), and intermediate states. For ligand unbinding, simple RCs might use the distance between the protein and ligand, while more sophisticated approaches use path collective variables (pathCVs) that describe progression along a pre-sampled pathway [13].

- Free Energy Profile: The projection of the high-dimensional energy landscape onto a chosen reaction coordinate. This profile reveals the energetic minima (stable states) and maxima (transition states) along the binding pathway, providing direct insight into the thermodynamics (affinity) and kinetics (rates) of the process.

Quantitative Benchmarking of Methodologies

The accuracy of advanced simulation methods is validated by their ability to reproduce experimentally determined binding free energies. The following table summarizes benchmark results for the dPaCS-MD/MSM approach applied to three different protein-ligand complexes, demonstrating strong agreement with experimental values [12].

Table 1: Standard Binding Free Energies (ΔG°) Calculated by dPaCS-MD/MSM for Model Complexes

| Protein–Ligand Complex | Calculated ΔG° (kcal/mol) | Experimental ΔG° (kcal/mol) | Agreement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin / Benzamidine | -6.1 ± 0.1 | -6.4 to -7.3 | Excellent |

| FKBP / FK506 | -13.6 ± 1.6 | -12.9 | Excellent |

| Adenosine A2A Receptor / T4E | -14.3 ± 1.2 | -13.2 | Excellent |

Different computational methods occupy distinct positions on the speed-accuracy spectrum, as outlined below. This allows researchers to select a method appropriate for their specific project stage, from high-throughput virtual screening to lead optimization.

Table 2: Performance Spectrum of Protein-Ligand Binding Affinity Prediction Methods

| Method Category | Typical Compute Time | Typical RMSE (kcal/mol) | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking | <1 minute (CPU) | 2.0 - 4.0 | High-throughput screening |

| MM/GBSA & MM/PBSA | Minutes to hours | Variable, often high | Medium-throughput rescoring |

| dPaCS-MD/MSM | Hours to days (GPU) | ~1.0 or less (from Table 1) | Pathway & affinity analysis |

| iMD-VR with FE | Hours (GPU + human) | Consistent internal results | Pathway exploration & profiling |

| Free Energy Perturbation | >12 hours (GPU) | ~1.0 | High-accuracy lead optimization |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Unbinding Pathway Sampling with dPaCS-MD

This protocol uses the dPaCS-MD method to efficiently sample ligand dissociation pathways [12].

Step 1: System Preparation

- Obtain the initial protein-ligand structure from a reliable source (e.g., PDB ID 3ATL for trypsin/benzamidine).

- Solvation and Ionization: Place the complex in a cubic water box with a minimum edge distance of 10-15 Å from the solute. Add ions (e.g., KCl or NaCl) to neutralize the system and achieve a physiological concentration of 150 mM.

- Force Field Assignment: Use a standard protein force field (e.g., AMBER ff14SB). Generate ligand parameters with tools like

Antechamberusing GAFF and AM1-BCC partial charges. - Energy Minimization and Equilibration: Perform steepest descent energy minimization to remove steric clashes. Equilibrate the system in the NPT ensemble (300 K, 1 atm) for at least 100-200 ps.

Step 2: Dissociation PaCS-MD (dPaCS-MD) Simulation

- Cycle Setup: Begin a cycle of multiple parallel, independent MD simulations (e.g., 10-100 trajectories) starting from the same equilibrated bound structure but with different initial atomic velocities.

- Short MD Runs: Run each trajectory for a short time (e.g., 0.1-0.5 ps).

- Structure Selection: At the end of the cycle, select the top N snapshots (e.g., 10) that have the longest protein-ligand distances.

- Cycle Iteration: Use the selected snapshots as new starting points for the next cycle of parallel MD runs, regenerating initial velocities. Repeat this process for dozens to hundreds of cycles to generate a tree of dissociation pathways.

Step 3: Markov State Model (MSM) Construction and Analysis

- Feature Selection: From the ensemble of dPaCS-MD trajectories, extract features that describe the protein-ligand geometry (e.g., interatomic distances, angles).

- Conformational Clustering: Use an algorithm (e.g., leader algorithm) to cluster all sampled conformations into discrete microstates based on a distance metric like distance RMS (DRMS).

- Build Transition Count Matrix: Count the transitions between microstates across the entire trajectory dataset over a specific lag time (τ).

- Compute Free Energy Profile: Diagonalize the transition matrix to compute the stationary probability distribution (π) of the microstates. The free energy of each state i is given by ( Gi = -kB T \ln(\pi_i) ). Project this onto a reaction coordinate (e.g., the distance from the binding site) to obtain the final free energy profile.

Protocol 2: Pathway Exploration and Free Energy Calculation with iMD-VR

This protocol leverages human spatial intuition to sample unbinding pathways, which are subsequently validated with free energy calculations [13].

Step 1: Interactive Pathway Sampling in VR

- System Setup: Prepare the protein-ligand system as in Protocol 1, applying mild restraints to the protein backbone to maintain overall structure while allowing side-chain flexibility.

- iMD-VR Session: Using a framework like

Narupa, load the simulation in a VR environment. The researcher, represented by VR controllers, can apply manual "force probes" to the ligand. - Pathway Generation: Interactively guide the ligand out of the binding pocket, exploring different potential egress routes. The goal is to generate multiple, diverse candidate pathways (e.g., 5-7 paths) for later analysis. Each pull takes only minutes of real time.

Step 2: Free Energy Profile Calculation via Umbrella Sampling

- Path Collective Variable (pathCV) Definition: Define a pathCV in a space of 6 collective variables that describe the ligand's position and orientation relative to the protein. This pathCV uses the iMD-VR-sampled trajectory as an initial guess for the minimum free energy path.

- Umbrella Sampling Setup: Extract snapshots along the iMD-VR-defined pathCV to set up the initial structures for multiple umbrella sampling (US) windows. Apply harmonic positional restraints to the ligand in each window.

- US Simulation: Run a short MD simulation (e.g., 1 ns per window) for each US window.

- Free Energy Reconstruction: Use the Weighted Histogram Analysis Method (WHAM) to combine the data from all US windows, removing the bias from the restraints to obtain the unbiased free energy profile along the pathCV.

Visualizing Workflows and Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and integration of the two primary protocols discussed in this article, from system setup to free energy analysis.

Diagram 1: Integrated Workflow for Binding Pathway Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Free Energy Calculation and Analysis

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in Protocols |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | MD Suite | Simulation engine and parameterization. | System preparation, force field assignment, running dPaCS-MD simulations [12] [15]. |

| GROMACS | MD Suite | High-performance MD simulation engine. | Running simulations, particularly for membrane-bound systems like A2A receptor [12]. |

| CHARMM-GUI | Web-based Tool | Building complex simulation systems. | Embedding membrane proteins (e.g., A2A) in lipid bilayers [12]. |

| Narupa | iMD-VR Framework | Interactive molecular dynamics in virtual reality. | Interactive sampling of ligand unbinding pathways [13]. |

| alchemical-analysis.py | Python Tool | Standardized analysis of alchemical free energy calculations. | Analyzing data from thermodynamic integration or free energy perturbation [16]. |

| WORDOM | Analysis Tool | Analysis of MD trajectories, including clustering. | Used in network analysis of unbinding simulations [14]. |

| SEEKR | Multiscale Tool | Tool combining BD and MD via milestoning. | Calculating association rate constants (k_on) [17]. |

Understanding protein-ligand binding is fundamental to drug discovery, yet directly observing these processes presents a significant challenge due to their occurrence across a vast timescale range—from nanoseconds to milliseconds. Conventional molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, while providing atomic-level detail, are computationally constrained to microsecond timescales, creating a critical gap for studying slower biological processes. This application note examines this methodological challenge and outlines integrated computational strategies that combine enhanced MD sampling with machine learning to bridge this temporal divide, enabling researchers to obtain both pathways and affinities for drug development applications.

The Timescale Gap in Protein-Ligand Binding

Protein-ligand interactions involve complex processes with inherently different temporal characteristics. While initial encounter and collision events can occur rapidly, functionally significant conformational changes often proceed on much slower timescales. For instance, the dissociation of phenol from an insulin hexamer is estimated to occur in the milliseconds range, a duration orders of magnitude longer than what was achievable with standard MD simulations at the time of study [8]. This discrepancy creates what is known as a "sampling problem" in computational biophysics—where biologically relevant events with high free-energy barriers occur too infrequently to be observed within practical simulation timescales. Traditional MD simulations of typical protein systems in solution comprising approximately 10⁴ particles have historically been restricted to several nanoseconds, sufficient for sampling equilibrium quantities but inadequate for observing rare events like conformational changes and complete binding/unbinding processes [8].

Table 1: Characteristic Timescales in Protein-Ligand Binding

| Process | Typical Timescale | Computational Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Local side chain fluctuations | Picoseconds to nanoseconds | Easily accessible with conventional MD |

| Ligand entry/exit from buried sites | Microseconds to milliseconds | Rare events requiring enhanced sampling |

| Large protein domain motions | Microseconds to seconds | Prohibitively expensive for brute-force MD |

| Allosteric transitions | Milliseconds to seconds | Difficult to observe directly with standard MD |

Computational Strategies to Bridge the Timescale Gap

Constrained MD and Free Energy Sampling

To overcome the timescale limitation, researchers have developed methods that bias the system to enforce the process along a predefined reaction coordinate (RC). Rather than observing the process in real time, these techniques explore pathways through the energy landscape, from which equilibrium and kinetic quantities can be determined using transition-state theory [8]. In the case of insulin-phenol complex dissociation, the distance between the centers of mass of the ligand and protein provided a reasonable RC description over most of the pathway [8]. The process is modeled in two steps: first, a fast constrained MD simulation establishes an approximate pathway, followed by excessively long MD simulations at fixed distances along the reaction pathway, allowing the system to relax so mean force and structural data can be measured under near-equilibrium conditions [8].

High-Throughput MD Datasets and Machine Learning

A complementary approach involves generating massive MD datasets to train machine learning models. The PLAS-20k dataset represents this paradigm, containing 97,500 independent simulations on 19,500 different protein-ligand complexes [18]. Each complex underwent five independent minimization and equilibration steps, followed by production runs, with binding affinities calculated using the MMPBSA (Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area) method [18]. This dataset enables the development of models that learn the relationship between structural features and binding affinities without requiring full simulations for new complexes. The retraining of the OnionNet model on PLAS-20k demonstrates how MD-generated data can serve as a baseline for predicting binding affinities, showing good correlation with experimental values and performing better than docking scores [18].

Geometric Deep Learning for Dynamic Docking

Recent advances in geometric deep learning have produced models like DynamicBind, which employs equivariant geometric diffusion networks to construct a smooth energy landscape that promotes efficient transitions between different equilibrium states [10]. This approach can recover ligand-specific conformations from unbound protein structures without needing holo-structures or extensive sampling, effectively addressing large conformational changes such as the DFG-in to DFG-out transition in kinase proteins [10]. Unlike traditional MD with its rugged energy landscape, DynamicBind creates a more funneled energy landscape, significantly lowering the free energy barrier between biologically relevant states and enabling efficient sampling of alternate states pertinent to ligand binding [10].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput MD Simulations for Affinity Calculation

The following protocol outlines the methodology used to generate the PLAS-20k dataset for large-scale binding affinity calculations [18]:

System Preparation:

- Obtain initial protein-ligand complex structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB).

- Model missing protein residues as loop regions using UCSF Chimera.

- Protonate protein chains at physiological pH (7.4) using the H++ server.

- Generate input files using the

tleapprogram from AMBERtools. - Model crystal waters using TIP3P force field.

- Apply Amber ff14SB force field for proteins and General AMBER force field (GAFF2) for ligands and cofactors using the

antechamberprogram. - Solvate each complex in an orthorhombic TIP3P water box with 10 Å extension from the protein surface.

- Add counter ions to maintain charge neutrality.

MD Simulation Workflow:

- Perform minimization using the L-BFGS minimizer with harmonic potential (10 kcal/mol/Ų) applied to protein backbone atoms (1000 steps, gradually reducing restraint force).

- Conduct additional minimization (1000 steps) after removing harmonic potential.

- Use a time step of 2 fs with constraints on bonds involving hydrogen atoms.

- Implement Langevin thermostat (friction coefficient 5 ps⁻¹) to gradually heat system from 50 K to 300 K (increasing 1 K every 100 steps).

- Perform simulations for 1 ns in NVT ensemble with backbone atoms restrained.

- Subject final coordinates to 4000 steps minimization, saving coordinates every 1000 steps to obtain five independent minimized conformations.

- For each minimized conformation, equilibrate in NVT ensemble at 300 K and 1 atm for 2 ns.

- Execute production run of 4 ns in NPT ensemble using Langevin thermostat and Monte Carlo barostat, saving trajectories every 100 ps for analysis.

Binding Affinity Calculation:

- Use five independent simulation trajectories for each protein-ligand complex.

- Calculate binding affinity using MMPBSA (Molecular Mechanics Poisson Boltzmann Surface Area) method with single trajectory approach.

- Consider two explicit water molecules near the active site.

- Compute binding affinity as: ΔGbind = ΔEMM + ΔG_Sol

- Where ΔEMM = ΔEele + ΔE_vdw (electrostatic and van der Waals interaction energies)

- And ΔGSol = ΔGpol + ΔG_np (polar and non-polar solvation contributions)

Protocol 2: DynamicBind for Ligand-Specific Conformation Prediction

This protocol describes the DeepBind methodology for predicting ligand-specific protein-ligand complex structures without extensive sampling [10]:

Input Preparation:

- Obtain apo-like protein structures (AlphaFold-predicted conformations) in PDB format.

- Prepare small-molecule ligands in SMILES or SDF format.

- Generate seed ligand conformations using RDKit.

Dynamic Docking Process:

- Randomly place the ligand around the protein.

- Execute 20 iterations with progressively smaller time steps:

- First 5 steps: Translate, rotate, and adjust internal torsional angles of ligand only.

- Remaining 15 steps: Simultaneously translate and rotate protein residues while modifying side-chain chi angles along with continued ligand adjustment.

- At each step, feed features and coordinates of protein and ligand into an SE(3)-equivariant interaction module.

- Use protein and readout modules to generate predicted translation, rotation, and dihedral updates for the current state.

Conformation Selection:

- Generate multiple diverse conformations.

- Apply contact-LDDT (cLDDT) scoring module (inspired by AlphaFold's LDDT score) to select the most suitable complex structure from predicted outputs.

- Use correlation between predicted cLDDT and actual ligand RMSD to identify high-quality complex structures.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for Protein-Ligand Binding Studies

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLAS-20k Dataset | MD Dataset | Provides MD trajectories & binding affinities for 19,500 PL complexes | Machine learning model training; Binding affinity prediction benchmarks [18] |

| OpenMM 7.2.0 | MD Software | High-performance MD simulation toolkit | Running production MD simulations with GPU acceleration [18] |

| AMBER Tools | MD Suite | Force field parameterization & system preparation | Generating topology files; Applying ff14SB/GAFF2 force fields [18] |

| UCSF Chimera | Modeling Software | Molecular visualization & structure analysis | Modeling missing residues in protein structures [18] |

| H++ Server | Web Service | Protein protonation at physiological pH | Adding hydrogen atoms to protein structures at pH 7.4 [18] |

| DynamicBind | Deep Learning Model | Equivariant geometric generative model | Predicting ligand-specific complex structures from apo conformations [10] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics | Chemical informatics & conformation generation | Generating initial ligand conformations from SMILES/SDF [10] |

The integration of molecular dynamics simulations with machine learning approaches has created powerful synergies for addressing the fundamental challenge of timescales in protein-ligand binding studies. While conventional MD provides the physical foundation and atomic-level detail, machine learning models trained on MD-generated datasets can extrapolate beyond direct simulation timescales and efficiently sample biologically relevant states. Constrained MD methods continue to offer valuable pathways for specific binding events, while next-generation geometric deep learning models like DynamicBind demonstrate remarkable capability in predicting ligand-induced conformational changes without exhaustive sampling. These computational strategies collectively enable researchers to bridge the nanosecond to millisecond gap, providing increasingly accurate predictions of binding pathways and affinities that accelerate drug discovery for previously challenging targets.

Methodologies in Action: Setting Up and Running MD Simulations for Binding Pathway Analysis

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide atomic-level insight into biological processes, with protein-ligand binding being of paramount importance in drug discovery. The central challenge in this field lies in the timescale gap between what simulations can achieve and the duration of functional biological processes. While conventional MD remains a valuable tool, enhanced sampling techniques have emerged to accelerate the exploration of complex energy landscapes. This Application Note provides a structured comparison between conventional MD and enhanced sampling methods—focusing on accelerated MD (aMD) and metadynamics—to guide researchers in selecting appropriate strategies for protein-ligand binding pathway analysis. We frame this discussion within the context of a broader thesis on using molecular dynamics for protein-ligand binding pathway analysis research, providing detailed protocols and quantitative comparisons to facilitate method selection and implementation.

Technical Comparison: Conventional MD vs. Enhanced Sampling

Fundamental Principles and Limitations

Conventional MD simulations solve Newton's equations of motion to simulate atomic trajectories without biasing potentials, theoretically providing a physically correct model of dynamics. However, these simulations frequently fail to observe functionally important conformational changes or binding/unbinding events because biological processes often occur on timescales (milliseconds to seconds) that vastly exceed what is computationally feasible (microseconds to milliseconds, even on specialized hardware) [19] [20]. This sampling problem arises from the rugged free energy landscapes of biomolecules, characterized by many local minima separated by high-energy barriers that are rarely crossed in straightforward simulations [21].

Enhanced sampling methods address this fundamental limitation by modifying the sampling process to accelerate barrier crossing and improve phase space exploration. These techniques can be broadly categorized into methods that: (1) add bias potentials to collective variables (CVs) such as metadynamics; (2) modify the potential energy landscape like aMD; (3) utilize replica-exchange approaches; or (4) employ path-sampling strategies [19] [20]. The efficacy of many enhanced sampling methods depends critically on the selection of appropriate CVs, which are low-dimensional representations of the system's slow degrees of freedom that describe the process of interest [22].

Quantitative Method Comparison

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Conventional MD, aMD, and Metadynamics

| Feature | Conventional MD | Accelerated MD (aMD) | Metadynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Unbiased Hamiltonian, Newtonian mechanics | Modified potential energy surface with boost potential | History-dependent bias potential discourages revisiting |

| Sampling Efficiency | Low for rare events | Moderate to high | High for CV space |

| Timescale Acceleration | None (baseline) | 10-1000x [19] | 10⁵-10¹⁵x for specific processes [22] |

| Key Parameters | Integration timestep (typically 2 fs) | Threshold energy (E), acceleration factor (α) | CVs, hill height and width, deposition rate |

| Free Energy Calculation | Possible but requires extremely long simulations | Requires reweighting [19] | Directly provides free energy surface |

| CV Dependence | None | No CVs required | Strongly CV-dependent |

| Implementation Complexity | Low | Moderate | High (requires careful CV selection) |

| Best Use Cases | Equilibrium fluctuations, local dynamics, system preparation | Exploring conformational space without predefined CVs | Barrier crossing, free energy calculations, pathway identification |

Key Applications in Protein-Ligand Studies

- Binding Pose Prediction: Metadynamics can identify stable binding modes and their relative free energies, overcoming kinetic traps that plague conventional MD [23] [24].

- Binding Affinity Estimation: Both metadynamics and aMD (with reweighting) can predict binding free energies, with metadynamics particularly effective when using optimal CVs [20] [25].

- Ligand Dissociation Kinetics: Metadynamics and Gaussian accelerated MD (GaMD, a variant of aMD) can estimate dissociation rates (koff) by reducing free energy barriers and applying kinetic corrections [20].

- Pathway Identification: Recent advances using true reaction coordinates (tRCs) with metadynamics can accelerate conformational changes by up to 10¹⁵-fold while maintaining physical pathways [22].

Method Selection Protocol

Decision Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the systematic approach to selecting the appropriate MD method based on research objectives and system characteristics:

Practical Selection Guidelines

Choose Conventional MD when:

- Characterizing local equilibrium fluctuations around a known structure

- Studying fast biological processes (nanoseconds-microseconds)

- Preparing and equilibrating systems for subsequent enhanced sampling

- Resources for method development are limited

Choose aMD when:

- Exploring unknown conformational landscapes without predefined reaction coordinates

- Studying complex transitions with multiple pathways

- System has large conformational flexibility without obvious CVs [19]

- Willing to perform reweighting analyses for quantitative free energies

Choose Metadynamics when:

Consider Hybrid Approaches:

- Combine short conventional MD simulations with machine learning to identify CVs for metadynamics [26] [27]

- Use aMD for initial exploration followed by targeted metadynamics for quantitative analysis

- Integrate multiple enhanced sampling methods to address different aspects of complex binding processes

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Conventional MD for Binding Pose Validation

Purpose: To validate and refine a docked protein-ligand complex through equilibrium simulations.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- System Preparation:

- Obtain protein-ligand complex from docking or experimental structure

- Parameterize ligand using appropriate force field (GAFF2 for small molecules, CGenFF for drug-like compounds)

- Solvate in explicit water box (TIP3P water model) with minimum 10 Å padding

- Add ions to neutralize system and achieve physiological concentration (0.15 M NaCl)

Equilibration:

- Perform energy minimization using steepest descent (5000 steps)

- Gradually heat system from 0 K to 300 K over 100 ps in NVT ensemble with position restraints on protein and ligand heavy atoms (force constant 1000 kJ/mol/nm²)

- Equilibrate pressure at 1 bar for 100 ps in NPT ensemble with same restraints

- Remove restraints and equilibrate further 100 ps in NPT ensemble

Production Simulation:

- Run unrestrained MD simulation for 100 ns-1 μs (length depends on system size and available resources)

- Use 2 fs integration timestep with LINCS constraints on hydrogen bonds

- Maintain temperature at 300 K using Nosé-Hoover thermostat and pressure at 1 bar using Parrinello-Rahman barostat

- Employ Particle Mesh Ewald for long-range electrostatics

Analysis:

- Calculate root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of protein and ligand to assess stability

- Compute root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) to identify flexible regions

- Monitor protein-ligand interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, salt bridges)

- Perform cluster analysis to identify dominant binding poses

Troubleshooting: If the ligand dissociates completely, the initial pose may be unstable - consider stronger restraints during equilibration or alternative initial poses. If the system fails to equilibrate, extend the restrained equilibration phases.

Protocol 2: GaMD for Enhanced Conformational Sampling

Purpose: To accelerate sampling of protein-ligand conformational space without predefined collective variables.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- System Preparation: Follow same preparation as Protocol 1

Conventional MD for Boost Potential Estimation:

- Run 20-100 ns conventional MD to collect potential energy statistics

- Calculate average potential energy and standard deviation

- Set boost potential parameters: lower bound E = V_max, acceleration factor α = 0.5-1.0 [20]

GaMD Production Simulation:

- Apply dual boost potential to dihedral and total potential energy components

- Run enhanced sampling simulation for 100-500 ns

- Use same simulation parameters as conventional MD

Reweighting:

- Collect trajectory frames and corresponding boost potentials

- Use cumulant expansion to second order to reweight probability distribution

- Calculate reweighted free energy surfaces along relevant coordinates

Analysis:

- Identify low-energy conformational states

- Compare with conventional MD results to assess sampling enhancement

- Calculate conformational populations and transitions

Troubleshooting: If reweighting results are poor, reduce acceleration factor α to improve energy landscape reconstruction. If sampling improvement is insufficient, increase simulation length or apply higher boost potential.

Protocol 3: Metadynamics for Binding Free Energy Calculation

Purpose: To calculate the binding free energy and identify unbinding pathways for a protein-ligand complex.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- System Preparation: Follow same preparation as Protocol 1

Collective Variable Selection:

- Identify CVs that distinguish bound and unbound states

- Common choices: ligand-protein distance, number of contacts, backbone RMSD

- For complex systems, use machine learning or dimensionality reduction on short MD to identify relevant CVs [26]

Well-Tempered Metadynamics Simulation:

- Set up metadynamics with well-tempered variant to ensure convergence

- Use Gaussian hill height of 0.1-1.0 kJ/mol and width adapted to CV scales

- Set deposition rate every 1-10 ps with bias factor of 10-100

- Run simulation until binding/unbinding events occur multiple times

- Typical simulation length: 100 ns-1 μs

Free Energy Calculation:

- Reconstruct free energy surface from bias potential

- Identify minimum free energy path between bound and unbound states

- Calculate binding free energy from difference between minima

Validation:

- Check convergence by monitoring free energy estimate over time

- Perform multiple independent runs to estimate uncertainty

- Compare with experimental data if available

Troubleshooting: If no unbinding events occur, check CVs for hidden barriers and consider adding additional CVs. If free energy doesn't converge, increase simulation length or adjust metadynamics parameters.

Table 2: Key Software Tools for MD Simulations and Enhanced Sampling

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Engine | High-performance MD simulations | Extremely fast, free, open-source, extensive enhanced sampling methods [19] |

| NAMD | MD Engine | Scalable MD simulations | Excellent parallel scaling, CUDA GPU support, extensive enhanced sampling [21] |

| AMBER | MD Suite | Biomolecular simulations | High-quality force fields, advanced sampling, free energy calculations [19] [28] |

| PLUMED | Sampling Library | Enhanced sampling algorithms | Works with multiple MD engines, vast array of enhanced sampling methods [21] |

| OpenMM | MD Library | GPU-accelerated simulations | Extremely fast on GPUs, Python API, custom forces [27] |

| PyEMMA | Analysis Tool | Markov state model analysis | Dimensionality reduction, MSM construction, validation [19] |

| MDAnalysis | Analysis Library | Trajectory analysis | Python library, extensive analysis algorithms, easy scripting [26] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Integration with Machine Learning

Machine learning approaches are increasingly combined with enhanced sampling to address key challenges. Deep learning can identify optimal collective variables from simulation data, analyze complex trajectories, and even replace traditional force fields [26]. For example, neural networks can be trained on short MD simulations to extract slow modes that serve as effective CVs for metadynamics, overcoming the traditional challenge of CV selection [26]. Recent approaches also use deep learning for Markov state model construction to identify metastable states and transition pathways from high-dimensional simulation data [19] [26].

True Reaction Coordinates for Optimal Sampling

The identification of true reaction coordinates (tRCs) represents a significant advancement in enhanced sampling. These coordinates, which control both conformational changes and energy relaxation, can accelerate sampling by factors up to 10¹⁵ while maintaining physical pathways [22]. The generalized work functional method enables computation of tRCs from energy relaxation simulations, requiring only a single protein structure as input. This approach has demonstrated remarkable acceleration for challenging processes like HIV-1 protease flap opening and ligand dissociation [22].

High-Throughput Binding Kinetics

Recent methodological developments aim to increase throughput for predicting binding kinetics, particularly residence times that correlate with drug efficacy. Advanced metadynamics protocols, GaMD, and weighted ensemble methods now enable reasonable estimation of dissociation rates for pharmaceutically relevant systems within practical computation times [20] [27]. These approaches typically combine enhanced sampling with clever CV selection and sometimes machine learning to achieve computational efficiency without sacrificing accuracy [27].

The choice between conventional MD and enhanced sampling techniques depends critically on the specific research questions, system characteristics, and available resources. Conventional MD remains valuable for studying equilibrium fluctuations and local dynamics, while enhanced sampling methods like aMD and metadynamics enable the investigation of rare events such as ligand binding and unbinding. As methods continue to evolve—particularly through integration with machine learning and improved identification of reaction coordinates—the throughput and applicability of MD simulations for drug discovery will further increase. By following the protocols and decision framework provided in this Application Note, researchers can select and implement the most appropriate strategies for their protein-ligand binding studies.

Within the broader scope of using molecular dynamics (MD) for protein-ligand binding pathway analysis, the initial setup of the simulation system is a critical determinant of success. This phase involves creating a biologically realistic model that faithfully represents the molecular environment in which binding occurs. For membrane proteins, which constitute a large fraction of drug targets, this process is particularly complex. The inherent challenges of embedding proteins in asymmetric lipid bilayers, parameterizing diverse ligands, and solvating the system appropriately must be overcome to produce simulation data that can reliably illuminate binding pathways and mechanisms [8] [29] [30]. This application note details standardized protocols for system parameterization, solvation, and the specific considerations required for membrane protein simulations, providing researchers with a robust foundation for subsequent binding pathway analysis.

Parameterization of Molecular Components

Force Field Selection and Consistency

The choice of force field is the primary cornerstone of any MD simulation, as it defines the potential energy functions and associated parameters governing atomic interactions.

- Self-Consistency: A fundamental rule is to avoid mixing and matching force fields. Force fields are designed to be internally consistent, and combining parameters from different force fields can yield questionable results that may not withstand scientific scrutiny [31].

- Comprehensive Coverage: Select a force field that provides parameters for all components of your system, including the protein, any ligands, lipids, ions, and water. GROMACS users can utilize the

pdb2gmxcommand to generate topology and coordinate files for their protein while selecting from available force fields [32].

Parameterization of Novel Molecules

When simulating non-standard ligands or cofactors not included in standard force field distributions, deriving new parameters is necessary. This process requires expert knowledge and should be approached with rigor.

- Derivation Consistency: New parameters must be derived in a manner consistent with the philosophical and technical approach of the parent force field. This may involve quantum mechanical calculations for AMBER-based force fields or fitting to experimental thermodynamic data for others like GROMOS [31].

- Source Verification: Exercise extreme caution when obtaining parameters from external sources. Just as one would not buy fine jewelry from an unverified street vendor, parameters should not be sourced from unvalidated online repositories without a clear explanation of their derivation methodology. The use of automated parameter-generation tools without subsequent validation can introduce significant artifacts [31].

Table 1: Key Considerations for Force Field and Parameterization

| Consideration | Description | Potential Pitfall |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field Self-Consistency | Use a single, unified force field for all system components. | Inaccurate energies and dynamics from parameter incompatibility. |

| Parameter Derivation | Follow the original force field's methodology for new molecules. | Parameters that are chemically unreasonable or unstable in simulation. |

| Source Validation | Use parameters from reputable, well-documented sources. | Introduction of unknown errors and simulation artifacts. |

Solvation and Ion Addition

Solvation and Periodic Boundary Conditions

To mimic a biological environment, the molecular system must be placed in a solvent box, most commonly water, and Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC) are applied to eliminate edge effects and simulate a continuous solution [32].

- Define the Simulation Box: Using a tool like

editconfin GROMACS, place the solute (e.g., protein-ligand complex) at the center of a box. Common box types include:- Cubic: A simple cube.

- Rhombic Dodecahedron: A more computationally efficient shape that minimizes the number of solvent atoms required while maintaining a good approximation of a spherical environment.

- The box should extend at least 1.0 nm from the solute surface to prevent interactions between the solute and its periodic images [32].

- Solvate the System: The

solvatecommand (also known asgenboxin older versions) fills the box with water molecules. The topology file is automatically updated to include the added water molecules [32].

Handling Membrane Systems

A particular challenge in membrane system solvation is the accidental placement of water molecules into the hydrophobic core of the lipid bilayer.

- Short MD Relaxation: A brief unrestrained MD run often allows the hydrophobic effect to expel these misplaced waters quickly without disrupting the membrane structure [31].

- Controlled Solvation: If a water-free hydrophobic core is required at the start, strategies include:

- Using the

-radiusoption ingmx solvateto increase the water exclusion radius. - Modifying the

vdwradii.datfile from the$GMXLIBdirectory, increasing the van der Waals radii for lipid carbon atoms to between 0.35 and 0.5 nm to prevent the solvation algorithm from detecting gaps large enough for a water molecule [31].

- Using the

System Neutralization and Ion Concentration

The final step in preparing the solvent environment is adding ions to achieve both charge neutrality and a physiologically relevant salt concentration.

- Preprocessing: Use the

gromppcommand to assemble topology, coordinates, and simulation parameters (mdpfile) into a single, portable binary input file (.tpr). - Ion Addition: The

genioncommand uses this.tprfile to replace water molecules with ions.- First, add sufficient counter-ions (e.g., Na⁺ for a negatively charged system, Cl⁻ for a positive one) to neutralize the system's net charge.

- Then, add additional pairs of ions to achieve the desired ionic concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl) [32].

Special Considerations for Membrane Proteins

Membrane proteins require a more complex setup to accurately model their native lipid bilayer environment. CHARMM-GUI's Membrane Builder is a widely used tool that simplifies this process [30].

System Construction with CHARMM-GUI

The following protocol outlines the construction of an outer membrane protein (OMP) system, demonstrating the principles for building a complex, heterogeneous membrane.

- Read and Manipulate Protein Coordinates:

- Input the protein structure by providing its PDB ID (e.g.,

5aywfor E. coli BamA) or uploading a file. Using the OPM (Orientations of Proteins in Membranes) database as a source often provides a pre-oriented structure [30]. - Select the specific protein chains and segments to include.

- Perform necessary structural manipulations, such as patching terminal groups (e.g., NTER for the N-terminus, CTER for the C-terminus) and defining disulfide bonds where present [30].

- Input the protein structure by providing its PDB ID (e.g.,

- Orient the Protein in the Membrane:

- CHARMM-GUI defines the Z-axis as the membrane normal, with Z=0 Å as the bilayer center. A pre-oriented structure from OPM can be used directly. Otherwise, the protein must be aligned and its hydrophobic region centered at Z=0 [30].

- For proteins with internal pores, the "Generate Pore Water" option can hydrate the internal cavities [30].

- Determine System Size and Lipid Composition:

- Box Type: Choose a rectangular or hexagonal prism box shape.

- Water Thickness: Set the water layer thickness on both sides of the membrane; a value of ~30 Å is often recommended for sufficient bulk water [30].

- Lipid Composition: This is critical for functional relevance. Select the "Heterogeneous Lipid" option to build a realistic membrane. For example, the outer membrane of E. coli BamA requires a model with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the upper leaflet and a specific mixture of phospholipids (e.g., PVCL2, PMPE, PMPG, PVPE, PVPG at a ratio of 2:8:1:8:2) in the lower leaflet [30].

Simulation Protocol for Membrane Proteins

After system construction, a staged equilibration protocol is essential to relax the system without distorting the protein or membrane.

- Energy Minimization: Perform an initial energy minimization to remove any steric clashes introduced during system setup [31].

- Membrane Equilibration with Restraints:

- Run a multi-stage MD simulation (typically 5-10 ns) with strong positional restraints (e.g., 1000 kJ/(mol·nm²)) applied to the heavy atoms of the protein.

- This allows the lipid membrane to adapt and pack efficiently around the protein's surface while preventing the protein from moving away from its experimentally determined structure [31].

- Unrestrained Equilibration: Gradually release the restraints in subsequent steps, allowing the entire system (protein, lipids, solvent) to equilibrate fully [31].

- Production MD: Finally, run a long, unrestrained production simulation for data collection and analysis of protein-ligand binding pathways [31].

Table 2: Protocol for Simulating Membrane Proteins in GROMACS

| Step | Key Action | Purpose | Typical Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. System Building | Use CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder to embed protein in a realistic lipid bilayer. | Create a native-like environment for the membrane protein. | N/A |

| 2. Energy Minimization | Run a steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm. | Remove bad van der Waals contacts and steric clashes. | Until maximum force < 1000 kJ/(mol·nm) |

| 3. Equilibration with Restraints | Run MD with strong positional restraints on protein heavy atoms. | Allow lipids and solvent to relax around a fixed protein. | 5-10 ns |

| 4. Unrestrained Equilibration | Run MD with no or very weak restraints. | Allow the entire system to reach equilibrium. | 5-20 ns |

| 5. Production MD | Run an unrestrained simulation. | Sample conformational states and ligand binding events. | >100 ns to µs |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function/Description | Example Sources/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure | Initial 3D atomic coordinates for the simulation. | RCSB PDB, OPM Database [30] [32] |

| Force Field | Empirical potential functions defining interatomic interactions. | CHARMM, AMBER, GROMOS, OPLS-AA [31] [32] |

| MD Simulation Engine | Software to perform the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion. | GROMACS, NAMD [33] [32] |

| System Builder | Tool to assemble macromolecules, lipids, solvent, and ions into a simulation box. | CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder [30] |

| Visualization Software | For inspection of structures, trajectories, and analysis results. | VMD, RasMol [33] [32] |

| Lipid Parameters | Force field-compatible definitions for lipid molecules. | Lipidbook, CHARMM-GUI [31] [30] |

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide an powerful computational framework for studying protein-ligand interactions at atomistic resolution, offering insights that are often challenging to obtain through experimental methods alone [34] [35]. The ability to simulate binding pathways is particularly valuable for pharmaceutical research, where understanding how drug molecules recognize their targets can accelerate effective therapeutic design [34]. G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) represent a particularly important class of drug targets, with approximately one-third of marketed drugs acting through these receptors [34]. This protocol focuses on applying enhanced sampling techniques to study the binding of chemically diverse ligands to the M3 muscarinic receptor, a GPCR target for treating cancer, diabetes, and obesity [34].

The challenge in conventional MD simulations lies in the timescale limitations, as ligand binding events often occur on microsecond to millisecond timescales, far beyond what routine simulations can achieve [34] [36]. Enhanced sampling methods like accelerated MD (aMD) address this limitation by effectively decreasing energy barriers, allowing researchers to observe binding events in significantly shorter simulation time [34]. This application note provides detailed methodologies for simulating ligands ranging from small endogenous neurotransmitters like acetylcholine (ACh) to complex pharmaceutical agents like tiotropium (TTP).

Ligand Case Studies and Binding Characteristics

Table 1: Characteristics of Ligands in M3 Muscarinic Receptor Binding Studies

| Ligand Name | Ligand Type | Molecular Characteristics | Primary Binding Site | Secondary Binding Site | Functional Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholine (ACh) | Endogenous neurotransmitter | Small molecule | Orthosteric site [34] | Extracellular vestibule [34] | Full agonist [34] |

| Arecoline (ARc) | Partial agonist | Small molecule | Orthosteric site [34] | Extracellular vestibule [34] | Partial agonist [34] |

| Tiotropium (TTP) | Pharmaceutical antagonist | Complex drug molecule | Orthosteric site [37] | Extracellular vestibule (allosteric) [34] [37] | Insurmountable antagonist [37] |

| Atropine | Antagonist | Small molecule | Orthosteric site [37] | Not observed [37] | Competitive antagonist [37] |

Key Binding Pathway Insights

The M3 muscarinic receptor exhibits two distinct binding sites relevant to ligand recognition: the orthosteric site deep within the binding pocket and an extracellular vestibule that serves as a metastable secondary binding site [34] [37]. Accelerated MD simulations have revealed that all three profiled ligands (ACh, ARc, and TTP) interact with the extracellular vestibule during their binding pathways, suggesting this region serves as a stepping stone toward the orthosteric site [34].

A particularly important finding from both simulation and functional studies is that tiotropium exhibits dual binding behavior, interacting stably with both the orthosteric site and the extracellular vestibule [37]. This dual binding mechanism prevents acetylcholine entry into the orthosteric binding pocket and contributes to tiotropium's insurmountable antagonism and prolonged duration of action [37]. The extended residence time at the M3 receptor (dissociation half-life >24 hours) differentiates tiotropium from shorter-acting antagonists like glycopyrrolate (dissociation half-life ~6 hours) [37].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

System Setup and Preparation

Initial Structure Preparation

- Begin with the inactive tiotropium-bound M3 receptor crystal structure (PDB: 4DAJ) determined at 3.40 Å resolution [34].

- Remove TTP from the X-ray structure for binding simulations [34].

- Omit the T4 lysozyme fusion protein used for crystallization, retaining only the receptor structure [34].

- Cap all chain termini with neutral groups (acetyl and methylamide) [34].

- Maintain disulphide bonds resolved in the crystal structure (C140³·²⁵-C220ᴱᶜᴸ² and C516⁶·⁶¹-C519⁷·²⁹) [34].

- Protonate Asp113²·⁵⁰ while keeping Asp147³·³² deprotonated in the orthosteric site [34].

- Set all other protein residues to standard CHARMM protonation states at neutral pH [34].

Simulation System Assembly

- Insert the prepared receptor into a palmitoyl-oleoyl-phosphatidyl-choline (POPC) lipid bilayer using the Membrane plugin in VMD [34].

- Remove all overlapping lipid molecules [34].

- Solvate the system in a water box using the Solvate plugin in VMD [34].

- Place ligand molecules at least 40 Å away from the receptor orthosteric site in the bulk solvent [34].

- Neutralize system charges with appropriate ions (e.g., 18 Cl⁻ ions for systems described) [34].

- The final simulation system should measure approximately 80 × 87 × 97 ų with ~55,500 atoms, including 130 lipid molecules and ~11,200 water molecules [34].

Accelerated MD Simulation Protocol

Parameter Settings and Equilibration

- Perform all simulations using NAMD2.9 or OpenMM software [34] [38].

- Apply the CHARMM27 parameter set with CMAP corrections for the protein [34].

- Use CHARMM36 parameters for POPC lipids [34].

- Employ the TIP3P model for water molecules [34].

- For ligand molecules, obtain parameters from the CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) database when available [34].

- For ligands not in CGenFF (e.g., TTP, ARc), compute parameters using the General Automated Atomic Model Parameterization (GAAMP) tool with ab initio quantum mechanical calculations [34].

- Apply a cutoff distance of 12 Å for van der Waals and short-range electrostatic interactions [34].

- Compute long-range electrostatic interactions using the particle-mesh Ewald summation method with a grid point density of 1/Å [34].

- Use a 2 fs integration time-step with the SHAKE algorithm applied to all hydrogen-containing bonds [34].

Enhanced Sampling Implementation

- Apply a non-negative boost potential to the system's potential energy when it drops below a predefined threshold [34].

- This effectively decreases energy barriers and accelerates transitions between low-energy states [34].

- For the M3 receptor system, hundreds-of-nanosecond aMD simulations can capture millisecond-timescale events [34].

- Run multiple independent trajectories (typically 5-32 replicates) to ensure sufficient sampling and statistical reliability [38].

Binding Analysis and Quantification

Pathway Analysis

- Monitor ligand proximity to key residues, particularly distance to Asp148 on helix 3 (Cγ atom) as a measure of orthosteric binding [37].

- Distances of ~15 Å typically correspond to ligand locations in the extracellular loop regions (allosteric binding site) [37].

- Classify binding poses using root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) calculations with a 5.0 Å cutoff to distinguish bound versus unbound states [38].

Binding Affinity Calculations

- Use the Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MMPBSA) method to compute binding free energies from simulation trajectories [18].

- Calculate binding affinity as: ΔGᴍᴍᴘʙꜱᴀ = ΔEᴍᴍ + ΔGꜱᴏʟ [18]

- Where ΔEᴍᴍ includes electrostatic (ΔEₑₗₑ) and van der Waals (ΔEᵥᴅ𝔀) interaction energies [18]