Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials: Achieving Accurate Force Calculations for Materials and Biomolecular Research

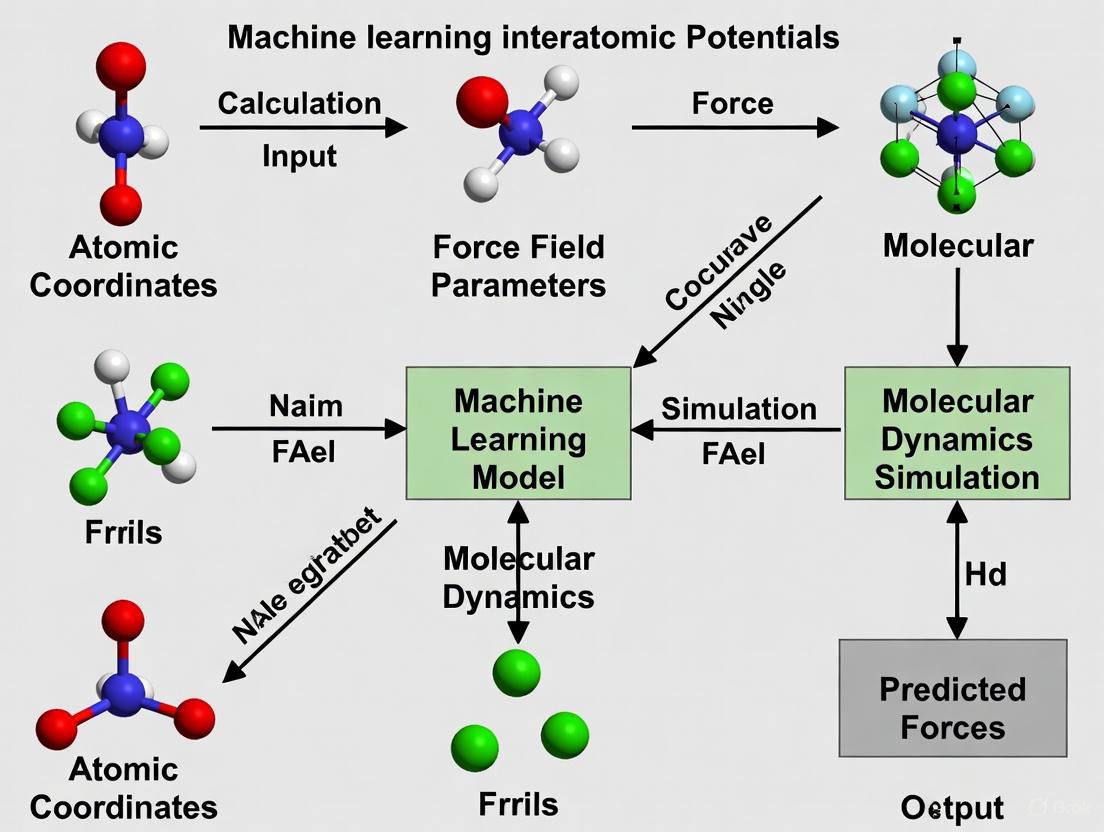

Machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) have emerged as a transformative technology, bridging the gap between the high accuracy of quantum mechanical methods and the computational efficiency of classical force fields.

Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials: Achieving Accurate Force Calculations for Materials and Biomolecular Research

Abstract

Machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) have emerged as a transformative technology, bridging the gap between the high accuracy of quantum mechanical methods and the computational efficiency of classical force fields. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals on how MLIPs enable accurate force and energy calculations, which are fundamental to reliable atomistic simulations. We explore the foundational principles of MLIPs, including the critical role of symmetry-equivariant architectures and advanced material descriptors. The review covers state-of-the-art methodologies and their applications across diverse domains, from electrocatalyst design to biomolecular modeling. We address key challenges in model training, uncertainty quantification, and transferability, while presenting rigorous validation frameworks and comparative performance benchmarks. By synthesizing the latest advances, this article serves as an essential guide for leveraging MLIPs to accelerate discovery in computational materials science and drug development.

Understanding Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials: From Quantum Mechanics to Accurate Force Fields

Computational scientists and materials researchers face a persistent challenge: choosing between the high accuracy of quantum mechanical methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT), the efficiency of classical force fields (FFs), or compromising on both. This trilemma has constrained progress in fields ranging from drug development to materials design, where simulating realistic systems at experimental conditions requires both quantum accuracy and nanoscale temporal/spatial scalability [1]. Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) have emerged as a transformative technology that bridges this divide by learning the quantum-mechanical potential energy surface (PES) from reference data, then enabling simulations with near-quantum accuracy at classical force field computational costs [2] [3].

The fundamental innovation of MLIPs lies in their data-driven approach. Unlike classical FFs with fixed mathematical forms, MLIPs use flexible machine learning models to map atomic configurations to energies and forces, effectively "learning physics from data" while preserving essential physical symmetries [1]. This paradigm shift enables researchers to capture complex atomic interactions—including bond formation/breaking and subtle non-covalent forces—that were previously inaccessible to efficient simulation methods [3]. For pharmaceutical researchers, this technology enables accurate modeling of molecular crystals, protein-ligand interactions, and drug formulation stability with unprecedented fidelity to quantum mechanical benchmarks.

Theoretical Foundation: How MLIPs Reconcile Accuracy and Efficiency

The Potential Energy Surface Framework

The concept of the Potential Energy Surface (PES) is fundamental to understanding atomistic simulations. The PES represents the total energy of a system as a function of its atomic coordinates, providing the foundation for determining stable structures, reaction pathways, and dynamical evolution [3]. In molecular dynamics based on Newton's laws, the force on each atom is derived from the PES through the relation ( Fi = -\partial E/\partial ri ), where the force is the negative gradient of the potential energy ( E ) with respect to atomic position ( r_i ) [3].

Traditional methods for constructing PES face significant limitations. Quantum mechanical (QM) approaches, particularly DFT, provide accurate PES descriptions but scale poorly with system size (typically O(N³) or worse), restricting applications to small systems containing hundreds of atoms [1] [3]. Classical force fields use simplified functional forms to enable rapid energy calculations but lack transferability and accuracy for complex chemistries, particularly when bond formation/breaking occurs [1] [3]. MLIPs resolve this by training on QM reference data to create surrogate models that maintain high accuracy while achieving computational efficiency comparable to classical MD [1].

Architectural Innovations in MLIPs

Modern MLIP architectures incorporate several key innovations that enable their high performance:

Geometric Equivariance: State-of-the-art MLIPs explicitly embed physical symmetries (rotational, translational, and sometimes reflectional invariance) directly into their network architectures [1]. Equivariant layers maintain internal feature representations that transform correctly under symmetry operations, ensuring that scalar predictions (e.g., total energy) remain invariant while vector targets (e.g., forces) exhibit proper equivariant behavior [1]. This approach parallels classical multipole theory in physics, encoding atomic properties as monopole, dipole, and quadrupole tensors and modeling their interactions via tensor products [1].

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): GNN-based MLIPs represent atomic systems as graphs, where atoms constitute nodes and chemical bonds form edges. Message-passing operations between connected nodes enable effective learning of local chemical environments without handcrafted descriptors [1]. Frameworks such as NequIP and MACE leverage these architectures to achieve superior data efficiency and accuracy across diverse materials systems [1] [4].

Foundation Models for Chemistry: Recent efforts have developed pre-trained MLIPs on large DFT datasets, creating foundation models that qualitatively reproduce PES across broad portions of the periodic table [4]. These models can be fine-tuned to high accuracy for specific applications with minimal additional data, dramatically reducing the computational cost of MLIP development for specialized applications [4].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Computational Methods for Atomistic Simulation

| Method | Accuracy Range | Computational Scaling | Typical System Size | Time Scale | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry (CCSD(T)) | Very High (Chemical Accuracy) | O(N⁷) | 10-100 atoms | Static calculations | Prohibitively expensive for dynamics |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | High (5-20 meV/atom) | O(N³) | 100-1,000 atoms | Picoseconds | System size, time scale limitations |

| Classical Force Fields | Low-Medium (>50 meV/atom) | O(N²) | 10⁶-10⁹ atoms | Nanoseconds to microseconds | Limited transferability, inaccurate for reactions |

| Machine Learning IPs | Medium-High (1-20 meV/atom) | O(N²) | 10³-10⁶ atoms | Nanoseconds | Training data requirements, transferability |

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks for Specific MLIP Implementations

| MLIP Framework | Architecture Type | Reported Energy MAE | Reported Force MAE | Key Applications Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeePMD | Deep Neural Network | <1 meV/atom | <20 meV/Å | Water systems, molecular crystals |

| MACE | Equivariant GNN | Sub-chemical accuracy | ~30 meV/Å | Molecular crystals, pharmaceuticals |

| NequIP | Equivariant GNN | ~1 meV/atom | ~15-20 meV/Å | Materials phase transitions |

| NeuralIL | Neural Network | DFT-level accuracy | DFT-level accuracy | Ionic liquids, charged fluids |

The performance data reveals MLIPs' unique position in the computational landscape. With energy mean absolute errors (MAEs) potentially below 1 meV/atom and force MAEs under 20 meV/Å, MLIPs approach the accuracy of the quantum methods on which they're trained while maintaining the O(N²) scaling characteristic of classical force fields [1] [4]. This enables simulations of systems containing thousands to millions of atoms at nanosecond timescales—regimes previously inaccessible to quantum-accurate methods [1].

Application Protocols for Pharmaceutical Research

Protocol 1: Predicting Molecular Crystal Stability

Molecular crystal stability prediction is crucial for pharmaceutical development, as crystal forms dictate drug stability, solubility, and bioavailability [4]. The following protocol enables accurate calculation of sublimation enthalpies—a key thermodynamic property—with sub-chemical accuracy (<4 kJ/mol) relative to experiment:

Step 1: Foundation Model Selection

- Begin with a pre-trained foundation model such as MACE-MP-0b3, which has been trained on diverse inorganic crystals from the Materials Project database [4].

- Foundation models provide qualitatively accurate PES across broad chemical spaces, serving as optimal starting points for system-specific refinement.

Step 2: Minimal Data Generation

- Sample the molecular crystal phase space around the equilibrium volume using short MD simulations at multiple lattice volumes.

- Use the foundation model itself to run these initial simulations, avoiding costly ab initio MD during data generation.

- Randomly sample approximately 10 structures per volume from the trajectories to create an initial training set of ~200 structures [4].

Step 3: Model Fine-Tuning

- Fine-tune the foundation model by optimizing parameters to minimize errors on energy, forces, and stress tensor components.

- Employ a balanced loss function that weights energy, force, and stress terms appropriately for the target properties.

- Typical training requires 50-100 epochs with batch sizes of 5-10 structures, though this should be adjusted based on dataset size.

Step 4: Validation and Iteration

- Test the fine-tuned model on equation of state (energy vs. volume) and vibrational properties.

- If accuracy is insufficient, particularly at extremes of volume or temperature, iteratively augment training data with additional structures from regions of poor performance.

- Final models should achieve energy root mean square errors (RMSE) below 1 meV/atom relative to target DFT references [4].

Step 5: Thermodynamic Property Calculation

- Use the validated MLIP to run isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble simulations at target temperatures and pressures.

- Calculate sublimation enthalpies from the difference between crystal and gas-phase free energies, incorporating anharmonicity and nuclear quantum effects via path integral methods when necessary.

- For the X23 molecular crystal benchmark, this protocol has achieved experimental agreement with average errors <4 kJ/mol [4].

Protocol 2: Modeling Charged Fluids and Ionic Liquids

Pharmaceutical applications increasingly utilize ionic liquids for drug formulation, extraction, and delivery. This protocol enables accurate simulation of these complex charged systems:

Step 1: Reference Data Generation

- Perform ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations of target ionic liquid systems using validated DFT functionals with appropriate dispersion corrections.

- For systems with proton transfer reactions, ensure sufficient sampling of reactive events through enhanced sampling techniques or extended trajectory lengths.

- Extract diverse configurations, energies, and atomic forces covering the relevant phase space.

Step 2: Neural Network Potential Training

- Employ a neural network architecture such as NeuralIL specifically designed for ionic liquids [5].

- Train on energies and forces using a committee of networks to enable uncertainty quantification.

- Implement active learning by iteratively retraining with configurations extracted from ML-MD simulations where prediction uncertainty is high [5].

Step 3: Large-Scale Production Simulation

- Deploy the trained MLIP for large-scale MD simulations of ionic liquid systems containing hundreds of ion pairs (thousands of atoms).

- Run 100+ ps trajectories to access relevant timescales for structural relaxation and transport properties.

- For reactive systems, validate that proton transfer events and equilibrium constants match reference AIMD and experimental data [5].

Step 4: Property Extraction and Analysis

- Calculate structural properties (radial distribution functions, hydrogen bonding patterns).

- Extract dynamic properties (mean square displacements, diffusion coefficients, vibrational densities of states).

- Compare with classical force field results to identify systematic improvements, particularly for transport properties typically underestimated by non-polarizable FFs [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Datasets for MLIP Development

| Tool/Dataset | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Pharmaceutical Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeePMD-kit | Software Package | DeePMD potential training and deployment | High-performance MLIP for large biomolecular systems |

| MACE | Software Framework | Equivariant GNN potentials | Molecular crystal modeling with high data efficiency |

| NeuralIL | Specialized MLIP | Ionic liquid simulations | Drug formulation with ionic liquid excipients |

| QM9 | Benchmark Dataset | 134k small organic molecules | MLIP validation for drug-like molecules |

| MD17/MD22 | Training Dataset | Molecular dynamics trajectories | Biomolecular force field training |

| X23 | Benchmark Dataset | 23 molecular crystals | Pharmaceutical crystal stability prediction |

Table 4: Computational Resources for Different Simulation Types

| Simulation Type | Typical Hardware | Time Scale Accessible | System Size Limit | Relative Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (AIMD) | HPC Cluster | 10-100 ps | 100-1,000 atoms | 1000× (reference) |

| Classical MD | Workstation/Small Cluster | ns-μs | 10⁶-10⁹ atoms | 1× |

| MLIP-MD | Workstation/Medium Cluster | 10-100 ns | 10³-10⁶ atoms | 10-100× |

Future Perspectives and Challenges

Despite rapid progress, MLIP technology faces several important challenges that pharmaceutical researchers should consider:

Data Quality and Efficiency: MLIP accuracy remains fundamentally limited by the quality and breadth of training data. Promising approaches include active learning, where models query reference calculations for configurations with high uncertainty, and multi-fidelity frameworks that combine expensive high-accuracy and cheaper lower-accuracy data [1]. For molecular crystals, recent demonstrations achieving sub-chemical accuracy with only ~200 reference structures represent an order-of-magnitude improvement in data efficiency [4].

Transferability and Generalization: MLIPs typically perform best for systems similar to their training data, struggling with out-of-distribution configurations. Foundation models trained on diverse materials datasets show improved transferability, while physically-constrained architectures that embed known symmetries and conservation laws enhance generalization [1] [4].

Interpretability and Explainability: The "black box" nature of complex MLIP architectures poses challenges for extracting physical insights. Research into interpretable AI techniques is crucial, particularly for pharmaceutical applications where mechanistic understanding is as important as predictive accuracy [1].

Scalability and Integration: As system sizes grow, MLIP computational costs and memory requirements increase significantly. Ongoing work on scalable message-passing architectures and efficient implementations will be essential for applying MLIPs to pharmaceutical-relevant systems such as protein-ligand complexes and amorphous solid dispersions [1].

For the pharmaceutical research community, MLIP technology promises to enable accurate prediction of polymorph stability, drug-excipient compatibility, and formulation performance under realistic conditions. By providing quantum accuracy at classical computational costs, these methods are poised to accelerate drug development and materials design while reducing empirical optimization cycles.

The development of machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) represents a paradigm shift in computational materials science and chemistry, enabling molecular dynamics simulations with near quantum-mechanical accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost. The core architectural principles underpinning these advances center on two complementary concepts: invariant descriptors, which provide symmetry-preserving representations of atomic environments, and equivariant neural networks, which embed physical symmetries directly into model architectures. These principles are fundamental for accurate force field and energy predictions in applications ranging from catalyst design to drug development. This document outlines the core theoretical frameworks, provides structured experimental protocols, and details the essential computational tools required for implementing these approaches in research settings.

Theoretical Framework and Key Concepts

Foundational Descriptors for Atomic Systems

Descriptors transform atomic configurations into mathematical representations suitable for machine learning. They are broadly categorized into three classes based on their construction strategy and physical interpretation [6].

Intrinsic statistical descriptors comprise elemental properties such as atomic number, valence electron count, ionization energy, and electronegativity. Tools like Magpie can generate over 100 such attributes for each element [6]. These descriptors require no quantum mechanical calculations, making them computationally inexpensive for initial high-throughput screening of material spaces, though they may lack detailed physical interpretability.

Electronic structure descriptors encode quantum mechanical properties including orbital occupancies, d-band center (εd), magnetic moments, and charge distributions [6]. For instance, the non-bonding d-orbital lone-pair electron count (Nie-d) has served as an effective descriptor for nitrogen reduction reaction activity [6]. While these descriptors offer direct connections to chemical reactivity, they typically require preliminary density functional theory (DFT) calculations.

Geometric and microenvironmental descriptors capture structural information such as interatomic distances, coordination numbers, local strain patterns, and symmetry functions. Examples include the metal second ionization energy combined with structural parameters like M-O-O triangle areas in metal-organic frameworks [6]. The Atom-Centered Symmetry Functions (ACSF) and Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) are seminal descriptors in this category, with SOAP particularly effective for predicting grain boundary energy with high accuracy (R² = 0.99) [7].

Table 1: Classification and Performance of Foundational Descriptors

| Descriptor Category | Examples | Data Requirements | Computational Cost | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic Statistical | Magpie attributes, elemental properties | None (elemental data) | Very Low | High-throughput screening of single-atom alloys, dual-atom catalysts [6] |

| Electronic Structure | d-band center, magnetic moments, orbital occupancies | DFT calculations | High | Catalyst mechanistic studies, reactivity prediction [6] |

| Geometric/Microenvironmental | SOAP, ACSF, coordination numbers, local strain | Atomic coordinates | Medium | Grain boundary energy prediction, complex materials [7] |

The Evolution toward Equivariant Architectures

Early MLIPs relied on invariant descriptors handcrafted to be unchanged under rotation and translation of the input structure. These include bond lengths, angles, and dihedral angles [1]. While effective, these approaches required careful manual feature engineering.

A fundamental advancement came with equivariant neural networks, which explicitly embed physical symmetries into the model architecture rather than just the input features. These networks maintain internal feature representations that transform predictably under symmetry operations like rotations and translations [1]. For example, scalar outputs like energy remain invariant, while vector quantities like forces transform equivariantly [1].

The Multi-ACE framework has emerged as a unifying mathematical construction that connects descriptor-based methods with message-passing neural networks [8]. This framework extends the Atomic Cluster Expansion (ACE) to multiple layers, creating a comprehensive design space that encompasses most equivariant MPNN-based interatomic potentials [8].

Diagram 1: Equivariant architecture workflow for MLIPs (76 characters)

Quantitative Comparison of Architectures and Performance

Performance Benchmarks of MLIP Architectures

Different MLIP architectures exhibit distinct performance characteristics across benchmark datasets. The choice between invariant and equivariant approaches involves trade-offs between accuracy, computational cost, and data efficiency.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of MLIP Architectures on Benchmark Tasks

| Architecture | Type | Key Features | Test Error (Energy/Forces) | Computational Efficiency | Notable Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeePMD [1] | Invariant | Deep neural network with local environment descriptors | ~1 meV/atom / ~20 meV/Å (water) | High (comparable to classical MD) | Large-scale water simulations [1] |

| NequIP [8] | Equivariant | Message-passing with equivariant features | State-of-the-art accuracy at release (2× improvement) | Moderate | General molecular dynamics [8] |

| BOTNet [8] | Equivariant | Simplified, interpretable NequIP variant | Competitive with NequIP | Higher than NequIP | Benchmark molecular datasets [8] |

| MACE [8] | Equivariant | Multi-ACE framework, tensor decomposition | State-of-the-art (2025) | Optimized via decomposition | Materials and molecules [8] |

| HIPNN [9] | Equivariant (lmax≥1) | Hierarchical message passing with tensor sensitivity | Chemically accurate (<1 kcal/mol) | Varies with lmax | Molecular property prediction [9] |

Algorithm Selection Guidelines for Different Data Regimes

The optimal choice of machine learning algorithm depends significantly on dataset size and feature dimensionality, with tree ensembles generally outperforming in medium-to-large sample regimes, while kernel methods excel with smaller datasets [6].

For medium-to-large datasets (N ≈ 2,600 samples, p ≈ 10 features), tree ensemble methods like Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR) have demonstrated superior performance, achieving test RMSE of 0.094 eV for CO adsorption energy prediction compared to 0.120 eV for Support Vector Regression (SVR) and 0.133 eV for Random Forest [6].

In small-data regimes (N ≈ 200 samples, p ≈ 10 features), kernel methods like Support Vector Regression with radial basis function kernels can achieve exceptional performance (test R² up to 0.98) when paired with physically-informed features [6].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol 1: Developing a Custom Equivariant MLIP

Objective: Implement and train an equivariant machine learning interatomic potential for molecular dynamics simulations of catalytic materials.

Materials and Computational Resources:

- Quantum chemistry reference data (energies, forces, stresses)

- High-performance computing cluster with GPU acceleration

- MLIP framework (e.g., DEEPMD-KIT, NequIP, MACE)

Procedure:

- Data Generation and Preparation:

- Perform ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations to sample relevant configurations

- Extract energies, atomic forces, and stress tensors from DFT calculations

- Split data into training (80%), validation (10%), and test sets (10%)

- Ensure coverage of relevant chemical and conformational space

Descriptor Selection and Feature Engineering:

- For invariant models: Compute SOAP or ACSF descriptors with optimized parameters

- For equivariant models: Design graph representation with appropriate cutoff radius (typically 5-6 Å)

- Include atomic numbers as node attributes

- Implement periodic boundary conditions for crystalline materials

Model Architecture Configuration:

- Select appropriate equivariant architecture (e.g., MACE, NequIP, BOTNet)

- Set tensor order (l_max) based on accuracy requirements (typically 1-3)

- Configure message-passing layers (2-3 layers often sufficient)

- Implement invariant readout function for energy conservation

Training and Optimization:

- Initialize model parameters following established schemes

- Employ combined loss function: L = λ₁Lenergy + λ₂Lforces + λ₃L_stresses

- Use Adam or stochastic gradient descent optimizer with learning rate decay

- Implement early stopping based on validation set performance

- Train until forces converge to <50-100 meV/Å accuracy

Validation and Deployment:

- Evaluate on test set to assess generalization

- Perform molecular dynamics simulations to verify stability

- Calculate relevant materials properties for experimental comparison

- Deploy for production simulations with appropriate monitoring

Protocol 2: Teacher-Student Knowledge Distillation for Efficient MLIPs

Objective: Create a computationally efficient student MLIP through knowledge distillation from a larger teacher model without sacrificing accuracy [9].

Rationale: Foundation MLIPs with up to 10⁹ parameters have high computational and memory requirements that limit large-scale MD simulations. Teacher-student training enables lighter-weight models with faster inference and reduced memory footprint [9].

Procedure:

- Teacher Model Training:

- Train a large, accurate teacher model (e.g., HIPNN with lmax=1) on quantum chemistry data

- Use standard energy and force loss functions: Lteacher = |EDFT - Epred|² + |FDFT - Fpred|²

- Validate teacher model achieving chemical accuracy (<1 kcal/mol)

Student Model Architecture Design:

- Design compact architecture with fewer parameters (30-50% reduction)

- Maintain same fundamental operations but reduced feature dimensions

- Ensure compatible atomic energy decomposition: Etotal = Σεi

Knowledge Distillation Training:

- Generate atomic energy predictions (ε_i) from teacher model on training set

- Train student using combined loss function: Lstudent = λQC(|EDFT - Estudent|² + |FDFT - Fstudent|²) + λKDΣ|εi,teacher - ε_i,student|²

- Use λQC = 0.5, λKD = 0.5 for balanced training

- Employ same optimizer settings as teacher training

Validation and Efficiency Assessment:

- Compare student accuracy to teacher on test set

- Benchmark inference speed and memory usage

- Verify stability in molecular dynamics simulations

- Deploy efficient student model for large-scale production runs

Diagram 2: Teacher-student knowledge distillation workflow (76 characters)

Key Software Frameworks and Descriptor Tools

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for MLIP Development

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Features | Reference/Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEEPMD-Kit [1] | Software Framework | MLIP implementation and training | Deep potential molecular dynamics, high efficiency | [1] |

| SOAP [7] | Descriptor | Atomic environment representation | Smooth overlap, high accuracy for structures | [7] |

| ACE [8] [7] | Descriptor & Framework | Atomic cluster expansion | Unified framework, complete basis | [8] [7] |

| NequIP [8] | Software Framework | Equivariant MLIP implementation | Message-passing, equivariant features | [8] |

| MACE [8] | Software Framework | Equivariant MLIP | Multi-ACE layers, state-of-the-art accuracy | [8] |

| HIPNN [9] | Software Framework | Message-passing neural network | Tensor sensitivity, teacher-student compatible | [9] |

Benchmark Datasets for MLIP Development

Table 4: Key Benchmark Datasets for Training and Validation

| Dataset | System Type | Size | Key Properties | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QM9 [1] | Small organic molecules | 134k molecules | Energies, HOMO/LUMO, dipoles | Molecular property prediction |

| MD17 [1] | Molecular dynamics trajectories | ~3-4M configurations | Energies, forces | MLIP training and validation |

| MD22 [1] | Biomolecular fragments | 0.2M configurations | Energies, forces | Large molecule MLIP testing |

The architectural principles of invariant descriptors and equivariant neural networks have fundamentally transformed the landscape of machine learning interatomic potentials. Invariant descriptors provide physically meaningful representations of atomic environments, while equivariant networks embed physical symmetries directly into learning architectures, enabling unprecedented accuracy in force field predictions. The emerging Multi-ACE framework offers a unifying mathematical foundation that connects these approaches, facilitating the development of next-generation MLIPs.

Future developments will likely focus on improving data efficiency through techniques like teacher-student training, extending to more complex physical phenomena including electronic properties and magnetic interactions, and enhancing interpretability to provide deeper physical insights. As these architectures continue to mature, they will enable increasingly accurate and efficient simulations across materials science, chemistry, and drug development, accelerating the discovery of novel materials and therapeutic compounds.

The accurate prediction of interatomic forces is a cornerstone of modern computational chemistry and materials science, enabling the exploration of molecular dynamics, catalyst design, and drug discovery. Machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) have emerged as transformative tools that bridge the gap between computationally expensive quantum mechanical methods like density functional theory (DFT) and efficient but often inaccurate classical force fields [1]. A fundamental challenge in developing robust MLIPs lies in ensuring their predictions respect the underlying physical laws governing atomic systems, particularly their behavior under spatial transformations. This is where the mathematical principles of SO(3) (rotation), SE(3) (rotation and translation), and E(3) (rotation, translation, and reflection) equivariance become critical [10].

Integrating these symmetries directly into neural network architectures ensures that model outputs transform consistently with their inputs. For instance, rotating a molecular system should correspondingly rotate the predicted force vectors, while the scalar energy should remain unchanged [11] [1]. Early MLIPs relied on invariant features such as interatomic distances and angles, which preserved symmetry but often lacked the expressive power to unambiguously describe complex local atomic environments [11]. The advent of equivariant models represents a paradigm shift, actively exploiting geometric symmetries to achieve richer representations, superior data efficiency, and enhanced prediction accuracy for both scalar (energy) and vector/tensor (forces, dipole moments) properties [11] [1] [10].

Fundamental Symmetry Groups and Their Physical Interpretation

In the context of molecular systems, physical symmetries are described by specific mathematical groups whose actions on 3D space dictate how physical observables must transform.

E(3) - The Euclidean Group: This group comprises all isometries of three-dimensional Euclidean space, including translations t ∈ ℝ³, rotations R ∈ SO(3), and reflections (where det R = ±1). An element g = (R, t) acts on a point x as g·x = R x + t [10]. E(3)-equivariance is fundamental for ensuring that all predictions transform consistently with physical laws under any rigid-body transformation of the entire system.

SE(3) - The Special Euclidean Group: A subgroup of E(3), SE(3) includes all rotations and translations but excludes reflections. This is particularly relevant for modeling chiral molecules and other systems where reflection symmetry may not hold.

SO(3) - The Special Orthogonal Group: This group contains all rotations about the origin in 3D space, without translations or reflections. SO(3)-equivariance is crucial for handling vectorial outputs like forces, which must rotate in the same way as the input coordinates [12].

A function is deemed equivariant if applying a group transformation to its input is equivalent to applying a corresponding transformation to its output. Formally, for a function f : X → Y and all g in a group G, equivariance satisfies: D_Y[g] f(x) = f(D_X[g] x), where D_X and D_Y are the group representations on the input and output spaces, respectively [10]. In practice, this means that for a rotated molecular configuration, an equivariant model will predict forces that are rotated accordingly, and energies that remain invariant.

Current Architectural Paradigms for Embedding Equivariance

Modern approaches to building equivariant MLIPs can be broadly categorized into three paradigms, each with distinct advantages and implementation strategies. The table below summarizes the core methodologies and representative models.

Table 1: Paradigms for Achieving Equivariance in Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials

| Paradigm | Core Methodology | Key Advantages | Representative Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hard-Wired Equivariance | Built-in architectural constraints using irreducible representations & tensor products [10]. | Guarantees symmetry; high data efficiency; state-of-the-art accuracy [1] [10]. | NequIP [1] [10], MACE [11] [13], MACE-MP-0 [13] |

| Scalar-Vector Dual Representations | Uses separate but interacting scalar and vector features to maintain SE(3)-equivariance [11]. | Balances performance and computational cost; more efficient than high-order tensor models [11]. | E2GNN [11], PaiNN [11], NewtonNet [11] |

| Learned Equivariance | Uses generic architectures (e.g., Transformers) with contrastive learning to steer models toward equivariance [12]. | Retains hardware efficiency and flexibility of standard models; no complex equivariant layers required [12]. | TransIP [12] |

The following diagram illustrates the core architectural logic and data flow shared by many equivariant GNNs for interatomic potential prediction.

Quantitative Performance of Equivariant Models

The adoption of equivariant architectures is driven by their demonstrably superior performance and data efficiency compared to invariant models. The following table synthesizes key quantitative results reported across multiple studies.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Equivariant and Invariant Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials

| Model / Framework | Architecture Type | Key Performance Results | Reference / Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|

| NequIP | E(3)-Equivariant GNN | Matched/surpassed state-of-the-art accuracy with 100-1000x less training data vs. non-equivariant methods [10]. | [10] |

| E2GNN | Efficient SE(3)-Equivariant GNN | Consistently outperformed representative baselines; achieved ab initio MD accuracy in solid, liquid, and gas systems [11]. | Catalysts, Molecules, Organic Isomers [11] |

| TransIP | Transformer with Learned Equivariance | Attained comparable performance to state-of-the-art equivariant baselines; 40-60% improvement over data augmentation baseline [12]. | Open Molecules (OMol25) [12] |

| MLIP for α-Fe | Machine-Learned Potential (MTP) | Predicted average grain boundary energy of 1.57 J/m², showing excellent agreement with experimental predictions [14]. | α-Fe Polycrystals [14] |

| MACE-MP-0 | Foundation Equivariant Model | Enabled high-throughput prediction of heat capacities for porous materials with accuracy comparable to bespoke ML models in a zero-shot manner [13]. | Porous Materials [13] |

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing an Equivariant GNN for Force Field Training

This protocol details the procedure for training an equivariant graph neural network for force and energy prediction, based on implementations such as E2GNN [11] and NequIP [10].

1. Data Preparation and Preprocessing

- Input Data: Gather reference data from ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) trajectories or density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Essential data includes atomic coordinates (ℝ^(M×3)), atomic numbers (Z), total energies (ℝ), and atomic forces (ℝ^(M×3)), where M is the number of atoms [11] [1].

- Graph Construction: Represent the atomic system as a graph 𝒢=(𝒱,ℰ,ℛ). Nodes (v_i ∈ 𝒱) correspond to atoms. Connect nodes with edges (ℰ) if the interatomic distance is within a predefined cutoff radius (e.g., 5 Å), ensuring a maximum number of neighbors N for computational efficiency [11].

2. Feature Initialization

- Scalar Features: Initialize node scalar features x_i^(0) as a trainable embedding vector dependent on the atomic number z_i: x_i^(0) = E(z_i) ∈ ℝ^F [11].

- Vector Features: Initialize node vector features x⃗_i^(0) to zero: x⃗_i^(0) = 0 ∈ ℝ^(F×3) [11].

3. Model Architecture and Training Configuration

- Equivariant Layers: Implement a series of equivariant interaction layers. Each layer should perform operations such as local message passing and update functions that preserve SO(3) equivariance [11] [10].

- Loss Function: Use a combined loss function that optimizes for both energy and forces: ℒ = λ_E ∥E_hat − E∥² + λ_F (1/(3N)) ∑_i^N ∑_α ∥F_hat_iα − F_iα∥² [10]. This ensures physical consistency, as forces are the negative gradient of the energy with respect to atomic positions.

- Radial Basis Functions: Employ Gaussian radial basis functions (λ_h, λ_u, λ_v) to encode interatomic distances, which are then used in the message-passing steps [11].

4. Validation and Deployment

- Validation: Evaluate the trained model on hold-out test sets from the AIMD trajectory, calculating mean absolute error (MAE) for energies and forces.

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Integrate the trained potential into MD simulation packages (e.g., LAMMPS). Run simulations in target ensembles (NVE, NVT) to validate the model's stability and its ability to reproduce structural and dynamic properties [11].

Protocol 2: Enhancing Generalization with Physics-Informed Sharpness-Aware Minimization (PI-SAM)

This protocol is designed for semiconductor materials and other challenging systems with out-of-distribution atomic configurations, based on the PI-SAM framework [15].

1. Base Model and Data Setup

- Select a suitable GNN architecture (invariant or equivariant) as the base model for predicting energies and forces [15].

- Prepare the training dataset, ensuring it includes diverse atomic configurations that reflect the target application's possible states, including defects and non-equilibrium structures if applicable.

2. Physics-Informed Regularization

- Energy-Force Consistency Loss: Add a regularization term that penalizes the discrepancy between predicted forces and the negative gradient of the predicted energy with respect to atomic positions. This explicitly enforces the physical relationship F = −∇E [15].

- Potential Energy Surface (PES) Curvature Regularization: Incorporate a term that encourages the model to learn the correct curvature of the PES, which is related to vibrational properties and stability [15].

3. Sharpness-Aware Minimization (SAM) Optimization

- During training, the SAM optimizer seeks parameters that minimize not only the loss value but also the loss "sharpness." It does this by considering worst-case perturbations of the model weights within a small neighborhood [15].

- The combined PI-SAM loss function is: ℒ_PI-SAM = ℒ_Base + λ_EF * ℒ_EnergyForce + λ_PES * ℒ_PES + ρ * SAM_Perturbation, where λ_EF and λ_PES are regularization coefficients [15].

4. Evaluation on Out-of-Distribution (OOD) Data

- Test the final model on a dedicated OOD test set containing atomic configurations not seen during training, such as novel defect structures or surfaces. Compare its performance against a model trained without PI-SAM to quantify the improvement in generalization [15].

The workflow for this protocol, integrating both physical constraints and advanced optimization, is outlined below.

This section catalogs critical datasets, software, and model frameworks necessary for research and development in equivariant MLIPs.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Equivariant MLIP Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Access / Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| QM9 | Dataset | Benchmarking model performance on stable small organic molecules (134k molecules) [1]. | https://figshare.com/collections/Quantumchemistrystructuresandpropertiesof134kilomolecules/978904 |

| MD17/MD22 | Dataset | Training and validation on molecular dynamics trajectories of organic molecules and biomolecular fragments [1]. | http://quantum-machine.org/datasets/#md-datasets |

| e3nn / E3x | Software Library | Provides abstractions for building E(3)-equivariant networks, managing irreducible representations and Clebsch-Gordan algebra [10]. | [10] |

| LAMMPS | Simulation Software | High-performance molecular dynamics simulator; supports integration of various MLIPs for large-scale simulations [14]. | [14] |

| MACE-MP-0 | Foundation Model | Pretrained equivariant potential (MACE architecture) for zero-shot property prediction on diverse materials [13]. | [13] |

| WANDER | Dual-Functional Model | A physics-informed neural network capable of predicting both atomic forces (like a force field) and electronic structures [16]. | [16] |

Advanced Applications and Future Outlook

The impact of equivariant models extends far beyond simple force prediction. They are now being applied to predict complex tensorial material properties such as dielectric constants, piezoelectric tensors, and elasticity tensors with state-of-the-art accuracy by decomposing these tensors into their spherical harmonic components [10]. In drug discovery and biophysics, equivariant GNNs like VN-EGNN are being used to identify protein binding sites, leveraging their ability to handle 3D molecular structures robustly [10].

A promising frontier is the development of multi-functional models that bridge the gap between force fields and electronic structure calculations. Frameworks like WANDER (Wannier-based dual functional model for simulating electronic band and structural relaxation) exemplify this trend. By using a deep potential molecular dynamics backbone and sharing information with a Wannier Hamiltonian module, WANDER can simultaneously predict atomic forces and electronic band structures, marking a significant step toward machine-learning models that offer multiple functionalities of first-principles calculations [16].

Future research will likely focus on improving the computational efficiency of equivariant models to enable simulations of even larger systems, extending these approaches to more complex symmetries and conservation laws, and enhancing interpretability to glean new physical insights from the learned representations [1] [10]. The integration of equivariant MLIPs into automated, multi-scale simulation workflows holds the potential to dramatically accelerate the design of new molecules and advanced materials.

Universal Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (uMLIPs) represent a transformative advancement in computational materials science, enabling accurate atomistic simulations across wide spans of the periodic table. These foundational models learn the mapping from atomic configurations to energies and forces from quantum mechanical data, achieving near-ab initio accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost of density functional theory (DFT) calculations [1]. The shift from system-specific potentials to universal models has been facilitated by innovative graph neural network architectures, the accumulation of large-scale DFT databases, and advanced training protocols [17] [1]. This progress has positioned uMLIPs as powerful tools for predicting diverse materials properties, from thermodynamic stability to vibrational spectra. However, significant challenges remain in their generalization to out-of-distribution regimes, data fidelity requirements, and computational scalability [1]. This article examines the current state of uMLIP development, benchmarks their performance across key applications, and provides detailed protocols for their evaluation and improvement.

Performance Benchmarks and Application-Specific Accuracy

Phonon Property Predictions

The accuracy of uMLIPs in predicting harmonic phonon properties—fundamental to understanding thermal and vibrational behavior—has been systematically evaluated using a dataset of approximately 10,000 ab initio phonon calculations [17]. As shown in Table 1, performance varies considerably across models, with some achieving high accuracy while others exhibit substantial errors despite excelling at energy and force predictions near equilibrium configurations [17].

Table 1: Performance of uMLIPs on phonon properties and structural relaxation

| Model | Phonon Prediction Accuracy | Geometry Relaxation Failure Rate (%) | Architecture Type | Forces as Energy Gradients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M3GNet | Moderate | ~0.20% | Three-body graph network | Yes |

| CHGNet | Moderate | 0.09% | Graph network | Yes |

| MACE-MP-0 | High | ~0.20% | Atomic cluster expansion | Yes |

| SevenNet-0 | Moderate | ~0.20% | Equivariant (NequIP-based) | Yes |

| MatterSim-v1 | High | 0.10% | M3GNet-based with active learning | Yes |

| ORB | Variable | High | Smooth overlap + graph network | No |

| eqV2-M | High | 0.85% | Equivariant transformer | No |

Notably, models that predict forces as separate outputs rather than as exact derivatives of the energy (ORB and eqV2-M) demonstrate higher failure rates in geometry relaxations, often due to high-frequency errors that prevent convergence [17]. This highlights a critical architectural consideration for uMLIP developers.

High-Pressure Applications

uMLIP performance deteriorates under extreme pressure conditions (0-150 GPa) due to limitations in training data coverage rather than algorithmic constraints [18]. Benchmark studies reveal that while these models excel at standard pressure, their predictive accuracy declines as pressure increases, manifested by inaccurate predictions of compressed bond lengths and volumes per atom [18]. As illustrated in Table 2, targeted fine-tuning on high-pressure configurations can significantly restore model robustness, underscoring the importance of representative training data.

Table 2: uMLIP performance under high-pressure conditions

| Pressure (GPa) | First-Neighbor Distance Range (Å) | Volume per Atom Range (ų) | Typical uMLIP Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.74 - ~5.0 | 10-40 (with tail >100) | Excellent |

| 25 | Narrowing | Narrowing | Good |

| 50 | Narrowing | Narrowing | Moderate |

| 100 | Narrowing | ~20 | Declining |

| 150 | 0.72 - ~3.3 | ~20 | Poor |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

DIRECT Sampling for Robust Training Set Selection

The DImensionality-Reduced Encoded Clusters with sTratified (DIRECT) sampling approach addresses the critical challenge of selecting representative training structures from large configuration spaces [19]. The protocol, visualized in Figure 1, consists of five key steps:

Figure 1: Workflow for DIRECT sampling

Step 1: Configuration Space Generation - Generate a comprehensive configuration space of N structures using methods such as AIMD simulations, random atom displacements, lattice strains, or sampling from universal MLIP molecular dynamics trajectories [19].

Step 2: Featurization/Encoding - Convert the configuration space into fixed-length vectors using the concatenated output of the final graph convolutional layer from pre-trained graph deep learning formation energy models (e.g., M3GNet trained on Materials Project formation energies) [19].

Step 3: Dimensionality Reduction - Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to the normalized features, retaining the first m principal components with eigenvalues >1 (Kaiser's rule) to represent the feature space [19].

Step 4: Clustering - Employ the Balanced Iterative Reducing and Clustering using Hierarchies (BIRCH) algorithm to group structures into n clusters based on their locations in the m-dimensional feature space, weighting PCs by explained variance [19].

Step 5: Stratified Sampling - Select k structures from each cluster based on Euclidean distance to centroids. When k=1, choose the feature closest to each centroid; for k>1, select features at constant index intervals after distance sorting [19].

Application of DIRECT sampling to the Materials Project relaxation trajectories dataset with over one million structures has yielded improved M3GNet universal potentials that extrapolate more reliably to unseen structures [19].

Active Learning for Infrared Spectra Prediction

The Python-based Active Learning Code for Infrared Spectroscopy (PALIRS) implements a four-step protocol for efficient IR spectra prediction [20], with the workflow detailed in Figure 2:

Figure 2: PALIRS active learning workflow

Step 1: Initial Dataset Preparation - Sample molecular geometries along normal vibrational modes from DFT calculations to create foundational training data [20].

Step 2: Initial MLIP Training - Train an ensemble of three MACE models on the initial structures to enable uncertainty quantification through force prediction variance [20].

Step 3: Active Learning Loop - Iteratively expand the training set through MLMD simulations at multiple temperatures (300K, 500K, 700K), selecting configurations with highest uncertainty in force predictions to enrich the dataset [20].

Step 4: Dipole Moment Model Training - Train a separate MACE model specifically for dipole moment predictions using the final active learning dataset [20].

Step 5: MLMD Production and IR Spectra Calculation - Perform production MLMD simulations using the refined MLIP, compute dipole moments along trajectories, and derive IR spectra via autocorrelation function analysis [20].

This protocol achieves accurate IR spectra predictions at a fraction of the computational cost of AIMD, with applications demonstrated for small organic molecules relevant to catalysis [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key computational resources for uMLIP development and application

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets | MDR Phonon Database [17], Alexandria [18], Materials Project [17] [19] | Provide standardized datasets for training and benchmarking uMLIP performance | Phonon calculations, high-pressure studies, universal potential development |

| MLIP Architectures | MACE [17] [18], M3GNet [17] [19], NequIP/SevenNet [17], CHGNet [17] | Core model architectures with different accuracy/efficiency trade-offs | Cross-materials applications, system-specific fine-tuning |

| Training Methodologies | DIRECT Sampling [19], Active Learning (PALIRS) [20] | Advanced strategies for robust training set selection and efficient data generation | Improving model generalizability, reducing computational cost |

| Specialized Software | DeePMD-kit [1], PALIRS [20] | Implementation frameworks for specific MLIP approaches and applications | Molecular dynamics, IR spectra prediction |

| Descriptor Schemes | Atomic Cluster Expansion [17], Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions [17] | Represent atomic environments for machine learning | Encoding structural and chemical information |

Critical Challenges and Future Directions

Despite rapid progress, uMLIPs face several significant challenges that limit their universal applicability. A primary concern is generalization to regimes underrepresented in training data, such as high-pressure environments [18] or metastable structures far from dynamical equilibrium [17]. Additionally, models that predict forces as separate outputs rather than energy gradients demonstrate higher failure rates in geometry relaxations [17], highlighting architectural limitations.

Future development should focus on several key areas: (1) incorporating diverse training data covering extreme conditions and rare configurations; (2) developing improved uncertainty quantification methods to detect extrapolation risks; (3) enhancing model architectures for better physical consistency; and (4) creating more comprehensive benchmark datasets spanning multiple materials classes and properties [17] [1] [18]. The integration of active learning strategies, multi-fidelity frameworks, and interpretable AI techniques will be crucial for advancing the next generation of truly universal interatomic potentials [1].

As uMLIP methodologies continue to mature, they hold immense promise for accelerating materials discovery across diverse applications, from catalyst design to high-pressure materials synthesis, ultimately bridging the gap between quantum mechanical accuracy and computational efficiency in atomistic simulations.

Machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) represent a paradigm shift in computational chemistry and materials science, offering near-quantum mechanical accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost of traditional density functional theory (DFT) calculations [21] [1]. The performance and generalizability of these models are fundamentally constrained by the breadth, diversity, and fidelity of their training data [1]. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of current data resources and practical protocols for developing and applying MLIPs across chemical spaces, from small molecules to complex biomolecular systems, within the broader context of force calculation research.

Current Landscape of MLIP Training Datasets

The development of MLIPs has been accelerated by the creation of large-scale, high-quality datasets. These resources vary significantly in scale, chemical diversity, and target applications, enabling researchers to select appropriate training data for specific use cases. The table below summarizes key datasets that have emerged as critical resources for training MLIPs.

Table 1: Overview of Major Datasets for MLIP Training

| Dataset Name | Data Scale | Elements Covered | Level of Theory | Key Features | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OMol25 [22] [23] | >100 million DFT calculations | 83 elements | ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD | Includes biomolecules, metal complexes, electrolytes, systems up to 350 atoms | Universal MLIPs, healthcare and energy storage technologies |

| QDπ [24] | 1.6 million structures | 13 elements (H, C, N, O, F, P, S, Cl, and others relevant to drug discovery) | ωB97M-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVPPD | Active learning curation, includes conformational energies, intermolecular interactions, tautomers | Drug discovery, biomolecular simulations |

| QM9 [1] | 134k molecules (~1M atoms) | C, H, O, N, F | Not specified in sources | Small organic molecules with ≤9 heavy atoms | Molecular property prediction |

| MD17/MD22 [1] | MD17: ~3-4M configurations; MD22: 0.2M configurations | Varies by subset | Not specified in sources | Molecular dynamics trajectories | Energy and force prediction |

The OMol25 dataset represents a significant milestone in dataset scale and diversity, requiring approximately 6 billion CPU core-hours to generate and containing configurations up to 10 times larger than previous molecular datasets [23]. Its unique value lies in blending "elemental, chemical, and structural diversity" including intermolecular interactions, explicit solvation, variable charge and spin states, conformers, and reactive structures [22].

For drug discovery applications, the QDπ dataset offers strategic advantages through its active learning curation process, which maximizes chemical diversity while minimizing redundant information [24]. This approach demonstrates that targeted, information-dense datasets can effectively cover relevant chemical spaces without requiring exhaustive computation of all possible structures.

Experimental Protocols for MLIP Development and Validation

Active Learning for Data Curation and Expansion

The QDπ dataset development employed a query-by-committee active learning strategy to efficiently sample chemical space [24]. The following protocol details this approach:

Procedure:

- Initialization: Begin with an initial set of structures with quantum mechanical reference data

- Committee Training: Train 4 independent MLIP models on the current dataset using different random seeds

- Candidate Screening: For each structure in source databases, calculate the standard deviation of energy and force predictions across the committee models

- Selection Criteria:

- Structures with standard deviations exceeding 0.015 eV/atom for energy or 0.20 eV/Å for forces are considered informative

- Select a random subset of up to 20,000 candidate structures for DFT calculation

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-4 until all structures in source databases either meet inclusion criteria or are excluded

Applications: This protocol is particularly valuable for pruning large datasets to remove redundancy or expanding small datasets through molecular dynamics sampling of thermally accessible conformations [24].

Benchmarking MLIPs for Charge-Related Properties

Recent research has evaluated MLIPs trained on the OMol25 dataset for predicting charge-sensitive molecular properties [25]. The following protocol outlines this benchmarking approach:

Procedure:

- System Preparation:

- Obtain molecular structures for both reduced and non-reduced states of target species

- For reduction potential calculations, include solvent information

Geometry Optimization:

- Optimize all structures using the target MLIP

- Use robust optimization algorithms (e.g., geomeTRIC 1.0.2)

- Apply convergence criteria for forces (e.g., <0.005 eV/Å)

Energy Evaluation:

- Calculate electronic energies for optimized structures

- For solvation effects, apply implicit solvation models (e.g., CPCM-X)

Property Calculation:

- Reduction potential: ΔE = E(non-reduced) - E(reduced) [in eV, equivalent to volts]

- Electron affinity: E(neutral) - E(anion) [in eV]

Validation:

- Compare predictions against experimental data

- Calculate mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), and R² values

Key Findings: This protocol revealed that despite not explicitly modeling Coulombic physics, OMol25-trained models like UMA-Small can predict reduction potentials for organometallic species with accuracy comparable to or exceeding traditional DFT methods [25].

Workflow Visualization for MLIP Development

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for developing and applying machine learning interatomic potentials, from data curation to model deployment:

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for MLIP Development

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Models | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Universal MLIP Models | UMA (Universal Model for Atoms) [23], MACE [26], CHGNet [26], MatterSim [26] | Pretrained foundational models for broad chemical spaces; can be used directly or fine-tuned for specific applications |

| Specialized MLIP Models | AIMNet2 [27], SevenNet [26], eqV2-M [17] | Models with specific strengths: AIMNet2 for charged systems and IR spectra, SevenNet and eqV2-M for high accuracy on derivatives |

| Software Platforms | AMS/MLPotential [27], DeePMD-kit [1], DP-GEN [24] | Integrated platforms for MLIP training, deployment, and active learning workflows |

| Benchmarking Resources | Matbench Discovery [17], MDR phonon database [17], Experimental redox datasets [25] | Standardized datasets and metrics for evaluating MLIP performance on specific properties |

Model Selection Guidelines

Choosing an appropriate MLIP requires careful consideration of the target application:

- For broad exploratory studies across diverse chemical spaces: Universal models like UMA and MatterSim provide excellent starting points [26] [23]

- For electronic property predictions: CHGNet incorporates charge information via magnetic moment constraints [26]

- For high-accuracy force and stress predictions: MACE and SevenNet demonstrate strong performance on elastic and phonon properties [26]

- For molecular systems with charges: AIMNet2 currently offers unique support for charged species and dipole moment predictions [27]

The evolving landscape of data resources for machine learning interatomic potentials is dramatically accelerating molecular simulations across chemical and materials spaces. The emergence of massive, diverse datasets like OMol25, coupled with strategically curated resources like QDπ, provides researchers with unprecedented opportunities to develop accurate, transferable models. The experimental protocols and resources outlined in this application note offer practical pathways for leveraging these data assets to advance force calculation research. As the field progresses, increased emphasis on data quality, specialized benchmarking, and model interpretability will further enhance the utility of MLIPs in scientific discovery and industrial applications, particularly in drug development and materials design.

Implementing MLIPs: Architectures, Training Strategies, and Domain Applications

Machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) have emerged as a transformative tool in computational materials science and drug discovery, bridging the gap between quantum-mechanical accuracy and molecular dynamics efficiency. These models learn the relationship between atomic configurations and potential energies from reference data, enabling simulations across extended time and length scales. The rapid evolution of MLIP architectures has given rise to distinct families, each with characteristic approaches to balancing accuracy, computational efficiency, and physical faithfulness. This application note provides a structured overview of the primary MLIP architecture families—graph networks, symmetry-equivariant models, and high-efficiency frameworks—contextualized within the broader thesis of enabling accurate force calculations for research applications. We summarize quantitative performance data, detail experimental protocols for model evaluation, and visualize key architectural relationships to equip researchers with practical guidance for selecting and implementing these advanced computational tools.

MLIP Architecture Families: Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

Architectural Paradigms and Their Evolution

MLIP architectures have evolved from using invariant descriptors to sophisticated symmetry-aware models. Invariant models initially dominated the field, relying on handcrafted features like bond lengths and angles that remain unchanged under rotational and translational transformations. While computationally efficient, these models face limitations in distinguishing structures with identical local features but different spatial arrangements [11]. Equivariant models represent a significant advancement by explicitly embedding the symmetries of Euclidean space (E(3)) directly into their architecture. These models ensure that their internal representations transform predictably under rotation, leading to superior data efficiency and accuracy [1]. Recently, high-efficiency frameworks have emerged, aiming to preserve the benefits of equivariance while reducing computational overhead through innovative representations and training paradigms [11] [28].

Table 1: Core MLIP Architecture Families and Their Characteristics

| Architecture Family | Core Principle | Representative Models | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invariant Graph Networks | Uses invariant features (distances, angles) to construct potential energy surface. | CGCNN [11], SchNet [11], MEGNet [11], M3GNet [29], ALIGNN [11] | Conceptual simplicity, computational efficiency. | Limited geometric awareness, struggles with stereoisomers and complex spatial configurations [11]. |

| Symmetry-Equivariant Models | Embeds E(3) symmetry directly into network operations via spherical harmonics/tensor products. | NequIP [11] [30], MACE [11] [31], Allegro [21] | High data efficiency & accuracy, excellent generalization from small datasets [11] [30]. | High computational cost and memory footprint from tensor operations [11]. |

| High-Efficiency Frameworks | Achieves equivariance without high-order tensors or uses learned symmetry compliance. | E2GNN [11], PaiNN [11], TransIP [28], CAMP [32] | Favorable accuracy-speed trade-off, scalability to larger systems [11] [28]. | Potential accuracy trade-offs vs. high-order equivariant models on complex tasks [11]. |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Benchmarking studies and model publications provide critical metrics for comparing the performance of different MLIP architectures across diverse datasets. The following table synthesizes reported performance data, offering a quantitative basis for model selection. It is crucial to note that performance is dataset-dependent, and these figures should serve as a guide rather than an absolute ranking.

Table 2: Reported Performance Metrics of Selected MLIP Models

| Model | Architecture Family | Dataset | Energy MAE | Force MAE | Key Benchmarking Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M3GNet | Invariant Graph Network | Materials Project (universal) [29] | - | - | Identified ~1.8M potentially stable materials; 1,578 verified by DFT [29]. |

| E2GNN | High-Efficiency Framework | Catalysts, molecules, organic isomers [11] | Outperforms baselines [11] | Outperforms baselines [11] | Achieved AIMD accuracy in solid, liquid, gas MD simulations [11]. |

| NequIP | Symmetry-Equivariant Model | Diverse systems (Li diffusion, water) [30] | - | - | Unprecedented accuracy & sample efficiency; 1000x fewer data than invariant models [30]. |

| DeePMD | Invariant/Descriptor-Based | ~10^6 water configs. [1] | <1 meV/atom | <20 meV/Å | Quantum accuracy with classical MD efficiency [1]. |

Experimental Protocols for MLIP Evaluation and Application

Standardized Benchmarking with MLIPAudit

Robust evaluation of MLIPs requires going beyond static energy and force errors to assess performance on downstream tasks. The MLIPAudit benchmarking suite provides a standardized framework for this purpose [31].

Protocol Objectives: To evaluate the accuracy, robustness, and transferability of MLIPs across a diverse set of molecular systems and simulation tasks, providing a holistic view of model utility beyond training metrics [31].

Procedure:

- System Preparation: Select benchmark systems from the MLIPAudit repository, which includes small organic compounds, molecular liquids, flexible peptides, and folded protein domains [31].

- Model Inference: Configure the target MLIP(s) using the provided tools, ensuring compatibility via an ASE calculator interface [31].

- Task Execution: Run the standardised benchmark tasks, which may include:

- Static Property Prediction: Calculate energies and forces on held-out validation sets, reporting RMSE and MAE [31].

- Molecular Dynamics Stability: Perform MD simulations to assess energy conservation and structural stability over time [31].

- Conformational Sampling: Evaluate the model's ability to reproduce correct populations of molecular conformers or protein secondary structures [31].

- Property Reproduction: Compare simulated properties (e.g., radial distribution functions, diffusion coefficients) against reference QM or experimental data [31].

- Results Submission and Comparison: Submit results to the MLIPAudit leaderboard for standardized comparison against pre-computed evaluations of published models [31].

Key Controls: Consistent cutoff distances, system sizes, and simulation parameters across all models compared; use of identical initial configurations and thermostats for dynamic simulations [31].

Molecular Dynamics Simulation with MLIPs

Applying a trained MLIP to run molecular dynamics simulations is a primary use case. This protocol outlines the steps for a typical NVT (constant number, volume, and temperature) simulation.

Protocol Objectives: To perform a stable MD simulation using a trained MLIP to study thermodynamic properties, dynamic behavior, and structural evolution of a molecular system.

Procedure:

- System Initialization:

- Coordinate Preparation: Obtain initial atomic coordinates from a crystal structure, previous simulation, or model builder.

- Box Size and Periodicity: Define the simulation box with periodic boundary conditions appropriate for the system (e.g., ~10 Å padding around solute for solvated systems).

- Model Loading: Load the trained MLIP model and its parameters into an MD engine that supports MLIPs (e.g., LAMMPS, ASE, SchNetPack).

Energy Minimization:

- Perform a geometry optimization (e.g., using the FIRE algorithm) to relax the structure to the nearest local energy minimum, minimizing internal stresses.

- Convergence Criterion: Set a force tolerance (e.g., 0.01 eV/Å) to terminate the minimization.

Equilibration Phase:

- Thermostat Coupling: Initialize velocities according to a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution for the target temperature. Use a thermostat (e.g., Nose-Hoover, Langevin) to maintain temperature.

- Integration: Use a time integrator like Velocity Verlet with a small time step (0.5-1.0 fs), as MLIPs can model high-frequency vibrations.

- Duration: Run for a sufficient time (e.g., 10-100 ps) for system properties (temperature, pressure, energy) to stabilize.

Production Run:

- Disable any strong coupling to external baths if measuring equilibrium properties.

- Continue the simulation, writing trajectories (atomic positions, velocities) and energies/forces to disk at regular intervals (e.g., every 10-100 steps) for subsequent analysis.

Analysis:

- Calculate relevant properties from the production trajectory, such as radial distribution functions, mean-squared displacement for diffusion coefficients, or root-mean-square deviation for structural stability.

Troubleshooting Note: Poor energy conservation or structural instability during dynamics can indicate a failure of the MLIP to generalize. This underscores the importance of rigorous benchmarking using protocols like MLIPAudit before relying on simulation results [31].

Visualization of MLIP Architectures and Workflows

Conceptual Hierarchy of MLIP Architectures

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and evolution between the major MLIP architecture families, highlighting their core strategies for handling geometric symmetries.

MLIP Benchmarking and Application Workflow

This flowchart outlines the standard workflow for developing, benchmarking, and applying an MLIP, from data generation to production simulation, incorporating feedback loops for model improvement.

Successful development and application of MLIPs rely on a suite of software tools, datasets, and computational resources. The following table details key components of the modern MLIP research toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Resources for MLIP Research and Development

| Resource Category | Specific Tool / Database | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmarking Suites | MLIPAudit [31] | Standardized framework for evaluating MLIP accuracy, robustness, and transferability across diverse molecular systems. |

| Reference Datasets | Materials Project [29], OMol25 [28], MD17/MD22 [1], QM9 [1] | Sources of high-quality reference data (energies, forces) from DFT calculations for training and testing MLIPs. |

| Software Packages | DeePMD-kit [1], ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) [31] | Software ecosystems for training MLIPs (DeePMD-kit) and running simulations with interoperability between codes (ASE). |

| Pre-trained Universal Models | M3GNet [29], MACE-MP [31], MACE-OFF [31] | Ready-to-use MLIPs trained on extensive datasets across the periodic table or organic molecules, enabling simulations without initial training. |

Application Notes

The selection and engineering of molecular descriptors are pivotal for developing robust machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs). These descriptors encode atomic environments into mathematical representations, enabling the prediction of potential energy surfaces with near-quantum accuracy. The choice of descriptor strategy directly impacts a model's data efficiency, computational cost, transferability, and accuracy across diverse chemical spaces [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Core Descriptor Strategies for Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials

| Descriptor Strategy | Core Principles | Key Advantages | Common Algorithms/Implementations | Target Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geometric Descriptors | Roto-translationally invariant descriptions of local atomic neighborhoods using distances, angles, and dihedral angles [1]. | - Strong inductive bias for molecular mechanics [33].- Computationally efficient.- Well-established and interpretable. | - Atom-Centered Symmetry Functions (ACSF) [34].- Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) [34].- Atomic Cluster Expansion (ACE) [34]. | Potential energy, atomic forces, elastic constants, phonon dispersion [35]. |

| Electronic Structure Descriptors | Utilizes features from quantum mechanical (QM) calculations, such as orbital interactions, to inform the model [33]. | - Superior for quantum chemical properties [33].- High data efficiency and transferability.- Can model electronic phenomena (e.g., charge transfer) [33]. | - OrbNet-Equi [33].- Machine Learning Hamiltonian (ML-Ham) methods [1]. | Electronic energies, dipole moments, frontier orbital energies (HOMO/LUMO), electron densities [33]. |

| Custom Composite Descriptors | Combines readily available database features with vectorized property matrices and empirical functions [36]. | - Mitigates data scarcity for specific applications.- Leverages low-cost computational features.- Highly tunable for specific property prediction. | - Hybrid feature engineering (e.g., mixing formation heat with vectorized electronegativity) [36].- Descriptor vectorization from property matrices [36]. | Band gaps, work functions, and other electronic structure properties of complex materials like 2D systems [36]. |

The integration of physical symmetries is a critical consideration. Equivariant models explicitly embed symmetries like rotation (SO(3)) and translation into their architecture. This ensures that scalar outputs like energy are invariant, while vector outputs like forces transform correctly, leading to significant improvements in data efficiency and physical consistency [1] [34]. For example, models like MACE and NequIP use equivariant operations to achieve high accuracy with fewer training samples [34] [37].

The paradigm of foundation MLIPs represents a shift towards universal potentials pre-trained on massive datasets. However, adapting these models to specific tasks or higher levels of theory often requires transfer learning. Frameworks like franken enable efficient adaptation by extracting atomic descriptors from pre-trained graph neural networks and fine-tuning them with minimal data, showcasing strong performance with as few as tens of training structures [34].

Protocols

Protocol 2.1: Implementing an Electronic-Structure-Informed Equivariant Model (e.g., OrbNet-Equi)

This protocol details the procedure for training a model that incorporates electronic structure features within an equivariant neural network, suitable for predicting quantum chemical properties [33].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| GFN-xTB Software | Provides efficient semi-empirical tight-binding calculations to generate initial mean-field electronic structure inputs [33]. |

| OrbNet-Equi Codebase | The core neural network architecture that is equivariant to isometric transformations of the molecular system [33]. |

| QM9 Dataset | A standard benchmark containing ~134,000 small organic molecules with quantum chemical properties [1]. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software (e.g., PySCF, ORCA) | High-fidelity methods (e.g., DFT) used to generate the target training data for energies, dipoles, and other properties [33]. |

Procedure

- Input Featurization: For a given molecular geometry, compute a tight-binding mean-field electronic structure using GFN-xTB. The inputs to the neural network are constructed as a stack of matrices—typically the Fock (F), density (P), core Hamiltonian (H), and overlap (S) matrices—represented in the atomic orbital basis [33].

- Descriptor Symmetry Handling: The atomic orbital features transform block-wise under 3D rotations. The equivariant network must be designed to process these features in a way that conserves the physical symmetries of the quantum chemical system [33].

- Model Training:

- Architecture: Employ an equivariant neural network that iteratively updates atomic representations by propagating information via the off-diagonal blocks of the input matrices. The network's forward pass should respect the equivariance condition: ( R \cdot \mathcal{F}(T[\Psi0]) \equiv \mathcal{F}(R \cdot T[\Psi0]) ), where ( R ) is a rotation and ( T ) is the input feature matrix [33].

- Training Data: Use a dataset like the ~236,000 molecules from small-molecule libraries (e.g., SDC21) with corresponding high-fidelity target values (e.g., DFT-level energies) [33].