Interpreting MSD Plots from Molecular Dynamics Simulations: A Practical Guide for Calculating Diffusion Coefficients in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on interpreting Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) plots from Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations.

Interpreting MSD Plots from Molecular Dynamics Simulations: A Practical Guide for Calculating Diffusion Coefficients in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on interpreting Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) plots from Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. It covers the foundational theory of MSD based on the Einstein relation, practical methodologies for calculation using common software tools like GROMACS and MDAnalysis, and troubleshooting for common issues such as non-linear plots and sampling errors. The guide also details validation techniques to ensure result accuracy and explores applications in biomedical research, including predicting drug solubility and modeling material properties. By bridging theoretical concepts with practical application, this resource aims to enhance the reliability and interpretation of diffusion data derived from MD simulations.

Understanding MSD: From Einstein's Relation to Diffusion Coefficients

Within molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and experimental biophysics, the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) serves as a fundamental metric for quantifying the random motion of particles. The Einstein relation provides the critical theoretical bridge connecting this microscopic motion, described by the MSD, to the macroscopic property of self-diffusivity (D). This connection is foundational for interpreting MD simulation data, enabling researchers to translate particle trajectories into quantitative diffusion coefficients that characterize system transport properties. For researchers in drug development, understanding this relationship is paramount for studying molecular interactions, protein folding, and ligand-binding kinetics in solution. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of the Einstein relation, its practical application in computing self-diffusivity from MSD, and the key experimental considerations for obtaining accurate results.

Theoretical Foundations of the Einstein Relation

Core Principles and Historical Context

The Einstein relation, independently derived by William Sutherland (1904), Albert Einstein (1905), and Marian Smoluchowski (1906), originated from the study of Brownian motion [1]. It represents an early and profound example of a fluctuation-dissipation relation, connecting the random fluctuating motion of a particle (diffusion) with its response to an external force (mobility) [1]. The classical form of the relation is expressed as:

[ D = \mu k_B T ]

Here, (D) is the diffusion coefficient, (\mu) is the particle's mobility (defined as the ratio of its terminal drift velocity to an applied force, (\mu = vd / F)), (kB) is the Boltzmann constant, and (T) is the absolute temperature [1].

Special Cases of the Einstein Relation

Two special forms of the Einstein relation are particularly relevant in physical and biophysical sciences.

Einstein-Smoluchowski Equation: This form applies to the diffusion of charged particles and is crucial for understanding ion transport. It links the diffusion coefficient (D) to the electrical mobility (\muq) [1]: [ D = \frac{\muq k_B T}{q} ] where (q) is the electrical charge of the particle.

Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland Equation: This form describes the diffusion of spherical particles through a liquid with a low Reynolds number. It is extensively used to determine the hydrodynamic radius ((Rh)) of molecules, a key parameter in drug development for assessing molecular size and conformation [1] [2]. [ D = \frac{kB T}{6 \pi \eta Rh} ] Here, (\eta) is the dynamic viscosity of the solvent, and (Rh) is the Stokes or hydrodynamic radius of the particle [1]. Albert Einstein defined (R_h) as the radius of a hypothetical sphere that diffuses at the same rate as the particle under the same conditions [2].

Table 1: Key Forms of the Einstein Relation and Their Applications

| Equation Name | Mathematical Form | Parameters | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Einstein Relation | ( D = \mu k_B T ) | (\mu): Mobility, (k_B): Boltzmann constant, (T): Temperature | Connects diffusivity and mobility in general statistical physics. |

| Einstein-Smoluchowski Equation | ( D = \frac{\muq kB T}{q} ) | (\mu_q): Electrical mobility, (q): Particle charge | Diffusion of charged particles (e.g., ions in solution). |

| Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland Equation | ( D = \frac{kB T}{6 \pi \eta Rh} ) | (\eta): Solvent viscosity, (R_h): Hydrodynamic radius | Determining the size of spherical particles or molecules in a solution. |

The MSD and Its Connection to Diffusivity

Defining the Mean Squared Displacement

The Mean Squared Displacement is a measure of the deviation of a particle's position over time relative to a reference position. For an ensemble of (N) particles, the MSD at a lag time (\tau) is defined in 3D space as [3]:

[ \text{MSD}(\tau) = \langle | \mathbf{r}(\tau) - \mathbf{r}(0) |^2 \rangle = \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^N | \mathbf{r}i(\tau) - \mathbf{r}_i(0) |^2 ]

where (\mathbf{r}i(0)) is the initial position vector of particle (i), and (\mathbf{r}i(\tau)) is its position after a time lag (\tau). The angle brackets (\langle \rangle) denote an ensemble average [4] [3].

The Einstein Relation for MSD and Self-Diffusivity

The fundamental connection between MSD and the self-diffusion coefficient (D) is provided by the Einstein relation, which states that for normal diffusion in an isotropic medium, the MSD grows linearly with time [5] [3]. The proportionality constant is related to the dimensionality of the system.

For a 3D system, the relation is [5]:

[ \text{MSD}(\tau) = 6D\tau ]

This can be rearranged to define the self-diffusivity as a limit of the MSD's time derivative [4]:

[ D = \frac{1}{6} \lim_{\tau \to \infty} \frac{d}{d\tau} \text{MSD}(\tau) ]

In practice, for a standard MD simulation, (D) is calculated by fitting a straight line to the linear portion of the MSD-vs-(\tau) curve and dividing the slope by (2d), where (d) is the dimensionality of the MSD [4]. For a 3D MSD ((d=3)), this gives:

[ D = \frac{\text{slope of MSD}(\tau)}{6} ]

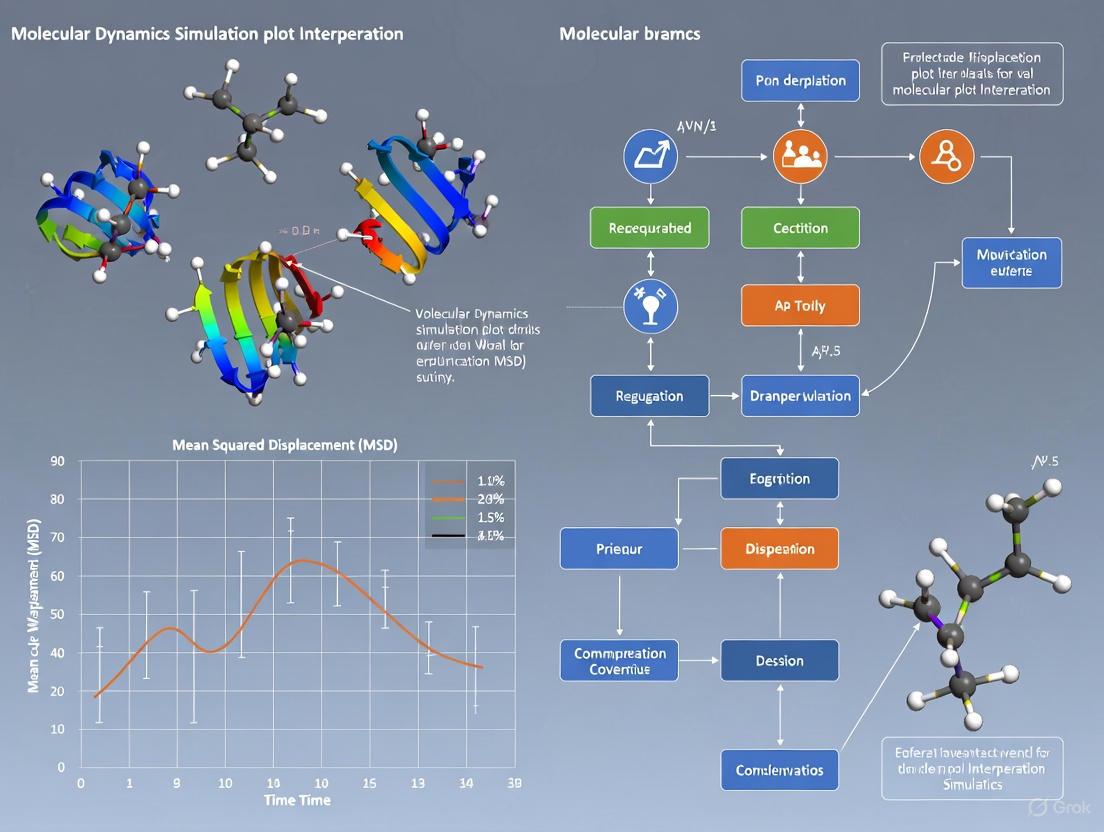

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from particle trajectories to the final diffusion coefficient.

Practical Protocols: From Simulation to Diffusivity

Computational Protocol for MSD Analysis

Accurate calculation of self-diffusivity from MD simulations requires careful implementation. The following protocol, based on tools like MDAnalysis and GROMACS, outlines the critical steps [4] [5].

Trajectory Preparation (Unwrapping Coordinates):

- The single most critical step is to use unwrapped particle coordinates [4]. When particles cross periodic boundaries, they must not be wrapped back into the primary simulation cell, as this introduces artificial discontinuities that severely corrupt the MSD calculation. In GROMACS, this can be achieved using

gmx trjconvwith the-pbc nojumpflag [4].

- The single most critical step is to use unwrapped particle coordinates [4]. When particles cross periodic boundaries, they must not be wrapped back into the primary simulation cell, as this introduces artificial discontinuities that severely corrupt the MSD calculation. In GROMACS, this can be achieved using

MSD Calculation:

- Select the atom group for analysis (e.g., all atoms, center of mass of molecules, specific residue types).

- Choose the desired dimensionality (

msd_type). A 3D MSD ('xyz') is standard for isotropic systems, but 1D or 2D MSDs can be calculated for studying anisotropic diffusion [4] [5]. - For long trajectories, use a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)-based algorithm (e.g.,

fft=Truein MDAnalysis) to compute the MSD with ( N \log(N) ) scaling instead of the naive ( N^2 ) scaling, significantly improving computational efficiency [4].

Identifying the Linear Regime:

- Plot the MSD against lag time ((\tau)) on both linear and log-log scales [4].

- The log-log plot is essential for identifying the diffusive regime, which appears as a line with a slope of 1. At very short time lags, particle motion may be ballistic (slope ≈ 2), while at very long time lags, the MSD may become noisy due to poor averaging [4].

- Select a sufficiently long, linear segment from the MSD((\tau)) plot for analysis, typically excluding the short-time non-diffusive regime [4].

Calculating Self-Diffusivity:

Table 2: Essential "Research Reagent Solutions" for MSD/Diffusivity Studies

| Item / Software | Function / Role | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Software(GROMACS, NAMD, LAMMPS) | Generates the particle trajectories from simulations. | Force field choice and simulation parameters (T, P) must match the experimental system. |

| Analysis Tools(MDAnalysis.analysis.msd, gmx msd) | Calculates the MSD from unwrapped trajectory files. | Ensure compatibility with trajectory file format. Use FFT-based algorithms for long trajectories. |

| Unwrapped Trajectory | The primary input data for a correct MSD calculation. | Must be generated during post-processing (e.g., gmx trjconv -pbc nojump); not the default output. |

| Solvent with Known Viscosity(e.g., SPC Water Model) | Used for validating the MSD protocol by calculating the diffusivity of a standard. | Allows for benchmarking against literature values to verify the analysis pipeline. |

Experimental Validation using Flow-Induced Dispersion Analysis (FIDA)

Beyond simulations, the Stokes-Einstein relation is applied experimentally to measure hydrodynamic radius ((R_h)) using techniques like Flow-Induced Dispersion Analysis (FIDA) [2]. This provides an absolute, first-principles measurement without assumptions or models.

Protocol Overview:

- A sample is injected into a capillary filled with a background electrolyte.

- Laminar flow creates a parabolic flow profile, dispersing the sample.

- The radial diffusion of molecules away from the flow axis is size-dependent. Smaller molecules diffuse faster, leading to a compact dispersion profile, while larger molecules diffuse slower, creating a more extended profile [2].

- The peak width ((2\sigma)) is used to calculate the diffusivity (D) via Fick's law of diffusion.

- The hydrodynamic radius (Rh) is then calculated using the Stokes-Einstein equation: ( Rh = \frac{k_B T}{6 \pi \eta D} ) [2].

This method is particularly powerful in drug development for studying biomolecular interactions (affinity, Kd), oligomerization, agglutination, and conformational changes, as the measured increase in (R_h) directly indicates binding or complex formation [2].

Critical Considerations and Limitations

Breakdown of the Stokes-Einstein Relation

While powerful, the Stokes-Einstein relation is not universally valid. A key limitation is its breakdown in specific materials, such as fragile glass formers and phase-change materials (PCMs), even at temperatures above their melting point [7]. In these systems, viscosity ((\eta)) and diffusivity ((D)) decouple, meaning that although viscosity may increase significantly upon cooling, the diffusivity can remain relatively high [7]. This breakdown is often attributed to dynamic heterogeneities and can have significant implications. For example, in PCMs, this decoupling is a favorable feature that enables fast phase-switching behavior critical for memory applications [7].

Other Common Pitfalls in MSD Analysis

- Finite Size Effects: The simulated system size can artificially influence the calculated diffusion coefficient. Corrections exist but are often system-dependent [4].

- Statistical Averaging: The MSD must be averaged over a sufficient number of particles and time origins. Poor averaging at long lag times leads to noisy, unreliable data [4] [3]. Combining multiple simulation replicates can improve statistics, but trajectories should not be simply concatenated due to artificial jumps between the end of one trajectory and the start of the next [4].

- Error Estimation: When reporting diffusion coefficients, it is essential to estimate errors, for example, by using block averaging or by calculating standard deviations across multiple replicates [4].

The Einstein relation provides an indispensable link between the microscopic observation of particle motion and the macroscopic property of self-diffusivity. For researchers employing molecular dynamics or analyzing experimental data, a rigorous application of this principle—ensuring proper trajectory unwrapping, correctly identifying the linear MSD regime, and being aware of the limitations like SER breakdown—is crucial for obtaining accurate and meaningful diffusion coefficients. Mastering this analysis unlocks the ability to quantify molecular size, study binding events, and fundamentally understand transport phenomena in complex systems, making it a cornerstone technique in modern chemical physics and drug development.

Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) is a fundamental metric in statistical mechanics and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for quantifying the spatial extent of random particle motion over time. It serves as the most common measure of the deviation of a particle's position from a reference point, effectively characterizing the portion of a system "explored" through random walk dynamics [3]. In the realm of molecular research, particularly in drug development, MSD analysis provides crucial insights into molecular mobility, diffusion mechanisms, and system thermodynamics, forming an essential bridge between atomic-level trajectories and macroscopic observable properties [8].

The MSD has deep roots in the study of Brownian motion and prominently appears in various physical formulations, including the Debye-Waller factor (describing vibrations within solids) and the Langevin equation (describing diffusion of Brownian particles) [3]. For researchers analyzing MD simulations, the MSD plot serves as a primary tool for extracting transport properties, particularly self-diffusion coefficients, which can inform understanding of drug binding kinetics, molecular flexibility, and material properties in biological systems.

Theoretical Foundations of the MSD Equation

Mathematical Definition

The fundamental definition of the MSD for a system of N particles at time t is expressed through the Einstein relation:

[ \text{MSD}(t) \equiv \left\langle |\mathbf{x}(t) - \mathbf{x}(0)|^2 \right\rangle = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} |\mathbf{x}^{(i)}(t) - \mathbf{x}^{(i)}(0)|^2 ]

where (\mathbf{x}^{(i)}(0) = \mathbf{x}_0^{(i)}) represents the reference position of particle (i), and (\mathbf{x}^{(i)}(t)) denotes its position at time (t) [3]. The angle brackets (\langle \ldots \rangle) represent the ensemble average, which in practical MD applications is approximated by averaging over all equivalent particles and multiple time origins.

For a single particle tracked across multiple time intervals, the MSD can be defined for different lag times ((\Delta t)). For a trajectory with positions recorded at discrete time points, the MSD for a specific lag time (n\Delta t) is calculated as:

[ \overline{\delta^2(n)} = \frac{1}{N-n} \sum{i=1}^{N-n} [\vec{r}{i+n} - \vec{r}_i]^2 ]

where (N) is the total number of frames in the trajectory, (\vec{r}_i) is the position at time step (i), and (n) represents the lag time in units of the time step [3].

Relationship to Diffusion Processes

The theoretical foundation of MSD is deeply connected to diffusion processes. For a Brownian particle in one dimension, the probability density function (p(x,t|x_0)) satisfies the diffusion equation:

[ \frac{\partial p(x,t|x0)}{\partial t} = D \frac{\partial^2 p(x,t|x0)}{\partial x^2} ]

with initial condition (p(x,t=0|x0) = \delta(x-x0)), where (D) is the diffusion coefficient [3]. The solution yields a Gaussian distribution:

[ P(x,t) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{4\pi Dt}} \exp\left(-\frac{(x-x_0)^2}{4Dt}\right) ]

From this distribution, the MSD is derived as the second moment:

[ \text{MSD} = \langle (x(t) - x_0)^2 \rangle = 2Dt ]

This linear relationship with time is characteristic of normal diffusion. In higher dimensions (n-dimensional Euclidean space), the MSD generalizes to:

[ \text{MSD} = \langle |\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x_0}|^2 \rangle = 2nDt ]

where (n) represents the dimensionality of the system [3].

Table 1: Key Mathematical Relationships in MSD Analysis

| Concept | Mathematical Expression | Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSD Definition | (\left\langle | \mathbf{x}(t) - \mathbf{x}(0) | ^2 \right\rangle) | Average squared displacement over particles and time origins |

| 1D Diffusion | (\langle (x(t) - x_0)^2 \rangle = 2Dt) | MSD grows linearly with time in one dimension | ||

| nD Diffusion | (\langle |\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{x_0}|^2 \rangle = 2nDt) | MSD in n dimensions scales with dimensionality | ||

| Einstein Relation | (Dd = \frac{1}{2d} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(r_d)) | Connects MSD slope to diffusion coefficient |

Practical Computation in Molecular Dynamics

Ensemble Averaging in Practice

In Molecular Dynamics simulations, the practical calculation of the ensemble average (\langle\ldots\rangle) requires careful consideration of both particle averages and time averages. While the theoretical definition suggests averaging over an infinite ensemble, practical MD simulations implement this through:

- Averaging over all equivalent atoms in the system (e.g., all water oxygen atoms)

- Averaging over multiple time origins along the trajectory to improve statistics [9] [10]

For a simulation of N atoms spanning a total time of (N_{k\tau}k\tau), the MSD at lag time (k\tau) can be computed as:

[ \text{MSD}(k\tau) = \frac{1}{N}\frac{1}{N{k\tau}}\sum{n=1}^{N}{\sum{i=1}^{N{k\tau}}{\Big|\vec{r}n\big(ik\tau\big)-\vec{r}n\big((i-1)k\tau\big)\Big|^2}} ]

This approach maximizes the number of samples by computing a "windowed" MSD, where the average is taken over all possible lag times (\tau \le \tau{max}), where (\tau{max}) is the length of the trajectory [9].

Algorithmic Considerations

The computation of MSD can be computationally intensive due to its (N^2) scaling with respect to (\tau_{max}) when using the simple windowed algorithm. However, an efficient algorithm with (N \log(N)) scaling based on Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) has been developed [9]. Key implementation considerations include:

- FFT-based computation: Can be accessed by setting

fft=Truein MDAnalysis implementation, but requires thetidynamicspackage [9] - Trajectory requirements: MSD calculation requires coordinates in the unwrapped convention, where atoms passing periodic boundaries are not wrapped back into the primary simulation cell [9]

- Memory management: MSD computation is memory intensive, requiring judicious use of start, stop, and step keywords for large trajectories [9]

Figure 1: Computational Workflow for MSD Analysis

Extracting Diffusion Coefficients from MSD

The Einstein Relation for Self-Diffusivity

The self-diffusivity (D_d) is closely related to the MSD through the Einstein relation:

[ Dd = \frac{1}{2d} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(r_d) ]

where (d) is the dimensionality of the MSD [9]. In practice, this derivative is estimated by fitting the MSD to a linear model over an appropriate time range where the MSD exhibits linear behavior.

For a 3D MSD (computed with msd_type='xyz'), the dimensionality factor (d) = 3, and the diffusion coefficient is calculated as:

[ D = \frac{\text{slope}}{6} ]

where "slope" is the slope of the linear regression of the MSD versus time plot [9].

Identifying the Linear Regime

A critical aspect of accurate diffusion coefficient calculation is selecting the appropriate linear segment of the MSD plot:

- Short time lags: Often exhibit ballistic regimes where MSD (\propto t^2) due to inertial effects

- Middle time lags: Represent the diffusive regime where MSD (\propto t), appropriate for calculating D

- Long time lags: May show poorly averaged data due to limited statistics [9]

The linear regime can be confirmed using a log-log plot, where the diffusive regime exhibits a slope of 1 [9]. The following protocol outlines the standard methodology:

Protocol: Calculating Self-Diffusivity from MSD

- Compute the MSD over the entire trajectory using appropriate parameters (e.g.,

fft=Truefor efficiency) - Generate a log-log plot of MSD versus lag time to identify the linear regime with slope ≈1

- Select start and end points for linear fitting, typically excluding short ballistic regimes and long noisy tails

- Perform linear regression on the selected MSD segment versus time

- Calculate the diffusion coefficient using (D = \frac{\text{slope}}{2d}) where (d) is the dimensionality

Table 2: MSD Interpretation Across Time Regimes

| Time Regime | MSD Behavior | Physical Interpretation | Suitability for D Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short Times | (\propto t^2) | Ballistic motion, inertial effects | Not suitable |

| Middle Times | (\propto t) | Normal diffusion, random walk | Ideal - linear fit provides D |

| Long Times | Flattening or noise | Limited statistics, constraints | Not suitable |

Advanced Considerations in MSD Analysis

Statistical Considerations and Error Analysis

For reliable MSD analysis, several statistical factors must be considered:

- Distribution modality: Atomic position distributions may be monomodal or multimodal, affecting MSD interpretation [8]

- Block averaging approach: Dividing trajectories into blocks and computing within-block MSD can provide more reliable variance estimates for multimodal distributions [8]

- Finite size effects: System size dependencies of diffusion coefficients should be considered, with corrections sometimes employed [9]

The analysis of variance technique can be applied to each atom in a simulated trajectory to determine whether total MSD or within-blocks MSD provides a better estimate of variance [8].

MSD in Anisotropic and Constrained Systems

In molecular dynamics studies of proteins and complex biological systems, MSD analysis must account for:

- Anisotropic diffusion: Different dimensional components (x, y, z) may exhibit different diffusion characteristics

- Constrained motion: Protein residues may experience different degrees of freedom depending on their position (core vs. surface) [8]

- Thermal adaptations: Comparative studies of thermophilic versus mesophilic proteins use MSD to investigate rigidity and atomic fluctuations related to thermal stability [8]

Experimental Protocols and Research Applications

Standard MSD Analysis Protocol

For researchers conducting MSD analysis in molecular dynamics simulations, the following detailed methodology ensures robust results:

Materials and Software Requirements

- MD simulation trajectory files (unwrapped coordinates)

- Analysis software (MDAnalysis, GROMACS

gmx msd, or equivalent) - Visualization tools (Matplotlib, Gnuplot)

Step-by-Step Procedure

Trajectory Preparation

- Ensure trajectories are unwrapped (no periodic boundary jumps)

- For GROMACS users: use

gmx trjconv -pbc nojump[9] - Select appropriate atom groups for analysis (e.g., protein backbone, specific residues, solvent)

MSD Computation

- Choose MSD dimensionality (

xyzfor 3D, or specific components) - Select FFT-based algorithm for better computational efficiency

- Run MSD calculation over entire trajectory

- Choose MSD dimensionality (

Visualization and Quality Assessment

- Plot MSD versus lag time using linear scales

- Create log-log plot to identify linear regime (slope = 1 for normal diffusion)

- Inspect for artifacts or unusual behavior

Diffusion Coefficient Extraction

- Select appropriate linear segment from MSD plot

- Perform linear regression (e.g., using

scipy.stats.linregress) - Calculate D = slope / (2*d) with proper dimensionality factor

- Report correlation coefficient to indicate quality of linear fit

Validation and Error Analysis

- Compare results from different trajectory segments

- Assess statistical uncertainty through block averaging

- Consider finite-size corrections if applicable

Table 3: Essential Tools for MSD Analysis in Molecular Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDAnalysis [9] [11] | Python Library | Trajectory analysis and MSD computation | Supports multiple formats, FFT-based algorithm, Python API |

| GROMACS gmx msd [5] | MD Analysis Tool | Direct MSD calculation from trajectories | Integrated with GROMACS, molecular center-of-mass options |

| CHARMM-GUI [12] | Web-Based Platform | Simulation setup and input generation | Streamlined interface, multiple MD package support |

| MDplot [13] | R Package | Automated visualization of MD output | Standardized plots, GROMOS/GROMACS/AMBER support |

| CHAPERONg [14] | Automation Tool | Automated GROMACS simulation and analysis | Bash/Python implementation, beginner-friendly |

| StreaMD [15] | Python Tool | High-throughput MD simulations | Distributed computing, protein-ligand systems |

The Mean Squared Displacement equation provides a powerful connection between atomic-level trajectories and macroscopic transport properties in molecular systems. Through proper application of ensemble averaging techniques and careful identification of the diffusive regime in MSD plots, researchers can extract valuable quantitative information about molecular mobility and diffusion mechanisms. For drug development professionals, these analyses offer insights into molecular flexibility, binding kinetics, and solvation dynamics that can inform rational design strategies.

As molecular dynamics simulations continue to evolve with increasing trajectory lengths and system sizes, robust MSD analysis remains an essential component of the computational biophysicist's toolkit. The ongoing development of automated analysis pipelines [14] [15] promises to make these techniques more accessible while maintaining the rigorous theoretical foundation established through decades of statistical mechanical research.

Within the field of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) is a fundamental metric for characterizing particle motion. It measures the average squared distance particles travel over time, providing crucial insights into the dynamics and transport properties of the system under study [3]. The MSD's progression over time reveals the nature of the diffusion process: normal (Brownian) diffusion, subdiffusion, or superdiffusion. The identification of a linear regime in the MSD plot is the primary signature of normal diffusion, a condition under which the calculation of a statistically robust self-diffusion coefficient becomes possible [4] [16]. This guide details the theoretical and practical aspects of identifying this critical linear regime, a foundational step for accurate material characterization in research areas ranging from solid-state ionics to drug development [17].

Theoretical Foundation of MSD and Normal Diffusion

The Mean Squared Displacement is formally defined for a (d)-dimensional space as: [ \text{MSD}(t) \equiv \langle | \mathbf{x}(t) - \mathbf{x}(0) |^2 \rangle = \dfrac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} |\mathbf{x}^{(i)}(t) - \mathbf{x}^{(i)}(0)|^2 ] where (\mathbf{x}(t)) is the position of a particle at time (t), (\mathbf{x}(0)) is its reference position, and the angle brackets denote an average over all (N) particles in the ensemble [3].

For a particle undergoing normal, Brownian motion, the MSD increases linearly with time [3] [16]. This relationship is described by the Einstein equation: [ \lim{t \to \infty} \text{MSD}(t) = 2d D t ] where (d) is the dimensionality of the MSD calculation (e.g., 1, 2, or 3), (D) is the self-diffusion coefficient, and (t) is time [4]. The generalized form of the MSD is often expressed as a power law: [ \langle x^2(t) \rangle = K{\alpha}t^{\alpha} ] Here, (K_{\alpha}) is the generalized diffusion coefficient and the exponent (\alpha) characterizes the type of diffusion [16]:

- (\alpha = 1): Normal diffusion. The MSD is linear with time.

- (\alpha < 1): Subdiffusion. Particle motion is restricted or hindered.

- (\alpha > 1): Superdiffusion. Motion is directed or facilitated.

The linear regime is thus defined as the time interval over which the MSD plot is well-described by (\alpha = 1).

A Practical Workflow for Identifying the Linear Regime

The process of identifying the linear regime and calculating the self-diffusivity is methodical. The following workflow outlines the key steps, from trajectory preparation to final calculation.

Diagram 1: A sequential workflow for identifying the linear regime in MSD analysis, covering data preparation, visualization, and analysis.

Critical Steps and Methodologies

Trajectory Preparation and MSD Computation

The first and most critical step is to ensure the MD trajectory is in an unwrapped convention. When atoms cross periodic boundaries, they must not be wrapped back into the primary simulation cell, as this would artificially truncate their displacement and lead to a severely underestimated MSD [4]. Simulation packages like GROMACS provide utilities (e.g., gmx trjconv -pbc nojump) to perform this unwrapping [4].

The MSD can then be computed for the desired dimensionality (xyz for 3D, x for 1D, etc.). For long trajectories, the computation can be computationally intensive. Efficient Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)-based algorithms, such as the one implemented in the MDAnalysis Python library (with fft=True), can be used to reduce the scaling from (N^2) to (N \log(N)) [4].

Visual Identification of the Linear Regime

Visual inspection is paramount for identifying the correct linear regime. The following two-step visualization approach is recommended:

- Log-Log Plot for Regime Identification: Plot the MSD against time on a log-log scale. On this plot, a line with a slope of 1 indicates the linear regime characteristic of normal diffusion. This plot is excellent for distinguishing between ballistic motion (slope ≈ 2 at short times), subdiffusion (slope < 1), and the target linear regime [4].

- Standard Linear Plot for Final Selection: Once the approximate region is identified from the log-log plot, inspect the same segment on a standard linear plot of MSD vs. time. The goal is to select a region that is visually linear, avoiding the curved, ballistic short-time region and the noisy, poorly averaged long-time region [4].

The following diagram illustrates the thought process for segmenting a typical MSD plot and selecting the appropriate region for analysis.

Diagram 2: A decision process for analyzing different regions of an MSD plot to identify the linear regime suitable for diffusion calculation.

Quantitative Linear Fit and Diffusion Calculation

After visually selecting the linear segment, a quantitative linear fit is performed. Using a standard linear regression model (e.g., scipy.stats.linregress), the slope of the MSD in the selected region is calculated [4].

The self-diffusion coefficient (D) is then computed using the Einstein relation:

[

D = \frac{\text{slope}}{2d}

]

where (d) is the dimensionality of the MSD [4]. For example, if a 3D MSD (msd_type='xyz') is analyzed, the dimensional factor (d = 3).

Error Estimation and Statistical Robustness

To ensure reliability, it is best practice to estimate the error in the calculated diffusion coefficient. Bootstrapping is a powerful method for this, which involves repeatedly resampling the particle trajectories with replacement and recalculating the MSD and (D) [16]. The standard deviation of the resulting distribution of (D) values provides a robust estimate of its error. Furthermore, combining results from multiple independent simulation replicates (rather than concatenating trajectories) and averaging the MSDs can significantly improve the statistical accuracy [4].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The following table details the essential "research reagents" – the software tools and data inputs – required for reliable MSD analysis.

Table 1: Essential Computational Tools for MSD Analysis

| Tool / Input | Function / Description | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Unwrapped Trajectory | The primary input data containing particle coordinates without periodic boundary wrapping [4]. | Using a wrapped trajectory is a fatal error; it artificially lowers the MSD. Generated via tools like gmx trjconv -pbc nojump in GROMACS [4]. |

| MSD Analysis Code | Software library to compute the MSD from the trajectory. | Tools like MDAnalysis.analysis.msd [4] or msd.py from specialized toolkits [16] are standard. Use FFT-based algorithms for long trajectories. |

| Linear Regression Tool | Fits a straight line to the identified linear segment of the MSD to extract its slope. | Standard in scientific libraries (e.g., scipy.stats.linregress). The choice of fit range (start and end times) is critical and must be justified [4]. |

| Bootstrapping Routine | A statistical method for estimating error by resampling particle data [16]. | Provides a confidence interval for the calculated diffusion coefficient. Often integrated into advanced MSD analysis scripts [16]. |

| Visualization Package | Generates log-log and linear plots of the MSD for visual inspection. | Essential for the correct identification of the linear regime. Libraries like matplotlib in Python are commonly used [4]. |

The identification of the linear regime in MSD plots is a cornerstone of diffusion analysis in molecular dynamics. It requires a combination of rigorous trajectory preparation, careful visual and quantitative analysis, and robust error estimation. By systematically applying the protocols outlined in this guide—using the correct unwrapped trajectories, leveraging log-log plots for identification, and applying linear fits to the appropriate segment—researchers can confidently characterize normal diffusion and accurately compute the self-diffusion coefficient, a key property in understanding material behavior across scientific disciplines.

Within the realm of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) stands as a fundamental metric for quantifying particle motion and characterizing system dynamics [3]. It measures the average squared distance a particle travels over time, providing crucial insights into diffusion processes, transport properties, and the onset of system equilibration [18]. The MSD's calculation and interpretation, however, are intrinsically tied to its dimensionality—the number of spatial dimensions over which the displacement is measured. Whether analyzing motion in one dimension (1D), two dimensions (2D), or three dimensions (3D), the choice of dimensionality directly influences the observed magnitude of the MSD, the calculation of derived properties like the self-diffusion coefficient, and the physical phenomena one can effectively study [3] [4].

This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of MSD across different dimensionalities, framed within the broader context of interpreting MSD plots from MD simulations. The central thesis is that a nuanced understanding of dimensionality is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for drawing accurate, physically meaningful conclusions from simulation data. We will explore the theoretical foundations, practical computation methods, and critical interpretation guidelines for 1D, 2D, and 3D MSD, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the framework needed to navigate this essential analysis.

Theoretical Foundations of MSD

The MSD is formally defined as a measure of the deviation of a particle's position with respect to a reference position over time [3]. It is the most common measure of the spatial extent of random motion and can be thought of as measuring the portion of the system "explored" by the random walker [3]. For a single particle in three dimensions, the MSD over a time interval ( \tau ) is given by: [ \text{MSD}(\tau) = \langle | \vec{r}(t0 + \tau) - \vec{r}(t0) |^2 \rangle ] where ( \vec{r}(t) ) is the position vector of the particle at time ( t ), and the angle brackets ( \langle \cdots \rangle ) denote an averaging procedure [19]. This average is typically performed over an ensemble of particles, over multiple time origins ( t_0 ) within a single trajectory, or both, under the assumption of a stationary process (time-translation invariance) [19].

The profound connection between MSD and diffusion is captured by the Einstein relation for a pure random walk, which states that for sufficiently long times in a homogeneous medium, the MSD grows linearly with time [3] [20]: [ \text{MSD}(\tau) = 2n D \tau ] Here, ( D ) is the self-diffusion coefficient, and ( n ) is the dimensionality of the motion (1, 2, or 3) [3]. This linear relationship is the hallmark of normal, Fickian diffusion. Deviations from linearity signal more complex dynamics. A slope less than one on a log-log plot (sub-linear growth) may indicate sub-diffusive motion, often observed in crowded environments like the cytoplasm or polymeric systems. A slope greater than one suggests super-diffusive or directed motion, characteristic of active transport processes, such as those driven by molecular motors [20]. A plateau in the MSD signifies constrained motion, where a particle is confined to a finite region, such as a chromatin locus within a nucleus [20].

Table 1: Interpreting MSD Plot Shapes

| MSD Trend | Mathematical Form | Physical Interpretation | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | ( \text{MSD} \propto \tau ) | Normal (Fickian) Diffusion | Unbound particle in simple liquid |

| Sub-linear | ( \text{MSD} \propto \tau^\alpha, \alpha<1 ) | Sub-diffusion, Crowded Environment | Particle in polymer network, cytoplasm |

| Super-linear | ( \text{MSD} \propto \tau^\alpha, \alpha>1 ) | Super-diffusion, Directed Motion | Active transport by molecular motors |

| Plateau | ( \text{MSD} \to \text{Constant} ) | Confined or Caged Motion | Chromatin in nucleus, particle in cage |

Dimensionality in MSD Analysis

Mathematical Definitions and Relationships

The dimensionality ( n ) in the MSD formula is not arbitrary but corresponds to the number of independent spatial degrees of freedom being tracked. The total MSD in 3D is a scalar sum of the squared displacements along each Cartesian axis [3]: [ \text{MSD}{\text{3D}}(\tau) = \langle (x(t+\tau)-x(t))^2 + (y(t+\tau)-y(t))^2 + (z(t+\tau)-z(t))^2 \rangle ] where ( x(t), y(t), z(t) ) are the particle's coordinates at time ( t ). Crucially, for a system undergoing isotropic diffusion, the mean-squared displacement is, on average, equally distributed among all available dimensions. This leads to the derivation of lower-dimensional MSDs from the full 3D value [3]: [ \text{MSD}{\text{2D}}(\tau) = \langle (x(t+\tau)-x(t))^2 + (y(t+\tau)-y(t))^2 \rangle = \frac{2}{3} \text{MSD}{\text{3D}}(\tau) ] [ \text{MSD}{\text{1D}}(\tau) = \langle (x(t+\tau)-x(t))^2 \rangle = \frac{1}{3} \text{MSD}_{\text{3D}}(\tau) ] These relationships hold strictly for isotropic diffusion in an unconfined, 3D space. Analyzing the same trajectory using different dimensionalities will yield MSD values that differ by these constant scaling factors. Consequently, the diffusion coefficient ( D ) extracted from the data must be adjusted for the dimensionality used in the calculation [4]: [ D = \frac{\text{MSD}(\tau)}{2n\tau} ] This ensures that the diffusivity is an intrinsic property of the particle and its environment, independent of how the measurement was performed.

Table 2: MSD and Diffusion Coefficient by Dimensionality

| Dimensionality (n) | MSD Formula | Diffusion Coefficient (D) | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1D | ( \text{MSD} = 2D\tau ) | ( D = \frac{\text{MSD}}{2\tau} ) | Diffusion along 1D paths, pore analysis |

| 2D | ( \text{MSD} = 4D\tau ) | ( D = \frac{\text{MSD}}{4\tau} ) | Lateral diffusion in membranes, surfaces |

| 3D | ( \text{MSD} = 6D\tau ) | ( D = \frac{\text{MSD}}{6\tau} ) | Bulk diffusion in solution, cytoplasm |

Practical Implications of Dimensionality Choice

The choice of MSD dimensionality is driven by the specific physical or biological question under investigation. Using the wrong dimensionality can lead to a significant miscalculation of the diffusion coefficient. For instance, extracting a 1D diffusion coefficient ( D{1D} ) from a 3D MSD trajectory without scaling (i.e., using ( D = \text{MSD}{3D}/(2\tau) ) instead of ( \text{MSD}_{3D}/(6\tau) )) would result in a value three times larger than the correct translational diffusion coefficient.

Furthermore, lower-dimensional analyses are often employed to study anisotropic motion. In a lipid bilayer, phospholipids diffuse freely within the 2D plane of the membrane but exhibit constrained motion in the third dimension. A 3D MSD analysis would obscure this detail, whereas separate 2D (in-plane) and 1D (out-of-plane) analyses can characterize the anisotropy directly [5]. Similarly, the motion of ions within a narrow ion channel is effectively 1D, as their motion is constrained by the channel pore.

Another critical consideration is the impact of substrate motion on the analysis. When the molecule of interest is embedded in a larger, moving substrate (e.g., a chromatin locus in a cell nucleus that undergoes translation and rotation), the observed MSD will contain both intrinsic and extrinsic contributions [19]. In such cases, a "two-point MSD" analysis, which tracks the relative vector or distance between two probes on the same substrate, can be used to isolate the intrinsic mobility from the global motion [19]. The mean-square change in the relative vector (MSCV) cancels out translational substrate motion, while the mean-square change in the distance (MSCD) cancels out both translational and rotational motion [19].

Computational Methods and Protocols

Calculating MSD from MD Trajectories

The practical computation of MSD from a molecular dynamics trajectory involves several key steps and considerations. The foundational formula for a single particle type, averaged over multiple time origins, is [3]: [ \overline{\delta^2(n)} = \frac{1}{N-n} \sum{i=1}^{N-n} (\vec{r}{i+n} - \vec{r}i)^2 ] where ( N ) is the total number of frames, ( n ) is the lag time (in units of frames), and ( \vec{r}i ) is the position vector of the particle in frame ( i ). This "windowed" calculation averages over all possible starting points ( i ) for a given lag time ( n\Delta t ), thereby maximizing statistical accuracy [4].

A critical prerequisite for a correct MSD calculation is the use of unwrapped coordinates [4]. Simulation packages often apply periodic boundary conditions (PBCs) and output "wrapped" coordinates, where particles that move across the box boundary are translated back into the primary unit cell. Using these wrapped coordinates directly would cause the MSD to artificially plateau at a value related to the box size. Therefore, trajectory coordinates must be unwrapped (e.g., using a tool like gmx trjconv in GROMACS with the -pbc nojump flag) prior to MSD analysis to ensure particles have continuous, physically meaningful paths [4].

The following workflow diagram outlines the key stages of a robust MSD analysis:

Diagram 1: MSD Analysis Workflow. A step-by-step protocol for calculating and interpreting Mean Squared Displacement from molecular dynamics trajectories.

A Protocol for Robust MSD Analysis

Trajectory Preparation: Load the trajectory into your analysis environment (e.g., MDAnalysis [4], GROMACS

gmx msd[5]). Ensure coordinates are unwrapped to account for periodic boundary conditions. This is an absolute requirement for obtaining physically meaningful results [4].Dimensionality Selection: Explicitly define the desired dimensionality (

msd_type) for the analysis. Options typically include:- 'xyz' for 3D MSD.

- 'xy', 'xz', 'yz' for 2D MSD in a specific plane.

- 'x', 'y', 'z' for 1D MSD along a specific axis [4]. This choice should be dictated by the system's geometry and the research question (e.g., use 'xy' for lateral membrane diffusion).

Calculation and Averaging: Execute the MSD calculation. The algorithm will compute the squared displacement for all possible time lags and starting points, then average the results. For better statistics, average over a large ensemble of equivalent particles (e.g., all water molecules, all lipids of a certain type). To combine multiple simulation replicates, compute the MSD for each replicate separately and then average the resulting MSD curves; do not simply concatenate trajectories, as this can create artificial jumps that inflate the MSD [4].

Linear Regression for Diffusion Coefficient:

- Plot the MSD against the lag time ( \tau ).

- Identify the linear regime, which typically excludes the short-time ballistic region and the long-time, poorly averaged region. A log-log plot can help identify this regime, as it will appear as a segment with a slope of 1 [4].

- Select a range of lag times (e.g., from ( \tau = 20 ) ps to ( \tau = 60 ) ps) and perform a linear fit.

- Extract the slope of the fit. The self-diffusivity is calculated as ( D = \frac{\text{slope}}{2n} ), where ( n ) is the dimensionality used in the MSD calculation [4].

Error Estimation: To assess the reliability of the calculated MSD and derived ( D ), divide the trajectory into multiple blocks (e.g., 3-5 blocks), compute the MSD for each block, and examine the standard deviation between blocks. This provides an estimate of the uncertainty stemming from finite sampling [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Tools and Reagents for MSD Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| MD Software (GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER) | Produces the initial MD trajectory by solving equations of motion. | Generating atomic-level data of protein in solvent [18]. |

| Unwrapped Trajectory | Trajectory with corrected periodic boundary crossings. | Mandatory input for correct MSD calculation [4]. |

| Analysis Packages (MDAnalysis.analysis.msd) | Implements optimized algorithms (windowed, FFT-based) for MSD computation. | Calculating 3D MSD of water for bulk diffusivity [4]. |

| Visualization (VMD, MDV, PyMOL) | Inspects trajectories, verifies unwrapping, and creates publication-quality figures. | Visualizing ion pathways in a channel protein [22]. |

| Test Datasets (MDAnalysisData) | Provides benchmark systems for validating analysis pipelines. | Testing MSD code on a known random walk system [23]. |

Advanced Considerations and Diagram

For complex systems, standard MSD analysis may require augmentation. A key challenge is isolating the intrinsic motion of a probe from the motion of its substrate. The following diagram illustrates the concept and utility of two-point MSD methods for this purpose:

Diagram 2: Isolating Motion via Two-Point MSD. Two-point MSD methods help isolate intrinsic probe motion from overall substrate movement.

The two primary measures are:

- Mean-Square Change in Vector (MSCV): Defined as ( \text{MSCV}(\tau) = \langle | \Delta \vec{d}(\tau) |^2 \rangle ), where ( \vec{d}(t) = \vec{r}1(t) - \vec{r}2(t) ) is the relative vector between two probes. The MSCV cancels out the translational motion of the substrate but remains sensitive to its rotational motion [19].

- Mean-Square Change in Distance (MSCD): Defined as ( \text{MSCD}(\tau) = \langle [ \Delta d(\tau) ]^2 \rangle ), where ( d(t) = |\vec{d}(t)| ) is the distance between probes. The MSCD is immune to both the translational and rotational motion of the substrate, thus providing a more robust measure of the intrinsic relative mobility of the probes [19].

These advanced techniques are particularly valuable in biological contexts, such as quantifying the dynamics of chromatin loci within a cell nucleus, where the motion of the nucleus itself can dominate the observed trajectories [19].

The dimensionality of Mean Squared Displacement analysis is a fundamental parameter that directly shapes the quantification and interpretation of particle motion in molecular dynamics simulations. A careful, deliberate approach to dimensionality selection—whether 1D, 2D, or 3D—is essential for accurately calculating diffusion coefficients and uncovering the underlying physical mechanisms of transport. As MD simulations continue to grow in their application to complex biological problems, including those in neuroscience and drug development, the principles outlined in this guide will serve as a critical foundation. By rigorously adhering to correct protocols for trajectory preparation, calculation, and dimensionality-aware interpretation, researchers can reliably extract profound insights from the seemingly stochastic dance of atoms, ultimately advancing our understanding of molecular function and interaction.

From Trajectory to Insight: A Step-by-Step Guide to Calculating and Applying MSD

Theoretical Foundation of Mean Squared Displacement

The Mean Squared Displacement is a fundamental metric in molecular dynamics for quantifying the spatial extent of random particle motion over time. It is the most common measure of the spatial extent of random motion, capturing the portion of the system "explored" by the random walker [3]. According to the Einstein relation, for a particle undergoing Brownian motion in an isotropic medium, the MSD exhibits a linear relationship with time: MSD(𝑡) = 2𝑛𝐷𝑡, where 𝑛 is the dimensionality of the diffusion (1, 2, or 3) and 𝐷 is the self-diffusion coefficient [5] [3]. This relationship provides the foundation for computing transport properties from MD simulations.

The practical calculation of MSD involves averaging the squared displacements of particles from their initial reference positions over time. The general expression for MSD at time lag 𝛿𝑡 is given by MSD(δt) = ⟨|r(δt) - r(0)|²⟩, where r(t) represents the position vector of a particle at time 𝑡, and the angle brackets ⟨·⟩ denote an ensemble average over all particles and/or multiple time origins [10] [24]. In MD simulations, this average is typically computed over all selected atoms in the system and across multiple time steps in the trajectory to improve statistical accuracy [10].

Visual inspection of the MSD plot is crucial for validating results [9]. For pure Brownian motion, the MSD curve appears as a straight line when plotted against time lag. Non-linear trends may indicate more complex dynamics such as confined motion (MSD plateaus at long times) or directed motion (MSD curves upward). A log-log plot of MSD versus time can help identify anomalous diffusion, where the slope 𝛼 of the curve (MSD(τ) ∝ τ^α) differentiates between sub-diffusion (α < 1), normal diffusion (α ≈ 1), and super-diffusion (α > 1) [24].

GROMACS Implementation: The gmx msd Module

Command Syntax and Essential Options

The GROMACS gmx msd module computes mean square displacements and diffusion constants using the Einstein relation [25] [26]. The basic command syntax is:

Table 1: Essential input and output file options for gmx msd

| Option | Default Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

-f |

traj.xtc |

Input trajectory file (xtc, trr, etc.) |

-s |

topol.tpr |

Input structure file (tpr, gro, etc.) |

-n |

index.ndx |

(Optional) Extra index groups file |

-o |

msdout.xvg |

Output file for MSD data |

-mol |

diff_mol.xvg |

(Optional) Output for per-molecule diffusion coefficients |

Table 2: Critical analysis parameters for gmx msd

| Option | Default | Description | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

-type |

unused |

MSD components: x, y, z, unused | Use for 1D diffusion analysis |

-lateral |

unused |

Lateral MSD: x, y, z, unused | Use -lateral z for membrane systems [27] |

-trestart |

10 ps | Time between reference points | Balance statistics and memory |

-beginfit |

-1 (10%) | Start time for linear fitting | Ensure MSD is linear in this region [25] |

-endfit |

-1 (90%) | End time for linear fitting | Avoid poorly averaged long-time data [25] |

-maxtau |

~1.8e+308 ps | Maximum time delta for MSD calculation | Use to avoid memory issues in long trajectories [25] |

-mol |

N/A | Compute MSD for individual molecules | Provides error estimate between molecules [25] |

Practical Workflow and Application Examples

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for calculating and analyzing MSD in GROMACS:

For specific application scenarios, the selection of appropriate atoms and parameters is critical:

Lipid lateral diffusion in membranes: Select one reference atom per lipid (typically the phosphorus atom P8 in phospholipids) and use the

-lateral zflag to compute diffusion in the xy-plane only [27]. The command sequence would be:Water diffusion: Select all water atoms or use the

-molflag to compute diffusion for individual water molecules. When using-mol, the chosen index group will be automatically split into molecules, and MSD will be calculated for each molecule's center of mass [25].Polymer or ion diffusion: Create an index group containing all atoms of interest and run a standard 3D MSD analysis. For large molecules, consider using center-of-mass positions with appropriate

-seltypeoptions.

The diffusion coefficient is determined by least squares fitting a straight line (D·t + c) through the MSD(t) curve between the time points specified by -beginfit and -endfit [25] [26]. When the default values are used (-1), fitting starts at 10% and goes to 90% of the total MSD time range. The resulting diffusion coefficient and error estimate are only accurate when the MSD is completely linear between these fitting limits [25].

Critical Considerations for Accurate MSD Analysis

Technical Considerations and Pitfalls

Several technical factors must be addressed to obtain reliable diffusion coefficients from MSD analysis:

Trajectory unwrapping: For correct MSD computation, coordinates must be in the unwrapped convention. When atoms pass periodic boundaries, they must not be wrapped back into the primary simulation cell [9]. In GROMACS, this can be achieved using

gmx trjconvwith the-pbc nojumpflag prior to MSD analysis.Statistical sampling: The MSD calculation requires adequate sampling over both particles and time origins. By default,

gmx msdcompares all trajectory frames against reference frames stored at-trestartintervals, which can lead to long analysis times and memory issues for large trajectories [25]. The-maxtauoption can cap the maximum time delta to improve performance.Linear regime selection: Proper identification of the linear regime of the MSD curve is essential [24]. The initial ballistic regime (at very short times) and the poorly averaged region (at long times) should be excluded from the fit. The linear segment represents the "middle" of the MSD plot where the Einstein relation holds [9].

Localization uncertainty: In analysis of single-particle tracking data, localization uncertainty affects the accuracy of diffusion coefficients [28]. While less critical in MD simulations with exact atomic positions, similar considerations apply when analyzing coarse-grained systems or when limited sampling introduces statistical noise.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools for MSD analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS Suite | MD simulation package with gmx msd module |

Primary tool for calculation [25] [26] |

| Index Groups | Selections of specific atoms/molecules | Created with gmx make_ndx [27] |

| Unwrapped Trajectory | Coordinates without PBC artifacts | Generated with gmx trjconv -pbc nojump [9] |

| Visualization Software | Tools for plotting MSD curves (e.g., Grace, matplotlib) | Essential for identifying linear regime [9] |

| Linear Regression Tools | Fitting MSD slope to obtain D | Built into gmx msd or external tools [25] |

Interpreting Results in Broader Research Context

The diffusion coefficients obtained through MSD analysis provide crucial insights into molecular mobility and system properties. In drug development, membrane permeability can be assessed by studying the diffusion of compounds through lipid bilayers. The research by Wang et al. demonstrated how diffusion behavior of air and nitrogen in cellulose during wood heat treatment correlates with mechanical property changes, with air exhibiting larger diffusion coefficients and greater impact on mechanical parameters [29].

When interpreting MSD results, researchers should consider:

System size effects: Diffusion coefficients calculated in finite simulation boxes with periodic boundary conditions may require correction for system-size effects [9] [28].

Anomalous diffusion: In complex environments like crowded cellular interiors or polymer matrices, diffusion may follow anomalous rather than normal Brownian patterns, identified by non-linear MSD curves in log-log plots [24].

Error analysis: The

gmx msdmodule provides an error estimate based on the difference between diffusion coefficients obtained from fits to the two halves of the fit interval [25]. When using the-moloption, additional statistics between individual molecules contribute to more accurate error estimates.

Proper MSD analysis following this practical workflow enables researchers to extract accurate transport properties from molecular dynamics simulations, facilitating connections between molecular-level dynamics and macroscopic material behavior in diverse applications from drug delivery to materials science.

Implementing MSD Analysis in Python using MDAnalysis

Within the broader context of interpreting Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) plots from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, this technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for implementing MSD analysis using the MDAnalysis Python library. MSD analysis serves as a fundamental technique for quantifying particle motion and calculating transport properties such as self-diffusivity, with critical applications in drug development for understanding molecular mobility, binding mechanisms, and solute behavior in biological systems. This whitepaper details theoretical foundations, practical implementation methodologies, data interpretation protocols, and advanced computational considerations to equip researchers with robust tools for extracting meaningful dynamical information from MD trajectories.

Theoretical Foundation of Mean Squared Displacement

The Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) represents a cornerstone analysis in molecular dynamics, providing quantitative insights into the spatial exploration of particles over time. Rooted in the study of Brownian motion, MSD analysis enables researchers to characterize diffusion mechanisms, phase transitions, and molecular mobility in complex systems [4] [30].

The Einstein formula defines the MSD for a given dimensionality as:

[MSD(r{d}) = \bigg{\langle} \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} |r{d} - r{d}(t0)|^2 \bigg{\rangle}{t_{0}}]

where (N) represents the number of equivalent particles, (r) denotes atomic coordinates, (d) indicates the desired dimensionality, and the angle brackets represent averaging over time origins ((t_0)) [4] [30] [31]. This formulation captures the average squared distance particles travel over time, providing a fundamental metric for understanding system dynamics.

The MSD's relationship with self-diffusivity ((D_d)) emerges from the asymptotic behavior of this function:

[Dd = \frac{1}{2d} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} MSD(r_{d})]

where (d) represents the dimensionality of the MSD [4] [30]. For normal diffusion, the MSD exhibits linear scaling with time ((MSD \propto t)), while anomalous diffusion (subdiffusion or superdiffusion) manifests as nonlinear power-law behavior ((MSD \propto t^{\alpha})) [10]. This relationship makes MSD analysis particularly valuable for characterizing transport properties in pharmaceutical research, where molecular mobility directly influences drug delivery efficiency and binding kinetics.

Computational Implementation

Prerequisites and Installation

Implementing MSD analysis requires the MDAnalysis library alongside its computational dependencies. Installation can be accomplished via pip:

The tidynamics package provides critical performance optimization for MSD calculations through Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) algorithms [4] [30], while scipy enables subsequent regression analysis for diffusivity calculations.

Core Implementation Workflow

The following workflow outlines the complete MSD analysis pipeline:

Table 1: Critical Parameters for EinsteinMSD Implementation

| Parameter | Options | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

select |

Atom selection string | 'all' | MDAnalysis atom selection query |

msd_type |

'xyz', 'xy', 'xz', 'yz', 'x', 'y', 'z' | 'xyz' | Dimensionality of MSD calculation |

fft |

Boolean (True/False) | True | FFT acceleration (requires tidynamics) |

non_linear |

Boolean (True/False) | False | Enable for non-uniformly sampled trajectories |

Essential Data Preprocessing

A critical prerequisite for accurate MSD analysis involves using unwrapped trajectories, where atoms that cross periodic boundaries are not wrapped back into the primary simulation cell [4] [30] [31]. Failure to use unwrapped coordinates introduces artificial plateaus in MSD plots and fundamentally corrupts diffusion coefficient calculations.

In MDAnalysis, this can be achieved using the NoJump transformation:

Alternatively, simulation packages provide native utilities for trajectory unwrapping, such as GROMACS's gmx trjconv -pbc nojump [4] [30].

Experimental Protocol for MSD Analysis

System Preparation and Selection Criteria

Proper atom selection fundamentally influences MSD interpretation. Researchers should employ precise selection queries to isolate molecular species of interest:

Dimensionality selection should align with the physical system: xyz for bulk diffusion, xy for membrane systems, and component-wise analysis (x, y, z) for anisotropic environments [4] [30].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete MSD analysis workflow from trajectory preparation to diffusivity calculation:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Critical Computational Components for MSD Analysis

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Unwrapped Trajectory | Eliminates periodic boundary artifacts | transformations.nojump.NoJump() |

| FFT Algorithm | Accelerates MSD calculation from O(N²) to O(NlogN) | EinsteinMSD(..., fft=True) |

| Dimensionality Control | Isolates specific diffusion components | msd_type='xy' for lateral diffusion |

| Selection Queries | Targets specific molecular species | select='resname SOL and name OW' |

| Linear Regression | Extracts diffusivity from MSD slope | scipy.stats.linregress() |

| Replicate Averaging | Improves statistical accuracy | np.concatenate((MSD1, MSD2)) |

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Identifying the Linear MSD Regime

The critical step in MSD analysis involves identifying the appropriate linear regime for diffusivity calculation. Researchers should generate log-log plots to objectively identify the time region where MSD exhibits linear scaling (slope ≈ 1 on log-log axes), excluding short-time ballistic motion and long-time poorly averaged regions [4] [30]:

The linear regime typically manifests as the intermediate time region where local constraints and inertial effects have diminished but statistical averaging remains robust.

Calculating Self-Diffusivity Coefficients

Once the linear regime is identified, self-diffusivity calculation proceeds through linear regression:

Table 3: MSD Interpretation Guide for Different Diffusion Regimes

| MSD Behavior | Time Dependence | Diffusion Classification | Common Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear MSD ~ t | MSD ∝ t¹ | Normal/Fickian Diffusion | Bulk fluids, simple liquids |

| Sublinear MSD | MSD ∝ tᵅ (α<1) | Subdiffusion | Crowded intracellular environments, polymer glasses |

| Superlinear MSD | MSD ∝ tᵅ (α>1) | Superdiffusion | Active transport, directed motion |

| MSD Plateau | MSD → constant | Confined Diffusion | Trapped particles, molecular cages |

Advanced Analysis: Combining Multiple Replicates

Robust MSD analysis requires ensemble averaging across multiple independent simulations. Crucially, trajectories should not be simply concatenated, as the discontinuity between simulations artificially inflates MSD values [4] [30]. Instead, researchers should calculate MSDs separately before averaging:

This approach preserves the statistical independence of replicates while maximizing sampling of the MSD ensemble average.

Technical Considerations and Optimization

Computational Efficiency and Memory Management

MSD calculation represents a memory-intensive operation, particularly for long trajectories. Several strategies mitigate computational demands:

The FFT-based algorithm (fft=True) reduces computational complexity from O(N²) to O(NlogN) for trajectories with substantial frame counts [4] [30]. For extremely large systems, researchers may additionally employ spatial decomposition strategies, calculating MSDs for molecular subgroups before ensemble averaging.

Error Analysis and Validation

Comprehensive MSD analysis requires careful error estimation through both statistical and bootstrap methods:

This rigorous approach to uncertainty quantification ensures reliable diffusivity estimates for comparative studies in pharmaceutical development.

Implementation of MSD analysis through MDAnalysis provides researchers with a robust, scalable framework for quantifying molecular transport properties from MD simulations. This guide has detailed the complete workflow from theoretical foundations through practical implementation, emphasizing critical considerations such as trajectory unwrapping, linear regime identification, and appropriate statistical averaging. For drug development professionals, these methodologies enable precise characterization of molecular mobility critical to understanding drug solubilization, membrane permeation, and binding kinetics. The provided protocols, visualization tools, and computational strategies equip researchers to implement MSD analysis effectively within broader investigations of molecular dynamics and diffusion-mediated processes.

Determining the Diffusion Coefficient: Linear Regression on the MSD Plot

The mean-squared displacement (MSD) plot, derived from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, serves as a fundamental gateway to understanding diffusive processes in materials and biological systems. The self-diffusivity, a critical parameter in drug delivery and membrane permeability studies, is quantitatively extracted from the linear slope of the MSD plot via the Einstein relation. This technical guide details a robust protocol for this procedure, emphasizing the critical importance of identifying the linear regime, performing weighted least squares regression, and accounting for statistical uncertainties that depend not only on simulation data but also on analysis choices [32]. We provide detailed methodologies, structured data tables, and visual workflows to equip researchers with the tools for accurate and reproducible determination of diffusion coefficients.

In the realm of molecular dynamics, the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) is a cornerstone metric for analyzing the spatial extent of random particle motion. It is defined as the average squared distance a particle travels over a time interval, or lag time, ( \delta t ) [3] [10]. For a system of ( N ) particles, the MSD is calculated as:

[ \text{MSD}(\delta t) = \left\langle \left| \vec{r}(\delta t) - \vec{r}(0) \right|^2 \right\rangle ]

where ( \vec{r}(t) ) is the position vector of a particle at time ( t ), and the angle brackets ( \langle \cdots \rangle ) denote an ensemble average, typically performed over all equivalent particles in the system and multiple time origins to improve statistics [4] [10].

The profound connection between MSD and diffusivity was established by Albert Einstein. The Einstein relation states that for normal (Brownian) diffusion in the long-time limit, the MSD grows linearly with time, and the slope is proportional to the self-diffusion coefficient ( D ) [3] [16]:

[ \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(t) = 2n D ]

Here, ( n ) is the dimensionality of the diffusion (e.g., ( n=3 ) for three-dimensional diffusion). Therefore, the diffusion coefficient is obtained from the slope ( K ) of a linear fit to the MSD curve:

[ D = \frac{K}{2n} ]

The central challenge, which forms the core of this guide, is to accurately determine this linear region and perform the regression to obtain a reliable and meaningful value for ( D ).

Core Concepts and Quantitative Data

A firm grasp of the following concepts is essential before embarking on the analysis.

The MSD Regime and Diffusivity Classes

The MSD is often expressed as a power law, ( \langle x^2(t) \rangle = K_{\alpha}t^{\alpha} ), where the exponent ( \alpha ) reveals the nature of the diffusion process [16]. The linear regression detailed in this guide is designed to extract ( D ) specifically from the linear regime where ( \alpha = 1 ).

Table 1: Classes of Diffusion and Their MSD Signatures

| Diffusivity Class | MSD Exponent (( \alpha )) | MSD Form | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subdiffusion | ( 0 < \alpha < 1 ) | ( K_{\alpha}t^{\alpha} ) | Confined, obstructed, or viscoelastic environments. |

| Normal Diffusion | ( \alpha = 1 ) | ( 2nDt ) | Standard Brownian motion in a homogeneous medium. |

| Superdiffusion | ( \alpha > 1 ) | ( K_{\alpha}t^{\alpha} ) | Active transport or flow-advected motion. |

Dimensionality of the MSD Analysis

The calculated MSD and the resulting diffusion coefficient depend on the spatial dimensions considered in the analysis. The choice of dimensionality should align with the specific scientific question, such as studying isotropic 3D diffusion in a bulk liquid or anisotropic 2D diffusion within a lipid membrane.

Table 2: MSD Dimensionality and the Corresponding Diffusion Coefficient

| MSD Type | Dimensions (n) | MSD Formula | Diffusion Coefficient (D) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1D (e.g., x) | 1 | ( \langle (x(t)-x(0))^2 \rangle ) | ( D = \frac{K}{2} ) |

| 2D (e.g., xy) | 2 | ( \langle (x(t)-x(0))^2 + (y(t)-y(0))^2 \rangle ) | ( D = \frac{K}{4} ) |

| 3D (xyz) | 3 | ( \langle |\vec{r}(t)-\vec{r}(0)|^2 \rangle ) | ( D = \frac{K}{6} ) |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

This section outlines the end-to-end workflow for a robust MSD analysis, from trajectory preparation to linear fitting.

Critical Pre-Analysis: Trajectory Unwrapping

A paramount prerequisite for a correct MSD calculation is the use of unwrapped particle trajectories [4] [16]. Standard MD trajectories often apply periodic boundary conditions (PBC), "wrapping" particles back into the primary simulation box as they cross the boundary. Using these wrapped coordinates would cause the MSD to saturate at the box size, severely underestimating the true diffusion.

- Protocol: Before MSD analysis, process your trajectory using a tool like

gmx trjconvin GROMACS with the-pbc nojumpor-pbc molflag [4] [25]. This corrects for periodic boundary crossings, ensuring the MSD reflects the true total path traveled.

The MSD Calculation Protocol

The MSD is computed as a function of lag time ( \tau ) by averaging over all possible time origins and particles.

- Algorithm: The "windowed" algorithm calculates the MSD for a range of lag times, maximizing statistical sampling [4]. For a trajectory with ( Nf ) frames, the MSD at lag time ( n \Delta t ) is: [ \text{MSD}(n\Delta t) = \frac{1}{N} \frac{1}{Nf - n} \sum{i=1}^{N} \sum{j=1}^{Nf - n} \left| \vec{r}i(t{j+n}) - \vec{r}i(t_j) \right|^2 ] where ( N ) is the number of particles and ( \Delta t ) is the time between saved frames.

- Implementation: This calculation is computationally intensive but is efficiently implemented in analysis suites like MDAnalysis (using the

EinsteinMSDclass, optionally with FFT acceleration) [4] and GROMACS (using thegmx msdtool) [25].

The Linear Regression Protocol

Once the MSD vs. lag time curve is obtained, the critical step is to perform linear regression on the appropriate segment.

Identify the Linear Regime: The MSD is typically non-linear at short times (ballistic regime) and poorly averaged at long times [4].

- Visual Inspection: Plot the MSD on a log-log scale. The linear (diffusive) regime appears as a segment with a slope of 1 [4].

- Protocol: Select a fitting window ( [\tau{\text{start}}, \tau{\text{end}}] ) that lies within this linear segment. A common rule of thumb is to start the fit after the initial curvature and end before the MSD becomes too noisy, for instance, between 20% and 60% of the total trajectory length [4] [25].

Perform Linear Regression: Using the selected data points ( (\taui, \text{MSD}i) ), fit a model ( y = m\tau + c ), where the slope ( m ) is the quantity of interest.

- Ordinary Least Squares (OLS): This is the most straightforward method, minimizing the sum of squared residuals [33]. The slope ( m ) and intercept ( c ) are calculated as: [ m = \frac{\sum (\taui - \bar{\tau})(\text{MSD}i - \overline{\text{MSD}})}{\sum (\tau_i - \bar{\tau})^2}, \quad c = \overline{\text{MSD}} - m\bar{\tau} ]

- Python Implementation (using

scipy.stats.linregressas in [4]): - Uncertainty Estimation: The standard error of the slope, provided by

linregress, is a starting point for uncertainty. However, note that advanced methods like bootstrapping (resampling particles or trajectory blocks) or using the difference in diffusivities from the first and second halves of the fit interval (as ingmx msd) provide more robust error estimates [32] [16] [25].

The following workflow diagram encapsulates the entire protocol from raw simulation data to the final diffusion coefficient.

Diagram Title: Workflow for determining the diffusion coefficient from an MD trajectory.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Tools for MSD Analysis and Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [25] | Software Suite | High-performance MD simulation engine. Its gmx msd tool directly calculates MSD and performs linear fitting. |

| MDAnalysis [4] | Python Library | A versatile toolkit for analyzing MD trajectories. The analysis.msd module provides the EinsteinMSD class. |

| Unwrapped Trajectory [4] [16] | Data | The fundamental input, generated by post-processing a wrapped trajectory to remove artifact from periodic boundaries. |

| Scipy / scikit-learn [33] | Python Library | Provides statistical functions (linregress) and linear models for performing the regression and evaluating fit quality. |

| Matplotlib [4] [33] | Python Library | The standard library for creating publication-quality plots of the MSD curve and the linear fit. |

Discussion: Navigating Uncertainty and Advanced Considerations

A critical, often overlooked aspect is that the uncertainty in the derived diffusion coefficient depends not only on the quality of the simulation data but also on the analysis protocol itself [32]. Choices such as the extent of the fitting window ( [\tau{\text{start}}, \tau{\text{end}}] ) and the statistical estimator (OLS, WLS) directly impact the result and its error bars. Researchers must therefore transparently report their fitting parameters and methodology to ensure reproducibility.

Furthermore, for non-ergodic systems or those with limited data, the time-averaged MSD for individual particles may differ from the ensemble-averaged MSD. In such cases, analyzing the MSD of individual molecules and examining the distribution of diffusivities can provide deeper insights than a single ensemble-average value [16] [25].

Determining the diffusion coefficient via linear regression on the MSD plot is a standard, yet nuanced, procedure in molecular dynamics analysis. Accuracy hinges on a disciplined protocol: using unwrapped trajectories, correctly identifying the linear diffusive regime, and applying robust linear regression with a clear account of statistical uncertainties. By adhering to the methodologies and considerations outlined in this guide, researchers can confidently extract this vital transport property, thereby strengthening the molecular-level interpretation of their simulations in fields ranging from drug development to materials science.