Initial Velocity Assignment in Molecular Dynamics: Foundations, Best Practices, and Impact on Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the critical yet often overlooked role of initial velocity assignment in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations for biomedical research.

Initial Velocity Assignment in Molecular Dynamics: Foundations, Best Practices, and Impact on Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the critical yet often overlooked role of initial velocity assignment in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations for biomedical research. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it bridges foundational theory and practical application. We explore the scientific principles governing velocity initialization, detail methodological best practices for achieving desired thermodynamic states, and address common troubleshooting scenarios to prevent simulation failures. Furthermore, the article covers rigorous validation techniques to ensure results are physically meaningful and comparable across studies. By synthesizing these aspects, this guide aims to enhance the reliability and efficiency of MD simulations in drug discovery, from target modeling to lead optimization.

The Science of Starting Right: Core Principles of Velocity Initialization

Linking Initial Conditions to Newton's Equations of Motion in MD Algorithms

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a computational microscope, predicting the temporal evolution of molecular systems by solving Newton's equations of motion for all atoms. The precision of this prediction is fundamentally constrained by the accuracy of the initial conditions assigned to the system. This technical guide examines the critical linkage between initial conditions—particularly velocity assignment—and the numerical integration of Newton's equations within MD algorithms. Framed within broader thesis research on initial conditions, we demonstrate how proper initialization establishes correct thermodynamic sampling, influences simulation stability, and ensures physical meaningfulness in biomedical and drug development applications. By integrating theoretical foundations with practical implementation protocols, this work provides researchers with a comprehensive framework for configuring MD simulations that yield biologically relevant trajectories.

Molecular dynamics simulations have transformed from specialized computational tools to indispensable assets in structural biology and drug discovery, enabling researchers to capture atomic-level processes at femtosecond resolution [1]. At its core, MD predicts how every atom in a molecular system will move over time based on a general model of physics governing interatomic interactions [1]. The simulation technique numerically integrates Newton's equations of motion for a molecular system comprising N atoms, where each atom's trajectory is determined by the net force acting upon it.

The fundamental relationship is expressed through Newton's second law:

Where F_i is the force on atom i, m_i is its mass, a_i is its acceleration, r_i is its position, and V is the potential energy function describing interatomic interactions [2].

The analytical solution to these equations remains intractable for systems exceeding two atoms, necessitating numerical integration approaches that discretize time into finite steps (δt) typically on the order of femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ seconds) [2]. Within this computational framework, initial conditions—specifically atomic positions and velocities—serve as the foundational inputs that determine the subsequent evolution of the system. Proper initialization establishes correct thermodynamic sampling, influences numerical stability, and ensures the physical meaningfulness of the resulting trajectory, making it a critical consideration within any research employing MD methodologies.

Theoretical Foundations: Newton's Equations and Numerical Integration

From Continuous Equations to Discrete Integration

The molecular dynamics algorithm transforms the continuous differential equations of motion into a discrete-time numerical approximation. This discretization enables computational solution through iterative application of a numerical integrator. The finite difference method forms the basis for most MD integration algorithms, with the Taylor expansion providing the mathematical foundation for approximating future atomic positions [2]:

The time step δt represents a critical computational parameter that balances numerical accuracy with simulation efficiency. As a general rule, the time step is kept one order of magnitude less than the timescale of the fastest vibrational frequencies in the system, typically ranging from 0.5 to 2 femtoseconds for all-atom simulations [3]. This ensures stability while capturing relevant atomic motions.

The Symplectic Integrator Family

Numerical integrators for MD must preserve important physical properties of the continuous system they approximate. Symplectic integrators conserve the symplectic form on phase space, providing superior long-term stability and energy conservation compared to non-symplectic alternatives [4]. The Verlet algorithm and its variants dominate modern MD implementations due to these desirable properties.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Symplectic Integrators in Molecular Dynamics

| Algorithm | Formulation | Properties | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Verlet | r(t+Δt) = 2r(t) - r(t-Δt) + Δt²a(t) |

Time-reversible, symplectic | Good numerical stability, minimal memory | No explicit velocity handling |

| Velocity Verlet | r(t+Δt) = r(t) + Δtv(t) + ½Δt²a(t)v(t+Δt) = v(t) + ½Δt[a(t) + a(t+Δt)] |

Time-reversible, symplectic | Explicit position and velocity update | Requires two force calculations per step |

| Leapfrog | v(t+½Δt) = v(t-½Δt) + Δta(t)r(t+Δt) = r(t) + Δtv(t+½Δt) |

Time-reversible, symplectic | Better energy conservation than basic Verlet | Non-synchronous position-velocity evaluation |

The Velocity Verlet algorithm has emerged as one of the most widely used methods in MD simulation [2] [5], as it explicitly calculates positions and velocities at the same time points while maintaining the symplectic property. The Leapfrog method offers similar numerical stability with a different computational structure that some implementations prefer [2].

Initial Velocity Assignment: Theory and Implementation

The Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution and Temperature Coupling

Initial velocities represent the thermal energy of the system and are typically sampled from the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution corresponding to a desired simulation temperature [6]. For a given temperature T, the probability distribution for the velocity component v_i in any direction is given by:

Where m_p is the particle mass, T_0 is the temperature, and k_B is the Boltzmann constant [7]. This relationship ensures that the initial kinetic energy of the system corresponds to the desired temperature through the equipartition theorem:

This fundamental connection between initial velocities and temperature makes velocity initialization a critical step in establishing the correct thermodynamic ensemble for the simulation [8].

Velocity Initialization Methodologies

Table 2: Methodologies for Initial Velocity Assignment in MD Simulations

| Method | Protocol | Application Context | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maxwell-Boltzmann Sampling | Sample velocities from distribution f(v_i) ∝ exp(-m_pv_i²/2k_BT) |

Standard initialization for NVT and NVE ensembles | Establishes immediate temperature proximity; may require brief equilibration |

| Zero Velocity | Set all v_i = 0 |

Specialized cases (cluster simulations, Car-Parrinello) | Eliminates initial kinetic energy; requires extended thermalization |

| File-Based Initialization | Read velocities from previous trajectory or restart file | Production simulations continuing from earlier runs | Maintains trajectory continuity; preserves prior sampling |

| Directed Velocity | Apply velocity in specific spatial directions | Non-equilibrium simulations, shear flow, targeted perturbation | Introduces directed energy for specialized studies |

The most common approach samples random initial velocities corresponding to the desired temperature T_d [8]. While alternative initializations are possible, starting with velocities corresponding to the target temperature significantly reduces equilibration time [8]. In specialized cases, such as simulations of clusters or Car-Parrinello simulations where electronic degrees of freedom move according to fictitious classical dynamics, starting with zero velocities may be preferable to maintain control over specific dynamic processes [8].

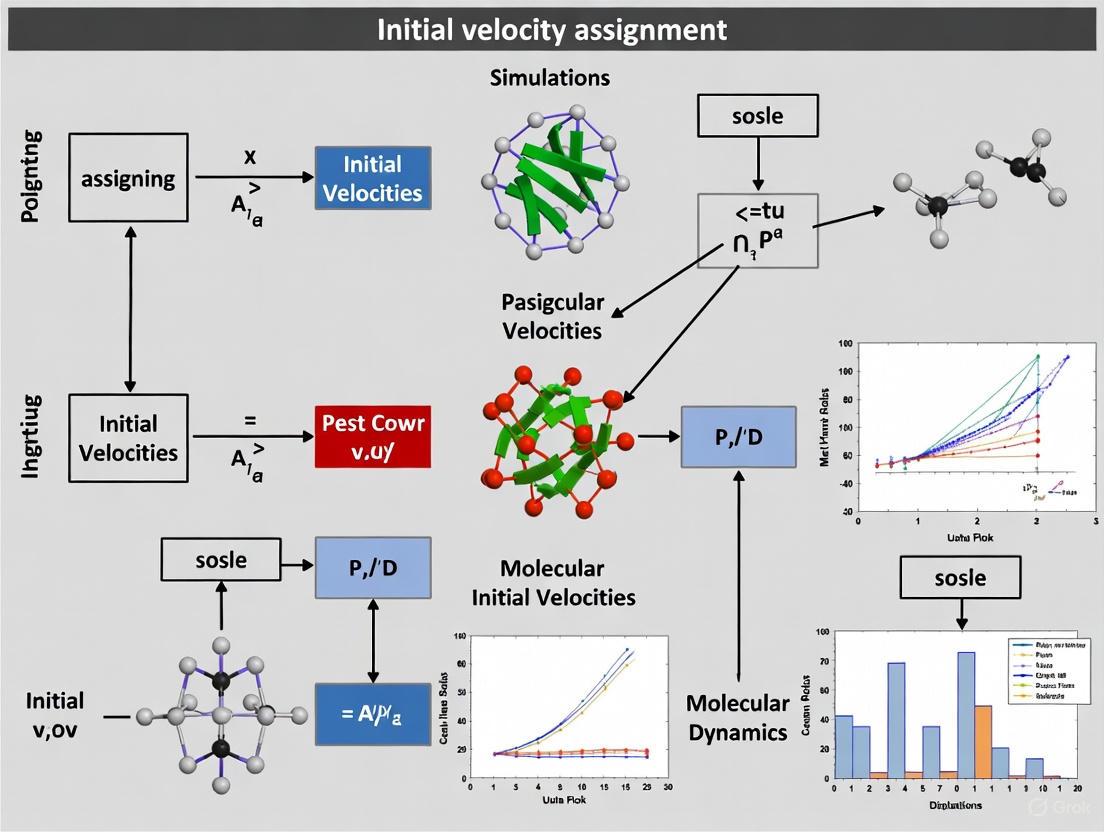

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete MD integration process with velocity initialization:

Figure 1: Molecular Dynamics Integration Workflow with Velocity Initialization

Practical Implementation: Protocols and Procedures

Velocity Initialization Experimental Protocol

Objective: Initialize atomic velocities to establish a specific simulation temperature while ensuring system stability.

Materials and System Requirements:

- Fully defined molecular system with atomic coordinates and forcefield parameters

- Target temperature (T_d) for simulation

- MD software package (e.g., AMS [9], ASE [5], or other MD engines)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

System Preparation

- Load atomic coordinates from experimental structure (e.g., PDB) or previous simulation

- Verify mass assignments for all atoms in the system

- Remove any pre-existing velocity information if starting a new simulation

Temperature Calibration

- Set target temperature T_d based on experimental conditions or research objectives

- Calculate expected kinetic energy:

KE_expected = (3/2)Nk_BT_d - For non-periodic systems, adjust degrees of freedom accordingly

Velocity Sampling

- For each atom i in the system:

- Generate three independent random velocity components (vx, vy, v_z) from Gaussian distribution with variance

k_BT_d/m_i - Apply velocity components to atom i

- Generate three independent random velocity components (vx, vy, v_z) from Gaussian distribution with variance

- Alternatively, use built-in software commands (e.g.,

InitialVelocitiesin AMS [9])

- For each atom i in the system:

System Preparation

- Compute center-of-mass velocity:

v_CM = Σ(m_iv_i)/Σm_i - Subtract v_CM from all atomic velocities:

v_i' = v_i - v_CM - Compute instantaneous temperature:

T_inst = (Σm_iv_i'²)/(3Nk_B) - If needed, apply slight scaling to achieve exact T_d:

v_i'' = v_i' × √(T_d/T_inst)

- Compute center-of-mass velocity:

Validation

- Verify that total linear momentum Σ(mivi) ≈ 0

- Confirm that kinetic energy corresponds to T_d within expected statistical fluctuations

- Proceed with equilibration phase of MD simulation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions for MD Simulations

| Resource Category | Specific Solution | Function in MD Research |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Source experimental initial structures [6] |

| Force Field Libraries | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS | Parameter sets for potential energy (V) calculations [3] |

| MD Simulation Engines | AMS [9], ASE [5], GROMACS, NAMD | Software implementing integration algorithms and force calculations |

| Specialized Hardware | GPU clusters [1] | Accelerate computationally intensive force calculations |

| Analysis Tools | VMD, MDTraj, MDAnalysis | Process trajectory data to extract physical insights [6] |

| Validation Databases | MolProbity, Validation Hub | Assess structural plausibility of initial models [6] |

Advanced Considerations in Initial Condition Management

Ensemble Transitions and Thermostat Coupling

While initial velocities establish the starting kinetic energy, most modern MD simulations employ thermostats to maintain temperature throughout the simulation. The choice of thermostat influences how initial conditions propagate through the trajectory. For the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble, total energy conservation makes proper velocity initialization particularly critical, as no external temperature control corrects deviations [5]. In canonical (NVT) ensemble simulations, the thermostat gradually corrects any discrepancies between the initial temperature and the target temperature, but appropriate initialization still significantly reduces equilibration time [8] [5].

The diagram below illustrates the relationship between initialization, integration, and ensemble control:

Figure 2: Integration Algorithm Structure with Thermostat Coupling

Specialized Initialization Scenarios

Certain research contexts demand specialized initialization approaches. In steered molecular dynamics, targeted velocities may be applied to specific atoms or domains to simulate forced unfolding or ligand dissociation [9]. For enhanced sampling methods like metadynamics or replica-exchange MD, diverse initial velocities across replicas facilitate better phase space exploration [9]. In membrane protein simulations, careful velocity initialization must account for the different environmental contexts of lipid-embedded versus solvent-exposed domains.

The integration of properly initialized atomic velocities with robust numerical algorithms for solving Newton's equations of motion constitutes the computational foundation of molecular dynamics simulation. The careful sampling of initial velocities from the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution establishes correct thermodynamic conditions. The coupling of these initial conditions with symplectic integrators like the Velocity Verlet algorithm ensures numerical stability and physical fidelity in the resulting trajectories. For research professionals in drug development and structural biology, understanding these fundamental connections enables both critical evaluation of existing simulation methodologies and informed advancement of new computational approaches for studying biomolecular function and interaction.

The Maxwell-Boltzmann (MB) distribution stands as a cornerstone of statistical mechanics, providing the fundamental probability distribution that describes the speeds of particles in an ideal gas at thermodynamic equilibrium. This whitepaper explores the theoretical foundations, experimental validations, and crucial applications of the MB distribution, with particular emphasis on its indispensable role in initializing molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. For researchers in drug development and computational sciences, proper implementation of MB-based velocity initialization ensures physical relevance and accelerates convergence in simulations of biomolecular interactions, protein folding, and ligand-receptor binding studies. We present comprehensive technical protocols, quantitative data analyses, and visualization frameworks to guide effective implementation of MB principles in computational research.

The Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, first derived by James Clerk Maxwell in 1860 and later expanded by Ludwig Boltzmann, represents a landmark achievement in statistical physics that connects microscopic particle behavior with macroscopic thermodynamic properties [10]. This distribution provides an exact description of particle speed or energy distributions in systems at thermal equilibrium, establishing the critical relationship between particle velocities and temperature that enables meaningful molecular simulations [11]. In molecular dynamics for drug development, proper sampling of initial atomic velocities according to the MB distribution directly impacts the physical accuracy and computational efficiency of simulations targeting protein dynamics, drug binding kinetics, and molecular recognition events.

The distribution's preservation of key statistical properties while enabling discrete modeling of continuous phenomena makes it particularly valuable for computational applications where continuous processes must be discretized for numerical simulation [11]. Recent extensions, including the discrete MB (DMB) model, have demonstrated its adaptability to modern computational requirements while maintaining theoretical rigor for lifetime and reliability data recorded in integer form, enhancing its applicability to discrete molecular simulation timesteps [11].

Mathematical Formalism

Probability Distribution Functions

The Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution describes the statistical distribution of speeds for non-interacting, non-relativistic classical particles in thermodynamic equilibrium [10]. For a three-dimensional system, the probability density function for velocity is given by:

$$f(\mathbf{v}) d^{3}\mathbf{v} = \biggl[\frac{m}{2\pi k{\text{B}}T}\biggr]^{3/2} \exp\left(-\frac{mv^{2}}{2k{\text{B}}T}\right) d^{3}\mathbf{v}$$

where $m$ is the particle mass, $k{\text{B}}$ is Boltzmann's constant, $T$ is the thermodynamic temperature, and $v^{2} = vx^2 + vy^2 + vz^2$ [10].

The corresponding speed distribution (magnitude of velocity) takes the form:

$$f(v) = 4\pi v^2 \biggl[\frac{m}{2\pi k{\text{B}}T}\biggr]^{3/2} \exp\left(-\frac{mv^{2}}{2k{\text{B}}T}\right)$$

This is the chi distribution with three degrees of freedom (the components of the velocity vector in Euclidean space), with a scale parameter measuring speeds in units proportional to $\sqrt{T/m}$ [10].

Table 1: Key Statistical Properties of the Maxwell-Boltzmann Speed Distribution

| Property | Mathematical Expression | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Most Probable Speed | $v{\text{mp}} = \sqrt{\frac{2kB T}{m}}$ | Speed at which distribution maximum occurs |

| Mean Speed | $\langle v \rangle = 2\sqrt{\frac{2k_B T}{\pi m}}$ | Average speed of all particles |

| Root-Mean-Square Speed | $v{\text{rms}} = \sqrt{\frac{3kB T}{m}}$ | Related to average kinetic energy |

| Scale Parameter | $a = \sqrt{\frac{k_B T}{m}}$ | Determines distribution width |

Thermodynamic Connections

The fundamental connection between kinetic energy and temperature emerges directly from the MB distribution through the equipartition theorem:

$$\left\langle \frac{1}{2} m vi^2 \right\rangle = \frac{1}{2} kB T \quad \text{for } i = x, y, z$$

Summing over all three dimensions and $N$ particles yields:

$$\left\langle \frac{1}{2} \sum{i=1}^N mi vi^2 \right\rangle = \frac{3}{2} N kB T$$

This relationship provides the foundational principle for initial velocity assignment in molecular dynamics simulations, ensuring the system begins with the correct kinetic energy corresponding to the desired simulation temperature [8].

Implementation in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Initial Velocity Assignment

In molecular dynamics simulations, Newton's equations of motion are solved to evolve particle positions and velocities over time. The integration requires initial positions and velocities, with the latter typically sampled from the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution corresponding to a desired temperature $T_d$ [8]. This critical initialization step ensures that the system begins with kinetic energy appropriate for the target temperature, significantly reducing equilibration time and improving simulation stability.

The alternative—starting with arbitrary or zero initial velocities—requires extended simulation time for the system to naturally evolve toward the correct temperature distribution through interatomic interactions [8]. As noted in MD simulations, "the random initial velocities are chosen such that they correspond to a certain desired temperature because the system of particles is expected to go to equilibrium at this temperature after running for a couple of time steps" [8]. This approach represents standard practice across major MD packages including SIESTA, ASE, and LAMMPS.

Practical Considerations and Algorithmic Implementation

The velocity initialization process involves drawing random velocities for each atom from the normal (Gaussian) distribution for each velocity component, then scaling to exactly match the target temperature [5]. For a system with $N$ atoms, the algorithm proceeds as:

- Component Sampling: For each atom $i$ and each spatial dimension $j$, sample $v{ij}$ from a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance $\frac{kB Td}{mi}$

- Center-of-Mass Correction: Remove net momentum by subtracting $\frac{1}{N}\sumi mi \vec{v}_i$ from each velocity

- Temperature Scaling: Scale all velocities by $\sqrt{Td / T{\text{current}}}$ where $T{\text{current}} = \frac{1}{3NkB} \sumi mi v_i^2$

Table 2: Molecular Dynamics Ensembles and Velocity Initialization

| Ensemble Type | Conserved Quantities | Role of MB Initialization | Common Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVE (Microcanonical) | Number of particles, Volume, Energy | Provides physically realistic starting velocities | Velocity Verlet [5] |

| NVT (Canonical) | Number of particles, Volume, Temperature | Accelerates convergence to target temperature | Nosé-Hoover, Langevin, Bussi [5] |

| NPT (Isothermal-Isobaric) | Number of particles, Pressure, Temperature | Ensures correct initial kinetic energy | Parrinello-Rahman, Nosé-Parrinello-Rahman [12] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for MB Distribution Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Velocity Verlet Integrator | Numerical integration of Newton's equations | ASE VelocityVerlet class with 5.0 fs timestep [5] |

| Thermostat Algorithms | Maintain constant temperature during simulation | Nosé-Hoover, Langevin, Bussi thermostats [5] |

| Trajectory Analysis Tools | Process and analyze simulation trajectories | SIESTA md2axsf for visualization [12] |

| Random Number Generators | Sample from normal distribution for velocity assignment | Mersenne Twister or Gaussian RNG [5] |

Experimental Validations

Historical Experimental Verification

The Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution received direct experimental validation through sophisticated atomic beam apparatus. The key experiment involved a gas of metal atoms produced in an oven at high temperature, escaping into a vacuum chamber through a small hole [13]. The resulting atomic beam passed through a rotating drum with a spiral groove that functioned as a velocity selector.

The cylindrical drum rotated at a constant rate, with a spiral groove cut with constant pitch around its surface. An atom traveling at the critical velocity $v_{\text{critical}} = 2ud$ (where $u$ is the rotation rate in cycles/second and $d$ is the drum length) could traverse the groove without colliding with the sides [13]. Atoms with speeds outside a narrow range around this critical value would collide with and stick to the groove walls. By varying the rotation rate and measuring the transmission rate, researchers could directly measure the velocity distribution, confirming its agreement with the Maxwell-Boltzmann prediction.

Modern Single-Particle Measurements

Recent advances have enabled experimental investigation of the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at the single-particle level. In one sophisticated approach, researchers employed optical tweezers to trap and track individual colloidal particles with unprecedented temporal resolution (10 ns) and spatial resolution (23 pm) [14]. This methodology allows observation of the transition from ballistic to diffusive Brownian motion, probing the fundamental assumptions underlying the MB distribution in condensed phases.

For heated particles in non-equilibrium conditions (Hot Brownian Motion), these techniques have revealed modifications to the effective temperature governing particle fluctuations, demonstrating the distribution's adaptability to non-equilibrium scenarios relevant to biological and materials systems [14].

Advanced Applications in Contemporary Research

Reactive Force Field Molecular Dynamics

The integration of Maxwell-Boltzmann initialization with reactive force fields (ReaxFF) has enabled sophisticated simulation of complex chemical processes in combustion and energy systems [15]. ReaxFF MD employs quantum chemistry-informed force fields that describe bond formation and breaking within the molecular dynamics framework, requiring proper thermal initialization via MB sampling to study processes like:

- Gas/liquid/solid fuel oxidation and pyrolysis pathways

- Catalytic combustion mechanisms

- Nanoparticle synthesis dynamics

- Electrochemical energy conversion processes

These simulations rely on correct initial velocity distributions to model energy transfer processes and reaction kinetics accurately, particularly in non-equilibrium systems where temperature gradients drive fundamental processes [15].

Discrete Maxwell-Boltzmann Formulations

Recent mathematical advances have produced discrete Maxwell-Boltzmann (DMB) models that extend the distribution's utility to inherently discrete or censored data scenarios common in reliability engineering and survival analysis [11]. The DMB formulation preserves the statistical properties of the continuous distribution while enabling direct application to:

- Lifetime data recorded in discrete time intervals

- Type-II censored sampling common in reliability testing

- Digital measurement systems with inherent discretization

- Molecular dynamics simulations with discrete timesteps

The DMB model demonstrates increasing hazard rate functions, making it particularly suitable for modeling negatively skewed failure processes where competing discrete models underperform [11].

Computational Protocols

Molecular Dynamics Initialization Protocol

For researchers implementing molecular dynamics simulations, the following protocol ensures proper application of Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution principles:

System Preparation

- Define atomic coordinates and force field parameters

- Select target temperature $T_d$ based on system requirements

- Choose appropriate timestep (typically 1-5 fs for systems with hydrogen, longer for heavier atoms) [5]

Velocity Initialization

- Sample each velocity component from Gaussian distribution: $v{ij} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sqrt{kB Td/mi})$

- Remove center-of-mass velocity: $\vec{v}i \leftarrow \vec{v}i - \frac{\sumj mj \vec{v}j}{\sumj m_j}$

- Calculate instantaneous temperature: $T{\text{inst}} = \frac{1}{3NkB} \sumi mi v_i^2$

- Scale velocities to exact temperature: $\vec{v}i \leftarrow \vec{v}i \times \sqrt{Td/T{\text{inst}}}$

Equilibration Phase

- Run with appropriate thermostat (Nose-Hoover, Langevin, or Bussi) for 10-100 ps

- Monitor temperature, pressure, and energy fluctuations

- Verify stabilization of thermodynamic properties before production run

Advanced Sampling Techniques

For specialized applications, several enhanced sampling methods build upon Maxwell-Boltzmann foundations:

- Replica Exchange MD: Multiple simulations at different temperatures with exchanges based on MB distributions

- Metadynamics: History-dependent potentials with proper thermal sampling

- Umbrella Sampling: Constrained dynamics with MB-informed initial conditions

These advanced techniques maintain theoretical consistency with statistical mechanics while addressing rare events and complex free energy landscapes encountered in drug binding studies and protein folding simulations.

The Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution remains an essential component of molecular simulation methodology, providing the statistical foundation that connects microscopic dynamics with macroscopic thermodynamics. Its proper implementation in velocity initialization ensures physical fidelity and computational efficiency across diverse applications from drug discovery to materials science. Recent developments in discrete formulations and single-particle experimental techniques continue to expand its relevance to emerging research domains, while reactive force field implementations enable increasingly complex chemical process modeling. For computational researchers in pharmaceutical development, mastery of MB sampling principles and their implementation represents a fundamental competency for extracting meaningful insights from molecular simulations of biomolecular interactions and therapeutic candidate evaluation.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the accurate representation of temperature is foundational for generating physically meaningful trajectories that can predict real-world behavior. Temperature in an MD system is not a direct control parameter but is instead a consequence of the atomic velocities. The relationship between the kinetic energy of the particles and the simulation temperature is quantitatively described by the equipartition theorem, making the initial assignment of atomic velocities a critical step in any MD protocol [16] [17]. This article examines the theoretical underpinnings of this relationship, details practical methodologies for velocity initialization, and explores its significance within the broader context of MD research, particularly for applications in drug development.

Theoretical Foundation: Kinetic Energy and Temperature

The thermodynamic temperature of a simulated system is intrinsically linked to the kinetic energy of its constituent particles through the principle of the equipartition of energy. This principle states that every degree of freedom in the system has an average energy of (kB T / 2) associated with it, where (kB) is the Boltzmann constant and (T) is the thermodynamic temperature [16].

For a system comprising (N) particles, the instantaneous kinetic energy ((K)) is calculated as: [ K = \sum{i}^{N} \frac{1}{2} mi vi^2 ] where (mi) and (vi) are the mass and velocity of particle (i), respectively. The average kinetic energy (\langle K \rangle) is related to the temperature by: [ \langle K \rangle = \frac{Nf kB T}{2} ] Here, (Nf) is the number of unconstrained translational degrees of freedom in the system. For a system in which the total momentum is zero (i.e., the center of mass is stationary), (Nf = 3N - 3) [8]. From this, the instantaneous kinetic temperature can be defined as: [ T{ins} = \frac{2K}{Nf kB} ] The average of (T_{ins}) over time equates to the thermodynamic temperature of the system [16]. It is crucial to note that temperature is a statistical property, meaningful only as an average over the system's degrees of freedom and over time.

The Rationale for Temperature-Based Initialization

A common practice in MD simulations is to initialize atomic velocities from a random distribution (typically Maxwell-Boltzmann) corresponding to a desired temperature, (T_d) [8]. This is performed for two primary reasons:

- Reduced Equilibration Time: Starting the simulation with the correct kinetic energy for the target temperature places the system closer to thermodynamic equilibrium, significantly reducing the computational time required for equilibration [8] [17].

- Controlled Energy Transfer: Appropriate initial kinetic energy facilitates a proper balance and transfer of energy between kinetic and potential terms from the outset of the simulation [8].

While it is technically possible to start a simulation with all velocities set to zero, this is generally inefficient. The system must then be heated through the potential energy landscape, which can prolong the equilibration process. However, specific scenarios, such as simulations of clusters or in Car-Parrinello dynamics for electronic degrees of freedom, may benefit from a zero-velocity start for better control [8].

Practical Implementation and Protocols

Methods for Assigning Initial Velocities

The following table summarizes the common methods for assigning initial velocities in MD simulations.

Table 1: Methods for Initial Velocity Assignment in Molecular Dynamics

| Method | Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Random from Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution | Velocities are randomly assigned based on a Gaussian distribution whose variance is determined by the desired temperature, (T_d) [18]. | This is the standard practice. It ensures the initial kinetic energy corresponds to (T_d), hastening equilibration [8]. |

| Zero Initial Velocities | All particle velocities are set to zero at the start of the simulation. | Not recommended for most production runs. It leads to a prolonged equilibration period as the system must be heated from a cold start [8]. |

| Reading from a File | Previously saved velocities from a checkpoint or another simulation are read to continue a trajectory. | Used for restarting simulations or to ensure consistency between related simulation runs. |

In software packages like GROMACS and AMS, these methods are formally implemented. For example, the AMS documentation specifies an InitialVelocities block where researchers can define the Type (e.g., Random) and the Temperature for the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution [9]. Similarly, studies on food proteins using GROMACS explicitly mention using a "Maxwell–Boltzmann velocity distribution" to randomly generate initial velocities at the desired treatment temperature [18].

Temperature Control During Simulation (Thermostats)

While initial velocities set the starting point, maintaining a constant temperature requires a thermostat—an algorithm that mimics the energy exchange with an external heat bath. The following table compares several common thermostat methods.

Table 2: Common Temperature Control Methods (Thermostats) in MD

| Thermostat Method | Fundamental Mechanism | Typical Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Velocity Rescaling | Directly rescales all velocities by a factor of (\sqrt{Td / T{ins}}) at intervals [16]. | Simple and effective for rapid equilibration, but is non-physical and can suppress legitimate temperature fluctuations. |

| Berendsen Thermostat | Couples the system to an external heat bath by weakly scaling velocities to drive the temperature toward (T_d) [16]. | Very effective for initial stages of equilibration as it efficiently removes excess energy. However, it produces an unphysical kinetic energy distribution [16]. |

| Nosé-Hoover Thermostat | Uses an extended Lagrangian formulation, introducing a fictitious variable that acts as a heat bath reservoir [16]. | A deterministic method that generates a correct canonical (NVT) ensemble. Its performance can be system-dependent [16]. |

| Langevin Thermostat | Applies stochastic (random) and frictional forces to particles, mimicking collisions with solvent molecules. | Excellent for local temperature control and is often used in solvated systems or for specific regions of a simulation, like thermostat zones in particle-solid collision studies [16]. |

The choice of thermostat can significantly impact simulation results. For instance, in simulations of energetic carbon cluster deposition on diamond, the Berendsen thermostat was effective at quickly removing excess energy initially, but resulted in higher final equilibrium temperatures compared to other methods like the Generalized Langevin Equation (GLEQ) approach [16].

Experimental Protocol: Validating System Equilibration

A critical step after system setup and velocity initialization is to ensure the system has reached a state of equilibrium before beginning production simulation and data collection. The following workflow diagram outlines a general protocol for system equilibration and validation.

Title: MD System Equilibration Workflow

Detailed Protocol Steps:

- Initial Velocity Assignment: Using the energy-minimized system coordinates as a starting point, assign initial atomic velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution corresponding to your desired simulation temperature, (T_d) [18].

- NVT Equilibration (Constant Number, Volume, Temperature): Run the initial equilibration phase with strong position restraints applied to the heavy atoms of the solute (e.g., protein) and potentially the solvent. This allows the solvent to relax and the temperature to stabilize around (T_d) without the system collapsing or distorting. Monitor the temperature time series to confirm it fluctuates stably around the target value [18].

- NPT Equilibration (Constant Number, Pressure, Temperature): Release the restraints on the solvent and apply a barostat to control the pressure. This phase allows the density of the system (e.g., a solvated protein in a box) to adjust to the correct value. Monitor both the temperature and the system density until they stabilize around their respective target values [18].

- Validation Check: Before moving to production, ensure that key properties like potential energy, root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the solute backbone, temperature, and pressure are stable over time. This indicates the system has reached equilibrium.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

The following table details key software and computational tools essential for conducting MD studies involving temperature and velocity initialization.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software for MD Simulations

| Tool/Solution | Function in Velocity/Temperature Setup |

|---|---|

| GROMACS | A widely-used MD software package that implements commands for generating initial velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution and supports numerous thermostats (e.g., velocity-rescaling, Nosé-Hoover) [18]. |

| AMS/SCM | The AMS software suite provides a dedicated InitialVelocities input block, allowing users to specify the method (Random, Zero, FromFile) and the target temperature for velocity generation [9]. |

| CHARMM-GUI | A web-based platform for setting up complex simulation systems. It generates input files that include parameters for initial velocity assignment and equilibration protocols using standard thermostats [18]. |

| CHARMM36m Force Field | A widely used molecular mechanics force field. It provides the empirical parameters for potential energy calculations, which govern how the initial kinetic energy is redistributed and converted into potential energy during simulation [18]. |

| Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution | The statistical distribution that defines the probability of a particle having a specific velocity at a given temperature. It is the theoretical basis for the random velocity generation algorithms in MD software [18]. |

Implications for Research and Drug Development

The careful initialization of velocities and temperature control is not merely a technicality but has profound implications for the reliability and interpretability of MD results, especially in drug discovery.

In protein-ligand binding studies, the activation of receptors like G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) involves large-scale conformational transitions that occur on microsecond to millisecond timescales [19]. Advanced sampling techniques, such as accelerated MD (aMD), are often employed to observe these transitions within computationally feasible timeframes [19]. In such studies, the initial conditions can influence the pathway and kinetics of the transition. For example, analysis of "collaborative sidechain motions" in the CXCR4 chemokine receptor during an aMD simulation revealed that the rotamerization of specific residues, initiated by the system's thermal energy, immediately preceded the large conformational change associated with activation [19]. This underscores how the initial thermal state can affect the observation of allosteric mechanisms and putative drug targets.

Furthermore, the statistical validity of simulation conclusions can be sensitive to equilibration quality. A study on the Ara h 6 peanut protein demonstrated that different simulation lengths (2 ns vs. 200 ns) could lead to different conclusions regarding the protein's structural changes under thermal processing [18]. Inadequate equilibration, potentially stemming from poor initial conditions, can be a contributing factor to such discrepancies, highlighting the necessity of robust initialization and thorough equilibration protocols for generating reproducible and reliable data for drug development decisions.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the assignment of initial atomic velocities is a critical yet frequently underestimated step that profoundly influences the trajectory of sampling and the rate of convergence to a physically meaningful ensemble. This technical guide examines the role of initial velocity assignment within the broader thesis that simulation initialization is a fundamental determinant of research outcomes in biomolecular studies and drug development. By synthesizing current methodologies, quantitative data, and practical protocols, we provide a framework for researchers to optimize this parameter, thereby enhancing the reliability and reproducibility of MD simulations for applications ranging from fundamental biophysics to rational drug design.

Molecular dynamics simulations function as a computational microscope, enabling the observation of atomic-scale motions that underpin biological function and drug-target interactions [6]. The deterministic nature of MD simulations means that the entire course of a simulation—from picosecond-scale fluctuations to microsecond-scale conformational changes—is fundamentally dictated by its initial conditions [20]. While significant attention is often paid to the preparation of the initial structure, the assignment of initial atomic velocities represents an equally critical initialization parameter that directly impacts how rapidly a simulation explores phase space and converges to a thermodynamically representative ensemble.

The broader thesis central to this whitepaper posits that careful consideration of initial velocity assignment is not merely a technical formality but a fundamental aspect of research methodology that can significantly influence the scientific conclusions drawn from simulation data. For researchers in drug development, where MD simulations increasingly inform decisions about target engagement and ligand optimization, understanding and controlling this parameter is essential for generating reliable, reproducible results. This guide provides a comprehensive examination of how initial velocities impact sampling completeness and convergence metrics, with practical strategies for optimizing their assignment across diverse research applications.

Theoretical Foundations of Velocity Initialization

The Statistical Mechanics Basis

In MD simulations, initial velocities are assigned to atoms based on the principles of statistical mechanics, which describe the distribution of molecular speeds in a system at thermal equilibrium. The standard approach involves sampling atomic velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution corresponding to the desired simulation temperature [21] [20]. For a three-dimensional system at temperature (T), this distribution for a single component of the velocity vector is given by:

[ P(vx) = \sqrt{\frac{m}{2\pi kB T}} \exp\left(-\frac{m vx^2}{2kB T}\right) ]

where (m) is the atomic mass, (vx) is the velocity component in the x-direction, and (kB) is Boltzmann's constant. The complete three-dimensional distribution results in atomic speeds that ensure the instantaneous temperature corresponds to the target temperature at simulation initiation, providing the kinetic energy required to overcome energy barriers and explore conformational space [6].

The Numerical Integration Context

The critical role of initial velocities becomes apparent when considering the numerical integration algorithms that propagate MD simulations forward in time. The velocity Verlet algorithm—among the most commonly used integrators—updates atomic positions and velocities at each time step using the forces computed from the potential energy field [21]. At the beginning of a simulation, these initial velocities determine the initial accelerations and directions of atomic motion, thereby influencing the specific trajectory through phase space that the system will follow. Since MD is inherently deterministic (with the same initial coordinates and velocities producing identical trajectories), the random seed used for velocity initialization effectively controls the unique pathway explored during the simulation [20]. This connection between initialization parameters and sampling pathway underscores why different velocity assignments can lead to markedly different convergence behaviors, particularly for complex biomolecular systems with rugged energy landscapes.

Practical Implementation and Methodologies

Standard Velocity Initialization Protocols

Implementing proper velocity initialization requires attention to several technical considerations. The following table summarizes the key parameters and their typical settings across major MD software packages:

Table 1: Standard initialization parameters in MD software

| Parameter | Typical Setting | Function | Software Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Velocity Distribution | Maxwell-Boltzmann | Samples velocities appropriate for target temperature | GROMACS, AMBER, QuantumATK [21] [20] |

| Random Seed | System clock or user-defined | Controls stochastic velocity assignment; ensures reproducibility | AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD |

| Temperature | User-defined (e.g., 300 K) | Reference for Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution | All major packages |

| COM Motion Removal | Enabled (default) | Eliminates overall translation | GROMACS, QuantumATK [21] |

The practical workflow for velocity initialization typically occurs after the system has been energy-minimized, immediately before the commencement of the production dynamics phase. Most simulation packages automatically handle the mathematical complexity of sampling from the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, requiring researchers only to specify the target temperature and occasionally the random seed for reproducibility purposes [20].

Ensemble-Specific Considerations

The impact of initial velocities varies depending on the thermodynamic ensemble employed:

- NVE Ensemble (Microcanonical): In isolated systems where total energy is conserved, the initial velocity assignment directly determines the system's total energy. Different velocity assignments will therefore sample different constant-energy hypersurfaces, potentially leading to varied dynamical behaviors [21].

- NVT Ensemble (Canonical): For temperature-coupled systems, the initial velocities establish the starting point for thermostat intervention. While thermostats eventually guide the system toward the target temperature, the initial kinetic energy affects how quickly equilibrium is established and which conformational states are initially explored [21].

Quantifying Impact on Sampling and Convergence

Convergence Assessment Methodologies

Evaluating whether MD simulations have sufficiently sampled the accessible conformational space requires robust metrics beyond simple simulation time. Research indicates that the root mean square deviation (RMSD) commonly used for biomolecular systems may be insufficient for assessing true convergence, particularly for systems featuring surfaces and interfaces [22]. More sophisticated approaches include:

- Kullback-Leibler divergence of principal component projections: This method assesses the similarity between probability distributions of essential dynamics modes sampled at different simulation intervals, with decreasing divergence indicating convergence [23].

- Linear partial density convergence: For heterogeneous systems with interfaces, the DynDen tool assesses convergence by monitoring the stability of density profiles for all system components over time [22].

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): By identifying the dominant modes of collective motion from the covariance matrix of atomic positions, researchers can project trajectories onto these essential subspaces and assess whether sampling has stabilized in these functionally relevant dimensions [6].

Table 2: Quantitative convergence assessment methods

| Method | Application Context | Convergence Indicator | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RMSD Decay Analysis | DNA duplex simulations | Average RMSD plateaus over longer time intervals | [23] |

| Kullback-Leibler Divergence | Principal component histograms | Divergence between trajectory segments approaches zero | [23] |

| Linear Density Profile Correlation | Interfaces and layered materials | Correlation coefficient between density profiles reaches stability | [22] |

| Mean Square Displacement (MSD) | Diffusion coefficient calculation | MSD becomes linear with time, indicating diffusive regime | [6] |

Empirical Evidence from Biomolecular Simulations

Recent studies provide quantitative insights into how initialization affects convergence timelines. Research on DNA duplexes demonstrated that structural and dynamical properties (excluding terminal base pairs) converge on the 1-5 μs timescale when using appropriate force fields and initialization protocols [23]. Importantly, aggregated ensembles of independent simulations starting from different initial conditions—including different velocity assignments—produced results consistent with extremely long simulations (∼44 μs) performed on specialized hardware, highlighting the value of replicated sampling with varied initialization [23].

In RNA refinement simulations, studies revealed that the benefit of MD depends critically on starting model quality, with poor initial structures rarely improving regardless of simulation length or initialization method [24]. This suggests that initial velocities primarily impact sampling within the basin of attraction defined by the starting coordinates, rather than facilitating transitions between structurally distinct states on practical simulation timescales.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Experimental Protocols

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key resources for velocity initialization and convergence studies

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Value | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| MD Software | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, QuantumATK | Implements velocity initialization and dynamics propagation |

| Force Fields | AMBER (ff99SB, parmbsc0), CHARMM C36, RNA-specific χOL3 | Defines potential energy surface and atomic interactions |

| Thermostat Algorithms | Nose-Hoover, Berendsen, Langevin | Regulates temperature during dynamics |

| Convergence Tools | DynDen, MDAnalysis, VMD | Quantifies sampling completeness and convergence |

| Water Models | TIP3P, SPC, TIP4P | Solvent representation affecting system dynamics |

Recommended Workflow for Systematic Velocity Studies

The following workflow provides a methodological framework for researchers investigating the impact of initial velocities on their specific systems:

- System Preparation: Construct initial coordinates and apply appropriate force field parameters [20].

- Energy Minimization: Remove steric clashes and unfavorable contacts while preserving the overall structure.

- Velocity Initialization Protocol:

- Generate multiple independent replicas (typically 3-5) with different random seeds for velocity assignment.

- Use the same target temperature for all replicas (e.g., 300 K).

- Ensure removal of center-of-mass motion to prevent overall drift.

- Equilibration Phase: Run simulations with temperature coupling to stabilize the system while allowing gradual relaxation.

- Production Dynamics: Conduct simulations without positional restraints using consistent parameters across replicas.

- Convergence Assessment: Apply multiple metrics (RMSD, PCA, density profiles) to quantify sampling completeness.

- Result Aggregation: Compare observables of interest across replicas to distinguish robust findings from trajectory-specific artifacts.

Implications for Research and Drug Development

For researchers in pharmaceutical settings, where simulation results increasingly inform experimental direction and investment decisions, the implications of proper velocity initialization extend beyond technical correctness to impact research validity and resource allocation. In drug discovery, where MD simulations predict binding affinities, mechanisms of action, and off-target effects, incomplete sampling due to suboptimal initialization can lead to misleading conclusions about drug-target interactions. Ensemble approaches with varied initial velocities provide a straightforward method to estimate the uncertainty associated with finite sampling time [23].

The broader thesis advanced here suggests that initialization parameters should be considered an integral component of experimental design in computational studies, akin to control experiments in wet-lab research. Just as experimental biologists replicate assays to establish statistical significance, computational researchers should employ multiple trajectory replicas with different initial velocities to distinguish robust results from chance observations. This approach is particularly valuable in studies of conformational dynamics, allostery, and mechanism, where the relevant states may be separated by significant energy barriers and accessed through rare events.

Initial velocity assignment in MD simulations represents a critical methodological parameter that significantly influences sampling behavior and convergence rates. Through its deterministic effects on trajectory pathways, velocity initialization directly impacts the reliability and reproducibility of simulation results, with particular consequences for research in structural biology and drug development. The experimental protocols and assessment methodologies outlined in this guide provide researchers with practical approaches to optimize this parameter and quantify its effects on their specific systems.

Looking forward, several emerging trends promise to further illuminate the relationship between initialization and sampling. Machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) are enabling longer timescales and larger systems [6], while advanced sampling techniques increasingly provide strategies to overcome the limitations of straightforward molecular dynamics. As these methodologies mature, the principles of careful initialization and convergence assessment remain fundamental to producing scientifically valid computational results that can reliably guide experimental research and drug development efforts.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Robust Velocity Assignment

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the assignment of initial atomic velocities is not merely a technical starting point but a foundational step that dictates the thermodynamic fidelity, convergence speed, and ultimate reliability of the entire simulation. The initial velocity assignment directly seeds the kinetic energy of the system, determining its initial temperature and influencing the trajectory through phase space. Within the broader thesis on MD methodologies, proper velocity assignment emerges as a critical precondition for achieving accurate ensemble averages, modeling realistic biomolecular behavior, and generating reproducible, scientifically valid results. This guide provides a structured, practical framework for researchers to implement rigorous velocity assignment protocols in production-scale simulations, with a particular emphasis on applications in drug development and molecular biology.

Theoretical Foundation: Velocity, Temperature, and Ensembles

The core principle governing velocity assignment is the equipartition theorem, which states that each translational degree of freedom contributes an average kinetic energy of ( \frac{1}{2}kB T ), where ( kB ) is Boltzmann's constant and ( T ) is the target temperature. For a system of ( N ) atoms, the instantaneous temperature is calculated from the velocities (( \vec{v}i )) and masses (( mi )) as:

[ T{\text{instantaneous}} = \frac{\sum{i=1}^{N} mi |\vec{v}i|^2}{3 N{dof} kB} ]

where ( N{dof} ) is the number of translational degrees of freedom. The initial velocities are assigned to satisfy this relation for the desired starting temperature, ( T{\text{target}} ) [1] [5].

The choice of velocity assignment strategy is intrinsically linked to the target thermodynamic ensemble:

- NVE (Microcanonical): Total energy is conserved. The initial velocities determine the system's total energy, which remains constant (barring numerical error). The Velocity Verlet integrator is commonly used for this ensemble [5].

- NVT (Canonical): The system is coupled to a thermostat to maintain a constant temperature. The initial velocities should still be consistent with the target temperature to minimize initial equilibration drift. Common thermostats include Langevin, Nosé-Hoover, and Bussi thermostats [5].

A Practical Protocol for Initial Velocity Assignment

The following step-by-step protocol is designed for typical production simulations of biomolecular systems, such as proteins in aqueous solution.

Step 1: System Preparation and Minimization

Before assigning velocities, the atomic coordinates must be energy-minimized to remove any bad contacts, clashes, or unphysical geometries introduced during system building. This provides a stable structural foundation. A steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm should be used until the maximum force falls below a chosen tolerance (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm).

Step 2: Selection of the Velocity Assignment Method

Choose a method appropriate for your simulation goals and software capabilities. The most common method is to draw velocities randomly from a Maxwell-Boltzmann (MB) distribution at the target temperature [1]. The probability distribution for the velocity component ( v_x ) of an atom of mass ( m ) is:

[ p(vx) = \sqrt{\frac{m}{2 \pi kB T}} \exp\left(-\frac{m vx^2}{2 kB T}\right) ]

Most modern MD software packages provide built-in functionality for this. For instance, in the AMS software, the InitialVelocities block allows the user to set Type Random and specify a Temperature value, often using a RandomVelocitiesMethod such as Boltzmann or Exact to draw from the MB distribution [9]. The ASE package similarly allows for random velocity assignment during the dynamics object creation [5].

Step 3: Implementation and Seeding

When implementing this in a simulation setup, the user must specify two key parameters: the target temperature and the random seed.

- Target Temperature: This should be the desired starting temperature of your simulation, typically 300 K for physiological conditions.

- Random Seed (or Seed Value): The random number generator used for velocity assignment must be seeded with a specific value. Using a different seed will generate a different set of initial velocities. For production runs, it is critical to document the seed value to ensure reproducibility. For robust results, consider running multiple independent simulations (replicas) with different initial velocity seeds to confirm that observed phenomena are not artifacts of a single initial condition.

Example: AMS Input Block

Step 4: Equilibration with Velocity Rescaling

Immediately after velocity assignment, the system must be equilibrated. The initial random velocities will not perfectly correspond to a stable equilibrium state at the target temperature. A short equilibration run (typically tens to hundreds of picoseconds) using a thermostat (e.g., Berendsen or Nosé-Hoover) is necessary to allow the system to relax and stabilize at the target temperature and pressure [5]. During this phase, properties like temperature and density should be monitored to confirm they have stabilized around their target values before beginning production simulation.

Methods Comparison and Data Presentation

The following tables summarize the key methods, parameters, and validation metrics for velocity assignment in production simulations.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Velocity Initialization Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Best Use Case | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random from Maxwell-Boltzmann [9] [1] | Draws velocities randomly from a Gaussian distribution defined by the target temperature. | Standard production runs (NVT, NPT); Starting from a minimized structure. | Physically correct; Simple to implement; Standard in all MD packages. | Requires a subsequent equilibration phase. |

| Zero Velocities [9] | Sets all atomic velocities to zero. | Energy minimization; The first step before velocity assignment. | Provides a stable, low-energy starting point. | Does not represent a physical thermodynamic state. |

| Read from File [9] | Loads a previously saved set of velocities from a file. | Restarting a previous simulation; Seeding a new run from a specific state of a previous run. | Allows for exact continuation of a simulation trajectory. | The saved state must be thermodynamically and structurally consistent with the current system. |

Table 2: Critical Parameters for Velocity Assignment and Validation

| Parameter | Typical Value / Setting | Description & Impact |

|---|---|---|

Target Temperature (temperature_K) |

300 K (physiological) | The temperature corresponding to the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution from which velocities are drawn [5]. |

| Random Seed | Integer value | Ensures the reproducibility of the stochastic velocity assignment process. |

Time Step (TimeStep or dt) |

1 - 5 fs [5] | The integration time step. Systems with light atoms (H) require shorter time steps (1-2 fs) for stability. |

| Validation Metric: Temperature | Calculated from velocities [5] | The instantaneous temperature computed from the kinetic energy must fluctuate around the target value after equilibration. |

| Validation Metric: Energy Drift | Minimal in NVE | In an NVE ensemble, the total energy should be conserved. A significant drift indicates an unstable simulation or too large a time step. |

Table 3: Essential Software and Computational Tools for MD Simulations

| Tool / Resource | Function in Simulation Workflow | Key Features for Velocity Handling |

|---|---|---|

| MD Software (AMS, ASE, GROMACS, NAMD, OpenMM) | Core simulation engine performing numerical integration of equations of motion. | Provides built-in commands for Maxwell-Boltzmann velocity initialization, thermostats, and barostats [9] [5]. |

| Visualization Software (VMD, PyMol) | Trajectory analysis and visual inspection of molecular structures and dynamics. | Allows visualization of atomic motions and debugging of simulation artifacts. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Local or cloud-based computing resources. | Necessary to achieve the required computational throughput for production-scale simulations (nanoseconds to microseconds). |

| Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) | Specialized hardware for massively parallel computation. | Drastically accelerates MD calculations, making longer and larger simulations feasible [1]. |

Workflow Visualization and Experimental Logic

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for system setup, velocity assignment, and production simulation, highlighting the critical decision points.

Validation, Troubleshooting, and Best Practices

A rigorous validation protocol is essential after velocity assignment and equilibration.

Validation Protocol: Monitor the temperature and potential energy of the system during the equilibration phase. These properties must reach a stable plateau, fluctuating around a steady average value, before the production simulation begins. For NVE simulations, the total energy must be conserved with minimal drift [5].

Common Issues and Solutions:

- System "Blows Up" (Unstable): This is often caused by an excessively large time step. Reduce the time step, particularly for systems with light atoms (e.g., hydrogen) or stiff bonds [5].

- Temperature is Incorrect: Confirm that the velocity assignment temperature and the thermostat target temperature are set to the same value. Ensure the thermostat coupling constant is not too strong or too weak.

- Poor Reproducibility: Always set and record the random seed used for velocity generation. This is mandatory for replicating results.

Best Practices for Production Runs:

- Run Multiple Replicas: Perform at least 2-3 independent simulations with different initial velocity seeds to confirm that results are statistically robust and not path-dependent.

- Document Parameters: Meticulously document all parameters related to velocity assignment, equilibration, and the thermostat in your research notes and publications.

- Match the Method to the Goal: Use Maxwell-Boltzmann assignment for standard equilibration. For specialized studies like replica exchange MD (REMD), the

ReplicaExchangeblock can be used to manage temperatures and velocities across replicas [9].

Precise and theoretically grounded assignment of initial velocities is a deceptively simple yet fundamentally important step in molecular dynamics. It bridges the gap between a static molecular structure and a dynamic, thermodynamically accurate simulation. By adhering to the structured protocols, validation checks, and best practices outlined in this guide, researchers can ensure their production simulations are built upon a solid foundation. This rigorous approach to initial conditions enhances the reliability of simulation data, which is paramount for making confident predictions in fields ranging from fundamental biophysics to rational drug design.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the initial assignment of atomic velocities and the subsequent equilibration phase are critically interlinked processes that determine the thermodynamic validity and sampling efficiency of the production run. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles and practical methodologies for ensuring parameter consistency between velocity generation and equilibration settings, framed within a broader thesis on the role of initial conditions in MD research. We provide a systematic analysis of integration algorithms, thermostat coupling parameters, and validation protocols essential for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to optimize simulation workflows. By establishing rigorous parameter-matching frameworks and quantitative diagnostic tools, this whitepaper aims to transform equilibration from a heuristic process to a systematically quantifiable procedure with clear termination criteria, thereby enhancing the reliability of MD applications in pharmaceutical research.

The initial velocity assignment in molecular dynamics simulations serves as the fundamental starting point for propagating Newton's equations of motion, effectively determining the system's initial phase in the 6N-dimensional phase space. In classical MD, the system topology remains constant, and the simulation numerically solves Newton's equations of motion to generate a dynamical trajectory [17] [25]. The initial conditions must provide positions and velocities for all atoms, with velocities typically assigned from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at the target temperature [25]. This initialization establishes the starting kinetic energy and influences how rapidly the system explores phase space during equilibration.

Proper equilibration is essential to ensure that subsequent production runs yield results neither biased by the initial configuration nor deviating from the target thermodynamic state [26]. The efficiency of this equilibration phase is largely determined by the initial configuration of the system in phase space [26]. Despite its fundamental importance, selection of equilibration parameters remains largely heuristic, with researchers often relying on experience, trial and error, or consultation with experts to determine appropriate thermostat strengths, equilibration durations, and algorithms [26]. This guide addresses these challenges by establishing rigorous parameter-matching protocols between velocity initialization and equilibration parameters.

Theoretical Foundation: Integrating Velocity Generation with Equations of Motion

Numerical Integration Algorithms and Velocity Requirements

MD simulations employ various integration algorithms that dictate specific requirements for velocity initialization and propagation. The most common integrators include:

- leap-frog (

md): The default GROMACS algorithm requiring velocities at t-½Δt for integration [27] [25] - velocity Verlet (

md-vv): A symplectic integrator that provides more accurate integration for Nose-Hoover and Parrinello-Rahman coupling [27] - stochastic dynamics (

sd): An accurate leap-frog stochastic dynamics integrator for Langevin dynamics [27]

Each algorithm imposes distinct requirements on velocity initialization and interacts differently with thermostating methods. The leap-frog algorithm, despite its name, actually requires velocities at the half-step (t-½Δt) when beginning a simulation, which affects how initial velocities are assigned and how temperature calculations are performed [25].

Statistical Mechanical Basis for Velocity Distributions

In classical MD simulations at equilibrium without magnetic fields, the phase space decouples and velocity specification involves random sampling from the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution [26] [25]:

[p(vi) = \sqrt{\frac{mi}{2 \pi kT}}\exp\left(-\frac{mi vi^2}{2kT}\right)]

where (k) is Boltzmann's constant, (T) is the target temperature, and (mi) is the atomic mass. To implement this distribution, normally distributed random numbers are generated and multiplied by the standard deviation of the velocity distribution (\sqrt{kT/mi}) [25]. The initial total energy typically does not correspond exactly to the required temperature, necessitating corrections where center-of-mass motion is removed and velocities are scaled to correspond exactly to T [25].

Practical Implementation: Parameter Matching Protocols

Velocity Initialization Parameters

Table 1: Key Parameters for Initial Velocity Generation

| Parameter | mdp Option | Function | Recommended Setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Velocity generation | gen_vel |

Enable/disable initial velocity assignment | yes for initial equilibration |

| Temperature | gen_temp |

Temperature for Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution (K) | Target temperature of simulation |

| Random seed | gen_seed |

Seed for random number generator | -1 for random seed based on system time |

| Velocity continuation | continuation |

Whether to continue from previous velocities | no for initial equilibration after minimization |

The gen_seed parameter is particularly critical for generating multiple replicas with different initial conditions. Setting gen_seed = -1 ensures that GROMACS generates a different random seed for each simulation based on system time, providing unique velocity distributions for parallel runs [28]. This approach is essential for enhanced sampling and statistical validation through replica simulations.

Thermostat Parameters for Equilibration

Table 2: Thermostat Parameters for Equilibration Phase

| Parameter | mdp Option | Function | Matching Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermostat type | tcoupl |

Temperature coupling algorithm | Must match stochastic nature of velocity generation |

| Reference temperature | ref_t |

Target temperature (K) | Must equal gen_temp from velocity generation |

| Coupling time | tau_t |

Thermostat coupling time constant (ps) | Shorter for initial equilibration, longer for production |

| Coupling groups | tc_grps |

Groups for independent temperature coupling | Should match system composition |

The thermostat coupling time constant (tau_t) deserves special attention. Research indicates that weaker thermostat coupling generally requires fewer equilibration cycles, and OFF-ON thermostating sequences outperform ON-OFF approaches for most initialization methods [26]. For the V-rescale thermostat, typical tau_t values range from 0.1-1.0 ps, with shorter values providing stronger coupling during initial equilibration.

Workflow for Consistent Parameter Implementation

Diagram 1: MD workflow with parameter matching. This workflow illustrates the sequential process for implementing consistent parameters between velocity generation and equilibration phases, with key parameter settings shown for each stage.

Diagnostic Framework: Validating Equilibration Success

Quantitative Metrics for Equilibration Assessment

A rigorous approach to equilibration validation implements temperature forecasting as a quantitative metric for system thermalization, enabling users to determine equilibration adequacy based on specified uncertainty tolerances in desired output properties [26]. This transforms equilibration from a heuristic process to a rigorously quantifiable procedure with clear termination criteria.

Table 3: Key Metrics for Equilibration Validation

| Metric | Calculation Method | Target Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature stability | Rolling average and standard deviation | Fluctuations < 1-2% of target | System maintaining target temperature |

| Energy drift | Linear regression of total energy over time | < 0.005 kJ/mol/ps per particle | Minimal energy exchange with thermostat |

| RMSD plateau | Time evolution of backbone atom positional deviation | Stable plateau with fluctuations | Structural relaxation completion |

| Property convergence | Cumulative average of key properties | Stable value with small fluctuations | Sampling adequacy for target properties |

The definition of equilibration can be operationalized as follows: "Given a system's trajectory, with total time-length T, and a property Ai extracted from it, and calling 〈Ai〉(t) the average of Ai calculated between times 0 and t, we will consider that property 'equilibrated' if the fluctuations of the function 〈Ai〉(t), with respect to 〈Ai〉(T), remain small for a significant portion of the trajectory after some convergence time, tc, such that 0 < tc < T" [29].

Common Pitfalls and Parameter Mismatches

Several common parameter mismatches can compromise equilibration quality:

- Temperature discrepancy: Mismatch between

gen_tempandref_tcreates immediate energy imbalances - Over-strong thermostat coupling: Excessively short

tau_tvalues can artificially suppress fluctuations - Inadequate equilibration duration: Terminating equilibration before property stabilization

- Inconsistent continuation settings: Using

continuation = nowhen restarting from previous runs

Research shows that initialization method selection is relatively inconsequential at low coupling strengths, while physics-informed methods demonstrate superior performance at high coupling strengths, reducing equilibration time [26]. This indicates that parameter matching becomes increasingly critical for complex systems with strong interactions.

Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery Research

Enhanced Sampling and Replica Strategies

In drug discovery applications, where MD simulations investigate dynamic interactions between potential small-molecule drugs and their target proteins, multiple replica simulations with different initial velocities provide essential statistical sampling [30] [28]. This approach accounts for variations in initial conditions and enhances conformational sampling of binding pockets.

The protocol for generating parallel runs involves:

- Creating identical starting structures after energy minimization

- Generating multiple TPR files with

gen_seed = -1to ensure different velocity distributions - Running parallel simulations with different initial velocities

- Aggregating results for statistical analysis

This methodology is particularly valuable for studying rare events and conformational transitions relevant to drug binding, where enhanced sampling techniques such as parallel tempering, metadynamics, and weighted ensemble path sampling can be combined with proper velocity initialization [30].

Machine Learning and Alternative Sampling Approaches

Recent advances in machine learning offer alternative approaches to sampling equilibrium distributions. Methods like Distributional Graphormer (DiG) use deep neural networks to transform a simple distribution toward the equilibrium distribution, conditioned on molecular descriptors [31]. These approaches can generate diverse conformations and provide estimations of state densities orders of magnitude faster than conventional MD, though they still benefit from proper initial velocity assignment when used in hybrid approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Velocity and Equilibration Studies

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

GROMACS grompp |

Preprocessing with parameter validation | Processing mdp files and generating TPR files |

| Maxwell-Boltzmann generator | Atomic velocity initialization | Creating physically correct initial velocities |

| V-rescale thermostat | Strong coupling for equilibration | Initial thermalization stages |

| Nose-Hoover thermostat | Weak coupling for production | Production phases after equilibration |

| Temperature forecasting | Equilibration adequacy assessment | Determining simulation convergence |

| Uncertainty quantification | Error estimation in properties | Establishing equilibration termination criteria |