How to Interpret Mean Square Displacement in MD Simulations: A Complete Guide for Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on interpreting Mean Square Displacement (MSD) in Molecular Dynamics simulations.

How to Interpret Mean Square Displacement in MD Simulations: A Complete Guide for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on interpreting Mean Square Displacement (MSD) in Molecular Dynamics simulations. It covers foundational theory, from the Einstein relation and diffusion coefficient calculation to distinguishing between normal and anomalous transport. The guide details practical methodologies for computation using popular tools like MDAnalysis and GROMACS, alongside advanced applications in biomolecular and materials science. Critical troubleshooting advice addresses common pitfalls like periodic boundary conditions and statistical reliability. Finally, it outlines validation frameworks and comparative analysis techniques, empowering scientists to robustly connect atomic-scale motion to macroscopic properties in therapeutic and material design.

Understanding MSD: From Einstein's Relation to Diffusion Types

Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) is a fundamental statistical measure used to quantify the average squared distance particles travel from their starting positions over time. It serves as a cornerstone in molecular dynamics (MD) for characterizing random motion, from Brownian particles in a solvent to atoms within a protein. In MD, the MSD provides a crucial link between microscopic particle trajectories and macroscopic transport properties, most notably the diffusion coefficient. The MSD's power lies in its ability to quantify the spatial extent of random motion, effectively measuring the portion of the system "explored" by a random walker [1]. This makes it an indispensable tool for researchers and drug development professionals who need to understand molecular mobility, predict material properties, and analyze diffusion mechanisms in complex biological systems.

Theoretical Foundations of MSD

Mathematical Definition

The MSD is mathematically defined as the ensemble average of the squared displacement of particles from their reference positions over time. For a system of N particles, the MSD at time ( t ) is expressed as:

[ \text{MSD}(t) = \left\langle \left| \mathbf{x}(t) - \mathbf{x}(0) \right|^2 \right\rangle = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \left| \mathbf{x}^{(i)}(t) - \mathbf{x}^{(i)}(0) \right|^2 ]

where ( \mathbf{x}^{(i)}(t) ) represents the position of particle ( i ) at time ( t ), and ( \mathbf{x}^{(i)}(0) ) is its reference position at time zero [1]. The angle brackets ( \langle \ldots \rangle ) denote the ensemble average over all particles. In practical MD applications, this ensemble average is often supplemented or replaced by a time average to improve statistics, especially in finite systems where ergodicity is assumed [2].

For different dimensional analyses, the MSD can be adapted to specific needs. The following table summarizes the common dimensional configurations used in MD analysis:

Table 1: MSD Dimensionality Configurations

| MSD Type | Dimensions Included | Mathematical Form |

|---|---|---|

| 1D (x) | x only | ( \langle (x(t) - x(0))^2 \rangle ) |

| 1D (y) | y only | ( \langle (y(t) - y(0))^2 \rangle ) |

| 1D (z) | z only | ( \langle (z(t) - z(0))^2 \rangle ) |

| 2D (xy) | x and y | ( \langle (x(t) - x(0))^2 + (y(t) - y(0))^2 \rangle ) |

| 2D (yz) | y and z | ( \langle (y(t) - y(0))^2 + (z(t) - z(0))^2 \rangle ) |

| 2D (xz) | x and z | ( \langle (x(t) - x(0))^2 + (z(t) - z(0))^2 \rangle ) |

| 3D (xyz) | x, y, and z | ( \langle (x(t) - x(0))^2 + (y(t) - y(0))^2 + (z(t) - z(0))^2 \rangle ) |

The Einstein Relation

The connection between MSD and diffusivity was first established by Albert Einstein in his seminal 1905 paper on Brownian motion. The Einstein relation states that for normal diffusion in d-dimensional space, the MSD grows linearly with time, and the slope is proportional to the diffusion coefficient D [3]:

[ \lim_{t \to \infty} \text{MSD}(t) = 2dDt ]

where ( d ) represents the dimensionality of the system (1, 2, or 3) [4]. This relationship provides a powerful bridge between microscopic particle motions and macroscopic transport properties, allowing researchers to compute diffusivity directly from particle trajectories.

The general form of the Einstein relation in the classical case is:

[ D = \mu k_B T ]

where ( D ) is the diffusion coefficient, ( \mu ) is the particle mobility (defined as the ratio of terminal drift velocity to applied force), ( k_B ) is the Boltzmann constant, and ( T ) is the absolute temperature [3]. Two important special cases of this relation have broad applications in materials science and biophysics:

- Einstein-Smoluchowski Equation: For diffusion of charged particles, ( D = \frac{\muq kB T}{q} ), where ( \mu_q ) is the electrical mobility and ( q ) is the particle charge [3].

- Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland Equation: For diffusion of spherical particles through a liquid with low Reynolds number, ( D = \frac{k_B T}{6\pi\eta r} ), where ( \eta ) is the dynamic viscosity and ( r ) is the hydrodynamic radius of the particle [3].

Computational Implementation in MD Simulations

Practical MSD Calculation

In molecular dynamics simulations, calculating MSD involves several critical steps and considerations. A practical implementation requires careful attention to trajectory preparation, algorithm selection, and statistical averaging. The following workflow outlines the complete process for computing MSD in MD simulations:

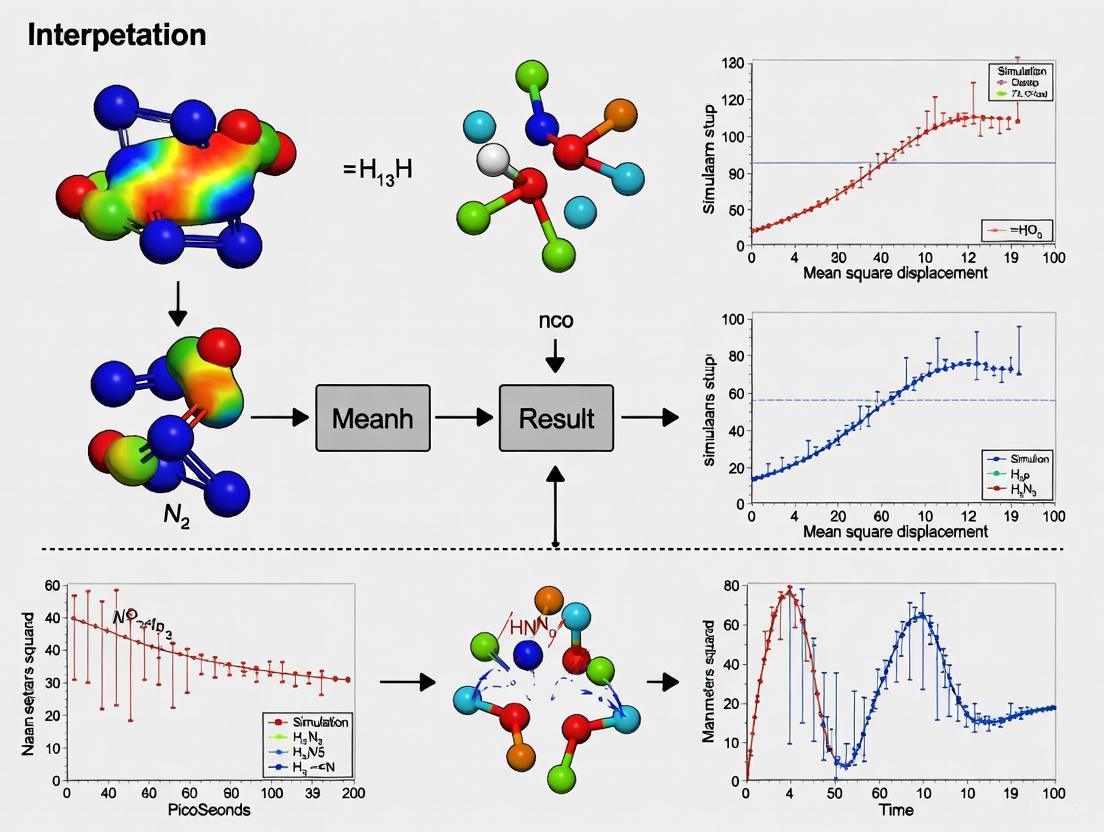

Diagram 1: MSD Calculation Workflow in MD Simulations

The first and most critical step is ensuring proper trajectory preparation. MD simulations typically use periodic boundary conditions, which can cause atoms that cross the box boundaries to be "wrapped" back into the primary cell. For accurate MSD calculations, unwrapped coordinates are essential [4]. As explicitly warned in the MDAnalysis documentation: "To correctly compute the MSD using this analysis module, you must supply coordinates in the unwrapped convention. That is, when atoms pass the periodic boundary, they must not be wrapped back into the primary simulation cell" [4]. Various simulation packages provide utilities for this conversion; for example, in GROMACS, this can be done using gmx trjconv with the -pbc nojump flag.

For the computation itself, two primary algorithms are commonly used:

- Windowed Algorithm: This approach computes the MSD by averaging over all possible time origins (lag times) within the trajectory. While conceptually straightforward, it scales with O(N²) computational complexity with respect to the number of frames, making it intensive for long trajectories [4].

- FFT-Based Algorithm: An algorithm with O(N log N) scaling based on Fast Fourier Transform is available and provides significant computational advantages for long trajectories [4]. This method requires the

tidynamicspackage and can be accessed in MDAnalysis by settingfft=True.

A Complete Code Implementation

The following Python code demonstrates a practical implementation of MSD calculation using the MDAnalysis library, incorporating best practices for robust analysis:

This implementation follows the methodology described in the MDAnalysis documentation [4], including the use of FFT for computational efficiency and proper handling of the linear regression for diffusivity calculation.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Identifying Diffusion Regimes

A crucial aspect of MSD analysis is identifying the different regimes of particle motion. When plotting MSD against lag time, the slope reveals important information about the diffusion mechanism:

Table 2: MSD Time Dependence and Diffusion Regimes

| MSD Behavior | Mathematical Form | Diffusion Type | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | MSD ~ t | Normal (Fickian) Diffusion | Unconstrained random walk |

| Power law with exponent <1 | MSD ~ tα (α<1) | Subdiffusion | Confined or obstructed motion |

| Power law with exponent >1 | MSD ~ tα (α>1) | Superdiffusion | Directed motion with active transport |

| Plateau | MSD → constant | Confined Diffusion | Motion restricted to limited space |

To accurately identify these regimes, particularly the linear segment needed for diffusivity calculations, a log-log plot is recommended [4]. On a log-log plot, a segment with slope = 1 indicates normal diffusion, while deviations from this slope indicate anomalous diffusion. This visualization technique helps distinguish the middle linear segment from ballistic motion at short time scales (slope ≈ 2) and poorly averaged data at long time scales.

Calculating Diffusion Coefficients

The diffusion coefficient is extracted from the linear portion of the MSD plot using the Einstein relation:

[ Dd = \frac{1}{2d} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(r_d) ]

where ( d ) is the dimensionality of the MSD [4]. In practice, this derivative is approximated by the slope of the linear fit to the MSD curve. The selection of the appropriate linear segment is critical, as the MSD must be in the diffusive regime rather than the ballistic regime (which occurs at very short times) or the saturated regime (which occurs at very long times due to finite size effects) [4].

The following table summarizes the conversion factors between MSD slope and diffusion coefficient for different dimensionalities:

Table 3: Converting MSD Slope to Diffusion Coefficient

| MSD Dimensionality | Conversion Formula | Theoretical MSD Form |

|---|---|---|

| 1D | D = slope / 2 | 2Dt |

| 2D | D = slope / 4 | 4Dt |

| 3D | D = slope / 6 | 6Dt |

Advanced Considerations and Methodological Challenges

Statistical Considerations in MD Analysis

In MD simulations, the calculation of ensemble averages requires special consideration due to limited system size and trajectory length. While in theoretical treatments, the MSD is defined as an ensemble average over many particles, in practical MD applications, researchers often employ time averaging to improve statistics [2]. This approach is valid for ergodic systems, where time averages equal ensemble averages.

For a trajectory with N frames, the time-averaged MSD for a single particle can be computed as:

[ \overline{\delta^2(n)} = \frac{1}{N-n} \sum_{i=1}^{N-n} \left[ \vec{r}(i+n) - \vec{r}(i) \right]^2 ]

where ( n ) is the lag time in units of the time step [1]. This formula calculates the average squared displacement over all possible time origins, significantly improving the statistics, particularly for long trajectories.

When analyzing complex systems like proteins, additional statistical techniques may be necessary. For example, in proteins where atomic position distributions may be multimodal (exhibiting multiple maxima), standard MSD calculations can yield biased results [5]. In such cases, a block analysis approach has been developed, where the trajectory is divided into blocks, and MSD is calculated within each block before averaging [5]. This method provides more reliable estimates of variance for atoms with multimodal distributions.

Common Pitfalls and Best Practices

Several factors must be considered when computing MSDs and diffusivities from MD simulations:

- Finite Size Effects: Diffusion coefficients calculated from MD simulations show system-size dependence due to periodic boundary conditions. Finite-size corrections, such as those proposed by Yeh and Hummer, may be necessary for accurate results [4].

- Trajectory Length: The trajectory must be long enough to observe the transition from ballistic to diffusive regime and to provide sufficient averaging for statistical reliability. As a rule of thumb, the MSD should increase at least by a factor of 10 beyond the ballistic regime [4].

- Frame Interval: Maintaining a relatively small elapsed time between saved frames is important to properly capture the dynamics, particularly for identifying the ballistic regime at short times [4].

- Statistical Uncertainty: Error estimation techniques, such as block averaging or bootstrap methods, should be employed to quantify uncertainties in computed diffusion coefficients [4].

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for MSD Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| MDAnalysis (Python) | Trajectory analysis and MSD computation | General MD analysis with support for multiple formats |

| tidynamics Python package | FFT-accelerated MSD calculation | Efficient MSD computation for long trajectories |

| GROMACS trjconv utility | Trajectory unwrapping with -pbc nojump |

Preparation of unwrapped trajectories for MSD |

| VMD (Visual Molecular Dynamics) | Trajectory visualization and validation | Visual inspection of particle diffusion |

| Matplotlib / Plotly | MSD data visualization and linear fitting | Identification of diffusive regime and slope calculation |

| Scipy.stats.linregress | Linear regression for diffusivity calculation | Quantitative extraction of diffusion coefficients |

The Mean Squared Displacement, connected to diffusion through the Einstein relation, provides a powerful framework for analyzing particle dynamics in molecular simulations. From its rigorous mathematical foundation to practical implementation in MD analysis, the MSD serves as an essential bridge between microscopic trajectories and macroscopic transport properties. For researchers in drug development and materials science, mastering MSD analysis enables the quantification of diffusion mechanisms in systems ranging from simple liquids to complex biological environments. By adhering to best practices in trajectory preparation, algorithm selection, and data interpretation, scientists can reliably extract meaningful diffusion coefficients and uncover fundamental insights into molecular mobility and system behavior.

Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) serves as a fundamental metric in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and single-particle tracking experiments, providing crucial insights into the random motion of particles. In statistical mechanics, MSD measures the deviation of a particle's position from its reference position over time, effectively quantifying the spatial extent of random motion and the portion of the system "explored" by a random walker [1]. For researchers in drug development and materials science, accurately interpreting MSD is essential for understanding diffusion mechanisms, binding events, and molecular transport phenomena that underlie drug efficacy and delivery systems.

The MSD's theoretical roots trace back to Albert Einstein's pioneering work on Brownian motion, where he demonstrated that the MSD of a Brownian particle increases linearly with time, with a slope proportional to the diffusion coefficient [1] [6]. In modern MD research, MSD analysis extends far beyond this simple Brownian case to characterize anomalous diffusion, subdiffusive behavior in crowded cellular environments, and superdiffusive transport phenomena—all highly relevant to pharmaceutical research where molecular mobility often determines biological activity.

This technical guide decodes the mathematical formulations and practical implementations of MSD calculations, with particular emphasis on the critical distinction between time-averaged and ensemble-averaged approaches. Within the context of MD simulation research, proper application of these formulas enables researchers to extract accurate diffusion coefficients, identify dynamical transitions, and validate simulation methodologies against experimental data.

Mathematical Foundations of MSD

Core MSD Equation

The MSD fundamentally measures the squared deviation of a particle's position over time. For a single particle in one dimension, the MSD at time t is defined as:

MSD ≡ ⟨|x(t) - x(0)|²⟩ [1]

where x(t) represents the particle's position at time t, x(0) is the reference position at time zero, and the angle brackets ⟨·⟩ denote an averaging procedure, the nature of which distinguishes between ensemble and time averages [1].

For Brownian motion in one dimension, Einstein proved that the MSD follows a simple linear relationship:

⟨(x(t) - x(0))²⟩ = 2Dt [1]

where D is the diffusion coefficient measured in m²/s. This relationship emerges from solving the one-dimensional diffusion equation for the probability density function of particle positions.

Extension to Multiple Dimensions

In molecular dynamics simulations, systems typically exist in three-dimensional space. For a particle with position vector r(t) = (x(t), y(t), z(t)), the three-dimensional MSD is defined as:

MSD ≡ ⟨|r(t) - r(0)|²⟩ = ⟨(x(t) - x(0))²⟩ + ⟨(y(t) - y(0))²⟩ + ⟨(z(t) - z(0))²⟩ [1]

Since the coordinates are statistically independent for isotropic diffusion, and following the same derivation as in one dimension, the MSD in n dimensions becomes:

MSD = 2nDt [1]

This relationship provides the crucial link between observed particle displacements and the diffusion coefficient in multiple dimensions, with significant implications for interpreting MD simulation results in pharmaceutical contexts where molecular mobility affects drug binding and distribution.

Generalized Diffusion Behavior

The MSD curve can reveal important mechanistic insights beyond simple Brownian diffusion. The general form of the MSD curve is often expressed as:

⟨x²(t)⟩ = Kᵃtᵃ [6]

where Kᵃ is the generalized diffusion coefficient and α is the scaling exponent. The value of α categorizes the diffusion behavior:

- α = 1: Normal Brownian diffusion

- α > 1: Superdiffusion (faster than expected)

- α < 1: Subdiffusion (slower than expected) [6]

In drug development contexts, subdiffusive behavior often indicates crowded intracellular environments or binding events, while superdiffusion may suggest active transport processes relevant to drug delivery mechanisms.

Table 1: Interpretation of MSD Scaling Exponents

| Scaling Exponent (α) | Diffusion Type | Common Molecular Context |

|---|---|---|

| α = 1 | Normal Brownian | Dilute solutions, simple liquids |

| α < 1 | Subdiffusive | Crowded cytoplasm, polymer networks, membrane domains |

| α > 1 | Superdiffusive | Active transport, directed motion with external forces |

Time-Averaged vs. Ensemble-Averaged MSD

Ensemble-Averaged MSD

The ensemble-averaged MSD follows the traditional statistical mechanics approach, calculating the average displacement across many particles at specific time intervals. For N particles, the ensemble average is defined as:

MSD ≡ ⟨|x(t) - x(0)|²⟩ = (1/N) ∑ᵢ₌₁ᴺ |x⁽ⁱ⁾(t) - x⁽ⁱ⁾(0)|² [1]

This approach measures the distance traveled from each particle's initial position, averaged over all particles in the system [6]. In MD simulations, this requires tracking multiple independent trajectories or multiple molecules simultaneously.

The key advantage of ensemble averaging lies in its conceptual simplicity and direct connection to theoretical ensemble averages in statistical mechanics. However, it requires sufficient particle statistics to achieve reliable averages, which can be computationally demanding for large systems or rare events.

Time-Averaged MSD

The time-averaged MSD adopts a different approach, focusing on a single particle's trajectory but averaging over multiple time origins along that trajectory. For a continuous time series of length T, the time-averaged MSD is defined as:

δ²(Δ) = (1/(T - Δ)) ∫₀ᵀ⁻Δ [r(t + Δ) - r(t)]² dt [1]

For discrete time series with N frames and time step Δt, this becomes:

δ²(n) = (1/(N - n)) ∑ᵢ₌₁ᴺ⁻ⁿ (rᵢ₊ₙ - rᵢ)² [1] [7]

where n is the time lag in units of Δt, and rᵢ represents the position at time iΔt [7]. The time-averaged MSD is statistically more robust than the ensemble average for single-particle trajectories, providing tighter error bars with limited data [6].

Comparative Analysis

For ergodic systems—where time averages and ensemble averages are equivalent—both MSD calculation methods should yield identical results [6]. However, in many practical MD scenarios, especially in complex biological environments relevant to drug action, ergodicity breaking can occur, making the choice of averaging method significant.

Table 2: Comparison of Time-Averaged and Ensemble-Averaged MSD

| Feature | Ensemble-Averaged MSD | Time-Averaged MSD |

|---|---|---|

| Averaging Domain | Across multiple particles at fixed time | Along single trajectory over multiple time origins |

| Data Requirements | Multiple parallel trajectories | Long single trajectory |

| Statistical Robustness | Limited by particle count | Limited by trajectory length |

| Error Bars | Wider with limited particles | Tighter with long trajectories [6] |

| Computational Cost | Lower for few time points | Higher due to multiple time origins |

| Ergodicity Assumption | Requires ergodic system | More robust to non-ergodicity |

Practical Implementation in MD Analysis

Computational Algorithms

Implementing efficient MSD calculations requires careful algorithmic consideration due to the computationally intensive nature of the calculations. The simplest "windowed" algorithm computes the MSD for all possible time lags τ ≤ τmax, where τmax is the trajectory length [4]. However, this naive approach scales as O(N²) with respect to trajectory length, becoming prohibitively expensive for long trajectories [4].

A more sophisticated approach utilizes Fast Fourier Transforms (FFT) to compute the MSD with O(N log N) scaling [4]. This FFT-based algorithm significantly reduces computational cost for long trajectories and is implemented in packages such as MDAnalysis (when setting fft=True) and tidynamics [4]. The FFT approach is particularly valuable in production MD analysis where trajectory lengths can encompass thousands to millions of frames.

Critical Implementation Considerations

Several practical considerations are essential for accurate MSD computation in MD simulations:

Unwrapped Coordinates: MSD calculations must use unwrapped coordinates that account for periodic boundary conditions without artificial wrapping. When atoms cross periodic boundaries, they should not be wrapped back into the primary simulation cell [4]. In GROMACS, this can be achieved using

gmx trjconvwith the-pbc nojumpflag [4].Trajectory Length and Sampling: Maintaining a relatively small elapsed time between saved frames is crucial for capturing relevant dynamics [4]. The linear segment of the MSD plot required for diffusivity calculation must be identified, excluding ballistic trajectories at short time-lags and poorly averaged data at long time-lags [4].

Statistical Error Estimation: Bootstrapping methods provide robust error estimation for MSD curves and derived diffusion coefficients. Typically, hundreds of bootstrap trials are recommended for reliable confidence intervals [6].

MDAnalysis Implementation Example

The MDAnalysis package provides a practical implementation of MSD calculation through its EinsteinMSD class [4]. A typical workflow includes:

Key parameters include:

select: Atom selection for analysismsd_type: Dimensionality of MSD ('xyz', 'xy', 'x', etc.)fft: Whether to use FFT-accelerated algorithm [4]

The dim_fac attribute provides the dimensionality factor d used in the diffusion coefficient calculation [4].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MSD Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in MSD Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| MDAnalysis | Python package | Trajectory analysis, MSD calculation, and diffusion coefficient estimation |

| GROMACS trjconv | Molecular dynamics utility | Coordinate unwrapping with -pbc nojump flag for proper MSD calculation |

| tidynamics | Python package | FFT-accelerated MSD algorithm for improved computational efficiency |

| Bootstrapping Algorithms | Statistical method | Error estimation for MSD curves and diffusion coefficients |

| Linear Regression Methods | Statistical analysis | Fitting MSD linear region to extract diffusion coefficients |

Diffusion Coefficient Extraction

The Einstein Relation

The self-diffusivity D is fundamentally related to the MSD through the Einstein relation:

Dd = (1/(2d)) lim(t→∞) d(MSD(r_d))/dt [4]

where d is the dimensionality of the MSD measurement [4]. For normal diffusion where MSD is linear with time, this simplifies to:

D = MSD/(2dt) [6]

where the differentiation is replaced by a simple slope calculation. For three-dimensional MSD (d=3), this becomes D = MSD/(6t) [1] [4].

Identifying the Linear Regime

Accurate diffusion coefficient calculation requires identifying the appropriate linear region of the MSD curve, which represents the regime where normal diffusion occurs. The initial ballistic regime (where MSD ∝ t²) and the long-time poorly averaged region should be excluded from the fit [4].

A log-log plot of MSD versus time can help identify the linear region, which appears with a slope of 1 on such a plot [4]. The linear region typically corresponds to the "middle" segment of the MSD curve, though the exact range depends on system properties and simulation conditions.

Practical Fitting Procedure

The following Python code demonstrates a typical procedure for extracting diffusion coefficients from MSD data:

This approach yields the self-diffusivity D, a crucial parameter for understanding molecular mobility in pharmaceutical systems, with direct relevance to drug diffusion through membranes, binding kinetics, and cellular uptake.

Methodological Validation and Best Practices

Finite-Size Effects and Corrections

MD simulations employ periodic boundary conditions, which introduce finite-size effects on calculated diffusion coefficients. The system size dependence of diffusivities from MD simulations with periodic boundary conditions has been systematically studied, with corrections proposed to estimate infinite-system diffusion values [4]. Yeh and Hummer demonstrated that diffusion coefficients scale approximately inversely with system size, providing correction methods to extrapolate to the infinite-size limit [4].

For accurate diffusion coefficients comparable to experimental values, researchers should either apply finite-size corrections or use sufficiently large system sizes to minimize these effects. System sizes of tens to hundreds of thousands of atoms are typically required for converged diffusivities in complex biomolecular systems.

Stationarity Testing

The assumption of stationary increments is fundamental to reliable MSD analysis. The Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test provides a statistical method for testing stationarity by examining whether a time series has a unit root [6]. The null hypothesis of the ADF test is that the series is non-stationary, with p-values below a threshold (typically 0.05) indicating stationarity [6].

Implementing stationarity testing ensures the validity of time-averaged MSD calculations and helps identify transitions in dynamical behavior that might affect diffusion coefficient accuracy. This is particularly important in pharmaceutical applications where molecular mobility may change due to conformational transitions or binding events.

Comprehensive Validation Protocol

Based on current best practices, the following validation protocol is recommended for robust MSD analysis:

Trajectory Quality Control: Verify unwrapped coordinates, adequate sampling frequency, and trajectory length sufficient to observe normal diffusion.

Ergodicity Assessment: Compare time-averaged and ensemble-averaged MSD curves where possible to identify potential ergodicity breaking.

Linear Region Identification: Use log-log plots to identify the true diffusive regime with slope ≈ 1, excluding ballistic and noisy regions.

Statistical Error Analysis: Implement bootstrapping with hundreds of trials (typically 200) to estimate confidence intervals for MSD curves and diffusion coefficients [6].

Finite-Size Assessment: Evaluate system size effects through multiple simulations or application of established correction methods.

Stationarity Verification: Apply statistical tests like ADF to confirm stationarity of increments, particularly for time-averaged MSD.

This comprehensive approach ensures the production of reliable, reproducible diffusion parameters that can meaningfully inform drug development decisions and mechanistic interpretations of molecular mobility.

Mean Squared Displacement analysis provides a powerful bridge between molecular dynamics simulations and experimental observables, with particular relevance to pharmaceutical research where molecular mobility directly impacts drug action. The critical distinction between time-averaged and ensemble-averaged MSD calculations, when properly understood and applied, enables researchers to extract accurate diffusion coefficients and identify anomalous transport behavior.

The mathematical framework presented here, combined with practical implementation guidelines and validation protocols, equips researchers with the tools to decode MSD formulas within their specific research contexts. As MD simulations continue to grow in complexity and temporal scope, employing statistically robust MSD methodologies becomes increasingly essential for generating reliable insights into molecular diffusion mechanisms underlying drug efficacy and delivery.

By adhering to the best practices outlined—including proper coordinate unwrapping, linear region identification, finite-size corrections, and comprehensive error analysis—researchers can ensure their MSD-derived parameters withstand rigorous scientific scrutiny and contribute meaningfully to drug development pipelines.

Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) analysis is a cornerstone technique in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and single-particle tracking (SPT) research for characterizing particle motion. The slope of the MSD curve as a function of time lag reveals critical information about the mode of diffusion and underlying physical mechanisms. This technical guide provides an in-depth framework for interpreting MSD slopes, detailing the distinctions between normal diffusion, anomalous diffusion (both sub and super-diffusion), and localized motion. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this whitepaper synthesizes current methodologies, quantitative benchmarks, and practical protocols to enhance accuracy in molecular motion analysis within complex biological systems.

The Mean Squared Displacement is a fundamental metric in statistical mechanics that quantifies the deviation of a particle's position from a reference point over time. In the realm of molecular dynamics and single-particle tracking, MSD analysis provides a powerful approach to decipher the nature of molecular motion and the properties of the surrounding environment. The MSD for a trajectory in ν dimensions is typically calculated as a function of the time lag (τ), providing a robust measure of the spatial extent of random motion [8]. The most common formulation is the time-averaged MSD (TAMSD), computed for a single-particle trajectory as:

where N is the number of points in the trajectory X(t), Δt is the time between frames, and the summation runs from j=1 to j=N-n [8]. For a more comprehensive analysis, this can be combined with ensemble averaging over multiple particles to yield the time- and ensemble-averaged mean-squared displacement (TEAMSD) [8]. The power of MSD analysis lies in its ability to distinguish between different modes of motion through the characteristic relationship between MSD and time lag, which forms the basis for interpreting diffusion mechanisms in molecular systems.

Theoretical Framework: MSD-Time Relationships

The functional form of the MSD-time relationship serves as a primary diagnostic tool for classifying diffusion modalities. The generalized MSD equation is expressed as:

where Dα is the generalized diffusion coefficient (or anomalous diffusion constant), α is the anomalous exponent, and ν is the dimensionality of the system [8]. A log-log plot of MSD versus time is commonly employed for analysis, where α represents the slope of the curve in such a plot [8]. The value and behavior of the anomalous exponent α provide critical insights into the nature of the diffusion process and the underlying physical mechanisms driving particle motion.

Diffusion Regimes and Their Physical Signatures

The diffusion regime is classified based on the value of the anomalous exponent α:

- Normal Diffusion (

α ≈ 1): Results from standard Brownian motion in a homogeneous environment where steps are uncorrelated and the central limit theorem applies. - Subdiffusion (

α < 1): Arises in crowded environments, binding interactions, or viscoelastic media where molecular crowding, temporary trapping, or restricted geometries impede free diffusion. - Superdiffusion (

α > 1): Occurs when active transport mechanisms, directed motion, or long-range correlations enhance displacement beyond normal diffusion. - Localized Motion (

α ≈ 0): Indicates particles are effectively confined to a limited spatial region, often due to binding or structural constraints.

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for classifying diffusion modes based on MSD analysis:

MSD Slope Interpretation Workflow

Quantitative Interpretation of MSD Slopes

Characteristic MSD Parameters for Different Diffusion Modes

The following table summarizes the key quantitative parameters for different diffusion modes, providing researchers with reference values for classification:

| Diffusion Mode | Anomalous Exponent (α) | MSD-Time Relationship | Diffusion Coefficient | Common Physical Origins |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Localized/Immobile | 0 ≤ α < 0.75 | MSD(τ) ≈ constant or weak power-law | D < 0.01 μm²/s [8] | Strong binding, molecular tethering, entrapment |

| Subdiffusion | 0.75 ≤ α < 1 | MSD(τ) ∝ τ^α (concave curvature) | Dα (anomalous constant) | Molecular crowding, transient binding, viscoelasticity |

| Normal Diffusion | 0.75 ≤ α ≤ 1.25 [8] | MSD(τ) ∝ τ (linear) | D = MSD/(2ντ) | Free Brownian motion, homogeneous environment |

| Superdiffusion | α > 1.25 [8] | MSD(τ) ∝ τ^α (convex curvature) | Dα (anomalous constant) | Active transport, directed motion with flow |

Practical Classification Criteria

In practice, researchers often establish specific numerical thresholds for motion classification. For example, in studies of GABAB receptors, trajectories were classified using the following operational criteria [8]:

- Immobile: D < 0.01 μm²/s

- Brownian diffusive: D ≥ 0.01 μm²/s and 0.75 ≤ α ≤ 1.25

- Sub-diffusive: D ≥ 0.01 μm²/s and α < 0.75

- Super-diffusive: D ≥ 0.01 μm²/s and α > 1.25

These thresholds should be adapted to specific experimental systems, as the exact values may vary based on temporal resolution, localization precision, and biological context.

Methodological Protocols for Accurate MSD Analysis

MSD Computation Protocol

Required Software Tools:

- MATLAB with @msdanalyzer class [9]

- MDAnalysis Python package [4]

- Custom scripts for specialized analysis (e.g., Hidden Markov Models)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Trajectory Preprocessing:

MSD Calculation:

- Implement the windowed algorithm or FFT-based approach for improved computational efficiency [4]

- For a trajectory with N points, compute MSD for lag times τ = 1, 2, ..., N-1 frames:

Linear Segment Identification:

Parameter Extraction:

- For normal diffusion: Perform linear regression on MSD vs τ to obtain D = slope/(2ν) [4]

- For anomalous diffusion: Perform power-law fitting on log(MSD) vs log(τ) to extract α and Dα

Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

Short Trajectories:

- Use the first few MSD points (short-term diffusion coefficient) [8]

- Implement maximum likelihood estimation methods

- Apply Bayesian inference approaches

Localization Noise:

- Measure localization precision from immobilized particles

- Correct MSD using: MSDcorrected(τ) = MSDmeasured(τ) - 4σ² (for 2D) where σ² is localization variance [8]

Heterogeneous Populations:

- Analyze individual trajectories rather than ensemble averages

- Implement change-point detection algorithms [10]

- Use machine learning classification approaches [8]

Advanced Analysis: Beyond Basic MSD Interpretation

Distribution-Based Analysis

Traditional MSD analysis relies on ensemble averages that may mask underlying heterogeneity. Advanced approaches exploit the distribution of parameters beyond displacements, including:

- Angular Distribution: More sensitive for quantifying caging and distinguishing rare transport mechanisms [8]

- Velocity Autocorrelation: Reveals directional persistence and active transport components [9]

- Time Distribution Analysis: Identifies trapping events and temporal heterogeneity

State Identification and Trajectory Segmentation

Molecular dynamics often involve transitions between different diffusion states. Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) can identify these states, their populations, and switching kinetics [8]. The implementation protocol includes:

- Feature Extraction: Calculate rolling-window MSD, velocity, and directionality metrics

- State Identification: Apply HMM or change-point detection algorithms [10]

- Kinetic Analysis: Quantify transition probabilities and state lifetimes

Machine Learning Approaches

Recent advances in machine learning demonstrate superior performance for analyzing anomalous diffusion, particularly for short or noisy trajectories [10]. The Anomalous Diffusion (AnDi) Challenge established benchmarks for three key tasks [10]:

- Anomalous Exponent Inference (T1): Accurate estimation of α from individual trajectories

- Model Classification (T2): Distinguishing between diffusion models (FBM, CTRW, LW, etc.)

- Trajectory Segmentation (T3): Identifying changepoints in diffusion characteristics

The following table outlines essential computational tools for advanced MSD analysis:

| Research Tool | Function | Implementation Platform |

|---|---|---|

| @msdanalyzer | MSD calculation, drift correction, ensemble analysis | MATLAB [9] |

| MDAnalysis.analysis.msd | MSD computation for MD trajectories | Python [4] |

| Hidden Markov Models | State identification and kinetics | Multiple (Python, MATLAB, R) |

| Random Forest Classifiers | Trajectory classification by motion type | Multiple [8] |

| Deep Neural Networks | Model identification and parameter inference | Python (TensorFlow, PyTorch) [8] |

Applications in Drug Development and Molecular Research

The interpretation of MSD slopes provides critical insights for pharmaceutical research and development:

Membrane Receptor Studies: MSD analysis of receptor dynamics reveals confinement zones, lipid interactions, and cytoskeletal influences on signaling platforms [8]. For example, studies of epidermal growth factor receptors, transferrin receptors, and neurotrophin receptors have employed MSD classification to understand trafficking and activation mechanisms [8].

Drug-Target Engagement: Changes in diffusion characteristics can indicate binding events, with successful drug-target interactions often manifesting as transitions from normal to subdiffusive motion due to complex formation.

Intracellular Transport: Analysis of vesicular and organellar dynamics distinguishes between diffusion-driven and motor-protein-driven transport, enabling quantification of active transport components in drug delivery systems.

Protein Dynamics and Stability: Atomic mean-square displacements from MD simulations characterize protein flexibility and thermostability, with applications in biologics engineering [5].

Accurate interpretation of MSD slopes is fundamental to understanding molecular mobility in biological systems. The framework presented here enables researchers to distinguish between normal diffusion, anomalous diffusion (sub and super-diffusion), and localized motion through careful analysis of MSD-time relationships. As the field advances, integration of classical MSD analysis with machine learning approaches and single-molecule statistics promises to unlock deeper insights into molecular mechanisms relevant to drug development and therapeutic innovation. Researchers are encouraged to apply these protocols with attention to experimental constraints and to leverage multiple complementary分析方法 to validate their findings.

The mean-square displacement (MSD) is a fundamental metric in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for characterizing particle motion and calculating transport properties like the self-diffusion coefficient. The MSD's proportionality to the observation time provides a direct pathway to the diffusion coefficient via the Einstein relation, but a critical, often overlooked, factor is the explicit dependence of this relationship on the dimensionality of the analysis. This guide details the rigorous theoretical foundations and practical methodologies for correctly computing diffusion coefficients from MD trajectories in one, two, and three dimensions, emphasizing the critical importance of the dimensionality factor. Proper application of these principles is essential for obtaining accurate, reproducible results in fields ranging from drug development, where diffusion influences binding kinetics, to materials science.

Theoretical Foundations of MSD and Diffusion

The mean-square displacement (MSD) is a measure of the spatial extent of random motion and serves as the cornerstone for quantifying diffusion. In a statistical ensemble, for a dimensionality d, the MSD is defined as the average squared distance a particle travels over a time interval, or lag time, δt [4] [2].

The Einstein Relation and Dimensionality

The self-diffusivity, Dd, is intrinsically linked to the MSD through the Einstein relation [4] [11]. This relation states that for normal diffusion, at long times, the MSD becomes linear with time, and the slope is proportional to the diffusion coefficient. [ Dd = \frac{1}{2d} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} MSD(r_{d}) ] where d is the dimensionality of the MSD [4]. In practice, for a linear regime of the MSD, the diffusivity is calculated as: [ D = \frac{\text{slope of MSD vs. time}}{2d} ] The factor of 2d is not arbitrary; it originates from the random walk nature of diffusion in d independent spatial dimensions. Using an incorrect prefactor is a common source of error, leading to values that are off by a factor of two or three.

Table 1: The Einstein Relation for Different Dimensionalities

| Dimensionality (d) | MSD Definition | Einstein Relation for D | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1D (e.g., x) | (\langle [x(t) - x(0)]^2 \rangle) | ( D = \frac{1}{2} \lim_{t\to\infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(t) ) | ||

| 2D (e.g., xy) | (\langle | \vec{r}(t) - \vec{r}(0) | ^2 \rangle ) in a plane | ( D = \frac{1}{4} \lim_{t\to\infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(t) ) |

| 3D (xyz) | (\langle | \vec{r}(t) - \vec{r}(0) | ^2 \rangle ) | ( D = \frac{1}{6} \lim_{t\to\infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(t) ) |

This relationship has its roots in the study of Brownian motion and is universally applicable across systems, from simple liquids to complex polymers, provided the underlying dynamics are diffusive [4] [12].

Practical Computation of the MSD from MD Trajectories

Translating the theoretical definition of MSD into a robust computational procedure requires careful consideration of averaging and trajectory handling.

The "Windowed" Algorithm for MSD Calculation

A direct but computationally intensive method is the "windowed" algorithm, which involves averaging over all possible time origins within a trajectory [4]. For a single particle, the MSD at a specific lag time kτ is calculated as: [ \text{MSD}(k\tau) = \frac{1}{N{k\tau}}\sum{i=1}^{N{k\tau}}{\Big|\vec{r}\big((i+k)\tau\big)-\vec{r}\big(i\tau\big)\Big|^2} ] where *Nkτ* is the number of time windows of length *kτ* in the trajectory. This calculation is then averaged over all *N* particles of interest in the system [4] [2]: [ \text{MSD}(k\tau) = \frac{1}{N}\sum{n=1}^{N} \left[ \frac{1}{N{k\tau}}\sum{i=1}^{N{k\tau}}{\Big|\vec{r}n\big((i+k)\tau\big)-\vec{r}_n\big(i\tau\big)\Big|^2} \right] ] This double averaging over both particles and time origins maximizes statistical accuracy and is essential for obtaining a smooth MSD curve.

Critical Preprocessing: Unwrapped Trajectories

A paramount prerequisite for a correct MSD calculation is the use of unwrapped coordinates [4]. MD simulations typically use periodic boundary conditions, and standard trajectory outputs often "wrap" particles back into the primary simulation box when they cross a boundary. Using these wrapped coordinates will artificially truncate the MSD. The analysis must be performed on unwrapped trajectories, which track the particles' true paths across periodic images. Some simulation software, like GROMACS, provides tools (e.g., gmx trjconv -pbc nojump) to generate these unwrapped trajectories [4].

Workflow for MSD Analysis and Diffusion Coefficient Extraction

The following diagram outlines the complete workflow from an MD simulation to a final diffusion coefficient, highlighting the key steps and decisions.

A Step-by-Step Protocol for Determining D

Step 1: Calculate and Plot the MSD

After computing the MSD using the windowed algorithm, plot it against the lag time. It is often insightful to use a log-log plot for initial analysis [4]. On a log-log scale, normal diffusion appears as a straight line with a slope of 1. This helps identify the linear, diffusive regime and distinguish it from short-time ballistic motion (slope ≈ 2) and long-time noisy averaging.

Step 2: Identify the Linear Regime

A segment of the MSD is required to be linear to accurately determine the self-diffusivity [4]. Visually inspect the MSD plot to identify the time interval where the curve is linear. This "middle" segment excludes short-time, non-diffusive ballistic motion and long-time, poorly averaged data [4] [12]. The linear regime can be confirmed by ensuring the slope on a log-log plot is approximately 1.

Step 3: Perform Linear Regression and Calculate D

Select the data points within the linear regime and perform a linear least-squares fit, where MSD(t) = slope × t + intercept [4]. The diffusion coefficient D is then calculated using the Einstein relation with the correct dimensional prefactor, as shown in Table 1. For a 3D MSD, this is: [ D = \frac{\text{slope}}{6} ] Always report the time range used for the fit along with the calculated D value.

Table 2: Expected Scaling of Diffusion Coefficients in Polymer Models

| Polymer Model | Solvent Treatment | Scaling of Diffusion Coefficient D | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rouse Model | Implicit (No HI) | ( D_{\mathrm{R}} \propto N^{-1} ) | N: number of monomers; γ: friction coefficient [11] |

| Zimm Model | Explicit (With HI) | ( D_{\mathrm{Z}} \propto N^{-\nu} ) | ν: Flory exponent (~0.6 in good solvent); η: viscosity [11] |

| Kirkwood-Zimm | Explicit (Finite Size) | ( D = \frac{D0}{N} + \frac{kB T}{6 \pi \eta } \langle \frac{1}{Rh} \rangle (1 - \langle \frac{Rh}{L} \rangle) ) | Rh: hydrodynamic radius; L: box size [11] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful calculation of diffusion coefficients relies on a suite of software tools and methodological considerations.

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Resources

| Tool/Resource | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Unwrapped Trajectory | A trajectory where atoms are not re-folded into the primary simulation box, preserving their true displacement. | Mandatory input for correct MSD calculation [4]. |

| MDAnalysis | A Python library for analyzing MD simulations. Contains the EinsteinMSD class for MSD calculation. |

Used to compute MSD with FFT-accelerated or windowed algorithms [4]. |

| tidynamics | A Python package for computing correlation functions and MSD. | Required by MDAnalysis for Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)-based MSD calculation (fft=True) [4]. |

| Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) | An algorithm that computes the MSD with O(N log N) scaling, much faster than the simple O(N²) method for long trajectories. | Essential for processing very long trajectories efficiently [4]. |

| Langevin Dynamics | An implicit solvent model that applies a frictional force and a random force to particles. | Models the Rouse regime for polymers, where hydrodynamic interactions are neglected [11]. |

| Lattice-Boltzmann (LB) Fluid | An explicit solvent model that simulates fluid dynamics on a lattice. | Models the Zimm regime for polymers, capturing hydrodynamic interactions [11]. |

Advanced Considerations and Best Practices

Finite-Size Effects

The calculated diffusion coefficient can be influenced by the finite size of the simulation box due to the long-range nature of hydrodynamic interactions [11]. A correction of the form ( (1 - \langle R_h / L \rangle) ), where L is the box length, can be applied, but accurately fitting this expression requires large systems and long simulation times [11].

Statistical Accuracy and Sampling

Obtaining a reliable MSD requires excellent statistical sampling. For single solute molecules in solution, this is particularly challenging, as even 80-nanosecond simulations can produce noisy, non-convergent MSD curves [13]. Efficient sampling strategies, such as averaging MSDs collected from multiple short simulations, can be beneficial [13].

The Green-Kubo Method

An alternative to the Einstein relation is the Green-Kubo method, which relates the diffusion coefficient to the integral of the velocity autocorrelation function (VACF) [11] [13]: [ D = \frac{1}{3} \int_0^{\infty} \langle \vec{v}(t) \cdot \vec{v}(0) \rangle dt ] While theoretically equivalent, in practice the MSD-based method is often preferred for its simpler convergence properties.

Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) is a fundamental metric in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, serving as a critical bridge between atomic-level motion and macroscopic material properties. This technical guide elucidates the theory behind MSD, provides detailed protocols for its calculation and analysis, and demonstrates its practical application in materials science and drug development. By framing MSD within the broader context of interpreting MD simulations, this whitepaper equips researchers with the methodologies to quantitatively link particle dynamics to properties such as diffusivity, viscosity, and phase behavior, thereby enabling more predictive material and pharmaceutical design.

In molecular dynamics simulations, the jostling of individual atoms presents a challenge: how does one translate this complex, microscopic motion into an understanding of a material's macroscopic behavior? The Mean Squared Displacement is a powerful and ubiquitous answer to this question. Rooted in the study of Brownian motion, MSD provides a statistical measure of the spatial extent of particle motion over time [14]. It is defined as the average squared distance a particle travels over a given time interval, serving as a direct gateway to understanding molecular mobility and the mechanisms of transport processes.

The power of MSD lies in its ability to connect the simulated atomic-scale trajectory—a prediction of how every atom in a system will move over time based on a molecular mechanics force field [15]—to experimentally accessible bulk properties. By applying the Einstein relation, the time evolution of MSD can be used to calculate the self-diffusion coefficient, a key macroscopic transport property [14]. This makes MSD an indispensable tool in fields ranging from the development of energy storage materials, where it helps screen for effective freezing point inhibitors in ice slurry systems [16], to drug discovery, where it can illuminate the dynamics of proteins and other biomolecules critical to neuronal signaling and pharmaceutical targeting [15].

Theoretical Foundations: From Atomic Trajectories to Macroscopic Properties

The Mathematical Definition of MSD

The MSD is calculated from particle trajectories obtained from an MD simulation. For a system of N particles, the MSD as a function of time lag, τ, is given by the Einstein formula:

[MSD(\tau) = \bigg{\langle} \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} |\vec{r}i(t0 + \tau) - \vec{r}i(t0)|^2 \bigg{\rangle}{t_{0}}]

Here, (\vec{r}i(t)) is the position of particle (i) at time (t), and the angle brackets denote an average over all possible starting times, (t0) [14]. This averaging is crucial for obtaining a statistically robust measure, especially in MD simulations where finite trajectory length can limit data quality.

The Critical Link: MSD and Self-Diffusivity

The most direct application of MSD is the calculation of the self-diffusion coefficient, (D). In the long-time limit, for a system undergoing normal (Fickian) diffusion, the MSD becomes a linear function of time. The self-diffusivity is then derived from the slope of this linear regime:

[D = \frac{1}{2d} \lim_{\tau \to \infty} \frac{d}{d\tau} MSD(\tau)]

where (d) is the dimensionality of the MSD [14]. For example, for a 3D MSD, the denominator factor is 6. This relationship is the primary conduit through which microscopic motion, as captured by MD, informs our understanding of macroscopic diffusion. It is critical to note that this derivation assumes particle motion is Brownian and that the displacement distribution is Gaussian; a significant non-Gaussianity can invalidate the simple relation between MSD and the dynamic structure factor [17].

MSD as a Probe of Dynamical Regimes

Beyond simple diffusion, the time-dependence of the MSD can reveal rich details about a system's dynamical behavior. A log-log plot of MSD(τ) versus τ is often used to identify different power-law regimes, (MSD(\tau) \sim \tau^{\alpha}), where the exponent α characterizes the type of motion [17]:

- α = 1: Indicates normal, Brownian diffusion.

- α < 1: Signifies sub-diffusion, common in confined or viscoelastic environments like polymer melts or cellular cytoplasm.

- α > 1: Suggests super-diffusion or ballistic motion, typically observed at very short time scales before particles undergo collisions.

For instance, in simulated polymer melts, the tube-reptation model predicts a series of power-law regimes for the MSD of polymer beads (e.g., τ¹/⁴, τ¹/²) corresponding to different relaxation mechanisms [17]. However, a continuous curvature in log-log plots often suggests these power-law regimes are not as distinct as once hypothesized [17].

Practical Computation: Protocols and Pitfalls

Essential Preprocessing of Trajectory Data

A critical, often overlooked, step in MSD calculation is the preparation of trajectory data. To accurately represent long-distance diffusion, coordinates must be in an "unwrapped" convention [14]. When atoms cross periodic boundaries, they must not be wrapped back into the primary simulation cell, as this would artificially truncate their displacements. Some simulation packages provide utilities for this, such as gmx trjconv in GROMACS with the -pbc nojump flag.

Calculation Methods and Algorithms

Two primary algorithms are used for MSD computation, each with distinct performance characteristics:

Table 1: Comparison of MSD Calculation Algorithms

| Algorithm | Description | Computational Scaling | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Windowed (Direct) | Directly implements the Einstein formula by averaging over all possible time origins for a given lag time. | O(τ_max²) with respect to maximum lag time | Conceptually simple, easy to implement | Computationally intensive for long trajectories |

| Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) | Leverages FFT to compute the autocorrelation of velocities, equivalent to the MSD. | O(τmax log(τmax)) | Much faster for long trajectories, preferred for production work | Requires the tidynamics package; more complex implementation |

The FFT-based method is generally recommended for its superior efficiency, and it is the default in tools like MDAnalysis when fft=True is specified [14].

A Step-by-Step Computational Protocol

The following workflow, implementable with tools like MDAnalysis, outlines a robust protocol for computing MSD and the diffusion coefficient [14]:

Figure 1: A computational workflow for calculating diffusion coefficients from MD trajectories using Mean Squared Displacement.

- Load Trajectory: Load the unwrapped trajectory into an analysis framework (e.g., MDAnalysis).

- Compute MSD: Instantiate and run the

EinsteinMSDclass. - Plot for Inspection: Visually inspect the MSD versus lag time to gauge data quality.

- Identify the Linear Regime: Use a log-log plot to find the region where the slope is approximately 1, indicating normal diffusion. Avoid short-time ballistic and long-time poorly averaged regions.

- Fit and Calculate D: Perform a linear regression on the linear segment of the MSD plot.

Uncertainty Quantification and Best Practices

The uncertainty in a derived diffusion coefficient depends not only on the simulation data but also on the analysis protocol, including the choice of statistical estimator and the fitting window [18]. To ensure robust results:

- Replicate Sampling: Combine MSDs from multiple independent simulation replicates by averaging

msds_by_particleacross runs, rather than concatenating trajectories [14]. - Report Fitting Ranges: Always explicitly state the lag-time range used for the linear fit, as this choice significantly impacts the result [18].

- Check for Gaussianity: For the diffusion coefficient to be meaningful, the distribution of particle displacements should be Gaussian. The non-Gaussianity parameter ( \alpha_2(t) ) can be used to check this [17].

MSD in Action: A Case Study in Energy Storage

The application of MSD is powerfully illustrated by research into ice slurry, a promising energy storage medium. A key challenge is controlling the supercooling of water using freezing point inhibitors like ethanol, NaCl, or SiO₂ nanoparticles. Molecular dynamics simulations were employed to investigate the interaction mechanism of these additives with water on a molecular scale [16].

In this study, MSD was used to analyze the transport properties of water molecules in the presence of different additives. The results demonstrated that ethanol and NaCl inhibited the formation of water-water hydrogen bonds and promoted the generation of water-additive bonds, which in turn weakened the diffusion motion of water molecules, as evidenced by a lower MSD. The addition of SiO₂ nanoparticles led to agglomeration, increasing the system's viscosity and further reducing its diffusion rate [16]. This direct link, established via MSD, between molecular structure, hydrogen bonding, and macroscopic diffusivity/viscosity provides a microscopic rationale for the efficacy of these additives, guiding the screening of improved freezing point inhibitors.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for MD Studies of Aqueous Systems

| Reagent / Material | Function in MD Simulation | Microscopic Effect Revealed by MSD | Impact on Macroscopic Property |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol (C₂H₅OH) | Freezing point inhibitor, alcoholic additive | Reduces water self-diffusion; inhibits water-water H-bonds [16] | Lowers freezing point; improves ice slurry fluidity [16] |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Ionic additive, freezing point depressant | Alters water structure and ion mobility; lowers MSD of water [16] | Prevents ice crystallization in pipelines [16] |

| Silicon Dioxide (SiO₂) | Nanoparticle additive | Causes agglomeration, increasing viscosity and reducing MSD [16] | Enhances heat transfer efficiency; shortens freezing time [16] |

| Water (H₂O) | Primary energy storage medium | Reference system for MSD and hydrogen-bond analysis [16] | Baseline for latent heat and fluidity properties [16] |

Advanced Applications and Future Outlook

MSD analysis continues to evolve, finding applications in increasingly complex systems. In drug development, MSD is used to study the dynamics of proteins like GPCRs and ion channels, where the mobility of different regions of the protein can be linked to function and ligand binding [15]. In materials science, MSD analysis of polymer melts tests the validity of longstanding models like reptation, with recent reviews suggesting a need for more nuanced interpretations of polymer dynamics beyond simple power-law regimes [17].

Future progress will be driven by more sophisticated analysis that moves beyond simple MSD. Researchers are increasingly correlating MSD with other metrics, such as the non-Gaussian parameter, to detect heterogeneous dynamics. Furthermore, the integration of machine learning with MD simulation data holds promise for automatically identifying dynamical regimes and predicting macroscopic properties from shorter, more computationally feasible simulations. As MD simulations become more powerful and accessible [15], the role of MSD as a primary tool for connecting the atomic and macroscopic worlds will only grow in importance.

Calculating and Applying MSD: From Code to Real-World Research

A Step-by-Step Guide to MSD Computation in GROMACS and MDAnalysis

Mean Square Displacement (MSD) analysis represents a cornerstone technique in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for characterizing molecular motion and quantifying transport properties. This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for implementing MSD computations within two prominent MD tools: GROMACS and MDAnalysis. By establishing standardized protocols and interpretation methodologies, we aim to enhance reproducibility and accuracy in diffusion coefficient calculations, thereby supporting critical research applications in materials science and drug development. The protocols outlined herein emphasize proper trajectory preprocessing, parameter selection, and linear fitting procedures essential for deriving meaningful diffusion data from MD trajectories.

Theoretical Foundation

The Mean Square Displacement (MSD) is a fundamental statistical measure quantifying the spatial deviation of particles from their reference positions over time. In molecular dynamics, MSD provides critical insights into atomic and molecular mobility, serving as the primary basis for calculating diffusion coefficients through the Einstein relation [1] [19]. The MSD for a system of N particles is defined as:

[ \text{MSD}(t) = \left\langle \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} | \mathbf{r}i(t) - \mathbf{r}_i(0) |^2 \right\rangle ]

where (\mathbf{r}_i(t)) denotes the position of particle (i) at time (t), and the angle brackets represent averaging over time origins [14] [1]. For Brownian motion in an isotropic medium, the MSD exhibits a linear relationship with time, expressed as (\text{MSD}(t) = 2dDt), where (d) represents the dimensionality of the diffusion and (D) is the self-diffusion coefficient [1] [20]. This relationship forms the theoretical foundation for extracting transport properties from MD trajectories.

Significance in Molecular Research

In pharmaceutical and biomolecular research, MSD analysis enables researchers to characterize molecular mobility in various environments, including lipid bilayers, protein interiors, and solvent domains. Accurate diffusion coefficient measurements inform drug delivery strategies, protein folding studies, and membrane permeability predictions. The interpretation of MSD curves extends beyond simple diffusion coefficients, revealing constrained motion in binding pockets, directed transport in channel proteins, and phase-dependent mobility in heterogeneous systems [21].

Computational Foundations

Prerequisite Knowledge

Implementing proper MSD analysis requires understanding of several MD fundamentals. Researchers must recognize the distinction between wrapped and unwrapped trajectories, as MSD calculations require coordinates that maintain molecular continuity across periodic boundaries [14] [22]. Additionally, familiarity with basic command-line operation and scripting proficiency (particularly in Python for MDAnalysis implementations) is essential for executing the protocols outlined in subsequent sections.

Essential Preprocessing Steps

Trajectory preprocessing represents a critical, often overlooked component of accurate MSD computation. For both GROMACS and MDAnalysis, trajectories must be "unwrapped" or treated with "nojump" corrections to prevent artificial displacement artifacts when molecules cross periodic boundaries [14] [22]. In GROMACS, this is achieved using gmx trjconv with the -pbc nojump flag, while MDAnalysis provides the NoJump transformation for this purpose. Center-of-mass motion removal may also be necessary for proper diffusion analysis in isolated systems [23].

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for MSD Computation

| Component | Specification | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| MD Trajectory File | GROMACS (.xtc, .trr), MDAnalysis-compatible | Contains atomic coordinates across simulation timeframe |

| Topology File | .tpr (GROMACS), .pdb, .gro (MDAnalysis) | Defines molecular structure and atom identities |

| Index File | .ndx (GROMACS) | Specifies atom groups for analysis |

| Selection Syntax | MDAnalysis text selection | Identifies atoms for MSD calculation |

| FFT Library | tidynamics (for MDAnalysis) | Accelerates MSD computation |

MSD Computation in GROMACS

Core Implementation

GROMACS provides the gmx msd utility for calculating mean square displacement directly from trajectory files. The basic command structure requires a trajectory file and corresponding topology, with options to specify analysis parameters [24] [23]:

This command computes the 3D MSD for groups defined in index.ndx, using reference points every 100 ps and fitting the MSD curve between 50 ps and 500 ps to determine the diffusion coefficient. The -type option enables dimensional control, allowing computation of lateral diffusion (-type xy) or axis-specific MSD components [24].

Critical Parameters and Optimization

Several parameters significantly impact the accuracy and efficiency of MSD calculations in GROMACS. The -trestart value determines the time between reference points for MSD computation, influencing statistical averaging. The -beginfit and -endfit parameters define the temporal region for linear regression, which should target the diffusive regime while avoiding ballistic motion at short times and poorly averaged displacements at long times [24] [23]. For large trajectories, the -maxtau option caps the maximum time delta for frame comparisons, preventing memory issues while maintaining accuracy in the well-sampled region [24].

Table 2: Essential GROMACS msd Parameters

| Parameter | Default Value | Recommended Setting | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

-type |

unused | xyz (3D) or xy (2D) | Dimensionality for MSD calculation |

-trestart |

10 ps | 50-200 ps | Time between reference points |

-beginfit |

-1 (10%) | Start of linear regime | Start time for fitting |

-endfit |

-1 (90%) | End of linear regime | End time for fitting |

-maxtau |

~1.8e+308 ps | 1/4-1/2 trajectory length | Maximum time delta for calculation |

Advanced Applications

For molecule-specific diffusion analysis, the -mol flag enables MSD computation for individual molecules based on center-of-mass motion [24] [23]. This approach automatically handles molecular continuity across periodic boundaries and provides diffusion coefficients for each molecule, enabling heterogeneity assessment in multi-component systems. The -ten option generates the full MSD tensor, valuable for anisotropic diffusion characterization in oriented systems such as lipid bilayers or liquid crystals [24].

MSD Computation in MDAnalysis

Core Implementation

MDAnalysis implements MSD analysis through the EinsteinMSD class, which provides a Python-based workflow compatible with diverse trajectory formats [14] [22]. The basic implementation requires universe creation, MSD object initialization, and trajectory analysis:

This script computes the 3D MSD for alpha carbon atoms using the FFT-accelerated algorithm, significantly improving computational efficiency for long trajectories [14]. The msd_type parameter offers dimensional flexibility, supporting specific coordinate combinations ('x', 'y', 'z', 'xy', etc.) for specialized diffusion analysis.

Critical Parameters and Optimization

The fft parameter represents a crucial optimization in MDAnalysis, enabling orders-of-magnitude speed improvement for long trajectories through Fast Fourier Transform computation [14] [22]. The select parameter accepts MDAnalysis selection strings, providing precise atomic grouping without external index files. For non-uniformly sampled trajectories, the non_linear parameter ensures proper MSD calculation when frame intervals vary [22].

Table 3: Essential MDAnalysis EinsteinMSD Parameters

| Parameter | Default Value | Recommended Setting | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

select |

'all' | MDAnalysis selection text | Atoms for MSD calculation |

msd_type |

'xyz' | 'xyz', 'xy', 'x', etc. | Dimensionality for MSD |

fft |

True | True (if tidynamics installed) | FFT acceleration |

non_linear |

False | True for uneven sampling | Handles non-uniform trajectories |

Diffusion Coefficient Extraction

MDAnalysis requires explicit fitting of the MSD curve to determine diffusion coefficients, typically implemented through linear regression:

This approach provides researchers with complete control over the fitting process, enabling careful selection of the diffusive regime and appropriate error analysis through regression statistics [14].

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Identifying Diffusion Regimes

Proper MSD interpretation requires distinguishing between different dynamical regimes present in the displacement data [21]. Short-time behavior often exhibits ballistic motion (MSD ∝ t²) where particles move with approximately constant velocity between collisions. The intermediate time scale typically reveals the diffusive regime (MSD ∝ t) essential for diffusion coefficient calculation. Long-time MSD values may display statistical fluctuations due to finite sampling, which should be excluded from diffusion fitting [14] [20].

Figure 1: MSD Interpretation Workflow - This diagram illustrates the process for identifying different regimes in an MSD plot and extracting the diffusion coefficient from the linear portion.

Optimal Fitting Strategies

The accurate determination of diffusion coefficients depends critically on selecting the appropriate fitting range within the MSD curve [20]. Research indicates that the optimal number of MSD points for fitting balances sufficient statistical averaging against inclusion of poorly sampled long-time displacements. For GROMACS, automated fitting between 10%-90% of the trajectory duration (achieved with -beginfit -1 -endfit -1) provides a reasonable default, though manual range specification based on visual MSD inspection often yields superior results [24] [23]. In MDAnalysis, the fitting range should target the region where the log-log MSD plot exhibits unit slope, confirming true diffusive behavior [14].

Error Analysis and Validation

Robust MSD analysis requires comprehensive error assessment. GROMACS provides error estimates based on differential fitting of trajectory halves, while MDAnalysis implementations can employ statistical techniques such as block averaging or bootstrap resampling [24] [20]. For experimental validation, researchers should compare computed diffusion coefficients against established reference values, such as water self-diffusion (2.3×10⁻⁵ cm²/s at 25°C), ensuring proper forcefield parameterization and simulation equilibration.

Comparative Workflow Analysis

Cross-Platform Methodology

The following diagram provides a unified workflow for MSD computation applicable to both GROMACS and MDAnalysis, highlighting platform-specific considerations:

Figure 2: Unified MSD Computation Workflow - This diagram illustrates the comprehensive procedure for MSD analysis, encompassing both GROMACS and MDAnalysis implementations with their respective processing steps.

Platform Selection Guidelines

GROMACS excels in computational efficiency for standard trajectory formats and integrated analysis pipelines, making it ideal for high-throughput screening applications. MDAnalysis offers superior flexibility for complex selection criteria, customized analysis workflows, and non-standard trajectory formats, particularly valuable for heterogeneous systems and method development. Research requiring molecule-specific diffusion coefficients or full MSD tensor analysis may benefit from GROMACS implementation, while investigations needing specialized fitting procedures or multi-trajectory averaging may prefer MDAnalysis.

MSD computation represents an essential methodology in molecular dynamics research, providing fundamental insights into molecular mobility and transport phenomena. This guide has established standardized protocols for GROMACS and MDAnalysis implementations, emphasizing proper trajectory preprocessing, parameter selection, and data interpretation techniques. By adhering to these structured approaches, researchers can ensure accurate, reproducible diffusion coefficient determination, thereby enhancing the reliability of molecular simulation data for drug development and materials design applications. Future methodology developments will likely focus on automated regime identification, enhanced error quantification, and machine learning approaches for analyzing heterogeneous diffusion in complex systems.

The mean squared displacement (MSD) is a fundamental metric in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for characterizing particle motion and calculating transport properties like self-diffusivity. Computed using the Einstein relation, the MSD quantifies the average squared distance particles travel over time: MSD(δt) = ⟨|r(δt) - r(0)|²⟩, where r represents particle position and the angle brackets denote averaging over both particles and time origins [1]. However, the accuracy of this calculation depends critically on a often-overlooked preprocessing step: handling periodic boundary conditions (PBC) and ensuring trajectories are in the "unwrapped" convention [4].

Without correct PBC handling, the MSD calculated from a simulation trajectory can be severely underestimated, leading to incorrect diffusion coefficients and fundamentally flawed interpretations of molecular mobility. This occurs because PBC artifacts introduce fictitious jumps in particle coordinates as molecules cross unit cell boundaries, breaking the continuous trajectories that MSD analysis requires. This technical guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with comprehensive methodologies for identifying and correcting PBC issues to ensure reliable MSD interpretation within broader molecular dynamics research.

The Core Challenge: PBC Artifacts in MSD Analysis

Understanding the Wrapping Problem

Molecular dynamics simulations typically employ periodic boundary conditions to model bulk systems while conserving computational resources. In this setup, when a particle exits the primary simulation box through one face, it simultaneously re-enters through the opposite face. While physically correct for the simulation, this creates a critical problem for MSD analysis: the coordinates stored in trajectory files often represent this "wrapped" configuration where molecules appear to jump to the opposite side of the box [25].

These artificial discontinuities violate the fundamental assumption of MSD analysis – that particle displacement reflects continuous Brownian motion. When molecules cross PBC boundaries, the MSD calculation interprets these jumps as reversed motion, leading to characteristic plateauing in MSD curves and artificially suppressed diffusion coefficients. The following table summarizes how PBC artifacts manifest in MSD analysis:

Table 1: Impact of PBC Artifacts on MSD Analysis

| Aspect | Correct MSD (Unwrapped) | Incorrect MSD (Wrapped) |

|---|---|---|

| Trajectory Continuity | Continuous paths across PBC | Artificial jumps at box edges |

| MSD Curve Shape | Linear at relevant timescales | Premature plateauing |

| Diffusion Coefficient | Accurate calculation | Severely underestimated |

| Physical Interpretation | Valid molecular mobility | Artificially confined system |

Visualizing the PBC Wrapping Problem

The following workflow diagram illustrates how PBC wrapping affects trajectories and the critical preprocessing steps needed for correction:

Diagram Title: PBC Correction Workflow for MSD Analysis

Practical Implementation: Correction Methodologies

Identifying Wrapped Trajectories

Before applying corrections, researchers must identify whether their trajectories require unwrapping. Visual inspection using tools like NGL Viewer often reveals telltale signs of PBC issues [25]:

- Molecules appearing to cross through each other without physical interaction

- Artificially stretched bonds across the simulation box

- Discontinuous motion where molecules jump to opposite box sides

Programmatic checks can include calculating the maximum displacement of atoms between consecutive frames - unexpectedly large values may indicate PBC crossings.