How to Choose a Statistical Ensemble for MD Simulation: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Selecting the appropriate statistical ensemble is a critical, non-trivial step in setting up molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, directly impacting the physical relevance and quantitative accuracy of the results for biomedical...

How to Choose a Statistical Ensemble for MD Simulation: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

Selecting the appropriate statistical ensemble is a critical, non-trivial step in setting up molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, directly impacting the physical relevance and quantitative accuracy of the results for biomedical systems. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals, guiding them from foundational concepts to advanced application. It covers the core theory behind major ensembles (NVE, NVT, NPT), outlines a methodology for selecting an ensemble based on the specific biological question and available experimental data, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges related to sampling and convergence, and finally, details rigorous validation protocols to ensure simulated conformational ensembles accurately reproduce experimental observables.

Understanding the Core Ensembles: The Statistical Mechanics Foundation of MD

What is a Statistical Ensemble? Connecting MD to Thermodynamics

In the realm of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, a statistical ensemble is a foundational theoretical framework that bridges the microscopic behavior of atoms and molecules with macroscopic thermodynamic observables. An ensemble is defined as a collection of virtual, independent copies of a system, each representing a possible microstate consistent with known macroscopic constraints [1] [2]. This conceptual framework allows researchers to calculate macroscopic properties by performing averages over all these possible microstates, effectively connecting the deterministic evolution of individual atoms described by Newton's equations of motion to the probabilistic nature of thermodynamics [3] [2]. The core purpose of employing statistical ensembles in MD is to provide a rigorous mathematical foundation for simulating systems under specific experimental conditions, such as constant temperature or pressure, thereby enabling the prediction of thermodynamic properties from atomistic models [4] [5].

The choice of statistical ensemble is a critical first step in designing an MD simulation, as it determines which thermodynamic quantities remain fixed during the simulation and consequently influences the structural, energetic, and dynamic properties that can be reliably calculated [5] [6]. Different ensembles represent systems with varying degrees of isolation from their environment, ranging from completely isolated systems (microcanonical ensemble) to completely open ones (grand canonical ensemble) [4]. The principle of ensemble equivalence states that in the thermodynamic limit (as system size approaches infinity), different ensembles yield equivalent results for macroscopic properties, though fluctuations may vary significantly between ensembles [2]. For molecular dynamics practitioners, understanding these nuances is essential for both interpreting simulation results and designing computationally efficient protocols that accurately mimic the experimental conditions of interest.

Theoretical Foundation: Connecting Microscopic States to Macroscopic Observables

The mathematical foundation of statistical ensembles rests on statistical mechanics, which applies statistical methods and probability theory to large assemblies of microscopic entities [1]. This approach addresses a fundamental disconnect: while the laws of mechanics (classical or quantum) precisely determine the evolution of a system from a known initial state, we rarely possess complete knowledge of a system's microscopic state in practical scenarios [1]. Statistical mechanics bridges this gap by introducing uncertainty about which specific state the system occupies, focusing instead on the distribution of possible states.

The connection between microscopic behavior and macroscopic observables is formalized through the concept of ensemble averages [2]. In this framework, every macroscopic property (denoted as A) corresponds to a microscopic function (denoted as a(x)) that depends on the positions and momenta of all particles in the system. The macroscopic observable is then calculated as the average of this microscopic function over all systems in the ensemble [6]:

A = ⟨a⟩ = 1/Z ∑ a(xλ)

Here, Z represents the total number of members in the ensemble, and xλ denotes the phase space coordinates of the λ-th member [6]. This averaging procedure effectively replaces the impractical task of tracking individual atomic motions with a statistically robust method for predicting thermodynamic behavior.

A key postulate underlying most equilibrium ensembles is the equal a priori probability postulate, which states that for an isolated system with exactly known energy and composition, the system can be found with equal probability in any microstate consistent with that knowledge [1]. This principle leads directly to the concept of entropy in the microcanonical ensemble, defined by Boltzmann's famous equation S = k log Ω, where Ω is the number of accessible microstates and k is Boltzmann's constant [7] [2]. From this foundation, we can derive all other thermodynamic potentials and relationships, creating a complete bridge between atomic-scale simulations and laboratory-measurable quantities.

Molecular dynamics simulations can be conducted in several thermodynamic ensembles, each characterized by which state variables are held constant during the simulation. The choice of ensemble determines the methods used to control temperature and pressure and influences which properties can be most accurately calculated [5]. The most commonly used ensembles in biomolecular simulations are the microcanonical (NVE), canonical (NVT), and isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensembles.

Table 1: Key Statistical Ensembles in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Ensemble | Constant Parameters | Primary Control Methods | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microcanonical (NVE) | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Energy (E) | Newton's equations without temperature/pressure control | Studying isolated systems; energy conservation studies [4] [5] |

| Canonical (NVT) | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Thermostats (e.g., velocity scaling, Nosé-Hoover) | Conformational searches in vacuum; systems where volume is fixed [4] [5] [6] |

| Isothermal-Isobaric (NPT) | Number of particles (N), Pressure (P), Temperature (T) | Thermostats + Barostats (volume rescaling) | Simulating laboratory conditions; studying density fluctuations [4] [5] |

| Grand Canonical (μVT) | Chemical potential (μ), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Particle exchange with reservoir | Systems with varying particle numbers (adsorption, open systems) [4] [1] |

Microcanonical Ensemble (NVE)

The microcanonical ensemble represents completely isolated systems that cannot exchange energy or matter with their surroundings [4] [2]. In this ensemble, the number of particles (N), the volume (V), and the total energy (E) all remain constant. The NVE ensemble is generated by solving Newton's equations of motion without any temperature or pressure control mechanisms, which ideally conserves the total energy of the system [5]. In practice, however, numerical errors in the integration algorithms can lead to minor energy drift [5]. According to the fundamental postulate of equal a priori probability, all accessible microstates in the NVE ensemble are equally probable, which leads to Boltzmann's definition of entropy: S = k log Ω, where Ω is the number of microstates consistent with the fixed energy [7] [2].

While the NVE ensemble provides the most direct implementation of Newtonian mechanics, it is generally not recommended for the equilibration phase of simulations because achieving a desired temperature without energy exchange with a thermal reservoir is difficult [5]. However, it remains valuable for production runs when researchers wish to explore the constant-energy surface of conformational space without perturbations introduced by temperature- or pressure-bath coupling, or when studying inherently isolated systems [5]. The microcanonical ensemble also serves as a fundamental starting point in statistical mechanics from which other ensembles can be derived [2].

Canonical Ensemble (NVT)

The canonical ensemble describes systems in thermal equilibrium with a much larger heat bath, allowing energy exchange but maintaining fixed particle number and volume [7] [2]. This ensemble is characterized by constant number of particles (N), constant volume (V), and constant temperature (T). The temperature control is typically implemented through various thermostating methods that adjust atomic velocities to maintain the desired kinetic temperature [4] [5]. In the NVT ensemble, the probability of finding the system in a particular microstate with energy E follows the Boltzmann distribution, proportional to e^(-E/kT) [2].

The central quantity in the canonical ensemble is the partition function Z = ∑ e^(-βE_i), where β = 1/kT, which serves as a generating function for all thermodynamic properties [2]. From the partition function, one can derive the Helmholtz free energy F = -kT log Z, which is minimized at equilibrium for systems at constant temperature and volume [2]. The NVT ensemble is particularly useful for studying systems where volume is constrained, such as conformational searches of molecules in vacuum without periodic boundary conditions, or when researchers wish to avoid the additional perturbations introduced by pressure control [5]. It also serves as the appropriate choice for simulating many in vitro experimental conditions where volume is fixed but temperature is controlled.

Isothermal-Isobaric Ensemble (NPT)

The isothermal-isobaric ensemble maintains constant number of particles (N), constant pressure (P), and constant temperature (T), making it perhaps the most relevant ensemble for simulating laboratory conditions where experiments are typically conducted at constant atmospheric pressure rather than constant volume [4] [5]. In this ensemble, the system is allowed to exchange both energy and volume with its surroundings, requiring implementation of both a thermostat to control temperature and a barostat to maintain constant pressure by adjusting the simulation box dimensions [4] [5]. For molecular systems in solution, the NPT ensemble ensures correct density and proper treatment of volumetric fluctuations.

The NPT ensemble is particularly valuable during equilibration phases to achieve desired temperature and pressure before potentially switching to other ensembles for production runs, though many modern simulations remain in NPT throughout [5]. This ensemble naturally captures the density fluctuations that occur in real systems at constant pressure and is essential for studying processes like phase transitions, biomolecular folding under physiological conditions, and materials under mechanical stress. The corresponding thermodynamic potential for the NPT ensemble is the Gibbs free energy, which is minimized at equilibrium for systems at constant temperature and pressure [2].

Practical Implementation: MD Simulation Protocols Using Different Ensembles

A typical molecular dynamics simulation protocol employs multiple ensembles in sequence to properly prepare and equilibrate the system before production data collection. The standard workflow progresses through initialization, minimization, equilibration in NVT and NPT ensembles, and finally production simulation in the desired target ensemble [4].

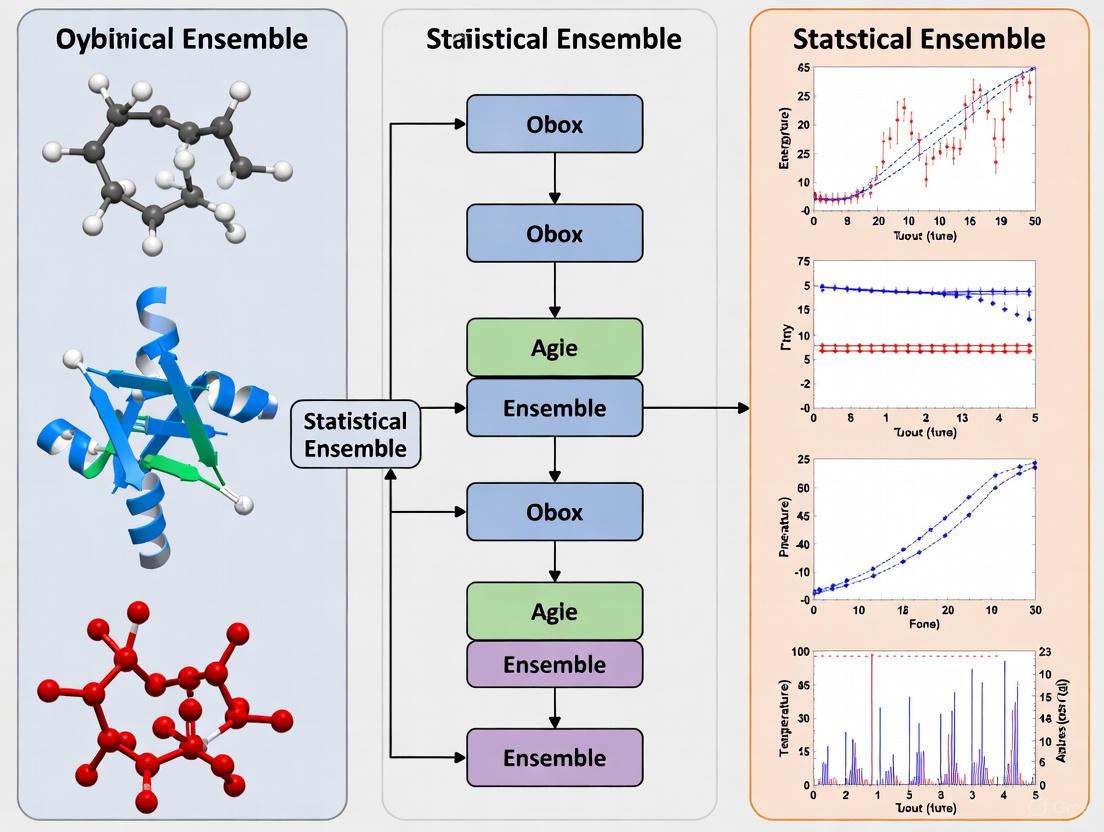

Diagram 1: Standard MD Simulation Workflow

System Setup and Energy Minimization

Before beginning any dynamics, the initial molecular structure must be prepared and optimized. This initial phase involves constructing the system with appropriate protonation states, solvation, and ion concentration to match the experimental conditions of interest [3]. Energy minimization follows, which relieves any steric clashes or unrealistic geometries in the initial configuration by finding the nearest local energy minimum. This step is crucial for preventing numerical instabilities when dynamics commence and is typically performed without temperature control.

NVT Equilibration Phase

The first equilibration stage employs the NVT ensemble to stabilize the system temperature. During this phase, the coordinates of solute atoms may be restrained with harmonic constraints while solvent and ions are allowed to move freely. Temperature is controlled using thermostats such as velocity rescaling, Nosé-Hoover, or Langevin dynamics [4] [5]. The NVT equilibration typically runs for hundreds of picoseconds to several nanoseconds, until the temperature fluctuates around the target value and the system kinetic energy distribution matches the theoretical Boltzmann distribution for the desired temperature.

NPT Equilibration Phase

Once the temperature has stabilized, the simulation switches to the NPT ensemble to achieve the correct system density and pressure. During this phase, both temperature and pressure controls are active, with barostats regulating the simulation box dimensions to maintain constant pressure [4] [5]. The NPT equilibration continues until properties such as density, potential energy, and system volume reach stable equilibrium with fluctuations around consistent average values. For biomolecular systems in water, this typically requires nanoseconds of simulation time depending on system size and complexity.

Production Simulation

After complete equilibration, the production simulation is conducted to collect data for analysis. While NPT is often maintained during production to mimic laboratory conditions, some researchers switch to NVE for production runs to avoid potential artifacts from the thermostat and barostat algorithms [5]. The production phase should be sufficiently long to ensure adequate sampling of the relevant conformational space, which for biomolecular systems can range from nanoseconds to microseconds or beyond, depending on the processes being studied [3]. Throughout this phase, trajectory data is saved at regular intervals for subsequent analysis of structural, dynamic, and thermodynamic properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Ensemble-Based MD Simulations

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Ensemble Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Thermostats | Nosé-Hoover, Berendsen, Velocity Rescaling, Langevin | Maintain constant temperature by scaling velocities or adding stochastic forces [4] [5] |

| Barostats | Parrinello-Rahman, Berendsen, Martyna-Tobias-Klein | Maintain constant pressure by adjusting simulation box dimensions [4] [5] |

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS, GROMOS | Provide potential energy functions and parameters for calculating atomic interactions [3] |

| Software Packages | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER, OpenMM | Implement ensemble methods and provide simulation workflows [4] [3] |

| Analysis Tools | MDTraj, VMD, GROMACS analysis suite | Calculate ensemble averages and fluctuations from trajectory data [3] |

Successful implementation of ensemble-based MD simulations requires careful selection of control algorithms and analysis methods. Thermostats are essential for NVT and NPT ensembles, with modern implementations like the Nosé-Hoover thermostat providing a rigorous extension of the phase space that generates the correct canonical distribution [4]. Similarly, barostats like the Parrinello-Rahman algorithm allow for fully flexible simulation boxes that can accommodate anisotropic changes in cell dimensions, which is particularly important for crystalline systems or materials under non-hydrostatic stress [5].

The choice of force field represents another critical decision point, as the accuracy of the potential energy function directly impacts the reliability of simulated thermodynamic properties [3]. Modern biomolecular force fields like CHARMM, AMBER, and OPLS are parameterized to reproduce experimental data such as densities, solvation free energies, and conformational preferences, ensuring that ensemble averages correspond to physically meaningful values [3]. Finally, robust analysis software is necessary to compute ensemble averages and fluctuations from trajectory data, transforming atomic coordinates and velocities into thermodynamic observables and structural insights.

The strategic selection of an appropriate statistical ensemble is a critical decision in molecular dynamics research that should align with both the scientific questions being addressed and the experimental conditions being modeled. For simulations aiming to reproduce typical laboratory environments, the NPT ensemble is generally most appropriate as it maintains constant temperature and pressure, matching common experimental conditions [4] [5]. For studies of isolated systems or when energy conservation is prioritized over experimental correspondence, the NVE ensemble may be preferable despite its limitations for equilibration [5]. The NVT ensemble remains valuable for specific applications where volume must be constrained, such as in some materials science applications or when comparing directly to constant-volume experimental data [5].

The principle of ensemble equivalence provides theoretical justification for expecting consistent results from different ensembles in the thermodynamic limit, though finite-size systems and specific fluctuation properties may show ensemble-dependent variations [2]. By understanding the theoretical foundations, practical implementations, and research applications of statistical ensembles, molecular simulation researchers can make informed decisions that enhance the reliability and relevance of their computational studies, particularly in drug discovery where accurate prediction of binding affinities and conformational dynamics depends critically on proper thermodynamic sampling [7] [8]. As MD simulations continue to grow in importance for complementing experimental approaches across structural biology and materials science, mastery of ensemble selection remains fundamental to generating physically meaningful and scientifically valuable results.

The microcanonical (NVE) ensemble is a fundamental statistical ensemble used in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to model isolated systems. It is defined by the conservation of three key parameters: the number of particles (N), the system Volume, and the total Energy [9] [5]. This ensemble represents a perfectly isolated system that cannot exchange energy or matter with its surroundings [4]. In practice, MD simulations sampling the NVE ensemble are performed by integrating Newton's equations of motion without any temperature or pressure control mechanisms, allowing the system's dynamics to evolve solely under the influence of its internal forces [5].

While the NVE ensemble provides the most direct representation of Newtonian mechanics, its application requires careful consideration. Without energy exchange with an external bath, the temperature of the system becomes a fluctuating property determined by the balance between kinetic and potential energy [4]. This makes the NVE ensemble less suitable for equilibration phases where achieving a specific target temperature is crucial, but highly valuable for production runs where minimal perturbation to the natural dynamics is desired, such as when calculating dynamical properties from correlation functions [5] [10].

Theoretical Foundation and Practical Considerations

Mathematical Underpinnings and Numerical Integration

In NVE simulations, the system evolves according to Newton's second law of motion, where the force Fᵢ on each particle i with mass mᵢ is calculated as the negative gradient of the potential energy function V with respect to the particle's position rᵢ: Fᵢ = -∇ᵢV = mᵢaᵢ [11]. The integration of these equations of motion is typically performed using numerical algorithms like the Verlet integrator or its variant, the Velocity Verlet algorithm, which updates particle positions and velocities at each time step (∆t) [11].

The Velocity Verlet algorithm is particularly favored because it provides positions, velocities, and accelerations synchronously and requires storing only one set of these values. Its iterative process follows these steps for each particle i [11]:

- Calculate new positions based on current positions, velocities, and accelerations: rᵢ(t + ∆t) = rᵢ(t) + vᵢ(t)∆t + ½ aᵢ(t)∆t²

- Compute new forces Fᵢ(t + ∆t) and accelerations aᵢ(t + ∆t) from the potential energy field using the new positions

- Update velocities using the average of current and new accelerations: vᵢ(t + ∆t) = vᵢ(t) + ½ [aᵢ(t) + aᵢ(t + ∆t)]∆t

A critical aspect of NVE simulations is energy conservation. The total energy Eₜₒₜ = Eₖ + Eₚ should remain constant throughout the simulation. Significant drift in total energy typically indicates either a programming error or, more commonly, the use of an excessively large time step (∆t) [11]. The optimal ∆t represents a compromise between computational efficiency and numerical stability, often chosen to be on the order of femtoseconds (1-2 fs) for atomistic simulations [9].

Comparison with Other Common Ensembles

The choice of ensemble depends on the system being studied and the properties of interest. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of major ensembles used in MD simulations.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Molecular Dynamics Ensembles

| Ensemble | Acronym | Constant Parameters | Typical Applications | Physical System Analog |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microcanonical | NVE | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Energy (E) | Studying natural dynamics, gas-phase reactions, calculating spectra [10] | Isolated system [4] |

| Canonical | NVT | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Conformational searches in vacuum, systems where volume is fixed [5] [4] | System in thermal contact with a heat bath [4] |

| Isothermal-Isobaric | NPT | Number of particles (N), Pressure (P), Temperature (T) | Simulating laboratory conditions, studying pressure-dependent phenomena [5] [10] | System in contact with thermal and pressure reservoirs [4] |

| Constant-Pressure, Constant-Enthalpy | NPH | Number of particles (N), Pressure (P), Enthalpy (H) | Specialized applications requiring constant enthalpy [5] | Adiabatic system at constant pressure |

| Grand Canonical | μVT | Chemical potential (μ), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Studying open systems, adsorption phenomena [4] | Open system exchanging particles with a reservoir [4] |

While ensembles are theoretically equivalent in the thermodynamic limit (infinite system size), practical simulations with finite particle counts yield different results depending on the chosen ensemble [10]. For instance, if calculating an infrared spectrum of a liquid, one would typically equilibrate in the NVT ensemble and then switch to NVE for the production run because thermostats can decorrelate velocities, which would disrupt spectrum calculations based on velocity correlation functions [10].

Practical Implementation: Protocols and Setup

Standard Workflow for NVE Production Simulations

A typical MD protocol does not use a single ensemble throughout but employs different ensembles for equilibration and production phases. The NVE ensemble is most commonly used for the final production run after the system has been properly equilibrated [4]. The following workflow diagram illustrates this standard procedure:

Diagram 1: Standard MD protocol with NVE production.

As shown in Diagram 1, the system first undergoes energy minimization to remove steric clashes and unfavorable contacts in the initial structure [12] [13]. This is followed by NVT equilibration to bring the system to the desired temperature, often using a thermostat like Nosé-Hoover or Andersen [9] [4]. Subsequently, NPT equilibration adjusts the system density to the target pressure using a barostat [4]. Only after these preparatory steps is the NVE production run performed, during which data is collected for analysis with minimal interference from thermostats or barostats [5] [4].

Implementing NVE in VASP: A Case Study

In the VASP software package, there are multiple ways to set up an NVE molecular dynamics run. The simplest and recommended approach is to use the Andersen thermostat with the collision probability set to zero, effectively disabling the thermostat. The following table summarizes the key INCAR tags for NVE ensemble implementation in VASP [9]:

Table 2: NVE Ensemble Implementation Parameters in VASP [9]

| Parameter | Required Value for NVE | Description | Purpose in NVE Context |

|---|---|---|---|

IBRION |

0 | Selects molecular dynamics algorithm | Enables MD simulation mode |

MDALGO |

1 (Andersen) or 2 (Nosé-Hoover) | Specifies molecular dynamics algorithm | Framework for thermostat control |

ANDERSEN_PROB |

0.0 | Sets collision probability with fictitious heat bath | Disables thermostat when using Andersen |

SMASS |

-3 | Controls mass of Nosé-Hoover thermostat virtual degree of freedom | Disables thermostat when using Nosé-Hoover |

ISIF |

< 3 | Determines which stress tensor components are calculated and whether cell shape/volume changes | Ensures constant volume throughout simulation |

TEBEG |

User-defined (e.g., 300) | Sets the simulation temperature | Determines initial velocity distribution |

NSW |

User-defined (e.g., 10000) | Number of time steps | Defines simulation length |

POTIM |

User-defined (e.g., 1.0) | Time step in femtoseconds | Determines integration interval |

An example INCAR file for NVE simulation using the Andersen thermostat approach would include these key lines [9]:

It is crucial to set ISIF < 3 to enforce constant volume throughout the calculation. In NVE MD runs, there is no direct control over temperature and pressure; their average values depend entirely on the initial structure and initial velocities [9].

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of NVE ensemble simulations requires specific computational tools and "reagents." The following table details essential components for setting up and running NVE simulations.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NVE Ensemble Simulations

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in NVE Simulations | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Software Packages | Amber [12], GROMACS [13], NAMD [12], CHARMM [12], VASP [9] | Provides core simulation engine with integrators and force fields | VASP requires specific INCAR parameters [9]; GROMACS uses .mdp files [13] |

| Force Fields | AMBER ff14SB [14], CHARMM36 [14], GROMOS 54A7 [14], OPLS [14] | Defines potential energy function and parameters for interatomic interactions | Choice depends on system composition (proteins, nucleic acids, lipids) [14] |

| Initial Structures | PDB files [13], Computationally designed models [12] | Provides starting atomic coordinates | Can come from experimental sources (X-ray, NMR) or computational modeling [13] |

| Visualization & Analysis | VMD [12], Rasmol [13], Grace [13], cpptraj [12] | Trajectory visualization and property calculation | VMD supports multiple trajectory formats and analytical measurements [12] |

| Parameter Files | GROMACS .mdp files [13], VASP INCAR files [9] | Specifies simulation parameters and algorithms | Critical for proper ensemble selection and control of simulation conditions |

Application Notes and Case Studies

Dynamical Property Calculations

The NVE ensemble is particularly well-suited for calculating time-dependent properties and correlation functions because it preserves the natural dynamics of the system without the interference of thermostats. For example, when calculating infrared spectra from MD simulations, the NVE ensemble is essential because thermostats are designed to decorrelate velocities, which would destroy the velocity autocorrelation functions used to compute spectra [10]. Similarly, transport properties such as diffusion coefficients and viscosity are more accurately determined from NVE simulations where the equations of motion are integrated without perturbation.

In studies of gas-phase reactions without a buffer gas, the NVE ensemble is often the appropriate choice as it most closely mimics the conditions of an isolated molecular collision [10]. The conservation of energy in such systems ensures that the reaction dynamics follow natural Hamiltonian mechanics without artificial energy exchange with a thermal reservoir.

Limitations and Considerations for Biomolecular Systems

While valuable for specific applications, the NVE ensemble has limitations for biomolecular simulations. A sudden temperature increase due to energy conservation (where decreased potential energy leads to increased kinetic energy) may cause proteins to unfold, potentially compromising the experiment [4]. This makes NVE less suitable for the equilibration phases of biomolecular simulations.

Additionally, most experimental conditions correspond to constant temperature and pressure (NPT ensemble) rather than constant energy [4] [10]. Therefore, if the goal is to compare simulation results directly with laboratory experiments conducted at constant pressure, NPT simulations would be more appropriate for the production phase. The NVE ensemble remains valuable for studying fundamental dynamics and properties where minimal external perturbation is desired.

Within the broader context of selecting statistical ensembles for MD research, the NVE ensemble occupies a specific and important niche. It serves as the foundation for simulating isolated systems and studying natural dynamics without thermodynamic constraints. When designing an MD study, researchers should consider the NVE ensemble for [5] [10]:

- Production phases following proper equilibration in NVT/NPT ensembles

- Calculating dynamical properties and time correlation functions

- Simulating isolated systems such as gas-phase reactions

- Studies requiring minimal perturbation of the natural dynamics

The equivalence of ensembles in the thermodynamic limit means that for sufficiently large systems and away from phase transitions, different ensembles should yield consistent results for thermodynamic properties [10]. However, for practical simulations with finite system sizes and specific dynamical investigations, the choice of ensemble matters significantly. The NVE ensemble provides the most direct numerical implementation of Newton's equations of motion, making it an essential tool in the MD practitioner's toolkit for specific applications where energy conservation and natural dynamics are paramount.

The canonical, or NVT, ensemble is a cornerstone of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, where the number of particles (N), the volume of the system (V), and the temperature (T) are all held constant. This ensemble represents a system in thermal equilibrium with a heat bath at a fixed temperature, allowing for energy exchange while maintaining a constant particle count and volume [15]. In practical terms, this is often the ensemble of choice for production runs in many MD studies, particularly in drug discovery where simulating biological molecules at a constant, physiologically relevant temperature is paramount [16] [4].

The selection of an appropriate statistical ensemble is a critical first step in designing any MD research project. The NVT ensemble is particularly well-suited for studying processes where volume changes are negligible or where the system is confined, such as ion diffusion in solids, adsorption and reactions on surfaces, and the dynamics of proteins in a pre-equilibrated solvent box [16]. Its implementation requires the use of a thermostat to control the temperature, a crucial component that differentiates it from the energy-conserving NVE (microcanonical) ensemble.

Fundamental Principles and Thermostat Selection

In the NVT ensemble, the probability of the system being in a microstate with energy (Ei) is given by the Boltzmann distribution: [Pi = \frac{e^{-Ei/(kB T)}}{Z}] where (Z) is the canonical partition function, (k_B) is Boltzmann's constant, and (T) is the absolute temperature [15]. This fundamental relationship ensures that the system samples configurations consistent with a constant temperature.

The core challenge in NVT simulations is enforcing constant temperature despite the natural energy conservation of Newton's equations of motion. This is achieved by coupling the system to a thermostat, which acts as a heat bath. The choice of thermostat involves a trade-off between physical rigor, computational efficiency, and stability. The table below summarizes the most common thermostats used in NVT simulations, categorized by their underlying methodology [17] [18] [19].

Table 1: Comparison of Thermostats for NVT Ensemble Molecular Dynamics

| Thermostat | Type | Key Principle | Ensemble Quality | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosé-Hoover Chain | Deterministic | Extended Lagrangian with dynamic scaling variable(s). | Correct NVT ensemble [18]. | General purpose; production runs requiring deterministic trajectories. |

| Langevin | Stochastic | Adds friction and a random force to the equation of motion. | Correct NVT ensemble [18]. | Solvated systems; stochastic dynamics; efficient sampling. |

| Bussi (VREScale) | Stochastic | Velocity rescaling with a stochastic term for correct fluctuations. | Correct NVT ensemble [18]. | General purpose; good alternative to Berendsen for correct sampling. |

| Berendsen | Deterministic | Scales velocities to exponentially decay towards target T. | Suppresses energy fluctuations [18]. | Fast equilibration and heating/cooling, not production. |

| Andersen | Stochastic | Randomly selects atoms and reassigns velocities from Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. | Correct NVT ensemble, but artificially decorrelates velocities [18]. | Studies where precise dynamical correlation is not critical. |

Recommended and Not Recommended Algorithms

Based on the literature, certain thermostats are preferred for production simulations due to their ability to correctly sample the canonical ensemble. The Langevin thermostat is simple, robust, and correctly samples the ensemble, making it a good general choice, especially for solvated systems [18]. The Nosé-Hoover chain thermostat is a deterministic and well-studied method that is also an excellent choice for production runs, though it can exhibit slow relaxation if the thermostat mass is poorly chosen [18]. The Bussi thermostat offers a simple stochastic approach that corrects the major flaw of the Berendsen thermostat (incorrect energy fluctuations) and is highly recommended [18].

Conversely, some thermostats should be avoided for production runs where correct sampling is required. The Berendsen thermostat is excellent for rapidly relaxing a system to a target temperature during equilibration but severely suppresses the natural energy fluctuations of the NVT ensemble, making it unsuitable for production calculations of thermodynamic properties [18]. The Andersen thermostat, while generating a correct ensemble, does so by randomizing the velocities of a subset of atoms, which artificially disrupts the dynamics and velocity correlations [18].

Practical Protocols for NVT Simulations

This section provides detailed methodologies for setting up and running NVT simulations using different software packages and thermostats.

Protocol 1: NVT Simulation with Nosé-Hoover Thermostat in VASP

The following protocol outlines the steps for an NVT simulation of a solid-state material using the Nosé-Hoover thermostat within the VASP software [17].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Software: VASP

- Thermostat: Nosé-Hoover (NHC)

- Input Files:

INCAR(control parameters),POSCAR(initial structure),POTCAR(pseudopotentials),KPOINTS(k-point mesh)

Procedure:

- System Preparation: Begin with a fully optimized structure (volume and shape) obtained from a previous volume relaxation (e.g., using

IBRION = 2andISIF = 3) or an NpT equilibration. This ensures the chosen volume is appropriate for the target temperature and pressure. - INCAR Parameter Configuration: In the main input file (

INCAR), set the following key parameters to configure the MD simulation for the NVT ensemble [17]:IBRION = 0(Selects molecular dynamics)MDALGO = 2(Selects the Nosé-Hoover thermostat)ISIF = 2(Computes stress but does not change cell volume/shape)TEBEG = 300(Sets the target temperature in Kelvin)NSW = 10000(Number of MD steps)POTIM = 1.0(Time step in femtoseconds)SMASS = 1.0(Mass parameter for the Nosé-Hoover thermostat inertia)

- Execution: Run VASP with the prepared input files.

- Analysis: Analyze the generated output files (e.g.,

OSZICAR,XDATCAR) for properties such as energy, temperature, and pressure over time to ensure equilibration and then production data collection.

Table 2: Key INCAR Parameters for NVT Simulation with Nosé-Hoover Thermostat in VASP

| Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

IBRION |

0 |

Algorithm: Molecular Dynamics |

MDALGO |

2 |

MD algorithm: Nosé-Hoover thermostat |

ISIF |

2 |

Calculate stress but do not vary volume |

TEBEG |

300 |

Temperature at start (K) |

NSW |

10000 |

Number of simulation steps |

POTIM |

1.0 |

Time step (fs) |

SMASS |

1.0 |

Nose mass-parameter |

Protocol 2: NVT Simulation with Berendsen Thermostat in ASE

This protocol demonstrates an NVT simulation for melting aluminium using the Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) and the Berendsen thermostat, useful for rapid equilibration [16].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Software: ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment)

- Calculator: EMT (Effective Medium Theory) or any other ASE-compatible calculator (e.g., GPAW, VASP)

- Thermostat: Berendsen

Procedure:

- System Setup: Create the initial atomic configuration. The example below builds a 3x3x3 supercell of FCC aluminium.

- Assign Calculator: Attach a potential energy calculator to the atoms object.

- Initialize Velocities: Set the initial atomic velocities to correspond to the target temperature.

- Configure and Run Dynamics: Create the NVT dynamics object and run the simulation.

Integration in a Broader MD Workflow and Ensemble Selection

The NVT ensemble is rarely used in isolation. It is typically one component of a multi-stage simulation protocol designed to prepare a system for a production run under the desired conditions. A standard MD workflow often proceeds as follows [4]:

Figure 1: A standard MD simulation workflow. The NVT ensemble is crucial for the initial temperature equilibration stage.

The choice between using NVT or isothermal-isobaric (NpT) ensemble for the production run depends on the scientific question. NVT is chosen when a fixed volume is essential, such as when simulating a crystal structure with a known lattice parameter, studying confined systems, or when the volume has been previously equilibrated in an NpT run to the correct density [20]. From a practical standpoint, NVT simulations are often preferred because they are simpler to implement and avoid the numerical complexities associated with fluctuating volume and moving periodic boundaries [20].

Advanced Applications and Best Practices

The Critical Role of Ensemble Simulations

A pivotal advancement in MD methodology is the recognition that single, long simulations are prone to irreproducibility due to the chaotic nature of molecular trajectories [21]. Instead, the field is moving towards ensemble-based approaches, where multiple independent replicas (each starting from different initial velocities) are run. This allows for robust estimation of the mean and variance of any calculated quantity of interest (QoI).

For a fixed computational budget (e.g., 60 ns), the question becomes how to allocate time between the number of replicas and the length of each simulation. Evidence suggests that running "more simulations for less time" (e.g., 20 replicas of 3 ns each) often provides better sampling and more reliable error estimates than a single 60 ns simulation or a few long runs [21]. This is because multiple replicas more effectively sample diverse regions of conformational space, which is crucial for obtaining statistically meaningful results, especially for properties like binding free energies that can exhibit non-Gaussian distributions [21].

Application in Drug Discovery: Ensemble Docking

The NVT ensemble is a key tool in structure-based drug discovery. A powerful application is ensemble docking, where an "ensemble" of target protein conformations is generated, often from an NVT MD simulation, and used to dock candidate ligands [22]. This approach accounts for the inherent flexibility and dynamics of the protein, which is critical for identifying hits that might be missed by rigid docking to a single static crystal structure. By simulating the protein at a constant, physiological temperature, NVT MD can reveal cryptic binding sites and functionally relevant conformational states that form the basis of a more comprehensive and successful virtual screening campaign.

Selecting the appropriate statistical ensemble is a critical first step in any Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation, as it determines which thermodynamic quantities remain constant and ultimately controls the physical relevance of the simulation to experimental conditions. The Isothermal-Isobaric (NPT) ensemble, also known as the constant-NPT ensemble, where N is the number of particles, P is the pressure, and T is the temperature, is uniquely positioned to mirror common laboratory conditions where experiments are typically conducted at controlled temperature and atmospheric pressure [10] [23]. Unlike the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble, which conserves energy and volume, or the canonical (NVT) ensemble, which maintains constant volume, the NPT ensemble allows the simulation cell volume to fluctuate, enabling the system to find its equilibrium density naturally [24] [25].

This ensemble is indispensable for studying phenomena where volume changes are intrinsically important, such as thermal expansion of solids, phase transitions, and the density prediction of fluids [26] [23]. From a thermodynamic perspective, the NPT ensemble connects directly to the Gibbs free energy (G = F + PV), the characteristic state function for systems at constant pressure and temperature [24] [23]. For researchers in drug development, employing the NPT ensemble is crucial for simulating solvated proteins, lipid bilayers, and other complex biological systems in a physiologically relevant environment, ensuring that structural properties and interaction energies are not artificially constrained by an incorrect system density [25].

Theoretical Foundation

Statistical Mechanics of the NPT Ensemble

In the NPT ensemble, the probability of a microstate i with energy E_i and volume V_i is proportional to e^{-β(E_i+PV_i)}, where β = 1/k_BT [23]. The partition function Δ(N,P,T) for a classical system is derived as a weighted sum over the canonical partition function Z(N,V,T):

$$ Δ(N,P,T) = \int Z(N,V,T) e^{-βPV} C dV $$

Here, C is a constant that ensures proper normalization [23]. This formulation shows that the NPT ensemble can be conceptually viewed as a collection of NVT systems at different volumes, each weighted by the Boltzmann factor e^{-βPV} [23]. The Gibbs free energy is obtained directly from the partition function: $$ G(N,P,T) = -k_BT \ln Δ(N,P,T) $$ This direct relationship makes the NPT ensemble the natural choice for calculating thermodynamic properties that depend on constant pressure, such as enthalpy and constant-pressure heat capacity [24].

Pressure Control: Barostat Algorithms

Maintaining constant pressure requires a barostat, an algorithm that adjusts the simulation cell volume based on the instantaneous internal pressure. Two prevalent methods are the Parrinello-Rahman and Berendsen barostats, each with distinct characteristics and applications [26].

The Parrinello-Rahman method is an extended system approach where the simulation cell itself is treated as a dynamical variable with a fictitious mass, allowing all cell parameters (angles and lengths) to fluctuate [27] [26]. This flexibility is essential for studying solids that may undergo anisotropic deformations or phase transitions [26]. Its equations of motion introduce an variable η for pressure control, which evolves according to: $$ \dot{\mathbf{η}} = \frac{V}{τP^2 N kB T0}(\mathbf{P(t)} - P0\mathbf{I}) + 3\frac{τT^2}{τP^2}ζ^2\mathbf{I} $$ where τ_P is the pressure control time constant and P(t) is the instantaneous pressure tensor [26].

The Berendsen barostat, in contrast, uses a simpler scaling method by weakly coupling the system to an external pressure bath, providing exponential relaxation of the pressure towards the desired value [26]. While efficient for rapid equilibration, it does not produce a rigorously correct ensemble [26]. A third approach, the "Langevin Piston" method, incorporates stochastic elements to dampen the oscillatory "ringing" behavior sometimes observed in barostats, thereby improving the relaxation to equilibrium [25].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Barostat Algorithms

| Algorithm | Type | Key Features | Typical Applications | Ensemble Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parrinello-Rahman | Extended System | Allows full cell fluctuations; Requires fictitious mass parameter | Solids, anisotropic materials, phase transitions | Excellent [26] |

| Berendsen | Weak Coupling | Fast pressure relaxation; Simple scaling | Rapid equilibration, pre-equilibration steps | Not rigorously correct [26] |

| Langevin Piston | Stochastic | Damped oscillations; Improved mixing time | General purpose, complex fluids | Good [25] |

Practical Implementation and Protocols

Key Parameters and Their Selection

Successful NPT simulations require careful parameter selection. The table below summarizes critical parameters for the Parrinello-Rahman barostat, drawing from examples in VASP and ASE [27] [26].

Table 2: Key Parameters for Parrinello-Rahman Barostat Implementation

| Parameter | Description | Physical Meaning | Typical Values/Examples | Selection Guidance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

pfactor |

Barostat parameter | Related to τ_P²B, where B is bulk modulus | ~10⁶ - 10⁷ GPa⋅fs² (for metals) [26] | System-dependent; requires estimation of bulk modulus [26] |

PMASS |

Fictitious mass of lattice degrees of freedom | Mass of the "piston" controlling volume changes | e.g., 1000 (VASP example) [27] | Higher mass = slower, more damped response [27] |

τ_P |

Pressure coupling time constant | Characteristic time for pressure relaxation | e.g., 20-100 fs [26] | Shorter times = tighter coupling, potential instability |

LANGEVIN_GAMMA_L |

Friction coefficient for lattice | Damping for lattice degrees of freedom | e.g., 10.0 (VASP example) [27] | Controls coupling with thermal bath [27] |

Workflow for an NPT Simulation

The following diagram outlines a general workflow for setting up and running an NPT MD simulation, incorporating decision points for key parameters.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Thermal Expansion of a Solid

Application: Calculating the coefficient of thermal expansion for fcc-Cu [26].

Objective: To determine the average lattice constant and volume of a metal at various temperatures under a constant external pressure of 1 bar.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for an NPT-MD Simulation

| Component | Function/Role | Example/Description |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | Engine for numerical integration of equations of motion | VASP [27], GROMACS [28], ASE [26], AMS [29], MOIL [25] |

| Force Field/Calculator | Defines interatomic potentials/energies and forces | ASAP3-EMT (for metals) [26], PFP (machine learning potential) [26], Classical force fields (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM) |

| Thermostat | Controls temperature by scaling velocities or adding stochastic forces | Nosé-Hoover [26], Langevin [27], Berendsen [26] |

| Barostat | Controls pressure by adjusting simulation cell volume | Parrinello-Rahman [27] [26], Berendsen [26], MTK [29] |

| Initial Configuration | Atomic structure to begin simulation | Bulk crystal structure (e.g., 3x3x3 supercell of fcc-Cu) [26] |

Step-by-Step Protocol:

System Preparation:

Parameter Selection:

- Force Field/Calculator: Select an appropriate potential. For demonstration, the ASAP3-EMT calculator provides a good balance of speed and accuracy for metals [26].

- Barostat: Choose the Parrinello-Rahman method. Set the

pfactorto 2×10⁶ GPa⋅fs², and the pressure (externalstress) to 1 bar [26]. - Thermostat: Couple with a Nosé-Hoover thermostat. Set the temperature coupling constant (

ttime) to 20 fs [26]. - Integration: Set the time step (

dt) to 1.0 fs. The total number of steps (nsteps) should be sufficient for equilibration and sampling (e.g., 20,000 steps for a 20 ps simulation) [26].

Initialization and Equilibration:

- Initialize atomic velocities from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution corresponding to the target temperature (e.g., 200 K for the first run) [26].

- Perform a short NVT simulation to equilibrate the temperature before applying the barostat.

- Start the NPT simulation, allowing both temperature and volume to relax towards equilibrium.

Production Run and Data Acquisition:

- After equilibration (judged by stability of potential energy and volume), begin the production run.

- Write the trajectory (atomic positions and cell vectors) and thermodynamic data (volume, energy, pressure, temperature) to file at regular intervals (e.g., every 100 steps).

Analysis:

- Calculate the average volume 〈V〉 from the production phase.

- The lattice constant a can be derived from the average volume per atom or the average cell vectors.

- Repeat the entire procedure for a series of temperatures (e.g., from 200 K to 1000 K in 100 K increments).

- Plot the average lattice constant a(T) versus temperature T. The linear coefficient of thermal expansion α is given by: $$ α = \frac{1}{a0} \frac{da}{dT} $$ where *a0* is the lattice constant at a reference temperature.

Advanced Considerations and Best Practices

Algorithmic Advances and Technical Challenges

Modern NPT algorithms incorporate several sophisticated concepts to improve accuracy and efficiency. The COMPEL algorithm, for instance, combines the ideas of molecular pressure, stochastic relaxation, and exact calculation of long-range force contributions via Ewald summation [25]. Using molecular pressure—calculating the virial based on molecular centers of mass rather than individual atoms—avoids the complications introduced by rapidly fluctuating covalent bond forces and reduces overall pressure fluctuations, which is particularly beneficial for molecular systems [25].

A significant challenge in NPT simulations is the accurate treatment of long-range interactions, especially for pressure calculation. Truncating non-bonded interactions at a cutoff introduces errors in the pressure estimation because the neglected attractive interactions are cumulative. At a typical cutoff of 10 Å, this error can be on the order of hundreds of atmospheres [25]. For electrostatics, Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) is a standard solution, and similar Ewald-style methods are increasingly being recommended for Lennard-Jones interactions to achieve high accuracy [25].

Barostat-Thermostat Interaction and Dynamics

The choice of thermostat can influence the performance of the barostat. The Nosé-Hoover-Langevin thermostat, which combines the extended system approach of Nosé-Hoover with degenerate noise, has been shown to accurately represent dynamical properties while maintaining ergodic sampling [25]. The following diagram illustrates the coupled nature of the equations of motion in an extended system NPT integrator like Parrinello-Rahman with a Nosé-Hoover thermostat.

The NPT ensemble is a cornerstone of modern molecular dynamics, providing the most direct link between simulation and a vast array of laboratory experiments conducted under constant temperature and pressure. Its implementation, while more complex than NVE or NVT due to the coupling between particle motion and cell dynamics, is made robust by well-established algorithms like Parrinello-Rahman and Berendsen. For researchers in drug development and materials science, mastering NPT simulations is essential for predicting densities of fluids, structural properties of solvated biomolecules, and behavior of materials under ambient or pressurized conditions. By carefully selecting barostat parameters, properly treating long-range interactions, and following a systematic equilibration protocol, scientists can reliably use the NPT ensemble to generate thermodynamic and structural data that are both statistically sound and experimentally relevant.

Statistical ensembles form the theoretical foundation for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, providing a framework for connecting microscopic simulations to macroscopic experimental observables. While theory defines distinct ensembles for isolated and open systems, practical MD applications require carefully designed multi-ensemble protocols to bridge the gap between computational models and laboratory reality. This application note examines ensemble equivalence principles and differences through the lens of practical drug development research, providing structured protocols for selecting appropriate ensembles based on research objectives, with particular emphasis on integrating experimental data for validating intrinsically disordered protein targets and calculating binding affinities for drug candidates.

Theoretical Foundations of Statistical Ensembles

Statistical ensembles represent the fundamental connection between the microscopic world of atoms and molecules and the macroscopic thermodynamic properties measured in experiments. In molecular dynamics, the choice of ensemble dictates the conserved thermodynamic quantities during a simulation, effectively defining the system's boundary conditions with its environment.

The four primary ensembles used in biomolecular simulations include:

Microcanonical Ensemble (NVE): Characterized by constant Number of atoms (N), Volume (V), and Energy (E), representing a completely isolated system that cannot exchange energy or matter with its surroundings. While theoretically simple, this ensemble rarely corresponds to experimental conditions and is prone to temperature drift during simulation [4].

Canonical Ensemble (NVT): Maintains constant Number of atoms (N), Volume (V), and Temperature (T) through coupling to a thermal reservoir or thermostat. This ensemble allows the system to exchange heat with its environment to maintain constant temperature, making it suitable for simulating systems in fixed volumes [4].

Isothermal-Isobaric Ensemble (NPT): Conserves Number of atoms (N), Pressure (P), and Temperature (T) through the combined use of thermostats and barostats. This ensemble most closely mimics common laboratory conditions for solution-based experiments and is therefore widely used in production simulations [4].

Grand Canonical Ensemble (μVT): Maintains constant Chemical potential (μ), Volume (V), and Temperature (T), allowing particle exchange with a reservoir. This ensemble is particularly valuable for studying processes like ligand binding and ion exchange, though it is computationally challenging and less commonly implemented [4].

Table 1: Thermodynamic Ensembles in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Ensemble | Conserved Quantities | System Type | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVE | Number of particles, Volume, Energy | Isolated system | Basic algorithm testing; studying energy conservation |

| NVT | Number of particles, Volume, Temperature | Closed system (thermal exchange) | Equilibration phases; simulations in fixed volumes |

| NPT | Number of particles, Pressure, Temperature | Closed system (thermal and work exchange) | Production simulations mimicking lab conditions |

| μVT | Chemical potential, Volume, Temperature | Open system (thermal and matter exchange) | Ligand binding, solvation studies, membrane permeation |

The principle of ensemble equivalence suggests that for large systems at equilibrium, different ensembles should yield identical thermodynamic properties. In practice, however, finite system size, force field inaccuracies, and insufficient sampling create significant disparities between ensembles. Furthermore, the choice of ensemble profoundly impacts the calculation of fluctuations and response functions, which differ fundamentally between ensembles despite converging for average values in the thermodynamic limit.

Application Notes: Ensemble Selection in Research Contexts

Integrating Experimental Data with IDP Ensemble Calculations

Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) represent a significant challenge for structural biology and drug development as they populate heterogeneous conformational ensembles rather than unique structures. Determining accurate atomic-resolution conformational ensembles of IDPs requires integration of MD simulations with experimental data from nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) [30].

Recent methodologies employ maximum entropy reweighting to refine ensembles derived from multiple force fields, demonstrating that in favorable cases where initial ensembles show reasonable agreement with experimental data, reweighted ensembles converge to highly similar conformational distributions regardless of the initial force field [30]. This approach facilitates the integration of MD simulations with extensive experimental datasets and represents progress toward calculating accurate, force-field independent conformational ensembles of IDPs at atomic resolution, which is crucial for rational drug design targeting IDPs [30].

The statistical ensemble for IDP characterization must adequately sample the diverse conformational space, making NPT ensembles at physiological temperature and pressure most appropriate. Enhanced sampling techniques are often required to overcome energy barriers and achieve sufficient convergence within feasible simulation timeframes.

Ensemble Approaches for Binding Energy Calculations

Accurate prediction of binding energies represents a critical application of MD simulations in drug development. Traditional approaches relying on single long MD simulations often produce non-reproducible results that deviate from experimental values. Recent research on DNA-intercalator complexes demonstrates that ensemble approaches with multiple replicas significantly improve accuracy and reproducibility [31].

For the Doxorubicin-DNA complex, MM/PBSA binding energies calculated from 25 replicas of 100 ns simulations yielded values of -7.3 ± 2.0 kcal/mol, closely matching experimental ranges of -7.7 ± 0.3 to -9.9 ± 0.1 kcal/mol. Importantly, similar accuracy was achieved with 25 replicas of shorter 10 ns simulations, yielding -7.6 ± 2.4 kcal/mol [31]. This suggests that reproducibility and accuracy depend more on the number of replicas than simulation length, enabling more efficient computational resource allocation.

Bootstrap analysis indicates that 6 replicas of 100 ns or 8 replicas of 10 ns provide an optimal balance between computational efficiency and accuracy within 1.0 kcal/mol of experimental values [31]. For binding energy calculations, NPT ensembles at physiological conditions are recommended, with sufficient equilibration before production runs.

Table 2: Ensemble MD Approaches for Binding Energy Prediction

| System | Simulation Strategy | Binding Energy (MM/PBSA) | Experimental Range | Recommended Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxorubicin-DNA | 25 replicas of 100 ns | -7.3 ± 2.0 kcal/mol | -7.7 ± 0.3 to -9.9 ± 0.1 kcal/mol | 6 replicas of 100 ns |

| Doxorubicin-DNA | 25 replicas of 10 ns | -7.6 ± 2.4 kcal/mol | -7.7 ± 0.3 to -9.9 ± 0.1 kcal/mol | 8 replicas of 10 ns |

| Proflavine-DNA | 25 replicas of 10 ns | -5.6 ± 1.4 kcal/mol (MM/PBSA) | -5.9 to -7.1 kcal/mol | 8 replicas of 10 ns |

Metrics for Comparing Conformational Ensembles

Comparing conformational ensembles presents unique challenges, particularly for disordered proteins and flexible systems. Traditional root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) metrics require structural superimposition and are often inadequate for heterogeneous ensembles. Distance-based metrics that compute matrices of Cα-Cα distance distributions between ensembles provide a powerful alternative [32].

The ensemble distance Root Mean Square (ens_dRMS) metric quantifies global structural similarity by calculating the root mean-square difference between the medians of inter-residue distance distributions of two ensembles [32]:

[ \text{ens_dRMS} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n}\sum{i,j}\left[d{\mu}^A(i,j) - d_{\mu}^B(i,j)\right]^2} ]

where (d{\mu}^A(i,j)) and (d{\mu}^B(i,j)) are the medians of the distance distributions for residue pairs i,j in ensembles A and B, respectively, and n equals the number of residue pairs [32].

This approach enables both local and global similarity comparisons between conformational ensembles and is particularly valuable for validating simulations against experimental data and assessing convergence between different force fields or simulation conditions.

Experimental Protocols

Standard Protocol for MD Simulation Setup

A typical MD procedure employs multiple ensembles across different stages of simulation to properly equilibrate the system before production runs [4]. The following protocol represents a robust approach for biomolecular systems:

Step 1: Initial System Preparation

- Obtain protein structure from PDB or homology modeling

- Solvate the system in an appropriate water box (TIP3P, SPC, TIP4P) with minimum 1.0 nm distance between protein and box edge

- Add ions to neutralize system charge and achieve physiological concentration (0.15 M NaCl)

- Perform initial energy minimization to remove steric clashes

Step 2: NVT Equilibration (100-500 ps)

- Apply position restraints on protein heavy atoms

- Use thermostat (Berendsen, Nosé-Hoover, or velocity rescale) to maintain target temperature (typically 300-310 K)

- Allow solvent and ions to relax around the restrained protein

- Monitor temperature stability and potential energy convergence

Step 3: NPT Equilibration (100-500 ps)

- Maintain position restraints on protein heavy atoms

- Couple system to pressure bath (Berendsen or Parrinello-Rahman barostat) at 1 bar

- Monitor density stabilization and potential energy convergence

- Gradually release position restraints if employing staged equilibration

Step 4: Production Simulation (≥100 ns)

- Remove all positional restraints

- Continue NPT ensemble for biomolecular systems in solution

- Save trajectory frames at appropriate intervals (10-100 ps)

- Monitor key stability metrics (RMSD, potential energy, temperature, pressure)

Step 5: Analysis

- Calculate properties of interest from production trajectory

- Perform statistical analysis considering autocorrelation times

- Compare with experimental data where available

- Assess convergence through block averaging or multiple replicas

Protocol for Conformational Ensemble Determination of IDPs

Determining accurate conformational ensembles of intrinsically disordered proteins requires integration of simulation and experimental data [30]:

Step 1: Enhanced Sampling Simulations

- Perform extended MD simulations (≥30 μs) using multiple state-of-the-art force fields (CHARMM36m, a99SB-disp, Amber99SB-ILDN)

- Employ enhanced sampling techniques (temperature replica exchange, metadynamics) to improve conformational sampling

- Generate initial ensemble of ≥30,000 structures for subsequent reweighting

Step 2: Experimental Data Collection

- Acquire NMR chemical shifts, residual dipolar couplings, J-couplings, and relaxation data

- Collect SAXS data to provide global structural information

- Curate comprehensive dataset of experimental observables for reweighting

Step 3: Forward Calculation of Experimental Observables

- Calculate experimental observables from each MD snapshot using appropriate forward models

- Compute ensemble-averaged values for comparison with experimental data

- Estimate uncertainties in both calculated and experimental values

Step 4: Maximum Entropy Reweighting

- Apply maximum entropy principle to minimally adjust simulation weights to match experimental data

- Use Kish ratio threshold (K = 0.10) to maintain effective ensemble size of ~3000 structures

- Automatically balance restraints from different experimental datasets without manual tuning

Step 5: Validation and Comparison

- Validate reweighted ensembles against experimental data not used in reweighting

- Compare ensembles from different force fields using ens_dRMS metrics

- Deposit final ensembles in public databases (Protein Ensemble Database)

Protocol for Ensemble Binding Free Energy Calculations

Accurate prediction of binding free energies using ensemble approaches [31]:

Step 1: System Preparation

- Prepare ligand-free and ligand-bound systems

- Use identical simulation parameters for both systems

- Ensure proper solvation and ionization

Step 2: Multiple Independent Simulations

- Launch multiple replicas (6-25) of both bound and unbound states

- Use different initial velocities for each replica

- For DNA-intercalator systems: 8 replicas of 10 ns or 6 replicas of 100 ns

Step 3: Ensemble Equilibration and Production

- Follow standard equilibration protocol (NVT followed by NPT)

- Perform production runs in NPT ensemble

- Save trajectories at frequent intervals for subsequent analysis

Step 4: Free Energy Calculation

- Use MM/PBSA or MM/GBSA methods on ensemble of trajectories

- Include entropy corrections through normal mode or quasi-harmonic analysis

- Account for deformation energies of host and ligand

Step 5: Statistical Analysis

- Calculate mean and standard deviation across replicas

- Perform bootstrap analysis to determine optimal replica number

- Compare with experimental values and assess statistical significance

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, CHARMM | Molecular dynamics engine for trajectory generation |

| Force Fields | CHARMM36m, a99SB-disp, AMBER99SB-ILDN | Mathematical representation of interatomic potentials |

| Water Models | TIP3P, TIP4P, SPC, a99SB-disp water | Solvation environment for biomolecular simulations |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | Replica Exchange MD (REMD), Metadynamics | Improved conformational sampling of complex landscapes |

| Reweighting Algorithms | Maximum Entropy Reweighting, Bayesian Inference | Integrating experimental data with simulation ensembles |

| Ensemble Comparison Metrics | ens_dRMS, Cα-Cα distance distributions | Quantitative comparison of conformational ensembles |

| Experimental Data | NMR chemical shifts, SAXS, J-couplings | Experimental restraints for validating and refining ensembles |

| Free Energy Methods | MM/PBSA, MM/GBSA, TI, FEP | Calculating binding affinities from simulation data |

The strategic selection of statistical ensembles bridges the gap between theoretical foundations and practical simulation realities in drug development research. While NPT ensembles most closely mimic laboratory conditions for most biomolecular applications, specialized research questions require tailored approaches incorporating multiple ensembles and enhanced sampling techniques. Critically, ensemble methods employing multiple replicas provide more reproducible and accurate results than single long simulations, particularly for binding free energy calculations. The integration of experimental data with simulation ensembles through maximum entropy reweighting approaches enables the determination of accurate conformational ensembles for challenging targets like intrinsically disordered proteins, advancing structure-based drug design capabilities. As MD simulations continue to grow in complexity and scope, rigorous ensemble design remains paramount for generating reliable, predictive models in pharmaceutical research.

A Practical Framework for Ensemble Selection in Biomedical Simulations

Mapping Your Research Goal to the Optimal Ensemble

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, a statistical ensemble defines the thermodynamic conditions under which a simulation proceeds, governing the conserved quantities (e.g., number of particles, energy, temperature, pressure) for a system. The ensemble provides the foundational framework for deriving thermodynamic properties through statistical mechanics, bridging the gap between the microscopic details of molecular motion and macroscopic observables. The choice of ensemble is not merely a technicality but a strategic decision that aligns the computational experiment with the target physical reality or research question. The main idea is that different ensembles represent systems with different degrees of separation from the surrounding environment, ranging from completely isolated systems (i.e., microcanonical ensemble) to completely open ones (i.e., grand canonical ensemble) [4].

Selecting the appropriate ensemble is paramount for achieving physically meaningful and scientifically relevant results. An ill-chosen ensemble can lead to unrealistic system behavior, such as sudden temperature spikes causing protein unfolding, or a failure to sample biologically critical conformational states. Furthermore, modern best practices in MD no longer rely on single, long simulations but emphasize ensemble-based approaches to ensure reliability, accuracy, and precision. These approaches involve running multiple replica simulations to properly characterize the probability distribution of any quantity of interest, which often exhibits non-Gaussian behavior [21]. This application note provides a structured guide to mapping common research goals in biomolecular simulation and drug development to their optimal statistical ensembles, complete with practical protocols and validation metrics.

The most frequently used ensembles in molecular dynamics simulations correspond to different sets of controlled thermodynamic variables, making each suitable for specific experimental conditions.

Table 1: Key Statistical Ensembles and Their Applications in MD

| Ensemble | Conserved Quantities | System Characteristics | Common Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVE (Microcanonical) | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Energy (E) | Isolated system; no exchange of energy or matter. Total energy is conserved, but fluctuations between kinetic and potential energy are allowed [4]. | - Studying energy-conserving systems- Fundamental property investigation in isolated conditions- Initial system relaxation (minimization) |

| NVT (Canonical) | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Closed system able to exchange heat with an external thermostat. Temperature is kept constant by scaling particle velocities [4]. | - Simulating systems in fixed volume at constant temperature- Protein folding studies- Equilibration phase before production runs |

| NPT (Isothermal-Isobaric) | Number of particles (N), Pressure (P), Temperature (T) | System able to exchange heat and adjust volume with the environment. Pressure is controlled by rescaling the simulation box dimensions [4]. | - Mimicking standard laboratory conditions- Studying phase transitions- Production runs for biomolecular systems in solution |

| μVT (Grand Canonical) | Chemical potential (μ), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Open system that can exchange both heat and particles with a large reservoir [4]. | - Studying adsorption processes- Simulating ion channels and membrane permeability- Systems with fluctuating particle numbers |

A typical MD simulation protocol does not utilize a single ensemble but strategically employs different ensembles in successive stages. A standard procedure involves an initial energy minimization followed by a simulation in the NVT ensemble to bring the system to the desired temperature. This is often followed by a simulation in the NPT ensemble to equilibrate the density (pressure) of the system. These initial steps are collectively known as the equilibration phase. Only after proper equilibration does the final production run begin, which is typically carried out in the NPT ensemble to mimic common laboratory conditions, and from which data for analysis are collected [4].

Ensemble Selection Guide: Mapping Research Goals to Ensemble Choice

The following section provides a detailed guide for selecting the optimal ensemble based on specific research objectives, particularly in the context of drug discovery and biomolecular simulation.

Table 2: Mapping Research Goals to Optimal Ensemble Selection

| Research Goal | Recommended Ensemble(s) | Technical Rationale | Protocol Notes & Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulating Standard Laboratory/Biological Conditions | NPT | Most biochemical experiments are performed at constant temperature and atmospheric pressure. NPT allows the simulation box to adjust its volume to maintain constant pressure [4]. | This is the default for most production simulations of biomolecules in solution. |

| Binding Free Energy Calculations | NPT (with ensemble-based methods) | Requires proper sampling of bound and unbound states under constant physiological conditions. Ensemble-based approaches (multiple replicas) are critical for reliable results, as free energy distributions are often non-Gaussian [21]. | Protocols like ESMACS (absolute binding) and TIES (relative binding) use 20-25 replicas. With limited resources, "run more simulations for less time" (e.g., 30x2 ns) is recommended over single long runs [21]. |

| Studiating Protein Folding/Unfolding | NVT or NPT | NVT is common for folding in explicit solvent. NPT is also widely used. Enhanced sampling methods (e.g., Weighted Ensemble) are often combined with these ensembles to overcome high energy barriers. | Weighted Ensemble MD can provide rigorous rate constants and pathways for rare events like folding by running multiple parallel trajectories with splitting and merging [33]. |

| Characterizing Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) | NPT (with advanced force fields) | IDPs exist as dynamic ensembles. NPT allows realistic sampling of their fluctuating sizes and shapes. Modern residue-specific force fields (e.g., ff99SBnmr2) with NPT can reproduce experimental NMR data without reweighting [34]. | Long simulation times (microseconds) or enhanced sampling are needed. Validation against NMR relaxation (R1, R2) and SAXS data (radius of gyration) is essential [34]. |

| Ensemble Docking for Drug Discovery | NPT for MD -> Multiple Frames | A single static structure is insufficient. Ensemble docking uses multiple snapshots from an NPT MD trajectory to represent druggable states, accounting for protein flexibility [35]. | Combine docking scores with machine learning (e.g., Random Forest, KNN) and drug descriptors to drastically improve active/decoy classification accuracy [35]. |

| Sampling Rare Events (e.g., Conformational Transitions) | NVT or NPT combined with Enhanced Sampling (e.g., Weighted Ensemble) | Standard MD may miss rare but crucial states. Enhanced path-sampling methods like Weighted Ensemble (WE) run multiple trajectories, splitting and merging them to efficiently sample rare transitions [36] [33]. | WE provides pathways and rigorous rate constants (e.g., Mean First Passage Times) without introducing bias into the dynamics. Optimal trajectory management reduces variance in estimates [36]. |

Workflow Diagram: Ensemble Selection and Simulation Protocol

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for selecting an ensemble and executing a simulation protocol, incorporating ensemble-based best practices.

Detailed Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol 1: Ensemble-Based Binding Free Energy Calculation (ESMACS)

This protocol calculates absolute binding free energies (ABFE) using the ESMACS (Enhanced Sampling of Molecular Dynamics with Approximation of Continuum Solvent) approach, which requires ensemble-based simulations for reliability [21].

System Preparation:

- Generate the molecular topology for the protein-ligand complex using a force field like CHARMM or AMBER.

- Solvate the complex in a water box (e.g., TIP3P) and add ions to neutralize the system.

Equilibration:

- Perform energy minimization (steepest descent, conjugate gradient) until the maximum force is below a threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm).

- Run a short NVT simulation (e.g., 100 ps) to heat the system to the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) using a thermostat (e.g., Berendsen, V-rescale).

- Run a short NPT simulation (e.g., 100 ps) to equilibrate the density of the system to 1 bar using a barostat (e.g., Berendsen).

Ensemble Production Runs: