How to Calculate Diffusion Coefficient from MD Trajectory: A Step-by-Step Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on calculating diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics trajectories.

How to Calculate Diffusion Coefficient from MD Trajectory: A Step-by-Step Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on calculating diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics trajectories. It covers fundamental theoretical concepts, practical implementation of Mean Squared Displacement and Velocity Autocorrelation Function methods, troubleshooting for common issues like finite-size effects, and advanced validation techniques. The content also explores the implications of accurate diffusion coefficient prediction for drug development, including applications in studying protein aggregation and biomolecular transport.

Understanding Diffusion Fundamentals: From Theory to MD Implementation

What is Molecular Diffusion? Core Concepts and Definitions

Molecular diffusion is a fundamental transport phenomenon central to disciplines spanning physics, chemistry, and biology. This technical guide details its core principles, mathematical foundations, and quantitative analysis, with a specific focus on calculating diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics (MD) trajectories. We frame diffusion within the context of irreversible thermodynamics as a spontaneous process driven by random molecular motion, leading to a net flux from regions of high chemical potential to low chemical potential until equilibrium is achieved [1] [2]. The document provides in-depth methodologies for experimental computation, including protocols for Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) and Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) analysis, essential for researchers in drug development and material science.

Molecular diffusion is defined as the thermal motion of atoms, molecules, or other particles in a gas or liquid at temperatures above absolute zero [1]. This motion results in the net flux of molecules from a region of higher concentration to one of lower concentration, a spontaneous and irreversible process that increases the entropy of a system and brings it closer to equilibrium [1] [2].

The process is driven by the intrinsic kinetic energy of particles, causing them to move randomly. In the absence of a concentration gradient, this movement persists but does not result in a net flux, a state described as self-diffusion [1]. The significance of molecular diffusion is profound, underlying critical processes such as chemical reactor design, catalyst operation, steel doping, semiconductor production [1], gas exchange in mammalian lungs [1], and nutrient uptake in biological cells [1].

Table 1: Key Definitions in Molecular Diffusion

| Term | Definition | Context |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Diffusion | Net transport of mass due to a concentration or chemical potential gradient [1]. | A non-equilibrium process described by Fick's laws. |

| Self-Diffusion / Tracer Diffusion | Spontaneous mixing of molecules in the absence of a concentration gradient [1]. | Can be tracked with isotopic tracers; occurs at equilibrium. |

| Diffusive Flux ((J)) | The amount of substance passing through a unit area per unit time [3] [2]. | Measurable rate of mass transfer. |

| Concentration Gradient ((dc/dx)) | The change in concentration with distance in a particular direction [1] [3]. | Provides the thermodynamic driving force for diffusion. |

| Dynamic Equilibrium | The state where molecules continue to move, but no net flux occurs due to a uniform concentration [1]. | A key outcome of molecular diffusion. |

Mathematical Framework: Fick's Laws

The quantitative description of diffusion is primarily governed by Fick's Laws [1].

Fick's First Law

Fick's First Law states that the diffusive flux is proportional to the negative of the concentration gradient. For one-dimensional diffusion of a component A, it is expressed as: [JA = -D{AB} \frac{dCA}{dx}] where (JA) is the flux of A, (D{AB}) is the diffusivity of A through medium B, and (dCA/dx) is the concentration gradient of A [1]. The negative sign indicates that the flux occurs in the direction of decreasing concentration.

Fick's Second Law

Fick's Second Law, also known as the diffusion equation, describes how the concentration changes with time: [\frac{\partial C(\mathbf{r},t)}{\partial t} = D \nabla^2 C(\mathbf{r},t)] where (\nabla^2) is the Laplace operator [4]. This partial differential equation can be solved for specific initial and boundary conditions to predict concentration profiles over time.

The Diffusion Coefficient (D)

The diffusion coefficient, (D), is a proportionality constant that quantifies how easily a substance diffuses through a specific medium [5]. It is influenced by factors such as temperature, the size and mass of the diffusing particles, and the viscosity of the medium [1] [3] [5].

Table 2: Typical Diffusion Coefficient Values and Influencing Factors

| Factor | Effect on Diffusion Coefficient (D) | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Increases with higher temperature [5]. | Higher kinetic energy overcomes viscous drag. |

| Particle Size/Mass | Decreases with larger/heavier particles [1]. | Larger molecules experience greater resistance. |

| Medium Viscosity | Decreases with higher viscosity [3]. | Diffusion is slower in liquids than in gases [3] [2]. |

| Medium State | Varies significantly between phases. | Self-diffusion coefficient of water: (2.299 \cdot 10^{-9} m^2/s) at 25°C [1]. |

| Example Values | Medium | Typical D ((m^2/s)) |

| Gas | (10^{-6} \text{ to } 10^{-5}) [3] | |

| Liquid | (10^{-10} \text{ to } 10^{-9}) [3] |

For diffusion in porous media, an effective diffusion coefficient ((D_{m,eff})) is used, which accounts for the porosity and tortuosity of the medium, making it smaller than the coefficient in a bulk solution [3].

Calculating Diffusion Coefficients from MD Trajectories

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide an atomic-level approach to study diffusion and calculate diffusion coefficients, crucial for validating force fields and understanding molecular transport [6]. Two primary methods are employed, both derived from the statistical mechanics of particle motion.

The Einstein Relation: Mean Squared Displacement (MSD)

The most common method uses the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD), which measures the average distance a particle travels over time [7] [8]. For 3D diffusion, the Einstein relation is: [\langle | \mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0) |^2 \rangle = 6Dt] where (\mathbf{r}(t)) is the position vector at time (t), and the angle brackets denote an average over many time origins and particles [8] [9]. The diffusion coefficient is calculated as one-sixth of the slope of the MSD versus time plot in the linear, diffusive regime: [D = \frac{1}{6} \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \langle | \mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0) |^2 \rangle] A critical consideration is ensuring the simulation is long enough to reach this diffusive regime, where MSD is proportional to time, as opposed to shorter-time ballistic regimes where MSD is proportional to (t^2) [8].

The Green-Kubo Relation: Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF)

An alternative method integrates the Velocity Autocorrelation Function [7] [6] [9]: [D = \frac{1}{3} \int_0^\infty \langle \mathbf{v}(t) \cdot \mathbf{v}(0) \rangle dt] where (\mathbf{v}(t)) is the velocity vector at time (t) [9]. This approach can provide insights into the dynamics of the diffusion process but may require more frequent saving of particle velocities during the simulation [7].

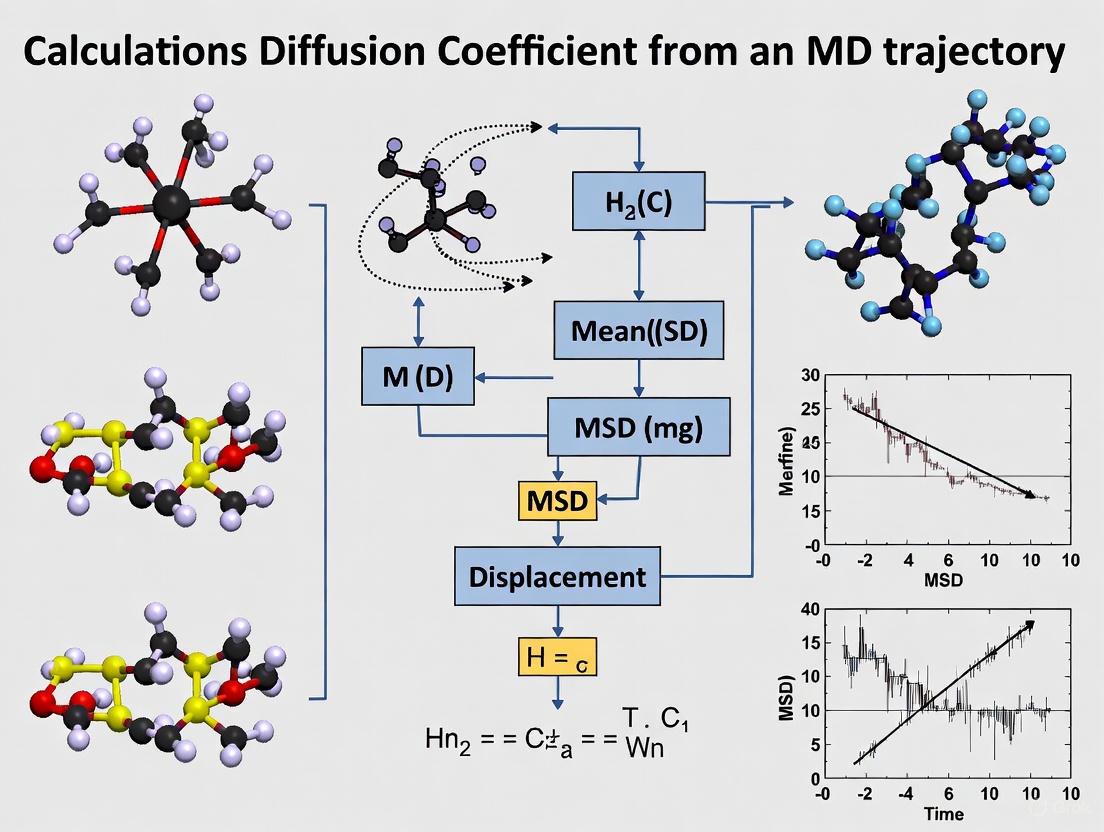

The following workflow outlines the standard protocol for calculating a diffusion coefficient via the MSD approach in an MD simulation:

Diagram 1: MSD Workflow for D Calculation.

Critical Considerations for MD Calculations

- Sampling and Convergence: Reliable calculation of a diffusion coefficient, especially for solutes at infinite dilution, often requires very long simulation times to achieve good statistics [6]. A strategy of averaging the MSD from multiple short simulations can be an efficient alternative [6].

- Finite-Size Effects: The diffusion coefficient measured in an MD simulation with periodic boundary conditions ((D{PBC})) is biased by hydrodynamic interactions with periodic images. A correction can be applied [8]: [D{\text{corrected}} = D{PBC} + \frac{2.84 kB T}{6 \pi \eta L}] where (k_B) is Boltzmann's constant, (T) is temperature, (\eta) is the solvent viscosity, and (L) is the box size.

- Temperature Dependence: Diffusion coefficients follow the Arrhenius equation, allowing extrapolation from simulations at higher temperatures [7]: [D(T) = D0 \exp(-Ea / kB T)] where (Ea) is the activation energy. Calculating (D) at multiple temperatures enables this extrapolation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Tool | Function / Description | Relevance to Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Software packages like GROMACS [8] and AMS [7] that perform MD simulations. | Provides the computational engine to simulate the motion of atoms and molecules over time. |

| Force Field | A set of empirical parameters (e.g., GAFF, AMBER) describing interatomic potentials [6]. | Defines the physics of interactions between atoms in the simulation; critical for accuracy. |

| Thermostat | An algorithm (e.g., Berendsen, Nosé-Hoover) to control temperature during MD [7]. | Maintains the system at a constant temperature, essential for the NVT or NPT ensembles. |

| Trajectory Analysis Tool | Tools like gmx msd in GROMACS [8] or analysis features in AMSmovie [7]. |

Processes the saved atomic positions from the MD simulation to compute the MSD or VACF. |

| Visualization Software | Programs like AMSmovie [7] or VMD. | Allows visual inspection of the simulation trajectory and properties like cell volume or temperature. |

Molecular diffusion is a cornerstone physical process with wide-ranging implications. A deep understanding of its principles, from Fick's macroscopic laws to the microscopic random walk, is indispensable. For modern researchers, molecular dynamics simulations offer a powerful avenue to quantitatively investigate diffusion and calculate diffusion coefficients directly from particle trajectories. Mastering the MSD and VACF methodologies, while accounting for practicalities like finite-size effects and sufficient sampling, enables accurate prediction of this critical transport property, facilitating advances in drug development, material science, and chemical engineering.

The Einstein-Smoluchowski relation represents a cornerstone of statistical physics, establishing a fundamental connection between random microscopic motion and macroscopic diffusion phenomena. First derived independently by Albert Einstein and Marian Smoluchowski in the early 1900s, this relation emerged from theoretical explanations of Brownian motion and provided the first quantitative link between molecular fluctuations and dissipative properties [10]. Its historical significance is profound, as it enabled Perrin's experiments determining Avogadro's number, which ultimately resolved the debate about atomic reality [10].

In contemporary research, this relationship provides the theoretical foundation for extracting transport properties from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. For computational researchers investigating molecular transport in biological systems or materials science, the Einstein-Smoluchowski relation enables the calculation of diffusion coefficients from particle trajectories, serving as a crucial bridge between atomistic simulations and macroscopic observables [11] [6].

Theoretical Foundations

Fundamental Equations

The classical Einstein-Smoluchowski relation states:

[ D = \mu k_B T ]

Here, (D) represents the diffusion coefficient, (\mu) is the mobility (defined as the ratio of terminal drift velocity to applied force, (\mu = vd/F)), (kB) is Boltzmann's constant, and (T) is absolute temperature [12]. This equation represents one of the first examples of a fluctuation-dissipation relation in statistical physics [10].

For charged particles, the equation takes a more specific form:

[ D = \frac{\muq kB T}{q} ]

where (\mu_q) is the electrical mobility and (q) is the particle charge [12].

Table 1: Special Forms of the Einstein Relation

| Equation Name | Formula | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Einstein-Smoluchowski | (D = \mu k_B T) | General particle diffusion |

| Electrical Mobility Equation | (D = \frac{\muq kB T}{q}) | Charged particles |

| Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland | (D = \frac{k_B T}{6\pi\eta r}) | Spherical particles in liquid |

| Rotational Diffusion | (Dr = \frac{kB T}{8\pi\eta r^3}) | Rotational motion of spheres |

Connection to Fick's Laws

The Einstein-Smoluchowski relation provides a kinetic foundation for Fick's laws of diffusion. While Fick's first law:

[ J = -D \frac{dc}{dx} ]

establishes flux (J) as proportional to the concentration gradient, the Einstein-Smoluchowski relation explains the microscopic origin of the diffusion coefficient (D) itself [13]. This connection becomes particularly valuable in MD simulations, where particle displacements can be directly measured and related to macroscopic diffusion through the mean-square displacement (MSD) relation:

[ \langle |\vec{r}(t) - \vec{r}(0)|^2 \rangle = 2nDt ]

where (n) represents dimensionality [6].

Computational Framework for MD Simulations

From Particle Trajectories to Diffusion Coefficients

In molecular dynamics research, the primary methodology for calculating diffusion coefficients involves analyzing mean-square displacement (MSD) of particles over time. The fundamental equation applied is:

[ D = \frac{1}{2n} \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \langle |\vec{r}(t) - \vec{r}(0)|^2 \rangle ]

where (n) is the dimensionality (typically 3 for MD simulations) [6]. Practical implementation requires careful attention to statistical convergence, as reliable results demand sufficient sampling of particle trajectories.

The Stokes-Einstein equation provides an alternative approach for spherical particles:

[ D = \frac{k_B T}{6\pi\eta r} ]

where (\eta) is solvent viscosity and (r) is the hydrodynamic radius [14]. This relation enables diffusion coefficient estimation from structural molecular properties, though its accuracy diminishes for non-spherical molecules or complex solvation environments.

Figure 1: MD to Diffusion Coefficient Workflow

Advanced Computational Techniques

For complex systems, researchers employ sophisticated algorithms to extract diffusion tensors. The Milestoning method maps atomically detailed dynamics to kinetics of coarse variables (CV) by partitioning CV space into cells and analyzing transitions between dividers (milestones) [11]. This approach enables efficient computation of diffusion properties even for activated processes.

Kramers-Moyal expansion of the discrete master equation provides another framework for determining space-dependent diffusion tensors from MD simulations [11]. This method calculates rate coefficients between milestones and converts them to potential of mean force and coordinate-dependent diffusion tensors.

Practical Implementation Protocols

MSD-Based Calculation Methodology

The standard protocol for diffusion coefficient calculation from MD trajectories involves:

Trajectory Preparation: Run MD simulation with appropriate force fields and periodic boundary conditions. For the General AMBER force field (GAFF), simulation boxes of sufficient size must be ensured to minimize finite-size effects [6].

MSD Computation: Calculate mean-square displacement using: [ \text{MSD}(t) = \langle |\vec{r}(t + t0) - \vec{r}(t0)|^2 \rangle ] where averaging occurs over both time origins ((t_0)) and particles [6].

Linear Regression: Fit the linear portion of MSD versus time curve to obtain the diffusion coefficient: [ D = \frac{1}{2n} \times \text{slope} ]

Convergence Validation: Ensure statistical reliability through multiple independent simulations or block averaging [6].

Table 2: Diffusion Coefficient Calculation Methods in MD

| Method | Key Equation | Advantages | Limitations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Einstein (MSD) | (D = \frac{1}{6N}\frac{d}{dt}\sum_{i=1}^N \langle | \vec{r}i(t)-\vec{r}i(0) | ^2\rangle) | Direct implementation | Requires long trajectories |

| Green-Kubo | (D = \frac{1}{3}\int_0^\infty\langle\vec{v}(t)\cdot\vec{v}(0)\rangle dt) | Theoretical rigor | Sensitive to noise | ||

| Milestoning | (D$ derived from transition rates between milestones [11] | Efficient for rare events | Complex implementation | ||

| Stokes-Einstein | (D = \frac{k_B T}{6\pi\eta r}) | Simple calculation | Limited to spherical particles |

Radius Estimation for Complex Molecules

For non-spherical molecules, the Stokes-Einstein relation requires careful estimation of molecular radius. Research demonstrates two effective approaches [14]:

Simple Radius ((rs)): Calculated from van der Waals volume (V{vdw}) using: [ rs = \left(\frac{3V{vdw}}{4\pi}\right)^{1/3} ]

Effective Radius ((re)): Derived from radius of gyration (rg): [ re = \sqrt{\frac{5}{3}} rg \approx 1.29 r_g ]

Studies show that for molecules with strong hydration ability, the effective radius provides superior agreement with experimental data, while for other compounds, the simple radius performs better [14].

Applications in Drug Development and Materials Science

Pharmaceutical Applications

In pharmaceutical research, diffusion coefficients play crucial roles in understanding drug delivery and pharmacokinetics. Passive transport of drug molecules—the driving force behind distribution to organs—directly depends on diffusion rates [14]. Computational estimation of diffusion coefficients provides valuable molecular descriptors for drug screening, especially when experimental measurement proves challenging.

Research demonstrates that theoretical estimation of diffusion coefficients for small drug-like molecules achieves reasonable agreement with experimental values (deviation ~0.3×10⁻⁶ cm²/s) [14]. This accuracy enables preliminary screening of candidate compounds based on transport properties before synthesis.

Biomolecular Systems

For proteins and other macromolecules, diffusion coefficients influence numerous biochemical processes, including protein aggregation and transportation in intercellular media [6]. MD simulations employing the Einstein-Smoluchowski relation can predict diffusion behavior under various thermodynamic conditions, sometimes unreachable by experiments.

Studies show excellent correlation (R² = 0.996) between predicted and experimental diffusion coefficients for proteins in aqueous solutions, validating the computational approach [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

| Tool/Software | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| AMS Trajectory Analysis [15] | Analyzes MD trajectories, computes MSD, radial distribution functions | Ionic conductivity studies, molecular centers of mass diffusion |

| LAMMPS [16] | MD simulation package with various force fields | General MD simulations of gases, liquids, biomolecules |

| General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) [6] | Provides parameters for organic molecules | Drug diffusion studies, biomolecular systems |

| Milestoning Algorithm [11] | Efficiently computes kinetics in coarse-grained space | Activated processes, rare events |

| MOE Software System [14] | Calculates stable molecular conformations | Molecular radius estimation for Stokes-Einstein equation |

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite the well-established theoretical foundation, practical application of the Einstein-Smoluchowski relation in MD simulations faces several challenges. For solutes at infinite dilution, convergence requires exceptionally long simulation times—up to 60-80 nanoseconds for reliable results [6]. This computational demand necessitates efficient sampling strategies, such as averaging MSD from multiple short simulations.

Recent research explores generalizations of the Einstein-Smoluchowski relation for anomalous diffusion systems, where mean-square displacement follows (\langle x^2(t) \rangle \propto t^\alpha) with (\alpha \neq 1) [10]. In such systems, which are common in cellular environments and complex fluids, the classical relation may break down, requiring modified theoretical frameworks.

The integration of machine learning with molecular dynamics promises enhanced prediction of diffusion properties, potentially reducing computational costs while maintaining accuracy. As force fields continue to improve and computational resources expand, the Einstein-Smoluchowski relation will remain fundamental to connecting molecular simulations with experimental observables in increasingly complex systems.

Fick's Laws of Diffusion and Their Molecular Interpretation

Fick's laws of diffusion form the foundational mathematical framework for describing the transport of mass through random molecular motion. First posited by physiologist Adolf Fick in 1855, these laws quantify how particles spread from regions of high concentration to regions of low concentration, ultimately striving toward equilibrium [17]. Fick's work was inspired by earlier experiments of Thomas Graham and developed through studies of salt diffusing between reservoirs through tubes of water [17]. These laws have proven universally applicable across scientific disciplines, describing diffusion in solids, liquids, and gases, and remain cornerstone principles in fields ranging from chemical engineering to pharmaceutical research [17] [18].

The significance of Fick's laws extends beyond mass transport, as they share remarkable mathematical similarity with other fundamental transport equations: Darcy's law for hydraulic flow, Ohm's law for charge transport, and Fourier's law for heat transport [17]. This connection underscores the universal nature of transport phenomena. For researchers investigating molecular dynamics, particularly in drug development where compound diffusion across biological barriers is critical, Fick's laws provide the theoretical basis for extracting quantitative diffusion parameters from computational simulations [7] [6].

Fundamental Principles of Fick's Laws

Fick's First Law: The Steady-State Condition

Fick's first law describes diffusion under steady-state conditions where concentration remains constant with time. It establishes that the diffusive flux is proportional to the negative concentration gradient. In one-dimensional form, it is expressed as [17]:

[ J = -D \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial x} ]

where:

- (J) represents the diffusion flux, measuring the amount of substance flowing through a unit area per unit time (dimensions of mol·m⁻²·s⁻¹ or g·m⁻²·s⁻¹)

- (D) is the diffusion coefficient or diffusivity (dimensions of m²·s⁻¹)

- (\phi) is the concentration (dimensions of mol·m⁻³ or g·m⁻³)

- (x) is the position coordinate

- The negative sign indicates that diffusion occurs down the concentration gradient

For multi-dimensional systems, Fick's first law employs the gradient operator [17]:

[ \mathbf{J} = -D \nabla \phi ]

At the molecular level, Fick's first law can be derived from the random walk of particles. Considering atomic jumps in a crystalline solid, where each plane contains (C\lambda) atoms per unit area, the net flux between adjacent planes with jump frequency (\nu) and jump distance (\lambda) becomes [19]:

[ J = -\frac{1}{6}\nu \lambda^2 \frac{\partial C}{\partial x} ]

This directly correlates to Fick's first law, with the diffusivity (D = \frac{1}{6}\nu \lambda^2) emerging from microscopic molecular parameters [19].

Fick's Second Law: The Time-Dependent Condition

Fick's second law predicts how diffusion causes concentration to change with time, making it essential for non-steady-state processes. In one dimension, it is expressed as [17]:

[ \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial t} = D \frac{\partial^2 \phi}{\partial x^2} ]

where:

- (\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial t}) represents the rate of change of concentration with time

For multi-dimensional systems, Fick's second law utilizes the Laplacian operator [17]:

[ \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial t} = D \nabla^2 \phi ]

This partial differential equation has identical mathematical form to the heat equation, with the diffusion coefficient (D) replacing thermal conductivity [17] [20]. The fundamental solution to this equation for an initial point source is a Gaussian distribution [17]:

[ \phi(x,t) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{4\pi Dt}} \exp\left(-\frac{x^2}{4Dt}\right) ]

Fick's second law can be derived from the first law by considering mass conservation. Applying the continuity equation for mass, which states that the rate of concentration change equals the negative divergence of the flux [20]:

[ \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial t} + \frac{\partial}{\partial x} J = 0 ]

Substituting Fick's first law into this equation yields:

[ \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial t} - \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left(D\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial x}\right) = 0 ]

Assuming a constant diffusion coefficient (D) allows simplification to the standard form of Fick's second law [20].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Fick's Laws of Diffusion

| Parameter | Symbol | Dimensions | Typical Values | Physical Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion Flux | (J) | [amount of substance]·[length]⁻²·[time]⁻¹ | Varies by application | Rate of flow through unit cross-sectional area |

| Diffusion Coefficient | (D) | [length]²·[time]⁻¹ | 10⁻¹¹–10⁻¹⁰ m²/s (biological molecules) [17] | Measure of mobility under concentration gradient |

| Concentration | (\phi) | [amount of substance]·[length]⁻³ | Varies by system | Number of molecules per unit volume |

| Concentration Gradient | (\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial x}) | [amount of substance]·[length]⁻⁴ | Determines direction and magnitude of flux | Spatial rate of concentration change |

Molecular Interpretation of Diffusion

Molecular Origins of Diffusive Behavior

At the molecular level, diffusion results from random thermal motion of particles. In gases and liquids, molecules undergo constant, random collisions that cause them to spread out progressively over time [13]. This random walk process can be quantified through the Einstein-Smoluchowski equation [13]:

[ D = \frac{\lambda^2}{2\tau} ]

where:

- (\lambda) represents the mean free path between collisions

- (\tau) is the mean time between collisions

This equation reveals that the diffusion coefficient depends fundamentally on the molecular step size and frequency. In more complex systems, the Stokes-Einstein relation provides another perspective, connecting diffusion to hydrodynamic properties [13]:

[ D = \frac{kT}{6\pi\eta a} ]

where:

- (k) is Boltzmann's constant

- (T) is absolute temperature

- (\eta) is solvent viscosity

- (a) is the hydrodynamic radius of the diffusing particle

This relationship highlights the inverse dependence of diffusivity on both molecular size and solvent viscosity, explaining why larger molecules diffuse more slowly and why diffusion rates increase with temperature [13].

The driving force for diffusion has been historically attributed to concentration gradients, though research suggests this may be an oversimplification. While Fick originally postulated concentration as the driving force, later scientific consensus shifted toward chemical potential gradients as the true thermodynamic driving force [21]. Recent investigations by Donohue and Aranovich have revealed limitations in both interpretations, particularly in non-ideal systems such as low-pressure gases, nanoporous materials, and systems with significant density gradients [21]. Their work identified "density waves" that create layered molecular buildups—termed the "Batman Profile" due to its distinctive graphical appearance—challenging the classical Fickian model of infinitesimal random molecular steps [21].

Classification of Diffusion Regimes

Diffusion processes are categorized based on their adherence to Fick's laws:

- Fickian (Normal) Diffusion: Processes that obey Fick's laws, typically observed in homogeneous systems under constant conditions [17] [18]

- Non-Fickian (Anomalous) Diffusion: Processes that deviate from Fick's laws, often occurring in complex environments like porous media or polymer systems [17]

The temperature dependence of diffusion follows Arrhenius behavior, expressed as [7]:

[ D = D0 \exp\left(-\frac{Ea}{k_B T}\right) ]

where:

- (D_0) is the pre-exponential factor

- (E_a) is the activation energy for diffusion

- (k_B) is Boltzmann's constant

- (T) is absolute temperature

This relationship enables extrapolation of diffusion coefficients to different temperatures, which is particularly valuable for estimating diffusion rates at physiological conditions from higher-temperature simulations [7].

Figure 1: Relationship between microscopic molecular motion and macroscopic diffusion laws

Calculating Diffusion Coefficients from Molecular Dynamics

Theoretical Framework for MD Diffusion Calculations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide a powerful approach for calculating diffusion coefficients by tracking the temporal evolution of particle positions and velocities. The diffusion coefficient (D) can be determined through two primary methods derived from different aspects of molecular motion [7].

The Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) method applies the Einstein relation, which states that for three-dimensional diffusion [6]:

[ \langle |\mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0)|^2 \rangle = 6Dt ]

where:

- (\langle |\mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0)|^2 \rangle) represents the ensemble-averaged mean squared displacement

- (\mathbf{r}(t)) is the position at time (t)

- The diffusion coefficient is obtained from the slope of MSD versus time [7]:

[ D = \frac{\text{slope}(MSD)}{6} ]

The Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) method employs the Green-Kubo relation, which connects diffusion to the time integral of velocity correlations [7] [6]:

[ D = \frac{1}{3} \int_{0}^{\infty} \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle dt ]

where:

- (\langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle) represents the velocity autocorrelation function

- This approach captures how a particle's velocity correlates with its initial velocity over time

Table 2: Comparison of MD Methods for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

| Method | Fundamental Relation | Advantages | Limitations | Convergence Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) | ( D = \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{\langle |\mathbf{r}(t)-\mathbf{r}(0)|^2 \rangle}{6t} ) | Intuitive physical interpretation, straightforward implementation | Requires long simulation times for reliable statistics, sensitive to initial conditions | MSD should show clear linear regime; slope should stabilize with increasing simulation time |

| Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) | ( D = \frac{1}{3} \int{0}^{t{\text{max}}} \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle dt ) | Faster convergence for some systems, provides additional dynamic information | More sensitive to numerical integration errors, requires high-frequency velocity sampling | Integral should plateau with increasing upper time limit; requires good statistics for velocity correlations |

Practical Implementation and Protocols

Implementing MD simulations for diffusion coefficient calculation requires careful attention to system preparation, simulation parameters, and analysis techniques. The following workflow outlines a standardized approach based on established protocols [7]:

System Preparation:

- Initial Structure Acquisition: Import crystal structures from CIF files or generate amorphous structures

- Structure Modification: Insert diffusing species (e.g., Li atoms in electrode materials) using builder tools or Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) methods

- Equilibration: Perform geometry optimization with lattice relaxation to stabilize the system

- Amorphous System Generation (if needed): Employ simulated annealing by heating to high temperature (e.g., 1600K) followed by rapid cooling

Production Simulation Setup:

- Thermostat Selection: Use Berendsen or other appropriate thermostats with damping constant of ~100 fs

- Simulation Duration: Typically 100,000+ production steps after equilibration

- Sampling Frequency: Set to 5-10 steps for accurate VACF calculation; can be higher for MSD-only analysis

- Temperature Control: Maintain constant temperature during production run

Analysis Procedure:

- MSD Method:

- Calculate MSD for the diffusing species

- Identify linear regime of MSD versus time plot

- Perform linear fit to MSD curve: ( \text{MSD}(t) = 6Dt + b )

- Extract (D) from slope: ( D = \text{slope}/6 )

- VACF Method:

- Compute velocity autocorrelation function: ( \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle )

- Integrate VACF over time

- Apply formula: ( D = \frac{1}{3} \int{0}^{t{\text{max}}} \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle dt )

For reliable results, researchers should address several critical considerations. Finite-size effects necessitate simulations with progressively larger supercells followed by extrapolation to the "infinite supercell" limit [7]. Statistical convergence requires sufficient sampling, which can be achieved through either multiple independent trajectories or extended simulation times [6]. For biologically relevant temperatures, Arrhenius extrapolation from multiple elevated temperatures (e.g., 600K, 800K, 1200K, 1600K) may be necessary due to impractical simulation timescales at room temperature [7].

Figure 2: Comprehensive workflow for calculating diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics simulations

Research Reagent Solutions for Diffusion Studies

Table 3: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for MD Diffusion Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Implementation Example | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Fields (GAFF, AMBER, CHARMM, ReaxFF) | Describes interatomic potentials and molecular interactions | ReaxFF for reactive systems (e.g., Li-S batteries) [7]; GAFF for organic molecules [6] | Bond stretching, angle bending, torsion, van der Waals, electrostatic terms |

| Solvation Modules | Models solvent effects and periodic boundary conditions | Implicit solvent for efficiency; Explicit solvent (TIP3P water) for accuracy [6] | Box size, solvent density, cutoff distances |

| Thermostats (Berendsen, Nosé-Hoover) | Maintains constant temperature during simulations | Berendsen thermostat with damping constant 100 fs [7] | Coupling strength, temperature ramp rates |

| Trajectory Analysis Tools | Processes MD output to extract diffusion parameters | AMSmovie for MSD/VACF analysis [7]; Custom scripts for batch processing | Sampling frequency, frame interval, fitting algorithms |

| System Building Tools | Prepares initial structures with desired composition | Molecular builders with SMILES support [7]; GCMC for optimal insertion | Composition control, spatial distribution, energy minimization |

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

Fick's laws of diffusion provide critical insights for drug development professionals, particularly in understanding passive transport of compounds across biological barriers. The exchange rate of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the lungs across the alveolar membrane follows Fick's first law, which can be expressed as [18]:

[ \text{Diffusion Flux} = -P(c2 - c1) ]

where:

- (P) is the permeability, an experimentally determined membrane 'conductance' for a given gas

- (c2 - c1) is the concentration difference across the membrane

This same principle applies to drug permeation across gastrointestinal barriers, blood-brain barrier, and cellular membranes. For drug delivery system design, Fick's second law helps predict drug release kinetics from controlled-release formulations, where the changing concentration gradient over time dictates release rates [18].

Molecular dynamics simulations enable precise calculation of diffusion coefficients for pharmaceutical compounds, providing insights that complement experimental measurements. For instance, MD studies using the General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) have demonstrated satisfactory prediction of diffusion coefficients for organic solutes in aqueous solution, with average unsigned errors of 0.137 × 10⁻⁵ cm²s⁻¹ [6]. This computational approach allows researchers to screen compound permeability early in drug development, potentially reducing reliance on laborious experimental measurements.

The temperature dependence of diffusion coefficients follows Arrhenius behavior, enabling extrapolation to physiological temperatures [7]:

[ \ln D(T) = \ln D0 - \frac{Ea}{k_B} \cdot \frac{1}{T} ]

This relationship is particularly valuable when direct simulation at 310 K (37°C) is computationally prohibitive due to slow dynamics at physiological temperatures.

Limitations and Advanced Considerations

While Fick's laws provide an excellent foundation for understanding diffusion, researchers must recognize their limitations. The standard formulation assumes constant diffusion coefficients, which is only strictly valid for dilute solutions [22]. In concentrated mixtures, Maxwell-Stefan diffusion more accurately describes the system, where diffusion coefficients become tensors and account for interactions between all chemical species present [22].

Recent research has identified fundamental limitations in Fick's law itself. Donohue and Aranovich demonstrated that neither concentration gradients nor chemical potential gradients fully explain diffusion in all systems [21]. Their work revealed that diffusion includes a wave phenomenon, particularly manifest in low-pressure gases, nanoporous materials, and systems with significant scale disparities [21]. These "density waves" create layered molecular buildups that deviate from the smooth concentration profiles predicted by classical Fickian diffusion.

For complex pharmaceutical systems, non-Fickian diffusion often occurs in polymer-based drug delivery systems, gels, and heterogeneous biological tissues. In these cases, anomalous diffusion models with time-dependent or fractional derivatives may be necessary to accurately describe the observed transport behavior [17] [18].

When implementing MD simulations for diffusion coefficient calculation, researchers should consider:

- Finite-size effects: Diffusion coefficients calculated in small simulation boxes may require extrapolation to infinite system size [7]

- Convergence requirements: Reliable diffusion coefficients necessitate sufficient sampling, achieved through either multiple independent trajectories or extended simulation times [6]

- Force field limitations: Different force fields may yield varying diffusion coefficients, requiring validation against experimental data [6]

- Composition dependence: In concentrated systems, diffusion coefficients become composition-dependent, necessitating specialized approaches like Maxwell-Stefan formulation [22]

Despite these limitations, Fick's laws remain fundamentally important for pharmaceutical researchers, providing the conceptual framework and mathematical foundation for understanding and quantifying molecular transport in drug development applications.

Why MD Simulations are Powerful for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as an indispensable tool for calculating diffusion coefficients (D), providing a unique bridge between microscopic particle motion and macroscopic transport properties. This computational technique enables researchers to obtain this critical parameter by analyzing the trajectories of atoms and molecules, offering atomic-level insights that are often challenging to acquire experimentally. The power of MD lies in its ability to study diffusion processes under various thermodynamic conditions, including those difficult to achieve in laboratory settings, while also revealing the fundamental molecular mechanisms governing mass transport.

Theoretical Foundations of Diffusion in MD

At the heart of MD-based diffusion coefficient calculations lies the Einstein relation, which connects the macroscopic diffusion coefficient to the microscopic mean squared displacement of particles. This relationship is derived from the statistical mechanics of random walks and Brownian motion, where the mean squared displacement increases linearly with time.

Mean Squared Displacement: The MSD is a measure of the average squared distance particles travel over time and is central to calculating diffusion coefficients. For a three-dimensional system, the diffusion coefficient is related to the slope of the MSD versus time plot through the equation: D = slope(MSD)/6 [7]. This approach is generally recommended for its straightforward implementation and interpretation.

Velocity Autocorrelation Function: As an alternative approach, the diffusion coefficient can be obtained through integration of the velocity autocorrelation function using the Green-Kubo relation: D = (1/3)∫₀∞⟨v(0)·v(t)⟩dt [7] [6]. This method theoretically equals the Einstein relation but requires setting the sampling frequency to small values for accurate results.

The diffusion coefficient D is also related to the friction coefficient ξ through the Einstein-Smoluchowski equation: D = kT/ξ, where k is the Boltzmann constant and T is the temperature. The friction coefficient depends on the sizes and shapes of molecules participating in diffusion [6].

Practical Protocols for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

MSD Method Protocol

The MSD approach is widely regarded as the more accessible and recommended method for calculating diffusion coefficients from MD trajectories:

Production Simulation: Run a sufficiently long MD simulation at the temperature of interest after proper equilibration. For accurate statistics, production runs of 100,000 steps or more are typically necessary [7].

Trajectory Sampling: Set an appropriate sample frequency to write atomic positions to disk. A higher sample frequency results in a larger trajectory file but provides better temporal resolution [7].

MSD Calculation: Compute the MSD for the atoms of interest using the formula: MSD(t) = ⟨[r(0) - r(t)]²⟩, where r(0) and r(t) represent atomic positions at time 0 and time t, respectively, and the angle brackets denote averaging over all atoms and time origins [7].

Linear Regression: Perform linear fitting on the MSD curve versus time. The diffusion coefficient is then calculated as one-sixth of the slope of this linear region: D = slope(MSD)/6 [7].

Table 1: Key Parameters for MSD-Based Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Production Steps | 100,000+ | Ensure sufficient sampling for statistics |

| Sample Frequency | 5-10 steps | Balance temporal resolution and file size |

| Equilibration Period | 10,000 steps | Allow system to reach equilibrium |

| MSD Time Origin | Multiple starting points | Improve averaging and statistics |

VACF Method Protocol

The VACF method provides an alternative approach with its own procedural requirements:

Velocity Tracking: Configure the MD simulation to save atomic velocities at regular intervals by setting an appropriate sampling frequency [7].

VACF Computation: Calculate the velocity autocorrelation function as: VACF(t) = ⟨v(0)·v(t)⟩, where v(0) and v(t) are velocity vectors at time 0 and time t [6].

Integration: Integrate the VACF over time to obtain the diffusion coefficient: D = (1/3)∫₀ᵗ⁼ᵗᵐᵃˣ VACF(t)dt [7] [6].

Convergence Check: Ensure the integral converges to a stable value with increasing tmax [7].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for calculating diffusion coefficients using both primary methods:

Critical Considerations and Methodological Refinements

Addressing Computational Challenges

Several technical challenges must be addressed to ensure accurate diffusion coefficient calculations:

Finite-Size Effects: The diffusion coefficient depends on the size of the simulation cell due to periodic boundary conditions. Typically, simulations should be performed for progressively larger supercells with extrapolation to the "infinite supercell" limit [7].

Sampling Strategies: For solutes at infinite dilution, where only one solute molecule exists in a simulation box, reliable prediction of diffusion coefficients requires exceptionally long MD simulations. An efficient sampling strategy involves averaging the MSD collected in multiple short MD simulations rather than relying on a single extended simulation [6].

Ballistic Regime: At very short time scales, particles exhibit ballistic motion before transitioning to diffusive behavior. Enhanced techniques that isolate this ballistic stage and apply thermodynamic corrections have been developed to refine estimates [23].

Temperature Dependence and Extrapolation

Calculating diffusion coefficients at low temperatures would require prohibitively long simulations to observe sufficient diffusion events. However, MD enables efficient estimation through studies at elevated temperatures followed by extrapolation using the Arrhenius equation:

D(T) = D₀exp(-Eₐ/kBT)

lnD(T) = lnD₀ - (Eₐ/kB) × (1/T)

where D₀ is the pre-exponential factor and Eₐ is the activation energy. The activation energy and pre-exponential factors can be obtained from an Arrhenius plot of ln(D(T)) against 1/T. This approach requires calculating trajectories for at least four different temperatures for each system [7].

Table 2: Comparison of Diffusion Coefficient Calculation Methods

| Aspect | MSD Method | VACF Method |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Einstein relation | Green-Kubo relation |

| Primary Data | Atomic positions | Atomic velocities |

| Computational Cost | Moderate | Moderate to High |

| Convergence | Good with sufficient sampling | Can be slower |

| Recommended Use | General purpose | Specialized studies |

| Key Formula | D = lim(t→∞) ⟨⎸r(t)-r(0)⎸²⟩/6t | D = (1/3)∫₀∞⟨v(0)·v(t)⟩dt |

Essential Software Tools and Analysis Libraries

The MD community has developed sophisticated software packages specifically designed for trajectory analysis and diffusion coefficient calculation:

AMSMovie: Integrated within the AMS package, this tool provides dedicated functions for calculating MSD and diffusion coefficients. It allows users to select specific atom types, set appropriate time windows, and automatically generate diffusion coefficient plots [7].

MDTraj: A modern, lightweight, and fast software package for analyzing MD simulations. It reads and writes trajectory data in various formats and provides numerous analysis capabilities with interoperability with the Python scientific ecosystem [24].

GROMACS: A complete modeling package that includes fast molecular dynamics and extensive trajectory analysis utilities. It is particularly known for high performance and comprehensive analysis tools [25] [26].

YASARA: A complete molecular graphics and modeling program that includes interactive molecular dynamics simulations and analysis capabilities. It can automatically generate detailed scientific reports with plots and tables ready for publication [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for MD Diffusion Studies

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | License |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [25] [26] | MD simulation & analysis | High performance MD, comprehensive analysis tools | Free open source (GNU GPL) |

| AMBER [25] [26] | MD simulation & analysis | Biomolecular focus, well-validated force fields | Proprietary, Free open source |

| NAMD [25] [26] | MD simulation | Parallel computing, CUDA support | Free academic use |

| LAMMPS [25] | MD simulation | Soft and solid-state materials, coarse-grain | Free open source |

| MDTraj [24] | Trajectory analysis | Python interoperability, wide format support | Open source |

| VMD [25] | Visualization & analysis | Extensive plugin ecosystem, publication-quality rendering | Free academic use |

| YASARA [27] | Modeling & analysis | Automated scientific reports, easy customization | Proprietary |

Applications Across Scientific Domains

The capability to calculate diffusion coefficients using MD simulations has enabled advances across multiple scientific disciplines:

Battery Research: MD simulations with the ReaxFF engine have been used to compute diffusion coefficients of lithium ions in cathode materials like Li₀.₄S, providing critical insights for battery optimization and design [7].

Biomedical Applications: Accurate prediction of diffusion coefficients for proteins and other macromolecules is crucial for understanding biochemical processes such as protein aggregation and transportation in intercellular media [6].

Materials Design: MD simulations facilitate the study of diffusion in diverse systems, from carbon sequestration applications to industrial process design, often under conditions that are challenging to probe experimentally [23].

Drug Development: Diffusion properties of drug molecules through membranes and biological barriers can be predicted using MD, providing valuable information for pharmacokinetic optimization [6].

The visualization challenges associated with analyzing these complex MD trajectories have prompted the development of advanced visualization techniques, including virtual reality environments and web-based tools that facilitate intuitive exploration of diffusion pathways and molecular mobility [28].

Molecular dynamics simulations provide a powerful framework for calculating diffusion coefficients by directly connecting atomic-level motion with macroscopic transport properties. The combination of theoretical rigor, practical computational tools, and methodological refinements has established MD as an essential approach for determining this critical parameter across scientific disciplines. As MD methodologies continue to advance with improved force fields, enhanced sampling algorithms, and more sophisticated analysis capabilities, the precision and applicability of diffusion coefficient calculations will further expand, enabling new discoveries in materials science, biochemistry, and pharmaceutical development.

Key Physical Factors Influencing Molecular Diffusion in Biological Systems

Molecular diffusion constitutes a fundamental transport mechanism governing numerous biological processes, from intracellular signaling to drug delivery. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of the key physical factors influencing molecular diffusion in biological systems, with particular emphasis on methodologies for calculating diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics (MD) trajectories. We synthesize current computational approaches, physical models, and experimental validation techniques relevant to researchers and drug development professionals. The article further presents detailed protocols for MD-based diffusion analysis and introduces visualization frameworks for understanding complex diffusional relationships in crowded cellular environments.

In biological systems, macromolecules are constantly moving through diffusion, which plays a fundamental role in processes ranging from protein-ligand binding and folding to intracellular transport and signaling [29]. Understanding how molecules find their binding partners, navigate the crowded cellular environment, and how their diffusional properties influence biological function represents a significant research focus in computational biophysics [29]. Molecular diffusion describes the spread of molecules through random motion driven by thermal energy, with the rate of movement being a function of temperature, fluid viscosity, and particle size and density [1]. This review systematically examines the physical factors governing molecular diffusion and provides researchers with methodologies for quantifying diffusion coefficients using molecular dynamics simulations, a crucial capability for predicting molecular behavior in biological contexts and pharmaceutical applications.

Key Physical Factors Governing Molecular Diffusion

The diffusional behavior of molecules in biological systems is influenced by several interconnected physical factors. These factors collectively determine the mobility, encounter rates, and ultimately the biological activity of molecular species.

Table 1: Key Physical Factors Influencing Molecular Diffusion

| Factor | Physical Effect | Impact on Diffusion Coefficient |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Increases thermal kinetic energy of molecules | Increases diffusion coefficient (linear relationship via Einstein-Smoluchowski equation D = kT/ξ) [6] [1] |

| Viscosity | Determines magnitude of frictional resistance | Inverse relationship with diffusion coefficient (D ∝ 1/η) [6] [1] |

| Molecular Size/Shape | Affects hydrodynamic radius and drag | Larger size reduces diffusion (D ∝ 1/R for spherical particles) [1] |

| Crowding Concentration | Increases collision frequency and steric hindrance | Decreases effective diffusion coefficient [29] |

| Electrostatic Interactions | Creates attractive/repulsive forces between molecules | Can either enhance or reduce encounter rates depending on charge complementarity [29] |

| Hydrodynamic Interactions | Mediates long-range coupling through solvent flow | Generally enhances diffusion, particularly important in crowded environments [29] |

The diffusion coefficient (D) quantifies the rate of molecular diffusion and can be calculated through multiple theoretical frameworks. The Einstein-Smoluchowski equation relates D to the friction coefficient ξ: D = kT/ξ, where k is Boltzmann's constant and T is temperature [6] [1]. Alternatively, from a microscopic perspective, D can be derived from the mean-square displacement (MSD) of particles over time: ⟨∣r̄ - r̄₀∣²⟩ = 2nDt, where n is the dimensionalty (typically 3 for biological systems) [6]. This relationship provides the foundation for calculating diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics trajectories.

Calculating Diffusion Coefficients from MD Trajectories

Molecular dynamics simulations enable the calculation of diffusion coefficients through statistical analysis of particle trajectories. Two primary methodologies dominate this approach: Einstein-based MSD analysis and Green-Kubo formalism.

Mean-Square Displacement (MSD) Analysis

The most common approach for calculating diffusion coefficients from MD trajectories relies on the Einstein relation, which connects macroscopic diffusion to microscopic particle displacements [6]. The method involves calculating the mean-square displacement of particles over time:

[ \text{MSD}(t) = \langle | \mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0) |^2 \rangle = 2nDt ]

where (\mathbf{r}(t)) is the position at time t, n is the dimensionality, and D is the diffusion coefficient [6]. In three dimensions (n=3), the relationship becomes MSD(t) = 6Dt, allowing D to be estimated as one-sixth of the slope of the MSD versus time plot in the linear regime [6].

Table 2: Comparison of Methods for Calculating Diffusion Coefficients from MD

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Calculation Approach | Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSD Analysis | Einstein relation | Linear regression of MSD(t) vs time | Intuitive but requires long simulations for convergence [6] |

| Green-Kubo | Velocity autocorrelation | Integration of ⟨v(t)·v(0)⟩ | Theoretically equivalent but different statistical properties [6] |

| Finite-Difference Fitting | Fick's second law | Matching MD concentration profiles to continuum models | Can provide estimates without extremely long trajectories [30] |

A significant challenge in MD-based diffusion coefficient calculation is the convergence problem, particularly for solutes at low concentrations. As demonstrated in studies of benzene in ethanol and phenol in water, reliable values of diffusion coefficients may not be obtained even after 60-80 nanoseconds of simulation time [6]. This has led to the development of efficient sampling strategies that average MSD data collected from multiple short MD simulations rather than relying on single extremely long trajectories [6].

Practical Considerations for MD Simulations

Accurate calculation of diffusion coefficients requires careful attention to MD simulation protocols. The following factors significantly impact results:

System Size and Periodic Boundary Conditions: Simulation boxes must be sufficiently large to minimize periodic image artifacts. A common approach involves defining a cubic box with edges approximately 1.4 nm from the protein periphery [31].

Solvation: Physiological environment must be mimicked through explicit solvation. The

solvatecommand in packages like GROMACS adds required water molecules, after which counterions are introduced to neutralize system charge [31].Trajectory Analysis: Tools like YASARA [27] and AMS Analysis [15] can process MD trajectories to compute MSD and other diffusional properties. These tools typically include options for atom selection, trajectory range specification, and convergence checks through block averaging [15].

Experimental Protocols for MD-Based Diffusion Analysis

Basic Workflow for MD Simulation of Proteins

This protocol outlines the key stages for setting up and running MD simulations for diffusion analysis [31]:

System Setup

- Obtain protein coordinates from RCSB PDB and convert to MD-specific format (e.g., .gro for GROMACS)

- Generate topology file containing molecular parameters, bonding, and force field information

- Select appropriate force field (e.g., ffG53A7 for proteins with explicit solvent)

Simulation Environment

- Define periodic boundary conditions using

editconfto create a simulation box - Solvate the system using

solvatecommand to add explicit water molecules - Neutralize system charge by adding appropriate counterions using

genion

- Define periodic boundary conditions using

Production Run and Analysis

- Energy minimization and equilibration before production MD

- Run production simulation with appropriate timestep and duration

- Extract trajectories for MSD analysis using tools like

gmx msdor custom scripts

Advanced Method: Hybrid MD/Continuum Approach

An innovative approach for estimating diffusion coefficients combines MD simulations with continuum modeling [30]:

MD Simulation Setup

- Perform MD simulations of the system using software like LAMMPS with appropriate force fields

- For gas systems, use Lennard-Jones potentials; for biomolecules, employ specialized force fields

Continuum Model Implementation

- Solve the diffusion equation using finite-difference methods: (\frac{\partial}{\partial t}u(\mathbf{x},t) = D\nabla^2 u(\mathbf{x},t))

- Implement periodic boundary conditions as described in Eq. 6a [30]

Parameter Estimation

- Bin MD particle trajectories to the finite-difference grid

- Estimate optimal diffusion coefficient by minimizing the difference between binned MD data and finite-difference solution using nonlinear least squares (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm) [30]

Visualization of Diffusional Processes and Relationships

Workflow for MD-Based Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

Factors Influencing Molecular Diffusion in Biological Systems

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential computational tools and parameters for MD-based diffusion studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for MD Diffusion Studies

| Item | Function/Purpose | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MD Software Suites | Engine for running molecular dynamics simulations | GROMACS [31], LAMMPS [30], AMS [15], YASARA [27] |

| Force Fields | Describes interatomic forces and system physics | AMBER/GAFF [6], CHARMM, Martini (coarse-grained) |

| Solvation Models | Mimics physiological aqueous environment | TIP3P, SPC water models [6] |

| Trajectory Analysis Tools | Extracts diffusional properties from MD trajectories | GROMACS analysis tools, YASARA [27], AMS Analysis [15] |

| Visualization Software | Enables inspection of structures and trajectories | RasMol [31], VMD, PyMOL |

| Specialized Analysis | Implements specific diffusion coefficient algorithms | BrownDye [29], SDA [29], BD_BOX [29] |

Molecular diffusion in biological systems is governed by a complex interplay of physical factors including molecular properties, solvent characteristics, and environmental conditions. Molecular dynamics simulations provide a powerful approach for calculating diffusion coefficients and understanding these relationships at atomic resolution. The MSD analysis method, while computationally demanding, offers a direct route to diffusion coefficients from particle trajectories. Advances in simulation methodologies, including Brownian dynamics and hybrid continuum-MD approaches, continue to enhance our ability to model diffusion in biologically relevant crowded environments. A comprehensive understanding of these factors and methodologies is essential for researchers investigating molecular transport in biological systems and developing computational approaches for drug discovery and development.

Practical Implementation: MSD and VACF Methods with Code Examples

The Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) method, rooted in the seminal work of Einstein and Smoluchowski on Brownian motion, is a cornerstone technique for quantifying particle diffusion and calculating transport properties from Molecular Dynamics (MD) trajectories [10]. The Einstein formulation provides a direct relationship between the random walk of particles at the microscopic level and macroscopic diffusion coefficients. Within the broader context of thesis research on calculating diffusion coefficients from MD, mastering the practical application of the MSD method is fundamental. This technical guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with an in-depth understanding of the Einstein formulation's practical implementation, covering the core theory, computational protocols, data analysis, and critical considerations for obtaining reliable diffusion data.

Theoretical Foundation

The Einstein Relation

The foundation of the MSD method is the Einstein relation, which connects the macroscopic diffusion coefficient (D) to the ensemble average of particle displacements [32]. For a three-dimensional system, the relation is expressed as:

[ D = \frac{1}{6} \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \langle | \mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0) |^2 \rangle ]

Here, (\mathbf{r}(t)) represents the position of a particle at time (t), and the angle brackets (\langle \cdot \rangle) denote the ensemble average over all particles and time origins [33] [6]. The term (\langle | \mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0) |^2 \rangle) is the MSD. For normal (Brownian) diffusion in an isotropic medium, the MSD increases linearly with time, and the diffusion coefficient is proportional to the slope of this linear relationship. The factor of 6 accounts for the three spatial dimensions (a factor of 2 per dimension) [7].

The Einstein-Smoluchowski relation further connects diffusion to mobility, forming a fundamental fluctuation-dissipation theorem [10]. This states that the diffusion coefficient (D), mobility (\mu), and temperature (T) are related by:

[ \mu = \frac{D}{k_B T} ]

where (k_B) is the Boltzmann constant. While this guide focuses on the diffusion coefficient, this relationship underpins the broader significance of MSD calculations in understanding transport phenomena.

MSD Formulations and Dimensionality

The general expression for the MSD of a particle over a time lag (\tau) is given by [33]:

[ MSD(\tau) = \bigg{\langle} \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} |\mathbf{r}i(\tau) - \mathbf{r}_i(0)|^2 \bigg{\rangle} ]

where (N) is the number of particles, and (\mathbf{r}_i) are their coordinates. The MSD can be calculated for specific dimensional components depending on the system of interest [33]. For example, surface diffusion might require a 2D MSD in the xy-plane. The dimensionality factor (d) in the denominator of the Einstein relation ((2d)) must match the MSD's dimensionality: (d=3) for 'xyz' (3D), (d=2) for 'xy', 'yz', or 'xz' (2D), and (d=1) for 'x', 'y', or 'z' (1D) [33].

Table 1: Diffusion Coefficient Formulas for Different Dimensionalities

| MSD Type | Dimensionality (d) | Einstein Relation (D = ...) |

|---|---|---|

| 3D ('xyz') | 3 | ( \frac{slope}{6} ) |

| 2D (e.g., 'xy') | 2 | ( \frac{slope}{4} ) |

| 1D (e.g., 'x') | 1 | ( \frac{slope}{2} ) |

Computational Methodology

Essential Preprocessing of MD Trajectories

A critical prerequisite for a correct MSD calculation is the use of unrapped coordinates [33]. MD simulations typically use periodic boundary conditions, and atoms that cross the box boundary are "wrapped" back into the primary cell. Using these wrapped coordinates for MSD analysis will result in incorrect, artificially small displacements. Therefore, the trajectory must be preprocessed to produce an "unwrapped" trajectory, where atoms maintain their continuity of motion across periodic images. Some simulation packages, like GROMACS, provide tools for this (e.g., gmx trjconv -pbc nojump) [33] [34].

Furthermore, the trajectory must be properly equilibrated. The initial portion of the simulation, before the system reaches equilibrium, should be discarded before analysis to avoid biased results [35]. The choice of time interval between saved frames in the trajectory ((\Delta t)) is also crucial. It must be small enough to capture the relevant dynamics but not so small as to create overly large trajectory files. A good practice is to save coordinates at intervals on the order of the picosecond timescale for typical molecular systems [7].

MSD Calculation Algorithms

There are two primary algorithms for computing the MSD from a discrete trajectory: the simple windowed algorithm and the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)-based algorithm.

Windowed Algorithm: This direct method calculates the MSD for a series of time lags ((\tau)) by averaging the squared displacements over all possible time origins within the trajectory [33]. While conceptually straightforward, this algorithm has a computational cost that scales with (O(N^2)), where (N) is the number of frames, making it slow for very long trajectories.

FFT-Based Algorithm: This is a more advanced and computationally efficient method that leverages FFT to compute the MSD with (O(N \log N)) scaling [33]. This algorithm is recommended for long trajectories due to its superior speed. It is implemented in libraries like

tidynamicsand can be accessed in analysis tools like MDAnalysis by settingfft=True[33].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in a robust MSD calculation protocol.

Linear Fitting and the Diffusion Coefficient

Once the MSD is computed, the self-diffusivity is determined by fitting a straight line to the MSD versus time lag curve [33] [34]. The slope of this line is equal to (2dD), where (d) is the dimensionality.

- Selecting the Linear Regime: Visual inspection of the MSD plot is essential [33]. The MSD is often not linear across all time lags. At very short time lags, particle motion may be ballistic (MSD (\propto t^2)), while at very long time lags, the MSD may become noisy due to poor averaging [33] [36]. The linear segment representing pure diffusion is the "middle" part of the MSD curve. A log-log plot of MSD versus time can help identify this regime, as it will have a slope of 1 for normal diffusion [33].

- Fitting Procedure: A linear model is fitted to the selected linear segment of the MSD. For example, using

scipy.stats.linregressin Python [33]:

The GROMACS gmx msd module automates this fitting, with options -beginfit and -endfit to define the fitting range. By default (-beginfit -1 and -endfit -1), it fits from 10% to 90% of the total time lag [34].

Practical Implementation and Tools

Software Solutions for MSD Analysis

Several software packages commonly used in MD research provide robust implementations for MSD analysis. The table below summarizes key features and considerations.

Table 2: Comparison of MSD Analysis Software Tools

| Software/Tool | MSD Command / Class | Key Features and Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| MDAnalysis | analysis.msd.EinsteinMSD |

Python library. Supports windowed and FFT algorithms (fft=True). Requires tidynamics for FFT. Mandatory unwrapped coordinates [33]. |

| GROMACS | gmx msd |

Command-line tool. Integrates with GROMACS workflow. Automates linear fitting. Can calculate diffusion per molecule (-mol) [34]. |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | md.analysis.DiffusionCoefficient |

Python library. Can calculate for specific atoms or molecules (using center of mass). Allows trajectory segmentation for statistics [35]. |

| AMS | MD Properties → MSD | GUI-based in AMSmovie. Directly plots MSD and calculates D from the slope [7]. |

A Scientist's Toolkit for MSD Analysis

This table details essential "research reagents" – the computational tools and data components required for a successful MSD experiment.

Table 3: Essential Computational Materials for MSD Analysis

| Item | Function and Specification |

|---|---|

| Unwrapped Trajectory File | The primary input data. Typically in formats like XTC, TRR, or DCD. Must contain unwrapped particle coordinates to ensure correct displacement calculations [33]. |

| Topology File | Defines the system structure (e.g., TPR, GRO, PDB). Used to select atom groups for analysis [34]. |

| Index File (Optional) | A file (e.g., GROMACS .ndx) specifying groups of atoms or molecules for which the MSD will be computed separately [34]. |

| FFT MSD Library (e.g., tidynamics) | A Python package that enables fast (O(N \log N)) MSD computation. Crucial for handling long trajectories efficiently [33]. |

| Linear Regression Function | A tool (e.g., scipy.stats.linregress, numpy.linalg.lstsq) for performing the linear fit on the MSD data to extract the slope and, consequently, D [33] [35]. |

Advanced Considerations and Validation

Error Estimation and Statistical Reliability

Obtaining a reliable diffusion coefficient requires careful statistical analysis. A single, short MD simulation often provides poor statistics. Two common strategies to improve reliability are:

- Averaging over Multiple Segments: The trajectory can be divided into multiple segments (blocks), and the MSD/D is calculated for each segment. The final reported D is the average over all segments, and the standard deviation provides an error estimate [35].

- Averaging over Multiple Runs: For solutes at infinite dilution, where only one molecule is present in the simulation box, a single long trajectory may be insufficient. An efficient sampling strategy is to run multiple independent simulations and average the MSDs collected from these short runs [6].

The GROMACS gmx msd tool provides an error estimate based on the difference in diffusion coefficients obtained from fits over the first and second halves of the fit interval [34].

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Several factors can lead to inaccurate MSD results:

- Finite-Size Effects: The calculated diffusion coefficient can depend on the size of the simulation box due to hydrodynamic interactions with periodic images [6]. Typically, simulations are performed for progressively larger supercells, and the diffusion coefficients are extrapolated to the "infinite supercell" limit [7].

- Anomalous Diffusion: In complex environments like crowded proteins or polymer matrices, diffusion may be anomalous, where the MSD scales as (\text{MSD} \propto t^{\alpha}) with (\alpha \ne 1) [36] [10]. In such cases, the standard Einstein relation does not apply directly, and the analysis must account for the anomalous exponent (\alpha).

- Memory and Performance: MSD calculation, especially the windowed method, is memory-intensive for long trajectories. Using the FFT-based algorithm or restricting the maximum time lag for analysis (e.g., with

-maxtauingmx msd) can mitigate this [33] [34].

The Mean Squared Displacement method, via the Einstein formulation, is a powerful and widely used technique for extracting diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics trajectories. Its successful application in research, including drug development where understanding molecular mobility is critical, depends on a rigorous practical workflow: using unwrapped trajectories, selecting an efficient computational algorithm, carefully identifying the linear regime of the MSD plot, and performing robust statistical analysis to estimate errors. Adherence to these detailed protocols ensures the production of reliable, reproducible diffusion data that can validly inform scientific conclusions and models.

Step-by-Step MSD Calculation from Trajectory Data

Theoretical Foundation: The Einstein Relation

The Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) is a fundamental measure in the analysis of stochastic processes, rooted in the study of Brownian motion. It quantifies the deviation of a particle's position from a reference position over time and provides a direct pathway to calculating the self-diffusion coefficient, D [37] [38].

For a particle undergoing random Brownian motion in an isotropic medium, the MSD exhibits a linear relationship with time. The Einstein relation formalizes this, stating that the MSD for a d-dimensional diffusion process is given by [37] [38]: [MSD(t) = \langle | \vec{r}(t) - \vec{r}(0) |^{2} \rangle = 2dDt] where:

- (\vec{r}(t)) is the position vector of the particle at time (t).

- (d) is the dimensionality of the diffusion (e.g., 1, 2, or 3).

- (D) is the self-diffusion coefficient.

- The angle brackets (\langle \rangle) denote an ensemble average, typically performed over all particles of the same type and/or over multiple time origins.

In practice, for a computational system containing (N) equivalent particles, the MSD is calculated from trajectory data using the following Einstein formula [37] [39]: [MSD(r{d}) = \bigg{\langle} \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} |r{d} - r{d}(t0)|^{2} \bigg{\rangle}{t{0}}] Here, the average is taken over all possible time origins ((t0)) and all (N) particles, maximizing statistical accuracy.

Critical Preprocessing of Trajectory Data

A critical and often overlooked step in MSD calculation is the proper preparation of trajectory data. Failure to correctly handle periodic boundary conditions is the most common source of error.

- Unwrapped Coordinates: The MSD calculation requires coordinates in an unwrapped (or "no-jump") convention [37] [39]. When a particle crosses a periodic boundary, it must not be wrapped back into the primary simulation cell. Using wrapped coordinates will cause artificial jumps in the measured particle paths, severely underestimating the true MSD and the resulting diffusion coefficient.

- How to Unwrap Trajectories:

Table: Essential Checks Before MSD Analysis

| Checkpoint | Description | Common Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|

| Coordinate Convention | Ensure trajectories are unwrapped. | Using wrapped trajectories invalidates results [37]. |

| Trajectory Length | Simulation must be long enough to observe diffusive behavior. | Short trajectories fail to reach linear MSD regime. |

| Frame Interval | Save frames with a small enough time interval. | Large time steps poorly capture particle motion [37]. |

| Equilibration | Confirm system is equilibrated before analysis. | Analyzing non-equilibrated data introduces artifacts. |

Practical Calculation Workflows

Core Calculation Procedure

The general workflow for a "windowed" MSD calculation involves averaging over all possible time origins within the trajectory [37]. For a trajectory with (T) total frames, the MSD at a lag time ( \tau = n \Delta t ) (where ( \Delta t ) is the time between frames) is:

[MSD(\tau) = \frac{1}{T-n} \sum{i=1}^{T-n} \frac{1}{N} \sum{j=1}^{N} \left[ \vec{r}j(t{i+n}) - \vec{r}j(ti) \right]^2]

This calculation is computationally intensive, scaling quadratically with the number of frames. However, Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)-based algorithms can compute the MSD with (N log(N)) scaling, offering dramatic speed improvements for long trajectories [37] [39].

Step-by-Step Implementation in MDAnalysis

The following Python code demonstrates a complete MSD calculation and diffusion coefficient extraction using MDAnalysis [37].

Implementation in GROMACS

In GROMACS, the gmx msd command provides a direct way to compute MSDs and diffusion coefficients [34].

Key gmx msd options for accurate results [34]: