From Atoms to Insights: A Comprehensive Guide to the Molecular Dynamics Workflow for Biomolecular Trajectories

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the molecular dynamics (MD) workflow for generating and analyzing atomic trajectories, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

From Atoms to Insights: A Comprehensive Guide to the Molecular Dynamics Workflow for Biomolecular Trajectories

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the molecular dynamics (MD) workflow for generating and analyzing atomic trajectories, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of MD simulations, from Newton's equations of motion and force field selection to the practical steps of system setup and equilibration. The content explores advanced methodologies and applications in biomedicine, including drug discovery and diagnostic design, and details modern optimization techniques such as coarse-graining and AI-driven automation. Finally, it addresses the critical processes of trajectory validation, analysis, and comparative benchmarking to ensure reliability and accuracy, offering a complete roadmap for leveraging MD simulations in scientific and industrial research.

The Fundamentals of Molecular Dynamics: Principles and Workflow Setup

Molecular Dynamics (MD) is a powerful computational technique for simulating the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. By analyzing these dynamic trajectories, researchers can understand complex processes in chemical physics, materials science, and biophysics that are difficult or impossible to observe experimentally. The foundation of MD lies in numerically integrating Newton's equations of motion for a system of interacting particles, where forces between particles and their potential energies are calculated using interatomic potentials or molecular mechanical force fields. The method essentially provides "statistical mechanics by numbers" and has been described as "Laplace's vision of Newtonian mechanics" for predicting future states by animating nature's forces [1].

In a molecular system comprising N atoms, a molecular geometry (R) at time t is described by the atomic positions of its constituents: R = (r₁, r₂, ..., r_N). The core physical principle is Newton's second law, which for each atom i is expressed as Fᵢ = mᵢaᵢ, where Fᵢ is the force acting on the atom, mᵢ is its mass, and aᵢ is its acceleration. Since acceleration is the second derivative of position with respect to time, this becomes Fᵢ = mᵢ(∂²rᵢ/∂t²). Crucially, the force can also be derived from the potential energy function V of the system as Fᵢ = -∂V/∂rᵢ [2]. For systems obeying the ergodic hypothesis, the time averages from MD simulations correspond to microcanonical ensemble averages, enabling the determination of macroscopic thermodynamic properties from microscopic simulations [1].

The Numerical Integration Challenge

The Time Step Dilemma

For molecular systems with more than two atoms, analytical solution of the equations of motion is impossible, necessitating numerical integration approaches. MD simulations use a class of numerical methods called finite difference methods, where integration is divided into many small finite time steps (δt) [2]. The choice of time step presents a critical dilemma: too large, and the simulation becomes unstable and inaccurate; too small, and the computation becomes prohibitively expensive. Since the fastest molecular motions (typically bond vibrations involving hydrogen atoms) occur on the order of 10⁻¹⁴ seconds, the time step must be sufficiently small to resolve these vibrations. Typical MD simulations use time steps of approximately 1 femtosecond (10⁻¹⁵ s) [1]. This time scale is small enough to avoid discretization errors while being large enough to make microsecond-scale simulations computationally feasible, though still demanding significant resources.

Desirable Properties of Integration Algorithms

Numerical integrators for MD must balance several competing demands. Time-reversibility ensures that taking k steps forward followed by k steps backward returns the system to its initial state, reflecting the time-symmetric nature of fundamental physical laws. Symplecticity is perhaps even more crucial—symplectic integrators conserve the phase-space volume and preserve the Hamiltonian structure of the equations of motion. In practical terms, this means they exhibit excellent long-term energy conservation without numerical drift, ensuring that simulated systems maintain physical behavior over extended simulation periods. For example, in planetary orbit simulations or constant-energy MD, symplectic methods prevent the artificial gain or loss of energy that would cause Earth to leave its orbit or a protein to undergo unphysical deformation [3]. The Velocity Verlet algorithm and its variants possess these desirable properties while maintaining computational efficiency.

The Velocity Verlet Algorithm

Mathematical Foundation and Derivation

The Velocity Verlet algorithm is one of the most widely used integration methods in molecular dynamics. It is classified as a second-order method because the local truncation error is proportional to Δt³, while the global error is proportional to Δt². The algorithm can be derived from Taylor expansions of position and velocity. The position expansion is:

r(t + Δt) = r(t) + v(t)Δt + (1/2)a(t)Δt² + O(Δt³)

Similarly, the velocity expansion is: v(t + Δt) = v(t) + a(t)Δt + (1/2)b(t)Δt² + O(Δt³)

where b(t) represents the third derivative of position with respect to time [2]. The Velocity Verlet algorithm cleverly rearranges these expansions to provide a numerically stable, time-reversible, and symplectic integration scheme.

The Integration Steps

The Velocity Verlet algorithm decomposes the integration into discrete steps that propagate the system forward in time:

- Half-step velocity update: vᵢ(t + ½Δt) = vᵢ(t) + (Fᵢ(t)/2mᵢ)Δt

- Full-step position update: rᵢ(t + Δt) = rᵢ(t) + vᵢ(t + ½Δt)Δt

- Force computation: Calculate new forces Fᵢ(t + Δt) based on the new positions

- Second half-step velocity update: vᵢ(t + Δt) = vᵢ(t + ½Δt) + (Fᵢ(t + Δt)/2mᵢ)Δt [4]

This scheme maintains synchronicity between position and velocity vectors at the same time steps, which is particularly useful for monitoring and analyzing system properties throughout the simulation [4]. The algorithm requires only one force evaluation per time step, which is computationally efficient since force calculation is typically the most expensive part of an MD simulation.

Workflow Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the sequential workflow of the Velocity Verlet algorithm within a single simulation time step:

Comparative Analysis of Integration Algorithms

The Verlet Family of Algorithms

The Velocity Verlet algorithm belongs to a family of related integration schemes, all based on the original Verlet algorithm. The basic Verlet algorithm calculates new positions using: r(t + Δt) = 2r(t) - r(t - Δt) + a(t)Δt²

While mathematically equivalent to Velocity Verlet, this formulation has practical disadvantages: velocities are not directly available (they must be calculated as v(t) = [r(t + Δt) - r(t - Δt)]/(2Δt)), and the algorithm is not self-starting as it requires positions from the previous time step [2]. The Leapfrog algorithm is another variant that uses the recurrence: vᵢ(t + ½Δt) = vᵢ(t - ½Δt) + (Fᵢ(t)/mᵢ)Δt rᵢ(t + Δt) = rᵢ(t) + vᵢ(t + ½Δt)Δt [4]

In this scheme, velocities and positions are "leapfrogged" over each other and are asynchronous in time, which can complicate analysis and visualization [2].

Quantitative Comparison of Integration Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Key Integration Algorithms in Molecular Dynamics

| Algorithm | Global Error | Time-Reversible | Symplectic | Velocity Handling | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euler Method | O(Δt) | No | No | Synchronous | Low (1 force evaluation/step) |

| Basic Verlet | O(Δt²) | Yes | Yes | Not directly available | Low (1 force evaluation/step) |

| Velocity Verlet | O(Δt²) | Yes | Yes | Synchronous | Low (1 force evaluation/step) |

| Leapfrog | O(Δt²) | Yes | Yes | Asynchronous (half-step offset) | Low (1 force evaluation/step) |

The Velocity Verlet algorithm provides an optimal balance for most MD applications, offering second-order accuracy, symplecticity, time-reversibility, and synchronous computation of positions and velocities with only one force evaluation per time step [3]. While higher-order methods like Runge-Kutta schemes exist, they typically lack the symplectic property and are not time-reversible, making them unsuitable for long-time-scale MD simulations where energy conservation is critical [3].

Practical Implementation in Molecular Dynamics Workflows

The Molecular Dynamics Simulation Cycle

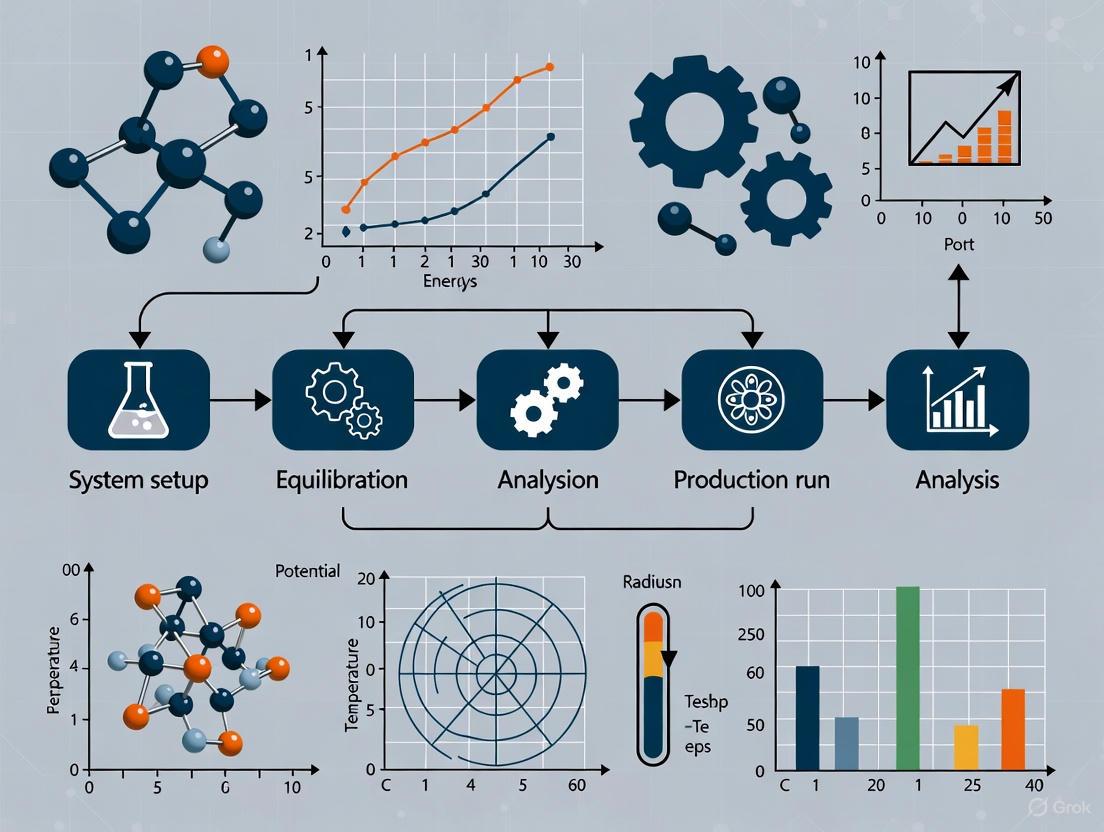

A complete MD simulation involves multiple stages that extend beyond the core integration algorithm. The typical workflow includes:

Initialization: The system is defined by initial positions (typically from experimental structures) and initial velocities (usually drawn from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution). The potential energy V arising from interatomic interactions is computed [2].

Force Computation: Forces on each atom are calculated as Fᵢ = -∂V/∂rᵢ. This is the most computationally intensive step, as it involves evaluating all bonded and non-bonded interactions in the system [2].

Integration: The Velocity Verlet algorithm propagates the system forward by one time step, updating positions and velocities.

Iteration: Steps 2-3 are repeated for the desired number of time steps, generating a trajectory of the system [2].

Analysis: The resulting trajectory is analyzed to extract physically meaningful properties, such as energies, structural changes, or dynamic correlations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for MD Simulations

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Molecular Dynamics

| Component | Type | Function/Purpose | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integration Algorithms | Software Component | Numerically solve equations of motion | Velocity Verlet, Leapfrog [2] [4] |

| Force Fields | Parameter Set | Define potential energy functions | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS [5] |

| Solvent Models | Parameter Set | Represent water and other solvents | TIP3P, SPC/E, implicit solvent [1] |

| Simulation Software | Application Platform | Implement MD algorithms and workflows | OpenMM, GROMACS, NAMD [5] [6] |

| Analysis Tools | Software Library | Process trajectories and compute properties | MDTraj, Crossflow [5] [7] |

| Enhanced Sampling | Advanced Method | Accelerate rare events | Metadynamics, Umbrella Sampling [8] |

Advanced Applications and Recent Developments

Specialized Applications of Velocity Verlet

The robustness of the Velocity Verlet algorithm has enabled its adaptation to specialized simulation scenarios. Researchers have developed modifications to handle strong external magnetic fields, where conventional techniques demand the simulation time step Δt be small compared to the Larmor oscillation time 2π/Ω. The modified Velocity Verlet approach builds the magnetic field directly into the propagation equations, making the choice of Δt independent of 2π/Ω and thus significantly improving efficiency for strongly magnetized systems [9]. Such specialized applications demonstrate the algorithm's flexibility and continued relevance across diverse physical scenarios.

Integration with Modern Computational Workflows

Contemporary research increasingly incorporates MD simulations into larger, automated workflows. Tools like Crossflow, a Python library built on Dask.distributed, enable researchers to construct complex computational workflows that integrate Velocity Verlet-based MD with other simulation and analysis tasks [7]. Similarly, MDCrow represents an LLM-based agentic system that can automate MD workflow setup and execution, including parameter selection, simulation running, and analysis [5]. These developments are making sophisticated MD simulations more accessible while maintaining the fundamental integration algorithms like Velocity Verlet at their core.

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of molecular dynamics continues to evolve, with several emerging trends building upon foundational integration methods. Machine learning approaches are being integrated with MD simulations for enhanced analysis of complex trajectories [8]. Quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) methods combine the accuracy of quantum chemistry with the efficiency of classical force fields, with Velocity Verlet often serving as the integration engine for the classical regions [8]. GPU-accelerated computing has dramatically expanded the accessible timescales of MD simulations, from nanoseconds in the 1990s to routine microsecond simulations today, all while relying on the same fundamental integration algorithms [8]. These advances ensure that the Velocity Verlet algorithm will remain a cornerstone of molecular simulation methodology for the foreseeable future.

In the molecular dynamics (MD) workflow for atomic trajectories research, the force field serves as the fundamental computational model that defines the potential energy of a system and governs the forces between atoms. The choice between an all-atom (AA) and a coarse-grained (CG) representation constitutes one of the most critical early decisions in any MD study, with profound implications for the balance between computational efficiency and atomistic detail. A force field consists of mathematical functions and parameters used to calculate the potential energy of a system at the atomistic level, typically including terms for both bonded interactions (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and nonbonded interactions (electrostatic and van der Waals forces) [10]. This technical guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for selecting appropriate force field resolutions based on their specific research objectives, system characteristics, and computational resources.

Fundamental Concepts: Resolution Levels and Physical Basis

All-Atom, United-Atom, and Coarse-Grained Representations

Molecular dynamics force fields exist along a spectrum of resolution, with each level offering distinct advantages and limitations for simulating atomic trajectories:

All-Atom (AA) Force Fields: AA force fields explicitly represent every atom in the system, including hydrogen atoms. This approach provides the highest level of detail, making it suitable for studying phenomena where atomic-level interactions are critical, such as precise ligand binding, chemical reactions, or detailed conformational changes [11] [10]. The CHARMM36 and AMBER ff19SB are examples of widely used AA force fields in biomolecular simulations [12].

United-Atom (UA) Force Fields: UA force fields represent aliphatic hydrogens implicitly by grouping them with their parent carbon atoms, thereby reducing the total number of particles in the system. This offers a middle ground between computational efficiency and atomic detail [11].

Coarse-Grained (CG) Force Fields: CG force fields significantly simplify the molecular representation by grouping multiple atoms into single interaction centers or "beads." Popular CG force fields like MARTINI and SIRAH can improve computational efficiency by several orders of magnitude, enabling the simulation of larger systems and longer timescales [12] [13]. This reduction in detail smooths the energy landscape and reduces molecular friction, allowing faster exploration of conformational space [13].

Table 1: Comparison of Force Field Resolutions for Molecular Dynamics

| Feature | All-Atom (AA) | United-Atom (UA) | Coarse-Grained (CG) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic Representation | Explicit representation of all atoms, including hydrogens | Aliphatic hydrogens grouped with carbon atoms | Multiple atoms grouped into single "beads" |

| Computational Cost | Highest | Moderate | Significantly reduced |

| Simulation Timescales | Nanoseconds to microseconds | Microseconds | Microseconds to milliseconds |

| Spatial Scales | Small to medium systems (up to ~1 million atoms) | Medium systems | Large systems (millions to billions of atoms) |

| Level of Detail | Atomic-level interactions | Atomic-level for heavy atoms, simplified for aliphatic groups | Mesoscopic, missing atomic details |

| Common Force Fields | CHARMM36, AMBER ff19SB, OPLS-AA | OPLS-UA, GROMOS | MARTINI, SIRAH, UNRES |

| Typical Applications | Ligand binding, detailed conformational changes, reaction mechanisms | Membrane systems, lipid bilayers | Large macromolecular complexes, cellular components |

Mathematical Foundations of Force Fields

The basic functional form of the potential energy in most molecular mechanics force fields follows a consistent pattern, though the specific implementation varies between different force fields. The total energy is typically decomposed into bonded and nonbonded components [10]:

[ E{\text{total}} = E{\text{bonded}} + E_{\text{nonbonded}} ]

Where the bonded terms are further decomposed as: [ E{\text{bonded}} = E{\text{bond}} + E{\text{angle}} + E{\text{dihedral}} ] And the nonbonded terms include: [ E{\text{nonbonded}} = E{\text{electrostatic}} + E_{\text{van der Waals}} ]

The bond stretching energy is typically modeled using a harmonic potential approximating Hooke's law: [ E{\text{bond}} = \frac{k{ij}}{2}(l{ij} - l{0,ij})^2 ] where ( k{ij} ) is the bond force constant, ( l{ij} ) is the actual bond length, and ( l_{0,ij} ) is the equilibrium bond length [10].

Electrostatic interactions are generally represented by Coulomb's law: [ E{\text{Coulomb}} = \frac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon0}\frac{qi qj}{r{ij}} ] where ( qi ) and ( qj ) are the atomic charges, ( r{ij} ) is the distance between atoms, and ( \varepsilon_0 ) is the vacuum permittivity [10].

Practical Selection Framework: Choosing the Appropriate Resolution

Systematic Decision Criteria for Force Field Selection

Selecting the appropriate force field resolution requires careful consideration of multiple scientific and practical factors. The following workflow provides a structured approach to this decision process:

The selection of force field resolution directly impacts the physical accuracy and computational feasibility of MD simulations. The following table summarizes key performance characteristics and limitations of each approach:

Table 2: Performance Characteristics and Limitations of Different Force Field Resolutions

| Aspect | All-Atom (AA) | Coarse-Grained (CG) |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy of Atomic Interactions | High - captures detailed atomic interactions and stereochemistry | Limited - loses atomic details, may miss specific interactions |

| Computational Efficiency | Lower - requires significant computational resources for meaningful simulations | Higher - enables simulation of larger systems and longer timescales |

| Sampling Efficiency | Slower - rugged energy landscape with high barriers | Faster - smoothed energy landscape with reduced friction [13] |

| Representation of Energetics | Direct - based on physical principles with some empirical parameterization | Indirect - often based on statistical potentials from databases [12] |

| Handling of Polarization Effects | Explicit - through polarizable force fields or fixed-charge approximations with scaling | Implicit - through effective parameters, with recent advances in polarizable CG models [13] |

| Transferability | Generally good for related systems, but requires careful validation | Can be limited, especially for systems not well-represented in training data [12] |

| Physical Interpretation | More straightforward connection to physical chemistry principles | Requires mapping back to atomic details for full interpretation |

Case Studies and Empirical Comparisons

Real-world comparisons between AA and CG simulations reveal practical performance differences that inform selection decisions. In a study comparing AA (CHARMM36) and CG (MARTINI) simulations of a POPC lipid bilayer under equibiaxial stretching, the CG system exhibited approximately half the von Mises stress values of the AA system despite identical simulation conditions [14]. This discrepancy was attributed to reduced friction and fewer entropic contributions in the CG representation, where multiple atoms are collapsed into single beads, particularly during non-equilibrium processes like deformation [14].

For intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) like amyloid-β, both AA and CG approaches can provide reasonable results, but CG methods may lack certain atomistic details, such as precise secondary structure recognition, due to the inherent simplifications in the model [12]. Recent improvements in CG force fields, particularly adjustments to protein-water interaction scaling in MARTINI, have enhanced their ability to capture IDP behavior more accurately [12].

Methodological Protocols: Implementation Guidelines

Standard Simulation Workflow for AA and CG Simulations

The following diagram illustrates the general MD workflow, highlighting key differences between AA and CG approaches:

Detailed Experimental Protocols

All-Atom Simulation Protocol for Intrinsically Disordered Proteins

Based on established methodologies for studying systems like amyloid-β [12]:

System Setup

- Obtain initial protein structure from experimental data or homology modeling

- Solvate the protein in an appropriate water model (OPC recommended for IDPs with AMBER ff19SB)

- Add ions to neutralize the system and achieve desired physiological concentration

Energy Minimization

- Apply steepest descent algorithm for 5,000-10,000 steps

- Use position restraints on protein heavy atoms (force constant: 1000 kJ/mol/nm²)

- Confirm significant reduction in potential energy and maximum force < 1000 kJ/mol/nm

Equilibration

- NVT equilibration for 100-500 ps with protein heavy atoms restrained

- Maintain temperature at 310 K using modified Berendsen thermostat

- NPT equilibration for 1-5 ns with protein heavy atoms restrained

- Maintain pressure at 1 bar using Parrinello-Rahman barostat

- Gradually release position restraints on protein backbone and side chains

Production Simulation

- Run multiple independent trajectories (3-5) of 100 ns - 1 µs each

- Use a 2-fs time step with bonds constrained to hydrogen atoms using LINCS

- Employ replica exchange molecular dynamics if enhanced sampling is required

Coarse-Grained Simulation Protocol Using MARTINI

System Preparation

- Convert atomistic structure to CG representation using appropriate mapping

- For proteins, use the martinize.py script with Elnedyn elastic network

- Solvate the system with standard MARTINI water molecules

- Add ions as needed for neutralization

Energy Minimization

- Perform steepest descent minimization for 1,000-5,000 steps

- No position restraints typically required for CG systems

Equilibration

- NVT equilibration for 10-100 ns with protein backbone restraints (force constant: 1000 kJ/mol/nm²)

- Maintain temperature using velocity rescale thermostat

- NPT equilibration for 50-200 ns with protein backbone restraints

- Maintain pressure at 1 bar using Parrinello-Rahman barostat

- Gradually release restraints in 2-3 stages

Production Simulation

- Run production for 1-10 µs depending on system size and processes of interest

- Use 10-20 fs time step

- For IDPs, apply protein-water interaction scaling (0.85-0.95) to prevent over-compaction

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Software | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Packages | GROMACS [14] [12], AMBER [12] | Molecular dynamics engine | High performance, extensive force field support |

| Visualization Software | VMD, ChimeraX [15] | Trajectory analysis and visualization | Multiple representation styles, scripting capability |

| Force Field Databases | MolMod [10], TraPPE [10] | Force field parameter repositories | Curated parameters for specific molecular classes |

| Analysis Tools | MDTraj, MDAnalysis | Trajectory analysis | Python-based, programmable analysis workflows |

| Specialized CG Tools | MARTINI [12] [13], SIRAH [12] | Coarse-grained force fields | Balanced detail and efficiency for large systems |

| Validation Resources | PDB, NMR data [12] | Simulation validation | Experimental reference data for force field testing |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of molecular dynamics continues to evolve with several emerging trends that impact force field selection and application. Machine learning approaches are increasingly being applied to both force field development and surrogate modeling of MD trajectories [13] [16]. Generative models of molecular trajectories, such as MDGen, represent a promising approach for learning flexible multi-task surrogate models from MD data, enabling applications in forward simulation, transition path sampling, trajectory upsampling, and dynamics-conditioned molecular design [16].

Polarizable force fields constitute another significant advancement, addressing the critical limitation of fixed-charge models in handling electronic polarization effects [13]. For CG models, recent developments include polarizable variants using Drude oscillators and QM-based polarizable models that more accurately capture the electrostatic environments in complex systems like ionic liquids [13].

Multi-scale modeling approaches that seamlessly integrate different resolutions are also gaining traction, allowing researchers to apply high-resolution AA models to critical regions while using efficient CG representations for less critical parts of the system. These advancements are progressively blurring the traditional boundaries between AA and CG approaches, offering researchers more nuanced options for balancing computational efficiency with physical accuracy.

As the field advances toward simulating increasingly complex systems, including entire cellular environments [15], the judicious selection and application of appropriate force fields will remain fundamental to generating physically meaningful atomic trajectories and extracting biologically significant insights from molecular dynamics simulations.

In molecular dynamics (MD) research, the initial system setup is a critical determinant of simulation reliability and accuracy. This phase transforms a static molecular structure into a dynamic model that approximates realistic experimental or physiological conditions. Proper configuration of the simulation box, solvation environment, and ion concentration establishes the physical context for atomic trajectory research, directly influencing the thermodynamic and kinetic properties extracted from simulations [17] [18]. For researchers and drug development professionals, rigorous implementation of these foundational steps ensures that subsequent trajectory analysis provides meaningful insights into molecular behavior, binding interactions, and dynamic processes relevant to therapeutic design.

The simulation setup process bridges the gap between isolated molecular structures and their behavior in complex environments. As MD simulations track the movement of individual atoms and molecules over time by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion, they offer a unique window into atomic-scale processes that are often difficult or impossible to observe experimentally [17] [19]. The accuracy of this "computational microscope" depends fundamentally on how well the simulated system represents reality, making initial setup decisions critical for generating physically meaningful trajectories.

Defining the Simulation Box and Boundary Conditions

Simulation Box Fundamentals

The simulation box defines the spatial domain containing all particles to be simulated. This finite volume must be carefully constructed to balance computational efficiency with physical accuracy, as its dimensions directly determine the number of atoms in the system and consequently the computational resources required [20]. The primary challenge lies in simulating biologically or materials-relevant behavior with a tractable number of atoms, typically thousands to millions rather than the Avogadro-scale numbers found in macroscopic systems [19].

The selection of box shape represents a critical early decision with significant implications for sampling efficiency. While a simple cubic box may be most intuitive, other geometries often provide better performance for biomolecular simulations [20].

Table 1: Common Simulation Box Geometries and Their Applications

| Box Type | Mathematical Definition | Primary Advantages | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cubic/Orthorhombic | Three equal or unequal edge lengths at 90° angles | Simple implementation; intuitive | General purpose; crystalline materials |

| Rhombic Dodecahedron | Twelve identical rhombic faces | Most efficient for spherical molecules; minimal volume | Globular proteins; micellar simulations |

| Truncated Octahedron | Eight hexagonal and six square faces | Good balance of efficiency and simplicity | Solvated proteins; nucleic acids |

| Hexagonal Prism | Two hexagonal bases with rectangular sides | Suitable for elongated molecules | DNA; filamentous proteins |

Periodic Boundary Conditions

Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBCs) represent the most widely adopted solution to the surface artifact problem inherent to finite simulation volumes. Rather than simulating an isolated cluster of atoms with artificial surfaces, PBCs create an infinite periodic system by tiling space with identical copies of the primary simulation cell [20]. Under this framework, each atom in the primary cell interacts not only with other atoms in the same cell but also with their periodic images in adjacent cells.

The mathematical implementation of PBCs treats particle coordinates as modular with respect to box dimensions. For a particle at position r = (x, y, z) in a cubic box of side length L, its periodic images appear at positions r + (iL, jL, kL) for all integer combinations of i, j, k [20]. When a particle exits the primary box through one face, it simultaneously re-enters from the opposite face, maintaining a constant number of particles throughout the simulation [20].

The minimum image convention governs interatomic interactions within PBCs, specifying that each atom interacts only with the single closest copy of every other atom (either the original or one of its images) [20]. This convention requires that the box dimensions exceed twice the non-bonded interaction cutoff distance (L > 2r_cut) to prevent atoms from interacting with multiple copies of the same particle. For typical biomolecular simulations with cutoff distances of 1.0-1.2 nm, this necessitates box sizes of at least 2.0-2.4 nm in each dimension [20].

Solvation: Creating the Aqueous Environment

Explicit vs. Implicit Solvent Models

Solvation refers to the process of surrounding solute molecules (proteins, nucleic acids, drug compounds) with solvent molecules to create a realistic environmental context. The choice between explicit and implicit solvent representations represents a fundamental trade-off between computational efficiency and physical accuracy [19].

Table 2: Comparison of Explicit and Implicit Solvation Methods

| Parameter | Explicit Solvent | Implicit Solvent |

|---|---|---|

| Representation | Individual solvent molecules (e.g., ~3 atoms for TIP3P water) | Continuum dielectric medium |

| Computational Cost | High (thousands of additional atoms) | Low (no additional atoms) |

| Accuracy for | Hydrogen bonding, specific hydration, diffusion | Thermodynamic properties, rapid screening |

| Common Models | TIP3P, TIP4P, SPC, OPC [21] [22] | Generalized Born (GB), Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) |

| Implementation | Solvent molecules added to simulation box | Dielectric constant assigned to extra-molecular space |

Explicit solvent models provide atomic detail of solute-solvent interactions at the expense of significantly increased system size and computational requirements. For a typical globular protein, water molecules can constitute 80-90% of the total atoms in the system [19]. Implicit solvent (continuum) models approximate the solvent as a dielectric medium characterized by a dielectric constant, dramatically reducing system complexity while potentially sacrificing specific interaction details [23] [19].

Practical Solvation Methodology

The technical process of solvation begins with placing the solute molecule in an appropriately sized simulation box, followed by insertion of solvent molecules into all regions not occupied by the solute. The solvatebox command in tools like tLEaP (AMBER) or solvation utilities in GROMACS automatically fill the available volume with solvent molecules arranged in pre-equilibrated configurations [21].

A critical consideration is ensuring sufficient solvent padding between the solute and box boundaries. For proteins, a minimum distance of 1.0-1.5 nm between any protein atom and the box edge is generally recommended to prevent artificial correlations between periodic images [21] [22]. This padding ensures that the solute does not interact with its own periodic images across the box boundaries, which would create unphysical constraints on conformational dynamics.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the sequential steps in system solvation:

Adding Ions: Neutralization and Physiological Conditions

Purpose of Ion Addition

The introduction of ions into the simulation system serves two primary purposes: neutralizing the overall system charge and establishing physiologically relevant salt concentrations. Most biomolecules carry substantial net charges under physiological conditions - for example, lysozyme possesses a charge of +8 [22]. Without counterions, these charged systems would generate unrealistic electrostatic interactions under periodic boundary conditions, leading to unphysical dynamics and artifacts in atomic trajectories [21].

Beyond neutralization, the addition of salt ions at appropriate concentrations mimics the physiological or experimental environment being modeled. Ionic composition affects conformational sampling, dynamics, and function of biological macromolecules through screening of electrostatic interactions and specific ion binding effects [21]. For simulations targeting biological relevance, 150 mM NaCl approximates physiological salt concentration, though specialized contexts may require different ionic compositions or concentrations [21].

Ion Placement Methods

Two principal methodologies exist for introducing ions into solvated systems: random placement and electrostatic potential-guided placement. Random placement substitutes randomly selected solvent molecules with ions, while potential-guided placement positions ions at points of favorable electrostatic potential relative to the solute [21].

The number of ions required for neutralization depends directly on the net charge of the solute macromolecule. For a system with net charge +Q, exactly Q counterions (typically Cl⁻ for positively charged solutes) must be added to achieve neutrality [21] [22]. To establish specific salt concentrations beyond neutralization, the number of additional ion pairs follows the formula:

Nions = 0.0187 × [Molarity] × Nwater

where N_water represents the number of water molecules in the system, and [Molarity] is the target salt concentration [21]. For increased accuracy, computational servers like SLTCAP can calculate ion numbers corrected for screening effects, which may yield slightly different values than this empirical formula [21].

Table 3: Ion Types and Properties in Common Force Fields

| Ion Type | Common Force Field Parameters | Hydration Properties | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Na⁺ | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS variants | Strong first hydration shell; low diffusion | Physiological mimicry; nucleic acid systems |

| K⁺ | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS variants | Weaker hydration; higher diffusion | Intracellular environments; ion channels |

| Cl⁻ | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS variants | Moderate hydration; anion interactions | General counterion; charge neutralization |

| Ca²⁺ | Specialized parameters | Strong coordination; slow exchange | Signaling systems; metalloproteins |

| Mg²⁺ | Specialized parameters | Tight hydration; high charge density | Nucleic acid folding; ATP-dependent enzymes |

The following workflow illustrates the ion addition process:

Integrated Workflow: From Structure to Solvated System

Complete Setup Procedure

Implementing a robust system setup requires sequential execution of the aforementioned steps, typically facilitated by MD preparation tools such as tLEaP (AMBER), GROMACS utilities, or CHARMM scripting. The following integrated protocol details a complete workflow from initial structure to solvated, ionized system ready for energy minimization:

Initial Structure Preparation: Obtain atomic coordinates from databases such as the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or Materials Project. Process the structure to remove heteroatoms, add missing residues or atoms, and assign protonation states appropriate for the target pH [22] [24].

Force Field Selection: Choose an appropriate force field (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS-AA) and water model consistent with the research objectives and compatible with the solute molecule [22] [18]. Apply force field parameters to generate molecular topology.

Simulation Box Definition: Center the solute in an appropriately sized box with geometry selected based on molecular shape. Ensure minimum distance of 1.0-1.5 nm between solute and all box boundaries [20] [22].

System Solvation: Fill the simulation box with water molecules using the selected water model. For explicit solvent simulations, this typically employs pre-equilibrated water configurations that are merged with the solute structure [21] [22].

Ion Addition: First, add sufficient counterions to neutralize the system net charge. Subsequently, add additional ion pairs to achieve the target physiological or experimental salt concentration [21] [25].

System Validation: Verify final system composition, check for atomic overlaps, and confirm appropriate charge distribution before proceeding to energy minimization.

The following diagram provides a comprehensive overview of the complete system setup workflow:

Table 4: Essential Software Tools and Databases for MD System Setup

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Primary Function | Access/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB); Materials Project; PubChem | Source experimental structures | https://www.rcsb.org/; https://materialsproject.org/ |

| Force Fields | AMBER (ff19SB); CHARMM36; OPLS-AA; GROMOS | Molecular mechanics parameters | [22] [24] |

| Setup Utilities | tLEaP (AMBER); pdb2gmx (GROMACS); CHARMM-GUI | Topology generation; system building | [21] [22] |

| Solvation Tools | Solvate tool (GROMACS); Solvate plugin (VMD) | Add explicit solvent molecules | [21] [22] |

| Ion Placement | Autoionize (VMD); genion (GROMACS); SLTCAP server | Add ions for neutralization/salt concentration | [21] [25] |

| Validation Tools | VMD; ChimeraX; GROMAC energy analysis | Visual inspection; energy sanity checks | [24] [18] |

The meticulous setup of simulation boxes, solvation environments, and ion distributions establishes the physical basis for meaningful molecular dynamics trajectories. These initial conditions directly control the quality and biological relevance of the dynamic behavior observed in atomic-level simulations. For research aimed at understanding molecular mechanisms or supporting drug development initiatives, rigorous implementation of these foundational steps aligns simulation outcomes with experimental observables, creating a robust platform for extracting scientifically valid insights from atomic trajectories. As MD simulations continue to bridge theoretical and experimental approaches in molecular science, standardized, well-documented system preparation remains indispensable for generating reproducible, physically-grounded computational results.

Within the broader molecular dynamics (MD) workflow for atomic trajectories research, the establishment of stable initial conditions is a critical prerequisite for obtaining physically meaningful and reproducible simulation data. This guide details the core protocols for energy minimization and system equilibration, two foundational steps that ensure a simulation starts from a stable, low-energy configuration. Proper execution of these steps mitigates instabilities caused by unphysical atomic overlaps, incorrect bond geometries, or high internal stresses, which could otherwise lead to simulation failure or inaccurate results. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, a rigorous approach to these initial phases is indispensable for the reliability of subsequent trajectory analysis.

Energy Minimization: Core Algorithms and Protocols

Energy minimization (EM), also known as energy optimization, is the process of iteratively adjusting atomic coordinates to find a local minimum on the potential energy surface. This step resolves steric clashes and unphysical conformations that may exist in the initial structure, often resulting from model building or experimental structure limitations.

Three common algorithms for energy minimization are the steepest descent, conjugate gradient, and L-BFGS methods [26]. The choice of algorithm involves a trade-off between robustness, computational efficiency, and the specific requirements of the system.

Steepest Descent: This robust algorithm is highly effective in the initial stages of minimization when the system is far from an energy minimum. It moves atomic coordinates in the direction of the negative energy gradient (the force). Although not the most efficient, it is very stable for poorly conditioned systems. The maximum displacement is dynamically adjusted based on whether a step decreases the potential energy; it is increased by 20% for successful steps and reduced by 80% for rejected steps [26].

Conjugate Gradient: This algorithm is more efficient than steepest descent as it approaches the energy minimum but can be less robust in the early stages. It uses information from previous steps to choose conjugate descent directions, leading to faster convergence near the minimum. A key limitation is that it cannot be used with constraints, meaning flexible water models are required if water is present [26].

L-BFGS (Limited-memory Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno): A quasi-Newtonian method, L-BFGS builds an approximation of the inverse Hessian matrix (the matrix of second derivatives) to achieve faster convergence. It typically converges faster than conjugate gradients but is not yet parallelized in all MD software packages due to its reliance on correction steps from previous iterations [26].

Table 1: Comparison of Energy Minimization Algorithms in GROMACS

| Algorithm | Strengths | Weaknesses | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steepest Descent | Robust, easy to implement, effective with large forces | Slow convergence near minimum | Initial minimization of poorly conditioned systems |

| Conjugate Gradient | More efficient closer to minimum | Less robust initially; cannot be used with constraints | Subsequent minimization after initial steepest descent |

| L-BFGS | Fastest convergence | Not yet fully parallelized in some software | Minimization of well-conditioned systems where speed is critical |

Practical Implementation and Stopping Criteria

A common and effective strategy is to use a hybrid approach, initiating minimization with the steepest descent algorithm and then switching to conjugate gradient or L-BFGS for final convergence. A real-world protocol for a solvated glycoprotein system, for instance, involved 10,000 steps of steepest descent followed by 10,000 steps of conjugate gradient [27].

The minimization process is typically stopped when the maximum force components in the system fall below a specified threshold, ε. An overly tight criterion can lead to endless iterations due to numerical noise. A reasonable value for ε can be estimated from the root-mean-square force of a harmonic oscillator at a given temperature. For a weak oscillator, this value is on the order of 1-10 kJ mol⁻¹ nm⁻¹, which provides an acceptable stopping criterion [26].

System Equilibration: Achieving Thermodynamic Equilibrium

Following energy minimization, the system must be equilibrated to bring it to the target temperature and pressure, allowing the solvent to relax around the solute and the system to adopt a representative configuration for the desired thermodynamic ensemble.

A Phased Equilibration Protocol

Equilibration is often performed in stages, gradually releasing positional restraints on the solute to prevent large structural distortions as the solvent environment stabilizes. A detailed protocol from a large-scale MD dataset (mdCATH) illustrates this process [28]:

- Restrained Equilibration: The system is equilibrated for 10 ns in the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature). During this phase, harmonic restraints are applied to the protein's Cα atoms (with a force constant of 1.0 kcal/mol/Ų) and all heavy atoms (0.1 kcal/mol/Ų) to maintain the protein's native structure.

- Unrestrained Equilibration: The restraints are removed, and the system is equilibrated for a further 10 ns in the NPT ensemble. This allows the entire system to fully relax.

Another protocol for a glycosylated system involved a 400 ps equilibration at 300 K with restraints on solute heavy atoms, followed by a 1 ns equilibration with restraints only on the Cα atoms before initiating production simulations [27].

Ensemble and Thermostat/Barostat Selection

The choice of thermodynamic ensemble and regulation methods is critical. The mdCATH dataset performed production runs in the NVT (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) ensemble to avoid issues with the poor reproduction of the water phase diagram by the TIP3P water model [28]. For temperature coupling, the Langevin thermostat (with a collision frequency of 2 ps⁻¹ in one study [27] and 0.1 ps⁻¹ in another [28]) and the Berendsen thermostat (with a very short time constant in automated workflows [29]) are commonly used, especially during equilibration. For pressure coupling, the Berendsen barostat is often used during equilibration due to its robustness, as in the protocol that used a 1 ps time constant [27].

Table 2: Example Equilibration and Production Parameters from Published Protocols

| Parameter | Protocol A (Glycoprotein) [27] | Protocol B (mdCATH Dataset) [28] |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field | AMBER14SB & GLYCAM06j | CHARMM22* |

| Water Model | TIP3P | TIP3P |

| Electrostatics | Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) | Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) |

| Equilibration Ensemble | NPT | NPT |

| Thermostat | Langevin (2 ps⁻¹) | Langevin (0.1 ps⁻¹) |

| Barostat | Berendsen (1 ps) | Monte Carlo |

| Positional Restraints | Heavy atoms, then Cα only | Cα and heavy atoms, then none |

| Production Ensemble | NPT | NVT |

Integrated Workflows and Visualization

The energy minimization and equilibration steps are integral parts of a larger, automated MD workflow. These steps are often embedded within larger simulation paradigms, such as active learning for machine learning potentials, where an initial structure is prepared, its energy is minimized, and it is equilibrated before active learning production cycles begin [30]. Specialized MD workflows also implement automated "first-aid" functions to rescue simulations that fail, which can include re-invoking minimization and equilibration protocols [31].

The following diagram outlines the logical progression from initial system construction to a production-ready simulation, highlighting the decision points within the energy minimization and equilibration phases.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Successful execution of energy minimization and equilibration protocols relies on a suite of software tools and "research reagents," which include force fields, solvent models, and analysis utilities.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MD Preparation

| Category | Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| MD Engines | GROMACS [26], AMBER [27], OpenMM (via drMD) [31], LAMMPS [32] | Software that performs the numerical integration of the equations of motion for energy minimization and dynamics. |

| Force Fields | CHARMM22* [28], AMBER14SB [27], GLYCAM06j [27], Martini [33] | Empirical potential functions defining bonded and non-bonded interactions between atoms. Critical for energy evaluation. |

| Solvent Models | TIP3P [27] [28] | A common 3-site water model used to solvate the system during the building phase. |

| Analysis & Visualization | VMD [32], Travis [32], HTMD [28] | Tools for visualizing trajectories, calculating properties like RMSD/RMSF, and checking the stability of equilibration. |

| System Building | PACKMOL [32], drMD [31] | Tools for creating initial simulation boxes by packing molecules (e.g., solute, water, ions) into a defined volume. |

Energy minimization and equilibration are not merely procedural formalities but are scientifically critical steps for ensuring the stability and physical validity of molecular dynamics simulations. By understanding the algorithms, implementing phased protocols with appropriate restraints and thermodynamic controls, and utilizing the available software tools effectively, researchers can generate reliable initial conditions. This rigorous approach lays the necessary foundation for obtaining accurate atomic trajectories, which is paramount for subsequent analysis in fields ranging from fundamental biophysics to computer-aided drug design.

This technical guide details the critical parameters for the production phase of a Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation, framed within the broader thesis of understanding the MD workflow for atomic trajectories research. The production run is the final stage where a physically sound trajectory is generated for subsequent analysis, making the correct configuration of time step, total steps, and ensemble controls paramount for obtaining reliable, publishable results. This document provides in-depth methodologies and structured data to guide researchers and drug development professionals in optimizing these core parameters.

The molecular dynamics workflow is a multi-stage process that progresses from system preparation and energy minimization through equilibration, culminating in the production run [22]. While equilibration stabilizes the system's temperature and pressure, the production simulation is where the actual trajectory used for data analysis is generated [34]. The parameters chosen for this phase directly control the physical accuracy, numerical stability, and statistical significance of the simulation. A well-configured production run samples the correct thermodynamic ensemble, conserves energy (or its extended equivalent), and avoids numerical artifacts, thereby providing a trustworthy foundation for analyzing atomic trajectories.

The Integration Time Step

The integration time step (dt) is the most fundamental numerical parameter, determining the interval at which Newton's equations of motion are solved. An excessively small dt leads to unrealistically long simulation times for a given number of steps, while an overly large dt causes instability and energy drift, potentially crashing the simulation [35].

Theoretical Foundation: The Nyquist Criterion and Fastest Vibrations

The upper limit for the time step is governed by the Nyquist sampling theorem, which states that the time step must be half or less of the period of the quickest dynamics in the system [35]. In practice, a more conservative ratio of 0.01 to 0.033 of the shortest vibrational period is recommended for accurate integration [35]. The highest-frequency motions in biomolecular systems are typically bond vibrations involving hydrogen atoms (e.g., C-H bonds with a period of ~11 femtoseconds), which would theoretically permit a time step of about 5 fs [35]. However, standard practice often uses a 2 fs time step when bonds involving hydrogens are constrained, providing a good balance between accuracy and efficiency [35].

Practical Validation: Monitoring Energy Conservation

Theoretical rules of thumb must be validated empirically. The most robust method for assessing time step appropriateness is to monitor the drift in the conserved quantity (e.g., total energy in an NVE ensemble) over a short simulation [35]. A reasonable rule of thumb is that the long-term drift should be less than 1 meV/atom/ps for publishable results, and can be up to 10 meV/atom/ps for qualitative work [35]. A significant drift indicates that the time step is too large or the integrator is not behaving time-reversibly.

Table 1: Guidelines for Time Step Selection

| System / Condition | Recommended Time Step (fs) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Standard atomistic (with H-bonds constrained) | 2 | Default for most biomolecular simulations with constraints [35] |

| Systems with light nuclei (H) | 0.25 - 1 | Necessary for accurate hydrogen dynamics [35] |

| Using mass repartitioning | 3 - 4 | Mass of light atoms is scaled up, allowing a larger dt [36] |

| Target energy drift (publishable) | Configure to achieve < 1 meV/atom/ps | Must be checked in an NVE simulation [35] |

| Target energy drift (qualitative) | Configure to achieve < 10 meV/atom/ps | Must be checked in an NVE simulation [35] |

The following workflow diagram outlines the process of selecting and validating a time step:

Total Simulation Steps and Time

The nsteps parameter determines the total number of integration steps and, when multiplied by the time step (dt), defines the total simulated time. The choice of nsteps is dictated by the scientific question, specifically the timescales of the processes under investigation [18].

Connecting Steps to Physical Time and Phenomena

The required simulation time can range from nanoseconds for local side-chain motions to microseconds or milliseconds for large conformational changes and protein folding [18]. It is critical to ensure that the total simulated time is long enough to sample the relevant biological process multiple times to obtain statistically meaningful results. For instance, a 1 ns simulation requires nsteps = 500,000 when using a 2 fs time step.

Thermostat and Barostat Controls

Thermostats and barostats are algorithms that maintain the temperature and pressure of the system, respectively, mimicking experimental conditions. Their proper configuration is essential for sampling the correct thermodynamic ensemble (e.g., NPT or NVT).

Thermostat Parameters

Thermostats maintain temperature by scaling particle velocities. Key parameters include the reference temperature (ref-t or temperature) and the coupling time constant (tau-t).

Table 2: Common Thermostat Algorithms and Parameters

| Thermostat | Algorithm Type | Key Parameters | Typical tau-t Value |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nose-Hoover [37] | Deterministic | tau-t |

0.5 - 1.0 ps | Produces a correct canonical ensemble; often preferred for production. |

| Berendsen [37] | Stochastic | tau-t |

0.1 - 0.5 ps | Strongly damped; good for equilibration but not production [37]. |

| Velocity Rescale | Stochastic | tau-t |

0.1 - 0.5 ps | Corrects Berendsen's flaws; suitable for production. |

| Langevin [36] | Stochastic | tau-t (inverse friction) |

~2 ps [36] | Good for production; tau-t of 2 ps provides lower friction than water's internal friction [36]. |

Barostat Parameters

Barostats control the system pressure by adjusting the simulation box size. The choice of barostat must be consistent with the thermostat to achieve the desired ensemble.

Table 3: Common Barostat Algorithms and Parameters

| Barostat | Algorithm Type | Key Parameters | Typical tau-p Value |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parrinello-Rahman | Deterministic | tau-p, compressibility |

1.0 - 5.0 ps | Produces a correct isobaric ensemble; often preferred for production. |

| Berendsen [37] | Stochastic | tau-p, compressibility |

0.5 - 1.0 ps | Strongly damped; good for equilibration but can produce an incorrect ensemble in production [37]. |

| MTK (Martyna-Tobias-Klein) | Deterministic | tau-p, compressibility |

1.0 - 5.0 ps | Extension of Nose-Hoover for pressure; used with Nose-Hoover thermostat for correct NPT ensemble. |

The relationship between these controls and the resulting thermodynamic ensemble is summarized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

This table details key software tools and "reagents" essential for conducting and analyzing MD production runs.

Table 4: Essential Software Tools for MD Production and Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Type / Function | Relevance to Production Runs |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [38] [22] | MD Simulation Engine | High-performance, open-source software for running production simulations; implements all discussed parameters and algorithms. |

| MDP File [36] | Parameter Input File | A plain-text file that contains all parameters (e.g., dt, nsteps, thermostat settings) for a GROMACS simulation [36]. |

| MDTraj [39] | Trajectory Analysis Library | A modern, fast Python library for analyzing production trajectories (e.g., calculating RMSD, Rgyr). |

| TrajMap.py [40] | Trajectory Visualization Tool | A Python script for creating trajectory maps—2D heatmaps that visualize backbone movements over time. |

| PLUMED | Enhanced Sampling Plugin | A library for adding advanced sampling methods to production runs, often necessary for simulating rare events. |

Integrated Protocol for a Production MD Run

This protocol outlines the steps for configuring and launching a production run using common MD software like GROMACS, based on the parameters detailed above.

- Prepare the Equilibrated System: Use the final coordinates and topology from the successful NPT equilibration step as the input for the production run [34].

- Configure the MDP Parameters:

- Integrator: Set

integrator = md(leap-frog) orintegrator = md-vv(velocity Verlet) [36]. - Time Step: Define

dt = 0.002for a 2 fs time step [35]. - Total Steps: Set

nsteps = 500000for a 1 ns simulation. Adjust based on the timescale of your process of interest [18]. - Thermostat: Enable with

pcoupl = nofor NVT or use a thermostat like Nose-Hoover (tcoupl = Nose-Hoover) with atau-t = 1.0and the desiredref-t[36] [37]. - Barostat: For NPT ensembles, use a barostat like Parrinello-Rahman (

pcoupl = Parrinello-Rahman) with atau-p = 5.0and the correctcompressibilityfor your solvent [37].

- Integrator: Set

- Run the Simulation: Execute the production simulation using the MD engine. For large systems, this is typically done on a high-performance computing cluster.

- Validate the Output:

- Check Log Files: Monitor the potential energy, temperature, and pressure for stability.

- Verify Conservation (NVE): If an NVE test was run, confirm the energy drift is within acceptable limits (< 1 meV/atom/ps) [35].

- Analyze the Trajectory: Use analysis tools like MDTraj [39] to compute properties such as Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) and Radius of Gyration (Rgyr) from the production trajectory [34] [40].

Advanced MD Techniques and Their Applications in Drug Discovery and Diagnostics

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a computational microscope, enabling researchers to observe and quantify atomic-scale motions that govern biological and chemical processes. However, conventional MD faces fundamental limitations in capturing rare events—transitions between stable states separated by high energy barriers—due to the femtosecond time steps required for numerical integration, which collectively restrict simulations to microsecond or millisecond timescales at best. Many processes of biological and chemical significance, including protein folding, ligand binding, and chemical reactions, occur on timescales ranging from milliseconds to hours, creating a formidable sampling gap [41].

Enhanced sampling methods have emerged to bridge this timescale divide, employing sophisticated algorithms to accelerate the exploration of configurational space. These methods can be broadly categorized into several strategic families: those that apply bias potentials in collective variable space (such as Umbrella Sampling and Metadynamics), approaches utilizing generalized ensembles or replica exchange, and path-sampling techniques [41]. The focus of this technical guide is on two foundational methods in the first category: Umbrella Sampling (US) and Metadynamics (MTD), which have become essential tools for simulating rare events and calculating free energy landscapes across diverse scientific domains from drug discovery to materials science [42] [43].

At the core of these methods lies the concept of the collective variable (CV)—a low-dimensional representation of the system's slow degrees of freedom that typically captures the essential physics of the transition process. Proper selection of CVs is critical for the success of any enhanced sampling simulation, as inadequate CVs may fail to distinguish between relevant states or miss important transition pathways entirely [43]. As we will explore, recent advances in machine learning are revolutionizing CV selection and bias potential construction, pushing the boundaries of what can be studied computationally [41] [44].

Theoretical Foundations of Umbrella Sampling

Principles and Mathematical Framework

Umbrella Sampling is a biased sampling technique designed to overcome energy barriers by enforcing systematic exploration along a predetermined reaction coordinate. The fundamental concept involves dividing the reaction pathway into discrete windows and applying harmonic restraints to maintain the system within each window during independent simulations [42]. The methodology follows a well-defined workflow: initially, configurations are generated along the reaction coordinate, often through steered molecular dynamics; these configurations are then used as starting points for multiple independent simulations with harmonic biases; finally, the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) is employed to reconstruct the unbiased free energy profile, known as the potential of mean force (PMF) [42].

The harmonic bias potential applied in each window takes the form:

$$ Ui(\xi) = \frac{1}{2}ki(\xi - \xi_i^0)^2 $$

where $ki$ represents the force constant, $\xi$ is the instantaneous value of the reaction coordinate, and $\xii^0$ is the center of the $i^{th}$ window. The force constant must be sufficiently strong to ensure adequate overlap between adjacent windows while allowing natural fluctuations within each window [42].

The power of Umbrella Sampling lies in its ability to reconstruct the unbiased free energy profile through post-processing of multiple biased simulations. The WHAM algorithm solves coupled equations to determine the unbiased probability distribution along the reaction coordinate:

$$ P(\xi) = \frac{\sum{i=1}^{N} ni(\xi)}{\sum{i=1}^{N} Ni e^{-(Fi - Ui(\xi))/k_B T}} $$

where $P(\xi)$ represents the unbiased probability distribution, $ni(\xi)$ denotes the histogram of values observed in window $i$, $Ni$ is the total number of samples in window $i$, $F_i$ is the free energy constant for window $i$, and $T$ is the simulation temperature [42] [43].

Practical Implementation Protocol

Implementing a complete Umbrella Sampling calculation requires careful execution of multiple stages. The following protocol outlines the key steps, with specific examples drawn from a GROMACS tutorial on studying peptide dissociation from Aβ42 fibrils [42]:

System Preparation: Generate molecular topology using standard tools like

pdb2gmx. For protein-ligand systems, special considerations for force field parameters may be necessary. Properly define position restraints for reference groups—in the Aβ42 example, Chain B was position-restrained while Chain A was pulled away [42].Unit Cell Definition: Create a simulation box with sufficient space along the pulling direction to prevent spurious periodic interactions. The Aβ42 tutorial emphasizes that "the pulling distance must always be less than half the length of the box vector along which the pulling is performed" to satisfy minimum image convention [42].

Solvation and Ion Addition: Solvate the system using tools like

solvateand add ions withgenionto achieve physiological concentration and neutralize charge [42].Energy Minimization and Equilibration: Perform standard energy minimization followed by NPT equilibration to relax the system to proper density and temperature [42].

Configuration Generation: Run a steered molecular dynamics simulation to generate configurations along the reaction coordinate. In the Aβ42 example, a 500ps MD simulation was used with a pulling rate of 0.01 nm/ps and force constant of 1000 kJ mol⁻¹ nm⁻², saving snapshots every 1ps [42].

Window Extraction: Extract frames corresponding to desired COM distances from the steered MD trajectory to serve as starting configurations for umbrella windows [42].

Umbrella Simulations: Run independent simulations for each window with harmonic restraints centered at specific values along the reaction coordinate.

PMF Construction: Use WHAM implementation (such as

gmx wham) to combine data from all windows and reconstruct the potential of mean force.

Table 1: Critical Pulling Parameters for Umbrella Sampling Configuration Generation in GROMACS

| Parameter | Setting | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

pull |

yes |

Activates pulling code |

pull_ncoords |

1 |

Defines one reaction coordinate |

pull_ngroups |

2 |

Two groups defining reaction coordinate endpoints |

pull_coord1_type |

umbrella |

Applies harmonic potential |

pull_coord1_geometry |

distance |

Simple distance increase |

pull_coord1_dim |

N N Y |

Pull along Z-axis only |

pull_coord1_rate |

0.01 nm/ps |

Pulling speed (10 nm/ns) |

pull_coord1_k |

1000 kJ mol⁻¹ nm⁻² |

Force constant |

Figure 1: Umbrella Sampling Workflow - This diagram illustrates the sequential steps in a complete Umbrella Sampling calculation, from system preparation through free energy analysis.

Metadynamics: Theory and Implementation

Core Algorithm and Mathematical Formulation

Metadynamics is an adaptive enhanced sampling technique that accelerates rare events by discouraging the system from revisiting previously sampled configurations in the collective variable space. Unlike Umbrella Sampling, which maintains the system in predefined windows, Metadynamics actively explores free energy landscapes by depositing repulsive potential energy "hills" at the system's current location in CV space [41]. This history-dependent bias potential gradually fills free energy basins, allowing the system to escape metastable states and explore new regions.

The time-dependent bias potential in Metadynamics takes the form:

$$ V{bias}(s,t) = \sum{ti < t} H \cdot \exp\left(-\frac{|s-s(ti)|^2}{2w^2}\right) $$

where $H$ represents the height of each Gaussian hill, $w$ determines its width, $s$ is the collective variable, $s(ti)$ is the value of the CV at time $ti$, and the summation runs over all previous hill depositions [43]. As the simulation progresses, the accumulated bias potential converges toward the negative of the underlying free energy surface:

$$ F(s) = -\lim{t \to \infty} V{bias}(s,t) + C $$

where $C$ is an arbitrary constant. This relationship enables direct estimation of free energies from the bias potential [43].

Well-tempered Metadynamics, a variant of the method, introduces a tempering parameter that reduces the hill height over time, ensuring more robust convergence. The hill height in well-tempered Metadynamics decays according to:

$$ H(t) = H0 \cdot \exp\left(-\frac{V{bias}(s,t)}{k_B \Delta T}\right) $$

where $H_0$ is the initial hill height, and $\Delta T$ is an effective temperature parameter that controls the rate of decay [41].

Practical Implementation Guide

Implementing Metadynamics requires careful parameter selection and monitoring. The following workflow outlines a typical Metadynamics simulation using the MindSponge framework, as demonstrated in a peptide system case study [45]:

Collective Variable Selection: Identify CVs that capture the essential dynamics of the process. Common choices include distances, angles, dihedral angles, or coordination numbers. For protein systems, torsion angles often serve as effective CVs [45].

Parameter Selection: Choose appropriate values for Gaussian height ($H$), width ($w$), and deposition stride ($δt$). These parameters significantly impact convergence and should be selected based on system properties and preliminary simulations [43].

Simulation Setup: Configure the Metadynamics simulation within your MD engine. In the MindSponge example, this involved defining a

Metadynamicsmodule and specifying CVs as torsion angles [45].Production Simulation: Run the biased simulation while monitoring the evolution of the bias potential and CV distributions.

Convergence Assessment: Verify that the free energy estimate has stabilized by examining the time evolution of the reconstructed profile.

Free Energy Analysis: Reconstruct the free energy surface from the accumulated bias potential.

Table 2: Metadynamics Parameters and Their Impact on Sampling

| Parameter | Role | Considerations for Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Height (H) | Controls the strength of each bias addition | Larger values accelerate exploration but reduce accuracy; typically 0.1-2 kJ/mol |

| Gaussian Width (w) | Determines the spatial extent of each bias addition | Should match the typical fluctuation scale of the CV; too small wastes computational effort |

| Deposition Stride (δt) | Time interval between hill additions | Must allow system relaxation between additions; typically 100-1000 steps |

| CV Grid Resolution | Discretization for bias storage | Finer grids increase memory usage but improve bias representation |

| Bias Factor (Well-Tempered) | Controls hill height decay | Higher values enable broader exploration but slow convergence |

The power of Metadynamics is evident when comparing biased and unbiased simulations. In a MindSponge demonstration, conventional MD of a peptide system remained trapped in a single energy minimum, while Metadynamics enabled broad exploration of the Ramachandran plot, visiting multiple conformational states within equivalent simulation time [45].

Hybrid and Advanced Approaches

Combined Metadynamics and Umbrella Sampling

The complementary strengths of Umbrella Sampling and Metadynamics have motivated the development of hybrid approaches that leverage the advantages of both methods. Metadynamics excels at exploring complex free energy landscapes and identifying reaction pathways, while Umbrella Sampling provides rigorous free energy estimates along predefined coordinates [43] [46]. A combined MTD/US method addresses the challenge of defining appropriate reaction coordinates for complex processes such as ion transport through protein channels [43].

In this hybrid approach, Metadynamics first identifies the ion transport pathway, which often follows a curved trajectory through the protein rather than a straight Cartesian coordinate. Umbrella Sampling simulations are then performed along this physically realistic pathway to obtain a converged potential of mean force [43]. This methodology avoids the discontinuity problem associated with normal Umbrella Sampling calculations that assume a straight-line reaction coordinate [43].

The mathematical framework for this combined approach involves computing the free energy along a curvilinear pathway parameterized by $α ∈ [0,1]$:

$$ F(s(α)) - F(s(0)) = \int0^α dα' \sum{i=1}^N \frac{dsi(α')}{dα'} \frac{∂F(s(α'))}{∂si} $$

where the mean force for each window can be estimated from Umbrella Sampling simulations using:

$$ \frac{∂F(s)}{∂sj} ≈ kT \int0^T dt (sj - sj(x(t))) $$

where $k$ is the force constant, $T$ is the simulation time, $sj$ is the equilibrium value of the reaction coordinate, and $sj(x(t))$ is its instantaneous value [43].

Machine Learning-Enhanced Sampling

The integration of machine learning with enhanced sampling represents a paradigm shift in molecular simulation methodology. Recent advances have produced three primary integration pathways: data-driven collective variable learning, intelligent bias potential optimization, and generative model-based sampling [41].

Data-Driven Collective Variable Learning employs supervised or unsupervised learning to automatically extract low-dimensional representations from simulation data. Techniques such as autoencoders, principal component analysis, and graph neural networks can capture slow modes of protein folding and conformational changes that might be difficult to identify through physical intuition alone [41]. For instance, deep learning classifiers like Deep-LDA and Deep-TDA can automatically distinguish between different thermodynamic states and identify relevant order parameters [41].

Bias Potential Learning and Optimization utilizes neural networks to directly approximate high-dimensional free energy surfaces, enabling intelligent bias construction. Methods such as VesNet, OPES, and Deep Bias NN implement dynamic adaptive biasing that updates based on incoming simulation data, creating a self-improving sampling workflow [41].

Generative Models and Reinforcement Learning represent the cutting edge of sampling methodology. Boltzmann generators employ normalizing flows to learn the equilibrium distribution and generate statistically independent configurations, effectively bypassing the rare event problem entirely [41]. Reinforcement learning approaches, such as the Adaptive CVgen method developed by the National Nanoscience Center, treat sampling as a decision process where an intelligent agent selects simulation parameters or biasing strategies to maximize exploration efficiency [44].

Table 3: Machine Learning Approaches for Enhanced Sampling

| Method Category | Key Algorithms | Advantages | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| CV Learning | Autoencoders, Deep-LDA, Deep-TDA | Automates feature detection; Handles high-dimensional data | Protein folding, RNA conformational changes |

| Bias Optimization | VesNet, OPES, Deep Bias NN | Accelerates convergence; Handles complex energy landscapes | Ligand binding, Chemical reactions |

| Generative Sampling | Boltzmann Generators, Diffusion Models, RL samplers | Direct sample generation; Avoids rare event problem | Protein structure prediction, Molecular design |

Figure 2: Machine Learning-Enhanced Sampling Framework - This diagram illustrates the three primary pathways for integrating machine learning with enhanced sampling methods and their key applications.

Research Applications and Case Studies

Biomolecular Systems: Protein Folding and Ligand Binding

Enhanced sampling methods have produced transformative insights into biomolecular structure and function. In protein folding, methods like Umbrella Sampling and Metadynamics have elucidated folding pathways and intermediate states that are inaccessible to experimental observation. The Adaptive CVgen method, which leverages reinforcement learning, has demonstrated remarkable versatility by simulating the folding of proteins with diverse secondary structures without parameter adjustment [44].

In drug discovery, enhanced sampling enables quantitative calculation of ligand binding affinities, a critical parameter in pharmaceutical development. Umbrella Sampling can be employed to compute the potential of mean force along a dissociation coordinate, providing the binding free energy directly. These approaches have been successfully applied to study the binding mechanisms of inhibitors to challenging targets such as KRAS, a historically "undruggable" oncoprotein [47].

Case Study: Cryptic Pocket Discovery in KRAS

KRAS represents a compelling case study in the application of enhanced sampling methods to address difficult biological problems. For decades, KRAS was considered undruggable due to its relatively flat surface with few apparent binding pockets and picomolar affinity for its natural ligands (GTP/GDP) [47]. The discovery of cryptic pockets—transient cavities that are not apparent in static crystal structures—revolutionized KRAS-targeted therapy development.

Researchers employed weighted ensemble molecular dynamics simulations using inherent normal modes as progress coordinates to systematically explore cryptic pocket dynamics in KRAS [47]. This approach leveraged the protein's intrinsic dynamics as a guide for sampling, revealing previously unrecognized binding sites. The simulations successfully predicted known cryptic pockets in KRAS, including the Switch-II pocket targeted by FDA-approved drugs sotorasib and adagrasib [47].