Free Energy and Entropy Calculations: From Theoretical Foundations to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the theoretical underpinnings and practical computational methods for calculating entropy and free energy, with a special focus on applications in biomolecular interactions and...

Free Energy and Entropy Calculations: From Theoretical Foundations to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the theoretical underpinnings and practical computational methods for calculating entropy and free energy, with a special focus on applications in biomolecular interactions and drug development. It bridges the gap between statistical thermodynamics and real-world computational chemistry, exploring foundational concepts like configurational entropy and the partition function, detailing advanced methods such as FEP, TI, and Umbrella Sampling, addressing common challenges in sampling and convergence, and offering a comparative analysis of technique performance. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this guide serves as a resource for understanding and applying these critical thermodynamic quantities to predict binding affinities, protein-ligand interactions, and guide molecular design.

The Statistical Thermodynamics Foundation: Understanding Entropy and Free Energy

In statistical mechanics, the partition function serves as the fundamental bridge connecting the microscopic world of atoms and molecules to the macroscopic thermodynamic properties observed in the laboratory. For researchers in drug development and molecular sciences, understanding this connection is paramount for predicting binding affinities, protein stability, and reaction equilibria from first principles. The partition function provides a complete statistical description of a system in thermodynamic equilibrium, enabling the calculation of all thermodynamic properties through appropriate derivatives [1]. This function encodes the statistical properties of a system and acts as the generating function for its thermodynamic variables, with its logarithmic derivatives yielding measurable quantities such as energy, entropy, and free energy [2].

The challenge in computational structural biology and drug design lies in the fact that while the partition function contains all thermodynamic information about a system, its direct calculation for complex biomolecular systems remains formidably difficult due to the extremely high dimensionality of the configurational space [3] [4]. This whitepaper examines the theoretical foundation of partition functions in entropy and free energy calculations, explores computational methodologies for leveraging this connection in practice, and highlights applications in pharmaceutical research.

Theoretical Foundations

Defining the Partition Function

In the canonical ensemble (constant N, V, T), the canonical partition function is defined as the sum over all possible microstates of the system. For a classical discrete system, it is expressed as:

[Z = \sumi e^{-\beta Ei}]

where (Ei) is the energy of microstate (i), (\beta = 1/kBT), (k_B) is Boltzmann's constant, and (T) is the absolute temperature [1]. For a classical continuous system, the partition function takes the form of an integral over phase space:

[Z = \frac{1}{h^{3N}} \int e^{-\beta H(\mathbf{q},\mathbf{p})} d^{3N}\mathbf{q} d^{3N}\mathbf{p}]

where (h) is Planck's constant, (H) is the Hamiltonian of the system, and (\mathbf{q}) and (\mathbf{p}) represent the position and momentum coordinates of all (N) particles [1].

The probability (P_i) of the system being in a specific microstate (i) is given by the Boltzmann distribution:

[Pi = \frac{e^{-\beta Ei}}{Z}]

This relationship demonstrates how the partition function (Z) serves as the normalization constant in the Boltzmann distribution [3].

Connecting to Macroscopic Thermodynamics

The fundamental connection between the partition function and macroscopic thermodynamics is established through the Helmholtz free energy (A):

[A = -k_B T \ln Z]

This relationship is significant because the Helmholtz free energy serves as the thermodynamic potential for the canonical ensemble, connecting the microscopic description to macroscopic observables [5]. Once the free energy is known, all other thermodynamic properties can be derived through appropriate thermodynamic relations.

The following table summarizes how key thermodynamic quantities are obtained from derivatives of the partition function:

| Thermodynamic Property | Mathematical Relation to Partition Function | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Helmholtz Free Energy (A) | (A = -k_B T \ln Z) | Thermodynamic potential at constant N, V, T |

| Internal Energy (U) | (U = kB T^2 \left(\frac{\partial \ln Z}{\partial T}\right){N,V}) | Total thermal energy of the system |

| Entropy (S) | (S = kB \ln Z + kB T \left(\frac{\partial \ln Z}{\partial T}\right)_{N,V}) | Measure of disorder or energy dispersal |

| Pressure (P) | (P = kB T \left(\frac{\partial \ln Z}{\partial V}\right){N,T}) | Mechanical force per unit area |

For a monatomic ideal gas, the application of these relations yields the familiar thermodynamic equations of state. The partition function can be factorized into translational components, leading to the internal energy (U = \frac{3}{2}NkBT) and the classic ideal gas law (PV = NkBT) [2].

Computational Approaches

The Computational Challenge

For biologically relevant systems, the direct calculation of the partition function is computationally intractable. A system of (N) point particles in a 3D box has (3N) position coordinates and (3N) momentum coordinates, creating a (6N)-dimensional phase space [4]. Even for a small protein with thousands of atoms, the partition function would require integration over tens of thousands of dimensions, making explicit calculation impossible with current computational resources.

This challenge is particularly acute for proteins and other biomolecules with rugged potential energy surfaces "decorated by a tremendous number of localized energy wells and wider ones that are defined over microstates" [3]. The enormous number of accessible conformational states creates a partition function that cannot be computed directly through enumeration or standard numerical integration techniques.

Practical Methodologies

Computational chemists employ sophisticated sampling strategies to overcome the intractability of direct partition function calculation. These methods work with probability ratios where the partition function cancels out, or compute free energy differences directly without explicitly calculating the full partition function.

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) and Thermodynamic Integration (TI): These methods compute free energy differences between two states by gradually transforming one system into another through a series of non-physical intermediate states. The approach, originally developed by Zwanzig, allows calculation of (\Delta A) without direct computation of the partition functions of either the initial or final states [4].

Potential of Mean Force (PMF) Calculations: These methods compute the free energy along a specific reaction coordinate, providing insights into transition states and activation energies for biological processes such as ligand binding and conformational changes [6].

End-Point Free Energy Methods: Techniques such as MM-PBSA and MM-GBSA approximate binding free energies using only the endpoints of a simulation (bound and unbound states), offering a computationally efficient albeit approximate alternative to more rigorous methods [6].

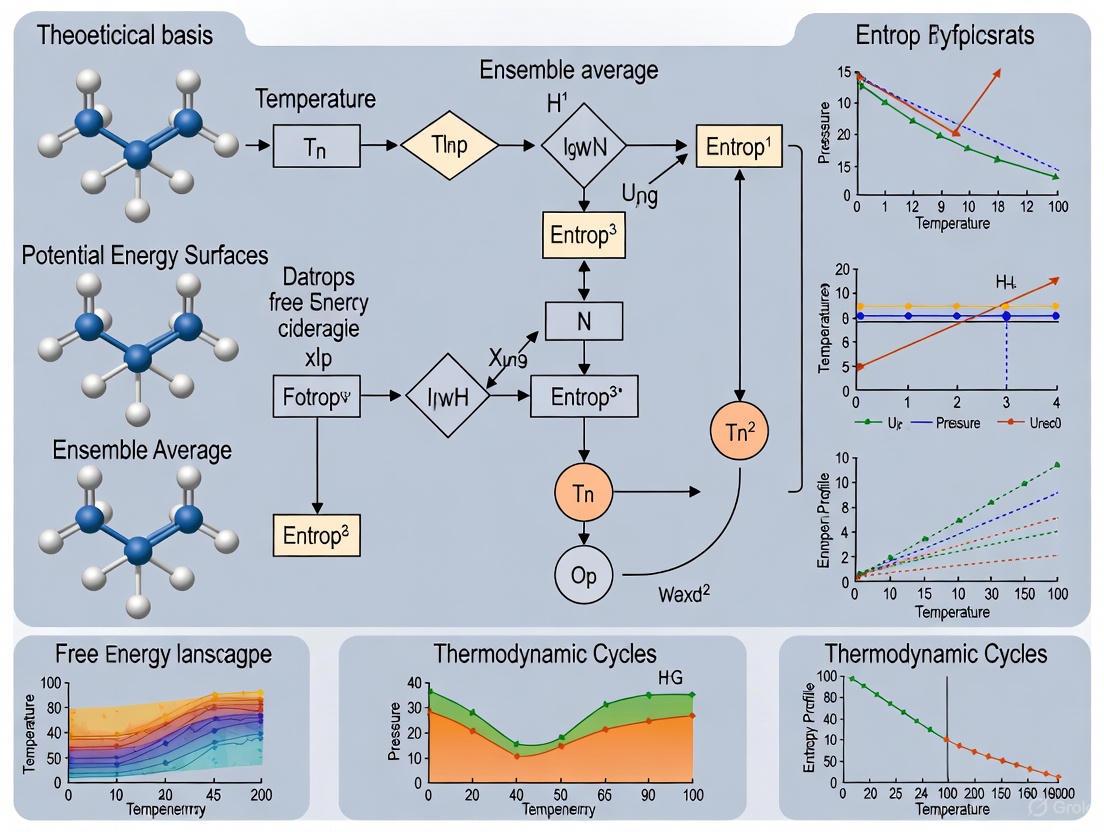

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow for connecting microscopic simulations to macroscopic properties:

Successful implementation of partition function-based calculations requires specialized computational tools and theoretical frameworks:

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Engines | GROMACS, LAMMPS, NAMD | Generate thermodynamic ensembles through numerical integration of Newton's equations |

| Monte Carlo Samplers | Various custom implementations | Sample configuration space according to Boltzmann probabilities |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | Metadynamics, Replica Exchange | Accelerate exploration of configuration space and barrier crossing |

| Free Energy Methods | FEP, TI, MBAR | Compute free energy differences without full partition function calculation |

| Analysis Frameworks | WHAM, MM-PBSA | Extract thermodynamic information from simulation data |

Applications in Drug Development

Binding Affinity Calculations

The central role of the partition function in drug development emerges in the calculation of binding free energies, which directly determine binding affinities. For a protein-ligand binding reaction (P + L \rightleftharpoons PL), the equilibrium constant (K) is related to the free energy change by:

[\Delta G = -k_B T \ln K]

This free energy difference can be expressed in terms of the partition functions of the protein-ligand complex ((Z{PL})), free protein ((ZP)), and free ligand ((Z_L)):

[\Delta G = -kB T \ln \left( \frac{Z{PL}}{ZP ZL} \right)]

Although the absolute partition functions are not computed directly, this relationship provides the theoretical foundation for all modern binding free energy calculation methods [6].

Conformational Selection and Induced Fit

Partition function analysis helps resolve fundamental questions in molecular recognition, particularly whether ligand binding occurs through "induced fit" or "conformational selection" mechanisms. The relative populations of different microstates are given by:

[\frac{pm}{pn} = \frac{Zm}{Zn}]

where (Zm) and (Zn) are the partition functions for microstates (m) and (n) [3]. This relationship allows researchers to determine whether a protein conformational change is induced by ligand binding or selected from pre-existing equilibrium fluctuations.

Entropy Calculations in Molecular Recognition

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments provide measurements of the free energy, enthalpy, and entropy of binding. Computational decomposition of these free energies into enthalpic and entropic components relies on the fundamental connection:

[S = -kB \sumi Pi \ln Pi]

where (P_i) is the Boltzmann probability of microstate (i) [6]. The entropic component, particularly the loss of conformational entropy upon binding, is a crucial determinant of specificity in drug-target interactions.

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between energy landscapes and free energy calculations:

Experimental Protocols

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) Protocol

Free Energy Perturbation provides a practical methodology for computing free energy differences without calculating the full partition function. Based on Zwanzig's formulation, the free energy difference between two states 0 and 1 is given by:

[\Delta A{0 \to 1} = -kB T \ln \langle \exp(-(E1 - E0)/kB T) \rangle0]

where the ensemble average (\langle \cdots \rangle_0) is taken over configurations sampled from state 0 [4].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- System Preparation: Construct initial and final states (e.g., drug candidate and slightly modified analog) with identical atom counts and similar geometries

- Hybrid Topology: Create a dual-topology system where both states coexist without interacting

- Lambda Staging: Divide the transformation into discrete λ windows (typically 12-24 windows)

- Equilibration: Run molecular dynamics simulations at each λ window to ensure proper sampling

- Production: Collect sufficient samples at each window for statistical precision

- Analysis: Use Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR) or Multistate BAR (MBAR) to compute (\Delta G) between end states

Potential of Mean Force (PMF) Calculation

The Potential of Mean Force provides the free energy profile along a specific reaction coordinate ξ:

[W(\xi) = -k_B T \ln \rho(\xi)]

where (\rho(\xi)) is the probability density along ξ [6].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Reaction Coordinate Selection: Identify a physically meaningful coordinate (e.g., distance between protein and ligand)

- Umbrella Sampling: Run multiple simulations with harmonic biasing potentials at different points along the coordinate

- WHAM Analysis: Use the Weighted Histogram Analysis Method to combine data from all windows

- Convergence Testing: Ensure sufficient sampling and statistical independence of results

- Error Analysis: Compute standard errors through block averaging or bootstrapping methods

The partition function remains the fundamental theoretical construct connecting microscopic molecular behavior to macroscopic observable properties in biological systems. While its direct computation remains intractable for biomolecular systems of pharmacological interest, its mathematical properties provide the foundation for all modern computational methods for predicting binding affinities, protein stability, and molecular recognition phenomena.

Ongoing methodological developments in enhanced sampling algorithms, combined with increasing computational resources, continue to expand the applicability of partition function-based methods in drug discovery. The theoretical framework outlined in this whitepaper provides researchers with the conceptual tools to understand, implement, and critically evaluate computational thermodynamics approaches in their drug development pipelines.

Entropy is a fundamental concept in thermodynamics and statistical mechanics, serving as a measure of disorder or randomness in a system. The statistical interpretation of entropy bridges the microscopic world of atoms and molecules with macroscopic thermodynamic properties. This framework is vital for predicting spontaneous reactions, equilibrium states, and has profound implications in fields ranging from materials science to drug design [7]. At its core, statistical mechanics uses probability theory to explain how the average behavior of vast numbers of particles gives rise to observable properties like pressure and temperature [8] [7]. The development of entropy concepts is a cornerstone of this field.

The modern understanding of entropy originates from the work of Ludwig Boltzmann, who, between 1872 and 1875, formulated a profound connection between entropy and atomic disorder. His work was later refined by Max Planck around 1900, leading to the famous equation known as the Boltzmann-Planck equation [9]. This formula provides a mechanical basis for entropy, defining it in terms of the number of possible microscopic arrangements, or microstates, available to a system. This paper will explore the theoretical basis of entropy, beginning with Boltzmann's foundational formula and delving into its specific components—configurational, vibrational, rotational, and translational—to provide a comprehensive guide for researchers engaged in entropy and free energy calculations.

Boltzmann's Entropy Formula: The Foundation

The Fundamental Equation and its Interpretation

Boltzmann's entropy formula establishes a direct relationship between the macroscopic property of entropy (S) and the number of microstates (W) consistent with a system's macroscopic conditions [9]. The formula is expressed as:

S = kB ln W

Here, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and ln denotes the natural logarithm [9]. The microstate count, W, is not all possible states of the system, but rather the number of ways the system can be arranged while still appearing the same to an external observer. For instance, for a system of N identical particles with Ni particles in the i-th microscopic condition, W is calculated using the formula for permutations: W = N! / ∏i Ni! [9]. The logarithmic connection simplifies the mathematics, as Boltzmann sought to minimize the product of factorials in the denominator by maximizing its logarithm [9].

A more general formulation, the Gibbs entropy formula, applies to systems where microstates may not be equally probable: SG = -kB ∑ pi ln pi, where pi is the probability of the i-th microstate [9]. Boltzmann's formula is a special case of this more general expression when all probabilities are equal.

Conceptual Workflow of Boltzmann's Formula

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between a system's macrostate, its microstates, and the resulting entropy, as defined by Boltzmann's formula.

Configurational Entropy

Definition and Calculation

Configurational entropy is the portion of a system's total entropy related to the number of ways its constituent particles can be arranged in space [10]. It is concerned with discrete representative positions, such as how atoms pack in an alloy or glass, the conformations of a molecule, or spin configurations in a magnet [10]. The calculation of configurational entropy directly employs the Boltzmann relation when all configurations are equally likely. If a system can be in states n with probabilities Pn, the configurational entropy is given by the Gibbs entropy formula: S = -kB ∑n=1W Pn ln Pn [10].

The field of combinatorics is essential for calculating configurational entropy, as it provides formalized methods for counting the number of ways to choose or arrange discrete objects [10]. A key application is in landscape ecology, where the macrostate can be defined as the total edge length between different cover classes in a mosaic, and the microstates are the unique arrangements of the lattice that produce that edge length [11]. This approach provides an objective measure of landscape disorder.

Advanced Methodology: Calculating Configurational Entropy in Complex Landscapes

For complex systems where enumerating all microstates is intractable, researchers use statistical methods. The following workflow outlines a practical protocol for calculating the relative configurational entropy of a landscape, a method that can be adapted to other complex systems [11].

Experimental Protocol [11]:

- System Definition: Represent the system under study as a discrete lattice with a defined dimensionality and number of classes (e.g., a 16x16 grid with two cover types).

- Randomization: Generate a large sample of random microstates (e.g., 100,000) by randomly permuting the elements of the observed lattice.

- Macrostate Calculation: For each generated microstate, compute the value of the macrostate property (e.g., total edge length between different classes).

- Distribution Fitting: The distribution of the macrostate property across all randomized microstates will typically follow a normal distribution. Fit a parametric normal probability density function to this distribution.

- Probability Estimation: Use the fitted distribution to determine the proportion (p) of randomized microstates that have the same macrostate property (e.g., edge length) as the original, observed system.

- Entropy Calculation: The relative configurational entropy of the observed system is then proportional to the logarithm of this probability (ln p). This relative measure allows for the comparison of entropy between different systems.

Illustrative Example: The Brick Wall

A simple example demonstrates how probability underlies configurational entropy. Consider constructing a wall from black and white bricks [8].

Table 1: Number of Possible Configurations for a Brick Wall

| Width of Wall (in bricks) | Bricks of Each Color | Different Brick Layers Possible |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | 2 black, 2 white | 6 |

| 6 | 3 black, 3 white | 20 |

| 10 | 5 black, 5 white | 252 |

| 20 | 10 black, 10 white | 184,756 |

| 50 | 25 black, 25 white | 1.26 × 1014 |

As the system size increases, the number of possible microstates grows exponentially. The probability of finding a highly ordered pattern (e.g., alternating bricks) becomes vanishingly small because there are vastly more irregular, "chaotic" configurations [8]. This illustrates the probabilistic nature of the Second Law: systems evolve toward states with higher entropy simply because those states are overwhelmingly more probable.

Vibrational, Rotational, and Translational Components

The total entropy of a molecule, particularly in the gas phase, can be partitioned into contributions from different modes of motion. The total entropy is the sum: STotal = St + Sr + Sv + Se + Sn + ..., where the subscripts denote translational, rotational, vibrational, electronic, and nuclear components [12]. The thermal energy required to reversibly heat a system from 0 K is the sum of the energies required to activate these various degrees of freedom.

Quantitative Partition Functions and Entropy

Each entropy component is derived from its corresponding partition function, which measures the number of accessible quantum states for that mode of motion [12].

Table 2: Entropy Components and Their Partition Functions

| Component | Partition Function (Q) | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Translational (St) | Qt = (2πm kBT / h2)3/2 V | m = molecular mass, T = temperature, V = volume, h = Planck's constant [12] |

| Rotational (Sr) - Linear Molecule | Qr = 8π2I kBT / (σ h2) | I = moment of inertia, σ = symmetry number [12] |

| Rotational (Sr) - Non-Linear | Qr = 8π2(8π3IAIBIC)1/2(kBT / h2)3/2/σ | IA, IB, IC = principal moments of inertia [12] |

| Vibrational (Sv) - per mode | Qv,i = [1 - exp(-hνi / kBT)]-1 | νi = frequency of the i-th vibrational mode [12] |

The entropy for each component is then calculated from the total partition function (Q) using the standard statistical mechanical relation: S = RT (∂lnQ/∂T)V + R lnQ [12]. For ideal monatomic gases, the translational entropy is given explicitly by the Sackur-Tetrode equation [12] [7]: S = R [ ln( (2πm kBT)3/2 V / (h3 N) ) + 5/2 ]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

In computational entropy and free energy research, "reagents" are the essential algorithms, software, and theoretical tools. The following table details key resources for conducting research in this field.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Entropy and Free Energy Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Boltzmann Constant (kB) | Fundamental physical constant linking microscopic states to macroscopic entropy [9]. | Used in all calculations of absolute entropy, including S = kB ln W and the Gibbs entropy formula. |

| Partition Functions (Q) | Statistical measures of accessible quantum states for different molecular motions [12]. | Serve as the starting point for calculating entropy, enthalpy, and free energies of ideal gases. |

| Thermodynamic Integration | A simulation-based method to calculate free energy differences between two states [7]. | Used for studying conformational changes, chemical reactions, and solvation effects by integrating the average force along a path. |

| Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) | Estimates free energy differences using the Zwanzig equation: ΔA = -kBT ln ⟨e-βΔU⟩0 [7]. | Applied to study ligand-binding affinities and solvation free energies; requires overlap in energy distributions between states. |

| Umbrella Sampling | An enhanced sampling method that applies a biasing potential to explore high-energy regions [7]. | Improves sampling of rare events; results from multiple simulations are combined using the Weighted Histogram Analysis Method (WHAM). |

| Replica Exchange MD (REMD) | A parallel sampling method that exchanges configurations between simulations at different temperatures [7]. | Helps overcome energy barriers, improving the exploration of conformational space, useful in protein folding studies. |

This guide has detailed the fundamental principles of entropy, beginning with Boltzmann's microscopic definition and extending to its modern computational applications. The decomposition of entropy into configurational and motional components provides a powerful framework for understanding and predicting the behavior of complex systems. The methodologies discussed, from combinatorial analysis for configurational entropy to partition functions for vibrational and rotational contributions, form the theoretical basis for contemporary research. Furthermore, the advanced computational tools in the Scientist's Toolkit, such as free energy perturbation and thermodynamic integration, empower researchers to apply these concepts to practical challenges in drug design and materials science. A deep understanding of these entropy components is indispensable for accurate free energy calculation, which remains a critical objective in computational chemistry and molecular design.

Within the theoretical framework of entropy and free energy calculations, thermodynamic potentials serve as fundamental tools for predicting the direction of chemical processes, phase changes, and biological interactions. These state functions provide scientists with the ability to determine the energetic feasibility of reactions under specific constraints, forming the mathematical foundation for everything from pharmaceutical development to materials science. The internal energy, U, of a system, described by the fundamental thermodynamic relation dU = TdS - PdV + ΣμᵢdNᵢ, represents the total energy content but proves inconvenient for studying systems interacting with their environment [13] [14]. To address this limitation, researchers utilize Legendre transformations to create alternative thermodynamic potentials—specifically Helmholtz and Gibbs free energies—that are minimized at equilibrium under different experimental conditions [13] [14].

The choice between Helmholtz and Gibbs free energy is not merely academic; it determines the accuracy of predictions in everything from drug-receptor binding affinity calculations to the synthesis of novel materials. This guide provides researchers with a comprehensive framework for selecting the appropriate potential based on their system's constraints, complete with mathematical foundations, practical applications, and advanced computational methodologies relevant to modern scientific inquiry.

Theoretical Foundations: From Internal Energy to Thermodynamic Potentials

The Fundamental Thermodynamic Relation

All thermodynamic potentials derive from the fundamental relation of internal energy, which for a reversible change is expressed as dU = TdS - PdV + ΣμᵢdNᵢ, where T represents temperature, S denotes entropy, P indicates pressure, V stands for volume, μᵢ represents the chemical potential of species i, and Nᵢ is the number of particles of type i [13] [14]. This equation identifies the natural variables of internal energy as S, V, and {Nᵢ} [14]. While mathematically complete, internal energy becomes impractical for experimental applications where entropy control is difficult, necessitating transformed potentials with more convenient natural variables.

Legendre Transformations and Natural Variables

The Helmholtz free energy (A) and Gibbs free energy (G) are obtained through Legendre transformations of internal energy, replacing entropy with temperature as a natural variable [13] [14]. This mathematical operation creates new potentials with different constant conditions where they are minimized at equilibrium:

- Helmholtz Free Energy:

A ≡ U - TSwith natural variables T, V, and {Nᵢ} [15] [14] - Gibbs Free Energy:

G ≡ U + PV - TS = H - TSwith natural variables T, P, and {Nᵢ} [16] [14] [17]

The natural variables are crucial because when a thermodynamic potential is expressed as a function of its natural variables, all other thermodynamic properties of the system can be derived through partial differentiation [14].

Figure 1: Relationship between thermodynamic potentials through Legendre transformations and their respective natural variables.

Helmholtz Free Energy: Theory and Applications

Conceptual Foundation and Mathematical Definition

Helmholtz free energy, denoted as A (or sometimes F), is defined as A ≡ U - TS, where U is internal energy, T is absolute temperature, and S is entropy [15] [18]. Physically, A represents the component of internal energy available to perform useful work at constant temperature and volume, sometimes called the "work function" [18] [19]. The differential form of Helmholtz energy is expressed as dA = -SdT - PdV + ΣμᵢdNᵢ, which confirms T and V as its natural variables [15] [14].

For processes occurring at constant temperature and volume, the change in Helmholtz energy provides the criterion for spontaneity and equilibrium: ΔA ≤ 0, where the equality holds at equilibrium [15] [19]. This means spontaneous processes at constant T and V always decrease the Helmholtz free energy, reaching a minimum at equilibrium. The negative of ΔA represents the maximum work obtainable from a system during an isothermal, isochoric process: w_max = -ΔA [15] [19].

Research Applications and Methodologies

Helmholtz free energy finds particular utility in several specialized research domains:

Explosives Research: The study of explosive reactions extensively employs Helmholtz free energy because these processes inherently involve dramatic pressure changes rather than constant pressure conditions [15].

Statistical Mechanics: Helmholtz energy provides a direct bridge between microscopic molecular properties and macroscopic thermodynamic behavior through the relationship

A = -kT ln Z, where Z is the canonical partition function [15]. This connection enables the calculation of thermodynamic properties from molecular-level information.Materials Science: In continuum damage mechanics, Helmholtz free energy potentials formulate constitutive equations that couple elasticity with damage evolution and plastic hardening [18].

Gibbs Free Energy: Theory and Applications

Conceptual Foundation and Mathematical Definition

Gibbs free energy, denoted as G, is defined as G ≡ U + PV - TS = H - TS, where H represents enthalpy [16] [14] [17]. This potential measures the maximum reversible non-PV work obtainable from a system at constant temperature and pressure [14] [17]. The differential form dG = -SdT + VdP + ΣμᵢdNᵢ confirms T and P as its natural variables [14].

For processes at constant temperature and pressure, the change in Gibbs free energy determines spontaneity: ΔG ≤ 0, with equality at equilibrium [16] [17]. This relationship incorporates both the enthalpy change (ΔH) and entropy change (ΔS) through the fundamental equation ΔG = ΔH - TΔS [16] [17]. A negative ΔG indicates a spontaneous process (exergonic), while a positive ΔG signifies a non-spontaneous process (endergonic) that requires energy input [17].

Research Applications and Methodologies

Gibbs free energy serves as the primary thermodynamic potential across numerous scientific disciplines:

Chemical Reaction Feasibility: Gibbs energy determines whether chemical reactions proceed spontaneously under constant pressure conditions, which encompasses most laboratory and industrial processes [16] [17].

Biological Systems: Biochemical reactions in living organisms, particularly those involving ATP hydrolysis and metabolic pathways, are governed by Gibbs free energy changes due to the essentially constant pressure conditions in biological systems [17].

Phase Equilibria: The Gibbs free energy difference between phases determines phase stability and transitions, making it fundamental to understanding melting, vaporization, and solubility [17].

Electrochemistry: The relationship

ΔG = -nFEᵢconnects Gibbs free energy to electrochemical cell potential, enabling calculation of theoretical battery voltages and fuel cell performance [17].

Comparative Analysis: Helmholtz vs. Gibbs Free Energy

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of Helmholtz and Gibbs free energy properties and applications

| Feature | Helmholtz Free Energy (A) | Gibbs Free Energy (G) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A ≡ U - TS [15] [18] | G ≡ U + PV - TS = H - TS [16] [14] [17] |

| Natural Variables | T, V, {Nᵢ} [15] [14] | T, P, {Nᵢ} [14] |

| Differential Form | dA = -SdT - PdV + ΣμᵢdNᵢ [15] [14] | dG = -SdT + VdP + ΣμᵢdNᵢ [14] |

| Constant Conditions | Constant T and V [15] | Constant T and P [16] [17] |

| Spontaneity Criterion | ΔA ≤ 0 [15] [19] | ΔG ≤ 0 [16] [17] |

| Physical Interpretation | Maximum total work obtainable [15] [19] | Maximum non-PV work obtainable [14] [17] |

| Primary Research Applications | Statistical mechanics, explosives research, constant-volume processes [15] | Chemical reactions, biological systems, phase equilibria, electrochemistry [16] [17] |

| Connection to Partition Function | A = -kT ln Z (Canonical ensemble) [15] | G = -kT ln Ξ (Grand canonical ensemble) |

Table 2: Work component analysis for Helmholtz and Gibbs free energy

| Work Component | Helmholtz Free Energy (A) | Gibbs Free Energy (G) |

|---|---|---|

| Pressure-Volume Work | Included in maximum work [19] | Already accounted for in definition |

| Non-PV Work | Included in maximum work [19] | Specifically what ΔG represents [14] |

| Total Work Capability | wmax = -ΔA (at constant T, V) [15] [19] | wnon-PV, max = -ΔG (at constant T, P) [14] [17] |

Figure 2: Decision framework for selecting the appropriate free energy potential based on system constraints.

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Free Energy Calculation Methods

Accurate prediction of free energy changes represents a cornerstone of computational chemistry and drug discovery. Several established methodologies enable researchers to calculate these critical parameters:

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP): This approach computes free energy differences by simulating the alchemical transformation of one molecule into another through a series of equilibrium intermediate states [20]. Each intermediate requires sufficient sampling to reach thermodynamic equilibrium, making FEP computationally intensive but highly accurate when properly implemented.

Thermodynamic Integration (TI): Similar to FEP, TI employs a pathway of intermediate states between the initial and final systems but uses numerical integration over the pathway rather than perturbation theory [20]. This method often provides smoother convergence for certain classes of transformations.

Nonequilibrium Switching (NES): This emerging methodology uses multiple short, bidirectional switches that drive the system far from equilibrium [20]. The collective statistics of these nonequilibrium trajectories yield accurate free energy differences with 5-10× higher throughput than equilibrium methods, making NES particularly valuable for high-throughput drug screening [20].

Table 3: Key resources for free energy calculations and thermodynamic studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Software | Molecular dynamics packages (GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD) | Simulate molecular systems for FEP, TI, and NES calculations [20] |

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS parameter sets | Provide potential energy functions for atomic interactions in simulations |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | Metadynamics, Replica Exchange MD | Accelerate configuration space sampling for complex transformations |

| Chemical Standards | Reference compounds with known ΔG values | Validate computational methods against experimental measurements |

| Analysis Tools | Free energy analysis plugins (alchemical analysis tools) | Process simulation trajectories to extract free energy differences |

The choice between Helmholtz and Gibbs free energy represents a fundamental strategic decision in theoretical and applied thermodynamics research. Helmholtz free energy provides the appropriate formalism for systems with constant volume and temperature, particularly in statistical mechanics, explosives research, and fundamental equation development. Conversely, Gibbs free energy serves as the universal standard for constant-pressure processes that dominate chemical, biological, and materials science applications.

Understanding the mathematical relationship between these potentials through Legendre transformations reveals how each possesses different natural variables that make them convenient for specific experimental constraints. As computational methods advance, particularly with emerging techniques like nonequilibrium switching, researchers can increasingly leverage these thermodynamic potentials to predict system behavior with greater accuracy and efficiency across diverse scientific domains from drug discovery to materials engineering.

In the field of molecular simulations, particularly in drug discovery research, free energy calculations have emerged as crucial computational tools for predicting binding affinities, solvation energies, and other essential thermodynamic properties. The accuracy of these predictions hinges on a fundamental understanding of what "free" energy represents physically and how it connects to the second law of thermodynamics. This technical guide examines the core physical concepts of free energy, bridging theoretical foundations with practical applications in modern computational chemistry. For researchers investigating protein-ligand interactions or developing novel therapeutics, grasping the precise meaning of the "free" in Gibbs and Helmholtz free energies is not merely academic—it directly impacts how we design simulations, interpret results, and advance the theoretical basis of entropy and free energy calculations.

The term "free" energy historically denoted the portion of a system's total energy available to perform useful work [5] [21]. In contemporary scientific practice, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) recommends using simply "Gibbs energy" and "Helmholtz energy" without the adjective "free" [5] [21], though the traditional terminology remains widespread in literature. This energy represents a bridge between the first and second laws of thermodynamics, incorporating both energy conservation and entropy-driven spontaneity in a single, experimentally accessible quantity.

Defining Free Energy: Fundamental Concepts

Historical Context and Terminology

The development of free energy concepts originated in 19th century investigations into heat engines and chemical affinity. Hermann von Helmholtz first coined the phrase "free energy" for the expression A = U - TS, seeking to quantify the maximum work obtainable from a thermodynamic system [5]. Josiah Willard Gibbs subsequently advanced the theory with his formulation of what we now call Gibbs energy, describing it as "the greatest amount of mechanical work which can be obtained from a given quantity of a certain substance in a given initial state" without changing its volume or exchanging heat with external bodies [21].

The historical term "free" specifically meant "available in the form of useful work" [5]. In this context, "free" energy distinguishes the energy available for work from the total energy, with the remaining energy being bound to the system's entropy. This conceptual framework resolved earlier debates between caloric theory and mechanical theories of heat, ultimately establishing entropy as a fundamental thermodynamic property [5].

Gibbs Energy vs. Helmholtz Energy

Two principal free energy functions dominate thermodynamic analysis, each applicable to different experimental conditions:

Gibbs energy (G) is defined as: [G = H - TS = U + pV - TS] where H is enthalpy, T is absolute temperature, S is entropy, U is internal energy, p is pressure, and V is volume [5] [22] [21]. This function is most useful for processes at constant pressure and temperature, common in chemical and biological systems [5].

Helmholtz energy (A), sometimes called the work function, is defined as: [A = U - TS] This function is most useful for processes at constant volume and temperature, making it particularly valuable in statistical mechanics and gas-phase reactions [5] [23].

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Free Energy Functions

| Feature | Gibbs Energy (G) | Helmholtz Energy (A) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | G = H - TS = U + pV - TS | A = U - TS |

| Natural Variables | T, p, {Nᵢ} | T, V, {Nᵢ} |

| Maximum Work | Non-pV work at constant T, p | Total work at constant T, V |

| Primary Application | Solution-phase chemistry, biochemistry | Physics, statistical mechanics, gas-phase systems |

| Differential Form | dG = Vdp - SdT + ΣμᵢdNᵢ | dA = -pdV - SdT + ΣμᵢdNᵢ |

Theoretical Framework: Connecting Free Energy to Work and Spontaneity

The Second Law Foundation

The second law of thermodynamics establishes that entropy of an isolated system never decreases during spontaneous evolution toward equilibrium [24]. For a system interacting with its surroundings, the total entropy change (system plus surroundings) must be greater than or equal to zero for a spontaneous process [25] [24]. This fundamental principle can be expressed mathematically as: [\Delta S{\text{universe}} = \Delta S{\text{system}} + \Delta S_{\text{surroundings}} \geq 0]

For researchers, this global entropy perspective presents practical challenges, as it requires knowledge of both system and surroundings. Free energy functions resolve this difficulty by incorporating both system entropy and energy transfers with the surroundings, providing a criterion for spontaneity based solely on system properties [25].

The connection between the second law and Gibbs energy emerges when we consider a system at constant temperature and pressure. The entropy change of the surroundings relates to the enthalpy change of the system: (\Delta S{\text{surroundings}} = -\Delta H{\text{system}}/T) [25] [22]. Substituting into the second law expression gives: [\Delta S{\text{system}} - \frac{\Delta H{\text{system}}}{T} \geq 0] Multiplying by -T (which reverses the inequality) yields: [\Delta H{\text{system}} - T\Delta S{\text{system}} \leq 0] Recognizing this expression as (\Delta G) produces the familiar spontaneity criterion: [\Delta G \leq 0] where (\Delta G = \Delta H - T\Delta S) [25] [22] [21].

Free Energy as Available Work

The "free" in free energy physically represents the maximum amount of reversible work obtainable from a system under specific constraints [5] [21] [23]. For Gibbs energy, this is the maximum non-pressure-volume work (non-pV work) obtainable from a system at constant temperature and pressure [21]. For Helmholtz energy, it represents the maximum total work (including pV work) obtainable at constant temperature [5] [23].

This relationship between work and free energy can be derived from the first law of thermodynamics. For a reversible process at constant temperature, the heat transferred is (q{\text{rev}} = T\Delta S), leading to: [\Delta A = \Delta U - T\Delta S = \Delta U - q{\text{rev}} = w{\text{rev}}] where (w{\text{rev}}) represents the reversible work [5]. Thus, the change in Helmholtz energy equals the reversible work done on or by the system.

In practical terms, free energy represents the energy "free" to do useful work after accounting for the energy tied up in entropy. The TS term represents the energy that is "bound" or unavailable for work, making U - TS (for Helmholtz) or H - TS (for Gibbs) the "free" or available portion [5] [21].

Table 2: Free Energy Relationships to Work and Spontaneity

| Condition | Spontaneity Criterion | Maximum Work Relationship | Practical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant T, P | ΔG < 0 (spontaneous) | -ΔG = w({}_{\text{non-pV, max}}) | Drug binding, solvation, chemical reactions |

| Constant T, V | ΔA < 0 (spontaneous) | -ΔA = w({}_{\text{total, max}}) | Bomb calorimetry, gas-phase reactions |

| Equilibrium | ΔG = 0 or ΔA = 0 | No net work possible | Phase transitions, reaction equilibrium |

Methodological Approaches: Calculating Free Energy Differences

Alchemical Transformations and Thermodynamic Cycles

In computational drug discovery, directly calculating absolute free energies is theoretically possible but practically challenging. Instead, researchers typically compute free energy differences between related states using alchemical transformations [26]. These transformations connect thermodynamic states of interest through unphysical pathways, enabling efficient computation through molecular dynamics (MD) or Monte Carlo simulations.

The fundamental framework for these calculations is the thermodynamic cycle, which allows substitution of difficult-to-calculate transformations with more computationally tractable ones [26]. For example, in binding free energy calculations, instead of directly computing the free energy change for ligand binding, researchers calculate solvation free energies and gas-phase decomposition energies around a cycle.

Figure 1: Thermodynamic Cycle for Binding Free Energy Calculation

Lambda Coupling and Pathway Selection

Modern free energy calculations typically employ a λ-parameter that gradually transforms the system from initial to final state [26]. This parameter acts as a coupling coordinate in the Hamiltonian, mixing potential energy functions of the initial and final states:

[U(\lambda) = (1 - \lambda)U{\text{initial}} + \lambda U{\text{final}}]

For complex transformations, particularly in biomolecular systems, separate λ-vectors often control different interaction types (e.g., Coulombic, Lennard-Jones, restraint potentials) to improve numerical stability and sampling efficiency [26]. The careful selection of λ values and pathway is crucial for obtaining converged results with acceptable statistical uncertainty.

Estimation Methods: FEP, TI, and BAR

Several computational estimators exist for extracting free energy differences from simulations along λ pathways:

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) uses the Zwanzig formula: [\Delta G{A\rightarrow B} = -kB T \ln \left\langle \exp\left(-\frac{UB - UA}{kB T}\right) \right\rangleA] which requires sufficient phase space overlap between states [26].

Thermodynamic Integration (TI) computes: [\Delta G = \int0^1 \left\langle \frac{\partial U(\lambda)}{\partial \lambda} \right\rangle\lambda d\lambda] by numerically integrating the average Hamiltonian derivative across λ values [26].

Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR) and its multistate extension (MBAR) provide optimal estimators for data from multiple states, minimizing variance in the free energy estimate [26].

Research Applications in Drug Discovery

Binding Affinity Prediction

The primary application of free energy calculations in pharmaceutical research is predicting protein-ligand binding affinities [26]. Since the binding constant K is directly related to the standard Gibbs energy change ((\Delta G^\circ = -RT \ln K)), accurate free energy methods can theoretically rank candidate compounds by binding strength without synthesizing them. This capability makes free energy calculations invaluable for lead optimization in drug discovery pipelines.

Relative binding free energy calculations, which transform one ligand into another within the binding site, have shown particular success in industrial applications. These approaches benefit from error cancellation that improves accuracy compared to absolute binding free energy methods.

Solvation and Transfer Free Energies

Hydration free energies serve as critical validation tests for free energy methods and force fields [26]. The standard thermodynamic cycle for hydration free energy calculations involves decoupling the molecule from its environment in both aqueous solution and gas phase [26]. These calculations probe the balance of solute-solvent interactions against the cost of cavity formation and conformational restructuring.

Figure 2: Thermodynamic Cycle for Hydration Free Energy Calculation

Implementation and Best Practices

Successful implementation of free energy calculations requires careful attention to multiple technical factors:

System preparation must ensure proper protonation states, realistic ligand geometries, and appropriate solvation. Sampling adequacy remains a persistent challenge, as slow degrees of freedom (sidechain rearrangements, water displacement) can introduce systematic errors. Enhanced sampling techniques such as Hamiltonian replica exchange (HREX) or expanded ensemble methods often improve conformational sampling across λ values [26].

Analysis best practices include convergence assessment through statistical checks, overlap analysis between adjacent λ states, and error estimation using block averaging or bootstrap methods [26]. Automated analysis tools like alchemical-analysis.py help standardize these procedures across research groups [26].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Free Energy Calculations

| Reagent/Software | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Engines (GROMACS, AMBER, DESMOND) | Propagate equations of motion, sample configurations | Core simulation machinery for all free energy methods |

| Force Fields (CHARMM, OPLS, AMBER) | Define potential energy functions | Determine accuracy of physical model; system-dependent selection |

| λ-Vector Schedules | Define alchemical pathway | Control transformation smoothness; impact convergence |

| Soft-Core Potentials | Prevent singularities at λ endpoints | Numerical stability when particles appear/disappear |

| Analysis Tools (alchemical-analysis.py) | Estimate ΔG from simulation data | Standardize analysis; statistical error quantification |

Future Directions and Theoretical Challenges

Despite significant advances, free energy calculations face ongoing challenges in accuracy, precision, and computational cost. Force field limitations, particularly in describing polarization and charge transfer effects, introduce systematic errors that limit predictive accuracy for novel chemical matter. Sampling bottlenecks persist for large-scale conformational changes or slow kinetic processes.

Theoretical developments continue to address these limitations through improved Hamiltonians (polarizable force fields), enhanced sampling algorithms (variational free energy methods), and machine learning approaches (neural network potentials). The integration of theoretical rigor with practical applicability remains the central challenge in advancing free energy research for drug discovery.

As computational power grows and methods refine, free energy calculations increasingly serve as the theoretical foundation for rational drug design, providing the crucial link between molecular structure and thermodynamic activity that drives modern pharmaceutical development.

The accurate prediction of binding free energy is a cornerstone of computational chemistry and drug design, with entropy representing one of its most formidable challenges. Under ambient conditions, binding is governed by the change in Gibbs free energy, ΔG = −RT ln K, where K is the equilibrium constant [27]. While energy evaluation from force-field Hamiltonians is relatively straightforward, entropy calculation requires knowing the probability distribution of all quantum states of a system involving both solutes and solvent [27]. This goes far beyond usual analyses of flexibility in molecular dynamics simulations that typically examine distributions in only one or a few coordinates.

The decomposition of entropy into contributions from multiple energy wells and correlated coordinates remains a fundamental problem in understanding molecular recognition, binding, and conformational changes. Traditional approximations, such as normal mode analysis applied to minimized configurations or quasiharmonic analysis based on coordinate covariance, often suffer from limitations including the Gaussian distribution assumption and poor handling of correlations between degrees of freedom [27]. This technical guide examines advanced methodologies for entropy decomposition within the broader context of theoretical entropy and free energy research, providing researchers with both theoretical frameworks and practical computational approaches.

Theoretical Foundations of Entropy Decomposition

The Statistical Mechanics of Entropy

In classical statistical mechanics, the entropy of a molecular system is intrinsically linked to the volume of phase space it samples. For the conformational entropy of a molecule, this relates to the configuration integral over all its degrees of freedom. The standard change in free energy upon molecular association can be expressed as a ratio of configuration integrals [28]:

[ \Delta G^\circ = -RT \ln \left( \frac{Z{N,AB}/ZN}{C^\circ(Z{N,A}/ZN)(Z{N,B}/ZN)} \right) ]

where (Z{N,AB}), (Z{N,A}), and (Z{N,B}) represent the configuration integrals of the complex, protein, and ligand, respectively, (ZN) is the configuration integral of the solvent, and (C^\circ) is the standard state concentration [28]. The challenge lies in evaluating these high-dimensional integrals, particularly when the energy landscape features multiple minima separated by significant barriers.

The Multiwell Energy Landscape Problem

Molecular systems typically sample multiple energy minima, or conformational states, with transitions between them contributing significantly to entropy. In the energy decomposition (Edcp) approach developed by Ohkubo et al., the conformational entropy of macromolecules is evaluated by leveraging the separability of the Hamiltonian into individual energy terms for various degrees of freedom [29]. This method operates on the principle that the density of states can be estimated from simulations spanning a wide range of temperatures, using techniques such as replica exchange molecular dynamics coupled with the weighted histogram analysis method [29].

Unlike the quasiharmonic approximation, which assumes a single Gaussian probability distribution and tends to overestimate entropy, the Edcp approach can accommodate correlations between separate degrees of freedom without assuming a specific form for the underlying fluctuations [29]. For the molecules studied, the quasiharmonic approximation produced good estimates of vibrational entropy but failed for conformational entropy, whereas the Edcp approach generated reasonable estimates for both [29].

Computational Methodologies for Entropy Calculation

The Energy-Entropy Method with Multiscale Cell Correlation

The Energy-Entropy method with Multiscale Cell Correlation (EE-MCC) represents a significant advancement in calculating host-guest binding free energy directly from molecular dynamics simulations [27]. In this framework, entropy is evaluated using Multiscale Cell Correlation, which utilizes force and torque covariance and contacts at two different length scales [27].

In MCC, the total entropy S is calculated in a multiscale fashion as the sum of four different kinds of terms [27]:

[ S = \sum{i}^{molecule} \sum{j}^{level} \sum{k}^{motion} \sum{l}^{minima} S_{ijkl} ]

Table: Entropy Decomposition in the MCC Framework

| Dimension | Levels | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Molecule (i) | Host, guest, water | Partitioned over each kind of molecule |

| Hierarchy (j) | Molecule (M), united atom (UA) | Two levels of structural hierarchy |

| Motion (k) | Translational, rotational | Classified by type of motion |

| Minima (l) | Vibrational, topographical | Arises from discretization of potential energy surface |

The MCC method applies the same entropy theory to all molecules in the system, providing a consistent framework for understanding how entropy changes are distributed over host, guest, and solvent molecules during binding events [27].

Energy Decomposition Approach

The Energy Decomposition (Edcp) approach provides an alternative method for computing conformational entropy via conventional simulation techniques [29]. This method requires only that the total energy of the system is available and that the Hamiltonian is separable, with individual energy terms for the various degrees of freedom [29]. Consequently, Edcp is general and applicable to any large polymer in implicit solvent.

A key advantage of Edcp is its ability to accommodate correlations present between separate degrees of freedom, unlike methods that evaluate the P ln P integral [29]. Additionally, the Edcp model assumes no specific form for the underlying fluctuations present in the system, in contrast to the quasiharmonic approximation [29].

Practical Implementation and Protocols

EE-MCC Implementation for Host-Guest Systems

The EE-MCC method has been tested on a series of seven host-guest complexes in the SAMPL8 "Drugs of Abuse" Blind Challenge [27]. The binding free energies calculated with EE-MCC were found to agree with experiment with an average error of 0.9 kcal mol⁻¹ [27]. The method revealed that the large loss of positional, orientational, and conformational entropy of each binding guest is compensated for by a gain in orientational entropy of water released to bulk, combined with smaller decreases in vibrational entropy of the host, guest, and contacting water [27].

The standard binding free energy ((\Delta G^\circ_{bind})) of host and guest molecules forming a host-guest complex in aqueous solution is determined from the Gibbs free energies G calculated directly from simulations [27]:

[ \Delta G^\circ{bind} = G{complex} + G{water} - (G{host} + G^\circ_{guest}) ]

In energy-entropy methods, G is evaluated from the enthalpy H and entropy S using G = H - TS, with the pressure-volume terms omitted to allow the approximation H ≈ E, where E is the system energy [27].

Diagram 1: EE-MCC Workflow for Binding Free Energy Calculation

Entropy Calculation Protocol for Macromolecules

For researchers implementing entropy decomposition methods, the following protocol provides a structured approach:

System Preparation: Construct molecular systems with appropriate force field parameters and solvation models.

Enhanced Sampling: Employ replica exchange molecular dynamics or other enhanced sampling techniques to ensure adequate coverage of energy wells [29].

Energy Decomposition: Implement the Edcp approach by decomposing the total energy into contributions from various degrees of freedom [29].

Density of States Estimation: Use the weighted histogram analysis method to estimate densities of states from simulations spanning a range of temperatures [29].

Multiscale Correlation Analysis: Apply MCC to account for correlations at different length scales, using force and torque covariance data [27].

Configuration Integral Evaluation: Calculate the configuration integrals for bound and unbound states, accounting for changes in conformational freedom [28].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Entropy Calculations

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Simulation engine for trajectory generation | AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | Improved sampling of energy landscape | Replica Exchange MD, Metadynamics |

| Force Fields | Molecular mechanical potential functions | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS |

| Implicit Solvent Models | Efficient solvation treatment | Generalized Born, PBSA |

| Correlation Analysis Tools | Quantify coordinate correlations | Custom MCC analysis scripts |

| Host-Guest Systems | Validation and benchmarking | SAMPL challenges, CB8 complexes |

Data Presentation and Quantitative Analysis

Performance Comparison of Entropy Methods

The table below summarizes quantitative comparisons between different entropy calculation methods based on published results:

Table: Performance Comparison of Entropy Calculation Methods

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Handles Correlations | Multiple Minima | Reported Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EE-MCC | Force/torque covariance, multiscale cells | Yes | Yes | 0.9 kcal mol⁻¹ error (SAMPL8) |

| Energy Decomposition (Edcp) | Energy term decomposition, WHAM | Yes | Yes | Reasonable for conformational entropy |

| Quasiharmonic Approximation | Coordinate covariance, single Gaussian | Limited | No | Good for vibrational entropy only |

| Normal Mode Analysis | Hessian matrix diagonalization | No | Limited | Requires minimized structures |

Entropy Compensation in Binding

The application of MCC to host-guest systems has revealed important quantitative insights into entropy compensation during binding. The method makes clear the origin of entropy changes, showing that the large loss of positional, orientational, and conformational entropy of each binding guest is compensated for by specific gains in other entropy components [27]:

- Gain in orientational entropy of water released to bulk

- Smaller decreases in vibrational entropy of the host, guest, and contacting water

- Compensation effects that make binding entropy favorable despite initial apparent entropy losses

Applications in Drug Development and Molecular Design

The theoretical framework for entropy decomposition has direct applications in drug development and molecular design. The accurate prediction of binding between molecules in solution is a key question in theoretical and computational chemistry with relevance to biology, pharmacology, and environmental science [27]. End-point free energy methods, which calculate free energy differences using only the initial and final states, present a desirable alternative to more computationally expensive alchemical transformations [28].

For drug development professionals, these methods offer insights into:

Entropy-Enthalpy Compensation: Understanding how entropy and enthalpy changes balance during binding to optimize drug candidates.

Solvent Effects: Quantifying the role of water in binding interactions, particularly the entropy gain from water release.

Conformational Selection: Evaluating how conformational entropy changes influence molecular recognition and binding affinity.

Specificity Design: Utilizing entropy decomposition to design selective binders that minimize unwanted interactions.

The application to FKBP12, a small immunophilin studied for its potential immunosuppressive and neuroregenerative effects, demonstrates how these methods can provide molecular insight into macroscopic binding properties [28]. For the ligand 4-hydroxy-2-butanone (BUT) binding to FKBP12, with only six heavy atoms and four rotatable bonds, the calculated change in free energy was only 10 kJ/mol lower than the experimental value (500 μM Ki), despite excluding changes in conformational free energy [28]. This small discrepancy is consistent with the low binding affinity of the ligand, which is unlikely to substantially perturb the protein's conformation or fluctuations [28].

Limitations and Future Directions

While current entropy decomposition methods represent significant advances, several limitations remain. The first-order approximation for evaluating configuration integrals assumes that changes in conformational freedom are minimal and that the energy landscape can be characterized from a sufficiently long MD simulation [28]. This simplification serves as a necessary stepping stone for more advanced evaluations but may not capture complex conformational changes.

Future directions in entropy decomposition research include:

Improved Configuration Integral Evaluation: Developing more sophisticated methods for evaluating the internal configuration integral of bound and free systems beyond first-order approximations.

Explicit Solvent Treatments: Extending methods to better handle explicit solvent effects without excessive computational cost.

Dynamic Correlation Analysis: Enhancing the treatment of time-dependent correlations between degrees of freedom.

Machine Learning Integration: Incorporating machine learning approaches to predict entropy contributions from structural features.

Experimental Validation: Expanding experimental benchmarking using well-characterized systems like the SAMPL challenges to validate and improve methods.

As these methods continue to evolve, they will provide increasingly accurate predictions of binding affinities and deeper insights into the fundamental role of entropy in molecular recognition and drug action.

Computational Methods in Practice: From Alchemical Transformations to Enhanced Sampling

The accurate prediction of binding affinity is a cornerstone of computational chemistry and structure-based drug design. Among the various strategies, end-point free energy methods, particularly Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) and Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA), have gained widespread popularity as tools with an intermediate balance between computational cost and predictive accuracy [30] [31]. These methods are termed "end-point" because they require sampling only the initial (unbound) and final (bound) states of the binding reaction, unlike more computationally intensive alchemical methods that must also sample numerous intermediate states [31].

This guide situates these methods within a broader thesis on the theoretical basis of entropy and free energy calculations. A central challenge in this field is the rigorous and efficient treatment of configurational entropy, a component that is notoriously difficult to compute but is fundamental to a complete understanding of molecular recognition [32] [33]. MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA attempts to approximate this term, and their successes and limitations provide valuable insights into the ongoing research in this area.

Theoretical Foundations

The Basic Formalism of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA

The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods estimate the binding free energy (ΔG_bind) for a ligand (L) binding to a receptor (R) to form a complex (PL) using the following fundamental equation [30] [31] [34]:

ΔGbind = Gcomplex - (Greceptor + Gligand)

The free energy of each species (X) is decomposed into several contributions [31]:

GX = EMM + G_solv - TΔS

Here, EMM represents the gas-phase molecular mechanics energy, Gsolv is the solvation free energy, and -TΔS is the entropic contribution to the free energy. The binding free energy is thus calculated as [34]:

ΔGbind = ΔEMM + ΔG_solv - TΔS

The diagram below illustrates the relationship between these components and the process of combining energy terms from separate simulations.

Decomposition of Energy Components

Molecular Mechanics Energy (ΔE_MM)

The gas-phase molecular mechanics energy is calculated using a classical force field and is typically decomposed as follows [31]:

ΔEMM = ΔEinternal + ΔEelectrostatic + ΔEvanderWaals

The internal term (ΔE_internal) includes energy from bonds, angles, and dihedrals. In the single-trajectory approach, which is most common, the internal energy change is assumed to be zero, as the same conformation is used for the complex, receptor, and ligand [30] [31].

Solvation Free Energy (ΔG_solv)

The solvation free energy is partitioned into polar and non-polar components [31] [34]:

ΔGsolv = ΔGpolar + ΔG_non-polar

- Polar Solvation (ΔG_polar): This term is calculated by solving the Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) equation in MM/PBSA or by using the faster but approximate Generalized Born (GB) model in MM/GBSA [31] [34]. This component describes the electrostatic interaction between the solute and a continuum solvent.

- Non-Polar Solvation (ΔG_non-polar): This term accounts for the hydrophobic effect and is typically modeled as being linearly proportional to the Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) [30] [31].

The Entropic Term (-TΔS)

The entropic contribution represents the change in conformational entropy upon binding. It is often estimated using normal mode analysis (NMA) or quasi-harmonic analysis [30] [31]. However, this term is computationally very expensive to calculate and is notoriously noisy [32] [35]. Consequently, it is frequently omitted from MM/PB(G)SA calculations, which is a significant approximation that can impact accuracy [30] [33]. This challenge directly relates to the core thesis of entropy calculation research, driving investigations into improved methods such as interaction entropy (IE) [33] or formulaic entropy [36].

Methodologies and Protocols

Workflow for Binding Affinity Calculation

A typical MM/PB(G)SA workflow involves several key stages, from initial structure preparation to the final energy analysis. The following diagram outlines this general protocol, which can be adapted based on specific research goals.

Key Protocol Decisions and Considerations

Trajectory Approach

- Single-Trajectory Approach (1A-MM/PBSA): The most common method. Only the complex is simulated, and snapshots for the unbound receptor and ligand are generated by simply deleting the other component. This assumes the bound conformation is identical to the unbound, but offers good precision and computational efficiency [30] [31].

- Multiple-Trajectory Approach (3A-MM/PBSA): Separate simulations are run for the complex, the free receptor, and the free ligand. This can account for conformational changes upon binding but introduces more noise and is computationally more expensive [30].

Solvation Models

The choice between PB and GB is a critical one. PB is generally considered more accurate but is computationally slower, while GB offers a faster approximation. A 2011 benchmark study found that MM/PBSA could be more accurate for absolute binding free energies, while certain GB models (like GBOBC [35]) were effective for relative ranking in drug design [35]. The performance is highly system-dependent [30] [37].

Dielectric Constant (ε)

The value of the interior dielectric constant (ε_in) is a key parameter. While a value of 1 is often used for the protein interior, studies have shown that results are quite sensitive to this parameter. Higher values (2, 4, or even higher for RNA systems [37]) are sometimes used to implicitly account for electronic polarization and protein reorganization [35].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for MM/PB(G)SA and Related Methods

| Method | Typical Accuracy (RMSE) | Typical Correlation (R/Pearson) | Relative Speed | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Docking & Scoring | 2–4 kcal/mol [32] | ~0.3 [32] | Very Fast | High-Throughput Virtual Screening, Pose Prediction |

| MM/GBSA | ~1–3 kcal/mol [32] [35] | Variable, can be >0.5 [35] [37] | Medium | Pose Selection, Lead Optimization, Ranking |

| MM/PBSA | ~1–3 kcal/mol [32] [35] | Variable, can be >0.5 [35] | Medium-Slow | Binding Affinity Estimation, Rationalization of SAR |

| Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) | ~1 kcal/mol [32] [38] | ~0.65+ [32] | Very Slow | High-Accuracy Binding Affinity Prediction |

Performance and Advanced Considerations

Benchmarking and System-Dependent Performance

The performance of MM/PB(G)SA is highly variable and depends on the specific biological system under investigation. For example:

- Protein-Ligand Systems: A 2011 benchmark on 59 protein-ligand systems showed that performance is sensitive to simulation length, dielectric constant, and the entropic term [35].

- RNA-Ligand Systems: A 2024 study found that MM/GBSA with a high interior dielectric constant (ε_in = 12-20) yielded a correlation of Rp = -0.513, outperforming standard docking scoring functions for binding affinity prediction, though it was less effective for pose prediction [37].

- Protein-Protein Interactions: A 2020 study on the Bcl-2 family showed that incorporating the interaction entropy (IE) method significantly improved the ability to recognize native from decoy structures, especially for protein-protein systems [33].

Advancements in Entropy Calculation

The treatment of entropy remains an active area of research, directly aligning with the thesis context. Recent developments aim to address the limitations of normal mode analysis:

- Interaction Entropy (IE) Method: This approach calculates the entropic term directly from MD simulation fluctuations, avoiding expensive NMA. Its integration has been shown to significantly improve the recognition of native structures in the Bcl-2 family [33].

- Formulaic Entropy: A 2024 pre-print proposed a formulaic approach to include entropy without extra computational cost, reporting systematic performance improvement for virtual screening [36].

Practical Application in Virtual Screening

MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA are often used as a rescoring tool in virtual screening (VS) workflows. Docking is first used to generate poses and rank a large library of compounds. The top-ranked hits are then rescored using MM/PB(G)SA, which provides a more rigorous estimation of the binding affinity than standard docking scores, potentially improving the enrichment factor and hit rates [34]. This protocol can be based on short MD simulations or even minimized structures to balance accuracy and throughput [34].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for MM/PB(G)SA Calculations

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER [35], GROMACS | MD Engine | Runs molecular dynamics simulations to generate conformational ensembles. | Force field choice (e.g., ff19SB) is critical. |

| MDTraj [32] | Analysis Tool | Analyzes MD trajectories; can compute SASA. | Useful for post-processing snapshot data. |

| OpenMM [32] | Toolkit | Performs MD simulations and energy calculations. | Includes implicit solvent models (e.g., GBN2). |

| MMPBSA.py (AMBER) | Automation | Automates the MM/PBSA/GBSA calculation process. | Standardizes the protocol and component averaging. |

| Normal Mode Analysis | Entropy Tool | Calculates the vibrational entropy term (-TΔS). | Computationally expensive and noisy [32] [30]. |

| Interaction Entropy (IE) | Entropy Tool | Provides an alternative method for entropy calculation from MD fluctuations [33]. | Can be more robust than normal mode analysis. |

| Generalized Born (GB) Models | Solvation Model | Approximates the polar solvation energy (ΔG_polar). | Faster but less accurate than PB; several variants exist (e.g., OBC, GBn2) [35] [37]. |

| Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) Solver | Solvation Model | Computes the polar solvation energy by solving the PB equation. | More accurate but computationally slower than GB. |

MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA occupy a crucial niche in computational chemistry, offering a balance between speed and rigor that makes them suitable for pose prediction, binding affinity ranking, and virtual screening rescoring. Their modular nature allows researchers to tailor the protocol to the specific problem at hand.

However, these methods are not a panacea. Their performance is system-dependent, and they rely on several approximations, the most significant being the treatment of conformational entropy and the use of continuum solvent models. The ongoing research into improving entropy calculations, as exemplified by the Interaction Entropy and formulaic entropy methods, is a direct response to these limitations and is central to advancing the field of free energy calculation. As such, while MM/PB(G)SA are powerful tools in their own right, their development and application provide critical insights and testbeds for the broader thesis of understanding and quantifying the role of entropy in molecular recognition.

Alchemical free energy (AFE) calculations are a class of rigorous, physics-based computational methods used to predict the free energy difference between distinct chemical states. As a state function, the free energy difference is independent of the pathway taken, which allows AFE methods to utilize non-physical or "alchemical" pathways to connect thermodynamic states of interest with greater computational efficiency than simulating the actual chemical process [39]. These methods have become indispensable tools in molecular modeling, particularly in structure-based drug design, where they are used to predict key properties such as protein-ligand binding affinities, solvation free energies, and the consequences of mutations [40] [41] [39].

The theoretical foundation of these methods is deeply rooted in statistical mechanics, linking microscopic simulations to macroscopic thermodynamic observables. For drug discovery, the primary application is the prediction of Relative Binding Free Energies (RBFEs), which enables the prioritization of lead compounds during optimization cycles. The accuracy of these methods can significantly impact the drug discovery pipeline, as even small increases in predictive power can greatly reduce the cost and time of developing new therapeutics [39]. This guide provides an in-depth examination of the two cornerstone alchemical methods: Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) and Thermodynamic Integration (TI).

Theoretical Foundations

Statistical Mechanical Basis of Free Energy

The fundamental goal of an alchemical free energy calculation is to determine the free energy difference between two thermodynamic states, typically labeled as state 0 and state 1. These states could represent a ligand in different environments (e.g., bound to a protein versus solvated in water) or two different chemical entities (e.g., a lead compound and a suggested analog). For a system at constant temperature (T) and volume, the difference in Helmholtz free energy (A) is given by:

$$A1 - A0 = -kB T \ln \frac{\int \exp[-E1(\vec{X})/kB T] d\vec{X}}{\int \exp[-E0(\vec{X})/k_B T] d\vec{X}}$$

Here, $kB$ is Boltzmann's constant, $\vec{X}$ represents a microstate of the system (the positions and velocities of all atoms), and $E0$ and $E_1$ are the potential energy functions of state 0 and state 1, respectively [41]. While this formal definition is exact, directly evaluating these configurational integrals is not feasible for complex biomolecular systems. FEP and TI provide practical computational frameworks to estimate this quantity.

The Alchemical Pathway