Force Fields in Molecular Dynamics: The Engine of Accurate Biomolecular Simulation and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical role force fields play in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, with a special focus on applications in drug discovery.

Force Fields in Molecular Dynamics: The Engine of Accurate Biomolecular Simulation and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical role force fields play in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, with a special focus on applications in drug discovery. It covers foundational concepts, from the basic mathematical formulation of classical force fields to the advanced treatment of electronic polarization in modern polarizable models. For researchers and drug development professionals, the article details practical methodologies, troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls, and a comparative analysis of major force fields like AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with current advancements, including machine learning force fields, this guide aims to empower scientists to select, apply, and validate force fields effectively, thereby enhancing the reliability of their computational studies.

The Bedrock of Simulation: Understanding Force Field Fundamentals and Historical Evolution

A force field is the fundamental mathematical model that defines the energy of a molecular system as a function of its atomic coordinates, thereby determining the forces that drive atomic motion in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations [1] [2]. In computational drug discovery and material science, force fields serve as the core engine, enabling the study of dynamical behaviors, physical properties, and intermolecular interactions at an atomic level [2]. The accuracy of these simulations is critically dependent on the force field, as inherent approximations in their mathematical forms can limit the reliability of the results [1]. While conventional molecular mechanics force fields (MMFFs) offer computational efficiency through fixed analytical forms, emerging machine learning force fields (MLFFs) promise to overcome accuracy limitations by capturing complex, non-pairwise interactions directly from data [2]. This technical guide examines the core principles, modern data-driven methodologies, and validation protocols that define the role of force fields in contemporary MD research.

The Mathematical Foundation of Force Fields

The total potential energy in a typical molecular mechanics force field is decomposed into a series of bonded and non-bonded interaction terms [2]. The canonical form is expressed as:

E~MM~ = E~MM~^bonded^ + E~MM~^non-bonded^

The bonded interactions are typically calculated as:

E~MM~^bonded^ = E~bond~ + E~angle~ + E~torsion~

E~MM~^bonded^ = ∑~bonds~ k~r~ (r - r~0~)^2^ + ∑~angles~ k~θ~ (θ - θ~0~)^2^ + ∑~torsions~ ∑~n~ k~ϕ~ [1 + cos(nϕ - ϕ~0~)]

The non-bonded interactions account for van der Waals forces and electrostatics, commonly described by a Lennard-Jones potential and Coulomb's law:

E~MM~^non-bonded^ = E~vdW~ + E~electrostatic~

E~MM~^non-bonded^ = ∑~i

The parameters for these terms—including equilibrium values (r~0~, θ~0~), force constants (k~r~, k~θ~), and atomic partial charges (q)—must be carefully parameterized to reproduce experimental observables or high-fidelity quantum mechanical calculations [2]. This decomposition, while computationally efficient, introduces inaccuracies due to its inherent approximations, particularly regarding the non-pairwise additivity of non-bonded interactions [2].

Table 1: Core Components of a Molecular Mechanics Force Field

| Energy Term | Mathematical Form | Physical Parameters | Role in Molecular Mechanics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | k~r~(r - r~0~)^2^ | k~r~ (force constant), r~0~ (eq. length) | Maintains covalent bond integrity |

| Angle Bending | k~θ~(θ - θ~0~)^2^ | k~θ~ (force constant), θ~0~ (eq. angle) | Preserves molecular geometry |

| Torsional Dihedral | k~ϕ~[1 + cos(nϕ - ϕ~0~)] | k~ϕ~ (barrier height), n (periodicity), ϕ~0~ (phase) | Governs rotation around bonds |

| van der Waals | 4ε[(σ/r)^12^ - (σ/r)^6^] | ε (well depth), σ (vdW radius) | Models dispersion/repulsion |

| Electrostatics | (q~i~q~j~)/(4πε~0~r) | q~i~, q~j~ (partial charges) | Captures Coulomb interactions |

Methodological Approaches to Force Field Development

Traditional Parameterization and Chemical Perception

Traditional force field development relies heavily on human expertise to define "chemical perception"—the rules that distinguish chemically unique environments for parameter assignment [3]. This process typically involves defining atom types or fragment types that encode specific chemical environments, determining which parameters are assigned to which molecular components [3]. Two primary philosophical approaches exist:

- Indirect Chemical Perception: Used in force fields like AMBER and CHARMM, this approach assigns all force field parameters (including valence terms) based solely on atom types and their connectivity, discarding other chemical information like bond orders once typing is complete [3].

- Direct Chemical Perception: Implemented in the SMIRKS Native Open Force Field (SMIRNOFF) format, this method uses SMIRKS pattern matching to assign parameters based on the full molecular graph, including elements, connectivity, and bond orders [3]. This approach enables more precise parameter assignment with fewer numerical parameters [3].

The definition of atom types has historically been a manual process, potentially leading to over- or under-fitting of data and creating challenges for systematic extension to new chemistries [3]. Automated approaches like SMARTY (for atom types) and SMIRKY (for fragment types) have been developed to address these limitations by using Monte Carlo sampling over hierarchical chemical perception trees, enabling more rigorous and statistically justified typing [3].

The Machine Learning Revolution

Machine learning force fields (MLFFs) represent a paradigm shift, using datasets of reference calculations to learn intricate mappings between molecular configurations and their corresponding energies and/or forces without being limited by fixed functional forms [4] [2]. MLFFs can achieve quantum-level accuracy while spanning the spatiotemporal scales of classical interatomic potentials [5]. Two primary learning strategies have emerged:

- Bottom-Up Learning: ML potentials are trained on high-fidelity simulations (typically Density Functional Theory calculations) providing energy, forces, and virial stress for various atomic configurations [5]. This approach benefits from straightforward training but can inherit inaccuracies from the underlying quantum method and may struggle with distribution shift if training data isn't sufficiently broad [5].

- Top-Down Learning: ML potentials are trained directly on experimental data, such as mechanical properties and lattice parameters [5]. While each data sample provides substantial information, this approach can yield under-constrained models due to the scarcity of experimental data [5].

A fused data learning strategy that concurrently leverages both DFT calculations and experimental measurements has demonstrated superior accuracy compared to models trained on a single data source [5]. This approach can correct known inaccuracies in DFT functionals while maintaining reasonable performance on off-target properties [5].

Advanced Descriptors for Machine Learning Force Fields

The descriptor—a mathematical representation used to encode atomic configurations—determines an MLFF's capability to capture different interaction types [4]. Descriptors can be categorized as:

- Local Descriptors: Consider only atoms within a specified cutoff distance, enhancing transferability but requiring additional terms to account for long-range interactions [4].

- Global Descriptors: Include all interatomic interactions, scaling quadratically with system size but naturally capturing non-local effects [4].

Recent research has developed automated procedures to identify essential features in global descriptors, substantially reducing dimensionality while preserving accuracy [4]. For a tetrapeptide molecule with 861 initial descriptor features, reduction to 344 features (236 short-range and 108 long-range) maintained model accuracy while improving computational efficiency two- to four-fold [4]. This demonstrates that a linearly scaling number of non-local features can sufficiently describe collective long-range interactions [4].

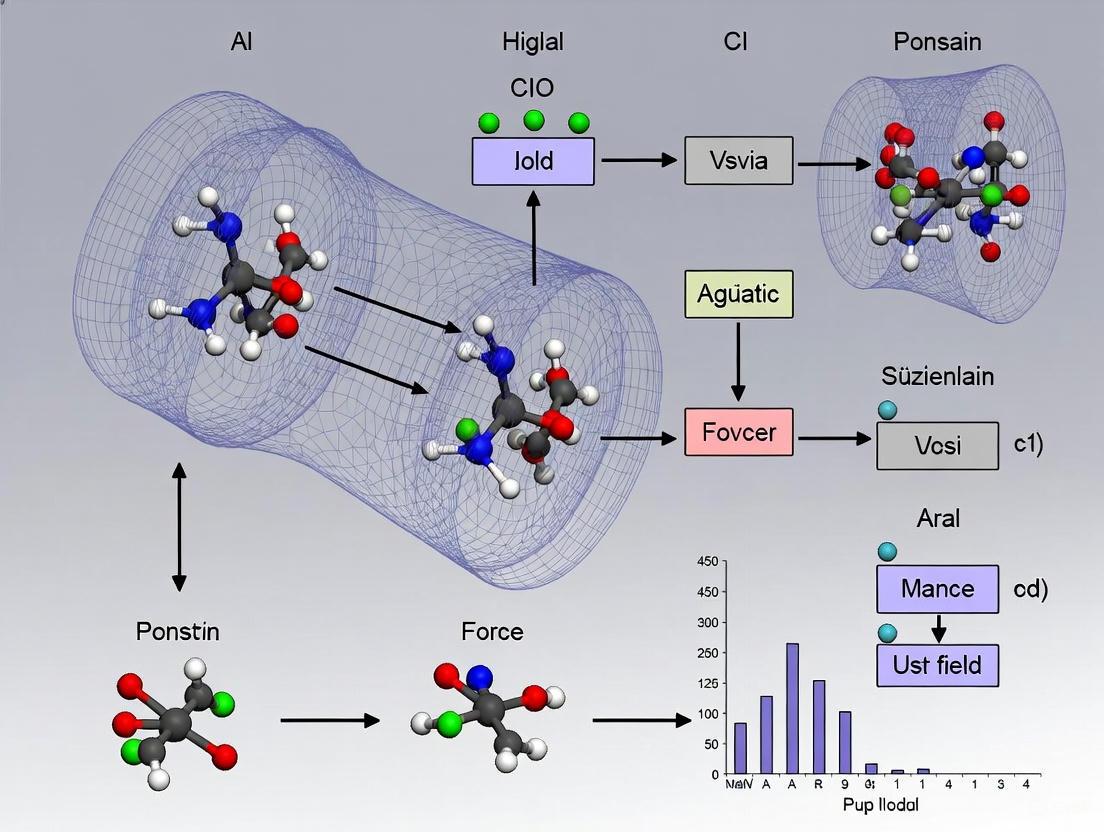

Diagram 1: Modern Force Field Development Workflow showing integrated data strategies.

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

Data Generation and Training Methodologies

Fused Data Learning Protocol (as implemented for titanium ML potential [5]):

DFT Database Construction:

- Generate diverse atomic configurations including equilibrated, strained, and randomly perturbed structures for relevant phases (hcp, bcc, fcc)

- Include configurations from high-temperature MD simulations and active learning approaches

- Target database size: ~5,700 samples with energies, forces, and virial stress

Experimental Data Curation:

- Collect temperature-dependent mechanical properties and lattice parameters

- Select representative temperatures across range of interest (e.g., 23K, 323K, 623K, 923K) to balance computational cost and temperature transferability

- Utilize experimentally determined lattice constants for NVT ensemble simulations

Alternating Training Regime:

- Initialize ML potential with DFT-pre-trained model to avoid unphysical trajectories

- Employ iterative training with alternating DFT and EXP trainers

- DFT trainer: Standard regression to match DFT-calculated energies, forces, virial stress

- EXP trainer: Optimization to match experimental observables using Differentiable Trajectory Reweighting (DiffTRe) method

- Switch trainers after processing all respective training data for one epoch

- Apply early stopping for model selection

Large-Scale Parameterization Protocol (as implemented in ByteFF development [2]):

Dataset Construction:

- Source molecules from ChEMBL and ZINC20 databases with diversity filters (aromatic rings, polar surface area, QED, element types, hybridization)

- Generate molecular fragments (<70 atoms) via graph-expansion algorithm that preserves local chemical environments

- Expand to various protonation states within pKa range 0.0-14.0 using Epik 6.5

- Final selection: 2.4 million unique fragments after deduplication

Quantum Chemistry Calculations:

- Optimization dataset: Geometry optimization of all fragments at B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP level using geomeTRIC optimizer

- Torsion dataset: 3.2 million torsion profiles at same theory level

- Compute analytical Hessian matrices for all optimized geometries

Model Training:

- Employ edge-augmented, symmetry-preserving graph neural network (GNN)

- Implement differentiable partial Hessian loss

- Apply iterative optimization-and-training procedure

- Enforce physical constraints: permutational invariance, chemical symmetry equivalence, charge conservation

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Force Field Development

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| SMIRNOFF Format | Force Field Specification | Enables direct chemical perception via SMIRKS patterns [3] |

| ForceBalance | Parameterization Software | Automates adjustment of force field parameters against experimental/theoretical data [3] |

| Open Force Field Tools | Chemical Perception Sampling | Automates discovery of atom types (SMARTY) and fragment types (SMIRKY) [3] |

| DiffTRe Method | Differentiable Simulation | Enables gradient-based optimization from experimental data without backpropagation through entire trajectory [5] |

| Graph Neural Networks | Machine Learning Architecture | Predicts MM parameters preserving molecular symmetry and physical constraints [2] |

| geomeTRIC Optimizer | Quantum Chemistry Tool | Optimizes molecular geometries at specified QM theory level [2] |

Validation and Benchmarking

Validating force fields requires comparison against both quantum mechanical references and experimental observables [1]. A robust validation protocol should include:

Property-Based Validation:

- Compare simulated mechanical properties (elastic constants) and structural parameters (lattice constants) against experimental measurements across temperature ranges [5]

- Evaluate accuracy in predicting relaxed geometries, torsional energy profiles, and conformational energies/forces [2]

- Assess performance on out-of-target properties (phonon spectra, liquid phase properties) to test transferability [5]

Convergence and Sampling Assessment:

Force Field Comparison Metrics:

- Report energy and force errors relative to quantum chemical references

- For MLFFs, compute test errors on held-out configurations, with typical chemical accuracy target being <1 kcal/mol for energies [4] [2]

- For conventional MMFFs, assess reproduction of experimental observables like solvation free energies, binding affinities, and spectral properties [1]

Diagram 2: Multi-faceted Force Field Validation Framework ensuring comprehensive assessment.

Applications in Drug Discovery and Materials Science

Force fields optimized through these advanced methodologies enable more reliable MD simulations across diverse applications:

In drug discovery, accurate force fields are crucial for predicting protein-ligand binding affinities, conformational dynamics of biomolecules, and solvation properties [2]. The expansion of synthetically accessible chemical space demands force fields with broad coverage of drug-like molecules [2]. Tools like ByteFF demonstrate how data-driven approaches can predict parameters for expansive chemical spaces, achieving state-of-the-art performance in predicting relaxed geometries and torsional energy profiles critical for conformational analysis [2].

In materials science, MLFFs trained via fused data strategies can correctly predict temperature-dependent material properties like lattice parameters and elastic constants, enabling accurate simulation of phase behavior and mechanical response [5]. The capacity to model long-range interactions efficiently through reduced descriptors allows investigation of complex materials including peptides, DNA base pairs, fatty acids, and supramolecular complexes [4].

Force fields constitute the fundamental mathematical engine that powers molecular dynamics simulations, bridging the quantum and classical worlds through either carefully parameterized analytical functions or data-driven machine learning models. The evolution from human-curated atom types to automated chemical perception and from single-source training to fused data strategies represents significant advances in the field. Contemporary force field development requires integrated methodologies combining high-quality quantum chemical data, experimental observables, physical constraints, and sophisticated machine learning architectures. As these tools continue to mature, they promise to enhance the accuracy and expand the scope of molecular simulations, ultimately strengthening their predictive power in drug discovery and materials design. The future of force field development lies in increasingly automated, physically informed, and data-driven approaches that can keep pace with the rapidly expanding chemical space while maintaining transferability and physical fidelity.

The potential energy function is the fundamental engine of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, dictating the forces acting on atoms and ultimately determining the simulated system's structural, dynamic, and thermodynamic properties. For researchers in drug development and materials science, the choice and accuracy of this function govern the predictive power of simulations, bridging the gap between atomic-scale interactions and macroscopic observables. The total potential energy (( U_{\text{total}} )) is a sum of contributions from bonded interactions, which maintain molecular geometry, and non-bonded interactions, which describe longer-range forces between atoms [6]. The accuracy of this potential is paramount, as it enables MD to elucidate mechanisms of drug binding, protein folding, and material failure from the atomistic scale up.

Core Components of the Potential Energy Function

The classical potential energy function is systematically decomposed into distinct terms that capture the physics of covalent bonding and intermolecular forces.

Bonded Interactions

Bonded interactions describe the energy associated with the covalent bond structure of a molecule and are typically modeled with harmonic or anharmonic potentials for 2-body, 3-body, and 4-body interactions [6].

2-Body: Bond Stretching This potential describes the energy of a spring-like vibration between two covalently bonded atoms. The harmonic potential is given by: ( U{\text{bond}} = k{ij}(r{ij} - r0)^2 ) where ( k{ij} ) is the spring constant, ( r{ij} ) is the instantaneous bond length, and ( r_0 ) is the equilibrium bond distance [6]. For reactive simulations, this harmonic term is often replaced by a more physically realistic Morse potential to allow for bond dissociation [7].

3-Body: Angle Bending This potential describes the energy penalty associated with bending the angle between three consecutively bonded atoms. Its harmonic form is: ( U{\text{angle}} = k{ijk}(\theta{ijk} - \theta0)^2 ) where ( k{ijk} ) is the angle constant, ( \theta{ijk} ) is the instantaneous angle, and ( \theta_0 ) is the equilibrium angle [6]. Some force fields include an additional Urey-Bradley term, which is a harmonic potential between the first and third atom of the angle to account for non-covalent interactions [6].

4-Body: Torsion Dihedral This potential describes the energy associated with rotation around a central bond connecting four consecutively bonded atoms. It is typically modeled by a periodic function: ( U{\text{dih}} = k{ijkl}[1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta)] ) where ( k_{ijkl} ) is the multiplicative constant, ( n ) is the periodicity, ( \phi ) is the dihedral angle, and ( \delta ) is the phase shift [6]. Multiple terms with different periodicities can be used for a single dihedral angle to create a complex rotational energy profile.

Table 1: Summary of Bonded Interaction Potential Energy Terms

| Interaction Type | Mathematical Formulation | Descriptive Parameters | Physical Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | ( U = k(r - r_0)^2 ) | Spring constant (( k )), Equilibrium distance (( r_0 )) | Maintains covalent bond length |

| Angle Bending | ( U = k{\theta}(\theta - \theta0)^2 ) | Angle constant (( k{\theta} )), Equilibrium angle (( \theta0 )) | Maintains covalent bond angle |

| Torsion Dihedral | ( U = k_{\phi}[1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta)] ) | Force constant (( k_{\phi} )), Periodicity (( n )), Phase (( \delta )) | Governs rotation around bonds |

Non-Bonded Interactions

Non-bonded interactions occur between atoms that are not directly connected by covalent bonds and are typically computed for all atom pairs, though often with a distance cutoff. They are primarily responsible for the packing and condensed-phase behavior of molecules [6].

van der Waals Forces The Lennard-Jones potential is the most common function used to model van der Waals interactions, which include both attractive (dispersion) and repulsive (Pauli exclusion) components. ( U_{\text{LJ}} = 4\epsilon \left[ \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{6} \right] ) Here, ( \epsilon ) is the depth of the potential well, ( \sigma ) is the finite distance at which the inter-particle potential is zero, and ( r ) is the distance between atoms [6]. This potential decays rapidly and is often truncated for computational efficiency.

Electrostatic Interactions The electrostatic potential between two charged atoms is described by Coulomb's law: ( U{\text{elec}} = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon0 \epsilonr} \frac{qi qj}{r} ) where ( qi ) and ( qj ) are the partial atomic charges, ( r ) is their separation, and ( \epsilonr ) is the dielectric constant [6]. Unlike the Lennard-Jones potential, the electrostatic potential decays slowly, making it computationally expensive to evaluate. Special long-range evaluation methods like Ewald summation or Particle Mesh Ewald are required to handle these interactions accurately.

Table 2: Summary of Non-Bonded Interaction Potential Energy Terms

| Interaction Type | Mathematical Formulation | Descriptive Parameters | Physical Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| van der Waals | ( U = 4\epsilon \left[ \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{6} \right] ) | Well depth (( \epsilon )), Zero-potential distance (( \sigma )) | Models short-range attraction and Pauli repulsion |

| Electrostatics | ( U = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon0\epsilonr} \frac{qi qj}{r} ) | Atomic charges (( qi, qj )), Dielectric constant (( \epsilon_r )) | Models long-range interactions between charges |

Advanced Force Field Methodologies

While classical harmonic force fields are highly successful for simulating systems near equilibrium, recent advances have focused on incorporating chemical reactivity and improving accuracy.

Reactive Force Fields with Morse Potentials

A key limitation of traditional force fields is their inability to simulate bond breaking and formation. A solution is to replace the harmonic bond potential with a Morse potential [7]: ( U{\text{Morse}} = D{ij} [ e^{-2\alpha{ij}(r{ij}-r{0,ij})} - 2e^{-\alpha{ij}(r{ij}-r{0,ij})} ] ) where ( D{ij} ) is the bond dissociation energy, ( \alpha{ij} ) controls the width of the potential well, and ( r_{0,ij} ) is the equilibrium bond length [7]. This method, as implemented in the Reactive INTERFACE Force Field (IFF-R), maintains the accuracy of non-reactive force fields while enabling simulations of bond dissociation and material failure, and is about 30 times faster than complex bond-order potentials like ReaxFF [7].

Machine Learning-Directed Force Field Development

Machine learning (ML) is revolutionizing force field development by overcoming the accuracy vs. efficiency trade-off. ML potentials use a multi-body construction of the potential energy with an unspecified functional form, allowing them to achieve quantum-level accuracy while remaining computationally efficient for large systems [5]. A key innovation is the fusion of data from both simulations and experiments during training [5]. This fused data learning strategy concurrently satisfies target objectives from Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations and experimentally measured properties, resulting in molecular models of higher accuracy than those trained on a single data source [5]. Machine learning-directed, multi-objective optimization workflows can evaluate millions of prospective parameter sets efficiently, leading to force fields that accurately predict a wide range of thermophysical properties not included in the training procedure [8].

Experimental Protocols for Force Field Parameterization and Validation

Developing a reliable force field requires rigorous parameterization and validation against experimental and high-level theoretical data.

Protocol for Parameterizing a Reactive Morse Potential

- Objective: To derive parameters (( D{ij}, \alpha{ij}, r_{0,ij} )) for a Morse bond potential that allows for bond dissociation while preserving the accuracy of the original harmonic force field.

- Step 1: Obtain Equilibrium Bond Length (( r_{0,ij} )) Use the equilibrium bond length from the existing harmonic force field or from high-resolution experimental crystallographic or spectroscopic data [7].

- Step 2: Determine Bond Dissociation Energy (( D_{ij} )) Obtain the bond dissociation energy from experimental thermochemical data or from high-level quantum mechanical calculations (e.g., CCSD(T) or MP2) [7].

- Step 3: Fit the Width Parameter (( \alpha{ij} )) The parameter ( \alpha{ij} ) is initially fitted to match the curvature of the Morse potential to the harmonic potential near the equilibrium distance. It can be further refined by matching the wavenumber of bond vibrations to experimental Infrared and Raman spectroscopy data [7]. Typical values are around ( 2.1 \pm 0.3 ) Å⁻¹ [7].

- Step 4: Validation The resulting parameter set must be validated by ensuring that the model still reproduces key bulk properties such as mass densities, vaporization energies, and elastic moduli [7].

Protocol for Fused Data Machine Learning Force Field Training

- Objective: To train an ML potential that reproduces both quantum mechanical (DFT) data and experimental observables.

- Step 1: DFT Database Construction Generate a diverse set of atomic configurations (e.g., equilibrated, strained, randomly perturbed, high-temperature). For each configuration, compute the target energy, forces, and virial stress using DFT [5].

- Step 2: Experimental Database Selection Select key experimental properties. For a metal like titanium, this could include temperature-dependent elastic constants and lattice parameters [5].

- Step 3: Concurrent Training Loop

The training alternates between a DFT trainer and an EXP trainer.

- DFT Trainer: For one epoch, modify the ML potential's parameters (( \theta )) to match the predicted energies, forces, and virial stress with the DFT database values [5].

- EXP Trainer: For one epoch, optimize parameters (( \theta )) such that properties computed from ML-driven MD simulations match the experimental values. Gradients are computed using methods like Differentiable Trajectory Reweighting (DiffTRe) [5].

- Step 4: Model Selection and Testing The final model is selected using early stopping. It is then tested on out-of-target properties (e.g., phonon spectra, properties of different phases) to assess its transferability and robustness [5].

Visualizing the Molecular Dynamics Workflow and Energy Components

The following diagrams illustrate the logical structure of an MD simulation and the contributions of the various energy terms to the total potential energy function.

Diagram 1: The core Molecular Dynamics simulation cycle, showing the iterative process of force calculation and integration that propagates the system through time.

Diagram 2: Hierarchical decomposition of the total potential energy function (U_total) into its primary bonded and non-bonded components, which are further broken down into specific energy terms.

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Methodologies for Force Field Research and Development

| Tool/Method Name | Type | Primary Function in Force Field Research |

|---|---|---|

| IFF-R (Reactive INTERFACE) | Reactive Force Field | Enables bond breaking in MD via Morse potentials; compatible with CHARMM, AMBER, etc. [7] |

| ReaxFF | Reactive Force Field | Models complex chemical reactions using bond-order formalism; requires many fit parameters [7] |

| Machine Learning Potentials | ML Force Field | Achieves quantum accuracy at classical MD cost; trained on DFT/experimental data [5] |

| DiffTRe Method | Training Algorithm | Enables top-down training of ML potentials on experimental data via differentiable trajectory reweighting [5] |

| MAPS | Software Platform | Aids in machine learning-directed, multi-objective optimization for developing accurate force fields [8] |

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation has established itself as a cornerstone technique in computational chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery. At the heart of every MD simulation lies the force field—a mathematical model that describes the potential energy of a molecular system as a function of the positions of its atoms. Force fields embody the physical laws governing atomic interactions, enabling researchers to simulate and predict the dynamic behavior of biological macromolecules, materials, and chemical systems with atomic-level resolution. The accuracy, transferability, and computational efficiency of a force field directly determine the reliability and scope of MD simulations, making their continuous refinement essential for advancing scientific discovery.

The evolution of force fields represents a persistent pursuit of balancing physical realism with computational tractability. From their early empirical beginnings to today's sophisticated data-driven and machine learning approaches, force fields have progressively expanded their coverage of chemical space while improving quantitative accuracy. This journey has been marked by key transitions: from united-atom to all-atom representations, from fixed-charge to polarizable electrostatics, and from expert-curated parameters to automated parameterization workflows. Understanding this historical progression provides critical context for current limitations and future directions in biomolecular modeling, particularly for applications in pharmaceutical research where accurately predicting molecular interactions can significantly accelerate drug discovery pipelines.

The Historical Evolution of Force Field Methodologies

The Pioneering Era: Foundation of Molecular Mechanics

The conceptual foundation for molecular mechanics force fields was established in the 1960s with the development of the Consistent Force Field (CFF), which introduced the methodology for deriving and validating force fields that could describe a wide range of compounds and physical observables including conformation, crystal structure, thermodynamic properties, and vibrational spectra [9]. This "consistent" philosophy emphasized the importance of developing parameters that could reproduce multiple experimental properties rather than just structural features. Concurrently, Allinger's MM force fields (MM1-MM4, 1976-1996) advanced the field by incorporating target data from electron diffraction, vibrational spectra, heats of formation, and crystal structures, with verification through comparison with high-level ab-initio quantum chemistry computations [9].

The first force field specifically targeting biological macromolecules emerged in 1975 with the Empirical Conformational Energy Program for Peptides (ECEPP), which extensively utilized crystal data of small organic compounds and semi-empirical QM calculations for parameter derivation [9]. This pioneering work established the framework for subsequent biomolecular force fields, though its limitations in handling diverse molecular environments soon became apparent. The 1980s witnessed the introduction of the Consistent Valence Force Field (CVFF) and early versions of CFF (CFF93, CFF95), which expanded applications to polymers and more complex organic systems [9]. The development of the COMPASS (Condensed-phase Optimized Molecular Potentials for Atomistic Simulation Studies) force field in 1998 represented a significant advancement for simulations of organic molecules, inorganic small molecules, and polymers, with later extensions in COMPASS II (2016) further expanding coverage to polymer and drug-like molecules found in popular databases [9].

The United-Atom Revolution and Its Limitations

A pivotal development in force field history was the introduction of the united-atom model, first implemented in UNICEPP in 1978, which represented nonpolar carbons and their bonded hydrogens as a single particle to significantly reduce computational demands [9]. This approach allowed researchers to extend simulation sizes and timescales, making large-scale biomolecular simulations feasible with limited computational resources. The united-atom methodology was subsequently adopted by all major protein force field developers, including GROMOS and early versions of CHARMM and AMBER [9].

However, limitations in united-atom representations eventually became apparent. The absence of explicit hydrogens prevented accurate treatment of hydrogen bonds, π-stacking interactions in aromatic systems could not be properly represented, and combining hydrogens with polar heavy atoms led to inaccurate dipole and quadrupole moments [9]. These shortcomings prompted a gradual return to all-atom representations in most modern biomolecular force fields, though contemporary implementations often combine united-atom representations for aliphatic hydrogens with explicit hydrogens for polar atoms to balance accuracy and efficiency [9].

The Modern Biomolecular Force Field Ecosystem

The contemporary landscape of biomolecular simulations is dominated by four principal all-atom, fixed-charge force field families: AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS, and OPLS, each with distinct philosophical approaches and optimization targets [9].

Table 1: Major Biomolecular Force Field Families and Their Characteristics

| Force Field | Development Focus | Parameterization Philosophy | Strengths | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | Proteins and nucleic acids | RESP charges fitted to QM electrostatic potential; fewer torsional potentials | Accurate structures and non-bonded energies | Protein-DNA complexes, drug binding |

| CHARMM | Biological macromolecules | Polarizable force fields; balanced parameterization | Comprehensive biomolecular coverage | Membrane proteins, lipid bilayers |

| GROMOS | Thermodynamic properties | Parameterized with twin-range cut-off; liquid properties | Accurate thermodynamic properties | Solvation studies, conformational analysis |

| OPLS | Liquid-state properties | Enthalpies of vaporization, liquid densities, solvation free energies | Accurate liquid-phase thermodynamics | Drug solubility, solution behavior |

AMBER force fields prioritize accurate description of structures and non-bonded energies, with van der Waals parameters obtained from crystal structures and lattice energies, and atomic partial charges fitted to quantum mechanical electrostatic potential without empirical adjustments [9]. The CHARMM force field development has emphasized balanced parameterization across different biomolecular classes, with recent versions incorporating polarizable force fields to better represent electrostatic interactions [9]. GROMOS and OPLS have traditionally been geared toward accurate description of thermodynamic properties, with OPLS specifically optimized for liquid-state simulations and properties such as heats of vaporization, liquid densities, and solvation properties [9].

Current State of Force Field Development and Applications

Quantitative Assessment of Modern Force Fields

Recent systematic evaluations have provided critical insights into the performance of current-generation force fields for complex biomolecular systems. A 2025 assessment of RNA force fields revealed both capabilities and limitations in modeling ligand-RNA complexes [10]. The study employed multiple force fields including OL3, DES-AMBER, and OL3cp with gHBfix21 terms, simulating 10 RNA–small molecule structures from the HARIBOSS curated database for 1 μs each [10]. Performance was quantified using RMSD, LoRMSD, RMSF, helical parameters, and contact map analyses, providing a comprehensive assessment of structural fidelity and interaction stability [10].

Table 2: Performance Metrics for RNA Force Fields in Ligand-RNA Complex Simulations [10]

| Force Field | Structural Stability (RMSD) | Ligand Binding (LoRMSD) | Native Contact Preservation | Terminal Fraying |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OL3 | Moderate | Variable | Partial retention | Significant |

| DES-AMBER | Good | Moderate stability | Improved but incomplete | Reduced |

| OL3cp gHBfix21 | Best maintenance | Most stable | Best preservation | Minimal |

The analysis demonstrated that newly refined force fields show better maintenance of intra-RNA interactions and reduced terminal fraying, though this occasionally comes at the expense of distorting the experimental RNA model [10]. Regarding RNA–ligand interactions and binding stability, the study concluded that further refinements are still needed to more accurately reproduce experimental observations and achieve consistently stable RNA–ligand complexes [10]. This comprehensive assessment highlighted the importance of critical analysis of experimental structures, noting that not all aspects of PDB-deposited structures are equally supported by experimental data, with some regions potentially reflecting modeling decisions made during limited experimental restraints [10].

Emerging Data-Driven and Machine Learning Approaches

The rapid expansion of synthetically accessible chemical space has exposed limitations in traditional look-up table approaches to force field development, prompting a shift toward data-driven methodologies [11]. Modern approaches leverage large-scale quantum mechanical datasets and machine learning to parameterize force fields with expansive chemical space coverage. The ByteFF force field, introduced in 2025, exemplifies this trend, utilizing an edge-augmented, symmetry-preserving molecular graph neural network trained on 2.4 million optimized molecular fragment geometries with analytical Hessian matrices and 3.2 million torsion profiles [2].

This data-driven approach addresses several limitations of conventional force fields. As noted in the development of ByteFF, "conventional MMFFs benefit from the computational efficiency of these terms, while suffering inaccuracies due to the inherent approximation, especially when non-pairwise additivity of non-bonded interactions are of significant importance" [2]. Machine learning force fields represent a different philosophical approach, mapping atomistic and molecular features and coordinates to the potential energy surface using neural networks without being limited by fixed functional forms [2]. Despite their superior accuracy, MLFFs face challenges of computational efficiency and extensive data requirements, which currently limit their applications in large-scale biomolecular simulations [2].

Concurrent development has focused on fusing simulation and experimental data for training ML potentials. A 2024 study demonstrated that combining DFT calculations with experimentally measured mechanical properties and lattice parameters can produce ML potentials with higher accuracy compared to models trained with a single data source [5]. This fused data learning strategy concurrently satisfies all target objectives, correcting inaccuracies of DFT functionals while maintaining accuracy for off-target properties [5].

Force Fields in Drug Discovery Applications

Force fields play increasingly critical roles in structure-based drug design, particularly through Free Energy Perturbation calculations for predicting binding affinities. Recent advances in FEP have addressed longstanding challenges, including lambda window selection, torsion parameter refinement, charge changes, and hydration environment treatment [12]. The development of the Open Force Field Initiative, a collaborative academic-commercial effort, has produced increasingly accurate ligand force fields that can be used in conjunction with macromolecular force fields such as AMBER [12].

Active Learning FEP represents an innovative workflow combining FEP with 3D-QSAR methods, leveraging the accuracy of FEP binding predictions with the speed of ligand-based QSAR approaches for efficient exploration of chemical space [12]. Absolute Binding Free Energy calculations further expand the scope of applicable systems by removing the requirement for similar ligand structures, enabling evaluation of diverse chemical scaffolds encountered in virtual screening [12]. These methodological advances, coupled with improved force fields, have transformed FEP from a specialized technique to a robust tool for lead optimization in pharmaceutical research.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Force Field Validation Protocol

Comprehensive validation of force field performance requires multiple complementary analyses applied to MD trajectories. The protocol described in the 2025 RNA force field assessment provides a robust framework for evaluation [10]:

System Preparation:

- Structures are selected from curated databases to capture diverse RNA architectures and binding modes

- Ligand parameters are generated using automated tools (ACpype) with Gaussian 16 and GAFF2 force field with RESP2 charges

- Systems are solvated in appropriate water models (OPC for AMBER, TIP4P-D for DES-AMBER) with 15 Å padding

- Neutralization with K+ ions and addition of salts to physiological concentration (0.15 M)

Simulation Parameters:

- Production runs: 1 μs unrestrained MD simulations under NPT conditions (1 atm, 298 K)

- Energy minimization, thermalization, and equilibration (10 ns) before production

- Velocity-rescale thermostat (τ = 0.1 ps, 300 K) and Berendsen isotropic barostat (τ = 2.0 ps, 1 bar)

- PME electrostatics with 1.0 nm real-space cutoff; van der Waals interactions with 1.0 nm cutoff

Analysis Metrics:

- RMSD: Calculated with respect to experimental structure and trajectory average, considering only heavy atoms

- LoRMSD: Ligand-only RMSD after aligning to RNA backbone to quantify ligand mobility relative to RNA

- RMSF: Atomic fluctuations from time-averaged positions calculated using MDAnalysis package

- Helical parameters: Major groove width, twist, and puckering (% north) computed with pytraj (nastruct)

- Contact maps: Residue-residue contacts defined when minimum heavy atom distance < 4.5 Å

- Contact-occupancy variation (σ): Standard deviation of occupancy time series measuring contact stability

Data-Driven Force Field Parameterization Methodology

The development of ByteFF illustrates modern data-driven force field parameterization [2]:

Dataset Construction:

- Molecular fragments generated from ChEMBL and ZINC20 databases using graph-expansion algorithm

- Fragments limited to <70 atoms with preservation of local chemical environments

- Expansion to various protonation states within pKa range 0.0-14.0 using Epik 6.5

- Final selection of 2.4 million unique fragments after deduplication

Quantum Chemistry Calculations:

- Optimization dataset: Geometry optimization at B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP level using geomeTRIC optimizer

- Torsion dataset: 3.2 million torsion profiles at same theory level

- Balance between accuracy (relative to CCSD(T)/CBS) and computational cost

Machine Learning Training:

- Graph neural network model preserving molecular symmetry and permutational invariance

- Differentiable partial Hessian loss for effective training on the dataset

- Iterative optimization-and-training procedure

- Physical constraints enforcement: charge conservation, chemical equivalency

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Resources for Force Field Development and Application

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Software | High-performance MD simulations with various force fields | Biomolecular simulation, method development |

| AMBER | MD Software | Suite for biomolecular simulation with AMBER force fields | Drug discovery, nucleic acid simulations |

| GAFF/GAFF2 | Force Field | General Amber Force Field for small molecules | Drug-like molecule parameterization |

| PLUMED | Plugin | Enhanced sampling algorithms and collective variables | Free energy calculations, metadynamics |

| OpenMM | Toolkit | Hardware-accelerated MD simulation platform | Custom simulation protocols, method development |

| VOTCA | Toolkit | Systematic coarse-graining | Coarse-grained model development |

| Wannier90 | Software | Maximally localized Wannier functions | Electronic structure analysis, ML potentials |

| MDAnalysis | Library | Trajectory analysis and manipulation | Simulation analysis, property calculation |

| ACpype | Tool | Automatic parameter generation for small molecules | Ligand parameterization for MD simulations |

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The future of force field development is evolving along several complementary trajectories. Physics-informed neural network approaches are bridging deep-learning force fields and electronic structure simulations, as demonstrated by the WANDER framework which enables simultaneous prediction of atomic forces and electronic properties using Wannier functions as the basis [13]. This integration marks a significant advancement toward multimodal machine-learning computational methods that can achieve multiple functionalities traditionally exclusive to first-principles calculations [13].

Addressing the limitations of fixed-charge electrostatics represents another frontier. The development of polarizable force fields like AMOEBA+ that incorporate charge penetration and intermolecular charge transfer offers more physical representation of electrostatic interactions [9]. The recently introduced Geometry-Dependent Charge Flux model considering charge flux contributions along bond and angle directions in AMOEBA+(CF) represents a step toward addressing the dependence of atomic charges on local molecular geometry, a factor largely ignored by most classical force fields [9].

For drug discovery applications, key challenges remain in improving the description of covalent inhibitors, modeling membrane-bound targets like GPCRs, and developing transferable parameters for diverse chemical space [12]. The integration of active learning approaches with high-throughput simulations and experimental data fusion promises to accelerate the design of formulations with optimized properties [14]. As force fields continue to evolve, their role in enabling predictive molecular simulations across chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery will only expand, solidifying their position as indispensable tools in scientific research.

The historical journey of force fields from simple analytical expressions to sophisticated data-driven models reflects the broader evolution of computational science. Each generation of force fields has expanded the frontiers of simulatable systems while improving quantitative accuracy, enabled by advances in theoretical understanding, computational resources, and experimental data. Current research directions—including machine learning potentials, polarizable electrostatics, and integration of electronic structure properties—promise to further extend the capabilities of molecular simulations.

For researchers in drug development and biomolecular science, understanding the capabilities, limitations, and appropriate application domains of different force fields is essential for designing reliable simulation studies. As the field progresses toward increasingly automated and data-driven parameterization, the fundamental role of force fields as the bridge between physical theory and predictive simulation remains constant. The continued refinement of these essential tools will undoubtedly unlock new opportunities for scientific discovery and technological innovation across the molecular sciences.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a computational microscope, enabling researchers to observe the motion and interactions of atoms over time. The force field is the fundamental engine of any MD simulation; it is a mathematical model that calculates the potential energy of a system of atoms based on their positions. The accuracy of any simulation in predicting structural, dynamic, and thermodynamic properties is therefore directly contingent on the quality and appropriateness of its underlying force field [15].

Despite the emergence of machine learning potentials, fixed-charge additive force fields remain the workhorses for biomolecular simulation due to their computational efficiency [16] [17]. This guide provides an in-depth exploration of three cornerstone force fields—AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS-AA—detailing their functional forms, parametrization philosophies, and applications, thereby equipping researchers with the knowledge to select the optimal model for their scientific inquiries.

The Theoretical Foundation of Force Fields

The Universal Functional Form

Classical additive force fields share a common functional form that decomposes the total potential energy into bonded and non-bonded interactions. The bonded terms describe the energy associated with the covalent structure, while the non-bonded terms describe interactions between atoms that are not directly bonded.

The general form of the potential energy function, ( V(\mathbf{r}^N) ), is universally represented by the following components [18] [17]:

- Bond Stretching: Energy required to stretch or compress a bond from its equilibrium length, modeled as a harmonic spring.

- Angle Bending: Energy associated with bending an angle from its equilibrium value, also treated harmonically.

- Torsional Rotations: Energy for rotation around bonds, typically modeled by a periodic cosine function.

- van der Waals Forces: Weak intermolecular forces described by the Lennard-Jones potential.

- Electrostatic Interactions: Coulombic forces between partial atomic charges.

Mathematical Formulations Across Force Fields

Table 1: Core Mathematical Components of Major Force Fields

| Energy Component | AMBER Form [18] | CHARMM Form [17] | Key Differentiators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bonds | ( \sum kb(l - l0)^2 ) | ( \sum Kb(b - b0)^2 ) | Identical harmonic potential |

| Angles | ( \sum ka(\theta - \theta0)^2 ) | ( \sum K\theta(\theta - \theta0)^2 ) | CHARMM includes Urey-Bradley term [19] |

| Dihedrals | ( \sum \frac{1}{2}V_n[1+\cos(n\omega - \gamma)] ) | ( \sum K_\phi(1+\cos(n\phi - \delta)) ) | Identical Fourier series form |

| Impropers | - | ( \sum K\psi(\psi - \psi0)^2 ) | CHARMM uses harmonic potential [20] |

| van der Waals | ( \sum \epsilon{ij}\left[\left(\frac{r{ij}^0}{r{ij}}\right)^{12} - 2\left(\frac{r{ij}^0}{r_{ij}}\right)^6\right] ) | ( \sum \epsilon{ij}\left[\left(\frac{R{min,ij}}{r{ij}}\right)^{12} - 2\left(\frac{R{min,ij}}{r_{ij}}\right)^6\right] ) | Identical LJ 6-12, different combining rules |

| Electrostatics | ( \sum \frac{qi qj}{4\pi\epsilon0 r{ij}} ) | ( \sum \frac{qi qj}{4\pi D r_{ij}} ) | Identical Coulomb's law |

A Deep Dive into Major Force Fields

The AMBER Force Field

Historical Development and Philosophy

The AMBER force field originated from Peter Kollman's group at UCSF and refers to both a software package and a family of force fields. The parametrization philosophy emphasizes fitting to quantum mechanical data of small model compounds, with partial atomic charges derived to approximate aqueous-phase electrostatics using the Hartree-Fock 6-31G* method, which intentionally overpolarizes bond dipoles to mimic the condensed phase environment [18] [16].

Significant development efforts have addressed initial limitations, such as the over-stabilization of α-helices in early versions (ff94, ff99). This led to the creation of ff99SB, which improved the balance of secondary structure elements by refitting backbone dihedral terms to quantum mechanical energies of glycine and alanine tetrapeptides [16].

Key Parameter Sets

Table 2: Prominent AMBER Force Field Parameter Sets

| Parameter Set | Primary Application | Key Features | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| ff19SB [18] | Proteins | State-of-the-art backbone torsions | Primary protein model with OPC water |

| ff14SB [18] | Proteins | Refined side-chain torsions | With TIP3P water or implicit solvent |

| OL3/OL24 [18] | Nucleic Acids (RNA/DNA) | Specific glycosidic torsion corrections | RNA and DNA simulations |

| GAFF/GAFF2 [18] | Small Organic Molecules | Drug-like molecule parameters | Ligand parameterization with AM1-BCC charges |

| GLYCAM-06j [18] | Carbohydrates | Developed by Rob Woods' group | Carbohydrate simulations |

| lipid21 [18] | Lipids | Comprehensive lipid parameter set | Lipid bilayer simulations |

The CHARMM Force Field

Functional Form and Extensions

The CHARMM force field employs a class I potential energy function that includes a Urey-Bradley term for angle vibrations and a harmonic potential for improper dihedrals [19] [17]. A distinctive feature is the CMAP correction, which applies a 2D grid-based energy correction to backbone dihedral angles (φ and ψ) to better reproduce quantum mechanical conformational energies [19] [20].

The force field defines multiple dihedral terms for the protein backbone: standard φ/ψ dihedrals along the main chain, plus additional φ'/ψ' dihedrals branched to the Cβ carbon, which are crucial for achieving correct conformational preferences for non-glycine residues [16].

The CHARMM Ecosystem

CHARMM encompasses specialized parameter sets for different biomolecular classes:

- Proteins: topall36prot.rtf and parall36prot.prm

- Nucleic Acids: topall36na.rtf and parall36na.prm

- Lipids: topall36lipid.rtf and parall36lipid.prm

- Carbohydrates: topall36carb.rtf and parall36carb.prm

The CHARMM General Force Field extends this ecosystem to drug-like molecules. CGenFF prioritizes quality over transferability, with parametrization focusing on accurate representation of heterocyclic scaffolds and functional groups common in pharmaceuticals [17]. The optimization protocol emphasizes quantum mechanical target data to ensure physical behavior in a polar, biological environment.

The OPLS-AA Force Field

Philosophy and Development

The Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations - All Atom force field, developed by William Jorgensen's group, emphasizes the reproduction of condensed-phase properties [16] [21]. The parametrization process heavily weights liquid densities and enthalpies of vaporization to ensure balanced solute-solvent and solvent-solvent interactions.

OPLS-AA utilizes geometric Lennard-Jones combining rules and specific 1,4 non-bonded scaling factors. Recent improvements in OPLS-AA/M refit peptide and protein torsional energetics using a larger training set of peptide conformations, leading to enhanced accuracy for protein simulations [21].

Implementation and Availability

OPLS-AA parameters are available in formats compatible with multiple MD software packages, including CHARMM and GROMACS. The LigParGen web server provides an automatic parameter generator for organic ligands, facilitating the simulation of drug-like molecules with OPLS-AA [21].

Force Field Parametrization: A Detailed Methodology

The creation of accurate force field parameters follows a rigorous, multi-stage process centered on quantum mechanical calculations and experimental validation.

Core Parametrization Protocol

Modern Data-Driven Approaches

Traditional parameterization approaches are being supplemented by modern data-driven methods that leverage machine learning. For example, ByteFF represents a next-generation force field that uses an edge-augmented, symmetry-preserving molecular graph neural network trained on 2.4 million optimized molecular fragment geometries and 3.2 million torsion profiles to predict parameters simultaneously across broad chemical space [11].

Hybrid approaches like ResFF integrate physics-based molecular mechanics terms with corrections from a lightweight equivariant neural network. This residual learning framework combines the interpretability of physical models with the expressiveness of neural networks, achieving state-of-the-art accuracy on benchmarks for conformational energies and torsional profiles [22].

Performance Benchmarking and Selection Guidelines

Comparative Performance Insights

Recent systematic benchmarking of twelve force fields across diverse peptides reveals that no single model performs optimally across all systems. Performance varies significantly between force fields, with some exhibiting strong structural biases while others allow more reversible fluctuations. The ability to balance disorder and secondary structure propensity remains a key challenge [15].

For proteins, the AMBER ff99SB force field demonstrated improved balance between major secondary structure elements compared to its predecessors, achieving better distributions of backbone dihedrals and improved agreement with experimental NMR data [16].

Selection Guidelines for Specific Applications

Table 3: Force Field Selection Guide for Biomolecular Simulations

| System Type | Recommended Force Field | Rationale | Compatible Solvent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins (General) | AMBER ff19SB [18] | State-of-the-art backbone torsions | OPC water model |

| Nucleic Acids | AMBER OL3/OL24 [18] | Specific glycosidic torsion corrections | Compatible with TIP3P |

| Drug Discovery | CHARMM CGenFF [17] | Optimized for drug-like molecules | Balanced with CHARMM water |

| Carbohydrates | CHARMM/GLYCAM-06j [18] | Specialized carbohydrate parameters | Varies by specific implementation |

| Lipid Membranes | CHARMM lipid21 [18] | Comprehensive lipid parameters | TIP3P water |

| Mixed Systems | Consistent Family | Maintain non-bonded balance | Use recommended water model |

When combining molecules parameterized with different force fields, extreme caution is required. The non-bonded parameters are developed using different strategies across force fields, and mixing them can yield improperly balanced intermolecular interactions [17]. It is strongly recommended to use parameters from a single, consistent force field family whenever possible.

Table 4: Key Computational Tools for Force Field Applications

| Tool/Resource | Function | Access/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| AMBER Software Suite [18] | MD simulation with AMBER force fields | Proprietary license (Amber), GPL (AmberTools) |

| CHARMM Modeling Software [19] [20] | Versatile program for atomic-level simulation | Academic licensing |

| LigParGen Server [21] | Automatic OPLS-AA parameter generator | Web server (free) |

| CGenFF Program [17] | CHARMM General Force Field parametrization | Part of CHARMM package |

| Antechamber Toolkit [17] | GAFF parameter generation for AMBER | Part of AmberTools |

| parmchk2 Utility | Validation of force field parameters | Part of AmberTools |

| Moltemplate [23] | Force field organization for LAMMPS | Open source |

The field of force field development is rapidly evolving. Machine learning approaches are being integrated to create more accurate and transferable potentials, as demonstrated by ByteFF and ResFF [11] [22]. Systematic benchmarking across diverse biological systems will continue to drive improvements, particularly for challenging targets like disordered peptides and conformational switches [15].

The choice of force field remains a critical decision in the planning of any molecular dynamics study. Researchers must consider their specific system composition, the properties of interest, and the need for compatibility between different molecular components. By understanding the philosophical underpinnings, functional forms, and parametrization strategies of the major force fields discussed in this guide, scientists can make informed decisions that maximize the physical relevance and predictive power of their computational investigations.

From Theory to Therapy: Applying Force Fields in Drug Discovery and Biomolecular Simulation

Force fields represent the foundational component of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, serving as the mathematical framework that defines the potential energy of a molecular system. In computational drug discovery, they are indispensable for predicting the behavior of drug-like molecules, from simple ligand-receptor interactions to complex solvation dynamics and membrane permeation. The traditional approach to force field parameterization has relied heavily on look-up tables derived from limited experimental data and quantum mechanical calculations on small model compounds. However, this method faces significant challenges in keeping pace with the rapid expansion of synthetically accessible chemical space, which now encompasses billions of potentially drug-like molecules. The central challenge lies in developing force fields that maintain high computational efficiency while achieving expansive chemical coverage and quantum-mechanical accuracy across diverse molecular structures [11] [24].

This whitepaper examines how modern parameterization strategies are addressing these challenges through data-driven approaches and machine learning algorithms. By leveraging extensive quantum mechanical datasets and sophisticated neural network architectures, researchers are developing next-generation force fields that promise to transform molecular dynamics from a specialized tool into a robust, predictive platform for drug development. The integration of these advanced force fields into MD research workflows enables more reliable simulation of biological processes, more accurate prediction of drug-target interactions, and ultimately, more efficient navigation of the vast pharmacological space [24] [25].

The Chemical Space Challenge in Drug Discovery

The concept of "chemical space" provides a framework for understanding the diversity of possible drug-like molecules. Current estimates suggest that the relevant chemical space for drug discovery encompasses approximately 10^63 organic molecules with up to 30 atoms of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, or sulfur [25]. This staggering number presents both opportunity and challenge: while it offers nearly limitless possibilities for drug design, it also makes comprehensive exploration through traditional experimental methods impossible.

Mapping the Drug-Relevant Chemical Space

In practice, drug discovery focuses on strategically selected regions of this vast chemical space. Analyses of approved drugs reveal distinct patterns and properties that differentiate them from random small molecules. Several key observations emerge from chemical space mapping studies:

- Aromatic Dominance: Approximately 81% of approved drugs (1,494 out of 1,834 molecules) contain at least one aromatic ring, highlighting the importance of these structurally stable components for molecular recognition and metabolic stability [25].

- Property Clustering: When visualized using techniques like Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP), drugs cluster in specific regions of chemical space defined by descriptors such as aromatic carbocycles, heterocycles, and fraction of sp3 carbons [25].

- Expanding Boundaries: Drugs approved after 2020 occupy slightly different regions of chemical space compared to historical drugs, reflecting evolving design strategies and new target classes [25].

Table 1: Chemical Space Characteristics of Approved Drugs

| Characteristic | Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Total Approved Drugs | 1,834 unique molecules | Representative of explored chemical space |

| Aromatic Containment | 81% (1,494 molecules) | Structural stability and interaction capability |

| Post-2020 Approvals | 87 unique molecules | Emerging trends in drug design |

| Clinical Candidates | 685 molecules | Near-future expansion of chemical space |

The pharmacological space—defined by the interactions between these chemicals and biological targets—is equally complex. Studies have identified 893 human and pathogen-derived biomolecules through which 1,578 FDA-approved drugs act, including 667 human genome-derived proteins targeted for human diseases [25]. This "druggable genome" represents only a fraction of the human proteome, highlighting the need for force fields that can accurately model interactions with both established and novel target classes.

Traditional vs. Modern Parameterization Approaches

Limitations of Traditional Force Fields

Traditional force field development has relied on transferable parameters derived from limited experimental data and quantum mechanical calculations on representative fragments. While this approach has produced workhorses like GAFF (General Amber Force Field), OPLS-AA (Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations-All Atom), and CGenFF (CHARMM General Force Field), significant limitations persist:

- Chemical Transferability: Parameters derived from small molecules may not accurately represent complex, drug-like compounds with multiple functional groups and unusual bonding patterns [26].

- Systematic Biases: Different force fields exhibit distinct structural biases, particularly for peptides and flexible molecules, with no single force field performing optimally across all system types [15].

- Limited Validation: Traditional parameterization often prioritizes reproduction of gas-phase quantum mechanics over complex condensed-phase behavior, leading to discrepancies in simulation accuracy [26].

These limitations become apparent in benchmarking studies. For example, in simulations of polyamide reverse-osmosis membranes, force fields exhibited significant variations in predicting mechanical properties, hydration dynamics, and ion rejection rates—discrepancies that directly impact the reliability of computational predictions for industrial applications [26].

Data-Driven Parameterization Strategies

Modern parameterization approaches address these limitations by leveraging large-scale quantum mechanical datasets and machine learning algorithms. The fundamental shift is from manual parameterization based on limited data to automated, data-driven parameterization across expansive chemical spaces.

ByteFF exemplifies this approach, utilizing an edge-augmented, symmetry-preserving molecular graph neural network (GNN) trained on 2.4 million optimized molecular fragment geometries with analytical Hessian matrices and 3.2 million torsion profiles calculated at the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP level of theory [11]. This extensive training dataset enables the model to predict all bonded and non-bonded MM force field parameters simultaneously across a broad chemical space, achieving state-of-the-art performance in predicting relaxed geometries, torsional energy profiles, and conformational energies and forces [11].

Hybrid Physical-Machine Learning Approaches

ResFF (Residual Learning Force Field) represents an alternative hybrid approach that integrates physics-based molecular mechanics covalent terms with residual corrections from a lightweight equivariant neural network [22]. Through a three-stage joint optimization, the physical and machine learning components are trained complementarily, resulting in a force field that outperforms both classical and pure neural network force fields across multiple benchmarks:

- Generalization accuracy (MAE: 1.16 kcal/mol on Gen2-Opt, 0.90 kcal/mol on DES370K)

- Torsional profiles (MAE: 0.45/0.48 kcal/mol on TorsionNet-500 and Torsion Scan)

- Intermolecular interactions (MAE: 0.32 kcal/mol on S66×8) [22]

This architecture merges the interpretability and constraints of physics-based models with the expressiveness of neural networks, enabling precise reproduction of energy minima and stable molecular dynamics of biological systems [22].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Quantum Mechanical Data Generation

The foundation of modern force field parameterization is high-quality quantum mechanical data. The protocol for generating these datasets typically involves:

Molecular Selection: Curating a diverse set of drug-like molecules and molecular fragments representing the target chemical space. This includes coverage of common scaffolds, functional groups, and ionization states.

Geometry Optimization: Performing quantum mechanical geometry optimizations at an appropriate level of theory (e.g., B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP) to identify energy minima [11].

Hessian Calculation: Computing analytical Hessian matrices for optimized geometries to obtain vibrational frequencies and force constants.

Torsional Scanning: Performing relaxed scans of rotatable bonds to characterize torsional energy profiles, a critical component for accurate conformational sampling [11].

Non-Covalent Interactions: Calculating intermolecular interaction energies for representative dimers using higher-level theories to capture dispersion, electrostatic, and induction effects accurately.

Machine Learning Model Training

Once the quantum mechanical dataset is prepared, the machine learning parameterization workflow follows a structured approach:

Diagram 1: Machine Learning Force Field Parameterization Workflow

The training process employs specialized strategies to ensure optimal performance:

- Multi-task Learning: Simultaneously predicting multiple parameter types (bonds, angles, torsions, non-bonded) to exploit correlations between them [11].

- Symmetry Preservation: Implementing architecture constraints to ensure equivalent atoms receive identical parameters regardless of molecular orientation [11].

- Residual Learning: In hybrid approaches like ResFF, training the neural network to predict corrections to physics-based terms rather than complete energies [22].

- Transfer Learning: Pre-training on large datasets of molecular fragments before fine-tuning on complete drug-like molecules.

Force Field Validation Protocols

Comprehensive validation is essential to ensure force field reliability across diverse applications. A robust validation protocol includes multiple components:

Table 2: Force Field Validation Metrics and Benchmarks

| Validation Category | Specific Metrics | Benchmark Datasets |

|---|---|---|

| Geometric Accuracy | Bond/angle deviations, RMSD to QM structures | Gen2-Opt, DES370K [22] |

| Energetic Accuracy | Conformational energies, torsion profiles | TorsionNet-500, Torsion Scan [22] |

| Non-covalent Interactions | Interaction energies, dimer profiles | S66×8 [22] |

| Dynamics Properties | Stability in MD, folding/unfolding balance | Peptide folding benchmarks [15] |

| Application-specific | Membrane permeability, solvation free energies | Polyamide membrane benchmarks [26] |

For peptide and protein systems, validation should include assessments of folding stability from extended states (μs timescales) and stability of native states (100s ns timescales) across diverse structural classes, including miniproteins, context-sensitive epitopes, and disordered sequences [15].

Successful implementation of modern force field parameterization requires leveraging specialized tools and resources. The following table summarizes key components of the computational chemist's toolkit for force field development and application.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Force Field Parameterization

| Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| ByteFF | Data-driven force field | Predicts MM parameters for drug-like molecules | General drug discovery applications [11] |

| ResFF | Hybrid ML-physics force field | Residual correction to physics-based terms | High-accuracy conformational sampling [22] |

| Martini | Coarse-grained force field | 4-to-1 mapping for enhanced sampling | Biomolecular complexes, membranes [27] |

| ChEMBL | Bioactivity database | Chemical and pharmacological space analysis | Target profiling, chemical space mapping [25] |

| GAFF | Traditional force field | Transferable parameters for small molecules | Baseline comparisons, established workflows [26] |

| SwissParam | Parameter assignment tool | Topology matching and charge assignment | Rapid parameterization for diverse compounds [26] |

Specialized Force Fields for Specific Applications

Beyond general-purpose force fields, specialized models have been developed for specific applications:

- Martini Force Field: A coarse-grained model using a four-to-one mapping scheme that enables simulation of larger systems and longer timescales. Martini includes topologies for lipids, proteins, nucleotides, saccharides, and drug-like molecules, making it particularly valuable for membrane permeation studies and large biomolecular complexes [27].

- Polymer-Optimized Force Fields: Models like PCFF include cross-correlation terms in bonded interactions that improve accuracy for polymeric systems like polyamide membranes, though they may require additional computational resources [26].

The choice between all-atom and coarse-grained representations depends on the specific research question, with all-atom models providing greater structural detail and coarse-grained models enabling access to larger length and timescales.

Implementation Workflow: From Parameterization to Simulation

Implementing a modern force field parameterization strategy requires careful planning and execution. The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from initial data generation to final simulation validation:

Diagram 2: Complete Force Field Development and Implementation Cycle

Practical Implementation Considerations

Successful implementation of data-driven force fields requires attention to several practical aspects:

- System Preparation: Ensure proper protonation states, tautomer distributions, and stereochemistry for drug-like molecules, as these significantly impact molecular interactions and dynamics.

- Solvation Models: Select appropriate water models (TIP3P, TIP4P) compatible with the chosen force field, as water model selection significantly impacts solvation free energies and membrane permeability predictions [26].

- Long-Range Interactions: Implement appropriate treatment of long-range electrostatics (PME, Ewald sums) to accurately capture ion-ion and ion-dipole interactions critical for drug-target binding [24].

- Enhanced Sampling: Apply accelerated sampling techniques (metadynamics, replica-exchange) to overcome barriers in conformational sampling, particularly for flexible drug-like molecules with multiple rotatable bonds.

The parameterization of force fields for drug-like molecules is undergoing a transformative shift from expert-driven, fragment-based approaches to automated, data-driven methodologies spanning expansive chemical spaces. Modern machine learning force fields like ByteFF and ResFF demonstrate that comprehensive quantum mechanical datasets coupled with appropriate neural network architectures can achieve unprecedented accuracy across diverse benchmarks while maintaining the computational efficiency required for practical drug discovery applications.

The implications for molecular dynamics research are profound. As force fields become more accurate and chemically comprehensive, MD simulations will transition from mainly qualitative tools to reliable predictive platforms capable of guiding experimental design and prioritizing synthetic targets. This is particularly valuable for exploring underutilized regions of chemical space and targeting novel protein classes beyond the well-characterized "druggable genome."

Future developments will likely focus on several key areas: (1) integrating active learning approaches to efficiently expand chemical coverage, (2) developing multi-scale methods that seamlessly transition between resolution levels, and (3) incorporating experimental data directly into the parameterization process. As these advancements mature, they will further solidify the role of molecular dynamics as an indispensable tool in computational drug discovery, enabling more efficient navigation of the vast chemical and pharmacological space towards novel therapeutics.

In the realm of computer-aided drug design (CADD), force fields serve as the fundamental mathematical framework that defines the potential energy of a molecular system based on the positions of its atoms. [28] They are computational models that describe the forces between atoms within molecules or between molecules, essentially functioning as the "rulebook" that governs atomic interactions in silico. [28] The accuracy of these force fields is paramount, as they directly influence the reliability of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and the prediction of key drug discovery parameters such as protein-ligand binding affinity. [29] [30] Force fields achieve this by characterizing the potential energy surface of molecular systems through a collection of atomic point masses that interact via both non-bonded and valence terms. [31]

The core application of force fields in CADD lies in their ability to enable accurate binding free energy calculations, which are crucial for ranking compounds by their predicted affinity for a drug target. [29] [32] Modern force fields have proven indispensable for a multitude of tasks in biomolecular simulation and drug design, including the enumeration of putative bioactive conformations, hit identification via virtual screening, prediction of membrane permeability, and estimation of protein-ligand binding free energies via alchemical free energy calculations. [31] As drug discovery increasingly shifts toward a computational "predict-first" approach, the development of more reliable and extensible force fields has become a critical focus of research. [33]

Technical Foundation: Mathematical Formulations of Force Fields

Core Energy Components

The basic functional form of a force field decomposes the total potential energy of a system into bonded and non-bonded interaction terms. [28] This can be generally expressed as:

[ E{\text{total}} = E{\text{bonded}} + E_{\text{nonbonded}} ]

Where the bonded term is further decomposed into: [ E{\text{bonded}} = E{\text{bond}} + E{\text{angle}} + E{\text{dihedral}} ] And the non-bonded term consists of: [ E{\text{nonbonded}} = E{\text{electrostatic}} + E_{\text{van der Waals}} ]

The following table summarizes the key mathematical functions governing these interactions in Class I force fields, which represent the most widely used type in biomolecular simulation due to their computational efficiency. [31] [28]

Table 1: Core Mathematical Components of a Classical Force Field

| Energy Component | Mathematical Formulation | Key Parameters | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|