Fick's Laws of Diffusion: Theory, Applications, and Modern Challenges in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Fick's Laws of Diffusion, from their foundational principles to their critical applications in drug development and biomedical engineering.

Fick's Laws of Diffusion: Theory, Applications, and Modern Challenges in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Fick's Laws of Diffusion, from their foundational principles to their critical applications in drug development and biomedical engineering. Tailored for researchers and scientists, it covers the mathematical formulation of both the first and second laws, detailed methodologies for measuring diffusion coefficients, and common pitfalls in applying these models to complex biological systems. The content further examines the limitations of classical Fickian diffusion and discusses advanced, non-Fickian frameworks essential for modeling modern controlled-release pharmaceuticals and nanoporous materials, offering a vital resource for optimizing therapeutic agent design and delivery.

The Foundations of Molecular Diffusion: Understanding Fick's Core Principles

Diffusion describes the random movement of particles from a region of high concentration to a region of low concentration, driven by a concentration gradient to ultimately achieve uniform distribution [1] [2]. This spontaneous process results from random thermal motions and serves as a fundamental mass transfer mechanism across scientific and engineering disciplines [3]. First mathematically described by Adolf Fick in 1855, diffusion principles form the core of our understanding of transport in gases, liquids, and solids [4] [1]. In biological systems, diffusion governs crucial processes including gas exchange in lungs, drug delivery mechanisms, and cellular signaling [5] [1], while industrial applications span pharmaceutical development, semiconductor fabrication, food processing, and environmental remediation [1] [6]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of diffusion theory, experimental methodologies, and research applications framed within contemporary molecular diffusion research.

Theoretical Foundations

Fundamental Principles

Diffusion occurs as a statistical consequence of random particle movements in a concentration gradient. Each particle moves independently, with the net directional flow occurring from high to low concentration regions due to purely probabilistic considerations [3] [2]. The diffusion coefficient (D) quantifies how quickly particles spread through a medium, with dimensions of area per time (m²/s) [4] [3]. This coefficient depends on temperature, viscosity, and particle size according to the Stokes-Einstein relation [4] [3]:

Table 1: Typical Diffusion Coefficient Values

| System Type | Diffusion Coefficient Range (m²/s) | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ions in solution | 0.6×10⁻⁹ to 2×10⁻⁹ | Na⁺, Cl⁻ in water |

| Biological molecules | 10⁻¹¹ to 10⁻¹⁰ | Proteins, DNA |

| Gases | 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻⁵ | Oxygen in air |

Two operational regimes characterize diffusion processes: steady-state diffusion occurs when concentration profiles remain constant over time (∂c/∂t = 0), while transient diffusion involves time-dependent concentration changes [2].

Fick's First Law

Fick's first law describes steady-state diffusion where the concentration profile does not change with time [4] [2]. It establishes that the diffusive flux is proportional to the negative concentration gradient:

For one-dimensional systems: J = -D(dφ/dx)

For multi-dimensional systems: J = -D∇φ

where J represents the diffusion flux (amount of substance per unit area per unit time), D is the diffusion coefficient, φ denotes concentration, and x is position [4]. The negative sign indicates that diffusion occurs down the concentration gradient [1]. In biological systems, Fick's first law generates the permeability equation: Diffusion Flux = -P(c₂-c₁), where P represents an experimentally determined membrane conductance [1].

Fick's Second Law

Fick's second law predicts how diffusion causes concentrations to change with time, making it essential for modeling transient diffusion processes [4] [3]. This partial differential equation relates temporal concentration changes to spatial variations:

For one-dimensional systems: ∂φ/∂t = D(∂²φ/∂x²)

For multi-dimensional systems: ∂φ/∂t = D∇²φ

where ∂φ/∂t represents the rate of concentration change over time [4] [7]. The second law derives from applying mass conservation to Fick's first law, assuming constant diffusion coefficient [4]. This equation shares identical mathematical form with the heat equation, enabling cross-disciplinary application of solution methods [4].

Experimental Methodologies

Laboratory-Scale Diffusion Analysis

Investigating diffusion phenomena at laboratory scale requires carefully controlled conditions to isolate mechanistic behavior. The following protocol, adapted from groundwater contaminant transport research, provides a robust methodology for visualizing and quantifying diffusion processes [6].

Experimental Setup for Diffusion Visualization

- Apparatus: Plexiglas tank (68cm × 40cm × 7cm) divided into mixing and porous media chambers

- Porous Media: High-permeability quartz sand (D₅₀ = 700μm) with embedded low-permeability lenses

- Tracer Selection: Sodium fluorescein (2g/L concentration) selected for non-toxidity, visibility, and fluorescence properties

- Monitoring System: 3CCD camera with UV illumination (Philips Actinic BL TL-D 18W-10 UV-A G13) for excitation

- Flow Control: Peristaltic pumps maintaining constant flow rate (~26 mL/min)

Experimental Procedure

- System Saturation: Completely saturate tank with deionized water to eliminate air pockets

- Tracer Introduction: Slowly inject fluorescein solution into mixing chamber

- Effluent Monitoring: Collect outlet samples periodically for fluorometer analysis

- Image Acquisition: Capture RGB format images during flushing and rest phases

- Data Processing: Apply Image Analysis techniques to determine concentration fields

- Flux Calculation: Compute diffusive fluxes from low-permeability zones using concentration gradients

This experimental design enables direct observation of both forward diffusion (into low-permeability zones) and back-diffusion (release from these zones), critical processes in environmental remediation and drug delivery systems [6].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Diffusion Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Experimental System |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Fluorescein | 2g/L in aqueous solution | Colored tracer for visualization and quantification |

| Quartz Sand | D₅₀ = 700μm, porosity ~0.3 | High-permeability matrix simulating aquifer or biological environment |

| Quartz Flour | D₅₀ = 12-15μm, porosity ~0.4 | Low-permeability lens material for diffusion studies |

| Sodium Bentonite | D₅₀ = 1.3μm, porosity ~0.5 | Very low-permeability material for contrast studies |

| UV Light Source | 254nm wavelength | Fluorescein excitation for image analysis |

Boundary Conditions in Diffusion Analysis

Appropriate boundary conditions are essential for solving Fick's laws across experimental and modeling applications [7]:

Dirichlet Conditions: Specify concentration values at system boundaries

- Constant surface concentration (e.g., saturated solution interface)

- Fixed concentration ratio at membrane boundaries

Neumann Conditions: Define flux values at system boundaries

- Constant flux application (e.g., evaporation rate)

- Impermeable boundary (zero flux condition)

Robin Conditions: Combine concentration and flux relationships

- Convective mass transfer at interfaces

- Reaction-diffusion boundaries in biological systems

Table 3: Boundary Condition Applications in Diffusion Models

| Condition Type | Mathematical Form | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Dirichlet | c(0,t) = c₀ | Constant source concentration, saturated systems |

| Neumann | -D(∂c/∂x) = J₀ | Controlled release systems, evaporation |

| Robin | -D(∂c/∂x) = h(c - c∞) | Convective mass transfer, reaction interfaces |

Advanced Applications and Research Implications

Pharmaceutical and Drug Development

In drug development, diffusion principles govern critical processes from API synthesis to targeted delivery systems. Membrane diffusion according to Fick's first law determines drug release rates from controlled-release formulations, with permeability coefficients optimized for specific therapeutic windows [1]. Back-diffusion phenomena from tissue reservoirs create long-term release profiles that impact dosing regimens and therapeutic efficacy [6]. Understanding these mechanisms enables rational design of nanocarrier systems and diffusion-controlled delivery platforms.

Environmental Remediation

Contaminant transport in groundwater systems exemplifies complex diffusion applications. Low-permeability zones act as contaminant reservoirs through forward diffusion during plume passage, followed by long-term back-diffusion that sustained concentration tails after primary source removal [6]. This process undermines remediation efforts and necessitates sophisticated models incorporating Fick's laws with hydrological parameters. Research demonstrates that diffusion-dominated transport in heterogeneous aquifers requires characterization of both high-permeability pathways and low-permeability storage zones for accurate prediction of contaminant persistence.

Biological and Medical Systems

Molecular diffusion within cellular environments presents unique challenges due to crowding, binding interactions, and compartmentalization. Intracellular diffusion coefficients for biological molecules typically range from 10⁻¹¹ to 10⁻¹⁰ m²/s, significantly lower than in dilute solutions due to molecular crowding [4] [3]. Educational visualization of these processes must balance accuracy with conceptual clarity, addressing common misconceptions about molecular agency while representing random thermal motion realistically [5]. Advanced imaging techniques combined with computational modeling based on Fick's laws enable quantification of transmembrane transport rates critical for understanding drug uptake and nutrient exchange.

Diffusion, mathematically formalized through Fick's laws, remains a cornerstone transport phenomenon with expanding applications across scientific and engineering disciplines. The fundamental principles established 170 years ago continue to inform contemporary research in pharmaceutical development, environmental management, and biological systems. Current challenges include extending diffusion theory to non-Fickian regimes, multi-component systems, and heterogeneous environments where classical relationships require modification. Emerging visualization and computational technologies enable increasingly sophisticated investigation of diffusion processes across spatial and temporal scales, ensuring continued relevance of these fundamental transport principles in addressing complex research and application challenges.

In 1855, a 26-year-old German physician and physiologist, Adolf Eugen Fick(1829-1901), published his seminal paper "Über Diffusion" in Annalen der Physik, establishing the fundamental laws of diffusion that bear his name [8] [9]. Fick, who excelled in mathematics and physics, approached physiology with a rigorous, quantitative mindset, believing that physical laws governing mass and energy transport were essential to understanding biological systems [8]. His work was inspired by earlier experiments on gases by Thomas Graham and drew a direct mathematical analogy to Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier's law of heat conduction [4] [9]. Remarkably, Fick first formulated his laws based on this theoretical analogy and physical reasoning, with experimental verification following the theoretical work [8] [10]. This groundbreaking publication not only laid the foundation for modern diffusion theory but also exemplified cross-disciplinary research, impacting fields from physical chemistry and engineering to medicine and materials science [9].

Theoretical Foundations: Fick's Laws of Diffusion

The Core Principles

Fick's laws provide a complete mathematical description of diffusion, defining the relationship between concentration gradients, flux, and temporal changes.

Table 1: Core Principles of Fick's Laws of Diffusion

| Law | Mathematical Expression | Key Variables | Fundamental Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fick's First Law | J = -D(dφ/dx) |

J: Diffusion Flux [(mol/m²s)]D: Diffusion Coefficient [(m²/s)]φ: Concentration [(mol/m³)]x: Position [m] |

The diffusive flux is proportional to the negative concentration gradient. It describes movement from high to low concentration. |

| Fick's Second Law | ∂φ/∂t = D(∂²φ/∂x²) |

t: Time [s]φ: Concentration [(mol/m³)]D: Diffusion Coefficient [(m²/s)]x: Position [m] |

The rate of change of concentration over time is proportional to the second derivative of the concentration gradient. |

Mathematical and Conceptual Analogy

Fick conceptualized diffusion as a binary process where solute particles move in one direction while water moves in the other [10]. He intuitively understood that the concentration gradient served as the driving force for this spontaneous process, analogous to how a temperature gradient drives heat flow [4] [9]. His first law provides a steady-state description, while the second law predicts how concentration evolves in non-steady-state, time-dependent scenarios [4] [3]. A process that obeys these relationships is termed normal or Fickian diffusion, while those that do not are classified as anomalous or non-Fickian diffusion [4] [11].

The 1855 Experiments: Methodology and Validation

Experimental Design and Setup

Fick's experimental validation, detailed in "On Liquid Diffusion," was elegantly simple yet powerful. His apparatus consisted of two reservoirs containing salt solutions at different concentrations, connected by a tube filled with water [4] [12]. This design allowed him to measure the concentrations and fluxes of salt diffusing between the reservoirs under a controlled concentration gradient [4]. He sought to test the hypothesis that the movement of particles in a solution could be described by the same mathematical formalism Fourier had established for heat flow [10] [9].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials in Fick's Experiments

| Research Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Salt (Solute) | The diffusing species whose transport was measured. Its concentration gradient provided the driving force for diffusion. |

| Water (Solvent) | The fluid medium within the connecting tube through which the salt diffusion occurred. |

| Glass Tube | Provided a confined, linear path for one-dimensional diffusion, simplifying the measurement of flux and gradient. |

| Fluid Membranes/Barriers | Used to study implications of binary diffusion and transport in more complex systems, relevant to biological membranes [10]. |

Protocol and Workflow

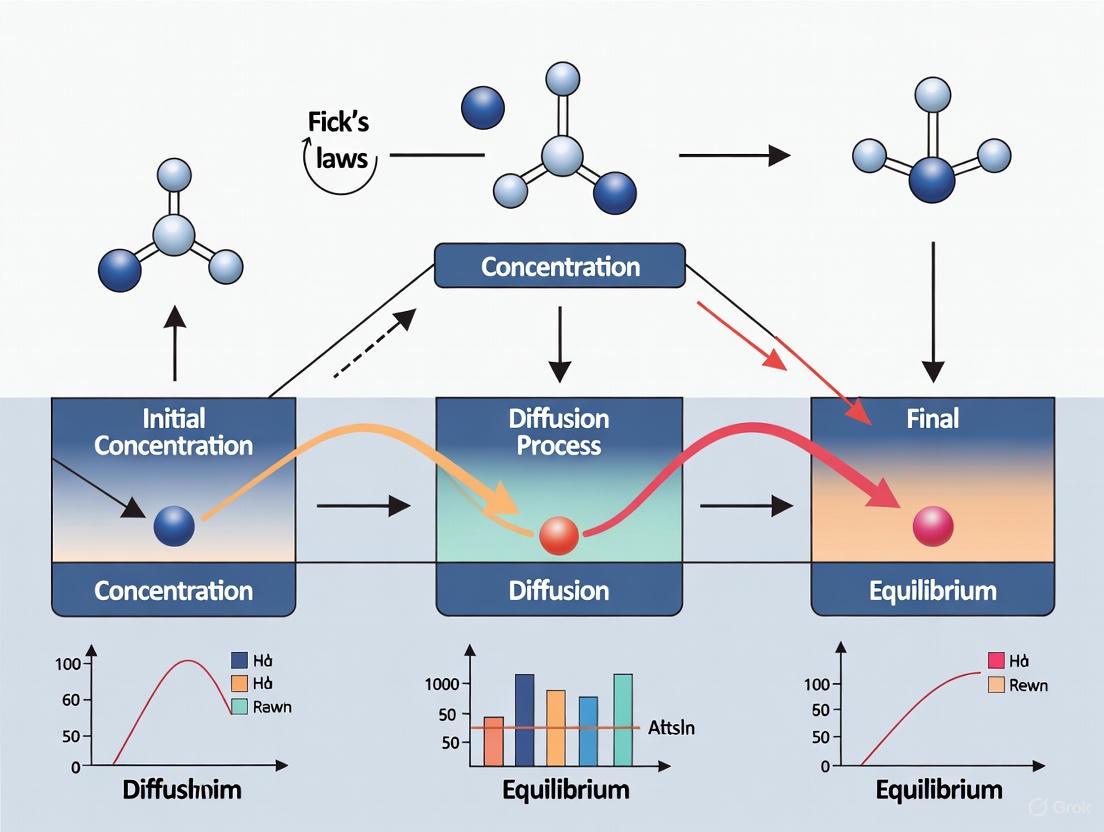

The following diagram outlines the general workflow derived from Fick's pioneering experimental approach.

Quantitative Findings and Diffusion Coefficients

Fick's experiments allowed him to verify the proportional relationship between flux and concentration gradient. While his original work focused on establishing this relationship, subsequent research has quantified diffusion coefficients for various substances, which are critical for practical applications.

Table 3: Typical Diffusion Coefficient (D) Values in Aqueous Solutions at Room Temperature

| Substance Category | Diffusion Coefficient (m²/s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ions | 0.6 × 10⁻⁹ to 2 × 10⁻⁹ |

Relatively similar values in dilute aqueous solutions [4]. |

| Biological Molecules | 10⁻¹¹ to 10⁻¹⁰ |

Larger molecules result in slower diffusion [4] [3]. |

| Small Gases/Molecules | ~10⁻⁹ |

Order of magnitude estimate for small solutes in water. |

The diffusion coefficient itself depends on factors such as temperature, viscosity of the fluid, and the size of the diffusing particles, as later described by the Stokes-Einstein relation [4] [3].

Beyond the Basics: Nuances and Later Refinements

Fick's Original Conceptualization

A careful reading of Fick's 1855 paper reveals that his conceptualization was more comprehensive than the common simplification of his first law. He visualized diffusion as a binary process with simultaneous counter-movement of salt and water [10]. He also intuitively described what would later be formalized as chemical potential, referring to a "force of suction... proportional to the difference of concentration" [10]. Furthermore, he dedicated significant discussion to the implications of diffusion through membranes, making his work immediately relevant to biological systems [10].

Modern Critiques and the Limits of Fick's Laws

While Fick's laws are foundational, their limitations in certain physical regimes have been a subject of ongoing research. For over a century, it has been recognized that concentration gradient is not the true thermodynamic driving force; rather, it is the gradient of chemical potential [13]. However, research in the 21st century has suggested that even the chemical potential gradient may not be the complete picture in all cases, and that the fundamental equation might require modification, especially in systems with large mean free paths (e.g., low-pressure gases, nanoporous materials) where wave-like density phenomena can occur [13]. These are active areas of research, demonstrating that the understanding of diffusion, initiated by Fick, continues to evolve.

Applications and Impact Across Disciplines

Fick's laws of diffusion have transcended their origin in physiology to become a cornerstone of modern science and technology.

- Biological and Medical Sciences: Fick's laws are fundamental to understanding gas exchange in the lungs (a application Fick himself pioneered with the Fick principle for cardiac output) [8], nutrient and drug transport across cell membranes [11] [14], and the design of controlled-release pharmaceuticals [11] [14].

- Semiconductor Fabrication: The diffusion equations are critical for processes like doping, where impurity atoms are diffused into silicon wafers to modulate electronic properties [11] [14].

- Materials Science and Engineering: Applications include modeling the carburization of steel, hydrogen storage in metals, and the development of novel materials [14].

- Food Science: Diffusion principles are applied to processes such as salting, drying, and flavoring [11].

- Environmental Engineering: Used to model the spread of contaminants in groundwater and pollutants in the atmosphere [12] [9].

Adolf Fick's 1855 work represents a paradigm shift in how scientists conceptualize and quantify the spontaneous mixing of substances. By forging a powerful analogy between mass and heat transport, he provided a mathematical framework that has proven remarkably durable and widely applicable. His laws remain the essential starting point for modeling transport phenomena across an immense spectrum of scientific and engineering disciplines. While modern research continues to explore the boundaries and refine the theory, particularly for non-Fickian and anomalous diffusion, Fick's groundbreaking insight continues to underpin our fundamental understanding of diffusion.

Fick's laws of diffusion, first posited by physiologist Adolf Fick in 1855, form the foundational framework for understanding molecular diffusion [4]. Inspired by the earlier experiments of Thomas Graham and analogous to contemporary scientific relationships like Ohm's law for charge transport and Fourier's law for heat transport, Fick's work established the fundamental principles governing the transport of mass through diffusive means [4]. Within this framework, Fick's First Law provides the essential relationship between the diffusive flux and the underlying concentration gradient that drives the process. This article presents an in-depth technical examination of Fick's First Law, detailing its physical meaning, mathematical expression, and derivation, with specific consideration for its applications in scientific research and drug development.

Physical Meaning of the Diffusion Flux

Conceptual Foundation

Diffusion can be described as the random movement of particles through space, typically due to a concentration gradient, and represents a spontaneous process resulting from random thermal motions between particles [3]. At its core, Fick's First Law postulates that the diffusive flux moves from regions of high concentration to regions of low concentration, with a magnitude proportional to the concentration gradient (spatial derivative) [4]. In more simplistic terms, the law encapsulates the concept that a solute will move from a region of high concentration to a region of low concentration across a concentration gradient [4].

The driving force for one-dimensional diffusion is the quantity −∂φ/∂x, which for ideal mixtures is the concentration gradient [4]. This spontaneous flow occurs as particles undergo random thermal motions, leading to a net displacement from regions of higher chemical potential to regions of lower chemical potential [3].

Definition of Diffusion Flux

In the context of Fick's First Law, the diffusion flux, typically denoted by J, is defined as the amount of substance that flows through a unit area during a unit time interval [4]. Mathematically, flux is defined by the number of particles moving past a given region divided by the area of that region multiplied by the time interval [3]. The standard units for flux are mol m⁻² s⁻¹, though variations exist depending on the specific formulation of the law and the system of units employed [3].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Fick's First Law

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Typical Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion Flux | J | Amount of substance flowing through unit area per unit time | mol m⁻² s⁻¹ |

| Concentration | φ, c | Amount of substance per unit volume | mol m⁻³ |

| Position | x | Distance along diffusion direction | m |

| Diffusion Coefficient | D | Proportionality constant characterizing mobility of diffusing species | m² s⁻¹ |

| Concentration Gradient | dφ/dx, dc/dx | Spatial rate of change of concentration | mol m⁻⁴ |

Mathematical Expression of Fick's First Law

Fundamental Equation

The fundamental mathematical expression of Fick's First Law in one spatial dimension states that the diffusion flux is proportional to the negative concentration gradient [4] [3]. The most common form of the equation, expressed in a molar basis, is:

[ J = -D \frac{d\varphi}{dx} ]

where:

- J is the diffusion flux [mol m⁻² s⁻¹]

- D is the diffusion coefficient or diffusivity [m² s⁻¹]

- dφ/dx is the concentration gradient [mol m⁻⁴]

- φ is the concentration [mol m⁻³]

- x is the position [m] [4] [3]

The negative sign in the equation indicates that the direction of diffusion is opposite to the direction of increasing concentration – meaning flow occurs from high to low concentration regions [4] [3].

Variations and Alternative Formulations

Several variations of Fick's First Law exist for different applications and systems. When expressed with the primary variable as mass fraction (y_i), the equation becomes:

[ \mathbf{J}i = -\frac{\rho D}{Mi} \nabla y_i ]

where:

- the index i denotes the ith species

- J_i is the diffusion flux of the ith species [mol m⁻² s⁻¹]

- M_i is the molar mass of the ith species

- ρ is the mixture density [kg m⁻³]

- y_i is the mass fraction of the ith species [4]

For chemical systems other than ideal solutions or mixtures, where the driving force is the gradient of chemical potential, Fick's First Law can be written as:

[ Ji = -\frac{D ci}{RT} \frac{\partial \mu_i}{\partial x} ]

where:

- c_i is the concentration [mol m⁻³]

- R is the universal gas constant [J K⁻¹ mol⁻¹]

- T is the absolute temperature [K]

- μ_i is the chemical potential [J mol⁻¹] [4]

In two or more dimensions, the gradient operator (∇) generalizes the first derivative, resulting in:

[ \mathbf{J} = -D \nabla \varphi ]

where J and ∇φ are vector quantities [4].

Table 2: Diffusion Coefficient Values for Different Systems

| System Type | Diffusing Species | Typical D Values [m²/s] | Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Solutions | Ions | 0.6–2 × 10⁻⁹ | Room Temperature [4] |

| Biological Systems | Molecules | 10⁻¹¹ – 10⁻¹⁰ | Room Temperature [4] |

| Gases | CO₂ in n-alkanes | Variable with pressure | High-pressure reservoirs [15] |

Derivation of Fick's First Law

Atomic-Scale Derivation Using the Random Walk Model

The derivation of Fick's First Law can be approached by considering atomic-scale motion within a crystal lattice, modeling diffusion as a random walk process [16]. Consider a crystal structure where each plane contains Cλ atoms per unit area, where C is the concentration and λ is the jump distance between atomic planes [16].

For an increment of distance (δx) of λ, the corresponding increment of concentration (δC) is given by:

[\partial C = \lambda \left{ {\frac{{\partial C}}{{\partial x}}} \right}] [16]

In a three-dimensional crystal, an atom can move in one of six directions. If the jump frequency is ν, the fluxes of atoms from left to right and from right to left are given by:

[{J{L \to R}} = \frac{1}{6}\nu C\lambda ] [{J{R \to L}} = \frac{1}{6}\nu (C + \partial C)\lambda ] [16]

The net flux J is therefore:

[ J = {J{L \to R}} - {J{R \to L}} ] [ J = - \frac{1}{6}\nu \partial C\lambda ] [ J = - \frac{1}{6}\nu \left{ {\frac{{\partial C}}{{\partial x}}} \right}{\lambda ^2} ] [ J \equiv - D\left{ {\frac{{\partial C}}{{\partial x}}} \right} ] [16]

where D = (1/6)νλ² is identified as the diffusivity of the diffusing species [16]. This derivation establishes Fick's First Law from fundamental atomic-scale motions.

Continuum Derivation from Mass Conservation

An alternative derivation approaches diffusion from a continuum perspective, considering the flow of particles due to a concentration gradient across a membrane [17] [18]. This approach defines the flow of particles across a membrane as:

[ J_{\text{diffusion}} = -D \frac{d[I]}{dx} ]

where J is the flow of particles due to diffusion, [I] is the ion concentration, dx is the membrane thickness, and D is the diffusivity constant [m²/s] [17]. The negative sign indicates that the flow of ions is from higher to lower concentration [17].

This derivation can be visualized by considering a still liquid in a long pipe of constant cross-sectional area, where a small quantity of dye is placed in a cross-section and allowed to diffuse [18]. Defining u(x,t) as the concentration of dye at position x along the pipe, Fick's law of diffusion assumes the mass flux J across a cross-section is given by:

[ J = -D u_x ]

where u_x = ∂u/∂x, and D > 0 is the diffusion constant [18].

Experimental Protocols and Research Methodologies

Molecular Dynamics Approaches

Modern computational methods enable the calculation of Fick diffusion coefficients through molecular dynamics simulations [15]. The modified Fourier Correlation Method (mFCM) represents an innovative approach to calculate binary Fick diffusion coefficients directly through equilibrium molecular dynamics (EMD) simulations [15].

Protocol: Modified Fourier Correlation Method (mFCM)

System Setup: Create a molecular model of the binary mixture of interest (e.g., CO₂ and n-alkane mixtures) at specified temperature, pressure, and composition conditions [15].

Equilibrium Simulation: Perform equilibrium molecular dynamics (EMD) simulations to generate trajectory data of molecular positions and velocities over time [15].

Structure Factor Calculation: Compute the partial time-dependent structure factors S_ij(q,t) from the EMD trajectories [15].

Diffusion Coefficient Extraction: Determine the binary Fick diffusion coefficient D₁₂ by analyzing the decay of concentration fluctuations in the Fourier domain, using the relationship:

[ \frac{dS{ij}(q,t)}{dt} = -D{12}(q)q^2S_{ij}(q,t) ]

which has the solution:

[ S{ij}(q,t) = S{ij}(q,0)e^{-D_{12}(q)q^2t} ]

where D₁₂(q) is the wavenumber-dependent Fick diffusion coefficient [15].

Thermodynamic Limit Evaluation: Assess finite-size effects and extrapolate to the thermodynamic limit, as the mFCM approach considerably reduces the finite-size effect of the simulation box on calculated diffusion coefficients [15].

Traditional Experimental Approaches

While molecular dynamics offers powerful computational approaches, traditional experimental methods remain valuable for measuring diffusion coefficients:

Protocol: Traditional Diffusion Cell Method

Apparatus Setup: Utilize a diffusion cell consisting of two well-mixed reservoirs separated by a permeable membrane or capillary tube [4].

Initial Conditions: Establish different initial concentrations in each reservoir to create a known concentration gradient across the membrane [4].

Flux Measurement: Monitor the change in concentration in one or both reservoirs over time to determine the flux J [4].

Diffusion Coefficient Calculation: Apply Fick's First Law (J = -D·dc/dx) to calculate the diffusion coefficient D from the measured flux and the known concentration gradient [4].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Diffusion Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Binary Fluid Mixtures (e.g., CO₂ + n-alkane) | Model system for studying mutual diffusion | High-pressure mass transfer, reservoir engineering [15] |

| Isotopically Labeled Compounds | Tracers for tracking diffusion pathways | Self-diffusion measurements in multicomponent systems [15] |

| Polymer Membranes | Barrier for studying vapour transmission | Packaging materials, drug delivery systems [19] |

| Electrolyte Solutions | Study ion diffusion in aqueous systems | Biological systems, battery research [4] [3] |

| Porous Media | Matrix for studying confined diffusion | Geology, construction materials, drug delivery [17] |

Applications in Drug Development and Research

Fick's First Law finds critical applications in pharmaceutical research and drug development, particularly in the design and optimization of drug delivery systems [20]. Understanding and controlling diffusion processes enables the development of controlled drug delivery systems that combat problems associated with conventional drug delivery, such as poor bioavailability and fluctuations in plasma drug levels [20].

In transdermal drug delivery, Fick's First Law directly informs the design of patches where the rate of drug transfer through the skin is proportional to the concentration difference across the skin layers and inversely proportional to the thickness of the membrane [19]. Similarly, in oral dosage forms, the dissolution and subsequent diffusion of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) through gastrointestinal membranes follow the principles established by Fick's First Law [20].

The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) classifies drugs into four categories based on their solubility and permeability characteristics, with Fick's First Law providing the fundamental basis for understanding the permeability aspects [20]. For BCS Class II drugs (high permeability, low solubility) and BCS Class IV drugs (low permeability, low solubility), diffusion limitations significantly impact bioavailability, necessitating sophisticated formulation strategies grounded in Fick's principles [20].

Limitations and Considerations

While Fick's First Law provides a fundamental description of diffusion processes, several limitations and considerations must be acknowledged for accurate application in research contexts:

Finite Medium Effects: Fick's law is derived for an infinite homogeneous medium, while real systems often have boundaries. The law remains valid for points away from edges by few mean free paths [17].

Nonuniform Media: For nonuniform media where scattering properties change sharply, Fick's law requires modification or re-evaluation, though it remains valid provided sharp changes don't lead to rapid flux variation [17].

Proximity to Sources or Sinks: Near strong sources or sinks, Fick's law may break down, though it remains valid at few mean free paths away from such boundaries [17].

Anisotropic Scattering: The assumption of isotropic scattering is not generally true. With moderate anisotropy, Fick's law can be used with a modified diffusion coefficient [17].

Highly Absorbing Media: In highly absorbing media where the flux varies rapidly spatially, higher-order terms may be necessary, and exact transport theory may be more appropriate [17].

Time-Dependent Flux: For time-dependent fluxes, Fick's law assumes instantaneous propagation, while physically there is finite travel time between collisions [17].

Fick's First Law provides the fundamental relationship between diffusive flux and concentration gradients, serving as a cornerstone for understanding mass transport phenomena across numerous scientific disciplines. From its basis in atomic-scale random walk processes to its manifestations in continuum systems, the law establishes a proportional relationship between flux and concentration gradient with the diffusion coefficient as the constant of proportionality. While the law has limitations in specific scenarios, modern research methodologies including molecular dynamics simulations continue to extend its applicability and precision. For drug development professionals and researchers, Fick's First Law remains an essential principle for designing and optimizing delivery systems, understanding bioavailability limitations, and developing controlled release strategies that maximize therapeutic efficacy while minimizing adverse effects.

Fick's second law is a fundamental partial differential equation that describes how the concentration of a substance changes with time due to diffusion. This law serves as the cornerstone for predicting time-dependent diffusion processes across numerous scientific and engineering disciplines, from pharmaceutical drug release to materials science. While Fick's first law describes the steady-state flux of particles under a constant concentration gradient, the second law addresses the more common non-steady-state scenarios where concentrations evolve over time [4] [17].

Derived from Fick's first law combined with the principle of mass conservation, Fick's second law mathematically expresses how the rate of change of concentration at a point in space is proportional to the second derivative of the concentration field [4] [21]. For one-dimensional systems, this is expressed as ∂C/∂t = D(∂²C/∂x²), where C represents concentration, t is time, x is position, and D is the diffusion coefficient [22] [4] [23]. In multiple dimensions, this generalizes to ∂C/∂t = D∇²C, where ∇² is the Laplace operator [4].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental relationship between Fick's first and second laws and their role in describing diffusion phenomena:

Fundamental Theory and Mathematical Formulation

Core Equation and Physical Interpretation

Fick's second law establishes that the time evolution of concentration is governed by the spatial curvature of the concentration profile. Where the concentration profile is concave up (positive second derivative), the concentration at that point will increase with time; where it is concave down (negative second derivative), the concentration will decrease [4]. The diffusion coefficient D (m²/s) determines the rate at which this process occurs and is typically temperature-dependent, following an Arrhenius relationship: D = D₀exp(-Eₐ/kBT) [23].

The derivation of Fick's second law combines Fick's first law, which states that the diffusive flux J is proportional to the negative concentration gradient (J = -D∂C/∂x), with the continuity equation from mass conservation (∂C/∂t = -∂J/∂x) [4] [21]. Substituting the first law into the continuity equation yields Fick's second law, assuming a constant diffusion coefficient [4] [21]. This derivation highlights how the second law naturally emerges from the conservation of mass when combined with the linear response approximation of the first law.

Analytical Solutions for Key Boundary Conditions

For specific initial and boundary conditions, Fick's second law admits exact analytical solutions that provide profound insight into diffusion behavior. The two most fundamental cases are the "thin source" and "infinite source" scenarios [22] [24].

Table 1: Boundary Conditions and Solutions for Fick's Second Law

| Scenario | Boundary Conditions | Solution | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thin Source | Fixed amount of solute B in semi-infinite medium; Initial concentration = 0 [22] [24] |

C(x,t) = B/√(πDt) · exp(-x²/(4Dt)) [22] [24] |

Dopant diffusion in semiconductors; tracer studies |

| Infinite Source | Constant surface concentration Cₛ in semi-infinite medium; Initial concentration = C₀ [22] [23] [24] |

C(x,t) = Cₛ - (Cₛ - C₀) · erf(x/(2√Dt)) [22] [23] [24] |

Case hardening of metals; drug release from transdermal patches |

The error function (erf) in the infinite source solution arises from integrating Gaussian distributions and is defined as erf(z) = (2/√π) ∫₀^z exp(-u²) du [22] [24]. This function exhibits a characteristic s-shaped profile that gradually penetrates deeper into the material over time, with the diffusion front progressing proportionally to √Dt [22] [23].

The following workflow illustrates how these analytical solutions are derived and applied to solve practical diffusion problems:

Experimental Methodologies and Measurement Techniques

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Diffusion Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Liposome Vesicles | Model membrane system for drug diffusion studies [25] | POPC phospholipids; 30-100 nm diameter [25] |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Polymer steric stabilizer for "stealth" liposomes [25] | Molecular weight: 1-10 kDa; conjugated to lipid heads [25] |

| Sucrose Solutions | Diffusion rate modifier in layered experimental systems [25] | Concentration: 0.1-1.0 M; D ≈ 4.586×10⁻¹⁰ m²/s [25] |

| Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs) | Alternative drug carrier system with Fickian release [25] | Composed of solid lipids stabilized with emulsifying layer [25] |

| Optical-Clearing Reagents | Enhance tissue transparency for diffusion imaging [25] | Commercially available formulations (e.g., FocusClear) [25] |

Protocol for Thin Source Diffusion Measurement

Objective: Quantify the diffusion coefficient of a tracer substance in a solid or gel matrix using the thin source method [22] [24].

Materials Preparation:

- Prepare sample plates of the matrix material with polished, parallel surfaces

- Create a thin layer of tracer material through vapor deposition, spin-coating, or brief immersion in a concentrated solution

- For radioactive tracers, ensure proper safety protocols and detection equipment

Experimental Procedure:

- Assemble the diffusion couple with the tracer layer at the interface

- Place in a temperature-controlled furnace or environmental chamber at the target temperature (±0.5°C)

- Maintain for predetermined time intervals (typically hours to days depending on D)

- Rapidly quench samples to room temperature to stop diffusion

- Section samples perpendicular to the diffusion direction and prepare for concentration profiling

Concentration Profiling:

- For chemical tracers: Use techniques like SEM-EDS, SIMS, or spectroscopic methods

- For radioactive tracers: Employ autoradiography or sequential sectioning with counting

- Measure concentration as a function of distance from the initial interface

Data Analysis:

- Plot concentration versus distance profiles for each diffusion time

- Fit data to the thin source solution:

C(x,t) = B/√(πDt) · exp(-x²/(4Dt)) - Extract D from the Gaussian width parameter using the relationship:

σ² = 2Dt - Repeat at multiple temperatures to determine activation energy

Eₐ

Advanced Applications and Current Research Frontiers

Drug Delivery Systems

Fick's second law provides the theoretical foundation for controlled-release drug delivery systems. In transdermal patches, the law predicts how drug molecules diffuse through skin layers over time, enabling optimization of therapeutic dosing [25]. Multi-vesicular liposomes employ concentric phospholipid bilayers to create diffusion barriers that control drug release kinetics according to Fickian principles [25]. Recent advances include "stealth liposomes" that use surface-grafted polyethylene glycol to evade immune detection while maintaining controlled diffusion profiles [25].

Numerical solutions of Fick's second law enable the design of complex multi-layered drug delivery systems. Researchers have demonstrated that specific layer sequences can create near-constant release rates (zero-order kinetics) by maintaining a constant concentration gradient at the delivery interface [25]. Finite-element simulations of Fick's law accurately predict how different layer compositions and thicknesses affect the temporal release profile, reducing experimental optimization time.

Diffusion Cloaking and Transformation Thermodynamics

A cutting-edge application of Fick's second law emerges in the field of diffusion cloaking, where engineered materials are designed to control mass flux in unconventional ways [25]. By creating composite structures with specifically ordered layers of different diffusivities, researchers can guide diffusion fronts around enclosed regions, effectively "hiding" objects from diffusing species [25]. This approach, derived from transformation thermodynamics, uses coordinate transformations of Fick's equation to design material parameters that manipulate diffusion pathways [25].

Experimental realizations have employed concentric layered structures with alternating high and low diffusivity materials. For example, a liposome nanoparticle (D ≈ 1.9×10⁻¹¹ m²/s) surrounded by alternating sucrose (D ≈ 4.586×10⁻¹⁰ m²/s) and chloroform (higher D) layers can exhibit markedly different external concentration profiles compared to uncloaked particles [25]. These structured diffusion media can maintain higher internal concentrations for extended periods, potentially enhancing drug stability and circulation time [25].

Numerical Approaches for Complex Systems

For realistic geometries, variable diffusion coefficients, or coupled physical processes, numerical methods are essential for solving Fick's second law [22] [24] [21]. The finite difference method discretizes the partial differential equation onto a spatial grid and marches forward in time using explicit or implicit schemes [22]. The finite element method handles complex geometries and boundary conditions more effectively, making it suitable for biological tissues or engineered devices with irregular shapes [25].

Commercial packages like COMSOL Multiphysics implement Fick's second law alongside other physics for coupled simulation of heat transfer, fluid flow, and chemical reaction [21]. For multi-component systems where diffusion coefficients depend on composition, the Maxwell-Stefan equations extend Fick's approach to account for inter-species interactions [21]. These advanced implementations remain rooted in the fundamental principles established by Fick's second law while addressing its limitations for concentrated solutions.

Table 3: Numerical Methods for Solving Fick's Second Law

| Method | Key Features | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Finite Difference | Simple implementation; Direct discretization of derivatives [22] | Stability limits (∆t ∝ (∆x)²); Suitable for regular geometries |

| Finite Element | Handles complex geometries; Adaptive meshing [25] | Higher computational cost; More complex implementation |

| Finite Volume | Conservative by construction; Handles discontinuous coefficients | Intermediate complexity; Widely used in fluid dynamics |

| Boundary Element | Reduces dimensionality; Only requires surface discretization | Dense matrices; Challenging for nonlinear problems |

Limitations and Extensions of Fick's Second Law

While Fick's second law provides an excellent description of diffusion in many systems, several important limitations must be recognized. The law assumes a constant diffusion coefficient, which fails for concentrated solutions where D becomes concentration-dependent [4] [21]. In such cases, the more general form ∂C/∂t = ∇·(D(C)∇C) must be used [4]. The derivation also assumes isotropic scattering and homogeneous media, limitations particularly relevant in neutron diffusion and composite materials [17].

Anomalous diffusion refers to cases where the mean squared displacement follows ⟨x²⟩ ∝ t^α with α ≠ 1, violating the fundamental assumption of Fickian diffusion [4]. This occurs in porous media, polymer networks, and intracellular environments where obstacles and binding sites create complex energy landscapes for diffusing particles [4] [17]. For such systems, fractional derivative formulations may better describe the transport physics.

When advection accompanies diffusion, the convection-diffusion equation extends Fick's second law: ∂C/∂t + v·∇C = D∇²C, where v is the velocity field [25] [21]. This coupled equation describes many environmental and physiological transport processes where bulk fluid motion significantly contributes to mass transfer. Similarly, reaction-diffusion systems incorporate source terms: ∂C/∂t = D∇²C + R(C), enabling modeling of chemical patterning and biological morphogenesis [25].

Within the study of molecular diffusion, the diffusion coefficient, denoted as (D), serves as a fundamental kinetic parameter that quantifies the rate at which particles spread from regions of high concentration to low concentration. This transport phenomenon, critical across disciplines from chemical engineering to pharmaceutical sciences, is macroscopically described by Fick's laws of diffusion [3]. The value of the diffusion coefficient is not an intrinsic constant; it is highly sensitive to environmental conditions, with temperature exerting one of the most profound influences. This temperature dependence is powerfully captured by the Arrhenius equation, a cornerstone of physical chemistry that relates the rate of a process to the thermal energy available to the system [26] [27].

Framed within a broader thesis on the theory of molecular diffusion, this whitepaper provides an in-depth examination of the diffusion coefficient. It will elucidate its physical significance, establish its fundamental units, and explore its temperature-driven behavior through the lens of the Arrhenius relationship. The discussion is extended to include practical methodologies for its experimental determination, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical guide.

Theoretical Foundations of Diffusion

Fick's Laws of Diffusion

The mathematical framework for diffusion was established by Adolf Fick in the 19th century. His two laws form the bedrock of quantitative diffusion analysis.

Fick's First Law describes the steady-state flux, where the concentration profile does not change with time. It states that the diffusive flux, (J), is proportional to the negative of the concentration gradient [3]. The law is expressed as: [ J = -D \dfrac{dc}{dx} ] where:

- (J) is the flux density (mol m⁻² s⁻¹),

- (D) is the diffusion coefficient (m²/s),

- (\dfrac{dc}{dx}) is the spatial concentration gradient (mol m⁻⁴). The negative sign indicates that diffusion occurs down the concentration gradient.

Fick's Second Law describes non-steady-state or transient diffusion, where concentrations change with time. It is derived from the first law and the principle of mass conservation [3] [28]: [ \dfrac{dc}{dt} = D \dfrac{d^2c}{dx^2} ] where (\dfrac{dc}{dt}) is the rate of change of concentration at a specific point. This partial differential equation can be solved for various initial and boundary conditions to model real-world diffusion processes.

Physical Significance and Typical Values of (D)

The diffusion coefficient parameterizes the random thermal motion of particles. Its value is a function of the diffusing substance, the medium through which diffusion occurs, temperature, and pressure [29]. The magnitude of (D) varies dramatically between states of matter, reflecting the differing molecular mobility.

Table 1: Typical Diffusion Coefficient Values in Different Phases at 25°C

| Phase | Solute | Solvent | D (m²/s) | D (cm²/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas [30] | CO₂ | Air | 1.6 × 10⁻⁵ | 0.160 |

| Gas [30] | H₂O | Air | 2.6 × 10⁻⁵ | 0.260 |

| Liquid [30] | CO₂ | Water | 1.6 × 10⁻⁹ | 1.6 × 10⁻⁵ |

| Liquid [30] | Ethanol | Water | 8.4 × 10⁻¹⁰ | 0.84 × 10⁻⁵ |

| Liquid [31] | Small Molecules | Water | ~10⁻¹⁰ to 10⁻⁹ | ~10⁻⁶ to 10⁻⁵ |

As evidenced in Table 1, diffusion coefficients in gases are typically ~10,000 times greater than in liquids, due to the lower density and greater mean free path in gases [30] [31]. In solids, diffusion is slower still, often described by a different physical mechanism involving crystal vacancies or interstitial sites [30].

Units of the Diffusion Coefficient

A dimensional analysis of Fick's first law reveals the units of (D). Rewriting the equation as (D = -J / (dc/dx)), the units can be derived as follows [3] [32]:

- Flux (J) has units of (amount of substance) per unit area per time (e.g., mol m⁻² s⁻¹).

- Concentration gradient (dc/dx) has units of (amount of substance) per volume per length (e.g., mol m⁻⁴).

Therefore, the units of (D) are: [ \dfrac{\text{mol m}^{-2} \text{s}^{-1}}{\text{mol m}^{-4}} = \text{m}^2/\text{s} ] The SI unit is square meters per second (m²/s), though the CGS unit of square centimeters per second (cm²/s) is also frequently used, where 1 m²/s = 10⁴ cm²/s [30] [32].

Temperature Dependence and the Arrhenius Equation

The Arrhenius Relationship

The strong temperature dependence of the diffusion coefficient is empirically and theoretically described by the Arrhenius equation [30] [26] [33]. For diffusion, it is expressed as: [ D = D0 \exp\left(-\frac{E{\text{A}}}{RT}\right) ] where:

- (D) is the diffusion coefficient at temperature (T) (m²/s),

- (D_0) is the pre-exponential factor or the maximum diffusion coefficient as (T \to \infty) (m²/s),

- (E_A) is the activation energy for diffusion (J/mol),

- (R) is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K),

- (T) is the absolute temperature (K) [30] [26].

The exponential term, (\exp(-EA/RT)), represents the fraction of molecules that possess sufficient energy to overcome the energy barrier, (EA), associated with the diffusion process (e.g., breaking free from a solvent cage or jumping into a vacancy) [26] [27].

Temperature Dependence Across Different Phases

The Arrhenius model is universally applicable, though the magnitude of (EA) and the physical interpretation of (D0) vary with the system.

- Solids: In crystalline solids, diffusion is an activated process where atoms move via interstitial or vacancy mechanisms. The Arrhenius equation is particularly well-suited, with (E_A) representing the energy required to form and move into a vacancy [30].

- Liquids: The temperature dependence in liquids is often modeled using the Stokes-Einstein equation, which relates (D) to the solvent viscosity (\mu): (D = kT / (6\pi \eta r)), where (r) is the hydrodynamic radius of the solute [3] [28]. Since viscosity itself is temperature-dependent and follows an Arrhenius-type relation, the overall dependence of (D) on (T) remains exponential [30] [31].

- Gases: According to the kinetic theory of gases, the diffusion coefficient in low-pressure gases is proportional to (T^{3/2}) [30] [29]. This is often incorporated into a modified Arrhenius form, (D \propto T^n \exp(-E_A/RT)), where (n) is a constant [26].

Table 2: Summary of Diffusion Coefficient Temperature Dependence

| Phase | Primary Model | Activation Energy, (E_A) | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solids | Arrhenius Equation [30] | High; energy for vacancy formation/atomic jumping [30] | Crystal structure, defect concentration, crystallinity [34] |

| Liquids | Stokes-Einstein / Arrhenius [30] [28] | Moderate; related to solvent viscosity and solute size [28] | Viscosity, solute radius, molecular association [29] |

| Gases | Chapman-Enskog Theory / Arrhenius [30] | Low; weak intermolecular forces [30] | Temperature, pressure, molecular size and mass [30] [29] |

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between temperature, activation energy, and the diffusion coefficient as governed by the Arrhenius equation.

Experimental Determination of the Diffusion Coefficient

Accurate measurement of (D) is crucial for material characterization, drug formulation, and process design. Several established methodologies exist, each suited to different systems.

Steady-State Flux Method

This method is typically used for membrane permeation studies. A membrane of thickness (h) separates a donor compartment with high concentration (Cd) from a receiver compartment with low concentration (Cr). After an initial transient period, a steady-state concentration profile is established within the membrane, and the flux (J_{ss}) becomes constant [28].

- Protocol:

- Mount a well-characterized membrane (e.g., polymer film) in a diffusion cell.

- Fill the donor compartment with a solution of known concentration (Cd). The receiver compartment is maintained at a much lower concentration (often zero via sink conditions).

- Agitate both compartments to minimize aqueous boundary layer effects, which can distort results [28].

- Periodically sample the receiver compartment and analyze the solute concentration.

- Plot the cumulative amount of solute permeated per unit area versus time. The linear portion of this plot corresponds to steady state, and its slope is (J{ss}).

- Calculation: The diffusion coefficient is calculated using a form of Fick's first law [28]: [ Dm = \frac{J{ss} \cdot h}{K \cdot \Delta C} ] where (K) is the partition coefficient of the solute between the membrane and the solution, and (\Delta C) is the concentration difference across the membrane. If boundary layers are significant, more complex analysis is required [28].

Lag Time Method

This technique leverages the transient period before steady state is achieved in a membrane permeation experiment [28].

- Protocol:

- Follow the initial steps of the steady-state flux method with a membrane initially free of solute.

- Extend the plot of cumulative permeation versus time. The x-intercept of the linear (steady-state) portion is the lag time, (t_L).

- Calculation: For a homogeneous membrane without significant boundary layer effects or solute adsorption, the diffusion coefficient is given by [28]: [ D = \frac{h^2}{6 \cdot t_L} ] This method is sensitive to the presence of impermeable domains or adsorptive fillers, which require a modified equation accounting for tortuosity ((\tau)) and binding capacity [28].

Sorption and Desorption Methods

These methods monitor the uptake or release of a solute by a polymer matrix over time [28].

- Protocol (Desorption):

- Equilibrate a polymer sample (e.g., a thin film) with the solute to a uniform initial concentration (C0).

- Immerse the sample in a large volume of well-agitated solvent (sink conditions).

- Measure the amount of solute released, (Qt), at multiple time points.

- Calculation: For early-time release data (where (Qt / Q\infty \leq 0.6)), the following short-time approximation is used [28]: [ Qt = \frac{2 \cdot C0 \cdot A}{\sqrt{\pi}} \sqrt{D \cdot t} ] where (A) is the surface area. A plot of (Qt) versus (\sqrt{t}) is linear, and its slope (k) is used to find (D): [ D = \pi \left( \frac{k}{2 \cdot C0 \cdot A} \right)^2 ]

The workflow for selecting and applying these key experimental methods is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Reagents for Diffusion Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Diffusion Cell (Franz Cell) | A two-chamber apparatus for membrane permeation studies. The donor and receiver compartments are separated by the test membrane [28]. | Material must be inert (e.g., glass). Standardized orifice area ensures reproducible flux measurements. |

| Semi-Permeable Membrane | Acts as the barrier through which solute diffusion is measured. Can be synthetic polymer, biological, or composite [28]. | Thickness ((h)) must be uniform and precisely measured. Material should be well-characterized (porosity, tortuosity). |

| Analytical Instrumentation | Used to quantify solute concentration in the receiver chamber or solution. Examples: HPLC, UV-Vis Spectrophotometer [28]. | Must have sufficient sensitivity and low limit of detection for the solute. Requires calibration with standard solutions. |

| Thermostated Water Bath | Maintains the entire diffusion cell apparatus at a constant, controlled temperature [28]. | Temperature stability is critical as (D) is highly temperature-sensitive. |

| Buffer Solutions | Provide the solvent medium for the solute, maintaining constant pH and ionic strength. | pH and ionic strength can affect solute charge, stability, and interaction with the membrane. |

Advanced Considerations and Applications

Diffusion in Porous and Composite Media

In porous media (e.g., tissues, catalyst pellets, composite materials), the path for diffusion is longer and more complex than in a free fluid. The effective diffusion coefficient, (D{\text{eff}}), is used to describe this macroscopic transport [30] [31]. It is related to the diffusion coefficient in the fluid filling the pores, (D), by: [ D{\text{eff}} = \frac{D \varepsilon \delta}{\tau} ] where (\varepsilon) is the porosity available for transport, (\delta) is the constrictivity (accounting for slowed diffusion in narrow pores), and (\tau) is the tortuosity (a measure of the winding nature of the pores) [30] [31]. Correlations such as the Millington-Quirk equation ((\tau = \varepsilon^{-1/3})) are often used to estimate tortuosity from porosity [31].

Application in Drug Development

In preformulation and drug delivery, the diffusion coefficient is a critical parameter. It helps predict:

- Drug Release Rates: From controlled-release formulations like transdermal patches and polymer-based tablets [28].

- Membrane Permeation: The passive transport of drug molecules across biological barriers like the skin, intestinal epithelium, or blood-brain barrier can be modeled using Fick's laws, with (D) being a key variable [28].

- Intrinsic Dissolution Rate: The diffusion coefficient is characteristic of a solid drug compound in a given solvent and is determined during preformulation to understand dissolution behavior [28].

The diffusion coefficient, (D), is a fundamental parameter that bridges the molecular-scale random walk of particles and the macroscopic laws of diffusion described by Fick. Its value is not static but is profoundly governed by temperature, a relationship elegantly quantified by the Arrhenius equation. Understanding this dependence is paramount for predicting and controlling mass transfer in systems ranging from industrial gas separations to the release of a pharmaceutical agent from a polymer matrix.

This guide has outlined the theoretical underpinnings of (D), its units, and the practical methodologies for its experimental determination, providing researchers with a foundational toolkit. The ability to accurately measure and model the diffusion coefficient, especially its temperature-driven changes, remains a critical capability in the advancement of material science, chemical engineering, and drug development research. Future work in this domain may focus on refining predictive models for complex, multi-component systems and further elucidating diffusion mechanisms in heterogeneous and biological environments.

Distinguishing Between Steady-State and Non-Steady-State Diffusion Regimes

Molecular diffusion, the process by which substances move from regions of high concentration to regions of low concentration, serves as a foundational transport mechanism across numerous scientific disciplines. Within chemical engineering, materials science, and pharmaceutical development, accurately predicting and controlling diffusion is paramount for optimizing processes ranging from drug delivery to metallurgical treatments. The mathematical framework for describing these phenomena was first established by Adolf Fick in 1855, whose two laws of diffusion remain the cornerstone of quantitative analysis in this field [4]. These laws enable researchers to distinguish between two fundamental modes of mass transport: steady-state and non-steady-state diffusion.

Understanding the distinction between these regimes is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for professionals designing controlled-release pharmaceuticals, developing novel materials, or modeling environmental contaminant dispersion. The steady-state regime describes systems where concentration profiles no longer change with time, while the non-steady-state regime characterizes the transient period during which concentrations evolve. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of both diffusion regimes, framed within the context of Fick's laws, and equips researchers with the methodologies needed to identify, analyze, and leverage each regime in experimental and applied settings.

Theoretical Foundations of Diffusion

Fick's First Law: The Foundation of Steady-State Diffusion

Fick's First Law provides the fundamental relationship for diffusion under steady-state conditions. It postulates that the diffusive flux is proportional to the negative of the concentration gradient [35] [4]. Mathematically, this is expressed as:

J = -D(∂C/∂x)

Where:

- J represents the diffusion flux, with dimensions of amount of substance per unit area per unit time (e.g., mol/m²s)

- D is the diffusion coefficient or diffusivity (m²/s)

- ∂C/∂x is the concentration gradient in the direction of the x-axis (mol/m⁴)

- The negative sign indicates that diffusion occurs "downhill" from regions of higher concentration to regions of lower concentration [35]

The diffusion coefficient, D, is a proportionality constant that reflects the mobility of the diffusing species within a specific medium. Its value depends on factors including temperature, pressure, and the nature of both the diffusing substance and the host medium [36]. Like many rate processes, diffusion is thermally activated, and the temperature dependence of the diffusion coefficient typically follows an Arrhenius-type relationship [35]:

D = D₀e^(-Ea/RT)

Where D₀ is a pre-exponential factor, Ea is the activation energy for diffusion, R is the universal gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature.

Fick's Second Law: Predicting Temporal Changes

For non-steady-state conditions where concentrations change with time, Fick's Second Law applies. This partial differential equation describes how the concentration evolves spatially and temporally [4] [36]. In one dimension, it is expressed as:

∂C/∂t = D(∂²C/∂x²)

Where:

- ∂C/∂t represents the rate of change of concentration with time

- ∂²C/∂x² describes the spatial curvature of the concentration profile

In multiple dimensions, this generalizes to ∂C/∂t = D∇²C, where ∇² is the Laplace operator [4]. The solution to this equation depends on the initial concentration distribution and the boundary conditions imposed on the system. For a simple case of diffusion from a constant source into a semi-infinite medium, the concentration field can be described by error functions.

Characterizing Diffusion Regimes

Fundamental Distinctions

The steady-state and non-steady-state diffusion regimes represent fundamentally different system conditions with distinct mathematical descriptions and practical implications.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Diffusion Regimes

| Feature | Steady-State Diffusion | Non-Steady-State Diffusion |

|---|---|---|

| Concentration Profile | Constant with time (∂C/∂t = 0) [35] | Changes with time (∂C/∂t ≠ 0) [35] |

| Governing Law | Fick's First Law [35] | Fick's Second Law [4] |

| Flux | Constant with time [35] | Varies with time [35] |

| Concentration Gradient | Constant and linear [35] | Changes with time and position [36] |

| Mathematical Complexity | Algebraic equation [35] | Partial differential equation [4] |

| Common Applications | Membrane processes, permeation studies [36] | Drug release kinetics, heat treatment of alloys [36] |

Conceptual Relationship Between Diffusion Regimes

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between the key parameters in both diffusion regimes and their governing laws:

This diagram illustrates how Fick's First Law establishes that the concentration gradient directly drives the diffusion flux. In non-steady-state conditions, spatial variations in this flux (its negative divergence) lead to temporal concentration changes, as described by Fick's Second Law. These concentration changes, in turn, modify the original gradient, creating a feedback loop that continues until a steady state is reached.

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Establishing Steady-State Diffusion Conditions

Protocol: Membrane Permeability Measurement

Objective: To determine the diffusion coefficient of a solute through a synthetic membrane under steady-state conditions.

Materials and Equipment:

- Diffusion cell with two compartments separated by a membrane

- Synthetic membrane of known thickness and area

- Analyte solution of known concentration

- Receiver solution (typically pure solvent)

- Analytical instrument (e.g., UV-Vis spectrophotometer, HPLC)

- Temperature-controlled water bath

- Magnetic stirrers and stir bars

- Sampling equipment (syringes, pipettes)

Procedure:

- Mount the membrane between the two compartments of the diffusion cell, ensuring no leaks.

- Fill the donor compartment with the analyte solution at concentration C₀.

- Fill the receiver compartment with the pure solvent.

- Maintain the entire apparatus at constant temperature using the water bath.

- Activate stirrers in both compartments to minimize boundary layer effects.

- At predetermined time intervals, sample small volumes from the receiver compartment.

- Analyze sample concentrations using appropriate analytical methods.

- Continue sampling until the flux calculated from receiver concentration vs. time becomes constant.

Data Analysis: Once steady state is achieved, the flux J is calculated from the steady-state slope of the receiver concentration vs. time curve. The diffusion coefficient can then be determined using Fick's First Law rearranged as:

D = -J / (ΔC/Δx)

Where ΔC is the concentration difference across the membrane and Δx is the membrane thickness.

Characterizing Non-Steady-State Diffusion

Protocol: Drug Release Kinetics from a Polymer Matrix

Objective: To measure the time-dependent concentration profiles of an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) released from a polymeric drug delivery system.

Materials and Equipment:

- Polymer matrix loaded with API

- Dissolution apparatus with paddles or baskets

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS) at physiological pH

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer or HPLC system

- Temperature-controlled dissolution vessels

- Automated sampling system

- Data acquisition software

Procedure:

- Place the API-loaded polymer matrix in the dissolution vessel containing PBS at 37°C.

- Operate the paddles at a standardized rotation speed (e.g., 50-100 rpm).

- At predetermined time points, automatically withdraw samples from the dissolution medium.

- Filter samples to remove any particulate matter.

- Analyze API concentration in each sample using calibrated analytical methods.

- Continue sampling until complete release is achieved or equilibrium is reached.

Data Analysis: Plot cumulative drug release versus time. The initial portion of the release curve (typically up to 60% release) often follows the Higuchi model for non-steady-state diffusion from a planar matrix:

Q = 2C₀√(Dt/π)

Where Q is the cumulative amount of drug released per unit area at time t, C₀ is the initial drug concentration in the matrix, and D is the diffusion coefficient. A plot of Q versus √t should yield a straight line with slope proportional to √D, allowing determination of the diffusion coefficient.

Quantitative Data in Diffusion Studies

Representative Diffusion Coefficients

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Diffusion Coefficients for Selected Systems

| Diffusing Substance | Solvent/Medium | Temperature (°C) | Diffusion Coefficient (m²/s) | Regime |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen | Air | 25 | 1.8 × 10⁻⁵ | Steady-state [35] |

| Sucrose | Water | 25 | 5.2 × 10⁻¹⁰ | Non-steady-state [35] |

| Ions | Water | 25 | (0.6-2)×10⁻⁹ | Non-steady-state [4] |

| Biological Molecules | Water | 25 | 10⁻¹⁰ to 10⁻¹¹ | Non-steady-state [4] |

| Au (Gold) | Pb (Lead) | 285 | 4.6 × 10⁻¹⁰ | Non-steady-state [35] |

Characteristic Times for Regime Transition

The transition from non-steady-state to steady-state diffusion can be characterized by the time required to approach equilibrium. For a membrane of thickness L, the characteristic time for establishing steady-state conditions is approximately:

τ ≈ L² / D

Where τ is the characteristic time. This relationship demonstrates that the time to reach steady state increases with the square of the diffusion distance and decreases with increasing diffusivity.

Table 3: Characteristic Times for Diffusion Regime Transition

| System | Diffusion Distance (L) | Diffusion Coefficient (D) | Characteristic Time (τ) | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug in polymer matrix | 100 μm | 10⁻¹² m²/s | ~2.8 hours | Release kinetics [36] |

| Oxygen in tissue | 1 mm | 10⁻⁹ m²/s | ~16.7 minutes | Oxygen microsensor [35] |

| Water in concrete | 10 cm | 10⁻¹⁰ m²/s | ~3.2 years | Gravimetric analysis [35] |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Diffusion Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Diffusion Experiments | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic membranes | Provide a controlled barrier of known thickness and properties | Permeability studies, mimicking biological barriers [36] |

| Radiolabeled compounds (³H, ¹⁴C) | Enable highly sensitive tracer detection without interference | Measuring low diffusion coefficients, in vivo tracking [35] |

| Fluorescent probes | Visualize concentration gradients and diffusion pathways | Microscopy-based diffusion measurements, cellular uptake [37] |

| Diffusion cells (Franz/Side-Bi-Side) | Create controlled compartments for flux measurements | Transdermal drug delivery research, membrane characterization [36] |

| Hydrogel matrices | Mimic biological tissues for controlled release studies | Drug delivery system development, tissue engineering [36] |

| Analytical standards | Quantify solute concentrations in diffusion experiments | HPLC/UV-Vis calibration for accurate concentration measurement [36] |

Advanced Considerations and Applications

Experimental Workflow for Diffusion Regime Analysis

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive experimental approach for characterizing diffusion regimes:

This workflow emphasizes the importance of time-series measurements to distinguish between diffusion regimes. The key decision point involves determining whether the system has reached a constant flux (steady state) or continues to exhibit temporal changes (non-steady state). This determination directly dictates the appropriate mathematical framework for data analysis.

Applications in Drug Development

In pharmaceutical research, distinguishing between diffusion regimes has profound implications. For transdermal drug delivery, steady-state diffusion across the skin barrier determines the maintenance dose rate, while non-steady-state diffusion governs initial loading and time to therapeutic effect [36]. In controlled-release oral formulations, the non-steady-state regime often dominates the release profile, with the diffusion front moving through a hydrogel matrix as the drug is released. Understanding these principles enables formulators to optimize dosage forms for specific release profiles—whether immediate, sustained, or pulsatile.

Advanced drug delivery systems increasingly employ stimuli-responsive materials where diffusion coefficients change in response to environmental triggers (pH, temperature, enzymes). In such systems, transitions between diffusion regimes may occur multiple times during delivery, requiring sophisticated modeling that combines both Fick's laws with kinetic equations describing the material response.

The distinction between steady-state and non-steady-state diffusion regimes represents a fundamental concept in mass transport theory with significant practical applications across scientific and engineering disciplines. Steady-state diffusion, characterized by time-invariant concentration profiles and governed by Fick's First Law, predominates in systems with constant driving forces. Non-steady-state diffusion, described by Fick's Second Law, captures the temporal evolution of concentration fields during transient processes. Researchers can successfully navigate between these regimes by employing appropriate experimental protocols, analytical techniques, and mathematical models, enabling precise control of diffusion processes in applications ranging from pharmaceutical development to materials engineering. As diffusion studies continue to evolve, particularly in complex biological and engineered systems, the foundational principles outlined in this guide remain essential for advancing both basic science and technological applications.

From Theory to Practice: Measuring Diffusivity and Applying Fick's Laws in Drug Development

The Taylor dispersion method stands as a powerful experimental technique for determining molecular diffusion coefficients within fluid systems. First elucidated by G. I. Taylor in 1953 and later extended by Rutherford Aris, this method leverages the interplay between convective flow and molecular diffusion to quantify diffusivity with remarkable precision [38]. The technique has found widespread application across diverse fields including pharmaceutical development, chemical engineering, and environmental science, where accurate knowledge of diffusion coefficients is essential for predicting mass transport phenomena.

This method operates within the theoretical framework established by Adolf Fick's laws of diffusion, which provide the fundamental mathematical description of diffusive processes [4] [39]. Fick's first law establishes that the diffusive flux of particles proceeds from regions of high concentration to low concentration with a magnitude proportional to the concentration gradient, while Fick's second law predicts how this concentration gradient evolves over time [4]. The Taylor dispersion method represents an ingenious application of these principles under flowing conditions, where apparent dispersion is enhanced by velocity gradients within the flow field.

Theoretical Foundation

Fick's Laws of Diffusion

The theoretical basis for molecular diffusion begins with Fick's empirical laws. Fick's first law relates the diffusive flux to the concentration gradient:

J = -D∇φ

Where J represents the diffusion flux (amount of substance per unit area per unit time), D is the diffusion coefficient (area per unit time), and ∇φ is the concentration gradient [4]. The negative sign indicates that diffusion occurs down the concentration gradient.

Fick's second law describes how diffusion causes concentrations to change over time:

∂φ/∂t = D∇²φ

This partial differential equation predicts the temporal evolution of concentration profiles due to diffusive processes [4]. For one-dimensional systems, this simplifies to ∂φ/∂t = D(∂²φ/∂x²).

Taylor Dispersion Theory

Taylor dispersion arises when a soluble substance is introduced into a fluid flowing through a small-diameter tube. The interaction between the fluid's parabolic velocity profile (Poiseuille flow) and transverse molecular diffusion creates an effective dispersive process that can be quantified [38].

In the canonical case of flow through a cylindrical tube, the fluid velocity follows a parabolic distribution:

u = w₀(1 - r²/a²)ẑ