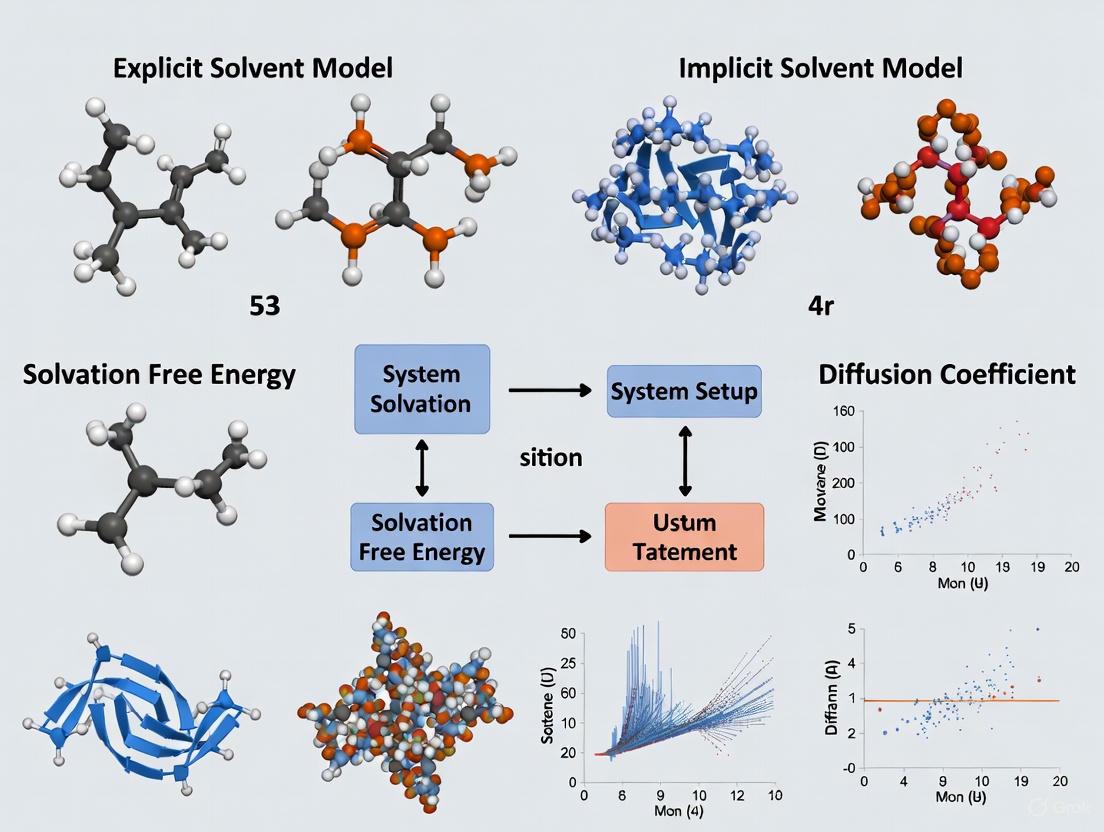

Explicit vs. Implicit Solvent Models in MD Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide for Computational Researchers

This article provides a systematic comparison of explicit and implicit solvent models in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, tailored for researchers and professionals in computational biophysics and drug development.

Explicit vs. Implicit Solvent Models in MD Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide for Computational Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of explicit and implicit solvent models in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, tailored for researchers and professionals in computational biophysics and drug development. It covers foundational principles, key methodologies like Generalized Born and Poisson-Boltzmann, and practical applications in protein folding and ligand binding. The content addresses common limitations and troubleshooting strategies and presents rigorous validation and performance comparisons, including speedups and accuracy. Finally, it explores hybrid approaches and future directions, offering a balanced perspective for selecting the appropriate solvent model for specific research objectives.

Understanding Solvent Models: From Explicit Water Molecules to Implicit Continuum

In molecular dynamics (MD) research, the choice of how to represent the solvent environment represents a fundamental compromise between computational accuracy and efficiency. Explicit solvent models treat each solvent molecule as a discrete particle, providing an atomistically detailed view of the solvation environment that captures specific molecular interactions, solvent structure, and dynamics with high fidelity. In contrast, implicit solvent models approximate the solvent as a continuous dielectric medium, offering significant computational acceleration at the potential cost of physical realism. This comparison guide objectively examines the performance characteristics, methodological foundations, and practical applications of explicit solvent models alongside emerging hybrid and machine learning approaches, providing researchers and drug development professionals with experimental data to inform their simulation strategies. The ongoing development of methods that bridge the explicit-implicit divide, particularly through machine learning potentials, promises to redefine the boundaries of what is computationally feasible in biomolecular simulation.

Fundamental Definitions and Theoretical Frameworks

Explicit and implicit solvent models operate on fundamentally different physical principles, each with distinct implications for simulation accuracy and computational demand. The core distinction lies in the representation of solvent molecules: explicit models maintain atomic-level detail, while implicit models use continuum approximations.

Explicit solvent models simulate each solvent molecule individually using classical force fields. In biomolecular simulations, the solute (e.g., protein, DNA, or ligand) is immersed in a box of explicit water molecules, typically employing three-site models like TIP3P or four-site models like TIP4P. These models naturally capture molecular details such as hydrogen bonding networks, water-bridged interactions, and solvent entropy contributions that arise from discrete molecular interactions. The particle mesh Ewald (PME) method is commonly employed to handle long-range electrostatic interactions in these explicitly solvated systems [1] [2].

Implicit solvent models, particularly Generalized Born (GB) models, replace discrete solvent molecules with a continuum representation characterized by a dielectric constant. The solvation free energy (ΔGsolv) is typically partitioned into polar (electrostatic) and non-polar components. The polar component is calculated using continuum electrostatics approaches such as Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) or Generalized Born (GB) approximations, while the non-polar contribution is often estimated based on solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) [1] [3]. This simplification dramatically reduces the number of particles in the simulation, but fails to capture specific solute-solvent interactions.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Explicit and Implicit Solvent Models

| Feature | Explicit Solvent Models | Implicit Solvent Models |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Representation | Discrete molecules | Dielectric continuum |

| Computational Demand | High | Low |

| Key Physical Interactions | Hydrogen bonding, specific water networks, molecular crowding | Bulk electrostatic screening, surface tension effects |

| Common Implementations | TIP3P, TIP4P water models with PME electrostatics | Generalized Born (GB), Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) |

| Sampling Speed | Limited by solvent viscosity | Accelerated due to reduced friction |

| Handling of Solvent Entropy | Natural, through molecular motions | Approximated empirically |

Quantitative Performance Comparison: Accuracy vs. Efficiency

Systematic comparisons between explicit and implicit solvent approaches reveal a complex performance landscape where the optimal choice depends heavily on the specific biological process under investigation and the computational resources available. The trade-offs between physical accuracy and simulation efficiency follow predictable patterns across different classes of biomolecular systems.

Conformational Sampling Efficiency

The sampling efficiency advantage of implicit solvent models varies significantly depending on the type and scale of conformational change being simulated. A comprehensive comparative study evaluating the particle mesh Ewald (PME) explicit solvent method against a popular Generalized Born (GB) implicit solvent model found speedup factors ranging from approximately 1-fold for small conformational changes (dihedral angle flips) to between 1-100 fold for large conformational changes (nucleosome tail collapse, DNA unwrapping), with approximately 7-fold speedup for mixed cases (miniprotein folding) [1]. This study attributed the accelerated sampling primarily to reduction in solvent viscosity rather than differences in free-energy landscapes between the solvent models. When algorithmic differences are combined with reduced viscosity, the combined speedups were approximately 2-fold, 1-60 fold, and 50-fold for small, large, and mixed conformational changes, respectively [1].

Structural Accuracy and Validation

The ability to recapitulate experimental solvent structures provides a critical validation metric for explicit solvent simulations. Research on endoglucanase crystals compared MD-simulated water positions with those determined by joint X-ray and neutron diffraction. When harmonic restraints were applied to bias the protein toward its crystal structure, the recall of crystallographic waters was excellent—with 98% of top waters within 1.4Å of MD water density peaks. However, unrestrained simulations showed markedly poorer performance, with only 51-62% recall in the same range [2]. This demonstrates that while explicit solvent models can accurately reproduce experimental solvent structure, the accuracy is highly dependent on proper restraint of the biomolecular framework.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Solvent Models

| Performance Metric | Explicit Solvent (PME/TIP3P) | Implicit Solvent (GB) |

|---|---|---|

| Sampling Speed (Relative) | 1x (baseline) | 1-100x (system-dependent) |

| Crystallographic Water Recall | 98% (restrained) | Not applicable |

| Computational Cost for Small Systems | Lower due to PME overhead | Higher (algorithmic advantage) |

| Computational Cost for Large Systems | Higher (scales with solvent atoms) | Lower (algorithmic disadvantage) |

| Free Energy Landscape Accuracy | Gold standard for specific interactions | May differ substantially from explicit |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Crystalline Molecular Dynamics Validation Protocol

The validation of explicit solvent models against experimental crystallographic data follows a rigorous protocol designed to maximize structural accuracy while maintaining computational feasibility:

System Preparation: The protein structure is derived from high-resolution joint X-ray and neutron diffraction data (e.g., 1.0Å X-ray, 1.5Å neutron), enabling experimentally assigned protonation states. Protonation states for exchangeable sites are modeled using neutron scattering density and chemical environment analysis [2].

Solvation and Ion Placement: The crystalline system is solvated within a 2×2×2 supercell with explicit solvent molecules. Counterions are added to neutralize the system, with additional ions included to match experimental mother liquor concentration (e.g., 50 mM). Alternative solvent models may include specific buffers like Tris-Cl [2].

Force Field Parameterization: Protein structures are parameterized using specialized force fields (e.g., amber99sb-ildn), with water modeled using TIP3P or other explicit water models. Ligands are parameterized using appropriate tools (e.g., GLYCAM for carbohydrates) [2].

Simulation with Restraints: Harmonic restraints are applied to protein non-hydrogen atoms to maintain the experimental crystal structure while allowing solvent dynamics. Simulations are typically run for tens of nanoseconds with coordinates recorded for analysis [2].

Water Density Analysis: Water scattering density maps are computed from MD trajectories using standard macromolecular crystallography methods. Peaks in MD water electron density are compared to crystallographic water positions with recall measured at various distance thresholds (0.5Å, 1.0Å, 1.4Å) [2].

This protocol demonstrates that with appropriate experimental restraints, explicit solvent models can successfully recover crystallographic water structures, establishing a benchmark for solvent model validation.

Machine Learning Potentials for Explicit Solvent Systems

Emerging machine learning approaches offer promising pathways to maintain explicit solvent accuracy while reducing computational cost. The active learning strategy for generating machine learning potentials (MLPs) for chemical processes in explicit solvents employs a sophisticated workflow:

Initial Data Generation: Create small training sets of configurations labeled with reference energies and forces. For reactions, initial training typically starts from transition state structures. Explicit solvent configurations are generated using cluster models with sufficient solvent molecules to cover the MLP's cut-off radius [4].

Active Learning Loop:

- Train initial MLP on the starting dataset

- Perform short MD simulations using the current MLP

- Evaluate structures using descriptor-based selectors (e.g., Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions - SOAP)

- Select underrepresented structures for retraining

- Iteratively expand the training set based on chemical space coverage [4]

Selector Implementation: Descriptor-based selectors analyze the SOAP descriptor space to identify regions poorly represented in the training set, providing a general metric applicable across different MLP approaches at low computational cost compared to committee-based uncertainty estimation [4].

This strategy has been successfully applied to study Diels-Alder reactions in water and methanol, demonstrating the ability to obtain reaction rates in agreement with experimental data while capturing explicit solvent effects [4].

Emerging Paradigms: Machine Learning and Quantum Approaches

The distinction between explicit and implicit solvent modeling is being redefined by machine learning approaches that capture explicit solvent accuracy with reduced computational overhead. Neural network potentials (NNPs) trained on massive quantum chemical datasets represent a particularly promising development. Meta's Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) dataset contains over 100 million calculations at the ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD level of theory, spanning biomolecules, electrolytes, and metal complexes [5]. Models trained on this dataset, such as the equivariant Smooth Energy Network (eSEN) and Universal Model for Atoms (UMA), achieve accuracy comparable to high-level density functional theory while enabling simulations of large systems that were previously computationally prohibitive [5].

These ML-based approaches demonstrate surprising capability in predicting charge-related properties despite not explicitly modeling Coulombic physics. In benchmarks of reduction potential and electron affinity predictions, OMol25-trained NNPs performed comparably or better than low-cost DFT and semiempirical methods for organometallic species, though with more variable performance on main-group species [6]. This suggests that ML models can learn complex solvation effects implicitly from training data, potentially bypassing the need for explicit physics-based modeling of certain interactions.

Another innovative approach bridges the gap between explicit and implicit modeling through graph neural networks that incorporate alchemical variables. The λ-Solvation Neural Network (LSNN) extends traditional force-matching by incorporating derivatives with respect to electrostatic and steric coupling factors (λelec and λsteric), enabling accurate solvation free energy predictions while maintaining computational efficiency comparable to implicit solvent models [7].

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Solvation Model Development and Validation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function/Purpose | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explicit Water Models | Force Field Parameters | Represent water molecules with atomic detail | TIP3P, TIP4P, OPC |

| Continuum Solvent Models | Implicit Solvation | Approximate solvent as dielectric continuum | Generalized Born (GB), Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) |

| Neural Network Potentials | Machine Learning Models | Learn potential energy surfaces from QM data | eSEN, UMA, ANI, MACE |

| Quantum Chemical Datasets | Training Data | Provide reference data for ML potential development | OMol25, SPICE, ANI-2x |

| Crystalline MD Protocols | Validation Methodology | Validate solvent models against experimental data | Joint X-ray/neutron refinement |

| Active Learning Frameworks | Sampling Algorithm | Efficiently explore chemical space for ML training | SOAP descriptor-based selectors |

Explicit solvent models remain the gold standard for simulating specific solute-solvent interactions, water-mediated processes, and accurately reproducing experimental solvent structures, particularly when validated against crystallographic data. The computational cost of these models continues to motivate the development of implicit solvent approaches for enhanced sampling and large-scale simulations. However, the emerging paradigm of machine learning potentials trained on extensive quantum chemical datasets promises to transcend the traditional explicit-implicit dichotomy, offering near-quantum accuracy with dramatically reduced computational cost. For researchers and drug development professionals, the optimal choice of solvent model depends critically on the specific scientific question, with explicit models providing unparalleled detail for mechanistic studies and ML-based approaches enabling previously intractable simulations of complex biomolecular processes in their native aqueous environments.

In computational chemistry and biophysics, accurately modeling the solvent environment is essential for realistic simulations of biomolecules, as most biological processes occur in aqueous solution [8] [3]. Two primary methodologies have emerged to address this challenge: explicit solvent models, which treat each solvent molecule as a discrete particle, and implicit solvent models, which replace the explicit solvent with a continuous, polarizable medium [9]. Implicit solvent models, the subject of this guide, offer a computationally efficient framework by approximating the average effect of the solvent on the solute [10]. This approach significantly reduces the number of particles in a simulation system, lowering computational cost and accelerating conformational sampling compared to explicit solvent simulations [11] [10]. The core idea of implicit solvation is to forgo the atomistic detail of individual solvent molecules in favor of a continuum representation described by macroscopic properties, primarily its dielectric constant [9]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of implicit solvent models against explicit and hybrid alternatives, detailing their theoretical foundations, performance data, methodological protocols, and practical applications in modern molecular research.

Theoretical Foundations of Implicit Solvation

The conceptual foundation of implicit solvent models rests on the partitioning of the solvation free energy into physically meaningful components [3]. Typically, the total solvation free energy (ΔG_solv) is decomposed into a polar (electrostatic) component and a non-polar component [12] [3].

The polar component (ΔGele) accounts for the interaction of the solute's charge distribution with the dielectric environment. This is typically computed by solving the Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) equation or its efficient approximation, the Generalized Born (GB) model [12] [3]. The non-polar component (ΔGnp) describes the free energy cost of forming a cavity in the solvent to accommodate the solute, along with van der Waals interactions [12]. This term is often modeled as being proportional to the Solvent-Accessible Surface Area (SASA) [8] [12]. Thus, the total solvation free energy can be approximated as: ΔGsolv ≈ ΔGGB + γ × SASA [7]

Where ΔG_GB is the polar Generalized Born energy and γ is a surface tension parameter [7]. This combination is widely known as the GBSA model. The following diagram illustrates the core conceptual relationship between these energy components and the overall solvation process.

Several popular implicit solvent models have been developed based on these principles. The Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM) and its variants, such as the Conductor-like Screening Model (COSMO) and the Solvation Model based on Density (SMD), are widely used in quantum chemistry calculations to describe solvation effects on electronic structure [8] [9] [3]. In classical molecular dynamics simulations, the GB model coupled with a SASA term (GBSA) is particularly popular due to its favorable balance of efficiency and accuracy [11] [10].

Performance Comparison: Implicit vs. Explicit Solvation

While implicit solvent models offer significant computational advantages, their accuracy in reproducing experimental data and explicit solvent benchmarks is a critical consideration. The table below summarizes key performance metrics for various solvation approaches, highlighting their respective strengths and limitations.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Solvation Methods

| Solvation Method | Computational Cost | Key Accuracy Metrics | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implicit Solvent (GBSA) [11] [10] | Low to Moderate | RNA stem-loop folding: Stem region RMSD <2 Å, loop region RMSD ~4 Å [11] | Protein folding simulations [11]; Long-timescale conformational sampling [10] |

| Explicit Solvent (TIP3P) [7] | Very High | Considered the "gold standard" for solvation energy calculations [7] | Detailed study of specific solute-solvent interactions; Validation of other models [9] |

| Explicit Solvent (IRS Method) [8] | High | Predictive accuracy comparable to SMD; Superior to PB/GBSA [8] | Accurate solvation energy calculations where explicit water effects are critical [8] |

| Machine Learning (ML-PCM) [13] | Low (after training) | Mean Unsigned Error (MUE) of 0.40-0.52 kcal/mol for solvation free energies [13] | High-throughput screening; Fast and accurate solvation energy predictions [13] |

| Machine Learning (LSNN) [7] | Low (after training) | Free energy predictions with accuracy comparable to explicit solvent [7] | Drug discovery; Free energy calculations where both speed and accuracy are needed [7] |

The computational efficiency of implicit solvent models is their most significant advantage. By drastically reducing the number of particles in a simulation system, they lower computational cost and, due to the absence of solvent viscosity, can accelerate conformational sampling compared to explicit solvent simulations [11] [10]. However, this efficiency can come at the cost of limited accuracy in capturing specific, atomistic solvent effects. For instance, in RNA stem-loop folding simulations, while implicit solvents (GB-neck2) successfully folded stem regions with high accuracy (RMSD <2 Å), the modeling of loop structures was less precise (RMSD ~4 Å), indicating a limitation in capturing the fine structural details often stabilized by specific solvent interactions [11].

Quantitative accuracy for solvation free energy prediction has seen remarkable improvements with machine-learning-augmented implicit models. The ML-PCM model improves the accuracy of widely accepted continuum solvation models by almost an order of magnitude, achieving a Mean Unsigned Error (MUE) of 0.40-0.52 kcal/mol compared to experimental data [13]. Similarly, the graph neural network-based LSNN model achieves free energy predictions with accuracy comparable to explicit-solvent alchemical simulations but at a much lower computational cost [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Implicit Solvent MD Simulation (GBSA)

The following workflow outlines a typical protocol for running molecular dynamics simulations using an implicit solvent model, as applied in studies of RNA stem-loop folding [11]:

- System Preparation: Start with an initial solute structure (e.g., an extended RNA conformation).

- Force Field Selection: Employ a refined atomistic force field (e.g., the DESRES-RNA force field).

- Implicit Solvent Model Selection: Apply a modern Generalized Born model (e.g., GB-neck2 with parameters refined for nucleic acids).

- Energy Minimization: Perform initial energy minimization to remove steric clashes.

- Equilibration and Production MD: Run conventional MD simulations at the target temperature (e.g., near the predicted melting temperature).

- Analysis: Calculate Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) of the resulting structures (e.g., for stem and loop regions separately) against experimental reference structures [11].

Protocol for Explicit-Solvent IRS Solvation Energy Calculation

The Interaction-Reorganization Solvation (IRS) method is an explicit solvent approach for calculating molecular solvation energies, providing a useful benchmark for implicit model performance [8].

- Simulation Setup: Generate molecular dynamics simulations of the solute molecule in explicit solvent.

- Conformational Sampling: Create an extensive conformational space of solute conformations in solution.

- Energy Decomposition: Decompose the solvation free energy into two terms:

- Solute-Solvent Interaction Free Energy (ΔGint): Computed directly from MD simulations as the sum of electrostatic (Eele) and van der Waals (Evdw) interactions between solute and solvent atoms [8].

- Reorganization Free Energy (ΔGreo): Derived by fitting a polynomial expansion of the interaction term along with cavitation parameters (e.g., SASA) from a training set of experimental solvation energies [8].

- Validation: Test the fitted model on a separate validation set to confirm predictive accuracy [8].

Protocol for Machine Learning Model Training (ML-PCM)

Machine learning models like ML-PCM are trained to correct or enhance traditional implicit solvent models [13].

- Data Set Curation: Utilize a large data set of experimental solvation free energies for diverse molecules.

- Feature Selection: Use SCRF energy components and solvation free energies computed from a baseline continuum model (e.g., CPCM) as input features.

- Model Training: Train a neural network to map the input features to the experimental solvation free energies.

- Model Validation: Screen appropriately trained models via a rigorous post-validation strategy to select the best-performing one (e.g., with the lowest MUE) [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Successful implementation and application of solvation models require a suite of computational tools and parameters. The following table details key resources mentioned in the cited research.

Table 2: Key Computational Reagents for Solvation Modeling

| Research Reagent / Parameter | Function / Purpose | Example Usage Context |

|---|---|---|

| Generalized Born (GB) Model [11] [10] [12] | Efficiently approximates the electrostatic component of solvation energy. | Core of GBSA implicit solvent for MD simulations [11] [10]. |

| Solvent-Accessible Surface Area (SASA) [8] [12] | Models the non-polar contribution to solvation energy (cavity formation + van der Waals). | Used in GBSA and as a descriptor in the IRS method [8]. |

| GB-neck2 Parameters [11] | A specific, refined set of GB parameters for nucleic acids. | Enables accurate folding of RNA hairpins in implicit solvent MD [11]. |

| DESRES-RNA Force Field [11] | An extensively refined atomistic force field for RNA molecules. | Provides accurate energetics for base stacking and pairing in simulations [11]. |

| AMBER-OL3 Force Field [11] | A standard classical force field for RNA systems in AMBER MD software. | The baseline force field upon which several refinements are built [11]. |

| Machine-Learned Potentials (MLPs) [14] | Surrogates for quantum chemistry methods, offering first-principles accuracy at reduced cost. | Used for solvation-aware atomistic modeling of complex systems [14]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) [7] | A type of neural network architecture that operates on graph-structured data. | Core of the LSNN model for predicting solvation free energies [7]. |

| Alchemical Coupling Parameters (λelec, λsteric) [7] | Variables that scale interaction energies in free energy calculations. | Used in training the LSNN model to enable accurate absolute free energy comparisons [7]. |

Implicit solvent models represent a powerful compromise between computational efficiency and physical realism, enabling the study of biomolecular processes that would be prohibitively expensive with explicit solvent [10] [3]. The continuum medium approximation excels at capturing bulk solvent effects, particularly those related to polarity, making it suitable for protein folding, conformational sampling, and rapid screening [11] [10].

However, the choice between implicit and explicit models remains application-dependent. Implicit models are ideal for large-scale conformational searches, long-time dynamics, and applications requiring high computational throughput. Explicit models are necessary when investigating processes where atomistic details of solvent structure (e.g., specific hydrogen bonds, water bridges, or ion coordination) are critical [9].

The future of solvation modeling lies in hybrid approaches and machine learning augmentation. ML-corrected implicit models like ML-PCM and LSNN demonstrate that it is possible to achieve near-explicit solvent accuracy at implicit solvent speeds [13] [7]. Furthermore, integrating a few explicit solvent molecules within a continuum bath (the cluster-continuum approach) can capture specific interactions while maintaining much of the efficiency of pure implicit models [9]. As these hybrid and machine-learning techniques mature, they will further blur the lines between the two paradigms, offering researchers an increasingly powerful and accurate toolkit for modeling the complex role of solvation in molecular phenomena.

The free energy of solvation and the potential of mean force (PMF) are cornerstone concepts in computational biophysics and drug design. The free energy of solvation quantifies the thermodynamic work required to transfer a molecule from the gas phase into a solvent, a property critically important for predicting drug solubility, membrane permeability, and binding affinities [3]. The potential of mean force, in turn, provides a statistical mechanical description of the effective energy landscape along a reaction coordinate, accounting for the averaged influence of all other degrees of freedom, particularly the solvent [7].

The calculation of these properties in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations hinges on the treatment of the solvent environment. Explicit solvent models represent solvent molecules individually, offering high fidelity but at a great computational cost. Implicit solvent models treat the solvent as a continuous dielectric medium, offering speed but potentially sacrificing accuracy in capturing specific molecular details [3]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these approaches, detailing their theoretical foundations, performance, and practical applications in modern research.

Theoretical Foundations

Free Energy of Solvation

The solvation free energy (( \Delta G_{\text{solv}} )) is a fundamental thermodynamic quantity that can be partitioned into contributions from different physical interactions. A common framework separates it into polar (electrostatic) and non-polar components [3]:

[ \Delta G{\text{solv}} = \Delta G{\text{ele}} + \Delta G_{\text{np}} ]

The polar component (( \Delta G{\text{ele}} )) arises from the interaction between the solute's charge distribution and the dielectric solvent environment. The non-polar component (( \Delta G{\text{np}} )) encompasses the free energy cost of forming a cavity in the solvent to accommodate the solute and the van der Waals interactions between the solute and solvent. This non-polar term is often further decomposed [3]:

[ \Delta G{\text{solv}} = \Delta G{\text{cav}} + \Delta G{\text{ele}} + \Delta G{\text{vdW}} ]

where ( \Delta G{\text{cav}} ) is the cavity formation energy and ( \Delta G{\text{vdW}} ) represents the van der Waals dispersion interactions.

Potential of Mean Force (PMF)

The Potential of Mean Force provides a statistical description of the effective energy along a chosen reaction coordinate. Formally, for a solute configuration ( \vec{r}A ), the solvation PMF (( \Delta W(\vec{r}A, T) )) is defined by integrating out all solvent degrees of freedom (( \vec{r}_S )) [15]:

[ \exp(-\beta \Delta W(\vec{r}A, T)) = \frac{\int \exp(-\beta (U{AS}(\vec{r}A, \vec{r}S) + US(\vec{r}S))) d\vec{r}S}{\int \exp(-\beta US(\vec{r}S)) d\vec{r}S} ]

Here, ( U{AS} ) represents the solute-solvent interaction energy, ( US ) is the solvent-solvent potential, and ( \beta = 1/k_B T ). The PMF thus encapsulates the averaged influence of the solvent on the solute, and its gradient gives the mean force acting on the solute atoms.

Comparative Analysis: Explicit vs. Implicit Solvent Models

Table 1: Comparison of Explicit and Implicit Solvent Models for Free Energy Calculations.

| Feature | Explicit Solvent Models | Implicit Solvent Models |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Approach | Discrete representation of individual solvent molecules [3] | Continuum dielectric medium representing average solvent behavior [3] |

| Computational Demand | High; majority of computation spent on solvent-solvent interactions [7] | Low; no solvent degrees of freedom to simulate [3] |

| Solvation Free Energy Components | Emerges naturally from explicit solute-solvent interactions | Separated into polar (e.g., GB/PB) and non-polar (e.g., SASA) terms [7] [3] |

| Treatment of Solvent Entropy | Inherently included but difficult to quantify [15] | Implicitly included in the solvation potential [15] |

| Handling of Specific Solvent Effects | Excellent for specific interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, water bridges) [16] | Poor; cannot capture specific, local solvent structuring [3] |

| Performance in Solvation Free Energy Prediction | Generally higher accuracy but can be forcefield-dependent [17] [16] | Often lower agreement with experiment (e.g., RMSD ~15 kJ/mol for organic solvents) [17] |

| Performance in Partitioning (LogP) | Good, often due to error cancellation [16] | Varies; SMD model can show good agreement [17] |

Performance and Limitations

Studies indicate that for calculating solvation free energies in organic solvents, implicit models like Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) and Generalized Born (GB) can show poor agreement with both explicit solvent calculations and experimental data, with root-mean-square deviations of approximately 15 kJ/mol [17]. A key identified weakness is the prediction of the apolar contribution, which involves complex solvent entropy effects [17].

Explicit solvent models, while accurate, are computationally intensive. Their accuracy is also sensitive to the empirical forcefield used, particularly the fixed-charge models for electrostatic interactions, which do not account for geometry-dependent polarization [18] [16]. For properties like octanol-water transfer free energies (LogP), explicit solvent methods can achieve remarkable accuracy (e.g., mean unsigned error < 1 kcal/mol with the ABCG2 charge model), often benefiting from systematic error cancellation between different environments [16].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Alchemical Free Energy Calculations with Explicit Solvent

Alchemical transformations are a standard explicit-solvent approach for calculating rigorous free energy differences. These methods leverage the fact that free energy is a state function, using an artificial pathway to connect the states of interest [18].

Core Protocol:

- Hamiltonian Definition: A hybrid Hamiltonian ( H(\vec{r}, \lambda) ) is defined as a linear combination of the Hamiltonians of the two end states (e.g., solute in solvent vs. solute in vacuum), controlled by an alchemical parameter ( \lambda ) that ranges from 0 to 1 [18]: [ H(\vec{r}, \lambda) = \lambda H1(\vec{r}) + (1-\lambda) H0(\vec{r}) ]

- Softcore Potentials: To avoid numerical singularities when atoms are decoupled, softcore potentials are used to modify the nonbonded interactions. A common form for the softcore Lennard-Jones potential is [18]: [ U(\lambda,r)=4\epsilon\lambda^n \left[ \left( \alpha{LJ}(1-\lambda)^m + \left( \frac{r}{\sigma} \right)^6 \right)^{-2} - \left( \alpha{LJ}(1-\lambda)^m + \left( \frac{r}{\sigma} \right)^6 \right)^{-1} \right] ] where ( \alpha_{LJ}, m, n ) are tunable softening parameters.

- Free Energy Estimation: The free energy difference is computed by sampling at multiple ( \lambda ) values. Using Thermodynamic Integration (TI), the free energy is calculated as [18]: [ \Delta G = \int0^1 \left\langle \frac{\partial H(\vec{r}, \lambda)}{\partial \lambda} \right\rangle\lambda d\lambda ]

Diagram 1: Alchemical free energy calculation workflow.

Machine Learning-Augmented Implicit Solvent Models

Recent advancements aim to overcome the accuracy limitations of traditional implicit models by using machine learning.

Core Protocol (LSNN Model):

- Model Architecture: A Graph Neural Network (GNN) is used to represent the implicit solvent potential. The model takes atomic coordinates, charges, and other atomistic features as input [7].

- Training Procedure: The key innovation is to move beyond simple force-matching. The model is trained by minimizing a loss function that includes derivatives with respect to both atomic coordinates and alchemical coupling parameters (( \lambda{\text{elec}} ) and ( \lambda{\text{steric}} )) [7]: [ \mathcal{L} = wF \left( \left\langle \frac{\partial U{\text{solv}}}{\partial \mathbf{r}i} \right\rangle - \frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{r}i} \right)^2 + w{\text{elec}} \left( \left\langle \frac{\partial U{\text{solv}}}{\partial \lambda{\text{elec}}} \right\rangle - \frac{\partial f}{\partial \lambda{\text{elec}}} \right)^2 + w{\text{steric}} \left( \left\langle \frac{\partial U{\text{solv}}}{\partial \lambda{\text{steric}}} \right\rangle - \frac{\partial f}{\partial \lambda{\text{steric}}} \right)^2 ] This ensures the model learns a potential that is consistent with both structural forces and free energy changes, making it suitable for PMF calculations.

- Free Energy Prediction: The trained model can be used to rapidly compute solvation free energies and conformational landscapes, offering accuracy near explicit solvent levels at a fraction of the cost [7].

Diagram 2: Machine learning-implicit solvent model development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools and Methods for Solvation Free Energy Calculations.

| Tool/Method | Type | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| GBSA/MMPBSA [15] | Implicit Solvent Model | Estimates free energies from MD snapshots by combining Generalized Born/Poisson-Boltzmann electrostatics with a Surface Area term. | Computationally efficient but accuracy is limited by the SASA approximation for non-polar contributions [17]. |

| Thermodynamic Integration (TI) [18] | Explicit Solvent Method | Calculates free energy differences by integrating the ensemble-averaged derivative of the Hamiltonian along an alchemical path. | Considered a rigorous "gold standard" but requires significant sampling at multiple λ windows [18]. |

| Alchemical Transfer Method (ATM) [18] | Explicit Solvent Method | A non-alchemical alternative that uses coordinate transformation to interpolate between two physical end states. | Can be easier to set up and is compatible with ML potentials [18]. |

| ABCG2 Charge Model [16] | Fixed-Charge Parametrization | An empirical protocol for deriving atomic partial charges for small molecules in forcefields. | Outperforms older models (AM1/BCC) and can achieve accuracy near costly QM/MM methods for LogP [16]. |

| Machine Learned Potentials (MLPs) [18] [7] | Potential Energy Model | Learns a quantum-mechanically accurate potential energy surface from data, used as a replacement for empirical forcefields. | High accuracy but computationally expensive; requires specialized free energy methods [18]. |

| λ-LSNN [7] | ML-Augmented Implicit Model | A graph neural network trained to predict forces and free energy derivatives for fast and accurate solvation calculations. | Aims to bridge the speed of implicit models with the accuracy of explicit ones [7]. |

The choice between explicit and implicit solvent models for calculating solvation free energy and PMF involves a fundamental trade-off between computational efficiency and physical accuracy. Explicit solvent models remain the gold standard for reliability, particularly for processes where specific solvent structure is critical, but their high cost limits application in high-throughput screening. Implicit models offer the speed necessary for large-scale studies but have documented limitations in accuracy. The most promising future direction lies in hybrid approaches and machine learning, where the physical rigor of explicit solvents or the speed of implicit models is enhanced with data-driven corrections, steadily closing the gap between computational feasibility and quantitative accuracy.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the accurate description of the solvent environment is fundamental because biological processes occur in an aqueous medium. Implicit solvent models have emerged as a powerful alternative to explicit solvent representations, significantly reducing computational cost by treating the solvent as a continuum rather than simulating individual water molecules. This approach replaces explicit water molecules with a potential of mean force, allowing for more efficient conformational sampling. The three major classes of implicit solvent models—SASA (Solvent Accessible Surface Area), Generalized Born (GB), and Poisson-Boltzmann (PB)—each provide distinct methodologies for estimating solvation effects. When combined in methods like MM/PB(GB)SA, they become essential tools for predicting binding free energies in drug discovery, enabling researchers to accelerate cost-efficient binding free energy calculations for various protein systems, including soluble and membrane-bound targets [19] [12].

Theoretical Foundations of Implicit Solvation

Fundamental Principles and Energy Components

Implicit solvation models compute the free energy of solvation (ΔGsol), which represents the work required to transfer a solute molecule from a vacuum to the solvent. This free energy is traditionally decomposed into three components related to a theoretical process: creation of a cavity within the solvent to accommodate the solute molecule (ΔGcav), van der Waals interactions between solute and solvent (ΔGvdW), and electrostatic interactions (ΔGele) [12].

The overall solvation free energy can be expressed as: ΔGsol = ΔGcav + ΔGvdW + ΔGele

In practical implementation, these components are often grouped into polar and nonpolar contributions: ΔGsol = ΔGpol + ΔG_np

Where ΔGpol represents the electrostatic component (calculated by PB or GB methods), and ΔGnp represents the nonpolar component (typically calculated using SASA-based approaches) [20] [12].

Relationship Between Model Classes

The relationship between SASA, GB, and PB models can be understood through their complementary roles in calculating these energy components. SASA models primarily address the nonpolar contribution (ΔGnp), which includes both cavity formation and van der Waals interactions. GB and PB methods focus on the polar component (ΔGpol), which describes the electrostatic interactions between the solute and solvent continuum [12]. In many modern implementations, these approaches are combined—for example, in GB/SA or PB/SA methods—to provide a comprehensive description of solvation effects.

Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) Models

Theoretical Basis and Algorithmic Implementation

The Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) model quantifies the surface area of a biomolecule that is accessible to a solvent molecule. The concept was first introduced by Lee and Richards in 1971, and the canonical computational method was developed by Shrake and Rupley in 1973 [21] [22]. The fundamental principle assumes that the nonpolar solvation free energy is proportional to the molecular surface area: ΔG_np = γ × SASA

Where γ is the surface tension parameter, typically with identical values for all atoms [20].

The Shrake-Rupley algorithm implements this concept by creating a mesh of points equidistant from each atom at a distance equal to the van der Waals radius plus the probe radius (typically 1.4Å, approximating a water molecule). The algorithm then counts how many of these points are not buried within other atoms, with the accessible area being proportional to the number of exposed points [22] [23]. This represents a numerical "rolling ball" approach where a sphere of solvent is rolled along the molecular surface [21].

Advanced SASA Algorithms and Recent Developments

Several algorithms have been developed to improve the accuracy and efficiency of SASA calculations:

- LCPO (Linear Combinations of Pairwise Overlaps): An analytical approximation method that estimates SASA based on neighbor atoms, with computation complexity of O(N²) where N is the number of atoms [20].

- dSASA (differentiable SASA): A recently developed exact geometric method that calculates SASA analytically using Alpha Complex theory and inclusion-exclusion method, implemented on GPUs for accelerated performance [20].

- pwSASA (pairwise SASA): A fast pairwise approximation method suitable for GPU implementation, though with limited transferability to non-protein systems [20].

The table below compares the key characteristics of these SASA calculation methods:

Table 1: Comparison of SASA Calculation Algorithms

| Algorithm | Method Type | Accuracy | Speed | Derivatives Available | System Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shrake-Rupley | Numerical | High (reference) | Slow | No | Universal |

| LCPO | Analytical approximation | Moderate (1-3 Ų error) | Medium (O(N²)) | Yes | Universal |

| pwSASA | Pairwise approximation | Variable (R²: 0.6-0.9) | Fast | Yes | Proteins only |

| dSASA | Exact analytical | High (>98% accuracy) | Fast (GPU-accelerated) | Yes | Universal |

Applications and Limitations in Biomolecular Simulations

SASA-based models find extensive application in calculating binding free energies, protein folding studies, and predicting protein-ligand interactions. The nonpolar term calculated via SASA is frequently combined with polar solvation terms from PB or GB models in methods like MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA for binding affinity prediction [19]. Recent work has demonstrated that including an accurate SASA-based nonpolar term in GB/SA MD simulations produces more stable trajectories and better simulated melting temperatures compared to simulations without this term [20].

A significant limitation of traditional SASA models is their empirical nature and the assumption of a uniform surface tension parameter (γ) for all atoms. Additionally, early implementations lacked reliable atomic derivatives, making them unsuitable for molecular dynamics simulations. However, newer methods like dSASA have addressed this limitation by providing exact analytical derivatives [20].

Generalized Born (GB) Models

Theoretical Foundation and Mathematical Formulation

The Generalized Born (GB) model is an approximation to the Poisson-Boltzmann equation that provides a computationally efficient method for calculating electrostatic solvation energies. Introduced by Still et al., the GB method aims to approximate the solution of the PB equation with simpler functional forms [12]. The model is based on the Born formula for a single ion, which provides an analytical solution for the solvation free energy of a spherical ion with charge q and radius α:

ΔGsolv = -(1/2)(1/εint - 1/ε_ext) × (q²/α)

GB models extend this concept to complex molecules of arbitrary shape by defining an effective Born radius for each atom, which represents its degree of burial within the solute molecule. The generalized form of the equation for multiple atoms is [12]:

ΔGele = -(1/2)(1/εint - 1/εext) × ΣΣ (qi qj / fGB(rij, Ri, R_j))

Where fGB is a function that depends on the distance between atoms (rij) and their effective Born radii (Ri, Rj).

Parameterization and Modern Implementations

The accuracy of GB models heavily depends on the calculation of effective Born radii. Recent developments have focused on parametrizing GB screening parameters to provide better matching of effective radii to reference methods, with pairwise decomposition versions being ideal for GPU implementation with parallel computing [20]. The latest GB models for proteins and nucleic acids have shown significant improvement in achieving agreement with PB electrostatic free energies.

GB models are particularly valuable in molecular dynamics simulations due to their computational efficiency. When combined with SASA-based nonpolar terms in GB/SA approaches, they can produce stable trajectories and improve folding stabilities in protein folding studies [20]. The performance of GB models has been enhanced through GPU implementations, with recent versions achieving nearly 20-fold acceleration compared to CPU versions [20].

Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) Models

Mathematical Framework and Numerical Solutions

The Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) equation provides a more rigorous approach to modeling electrostatic interactions in implicit solvent. It is a differential equation that describes the electrostatic potential around a solute molecule with a dielectric discontinuity at the solute-solvent interface. The general form of the PB equation is [12]:

∇ · [ε(r)∇Φ(r)] = -ρ(r)/ε₀ - Σ ci^b zi q e^(-zi q Φ(r)/kB T)

Where:

- Φ(r) is the electrostatic potential

- ε(r) is the position-dependent dielectric constant

- ρ(r) is the fixed charge density of the solute

- c_i^b is the bulk concentration of ion i

- z_i is the valence of ion i

- q is the unit charge

- k_B is Boltzmann's constant

- T is the temperature

For systems where the exponential term is small, the equation can be linearized to [12]:

∇ · [ε(r)∇Φ(r)] = -ρ(r)/ε₀ + Σ (ci^b zi² q² Φ(r))/(k_B T)

Applications, Challenges, and Recent Advances

PB models are considered the gold standard for electrostatic calculations in implicit solvent modeling due to their theoretical rigor. They are widely used in binding free energy calculations, pKa prediction, and analysis of molecular interactions. However, several challenges limit their application in MD simulations: nonlinearity, dielectric jumps, charge singularity, and geometric complexity make PB solutions computationally demanding [24].

Recent advances include the development of more efficient numerical solvers and machine learning approaches. The second-order accurate MIBPB solver has demonstrated high accuracy, while PB-based machine learning (PBML) models have been developed to provide accurate electrostatic solvation free energies with significantly reduced computational cost [24]. These ML approaches can rapidly predict PB-quality electrostatic solvation energies for new biomolecules or conformations generated by molecular dynamics.

Comparative Analysis of Model Performance

Accuracy and Efficiency in Binding Free Energy Prediction

Comprehensive benchmarks comparing MM/PB(GB)SA methods have been conducted on both soluble and membrane protein systems. These studies evaluate different parameters including ligand charges, protein force fields, GB models, nonpolar optimization methods, and dielectric constants [19]. The results reveal several key insights into the relative performance of these implicit solvent approaches.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Implicit Solvent Methods in Binding Free Energy Prediction

| Method | System Type | Accuracy (RMSE) | Computational Cost | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM/PBSA | Soluble proteins | 1.5-2.5 kcal/mol [19] | High | High accuracy for electrostatic interactions | Slow, computationally expensive |

| MM/GBSA | Soluble proteins | 1.6-2.7 kcal/mol [19] | Medium | Balanced speed/accuracy | Dependent on GB model parameterization |

| MM/PBSA | Membrane proteins | Case-dependent [19] | High | Handles dielectric heterogeneity | Requires membrane-specific parameters |

| MM/GBSA | Membrane proteins | Case-dependent [19] | Medium | Faster than PBSA for membranes | Membrane dielectric constant needs optimization |

| Docking | Both | >3.0 kcal/mol [19] | Low | Very fast | Lowest accuracy |

| FEP | Both | 1.4-2.3 kcal/mol [19] | Very High | Highest theoretical accuracy | Extremely computationally expensive |

Systematic Benchmarking Studies

A notable benchmarking study performed on 140 ligands bound to six soluble proteins and 37 ligands bound to three membrane proteins revealed that MM/PB(GB)SA shows competitive performance with the more rigorous Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) method, while docking scored significantly worse [19]. The study emphasized that parameters for MM/PB(GB)SA calculations need to be optimized for specific systems, with no universal parameter set guaranteeing accuracy across all applications.

For membrane protein systems—particularly important drug targets like GPCRs—specific considerations such as membrane dielectric constants significantly impact the accuracy of both PB and GB models [19]. The performance in these systems is case-dependent, requiring careful parameterization for reliable results.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Protocol for MM/PB(GB)SA Binding Free Energy Calculations

The typical workflow for MM/PB(GB)SA calculations involves multiple stages of system preparation, simulation, and energy analysis:

System Preparation

- Obtain protein-ligand complex structures from crystallography or docking

- Assign protonation states at physiological pH (e.g., pH 7.0)

- Generate ligand charges using appropriate methods (CGenFF, AM1-BCC, RESP-HF, RESP-DFT) [19]

Molecular Dynamics Simulation

- Perform explicit solvent MD simulation to generate conformational ensembles

- Extract snapshots at regular intervals for end-point free energy calculations

Energy Calculation

- Calculate molecular mechanics energy (ΔE_MM) including bond, angle, dihedral, electrostatic, and van der Waals contributions

- Compute polar solvation energy (ΔG_PB/GB) using PB or GB models

- Calculate nonpolar solvation energy (ΔG_SA) using SASA-based methods

- Optionally estimate entropy term (-TΔS), though this is often omitted due to high computational cost and large errors [19]

The binding free energy is then computed as: ΔGbind = ΔEMM + ΔGsolv - TΔS ΔGsolv = ΔGPB/GB + ΔGSA

Protocol for SASA-Based Binding Energy Estimation

For rapid binding affinity estimation using SASA-based models:

Structure Preparation

- Obtain or generate complex structures

- Identify binding interfaces

Buried Surface Area (BSA) Calculation

- Calculate solvent accessible surface area (SASA) for free components and complex

- Compute BSA as: BSA = SASAprotein + SASAligand - SASA_complex

Free Energy Calculation

- Apply empirical relationship: ΔG_binding = γ × BSA

- Use appropriate surface tension parameter (γ), typically in the range of -7 to -25 cal mol⁻¹ Å⁻² [21]

The free energy density γ varies depending on the system and methodology, with values of -15 ± 1.2 cal mol⁻¹ Å⁻² reported for hydrophobic residues, -7 cal mol⁻¹ Å⁻² when considering only ligand burial, and -25 cal mol⁻¹ Å⁻² when considering total hydrophobic burial [21].

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Implicit Solvent Simulations

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Features | Applicable Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | Software Suite | MD simulations with implicit solvent | GPU acceleration, MMPBSA.py, GB/SA implementation | SASA, GB, PB |

| APBS | Software Tool | Electrostatic calculations | Solves PB equation, PDB2PQR conversion | PB |

| MDTraj | Python Library | Trajectory analysis | Shrake-Rupley SASA implementation, efficient analysis | SASA |

| HYDROPRO | Software Tool | Hydrodynamic properties | Calculates hydrodynamic radius, diffusion constants | SASA-based properties |

| g_mmpbsa | GROMACS Tool | MM/PBSA calculations | Integration with GROMACS, automated binding energy | GB, PB, SASA |

| PDB2PQR | Software Tool | Structure preparation | Adds hydrogens, assigns charges, creates PQR files | PB |

| MMPBSA.py | AMBER Tool | Binding free energy | End-point free energy method, trajectory analysis | GB, PB, SASA |

| GSnet | Machine Learning Model | Property prediction | Graph neural network for SASA and pKa prediction | ML-enhanced SASA |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

Machine Learning-Enhanced Implicit Solvent Models

Recent advances integrate machine learning with traditional implicit solvent models to overcome computational limitations. Graph neural networks like GSnet demonstrate remarkable capability in predicting molecular properties including SASA and residue-specific pKa values directly from 3D protein structures [25]. These ML approaches achieve accuracy comparable to simulation-based methods while enabling high-throughput applications across proteome-wide studies.

PB-based machine learning (PBML) models trained with accurate numerical solvers can provide PB-quality electrostatic solvation free energies for biomolecular structures with significantly reduced computational cost [24]. This integration of physical models with data-driven approaches represents a promising direction for maintaining accuracy while dramatically improving efficiency.

Advanced SASA Algorithms and GPU Acceleration

The development of exact analytical methods like dSASA implemented on GPUs addresses longstanding challenges in SASA calculation accuracy and efficiency [20]. These methods enable stable GB/SA MD simulations with inclusion of nonpolar terms, improving the performance of implicit solvent simulations for protein folding and binding studies. The GPU implementation of these algorithms achieves up to 20-fold acceleration compared to CPU versions, making implicit solvent simulations more practical for large biomolecular systems.

Application to Challenging Systems

While implicit solvent models have traditionally excelled with soluble proteins, recent research focuses on extending their applicability to more challenging systems like membrane proteins, nucleic acids, and glycans [19] [12]. For membrane proteins, careful optimization of membrane dielectric constants and other system-specific parameters has shown promising results in benchmarking studies [19]. The development of models that can handle the unique dielectric and solvation properties of these systems remains an active area of research.

SASA, Generalized Born, and Poisson-Boltzmann models represent complementary approaches within the implicit solvent modeling paradigm, each with distinct strengths and optimal application domains. SASA models provide efficient calculation of nonpolar solvation contributions, GB models offer a balanced approach for electrostatic interactions with moderate computational cost, and PB methods deliver high accuracy for electrostatic calculations at greater computational expense.

The choice between these models depends on the specific research requirements, balancing accuracy needs with computational resources. For high-throughput virtual screening, MM/GBSA with SASA-based nonpolar terms often provides the best compromise. For detailed mechanistic studies requiring high electrostatic accuracy, MM/PBSA remains preferable when computational resources permit. Recent advances in machine learning integration and GPU acceleration are blurring these traditional trade-offs, enabling faster simulations without sacrificing accuracy.

As implicit solvent models continue to evolve, their importance in drug discovery and biomolecular simulation is likely to grow, particularly through hybrid approaches that combine physical rigor with data-driven efficiency. These developments will further establish implicit solvent methods as indispensable tools for researchers studying biomolecular structure, function, and interactions.

The accurate modeling of solvent effects is a cornerstone of reliable molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, profoundly influencing the study of biomolecular structure, dynamics, and function. The computational landscape is dominated by two distinct paradigms: explicit solvent models, which treat each solvent molecule individually, and implicit solvent models, which average solvent effects into a continuous polarizable medium [3] [26]. Explicit models are considered the gold standard for realism but carry a prohibitive computational cost, as simulating the thousands of solvent molecules in a typical system requires significant resources [10]. Implicit solvent models emerged as an efficient alternative, dramatically reducing computational expense and accelerating conformational sampling by eliminating solvent viscosity [27] [10]. This guide traces the theoretical evolution from foundational continuum concepts to modern machine-learning-driven formulations, providing a comparative analysis of their performance, applications, and limitations within MD research.

Historical Development of Implicit Solvent Theory

The conceptual foundation of implicit solvation rests on early dielectric theories developed by Onsager and Debye, who first treated solvents as dielectric continua to estimate solvation energies from bulk properties like dielectric constant and molecular polarizability [3]. This established the core principle of partitioning the solvation free energy (( \Delta G_{solv} )) into physically distinct components.

The Born model, a seminal advance, provided an analytical solution for the electrostatic solvation energy of a spherical ion in a continuum dielectric [7]. Its simplicity laid the groundwork for more complex approximations. Subsequent developments introduced the Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) equation, a rigorous framework describing electrostatic interactions between a solute and a dielectric medium with ionic strength effects [3]. While accurate, solving the PB equation numerically remains computationally demanding for large systems.

To address this bottleneck, the Generalized Born (GB) model was developed as an efficient pairwise approximation to the PB formalism [11] [10]. GB models estimate the electrostatic solvation energy using an analytical formula, enabling rapid calculations for large biomolecules. Modern iterations like GB-neck and GB-neck2 have been parameterized to better reproduce PB solvation energies for proteins and nucleic acids [11].

Concurrently, advancements in quantum chemistry spurred the creation of models like the Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM) and the Conductor-like Screening Model (COSMO), which integrate solvation effects directly into electronic structure calculations [3] [28]. The most recent paradigm shift incorporates Machine Learning (ML). ML-based implicit solvent models, such as Graph Neural Network Implicit Solvent (GNNIS) models, are trained on data from explicit-solvent simulations to learn and predict the explicit-solvent effect, offering a new route to achieving high accuracy with the speed of a continuum model [28] [7].

Comparative Performance Analysis of Solvation Models

The performance of implicit solvent models is benchmarked against explicit solvent references and experimental data across various metrics. The following table summarizes key quantitative comparisons.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Implicit vs. Explicit Solvent Models

| Performance Metric | Explicit Solvent (TIP3P, PME) | Generalized Born (GB) Implicit Solvent | Machine Learning Implicit Solvent (GNNIS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Speed | Baseline (1x) | 1x to 100x faster for conformational sampling [27] | Computational speedup comparable to implicit models, but with added training cost [7] |

| Solvation Free Energy Accuracy | High (reference) | Moderate; errors in non-polar component [7] | Near-explicit solvent accuracy for small molecules [7] |

| Conformational Sampling Efficiency | Limited by solvent viscosity | High efficiency due to low viscosity [27] [10] | High efficiency, learns from explicit solvent data [28] |

| Protein Folding Accuracy | Accurate, but computationally intensive | GB-neck2 with ff14SBonlysc folds diverse proteins, better balance than explicit TIP3P in some cases [11] | N/A |

| RNA Stem-Loop Folding | Achieved with specialized force fields | Successful folding of 26 RNA stem-loops to near-native structures (stem RMSD <2 Å) [11] | N/A |

| Handling of Explicit Solvent Effects | Naturally includes specific effects (e.g., H-bonds) | Poor; lacks atomic detail [26] [4] | Good; designed to capture explicit-solvent effects missing from continuum models [28] |

The table shows a clear trade-off. Implicit solvents like GB offer dramatic speedups, between 1-fold and 100-fold for large conformational changes, primarily due to reduced solvent viscosity [27]. This enables the folding of proteins and RNA stem-loops that is challenging with explicit solvents [11]. However, traditional implicit models fail to capture specific solute-solvent interactions, such as hydrogen bonds. ML-based models are emerging to bridge this accuracy gap, with GNNIS demonstrating an ability to reproduce experimental NMR and IR trends that are unattainable by state-of-the-art implicit models like SMD paired with static QM calculations [28].

Table 2: Comparison of Fundamental Solvation Model Types

| Characteristic | Explicit Solvent | Continuum Implicit Solvent (e.g., PB/GB) | Machine-Learned Implicit Solvent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Newtonian mechanics for all atoms | Continuum electrostatics & empirical terms | Data-driven; trained on explicit solvent simulations |

| Solvent Representation | Individual molecules | Dielectric continuum | Mathematical approximation of mean forces |

| Computational Cost | Very High | Low | Low (after training) |

| Sampling Speed | Slow | Fast | Fast |

| Key Strengths | High realism, captures specific effects | Computational efficiency, fast sampling | Balances speed and accuracy for specific effects |

| Key Limitations | Extreme computational demand, slow dynamics | Poor for specific interactions, parameter sensitivity | Training data dependency, generalizability concerns |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Workflow for Developing Machine Learning Potentials for Solvation

The creation of robust MLPs for solvation employs an iterative active learning (AL) strategy to ensure data efficiency and comprehensive coverage of the chemical space [4]. The workflow, depicted in the diagram below, involves several key stages.

Diagram Title: Active Learning Workflow for ML Potentials

Detailed Methodology:

- Initial Data Generation: A small set of initial configurations is generated and labeled with reference energies and forces from quantum chemistry calculations. This typically includes:

- The solute in the gas phase or with an implicit solvent, with geometries sampled by randomly displacing atomic coordinates, often starting from a transition state for reactions.

- Cluster models containing the solute and a limited number of explicit solvent molecules placed at relevant positions, ensuring the solvent shell radius is at least as large as the MLP's cut-off radius [4].

- MLP Training and Validation: An initial MLP is trained on this dataset. Its stability is tested by running short MD simulations (e.g., starting at 2 fs and progressively increasing).

- Active Learning Loop: Structures from the MLP-driven MD are evaluated by a descriptor-based selector, such as Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP). This measures the similarity of new configurations to the existing training set.

- Uncertain/New Configuration: If a structure lies in an under-sampled region of the chemical space (high "uncertainty"), it is added to the training set.

- Well-Represented Configuration: If the structure is similar to existing training data, the MLP is considered reliable for that region.

- Iteration and Production: The process of re-training the MLP with the expanded dataset and running new MD continues until the MLP's predictions converge and no new significant configurations are found. The final, validated MLP is then used for production simulations [4].

Protocol for RNA Folding Simulations with Implicit Solvent

A specific application demonstrating the power of implicit solvent is the de novo folding of RNA stem-loops [11].

- Force Field: The DESRES-RNA force field (an extensive revision of the AMBER RNA force field) or the AMBER-OL3 force field is used.

- Solvation Model: The GB-neck2 implicit solvent model, parameterized for nucleic acids.

- System Preparation: Simulations start from the extended conformations of 26 different RNA stem-loops (10 to 36 residues), with and without bulges or internal loops.

- Simulation Type: Conventional molecular dynamics simulations are run, without enhanced sampling techniques.

- Analysis: Success is measured by the formation of all native base pairs in the stem regions and the calculation of the root mean square deviation (RMSD) relative to experimentally determined structures. Successful folding is defined as achieving RMSD values of <2 Å for stem regions and <5 Å for the entire molecule [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

This section details key computational tools and datasets referenced in the studies, essential for replicating and advancing research in this field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| OMol25 Dataset | Dataset | Provides over 100M high-accuracy quantum chemical calculations for training and benchmarking NNPs [29]. | Used to train Meta's Universal Model for Atoms (UMA); covers biomolecules, electrolytes, and metal complexes [29]. |

| GB-neck2 | Implicit Solvent Model | An optimized Generalized Born model for accurate calculation of solvation energies in biomolecular simulations [11]. | Successfully used in folding proteins and RNA stem-loops with the AMBER force field [11]. |

| DESRES-RNA Force Field | Molecular Force Field | An extensively refined AMBER force field for RNA that accurately reproduces energetics of base stacking and pairing [11]. | Combined with GB-neck2 or TIP4P-D water for successful RNA folding simulations [11]. |

| Graph Neural Network Implicit Solvent (GNNIS) | Machine Learning Model | A graph neural network that learns explicit-solvent effects from MD data to correct continuum model predictions [28]. | Transfers knowledge from MM to QM, applicable to various organic solvents without needing QM/MM training data [28]. |

| Open-Molman | Software Library | An open-source toolkit containing implementations of modern NNP architectures like eSEN and UMA [29]. | Provides pre-trained models for molecular modeling on datasets like OMol25 [29]. |

| AMBER | MD Software Package | A suite of biomolecular simulation programs that includes implementations of various force fields and implicit solvent models like GB-neck2 [11]. | Widely used for MD simulations of proteins and nucleic acids in explicit and implicit solvent [27] [11]. |

| LSNN (λ-Solvation Neural Network) | Machine Learning Model | A GNN trained to match forces and derivatives of alchemical variables, enabling accurate solvation free energy calculations [7]. | Overcomes the limitation of standard force-matching by ensuring energy predictions are suitable for absolute free energy comparisons [7]. |

The journey from the foundational Born model to modern analytical formulations illustrates a consistent drive to balance computational efficiency with physical accuracy in solvation modeling. While classical continuum models like PB and GB remain vital tools for large-scale conformational sampling, the frontier of the field is being reshaped by machine learning. ML-based implicit solvent models, trained on massive datasets like OMol25 or knowledge transferred from classical simulations, represent a paradigm shift. They promise to capture the explicit-solvent effects that have long been the Achilles' heel of continuum approaches, potentially offering a new generation of models that do not force a strict choice between accuracy and speed. For researchers in drug development and biophysics, this evolution opens the door to more reliable and ambitious simulations of biomolecular processes in their native aqueous environments.

Implementing Solvent Models: Methodologies and Practical Applications in Biomedicine

Implicit solvent models provide a computationally efficient framework for modeling solvation effects in molecular simulations by replacing the explicit simulation of solvent molecules with a continuum mean-field approximation. This approach drastically reduces the number of particles in a simulation system, lowering computational cost and accelerating conformational sampling. [7] [11] Within this paradigm, the Generalized Born Surface Area (GB/SA) and Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (PBSA) frameworks have emerged as two of the most popular methods for calculating binding affinities and solvation free energies in drug discovery and biomolecular research. [30] These end-point methods, notably Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) and Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA), are widely used for predicting protein-ligand binding free energies, helping to reduce costs and accelerate early-stage drug development. [31] [7] This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these frameworks, their performance, and their implementation within the AMBER and CHARMM software suites.

Theoretical Foundations of GB/SA and PBSA

Both MM/GBSA and MM/PBSA methods calculate the binding free energy (ΔG_bind) of a complex in solution as the difference between the free energy of the complex and its isolated receptor and ligand components. The general equation is:

ΔGbind = Gcomplex - (Greceptor + Gligand)

The free energy for each entity (complex, receptor, ligand) is estimated as a sum of molecular mechanics energy, polar solvation energy, and non-polar solvation energy:

G = EMM + Gsolv = (Eint + Eele + Evdw) + (Gpol + G_np) [30]

Here, EMM is the molecular mechanics gas-phase energy, comprising internal (Eint), electrostatic (Eele), and van der Waals (Evdw) components. Gsolv is the solvation free energy, decomposed into a polar (Gpol) contribution and a non-polar (G_np) contribution. [30]

The key difference between MM/GBSA and MM/PBSA lies in the treatment of the polar solvation term, G_pol, while the non-polar term is typically modeled using the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA).

- Polar Solvation (Gpol) in PBSA: The PBSA method uses the Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) equation to compute Gpol. The PB equation is an electrostatic continuum model that numerically solves for the electrostatic potential of a solute embedded in a dielectric continuum, providing a rigorous and theoretically sound solution. However, this numerical calculation is computationally demanding. [30] [32]

- Polar Solvation (Gpol) in GBSA: The GBSA method approximates the solution of the PB equation using the Generalized Born (GB) model. The GB model provides an analytical approximation for Gpol, which is significantly faster to compute but relies on empirical parameters and can be less accurate for certain systems, particularly those with complex electrostatic environments. [30] [32] [11]

- Non-Polar Solvation (Gnp): Both methods often use a SASA-based term for the non-polar contribution, which accounts for cavity formation and van der Waals interactions between the solute and solvent. The general form is Gnp = γ × SASA + b, where γ is a surface tension coefficient and b is a constant. [30] [33] It is worth noting that the specific parameters for this equation can differ between PB and GB calculations within the same software package. [34]

The following workflow diagram illustrates how these components are integrated in a typical binding free energy calculation.

Performance Comparison: Accuracy, Speed, and Applicability

The choice between MM/GBSA and MM/PBSA involves a trade-off between computational speed and accuracy, which can vary significantly depending on the system and parameters.

Quantitative Performance Data

The table below summarizes key findings from a recent head-to-head comparison study on the CB1 cannabinoid receptor and other systems.

| Performance Metric | MM/GBSA | MM/PBSA | System / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation with Experiment (Pearson's r) | 0.433 - 0.652 [31] | 0.100 - 0.486 [31] | CB1 receptor ligands (46 compounds) [31] |

| Calculation Speed | Faster [31] [32] | Slower [31] [32] | GB is an analytical approximation; PB requires numerical solving [31] |

| Result Agreement | Can show large differences [32] | Can show large differences [32] | Example: GB=-57.25 vs. PB=-2.53 kcal/mol for a protein-ligand complex [32] |

| SASA Calculation | Uses surften (e.g., 0.0072) & surfoff [34] |

Uses cavity_surften (e.g., 0.0378) & cavity_offset [34] |

Different non-polar models in AMBER can cause SASA value differences [34] |

| Solute Dielectric Constant (ε_in) | Improved correlations with larger values (ε=2,4) [31] | Improved correlations with larger values (ε=2,4) [31] | System-dependent; higher ε_in can better capture polarization [31] |

Critical Performance Factors

Several parameters critically influence the performance of both methods:

- Sampling and Starting Structures: Using ensembles from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations consistently provides better results than using single, energy-minimized structures. [31]

- Solute Dielectric Constant (εin): The choice of the internal dielectric constant is highly system-dependent. Studies on the CB1 receptor showed that improved correlations with experimental binding affinities were observed with larger εin values (2 or 4) compared to a value of 1. [31]

- Entropy Compensation: The incorporation of entropic terms (usually calculated via normal mode or quasi-harmonic analysis) is computationally expensive and often fails to improve, or can even degrade, the correlation with experimental data. [31]

- GB Model Variants: Within the GB framework, the choice of specific model (e.g., GBHCT, GBOBC1, GBOBC2, GBNeck, GBNeck2) can exert a varying effect on the results, and no single model is universally superior. [31]

- Non-Polar Model: The treatment of the non-polar solvation term is a significant source of variation. As noted in AMBER documentation, MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA can use different equations and parameters for this term, leading to different SASA values and final results. [34]

Software Implementation: AMBER vs. CHARMM

Implementation in AMBER

The AMBER software package provides extensive and well-documented support for both MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA calculations, primarily through the MMPBSA.py and gmx_MMPBSA tools. [31] [30]

- Force Field Compatibility: While AMBER force fields are native,

MMPBSA.pycan be used with CHARMM-generated topologies converted via thechambertool. However, caution is advised as this combination is less tested. [35] - GB Model Selection: AMBER offers multiple GB models (

igbkeyword).igb=5(GBOBC1) is often cited as a preferred model for its balance of accuracy and speed, though the optimal choice may be system-dependent. [31] [35] - PBSA Radii Setting: When using non-AMBER force fields, it is recommended to use

radiopt=0to employ the intrinsic atomic radii from the force field, as the optimized radii (radiopt=1) are parameterized specifically for AMBER atom types. [35] - SASA Algorithms: AMBER has evolved through several SASA algorithms:

- LCPO: A fast CPU-based algorithm, but can become a bottleneck in GPU-accelerated simulations due to CPU/GPU data transfer. [33]