Explicit vs. Implicit Solvent Models in MD: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomolecular Simulation and Drug Design

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are indispensable for understanding biomolecular structure and function, but the choice of solvent model critically impacts the accuracy and feasibility of these studies.

Explicit vs. Implicit Solvent Models in MD: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomolecular Simulation and Drug Design

Abstract

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are indispensable for understanding biomolecular structure and function, but the choice of solvent model critically impacts the accuracy and feasibility of these studies. This article provides a rigorous comparison of explicit and implicit solvent models for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational theories of both approaches, details their methodological applications in areas like protein folding and ligand binding, and offers practical guidance for troubleshooting common pitfalls. By synthesizing recent advances, including machine learning-augmented models and high-accuracy explicit methods, this review serves as a strategic resource for selecting and optimizing solvent models to achieve reliable results in biomedical research.

Understanding the Core Principles: From Discrete Molecules to Continuum Dielectrics

In the field of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the choice between explicit and implicit solvent models represents a fundamental trade-off between computational accuracy and efficiency. This guide objectively compares these paradigms, supported by experimental data, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the appropriate tool for their investigations.

Molecular dynamics simulations have become an established technique in structural biology, complementing experimental approaches [1]. The treatment of solvation—how water and ions surrounding a biomolecule are modeled—is a critical determinant of simulation success and reliability. Explicit solvent models atomistically represent individual water molecules and are widely considered the gold standard for accuracy. In contrast, implicit solvent models treat the solvent as a dielectric continuum, offering significant computational advantages by approximating solvation effects without simulating every solvent molecule [1]. While implicit models like Generalized Born (GB) are faster and easier to set up, their ability to reproduce experimentally observed structures varies considerably across different force fields and biological systems [1].

Experimental Comparison: A Systematic Investigation

Benchmark Study on Peptide Helical Content

A 2022 systematic investigation tested the performance of implicit solvent models using five experimentally characterized peptides with differing α-helical content [1]. The study evaluated 65 combinations of force fields and GB models in over 800 μs of molecular dynamics simulations.

Methodology:

- Peptide Systems: Five de novo peptides comprising alternating blocks of glutamate (Glu, E) and lysine (Lys, K) with experimentally determined helical contents ranging from 19% to 92% [1].

- Simulation Conditions: Replicated experimental conditions (278.15 K, ionic concentration of 0.137 mol/L); peptides were N-terminally acetylated and C-terminally amidated with Glu and Lys side chains treated as fully ionized [1].

- GB Models Tested: Five AMBER GB models: igb1 (Hawkins, Cramer, Truhlar), igb2 (Onufriev, Bashford, Case), igb5 (modified igb2), igb7 (GBn by Mongan et al.), and igb8 (modified GBn by Nguyen et al.) [1].

- Force Fields Evaluated: Thirteen AMBER force fields including ff94, ff96, ff98, ff99, ff99SB, ff99SBildn, ff99SBnmr, ff03.r1, ff14SB, ff14SBonlysc, ff14ipq, fb15, and ff15ipq [1].

- Simulation Protocol: Each system underwent 6 μs simulations after minimization, heating, and equilibration, with the first 250 ns discarded as equilibration [1].

The table below summarizes key findings from this comprehensive study:

Table 1: Performance of Selected Force Field-GB Model Combinations on Peptide A4(K4E4)1A4 (92% Experimental Helicity)

| Force Field | GB Model | Median α-Helicity | Performance Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| ff99SBnmr | igb5 | ~87% | Best performance, slight terminal unfolding |

| ff94 | Multiple | >75% | Consistently captured helical structure |

| ff98 | Multiple | >75% | Consistently captured helical structure |

| ff14SBonlysc | igb8 | Minimal | Failed to maintain starting α-helix |

| ff14ipq | Multiple | <50% | Poor performance across GB models |

| ff15ipq | Multiple | <50% | Poor performance across GB models |

| fb15 | Multiple | <50% | Poor performance across GB models |

| ff96 | igb5 | ~83% | Good helicity capture |

| ff96 | igb8 | β-hairpin formation | Incorrect structural prediction |

Critical Findings and Limitations

The investigation revealed that GB models generally did not reproduce the experimentally observed α-helical content, with none performing well for all five peptides [1]. The results demonstrated extreme sensitivity to both the GB model and force field combination, with some systems predicting completely incorrect secondary structures like β-sheets despite no experimental evidence for these states [1]. The authors concluded that these implicit solvent models were "not usefully predictive in this context" [1].

Explicit Solvent: The Verified Gold Standard

Demonstrated Accuracy for Complex Systems

Unlike implicit models, explicit solvent simulations have successfully reproduced experimental helicities for charged peptide systems, including naturally occurring ER/K motifs (alternating repeats of Glu and Lys or Arg) [1]. These motifs form stable α-helical structures in the absence of tertiary interactions, and MD simulations with explicit TIP3P water models have accurately captured their experimental behavior [1].

In DNA simulations, explicit solvent models with the ff99 force field have provided excellent agreement with experimental data from x-ray crystallography and NMR for canonical DNA structures [2]. Furthermore, combined quantum-mechanical/molecular-mechanical approaches have verified that molecular-mechanical force fields with explicit solvent can reliably describe both backbone and base-base interactions within highly distorted nucleic acid structures produced by stretching DNA [2].

Robust Force Field Validation

A systematic evaluation of force fields against NMR experiments revealed that explicit solvent simulations achieve high accuracy when paired with optimized force fields [3]. The study evaluated 524 NMR measurements (chemical shifts and J couplings) across dipeptides, tripeptides, tetra-alanine, and ubiquitin, finding that explicit solvent simulations with ff99sb-ildn-phi and ff99sb-ildn-nmr force fields recovered NMR observables with accuracy close to the uncertainty inherent in comparison methods [3].

Implicit Solvent: Context-Dependent Utility

Specific Applications Where GB Models Succeed

Despite limitations in peptide folding predictions, implicit solvent models have demonstrated value in specific contexts:

Table 2: Successful Applications of Implicit Solvent Models

| Application Area | Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Mini-protein Folding | OBC I and OBC II GB methods yielded >30% native structure population for chignolin in multicanonical MD simulations | [4] |

| Protein-Peptide Binding Affinity | MM/GBSA with ff03 force field and GBOBC1 model showed good correlation (rp = 0.735) with experimental data for medium-size peptides | [5] |

| Binding Pose Prediction | MM/GBSA with ff03 force field outperformed specialized protein-peptide docking algorithms in recognizing near-native binding poses | [5] |

Computational Efficiency Advantages

The primary advantage of implicit solvent models remains their significantly reduced computational cost by avoiding explicit representation of numerous water molecules [1]. This efficiency enables more rapid conformational sampling, making implicit solvents potentially attractive for protein design pipelines that must evaluate many constructs [1]. Additionally, because protein dynamics are not damped by solvent viscosity in implicit models, conformational space sampling is accelerated [1].

Methodological Protocols

Explicit Solvent Simulation Protocol

For the DNA stretching studies that validated explicit solvent approaches [2]:

- System Preparation: DNA structures built using NUCGEN module in AMBER, neutralized with potassium counterions, and solvated in an elongated rectangular periodic box with 31,000+ water molecules [2].

- Electrostatics: Particle mesh Ewald method for long-range electrostatic interactions [2].

- Constraints: All covalent bonds to hydrogen constrained with SHAKE, allowing 2 fs integration timestep [2].

- Ensemble: Constant temperature (298 K) and pressure (1 atm) using velocity rescaling thermostat and Parrinello-Rahman barostat [2].

- Equilibration: Multistage protocol including 1 ns thermalization and equilibration before production simulations [2].

Implicit Solvent Simulation Protocol

For the GB model evaluation on peptide systems [1]:

- Solvent Models: Five GB models (igb1, igb2, igb5, igb7, igb8) tested with 13 different force fields [1].

- Simulation Setup: Peptides N-terminally acetylated and C-terminally amidated, starting from fully α-helical structures [1].

- Conditions: 278.15 K, ionic concentration of 0.137 mol/L to mimic phosphate buffered saline [1].

- Simulation Length: 6 μs per system with first 250 ns discarded as equilibration [1].

- Analysis: 5,750 frames (saved every 1 ns) analyzed for each peptide [1].

Experimental Validation Workflow for Solvent Models

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Solvent Modeling Research

| Tool Name | Type | Function | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | MD Software Suite | Implements multiple GB models and force fields | Used in key benchmarking studies [1] |

| TIP3P | Explicit Water Model | Three-site water model for explicit solvation | Successful with ER/K motif peptides [1] |

| GBOBC (igb5, igb8) | Implicit Solvent Model | Onufriev, Bashford, Case GB model with rescaling functions | Among best-performing GB variants [1] |

| ff99SBnmr | Force Field | Optimized for NMR data reproduction | Best performance with igb5 for helical peptides [1] |

| ff99SB-ildn | Force Field | Side chain and backbone torsion modifications | High accuracy for NMR observables [3] |

| ff14SB | Force Field | Updated AMBER protein force field | Better with explicit solvent than implicit [1] |

| PLUMED | Enhanced Sampling Plugin | Implements metadynamics and collective variables | Used in nucleobase dimer studies [6] |

| MM/PBSA & MM/GBSA | End-Point Methods | Calculate binding free energies from MD trajectories | Useful for protein-peptide complexes [5] |

The paradigm defining explicit solvent as the gold standard and implicit solvent as an efficient approximation remains fundamentally valid based on current experimental evidence. Explicit solvent simulations provide superior accuracy and reliability across diverse biological systems, from maintaining secondary structure in designed peptides to modeling distorted DNA conformations. Implicit solvent models offer computational efficiency but demonstrate inconsistent performance that is highly dependent on specific force field combinations and system characteristics. For research requiring high confidence in structural predictions, explicit solvents are recommended, while implicit models may serve specialized applications where their limitations are understood and their computational advantages are necessary.

In molecular dynamics (MD) research, accurately representing the solvent environment—typically water—is crucial for simulating biologically relevant processes. The central challenge lies in balancing computational cost with physical accuracy. This has led to two principal approaches: explicit solvent models, which simulate individual water molecules and are considered the gold standard for accuracy but are immensely computationally expensive, and implicit solvent models, which treat the solvent as a continuous medium, offering a faster, albeit sometimes less precise, alternative [7] [8]. Implicit solvation provides a computationally efficient framework to model solvation effects by approximating the mean forces exerted by the solvent, thus eliminating the need to simulate countless solvent molecules [7]. This guide provides a objective comparison of the dominant implicit solvent models, their performance, and the emerging machine-learning methodologies that are reshaping the field.

Classical Implicit Solvation Theories

The goal of implicit solvation is to calculate the solvation free energy (ΔGsolv), which is the free energy change associated with transferring a solute from a vacuum to a solvent [9]. Classical theories decompose this energy into polar (electrostatic) and non-polar contributions.

Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) Model

The Poisson-Boltzmann equation is a fundamental physics-based model for calculating the electrostatic component of solvation. It describes the electrostatic potential around a solute molecule immersed in a solvent containing ions [9].

Theoretical Foundation: The PB equation is expressed as: [ \vec{\nabla} \cdot \left[\epsilon(\vec{r}) \vec{\nabla} \Psi(\vec{r})\right] = -\rho^{f}(\vec{r}) - \sum{i} c{i}^{\infty} z{i} q \lambda(\vec{r}) e^{\frac{-z{i} q \Psi(\vec{r})}{kT}} ] Where (\epsilon(\vec{r})) is the dielectric constant, (\Psi(\vec{r})) is the electrostatic potential, (\rho^{f}(\vec{r})) is the fixed charge density, (c{i}^{\infty}) and (z{i}) are the bulk concentration and valence of ion i, and (\lambda(\vec{r})) is a function defining the accessibility of the position (\vec{r}) to ions [9].

Applications and Protocols: The PB equation is typically solved numerically using software like APBS (Adaptive Poisson-Boltzmann Solver) [10]. A standard protocol involves:

- Preparing the molecular structure and assigning atomic charges and radii.

- Defining the dielectric boundary, often with the solute interior having a low dielectric constant (e.g., 2-4) and the solvent a high one (e.g., 80).

- Setting ion concentrations and temperature to match physiological conditions.

- Solving the PB equation on a grid to obtain the electrostatic potential and subsequently, the polar solvation energy [10] [11].

Generalized Born (GB) Model

The Generalized Born model is a popular approximation to the PB equation, offering a good balance of accuracy and computational speed. It models the solute as a set of spheres interacting via a Coulomb potential with a distance-dependent dielectric function [9].

Theoretical Foundation: The fundamental equation for the polar solvation energy in the GB model is: [ G{s} = -\frac{1}{8\pi \epsilon{0}} \left(1 - \frac{1}{\epsilon}\right) \sum{i,j}^{N} \frac{q{i} q{j}}{f{GB}} ] Where ( f{GB} = \sqrt{r{ij}^{2} + a{ij}^{2} e^{-D}} ) and ( D = \left( \frac{r{ij}}{2a{ij}} \right)^{2} ), ( a{ij} = \sqrt{a{i} a{j}} ). Here, (qi) and (ai) are the charge and Born radius of atom i, and (r_{ij}) is the distance between atoms i and j [9].

Applications and Protocols: GB is widely used in MD simulations and binding free energy calculations (MM/GBSA). A typical workflow involves:

- Pre-computing or estimating the Born radii for each atom, which represent their degree of burial within the solute.

- Using the Born radii and interatomic distances to calculate the effective electrostatic screening between every pair of atoms during an MD simulation or energy calculation [12] [11].

Non-Polar Contributions and Solvent-Accessible Surface Area (SASA)

The non-polar contribution to solvation arises from cavity formation and van der Waals interactions. It is often modeled as being proportional to the Solvent-Accessible Surface Area (SASA) [11] [9]. [ \Delta G{\text{non-polar}} = \sum{i} \sigma{i} \cdot \text{SASA}{i} ] Where (\sigma_{i}) is an atom-specific parameter [9]. Models that combine GB for the polar part and SASA for the non-polar part are referred to as GBSA (Generalized Born Surface Area) models [7] [12].

Table 1: Core Components of Classical Implicit Solvent Models.

| Model Component | Theoretical Basis | Primary Function | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) | Continuum electrostatics with ionic solution | Calculate polar solvation energy | Dielectric constants, ion concentration, atomic radii |

| Generalized Born (GB) | Approximation of PB for spheres | Efficiently estimate polar solvation energy | Born radii, effective Coulomb screening |

| SASA | Empirical linear energy relations | Estimate non-polar solvation energy | Atom-specific solvation parameters ((\sigma_i)), surface area |

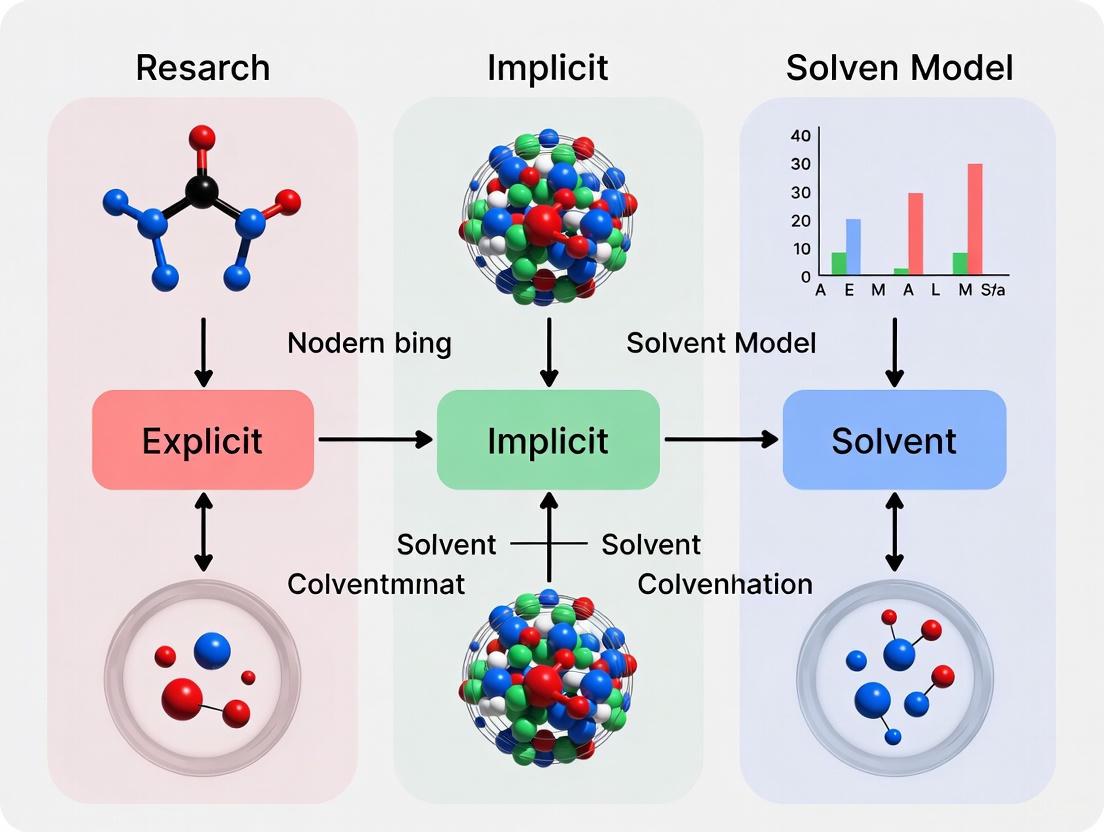

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and computational workflow between these core components when applied to a solute molecule.

Diagram 1: Workflow of implicit solvation energy calculation.

Quantitative Model Performance Comparison

The performance of implicit solvent models is routinely benchmarked against explicit solvent calculations and experimental data.

Accuracy in Solvation and Binding Energy Calculations

Studies consistently show that the performance of implicit models is system-dependent and sensitive to parameterization.

Table 2: Accuracy comparison of implicit solvent models for small molecules and protein-ligand binding.

| System Tested | Model | Performance Metric | Result | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 104 Small Molecules [10] | PCM, GB, COSMO, PB | Correlation with explicit solvent energies | R = 0.82 - 0.97 | All models show high correlation for small molecules. |

| 104 Small Molecules [10] | PCM, GB, COSMO, PB | Correlation with experimental hydration energies | R = 0.87 - 0.93 | Good agreement with experiment for small molecules. |

| 15 Protein-Ligand Complexes [10] | PCM, GB, COSMO, PB | Deviation from explicit solvent desolvation energies | Up to 10 kcal/mol | Substantial errors in binding desolvation penalties. |

| 59 Ligands, 6 Proteins (MM/GBSA) [12] | GB (Onufriev & Case) | Success in ranking binding affinities | Most Successful | Performance varies; this specific GB model was best for ranking. |

| 59 Ligands, 6 Proteins (MM/PBSA) [12] | PB | Accuracy in absolute binding free energies | Better than MM/GBSA | More accurate for absolute values, but computationally heavier. |

Computational Efficiency and Practical Considerations

A key advantage of implicit models is their computational speed. While explicit solvent simulations might require simulating tens of thousands of water molecules, implicit models reduce this to a calculation of the solute's interaction with a continuum [7] [8]. Among implicit models, GB is generally 2-3 orders of magnitude faster than numerical PB solvers, making it the preferred choice for long MD simulations or high-throughput screening [10]. However, the choice of model often involves a trade-off:

- Solute Dielectric Constant: Predictions are highly sensitive to the solute dielectric constant ((\epsilon_{in})). This parameter must be carefully determined based on the characteristics of the binding interface [12].

- Conformational Sampling: While implicit solvents speed up sampling by reducing viscosity, this can also lead to unrealistic kinetics. Furthermore, entropy calculations can show large fluctuations and require extensive sampling for stable predictions [12].

- Limitations: Implicit models struggle with specific effects like ion specificity, heterogeneous interfaces (e.g., membranes), and entropic contributions from the solvent itself, such as the hydrophobic effect [8] [9].

Beyond the Classics: Machine Learning and Hybrid Approaches

Traditional implicit models have well-documented limitations. A major drawback of even ML-based solvation models is their reliance on force-matching alone, which leaves the energy defined only up to an arbitrary constant, making them unsuitable for absolute free energy comparisons [7]. Recent research is focused on overcoming these challenges.

Machine Learning-Augmented Implicit Solvation

Machine learning (ML) is being used to develop more accurate and data-efficient potentials.

- ML-Corrected Models: One approach uses ML as a surrogate for PB, learning solvent-averaged potentials for MD, or supplying residual corrections to GB/PB baselines [8]. For example, the LSNN (λ-Solvation Neural Network) model goes beyond simple force-matching. It is a graph neural network trained to match both forces and derivatives of alchemical variables ((\lambda{elec}), (\lambda{steric})), ensuring that solvation free energies can be meaningfully compared across molecules [7].

- ML for Solubility Prediction: Models like FastSolv use static molecular embeddings trained on large datasets (e.g., BigSolDB) to predict a molecule's solubility in various organic solvents with high accuracy, which is crucial for drug synthesis and formulation [13].

- Universal Models and Datasets: The release of massive datasets like OMol25 (with over 100 million quantum chemical calculations) and pre-trained models like the Universal Model for Atoms (UMA) are establishing new benchmarks. These models demonstrate performance matching high-accuracy DFT on molecular energy benchmarks, making them powerful tools for applications previously limited by computational cost [14].

Explicit Solvation with Machine Learning Potentials

A parallel frontier involves using ML potentials to model explicit solvents, offering accuracy near quantum mechanics but at a fraction of the cost. A 2024 study presented a general strategy using active learning (AL) with descriptor-based selectors to build efficient training sets for reactions in explicit solvents [15]. This approach was successfully applied to a Diels-Alder reaction in water and methanol, yielding reaction rates in agreement with experimental data and allowing detailed analysis of solvent effects on the mechanism [15].

The workflow for developing such potentials, which combines the strengths of explicit solvent representation with the speed of ML, is illustrated below.

Diagram 2: Active learning workflow for ML potentials in explicit solvent.

Table 3: Key Software, Datasets, and Models for Modern Solvation Research.

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Solvation |

|---|---|---|---|

| APBS [10] | Software | Numerical PB Solver | High-accuracy reference for polar solvation energy. |

| DISOLV, GBNSR6 [10] | Software | GB and other Implicit Model Implementations | Fast, accurate calculation of solvation energies for ligands/proteins. |

| MM/PBSA & MM/GBSA [12] | Computational Method | Binding Free Energy Estimation | End-to-end protocol for ranking protein-ligand binding affinities. |

| BigSolDB [13] | Dataset | Experimental Solubility Data | Training and benchmarking for solubility prediction models. |

| OMol25 Dataset [14] | Dataset | Quantum Chemical Calculations | Massive dataset for training generalist ML potentials (biomolecules, electrolytes). |

| UMA / eSEN Models [14] | Pre-trained ML Model | Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | Fast, accurate energy/force predictions for diverse molecular systems. |

| Active Learning Selectors [15] | Algorithm | Uncertainty Quantification | Enables data-efficient training of ML potentials for explicit solvent reactions. |

The field of implicit solvation is in a dynamic state of evolution. Classical models like Poisson-Boltzmann and Generalized Born remain vital tools, with GB offering the best practical combination of speed and accuracy for many applications like MD and MM/GBSA. However, the future lies in hybridization and intelligent automation. The integration of machine learning is proving to be a paradigm shift, both for creating next-generation implicit models capable of predicting absolute free energies and for making explicit solvent simulations at quantum mechanical accuracy tractable for complex systems in solution. For researchers in drug development, this progression promises increasingly reliable and rapid predictions of solvation and binding, ultimately accelerating the design of new therapeutics.

The accurate calculation of solvation free energies (ΔGsolv) constitutes a cornerstone of computational chemistry and drug design, directly influencing processes ranging from protein-ligand binding and protein folding to the prediction of physicochemical properties critical to pharmaceutical development [16] [11] [17]. The efficacy of a drug candidate, for instance, is profoundly affected by its solubility and bioavailability, properties governed by its interaction with aqueous environments [17]. At its core, solvation free energy represents the free energy change associated with transferring a solute molecule from the gas phase into a solvent. The computation of this property, however, presents a significant challenge, primarily revolving around the treatment of the solvent environment.

Two fundamental philosophies guide this treatment: explicit and implicit solvent models. Explicit models atomistically represent solvent molecules, providing a detailed picture of solute-solvent interactions at the cost of dramatically increased computational demand due to the many additional degrees of freedom [18] [15]. Implicit models, in contrast, represent the solvent as a continuous dielectric medium, offering substantial computational efficiency and smoother energy surfaces, thereby facilitating tasks like conformational sampling [11] [19]. A persistent question in the field, which frames this review, is how these different approaches handle the physical decomposition of solvation free energy into its constituent parts—polar, non-polar, and cavitation contributions. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the protocols, performance, and underlying assumptions of explicit and implicit solvent methodologies for decomposing solvation free energy, equipping researchers with the knowledge to select the appropriate tool for their investigations.

Theoretical Framework: Decomposing Solvation Free Energy

The process of solvation is conceptually and computationally decomposed into distinct stages, each associated with a specific thermodynamic contribution. While the overall solvation free energy (ΔGsolv) is a state function, its components are pathway-dependent [16]. Nevertheless, a standard decomposition proves invaluable for interpretation and model development.

The most prevalent framework breaks down ΔGsolv into non-polar and electrostatic components [16] [11]. The non-polar contribution (ΔGnon-polar) itself contains two primary elements:

- Cavitation (ΔGcav): The free energy required to create a cavity in the solvent to accommodate the solute molecule.

- van der Waals Interactions (ΔGvdW): The attractive and repulsive dispersive interactions between the solute and the solvent molecules once the cavity is formed.

The electrostatic contribution (ΔGele) involves the free energy change from charging the solute within the newly formed cavity [16] [11]. This can be summarized as: ΔGsolv = ΔGnon-polar + ΔGele ≈ (ΔGcav + ΔGvdW) + ΔGele

Table 1: Theoretical Components of Solvation Free Energy

| Component | Description | Physical Origin |

|---|---|---|

| Cavitation (ΔGcav) | Energy cost to create a solute-sized cavity in the solvent. | Primarily entropic, related to solvent reorganization. |

| van der Waals (ΔGvdW) | Dispersion/repulsion energy between solute and solvent. | Induced dipole-dipole interactions. |

| Electrostatic (ΔGele) | Energy change from polarizing the solvent with the solute's charge. | Coulombic interactions between solute charges and solvent dielectric. |

This decomposition is not merely theoretical; it is operationalized differently by explicit and implicit solvent models, leading to variations in interpretation and accuracy.

Methodological Comparison: Explicit vs. Implicit Solvent Protocols

Explicit Solvent Models

Explicit solvent models use atomistic simulations, such as Molecular Dynamics (MD) or Monte Carlo, with thousands of discrete solvent molecules. The decomposition of ΔGsolv is typically achieved through thermodynamic integration (TI) or free energy perturbation (FEP) by defining a non-physical pathway [16] [20].

A common protocol involves a two-step decoupling process:

- Decharge: The electrostatic charges of the solute are gradually turned off (scaled by a coupling parameter λelec from 1 to 0) while the van der Waals interactions remain fully active. The free energy change for this step approximates -ΔGele.

- Vanish: The van der Waals interactions of the now-uncharged solute are gradually turned off (λvdW from 1 to 0), effectively removing the solute's physical presence from the solvent. The free energy change for this step corresponds to the non-polar component (ΔGcav + ΔGvdW).

Advanced techniques like Grid Inhomogeneous Solvation Theory (GIST) map these thermodynamic quantities onto a 3D grid around the solute, providing a spatial decomposition of solvation thermodynamics [20]. PME-GIST, which uses the Particle Mesh Ewald method for long-range electrostatics, has shown remarkable agreement with TI, with R² = 0.99 and a mean unsigned difference of 0.4 kcal/mol for a set of small molecules [20].

Implicit Solvent Models

Implicit solvent models forgo explicit solvent molecules, instead representing the solvent as a continuum with a defined dielectric constant (e.g., ε = 78.4 for water). The decomposition is handled by separate terms in an energy function.

Electrostatic Component (ΔGele): This is calculated by solving the Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) equation or, more commonly for efficiency, using a Generalized Born (GB) model [21] [11]. These methods compute the electrostatic work of charging the solute in the presence of the dielectric continuum.

Non-Polar Component (ΔGnon-polar): This is most frequently estimated using a simple model based on the Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) [11] [22]. The formula is typically: ΔGnon-polar = γ × SASA + b where γ is a surface tension parameter and b is a constant [11]. This single term aims to capture the combined effects of cavitation and van der Waals interactions, a significant simplification compared to explicit models. Some modern implicit models, such as the ESE (easy solvation evaluation) approach, introduce additional correction terms, including a volume-dependent component (ζV) to better account for these effects [21].

Table 2: Comparison of Solvation Free Energy Calculation Methodologies

| Feature | Explicit Solvent Models | Implicit Solvent Models |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Representation | Atomistic (many explicit molecules) | Dielectric Continuum |

| Key Methods | Thermodynamic Integration (TI), Free Energy Perturbation (FEP), GIST | Poisson-Boltzmann (PB), Generalized Born (GB), SASA |

| Treatment of ΔGele | Calculated via coupling parameter λelec during simulation | Solved numerically (PB) or analytically (GB) |

| Treatment of ΔGnon-polar | Calculated via coupling parameter λvdW; separates cavitation and vdW | Modeled via SASA (or SASA+V) as a single combined term |

| Computational Cost | Very High | Low to Moderate |

| Sampling Challenge | High (requires extensive conformational sampling) | Low (instantaneous response) |

| Handling of Specific Solute-Solvent Interactions | Excellent (e.g., H-bonds) | Poor |

The workflow below illustrates the logical relationship between the fundamental question of solvation free energy, the two primary modeling approaches, and their associated techniques for decomposition.

Performance and Experimental Data Comparison

Quantitative comparisons reveal the strengths and weaknesses of each approach. A 2017 study in the Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation compared implicit and explicit models against experimental solvation free energies for organic molecules in organic solvents, finding that "all the implicit models they tested were in worse agreement with experiment than an explicit model, in some cases substantially worse" [23].

The performance gap is particularly notable for the non-polar component. Explicit solvent models like TI can capture the complex balance between the energetically unfavorable cavitation penalty and the favorable van der Waals interactions. In contrast, the SASA model's simple linear approximation is a known source of error [16] [11]. Research on proximal distribution functions (pDFs) has shown that while SASA-based methods can roughly approximate ΔGvdW, they struggle with chemical accuracy, whereas pDF-reconstruction from explicit simulations can achieve ~1 kcal/mol accuracy compared to benchmark TI [16].

For the electrostatic component, Linear Response Theory (LRT), which approximates ΔGele as half of the average solute-solvent electrostatic interaction energy from an explicit simulation, often provides a good estimate [16]. Implicit models like COSMO and GB are also based on a linear response approximation and can perform well for polar molecules, though they fail to capture non-linear effects such as those from strong, specific hydrogen bonding [21] [18].

Table 3: Experimental Data and Performance Benchmarks

| System / Molecule Type | Explicit Model Result | Implicit Model Result | Experimental Reference | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Organic Molecules (hydrophobic to hydrophilic) | PME-GIST vs. TI: R² = 0.99, MUD = 0.4 kcal/mol [20] | Not specified | FreeSolv Database [20] | Explicit models (PME-GIST) show near-quantitative agreement with rigorous TI. |

| Small Peptides (e.g., polyalanine) | pDF-based ΔGvdW within ~1 kcal/mol of TI [16] | SASA-based models show "far from exact" correlation [16] | N/A (Theory-based benchmark) | Decomposition of non-polar energy is more accurate with explicit-solvent derived pDFs. |

| Diels-Alder Reaction (in water) | ML/Explicit model agrees with exp. rates; reveals stepwise mechanism [15] | Implicit solvent predicts concerted mechanism [15] | Experimental kinetics [15] | Explicit solvent is critical for capturing correct mechanism and kinetics. |

| General Organic Molecules (in organic solvents) | Better agreement with experiment [23] | "Worse agreement... than an explicit model" [23] | Experimental solvation free energies [23] | Explicit models are generally more accurate for solvation free energies. |

MUD: Mean Unsigned Difference

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

This section details key computational tools and "reagents" used in modern solvation free energy studies.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Decomposition |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | Software Suite | Molecular Dynamics | Includes TI for explicit ΔG decomposition and MM/PBSA for implicit ΔG decomposition [20] [22]. |

| CPPTRAJ | Analysis Tool | Trajectory Analysis | Implements GIST and PME-GIST for spatial decomposition of solvation thermodynamics [20]. |

| GAFF2 | Force Field | Molecular Parameters | Provides parameters for organic solutes, used in both explicit and implicit studies [20]. |

| TIP3P | Water Model | Explicit Solvent | A standard 3-site model for representing water molecules in explicit solvent simulations [20]. |

| GB-Neck2 | Implicit Model | Generalized Born | A modern GB model used as a baseline for implicit solvation, e.g., in QM-GNNIS [19]. |

| COSMO | Implicit Model | Continuum Electrostatics | A popular dielectric continuum model used in methods like ESE-PM7 [21]. |

| Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) | Emerging Tool | Accelerated Sampling | Trained on QM or MM data to run explicit solvent MD at quantum-level accuracy but lower cost (e.g., for Diels-Alder reactions) [15]. |

The decomposition of solvation free energy into polar, non-polar, and cavitation contributions reveals a consistent performance gap between explicit and implicit solvent models. Explicit models, through rigorous but costly methods like TI, provide a more physically detailed and generally more accurate decomposition, particularly for the non-polar component and in systems where specific solute-solvent interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds) are critical [16] [23] [20]. Implicit models offer unparalleled speed and are invaluable for high-throughput screening and conformational analysis, but their simplified treatment of non-polar effects and dielectric response can lead to significant errors, especially for charged and complex molecular species [18] [23].

The future of the field lies in harnessing new technologies to bridge this accuracy-efficiency gap. Machine learning (ML) is a particularly promising avenue. For explicit solvents, ML potentials (MLPs) are being trained to perform ab initio-quality molecular dynamics at a fraction of the cost, making rigorous free energy calculations with explicit solvent feasible for larger systems [15]. For implicit solvents, graph neural networks (GNNs) are being developed to learn a "correction" to traditional continuum models, effectively incorporating explicit solvent effects learned from classical simulations, as demonstrated by the QM-GNNIS model [19]. These advances suggest a future where researchers will not have to choose strictly between accuracy and efficiency, but can leverage hybrid and machine-learning-enhanced approaches to obtain a precise and tractable decomposition of solvation thermodynamics for their drug discovery and biomolecular modeling projects.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the treatment of the solvent environment is a foundational choice that directly dictates the balance between computational feasibility and physical accuracy. Solvent models are computational methods that account for the behavior of solvated condensed phases, enabling simulations applicable to biological, chemical, and environmental processes [24]. Researchers are primarily faced with two divergent paths: explicit models, which treat each solvent molecule as an individual entity, and implicit models, which replace discrete solvent molecules with a continuum dielectric medium [25] [26] [24]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these approaches, framing the critical trade-off between the high computational cost of explicit models and the reduced physical realism of implicit ones. The decision between these models influences every aspect of a simulation, from the conformational sampling of biomolecules to the prediction of binding affinities in drug design. By examining recent experimental data and methodological advances, including emerging machine-learning hybrids, this article equips computational scientists with the evidence needed to make informed modeling choices tailored to their specific research objectives.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Differences

The conceptual underpinnings of implicit and explicit solvent models are fundamentally distinct, leading to their characteristic strengths and weaknesses. Implicit solvent models trace their origins to early dielectric theories of solvation from Onsager and Debye. These models treat the solvent as a polarizable continuum, characterized primarily by its dielectric constant [25] [26]. The solvation free energy (ΔGsolv) is typically partitioned into polar (ΔGele) and non-polar (ΔG_np) components. The polar term accounts for electrostatic interactions, often computed by solving the Poisson-Boltzmann equation or its Generalized Born approximation, while the non-polar term describes contributions from cavity formation, dispersion, and repulsion, frequently modeled using solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) [25] [26] [7].

In contrast, explicit solvent models incorporate actual solvent molecules—such as TIP3P, TIP4P, or OPC water models—as discrete particles with their own coordinates and degrees of freedom [27]. This provides an atomistic representation of the solvent, allowing for the direct simulation of specific molecular interactions like hydrogen bonding, solvent structure, and collective solvent dynamics [28] [15]. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each approach.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Solvent Models

| Feature | Implicit Solvent Models | Explicit Solvent Models |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Continuum electrostatics (e.g., Poisson-Boltzmann, Generalized Born) [25] [26] | Atomistic force fields (e.g., TIP3P, SPC/E, OPC) [27] |

| Solvent Representation | Homogeneous dielectric medium [24] | Individual, discrete solvent molecules [28] |

| Key Interactions Captured | Mean-field electrostatic and non-polar effects [25] | Specific interactions (H-bonding, van der Waals), solvent structure, entropy [28] [15] |

| Typical Computational Scaling | Favorable; faster conformational sampling [29] | Costly; scales with the number of solvent atoms [29] |

| Primary Advantage | Computational efficiency [25] [29] | Physical realism and detailed solvent depiction [28] [15] |

| Primary Limitation | Poor treatment of specific solvent effects (e.g., H-bonds) [30] [25] | High computational cost and need for extensive sampling [25] [15] |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Benchmarking studies consistently reveal performance gaps between implicit and explicit solvents, particularly for systems dependent on specific solute-solvent interactions. A critical 2025 study on the aqueous reduction potential of the carbonate radical anion (CO₃•⁻) demonstrated a stark failure of implicit models. The SMD implicit solvation model predicted only one-third of the measured reduction potential, while explicit solvation with 18 water molecules at the ωB97xD/6-311++G(2d,2p) level yielded accurate results [30]. This system, with its strong hydrogen-bonding interactions, highlights the inherent limitation of continuum models in capturing complex solvent effects.

Similarly, a 2025 benchmark of heparin dodecamer simulations compared five explicit solvent models (TIP3P, TIP4P, TIP5P, SPC/E, OPC) and found significant conformational differences. TIP3P and SPC/E produced stable heparin structures, whereas TIP4P, TIP5P, and OPC introduced greater structural variability [27]. This underscores that even among explicit models, the choice of water model can profoundly influence outcomes. The study also noted that implicit models poorly reproduced experimental ring puckering conformations of heparin, a failure attributed to their inability to model specific molecular interactions [27].

Table 2: Comparative Performance in Biomolecular Simulations

| System / Property | Implicit Model Performance | Explicit Model Performance | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonate Radical Reduction Potential [30] | Poor (predicted only ~33% of experimental value with SMD) | Excellent (accurate prediction with 18 explicit H₂O molecules) | Explicit solvation is essential for modeling electron transfer reactions with extensive solvent interactions [30]. |

| Heparin Dodecamer Conformations [27] | Poor reproduction of experimental ring puckering [27] | Good to excellent, depending on the explicit model used (TIP3P, OPC best) | Explicit solvents are necessary for accurate conformational sampling of highly flexible, charged biomolecules [27]. |

| Protein-GAG Binding Affinities [27] | Applicable for high-affinity complexes; less accurate for electrostatically driven binding | More accurate; effect of solvent choice diminishes with increasing binding affinity | Explicit models better capture the electrostatic environment critical for weak to moderate affinity interactions [27]. |

| Solvation Free Energy (ΔG_solv) | Efficient but can lack accuracy, especially for non-polar contributions [7] | High accuracy but computationally expensive; considered the "gold standard" [7] | ML-based implicit models are emerging to bridge this accuracy gap [7]. |

| Computational Cost | Lower cost; faster conformational search; efficient for large systems [29] | High cost; slow conformational transitions due to solvent viscosity; poor scaling [29] | Implicit solvents can be 10-1000x faster than explicit solvent simulations for equivalent solute systems. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol A: Assessing Reduction Potential with Explicit Solvation

A detailed methodology for evaluating the reduction potential of the carbonate radical anion, which requires explicit solvation for accuracy, is as follows [30]:

- System Preparation: The radical and ionic forms of carbonate (CO₃•⁻ and CO₃²⁻) are modeled individually. A cluster of explicit water molecules is added manually around the solute. The number of waters is critical; for instance, 18 water molecules are used with the ωB97xD functional, while 9 suffice for M06-2X [30].

- Geometry Optimization and Validation: Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations are performed (e.g., with Gaussian 16). The 6-311++G(2d,2p) basis set is used with functionals that include dispersion corrections (ωB97xD, M06-2X). The implicit SMD solvation model remains active to represent the bulk solvent. All structures are optimized to minimum energy, confirmed by the absence of imaginary vibrational frequencies [30].

- Conformational Sampling: For explicitly solvated systems, three different initial geometries are prepared by varying the angles and positions of the water molecules to sample conformational space. The energies from these replicates are used to calculate an average reduction potential and standard deviation [30].

- Energy and Potential Calculation: The reduction potential (E°) is calculated from the Gibbs free energy difference (ΔGrxn) between the oxidant (radical) and reduced (ion) species using the equation: ΔGrxn = -nFE⁰ - ESHE, where F is Faraday's constant, n is the number of electrons transferred (1), and ESHE is the standard hydrogen electrode potential (4.47 V) [30].

Protocol B: MD Simulations of Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) with Explicit Solvents

A 2025 study on a heparin dodecamer provides a protocol for benchmarking explicit solvent models in biomolecular MD [27]:

- System Setup: The heparin dodecamer (from PDB ID: 1HPN) is solvated in an octahedral periodic box with a specific water model (e.g., TIP3P, TIP4P, TIP5P, SPC/E, OPC). A 6 Å water layer is added between the solute and the box boundary. The system is neutralized with Na⁺ counterions [27].

- Force Field and Simulation Parameters: The CHARMM36m force field is applied. Energy minimization is performed using a steepest descent algorithm with positional restraints on the solute. Equilibration is first conducted in the NVT ensemble for 125 ps at 300 K, followed by NPT equilibration [27].

- Production MD and Analysis: Multiple 5 μs production runs are performed (one for each solvent model) in the NPT ensemble. Structures are saved every 100 ps for analysis. Key metrics include Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD), radius of gyration (R_g), end-to-end distance, glycosidic linkage torsion angles, and monosaccharide ring puckering conformations [27].

The workflow for this type of comparative analysis is summarized in the following diagram:

Emerging Hybrid and Machine Learning Approaches

To bridge the divide between cost and realism, hybrid and machine learning (ML) methodologies are rapidly advancing. Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) schemes are a classic hybrid where a QM core (solute and key solvents) is embedded in an MM solvent region, which may itself be surrounded by an implicit solvent continuum [24]. This provides an atomistic description where it matters most while managing computational expense.

More recently, machine learning potentials (MLPs) have emerged as powerful surrogates. A 2024 study presented a strategy for generating reactive MLPs to model chemical processes in explicit solvents. This approach combines active learning with descriptor-based selectors to build data-efficient training sets that span the relevant chemical and conformational space, enabling the accurate modeling of a Diels-Alder reaction in water and methanol [15].

Simultaneously, ML is being used to correct implicit models. A novel Graph Neural Network-based implicit solvent model, the λ-Solvation Neural Network (LSNN), was trained not only on forces but also on derivatives of alchemical variables. This allows the model to predict solvation free energies with accuracy comparable to explicit-solvent simulations while offering significant computational speedups [7]. Another approach, QM-GNNIS, transfers knowledge from classical MM interactions to quantum mechanical calculations, creating an implicit solvent model that incorporates explicit-solvent effects as a correction to a continuum model [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Models

Selecting the appropriate solvent model is a key step in designing computationally sound experiments. The table below catalogs essential models and their applications.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions: Key Solvent Models and Their Functions

| Model Name | Type | Primary Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| SMD [30] [25] | Implicit | A widely used universal solvation model for predicting solvation free energies across diverse solvents in DFT calculations. |

| PCM/COSMO [25] [24] | Implicit | Quantum chemistry continuum models for incorporating solvation effects into electronic structure calculations. |

| Generalized Born (GB) [25] [29] | Implicit | Efficient pairwise approximation to Poisson-Boltzmann electrostatics; widely used in MD simulations of biomolecules. |

| TIP3P [27] | Explicit | A standard 3-site water model offering a balance of computational efficiency and reliability in biomolecular simulations. |

| OPC [27] | Explicit | A highly accurate 4-site water model designed to better reproduce multiple physical properties of water. |

| SPC/E [27] | Explicit | An extended simple point charge model with a polarization correction, improving performance over SPC. |

| CHARMM36m [27] | Force Field | A widely used biomolecular force field for proteins and nucleic acids, often paired with TIP3P water. |

| ωB97xD [30] | DFT Functional | A density functional including dispersion corrections, crucial for accurately modeling solvated systems with intermolecular interactions. |

| LSNN [7] | ML Solvent | A graph neural network-based implicit solvent model trained to provide accurate solvation free energies. |

| QM-GNNIS [19] | ML Solvent | A machine-learned implicit solvent model that emulates a QM/MM setup by transferring knowledge from classical simulations. |

The critical trade-off between computational cost and physical realism in solvent modeling remains a central challenge in computational chemistry and biophysics. Implicit solvent models provide an indispensable tool for high-throughput screening, large-system exploration, and situations where specific solvent interactions are secondary. Conversely, explicit solvent models are the unequivocal choice for studying mechanisms where atomistic solvent details—such as hydrogen bonding, ion-specific effects, and solvent structure—are paramount [30] [15] [27].

The future of the field lies in intelligent hybridization and the targeted application of machine learning. Methods like QM/MM, ML-corrected implicit models, and machine learning potentials for explicit solvents are not one-size-fits-all solutions but represent a growing toolbox [19] [15] [7]. These advances promise to gradually blur the hard line of the existing trade-off, offering researchers a spectrum of options. The most appropriate model will always depend on the specific scientific question, but the ongoing innovation ensures that researchers can increasingly approach complex solvation phenomena without being strictly bound by the traditional constraints of computational cost.

Strategic Implementation: Choosing the Right Model for Your Biomolecular System

Solvent effects profoundly influence the structure, dynamics, and function of molecules in computational chemistry, impacting processes from protein folding and catalytic reactions to drug binding. [31] Researchers must continually choose between two fundamental approaches: explicit solvent models, which treat solvent molecules as discrete particles, and implicit solvent models, which represent the solvent as a continuous dielectric medium. [31] [15] While implicit models offer computational simplicity and efficiency, they inherently average out specific molecular interactions, which can be critical for accurate predictions. [31] This guide provides a objective comparison of these approaches, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to help researchers select the appropriate model for their specific system.

Fundamental Model Comparisons

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundations

Implicit Solvent Models calculate solvation free energy (ΔGsolv) by combining polar (ΔGele) and non-polar (ΔG*np*) components. The polar term describes the interaction of the solute's charge distribution with the dielectric environment, typically solved via Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) equation or Generalized Born (GB) approximation. The non-polar term accounts for cavity formation, van der Waals interactions, and solvent-accessible surface area. [31] [32]

Explicit Solvent Models simulate individual solvent molecules, capturing specific interactions like hydrogen bonding, charge transfer, and solvent structure. While more accurate, these models require significantly more computational resources as thousands of solvent molecules must be simulated and extensive sampling is needed for statistically meaningful ensembles. [15]

Decision Framework: When to Choose Which Model

Table 1: Solvent Model Selection Guide Based on System Characteristics

| System Characteristic | Recommended Model | Rationale and Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Charged/Ionic Species | Explicit or Hybrid | Implicit models significantly underpredict reduction potentials; for carbonate radical, implicit captured only 1/3 of experimental value. [30] |

| Strong Hydrogen Bonding | Explicit or Hybrid | Explicit solvation essential for systems with extensive intermolecular interactions (e.g., kosmotropic ions). [30] |

| Radical Species | Explicit or Hybrid | Accurate modeling of charge transfer and specific interactions requires explicit solvent molecules. [30] |

| Neutral Molecules/Polar Reactions | Implicit often sufficient | For Ag-catalyzed furan formation, implicit (SMD) and explicit (QM/MM) models agreed on favorable pathway. [33] |

| Large Biomolecular Systems | Implicit or Hybrid | Computational efficiency of implicit models enables simulation of large systems and enhanced sampling. [31] |

| Binding Site Desolvation | Implicit often parameterized | PB and GB methods demonstrated good accuracy for protein-ligand desolvation energies. [32] |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Accuracy Benchmarks Across Chemical Systems

Table 2: Quantitative Accuracy Comparison of Solvent Models for Different Chemical Properties

| System/Property | Implicit Model Performance | Explicit/Hybrid Model Performance | Experimental Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonate Radical Reduction Potential | ~0.5 V (severe underprediction) [30] | 1.57 V (matches experiment) with 9-18 explicit waters [30] | 1.57 V [30] |

| Ionic Solvation Free Energy | RMSD: 2.6 kcal/mol (anions), 3.9 kcal/mol (cations) with cluster-continuum [34] | N/A | Experimental hydration energies [34] |

| Small Molecule Solvation Energy | Correlation with experiment: 0.87-0.93 [32] | N/A | Experimental hydration energies [32] |

| Ag-catalyzed Furan Formation Barriers | SMD model correctly identified favorable pathway [33] | QM/MM MD confirmed implicit model predictions [33] | Experimental reaction outcomes [33] |

| Protein-Ligand Desolvation | Substantial discrepancy (up to 10 kcal/mol) with explicit reference [32] | Reference TI calculations with TIP3P [32] | Thermodynamic Integration [32] |

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Hybrid Cluster-Continuum Method for Ionic Solvation

Objective: Calculate accurate solvation free energies for ionic species. [34]

Methodology Details:

- Step 1 - Sampling: Generate 100 different initial cluster geometries from classical molecular dynamics simulations of the solute in bulk solvent. [34]

- Step 2 - Cluster Definition: For each solute, create clusters consisting of the solute and its closest 5 water molecules, selected based on distance to hydrophile atoms. [34]

- Step 3 - QM Optimization: Fully optimize cluster geometries at HF/6-31+G(d) level with entropy determined from vibrational frequency calculations at 298K. [34]

- Step 4 - Continuum Calculation: Calculate solvation free energy of clusters using continuum models (Poisson-Boltzmann or IEF-PCM). [34]

- Step 5 - Thermodynamic Cycle: Compute final solvation free energy using: ΔGsolv(A) = ΔGclust,g(A(H₂O)ₙ) + ΔGsolv(A(H₂O)ₙ) - ΔGsolv((H₂O)ₙ) - RTln([H₂O]/n) [34]

Key Findings: This hybrid approach yielded unsigned average errors of 2.1 kcal/mol for anions and 2.8 kcal/mol for cations, significantly improving upon pure continuum models. [34]

Explicit Solvation for Carbonate Radical Reduction Potential

Objective: Determine accurate reduction potential for CO₃˙⁻ radical. [30]

Methodology Details:

- System Preparation: Manually place explicit water molecules (varying from 0 to 18) around carbonate species, ensuring hydrogen bonding interactions. [30]

- Conformational Sampling: For each solvation level, prepare three different geometries with varied water positions and angles to sample conformational space. [30]

- QM Calculations: Perform DFT calculations (ωB97xD/6-311++G(2d,2p) and M06-2X/6-311++G(2d,2p)) with SMD implicit solvent still active. [30]

- Energy Conversion: Calculate reduction potential using: ΔGrxn = -nFE⁰ - ESHE, where ESHE = 4.47 V. [30]

- Validation: Average potentials from three geometries and compare with experimental value (1.57 V). [30]

Key Findings: Implicit solvation alone severely underpredicted the reduction potential. Accurate results required 18 explicit waters for ωB97xD and 9 explicit waters for M06-2X, with functionals containing dispersion corrections performing significantly better. [30]

QM/MM vs Implicit for Ag-Catalyzed Furan Formation

Objective: Compare implicit and explicit solvent models for predicting reaction barriers and energies. [33]

Methodology Details:

- System Setup: Place reactant in periodic box with 112 DMF molecules, treating solute with DFT (PBE+D3) and solvent with CHARMM force field. [33]

- Sampling Protocol: After equilibration, perform blue moon sampling with thermodynamic integration using C–O distance as reaction coordinate. [33]

- Convergence: Collect data from 13-16 reaction coordinate points with at least 5 ps production runs per point. [33]

- Parallel Implicit Calculations: Optimize structures and transition states with SMD implicit solvent model at M06/6-31G* level. [33]

Key Findings: Both methodologies correctly identified the most favorable pathway. No direct solvent participation was observed despite significant pairwise interactions, justifying the use of implicit models for similar systems. [33]

Visualizing Workflows and Decision Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Computational Tools for Solvent Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function and Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| IEF-PCM [34] [35] | Implicit Solvent | Polarizable Continuum Model for quantum chemistry calculations | Integrated in Gaussian; used with SQD for quantum computing solvation [34] [35] |

| SMD [30] [33] | Implicit Solvent | Universal solvation model for predicting solvation energies | Parameterized for various solvents; often used with explicit water clusters [30] [33] |

| GBNSR6 [32] | Implicit Solvent | Generalized Born method for biomolecular simulations | High accuracy for small molecule hydration energies [32] |

| APBS [32] | Implicit Solvent | Poisson-Boltzmann equation solver for electrostatics | Reference for electrostatic calculations; suitable for protein-ligand desolvation [32] |

| BigSolDB [13] | Dataset | Comprehensive solubility database for training ML models | ~800 molecules in 100+ organic solvents; enables ML solubility prediction [13] |

| FastSolv [13] | Machine Learning | Predicts solubility in organic solvents | Based on FastProp architecture; uses static molecular embeddings [13] |

| ChemProp [13] | Machine Learning | Message-passing neural network for molecular property prediction | Learns molecular representations during training; applicable to solubility [13] |

| CP2K [33] | QM/MM Package | Molecular dynamics with hybrid quantum/classical methods | Performs QM/MM MD with explicit solvent for reaction barriers [33] |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

Machine Learning Potentials for Explicit Solvation

Machine learning potentials (MLPs) are emerging as powerful surrogates for modeling chemical processes in explicit solvents at quantum mechanical accuracy but with significantly reduced computational cost. [15] Active learning strategies combined with descriptor-based selectors enable efficient construction of training sets that span the relevant chemical and conformational space. [15] This approach has been successfully applied to study Diels-Alder reactions in water and methanol, obtaining reaction rates in agreement with experimental data. [15]

Quantum Computing with Implicit Solvation

Recent advances have extended quantum computational chemistry to solvated molecules using implicit solvent models. [35] The SQD-IEF-PCM method combines quantum-generated samples with classical continuum solvation, achieving chemical accuracy on IBM quantum hardware for small polar molecules in solution. [35] This represents a significant step toward practical quantum chemistry for biologically relevant systems.

Integrated Workflows and Automation

Future directions point toward hybridization as best practice, combining continuum cores refined by improved physics, machine learning correctors with uncertainty quantification, and quantum-continuum modules for chemically demanding steps. [31] Automated workflows that intelligently switch between solvent representations based on system requirements will likely become standard in computational chemistry pipelines.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are indispensable tools in biophysics and drug discovery, but their computational cost remains a significant barrier. The treatment of solvent—the environment in which biomolecules reside—is a primary factor determining this cost. Implicit solvent models, which replace explicit solvent molecules with a continuum representation, offer a powerful alternative to explicit solvent simulations for specific applications. By approximating the average effect of the solvent, these models drastically reduce the number of particles in a simulation system, leading to substantial computational savings [31] [36]. The core of this approach is the Potential of Mean Force (PMF), a free energy that represents the thermally averaged force exerted by the solvent on the solute [37]. The strategic use of implicit solvents is not about universally replacing explicit models, but about knowing when their trade-off between efficiency and accuracy is most advantageous for accelerating conformational sampling and free energy calculations.

Performance Comparison: Implicit vs. Explicit Solvent Models

The choice between implicit and explicit solvent models involves a balance between computational speed and physical accuracy. The following sections provide a quantitative and qualitative comparison to guide this decision.

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

The performance gain from implicit solvent models is highly system-dependent. The table below summarizes documented speedups in conformational sampling for a Generalized Born (GB) implicit solvent model compared to explicit solvent (TIP3P water with Particle Mesh Ewald).

Table 1: Documented Speedups in Conformational Sampling for GB Implicit Solvent vs. Explicit Solvent

| Type of Conformational Change | Representative System | Approximate Sampling Speedup | Primary Factor for Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Changes | Dihedral angle flips in a protein [38] | ~1-fold (minimal) | Algorithmic efficiency |

| Mixed Changes | Folding of a miniprotein [38] | ~7-fold | Reduced solvent viscosity |

| Large Changes | Nucleosome tail collapse, DNA unwrapping [38] | ~1- to 100-fold | Reduced solvent viscosity |

| Stem-Loop RNA Folding | 10-36 residue RNA stem-loops [36] | Significant (de novo folding achieved) | Reduced particle count & viscosity |

Beyond sampling speed, implicit solvent models offer direct computational advantages by reducing the number of interacting particles. However, the performance gain is also influenced by the system size and the algorithms used.

Table 2: Computational and Performance Characteristics

| Characteristic | Implicit Solvent (Generalized Born) | Explicit Solvent (TIP3P/Particle Mesh Ewald) |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Cost | Lower for small systems; can be slower for very large systems [38] | Consistently high due to large number of solvent atoms |

| Sampling Speed | Accelerated due to lower solvent viscosity [38] [36] | Limited by the physical viscosity of water |

| Solvent Description | Continuum dielectric medium [31] | Discrete, explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P, TIP4P) |

| Handling of Solvent Structure | Poor for specific interactions (e.g., H-bonds, water bridges) [31] | Accurate for specific solvent-solute interactions |

Qualitative Comparison and Applicability

The accuracy of implicit solvent models is not uniform across all problem types. Their performance must be evaluated based on the specific scientific question.

Table 3: Qualitative Comparison and Model Applicability

| Aspect | Implicit Solvent | Explicit Solvent |

|---|---|---|

| Electrostatics | Approximate (GB/PB); good for long-range effects [31] | Naturally included; excellent for short and long-range |

| Non-Polar Contributions | Often simplified (e.g., SASA term) [7] | Naturally included via van der Waals interactions |

| Ion & Salt Effects | Approximate, via ionic strength parameter [31] | Explicit ions; can capture specific ion binding |

| Solvent Entropy | Implicitly included in the PMF [37] | Explicitly sampled |

| Ideal Use Cases | Conformational sampling, loop modeling, initial binding poses, large-scale transitions [38] [36] | Detailed mechanism studies, specific solvent roles, parameterizing new models |

Experimental Protocols and Validation

The validity of implicit solvent simulations is well-supported by experimental and explicit-solvent benchmark data. Reproducible protocols are key to their successful application.

Protocol for Quenched Molecular Dynamics (QMD) with Implicit Solvent

A stringent test for any energy model is its ability to reproduce the local energy minima found by explicit solvent simulations. The following protocol, adapted from a study on the PHF6 peptide, outlines this process:

- System Setup: The solute (e.g., a peptide or protein) is parameterized with a standard force field (e.g., CHARMM19/AMBER). The termini are often patched to reflect charged terminal groups under physiological conditions [39].

- High-Temperature MD: The system is heated to a high temperature (e.g., 1000 K) and simulated for a defined period (e.g., 10 ns). This high temperature ensures broad exploration of the conformational space [39].

- Structure Quenching: Structures are periodically extracted from the high-temperature trajectory (e.g., every 10 ps). Each snapshot is then subjected to extensive energy minimization (e.g., 2500 steps of steepest descent followed by 2500 steps of conjugate gradients) to locate the nearest local energy minimum [39].

- Analysis: The resulting set of minimized structures is analyzed and compared to a reference set generated with explicit solvent. Metrics include the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of structures and the relative stability of different minima [39].

Application Example: This protocol was used to demonstrate that several implicit solvent models (GB, GBSW, EEF1) could reproduce the set of local energy minima for the PHF6 peptide obtained from explicit solvent QMD. All models correctly predicted that the most stable structure was an extended β-conformation, a finding consistent with its role in Alzheimer's disease pathology [39].

Protocol for Free Energy Calculation with ML-Augmented Implicit Solvent

Traditional implicit solvent models can struggle with accurate free energy calculations. A modern machine learning (ML) approach overcomes key limitations:

- Data Generation: A training set is generated from explicit-solvent alchemical simulations, which provide reference forces and the derivatives of the solvation free energy with respect to alchemical coupling parameters (λelec for electrostatic and λsteric for steric interactions) [7].

- Network Architecture: A Graph Neural Network (GNN) is designed to take atomic representations (coordinates, charges, GB parameters) as input [7].

- Multi-Term Loss Function: The GNN is trained using a novel loss function that goes beyond simple force-matching:

ℒ = w_F (⟨∂U_solv/∂r_i⟩ - ∂f/∂r_i)² + w_elec (⟨∂U_solv/∂λ_elec⟩ - ∂f/∂λ_elec)² + w_steric (⟨∂U_solv/∂λ_steric⟩ - ∂f/∂λ_steric)²This ensures the model accurately captures not only conformational forces but also the true solvation free energy landscape [7]. - Free Energy Prediction: The trained model (e.g., LSNN, λ-Solvation Neural Network) can then predict solvation free energies with accuracy comparable to explicit-solvent calculations but at a fraction of the computational cost [7].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Implicit Solvent Simulations

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Generalized Born (GB) Models | Efficiently approximates the polar solvation free energy; a core component of most implicit solvent MD. | Conformational sampling, protein folding simulations [39] [36]. |

| Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) Solver | Provides a more rigorous, but computationally expensive, solution for electrostatic solvation. | Benchmarking GB models; single-point free energy calculations [31]. |

| GB-neck2 (AMBER) | A refined GB model parameterized for proteins and nucleic acids. | Folding of proteins and RNA stem-loops [36]. |

| Machine Learning Potentials (e.g., LSNN) | Graph Neural Networks trained to predict solvation forces and free energies. | High-accuracy solvation free energy calculations for drug discovery [7]. |

| Variational Implicit-Solvent Model (VESIS) | A mesoscale model that couples solute flexibility with a continuum solvent. | Studying protein-protein interactions and large-scale conformational changes [40]. |

| FlexiSol Benchmark Set | A public dataset of solvation energies for flexible, drug-like molecules. | Parameterizing and testing the transferability of new solvation models [41]. |

Workflow and Decision Pathway

The decision to use an implicit or explicit solvent model depends on the research goal, system properties, and available resources. The following workflow diagram outlines the key decision points.

Implicit solvent models are powerful tools for accelerating molecular simulations, offering substantial speedups in conformational sampling for processes involving large-scale motions, folding, and loop rearrangements. Their ability to reproduce key features of the energy landscape, as validated against explicit solvent benchmarks, makes them suitable for rapid exploration of conformational space and for specific free energy calculations, especially when enhanced with modern machine learning techniques. However, explicit solvent remains the gold standard for studies where atomic-level details of solvent structure and specific solute-solvent interactions are paramount. The informed researcher should therefore select a solvent model not by default, but through a strategic evaluation of the scientific question at hand, leveraging the unique strengths of each approach.

Predicting the binding affinity between a small molecule (ligand) and a target protein is a cornerstone of computational drug discovery. The strength of this binding determines a candidate drug's efficacy, making accurate affinity prediction critical for prioritizing compounds before costly synthesis and experimental testing [42] [43]. These computational methods exist on a wide spectrum, trading off between speed and accuracy. At one end, molecular docking offers fast but approximate results, while at the other, rigorous methods like free energy perturbation (FEP) provide high accuracy at a massive computational cost [42]. This guide objectively compares the performance of various affinity prediction methods, with a particular focus on the role of explicit versus implicit solvent models within molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, a central thesis in modern simulation research.

Landscape of Computational Methods

Computational approaches for binding affinity prediction are broadly classified into physics-based and data-driven methods [43]. The following table summarizes the performance characteristics of the primary methodologies in use today.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Key Binding Affinity Prediction Methods

| Method | Typical RMSE (kcal/mol) | Typical Correlation (R) | Speed | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking | 2–4 [42] | ~0.3 [42] | Fast (minutes on CPU) [42] | High-throughput screening; fast pose prediction [42] | Low quantitative accuracy; heuristic scoring functions [42] |

| MM/PBSA & MM/GBSA | Variable, often high [42] | Variable, often low [42] | Medium (hours-days) [42] | Lower cost than FEP; physics-based insights [42] | Sensitive to trajectory & parameters; error cancellation issues [42] |

| Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) | ~1 [42] | 0.65+ [42] | Slow (12+ hours GPU per compound) [42] | High accuracy; rigorous statistical mechanics basis [43] | Extremely high computational cost; expert setup required [42] |

| Trajectory Similarity (JS-Divergence) | Not Reported | 0.70–0.88 (for specific targets) [43] | Medium [43] | Does not require ligand structural similarity [43] | Correlation sign ambiguity without experimental data [43] |

A clear "methods gap" exists between fast, inaccurate docking and slow, accurate FEP [42]. Hybrid approaches that combine molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with machine learning (ML) analysis are actively being developed to fill this gap, and the choice of solvent model in these MD simulations is a critical factor influencing their accuracy and cost.

Explicit vs. Implicit Solvation: A Critical Comparison

The treatment of solvent (typically water) in simulations is a fundamental choice. Explicit solvent models simulate individual water molecules, while implicit solvent models treat the solvent as a continuous dielectric medium [30] [23].

Performance and Applicability

Table 2: Explicit vs. Implicit Solvent Models in Molecular Simulations

| Characteristic | Explicit Solvent Models | Implicit Solvent Models |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Realism | High; captures specific interactions (e.g., H-bonds), charge transfer, and solvation shell structure [30] [23] | Low; approximates electrostatic and non-electrostatic effects via a continuum [30] |

| Computational Cost | High; dramatically increases the number of particles in the system [23] | Low; adds a modest computational overhead to a gas-phase calculation [23] |

| Best Suited For | Processes with strong, specific solute-solvent interactions (e.g., reduction potentials of radicals, binding involving charged species) [30] | Large systems where sampling is priority; non-polar/weakly polar solutes [23] |

| Known Limitations | Cost limits system size and simulation time; requires careful conformational averaging [23] | Poor performance for polar solutes and systems where H-bonding is critical [30] [23] |

Evidence strongly suggests that explicit solvation is necessary for systems where solvent interactions are crucial. For instance, in predicting the aqueous reduction potential of the carbonate radical, implicit solvation methods captured only one-third of the measured value, while explicit solvation with a sufficient number of water molecules yielded accurate results [30]. The general consensus is that when computational resources allow, explicit models are more reliable, as they more closely match physical reality [23].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methods

MM/GBSA with Implicit Solvent

The MM/GBSA (Molecular Mechanics with Generalized Born and Surface Area solvation) method is a popular, albeit sometimes unreliable, approach for affinity estimation from MD trajectories [42].

Detailed Workflow:

- System Setup: A protein-ligand complex is pruned to a fixed radius around the binding site, then solvated in an implicit or explicit solvent box and ions are added for neutrality. The system energy is minimized [42].

- Equilibration: The system is gradually heated to 300 K to avoid large initial forces, followed by a short simulation (e.g., in the NPT ensemble) for equilibration (e.g., 10 ns) [42].

- Production MD: A short (e.g., 4 ns) MD simulation is run in the NPT ensemble. Snapshots are saved every 10 ps, resulting in hundreds of frames for analysis [42].

- Free Energy Calculation: The binding free energy (ΔG) for each snapshot is approximated using the formula:

ΔG ≈ ΔHgas + ΔGsolvent - TΔS

where: