Enhanced Sampling with Replica-Exchange MD: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomolecular Simulation and Drug Discovery

Replica-Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD) has emerged as a powerful computational technique to overcome the timescale limitations of conventional molecular dynamics, enabling the study of complex biomolecular processes like protein folding,...

Enhanced Sampling with Replica-Exchange MD: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomolecular Simulation and Drug Discovery

Abstract

Replica-Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD) has emerged as a powerful computational technique to overcome the timescale limitations of conventional molecular dynamics, enabling the study of complex biomolecular processes like protein folding, aggregation, and drug binding. This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational theory of REMD, detailed methodological protocols for major simulation packages like GROMACS and AMBER, and advanced Hamiltonian exchange variants. It offers practical solutions for optimizing replica exchange efficiency and troubleshooting common problems, supported by validation case studies on peptides and proteins. By integrating the latest methodological advances, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to apply REMD for enhanced conformational sampling in biomedical research.

Understanding Replica-Exchange MD: Breaking the Sampling Barrier in Biomolecular Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are a cornerstone of computational chemistry and structural biology, enabling the study of biomolecular behavior at an atomic level. However, a significant limitation of conventional MD is the sampling problem: the tendency for simulations to become trapped in local energy minima, unable to cross high energy barriers to explore other relevant conformational states within practical simulation timescales [1] [2]. This problem is particularly acute for complex biomolecular processes such as protein folding, conformational changes, and peptide aggregation, which involve rare events separated by energy barriers of 8-12 kcal/mol and occur over timescales much longer than what is typically accessible to MD simulations [3].

The replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) method has emerged as a powerful enhanced sampling technique to overcome these limitations [1]. By combining MD simulations with a Monte Carlo algorithm, REMD facilitates escape from local minima and achieves more comprehensive exploration of conformational space, making it particularly valuable for studying complex phenomena like protein aggregation associated with Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and type II diabetes [1] [4].

Theoretical Foundation of Replica Exchange MD

Basic Principles of REMD

REMD employs multiple parallel simulations (replicas) of the same system, each running at a different temperature [1]. These replicas are simulated simultaneously, and at regular intervals, an exchange of temperatures between neighboring replicas is attempted based on the Metropolis criterion [5]. This approach generates a generalized ensemble that enables the system to overcome energy barriers efficiently while maintaining proper Boltzmann sampling at all temperatures [5].

The core exchange mechanism involves periodically attempting to swap the configurations of two replicas (i and j) at temperatures Ti and Tj. The acceptance probability for this exchange is given by:

[ P(1 \leftrightarrow 2)=\min\left(1,\exp\left[ \left(\frac{1}{kB T1} - \frac{1}{kB T2}\right)(U1 - U2) \right] \right) ]

where U1 and U2 are the potential energies of the two replicas, kB is Boltzmann's constant, and T1 and T_2 are the respective temperatures [5]. This probability depends on both the temperature difference and the potential energy difference between replicas.

REMD Variants and Extensions

Several variants of REMD have been developed to address specific sampling challenges:

- Temperature REMD (T-REMD): The standard approach using different temperatures [6].

- Hamiltonian REMD (H-REMD): Uses different Hamiltonians across replicas, often through varying λ values in free energy calculations [5] [6].

- Gibbs Sampling REMD: Allows exchanges between non-neighboring replicas, potentially improving sampling efficiency [5].

- Replica Exchange with Solute Tempering: Specifically scales temperatures for solute degrees of freedom to reduce the total number of replicas needed [6].

Table 1: Comparison of Key REMD Variants

| REMD Variant | Replica Coordinate | Key Advantage | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature REMD | Temperature | Simple implementation | Protein folding, peptide aggregation |

| Hamiltonian REMD | Force field parameters | Efficient for large systems | Free energy calculations, ligand binding |

| Gibbs Sampling REMD | Temperature or Hamiltonian | Exchanges non-adjacent replicas | Complex systems with rough energy landscapes |

| Solute Tempering REMD | Solute temperature | Reduced replica count for explicit solvent | Biomolecular systems in aqueous environment |

REMD Protocol: A Practical Application to Peptide Aggregation

Case Study: hIAPP(11-25) Dimerization

To illustrate a practical REMD application, we examine the dimerization of the 11-25 fragment of human islet amyloid polypeptide (hIAPP(11-25)), a system relevant to type II diabetes [1]. The peptide sequence (RLANFLVHSSNNFGA) is capped with an acetyl group at the N-terminus and a NH_2 group at the C-terminus to match experimental conditions [1].

Experimental Setup and Parameters

The REMD simulation protocol requires careful selection of several key parameters:

- Number of replicas: Sufficient to cover the desired temperature range with adequate overlap between adjacent replicas.

- Temperature distribution: Typically following a geometric progression to maintain relatively constant exchange probabilities.

- Exchange frequency: Balanced to allow sufficient decorrelation between exchange attempts while facilitating random walks through temperature space.

Table 2: Key Parameters for hIAPP(11-25) REMD Study

| Parameter | Value/Range | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Number of replicas | 24-48 | Dependent on system size and temperature range |

| Temperature range | 300-500 K | Enables barrier crossing while maintaining stability |

| Exchange attempt frequency | Every 1-2 ps | Balances communication overhead and sampling efficiency |

| Simulation length per replica | 50-200 ns | Ensures sufficient conformational sampling |

| Solvation | Explicit water molecules | Maintains realistic solvation effects |

| Force field | CHARMM or AMBER | Accurate protein representation |

For a system with all bonds constrained, the number of degrees of freedom Ndf is approximately 2 × Natoms. The optimal temperature spacing can be estimated using the formula:

[ \epsilon \approx 2/\sqrt{c \cdot N_{df}} ]

where c ≈ 2 for protein/water systems, providing an exchange probability of approximately 0.135 [5].

Workflow for REMD Simulations

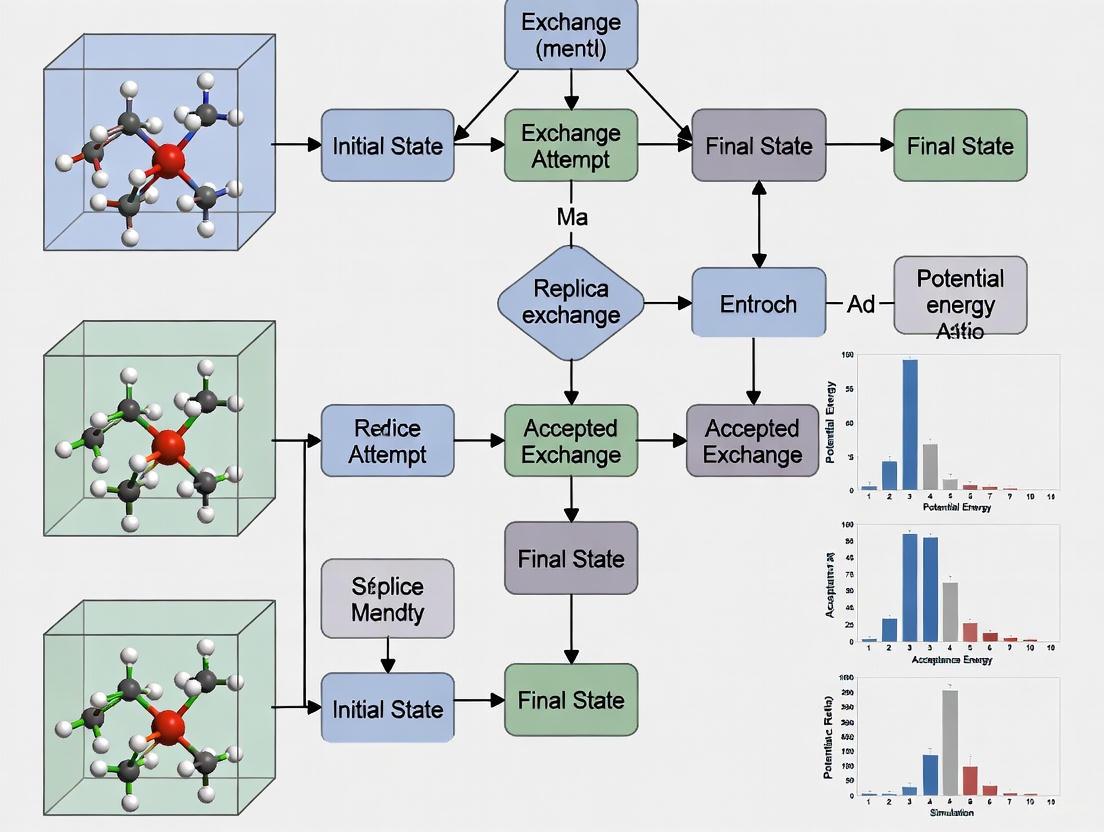

The following diagram illustrates the complete REMD workflow from system preparation to analysis:

Diagram 1: Complete REMD workflow from system setup to analysis.

The Replica Exchange Mechanism

The core exchange process in REMD operates as follows:

Diagram 2: The replica exchange mechanism showing the periodic exchange attempts.

Successful REMD simulations require specific computational tools and resources:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for REMD Simulations

| Resource | Function/Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD simulation software with REMD implementation | GROMACS-4.5.3 or later versions [1] |

| AMBER | Alternative MD package with REMD capabilities | AMBER for biomolecular systems [7] |

| MPI Library | Enables parallel processing across computing nodes | Standard MPI for replica communication [1] |

| HPC Cluster | Provides necessary computational resources | Cluster with Intel Xeon CPUs (2 cores/replica) [1] |

| VMD | Molecular visualization and analysis | Visual Molecular Dynamics for modeling [1] |

| Linux Environment | Scripting and simulation management | Bash scripts for automation [1] |

Analysis of REMD Results and Validation

Analyzing REMD Outputs

Proper analysis of REMD simulations involves several key steps:

- Replica exchange monitoring: Track acceptance rates to ensure adequate overlap between neighboring replicas (ideal range: 15-25%) [5].

- Convergence assessment: Monitor property distributions across replicas to verify simulation convergence.

- Free energy calculation: Reconstruct free energy landscapes using weighted histogram analysis or similar methods.

- Trajectory analysis: Identify key conformational states and transition pathways.

Troubleshooting Common REMD Problems

Several issues commonly arise in REMD simulations:

- Low exchange rates: Typically indicates insufficient temperature overlap, requiring adjustment of temperature distribution.

- Replica trapping: Despite exchanges, some replicas may remain trapped, potentially requiring longer simulation times or adjusted parameters.

- Poor randomization: Inadequate random walks through temperature space can limit sampling efficiency.

Comparative Performance: Conventional MD vs. REMD

REMD simulations offer significant advantages over conventional MD for systems with complex energy landscapes:

Table 4: Performance Comparison Between Conventional MD and REMD

| Parameter | Conventional MD | REMD |

|---|---|---|

| Barrier crossing efficiency | Limited by local minima | Enhanced through temperature exchanges |

| Conformational sampling | Often incomplete | Comprehensive exploration |

| Simulation time requirements | May require μs-ms timescales | More efficient for rare events |

| Computational resource demands | Lower per simulation | Higher due to multiple replicas |

| Ergodicity | Often poor for complex systems | Significantly improved |

Studies have demonstrated that REMD can be 10-100 times more efficient than conventional MD for sampling the canonical distribution, particularly at low temperatures where energy barriers are most problematic [8].

REMD has established itself as a powerful solution to the sampling problem in conventional MD simulations, particularly for studying biomolecular processes involving high energy barriers. The method's ability to facilitate escape from local minima while maintaining proper thermodynamic sampling has made it invaluable for investigating protein folding, peptide aggregation, and other complex phenomena.

Future developments in REMD methodology will likely focus on several key areas: (1) reducing computational demands through more efficient algorithms and targeted sampling; (2) integration with machine learning approaches for enhanced analysis and parameter optimization; and (3) development of specialized variants for specific applications such as membrane systems and drug discovery [7] [6]. As these advancements mature, REMD will continue to expand our ability to explore complex biomolecular systems and processes that remain inaccessible to conventional simulation approaches.

Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD) is a powerful enhanced sampling technique that overcomes the limitations of conventional molecular dynamics simulations by preventing trapping in local energy minima. This protocol outlines the fundamental principles of REMD, focusing on its core mechanism of running parallel replicas at different temperatures and periodically swapping their configurations. We provide a detailed application note for studying biomolecular systems, using the dimerization of an amyloid peptide fragment as a case study. Within the broader context of enhanced sampling research, REMD enables efficient exploration of complex free energy landscapes, making it particularly valuable for studying protein folding, aggregation, and ligand-receptor interactions in drug discovery.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are invaluable tools for studying biomolecular processes at atomic resolution. However, conventional MD simulations often fail to adequately sample the complete conformational space of complex systems within practical simulation timescales, as they can become trapped in local minimum-energy states [1]. This limitation is particularly problematic for processes with high energy barriers such as protein folding, conformational changes, and protein aggregation events associated with neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and type II diabetes [1].

Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD), also known as parallel tempering, addresses this sampling problem through a parallel sampling strategy [9]. By combining MD simulations with a Monte Carlo algorithm, REMD enables efficient barrier crossing and comprehensive sampling of biomolecular conformational landscapes [1]. The method has gained significant popularity in computational biophysics and structural biology due to its parallel efficiency and effectiveness in mapping complex free energy surfaces [1].

In drug discovery contexts, REMD has proven particularly valuable for studying binding events and residence times - critical parameters for drug efficacy that extend beyond traditional affinity measurements [10]. The temporal stability of ligand-receptor complexes, quantified as residence time, is increasingly recognized as a crucial factor in drug design, as it influences both therapeutic efficacy and pharmacodynamic properties [10].

Theoretical Foundations

Core REMD Algorithm

The REMD method employs multiple non-interacting copies (replicas) of the same system simulated simultaneously at different temperatures or with different Hamiltonians [1]. The fundamental operation involves periodically attempting to swap the configurations between neighboring replicas based on a Metropolis criterion [1] [11].

For temperature-based REMD, which is the most common implementation, the exchange probability between two replicas (i and j) at temperatures Ti and Tj with potential energies Ui and Uj is given by:

[P(i \leftrightarrow j) = \min\left(1, \exp\left[ \left(\frac{1}{kB Ti} - \frac{1}{kB Tj}\right)(Ui - Uj) \right] \right)]

where k_B is Boltzmann's constant [11]. This acceptance criterion ensures detailed balance is maintained, preserving the correct Boltzmann distribution at each temperature.

Ensemble Extensions

While initially developed for the canonical (NVT) ensemble, REMD has been extended to other thermodynamic ensembles. For the isobaric-isothermal (NPT) ensemble, the exchange probability incorporates volume terms:

[P(1 \leftrightarrow 2)=\min\left(1,\exp\left[ \left(\frac{1}{kB T1} - \frac{1}{kB T2}\right)(U1 - U2) + \left(\frac{P1}{kB T1} - \frac{P2}{kB T2}\right)\left(V1-V2\right) \right] \right)]

where P1 and P2 are reference pressures and V1 and V2 are instantaneous volumes [11]. In practice, the volume term is often negligible unless pressure differences are large or during phase transitions [11].

Hamiltonian replica exchange represents an alternative approach where replicas differ not in temperature but in their potential energy functions, typically implemented through free energy pathways with different λ values [11]. The acceptance probability for Hamiltonian exchange is:

[P(1 \leftrightarrow 2)=\min\left(1,\exp\left[ \frac{1}{kB T} (U1(x1) - U1(x2) + U2(x2) - U2(x_1)) \right]\right)]

Hybrid approaches combining both temperature and Hamiltonian exchange are also possible [11].

Temperature Spacing and Replica Number

Proper temperature selection is critical for REMD efficiency. The energy difference between neighboring temperatures can be approximated as:

[U1 - U2 = N{df} \frac{c}{2} kB (T1 - T2)]

where Ndf is the number of degrees of freedom and c is approximately 1 for harmonic systems and around 2 for protein/water systems [11]. For a target exchange probability P ≈ 0.135, the optimal temperature spacing gives (\epsilon \approx 2/\sqrt{c\,N{df}}) where (T2 = (1+\epsilon) T1) [11]. With all bonds constrained, (N{df} \approx 2\, N{atoms}), yielding (\epsilon \approx 1/\sqrt{N_{atoms}}) for c = 2 [11].

Table 1: Temperature Spacing Guidelines for REMD Simulations

| System Size (N_atoms) | Recommended ε | Typical Temperature Spacing (K) | Expected Acceptance Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 | 0.032 | 10-15 | 0.15-0.25 |

| 5,000 | 0.014 | 5-8 | 0.15-0.25 |

| 10,000 | 0.010 | 3-5 | 0.15-0.25 |

| 20,000 | 0.007 | 2-3 | 0.15-0.25 |

REMD Workflow and Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the complete REMD simulation workflow, from system setup to data analysis:

REMD Simulation Workflow

System Preparation and Initialization

The first step in any REMD simulation is constructing proper initial configurations. For the hIAPP(11-25) dimer case study [1]:

Peptide Preparation: The 15-residue peptide (sequence: RLANFLVHSSNNFGA) is capped with an acetyl group at the N-terminus and a NH₂ group at the C-terminus to match experimental conditions [1].

Solvation: Place the peptide in an appropriate water box (typically TIP3P water model for biomolecular systems) with sufficient padding (≥1.0 nm) from box edges.

Ion Addition: Add ions to neutralize system charge and achieve physiological salt concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).

Energy Minimization: Perform steepest descent energy minimization until the maximum force is below a specified threshold (typically 1000 kJ/mol/nm).

Equilibration: Conduct conventional MD equilibration in two phases:

- NVT equilibration (constant particle number, volume, and temperature) for 100-500 ps

- NPT equilibration (constant particle number, pressure, and temperature) for 100-500 ps

Temperature Distribution Setup

Using the guidelines in Section 2.3, determine the temperature range and distribution:

- Identify the temperature of interest (typically 300 K for physiological conditions).

- Determine the highest temperature needed to overcome relevant energy barriers (often 400-500 K for protein systems).

- Calculate the number of replicas needed using the formula for ε and system size.

- Use online tools like the GROMACS REMD calculator to optimize temperature distribution.

Table 2: Example Temperature Distribution for a 20,000-Atom System

| Replica Index | Temperature (K) | Energy Overlap | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 300 | 0.18 | Production sampling |

| 2 | 303 | 0.19 | Barrier crossing |

| 3 | 306 | 0.20 | Barrier crossing |

| ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 16 | 400 | 0.16 | Enhanced sampling |

Exchange Protocol Implementation

The replica exchange process follows a specific pattern to maintain detailed balance:

Exchange Intervals: Attempt exchanges at regular intervals (typically every 100-1000 MD steps).

Pair Selection: Use alternating even-odd pairing scheme:

- On odd attempts: try pairs (0-1), (2-3), (4-5), ...

- On even attempts: try pairs (1-2), (3-4), (5-6), ...

Exchange Procedure:

- Calculate potential energies for neighboring replicas

- Apply Metropolis criterion to determine exchange acceptance

- If accepted: swap coordinates and rescale velocities

- If rejected: continue with original configurations

Velocity Rescaling: After accepted exchange, scale velocities by (\sqrt{T{new}/T{old}}) to maintain proper kinetic energy distribution.

Case Study: hIAPP(11-25) Dimerization

Experimental Protocol

This case study follows the dimerization of the 11-25 fragment of human islet amyloid polypeptide (hIAPP) associated with type II diabetes [1].

System Details:

- Peptide: hIAPP(11-25) acetyl-RLANFLVHSSNNFGA-NH₂

- Force Field: CHARMM27 or AMBER99SB-ILDN

- Water Model: TIP3P

- Box Size: ~6.0×6.0×6.0 nm³

- Ions: Na⁺ and Cl⁻ to 150 mM concentration

- Total Atoms: ~25,000

REMD Parameters:

- Number of Replicas: 24

- Temperature Range: 300-400 K

- Exchange Attempt Frequency: Every 2 ps (1000 steps with 2 fs timestep)

- Simulation Length: 100-200 ns per replica

- Total Simulation Time: 2.4-4.8 μs aggregate

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for REMD

| Item | Function/Description | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| MD Software | Simulation engine with REMD implementation | GROMACS [1], AMBER [1], CHARMM [1], NAMD [1] |

| HPC Cluster | Parallel computing resources | Local clusters, cloud computing, supercomputing centers |

| MPI Library | Message passing interface for parallelization | OpenMPI, MPICH, Intel MPI |

| Visualization Tools | Trajectory analysis and structure visualization | VMD [1], PyMol, ChimeraX |

| Force Fields | Molecular mechanics parameters | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS-AA |

| Solvation Models | Water and ion representations | TIP3P, TIP4P, SPC/E |

| Analysis Tools | Trajectory processing and metrics | GROMACS analysis tools, MDAnalysis, MDTraj |

Data Analysis Methods

Replica Trajectory Processing:

- Reconstruct continuous trajectories from exchange events

- Align structures to remove global rotation/translation

- Calculate root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) and radius of gyration

Free Energy Calculations:

- Use weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) or multistate Bennett acceptance ratio (MBAR)

- Construct free energy surfaces as functions of collective variables (e.g., inter-chain distance, β-sheet content)

Cluster Analysis:

- Identify dominant conformational states

- Calculate state populations and transition probabilities

Residence Time Analysis:

- For drug-target applications, analyze bound state durations [10]

- Calculate dissociation rate constants (k_off) from bound state lifetimes

Applications in Drug Discovery

REMD provides particular value in drug discovery through its ability to accurately sample ligand-receptor interactions and quantify residence times - an emerging critical parameter in drug design [10]. The temporal stability of ligand-receptor complexes, defined as residence time (RT = 1/k_off), increasingly correlates with in vivo drug efficacy beyond traditional affinity-based metrics [10].

REMD enhances sampling of ligand binding modes and dissociation pathways, providing atomic-level insights into molecular determinants of prolonged residence times. For G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) - major drug targets - REMD can simulate the "energy cage" phenomenon where conformational changes create steric hindrance that traps ligands in binding pockets, significantly extending residence times [10].

The following diagram illustrates how REMD samples the energy landscape for ligand-receptor dissociation:

REMD Sampling of Ligand Dissociation

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common Issues and Solutions:

Low Exchange Acceptance Rates:

- Problem: <10% acceptance between neighboring replicas

- Solution: Reduce temperature spacing or increase replica count

Temperature Gap Issues:

- Problem: Replicas becoming trapped at specific temperatures

- Solution: Implement adaptive temperature schemes or adjust distribution

Poor Equilibration:

- Problem: System not reaching equilibrium distribution

- Solution: Extend equilibration time or check initial configuration

Resource Constraints:

- Problem: Computational limitations for large replica counts

- Solution: Implement Hamiltonian replica exchange or multiplexed REMD [12]

Performance Optimization:

Parallelization Strategy: Use one MPI process per replica with 2-4 CPU cores per replica for optimal throughput.

Exchange Frequency Balance: Balance between communication overhead (too frequent) and poor mixing (too infrequent) - typically 100-1000 steps.

Checkpointing: Implement regular trajectory saving and restart files to protect against system failures during long simulations.

REMD represents a sophisticated enhanced sampling approach that effectively addresses the sampling limitations of conventional molecular dynamics. Through its parallel replica framework and temperature swapping mechanism, REMD enables comprehensive exploration of complex biomolecular energy landscapes. The method has proven particularly valuable for studying challenging processes like protein aggregation and ligand-receptor interactions, where accurate characterization of free energy surfaces and kinetic parameters is essential.

As computational resources continue to grow and REMD methodologies further develop, this approach will play an increasingly important role in bridging molecular simulations with experimental observations, particularly in drug discovery where parameters like residence time provide critical insights beyond traditional affinity measurements. The continued refinement of REMD protocols and their integration with other enhanced sampling methods promises to expand the scope of addressable biological questions in computational biophysics and structural biology.

Replica-exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) is a powerful enhanced sampling technique that overcomes the limitations of conventional molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which often struggle with insufficient sampling due to high energy barriers separating local minima on the rough energy landscapes of biomolecules [13]. By combining MD simulations with the Monte Carlo algorithm, REMD enables efficient exploration of conformational space, making it particularly valuable for studying complex biological processes such as protein folding, peptide aggregation, and ligand binding [1] [14]. The mathematical heart of this method lies in its acceptance criterion, which determines the probability of exchanging configurations between replicas while maintaining proper thermodynamic ensembles. This foundation has enabled REMD to become a cornerstone technique in computational biophysics and drug discovery, with applications ranging from amyloid formation studies to kinase-inhibitor binding characterization [1] [15].

Theoretical Framework

Fundamental Acceptance Probability

The replica exchange method operates by simulating multiple non-interacting copies (replicas) of a system at different temperatures or with different Hamiltonians [1]. After a fixed time interval, exchanges between neighboring replicas are attempted with a probability derived from the Metropolis criterion [14]. For the canonical ensemble (NVT) with exchanges based solely on temperature, the probability of exchanging replicas i and j is given by:

P(i j) = min(1, exp(Δ))

where Δ = (βi - βj)(Ui - Uj)

Here, β = 1/kBT is the inverse temperature, kB is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, and U represents the potential energy of the specified replica [1]. This elegant formula ensures detailed balance is maintained, guaranteeing correct thermodynamic sampling at all temperatures [16] [1].

The derivation of this criterion begins by considering the detailed balance condition, which requires:

ρREM(X)w(X→X') = ρREM(X')w(X'→X)

where ρ_REM(X) is the probability of the generalized ensemble being in state X, and w(X→X') is the transition probability from state X to X' [1]. For the exchange of two replicas, the resulting ratio of transition probabilities simplifies to exp(-Δ), leading directly to the Metropolis criterion shown above [1].

Extended Forms for Various Ensembles

The fundamental acceptance criterion extends naturally to more complex simulation conditions. For isobaric-isothermal ensemble (NPT) simulations, where pressure and volume fluctuations become relevant, Okabe et al. proposed an extended acceptance criterion:

P(1 2) = min(1, exp[ (1/kBT1 - 1/kBT2)(U1 - U2) + (P1/kBT1 - P2/kBT2)(V1 - V2) ])

where P1 and P2 are reference pressures and V1 and V2 are instantaneous volumes [16]. In most practical applications, the volume difference term is negligible unless large pressure differences exist or during phase transitions [16].

For Hamiltonian replica exchange (H-REMD), where different replicas employ different potential energy functions (typically defined through a λ-parameter pathway), the acceptance probability becomes:

P(1 2) = min(1, exp[ 1/kBT (U1(x1) - U1(x2) + U2(x2) - U2(x_1)) ])

where U1 and U2 represent different potential energy functions [16]. This approach is particularly valuable in free energy calculations and for systems where temperature exchanges would be inefficient.

When combining both temperature and Hamiltonian exchanges simultaneously, the acceptance criterion extends to:

P(1 2) = min(1, exp[ (U1(x1) - U1(x2))/kBT1 + (U2(x2) - U2(x1))/kBT2 ]) [16]

Table 1: Summary of Replica Exchange Acceptance Criteria for Different Ensembles

| Ensemble Type | Acceptance Probability Formula | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Canonical (NVT) | P = min(1, exp[(β_i - β_j)(U_i - U_j)]) |

Basic protein folding, peptide conformational sampling |

| Isobaric-Isothermal (NPT) | P = min(1, exp[(β_i - β_j)(U_i - U_j) + (β_iP_i - β_jP_j)(V_i - V_j)]) |

Systems with significant volume fluctuations |

| Hamiltonian (H-REMD) | P = min(1, exp[β(U_1(x_1) - U_1(x_2) + U_2(x_2) - U_2(x_1))]) |

Free energy calculations, alchemical transformations |

| Combined Temperature & Hamiltonian | P = min(1, exp[(U_1(x_1) - U_1(x_2))/k_BT_1 + (U_2(x_2) - U_2(x_1))/k_BT_2]) |

Complex systems requiring multi-dimensional enhanced sampling |

Parameter Optimization and Practical Considerations

Temperature Spacing and Replica Allocation

Proper temperature selection is crucial for achieving adequate exchange probabilities between adjacent replicas. The energy difference between two replicas at different temperatures can be approximated as:

U1 - U2 = Ndf × (c/2) × kB × (T1 - T2)

where Ndf is the total number of degrees of freedom and c is approximately 1 for harmonic potentials and around 2 for protein/water systems [16]. For a constant exchange probability, the relative temperature spacing ε = (T2 - T1)/T1 should follow:

ε ≈ 2/√(c × N_df)

With all bonds constrained, Ndf ≈ 2 × Natoms, leading to ε ≈ 1/√N_atoms for c = 2 [16]. The GROMACS REMD calculator implements these relationships to propose optimal temperature sets based on the temperature range and number of atoms [16].

Table 2: Optimal Parameter Selection for REMD Simulations

| Parameter | Theoretical Guidance | Practical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature Spacing | ε ≈ 1/√N_atoms for protein/water systems |

Use REMD calculators; ensure exchange rates of 10-20% |

| Number of Replicas | Determined by temperature range and spacing | Balance computational cost with sampling efficiency; typically 8-32 replicas |

| Exchange Attempt Frequency | Shorter intervals enhance temperature space traversals | Balance with thermal relaxation; typically 0.1-1 ps for explicit solvent |

| Thermostat Coupling Constant | System-dependent | Shorter constants (0.2 ps) reduce artifacts with frequent exchanges |

Exchange Attempt Intervals and Artifact Prevention

The time interval between replica exchange attempts (tatt) significantly impacts both sampling efficiency and potential artifacts. While shorter intervals enhance traversals in temperature space [17], excessively frequent attempts can cause deviations from proper thermodynamic ensembles. Research on an alanine octapeptide in implicit solvent revealed that with extremely short exchange intervals (0.001 ps), the ensemble average temperature deviated from the thermostat temperature by approximately 7 K [17]. Artifacts in potential energy and secondary structure content were also observed with short tatt values [17].

The optimal exchange interval balances sufficient thermal relaxation between attempts with adequate sampling efficiency. For explicit solvent simulations, intervals of 0.1-1.0 ps are commonly used [17]. The thermostat coupling time constant (τ) also influences this balance - shorter τ values (e.g., 0.2 ps) reduce artifacts when using short t_att [17], as they enable faster thermal equilibration after exchanges.

Implementation Protocols

Standard Temperature REMD Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and parameter relationships in a standard temperature REMD simulation:

Advanced Implementation: gREST/REUS for Protein-Ligand Systems

For complex biological processes like protein-ligand binding, advanced REMD variants such as generalized Replica Exchange with Solute Tempering (gREST) combined with Replica Exchange Umbrella Sampling (REUS) provide enhanced sampling efficiency [15]. In this approach, the "solute" region (typically the ligand and binding site residues) is simulated at different "temperatures" while the protein-ligand distance serves as a collective variable for umbrella sampling exchanges [15].

The implementation protocol involves:

- Solute Definition: Selecting the ligand and key binding site residues as the solute region for gREST [15]

- Collective Variable Selection: Defining appropriate reaction coordinates (e.g., protein-ligand distance, interaction angles) [15]

- Replica Distribution: Optimizing the distribution of replicas across the two-dimensional parameter space [15]

- Initial Structure Preparation: Carefully preparing initial structures for each replica by pulling ligands from binding sites [15]

This methodology has been successfully applied to study kinase-inhibitor binding for systems including c-Src kinase with PP1 and Dasatinib, and c-Abl kinase with Imatinib [15].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for REMD Simulations

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD simulation package with REMD implementation | Requires MPI installation; efficient for large systems [16] [1] |

| AMBER | MD simulation package alternative | Supports various REMD variants [13] |

| VMD | Molecular visualization and analysis | Essential for trajectory analysis and figure generation [1] |

| MPI Library | Message passing interface for parallel computation | Required for multi-replica communication [16] |

| HPC Cluster | High-performance computing resources | Typically 2 cores per replica; Intel Xeon X5650 or better [1] |

| REMD Calculator | Temperature set optimization | Web-based tool for determining temperature spacing [16] |

| WHAM/MBAR | Weighted histogram analysis methods | Free energy calculation from REMD trajectories [17] |

Replica-Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD) has established itself as a cornerstone method for enhanced sampling in computational biophysics and drug development. It effectively overcomes the problem of sampling rare events and crossing high energy barriers by running multiple parallel simulations under different conditions and allowing controlled exchanges between them. This facilitates a more thorough exploration of complex biomolecular conformational landscapes, such as protein folding, peptide plasticity, and ligand-receptor interactions. For researchers focused on accelerated drug discovery, understanding the key variants of REMD is crucial for selecting the optimal strategy for a given biological problem. The core REMD framework has evolved into several specialized methods, primarily Temperature REMD (T-REMD), Hamiltonian REMD (H-REMD), and advanced sampling schemes like Gibbs Sampling. This article details these variants, providing structured comparisons, explicit protocols, and practical toolkits for their application in cutting-edge research.

Quantitative Comparison of Key REMD Variants

The choice of REMD variant significantly impacts the computational efficiency and sampling quality of a study. Each method has distinct strengths, optimal use cases, and resource requirements. The table below provides a concise comparison of the three primary variants to guide method selection.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major REMD Variants

| Variant | Exchange Parameter | Key Advantage | Primary Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature REMD (T-REMD) [18] [6] | Simulation Temperature | Conceptually simple; promotes global unfolding and refolding. | Protein folding; studying conformational landscapes of biomolecules. [6] | Number of replicas scales with system size; can be inefficient for large systems. [6] |

| Hamiltonian REMD (H-REMD) [18] [6] | System Hamiltonian (e.g., via λ parameters) | Often requires fewer replicas than T-REMD; targets specific interactions. | Solvation; protein-ligand binding; alchemical free energy calculations. [6] | Requires a defined pathway (e.g., for λ); sampling efficiency depends on parameter selection. [6] |

| Gibbs Sampling REMD [18] [19] | All possible pairs of replicas | Enhanced mixing by considering all exchange pairs simultaneously. | Complex systems with rough energy landscapes where neighbor exchanges are insufficient. | Higher communication cost; permutation complexity can increase computational overhead. [18] |

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol for Temperature REMD (T-REMD)

Temperature REMD is the most straightforward variant, where replicas are run at different temperatures. Exchanges are attempted between neighboring temperatures based on a criterion that preserves the Boltzmann ensemble. [18]

Workflow Overview:

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of a T-REMD simulation, from setup to analysis.

Detailed Methodology:

System Preparation:

- Prepare the initial structure (e.g., protein, protein-ligand complex) and topology files using a molecular dynamics package like GROMACS.

- Solvate the system in an appropriate water box and add ions to neutralize the charge.

Temperature Selection and Replica Setup:

- Determine the number of replicas (N): This is critical for maintaining a reasonable exchange probability (typically 10-20%). The number required depends on the system size and the desired temperature range. An estimate for the temperature spacing factor ϵ is given by ϵ ≈ 1/√N_atoms for systems with constrained bonds. [18]

- Generate temperatures: Use a REMD calculator or the formula Tk = T0 * exp(ϵ * k), where T_0 is the target temperature and k is the replica index, to generate a set of temperatures that ensure good overlap in potential energy distributions between neighbors.

Simulation Execution:

- Equilibration: Equilibrate each replica independently at its assigned temperature (T₁, T₂, ..., Tₙ) using standard MD protocols (energy minimization, NVT, NPT).

- Production REMD: Run the production simulation using an MD engine equipped with REMD functionality (e.g.,

mdrunin GROMACS with MPI). - Exchange Attempts: At regular intervals (e.g., every 100-1000 steps), attempt to exchange the coordinates and velocities of neighboring replicas. The acceptance probability for exchange between replica 1 (at T₁, energy U₁) and replica 2 (at T₂, energy U₂) is calculated as: P(1 2) = min(1, exp[ (1/kB T₁ - 1/kB T₂) (U₁ - U₂) ]) [18]

- GROMACS and other packages typically use a "neighbor-only" exchange scheme with alternating odd/even pairs to satisfy detailed balance. [18]

Post-Processing and Analysis:

- Trace Replica Trajectories: Analyze the continuous trajectory of the replica at the target temperature (T₀).

- Reweighting: Use statistical methods (e.g., Weighted Histogram Analysis Method - WHAM) to combine data from all temperatures and compute the Boltzmann-weighted ensemble at the target temperature.

- Monitor Convergence: Track metrics like replica exchange rates and the diffusion of replicas through temperature space to ensure proper mixing. [6]

Protocol for Hamiltonian REMD (H-REMD)

In H-REMD, replicas differ not in temperature but in their Hamiltonian, typically by scaling interaction parameters along a defined pathway, such as in alchemical free energy calculations. [18] [6]

Workflow Overview:

The diagram below outlines the specific workflow for an H-REMD simulation, highlighting the differences from T-REMD.

Detailed Methodology:

Define the λ Pathway:

- In the molecular dynamics parameter file (e.g.,

gromacs.mdp), define a series of λ values that progressively scale the Hamiltonian. For example, λ=0 might represent the fully interacting state, while λ=1 represents a non-interacting state for a solute.

- In the molecular dynamics parameter file (e.g.,

Replica Setup:

- The number of replicas is equal to the number of λ states. The spacing of λ values should be chosen to ensure sufficient overlap in the potential energy distributions between adjacent λ windows for a good acceptance rate.

Simulation Execution:

- Equilibration: Equilibrate each replica at its assigned λ value.

- Production H-REMD: Run the production simulation. The acceptance probability for an exchange between replica 1 (with coordinates x₁ and Hamiltonian U₁) and replica 2 (with coordinates x₂ and Hamiltonian U₂) is: P(1 2) = min(1, exp[ (U₁(x₁) - U₁(x₂) + U₂(x₂) - U₂(x₁)) / k_B T ]) [18]

- This criterion ensures that the correct Boltzmann distribution is maintained for all Hamiltonians.

Post-Processing and Analysis:

- The primary output is a set of configurations sampled for each λ value, with enhanced sampling due to exchanges.

- Use free energy estimation methods (e.g., MBAR, WHAM) on the combined data from all λ windows to calculate conformational free energies or relative binding free energies.

Advanced Approach: Gibbs Sampling Replica Exchange

Gibbs sampling is an advanced variant that can be applied to both temperature and Hamiltonian replica exchange. Unlike standard REMD, which only attempts exchanges between neighboring replicas, Gibbs sampling evaluates all possible pair permutations in a single step. [18] [19]

Key Principles and Protocol:

Concept: In each exchange step, Gibbs sampling considers the entire set of replicas and their states (temperatures or Hamiltonians). It samples a new permutation of states assigned to replicas from the conditional probability distribution given the current energies and coordinates. [18] [19]

Acceptance Criterion: The acceptance probability is calculated for a potential permutation of states among all replicas. This global assessment can lead to more efficient mixing, as it allows for long-range swaps in a single step that would require many steps in a neighbor-exchange scheme.

Implementation:

- The method is implemented in packages like GROMACS. [18]

- The main computational consideration is the increased communication cost, as determining the optimal permutation may require multiple rounds of communication. However, it does not typically require additional potential energy calculations. [18]

When to Use: Gibbs sampling is particularly beneficial for systems with very rough energy landscapes where the standard neighbor-exchange method leads to slow diffusion of replicas through parameter space. [19]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of REMD simulations relies on a suite of software tools and computational resources. The following table lists essential components of a modern REMD research pipeline.

Table 2: Essential Tools and Resources for REMD Simulations

| Tool Category | Example Software/Resource | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Engines | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, OpenMM | Core MD engines that perform the numerical integration of equations of motion; most support REMD variants. |

| REMD Setup & Analysis | GROMACS mdrun (with MPI), PyRETIS, PLUMED |

Software-specific utilities for launching parallel REMD simulations and analyzing results (e.g., replica trajectories, free energies). |

| Free Energy Analysis | WHAM, MBAR, alchemical-analysis.py | Post-processing tools to compute potential of mean force (PMF) and free energies from replica exchange data. |

| Enhanced Sampling Modules | PLUMED (plugin), REST2 | Specialized modules that can be integrated with MD engines to implement advanced H-REMD protocols like Replica Exchange with Solute Tempering (REST2). [20] |

| Computational Infrastructure | High-Performance Computing (HPC) cluster, MPI library | Essential hardware and software for running dozens to hundreds of replicas in parallel. |

Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD) has emerged as a powerful enhanced sampling technique that effectively overcomes the timescale limitations of conventional molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. By enabling efficient exploration of complex free energy landscapes, REMD provides unique insights into biological processes that are otherwise challenging to study, particularly protein folding and the aggregation of amyloidogenic peptides associated with neurodegenerative diseases. This application note details the fundamental principles of REMD, presents structured quantitative data on its implementation, and provides explicit protocols for investigating amyloid-β (Aβ) aggregation, a process central to Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. The content is framed within the context of utilizing REMD for advanced sampling research, with practical information tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

REMD Fundamentals and Methodological Framework

The REMD method operates by simulating multiple non-interacting copies (replicas) of a system simultaneously at different temperatures or with different Hamiltonians, then periodically attempting to exchange configurations between adjacent replicas based on a Metropolis criterion [1]. This approach generates a generalized ensemble that facilitates escape from local energy minima, enabling comprehensive sampling of conformational space. The mathematical foundation relies on the acceptance probability for exchanges between replicas i and j at temperatures T_m and T_n:

[ w(X \rightarrow X') = min(1, exp{βn - βm ]

where (β = 1/kBT), (kB) is Boltzmann's constant, and (V(q^{[i]})) and (V(q^{[j]})) are the potential energies of configurations i and j, respectively [1]. This formulation satisfies the detailed balance condition and ensures proper sampling of the canonical ensemble. The method can be adapted to various ensembles, including isothermal-isobaric (NPT) conditions, by incorporating appropriate terms for pressure and volume in the exchange probability [21].

Table 1: Key Parameters and Typical Values for REMD Simulations of Amyloid Systems

| Parameter | Typical Value/Range | Application Context | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Replicas | 8-40 [22] [23] | Peptide aggregation studies | Ensures sufficient acceptance ratio (15-25%) |

| Temperature Range | 283.8 K - 418.7 K [22] or 310 K - 389 K [23] | Enhanced conformational sampling | Lower bound near physiological, upper bound below force field denaturation |

| Exchange Attempt Frequency | Every 2 ps [23] or 40 ps [22] | Balance between sampling and computational overhead | Frequent enough for efficient walking, minimal communication overhead |

| Simulation Length per Replica | 100-200 ns [23] | Aβ aggregation and inhibition studies | Sufficient for convergence of structural properties |

| Acceptance Ratio | 16-25% [22] [23] | Optimal replica walking | Balance between temperature space diffusion and computational efficiency |

REMD Protocol for Amyloid-β Aggregation Studies

System Preparation and Initial Configuration

The initial step involves constructing physiologically relevant starting configurations of the amyloid system. For studying Aβ trimer formation with inhibitors such as amentoflavone (AMF):

- Obtain Peptide Structure: Source the initial Aβ(1-42) structure from the Protein Data Bank (e.g., PDB ID: 1IYT) [23].

- Generate Extended Conformation: Perform high-temperature simulated annealing on the crystal structure to obtain a fully extended coil conformation, which serves as an aggregation-competent state [23].

- Build Multimeric System: Randomly place three extended Aβ monomers in a cubic water box with dimensions of 80 Å × 80 Å × 80 Å [23].

- Add Inhibitor Molecules: For inhibition studies, randomly distribute inhibitor molecules (e.g., AMF) within the simulation box. A low-concentration system may contain three AMF molecules (1:1 molar ratio with monomers), while a high-concentration system may contain seven molecules to assess saturation effects [23].

- Solvation and Neutralization: Hydrate the system using explicit water models (TIP3P) and add counterions (e.g., Na+) to maintain charge neutrality [23].

REMD Simulation Workflow

The following workflow outlines the complete REMD procedure for studying amyloid aggregation:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for REMD Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Components | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| MD Software Packages | GROMACS [1] [23], AMBER [22] [21] | Primary simulation engines with REMD implementation |

| Visualization Software | VMD (Visual Molecular Dynamics) [1] | Molecular modeling, trajectory analysis, and structure visualization |

| Force Fields | CHARMM36m [23], AMBER force fields [22] | Define potential energy functions and molecular parameters |

| Solvent Models | TIP3P water model [23] | Explicit solvent representation |

| High-Performance Computing | HPC cluster with MPI, NVIDIA/AMD GPUs [1] [21] | Parallel execution of multiple replicas with accelerated performance |

| Analysis Methods | MM/PBSA [23], secondary structure analysis, clustering | Energetic and structural characterization of aggregates |

Simulation Parameters and Analysis

After system preparation, implement the following simulation protocol:

- Energy Minimization: Use the steepest descent algorithm to remove steric clashes and achieve a stable initial structure [23].

- Equilibration:

- REMD Production Simulation:

- Utilize 40 replicas with temperatures logarithmically spaced between 310 K and 389 K [23].

- Attempt exchanges between neighboring replicas every 2 ps, achieving an acceptance ratio of approximately 25% [23].

- Run each replica for 200 ns, using the final 100 ns for analysis to ensure proper equilibration [23].

- Apply a 14 Å cutoff for nonbonded interactions and treat long-range electrostatics with the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method [23].

- Constrain bond lengths involving hydrogen atoms using the SHAKE algorithm [23].

- Analysis Methods:

Application to Amyloid-β Aggregation and Inhibition

REMD simulations have revealed critical insights into the molecular mechanisms of Aβ aggregation and inhibition. Studies demonstrate that Aβ peptides preferentially form β-hairpin structures that promote intermolecular β-sheet formation, particularly at hydrophilic/hydrophobic interfaces [24]. The hydrophobic core region (¹⁶KLVFFAEDV²⁴) plays a pivotal role in initiating aggregation [23].

For inhibitory mechanisms, REMD simulations show that natural compounds like amentoflavone (AMF) preferentially bind to the ¹⁶KLVFFAEDV²⁴ segment through hydrophobic interactions with key residues (Leu-17, Phe-20, Val-24), thereby disrupting β-sheet formation and stabilizing disordered coil conformations that are less prone to aggregation [23]. These atomic-level insights guide the rational design of inhibitors that target specific aggregation-prone regions.

The following diagram illustrates the amyloid aggregation pathway and inhibition mechanism:

Advanced REMD Implementations and Computational Tools

Recent advancements in REMD methodologies have expanded its applications in amyloid research:

- Constant pH REMD: Enables simulation of protonation state changes alongside conformational dynamics, particularly useful for studying pH-dependent aggregation [21].

- Hamiltonian REMD: Utilizes different Hamiltonians rather than temperatures for enhanced sampling, often providing improved efficiency for specific molecular interactions [24].

- Replica-Permutation Method: An improved alternative to traditional REMD that permutes temperatures among three or more replicas using the Suwa-Todo algorithm, providing statistically more reliable data [24].

- GPU Acceleration: Modern implementations in AMBER and GROMACS leverage GPU computing, dramatically accelerating simulation times and enabling larger system sizes [21].

Table 3: Comparison of REMD Software Implementations

| Software | REMD Variants Supported | Key Features | Performance Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Temperature REMD, Hamiltonian REMD | Extensive analysis tools, GPU acceleration | ~1.7 μs/day for DHFR (23,000 atoms) on RTX 4090 [21] |

| AMBER | Temperature REMD, NPT REMD, constant pH REMD | Advanced thermodynamics, well-validated force fields | ~82 ns/day for STMV (1M atoms) on RTX 4090 [21] |

| NAMD | Temperature REMD | Strong scalability for large systems | Varies with system size and core count |

When planning REMD simulations of amyloid systems, careful consideration of replica numbers and temperature distributions is essential for achieving optimal acceptance ratios (typically 15-25%). The temperature list should be generated using established algorithms to ensure approximately uniform exchange probabilities across adjacent replicas [23]. Additionally, system setup should incorporate sufficient explicit solvent molecules to properly solvate the amyloid peptides, with periodic boundary conditions applied to minimize edge effects [22] [23].

Implementing REMD: Practical Protocols from System Setup to Analysis

Replica-Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD) is an advanced enhanced sampling technique that enables efficient exploration of complex free energy landscapes, a critical capability in modern computational biology and drug development. This protocol provides a detailed, application-oriented guide for implementing REMD simulations, framed within the broader context of accelerating molecular research. By allowing systems to escape local energy minima through non-physical temperature exchanges, REMD provides superior conformational sampling compared to conventional molecular dynamics, making it particularly valuable for studying protein folding, ligand binding, and molecular recognition processes relevant to pharmaceutical development. The workflow presented here encompasses the complete trajectory from initial system preparation through production simulation and data analysis, with specific attention to methodological rigor and computational efficiency.

REMD Workflow Protocol

System Preparation and Initialization

Initial Structure Preparation The foundation of any successful REMD simulation begins with meticulous system preparation. Obtain your initial molecular structure from experimental sources (Protein Data Bank) or through homology modeling, ensuring proper protonation states corresponding to physiological pH. Utilize tools like PDB2PQR or PROPKA3 to assign appropriate protonation states for histidine residues and acidic/basic amino acids. Solvate the system in an appropriate water model (TIP3P, TIP4P-EW) extending at least 10-12 Å beyond the solute in all dimensions. Add physiological ion concentrations (typically 0.15M NaCl) using Monte Carlo ion placement methods to achieve charge neutrality. Energy minimization should be performed using a two-stage approach: initial steepest descent (5,000-10,000 steps) followed by conjugate gradient minimization (5,000 steps) until forces converge below 10 kJ/mol/nm.

Topology and Parameter Generation For non-standard residues or small molecule ligands, develop accurate force field parameters using programs like CGenFF (for CHARMM force fields) or GAUSSIAN-based parametrization workflows (for AMBER force fields). Consistently validate these parameters through comparison with quantum mechanical calculations and experimental data where available. This validation step is particularly crucial for drug discovery applications where ligand interactions dictate binding affinity and specificity.

Replica Exchange Parameterization

Temperature Distribution Optimization A critical step in REMD setup involves determining the optimal number and distribution of replicas across temperatures. The temperature range should span from the target temperature (typically 300K) to the highest temperature where the native structure becomes unstable (often 400-500K for proteins). Use the temperature predictor tool in your MD software or implement the following approach to calculate the number of replicas required:

The number of replicas (N) needed can be estimated using the formula that ensures sufficient exchange probability (typically 20-25%) between adjacent replicas. For a system with M degrees of freedom, the average acceptance probability P between temperatures Ti and Tj is approximately:

P = erfc( √[(βj - βi)² * ΔU² / 2] )

where β = 1/k_BT and ΔU is the potential energy difference. Implement an iterative approach to determine the minimal number of replicas that maintains >20% exchange probability between all adjacent temperature pairs, balancing computational cost against sampling efficiency.

Exchange Attempt Frequency Configure exchange attempts between adjacent replicas every 1-2 ps of simulation time. This frequency represents a compromise between sampling efficiency and computational overhead. Too frequent exchanges increase communication costs in parallel computing environments, while too infrequent exchanges reduce the sampling benefits of the REMD approach.

Table 1: Key Parameters for REMD Setup

| Parameter | Recommended Value | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Replicas | System-dependent (typically 24-72) | Ensures >20% exchange probability between adjacent temperatures |

| Temperature Range | 300K - 400-500K | Balances native state sampling with enhanced exploration |

| Exchange Attempt Frequency | 1-2 ps | Optimizes trade-off between sampling and computational overhead |

| Simulation Length per Replica | 50-200 ns | Provides sufficient statistical sampling at each temperature |

| Energy Minimization Convergence | 10 kJ/mol/nm | Ensures stable initial configuration before dynamics |

Production Simulation

Equilibration Protocol Before initiating the production REMD simulation, perform careful equilibration at each temperature level. Begin with a 100-ps NVT ensemble simulation with position restraints (force constant 1000 kJ/mol/nm²) on heavy atoms, followed by 100-ps NPT equilibration with semi-isotropic pressure coupling. Gradually release position restraints during a final 100-ps NPT equilibration phase. Monitor potential energy, density, and root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) to confirm equilibration at each temperature before commencing production sampling.

Production REMD Execution Launch production REMD simulations using parallel computing resources, with each replica assigned to a separate CPU core or node. Implement a temperature exchange scheme (typically Monte Carlo-based) that periodically attempts to swap configurations between adjacent temperatures based on the Metropolis criterion. The acceptance probability for exchange between replicas i and j at temperatures Ti and Tj with potential energies Ui and Uj is:

Paccept = min(1, exp[(βi - βj) * (Ui - U_j)])

where β = 1/(k_BT). Continuously monitor key parameters including acceptance ratios, temperature distributions, potential energies, and structural metrics to ensure proper simulation behavior. Implement restart functionality to protect against system failures and enable simulation extension.

Analysis and Validation

Convergence Assessment Determine simulation convergence through multiple complementary approaches. Monitor the time evolution of potential energy, radius of gyration, secondary structure content, and root-mean-square deviation (RMSD). Calculate the statistical inefficiency for key observables to ensure adequate sampling of conformational space. Implement replica permutation analysis to verify efficient random walk through temperature space, which is essential for proper REMD performance.

Free Energy Calculations Extract thermodynamic information from REMD simulations using weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) or multistate Bennett acceptance ratio (MBAR). These techniques reconstruct the free energy landscape as a function of relevant reaction coordinates (e.g., root-mean-square deviation, native contacts, dihedral angles). Validate free energy profiles through comparison with experimental data when available, or through internal consistency checks using different subsets of the simulation data.

Table 2: Essential Analysis Metrics for REMD Simulations

| Analysis Type | Key Metrics | Interpretation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Sampling Quality | Replica mixing, Potential energy distributions, Acceptance ratios | >20% exchange probability indicates proper temperature spacing; Random walk in temperature space indicates efficient sampling |

| Structural Properties | RMSD, Radius of gyration, Secondary structure retention, Native contacts | Stable structural metrics at target temperature indicate proper folding; Comparison with experimental data validates simulations |

| Convergence | Statistical inefficiency, autocorrelation times, Block averaging | Low statistical inefficiency (<10% of trajectory length) suggests sufficient sampling; Consistent block averages indicate convergence |

| Free Energy | WHAM/MBAR convergence, Free energy profiles, Error estimates | Small standard errors in free energy differences (<0.5 kT) suggest sufficient sampling; Smooth free energy profiles indicate adequate data |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for REMD Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Software | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Engines | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, OPENMM | REMD simulation execution | Provides core molecular dynamics capabilities with enhanced sampling algorithms; GROMACS offers excellent performance for biomolecular systems |

| System Preparation | CHARMM-GUI, PDB2PQR, tleap | Initial structure setup | Handles solvation, ionization, and topology generation; CHARMM-GUI provides web-based interface for complex system building |

| Analysis Tools | MDTraj, PyEMMA, CPPTRAJ | Trajectory analysis and visualization | Processes simulation trajectories to extract structural and thermodynamic metrics; PyEMMA specializes in Markov state models for kinetics |

| Free Energy Methods | WHAM, MBAR, Alanine Scanning | Thermodynamic calculations | Extracts free energies and other thermodynamic properties from simulation data; MBAR provides optimal estimation of free energy differences |

| Visualization | VMD, PyMOL, Chimera | Structural visualization and rendering | Enables inspection of molecular structures and dynamics; VMD offers extensive analysis plugins and rendering capabilities |

Workflow Visualization

REMD Workflow Overview

Replica Exchange Mechanism

Temperature Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics (T-REMD) is an enhanced sampling method that overcomes the limitations of conventional molecular dynamics (MD) in exploring complex free energy landscapes. In conventional MD, systems often become trapped in local energy minima, preventing adequate sampling of all relevant conformational states within feasible simulation times [1]. T-REMD addresses this challenge by running multiple parallel simulations (replicas) of the same system at different temperatures and periodically attempting exchanges between them based on a Metropolis criterion [1] [13]. This approach enables more efficient exploration of conformational space, making it particularly valuable for studying complex biomolecular processes such as protein folding, peptide aggregation, and ligand binding [1] [25].

The fundamental principle behind T-REMD is that higher temperature replicas can overcome energy barriers more easily, while lower temperature replicas provide proper Boltzmann-weighted sampling [25]. By allowing configurations to diffuse through temperature space, the method facilitates escape from local minima and accelerates convergence of thermodynamic properties [13]. The mathematical foundation ensures that each temperature maintains the correct canonical ensemble, enabling direct comparison with experimental observables [1] [25]. For researchers investigating complex biological phenomena with rugged energy landscapes, T-REMD provides a powerful tool for obtaining statistically meaningful conformational ensembles within practical computational timeframes.

Theoretical Foundation of T-REMD

Mathematical Framework

In T-REMD, the system consists of M non-interacting replicas simulated in parallel at different temperatures T₁, T₂, ..., Tₘ [1]. Each replica has coordinates q and momenta p, with the Hamiltonian given by H(q,p) = K(p) + V(q), where K(p) is the kinetic energy and V(q) is the potential energy [1]. In the canonical ensemble (NVT), the probability of finding the system in state x ≡ (q,p) at temperature T is ρ𝐵(x,T) = exp[-βH(q,p)], where β = 1/k𝐵T and k𝐵 is Boltzmann's constant [1].

The core of the REMD algorithm involves periodically attempting exchanges between neighboring replicas. The probability of accepting an exchange between replica i at temperature Tₘ and replica j at temperature Tₙ is given by the Metropolis criterion:

[w(X \rightarrow X') = \min(1, \exp(-\Delta))]

where Δ = (βₙ - βₘ)(V(qⁱ) - V(qʲ)) [1]. This acceptance criterion ensures detailed balance is maintained, guaranteeing convergence to the correct equilibrium distribution [1] [26]. For simulations in the isobaric-isothermal ensemble (NPT), the Hamiltonian includes an additional PV term, but the volume contribution to the exchange probability is typically negligible [1].

Key Concepts for Efficient Sampling

The effectiveness of T-REMD depends on several factors. The temperature spacing must be close enough to provide adequate exchange probabilities between neighboring replicas, typically targeting 20-30% acceptance rates [27]. The number of replicas required increases with system size and the temperature range to be covered, creating a trade-off between computational cost and sampling efficiency [28]. The highest temperature should be chosen to sufficiently accelerate barrier crossing while avoiding denaturation of key structural elements if maintaining native structure is important [13]. Replica diffusion through temperature space should be efficient, with replicas completing multiple round trips between extreme temperatures during the simulation [25].

Determining Replica Number and Temperature Distribution

Factors Influencing Replica Setup

The number of replicas and their temperature distribution are critical parameters that directly impact the efficiency and success of T-REMD simulations. The number of required replicas increases with the system size (number of atoms) and the square root of the number of degrees of freedom [28] [25]. For large systems in explicit solvent, T-REMD can become impractical due to the large number of replicas needed to maintain adequate exchange probabilities [28]. The temperature range between the lowest temperature of interest (typically 300 K for biological systems) and the highest temperature (selected to enhance sampling without causing unphysical behavior) also directly affects replica count [13] [27].

Temperature Distribution Calculation

An optimal temperature distribution should provide approximately equal acceptance probabilities between all neighboring replica pairs [27]. The potential energy variance of the system dictates the temperature spacing, with the relationship given by:

[\sigma^2E = \left(\frac{\partial^2 \ln Q}{\partial \beta^2}\right) = kB T^2 C_v]

where Q is the partition function and Cᵥ is the heat capacity [27]. For complex biomolecular systems, this relationship leads to the practical observation that the number of replicas needed to cover a fixed temperature range scales approximately with the square root of the number of degrees of freedom in the system [28].

Online tools such as the Temperature Generator for T-REMD Simulations (available at https://jerkwin.github.io/gmxtools/remd_tgenerator/) can calculate appropriate temperature distributions based on system characteristics [27]. These tools require inputs including:

- Number of protein atoms and water molecules

- Upper and lower temperature limits

- Information about constraints and virtual sites

- Desired exchange probability (typically 0.2-0.3)

Table 1: Approximate Replica Requirements for Different System Sizes

| System Size (atoms) | Temperature Range (K) | Estimated Replicas | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5,000-10,000 | 300-500 | 12-24 | Suitable for small peptides in explicit solvent [27] |

| 50,000-100,000 | 300-500 | 24-48 | Medium-sized proteins require significant resources [28] |

| >140,000 | 300-500 | 48+ | May become impractical; consider H-REMD alternatives [28] |

Practical Implementation Protocol

System Preparation and Equilibration

The initial steps of T-REMD mirror those of conventional MD simulations [1]. For the hIAPP(11-25) dimer case study [1], the protocol begins with constructing the initial system configuration. The peptide sequence (RLANFLVHSSNNFGA) is capped with an acetyl group at the N-terminus and a NH₂ group at the C-terminus to match experimental conditions [1]. The system is then solvated in an appropriate water model (e.g., TIP3P) and neutralized with counterions.

Energy minimization is performed using steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithms to remove bad contacts [1]. This is followed by stepwise equilibration: first in the NVT ensemble to stabilize temperature, then in the NPT ensemble to stabilize density and pressure [1] [29]. During equilibration, position restraints are typically applied to protein heavy atoms, gradually releasing them as the system relaxes. The length of equilibration varies with system size and complexity but should continue until key properties (energy, density, temperature) have stabilized.

T-REMD Production Simulation

Once equilibrated, the production T-REMD simulation is initiated using multiple replicas. The following workflow outlines the key steps:

Figure 1: T-REMD Implementation Workflow

For GROMACS implementations, the process involves specific commands [29]:

Prepare MDP Files: Create a directory for each temperature containing a

replex.mdpfile with the corresponding temperature parameter.Generate TPR Files: For each temperature directory, run:

Launch T-REMD: Execute the production simulation using:

The

-replex 1000flag specifies exchange attempts every 1000 steps [29].

Exchange attempts should occur frequently enough to allow replicas to diffuse through temperature space, but not so frequently that they interrupt local sampling. Typical exchange attempt frequencies range from 100 to 2000 steps, depending on the system and computational resources [29].

Monitoring and Validation

During execution, key metrics should be monitored to ensure proper simulation behavior. Exchange probabilities between all neighboring replica pairs should be calculated and should ideally fall between 0.2 and 0.3 [27]. If probabilities are too low, additional replicas may be needed; if too high, some replicas may be redundant. Replica trajectories through temperature space should be examined to ensure all replicas are making multiple round trips between temperature extremes during the simulation [25]. Potential energy distributions should show sufficient overlap between neighboring replicas to support the observed exchange probabilities [27].

Table 2: Essential Tools and Resources for T-REMD Simulations

| Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [1] [29] | MD simulation package with T-REMD implementation | Versions 4.5.3 and above support T-REMD; highly parallelized for HPC environments |

| AMBER [25] [30] | Alternative MD package with REMD capabilities | Supports various REMD variants including Reservoir REMD |

| Temperature Generator [27] | Web tool for calculating temperature distributions | Inputs: system size, temperature range, desired exchange probability |

| VMD [1] | Molecular visualization and analysis | Critical for system setup, trajectory analysis, and result interpretation |

| MPI Library [1] | Message passing interface for parallel computation | Required for running multi-replica simulations on HPC clusters |

| HPC Cluster [1] | High-performance computing resources | Minimum 2 cores per replica recommended for efficient parallelization |

Advanced Considerations and Optimization

Limitations and Alternative Approaches

While T-REMD is powerful for enhancing conformational sampling, it has limitations that researchers should consider. For large systems (>100,000 atoms), T-REMD becomes increasingly impractical due to the large number of replicas required [28]. In such cases, Hamiltonian REMD (H-REMD) variants may be more efficient, where different replicas use modified Hamiltonians instead of different temperatures [30] [28]. Reservoir REMD (RREMD) can accelerate convergence by 5-20x by pre-generating a reservoir of structures at high temperature and exchanging them with the highest temperature replica during simulation [25]. Multidimensional REMD (M-REMD) combines temperature and Hamiltonian exchanges for even more efficient sampling, particularly for complex biomolecules like nucleic acids [30].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Several common problems can arise in T-REMD simulations with specific solutions. If exchange probabilities are too low, consider adding more replicas to reduce temperature spacing or extending the simulation time to improve energy distribution overlap [27]. If specific replicas become trapped at temperature extremes, check for insufficient equilibration or inadequate sampling of intermediate replicas [25]. For poor replica diffusion through temperature space, ensure temperature spacing is even and consider adjusting the exchange attempt frequency [25] [29]. When the highest temperature replica samples unphysical conformations, reduce the maximum temperature or implement restraints to maintain relevant structural features [13].

Analysis Methods for T-REMD Simulations

Free Energy Landscape Calculation

The primary advantage of T-REMD is the ability to calculate free energy landscapes along reaction coordinates of interest. The weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) or multistate Bennett acceptance ratio (MBAR) can be used to combine data from all temperatures to construct free energy surfaces at the temperature of interest [1]. These surfaces reveal stable states, transition barriers, and the overall conformational landscape, providing insights into biological mechanisms [1] [13].

Convergence Assessment

Several methods can assess simulation convergence. Replica convergence can be evaluated by monitoring the time evolution of potential energy, radius of gyration, or other order parameters at each temperature [30]. Statistical convergence can be assessed by comparing block averages of key properties or running multiple independent simulations and comparing their distributions [30]. For structural convergence, cluster analysis can identify the predominant conformational families and track their population stability over time [30].

When properly implemented with appropriate temperature distributions and replica counts, T-REMD provides significantly accelerated sampling compared to conventional MD, enabling the study of complex biomolecular processes that would otherwise be computationally prohibitive [1] [13]. The protocols outlined here provide a foundation for researchers to implement this powerful method in their enhanced sampling studies.

Hamiltonian Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics (H-REMD) represents a powerful advanced sampling technique that addresses a fundamental limitation in conventional molecular dynamics (MD): the inadequate sampling of complex biomolecular energy landscapes due to high energy barriers separating functionally relevant states [13]. While temperature-based REMD (T-REMD) enhances sampling by elevating thermal energy, its computational demand scales dramatically with system size, making it prohibitive for large biomolecular systems [31]. H-REMD circumvents this limitation by modifying the Hamiltonian (force field) across replicas while maintaining constant temperature, enabling efficient barrier crossing through coordinate-space rather than temperature-space walks [30] [5].

This protocol focuses specifically on the implementation of H-REMD through targeted force field modifications at identified "hot-spot" residues—amino acids critically responsible for stabilizing the native protein fold [31]. By selectively perturbing interactions only at these key positions, researchers can achieve enhanced sampling of folding/unfolding transitions and conformational changes with significantly fewer replicas than T-REMD requires, making all-atom simulations of reversible folding events feasible even for small to medium-sized proteins [31].

Theoretical Foundation

In H-REMD, multiple non-interacting replicas of the system are simulated simultaneously using different Hamiltonians. At regular intervals, exchanges between neighboring replicas are attempted with a probability designed to preserve detailed balance:

{{< formula >}} P(1 \leftrightarrow 2)=\min\left(1,\exp\left[ \frac{1}{kB T} (U1(x1) - U1(x2) + U2(x2) - U2(x_1)) \right]\right) {{< /formula >}}