Enhanced Sampling Methods for Rare Event Tracking in Molecular Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of enhanced sampling methods for tracking rare events in molecular dynamics simulations, a critical challenge in computational drug discovery.

Enhanced Sampling Methods for Rare Event Tracking in Molecular Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of enhanced sampling methods for tracking rare events in molecular dynamics simulations, a critical challenge in computational drug discovery. We explore foundational concepts of rare events and their impact on simulating biologically relevant timescales, then delve into advanced methodologies including machine learning-enhanced approaches like AMORE-MD and deep-learned collective variables. The guide addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies for improving sampling efficiency, while presenting rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses across different molecular systems. Targeted at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes current innovations to help overcome sampling limitations in studying protein conformational changes, ligand binding, and other pharmaceutically relevant rare events.

Understanding Rare Events in Molecular Dynamics: Why Enhanced Sampling is Essential for Drug Discovery

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations provide a computational microscope for observing physical, chemical, and biological processes at the atomic scale. [1] By integrating Newton's equations of motion, MD generates trajectories that reveal the dynamic evolution of atomic configurations, enabling direct calculation of thermodynamic and kinetic properties. However, the effectiveness of MD is often severely constrained by the rare events problem. [1] Many processes of fundamental importance—including protein folding, drug binding, and chemical reactions—unfold on timescales from milliseconds to seconds or longer, far exceeding the practical reach of conventional MD simulations, which typically struggle to surpass microsecond timescales even with powerful supercomputers. [1] This limitation arises from the intrinsic serial nature of MD and the necessity of using integration timesteps on the femtosecond scale to capture the fastest molecular motions. [1]

Rare events are transitions between metastable states that occur infrequently relative to the timescales of local atomic vibrations. These transitions represent the "special" regions of dynamic space that systems are unlikely to visit through brute-force simulation alone. [2] Familiar examples include the nucleation of a raindrop from supersaturated water vapour, protein folding, and ligand-receptor binding events. [2] The computational challenge lies in the fact that while these events are rare, they often govern the functionally relevant behavior of molecular systems.

Enhanced sampling methods have been developed to address this fundamental sampling challenge by selectively accelerating the exploration of configurational space. [1] These approaches employ various strategies to overcome energy barriers that would otherwise be insurmountable within accessible simulation timescales. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of these methods, focusing on their theoretical foundations, practical implementation, and relative performance across different application domains in molecular research and drug development.

Theoretical Framework: Enhanced Sampling Methodologies

Collective Variable-Based Approaches

Many enhanced sampling methods rely on the identification of Collective Variables which are functions of the atomic coordinates designed to capture the slow and thermodynamically relevant modes of the system. [1] These CVs are conceptually similar to reaction coordinates in chemistry or order parameters in statistical physics. The equilibrium distribution along the CVs is obtained by marginalizing the full Boltzmann distribution, defining the Free Energy Surface according to the relationship:

$$F(\mathbf{s}) = -\frac{1}{\beta} \log p(\mathbf{s})$$

where $F(\mathbf{s})$ represents the free energy, $\beta = 1/(k_B T)$ is the inverse temperature, and $p(\mathbf{s})$ is the probability distribution along the CVs. [1] The FES provides a low-dimensional, typically smoother thermodynamic landscape where metastable states correspond to local minima and reaction pathways to transitions between them.

Table 1: Classification of Enhanced Sampling Methods

| Method Category | Representative Techniques | Theoretical Basis | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Path Sampling | Transition Path Sampling, Forward Flux Sampling, Weighted Ensemble | Stochastic trajectory ensembles | Directly captures transition mechanisms without predefined reaction coordinates |

| Collective Variable-Based | Metadynamics, Umbrella Sampling | Biased sampling along predefined CVs | Accelerates transitions along specific degrees of freedom |

| Alchemical Methods | Free Energy Perturbation, Thermodynamic Integration | Non-physical intermediate states | Computes free energy differences for transformations |

| Temperature-Based | Replica Exchange | Parallel simulations at different temperatures | Enhances conformational sampling without predefined CVs |

The Alchemical Pathway

Alchemical free energy calculations represent a distinct class of enhanced sampling that computes free energy differences using non-physical intermediate states. [3] These "alchemical" transformations use bridging potential energy functions representing intermediate states that cannot exist as real chemical species. The data collected from these bridging states enables efficient computation of transfer free energies with orders of magnitude less simulation time than simulating the transfer process directly. [3] Common applications include calculating relative and absolute binding free energies, hydration free energies, and the effects of protein mutations.

Methodological Comparison of Sampling Techniques

Rare Event Sampling Algorithms

The field of rare event sampling encompasses numerous specialized algorithms designed to selectively sample unlikely transition regions of dynamic space. [2] These methods can be broadly categorized into those that assume thermodynamic equilibrium and those that address non-equilibrium conditions. When a system is out of thermodynamic equilibrium, time-dependence in the rare event flux must be considered, requiring methods that maintain a steady current of trajectories into target regions of configurational space. [2]

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Rare Event Sampling Methods

| Method | Computational Efficiency | Parallelization Potential | Required Prior Knowledge | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition Path Sampling | Moderate | Moderate | Reaction mechanism | Barrier crossing, nucleation events |

| Forward Flux Sampling | High | High | Initial and target states | Non-equilibrium systems, biochemical networks |

| Weighted Ensemble | High | High | Initial and target states | Biomolecular association, conformational changes |

| Replica Exchange TIS | Low | High | Initial and target states | Complex biomolecular transitions |

| Alchemical FEP | Moderate-High | Moderate | End-state structures | Binding free energies, mutation studies |

| Metadynamics | Moderate | Low-Moderate | Collective variables | Conformational landscapes, drug binding |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Evaluating the performance of enhanced sampling methods requires careful consideration of multiple metrics. For methods that reconstruct free energy surfaces, the convergence rate of free energy estimates is crucial. The normalized DIFFENERGY measure represents the overall ratio of valid energy information still lost by the model algorithm compared to the information lost in truncated data. [4] This can be calculated globally or locally to assess reconstruction quality:

$$\text{GDF} = \frac{\sum{n\in N}\sum{m\in M\text{com}} |\text{DIFF}\text{model}[n][m]|^2}{\sum{n\in N}\sum{m\in M\text{com}} |\text{DIFF}\text{trunc}[n][m]|^2}$$

where $\text{DIFF}_\text{method}$ represents the complex difference between frequency domain data for the reconstruction technique and the standard "full" data set. [4]

Additional practical considerations include implementation complexity, computational overhead, and robustness to poor initial conditions. Methods that require minimal prior knowledge of the reaction pathway (e.g., Weighted Ensemble, FFS) typically offer greater ease of use but may require more sampling to characterize precise mechanisms.

Integrated Workflows and Machine Learning Advances

AI-Enhanced Sampling Algorithms

Recent years have witnessed a growing integration of machine learning techniques with enhanced sampling methods. [1] ML has significantly impacted several aspects of atomistic modeling, particularly through the data-driven construction of collective variables. [1] These tools are especially useful for learning structural representations and uncovering meaningful patterns from large datasets, moving beyond traditional hand-crafted CVs that often rely heavily on physical intuition and prior knowledge of the system.

The AI+RES algorithm represents a novel approach that uses ensemble forecasts of an AI weather emulator as a score function to guide highly efficient resampling of physical models. [5] This synergistic integration of AI with rare event sampling has demonstrated 30-300x cost reductions for studying extreme weather events, with promising applications to molecular simulation. [5] Similar principles can be applied to biomolecular systems, where AI emulators guide sampling of rare conformational transitions.

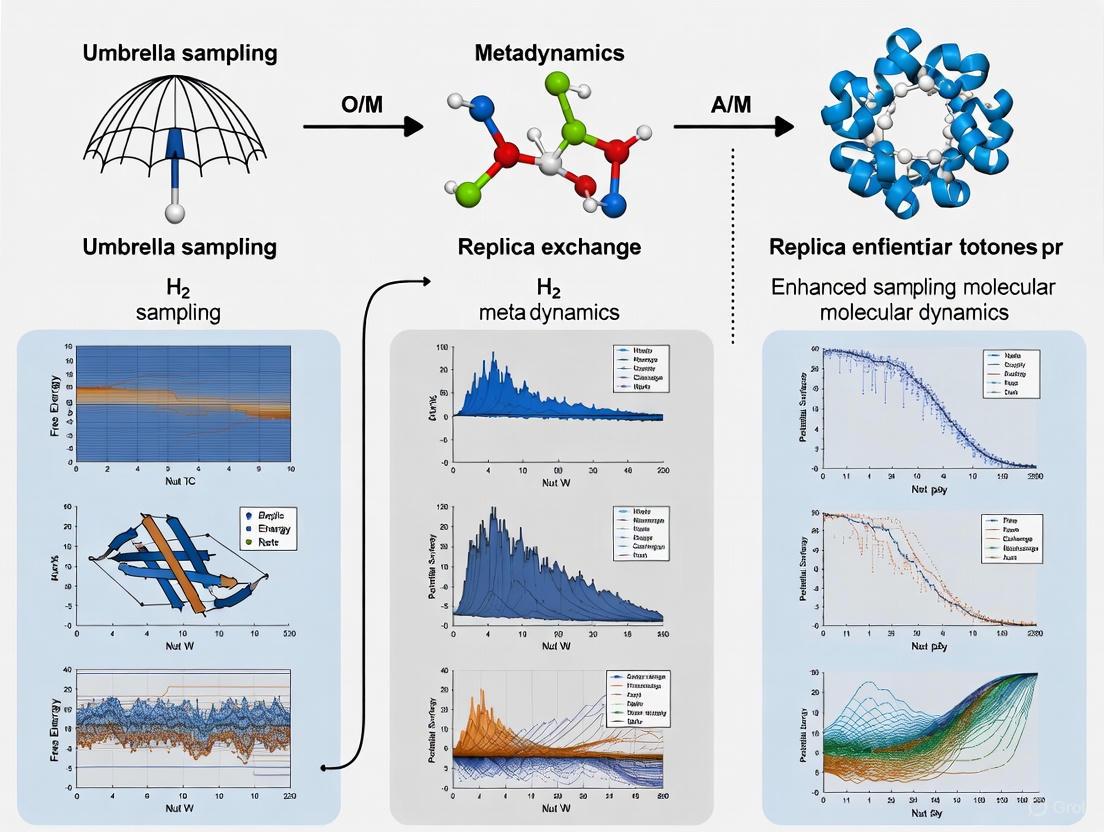

Diagram 1: ML-Enhanced Sampling Workflow. This workflow integrates machine learning with traditional enhanced sampling for improved collective variable discovery and validation.

Multi-Scale Simulation Frameworks

Modern enhanced sampling often employs multi-scale frameworks that combine different methodologies in hierarchical approaches. Coarse-grained simulation techniques have been developed that maintain full protein flexibility while including all heavy atoms of proteins, linkers, and dyes. [6] These methods sufficiently reduce computational demands to simulate large or heterogeneous structural dynamics and ensembles on slow timescales found in processes like protein folding, while still enabling quantitative comparison with experimental data such as FRET efficiencies. [6]

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Standardized Benchmarking Approaches

Robust comparison of enhanced sampling methods requires standardized benchmarking protocols. For binding free energy calculations, the absolute binding free energy protocol involves alchemically transferring a ligand from its bound state (protein-ligand complex) to its unbound state (separated in solution). [3] This typically employs a double-decoupling scheme where the ligand is first decoupled from its binding site, then from the solution phase.

For methods relying on collective variables, validation typically involves comparing the reconstructed free energy surface with reference calculations or experimental data. The convergence rate of free energy differences between metastable states serves as a key metric, with faster convergence indicating superior sampling efficiency. Statistical errors should be quantified using block analysis or bootstrap methods to ensure reliability.

Quantitative Comparison with Experimental Data

Enhanced sampling methods must ultimately be validated against experimental observations. For biomolecular folding and binding, this includes comparison with:

- FRET efficiency measurements for distance distributions [6]

- Binding affinity constants from calorimetry or assay data [3]

- Relaxation rates from NMR spectroscopy

- Population distributions from single-molecule experiments

Simulations of FRET dyes with coarse-grained models have demonstrated quantitative agreement with experimentally determined FRET efficiencies, highlighting how simulations and experiments can complement each other to provide new insights into biomolecular dynamics and function. [6]

The field of enhanced sampling is supported by numerous specialized software packages that implement the various algorithms discussed. These tools can be integrated with mainstream molecular dynamics engines to create comprehensive sampling workflows.

Table 3: Essential Research Software Tools for Enhanced Sampling

| Software Tool | Compatible MD Engines | Implemented Methods | Specialized Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| PyRETIS | GROMACS, CP2K | TIS, RETIS | Path sampling analysis, order parameter flexibility |

| WESTPA | AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD | Weighted Ensemble | Extreme scale parallelization, adaptive sampling |

| PLUMED | Most major MD codes | Metadynamics, Umbrella Sampling, VES | Extensive CV library, machine learning integration |

| mistral (R package) | Standalone analysis | Various rare event methods | Statistical analysis of rare events |

| freshs.org | Various | FFS, SPRES | Distributed computing for parallel sampling trials |

| PyVisA | PyRETIS output | Path analysis with ML | Visualization and analysis of path sampling trajectories |

Enhanced sampling methods have become indispensable tools for overcoming the fundamental timescale limitations of molecular dynamics simulations. While no single method universally outperforms all others in every application, clear patterns emerge from comparative analysis. Collective variable-based methods excel when prior knowledge of the reaction mechanism exists, while path sampling approaches offer advantages when such knowledge is limited. Alchemical methods remain the gold standard for free energy calculations in drug design applications.

The future of enhanced sampling lies in increasingly automated and integrated approaches that combine the strengths of multiple methodologies. [1] Machine learning is playing a transformative role in this evolution, particularly through the data-driven construction of collective variables and the development of generative approaches for exploring configuration space. [1] As these technologies mature, they promise to make advanced sampling capabilities accessible to a broader range of researchers, ultimately accelerating discovery across chemistry, materials science, and drug development.

For practitioners, method selection should be guided by the specific scientific question, available structural knowledge, computational resources, and validation possibilities. By understanding the relative strengths and limitations of different enhanced sampling approaches, researchers can make informed decisions that maximize sampling efficiency and ensure reliable results for studying rare but critical molecular events.

In drug discovery, many processes crucial for understanding disease mechanisms and therapeutic interventions are governed by rare events—infrequent but consequential molecular transitions that occur on timescales far beyond the reach of conventional simulation methods. These include protein folding, conformational changes, and ligand binding/unbinding events [1] [7]. The ability to accurately track and quantify these rare events is paramount for advancing structure-based drug design. This guide objectively compares enhanced sampling methods in molecular dynamics (MD) research, evaluating their performance in overcoming the rare event problem to provide reliable thermodynamic and kinetic data.

Enhanced Sampling Methods: A Comparative Framework

Enhanced sampling methods accelerate the exploration of a system's free energy landscape by focusing computational resources on overcoming energy barriers associated with rare events [1]. The table below compares the core methodologies, primary applications, and key outputs of several prominent techniques.

| Method | Core Methodology | Primary Applications in Drug Discovery | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metadynamics [1] [7] | Systematically biases simulation along pre-defined Collective Variables (CVs) to fill free energy minima. | Protein conformational changes, ligand binding pathways, calculation of binding free energies and unbinding rates [7]. | Free Energy Surface (FES), binding affinities, transition states. |

| Umbrella Sampling [7] | Restrains simulations at specific values along a reaction coordinate using harmonic potentials. | Calculation of Potential of Mean Force (PMF) for processes like ligand unbinding and protein folding [7]. | Free energy profiles (PMF), relative binding free energies. |

| Replica Exchange MD (REMD) [7] | Runs multiple replicas of the system at different temperatures; exchanges configurations to enhance barrier crossing. | Exploring protein folding landscapes, protein structure prediction starting from extended conformations [7]. | Equilibrium populations, folded protein structures. |

| Accelerated MD [7] | Modifies the potential energy surface to lower energy barriers across the entire system. | Studying slow conformational changes in proteins and biomolecules. | Kinetics of conformational transitions, identification of metastable states. |

| Reinforcement Learning (RL) [1] | Uses ML agents to learn optimal biasing strategies through interaction with the simulation. | Discovering novel reaction pathways and efficient sampling strategies without pre-defined CVs. | Optimized sampling policies, previously unknown transition paths. |

| Generative Models [1] | Learns and generates realistic molecular configurations from the equilibrium distribution. | Efficiently sampling complex molecular ensembles and designing novel molecular structures. | Representative ensemble of structures, new candidate molecules. |

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

The true test of an enhanced sampling method lies in its predictive accuracy and computational efficiency when applied to real-world drug discovery problems. The following tables summarize key experimental findings.

Table 1: Performance in Protein Structure Prediction

| Method | System (Study) | Key Result | Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brute-Force MD | 12 small proteins (DESRES) [7] | Successfully folded proteins but required special-purpose supercomputer (Anton) and simulations near protein's melting temperature. | Long-time atomistic MD simulations in explicit water on specialized hardware [7]. |

| MELD | 20 small proteins (up to 92 residues) [7] | Accurately found native structures (<4 Å RMSD) for 15 out of 20 proteins, starting from extended states. | "Melds" generic structural information into MD simulations to guide and accelerate conformational searching [7]. |

Table 2: Performance in Ligand Binding Affinity Prediction

| Method / Approach | System (Study) | Accuracy (RMS Error) | Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) | 8 proteins with ~200 ligands [7] | < 2.0 kcal/mol | Alchemical transformation methods using free energy perturbation (FEP) and related techniques [7]. |

| Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) | Cyt C Peroxidase with 19 ligands [7] | ~2.0 kcal/mol | Methods of mean force or alchemical transformation without a reference compound [7]. |

| Infrequent Metadynamics | Trypsin-benzamidine complex [7] | Successfully computed unbinding rates | Enhanced sampling technique used to accelerate rare unbinding events and extract kinetic rates [7]. |

The Machine Learning Revolution in Sampling

Machine learning (ML) has profoundly impacted enhanced sampling, primarily through the data-driven construction of collective variables (CVs) [1]. ML models can analyze simulation data to identify the slowest and most relevant modes of a system, automatically generating low-dimensional CVs that capture the essence of the rare event. This moves beyond traditional, intuition-based CVs, which can be difficult to define for complex processes. ML has also been integrated directly into biasing schemes, with reinforcement learning agents learning optimal policies for applying bias, and generative models creating new, thermodynamically relevant configurations [1].

Machine Learning Enhanced Sampling Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of enhanced sampling studies requires a suite of specialized software and force fields.

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) [1] | Provides near ab-initio quantum mechanical accuracy for molecular interactions at a fraction of the computational cost, enabling more accurate force fields for MD simulations. |

| GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD [8] | Widely used, high-performance MD simulation engines that perform the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion for the molecular system. |

| MELD (Modeling Employing Limited Data) [7] | Accelerates conformational searching by incorporating external, often vague, structural information to guide simulations toward biologically relevant states. |

| MDplot [8] | An R package that automates the visualization and analysis of standard and complex MD simulation outputs, such as RMSD, RMSF, and hydrogen bonding over time. |

| MDtraj & bio3d [8] | Software packages for analyzing MD trajectories, enabling tasks like principal component analysis (PCA) and calculation of RMSD and RMSF. |

| Origin [9] | Software used for creating publication-quality graphs from MD data, supporting various data analysis operations like curve fitting and integration. |

The integration of enhanced sampling with machine learning is rapidly transforming the field, enabling more automated and insightful investigations of rare events in drug discovery [1]. Current research focuses on developing more powerful and data-efficient ML models for CV discovery, improving the accuracy of molecular representations through machine learning potentials, and leveraging generative models to explore chemical space. As these methodologies mature, they promise to deepen our understanding of molecular mechanisms and significantly accelerate the development of novel therapeutics.

Understanding the dynamics and function of proteins and other biomolecules requires a framework that describes their complex energy landscape. Biomolecules exist on a rugged energy landscape characterized by numerous valleys, or metastable states, separated by free energy barriers [10] [11]. The valleys correspond to functionally important conformations, with the deepest valley typically representing the native structure. Transitions between these states are critical for biological processes such as enzymatic reactions, allostery, substrate binding, and protein-protein interactions [11]. However, the high energy barriers (often 8–12 kcal/mol) that separate these metastable states make transitions rare events, occurring on timescales from milliseconds to hours, which are largely inaccessible to standard molecular dynamics (MD) simulations [10] [12]. This article explores the key theoretical concepts—metastable states, free energy barriers, and reaction coordinates—that underpin advanced computational methods designed to overcome these sampling challenges.

Defining the Core Concepts

Metastable States

In chemistry and physics, metastability describes an intermediate energetic state within a dynamical system other than the system's state of least energy [13]. A metastable state is long-lived but not eternal; given sufficient time or an external perturbation, the system will eventually transition to a more stable state.

- Physical Analogy: A ball resting in a hollow on a slope is a simple example. A slight push will return it to the hollow, but a stronger push will send it rolling down the slope [13].

- In Molecular Systems: For biomolecules, metastable states are local minima on the potential energy surface, representing stable configurations such as different protein conformations or ligand-bound states [14]. The system spends a prolonged period fluctuating within one of these minima before a rare, large thermal fluctuation provides enough energy to overcome the barrier to an adjacent state.

- Kinetic Persistence: The longevity of a metastable state is known as kinetic stability or kinetic persistence. The system is "stuck" not because there is no lower-energy alternative, but because the kinetics of the atomic motions result in a high barrier that must be crossed [13].

Free Energy Barriers and Surfaces

The thermodynamics and kinetics of transitions between metastable states are described by free energy surfaces.

- Free Energy Surface (FES): The FES provides a low-dimensional, thermodynamic landscape of the system. It is derived from the equilibrium probability distribution (p(\mathbf{s})) along a set of collective variables (CVs) or reaction coordinates: (F(\mathbf{s}) = -k_B T \ln p(\mathbf{s})) [1] [15]. Metastable states correspond to local minima on this surface.

- Free Energy Barrier: The activation barrier between two metastable states is the difference in free energy between the local minimum (the reactant state) and the highest point along the most probable pathway (the transition state) [14]. The height of this barrier determines the reaction rate according to the Arrhenius equation, making it a central quantity in chemical kinetics [10].

- Saddle Points and Transition States: The highest energy point along the minimum energy path connecting reactant and product valleys is a saddle point on the FES. This point corresponds to the transition state (TS), a metastable configuration where the system has a maximum energy and a single imaginary frequency [14]. The committor probability, (p_B), has a value of 0.5 at the transition state, meaning a trajectory launched from this point is equally likely to proceed to the reactant or product basin [10] [11].

Reaction Coordinates and the Committor

The Reaction Coordinate (RC) is a fundamental concept for understanding and simulating rare events.

- Definition: The RC is a low-dimensional representation of the progress of a transition. It is typically the one-dimensional coordinate representing the minimum energy path (MEP) on the potential or free energy surface, connecting the reactant and product valleys through the transition state [14].

- The Committor Criterion: In complex systems, the RC is not always obvious. The rigorous, objective definition of the true RC is based on the committor, (pB) [10]. The committor is the probability that a dynamic trajectory initiated from a given system conformation, with initial momenta drawn from the Boltzmann distribution, will reach the product state before the reactant state [10] [11]. A conformation with (pB = 0) is firmly in the reactant state, (pB = 1) is in the product state, and (pB = 0.5) defines the transition state [11].

- True Reaction Coordinates (tRCs): The few essential coordinates that can accurately predict the committor for any conformation are termed true reaction coordinates. They encapsulate the essence of the activated dynamics, rendering all other coordinates in the system irrelevant for describing the transition [11].

The logical and physical relationships between these core concepts are illustrated in the following diagram.

Figure 1: The interrelationships between the core theoretical concepts of free energy landscapes, metastable states, free energy barriers, reaction coordinates, and the committor.

Enhanced Sampling Methods: A Comparative Guide

Enhanced sampling methods are computational strategies designed to accelerate the exploration of configuration space and facilitate the crossing of high free energy barriers. They can be broadly categorized based on their reliance on pre-defined collective variables. The table below provides a high-level comparison of these major categories.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Major Enhanced Sampling Method Categories

| Method Category | Key Representatives | Core Principle | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV-Biasing Methods | Umbrella Sampling [12], Metadynamics [11] [12], Adaptive Biasing Force (ABF) [11] [12] | Applies a bias potential or force along user-selected Collective Variables (CVs) to discourage the system from remaining in minima. | Directly calculates free energy along chosen CVs; highly efficient when CVs are good approximations of the true RC [12]. | Prone to "hidden barriers" in orthogonal degrees of freedom if CVs are poorly chosen; requires substantial a priori intuition [10] [12]. |

| Unconstrained / Path-Based Methods | Replica Exchange/Parallel Tempering [12], Transition Path Sampling (TPS) [11], Accelerated MD (aMD) [12] | Enhances sampling without system-specific CVs, e.g., by running at multiple temperatures or harvesting unbiased transition paths. | No need for pre-defined CVs; avoids hidden barrier problem; excellent for exploring unknown pathways [12]. | Computationally expensive (many replicas); analysis can be complex; may be less efficient for a specific barrier [12]. |

| Machine Learning (ML)-Driven Methods | ML-CVs [1], Extended Auto-encoders [16], Reinforcement Learning [16] | Uses machine learning to identify slow modes and optimal CVs from simulation data or to learn and apply bias potentials. | Can discover complex, non-intuitive RCs; reduces reliance on expert intuition; powerful for high-dimensional data [1]. | Requires significant training data; risk of overfitting; "black box" nature can hinder interpretability [1]. |

The Central Role of the Reaction Coordinate

The choice of the reaction coordinate is arguably the most critical factor determining the success of CV-biasing enhanced sampling methods. The true RC is widely recognized as the optimal CV for acceleration [10] [11].

- Optimal Acceleration: When the biased CVs align with the true RC, the bias potential efficiently drives the system over the actual activation barrier, leading to highly accelerated barrier crossing. For example, biasing the true RC for HIV-1 protease flap opening accelerated a process with an experimental lifetime of (8.9 \times 10^5) seconds to just 200 picoseconds in simulation—a factor of over (10^{15}) [11].

- The Hidden Barrier Problem: If the biased CVs do not align with the true RC, the infamous "hidden barrier" in the orthogonal space remains. The bias potential pushes the system along a non-optimal path, but the true barrier along the RC is not overcome, preventing effective sampling and leading to non-physical trajectories [10] [11] [12].

- Physical Nature of the RC: Recent advances through energy flow theory and the generalized work functional (GWF) method reveal that true RCs are the optimal channels of energy flow in biomolecules. They are the coordinates that incur the highest energy cost (potential energy flow) during a conformational change, making them the essential degrees of freedom that must be activated to drive the process [10] [11].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following table summarizes reported performance metrics for different enhanced sampling approaches, highlighting the dramatic acceleration achievable with optimal RCs.

Table 2: Reported Performance Metrics of Enhanced Sampling Methods

| System / Process | Sampling Method | Key Collective Variable(s) | Acceleration / Performance | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 Protease Flap Opening & Ligand Unbinding | Metadynamics with True RC | True RC from Energy Flow/GWF | Acceleration of (10^5) to (10^{15})-fold; process with (8.9 \times 10^5) s lifetime reduced to 200 ps [11]. | [11] |

| Peptide Helical-Collapsed Interconversion | Unsupervised Optimized RC | Data-driven RC | Accurate reconstruction of equilibrium properties and kinetic rates from enhanced sampling data [17]. | [17] |

| General Biomolecular Processes | Replica Exchange / Parallel Tempering | None (Temperature) | Avoids hidden barriers but requires many replicas; efficiency depends on system size and temperature range [12]. | [12] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Identifying True Reaction Coordinates via Energy Flow

A cutting-edge methodology for identifying true RCs without prior knowledge of natural reactive trajectories involves analyzing energy relaxation from a non-equilibrium state [11]. The workflow is as follows:

- System Preparation: Start with a single protein structure, typically the native state from AlphaFold or crystal structures [11].

- Energy Relaxation Simulation: Run a short MD simulation initiated from a non-equilibrium configuration (e.g., a slightly distorted structure). During this simulation, the system relaxes, and energy flows through various molecular degrees of freedom.

- Calculate Potential Energy Flows (PEFs): For each coordinate (qi), compute the mechanical work done on it, (\Delta Wi), which represents the energy cost of its motion [11]. This is the PEF through that coordinate.

- Apply the Generalized Work Functional (GWF): The GWF method generates an orthonormal coordinate system called singular coordinates (SCs), which disentangle the tRCs from non-essential coordinates by maximizing the PEFs through individual coordinates [11].

- Identify tRCs: The singular coordinates with the highest potential energy flows are identified as the true reaction coordinates, as they are the dominant channels for energy flow during the conformational change.

Workflow for Enhanced Sampling with ML-Derived Collective Variables

The integration of machine learning has created a powerful and increasingly automated workflow for enhanced sampling.

Figure 2: An iterative workflow for employing machine learning to discover and exploit collective variables for enhanced sampling.

- Initial Sampling: Perform short, unbiased MD simulations or use other enhanced sampling methods (e.g., temperature acceleration) to generate a preliminary dataset of configurations that sample relevant metastable states and some transitions [1].

- Feature Selection: From the simulation data, compute a large pool of candidate order parameters or features (e.g., distances, angles, dihedrals, root mean square deviation (RMSD), principal components) [1] [16].

- ML Model Training: Employ machine learning techniques to identify the slowest modes or the function that best describes the committor. Common approaches include:

- Variational Autoencoders (VAEs): To learn a low-dimensional latent space that encodes the essential features of the molecular configurations [16].

- Time-lagged Autoencoders (TAEs): To specifically identify slow collective variables [1].

- Reinforcement Learning / Likelihood Maximization: To directly approximate the committor function from path data [16].

- CV Validation: The output of the ML model (e.g., the latent space dimension or a learned function) is used as the CV. Its quality can be tested by computing committor distributions for configurations along the CV; a good CV will yield a sharp transition at (p_B=0.5) [10] [16].

- Enhanced Sampling: Use the validated ML-derived CV in a biasing method like metadynamics or umbrella sampling to perform production-level enhanced sampling.

- Iterative Refinement: The production sampling data can be fed back into the ML model to retrain and improve the CVs, leading to a self-consistent and highly optimized sampling protocol [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Modern research in this field relies on a suite of sophisticated software tools and libraries that implement the algorithms and theories discussed. The table below details key resources.

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Enhanced Sampling and Analysis

| Tool Name | Type/Category | Key Features and Functions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLUMED | Library for Enhanced Sampling | A versatile plugin that works with multiple MD engines (GROMACS, AMBER, etc.) for CV analysis and a vast array of enhanced sampling methods like metadynamics and umbrella sampling. | [15] |

| SSAGES / PySAGES | Suite for Advanced General Ensemble Simulations | Provides a range of advanced sampling methods and supports GPU acceleration. PySAGES is a modern Python implementation based on JAX, offering a user-friendly interface and easy integration with ML frameworks. | [15] |

| OpenMM | MD Simulation Package | A high-performance toolkit for molecular simulation that includes built-in support for some enhanced sampling methods and serves as a backend for PySAGES. | [15] |

| Machine Learning Potentials | Interatomic Potentials | ML models (e.g., neural network potentials) that provide near-ab initio accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost, enabling more accurate simulations of reactive events. | [1] |

| Transition Path Sampling (TPS) | Path Sampling Methodology | A framework for generating ensembles of unbiased reactive trajectories (natural transition paths) between defined metastable states, providing direct insight into transition mechanisms. | [11] |

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations provide an atomic-resolution "computational microscope" for studying biological systems, predicting how every atom in a protein or molecular system will move over time based on physics governing interatomic interactions [18]. Despite significant methodological and hardware advances, conventional MD simulations face a fundamental limitation: many biologically critical processes occur on timescales that far exceed what standard simulation approaches can achieve. These processes include protein folding, ligand binding, conformational changes in proteins, and other rare events that are essential for understanding biological function and drug development [1].

The core of this timescale disparity lies in the rare events problem. While functionally important biological processes occur on microsecond to second timescales, conventional MD simulations must use femtosecond timesteps (10^-15 seconds) to maintain numerical stability, requiring billions to trillions of integration steps to capture biologically relevant phenomena [1] [18]. This limitation means that many processes of central importance in neuroscience, drug discovery, and molecular biology remain inaccessible to conventional MD approaches without enhanced sampling methodologies.

Quantitative Evidence: The Experimental Case for Timescale Limitations

Case Study: Sampling Limitations in a Zinc Finger Protein

A compelling study on the zinc finger domain of NEMO protein provides quantitative evidence of how simulation timescale directly impacts sampling completeness. Researchers conducted simulations at multiple timescales and compared their ability to capture protein fluctuations and conformational diversity [19].

Table 1: Comparison of Simulation Performance and Sampling Across Timescales for NEMO Zinc Finger Domain

| Trajectory Length | Platform | Average Speed (ns/day) | Sampling Completeness | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 ns | CPU/NAMD | 3.95-4.15 | Limited | Converged quickly but sampled only local minima near crystal structure |

| 30 ns | CPU/NAMD | 4.15 | Limited | Similar to 15ns simulations with minimal additional sampling |

| 1 μs | GPU/ACEMD | 175 | Moderate | Revealed conformational changes absent in shorter simulations |

| 3 μs | GPU/ACEMD | 224 | Extensive | Sampled unique conformational space with larger fluctuations |

The RMS fluctuations analysis demonstrated that microsecond simulations captured significantly greater protein flexibility, particularly in residues 6-16, which include zinc-binding cysteines [19]. Clustering analysis further revealed that longer timescales probed configuration space not evident in the nanosecond regime, with microsecond simulations accessing stable conformations that could play significant roles in biological function and molecular recognition [19].

The Hardware and Software Landscape

Recent advances in specialized hardware, particularly Graphics Processing Units (GPUs), have dramatically improved simulation capabilities. GPU-based systems can achieve speeds of 175-224 ns/day for systems of approximately 11,500 atoms, making microsecond-timescale simulations more accessible [19]. However, even with these improvements, the millisecond-to-second timescales of many biological processes remain challenging for conventional MD [18].

Methodological Limitations: When Conventional MD Falls Short

Inadequate Sampling of Rare Events

Conventional MD simulations face fundamental challenges in sampling rare events, which are transitions between metastable states that occur infrequently but are critical for biological function. These include:

- Protein folding and unfolding: Requiring milliseconds to seconds [1]

- Ligand binding and unbinding: Often occurring on microsecond to millisecond timescales [1]

- Conformational changes in proteins: Essential for function but often rare events [18]

- Diffusional processes: Such as ion transport through channels [20]

The problem arises because conventional MD must overcome energy barriers through spontaneous fluctuations, which become exponentially less likely as barrier height increases. This leads to inadequate sampling of transition pathways and inaccurate estimation of kinetic parameters [1].

The Machine Learning Potential Challenge

Even with the emergence of machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) that promise near-ab initio accuracy at lower computational cost, timescale challenges persist. Studies reveal that MLIPs with low average errors in energies and forces may still fail to accurately reproduce rare events and atomic dynamics [21].

One study found that MLIPs showed discrepancies in diffusions, rare events, defect configurations, and atomic vibrations compared to ab initio methods, even when vacancy structures and their migrations were included in training datasets [21]. This suggests that low average errors in standard metrics are insufficient to guarantee accurate prediction of rare events, highlighting the need for specialized enhanced sampling approaches.

Enhanced Sampling Methods: Overcoming Timescale Limitations

Enhanced sampling methods have been developed specifically to address the timescale limitations of conventional MD. These approaches accelerate the exploration of configurational space through various strategies [1]:

- Collective Variable (CV)-based methods: Bias dynamics along selected CVs to accelerate barrier crossing

- Path sampling strategies: Directly sample transition pathways between states

- Parallel trajectory methods: Run multiple trajectories to improve sampling efficiency

Table 2: Comparison of Enhanced Sampling Methods for Rare Events

| Method Category | Representative Techniques | Key Features | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Path Sampling | Weighted Ensemble (WE), Transition Path Sampling | Maintains rigorous kinetics through trajectory weighting | Protein folding, conformational changes |

| Collective Variable-Based | Metadynamics, Umbrella Sampling | Accelerates sampling along predefined coordinates | Ligand binding, barrier crossing |

| Reinforcement Learning | WE-RL, FAST, AdaptiveBandit | Automatically identifies effective progress coordinates | Complex systems with unknown reaction coordinates |

| Markov State Models | MSM-based adaptive sampling | Builds kinetic models from many short simulations | Large-scale conformational changes |

Machine Learning-Enhanced Sampling

The integration of machine learning with enhanced sampling has created powerful new approaches:

- Data-driven collective variables: ML algorithms automatically identify relevant slow modes and reaction coordinates from simulation data [1]

- Reinforcement learning guidance: RL policies identify effective progress coordinates among multiple candidates during simulation [22]

- Generative models: Novel strategies for efficient sampling of rare events [1]

These ML-enhanced methods are particularly valuable for complex systems where the relevant reaction coordinates are not known in advance, reducing the trial-and-error approach traditionally required in enhanced sampling [22].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Weighted Ensemble with Reinforcement Learning Protocol

The Weighted Ensemble with Reinforcement Learning (WE-RL) strategy represents a cutting-edge approach for rare event sampling [22]:

- Initialization: Initiate multiple weighted trajectories from starting states

- Dynamics phase: Run ensemble dynamics in parallel for fixed time intervals (τ)

- Clustering: Apply k-means clustering across all candidate progress coordinates

- Reward calculation: Compute rewards for clusters based on progress coordinate effectiveness

- Optimization: Maximize cumulative reward using Sequential Least SQuares Programming (SLSQP)

- Resampling: Split trajectories in high-reward clusters, merge in high-count clusters

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-6 for multiple WE iterations

This "binless" framework automatically identifies relevant progress coordinates during simulation, adapting to changing reaction coordinates in multi-step processes [22].

WE-RL Sampling Workflow: This diagram illustrates the reinforcement learning-guided weighted ensemble method that automatically identifies effective progress coordinates during simulation [22].

Practical Considerations for Simulation Design

When designing MD simulations to study biological processes, several critical factors must be addressed [20]:

- Equilibration time: Ensure sufficient equilibration before production runs

- Diffusive behavior confirmation: Verify transition from subdiffusive to diffusive behavior

- Temperature dependence: Evaluate diffusion data across multiple temperatures

- Validation: Compare simulation results with available experimental data

- Force field selection: Choose appropriate physical models for the system of interest

Proper simulation design is essential for obtaining reliable results, particularly when studying rare events that conventional MD might miss [20].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Molecular Dynamics

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | ACEMD, NAMD | Production MD simulation with GPU acceleration |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | Weighted Ensemble, Metadynamics | Accelerate rare event sampling |

| Machine Learning Potentials | DeePMD, GAP, NequIP | Near-quantum accuracy with lower computational cost |

| Analysis & Visualization | VMD, MDOrion | Trajectory analysis, clustering, and visualization |

| Specialized Hardware | GPU clusters, ANTON | High-performance computing for microsecond+ simulations |

The timescale disparity between conventional MD simulations and biologically relevant processes remains a significant challenge in computational molecular biology. While hardware advances have pushed the boundaries of accessible timescales, fundamental limitations persist for processes requiring milliseconds to seconds. Enhanced sampling methods, particularly those integrated with machine learning approaches, provide powerful strategies to overcome these limitations.

The future of accurate MD simulation of biological systems lies in the continued development of enhanced sampling methodologies that can efficiently capture rare events, correctly describe energy landscapes, and provide accurate kinetic information. As these methods become more sophisticated and automated, they will increasingly enable researchers to address fundamental biological questions that were previously beyond the reach of computational approaches.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have evolved from a specialized computational technique to an indispensable tool in biomedical research, offering unprecedented insights into biomolecular processes and playing a pivotal role in modern therapeutic development [23]. By tracking the movement of individual atoms and molecules over time, MD acts as a virtual microscope with exceptional resolution, enabling researchers to visualize atomic-scale dynamics that are difficult or impossible to observe experimentally [24]. This capability is fundamentally transforming drug development pipelines, from initial target identification to lead optimization, by providing a deeper understanding of structural flexibility and molecular interactions.

The Computational Engine of Drug Discovery

At its core, MD simulation calculates the time-dependent behavior of a molecular system. The fundamental workflow involves preparing an initial structure, assigning initial velocities to atoms based on the desired temperature, and then iteratively calculating interatomic forces to solve Newton's equations of motion [24]. The accuracy of these simulations heavily depends on the force field selected—the mathematical model describing potential energy surfaces for molecular systems. Widely adopted software packages such as GROMACS, AMBER, and DESMOND leverage rigorously tested force fields and have shown consistent performance across diverse biological applications [23].

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for conducting MD simulations in drug discovery:

MD Simulation Workflow in Drug Discovery

Essential Research Toolkit for MD Simulations

Successful implementation of MD in drug discovery requires specialized software and resources. The table below details key components of the MD research toolkit:

| Tool Category | Representative Examples | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Software Packages | GROMACS, AMBER, Desmond, NAMD, OpenMM [25] | Molecular mechanics calculations | High-performance MD, GPU acceleration, comprehensive analysis tools |

| Force Fields | GROMOS, CHARMM, AMBER force fields [26] [25] | Define potential energy functions | Parameterized for proteins, nucleic acids, lipids; determine simulation reliability |

| Visualization & Analysis | VMD, YASARA, MOE, Ascalaph Designer [25] | Trajectory analysis and visualization | Interactive 3D visualization, measurement tools, graphical data representation |

| Specialized Drug Discovery Platforms | Schrödinger, Cresset Flare, Chemical Computing Group MOE, deepmirror [27] | Integrated drug design | Combine MD with other modeling techniques, user-friendly interfaces, AI integration |

Key Applications Transforming Drug Development

Target Modeling and Characterization

MD simulations provide critical insights into protein behavior and flexibility that static crystal structures cannot capture. By simulating the dynamic motion of drug targets, researchers can identify allosteric sites, understand conformational changes, and characterize binding pockets in physiological conditions [28]. This detailed structural knowledge enables more rational drug design approaches, moving beyond rigid lock-and-key models to account for the inherent flexibility of biological macromolecules.

Binding Pose Prediction and Validation

Accurately predicting how a ligand binds to its target is fundamental to drug design. MD simulations can refine and validate binding poses obtained from docking studies by assessing their stability over time. The dynamic trajectory analysis helps identify transient interactions and conformational adjustments that occur upon binding, providing more reliable predictions than static docking alone [28]. This application is particularly valuable for understanding binding mechanisms and optimizing ligand interactions.

Virtual Screening and Lead Optimization

MD enhances virtual screening by evaluating binding affinities and specific interactions at a granular level. Advanced techniques like Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) calculations, implemented in platforms such as Schrödinger and Cresset Flare, quantitatively predict binding free energies with remarkable accuracy [27]. This enables prioritization of lead compounds with optimal binding characteristics. Additionally, MD facilitates lead optimization by providing atomic-level insights into structure-activity relationships, guiding chemical modifications to improve potency, selectivity, and other drug properties [28].

Solubility and ADMET Prediction

Predicting aqueous solubility—a critical determinant of bioavailability—has been enhanced through MD simulations. Recent research has demonstrated that MD-derived properties combined with machine learning can effectively predict drug solubility [26]. Key MD-derived properties influencing solubility predictions include:

- Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA): Measures surface area exposed to solvent

- Coulombic and Lennard-Jones (LJ) interaction energies: Quantify electrostatic and van der Waals interactions

- Estimated Solvation Free Energies (DGSolv): Predicts energy changes during solvation

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures conformational stability

In one study, a Gradient Boosting algorithm applied to these MD-derived properties achieved a predictive R² of 0.87, demonstrating performance comparable to models based on traditional structural descriptors [26].

Comparative Analysis of MD Software Platforms

The selection of appropriate MD software significantly impacts research outcomes. The table below compares leading platforms based on key capabilities:

| Software | Key Strengths | Specialized Features | Licensing |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | High performance, excellent scalability, free open source [25] | Extensive analysis tools, GPU acceleration, active development | Free open source (GNU GPL) |

| AMBER | Biomolecular simulations, comprehensive analysis tools [25] | Advanced force fields, well-suited for nucleic acids, drug discovery | Proprietary, free open source components |

| DESMOND | User-friendly interface, integrated workflows [25] | Advanced sampling methods, strong industry adoption | Proprietary, commercial or gratis |

| Schrödinger | Quantum mechanics integration, free energy calculations [29] [27] | FEP+, Glide docking, LiveDesign platform | Proprietary, modular licensing |

| OpenMM | High flexibility, Python scriptable, cross-platform [25] | Custom force fields, extensive plugin ecosystem | Free open source (MIT) |

| NAMD/VMD | Fast parallel MD, excellent visualization [25] | Scalable to large systems, interactive analysis | Free academic use |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of MD simulations is rapidly evolving, with several trends shaping its future applications in drug development:

Integration with Artificial Intelligence

Machine learning and deep learning technologies are being incorporated into MD workflows to enhance both accuracy and efficiency [23]. AI approaches are addressing longstanding challenges in force field parameterization, sampling efficiency, and analysis of high-dimensional simulation data. Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) represent a particularly significant advancement, enabling highly accurate simulations of complex material systems that were previously computationally prohibitive [24].

Enhanced Sampling for Rare Events

The need to study rare but critical molecular events—such as protein folding, conformational changes, and ligand unbinding—has driven the development of enhanced sampling methods. These techniques, including replica exchange metadynamics and variationally enhanced sampling, allow researchers to overcome the timescale limitations of conventional MD simulations, providing insights into processes that occur on millisecond to second timescimescales that are directly relevant to drug action.

Clinical Translation and Success Stories

The impact of MD-driven drug discovery is increasingly demonstrated by clinical successes. Notable examples include:

ISM001-055: An idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis drug designed using Insilico Medicine's generative AI platform, which progressed from target discovery to Phase I trials in just 18 months—significantly faster than traditional timelines [29].

Zasocitinib (TAK-279): A TYK2 inhibitor originating from Schrödinger's physics-enabled design platform, now advancing into Phase III clinical trials [29].

Exscientia's AI-Designed Compounds: Exscientia reported designing eight clinical compounds "at a pace substantially faster than industry standards," with in silico design cycles approximately 70% faster and requiring 10× fewer synthesized compounds than industry norms [29].

The following diagram illustrates how MD integrates with modern AI approaches in next-generation drug discovery:

MD and AI Integration in Drug Discovery

Molecular dynamics simulations have fundamentally transformed drug development pipelines by providing atomic-level insights into biological processes and drug-target interactions. As MD technologies continue to evolve—particularly through integration with artificial intelligence and enhanced sampling methods—their impact on drug discovery is expected to grow significantly. The ability to accurately simulate and predict molecular behavior not only accelerates the development timeline but also increases the likelihood of clinical success by enabling more informed decision-making throughout the drug development process. With the global molecular modeling market projected to reach $17.07 billion by 2029, driven largely by pharmaceutical R&D demands [30], MD simulations will undoubtedly remain a cornerstone technology in the ongoing evolution of rational drug design.

Advanced Enhanced Sampling Techniques: Machine Learning Approaches and Practical Implementations

Enhanced sampling methods are crucial in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to overcome the timescale limitation of observing rare events, such as protein folding, ligand unbinding, or phase transitions [31] [1]. These techniques rely on biasing the system along low-dimensional functions of atomic coordinates known as collective variables (CVs), which are designed to capture the slow degrees of freedom essential for the process under study [32] [1]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three prominent CV-based methods—Umbrella Sampling, Metadynamics, and On-the-fly Probability Enhanced Sampling (OPES)—focusing on their performance, underlying mechanisms, and practical application in drug development research.

Fundamental Principles

- Umbrella Sampling (US): This method uses a series of harmonic restraints positioned along a predefined CV to force the system into specific regions of configuration space. The data from these independent simulations are then reconstructed into a free energy profile using methods such as the Weighted Histogram Analysis Method (WHAM) [33] [34].

- Metadynamics (MetaD): MetaD accelerates sampling by actively discouraging the system from revisiting previously explored states. It achieves this by periodically adding a repulsive Gaussian bias potential to the underlying energy landscape along the selected CVs. Over time, the sum of these Gaussians converges to the negative of the underlying free energy surface [31] [34].

- On-the-fly Probability Enhanced Sampling (OPES): Introduced as an evolution of MetaD, OPES aims to converge faster by targeting a specified probability distribution for the CVs. It builds its bias potential based on an on-the-fly estimation of the free energy, which is continuously updated as the simulation progresses. This method is noted for having fewer parameters and a more straightforward reweighting scheme [34] [32].

Performance Comparison

A direct comparative study on calculating the free energy of transfer of small solutes into a model lipid membrane revealed key performance differences between MetaD and US [33].

Table 1: Performance comparison of MetaD and Umbrella Sampling for free energy calculation

| Feature | Metadynamics | Umbrella Sampling |

|---|---|---|

| Free Energy Estimate | Consistent with Umbrella Sampling [33] | Consistent with Metadynamics [33] |

| Statistical Efficiency | Can be more efficient; lower statistical uncertainties within the same simulation time [33] | Generally efficient, but may require careful error analysis [33] |

| Primary Challenge | Identification of effective collective variables [31] [34] | May require many windows and careful overlap for reconstruction [33] |

| Bias Potential | Time-dependent, sum of Gaussians [34] | Static, harmonic restraints in separate simulations [33] |

Table 2: Key characteristics of the three enhanced sampling methods

| Feature | Umbrella Sampling | Metadynamics | OPES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bias Type | Harmonic restraint (static) | Gaussian potential (time-dependent) | Adaptive potential (time-dependent) |

| Free Energy Convergence | Post-processing required (e.g., WHAM) | Approximated from bias potential | Directly targeted by the method [34] |

| Reported Advantages | Well-established, rigorous | Efficient exploration, lower statistical error [33] | Faster convergence, robust parameters [34] |

| Typical CV Requirements | 1-2 CVs | 1-3 CVs (single-replica) [34] | 1-few CVs [32] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for Free Energy of Solute Transfer

A benchmark study compared United-Atom and Coarse-Grained models for calculating the water-membrane free energy of transfer of polyethylene and polypropylene oligomers using both MetaD and US [33].

- System Preparation: Construct a simulation box containing a phosphatidylcholine lipid membrane, water molecules, and the solute (e.g., polyethylene oligomer). This is done for both united-atom and coarse-grained resolution models.

- Collective Variable Definition: The key CV is the distance between the solute and the membrane center, which describes the transfer process.

- Umbrella Sampling Protocol: A series of independent simulations are set up, each with a harmonic restraint (e.g., with a force constant of several kJ/mol/nm²) applied to the CV at different locations, spanning from the water phase to the membrane core. Each simulation (window) must run for a sufficient time to ensure local sampling.

- Metadynamics Protocol: A single (or multiple walker) simulation is run where a Gaussian bias potential is periodically added to the system along the CV. Key parameters to optimize include the Gaussian height, width, and deposition rate.

- Analysis and Error Estimation: For US, the data from all windows are combined using WHAM to construct the free energy profile. For MetaD, the free energy is estimated as the negative of the accumulated bias potential (after a certain time). Special attention must be paid to statistical error estimation, for which specific procedures have been proposed for MetaD [33].

Workflow for Enhanced Sampling Simulations

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for conducting an enhanced sampling simulation, highlighting the parallel steps for MetaD, US, and OPES.

Generalized workflow for enhanced sampling simulations. FES: Free Energy Surface.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of enhanced sampling methods relies on a suite of software tools and theoretical concepts.

Table 3: Essential tools for collective variable-based enhanced sampling

| Tool / Concept | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| PLUMED | Software Library | A core library for enhancing molecular dynamics simulations; implements US, MetaD, OPES, and CV analysis [35] [34]. |

| Collective Variables (CVs) | Theoretical Concept | Low-dimensional functions of atomic coordinates that describe the slow dynamics of a process; the choice is critical for success [35] [32]. |

| Machine Learning for CV Discovery | Methodological Approach | Data-driven techniques (e.g., DeepLDA, TICA, autoencoders) to automate the discovery of optimal CVs from simulation data [35] [32] [1]. |

| Weighted Histogram Analysis Method (WHAM) | Analysis Algorithm | A standard method for unbinding and combining data from multiple simulations, such as those from Umbrella Sampling [33]. |

| Gromacs / NAMD / OpenMM | MD Engine | Molecular dynamics software packages that integrate with PLUMED to perform enhanced sampling simulations [35]. |

| Well-Tempered Metadynamics | Algorithmic Variant | A variant of MetaD where the height of the added Gaussians decreases over time, improving convergence and stability [34]. |

Collective Variables: The Central Challenge

The selection of appropriate CVs is arguably the most critical step in any of these methods, as the efficiency of the sampling hinges on their ability to distinguish between metastable states and describe the transition pathways [31] [35]. CVs can be broadly categorized as follows:

- Geometric CVs: These are intuitive and based on structural parameters. Common examples include:

- Distances: Between atoms or centers of mass of groups [35].

- Dihedral Angles: Torsion angles like protein backbone φ and ψ angles [35].

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures deviation from a reference structure [35].

- Switching Functions: Smoothed functions of distances, useful for defining contacts [35].

- Abstract CVs: These are often linear or non-linear combinations of geometric variables discovered through data analysis techniques. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Time-Lagged Independent Component Analysis (TICA) are linear methods, while autoencoders and other neural networks provide non-linear transformations [35]. The rise of machine learning has significantly advanced the discovery of such abstract CVs [32] [1].

Advancements and Future Directions

The field of enhanced sampling is rapidly evolving, with several promising research directions:

- Integration of Machine Learning: ML is being used not only for CV discovery but also to develop high-dimensional bias potentials and novel biasing schemes [32] [1]. For instance, neural networks can approximate bias potentials for many CVs, overcoming a key limitation of standard MetaD [34].

- Hybrid Methods: Combining different enhanced sampling strategies can yield greater acceleration. For example, recent work has shown that combining Metadynamics with Stochastic Resetting (SR) can lead to speedups greater than either method alone, and can even mitigate the performance loss when using suboptimal CVs [31].

- Kinetics and Reinforcement Learning: While many methods focus on thermodynamics (free energies), there is growing interest in recovering accurate kinetics. Furthermore, concepts from reinforcement learning are being explored to automatically identify effective progress coordinates on the fly [22].

- The OPES Method: As a newer approach, OPES represents a shift towards methods with more robust convergence properties and has quickly become a method of choice in several research groups [34] [32].

Umbrella Sampling, Metadynamics, and OPES are powerful tools for studying rare events in molecular dynamics. Umbrella Sampling is a well-established, rigorous method, while Metadynamics often proves to be more efficient for exploration. OPES emerges as a promising method offering faster convergence. The choice between them depends on the specific scientific problem, system complexity, and available computational resources. Ultimately, the identification of good collective variables remains the most significant challenge, a task in which modern machine-learning techniques are proving increasingly invaluable.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide atomistic resolution for studying physical, chemical, and biological processes, functioning as a "computational microscope" [1]. However, their effectiveness is severely constrained by the rare-events problem—the fact that many processes of interest, such as protein folding, ligand binding, or conformational changes in biomolecules, occur on timescales (milliseconds to seconds) that far exceed the reach of conventional MD simulations [1]. These rare events are characterized by high free energy barriers that separate metastable states, making spontaneous transitions infrequent on simulation timescales. Enhanced sampling methods have been developed to address this fundamental limitation by accelerating the exploration of configurational space. A central challenge in these methods is the identification of appropriate collective variables (CVs)—low-dimensional descriptors that capture the slow, relevant modes of the system [1]. Traditional approaches rely on expert intuition to select CVs, such as interatomic distances or torsion angles, but this becomes increasingly difficult as system complexity grows. The emergence of machine learning (ML) has transformed this landscape by enabling data-driven discovery of CVs, yet these learned representations often lack chemical interpretability. The AMORE-MD framework represents a significant advancement by combining the power of deep-learned reaction coordinates with atomic-level interpretability, addressing a critical gap in molecular simulation methodologies [36].

Methodological Framework of AMORE-MD

Theoretical Foundations: Koopman Operator Theory and ISOKANN

The AMORE-MD framework is built upon a rigorous mathematical foundation from dynamical systems theory. It employs the ISOKANN algorithm to learn a neural membership function (χ) that approximates the dominant eigenfunction of the backward Koopman operator [36]. The Koopman operator provides a powerful alternative to direct state-space analysis by describing how observable functions evolve in time. For a molecular system, the time evolution of an observable is governed by the infinitesimal generator ℒ, with the Koopman operator 𝒦_τ = exp(ℒτ) propagating observables forward in time [36].

The key insight is that the slowest relaxation processes in a molecular system correspond to the non-trivial eigenfunctions of the Koopman operator with the largest eigenvalues. AMORE-MD constructs a membership function χ:Ω→[0,1] as a linear combination of the constant eigenfunction Ψ0=1 and the dominant slow eigenfunction Ψ1, representing the grade of membership to one of two fuzzy sets (e.g., metastable states) [36]. The dynamics of χ are governed by a macroscopic rate equation: ℒχ = -ε1 χ + ε2(1-χ), where χ(x)≈1 and χ(x)≈0 represent perfect membership to states A and B, respectively, while χ(x)≈0.5 corresponds to transition states [36]. This theoretical foundation allows AMORE-MD to directly capture the slowest dynamical processes without predefined assumptions about system metastability.

Core Computational Workflow

The AMORE-MD framework implements a systematic workflow to extract mechanistically interpretable information from molecular dynamics data:

Slow-Mode Learning: The ISOKANN algorithm iteratively learns the membership function χ through a self-supervised training procedure. The neural network parameters are optimized by minimizing the loss function 𝒥(θ) = ‖χθ - S𝒦τχ_θ-1‖² over molecular configurations separated by a lag time τ, where S represents an affine shift-scale transformation that prevents collapse to trivial constant solutions [36].

Pathway Reconstruction: Once χ is learned, AMORE-MD reconstructs transition pathways as minimum-energy paths (χ-MEPs) aligned with the gradient of χ. This is achieved through orthogonal energy minimization along the gradient of χ, producing a representative trajectory that follows the dominant kinetic mode without requiring predefined collective variables, endpoints, or initial path guesses [36].

Atomic Sensitivity Analysis: The framework quantifies atomic contributions through gradient-based sensitivity analysis (χ-sensitivity), calculating ∇χ with respect to atomic coordinates. This identifies which specific atomic distances or movements contribute most strongly to changes in the reaction coordinate [36].

Iterative Sampling Refinement: The χ-MEP can initialize new simulations for iterative sampling and retraining of χ, progressively improving coverage of rare transition states. This iterative approach enriches sampling in transition regions and enhances the robustness of the learned reaction coordinate [36].

Table 1: Core Components of the AMORE-MD Framework

| Component | Mathematical Basis | Function | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISOKANN Algorithm | Koopman operator theory, Von Mises iteration | Learns membership function χ representing slowest dynamical process | Neural network mapping configurations to [0,1] |

| χ-MEP | Gradient following, orthogonal energy minimization | Reconstructs most probable transition pathway | Atomistic trajectory between metastable states |

| χ-Sensitivity | Gradient-based attribution | Quantifies atomic contributions to the reaction coordinate | Per-atom sensitivity maps |

| Iterative Sampling | Enhanced sampling theory | Improves coverage of transition states | Refined reaction coordinate and pathways |

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for ML-Enhanced Sampling

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in AMORE-MD |

|---|---|---|

| ISOKANN Algorithm | Learning membership functions from Koopman operator theory | Core component for identifying slow dynamical modes [36] |

| PySAGES Library | Enhanced sampling methods with GPU acceleration | Potential platform for implementing related sampling methods [15] |

| COLVARS Module | Steered rare-event sampling with collective variables | Comparative method for pathway analysis [37] |

| Graph Neural Networks | Learning descriptor-free collective variables | Alternative approach for geometric systems [36] |

| VAMPnets | Deep learning for molecular kinetics | Comparative neural network approach for dynamics [36] |

| PLUMED/SSAGES | Enhanced sampling libraries | Traditional frameworks for biased sampling simulations [15] |

Comparative Analysis: AMORE-MD vs. Alternative Approaches

Methodological Comparison with Established Techniques

AMORE-MD occupies a unique position in the landscape of enhanced sampling methods by bridging the gap between data-driven CV discovery and chemical interpretability. Traditional approaches like Umbrella Sampling and Metadynamics rely heavily on expert intuition for selecting appropriate collective variables, which becomes problematic for complex systems where relevant coordinates are not obvious [15]. These methods apply biases along predefined CVs to overcome energy barriers but may miss important aspects of the transition mechanism if the CVs are suboptimal.

More recent machine learning approaches, such as VAMPnets and other deep learning architectures, automatically discover relevant features from simulation data but often function as "black boxes" with limited interpretability [36]. These methods excel at identifying slow molecular modes but provide little direct insight into the atomistic mechanisms driving transitions.

The String Method and Nudged Elastic Band approaches provide clear atomistic pathways but require predefined endpoints and collective variables, making their interpretability dependent on these initial choices [36]. Similarly, Transition Path Theory offers a rigorous framework for analyzing mechanisms but faces computational intractability in high-dimensional systems [36].

AMORE-MD distinguishes itself by requiring no a priori specification of collective variables, endpoints, or pathways while maintaining atomic-level interpretability through its gradient-based analysis [36]. This unique combination addresses a critical limitation in the current methodological landscape.

Performance Benchmarking Across Model Systems

The AMORE-MD framework has been validated across representative systems of increasing complexity, demonstrating both its accuracy and interpretability:

Müller-Brown Potential: In this controlled benchmark, the χ-MEP successfully recovered the known zero-temperature string, validating the pathway reconstruction methodology [36].

Alanine Dipeptide: For this well-characterized molecular system with understood metastabilities, AMORE-MD correctly identified the dominant transition mechanisms without prior knowledge of dihedral angles, recovering the known structural rearrangements at atomic resolution [36].

VGVAPG Hexapeptide: In this more complex biological system (an elastin-derived hexapeptide in implicit solvent), the framework successfully handled multiple transition tubes and provided chemically interpretable descriptions of conformational transitions [36].

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of Enhanced Sampling Methods

| Method | Predefined CVs Required | Endpoints Required | Interpretability | Computational Efficiency | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMORE-MD | No | No | High (atomic sensitivity) | Medium (neural network training) | Unknown mechanisms |

| Umbrella Sampling | Yes | No | Medium (depends on CV choice) | High | Known reaction coordinates |

| Metadynamics | Yes | No | Medium (depends on CV choice) | Medium | Free energy estimation |

| String Method | Yes | Yes | High (if CVs relevant) | Medium | Pathway between known states |

| VAMPnets | No | No | Low (black box) | Medium | Automated feature discovery |

| Transition Path Sampling | No | Yes | Medium (path ensemble) | Low | Rare event mechanisms |

Integration with Modern Machine Learning Potentials