Diffusion Coefficient in Molecular Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the diffusion coefficient in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Diffusion Coefficient in Molecular Dynamics: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the diffusion coefficient in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the fundamental principles derived from Fick's laws and the Einstein-Smoluchowski equation, detailing how MD simulations leverage the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) and Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) to compute this critical parameter. The guide explores key methodological approaches, including the use of force fields like GAFF, and addresses common challenges such as finite-size effects and sampling inefficiencies. It further discusses validation strategies against experimental data and comparative analysis with empirical correlations, highlighting the practical applications of diffusion coefficients in processes like drug delivery, protein aggregation, and pharmaceutical formulation optimization.

The Fundamentals of Molecular Diffusion: From Theory to MD Simulation

The diffusion coefficient, often denoted as (D), is a fundamental parameter in molecular dynamics research that quantifies the rate of molecular transport driven by random thermal motion. This critical property connects microscopic particle movements to macroscopic concentration changes, serving as a pivotal bridge between atomic-scale simulations and predictive models for material behavior and drug transport. In molecular dynamics, the diffusion coefficient provides crucial insights into molecular mobility, transport mechanisms, and material properties across diverse systems ranging from metallic alloys to biological tissues. The conceptual foundation for understanding diffusion was established in 1855 by physiologist Adolf Fick, who formulated his now-famous laws of diffusion by drawing analogies between mass transport and the earlier discoveries of Fourier (heat conduction) and Ohm (electrical conduction) [1]. These laws form the mathematical bedrock for quantifying diffusive processes across scientific disciplines.

Fick's work was originally inspired by Thomas Graham's experiments on salt diffusing through water, and at the time, diffusion in solids was not considered generally possible [1]. Today, Fick's laws form the core of our understanding of diffusion in solids, liquids, and gases, with the diffusion coefficient serving as the essential proportionality constant that relates concentration gradients to mass transport rates. For diffusion processes that obey Fick's laws, the behavior is classified as normal or Fickian diffusion; otherwise, it is termed anomalous or non-Fickian diffusion [1].

Fick's Laws of Diffusion

Fick's First Law

Fick's first law describes the steady-state condition where the concentration profile does not change with time. It establishes that the diffusive flux moves from regions of high concentration to regions of low concentration with a magnitude proportional to the concentration gradient [1] [2]. In one-dimensional form, the law is expressed as:

[ J = -D \frac{d\varphi}{dx} ]

where:

- (J) is the diffusion flux, with dimensions of amount of substance per unit area per unit time (e.g., mol m⁻² s⁻¹)

- (D) is the diffusion coefficient (m² s⁻¹)

- (\varphi) is the concentration (mol m⁻³)

- (x) is the position (m) [1]

The negative sign indicates that diffusion occurs down the concentration gradient. In multiple dimensions, this generalizes to:

[ \mathbf{J} = -D \nabla \varphi ]

where (\nabla) is the gradient operator [1]. The driving force for one-dimensional diffusion is the quantity (-\partial\varphi/\partial x), which for ideal mixtures is the concentration gradient.

For non-ideal systems or concentrated mixtures, the driving force becomes the gradient of chemical potential. In such cases, Fick's first law can be expressed as:

[ Ji = -\frac{Dci}{RT} \frac{\partial \mu_i}{\partial x} ]

where (\mu_i) is the chemical potential of species (i), (R) is the universal gas constant, and (T) is the absolute temperature [1]. This formulation extends the applicability of Fick's law beyond ideal solutions.

Fick's Second Law

Fick's second law predicts how diffusion causes concentrations to change with time, making it essential for modeling transient processes. It is derived from Fick's first law combined with the principle of mass conservation [1]. In one dimension, it states:

[ \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial t} = D \frac{\partial^2 \varphi}{\partial x^2} ]

where:

- (\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial t}) is the rate of change of concentration with time

- (\frac{\partial^2 \varphi}{\partial x^2}) is the second derivative of concentration with respect to position [1] [2]

This partial differential equation describes how the concentration evolves over time and space due to diffusion. For multi-dimensional systems, Fick's second law incorporates the Laplacian operator:

[ \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial t} = D \nabla^2 \varphi ]

If the diffusion coefficient is not constant but depends on concentration or position, the equation becomes [1]:

[ \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial t} = \nabla \cdot (D \nabla \varphi) ]

Fick's second law has the same mathematical form as the heat equation, and its fundamental solution for a point source in one dimension is a Gaussian distribution [1]:

[ \varphi(x,t) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{4\pi Dt}} \exp\left(-\frac{x^2}{4Dt}\right) ]

This solution demonstrates that the variance of the concentration distribution increases linearly with time, a characteristic feature of diffusive processes.

Physical Interpretation of the Diffusion Coefficient

The diffusion coefficient (D) represents the magnitude of diffusional mobility, quantifying how quickly particles spread through a medium due to random thermal motion [2]. While its dimensions (length²/time) might suggest a velocity, it's more accurately conceptualized as the flux of material under a unit concentration gradient [3].

A key interpretation comes from the Einstein-Smoluchowski equation, which relates the diffusion coefficient to mean squared displacement:

[ D = \frac{\langle x^2 \rangle}{2t} \quad \text{(in one dimension)} ]

where (\langle x^2 \rangle) is the mean squared displacement of particles after time (t) [3]. For three-dimensional diffusion, this relationship becomes:

[ D = \frac{\langle r^2 \rangle}{6t} ]

where (\langle r^2 \rangle) is the three-dimensional mean squared displacement [3]. This formulation connects molecular-level movements to the macroscopic diffusion coefficient, making it particularly valuable in molecular dynamics simulations where particle trajectories are tracked over time.

From a physical perspective, the diffusion coefficient can be understood through the Stokes-Einstein relation for spherical particles in a continuous medium:

[ D = \frac{kT}{6\pi\eta a} ]

where:

- (k) is Boltzmann's constant

- (T) is absolute temperature

- (\eta) is the dynamic viscosity of the medium

- (a) is the hydrodynamic radius of the diffusing particle [2]

This equation reveals that the diffusion coefficient increases with temperature but decreases with larger particle size or higher viscosity, reflecting the microscopic interactions between diffusing particles and their environment.

The temperature dependence of the diffusion coefficient follows an Arrhenius-type relationship [2]:

[ D = D0 e^{-Ea/RT} ]

where (Ea) is the activation energy for diffusion, (R) is the gas constant, and (D0) is a pre-exponential factor. This temperature sensitivity is crucial for predicting diffusion behavior in various thermal environments encountered in industrial processes and biological systems.

Quantitative Values and Measurement Contexts

The diffusion coefficient varies significantly across different materials and systems, reflecting the diverse environments in which molecular transport occurs. The table below summarizes typical diffusion coefficient values across various scientific domains.

Table 1: Typical Diffusion Coefficient Values in Different Systems

| System Type | Diffusion Coefficient Range (m²/s) | Context and Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Ions in water [1] | (0.6 - 2 \times 10^{-9}) | Room temperature, dilute aqueous solutions |

| Biological molecules [1] | (10^{-11} - 10^{-10}) | Proteins, nucleic acids in aqueous environments |

| Hydrogen in α-iron (bulk) [4] | (10^{-8} - 10^{-9}) | 300-1000 K, molecular dynamics simulations |

| Hydrogen in α-iron grain boundaries [4] | ~1% of bulk values | Significant reduction due to trapping effects |

| Glucose in water [5] | (6.68 \times 10^{-10}) | 25°C, infinite dilution |

| Sorbitol in water [5] | (5.93 \times 10^{-10}) | 25°C, infinite dilution |

These values demonstrate how diffusion coefficients span multiple orders of magnitude depending on the system. The significantly reduced diffusion of hydrogen in iron grain boundaries (approximately 1% of bulk values) highlights how microstructural features can dramatically impede molecular transport, with important implications for materials design against hydrogen embrittlement [4].

In medical imaging, the Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) derived from Diffusion-Weighted MRI provides quantitative information about tissue microstructure. Lower ADC values typically indicate more restricted water diffusion, often associated with higher cellularity in malignant tumors [6]. For example, in breast lesion characterization, ADC values have proven diagnostically valuable, with minimum ADC value (ADC_min) emerging as the most effective single indicator for differentiating malignant from benign tumors [6].

Table 2: Advanced Diffusion Metrics in Medical Imaging

| Metric | Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ADC_avg [6] | Average Apparent Diffusion Coefficient | Conventional diffusion assessment |

| ADC_min [6] | Minimum ADC value within region of interest | Captures areas of most restricted diffusion |

| rADC_min [6] | Relative ADC_min normalized to reference tissue | Reduces inter-individual variability |

| ADC_cv [6] | Coefficient of variation of ADC values | Quantifies heterogeneity within lesion |

| βCTRW [7] | Spatial diffusion parameter from Continuous-Time Random Walk model | Superior performance in lymph node characterization |

Experimental and Computational Determination

Molecular Dynamics Approaches

In molecular dynamics (MD) research, diffusion coefficients are typically calculated from the mean squared displacement (MSD) of particles over time using the relationship:

[ D = \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{1}{6N} \sum{i=1}^{N} \langle |\vec{r}i(t) - \vec{r}i(0)|^2 \rangle ]

where (\vec{r}_i(t)) is the position of particle (i) at time (t), (N) is the number of particles, and the angle brackets denote an ensemble average [4].

A high-throughput MD study on hydrogen diffusion in α-iron grain boundaries exemplifies this approach, where 512 different grain boundary structures were generated and analyzed [4]. The simulation protocol involved:

- Structure generation using Monte-Carlo sampling from the SO(3) group

- Annealing process to reach equilibrated states

- Diffusion simulation employing hydrogen atoms as probes for MSD calculation

- Machine learning analysis to predict diffusion coefficients from structural features [4]

This comprehensive study revealed that hydrogen diffusion in grain boundaries is markedly reduced compared to bulk iron (approximately 99% decrease), highlighting the potential of grain boundary engineering as a strategy to mitigate hydrogen embrittlement in metals [4].

Uncertainty in MD-derived diffusion coefficients depends not only on simulation data but also on analysis protocols, including the choice of statistical estimator (OLS, WLS, GLS) and data processing decisions such as fitting window extent and time-averaging [8]. This emphasizes the importance of standardized analysis protocols for reliable comparison of diffusion coefficients across different studies.

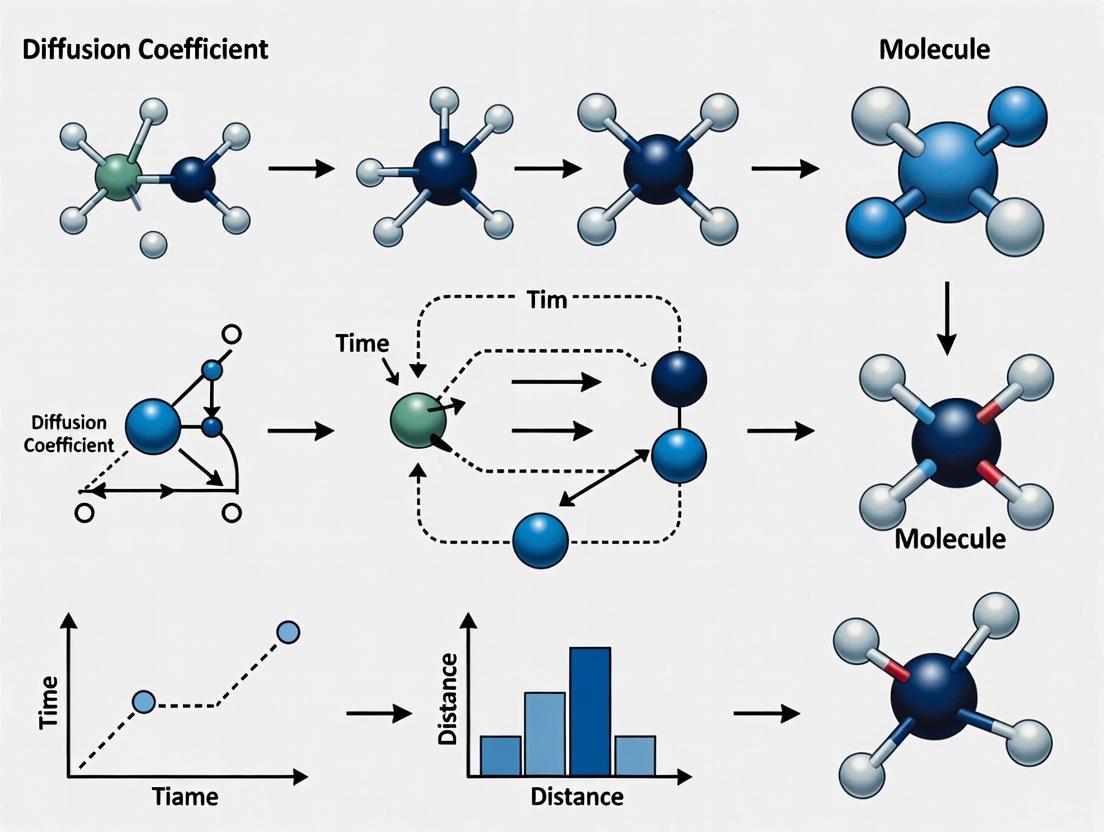

Figure 1: Molecular Dynamics Workflow for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

Experimental Measurement Techniques

Experimental determination of diffusion coefficients employs various methodologies depending on the system and conditions:

Taylor Dispersion Method: This widely used technique involves injecting a small pulse of solution into a capillary tube with laminar flow. The dispersion of the pulse as it travels through the tube is measured, and the diffusion coefficient is extracted from the variance of the resulting concentration profile [5]. For a binary system, the differential equation governing this process is:

[ \frac{\partial c}{\partial t} + 2u\left[1 - \left(\frac{r}{R}\right)^2\right] \frac{\partial c}{\partial z} = D\left(\frac{\partial^2 c}{\partial z^2} + \frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial}{\partial r}\left(r\frac{\partial c}{\partial r}\right)\right) ]

where (u) is the average velocity, (R) is the tube radius, (r) is the radial coordinate, and (z) is the axial coordinate [5].

MRI Diffusion Measurements: In medical and materials science applications, diffusion coefficients are measured using Diffusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging (DWI). This technique applies magnetic field gradients to encode molecular displacement, generating Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) maps that reflect tissue microstructure [9] [6]. The basic relationship is:

[ \ln\left(\frac{S(b)}{S(0)}\right) = -b \cdot \text{ADC} ]

where (S(b)) is the signal intensity at diffusion weighting (b), and (S(0)) is the signal without diffusion weighting [6].

Advanced Diffusion Models: Beyond conventional DWI, non-Gaussian diffusion models such as Continuous-Time Random Walk (CTRW), Fractional-Order Calculus (FROC), and Stretched-Exponential Model (SEM) provide enhanced characterization of tissue heterogeneity [7]. These models have demonstrated superior performance in differentiating benign from metastatic lymph nodes, with the CTRW parameter βCTRW emerging as a particularly effective biomarker [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Diffusion Coefficient Studies

| Material/Reagent | Function and Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| NIST-traceable diffusion phantoms [9] | Reference standards for calibrating MRI diffusion measurements | Quality assurance across multiple scanners in multi-center studies |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) solutions [9] | Mimic tissue diffusion properties at known concentrations | MRI scanner validation and protocol harmonization |

| α-iron grain boundary models [4] | Computational models for hydrogen diffusion studies | Investigating hydrogen embrittlement in metals |

| Aqueous glucose/sorbitol solutions [5] | Model systems for molecular diffusion in liquids | Reactor design and optimization for sorbitol production |

| Head and neck phased-array coils [7] | Specialized MRI detectors for specific anatomical regions | Clinical differentiation of benign and metastatic lymph nodes |

The diffusion coefficient represents a fundamental bridge between molecular-scale dynamics and macroscopic transport phenomena across scientific disciplines. From its theoretical foundation in Fick's laws to its practical application in molecular dynamics research, this parameter provides crucial insights into material behavior, biological function, and industrial processes. Contemporary research continues to refine our understanding of diffusion, with advanced computational approaches enabling high-throughput screening of material systems and sophisticated MRI techniques revealing tissue microstructural features. As molecular dynamics methodologies advance and experimental techniques become more precise, the diffusion coefficient will maintain its central role in quantifying and predicting molecular transport in increasingly complex systems.

The Einstein relation stands as a cornerstone of physical chemistry and materials science, providing a fundamental bridge between the random microscopic motion of molecules and macroscopic transport properties measurable in the laboratory. In the context of molecular dynamics research, this principle offers a powerful pathway for determining the self-diffusion coefficient (D), a critical parameter quantifying the rate at of molecular transport in gases, liquids, and solids. This relation, also known as the Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland equation in its hydrodynamic form, connects the diffusion coefficient to mobility, temperature, and viscosity, enabling researchers to predict molecular movement from easily measurable bulk properties.

Originally derived by Albert Einstein in 1905 and independently by William Sutherland and Marian Smoluchowski around the same time, the relation emerged from the study of Brownian motion - the random jittering of pollen particles in water observed under a microscope [10] [11]. Einstein's profound insight was that this seemingly random motion provided direct evidence for the existence of atoms and molecules, bridging the atomic and macroscopic worlds. Today, this relation finds critical applications across scientific disciplines, from understanding antibiotic resistance in biology to designing better battery materials and pharmaceuticals [11].

Theoretical Foundations of the Einstein Relation

Fundamental Equations and Their Physical Interpretation

The Einstein relation exists in several forms, each tailored to specific physical contexts. The most general form of the classical relation states:

D = μkBT

Where D is the diffusion coefficient (m²/s), μ is the mobility or the ratio of the particle's terminal drift velocity to an applied force (m·s⁻¹/N), kB is the Boltzmann constant (1.38 × 10⁻²³ J/K), and T is the absolute temperature (K) [10]. This fluctuation-dissipation relation reveals the deep connection between the random fluctuations responsible for diffusion and the dissipative friction governing mobility.

For specific applications, two specialized forms are particularly important:

Table 1: Key Formulations of the Einstein Relation

| Equation Name | Formula | Application Context | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Einstein-Smoluchowski | D = (μqkBT)/q | Diffusion of charged particles | μq = electrical mobility, q = particle charge |

| Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland | D = kBT/(6πηr) | Diffusion of spherical particles in liquid with low Reynolds number | η = dynamic viscosity, r = hydrodynamic radius |

The Stokes-Einstein-Sutherland equation specifically applies to spherical particles diffusing in a continuum fluid with low Reynolds number, where the friction coefficient ζ = 6πηr follows from Stokes' law [12] [10]. This formulation has proven remarkably versatile, operating not only in simple atomic fluids but also in complex molecular fluids like water [12].

Microscopic Interpretation and Modifications

At the microscopic scale, the Stokes-Einstein relation can be reformulated without the hydrodynamic radius concept:

DηΔ/(kBT) = αSE

Where Δ = ρ⁻¹/³ represents the mean interatomic separation (with ρ as the atomic number density) and αSE is a dimensionless coefficient that is only weakly system-dependent [12]. This formulation eliminates the ambiguity in defining a hydrodynamic radius for atoms and small molecules.

Zwanzig's theoretical approach based on a vibrational picture of atomic dynamics provides a microscopic foundation for this relation. In dense fluids, atoms exhibit solid-like vibrations around local equilibrium positions with an amplitude ⟨δr²⟩ = 6kBT/(m⟨ω²⟩), where m is atomic mass and ⟨ω²⟩ is the mean-square vibrational frequency [12]. The characteristic timescale for diffusion is the Maxwell relaxation time τM = η/G∞, where G∞ is the instantaneous shear modulus [12]. This leads to a diffusion coefficient D = (kBT/m)τM/⟨ω²⟩, recovering Zwanzig's result when using the Debye approximation for the collective excitation spectrum.

For degenerate semiconductors, the classical Einstein relation must be modified to account for Fermi-Dirac statistics, becoming:

D/μ = (kBTL/q) × [F₁/₂(ηc)/F₋₁/₂(ηc)]

where Fⱼ(ηc) are Fermi-Dirac integrals of order j and ηc is the reduced Fermi energy [13]. Further modifications are needed for nonparabolic energy bands, highlighting how the relation adapts to different physical contexts.

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Determining Diffusion Coefficients from Molecular Dynamics

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the Einstein relation provides the most direct method for calculating self-diffusion coefficients from the mean squared displacement (MSD) of particles [14]. The key equation is:

D = lim(t→∞) 1/(2d·t·N) · Σᵢ⟨|rᵢ(t) - rᵢ(0)|²⟩

Where d is the dimension of the system, N is the number of particles, rᵢ(t) is the position of particle i at time t, and the angle brackets denote an ensemble average [14]. The MSD ⟨|rᵢ(t) - rᵢ(0)|²⟩ is computed from the simulation trajectory, and D is obtained from the slope of the MSD versus time in the diffusive regime.

Figure 1: Workflow for calculating diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics simulations using the Einstein relation

Addressing Computational Challenges

Several technical challenges must be addressed for accurate determination of diffusion coefficients from MD simulations:

Finite-size effects: Periodic boundary conditions create artificial confinement that affects long-range hydrodynamic interactions. This can be mitigated by extrapolating results to the thermodynamic limit or applying hydrodynamic corrections based on viscosity calculations [14] [15].

Ballistic regime: At short timescales, particle motion is ballistic (MSD ∝ t²) rather than diffusive (MSD ∝ t). Including this regime in the fit introduces significant errors, requiring careful identification of the appropriate timescale for diffusion [14].

Statistical uncertainty: The whole MD trajectory cannot be simply fitted due to correlation of the trajectory. Instead, the simulation is divided into multiple segments, and the diffusion coefficient is calculated for each segment, with the standard deviation across segments providing the uncertainty estimate [14].

Specialized computational tools like the MD2D Python module have been developed to address these challenges, implementing algorithms to automatically exclude the ballistic regime, estimate uncertainties through ensemble averaging, and apply finite-size corrections [14].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Diffusion Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| MD2D Python Module | Accurately determines D from MSD using Einstein relation | Molecular dynamics simulations |

| Low Mode MD (MOE) | Calculates stable molecular conformations | Molecular modeling for radius estimation |

| MMFF94x Force Field | Describes molecular interactions in MD | Conformational analysis and dynamics |

| Green-Kubo Formalism | Calculates transport properties from correlation functions | Alternative to Einstein relation for viscosity |

| Bead and Shell Models | Calculate hydrodynamic properties | Protein diffusion studies |

Applications Across Scientific Disciplines

Validation in Water Models and Aqueous Systems

Water, as the universal biological solvent, represents a critical test case for the Einstein relation. Recent studies have confirmed that the microscopic Stokes-Einstein relation without hydrodynamic radius holds remarkably well for various water models including TIP4P/2005, TIP4P-FB, TIP3P-FB, OPC, and OPC3 across temperatures from 273 to 373 K [12]. The relation DηΔ/(kBT) = αSE demonstrates excellent agreement with simulation data, with the coefficient αSE confined to a narrow range between 0.132 and 0.181 depending on the ratio of transverse to longitudinal sound velocities [12].

However, below approximately 290 K, supercooled water exhibits a breakdown of the classical Stokes-Einstein relation, replaced by a fractional Stokes-Einstein relation with D ∝ (τ/T)^{-ζ} where ζ ≈ 3/5 [16]. This transition coincides with structural changes in water, specifically the development of local structure similar to low-density amorphous ice, highlighting how deviations from the classical relation can provide insights into fundamental structural transformations [16].

Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Applications

In drug discovery and development, the Einstein relation enables prediction of molecular diffusion coefficients through the Stokes-Einstein equation D = kBT/(6πηr), where r is the molecular radius [17]. This approach has been successfully applied to sugars, amino acids, and various drug molecules including aspirin, loxoprofen, and salbutamol [17].

Two approaches for estimating molecular radii from stable conformations have been developed:

- Simple radius (rs): Derived from the van der Waals volume assuming a spherical shape

- Effective radius (re): Incorporates molecular shape through the radius of gyration (re = 1.29rg)

For molecules with strong hydration ability, the effective radius provides the best agreement with experimental diffusion coefficients, while for other compounds, the simple radius works better, with deviations of approximately 0.3 × 10⁻⁶ cm²/s from experimental values [17].

In biological systems, the validity of the Stokes-Einstein relation has been confirmed for protein motion inside live bacteria, despite the crowded and complex nature of the cytoplasm [11]. This finding has important implications for understanding antibiotic resistance and the mechanical properties of cancer cells, as it provides a foundation for assessing cellular mechanical properties based on the Einstein relation [11].

Advanced Materials and Semiconductor Physics

The Einstein relation plays a crucial role in semiconductor device design and analysis, where it connects carrier diffusion coefficients to mobilities [13]. For degenerate semiconductors with nonparabolic energy bands, the classical relation must be generalized to account for the increased density of states and average kinetic energy of carriers [13]. The development of accurate generalized Einstein relations for these materials enables precise modeling of carrier transport in advanced electronic and optoelectronic devices.

Current Research Frontiers and Methodological Advances

Recent advances in molecular dynamics methodologies have focused on improving the accuracy of diffusion coefficient calculations from simulations. Key developments include:

Excess entropy scaling (EES): Relates structural disorder to transport properties, providing an alternative approach to diffusion coefficient estimation with reduced computational cost [15].

Finite-size effect corrections: Improved hydrodynamic corrections that account for the influence of periodic boundary conditions on long-range interactions [14] [15].

Advanced sampling techniques: Enhanced methods for exploring molecular conformation space to improve radius estimates for the Stokes-Einstein equation [17].

Multiscale modeling approaches: Integration of atomistic simulations with mesoscale coarse-grained models to extend the applicability of the Einstein relation to complex biomolecular systems [17].

Figure 2: Current research frontiers expanding beyond the classical Einstein relation

The Einstein relation remains a vital principle connecting microscopic molecular motion to macroscopic transport phenomena across an expanding range of scientific disciplines. From its foundational role in establishing the physical reality of atoms to its current applications in drug discovery, semiconductor design, and nanomaterials characterization, this relation continues to enable researchers to extract fundamental molecular-scale information from measurable bulk properties.

Ongoing methodological developments in molecular dynamics simulations, combined with theoretical advances generalizing the relation to complex systems, ensure that the Einstein relation will maintain its central position in molecular dynamics research. As computational power increases and experimental techniques for measuring diffusion coefficients improve, the Einstein relation provides the essential conceptual framework bridging these domains, continuing its century-long legacy as one of the most profound connections between the microscopic and macroscopic worlds.

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the two principal methods for calculating diffusion coefficients in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations: the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) approach via the Einstein relation and the Green-Kubo relation based on velocity autocorrelation. Within the broader context of understanding diffusion coefficients in MD research, we detail the theoretical foundations, practical implementation protocols, and comparative applications of these methods. The content is structured to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the necessary knowledge to accurately compute and interpret diffusion data, supported by quantitative comparisons, experimental workflows, and essential computational toolkits.

In molecular dynamics research, the diffusion coefficient (D) is a fundamental transport property that quantifies the rate at which particles spread through a medium via random, thermally-driven motion. It serves as a crucial parameter in numerous applications, from predicting drug release rates in pharmaceutical development to understanding atomic migration in materials science. The self-diffusion coefficient, which describes the motion of a particle within a homogeneous system of identical particles, can be rigorously calculated from MD simulations using two primary theoretical frameworks: the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) method, derived from the Einstein relation, and the Green-Kubo relation, which utilizes the velocity autocorrelation function (VACF). This guide delineates the key equations, protocols, and practical considerations for applying these methods to extract accurate diffusion coefficients from particle trajectories.

Theoretical Foundations

Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) and the Einstein Relation

The Mean Squared Displacement is the most common measure of the spatial extent of random motion in a system. It is defined as the average squared distance a particle travels over time t [18]: [ \text{MSD}(t) \equiv \left\langle |\mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0)|^{2} \right\rangle ] where (\mathbf{r}(t)) is the position of a particle at time t, and the angle brackets denote an ensemble average over all particles in the system and multiple time origins.

For a pure random walk (diffusive motion) in an n-dimensional space, the MSD becomes linear with time [18]: [ \text{MSD}(t) = 2nDt ] where D is the self-diffusion coefficient. This leads to the Einstein relation for diffusion [19] [20]: [ D = \frac{1}{2n} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(t) ] In three dimensions (n=3), this simplifies to: [ D = \frac{1}{6} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(t) ] In practice, D is calculated from the slope of the linear portion of the MSD versus time curve [21].

The Green-Kubo Relation

The Green-Kubo relations provide an exact mathematical expression for transport coefficients, including the self-diffusion coefficient, in terms of the integral of an equilibrium time correlation function [22]. For self-diffusion, the relevant correlation function is the velocity autocorrelation function (VACF).

The Green-Kubo relation for the self-diffusion coefficient is given by [22] [23]: [ D = \frac{1}{3} \int_{0}^{\infty} \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle \, dt ] where (\mathbf{v}(t)) is the velocity vector of a particle at time t, and the angle brackets represent the ensemble average over all particles and time origins. The integrand, (\langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle), is the velocity autocorrelation function, which describes how a particle's velocity correlates with itself over time.

Connecting the Theories: MSD and VACF

While the MSD and Green-Kubo approaches may appear distinct, they are mathematically equivalent. The MSD can be expressed as the integral of the VACF: [ \frac{d}{dt} \text{MSD}(t) = 2 \int_{0}^{t} \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t') \rangle \, dt' ] This relationship confirms that both methods will yield identical diffusion coefficients for a system in the thermodynamic limit, provided sufficient sampling.

Table 1: Key Equations for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

| Method | Fundamental Formula | Diffusion Coefficient (3D) | Type of Average |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSD (Einstein) | (\text{MSD}(t) = \langle |\mathbf{r}(t) - \mathbf{r}(0)|^{2} \rangle) | ( D = \frac{1}{6} \times \text{slope of MSD}(t) ) | Ensemble over particles and time origins |

| Green-Kubo | ( \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle ) | ( D = \frac{1}{3} \int_{0}^{\infty} \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle dt ) | Ensemble over particles and time origins |

Computational Methodologies

Calculating Diffusion Coefficients via MSD

The following protocol outlines the steps for computing diffusion coefficients using the MSD approach, as implemented in software packages like MDAnalysis [20] and AMS [21].

Experimental Protocol: MSD Workflow

Trajectory Preparation: Ensure atomic coordinates are in the "unwrapped" convention. When atoms cross periodic boundaries, they must not be wrapped back into the primary simulation cell, as this would artificially truncate displacements [20]. In GROMACS, this can be achieved using

gmx trjconvwith the-pbc nojumpflag.System Selection: Choose an appropriate atom group for analysis (e.g., all water molecules, specific drug molecules, or particular ion types). For molecules, the MSD can be calculated using center-of-mass positions [19].

MSD Computation: Calculate the MSD as a function of lag time ((\tau)). This is typically done using a "windowed" approach, averaging over all possible time origins within the trajectory to maximize statistics [20]: [ \text{MSD}(\tau) = \bigg\langle \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} |\mathbf{r}i(t0 + \tau) - \mathbf{r}i(t0)|^2 \bigg\rangle{t_0} ] For long trajectories, use Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)-based algorithms (e.g., with

fft=Truein MDAnalysis) for computationally efficient O(N log N) scaling [20].Linear Regression: Plot the MSD against lag time and identify the linear (diffusive) regime. Exclude short-time ballistic and long-time poorly averaged regions [20]. The slope is obtained by fitting a linear model, ( \text{MSD}(t) = m \cdot t + c ), to this linear segment.

Diffusion Coefficient Calculation: For a 3D system, compute the diffusion coefficient as ( D = m / 6 ) [21].

Diagram 1: MSD Analysis Workflow

Calculating Diffusion Coefficients via the Green-Kubo Relation

The following protocol details the calculation of diffusion coefficients via integration of the velocity autocorrelation function, as implemented in codes like AMS [21].

Experimental Protocol: Green-Kubo Workflow

Trajectory Requirements: Ensure the MD trajectory includes velocity data saved at a sufficiently high frequency (small time interval) to accurately capture the short-time dynamics of the VACF [21].

VACF Computation: Calculate the velocity autocorrelation function for the selected atom group [21]: [ \text{VACF}(t) = \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} \langle \mathbf{v}i(t0) \cdot \mathbf{v}i(t0 + t) \rangle{t0} ] This involves correlating the velocity at time (t0) with the velocity at time (t0 + t) for all particles and averaging over all available time origins (t0).

Integration: Numerically integrate the VACF over time to obtain the time-dependent diffusion coefficient [21]: [ D(t) = \frac{1}{3} \int_{0}^{t} \text{VACF}(t') \, dt' ]

Plateau Identification: Monitor (D(t)) as a function of the upper integration limit. The plateau value, once (D(t)) converges, is the calculated self-diffusion coefficient [21].

Diagram 2: Green-Kubo Analysis Workflow

Quantitative Data and Comparative Analysis

Example Data from Molecular Systems

The following table compiles diffusion coefficient data from various MD studies, illustrating the application of these methods across different systems.

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Diffusion Coefficients from MD Simulations

| System | Temperature (K) | Method | Diffusion Coefficient (m²/s) | Reference/Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPC Water | Not Specified | MSD | Calculated via gmx msd |

GROMACS Manual [19] |

| Li+ in Li0.4S | 1600 | MSD | ( 3.09 \times 10^{-8} ) | AMS Tutorial [21] |

| Li+ in Li0.4S | 1600 | Green-Kubo (VACF) | ( 3.02 \times 10^{-8} ) | AMS Tutorial [21] |

| Fe-Cr-Ni Alloy Melts | 1950 | MSD | Order: DNi > DFe > DCr | Materials Study [23] |

Critical Considerations for Accurate Results

- Trajectory Length: Simulations must be long enough to observe fully diffusive behavior (linear MSD). For slow-diffusing systems like drugs in polymers, sub-diffusive dynamics from short simulations can lead to dramatic over-prediction of D [24].

- Finite-Size Effects: The calculated diffusion coefficient depends on the size of the simulation supercell due to periodic boundary conditions. A common practice is to perform simulations for progressively larger supercells and extrapolate to the "infinite supercell" limit [21].

- Statistical Averaging: For the Green-Kubo method, the VACF must be well-converged. This often requires long simulation times because the integral's accuracy depends on the noisy tail of the VACF at long times [23].

Table 3: Comparison of MSD and Green-Kubo Methods

| Feature | MSD (Einstein) Method | Green-Kubo Method |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Quantity | Particle positions, (\mathbf{r}(t)) | Particle velocities, (\mathbf{v}(t)) |

| Primary Output | (\text{MSD}(t) = \langle |\Delta \mathbf{r}(t)|^2 \rangle) | (\text{VACF}(t) = \langle \mathbf{v}(0) \cdot \mathbf{v}(t) \rangle) |

| Calculation of D | Slope of linear MSD region: ( D = \frac{\text{slope}}{6} ) | Integral of VACF: ( D = \frac{1}{3} \int_{0}^{\infty} \text{VACF}(t) dt ) |

| Key Practical Step | Identifying the linear diffusive regime | Identifying the plateau in ( D(t) ) |

| Computational Note | FFT-based algorithms available for efficiency [20] | Requires high-frequency velocity output [21] |

| Convergence | Can be easier to assess visually | Integral can be noisy; sensitive to VACF tail [23] |

| Dimensionality | Can be calculated for 1D, 2D, or 3D [19] [20] | Typically calculated for 3D |

Applications in Research and Development

Drug Development and Delivery

Predicting the diffusion coefficients of drug molecules in polymeric carrier systems is critical for designing controlled-release pharmaceuticals. MD simulations using MSD analysis allow researchers to predict drug release rates without resource-intensive laboratory experiments. For instance, studies have focused on accurately predicting diffusion coefficients for small to medium-sized molecules in polymer matrices, which is fundamental for modeling drug elution from implantable devices [24].

Materials Science and Metallurgy

In materials science, MD simulations are used to investigate the relationship between atomic-scale structure and macroscopic transport properties. For example, a study on Fe-Cr-Ni alloy melts used MSD to determine the self-diffusion coefficients of the constituent atoms, finding the order Ni > Fe > Cr. These diffusion coefficients were then linked to the alloys' viscosity via the Stokes-Einstein relation, providing atomic-scale insights into properties relevant for industrial processes like casting and solidification [23].

Table 4: Essential Software and Computational Tools

| Tool / "Reagent" | Type | Primary Function in Analysis | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Software Package | Performs MD simulations and analyzes trajectories via gmx msd. |

Calculating the self-diffusion coefficient of water molecules [19]. |

| MDAnalysis | Python Library | Analyzes MD trajectories; includes EinsteinMSD class for MSD calculation. |

Custom analysis scripts for calculating MSD and diffusivity in complex biomolecular systems [20]. |

| AMS | Software Suite (SCM) | MD simulations and analysis; GUI tools for MSD and VACF calculation. | Studying Li-ion diffusion in battery cathode materials [21]. |

| ReaxFF Force Field | Interaction Potential | Describes bond formation/breaking in reactive MD simulations. | Simulating chemical reactions and diffusion in complex materials like lithiated sulfur [21]. |

| tidynamics Python Package | Python Library | Provides efficient FFT-based MSD algorithm. | Accelerating MSD computation for very long trajectories within MDAnalysis [20]. |

The Mean Squared Displacement and Green-Kubo relation represent two foundational pillars for computing diffusion coefficients from molecular dynamics trajectories. While the MSD method offers an intuitive approach based on particle displacements, the Green-Kubo relation provides a powerful framework based on fluctuation-dissipation theory using velocity correlations. Both methods are mathematically equivalent in the limit of infinite sampling and system size, yet each presents distinct practical considerations regarding convergence, computational efficiency, and analysis. Mastery of these techniques, including an understanding of their implementation protocols and potential pitfalls such as finite-size effects and sub-diffusive dynamics, is essential for researchers across diverse fields—from drug development to materials engineering—to reliably extract this critical transport parameter from atomistic simulations.

Molecular Mechanics (MM) force fields are the cornerstone of computational chemistry, enabling the study of biomolecular systems at a scale impractical for quantum mechanical methods. These classical models approximate the quantum mechanical energy surface, reducing computational cost by orders of magnitude and making simulations of large systems, such as proteins in solution, feasible [25]. The General AMBER Force Field (GAFF) was developed specifically to address a critical gap in rational drug design. While traditional AMBER force fields enjoyed a strong reputation for studying proteins and nucleic acids, their limited parameters for organic molecules prevented widespread use in pharmaceutical applications [26]. GAFF was therefore created to be a general, complete, and compatible force field for drug design, providing parameters for almost all organic molecules comprised of C, N, O, H, S, P, F, Cl, Br, and I [26]. Its development allows for the automated study of a vast number of molecules, such as in database searching, making it a vital tool in modern Computational Structure-Based Drug Discovery (CSBDD) [26] [25].

The significance of accurately modeling diffusion processes in molecular dynamics (MD) cannot be overstated within drug discovery. The diffusion coefficient (D) is a key property for understanding molecular mobility, and its accurate prediction is indispensable for chemical engineering design, mass transfer, and processing [27]. Furthermore, in biochemical contexts, diffusion is involved in fundamental processes like protein aggregation and transport within intercellular media [27]. Assessing the performance of force fields like GAFF in predicting such dynamic properties is, therefore, essential for validating their use in probing biomolecular interactions.

Mathematical Foundation of Force Fields

Class I additive potential energy functions, which form the basis of GAFF and other major biomolecular force fields, calculate the total potential energy of a system as a sum of bonded and non-bonded interactions [25]. The general form of this potential energy function is:

\[ E_{\text{total}} = E_{\text{bonded}} + E_{\text{non-bonded}} \]

Bonded Interactions

The bonded term describes the energy associated with the covalent structure of the molecules and is composed of several components [25]:

\[ E_{\text{bonded}} = \sum_{\text{bonds}} K_b(b - b_0)^2 + \sum_{\text{angles}} K_\theta(\theta - \theta_0)^2 + \sum_{\text{dihedrals}} \sum_{n=1}^{6} K_{\phi,n}(1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta_n)) + \sum_{\text{improper}} K_{\varphi}(\varphi - \varphi_0)^2 \]

The following table details the parameters and their physical significance for these bonded terms:

Table 1: Components of the Bonded Potential Energy Function in Class I Force Fields

| Component | Mathematical Form | Parameters | Physical Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | \( K_b(b - b_0)^2 \) | \( b_0 \), \( K_b \) | Energy required to stretch or compress a bond from its equilibrium length, modeled as a harmonic oscillator. |

| Angle Bending | \( K_\theta(\theta - \theta_0)^2 \) | \( \theta_0 \), \( K_\theta \) | Energy required to bend an angle from its equilibrium value, modeled as a harmonic oscillator. |

| Torsional Rotation | \( \sum K_{\phi,n}(1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta_n)) \) | \( K_{\phi,n} \), \( n \), \( \delta_n \) | Energy barrier for rotation around a central bond, described by a periodic cosine function. |

| Improper Dihedrals | \( K_{\varphi}(\varphi - \varphi_0)^2 \) | \( \varphi_0 \), \( K_{\varphi} \) | Energy to maintain chirality at a center or to enforce planarity (e.g., in aromatic rings). |

Non-Bonded Interactions

The non-bonded term describes interactions between atoms that are not directly bonded and is crucial for modeling intermolecular forces and long-range interactions within a molecule. It is given by:

\[ E_{\text{non-bonded}} = \sum_{\text{non-bonded pairs } ij} \frac{q_i q_j}{4\pi D r_{ij}} + \sum_{\text{non-bonded pairs } ij} \epsilon_{ij} \left[ \left( \frac{R_{\min,ij}}{r_{ij}} \right)^{12} - 2 \left( \frac{R_{\min,ij}}{r_{ij}} \right)^{6} \right] \]

This sum consists of:

- Electrostatics: Modeled by the Coulomb potential between fixed partial atomic charges \( qi \) and \( qj \). This is an additive model, as the charges do not polarize in response to their environment [25].

- van der Waals forces: Modeled by the Lennard-Jones 6-12 potential. The \( R^{-12} \) term describes Pauli repulsion at short ranges, while the \( R^{-6} \) term describes attractive dispersion forces. The parameters \( R_{\min,ij} \) and \( \epsilon_{ij} \) define the equilibrium distance and well depth for a given atom pair [25].

GAFF Parameterization Methodology

The accuracy of a force field is entirely dependent on the quality and derivation of its parameters. GAFF employs a systematic approach to parameterize its various terms.

Atom Typing and Charge Assignment

A foundational concept in GAFF is its general atom typing system. Unlike traditional AMBER force fields, GAFF defines atom types that cover a broader swath of organic chemical space. These include basic types (e.g., c3 for sp3 carbon, ca for aromatic carbon) and special types for conjugated systems and small rings [26]. This comprehensive typing scheme allows GAFF to automatically assign parameters to a wide range of drug-like molecules.

For assigning partial charges, the primary method in GAFF is the HF/6-31G* RESP charge. However, for high-throughput applications like database searching, the AM1-BCC method is sanctioned as it was parameterized to reproduce the HF/6-31G* RESP charges efficiently. The van der Waals parameters in GAFF are identical to those used in the traditional AMBER force field [26].

Derivation of Equilibrium Values and Force Constants

The parameterization of bond lengths and angles in GAFF relies on multiple sources of reference data:

- Crystallographic data from the Cambridge Structure Database (CSD).

- High-level ab initio calculations at the MP2/6-31G* level [26].

Force constants for bonds were derived using empirical functions, with the parameter m set to 4.0 as a compromise to fit parameters from the traditional AMBER force field [26]. The derivation of angle force constants also employs an empirical function based on atomic parameters.

Table 2: Sample Bond Length Parameters in GAFF [26]

| Atom i | Atom j | Equilibrium Length \( r_{eq} \) (Å) | Force Constant \( K_{ij} \) (mdyn/Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | C | 1.526 | 7.643 |

| C | O | 1.440 | 7.347 |

| C | N | 1.470 | 7.504 |

| H | C | 1.090 | 6.217 |

| H | O | 0.960 | 5.794 |

| N | O | 1.420 | 7.526 |

Torsional Parameterization

Torsional parameters are among the most critical for correctly reproducing conformational energetics. GAFF's strategy for torsional angle parameterization is a two-step process:

- Perform torsional scanning: The rotational profile for a dihedral is determined using high-level quantum calculations (MP4/6-311G(d,p)//MP2/6-31G*).

- Apply PARMSCAN: This tool finds the optimal torsional angle parameters (\( V_n \), \( n \), \( \gamma \)) that best reproduce the quantum mechanical rotational profile [26].

The Diffusion Coefficient in Molecular Dynamics Research

The diffusion coefficient (D) is a key dynamic property that quantifies the rate of particle spread through random motion. In the context of MD, it provides a critical link between microscopic simulations and macroscopic observables, and serves as a rigorous test for force field accuracy.

Theoretical Definition

For a molecule M in a viscous environment, its diffusion can be described by the diffusion equation (Fick's second law): \[ \frac{\partial}{\partial t} c(\vec{r},t) = D \nabla^2 c(\vec{r},t) \] where \( c(\vec{r},t) \) is the probability distribution of finding M at point \( \vec{r} \) at time t [27]. From a microscopic perspective, D is most commonly calculated in MD simulations using the Einstein relation, which relates it to the mean-squared displacement (MSD) of particles over time: \[ \langle | \vec{r}(t) - \vec{r}(0) |^2 \rangle = 2nDt \] where \( n \) is the dimensionality (e.g., 3 for 3D diffusion) [27] [21]. The diffusion coefficient is then calculated as the slope of the MSD versus time plot: \( D = \frac{\text{slope}}{6} \) in three dimensions [21].

An alternative approach uses the Green-Kubo relation, which relates D to the integral of the velocity autocorrelation function (VACF): \[ D = \frac{1}{3} \int_{0}^{\infty} \langle \vec{v}(0) \cdot \vec{v}(t) \rangle dt \] where \( \vec{v}(t) \) is the velocity vector at time t [21].

Computational Protocol for Calculating D

Calculating a reliable diffusion coefficient from MD requires careful simulation design and analysis. The following diagram illustrates a standard workflow for this calculation, from system preparation to analysis.

Diagram 1: MD Workflow for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

Key steps and considerations in this protocol include:

- System Preparation: Building the initial configuration, such as inserting solute molecules into a solvent box. For complex systems like lithiated sulfur cathodes, this may involve importing crystal structures and inserting particles using builder tools or Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) [21].

- Equilibration: A critical step to relax the system to the target temperature and density. This is typically done using thermostats (e.g., Berendsen) and barostats in sequential NVT and NPT ensemble simulations [21].

- Production Run: A sufficiently long MD simulation is performed to collect trajectory data. The sample frequency must be set appropriately to capture molecular motion without generating excessively large files [21].

- MSD Analysis: The recommended method for calculating D. The MSD plot should be linear in the diffusive regime; a non-linear plot indicates insufficient simulation time or incomplete equilibration [21]. The fitting window for the linear regression must be chosen carefully, as the uncertainty in D depends on this analysis protocol, not just the simulation data itself [8].

- Sampling Strategy: For solutes at infinite dilution, where only one molecule may be present in the simulation box, achieving good statistics is challenging. One efficient strategy involves averaging the MSD collected in multiple, short MD simulations rather than relying on one extremely long trajectory [27].

Validation of GAFF for Diffusion Studies

The performance of GAFF in predicting diffusion coefficients has been rigorously evaluated. In one comprehensive study, GAFF was used to predict diffusion coefficients for 17 solvents, 5 organic compounds in aqueous solutions, 4 proteins in aqueous solutions, and 9 organic compounds in non-aqueous solutions [27]. The key findings were:

- Organic solutes in aqueous solution: Diffusion coefficients were well predicted, with an average unsigned error (AUE) of \( 0.137 \times 10^{-5} \text{cm}^2 \text{s}^{-1} \) and a root-mean-square error (RMSE) of \( 0.171 \times 10^{-5} \text{cm}^2 \text{s}^{-1} \) [27].

- Proteins and organic solvents: While the absolute values of D were harder to predict, excellent correlations with experimental data were achieved for proteins in aqueous solutions (R² = 0.996) and organic compounds in non-aqueous solutions (R² = 0.834) [27].

Further validation comes from applied studies. For example, MD simulations were used to investigate the interfacial diffusion of rejuvenators (e.g., bio-oil, engine-oil) in aged bitumen. The magnitude of the diffusion coefficients ranged from \( 10^{-11} \) to \( 10^{-10} \text{m}^2/\text{s} \), and the order of diffusive capacity (Bio-oil > Engine-oil > Naphthenic-oil > Aromatic-oil) predicted by MD agreed well with experimental results from diffusion tests and dynamic shear rheometer characterizations [28]. This demonstrates GAFF's practical utility in predicting quantitatively accurate trends and values for complex, multi-component systems.

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

The following table details key computational "reagents" and tools necessary for conducting MD studies with GAFF.

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit for GAFF-Based Molecular Dynamics

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field File (GAFF) | Contains all parameters (bonds, angles, dihedrals, non-bonded) for organic molecules. | Provides the energy function for the MD simulation; loaded at the start of the simulation. |

| HF/6-31G* RESP or AM1-BCC Charges | Partial atomic charges assigned to each atom to model electrostatic interactions. | Derived for the solute molecule prior to simulation and incorporated into the force field definition. |

| Thermostat (e.g., Berendsen) | Algorithm to control the temperature of the system by scaling velocities. | Used during equilibration and production phases to maintain the target temperature (e.g., 300 K). |

| Barostat | Algorithm to control the pressure of the system by adjusting the simulation box size. | Used during NPT equilibration to achieve the correct system density. |

| Solvent Model (e.g., TIP3P water) | A pre-parameterized model representing solvent molecules. | Added to the simulation box to solvate the solute, creating a realistic environment. |

| Trajectory Analysis Tool (e.g., AMSmovie) | Software for analyzing MD trajectories to compute properties like MSD and VACF. | Used post-simulation to calculate the MSD of atoms and perform linear fitting to obtain D. |

| Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD) | A measure of the average squared distance particles travel over time. | The primary metric calculated from the trajectory to determine the diffusion coefficient via the Einstein relation. |

Advanced Protocols and Considerations

Enhancing Sampling and Accuracy

Several advanced protocols can be employed to improve the reliability of computed diffusion coefficients:

- Simulated Annealing for Amorphous Systems: For modeling non-crystalline materials like amorphous Li₀.₄S, a simulated annealing protocol can be used. This involves heating the system to a high temperature (e.g., 1600 K) and then rapidly cooling it to room temperature to generate a realistic amorphous structure before the production MD run [21].

- Extrapolation to Lower Temperatures: Directly calculating D at low temperatures (e.g., 300 K) can be prohibitively slow due to reduced molecular mobility. A workaround is to use the Arrhenius equation \( D(T) = D_0 \exp(-E_a / k_B T) \). By running simulations at multiple elevated temperatures (e.g., 600 K, 800 K, 1200 K, 1600 K) and plotting \( \ln(D(T)) \) against \( 1/T \), the activation energy \( Ea \) and pre-exponential factor \( D0 \) can be derived, allowing for extrapolation of D to lower, experimentally relevant temperatures [21].

- Addressing Finite-Size Effects: The calculated diffusion coefficient can depend on the size of the simulation box due to periodic boundary condition artifacts. A robust approach is to perform simulations for progressively larger supercells and extrapolate the calculated diffusion coefficients to the "infinite supercell" limit [21].

- Uncertainty Quantification: The statistical uncertainty in a diffusion coefficient estimated from MSD regression depends not only on the simulation data but also on the choice of statistical estimator (e.g., Ordinary Least Squares, Weighted Least Squares) and data processing decisions (e.g., the fitting window). Researchers should be transparent about their analysis protocol to avoid incorrect uncertainty estimates [8].

In molecular dynamics (MD) research, the diffusion coefficient (D) is a fundamental transport property that quantifies the rate at which particles, such as atoms or molecules, spread through a medium due to random thermal motion. It is a critical parameter for predicting material behavior in processes ranging from chemical reactions in industrial reactors to drug delivery across cellular membranes. This whitepaper examines the core factors influencing diffusion coefficients, drawing upon contemporary molecular dynamics simulation studies and experimental data. The discussion is framed within the context of calculating and applying diffusion coefficients in MD research, providing scientists with a technical guide to the principles, measurement methodologies, and key influencing factors.

Theoretical Foundations of Diffusion

The phenomenological description of diffusion is primarily governed by Fick's laws. Fick's first law states that the diffusive flux, J, is proportional to the negative gradient of the concentration. In one dimension, it is expressed as:

J = -D ∂φ/∂x

where J is the diffusion flux, D is the diffusion coefficient, and ∂φ/∂x is the concentration gradient [1]. This law describes the steady-state condition where the flux is constant.

Fick's second law predicts how diffusion causes the concentration to change with time. It is a partial differential equation:

∂φ/∂t = D ∂²φ/∂x²

where ∂φ/∂t is the rate of change of concentration over time [1]. This law is crucial for modeling transient diffusion processes. A diffusion process that obeys these relationships is termed Fickian or normal diffusion; otherwise, it is considered anomalous [1].

In molecular dynamics simulations, the diffusion coefficient is typically calculated from the mean-squared displacement (MSD) of particles using the Einstein relation:

D = (1/(6Nα)) lim(t→∞) d/dt Σᵢⁿ 〈|rᵢ(t) - rᵢ(0)|²〉

where N is the number of dimensions, rᵢ(t) is the position of particle i at time t, and the angle brackets denote an ensemble average [29] [30]. The linear portion of the MSD versus time plot is used for the calculation.

Core Factors Influencing Diffusion Coefficients

Temperature

Temperature is a dominant factor influencing diffusion coefficients, with an exponential relationship described by the Arrhenius equation:

D = D₀ exp(-Eₐ/RT)

where D₀ is the pre-exponential factor, Eₐ is the activation energy for diffusion, R is the universal gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature [29].

- Molecular Dynamics Evidence: A study on hydrogen diffusion in tungsten using MD simulations across 1400 K to 2700 K demonstrated that the diffusion coefficient increases exponentially with temperature. The analysis yielded an activation energy (Eₐ) of 1.48 eV and a pre-exponential factor (D₀) of 3.2×10⁻⁶ m²/s [29]. Similarly, research on the diffusion of small molecules (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄) in supercritical water within carbon nanotubes found that the confined self-diffusion coefficient of solutes increases linearly with temperature in the range of 673-973 K [30].

- Sensitivity in Energetic Materials: An MD study on the explosive DNTF (3,4-Bis(3-nitrofurazan-4-yl) furoxan) revealed that its self-diffusion coefficient is highly sensitive to temperature changes. The growth rate of the coefficient was significantly faster between 350 K and 400 K compared to the 250 K to 350 K range [31].

Table 1: Effect of Temperature on Diffusion Coefficients from MD Studies

| System | Temperature Range | Observed Effect on D | Activation Energy (Eₐ) / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| H in Tungsten [29] | 1400 K - 2700 K | Exponential increase | Eₐ = 1.48 eV |

| Solutes in SCW/CNT [30] | 673 K - 973 K | Linear increase | - |

| DNTF Energetic Material [31] | 250 K - 450 K | Accelerated increase from 350 K | More sensitive than pressure |

Viscosity

The relationship between diffusion and viscosity is classically described by the Stokes-Einstein equation:

D = kₑT / (6πŋr)

where kₑ is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, ŋ is the dynamic viscosity, and r is the hydrodynamic radius of the diffusing particle.

- Experimental Validation via NMR: A Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) relaxometry study of fifteen different kinds of oils established a clear inverse relationship between diffusion coefficients and viscosity. The diffusion of oil molecules was found to be approximately 200 times slower than the self-diffusion of bulk water, and the diffusion coefficients followed a linear relationship with the reciprocal of viscosity across most oil types [32]. This confirms the macroscopic property of viscosity is a direct indicator of the molecular-level mobility in a fluid.

- Compositional Deviations: The same study noted that certain oils, such as hazelnut and olive oil, deviated from the general trend due to their specific compositions, suggesting that molecular interactions and structures can modify the classic Stokes-Einstein relationship [32].

Table 2: Diffusion-Viscosity Relationship in Various Oils at Room Temperature [32]

| Oil Type | Diffusion Coefficient, D (×10⁻¹¹ m²/s) | Viscosity, ŋ (×10⁻² N·s/m²) |

|---|---|---|

| Hemp | 1.38 | 5.30 |

| Rapeseed | 1.17 | 5.61 |

| Sunflower | 1.15 | 5.52 |

| Olive | 0.97 | 6.13 |

| Hazelnut | 0.85 | 6.39 |

Molecular Size

The size of the diffusing particle directly impacts its mobility, with larger molecules generally experiencing slower diffusion.

- Biological Systems: Research on GPI-anchored proteins in trypanosomes provides a clear example. The lateral diffusion coefficient of the Variant Surface Glycoprotein (VSG) was measurably influenced by the size of its extra-membrane domain. Artificially increasing the protein's size by binding monovalent streptavidin reduced the diffusion coefficient three-fold. Conversely, proteolytic cleavage to create a smaller protein nearly doubled its diffusion coefficient compared to the native state [33].

- Confined Fluids: The influence of molecular size is also evident in nano-confined systems. In studies of supercritical water mixtures within carbon nanotubes, different small molecules (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄) exhibit distinct diffusion coefficients under identical conditions, a variation attributable in part to their different molecular sizes and masses [30].

Methodologies for Determining Diffusion Coefficients

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Protocol

MD simulations are a powerful tool for calculating diffusion coefficients and elucidating underlying mechanisms. A standard protocol involves:

- System Preparation: Construct a simulation box containing the atoms or molecules of interest. For example, a study on tungsten placed hydrogen atoms in the tetrahedral sites of a perfect BCC tungsten lattice [29].

- Force Field Selection: Choose an appropriate interatomic potential. The Embedded Atom Model (EAM) potential was used for W-H interactions [29], while the SPC/E model is common for water [30].

- Equilibration: Perform simulations in the NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) or NVT (constant Number, Volume, and Temperature) ensembles to relax the system to a state of thermodynamic equilibrium. For instance, a 10-ps NPT simulation was used to relieve internal stresses in a DNTF crystal study [31].

- Production Run: Conduct a longer simulation in the NVE (constant Number, Volume, and Energy) or NVT ensemble while recording particle trajectories. A typical simulation for DNTF lasted 1000 ps with a 1 fs time step [31].

- MSD Calculation and Analysis: Calculate the MSD from the particle trajectories and apply the Einstein relation to determine D. The linear section of the MSD-versus-time curve is used for the fit [29] [30].

Advanced Analysis and Machine Learning

Modern analysis addresses challenges in MSD data. A 2025 study highlighted that the uncertainty in MD-derived diffusion coefficients depends not only on simulation data but also on the choice of statistical estimator (OLS, WLS, GLS) and data processing decisions, such as the fitting window [8]. Furthermore, machine learning clustering methods have been developed to optimize anomalous MSD-time data, effectively extracting more reliable diffusion coefficients from complex systems like nano-confined fluids [30].

Experimental Validation and Techniques

While MD provides atomic-level insight, experimental validation is crucial.

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Relaxometry: This technique is used to probe molecular dynamics and determine translation diffusion coefficients, especially in complex liquids like oils. It can distinguish between translational and rotational dynamics and provides insight into the mechanism of motion [32].

- Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP): This method is widely used to measure the lateral diffusion of molecules in biological membranes, such as the GPI-anchored VSG proteins in trypanosomes [33].

The synergy between simulation and experiment is key to a comprehensive understanding, as experimental data can validate simulation models, which in turn can provide atomistic details that are difficult to capture experimentally.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for Diffusion Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| LAMMPS | A widely used MD simulation software package for calculating particle trajectories and MSD [29]. |

| Materials Studio | A modeling and simulation environment used for building crystal structures and running MD simulations (e.g., for DNTF) [31]. |

| EAM Potential | An interatomic potential used to describe metallic interactions, such as in tungsten-hydrogen systems [29]. |

| SPC/E Water Model | An empirical model for simulating water molecules in MD studies, such as supercritical water systems [30]. |

| GPI-Anchored Proteins | A class of biologically relevant molecules used to study the effect of molecular size on diffusion in cell membranes [33]. |

| Monovalent Streptavidin (mSAV) | A reagent used to selectively and uniformly increase the size of membrane proteins (like VSG) without cross-linking, for diffusion studies [33]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | A common nano-confined environment used to study the effects of spatial restriction on fluid diffusion [30]. |

The diffusion coefficient is a vital parameter in molecular dynamics research, whose value is determined by a complex interplay of intrinsic and extrinsic factors. As demonstrated by contemporary studies, temperature exerts a powerful, often exponential, influence through the Arrhenius relationship. Viscosity, as a macroscopic fluid property, dictates the frictional resistance to particle motion, generally following an inverse relationship with the diffusion coefficient. Finally, the size of the diffusing molecule is a key determinant, with larger entities diffusing more slowly, a principle that holds true from simple fluids to complex biological membranes. Accurate determination of diffusion coefficients requires rigorous MD protocols and sophisticated data analysis, including emerging machine learning methods. Understanding these factors is essential for researchers and drug development professionals to predict material behavior, optimize industrial processes, and design effective therapeutic agents.

Practical MD Protocols: Calculating Diffusion Coefficients from Simulation Trajectories

In molecular dynamics (MD) research, the diffusion coefficient (D) is a fundamental transport property that quantifies the tendency of molecules to spread through random motion from a region of high concentration to a region of low concentration. Accurate prediction of diffusion coefficients is indispensable not only for developing high-quality molecular mechanic force fields but also for chemical engineering design for production, mass transfer, and processing [27]. Development of reliable methods for predicting diffusion coefficients for proteins and other macromolecules is of great interest since diffusion is involved in a number of biochemical processes, such as protein aggregation and transportation in intercellular media [27]. MD simulation serves as a computational microscope that enables researchers to investigate these processes with atomic detail, often under thermodynamic conditions unreachable by experiments [34].

Theoretical Foundation of Diffusion in MD

Molecular diffusion describes the spread of molecules through random motion. For one molecule M in an environment where viscous force dominates, its diffusion behavior is described by the diffusion equation:

$$\frac{\partial}{\partial t}c(\vec{r},t) = D\nabla^2c(\vec{r},t)$$

where $c(\vec{r},t)$ describes the probability distribution of finding M near point $\vec{r}$ at time t, and D is the diffusion coefficient [27]. This equation can be derived from Fick's first law ($\vec{J} = -D\nabla c$) combined with the constraint of particle conservation.

From a microscopic perspective, the mean-square displacement (MSD) of particles over time provides a direct route to calculating D through the Einstein relation:

$$\langle |\vec{r}(t) - \vec{r}(0)|^2 \rangle = 2nDt$$

where n is the dimensionality of the system [27]. For three-dimensional MD simulations, n = 3, simplifying the relationship to $\langle |\vec{r}(t) - \vec{r}(0)|^2 \rangle = 6Dt$.

Alternatively, D can be calculated using the Green-Kubo relation that integrates the velocity autocorrelation function (VACF):

$$D = \frac{1}{3}\int_0^\infty \langle \vec{v}(t) \cdot \vec{v}(0) \rangle dt$$ [27]

Both approaches are theoretically equivalent, though the MSD method is more commonly employed in practice due to its straightforward implementation.

Figure 1: Comprehensive workflow for MD simulation and diffusion analysis

Computational Protocols for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

System Setup and Equilibration

The initial step involves preparing a stable, equilibrated system. For studying Li+ diffusion in battery materials, this typically begins with importing a crystal structure (e.g., from a CIF file) and generating the desired composition. For instance, in a Li~0.4~S cathode system, Li atoms can be randomly inserted into the sulfur structure using builder functionality [21]. The system should then undergo careful equilibration through:

- Geometry optimization with lattice relaxation: This ensures the system reaches a local energy minimum. During optimization, the unit cell volume typically increases significantly (e.g., from ~3300 ų to ~4400 ų) [21].

- Simulated annealing for amorphous systems: For systems requiring amorphous structures, perform MD with specific temperature profiles: maintain at 300 K for 5000 steps, heat from 300 K to 1600 K over 20000 steps, then rapidly cool to 300 K over 5000 steps [21].

- Equilibration MD: Run sufficient steps (e.g., 10000) at the target temperature to ensure the system is stabilized before production dynamics [21].

Production Simulation Parameters

Production simulations require careful parameter selection:

- Simulation length: For reliable diffusion coefficients, extended simulations are necessary. While 100,000 steps might suffice for preliminary results, much longer simulations (multiple nanoseconds) are often required for convergence, particularly for solutes in solution [27].

- Thermostat selection: Use a thermostat like Berendsen with appropriate damping constants (e.g., 100 fs) to maintain target temperature [21].

- Sampling frequency: Set sample frequency to capture trajectory data at appropriate intervals. For MSD analysis, sample frequency can be higher, while VACF analysis requires more frequent sampling (smaller intervals) [21].

- Force field considerations: The General AMBER force field (GAFF) has demonstrated good performance in predicting diffusion coefficients of organic solutes in aqueous solution, with average unsigned error of 0.137 ×10⁻⁵ cm²s⁻¹ [27].

Analysis Methods for Diffusion Coefficients

Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) Method

The MSD approach is generally recommended for its straightforward implementation [21]:

- Calculate MSD from the trajectory: $MSD(t) = \langle [\vec{r}(0) - \vec{r}(t)]^2 \rangle$

- Perform linear regression on the MSD curve over an appropriate time window

- Extract diffusion coefficient: $D = \frac{\text{slope}(MSD)}{6}$

The MSD should ideally be a straight line; deviations from linearity indicate insufficient sampling or non-diffusive behavior. For accurate results, ensure the simulation is sufficiently long to achieve a stable linear regime [21].

Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) Method

The VACF method provides an alternative approach:

- Compute the velocity autocorrelation function: $\langle \vec{v}(0) \cdot \vec{v}(t) \rangle$

- Integrate the VACF over time

- Calculate diffusion coefficient: $D = \frac{1}{3} \int0^{t{max}} \langle \vec{v}(0) \cdot \vec{v}(t) \rangle dt$ [21]

The resulting diffusion coefficient plot should ideally converge to a horizontal line for large enough times.

Table 1: Comparison of Diffusion Coefficient Calculation Methods

| Method | Key Equation | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSD | $D = \frac{\langle |\vec{r}(t) - \vec{r}(0)|^2 \rangle}{6t}$ | Straightforward implementation, intuitive interpretation | Requires long simulations for convergence, sensitive to statistical noise | Most systems, particularly when direct trajectory analysis is preferred |

| VACF | $D = \frac{1}{3}\int_0^\infty \langle \vec{v}(t) \cdot \vec{v}(0) \rangle dt$ | Faster convergence for some systems, provides dynamical information | Sensitive to velocity sampling frequency, more complex implementation | Systems where velocity correlations are of interest |

Addressing Statistical Uncertainty and Sampling Challenges

A critical consideration in diffusion coefficient calculation is the statistical uncertainty, which depends not only on the input simulation data but also on the choice of statistical estimator (OLS, WLS, GLS) and data processing decisions (fitting window extent, time-averaging) [8]. To improve statistics:

- Use multiple independent simulations: Averaging MSD collected in multiple short-MD simulations can be more efficient than a single long simulation for predicting diffusion coefficients of solutes at infinite dilution [27].

- Address finite-size effects: The diffusion coefficient depends on supercell size unless the supercell is very large. Typically, perform simulations for progressively larger supercells and extrapolate to the "infinite supercell" limit [21].

- Careful fitting window selection: Choose the MSD fitting window to avoid short-time ballistic regimes and long-time statistical noise.

For solutes in solution, convergence is particularly challenging. As demonstrated in studies, reliable prediction of diffusion coefficients for single solute molecules in solution may require extremely long simulation times (e.g., >60 nanoseconds) to obtain statistically meaningful results [27].

Advanced Applications and Extensions

Temperature Dependence and Arrhenius Behavior

Diffusion coefficients typically exhibit Arrhenius temperature dependence:

$$D(T) = D0 \exp(-Ea / k_B T)$$

$$\ln D(T) = \ln D0 - \frac{Ea}{k_B} \cdot \frac{1}{T}$$

where $D0$ is the pre-exponential factor, $Ea$ is the activation energy, $k_B$ is Boltzmann's constant, and $T$ is temperature [21]. To extract these parameters:

- Calculate diffusion coefficients at multiple temperatures (e.g., 600 K, 800 K, 1200 K, 1600 K)

- Plot $\ln(D(T))$ versus $1/T$

- Perform linear regression to obtain $Ea$ from the slope and $D0$ from the intercept

This enables extrapolation to temperatures that would require prohibitively long simulation times (e.g., room temperature) [21].

Large-Scale Simulations with AMBER Force Fields