Cross-Validating MD Simulations with Cryo-EM and X-ray Data: A Framework for Robust Structural Biology

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on integrating Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations with experimental structural data from cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and X-ray crystallography.

Cross-Validating MD Simulations with Cryo-EM and X-ray Data: A Framework for Robust Structural Biology

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on integrating Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations with experimental structural data from cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and X-ray crystallography. It covers the foundational principles of each technique, practical methodologies for cross-validation, strategies for troubleshooting and optimization, and a comparative analysis of validation metrics. By outlining robust frameworks for data compatibility and model assessment, this resource aims to enhance the reliability of dynamic structural models, thereby accelerating drug discovery and the understanding of complex biological mechanisms.

The Structural Trinity: Foundational Principles of MD, Cryo-EM, and X-ray Crystallography

Understanding the Resolution and Dynamic Range of Each Technique

In structural biology, the resolution of a technique defines its ability to distinguish fine details in a macromolecular structure, while its dynamic range—often an overlooked parameter—determines its capacity to resolve structural features of vastly different stabilities or electron densities within the same sample. For researchers cross-validating molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with experimental data, understanding these technical parameters is crucial for assessing the reliability and interpretive limits of structural models. Recent breakthroughs in cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and artificial intelligence (AI)-based structure prediction have revolutionized protein modeling by enabling near-atomic resolution visualization [1]. Meanwhile, time-resolved X-ray crystallography has achieved unprecedented temporal resolution, capturing biomolecular reactions at sub-10 millisecond timescales [2]. This guide objectively compares the resolution and dynamic range of predominant structural techniques, providing a framework for selecting appropriate methods to validate MD simulations across different biological contexts and temporal scales.

Technical Comparison of Structural Techniques

Table 1: Resolution and Dynamic Range Characteristics of Major Structural Biology Techniques

| Technique | Typical Resolution Range | Effective Dynamic Range | Temporal Resolution | Key Strengths | Principal Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | ~1.0-3.0 Å (Atomic) | Limited by crystal packing constraints | Milliseconds to hours (Time-resolved variants) [2] | Atomic resolution; Well-established workflows | Requires high-quality crystals; Limited to crystallizable samples |

| Cryo-EM (Single Particle) | ~1.8-4.0 Å (Near-atomic to Atomic) | Capable of resolving multiple conformational states [3] | Static snapshots (Milliseconds with time-resolved variants) [4] | Handles large complexes; No crystallization needed | Radiation damage; Sample thickness limitations |

| NMR Spectroscopy | ~1.0-3.5 Å (Atomic for small proteins) | Excellent for dynamic processes across timescales | Picoseconds to seconds | Solution-state dynamics; Atomic-level interaction data | Size limitations; Complex spectral analysis |

| MD Simulations | N/A (Computational model) | Theoretically unlimited for observable states | Femtoseconds to milliseconds | Atomic-level dynamics; Full temporal resolution | Force field dependencies; Sampling limitations |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Structural Techniques

| Technique | Sample Consumption | Data Collection Time | Minimum Sample Size | Optimal Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serial X-ray Crystallography | ~450 ng (theoretical minimum) [5] | Minutes to days | Microcrystals (≥1-20 μm) [2] | Membrane proteins; Enzyme mechanisms |

| Cryo-EM SPA | ≤1 mg/mL [6] | Days to weeks | ~50 kDa complexes | Large macromolecular complexes; Flexible assemblies |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Milligram quantities | Hours to days | Proteins < 40-50 kDa [1] | Small protein dynamics; Drug binding interactions |

| Integrative Modeling | Varies by input data | Computational (days to months) | No inherent size limit | Heterogeneous systems; Multi-domain proteins |

Experimental Protocols for Technique Validation

Time-Resolved Mix-and-Quench X-ray Crystallography

This protocol enables high-resolution structural studies of enzymatic reactions with millisecond temporal resolution, providing valuable experimental data for validating MD simulations of dynamic processes [2].

Key Steps:

- Reaction Initiation: Rapidly mix protein crystals with substrate/ligand solution using precision dispensing systems

- Reaction Quenching: After precisely controlled time intervals (as short as 8 ms), rapidly cool samples to cryogenic temperatures (≤200 K) to trap intermediate states

- Data Collection: Collect X-ray diffraction data from quenched samples using standard cryocrystallography beamlines

- Structure Determination: Solve structures at multiple time points to reconstruct reaction trajectories

Critical Parameters:

- Temporal resolution determined by mixing efficiency, diffusion rates, and quenching speed

- Sample consumption can be as low as one crystal per time point [2]

- Optimal for studying ligand binding, enzymatic catalysis, and conformational changes

Ensemble Refinement for Cryo-EM Structures

Standard cryo-EM analysis condenses single-particle images into a single structure, which can misrepresent flexible molecules. This protocol uses MD simulations with cryo-EM density maps to better account for structural dynamics [3].

Metainference Workflow:

- Initial Model Preparation: Identify potentially mismodeled regions in the static cryo-EM structure through visual inspection and secondary structure prediction

- Helix Remodeling: Run short MD simulations (2.5 ns) with restraints to correctly remodel improperly paired RNA helices or protein domains

- Ensemble Refinement: Perform metainference MD simulations using multiple replicas (minimum 8) guided by cryo-EM density restraints

- Validation: Assess ensemble compatibility with experimental data and structural biology principles

- Trajectory Analysis: Identify flexible regions and functionally relevant conformational states

Application Notes:

- Particularly valuable for RNA-containing structures and flexible proteins [3]

- Requires significant computational resources for multi-replica simulations

- Effectively resolves heterogeneity in cryo-EM maps with resolutions of 2.5-4.0 Å

Tilt-Corrected Bright-Field STEM for Thick Samples

Conventional cryo-EM faces challenges with thick specimens due to inelastic scattering. This protocol describes a dose-efficient approach for imaging thick biological samples while maintaining high resolution [6].

Procedure:

- 4D-STEM Data Collection: Acquire convergent beam electron diffraction patterns over a 2D grid of probe positions using a pixelated detector

- Shift Measurement: Calculate aberration-induced image shifts between images formed from individual detector pixels

- Tilt Correction: Apply computed shifts to align individual images

- Image Integration: Sum shift-corrected images to produce a final high signal-to-noise ratio image

Performance Characteristics:

- Provides 3-5× improvement in dose efficiency compared to energy-filtered TEM for samples beyond 500 nm thickness [6]

- Enables sub-nanometer resolution single-particle analysis of virus-like particles from minimal particle counts

- Computationally efficient compared to iterative ptychography

Workflow Visualization

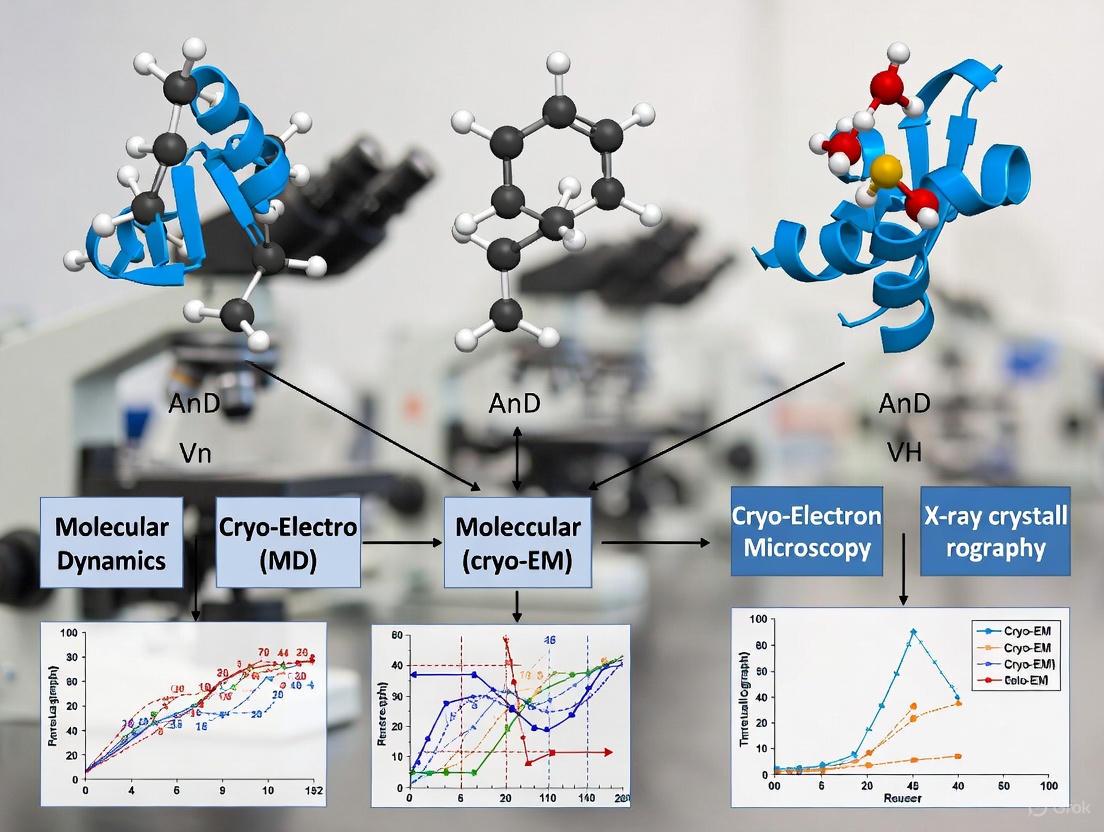

Figure 1: Integrated workflow for cross-validating molecular dynamics simulations with experimental structural biology techniques. The pipeline begins with sample preparation and proceeds through specialized data collection methods, integration of experimental constraints, and final validation and refinement of MD simulations.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Structural Biology Techniques

| Reagent/Material | Primary Technique | Function | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Electron Detectors | Cryo-EM | Capture high-resolution images with improved signal-to-noise | ~95% quantum efficiency; Rapid frame rates [1] |

| Microfluidic Mixers | Time-resolved Crystallography | Rapid reaction initiation for time-resolved studies | Sub-millisecond mixing; Minimal sample consumption [2] |

| Cryogenic Sample Supports | Cryo-EM & Crystallography | Maintain native sample structure at cryogenic temperatures | Low background scattering; Optimal ice thickness |

| Pixelated STEM Detectors | Cryo-STEM | 4D-STEM data acquisition for thick samples | Rapid CBED pattern collection; High dynamic range [6] |

| Metainference Software | Integrative Modeling | Ensemble refinement from cryo-EM data | Bayesian framework; Multi-replica MD support [3] |

The resolution and dynamic range of structural biology techniques collectively determine their effectiveness for validating molecular dynamics simulations. While X-ray crystallography provides exceptional atomic resolution for well-behaved crystalline samples, cryo-EM offers unique capabilities for visualizing large complexes and multiple conformational states. The emerging emphasis on ensemble refinement and time-resolved methods addresses the critical need to capture biomolecular dynamics rather than static snapshots. For researchers cross-validating MD results, the strategic selection of complementary techniques—each with characteristic resolution and dynamic range profiles—enables robust validation of simulation trajectories. Future advancements in detector technology, sample delivery systems, and integrative computational methods will further bridge the gap between experimental structural biology and molecular simulations, ultimately providing more complete understanding of biomolecular function across temporal and spatial scales.

Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has revolutionized structural biology by enabling the visualization of macromolecular complexes in near-native states without requiring crystallization. This transformation, often termed the "resolution revolution," has positioned cryo-EM as a powerful complement to established techniques like X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [7] [1]. The unique capability of cryo-EM to image vitrified hydrated samples preserves biological structures in functional conformations, providing unprecedented insights into dynamic cellular processes [7]. By early 2025, single-particle cryo-EM is poised to surpass X-ray crystallography as the most used method for experimentally determining new structures [8], marking a significant milestone in structural biology.

The technique's particular strength lies in its ability to handle structural heterogeneity and resolve multiple functional states within a single sample. This has proven invaluable for studying challenging targets such as membrane proteins, large complexes, and transient assemblies that have long eluded crystallization [1] [9]. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) with cryo-EM has accelerated structure determination, enabling researchers to build accurate atomic models from medium-resolution maps and explore conformational diversity at unprecedented speed and scale [10] [11].

Comparative Analysis of Structural Biology Techniques

Technical Comparison of Major Methods

The three primary techniques in structural biology—cryo-EM, X-ray crystallography, and NMR spectroscopy—each offer distinct advantages and limitations. Understanding their complementary strengths is essential for selecting the appropriate method for specific research questions.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Structural Biology Techniques

| Parameter | Cryo-EM | X-ray Crystallography | NMR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample State | Vitrified solution in near-native state | Crystalline lattice | Solution state |

| Sample Requirement | ~0.5-5 mg/mL, small volume [12] | 5-10 mg/mL, requires crystallization [12] | >200 µM, 250-500 µL volume [12] |

| Size Range | >50 kDa [7] | No strict upper limit, but crystallization challenging for large complexes | Generally <40 kDa [1] |

| Resolution Range | 1.5-10 Å (typically 2-4 Å) [11] [7] | 1-3 Å [13] | 1.5-3.5 Å for small proteins |

| Throughput | Medium-high, rapidly improving | High for crystallizable targets | Low-medium |

| Key Strengths | Handles flexibility and heterogeneity; no crystallization needed; visualizes large complexes | Atomic resolution; well-established workflows; high throughput for crystallizable targets | Studies dynamics in solution; no crystallization needed; provides thermodynamic parameters |

| Major Limitations | Radiation damage; requires significant computational resources | Cannot study molecules resistant to crystallization | Limited to smaller proteins; complex data analysis |

Quantitative Impact Assessment Across Techniques

The rapid adoption of cryo-EM is reflected in structural databases. According to recent Protein Data Bank (PDB) statistics, cryo-EM accounted for approximately 31.7% of structures released in 2023, while X-ray crystallography remained dominant at 66%, and NMR contributed only 1.9% [13]. This represents a dramatic shift from the early 2000s when cryo-EM contributions were almost negligible [13]. The growth is largely attributed to technological developments in direct electron detectors [1], improved image processing algorithms [7], and the integration of AI-based modeling tools [10].

The resolution achievable by cryo-EM has improved substantially, with current single-particle analyses routinely reaching 2-4 Å resolution, sufficient for de novo model building [10]. In exceptional cases, such as the β-galactosidase structure, resolutions of 1.5 Å have been achieved for the protein core, though bound ligands may be resolved to lower resolutions (3-3.5 Å) [11]. This positions cryo-EM between X-ray crystallography (routinely achieving 1-3 Å resolution) [13] and NMR (typically providing structural ensembles rather than single conformations) [12].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Cryo-EM Single Particle Analysis Workflow

The standard single-particle cryo-EM workflow involves multiple steps from sample preparation to final model validation, each requiring specialized instrumentation and expertise.

Sample Preparation and Vitrification: The process begins with purifying the macromolecular complex to homogeneity and vitrifying it by rapid plunge-freezing in liquid ethane. This preserves the sample in a thin layer of amorphous ice, maintaining near-native hydration and preventing ice crystal formation [7].

Data Acquisition: Vitrified samples are imaged using transmission electron microscopes equipped with direct electron detectors. Modern detectors provide dramatically improved signal-to-noise ratios, accurate electron counting, and rapid frame rates that enable correction of beam-induced motion [1]. Typically, hundreds to thousands of micrographs are collected with electron doses of 20-40 electrons/Ų to minimize radiation damage [7].

Image Processing and 3D Reconstruction: Individual particle images are extracted from micrographs and classified by orientation using computational approaches like projection-matching [7]. The "projection-slice theorem" is fundamental to this process, stating that the Fourier transform of a 2D projection corresponds to a central slice through the 3D Fourier transform of the structure [7]. Initial models are generated ab initio or by using known structures as references, followed by iterative refinement to produce the final 3D reconstruction [7].

Model Building and Validation: Atomic models are built into the cryo-EM density map using manual or automated approaches. Recent methods integrate AI-based structure prediction with density-guided molecular dynamics simulations to improve accuracy, particularly for conformational transitions and ligand binding sites [10] [11].

Integrative Approaches Combining AI and Cryo-EM

Recent advances have demonstrated the power of combining AlphaFold2-based models with cryo-EM data to resolve alternative conformational states, particularly for membrane proteins where traditional fitting approaches struggle [10].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Cryo-EM Integration

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Role | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | Generative AI for protein structure prediction from sequence | Generating initial structural models for flexible fitting [10] |

| GROMACS with Density-Guided MD | Molecular dynamics software with cryo-EM map biasing potential | Flexible fitting of AI-generated models to experimental density [10] |

| ChimeraX | Molecular visualization and analysis | Rigid-body alignment of predicted models to cryo-EM maps [11] |

| GOAP Score | Generalized orientation-dependent all-atom potential | Quality assessment of protein geometry during refinement [10] |

| ModelAngelo | Automated model building for cryo-EM maps | De novo model building without templates [10] |

The protocol involves several key steps: First, multiple initial models are generated by stochastic subsampling of the multiple sequence alignment (MSA) space in AlphaFold2 to create structural diversity [10]. Next, structure-based k-means clustering identifies representative models, reducing computational costs while maintaining conformational diversity [10]. These cluster representatives then undergo density-guided molecular dynamics simulations where a biasing potential moves atoms toward the experimental map while maintaining proper stereochemistry [10]. Finally, the optimal model is selected based on a compound score balancing map fit (cross-correlation) and model quality (GOAP score) [10].

This approach has successfully resolved state-dependent conformational changes in membrane proteins including the calcitonin receptor-like receptor (helix bending), L-type amino acid transporter (rearrangement of neighboring helices), and alanine-serine-cysteine transporter (substantial conformational transition involving most transmembrane helices) [10]. The method is particularly valuable for medium-resolution maps (3-4 Å) where de novo building remains challenging [10].

Ligand Building in Cryo-EM Maps

A specialized application combining AI and cryo-EM focuses on resolving protein-ligand interactions, which is crucial for drug discovery but challenging due to typically lower ligand resolution [11]. The protocol takes three inputs: (1) protein amino acid sequence, (2) ligand specification (SMILES string), and (3) experimental cryo-EM map [11].

First, protein-ligand complex structures are predicted using AlphaFold3-like models (e.g., Chai-1) based solely on sequence and ligand information [11]. The predicted complexes are rigid-body aligned to the target cryo-EM map. Finally, density-guided molecular dynamics simulations refine the model, improving ligand model-to-map cross-correlation from 40-71% to 82-95% compared to deposited structures [11]. This pipeline has been successfully validated on biomedically relevant targets including kinases, GPCRs, and solute transporters not present in the AI training data [11].

Cross-Validation with Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide a critical bridge between static structural snapshots and biological function by modeling macromolecular motions. Cryo-EM density maps serve as excellent constraints for validating and refining MD simulations [10] [11]. In density-guided simulations, a biasing potential is added to the classical forcefield to move atoms toward the experimental map, enabling the exploration of conformational transitions while maintaining agreement with experimental data [10].

This approach is particularly valuable for studying functional mechanisms in membrane proteins, which often undergo substantial conformational changes. For example, in the calcitonin receptor-like receptor, density-guided simulations revealed bending of TM6 upon activation, a transition that could not be captured using standard fitting approaches starting from a single initial structure [10]. Similarly, for transporters like LAT1 and ASCT2, integrative modeling has elucidated the rearrangement of helices during substrate transport cycles [10].

The cross-validation process monitors multiple quality metrics during simulations, including model-to-map cross-correlation (fitting quality), protein-ligand interaction energy (favorable interactions without clashes), and GOAP score (structural geometry) [11]. By selecting simulation frames that optimize both fit and geometry, researchers obtain models that are consistent with both experimental data and physical principles [10].

Cryo-EM has firmly established itself as a cornerstone technique in structural biology, providing unique capabilities for visualizing macromolecular complexes in near-native states. Its integration with AI-based structure prediction and molecular dynamics simulations has created a powerful framework for elucidating biological mechanisms at unprecedented resolution and scale. As detector technology, image processing algorithms, and modeling approaches continue to advance, cryo-EM is poised to drive further discoveries in basic biology and drug development, particularly for challenging targets that have long resisted structural characterization.

The complementary strengths of cryo-EM, X-ray crystallography, and NMR spectroscopy ensure that each technique will continue to play vital roles in structural biology. However, the unique ability of cryo-EM to handle structural heterogeneity without crystallization positions it as an essential tool for studying the dynamic complexes that underlie cellular function. The ongoing integration of experimental and computational approaches promises to accelerate our understanding of structure-function relationships across diverse biological systems.

Determining the three-dimensional structure of biological macromolecules at atomic resolution is fundamental to understanding the mechanisms of life and disease. Among the techniques available to structural biologists, X-ray crystallography has long been the gold standard for achieving atomic-level precision, typically defined as resolutions better than 1.2 Å, where individual atoms become clearly distinguishable. [14] This capability provides critical insights into enzyme mechanisms, drug-target interactions, and the molecular basis of diseases.

The field of structural biology is powered by three principal techniques: X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). According to the Protein Data Bank (PDB) statistics, as of 2023, X-ray crystallography accounted for approximately 66% (over 9,601 structures) of all published protein structures, while cryo-EM accounted for 31.7% (4,579 structures), and NMR contributed only 1.9% (272 structures). [14] Although the proportion of structures determined by X-ray crystallography has declined with the recent rise of cryo-EM, it remains the dominant method in structural biology.

The precision offered by X-ray crystallography enables researchers to visualize not just the overall fold of a protein, but also the precise bond lengths and angles within active sites, the geometry of ligand binding, and the organization of solvent molecules. This information is indispensable for structure-based drug design, where atomic-level details guide the optimization of small molecules for enhanced potency and selectivity. This guide explores how X-ray crystallography achieves this precision, compares its capabilities with alternative structural methods, and examines its evolving role in the era of integrative structural biology.

Fundamental Principles and Technical Evolution

The Physical Basis of X-ray Crystallography

X-ray crystallography determines molecular structure by analyzing the diffraction patterns produced when X-rays interact with the electron clouds of atoms in a crystalline sample. The technique is governed by Bragg's Law (nλ = 2dsinθ), which relates the wavelength of incident X-rays (λ), the distance between crystal planes (d), and the angle of incidence (θ) to produce constructive interference. [14] By measuring the angles and intensities of these diffracted beams, scientists can compute a three-dimensional electron density map and build an atomic model that fits this experimental data.

The fundamental process involves several critical steps, each contributing to the final precision of the structure. It begins with protein crystallization, where the purified macromolecule is coaxed into forming a highly ordered crystal lattice. When exposed to an X-ray beam, typically from a synchrotron radiation source, the crystal produces a diffraction pattern that is captured by a detector. The resulting data undergoes complex computational processing to solve the "phase problem" – determining the phase angles associated with each diffracted wave – which is essential for electron density map calculation. The final stage involves iterative model building and refinement, where an atomic model is adjusted to achieve the best possible fit to the experimental electron density while maintaining realistic geometric constraints. [14]

Specialized Techniques Enhancing Precision

X-ray crystallography has evolved beyond conventional approaches to address increasingly challenging biological questions through specialized methodologies:

- Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX): Utilizes extremely short X-ray pulses from free-electron lasers to collect diffraction data from microcrystals before radiation damage occurs, enabling studies of radiation-sensitive samples and time-resolved structural dynamics. [14]

- Anomalous Dispersion Methods (SAD/MAD): Exploit the anomalous scattering properties of specific elements (often incorporated as selenomethionine or heavy atoms) to solve the phase problem, enabling de novo structure determination without homologous models. [14]

- Quantum Crystallography: Emerging approaches use quantum mechanical methods to refine crystal structures beyond the limitations of the independent atom model, providing more accurate descriptions of electron density distributions and chemical bonding. [15] [16]

These advanced techniques demonstrate how X-ray crystallography continues to evolve, pushing the boundaries of atomic-level precision while addressing increasingly complex biological systems.

Comparative Analysis of Structural Biology Techniques

Performance Metrics Across Methods

The precision and applicability of structural biology methods vary significantly across different biological contexts. The table below provides a systematic comparison of X-ray crystallography with cryo-EM and NMR spectroscopy based on key performance metrics.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Structural Biology Techniques

| Feature | X-ray Crystallography | Cryo-Electron Microscopy | NMR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Resolution Range | 1.0 - 3.0 Å (Atomic) [14] | 3.0 - 10.0+ Å (Near-atomic to Molecular) [17] [18] | 3D Structures limited to < 100 kDa [14] |

| Sample Requirements | High-quality, well-ordered crystals | Purified complex in solution (vitreous ice) | Highly soluble, isotopically labeled protein in solution |

| Sample Size Limitations | Crystal size > few micrometers | Size > 50 kDa preferred [19] | Molecular weight < 40-50 kDa [14] |

| Throughput | Medium (crystallization bottleneck) | Increasingly high with automation | Low (data collection and analysis) |

| Information on Dynamics | Limited (static snapshot) | Multiple conformations possible (computational sorting) | Direct observation of dynamics at various timescales |

| Key Strengths | Atomic-level precision, High throughput once crystals obtained, Mature methodology | Handles large complexes, No crystallization needed, Visualizes multiple states | Studies dynamics in solution, No crystallization needed, Provides atomic detail for small proteins |

| Key Limitations | Crystallization bottleneck, Crystal packing artifacts, Radiation damage | Lower resolution for many targets, Complex data processing, Expensive equipment | Size limitation, Spectral complexity, Specialized expertise required |

Quantitative Resolution and Throughput Analysis

Beyond qualitative comparisons, quantitative metrics reveal distinct performance characteristics. The achievable resolution directly impacts the biological questions that can be addressed, particularly regarding drug discovery where atomic-level ligand placement is crucial.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Structural Biology Techniques

| Metric | X-ray Crystallography | Cryo-EM | NMR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structures in PDB (2023) | ~9,601 (66%) [14] | ~4,579 (32%) [14] | ~272 (2%) [14] |

| Typical Data Collection Time | Seconds to minutes (synchrotron) | Days to weeks | Days to weeks |

| Information Content | Time-averaged electron density | Single-particle reconstructions | Chemical shifts, distance restraints |

| Ligand Binding Studies | Excellent (precise binding mode) | Good (if resolution < 3.5 Å) [17] | Good (binding constants, mapping) |

| Membrane Protein Structures | Possible with special techniques (LCP) [1] | Excellent (no crystallization needed) [1] | Challenging (with solid-state NMR) |

The data shows that while cryo-EM is rapidly growing, particularly for large complexes, X-ray crystallography remains the most prolific method and provides the highest resolution structures, making it indispensable for applications requiring atomic-level precision.

Experimental Protocols for High-Precision Structure Determination

Workflow for Atomic-Resolution X-ray Crystallography

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for determining a protein structure at atomic resolution using X-ray crystallography:

Key Methodological Considerations for Atomic Precision

Achieving truly atomic resolution (better than 1.2 Å) requires meticulous attention to each step of the process:

Protein Engineering and Crystallization: Protein construct optimization often involves removing flexible regions to enhance crystallization propensity. Advanced crystallization techniques like lipidic cubic phase (LCP) crystallization have revolutionized membrane protein structural biology, enabling high-resolution structures of GPCRs and transporters. [1] The quality of diffraction is directly determined by crystal lattice order, making crystallization optimization critical for high-resolution studies.

Data Collection at Synchrotron Sources: Modern synchrotron beamlines provide intense, tunable X-ray sources with micro-focus capabilities that enable data collection from smaller crystals. Complete, high-resolution datasets require collecting hundreds of diffraction images with precise crystal orientation. For radiation-sensitive samples, cryo-cooling (typically to 100K) is essential to mitigate radiation damage during data collection. [14]

Phase Determination Methods: Molecular replacement remains the most common method when a homologous structure exists. For novel folds with no structural homologs, experimental phasing methods like Single-wavelength Anomalous Dispersion (SAD) or Multi-wavelength Anomalous Dispersion (MAD) are employed, requiring incorporation of anomalous scatterers (e.g., selenomethionine) into the protein. [14]

Model Building and Refinement Protocols: Atomic-resolution electron density maps allow for unambiguous placement of protein atoms, bound ligands, and solvent molecules. The refinement process involves iterative cycles of adjusting atomic coordinates and temperature factors to minimize the difference between observed and calculated structure factors (R-factors), while maintaining proper stereochemistry. [14] The precision of bond lengths and angles reaches ±0.001-0.003 Å and ±0.1-0.3°, respectively, at atomic resolution.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful structure determination requires specialized reagents and computational tools throughout the experimental pipeline. The following table details essential resources for high-precision X-ray crystallography.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for X-ray Crystallography

| Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallization Reagents | Commercial screening kits (e.g., from Hampton Research, Molecular Dimensions) | Provide systematic sampling of chemical space to identify initial crystallization conditions |

| Cryoprotectants | Glycerol, ethylene glycol, various cryosolutions | Protect crystals from ice formation during flash-cooling in liquid nitrogen |

| Phasing Reagents | Halide salts, heavy atom compounds (e.g., K₂PtCl₄, CH₃HgCl), selenomethionine | Introduce anomalous scatterers for experimental phasing (SAD/MAD) |

| Ligand Soaking | Components for co-crystallization or crystal soaking | Enable structural studies of protein-ligand complexes for drug discovery |

| Data Processing Software | XDS, HKL-2000, DIALS, CCP4 | Process raw diffraction images to integrated intensities and structure factors |

| Phasing Software | PHASER (Molecular Replacement), SHELXC/D/E, Auto-Rickshaw | Solve the phase problem to calculate electron density maps |

| Model Building Tools | Coot, O | Fit and adjust atomic models into electron density maps |

| Refinement Programs | phenix.refine, REFMAC5, BUSTER | Optimize atomic parameters against diffraction data with geometric restraints |

| Validation Tools | MolProbity, PDB-REDO, wwPDB Validation Server | Assess model quality and identify potential errors before deposition |

Cross-Validation with Computational and Hybrid Methods

Integrating X-ray Crystallography with Molecular Dynamics

The combination of X-ray crystallography with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations creates a powerful synergy for understanding both structure and dynamics. While crystallography provides the precise atomic coordinates, MD simulations can explore conformational flexibility around this starting structure. Cross-validation involves comparing MD simulation trajectories with crystallographic data beyond the atomic coordinates:

- B-factor Validation: The atomic displacement parameters (B-factors) derived from crystallography reflect atomic mobility and can be compared to root-mean-square fluctuations calculated from MD simulations. [15]

- Covalent Geometry: Bond lengths and angles from simulation averages can be validated against high-resolution crystal structures, with typical agreement within 0.01-0.02 Å for bonds and 1-2° for angles. [15]

- Electron Density Residuals: Quantum mechanical calculations applied to MD snapshots can generate theoretical electron density maps for comparison with experimental maps, identifying regions where static crystal structures may differ from dynamic behavior in solution.

Quantum Crystallography for Enhanced Precision

Emerging methods collectively termed Quantum Crystallography (QCr) use quantum mechanical calculations to enhance the precision and information content derived from crystal structures. [16] These approaches address limitations of the conventional independent atom model (IAM), which neglects the deformation of electron density due to chemical bonding:

- Hirshfeld Atom Refinement (HAR): Uses quantum-mechanically derived electron densities to improve the accuracy of hydrogen atom positions, which are typically poorly resolved by X-rays alone. HAR can achieve X—H bond lengths comparable to neutron diffraction standards. [16]

- Quantum-Based Restraints: Instead of relying on generic library values for bond lengths and angles during refinement, structure-specific restraints can be computed using quantum mechanical methods (e.g., molecule-in-cluster computations), resulting in more chemically accurate molecular geometries. [15]

- Multipolar Electron Density Models: These advanced models go beyond the spherical atom approximation to represent the aspherical nature of electron density in chemical bonds, lone pairs, and aromatic systems, providing more accurate structural parameters and insights into chemical bonding. [16]

Hybrid Approaches with Cryo-EM and AI

The integration of X-ray crystallography with cryo-EM and artificial intelligence represents the cutting edge of structural biology:

- AI-Assisted Model Building: Deep learning approaches like ModelAngelo and DeepTracer, originally developed for cryo-EM, are being adapted to improve automated model building in crystallography, particularly for interpreting lower-resolution electron density maps. [17] [20]

- Cross-Validation with Cryo-EM: For large complexes that prove difficult to crystallize, cryo-EM can provide a medium-resolution envelope into which high-resolution crystal structures of individual components can be fitted, combining the precision of crystallography with the size capability of cryo-EM. [18]

- AlphaFold Integration: Structures predicted by AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3 can serve as starting models for molecular replacement in crystallography, significantly accelerating structure solution, particularly when experimental phases are difficult to obtain. [20] The following diagram illustrates this integrative approach:

X-ray crystallography remains an indispensable technique for achieving atomic-level precision in structural biology, continuing to produce the majority of high-resolution structures despite increasing competition from cryo-EM. Its unparalleled ability to provide precise atomic coordinates, detailed ligand binding information, and explicit solvent structures makes it particularly valuable for drug discovery and mechanistic studies.

The future of crystallography lies in its integration with complementary techniques. As quantum crystallographic methods mature, they will push the precision of charge density analysis and hydrogen atom positioning beyond current limits. [15] [16] Simultaneously, hybrid approaches that combine crystallographic data with cryo-EM, molecular dynamics simulations, and AI-based structure prediction will enable the solution of increasingly complex biological problems. [20] For the foreseeable future, X-ray crystallography will continue to provide the foundational atomic coordinates upon which our understanding of biological structure-function relationships is built, while evolving to incorporate new computational and experimental methodologies that enhance its precision and applicability.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as a powerful computational microscope, enabling researchers to observe the motion and energetics of biomolecules at an atomic level. This guide provides an objective comparison of its performance against other structural biology techniques, focusing on its integration with cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and X-ray crystallography for cross-validation. The supporting experimental data and protocols outlined here offer a framework for researchers and drug development professionals to apply these integrated approaches.

Comparative Performance of MD with Experimental Structural Biology Techniques

The table below summarizes a quantitative comparison of Molecular Dynamics simulations with primary experimental structural biology methods, highlighting their respective strengths, limitations, and optimal use cases.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of MD Simulations with Key Experimental Techniques

| Method | Key Performance Metrics | Typical System Size & Scope | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | - Provides time-resolution (fs to ms) [21]- Calculates interaction energies (e.g., PMF, van der Waals) [21]- Quantifies thermal fluctuations (thermal factor) [21] | - ~600 molecules for 50 ns simulation [21]- Full atomic detail of biomolecules in explicit solvent | - Captures dynamics and kinetics- Provides energetic insights- Simulates under physiological conditions | - Computationally expensive for large systems/long timescales- Force field accuracy is critical |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) | - Resolution (often 2.5-4.0 Å for dynamic systems) [22]- Map-to-model cross-correlation (e.g., 0.70-0.90) [10] | - Large complexes (>100 kDa)- Multiple structural states from one sample [23] | - Visualizes large, flexible complexes- Can resolve multiple conformational states [23] | - Can misrepresent flexible regions in single-state models [22]- Sample preparation and vitrification challenges |

| X-ray Crystallography | - Resolution (often <2.0 Å for well-diffracting crystals)- R-factor & R-free (e.g., <0.20) | - Requires high-quality crystals- Typically a single, static conformation | - Provides high atomic precision- Well-established refinement pipelines | - May contain questionable backbone conformations from modeling [24]- Difficult for membrane proteins and dynamic systems |

Integrated Workflows for Cross-Validation

The true power of modern structural biology lies in combining MD simulations with experimental data. The following workflows and case studies demonstrate how these methods are integrated for robust, dynamically-aware structure determination.

Workflow 1: MD for Validating and Refining Crystal Structures

X-ray crystallography provides high-resolution structural snapshots, but the resulting models can contain local misconformations introduced during crystallization or model building [24]. MD simulations are used to assess and refine these structures.

Experimental Protocol: Detecting Questionable Conformations in Crystal Structures [24]

- Energy Minimization: A set of non-redundant X-ray protein structure models undergoes an energy-minimization step to relax atomic geometry and reduce potential energy.

- Conformation Comparison: The local conformations of the original X-ray model and the energy-minimized model are compared using a structural alphabet (HMM-SA) to identify residues with "questionable conformations."

- MD Simulation & Validation: Molecular dynamics simulations are performed (e.g., on HIV-2 protease) to sample local conformations. Residues identified as questionable are further investigated to determine if their crystallographic conformation is sparsely sampled during MD or is a structural outlier, raising questions about its biological relevance.

Workflow 2: Cryo-EM and MD for Modeling Alternative States

A common challenge arises when a cryo-EM map is resolved for a protein in a functional state that differs substantially from any available template structure. A combined AI-MD workflow can successfully address this.

Experimental Protocol: Modeling Alternative States with AlphaFold2 and Density-Guided MD [10]

- Ensemble Generation: Generate a diverse set of initial models by stochastically subsampling the multiple sequence alignment (MSA) depth in AlphaFold2 (e.g., 1250 models per system).

- Model Filtering & Clustering: Filter models based on a structure-quality score (e.g., GOAP). Align the filtered models to a known-state structure and cluster them using k-means based on Cartesian coordinates.

- Density-Guided Simulation: Perform density-guided molecular dynamics simulations from each cluster representative. A biasing potential is added to the classical forcefield to move atoms toward the experimental cryo-EM density map.

- Model Selection: Monitor the cross-correlation (map fit) and GOAP score (model quality) during simulations. Select the final model based on the highest compound score, balancing fit and geometry.

Figure 1: AI and MD Workflow for Cryo-EM States.

Case Study: Unveiling Full-Length ACE Dynamics

Research on human angiotensin-I converting enzyme (ACE) showcases the power of integrating cryo-EM with MD. While cryo-EM resolved multiple structural states of the glycosylated full-length dimer, MD simulations were critical to elucidate the conformational dynamics and identify key regions mediating change, providing insights for designing domain-specific modulators [23].

Advanced Applications: Tackling RNA Flexibility with Ensemble Refinement

RNA molecules are inherently flexible, and standard single-structure approaches in cryo-EM often lead to mis-modeling of flexible helical regions [22]. Metainference, a Bayesian ensemble refinement method, combines MD with cryo-EM data to model a structural ensemble that better represents the molecule's dynamics.

Experimental Protocol: Ensemble Refinement for RNA Macromolecules [22]

- Initial Model Inspection & Preparation: Visually inspect the deposited cryo-EM structure and identify regions (e.g., RNA helices) that are not properly paired according to the predicted secondary structure.

- Helix Remodeling: Run a short MD simulation (e.g., 2.5 ns) with restraints to remodel the identified helices into canonical, properly paired duplexes.

- Metainference Simulation: Perform metainference MD simulations using multiple replicas (e.g., 8-64). The simulation is guided by a hybrid energy function that enforces agreement between the average of the simulated ensemble and the experimental cryo-EM density map.

- Ensemble Analysis: Analyze the resulting ensemble of structures to characterize the inherent plasticity and flexibility of the macromolecule, ensuring flexible regions are not misinterpreted as a single, static conformation.

Figure 2: Ensemble Refinement for RNA Structures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Successful integration of MD with experimental data relies on a suite of specialized software and tools.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Integrated Structural Biology

| Tool Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [21] [10] | Molecular Dynamics Software | Performs all-atom MD, simulated annealing, and density-guided simulations for structure refinement and dynamics analysis. |

| AlphaFold2 [10] [25] | AI-Based Structure Prediction | Generates initial protein structural models from sequence, used to create diverse starting ensembles for MD refinement. |

| CryoSPARC [26] [23] | Cryo-EM Data Processing | Processes single-particle cryo-EM data for 2D classification, 3D reconstruction, and heterogeneity analysis. |

| Chimera/X [27] [28] | Visualization & Analysis | Visualizes and analyzes 3D density maps (cryo-EM, AFM-derived) and atomic models, and calculates map-model correlations. |

| GOAP [10] | Model Quality Metric | Scores protein structural geometry to assess model quality and prevent overfitting during density-guided simulations. |

| Metainference [22] | Ensemble Refinement Method | Enables cryo-EM-guided MD ensemble refinement within integrative modeling platforms like PLUMED. |

The Complementary Nature of Experimental and Computational Data

In modern structural biology and drug development, the integration of experimental and computational data has transformed our ability to understand complex biological systems at molecular resolution. For decades, X-ray crystallography served as the dominant technique for atomic-resolution structure determination, accounting for approximately 84% of structures in the Protein Data Bank [12]. However, the recent "resolution revolution" in cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has established it as a powerful complementary method, particularly for large macromolecular complexes and membrane proteins that defy crystallization [29] [30]. Simultaneously, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have evolved into "virtual molecular microscopes" that provide the atomistic details underlying protein dynamics, serving as both a validation tool and a bridge between experimental techniques [31] [32].

This comparison guide examines the complementary strengths and limitations of these principal structural biology methods, with a specific focus on how MD simulations are cross-validated against and enhance experimental data from cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography. For researchers in structural biology and drug development, understanding this integrative approach is crucial for selecting appropriate methodologies and maximizing structural insights.

Technical Principles and Comparative Analysis

Fundamental Principles of Each Technique

X-ray crystallography relies on Bragg's Law of X-ray diffraction by crystals. When X-rays strike a well-ordered three-dimensional crystal, they scatter at various angles, producing a diffraction pattern of sharp spots. The intensities of these spots, combined with phase information obtained through experimental or computational means, allow reconstruction of the electron density map and subsequent atomic model building [29]. The quality of the final structure heavily depends on crystal order, requiring extensive sample optimization and often molecular engineering [29].

Cryo-electron microscopy uses high-energy electrons rather than X-rays. In single-particle cryo-EM, molecules are flash-frozen in thin ice layers and imaged directly in a transmission electron microscope. The magnetic objective lens produces both diffraction patterns and magnified images containing full structural information. Hundreds of thousands of particle images are computationally aligned, classified, and averaged to reconstruct a three-dimensional density map [29] [30]. This method preserves molecules in a near-native state without crystallization, but must contend with structural heterogeneity and radiation damage [29].

Molecular dynamics simulations employ computational methods to probe dynamical properties of atomistic systems. MD simulations numerically solve Newton's equations of motion for all atoms in a molecular system, using empirical force fields to describe atomic interactions. This allows researchers to visualize protein motions and conformational changes across temporal and spatial scales that may be difficult to access experimentally [31].

Technical Comparison and Method Selection

The table below summarizes the key technical characteristics and requirements of each method, providing guidance for researchers selecting appropriate structural biology approaches.

Table 1: Technical comparison of structural biology methods

| Parameter | X-ray Crystallography | Cryo-EM | Molecular Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal Molecular Size | <100 kDa [33] | >100 kDa [33] | No inherent size limit |

| Typical Resolution | 1.0-2.5 Å (up to sub-1Å possible) [33] | 2.5-4.0 Å (2-3Å maximum) [33] | N/A (atomistic by definition) |

| Sample Requirement | >2 mg, highly pure and homogeneous [33] [12] | 0.1-0.2 mg, moderate heterogeneity acceptable [33] | Atomic coordinates only |

| Sample State | Crystalline lattice [29] | Vitreous ice (near-native) [29] [30] | In silico solution environment |

| Temporal Information | Static snapshot [29] | Multiple static snapshots (heterogeneity) [33] | Dynamic trajectories (fs to μs) [31] |

| Key Limitations | Crystal packing artifacts, radiation damage [29] | Beam-induced motion, preferred orientation [30] | Force field accuracy, sampling limitations [31] |

| Best Applications | Small soluble proteins, atomic-resolution ligand binding [33] [12] | Large complexes, membrane proteins, flexible systems [29] [33] | Conformational dynamics, mechanism elucidation [31] [32] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Sample Preparation and Data Collection

X-ray Crystallography Workflow:

- Protein Purification: Samples must be purified to homogeneity, typically requiring >2 mg of protein at ~10 mg/mL concentration [12].

- Crystallization: Through vapor diffusion or other methods, proteins are slowly brought out of solution to form ordered crystals. This can take weeks to months and represents the major bottleneck [12].

- Cryoprotection: Crystals are cryo-cooled to minimize radiation damage during data collection [12].

- Data Collection: X-ray diffraction data are collected at synchrotron facilities, with patterns recorded over minutes to hours [12].

- Phasing and Model Building: The "phase problem" is solved through molecular replacement or experimental phasing, followed by iterative model building and refinement [29] [12].

Cryo-EM Workflow:

- Grid Preparation: Ultra-thin carbon or gold grids are cleaned and prepared for sample application [30].

- Vitrification: Samples (3-5 μL) are applied to grids, blotted to remove excess liquid, and plunge-frozen in liquid ethane to form vitreous ice [30].

- Data Collection: Using direct electron detectors, thousands to millions of particle images are collected in "movie mode" over hours to days, using low electron doses (~20-40 electrons/Ų) to minimize radiation damage [30].

- Image Processing: Motion correction, contrast transfer function estimation, particle picking, 2D classification, and 3D reconstruction are performed using extensive computational resources [30] [34].

Molecular Dynamics Workflow:

- System Preparation: Initial coordinates are obtained from experimental structures (PDB), then solvated in water boxes with ions to achieve physiological conditions [31].

- Force Field Selection: Appropriate force fields (AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS) are selected based on the system and research question [31].

- Energy Minimization and Equilibration: Systems are energy-minimized and gradually heated to target temperature with restrained protein atoms [31].

- Production Simulation: Unrestrained MD simulations are run for nanoseconds to microseconds, with coordinates saved at regular intervals for analysis [31].

- Enhanced Sampling (if needed): For slower processes, methods like replica-exchange or metadynamics may be employed to improve conformational sampling [32].

Integrated Structural Biology Workflow

The following diagram illustrates how these techniques converge in an integrated approach to structural biology:

Integrated Structural Biology Workflow

Cross-Validation Frameworks and Protocols

Validating Molecular Dynamics with Experimental Data

The accuracy of MD simulations is typically benchmarked against experimental observables. Key validation protocols include:

NMR Validation:

- J-couplings and Chemical Shifts: Back-calculated from MD trajectories using empirical predictors and compared to experimental NMR data [31] [32].

- Relaxation Parameters: NMR-derived order parameters (S²) compared to those calculated from MD simulations to validate internal dynamics [31].

- Residual Dipolar Couplings: Compared between experiment and simulation to validate molecular orientation and dynamics [32].

Cryo-EM Validation:

- Flexible Fitting: MD simulations with cryo-EM density restraints allow refinement of structures into medium-resolution maps while maintaining proper stereochemistry [32].

- Heterogeneity Analysis: Cryo-EM class averages representing different conformational states can be compared to MD-generated ensembles [34] [32].

- Map-Model Correlation: Quantitative metrics (FSC, Q-score) assess agreement between atomic models and cryo-EM density maps [34].

X-ray Crystallography Validation:

- B-factor Analysis: Crystallographic B-factors (temperature factors) compared to atomic positional fluctuations from MD simulations [31].

- Ensemble Refinement: X-ray structures refined against ensemble models from MD simulations to account for conformational heterogeneity [35].

- Ligand Binding: MD simulations of ligand-protein complexes validated against crystallographic electron density [33] [12].

Quantitative Validation Metrics

Table 2: Metrics for cross-validating MD simulations with experimental data

| Validation Metric | Experimental Source | Computational Calculation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) | X-ray crystallography [29] | Backbone atom deviation from experimental structure | Measures structural conservation during simulation; <2-3 Å typically acceptable |

| Radius of Gyration (Rg) | SAXS [32] | Mass-weighted root mean square distance of atoms from center of mass | Assesses global compactness; should match experimental Rg within uncertainty |

| J-couplings | NMR [32] | Empirical calculators (e.g., Karplus equation) from dihedral angles | Validates local conformation and dynamics |

| Order Parameters (S²) | NMR relaxation [31] | Angular fluctuations of bond vectors from MD trajectories | Quantifies residue-specific flexibility; range 0-1 (rigid) |

| Map Correlation Coefficient | Cryo-EM [34] | Correlation between simulated density and experimental map | Assesses model-map agreement; >0.7 typically indicates good fit |

| Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering Profile | SAXS [32] | CRYSOL or other methods to compute theoretical profile from MD frames | Validates overall shape and dimensions in solution |

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful integration of experimental and computational approaches requires specific reagents and computational resources. The following table details essential materials for these methodologies.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational resources

| Category | Specific Items | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Detergents (DDM, LMNG) [33] | Solubilization and stabilization of membrane proteins for structural studies |

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) materials [12] | Membrane protein crystallization matrix mimicking native lipid environment | |

| Cryo-protectants (glycerol, ethylene glycol) [12] | Prevent ice crystal formation during cryo-cooling of crystals or vitreous ice preparation | |

| Crystallization | Sparse matrix screens (Hampton Research) [12] | Pre-formulated crystallization condition arrays for initial crystal screening |

| SeMet media (Molecular Dimensions) [12] | Selenium-methionine labeling for experimental phasing via SAD/MAD | |

| Cryo-EM | UltrAuFoil grids (Quantifoil) [30] | Gold substrates with regular hole patterns for optimal ice thickness |

| Direct electron detectors (Gatan, FEI) [30] | High-sensitivity cameras enabling single-particle cryo-EM resolution revolution | |

| MD Simulations | Force fields (AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS) [31] | Empirical potential energy functions defining atomic interactions in simulations |

| Enhanced sampling algorithms (REMD, metadynamics) [32] | Computational methods to accelerate sampling of rare events in MD | |

| Software Resources | Processing suites (PHENIX, CCP4, CryoSPARC, RELION) [34] [12] | Integrated software for experimental data processing and structure determination |

| Visualization/analysis (ChimeraX, VMD, PyMOL) [29] [31] | Tools for model building, simulation analysis, and results visualization |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Challenges

Synergistic Applications in Structure-Based Drug Design

The complementary use of experimental and computational methods has proven particularly valuable in drug discovery:

Membrane Protein Drug Targeting: Cryo-EM enables structure determination of membrane proteins like GPCRs and ion channels in near-native lipid environments, while MD simulations reveal drug-binding pathways and allosteric mechanisms that may be invisible to static structures [33]. X-ray crystallography provides atomic-level details of drug-target interactions for optimizing lead compounds [12].

Ligand Screening and Validation: X-ray crystallography remains the gold standard for fragment-based lead discovery through techniques like XCHEM, providing unambiguous electron density for bound ligands [12]. MD simulations can prioritize which fragments to test experimentally by predicting binding affinities and residence times [33].

Conformational Selection Drug Design: Cryo-EM can capture multiple conformational states of a drug target in a single sample [33], while MD simulations map the energy landscape between these states [31]. This enables design of drugs that stabilize specific conformations with therapeutic benefit.

Current Limitations and Validation Challenges

Despite significant advances, important challenges remain in integrating these methodologies:

Cryo-EM Validation: Single-particle cryo-EM structure validation is an area of much-needed development [34]. The reported resolution should not always be taken at face value, as local resolution variations and reconstruction artifacts can mislead interpretation. Development of robust validation metrics comparable to those in crystallography (Rfree, Ramachandran outliers) is ongoing [34].

Force Field Accuracy: Different MD packages (AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD) and force fields can produce divergent results, particularly for larger conformational changes [31]. While most differences are attributed to force fields themselves, other factors including water models, constraint algorithms, and treatment of non-bonded interactions significantly influence outcomes [31].

Experimental Interpretation: Experimental data represent ensemble averages over space and time, with underlying distributions often obscured [31]. Multiple conformational ensembles may produce averages consistent with experiment, creating ambiguity about which computational results are correct [31].

The following diagram illustrates the framework for validating and integrating MD simulations with experimental data:

MD-Experimental Data Validation Framework

The complementary nature of experimental and computational data in structural biology represents a paradigm shift in how we investigate biological macromolecules. No single method provides a complete picture: X-ray crystallography delivers atomic precision but sacrifices dynamic information and requires crystallization; cryo-EM captures near-native states and conformational heterogeneity but typically at lower resolution; MD simulations provide atomistic dynamics but depend on force field accuracy and sufficient sampling.

The most powerful insights emerge from integration rather than competition between these approaches. As cryo-EM continues its resolution revolution [30], MD force fields improve through experimental validation [31] [32], and X-ray methods advance through aspherical electron density models [35], the synergy between them will only deepen. For researchers in drug discovery and structural biology, the strategic combination of these techniques—using each to validate, inform, and extend the others—represents the most promising path toward understanding complex biological mechanisms and developing effective therapeutics.

The future lies not in declaring a "winner" among these techniques, but in developing more sophisticated frameworks for their integration, creating a whole that is truly greater than the sum of its parts in elucidating the structural and dynamic basis of biological function.

A Practical Workflow for Integrating and Validating Structural Data

The Relaxed Complex Method (RCM) is a powerful computational structure-based drug design strategy that synergistically combines Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations with molecular docking to better account for protein flexibility. This guide objectively compares the RCM's performance against standard rigid docking, providing supporting data on its enhanced ability to identify true bioactive compounds and mitigate false positives. Furthermore, it details the experimental protocols for implementing RCM and frames its utility within the broader context of cross-validating computational results with experimental structural data from cryo-Electron Microscopy (cryo-EM) and X-ray crystallography.

Conventional molecular docking, a cornerstone of virtual screening, typically relies on a single, static protein structure derived from X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM. A significant limitation of this approach is its inability to fully capture the dynamic nature of proteins, which constantly sample a diverse array of conformations in solution. This rigidity can lead to the dismissal of potentially potent compounds that require a specific, but unrepresented, protein conformation for binding.

The RCM directly addresses this limitation through a fundamental paradigm shift. Instead of docking into one structure, it utilizes multiple snapshots extracted from an MD simulation trajectory of the target protein. MD simulations provide atomic-level insights into the temporal evolution and intrinsic flexibility of a protein, capturing fluctuations, loop movements, and side-chain rearrangements. By docking compound libraries into this ensemble of snapshots, the RCM effectively screens against a more physiologically relevant representation of the protein's conformational landscape. This increases the probability of identifying hits that bind to low-energy, but experimentally captured, states of the protein, thereby improving the success rate of virtual screening campaigns [36] [37] [38].

Performance Comparison: RCM vs. Standard Docking

The superior performance of the RCM over standard single-structure docking is demonstrated by its improved metrics in virtual screening, particularly in enrichment power and the reduction of false positives.

Case Study: Virtual Screening for Mdmx Inhibitors

A seminal study tested a two-stage virtual screening protocol on 130 nutlin-class compounds targeting the Mdmx protein [36] [37]. The protocol involved an initial docking screen using AutoDock, followed by MD simulation of the top-ranked complexes. The stability of the ligand-protein complex during MD was measured by its Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) from the initial docked pose.

The performance was quantitatively assessed using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis, which plots the true positive rate against the false positive rate. The key findings are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Performance comparison of screening methods for Mdmx inhibitors [36] [37].

| Screening Method | Performance | Key Metric | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Docking Score Alone | Modest | AutoDock Score | Admitted many false positives |

| MD RMSD Filter | Dramatically Improved | Ligand RMSD | Effectively sieved out false positives |

| Two-Step Protocol | Excellent | Combined Score & RMSD | High correlation with experimental potency |

The study found that weakly binding or non-binding compounds exhibited significant ligand drifting during MD simulations, leading to high RMSD values. Using this RMSD as a filter dramatically improved the protocol's ability to distinguish true active compounds from inactive ones, a task at which the docking score alone performed only modestly [36] [37].

Benchmarking Docking Programs and Workflows

The choice of docking software itself is a critical variable. A benchmarking study evaluating five popular docking programs (GOLD, AutoDock, FlexX, MVD, and Glide) on cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes highlighted significant differences in their ability to correctly predict binding poses [39].

Table 2: Performance of docking programs in pose prediction and virtual screening for COX enzymes [39].

| Docking Program | Pose Prediction Success (RMSD < 2 Å) | Virtual Screening AUC Range | Enrichment Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glide | 100% | 0.61 - 0.92 | 8 - 40x |

| GOLD | 82% | Data not specified | Data not specified |

| AutoDock | 59% | Data not specified | Data not specified |

| FlexX | 59% | Data not specified | Data not specified |

| MVD | Not specified | Not tested | Not tested |

This study reinforces that while some docking programs are highly accurate, even the best performer can generate false positives. The RCM workflow, which can incorporate any docking engine, adds a crucial post-docking validation step via MD, improving the reliability of the final hit list regardless of the specific docking tool used [39].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A Standard RCM Protocol

The following workflow outlines a typical RCM pipeline for virtual screening:

Detailed Methodologies:

- System Preparation: The process begins with a high-resolution 3D structure of the target protein, typically from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The structure is prepared for simulation by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, and parameterizing any non-standard residues or small molecules using tools like Antechamber and the General Amber Force Field (GAFF) [36].

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation: The prepared system is solvated in a water box (e.g., using the TIP3P model) and neutralized with counter-ions. After energy minimization and equilibration, a production MD run is performed (e.g., using AMBER, GROMACS) to simulate the protein's motion under near-physiological conditions. Simulations typically range from nanoseconds to microseconds [36] [38].

- Snapshot Extraction: Hundreds to thousands of snapshots are extracted from the stable portion of the MD trajectory at regular time intervals. These snapshots represent the ensemble of protein conformations for docking.

- Ensemble Docking: A library of candidate compounds is docked into the binding site of each extracted snapshot using a docking program of choice (e.g., AutoDock Vina, Glide). Each compound generates multiple scores and poses across the conformational ensemble [36] [39].

- Post-Docking Analysis and MD Validation: The top-ranked compounds from the ensemble docking are selected. These compounds are then subjected to a second, more rigorous MD simulation in complex with the protein. The stability of the binding pose is quantified by calculating the ligand RMSD over the simulation time. Compounds that maintain a low RMSD (e.g., < 2-3 Å) are considered stable and prioritized as final hits, as this indicates a persistent binding mode unlikely to be a false positive [36] [37].

Cross-Validation with Experimental Structural Data

The RCM exists within an ecosystem of structural biology techniques. Cross-validation with experimental methods like cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography is crucial for verifying computational predictions and refining models.

Integration with Cryo-EM: Cryo-EM has become a powerhouse for determining the structures of large biomolecular complexes that are difficult to crystallize. However, maps for flexible regions are often at low resolution. MD simulations, including those used in RCM, are instrumental in interpreting these maps.

- MD Flexible Fitting (MDFF): This class of methods uses the cryo-EM density map as a restraint to guide an MD simulation, forcing the atomic model to fit into the experimental density. This is particularly useful for modeling flexible loops and domains [38].

- Capturing Transient States: MD simulations have demonstrated a remarkable ability to predict short-lived conformational states that are essential for function. A prominent example is the prediction of the active conformation of the CRISPR-Cas9 system through MD, a state that was later confirmed by a cryo-EM structure, showcasing the predictive power of MD to complement cryo-EM [38].

Integration with X-ray Crystallography: X-ray structures provide the initial, high-resolution models for MD simulations. The cross-validation is often a cyclical process:

- The crystal structure serves as the starting point for the MD simulation in the RCM.

- The conformational ensemble generated by MD can help explain binding affinity differences for ligands co-crystallized with the same protein and provide mechanistic insights that a single structure cannot.

- New crystal structures of protein-ligand complexes can subsequently be used to validate the binding poses predicted by the RCM docking step.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 3: Key software and resources used in RCM and structural cross-validation.

| Category | Item/Software | Primary Function | Key Features/Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Engines | AMBER | Molecular Dynamics | Performs energy minimization, MD simulations; uses AMBER99SB force field [36]. |

| GROMACS | Molecular Dynamics | High-performance MD engine; includes tools for cryo-EM density refinement [38]. | |

| Docking Software | AutoDock Vina | Molecular Docking | Docks flexible ligands into rigid protein binding sites; used for initial screening [36] [39]. |

| Glide | Molecular Docking | High-accuracy docking program; top performer in pose prediction benchmarks [39]. | |

| GOLD | Molecular Docking | Uses genetic algorithm for docking; good performance in benchmarks [39]. | |

| Cryo-EM Integration | MDFF | Flexible Fitting | Fits atomic models into cryo-EM density maps using MD simulations [38]. |

| Situs | Flexible Fitting | Package for docking atomic structures into low-resolution density maps [38]. | |

| Analysis & Visualization | UCSF Chimera | Molecular Visualization | Fits and analyzes MD-derived structures with experimental (cryo-EM) maps [38]. |

| Benchmarking Resources | ZDOCK Benchmark | Protein Docking Benchmark | Provides test cases for evaluating protein-protein docking algorithms [40]. |

The Relaxed Complex Method stands as a superior alternative to standard rigid docking by explicitly incorporating protein flexibility through the use of MD-generated structural ensembles. Quantitative benchmarks demonstrate that this approach, particularly when combined with MD stability checks (RMSD filtering), significantly enhances the identification of true bioactive compounds and reduces false positives in virtual screening. The implementation of RCM requires a structured workflow involving system preparation, MD simulation, ensemble docking, and post-docking validation.

Furthermore, the power of MD simulations, the core of RCM, is magnified when its predictions are cross-validated with experimental structural biology techniques. The synergy between MD and cryo-EM—through methods like MDFF—and with X-ray crystallography creates a powerful feedback loop for model validation and refinement. This integrated approach provides researchers and drug developers with a more robust and reliable framework for uncovering novel therapeutic agents and understanding complex biological mechanisms at an atomic level.

Single-particle cryo-electron microscopy has emerged as a powerful tool for determining the structures of large macromolecules and complexes, often at subnanometer resolution. A common practice involves refining or flexibly fitting atomic models into experimentally derived cryo-EM density maps. However, these maps are typically at significantly lower resolution than electron density maps from X-ray diffraction experiments, creating a fundamental challenge: the number of parameters to be determined far exceeds the number of experimental observables [41]. This imbalance makes overfitting and misinterpretation of density a serious problem in the field.

Cross-validation approaches have been standard in X-ray crystallography for decades, but their adaptation to cryo-EM has been complicated by the very different nature of the experiment. The critical importance of cross-validation in cryo-EM stems from the low observation-to-parameter ratio at typical resolutions, making refinement highly susceptible to overfitting noisy density features [41]. Without proper validation, researchers risk building models that appear to fit the data well but actually represent incorrect interpretations of noisy or correlated density information.

The Overfitting Problem in Cryo-EM Reconstruction and Modeling

Fundamental Challenges in Cryo-EM Data Analysis

In single-particle cryo-EM, the reconstruction process combines thousands of projection images of individual particles to reconstruct a 3D density distribution representing an average over these particles. The resulting density maps typically reside in the medium- to low-resolution range of approximately 4-20 Å [41]. Unlike X-ray crystallography where the relationship between observations and parameters is more straightforward, cryo-EM faces several unique challenges:

- Parameter-to-observation imbalance: For large macromolecules, the number of atomic coordinates (parameters) vastly exceeds the number of experimental observables [41]

- Correlations in Fourier components: Neighboring structure factors in cryo-EM reconstructions are strongly correlated due to centering, smoothing, and image alignment procedures [41]

- Progressive signal-to-noise decline: The signal-to-noise ratio decreases for higher spatial frequencies, as measured by Fourier shell correlation [41]

Statistical Foundations of Overfitting

From a statistical perspective, overfitting represents a bias in parameter estimation that systematically distorts the reconstructed structure. The estimated structure can be modeled as:

[ \hat{V}(r) = V(r) + \Delta V(r) + \varepsilon(r) ]

Where (\hat{V}(r)) is the estimated structure, (V(r)) is the true underlying structure, (\Delta V(r)) is the structural bias (overfitting), and (\varepsilon(r)) is random fluctuation with zero mean [42]. While random noise decreases with more measurements, the bias systematically prevents visualization of the true structure and may stem from missing information, incorrect priors, local minima in parameter searches, or algorithmic limitations [42].

Table 1: Common Sources of Overfitting in Cryo-EM

| Source Type | Specific Examples | Impact on Model Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Algorithmic | Excessive weight on data versus prior, incorrect initial volume, misestimation of alignment parameters | Introduction of features not present in true structure |