Convergence Challenges in Long MD Simulations: Understanding and Optimizing Diffusion Analysis for Biomolecular Research

This article addresses the critical yet often overlooked challenge of achieving convergence in long-scale Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, with a specific focus on diffusion processes critical for drug development and...

Convergence Challenges in Long MD Simulations: Understanding and Optimizing Diffusion Analysis for Biomolecular Research

Abstract

This article addresses the critical yet often overlooked challenge of achieving convergence in long-scale Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, with a specific focus on diffusion processes critical for drug development and biomolecular research. We explore the fundamental definition of equilibrium in MD and why standard metrics like energy and density are insufficient. The content provides a methodological guide for accurately calculating diffusion coefficients, highlighting common pitfalls and optimization strategies. Furthermore, it covers advanced validation techniques and comparative analysis of emerging machine learning approaches, offering researchers a comprehensive framework for obtaining reliable, converged results from their simulations.

Defining Convergence and Equilibrium in MD: Why Your Simulation Might Not Be What It Seems

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What does it mean for an MD simulation to be "at equilibrium," and why is this critical for the validity of my results?

In Molecular Dynamics, a system is considered at equilibrium when its properties have converged, meaning they fluctuate around stable average values rather than displaying a continuous drift. This is critical because the fundamental assumption of most analyses is that the simulation is sampling from a stable, equilibrium distribution. If this is not true, calculated properties and free energies may not be meaningful, potentially invalidating the study's conclusions [1]. A practical working definition is that a property is considered equilibrated if the fluctuations of its running average, calculated from the start of the simulation, remain small after a certain convergence time [1].

Q2: I don't see a clear plateau in my protein's Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) plot. Does this mean my simulation has not converged?

Not necessarily. While a plateau in RMSD is often used as an intuitive gauge for equilibration, relying on it alone can be misleading. A scientific survey has demonstrated that scientists show no mutual consensus when determining the point of equilibrium from RMSD plots, and their decisions can be biased by factors like plot color and y-axis scaling [2]. While RMSD can indicate whether the protein has moved away from its initial crystal structure, it should not be the sole metric for convergence. A more robust approach is to monitor multiple, complementary properties [2].

Q3: My simulation was interrupted after a week of running. Do I have to start over from the beginning?

No, you do not need to start over. Modern MD software like GROMACS is designed to handle this exact situation. The program periodically writes checkpoint files (.cpt) that contain the full-precision positions and velocities of all atoms, along with the state of the algorithms. To restart, you simply use the -cpi option to point to the last checkpoint file. By default, gmx mdrun will append new data to the existing output files, making the interruption nearly seamless [3]. You can also use gmx convert-tpr to extend the simulation time defined in your input (.tpr) file before restarting [3].

Q4: Why is my restarted simulation not perfectly reproducible, even from a checkpoint file?

MD is a fundamentally chaotic process, and tiny differences in floating-point arithmetic—such as those caused by using a different number of CPU cores, different types of processors, or dynamic load balancing—will cause trajectories to diverge exponentially [3]. However, this is generally not a problem for scientific conclusions. The Central Limit Theorem ensures that observables (like energy or diffusion constants) will converge to their correct equilibrium values over a sufficiently long simulation, even if any single trajectory is not perfectly reproducible [3]. Reproducibility of a single trajectory is typically only crucial for debugging or capturing specific rare events.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Diagnosing Non-Convergence in Long-Timescale Simulations

Problem: You have run a multi-microsecond simulation, but key properties of interest still do not appear to have converged to a stable average.

Investigation and Resolution Protocol:

- Monitor Multiple Metrics: Do not rely on a single property like RMSD. Create a comprehensive analysis protocol that includes:

- Energetic properties: Total potential energy, kinetic energy.

- Structural properties: Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) of different domains, radius of gyration, specific inter-residue distances, and hydrogen bond counts [2] [4].

- Dynamical properties: Mean-square displacement (MSD) for diffusion, autocorrelation functions of velocities or dihedral angles [1].

- Check for "Partial Equilibrium": Understand that your system can be in a state of partial equilibrium. Some properties that depend on high-probability regions of conformational space (e.g., the average distance between two protein domains) may converge in multi-microsecond trajectories. In contrast, properties that depend on infrequent transitions to low-probability conformations (e.g., transition rates between conformational states) may require much longer simulation times to converge [1].

- Quantify Uncertainty: For any average property you calculate, also compute its statistical uncertainty or standard error, for instance, using block averaging analysis. A large uncertainty is a clear indicator of inadequate sampling.

- Consider System Size and Complexity: Acknowledge that convergence time is system-dependent. A small peptide like dialanine may equilibrate quickly, whereas a large, multi-domain protein or a system with slow, collective motions will require significantly more simulation time [1] [4].

Table 1: Convergence Criteria for Key Properties

| Property Category | Example Metrics | Interpretation of Convergence | Common Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energetic | Total Potential Energy, Temperature | Fluctuates around a stable mean with no drift; energy distribution is Boltzmann-like. | System may be trapped in a local energy minimum. |

| Structural (Global) | RMSD, Radius of Gyration | Running average reaches a plateau with small fluctuations. | RMSD plateau is not a guarantee of full convergence [2]. |

| Structural (Local) | RMSF, Hydrogen Bond Count | Stable profile or average for different regions of the biomolecule. | Some local regions may be dynamic while others are stable. |

| Dynamical | Mean-Square Displacement (MSD) | MSD vs. time plot is linear, indicating normal diffusive behavior. | Sub-diffusive motion may persist for long times in some systems [1]. |

Issue 2: Managing and Restarting Long Simulations

Problem: You need to manage a simulation that is longer than the maximum runtime allowed by your computing cluster's queue system.

Step-by-Step Resolution:

- Before the Job Stops: Ensure your

mdruncommand includes the-cptflag to set the frequency (e.g., every 15 minutes) at which checkpoint files are written. This minimizes data loss if a job is terminated unexpectedly [3]. - Standard Restart Procedure:

- Use

gmx convert-tprto create a new input file that extends the simulation time. This adds 10,000 ps (10 ns) to the simulation defined inprevious.tprand writes a new input filenext.tpr. - Restart the simulation using the new input file and the last checkpoint file.

- By default, the output files (

.trr,.xtc,.edr) will be appended seamlessly [3].

- Use

- Troubleshooting File Issues:

- If you encounter checksum errors because output files were modified, or if you want to keep the output of each run segment separate, use the

-noappendflag withmdrun. This will write new output files with a.partXXXXsuffix [3] [5]. - Always back up your final checkpoint and output files from each segment, as file systems can be unreliable [3].

- If you encounter checksum errors because output files were modified, or if you want to keep the output of each run segment separate, use the

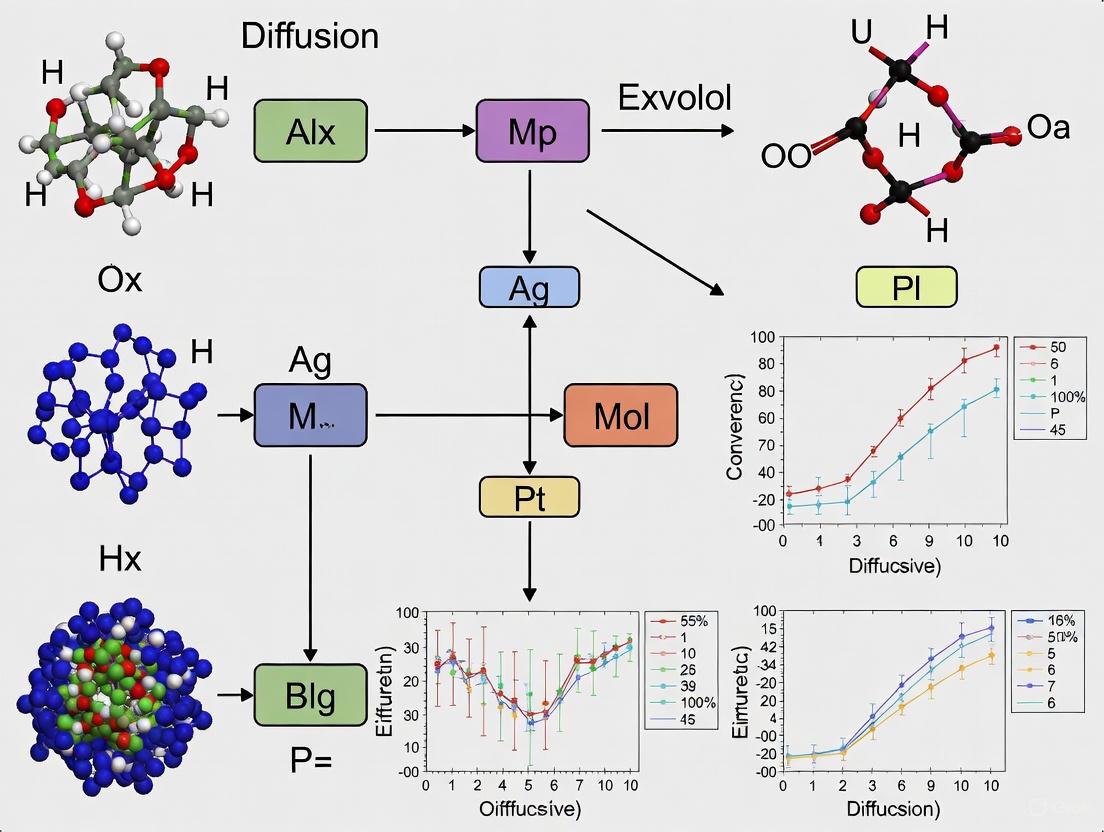

The following diagram illustrates the robust workflow for managing and restarting long simulations:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Long-Timescale MD

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS MD Engine | High-performance software to perform the integration of Newton's equations of motion. | Central simulation workhorse; efficient for both CPU and GPU hardware [3] [4]. |

| Checkpoint File (.cpt) | A binary file saving the full-precision state of the simulation, allowing for exact restarts. | Critical for managing long simulations on queue-based systems; should be backed up frequently [3]. |

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | Machine-learned potentials that can approach quantum-mechanical accuracy at a fraction of the cost. | Emerging tool to improve force field accuracy for studying complex phenomena like bond breaking [6]. |

| Denoising Diffusion Models | A generative model that learns to remove noise from molecular structures, approximating the physical force field. | Novel approach for sampling conformational states and generating equilibrium distributions; can be pre-trained without expensive force data [6]. |

| Convergence Metrics Suite | A collection of scripts to calculate RMSD, RMSF, energy trends, H-bonds, and other properties. | Essential for diagnosing equilibration; should be applied comprehensively, not relying on a single metric [1] [2]. |

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, a system is considered to be in thermodynamic equilibrium when its properties no longer exhibit a directional drift and fluctuate around a stable average value. For practical applications, we define two key states:

- Partial Equilibrium: A state where a specific subset of the system's properties has converged to a stable average. These properties are typically those that depend predominantly on high-probability regions of the conformational space. A system can be in partial equilibrium for some properties but not others.

- Full Equilibrium: A state where all measurable properties of the system, including those dependent on low-probability conformational states, have converged. This requires a comprehensive exploration of the system's phase space.

A working definition for an "equilibrated" property is as follows: Given a trajectory of length T and a property Aᵢ, with 〈Aᵢ〉(t) being its average from time 0 to t, the property is considered equilibrated if the fluctuations of 〈Aᵢ〉(t) around the final average 〈Aᵢ〉(T) remain small for a significant portion of the trajectory after a convergence time, t꜀ [1].

Key Concepts: Partial vs. Full Equilibrium

The core difference between partial and full equilibrium lies in the scope of conformational sampling.

- Partial Equilibrium focuses on a single market or, in the context of MD, a specific set of properties, holding other factors constant (

ceteris paribus) [7]. In MD, this means that while some metrics (e.g., density, RMSD of a stable core) may have stabilized, the system may not have fully sampled all relevant conformational states, particularly those with low probability but high functional significance [1]. - General/Full Equilibrium involves analyzing all markets—or all degrees of freedom in a molecular system—simultaneously, accounting for feedback effects between them [7]. In MD, this corresponds to the system having sufficiently sampled both high-probability and low-probability regions of the conformational space, allowing for the accurate calculation of all thermodynamic properties, including free energy and entropy [1].

The following table summarizes the practical distinctions in an MD context.

Table 1: Characteristics of Partial vs. Full Equilibrium in MD Simulations

| Aspect | Partial Equilibrium | Full Equilibrium |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A specific set of properties has converged. | All measurable properties have converged. |

| Conformational Sampling | Limited to high-probability regions. | Comprehensive, including low-probability states. |

| Dependent Properties | Averages (e.g., distance, total energy, density). | Free energy, entropy, transition rates. |

| Time to Achieve | Relatively faster (picoseconds to nanoseconds). | Significantly slower (microseconds or longer). |

| Practical Implication | Suitable for estimating structural averages. | Required for calculating kinetics and thermodynamics. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying Convergence Problems

Q1: My system's energy and density stabilized quickly. Can I trust my simulation data?

A: Not necessarily. The rapid stabilization of global metrics like potential energy and density is a common pitfall and can be misleading. These properties often reach a plateau long before the system attains a fully equilibrated state at a structural or dynamical level [8] [9].

- Diagnosis: Check more sensitive, system-specific properties.

- For a protein, plot the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) of the backbone atoms. A system that has not found its stable conformation will show a drifting RMSD.

- For a polymer or amorphous system (e.g., asphalt, xylan), analyze the Radial Distribution Function (RDF) between key components. Non-converged RDFs appear as fluctuating curves with superimposed, irregular peaks, indicating ongoing structural reorganization [9].

- Solution: Extend the equilibration phase until these structural metrics stabilize. For complex systems, this can require simulation times on the order of microseconds [1] [8].

Q2: How can I determine which properties have reached partial equilibrium?

A: You need to perform a multi-property time-series analysis.

- Diagnosis:

- Select a portfolio of properties: global (energy, density), structural (RMSD, RDF, radius of gyration), and dynamical (diffusion coefficients, mean-square displacement).

- Calculate the running average for each property throughout the trajectory.

- A property is considered converged when its running average plateaus and exhibits stable fluctuations. The time at which this occurs is its individual convergence time, t꜀.

- Solution: A system can be considered to be in a state of partial equilibrium for a specific research question once all properties relevant to that question have reached their individual t꜀. For example, if your study focuses on average structure, convergence of RMSD and RDFs may be sufficient.

Q3: My simulation is too short to reach full equilibrium. Are my results invalid?

A: Not necessarily. The validity depends on the scientific question you are asking.

- For studies of average structure and high-probability states, a state of partial equilibrium may be sufficient. Many properties with biological interest, such as average distances between domains, can converge in multi-microsecond trajectories [1].

- For studies of rare events, kinetics, or thermodynamics, a lack of full equilibrium can invalidate the results. Properties like free energy, entropy, and transition rates between low-probability conformations explicitly depend on adequate sampling of the entire conformational space and may require much longer simulations or enhanced sampling techniques [1].

Essential Methodologies for Convergence Analysis

Experimental Protocol: Checking for Equilibration

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide to assess whether your system has reached a state suitable for production data analysis.

Objective: To determine the convergence time (t꜀) for key properties and establish if the system is in partial or full equilibrium. Principle: A converged property will fluctuate around a stable mean. Its running average will reach a plateau.

- Simulation: Run an unrestrained MD simulation for the longest feasible timescale.

- Data Extraction: From the trajectory, calculate the following properties as functions of time:

- Potential Energy, Total Energy

- Density

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) of the biomolecule/polymer backbone

- Radial Distribution Functions (RDFs) between key molecular components

- Radius of Gyration (for polymers)

- Mean-Square Displacement (MSD) of solvent and solute

- Running Average Calculation: For each property, calculate the cumulative running average from time 0 to t for all data points in the trajectory.

- Visual Inspection & Quantification:

- Plot the running average of each property versus time.

- Identify the time point, t꜀, after which the running average exhibits no discernible directional drift and only fluctuates within a small, stable margin.

- The largest t꜀ among all properties critical to your study defines the minimum equilibration time required.

- Decision Point:

- If all properties of interest have a defined t꜀, discard the data from 0 to t꜀ and use the remaining trajectory for analysis.

- If critical properties do not plateau, the simulation has not reached the required equilibrium state, and a longer simulation is needed.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing equilibrium and convergence issues in MD simulations.

Quantitative Data on Convergence Timescales

Empirical studies across different molecular systems provide critical reference points for the timescales required to achieve convergence. The data below, synthesized from recent literature, highlights that convergence is system-dependent and that common metrics like energy are poor indicators of true equilibrium.

Table 2: Documented Convergence Timescales from MD Studies

| System | Property Type | Time to Converge | Key Insight | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dialanine (Toy Model) | Mixed | > Microseconds | Even in a simple 22-atom system, some properties remain unconverged in typical simulation timescales. | [1] |

| Hydrated Amorphous Xylan | Structural & Dynamical | ~1 Microsecond | Phase separation occurred despite constant energy and density; specialized parameters were needed to detect true equilibration. | [8] |

| Asphalt System | Thermodynamic (Density, Energy) | Picoseconds/Nanoseconds | Energy and density converge rapidly but are insufficient to demonstrate system equilibrium. | [9] |

| Asphalt System | Structural (RDF - Asphaltene) | Much slower than density | The asphaltene-asphaltene RDF curve converges much slower than other components and is a better indicator of true equilibrium. | [9] |

| Biomolecules (General) | Properties of Biological Interest | Multi-microseconds | Many biologically relevant average properties converge in multi-microsecond trajectories. | [1] |

| Biomolecules (General) | Transition Rates | > Multi-microseconds | Rates of transition to low-probability conformations may require significantly more time. | [1] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function in Convergence Research | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Biomolecular Force Fields (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER) | Defines potential energy surface. | The accuracy of the force field is paramount, as an inaccurate potential energy function will drive the system toward an incorrect equilibrium state. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD, OpenMM) | Engine for performing simulations. | These packages are used to integrate the equations of motion and generate the trajectory. Their efficiency enables longer simulations. |

| Trajectory Analysis Tools (e.g., MDAnalysis, VMD, GROMACS tools) | Calculates properties from simulation data. | Used to compute metrics like RMSD, RDF, and energy from the raw trajectory files for convergence analysis. |

| Enhanced Sampling Algorithms (e.g., Metadynamics, Umbrella Sampling) | Accelerates sampling of rare events. | These techniques are used when the timescale to reach full equilibrium is computationally prohibitive, as they bias the simulation to explore conformational space more quickly. |

| Radial Distribution Function (RDF) | Probes local structure and packing. | A key metric for material systems like polymers and asphalt; its convergence indicates stable intermolecular interactions [9]. |

| Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) | Measures structural stability. | A standard metric for biomolecular simulations; a plateauing RMSD suggests the structure has settled into a stable conformational basin. |

What are the most common causes for a 'simple' system like dialanine failing to converge?

Even for a small molecule like dialanine, obtaining a converged conformational ensemble can be challenging. The most frequent issues are related to inadequate simulation setup and parameters.

- Insufficient Sampling: This is the most prevalent cause. A single, short simulation is unlikely to adequately explore the entire conformational landscape, including all possible side-chain rotamers and backbone angles. Multiple independent simulations with different initial velocities are required for statistically meaningful results [10].

- Inadequate Minimization and Equilibration: Rushing through energy minimization and equilibration steps leads to instabilities. Minimization removes bad atomic contacts, while equilibration allows temperature and pressure to stabilize properly within the chosen thermodynamic ensemble. Without proper equilibration, the production run does not represent the correct physical state [10].

- Poor Starting Structure: An initial structure with unrealistic bond lengths, angles, or steric clashes can prevent the system from ever reaching a stable, converged state. It is a common mistake to assume a structure is ready for simulation without thorough preparation [10].

- Incorrect Simulation Parameters: Using an inappropriate timestep can cause numerical instability or waste resources. Similarly, misconfigured thermostats, barostats, or cut-off distances can prevent the system from maintaining the correct ensemble, leading to non-physical behavior [10].

- Force Field Incompatibility: Using a force field that is not well-parameterized for peptides or specific chemical groups in dialanine can produce inaccurate torsional profiles and conformational energies [10].

What is a step-by-step protocol to diagnose unconverged properties?

Follow this systematic workflow to identify the root cause of convergence problems.

1. Inspect Simulation Logs and Output Files:

- Check the

md.logfile for errors and warnings. - Verify that energy minimization converged by confirming that the maximum force is below the tolerance threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm).

- Plot key thermodynamic properties from the

ener.edrfile throughout the equilibration and production phases. Look for stable plateaus in potential energy, temperature, pressure (for NPT), and density (for NPT).

2. Analyze Basic Structural Metrics:

- Calculate the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) to ensure the structure has stabilized relative to the starting conformation. However, do not rely on RMSD alone [10].

- Calculate the Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) to check for unusually high flexibility in specific residues.

- Monitor the Radius of Gyration to assess global compactness.

3. Check for Convergence of the Property of Interest:

- For a property like the dialanine conformational distribution (e.g., defined by Ramachandran plot basins), split the total simulation time into sequential blocks.

- Calculate the property for each block. If the property fluctuates significantly between blocks and does not show a stable average, sampling is insufficient.

What quantitative checks and validation methods should I use?

Beyond visual inspection, use quantitative measures to validate your simulation. The following table summarizes key observables to monitor for a dialanine system.

Table 1: Key Properties for Validating a Dialanine Simulation

| Property | Description | What to Look For | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potential Energy | Total potential energy of the system. | A stable, fluctuating plateau during production. No drift. | Check md.log and plot from ener.edr. |

| Temperature & Pressure | Instantaneous temperature and pressure. | Average matches the set value (e.g., 300 K, 1 bar) with stable fluctuations. | Plot from ener.edr; use gmx energy. |

| Ramachandran Plot | Distribution of backbone dihedral angles (φ, ψ). | Populations in known stable basins (e.g., αR, β, C7eq, C7ax). | Compare with experimental data (NMR J-couplings) or high-level theory. |

| Side-Chain Rotamers | Distribution of χ1 and χ2 dihedral angles. | Realistic rotameric states without unnatural preferences. | Compare with statistics from protein data bank. |

| Convergence Analysis | Statistical independence of sampled states. | A flat line indicating no further states are being discovered. | Calculate a statistical measure, such as the autocorrelation time of dihedral angles. |

How can I fix a simulation that will not converge?

Here are targeted solutions based on the diagnosed problem.

- Increase Sampling: Run multiple independent simulations (replicas) with different initial random seeds for velocities. This is the most effective strategy for improving convergence [10]. Consider using enhanced sampling methods if specific high-energy barriers are the issue.

- Extend an Existing Simulation: If a simulation is stable but has not converged, you can extend it using the checkpoint file. This ensures continuity.

If you encounter issues with appending, use the

-noappendflag to write a new set of output files [3] [5]. - Review and Correct Setup:

- Minimization & Equilibration: Ensure minimization converges and that equilibration is long enough for all properties to stabilize.

- Parameters: Use a timestep appropriate for your chosen constraints (e.g., 2 fs with bond constraints on hydrogens). Verify all other simulation parameters.

- Force Field: Switch to a modern, widely validated force field designed for proteins/peptides (e.g., CHARMM36, AMBER ff19SB, OPLS-AA/M).

How do I restart a simulation correctly after a crash or scheduled halt?

GROMACS is designed for robust restarts from checkpoint files, which provide exact continuity.

Standard Restart from Checkpoint:

By default,

mdrunwill append to the original output files. The checksums of these files are verified; if the files have been modified, the restart will fail [3].Restart with New Output Files: To avoid appending, use the

-noappendflag. This creates new output files with a.partXXXXsuffix [3] [5].Extending a Completed Simulation: To add more time to a simulation that finished normally, use

gmx convert-tprto create a new run input file with extended time, then restart from the final checkpoint [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Software and Analysis Tools

| Item | Function | Application in Dialanine Case Study |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics simulation package. | Performing energy minimization, equilibration, and production MD runs. |

gmx convert-tpr |

GROMACS utility tool. | Modifying the run input file to extend simulation time. |

| Checkpoint File (.cpt) | A binary file written by mdrun. |

Contains full-precision coordinates, velocities, and algorithm states for an exact restart. |

gmx energy |

GROMACS analysis tool. | Extracting and plotting thermodynamic properties (energy, temperature, pressure) for validation. |

gmx rama |

GROMACS analysis tool. | Calculating backbone dihedral angles and generating Ramachandran plots. |

| Visualization Software (VMD, PyMOL) | Molecular visualization and analysis. | Visualizing trajectories, checking for structural artifacts, and creating figures. |

Workflow Diagram: Troubleshooting Unconverged MD Simulations

The following diagram outlines the logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving convergence issues in molecular dynamics simulations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental "timescale problem" in Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations? The timescale problem refers to the critical challenge that while many biological processes of interest, such as protein-ligand recognition or large conformational changes, occur on timescales of milliseconds to seconds, all-atom MD simulations are often limited to microseconds of simulated time. This creates a gap where simulations may not be long enough to observe the true equilibrium state of the system [11] [12].

Q2: If my simulation's energy and RMSD values look stable, does that mean it has reached equilibrium? Not necessarily. While stability in root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) and potential energy are standard metrics used to check for equilibration, research has shown that they can be misleading. A system can appear stable in these metrics while other important structural or dynamic properties have not yet converged. Relying solely on RMSD to determine equilibrium is not considered reliable [11] [2].

Q3: Is it possible for some properties of my system to be equilibrated while others are not? Yes. This state is known as partial equilibrium. Properties that are averages over highly probable regions of conformational space (e.g., average distances between domains) can converge relatively quickly. In contrast, properties that depend on sampling low-probability regions or rare events (e.g., transition rates between conformational states or the accurate calculation of free energy) can require vastly longer simulation times to converge [11] [1].

Q4: Can using algorithms that allow for longer integration time steps help solve the timescale problem? They can help, but with important caveats. Methods like Hydrogen Mass Repartitioning (HMR) allow the use of longer time steps (e.g., 4 fs instead of 2 fs), which speeds up the wall-clock time of the simulation. However, studies have shown that this can sometimes alter the dynamics of the process being studied. For instance, one investigation found that HMR slowed down protein-ligand recognition, negating the intended performance benefit for that specific process [12].

Q5: How long might a simulation actually need to run to achieve true, full equilibrium? The required time is highly system-dependent. For some average structural properties, convergence can be achieved in multi-microsecond trajectories. However, full convergence of all properties, especially those involving rare events, may require timescales that are currently inaccessible—potentially up to hundreds of seconds, as suggested by some experimental comparisons [11] [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Diagnosing Unconverged Simulations

Problem: You suspect your simulation has not reached a true equilibrium state, even though it has been running for a considerable amount of time.

Solution:

- Check Multiple Metrics: Do not rely on a single metric like RMSD. Monitor a suite of properties simultaneously, including:

- Test for Stationarity: Divide the trajectory into multiple segments and check if the average and distribution of key properties are consistent across all segments. A system in equilibrium should not show a directional drift in these properties over time.

- Run Replicates: Perform multiple independent simulations starting from different initial conditions. If they all converge to the same distribution of conformations, it is a strong indicator of proper sampling and equilibrium [14].

Issue 2: Planning Simulations for Biologically Relevant Timescales

Problem: You need to study a biological process that is known to be slow, but microsecond-scale simulations are computationally prohibitive.

Solution:

- Define the Property of Interest: Clearly identify what you want to measure. If it is a high-probability structural average, a shorter simulation might be sufficient. If it involves a rare event, enhanced sampling is almost certainly required [11].

- Consider Enhanced Sampling Methods: Utilize advanced techniques designed to accelerate the sampling of rare events. These include:

- Metadynamics

- Parallel Tempering (Replica-Exchange)

- Accelerated MD

- Machine Learning-Augmented Sampling: Recent research shows that generative diffusion models (DDPM) can be trained on short MD trajectories to efficiently sample conformational space, including rare states, though they require careful validation [13].

- Validate with Long Trajectories: Whenever possible, validate the results from enhanced sampling or short simulations against a few long, unbiased simulations to ensure the conclusions are robust [12].

Quantitative Data on Convergence Timescales

The table below summarizes findings from various studies on the convergence timescales for different molecular systems and properties.

Table 1: Empirical Convergence Timescales from MD Studies

| System | Size | Simulation Length | Converged Properties | Unconverged Properties | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dialanine | 22 atoms | Not Specified (ns-us scale) | Many properties | Some specific properties remained unconverged, even in a small toy model | [11] |

| Hydrated Amorphous Xylan | Oligomers | ~1 µs | Density, Energy | Structural & dynamical heterogeneity required ~1 µs to equilibrate | [8] |

| Ara h 6 Peanut Protein | 127 residues | 2 ns, 20 ns, 200 ns | Varies | RMSD, Rg, SASA, H-bonds yielded different statistical conclusions at 2 ns vs. 200 ns | [14] |

| General Proteins | Varies | Multi-microseconds | Properties with high biological interest | Transition rates to low-probability conformations | [11] [1] |

| Protein-Ligand Recognition | 3 Independent Proteins | 176 µs cumulative | Native bound pose reproduction | Ligand binding process was retarded when using HMR with a 3.6 fs timestep | [12] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: A Robust Workflow for Equilibration Diagnosis

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for rigorously assessing whether a simulation has reached equilibrium.

Title: Workflow for Equilibration Diagnosis

Procedure:

- Calculate Multiple Metrics: From your trajectory, extract time-series data for a comprehensive set of properties. This should include both global metrics (e.g., total energy, overall RMSD, Rg) and local metrics relevant to your biological question (e.g., specific residue-residue distances, active site dihedral angles) [11] [14].

- Check Metric Stationarity: For each property, analyze the running average ( \langle Ai \rangle(t) ). A property is considered equilibrated if its running average fluctuates around a stable value with small deviations for a significant portion of the trajectory after a convergence time ( tc ) [11] [1].

- Perform Statistical Testing: For a more rigorous assessment, use statistical tests. A common method is to split the trajectory into multiple (e.g., 3-5) consecutive blocks. Perform a one-way ANOVA or a similar test to check if the means of the property of interest are statistically identical across all blocks. A lack of significant difference supports the hypothesis of equilibrium [14].

- Analyze Convergence Time: Once equilibrium is confirmed, discard the data from the initial non-equilibrated portion ( ( t < tc ) ) of the trajectory. Only the data from ( tc ) to the end should be used for production analysis.

Protocol 2: Assessing the Impact of Simulation Length

This protocol, based on a statistical study of the Ara h 6 protein, outlines how to test if your simulation length is sufficient for robust conclusions.

Title: Simulation Length Sufficiency Test

Procedure:

- Run Triplicate Simulations: For the system under investigation, run multiple independent simulation replicates (at least 3) at different simulation lengths (e.g., 2 ns, 20 ns, and 200 ns, if computationally feasible) [14].

- Extract Key Geometric Features: For each replicate, calculate the key properties used in your analysis (e.g., RMSD, Rg, SASA, number of hydrogen bonds) [14].

- Perform Two-Way ANOVA: Use a two-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to statistically analyze the results. The two factors are "simulation length" and "experimental condition" (e.g., temperature, mutation). This test will determine if the simulation length has a statistically significant effect on the measured outcomes [14].

- Interpret the Result: If the ANOVA returns a p-value < 0.05 for the "simulation length" factor, it indicates that the conclusions you draw are highly dependent on how long you ran your simulation. In this case, the shortest simulation length is likely insufficient, and you should base your conclusions on the longest, most stable trajectories [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software and Methodologies for Convergence Analysis

| Tool / Method | Category | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Engine | A highly optimized software package for performing MD simulations of biomolecules. | Often used with force fields like CHARMM36m and water models like TIP3P [14]. |

| CHARMM36m | Force Field | Defines the potential energy function and parameters for the atoms in the system. | Essential for accurate simulation of biomolecules; requires specific simulation settings [14]. |

| Hydrogen Mass Repartitioning (HMR) | Performance Algorithm | Allows for longer integration time steps (e.g., 4 fs) by increasing the mass of hydrogen atoms. | Can alter kinetics (e.g., slow ligand binding); may not provide a net performance gain for all processes [12]. |

| Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) | Analysis Metric | Measures the average distance between atoms of superimposed structures. | Not a reliable standalone indicator of equilibrium. Can be misleading and subjective [11] [2]. |

| Running Average Plot | Diagnostic Tool | A plot of the cumulative average of a property over time, used to visually identify a convergence plateau. | Core to the practical definition of equilibration for a specific property [11] [1]. |

| Statistical Tests (e.g., ANOVA) | Diagnostic Tool | Provides a quantitative, objective method to compare means of a property from different trajectory segments or simulations. | Helps overcome the subjectivity of visual inspection of plots [14] [2]. |

| Generative Diffusion Models (DDPM) | Enhanced Sampling | Machine learning models that can augment MD sampling by generating plausible conformations, including rare states. | Can provide computational savings but requires rigorous validation against physical principles [13]. |

Accurate Calculation of Diffusion Coefficients: From Einstein Relation to Advanced Protocols

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental definition of MSD and how is it calculated? The Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD) is a statistical measure quantifying the average squared distance particles move from their initial positions over time. It is the most common measure of the spatial extent of random motion [15]. The standard Einstein formula for MSD is expressed as: [MSD(\tau) = \langle | \mathbf{r}(\tau) - \mathbf{r}(0) |^2 \rangle] where (\mathbf{r}(t)) represents the position vector at time (t), (\tau) is the lag time, and (\langle \cdot \rangle) denotes the ensemble average over all particles [16] [15]. In practical computation for a single trajectory, this is often calculated as a time average: [\delta^2(n) = \frac{1}{N-n}\sum{i=1}^{N-n} (\mathbf{r}{i+n} - \mathbf{r}_i)^2] where (N) is the total number of frames and (n) is the lag time in units of the timestep [15].

FAQ 2: What is the Einstein relation, and how does it connect MSD to diffusivity? The Einstein relation provides the crucial link between the microscopic motion captured by MSD and the macroscopic self-diffusion coefficient (D). For normal diffusion in an (n)-dimensional space, the relation is: [Dn = \frac{1}{2n} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} MSD(t)] where (n) is the dimensionality of the MSD [16] [17]. This means that in the regime of normal diffusion, the MSD grows linearly with time, and the slope of this linear portion is equal to (2nD). For a 3D system, this simplifies to (D = \frac{slope}{6}) [16].

FAQ 3: Why is my MSD plot not linear, and what does this imply about particle dynamics? Deviations from linearity in MSD plots provide critical insights into particle dynamics [17]:

- A linear MSD indicates normal, Fickian diffusion.

- A sub-linear MSD (slope <1 on a log-log plot) suggests anomalous sub-diffusion, often caused by crowding, binding, or viscoelastic environments [1].

- A super-linear MSD (slope >1) indicates super-diffusion, which can be driven by active transport processes. The slope of the MSD vs. time graph on a log-log plot can help identify these regimes and the underlying diffusion mechanism [17].

FAQ 4: My diffusion coefficient values vary between simulation replicates. Is this a convergence issue? Yes, this is a classic symptom of insufficient sampling. In molecular dynamics, a system is considered equilibrated only when the fluctuations of a property's running average remain small for a significant portion of the trajectory after a convergence time (t_c) [1]. If your trajectory is shorter than the slowest relevant relaxation time in the system, measured properties like the MSD slope will not be converged. For large or complex biomolecules, convergence of dynamical properties may require simulation timescales far longer than typically used [1].

Troubleshooting Common MSD Analysis Problems

Problem 1: Non-Linear MSD in a Simple System

- Symptoms: The MSD curve is not linear, even for a supposedly simple fluid or a random walk simulation.

- Solutions:

- Check Particle Unwrapping: Ensure you are using unwrapped coordinates. If atoms are wrapped back into the primary simulation box upon crossing periodic boundaries, the calculated displacements and MSD will be incorrect [16]. Use tools like

gmx trjconv -pbc nojumpin GROMACS. - Verify Lag Time Range: The linear slope used for diffusion calculation should be taken from the "middle" of the MSD plot. Exclude very short lag times (ballistic regime) and very long lag times (poor statistics due to few averages) [16]. Use a log-log plot to identify the linear region, which should have a slope of 1 [16].

- Confirm System Equilibrium: Plot the potential energy and RMSD of your trajectory. If these properties have not reached a stable plateau, the system is not equilibrated, and MSD analysis should not be performed on the non-equilibrium data [1].

- Check Particle Unwrapping: Ensure you are using unwrapped coordinates. If atoms are wrapped back into the primary simulation box upon crossing periodic boundaries, the calculated displacements and MSD will be incorrect [16]. Use tools like

Problem 2: High Noise and Poor Statistics in MSD

- Symptoms: The MSD curve is very noisy, making it difficult to fit a reliable slope.

- Solutions:

- Increase Sampling: Run longer simulations or combine multiple independent replicates. When combining, average the MSDs from each replicate (

MSD1.results.msds_by_particle,MSD2.results.msds_by_particle), not the trajectories themselves, to avoid artificial inflation from jumps between trajectory endpoints [16]. - Use FFT-Based Algorithms: The simple windowed MSD algorithm scales with (N^2), which is computationally intensive for long trajectories. Using an FFT-based algorithm (e.g., by setting

fft=TrueinMDAnalysis.analysis.msd.EinsteinMSD) reduces this to (N log(N)) scaling, allowing for better statistics from longer trajectories [16]. - Increase Particle Count: If possible, calculate the MSD over a larger ensemble of equivalent particles to improve the ensemble average [16] [15].

- Increase Sampling: Run longer simulations or combine multiple independent replicates. When combining, average the MSDs from each replicate (

Problem 3: Inconsistent Diffusion Coefficients from Different Trajectory Lengths

- Symptoms: The calculated diffusion coefficient (D) changes significantly when calculated from different segments or lengths of the same trajectory.

- Solutions:

- Run Convergence Tests: This is a clear sign of non-convergence. Calculate the running (time-dependent) diffusion coefficient (D(t)). (D) is only reliable once (D(t)) has reached a stable plateau [1].

- Simulate for Longer Timescales: Some properties, especially those involving transitions to low-probability conformations, may require multi-microsecond or even longer simulations to converge, even for relatively small proteins [1].

- Focus on Partial Equilibrium: Understand that your system may be in "partial equilibrium," where some average properties (like a domain distance) have converged, while others (like transition rates or diffusivity) have not. Frame your conclusions accordingly [1].

Quantitative Data and Experimental Protocols

Table 1: Key Quantitative Relationships for MSD and Diffusion

| Concept | Mathematical Formula | Parameters and Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| MSD Definition | ( MSD(\tau) = \langle | \mathbf{r}(\tau) - \mathbf{r}(0) |^2 \rangle ) [15] | (\mathbf{r}): position; (\tau): lag time; (\langle \cdot \rangle): ensemble average. |

| Einstein Relation | ( Dd = \frac{1}{2d} \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{d}{dt} MSD(r_d) ) [16] | (D_d): diffusivity in (d) dimensions; (d): dimensionality (1, 2, or 3). |

| Theoretical MSD (nD) | ( MSD = 2nDt ) [15] | (n): dimensions; (D): diffusion coefficient; (t): time. Predicts linear growth for normal diffusion. |

| Contrast Ratio | (L1 + 0.05) / (L2 + 0.05) [18] [19] |

Formula for calculating luminance contrast. A ratio of at least 4.5:1 for large text or 7:1 for standard text is required for enhanced visibility [18] [19]. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common MSD Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Linear MSD | Non-equilibrium system; ballistic regime at short times; poor averaging at long times; wrapped coordinates [16] [1]. | Use unwrapped coordinates; select linear "middle" segment for fitting; ensure system equilibration before production run [16]. |

| Noisy MSD Curve | Insufficient trajectory length; poor sampling; small number of particles [16] [1]. | Run longer simulations; combine multiple replicates; use FFT-based algorithm; increase ensemble size [16]. |

| Non-Converged D | Trajectory shorter than system's slowest relaxation timescales [1]. | Perform running average tests; simulate for multi-microsecond+ timescales; report D only from converged region [1]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Calculating MSD and Self-Diffusivity

This protocol uses MDAnalysis [16] as a reference framework.

Step 1: System Preparation and Trajectory Unwrapping

- Critical Preprocessing: Before analysis, process your trajectory to ensure all particle coordinates are unwrapped. This means that when a particle crosses a periodic boundary, its coordinates should continue to increase (or decrease) linearly rather than being wrapped back into the primary simulation box. In GROMACS, this can be achieved with a command like

gmx trjconv -pbc nojump[16]. Using wrapped coordinates is a common error that invalidates MSD results.

Step 2: MSD Computation with MDAnalysis

- Load Modules and Data:

- Initialize and Run Analysis:

select='all': Can be changed to a specific atom selection.msd_type='xyz': Calculates the 3D MSD. Other options include 'x', 'y', 'z', or planar combinations like 'xy'.fft=True: Uses the faster FFT-based algorithm. Requires thetidynamicspackage [16].

Step 3: Visualization and Identification of the Linear Regime

- Plot MSD vs. Lag Time:

- Use a Log-Log Plot to identify the linear segment, which will appear with a slope of 1 [16].

Step 4: Fitting the MSD and Calculating Self-Diffusivity

- Linear Fit: Select a range from the linear part of the MSD plot (e.g., between

start_timeandend_time). - Calculate D: The resulting (D) has units of Ų/ps. To convert to more standard cm²/s, note that 1 Ų/ps = 10⁻⁴ cm²/s.

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

MSD Analysis and Convergence Workflow

The following diagram outlines the core workflow for a robust MSD analysis, integrating checks for convergence as emphasized in recent literature [1].

MSD Analysis and Convergence Workflow: This chart details the process from trajectory preparation to reporting a converged diffusion coefficient, highlighting critical checks for linearity and convergence.

The Einstein Relation Conceptual Diagram

This diagram illustrates the fundamental connection between particle motion, the MSD plot, and the diffusion coefficient via the Einstein relation.

Einstein Relation Conceptual Link: This visualization shows how the particle trajectory is processed into an MSD plot, from which the diffusion coefficient is derived using the Einstein relation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MD and MSD Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Unwrapped Trajectory | Provides the true path of particles across periodic boundaries, which is critical for a correct MSD calculation [16]. | Use simulation package utilities (e.g., gmx trjconv -pbc nojump in GROMACS) to convert a wrapped trajectory to an unwrapped one before analysis. |

| MSD Analysis Code | Implements the Einstein relation to compute the MSD from particle coordinates. | Libraries like MDAnalysis.analysis.msd [16] or tidynamics provide efficient, validated implementations, including FFT-based algorithms. |

| Linear Fitting Routine | Extracts the slope from the linear portion of the MSD vs. time plot to compute the diffusion coefficient (D) [16]. | Use robust linear regression (e.g., scipy.stats.linregress) and carefully select the linear time regime for fitting. |

| Long-Timescale MD Engine | Generates the trajectory data necessary to study slow diffusion processes and achieve convergence [1]. | Specialized hardware (ANTON) or software (GROMACS, NAMD, OpenMM) enable microsecond-to-millisecond simulations for adequate sampling. |

| Convergence Metric | Determines whether a simulated property, like the diffusion coefficient, has stabilized and is reliable [1]. | Scripts to calculate the running average (D(t)) over time. The property is considered converged when its running average plateaus with small fluctuations. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My calculated diffusion coefficient seems unrealistically high. Could my simulation be measuring ballistic motion instead of true diffusion?

A: Yes, this is a common error. Molecular dynamics simulations exhibit different dynamical regimes at different timescales. At short timescales, particle motion is ballistic (where mean squared displacement, or MSD, is proportional to t²), before transitioning to the diffusive regime (where MSD is proportional to t) at longer timescales. Calculating the diffusion coefficient from the ballistic regime will yield incorrectly high values [20].

- How to check: Always plot the MSD as a function of time on a log-log scale. The diffusion coefficient, D, should only be calculated from the linear portion of the MSD curve in the diffusive regime. The plot below illustrates the distinct regimes and the correct region for calculating D.

- Solution: Ensure your production simulation is long enough for the molecule of interest to reach the diffusive regime. This can require simulations spanning hundreds of nanoseconds to microseconds for larger biomolecules [1] [20].

Q2: How can I quantify the statistical uncertainty in my calculated diffusion coefficient?

A: The statistical uncertainty in a diffusion coefficient obtained from MD simulation is a significant source of potential error. It arises from finite sampling and can be addressed with the following methodologies [21]:

- Multiple Independent Trajectories: The most robust approach is to run an ensemble of multiple independent simulations (e.g., 40 trajectories as in one pesticide study [22]) starting from different initial conditions. The diffusion coefficient calculated from each trajectory can be averaged, and the standard error of the mean provides a direct measure of statistical uncertainty.

- Block Averaging: For a single long trajectory, you can use block averaging. The trajectory is split into multiple consecutive blocks, and D is calculated for each block. The standard deviation across these blocks gives an estimate of the error [22] [20].

- Analytical Expressions: Recent research has provided closed-form expressions for estimating the relative uncertainty in D. These methods often involve analyzing the MSD and the number of particles that have undergone a jump event [21].

Q3: My simulation system is small due to computational limits. How does this affect my calculated diffusion coefficient?

A: Using a small simulation box introduces finite-size effects, which can artificially reduce the calculated diffusion coefficient. In systems with Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC), a particle interacts with its own periodic images, which hinders its long-range hydrodynamic motion [20].

- How to check: If your computed D is lower than experimental values and your box is small (e.g., less than 5-10 nm in dimension), finite-size effects are likely a contributing factor.

- Solution:

- Use a larger simulation box where computationally feasible.

- Apply a correction. The Yeh-Hummer correction is a standard method for this: ( D{\text{corrected}} = D{PBC} + \frac{2.84 k{B}T}{6 \pi \eta L} ) where ( D{PBC} ) is the calculated diffusion coefficient, ( k_{B} ) is Boltzmann's constant, ( T ) is temperature, ( \eta ) is the shear viscosity of the solvent, and ( L ) is the box length [20].

Q4: How long does a simulation need to be to achieve a converged diffusion coefficient?

A: Simulation time required for convergence is system-dependent. "Convergence" means that the average value of a property (like MSD) stabilizes and its fluctuations become small over a significant portion of the trajectory [1].

- For small molecules like pesticides in water, studies using 40 trajectories of 40-50 ns each have shown good agreement with experiment [22].

- For biomolecules like proteins and DNA, convergence of global structural and dynamic properties often requires multi-microsecond simulations. One study on a DNA duplex found convergence on the 1–5 μs timescale [23]. However, convergence for specific properties, like transition rates to low-probability conformations, may require even longer times [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Errors and Solutions

| Error Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unphysically high D | Calculation performed in ballistic motion regime. | Plot log(MSD) vs. log(time). Look for slope of ~1 for diffusion. | Extend simulation time until diffusive regime is reached [20]. |

| Large variation in D between runs | High statistical uncertainty due to insufficient sampling. | Run multiple independent trajectories; calculate standard error. | Use ensemble simulations (≥20 trajectories) [22] [21]. |

| Low D compared to experiment | Finite-size effects from a small simulation box. | Check box size; apply Yeh-Hummer correction. | Increase box size or apply finite-size correction [20]. |

| Non-linear MSD plot | System not in equilibrium or simulation too short. | Check energy and RMSD plots for equilibration. | Ensure proper system equilibration before production run [1] [4]. |

| Erratic MSD curve | Poor statistics or trajectory frame output too infrequent. | Check if MSD averages smooth out with more data. | Increase simulation length and save trajectory frames more frequently [20]. |

Experimental Protocols for Reliable Diffusion Coefficients

Protocol 1: Standard MSD-Based Calculation

This is the most common method for calculating the translational diffusion coefficient in homogeneous, isotropic systems [20].

- System Preparation: Build and equilibrate your system (solute in solvent) using standard energy minimization and NPT equilibration protocols to stabilize density [4].

- Production Simulation: Run a production simulation in the NVT ensemble. The length must be sufficient to reach the diffusive regime for your specific molecule [22].

- Trajectory Processing: Ensure particle positions are "unwrapped" to account for crossings of periodic boundaries, which is crucial for a correct MSD calculation [22].

- MSD Calculation: Calculate the mean squared displacement using the Einstein relation: ( \text{MSD}(t) = \langle | \mathbf{r}(t') - \mathbf{r}(t' + t) |^2 \rangle ) where the angle brackets denote an average over all molecules of interest and multiple time origins, ( t' )citation:7].

- Diffusion Coefficient Extraction: Fit the linear portion of the MSD(t) vs. time (t) curve to the equation: ( \text{MSD}(t) = 2n D t + C ) where ( n ) is the dimensionality (e.g., 6 for 3D diffusion), ( D ) is the diffusion coefficient, and ( C ) is a constant. The slope is equal to ( 2nD )citation:7].

Protocol 2: Ensemble Approach for Error Estimation

This protocol is recommended for obtaining reliable statistics and quantifying uncertainty [22].

- Initial Structure: Start from a single, well-equilibrated system.

- Generate Ensembles: Create an ensemble of 20-40 independent simulations by assigning different random seeds for initial velocities [22].

- Parallel Execution: Run all simulations independently for the same duration.

- Individual Analysis: Calculate the diffusion coefficient ( D_i ) for each trajectory ( i ) using the MSD method (Protocol 1).

- Statistical Analysis: Compute the final diffusion coefficient as the mean of all ( Di ) values. The standard error of the mean (SEM) provides the statistical uncertainty: ( D = \frac{1}{N}\sum{i=1}^{N} Di \quad , \quad \delta D = \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{N}} ) where ( \sigma ) is the standard deviation of the ( Di ) values and ( N ) is the number of trajectories [22].

Workflow Visualization

MSD Analysis Workflow for Diffusion Coefficient Calculation

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Calculation | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics Engine (e.g., GROMACS) | Software to perform the numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion and generate the simulation trajectory. | Ensure the version supports necessary force fields and analysis tools like gmx msd [20]. |

| Force Field (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS) | A set of empirical parameters describing interatomic interactions; critical for realistic dynamics. | Select a force field validated for your specific class of molecules (e.g., proteins, DNA, small organics) [4]. |

| Solvent Model (e.g., TIP3P, SPC/E) | Represents the water environment, which strongly influences solute diffusion. | The choice affects simulated viscosity and diffusion; TIP3P water may overestimate diffusion coefficients [22]. |

MSD Analysis Tool (e.g., gmx msd, custom scripts) |

Computes the Mean Squared Displacement from the simulation trajectory. | Must correctly handle unwrapping of coordinates and averaging over molecules and time origins [20]. |

| Finite-Size Correction | Analytical formula to correct for artificial hydrodynamic hindrance in small periodic boxes. | The Yeh-Hummer correction is standard practice for obtaining bulk-like values from PBC simulations [20]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary methods for calculating diffusion coefficients in molecular dynamics simulations?

The two primary methods for calculating diffusion coefficients are the Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) approach via the Einstein relation and the Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) method [24] [25].

- MSD (Einstein Relation): This method calculates the diffusion coefficient (D) from the slope of the mean squared displacement of particles over time, using the formula ( D = \frac{\text{slope(MSD)}}{6} ) for 3D systems [24] [25]. The MSD is defined as ( MSD(r{d}) = \bigg{\langle} \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} |r{d} - r{d}(t0)|^2 \bigg{\rangle}{t_{0}} ) [25].

- VACF (Green-Kubo): This method computes the diffusion coefficient by integrating the velocity autocorrelation function: ( D = \frac{1}{3} \int{t=0}^{t=t{max}} \langle \textbf{v}(0) \cdot \textbf{v}(t) \rangle \rm{d}t ) [24].

The MSD method is generally recommended for its relative simplicity, but it requires a linear regime in the MSD plot for accurate results [24] [25].

Q2: Why might my MSD plot not show a linear regime, and how can I fix this?

A non-linear MSD plot often indicates that the simulation has not run for a sufficient duration to observe normal diffusion [24] [25]. The linear segment represents the regime where particles exhibit Fickian (random walk) diffusion, and it is crucial for accurately determining the self-diffusivity [25].

- Solution: Extend your production simulation time. In the example of lithium ions in a sulfide cathode, 100,000 production steps were used, but longer trajectories may be necessary for better statistics [24]. Visually inspect the MSD plot or use a log-log plot to identify a segment with a slope of 1, which indicates the linear regime [25].

Q3: What are finite-size effects, and how do they impact diffusion coefficient calculations?

Finite-size effects refer to artifacts in simulation results caused by using a simulation box that is too small [24]. These effects can lead to inaccuracies in the calculated diffusion coefficients because the confined space artificially influences particle motion [26] [24].

- Solution: It is recommended to perform simulations for progressively larger supercells and extrapolate the calculated diffusion coefficients to the "infinite supercell" limit [24]. Recent research on methane/n-hexane mixtures also highlights the need for careful force field selection alongside finite-size corrections [26].

Q4: My simulation consumes too much memory during MSD analysis. What can I do?

Computation of MSDs can be highly memory intensive, especially with long trajectories and many particles [25].

- Solution: The

MDAnalysis.analysis.msdmodule suggests using thestart,stop, andstepkeywords to control which frames are incorporated into the analysis, reducing memory load [25]. Additionally, using the FFT-based algorithm (withfft=True), which has ( N log(N) ) scaling instead of ( N^2 ), can significantly improve performance, though it requires thetidynamicspackage [25].

Q5: How can I obtain a diffusion coefficient at physiological temperatures when high temperatures are required for sampling?

Calculating diffusion coefficients at low temperatures (e.g., 300 K) can be computationally prohibitive due to slow dynamics [24].

- Solution: Use the Arrhenius equation to extrapolate from higher temperatures. Calculate diffusion coefficients (D) at several elevated temperatures (e.g., 600 K, 800 K, 1200 K, 1600 K) [24]. Then, plot ( \ln(D(T)) ) against ( 1/T ). The slope of the linear fit gives ( -Ea/kB ), allowing you to calculate the activation energy (( Ea )) and pre-exponential factor (( D0 )), which can be used to extrapolate D to lower temperatures [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Non-Converging Diffusion Coefficient in Long MD Simulations

Problem: The calculated diffusion coefficient does not converge even after a long simulation time. This is a common convergence problem in diffusion research [24] [25].

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Check the MSD Plot: The slope of the MSD vs. time plot should be linear in the diffusive regime. If the MSD line is not straight, the simulation may be too short or may still be in the ballistic regime [24].

- Verify Trajectory Unwrapping: A critical pre-processing step is to use unwrapped coordinates [25]. If atoms are wrapped back into the primary simulation cell when they cross periodic boundaries, it will artificially lower the MSD.

- Action: Use utilities from your simulation package (e.g.,

gmx trjconv -pbc nojumpin GROMACS) to output unwrapped trajectories before MSD analysis [25].

- Action: Use utilities from your simulation package (e.g.,

- Improve Sampling with Advanced Methods: Consider using enhanced sampling techniques or alternative calculation methods.

- Action: Excess Entropy Scaling (EES) has emerged as a promising complementary approach that can reduce sampling error and computational expense compared to traditional methods [26].

Issue 2: High Uncertainty in Calculated Diffusion Coefficients

Problem: The calculated diffusivity has a large error margin, making results unreliable.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Insufficient Averaging: The average in the MSD calculation may be poor, especially at long lag-times [25].

- Combine Multiple Replicates: Running a single long trajectory might not provide adequate statistical sampling.

- Action: Run multiple independent simulation replicates and combine the MSDs by averaging them. Important: Do not simply concatenate trajectory files, as the jump between the end of one trajectory and the start of the next will artificially inflate the MSD. Instead, calculate MSDs for each replicate separately and then average the results [25].

- Select the Correct Linear Regime: Using an inappropriate segment of the MSD plot for the linear fit is a major source of error [25].

- Action: Generate a log-log plot of the MSD. The linear (diffusive) regime will have a slope of 1. Use this to select the start and end times (

start_timeandend_time) for your linear regression [25].

- Action: Generate a log-log plot of the MSD. The linear (diffusive) regime will have a slope of 1. Use this to select the start and end times (

Issue 3: Force Field Selection and System Setup Errors

Problem: The simulation model itself is flawed, leading to inaccurate physical results.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Force Field Inadequacy: The chosen force field may not accurately represent the interactions in your specific system [26].

- Action: Systematically test different force fields against available experimental data. Recent studies on binary fluid mixtures and methane/n-hexane systems underscore that force field parameterization is as important as finite-size corrections [26].

- Inadequate Equilibration: The system may not be fully equilibrated before the production run.

- Action: Follow a rigorous equilibration protocol. For amorphous systems (e.g., a lithiated sulfur cathode), this can involve simulated annealing: heating the system to a high temperature (e.g., 1600 K) and then rapidly cooling it to the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) to generate a realistic amorphous structure before the production MD [24].

The table below summarizes key methods and considerations for calculating diffusion coefficients, synthesized from the search results.

Table 1: Methods for Calculating Diffusion Coefficients from MD Simulations

| Method | Principle Formula | Key Advantages | Key Challenges & Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Squared Displacement (MSD) [24] [25] | ( D = \frac{1}{2d} \cdot \frac{\text{slope(MSD)}}{\text{time}} )For 3D: ( D = \frac{\text{slope(MSD)}}{6} ) [24] | Intuitively connected to particle trajectory; widely used and implemented [25]. | Requires identification of a linear regime; sensitive to finite-size effects; long simulation times needed for convergence [24] [25]. |

| Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) [24] | ( D = \frac{1}{3} \int{0}^{t{max}} \langle \textbf{v}(0) \cdot \textbf{v}(t) \rangle \rm{d}t ) [24] | Can provide insights into dynamical processes; may converge faster than MSD in some cases [24]. | Requires higher sampling frequency (smaller time between saved frames) to accurately capture velocities [24]. |

| Excess Entropy Scaling (EES) [26] | Relates diffusion coefficient (D) to the excess entropy of the system, a thermodynamic property [26]. | Promises reduced computational expense and sampling error compared to MSD and VACF methods [26]. | Less universally implemented; requires accurate calculation of entropy [26]. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Calculating Diffusion Coefficient via MSD

This protocol is adapted from studies on lithium ions in a sulfide cathode and random walk systems [24] [25].

System Preparation and Equilibration:

- For crystalline materials: Import a CIF file and equilibrate the geometry with a geometry optimization including lattice relaxation [24].

- For amorphous materials: Use simulated annealing. Heat the system over 20,000 steps from 300 K to 1600 K, hold at high temperature, then cool rapidly to the target temperature over 5,000 steps (e.g., using a Berendsen thermostat with a 100 fs damping constant) [24]. Follow this with a further geometry optimization.

- Ensure the final equilibrated structure is used for the production run.

Production Molecular Dynamics:

- Set up an MD simulation at the desired temperature (e.g., using a Berendsen thermostat) [24].

- Use a sufficient number of steps (e.g., 100,000 production steps after 10,000 equilibration steps) [24].

- Set the

Sample frequencyto save atomic coordinates every few steps (e.g., every 5 steps). The time between saved frames issample_frequency * time_step[24]. - Critical: Configure your simulation or post-processing to output unwrapped coordinates [25].

MSD Calculation and Analysis:

- Load the production trajectory using a tool like

MDAnalysis[25]. - Compute the MSD using the

EinsteinMSDclass. For better performance, setfft=True(requirestidynamics) [25]. - Plot the MSD against lag-time. Also, create a log-log plot to identify the linear regime (which will have a slope of 1) [25].

- Select a linear segment of the MSD plot, avoiding the short-time ballistic regime and the long-time noisy tail.

- Perform a linear regression (e.g., using

scipy.stats.linregress) on the selected segment [25]. - Calculate the diffusion coefficient using ( D = \frac{\text{slope}}{2d} ), where ( d ) is the dimensionality of the MSD (e.g., 3 for 'xyz') [25].

- Load the production trajectory using a tool like

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software Tools and Modules for MD Diffusion Analysis

| Tool / Module | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ReaxFF Force Field [24] | A reactive force field capable of modeling bond formation and breaking. | Used in MD simulations of complex materials, such as studying lithium ion diffusion in lithiated sulfur cathode materials [24]. |

| MDAnalysis (Python module) [25] | A versatile toolkit for analyzing MD trajectories. Includes the EinsteinMSD class for robust MSD calculation with both windowed and FFT algorithms. |

Can be used to analyze trajectories from various simulation packages. Essential for post-processing trajectories to compute MSDs and self-diffusivities [25]. |

| tidynamics (Python module) [25] | A library for computing correlation functions and MSDs with efficient FFT algorithms. | A required dependency for using the fft=True option in MDAnalysis.analysis.msd, which speeds up MSD calculation significantly [25]. |

| SCM/AMS Software [24] | A commercial modeling suite that includes the ReaxFF engine and tools for building structures, simulated annealing, and calculating diffusion coefficients. | Provides an integrated environment for running the entire workflow from system building (e.g., inserting Li atoms into a sulfur matrix) to MD simulation and analysis [24]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How can I determine if my molecular dynamics (MD) simulation of a solvated protein has truly reached equilibrium?

A primary challenge in long MD simulations is confirming that the system has reached a converged, equilibrium state. Relying solely on the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the protein is a common but unreliable method [2]. Studies show that different scientists identify different "convergence points" on the same RMSD plot, indicating high subjectivity [2]. A more robust approach is to monitor the convergence of the linear partial density of all system components, particularly for interfaces, using tools like DynDen [27]. Furthermore, true equilibrium requires that multiple properties (e.g., energy, solvent dynamics) reach a stable plateau, not just a single metric [1].

Q2: Why does the diffusion of water molecules near a protein surface appear slower than in the bulk? This is an expected and well-observed phenomenon. Molecular dynamics simulations show that the overall translational diffusion rate of water at the biomolecular interface is lower than in the bulk solution [28] [29]. This retardation effect is anisotropic: the diffusion rate is higher parallel to the solute surface and lower in the direction normal to the surface, and this effect can persist up to 15 Å away from the solute [28]. Characteristic depressions in the diffusion coefficient profile also correlate with solvation shells [28].

Q3: My simulation results for solvent dynamics are inconsistent. What could be a fundamental issue with my setup? A common but often overlooked issue is that the simulation may not have reached thermodynamic equilibrium, even if it has run for a long time. The initial structure from crystallography (e.g., from the Protein Data Bank) is not in a physiological equilibrium state [1]. If the subsequent "equilibration" phase is too short, the system's properties, including solvent dynamics, will not be converged. It is essential to check for convergence of multiple structural and dynamical properties over multi-microsecond trajectories before trusting the results [1].

Q4: Are the convergence problems different for simulations featuring surfaces or interfaces?

Yes. The root mean square deviation (RMSD) is particularly unsuitable for systems with surfaces and interfaces [27]. For these systems, the DynDen tool provides a more effective convergence criterion by tracking the linear partial density of each component in the simulation [27]. This method can also help identify slow dynamical processes that conventional analysis might miss [27].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-convergent solvent diffusion profiles | Simulation too short; system not in equilibrium [1] | Extend simulation time; use DynDen to monitor density convergence of all components [27]. |

| Unrealistically high water mobility near solute | Inadequate equilibration of the solvation shell [28] | Ensure the simulation passes the "plateau" check for energy and other key metrics before production run [1]. |

| Inconsistent diffusion coefficients for ions | Sampling from a non-equilibrium trajectory [1] | Verify convergence of ion behavior specifically; calculate diffusion coefficients as a function of distance from the solute only after equilibrium is reached [28]. |

| Difficulty identifying equilibrium point | Over-reliance on intuitive RMSD inspection [2] | Employ a multi-faceted analysis: check time-averaged means of key properties and their fluctuations, don't depend on RMSD alone [1] [2]. |

Quantitative Data on Solvent Diffusion

Table 1: Diffusion Coefficients of Solvent Species Near Biomolecular Surfaces Data derived from MD simulations of myoglobin and a DNA decamer. "D_parallel" and "D_perp" refer to diffusion coefficients in directions parallel and normal to the solute surface, respectively. Bulk diffusion is the reference value. [28] [29]

| Solvent Species | Location Relative to Solute | Relative Diffusion Coefficient (vs. Bulk) | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water | Bulk Solution | 1.00 | Reference value. |

| Water | Interface (Overall) | Lower than bulk | Magnitude of change is similar for protein and DNA [28]. |

| Water | Interface (D_parallel) | Higher than average interface value | Anisotropic diffusion is observed [28]. |

| Water | Interface (D_perp) | Lower than average interface value | Anisotropic diffusion is observed [28]. |

| Water | First Solvation Shell | Lower than bulk (characteristic depression) | Correlates with peaks in radial distribution function [28]. |

| Sodium Ion (Na⁺) | Varies with distance | Lower near solute, increasing to bulk | Similar radial profile features as water [28]. |

| Chlorine Ion (Cl⁻) | Varies with distance | Lower near solute, increasing to bulk | Similar radial profile features as water [28]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Assessing Convergence in MD Simulations of Interfaces

Purpose: To reliably determine if an MD simulation of a system with an interface (e.g., protein-solvent) has reached equilibrium. Background: Standard metrics like RMSD are insufficient for interfacial systems [27] [2].

- System Preparation: Build your simulation system with the biomolecule solvated in a water box, adding necessary ions.

- Equilibration: Perform standard energy minimization, heating, and pressurization steps.

- Production Simulation: Run a long, unrestrained MD simulation.

- Data Extraction: From the trajectory, calculate the linear density profile for each component (e.g., protein atoms, water, ions) along the axis perpendicular to the interface.